フィルター・バブル

Filter bubble

☆ フィルターバブル(filter bubble)やイデオロギーフレームとは、パーソナライズされた検 索、レコメンデーションシステム、アルゴリズムによるキュレーションから生じる知的孤立状態のことである。検索結果は、位置情報、過去のクリック行 動、検索履歴など、ユーザーに関する情報に基づいている。その結果、ユーザーは自分の視点と異なる情報から切り離され、事実上、自分の文化的または イデオロギー的なバブルの中に隔離されることになり、その結果、限定され、カスタマイズされた世界観を持つことになる。このようなアルゴリズムに よって行われる選択は、時にしか透明にならない。代表的な例としては、グーグルのパーソナライズ検索結果やフェイスブックのパーソナライズされた ニュースストリームが挙げられる。※キュレーション(Curation)とは、インターネット上に存在する膨大な情報を独自の基準で収集・選別・編集し、情報に新しい価値を付加した状態で共有すること。※※アルゴリズム(algorithm) とは、解が定まっている「計算可能」問題に対して、解をもとめるための形式的な(formalな)手続きのことを言う。

| A filter bubble or

ideological frame is a state of intellectual isolation[1] that can

result from personalized searches, recommendation systems, and

algorithmic curation. The search results are based on information about

the user, such as their location, past click-behavior, and search

history.[2] Consequently, users become separated from information that

disagrees with their viewpoints, effectively isolating them in their

own cultural or ideological bubbles, resulting in a limited and

customized view of the world.[3] The choices made by these algorithms

are only sometimes transparent.[4] Prime examples include Google

Personalized Search results and Facebook's personalized news-stream. However there are conflicting reports about the extent to which personalized filtering happens and whether such activity is beneficial or harmful, with various studies producing inconclusive results. The term filter bubble was coined by internet activist Eli Pariser circa 2010. In Pariser's influential book under the same name, The Filter Bubble (2011), it was predicted that individualized personalization by algorithmic filtering would lead to intellectual isolation and social fragmentation.[5] The bubble effect may have negative implications for civic discourse, according to Pariser, but contrasting views regard the effect as minimal[6] and addressable.[7] According to Pariser, users get less exposure to conflicting viewpoints and are isolated intellectually in their informational bubble.[8] He related an example in which one user searched Google for "BP" and got investment news about British Petroleum, while another searcher got information about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, noting that the two search results pages were "strikingly different" despite use of the same key words.[8][9][10][6] The results of the U.S. presidential election in 2016 have been associated with the influence of social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook,[11] and as a result have called into question the effects of the "filter bubble" phenomenon on user exposure to fake news and echo chambers,[12] spurring new interest in the term,[13] with many concerned that the phenomenon may harm democracy and well-being by making the effects of misinformation worse.[14][15][13][16][17][18] |

フィルターバブルやイデオロギーフレームとは、パーソナライズされた検

索、レコメンデーションシステム、アルゴリズムによるキュレーション[1](Algorithmic curation)から生じる知的孤立状態のことである。検索結果は、位置情報、過去のクリック行

動、検索履歴など、ユーザーに関する情報に基づいている[2]。その結果、ユーザーは自分の視点と異なる情報から切り離され、事実上、自分の文化的または

イデオロギー的なバブルの中に隔離されることになり、その結果、限定され、カスタマイズされた世界観を持つことになる[3]。このようなアルゴリズムに

よって行われる選択は、時にしか透明にならない[4]。代表的な例としては、グーグルのパーソナライズ検索結果やフェイスブックのパーソナライズされた

ニュースストリームが挙げられる。 しかし、パーソナライズされたフィルタリングがどの程度行われているのか、またそのような活動が有益なのか有害なのかについては相反する報告があり、様々 な研究が決定的な結果を出していない。 フィルターバブルという言葉は、2010年頃にインターネット活動家のイーライ・パリサーによって作られた。パリジャーによる同名の影響力のある著書 『フィルター・バブル』(2011年)では、アルゴリズムによるフィルタリングによって個別化されたパーソナライゼーションは、知的孤立と社会的分断をも たらすと予測されていた[5]。パリジャーによれば、バブル効果は市民的言説に否定的な意味を持つかもしれないが、対照的な見解では、その影響は最小限 [6]で対処可能であるとされている[7]。 [8]彼は、あるユーザーがグーグルで「BP」と検索し、ブリティッシュ・ペトロリアムに関する投資ニュースを得たのに対し、別の検索者はディープウォー ター・ホライズンの原油流出事故に関する情報を得た例を挙げ、同じキーワードを使用しているにもかかわらず、2つの検索結果ページは「著しく異なってい た」と指摘した[8][9][10][6]。2016年の大統領選の結果は、ツイッターやフェイスブックなどのソーシャルメディアプラットフォームの影響 と関連付けられ[11]、その結果、フェイクニュースやエコーチェンバーにユーザーがさらされる「フィルターバブル」現象の影響が疑問視され[12]、こ の言葉に対する新たな関心に拍車をかけ[13]、この現象が誤情報の影響を悪化させることによって民主主義や幸福に害を及ぼすのではないかと懸念する声が 多く聞かれた[14][15][13][16][17][18]。 |

