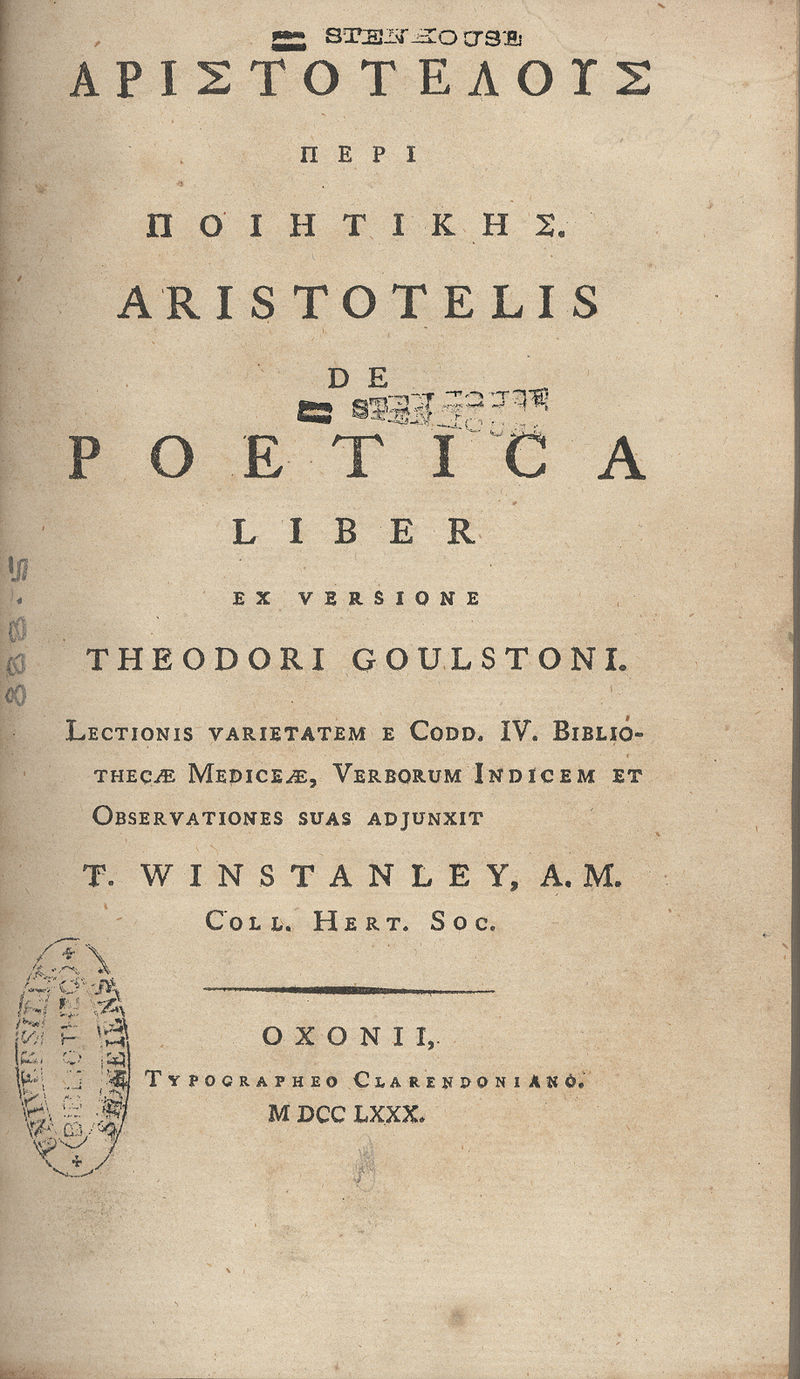

アリストテレス「詩学」

Aristoteles Collected Works: Poetics

アリストテレス「詩学」

Aristoteles Collected Works: Poetics

解説:池田光穂

詩学 (アリストテレス)—— ウィキペディア(日本語より)「『詩学』(しがく、希: Περὶ Ποιητικῆς、羅: De Poetica、英: Poetics)は、詩作について論じた古代ギリシャの哲学者アリストテレスの著作。原題の 「ペリ・ポイエーティケース」は、直訳すると「創作術につい て」、意訳すると「詩作(ポイエーシス)の技術について」といった程度の意味[1]。 彼の著作中では、『弁論術』と共に、制作学(創作学)に分類される著作である(どちらも「修辞・文芸」的要素と「演劇」的要素の組み合わせによって成り 立っている)。またプラトンによる『国家』第10巻と共に、文芸論・物語論・演劇論の起源とされている。」

「プラトンとアリストテレスによる評価の差異 アリストテレスの師であるプラトンは、『ソクラテスの弁明』『イオン』『国家』第10巻などで述べているように、詩(創作)の魅力は認めるものの、それは 「弁論術・論争術・ソフィストの術(詭弁術)」や「絵画の術」と同じように、対象の真実についての知識や技術を持ち合わせないままそれを(感覚・感情・快 楽を刺激するように誇張的に)「模倣」(真似)して、人々の魂を誘導し、対象の真実から遠ざけていってしまうものであり、また更にそれを扱う詩人(作家) の中にも、弁論家・ソフィストと同じようにそのことに無自覚で、それらの術を以て知りもしないことを知っていると思い込んでいる傲慢な者が少なからずいる として、批判的に扱っている。 それに対してアリストテレスは、『弁論術』の場合と同じく、プラトンの考え方を引き継ぎつつも、それを肯定的に捉え直そうと努めている。すなわち「模 倣」(再現)を行い、「模倣」(再現)によって学び(真似び)、また「模倣」(再現)されたものを見て悦ぶというのは、人間の本性に根ざした自然な傾向で あるとして、詩作をそうした人間性質の反映の一種(「人間の営為」の「模倣」(再現))として捉え、その性質の完成という目的(テロス)に向けた発展過程 として、詩作的営みの全体像を説明しようとしている(第4章)。したがって、本書『詩学』において、アリストテレスの関心と記述は専ら、詩 作の最も発展成熟した形態としての「悲劇」とその構造分析に費やされている。」

La Poética1 o Sobre la poética

(Περὶ Ποιητικῆς) es una obra de Aristóteles escrita en el siglo iv a.

C., entre la fundación de su escuela en Atenas, en el 335 a. C., y su

partida definitiva de la ciudad, en el 323 a. C. Su tema principal es

la reflexión estética a través de la caracterización y descripción de

la tragedia. Aristóteles se propone hablar «del arte poético en sí

mismo y de sus formas, de la potencialidad que posee cada una de ellas,

y de qué modo se han de componer las tramas para que la composición

poética resulte bella».2 La Poética1 o Sobre la poética

(Περὶ Ποιητικῆς) es una obra de Aristóteles escrita en el siglo iv a.

C., entre la fundación de su escuela en Atenas, en el 335 a. C., y su

partida definitiva de la ciudad, en el 323 a. C. Su tema principal es

la reflexión estética a través de la caracterización y descripción de

la tragedia. Aristóteles se propone hablar «del arte poético en sí

mismo y de sus formas, de la potencialidad que posee cada una de ellas,

y de qué modo se han de componer las tramas para que la composición

poética resulte bella».2Al parecer, la obra estaba compuesta originalmente por dos partes:3 un primer libro sobre la tragedia y la epopeya, y un segundo sobre la comedia y la poesía yámbica, que se perdió, aparentemente durante la Edad Media, y del que nada se conoce. Básicamente, la Poética consta de un trabajo de definición y caracterización de la tragedia y otras artes imitativas. Junto a estas consideraciones aparecen otras, menos desarrolladas, acerca de la historia y su comparación con la poesía (las artes en general), consideraciones lingüísticas y otras sobre la mímesis. La Poética es una de las obras aristotélicas tradicionalmente conocidas como esotéricas o acromáticas. Esto implica que no habría sido publicada, sino que constituía un conjunto de cuadernos de notas destinados a la enseñanza y que servían de guía o apunte para el maestro. Estaban destinados a ser oídos y no a ser leídos. El más antiguo de los códices que contienen el texto de la Poética (ya sin la Comedia) es el Codex Parisinus 1741, escrito a mediados del siglo xii. |

『詩

学』または『詩学について』(ギリシャ語:Περὶ

Ποιητικῆς)は、アリストテレスが紀元前4世紀に著した著作である。紀元前335年にアテナイで学派を創設してから紀元前323年に同地を離れる

までの間に書かれた。その主なテーマは、悲劇の性格付けと描写を通じた審美的な考察である。アリストテレスは「詩作そのものとその形式、それぞれの持つ潜

在的可能性、そして詩作が美しいものとなるようプロットを構成すべき方法」について語ろうとした。2 『詩

学』または『詩学について』(ギリシャ語:Περὶ

Ποιητικῆς)は、アリストテレスが紀元前4世紀に著した著作である。紀元前335年にアテナイで学派を創設してから紀元前323年に同地を離れる

までの間に書かれた。その主なテーマは、悲劇の性格付けと描写を通じた審美的な考察である。アリストテレスは「詩作そのものとその形式、それぞれの持つ潜

在的可能性、そして詩作が美しいものとなるようプロットを構成すべき方法」について語ろうとした。2この著作は、当初は2つの部分から構成されていたらしい。すなわち、悲劇と叙事詩に関する第1巻と、喜劇と脚韻詩に関する第2巻である。第2巻は中世の間に失われたらしく、何も知られていない。 基本的に、『詩学』は悲劇とその他の模倣芸術の定義と特徴づけに関する著作で構成されている。これらの考察に加え、歴史と詩(芸術一般)との比較、言語に関する考察、模倣に関する考察など、あまり発展していない考察もある。 『詩学』は、伝統的に難解または無彩色として知られるアリストテレスの著作のひとつである。これは、出版されることはなく、むしろ教育を目的としたノート ブックのセットとして、教師のためのガイドやメモとして構成されたことを意味する。それらは、読まれるのではなく、聞かれることを意図していた。 『詩学』のテキスト(『喜劇』は含まれていない)が収められた写本の中で最も古いものは、12世紀半ばに書かれた『パリ写本』1741である。 |

Principales temas tratados Aristóteles, según una copia del siglo i o siglo ii de una escultura de Lisipo. La obra consta de 26 capítulos. En los seis primeros se hace una caracterización general de las artes, aunque en los ejemplos del capítulo 1 solo se mencionan artes literarias, dramáticas y musicales. Se afirma que "todas vienen a ser, en conjunto, imitaciones. Pero se diferencian entre sí por tres cosas: por imitar con medios diversos, o por imitar objetos diversos, o por imitarlos diversamente" (47a 16-19)4 Los medios de imitación (o mimesis) son el ritmo, el lenguaje y la armonía. Las artes se diferencian allí porque usan distintos medios (a través de la música o el verso), o porque usan algunos y no otros, o porque usándolos todos los usan o a la vez o alternadamente. Las artes musicales (“aulética”, “citarística”, “el arte de tocar la siringa”) usan el ritmo y la armonía. La danza, por su parte, solo usa el ritmo (“mediante ritmos convertidos en figuras, imitan caracteres, pasiones y acciones”)(47a 25-30). Aristóteles nos dice que el arte que imita solo por medio del lenguaje (la literatura) no tenía denominación en ese momento, aunque luego admite que “la gente, asociando al verso la condición de poeta, llama a unos poetas elegíacos y a otros poetas épicos, dándoles el nombre de poetas no por la imitación, sino en común por el verso. En efecto, también a los que exponen en verso algún tema de medicina o de física suelen llamarlos así”(47b 13-16). En cuanto a las artes que usan los tres medios (ditirambo —composición lírica griega—, momo —burlas, utilización del sentido irónico...—, tragedia y comedia), las dos primeras las utilizaban simultáneamente a lo largo de todo el poema y las dos restantes solo en las partes líricas. La diferencia en cuanto al objeto imitado sería que, "puesto que los que imitan imitan a hombres que actúan y estos deben ser esforzados o de baja calidad... o bien los hacen mejores que solemos ser nosotros, o bien peores o incluso iguales" (48a 1-5). Por último, la distinción en cuanto al modo de imitar se refiere a la diferencia entre la poesía épica y la poesía dramática: en un caso se narran los hechos (o se mezcla narración con aparición en primera persona de los personajes, como en Homero) y en el otro se presenta "a todos los imitados como operantes y actuantes"(48a 23). En el capítulo 4 se realiza una descripción del origen y el desarrollo de la poesía (ποιητική) en la que se afirma que ésta surge por dos factores naturales en el hombre:5 la tendencia a la imitación por un lado, y el ritmo y la armonía por otro. Los hombres "nobles" imitaban las acciones nobles y creaban, al comienzo, "himnos y encomios"; por otro lado, los hombres "vulgares" imitaban las acciones de los "hombres inferiores" y componían "invectivas". Luego los nobles pasaron a componer en verso heroico y los vulgares en yambos. Luego los nobles pasarían a dedicarse a la tragedia y los otros a la comedia. El estagirita concluye: "Habiendo nacido al principio como improvisación -tanto ella [la tragedia] como la comedia...- fue tomando cuerpo, al desarrollar sus cultivadores todo lo que de ella iba apareciendo; y, después de sufrir muchos cambios, la tragedia se detuvo, una vez que alcanzó su propia naturaleza." En el capítulo 5 se hacen consideraciones generales y superficiales acerca del origen y las características de la comedia y la epopeya. Como Aristóteles señala a principios del capítulo siguiente, “del arte de imitar en hexámetros [la epopeya] y de la comedia hablaremos después” (49b 23). De hecho, los últimos capítulos del libro I están dedicados al estudio de la epopeya, pero de la comedia no se encuentra un estudio detallado en esta obra. |

