ロシアフォルマリズム

Russian

formalism

ロシアフォルマリズム

Russian

formalism

ロシア形式主義(ロシア・フォルマリズム)は、 1910年代から1930年代にかけてのロシアにおける文芸批評の学派である。ヴィクトール・シュクロフスキー、ユーリ・ティニアノフ、ウラジーミル・プ ロップ、ボリス・アイシェンバウム、ロマン・ヤコブソン、ボリス・トマシエフス キー、グリゴリー・グーコフスキーなど、ロシアやソ連で大きな影響を与えた 学者たちが、詩的言語や文学の特殊性や自律性を確立し、1914年から1930年代に文学評論に大きな変革を起こした。ロシアフォルマリズムは、ミハイル・バフ チンやジュリ・ロトマンなどの思想家や、構造主義全体に大きな影響を与えた。また、構造主義、ポスト構造主義の時代に発展した現代文芸批評にも影 響を与え た。スターリン政権下では、エリート主義的な芸術を指す蔑称となった[1]。

| Russian

formalism Russian formalism was a school of literary criticism in Russia from the 1910s to the 1930s. It includes the work of a number of highly influential Russian and Soviet scholars such as Viktor Shklovsky, Yuri Tynianov, Vladimir Propp, Boris Eichenbaum, Roman Jakobson, Boris Tomashevsky, Grigory Gukovsky who revolutionised literary criticism between 1914 and the 1930s by establishing the specificity and autonomy of poetic language and literature. Russian formalism exerted a major influence on thinkers like Mikhail Bakhtin and Juri Lotman, and on structuralism as a whole. The movement's members had a relevant influence on modern literary criticism, as it developed in the structuralist and post-structuralist periods. Under Stalin it became a pejorative term for elitist art.[1] |

ロシア形式主義(ロシア・フォルマリズム) ロシア形式主義(ロシア・フォルマリズム)は、1910年代から1930年代にかけてのロシアにおける文芸批評の学派である。ヴィクトール・シュクロフス キー、ユーリ・ティニアノフ、ウラジーミル・プロップ、ボリス・アイシェンバウム、ロマン・ヤコブソン、ボリス・トマシエフスキー、グリゴリー・グーコフ スキーなど、ロシアやソ連で大きな影響を与えた学者たちが、詩的言語や文学の特殊性 や自律性を確立し、1914年から1930年代に文学評論に大きな変 革 を起こした。ロシアフォルマリズムは、ミハイル・バフチンやジュリ・ロトマンなどの思想家や、構造主義全体に大きな影響を与えた。また、構造主義、ポスト 構造主 義の時代に発展した現代文芸批評にも影響を与えた。スターリン政権下では、エリート主義的な芸術を指す蔑称となった[1]。 |

| Russian

formalism was a diverse movement, producing no unified doctrine, and no

consensus amongst its proponents on a central aim to their endeavours.

In fact, "Russian Formalism" describes two distinct movements: the

OPOJAZ (Obshchestvo Izucheniia Poeticheskogo Yazyka, Society for the

Study of Poetic Language) in St. Petersburg and the Moscow Linguistic

Circle.[2] Therefore, it is more precise to refer to the "Russian

Formalists", rather than to use the more encompassing and abstract term

of "Formalism". The term "formalism" was first used by the adversaries of the movement, and as such it conveys a meaning explicitly rejected by the Formalists themselves. In the words of one of the foremost Formalists, Boris Eichenbaum: "It is difficult to recall who coined this name, but it was not a very felicitous coinage. It might have been convenient as a simplified battle cry but it fails, as an objective term, to delimit the activities of the 'Society for the Study of Poetic Language'."[3] Russian Formalism is the name now given to a mode of criticism which emerged from two different groups, The Moscow Linguistic Circle (1915) and the Opojaz group (1916). Although Russian Formalism is often linked to American New Criticism because of their similar emphasis on close reading, the Russian Formalists regarded themselves as a developers of a science of criticism and are more interested in a discovery of systematic method for the analysis of poetic text. |

ロ

シア形式主義は多様な運動であり、統一された教義はなく、その努力の中心的な目的について支持者の間でコンセンサスが得られていたわけでもない。実際、

「ロシア形式主義」は、サンクトペテルブルクのOPOJAZ(Obshchestvo Izucheniia Poeticheskogo

Yazyka、詩的言語研究協会)とモスクワ言語学サークルという2つの異なる運動を指す[2]。したがって、「形式主義」という包括的かつ抽象的な用語

を使うよりも、むしろ「ロシア形式主義者」と呼んだ方が正確であろう。 「形式主義=フォルマリズム」という用語は、この運動の敵対勢力によっ て初めて使われたものであり、形式主義者自身が明確に否定している意味を含んでいる。形式主義者の第一 人者であるボリス・アイシェンバウムの言葉を借りれば、「誰がこの名前を作ったか思い出すのは難しいが、それはあまり愉快な造語ではなかった。ロシア形式 主義は、モスクワ言語学サークル(1915年)とオポジャズ(1916年)という2つの異なるグループから生まれた批評の様式に与えられる名称である。ロ シア形式主義は、精読を重視する点でアメリカの新批評と類似しているが、ロシア形式主義者は自らを批評の科学の開発者とみなし、詩文分析のための体系的方 法の発見により関心を寄せている。 |

| Russian

formalism is distinctive for its emphasis on the functional role of

literary devices and its original conception of literary history.

Russian Formalists advocated a "scientific" method for studying poetic

language, to the exclusion of traditional psychological and

cultural-historical approaches. As Erlich points out, "It was intent

upon delimiting literary scholarship from contiguous disciplines such

as psychology, sociology, intellectual history, and the list

theoreticians focused on the 'distinguishing features' of literature,

on the artistic devices peculiar to imaginative writing" (The New

Princeton Encyclopedia 1101). Two general principles underlie the Formalist study of literature: first, literature itself, or rather, those of its features that distinguish it from other human activities, must constitute the object of inquiry of literary theory; second, "literary facts" have to be prioritized over the metaphysical commitments of literary criticism, whether philosophical, aesthetic or psychological (Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 16). To achieve these objectives several models were developed. The formalists agreed on the autonomous nature of poetic language and its specificity as an object of study for literary criticism. Their main endeavor consisted in defining a set of properties specific to poetic language, be it poetry or prose, recognizable by their "artfulness" and consequently analyzing them as such. |

