ローマン・ヤコブソン

Roman

Osipovich Jakobson, 1896-1982

ローマン・ヤコブソン

Roman

Osipovich Jakobson, 1896-1982

★ローマン・オシポヴィッチ・ヤコブソン(ロシア語:Рома́н О́сипович

Якобсо́н、1896年10月11日[1]-1982年7月18日[2])はロシア系アメリカの言語学者、文学理論家

■ロマン・ヤコブソン略伝(Roman Osipovich Jakobson, 1896-1982)

1896 モスクワで生まれる

1914 ラザーレフ東洋語研究所 学士相当学位授与

1915 モスクワ言語学サークル・会長(〜1920)

1918 モスクワ大学 修士相当学位授与

1920 モスクワ高等演劇学校 正音学教授

1926 プラハ言語学サークル 副会長(〜1939)

1930 プラハ大学 博士号授与

1933 マサリク大学(チェコスロヴァキア・ブルノ市) 助教授(ロシア文献学)

1934 同大学 客員教授

1937 同大学 副教授(ロシア文献学・古代チェク文学)

1942 高等研究自由学院 (Ecole Libre des Hautes Etudes) 教授(言語学)(〜1946)

1943 コロンビア大学 客員教授(言語学)(〜1946)

1946 コロンビア大学 教授(チェコスロヴァキア学)

1949 ハーバード大学 教授(スラブ語・スラブ文学・一般言語学)(〜1969)

1957 マサチューセッツ工科大学 教授

1982 ケンブリッジ・マサチューセッツで死去(85歳)

★

| Roman

Osipovich Jakobson (Russian: Рома́н О́сипович Якобсо́н;

October 11,

1896[1] – July 18,[2] 1982) was a Russian-American linguist and

literary theorist. A pioneer of structural linguistics, Jakobson was one of the most celebrated and influential linguists of the twentieth century. With Nikolai Trubetzkoy, he developed revolutionary new techniques for the analysis of linguistic sound systems, in effect founding the modern discipline of phonology. Jakobson went on to extend similar principles and techniques to the study of other aspects of language such as syntax, morphology and semantics. He made numerous contributions to Slavic linguistics, most notably two studies of Russian case and an analysis of the categories of the Russian verb. Drawing on insights from C. S. Peirce's semiotics, as well as from communication theory and cybernetics, he proposed methods for the investigation of poetry, music, the visual arts, and cinema. Through his decisive influence on Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roland Barthes, among others, Jakobson became a pivotal figure in the adaptation of structural analysis to disciplines beyond linguistics, including philosophy, anthropology, and literary theory; his development of the approach pioneered by Ferdinand de Saussure, known as "structuralism", became a major post-war intellectual movement in Europe and the United States. Meanwhile, though the influence of structuralism declined during the 1970s, Jakobson's work has continued to receive attention in linguistic anthropology, especially through the ethnography of communication developed by Dell Hymes and the semiotics of culture developed by Jakobson's former student Michael Silverstein. Jakobson's concept of underlying linguistic universals, particularly his celebrated theory of distinctive features, decisively influenced the early thinking of Noam Chomsky, who became the dominant figure in theoretical linguistics during the second half of the twentieth century.[3] |

ローマン・オシポヴィッチ・ヤコブソン(ロシア語:Рома́н

О́сипович Якобсо́н、1896年10月11日[1]-1982年7月18日[2])はロシア系アメリカの言語学者、文学理論家である。 構造言語学のパイオニアであるヤコブソンは、20世紀で最も有名で影響力のある言語学者の一人であった。ニコライ・トルベツコイとともに、言語音体系の分 析のための画期的な新技術を開発し、事実上、現代の音韻論の学問分野を確立した。ヤコブソンは、同様の原理と技術を、構文論、形態論、意味論など、言語の 他の側面の研究にも拡張していった。彼はスラブ言語学に多くの貢献をしたが、中でもロシア語の格に関する2つの研究と、ロシア語の動詞のカテゴリーに関す る分析が有名である。また、C.S.ペリスの記号論やコミュニケーション論、サイバネティクスからの示唆をもとに、詩、音楽、視覚芸術、映画を研究するた めの方法を提案した。 ヤコブソンは、クロード・レヴィ=ストロースやロラン・バルトなどに決定的な影響を与え、構造分析を哲学、人類学、文学など言語学以外の分野に適用する上 で極めて重要な人物となった。フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールが開拓したアプローチを「構造主義」として展開し、戦後の欧米で大きな知的運動となるに至っ た。一方、1970年代に構造主義の影響力は低下したが、ヤコブソンの研究は言語人類学、特にデル・ハイムズが展開したコミュニケーションの民族誌やヤコ ブソンの元教え子マイケル・シルバースタインが展開した文化の記号論を通じて、引き続き注目されている。ヤコブソンの言語的普遍性の概念、特に彼の有名な特徴点理論は、20世紀後半に理論言語学の支 配者となったノーム・チョムスキーの初期の思考に決定的な影響を与えた[3]。 |

| Life and work Jakobson was born in the Russian Empire on 11 October 1896[1] to well-to-do parents of Jewish descent, the industrialist Osip Jakobson and chemist Anna Volpert Jakobson,[1] and he developed a fascination with language at a very young age. He studied at the Lazarev Institute of Oriental Languages and then at the Historical-Philological Faculty of Moscow University.[4] As a student he was a leading figure of the Moscow Linguistic Circle and took part in Moscow's active world of avant-garde art and poetry; he was especially interested in Russian Futurism, the Russian incarnation of Italian Futurism. Under the pseudonym 'Aliagrov', he published books of zaum poetry and befriended the Futurists Vladimir Mayakovsky, Kazimir Malevich, Aleksei Kruchyonykh and others. It was the poetry of his contemporaries that partly inspired him to become a linguist. The linguistics of the time was overwhelmingly neogrammarian and insisted that the only scientific study of language was to study the history and development of words across time (the diachronic approach, in Saussure's terms). Jakobson, on the other hand, had come into contact with the work of Ferdinand de Saussure, and developed an approach focused on the way in which language's structure served its basic function (synchronic approach) – to communicate information between speakers. Jakobson was also well known for his critique of the emergence of sound in film. Jakobson received a master's degree from Moscow University in 1918.[1] |