主なトピック アリストテレス、リシッポスの彫刻の1世紀または2世紀の写本による。 この作品は26章から構成されている。 最初の6章では、芸術全般の一般的な特徴が述べられているが、第1章の例では文学、演劇、音楽の芸術のみが言及されている。「それらはすべて、全体として 模倣である。しかし、それらは3つの点で互いに異なる。すなわち、異なる手段で模倣すること、異なる対象を模倣すること、異なる方法で模倣することによっ てである」(47a 16-19)4。 模倣(またはミメーシス)の手段は、リズム、言語、そしてハーモニーである。芸術は、異なる手段(音楽や詩)を用いる点で異なる。あるいは、ある手段を用 い、他の手段を用いない点で異なる。あるいは、それらすべてを用いるが、同時に用いるか、交互に用いるかの点で異なる。音楽芸術(「アウレティクス」、 「シタリスティクス」、「シリンクスを奏でる術」)はリズムとハーモニーを用いる。一方、舞踏はリズムのみを用いる(「リズムを数字に変換することで、人 物、情熱、行動を模倣する」)(47a 25-30)。アリストテレスは、言語のみで模倣する芸術(文学)には当時まだ名前がなかったと述べているが、後に「人々は詩人の状態を詩と関連づけ、あ る詩人を哀歌詩人、またある詩人を叙事詩詩人と称し、模倣のためではなく、詩という共通点から詩人の名を与えている。実際、医学や身体に関するテーマを詩 で表現する人も、通常はこうして詩人と呼ばれる」(47b 13-16)。3つの手段(ディティルバム - ギリシャの叙情詩 -、モメ - 嘲笑、皮肉の使用... -、悲劇、喜劇)を用いる芸術に関しては、最初の2つは詩全体を通して同時に用いられ、残りの2つは叙情的な部分のみで用いられた。 模倣の対象の違いは、「模倣する者は行動する人間を模倣するが、その人間は精力的であるか、あるいは質が低いかのどちらかでなければならない。そのため、 模倣された人物は、通常よりも優れているか、劣っているか、あるいは同じになる」ということである(48a 1-5)。最後に、模倣の方法における区別とは、叙事詩と劇詩の違いを指している。前者は出来事を語るものであり(あるいは、ホメロスのように、語り口調 の中に登場人物の一人称の描写が混在する)、後者は「模倣されたものはすべて、活動し行動しているように表現される」(48a 23)ものである。 第4章では、詩(ποιητική)の起源と発展について説明されており、そこでは、詩は人間に内在する2つの自然要因から生じるとしている。すなわち、 一方では模倣の傾向であり、他方ではリズムとハーモニーである。「高貴な」人間は高貴な行動を模倣し、当初は「賛美歌や賛辞」を創作した。一方、「卑俗 な」人間は「劣った人間」の行動を模倣し、「非難の言葉」を書いた。その後、貴族は英雄詩を、卑俗な人間は脚韻詩を創作するようになった。そして貴族は悲 劇に、卑俗な人間は喜劇に専念するようになった。スタギライトは次のように結論づけている。「悲劇も喜劇も、当初は即興として生まれたが、それを育む人々 がその中に現れるものをすべて発展させるにつれ、形を成していった。そして、多くの変化を経た後、悲劇は、悲劇の持つ本質に到達し、そこで止まった。 第5章では、喜劇と叙事詩の起源と特徴について、一般的な表面的な考察がなされている。アリストテレスが次の章の冒頭で指摘しているように、「六歩格の模 倣術(叙事詩)と喜劇については、後ほど語ることにする」(49b 23)と述べている。実際、第1巻の最後の章は叙事詩の研究に割かれているが、喜劇の詳細な研究は本作品には見られない。 |

| Definición de la tragedia y sus elementos esenciales El siguiente es uno de los capítulos centrales de la obra, donde se define la tragedia y se señalan las seis partes o sus elementos esenciales. Además es aquí donde se señala por única vez la famosa “cláusula adicional” de la tragedia, la catarsis. Según Aristóteles, “la tragedia [es] imitación de una acción esforzada y completa, de cierta amplitud, en lenguaje sazonado, separada cada una de las especies en las distintas partes, actuando los personajes y no mediante relato, y que mediante temor y compasión lleva a cabo la purgación de tales afecciones” (19b 24-26). A diferencia, la comedia es “imitación de personas de baja estofa, pero no de cualquier defecto, sino que lo cómico es una parte de lo feo. Efectivamente, lo cómico es un defecto y una fealdad que no contiene ni dolor ni daño, del mismo modo que la máscara cómica es algo feo y deforme, pero sin dolor.”6 Más adelante el filósofo dirá que los elementos esenciales de la tragedia son seis: fábula (mythos), caracteres (êthê), pensamiento (diánoia), elocución (lexis), melopeya (melopoiia) y espectáculo (opsis).7 |

悲劇の定義とその本質的要素 以下は、この作品の中心的な章のひとつであり、悲劇の定義と、その6つの部分または本質的要素が指摘されている。また、悲劇の有名な「付加条項」であるカタルシスが唯一言及されているのもこの章である。 アリストテレスによれば、「悲劇とは、ある規模で、威厳のあるスタイルで、各部分が区別され、登場人物が語るものであり、物語を語るものではなく、恐怖と 哀れみを通して、そうした感情の浄化作用となるような、完全かつ完全に演出された行動の模倣である」(19b 24-26)。それに対して喜劇は、「品性の低い人間を模倣するものだが、どんな欠点でもよいというわけではなく、むしろ滑稽さは醜さの一部である。実 際、滑稽さは欠点であり醜さであるが、痛みも害も含まない。滑稽な仮面が醜く変形したものでありながら、痛みを含まないのと同じである。」6 後に、哲学者は悲劇の本質的な要素は6つあると述べる。寓話(ミトス)、登場人物(エテー)、思考(ディアノーア)、言葉(レクシス)、旋律(メロポイエア)、視覚(オプシス)である。7 |

| La fábula Considerada fundamental para Aristóteles ya que, sin ella, la tragedia no podría llevarse a cabo. Destaca las características y lo que representa la fábula para la composición y realización de una tragedia y sus componentes que para él eran necesarios. |

寓話 アリストテレスにとって、悲劇はそれなしでは起こりえないため、根本的なものと考えられていた。彼は、悲劇とその構成要素の実現に必要なものとして、その特徴と寓話が何を表しているかを強調した。 |

| Unidad de la acción Según el filósofo, la tragedia es imitación de una única acción8 de larga duración, siempre que pueda recordarse en su conjunto, completa y entera (o sea con principio, medio y fin). Cuando Aristóteles habla de la unidad de la acción imitada en la fábula, descarta dos posibilidades: que se imiten todas las acciones de un solo sujeto o todas aquellas sucedidas durante un determinado tiempo. La idea que pretende imponer es que hay una fábula, una “historia”, que se pretende contar y que solamente deben incluirse en ella aquellas acciones que sean indispensables para el desarrollo de ésta. |

行動の統一性 哲学者によれば、悲劇とは、全体として、完全かつ完全に(つまり、始まり、中盤、終わりとともに)記憶されることができるという条件のもとで、単一の持続的な行動の模倣である。 アリストテレスが寓話で模倣される行動の統一性について語る際、彼は2つの可能性を排除している。すなわち、単一の主体の行動すべてが模倣されるか、また は特定の期間に起こった行動すべてが模倣されるか、という2つの可能性である。彼が主張しようとしている考えは、語られることを意図した寓話、つまり「物 語」があり、その物語の展開に不可欠な行動のみが寓話に盛り込まれるべきである、というものである。 |

Fábula y verosimilitud Teatro de Epidauro. La fábula, en efecto, es para Aristóteles el elemento esencial de la tragedia. Sin la fábula no hay tragedia, pero, en cierta forma, sí la hay sin los cinco elementos restantes. Esto es porque la tragedia también puede desencadenar el placer que le es propio, simplemente por su lectura y sin necesidad de representación. Se describe en el texto que la fábula es “la estructuración de los hechos” y que ésta debe darse de forma “verosímil o necesaria”. La verosimilitud-necesidad se refiere a la necesidad de un ordenamiento lógico en términos de causa-efecto en el ordenamiento de la tragedia. Este orden o estructuración debe darse de forma tal que, si se suprimiese alguno de los sucesos imitados o se agregase otro, se dislocaría totalmente el conjunto de la obra. |

寓話と真実味 エピダウロスの劇場。 アリストテレスにとって、寓話は悲劇の本質的な要素である。寓話がなければ悲劇は存在しないが、ある意味では、残りの5つの要素がなくても悲劇は存在する。なぜなら、悲劇は、それを表現する必要がなく、読むだけで悲劇特有の喜びを引き起こすことができるからだ。 テキストでは、寓話を「出来事の構造化」と表現し、それが「妥当または必要」な方法で起こるべきだと述べている。妥当性・必要性とは、悲劇の順序付けにお いて因果関係に基づく論理的な順序が必要であることを意味する。この順序や構造は、模倣された出来事のいずれかが削除されたり、別の出来事が追加されたり した場合、作品全体が完全に崩壊してしまうようなものでなければならない。 |

| Peripecia, agnición o anagnórisis y lance patético Aristóteles parte del supuesto de que en la tragedia la acción se desarrolla en un sentido hasta que en cierta forma el personaje comete un error que lo lleva a pasar “de la dicha al infortunio”. A este cambio de suerte en sentido contrario se le llama, la mayor parte de las veces, peripecia. Por otro lado, se llama agnición (agnitio, en latín) al paso de la ignorancia al conocimiento, “para amistad o para odio”, que un personaje experimenta acerca de la identidad de alguno o varios de los demás o del personaje acerca de algún hecho. En griego se usaba la palabra anagnórisis, que significa lo mismo que agnitio: reconocimiento. Ambas son intercambiables, su uso depende de la tradición lingüística del usuario. Junto a estos dos conceptos, propios de toda tragedia compleja, existe otro llamado lance patético, que es aquel evento que cambia el sentido de la acción mediante las muertes fuera de escena, las tormentas o las heridas y eventos semejantes, es decir, no hay visión de los hechos. Anagnórisis y peripecia son términos fundamentales para entender los grados que el estagirita establece sobre el valor de una clase de tragedia respecto de otra, en virtud de su capacidad para desencadenar la catarsis. |

ペリペテイア、アグニッションまたはアナグノリシス、そしてパセティック・フォールアキ アリストテレスは、悲劇においては、登場人物があるミスを犯すまでは、行動がひとつの方向へと展開していくという前提から出発する。このミスにより、登場 人物は「幸福から不幸」へと転落する。この幸運の逆転は、ペリペテイアと呼ばれることが多い。一方、アグニチオ(ラテン語ではアグニティオ)は、登場人物 が他者(複数)の正体や、ある出来事について、無知から知識を得ることを指す。ギリシャ語ではアナグノリシスという言葉が使われており、アグニチオと同じ 意味である「認識」を意味する。両者は互換性があり、使用者は言語の伝統によって使い分ける。この2つの概念に加え、複雑な悲劇に典型的なものとして、も う1つ「哀れな場面」と呼ばれるものがある。これは、舞台裏での死や嵐、負傷などの類似した出来事によって、行動の意味が変化する出来事を指す。つまり、 その出来事の様子は描かれない。 アナグノリシスとペリペテイアは、カタルシスを引き起こす能力によって、ある種の悲劇が別の悲劇よりも価値があるとするスタギリテの考え方を理解する上で、基本的な用語である。 |

| Tipos de agnición Según Aristóteles, hay varias clases de agnición: ... la menos artística y la más usada por incompetencia, … la que se produce por señales". La agnición o el reconocimiento mediante señales consiste en que un personaje logre identificar a otro debido a particularidades corporales o del atuendo de este último. De hecho, puede ser que lo reconozca por señales corporales “congénitas” o señales “adquiridas”, “y, de éstas, unas impresas en el cuerpo, como las cicatrices, y otras fuera de él, como los collares (54b 20-25) y pone como ejemplo que la nodriza de Ulises le reconociera cuando iba disfrazado de mendigo, por una señal, una cicatriz que tenía Ulises. En segundo lugar de peor a mejor, vienen las agniciones "... fabricadas por el poeta", aquéllas en que algún personaje desvela lo que no se sabía explícitamente y de forma no muy verosímil ni necesaria. "La tercera se produce por el recuerdo, cuando uno, al ver algo, se da cuenta”, "La cuarta es la que procede de un silogismo, como en las Coéforos: ha llegado alguien parecido a mí; pero nadie es parecido a mí sino Orestes, luego ha llegado éste". Es decir, esta agnición es la que se produce por un pensamiento lógico. Al mismo nivel, en tanto agnición, se encuentran los paralogismos, razonamientos con forma silogística pero lógicamente errados, p.e. por afirmar el consecuente. La quinta y "mejor agnición de todas" es la que resulta de los hechos mismos, produciéndose la sorpresa por circunstancias verosímiles. |