ロ

シア形式主義は、文学装置の機能的役割を強調し、文学史に対する独自の概念を持つ点

で特徴的である。ロシア形式主義は、詩的言語を研究するための「科学

的」な方法を提唱し、従来の心理学的、文化史的なアプローチを排除した。エルリッヒが指摘するように、「文学研究を心理学、社会学、知的歴史学などの隣接

する学問から切り離すことを意図し、理論家たちは文学の『特徴』、想像的な文章に特有な芸術的装置に焦点を当てた」(The New

Princeton Encyclopedia 1101)。 第一に、文学それ自体、あるいはむしろ文学を他の人間活動から区別するその特徴が、文学理論の探究対象を構成しなければならない。第二に、哲学的、美学 的、心理学的といった文学批判の形而上学的約束事よりも「文学的事実」が優先されなければならない(シュタイナー「ロシア形式主義」16頁)。これらの目 的を達成するために、いくつかのモデルが開発された。 形式主義者たちは、詩的言語(poetic language)の自律性と、文学批評の研究対象としてのその特異性に同意した。彼らの主な努力は、詩であれ散文であれ、その「芸術性」 によって認識される詩的言語に固有の一連の特性を定義し、その結果、それらを分析することにあった。 |

| Mechanistic The OPOJAZ, the Society for the Study of Poetic Language group, headed by Viktor Shklovsky was primarily concerned with the Formal method and focused on technique and device. "Literary works, according to this model, resemble machines: they are the result of an intentional human activity in which a specific skill transforms raw material into a complex mechanism suitable for a particular purpose" (Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 18). This approach strips the literary artifact from its connection with the author, reader, and historical background. A clear illustration of this may be provided by the main argument of one of Viktor Shklovsky's early texts, "Art as Device" (Iskússtvo kak priyóm, 1916):[4] art is a sum of literary and artistic devices that the artist manipulates to craft his work. Shklovsky's main objective in "Art as Device" is to dispute the conception of literature and literary criticism common in Russia at that time. Broadly speaking, literature was considered, on the one hand, to be a social or political product, whereby it was then interpreted in the tradition of the great critic Belinsky as an integral part of social and political history. On the other hand, literature was considered to be the personal expression of an author's world vision, expressed by means of images and symbols. In both cases, literature is not considered as such, but evaluated on a broad socio-political or a vague psychologico-impressionistic background. The aim of Shklovsky is therefore to isolate and define something specific to literature or "poetic language": these, as we saw, are the "devices" which make up the "artfulness" of literature. Formalists do not agree with one another on exactly what a device or "priyom" is, nor how these devices are used or how they are to be analyzed in a given text. The central idea is that more general: poetic language possesses specific properties, which can be analyzed as such. Some OPOJAZ members argued that poetic language was the major artistic device. Shklovsky insisted that not all artistic texts defamiliarize language, and that some of them achieve defamiliarization (ostranenie) by manipulating composition and narrative. The Formalist movement attempted to discriminate systematically between art and non-art. Therefore, its notions are organized in terms of polar oppositions. One of the most famous dichotomies introduced by the mechanistic Formalists is a distinction between story and plot, or fabula and "sjuzhet". Story, fabula, is a chronological sequence of events, whereas plot, sjuzhet, can unfold in non-chronological order. The events can be artistically arranged by means of such devices as repetition, parallelism, gradation, and retardation. The mechanistic methodology reduced literature to a variation and combination of techniques and devices devoid of a temporal, psychological, or philosophical element. Shklovsky very soon realized that this model had to be expanded to embrace, for example, contemporaneous and diachronic literary traditions (Garson 403). |

機械論的 ヴィクトール・シュクロフスキーが率いる「詩的言語研究会」(OPOJAZ)は、主に形式手法に関心を持ち、技法と装置に焦点を当てた。「文学作品は、こ のモデルによれば、機械に似ている。特定の技能が原料を特定の目的に適した複雑なメカニズムに変えるという、意図的な人間の活動の結果である」 (Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 18)。このアプローチは、文学という芸術品から、作者、読者、歴史的背景との結びつきを奪ってしまう。 このことを明確に示すのが、ヴィクトル・シュクロフスキーの初期のテクストの一つである「装置としての芸術」(Iskússtvo kak priyóm, 1916)の主要な議論である[4] 。 シュクロフスキーの「装置としての芸術」の主な目的は、当時のロシア で一般的だった文学と文芸批評の概念に異議を唱えることである。大まかに言えば、文学 は一方では社会的あるいは政治的な産物であると考えられ、偉大な批評家ベリンスキーの伝統に従って、文学は社会的・政治的歴史の不可欠の一部であると解釈 された。一方、文学は作者の世界観の個人的な表現であり、イメージやシンボルによって表現されるものと考えられていた。どちらの場合も、文学はそのような ものとしてではなく、広範な社会・政治的背景、あるいは漠然とした心理・印象派的背景の上に評価される。したがって、シュクロフスキーの目的は、文学ある いは「詩的言語」に固有のものを分離して定義することである。これらは、見たように、文学の「芸術性」を構成する「装置」である。 形式主義者たちは、装置や「プリヨム」が何であるか、またこれらの装置がどのように使われ、与えられたテキストにおいてどのように分析されるべきかについ て、互いに正確に同意しているわけではない。中心的な考え方は、より一般的なものとして、詩的な言語には特定の性質があり、それを分析することができると いうものである。 OPOJAZのメンバーの中には、詩的言語が主要な芸術的装置であると主張する者もいた。シュクロフスキーは、すべての芸術的テキストが言語を不慣れにし ているわけではなく、そのうちのいくつかは、構成と物語を操作することによって不慣れ化(ostranenie)を達成すると主張した。 形式主義運動は、芸術と非芸術を体系的に弁別しようとした。そのた め、その概念は両極の対立という観点から整理されている。機械論的な形式主義者が導入し た最も有名な二項対立のひとつが、物語とプロット、あるいはファブラと「スジュゼット」の区別である。ストーリー(fabula)は時系列に沿った出来事 の連続であるのに対し、プロット(sjuzhet)は非時系列に展開することができる。反復、並列、グラデーション、遅延などの工夫によって、出来事を芸 術的にアレンジすることができる。 機械論的な方法論は、文学を時間的、心理的、哲学的な要素を欠いた技術や装置の変化と組み合わせに還元してしまった。シュクロフスキーはすぐに、このモデ ルは、例えば同時代的、通時的な文学的伝統を包含するように拡張されなければならないことに気づいた(Garson 403)。 |

| Organic Disappointed by the constraints of the mechanistic method some Russian Formalists adopted the organic model. "They utilized the similarity between organic bodies and literary phenomena in two different ways: as it applied to individual works and to literary genres" (Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 19). An artefact, like a biological organism, is not an unstructured whole; its parts are hierarchically integrated. Hence the definition of the device has been extended to its function in text. "Since the binary opposition – material vs. device – cannot account for the organic unity of the work, Zhirmunsky augmented it in 1919 with a third term, the teleological concept of style as the unity of devices" (Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 19). The analogy between biology and literary theory provided the frame of reference for genre studies and genre criticism. "Just as each individual organism shares certain features with other organisms of its type, and species that resemble each other belong to the same genus, the individual work is similar to other works of its form and homologous literary forms belong to the same genre" (Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 19). The most widely known work carried out in this tradition is Vladimir Propp's "Morphology of the Folktale" (1928). Having shifted the focus of study from an isolated technique to a hierarchically structured whole, the organic Formalists overcame the main shortcoming of the mechanists. Still, both groups failed to account for the literary changes which affect not only devices and their functions but genres as well. |

