Ἀριστοτέλης

アリストテレス

Ἀριστοτέλης

解説:池田光穂

★

アリストテレス(/ˈær↪Ll_26A;[1] ギリシア語: Ἀριστοτέλης Aristotélēs, 発音[aristotél-];

BC

384-322)は古代ギリシアの哲学者であり、博学者である。彼の著作は自然科学、哲学、言語学、経済学、政治学、心理学、芸術など多岐にわたる。アテ

ネのリセウムにおけるペリパトス哲学の創始者であり、アリストテレス学派の伝統の始まりとなった。

アリストテレスの生涯についてはほとんど知られていない。彼は古典期ギリシャ北部の都市スタギラに生まれた。父ニコマコスはアリストテレスが幼い頃に亡く

なり、後見人に育てられた。17、18歳でアテネのプラトンのアカデミーに入り、37歳(紀元前347年頃)まで在籍した。プラトンが亡くなった直後、ア

リストテレスはアテネを去り、マケドンのフィリップ2世の要請を受けて、紀元前343年から息子のアレクサンダー大王の家庭教師を務めた。アリストテレス

はリセウムに図書館を設立し、何百冊もの著書の多くをパピルスの巻物にした。

アリストテレスは出版用に多くの優美な論考や対話篇を書いたが、現存するのは彼の原著の3分の1程度であり、出版を意図したものは皆無である。アリストテ

レスは、それ以前に存在したさまざまな哲学を複雑に統合した。彼の教えと探求方法は世界的に大きな影響を及ぼし、その結果、彼の哲学は世界中に影響を及ぼ

し、現代の哲学的議論の対象であり続けている。

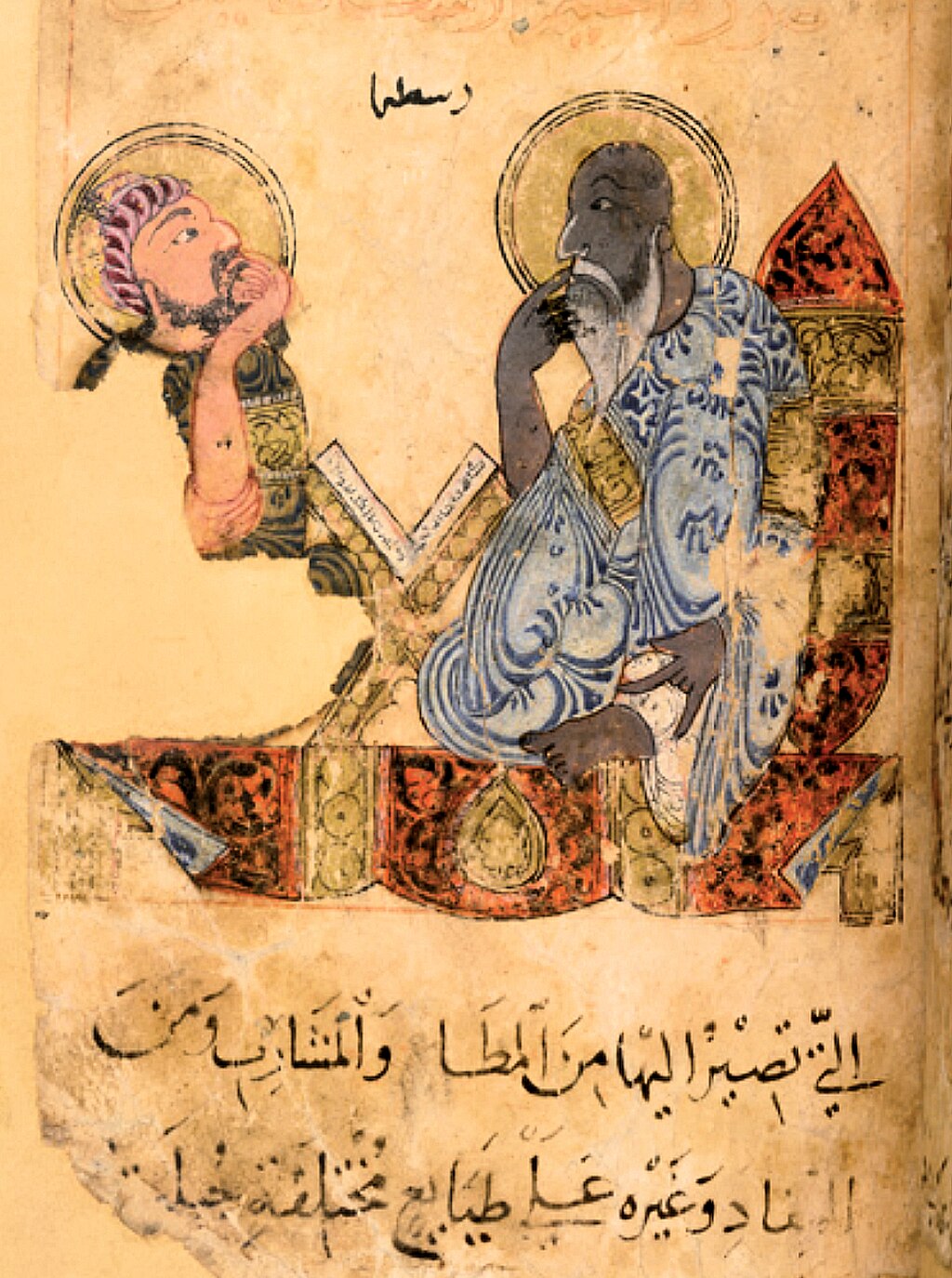

アリストテレスの見解は、中世の学問に大きな影響を与えた。アリストテレスの物理学の影響は、古代末期から中世初期、そしてルネサンスにまで及び、啓蒙時

代に古典力学のような理論が発展するまで、体系的に置き換えられることはなかった。アリストテレスの生物学に見られる動物学的観察の中には、タコのヘクト

コティル(生殖腕)など、19世紀まで信じられていなかったものもある。アリストテレスは中世のユダヤ・イスラム哲学や、キリスト教神学、特に初代教会の

新プラトン主義やカトリック教会のスコラ学の伝統に影響を与えた。アリストテレスは、中世のイスラム学者たちの間では「最初の教師」として、またトマス・

アクィナスなどの中世キリスト教徒たちの間では単に「哲学者」として崇められ、詩人ダンテは彼を「知る者の師」と呼んだ。アリストテレスの著作には、論理

学の形式的研究として知られる最古のものが含まれており、ピーター・アベラールやジャン・ブリダンといった中世の学者たちによって研究された。アリストテ

レスの論理学への影響は19世紀まで続いた。さらに、彼の倫理学は常に影響力を持ち続けていたが、近代の徳倫理学の登場により、再び関心を集めるように

なった。

| Aristotle

(/ˈærɪˌstɒtəl/;[1] Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης Aristotélēs, pronounced

[aristotélɛːs]; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher and

polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the

natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics,

psychology and the arts. As the founder of the Peripatetic school of

philosophy in the Lyceum in Athens, he began the wider Aristotelian

tradition that followed, which set the groundwork for the development

of modern science. Little is known about Aristotle's life. He was born in the city of Stagira in northern Greece during the Classical period. His father, Nicomachus, died when Aristotle was a child, and he was brought up by a guardian. At 17 or 18 he joined Plato's Academy in Athens and remained there till the age of 37 (c. 347 BC). Shortly after Plato died, Aristotle left Athens and, at the request of Philip II of Macedon, tutored his son Alexander the Great beginning in 343 BC. He established a library in the Lyceum which helped him to produce many of his hundreds of books on papyrus scrolls. Though Aristotle wrote many elegant treatises and dialogues for publication, only around a third of his original output has survived, none of it intended for publication. Aristotle provided a complex synthesis of the various philosophies existing prior to him. His teachings and methods of inquiry have had a significant global impact, and as a result, his philosophy has exerted an influence across the world and it continues to be a subject of contemporary philosophical discussion. Aristotle's views profoundly shaped medieval scholarship. The influence of his physical science extended from late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages into the Renaissance, and was not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics were developed. Some of Aristotle's zoological observations found in his biology, such as on the hectocotyl (reproductive) arm of the octopus, were disbelieved until the 19th century. He influenced Judeo-Islamic philosophies during the Middle Ages, as well as Christian theology, especially the Neoplatonism of the Early Church and the scholastic tradition of the Catholic Church. Aristotle was revered among medieval Muslim scholars as "The First Teacher", and among medieval Christians like Thomas Aquinas as simply "The Philosopher", while the poet Dante called him "the master of those who know". His works contain the earliest known formal study of logic, and were studied by medieval scholars such as Peter Abelard and Jean Buridan. Aristotle's influence on logic continued well into the 19th century. In addition, his ethics, though always influential, gained renewed interest with the modern advent of virtue ethics. |

アリストテレス(/ˈær↪Ll_26A;[1] ギリシア語:

Ἀριστοτέλης Aristotélēs, 発音[aristotél-]; BC

384-322)は古代ギリシアの哲学者であり、博学者である。彼の著作は自然科学、哲学、言語学、経済学、政治学、心理学、芸術など多岐にわたる。アテ

ネのリセウムにおけるペリパトス哲学の創始者であり、アリストテレス学派の伝統の始まりとなった。 アリストテレスの生涯についてはほとんど知られていない。彼は古典期ギリシャ北部の都市スタギラに生まれた。父ニコマコスはアリストテレスが幼い頃に亡く なり、後見人に育てられた。17、18歳でアテネのプラトンのアカデミーに入り、37歳(紀元前347年頃)まで在籍した。プラトンが亡くなった直後、ア リストテレスはアテネを去り、マケドンのフィリップ2世の要請を受けて、紀元前343年から息子のアレクサンダー大王の家庭教師を務めた。アリストテレス はリセウムに図書館を設立し、何百冊もの著書の多くをパピルスの巻物にした。 アリストテレスは出版用に多くの優美な論考や対話篇を書いたが、現存するのは彼の原著の3分の1程度であり、出版を意図したものは皆無である。アリストテ レスは、それ以前に存在したさまざまな哲学を複雑に統合した。彼の教えと探求方法は世界的に大きな影響を及ぼし、その結果、彼の哲学は世界中に影響を及ぼ し、現代の哲学的議論の対象であり続けている。 アリストテレスの見解は、中世の学問に大きな影響を与えた。アリストテレスの物理学の影響は、古代末期から中世初期、そしてルネサンスにまで及び、啓蒙時 代に古典力学のような理論が発展するまで、体系的に置き換えられることはなかった。アリストテレスの生物学に見られる動物学的観察の中には、タコのヘクト コティル(生殖腕)など、19世紀まで信じられていなかったものもある。アリストテレスは中世のユダヤ・イスラム哲学や、キリスト教神学、特に初代教会の 新プラトン主義やカトリック教会のスコラ学の伝統に影響を与えた。アリストテレスは、中世のイスラム学者たちの間では「最初の教師」として、またトマス・ アクィナスなどの中世キリスト教徒たちの間では単に「哲学者」として崇められ、詩人ダンテは彼を「知る者の師」と呼んだ。アリストテレスの著作には、論理 学の形式的研究として知られる最古のものが含まれており、ピーター・アベラールやジャン・ブリダンといった中世の学者たちによって研究された。アリストテ レスの論理学への影響は19世紀まで続いた。さらに、彼の倫理学は常に影響力を持ち続けていたが、近代の徳倫理学の登場により、再び関心を集めるように なった。 |