生涯と仕事 ヤコブソンは1896年10月11日にロシア帝国でユダヤ系の裕福な両親、実業家オシップ・ヤコブソンと化学者アンナ・ヴォルパート・ヤコブソンの間に生 まれ[1]、幼い頃から言語に魅了された。学生時代はモスクワ言語学サークルの中心的存在で、モスクワの活発な前衛芸術や詩の世界に参加し、特にイタリア 未来派のロシア化であるロシア未来派に関心を抱いた[4]。「アリャグロフ」というペンネームで、ザウムの詩集を出版し、未来派のウラジーミル・マヤコフ ス キー、カジミール・マレーヴィチ、アレクセイ・クルキョーニフらと親交を深めた。言語学者を目指すきっかけとなったのは、同時代の詩人たちの詩であった。 当時の言語学は新語法主義が主流で、言葉の歴史や発達を時系列的に研究することだけが科学的な研究であると主張した(ソシュール流に言えば通時的アプロー チ)。一方、ヤコブソンは、フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールの研究に触れ、言語の構造が話者間の情報伝達という基本的な機能をどのように果たしているかに 着目するアプローチ(共時的アプローチ)を展開した。また、映画における音響の出現を批判したことでも知られる。ヤコブソンは1918年にモスクワ大学で 修士号を取得した[1]。 |

| In Czechoslovakia Although he was initially an enthusiastic supporter of the Bolshevik revolution, Jakobson soon became disillusioned as his early hopes for an explosion of creativity in the arts fell victim to increasing state conservatism and hostility.[5] He left Moscow for Prague in 1920, where he worked as a member of the Soviet diplomatic mission while continuing with his doctoral studies. Living in Czechoslovakia meant that Jakobson was physically close to the linguist who would be his most important collaborator during the 1920s and 1930s, Prince Nikolai Trubetzkoy, who fled Russia at the time of the Revolution and took up a chair at Vienna in 1922. In 1926 the Prague school of linguistic theory was established by the professor of English at Charles University, Vilém Mathesius, with Jakobson as a founding member and a prime intellectual force (other members included Nikolai Trubetzkoy, René Wellek and Jan Mukařovský). Jakobson immersed himself in both the academic and cultural life of pre-World War II Czechoslovakia and established close relationships with a number of Czech poets and literary figures. Jakobson received his Ph.D. from Charles University in 1930.[1] He became a professor at Masaryk University in Brno in 1933. He also made an impression on Czech academics with his studies of Czech verse. Roman Jakobson proposed the Atlas Linguarum Europae in the late 1930s, but World War II disrupted this plan and it laid dormant until being revived by Mario Alinei in 1965.[6] |

チェコスロバキア時代 1920年、モスクワからプラハに移り、ソ連外交団の一員として働きながら、博士課程での研究を続けた。チェコスロバキアに住んでいたことで、1920年 代から1930年代にかけて最も重要な協力者となる言語学者、ニコライ・トルベツコイ王子(革命時にロシアから亡命し、1922年にウィーンで教職に就い た)と物理的に近くなることができた。1926年、シャルル大学英語教授ヴィレム・マテシウスによってプラハ言語学派が設立され、ヤコブソンはその創設メ ンバーであり、主要な知的勢力となった(他のメンバーはニコライ・トラベツコイ、ルネ・ヴェレク、ヤン・ムカジェフスキーなど)。ヤコブソンは、第二次世 界大戦前のチェコスロバキアの学術・文化活動に没頭し、多くのチェコの詩人や文学者たちと親密な関係を築いた。1930年にカレル大学で博士号を取得し [1]、1933年にはブルノのマサリク大学の教授に就任した。また、チェコ語の詩の研究により、チェコの学者に印象を残した。 ローマン・ヤコブソンは1930年代後半にAtlas Linguarum Europaeを提案したが、第二次世界大戦でこの計画は中断され、1965年にマリオ・アリネイによって復活するまで休眠状態であった[6]。 |

| Escapes before the war Jakobson escaped from Prague in early March 1939[1] via Berlin for Denmark, where he was associated with the Copenhagen linguistic circle, and such intellectuals as Louis Hjelmslev. He fled to Norway on 1 September 1939,[1] and in 1940 walked across the border to Sweden,[1] where he continued his work at the Karolinska Hospital (with works on aphasia and language competence). When Swedish colleagues feared a possible German occupation, he managed to leave on a cargo ship, together with Ernst Cassirer (the former rector of Hamburg University) to New York City in 1941[1] to become part of the wider community of intellectual émigrés who fled there. |

戦前の逃避行 ヤコブソンは1939年3月初旬にプラハを脱出し[1]、ベルリン経由でデンマークに向かい、そこでコペンハーゲン言語学サークルやルイス・ イェルムスレフのような知識人と関わりを持った。1939年9月1日にノルウェーに逃げ、1940年には国境を越えてスウェーデンに渡り、カロリンスカ病 院で研究を続けた(失語症と言語能力に関する研究を行った)[1]。スウェーデンの同僚たちがドイツの占領を恐れたため、彼はエルンスト・カッシーラー (ハンブルク大学元学長)と共に貨物船で1941年にニューヨークへ逃れることに成功し[1]、ニューヨークから逃れた幅広い知的移住者のコミュニティの 一員となる。 |

| Career in the United States and

later life In New York, he began teaching at The New School, still closely associated with the Czech émigré community during that period. At the École libre des hautes études, a sort of Francophone university-in-exile, he met and collaborated with Claude Lévi-Strauss, who would also become a key exponent of structuralism. He also made the acquaintance of many American linguists and anthropologists, such as Franz Boas, Benjamin Whorf, and Leonard Bloomfield. When the American authorities considered "repatriating" him to Europe, it was Franz Boas who actually saved his life.[citation needed] After the war, he became a consultant to the International Auxiliary Language Association, which would present Interlingua in 1951. In 1949[1] Jakobson moved to Harvard University, where he remained until his retirement in 1967.[1] His universalizing structuralist theory of phonology, based on a markedness hierarchy of distinctive features, achieved its canonical exposition in a book published in the United States in 1951, jointly authored by Roman Jakobson, C. Gunnar Fant and Morris Halle.[7] In the same year, Jakobson's theory of 'distinctive features' made a profound impression on the thinking of young Noam Chomsky, in this way also influencing generative linguistics.[8] He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1960.[9] In his last decade, Jakobson maintained an office at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he was an honorary Professor Emeritus. In the early 1960s Jakobson shifted his emphasis to a more comprehensive view of language and began writing about communication sciences as a whole. He converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity in 1975.[10] Jakobson died in Cambridge, Massachusetts on 18 July 1982.[1] His widow died in 1986. His first wife, who was born in 1908, died in 2000. |

