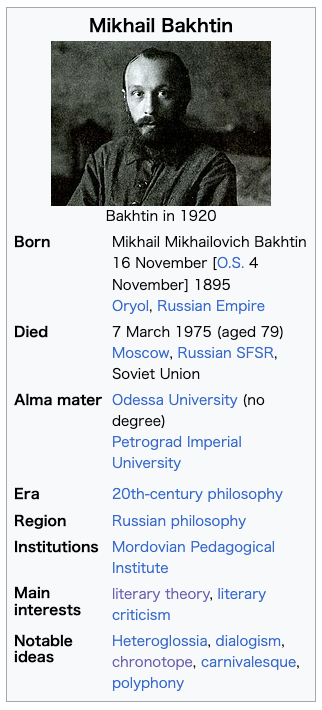

ミハイル・ミハイロビッチ・バフチン

Михаил Михайлович

Бахти́н, Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin, 1895-1975

弁士:池田光穂

ミハイル・ミハイロヴィチ・バフチン[Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin](/bʌːn/ bukh-TEEN; Russian: Михаи́л Миха́йлович Бахти́н, IPA: [mʲɪɐˈ mʲɪdʑ bɐxˈtʲ; 16 November [O. S. 11月4日] 1895年11月16日 - 1975年3月7日。 S. 11月4日] 1895年 - 1975年3月7日[2])はロシアの哲学者、文芸批評家で、言語哲学、倫理学、文学理論に取り組んだ。さまざまなテーマに関する彼の著作は、異なる伝統 (マルクス主義、記号論、構造主義、宗教批評)や、文芸批評、歴史学、哲学、社会学、人類学、心理学など多様な分野で活躍する学者たちに影響を与えた。バ フチンは、1920年代にソビエト連邦で起こった美学と文学に関する議論に積極的に参加したが、1960年代にロシアの学者たちによって再発見されるま で、彼の独特の立場がよく知られるようになることはなかった。

※年譜作成は、 桑野隆「バフチン略年譜」『バフチン』Pp.243-247、平凡社、2011年。ホルクイス ト『ダイアローグの思想』などを参考に した。

| Mikhail

Mikhailovich Bakhtin (/bʌxˈtiːn/ bukh-TEEN; Russian: Михаи́л

Миха́йлович Бахти́н, IPA: [mʲɪxɐˈil mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ bɐxˈtʲin]; 16

November [O.S. 4 November] 1895 – 7 March[2] 1975) was a Russian

philosopher and literary critic who worked on the philosophy of

language, ethics, and literary theory. His writings, on a variety of

subjects, inspired scholars working in a number of different traditions

(Marxism, semiotics, structuralism, religious criticism) and in

disciplines as diverse as literary criticism, history, philosophy,

sociology, anthropology and psychology. Although Bakhtin was active in

the debates on aesthetics and literature that took place in the Soviet

Union in the 1920s, his distinctive position did not become well known

until he was rediscovered by Russian scholars in the 1960s. |

ミハイル・ミハイロヴィチ・バフチン[Mikhail

Mikhailovich Bakhtin](/bʌːn/

bukh-TEEN; Russian: Михаи́л Миха́йлович Бахти́н, IPA: [mʲɪɐˈ mʲɪdʑ

bɐxˈtʲ; 16 November [O. S. 11月4日] 1895年11月16日 - 1975年3月7日。 S. 11月4日]

1895年 -

1975年3月7日[2])はロシアの哲学者、文芸批評家で、言語哲学、倫理学、文学理論に取り組んだ。さまざまなテーマに関する彼の著作は、異なる伝統

(マルクス主義、記号論、構造主義、宗教批評)や、文芸批評、歴史学、哲学、社会学、人類学、心理学など多様な分野で活躍する学者たちに影響を与えた。バ

フチンは、1920年代にソビエト連邦で起こった美学と文学に関する議論に積極的に参加したが、1960年代にロシアの学者たちによって再発見されるま

で、彼の独特の立場がよく知られるようになることはなかった。 |

| Early life Bakhtin was born in Oryol, Russia, to an old family of the nobility. His father was the manager of a bank and worked in several cities. For this reason Bakhtin spent his early childhood years in Oryol, in Vilnius, and then in Odessa, where in 1913 he joined the historical and philological faculty at the local university (the Odessa University). Katerina Clark and Michael Holquist write: "Odessa..., like Vilnius, was an appropriate setting for a chapter in the life of a man who was to become the philosopher of heteroglossia and carnival. The same sense of fun and irreverence that gave birth to Babel's Rabelaisian gangster or to the tricks and deceptions of Ostap Bender, the picaro created by Ilf and Petrov, left its mark on Bakhtin."[3] He later transferred to Petrograd Imperial University to join his brother Nikolai. It is here that Bakhtin was greatly influenced by the classicist F. F. Zelinsky, whose works contain the beginnings of concepts elaborated by Bakhtin..[4] |

生い立ち バフチンはロシアのオリョールで、古い貴族の家に生まれた。父親は銀行の支店長で、いくつかの都市で働いていた。そのためバフチンは幼少期をオリョール、 ヴィリニュス、そしてオデッサで過ごし、1913年に地元の大学(オデッサ大学)の歴史言語学部に入学した。カテリーナ・クラークとマイケル・ホルキスト はこう書いている: 「オデッサは...ヴィリニュスと同様、異言語とカーニバルの哲学者となる男の人生の一章にふさわしい舞台だった。バベルのラブレーのようなギャングス ターや、イルフとペトロフによって創作されたピカロであるオスタップ・ベンダーのトリックや欺瞞を生んだのと同じ遊び心と不遜さは、バフチンにその足跡を 残した」[3] 。ここでバフチンは古典学者F.F.ゼリンスキーから大きな影響を受け、彼の著作にはバフチンが精緻化した概念の始まりが含まれている。 |

| Career Bakhtin completed his studies in 1918. He then moved to a small city in western Russia, Nevel (Pskov Oblast), where he worked as a schoolteacher for two years. It was at that time that the first "Bakhtin Circle" formed. The group consisted of intellectuals with varying interests, but all shared a love for the discussion of literary, religious, and political topics. Included in this group were Valentin Voloshinov; Matvei Isaevich Kagan; Lev Vasilievich Pumpianskii; Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinskii; and, eventually, P. N. Medvedev, who joined the group later in Vitebsk. Vitebsk was "a cultural centre of the region" the perfect place for Bakhtin "and other intellectuals [to organize] lectures, debates and concerts."[4] German philosophy was the topic talked about most frequently and, from this point forward, Bakhtin considered himself more a philosopher than a literary scholar. It was in Nevel, also, that Bakhtin worked tirelessly on a large work concerning moral philosophy that was never published in its entirety. However, in 1919, a short section of this work was published and given the title "Art and Responsibility". This piece constitutes Bakhtin's first published work. Bakhtin relocated to Vitebsk in 1920. It was here, in 1921, that Bakhtin married Elena Aleksandrovna Okolovich. Later, in 1923, Bakhtin was diagnosed with osteomyelitis, a bone disease that ultimately led to amputation of a leg in 1938. This illness hampered his productivity and rendered him an invalid.[5]  Bakhtin Circle, Leningrad, 1924–26. In 1924, Bakhtin moved to Leningrad, where he assumed a position at the Historical Institute and provided consulting services for the State Publishing House. It is at this time that Bakhtin decided to share his work with the public, but, just before "On the Question of the Methodology of Aesthetics in Written Works" was to be published, the journal in which it was to appear stopped publication. This work was eventually published 51 years later. Repression and misplacement of his manuscripts would plague Bakhtin throughout his career. In 1929, "Problems of Dostoevsky's Art", Bakhtin's first major work, was published. It is here that Bakhtin introduces the concept of dialogism. However, just as this book was introduced, on 8 December 1928, right before Voskresenie's 10th anniversary, Meyer, Bakhtin and a number of others associated with Voskresenie were apprehended by the Soviet secret police, the OGPU (Hirschkop 1999: p. 168). The leaders received sentences of up to ten years in labor camps of Solovki, though after an appeal to consider the state of his health, Bakhtin's sentence was commuted to exile to Kazakhstan, where he and his wife spent six years in Kustanai (now Kostanay). In 1936, they moved to Saransk (then in Mordovian ASSR, now the Republic of Mordovia), where Bakhtin taught at the Mordovian Pedagogical Institute.[6][7] During the six years he spent working as a book-keeper in the town of Kustanai, he wrote several important essays, including "Discourse in the Novel". In 1936, living in Saransk, he became an obscure figure in a provincial college, dropping out of view and teaching only occasionally. In 1937, Bakhtin moved to Kimry, a town located one hundred kilometers from Moscow. Here, he completed work on a book concerning the 18th-century German novel, which was subsequently accepted by the Sovetskii Pisatel' Publishing House. However, the only copy of the manuscript disappeared during the upheaval caused by the German invasion of 1941. After the amputation of a leg in 1938, Bakhtin's health improved and he became more prolific. In 1940, and until the end of World War II, Bakhtin lived in Moscow, where he submitted a dissertation on François Rabelais to the Gorky Institute of World Literature to obtain a postgraduate title,[8] although the dissertation could not be defended until the war ended. In 1946 and 1949, the defense of this dissertation divided the scholars of Moscow into two groups: those official opponents guiding the defense, who accepted the original and unorthodox manuscript, and those other professors who were against the manuscript's acceptance. The book's earthy, anarchic topic was the cause of many arguments that ceased only when the government intervened. Ultimately, Bakhtin was denied a higher doctoral degree (Doctor of Sciences) and granted a lesser degree (Candidate of Sciences, a research doctorate), by the State Accrediting Bureau. Later, Bakhtin was invited back to Saransk, where he took on the position of chair of the General Literature Department at the Mordovian Pedagogical Institute. When, in 1957, the Institute changed from a teachers' college to a university, Bakhtin became head of the Department of Russian and World Literature. In 1961, Bakhtin's deteriorating health forced him to retire, and in 1969, in search of medical attention, he moved back to Moscow, where he lived until his death in 1975.[9] Bakhtin's works and ideas gained popularity only after his death, and he endured difficult conditions for much of his professional life, a time in which information was often seen as dangerous and therefore was often hidden. As a result, the details provided now are often of uncertain accuracy. Also contributing to the imprecision of these details is the limited access to Russian archival information during Bakhtin's life. It was only after the archives became public that scholars realized that much of what they thought they knew about Bakhtin's life was false or skewed, largely by Bakhtin himself.[10] |

経歴 バフチンは1918年に学業を終えた。その後、ロシア西部の小都市ネヴェル(プスコフ州)に移り、2年間学校の教師として働いた。その頃、最初の「バフチ ン・サークル」が結成された。このサークルは、さまざまな関心を持つ知識人で構成されていたが、文学、宗教、政治的なトピックについて議論するのが好きだ という点で共通していた。このグループには、ヴァレンティン・ヴォロシノフ、マトヴェイ・イサエヴィチ・カガン、レフ・ヴァシリエヴィチ・ポンピアンスキ イ、イヴァン・イヴァノヴィチ・ソラーチンスキイ、そして最終的には、ヴィテブスクで後にグループに加わったP.N.メドヴェージェフが含まれていた。 ヴィテブスクは「この地方の文化の中心地」であり、バフチンと他の知識人が「講演会、討論会、コンサートを開催する」のに最適な場所であった[4]。ドイ ツ哲学が最も頻繁に語られるテーマであり、この時点からバフチンは自らを文学者よりも哲学者であると考えていた。バフチンが道徳哲学に関する大作に精力的 に取り組んだのもネヴェルでのことであった。しかし1919年、この著作の短い部分が出版され、『芸術と責任』というタイトルが与えられた。この作品はバ フチンの最初の出版作品となった。バフチンは1920年にヴィテブスクに移住した。1921年、バフチンはここでエレナ・アレクサンドロヴナ・オコロ ヴィッチと結婚した。その後、1923年にバフチンは骨の病気である骨髄炎と診断され、最終的には1938年に足を切断することになった。この病気は彼の 生産性を妨げ、病人となった[5]。  バフチンのサークル、レニングラード、1924-26年。 1924年、バフチンはレニングラードに移り住み、歴史研究所の職を得るとともに、国営出版社のコンサルティングを行った。この時、バフチンは自分の著作 を一般に公開することを決意したが、『著作における美学の方法論の問題について』が出版される直前、掲載されるはずだった雑誌が休刊してしまった。この作 品は結局、51年後に出版された。原稿の抑圧と置き忘れは、バフチンのキャリアを通じて悩まされることになる。1929年、バフチンの最初の主要著作であ る『ドストエフスキーの芸術問題』が出版された。ここでバフチンは対話主義の概念を導入している。しかし、この本が紹介された矢先の1928年12月8 日、ヴォスクレゼニ創立10周年を目前に控え、マイヤー、バフチンをはじめとするヴォスクレゼニに関係する多くの人々が、ソ連の秘密警察OGPUに逮捕さ れた(Hirschkop 1999: p. 168)。指導者たちはソロヴキの労働収容所で最高10年の刑を受けたが、保健状態を考慮するよう訴えた結果、バフチンの刑はカザフスタンへの流刑に減刑 され、夫妻はクスタナイ(現在のコスタナイ)で6年間を過ごした。1936年にはサランスク(当時モルドヴィア連邦、現モルドヴィア共和国)に移り、バフ チンはモルドヴィア教育学院で教鞭をとった[6][7]。 クスタナイの町で簿記係として働いた6年間に、「小説における言説」を含むいくつかの重要なエッセイを書いた。1936年、サランスクに住んでいた彼は、 地方の大学で無名の人物となり、視野から脱落し、時折教えるだけになった。1937年、バフチンはモスクワから100キロ離れた町キムリーに移り住んだ。 ここで彼は18世紀のドイツ小説に関する本の執筆を完了し、その後ソヴェツキイ・ピサテル出版社に受理された。しかし、1941年のドイツ侵攻による動乱 の中で、唯一の原稿が消失してしまった。 1938年に足を切断した後、バフチンの保健状態は回復し、多作になった。1940年から第二次世界大戦が終わるまで、バフチンはモスクワに住み、ゴーリ キー世界文学研究所にフランソワ・ラブレーに関する論文を提出し、大学院の称号を得た[8]。1946年と1949年、この論文の弁明はモスクワの学者た ちを2つのグループに分けた。弁明を指導する公式の反対派は、独創的で異端な原稿を受け入れ、その他の教授たちは原稿の受け入れに反対した。この本の土俗 的でアナーキーなテーマは、多くの論争の原因となったが、政府が介入して初めて収まった。最終的にバフチンは、国家認定局から高等博士号(理学博士)の授 与を拒否され、それ以下の学位(理学候補、研究博士)を与えられた。その後、バフチンは再びサランスクに招かれ、モルドヴィア教育学研究所の一般文学科の 学科長に就任した。1957年、モルドヴィア教育学院が教員養成学校から大学に変わると、バフチンはロシア文学・世界文学科の主任となった。1961年、 バフチンは保健の悪化により引退を余儀なくされ、1969年、治療を求めてモスクワに戻り、そこで1975年に亡くなるまで過ごした[9]。 バフチンの作品と思想が人気を博したのは彼の死後であり、彼はその職業人生の大半を、情報がしばしば危険視され、それゆえしばしば隠されていた時代、困難 な状況に耐えていた。その結果、現在提供されている詳細は、しばしば正確性に欠ける。また、バフチンの生涯において、ロシアのアーカイブ情報へのアクセス が限られていたことも、これらの詳細の不正確さの一因となっている。学者たちがバフチンの生涯について知っていると思っていたことの多くが、主にバフチン 自身による虚偽や歪曲であったことに気づいたのは、公文書館が公開されるようになってからであった[10]。 |

