iGen (i-Generation, internet-Generation)

Narcissism-ization and emaerging new solitude among the Digital Natives

このページは科学研究費補助 金・基盤研究(C)「スマートメディア ユーザーのナルシズム化と新しい孤独の誕生:民族誌的研究」(←科研の公式サイト)英文タイトルは上掲のものと同じ)の研究プロジェクト(「Work_Place:スマートメディアユーザーのナルシズム化…」)に 準拠した資料ページである。そして、このページは「デジタル・ネイ ティブ族における孤独とはなにか?」より派生したものである。

● iGen (i-Generation, internet-Generation) における心理的な性向について

| iGen: Why Today's

Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant,

Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What That Means

for the Rest of Us[a] is a 2017 nonfiction book by Jean

Twenge which studies the lifestyles, habits and values of Americans

born 1995–2012,[1] the first generation to reach adolescence after

smartphones became widespread. Twenge refers to this generation as the

"iGeneration" (also known as Generation Z). Although she argues there

are some positive trends, she expresses concern that the generation is

being isolated by technology. |

iGen: Why Today's

Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant,

Less Happy and Completely Unpared for Adulthood and What That Means for

the Rest of

Us[a]はジャン・トウェンジによる2017年のノンフィクションで、1995年

から2012年に生まれたアメリカ人のライフスタイル、習慣、価値観を

研究し、スマートフォン普及後初めて青年期に達した世代[1]としたものである。トゥエンジはこの世代を「iGeneration」(ジェネレーションZ

とも呼ばれる)と呼んでいる。彼女は、いくつかのポジティブな傾向が

あると主張する一方で、この世代がテクノロジーによって孤立していることに懸念を表明

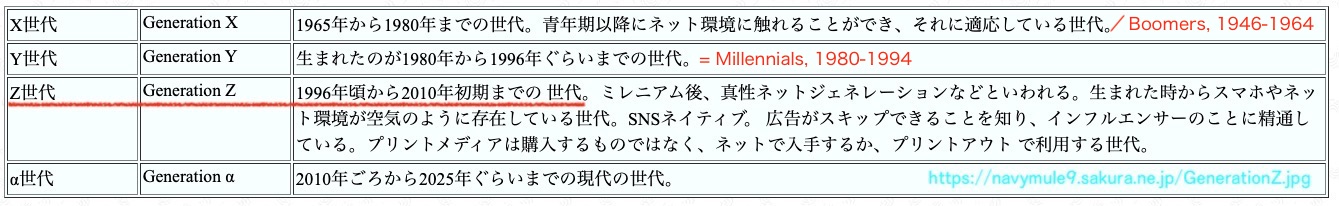

している。 ●Z 世代の定義は1996-2010年代初期なので iGen世代と被る。 |

| In iGen, Jean Twenge examines

the advantages, disadvantages and consequences of technology in the

lives of the current generation of teens/young adults. She argues that

generational divides are more prominent than ever and parents,

educators and employers have a strong desire to understand the newer

generation. Social media and texting have replaced many face-to-face

social activities that older generations grew up with, therefore,

iGeners are spending less time interacting in person. Twenge concludes

this has led them to experience higher levels of anxiety, depression,

and loneliness than seen in prior generations. She argues that use of technology is not the only thing that distinguishes iGeners from generations prior— the way in which their time is spent contributes to changes in their behaviors and attitudes toward religion, sexuality and politics. Twenge argues that iGeners' socialization skills and wants for the future have taken a turn towards an atypical, yet safe route. She elaborates on these topics throughout different chapters of the book. Each of these changes factor into her overall argument: that iGeners are unlike any generation seen before, and earlier generations must learn to understand them in order to keep up. With their new developmental ways, their impact will be unlike any before them. Her evaluations are based on four databases: Monitoring the Future, The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, The American Freshman Survey, and the General Social Survey. Each of these surveys asked iGeners quantitative and qualitative questions to determine if being raised synergistically with technology has made them less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy, less resilient to the challenge of adulthood, as Twenge asserts. In addition to the databases, Twenge conducted interviews with young adults across the country to collect first hand data about the challenges growing up with technology being presented to the current generation of teens and young adults.[2] |