認識の種類 アリストテレスによれば、認識にはいくつかの種類がある。 最も芸術的ではなく、無能なために最もよく使われるもの、... 記号によって生み出されるもの」。 記号による認識または識別とは、特定の身体的特徴や服装によって、ある人物が他の人物を識別できることを指す。実際、彼は「先天的」な身体のサインや「後 天的」なサインによって相手を認識しているのかもしれない。そして、これらのうち、傷跡のように身体に刻み込まれているものもあれば、ネックレスのように 身体の外にあるものもある (54b 20-25)。 そして、一例として、乞食に変装したオデュッセウスを、オデュッセウスの傷跡というサインによって、彼の乳母が認識したことを挙げている。 最悪から最高まで2番目にくるのは、「詩人によって作り出された」アグニッション(agnitions)で、登場人物が、明白に知られていなかったことを明らかにするもので、あまり説得力のない、あるいは必要のない方法で示されるものである。 「3番目は、それを見て何かを理解したときに記憶によって生み出されるものだ。 4番目は、三段論法から生み出されるもので、例えば『コエフォロス』のように、私に似た人物が到着した。しかし、私に似た人物はオレステス以外にはいな い。したがって、彼が到着したのだ。言い換えれば、このアグニッションは論理的思考によって生み出される。アグニッションに関して言えば、同等のレベルに あるものに、三段論法の形式で論じられるものの論理的に誤りがあるパラロジズムがある。例えば、帰結を肯定することなどである。 5番目で「最高の」アグニッションは、事実そのものから生じるもので、妥当な状況に驚きを生み出す。 |

| Clasificaciones internas a la tragedia En la división entre fábulas simples, episódicas y complejas, se dice que las primeras son aquellas en que el cambio de fortuna se da sin peripecia ni agnición, las segundas son aquellas en que ni siquiera se da la verosimilitud o necesidad en la sucesión de las acciones y las terceras designan a las que presentan al cambio de suerte acompañado de peripecia y agnición. Como es de suponer, esta última categoría es la superior. La clasificación siguiente se refiere a las distintas formas de desarrollar el lance patético (pathos), la resolución de la obra trágica, para promover la catarsis en su plenitud. Esto se da combinando adecuadamente la ejecución de la acción central con la agnición o la falta de ella acerca de lo que se está efectuando. Además es preferible que el desenlace trágico muestre a dos personas que son parientes o amigas que se violentan, dado que esto es lo que impacta más a los espectadores. En orden de mayor a menor valor catártico, Aristóteles propone cuatro tipos de desenlace: Que un personaje esté a punto de desarrollar la acción9 y obtenga la agnición justo antes de efectuarla; que el personaje efectúe la acción y que, luego de finalizada ésta, obtenga la agnición sobre su acción; que el personaje lleve a cabo la acción con agnición, y, por último, que el personaje esté a punto de efectuar la acción con agnición y no la lleve a cabo. |

悲劇の内部分類 単純な寓話、エピソード的な寓話、複雑な寓話の区分において、前者は、幸運の変化が何事もなく、また認識されることもなく起こるもの、後者は、行動の連続 に真実味や必然性さえないもの、そして3番目は、幸運の変化が事件や認識を伴って起こるものを指すと言われている。予想通り、この最後のカテゴリーが最も 高い。 次の分類は、悲劇的作品の解決策であるパトス(哀れみ)のプロットを展開させるさまざまな方法について言及しており、カタルシスを最大限に促進する。これ は、中心となる行動の遂行と、その行動についての認識の有無を適切に組み合わせることで達成される。また、悲劇的な結末では、親戚や友人である2人が互い に暴力を振るう場面を見せるのが望ましい。なぜなら、それが観客に最も強いインパクトを与えるからだ。 カタルシス効果の大きい順に、アリストテレスは4つの結末のタイプを提案している。 登場人物が間もなく行動を起こそうとし、その直前に気づきを得る。 登場人物がその行動を起こし、それが終わった後に自分の行動について気づきを得る。 登場人物が気づきを得た上で行動を起こし、最後に 登場人物が気づきを得た上で行動を起こそうとし、それを実行しない。 |

| Los caracteres En un nivel general, se puede decir que Aristóteles llama caracteres a lo que hoy llamamos personajes. Según el filósofo “habrá caracteres si, … las palabras y las acciones manifiestan una decisión” (54a 17). O sea los personajes se definen por sus acciones y no por su ‘caracterización’ ya sea por medio de la vestimenta u otros ‘’aderezos’’.  Máscaras romanas de la tragedia y la comedia. Aunque son romanas y del siglo ii, es probable que se asemejen a las utilizadas en el teatro griego para designar los caracteres. Aristóteles explica que los personajes deben ser intermedios entre vicio y virtud, aquel "que ni sobresale por su virtud y justicia ni cae en la desdicha por su bajeza y maldad, sino por algún yerro, siendo de los que gozaban de gran prestigio y felicidad, como Edipo y Tiestes…"(53a 8-11). Además, había de dos tipos: los que realizaban acciones nobles (solían relacionarse con los de las personas de clase alta) y los que realizaban acciones vulgares (los de clase baja). El postular la representación de caracteres ni virtuosos ni viciosos, sino en un grado intermedio entre ambas cualidades, pasa por varios motivos. Por un lado, no sería bueno representar a una persona virtuosa pasando de la dicha al infortunio, “pues esto no inspira temor ni compasión, sino repugnancia” (53b 35). En el sentido opuesto, tampoco sería bueno que una persona viciosa pasase en la fábula de la desdicha a la dicha, ya que eso no inspira ni compasión ni simpatía ni temor. La "'compasión'" se refiere al personaje que es inocente y no merecería sufrir las consecuencias de su yerro ignorante, el temor a la situación que se nos presenta cuando vemos todas las cosas que le pasan a alguien que es semejante, en cualidades, a nosotros. |

キャラクター 一般的に言って、アリストテレスは、今日私たちがキャラクターと呼ぶものを「キャラクター」と呼んでいたと言える。哲学者によれば、「言葉と行動が意思表 示となる場合、キャラクターが存在する」(54a 17)ということだ。つまり、キャラクターはその行動によって定義され、服装やその他の「装い」によってではない。  悲劇と喜劇のローマの仮面(のモザイク画)。ローマの2世紀のものだが、おそらくギリシャ劇で登場人物を表現するために使われた仮面と似ているだろう。 アリストテレスは、登場人物は「美徳や正義に秀でているわけでもなく、卑しさや邪悪さによって不幸に陥るわけでもなく、何らかの過ちによって、オイディプ スやテセウスといった、高い名声と幸福を享受していた人物たちの中にいるような人物」であるべきだと説明している(53a 8-11)。さらに、高貴な行動を取る者(彼らは上流階級の人々と付き合っていた)と、下品な行動を取る者(下層階級の人々)の2種類があった。 登場人物を、高潔でも悪徳でもない、その両方の性質の中間的な度合いとして表現する理由はいくつかある。一方では、善良な人物が幸福から不幸へと転落する 姿を描くのは良くない。「なぜなら、それは恐怖も同情も呼び起こさず、嫌悪感だけしか呼び起こさないからだ」(53b 35)。他方では、悪人が不幸から幸福へと転落する姿を描くのも良くない。なぜなら、それは同情も共感も呼び起こさず、恐怖も呼び起こさないからだ。 「『同情』とは、無実であり、無知による過ちの結果として苦しむべきではない人物のことを指す。自分と似た性質を持つ人物に起こっていることをすべて目にしたときに生じる、その状況に対する恐怖である。 |

| A la vez se describen cuatro cualidades indispensables de los caracteres:10 Bondad Se trata aquí de una bondad moral del personaje y no de una bondad en la representación poética, “y esto es posible en todo género de personas; pues también puede haber una mujer buena, y un esclavo…”(54a 20). Propiedad El carácter presentado debe ser apropiado; por ejemplo, “es posible que el carácter sea varonil, pero no es apropiado a una mujer ser varonil o temible” (54a 23). Semejanza En el caso de que se presenten personajes históricos o que ya hubiesen sido presentados en otras obras poéticas, el poeta tendrá que representarlos de forma semejante a la que la tradición ha consagrado, aunque se le permita embellecerlos. Consecuencia Este punto propone también para los personajes la regla de la verosimilitud o necesidad, que supone una coherencia en la forma en que se presenta el carácter a lo largo de la tragedia. Por ello, “aunque sea inconsecuente la persona imitada y que reviste tal carácter, debe, sin embargo, ser consecuentemente inconsecuente” (54a 25). |

同時に、登場人物に不可欠な4つの資質が説明されている。 善良さ これは登場人物の道徳的な善良さについてであり、詩的な表現における善良さではない。「これはあらゆる人々において可能である。なぜなら、善良な女性や奴隷も存在しうるからだ」(54a 20)。 適切さ 登場人物は適切でなければならない。例えば、「登場人物が男らしいことは可能だが、女性が男らしいことや恐ろしいことは適切ではない」(54a 23)。 類似性 歴史上の人物やすでに他の詩的作品で登場している人物の場合、詩人はそれらを伝統が確立した方法に類似した方法で表現しなければならないが、それらを装飾することは許される。 結果 この点も登場人物には真実味や必然性のルールが適用され、悲劇全体を通して登場人物が首尾一貫した方法で表現されることを意味する。したがって、「模倣さ れ、そのキャラクターを演じる人物は取るに足らない人物であっても、首尾一貫して取るに足らない人物でなければならない」(54a 25)。 |

| Pensamiento y elocución El pensamiento (o, más bien, "razonamiento discursivo", debate, conflicto dialógico, que es lo que significa dianoia) es el tercer elemento esencial de la tragedia. Aristóteles dice que le corresponde "todo lo que debe alcanzarse mediante las partes del discurso. Son partes de esto demostrar, refutar, despertar pasiones, por ejemplo compasión y temor, ira y otras semejantes, y además amplificar y disminuir"(56a 35). En este caso se trata de aquello que hace un personaje para convencer o refutar a otro y no a los espectadores. De todos modos el tratamiento de Aristóteles de este punto no es amplio, ya que reconoce que es propio del arte descrito en la Retórica. La elocución es la “expresión mediante las palabras”(50b 15), tampoco es un arte propio de la tragedia, sino de los actores y directores de escena. Sus modos son el mandato, la súplica, la narración, la amenaza, la pregunta, la respuesta, etc. En los capítulos 20, 21 y 22, que muchos han considerado apócrifos, Aristóteles desarrolla una teoría lingüística, o de la elocución, en la que define, entre otros conceptos, los de: sílaba, conjunción, nombre, verbo, artículo, caso, enunciación y metáfora. |

思考と言語表現 思考(あるいは「弁証的推論」、討論、弁証法的な対立、すなわちディアノイア)は悲劇の3つ目の本質的な要素である。アリストテレスは、思考は「品詞を通 じて達成されなければならないあらゆるもの」に相当すると述べている。その一部は、例えば同情や恐怖、怒りなど、情動を喚起したり、反駁したり、増幅した り、減じたりすることである」(56a 35)。この場合、登場人物が他の登場人物を説得したり反駁したりすることについてであり、観客についてではない。いずれにしても、アリストテレスは『弁 論術』で説明されている芸術にふさわしいものとして、この点に関する彼の考察は広範なものではない。 「言葉による表現」である演説術(50b 15)は、悲劇特有の芸術ではなく、俳優や舞台監督のためのものである。その様式は、命令、懇願、物語、脅し、質問、回答などである。 第20章、第21章、第22章では、多くの人が偽書であると考えているが、アリストテレスは言語理論、すなわち発声理論を展開し、音節、接続詞、名詞、動詞、冠詞、格、発声、隠喩などの概念を定義している。 |

| Melopeya y espectáculo Aristóteles dice que la melopeya es el más importante de los aderezos de la tragedia. Sin embargo, considera que su significado es obvio y no lo explica. En general, podría decirse que este elemento se refiere a las intervenciones del coro, que eran muy importantes en la tragedia clásica. El espectáculo es el elemento de la tragedia “menos propio de la poética”, ya que es “cosa seductora”, y para nada indispensable (50b 18). En esta categoría entrarían lo que hoy llamamos escenografía y efectos especiales. |

メロポイエアとスペクタクル アリストテレスは、メロポイエアは悲劇の装飾の中で最も重要であると述べている。しかし、その意味は明白であると考え、説明はしていない。一般的に、この要素は古典悲劇において非常に重要な役割を果たした合唱団の介入を指していると言える。 スペクタクルは「詩学に最もふさわしくない」悲劇の要素である。なぜなら、それは「魅惑的なもの」であり、まったく不可欠なものではないからだ(50b 18)。このカテゴリーには、今日で言うところの舞台美術や特殊効果などが含まれる。 |

| Otras consideraciones Diferencias entre la poesía y la historia En época de Aristóteles casi todo se escribía en verso, incluso la poesía lírica y la ciencia, y poeta era cualquiera que escribiera verso. Aristóteles es el primero en distinguir entre los que escriben literatura en verso y los que escriben ciencia en verso. Por otra parte, también hay que distinguir entre los que escriben literatura y los que escriben historia. "No corresponde al poeta decir lo que ha sucedido, sino lo que podría suceder, esto es, lo posible según la verosimilitud o la necesidad. En efecto, el historiador y el poeta no se diferencian por decir las cosas en verso o en prosa (...) la diferencia está en que uno dice lo que ha sucedido, y el otro, lo que podría suceder. Por eso también la poesía es más filosófica y elevada que la historia, pues la poesía dice más bien lo general y la historia, lo particular". Consideraciones sobre la mímesis o imitación Cuando contemplamos la obra de arte pueden suceder dos cosas, que uno conozca lo que el artista ha hecho, en cuyo caso el placer producido deriva solo de su habilidad, o que no lo conozca, en cuyo caso solo podrá producir placer la ejecución de la imitación, la utilización de los recursos imitativos. Por tanto, la mímesis, o imitación poética, no es sencillamente una "imitación" de lo real, sino que es un "artificio", una "elaboración del poeta" sobre lo real, a la que además imprime su propio estilo. La segunda parte perdida de la Poética Se cree que el llamado Tractatus Coislinianus contiene quizá un epítome o resumen del segundo libro perdido de la Poética de Aristóteles, que iba a tratar sobre la comedia.3 La novela El nombre de la rosa de Umberto Eco se centra en la desaparición de la segunda parte de la Póetica de Aristóteles. |