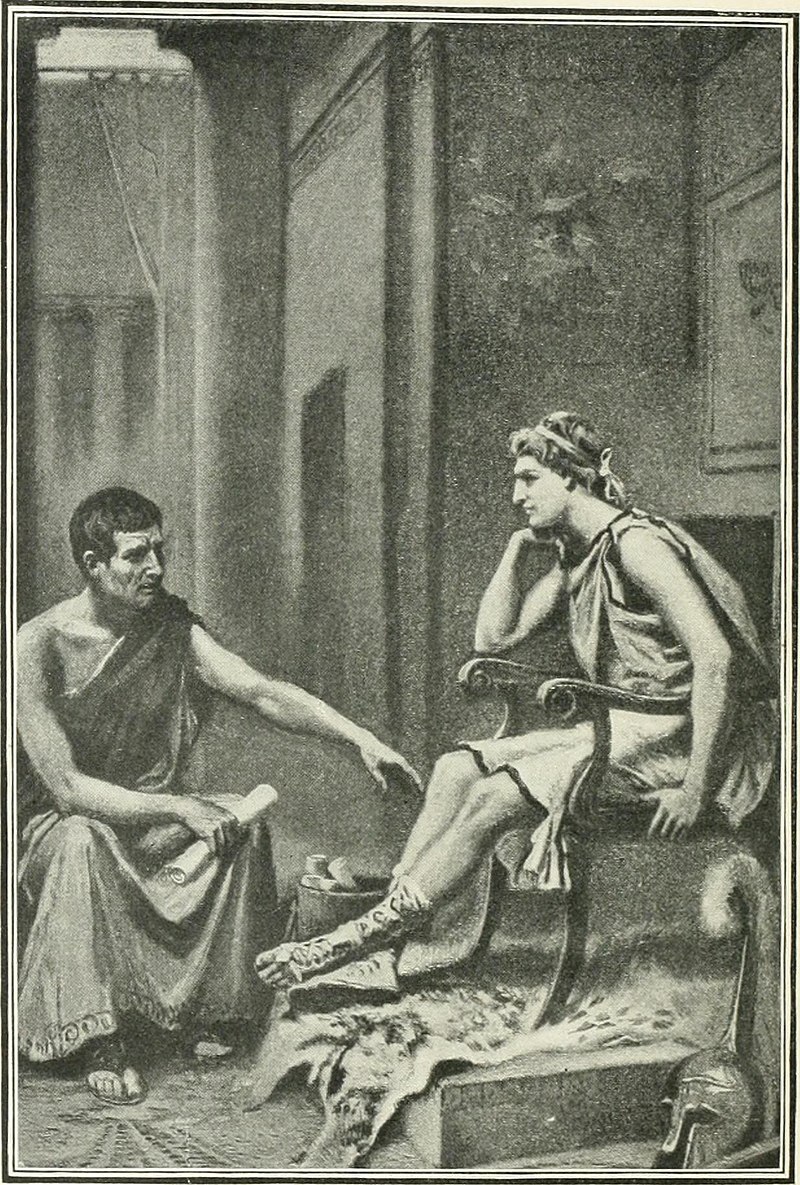

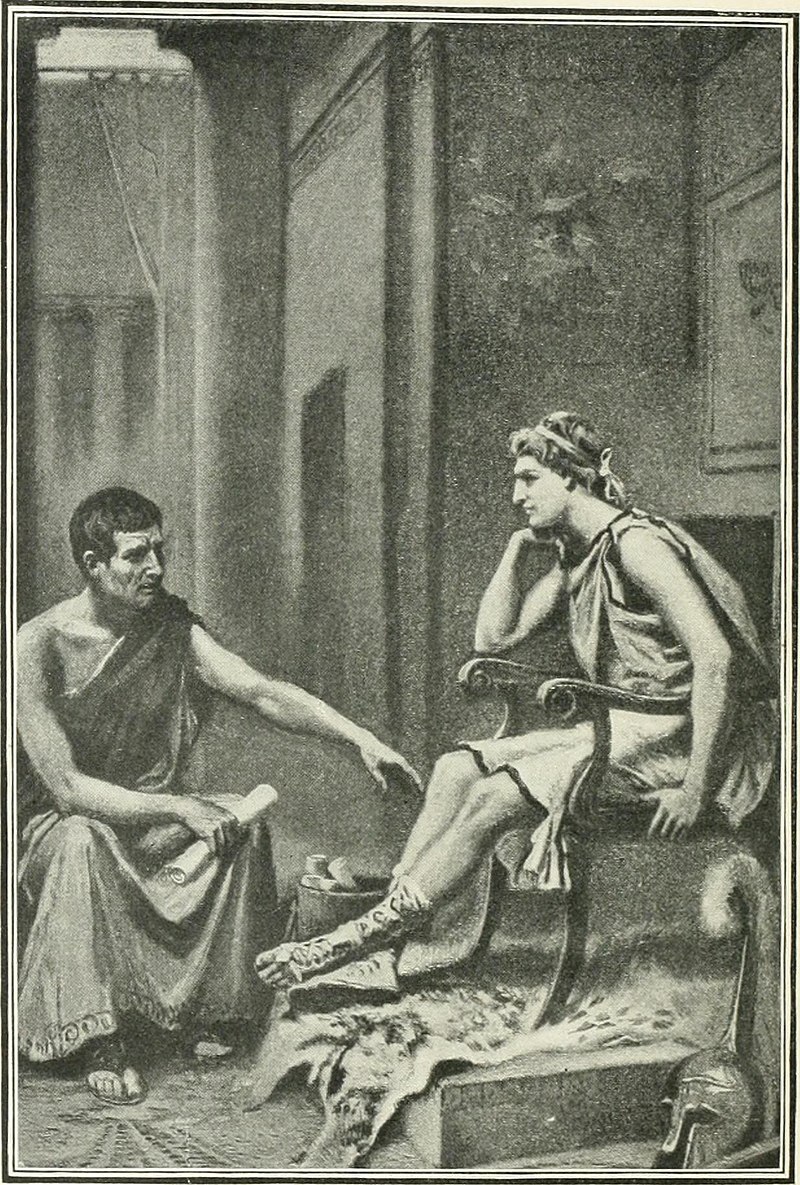

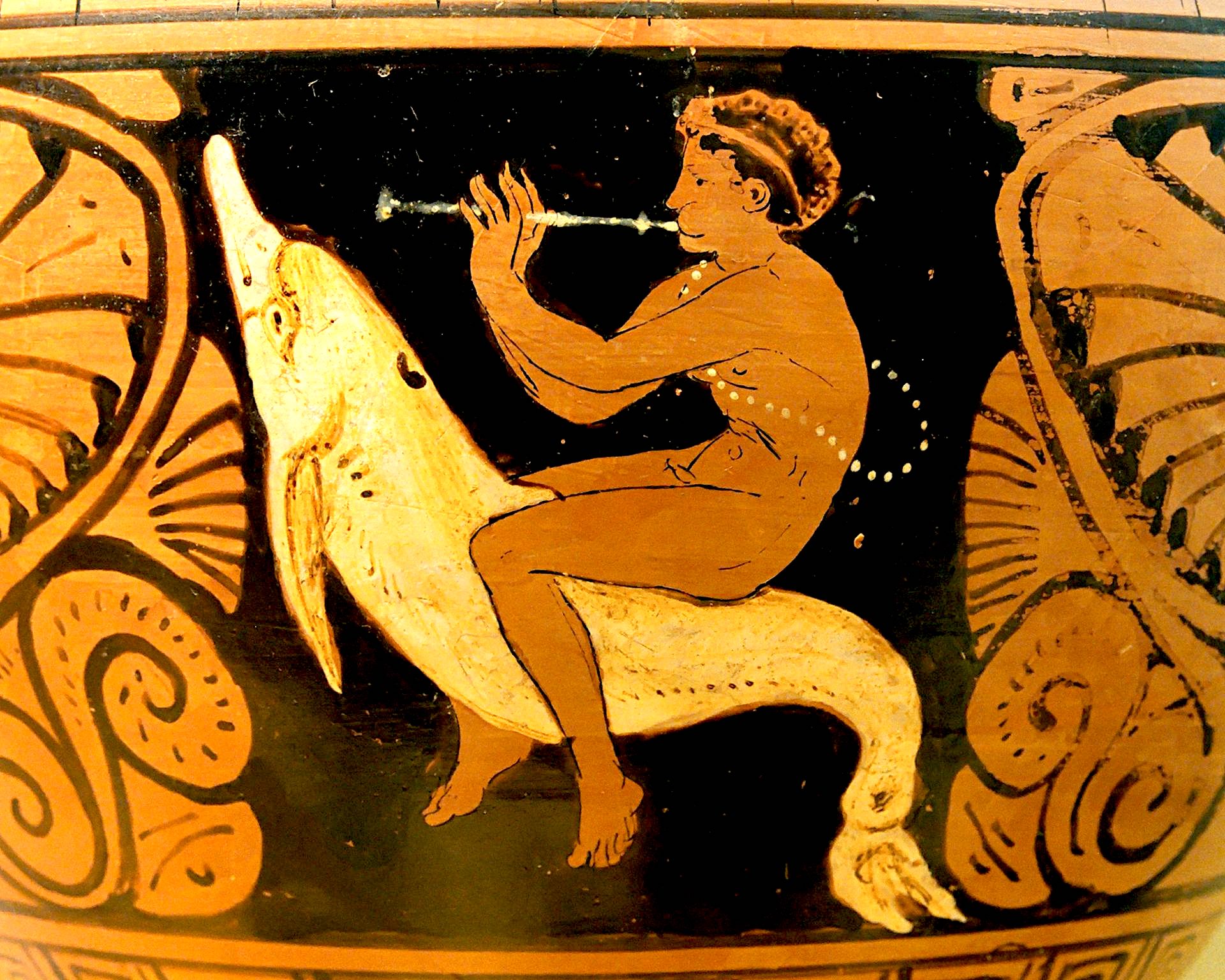

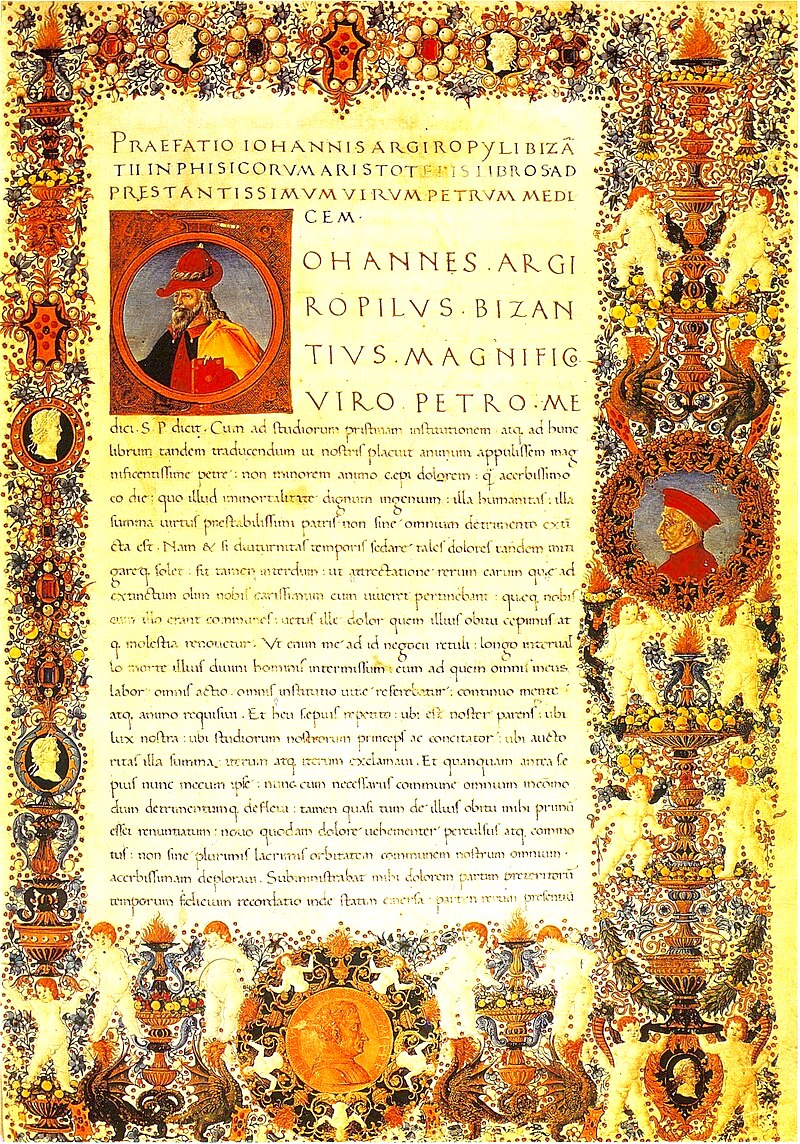

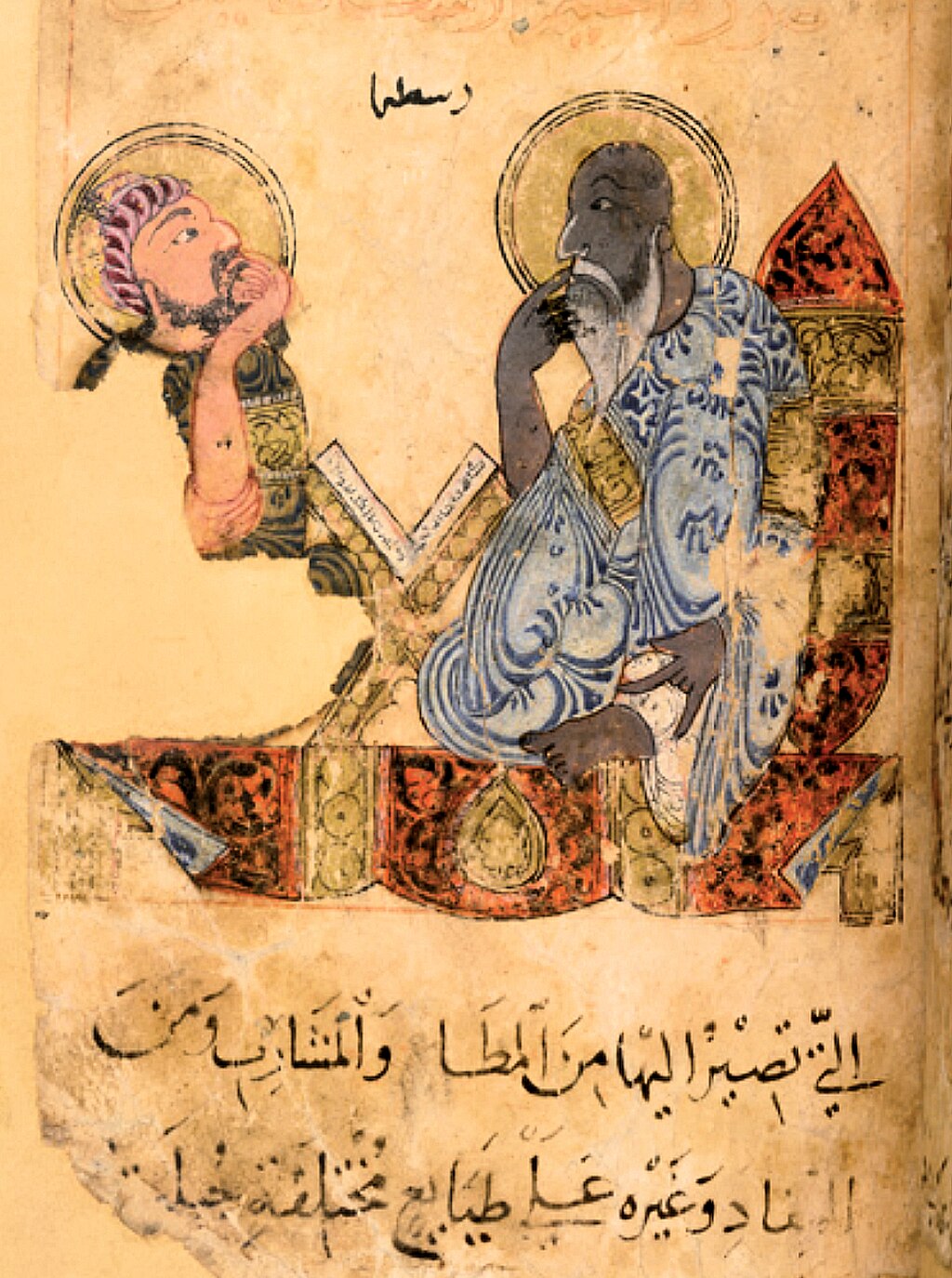

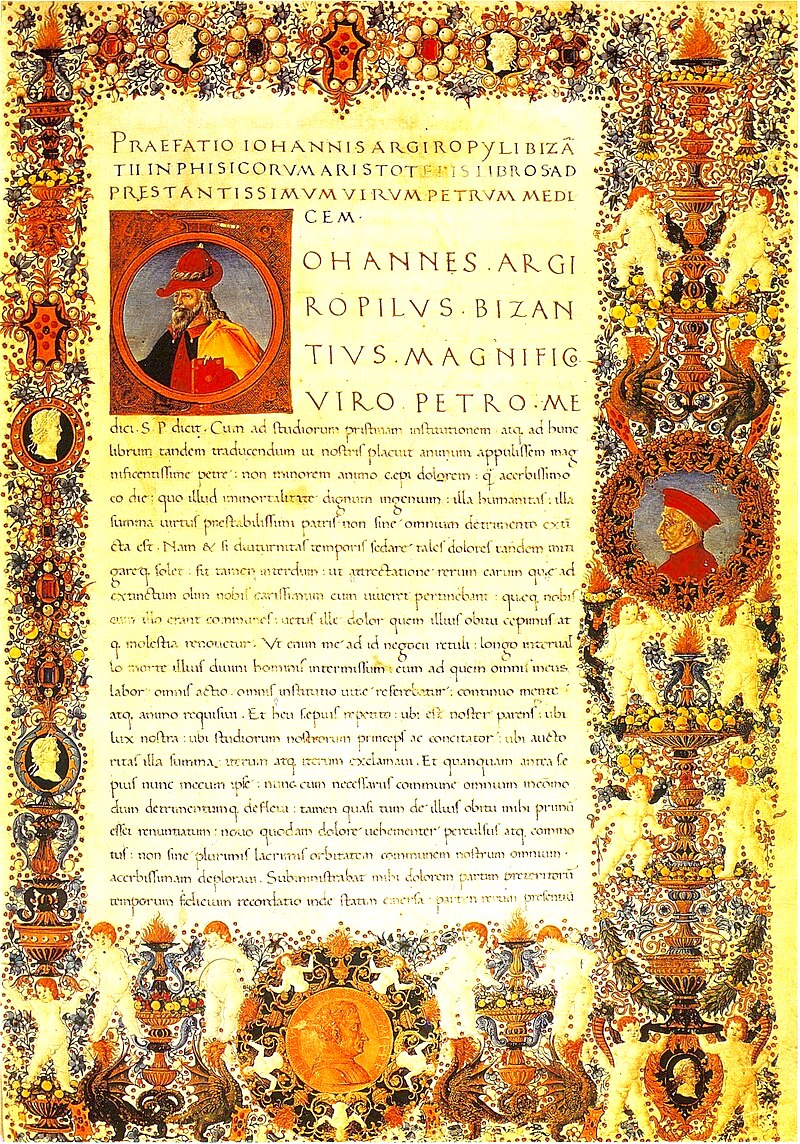

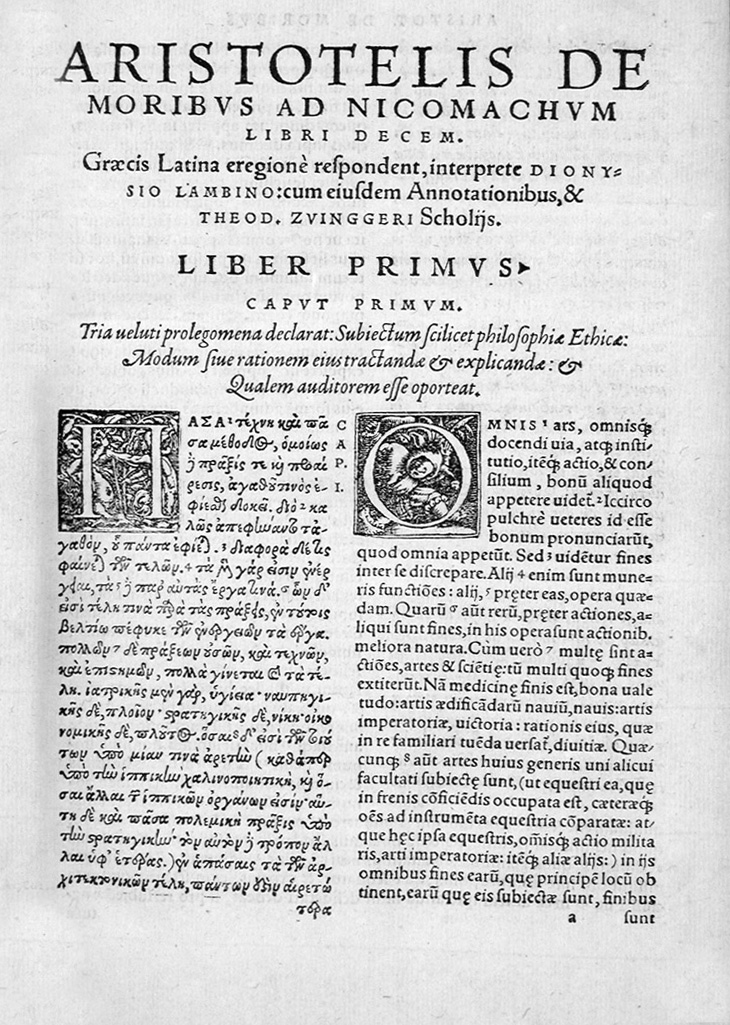

| Life In general, the details of Aristotle's life are not well-established. The biographies written in ancient times are often speculative and historians only agree on a few salient points.[A] Aristotle was born in 384 BC[B] in Stagira, Chalcidice,[2] about 55 km (34 miles) east of modern-day Thessaloniki.[3][4] His father, Nicomachus, was the personal physician to King Amyntas of Macedon. While he was young, Aristotle learned about biology and medical information, which was taught by his father.[5] Both of Aristotle's parents died when he was about thirteen, and Proxenus of Atarneus became his guardian.[6] Although little information about Aristotle's childhood has survived, he probably spent some time within the Macedonian palace, making his first connections with the Macedonian monarchy.[7]  School of Aristotle in Mieza, Macedonia, Greece At the age of seventeen or eighteen, Aristotle moved to Athens to continue his education at Plato's Academy.[8] He probably experienced the Eleusinian Mysteries as he wrote when describing the sights one viewed at the Eleusinian Mysteries, "to experience is to learn" [παθείν μαθεĩν].[9] Aristotle remained in Athens for nearly twenty years before leaving in 348/47 BC. The traditional story about his departure records that he was disappointed with the Academy's direction after control passed to Plato's nephew Speusippus, although it is possible that he feared the anti-Macedonian sentiments in Athens at that time and left before Plato died.[10] Aristotle then accompanied Xenocrates to the court of his friend Hermias of Atarneus in Asia Minor. After the death of Hermias, Aristotle travelled with his pupil Theophrastus to the island of Lesbos, where together they researched the botany and zoology of the island and its sheltered lagoon. While in Lesbos, Aristotle married Pythias, either Hermias's adoptive daughter or niece. They had a daughter, whom they also named Pythias. In 343 BC, Aristotle was invited by Philip II of Macedon to become the tutor to his son Alexander.[11][12]  "Aristotle tutoring Alexander" by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris Aristotle was appointed as the head of the royal Academy of Macedon. During Aristotle's time in the Macedonian court, he gave lessons not only to Alexander but also to two other future kings: Ptolemy and Cassander.[13] Aristotle encouraged Alexander toward eastern conquest, and Aristotle's own attitude towards Persia was unabashedly ethnocentric. In one famous example, he counsels Alexander to be "a leader to the Greeks and a despot to the barbarians, to look after the former as after friends and relatives, and to deal with the latter as with beasts or plants".[13] By 335 BC, Aristotle had returned to Athens, establishing his own school there known as the Lyceum. Aristotle conducted courses at the school for the next twelve years. While in Athens, his wife Pythias died and Aristotle became involved with Herpyllis of Stagira. They had a son whom Aristotle named after his father, Nicomachus. If the Suda – an uncritical compilation from the Middle Ages – is accurate, he may also have had an erômenos, Palaephatus of Abydus.[14]  Portrait bust of Aristotle; an Imperial Roman (1st or 2nd century AD) copy of a lost bronze sculpture made by Lysippos This period in Athens, between 335 and 323 BC, is when Aristotle is believed to have composed many of his works.[12] He wrote many dialogues, of which only fragments have survived. Those works that have survived are in treatise form and were not, for the most part, intended for widespread publication; they are generally thought to be lecture aids for his students. His most important treatises include Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics, Politics, On the Soul and Poetics. Aristotle studied and made significant contributions to "logic, metaphysics, mathematics, physics, biology, botany, ethics, politics, agriculture, medicine, dance, and theatre."[15] Near the end of his life, Alexander and Aristotle became estranged over Alexander's relationship with Persia and Persians. A widespread tradition in antiquity suspected Aristotle of playing a role in Alexander's death, but the only evidence of this is an unlikely claim made some six years after the death.[16] Following Alexander's death, anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens was rekindled. In 322 BC, Demophilus and Eurymedon the Hierophant reportedly denounced Aristotle for impiety,[17] prompting him to flee to his mother's family estate in Chalcis, on Euboea, at which occasion he was said to have stated: "I will not allow the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy"[18][19][20] – a reference to Athens's trial and execution of Socrates. He died in Chalcis, Euboea[2][21][15] of natural causes later that same year, having named his student Antipater as his chief executor and leaving a will in which he asked to be buried next to his wife.[22] |

生涯 一般に、アリストテレスの生涯の詳細は定かではない。古代に書かれた伝記は推測の域を出ないことが多く、歴史家はいくつかの重要な点についてのみ同意して いる[A]。 アリストテレスは紀元前384年[B]、現在のテッサロニキから55kmほど東にあるカルキディツェのスタギラで生まれた[2]。アリストテレスが幼少の 頃、父から教えられた生物学と医学について学んだ[5]。アリストテレスが13歳頃に両親ともに死去し、アタルネウスのプロクセノスが後見人となった [6]。アリストテレスの幼少期に関する情報はほとんど残っていないが、おそらくマケドニア王宮内で過ごし、マケドニア王政との最初の接点を持ったと思わ れる[7]。  ギリシャ、マケドニア、ミエザのアリストテレス学校 17歳か18歳のとき、アリストテレスはプラトンのアカデミーで教育を受けるためにアテネに移り住んだ[8]。エレウシノの秘儀で見た光景について「経験 することは学ぶことである」[παθείν μαθεν] [9] と書いているように、おそらく彼はエレウシノの秘儀を経験したのであろう。プラトンの甥スペウシッポスにアカデミーの支配権が移った後、アカデミーの方向 性に失望したというのが伝統的な話だが、当時のアテネの反マケドニア感情を恐れて、プラトンが死ぬ前に去った可能性もある[10]。ヘルミアスの死後、ア リストテレスは弟子のテオフラストスとともにレスボス島を訪れ、島とその保護されたラグーンの植物学と動物学を研究した。レスボス島滞在中、アリストテレ スはハーミアスの養女か姪であるピシアスと結婚した。二人の間には娘が生まれ、ピュティアスと名付けられた。紀元前343年、アリストテレスはマケドンの フィリップ2世に招かれ、息子のアレクサンダーの家庭教師となった[11][12]。  「アレクサンダーの家庭教師をするアリストテレス」ジャン・レオン・ジェローム・フェリス作 アリストテレスはマケドンの王立アカデミーの責任者に任命された。アリストテレスがマケドニア宮廷にいた頃、彼はアレクサンダーだけでなく、後の2人の王 にも教えを授けた: アリストテレスはアレクサンダーに東方征服を勧めたが、アリストテレス自身のペルシアに対する態度は臆面もなく民族中心主義的であった。有名な例では、ア レクサンダーに「ギリシア人には指導者となり、蛮族には専制君主となり、前者には友人や親戚のように世話をし、後者には獣や植物のように対処するように」 と助言している[13]。 紀元前335年までにアリストテレスはアテネに戻り、リセウムとして知られる自身の学校を設立した。アリストテレスはその後12年間、この学校で講義を 行った。アテネ滞在中に妻ピュティアスが亡くなり、アリストテレスはスタギラのヘルピリスと関係を持った。二人の間には息子が生まれ、アリストテレスは父 にちなんでニコマコスと名づけた。中世の無批判な編纂物である『スダ』が正確であれば、アビドゥスのパラエファタスというエロメノスがいた可能性もある [14]。  アリストテレスの肖像胸像;リュシッポスによって制作された失われたブロンズ像の帝政ローマ時代(紀元1~2世紀)の複製。 紀元前335年から紀元前323年にかけてのアテナイ時代は、アリストテレスが多くの著作を残したと考えられている時期である[12]。現存するこれらの 著作は論考形式であり、ほとんどの場合、広く出版されることは意図されていなかった。アリストテレスの最も重要な著作は、『物理学』、『形而上学』、『ニ コマコス倫理学』、『政治学』、『魂について』、『詩学』などである。アリストテレスは「論理学、形而上学、数学、物理学、生物学、植物学、倫理学、政治 学、農業、医学、舞踊、演劇」を研究し、多大な貢献をした[15]。 アレキサンダーとアリストテレスは、アレキサンダーとペルシャとの関係をめぐって疎遠になった。古代には、アレクサンダーの死にアリストテレスが関与して いるとする伝承が広まっていたが、その唯一の証拠は、アレクサンダーの死後6年ほど経ってからなされたありもしない主張である。紀元前322年、デモフィ ロスとエウリュメドン(エウロファント)がアリストテレスを不敬罪で糾弾し、アリストテレスは母の実家であるエウボイアのカルキスに逃れたとされる [17]: 「私はアテネ人が哲学に対して二度も罪を犯すことを許さない」[18][19][20]-アテネによるソクラテスの裁判と処刑を指している。彼は同年末に エウボイアのカルキスで自然死し[2][21][15]、弟子のアンティパテルを遺言執行人に指名し、妻の隣に埋葬するようにという遺言を残した [22]。 |