Jean

Twengeは、『iGen』の中で、現在の10代/20代の若者の生活におけるテクノロジーの利点、欠点、結果について考察している。世代間の隔たりは

かつてないほど顕著であり、親や教育者、雇用主は新しい世代を理解したいと強く願っている、と彼女は主張している。旧世代が行っていた対面式の社会活動の多くがソーシャルメディアやテキストに取って代わられた

ため、iGenersは直接会って交流する時間が少なくなっている。このため、iGenersは以前の世代よりも高いレベルの不安、うつ、孤独を経験する

ようになったとTwenge氏は結論付けている。 iGenersを前の世代と区別するのはテクノロジーの使用だけではない。彼らの時間の使い方は、宗教、セクシュアリティ、政治に対する彼らの行動や態度 の変化に寄与していると、彼女は主張している。Twengeは、iGenersの社会化スキルや将来への希望が、非典型的でありながら安全な方向へ向かっ ていると論じている。彼女は、本書のさまざまな章を通じて、これらのトピックを詳しく説明している。iGenersはこれまでのどの世代とも違うので、前の世代は彼らを理解することを学ばなけれ ばならない、というのが彼女の主張である。iGenersはこれまでにない世代であり、前の世代は彼らを理解することを学ばなければついて いけない、というのが本書の主張である。 彼女の評価は、4つのデータベースに基づいている。モニタリング・ザ・フューチャー、青少年リスク行動監視システム、アメリカ新入生調査、一般社会調査の 4つのデータベースに基づいている。これらの調査はそれぞれ、iGenersに定量的・定性的な質問を投げかけ、Twengeが主張するように、テクノロ ジーと相乗的に育てられたことによって、反抗的でなくなったか、寛容でなくなったか、幸福でなくなったか、大人への挑戦に対する弾力性がなくなったかを 判 断している。データベースに加えて、Twengeは全米の若年層へのインタビューを実施し、現在の10代や若年層に提示されているテクノロジーとともに成 長する課題についての直接のデータを収集した[2]。 ●4つの価値評価尺度 1)反抗的 2)寛容 3)幸福感 4)大人への挑戦への弾力性 |

| Reception Sonia Livingstone at the London School of Economics wrote that the book attracted "an avalanche of both eulogistic and critical reviews." She was cautious about Twenge's findings, noting some graphs that did not fit them and suggesting other potential factors were at play. She did agree that there had been a recent downturn of mental health among the youth and concluded: "Let's hope the questions raised here foster more and better research about and with young people growing up in the digital age."[3] Marilyn Gates gave the book a positive review in the New York Journal of Books, calling it "an important barometer of youth mental health" and "a must-read for parents, teachers, employers, and anybody trying to make sense of iGen behavior and what this bodes for the future." She described Twenge as a "highly skilled and empathetic interviewer" and also praised her writing for being easy to understand. She highlighted some flaws, such as data cherry-picked "for maximum shock value", correlation being treated as causation and that it did not entirely avoid "youth bashing".[4] Annalisa Quinn at NPR was skeptical, arguing that the book was part of the familiar trend of older generations feeling superior to younger ones ("one of our great human traditions"). She was particularly critical of how Twenge "draws her conclusions first and then collects evidence that supports those conclusions, ignoring evidence that doesn't."[5] In the United Arab Emirates newspaper The National, Steve Donoghue said it drew alarmist conclusions despite data on the contrary: "Even Twenge's own charts and numbers, read with optimism, tend to indicate that members of iGen are generally far more socially aware, far less given to prejudice, and far, far sharper than their parents."[6] |