その他の考察 詩と歴史の違い アリストテレスの時代には、ほとんどすべてのものが詩の形で書かれていた。抒情詩や科学でさえもである。詩を書く者は誰でも詩人であった。アリストテレス は、詩の形で文学を書く者と、詩の形で科学を書く者とを区別した最初の人物である。一方、文学を書く者と歴史を書く者との間にも区別がなされなければなら ない。「詩人が語るべきは、起こったことではなく、起こりうることであり、つまり、可能性や必然性に従って起こりうることを語るべきなのだ。実際、詩人か 歴史家かを区別するのは、詩か散文のどちらで物事を語るかではない。違いは、一方は起こったことを語り、他方は起こりうることを語るということだ。この理 由からも、詩は歴史よりも哲学的で高尚である。なぜなら、詩は一般を語り、歴史は特殊を語るからだ。 ミメーシス(模倣)についての考察 芸術作品を鑑賞する際には、2つのことが起こり得る。すなわち、芸術家が何を為したのかが分かる場合、そこから得られる喜びは芸術家の技量のみに由来す る。あるいは、芸術家が何を為したのかが分からない場合、そこから得られる喜びは模倣の実行、模倣の手段の使用のみに由来する。 したがって、ミメーシス、すなわち詩的模倣は、単に現実の「模倣」ではなく、むしろ現実の「人工物」、すなわち「詩人による現実の加工」であり、そこに詩人のスタイルも刻み込まれる。 『詩学』の第2巻の失われた部分 いわゆる『コイスリアヌス小論文』には、アリストテレスの『詩学』の第2巻(喜劇を扱うもの)の要約が含まれている可能性があると考えられている。 ウンベルト・エーコの小説『薔薇の名前』は、アリストテレスの『詩学』の第2巻の消失を軸に展開する。 |

| Influencia posterior de la Poética Traducción al árabe de la Poética de Aristóteles por Abu Bishr Matta ibn Yunus La obra no fue demasiado reconocida en su época, en parte porque se entendía que coincidía con la Retórica, que era más famosa. Esto sucedía porque en la época clásica ambas disciplinas no estaban separadas y se entendían como dos versiones de la misma cosa. Sin embargo, posteriormente su influencia sería importante y muchos temas de la obra serían discutidos, entre ellos la mímesis, la catarsis y la división entre artes imitativas y el resto de las tekhné (artes, en sentido amplio). Además, Aristóteles afirma que puede haber tres interpretaciones distintas: la primera es visión normativa (al tiempo en el que se encuentran), la segunda la visión analítico-descriptiva (utilizar un lenguaje con las técnicas de la filosofía aristotélica), y la última es la biológica (que posean una cierta extensión y un alto nivel, como un animal que está perfectamente organizado, para que la obra poética se clasifique como una buena obra lograda). Alrededor del año 20 antes de Cristo, Horacio escribió su propia Poética, obra de intención normativa no sólo dedicada al ámbito dramático, sino al narrativo en general. En esta obra la influencia de la poética aristotélica es notoria. Horacio, que había estudiado en Atenas, recoge temas tratados anteriormente por Aristóteles y los resuelve de la misma forma: la necesidad de la congruencia (verosimilitud) en la acción de los personajes, la postulación del valor paralelo del talento y la inspiración divina en el artista como creador y la necesidad de evitar la intervención de los dioses en la fábula. Como es sabido, el texto aristotélico permaneció perdido por siglos, por lo que la poética de Horacio fue el texto más influyente durante largo tiempo. Las primeras traducciones conocidas de la obra aristotélica se realizaron en el mundo árabe, y la más antigua fue la de un cristiano nestoriano llamado Abu Baschar, que la tradujo del siríaco (alrededor del 935 d. C.). Le seguiría la famosa versión de Averroes en el siglo xii a partir de la de Abu-Baschar, y la menos conocida de al-Farabi, que veía la importancia de lo poético como facultad lógica de la expresión. La traducción de Averroes, que con el tiempo sería muy influyente, contenía algunas interpretaciones y desvíos del texto original, básicamente por dos motivos: las diferencias del manuscrito que se tomaba como fuente con el original aristotélico11 y los intereses interpretativos propios de la situación histórica. Es conocida, por ejemplo, la interpretación de Averroes, según la cual la finalidad de la tragedia es educar en un sentido moralista. La primera traducción de la Poética al latín la realizó Hernán Alamán en el siglo xiii en España, otra traducción la hizo en ese mismo país Mantino de Tortosa en el siglo siguiente, ambas a partir de una versión abreviada de la traducción de Averroes. Habría que esperar, sin embargo, hasta el siglo xvi para que la influencia de la Poética se tornara mayor. Algunas traducciones que contribuyeron a ello fueron la de Giorgio Valla en 1498 en Venecia, la edición de la imprenta Aldina del texto original griego en 1508, seguida por otras traducciones como las de 1536 (Pazzi), 1548 (Robortello) y 1549 (Segni, que fue la primera traducción en italiano) ; la primera traducción directa del griego al latín fue la de Guillermo de Moerbeke. In Librum Aristotelis de Arte Poetica Explicationes, del influyente Francesco Robortello, sería el primer comentario completo de la obra en cuestión. Los tratados sobre la Poética se harían cada vez más comunes, entre ellos De Arte Poetica, de Vida (autor latino), en 1527, seguido por otros de una variedad de autores: Trissino, Daniello, Maggi y Lombardi, Muzio, Varchi, Cintio, Minturno, Vettori y Castelvetro. Horacio mantenía su peso en los comentarios, pero se iría más a Aristóteles con el tiempo. Como se habrá podido notar, el comienzo fue netamente italiano, seguido cada vez con más ímpetu por franceses, españoles e ingleses a finales del siglo xvi. En la segunda mitad del siglo, surge la famosa doctrina de las unidades aristotélicas, fuertemente discutida incluso durante su tiempo (véase la nota 6). De la mano de Agnolo Segni y V. Maggi (o, según algunos autores, de Castelvetro) se estableció como regla que los eventos en una obra no podrían durar más de doce horas y que la acción desarrollada debía ser una o dos relacionadas, ocurrida en un espacio limitado al espacio real de la escena. No podrían representarse grandes espacios o cambios de espacio, ni sucesiones temporales, como el paso del día a la noche o de varios días o incluso meses o años, dado que esto no sería necesariamente creíble para el espectador. Como se ve, la doctrina de las unidades está causada, en gran parte, por una interpretación del postulado aristotélico sobre lo "verosímil o necesario" en la tragedia muy diversa de la interpretación actual como coherencia interna. Entre los eruditos españoles comentaristas de la Poética de los siglos XVI al XVIII destacan Alonso López Pinciano, quien primero siguió la estela de los preceptistas italianos, con su obra Philosophia antigua poética (1596); Francisco Cascales, que escribió sus Tablas poéticas en (1604), e Ignacio de Luzán, con su Poética (1737), ya de espíritu neoclásico ilustrado. Hay que recordar, asimismo, que Lope de Vega redactó una poética en verso que justificaba su propia creación teatral y discrepaba en varios aspectos de las poéticas renacentistas que seguían las normas neoaristotélicas. Todo ello aparece en su poema Arte nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo, de 1609. La perspectiva estética aristotélica siguió vigente, no sólo en el arte dramático sino con una influencia extendible a las demás artes, hasta el siglo xviii, cuando, por varios motivos, entraría en declive. El romanticismo pasará a valorar al arte no como un acto en esencia creativo (poiético) sino expresivo, que refleja el sentir y la perspectiva subjetiva del artista y no apunta a reflejar o imitar miméticamente la realidad. El planteamiento kantiano del desinterés necesario para la experiencia de belleza influirá sobre el rechazo progresivo de la perspectiva finalista del arte como catártico. Tres fundamentos de la teoría aristotélica estaban siendo cuestionados: la catarsis, el arte como creación y la mimesis, pero un tercer principio, el de la verosimilitud o necesidad, permanecerá, aunque algo cambiado, en la caracterización del arte como un mundo interno con leyes propias no necesariamente contrarias a las del mundo real, pero sí diferentes (a este principio se le da comúnmente el nombre de heterocosmia). |

後の『詩学』の影響 アブー・ビスハーン・マッタ・イブン・ユヌスによるアリストテレスの『詩学』のアラビア語訳 この作品は当時あまり知られていなかったが、その理由の一つは、より有名な『修辞学』と内容が重複していると考えられていたためである。これは古典時代にはこの2つの学問分野は別個のものではなく、同じものの2つのバージョンであると考えられていたためである。 しかし、後に重要な影響を及ぼし、作品の多くのトピックが議論されることになる。ミメーシス、カタルシス、模倣芸術とその他のテクネ(広義の芸術)の区分 などである。さらに、アリストテレスは、3つの異なる解釈が可能であると述べている。1つ目は(当時における)規範的な見解、2つ目は分析的・記述的な見 解(アリストテレス哲学のテクニックを用いた言語を使用)、そして最後は生物学的な見解(詩作が優れた完成された作品として分類されるためには、動物のよ うに完全に組織化された一定の拡張性と高いレベルを有している必要がある)である。 紀元前20年頃、ホラティウスは『詩作法』を著した。これは、演劇分野のみならず、物語全般を対象とした規範的な意図を持つ作品である。この作品では、ア リストテレスの『詩学』の影響が顕著である。アテネで学んだホラティウスは、アリストテレスが以前に扱った主題を取り上げ、同様の方法で解決した。登場人 物の行動における整合性(妥当性)の必要性、創造者としての芸術家における才能と神の霊感の価値の同等性の仮定、寓話における神の介入を避ける必要性など である。 周知の通り、アリストテレスのテキストは数世紀にわたって失われたままであったため、ホラティウスの『詩学』が長い間最も影響力のあるテキストであった。 アリストテレスの作品の最初の翻訳はアラブ世界で行われ、最も古いものはネストリウス派キリスト教徒のアブ・バシャールによるもので、シリア語から翻訳さ れた(西暦935年頃)。これに続いて、12世紀にアヴェロエスがアブ・バシャルによる翻訳を基に有名な翻訳を、また、表現の論理的能力としての詩の重要 性を認識したアル・ファラビーによるあまり知られていない翻訳が行われた。アヴェロエスの翻訳は、時を経るにつれて大きな影響力を持つようになったが、そ の中にはいくつかの解釈や原文からの逸脱が含まれており、その理由は基本的に2つある。すなわち、出典とされた写本とアリストテレスの原典との相違11 と、歴史的状況における解釈上の関心である。アヴェロエスの解釈はよく知られており、例えば、悲劇の目的は道徳的な意味での教育にあるという解釈がそれで ある。 『詩学』のラテン語訳は、13世紀のスペインでヘルナン・アラマンによって初めて行われたが、その次の世紀には同じスペインでマティーノ・デ・トルトサに よる訳書が出版された。いずれもアヴェロエスの訳書を要約したものに基づいている。しかし、『詩学』の影響力が大きくなるのは16世紀に入ってからであ る。これに貢献した翻訳としては、1498年にヴェネツィアでジョルジョ・ヴァッラが手がけたもの、1508年にアルダ・プレスが出版したギリシャ語原文 の版、それに続く1536年(パッツィ)、1548年(ロベルトレッロ)、1549年(セーニ、イタリア語への最初の翻訳)などの翻訳がある。ギリシャ語 から ラテン語への最初の直接翻訳は ウィリアム・オブ・モールベークによるラテン語訳が最初である。 影響力のあるフランチェスコ・ロベルトエッロによる『アリストテレス詩作法注釈書』は、この作品に関する最初の完全な注釈書である。ヴィダ(ラテン語作 家)による『詩作術』をはじめ、1527年には『詩作術』に関する論文がますます一般的になり、その後もトリッシーノ、ダニエッロ、マッギ、ロンバル ディ、ムツィオ、ヴァルキ、チンティオ、ミントゥルノ、ヴェットーリ、カステルヴェトロなど、さまざまな作家による論文が発表された。ホラティウスは論評 で一定の地位を維持したが、アリストテレスは時が経つにつれ、より重要性を増していった。 お気づきかもしれないが、冒頭は明らかにイタリア的であり、16世紀末にはフランス、スペイン、イギリスが勢いを増して続いた。 世紀後半には、アリストテレスの単位に関する有名な教義が現れ、当時から激しい議論が交わされていた(注6参照)。アゴスティーノ・セーニとV.マッギ (または、一部の著者の見解によるとカステルヴェトロ)のおかげで、劇中の出来事は12時間を超えてはならないという規則が確立された。また、展開される 行動は、舞台という現実の空間内に限定された1つまたは2つの関連する出来事でなければならない。大空間や空間転換は表現できず、また、昼から夜への移り 変わりや、数日、あるいは数ヶ月、数年にわたる時間経過も表現できない。なぜなら、観客にとって必ずしも納得できるものではないからだ。このように、単一 性の教義は、悲劇における「説得力のある、あるいは必要な」というアリストテレスの命題の解釈に、大きな部分で起因している。これは、現在の内的な一貫性 という解釈とは大きく異なる。 16世紀から18世紀にかけて『詩学』について論じたスペインの学者の中で、まずイタリアの教義の継承者として『古代詩学』(1596年)を著したアロン ソ・ロペス・ピンシアーノ、次に『詩学表』(1604年)を著したフランシスコ・カスカルス、そして啓蒙的新古典主義の精神に則った『詩学』(1737 年)を著したイグナシオ・デ・ルサーンが際立っている。また、ロペ・デ・ベガが詩の作品を書き、自身の演劇創作を正当化し、新アリストテレス学派の規範に 従うルネサンスの詩学といくつかの点で意見を異にしていたことも忘れてはならない。これらはすべて、1609年の詩『Arte nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo(この時代における喜劇の新しい芸術)』に示されている。 アリストテレス的美学の視点は、劇芸術のみならず、他の芸術にも影響を及ぼし、18世紀まで勢力を保っていたが、さまざまな理由により衰退期を迎えることとなった。 ロマン主義は、芸術を本質的に創造的な行為(詩作)としてではなく、表現行為として評価するようになった。現実を反映したり模倣したりすることを目的とす るのではなく、芸術家の感情や主観的な視点が反映されるべきであるという考え方である。美を体験するために必要な無関心というカントの考え方は、芸術を浄 化作用として捉える最終的な視点が徐々に否定されるようになったことに影響を与えた。 アリストテレスの理論の3つの基礎、すなわちカタルシス、創造としての芸術、ミメーシスが疑問視されていたが、3つ目の原則である「真実らしさ」または 「必然性」は、多少は変化したとしても、芸術を現実世界とは必ずしも相反しない独自の法則を持つ内的世界として特徴づけるものとして残ることになる(この 原則は一般的に「ヘテロコスミア」と呼ばれている)。 |

