Z世代・ジェネレーションZ

Generation

Z

Z世代とは、1996年ごろから2010年までに生 まれた世代である。ミレニアム以降の時代の真性ネットジェネレーションなどと言われる。生まれた時からスマホやネット環境が空気のように存在している世 代。SNSネイティブ、インターネットゲームに普通に使える。広告がスキップできることを知り、インフルエンサーについてよく知っている。プリントメディ アは購入するものではなく、ネットで入手するか、プリントアウトで利用する世代。紙メディアの新聞を電車の中で読んだことがないし、また、理解できない (→「ネットジェネレーションの特徴」「デジタル・ネイティブ族における孤独」)。

なぜZ世代かというと、パソコンやインターネットの 黎明期からのX世代、インターネツトが普通につかえる、その次のY世代の後にやってきた世代。アルファベットの順はZで終わるので、それ以降の世代はアル ファ(α)世代という。

◎Z世代のICT利用実態:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generation_Z

| Use of ICT in general Generation Z is one of the first cohorts to have Internet technology readily available at a young age.[211] With the Web 2.0 revolution that occurred throughout the mid-late 2000s and 2010s, they have been exposed to an unprecedented amount of technology in their upbringing, with the use of mobile devices growing exponentially over time. Anthony Turner characterizes Generation Z as having a "digital bond to the Internet", and argues that it may help youth to escape from emotional and mental struggles they face offline.[4] According to U.S. consultants Sparks and Honey in 2014, 41% of Generation Z spend more than three hours per day using computers for purposes other than schoolwork, compared with 22% in 2004.[212] In 2015, an estimated 150,000 apps, 10% of apps in Apple's App Store, were educational and aimed at children up to college level,[213] though opinions are mixed as to whether the net result will be deeper involvement in learning[213] and more individualized instruction, or impairment through greater technology dependence[214] and a lack of self-regulation that may hinder child development.[214] Parents of Gen Zers fear the overuse of the Internet, and dislike the ease of access to inappropriate information and images, as well as social networking sites where children can gain access to people worldwide. Children reversely feel annoyed with their parents and complain about parents being overly controlling when it comes to their Internet usage.[215] A 2015 study by Microsoft found that 77% of respondents aged 18 to 24 said yes to the statement, "When nothing is occupying my attention, the first thing I do is reach for my phone," compared to just 10% for those aged 65 and over.[216] In a TEDxHouston talk, Jason Dorsey of the Center for Generational Kinetics stressed the notable differences in the way that Millennials and Generation Z consume technology, with 18% of Generation Z feeling that it is okay for a 13-year-old to have a smartphone, compared with just 4% for the previous generation.[217][218][219] An online newspaper about texting, SMS and MMS writes that teens own cellphones without necessarily needing them; that receiving a phone is considered a rite of passage in some countries, allowing the owner to be further connected with their peers, and it is now a social norm to have one at an early age.[220] An article from the Pew Research Center stated that "nearly three-quarters of teens have or have access to a smartphone and 30% have a basic phone, while just 12% of teens 13 to 15 say they have no cell phone of any type".[221] These numbers are only on the rise and the fact that the majority own a cell phone has become one of this generation's defining characteristics. Consequently, "24% of teens go online 'almost constantly'."[221] A survey of students from 79 countries by the OECD found that the amount of time spent using an electronic device has increased, from under two hours per weekday in 2012 to close to three in 2019, at the expense of extracurricular reading.[32] Psychologists have observed that sexting—or the transmission of sexually explicit content via electronic devices—has seen noticeable growth among contemporary adolescents. Older teenagers are more likely to participate in sexting. Besides some cultural and social factors such as the desire for acceptance and popularity among peers, the falling age at which a child receives a smartphone may contribute to the growth in this activity. However, while it is clear that sexting has an emotional impact on adolescents, it is still not clear how it precisely affects them. Some consider it a high-risk behavior because of the ease of dissemination to third parties leading to reputational damage and the link to various psychological conditions including depression and even suicidal ideation. Others defend youths' freedom of expression over the Internet. In any case, there is some evidence that at least in the short run, sexting brings positive feelings of liveliness or satisfaction. However, girls are more likely than boys to be receiving insults, social rejections, or reputational damage as a result of sexting.[16] |

一般的なICTの利用 ジェネレーションZは、幼少期にインターネット技術を容易に利用できた最初のコーホートのひとつである[211]。2000年代半ばから2010年代を通 じて起こったWeb 2.0革命により、彼らは、モバイル機器の使用が時間とともに指数関数的に増加し、これまでにない量のテクノロジーに触れて育ってきた。アンソニー・ターナーは、ジェネレーションZを「インターネットとのデジタルな絆」を持ってい ると特徴づけ、若者がオフラインで直面する感情的・精神的な葛藤から逃れる手助けをしているのではないかと論じている[4]。 2014年の米国のコンサルタントであるスパークス・アンド・ハニーによれば、ジェネレーションZの41%が学業以外の目的で1日3時間以上コンピュータ を使用しており、2004年の22%と比較している[212]。 2015 年には、AppleのApp Storeにおけるアプリの10%にあたる推定15万個のアプリが、大学レベルまでの子どもを対象とした教育的なアプリであったが、正味の結果として学習 への深い関与がもたらされるか[213]、より個別指導的なものとなるか、より大きな技術依存による障害[214]や自己統制力の欠如が子どもの発達に妨 げになるか、意見はまちまちである[213]。 Z世代の親はインターネットの使いすぎを恐れ、不適切な情報や画像に簡単にアクセスできることや、子どもが世界中の人々とアクセスできるSNSを嫌ってい る[214]。子どもたちは逆に親をうっとうしく感じ、インターネットの利用に関して親が過度に支配していることに不満を抱いている[215]。 マイクロソフトによる2015年の調査では、18歳から24歳の回答者 の77%が「何も私の注意を占めていないとき、私が最初にすることは携帯電話に手を伸ばすことだ」という文にイエスと答えたのに対し、65歳以上ではわず か10%であったことがわかった[216]。 ※MacSpadden, Kevin (May 14, 2015). "You Now Have a Shorter Attention Span Than a Goldfish". Time. Retrieved December 9, 2020. TEDxHoustonの講演で、Center for Generational KineticsのJason Dorseyは、ミレニアル世代とジェネレーションZがテクノロジーを消費する方法の顕著な違いを強調し、ジェネレーションZの18%が13歳がスマートフォンを持ってもいいと感じているが、前の世代 ではわずか4%であった。 [217][218][219] テキスト、SMS、MMSに関するオンライン新聞は、10代の若者は必ずしも携帯電話を必要とせず所有しており、携帯電話を受け取ることは国によっては通 過儀礼と考えられ、所有者は仲間たちとさらにつながることができ、今では幼少期に持つことが社会通念になっている、と書いている。 [220] Pew Research Center の記事では、「10 代のほぼ 4 分の 3 がスマートフォンを持っているか、アクセスすることができ、30% が基本的な電話を持っている一方で、13 から 15 歳の 10 代のわずか 12%は、いかなる種類の携帯電話も持っていないと答えている」[221] と述べている。その結果、「10代の若者の24%が『ほぼ常時』オンラインに接続している」[221]。 OECDによる79カ国の学生を対象とした調査では、電子機器の使用時 間が増加し、2012年には平日1日あたり2時間未満だったのが、2019年には3時間近くになり、課外での読書が犠牲になっていることが判明した[32]。 心理学者の観察によると、セクスティング(電子機器を通じて性的な内 容を送信すること)が現代の青少年の間で顕著に増加しているそうである。年齢が高い ほど、セクスティングに参加する傾向がある。仲間に受け入れられたい、人気を得たいという文化的・社会的な要因に加え、子どもがスマート フォンを手にする年齢が下がっていることも、この行為の増加に寄与しているかもしれない。しかし、セ クスティングが思春期の子どもたちに感情的な影響を与えることは明らかであるが、それが具体的にどのような影響を与えるかはまだ明らかになっていない。第 三者への拡散が容易で風評被害につながることや、うつ病や自殺願望を含むさまざまな心理状態に関連することから、リスクの高い行為であると考える人もい る。また、若者のインターネット上での表現の自由を擁護する意見もある。いずれにせよ、少なくとも短期的には、セクスティングが快活さや満足感といったポ ジティブな感情をもたらすという証拠がいくつかある。しかし、女子は男子よりも、セクスティングの結果として侮辱、社会的拒絶、あるいは風評被害を受けて いる可能性が高い[16]。 ※Del Rey, Rosario; Ojeda, Mónica; Casas, José A.; Mora-Merchán, Joaquín A.; Elipe, Paz (August 21, 2019). Rey, Lourdes (ed.). "Sexting Among Adolescents: The Emotional Impact and Influence of the Need for Popularity". Educational Psychology. Frontiers in Psychology. 10 (1828): 1828. |

| Digital literacy Despite being labeled as 'digital natives', the 2018 International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS), conducted on 42,000 eighth-graders (or equivalents) from 14 countries and education systems, found that only two percent of these people were sufficiently proficient with information devices to justify that description, and only 19% could work independently with computers to gather information and to manage their work.[6] ICILS assesses students on two main categories: Computer and Information Literacy (CIL), and Computational Thinking (CT). For CIL, there are four levels, one to four, with Level 4 being the highest. Although at least 80% of students from most countries tested reached Level 1, only two percent on average reached Level 4. Countries or education systems whose students scored near or above the international average of 496 in CIL were, in increasing order, France, North Rhine-Westphalia, Portugal, Germany, the United States, Finland, South Korea, Moscow, and Denmark. CT is divided into four levels, the Upper, Middle, and Lower Regions. International averages for the proportions of students reaching each of these were 18%, 50%, and 32%, respectively. Countries or education systems whose students scored near or above the international average of 500 were, in increasing order, the United States, France, Finland, Denmark, and South Korea. In general, female eighth-graders outperformed their male counterparts in CIL by an international average of 18 points but were narrowly outclassed by their male counterparts in CT. (Narrow gaps made estimates of averages have higher coefficients of variation.)[222] In the United States, where the computer-based tests were administered by the National Center for Education Statistics,[6] 72% of eighth-graders said they searched for information on the Internet at least once a week or every school day, and 65% reported they were autodidactic information finders on the Internet.[222] |

デジタルリテラシー デジタルネイティブ」というレッテルを貼られているにもかかわらず、14の国と教育システムの中学2年生(またはそれに相当する生徒)42,000人を対 象に行われた2018年国際コンピュータ・情報リテラシー調査(ICILS)では、この人たちのうち、その表現を正当化できるほど情報機器に精通している のはわずか2%、コンピュータを使って情報収集や仕事の管理を独自に行える人はわずか19%であった [6]。 ICILSは主に2種類の項目について学生を評価している。ICILSは、コンピュータと情報のリテラシー(CIL)とコンピューテーショナル・シンキン グ(CT)の2つの主要なカテゴリーで学生を評価する。CILについては、1~4の4つのレベルがあり、レベル4が最も高い。ほとんどの国の生徒がレベル 1には80%以上達しているものの、レベル4には平均で2%しか達していない。CILで国際平均の496点に近い、あるいはそれ以上のスコアを出した国や 教育システムは、フランス、ノルトライン・ヴェストファーレン州、ポルトガル、ドイツ、アメリカ、フィンランド、韓国、モスクワ、デンマークの順であっ た。CTは、上・中・下の4つのレベルに分かれている。それぞれのレベルに到達した生徒の割合の国際平均は、それぞれ18%、50%、32%であった。国 際平均の500点に近い、あるいはそれ以上のスコアを獲得した国や教育制度は、アメリカ、フランス、フィンランド、デンマーク、韓国の順であった。一般 に、中学2年生の女子はCILで男子に国際平均18点差をつけていたが、CTでは男子に僅差で負けていた(僅差だと平均の推定値の変動係数が大きくなる) [222]。 )[222] コンピュータベースのテストが全米教育統計センターによって実施されたアメリカでは[6]、中学2年生の72%が少なくとも週に1回、あるいは学校では毎 日インターネットで情報を検索すると答え、65%がインターネット上で自習的に情報を探すと報告した[222]。 |