| Works and ideas Toward a Philosophy of the Act Toward a Philosophy of the Act was first published in the USSR in 1986 with the title K filosofii postupka. The manuscript, written between 1919 and 1921, was found in bad condition with pages missing and sections of text that were illegible. Consequently, this philosophical essay appears today as a fragment of an unfinished work.Toward a Philosophy of the Act comprises only an introduction, of which the first few pages are missing, and part one of the full text. However, Bakhtin's intentions for the work were not altogether lost: he provided an outline in the introduction, in which he stated that the essay was to contain four parts.[11] The first part of the essay provides an analysis of performed acts or deeds that comprise "the world actually experienced", as opposed to "the merely thinkable world."[citation needed] For the three subsequent and unfinished parts of Toward a Philosophy of the Act, Bakhtin states the topics he intended to discuss: the second part would have dealt with aesthetic activity and the ethics of artistic creation; the third with the ethics of politics; and the fourth with religion.[12] Toward a Philosophy of the Act reveals a Bakhtin in the process of developing his moral system by decentralizing the work of Kant, with a focus on ethics and aesthetics. It is here that Bakhtin lays out three claims regarding the acknowledgment of the uniqueness of one's participation in Being: I both actively and passively participate in Being. My uniqueness is given but it simultaneously exists only to the degree to which I actualize this uniqueness (in other words, it is in the performed act and deed that has yet to be achieved). Because I am actual and irreplaceable I must actualize my uniqueness. Bakhtin further states: "It is in relation to the whole actual unity that my unique thought arises from my unique place in Being."[13] Bakhtin deals with the concept of morality whereby he attributes the predominating legalistic notion of morality to human moral action. According to Bakhtin, the I cannot maintain neutrality toward moral and ethical demands which manifest themselves as one's voice of consciousness.[14] It is here also that Bakhtin introduces an "architectonic" or schematic model of the human psyche, consisting of three components: "I-for-myself", "I-for-the-other", and "other-for-me". The I-for-myself is an unreliable source of identity; Bakhtin argues that it is the I-for-the-other through which human beings develop a sense of identity. The I-for-the-other serves as an amalgamation of the way in which others view the subject. Conversely, other-for-me describes the way in which others incorporate the subject's perceptions of them into their own identities. Identity, as Bakhtin describes it here, does not belong merely to the individual. Instead, it is shared by all.[15] |

作品とアイデア 行為の哲学に向けて 『行為の哲学に向けて』は1986年に『K filosofii postupka』というタイトルでソ連で初めて出版された。1919年から1921年にかけて書かれた原稿は、ページが欠けていたり、文章の一部が判読 できないなど、ひどい状態で発見された。その結果、この哲学的エッセイは今日、未完の作品の断片として登場している。『行為の哲学に向けて』は、最初の数 ページが欠落している序論と、全文の第一部のみで構成されている。しかし、この作品に対するバフチンの意図主義が完全に失われたわけではない。彼は序論で アウトラインを示し、その中でこのエッセイは4つの部分から構成されると述べている[11] 。 「第2部では美的活動と芸術的創造の倫理を、第3部では政治の倫理を、そして第4部では宗教を扱うことになっていただろう[12]。 『行為の哲学に向けて』は、倫理学と美学に焦点を当てながら、カントの仕事を分散させることによって、自身の道徳体系を発展させる過程にあるバフチンを明ら かにしている。バフチンはここで、存在への参加の独自性を認めることについて、3つの主張を展開している: 1. 私は能動的にも受動的にも存在に参加している。 2. 私の独自性は与えられているが、それは同時に、私がこの独自性を現実化する程度にのみ存在する(言い換えれば、それはまだ達成されていないパフォーマーと しての行為や行いの中にある)。 3. 私は現実的でかけがえのない存在であるからこそ、私は私の独自性を現実化しなければならない。 バフチンはさらに言う: 「私の独自な思考が、存在における私の独自な位置から生じるのは、実在する統一体全体との関係においてである」[13]。バフチンは道徳の概念を扱い、そ れによって道徳の優勢な法治主義的概念を人間の道徳的行為に帰する。バフチンによれば、自分の意識の声として現れる道徳的・倫理的要求に対して、「私」は 中立性を保つことができない[14]。 バフチンはここでもまた、3つの構成要素からなる人間精神の「建築的」あるいは図式的モデルを導入している: 「自己のための自己」、「他者のための自己」、「私のための他者」である。バフチンは、「自己のための自己」はアイデンティティの信頼できない源であり、 人間がアイデンティティの感覚を発達させるのは「他者のための自己」であると主張する。他者にとっての私とは、他者が主体をどのように見ているかを統合し たものである。逆に、他者にとっての他者とは、他者が自分に対する主体の認識を自分のアイデンティティに組み込む方法を示している。バフチンがここで述べ ているように、アイデンティティは単に個人に属するものではない。むしろ、それは万人によって共有されるものである[15]。 |

| Problems of Dostoevsky's

Poetics: polyphony and unfinalizability Main article: Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics During his time in Leningrad, Bakhtin shifted his view away from the philosophy characteristic of his early works and towards the notion of dialogue.[16] It was at this time that he began his engagement with the work of Fyodor Dostoevsky. Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics is considered to be Bakhtin's seminal work, a work in which he introduces a number of important concepts. The work was originally published in Russia as Problems of Dostoevsky's Creative Art (Russian: Проблемы творчества Достоевского) in 1929, but was revised and extended in 1963 under the new title. It is the later work that is best known in the West.[17] The concept of unfinalizability is particularly important to Bakhtin's analysis of Dostoevsky's approach to character, although he frequently discussed it in other contexts.[18] He summarises the general principle behind unfinalizability in Dostoevsky thus: Nothing conclusive has yet taken place in the world, the ultimate word of the world and about the world has not yet been spoken, the world is open and free, everything is still in the future and will always be in the future.[19][20] On the individual level, this means that a person can never be entirely externally defined: the ability to never be fully enclosed by others' objectifications is essential to subjective consciousness. Though external finalization (definition, description, causal or genetic explanation etc) is inevitable and even necessary, it can never be the whole truth, devoid of the living response. Bakhtin is critical of what he calls the monologic tradition in Western thought that seeks to finalize humanity, and individual humans, in this way.[21] He argues that Dostoevsky always wrote in opposition to ways of thinking that turn human beings into objects (scientific, economic, social, psychological etc.) – conceptual frameworks that enclose people in an alien web of definition and causation, robbing them of freedom and responsibility: "He saw in it a degrading reification of a person's soul, a discounting of its freedom and its unfinalizability... Dostoevsky always represents a person on the threshold of a final decision, at a moment of crisis, at an unfinalizable, and unpredeterminable, turning point for their soul."[22] 'Carnivalization' is a term used by Bakhtin to describe the techniques Dostoevsky uses to disarm this increasingly ubiquitous enemy and make true intersubjective dialogue possible. The "carnival sense of the world", a way of thinking and experiencing that Bakhtin identifies in ancient and medieval carnival traditions, has been transposed into a literary tradition that reaches its peak in Dostoevsky's novels. The concept suggests an ethos where normal hierarchies, social roles, proper behaviors and assumed truths are subverted in favor of the "joyful relativity" of free participation in the festival. According to Morson and Emerson, Bakhtin's carnival is "the apotheosis of unfinalizability".[23] Carnival, through its temporary dissolution or reversal of conventions, generates the 'threshold' situations where disparate individuals come together and express themselves on an equal footing, without the oppressive constraints of social objectification: the usual preordained hierarchy of persons and values becomes an occasion for laughter, its absence an opportunity for creative interaction.[24] In carnival, "opposites come together, look at one another, are reflected in one another, know and understand one another."[25] Bakhtin sees carnivalization in this sense as a basic principle of Dostoevsky's art: love and hate, faith and atheism, loftiness and degradation, love of life and self-destruction, purity and vice, etc. "everything in his world lives on the very border of its opposite."[25] Carnivalization and its generic counterpart—Menippean satire—were not a part of the earlier book, but Bakhtin discusses them at great length in the chapter "Characteristics of Genre and Plot Composition in Dostoesky's Works" in the revised version. He traces the origins of Menippean satire back to ancient Greece, briefly describes a number of historical examples of the genre, and examines its essential characteristics. These characteristics include intensified comicality, freedom from established constraints, bold use of fantastic situations for the testing of truth, abrupt changes, inserted genres and multi-tonality, parodies, oxymorons, scandal scenes, inappropriate behaviour, and a sharp satirical focus on contemporary ideas and issues.[26][27] Bakhtin credits Dostoevsky with revitalizing the genre and enhancing it with his own innovation in form and structure: the polyphonic novel.[28] According to Bakhtin, Dostoevsky was the creator of the polyphonic novel, and it was a fundamentally new genre that could not be analysed according to preconceived frameworks and schema that might be useful for other manifestations of the European novel.[29] Dostoevsky does not describe characters and contrive plot within the context of a single authorial reality: rather his function as author is to illuminate the self-consciousness of the characters so that each participates on their own terms, in their own voice, according to their own ideas about themselves and the world. Bakhtin calls this multi-voiced reality "polyphony": "a plurality of independent and unmerged voices and consciousnesses, a genuine polyphony of fully valid voices..."[30] Later he defines it as "the event of interaction between autonomous and internally unfinalized consciousnesses."[25] |