アメリカでのキャリアとその後の人生 ニューヨークでは、ニュースクールで教鞭をとり、当時はまだチェコ移民のコミュニティと密接に関係していた。亡命フランス語大学のようなものであったエ コール・リーブル・デ・オート・エテュードでは、後に構造主義の重要な提唱者となるクロード・レヴィ=ストロースと出会い、共同研究を行う。また、フラン ツ・ボース、ベンジャミン・ウォーフ、レナード・ブルームフィールドなど、多くのアメリカの言語学者、人類学者と知り合うことができた。戦後は国際補助語 協会の顧問となり、1951年にインターリングアを発表することになる。 1949年[1]、ヤコブソンはハーバード大学に移り、1967年に退職するまで在籍した[1]。特徴的な特徴の顕著性階層に基づく、彼の普遍化した構造 主義の音韻論は、1951年に米国で出版された、ローマン・ヤコブソン、C. Gunnar Fant、Morris Halの共著でその正統な解説に到達している。同年、ヤコブソンの「顕著な特徴」理論は、若き日のノーム・チョムスキーの思考に大きな影響を与え、生成言 語学にも影響を与えた[8]。 1960年にオランダ王立芸術科学アカデミー外国人会員に選出された[9]。 晩年の10年間は、マサチューセッツ工科大学にオフィスを構え、名誉教授を務めていた。1960年代初頭、ヤコブソンは言語のより包括的な見方に重点を移 し、コミュニケーション科学全体について執筆するようになった。1975年に東方正教会に改宗している[10]。 1982年7月18日にマサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジで死去した[1]。1986年に未亡人が死去した。1908年生まれの最初の妻は2000年に亡く なっている。 |

| Intellectual contributions According to Jakobson's own personal reminiscences, the most decisive stage in the development of his thinking was the period of revolutionary anticipation and upheaval in Russia between 1912 and 1920, when, as a young student, he fell under the spell of the celebrated Russian futurist wordsmith and linguistic thinker Velimir Khlebnikov.[11] Offering a slightly different picture, the preface to the second edition of The Sound Shape of Language argues that this book represents the fourth stage in "Jakobson's quest to uncover the function and structure of sound in language."[12] The first stage was roughly the 1920s to 1930s where he collaborated with Trubetzkoy, in which they developed the concept of the phoneme, and elucidated the structure of phonological systems. The second stage, from roughly the late 1930s to the 1940s, during which he developed the notion that "binary distinctive features" were the foundational element in language, and that such distinctiveness is "mere otherness" or differentiation.[12] In the third stage in Jakobson's work, from the 1950s to 1960s, he worked with the acoustician C. Gunnar Fant and Morris Halle (a student of Jakobson's) to consider the acoustic aspects of distinctive features. |

知的貢献 ヤコブソンの個人的な回想によれば、彼の思考の発展における最も決定的な段階は、1912年から1920年にかけてのロシアにおける革命的な予期と激動の 時期であり、若い学生として、著名なロシアの未来派の言葉使いであり言語思想家であるヴェリミール・フレーブニコフに魅了された時である[11]。 少し異なるイメージを提供するものとして、『The Sound Shape of Language』第2版の序文では、本書は「言語における音の機能と構造を明らかにするヤコブソンの探求」の第4段階を代表するものであると論じている [12] 第1段階は、およそ1920年代から1930年代にトルベツコイと共同して、音素の概念を発展させて、音韻体系の構造を明らかにするところであった。第二 段階は、おおよそ1930年代後半から1940年代にかけてで、「二元的な特徴」が言語の基礎的要素であり、そのような識別性は「単なる他者性」あるいは 分化であるという考え方を展開した[12] ヤコブソンの研究の第三段階は、1950年代から1960年代に、音響学者C・ガンナー・ファントやモリス・ハレ(ヤコブソンの学生)と共に特徴量の音響 的側面を検討したものであった。 |

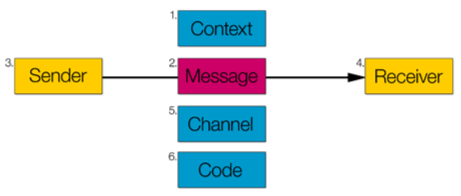

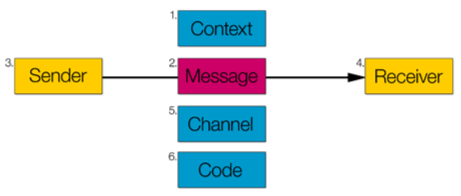

| The communication functions Influenced by the Organon-Model by Karl Bühler, Jakobson distinguishes six communication functions, each associated with a dimension or factor of the communication process [n.b. – Elements from Bühler's theory appear in the diagram below in yellow and pink, Jakobson's elaborations in blue]:  Functions Functionsreferential (: contextual information) aesthetic/poetic (: auto-reflection) emotive (: self-expression) conative (: vocative or imperative addressing of receiver) phatic (: checking channel working) metalingual (: checking code working)[13] |

コミュニケーション機能 ヤコブソンは、カール・ビューラーによるオルガノンモデルの影響を受けて、6つのコミュニケーション機能を区別し、それぞれがコミュニケーションプロセス の次元や要因に関連している[注:下の図では、ビューラーの理論の要素が黄色とピンクで、ヤコブソンの精緻化が青で表示されている]。  機能 機能参照(:文脈情報) 美的/詩的(:自己反省) 感情的(:自己表現) Conative(:受け手への呼びかけ、命令形) ファティック(:チャンネル操作の確認) メタリンガル(:コードの確認)[13]。 |

| One of the six functions is always the dominant function in a text and usually related to the type of text. In poetry, the dominant function is the poetic function: the focus is on the message itself. The true hallmark of poetry is according to Jakobson "the projection of the principle of equivalence from the axis of selection to the axis of combination". Very broadly speaking, it implies that poetry successfully combines and integrates form and function, that poetry turns the poetry of grammar into the grammar of poetry, so to speak. Jakobson's theory of communicative functions was first published in "Closing Statements: Linguistics and Poetics" (in Thomas A. Sebeok, Style In Language, Cambridge Massachusetts, MIT Press, 1960, pp. 350–377). Despite its wide adoption, the six-functions model has been criticized for lacking specific interest in the "play function" of language that, according to an early review by Georges Mounin, is "not enough studied in general by linguistics researchers".[14] | 6