| Use of social media networks The use of social media has become integrated into the daily lives of most Gen Zers with access to mobile technology, who use it primarily to keep in contact with friends and family. As a result, mobile technology has caused online relationship development to become a new generational norm.[223] Gen Z uses social media and other sites to strengthen bonds with friends and to develop new ones. They interact with people who they otherwise would not have met in the real world, becoming a tool for identity creation.[215] The negative side to mobile devices for Generation Z, according to Twenge, is they are less "face to face", and thus feel more lonely and left out.[224] Focus group testing found that while teens may be annoyed by many aspects of Facebook, they continue to use it because participation is important in terms of socializing with friends and peers. Twitter and Instagram are seen to be gaining popularity among members of Generation Z, with 24% (and growing) of teens with access to the Internet having Twitter accounts.[225] This is, in part, due to parents not typically using these social networking sites.[225] Snapchat is also seen to have gained attraction in Generation Z because videos, pictures, and messages send much faster on it than in regular messaging. TikTok has gained increasing popularity among Gen Z users, surpassing Instagram in 2021.[226] So as of 2022, TikTok has around 689 million active users, 43% of whom are from Gen Z.[227][228] Based on current growth figures, it is predicted that by the end of 2023, TikTok audience will grow by 1.5 billion active users, 70% of whom will be from Generation Z.[229] Speed and reliability are important factors in members of Generation Z's choice of social networking platform. This need for quick communication is presented in popular Generation Z apps like Vine and the prevalent use of emojis.[230] A study by Gabrielle Borca, et al found that teenagers in 2012 were more likely to share different types of information than teenagers in 2006.[225] However, they will take steps to protect information that they do not want being shared, and are more likely to "follow" others on social media than "share".[231] A survey of U.S. teenagers from advertising agency J. Walter Thomson likewise found that the majority of teenagers are concerned about how their posting will be perceived by people or their friends. 72% of respondents said they were using social media on a daily basis, and 82% said they thought carefully about what they post on social media. Moreover, 43% said they had regrets about previous posts.[232] A 2019 Childwise survey of 2,000 British children aged five to sixteen found that the popularity of Facebook halved compared to the previous year. Children of the older age group, fifteen to sixteen, reported signs of online fatigue, with about three of ten saying they wanted to spend less time on the Internet.[109] |

ソーシャルメディア・ネットワークの利用 ソーシャルメディアの利用は、モバイルテクノロジーを利用できるほとん どのZ世代の日常生活に溶け込んでおり、彼らは主に友人や家族と連絡を取り合うために利用している。その結果、モバイルテクノロジーは、オンラインでの人 間関係の構築を新しい世代の規範とする原因となった。Z世代にとってのモバイル機器のマイナス面は、Twengeによると、「face to face」が少なくなり、その結果、孤独感や取り残された感が強くなることである[224]。 ※"ICILS 2018 U.S. Results". National Center for Education Statistics. 2019. フォーカスグループのテストでは、10代の若者はフェイスブックの多くの側面に悩まされるかもしれないが、友人や仲間との社交という点では参加が重要なので使い続けていることがわかっ た。ツ イッターとインスタグラムはジェネレーションZの間で人気を集めていると見られ、インターネットにアクセスできる10代の24%(さらに増加中)がツイッ ターのアカウントを持っている[225]。これは、親が通常これらのソーシャルネットワークサイトを使用していないことが一因である[225]。 2022年現在、TikTokのアクティブユーザーは約6億8900万人で、そのうちの43%がZ世代である[227][228]。現在の成長率から、2023年末までにTikTokのオーディエンスは15億アクティブユー ザー増加し、そのうちの70%がZ世代になると予測されている[229] スピードと信頼性がZ世代のメンバーがソーシャルネットワークのプラットフォームを選択する際の重要な要素になる。この素早いコミュニケーションのニーズ は、VineのようなジェネレーションZの人気アプリや、絵文字の普及に現れている[230]。 ※[225]Madden, Mary; et al. (May 21, 2013). "Teens, Social Media, and Privacy". Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 10, 2015. [229] "New Report Suggests TikTok Will Surpass 1.5 Billion Users in 2022". socialmediatoday.com. ガブリエル・ボルカらによる調査では、2012年のティーンエイジャーは、2006 年のティーンエイジャーよりもさまざまな種類の情報を共有する傾向があることがわかった[225]。 しかし、共有されたくない情報を守るための手段をとり、ソーシャルメディアでは「共有」よりも「フォロー」する傾向がある[231] 広告会社J・ウォルター・トムソンによる米国のティーンエイジャーへの調査は、同様に、大多数のティーンエイジャーが自分の投稿が人々や友人からどう思わ れるかに関心を持っていると示している。回答者の72%が日常的にソーシャルメディアを利用していると答え、82%がソーシャルメディアに投稿する内容に ついて慎重に考えていると答えた。さらに、43%が以前の投稿について後悔していると回答している[232]。 2019年にChildwiseが5歳から16歳のイギリスの子ども2,000人を 対象に行った調査では、Facebookの人気は前年と比較して半減していることがわかった。15歳から16歳という高年齢層の子どもたちは、オンライン 疲労の兆候を報告し、10人中約3人がインターネットに費やす時間を減らしたいと回答している[109]。 ※[109]Coughlan, Sean (January 30, 2019). "The one about Friends still being most popular". BBC News. |

| Effects of screen time In his 2017 book Irresistible, professor of marketing Adam Alter explained that not only are children addicted to electronic gadgets, but their addiction jeopardizes their ability to read non-verbal social cues.[233] A 2019 meta-analysis of thousands of studies from almost two dozen countries suggests that while as a whole, there is no association between screen time and academic performance, when the relation between individual screen-time activity and academic performance is examined, negative associations are found. Watching television is negatively correlated with overall school grades, language fluency, and mathematical ability while playing video games was negatively associated with overall school grades only. According to previous research, screen activities not only take away the time that could be spent on homework, physical activities, verbal communication, and sleep (the time-displacement hypothesis) but also diminish mental activities (the passivity hypothesis). Furthermore, excessive television viewing is known for harming the ability to pay attention as well as other cognitive functions; it also causes behavioral disorders, such as having unhealthy diets, which could damage academic performance. Excessive video gaming, on the other hand, is known for impairing social skills and mental health, and as such could also damage academic performance. However, depending on the nature of the game, playing it could be beneficial for the child; for instance, the child could be motivated to learn the language of the game in order to play it better. Among adolescents, excessive Internet surfing is well known for being negatively associated with school grades, though previous research does not distinguish between the various devices used. Nevertheless, one study indicates that Internet access, if used for schoolwork, is positively associated with school grades but if used for leisure, is negatively associated with it. Overall, the effects of screen time are stronger among adolescents than children.[7] Research conducted in 2017 reports that the social media usage patterns of this generation may be associated with loneliness, anxiety, and fragility and that girls may be more affected than boys by social media. According to 2018 CDC reports, girls are disproportionately affected by the negative aspects of social media than boys.[234] Researchers at the University of Essex analyzed data from 10,000 families, from 2010 to 2015, assessing their mental health utilizing two perspectives: Happiness and Well-being throughout social, familial, and educational perspectives. Within each family, they examined children who had grown from 10 to 15 during these years. At age 10, 10% of female subjects reported social media use, while this was only true for 7% of the male subjects. By age 15, this variation jumped to 53% for girls, and 41% for boys. This percentage influx may explain why more girls reported experiencing cyberbullying, decreased self-esteem, and emotional instability more than their male counterparts.[235] Other researchers hypothesize that girls are more affected by social media usage because of how they use it. In a study conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2015, researchers discovered that while 78% of girls reported making a friend through social media, only 52% of boys could say the same.[236] However, boys are not explicitly less affected by this statistic. They also found that 57% of boys claimed to make friends through video gaming, while this was only true for 13% of girls.[236] Another Pew Research Center survey conducted in April 2015, reported that women are more likely to use Pinterest, Facebook, and Instagram than men. In counterpoint, men were more likely to utilize online forums, e-chat groups, and Reddit than women.[236] Cyberbullying is more common now than among Millennials, the previous generation. It is more common among girls, 22% compared to 10% for boys. This results in young girls feeling more vulnerable to being excluded and undermined.[237][238] According to a 2020 report by the British Board of Film Classification, "many young people felt that the way they viewed their overall body image was more likely the result of the kinds of body images they saw on Instagram."[197] |

スクリーンタイムによる影響 2017年の著書『Irresistible』において、マーケティング学のアダム・アルター教授は、子どもたちが電子ガジェット依存になっているだけで なく、その依存が非言語的な社会的合図を読み取る能力を危うくすると説明している[233]。 ※[233]Stevens, Heidi (March 13, 2017). "'Irresistible' technology is making our kids miss social cues". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 10, 2020. 2019年に行われたほぼ20カ国の数千の研究のメタ分析では、全体としてスクリー ンタイムと学力との間に関連はないが、個々のスクリーンタイム活動と学力との関係を調べると、負の関連性があることが示唆されている。テレ ビを見ることは、学校の総合成績、言語の流暢さ、数学的能力と負の相関があり、ビデオゲームをすることは、学校の総合成績のみと負の相関があった。先行研究によると、スクリーン活動は、宿題、身体活動、言語コミュニケーション、睡眠に費やせ る時間を奪うだけでなく(時間変位仮説)、精神活動も低下させる(受動性仮説)。 また、テレビの過剰視聴は、注意力などの認知機能を低下させることが知られており、不健康な食生活などの行動障害を引き起こし、学業成績を低下させる可能 性がある。一方、過度のビデオゲームは、社会的スキルや精神的な健康を損なうことが知られており、そのため学業成績も損なわれる可能性がある。しかし、 ゲームの内容によっては、そのゲームをすることが子どものためになることもある。例えば、そのゲームの言語を学ぶことで、より良いゲームをするための動機 付けになることもあるのだ。青少年において、過度のインターネットサーフィンが学校の成績と負の相関があることはよく知られているが、これまでの研究で は、使用する様々なデバイスを区別していない。とはいえ、ある研究によると、イン ターネットへのアクセスは、学業に利用される場合は学校の成績と正の相関があるが、余暇に利用される場合は負の相関があることが示されている。全体的に、 スクリーンタイムの影響は、子どもよりも青少年でより強い[7]。 ※[7]Adelantado-Renau, Mireia; Moliner-Urdiales, Diego; et al. (September 23, 2019). "Association Between Screen Media Use and Academic Performance Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Pediatrics. American Medical Association. 173 (11): 1058–1067. 2017年に行われた研究では、この世代のソーシャルメディアの利用パターンが孤独、不安、脆さと関連している可能性があり、少女は少年よりもソーシャル メディアの影響を受けている可能性があると報告されている。2018年のCDCの報告によると、女の子は男の子よりもソーシャルメディアの負の側面から不 釣り合いに影響を受けている[234] 。エセックス大学の研究者は、2010年から2015年にかけて、1万家族のデータを分析し、2つの視点を活用してメンタルヘルスを評価した。社会的、家 族的、教育的な視点を通して、幸福と幸福感を評価した。各家族の中で、この間に10歳から15歳に成長した子どもたちを調査した。10歳の時点で、女性被 験者の10%がソーシャルメディアの利用を報告していたが、男性被験者では7%にとどまった。15歳になると、このばらつきは女子で53%、男子で41% に跳ね上がった。この割合の流入は,より多くの女子がいじめ,自尊心の低下,情緒不安定を経験したと男性よりも多く報告した理由を説明するかもしれない [235]。 ※[235]Booker, Cara L.; Kelly, Yvonne J.; Sacker, Amanda (March 20, 2018). "Gender differences in the associations between age trends of social media interaction and well-being among 10-15 year olds in the UK". BMC Public Health. 18 (1): 321. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5220-4 他の研究者は、女子がソーシャルメディアの利用によってより影響を受けるのは、その 利用方法によるものだという仮説を立てている。2015年にピュー・リサーチ・センターが行った調査では、研究者は、女子の78%がソーシャルメディアを 通じて友人を作ったと報告する一方で、男子の52%だけが同じことを言えることを発見した[236]。 しかし、男子はこの統計によって明確に影響を受けにくいというわけではない。彼らはまた、少年の57%がビデオゲームを通じて友達を作ると主張したのに対 し、これは少女の13%にしか当てはまらないことを発見した[236]。 2015年4月に行われた別のPew Research Centerの調査では、女性が男性よりもPinterest、Facebook、Instagramを使う傾向があると報告されている。反対に、男性は 女性よりもオンラインフォーラム、電子チャットグループ、Redditを利用する傾向が強かった[236]。 ※[236] "Men catch up with women on overall social media use". Pew Research Center. August 28, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2018. ネットいじめ(cyberbullying)は、前の世 代であるミレニアルズに比べ、現在ではより一般的である。男子が10%であるのに対し、女子は22%と、より一般的である。この結果、若い女の子は排除さ れたり貶められたりすることに対してより弱く感じている[237][238]。 ※[237]"Smartphones and Social Media". Child Mind Institute. [238]wenge, Jean (August 22, 2017). IGen: Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy--and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood--and What That Means for the Rest of Us. Atria Books 英国映画分類委員会による2020年の報告によれば、「多くの若者は、自分の全体的な身体イメージの見方が、Instagramで見た種類の身体イメージ の結果である可能性が高いと感じていた」[197]。 |

| 9X Generation (Vietnam) Boomerang Generation Cusper Generation K, a demographic cohort defined by Noreena Hertz Generation Z in the United States Post-90s and Little Emperor Syndrome (China) Strawberry Generation (Taiwan) Thumb tribe Puriteen |