オーガニック 機械論的手法の制約に失望したロシアのフォーマリストの一部は、有機的モデルを採用し た。「彼らは有機体と文学的現象との類似性を、個々の作品に適用する 場合と文学のジャンルに適用する場合の二つの異なる方法で利用した」(Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 19)。 人工物は、生物体のように非構造的な全体ではなく、その部分は階層的に統合されている。それゆえ、装置の定義はテキストにおけるその機能にまで拡張され た。「素材対装置という二項対立では作品の有機的統一を説明できないので、ジルムンスキーは1919年に第三の用語、装置の統一としてのスタイルという目 的論的概念でそれを補強した」(Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 19)。 生物学と文学理論のアナロジーは、ジャンル研究とジャンル批評の参照枠 を提供した。「個々の生物がその種の他の生物と一定の特徴を共有し、互いに類似する 種が同じ属に属するように、個々の作品はその形式の他の作品と類似し、同種の文学形式は同じジャンルに属する」(Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 19)。この伝統に則って行われた最も広く知られた研究は、ウラジーミル・プロップ(Vladimir Propp, 1895-1970)の「昔話の形態学」(1928年)である。 研究の焦点を孤立した技法から階層的に構造化された全体へと移した有機的形式主義者たちは、機械主義者たちの主な欠点を克服していた。しかし、両派とも、 装置やその機能だけでなく、ジャンルにも影響を与える文学的な変化を考慮することはできなかった。 |

| Systemic The diachronic dimension was incorporated into the work of the systemic Formalists. The main proponent of the "systemo-functional" model was Yury Tynyanov. "In light of his concept of literary evolution as a struggle among competing elements, the method of parody, 'the dialectic play of devices,' become an important vehicle of change" (Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 21). Since literature constitutes part of the overall cultural system, the literary dialectic participates in cultural evolution. As such, it interacts with other human activities, for instance, linguistic communication. The communicative domain enriches literature with new constructive principles. In response to these extra-literary factors the self-regulating literary system is compelled to rejuvenate itself constantly. Even though the systemic Formalists incorporated the social dimension into literary theory and acknowledged the analogy between language and literature the figures of author and reader were pushed to the margins of this paradigm. |

体系的(システミック) 通時的な次元は、システマティックな形式主義者たちの仕事に取り入れ られた。システマティック・フォーマル」の主唱者はユーリー・ティニャノフであった。 文学の進化を競合する要素間の闘争とする彼の概念に照らせば、パロディの方法、「装置の弁証法的遊び」は、変化の重要な手段となった」(Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 21)。 文学は文化システム全体の一部を構成しているため、文学的弁証法は文化 的進化に参加している。そのため、文学は他の人間活動、例えば言語的コミュニケー ションと相互作用する。コミュニケーション領域は、文学を新しい構成原理で豊かにする。このような文学外の要因に対応して、自己調整的な文学システムは絶 えず自己を若返らせることを余儀なくされる。体系的形式主義者たちは、文学理論に社会的次元を取り入れ、言語と文学の間の類似性を認めたが、作者と読者の 姿はこのパラダイムの周辺に追いやられていた。 |

| Linguistic The figures of author and reader were likewise downplayed by the linguistic Formalists Lev Jakubinsky and Roman Jakobson. The adherents of this model placed poetic language at the centre of their inquiry. As Warner remarks, "Jakobson makes it clear that he rejects completely any notion of emotion as the touchstone of literature. For Jakobson, the emotional qualities of a literary work are secondary to and dependent on purely verbal, linguistic facts" (71). As Ashima Shrawan explains, "The theoreticians of OPOJAZ distinguished between practical and poetic language . . . . Practical language is used in day-to-day communication to convey information. . . . In poetic language, according to Lev Jakubinsky, 'the practical goal retreats into background and linguistic combinations acquire a value in themselves. When this happens, language becomes de-familiarized and utterances become poetic'" (The Language of Literature and Its Meaning, 68). Eichenbaum criticised Shklovsky and Jakubinsky for not disengaging poetry from the outside world completely, since they used the emotional connotations of sound as a criterion for word choice. This recourse to psychology threatened the ultimate goal of formalism to investigate literature in isolation. A definitive example of focus on poetic language is the study of Russian versification by Osip Brik. Apart from the most obvious devices such as rhyme, onomatopoeia, alliteration, and assonance, Brik explores various types of sound repetitions, e.g. the ring (kol'co), the juncture (styk), the fastening (skrep), and the tail-piece (koncovka) ("Zvukovye povtory" (Sound Repetitions); 1917). He ranks phones according to their contribution to the "sound background" (zvukovoj fon) attaching the greatest importance to stressed vowels and the least to reduced vowels. As Mandelker indicates, "his methodological restraint and his conception of an artistic 'unity' wherein no element is superfluous or disengaged, … serves well as an ultimate model for the Formalist approach to versification study" (335). |

言語学的 作者と読者という人物も、言語形式主義者のレフ・ヤクビンスキーとローマン・ヤコブソンによって同様に軽視された。このモデルの信奉者たちは、詩的な言語 を研究の中心に据えた。ワーナーは、「ヤコブソンは、文学の試金石としての感情という概念を完全に否定していることが明らかである。ヤコブソンにとって、 文学作品の情緒的特質は、純粋に言語的な事実に対して二次的なものであり、依存するものである」(71)。 アシマ・シュラワンが説明するように、「オポージャズの理論家たちは、実用的言語と詩的言語を区別していた ... .... 実用的な言語は、情報を伝えるために日々のコミュニケーションで使われる。. . . 詩的な言語では、レフ・ヤクビンスキーによれば、「実用的な目標は背景に退き、言語の組み合わせはそれ自体で価値を獲得する」のだそうだ。このとき、言語 は脱友好的になり、発言は詩的になる」(『文学の言語とその意味』68)。 アイシェンバウムは、シュクロフスキーとヤクビンスキーが、言葉の選択の基準として音の持つ感情的な意味合いを用いていたため、詩を外界から完全に切り離 すことはできなかったと批判している。この心理学への依拠は、文学を単独で調査するという形式主義の究極の目標を脅かすものであった。 詩的言語に焦点を当てた決定的な例は、オシップ・ブリックによるロシア詩の研究である。韻、オノマトペ、叙述、同音異義語などの最も明白な装置とは別に、 ブリクは様々なタイプの音の反復、例えば、環(kol'co)、接合部(styk)、固定部(skrep)、尾部(koncovka)を探求した (「Zvukovye povtory」(音の反復); 1917年)。彼は「音の背景」(zvukovoj fon)に対する寄与度に応じて電話をランク付けし、強調母音を最も重要視し、減音母音を最も重要視している。マンデルカーが示すように、「彼の方法論的 な抑制と、どの要素も余分であったり外されたりしていない芸術的な『統一』の概念は、...詩文研究に対する形式主義的アプローチの究極のモデルとしてよ く機能している」(335頁)。 |

| Textual analysis In "A Postscript to the Discussion on Grammar of Poetry," Jakobson redefines poetics as "the linguistic scrutiny of the poetic function within the context of verbal messages in general, and within poetry in particular" (23). He fervently defends linguists' right to contribute to the study of poetry and demonstrates the aptitude of the modern linguistics to the most insightful investigation of a poetic message. The legitimacy of "studies devoted to questions of metrics or strophics, alliterations or rhymes, or to questions of poets' vocabulary" is hence undeniable (23). Linguistic devices that transform a verbal act into poetry range "from the network of distinctive features to the arrangement of the entire text" (Jakobson 23). Jakobson opposes the view that "an average reader" uninitiated into the science of language is presumably insensitive to verbal distinctions: "Speakers employ a complex system of grammatical relations inherent to their language even though they are not capable of fully abstracting and defining them" (30). A systematic inquiry into the poetic problems of grammar and the grammatical problems of poetry is therefore justifiable; moreover, the linguistic conception of poetics reveals the ties between form and content indiscernible to the literary critic (Jakobson 34). |