ドストエフスキーの詩学の問題点:ポリフォニーとアンファイナライズ可

能性 主な記事 ドストエフスキー詩学の問題点 レニングラード滞在中、バフチンは初期作品に見られる哲学的視点から離れ、対話という概念へと関心を移した[16]。この時期に彼はフョードル・ ドストエフスキーの作品研究に着手した。『ドストエフスキーの詩学問題』はバフチンの代表作とされ、数多くの重要な概念が提示されている。この著作は 1929年にロシアで『ドストエフスキーの創作芸術の問題』(ロシア語: Проблемы творчества Достоевского)として初版が刊行されたが、1963年に改訂・増補され新題名で出版された。西洋で広く知られるのは後者の著作である。 [17] 未完成性の概念は、バフチンがドストエフスキーの登場人物描写を分析する上で特に重要である。ただし彼は他の文脈でも頻繁にこの概念を論じている[18]。彼はドストエフスキーにおける未完成性の背後にある一般原理を次のように要約する: 世界において決定的なことはまだ何も起きていない。世界についての最終的な言葉はまだ語られていない。世界は開かれて自由であり、あらゆるものはまだ未来にあり、永遠に未来にあるのだ。[19][20] 個 人的レベルでは、これは人間が完全に外部から定義されることは決してないことを意味する。他者による客観化に完全に閉じ込められることがない能力こそが、 主観的意識の本質である。外部からの確定(定義、記述、因果的・遺伝的説明など)は避けられず、むしろ必要だが、それは生きている応答を欠いた完全な真実 にはなりえない。バフチンは、西洋思想における「モノロジックな伝統」と呼ぶものを批判している。これは人間性、そして個々の人間をこのように確定しよう とするものだ[21]。彼はドストエフスキーが常に、人間を客体化する思考様式(科学的、経済的、社会的、心理学的など)に反対して執筆したと論じる。つ まり、人々を定義と因果関係の疎外された網に閉じ込め、自由と責任を奪う概念的枠組みに反対していたのだ: 「彼はそこに、人の人格を物象化し、その自由と決定不能性を軽視する姿勢を見た…ドストエフスキーは常に、最終決断の瀬戸際、危機的瞬間、人格にとって決 定不能かつ予見不可能な転換点に立つ人間を描いている」[22] 「カーニバル化」とは、バフチンがドストエフスキーの手法 を描写するために用いた用語である。この手法は、ますます遍在化する敵を無力化し、真の相互主観的対話を可能にするものだ。バフチンが古代・中世のカーニ バル伝統に見出した「世界のカーニバル的感覚」という思考・体験様式は、文学的伝統へと転移し、ドストエフスキーの小説において頂点を極めた。この概念 は、通常の階層構造、社会的役割、適切な行動規範、既成の真実が覆され、祭典への自由な参加による「喜びに満ちた相対性」が優先される倫理観を示唆してい る。モーソンとエマーソンによれば、バフチンのカーニバルは「未完成性の神格化」である[23]。カーニバルは、慣習の一時的な解体や逆転を通じて、社会 的な客観化の抑圧的な制約なしに、異なる個人が集い平等な立場で自己表現する「境界」状況を生み出す。通常は予め決められた人格や価値の階層構造が、笑い のもととなり、その不在が創造的な相互作用の機会となるのだ[24]。カーニバルにおいては「対立するものが集い、互いを見つめ合い、互いに映し合われ、 互いを知り理解し合う」のである。バフチンはこの意味でのカーニバル化を、ドストエフスキー芸術の基本原理と見なす。愛と憎しみ、信仰と無神論、高潔と堕 落、生への愛と自滅、純潔と悪徳など、「彼の世界ではあらゆるものが、その対極の境界線上で生きている」のだ。 カーニバル 化とそのジャンル上の対応物であるメニッペイア風風刺は、初期の著作には含まれていなかったが、バフチンは改訂版における「ドストエフスキー作品における ジャンル特性とプロット構成の特徴」の章でこれらを詳細に論じている。彼はメニッペイア風風刺の起源を古代ギリシャに遡り、このジャンルの歴史的例をいく つか簡潔に紹介し、その本質的特徴を検証する。これらの特徴には、強化された滑稽性、既存の制約からの解放、真実を検証するための幻想的状況の大胆な使 用、急激な変化、挿入されたジャンルと多声性、パロディ、逆説的表現、スキャンダラスな場面、不適切な行動、そして現代の思想や問題に対する鋭い風刺的焦 点が含まれる。[26][27] バフチンは、このジャンルを再活性化し、形式と構造における独自の革新——すなわちポリフォニック小説——によってそれを高めた功績をドストエフスキーに 認めている。[28] バフチンの見解によれば、ドストエフスキーはポリフォニック小説の創始者であり、それは根本的に新し いジャンルであった。このジャンルは、ヨーロッパ小説の他の形態には有用かもしれない既成の枠組みや図式によって分析することはできなかった。[29] ドストエフスキーは、単一の作者的現実という文脈の中で登場人物を描写したり、筋書きを考案したりするのではない。むしろ、作者としての彼の機能は、登場 人物たちの自己意識を照らし出すことにある。そうすることで、各人物が、自分自身と世界についての独自の考えに基づき、独自の条件と独自の声をもって参加 するのだ。バフチンはこの多声的な現実を「ポリフォニー」と呼ぶ。「独立し融合しない複数の声と意識、完全に有効な声による真のポリフォニーである」 [30]。後に彼はこれを「自律的で内部的に未確定な意識同士の相互作用の出来事」と定義する[25]。 |

| Rabelais and His World: carnival

and grotesque Main article: Rabelais and His World During World War II Bakhtin submitted a dissertation on the French Renaissance writer François Rabelais which was not defended until some years later. The controversial ideas discussed within the work caused much disagreement, and it was consequently decided that Bakhtin be denied his higher doctorate. Thus, due to its content, Rabelais and Folk Culture of the Middle Ages and Renaissance was not published until 1965, at which time it was given the title Rabelais and His World[31] (Russian: Творчество Франсуа Рабле и народная культура средневековья и Ренессанса, Tvorčestvo Fransua Rable i narodnaja kul'tura srednevekov'ja i Renessansa). In Rabelais and His World, a classic of Renaissance studies, Bakhtin concerns himself with the openness of Gargantua and Pantagruel; however, the book itself also serves as an example of such openness. Throughout the text, Bakhtin attempts two things: he seeks to recover sections of Gargantua and Pantagruel that, in the past, were either ignored or suppressed, and conducts an analysis of the Renaissance social system in order to discover the balance between language that was permitted and language that was not. It is by means of this analysis that Bakhtin pinpoints two important subtexts: the first is carnival (carnivalesque) which Bakhtin describes as a social institution, and the second is grotesque realism which is defined as a literary mode. Thus, in Rabelais and His World Bakhtin studies the interaction between the social and the literary, as well as the meaning of the body and the material bodily lower stratum.[32] In Rabelais and His World, Bakhtin intentionally refers to the distinction between official festivities and folk festivities. While official festivities aim to supply a legacy for authority, folk festivities have a critical centrifugal social function. Carnival, in this sense is categorized as a folk festivity by Bakhtin.[33] In his chapter on the history of laughter, Bakhtin advances the notion of its therapeutic and liberating force, arguing that "laughing truth ... degraded power".[34] |

ラブレーとその世界:カーニバルとグロテスク 主な記事 ラブレーとその世界 第二次世界大戦中、バフチンはフランス・ルネサンス期の作家フランソワ・ラブレーに関する論文を提出したが、数年後まで擁護されなかった。その論文で論じ られた物議を醸すような考え方は、多くの意見の相違を引き起こし、その結果、バフチンは高等博士号の取得を拒否されることになった。そのため、『ラブレー と中世・ルネサンスの民俗文化』はその内容から1965年まで出版されず、その時点で『ラブレーとその世界』[31](ロシア語: Творчество・Франсуа Рабле и народная культура средневековья и Ренессанса, Tvorčestvo Fransua Rable i narodnaja kul'tura srednevekov'ja i Renessansa)。 ルネサンス研究の古典である『ラブレーとその世界』において、バフチンはガルガンチュアとパンタグリュエルの開放性に関心を寄せている。それは、過去に無 視され、あるいは抑圧された『ガルガンチュア』と『パンタグリュエル』の部分を回復しようとすることと、ルネサンスの社会システムを分析し、許される言語 と許されない言語のバランスを発見することである。この分析によって、バフチンは2つの重要なサブテキストを突き止める。1つ目は、バフチンが社会制度と して説明するカーニヴァル(カーニヴァレスク)であり、2つ目は、文学様式として定義されるグロテスク・リアリズムである。このように、『ラブレーとその 世界』においてバフチンは、社会科学と文学の相互作用、また身体と物質的な身体的下層の意味について研究している[32]。 ラブレーとその世界』においてバフチンは意図主義的に公的な祝祭と民俗的な祝祭の区別に言及している。公的な祝祭が権威に遺産を供給することを目的として いるのに対して、民俗的な祝祭は批判的な遠心的社会的機能を有している。この意味でカーニバルは、バフチンによって民俗的な祝祭として分類されている [33]。 笑いの歴史に関する章において、バフチンは「笑う真実は......権力を劣化させる」と主張し、その治療的かつ解放的な力という概念を進めている [34]。 |

| The Dialogic Imagination:

chronotope and heteroglossia Main article: The Dialogic Imagination The Dialogic Imagination (first published as a whole in 1975) is a compilation of four essays concerning language and the novel: "Epic and Novel" (1941), "From the Prehistory of Novelistic Discourse" (1940), "Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel" (1937–1938), and "Discourse in the Novel" (1934–1935). It is through the essays contained within The Dialogic Imagination that Bakhtin introduces the concepts of heteroglossia, dialogism and chronotope, making a significant contribution to the realm of literary scholarship.[35] Bakhtin explains the generation of meaning through the "primacy of context over text" (heteroglossia), the hybrid nature of language (polyglossia) and the relation between utterances (intertextuality).[36][37] Heteroglossia is "the base condition governing the operation of meaning in any utterance."[38] To make an utterance means to "appropriate the words of others and populate them with one's own intention."[39] Bakhtin's deep insights on dialogicality represent a substantive shift from views on the nature of language and knowledge by major thinkers such as Ferdinand de Saussure and Immanuel Kant.[40][41] In "Epic and Novel", Bakhtin demonstrates the novel's distinct nature by contrasting it with the epic. By doing so, Bakhtin shows that the novel is well-suited to the post-industrial civilization in which we live because it flourishes on diversity. It is this same diversity that the epic attempts to eliminate from the world. According to Bakhtin, the novel as a genre is unique in that it is able to embrace, ingest, and devour other genres while still maintaining its status as a novel. Other genres, however, cannot emulate the novel without damaging their own distinct identity.[42] "From the Prehistory of Novelistic Discourse" is a less traditional essay in which Bakhtin reveals how various different texts from the past have ultimately come together to form the modern novel.[43] "Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel" introduces Bakhtin's concept of chronotope. This essay applies the concept in order to further demonstrate the distinctive quality of the novel.[43] The word chronotope literally means "time space" (a concept he refers to that of Einstein) and is defined by Bakhtin as "the intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships that are artistically expressed in literature."[44] In writing, an author must create entire worlds and, in doing so, is forced to make use of the organizing categories of the real world in which the author lives. For this reason chronotope is a concept that engages reality.[45] The final essay, "Discourse in the Novel", is one of Bakhtin's most complete statements concerning his philosophy of language. It is here that Bakhtin provides a model for a history of discourse and introduces the concept of heteroglossia.[43] The term heteroglossia refers to the qualities of a language that are extralinguistic, but common to all languages. These include qualities such as perspective, evaluation, and ideological positioning. In this way most languages are incapable of neutrality, for every word is inextricably bound to the context in which it exists.[46] |

対話的想像力:クロノトープとヘテログロシア 主な記事 対話的想像力 『対話的想像力』(1975年初版)は、言語と小説に関する4つのエッセイをまとめたものである: 「叙事詩と小説」(1941年)、「小説的言説の前史から」(1940年)、「小説における時間とクロノトープの形式」(1937-1938年)、「小説 における言説」(1934-1935年)である。バフチンは『対話的想像力』に収録されたエッセイを通じて、異言語性、対話主義、クロノトープの概念を紹 介し、文学研究の領域に大きく貢献した[35]。バフチンは「テクストよりもコンテクストの優位性」(異言語性)、言語のハイブリッドな性質(多言語 性)、発話間の関係(間テクスト性)を通じて意味の生成について説明している。 [36][37]異言語性とは「あらゆる発話における意味の作動を支配する基本条件」[38]であり、発話をするということは「他者の言葉を流用し、自分 の意図でその言葉を人口に膾炙させる」ことを意味する[39]。バフチンの対話性に関する深い洞察は、フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールやイマニュエル・カ ントといった主要な思想家による言語と知識の本質に関する見解からの実質的な転換を意味する[40][41]。 「叙事詩と小説」において、バフチンは叙事詩と対比させることによって、小説の独特な性質を示している。そうすることで、バフチンは、小説は多様性の上に 栄えるので、我々が生きる産業革命後の文明に適していることを示す。叙事詩が世界から排除しようとするのは、この同じ多様性である。バフチンによれば、小 説というジャンルは、小説としての地位を保ちながら、他のジャンルを受け入れ、摂取し、むさぼり食うことができるという点でユニークである。しかし他の ジャンルは、独自のアイデンティティを損なうことなく小説を模倣することはできない[42]。 「小説的言説の前史から "はあまり伝統的ではないエッセイであり、バフチンは過去からの様々な異なるテキストが最終的にどのように集まって現代の小説を形成したかを明らかにしている[43]。 「小説における時間とクロノトープの形態」はバフチンのクロノトープという概念を紹介している。クロノトープとは文字通り「時間空間」を意味し(アイン シュタインの概念になぞらえている)、バフチンによって「文学において芸術的に表現される時間的・空間的関係の本質的なつながり」と定義される[44]。 この理由から、クロノトープは現実と関わる概念なのである[45]。 最後のエッセイ「小説における言説」は、言語哲学に関するバフチンの最も完全な記述の一つである。ここでバフチンは言説史のモデルを提示し、ヘテログロシ アの概念を導入している[43]。ヘテログロシアという用語は、言語外的ではあるがすべての言語に共通する言語の特質を指している。これには、視点、評 価、イデオロギー的位置づけなどの性質が含まれる。このように、ほとんどの言語は中立性を保つことができず、すべての単語はそれが存在する文脈と密接不可 分に結びついているからである[46]。 |

| Speech Genres and Other Late

Essays In Speech Genres and Other Late Essays Bakhtin moves away from the novel and concerns himself with the problems of method and the nature of culture. There are six essays that comprise this compilation: "Response to a Question from the Novy Mir Editorial Staff", "The Bildungsroman and Its Significance in the History of Realism", "The Problem of Speech Genres", "The Problem of the Text in Linguistics, Philology, and the Human Sciences: An Experiment in Philosophical Analysis", "From Notes Made in 1970–71", and "Toward a Methodology for the Human Sciences". "Response to a Question from the Novy Mir Editorial Staff" is a transcript of comments made by Bakhtin to a reporter from a monthly journal called Novy Mir that was widely read by Soviet intellectuals. The transcript expresses Bakhtin's opinion of literary scholarship whereby he highlights some of its shortcomings and makes suggestions for improvement.[47] "The Bildungsroman and Its Significance in the History of Realism" is a fragment from one of Bakhtin's lost books. The publishing house to which Bakhtin had submitted the full manuscript was blown up during the German invasion and Bakhtin was in possession of only the prospectus. However, due to a shortage of paper, Bakhtin began using this remaining section to roll cigarettes. So only a portion of the opening section remains. This remaining section deals primarily with Goethe.[48] |

