コールアウト文化・キャンセルカルチャー

call-out culture, cancel culture

キャンセル文化またはコールアウト文化とは、 2010年代後半から 2020年代初頭にかけての言葉であり、オンライン、ソーシャルメディア、または個 人を問わず、誰かが社会的または職業的サークルから突き放される排斥の 形態を指すのに使われる。この排斥(cancelled, called-out)の対象となった人々は「キャンセル」されたと言われている。「キャンセル文化」という表現は主にネガ ティブな意味合いを持ち、言論の自由と検閲に関する議論において使用されている。

日本語のあるサイトには、キャンセルカルチャーを「社会的に好ましくない発言や言動をしたと

して個人や組織をソーシャルメディアサービスなどで批判し(炎上させる)、不買運動やボイコットすること」と書かれてあるが「社会的に好ましくない発言や

言動」は、キャンセルカルチャーにどっぷり使っている人の弁や正当化なので、「自分

たちが気に入らない発言や言動をした、社会的に好ましくない発言や言動を煽り、社会空間から排除してしまおうとする文化や社会のスタイルをキャンセルカル

チャー(またはコールアウト文化)という」と定義したほうがいいだろう。

キャンセル・カルチャーは、抑圧された人びとが抑圧 の歴史を告発することに、違和感を示し、逆に抑圧者の末裔の人が、その事実をしり、トラウマを感じ、また、学校教育のなかで、例えば「黒人差別の歴史を学 ぶことを通して白人は自虐的になるので、むしろ教えないほうがいい」と言挙げする性向や態度のことを指している。このようなキャンセルカルチャーは、近年 では、ブラックライブズ・マター(#BLM)のような抑圧された人びとが抑圧の歴史を告発する運動の隆盛に、裏打ちして、そのような「告発する人たち」の集団から阻害 されたり、排除されている人たちからでる異議申し立てである。

★以下に紹介するネイチャーの記事は、SNS運用会社そのものが、フェイクニュースを流す ユーザーをコールアウトすることについて報道している。

「オンラインの誤情報は、社会の基盤を脅かし、意見

の対立を招き、選挙の安定性さえも損なわせるものとして取り上げられることが多い。今週号では、誤情報の弊害を調べ、その真のリスクを評価しようとする論

文と記事がいくつか掲載されている。D

Lazerたちの論文では、2021年1月に米国連邦議会議事堂で発生した暴力的事件を受けて、ツイッターが誤情報の発信者7万人をプラットフォームから

排除したことの影響が検証されている。W Ahmadたちは別の論文で、広告収入と誤情報の関係について調査している。U

EckerたちによるCommentでは、誤情報が民主主義や選挙にもたらすリスクが論じられており、それに続くK GarimellaとS

ChauchardによるCommentでは、インドにおけるAIが生成した誤情報の蔓延について評価されている。またD

RothschildたちはPerspectiveで、誤情報の害について取り上げ、その脅威を誇張する一般的な誤解に重点を置いて、誤情報の影響とそれ

に対抗するための取り組みの両方を評価する改善策を提案している」フェイクニュース?:

オンラインの誤情報がもたらす脅威を探る, 2024年6月6日 Nature 630, 8015

◎キャンセルカルチャー:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cancel_culture

| Cancel culture or

call-out culture is a

phrase contemporary to the late 2010s and early 2020s used to

refer to a form of ostracism in which someone is thrust out of social

or professional circles – whether it be online, on social media, or in

person. Those subject to this ostracism are said to have been

"cancelled".[1][a][4] The expression "cancel culture" has mostly

negative connotations and is used in debates on free speech and

censorship.[5][6] The notion of cancel culture is a variant on the term call-out culture. It is often said to take the form of boycotting or shunning an individual (often a celebrity) who is deemed to have acted or spoken in an unacceptable manner.[2][7][8][9][10] Some critics argue that cancel culture has a chilling effect on public discourse, is unproductive, does not bring real social change, causes intolerance, and amounts to cyberbullying.[11][12] Others argue that calls for "cancellation" are themselves a form of free speech and that they promote accountability, give disenfranchised people a voice, and are simply another form of boycotting.[12][13][14][15] Some public figures claim to have been "cancelled" while continuing their careers as before.[16][17] |

キャ

ンセル文化またはコールアウト文化とは、2010年代後半から

2020年代初頭にかけての言葉であり、オンライン、ソーシャルメディア、または個人を問わず、誰かが社会的または職業的サークルから突き放される排斥の

形態を指すのに使われる。この排斥の対象となった人々は「キャンセル」されたと言われている[1][a][4]。「キャンセル文化」という

表現は主にネガ

ティブな意味合いを持ち、言論の自由と検閲に関する議論において使用される[5][6]。 キャンセル文化の概念は、コールアウト文化という用語の変形である。それはしばしば容認できない行動や発言をしたとみなされる個人(しばしば有名人)をボ イコットしたり敬遠したりする形を取ると言われている[2][7][8][9][10]。 一部の批評家は、キャンセル文化は公共の言論を冷え込ませる効果があり、非生産的 で、真の社会変革をもたらさず、不寛容を引き起こし、ネットいじめに等し いと主張する[11][12]。 他方、「キャンセル」の要求自体が言論の自由の一形態であり、説明責任を促進し、権利を奪われた人々に声を与え、単に不買運動の別の形であることを主張す る。 [12][13][14][15] 一部の公的人物はこれまで通りキャリアを続けながら「キャンセルされた」ことがあると主張する[16][17]。 |

| Origins "Call-out culture" has been in use as part of the #MeToo movement.[18] The #MeToo movement encouraged women (and men) to call out their abusers on a forum where the accusations would be heard, especially against very powerful individuals.[19] Additionally, the Black Lives Matter Movement, which seeks to highlight inequalities, racism and discrimination in the black community, repeatedly called out black men being killed by police.[20] In March 2014, activist Suey Park called out "a blatantly racist tweet about Asians" from the official Twitter account of The Colbert Report using the hashtag #cancelColbert, which generated widespread outrage against Stephen Colbert and an even greater amount of backlash against Park, even though the Colbert Report tweet was a satirical tweet.[21][22] By around 2015, the concept of canceling had become widespread on Black Twitter to refer to a personal decision, sometimes seriously and sometimes in jest, to stop supporting a person or work.[23][24][25] According to Jonah Engel Bromwich of The New York Times, this usage of the word "cancellation" indicates the "total disinvestment in something (anything)".[26][27] After numerous cases of online shaming gained wide notoriety, the term cancellation was increasingly used to describe a widespread, outraged, online response to a single provocative statement, against a single target.[28] Over time, as isolated instances of cancellation became more frequent and the mob mentality more apparent, commentators began seeing a "culture" of outrage and cancellation.[29] The phrase cancel culture gained popularity since late 2019,[30] most often as a recognition that society will exact accountability for offensive conduct.[31][32] More recently, the phrase has become a shorthand employed by conservatives in the United States to refer to what are perceived to be disproportionate reactions to politically incorrect speech.[5] In 2020, Ligaya Mishan wrote in The New York Times, "The term is shambolically applied to incidents both online and off that range from vigilante justice to hostile debate to stalking, intimidation and harassment. ... Those who embrace the idea (if not the precise language) of canceling seek more than pat apologies and retractions, although it's not always clear whether the goal is to right a specific wrong or redress a larger imbalance of power."[4][33] |

起源 "呼びかけ文化 "は#MeToo運動の一環として使われるようになった[18]。#MeToo運動は女性(と男性)に対して、特に非常に力のある個人に対して、告発が聞 かれるような場で加害者を呼び出すことを奨励した[19]。 さらに、黒人コミュニティにおける不平等、人種差別、差別を強調しようとするブラックライブズマッター運動は、警察に殺される黒人男性に繰り返し呼びかけ を行なった[20]。 2014年3月、活動家のスエイ・パークがハッシュタグ#cancelColbertを使って『コルベア・レポート』の公式Twitterアカウントから 「アジア人に関する露骨な人種差別ツイート」を呼びかけたところ、スティーブン・コルベアに対する怒りが広がり、コルベア・レポートのツイートは風刺ツ イートだったのに、パークに対する反発はさらに大きくなった[21][22] 2015年頃までにブラックTwitterでは、個人や作品に対して支援をやめるという個人の決断、時に真剣に、時に冗談で、という意味でキャンセルとい うコンセプトは浸透してきている。 [23][24][25] ニューヨーク・タイムズのジョナ・エンゲル・ブロミッチによれば、「キャンセル」という言葉のこの用法は、「何か(何か)に対する完全な不投資」を示す [26][27] 多数のオンライン恥辱のケースが広く知られるようになると、キャンセルという言葉は、単一の挑発的発言に対する、単一のターゲットに対する、広範囲にわた る憤怒のオンライン反応を表すためにますます使用されるようになった。 [28] 時とともに、キャンセルの孤立した事例がより頻繁になり、群集心理がより明らかになるにつれて、コメンテーターは怒りとキャンセルの「文化」を見るように なった[29]。 キャンセル文化というフレーズは2019年後半から人気を博し[30]、最も頻繁に社会が攻撃的な行為に対する説明責任を厳格に果たすという認識として使 われた[31][32]。 より最近では、このフレーズは米国の保守派が政治的に正しくないスピーチに対する不当な反応と認識されるものに言及するために用いる略語になっている [5]。 2020年、リガヤ・ミシャンはニューヨーク・タイムズ紙に「この言葉は、自警団的正義から敵対的議論、ストーキング、脅迫、嫌がらせに至るまで、オンラ インとオフの両方の事件に不安定に適用されている」と書いている[5]。... 正確な言語ではないにせよ)キャンセルのアイデアを受け入れる人々は、それは常に目標が特定の間違いを正すか、権力の大きな不均衡を是正することであるか どうかは明らかではないが、パット謝罪と撤回以上のものを求めている"[4][33]。 |