9X世代(ベトナム) ブーメラン世代 カスパー ジェネレーションK、ノリーナ・ハーツが定義した人口動態コホート ジェネレーションZ(米国) ポスト90年代と小皇帝症候群(中国) ストロベリージェネレーション(台湾) 親指族 プリテーン |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generation_Z |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

◎Z世代=新人類論の登場

Z世代が、成年を迎えた2016年以降ごろから、ま ず米国において、ひきつづいて日本では2020年頃から、それ以前の世代の基本的性格(パーソナリティ特性)が異なるという一般的世論が登場してきた。多 くは、山極寿一『スマホを捨てたい子どもたち:野生に学ぶ「未知の時代」の生き方』ポプラ社、2020年や、原田曜平『Z世代 若者はなぜインスタ・TikTokにハマるのか?』光文社、2020年など、彼らZ世代を旧世代が理解できない、奇矯なものとして表象している。そして、 旧世代の生き方に回帰すべきだと主張(山極)したり、旧世代が理解できないものだから、むしろ、それに付き合い、今後の社会を支えるZ世代とともに新しい 日本経済と社会を推進して行こうという主張(原田)などに分けられる特徴を持つ。これらの共通は、自分たちの「独自解釈」にもとづいて、Z世代を理解する ことができ、かつ、彼らを善導していこうという「意志」によって支えられていることがその特徴である。

| Generation Z (or

more commonly Gen Z for short),

colloquially known as zoomers,[1][2] is the demographic cohort

succeeding Millennials and preceding Generation Alpha. Researchers and

popular media use the mid to late 1990s as starting birth years and the

early 2010s as ending birth years. Most members of Generation Z are

children of Generation X.[3] As the first social generation to have grown up with access to the Internet and portable digital technology from a young age, members of Generation Z, even if not necessarily digitally literate, have been dubbed "digital natives."[4][5][6] Moreover, the negative effects of screen time are most pronounced in adolescents compared to younger children.[7] Compared to previous generations, members of Generation Z tend to live more slowly than their predecessors when they were their age;[8][9] have lower rates of teenage pregnancies; and consume alcohol less often (but not necessarily other psychoactive drugs).[10][11][12][13] Generation Z teenagers are more concerned than older generations with academic performance and job prospects,[14][8] and are better at delaying gratification than their counterparts from the 1960s despite concerns to the contrary.[15] Sexting among adolescents has grown in prevalence; the consequences of this remain poorly understood.[16] Additionally, Gen Z subcultures have been quieter though they have not necessarily disappeared.[17][18] Globally, there is evidence that the average age of pubertal onset among girls has decreased considerably compared to the 20th century with implications for their welfare and their future.[19][20][21][22][23] Additionally, the prevalence of allergies among adolescents and young adults in Generation Z is greater than the general population;[24][25] there is greater awareness and diagnosis of mental health conditions;[14][12][26][27] and sleep deprivation is more frequently reported.[5][28][29] In many countries, Gen Z youth are more likely to be diagnosed with intellectual disabilities and psychiatric disorders than older generations.[30][31] Around the world, members of Generation Z are spending more time on electronic devices and less time reading books than before,[32][33][34] with implications for their attention spans,[35][36] vocabulary,[37][38] academic performance,[39] and future economic contributions.[32] In Asia, educators in the 2000s and 2010s typically sought out and nourished top students; in Western Europe and the United States, the emphasis was on poor performers.[40] Furthermore, East Asian and Singaporean students consistently earned the top spots in international standardized tests in the 2010s.[41][42][43][44] |

ジェネレーションZ(Generation Z、略してGen

Z)は、俗にズーマーと呼ばれ[1][2]、ミレニアルズに続く世代であり、ジェネレーション・アルファに先行する人口動態のコホートである。研究者や一

般的なメディアは、1990年代半ばから後半を出生年として、2010年代前半を出生年としている。ジェネレーションZのメンバーの大半はジェネレーショ

ンXの子供である[3]。 ジェネレーションZのメンバーは、幼少期からインターネットやポータブルデジタルテクノロジーにアクセスしながら成長した最初の社会的世代として、必ずし もデジタルリテラシーがなくても、「デジタルネイティブ」と呼ばれている[4][5][6]。さらに、スクリーンタイムの悪影響は、若い子供と比較して青 年期に最も顕著に見られる[7]。 [7] 以前の世代と比較して、ジェネレーションZのメンバーは、彼らの年齢であった先達よりもゆっくりと生きる傾向があり[8][9]、10代の妊娠率が低く、 アルコールを消費する頻度が低い(ただし、必ずしも他の精神作用性薬物を消費するわけではない)。 [10][11][12][13] Z世代のティーンエイジャーは、学業成績や仕事の見通しについて上の世代よりも関心が高く[14][8]、それとは逆に懸念されていたにもかかわらず 1960年代の世代よりも満足を遅らせることが上手である[15] 青年間でのセクスティングは普及しているがその結果はまだよく分かっていない。 16] さらにZ世代サブカルは必ずしも消えてはいないがより静かなものになってきた[17][18]。 世界的に、女子の思春期開始の平均年齢は20世紀と比較してかなり低下しているという証拠があり、女子の福祉と将来に対する含意をもっている。 [19][20][21][22][23] さらに、ジェネレーションZの青年・若年層におけるアレルギーの有病率は一般集団よりも高く、[24][25] 精神状態の認識や診断も高く、[14][12][26][27] 睡眠不足がより頻繁に報告される。 [5][28][29] 多くの国でジェネレーションZの若者は知的障害や精神障害の診断を受ける傾向が上の世代より高くなっている[30][31]。 世界中でZ世代のメンバーは以前より電子機器に費やす時間が増え、本を読む時間が減っており[32][33][34]、注意持続時間[35][36]、語 彙力[37][38]、学力、将来の経済貢献への影響が指摘されている。 [さらに、2010年代の国際標準化テストでは、東アジアとシンガポールの学生が常に上位を獲得していた[41][42][43][44]。 |

| Etymology and nomenclature The name Generation Z is a reference to the fact that it is the second generation after Generation X, continuing the alphabetical sequence from Generation Y (Millennials).[46][47] Other proposed names for the generation include iGeneration,[48] Homeland Generation,[49] Net Gen,[48] Digital Natives,[48] Neo-Digital Natives,[50][51] Pluralist Generation,[48] Internet Generation,[52] Centennials,[53] and Post-Millennials.[54] The term Internet Generation is in reference to the fact that the generation is the first to have been born after the mass-adoption of the Internet.[52] Psychology professor and author Jean Twenge used the term iGeneration (or iGen for short), originally intending to use it as the title of her 2006 book about Millennials, Generation Me, before being overruled by her publisher, Atria Publishing Group. At that time, there were iPods and iMac computers but no iPhones or iPads. Twenge later used the term for her 2017 book iGen. The name has also been asserted to have been created by demographer Cheryl Russell in 2009.[48] In 2014, author Neil Howe coined the term Homeland Generation as a continuation of the Strauss–Howe generational theory with William Strauss. The term Homeland refers to being the first generation to enter childhood after protective surveillance state measures, like the Department of Homeland Security, were put into effect following the September 11 attacks.[49] The Pew Research Center surveyed the various names for this cohort on Google Trends in 2019 and found that in the U.S., the term Generation Z was overwhelmingly the most popular. The Merriam-Webster and Oxford dictionaries both have official entries for Generation Z.[45] In Japan, the cohort is described as Neo-Digital Natives, a step beyond the previous cohort described as Digital Natives. Digital Natives primarily communicate by text or voice, while Neo-Digital Natives use video, video-telephony, and movies. This emphasizes the shift from PC to mobile and text to video among the Neo-Digital population.[50][51] Zoomer is an informal term used to refer to members of Generation Z, often in an ironic, humorous, or mocking tone.[2] It combines the shorthand boomer, referring to baby boomers, with the "Z" from Generation Z. Prior to this, zoomer was used in the 2000s to describe particularly active baby boomers.[1] Zoomer in its current incarnation skyrocketed in popularity in 2018, when it was used in a 4chan internet meme mocking Gen Z adolescents via a Wojak caricature dubbed a "Zoomer".[55][56] Merriam-Webster's records suggest the use of the term zoomer in the sense of Generation Z dates back at least as far as 2016. It was added to the Merriam-Webster dictionary in October 2021.[1] |

語源と命名法 ジェネレーションZという名称は、ジェネレーションY(ミレニアル世代)からアルファベット順で続いて、ジェネレーションXに続く第二世代であることにち なんでいる[46][47]。 この世代の他の提案された名称には、iGeneration、[48] Homeland Generation、[49] Net Gen、[48] Digital Natives、[48] Neo-Digital Natives、[50] [51] Pluralist Generation、[48] Internet Generation、[52] Centennials、[53] Post-Millennials がある。 インターネット世代という言葉はインターネットの大衆的普及後最初に誕生した世代という事実に対してのもの[54]である。 心理学教授で作家のジーン・トウェンジはiGeneration(または略してiGen)という用語を使い、当初はミレニアルズについての彼女の2006 年の著書『Generation Me』のタイトルとして使うつもりだったが、出版社のアトリア・パブリッシング・グループに却下された。当時、iPodやiMacはあったが、 iPhoneやiPadはなかった。Twengeは後に2017年の著書『iGen』でこの言葉を使った。 また、この名前は2009年に人口統計学者のCheryl Russellによって作られたと主張されている[48]。 2014年、作家のニール・ハウはウィリアム・ストラウスとのストラウス・ハウ世代論の続きとして、ホームランド・ジェネレーションという用語を作った。 ホームランドという言葉は、9月11日の攻撃を受けて国土安全保障省のような保護監視国家対策が実施された後に子供時代を迎える最初の世代であることを指 している[49]。 ピュー・リサーチ・センターが2019年にGoogle Trendsでこのコホートに対する様々な名称を調査したところ、アメリカではジェネレーションZという言葉が圧倒的に人気があることがわかった。メリア ム・ウェブスター辞書とオックスフォード辞書には、いずれもジェネレーションZの公式項目がある[45]。 日本では、この世代はネオ・デジタル・ネイティブと呼ばれ、デジタル・ネイティブと呼ばれる以前の世代より一歩進んだ世代とみなされている。デジタルネイ ティブは主にテキストや音声でコミュニケーションをとるが、ネオデジタルネイティブはビデオやテレビ電話、映画などを利用する。これは、ネオデジタル層に おけるPCからモバイル、テキストからビデオへの移行を強調するものである[50][51]。 ズーマーとは、ジェネレーションZのメンバーを指すために使われる非公式な用語で、しばしば皮肉やユーモア、嘲笑のトーンで使われる[2]。これはベビー ブーマーを指す略語ブーマーと、ジェネレーションZの「Z」を組み合わせたものである。これに先立ち、zoomerは2000年代に特に活動的なベビー ブーマーを表すために使われていた[1]。 現在の形におけるzoomerは2018年に人気が急上昇し、「zoomer」と吹き替えられたWojak風刺画を介してZ世代青年をあざける4chan インターネットミームに使われた[55][56] Merriam-Websterの記録はZ世代の意味におけるzoomerの使用が少なくとも2016年に溯ることを示唆している。2021年10月にメ リアム・ウェブスターの辞書に追加された[1]。 |