| Segunda Poética Metafísica |

詩学(第二部) 形而上学(アリストテレス) |

| Segunda Poética es como se

conoce a la segunda parte de la obra Poética, de Aristóteles, en la

cual se trataría de los estudios sobre la comedia como un medio de la

liberación anímica (catarsis). Sobre el Segundo libro de Poética se ha especulado mucho, se afirma que nunca se ha escrito, que se extravió durante la Edad Media o que se trataba solo de un escrito de un comentarista de la obra aristotélica. Existe un documento bizantino del siglo x llamado Tractatus Coislinianusen el que se resume un posible contenido de la obra.1 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Segunda_Po%C3%A9tica |

『詩学』第2巻は、アリストテレスの著作『詩学』の第2部につけられた名称であり、感情の解放(カタルシス)の手段としての喜劇の研究を扱っている。 『詩学』第2巻については多くの推測がなされているが、それは書かれたことはなく、中世の間に失われたか、あるいはアリストテレスの作品の注釈者の著作にすぎないと言われている。 10世紀のビザンチン文書である『コイスリアヌス論文集』には、その作品の可能性のある内容がまとめられている。 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Po%C3%A9tica_(Arist%C3%B3teles) |

|

★アリストテレス「詩学」テキスト

●構造

第1章 - 論述の範囲、詩作と再現、再現の媒体について。

第2章 - 再現する対象の差異について。

第3章 - 再現の方法の差異について、劇という名称の由来について、悲劇・喜劇の発祥地についてのドーリス人の主張。

第4章 - 詩作の起源とその発展について。

第5章 - 喜劇について、悲劇と叙事詩の相違について。

---

第6章 - 悲劇の定義と悲劇の構成要素について。

第7章 - 筋の組み立て、その秩序と長さについて。

第8章 - 筋の統一について。

第9章 - 詩と歴史の相違、詩作の普遍的性格、場面偏重の筋、驚きの要素について。

第10章 - 単一な筋と複合的な筋について。

第11章 - 逆転と認知、苦難について。

第12章 - 悲劇作品の部分について。

第13章 - 筋の組みたてにおける目標について。

第14章 - おそれとあわれみの効果の出し方について。

第15章 - 性格の描写について。

第16章 - 認知の種類について。

第17章 - 悲劇の制作について―矛盾・不自然の回避、普遍的筋書きの作成。

第18章 - ふたたび悲劇の制作について―結び合わせ、解決、悲劇の種類。

---

第19章 - 思想、語法について。

第20章 - 語法について。

第21章 - 詩的語法に関する考察。

第22章 - 文体(語法)についての注意。

---

第23章 - 叙事詩について。―その一

第24章 - 叙事詩について。―その二

第25章 - 詩に対する批判とその解決。

第26章 - 叙事詩と悲劇の比較。

| I I propose to treat of Poetry in itself and of its various kinds, noting the essential quality of each; to inquire into the structure of the plot as requisite to a good poem; into the number and nature of the parts of which a poem is composed; and similarly into whatever else falls within the same inquiry. Following, then, the order of nature, let us begin with the principles which come first. Epic poetry and Tragedy, Comedy also and Dithyrambic: poetry, and the music of the flute and of the lyre in most of their forms, are all in their general conception modes of imitation. They differ, however, from one: another in three respects,―the medium, the objects, the manner or mode of imitation, being in each case distinct. For as there are persons who, by conscious art or mere habit, imitate and represent various objects through the medium of colour and form, or again by the voice; so in the arts above mentioned, taken as a whole, the imitation is produced by rhythm, language, or 'harmony,' either singly or combined. Thus in the music of the flute and of the lyre, 'harmony' and rhythm alone are employed; also in other arts, such as that of the shepherd's pipe, which are essentially similar to these. In dancing, rhythm alone is used without 'harmony'; for even dancing imitates character, emotion, and action, by rhythmical movement. There is another art which imitates by means of language alone, and that either in prose or verse―which, verse, again, may either combine different metres or consist of but one kind―but this has hitherto been without a name. For there is no common term we could apply to the mimes of Sophron and Xenarchus and the Socratic dialogues on the one hand; and, on the other, to poetic imitations in iambic, elegiac, or any similar metre. People do, indeed, add the word 'maker' or 'poet' to the name of the metre, and speak of elegiac poets, or epic (that is, hexameter) poets, as if it were not the imitation that makes the poet, but the verse that entitles them all indiscriminately to the name. Even when a treatise on medicine or natural science is brought out in verse, the name of poet is by custom given to the author; and yet Homer and Empedocles have nothing in common but the metre, so that it would be right to call the one poet, the other physicist rather than poet. On the same principle, even if a writer in his poetic imitation were to combine all metres, as Chaeremon did in his Centaur, which is a medley composed of metres of all kinds, we should bring him too under the general term poet. So much then for these distinctions. There are, again, some arts which employ all the means above mentioned, namely, rhythm, tune, and metre. Such are Dithyrambic and Nomic poetry, and also Tragedy and Comedy; but between them the difference is, that in the first two cases these means are all employed in combination, in the latter, now one means is employed, now another. Such, then, are the differences of the arts with respect to the medium of imitation. |

1. 論述の範囲、詩作と再現、再現の媒

体について 私たちの主題は、創作(従来訳は詩作)の技術それ自体とその様々な種である。つまり、その一つ一つがどの ような能力を持っているのか、創作が上手く行くためには物語はどのように構成されるべき なのか、さらに創作はどのような部分を幾つ持つのかであるが、同様にまた創作術の探求に 属する限りの他の事柄についても論じるだろう。私たちは、本性上第一に来る諸規定を第一 に論じることで議論を始めることにしよう(1447a9-13)。 ——北野正弘訳(2015) περὶ ποιητικῆς αὐτῆς τε καὶ τῶν εἰδῶν αὐτῆς, ἥν τινα δύναμιν ἕκαστον ἔχει, καὶ πῶς δεῖ συνίστασθαι τοὺς μύθους [10] εἰ μέλλει καλῶς ἕξειν ἡ ποίησις, ἔτι δὲ ἐκ πόσων καὶ ποίων ἐστὶ μορίων, ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ περὶ τῶν ἄλλων ὅσα τῆς αὐτῆς ἐστι μεθόδου, λέγωμεν ἀρξάμενοι κατὰ φύσιν πρῶτον ἀπὸ τῶν πρώτων. Aristotle, Poetics(ギ リシャ語テキスト) 私は、詩それ自体とその様々な種類を扱い、それぞれの本質的な質に注目することを提案する。良い詩に必要なプロットの構造について、詩が構成される部分の 数と性質について、そして同様に、同じ調査の範囲内にある他のあらゆるものについて、調査することを提案する。それでは、自然の摂理に従って、まず最初に 来る原理から始めよう。 叙事詩と悲劇、喜劇とディサイラムの詩、そしてフルートと竪琴の音楽は、そのほとんどの形式において、すべてその一般的概念において模倣の様式である。し かし、これらは3つの点で互いに異なる。-媒体、対象、模倣の方法または態様は、それぞれのケースで異なっている。 意識的な芸術や単なる習慣によって、色や形を媒介に、あるいはまた声を媒介に、さまざまな対象を模倣し表現する人々がいるように、全体としてみれば、上記 の芸術において、模倣はリズム、言語、あるいは「調和」によって、単独または複合的に生み出されている。 フルートと竪琴の音楽では、「ハーモニー」とリズムだけが用いられる。 ダンスでは、「ハーモニー」なしでリズムだけが使われる。ダンスでさえ、リズミカル な動きによって、性格、感情、行動を模倣するからである。(→「君もラッパーになれ る」) 言語のみによって模倣する別の芸術があり、それは散文か詩のどちらかである。詩は、やはり異なる音律を組み合わせたり、一種類だけで構成されたりするが、 これはこれまで名称がなかった。ソフロンやクセナルコスのパントマイムやソクラテスの対話に適用できる共通の用語はなく、他方、イアンビック、エレジアッ ク、あるいは類似の音律による詩の模倣にも適用できないからである。実際、人々はメトルの名称に「製作者」や「詩人」という言葉を付け加え、エレジアック 詩人や叙事詩(つまりヘキサメター)詩人について語るが、それはまるで詩人を作るのは模倣ではなく、詩がすべて無差別にその名を与える資格があるかのよう である。医学や自然科学の論文が詩で発表されるときでさえ、慣習的に作者には詩人の 名が与えられる。しかし、ホメロスとエンペドクレスには音律以外に共通 点はなく、詩人というより、一方を詩人、他方を物理学者と呼ぶのが正しいだろう。同じ原理で、シェレモンが『ケンタウルス』で行ったように、詩的な模倣を 行う作家があらゆる音律を組み合わせて、あらゆる種類の音律からなるメドレーを作ったとしても、我々は彼をも詩人という一般用語に引き入れるべきである。 このような区別はここまでである。 また、上記の手段、すなわちリズム、調性、メトレをすべて用いる芸術もある。しかし両者の違いは、前二者の場合、これらの手段はすべて組み合わせて使わ れ、後者では、ある手段が使われたり、別の手段が使われたりすることである。 このように、模倣の媒体に関する芸術の違いは、次のようなものである。 |

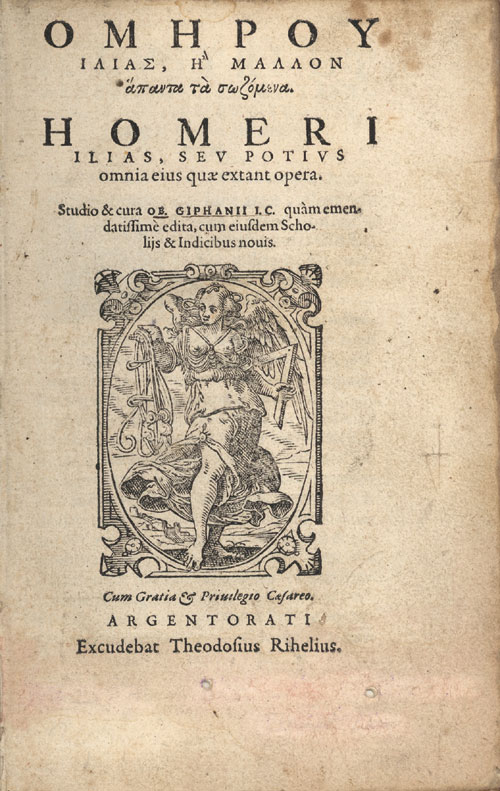

| II Since the objects of imitation are men in action, and these men must be either of a higher or a lower type (for moral character mainly answers to these divisions, goodness and badness being the distinguishing marks of moral differences), it follows that we must represent men either as better than in real life, or as worse, or as they are. It is the same in painting. Polygnotus depicted men as nobler than they are, Pauson as less noble, Dionysius drew them true to life. Now it is evident that each of the modes of imitation above mentioned will exhibit these differences, and become a distinct kind in imitating objects that are thus distinct. Such diversities may be found even in dancing, flute-playing, and lyre-playing. So again in language, whether prose or verse unaccompanied by music. Homer, for example, makes men better than they are; Cleophon as they are; Hegemon the Thasian, the inventor of parodies, and Nicochares, the author of the Deiliad, worse than they are. The same thing holds good of Dithyrambs and Nomes; here too one may portray different types, as Timotheus and Philoxenus differed in representing their Cyclopes. The same distinction marks off Tragedy from Comedy; for Comedy aims at representing men as worse, Tragedy as better than in actual life. |