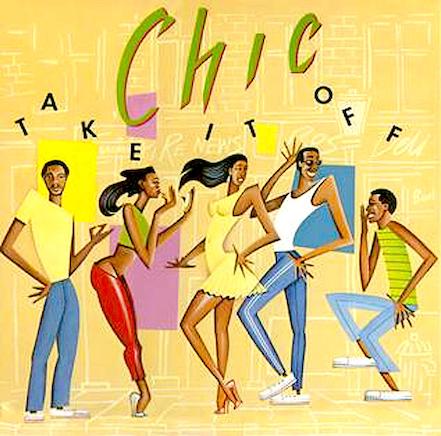

| Etymology The 1981 Chic album Take It Off includes the song "Your Love Is Cancelled" which compares a breakup to the cancellation of TV shows. The song was written by Nile Rodgers following a bad date Rodgers had with a woman who expected him to misuse his celebrity status on her behalf. "Your Love Is Cancelled" inspired screenwriter Barry Michael Cooper to include a reference to a woman being "cancelled" in the 1991 film New Jack City.[23] This usage introduced the term to African-American Vernacular English, where it eventually became more common.[34] |

語源 1981年のシックのアルバム『テイク・イット・オフ』には、別れをテレビ番組の打ち切りに例えた「ユア・ラヴ・イズ・キャンセルド」という曲が収録され ている。この曲は、ナイル・ロジャースが、自分の有名人としての地位を悪用することを期待した女性とのデートがうまくいかなかったことをきっかけに書いた ものだ。また、「Your Love Is Cancelled」は脚本家のバリー・マイケル・クーパーに触発され、1991年の映画『ニュー・ジャック・シティ』で女性が「キャンセル」されること への言及を含んだ[23]。 この用法によりこの言葉はアフリカ系アメリカ人の言語英語へと導入され、最終的にはより一般的になった[34]。 |

| Academic analysis An article written by Pippa Norris, a professor at Harvard University, states that the controversies surrounding cancel culture are between the ones who argue it gives a voice to those in marginalized communities, while the opposing side argues cancel culture is dangerous because it prevents free speech and/or the opportunity for open debate.[35] Norris emphasizes the role of social media in contributing to the rise of cancel culture.[36][35] Additionally, online communications studies have demonstrated the intensification of cultural wars through activists that are connected through digital and social networking sites.[37][35] Norris also mentions that the spiral of silence theory may be a contributing factor as to why people are hesitant to voice their own minority views on social media sites in fear that their views and opinions, specifically political opinions, will be chastised because their views violate the majority group's norms and understanding.[35] In the book The Coddling of the American Mind (2018), social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and free-speech activist Greg Lukianoff argue that call-out culture arises on college campuses from what they term "safetyism:" a moral culture in which people are unwilling to make tradeoffs demanded by the practical or moral concerns of others.[38][39] Keith Hampton, professor of media studies at Michigan State University, contends that the practice contributes to the polarization of American society, but does not lead to changes in opinion.[40] Cancel culture has been described by media studies scholar Eve Ng as "a collective of typically marginalized voices 'calling out' and emphatically expressing their censure of a powerful figure."[41] Cultural studies scholar Frances Lee states that call-out culture leads to self-policing of "wrong, oppressive, or inappropriate" opinions.[42][43] According to Lisa Nakamura, University of Michigan professor of media studies, canceling someone is a form of "cultural boycott" and cancel culture is the "ultimate expression of agency" which is "born of a desire for control [as] people have limited power over what is presented to them on social media" and a need for "accountability which is not centralized".[10][44][45] Some academics proposed alternatives and improvements to cancel culture. Critical multiculturalism professor Anita Bright proposed "calling in" rather than "calling out" in order to bring forward the former's idea of accountability but in a more "humane, humble, and bridge-building" light.[46] Clinical counsellor Anna Richards, who specializes in conflict mediation, says that "learning to analyze our own motivations when offering criticism" helps call-out culture work productively.[47] Professor Joshua Knobe, of the Philosophy Department at Yale, contends that public denunciation is not effective, and that society is too quick to pass judgement against those they view as public offenders or persona non grata. Knobe asserts that these actions have the opposite effect on individuals, and that it is best to bring attention to the positive actions in which most of society participates.[48] |

学術的な分析 ハーバード大学の教授であるピッパ・ノリスによって書かれた論文によれば、キャンセル文化をめぐる論争は、それが疎外されたコミュニティの人々に声を与え るものであると主張する側と、言論の自由や開かれた議論の機会を妨げるのでキャンセル文化は危険であると反対する側の間で行われている[35]。 ノリスはキャンセル文化の隆盛に寄与するソーシャルメディアの役割を強調する[36][35]。 [36][35] さらに、オンラインコミュニケーション研究は、デジタルやソーシャルネットワーキングサイトを通じてつながっている活動家を通じて文化戦争の激化を実証し ている。 37][35] ノリスはまた、沈黙のスパイラル理論が、なぜ人々がソーシャルメディアサイトで自らの少数意見を述べることをためらうかの一因である可能性に言及してい る、彼らの見解や意見、特に政治的意見が多数派の規範と理解に反するために非難されることを恐れている[35][36] 。 書籍『The Coddling of the American Mind』(2018年)で、社会心理学者のジョナサン・ハイトと言論の自由の活動家のグレッグ・ルキアノフは、彼らが「安全主義」と呼ぶものから大学 キャンパスで呼びかけ文化が生じると主張しています:人々は他者の現実的または道徳的な懸念によって要求されるトレードオフをすることを望まない道徳文化 [38][39] ミシガン州立大学メディア学教授のキース・ハンプソンは、その慣習がアメリカ社会の分極化に貢献するが意見の変更につながらない、と論じています。 40] キャンセル文化はメディア研究者のイブ・ングによって「典型的に疎外された声の集団が、強力な人物に対する非難を『呼びかけ』、強調的に表現すること」と して説明されている[41] 文化研究者のフランシス・リーは、コールアウト文化が「間違った、抑圧的な、あるいは不適切な」意見の自己検閲につながると述べる[42][43]。 [42][43] ミシガン大学のメディア研究教授であるリサ・ナカムラによれば、誰かをキャンセルすることは「文化的ボイコット」の一形態であり、キャンセル文化は「コン トロールへの欲求から生まれた(ソーシャルメディア上で提示されるものに対する人々の力は限られているので)」「中央集権ではない説明責任」の必要性であ る、代理性の究極の表現[10][44][45]とされている。 一部の学者は、キャンセル・カルチャーの代替案や改善策を提案している。批判的多文化主義のアニタ・ブライト教授は、前者の説明責任の考えを前面に押し出 しながらも、より「人道的で、謙虚で、橋渡し的」な観点から「コールイン」を提案した[46]。紛争調停を専門とする臨床カウンセラーのアナ・リチャーズ は、「批判するときに自分自身の動機を分析することを学ぶ」ことがコールアウト文化を生産的に働かせる助けになると語っている[47]。 イェール大学哲学科のジョシュア・クノーブ教授は、公然たる糾弾は効果的ではなく、社会は公然たる犯罪者あるいはペルソナ・ノン・グラータとみなす人に対 して判断を下すのが早すぎると主張する。ノベはこれらの行為は個人に対して逆の効果をもたらし、社会のほとんどが参加している肯定的な行為に注意を向ける ことが最善であると主張している[48]。 |

| Reactions The expression cancel culture has mostly negative connotations and is used in debates on free speech and censorship.[5][6] Former US President Barack Obama warned against social media call-out culture, saying: "People who do really good stuff have flaws. People who you are fighting may love their kids and, you know, share certain things with you."[49] Former US President Donald Trump criticized cancel culture in a speech in July 2020, comparing it to totalitarianism and saying that it is a political weapon used to punish and shame dissenters by driving them from their jobs and demanding submission. He was criticized as being hypocritical for having attempted to "cancel" a number of people and companies in the past himself.[50] Trump made similar claims during the 2020 Republican National Convention when he stated that the goal of cancel culture is to make decent Americans live in fear of being fired, expelled, shamed, humiliated, and driven from society.[35] Pope Francis said that cancel culture is "a form of ideological colonization, one that leaves no room for freedom of expression", saying that it "ends up cancelling all sense of identity".[51][52][53] Patrisse Khan-Cullors, the co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement, states that social activism does not just involve going online or going to a protest to call someone out, but is work entailing strategy sessions, meetings, and getting petitions signed [19] Some argue that cancel culture does have its benefits, such as allowing less powerful people to have a voice, helps marginalized people hold others accountable when the justice system doesn't work, and cancelling is a tool to bring about social change.[19] Lisa Nakamura, a professor at the University of Michigan, describes cancel culture as "a cultural boycott" and says it provides a culture of accountability.[54] Meredith Clark, an assistant professor at the University of Virginia, states that cancel culture gives power to disenfranchised voices.[19] Osita Nwanevu, a staff writer for The New Republic, states that people are threatened by cancel culture because it's a new group of young progressives, minorities, and women who have "obtained a seat at the table" and are debating matters of justice and etiquette.[55] |