Concept The term filter bubble was coined by internet activist Eli Pariser, circa 2010. Pariser defined his concept of a filter bubble in more formal terms as "that personal ecosystem of information that's been catered by these algorithms."[8] An internet user's past browsing and search history is built up over time when they indicate interest in topics by "clicking links, viewing friends, putting movies in [their] queue, reading news stories," and so forth.[19] An internet firm then uses this information to target advertising to the user, or make certain types of information appear more prominently in search results pages.[19] This process is not random, as it operates under a three-step process, per Pariser, who states, "First, you figure out who people are and what they like. Then, you provide them with content and services that best fit them. Finally, you tune in to get the fit just right. Your identity shapes your media."[20] Pariser also reports: According to one Wall Street Journal study, the top fifty Internet sites, from CNN to Yahoo to MSN, install an average of 64 data-laden cookies and personal tracking beacons. Search for a word like "depression" on Dictionary.com, and the site installs up to 223 tracking cookies and beacons on your computer so that other Web sites can target you with antidepressants. Share an article about cooking on ABC News, and you may be chased around the Web by ads for Teflon-coated pots. Open—even for an instant—a page listing signs that your spouse may be cheating and prepare to be haunted by DNA paternity-test ads.[21] Accessing the data of link clicks displayed through site traffic measurements determines that filter bubbles can be collective or individual.[22] As of 2011, one engineer had told Pariser that Google looked at 57 different pieces of data to personally tailor a user's search results, including non-cookie data such as the type of computer being used and the user's physical location.[23] Pariser's idea of the filter bubble was popularized after the TED talk in May 2011, in which he gave examples of how filter bubbles work and where they can be seen. In a test seeking to demonstrate the filter bubble effect, Pariser asked several friends to search for the word "Egypt" on Google and send him the results. Comparing two of the friends' first pages of results, while there was overlap between them on topics like news and travel, one friend's results prominently included links to information on the then-ongoing Egyptian revolution of 2011, while the other friend's first page of results did not include such links.[24] In The Filter Bubble, Pariser warns that a potential downside to filtered searching is that it "closes us off to new ideas, subjects, and important information,"[25] and "creates the impression that our narrow self-interest is all that exists."[9] In his view, filter bubbles are potentially harmful to both individuals and society. He criticized Google and Facebook for offering users "too much candy and not enough carrots."[26] He warned that "invisible algorithmic editing of the web" may limit our exposure to new information and narrow our outlook.[26] According to Pariser, the detrimental effects of filter bubbles include harm to the general society in the sense that they have the possibility of "undermining civic discourse" and making people more vulnerable to "propaganda and manipulation."[9] He wrote: A world constructed from the familiar is a world in which there's nothing to learn ... (since there is) invisible autopropaganda, indoctrinating us with our own ideas. — Eli Pariser in The Economist, 2011[27] Many people are unaware that filter bubbles even exist. This can be seen in an article in The Guardian, which mentioned the fact that "more than 60% of Facebook users are entirely unaware of any curation on Facebook at all, believing instead that every single story from their friends and followed pages appeared in their news feed."[28] A brief explanation for how Facebook decides what goes on a user's news feed is through an algorithm that takes into account "how you have interacted with similar posts in the past."[28] Extensions of concept A filter bubble has been described as exacerbating a phenomenon that called splinternet or cyberbalkanization,[Note 1] which happens when the internet becomes divided into sub-groups of like-minded people who become insulated within their own online community and fail to get exposure to different views. This concern dates back to the early days of the publicly accessible internet, with the term "cyberbalkanization" being coined in 1996.[29][30][31] Other terms have been used to describe this phenomenon, including "ideological frames"[9] and "the figurative sphere surrounding you as you search the internet."[19] The concept of a filter bubble has been extended into other areas, to describe societies that self-segregate according political views but also economic, social, and cultural situations.[32] That bubbling results in a loss of the broader community and creates the sense that for example, children do not belong at social events unless those events were especially planned to be appealing for children and unappealing for adults without children.[32] Barack Obama's farewell address identified a similar concept to filter bubbles as a "threat to [Americans'] democracy," i.e., the "retreat into our own bubbles, ...especially our social media feeds, surrounded by people who look like us and share the same political outlook and never challenge our assumptions... And increasingly, we become so secure in our bubbles that we start accepting only information, whether it's true or not, that fits our opinions, instead of basing our opinions on the evidence that is out there."[33] Comparison with echo chambers Further information: Echo chamber (media) Both "echo chambers" and "filter bubbles" describe situations where individuals are exposed to a narrow range of opinions and perspectives that reinforce their existing beliefs and biases, but there are some subtle differences between the two, especially in practices surrounding social media.[34][35] Specific to news media, an echo chamber is a metaphorical description of a situation in which beliefs are amplified or reinforced by communication and repetition inside a closed system.[36][37] Based on the sociological concept of selective exposure theory, the term is a metaphor based on the acoustic echo chamber, where sounds reverberate in a hollow enclosure. With regard to social media, this sort of situation feeds into explicit mechanisms of self-selected personalization, which describes all processes in which users of a given platform can actively opt in and out of information consumption, such as a user's ability to follow other users or select into groups.[38] In an echo chamber, people are able to seek out information that reinforces their existing views, potentially as an unconscious exercise of confirmation bias. This sort of feedback regulation may increase political and social polarization and extremism. This can lead to users aggregating into homophilic clusters within social networks, which contributes to group polarization.[39] "Echo chambers" reinforce an individual's beliefs without factual support. Individuals are surrounded by those who acknowledge and follow the same viewpoints, but they also possess the agency to break outside of the echo chambers.[40] On the other hand, filter bubbles are implicit mechanisms of pre-selected personalization, where a user's media consumption is created by personalized algorithms; the content a user sees is filtered through an AI-driven algorithm that reinforces their existing beliefs and preferences, potentially excluding contrary or diverse perspectives. In this case, users have a more passive role and are perceived as victims of a technology that automatically limits their exposure to information that would challenge their world view.[38] Some researchers argue, however, that because users still play an active role in selectively curating their own newsfeeds and information sources through their interactions with search engines and social media networks, that they directly assist in the filtering process by AI-driven algorithms, thus effectively engaging in self-segregating filter bubbles.[41] Despite their differences, the usage of these terms go hand-in-hand in both academic and platform studies. It is often hard to distinguish between the two concepts in social network studies, due to limitations in accessibility of the filtering algorithms, that perhaps could enable researchers to compare and contrast the agencies of the two concepts.[42] This type of research will continue to grow more difficult to conduct, as many social media networks have also begun to limit API access needed for academic research.[43] |