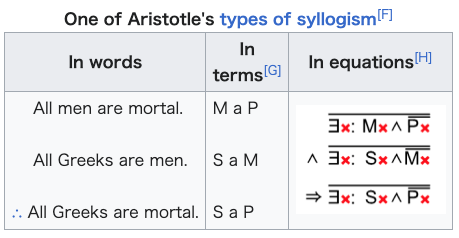

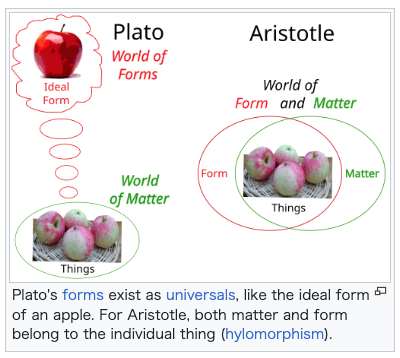

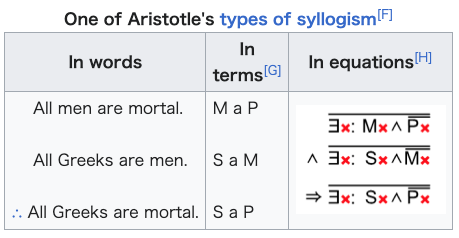

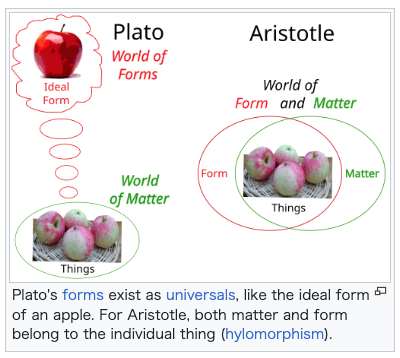

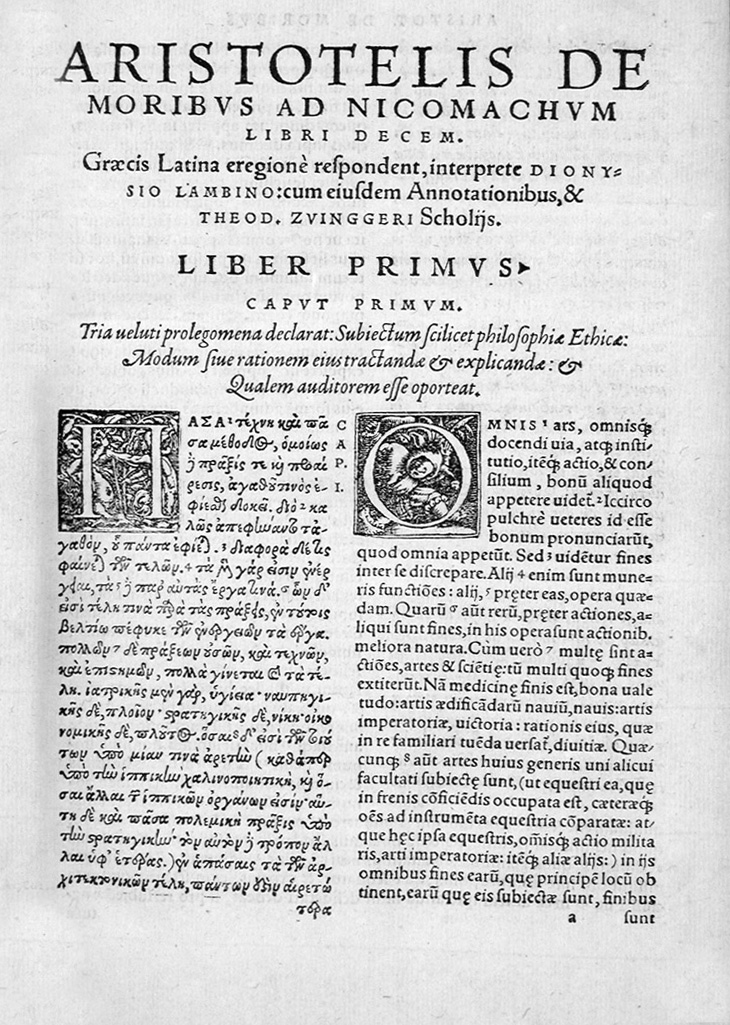

| Theoretical philosophy Logic Main article: Term logic Further information: Non-Aristotelian logic With the Prior Analytics, Aristotle is credited with the earliest study of formal logic,[23] and his conception of it was the dominant form of Western logic until 19th-century advances in mathematical logic.[24] Kant stated in the Critique of Pure Reason that with Aristotle logic reached its completion.[25] Organon Main article: Organon  One of Aristotle's types of syllogism[C] In words In terms[D] In equations[E] All men are mortal. All Greeks are men. ∴ All Greeks are mortal. M a P S a M S a P What is today called Aristotelian logic with its types of syllogism (methods of logical argument),[26] Aristotle himself would have labelled "analytics". The term "logic" he reserved to mean dialectics. Most of Aristotle's work is probably not in its original form, because it was most likely edited by students and later lecturers. The logical works of Aristotle were compiled into a set of six books called the Organon around 40 BC by Andronicus of Rhodes or others among his followers.[28] The books are: Categories On Interpretation Prior Analytics Posterior Analytics Topics On Sophistical Refutations  Plato (left) and Aristotle in Raphael's 1509 fresco, The School of Athens. Aristotle holds his Nicomachean Ethics and gestures to the earth, representing his view in immanent realism, whilst Plato gestures to the heavens, indicating his Theory of Forms, and holds his Timaeus.[29][30] The order of the books (or the teachings from which they are composed) is not certain, but this list was derived from analysis of Aristotle's writings. It goes from the basics, the analysis of simple terms in the Categories, the analysis of propositions and their elementary relations in On Interpretation, to the study of more complex forms, namely, syllogisms (in the Analytics)[31][32] and dialectics (in the Topics and Sophistical Refutations). The first three treatises form the core of the logical theory stricto sensu: the grammar of the language of logic and the correct rules of reasoning. The Rhetoric is not conventionally included, but it states that it relies on the Topics.[33] Metaphysics Main article: Metaphysics (Aristotle) The word "metaphysics" appears to have been coined by the first century AD editor who assembled various small selections of Aristotle's works to the treatise we know by the name Metaphysics.[34] Aristotle called it "first philosophy", and distinguished it from mathematics and natural science (physics) as the contemplative (theoretikē) philosophy which is "theological" and studies the divine. He wrote in his Metaphysics (1026a16): if there were no other independent things besides the composite natural ones, the study of nature would be the primary kind of knowledge; but if there is some motionless independent thing, the knowledge of this precedes it and is first philosophy, and it is universal in just this way, because it is first. And it belongs to this sort of philosophy to study being as being, both what it is and what belongs to it just by virtue of being.[35] Substance Further information: Hylomorphism Aristotle examines the concepts of substance (ousia) and essence (to ti ên einai, "the what it was to be") in his Metaphysics (Book VII), and he concludes that a particular substance is a combination of both matter and form, a philosophical theory called hylomorphism. In Book VIII, he distinguishes the matter of the substance as the substratum, or the stuff of which it is composed. For example, the matter of a house is the bricks, stones, timbers, etc., or whatever constitutes the potential house, while the form of the substance is the actual house, namely 'covering for bodies and chattels' or any other differentia that let us define something as a house. The formula that gives the components is the account of the matter, and the formula that gives the differentia is the account of the form.[36][34] Immanent realism Main article: Aristotle's theory of universals  Plato's forms exist as universals, like the ideal form of an apple. For Aristotle, both matter and form belong to the individual thing (hylomorphism). Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle's philosophy aims at the universal. Aristotle's ontology places the universal (katholou) in particulars (kath' hekaston), things in the world, whereas for Plato the universal is a separately existing form which actual things imitate. For Aristotle, "form" is still what phenomena are based on, but is "instantiated" in a particular substance.[34] Plato argued that all things have a universal form, which could be either a property or a relation to other things. When one looks at an apple, for example, one sees an apple, and one can also analyse a form of an apple. In this distinction, there is a particular apple and a universal form of an apple. Moreover, one can place an apple next to a book, so that one can speak of both the book and apple as being next to each other. Plato argued that there are some universal forms that are not a part of particular things. For example, it is possible that there is no particular good in existence, but "good" is still a proper universal form. Aristotle disagreed with Plato on this point, arguing that all universals are instantiated at some period of time, and that there are no universals that are unattached to existing things. In addition, Aristotle disagreed with Plato about the location of universals. Where Plato spoke of the forms as existing separately from the things that participate in them, Aristotle maintained that universals exist within each thing on which each universal is predicated. So, according to Aristotle, the form of apple exists within each apple, rather than in the world of the forms.[34][37] Potentiality and actuality Concerning the nature of change (kinesis) and its causes, as he outlines in his Physics and On Generation and Corruption (319b–320a), he distinguishes coming-to-be (genesis, also translated as 'generation') from: growth and diminution, which is change in quantity; locomotion, which is change in space; and alteration, which is change in quality.  Aristotle argued that a capability like playing the flute could be acquired – the potential made actual – by learning. Coming-to-be is a change where the substrate of the thing that has undergone the change has itself changed. In that particular change he introduces the concept of potentiality (dynamis) and actuality (entelecheia) in association with the matter and the form. Referring to potentiality, this is what a thing is capable of doing or being acted upon if the conditions are right and it is not prevented by something else. For example, the seed of a plant in the soil is potentially (dynamei) a plant, and if it is not prevented by something, it will become a plant. Potentially beings can either 'act' (poiein) or 'be acted upon' (paschein), which can be either innate or learned. For example, the eyes possess the potentiality of sight (innate – being acted upon), while the capability of playing the flute can be possessed by learning (exercise – acting). Actuality is the fulfilment of the end of the potentiality. Because the end (telos) is the principle of every change, and potentiality exists for the sake of the end, actuality, accordingly, is the end. Referring then to the previous example, it can be said that an actuality is when a plant does one of the activities that plants do.[34] For that for the sake of which (to hou heneka) a thing is, is its principle, and the becoming is for the sake of the end; and the actuality is the end, and it is for the sake of this that the potentiality is acquired. For animals do not see in order that they may have sight, but they have sight that they may see.[38] In summary, the matter used to make a house has potentiality to be a house and both the activity of building and the form of the final house are actualities, which is also a final cause or end. Then Aristotle proceeds and concludes that the actuality is prior to potentiality in formula, in time and in substantiality. With this definition of the particular substance (i.e., matter and form), Aristotle tries to solve the problem of the unity of the beings, for example, "what is it that makes a man one"? Since, according to Plato there are two Ideas: animal and biped, how then is man a unity? However, according to Aristotle, the potential being (matter) and the actual one (form) are one and the same.[34][39] Epistemology Aristotle's immanent realism means his epistemology is based on the study of things that exist or happen in the world, and rises to knowledge of the universal, whereas for Plato epistemology begins with knowledge of universal Forms (or ideas) and descends to knowledge of particular imitations of these.[33] Aristotle uses induction from examples alongside deduction, whereas Plato relies on deduction from a priori principles.[33] |

理論哲学 論理学 主な記事 論理学用語 更なる情報 非アリストテレス的論理学 アリストテレスは『先行論理学』によって、形式論理学の最古の研究を行ったとされており[23]、19世紀に数理論理学が進歩するまでは、アリストテレス が提唱した形式論理学が西洋論理学の主流であった[24]。 オルガノン 主な記事 オルガノン  アリストテレスのシロジズムのタイプの一つ[C]。 言葉において 項において[D] 方程式において[E] すべての人間は死すべきものである。 すべてのギリシア人は人間である。 ∴ すべてのギリシア人は死すべき存在である。 M a P S a M S a P 今日、アリストテレス論理学と呼ばれているものは、シロジズム(論理的論証の方法)の種類[26]を持ち、アリストテレス自身は「分析学」と呼んでいた。 論理学」という用語は弁証法を意味する。アリストテレスの著作の大半は、学生や後の講師たちによって編集されたものである可能性が高いため、おそらく原型 をとどめていない。アリストテレスの論理学的著作は、紀元前40年頃、ロードス島のアンドロニコスまたは彼の信奉者たちによって、『オルガノン』と呼ばれ る6冊の書物にまとめられた[28]: カテゴリー 解釈について 先行分析学 事後分析学 トピックス 詭弁的反論について  ラファエロの1509年のフレスコ画『アテネの学校』に描かれたプラトン(左)とアリストテレス。アリストテレスは『ニコマコス倫理学』を手にし、地に向 かって身振りをする。これは彼の内在的実在論における見解を表しており、一方プラトンは天に向かって身振りをし、『形相論』を示し、『ティマイオス』を手 にしている[29][30]。 書物(あるいは書物が構成されている教え)の順序は定かではないが、このリストはアリストテレスの著作の分析から導き出されたものである。基本的なこと、 すなわち『カテゴリー』における単純な用語の分析、『解釈論』における命題とその初等的な関係の分析から、より複雑な形式の研究、すなわち(『アナリティ クス』における)シロギス[31][32]と(『トピックス』と『詭弁的反駁』における)弁証法に至る。最初の3つの論考は、論理学の言語の文法と推論の 正しい規則という、厳密な意味での論理理論の中核をなすものである。修辞学』は慣例的に含まれていないが、『トピックス』に依拠していると述べている [33]。 形而上学 主な記事 形而上学(アリストテレス) アリストテレスは『形而上学』を「第一哲学」と呼び、数学や自然科学(物理学)とは区別して、「神学的」であり神的なものを研究する観照哲学 (theoretikē)と呼んだ。彼は『形而上学』(1026a16)にこう書いている: もし複合的な自然のもののほかに独立したものがなければ、自然の研究は第一の種類の知識であろう。しかし、もし何か動かない独立したものがあれば、これに ついての知識はそれに先立つものであり、第一の哲学である。そして、存在することを存在することとして研究することは、この種の哲学に属する。 物質 さらなる情報 同形論 アリストテレスは『形而上学』(第VII書)の中で、物質(ouusia)と本質(to ti ên einai、「あるべき姿」)の概念を検討し、特定の物質は物質と形態の両方の組み合わせであると結論づけた。第VIII巻で彼は、物質の物質を基質、つ まり物質が構成されているものと区別する。例えば、家の物質とは、煉瓦、石、材木など、潜在的な家を構成するものであり、物質の形とは、実際の家、すなわ ち「身体と家畜を覆うもの」、あるいは何かを家として定義させるその他の微分要素である。構成要素を与える公式は物質の説明であり、差異を与える公式は形 の説明である[36][34]。 内在的実在論 主な記事 アリストテレスの普遍論  プラトンの形は、リンゴの理想形のように普遍として存在する。アリストテレスにとっては、物質も形も個々の事物に属する(hylomorphism)。 師プラトンと同様、アリストテレスの哲学も普遍を目指す。アリストテレスの存在論は、普遍的なもの(katholou)を特殊なもの(kath' hekaston)、すなわち世界の事物の中に位置づけるが、プラトンにとっての普遍的なものとは、実際の事物が模倣する別個に存在する形である。アリス トテレスにとって「形」とは、現象が基礎とするものであることに変わりはないが、特定の物質において「インスタンス化」されたものである[34]。 プラトンは、すべての事物は普遍的な形を持っており、それは性質であるか他の事物との関係であるかのいずれかであると主張していた。例えばリンゴを見ると き、人はリンゴを見るが、リンゴの形を分析することもできる。この区別において、特定のリンゴと普遍的なリンゴの形がある。さらに、人は本の隣にリンゴを 置くことができ、本とリンゴの両方が隣にあると言うことができる。プラトンは、特定の事物の一部ではない普遍的な形も存在すると主張した。例えば、特定の 善は存在しない可能性があるが、それでも「善」は適切な普遍的形式である。アリストテレスはこの点でプラトンと対立し、すべての普遍はある時期にインスタ ンス化されるものであり、現存する事物に付随しない普遍は存在しないと主張した。さらに、アリストテレスは普遍の位置についてもプラトンと意見が合わな かった。プラトンは形式を、それに参加する事物とは別個に存在するものとして語ったが、アリストテレスは、普遍は、それぞれの普遍が前提とする事物の中に 存在すると主張した。したがって、アリストテレスによれば、リンゴの形は形の世界の中ではなく、それぞれのリンゴの中に存在する[34][37]。 潜在性と実在性 変化(キネシス)の本質とその原因に関して、『物理学』と『生成と腐敗について』(319b-320a)で概説しているように、彼は「生起」 (genesis、「生成」とも訳される)を次のように区別している: 量の変化である成長と減少; 運動:空間における変化。 質における変化である「変化」である。  アリストテレスは、フルート演奏のような能力は、学習によって獲得される、つまり潜在能力が現実になると主張した。 あるべき姿とは、変化を受けたものの基体そのものが変化することである。その特殊な変化において、彼は潜在性(dynamis)と現実性 (entelecheia)という概念を、物質と形態に関連して導入している。潜在性とは、条件が整い、何か他のものに妨げられなければ、あるものがなし うること、あるいは作用されうることである。例えば、土の中の植物の種は潜在的に(dynamei)植物であり、何かに妨げられなければ植物になる。潜在 的な存在は「行動する」(poiein)か「行動される」(paschein)のどちらかであり、それは生得的なものか学習されたものかのどちらかであ る。例えば、目は視覚の潜在能力を持っている(生得的-作用される)が、フルートを演奏する能力は学習によって持つことができる(運動-作用する)。実際 とは、潜在性の終末の成就である。目的(テロス)はあらゆる変化の原理であり、潜在性は目的のために存在するのだから、それに応じて現実性は目的である。 そこで先の例を参照すると、アクチュアリティとは、植物が植物が行う活動の一つを行うときのことである、と言うことができる[34]。 というのも、あるものが存在する(hou heneka)のはそのためであり、存在するのは目的のためであり、実在は目的であり、潜在性が獲得されるのはこのためだからである。動物は視力を得るた めに視力を得るのではなく、視力を得るために視力を得るのである[38]。 要約すると、家を作るために使用される物質は家であるための潜在性を持っており、建築の活動と最終的な家の形態はともに実在性であり、それはまた最終的な 原因あるいは目的でもある。そしてアリストテレスは、式において、時間において、実質性において、実在性は潜在性に先立つと結論づける。この特定の実体 (すなわち、物質と形態)の定義によって、アリストテレスは、例えば、「人間を一つにするものは何か」というような存在の単一性の問題を解決しようとす る。プラトンによれば、イデアには動物と二足動物の二つがある。しかしアリストテレスによれば、潜在的な存在(物質)と現実的な存在(形態)は一体である [34][39]。 認識論 アリストテレスの内在的実在論は、彼の認識論が世界に存在するもの、あるいは起こるものの研究に基づき、普遍的なものの知識へと昇華することを意味する が、プラトンの認識論は普遍的な形式(あるいはイデア)の知識から始まり、これらの特定の模倣の知識へと下降する[33]。 |