反応 キャンセル・カルチャーという表現は、ほとんどが否定的な意味合いで、言論の自由や検閲に関する議論に使われる[5][6]。 前アメリカ大統領のバラク・オバマは、ソーシャルメディア上の呼びかけ文化に警告を発し、次のように述べた。「本当に良いことをする人には欠点がある。あ なたが戦っている人は、子供を愛しているかもしれないし、あることを共有しているかもしれない」[49]。ドナルド・トランプ前米大統領は2020年7月 の演説で、呼びかけ文化を全体主義と比較し、反対者を仕事から追い出して服従を求め、罰したり恥をかかせるための政治武器であると批判した。彼は過去に自 ら多くの人や企業を「キャンセル」しようとしたことから偽善的であると批判された[50]。 トランプは2020年の共和党全国大会において、キャンセル文化の目的はまともなアメリカ人を解雇、追放、辱め、屈辱、社会から追い出すことに怯えて生活 させることだと述べ、同様の主張をしている[35]。 ローマ法王フランシスコは、キャンセル文化は「イデオロギーの植民地化の一形態であり、表現の自由の余地がないもの」であり、「アイデンティティのすべて の感覚をキャンセルすることになる」と述べている[51][52][53] ブラックライブスマターの共同創設者のパトリッセ・カーン・カラーズは、社会活動とは単に誰かを訴えるためにオンラインや抗議に行くことではなく、戦略会 議、会議、署名した請願書を得ることに伴う作業である、と述べている[19]。 キャンセル文化には、力の弱い人たちが声を上げることを可能にし、司法制度が機能しないときに疎外された人たちが他の人たちに責任を負わせることを助け、 キャンセルは社会変革をもたらすツールであるなどの利点があると主張する人もいる[19]。ミシガン大学教授のリサ中村は、キャンセル文化を「文化の不買 運動」として説明し、それが説明責任の文化を提供すると述べている。 [54] バージニア大学の助教授であるメレディス・クラークは、キャンセル文化は権利を奪われた声に力を与えると述べている[19] ニュー・リパブリックのスタッフライターであるオシタ・ヌワネヴは、人々がキャンセル文化に脅かされるのは、それが「テーブルに座る席を得た」若い進歩主 義者や少数派、女性の新しいグループであり、正義と礼儀作法の問題について討論しているためだと述べる[55]。 |

| Open letter Main article: A Letter on Justice and Open Debate Dalvin Brown, writing in USA Today, has described an open letter signed by 153 public figures and published in Harper's Magazine as marking a "high point" in the debate on the topic.[5] The letter set out arguments against "an intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty."[56][57][58] A response letter organized by lecturer Arionne Nettles, "A More Specific Letter on Justice and Open Debate", was signed by over 160 people in academia and media. It criticized the Harper's letter as a plea to end cancel culture by successful professionals with large platforms who wanted to exclude others who have been "cancelled for generations.” The writers ultimately stated that the Harper's letter was intended to further silence already marginalized people. They wrote: "It reads as a caustic reaction to a diversifying industry — one that's starting to challenge diversifying norms that have protected bigotry."[59][60] |

公開書簡 主な記事 正義とオープン・ディベートに関する書簡 USA Todayに寄稿したDalvin Brownは、153人の公人が署名し、Harper's Magazineに掲載された公開書簡を、このテーマに関する議論における「高み」を示すものとして説明している[5]。 その手紙は、「反対意見に対する不寛容、公的な恥や排斥の流行、目も当てられない道徳的確信で複雑な政策課題を溶解する傾向」に対する議論を提示したもの である[56][57][58]。 講師のアリオン・ネトルズによって組織された回答書「正義と開かれた議論に関するより具体的な手紙」には、学界とメディアの160人以上が署名している。 それは、ハーパーズ・レターを、大きなプラットフォームを持つ成功した専門家が、"何世代にもわたってキャンセルされてきた "他の人々を排除しようとするキャンセル文化の終結を訴えたものだと批判している。執筆者たちは最終的に、ハーパーズレターはすでに疎外されている人々を さらに黙らせるためのものだと述べている。彼らは「多様化する業界、つまり偏見を守ってきた多様化する規範に挑戦し始めた業界に対する苛烈な反応として読 み取れる」と書いています[59][60]。 |

| American public opinion A survey conducted on 10,000 Americans by Pew Research Center asked a series of different questions in regard to cancel culture, specifically on who has heard of the term cancel culture and how Americans define cancel culture.[61] In September 2020, 44% of Americans said that they have at least heard a fair amount about the new phrase, while 22% have heard a great deal and 32% said they have heard nothing at all.[61] 43% Americans aged 18–29 have heard a great deal about cancel culture, compared to only 12% of Americans over the age of 65 who say they have heard a great deal.[61] Additionally, within that same study, the 44% of Americans who had heard a great deal about cancel culture, were then asked how they defined cancel culture. 49% of those Americans state that it describes actions people take to hold others accountable, 14% describe cancel culture as censorship of speech or history, and 12% define it as mean-spirited actions taken to cause others harm.[61] It was found that men were more likely to have heard or know of cancel culture, and that those who identify with the Democratic Party (46%) are more likely to know the term than those in the Republican Party (44%).[61] A poll of American registered voters conducted by Morning Consult in July 2020 showed that cancel culture, defined as "the practice of withdrawing support for (or canceling) public figures and companies after they have done or said something considered objectionable or offensive", was common: 40% of respondents said they had withdrawn support from public figures and companies, including on social media, because they had done or said something considered objectionable or offensive, with 8% having engaged in this often. Behavior differed according to age, with a majority (55%) of voters 18 to 34 years old saying they have taken part in cancel culture, while only about a third (32%) of voters over 65 said they had joined a social media pile-on.[62] Attitude towards the practice was mixed, with 44% of respondents saying they disapproved of cancel culture, 32% who approved, and 24% who did not know or had no opinion. Furthermore, 46% believed cancel culture had gone too far, with only 10% thinking it had not gone far enough. Additionally, 53% believed that people should expect social consequences for expressing unpopular opinions in public, such as those that may be construed as deeply offensive to other people.[63] A March 2021 poll by the Harvard Center for American Political Studies and the Harris Poll found that 64% of respondents viewed "a growing cancel culture" as a threat to their freedom, while the other 36% did not. 36% of respondents said that cancel culture is a big problem, 32% called it a moderate problem, 20% called it a small problem, and 13% said it is not a problem. 54% said they were concerned that if they expressed their opinions online, they would be banned or fired, while the other 46% said they were not concerned.[64] A November 2021 Hill/HarrisX poll found that 71% of registered voters strongly or somewhat felt that cancel culture went too far, with similar numbers of Republicans (76%), Democrats (70%), and independents (68%) saying so.[65] The same poll found that 69% of registered voters felt that cancel culture unfairly punishes people for their past actions or statements, compared to 31% who said it did not. Republicans were more likely to agree with the statement (79%), compared to Democrats (65%) and independents (64%).[66] |

アメリカの世論 ピュー・リサーチ・センターが1万人のアメリカ人に対して行った調査では、キャンセル・カルチャーに関して、特にキャンセル・カルチャーという言葉を誰が 聞いたことがあるか、アメリカ人がどのようにキャンセル・カルチャーを定義するかについて一連の異なる質問をした[61]。 2020年9月に、44%のアメリカ人がこの新しい言葉について少なくともかなり聞いたことがあると答え、22%がとても聞いたことがあり、32%がまっ たく聞いたことがないと答えた。 [61] 18-29歳のアメリカ人の43%がキャンセルカルチャーについてかなり聞いたことがあると答えたのに対し、65歳以上のアメリカ人の12%だけがかなり 聞いたことがあると答えた[61] さらに、その同じ調査の中で、キャンセルカルチャーについてかなり聞いたことがある44%のアメリカ人に、キャンセルカルチャーをどう定義するかを質問し た。それらのアメリカ人の49%は、それが他者に責任を負わせるために人々が取る行動を記述していると述べ、14%はキャンセル文化を言論や歴史の検閲と して記述し、12%はそれを他人に害を与えるために取られた意地の悪い行動として定義した[61]。 キャンセル文化を聞いたことがあるか知っている可能性は男性の方が高く、民主党に属する人(46%)は共和党の人(44%)よりもその用語を知っている可 能性が高いことが分かった[61]。 Morning Consultが2020年7月に実施したアメリカの登録有権者を対象とした世論調査では、「公人や企業が好ましくない、あるいは不快と思われることをし たり言ったりした後に支持を取り下げる(あるいは取り消す)行為」と定義されるキャンセル文化は一般的で、回答者の40%が「公人や企業が好ましくない、 あるいは不快と思われることをしたり言ったりしたのでソーシャルメディアも含めて支援を取り消した経験があり、頻繁に実行したことがある」は8%と回答し た。年齢別では、18歳から34歳の有権者の過半数(55%)が「キャンセルカルチャーに参加したことがある」と回答したのに対し、65歳以上の有権者の 約3分の1(32%)だけが「ソーシャルメディア上の非難に参加したことがある」と答えている[62]。さらに、46%がキャンセルカルチャーは行き過ぎ たと考え、10%だけが十分に行き過ぎていないと考えていた。さらに、53%は、他の人々を深く傷つけると解釈されるような不人気な意見を公共の場で表明 することに対して、社会的な結果を期待すべきであると考えていた[63]。 ハーバード大学アメリカ政治研究センターとハリス・ポールによる2021年3月の世論調査では、回答者の64%が「拡大するキャンセル文化」を自由への脅 威とみなし、残りの36%はそうでないことがわかった。キャンセル文化が大きな問題だと答えた人は36%、中程度の問題だと答えた人は32%、小さな問題 だと答えた人は20%、問題ではないと答えた人は13%であった。54%がオンラインで意見を述べたら禁止されたり解雇されたりすることを懸念していると 答え、残りの46%は懸念していないと答えた[64]。 2021年11月のヒル/ハリスXの世論調査によれば、登録有権者の71%がキャンセル文化が行き過ぎだと強くあるいは多少感じており、共和党 (76%)、民主党(70%)、無党派層(68%)が同数そう述べていた[65]。 同じ世論調査で、登録有権者の69%がキャンセル文化が過去の行動や発言に対して不当に罰すると感じており、一方そうでないと答えたのは31%であること が判明した。共和党員は民主党員(65%)、無党派層(64%)と比べて、この声明に同意する傾向が強かった(79%)[66]。 |