受容と批判 ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスのソニア・リビングストーンは、 この本が「賛美と批判の両方のレビューで雪崩を打った」と書いている。彼女(ソニ ア)は Twengeの発見に対して慎重で、いくつかのグラフがそれに当てはまらないことを指摘し、他の潜在的な要因が作用していることを示唆した。 彼女は、最 近、若者の間で精神的な健康状態が悪化していることには同意し、こう結論づけた。「ここで提起された疑問が、デジタル時代に成長する若者についての、そし て若者たちとのより良い研究を促進することを期待しよう」[3]。 マリリン・ゲイツは、ニューヨーク・ジャーナル・オブ・ ブックスで、この本を「若者の精神衛生に関する重要なバロメーター」、「親、教師、雇用主、そして iGenの行動とそれが将来にもたらす意味を理解しようとするすべての人にとって必読書」と呼び、肯定的な評価を与えています]。彼女はTwengeを 「高度に熟練した共感できるインタビュアー」と評し、また彼女の文章がわかりやすいと賞賛しています。彼女は、「最大限の衝撃を与えるために」データが選ばれていること、相関関係が因果関係として扱われて いること、「若者バッシング」を完全に回避できていないことなど、いくつかの欠点を強調した[4]。 ●マリリン・ゲイツの危惧 1)インパクトを与えるためにデータが恣意的に取られていないか? 2)相関関係を因果関係とする誤謬 3)若者バッシングにならずに客観評価できているのか? NPRのアナリサ・クインは懐疑的で、この本は、年上の世代が年下の世代に対して優 越感を感じるというおなじみの傾向(「人類の偉大な伝統のひとつ」)の一部であると論じた。彼女は特に、Twengeが「最初に結論を出し、その結論を支持する証拠を集め、そうでない証 拠を無視する」方法を批判した[5]。アラブ首長国連邦の新聞The Nationalでは、Steve Donoghueが、反対のデータにもかかわらず、警戒すべき結論を導き出したと述べている。"Twenge自身の図表や数字でさえ、楽観的に読むと、iGenのメンバーは一般的に彼らの親 よりもはるかに社会的な意識が高く、偏見を持つことが少なく、はるかに、はるかに鋭いことを示す傾向がある"[6]と述べている。 |

| 1. "Move Over,

Millennials: How 'iGen' Is Different From Any Other Generation". The

California State University. August 22, 2017. 2. Twenge, Jean M. (2017-08-22). IGen : why today's super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy-- and completely unprepared for adulthood (and what this means for the rest of us) (First Atria books hardcover ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9781501151989. OCLC 965140529. 3. Book review: iGen: why today's super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy – and completely unprepared for adulthood 4. "a book review by Marilyn Gates: iGen: Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What That Means for the Rest of Us". www.nyjournalofbooks.com. Retrieved 2018-04-23. 5. Quinn, Annalisa (September 17, 2017). "Move Over Millennials, Here Comes 'iGen'... Or Maybe Not". NPR. 6. "Book review: Jean Twenge's latest spotlights dangers of being a part of the smartphone generation". The National. Retrieved 2018-04-23. |

1. "Move Over,

Millennials: How 'iGen' Is Different From Any Other Generation". The

California State University. August 22, 2017. 2. Twenge, Jean M. (2017-08-22). IGen : why today's super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy-- and completely unprepared for adulthood (and what this means for the rest of us) (First Atria books hardcover ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9781501151989. OCLC 965140529. 3. Book review: iGen: why today's super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy – and completely unprepared for adulthood 4. "a book review by Marilyn Gates: iGen: Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What That Means for the Rest of Us". www.nyjournalofbooks.com. Retrieved 2018-04-23. 5. Quinn, Annalisa (September 17, 2017). "Move Over Millennials, Here Comes 'iGen'... Or Maybe Not". NPR. 6. "Book review: Jean Twenge's latest spotlights dangers of being a part of the smartphone generation". The National. Retrieved 2018-04-23. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IGen_(book) |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| A highly readable and

entertaining first look at how today's members of iGen-the children,

teens, and young adults born in the mid-1990s and later-are vastly

different from their Millennial predecessors, and from any other

generation, from the renowned psychologist and author of Generation Me.