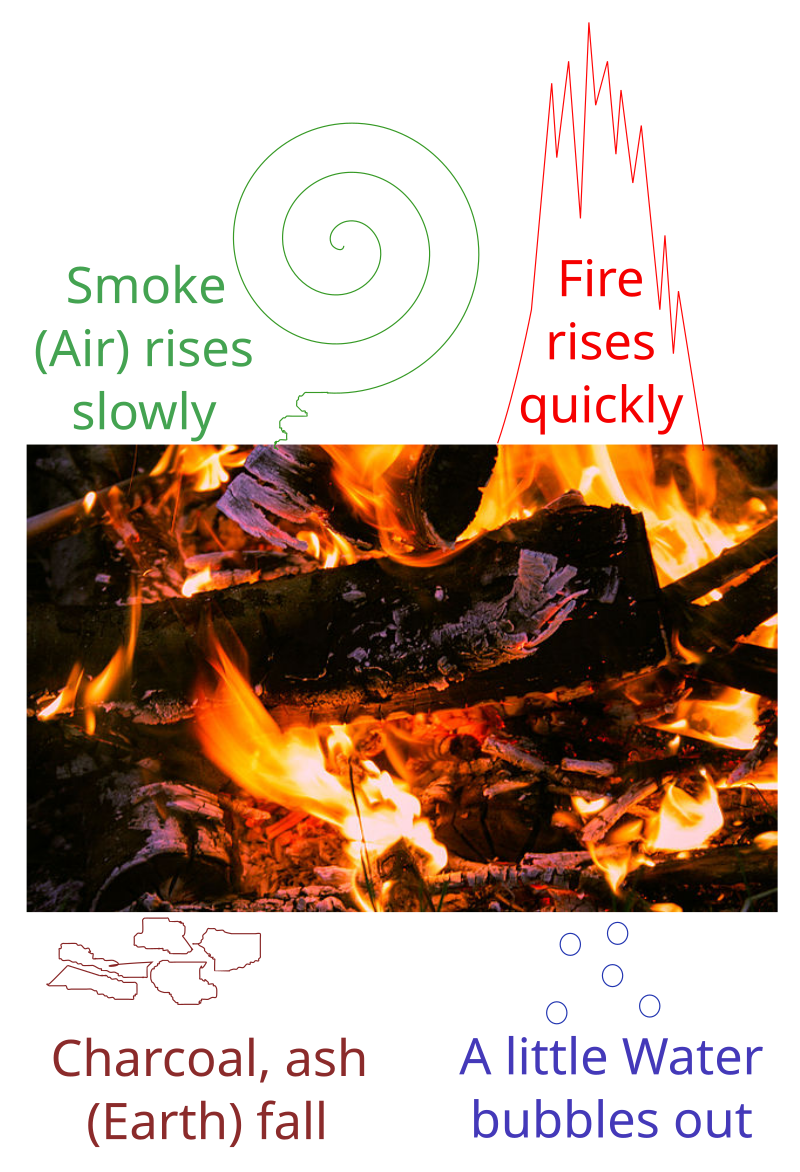

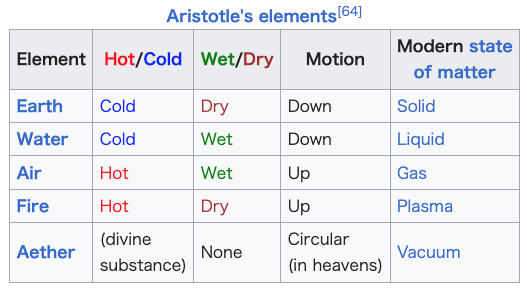

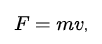

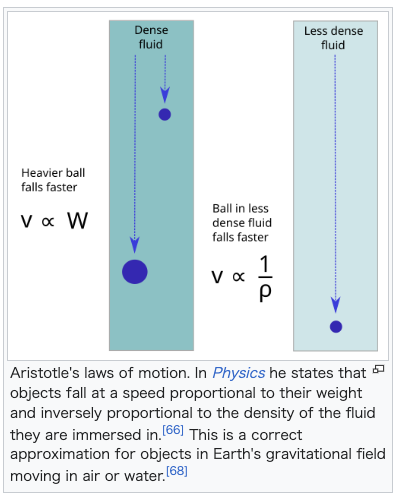

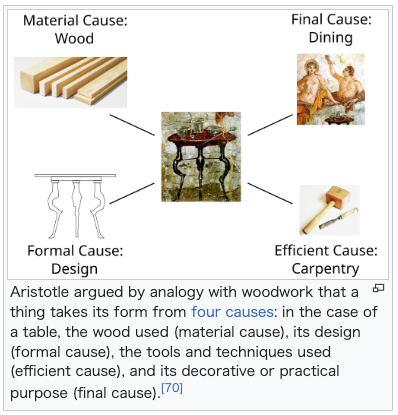

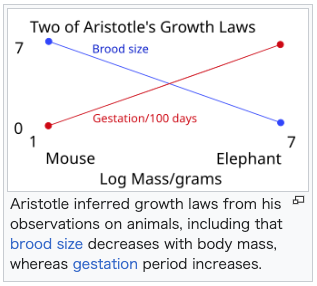

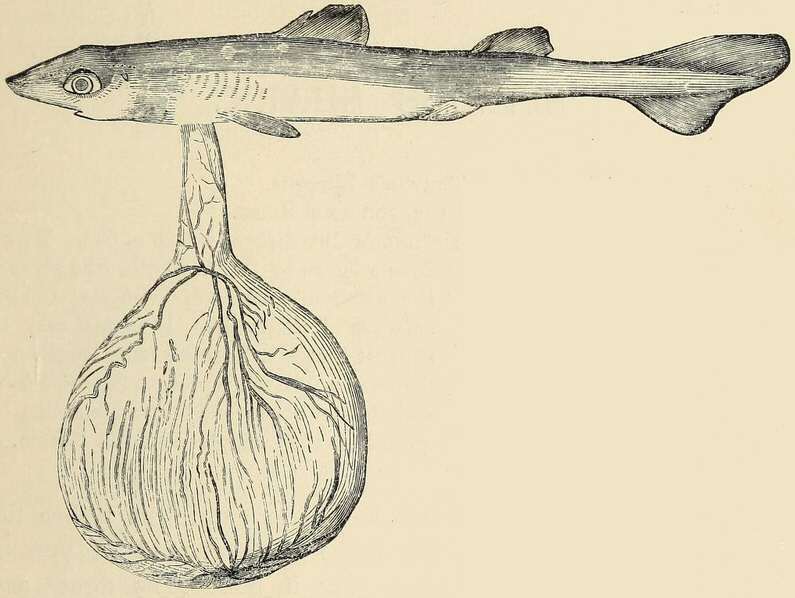

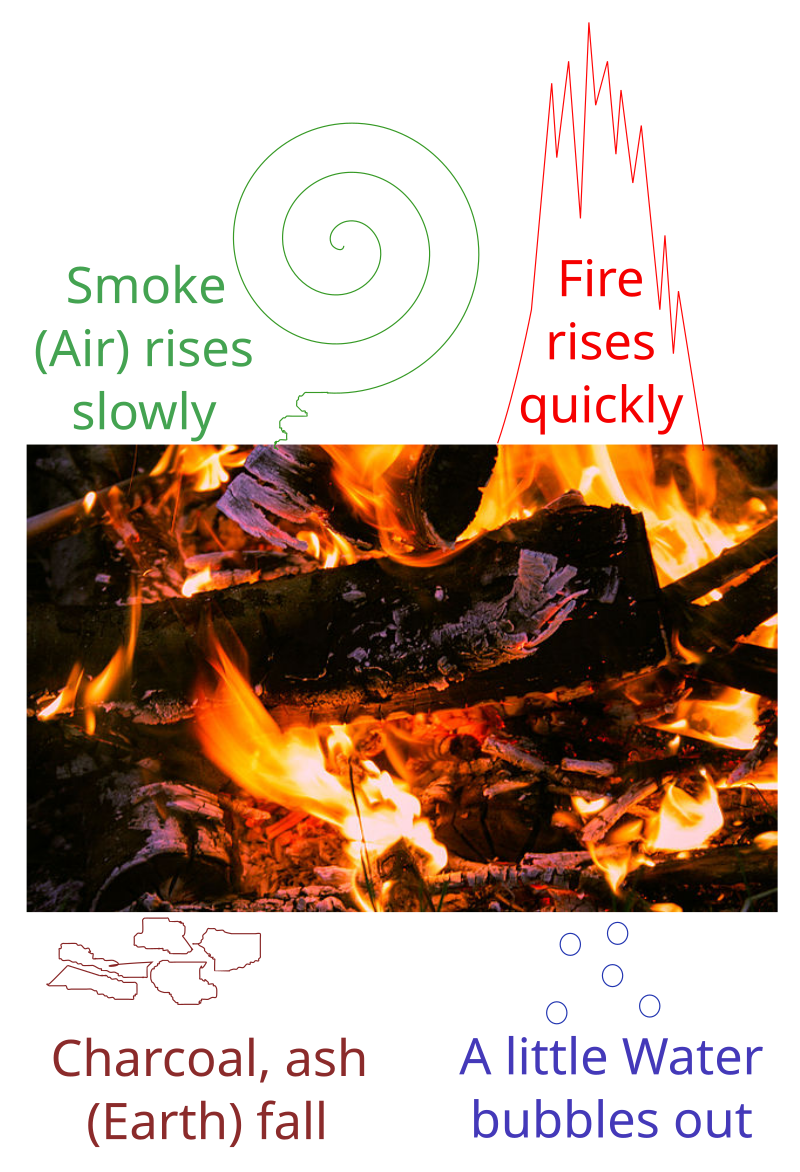

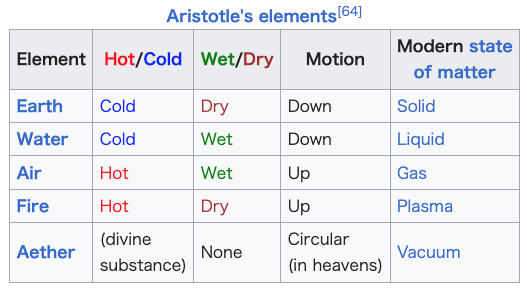

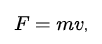

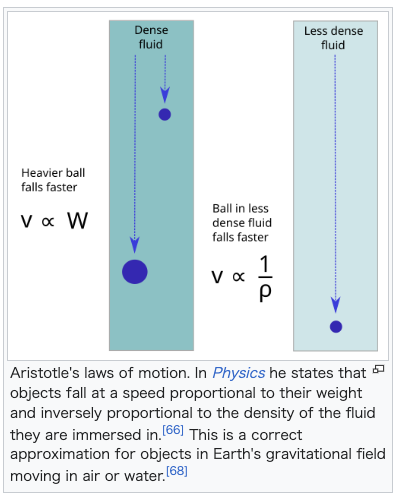

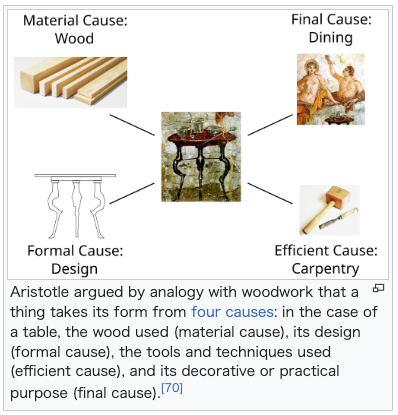

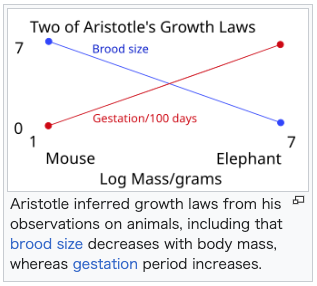

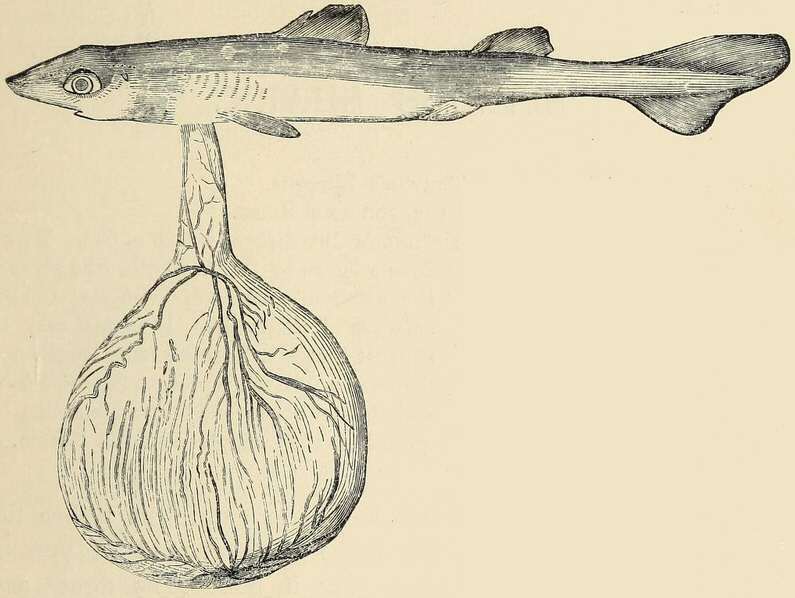

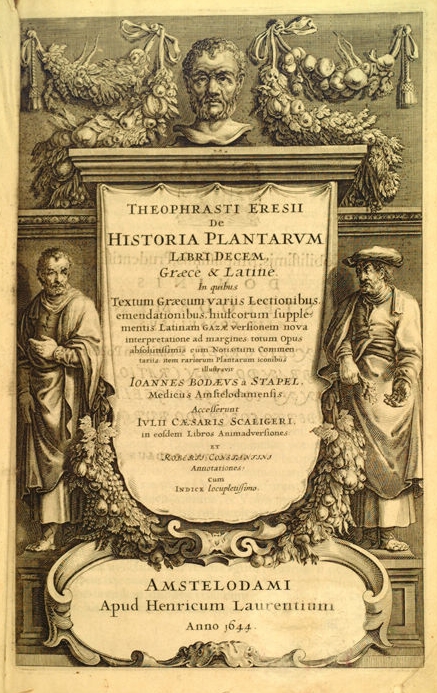

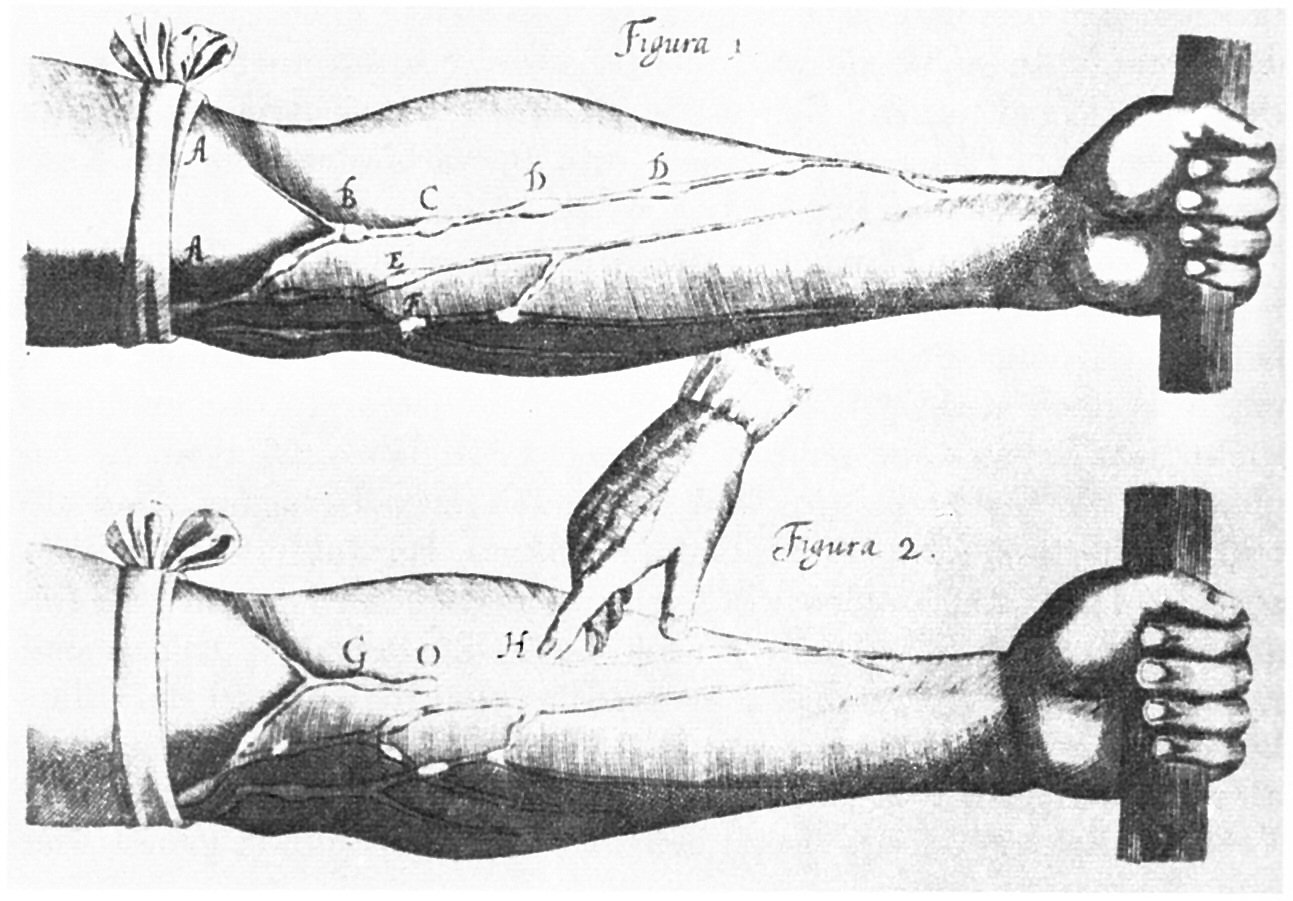

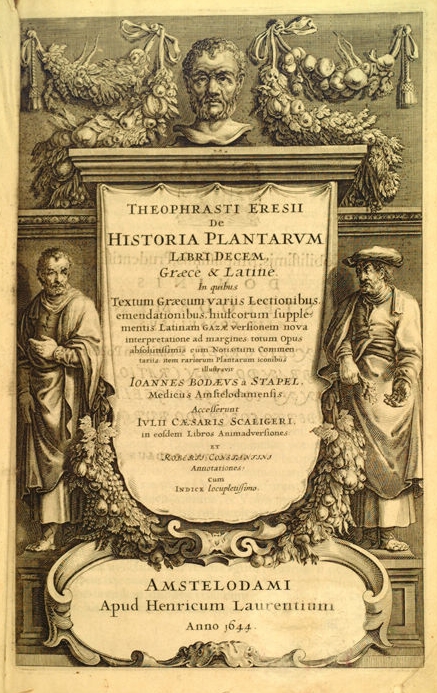

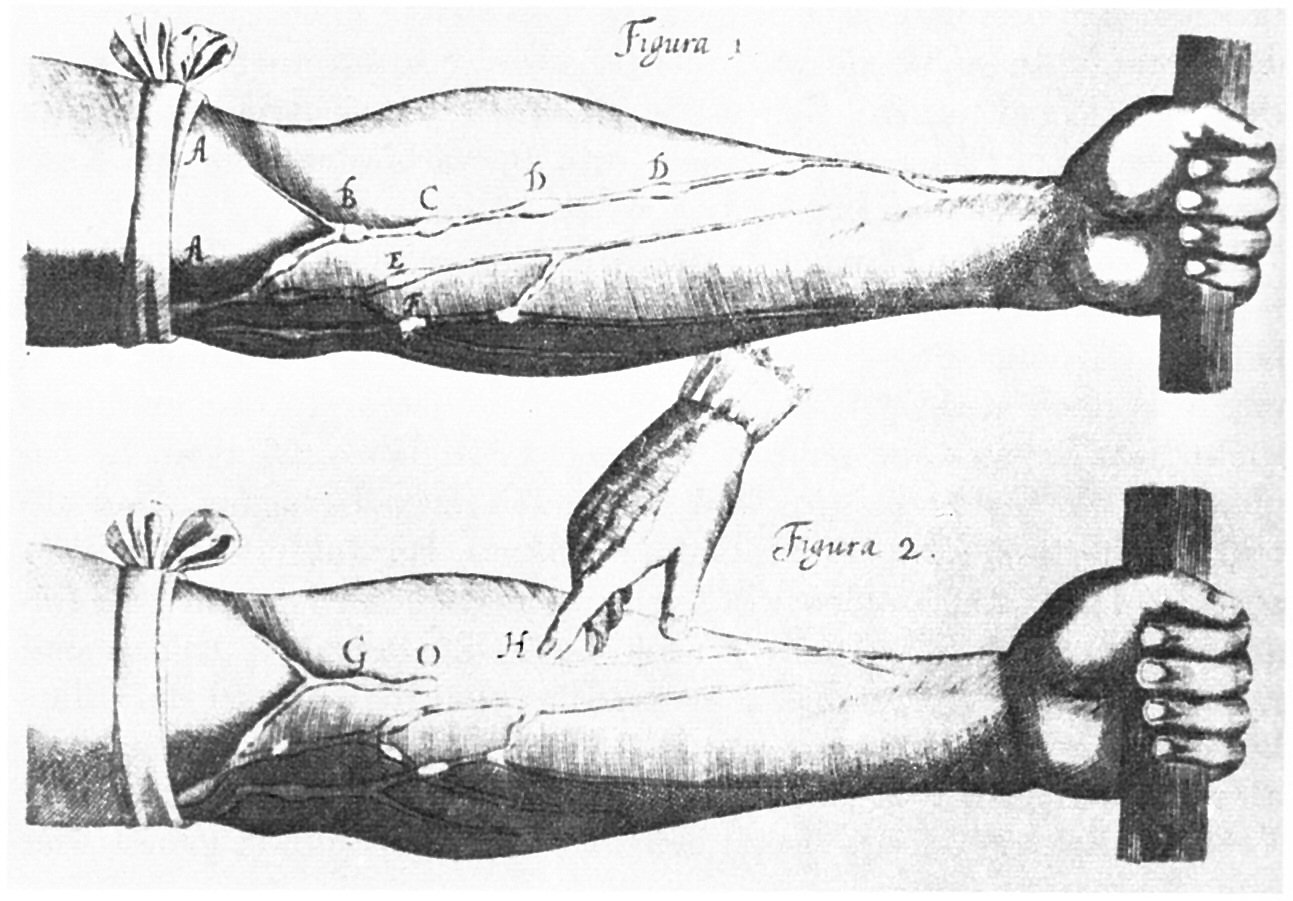

| Natural philosophy Aristotle's "natural philosophy" spans a wide range of natural phenomena including those now covered by physics, biology and other natural sciences.[40] In Aristotle's terminology, "natural philosophy" is a branch of philosophy examining the phenomena of the natural world, and includes fields that would be regarded today as physics, biology and other natural sciences. Aristotle's work encompassed virtually all facets of intellectual inquiry. Aristotle makes philosophy in the broad sense coextensive with reasoning, which he also would describe as "science". However, his use of the term science carries a different meaning than that covered by the term "scientific method". For Aristotle, "all science (dianoia) is either practical, poetical or theoretical" (Metaphysics 1025b25). His practical science includes ethics and politics; his poetical science means the study of fine arts including poetry; his theoretical science covers physics, mathematics and metaphysics.[40] Physics  The four classical elements (fire, air, water, earth) of Empedocles and Aristotle illustrated with a burning log. The log releases all four elements as it is destroyed. Main article: Aristotelian physics Five elements Main article: Classical element In his On Generation and Corruption, Aristotle related each of the four elements proposed earlier by Empedocles, earth, water, air, and fire, to two of the four sensible qualities, hot, cold, wet, and dry. In the Empedoclean scheme, all matter was made of the four elements, in differing proportions. Aristotle's scheme added the heavenly aether, the divine substance of the heavenly spheres, stars and planets.[41]  Aristotle's elements[41] Element Hot/Cold Wet/Dry Motion Modern state of matter Earth Cold Dry Down Solid Water Cold Wet Down Liquid Air Hot Wet Up Gas Fire Hot Dry Up Plasma Aether (divine substance) — Circular (in heavens) Vacuum Motion Further information: History of classical mechanics Aristotle describes two kinds of motion: "violent" or "unnatural motion", such as that of a thrown stone, in the Physics (254b10), and "natural motion", such as of a falling object, in On the Heavens (300a20). In violent motion, as soon as the agent stops causing it, the motion stops also: in other words, the natural state of an object is to be at rest,[42][F] since Aristotle does not address friction.[43] With this understanding, it can be observed that, as Aristotle stated, heavy objects (on the ground, say) require more force to make them move; and objects pushed with greater force move faster.[44][G] This would imply the equation[44]  incorrect in modern physics.[44] Natural motion depends on the element concerned: the aether naturally moves in a circle around the heavens,[H] while the 4 Empedoclean elements move vertically up (like fire, as is observed) or down (like earth) towards their natural resting places.[45][43][I]  Aristotle's laws of motion. In Physics he states that objects fall at a speed proportional to their weight and inversely proportional to the density of the fluid they are immersed in.[43] This is a correct approximation for objects in Earth's gravitational field moving in air or water.[45] In the Physics (215a25), Aristotle effectively states a quantitative law, that the speed, v, of a falling body is proportional (say, with constant c) to its weight, W, and inversely proportional to the density,[J] ρ, of the fluid in which it is falling:;[45][43]  Aristotle implies that in a vacuum the speed of fall would become infinite, and concludes from this apparent absurdity that a vacuum is not possible.[45][43] Opinions have varied on whether Aristotle intended to state quantitative laws. Henri Carteron held the "extreme view"[43] that Aristotle's concept of force was basically qualitative,[46] but other authors reject this.[43] Archimedes corrected Aristotle's theory that bodies move towards their natural resting places; metal boats can float if they displace enough water; floating depends in Archimedes' scheme on the mass and volume of the object, not, as Aristotle thought, its elementary composition.[45] Aristotle's writings on motion remained influential until the Early Modern period. John Philoponus (in Late antiquity) and Galileo (in Early modern period) are said to have shown by experiment that Aristotle's claim that a heavier object falls faster than a lighter object is incorrect.[40] A contrary opinion is given by Carlo Rovelli, who argues that Aristotle's physics of motion is correct within its domain of validity, that of objects in the Earth's gravitational field immersed in a fluid such as air. In this system, heavy bodies in steady fall indeed travel faster than light ones (whether friction is ignored, or not[45]), and they do fall more slowly in a denser medium.[44][K] Newton's "forced" motion corresponds to Aristotle's "violent" motion with its external agent, but Aristotle's assumption that the agent's effect stops immediately it stops acting (e.g., the ball leaves the thrower's hand) has awkward consequences: he has to suppose that surrounding fluid helps to push the ball along to make it continue to rise even though the hand is no longer acting on it, resulting in the Medieval theory of impetus.[45] Four causes Main article: Four causes  Aristotle argued by analogy with woodwork that a thing takes its form from four causes: in the case of a table, the wood used (material cause), its design (formal cause), the tools and techniques used (efficient cause), and its decorative or practical purpose (final cause).[47] Aristotle suggested that the reason for anything coming about can be attributed to four different types of simultaneously active factors. His term aitia is traditionally translated as "cause", but it does not always refer to temporal sequence; it might be better translated as "explanation", but the traditional rendering will be employed here.[48][49] Material cause describes the material out of which something is composed. Thus the material cause of a table is wood. It is not about action. It does not mean that one domino knocks over another domino.[48] The formal cause is its form, i.e., the arrangement of that matter. It tells one what a thing is, that a thing is determined by the definition, form, pattern, essence, whole, synthesis or archetype. It embraces the account of causes in terms of fundamental principles or general laws, as the whole (i.e., macrostructure) is the cause of its parts, a relationship known as the whole-part causation. Plainly put, the formal cause is the idea in the mind of the sculptor that brings the sculpture into being. A simple example of the formal cause is the mental image or idea that allows an artist, architect, or engineer to create a drawing.[48] The efficient cause is "the primary source", or that from which the change under consideration proceeds. It identifies 'what makes of what is made and what causes change of what is changed' and so suggests all sorts of agents, non-living or living, acting as the sources of change or movement or rest. Representing the current understanding of causality as the relation of cause and effect, this covers the modern definitions of "cause" as either the agent or agency or particular events or states of affairs. In the case of two dominoes, when the first is knocked over it causes the second also to fall over.[48] In the case of animals, this agency is a combination of how it develops from the egg, and how its body functions.[50] The final cause (telos) is its purpose, the reason why a thing exists or is done, including both purposeful and instrumental actions and activities. The final cause is the purpose or function that something is supposed to serve. This covers modern ideas of motivating causes, such as volition.