つの機能のうち1つは、常にテキストの中で支配的な機能であり、通常、テキストの種類に関係する。詩の場合、支配的な機能は詩的機能であり、メッセージそ

のものに焦点が当てられている。ヤコブソンによれば、詩の真の特徴は「等価性の原理を、選択の軸から組み合わせの軸に投影すること」である。非常に大雑把

に言えば、詩が形式と機能をうまく組み合わせ、統合していること、いわば詩が文法の詩を詩の文法に変えていることを意味しているのである。ヤコブソンのコ

ミュニケーション機能論は、「クロージング・ステートメンツ」で初めて発表された。Linguistics and Poetics" (in

Thomas A. Sebeok, Style In Language, Cambridge Massachusetts, MIT

Press, 1960, pp. 350-377)

に掲載された。広く採用されているにもかかわらず、6機能モデルはジョルジュ・ムーニンによる初期のレビューによれば「言語学の研究者によって一般的に十

分に研究されていない」言語の「遊びの機能」に対する特定の関心を欠いていると批判されてきた[14]。 |

| Legacy Jakobson's three principal ideas in linguistics play a major role in the field to this day: linguistic typology, markedness, and linguistic universals. The three concepts are tightly intertwined: typology is the classification of languages in terms of shared grammatical features (as opposed to shared origin), markedness is (very roughly) a study of how certain forms of grammatical organization are more "optimized" than others, and linguistic universals is the study of the general features of languages in the world. He also influenced Nicolas Ruwet's paradigmatic analysis.[13] Jakobson has also influenced Friedemann Schulz von Thun's four sides model, as well as Michael Silverstein's metapragmatics, Dell Hymes's ethnography of communication and ethnopoetics, the psychoanalysis of Jacques Lacan, and philosophy of Giorgio Agamben. Jakobson's legacy among researchers specializing in Slavics, and especially Slavic linguistics in North America, has been enormous, for example, Olga Yokoyama. |

レガシー(遺産) ヤコブソンの言語学における3つの主要な考え方は、言語類型論、顕著性、言語的普遍性という、今日までこの分野で大きな役割を担っている。この3つの概念 は密接に絡み合っており、類型論は(起源を共有するのではなく)文法的特徴を共有する観点から言語を分類すること、顕著性は(非常に大まかに言えば)ある 文法構成の形態が他よりもいかに「最適化」されているかという研究、言語普遍性は世界の言語の一般的特徴に関する研究である。彼はニコラ・ルウェのパラダ イム分析にも影響を与えた[13]。 ヤコブソンはフリーデマン・シュルツ・フォン・トゥーンの4面モデルや、マイケル・シルバースタインのメタ語用論、デル・ハイムズのコミュニケーションと エスノポエティックスの民族誌、ジャック・ラカンの精神分析、ジョルジョ・アガンベンの哲学にも影響を及ぼしている[13]。 スラブ語、特に北米のスラブ言語学を専門とする研究者の間でヤコブソンが残した遺産は膨大であり、例えば、オルガ・ヨコヤマがいる。 |

| Bibliography Jakobson R., Remarques sur l'evolution phonologique du russe comparée à celle des autres langues slaves. Prague, 1929 (Annotated English translation by Ronald F. Feldstein: Remarks on the Phonological Evolution of Russian in Comparison with the Other Slavic Languages. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA and London, 2018.)[15] Jakobson R., K charakteristike evrazijskogo jazykovogo sojuza. Prague, 1930 Jakobson R., Child Language, Aphasia and Phonological Universals, 1941 Jakobson R., On Linguistic Aspects of Translation, essay, 1959 Jakobson R., "Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics," in Style in Language (ed. Thomas Sebeok), 1960 Jakobson R., Selected Writings (ed. Stephen Rudy). The Hague, Paris, Mouton, in six volumes (1971–1985): I. Phonological Studies, 1962 II. Word and Language, 1971 III. The Poetry of Grammar and the Grammar of Poetry, 1980 IV. Slavic Epic Studies, 1966 V. On Verse, Its Masters and Explores, 1978 VI. Early Slavic Paths and Crossroads, 1985 VII. Contributions to Comparative Mythology, 1985 VIII. Major Works 1976–1980. Completion Volume 1, 1988 IX.1. Completion, Volume 2/Part 1, 2013 IX.1. Completion, Volume 2/Part 2, 2014 Jakobson R., Questions de poetique, 1973 Jakobson R., Six Lectures of Sound and Meaning, 1978 Jakobson R., The Framework of Language, 1980 Jakobson R., Halle M., Fundamentals of Language, 1956 Jakobson R., Waugh L., The Sound Shape of Language, 1979 Jakobson R., Pomorska K., Dialogues, 1983 Jakobson R., Verbal Art, Verbal Sign, Verbal Time (ed. Krystyna Pomorska and Stephen Rudy), 1985 Jakobson R., Language in Literature,( ed. Krystyna Pomorska and Stephen Rudy), 1987 Jakobson R. "Shifters and Verbal Categories." On Language. (ed. Linda R. Waugh and Monique Monville-Burston). 1990. 386–392. Jakobson R., La Génération qui a gaspillé ses poètes, Allia, 2001. |