コンセプト フィルターバブルという言葉は、2010年頃にインターネット活動家のイーライ・パリサーによって作られた。 パリジャーは、フィルターバブルの概念をより正式な言葉で「これらのアルゴリズムによってケータリングされた情報の個人的なエコシステム」と定義した [8]。インターネットユーザーの過去の閲覧や検索の履歴は、「リンクをクリックする、友達を見る、映画を(自分の)キューに入れる、ニュース記事を読 む」などによってトピックへの興味を示すと、時間とともに蓄積される[19]。 このプロセスはランダムではなく、3段階のプロセスで行われるとパライサーは述べている。次に、彼らに最適なコンテンツとサービスを提供する。そして最後に、彼らにぴったり合うように調整する。あなたのアイデンティティがメディアを形成するのです」[20]: ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル紙のある調査によると、CNNからヤフー、MSNに至るまで、トップ50のインターネット・サイトは、平均64個のデー タ満載のクッキーと個人追跡用ビーコンをインストールしている。Dictionary.comで "depression "のような単語を検索すると、そのサイトは最大223個のトラッキング・クッキーとビーコンをあなたのコンピューターにインストールし、他のウェブサイト があなたに抗うつ剤を提供できるようにする。ABCニュースで料理に関する記事をシェアすると、テフロン加工の鍋の広告にウェブ上を追いかけ回されるかも しれない。配偶者が浮気をしているかもしれない兆候をリストアップしたページを一瞬でも開けば、DNA父子鑑定の広告に悩まされることになる[21]。 サイトのトラフィック測定を通じて表示されるリンククリックのデータにアクセスすると、フィルターバブルは集団的なものにも個人的なものにもなり得ることが判明する[22]。 2011年の時点で、あるエンジニアがパリジャーに語ったところによると、グーグルはユーザーの検索結果を個人的に調整するために、使用しているコンピュータの種類やユーザーの物理的な位置などのクッキー以外のデータを含む57の異なるデータを調べていた[23]。 2011年5月に行われたTEDの講演で、フィルターバブルがどのように機能し、どこで見ることができるかの例を示した後、フィルターバブルというパリ サーのアイデアは広まった。フィルターバブル効果を実証するためのテストで、パリジャーは数人の友人にグーグルで「エジプト」という単語を検索し、その結 果を送ってくれるよう頼んだ。2人の友人の検索結果の最初のページを比較すると、ニュースや旅行といったトピックでは重複していたものの、1人の友人の検 索結果には、当時進行中だった2011年のエジプト革命に関する情報へのリンクが目立つように含まれていたのに対し、もう1人の友人の検索結果の最初の ページには、そのようなリンクは含まれていなかった[24]。 フィルター・バブル』の中でパリジャーは、フィルター検索がもたらす潜在的なマイナス面は、「新しいアイデアやテーマ、重要な情報に対して私たちを閉ざ す」[25]ことであり、「私たちの狭い自己利益が存在するすべてであるという印象を生み出す」[9]ことであると警告している。彼はグーグルとフェイス ブックが「アメが多すぎてニンジンが足りない」[26]とユーザーを批判し、「目に見えないアルゴリズムによるウェブの編集」が新しい情報に触れる機会を 制限し、視野を狭める可能性があると警告している[26]。 パリジャーによれば、フィルターバブルの有害な影響には、「市民的な言論を弱体化させ」、「プロパガンダや操作」に対して人々をより脆弱にする可能性があ るという意味で、一般社会に対する害も含まれる[9]: 見慣れたものから構築された世界は、学ぶべきものが何もない世界である......(そこには)目に見えないオートプロパガンダがあり、私たち自身の考えを教え込んでいるのだから。 - 2011年『エコノミスト』誌のイーライ・パリサー[27]。 多くの人はフィルターバブルが存在することすら知らない。これはGuardian紙の記事で見ることができる。「フェイスブックのユーザーの60%以上 は、フェイスブック上でキュレーションが行われていることにまったく気づいておらず、その代わりに、自分の友人やフォローしたページからのストーリーがす べてニュースフィードに表示されると信じている」という事実に触れている。 概念の拡張 フィルターバブルは、インターネットが同じような考えを持つ人々の小集団に分断され、自分たちのオンラインコミュニティ内で孤立し、異なる意見に触れるこ とができなくなることで起こる、スプリネット化またはサイバーバルカナイゼーションと呼ばれる現象[注釈 1]を悪化させると説明されてきた。この懸念は、1996年に「サイバーバルカナイゼーション」という用語が作られた、一般にアクセス可能なインターネッ トの初期にまでさかのぼる[29][30][31]。この現象を説明するために、「イデオロギーフレーム」[9]や「インターネットを検索する際にあなた を取り囲む比喩的な球体」[19]など、他の用語も使われてきた。 フィルター・バブルの概念は他の分野にも拡張され、政治的見解だけでなく、経済的、社会的、文化的な状況によって自己分離する社会を表現している [32]。そのバブル化はより広範なコミュニティの喪失をもたらし、例えば、それらのイベントが子どもにとって魅力的で、子どものいない大人にとって魅力 的でないように特別に計画されていない限り、子どもは社交的なイベントにふさわしくないという感覚を生み出す[32]。 バラク・オバマの告別式演説は、「(アメリカ人の)民主主義に対する脅威」として、フィルターバブルと同様の概念、すなわち「自分自身のバブル、...特 にソーシャルメディアのフィードに引きこもり、自分たちと同じように見え、同じ政治的展望を共有し、自分たちの前提に異議を唱えることのない人々に囲まれ る...」ことを挙げている。そしてますます、私たちは自分のバブルの中で安心しきってしまい、世の中にある証拠に基づいて意見を述べるのではなく、それ が真実であろうとなかろうと、自分の意見に合う情報だけを受け入れるようになる」[33]。 エコーチェンバーとの比較 さらなる情報 エコーチェンバー(メディア) エコーチェンバー」と「フィルターバブル」はどちらも、個人が既存の信念や偏見を強化するような狭い範囲の意見や視点にさらされる状況を表しているが、この2つの間には、特にソーシャルメディアにまつわる慣行において、微妙な違いがある[34][35]。 ニュースメディアに特有なエコーチェンバー(反響室)とは、閉ざされたシ ステム内でのコミュニケーションや反復によって、信念が増幅され たり強化されたりする状況を比喩的に表現したものである[36][37]。社会学 的な選択的暴露理論の概念に基づくこの用語は、中空の囲いの中で 音が反響する音響反響室に基づく比喩である。ソーシャルメディアに関して言えば、この種の状況は、自己選択的パーソナライゼーションの明示的なメカニズム に食い込む。このメカニズムは、ユーザーが他のユーザーをフォローしたり、グループに選択したりするなど、あるプラットフォームのユーザーが情報消費を積 極的にオプトインしたりオプトアウトしたりできるすべてのプロセスを記述している[38]。 エコーチェンバーでは、人々は無意識のうちに確証バイアスを働かせ、既存の見解を補強する情報を探し求めることができる。このようなフィードバック規制 は、政治的・社会的な偏向や過激主義を増加させる可能性がある。エコー・チェンバー」は、事実の裏付けなしに個人の信念 を強化する。個人は同じ視点を認め、それに従う人々 に囲まれているが、エコーチェンバーの外に出る主体性も持っている[40]。 一方、フィルターバブルは、あらかじめ選択されたパーソナライゼーションの暗黙のメカニズムであり、ユーザーのメディア消費はパーソナライズされたアルゴ リズムによって作成される。ユーザーが見るコンテンツは、既存の信念や嗜好を強化するAI主導のアルゴリズムによってフィルタリングされ、反対意見や多様 な視点を排除する可能性がある。この場合、ユーザーはより受動的な役割を担っており、自分の世界観に挑戦するような情報への接触を自動的に制限するテクノ ロジーの犠牲者として認識されている[38]。しかし、検索エンジンやソーシャルメディアネットワークとのインタラクションを通じて、ユーザーは依然とし て自分のニュースフィードや情報源を選択的にキュレーションするという能動的な役割を担っているため、AI主導のアルゴリズムによるフィルタリングプロセ スを直接的に支援し、その結果、効果的に自己隔離的なフィルターバブルに関与していると主張する研究者もいる[41]。 その違いにもかかわらず、これらの用語の用法は学術的にもプラットフォーム研究においても密接に関連している。多くのソーシャル・メディア・ネットワーク が学術研究に必要なAPIアクセスを制限し始めているため[42]、この種の研究を実施することは今後も難しくなっていくだろう[43]。 |