| Criticism of the concept A number of professors, politicians, journalists, and activists question the validity of cancel culture as an actual phenomenon.[16][67][68][69] Connor Garel, writing for Vice, states that cancel culture "rarely has any tangible or meaningful effect on the lives and comfortability of the cancelled."[17] Danielle Kurtzleben, a political reporter for NPR, wrote in 2021 that overuse of the phrase cancel culture in American politics, particularly by Republicans, has made it "arguably background noise". Per Kurtzleben and others, the term has undergone semantic bleaching to lose its original meaning.[70] Historian C. J. Coventry argues that the term has been incorrectly applied, and that it more accurately reflects the propensity of people to hide historical instances of injustice.[71][b] Another historian, David Olusoga, made a similar argument, and said it is not limited to the left.[15][c] Indigenous governance professor and activist Pamela Palmater writes in Maclean's magazine that cancel culture differs from accountability; her article covers the public backlash surrounding Canadian politicians who vacationed during COVID-19, despite pandemic restrictions forbidding such behavior.[14] Former US Secretary of Labor Eugene Scalia says that cancel culture is a form of free speech, and is therefore protected under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. According to Scalia, cancel culture can interfere with the right to counsel, as some lawyers would not be willing to risk their personal and professional reputation on controversial topics.[72] Sarah Manavis wrote for the New Statesman magazine that while free speech advocates are more likely to make accusations of cancel culture, criticism is part of free speech and rarely results in consequences for those in power who are criticized. She argues that social media is an extension and reincarnation of a longer tradition of expression in a liberal society, "a new space for historical power structures to be solidified" and that online criticism by people who do not hold actual power in society tends to not affect existing power structures. She adds that most prominent people who criticized public opinion as canceling still have highly profitable businesses and concludes by saying, "So even if you fear the monster under the bed, it will never do you harm. It can't, because it was never there in the first place. Repercussions rarely come for those in power. Why punch down, when you've already won?"[13] |

概念に対する批判 多くの教授、政治家、ジャーナリスト、活動家が実際の現象としてのキャンセル文化の妥当性を疑問視している[16][67][68][69] コナー・ガレルはViceに執筆し、キャンセル文化は「キャンセルされた人々の生活や快適さに具体的で意味のある影響を及ぼすことはほとんどない」 [17] NPRの政治記者、ダニエル・カーツレーベンは2021年にアメリカの政治において、特に共和党によってキャンセル文化という言葉が過度に使用されて、そ れが「間違いなく背景雑音」になっていると記している。カーツルベンらによれば、この言葉は意味的な漂白を経て本来の意味を失っている[70]。 歴史家のC・J・コベントリーは、この用語は間違って適用されており、歴史的な不正の事例を隠そうとする人々の傾向をより正確に反映していると主張してい る[71][b]。 別の歴史家のデヴィッド・オルソガは同様の議論を行い、それは左派に限った話ではないと言っていた。 [15][c] 先住民ガバナンスの教授で活動家のパメラ・パルメーターは、キャンセルカルチャーは説明責任とは異なるとマクリーンズ誌に書いている。彼女の記事は、パン デミック規制がそのような行動を禁止しているにもかかわらず、COVID-19の間に休暇をとったカナダの政治家を取り巻く国民の反発をカバーしている。 14] 元アメリカ労働長官のユージン・スカリアが、キャンセルカルチャーは言論の自由の一形態であり、したがって合衆国憲法修正第一条の下で保護されていると述 べている。スカリアによれば、論争的な話題で個人的、職業的評判を危険にさらすことを望まない弁護士もいるため、キャンセル文化は弁護士の権利を妨害する ことができる[72]。 サラ・マナヴィスはニューステーツマン誌に、言論の自由の擁護者はキャンセル文化を非難する傾向が強いが、批判は言論の自由の一部であり、批判された権力 者に結果がもたらされることはほとんどない、と書いている。彼女は、ソーシャルメディアは自由主義社会における表現の長い伝統の延長と生まれ変わりであ り、「歴史的な権力構造が固まる新しい空間」であり、社会で実際の権力を握っていない人によるオンライン批判は既存の権力構造に影響しない傾向があると論 じています。また、世論が取り消すと批判した著名人の多くは、今でも高収益のビジネスを行っていると付け加え、最後に「だから、ベッドの下のモンスターを 恐れても、それは決してあなたに害を与えることはないのです。なぜなら、もともとそこにいなかったのだから。権力者には、めったに報復はない。すでに勝っ たのに、なぜ殴り倒すのか」[13]。 |

| Consequence culture Some media commentators including LeVar Burton and Sunny Hostin have stated that cancel culture should be renamed consequence culture.[73] The terms have different connotations: cancel culture focusing on the effect whereby discussion is limited by a desire to maintain one certain viewpoint, whereas consequence culture focuses on the idea that those who write or publish opinions or make statements should bear some responsibility for the effects of these on people.[74] |

結果文化 ルヴァー・バートンやサニー・ホスティンを含む一部のメディアコメンテーターは、キャンセル文化は結果文化と改名されるべきだと述べている[73]。この 言葉は異なる意味合いを持つ。キャンセル文化は議論がある特定の視点を維持したいという欲求によって制限される効果に焦点を当て、一方結果文化は意見を書 いたり発表したり、発言をする人はそれが人々に与える影響について何らかの責任を負うべきという考えに基づいている[74]。 |

| In popular culture The American animated television series South Park mocked cancel culture with its own "#CancelSouthPark" campaign in promotion of the show's twenty-second season (2018).[75][76][77][78] In the season's third episode, "The Problem with a Poo", there are references to the 2017 documentary The Problem with Apu, the cancellation of Roseanne after a controversial tweet by Roseanne Barr, and the Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court nomination.[79][80] In 2019, cancel culture was a primary theme in the stand-up comedy show Sticks & Stones by Dave Chappelle.[81] |

大衆文化において アメリカのテレビアニメシリーズ『サウスパーク』は、番組の第22シーズン(2018年)のプロモーションで、独自の 「#CancelSouthPark」キャンペーンでキャンセル文化を嘲笑した[75][76][77][78]。 シーズン第3話の「The Problem with a Poo」では、2017年のドキュメンタリー映画『The Problem with Apu』、ロザンヌ・バールによる物議を醸したツイートの後のロザンヌのキャンセル、ブレット・カバノー最高裁判所指名に言及されている[79] [80]。 2019年、デイヴ・チャペルによるスタンドアップコメディ番組『Sticks & Stones』では、キャンセル文化が主要なテーマとなった[81]。 |

| See also icon Society portal Blacklisting Culture war Deplatforming Divestment Moral entrepreneur Online shaming Persona non grata Shunning Social exclusion Social justice warrior – Pejorative term for a progressive person Woke |

こちらもご覧ください アイコン社会ポータル ブラックリスト 文化戦争 デプラットフォーム ディベストメント 道徳的起業家 オンライン恥さらし ペルソナ・ノン・グラータ シャイニング 社会的排除 社会正義の戦士 - 進歩的な人物の蔑称 目覚めた人 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cancel_culture |

Etymology

of "Cancel culture"

The 1981 Chic album Take It Off includes the song "Your Love Is

Cancelled" which compares a breakup to the cancellation of TV shows.

The song was written by Nile Rodgers following a bad date Rodgers had

with a woman who expected him to misuse his celebrity status on her

behalf. "Your Love Is Cancelled" inspired screenwriter Barry Michael

Cooper to include a reference to a woman being "cancelled" in the 1991

film New Jack City. This usage introduced the term to African-American

Vernacular English, where it eventually became more common.

語源

1981年のシックのアルバム『テイク・イット・オフ』には、別れをテレビ番組の打ち切りに例えた「ユア・ラヴ・イズ・キャンセルド」という曲が収録され

ている。この曲は、ナイル・ロジャースが、自分の有名人としての地位を悪用することを期待した女性とのデートがうまくいかなかったことをきっかけに書いた

ものだ。また、「Your Love Is

Cancelled」は脚本家のバリー・マイケル・クーパーに触発され、1991年の映画『ニュー・ジャック・シティ』で女性が「キャンセル」されること

への言及を含んだ[23]。 この用法によりこの言葉はアフリカ系アメリカ人の言語英語へと導入され、最終的にはより一般的になった[34]。

◎パーソナリティ研究(心理学の歴史)出典:Personality.

| Personality is the

characteristic sets of behaviors, cognitions, and emotional patterns

that are formed from biological and environmental factors, and which

change over time.[1][2] While there is no generally agreed-upon

definition of personality, most theories focus on motivation and

psychological interactions with the environment one is surrounded

by.[3] Trait-based personality theories, such as those defined by

Raymond Cattell, define personality as traits that predict an

individual's behavior. On the other hand, more behaviorally-based

approaches define personality through learning and habits.