2. 論述の範囲、詩作と再現、再現の媒

体について 模倣の対象は行動する人間であり、これらの人間は高いタイプか低いタイプのどちらかでなければならないので(道徳的性格は主にこれらの区分に答え、善と悪 は道徳的差異の識別マークである)、我々は人間を実生活より良いものとして、または悪いものとして、またはそのままの形で表現しなければならないことにな る。絵画の世界でも同じである。ポリグノトスは人間を実際よりも高貴に、パウソンはそれほど高貴でなく、ディオニュソスは実生活に忠実に描いた。 さて、上記のような模倣の様式は、それぞれこのような差異を示し、このように異なる対象を模倣することによって、異なる種類となることは明らかである。こ のような多様性は、ダンス、フルート演奏、竪琴演奏においてさえも見出すことができる。また、散文であれ、音楽が伴わない詩であれ、言語においても同様で ある。例えば、ホメロスは人を実際よりも良くし、クレオフォンは実際と同じにし、パロディの発明者であるターシャ人のヘゲモンや、『デイリアス』の作者ニ コチャレスは実際よりも悪くしている。このことは、ディシラムとノームについても同様である。ティモテウスとフィロクセヌスがキュクロプスを表現する際に 異なったように、ここでも異なるタイプを描くことができる。同じように、悲劇と喜劇を区別する。喜劇は人間を実際の生活よりも悪く、悲劇はより良く表現す ることを目的としているからである。 |

| III There is still a third difference―the manner in which each of these objects may be imitated. For the medium being the same, and the objects the same, the poet may imitate by narration―in which case he can either take another personality as Homer does, or speak in his own person, unchanged―or he may present all his characters as living and moving before us. These, then, as we said at the beginning, are the three differences which distinguish artistic imitation,―the medium, the objects, and the manner. So that from one point of view, Sophocles is an imitator of the same kind as Homer―for both imitate higher types of character; from another point of view, of the same kind as Aristophanes―for both imitate persons acting and doing. Hence, some say, the name of 'drama' is given to such poems, as representing action. For the same reason the Dorians claim the invention both of Tragedy and Comedy. The claim to Comedy is put forward by the Megarians,―not only by those of Greece proper, who allege that it originated under their democracy, but also by the Megarians of Sicily, for the poet Epicharmus, who is much earlier than Chionides and Magnes, belonged to that country. Tragedy too is claimed by certain Dorians of the Peloponnese. In each case they appeal to the evidence of language. The outlying villages, they say, are by them called {kappa omega mu alpha iota}, by the Athenians {delta eta mu iota}: and they assume that Comedians were so named not from {kappa omega mu 'alpha zeta epsilon iota nu}, 'to revel,' but because they wandered from village to village (kappa alpha tau alpha / kappa omega mu alpha sigma), being excluded contemptuously from the city. They add also that the Dorian word for 'doing' is {delta rho alpha nu}, and the Athenian, {pi rho alpha tau tau epsilon iota nu}. This may suffice as to the number and nature of the various modes of imitation. |

3. 再現の方法の差異について 劇とい

う名称の由来について 悲劇・喜劇の発祥地についてのドーリス人の主張 第三の違いは、これらの対象がそれぞれどのように模倣されうるか、という点である。媒体が同じであり、対象も同じであるため、詩人は語りによって模倣する ことができる。この場合、ホメロスのように別の人格になりきることも、そのままの姿で語ることもできるし、すべての登場人物を生きていて目の前で動いてい るように見せることもできる。 つまり、冒頭で述べたように、芸術的模倣を区別する三つの違い、すなわち媒体、対象、方法である。つまり、ある観点から見れば、ソフォクレスはホメロスと 同じ種類の模倣者であり、両者ともより高いタイプのキャラクターを模倣している。別の観点から見れば、アリストファネスと同じ種類の模倣者であり、両者と も行動し実行する人物を模倣しているのである。それゆえ、このような詩には、行動を表現するものとして「ドラマ」という名前が付けられたと言う人もいる。 同じ理由で、ドーリア人は悲劇と喜劇の両方の発明を主張する。喜劇の発明は、ギリシャのメガリア人が主張している。メガリア人はギリシャの民主主義のもと で喜劇が生まれたと主張しているが、シチリアのメガリア人も同様で、キオニデスやマグネスよりもずっと以前の詩人エピカルモスはこの国に属していたからで ある。悲劇はペロポネソス半島のあるドーリア人によっても主張されている。いずれの場合も、彼らは言語の証拠に訴えている。彼らは、辺境の村々を彼らは {kappa omega mu alpha iota}と呼び、アテネ人は{delta eta mu iota}と呼ぶという。そして彼らは、コメデイア人は{kappa omega mu 'alpha zeta epsilon iota nu}の「宴を開く」からではなく、村から村へ放浪し(kappa alpha tau alpha / kappa omega mu alpha sigma)、都市から軽蔑的に排除されるのでそう呼ばれたと推測している。また、ドーリア語の「する」は{delta rho alpha nu}であり、アテネ語の{pi rho alpha tau tau epsilon iota nu}であることも付け加えている。 模倣の様々な様式の数と性質については、これで十分であろう。 |

| IV Poetry in general seems to have sprung from two causes, each of them lying deep in our nature. First, the instinct of imitation is implanted in man from childhood, one difference between him and other animals being that he is the most imitative of living creatures, and through imitation learns his earliest lessons; and no less universal is the pleasure felt in things imitated. We have evidence of this in the facts of experience. Objects which in themselves we view with pain, we delight to contemplate when reproduced with minute fidelity: such as the forms of the most ignoble animals and of dead bodies. The cause of this again is, that to learn gives the liveliest pleasure, not only to philosophers but to men in general; whose capacity, however, of learning is more limited. Thus the reason why men enjoy seeing a likeness is, that in contemplating it they find themselves learning or inferring, and saying perhaps, 'Ah, that is he.' For if you happen not to have seen the original, the pleasure will be due not to the imitation as such, but to the execution, the colouring, or some such other cause.  Imitation, then, is one

instinct of our nature. Next, there is the

instinct for 'harmony' and rhythm, metres being manifestly sections of

rhythm. Persons, therefore, starting with this natural gift developed

by degrees their special aptitudes, till their rude improvisations gave

birth to Poetry. Imitation, then, is one

instinct of our nature. Next, there is the

instinct for 'harmony' and rhythm, metres being manifestly sections of

rhythm. Persons, therefore, starting with this natural gift developed

by degrees their special aptitudes, till their rude improvisations gave

birth to Poetry.Poetry now diverged in two directions, according to the individual character of the writers. The graver spirits imitated noble actions, and the actions of good men. The more trivial sort imitated the actions of meaner persons, at first composing satires, as the former did hymns to the gods and the praises of famous men. A poem of the satirical kind cannot indeed be put down to any author earlier than Homer; though many such writers probably there were. But from Homer onward, instances can be cited,―his own Margites, for example, and other similar compositions. The appropriate metre was also here introduced; hence the measure is still called the iambic or lampooning measure, being that in which people lampooned one another. Thus the older poets were distinguished as writers of heroic or of lampooning verse. As, in the serious style, Homer is pre-eminent among poets, for he alone combined dramatic form with excellence of imitation, so he too first laid down the main lines of Comedy, by dramatising the ludicrous instead of writing personal satire. His Margites bears the same relation to Comedy that the Iliad and Odyssey do to Tragedy. But when Tragedy and Comedy came to light, the two classes of poets still followed their natural bent: the lampooners became writers of Comedy, and the Epic poets were succeeded by Tragedians, since the drama was a larger and higher form of art. Whether Tragedy has as yet perfected its proper types or not; and whether it is to be judged in itself, or in relation also to the audience,―this raises another question. Be that as it may, Tragedy―as also Comedy―was at first mere improvisation. The one originated with the authors of the Dithyramb, the other with those of the phallic songs, which are still in use in many of our cities. Tragedy advanced by slow degrees; each new element that showed itself was in turn developed. Having passed through many changes, it found its natural form, and there it stopped. Aeschylus first introduced a second actor; he diminished the importance of the Chorus, and assigned the leading part to the dialogue. Sophocles raised the number of actors to three, and added scene-painting. Moreover, it was not till late that the short plot was discarded for one of greater compass, and the grotesque diction of the earlier satyric form for the stately manner of Tragedy. The iambic measure then replaced the trochaic tetrameter, which was originally employed when the poetry was of the Satyric order, and had greater affinities with dancing. Once dialogue had come in, Nature herself discovered the appropriate measure. For the iambic is, of all measures, the most colloquial: we see it in the fact that conversational speech runs into iambic lines more frequently than into any other kind of verse; rarely into hexameters, and only when we drop the colloquial intonation. The additions to the number of 'episodes' or acts, and the other accessories of which tradition; tells, must be taken as already described; for to discuss them in detail would, doubtless, be a large undertaking. |

4. 詩作の起源とその発展について 一般に詩は二つの原因から生まれたと思われるが、いずれも人間の本性に深く横たわっている。第一に、模倣の本能は子供の頃から人間に備わっている。他の動 物と異なる点は、人間は生き物の中で最も模倣的であり、模倣を通じて最も初期の教訓を学ぶことである。また、模倣されたものに感じる喜びは、それに劣らず 普遍的である。このことは、経験上の事実として証明されている。それ自体は苦痛を伴うものであっても、それが忠実に再現されると、喜びを感じるのである。 この原因はまた、学ぶことが、哲学者のみならず一般的な人間にとって最も生き生きとした喜びを与えるからである。このように、人が似顔絵を見て喜ぶのは、 それを観賞しているうちに、自分自身が学習したり推論したりして、おそらく「ああ、これは彼だ」と言うことに気づくからである。たまたま原画を見たことが ない場合、その喜びは模写そのものではなく、技巧や色彩など、他の原因によるものだろう。  つまり、模倣は人間の本能の1つである。次に、「調

和」と「リズム」に対する本能があり、メートルは明らかにリズムの一部である。したがって、この天賦の

才から出発した人々は、次第に特別な才能を開花させ、その無骨な即興が詩を誕生させるに至ったのである。 つまり、模倣は人間の本能の1つである。次に、「調

和」と「リズム」に対する本能があり、メートルは明らかにリズムの一部である。したがって、この天賦の

才から出発した人々は、次第に特別な才能を開花させ、その無骨な即興が詩を誕生させるに至ったのである。詩は、書き手の個性によって、二つの方向に分かれた。重厚な精神の持ち主は、高貴な行為や善良な人物の行為を模倣した。よりくだらないものは、より卑しい 人物の行為を模倣し、最初は風刺詩を作り、前者が神々への賛美歌や有名人の賛美を作ったように、風刺詩を作るようになった。風刺的な詩は、ホメロスより以 前の作者によるものではありえないが、そのような作者はおそらく多くいたのだろう。しかし、ホメロス以降には、例えばホメロス自身の『マルギテス』や、そ の他の類似の作品の例を挙げることができる。適切な音律もここに導入された。それゆえ、この音律は現在でもイアンビック音律またはランプーン音律と呼ば れ、人々が互いにランプーンし合う音律となっているのである。このように、古い詩人たちは、英雄的な詩の作者として、あるいは風刺的な詩の作者として区別 されていた。 真面目なスタイルでは、ホメロスが詩人の中で傑出しているが、それは彼だけが劇的な形式と優れた模倣を組み合わせたからであり、彼もまた、個人的な風刺を 書く代わりに滑稽なものを劇化して、喜劇の本筋を最初に打ち立てた。彼の『マルギテス』は、『イリアス』や『オデュッセイア』が悲劇と同じように、喜劇と 同じような関係にある。しかし、悲劇と喜劇が登場すると、2つの詩人階級は依然としてその自然な傾向に従っていた。風刺詩人は喜劇の作家となり、叙事詩人 は悲劇家に引き継がれた。 悲劇がまだ適切な型を完成していないのか、また、それ自体で判断するのか、それとも観客との関係で判断するのか、これは別の問題を提起している。それはと もかく、悲劇も喜劇と同様に、最初は単なる即興であった。一方は『ディシラム』の作者から、もう一方は、今でも多くの都市で使われている男根の歌の作者か ら生まれた。悲劇はゆっくりとした経過をたどり、新しい要素が現れるたびに、それを発展させていった。多くの変化を経て、悲劇はその自然な形を見つけ、そ こで止まった。 アイスキュロスはまず二人目の俳優を導入し、合唱の重要性を減らして、対話に主役の座を割り当てた。ソフォクレスは俳優の数を3人に増やし、場面転換を加 えた。さらに、短い筋書きを捨ててより広い範囲の筋書きにし、初期の風刺的な形式のグロテスクな語法を悲劇の堂々とした態度に変えたのは、遅くまで待たね ばならなかった。この小節は、もともと詩がサテュロス風のもので、踊りと親和性の高いものであったときに使われていた。対話が導入されると、自然は自ら適 切な小節を発見した。それは、会話文が他のどの詩よりも頻繁にイアンビック行に入り、ヘキサメターにはほとんど入らず、口語的なイントネーションを取り除 いた場合にのみ入るという事実からもわかる。また、「エピソード」や「幕」の数の増加や、その他伝統的に語られてきた付属物については、すでに説明したと おりとしなければならない。 |

| V Comedy is, as we have said, an imitation of characters of a lower type, not, however, in the full sense of the word bad, the Ludicrous being merely a subdivision of the ugly. It consists in some defect or ugliness which is not painful or destructive. To take an obvious example, the comic mask is ugly and distorted, but does not imply pain. The successive changes through which Tragedy passed, and the authors of these changes, are well known, whereas Comedy has had no history, because it was not at first treated seriously. It was late before the Archon granted a comic chorus to a poet; the performers were till then voluntary. Comedy had already taken definite shape when comic poets, distinctively so called, are heard of. Who furnished it with masks, or prologues, or increased the number of actors,―these and other similar details remain unknown. As for the plot, it came originally from Sicily; but of Athenian writers Crates was the first who, abandoning the 'iambic' or lampooning form, generalised his themes and plots. Epic poetry agrees with Tragedy in so far as it is an imitation in verse of characters of a higher type. They differ, in that Epic poetry admits but one kind of metre, and is narrative in form. They differ, again, in their length: for Tragedy endeavours, as far as possible, to confine itself to a single revolution of the sun, or but slightly to exceed this limit; whereas the Epic action has no limits of time. This, then, is a second point of difference; though at first the same freedom was admitted in Tragedy as in Epic poetry. Of their constituent parts some are common to both, some peculiar to Tragedy, whoever, therefore, knows what is good or bad Tragedy, knows also about Epic poetry. All the elements of an Epic poem are found in Tragedy, but the elements of a Tragedy are not all found in the Epic poem. |