スピーチのジャンルと他の後期エッセイ バフチンは小説から離れ、方法と文化の本質の問題に取り組んでいる。この集大成を構成する6つのエッセイがある: 「NovyMir編集部からの質問への回答」、「現実主義の歴史におけるビルドゥングスロマンとその意義」、「音声ジャンルの問題」、「言語学、言語学、 人間科学におけるテキストの問題: 哲学的分析の実験」、「1970-71年のノートより」、「人間科学のための方法論に向けて」。 「Novy Mir編集部からの質問に対する回答」は、ソ連の知識人に広く読まれていたNovy Mirという月刊誌の記者にバフチンが答えたコメントの記録である。この原稿には、文学研究に対するバフチンの意見が述べられており、彼は文学研究の欠点 を強調し、改善のための提案を行っている[47]。 「ビルドゥングスロマンとリアリズムの歴史におけるその意義」は、バフチンの失われた著書のひとつからの断片である。バフチンが全原稿を提出した出版社は ドイツ軍の侵攻で爆破され、バフチンは趣意書だけを手にしていた。しかし、紙不足のため、バフチンはこの残った部分でタバコを巻き始めた。そのため、冒頭 部分の一部しか残っていない。この残された部分は主にゲーテについて扱っている[48]。 |

| "The Problem of Speech Genres"

deals with the difference between Saussurean linguistics and language

as a living dialogue (translinguistics). In a relatively short space,

this essay takes up a topic about which Bakhtin had planned to write a

book, making the essay a rather dense and complex read. It is here that

Bakhtin distinguishes between literary and everyday language. According

to Bakhtin, genres exist not merely in language, but rather in

communication. In dealing with genres, Bakhtin indicates that they have

been studied only within the realm of rhetoric and literature, but each

discipline draws largely on genres that exist outside both rhetoric and

literature. These extraliterary genres have remained largely

unexplored. Bakhtin makes the distinction between primary genres and

secondary genres, whereby primary genres legislate those words,

phrases, and expressions that are acceptable in everyday life, and

secondary genres are characterized by various types of text such as

legal, scientific, etc.[49] "The Problem of the Text in Linguistics, Philology, and the Human Sciences: An Experiment in Philosophical Analysis" is a compilation of the thoughts Bakhtin recorded in his notebooks. These notes focus mostly on the problems of the text, but various other sections of the paper discuss topics he has taken up elsewhere, such as speech genres, the status of the author, and the distinct nature of the human sciences. However, "The Problem of the Text" deals primarily with dialogue and the way in which a text relates to its context. Speakers, Bakhtin claims, shape an utterance according to three variables: the object of discourse, the immediate addressee, and a superaddressee. This is what Bakhtin describes as the tertiary nature of dialogue.[50] "From Notes Made in 1970–71" appears also as a collection of fragments extracted from notebooks Bakhtin kept during the years of 1970 and 1971. It is here that Bakhtin discusses interpretation and its endless possibilities. According to Bakhtin, humans have a habit of making narrow interpretations, but such limited interpretations only serve to weaken the richness of the past.[51] The final essay, "Toward a Methodology for the Human Sciences", originates from notes Bakhtin wrote during the mid-seventies and is the last piece of writing Bakhtin produced before he died. In this essay he makes a distinction between dialectic and dialogics and comments on the difference between the text and the aesthetic object. It is here also, that Bakhtin differentiates himself from the Formalists, who, he felt, underestimated the importance of content while oversimplifying change, and the Structuralists, who too rigidly adhered to the concept of "code."[52] |

「音声ジャンルの問題」は、ソシュール言語学と生きた対話としての言語

(トランスリンギュースティックス)の相違を扱っている。このエッセイは、バフチンが一冊の本を書く予定だったテーマを比較的短いスペースで取り上げてお

り、かなり濃密で複雑な読み物となっている。バフチンはここで、文学的言語と日常的言語を区別している。バフチンによれば、ジャンルは単に言語の中に存在

するのではなく、むしろコミュニケーションの中に存在する。バフチンはジャンルを扱うにあたって、それらが修辞学と文学の領域内だけで研究されてきたこと

を示すが、それぞれの学問は修辞学と文学の両者の外部に存在するジャンルを主に利用している。これらの文学外のジャンルはほとんど未解明のままである。バ

フチンは一次的ジャンルと二次的ジャンルを区別しており、一次的ジャンルは日常生活で許容される単語、フレーズ、表現を法制化したものであり、二次的ジャ

ンルは法律、科学など様々な種類のテキストによって特徴づけられる[49]。 「言語学、言語学、人間科学におけるテキストの問題: 哲学的分析の実験』は、バフチンがノートに記録した考えをまとめたものである。これらのノートは主にテクストの問題に焦点をあてているが、論文の他の様々 なセクションでは、音声ジャンル、著者の地位、人間科学の明確な性質など、彼が他の場所で取り上げたトピックについて論じている。しかし、「テクストの問 題」は主に対話と、テクストがその文脈とどのように関わるかを扱っている。バフチンは、話し手は3つの変数、すなわち、談話の対象、直属の宛先、そして上 位の宛先に従って発話を形成すると主張する。これがバフチンの言う対話の三次性である[50]。 「1970-71年のノートから "は、1970年から1971年にかけてバフチンがつけていたノートから抜粋された断片のコレクションでもある。バフチンはここで、解釈とその無限の可能 性について論じている。バフチンによれば、人間には狭い解釈をする習慣があるが、そのような限定的な解釈は過去の豊かさを弱めるだけである[51]。 最後のエッセイ「人間科学のための方法論に向けて」は、バフチンが70年代半ばに書いたメモに由来し、バフチンが生前に書いた最後の文章である。このエッ セイの中で、彼は弁証法と対話法を区別し、テクストと美的対象との差異についてコメントしている。バフチンが、変化を単純化しすぎる一方で内容の重要性を 過小評価していると感じていた形式主義者たちや、「コード」の概念にあまりにも厳格に固執していた構造主義者たちとの違いを示しているのもここである [52]。 |

| Disputed texts Some of the works which bear the names of Bakhtin's close friends V. N. Voloshinov and P. N. Medvedev have been attributed to Bakhtin – particularly Marxism and Philosophy of Language and The Formal Method in Literary Scholarship. These claims originated in the early 1970s and received their earliest full articulation in English in Clark and Holquist's 1984 biography of Bakhtin. In the years since then, however, most scholars have come to agree that Vološinov and Medvedev ought to be considered the true authors of these works. Although Bakhtin undoubtedly influenced these scholars and may even have had a hand in composing the works attributed to them, it now seems clear that if it was necessary to attribute authorship of these works to one person, Voloshinov and Medvedev respectively should receive credit.[53] Bakhtin had a difficult life and career, and few of his works were published in an authoritative form during his lifetime.[54] As a result, there is substantial disagreement over matters that are normally taken for granted: in which discipline he worked (was he a philosopher or literary critic?), how to periodize his work, and even which texts he wrote (see below). He is known for a series of concepts that have been used and adapted in a number of disciplines: dialogism, the carnivalesque, the chronotope, heteroglossia and "outsidedness" (the English translation of a Russian term vnenakhodimost, sometimes rendered into English—from French rather than from Russian—as "exotopy"). Together these concepts outline a distinctive philosophy of language and culture that has at its center the claims that all discourse is in essence a dialogical exchange and that this endows all language with a particular ethical or ethico-political force. |

論争になっているテキスト バフチンの親友であったV.N.ヴォロシノフやP.N.メドヴェージェフの名を冠した著作のいくつかは、バフチンの著作であるとされてきた-特に『マルク ス主義と言語哲学』と『文学研究における形式的方法』である。これらの主張は1970年代初頭に生まれ、クラークとホルキストによる1984年のバフチン の伝記において、英語での最初の完全な表現がなされた。しかし、それ以来、ほとんどの学者たちは、ヴォロシーノフとメドヴェージェフがこれらの著作の真の 著者であると考えるべきだという点で一致するようになった。バフチンは間違いなくこれらの学者たちに影響を与え、彼らの著作とされる作品の構成に手を貸し たかもしれないが、これらの作品の著作権を一人の人格に帰属させる必要があるとすれば、ヴォロシノフとメドヴェージェフがそれぞれ名声を得るべきであるこ とは、現在では明らかである。 [53]バフチンは困難な人生とキャリアを送ったため、彼の著作のうち、生前に権威ある形で出版されたものはほとんどない[54]。その結果、彼がどの分 野で仕事をしたのか(哲学者なのか文芸批評家なのか)、彼の仕事をどのように時代区分するのか、さらには彼がどのテキストを書いたのか(後述)など、通常 は当然とされている事柄について、かなりの意見の相違がある。彼は、対話主義、カーニヴァレスク、クロノトープ、ヘテログロシア、「アウトサイド性」(ロ シア語の用語ヴネナホディモストの英訳で、ロシア語からではなくフランス語から「エキソトピー」として英語化されることもある)といった、多くの分野で使 用され、転用されてきた一連の概念で知られている。これらの概念はともに、言語と文化に関する独特の哲学を概説しており、その中心には、すべての言説は本 質的に対話的な交換であり、このことがすべての言語に特定の倫理的あるいは倫理政治的な力を与えているという主張がある。 |

| Legacy As a literary theorist, Bakhtin is associated with the Russian Formalists, and his work is compared with that of Juri Lotman; in 1963 Roman Jakobson mentioned him as one of the few intelligent critics of Formalism.[55] During the 1920s, Bakhtin's work tended to focus on ethics and aesthetics in general. Early pieces such as Towards a Philosophy of the Act and Author and Hero in Aesthetic Activity are indebted to the philosophical trends of the time—particularly the Marburg school neo-Kantianism of Hermann Cohen, including Ernst Cassirer, Max Scheler and, to a lesser extent, Nicolai Hartmann. Bakhtin began to be discovered by scholars in 1963,[55] but it was only after his death in 1975 that authors such as Julia Kristeva and Tzvetan Todorov brought Bakhtin to the attention of the Francophone world, and from there his popularity in the United States, the United Kingdom, and many other countries continued to grow. In the late 1980s, Bakhtin's work experienced a surge of popularity in the West. Bakhtin's primary works include Toward a Philosophy of the Act, an unfinished portion of a philosophical essay; Problems of Dostoyevsky's Art, to which Bakhtin later added a chapter on the concept of carnival and published with the title Problems of Dostoyevsky's Poetics; Rabelais and His World, which explores the openness of the Rabelaisian novel; The Dialogic Imagination, whereby the four essays that comprise the work introduce the concepts of dialogism, heteroglossia, and chronotope; and Speech Genres and Other Late Essays, a collection of essays in which Bakhtin concerns himself with method and culture. In the 1920s there was a "Bakhtin school" in Russia, in line with the discourse analysis of Ferdinand de Saussure and Roman Jakobson.[56] |

遺産 文学理論家として、バフチンはロシアの形式主義者たちと結びついており、彼の仕事はジュリ・ロトマンと比較されている。1963年、ロマン・ヤコブソンは 彼を形式主義の数少ない知的な批評家のひとりとして挙げている[55]。1920年代、バフチンの仕事は倫理学と美学一般に焦点を当てる傾向があった。行 為の哲学に向けて』や『美的活動における著者と英雄』などの初期の作品は、当時の哲学的傾向、特にエルンスト・カッシーラー、マックス・シェーラー、そし てより少ない程度ではあるがニコライ・ハルトマンを含むヘルマン・コーエンのマールブルク学派の新カント主義に負うところが大きい。バフチンは1963年 に学者たちによって発見され始めたが[55]、ユリア・クリステヴァやツヴェタン・トドロフといった著者がバフチンをフランス語圏の世界に注目させたのは 1975年の死後であり、そこからアメリカ、イギリス、その他多くの国々でバフチンの人気は高まり続けた。1980年代後半、バフチンの作品は欧米で人気 が急上昇した。 バフチンの主な著作には、哲学的エッセイの未完の部分である『行為の哲学に向けて』、後にカーニバルの概念に関する章を加え、『ドストエフスキーの詩学の 問題』というタイトルで出版された『ドストエフスキーの芸術の問題』などがある; ラブレー小説の開放性を探求する『ラブレーとその世界』、対話主義、ヘテログロシア、クロノトープの概念を紹介する4つのエッセイからなる『対話的想像 力』、バフチンが方法と文化に関心を寄せるエッセイ集『発話ジャンルおよびその他の後期エッセイ』などである。 1920年代には、フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールやロマン・ヤコブソンの言説分析に沿った「バフチン学派」がロシアに存在した[56]。 |

| Influence He is known today for his interest in a wide variety of subjects, ideas, vocabularies, and periods, as well as his use of authorial disguises, and for his influence (alongside György Lukács) on the growth of Western scholarship on the novel as a premiere literary genre. As a result of the breadth of topics with which he dealt, Bakhtin has influenced such Western schools of theory as Neo-Marxism, Structuralism, Social constructionism, and Semiotics. Bakhtin's works have also been useful in anthropology, especially theories of ritual.[57] However, his influence on such groups has, somewhat paradoxically, resulted in narrowing the scope of Bakhtin's work. According to Clark and Holquist, rarely do those who incorporate Bakhtin's ideas into theories of their own appreciate his work in its entirety.[58] While Bakhtin is traditionally seen as a literary critic, there can be no denying his impact on the realm of rhetorical theory. Among his many theories and ideas Bakhtin indicates that style is a developmental process, occurring within both the user of language and language itself. His work instills in the reader an awareness of tone and expression that arises from the careful formation of verbal phrasing. By means of his writing, Bakhtin has enriched the experience of verbal and written expression which ultimately aids the formal teaching of writing.[59] Some even suggest that Bakhtin introduces a new meaning to rhetoric because of his tendency to reject the separation of language and ideology.[60] According to Leslie Baxter, for Bakhtin, "all language use is riddled with multiple voices (to be understood more generally as discourses, ideologies, perspectives, or themes)" and thus "meaning-making in general can be understood as the interplay of those voices."[61] |