参考文献 ヤコブソン、R.、ロシア語の音韻論的進化について、他のスラブ諸言語と比較した考察。プラハ、1929年(ロナルド・F・フェルドスタインによる注釈付 き英訳:ロシア語の音韻論的進化について、他のスラブ諸言語と比較した考察。MIT Press:マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジおよびロンドン、2018年)[15] ヤコブソン、R.、K. 特徴的なユーラシア言語の統合。プラハ、1930年 ヤコブソン、R.、幼児語、失語症、音韻論的普遍性、1941年 ヤコブソン、R.、翻訳の言語学的側面について、エッセイ、1959年 ヤコブソン R., 「結語:言語学と詩学」『言語のスタイル』(トーマス・セボック編)、1960年 ヤコブソン R., 『ヤコブソン著作集』(スティーブン・ルディ編)。ハーグ、パリ、ムートン社、全6巻(1971年~1985年): I. 音韻論的研究、1962年 II. 語と言語、1971年 III. 詩の文法と文法の詩、1980年 IV. スラブ叙事詩研究、1966年 V. 詩について、その巨匠たちと探求、1978年 VI. 初期スラブの道と岐路、1985年 VII. 比較神話学への貢献、1985年 VIII. 主要作品 1976年~1980年。 完成 第1巻、1988年 IX.1. 完成 第2巻/第1部、2013年 IX.1. 完成 第2巻/第2部、2014年 ヤコブソンR.、詩学に関する問題、1973年 ヤコブソン、音と意味の6講、1978年 ヤコブソン、言語の枠組み、1980年 ヤコブソン、ホール、言語の基礎、1956年 ヤコブソン、ウォー、言語の音の形、1979年 ヤコブソン、ポモルスカ、対話、1983年 ヤコブソン、R. 『言語芸術、言語記号、言語時間』(編:クリスティーナ・ポモルスカ、スティーブン・ルディー)、1985年 ヤコブソン、R. 『文学における言語』(編:クリスティーナ・ポモルスカ、スティーブン・ルディー)、1987年 ヤコブソン R. 「シフトと言語カテゴリー」『言語について』リンダ・R・ウォー、モニーク・モンヴィル=バーストン編、1990年、386-392ページ。 ヤコブソン R. 『詩人を浪費した世代』Allia、2001年。 |

| References Esterhill, Frank (2000). Interlingua Institute: A History. New York: Interlingua Institute. Further reading Armstrong, D., and van Schooneveld, C.H., Roman Jakobson: Echoes of His Scholarship, 1977. Brooke-Rose, C., A Structural Analysis of Pound's 'Usura Canto': Jakobson's Method Extended and Applied to Free Verse, 1976. Caton, Steve C., "Contributions of Roman Jakobson", Annual Review of Anthropology, vol 16: pp. 223–260, 1987. Culler, J., Structuralist Poetics: Structuralism, Linguistics, and the Study of Literature, 1975. Groupe μ, Rhétorique générale, 1970. [A General Rhetoric, 1981] Holenstein, E., Roman Jakobson's Approach to Language: Phenomenological Structuralism, Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press, 1975. Ihwe, J., Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik. Ergebnisse und Perspektiven, 1971. Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C., L'Enonciation: De la subjectivité dans le langage, 1980. Knight, Chris. "Russian Formalism", chapter 10 in Decoding Chomsky: Science and revolutionary politics (pbk), London & New Haven: Yale University Press. Koch, W. A., Poetry and Science, 1983. Le Guern, M., Sémantique de la metaphore et de la métonymie, 1973. Lodge, D., The Modes of Modern Writing: Metaphor, Metonymy, and the Typology of Modern Literature, 1977. Riffaterre, M., Semiotics of Poetry, 1978. Steiner, P., Russian Formalism: A Metapoetics, 1984. Todorov, T., Poétique de la prose, 1971. Waugh, L., Roman Jakobson's Science of Language, 1976. |

参考文献 Esterhill, Frank (2000). Interlingua Institute: A History. New York: Interlingua Institute. その他の参考文献 Armstrong, D., and van Schooneveld, C.H., Roman Jakobson: Echoes of His Scholarship, 1977. Brooke-Rose, C., A Structural Analysis of Pound's 'Usura Canto': Jakobson's Method Extended and Applied to Free Verse, 1976. Caton, Steve C., 「Contributions of Roman Jakobson」, Annual Review of Anthropology, vol 16: pp. 223–260, 1987. カラー、J.著『構造主義詩学:構造主義、言語学、文学研究』1975年 グループレット著『一般修辞学』1970年 [『A General Rhetoric』1981年] ホーレンシュタイン著『ロマン・ヤコブソンの言語へのアプローチ:現象学的構造主義』ブルーミントンおよびロンドン:インディアナ大学出版、1975年 Ihwe, J., Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik. Ergebnisse und Perspektiven, 1971. Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C., L'Enonciation: De la subjectivité dans le langage, 1980. Knight, Chris. 「Russian Formalism」, chapter 10 in Decoding Chomsky: Science and revolutionary politics (pbk), London & New Haven: Yale University Press. Koch, W. A., Poetry and Science, 1983. Le Guern, M., Sémantique de la metaphore et de la métonymie, 1973. Lodge, D., The Modes of Modern Writing: Metaphor, Metonymy, and the Typology of Modern Literature, 1977. リファテッレ、M.『詩の記号論』1978年 スタイナー、P.『ロシア・フォルマリズム:メタ詩学』1984年 トドロフ、T.『散文の詩学』1971年 ウォー、L.『ロマン・ヤコブソンの言語学』1976年 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Jakobson |