テキスト分析 ヤコブソンは「詩の文法に関する議論のあとがき」で、詩学を「一般的な言語メッセー ジ、特に詩の文脈における詩的機能の言語学的精査」(23)として再定 義している。彼は言語学者が詩の研究に貢献する権利を熱烈に擁護し、詩的なメッセージを最も洞察的に調査する現代言語学の適性を実証してい るのである。し たがって、「メトリックスやストロフィクス、叙述や韻律の問題、あるいは詩人の語彙の問題に専念する研究」の正当性は否定できない(23)。言語行為を詩 に変える言語的装置は、「特徴的な特徴のネットワークからテキスト全体の配置まで」(ヤコブソン 23)及ぶのである。 ヤコブソンは、言語の科学に通じていない「平均的な読者」は言葉の区別に鈍感であろうという見解に反論する。「話し手は、その言語に固有の複雑な文法的関 係のシステムを、たとえそれを完全に抽象化し定義する能力がないとしても採用している」(30)。したがって、文法の詩的問題と詩の文法的 問題を系統的に 探求することは正当化される。さらに、詩学の言語学的概念は、文芸評論家にとっては見分けがつかない形式と内容の結びつきを明らかにする(ヤコブソン 34)。(→「デカルト派言語学」) |

| Literature definition attempts Roman Jakobson described literature as "organized violence committed on ordinary speech." Literature constitutes a deviation from average speech that intensifies, invigorates, and estranges the mundane speech patterns. In other words, for the Formalists, literature is set apart because it is just that: set apart. The use of devices such as imagery, rhythm, and meter is what separates "Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, exhibit number one is what the seraphs, the misinformed, simple, noble-winged seraphs, envied. Look at this tangle of thorns (Nabokov Lolita 9)", from "the assignment for next week is on page eighty four." This estrangement serves literature by forcing the reader to think about what might have been an ordinary piece of writing about a common life experience in a more thoughtful way. A piece of writing in a novel versus a piece of writing in a fishing magazine. At the very least, literature should encourage readers to stop and look closer at scenes and happenings they otherwise might have skimmed through uncaring. The reader is not meant to be able to skim through literature. When addressed in a language of estrangement, speech cannot be skimmed through. "In the routines of everyday speech, our perceptions of and responses to reality become stale, blunted, and as the Formalists would say 'automatized'. By forcing us into a dramatic awareness of language, literature refreshes these habitual responses and renders objects more perceptible" (Eagleton 3). |

literature definition attempts ローマン・ヤコブソンは文学を "通常の会話に加えられる組織的な暴力 "と表現した。文学は、平均的な会話からの逸脱を構成し、平凡な会話パターンを強め、活性化させ、疎外する。言い換えれば、形式主義者に とって、文学は、 まさにそうであるがゆえに、別格である。イメージ、リズム、拍子記号といった装置を用いることで、「陪審員の皆さん、展示品第一号は、誤った知識を持ち、 単純で、高貴な翼を持つセラフがうらやむものです」を分けているのである。この茨の絡まりを見よ(ナボコフ ロリータ 9)」と「来週の課題は84ページだ」を分けている。 「この疎外感は、ありふれた人生経験について書かれた普通の文章だったかもしれない ものを、より思慮深く考えることを読者に強いることで、文学に役立ってい る。小説の一文と釣り雑誌の一文。少なくとも、文学は読者に、そうでなければ無関心に読み飛ばしてしまうような場面や出来事を、立ち止まってよく見 てみるように促すものでなければならない。読者は文学を読み流すことができるようにはなっていない。疎遠の言葉で語られる場合、会話は読み流すこと ができない。日常的な会話というルーティンの中で、私たちの現実に対する認識や反応は陳腐化し、鈍化し、形式主義者が言うように「自動化」されてしまう。 文学は、われわれを言語に対する劇的な意識に駆り立てることによって、こうした習慣的な反応をリフレッシュし、対象をより知覚しやすくする」 (Eagleton 3)。 |

| Political offense One of the sharpest critiques of the Formalist project was Leon Trotsky's Literature and Revolution (1924).[5] Trotsky does not wholly dismiss the Formalist approach, but insists that "the methods of formal analysis are necessary, but insufficient" because they neglect the social world with which the human beings who write and read literature are bound up: "The form of art is, to a certain and very large degree, independent, but the artist who creates this form, and the spectator who is enjoying it, are not empty machines, one for creating form and the other for appreciating it. They are living people, with a crystallized psychology representing a certain unity, even if not entirely harmonious. This psychology is the result of social conditions" (180, 171). The leaders of the movement began to be politically persecuted in the 1920s, when Stalin came to power, which largely put an end to their inquiries. In the Soviet period under Joseph Stalin, the authorities further developed the term's pejorative associations to cover any art which used complex techniques and forms accessible only to the elite, rather than being simplified for "the people" (as in socialist realism). |

政治的攻撃 形式主義的なプロジェクトに対する最も鋭い批判の1つがLeon Trotskyの『文学と革命』(1924年)である[5]。Trotskyは形式主義のアプローチを完全に否定はしていないが、「形式分析の方法は必要 だが不十分」だと主張している。なぜなら彼らが文学を書いて読む人間が結びついている社会世界を軽視しているからである。「芸術の形式は、ある意味で非常 に大きな独立性を持っているが、この形式を作り出す芸術家も、それを楽しむ観客も、一方は形式を作り、他方はそれを鑑賞するための、空っぽの機械ではない のだ。彼らは生きている人間であり,完全に調和しているわけではないにせよ,ある種の統一性を代表するような心理を結晶化させたものである.この心理は社 会的条件の結果である」(180, 171)。 この運動の指導者たちは、スターリンが権力を握った1920年代から政治的に迫害されるようになり、彼らの問い合わせはほとんどなくなってしまった。ス ターリン政権下のソ連時代には、この言葉の蔑称としての性格がさらに強まり、「民衆」向けに単純化されたものではなく、エリート層のみがアクセスできる複 雑な技法や形式を用いた芸術(社会主義リアリズムのように)にも適用されるようになった。 |

| Legacy Russian formalism was not a uniform movement; it comprised diverse theoreticians whose views were shaped through methodological debate that proceeded from the distinction between poetic and practical language to the overarching problem of the historical-literary study. It is mainly with this theoretical focus that the Formalist School is credited even by its adversaries such as Yefimov: The contribution of our literary scholarship lies in the fact that it has focused sharply on the basic problems of literary criticism and literary study, first of all on the specificity of its object, that it modified our conception of the literary work and broke it down into its component parts, that it opened up new areas of inquiry, vastly enriched our knowledge of literary technology, raised the standards of our literary research and of our theorizing about literature effected, in a sense, a Europeanization of our literary scholarship…. Poetics, once a sphere of unbridled impressionism, became an object of scientific analysis, a concrete problem of literary scholarship ("Formalism V Russkom Literaturovedenii", quoted in Erlich, "Russian Formalism: In Perspective" 225). The diverging and converging forces of Russian formalism gave rise to the Prague school of structuralism in the mid-1920s and provided a model for the literary wing of French structuralism in the 1960s and 1970s. "And, insofar as the literary-theoretical paradigms which Russian Formalism inaugurated are still with us, it stands not as a historical curiosity but a vital presence in the theoretical discourse of our day" (Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 29). There is no direct historical relationship between New Criticism and Russian Formalism, each having developed at around the same time (RF: 1910-20s and NC: 1940s-50s) but independently of the other. Despite this, there are several similarities: for example, both movements showed an interest in considering literature on its own terms, instead of focusing on its relationship to political, cultural or historical externalities, a focus on the literary devices and the craft of the author, and a critical focus on poetry. |