[48] In the case of living things, it implies adaptation to a particular way of life.[50] Optics Further information: History of optics Aristotle describes experiments in optics using a camera obscura in Problems, book 15. The apparatus consisted of a dark chamber with a small aperture that let light in. With it, he saw that whatever shape he made the hole, the sun's image always remained circular. He also noted that increasing the distance between the aperture and the image surface magnified the image.[51] Chance and spontaneity Further information: Accident (philosophy) According to Aristotle, spontaneity and chance are causes of some things, distinguishable from other types of cause such as simple necessity. Chance as an incidental cause lies in the realm of accidental things, "from what is spontaneous". There is also more a specific kind of chance, which Aristotle names "luck", that only applies to people's moral choices.[52][53] Astronomy Further information: History of astronomy In astronomy, Aristotle refuted Democritus's claim that the Milky Way was made up of "those stars which are shaded by the earth from the sun's rays," pointing out partly correctly that if "the size of the sun is greater than that of the earth and the distance of the stars from the earth many times greater than that of the sun, then... the sun shines on all the stars and the earth screens none of them."[54] He also wrote descriptions of comets, including the Great Comet of 371 BC.[55] Geology and natural sciences Further information: History of geology  Aristotle noted that the ground level of the Aeolian islands changed before a volcanic eruption. Aristotle was one of the first people to record any geological observations. He stated that geological change was too slow to be observed in one person's lifetime.[56][57] The geologist Charles Lyell noted that Aristotle described such change, including "lakes that had dried up" and "deserts that had become watered by rivers", giving as examples the growth of the Nile delta since the time of Homer, and "the upheaving of one of the Aeolian islands, previous to a volcanic eruption."'[58] Aristotle also made many observations about the hydrologic cycle and meteorology (including his major writings "Meteorologica"). For example, he made some of the earliest observations about desalination: he observed early – and correctly – that when seawater is heated, freshwater evaporates and that the oceans are then replenished by the cycle of rainfall and river runoff ("I have proved by experiment that salt water evaporated forms fresh and the vapor does not when it condenses condense into sea water again.")[59] Biology Main article: Aristotle's biology  Among many pioneering zoological observations, Aristotle described the reproductive hectocotyl arm of the octopus (bottom left). Empirical research Aristotle was the first person to study biology systematically,[60] and biology forms a large part of his writings. He spent two years observing and describing the zoology of Lesbos and the surrounding seas, including in particular the Pyrrha lagoon in the centre of Lesbos.[61][62] His data in History of Animals, Generation of Animals, Movement of Animals, and Parts of Animals are assembled from his own observations,[63] statements given by people with specialized knowledge such as beekeepers and fishermen, and less accurate accounts provided by travellers from overseas.[64] His apparent emphasis on animals rather than plants is a historical accident: his works on botany have been lost, but two books on plants by his pupil Theophrastus have survived.[65] Aristotle reports on the sea-life visible from observation on Lesbos and the catches of fishermen. He describes the catfish, electric ray, and frogfish in detail, as well as cephalopods such as the octopus and paper nautilus. His description of the hectocotyl arm of cephalopods, used in sexual reproduction, was widely disbelieved until the 19th century.[66] He gives accurate descriptions of the four-chambered fore-stomachs of ruminants,[67] and of the ovoviviparous embryological development of the hound shark.[68] He notes that an animal's structure is well matched to function so birds like the heron (which live in marshes with soft mud and live by catching fish) have a long neck, long legs, and a sharp spear-like beak, whereas ducks that swim have short legs and webbed feet.[69] Darwin, too, noted these sorts of differences between similar kinds of animal, but unlike Aristotle used the data to come to the theory of evolution.[70] Aristotle's writings can seem to modern readers close to implying evolution, but while Aristotle was aware that new mutations or hybridizations could occur, he saw these as rare accidents. For Aristotle, accidents, like heat waves in winter, must be considered distinct from natural causes. He was thus critical of Empedocles's materialist theory of a "survival of the fittest" origin of living things and their organs, and ridiculed the idea that accidents could lead to orderly results.[71] To put his views into modern terms, he nowhere says that different species can have a common ancestor, or that one kind can change into another, or that kinds can become extinct.[72] Scientific style  Aristotle inferred growth laws from his observations on animals, including that brood size decreases with body mass, whereas gestation period increases. He was correct in these predictions, at least for mammals: data are shown for mouse and elephant. Aristotle did not do experiments in the modern sense.[73] He used the ancient Greek term pepeiramenoi to mean observations, or at most investigative procedures like dissection.[74] In Generation of Animals, he finds a fertilized hen's egg of a suitable stage and opens it to see the embryo's heart beating inside.[75][76] Instead, he practiced a different style of science: systematically gathering data, discovering patterns common to whole groups of animals, and inferring possible causal explanations from these.[77][78] This style is common in modern biology when large amounts of data become available in a new field, such as genomics. It does not result in the same certainty as experimental science, but it sets out testable hypotheses and constructs a narrative explanation of what is observed. In this sense, Aristotle's biology is scientific.[77] From the data he collected and documented, Aristotle inferred quite a number of rules relating the life-history features of the live-bearing tetrapods (terrestrial placental mammals) that he studied. Among these correct predictions are the following. Brood size decreases with (adult) body mass, so that an elephant has fewer young (usually just one) per brood than a mouse. Lifespan increases with gestation period, and also with body mass, so that elephants live longer than mice, have a longer period of gestation, and are heavier. As a final example, fecundity decreases with lifespan, so long-lived kinds like elephants have fewer young in total than short-lived kinds like mice.[79] Classification of living things Further information: Scala naturae  Classification of living things Further information: Scala naturae Aristotle recorded that the embryo (fetus pictured) of a dogfish was attached by a cord to a kind of placenta (the yolk sac), like a higher animal; this formed an exception to the linear scale from highest to lowest.[107] Aristotle distinguished about 500 animal species,[108][109] arranging them in a nonreligious graded scale of perfection, with man at the top. The highest gave live birth to hot and wet creatures, the lowest laid cold, dry mineral-like eggs.[110][111] He grouped what a zoologist would call vertebrates as "animals with blood", and invertebrates as "animals without blood". Those with blood were divided into live-bearing (mammals), and egg-laying (birds, reptiles, fish). Those without blood were insects, crustacea and hard-shelled molluscs. He recognised that animals did not exactly fit onto a scale, and noted exceptions, such as that sharks had a placenta. To a biologist, the explanation is convergent evolution.[112] Philosophers of science have concluded that Aristotle was not interested in taxonomy,[113][114] but zoologists think otherwise.[115][116][117]  |