****

| Jakobsons

Beitrag zur Literaturwissenschaft und Poetik Ausgehend von Erkenntnissen aus der Phonologie wendet Jakobson linguistische Konzepte auf die Poesie an und erklärt: „Poesie ist Sprache in ihrer ästhetischen Funktion“. In seiner Schrift Die neueste russische Poesie schreibt er: „Die Einstellung auf den Ausdruck, auf die sprachliche Masse ist das einzige für die Poesie wesentliche Moment.“ Dabei meint Ausdruck den aus der Form hervorgehenden Sinn. Die Funktion der Sprache als Sozialkontakt reduziert sich in der Poesie auf ein Minimum. Jakobson hebt immer die Unterschiede zwischen praktischer und poetischer Sprache hervor. Gegenstand der Literaturwissenschaften und der Poesie ist nach Jakobson die Literarizität (später nannte er sie Poetizität), das meint den Faktor, der einen Text zu einem literarischen Kunstwerk macht. Jakobson meint, die Art und Weise, wie die Laute miteinander verbunden sind, also der lautliche Stoff der Sprache, sei für die Sinnhaftigkeit einer Aussage ausschlaggebend. Die Unterscheidung zwischen Phonetik und Phonologie hat bei diesem Gedanken Pate gestanden. Bei der Analyse poetischer Texte spielt für ihn die intersubjektive Absicherung eine bedeutende Rolle, um Vergleichbarkeit und Prüfbarkeit zu gewährleisten. Das Subjekt ist, wie schon bei Humboldt, nur untergeordnet wichtig, da die Sprache nur ihren eigenen Regeln gehorcht und das bewusste Sprachverhalten des Subjekts untergraben oder gar entwerten kann. Für die Geschichte der Linguistik war seine Unterscheidung (sowohl auf lexikalischer, als auch auf semantischer Ebene) zwischen Merkmalhaftigkeit und Merkmallosigkeit maßgeblich. Während etwa der Begriff „Katze“ einen merkmallosen Begriff darstellt, ist das Wort „Kater“ als merkmalhaft anzusehen (mit „Katze“ bezeichnen wir das Tier an sich, eine geschlechtsspezifische Angabe ist nicht klar ersichtlich, während wir mit „Kater“ ausschließlich männliche Katzen bezeichnen). Nach Jakobson zeigt sich die poetische Sprache als besonders merkmalhaft gegenüber der merkmallosen, „normalen“ Sprache. Die von ihm begründete poetische Funktion von Sprache macht literarische Texte der linguistischen Analyse zugänglich. In seinen Werken zu diesem Thema hält er am Formalismus fest. Kritiker warfen ihm vor, diese Betrachtungsweise hindere ihn daran, das Wesen der Poesie zu erfassen. Indem er die Sprache als Träger des Unbewussten identifiziert, bringt er eine wichtige Vorleistung für die spätere Entwicklung der Psychoanalyse. Jakobson meint außerdem, dass wir stets die poetisch passenden Worte aus vielen äquivalenten Worten wählen. Wir entscheiden nach phonologischen Kriterien, die die Bedeutung der Aussage lautsemantisch färben. Durch diese Identifizierung der Poesie als Kunst, die der Ausgangspunkt jeder wissenschaftlichen Analyse über die Grundlagen der Sprache sein soll, privilegiert er sie deutlich gegenüber allen anderen literarischen Formen, was ihm ebenfalls häufig vorgeworfen wurde. „Die in der morphologischen und syntaktischen Struktur der Sprache verborgene Quelle der Poesie, kurz die Poesie der Grammatik und ihr literarisches Produkt, die Grammatik der Poesie, sind den Kritikern selten bekannt, wurden von den Linguisten fast gänzlich übersehen und von schöpferischen Schriftstellern meisterhaft gehandhabt.“ – Roman Jakobson: Jakobson 1979: S. 116 |

ヤコブソンの文学研究と詩学への貢献 音韻論の知見に基づき、ヤコブソンは言語学の概念を詩に適用し、「詩とは、その美的 機能における言語である」と説明している。彼のエッセイ「最新のロシア詩」では、「表現、言語の質量に重点を置くことが、詩にとって唯一の 本質的な瞬間である」と書いている。この文脈において、表現とは形式から生じる意味を指す。詩においては、社会的な接触の手段としての言語の機能は最小限 に抑えられる。ヤコブソンは常に実用的な言語と詩的な言語の違いを強調している。ヤコブソンによると、文学研究と詩の主題は文学性(後に彼はそれを詩性と 呼んだ)であり、これはテキストを文学的な芸術作品とする要因を指す。ヤコブソンは、音の組み合わせ方、すなわち言語の音声的要素が、文の意味を伝える上 で極めて重要であると考えた。音声学と音韻論の区別は、この考えから生まれた。 詩のテキストを分析する際には、比較可能性と検証可能性を確保するために、彼にとって主観間の検証が重要な役割を果たす。主題は、フンボルトと同様に、二 次的な重要性しか持たない。なぜなら、言語は独自のルールに従うだけであり、主題の意識的な言語行動を損なう、あるいは価値を下げることさえあり得るから だ。 彼の特性と特徴のないものとの区別(語彙レベルと意味レベルの両方)は、言語学の歴史において極めて重要であった。例えば、「cat」という語は特徴を持 たないが、「tomcat」という語は特徴を持つと考えられる(「cat」という語は動物そのものを指すために使用され、性別を特定するような意味合いは 明確ではないが、「tomcat」という語は雄猫のみを指すために使用される)。ヤコブソンによれば、詩的な言語は特徴を持たない「通常の」言語と比較し て、特に特徴的である。 彼が確立した言語の詩的機能により、文学作品は言語分析に利用可能となった。このテーマに関する彼の作品では、形式主義に固執している。批評家たちは、彼 がこのアプローチを取ることで詩の本質を理解することを妨げていると非難した。 言語を無意識の伝達手段とみなすことで、ヤコブソンは後の精神分析の発展に重要な貢献をした。ヤコブソンはまた、私たちは常に多くの同義語の中から詩的に 適切な言葉を選ぶと考えている。私たちは音韻論的な基準に基づいて決定し、音韻論の観点から文の意味を色付けする。 言語の基礎に関するあらゆる科学的分析の出発点となるべき芸術として詩を位置づけることで、彼は明らかに、他のあらゆる文学形式よりも詩を優遇している。 この見解もまた、しばしば批判されてきた。 「言語の形態論的・統語論的構造に隠された詩の源泉、つまり文法の詩、その文学的産物である詩の文法は、批評家にはほとんど知られておらず、言語学者には ほぼ完全に無視されてきたが、創造的な作家たちによって見事に扱われてきた。」 – ローマン・ヤコブソン:Jakobson 1979: p. 116 |