レガシー ロシアの形式主義は一様な運動ではなく、詩的言語と実用言語の区別から歴史的文学研 究という包括的な問題まで、方法論的な議論を通じて多様な理論家たちの 見解が形成された。イエフィモフのような敵対者からも、形式主義学派が評価されているのは、主にこのような理論的な焦点によるものである。 我々の文学研究の貢献は、文学批評と文学研究の基本的問題、とりわけその対象の特殊性に鋭く焦点を当てたこと、文学作品の概念を修正し、それを構成要素に 分解したこと、新しい研究領域を開拓し、文学技術に関する知識を大幅に豊かにし、文学研究および文学に関する理論化の水準を高め、ある意味で我々の文学研 究のヨーロッパ化を効果的に行ったことにある......。かつては奔放な印象派の領域であった詩学は、科学的分析の対象となり、文学研究の具体的な問題 となった(「形式主義 V Russkom Literaturovedenii」、エルリッヒ、「ロシア形式主義:展望」225より引用)。 ロシア形式主義の発散と収束の力は、1920年代半ばに構造主義のプラハ学派を 生み出し、1960年代から1970年代にかけてのフランス構造主義の文学 の翼にモデルを提供することになったのである。「そして、ロシア形式主義が創始した文学理論的パラダイムが今も私たちとともにある限り、それは歴史的好奇 心としてではなく、現代の理論的言説における重要な存在である」(Steiner, "Russian Formalism" 29). 新批評とロシア形式主義の間には直接的な歴史的関係はなく、それぞれがほぼ同時期(RF:1910-20年代、NC:1940-50年代)に独立して発展 したものである。しかし、政治的、文化的、歴史的な外部性との関係ではなく、文学を独自の観点から考察することに関心を示したこと、文学的装置や作家の技 巧に焦点を当てたこと、詩を批評の対象としたことなど、いくつかの共通点がある。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_formalism |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

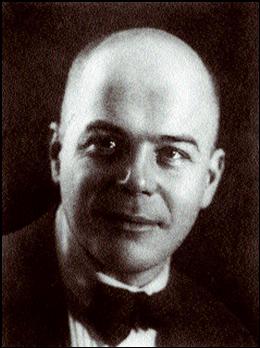

Víktor Shklovski (1893–1984) es

considerado el padre del Formalismo ruso.

Vladímir Propp (1895-1970)

++++

| Le terme formalisme russe

désigne une école de linguistes et de théoriciens de la littérature

qui, de 1914 à 1930, révolutionna le domaine de la critique littéraire

en lui donnant un cadre et une méthode novatrice. On peut distinguer le

groupe de Moscou mené par Roman Jakobson, et celui de

Saint-Pétersbourg, l'OPOYAZ, conduit par Victor Chklovski. Les formalistes russes auront une influence considérable sur la sémiologie et la linguistique du xxe siècle, notamment par le biais du structuralisme. |

ロシア形式主義とは、1914年から1930年にかけて、革新的な枠組

みと方法を文芸批評に提供し、文芸批評の分野に革命をもたらした言語学者と文学理論家の一派を指す。ロマン・ヤコブソン率いるモスクワ学派と、ヴィクト

ル・シュクロフスキー率いるサンクトペテルブルク学派(OPOYAZ)を区別することができる。 ロシアの形式主義者たちは、特に構造主義を通じて、20世紀の意味論や言語学に多大な影響を与えた。 |

| Les acteurs du formalisme russe Ossip Brik (1888-1945) et Roman Jakobson (1896-1982) s'occupent des structures rythmiques et métriques au cœur des poèmes. Victor Chklovski (1893-1984), Boris Eichenbaum (1886-1959) étudient les constructions narratives des récits. Victor Vinogradov (ru) (1895-1969) étudie les faits de style. Iouri Tynianov (1894-1943) est spécialiste de « la dialectique des genres ». Grigori Vinokour (ru) (1896-1947), linguiste Viktor Jirmounsky (1891-1971) Vladimir Propp (1895-1970) a appliqué cette analyse pour une typologie des contes. Cette répartition des tâches en critique littéraire vient de l'idée que la littérature est une technique, un ensemble de procédés. |

ロシア形式主義の主役たち オシップ・ブリク(1888-1945)とロマン・ヤコブソン(1896-1982)は、詩の中心にあるリズムと計量構造に注目した。 ヴィクトル・シクロフスキ(1893-1984)とボリス・アイヘンバウム(1886-1959)は、物語の物語構造を研究した。 ヴィクトル・ヴィノグラードフ(ru)(1895-1969)は文体的事実を研究した。 ユーリ・ティニアノフ(1894-1943)は「ジャンルの弁証法」を専門とした。 グリゴリ・ヴィノクール(ru)(1896-1947)言語学者。 ヴィクトル・ジルムンスキー(1891年-1971年) ウラジーミル・プロップ(1895-1970)は、この分析を童話の類型論に応用した。 文芸批評におけるこのような作業の分担は、文学は技術であり、一連の手続きであるという考え方に由来する。 |

| Histoire du formalisme Ce courant de critique littéraire se développe en Russie entre 1915 et 1930, mais ce mouvement n'a été découvert en France que vers 1960. Il commence par la création en 1915 du Cercle linguistique de Moscou pour « Promouvoir la linguistique et la poétique ». Il est aidé ensuite par la collaboration de l'OPOYAZ, qui aide les formalistes par l'apport des poètes futuristes comme Vladimir Maïakovski. La revue Poetica est publiée avec l'aide des formalistes par l'institut d'État d'histoire des arts. Le mot « formaliste » est d'abord une critique qui leur est adressée, mais dont ils se défendent, affirmant préférer « les qualités intrinsèques du matériau littéraire ». |

形式主義の歴史 この文芸批評の潮流は1915年から1930年にかけてロシアで発展したが、フランスで発見されたのは1960年である。 1915年に「言語学と詩学の促進」を目的としてモスクワ言語学サークルが設立されたことに始まる。その後、ウラジーミル・マヤコフスキーのような未来派 詩人の寄稿によって形式主義者を支援したOPOYAZの協力によって助けられた。 ポエティカ』誌は、形式主義者たちの協力を得て、国立美術史研究所から出版された。当初、「形式主義者」という言葉は彼らに向けられた批判だったが、彼ら は「文学的素材の本質的な特質」を好むと主張し、自らを弁護した。 |

| Grandes idées Le formalisme naît en réaction contre une méthode de critique qui s'attachait à l'étude des symboles et d'éléments qui influencent l'œuvre (l'histoire, la société...). Contre cette manière de faire, les formalistes proposent d'étudier la littérarité (« Ce qui fait d'une œuvre une œuvre littéraire », selon Jakobson). Ainsi les formalistes étudient en détail la structure des œuvres, les personnages, la structure précise du vers. L'histoire littéraire est révisée à partir d'une dialectique proche du marxisme. |