自然哲学 アリストテレスの「自然哲学」は、現在では物理学、生物学、その他の自然科学がカバーしているものを含む、自然現象の広い範囲に及んでいる[40]。アリ ストテレスの用語では、「自然哲学」は自然界の現象を考察する哲学の一分野であり、今日では物理学、生物学、その他の自然科学とみなされる分野を含んでい る。アリストテレスの研究は、事実上、知的探究のあらゆる側面を網羅していた。アリストテレスは広義の哲学を推論と同義としており、推論を「科学」とも表 現している。しかし、アリストテレスが用いた科学という言葉は、「科学的方法」という言葉とは異なる意味を持つ。アリストテレスにとって、「すべての科学 (ディアノイア)は実践的であり、詩的であり、理論的である」(『形而上学』1025b25)。彼の実践的科学には倫理学と政治学が含まれ、彼の詩的科学 とは詩を含む美術の研究を意味し、彼の理論的科学には物理学、数学、形而上学が含まれる[40]。 物理学  エンペドクレスとアリストテレスの古典的な四大元素(火、空気、水、土)を燃える丸太で図解したもの。丸太は破壊されると四元素を放出する。 主な記事 アリストテレスの物理学 五大元素 主な記事 古典的元素 アリストテレスは『生成と腐敗』(On Generation and Corruption)の中で、エンペドクレスが先に提唱した地、水、空気、火の四元素を、四つの感性的性質のうちの二つ、熱、冷、湿、乾にそれぞれ関連 づけた。エンペドクレスの図式では、すべての物質は4つの元素からできており、その比率は異なっていた。アリストテレスのスキームでは、天球、星、惑星の 神的物質である天のエーテルが加えられた[41]。  アリストテレスの元素[41]。 元素 熱い/冷たい 湿った/乾いた 運動 現代の状態 物質の 地球 冷たい 乾いた 固体 水 冷たい 湿った 液体 空気 火 熱乾 プラズマ エーテル 円形 真空 運動 さらなる情報 古典力学の歴史 アリストテレスは2種類の運動について述べている: 物理学』(254b10)では、投げられた石のような「暴力的な」あるいは「不自然な運動」を、『天上論』(300a20)では、落下する物体のような 「自然な運動」を述べている。アリストテレスは摩擦に言及していないので[42][F]、このように理解すれば、アリストテレスが述べているように、(例 えば地面にある)重い物体を動かすにはより大きな力が必要であり、より大きな力で押された物体はより速く動くことが観察される[44][G]。  {F=mv} となる、 現代物理学では正しくない[44]。 自然運動は関係する要素に依存する:エーテルは自然に天の周りを円を描くように動くが[H]、4つのエンペドクリーン要素はその自然な休息場所に向かって 垂直に上へ(観察されているように火のように)、または下へ(地のように)動く[45][43][I]。  アリストテレスの運動の法則。物理学において、彼は、物体は、その重量に比例し、それが浸している流体の密度に反比例する速度で落下すると述べている [43]。これは、地球の重力場において空気や水中で運動する物体については正しい近似値である[45]。 アリストテレスは『物理学』(215a25)において、落下する物体の速度vはその重量Wに比例し(例えば定数cで)、落下する流体の密度[J]ρに反比 例するという量的法則を効果的に述べている;[45][43]。  アリストテレスは真空では落下速度が無限大になることを暗示し、この明らかな不条理から真空はあり得ないと結論付けている[45][43]。アリストテレ スが量的法則を述べることを意図していたかどうかについては様々な意見がある。アンリ・カルテロンはアリストテレスの力の概念は基本的に定性的なものであ るという「極端な見解」[43]を持っていたが[46]、他の著者はこれを否定している[43]。 アルキメデスは、物体は自然に静止する場所に向かって移動するというアリストテレスの理論を修正した。金属製の船は十分な水を変位させれば浮くことができ るが、アルキメデスの図式では浮くかどうかは物体の質量と体積に依存しており、アリストテレスが考えていたように物体の素組成に依存しているわけではな かった[45]。 ア リストテレスの運動に関する著作は、近世初期まで影響力を保った。ヨハネス・フィロポノス(古代末期)とガリレオ(近世初期)は、重い物体が軽い物体より 速く落下するというアリストテレスの主張が誤りであることを実験で示したと言われている。[40] これとは反対の見解をカルロ・ロヴェッリが示している。彼は、アリストテレスの運動物理学はその有効範囲内では正しいと主張する。その範囲とは、空気のよ うな流体に浸された地球の重力場における物体の運動である。この体系では、安定した落下状態にある重い物体は確かに軽い物体よりも速く移動する(摩擦を無 視する場合も、無視しない場合も[45])。また、より密度の高い媒体では確かに落下速度が遅くなる。[44][K] ニュートンの「強制された」運動はアリストテレスの「暴力的な」運動に対応し、その外部作用因子を持つが、その作用因子の効果はその作用因子が作用するの を止めるとすぐに止まる(例えば、ボールが投げる人の手から離れる)というアリストテレスの仮定は厄介な結果をもたらす。 4つの原因 主な記事 4つの原因  アリストテレスは木工品に例えて、物事は4つの原因からその形を取ると主張した。テーブルの場合、使用される木材(物質的原因)、そのデザイン(形式的原 因)、使用される道具と技術(効率的原因)、そして装飾的または実用的な目的(最終的原因)である[47]。 アリストテレスは、何事も生じる理由は4つの異なるタイプの同時に活動的な要因に帰することができると示唆した。彼の用語アイティアは伝統的に「原因」と 訳されているが、必ずしも時間的な順序を指しているわけではない。 物質的原因(material cause)は、何かが構成されている物質について述べている。したがって、テーブルの物質的原因は木材である。それは作用に関するものではない。あるド ミノが別のドミノを倒すという意味ではない[48]。 形式的原因はその形、すなわちその物質の配置である。形式的原因は、物事が何であるか、物事が定義、形式、パターン、本質、全体、総合、原型によって決定 されることを教えてくれる。全体(すなわちマクロ構造)が部分の原因であり、この関係は全体部分因果として知られている。平易に言えば、形式的原因とは、 彫刻を生み出す彫刻家の心の中の考えである。形式的原因の単純な例は、芸術家、建築家、技師が図面を描くための心的イメー ジやアイデアである[48]。 効率的原因とは、「第一の原因」、すなわち考察の対象となる変化がそこから生じるも のである。それは「作られるものを作るもの、変化するものを変化させるもの」を特定し、変化や運動や休息の源として作用する、非生物であれ生物であれ、あ らゆる種類の作用因子を示唆する。原因と結果の関係としての因果関係の現在の理解を代表するように、これは「原因」の現代的な定義を、エージェントや代理 人、あるいは特定の出来事や状態のいずれかとしてカバーしている。2つのドミノの場合、1つ目が倒されると2つ目も倒される[48]。動物の場合、この エージェンシーは卵からどのように発達するか、そしてどのように身体が機能するかの組み合わせである[50]。 最終原因(テロス)とはその目的であり、あるものが存在する、あるいは行われる理由である。最終原因とは、何かが果たすべき目的や機能のことである。生物 の場合は、特定の生活様式への適応を意味する[50]。 光学 さらなる情報 光学の歴史 アリストテレスは『問題』第15巻において、カメラ・オブスクラを用いた光学の実験を記述している。その装置は、光を取り入れる小さな開口部を持つ暗い部 屋から成っていた。この装置で彼は、どのような形の穴を開けても、太陽の像が常に円形のままであることを見た。彼はまた、開口部と像の表面との間の距離を 大きくすると像が拡大することにも気づいた[51]。 偶然性と自発性 更なる情報 偶然(哲学) アリストテレスによれば、自然発生性と偶然性は、単純な必然性などの他のタイプの原因とは区別される、ある物事の原因である。偶発的な原因としての偶然性 は、「自然発生的なものから」という偶発的なものの領域にある。また、アリストテレスは「運」と名付けているが、それは人々の道徳的な選択にのみ適用され る、より特殊な種類の偶然性も存在する[52][53]。 天文学 更なる情報 天文学の歴史 天文学において、アリストテレスは天の川が「太陽の光から地球によって遮られている星々」から構成されているというデモクリトスの主張に反論し、「太陽の 大きさが地球の大きさよりも大きく、地球から星の距離が太陽の距離の何倍も大きいのであれば、...太陽はすべての星を照らし、地球はそれらの星を映して いない」[54]と一部正しく指摘した[55]。 地質学と自然科学 更なる情報 地質学の歴史  アリストテレスは、エオリア諸島の地盤が火山噴火の前に変化することを指摘した。 アリストテレスは、地質学的観察を記録した最初の人物の一人である。地質学者のチャールズ・ライエルは、アリストテレスが「干上がった湖」や「川が水を供 給するようになった砂漠」など、そのような変化を記述していることに注目し、ホメロスの時代からのナイルデルタの成長や、「火山噴火の前のエオリア諸島の 一つの隆起」を例として挙げている[56][57]。 「58]アリストテレスはまた、水循環と気象学(主要な著作である『メテオロロジカ』を含む)について多くの観察を行っている。例えば、海水が加熱される と淡水が蒸発し、その後、降雨と河川流出のサイクルによって海水が補給されることを早くから(そして正しく)観察していた(「私は、蒸発した塩水が淡水と なり、蒸気が凝縮しても再び海水になることはないことを実験によって証明した」)[59]。 生物学 主な記事 アリストテレスの生物学  アリストテレスは動物学の先駆的な観察の中で、タコの生殖腕(左下)について記述している。 実証的研究 アリストテレスは生物学を体系的に研究した最初の人物であり[60]、彼の著作の大部分を生物学が占めている。動物の歴史』、『動物の発生』、『動物の運 動』、『動物の部位』における彼のデータは、彼自身の観察、[63]養蜂家や漁師のような専門的な知識を持つ人々による記述、海外からの旅行者によるあま り正確でない記述から組み立てられている。 [植物学に関する彼の著作は失われてしまったが、弟子のテオフラストスによる植物に関する2冊の本が現存している[65]。 アリストテレスは、レスボス島での観察や漁師の漁獲物から見える海の生物について報告している。ナマズ、電気エイ、カエルアンコウ、タコやオウムガイなど の頭足類について詳しく記述している。有性生殖に使われる頭足類のヘクトコティルアームに関する彼の記述は、19世紀まで広く信じられていなかった [66]。彼は反芻動物の前胃が4室に分かれていること[67]や、ハウンドシャークの卵胎生について正確な記述を行っている[68]。 ダーウィンは、動物の構造は機能によく適合しており、サギのような鳥類(柔らかい泥のある沼地に住み、魚を捕って生活する)は長い首、長い脚、鋭い槍のよ うなくちばしを持つが、泳ぐアヒルは短い脚と網状の足を持つ、と述べている。 [ダーウィンもまた、似たような種類の動物間のこの種の違いに注目したが、アリストテレスとは異なり、進化論に到達するためにそのデータを使用した。アリ ストテレスにとって、冬の熱波のような事故は、自然の原因とは区別して考えなければならない。したがって彼は、生物とその器官の「適者生存」の起源に関す るエンペドクレスの唯物論に批判的であり、偶然が秩序だった結果をもたらすという考えを嘲笑していた[71]。 彼の見解を現代的な用語に置き換えると、異なる種が共通の祖先を持つことができるとも、ある種が別の種に変化することができるとも、ある種が絶滅すること ができるとも、彼はどこにも言っていない[72]。 科学的スタイル  アリストテレスは動物の観察から成長の法則を推論した。これらの予測は、少なくとも哺乳類については正しかった。 アリストテレスは現代的な意味での実験を行わなかった[73]。彼は古代ギリシア語のペペイラメノイ(pepeiramenoi)という用語を、観察、あ るいはせいぜい解剖のような調査的手順を意味するものとして使用していた[74]。 その代わりに彼は、体系的にデータを収集し、動物群全体に共通するパターンを発見し、そこから可能性のある因果関係を推論するという、異なるスタイルの科 学を実践した[77][78]。このスタイルは、ゲノミクスのような新しい分野で大量のデータが利用可能になった場合、現代の生物学では一般的である。実 験科学のような確実性は得られないが、検証可能な仮説を設定し、観察されたことについて物語的な説明を構築する。この意味で、アリストテレスの生物学は科 学的である[77]。 アリストテレスは、彼が収集し記録したデータから、彼が研究した四肢動物(陸生胎生哺乳類)の生活史的特徴に関連する非常に多くの規則を推測した。これら の正しい予測の中には次のようなものがある。子房の大きさは(成獣の)体格とともに減少し、ゾウはネズミよりも1回の子房で産む子供の数が少ない(通常は 1匹だけ)。寿命は妊娠期間とともに増加し、また体重とともに増加する。最後の例として、繁殖力は寿命とともに減少するため、ゾウのように長命な種類は、 ネズミのように短命な種類に比べて、合計で産む子供の数が少ない[79]。 生物の分類 さらなる情報 自然観  生物の分類 詳細情報:Scala naturae アリストテレスは、イネザメの胚(写真)は、高等動物と同様に、一種の 胎盤(卵黄嚢)に臍帯でつながれていることを記録している。これは、最高から最低への直線的な階層構造からの例外だった。[107] アリストテレスは約 500 種の動物を区別し[108][109]、人間を最上位とする非宗教的な完成度の階層に分類した。最上位は、熱く湿った生物を産む生き物であり、最下位は、 冷たく乾燥した鉱物のような卵を産む生き物だった。[110][111] 彼は、現代の動物学者が「脊椎動物」と呼ぶものを「血液を有する動物」に、無脊椎動物を「血液を有しない動物」に分類した。血液を有する動物は、胎生(哺 乳類)と卵生(鳥類、爬虫類、魚類)に分けられた。血液を有しない動物は、昆虫、甲殻類、硬い殻を持つ軟体動物であった。彼は、動物が正確に階層に分類で きないことを認識し、サメが胎盤を持つなどの例外を指摘した。生物学者は、この説明を収斂進化と解釈している。[112] 科学哲学者たちは、アリストテレスは分類学に興味がなかったと結論付けている。[113][114] しかし、動物学者は異なる見解を持っている。[115][116][117]  |