With generational divides wider than ever, parents, educators, and

employers have an urgent need to understand today's rising generation

of teens and young adults. Born in the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s and

later, iGen is the first generation to spend their entire adolescence

in the age of the smartphone. With social media and texting replacing

other activities, iGen spends less time with their friends in

person-perhaps why they are experiencing unprecedented levels of

anxiety, depression, and loneliness. But technology is not the only

thing that makes iGen distinct from every generation before them; they

are also different in how they spend their time, how they behave, and

in their attitudes toward religion, sexuality, and politics. They

socialize in completely new ways, reject once sacred social taboos, and

want different things from their lives and careers. More than previous

generations, they are obsessed with safety, focused on tolerance, and

have no patience for inequality. iGen is also growing up more slowly

than previous generations: eighteen-year-olds look and act like

fifteen-year-olds used to. As this new group of young people grows into

adulthood, we all need to understand them: Friends and family need to

look out for them; businesses must figure out how to recruit them and

sell to them; colleges and universities must know how to educate and

guide them. And members of iGen also need to understand themselves as

they communicate with their elders and explain their views to their

older peers. Because where iGen goes, so goes our nation-and the world.

by "Nielsen BookData" |

本書は、1990年代半ば以降に生まれた子供、10代、20代の若者で

あるiGenが、ミレニアル世代や他のどの世代とも大きく異なることを、著名な心理学者で『ジェネレーション・ミー』の著者である著者が読みやすく、楽し

く解説する初めての書です。世代間の溝がかつてないほど広がっている今、親や教育者、雇用主は、今日の10代と20代の若者たちを理解することが急務と

なっている。1990年代半ばから2000年代半ば以降に生まれたiGenは、思春期をスマートフォンの時代で過ごした最初の世代である。ソーシャルメ

ディアやテキストが他の活動に取って代わり、iGenは友人と直接会う時間が減っている。おそらく、彼らがかつてないレベルの不安、うつ、孤独を経験して

いる理由であろう。しかし、iGenがそれ以前のすべての世代と異なるのはテクノロジーだけでは

ない。時間の使い方、行動様式、宗教、セクシュアリティ、政治に対する考え方も異なっている。彼らはまったく新しい方法で社交し、かつての神聖な社会的タ

ブーを否定し、人生やキャリアに異なるものを求めている。また、iGenは前の世代よりも成長が遅く、18歳の若者はかつての15歳の若者のような姿と振

る舞いをしている。この新しい若者たちが大人になっていく過程で、私たち全員が彼らを理解する必要がある。友人や家族は彼らに気を配り、企業は彼らを採用

し、販売する方法を考えなければならないし、大学は彼らを教育し、指導する方法を知らなければならない。そして、iGenのメンバーは、年長者とコミュニ

ケーションをとり、年上の仲間に自分の意見を説明する際に、自分自身を理解する必要がある。なぜなら、iGenの行く末は、わが国、そして世界の行く末を

左右するからなのである。 |

| As seen in Time, USA TODAY, The

Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, and on CBS This Morning, BBC, PBS,