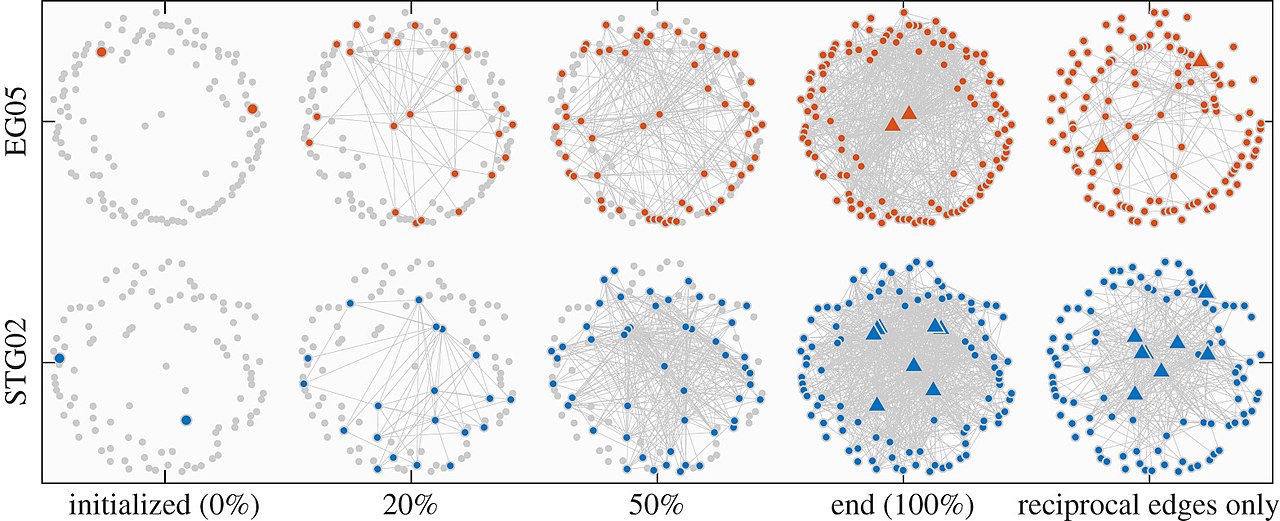

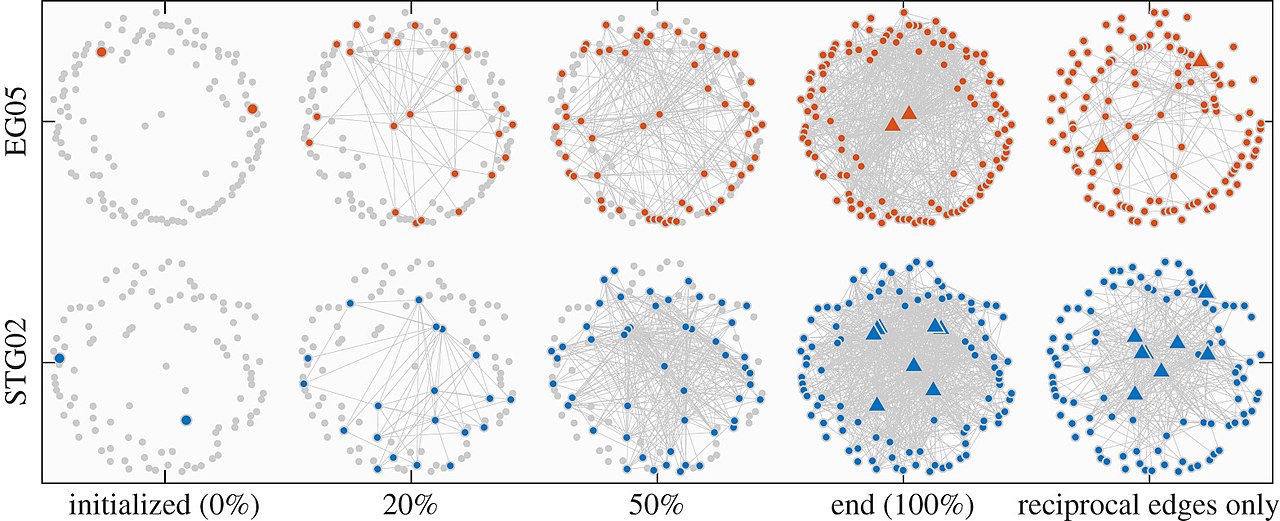

| Reactions and studies Media reactions There are conflicting reports about the extent to which personalized filtering happens and whether such activity is beneficial or harmful. Analyst Jacob Weisberg, writing in June 2011 for Slate, did a small non-scientific experiment to test Pariser's theory which involved five associates with different ideological backgrounds conducting a series of searches, "John Boehner," "Barney Frank," "Ryan plan," and "Obamacare," and sending Weisberg screenshots of their results. The results varied only in minor respects from person to person, and any differences did not appear to be ideology-related, leading Weisberg to conclude that a filter bubble was not in effect, and to write that the idea that most internet users were "feeding at the trough of a Daily Me" was overblown.[9] Weisberg asked Google to comment, and a spokesperson stated that algorithms were in place to deliberately "limit personalization and promote variety."[9] Book reviewer Paul Boutin did a similar experiment to Weisberg's among people with differing search histories and again found that the different searchers received nearly identical search results.[6] Interviewing programmers at Google, off the record, journalist Per Grankvist found that user data used to play a bigger role in determining search results but that Google, through testing, found that the search query is by far the best determinant of what results to display.[44] There are reports that Google and other sites maintain vast "dossiers" of information on their users, which might enable them to personalize individual internet experiences further if they choose to do so. For instance, the technology exists for Google to keep track of users' histories even if they don't have a personal Google account or are not logged into one.[6] One report stated that Google had collected "10 years' worth" of information amassed from varying sources, such as Gmail, Google Maps, and other services besides its search engine,[10][failed verification] although a contrary report was that trying to personalize the internet for each user, was technically challenging for an internet firm to achieve despite the huge amounts of available data.[citation needed] Analyst Doug Gross of CNN suggested that filtered searching seemed to be more helpful for consumers than for citizens, and would help a consumer looking for "pizza" find local delivery options based on a personalized search and appropriately filter out distant pizza stores.[10][failed verification] Organizations such as the Washington Post, The New York Times, and others have experimented with creating new personalized information services, with the aim of tailoring search results to those that users are likely to like or agree with.[9] Academia studies and reactions A scientific study from Wharton that analyzed personalized recommendations also found that these filters can create commonality, not fragmentation, in online music taste.[45] Consumers reportedly use the filters to expand their taste rather than to limit it.[45] Harvard law professor Jonathan Zittrain disputed the extent to which personalization filters distort Google search results, saying that "the effects of search personalization have been light."[9] Further, Google provides the ability for users to shut off personalization features if they choose[46] by deleting Google's record of their search history and setting Google not to remember their search keywords and visited links in the future.[6] A study from Internet Policy Review addressed the lack of a clear and testable definition for filter bubbles across disciplines; this often results in researchers defining and studying filter bubbles in different ways.[47] Subsequently, the study explained a lack of empirical data for the existence of filter bubbles across disciplines[12] and suggested that the effects attributed to them may stem more from preexisting ideological biases than from algorithms. Similar views can be found in other academic projects, which also address concerns with the definitions of filter bubbles and the relationships between ideological and technological factors associated with them.[48] A critical review of filter bubbles suggested that "the filter bubble thesis often posits a special kind of political human who has opinions that are strong, but at the same time highly malleable" and that it is a "paradox that people have an active agency when they select content but are passive receivers once they are exposed to the algorithmically curated content recommended to them."[49] A study by Oxford, Stanford, and Microsoft researchers examined the browsing histories of 1.2 million U.S. users of the Bing Toolbar add-on for Internet Explorer between March and May 2013. They selected 50,000 of those users who were active news consumers, then classified whether the news outlets they visited were left- or right-leaning, based on whether the majority of voters in the counties associated with user IP addresses voted for Obama or Romney in the 2012 presidential election. They then identified whether news stories were read after accessing the publisher's site directly, via the Google News aggregation service, web searches, or social media. The researchers found that while web searches and social media do contribute to ideological segregation, the vast majority of online news consumption consisted of users directly visiting left- or right-leaning mainstream news sites and consequently being exposed almost exclusively to views from a single side of the political spectrum. Limitations of the study included selection issues such as Internet Explorer users skewing higher in age than the general internet population; Bing Toolbar usage and the voluntary (or unknowing) sharing of browsing history selection for users who are less concerned about privacy; the assumption that all stories in left-leaning publications are left-leaning, and the same for right-leaning; and the possibility that users who are not active news consumers may get most of their news via social media, and thus experience stronger effects of social or algorithmic bias than those users who essentially self-select their bias through their choice of news publications (assuming they are aware of the publications' biases).[50] A study by Princeton University and New York University researchers aimed to study the impact of filter bubble and algorithmic filtering on social media polarization. They used a mathematical model called the "stochastic block model" to test their hypothesis on the environments of Reddit and Twitter. The researchers gauged changes in polarization in regularized social media networks and non-regularized networks, specifically measuring the percent changes in polarization and disagreement on Reddit and Twitter. They found that polarization increased significantly at 400% in non-regularized networks, while polarization increased by 4% in regularized networks and disagreement by 5%.[51] Platform studies While algorithms do limit political diversity, some of the filter bubbles are the result of user choice.[52] A study by data scientists at Facebook found that users have one friend with contrasting views for every four Facebook friends that share an ideology.[53][54] No matter what Facebook's algorithm for its News Feed is, people are more likely to befriend/follow people who share similar beliefs.[53] The nature of the algorithm is that it ranks stories based on a user's history, resulting in a reduction of the "politically cross-cutting content by 5 percent for conservatives and 8 percent for liberals."[53] However, even when people are given the option to click on a link offering contrasting views, they still default to their most viewed sources.[53] "[U]ser choice decreases the likelihood of clicking on a cross-cutting link by 17 percent for conservatives and 6 percent for liberals."[53] A cross-cutting link is one that introduces a different point of view than the user's presumed point of view or what the website has pegged as the user's beliefs.[55] A recent study from Levi Boxell, Matthew Gentzkow, and Jesse M. Shapiro suggest that online media isn't the driving force for political polarization.[56] The paper argues that polarization has been driven by the demographic groups that spend the least time online. The greatest ideological divide is experienced amongst Americans older than 75, while only 20% reported using social media as of 2012. In contrast, 80% of Americans aged 18–39 reported using social media as of 2012. The data suggests that the younger demographic isn't any more polarized in 2012 than it had been when online media barely existed in 1996. The study highlights differences between age groups and how news consumption remains polarized as people seek information that appeals to their preconceptions. Older Americans usually remain stagnant in their political views as traditional media outlets continue to be a primary source of news, while online media is the leading source for the younger demographic. Although algorithms and filter bubbles weaken content diversity, this study reveals that political polarization trends are primarily driven by pre-existing views and failure to recognize outside sources. A 2020 study from Germany utilized the Big Five Psychology model to test the effects of individual personality, demographics, and ideologies on user news consumption.[57] Basing their study on the notion that the number of news sources that users consume impacts their likelihood to be caught in a filter bubble—with higher media diversity lessening the chances—their results suggest that certain demographics (higher age and male) along with certain personality traits (high openness) correlate positively with a number of news sources consumed by individuals. The study also found a negative ideological association between media diversity and the degree to which users align with right-wing authoritarianism. Beyond offering different individual user factors that may influence the role of user choice, this study also raises questions and associations between the likelihood of users being caught in filter bubbles and user voting behavior.[57] The Facebook study found that it was "inconclusive" whether or not the algorithm played as big a role in filtering News Feeds as people assumed.[58] The study also found that "individual choice," or confirmation bias, likewise affected what gets filtered out of News Feeds.[58] Some social scientists criticized this conclusion because the point of protesting the filter bubble is that the algorithms and individual choice work together to filter out News Feeds.[59] They also criticized Facebook's small sample size, which is about "9% of actual Facebook users," and the fact that the study results are "not reproducible" due to the fact that the study was conducted by "Facebook scientists" who had access to data that Facebook does not make available to outside researchers.[60] Though the study found that only about 15–20% of the average user's Facebook friends subscribe to the opposite side of the political spectrum, Julia Kaman from Vox theorized that this could have potentially positive implications for viewpoint diversity. These "friends" are often acquaintances with whom we would not likely share our politics without the internet. Facebook may foster a unique environment where a user sees and possibly interacts with content posted or re-posted by these "second-tier" friends. The study found that "24 percent of the news items liberals saw were conservative-leaning and 38 percent of the news conservatives saw was liberal-leaning."[61] "Liberals tend to be connected to fewer friends who share information from the other side, compared with their conservative counterparts."[62] This interplay has the ability to provide diverse information and sources that could moderate users' views. Similarly, a study of Twitter's filter bubbles by New York University concluded that "Individuals now have access to a wider span of viewpoints about news events, and most of this information is not coming through the traditional channels, but either directly from political actors or through their friends and relatives. Furthermore, the interactive nature of social media creates opportunities for individuals to discuss political events with their peers, including those with whom they have weak social ties."[63] According to these studies, social media may be diversifying information and opinions users come into contact with, though there is much speculation around filter bubbles and their ability to create deeper political polarization. One driver and possible solution to the problem is the role of emotions in online content. A 2018 study shows that different emotions of messages can lead to polarization or convergence: joy is prevalent in emotional polarization, while sadness and fear play significant roles in emotional convergence.[64] Since it is relatively easy to detect the emotional content of messages, these findings can help to design more socially responsible algorithms by starting to focus on the emotional content of algorithmic recommendations.  Visualization of the process and growth of two social media bots used in the 2019 Weibo study. The diagrams represent two aspects of the structure of filter bubbles, according to the study: large concentrations of users around single topics and a uni-directional, star-like structure that impacts key information flows. Social bots have been utilized by different researchers to test polarization and related effects that are attributed to filter bubbles and echo chambers.[65][66] A 2018 study used social bots on Twitter to test deliberate user exposure to partisan viewpoints.[65] The study claimed it demonstrated partisan differences between exposure to differing views, although it warned that the findings should be limited to party-registered American Twitter users. One of the main findings was that after exposure to differing views (provided by the bots), self-registered republicans became more conservative, whereas self-registered liberals showed less ideological change if none at all. A different study from The People's Republic of China utilized social bots on Weibo—the largest social media platform in China—to examine the structure of filter bubbles regarding to their effects on polarization.[66] The study draws a distinction between two conceptions of polarization. One being where people with similar views form groups, share similar opinions, and block themselves from differing viewpoints (opinion polarization), and the other being where people do not access diverse content and sources of information (information polarization). By utilizing social bots instead of human volunteers and focusing more on information polarization rather than opinion-based, the researchers concluded that there are two essential elements of a filter bubble: a large concentration of users around a single topic and a uni-directional, star-like structure that impacts key information flows. In June 2018, the platform DuckDuckGo conducted a research study on the Google Web Browser Platform. For this study, 87 adults in various locations around the continental United States googled three keywords at the exact same time: immigration, gun control, and vaccinations. Even in private browsing mode, most people saw results unique to them. Google included certain links for some that it did not include for other participants, and the News and Videos infoboxes showed significant variation. Google publicly disputed these results saying that Search Engine Results Page (SERP) personalization is mostly a myth. Google Search Liaison, Danny Sullivan, stated that “Over the years, a myth has developed that Google Search personalizes so much that for the same query, different people might get significantly different results from each other. This isn’t the case. Results can differ, but usually for non-personalized reasons.”[67] When filter bubbles are in place, they can create specific moments that scientists call 'Whoa' moments. A 'Whoa' moment is when an article, ad, post, etc., appears on your computer that is in relation to a current action or current use of an object. Scientists discovered this term after a young woman was performing her daily routine, which included drinking coffee when she opened her computer and noticed an advertisement for the same brand of coffee that she was drinking. "Sat down and opened up Facebook this morning while having my coffee, and there they were two ads for Nespresso. Kind of a 'whoa' moment when the product you're drinking pops up on the screen in front of you."[68] "Whoa" moments occur when people are "found." Which means advertisement algorithms target specific users based on their "click behavior" to increase their sale revenue. Several designers have developed tools to counteract the effects of filter bubbles (see § Countermeasures).[69] Swiss radio station SRF voted the word filterblase (the German translation of filter bubble) word of the year 2016.[70] |