影響力 今日、バフチンは、さまざまな主題、思想、語彙、時代への関心、作者の偽装を用いたこと、また、(ギョルジ・ルカーチと並んで)小説を第一の文学ジャンル として西洋の学問の発展に影響を与えたことで知られている。バフチンが扱った幅広いテーマの結果、ネオ・マルクス主義、構造主義、社会構築主義、記号論と いった西洋の理論学派に影響を与えた。バフチンの著作は人類学、特に儀式論においても有用であった[57]。しかし、そのようなグループに対する彼の影響 は、やや逆説的ではあるが、バフチンの著作の範囲を狭める結果となっている。クラークとホルキストによれば、バフチンの思想を自らの理論に取り入れる者 は、バフチンの仕事を全体として評価することは稀である[58]。 バフチンは伝統的に文芸批評家として見られているが、修辞理論の領域における彼の影響を否定することはできない。バフチンは彼の多くの理論やアイデアの中 で、文体は言語の使用者と言語自体の両方の中で発生する発展的なプロセスであることを示している。彼の著作は、言葉の言い回しの注意深い形成から生じる口 調や表現への意識を読者に植え付ける。言語とイデオロギーの分離を否定するバフチンの傾向から、バフチンは修辞学に新たな意味を導入したと指摘する者もい る。 [60] レスリー・バクスターによれば、バフチンにとって「すべての言語使用は複数の声(より一般的には言説、イデオロギー、視点、またはテーマとして理解され る)に満ちている」のであり、したがって「一般的に意味形成はそれらの声の相互作用として理解することができる」[61]。 |

| Bakhtin and communication studies Bakhtin has been called "the philosopher of human communication".[62][63] Kim argues that Bakhtin's theories of dialogue and literary representation are potentially applicable to virtually all academic disciplines in the human sciences.[63] According to White, Bakhtin's dialogism represents a methodological turn towards "the messy reality of communication, in all its many language forms."[64] While Bakhtin's works focused primarily on text, interpersonal communication is also key, especially when the two are related in terms of culture. Kim states that "culture as Geertz and Bakhtin allude to can be generally transmitted through communication or reciprocal interaction such as a dialogue."[63] |

バフチンとコミュニケーション研究 バフチンは「人間コミュニケーションの哲学者」と呼ばれている[62][63]。 キムは、バフチンの対話と文学的表象の理論は、人間科学における事実上すべての学問分野に潜在的に適用可能であると論じている[63]。 ホワイトによれば、バフチンの対話主義は、「あらゆる多くの言語形態における、コミュニケーションの厄介な現実」[64]に対する方法論的転回を表してい る。キムは、「ギアーツやバフチンが言及するような文化は、一般的にコミュニケーションや対話のような相互的な相互作用を通じて伝達されうる」と述べてい る[63]。 |

| Communication and culture According to Leslie Baxter, "Bakhtin's life work can be understood as a critique of the monologization of the human experience that he perceived in the dominant linguistic, literary, philosophical, and political theories of his time."[65] He was "critical of efforts to reduce the unfinalizable, open, and multivocal process of meaning-making in determinate, closed, totalizing ways."[65] For Baxter, Bakhtin's dialogism enables communication scholars to conceive of difference in new ways. The background of a subject must be taken into consideration when conducting research into their understanding of any text, since "a dialogic perspective argues that difference (of all kinds) is basic to the human experience."[65] Culture and communication become inextricably linked, as one's understanding of a given utterance, text, or message, is contingent upon one's cultural background and experience. Kim argues that "his ideas of art as a vehicle oriented towards interaction with its audience in order to express or communicate any sort of intention is reminiscent of Clifford Geertz's theories on culture."[63] |

コミュニケーションと文化 レスリー・バクスターによれば、「バフチンのライフワークは、同時代の支配的な言語学、文学、哲学、政治理論に感じられた、人間経験のモノローグ化に対す る批判として理解することができる」[65]。対話の視点は、(あらゆる種類の)差異が人間の経験にとって基本的なものであると主張する」[65]からで ある。ある発話、テキスト、メッセージに対する理解は、その人の文化的背景や経験によって左右されるため、文化とコミュニケーションは表裏一体の関係にあ る。 キムは、「何らかの意図を表現したり伝達したりするために、観客との相互作用を志向する乗り物としての芸術に対する彼の考えは、文化に関するクリフォー ド・ギアーツの理論を彷彿とさせる」と論じている[63]。 |

| Carnivalesque and communication Sheckels contends that "what [... Bakhtin] terms the 'carnivalesque' is tied to the body and the public exhibition of its more private functions [...] it served also as a communication event [...] anti-authority communication events [...] can also be deemed 'carnivalesque'."[66] Essentially, the act of turning society around through communication, whether it be in the form of text, protest, or otherwise serves as a communicative form of carnival, according to Bakhtin. Steele furthers the idea of carnivalesque in communication as she argues that it is found in corporate communication. Steele states "that ritualized sales meetings, annual employee picnics, retirement roasts and similar corporate events fit the category of carnival."[67] Carnival cannot help but be linked to communication and culture as Steele points out that "in addition to qualities of inversion, ambivalence, and excess, carnival's themes typically include a fascination with the body, particularly its little-glorified or 'lower strata' parts, and dichotomies between 'high' or 'low'."[68] The high and low binary is particularly relevant in communication as certain verbiage is considered high, while slang is considered low. Moreover, much of popular communication including television shows, books, and movies fall into high and low brow categories. This is particularly prevalent in Bakhtin's native Russia, where postmodernist writers such as Boris Akunin have worked to change low brow communication forms (such as the mystery novel) into higher literary works of art by making constant references to one of Bakhtin's favorite subjects, Dostoyevsky. |

カーニヴァレスクとコミュニケーション シェケルスは、「バフチンが『カーニヴァレスク』と呼ぶものは、身体と、より私的な機能の公的な展示と結びついている[......]コミュニケーショ ン・イベントとしても機能している[......]反権力的なコミュニケーション・イベントも[......]『カーニヴァレスク』とみなすことができ る」と論じている[66]。基本的に、コミュニケーションを通じて社会を好転させる行為は、それがテキストや抗議などの形式であれ、バフチンによれば、 カーニヴァルのコミュニケーション形式として機能する。スティールは、コミュニケーションにおけるカーニバルの考え方が企業コミュニケーションに見られる と主張し、さらに議論を深めている。スティールは、「儀式化された営業会議、年に一度の従業員ピクニック、退職祝賀会、そして同様の企業イベントは、カー ニバルのカテゴリーに当てはまる」と述べている。 反転、両義性、過剰の特質に加えて、カーニバルのテーマには通常、身体、特にあまり美化されない部分や「下層」の部分への憧れ、そして「高」か「低」かの 二項対立が含まれている」[68]とスティールが指摘するように、カーニバルはコミュニケーションや文化と結びつかずにはいられない。さらに、テレビ番 組、本、映画を含む一般的なコミュニケーションの多くは、高尚と低俗のカテゴリーに分類される。これは特にバフチンの母国ロシアで顕著であり、ボリス・ア クーニンのようなポストモダニズム作家は、バフチンのお気に入りの題材のひとつであるドストエフスキーに絶えず言及することで、(推理小説のような)低俗 なコミュニケーション形式をより高尚な文学作品に変えようと努めてきた。 |

| Bibliography Bakhtin, M.M. (1929) Problems of Dostoevsky's Art, (Russian) Leningrad: Priboj. Bakhtin, M.M. (1963) Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics, (Russian) Moscow: Khudozhestvennaja literatura. Bakhtin, M.M. (1968) Rabelais and His World. Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1975) Questions of Literature and Aesthetics, (Russian) Moscow: Progress. Bakhtin, M.M. (1979) [The] Aesthetics of Verbal Art, (Russian) Moscow: Iskusstvo. Bakhtin, M.M. (1981) The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M.M. Bakhtin. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin and London: University of Texas Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1984) Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics. Ed. and trans. Caryl Emerson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1986) Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Trans. Vern W. McGee. Austin, Tx: University of Texas Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1990) Art and Answerability. Ed. Michael Holquist and Vadim Liapunov. Trans. Vadim Liapunov and Kenneth Brostrom. Austin: University of Texas Press [written 1919–1924, published 1974–1979] Bakhtin, M.M. (1993) Toward a Philosophy of the Act. Ed. Vadim Liapunov and Michael Holquist. Trans. Vadim Liapunov. Austin: University of Texas Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1996–2012) Collected Writings, 6 vols., (Russian) Moscow: Russkie slovari. Bakhtin, M.M., V.D. Duvakin, S.G. Bocharov (2002), M.M. Bakhtin: Conversations with V.D. Duvakin (Russian), Soglasie. Bakhtin, M.M. (2004) "Dialogic Origin and Dialogic Pedagogy of Grammar: Stylistics in Teaching Russian Language in Secondary School". Trans. Lydia Razran Stone. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology 42(6): 12–49. Bakhtin, M.M. (2014) "Bakhtin on Shakespeare: Excerpt from 'Additions and Changes to Rabelais'". Trans. Sergeiy Sandler. PMLA 129(3): 522–537. |

書誌 Bakhtin, M.M. (1929) Problems of Dostoevsky's Art, (Russian) Leningrad: Priboj. Bakhtin, M.M. (1963) Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics, (Russian) Moscow: Khudozhestvennaja literatura. Bakhtin, M.M. (1968) Rabelais and His World. Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1975) Questions of Literature and Aesthetics, (Russian) Moscow: Progress. Bakhtin, M.M. (1979) [The] Aesthetics of Verbal Art, (Russian) Moscow: Iskusstvo. Bakhtin, M.M. (1981) The Dialogic Imagination: M.M.バフチンによる4つのエッセイ。Ed. Michael Holquist. Michael Holquist. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. オースティンとロンドン: University of Texas Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1984) Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics. Ed. and trans. Caryl Emerson. ミネアポリス: University of Minnesota Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1986) Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Trans. Vern W. McGee. Austin, Tx: University of Texas Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1990) Art and Answerability. Ed. Michael Holquist and Vadim Liapunov. Trans. Vadim Liapunov and Kenneth Brostrom. Austin: University of Texas Press [1919-1924年執筆、1974-1979年出版]. Bakhtin, M.M. (1993) Toward a Philosophy of the Act. Ed. Vadim Liapunov and Michael Holquist. Trans. Vadim Liapunov. Austin: University of Texas Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1996-2012) Collected Writings, 6 vols., (Russian) Moscow: Russkie slovari. Bakhtin, M.M., V.D. Duvakin, S.G. Bocharov (2002), M.M. Bakhtin: Conversations with V.D. Duvakin (Russian), Soglasie. Bakhtin, M.M. (2004) 「Dialogic Origin and Dialogic Pedagogy of Grammar: Stylistics in Teaching Russian Language in Secondary School」. Trans. Lydia Razran Stone. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology 42(6): 12-49. Bakhtin, M.M. (2014) "Bakhtin on Shakespeare: ラブレーへの追加と変更』より抜粋」。Trans. Sergeiy Sandler. PMLA 129(3): 522-537. |