| Date and age range The Oxford Dictionaries describes Generation Z as "the generation born in the late 1990s or the early 21st century, perceived as being familiar with the use of digital technology, the internet, and social media from a very young age."[57] The Oxford Learner's Dictionaries describes Gen Z as "the group of people who were born between the late 1990s and the early 2010s".[58] The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines Generation Z as "the generation of people born in the late 1990s and early 2000s."[59] The Pew Research Center specified 1997 as their starting birth year for Generation Z, choosing this date for "different formative experiences", such as new technological and socioeconomic developments, as well as growing up in a world after the September 11 attacks.[60] Pew has not specified an endpoint for Generation Z, but used 2012 as a tentative endpoint for their 2019 report.[60] Major media outlets have cited Pew's definition including The New York Times,[61] The Wall Street Journal,[62] PBS,[63] NBC News,[64] NPR,[65] The Washington Post,[66] CNBC,[67] Axios,[68] Forbes,[69] Newsweek[70] and Time Magazine.[71] Statistics Canada cites Pew Research Center and describes Generation Z as spanning from 1997 to 2012.[72] The United States Library of Congress explains that "defining generations is not an exact science", although cites Pew's 1997-2012 definition to define Generation Z in one of their consumer research reports.[73] Gallup[74] and Ipsos MORI[75] start Generation Z at 1997; the Associated Press also use 1997 as the starting point for Gen Z.[76] USA Today cites 1997 to 2012 as Generation Z.[77] A US Census publication in 2020 described Generation Z as the “young and mobile” population with oldest members of the cohort born after 1996.[78] William H. Frey, senior fellow of the Brookings Institution cited Pew Research Center's definition in their 2020 Census analysis.[79][80] Psychologist Jean Twenge has defined Generation Z as the "iGeneration" using a range of those born between 1995 and 2012.[81] Australia's McCrindle Research Centre defines Generation Z as those born between 1995 and 2009.[82] Various media outlets have used 1995 as the starting birth year to describe Gen Z, including United Press International,[83] Financial Times,[84][85] Fortune,[86] CBS News,[87] Inc.,[88] and Bloomberg Law.[89] The World Economic Forum,[90] Deloitte,[91] McKinsey,[92] and PricewaterhouseCoopers[93] also use 1995 as the starting point for Gen Z. The Center for Generational Kinetics define Generation Z as those born from 1996 to 2015.[94] Individuals born in the Millennial and Generation Z cusp years have been sometimes identified as a "microgeneration" with characteristics of both generations. The most common name given for these cuspers is Zillennials.[95][96] |

年代と年齢層 オックスフォード辞書は、ジェネレーションZを「1990年代後半または21世紀初頭に生まれ、非常に若い頃からデジタル技術、インターネット、ソーシャ ルメディアの使用に精通していると認識されている世代」と説明している[57]。 オックスフォードラーナーズディクショナリーは、ジェネレーションZを「1990年代後半から2010年代初頭にかけて生まれた人々のグループ」と説明し ている[58]。 メリアム-ウェブスターオンライン辞書はジェネレーションZを「1990年代後半と2000年代初めに生まれた人々の世代」[59]として定義している。 ピュー・リサーチ・センターはジェネレーションZのための彼らの開始出生年として1997年を指定し、新しい技術や社会経済的発展、また9月11日の攻撃 の後の世界で育つといった「異なる形成的経験」のためにこの日を選んだ[60]。 ピューはジェネレーションZのエンドポイントを特定していないが、彼らの2019年のレポートでは暫定的に2012年をエンドポイントとして使用してい る。 [60] 主要なメディアは、ニューヨークタイムズ、[61] ウォールストリートジャーナル、[62] PBS、[63] NBCニュース、[64] NPR、[65] ワシントンポスト、[66] CNBC、[67] Axios、[68] Forbes、[69] ニュースウィーク [70] とタイム誌を含めてピュアの定義に言及していた。 71] 統計カナダは、ピュ・リサーチセンターを引用して、Z世代は1997年から2012年のスパンになると記述している。 72] アメリカ議会図書館は「世代の定義は正確な科学ではない」と説明しているが、消費者調査レポートのひとつでジェネレーションZを定義するためにピューの 1997年から2012年の定義を引用している[73] ギャラップ[74]とイプソスモリ[75]はジェネレーションZを1997年から始めており、AP通信も1997年をZ世代の出発点として使用している [76]。 [76] USA Todayは1997年から2012年までをジェネレーションZとして挙げている[77]。2020年のアメリカの国勢調査の出版物はジェネレーションZ を1996年以降に生まれたコーホートの最も古いメンバーを持つ「若くてモバイルな」人口として説明していた[78]。ブルッキングス研究所のシニアフェ ローのウィリアムHフレイはピュー・リサーチセンターの定義を彼らの2020年国勢調査分析で引用している[79][80]。 心理学者のジーン・トウェンジはジェネレーションZを1995年から2012年の間に生まれた者の範囲を使って「iGeneration」と定義している [81]。オーストラリアのマクリンドル研究センターはジェネレーションZを1995年から2009年の間に生まれた者と定義している[82]。様々なメ ディアは、ジェネラルZについて述べるために1995年を開始生年として使用していた。United Press International, [83] Financial Times, [84] [85] Fortune, [86] CBS News,[87] Inc.などのメディアがある。 [88] and Bloomberg Law.[89] World Economic Forum, [90] Deloitte, [91] McKinsey, [92] and PricewaterhouseCoopers[93] also use 1995 as the starting point for Gen Z. The Center for Generational Kinetics define Generation Z as those born from 1996 to 2015[94]は、Z世代を1996年から2015年までと定義しています。 ミレニアル世代とジェネレーションZの尖点の年に生まれた個人は、両方の世代の特徴を持つ「マイクロジェネレーション」として識別されることもある。これ らのカスパーに与えられる最も一般的な名称は、ジレニアルである[95][96]。 |

| Happiness and personal values The Economist has described Generation Z as a more educated, well-behaved, stressed and depressed generation in comparison to previous generations.[14] In 2016, the Varkey Foundation and Populus conducted an international study examining the attitudes of over 20,000 people aged 15 to 21 in twenty countries: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Nigeria, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They found that Gen Z youth were happy overall with the states of affairs in their personal lives (59%). The most unhappy young people were from South Korea (29%) and Japan (28%) while the happiest hailed from Indonesia (90%) and Nigeria (78%) (see right). In order to determine the overall 'happiness score' for each country, researchers subtracted the percentage of people who said they were unhappy from that of those who said they were happy. The most important sources of happiness were being physically and mentally healthy (94%), having a good relationship with one's family (92%), and one's friends (91%). In general, respondents who were younger and male tended to be happier. Religious faith came in last at 44%. Nevertheless, religion was a major source of happiness for Gen Z youth from Indonesia (93%), Nigeria (86%), Turkey (71%), China, and Brazil (both 70%). The top reasons for anxiety and stress were money (51%) and school (46%); social media and having access to basic resources (such as food and water) finished the list, both at 10%. Concerns over food and water were most serious in China (19%), India (16%), and Indonesia (16%); young Indians were also more likely than average to report stress due to social media (19%).[97] According to the aforementioned study by the Varkey Foundation, the most important personal values to these people were helping their families and themselves get ahead in life (both 27%), followed by honesty (26%). Looking beyond their local communities came last at 6%. Familial values were especially strong in South America (34%) while individualism and the entrepreneurial spirit proved popular in Africa (37%). People who influenced youths the most were parents (89%), friends (79%), and teachers (70%). Celebrities (30%) and politicians (17%) came last. In general, young men were more likely to be influenced by athletes and politicians than young women, who preferred books and fictional characters. Celebrity culture was especially influential in China (60%) and Nigeria (71%) and particularly irrelevant in Argentina and Turkey (both 19%). For young people, the most important factors for their current or future careers were the possibility of honing their skills (24%), and income (23%) while the most unimportant factors were fame (3%) and whether or not the organization they worked for made a positive impact on the world (13%). The most important factors for young people when thinking about their futures were their families (47%) and their health (21%); the welfare of the world at large (4%) and their local communities (1%) bottomed the list.[97] |

幸せと個人の価値観 エコノミストは、ジェネレーションZを、以前の世代と比較して、より教育的で、品行方正で、ストレスや鬱の多い世代と説明している[14]。 2016年に、バーキー財団とポピュラスは、20カ国の15歳から21歳の2万人以上の人々の意識を調べる国際調査を実施した。アルゼンチン、オーストラ リア、ブラジル、カナダ、中国、フランス、ドイツ、インド、インドネシア、イスラエル、イタリア、日本、ニュージーランド、ナイジェリア、ロシア、南アフ リカ、韓国、トルコ、イギリス、アメリカの20カ国の15歳から21歳の20,000人以上の人々の意識を調査する国際調査を実施した。その結果、Z世代 の若者は私生活の状況に全体的に満足していることがわかった(59%)。最も不幸なのは韓国(29%)と日本(28%)、最も幸福なのはインドネシア (90%)とナイジェリア(78%)であった(右図)。各国の総合的な「幸福度」を決定するために、研究者は「幸福である」と答えた人の割合から「不幸で ある」と答えた人の割合を差し引いた。幸福の源泉として最も重要なのは、「心身ともに健康であること」(94%)、「家族との関係が良好であること」 (92%)、「友人がいること」(91%)であった。一般に、回答者の年齢が若いほど、また男性ほど、幸福度が高い傾向がある。宗教は44%で最下位。し かし、インドネシア(93%)、ナイジェリア(86%)、トルコ(71%)、中国、ブラジル(ともに70%)のZ世代の若者にとって、宗教は幸福の大きな 源となっている。不安やストレスの理由のトップは、お金(51%)と学校(46%)で、ソーシャルメディアと基本的な資源(食べ物や水など)へのアクセス は、ともに10%でリストアップされている。食料と水に関する心配は、中国(19%)、インド(16%)、インドネシア(16%)で最も深刻で、インドの 若者もソーシャルメディアによるストレスを報告する傾向が平均より強かった(19%)[97]。 前述のバーキー財団の調査によると、彼らにとって最も重要な個人的価値は、家族と自分の出世を助けること(ともに27%)、次いで正直であること (26%)でした。また、「地域社会への貢献」は6%で最下位でした。特に南米では家族的な価値観が強く(34%)、アフリカでは個人主義や起業家精神が 人気を集めている(37%)。若者に最も影響を与えたのは、両親(89%)、友人(79%)、教師(70%)であった。有名人(30%)、政治家 (17%)は最下位だった。一般に、若い男性はスポーツ選手や政治家から影響を受ける傾向が強く、若い女性は本やフィクションの登場人物から影響を受ける 傾向が強かった。有名人文化は、中国(60%)とナイジェリア(71%)で特に影響力があり、アルゼンチンとトルコ(ともに19%)では特に無関係であっ た。若者にとって、現在または将来のキャリアにとって最も重要な要素は、自分のスキルを磨くことができるかどうか(24%)、収入(23%)であり、最も 重要でない要素は、名声(3%)、働いている組織が世界に良い影響を与えているかどうか(13%)であった。若者が自分の将来について考えるときに最も重 要な要素は、家族(47%)と健康(21%)であり、世界全体の福祉(4%)と地域社会(1%)が最下位であった[97]。 |

|

Overall happiness among young

people around the world in 2016. Data available at https://www.varkeyfoundation.org/media/4487/global-young-people-report-single-pages-new.pdf |