CNN, and NPR, iGen is crucial reading to understand how the children,

teens, and young adults born in the mid-1990s and later are vastly

different from their Millennial predecessors, and from any other

generation. With generational divides wider than ever, parents,

educators, and employers have an urgent need to understand today's

rising generation of teens and young adults. Born in the mid-1990s up

to the mid-2000s, iGen is the first generation to spend their entire

adolescence in the age of the smartphone. With social media and texting

replacing other activities, iGen spends less time with their friends in

person-perhaps contributing to their unprecedented levels of anxiety,

depression, and loneliness. But technology is not the only thing that

makes iGen distinct from every generation before them; they are also

different in how they spend their time, how they behave, and in their

attitudes toward religion, sexuality, and politics. They socialize in

completely new ways, reject once sacred social taboos, and want

different things from their lives and careers. More than previous

generations, they are obsessed with safety, focused on tolerance, and

have no patience for inequality. With the first members of iGen just

graduating from college, we all need to understand them: friends and

family need to look out for them; businesses must figure out how to

recruit them and sell to them; colleges and universities must know how

to educate and guide them. And members of iGen also need to understand

themselves as they communicate with their elders and explain their

views to their older peers. Because where iGen goes, so goes our

nation-and the world. - Nielsen

BookData. |

タイム、USAトゥデイ、アトランティック、ウォールストリートジャー

ナル、CBSディスモーニング、BBC、PBS、CNN、NPRで紹介されたこの本は、1990年代半ば以降に生まれた子供、ティーン、ヤングアダルト

が、ミレニアルの前世代とも、他のどの世代とも大きく異なることを理解する上で極めて重要な一冊である。世代間の溝がかつてないほど広がっている現在、

親、教育者、雇用主は、今日の10代と20代の若者たちの世代を理解することが急務となっている。1990年代半ばから2000年代半ばまでに生まれた

iGenは、スマートフォンの時代に思春期を過ごした最初の世代である。ソーシャルメディアやメールが他の活動に取って代わり、iGenは友人と直接会う

時間が少なくなり、おそらくこれまでにないレベルの不安、うつ、孤独を感じるようになったのだろう。しかし、iGenがそれ以前のすべての世代と異なるの

はテクノロジーだけではない。時間の使い方、行動様式、宗教、セクシュアリティ、政治に対する考え方にも違いがある。彼らはまったく新しい方法で社交し、

かつての神聖な社会的タブーを否定し、人生やキャリアに異なるものを求めている。前の世代よりも、彼らは安全にこだわり、寛容さを重視し、不平等には我慢

がならない。友人や家族は彼らに気を配り、企業は彼らを採用し、売り込む方法を考え、大学は彼らを教育し、導く方法を知らなければならない。そして、

iGenのメンバーは、年長者とコミュニケーションをとり、年上の仲間に自分の意見を説明する際に、自分自身を理解する必要がある。なぜなら、iGenの

行く末は、わが国(=米国)、そして世界の行く末を左右するからだ。 |

| Contents 0. WHO IS iGEN, AND HOW DO WE KNOW? 1. IN NO HURRY: GROWING UP SLOWLY 2. INTERNET: ONLINE TIME-OH, AND OTHER MEDIA, TOO 3. IN PERSON NO MORE: l'M WITH YOU, BUT ONLY VIRTUALLY 4. INSECURE: THE NEW MENTAL HEALTH CRISIS 5. IRRELIGIOUS: LOSING MY RELIGION (AND SPIRITUALITY) 6. INSULATED BUT NOT INTRINSIC: MORE SAFETY AND LESS COMMUNITY 7. INCOME INSECURITY: WORKING TO EARN, BUT NOT TO SHOP 8. INDEFINITE: SEX, MARRIAGE, AND CHILDREN 9. INCLUSIVE: LGBT, GENDER, AND RACE ISSUES IN THE NEW AGE 10. INDEPENDENT: POLITICS 11. UNDERSTANDING-AND SAVING-iGEN |

内容 0. iGENとは何者か、そしてなぜわかるのか? 1. 急がず、ゆっくり成長していく。 2. インターネット:ネットの時間-ああ、他のメディアも 3. もはや手も足もでない:そばにいる、でもバーチャルだけ 4. 安全でない:新たな精神衛生上の危機 5. 無宗教:私の宗教(と霊性)を失う 6. 絶縁されているが、本質的でない:より安全で、より少ないコミュニティ 7. 収入の不安:稼ぐために働くが、買い物のために働かない 8. 不定型:セックス、結婚、そして子供 9. 包括的:新時代のLGBT、ジェンダー、人種問題 10. 独立:政治 11. iGENを理解し、守る |