Nevertheless, most theories view personality as relatively stable.[1] The study of the psychology of personality, called personality psychology, attempts to explain the tendencies that underlie differences in behavior. Psychologists have taken many different approaches to the study of personality, including biological, cognitive, learning, and trait-based theories, as well as psychodynamic, and humanistic approaches. The various approaches used to study personality today reflect the influence of the first theorists in the field, a group that includes Sigmund Freud, Alfred Adler, Gordon Allport, Hans Eysenck, Abraham Maslow, and Carl Rogers. |

パーソナリティとは、生物学的および環境的要因から形成され、時間とと

もに変化する行動、認知、感情のパターンの特徴的な集合である[1][2]。一般的に合意されたパーソナリティの定義はないが、ほとんどの理論は動機と人

の周囲の環境との心理的相互作用に焦点を当てている。レイモンドキャッテルの定義に代表される特性論的性格理論は、個人の行動を予測する特徴として性格を

定義している[3]。一方、より行動学に基づいたアプローチでは、学習や習慣を通して性格を定義する。とはいえ、ほとんどの理論では、性格は比較的安定し

ていると見なされている[1]。 人格心理学と呼ばれる人格の心理を研究する学問は、行動の違いの根底にある傾向を 説明しようとするものである。心理学者は、生物学的、認知的、学習的、および特性ベースの理論、さらに精神力動的、および人間論的アプローチなど、性格の 研究にさまざまなアプローチを取ってきた。今日、パーソナリティの研究に用いられている様々なアプローチは、この分野の最初の理論家であるジークムント・ フロイト、アルフレッド・アドラー、ゴードン・オールポート、ハンス・アイゼンク、アブラハム・マズロー、カール・ロジャースなどの影響を反映している。 |

| Measuring Personality can be determined through a variety of tests. Due to the fact that personality is a complex idea, the dimensions of personality and scales of such tests vary and often are poorly defined. Two main tools to measure personality are objective tests and projective measures. Examples of such tests are the: Big Five Inventory (BFI), Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2), Rorschach Inkblot test, Neurotic Personality Questionnaire KON-2006,[4] or Eysenck's Personality Questionnaire (EPQ-R). All of these tests are beneficial because they have both reliability and validity, two factors that make a test accurate. "Each item should be influenced to a degree by the underlying trait construct, giving rise to a pattern of positive intercorrelations so long as all items are oriented (worded) in the same direction."[5] A recent, but not well-known, measuring tool that psychologists use is the 16PF. It measures personality based on Cattell's 16-factor theory of personality. Psychologists also use it as a clinical measuring tool to diagnose psychiatric disorders and help with prognosis and therapy planning.[6] Personality is frequently broken into factors or dimensions, statistically extracted from large questionnaires through factor analysis. When brought back to two dimensions, often the dimensions of introvert-extrovert and neuroticism (emotionally unstable-stable) are used as first proposed by Eysenck in the 1960s.[7] |

測定方法 パーソナリティは、さまざまなテストによって判定することができる。パーソナリティは複雑な考え方であるため、パーソナリティの次元やそのテストの尺度は 様々で、しばしば定義が曖昧になることがある。パーソナリティを測定する主な手段は、客観的テストと投影法の2つである。そのようなテストの例としては ビッグファイブ・インベントリー(BFI)、ミネソタ多面的性格検査(MMPI-2)、ロールシャッハ・インクブロットテスト、神経症的性格調査票KON -2006、[4] あるいはアイゼンクの性格調査票(EPQ-R)である。これらのテストはすべて、テストを正確にする2つの要素である信頼性と妥当性の両方を備えているた め有益である。「各項目は、すべての項目が同じ方向を向いている限り、基礎となる特性構成にある程度影響され、正の相互相関のパターンを生じるはずであ る」 [5] 最近の、しかしあまり知られていない、心理学者が使用する測定ツールは、16PFである。これは、キャッテルの16因子性格理論に基づいて性格を測定する ものです。心理学者はまた、精神疾患を診断し、予後や治療計画に役立てるための臨床的な測定ツールとして使用している[6]。 性格はしばしば因子や次元に分けられ、因子分析を通じて大規模な質問票から統計的に抽出される。2つの次元に戻すと、1960年代にアイゼンクが最初に提 唱した内向-外向と神経症(情緒不安定-安定)の次元が使われることが多い[7]。 |

| Five-factor inventory Many factor analyses found what is called the Big Five, which are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (or emotional stability), known as "OCEAN". These components are generally stable over time, and about half of the variance appears to be attributable to a person's genetics rather than the effects of one's environment.[8][9] Some research has investigated whether the relationship between happiness and extraversion seen in adults also can be seen in children. The implications of these findings can help identify children who are more likely to experience episodes of depression and develop types of treatment that such children are likely to respond to. In both children and adults, research shows that genetics, as opposed to environmental factors, exert a greater influence on happiness levels. Personality is not stable over the course of a lifetime, but it changes much more quickly during childhood, so personality constructs in children are referred to as temperament. Temperament is regarded as the precursor to personality.[10] Another interesting finding has been the link found between acting extraverted and positive affect. Extraverted behaviors include acting talkative, assertive, adventurous, and outgoing. For the purposes of this study, positive affect is defined as experiences of happy and enjoyable emotions.[11] This study investigated the effects of acting in a way that is counter to a person's dispositional nature. In other words, the study focused on the benefits and drawbacks of introverts (people who are shy, socially inhibited, and non-aggressive) acting extraverted, and of extraverts acting introverted. After acting extraverted, introverts' experience of positive affect increased[11] whereas extraverts seemed to experience lower levels of positive affect and suffered from the phenomenon of ego depletion. Ego depletion, or cognitive fatigue, is the use of one's energy to overtly act in a way that is contrary to one's inner disposition. When people act in a contrary fashion, they divert most, if not all, (cognitive) energy toward regulating this foreign style of behavior and attitudes. Because all available energy is being used to maintain this contrary behavior, the result is an inability to use any energy to make important or difficult decisions, plan for the future, control or regulate emotions, or perform effectively on other cognitive tasks.[11] One question that has been posed is why extroverts tend to be happier than introverts. The two types of explanations that attempt to account for this difference are instrumental theories and temperamental theories.[8] The instrumental theory suggests that extraverts end up making choices that place them in more positive situations and they also react more strongly than introverts to positive situations. The temperamental theory suggests that extroverts have a disposition that generally leads them to experience a higher degree of positive affect. In their study of extraversion, Lucas and Baird[8] found no statistically significant support for the instrumental theory but did, however, find that extraverts generally experience a higher level of positive affect. Research has been done to uncover some of the mediators that are responsible for the correlation between extraversion and happiness. Self-esteem and self-efficacy are two such mediators. Self-efficacy is one's belief about abilities to perform up to personal standards, the ability to produce desired results, and the feeling of having some ability to make important life decisions.[12] Self-efficacy has been found to be related to the personality traits of extraversion and subjective well-being.[12] Self-efficacy, however, only partially mediates the relationship between extraversion (and neuroticism) and subjective happiness.[12] This implies that there are most likely other factors that mediate the relationship between subjective happiness and personality traits. Self-esteem maybe another similar factor. Individuals with a greater degree of confidence about themselves and their abilities seem to have both higher degrees of subjective well-being and higher levels of extraversion.[13] Other research has examined the phenomenon of mood maintenance as another possible mediator. Mood maintenance is the ability to maintain one's average level of happiness in the face of an ambiguous situation – meaning a situation that has the potential to engender either positive or negative emotions in different individuals. It has been found to be a stronger force in extroverts.[14] This means that the happiness levels of extraverted individuals are less susceptible to the influence of external events. This finding implies that extraverts' positive moods last longer than those of introverts.[14] |