| Common culture During the 2000s and especially the 2010s, youth subcultures that were as influential as what existed during the late 20th century became scarcer and quieter, at least in real life though not necessarily on the Internet, and more ridden with irony and self-consciousness due to the awareness of incessant peer surveillance.[17][18] In Germany, for instance, youth appears more interested in a more mainstream lifestyle with goals such as finishing school, owning a home in the suburbs, maintaining friendships and family relationships, and stable employment, rather than popular culture, glamor, or consumerism.[98] Boundaries between the different youth subcultures appear to have been blurred, and nostalgic sentiments have risen.[17][18] Although an aesthetic dubbed 'cottagecore' in 2018 has been around for many years,[99] it has become a subculture of Generation Z,[100] especially on various social media networks in the wake of the mass lockdowns imposed to combat the spread of COVID-19.[101] It is a form of escapism[99] and aspirational nostalgia.[102] Cottagecore became even more popular thanks to the commercial success of the 2020 album Folklore by singer and songwriter Taylor Swift.[103][104][105] Nostalgia culture among Generation Z even extends to the usage of automobiles; in some countries, such as Indonesia, there are social media communities surrounding the purchasing used cars from earlier decades.[106] A survey conducted by OnePoll in 2018 found that while museums and heritage sites remained popular among Britons between the ages of 18 and 30, 19% did not visit one in the previous year. There was a big gender gap in attitudes, with 16% of female respondents and 26% of male respondents saying they never visited museums. Generation Z preferred staying home and watching television or browsing social media networks to visiting museums or galleries. The researchers also found that cheaper tickets, more interactive exhibitions, a greater variety of events, more food and beverage options, more convenient opening hours, and greater online presence could attract the attention of more young people.[107] On the other hand, vintage fashion is growing in popularity among Millennial and Generation Z consumers.[108] A 2019 report by Childwise found that children between the ages of five and sixteen in the U.K. spent an average of three hours each day online. Around 70% watched Netflix in the past week and only 10% watched their favorite programs on television. Among those who watched on-demand shows, 58% did so on a mobile phone, 51% on a television set, 40% via a tablet, 35% on a gaming console, and 27% on a laptop. About one out of four came from families with voice-command computer assistants such as Alexa. YouTube and Snapchat are the most popular gateways for music and video discovery. Childwise also found that certain television series aired between the 1990s and early 2000s, such as Friends, proved popular among young people of the 2010s.[109] Figures from Nielsen and Magna Global revealed that the viewership of children's cable television channels such as Disney Channel, Cartoon Network, and Nickelodeon continued their steady decline from the early 2010s, with little to no alleviating effects due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced many parents and their children to stay at home. On the other hand, streaming services saw healthy growth.[110][111] Disney Channel in particular lost a third of their viewers in 2020, leading to closures in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Southeast Asia.[111] During the first two decades of the 21st century, writing and reading fan fiction and creating fandoms of fictional works became a prevalent activity worldwide. Demographic data from various depositories revealed that those who read and wrote fan fiction were overwhelmingly young, in their teens and twenties, and female.[112][113][114] For example, an analysis published in 2019 by data scientists Cecilia Aragon and Katie Davis of the site fanfiction.net showed that some 60 billion words of contents were added during the previous 20 years by 10 million English-speaking people whose median age was 151⁄2 years.[114] Fan fiction writers base their work on various internationally popular cultural phenomena such as K-pop, Star Trek, Harry Potter, Twilight, Doctor Who, Star Wars, and various works of Walt Disney, known as 'canon', as well as other things they considered important to their lives, like natural disasters.[112][113][114] Much of fan fiction concerns the romantic pairing of fictional characters of interest, or 'shipping'.[115] Aragon and Davis argued that writing fan fiction stories could help young people combat social isolation and hone their writing skills outside of school in an environment of like-minded people where they can receive (anonymous) constructive feedback, what they call 'distributed mentoring'.[114] Informatics specialist Rebecca Black added that fan fiction writing could also be a useful resource for English-language learners. Indeed, the analysis of Aragon and Davis showed that for every 650 reviews a fan fiction writer receives, their vocabulary improved by one year of age, though this may not generalize to older cohorts.[116] On the other hand, children browsing fan fiction contents might be exposed to cyberbullying, crude comments, and other inappropriate materials.[115] Generation Z has a plethora of options when it comes to music consumption, allowing for a highly personalized experience.[117] According to digital media company Sweety High's 2018 Gen Z Music Consumption & Spending Report, Spotify ranked first for music listening among Gen Z females, terrestrial radio ranked second, while YouTube was reported to be the preferred platform for music discovery.[118] Additional research showed that within the past few decades, popular music has gotten slower; that majorities of listeners young and old preferred older songs rather than keeping up with new ones; that the language of popular songs was becoming more negative psychologically; and that lyrics were becoming simpler and more repetitive, approaching one-word sheets, something measurable by observing how efficiently lossless compression algorithms (such as the LZ algorithm) handled them.[119] Sad music is quite popular among adolescents, though it can dampen their moods, especially among girls.[117] A 2020 survey conducted by The Center for Generational Kinetics, on 1000 members of Generation Z and 1000 Millennials, suggests that Generation Z still would like to travel, despite the COVID-19 pandemic and the recession it induced. However, Generation Z is more likely to look carefully for package deals that would bring them the most value for their money, as many of them are already saving money for buying a house and for retirement, and they prefer more physically active trips. Mobile-friendly websites and social-media engagements are both important.[120] In South Korea, people below the age of 40 are increasingly interested in relocating from the cities, especially Seoul, to the countryside and working on the farm. Working in a conglomerate like Samsung or Hyundai no longer appeals to young people, many of whom prefer to avoid becoming a workaholic or are pessimistic about their ability to be as successful as their fathers.[121] They take advantage of the Internet to market and sell their fresh produce. In the United Kingdom, teenagers now prefer to get their news from social-media networks such as Instagram and TikTok and the video-sharing site YouTube rather than more traditional media, such as radio or television.[122] |

コモンカルチャー 2000年代、特に2010年代には、20世紀後半に存在したような影響力のある若者のサブカルチャーは、少なくともインターネット上とは限らないが実生 活では希薄で静かになり、絶え間ない仲間の監視の意識から皮肉と自意識にまみれるようになった[17][18]。 [例えばドイツでは、若者は大衆文化、グラマー、消費主義よりも、学校を卒業し、郊外に家を持ち、友人関係や家族関係を維持し、安定した雇用といった目標 を持ったより主流のライフスタイルに関心があるようである[98]。 異なる若者のサブカルチャーの間の境界は曖昧になっているように見え、ノスタルジックな感情が高まっている[17][18]。 2018年に「コッタグコア」と呼ばれる美学は何年も前から存在していたが[99]、特にCOVID-19の拡散と戦うために課せられた大量のロックダウ ンに伴って様々なソーシャルメディアネットワークにおいてZ世代のサブカルチャーになっている[100]。 [101] それは逃避主義[99]と願望的なノスタルジアの一形態である[102] コタツコアは、シンガーソングライターのテイラー・スウィフトによる2020年のアルバム『フォークロア』の商業的成功のおかげでさらに人気となった [103][104][105]。 ジェネレーションZの間のノスタルジア文化は、自動車の使用にまで及んでいる。インドネシアのようないくつかの国では、以前の数十年の中古車の購入を取り 巻くソーシャルメディアのコミュニティが存在している[106]。 2018年にOnePollが実施した調査では、18歳から30歳までの英国人の間で博物館や遺産は依然として人気があるが、19%は前年度に博物館を訪 問していないことがわかった。意識には大きな男女差があり、女性回答者の16%、男性回答者の26%が「博物館を訪れたことがない」と回答している。Z世 代は、博物館や美術館を訪れるよりも、家にいてテレビを見たり、ソーシャルメディアネットワークを閲覧したりすることを好んでいた。研究者は、より安いチ ケット、よりインタラクティブな展示、より多様なイベント、より多くの飲食の選択肢、より便利な開館時間、およびより多くのオンラインプレゼンスが、より 多くの若者の注目を集めることができることも明らかにした[107]。 一方、ミレニアルとジェネレーションZの消費者の間でヴィンテージファッションが人気を高めている[108]。 Childwiseによる2019年のレポートによると、英国の5歳から16歳までの子どもたちは毎日平均3時間をオンラインで過ごしていることがわかっ た。約70%が過去1週間にNetflixを視聴し、テレビで好きな番組を視聴したのはわずか10%でした。オンデマンド番組を視聴した人のうち、58% が携帯電話、51%がテレビ、40%がタブレット、35%がゲーム機、27%がノートパソコンで視聴していた。4人に1人は、Alexaなどの音声コマン ド型コンピュータアシスタントを使用している家庭の出身です。音楽とビデオの発見のゲートウェイとして最も人気があるのは、YouTubeと Snapchatです。チャイルドワイズはまた、フレンズなど1990年代から2000年代初頭に放送された特定のテレビシリーズが2010年代の若者の 間で人気があることを証明した[109]。 ニールセンとマグナ・グローバルの数字は、ディズニー・チャンネル、カートゥーンネットワーク、ニコロデオンなどの子ども向けケーブルテレビチャンネルの 視聴率が2010年代初頭から着実に減少し続け、多くの親とその子どもが家にいることを強いられたコビド19の流行による緩和効果はほとんどないことを明 らかにした。一方でストリーミングサービスは健全な成長を遂げた[110][111]。 特にディズニー・チャンネルは2020年に視聴者の3分の1を失い、北欧、イギリス、オーストラリア、東南アジアで閉鎖に至った[111]。 21世紀の最初の20年間、ファン・フィクションを書いたり読んだり、フィクション作品のファンダムを作ったりすることが、世界中で広く行われるように なった。様々な寄託先からの人口統計学的データから、ファン・フィクションを読んだり書いたりする人々は圧倒的に若い、10代から20代の、女性であるこ とが明らかになった[112][113][114]。例えば、データ科学者のセシリア・アラゴンとケイティ・デーヴィスが2019年に発表したサイト fanfiction.netの分析は、年齢の中央値が151/2年だった1000万の英語圏の人々が過去20年間に追加したコンテンツ約600億ワード が示されることを示していた。 [114] ファンフィクション作家は、K-POP、スタートレック、ハリーポッター、トワイライト、ドクター・フー、スターウォーズ、ウォルト・ディズニーの様々な 作品など国際的に人気のある文化現象、また自然災害など自分たちの生活にとって重要だと考えるものに基づいて作品を制作している。 [アラゴンとデイヴィスは、ファンフィクションストーリーを書くことは、若者が社会的孤立と戦い、学校の外で同じ考えを持つ人々の環境の中で文章力を磨 き、彼らが「分散型メンタリング」と呼ぶ、(匿名の)建設的なフィードバックを受けるのに役立つと主張した[114] 情報学の専門家レベッカ・ブラックは、ファンフィクションライティングが英語学習者にとって役立つリソースにもなりうると付け加えている。実際、アラゴン とデイヴィスの分析によれば、ファンフィクションライターが650件のレビューを受けるごとに、彼らの語彙は1歳分向上することが示されているが、これは より年齢の高いコホートには一般化しないかもしれない[116]。 一方で、ファンフィクションコンテンツを閲覧する子どもは、ネットいじめ、下品なコメント、その他の不適切な材料にさらされるかもしれない[115]。 ジェネレーションZは、音楽消費に関して多くの選択肢を持っており、高度に個人化された体験を可能にしている[117]。 デジタルメディア企業のスイーティ・ハイの「2018 Gen Z Music Consumption & Spending Report」によると、ジェネレーションZ女性の間で音楽を聴くためにスポティファイが1位、地上波ラジオが2位、YouTubeが音楽発見のために好 ましいプラットフォームであると報告された。 [118]追加の調査は、過去数十年の間にポピュラー音楽が遅くなったこと、老若男女のリスナーの大多数が新しい曲に追いつくよりも古い曲を好むこと、ポ ピュラー曲の言葉が心理的によりネガティブになっていること、歌詞がより単純で反復的になり、一語板に近づいていること、ロスレス圧縮アルゴリズム(LZ アルゴリズムなど)がいかに効率的にそれらを処理するかが観測できるものを示した[119] 哀愁の音楽は思春期にかなり人気があるが、特に女の子の間で彼らの気分を弱めることは可能だ[117]. ジェネレーション・キネティクス・センターがジェネレーションZのメンバー1000人とミレニアル世代1000人に対して行った2020年の調査は、ジェ ネレーションZが、COVID-19の大流行とそれが誘発した不況にもかかわらず、依然として旅行が好きであることを示唆している。しかし、ジェネレー ションZの多くは、住宅購入や退職のためにすでにお金を貯めており、より体を動かす旅行を好むため、最もお得なパッケージ旅行を慎重に探す傾向がある。モ バイルフレンドリーなウェブサイトとソーシャルメディアへの関与は、いずれも重要である[120]。 韓国では、40歳以下の人たちは、都市、特にソウルから田舎に移って、農場で働くこと にますます関心を寄せている。サムスンやヒュンダイのようなコングロマリットで働くことはもはや若者にとって魅力的ではなく、彼らの多くは仕事中毒になる ことを避けたがるか、父親のように成功する能力について悲観的である[121]。彼らはインターネットを活用して、新鮮な野菜を販売し、マーケティングを 行っている。イギリスでは、いまやティーンエイジャーはラジオやテレビといった伝統的なメディアよりも、インスタグラムやティックトックといったソーシャ ルメディアネットワークや動画共有サイトであるYouTubeからニュースを入手することを好むようになっている[122]。 |