主な考え方 形式主義は、象徴や作品に影響を与えた要素(歴史、社会など)の研究に焦点を当てた批評方法への反発として生まれた。このアプローチに対して、形式主義者 たちは文学性(ヤコブソンによれば「作品を文学作品たらしめているもの」)の研究を提唱した。そこで形式主義者たちは、作品の構造、登場人物、詩の正確な 構造を詳細に研究した。 文学史はマルクス主義に近い弁証法に基づいて修正された。 |

| Bibliographie Michel Aucouturier, Le Formalisme russe, Paris, PUF, 1994 (coll. « Que sais-je ? »), 128 p. Catherine Depretto, Le Formalisme en Russie, Paris, Institut d'études slaves, 2009 Véra Fosty, « Le formalisme russe, une théorie de la littérature », in Le Langage et l'Homme, Janvier 1969, pp. 218-221. Tzvetan Todorov, Théorie de la littérature, Paris, Seuil 1965 Roman Jakobson, Essais de linguistique générale, Paris, Minuit, 1963 Jean-Yves Tadié, La Critique littéraire au xxe siècle, Paris, Belfond, 1987. |

|

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Formalisme_russe |

+++

| El término formalismo ruso

designa un movimiento intelectual que marca el nacimiento de la teoría

literaria y de la crítica literaria como disciplinas autónomas y que

también tuvo su influencia en la evolución de los estudios

lingüísticos.1 Esta etapa literaria tiene lugar entre 1904 y 1928

teniendo tras de sí, un papel fundamental los sucesos históricos

(bélicos en su totalidad) que acontecían por aquel entonces. Desde un

primer momento el término formalismo ruso engloba un conjunto de

estudios y teorías que distan de ser homogéneas, pero que tienen en

común el tratamiento de la literatura con base en un objeto de estudio:

la «literariedad», que en otras palabras, comprendería el conjunto de

características necesarias para poder distinguir si un texto es

literario o no. Al definir esa propiedad, el formalismo buscó conferir

un estatuto científico al estudio de la literatura. El origen de este

movimiento se genera con la creación del Círculo lingüístico de Moscú

en 1915 y la Sociedad para el Estudio del Lenguaje Poético, OPOYAZ, en

1916. De manera más precisa, este movimiento nació durante la Primera Guerra Mundial en la Rusia prerrevolucionaria.1 Fue una época que, como no podía ser de otra manera, establecía un estado de enfrentamiento y polémica constante (llegando a su pico más alto con la Revolución de Octubre de 1917). Entre los principales investigadores del movimiento figuran Víktor Shklovski –considerado el padre del formalismo–, Borís Tomashevski, Yuri Tyniánov, Borís Eichenbaum, Vladímir Propp y Román Jakobson. Algunos de ellos debieron emigrar a causa de las presiones del gobierno soviético y en su exilio, influyeron en el desarrollo de nuevos paradigmas de la teoría literaria y de lingüística como la Escuela de Praga o el estructuralismo. Dentro del formalismo ruso, destacan 3 etapas las cuales denominan el estilo literario por el que se decantará dicho movimiento. En la primera etapa (1916-1920) predomina, primeramente, el rechazo hacia la historia de la literatura tradicional, del subjetivismo y del lenguaje poético per se. Con esto último, se introduce el conocido desvío literario por el cual se abandona el lenguaje estándar o característico de las obras literarias (dependientemente de su género) y se impone un estilo que crea una sensación de extrañamiento en el lector ya que, como se ha mencionado, sale del lenguaje común. Esta técnica era muy usada por Víktor Shklovski y Jan Mukařovský. En la segunda etapa (1921-1926), se genera un debate entre las sociedades que desarrollaron este movimiento: mientras que la OPOYAZ constata que la lengua y literatura son diferentes, el Círculo Lingüístico se opone diciendo que ambas son complementarias ya que la literatura es parte de la lingüística. A pesar de ello, ambas llegan a un punto de conexión, y es que ambas rechazan el historicismo. La última etapa del formalismo (1926-1928) se definiría como la decadencia de la literatura y la realidad. Además, la literatura, gracias a Shklovski, empieza a tener ámbitos sociológicos. Con todo ello y marcandose así el final de este movimiento, en 1925, se creó la Asociación Rusa de Escritores Proletarios (RAPP). |

ロシア形式主義という用語は、文学理論や文芸批評を自律的な学問分野と

して誕生させ、言語学の発展にも影響を与えた知的運動を指す1。当初から、ロシア語フォーマリズムという用語は、均質とはほど遠い一連の研究や理論を包含

していたが、「文学性」という研究対象に基づいて文学を扱うという点では共通していた。この性質を定義することで、形式主義は文学研究に科学的地位を与え

ようとした。この運動の起源は、1915年のモスクワ言語学サークルと1916年の詩的言語研究協会(OPOYAZ)の創設にある。 より正確には、この運動は革命前のロシアで第一次世界大戦中に生まれた1。この時期は、当然のことながら、絶え間ない対立と極論の状態が確立していた (1917年の十月革命で最高潮に達した)。 この運動の主要な研究者の中には、形式主義の父とされるヴィクトル・シュクロフスキー、ボリス・トマシェフスキー、ユーリ・ティニャノフ、ボリス・アイヘ ンバウム、ウラジーミル・プロップ、ロマン・ヤコブソンらがいた。彼らの中には、ソ連政府からの圧力のために移住を余儀なくされた者もおり、亡命先でプラ ハ学派や構造主義といった文学理論や言語学の新しいパラダイムの発展に影響を与えた。 ロシア形式主義の中には、この運動が発展した文学スタイルを規定する3つの段階がある。第一段階(1916-1920年)は、まず伝統的な文学史、主観主 義、詩的言語それ自体の否定によって支配された。後者では、よく知られている文学的逸脱が導入され、文学作品の(ジャンルによる)標準的な、あるいは特徴 的な言語が放棄され、前述のように一般的な言語から逸脱しているため、読者に疎外感を与える文体が押し付けられる。この手法は、ヴィクトル・シュクロフス キやヤン・ムカジェフスキーによって広く用いられた。 第2段階(1921年~1926年)では、この運動を発展させた学会の間で論争が起こった。OPOYAZが言語と文学は別物であると述べたのに対し、言語 学サークルは、文学は言語学の一部であるため、両者は補完関係にあると反対した。にもかかわらず、両者には歴史主義を否定するという共通点がある。形式主 義の最終段階(1926~1928年)は、文学と現実の退廃と定義されるだろう。さらに、シュクロフスキーのおかげで、文学は社会学的な領域を持ち始め た。1925年にロシア・プロレタリア作家協会(RAPP)が設立され、この運動は終焉を迎える。 |