5因子インベントリ 多くの因子分析により、ビッグファイブと呼ばれる、経験への開放性、良心性、外向性、同意性、神経症(または情緒安定性)、「OCEAN」と呼ばれるもの が発見された。これらの構成要素は概して経時的に安定しており、分散の約半分は環境の影響ではなく、その人の遺伝に起因する[8][9]。 大人で見られる幸福感と外向性の関係が子供でも見られるかどうかを調査した研究がある。これらの知見は、うつ病を発症しやすい子どもを特定し、そのような 子どもが反応しやすい治療法を開発するために役立つ。子供でも大人でも、幸福度には環境要因よりも遺伝的要因が大きく影響することが研究により明らかに なっている。人格は一生を通じて安定しているわけではないが、幼少期にはより早く変化する。したがって、子供の人格構成は気質と呼ばれます。気質はパーソ ナリティの前段階とみなされている[10]。 もう1つの興味深い発見は、外向的な行動とポジティブな感情との間に見出された関連性である。外向的な行動には、おしゃべり、自己主張、冒険、外向的な行 動などが含まれる。この研究では、ポジティブな感情とは、幸せで楽しい感情の経験と定義されている[11]。つまり、内向的な人(シャイで社会的抑制があ り、攻撃的でない人)が外向的に行動することと、外向的な人が内向的に行動することの利点と欠点に注目した研究であった。内向的な人は外向的に行動した 後、ポジティブな感情の経験が増加した[11]が、外向的な人はポジティブな感情のレベルが低く、自我の枯渇という現象に悩まされるようであった。自我の 枯渇、あるいは認知疲労とは、自分のエネルギーを使って、自分の内的な気質に反する行動をあからさまにすることである。人は相反する行動をとるとき、すべ てとは言わないまでも、ほとんどの(認知)エネルギーをこの異質な行動や態度の調節に振り向けるのです。利用可能なすべてのエネルギーがこの反対の行動を 維持するために使われているので、その結果、重要または困難な決定をする、将来の計画を立てる、感情を制御または調節する、あるいは他の認知的作業を効果 的に行うためのエネルギーを一切使うことができなくなる[11]。 なぜ外向的な人は内向的な人よりも幸福になる傾向があ るのかという疑問がある。この違いを説明しようとする2つのタイプの説明は、道具的理論と気質的理論である[8]。道具的理論は、外向的な人は結局よりポ ジティブな状況に身を置く選択をし、またポジティブな状況に対して内向的な人よりも強く反応することを示唆している。気質的理論は、外向的な人は一般的に より高度な肯定的感情を経験するような気質をもっていることを示唆している。ルーカスとベアード[8]は外向性についての研究において、道具説を統計的に 有意に支持する結果は得られなかったが、外向性の人は一般的に高いレベルの肯定的感情を経験することを明らかにした。 外向性と幸福の相関をもたらす媒介要因のいくつかを明らかにするための研究が行われています。自尊心と自己効力感はそのような媒介物である。 自己効力感とは、個人的な標準にしたがって実行する能力、望む結果を生み出す能力、人生の重要な決定を行うある程度の能力があるという感覚に関する人の信 念である[12]。自己効力感は、外向性の性格特性および主観的幸福と関係があることが分かっている[12]。 しかし、自己効力感は外向性(および神経症)と主観的幸福の関係を部分的にしか媒介しません[12]。このことは、主観的幸福と人格特性の関係を媒介する 他の因子がある可能性が高いことを示唆しています。自尊心も同様の要因の1つかもしれない。自分自身と自分の能力に対してより大きな自信を持つ個人は、よ り高い主観的幸福度とより高い外向性の両方を持つようです[13]。 他の研究では、もう1つの可能な媒介因子として気分の維持の現象が検討されている。気分の維持とは、曖昧な状況、つまり個人によってポジティブまたはネガ ティブな感情を引き起こす可能性のある状況に直面しても、自分の平均的な幸福のレベルを維持する能力です。これは、外向的な人の幸福度が外的な出来事の影 響を受けにくいことを意味する[14]。この発見は、外向的な人のポジティブな気分は内向的な人のそれよりも長く続くことを意味する[14]。 |

| Developmental biological model Modern conceptions of personality, such as the Temperament and Character Inventory have suggested four basic temperaments that are thought to reflect basic and automatic responses to danger and reward that rely on associative learning. The four temperaments, harm avoidance, reward dependence, novelty-seeking and persistence, are somewhat analogous to ancient conceptions of melancholic, sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic personality types, although the temperaments reflect dimensions rather than distance categories. The harm avoidance trait has been associated with increased reactivity in insular and amygdala salience networks, as well as reduced 5-HT2 receptor binding peripherally, and reduced GABA concentrations. Novelty seeking has been associated with reduced activity in insular salience networks increased striatal connectivity. Novelty seeking correlates with dopamine synthesis capacity in the striatum and reduced auto receptor availability in the midbrain. Reward dependence has been linked with the oxytocin system, with increased concentration of plasma oxytocin being observed, as well as increased volume in oxytocin-related regions of the hypothalamus. Persistence has been associated with increased striatal-mPFC connectivity, increased activation of ventral striatal-orbitofrontal-anterior cingulate circuits, as well as increased salivary amylase levels indicative of increased noradrenergic tone.[15] |

発達生物学的モデル 気質・性格診断法(Temperament and Character Inventory)に代表される現代の性格概念は、4つの基本的な気質を示唆しており、これらは危険と報酬に対する、連想学習に依存した基本的かつ自動 的な反応を反映していると考えられている。この4つの気質は、危険回避、報酬依存、新規性追求、持続性であり、古代のメランコリック、サングイン、コレ リック、ファグマティックの性格類型に類似しているが、気質は距離の区分ではなく、次元を反映している。 危害回避特性は、島および扁桃体の感覚ネットワークの反応性の増大、末梢での5-HT2受容体結合の減少、およびGABA濃度の低下と関連している。新規 性追求は、島サライエンスネットワークの活性低下と線条体結合の増加と関連している。新規性追求は線条体のドーパミン合成能力および中脳の自己受容体利用 能の低下と相関する。報酬依存はオキシトシン系と関連しており、血漿オキシトシン濃度の上昇、視床下部のオキシトシン関連領域の容積増加が観察される。持 続性は線条体-MPFC結合の増加、腹側線条体-眼窩前頭-前帯状回路の活性化の増加、およびノルアドレナリン作動性の増加を示す唾液アミラーゼレベルの 増加と関連している[15]。 |

| Environmental influences It has been shown that personality traits are more malleable by environmental influences than researchers originally believed.[9][16] Personality differences predict the occurrence of life experiences.[16] One study has shown how the home environment, specifically the types of parents a person has, can affect and shape their personality. Mary Ainsworth's strange situation experiment showcased how babies reacted to having their mother leave them alone in a room with a stranger. The different styles of attachment, labeled by Ainsworth, were Secure, Ambivalent, avoidant, and disorganized. Children who were securely attached tend to be more trusting, sociable, and are confident in their day-to-day life. Children who were disorganized were reported to have higher levels of anxiety, anger, and risk-taking behavior.[17] Judith Rich Harris's group socialization theory postulates that an individual's peer groups, rather than parental figures, are the primary influence of personality and behavior in adulthood. Intra- and intergroup processes, not dyadic relationships such as parent-child relationships, are responsible for the transmission of culture and for environmental modification of children's personality characteristics. Thus, this theory points at the peer group representing the environmental influence on a child's personality rather than the parental style or home environment.[18] Tessuya Kawamoto's Personality Change from Life Experiences: Moderation Effect of Attachment Security talked about some significant laboratory tests. The study mainly focused on the effects of life experiences on change in personality and life experiences. The assessments suggested that "the accumulation of small daily experiences may work for the personality development of university students and that environmental influences may vary by individual susceptibility to experiences, like attachment security".[19] Some studies suggest that a shared family environment between siblings has less influence on personality than individual experiences of each child. Identical twins have similar personalities largely because they share the same genetic makeup rather than their shared environment.[20] |

環境による影響 性格特性は、研究者が当初考えていたよりも環境の影響によってより可鍛性であることが示されている[9][16]。性格の違いは人生経験の発生を予測する ものである[16]。 ある研究では、家庭環境、特に人が持つ両親のタイプがどのように影響を与え、性格を形成することができるかが示されている。メアリー・エインズワースの奇 妙な状況実験は、母親が見知らぬ人と部屋に一人で残されたときに赤ちゃんがどのように反応するかを紹介しました。エインズワースは、愛着の異なるスタイル を、安全、両価、回避、無秩序と名付けました。安全な愛着を持つ子どもは、より信頼性が高く、社交的で、日々の生活に自信を持っている傾向がある。無秩序 な子どもは、不安、怒り、危険を冒す行動のレベルが高いことが報告されている[17]。 ジュディス・リッチ・ハリスの集団社会化理論は、親の人物よりもむしろ個人の仲間集団が成人期の人格と行動に主要な影響を与えることを仮定している。親子 関係のような二者関係ではなく、集団内および集団間の過程が、文化の伝達と子どもの人格特性の環境的修正に関与しているのである。したがって、この理論 は、親のスタイルや家庭環境ではなく、ピアグループが子どものパーソナリティに対する環境的影響を代表することを指摘している[18]。 川本哲也の人生経験からのパーソナリティ変化。18] 川本哲也のPersonality Change from Life Experiences: Moderation Effect of Attachment Securityはいくつかの重要な実験結果について話している。この研究では、主に人生経験が人格の変化に及ぼす影響と人生経験に焦点を当てた。評価は 「日々の小さな経験の積み重ねが大学生の人格形成に働く可能性があり、環境の影響は愛着保障のような経験に対する個人の感受性によって異なる可能性があ る」ことを示唆した[19]。 兄弟間で共有する家庭環境は、それぞれの子どもの個人的な経験よりも性格への影響が少ないことを示唆する研究もある。一卵性双生児が似たような性格を持つ のは、共有した環境よりもむしろ同じ遺伝子構成を共有していることが主な理由です[20]。 |