| Reading habits In New Zealand, child development psychologist Tom Nicholson noted a marked decline in vocabulary usage and reading among schoolchildren, many of whom are reluctant to use the dictionary. According to a 2008 survey by the National Education Monitoring Project, about one in five four-year and eight-year pupils read books as a hobby, a ten-percent drop from 2000.[37] In the United Kingdom, a survey of 2,000 parents and children from 2013 by Nielsen Book found that 36% of children read books for pleasure on a daily basis, 60% on a weekly basis, and 72% were read to by their parents at least once per week. Among British children, the most popular leisure activities were watching television (36%), reading (32%), social networking (20%), watching YouTube videos (17%), and playing games on mobile phones (16%). Between 2012 and 2013, children reported spending more time with video games, YouTube, and texting but less time reading (down eight percent). Among children between the ages of 11 and 17, the share of non-readers grew from 13% to 27% between 2012 and 2013, those who read once to thrice a month (occasional readers) dropped from 45% to 38%, those who read for no more than an average of 15 minutes per week (light readers) rose from 23% to 27%, those who read between 15 and 45 minutes per week (medium readers) declined from 23% to 17%, and those who read at least 45 minutes a week (heavy readers) grew slightly from 15% to 16%.[123] A survey by the National Literacy Trust from 2019 showed that only 26% of people below the age of 18 spent at least some time each day reading, the lowest level since records began in 2005. Interest in reading for pleasure declined with age, with five- to eight-year-olds being twice as likely to say they enjoyed reading compared to fourteen- to sixteen-year-olds. There was a significant gender gap in voluntary reading, with only 47% of boys compared to 60% of girls said they read for pleasure. One in three children reported having trouble finding something interesting to read.[33] The aforementioned Nielsen Book survey found that the share of British households with at least one electronic tablet rose from 24% to 50% between 2012 and 2013.[123] According to a 2020 Childwise report based on interviews with 2,200 British children between the ages of five and sixteen, young people today are highly dependent on their mobile phones. Most now get their first device at the age of seven. By the age of eleven, having a cell phone became almost universal. Among those aged seven to sixteen, the average time spent on the phone each day is three and a third hours. 57% said they went to bed with their phones beside them and 44% told the interviewers they felt "uncomfortable" in the absence of their phones. Due to the nature of this technology—cell phones are personal and private devices—it can be difficult for parents to monitor their children's activities and shield them from inappropriate content.[124] |

読書習慣 ニュージーランドでは、児童発達心理学者のトム・ニコルソンが、小学生の間で語彙の使用量と読書量が著しく減少しており、その多くが辞書を使いたがらない ことを指摘している[37]。国家教育モニタリングプロジェクトによる2008年の調査によると、4年生と8年生の生徒の約5人に1人が趣味で本を読んで おり、2000年から10%減少している[37]。 イギリスでは、ニールセン・ブックが2013年に2000人の親子を対象に行った調査によると、36%の子供が日常的に、60%が週単位で、72%が週に 1回以上親から本を読んでもらうことを趣味としていることがわかった。イギリスの子どもたちの間で、最も人気のある余暇活動は、テレビ鑑賞(36%)、読 書(32%)、ソーシャルネットワーク(20%)、YouTube動画の視聴(17%)、携帯電話でゲームをする(16%)でした。2012年から 2013年にかけて、子どもたちはビデオゲーム、YouTube、メールに費やす時間は増えたが、読書に費やす時間は減った(8%減)と回答しています。 11歳から17歳の子どもでは、2012年から2013年にかけて、読書をしない人の割合が13%から27%に増え、月に1~3回読む人(臨時読者)は 45%から38%に減り、週に平均15分以上読まない人(ライトリーダー)は23%から27%に増え、週に15~45分読む人(ミドルリーダー)は23% から17%に減り、週に45分以上読む人(ヘビーリーダー)は15%から16%と微増している[123]。 2019年のナショナル・リテラシー・トラストによる調査では、18歳以下の人々のうち、毎日少なくともいくらかの時間を読書に費やしているのは26%の みであり、2005年に記録が始まって以来最低の水準であることが示された。趣味の読書への関心は年齢とともに低下し、5~8歳は14~16歳に比べて読 書が楽しいと答える割合が2倍になった。また、読書を趣味としている人の割合は、男子が47%であるのに対し、女子は60%と、男女間で大きな差がありま した。3人に1人の子どもは、何か面白い読み物を見つけるのに苦労していると報告した[33]。 前述のNielsen Bookの調査によると、少なくとも1台の電子タブレットを持つ英国の家庭の割合は、2012年から2013年の間に24%から50%に上昇した [123]。5歳から16歳までの英国の子供2,200人へのインタビューに基づく2020年のChildwiseレポートによると、今日の若者は携帯電 話への依存度が高いことが分かっている。ほとんどの子どもは、7 歳で最初の端末を手にする。11歳までには、携帯電話を持つことがほぼ一般的になっています。7歳から16歳では、1日の平均使用時間は3.3時間。ま た、57%が「携帯電話を横に置いて寝る」と答え、44%が「携帯電話がないと落ち着かない」と答えている。携帯電話は個人的でプライベートな機器である ため、親が子どもの行動を監視し、不適切なコンテンツから子どもを守ることは難しい[124]。 |

|

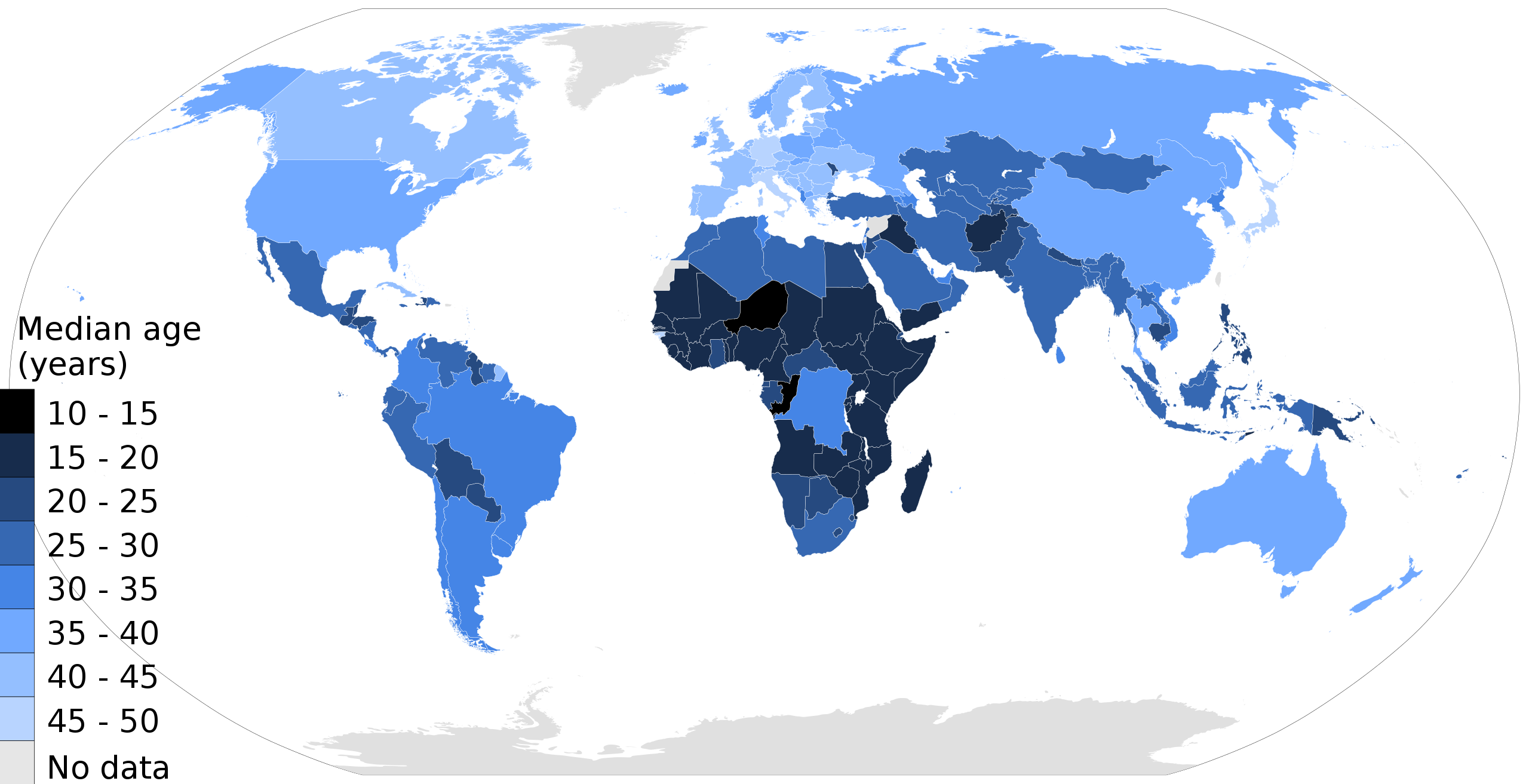

Median age by country in years

in 2017. The youth bulge is evident in parts of Southeast Asia, the

Middle East, Africa, and Latin America. - Ms Sarah Welch - Own work,

data from United Nations ESA (2017) |

|

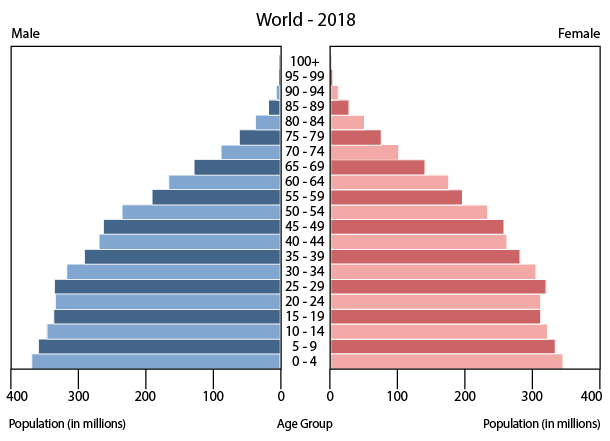

Population pyramid of the World

in 2018.- CIA Factbook - CIA World Factbook 2019 |

| Although many countries have

aging populations and declining birth rates, Generation Z is currently

the largest generation on Earth.[125] Bloomberg's analysis of United

Nations data predicted that, in 2019, members of Generation Z accounted

for 2.47 billion (32%) of the 7.7 billion inhabitants of Earth,

surpassing the Millennial population of 2.43 billion. The generational

cutoff of Generation Z and Millennials for this analysis was placed at

2000 to 2001.[126][127] Africa Generation Z currently comprises the majority of the population of Africa.[128] In 2017, 60% of the 1.2 billion people living in Africa fell below the age of 25.[129] In 2019, 46% of the South African population, or 27.5 million people, are members of Generation Z.[130] Statistical projections from the United Nations in 2019 suggest that, in 2020, the people of Niger had a median age of 15.2, Mali 16.3, Chad 16.6, Somalia, Uganda, and Angola all 16.7, the Democratic Republic of the Congo 17.0, Burundi 17.3, Mozambique and Zambia both 17.6. This means that more than half of their populations were born in the first two decades of the 21st century. These are the world's youngest countries by median age.[131] Asia According to a 2020 McKinsey & Company analysis, Generation Z (defined as born from 1996 to 2012) will account for a quarter of the population of the Asia-Pacific region by 2025.[132] As a result of cultural ideals, government policy, and modern medicine, there have been severe gender population imbalances in China and India. According to the United Nations, in 2018, there were 112 Chinese males for every hundred females ages 15 to 29; in India, there were 111 males for every hundred females in that age group. China had a total of 34 million excess males and India 37 million, more than the entire population of Malaysia. Together, China and India had a combined 50 million excess males under the age of 20. Such a discrepancy fuels loneliness epidemics, human trafficking (from elsewhere in Asia, such as Cambodia and Vietnam), and prostitution, among other societal problems.[133] |