Origen Yuri Tyniánov.  Román Ósipovich Yakobsón. Se formó con estudiantes que se reunían en la OPOYAZ, Sociedad para el Estudio del Lenguaje Poético, que duró desde 1916 hasta 1925. En 1930, el régimen estalinista condenó formal y categóricamente sus perspectivas por su falta de contenido social; esta interdicción obligó a sus componentes al exilio y a relegar sus obras a la oscuridad. En esta época los trabajos de los formalistas rusos se transformaron en una rareza bibliográfica. Pero, mientras, algunas apariciones en Europa provocaron el interés del estructuralismo francés, que utilizó largamente el formalismo ruso para formular algunas de sus teorías. El formalismo ruso entra en Europa en plena época del estructuralismo a través de la obra de Tzvetan Todorov Teoría de la literatura de los formalistas rusos, en la que podemos encontrar artículos de Shklovski, Eichenbaum, Tyniánov, Vinográdov, Roman Jakobson, Ósip Brik, Tomashevski y Propp. Este último escribe el prólogo de la obra, en el que afirma que el Círculo lingüístico de Moscú —del que él mismo es el fundador— es anterior a la OPOYAZ. El formalismo ruso, por tanto, modificó las posturas respecto a los conceptos de arte, literatura y texto en el transcurso del siglo xx y abrió el camino de la nueva crítica angloamericana (New criticism) e, incluso, a la crítica marxista. De manera complementaria, esta nueva crítica angloamericana definida como New Criticism, ocurrió entre 1930 y 1948 teniendo como figura principal al escritor John Crowe Ransom. Se trata de una nueva forma de hacer crítica literaria. Se propugna la ciencia de la literatura (según autores ilustres como Ezra Pound y Thomas S. Elliot). Lo que este movimiento viene a explicar y desarrollar desde los años 30 en adelante, es que para valorar el texto, hay que leer atentamente el texto (el llamado "close reading") ya que de esta forma se podrán percibir elementos de la obra |

由来 ユーリ・ティニャノフ  ロマン・オシポヴィチ・ヤコブソン 1916年から1925年まで続いた詩的言語研究会(OPOYAZ)に集まった学生たちによって結成された。1930年、スターリニスト政権は、その視点 が社会的な内容を欠いているとして、正式に断固として非難した。この差し止めによって、メンバーは亡命せざるを得なくなり、彼らの作品は無名に追いやられ た。この時、ロシア形式主義者の作品は書誌的に希少なものとなった。しかし、その一方で、ヨーロッパに現れたいくつかの作品は、フランス構造主義の関心を 呼び起こし、フランス構造主義はロシア形式主義を大いに利用して、その理論のいくつかを定式化した。ツヴェタン・トドロフの『ロシア形式主義者の文学論』 (Theory of Literature of the Russian Formalists)には、シュクロフスキ、アイチェンバウム、ティニャノフ、ヴィノゴルドフ、ロマン・ヤコブソン、オシップ・ブリク、トマシェフス キ、プロップの論文が収められている。プロップはこの著作の序文を書いており、その中で、彼自身が創設者であるモスクワ言語学サークルがオポヤズより先で あると述べている。 それゆえ、ロシアのフォーマリズムは、20世紀の過程で芸術、文学、テクストの概念に関する立場を変え、英米批評(新批評)、さらにはマルクス主義批評へ の道を開いた。 この新しい英米批評は、1930年から1948年にかけて、作家ジョン・クロウ・ランサムを中心に、新批評として定義された。それは新しい形の文芸批評で あった。エズラ・パウンドやトーマス・S・エリオットといった著名な作家によれば)文学の科学を提唱している。この運動が1930年代以降に説明し発展さ せたのは、テクストを評価するためには、テクストを注意深く読むこと(いわゆる「精読」)が必要であるということである。 |

| El arte como recurso y la

narrativa La literatura es una estructura peculiar del lenguaje, peculiaridad que se basa en que su uso está fuera de cualquier utilidad pragmática. Además de esto, su cualidad de objeto elaborado, hace que se diferencie del lenguaje práctico. En consecuencia, Shklovski crea el concepto de desautomatización como mecanismo de creación de la literariedad en el lenguaje: es la ruptura de automaticidad de la percepción. El extrañamiento ante lo no conocido. Hay ruptura entre significante y significado. Un proceso de desautomatización es la metáfora, porque debemos realizar un proceso de comprensión para alcanzar el verdadero significado de esas palabras metafóricas, al haberlas privado de una relación directa. Así pues, una obra es literaria no por su cantidad de metáforas, sino por la desautomatización de las mismas. Buscar una manera de presentar las cosas como nunca vistas, singularizándolas, sacándolas de contexto para hacerlas llamativas. Otra de las innovaciones en la primera etapa del formalismo ruso, es la modificación del término trama o syuzhet (сюжет, del francés sujet). Para Aristóteles trama era la "disposición artística de los acontecimientos que conforman la narración". El formalismo extiende este concepto, al incluir los recursos¹ utilizados para prolongar o interrumpir la narración cuyo efecto sería el de impedir que los acontecimientos narrados sean tomados automáticamente. Para los formalistas, la trama es un relato no necesariamente cronológico de diversos acontecimientos, presentados por un autor o narrador a un lector. En este sentido, es un concepto que se opone al de fábula, más referido a la secuencia de acontecimientos de una historia según el orden causal y temporal en el que ocurren los hechos (en terminología inglesa, la distinción plot/story corresponde a syuzhet/fábula). A la unidad de trama más pequeña, Borís Tomashevski la define como motivo². Según este formalista, el foco en potencial del arte está en aquellos motivos que no son esenciales para la narración. En un proceso mayor, en que el tema, las ideas y las referencias a la realidad se presentan como excusa del escritor para justificar los recursos formales; estos procesos externos y no literarios fueron llamados por Shklovski motivación. Posteriormente, y con Jonathan Culler como máximo representante, la idea antigua de los primeros formalistas de que el texto solo puede explicarse separando la expresión del contenido, es modificada por formalistas posteriores. |

資源としての芸術と物語 文学は言語の特殊な構造であり、その特殊性は、その使用がいかなる語用論的有用性からも外れているという事実に基づいている。加えて、その精巧な対象物と しての性質が、実用的な言語とは一線を画している。 その結果、シュクロフスキーは、言語における文学性を生み出すメカニズムとして、脱自動化という概念を生み出した。それは知覚の自動性の断絶である。シニ フィアンとシニフィエの間には断絶がある。メタファーとは脱自動化のプロセスであり、直接的な関係を奪われたメタファーの言葉の真の意味に到達するために は、理解のプロセスを経なければならないからである。したがって、ある作品が文学的であるのは、そのメタファーの量によるのではなく、これらのメタファー の脱オートマティゼーションによるのである。物事をこれまでに見たことのないように表現し、特異化し、文脈から切り離して、印象的なものにする方法を模索 するのである。 ロシア形式主義の第一段階におけるもう一つの革新は、プロットまたはシューゼット(сюжет、フランス語のsujetから)という用語の修正である。ア リストテレスにとってプロットとは「物語を構成する出来事の芸術的配置」であった。形式主義はこの概念を拡張し、物語を長引かせたり中断させたりするため に用いられる装置¹を含める。形式主義者にとってプロットとは、作者や語り手が読者に提示する、さまざまな出来事の必ずしも時系列的ではない説明である。 この意味で、寓話とは対照的な概念であり、寓話は物語中の出来事の順序を、その出来事が起こる因果的・時間的順序に従ってより重視する(英語の用語では、 プロット/ストーリーの区別はsyuzhet/寓話に相当する)。 ボリス・トマシェフスキーは、プロットの最小単位をモチーフ²と定義している。この形式主義者によれば、芸術の潜在的な焦点は、物語にとって本質的でない モチーフにある。テーマ、アイデア、現実への言及が、形式的資源を正当化するための作家の言い訳として提示される、より大きなプロセスにおいて、これらの 外的で非文学的なプロセスは、シュクロフスキーによって動機づけと呼ばれた。 その後、ジョナサン・カラーを代表として、テキストは表現と内容を分離することでしか説明できないという初期の形式主義者の考えは、後の形式主義者によっ て修正される。 |