| Cross-cultural studies There has been some recent debate over the subject of studying personality in a different culture. Some people think that personality comes entirely from culture and therefore there can be no meaningful study in cross-culture study. On the other hand, many believe that some elements are shared by all cultures and an effort is being made to demonstrate the cross-cultural applicability of "the Big Five".[21] Cross-cultural assessment depends on the universality of personality traits, which is whether there are common traits among humans regardless of culture or other factors. If there is a common foundation of personality, then it can be studied on the basis of human traits rather than within certain cultures. This can be measured by comparing whether assessment tools are measuring similar constructs across countries or cultures. Two approaches to researching personality are looking at emic and etic traits. Emic traits are constructs unique to each culture, which are determined by local customs, thoughts, beliefs, and characteristics. Etic traits are considered universal constructs, which establish traits that are evident across cultures that represent a biological basis of human personality.[22] If personality traits are unique to the individual culture, then different traits should be apparent in different cultures. However, the idea that personality traits are universal across cultures is supported by establishing the Five-Factor Model of personality across multiple translations of the NEO-PI-R, which is one of the most widely used personality measures.[23] When administering the NEO-PI-R to 7,134 people across six languages, the results show a similar pattern of the same five underlying constructs that are found in the American factor structure.[23] Similar results were found using the Big Five Inventory (BFI), as it was administered in 56 nations across 28 languages. The five factors continued to be supported both conceptually and statistically across major regions of the world, suggesting that these underlying factors are common across cultures.[24] There are some differences across culture, but they may be a consequence of using a lexical approach to study personality structures, as language has limitations in translation and different cultures have unique words to describe emotion or situations.[23] Differences across cultures could be due to real cultural differences, but they could also be consequences of poor translations, biased sampling, or differences in response styles across cultures.[24] Examining personality questionnaires developed within a culture can also be useful evidence for the universality of traits across cultures, as the same underlying factors can still be found.[25] Results from several European and Asian studies have found overlapping dimensions with the Five-Factor Model as well as additional culture-unique dimensions.[25] Finding similar factors across cultures provides support for the universality of personality trait structure, but more research is necessary to gain stronger support.[23] |

通文化研究 最近、異文化におけるパーソナリティの研究というテーマについて、いくつかの議論がなされている。パーソナリティは完全に文化から来るものであり、した がって異文化研究において意味のある研究はできないと考える人もいる。その一方で、いくつかの要素はすべての文化に共有されていると考える人も多く、 「ビッグファイブ」の異文化適用性を実証しようとする取り組みが行われている[21]。 異文化評価は、文化や他の要因に関係なく人間に共通の特徴があるかどうかという、性格特性の普遍性に依存する。もし、性格に共通の基盤があるならば、特定 の文化の中ではなく、人間の特性に基づいて研究することができる。これは、評価ツールが国や文化を超えて同様の構成要素を測定しているかどうかを比較する ことで測定することができる。パーソナリティを研究するための2つのアプローチは、エミック特性とエティック特性を見ることである。エミック特性は、それ ぞれの文化に固有の構成要素であり、地域の慣習、思考、信念、特性によって決定される。エティック特性は普遍的な構成概念と考えられており、人間の人格の 生物学的基礎を代表する文化間で明白な特徴を確立しています[22]。もし人格特性が個々の文化に固有のものであれば、異なる文化で異なる特性が明らかに なるはずである。しかし、人格特性が文化間で普遍的であるという考えは、最も広く使われている人格測定の1つであるNEO-PI-Rの複数の翻訳版にわ たって人格の5因子モデルを確立することによって支持されている[23]。 NEO-PI-Rを6言語にわたる7,134人に投与したところ、アメリカの因子構造で見られるのと同じ5つの基礎構成が見られる同様のパターンを示す結 果が得られた[23]。 同様の結果は、28の言語にわたって56カ国で実施されたビッグファイブインベントリー(BFI)を使用しても見いだされた。24]文化間の違いはいくつ かあるが、言語には翻訳における限界があり、異なる文化は感情や状況を表現するユニークな言葉を持っているので、人格構造を研究するために語彙的アプロー チを使用した結果であるかもしれない[23]。 [24] ある文化圏で開発された性格質問票を調べることも、文化圏を超えた特質の普遍性を証明する有用な証拠となり得る。 |

| Historical development of concept The modern sense of individual personality is a result of the shifts in culture originating in the Renaissance, an essential element in modernity. In contrast, the Medieval European's sense of self was linked to a network of social roles: "the household, the Kinship network, the guild, the corporation – these were the building blocks of personhood". Stephen Greenblatt observes, in recounting the recovery (1417) and career of Lucretius' poem De rerum natura: "at the core of the poem lay key principles of a modern understanding of the world."[26] "Dependent on the family, the individual alone was nothing," Jacques Gélis observes.[27] "The characteristic mark of the modern man has two parts: one internal, the other external; one dealing with his environment, the other with his attitudes, values, and feelings."[28] Rather than being linked to a network of social roles, the modern man is largely influenced by the environmental factors such as: "urbanization, education, mass communication, industrialization, and politicization."[28] In 2006, for example, scientists reported a relationship between personality and political views as follows: "Preschool children who 20 years later were relatively liberal were characterized as: developing close relationships, self-reliant, energetic, somewhat dominating, relatively under-controlled, and resilient. Preschool children subsequently relatively conservative at age 23 were described as: feeling easily victimized, easily offended, indecisive, fearful, rigid, inhibited, and relatively over-controlled and vulnerable."[29] |

概念の歴史的展開 近代における個人の人格意識は、近代に不可欠なルネサンスに端を発した文化の変遷の結果である。これに対し、中世ヨーロッパ人の自己意識は、社会的役割の ネットワークと結びついていた。「家庭、親族、ギルド、会社、これらが人間らしさの構成要素であった」。スティーブン・グリーンブラットは、ルクレティウ スの詩『De rerum natura』の復興(1417年)とその経歴を語る中で、「この詩の中核には、世界に対する近代的理解の重要な原則があった」[26]と述べている。 [現代人の特徴的なマークは2つの部分を持っている。1つは内的なもの、もう1つは外的なもので、1つは彼の環境を扱い、もう1つは彼の態度、価値、感情 を扱っている」[28] 社会的役割のネットワークにつながるのではなく、現代人は主に次のような環境要因によって影響されている。「例えば、2006年、科学者たちは、人格と政 治的見解の間に次のような関係があることを報告している[28]。「20年後に比較的リベラルになった未就学児の特徴は、親密な関係を築く、自立してい る、精力的、やや支配的、比較的支配されている、弾力的である、などであった。その後23歳で比較的保守的になった園児は、次のように記述されていた:被 害を受けやすい、気分を害しやすい、優柔不断、恐怖心、硬直的、抑制的、比較的過剰に制御され傷つきやすいと感じる」[29]. |

| Temperament and philosophy William James (1842–1910) argued that temperament explains a great deal of the controversies in the history of philosophy by arguing that it is a very influential premise in the arguments of philosophers. Despite seeking only impersonal reasons for their conclusions, James argued, the temperament of philosophers influenced their philosophy. Temperament thus conceived is tantamount to a bias. Such bias, James explained, was a consequence of the trust philosophers place in their own temperament. James thought the significance of his observation lay on the premise that in philosophy an objective measure of success is whether philosophy is peculiar to its philosopher or not, and whether a philosopher is dissatisfied with any other way of seeing things or not.[30] |

気質と哲学 ウィリアム・ジェームズ(1842-1910)は、哲学者の議論において気質が非常に大きな影響力を持つ前提であると主張し、哲学史における論争の多くを 説明した。ジェームズは、結論に対して非人格的な理由のみを求めるにもかかわらず、哲学者の気質が彼らの哲学に影響を及ぼすと主張した。このように考える 気質とは、バイアスに等しいものである。このような偏りは、哲学者が自分の気質を信頼している結果であると、ジェームズは説明した。ジェームズは、哲学に おける成功の客観的な尺度は、哲学がその哲学者固有のものであるかどうか、哲学者が他のものの見方に不満を持っているかどうかであるという前提に、彼の観 察の意義があると考えた[30]。 |

| Mental make-up James argued that temperament may be the basis of several divisions in academia, but focused on philosophy in his 1907 lectures on Pragmatism. In fact, James' lecture of 1907 fashioned a sort of trait theory of the empiricist and rationalist camps of philosophy. As in most modern trait theories, the traits of each camp are described by James as distinct and opposite, and maybe possessed in different proportions on a continuum, and thus characterize the personality of philosophers of each camp. The "mental make-up" (i.e. personality) of rationalist philosophers is described as "tender-minded" and "going by "principles", and that of empiricist philosophers is described as "tough-minded" and "going by "facts." James distinguishes each not only in terms of the philosophical claims they made in 1907, but by arguing that such claims are made primarily on the basis of temperament. Furthermore, such categorization was only incidental to James' purpose of explaining his pragmatist philosophy and is not exhaustive.[30] |