●寂しさの増加モデル

●ミー・ジェネレーション

| The "Me" generation

is a term referring to Baby Boomers in the United States and the

self-involved qualities associated with this generation.[1] The 1970s

was dubbed the "Me decade" by writer Tom Wolfe;[2] Christopher Lasch

wrote about the rise of a culture of narcissism among younger Baby

Boomers.[3] The phrase became popular at a time when "self-realization"

and "self-fulfillment" were becoming cultural aspirations to which

young people supposedly ascribed higher importance than social

responsibility. |

「私=ミー」世代とは、アメリカのベビーブーマー世代とその世代に関連

する自己中心的な性質を指す言葉である[1] 。 1970年代は作家のトム・ウルフによって「私の10年」と呼ばれ[2]

、クリストファー・ラッシュは若いベビーブーマー世代のナルシズム文化の台頭について書いた。

自己実現」「自己充足」が若者の間で社会的責任よりも重要視されて文化的願望になっていた時期にこのフレーズは流行した[3] 。 |

| Origins The cultural change in the United States during the 1970s that was experienced by the Baby Boomers, upon when the majority of them became of age, is complex. The 1960s are remembered as a time of political protests, and radical experimentation with new cultural experiences (the Sexual Revolution, happenings, mainstream awareness of Eastern religions), which were practiced by older Boomers. The Civil Rights Movement, gave rebellious young people serious goals. Cultural experimentation was justified as being directed toward spiritual or intellectual enlightenment. The mid to late 1970s, in contrast, was a time of increased economic crisis and disillusionment with idealistic politics among the young, particularly after the resignation of Richard Nixon and the end of the Vietnam War. Unapologetic hedonism became acceptable among the young.[citation needed] The new introspectiveness announced the demise of an established set of traditional faiths centred on work and the postponement of gratification, and the emergence of a consumption-oriented lifestyle ethic centred on lived experience and the immediacy of daily lifestyle choices.[4] By the mid-1970s, Tom Wolfe and Christopher Lasch were speaking out critically against the culture of narcissism.[3] These criticisms were widely repeated throughout American popular media. The development of a youth culture focusing so heavily on self-fulfillment was also perhaps a reaction against the traits that characterized the older Silent Generationers, which had grown up during the Great Depression and became of age in the 1950s from when the Civil Rights Movement had begun. That generation had learned values associated with self-sacrifice. The deprivations of the Depression had taught that generation to work hard, frugally save money, and to cherish family and community ties. Loyalty to institutions, traditional religious faiths, and other common bonds were what that generation considered to be the cultural foundations of their country.[5] Generation Xers, upon maturing in the 1990s, gradually abandoned those values in large numbers, a development that was entrenched during the 1970s. The 1970s have been described as a transitional era when the self-help of the 1960s became self-gratification, and eventually devolved into the selfishness of the 1980s.[6] |