反応と研究 メディアの反応 パーソナライズされたフィルタリングがどの程度行われているか、またそのような活動が有益か有害かについては、相反する報告がある。アナリストのジェイコ ブ・ワイズバーグは、2011年6月に『Slate』に寄稿し、パリサーの理論を検証するために、イデオロギー的背景の異なる5人の仲間に「ジョン・ベイ ナー」、「バーニー・フランク」、「ライアン・プラン」、「オバマケア」という一連の検索をさせ、その結果のスクリーンショットをワイズバーグに送るとい う非科学的な小規模実験を行った。ワイズバーグは、フィルターバブルは機能していないと結論づけ、ほとんどのインターネットユーザーが「デイリーミーの谷 で餌を食っている」という考えは誇張されすぎていると書いた[9]。ワイズバーグがグーグルにコメントを求めたところ、広報担当者は、「パーソナライズを 意図的に制限し、多様性を促進する」アルゴリズムが導入されていると述べた。 「6]オフレコでグーグルのプログラマーにインタビューしたところ、ジャーナリストのPer Grankvistは、以前は検索結果の決定にユーザーデータが大きな役割を果たしていたが、グーグルはテストを通じて、検索クエリがどのような結果を表 示するか決定する上で圧倒的に優れていることを発見した[44]。 グーグルや他のサイトが、ユーザーに関する膨大な情報の「書類」を保持しているという報告もあり、そうすることを選択すれば、個々のインターネット体験を さらにパーソナライズすることが可能になるかもしれない。例えば、グーグルは、個人的なグーグルアカウントを持っていなかったり、ログインしていなかった りしても、ユーザーの履歴を追跡する技術が存在する[6]。あるレポートでは、グーグルは、Gmail、グーグルマップ、検索エンジン以外の他のサービス など、様々なソースから蓄積された「10年分」の情報を収集していると述べている[10][検証失敗]。 [CNNのアナリストであるダグ・グロスは、フィルタリングされた検索は市民よりも消費者にとってより有用であるように思われ、「ピザ」を探している消費 者がパーソナライズされた検索に基づいて地元のデリバリーオプションを見つけ、遠くのピザ店を適切にフィルタリングするのに役立つだろうと示唆した [10][検証失敗]。 ワシントン・ポストやニューヨーク・タイムズなどの組織は、ユーザーが好感を持ったり同意したりしそうなものに検索結果を調整することを目的として、新し いパーソナライズされた情報サービスを作成する実験を行っている[9]。 学界の研究と反応 パーソナライズされたレコメンデーションを分析したウォートン大学の科学的研究は、これらのフィルターがオンライン音楽の嗜好の分断ではなく、共通性を生 み出すことができることも発見した[45]。 [45]ハーバード大学の法学教授であるジョナサン・ジットレインは、パーソナライゼーション・フィルタがグーグルの検索結果をどの程度歪めるかについて 異論を唱えており、「検索パーソナライゼーションの効果は軽微である」と述べている[9]。さらに、グーグルは、グーグルの検索履歴の記録を削除し、検索 キーワードや訪問したリンクを今後グーグルに記憶させないように設定することで、ユーザーが選択すればパーソナライゼーション機能を停止できる機能を提供 している[46]。 Internet Policy Reviewの研究では、分野横断的なフィルターバブルの明確で検証可能な定義の欠如を取り上げた。このため、研究者はしばしばフィルターバブルを異なる 方法で定義し、研究している[47]。その後、この研究は、分野横断的なフィルターバブルの存在に関する実証データの欠如を説明し[12]、フィルターバ ブルに起因する効果は、アルゴリズムよりも既存のイデオロギー的バイアスに起因する可能性があることを示唆した。フィルター・バブルに関する批判的な論評 は、「フィルター・バブルのテーゼは、しばしば、強い意見を持ちながら、同時に非常に可鍛性である特別な種類の政治的人間を想定している」とし、「人々が コンテンツを選択するときには能動的な主体性を持つが、アルゴリズムによってキュレーションされたコンテンツに一旦さらされると、受動的な受信者になって しまうというパラドックス」であることを示唆している[49]。 オックスフォード大学、スタンフォード大学、マイクロソフトの研究者による研究では、2013年3月から5月にかけて、インターネット・エクスプローラー 用のビング・ツールバー・アドオンの米国ユーザー120万人の閲覧履歴を調査した。その中から積極的にニュースを購読している5万人のユーザーを選び、 2012年の大統領選挙でユーザーのIPアドレスに関連する郡の有権者の大多数がオバマに投票したかロムニーに投票したかに基づいて、彼らが訪問した ニュースが左寄りか右寄りかを分類した。次に、ニュース記事が出版社のサイトに直接アクセスした後に読まれたのか、グーグルニュースのアグリゲーション サービス、ウェブ検索、ソーシャルメディアのどれを経由して読まれたのかを特定した。その結果、ウェブ検索やソーシャルメディアはイデオロギーの分離に寄 与するものの、オンラインニュース消費の大部分は、ユーザーが左寄りまたは右寄りの主流ニュースサイトに直接アクセスし、その結果、政治スペクトルの片側 からの見解にほぼ独占的に接することになることがわかった。この研究の限界には、インターネット・エクスプローラーの利用者の年齢が一般のインターネット 人口よりも高いこと、ビング・ツールバーの利用や、プライバシーをあまり気にしない利用者が自発的に(あるいは知らずに)閲覧履歴を共有していること、左 寄りの出版物の記事はすべて左寄りであり、右寄りの記事も同じであるという仮定など、選択の問題が含まれる; そして、積極的なニュース消費者ではないユーザーは、ニュースのほとんどをソーシャルメディア経由で入手する可能性があり、その結果、(出版物の偏りを認 識していると仮定した場合)ニュース出版物の選択を通じて本質的に偏りを自己選択するユーザーよりも、ソーシャルバイアスやアルゴリズムバイアスの影響を 強く受ける可能性がある。 [50] プリンストン大学とニューヨーク大学の研究者による研究は、フィルターバブルとアルゴリズムによるフィルタリングがソーシャルメディアの偏向に与える影響 を研究することを目的としている。彼らは「確率的ブロックモデル」と呼ばれる数学的モデルを使い、レディットとツイッターの環境で仮説を検証した。研究者 たちは、正則化されたソーシャルメディア・ネットワークと正則化されていないネットワークにおける分極化の変化を測定し、特にRedditと Twitterにおける分極化と意見の不一致の変化率を測定した。研究者たちは、非正規化ネットワークでは分極化が400%と有意に増加し、正規化ネット ワークでは分極化が4%、意見の不一致が5%増加したことを発見した[51]。 プラットフォーム研究 アルゴリズムが政治的多様性を制限する一方で、フィルターバブルの一部はユーザーの選択の結果である[52]。フェイスブックのデータサイエンティストに よる研究では、ユーザーはイデオロギーを共有する4人のフェイスブックの友人ごとに対照的な見解を持つ1人の友人を持っていることがわかった[53] [54]。 [53][54]フェイスブックのニュースフィードのアルゴリズムがどのようなものであっても、人々は同じような信条を共有する人と友達になったりフォ ローしたりする可能性が高い[53]。アルゴリズムの性質は、ユーザーの履歴に基づいてストーリーをランク付けすることであり、その結果、「政治的に横断 的なコンテンツは保守派で5パーセント、リベラル派で8パーセント減少する。 「しかし、人々が対照的な見解を提供するリンクをクリックする選択肢を与えられても、最もよく閲覧しているソースをデフォルトにする[53]。「ユーザー の選択によって、横断的なリンクをクリックする可能性は、保守派で17パーセント、リベラル派で6パーセント減少する。 「クロスカッティングリンクとは、ユーザーが想定している視点や、ウェブサイトがユーザーの信条として定めているものとは異なる視点を紹介するリンクのこ とである[55]。レヴィ・ボクセル、マシュー・ゲンツコウ、ジェシー・M・シャピロの最近の研究では、オンラインメディアは政治的偏向の原動力ではない ことが示唆されている[56]。イデオロギーの分裂が最も激しいのは75歳以上のアメリカ人であり、2012年の時点でソーシャルメディアを利用している と回答したのはわずか20%であった。対照的に、18歳から39歳のアメリカ人の80%が2012年時点でソーシャルメディアを利用していると回答してい る。このデータは、オンラインメディアがほとんど存在しなかった1996年当時と比べて、2012年の若年層はそれほど偏向していないことを示唆してい る。