| La dominante El problema que los elementos de la obra puedan permitir la automatización y de que el recurso pudiera realizar distintas funciones estéticas en varias obras, hizo que los formalistas consideraran las obras literarias como sistemas dinámicos donde los elementos interactúan en un escenario de fondo, de acuerdo a un guion central. Ese guion central, o dominancia sobre los otros elementos, Roman Jakobson lo define como el componente central de una obra de arte que rige, determina y transforma a los demás. |

支配的なもの 作品の要素が自動化を可能にし、リソースがさまざまな作品において異なる美的機能を発揮しうるという問題から、形式主義者たちは文学作品を、中心的な脚本 に従って背景となるシナリオの中で要素が相互作用する動的なシステムとして考えるようになった。この中心的な台本、つまり他の要素に対する優位性を、ロー マン・ヤコブソンは、他の要素を支配し、決定し、変容させる芸術作品の中心的な構成要素として定義している。 |

La escuela de Bajtín Círculo de Bajtín. Sentados, de izquierda a derecha: Bajtín, María Yúdina, Valentín Volóshinov, Lev Pumpianski, Pável Medvédev. De pie, Konstantín Váguinov y su esposa (mediados de los años 1920). En esta etapa del formalismo, se crea el conocido Círculo de Bajtín, donde el propio Míjail Batjín (influenciado por grandes figuras como Fiódor Dostoyevski o Karl Marx) y otros autores representativos del movimiento (María Yúdina, Valentín Volóshinov, Lev Pumpianski o Pável Medvédev) dan un enfoque marxista a la lingüística de Saussure. Dicho enfoque programaba que toda ideología no puede separarse de su materia social, el lenguaje. Además, uno de los temas principales que se comentaban era la filosofía alemana (a raíz de los sucesos bélicos) y la filosofía moral. Gracias a la creación de este círculo de escritores, Batjín empezó a considerarse como un filósofo y no como un escritor (saliendo a la luz un escrito parcial datado de 1919 bajo el título Arte y Responsabilidad y que pasó a ser una de sus obras cumbre). En la misma línea, Valentín Volóshinov propone que las palabras "eran signos sociales, dinámicos y activos, capaces de adquirir significados y connotaciones distintas para las diversas clases sociales, en situaciones sociales e históricas diferentes". Bajtín proyectó esta dinámica visión del lenguaje al campo de la crítica literaria. Finalmente, el entronque del formalismo conduce a la crítica marxista. Tanto los formalistas como la naciente crítica marxista consideran que las estructuras, el conjunto específico de recursos, el catálogo de obras, el cuerpo de géneros, son inseparables del medio social que lo produce y de las ideas predominantes de moda. Y es donde nace la función estética: el arte como producto de la sociedad. |

バフチン学派 バフチンのサークル。左からバフチン、マリア・ユディナ、ヴァレンティン・ヴォルシノフ、レフ・ポンピアンスキー、パーヴェル・メドヴェージェフ。立って いるのは、コンスタンチン・ヴァギノフとその妻(1920年代半ば)。 この形式主義の段階で、ミハイル・バフチン自身(フョードル・ドストエフスキーやカール・マルクスといった偉大な人物の影響を受けている)と、この運動の 代表的な作家たち(マリア・ユディナ、ヴァレンティン・ヴォルシノフ、レフ・ポンピアンスキー、パーヴェル・メドヴェージェフ)が、ソシュールの言語学に 対してマルクス主義的なアプローチをとった、よく知られたバフチン・サークルが作られた。このようなアプローチは、いかなるイデオロギーも、その社会的な 問題である言語から切り離すことはできないとプログラムした。さらに、主な議論のテーマのひとつは、(戦争後の)ドイツ哲学と道徳哲学であった。このよう な作家のサークルができたおかげで、バチンは自らを作家としてではなく、哲学者として考えるようになった(1919年に書かれた『芸術と責任』というタイ トルの部分的な文章が明るみに出て、彼の最も重要な作品のひとつとなった)。 同じように、ヴァレンティン・ヴォロシノフは、言葉は「社会的標識であり、動的で活動的であり、異なる社会階級、異なる社会的・歴史的状況において、異な る意味や含蓄を獲得することができる」と提唱した。バフチンは、この動的な言語観を文芸批評の分野に投影した。 最後に、形式主義のつながりはマルクス主義批評につながる。形式主義者と新生マルクス主義批評はともに、構造、具体的な資源の集合、作品目録、ジャンルの 体系を、それを生み出す社会的環境と流行の思想から切り離すことができないとみなしている。そして、ここから美的機能が生まれる。社会の産物としての芸術 である。 |

| Otros formalistas En el ámbito hispánico han sido especialmente seguidas las aportaciones de Nicolás Cardozo (1925-1991) en el campo de la crítica literaria, tomando aportes de Tyniánov sobre los métodos literarios y Fernando Lázaro Carreter. En el ámbito ruso, otro de los que más destaca es Ósip Brik (1888-1945). |

その他の形式主義者 スペイン語圏では、ニコラス・カルドゾ(1925-1991)の文芸批評の分野での貢献が特にフォローされており、ティニアノフやフェルナンド・ラサロ・ カレテルから文学的方法についての貢献を受けている。ロシアの分野では、オシップ・ブリク(1888-1945)も著名である。 |

| Ferdinand de Saussure Funcionalismo lingüístico Roland Barthes Semiótica Tzvetan Todorov Yuri Lotman Ósip Brik Tópico literario Formalismo (arte) Formalismo (teoría del arte) Formalismo (música) New Criticism Ezra Pound T.S.Elliot Marxismo Crítica literaria marxista Doctrina Zhdánov |

フェルディナン・ド・ソシュール 言語機能主義 ロラン・バルト 記号論 ツヴェタン・トドロフ ユーリ・ロトマン オシップ・ブリック 文学トピック フォーマリズム(芸術) 形式主義(芸術理論) 形式主義(音楽) 新批評 エズラ・パウンド T.S.エリオット マルクス主義 マルクス主義文芸批評 ジューダノフ・ドクトリン |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Formalismo_ruso |

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

☆

☆

☆