精神的気質 ジェームズは、学問におけるいくつかの区分の基礎に気質があるのではないかと主張したが、1907年の「プラグマティズム」の講義では哲学に焦点を当て た。実際、1907年のジェームズの講義は、哲学の経験主義陣営と合理主義陣営の特性論のようなものをファッション化した。現代の多くの特性論と同様、 ジェイムズによって、各陣営の特性は、それぞれ別個の、反対 のものとして記述され、おそらく連続体上の異なる割合で保有され、したがって、各陣営 の哲学者の性格を特徴付ける。合理主義的哲学者の「メンタル・メイクアップ」(性格)は、「優しい心」「"原理 "に従う」と表現され、経験主義的哲学者のそれは、「厳しい心」「"事実 "に従う」と表現される。ジェームズは、1907年当時の哲学的主張の観点からだけでなく、そうした主張が主として気質に基づいてなされることを論証する ことによって、それぞれを区別しているのである。さらに、このような分類はジェームズのプラグマティズム哲学を説明する目的に付随するものでしかなく、網 羅的なものではない[30]。 |

| Empiricists and rationalists According to James, the temperament of rationalist philosophers differed fundamentally from the temperament of empiricist philosophers of his day. The tendency of rationalist philosophers toward refinement and superficiality never satisfied an empiricist temper of mind. Rationalism leads to the creation of closed systems, and such optimism is considered shallow by the fact-loving mind, for whom perfection is far off.[31] Rationalism is regarded as pretension, and a temperament most inclined to abstraction.[32] Empiricists, on the other hand, stick with the external senses rather than logic. British empiricist John Locke's (1632–1704) explanation of personal identity provides an example of what James referred to. Locke explains the identity of a person, i.e. personality, on the basis of a precise definition of identity, by which the meaning of identity differs according to what it is being applied to. The identity of a person is quite distinct from the identity of a man, woman, or substance according to Locke. Locke concludes that consciousness is personality because it "always accompanies thinking, it is that which makes everyone to be what he calls self,"[33] and remains constant in different places at different times. Rationalists conceived of the identity of persons differently than empiricists such as Locke who distinguished identity of substance, person, and life. According to Locke, Rene Descartes (1596–1650) agreed only insofar as he did not argue that one immaterial spirit is the basis of the person "for fear of making brutes thinking things too."[34] According to James, Locke tolerated arguments that a soul was behind the consciousness of any person. However, Locke's successor David Hume (1711–1776), and empirical psychologists after him denied the soul except for being a term to describe the cohesion of inner lives.[30] However, some research suggests Hume excluded personal identity from his opus An Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding because he thought his argument was sufficient but not compelling.[35] Descartes himself distinguished active and passive faculties of mind, each contributing to thinking and consciousness in different ways. The passive faculty, Descartes argued, simply receives, whereas the active faculty produces and forms ideas, but does not presuppose thought, and thus cannot be within the thinking thing. The active faculty mustn't be within self because ideas are produced without any awareness of them, and are sometimes produced against one's will.[36] Rationalist philosopher Benedictus Spinoza (1632–1677) argued that ideas are the first element constituting the human mind, but existed only for actually existing things.[37] In other words, ideas of non-existent things are without meaning for Spinoza, because an idea of a non-existent thing cannot exist. Further, Spinoza's rationalism argued that the mind does not know itself, except insofar as it perceives the "ideas of the modifications of body", in describing its external perceptions, or perceptions from without. On the contrary, from within, Spinoza argued, perceptions connect various ideas clearly and distinctly.[38] The mind is not the free cause of its actions for Spinoza.[39] Spinoza equates the will with the understanding and explains the common distinction of these things as being two different things as an error which results from the individual's misunderstanding of the nature of thinking.[40] |

経験主義者と合理主義者 ジェイムズによれば、合理主義の哲学者の気質は、当時の経験主義の哲学者の気質とは根本的に異なるものであった。合理主義の哲学者は、洗練された表面的な ものを求める傾向があり、経験主義の哲学者の心を満足させることはなかった。合理主義は閉じたシステムの創造につながり、そのような楽観主義は、完璧が遠 いところにある事実を愛する心によって浅はかであると見なされる[31]。合理主義は気取りであり、抽象化に最も傾いた気質であると見なされる[32]。 一方、経験主義者は論理よりも外的感覚に固執する。イギリスの経験主義者ジョン・ロック(1632-1704)の個人的アイデンティティの説明は、ジェー ムズの言及したことの一例を示している。ロッ クは、アイデンティティの正確な定義に基づいて、人のアイデンティティ、すなわち人格を説明しているが、これによって、アイデンティティの意味は、それが 適用されるものによって異なることになる。ロックによれば、人の同一性は、男、女、あるいは物質の同一性とは全く異なるものである。ロックは意識が人格で あると結論付けているが、それは「常に思考を伴い、それはすべての人を彼が自己と呼ぶものにするものであり」[33]、異なる場所で異なる時間において不 変であるためである。 合理主義者はロックなどの経験主義者が物質、人、生命の同一性を区別するのとは異なる人物の同一性を観念していた(「人間知性論」第二版, 28章:9)。ロックによれば、ルネ・デカルト (1596-1650)は「ブルートもものを考えるようになることを恐れて」一つの非物質的精神が人の基礎であることを主張しない限りにおいてのみ同意し た[34]。しかしロックの後継者であるデイヴィッド・ヒューム(1711-1776)や彼以降の経験的心理学者は、内的生活の結束を表す言葉であること を除いて魂を否定した[30]。しかしいくつかの研究は、ヒュームの論考『人間理解に関する探究』から個人のアイデンティティを除外したのは彼の議論が十 分ではあるが説得力がないと考えたからだと示唆している[35] デカルト自身、心の能動性と受動性はそれぞれ異なる方法で思考と意識に貢献していることを区別した。受動的な能力は単に受け取るだけであり、能動的な能力 は考えを生み出し形成するが、思考を前提としないので、考えるものの中にあるはずがないとデカルトは主張した。能動的な能力は自己の中にあってはならな い、なぜなら考えはそれを意識することなく生み出され、時には自分の意志に反して生み出されるからである[36]。 合理主義の哲学者であるベネディクトゥス・スピノザ(1632-1677)は、観念 は人間の心を構成する最初の要素であるが、実際に存在するものに対してのみ存在すると主張した[37]。 つまり存在しないものに対する観念は存在できないため、スピノザにとって存在しないものの観念は意味がないのである。さらにスピノザの合理主義は、外的な知覚、すなわち外からの知覚を記述する際に、「身体の変化の観念」を知覚する限りにおい て、心は自分自身を知らないと主張した。それに対して、スピノザは内部からの知覚は様々な考えを明確かつはっきりと結びつけると主張した [38]。スピノザにとって心はその行為の自由な原因ではない[39]。スピノザは 意志と理解を同一視して、これらが異なるものであると一般的に区別することを個人の思考の本質に対する誤解に起因する誤りとして説明する[40]。 |

| Biology The biological basis of personality is the theory that anatomical structures located in the brain contribute to personality traits. This stems from neuropsychology, which studies how the structure of the brain relates to various psychological processes and behaviors. For instance, in human beings, the frontal lobes are responsible for foresight and anticipation, and the occipital lobes are responsible for processing visual information. In addition, certain physiological functions such as hormone secretion also affect personality. For example, the hormone testosterone is important for sociability, affectivity, aggressiveness, and sexuality.[21] Additionally, studies show that the expression of a personality trait depends on the volume of the brain cortex it is associated with.[41] |

生物学 パーソナリティの生物学的基盤とは、脳にある解剖学的構造がパーソナリティの特徴に寄与しているという理論である。これは、脳の構造が様々な心理的プロセ スや行動とどのように関係しているかを研究する神経心理学に由来する。例えば、人間の場合、前頭葉は先見性や予測性を、後頭葉は視覚情報を処理する役割を 担っている。また、ホルモン分泌などの生理的な働きも、性格に影響を与える。例えば、テストステロンというホルモンは社交性、情緒性、攻撃性、性欲に重要 である[21]。 さらに、ある性格特性の発現はそれが関連する大脳皮質の容積に依存するという研究結果もある[41]。 |

| Personology Personology confers a multidimensional, complex, and comprehensive approach to personality. According to Henry A. Murray, personology is: The branch of psychology which concerns itself with the study of human lives and the factors that influence their course which investigates individual differences and types of personality ... the science of men, taken as gross units ... encompassing "psychoanalysis" (Freud), "analytical psychology" (Jung), "individual psychology" (Adler) and other terms that stand for methods of inquiry or doctrines rather than realms of knowledge.[42] From a holistic perspective, personology studies personality as a whole, as a system, but at the same time through all its components, levels, and spheres.[43][44] |

ペルソロジー ペルソロジーとは、人格に対する多次元的、複雑かつ包括的なアプローチを意味する。ヘンリー・A・マレーによれば、パーソノロジーは次のようなものであ る。 心理学の一分野であり、人間の生活とその経過に影響を与える要因の研究に関わり、個人差と人格のタイプを調査する...総体的な単位としてとらえた人間の 科学...「精神分析」(フロイト)、「分析心理」(ユング)、「個人心理」(アドラー)や知識の領域ではなく、調査の方法や教義を示す他の用語を包含し ている[42]。 全体的な観点から、人格学は人格を全体として、システムとして、しかし同時にそのすべての構成要素、レベル、球を通して研究する[43][44]。 |

| Association for Research in

Personality, an academic organization Cult of personality, political institution in which a leader uses mass media to create a larger-than-life public image Differential psychology Human variability Offender profiling Personality and Individual Differences, a scientific journal published bi-monthly by Elsevier Personality computing Personality crisis Personality disorder Personality rights, consisting of the right to individual publicity and privacy Personality style Trait theory |

パーソナリティ研究会、学術団体 カルト・オブ・パーソナリティ、指導者がマスメディアを利用して、より大きなパブリックイメージを作り出す政治的制度 微分心理学 人間の変動性 犯罪者プロファイリング Personality and Individual Differences: エルゼビア社が隔月で発行する科学雑誌。 パーソナリティコンピューティング パーソナリティの危機 パーソナリティ障害 パーソナリティの権利(個人の肖像権およびプライバシー権から成る) パーソナリティスタイル 特性理論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Personality |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