多くの国が高齢化と出生率の低下を抱えているが、ジェネレーションZは

現在地球上で最大の世代である[125]。ブルームバーグの国連データの分析では、2019年に、ジェネレーションZのメンバーは地球の人口77億人のう

ち24億7000万人(32%)を占め、ミレニアム世代の人口24億3000万人を上回ることが予測された。この分析のためのジェネレーションZとミレニ

アルズの世代的な切り口は、2000年から2001年に置かれた[126][127]。 アフリカ ジェネレーションZは現在アフリカの人口の大部分を構成している[128]。 2017年には、アフリカに住む12億人のうち60%が25歳以下に該当していた[129]。 2019年には、南アフリカの人口の46%、すなわち2750万人がジェネレーションZのメンバーである[130]。 2019年の国連の統計予測は、2020年に、ニジェールの人々の年齢の中央値が15.2、マリ16.3、チャド16.6、ソマリア、ウガンダ、アンゴラ はいずれも16.7、コンゴ民主共和国は17.0、ブルンジ17.3、モザンビークとザンビアはいずれも17.6であることを示唆した。つまり、人口の半 数以上が21世紀に入ってから20年以内に生まれたことになる。これらは、年齢の中央値で見て、世界で最も若い国々である[131]。 アジア 2020年のマッキンゼー・アンド・カンパニーの分析によれば、ジェネレーションZ(1996年から2012年に生まれたと定義される)は2025年まで にアジア太平洋地域の人口の4分の1を占めるようになる[132]。 文化的な理想、政府の政策、現代医学の結果として、中国とインドでは深刻な男女の人口のアンバランスが発生している。国連によれば、2018年には、15 歳から29歳までの女性100人に対して、中国の男性は112人であり、インドでは、その年齢層の女性100人に対して、男性は111人であった。中国の 男性超過数は3400万人、インドは3700万人で、マレーシアの全人口を上回った。中国とインドを合わせると、20歳未満の男性が5,000万人もいる ことになる。このような不一致は、孤独の伝染、人身売買(カンボジアやベトナムなどアジアの他の地域から)、売春などの社会的な問題を煽っている [133]。 |

|

The population pyramid of Japan

illustrates the age and sex structure of population and may provide

insights about political and social stability, as well as economic

development. The population is distributed along the horizontal axis,

with males shown on the left and females on the right. The male and

female populations are broken down into 5-year age groups represented

as horizontal bars along the vertical axis, with the youngest age

groups at the bottom and the oldest at the top. The shape of the

population pyramid gradually evolves over time based on fertility,

mortality, and international migration trends.- Central Intelligence

Agency (CIA). - CIA World Factbook, 2017. |

| Europe Out of the approximately 66.8 million people of the UK in 2019, there were approximately 12.6 million people (18.8%) in Generation Z, if defined as those born from 1997 to 2012.[134] Generation Z is the most diverse generation in the European Union in regards to national origin.[135] In Europe generally, 13.9% of those ages 14 and younger in 2019 (which includes older Generation Alpha) were born in another EU Member State, and 6.6% were born outside the EU. In Luxembourg, 20.5% were born in another country, largely within the EU (6.6% outside the EU compared to 13.9% in another member state); in Ireland, 12.0% were born in another country; in Sweden, 9.4% were born in another country, largely outside the EU (7.8% outside the EU compared to 1.6% in another member state). In Finland, 4.5% of people aged 14 and younger were born abroad and 10.6% had a foreign-background in 2021.[136] However, Gen Z from eastern Europe is much more homogenous: in Croatia, only 0.7% of those aged 14 and younger were foreign-born; in the Czech Republic, 1.1% aged 14 and younger were foreign-born.[135] Higher portions of those ages 15 to 29 in 2019 (which includes younger Millennials) were foreign born in Europe. Luxembourg had the highest share of young people (41.9%) born in a foreign country. More than 20% of this age group were foreign-born in Cyprus, Malta, Austria and Sweden. The highest shares of non-EU born young adults were found in Sweden, Spain and Luxemburg. Like with those under age 14, countries in eastern Europe generally have much smaller populations of foreign-born young adults. Poland, Lithuania, Slovakia, Bulgaria and Latvia had the lowest shares of foreign-born young people, at 1.4 to 2.5% of the total age group.[135] |

ヨーロッパ 2019年の英国の約6680万人のうち、1997年から2012年に生まれた者と定義すれば、ジェネレーションZの人々は約1260万人(18.8%) であった[134]。 ジェネレーションZは、国の出身に関して欧州連合で最も多様な世代である[135]。 欧州一般では、2019年に14歳以下の者(より高齢のジェネレーション・アルファを含む)の13.9%が他のEU加盟国で生まれ、6.6%がEU外で生 まれていた。ルクセンブルクでは、20.5%が他国、主にEU域内で生まれ(他加盟国の13.9%に対してEU域外は6.6%)、アイルランドでは 12.0%が他国で生まれ、スウェーデンでは9.4%が他国、主にEU域外で生まれ(他加盟国の1.6%に対してEU域外は7.8%)であった。フィンラ ンドでは、14歳以下の人々の4.5%が外国で生まれ、10.6%が2021年に外国の背景を持っていた[136]。 しかし、東ヨーロッパのZ世代はより均質で、クロアチアでは14歳以下の人々の0.7%が外国生まれで、チェコ共和国では14歳以下の人々は1.1%で あった[135]。 2019年の15歳から29歳の人々(より若いミレニアル世代を含む)のより高い部分は、ヨーロッパで外国生まれであった。ルクセンブルクは、外国で生ま れた若者の割合が最も高かった(41.9%)。キプロス、マルタ、オーストリア、スウェーデンでは、この年齢層の20%以上が外国生まれだった。EU圏外 で生まれた若者の割合が最も高かったのは、スウェーデン、スペイン、ルクセンブルクであった。14歳以下と同様、東欧諸国では一般に外国生まれの若年層の 人口がかなり少ない。ポーランド、リトアニア、スロバキア、ブルガリア、ラトビアは外国生まれの若者の割合が最も低く、年齢層全体の1.4から2.5%で あった[135]。 |

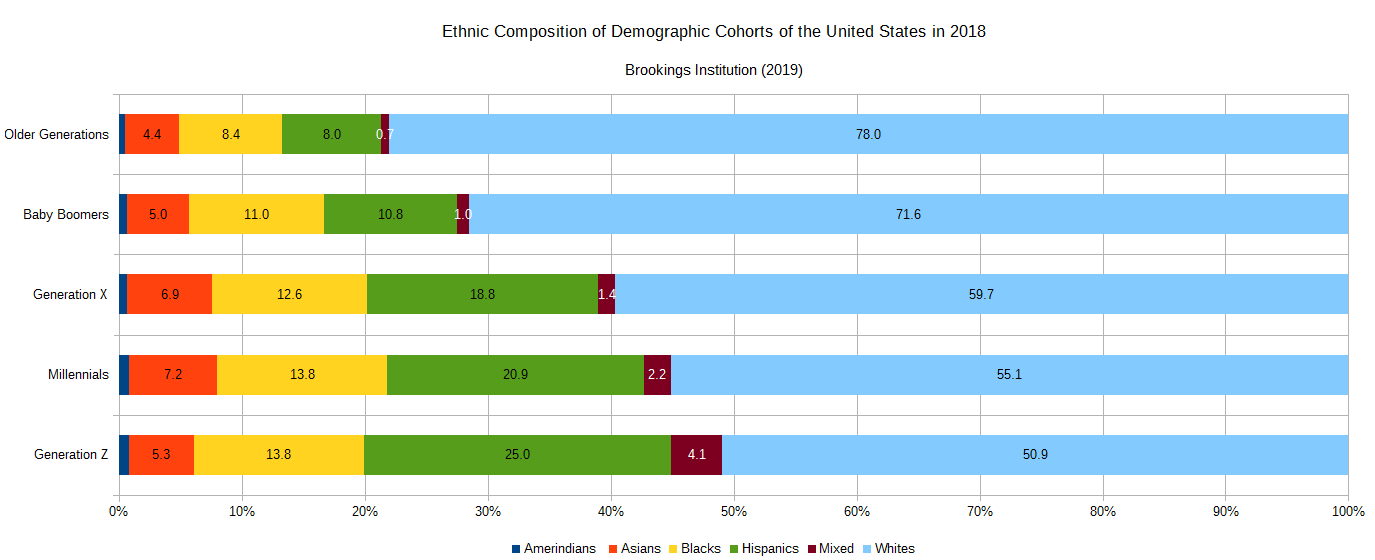

| North America A report by demographer William Frey of the Brookings Institution stated that in the United States, the Millennials are a bridge between the largely white pre-Millennials (Generation X and their predecessors) and the more diverse post-Millennials (Generation Z and their successors).[138] Frey's analysis of U.S. Census data suggests that as of 2019, 50.9% of Generation Z is white, 13.8% is black, 25.0% Hispanic, and 5.3% Asian.[139] 29% of Generation Z are children of immigrants or immigrants themselves, compared to 23% of Millennials when they were at the same age.[140] Members of Generation Z are slightly less likely to be foreign-born than Millennials;[141] the fact that more American Latinos were born in the U.S. rather than abroad plays a role in making the first wave of Generation Z appear better educated than their predecessors. However, researchers warn that this trend could be altered by changing immigration patterns and the younger members of Generation Z choosing alternate educational paths.[142] As a demographic cohort, Generation Z is smaller than the Baby Boomers and their children, the Millennials.[143] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Generation Z makes up about one quarter of the U.S. population, as of 2015.[144] There was an 'echo boom' in the 2000s, which certainly increased the absolute number of future young adults, but did not significantly change the relative sizes of this cohort compared to their parents.[145] According to a 2022 Gallup survey, 20.8%, or about one in five, members of Gen Z identify as LGBTQ+.[146] |

北アメリカ ブルッキングス研究所の人口統計学者ウィリアム・フレイの報告書は、米国において、ミレニアルズは、大部分が白人のプレミレニアルズ(ジェネレーションX とその先達)と、より多様なポストミレニアルズ(ジェネレーションZとその後継者)の間の橋渡し役であると述べている。 138] フレイの米国国勢調査データの分析によれば、2019年時点で、ジェネレーションZの50.9%は白人、13.8%は黒人、25.0%はヒスパニック、 5.3%はアジア人である[139] ジェネレーションZの29%は移民の子供、または自身が移民であるが、同じ年齢であったミレニアルの23%と比べて、移民の子供は少ない[140] [149]。 ジェネレーションZのメンバーは、ミレニアル世代よりも外国生まれの割合がわずかに低い[141]。より多くのアメリカのラテン系住民が外国ではなくアメ リカで生まれたという事実は、ジェネレーションZの第一波が彼らの前任者よりも教育水準が高いと思わせる役割を担っている。しかし、研究者は、移民のパ ターンの変化やジェネレーションZの若いメンバーが別の教育の道を選ぶことによってこの傾向が変化する可能性があると警告している[142]。 米国国勢調査局によれば、ジェネレーションZは、2015年時点で、米国の人口の約4分の1を構成している[144]。 2000年代には「エコーブーム」があり、それは確かに将来の若年成人の絶対数を増加させていたが、彼らの親と比較してこのコーホートの相対的規模は大き く変化しなかった[145]。 2022年のギャラップ社の調査によれば、20.8%、つまり約5人に1人のZ世代のメンバーはLGBTQ+として認識している[146]。 |

|

Ethnic composition of U.S.

demographic cohorts estimated by William Frey of the Brookings

Institution using data from the U.S. Census. Data available at

https://www.brookings.edu/research/less-than-half-of-us-children-under-15-are-white-census-shows/. |

| Education Since the mid-20th century, enrollment rates in primary schools has increased significantly in developing countries.[147] In 2019, the OECD completed a study showing that while education spending was up 15% over the previous decade, academic performance had stagnated. The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study organization showed that the highest-scoring students in mathematics came from Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. In science, the highest-scoring countries were Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Russia, and Hong Kong.[148] Different nations and territories approach the question of how to nurture gifted students differently. During the 2000s and 2010s, whereas the Middle East and East Asia (especially China, Hong Kong, and South Korea) and Singapore actively sought them out and steered them towards top programs, Europe and the United States had in mind the goal of inclusion and chose to focus on helping struggling students. In 2010, for example, China unveiled a decade-long National Talent Development Plan to identify able students and guide them into STEM fields and careers in high demand; that same year, England dismantled its National Academy for Gifted and Talented Youth and redirected the funds to help low-scoring students get admitted to elite universities. Developmental cognitive psychologist David Geary observed that Western educators remained "resistant" to the possibility that even the most talented of schoolchildren needed encouragement and support and tended to concentrate on low performers. In addition, even though it is commonly believed that past a certain IQ benchmark (typically 120), practice becomes much more important than cognitive abilities in mastering new knowledge, recently published research papers based on longitudinal studies, such as the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth (SMPY) and the Duke University Talent Identification Program, suggest otherwise.[149] Since the early 2000s, the number of students from emerging economies going abroad for higher education has risen markedly. This was a golden age of growth for many Western universities admitting international students.[150] In the late 2010s, around five million students trotted the globe each year for higher education, with the developed world being the most popular destinations and China the biggest source of international students.[150] In 2019, the United States was the most popular destination for international students, with 30% of its international student body coming from mainland China, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan.[151] However, geopolitical tensions and COVID-19 have ended the golden age for these universities.[152][150] |