5. 喜劇について 悲劇と叙事詩の相違

について 喜劇は、これまで述べてきたように、より低いタイプのキャラクターの模倣である。しかし、悪いという言葉の完全な意味ではなく、滑稽は単に醜いものの下位 分類に過ぎないのである。それは、苦痛や破壊を伴わない何らかの欠陥や醜さによって成り立つ。分かりやすい例を挙げると、滑稽な仮面は醜く歪んでいるが、 痛みを伴わない。 悲劇が通過した連続的な変化とその作者はよく知られているが、喜劇は歴史を持たず、なぜなら最初はまじめに扱われなかったからである。アルコンが詩人に喜 劇の合唱を許可したのは遅く、それまでは出演者は任意であった。喜劇は、喜劇詩人と呼ばれる人たちが耳にしたときには、すでに明確な形をとっていた。誰が 仮面をつけたのか、プロローグをつけたのか、役者の数を増やしたのか-これらや他の類似の詳細は不明である。しかし、アテネの作家の中では、クラテスが初 めて、「イアンビック」または「ランプーン」の形式を捨て、テーマとプロットを一般化した。 叙事詩は、より高いタイプの人物の詩による模倣である限り、悲劇と一致する。両者は、叙事詩が一種類の音律しか認めず、形式が物語的であるという点で異な る。悲劇は、できる限り太陽の一回転に収まるように、あるいはその限界をわずかに超えるように努力するが、叙事詩の行為には時間の限界がない。この点が第 二の相違点である。しかし、当初は悲劇にも叙事詩と同じ自由が認められていた。 その構成部分のうち、あるものは両者に共通し、あるものは悲劇に特有である。したがって、何が良い悲劇か悪い悲劇かを知る者は、叙事詩についても知ってい るのである。叙事詩の要素はすべて悲劇に見られるが、悲劇の要素がすべて叙事詩に見られるわけではない。 |

| VI Of the poetry which imitates in hexameter verse, and of Comedy, we will speak hereafter. Let us now discuss Tragedy, resuming its formal definition, as resulting from what has been already said. Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play; in the form of action, not of narrative; through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions. By 'language embellished,' I mean language into which rhythm, 'harmony,' and song enter. By 'the several kinds in separate parts,' I mean, that some parts are rendered through the medium of verse alone, others again with the aid of song. Now as tragic imitation implies persons acting, it necessarily follows, in the first place, that Spectacular equipment will be a part of Tragedy. Next, Song and Diction, for these are the medium of imitation. By 'Diction' I mean the mere metrical arrangement of the words: as for 'Song,' it is a term whose sense every one understands. Again, Tragedy is the imitation of an action; and an action implies personal agents, who necessarily possess certain distinctive qualities both of character and thought; for it is by these that we qualify actions themselves, and these―thought and character―are the two natural causes from which actions spring, and on actions again all success or failure depends. Hence, the Plot is the imitation of the action: for by plot I here mean the arrangement of the incidents. By Character I mean that in virtue of which we ascribe certain qualities to the agents. Thought is required wherever a statement is proved, or, it may be, a general truth enunciated. Every Tragedy, therefore, must have six parts, which parts determine its quality―namely, Plot, Character, Diction, Thought, Spectacle, Song. Two of the parts constitute the medium of imitation, one the manner, and three the objects of imitation. And these complete the list. These elements have been employed, we may say, by the poets to a man; in fact, every play contains Spectacular elements as well as Character, Plot, Diction, Song, and Thought. But most important of all is the structure of the incidents. For Tragedy is an imitation, not of men, but of an action and of life, and life consists in action, and its end is a mode of action, not a quality. Now character determines men's qualities, but it is by their actions that they are happy or the reverse. Dramatic action, therefore, is not with a view to the representation of character: character comes in as subsidiary to the actions. Hence the incidents and the plot are the end of a tragedy; and the end is the chief thing of all. Again, without action there cannot be a tragedy; there may be without character. The tragedies of most of our modern poets fail in the rendering of character; and of poets in general this is often true. It is the same in painting; and here lies the difference between Zeuxis and Polygnotus. Polygnotus delineates character well: the style of Zeuxis is devoid of ethical quality. Again, if you string together a set of speeches expressive of character, and well finished in point of diction and thought, you will not produce the essential tragic effect nearly so well as with a play which, however deficient in these respects, yet has a plot and artistically constructed incidents. Besides which, the most powerful elements of emotional: interest in Tragedy Peripeteia or Reversal of the Situation, and Recognition scenes―are parts of the plot. A further proof is, that novices in the art attain to finish: of diction and precision of portraiture before they can construct the plot. It is the same with almost all the early poets. The Plot, then, is the first principle, and, as it were, the soul of a tragedy: Character holds the second place. A similar fact is seen in painting. The most beautiful colours, laid on confusedly, will not give as much pleasure as the chalk outline of a portrait. Thus Tragedy is the imitation of an action, and of the agents mainly with a view to the action. Third in order is Thought,―that is, the faculty of saying what is possible and pertinent in given circumstances. In the case of oratory, this is the function of the Political art and of the art of rhetoric: and so indeed the older poets make their characters speak the language of civic life; the poets of our time, the language of the rhetoricians. Character is that which reveals moral purpose, showing what kind of things a man chooses or avoids. Speeches, therefore, which do not make this manifest, or in which the speaker does not choose or avoid anything whatever, are not expressive of character. Thought, on the other hand, is found where something is proved to be, or not to be, or a general maxim is enunciated. Fourth among the elements enumerated comes Diction; by which I mean, as has been already said, the expression of the meaning in words; and its essence is the same both in verse and prose. Of the remaining elements Song holds the chief place among the embellishments. The Spectacle has, indeed, an emotional attraction of its own, but, of all the parts, it is the least artistic, and connected least with the art of poetry. For the power of Tragedy, we may be sure, is felt even apart from representation and actors. Besides, the production of spectacular effects depends more on the art of the stage machinist than on that of the poet. |

6. 悲劇の定義と悲劇の構成要素につい

て ヘキサメートル詩で模倣する詩と喜劇については、この後で述べる。次に、悲劇について、すでに述べたことの結果として、その形式的な定義を再開して論じよう。 悲劇とは、重大で完結した、ある程度の規模を持つ行為の模倣である。あらゆる種類の芸術的装飾で彩られた言語によって表現され、それらの装飾は劇の別々の 部分に見られる。物語ではなく行為の形式によって、哀れみと恐怖を通じて、これらの感情の適切な浄化をもたらす。ここで「装飾された言語」とは、韻律や 「調和」、歌が入り込んだ言語を意味する。「各部分が別々に配置される」とは、ある部分は詩のみによって表現され、またある部分は歌の助けを借りて表現さ れることを意味する。 悲劇の模倣は人格の演技を意味するので、まず第一に、必然的に、スペクタクルな装置が悲劇の一部となる。次に、歌と語法であるが、これらは模倣の媒体であ る。ディクション」とは、言葉の単なる計量的配列のことであり、「歌」については、誰もがその意味を理解する用語である。 また、悲劇は行為の模倣であり、行為には人格的な主体が含まれ、その主体は必然的に、人格と思考の両方においてある種の特徴的な特質を有している。した がって、筋書きとは行為の模倣であり、筋書きとは事件の配置を意味する。性格とは、行為者にある特質を与えることを意味する。思想が必要とされるのは、あ る主張が証明される場合、あるいは一般的な真理が宣言される場合であろう。したがって、あらゆる悲劇には6つの部分が必要であり、この部分がその質を決定 する。すなわち、筋、性格、語法、思考、スペクタクル、歌である。部分のうち2つは模倣の媒体を構成し、1つは模倣の方法、3つは模倣の対象を構成する。 そしてこれらがリストを完成させる。これらの要素は、詩人たちがこぞって採用してきたと言える。実際、どの劇にも、キャラクター、プロット、語法、歌、思 想のほかに、スペクタクルの要素が含まれている。 しかし何よりも重要なのは、事件の構造である。悲劇は人間の模倣ではなく、行為と人生の模倣であり、人生は行為から成り立ち、その終わりは行為様式であっ て、資質ではないからだ。人生とは行動であり、その目的とは行動様式であって、資質ではないのである。したがって、ドラマチックなアクションは、人格を表 現するためにあるのではない。それゆえ、事件と筋書きは悲劇の目的であり、目的こそがすべての最重要事項なのである。行動なくして悲劇はありえない。現代 の詩人たちの悲劇は、人物の描写に失敗している。それは絵画においても同じで、ゼウキスとポリグノトスの違いはここにある。ポリグノトスは人物描写に優れ ているが、ゼウクシスの作風には倫理性がない。また、性格を表現し、語法と思想の点でよく仕上がった一連の演説を並べたとしても、これらの点で不十分で あっても、筋書きと芸術的に構成された事件を持つ戯曲ほど、本質的な悲劇的効果は得られないだろう。その上、悲劇における最も強力な感情的要素である「ペ リペテイア」(状況の反転)や「認識」の場面は、プロットの一部である。さらにその証拠に、この芸術の初心者は、プロットを構築する前に、ディクションの 完成度と肖像画の正確さに到達している。これは、ほとんどすべての初期の詩人について同じである。 筋書きは悲劇の第一の原則であり、いわば魂である: 性格はその次である。同じようなことが絵画にも見られる。どんなに美しい色彩でも、肖像画のチョークで描かれた輪郭と同じような喜びは得られない。このよ うに、悲劇とは行為を模倣することであり、行為者を模倣することである。 第三に思考がある。つまり、与えられた状況において可能かつ適切なことを述べる能力だ。弁論においては、これが政治術と修辞術の役割である。実際、古代の 詩人たちは登場人物に市民生活の言葉を語らせ、現代の詩人たちは修辞家の言葉を語らせている。性格とは、道徳的目的を明らかにし、人が何を選び、何を避け るかを示すものである。したがって、これを明らかにしない演説、あるいは演説者が何も選ばず、何も避けない演説は、性格を表現していない。一方、思考は、 何かが存在する、あるいは存在しないことが証明されたり、一般的な格律が述べられたりする時に見出される。 列挙した要素の中で4番目に挙げられるのは「ディクション」である。ディクションとは、すでに述べたように、意味を言葉で表現することを意味する。 残りの要素の中で、「歌」は装飾の中で最も重要な位置を占めている。 スペクタクルは、確かに、それ自体の感情的な魅力を持っているが、すべての部分の中で、最も芸術的でなく、詩の芸術と最も関係が薄い。というのも、悲劇の 力は、表現と俳優を離れても感じられるからである。その上、スペクタクルな効果を生み出すには、詩人の技よりも舞台装置職人の技に頼るところが大きい。 |

| VII These principles being established, let us now discuss the proper structure of the Plot, since this is the first and most important thing in Tragedy. Now, according to our definition, Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is complete, and whole, and of a certain magnitude; for there may be a whole that is wanting in magnitude. A whole is that which has a beginning, a middle, and an end. A beginning is that which does not itself follow anything by causal necessity, but after which something naturally is or comes to be. An end, on the contrary, is that which itself naturally follows some other thing, either by necessity, or as a rule, but has nothing following it. A middle is that which follows something as some other thing follows it. A well constructed plot, therefore, must neither begin nor end at haphazard, but conform to these principles. Again, a beautiful object, whether it be a living organism or any whole composed of parts, must not only have an orderly arrangement of parts, but must also be of a certain magnitude; for beauty depends on magnitude and order. Hence a very small animal organism cannot be beautiful; for the view of it is confused, the object being seen in an almost imperceptible moment of time. Nor, again, can one of vast size be beautiful; for as the eye cannot take it all in at once, the unity and sense of the whole is lost for the spectator; as for instance if there were one a thousand miles long. As, therefore, in the case of animate bodies and organisms a certain magnitude is necessary, and a magnitude which may be easily embraced in one view; so in the plot, a certain length is necessary, and a length which can be easily embraced by the memory. The limit of length in relation to dramatic competition and sensuous presentment, is no part of artistic theory. For had it been the rule for a hundred tragedies to compete together, the performance would have been regulated by the water-clock,―as indeed we are told was formerly done. But the limit as fixed by the nature of the drama itself is this: the greater the length, the more beautiful will the piece be by reason of its size, provided that the whole be perspicuous. And to define the matter roughly, we may say that the proper magnitude is comprised within such limits, that the sequence of events, according to the law of probability or necessity, will admit of a change from bad fortune to good, or from good fortune to bad. |