原点 ベビーブーマーたちが経験した1970年代の米国における文化的変化は、彼らの大半が成人した時点で、複雑な様相を呈している。1960年代は、政治的な 抗議行動や、新しい文化体験(性革命、ハプニング、東洋宗教の主流化など)の過激な実験が行われた時代として記憶されており、これらは年長のブーマーが実 践していたことであった。公民権運動は、反抗的な若者たちに重大な目標を与えた。文化的な実験が精神的、知的な啓発に向けられるものとして正当化された。 一方、1970年代半ばから後半にかけては、経済危機が深刻化し、特にリチャード・ニクソンの辞任とベトナム戦争の終結により、若者の間で理想主義的な政 治に対する幻滅が起こりました。特にリチャード・ニクソンの辞任とベトナム戦争が終結した後は、若者の間で無遠慮な快楽主義が受け入れられるようになった [citation needed]。 新しい内省は、労働と満足の先送りを中心とした伝統的な信仰の確立されたセットの終焉と、生きた経験と日々のライフスタイルの選択の即時性を中心とした消 費志向のライフスタイルの倫理の出現を告げた[4]。 1970年代半ばまでに、トム・ウルフとクリストファー・ラッシュはナルシシズムの文化に対して批判的に発言していた[3]。 これらの批判はアメリカの大衆メディアを通じて広く繰り返された。 自己実現に重きを置く若者文化の発展は、おそらく、大恐慌の時代に発展してきたサイレント世代が公民権運動が始まった1950年代から成人したことに起因 する特徴への反動であった。この世代は、自己犠牲の精神を学んでいた。大恐慌の窮乏から、勤勉に働き、倹約し、家族や地域社会の絆を大切にすることを学ん だ世代である。制度への忠誠、伝統的な宗教的信仰、その他の共通の絆は、その世代が自国の文化的基盤であると考えていた[5] ジェネレーションXは、1990年代に成熟すると、徐々にその価値観を大量に放棄し、1970年代にはその傾向が強くなった。 1970年代は、1960年代の自助努力が自己満足に変わり、やがて1980年代の利己主義に発展する過渡期と言われている[6]。 |

| Characteristics Health and exercise fads, New Age spirituality such as Scientology, hot tub parties, self-help programs such as EST (Erhard Seminars Training), and the growth of the self-help book industry became identified with the Baby Boomers during 1970s. Human potential, emotional honesty, "finding yourself", and new therapies became signatures of the culture.[7] The marketing of lifestyle products, eagerly consumed by Baby Boomers with disposable income during the 1970s, became an inescapable part of the culture. Revlon's marketing staff did research into young women's cultural values during the 1970s, revealing that young women were striving to compete with men in the workplace and to express themselves as independent individuals. Revlon launched the "lifestyle" perfume Charlie, with marketing aimed at glamorizing the values of the new 1970s woman, and it became the world's best-selling perfume.[8] The introspection of the Baby Boomers and their focus on self-fulfillment has been examined in a serious light in pop culture. Films such as An Unmarried Woman (1978), Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), Ordinary People (1980) and The Big Chill (1983) brought the inner struggles of Baby Boomers to a wide audience. The self-absorbed side of 1970s life was given a sharp and sometimes poignant satirization in Manhattan (1979). More acerbic lampooning came in Shampoo (1975) and Private Benjamin (1980). The Me generation has also been satirized in retrospect, as the generation called "Baby Boomers" reached adulthood, for example, in Parenthood (1989). Forrest Gump (1994) summed up the decade with Gump's cross-country jogging quest for meaning during the 1970s, complete with a tracksuit, which was worn as much as a fashion statement as an athletic necessity during the era. The satirization of the Me generation's "me first" attitude was the focus of the television sitcom Seinfeld, which does not include conscious moral development for its Boomer characters, but rather the opposite. Its plots do not have teaching lessons for its audience and its creators explicitly held that it was a "show about nothing".[9] |