この調査は、年齢層による違いや、人々が先入観に訴える情報を求めるためにニュース消費が偏向したままであることを浮き彫りにしている。伝統的なメ ディアがニュースの主要な情報源であり続ける一方で、若い層にとってはオンラインメディアが主要な情報源である。アルゴリズムとフィルターバブルはコンテ ンツの多様性を弱めるが、この研究は、政治的偏向の傾向は主に既存の見解と外部ソースを認識しないことによって引き起こされることを明らかにした。 2020年にドイツで行われた研究では、ビッグファイブ心理学モデルを利用して、個人のパーソナリティ、デモグラフィック、イデオロギーがユーザーの ニュース消費に及ぼす影響を検証している[57]。ユーザーが消費するニュースソースの数がフィルターバブルに巻き込まれる可能性に影響し、メディアの多 様性が高ければ可能性は低くなるという考え方に基づき、その結果、特定のデモグラフィック(年齢が高い、男性)と特定のパーソナリティ特性(開放性が高 い)が、個人が消費するニュースソースの数と正の相関関係があることが示唆された。また、メディアの多様性と、ユーザーが右派権威主義に傾倒する度合いと の間には、否定的なイデオロギー的関連性があることもわかった。この研究は、ユーザーの選択の役割に影響を与える可能性のあるさまざまな個々のユーザー要 因を提示するだけでなく、ユーザーがフィルターバブルに巻き込まれる可能性とユーザーの投票行動との間の疑問や関連性も提起している[57]。 フェイスブックの研究は、アルゴリズムがニュースフィードのフィルタリングにおいて、人々が想定しているほど大きな役割を果たしているかどうか「結論が出 ていない」ことを発見した[58]。また、「個人の選択」、つまり確証バイアスも同様に、ニュースフィードからフィルタリングされるものに影響を与えるこ とを発見した[58]。フィルターバブルに抗議するポイントは、アルゴリズムと個人の選択がニュースフィードをフィルタリングするために一緒に働くことで あるため、一部の社会科学者はこの結論を批判した。 [59]彼らはまた、フェイスブックのサンプル数が「実際のフェイスブックユーザーの9%」程度と少ないこと、そして、フェイスブックが外部の研究者に公 開していないデータにアクセスできる「フェイスブックの科学者」によって研究が行われたため、研究結果が「再現不可能」であることを批判した[60]。 この研究では、平均的なユーザーのフェイスブックの友人のうち、政治スペクトルの反対側を購読しているのは15~20%程度であることがわかったが、 Voxのジュリア・カマンは、これは視点の多様性にとって潜在的にポジティブな意味を持つ可能性があると推論している。これらの "友達 "は、インターネットがなければ政治を共有することもないような知人であることが多い。フェイスブックは、こうした「第二層」の友人が投稿したり再投稿し たりするコンテンツをユーザーが目にし、場合によっては交流するようなユニークな環境を醸成しているのかもしれない。この研究では、「リベラル派が見た ニュースの24%は保守寄りであり、保守派が見たニュースの38%はリベラル寄りであった」[61]。「リベラル派は、保守派の友人と比較して、反対側の 情報を共有する友人とのつながりが少ない傾向がある」[62]。 同様に、ニューヨーク大学によるツイッターのフィルター・バブルの研究は、「個人は現在、ニュース・イベントに関するより幅広い視点にアクセスできるよう になり、こうした情報のほとんどは、従来のチャネルを通じてではなく、政治的アクターから直接、あるいは友人や親戚を通じてもたらされている」と結論付け ている。さらに、ソーシャルメディアの双方向性は、個人が社会的つながりの弱い仲間も含めて政治的出来事について議論する機会を生み出している。 この問題の1つの要因であり、解決策となりうるのが、オンラインコンテンツにおける感情の役割だ。2018年の研究では、メッセージの異なる感情が分極化 または収束につながる可能性があることを示している:喜びは感情的な分極化で優勢である一方、悲しみと恐怖は感情的な収束で重要な役割を果たしている [64]。メッセージの感情的なコンテンツを検出することは比較的容易であるため、これらの知見は、アルゴリズムによる推奨の感情的なコンテンツに焦点を 当て始めることによって、より社会的責任のあるアルゴリズムを設計するのに役立つ可能性がある。  2019年のWeibo研究で使用された2つのソーシャルメディアボットのプロセスと成長の視覚化。この図は、研究によると、フィルターバブルの構造の2 つの側面を表している:1つのトピックの周りにユーザーが大きく集中することと、主要な情報の流れに影響を与える一方向の星のような構造。 ソーシャルボットは、フィルターバブルやエコーチェンバーに起因する分極化と関連する効果を検証するために、さまざまな研究者によって利用されている [65][66]。2018年の研究では、党派的な視点に意図的にユーザーをさらすことを検証するために、Twitter上でソーシャルボットを使用した [65]。この研究では、異なる意見にさらされることによる党派的な違いを実証したと主張しているが、調査結果は党派的に登録されたアメリカの Twitterユーザーに限定されるべきであると警告している。主な調査結果の1つは、(ボットによって提供された)異なる見解に触れた後、自己登録した 共和党員はより保守的になったが、自己登録したリベラル派は、全く変化がない場合はイデオロギーの変化が少なかったというものであった。中華人民共和国の 別の研究では、中国最大のソーシャル・メディア・プラットフォームである微博(ウェイボー)上のソーシャル・ボットを利用し、フィルター・バブルが分極化 に与える影響について、その構造を検証している[66]。1つは、似たような意見を持つ人々がグループを形成し、似たような意見を共有し、異なる視点から 自分自身を遮断すること(意見の分極化)であり、もう1つは、人々が多様なコンテンツや情報源にアクセスしないこと(情報の分極化)である。人間のボラン ティアではなくソーシャルボットを活用し、オピニオンベースよりも情報の偏向に注目することで、研究者たちはフィルターバブルには2つの本質的な要素があ ると結論づけた。それは、1つのトピックにユーザーが大きく集中することと、主要な情報の流れに影響を与える一方向的な星のような構造だ。 2018年6月、プラットフォームのDuckDuckGoは、Google Web Browser Platformに関する調査研究を実施した。この調査では、米国本土のさまざまな場所にいる87人の成人が、移民、銃規制、予防接種という3つのキー ワードをまったく同時にググった。プライベート・ブラウジング・モードでも、ほとんどの人が自分だけの結果を見た。グーグルは、ある人には特定のリンクを 含め、他の参加者には含めず、ニュースやビデオのインフォボックスには大きなばらつきを示した。Googleはこれらの結果について、検索エンジン結果 ページ(SERP)のパーソナライゼーションはほとんど神話であると公式に反論した。Google Search Liaisonのダニー・サリバン氏は、「長年にわたり、Google Searchはパーソナライズしているため、同じクエリでも人によって結果が大きく異なるという俗説が広まってきました。これは事実ではありません。結果 は異なることがありますが、通常はパーソナライズされていない理由によるものです」[67]。 フィルターバブルが配置されると、科学者が「Whoa」モーメントと呼ぶ特定の瞬間を作り出すことができる。Whoa'モーメントとは、ある記事、広告、 投稿などが、現在の行動やオブジェクトの現在の使用に関連してコンピューター上に表示されることである。科学者たちがこの言葉を発見したのは、ある若い女 性がコーヒーを飲むという日課をこなしているときにパソコンを開き、自分が飲んでいるのと同じ銘柄のコーヒーの広告に気づいたことがきっかけだった。「今 朝、コーヒーを飲みながらフェイスブックを開いたら、ネスプレッソの広告が2つあった。自分が飲んでいる製品が目の前のスクリーンに出てくるのは、ちょっ とした "おっと "の瞬間です」[68]。"おっと "の瞬間は、人々が "発見 "されたときに起こる。つまり、広告アルゴリズムは、販売収入を増やすために、「クリック行動」に基づいて特定のユーザーをターゲットにする。 いくつかのデザイナーがフィルターバブルの影響を打ち消すツールを開発している(§対策を参照)[69]。スイスのラジオ局SRFは、2016年の流行語大賞にフィルターバブル(フィルターバブルのドイツ語訳)を選出した[70]。 |