| Der Strukturalismus nach Jakobson Jakobson war Anhänger der strukturalistischen Schule, zunächst des Prager Strukturalistenkreises, und leistete wertvolle Beiträge zu deren Weiterentwicklung. Nach strukturalistischer Denkweise werden Gegenstände durch ihre Beziehung zu anderen Elementen des Systems konstituiert, die ohne dieses nicht existieren könnten und in ihren Eigenschaften beschrieben werden sollen. Der Prager Strukturalismus hält funktionale Erklärungen für immanente Erklärungen und stellt sich somit gegen das vorherrschende Bild mechanisch-kausaler Beziehungen. Jakobson soll anlässlich des ersten Internationalen Linguistenkongresses 1929 in einer Rede den Begriff des Strukturalismus eingeführt haben, was jedoch von mehreren Seiten bestritten wird. Die Betrachtung der Struktur als linguistische Interpretationsmethode ist als Abwendung vom vorherrschenden Positivismus und Atomismus der Junggrammatiker zu sehen. Charakteristisch für den Prager Strukturalismus zwischen 1929 und 1939 ist eine Linguistik, die von der Einbettung und dem Ursprung in alltäglichen Erfahrungen und Fragestellungen ausgeht. Zum Verhältnis der Linguistik gegenüber anderen Wissenschaften meinte Jakobson, die Wechselbeziehungen zwischen den Humanwissenschaften fänden in der Linguistik ihren Mittelpunkt und diese fungiere als die progressivste und exakteste unter den Humanwissenschaften als Modell für alle übrigen dieser Disziplin. Diese Bedeutung der Errungenschaften der Linguistik für andere Wissenschaftsfelder hebt er in seinen Werken immer wieder hervor. Als Grundlage für die Interpretation poetischer Texte sieht er die Mehrdeutigkeit. Jakobson prägte auch die Begriffe Ikonizität (Ähnlichkeit) und Kontrast (Indexikalität). Diese lassen sich schließlich auf paradigmatischer bzw. syntagmatischer Achse ansiedeln (siehe Paradigma bzw. Syntagma). Jakobson unterscheidet außerdem zwischen Metapher und Metonymie. Diese sogenannte „binaristische Grundstruktur“ der Sprache ist allen sprachlichen Operationen eigen. |

ヤコブソンの構造主義 ヤコブソンは構造主義派の信奉者であり、当初はプラハ構造主義サークルのメンバーであった。そして、そのさらなる発展に多大な貢献をした。構造主義の考え 方によると、対象はシステム内の他の要素との関係によって構成され、それらなしには存在できず、その特性が記述される。プラハ・ストラクチュラリズムは、 機能的な説明を内在的な説明とみなし、機械的因果関係という一般的な見解に反対している。ヤコブソンは1929年の第1回国際言語学会議での講演で「スト ラクチュラリズム」という用語を導入したとされるが、これには異論もある。 構造を言語学的な解釈方法として考察することは、当時の実証主義や原子論的な考え方から離れることと見なされる。1929年から1939年にかけてのプラ ハ構造主義の主な特徴は、日常的な経験や疑問から出発する言語学である。言語学とその他の科学との関係について、ヤコブソンは、人文科学の相互関係の中心 は言語学にあり、言語学は人文科学の中でも最も進歩的で正確な学問であるため、他のすべての学問のモデルとなる、と信じていた。彼は、自身の著作の中で、 言語学の成果が他の科学分野にとって重要であることを繰り返し強調した。 彼は、詩のテキストの解釈の基礎として曖昧性を重視している。ヤコブソンはまた、「イコノシティ(類似性)」と「コントラスト(指示性)」という用語を考 案した。これらは最終的には、パラダイム軸またはシナグマ軸(パラダイムまたはシナグマを参照)によって分類することができる。ヤコブソンはまた、メタ ファーとメトニミーを区別している。この言語のいわゆる「二元論的基礎構造」は、すべての言語操作に内在している。 |

| Unterschiede zu gängigen

Konzepten des Strukturalismus Jakobsons Strukturalismus unterscheidet sich in wesentlichen Punkten von den Ansichten de Saussures. So widerspricht er ihm etwa bei der Arbitrarität der Zeichen und spricht sich für eine Betrachtung des Objekts bei der Einbettung in das Regelsystem aus, das die Willkürlichkeit einschränkt. Die Regeln des sprachlichen Codes sieht er als Merkmale aller Sprachen, so etwa grundlegende Eigenschaften wie die Trennung von Vokal und Konsonant. Ein radikaler Unterschied zu anderen Sichtweisen zeigt sich auch in der Betrachtungsweise von An- und Abwesenheit von Objekten. Diese wären ohne die Existenz des jeweils anderen nicht bestimmbar (als Beispiel dafür ist die Gebundenheit nasaler Vokale an nasale Konsonanten und orale Vokale zu erwähnen). In diesem Sinne sind alle Zeichen nach Jakobson in einer gewissen Weise motiviert, unmotivierte Zeichen existieren nicht. Außerdem vertritt er im Gegensatz zu den Ansichten Saussures die Meinung, dass Synchronie und Diachronie eine untrennbare dynamische Einheit bilden. Als Differenz zum amerikanischen Strukturalismus kann die duale Betrachtungsweise zu Code und Nachricht und das Festhalten am Funktionalismus gesehen werden. Indem er auf die dynamischen Aspekte sowohl der Synchronie als auch der Diachronie hinweist, meint er, dass Synchronie und Diachronie keine unüberwindbaren Antithesen darstellen. „Die Elimination der Statik, die Vertreibung des Absoluten, das ist der wesentliche Zug der neuen Zeit, die Frage nach brennender Aktualität. Gibt es eine absolute Ruhe, und sei es auch nur in der Form eines absoluten Begriffs ohne reale Existenz in der Natur, aus dem Relativitätsprinzip folgt, dass es keine absolute Ruhe gibt.“ – Roman Jakobson: Jakobson 1988: S. 44 Aus dieser Aussage lässt sich Jakobsons Hang zur Relativität, also gegen die Dinge, wie wir sie nur aus unserer bestimmten Perspektive heraus sehen, erkennen. Ein schwerwiegender Unterschied zum romantischen Strukturalismus zeigt sich in Jakobsons Ansichten über die Funktionen des Individuums, indem er dem gängigen Bild des individuellen Empfindens und dessen Orientierung an der Hermeneutik widerspricht und das Subjekt nur als eine Funktion unter vielen erwähnt. |