7. 筋の組み立て、その秩序と長さにつ

いて これらの原則が確立されたので、次にプロットの適切な構造について論じよう。 さて、我々の定義によれば、悲劇とは、完全で、全体的で、一定の大きさを持つ行為の模倣である。全体とは、始まり、中間、終わりを持つものである。始まり とは、それ自体は因果的必然性によって何ものにも従わないが、その後に何かが自然に存在する、あるいは存在するようになることである。それとは反対に、終 わりとは、それ自体が必然的に、あるいは規則として、他のものに自然に従うが、その後に何も続かないものである。中間とは、他のものがそれに続くように、 何かに続くものである。したがって、よく構成された筋書きは、行き当たりばったりで始まったり終わったりしてはならない。 美は大きさと秩序に依存するからである。というのは、美は大きさと秩序に依存するからである。したがって、非常に小さな動物有機体は美しくはありえない。 また、巨大なものも美しくはありえない。なぜなら、目はすべてを一度に受け止めることができないので、全体の統一感や感覚は観客にとって失われてしまうか らである。したがって、生き物や生物の場合、一定の大きさが必要であり、それは一望すれば容易に理解できる大きさであるように、筋書きにおいても一定の長 さが必要であり、それは記憶によって容易に理解できる長さである。劇的な競争や感覚的な表現との関係における長さの限界は、芸術理論の一部ではない。もし 100の悲劇を一緒に上演することがルールであったなら、パフォーマティは水時計によって調節されたであろう。長さが長ければ長いほど、全体が明瞭であれ ば、その大きさゆえに作品はより美しくなる。大雑把に定義するならば、適切な大きさは、確率や必然性の法則に従って、悪運から善運へ、あるいは善運から悪 運への変化を許容するような限界の範囲内で構成される、ということである。 |

| VIII Unity of plot does not, as some persons think, consist in the Unity of the hero. For infinitely various are the incidents in one man's life which cannot be reduced to unity; and so, too, there are many actions of one man out of which we cannot make one action. Hence, the error, as it appears, of all poets who have composed a Heracleid, a Theseid, or other poems of the kind. They imagine that as Heracles was one man, the story of Heracles must also be a unity. But Homer, as in all else he is of surpassing merit, here too―whether from art or natural genius―seems to have happily discerned the truth. In composing the Odyssey he did not include all the adventures of Odysseus―such as his wound on Parnassus, or his feigned madness at the mustering of the host―incidents between which there was no necessary or probable connection: but he made the Odyssey, and likewise the Iliad, to centre round an action that in our sense of the word is one. As therefore, in the other imitative arts, the imitation is one when the object imitated is one, so the plot, being an imitation of an action, must imitate one action and that a whole, the structural union of the parts being such that, if any one of them is displaced or removed, the whole will be disjointed and disturbed. For a thing whose presence or absence makes no visible difference, is not an organic part of the whole. |

8. 筋の統一について ある人が考えるように、筋書きの統一は、主人公の統一にあるのではない。というのも、一人の人間の人生には、統一することのできない無限にさまざまな出来 事があるからである。それゆえ、ヘラクレス詩やテセイド詩、あるいはこの種の詩を作った詩人たちはみな、このような誤りを犯しているのである。彼らは、ヘ ラクレスが一人の人間であったように、ヘラクレスの物語もまた一つのものでなければならないと考えている。しかしホメロスは、他のすべてにおいて卓越した 才能を発揮しているように、ここでもまた、芸術的なものであれ、天賦の才能によるものであれ、真理を見事に見抜いているように思われる。彼は『オデュッセ イア』を書くにあたって、オデュッセウスの冒険--たとえば、パルナッソスでの傷や、軍勢の招集の際の見せかけの狂気など--をすべて盛り込まなかった。 それゆえ、他の模倣芸術において、模倣される対象が一つであれば模倣も一つであるように、筋書きは、行為の模倣である以上、一つの行為、それも全体を模倣 しなければならない。あってもなくても目に見える違いがないものは、全体の有機的な一部ではないからだ。 |

| IX It is, moreover, evident from what has been said, that it is not the function of the poet to relate what has happened, but what may happen,―what is possible according to the law of probability or necessity. The poet and the historian differ not by writing in verse or in prose. The work of Herodotus might be put into verse, and it would still be a species of history, with metre no less than without it. The true difference is that one relates what has happened, the other what may happen. Poetry, therefore, is a more philosophical and a higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular. By the universal, I mean how a person of a certain type will on occasion speak or act, according to the law of probability or necessity; and it is this universality at which poetry aims in the names she attaches to the personages. The particular is―for example―what Alcibiades did or suffered. In Comedy this is already apparent: for here the poet first constructs the plot on the lines of probability, and then inserts characteristic names;―unlike the lampooners who write about particular individuals. But tragedians still keep to real names, the reason being that what is possible is credible: what has not happened we do not at once feel sure to be possible: but what has happened is manifestly possible: otherwise it would not have happened. Still there are even some tragedies in which there are only one or two well known names, the rest being fictitious. In others, none are well known, as in Agathon's Antheus, where incidents and names alike are fictitious, and yet they give none the less pleasure. We must not, therefore, at all costs keep to the received legends, which are the usual subjects of Tragedy. Indeed, it would be absurd to attempt it; for even subjects that are known are known only to a few, and yet give pleasure to all. It clearly follows that the poet or 'maker' should be the maker of plots rather than of verses; since he is a poet because he imitates, and what he imitates are actions. And even if he chances to take an historical subject, he is none the less a poet; for there is no reason why some events that have actually happened should not conform to the law of the probable and possible, and in virtue of that quality in them he is their poet or maker. Of all plots and actions the epeisodic are the worst. I call a plot 'epeisodic' in which the episodes or acts succeed one another without probable or necessary sequence. Bad poets compose such pieces by their own fault, good poets, to please the players; for, as they write show pieces for competition, they stretch the plot beyond its capacity, and are often forced to break the natural continuity. But again, Tragedy is an imitation not only of a complete action, but of events inspiring fear or pity. Such an effect is best produced when the events come on us by surprise; and the effect is heightened when, at the same time, they follow as cause and effect. The tragic wonder will thee be greater than if they happened of themselves or by accident; for even coincidences are most striking when they have an air of design. We may instance the statue of Mitys at Argos, which fell upon his murderer while he was a spectator at a festival, and killed him. Such events seem not to be due to mere chance. Plots, therefore, constructed on these principles are necessarily the best. |

9. 詩と歴史の相違、詩作の普遍的性

格、場面偏重の筋、驚きの要素について 「歴史家は実際に起こったことを語るが、詩人は起こりうるようなことを語るということである。それゆえ、詩作(ポイエーシス)は歴史(ヒストリアー)より もいっそう哲学的であり、いっそう重大な意義をもつのである。というのも、詩作は普遍的な事柄を語り、歴史は個別的な事柄を語るからである」アリストテレ ス「詩学」1451b、朴一功訳、『アリストテレス全集』岩波書店、2017年 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ さらに、これまで述べてきたことから明らかなように、詩人の役割は、起こったことではなく、起こりうること、つまり確率や必然性の法則にしたがって可能な ことを語ることである。詩人と歴史家は、詩で書くか散文で書くかの違いではない。ヘロドトスの作品を詩にしても、それは歴史の一種であることに変わりはな く、メトレがない場合と同様に、メトレがある場合にも変わりはない。真の違いは、一方は起こったことを報告し、他方は起こりうることを報告することであ る。それゆえ、詩は歴史よりも哲学的で高尚なものである。詩は普遍的なものを、歴史は特殊なものを表現する傾向があるからである。普遍的なものとは、ある 種の人間が、確率や必然の法則に従って、時にどのように発言したり行動したりするかを意味し、詩が人物に付ける名前において目指しているのは、この普遍性 なのである。特殊とは、たとえばアルキビアデスが何をし、何に苦しんだかということである。喜劇では、このことはすでに明らかである。なぜなら、ここで は、詩人はまず確率の線上にプロットを構築し、次に特徴的な名前を挿入するからである--特定の個人について書く風刺作家とは異なる。しかし、悲劇家は依 然として実名にこだわる。その理由は、可能なことは信頼できることであり、起こっていないことは、すぐに可能であると確信できないからである。しかし、起 こったことは明らかに可能であり、さもなければ起こらなかったであろう。それでも、よく知られた名前が1人か2人しか出てこない悲劇もあり、残りは架空の ものである。また、アガトンの『アンテウス』のように、事件も名前も架空のものでありながら、それ以上に楽しみを与えてくれるものもない。したがって、悲 劇によく登場する伝説を、何としてでも守らなければならないわけではない。実際、それを試みるのは不合理なことである。なぜなら、知られている題材でさ え、少数の人にしか知られておらず、しかもすべての人に喜びを与えるからである。なぜなら、詩人は模倣するから詩人なのであり、模倣するのは行動だからで ある。そして、たとえ彼が歴史的な題材を取る機会があったとしても、彼が詩人であることに変わりはない。なぜなら、実際に起こったいくつかの出来事が、可 能性と確率の法則に適合しない理由はなく、その性質によって彼はその詩人または製作者なのである。 すべての筋書きと行動の中で、「エピソード的」なものは最悪である。私はプロットを「epeisodic」と呼んでいるが、これはエピソードや行為が確率 的あるいは必然的な順序を経ずに互いに連続するものである。悪い詩人は自分の責任でこのような作品を作るが、良い詩人は演奏家を喜ばせるために作る。なぜ なら、彼らは競争のためにショーピースを書くので、プロットをその能力を超えて引き伸ばし、しばしば自然の連続性を壊すことを余儀なくされるからである。 しかし、繰り返すが、悲劇は、完全な行動の模倣であるだけでなく、恐怖や憐れみを刺 激する出来事の模倣でもある。このような効果は、出来事が不意打ちで襲ってくるときに最もよく発揮され、同時にそれらが原因となり結果となるとき、その効 果は増大する。偶然の一致であっても、それが意図的なものであれば、最も印象的である。例えば、アルゴスのミテュスの像が、祭りで見物していた殺人者の上 に落ちてきて、彼を殺してしまった。このような出来事は、単なる偶然の産物ではないようだ。したがって、このような原則に基づいて構築されたプロットは、 必然的に最良のものとなる。 |

| X Plots are either Simple or Complex, for the actions in real life, of which the plots are an imitation, obviously show a similar distinction. An action which is one and continuous in the sense above defined, I call Simple, when the change of fortune takes place without Reversal of the Situation and without Recognition. A Complex action is one in which the change is accompanied by such Reversal, or by Recognition, or by both. These last should arise from the internal structure of the plot, so that what follows should be the necessary or probable result of the preceding action. It makes all the difference whether any given event is a case of propter hoc or post hoc. |

10. 単一な筋と複合的な筋について プロットは単純か複雑かのどちらかであり、プロットが模倣である現実の生活における行動も、明らかに同様の区別を示すからである。単純な行動とは、状況が 逆転することなく、また認識されることなく、運勢の変化が起こるものである。複雑な行動とは、そのような逆転、あるいは認識、あるいはその両方を伴う変化 である。複雑なアクションとは、そのような「逆転」や「認識」、あるいはその両方を伴う変化をいう。これらの最後の変化は、プロットの内部構造から生じる ものであり、その後に続くものは、先行するアクションの必然的な結果、あるいは可能性の高い結果でなければならない。ある出来事がpropter hocのケースであるかpost hocのケースであるかは、すべての違いを生む。 |

| XI Reversal of the Situation is a change by which the action veers round to its opposite, subject always to our rule of probability or necessity. Thus in the Oedipus, the messenger comes to cheer Oedipus and free him from his alarms about his mother, but by revealing who he is, he produces the opposite effect. Again in the Lynceus, Lynceus is being led away to his death, and Danaus goes with him, meaning, to slay him; but the outcome of the preceding incidents is that Danaus is killed and Lynceus saved. Recognition, as the name indicates, is a change from ignorance to knowledge, producing love or hate between the persons destined by the poet for good or bad fortune. The best form of recognition is coincident with a Reversal of the Situation, as in the Oedipus. There are indeed other forms. Even inanimate things of the most trivial kind may in a sense be objects of recognition. Again, we may recognise or discover whether a person has done a thing or not. But the recognition which is most intimately connected with the plot and action is, as we have said, the recognition of persons. This recognition, combined, with Reversal, will produce either pity or fear; and actions producing these effects are those which, by our definition, Tragedy represents. Moreover, it is upon such situations that the issues of good or bad fortune will depend. Recognition, then, being between persons, it may happen that one person only is recognised by the other-when the latter is already known―or it may be necessary that the recognition should be on both sides. Thus Iphigenia is revealed to Orestes by the sending of the letter; but another act of recognition is required to make Orestes known to Iphigenia. Two parts, then, of the Plot―Reversal of the Situation and Recognition―turn upon surprises. A third part is the Scene of Suffering. The Scene of Suffering is a destructive or painful action, such as death on the stage, bodily agony, wounds and the like. |