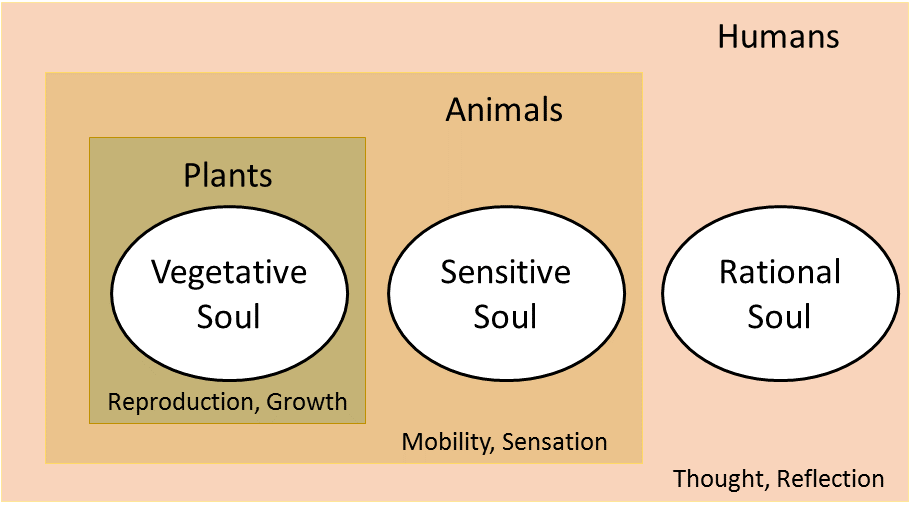

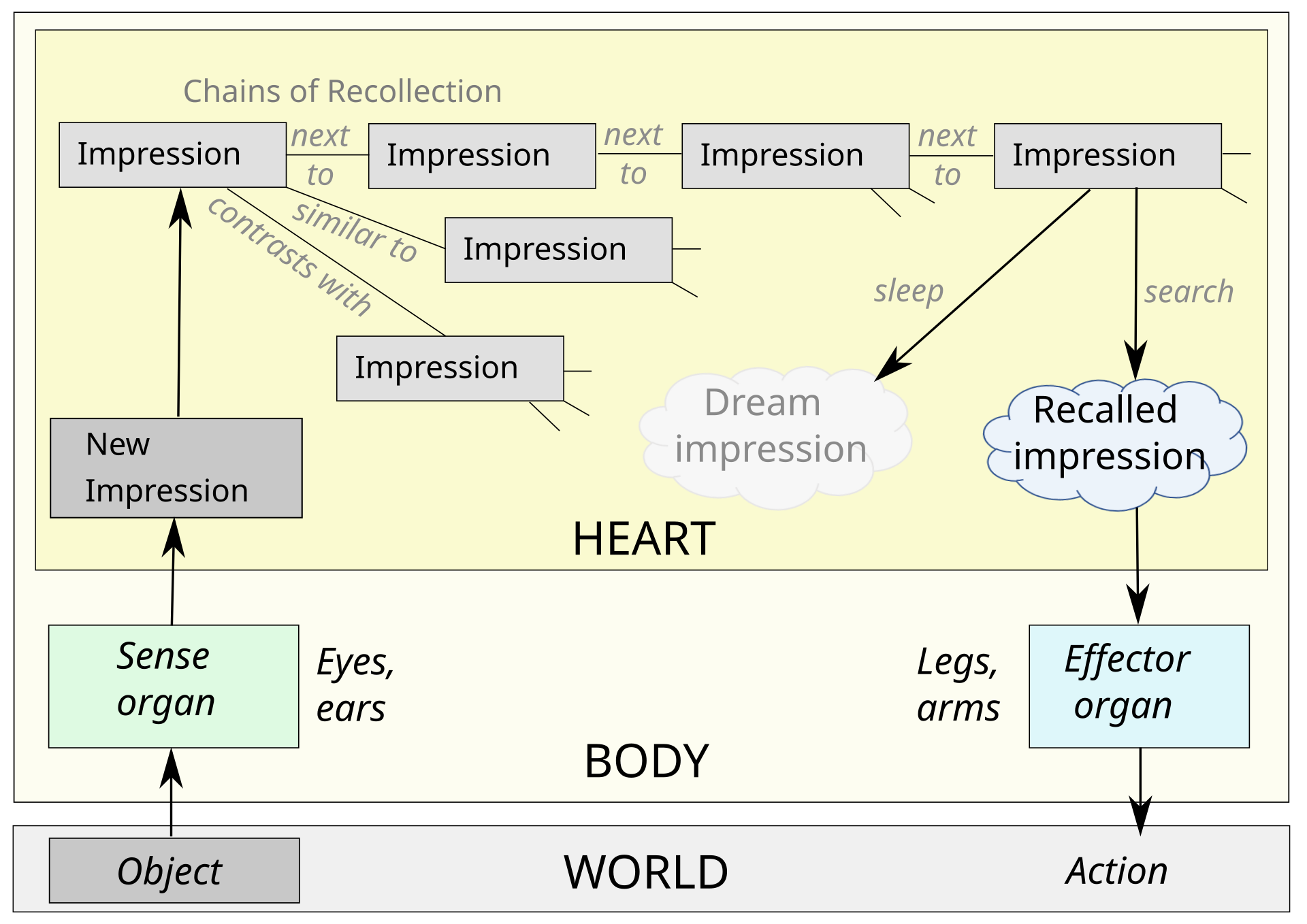

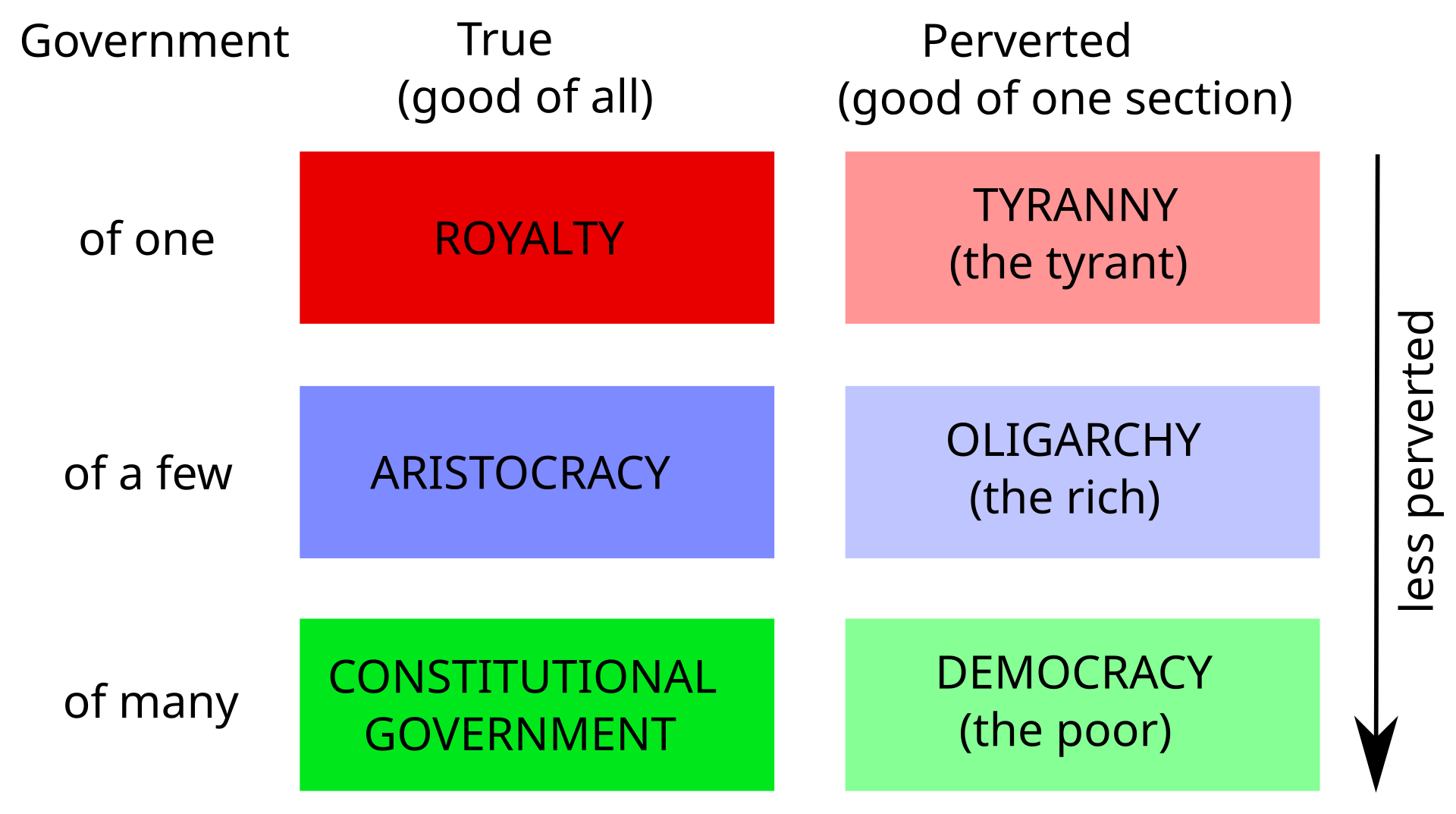

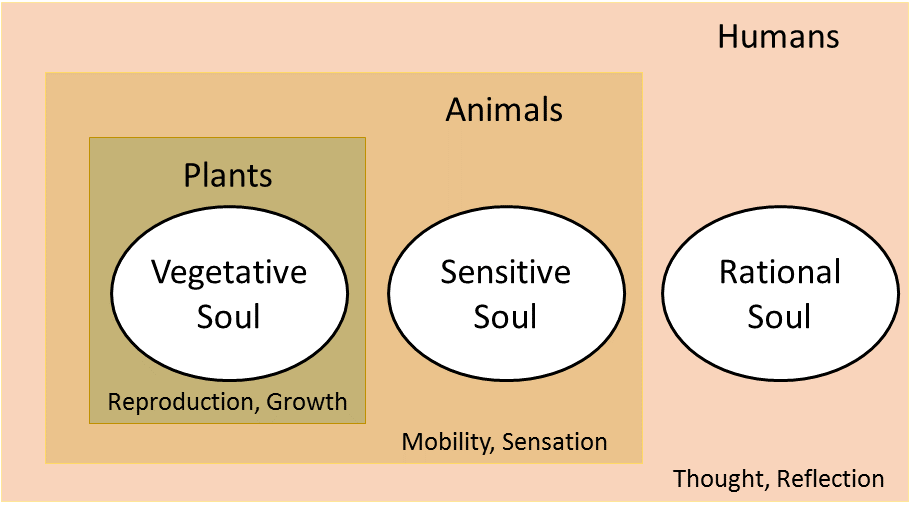

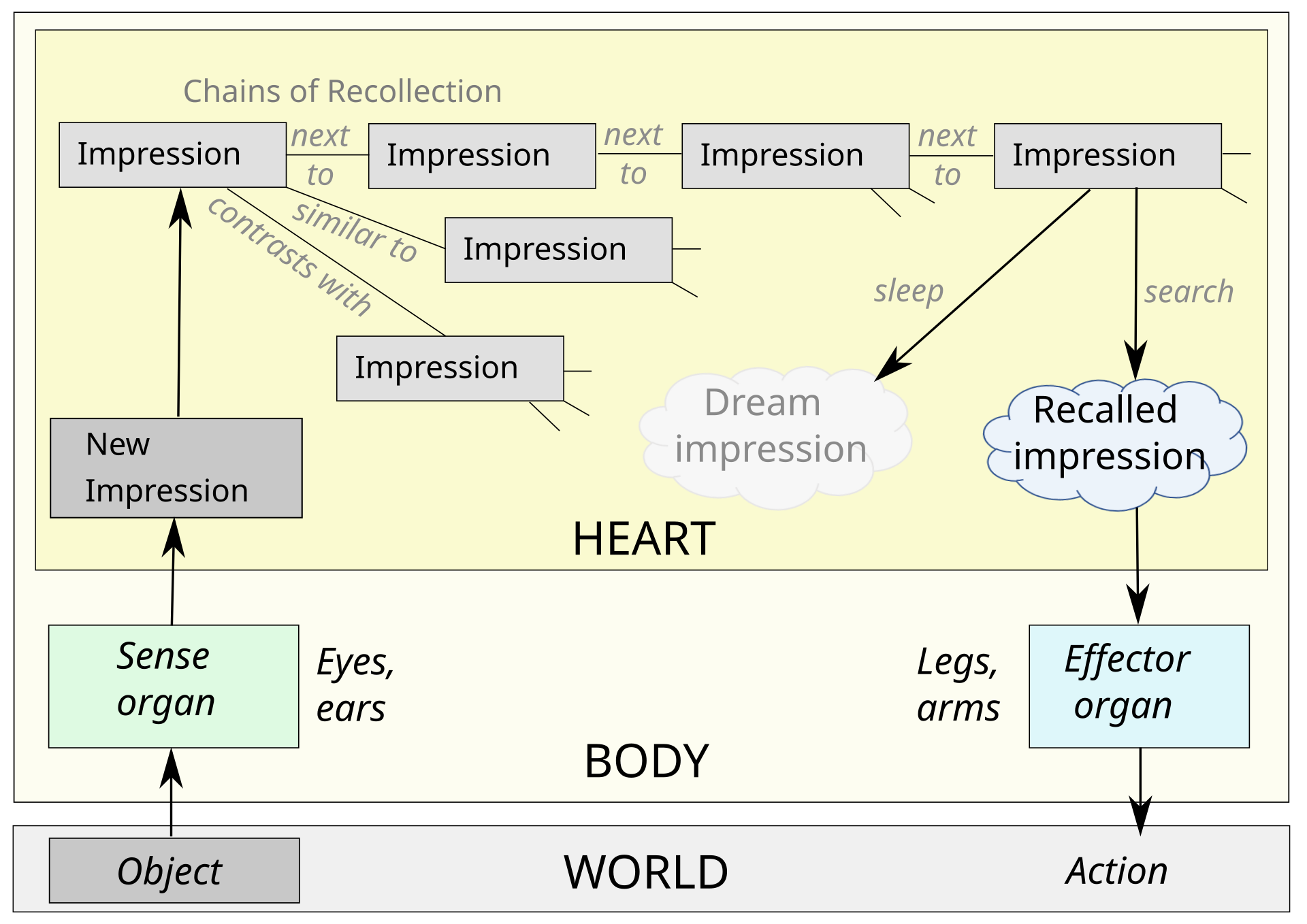

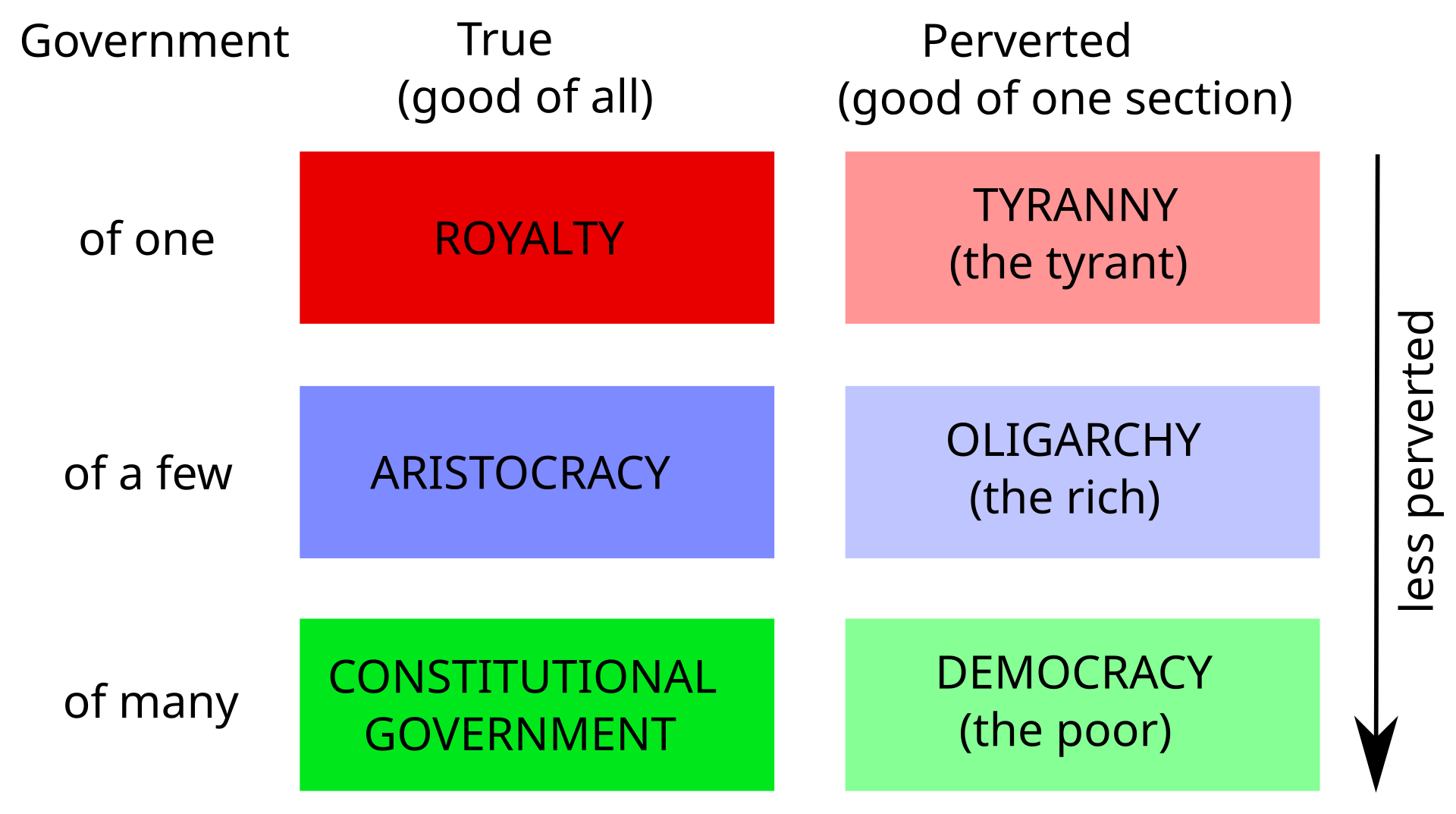

| Psychology Soul Further information: On the Soul  Aristotle proposed a three-part structure for souls of plants, animals, and humans, making humans unique in having all three types of soul. Aristotle's psychology, given in his treatise On the Soul (peri psychēs), posits three kinds of soul ("psyches"): the vegetative soul, the sensitive soul, and the rational soul. Humans have a rational soul. The human soul incorporates the powers of the other kinds: Like the vegetative soul it can grow and nourish itself; like the sensitive soul it can experience sensations and move locally. The unique part of the human, rational soul is its ability to receive forms of other things and to compare them using the nous (intellect) and logos (reason).[92] For Aristotle, the soul is the form of a living being. Because all beings are composites of form and matter, the form of living beings is that which endows them with what is specific to living beings, e.g. the ability to initiate movement (or in the case of plants, growth and chemical transformations, which Aristotle considers types of movement).[11] In contrast to earlier philosophers, but in accordance with the Egyptians, he placed the rational soul in the heart, rather than the brain.[93] Notable is Aristotle's division of sensation and thought, which generally differed from the concepts of previous philosophers, with the exception of Alcmaeon.[94] In On the Soul, Aristotle famously criticizes Plato's theory of the soul and develops his own in response to Plato's. The first criticism is against Plato's view of the soul in the Timaeus that the soul takes up space and is able to come into physical contact with bodies.[95] 20th-century scholarship overwhelmingly opposed Aristotle's interpretation of Plato and maintained that he had misunderstood Plato.[96] Today's scholars have tended to re-assess Aristotle's interpretation and have warmed up to it.[97] Aristotle's other criticism is that Plato's view of reincarnation entails that it is possible for a soul and its body to be mis-matched; in principle, Aristotle alleges, any soul can go with any body, according to Plato's theory.[98] Aristotle's claim that the soul is the form of a living being is meant to eliminate that possibility and thus rule out reincarnation.[99] Memory According to Aristotle in On the Soul, memory is the ability to hold a perceived experience in the mind and to distinguish between the internal "appearance" and an occurrence in the past.[100] In other words, a memory is a mental picture (phantasm) that can be recovered. Aristotle believed an impression is left on a semi-fluid bodily organ that undergoes several changes in order to make a memory. A memory occurs when stimuli such as sights or sounds are so complex that the nervous system cannot receive all the impressions at once. These changes are the same as those involved in the operations of sensation, Aristotelian 'common sense', and thinking.[101][102] Aristotle uses the term 'memory' for the actual retaining of an experience in the impression that can develop from sensation, and for the intellectual anxiety that comes with the impression because it is formed at a particular time and processing specific contents. Memory is of the past, prediction is of the future, and sensation is of the present. Retrieval of impressions cannot be performed suddenly. A transitional channel is needed and located in past experiences, both for previous experience and present experience.[103] Because Aristotle believes people receive all kinds of sense perceptions and perceive them as impressions, people are continually weaving together new impressions of experiences. To search for these impressions, people search the memory itself.[104] Within the memory, if one experience is offered instead of a specific memory, that person will reject this experience until they find what they are looking for. Recollection occurs when one retrieved experience naturally follows another. If the chain of "images" is needed, one memory will stimulate the next. When people recall experiences, they stimulate certain previous experiences until they reach the one that is needed.[105] Recollection is thus the self-directed activity of retrieving the information stored in a memory impression.[106] Only humans can remember impressions of intellectual activity, such as numbers and words. Animals that have perception of time can retrieve memories of their past observations. Remembering involves only perception of the things remembered and of the time passed.[107]  Senses, perception, memory, dreams, action in Aristotle's psychology. Impressions are stored in the sensorium (the heart), linked by his laws of association (similarity, contrast, and contiguity). Aristotle believed the chain of thought, which ends in recollection of certain impressions, was connected systematically in relationships such as similarity, contrast, and contiguity, described in his laws of association. Aristotle believed that past experiences are hidden within the mind. A force operates to awaken the hidden material to bring up the actual experience. According to Aristotle, association is the power innate in a mental state, which operates upon the unexpressed remains of former experiences, allowing them to rise and be recalled.[108][109] Dreams Further information: Dream § Other Aristotle describes sleep in On Sleep and Wakefulness.[110] Sleep takes place as a result of overuse of the senses[111] or of digestion,[112] so it is vital to the body.[111] While a person is asleep, the critical activities, which include thinking, sensing, recalling and remembering, do not function as they do during wakefulness. Since a person cannot sense during sleep they cannot have desire, which is the result of sensation. However, the senses are able to work during sleep,[113] albeit differently,[110] unless they are weary.[111] Dreams do not involve actually sensing a stimulus. In dreams, sensation is still involved, but in an altered manner.[111] Aristotle explains that when a person stares at a moving stimulus such as the waves in a body of water, and then looks away, the next thing they look at appears to have a wavelike motion. When a person perceives a stimulus and the stimulus is no longer the focus of their attention, it leaves an impression.[110] When the body is awake and the senses are functioning properly, a person constantly encounters new stimuli to sense and so the impressions of previously perceived stimuli are ignored.[111] However, during sleep the impressions made throughout the day are noticed as there are no new distracting sensory experiences.[110] So, dreams result from these lasting impressions. Since impressions are all that are left and not the exact stimuli, dreams do not resemble the actual waking experience.[114] During sleep, a person is in an altered state of mind. Aristotle compares a sleeping person to a person who is overtaken by strong feelings toward a stimulus. For example, a person who has a strong infatuation with someone may begin to think they see that person everywhere because they are so overtaken by their feelings. Since a person sleeping is in a suggestible state and unable to make judgements, they become easily deceived by what appears in their dreams, like the infatuated person.[110] This leads the person to believe the dream is real, even when the dreams are absurd in nature.[110] In De Anima iii 3, Aristotle ascribes the ability to create, to store, and to recall images in the absence of perception to the faculty of imagination, phantasia.[11] One component of Aristotle's theory of dreams disagrees with previously held beliefs. He claimed that dreams are not foretelling and not sent by a divine being. Aristotle reasoned naturalistically that instances in which dreams do resemble future events are simply coincidences.[115] Aristotle claimed that a dream is first established by the fact that the person is asleep when they experience it. If a person had an image appear for a moment after waking up or if they see something in the dark it is not considered a dream because they were awake when it occurred. Secondly, any sensory experience that is perceived while a person is asleep does not qualify as part of a dream. For example, if, while a person is sleeping, a door shuts and in their dream they hear a door is shut, this sensory experience is not part of the dream. Lastly, the images of dreams must be a result of lasting impressions of waking sensory experiences.[114] Practical philosophy Aristotle's practical philosophy covers areas such as ethics, politics, economics, and rhetoric.[40] Virtues and their accompanying vices[15] Too little Virtuous mean Too much Humbleness High-mindedness Vainglory Lack of purpose Right ambition Over-ambition Spiritlessness Good temper Irascibility Rudeness Civility Obsequiousness Cowardice Courage Rashness Insensibility Self-control Intemperance Sarcasm Sincerity Boastfulness Boorishness Wit Buffoonery Shamelessness Modesty Shyness Callousness Just resentment Spitefulness Pettiness Generosity Vulgarity Meanness Liberality Wastefulness  Ethics Main article: Aristotelian ethics Aristotle considered ethics to be a practical rather than theoretical study, i.e., one aimed at becoming good and doing good rather than knowing for its own sake. He wrote several treatises on ethics, most notably including the Nicomachean Ethics.[116] Aristotle taught that virtue has to do with the proper function (ergon) of a thing. An eye is only a good eye in so much as it can see, because the proper function of an eye is sight. Aristotle reasoned that humans must have a function specific to humans, and that this function must be an activity of the psuchē (soul) in accordance with reason (logos). Aristotle identified such an optimum activity (the virtuous mean, between the accompanying vices of excess or deficiency[15]) of the soul as the aim of all human deliberate action, eudaimonia, generally translated as "happiness" or sometimes "well-being". To have the potential of ever being happy in this way necessarily requires a good character (ēthikē aretē), often translated as moral or ethical virtue or excellence.[117] Aristotle taught that to achieve a virtuous and potentially happy character requires a first stage of having the fortune to be habituated not deliberately, but by teachers, and experience, leading to a later stage in which one consciously chooses to do the best things. When the best people come to live life this way their practical wisdom (phronesis) and their intellect (nous) can develop with each other towards the highest possible human virtue, the wisdom of an accomplished theoretical or speculative thinker, or in other words, a philosopher.[118] Politics Main article: Politics (Aristotle) In addition to his works on ethics, which address the individual, Aristotle addressed the city in his work titled Politics. Aristotle considered the city to be a natural community. Moreover, he considered the city to be prior in importance to the family, which in turn is prior to the individual, "for the whole must of necessity be prior to the part".[119] He famously stated that "man is by nature a political animal" and argued that humanity's defining factor among others in the animal kingdom is its rationality.[120] Aristotle conceived of politics as being like an organism rather than like a machine, and as a collection of parts none of which can exist without the others. Aristotle's conception of the city is organic, and he is considered one of the first to conceive of the city in this manner.[121]  Aristotle's classifications of political constitutions The common modern understanding of a political community as a modern state is quite different from Aristotle's understanding. Although he was aware of the existence and potential of larger empires, the natural community according to Aristotle was the city (polis) which functions as a political "community" or "partnership" (koinōnia). The aim of the city is not just to avoid injustice or for economic stability, but rather to allow at least some citizens the possibility to live a good life, and to perform beautiful acts: "The political partnership must be regarded, therefore, as being for the sake of noble actions, not for the sake of living together." This is distinguished from modern approaches, beginning with social contract theory, according to which individuals leave the state of nature because of "fear of violent death" or its "inconveniences".[L] In Protrepticus, the character 'Aristotle' states:[122] For we all agree that the most excellent man should rule, i.e., the supreme by nature, and that the law rules and alone is authoritative; but the law is a kind of intelligence, i.e. a discourse based on intelligence. And again, what standard do we have, what criterion of good things, that is more precise than the intelligent man? For all that this man will choose, if the choice is based on his knowledge, are good things and their contraries are bad. And since everybody chooses most of all what conforms to their own proper dispositions (a just man choosing to live justly, a man with bravery to live bravely, likewise a self-controlled man to live with self-control), it is clear that the intelligent man will choose most of all to be intelligent; for this is the function of that capacity. Hence it's evident that, according to the most authoritative judgment, intelligence is supreme among goods.[122] As Plato's disciple Aristotle was rather critical concerning democracy and, following the outline of certain ideas from Plato's Statesman, he developed a coherent theory of integrating various forms of power into a so-called mixed state: It is … constitutional to take … from oligarchy that offices are to be elected, and from democracy that this is not to be on a property-qualification. This then is the mode of the mixture; and the mark of a good mixture of democracy and oligarchy is when it is possible to speak of the same constitution as a democracy and as an oligarchy. — Aristotle. Politics, Book 4, 1294b.10–18 To illustrate this approach, Aristotle proposed a first-of-its-kind mathematical model of voting, albeit textually described, where the democratic principle of "one voter–one vote" is combined with the oligarchic "merit-weighted voting"; for relevant quotes and their translation into mathematical formulas see.[123] Aristotle's views on women influenced later Western philosophers, who quoted him as an authority until the end of the Middle Ages, but these views have been controversial in modern times. Aristotle's analysis of procreation describes an active, ensouling masculine element bringing life to an inert, passive female element. The biological differences are a result of the fact that the female body is well-suited for reproduction, which changes her body temperature, which in turn makes her, in Aristotle's view, incapable of participating in political life.[124] On this ground, proponents of feminist metaphysics have accused Aristotle of misogyny[125] and sexism.[126] However, Aristotle gave equal weight to women's happiness as he did to men's, and commented in his Rhetoric that the things that lead to happiness need to be in women as well as men.[M] Economics Main article: Politics (Aristotle) Aristotle made substantial contributions to economic thought, especially to thought in the Middle Ages.[128] In Politics, Aristotle addresses the city, property, and trade. His response to criticisms of private property, in Lionel Robbins's view, anticipated later proponents of private property among philosophers and economists, as it related to the overall utility of social arrangements.[128] Aristotle believed that although communal arrangements may seem beneficial to society, and that although private property is often blamed for social strife, such evils in fact come from human nature. In Politics, Aristotle offers one of the earliest accounts of the origin of money.[128] Money came into use because people became dependent on one another, importing what they needed and exporting the surplus. For the sake of convenience, people then agreed to deal in something that is intrinsically useful and easily applicable, such as iron or silver.[129] Aristotle's discussions on retail and interest was a major influence on economic thought in the Middle Ages. He had a low opinion of retail, believing that contrary to using money to procure things one needs in managing the household, retail trade seeks to make a profit. It thus uses goods as a means to an end, rather than as an end unto itself. He believed that retail trade was in this way unnatural. Similarly, Aristotle considered making a profit through interest unnatural, as it makes a gain out of the money itself, and not from its use.[129] Aristotle gave a summary of the function of money that was perhaps remarkably precocious for his time. He wrote that because it is impossible to determine the value of every good through a count of the number of other goods it is worth, the necessity arises of a single universal standard of measurement. Money thus allows for the association of different goods and makes them "commensurable".[129] He goes on to state that money is also useful for future exchange, making it a sort of security. That is, "if we do not want a thing now, we shall be able to get it when we do want it".[129] Rhetoric Part of a series on Rhetoric History Concepts Genres Criticism Rhetoricians Works Subfields Related vte Main article: Rhetoric (Aristotle) Aristotle's Rhetoric proposes that a speaker can use three basic kinds of appeals to persuade his audience: ethos (an appeal to the speaker's character), pathos (an appeal to the audience's emotion), and logos (an appeal to logical reasoning).[130] He also categorizes rhetoric into three genres: epideictic (ceremonial speeches dealing with praise or blame), forensic (judicial speeches over guilt or innocence), and deliberative (speeches calling on an audience to make a decision on an issue).[131] Aristotle also outlines two kinds of rhetorical proofs: enthymeme (proof by syllogism) and paradeigma (proof by example).[132] Poetics Main article: Poetics (Aristotle) Aristotle writes in his Poetics that epic poetry, tragedy, comedy, dithyrambic poetry, painting, sculpture, music, and dance are all fundamentally acts of mimesis ("imitation"), each varying in imitation by medium, object, and manner.[133][134] He applies the term mimesis both as a property of a work of art and also as the product of the artist's intention[133] and contends that the audience's realisation of the mimesis is vital to understanding the work itself.[133] Aristotle states that mimesis is a natural instinct of humanity that separates humans from animals[133][135] and that all human artistry "follows the pattern of nature".[133] Because of this, Aristotle believed that each of the mimetic arts possesses what Stephen Halliwell calls "highly structured procedures for the achievement of their purposes."[136] For example, music imitates with the media of rhythm and harmony, whereas dance imitates with rhythm alone, and poetry with language. The forms also differ in their object of imitation. Comedy, for instance, is a dramatic imitation of men worse than average; whereas tragedy imitates men slightly better than average. Lastly, the forms differ in their manner of imitation – through narrative or character, through change or no change, and through drama or no drama.[137]  The Blind Oedipus Commending his Children to the Gods (1784) by Bénigne Gagneraux. In his Poetics, Aristotle uses the tragedy Oedipus Tyrannus by Sophocles as an example of how the perfect tragedy should be structured, with a generally good protagonist who starts the play prosperous, but loses everything through some hamartia (fault).[138] While it is believed that Aristotle's Poetics originally comprised two books – one on comedy and one on tragedy – only the portion that focuses on tragedy has survived. Aristotle taught that tragedy is composed of six elements: plot-structure, character, style, thought, spectacle, and lyric poetry.[139] The characters in a tragedy are merely a means of driving the story; and the plot, not the characters, is the chief focus of tragedy. Tragedy is the imitation of action arousing pity and fear, and is meant to effect the catharsis of those same emotions. Aristotle concludes Poetics with a discussion on which, if either, is superior: epic or tragic mimesis. He suggests that because tragedy possesses all the attributes of an epic, possibly possesses additional attributes such as spectacle and music, is more unified, and achieves the aim of its mimesis in shorter scope, it can be considered superior to epic.[140] Aristotle was a keen systematic collector of riddles, folklore, and proverbs; he and his school had a special interest in the riddles of the Delphic Oracle and studied the fables of Aesop.[141] |