| Dialogue (Bakhtin) Lev Vygotsky Menippean satire Pavel Medvedev |

対話(バフチン) レフ・ヴィゴツキー メニッペ風刺 パヴェル・メドヴェージェフ |

| Sources Boer, Roland (ed.), Bakhtin and Genre Theory in Biblical Studies. Atlanta/Leiden, Society of Biblical Literature/Brill, 2007. Bota, Cristian, and Jean-Paul Bronckart. Bakhtine démasqué: Histoire d'un menteur, d'une escroquerie et d'un délire collectif. Paris: Droz, 2011. [English translation: Unmasking Bakhtin: The story of the lie that took over the humanities. Geneva: Droz, 2019.] Brandist, Craig. The Bakhtin Circle: Philosophy, Culture and Politics London, Sterling, Virginia: Pluto Press, 2002. Carner, Grant Calvin Sr (1995) "Confluence, Bakhtin, and Alejo Carpentier's Contextos in Selena and Anna Karenina" Doctoral Dissertation (Comparative Literature) University of California at Riverside. Clark, Katerina, and Michael Holquist. Mikhail Bakhtin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984. Emerson, Caryl, and Gary Saul Morson. "Mikhail Bakhtin." The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism. Eds. Michael Groden, Martin Kreiswirth and Imre Szeman. Second Edition 2005. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 25 Jan. 2006 http://litguide.press.jhu.edu/cgibin/view.cgi?eid=22&query=Bakhtin[permanent dead link]. Farmer, Frank. "Introduction." Landmark Essays on Bakhtin, Rhetoric, and Writing. Ed. Frank Farmer. Mahwah: Hermagoras Press, 1998. xi–xxiii. Gratchev, Slav, and Mancing, Howard. "Mikhail Bakhtin's Heritage in Literature, Arts, and Philosophy." Lexington Books, 2018. Gratchev, Slav and Marinova, Margarita. "Mikhail Bakhtin: The Duvakin Interviews, 1973." Bucknell UP,2019. Green, Barbara. Mikhail Bakhtin and Biblical Scholarship: An Introduction. SBL Semeia Studies 38. Atlanta: SBL, 2000. Guilherme, Alexandre and Morgan, W. John, 'Mikhail M. Bakhtin (1895–1975)-dialogue as the dialogical imagination'. Chapter 2 in Philosophy, Dialogue, and Education: Nine modern European philosophers, Routledge, London and New York, pp. 24–38, ISBN 978-1-138-83149-0. David Hayman Toward a Mechanics of Mode: Beyond Bakhtin Novel: A Forum on Fiction, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Winter, 1983), pp. 101–120 doi:10.2307/1345079 Jane H. Hill The Refiguration of the Anthropology of Language (review of Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics) Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Feb., 1986), pp. 89–102 Hirschkop, Ken. "Bakhtin in the sober light of day." Bakhtin and Cultural Theory. Eds. Ken Hirschkop and David Shepherd. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2001. 1–25. Hirschkop, Ken. Mikhail Bakhtin: An Aesthetic for Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Holquist, Michael. [1990] Dialogism: Bakhtin and His World, Second Edition. Routledge, 2002. Holquist, Michael. "Introduction." Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. By Mikhail Bakhtin. Eds. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986. ix–xxiii. Holquist, Michael. Introduction to Mikhail Bakhtin's The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1981. xv–xxxiv Holquist, M., & C. Emerson (1981). Glossary. In MM Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by MM Bakhtin. İlim, Fırat. Bahtin: Diyaloji, Karnaval ve Politika, Ayrıntı Yayınları, İstanbul, 2017, ISBN 978-605-314-220-1 Klancher, Jon. "Bakhtin’s Rhetoric." Landmark Essays on Bakhtin, Rhetoric, and Writing. Ed. Frank Farmer. Mahwah: Hermagoras Press, 1998. 23–32. Liapunov, Vadim. Toward a Philosophy of the Act. By Mikhail Bakhtin. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993. Lipset, David and Eric K. Silverman, "Dialogics of the Body: The Moral and the Grotesque in Two Sepik River Societies." Journal of Ritual Studies Vol. 19, No. 2, 2005, 17–52. Magee, Paul. 'Poetry as Extorreor Monolothe: Finnegans Wake on Bakhtin'. Cordite Poetry Review 41, 2013. Maranhão, Tullio (1990) The Interpretation of Dialogue University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-50433-6 Meletinsky, Eleazar Moiseevich, The Poetics of Myth (Translated by Guy Lanoue and Alexandre Sadetsky) 2000 Routledge ISBN 0-415-92898-2 Morson, Gary Saul, and Caryl Emerson. Mikhail Bakhtin: Creation of a Prosaics. Stanford University Press, 1990. O'Callaghan, Patrick. Monologism and Dialogism in Private Law The Journal Jurisprudence, Vol. 7, 2010. 405–440. Pechey, Graham. Mikhail Bakhtin: The Word in the World. London: Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-0-415-42419-6 Schuster, Charles I. "Mikhail Bakhtin as Rhetorical Theorist." Landmark Essays on Bakhtin, Rhetoric, and Writing. Ed. Frank Farmer. Mahwah: Hermagoras Press, 1998. 1–14. Thorn, Judith. "The Lived Horizon of My Being: The Substantiation of the Self & the Discourse of Resistance in Rigoberta Menchu, Mm Bakhtin and Victor Montejo." University of Arizona Press. 1996. Townsend, Alex, Autonomous Voices: An Exploration of Polyphony in the Novels of Samuel Richardson, 2003, Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt/M., New York, Wien, 2003, ISBN 978-3-906769-80-6 / US ISBN 978-0-8204-5917-2 Sheinberg, Esti (29 December 2000). Irony, satire, parody and the grotesque in the music of Shostakovich. UK: Ashgate. p. 378. ISBN 0-7546-0226-5. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Vice, Sue. Introducing Bakhtin. Manchester University Press, 1997 Voloshinov, V.N. Marxism and the Philosophy of Language. New York & London: Seminar Press. 1973 Young, Robert J.C., 'Back to Bakhtin', in Torn Halves: Political Conflict in Literary and Cultural Theory Manchester: Manchester University Press; New York, St Martin's Press, 1996 ISBN 0-7190-4777-3 Mayerfeld Bell, Michael and Gardiner, Michael. Bakhtin and the Human Sciences. No last words. London-Thousand Oaks-New Delhi: SAGE Publications. 1998. Michael Gardiner Mikhail Bakhtin. SAGE Publications 2002 ISBN 978-0-7619-7447-5. Maria Shevtsova, Dialogism in the Novel and Bakhtin's Theory of Culture New Literary History, Vol. 23, No. 3, History, Politics, and Culture (Summer, 1992), pp. 747–763. doi:10.2307/469228 Stacy Burton Bakhtin, Temporality, and Modern Narrative: Writing "the Whole Triumphant Murderous Unstoppable Chute" Comparative Literature, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Winter, 1996), pp. 39–64. doi:10.2307/1771629 Vladislav Krasnov Solzhenitsyn and Dostoevsky A study in the Polyphonic Novel by Vladislav Krasnov University of Georgia Press ISBN 0-8203-0472-7 Maja Soboleva: Die Philosophie Michail Bachtins. Von der existentiellen Ontologie zur dialogischen Vernunft. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 2009. (in French) Jean-Paul Bronckart, Cristian Bota: Bakhtine démasqué : Histoire d'un menteur, d'une escroquerie et d'un délire collectif, Editeur : Droz, ISBN 2-600-00545-5 |

情報源 Boer, Roland (ed.), Bakhtin and Genre Theory in Biblical Studies. Atlanta/Leiden, Society of Biblical Literature/Brill, 2007. Bota, Cristian, and Jean-Paul Bronckart. Bakhtine démasqué: Histoire d'un menteur, d'une escroquerie et d'un délire collectif. Paris: Droz, 2011. [英訳: Unmasking Bakhtin: The story of the lie that took over the humanities. ジュネーブ: Droz, 2019.]. Brandist, Craig. The Bakhtin Circle: Philosophy, Culture and Politics London, Sterling, Virginia: Pluto Press, 2002. Carner, Grant Calvin Sr (1995) 「Confluence, Bakhtin, and Alejo Carpentier's Contextos in Selena and Anna Karenina」 カリフォルニア大学リバーサイド校博士論文(比較文学)。 Clark, Katerina, and Michael Holquist. ミハイル・バフチン. ケンブリッジ: Harvard University Press, 1984. Emerson, Caryl, and Gary Saul Morson. 「Mikhail Bakhtin.」. The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism. Eds. Michael Groden, Martin Kreiswirth and Imre Szeman. The Johns Hopkins University Press. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 25 Jan. 2006 http://litguide.press.jhu.edu/cgibin/view.cgi?eid=22&query=Bakhtin[permanent dead link]. Farmer, Frank. 「Introduction.」. Landmark Essays on Bakhtin, Rhetoric, and Writing. Ed. Frank Farmer. Mahwah: Hermagoras Press, 1998. Gratchev, Slav, and Mancing, Howard. 「Mikhail Bakhtin's Heritage in Literature, Arts, and Philosophy.」. Lexington Books, 2018. Gratchev, Slav and Marinova, Margarita. 「Mikhail Bakhtin: The Duvakin Interviews, 1973.」. Bucknell UP,2019. グリーン,バーバラ.ミハイル・バフチンと聖書学: 序論. SBL Semeia Studies 38. アトランタ: SBL, 2000. Guilherme, Alexandre and Morgan, W. John, 'Mikhail M. Bakhtin (1895-1975)-dialogue as the dialogical imagination'. 哲学・対話・教育』第2章: 9人の近代ヨーロッパの哲学者たち, Routledge, London and New York, pp.24-38, ISBN 978-1-138-83149-0. David Hayman Toward a Mechanics of Mode: バフチン小説を越えて: フィクション・フォーラム』16巻2号(1983年冬号)101-120頁 doi:10.2307/1345079 ジェーン・H・ヒル 言語人類学の再構築(『ドストエフスキー詩学の問題点』書評) 『文化人類学』第1巻第1号(1986年2月)89-102頁 Hirschkop, Ken. 「Bakhtin in the sober light of day.」. Bakhtin and Cultural Theory. Eds. Ken Hirschkop and David Shepherd. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2001. 1-25. Hirschkop, Ken. ミハイル・バフチン: An Aesthetic for Democracy. オックスフォード: Oxford University Press, 1999. Holquist, Michael. [1990] Dialogism: Bakhtin and His World, Second Edition. Routledge, 2002. Holquist, Michael. 「はじめに」. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. ミハイル・バフチン著。Eds. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986. Holquist, Michael. ミハイル・バフチン『対話的想像力』序論: 4つのエッセイ。Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1981. Holquist, M., & C. Emerson (1981). 用語集。MM Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: 4 Essays by MM Bakhtin. İlim, Fırat. Bahtin: Diyaloji, Karnaval ve Politika, Ayrıntı Yayınları, İstanbul, 2017, ISBN 978-605-314-220-1. Klancher, Jon. 「Bakhtin's Rhetoric.」. Landmark Essays on Bakhtin, Rhetoric, and Writing. Ed. Frank Farmer. Mahwah: Hermagoras Press, 1998. 23-32. Liapunov, Vadim. 行為の哲学に向けて. ミハイル・バフチン著。Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993. Lipset, David and Eric K. Silverman, 「Dialogics of the Body: The Moral and the Grotesque in Two Sepik River Societies.」. Journal of Ritual Studies Vol.19, No.2, 2005, 17-52. Magee, Paul. Poetry as Extorreor Monolothe: フィネガンズ・ウェイクとバフチン」。Cordite Poetry Review 41, 2013. Maranhão, Tullio (1990) The Interpretation of Dialogue シカゴ大学出版局 ISBN 0-226-50433-6 Meletinsky, Eleazar Moiseevich, The Poetics of Myth (Guy Lanoue and Alexandre Sadetsky 訳) 2000 Routledge ISBN 0-415-92898-2 Morson, Gary Saul, and Caryl Emerson. ミハイル・バフチン: Creation of a Prosaics. Stanford University Press, 1990. O'Callaghan, Patrick. 私法におけるモノローグ主義と対話主義 Journal Jurisprudence, Vol.7, 2010. 405-440. Pechey, Graham. Mikhail Bakhtin: The Word in the World. London: Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-0-415-42419-6 Schuster, Charles I. 「Mikhail Bakhtin as Rhetorical Theorist.」. Landmark Essays on Bakhtin, Rhetoric, and Writing. Ed. Frank Farmer. Mahwah: Hermagoras Press, 1998. 1-14. Thorn, Judith. 「The Lived Horizon of My Being: The Substantiation of the Self & the Discourse of Resistance in Rigoberta Menchu, Mm Bakhtin and Victor Montejo.」. University of Arizona Press. 1996. Townsend, Alex, Autonomous Voices: An Exploration of Polyphony in the Novels of Samuel Richardson, 2003, Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt/M., New York, Wien, 2003, ISBN 978-3-906769-80-6 / US ISBN 978-0-8204-5917-2. Sheinberg, Esti (29 December 2000). ショスタコーヴィチの音楽における皮肉、風刺、パロディ、グロテスク. イギリス: p. 378. ISBN 0-7546-0226-5. 2007年10月17日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。 Vice, Sue. バフチン入門. マンチェスター大学出版、1997年 Voloshinov, V.N. Marxism and the Philosophy of Language. New York & London: Seminar Press. 1973 Young, Robert J.C., 'Back to Bakhtin', in Torn Halves: Torn Halves: Political Conflict in Literary and Cultural Theory Manchester: Manchester University Press; New York, St Martin's Press, 1996 ISBN 0-7190-4777-3. Mayerfeld Bell, Michael and Gardiner, Michael. バフチンと人間科学. No last words. London-Thousand Oaks-New Delhi: SAGE Publications. 1998. マイケル・ガーディナー ミハイル・バフチン. SAGE Publications 2002 ISBN 978-0-7619-7447-5. Maria Shevtsova, Dialogism in the Novel and Bakhtin's Theory of Culture 新文学史, Vol.23, No.3, History, Politics, and Culture (Summer, 1992), pp.747-763. ステイシー・バートン バフチン、時間性、そして現代の物語: 比較文学』第48巻第1号(1996年冬号)39-64頁。 ヴラディスラフ・クラスノフ著『ソルジェニーツィンとドストエフスキー ポリフォニック・ノベルの研究』 ジョージア大学出版会 ISBN 0-8203-0472-7 マーヤ・ソボレワ Die Philosophie Michail Bachtins. Von der existentiellen Ontologie zur dialogischen Vernunft. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 2009. (in French) Jean-Paul Bronckart, Cristian Bota: Bakhtine démasqué : Histoire d'un menteur, d'une escroquerie et d'un délire collectif, Editeur : Droz, ISBN 2-600-00545-5. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mikhail_Bakhtin |

★クラークとホルクイスト『ミハイル・バフチー ンの世界』では、彼の伝記と思想を、(I)1895-1917、(II)1918-1924、(III)1924-1929、(IV)1930-1945、(V)1945-1975、の五つの時期にわけてい る。このページでも、その時期にわけて紹介する。

(I)1895-1917:コルシカの双生

児:クラークとホルクイスト『ミハイル・バフチーンの世界』より

1895 11月16日(旧暦11月4日)この世に生を受ける(Oryol, Russian Empire)。初等教育は家庭で受ける。家庭教師はドイツ人で、そのため幼年よりドイツ語、ロシア語のバイリンガルに育つ。

1905 (銀行員の父の転勤で)家族でヴィリノ(現リトアニアのヴィリニュス)に移住。ヴィリノ第一ギムナ ジウムに入学。住民はリトアニア語のほかにポーランドを話していた。東のエルサレムといい、イディッシュ語やヘブライ語も話される。

1911 (銀行員の父の転勤で)家族で(兄ニコライ以外)オデッサに移住。オデッサのギムナジウムに転校。オデッサも東ヨーロッパのユダヤ人 住民の飛び地でユダヤ人文化が豊富。ブーバー、キルケゴール、ドイツの体系哲学に親しむ。

1913-1916 ノヴォロシア(現オデッサ)大学の文学部の講義に出席。

1914 兄ニコライの入学に関連して、ペトログラード大学の授業にも出席。(ニコライとは1918年まで一緒だったが、その後離れ離れになり、後に バーミンガム大学の言語学教授になったが生涯再会することはなかった)

1916 ペトログラードに移住。一八年までペトログラード(現サンクト・ベテルブルグ)大学古典文献学・哲 学部の授業に(おそらく聴講生として)入学。ペテルブルグ宗教・哲学教会を訪れ、メイエルと知り合う。指導教授はファジェーイ・ゼリンスキイ。