| Countermeasures By individuals In The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You,[71] internet activist Eli Pariser highlights how the increasing occurrence of filter bubbles further emphasizes the value of one's bridging social capital as defined by Robert Putman. Pariser argues that filter bubbles reinforce a sense of social homogeneity, which weakens ties between people with potentially diverging interests and viewpoints.[72] In that sense, high bridging capital may promote social inclusion by increasing our exposure to a space that goes beyond self-interests. Fostering one's bridging capital, such as by connecting with more people in an informal setting, may be an effective way to reduce the filter bubble phenomenon. Users can take many actions to burst through their filter bubbles, for example by making a conscious effort to evaluate what information they are exposing themselves to, and by thinking critically about whether they are engaging with a broad range of content.[73] Users can consciously avoid news sources that are unverifiable or weak. Chris Glushko, the VP of Marketing at IAB, advocates using fact-checking sites to identify fake news.[74] Technology can also play a valuable role in combating filter bubbles.[75] Some browser plug-ins are aimed to help people step out of their filter bubbles and make them aware of their personal perspectives; thus, these media show content that contradicts with their beliefs and opinions. In addition to plug-ins, there are apps created with the mission of encouraging users to open their echo chambers. News apps such as Read Across the Aisle nudge users to read different perspectives if their reading pattern is biased towards one side/ideology.[76] Although apps and plug-ins are tools humans can use, Eli Pariser stated "certainly, there is some individual responsibility here to really seek out new sources and people who aren't like you."[52] Since web-based advertising can further the effect of the filter bubbles by exposing users to more of the same content, users can block much advertising by deleting their search history, turning off targeted ads, and downloading browser extensions. Some use anonymous or non-personalized search engines such as YaCy, DuckDuckGo, Qwant, Startpage.com, Disconnect, and Searx in order to prevent companies from gathering their web-search data. Swiss daily Neue Zürcher Zeitung is beta-testing a personalized news engine app which uses machine learning to guess what content a user is interested in, while "always including an element of surprise"; the idea is to mix in stories which a user is unlikely to have followed in the past.[77] The European Union is taking measures to lessen the effect of the filter bubble. The European Parliament is sponsoring inquiries into how filter bubbles affect people's ability to access diverse news.[78] Additionally, it introduced a program aimed to educate citizens about social media.[79] In the U.S., the CSCW panel suggests the use of news aggregator apps to broaden media consumers news intake. News aggregator apps scan all current news articles and direct you to different viewpoints regarding a certain topic. Users can also use a diversely-aware news balancer which visually shows the media consumer if they are leaning left or right when it comes to reading the news, indicating right-leaning with a bigger red bar or left-leaning with a bigger blue bar. A study evaluating this news balancer found "a small but noticeable change in reading behavior, toward more balanced exposure, among users seeing the feedback, as compared to a control group".[80] By media companies In light of recent concerns about information filtering on social media, Facebook acknowledged the presence of filter bubbles and has taken strides toward removing them.[81] In January 2017, Facebook removed personalization from its Trending Topics list in response to problems with some users not seeing highly talked-about events there.[82] Facebook's strategy is to reverse the Related Articles feature that it had implemented in 2013, which would post related news stories after the user read a shared article. Now, the revamped strategy would flip this process and post articles from different perspectives on the same topic. Facebook is also attempting to go through a vetting process whereby only articles from reputable sources will be shown. Along with the founder of Craigslist and a few others, Facebook has invested $14 million into efforts "to increase trust in journalism around the world, and to better inform the public conversation".[81] The idea is that even if people are only reading posts shared from their friends, at least these posts will be credible. Similarly, Google, as of January 30, 2018, has also acknowledged the existence of a filter bubble difficulties within its platform. Because current Google searches pull algorithmically ranked results based upon "authoritativeness" and "relevancy" which show and hide certain search results, Google is seeking to combat this. By training its search engine to recognize the intent of a search inquiry rather than the literal syntax of the question, Google is attempting to limit the size of filter bubbles. As of now, the initial phase of this training will be introduced in the second quarter of 2018. Questions that involve bias and/or controversial opinions will not be addressed until a later time, prompting a larger problem that exists still: whether the search engine acts either as an arbiter of truth or as a knowledgeable guide by which to make decisions by.[83] In April 2017 news surfaced that Facebook, Mozilla, and Craigslist contributed to the majority of a $14M donation to CUNY's "News Integrity Initiative," poised at eliminating fake news and creating more honest news media.[84] Later, in August, Mozilla, makers of the Firefox web browser, announced the formation of the Mozilla Information Trust Initiative (MITI). The +MITI would serve as a collective effort to develop products, research, and community-based solutions to combat the effects of filter bubbles and the proliferation of fake news. Mozilla's Open Innovation team leads the initiative, striving to combat misinformation, with a specific focus on the product with regards to literacy, research and creative interventions.[85] |