特徴 健康や運動の流行、サイエントロジーのようなニューエイジの精神性、温泉パーティー、EST(エアハードセミナーズトレーニング)のような自己啓発プログ ラム、自己啓発本の産業の成長は、1970年代にベビーブーマーと同一視されるようになった[7]。人間の可能性、感情的な正直さ、「自分探し」、新しい 療法が文化の特徴になった[7] 。また、ライフスタイル製品のマーケティングは、1970年代に可処分所得をもつベビーブーマーが熱心に消費し、文化の不可避な一部となった。レブロンの マーケティング担当者は、1970年代の若い女性の文化的価値観を調査し、若い女性が職場で男性と競争し、独立した個人として自己表現することに努力して いることを明らかにした。レブロンは「ライフスタイル」香水チャーリーを発売し、新しい1970年代の女性の価値観を華やかにすることを目的としたマーケ ティングを行い、世界で最も売れた香水となった[8]。 ベビーブーマーの内省と自己実現への焦点は、ポップカルチャーの中で深刻に検討されてきた。未婚の女』(1978年)、『クレイマー対クレイマー』 (1979年)、『普通の人々』(1980年)、『ビッグチル』(1983年)などの映画は、ベビーブーマーの内面の葛藤を多くの観客に届けた。マンハッ タン』(1979年)では、1970年代の自己中心的な生活が鋭く、時に痛烈に風刺された。シャンプー』(1975年)や『プライベート・ベンジャミン』 (1980年)では、より辛辣な風刺がなされた。また、「ベビーブーマー」と呼ばれる世代が大人になるにつれ、『Parenthood』(1989)な ど、「私」の世代が回顧的に風刺されるようになった。フォレスト・ガンプ』(1994年)は、1970年代にガンプがクロスカントリー・ジョギングで意味 を追求し、トラックスーツを着用することでこの10年間を総括した。トラックスーツは、この時代に運動必需品であると同時にファッションステートメントと して着用されたものである。 ミー(Me)世代の「自分第一主義」の風刺は、テレビのシットコム『となりのサインフェルド』の焦点であったが、この作品はブーマーの登場人物に意識的な 道徳的成長を求めず、むしろその逆を行く。そのプロットは視聴者に対する教訓を持たず、制作者はそれが「何もない番組」であると明確に掲げていた[9]。 |

| Persistence of the label The term "Me generation" has persisted over the decades and is connected to Baby Boomers.[10] Some writers, however, have also named the Millennials, upon maturing in the 2010s, as "The Me Generation" or "Generation Me",[11] and Elspeth Reeve in The Atlantic noted that narcissism is a symptom of youth in most generations. Presumably, this even includes the Greatest Generationers, upon maturing in the 1930s.[12] The 1970s was also an era of rising unemployment among the young, continuing erosion of faith in conventional social institutions, and political and ideological aimlessness. This was the environment that popularized Punk rock among America's disaffected youth. By 1980, when Ronald Reagan was elected president, Baby Boomers increasingly adopted conservative political and cultural priorities. As Eastern religions and rituals such as yoga grew during the 1970s, at least one writer observed a New Age corruption of the popular understanding of "realization" taught by Neo-Vedantic practitioners, away from spiritual realization and toward "self-realization".[13] The leading edge of the Baby Boomers, who were counter-culture "hippies" and political activists during the 1960s, have been referred to sympathetically as the "Now generation", in contrast to the Me generation.[14] |

ラベルの持続性 しかし、一部の作家は2010年代に成熟したミレニアル世代を「ミー世代」または「ジェネレーション・ミー」と呼んでおり[11]、Elspeth Reeve『The Atlantic』は、自己愛はほとんどの世代で若者の症状であると指摘している。おそらくこれは、1930年代に成熟したグレイテストジェネレーション も含む[12]。1970年代はまた、若者の失業率が上昇し、従来の社会制度への信頼が失われ続け、政治的・思想的無目標の時代であった。このような環境 が、アメリカの不満を抱えた若者の間でパンクロックを流行らせたのである。1980年、レーガンが大統領になると、ベビーブーマーは保守的な政治・文化志 向を強めていく。 1970年代に東洋の宗教やヨーガのような儀式が発展するにつれて、少なくともある作家は、ネオ・ヴェダンティックの実践者によって教えられた「実現」の 一般的な理解が、精神の実現から「自己実現」へと向かうニューエイジの腐敗を観察した[13]。1960年代にカウンターカルチャー「ヒッピー」や政治活 動家だったベビーブーマーの先端は、ミーの世代に対して「今世代」と同情的に呼ばれてきた[14]。 |

| Generation Jones OK boomer The "Me" Decade and the Third Great Awakening The Culture of Narcissism Snowflake (Derogatory) Us Festival |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Me_generation |

リンク

リンク(雑多な)

文献(世代論)

文献(参照文献)

文献(タークル先生関連)

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099