心理学 ソウル さらなる情報 魂について  アリストテレスは、植物、動物、人間の魂について3つの部分からなる構造を提唱し、人間は3種類の魂すべてを持つというユニークな存在であるとした。 アリストテレスの心理学は、その論文『魂について』(peri psychēs)の中で、植物的魂、感性的魂、理性的魂の3種類の魂(「サイケ」)を仮定している。人間は理性的な魂を持っている。人間の魂は他の種類の 力を取り入れている: 植物的な魂のように成長し、自らを養うことができ、繊細な魂のように感覚を経験し、局所的に動くことができる。人間の理性的な魂のユニークな部分は、他の ものの形を受け取り、ヌース(知性)とロゴス(理性)を用いてそれらを比較する能力である[92]。 アリストテレスにとって、魂とは生きとし生けるものの形態である。すべての存在は形と物質の複合体であるため、生き物の形とは、生き物に固有のもの、例え ば運動(植物の場合は成長や化学変化であり、アリストテレスはこれを運動の一種とみなしている)を開始する能力を与えるものである。 [11] それ以前の哲学者たちとは対照的に、しかしエジプト人たちに倣って、彼は理性的な魂を脳ではなく心臓に置いた[93]。注目すべきはアリストテレスの感覚 と思考の区分であり、これはアルクメイオンを除く以前の哲学者たちの概念とは概して異なっていた[94]。 アリストテレスは『魂について』において、プラトンの魂の理論を批判し、プラトンの理論に対抗して彼自身の理論を展開したことで有名である。最初の批判は 『ティマイオス』におけるプラトンの魂観に対するもので、魂は空間を占め、肉体と物理的に接触することができるというものである[95]。20世紀の学問 は圧倒的にアリストテレスのプラトン解釈に反対し、彼はプラトンを誤解していると主張していた[96]。 [97]アリストテレスのもう一つの批判は、プラトンの輪廻転生観は魂とその肉体が不一致になる可能性を伴うということである。アリストテレスは、プラト ンの理論によれば、原理的にはどのような魂もどのような肉体にも行くことができると主張している[98]。 記憶 アリストテレスは『魂について』の中で、記憶とは知覚された経験を心に留める能力であり、内的な「外見」と過去の出来事とを区別する能力であると述べてい る。アリストテレスは、半流動性の身体器官に印象が残り、それが記憶を作るためにいくつかの変化を遂げると考えた。視覚や聴覚などの刺激が非常に複雑で、 神経系が一度にすべての印象を受け取ることができない場合に記憶が生じる。これらの変化は、感覚、アリストテレス的な「常識」、および思考の作用に関与す るものと同じである[101][102]。 アリストテレスは「記憶」という用語を、感覚から発展しうる印象における経験の実際の保持と、特定の時間に形成され特定の内容を処理するために印象に付随 する知的不安に対して使用している。記憶は過去のものであり、予測は未来のものであり、感覚は現在のものである。印象の検索はいきなり行うことはできな い。以前の経験にも現在の経験にも、過渡的なチャンネルが必要であり、過去の経験の中に位置する[103]。 アリストテレスは、人はあらゆる種類の感覚知覚を受け取り、それらを印象として知覚していると考えているため、人は絶えず新しい印象の経験を織り交ぜてい る。これらの印象を探すために、人は記憶そのものを探す[104]。記憶の中で、特定の記憶の代わりにある経験が提示されると、その人は探しているものが 見つかるまでこの経験を拒絶する。想起は、検索された体験が自然に別の体験に続くときに起こる。イメージ」の連鎖が必要であれば、ある記憶が次の記憶を刺 激する。人は経験を想起するとき、必要な経験に到達するま で、ある特定の過去の経験を刺激する[105]。このように想起とは、記憶の印象に蓄えられた 情報を取り出すという自己主導的な活動である[106]。時間の知覚を持つ動物は、過去の観察の記憶を取り出すことができる。記憶には、記憶された事柄と 経過した時間の知覚のみが含まれる[107]。  アリストテレスの心理学における感覚、知覚、記憶、夢、行動。印象はセンソリウム(心)に記憶され、彼の連想の法則(類似性、対照性、連続性)によって結 びつけられる。 アリストテレスは、ある印象の想起に終始する思考の連鎖は、彼の連想の法則に記述されている類似性、対照性、連続性といった関係で体系的に結びついている と考えた。アリストテレスは、過去の経験は心の中に隠されていると考えた。隠されたものを呼び覚まし、実際の経験を呼び起こす力が働く。アリストテレスに よれば、連想とは精神状態に生得的に備わっている力であり、それはかつての経験の表現されていない残骸に働きかけ、それらを浮かび上がらせ、想起させるこ とを可能にする[108][109]。 夢 さらなる情報 夢§その他 アリストテレスは『睡眠と覚醒について』の中で睡眠について述べている[110]。睡眠は感覚[111]や消化[112]を酷使した結果として起こるた め、身体にとって不可欠である[111]。睡眠中は感覚を感じることができないので、感覚の結果である欲求を持つことができない。しかし、感覚は、疲労し ていない限り[110]、異なるとはいえ[113]、睡眠中も働くことができる[111]。 夢は実際に刺激を感じることを伴わない。アリストテレスは、人が水面の波のような動く刺激を凝視し、それから目をそらすと、次に見るものが波のような動き をしているように見えると説明している[111]。人がある刺激を知覚し、その刺激がもはや注意の焦点ではなくなると、その刺激は印象を残す[110]。 体が起きていて感覚が正常に機能しているとき、人は常に新しい刺激に遭遇して知覚するため、以前に知覚した刺激の印象は無視される[111]。しかし睡眠 中は、新しい気が散るような感覚体験がないため、一日を通して作られた印象に気づく。印象がすべてであり、正確な刺激ではないため、夢は実際の覚醒時の経 験とは似ていない[114]。アリストテレスは、眠っている人を刺激に対する強い感情に支配されている人に例えている。例えば、誰かに強い恋心を抱いてい る人は、その感情に圧倒されるあまり、その人がどこにでもいると思い始めるかもしれない。眠っている人は暗示にかかりやすい状態にあり、判断することがで きないので、熱中している人のように夢に現れるものに簡単に騙されるようになる[110]。 アリストテレスは『デ・アニマ』Ⅲ3において、知覚がない状態でイメージを創造し、記憶し、想起する能力を想像の能力であるファンタジアに帰している [11]。 夢に関するアリストテレスの理論の1つの要素は、以前から信じられていた信念とは異なっている。彼は夢は予言ではなく、神の存在によって送られるものでも ないと主張した。アリストテレスは、夢が未来の出来事に似ている例は単なる偶然であると自然主義的に推論した。目が覚めた後に一瞬だけ映像が現れたり、暗 闇の中で何かを見たりしても、それが起こったときに目を覚ましていたため、夢とは見なされない。第二に、人が眠っている間に知覚された感覚体験は、夢の一 部とは認められない。例えば、眠っている間にドアが閉まり、夢の中でドアが閉まる音が聞こえたとしても、この感覚体験は夢の一部ではない。最後に、夢のイ メージは、起きているときの感覚体験の印象が持続した結果でなければならない[114]。 実践哲学 アリストテレスの実践哲学は倫理学、政治学、経済学、修辞学などの領域をカバーしている[40]。 美徳とそれに伴う悪徳[15]。 徳が少なすぎる 徳が高すぎる 謙虚さ 高慢さ 虚栄心 目的の欠如 正しい野心 過大な野心 無精 無作法 礼儀正しさ 卑屈さ 臆病 勇気 無謀 不感症 自制心 軽率 皮肉 誠実 自惚れ 無愛想 ウィット 恥知らず 控えめ 無愛想 ただ憤慨すること 辛辣さ 寛大さ 下品さ 卑屈さ 自由さ 無駄遣い  倫理 主な記事 アリストテレス倫理学 アリストテレスは倫理学を理論的な学問ではなく実践的な学問であると考えていた。彼は倫理学に関するいくつかの論考を著し、特に『ニコマコス倫理学』など が有名である[116]。 アリストテレスは、徳は物事の適切な機能(エルゴン)と関係があると説いた。目の本来の機能は視力であるから、目は見える限りにおいて良い目である。アリ ストテレスは、人間には人間固有の機能があるはずで、その機能は理性(ロゴス)に従ったプシュケー(魂)の活動でなければならないと推論した。アリストテ レスは、そのような魂の最適な活動(過不足[15]という付随する悪徳の間にある有徳の平均値)を、人間のすべての意図的な行動の目的であるエウダイモニ ア(一般に「幸福」、あるいは「幸福」と訳されることもある)と特定した。このように幸福になる可能性を持つためには、道徳的または倫理的な美徳や卓越性 としばしば訳される善良な人格(ēthikē aretē)が必然的に必要とされる[117]。 アリストテレスは、高潔で潜在的に幸福な人格を獲得するためには、意図的にではなく、教師や経験によって習慣化される幸運に恵まれるという最初の段階が必 要であり、意識的に最善のことを選択するという後の段階につながると説いている。最良の人々がこのように人生を生きるようになったとき、彼らの実践的な知 恵(フロネシス)と知性(ヌース)は、可能な限り最高の人間の徳、すなわち熟達した理論的あるいは思索的な思想家、言い換えれば哲学者の知恵に向かって互 いに発展することができる[118]。 政治 主な記事 政治学(アリストテレス) 個人を扱った倫理学の著作に加えて、アリストテレスは『政治学』という著作で都市を扱った。アリストテレスは都市を自然な共同体であると考えた。さらに、 彼は都市を家族よりも重要なものであり、それは個人よりも重要なものであると考えた。アリストテレスの都市観は有機的であり、彼はこのように都市を考えた 最初の人物の一人と考えられている[121]。  アリストテレスの政治的構成の分類 近代国家としての政治的共同体についての一般的な近代の理解は、アリストテレスの理解とはかなり異なっている。アリストテレスはより大きな帝国の存在と可 能性を認識していたが、アリストテレスが考える自然な共同体とは、政治的な「共同体」あるいは「パートナーシップ」(コイノニア)として機能する都市(ポ リス)であった。都市の目的は、不正を避けることや経済的安定のためだけでなく、少なくとも一部の市民が良い生活を送り、美しい行いをする可能性を認める ことにある: 「したがって、政治的パートナーシップは、共に生きるためではなく、崇高な行為のためにあると見なされなければならない」。これは、社会契約論に始まる、 個人が「暴力的な死への恐怖」やその「不都合」のために自然状態から離れるという近代的なアプローチとは区別される[L]。 Protrepticus』において、登場人物の「アリストテレス」は次のように述べている[122]。 われわれは皆、最もすぐれた人間が支配すべきこと、すなわち生来の至高者が支配すべきこと、そして法が支配し、単独で権威を有することに同意するが、法は 一種の知性であり、すなわち知性に基づく言説である。そしてまた、知性ある人間以上に正確な基準、善きものの基準があるだろうか。もしその選択が彼の知性 に基づくものであるならば、この人が選ぶものはすべて良いものであり、その反対は悪いものだからである。そして、誰もが自分自身の適切な性質に適合するも の(公正な人は公正に生きることを選び、勇気のある人は勇敢に生きることを選び、同様に自制心のある人は自制心をもって生きることを選ぶ)を最も多く選ぶ のだから、知性ある人が知性的であることを最も多く選ぶことは明らかである。それゆえ、最も権威ある判断によれば、知性は財の中で最高のものであることは 明らかである[122]。 プラトンの弟子であったアリストテレスは、民主主義に関してむしろ批判的であり、プラトンの『ステーツマン』からあるアイデアの輪郭に従って、さまざまな 権力の形態をいわゆる混合国家に統合する首尾一貫した理論を展開した: それは......官職が選挙で選ばれることを寡頭政治から取り入れ、財産的資格によらないことを民主主義から取り入れることは......合憲である。 民主政と寡頭政治がうまく混在している証は、同じ憲法を民主政としても寡頭政治としても語ることができる場合である。 - アリストテレス 政治学』第4巻1294b.10-18 このアプローチを説明するために、アリストテレスは「一人の有権者が一票を投じる」という民主主義の原則と寡頭政治の「功績加重投票」を組み合わせた、文 章で記述されたものではあるが、世界初の投票の数学的モデルを提案した[123]。 アリストテレスの女性観は後世の西洋哲学者たちに影響を与え、中世末期まで権威として引用されたが、これらの見解は現代においても論争を呼んでいる。アリ ストテレスの子作りに関する分析では、能動的でアンソウルな男性的要素が、不活性で受動的な女性的要素に生命をもたらすとされている。生物学的な違いは、 女性の身体が生殖に適しているという事実の結果であり、それによって体温が変化し、その結果、アリストテレスの見解では、女性は政治生活に参加することが できなくなる。 [124] この根拠に基づいて、フェミニストの形而上学の支持者たちはアリストテレスを女性差別[125]や性差別で非難してきた[126]。 しかし、アリストテレスは女性の幸福にも男性の幸福と同等の重みを与えており、『修辞学』において幸福につながるものは男性だけでなく女性にも必要である とコメントしている[M]。 経済学 主な記事 政治学(アリストテレス) アリストテレスは経済思想、特に中世の思想に多大な貢献をしている[128]。ライオネル・ロビンスの見解によれば、私有財産に対する批判に対する彼の回 答は、社会的取り決めの全体的な有用性に関連するものとして、哲学者や経済学者における後の私有財産の支持者を先取りしていた[128]。アリストテレス は、共同体的取り決めは社会にとって有益に見えるかもしれないが、また私有財産はしばしば社会的争いの原因として非難されるが、そのような弊害は実際には 人間の本性に由来すると考えていた。アリストテレスは『政治学』において、貨幣の起源について最も古い説のひとつを述べている[128]。貨幣が使われる ようになったのは、人々が互いに依存し合うようになり、必要なものを輸入し、余剰分を輸出するようになったからである。そして人々は利便性を高めるため に、鉄や銀のような本質的に有用で容易に適用できるものを取引することに同意した[129]。 小売と利子に関するアリストテレスの議論は、中世の経済思想に大きな影響を与えた。彼は小売業を低く評価しており、家計を管理するために必要なものを調達 するために貨幣を使用するのとは反対に、小売業は利益を上げようとすると考えていた。そのため、小売業はそれ自体を目的とするのではなく、商品を手段とし て使用する。アリストテレスは、小売業はこのように不自然であると考えた。同様に、アリストテレスは利子によって利潤を得ることは、貨幣の使用からではな く、貨幣自体から利潤を得ることになるため、不自然であると考えた[129]。 アリストテレスは貨幣の機能について、当時としてはおそらく著しく早熟な要約を与えている。彼は、すべての財の価値を、それが価値を持つ他の財の数を数え ることによって決定することは不可能であるため、単一の普遍的な測定基準が必要であると書いている。こうして貨幣は、異なる財の関連付けを可能にし、それ らを「通約可能」にするのである。つまり、「今欲しいものがなくても、欲しいときに手に入れることができる」のである[129]。 レトリック シリーズ レトリック 歴史 概念 ジャンル 批評 修辞学者 作品 サブフィールド 関連 ヴテ 主な記事 修辞学(アリストテレス) アリストテレスの『修辞学』では、話し手は聴衆を説得するために、エトス(話し手の人格への訴え)、パトス(聴衆の感情への訴え)、ロゴス(論理的推論へ の訴え)の3種類の基本的な訴えを用いることができると提唱している。 [アリストテレスはまた、レトリックをエピデクティック(賞賛や非難を扱う儀式的な演説)、フォレンジック(有罪や無罪をめぐる裁判的な演説)、デリバラ ティブ(ある問題に関して聴衆に決定を下すよう求める演説)の3つのジャンルに分類している[131]。 アリストテレスはまた、エンシメーム(シロジズムによる証明)とパラデグマ(例による証明)の2種類の修辞的証明の概要を述べている[132]。 詩学 主な記事 詩学(アリストテレス) アリストテレスは『詩学』の中で、叙事詩、悲劇、喜劇、ディトラム詩、絵画、彫刻、音楽、舞踊はすべて基本的にミメーシス(「模倣」)の行為であり、それ ぞれ媒体、対象、方法によって模倣の仕方が異なると書いている[133][134]。 彼はミメーシスという用語を芸術作品の特性として、また芸術家の意図の産物として適用し[133]、観客がミメーシスを理解することが作品そのものを理解 するために不可欠であると主張している。 [133]アリストテレスは、模倣は人間を動物から引き離す人間の自然な本能であり[133][135]、人間の芸術性はすべて「自然の型に従う」もので あると述べている[133]。形式はまた、模倣の対象においても異なる。たとえば喜劇は、平均より悪い人間を劇的に模倣するのに対し、悲劇は平均より少し 良い人間を模倣する。最後に、形式は模倣の方法--物語か性格か、変化か変化でないか、ドラマかドラマでないか--においても異なる[137]。  ベニーニュ・ガニェロー作『神々に子供を託す盲目のオイディプス』(1784年)。アリストテレスは『詩学』の中で、完璧な悲劇がどのように構成されるべ きかの例として、ソフォクレスの悲劇『オイディプス』(Oedipus Tyrannus)を用いている。 アリストテレスの『詩学』はもともと喜劇と悲劇の2冊で構成されていたと考えられているが、悲劇に焦点を当てた部分のみが現存している。アリストテレス は、悲劇は6つの要素、すなわち筋立て、キャラクター、スタイル、思想、スペクタクル、抒情詩から構成されると説いた[139]。悲劇の登場人物は物語を 動かすための手段に過ぎず、登場人物ではなく筋立てこそが悲劇の主眼である。悲劇は憐憫と恐怖を喚起する行為の模倣であり、同じ感情のカタルシスをもたら すことを意図している。アリストテレスは『詩学』の最後を、叙事詩と悲劇の模倣のどちらが優れているかという議論で締めくくっている。アリストテレスは、 悲劇は叙事詩の属性をすべて備えており、見世物や音楽といった付加的な属性も備えている可能性があり、より統一的で、より短い範囲でミメーシスの目的を達 成することができるため、叙事詩よりも優れていると考えることができると示唆している[140]。アリストテレスは、なぞなぞ、民間伝承、ことわざの体系 的な収集に熱心であり、彼と彼の学派はデルフィの神託のなぞなぞに特別な関心を持ち、イソップの寓話を研究していた[141]。 |