教育 20世紀半ば以降、発展途上国では小学校への就学率が大幅に上昇した[147]。 2019年、OECDは、教育支出が過去10年間で15%増加した一方で、学力は停滞していることを示す調査を完了した。国際数学・科学調査機関の動向で は、数学で最も得点の高い学生は、シンガポール、香港、韓国、台湾、日本からであった。科学では、シンガポール、韓国、日本、ロシア、香港が最高得点の国 であった[148]。 国や地域によって、才能ある生徒をどのように育てるかとい う問題への取り組み方は異なっている。2000年代から2010年代にかけて、中東、東アジア(特に中国、 香港、韓国)およびシンガポールでは、積極的に彼らを探し出 し、トッププログラムに導くのに対し、ヨーロッパと米国では、包 摂という目標を念頭に置き、困難な生徒の支援に焦点を当てること を選択した。例えば、中国は2010年に10年にわたる国家人材開発計画を発表し、能力のある学生を特定し、需要の高いSTEM分野や職業に導くことにし た。同年、イギリスは国立英才アカデミーを解体し、低得点の学生がエリート大学に入学できるよう、その資金を振り向けることにした。発達認知心理学者のデ イビッド・ギアリーは、欧米の教育者たちは、最も優秀な学童であっても励ましや支援が必要だという可能性に「抵抗感」を持ち続け、成績の悪い生徒に集中す る傾向があると指摘した。さらに、あるIQ基準(通常120)を過ぎると、新しい知識を習得するためには認知能力よりも練習の方がはるかに重要になると一 般的に考えられているにもかかわらず、最近発表された「数学的に早熟な青少年の研究」(SMPY)や「デューク大学の才能発掘プログラム」などの縦断研究 に基づく研究論文では、そうでないことが示唆されている[149]。 2000年代初頭以降、新興国から海外へ高等教育を受けに行く学生の数は顕著に増加した。これは、留学生を受け入れる多くの西洋の大学にとって成長の黄金 時代であった[150]。 2010年代後半には、毎年約500万人の学生が高等教育のために世界を闊歩し、先進国が最も人気のある目的地であり、中国が留学生の最大の供給源であっ た。 [150] 2019年には、米国は留学生にとって最も人気のある目的地であり、その留学生の30%は中国本土、オーストラリア、カナダ、イギリス、日本から来ていた [151] しかしながら、地政学的緊張とCOVID-19はこれらの大学の黄金時代を終わらせた[152][150]。 |

| Health issues Mental Data from the British National Health Service (NHS) showed that between 1999 and 2017, the number of children below the age of 16 experiencing at least one mental disorder increased from 11.4% to 13.6%. The researcher interviewed older adolescents (aged 17–19) for the first time in 2017 and found that girls were two-thirds more likely than younger girls and twice more likely than boys from the same age group to have a mental disorder. In England, hospitalizations for self-harm doubled among teenage girls between 1997 and 2018, but there was no parallel development among boys. While the number of children receiving medical attention for mental health problems has clearly gone up, this is not necessarily an epidemic as the number of self-reports went up even faster possibly due to the diminution of stigma. Furthermore, doctors are more likely than before to diagnose a case of self-harm when previously they only treated the physical injuries.[27] A 2020 meta-analysis found that the most common psychiatric disorders among adolescents were ADHD, anxiety disorders, behavioral disorders, and depression, consistent with a previous one from 2015.[31] A 2021 UNICEF report stated that 13% of ten to nineteen year olds around the world had a diagnosed mental health disorder whilst suicide was the fourth most common cause of death among fifteen to nineteen year olds. It commented that "disruption to routines, education, recreation, as well as concern for family income, health and increase in stress and anxiety, [caused by the COVID-19 pandemic] is leaving many children and young people feeling afraid, angry and concerned for their future." It also noted that the pandemic had widely disrupted mental health services.[153] Sleep deprivation Sleep deprivation is on the rise among contemporary youths,[154][28] due to a combination of poor sleep hygiene (having one's sleep disrupted by noise, light, and electronic devices), caffeine intake, beds that are too warm, a mismatch between biologically preferred sleep schedules at around puberty and social demands, insomnia, growing homework load, and having too many extracurricular activities.[28][29] Consequences of sleep deprivation include low mood, worse emotional regulation, anxiety, depression, increased likelihood of self-harm, suicidal ideation, and impaired cognitive functioning.[28][29] In addition, teenagers and young adults who prefer to stay up late tend to have high levels of anxiety, impulsivity, alcohol intake, and tobacco smoking.[155] A study by Glasgow University found that the number of schoolchildren in Scotland reporting sleep difficulties increased from 23% in 2014 to 30% in 2018. 37% of teenagers were deemed to have low mood (33% males and 41% females), and 14% were at risk of depression (11% males and 17% females). Older girls faced high pressure from schoolwork, friendships, family, career preparation, maintaining a good body image and good health.[156] In Canada, teenagers sleep on average between 6.5 and 7.5 hours each night, much less than what the Canadian Paediatric Society recommends, 10 hours.[157] According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, only one out of five children who needed mental health services received it. In Ontario, for instance, the number of teenagers getting medical treatment for self-harm doubled in 2019 compared to ten years prior. The number of suicides has also gone up. Various factors that increased youth anxiety and depression include over-parenting, perfectionism (especially with regards to schoolwork), social isolation, social-media use, financial problems, housing worries, and concern over some global issues such as climate change.[158] |

健康問題 メンタル(Mental) 英国国民保健サービス(NHS)のデータによると、1999年から2017年の間に、少なくとも1つの精神障害を経験した16歳以下の子どもは、 11.4%から13.6%に増加したことが明らかになった。研究者が2017年に初めて年長の青年(17~19歳)にインタビューしたところ、女子は年少 の女子より3分の2、同年代の男子より2倍の確率で精神障害を抱えていることがわじかった。イギリスでは、1997年から2018年にかけて、10代の女 子で自傷行為による入院が2倍に増えたが、男子では並行した進展は見られなかった。精神的な問題で医療機関を受診する子どもの数は明らかに増えているが、 スティグマの薄れからか自己申告の数はさらに速く増えており、これは必ずしも流行とは言えない。さらに、以前は身体的な傷害を治療するだけだったのが、医 師が自傷行為のケースを診断する可能性が以前より高くなった[27]。 2020年のメタアナリシスでは、青年の間で最も一般的な精神疾患はADHD、不安障害、行動障害、うつ病であり、2015年の以前のものと一致している ことが分かった[31]。 2021年のユニセフの報告書は、世界中の10歳から19歳の13%が精神的健康障害と診断されている一方で、自殺は15歳から19歳の間で4番目に多い 死因であると述べていた。また、「日常生活、教育、レクリエーションの崩壊、家族の収入や健康への不安、ストレスや不安の増大が(COVID-19の大流 行によって)多くの子どもや若者を恐怖、怒り、将来への不安にさせています」とコメントしています。また、パンデミックは精神保健サービスを広く混乱させ たと指摘した[153]。 睡眠不足 睡眠不足は現代の若者の間で増加しており[154][28]、その原因は睡眠衛生の悪化(騒音、光、電子機器によって睡眠が妨げられる)、カフェインの摂 取、暖かすぎるベッド、思春期頃に生物学的に望ましい睡眠スケジュールと社会の要求とのミスマッチ、不眠症、宿題量の増加、課外活動の多さなどが組み合わ さっているためである。 [28][29] 睡眠不足の結果には、低い気分、悪い感情調節、不安、うつ病、自傷行為の可能性の増加、自殺念慮、および認知機能の低下が含まれる。 [28][29] さらに、夜更かしを好む10代と若年成人は不安、衝動性、アルコール摂取、タバコ喫煙のレベルが高くなる傾向がある[155]。 グラスゴー大学の調査によると、スコットランドでは睡眠障害を訴える小学生が2014年の23%から2018年の30%に増加したことがわかりました。 ティーンエイジャーの37%が低気分と判断され(男性33%、女性41%)、14%がうつ病のリスクがあるとされた(男性11%、女性17%)。年長の少 女は、学業、友人関係、家族、キャリア準備、良いボディイメージの維持、健康などの高いプレッシャーに直面していた[156]。 カナダでは、ティーンエイジャーは毎晩平均6.5時間から7.5時間眠っており、カナダ小児科学会が推奨する10時間よりはるかに少ない[157]。カナ ダ精神衛生協会によると、精神衛生サービスを必要とする5人の子どものうち1人だけがサービスを受けている。例えばオンタリオ州では、自傷行為で治療を受 けるティーンエイジャーの数は、10年前と比較して2019年に2倍になった。自殺の件数も増えています。若者の不安やうつ病を増加させた様々な要因に は、過剰な子育て、完璧主義(特に学業に関して)、社会的孤立、ソーシャルメディアの利用、金銭的問題、住宅に関する心配、気候変動など一部のグローバル な問題に対する懸念が含まれる[158]。 |

| Cognitive abilities A 2010 meta-analysis by an international team of mental health experts found that the worldwide prevalence of intellectual disability (ID) was around one percent. But the share of individuals with such a condition in low- to middle-income countries were up to twice as high as their wealthier counterparts because they lacked the sources needed to tackle the problem, such as preventing children from being born with ID due to hereditary conditions with antenatal genetic screening, poor child and maternal care facilities, and inadequate nutrition, leading to, for instance, iodine deficiency. The researchers also found that ID was more common among children and adolescents than adults.[30] A 2020 literature review and meta-analysis confirmed that the incidence of ID was indeed more common than estimates from the early 2000s.[31] In 2013, a team of neuroscientists from the University College London published a paper on how neurodevelopmental disorders can affect a child's educational outcome. They found that up to 10% of the human population have specific learning disabilities or about two to three children in a (Western) classroom. Such conditions include dyscalculia, dyslexia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism spectrum disorder. They are caused by abnormal brain development due to complicated environmental and genetic factors. A child may have multiple learning disorders at the same time. For example, among children with ADHD, 33-45% also have dyslexia and 11% have dyscalculia. Normal or high levels of intelligence offer no protection. Each child has a unique cognitive and genetic profile and would benefit from a flexible education system.[159][160] A 2017 study from the Dominican Republic suggests that students from all sectors of the educational system utilize the Internet for academic purposes, yet those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to rank the lowest in terms of reading comprehension skills.[161] A 2020 report by psychologist John Protzko analyzed over 30 studies and found that children have become better at delaying gratification over the previous 50 years, corresponding to an average increase of 0.18 standard deviations per decade on the IQ scale. This is contrary to the opinion of the majority of the 260 cognitive experts polled (84%), who thought this ability was deteriorating. Researchers test this ability using the Marshmallow Test. Children are offered treats: if they are willing to wait, they get two; if not, they only get one. The ability to delay gratification is associated with positive life outcomes, such as better academic performance, lower rates of substance use, and healthier body weights. Possible reasons for improvements in the delaying gratification include higher standards of living, better-educated parents, improved nutrition, higher preschool attendance rates, more test awareness, and environmental or genetic changes. This development does not mean that children from the early 20th century were worse at delaying gratification and those from the late 21st will be better at it, however. Moreover, some other cognitive abilities, such as simple reaction time, color acuity, working memory, the complexity of vocabulary usage, and three-dimensional visuospatial reasoning have shown signs of secular decline.[15] In a 2018 paper, cognitive scientists James R. Flynn and Michael Shayer argued that the observed gains in IQ during the 20th century—commonly known as the Flynn effect—had either stagnated or reversed, as can be seen from a combination of IQ and Piagetian tests. In the Nordic nations, there was a clear decline in general intelligence starting in the 1990s, an average of 6.85 IQ points if projected over 30 years. In Australia and France, the data remained ambiguous; more research was needed. In the United Kingdom, young children experienced a decline in the ability to perceive weight and heaviness, with heavy losses among top scorers. In German-speaking countries, young people saw a fall in spatial reasoning ability but an increase in verbal reasoning skills. In the Netherlands, preschoolers and perhaps schoolchildren stagnated (but seniors gained) in cognitive skills. What this means is that people were gradually moving away from abstraction to concrete thought. On the other hand, the United States continued its historic march towards higher IQ, a rate of 0.38 per decade, at least up until 2014. South Korea saw its IQ scores growing at twice the average U.S. rate. The secular decline of cognitive abilities observed in many developed countries might be caused by diminishing marginal returns due to industrialization and to intellectually stimulating environments for preschoolers, the cultural shifts that led to frequent use of electronic devices, the fall in cognitively demanding tasks in the job market in contrast to the 20th century, and possibly dysgenic fertility.[162] |