(II)1918-1924:ネーヴェリとヴィテプス ク:クラークとホルクイスト『ミハイル・バフチーンの世界』より

1918 ペトログラード卒業。初夏にネーヴェリに移住。ネーヴェリ統一労働者学校で歴史、社会学、ロシア語を教える。サークル 「カント・セミナー」を結成。サークルは1919年夏にかけてもっとも活発に活動。

1919 9月13日、ネーヴェリの日刊紙『芸術の日』に「芸術と責任」を寄稿

1920 秋頃にヴィテプスクに移住。当時の友人は、マートヴェイ・イサーエヴィチ・カガーン(1889-1937)。カガーンは、マーブルグでヘルマン・コーエ ンから学んだユダヤ人であった。カガーンは1914年に授業をはじめるが第一次大戦で、ドイツの敵国人とされ、ロシアに送還された経験をもつ。

ca. 1920-1924 「行為の哲学によせて」(1918年に執筆開始との説もあり)と「美的活動における作者と主人公」、さらには「道徳の主体と法の主 体」やドストエフスキー論にも取り組む。関連する作家としては、ヴァレンチン・ヴォローシノフ、パーヴェル・メドヴェージェフ。当時の支配的哲学は(ヘル マン・コーエンが切り開いた)新カント派の哲学。

1921 2月骨髄炎が悪化し入院。7月16日Elena Aleksandrovna Okolovichと結婚

(III)1924-1929: レニングラード・サーク ル:クラークとホルクイスト『ミハイル・バフチーンの世界』より

1924 夫妻でレニングラード(現サンクト・ベテルブルグ)に移住。

1924-1925 宗教哲学や人文科学の問題を審議する小規模な哲学サークルで活動。「芸術作品における主 人公と作者」という連続講義もおこなっている。

1924-1928 哲学や文学をテーマとした報告や講義をいくつかの個人宅でおこなう(これが1928年の逮捕の原因となる)。

1924 「言語作品の美学の方法論の問題によせて1:言語芸術作品における形式・内容・素材の問題」を執筆 するが、掲載予定の雑誌が廃刊になる。

1925-1931 ヴォローシノフ名で『フロイト主義』を出版。メドヴェージェフ名で『文学研究における形

式的方法』を出版。ヴォ

ローシノフ名で『マ

ルクス主義と言語哲

学』、カナーエフ名で「現代の生気論」といった著書やいくつかの論文が公刊。

1927 ボロシノフ名義で『フロイト主義』を公刊

1928 メドベジェフ名義で『文学研究における形式的方法』を公刊。ロシア・フォルマリストへの批判。

1928 12月24日反ソヴィエト的活動のかどで逮捕。

1929年 1月5日病気を理由に釈放、自宅軟禁となる。

1929 6月初頭、本名で『ド ストエフスキーの創作の諸問題』公刊(平凡社ライブラリー)。ボロシノフ名義で『マルク ス主義と言語哲学』公刊(→「スカースとバフチン」)。序文を書いた『トルストイ全集』11巻および13巻が出版。

1929 Bakhtin, M.M. (1929) Problems of Dostoevsky's Art, (Russian) Leningrad: Priboj.

1929 7月17日〜12月23日治療のためレニングラード市内の病院に入院。7月22日ソロフキ強制収容 所への5年間流刑判決(→猶予され入院が許可されてクスタナイ市への流刑に変更)

(IV)1930-1945: クスタナイ、サランス ク、サヴェロヴォ:クラークとホルクイスト『ミハイル・バフチーンの世界』より

1930 2月23日カザフスタン共和国のクスタナイ市への流刑に変更。3月29日クスタナイ市へ出発。

1930-1936年 『小説のなかの言葉』に取り組む

1931 4月23日クスタナイ市地域消費者組合に会計・経理係として就職。

1934 3月「コルホーズ員たちの需要の研究の試み」(論文)が『ソヴィエト商業』誌(1934年12号) に掲載。7月流刑期間終了。

1936 9月9日モルドヴィア教育大学(サランスク)の文学講座の教員

1936-1938 『教養小説とそれがリアリズム史上に持つ意義』を執筆(ただし「ソヴィエト作家」出版所 に提出されていたタイプ原稿は戦争中に消滅したと言われる)。

1937 6月3日「ブルジョア的客観主義」との理由で大学を解雇。ただし7月1日解雇理由が「当人の自由意 志」に変更。秋、一時的にモスクワに移り、妹ナターリヤ夫妻の家で暮らす。

1937-1938-1945年 1937-1938年にかけての冬、サヴョロヴォに腰をすえる。モスクワにひんぱんに通いながら、1945年9月ま で暮らす。サヴョロヴォ期:「叙事詩の歴史における『イーゴリ遠征譚』」、「小説の理論の問題によせ て」、「笑いの理論の問題によせて」、「修辞学は虚偽の度合いに応じて」「意識と自己評価の問題によせて」、「フローベールについて」、「中学校でのロシ ア語の授業における「文体論の問題」

1938 大粛正の時代

1938 2月右足を手術で切断。「リアリズム史上におけるフランソワ・ラブレー」に取り組み、1940年末 に完成。

1940 4月モスクワの中央文学者会館で関かれたシェークスピア作品会議に参加。10月14日モスクワの世 界文学研究所文学理論部門で「小説のなかの言葉」という題で報告。10月から11月にかけて『文学百科』第10巻のなかの「風刺」の項を執筆するが、この 巻自体が刊行されず。

1940-1943年 「人文科学の哲学的基礎によせて」に取り組んでいたと推定(桑野)。

1941 3月24日 世界文学研究所で「文学のジャンルとしての小説」という題で報告。秋、カリーニン(現 トヴェリ)州キムルイ区イリインスコエ村の中学校教師となる。12月15日キムルイ市ヤロスラヴリ鉄道第三九中学校に、ロシア語、ロシア文学、ドイツ語の 教師として採用。

1942 1月18日キムルイ市第一四中学の教師。

1944 「ラブレー論の増補。改訂」を執筆。

(V)1945-1975: サランスクからモスクワ へ:クラークとホルクイスト『ミハイル・バフチーンの世界』より

1945 8月18日モルドヴィア教育大学(サランスク)の世界文学准教授に任命。9月サランスクに移住。10月1日世界文学講座の主任。

1946 4月10日〜11日モルドヴィア教育大学教員研修会の総会で「中世・ルネサンスの民衆文化」という 題で報告。11月15日「リアリズム史上におけるフランソワ・ラブレー」の博士論文審査(最終的に博士号付与は1951年6月9日拒絶され、博士候補のま まとなる)。

1947 1月15日〜16日モルドヴィア教育大学教員研修会で「リアリズム史上におけるフランソワ・ラブ レー」という題で報告。

1948 2月11日モルドヴィア教育大学教員研修会で「小説の文体論の基本的問題」という題で報告。9月15日講座会議で「西洋 諸国の文学にロシア文学が及ぼした影響の問題を世界文学講義で解明することについて」という題で報告。10月6日講座会議で自己の研究テーマ「ルネサンス 期のブルジョア的概念」の進行状況を報告。

1949 3月1日反愛国主義的な劇評家グループに関する、新聞『プラヴダ』と『文化と生活』の記事を審議す る諸講座合同会議に参加。10月11日講座会議で、年報『文学モルドヴィア』にプーシキンの散文をめぐる論考を執筆する役目を引き受ける。

1950 3月31日講座の近代中国文学研究サークルにおいて、「中国文学の特徴と、古代から現在までの概 観」という題で報告。9月28日共和国青年作家会議において、「文学の類と種」という題で講義。10月18日「言語学に関するスターリンの天才的著作」の 審議にあてられたロシア文学講座・外国文学講座合同会議で、「言語をめぐるスターリンの学説を文学研究の問題に応用する」という題で報告。

1951 「リアリズム史上におけるフランソワ・ラブレー」の博士論文審査につき最終的に博士号付与は1951年6月9 日審査委員会に拒絶される。9月26日ロシア文学講座・外国文学講座合同会議で、「ソヴィエトの文学研究の発達の基本的方途」という題で報告。

1952 2月6日同志スターリンの誕生日を記念した理論会議の演説で「数多くの観念論的語句」を使い、「芸 術に誤った定義づけを与え」、「社会的発展を伝統の力でもって説明しようとした」として、モルドヴィア教育大学教授会で非難を受ける。6月2日上級審議委 員会が準博士号を授与。同日、モスクワのグネーシン研究所でユージナの生徒たちのために「バラードとその特性」という題で講義。

1953 「ことばのジャンルの問題」に取り組む。

1953 2月25日諸講座合同会議で、「ソヴィエト文学における典型的なるものの問題とモルドヴィア教育大 学における文学教育の課題」という題で報告。11月18日別の諸講座合同会議で、「ソ連邦共産党中央委員会七月総会の決議とソ連邦共産党中央委員会テーゼ 「ソヴィエト連邦共産党50周年」にてらしての社会科学教育の課題」で報告。

1954 12月12日モルドヴィアドラマ劇場の「マリー・チュードル」の劇評を執筆。

1956 4月11日講座の公開会議で、「典型的なるものの問題とその意義」という題で報告。

1957 「美的カテゴリーの問題」に取り組む。

1958 3月モルドヴィア大学(モルドヴィア教育大学が1957年に改称)文学部ロシア文学。外国文学講座 の主任となる。

1959 5月17日モルドヴィアドラマ劇場で上演されたメルクシキン作「夜明けにて」の劇評を執筆。

1960 11月コージノフら4名の文 学研究者たちから手紙を受け取る(→バフチンの作品と思想の社会的再発見の契機)。

1961 6月20日コージノフらがサランスクを訪問。8月1日大学を退職し、年金生活に入る。

1961-1962 ドストエフスキー論の改訂に取り組む

1963 9月に、1929年公刊の改訂版『ドストエフスキーの詩学の諸問題』(ちくま学芸文庫)を公刊

1963 Bakhtin, M.M. (1963) Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics, (Russian) Moscow: Khudozhestvennaja literatura.

1965 『フランソワ・ラブレーの作品と中世。ルネサンスの民衆文化』が公刊(英訳は3年後)

1967 レニングラード市裁判所最高会議はバフチンの名誉回復を決議。

1968 Bakhtin, M.M. (1968) Rabelais and His World. Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

1969 モユクワ市クンツェヴォのクレムリン病院で治療を受けるため、妻とともにサランスクをあとにする。

1970 ソ連邦作家同盟に加入

1971 妻Elena Aleksandrovna Okolovichが死去

1972 7月31日 モスクワで居住証明書を受けとる。

1973-1974 『文学と美学の問題』の出版を準備。この本に入れるために、教養小説をめぐる著書

(1936-1938、ただし保存されていない)の準備稿からなる大部の断片を「小説における時間とクロノトポスの形式」に改稿

1975 3月7日 死亡、『文学と美学の諸問題』公刊

1975 Bakhtin, M.M. (1975) Questions of Literature and Aesthetics, (Russian) Moscow: Progress.

1979 『文学と美学の諸問題』

1979 Bakhtin, M.M. (1979) [The] Aesthetics of Verbal Art, (Russian) Moscow: Iskusstvo.

1981 Bakhtin, M.M. (1981) The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin and London: University of Texas Press.

1984 Bakhtin, M.M. (1984) Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Ed. and trans. Caryl Emerson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

1986 Bakhtin, M.M. (1986) Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Trans. Vern W. McGee. Austin, Tx: University of Texas Press.

1990 Bakhtin, M.M. (1990) Art and Answerability. Ed. Michael Holquist and Vadim Liapunov. Trans. Vadim Liapunov and Kenneth Brostrom. Austin: University of Texas Press [written 1919–1924, published 1974-1979]

1993 Bakhtin, M.M. (1993) Toward a Philosophy of the Act. Ed. Vadim Liapunov and Michael Holquist. Trans. Vadim Liapunov. Austin: University of Texas Press.

1996-2012 Bakhtin, M.M. (1996–2012) Collected Writings, 6 vols., (Russian) Moscow: Russkie slovari.

2002 Bakhtin, M.M., V.D. Duvakin, S.G. Bocharov (2002), M.M. Bakhtin: Conversations with V.D. Duvakin (Russian), Soglasie.

2004 Bakhtin, M.M. (2004) “Dialogic Origin and Dialogic Pedagogy of Grammar: Stylistics in Teaching Russian Language in Secondary School”. Trans. Lydia Razran Stone. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology 42(6): 12–49

2014 Bakhtin, M.M. (2014) “Bakhtin on Shakespeare:

Excerpt from ‘Additions and Changes to Rabelais’”. Trans. Sergeiy

Sandler. PMLA 129(3): 522–537.