現在の構造主義の概念との相違点 ヤコブソンの構造主義は、ド・ソーシュールの見解とは重要な点で異なっている。例えば、ヤコブソンは記号の恣意性についてド・ソーシュールと意見を異に し、恣意性を制限する規則の体系に埋め込まれた対象を考慮することに賛成している。ヤコブソンは、言語コードの規則を、母音と子音の分離のような基本的な 特性など、あらゆる言語の特徴として捉えている。 ヤコブソンの対象の有無に対する見方にも、他の視点とは根本的に異なる点が見られる。 これらは、他方の存在なしには定義できない(例:鼻母音と鼻子音、口母音の関係)。この意味において、ヤコブソンによれば、すべての記号はある意味で動機 づけられている。動機のない記号は存在しない。さらに、ソシュールの見解とは対照的に、ヤコブソンは共時性と通時性は不可分の動的な統一体をなすものであ ると主張している。コードとメッセージに対する二重のアプローチと機能主義への固執は、アメリカ構造主義との相違点として見ることができる。同期性と非同 期性の両方の動的な側面を指摘することで、同期性と非同期性は乗り越えられない対立概念ではないと彼は考えている。 「静的なものの排除、絶対的なものの追放、それが新しい時代の重要な特徴であり、燃えるような今日的な問題である。もし絶対的な静止が存在するとすれば、 それが自然界に実在しない絶対的概念の形だけだとしても、相対性の原理からすれば、絶対的な静止は存在しないということになる。」 – ロマン・ヤコブソン:Jakobson 1988: p. 44 ヤコブソンの相対性への傾倒、すなわち、物自体は我々の特定の視点からしか見えないという考えは、この発言から見て取れる。ロマン主義的構造主義との大き な違いは、ヤコブソンが個々の機能に関する見解において、解釈学に対する一般的な個々の感情とその志向性というイメージに異を唱え、主題を多くの機能のう ちの1つとしてのみ言及している点にある。 |

| Phänomenologischer

Strukturalismus „Strukturalismus heißt, nach Jakobson, Phänomene als ein strukturiertes Ganzes zu betrachten und die statischen oder dynamischen Gesetze dieses Systems freizulegen.“ (Pichler 1991, S. 101) Somit schließt er an Husserls Ansichten über die Phänomenologie der Sprache an. In seinen Werken bezieht sich Jakobson auch oftmals auf Holenstein, indem die Phänomenologie als Fundamentalbetrachtung für den Strukturalismus fungiert. Er sieht in jedem Begriff eine phänomenologische Bestimmung. Jakobson berücksichtigt unter anderem die subjektorientierten Fragestellungen und die Abhängigkeit der Urteilenden von ihrem jeweiligen Standpunkt. Er spricht sich für die „Einklammerung des Unwesentlichen“, anstatt der „Anhäufung und Synthese vorhandenen Wissens“ aus und meint, dadurch den Gegenstand an sich betrachten zu können. Hierbei spielt jedoch die Einstellung des Beobachters eine maßgebliche Rolle. Diese phänomenologische Einstellung stellt für Jakobson ein unbestreitbares Faktum dar, das für die Dominanz der einen oder anderen Sprachfunktion entscheidend ist. Das strenge Festhalten an der Phänomenologie und die daraus resultierende Ausblendung des Kontextes provozierte schließlich den Poststrukturalismus als Gegenbewegung. |

現象学的構造主義 「ヤコブソンによれば、構造主義とは、現象を構造化された全体として捉え、そのシステムの静的または動的な法則性を明らかにすることである。」 (Pichler 1991, p. 101)このようにして、彼は言語の現象学に関するフッサールの見解と結びついている。彼の作品では、ヤコブソンもまた、現象学が構造主義の根本的な考察 として作用しているという点で、ホルシュタインを頻繁に参照している。彼はあらゆる概念に現象学的決定を見出している。 ヤコブソンは、とりわけ、主題志向的な問いや、それぞれの視点に依存する裁判官の立場を考慮している。彼は「既存の知識を蓄積し、統合する」のではなく、 「本質的でないものを排除する」ことを主張し、それによって対象そのものを見つめることができると考えている。しかし、この文脈においては観察者の態度が 重要な役割を果たす。ヤコブソンにとって、この現象学的態度は、言語機能の優位性を決定する疑いのない事実である。現象学に厳格に従うこと、およびその結 果として文脈が排除されることは、最終的にポスト構造主義という対抗運動を引き起こした。 |

| Formalismus – Strukturalismus Die 1928 von Jakobson und Tynjanow postulierten Prager Thesen weisen die mechanistischen Ansätze des russischen Formalismus, die Analyse durch Klassifizierung und Terminologisierung ersetzen, zurück und stellen somit den Übergang zum Strukturalismus dar. Der Wunsch nach einer Zerstückelung des Wissens solle abgelegt werden und ganzheitlichen Verfahren und Betrachtungsweisen weichen. Dennoch lässt sich aus Jakobsons Werken ein gewisser Hang zum Hegelianismus und damit eine Verbindung zum russischen Denken auffinden. Immer wieder distanziert er sich zwar vom Formalismus, also von einseitiger Betrachtung eines einzelnen Aspekts, dennoch sind Spuren seiner anfänglichen Prägung durch diese Schule in seinem Werk zu erkennen. Jakobson macht auch auf die Notwendigkeit der ganzheitlichen Untersuchung sowohl in der Linguistik, als auch in der Poetik aufmerksam. Er ersetzt das mechanische Verfahren durch die Konzeption eines zielorientierten Systems. Außerdem meint er in Bezug auf den teleologischen Charakter der poetischen Sprache, dass dieser sowohl bei der Poesie als auch in der Alltagssprache offensichtlich sei. |

フォルマリズム - 構造主義 1928年にヤコブソンとティンジャノフが提唱した「プラハ・テーゼ」は、分析を分類や用語に置き換えるロシア・フォルマリズムの機械論的アプローチを否 定し、構造主義への移行を表明した。知識の断片化への欲求は放棄され、全体論的な方法やアプローチに道を譲るべきである。とはいえ、ヤコブソンの作品には ヘーゲル主義的な傾向が認められ、ロシア思想とのつながりも見られる。ヤコブソンはフォルマリズム、すなわち単一の側面を一方的に考察するアプローチから 自らを繰り返し遠ざけているが、彼の作品には、この学派の影響の痕跡が依然として認められる。ヤコブソンはまた、言語学と詩学の両方において、全体論的ア プローチの必要性を指摘している。彼は機械的な方法を目的志向的なシステムの概念に置き換えている。さらに、詩的言語の目的論的な性格について、これは詩 と日常言語の両方に明らかであると考えている。 |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Ossipowitsch_Jakobson |

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