**

| ■ミハイル・バフチーンの世界 | Holquist, Michael, ダイアローグの思想 : ミハイル・バフチンの可能性. |

|

序論 1.コルシカの双生児 1895-1917 2.ネーヴェリとヴィテプスク 1918-1924 3.責任の構築学 4.レニングラード・サークル 1924-1929 5.宗教活動と逮捕 6.テクストをめぐる論争 7.フロイト主義 8.フォルマリスト 9.生活の言説と芸術の言説 10.マルクス主義と言語哲学 11.ドストエフスキーの詩学 12.クスタナイ、サランスク、サヴェロヴォ 1930-1945 13.小説の理論 14.ラブレーと民衆文化 15.サランスクからモスクワへ 1945-1975 結び ミハイール・バフチーンの世界 / カテリーナ・クラーク, マイケル・ホルクイスト共著 ; 川端香男里, 鈴木晶共訳,東京 : せりか書房 , 1990.1 |

言語・存在・小説の本質をダイアローグとみなすバフチンの思想をダイア

ローグをめぐる思想史の流れの中で鮮明にとらえなおすとともに、「歴史と詩学のダイアローグ」としてのバフチンの文学理論の隠された可能性を英・米・露の

諸作品の解読作業を通して探究する。 第1章 バフチンの生涯 第2章 ダイアローグとしての存在 第3章 ダイアローグとしての言語 第4章 ダイアローグとしての小説性—教育の小説と小説の教育 第5章 歴史と詩学のダイアローグ 第6章 ダイアローグとしての創作者行為—応答性の構築学 |

***

ど うしてラブレーとバフチンなのかというと、前者は、後者がカーニバル論(ないしはカーニバル文学)として取り上げた著名な研究に由来し ます。バフチンにとって重要な作家は、セルバンテスやドストエフスキーなどがあげられますが、カーニバルのバフチンというと、ラブレーの存在は無視するこ とができません。また、クラークとホルクイストによるバフチンの伝記によりと、隠棲的な生き方あるいは著作における複数の著者性に帰してみたいと思いま す。すなわちバフチンはヴォロシノフ やメドヴェージェフという実在するあるいはペンネームで書くことでスターリズム下の政治状況を生き延びたといわれています。他方、ルネサンス期の医師で あったラブレーの評判は毀誉褒貶であ り、また偽作やペンネームあるいは正体すら不明の点が多いというのです。私(池田)はバフチンとラブレーとのそれぞれの人生の年代記の比較をおこない、年 表における対話論理を実践してみたい 気に駆られます。

バ フチンの有名な真理観は、特定の唯一の視点(単声的論理)から絶対的なものをみるというものではなく、(i)複数の視点から複数の可能性のあ る声が交錯するポリフォニー(多声)なものであり、また(ii)それらの複数の声は互いに対話して別のものに展開する(対話的論理→「対話論理」)というものです。

ま た、これも有名なバフチンのテキスト論があります。それは、小説(とりわけドストエフスキーの作品)を、批評家が登場人物と対等な視点にたつ 内在的な理解も、また、歴史的所産やイデオロギー作用の結果(=表象)として読むことにも彼は限界を感じます。ではどうすればよいのか?——バフチンによ れば、小説の登場人物は、それぞれ個性をもった人格であり、読者からは解釈されることを待つ主体であると同時に、 自らが何者であるのかについて行為や発 話を通して主張するというものです。【バフチンのテキスト論】Mikhail Bakhtin, 1895-1975

こ こには、どの人物のどの主張のなかに「真理」があるわけではなく、対話をおこない、複雑な動きをしている多元的な状況そのものが、「ありのま ま」の真実であるということです。この「ありのまま」という表現は、日本人には「自然に」とならんでありきたりの用語ですが、肯定も否定もされない点で価 値中立的であり、また安易な道徳的判断を拒絶します。そしてありのままが基調となるのは、事物の複数性、視点の多様性ということに集約されます。どこか文化相対主義と似ていますね。【バフチンの 真理観】Mikhail Bakhtin, 1895-1975

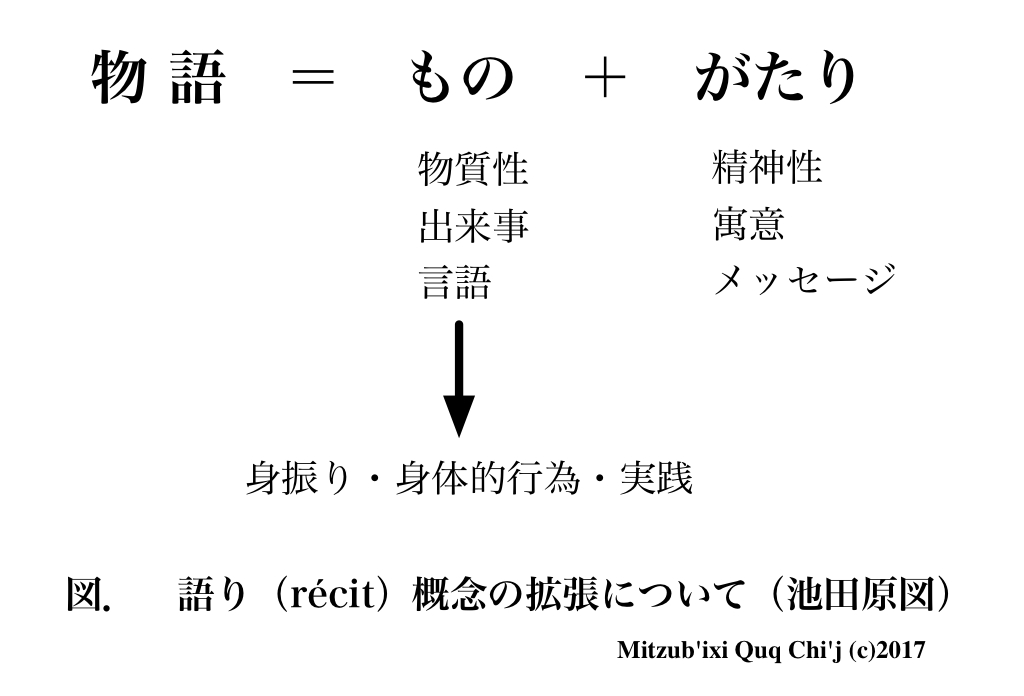

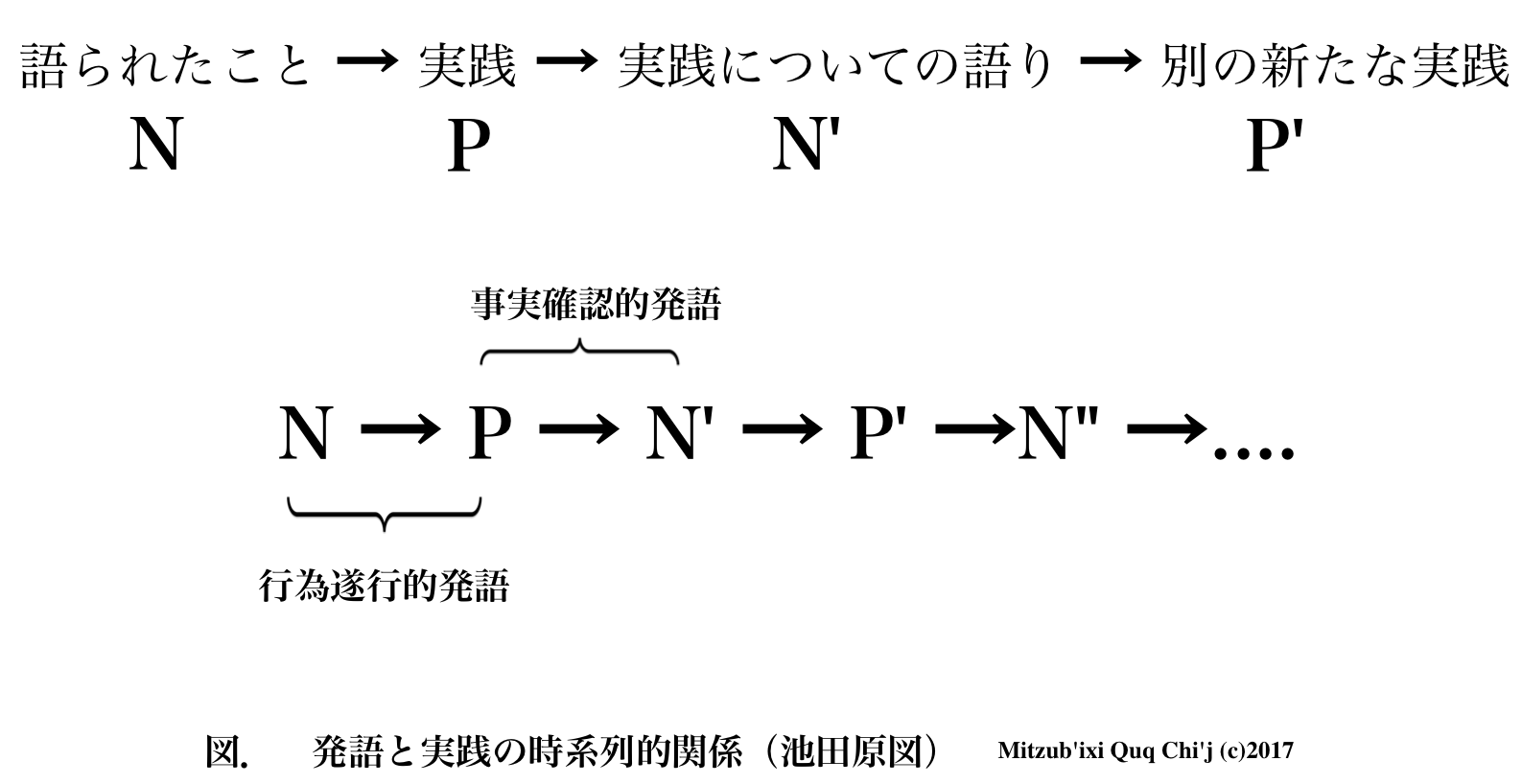

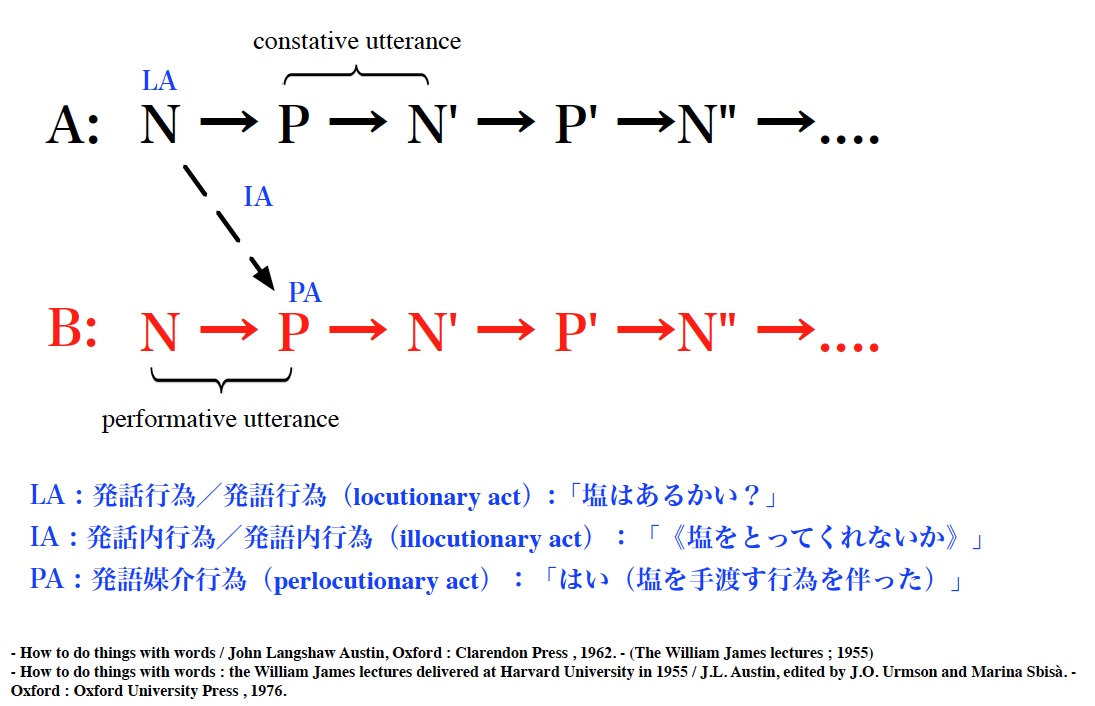

さ て、最近(2017年2月25日)の私の関心は、バフチン『』(1929)で指摘された、ドストエフスキー文学のポリフォニー論であるが、そこで指摘され ている、登場人物=主人公たちが、それぞれに固有の主体性をもち、著者であるドストエフスキーから自由になること、である。つまり、発話主体が、語りを通 してどのようにして自己を自由な存在にするのかというポイントである。私の予感なのではあるが、それは、まず、物語は、「出来事」についての「語り」とい う二重性をもつことにある。それゆえ、語りは、何らかの形で、出来事を作り上げる能力(conatus)をもつ。そして、それらの語る主体のみで時速的な ものなのではなくて、他者の存在を媒介にして可能になると考えられる。発話や語り(Narrative, N)は、行為遂行的発話(例:「僕は宿題をこれから行う」)を通して実践(Practice, Praxis, P)を生み出す。しかし、それは、学校や塾の先生あるいは保護者に対してのまさにパフォーマンス(=これからやります)ということなのだ。実際に出来た宿 題を見せて、僕は事実確認的発語(constative uttrance)つまり「ここに宿題があるよ」(=ようやく、宿題ができたよ!)ということができる。これは、重要な他者の存在により、ようやく可能に なる。私たちは、他者の存在を抜きにして、「私は〜します」と言うことができない(もちろん自分で自分に約束することはできるが、その際は「発語する主 体」と「それを聞く主体」は分離しているわけだ)。このことを、オースティンが、2つの発語概念の区別の後に打ち立てた、発話行為/発語行為 (locutionary act)・発話内行為/発語内行為(illocutionary act)・発語媒介行為(perlocutionary act)という区分をからみてみると、発語/発話の社会性というものがより明確になる。それが下図の3番目の図である。そこでは発話の流れは、A氏がB氏 に対して「塩はあるかい?」と発語し、2人の間で《塩を取ってほしい》という合意ができあがり、そしてB氏が、黙ってあるいは、ハイと言いながら塩をA氏 に渡すという手順がみられる。発語には行為を誘発する作用があるのだ。これは、指摘されると自明なことだと分かるが、私たちは暗黙の前提でこれらのこと を、夥しい発語を通して、そうして、さまざまな意味のやり取りの失敗と成功を重ねながら行っている。

|

|

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

ミハイル・バフチン

Михаил Михайлович Бахти Mikhail Bakhtin/1895−1975

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

ポリフォニー小説としての『白い巨塔』(1963-1965)山崎豊子原作

+++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