対策 個人による フィルター・バブル』の中で: What the Internet Is Hiding from You』[71]において、インターネット活動家のイーライ・パリサーは、フィルター・バブルの増加によって、ロバート・プットマンによって定義された橋 渡し的社会資本の価値がさらに強調されることを強調している。パ リサーは、フィルター・バブルは社会的同質性の感覚を強化し、潜在的 に異なる関心や視点を持つ人々の間の結びつきを弱めると論じてい る[72]。その意味で、高いブリッジング・キャピタルは、利己的な利 益を超えた空間への露出を増やすことによって、社会的包摂を促進す る可能性がある。インフォーマルな場でより多くの人とつながるなど、自分のブリッジング・キャピタルを育てることは、フィルター・バブル現象を軽減する効 果的な方法かもしれない。 たとえば、自分がどのような情報にさらされているかを意識的に評価する努力をしたり、幅広いコンテンツに関与しているかどうかを批判的に考えたりすること で、ユーザーはフィルターバブルを破裂させるために多くの行動をとることができる[73]。IABのマーケティング担当副社長であるクリス・グラシュコ は、フェイクニュースを特定するためにファクトチェックサイトを利用することを提唱している[74]。フィルターバブルに対抗するために、テクノロジーも 貴重な役割を果たすことができる[75]。 ブラウザのプラグインのなかには、人々がフィルターバブルから抜け出し、個人的な視点を意識するようにすることを目的としたものがある。プラグインに加 え、ユーザーにエコーチェンバーを開かせることを使命として作られたアプリもある。Read Across the Aisle」のようなニュースアプリは、ユーザーが読書パターンが片方やイデオロギーに偏っている場合、異なる視点を読むように促す[76]。アプリやプ ラグインは人間が使うことができるツールだが、Eli Pariserは「確かに、新しい情報源や自分とは違う人々を本当に探し求めることは、ここにいる個人の責任でもある」と述べている[52]。 ウェブベースの広告は、ユーザーをより多くの同じコンテンツにさらすことで、フィルターバブルの効果をさらに高める可能性があるため、ユーザーは検索履歴 を削除し、ターゲット広告をオフにし、ブラウザ拡張機能をダウンロードすることで、多くの広告をブロックすることができる。YaCy、 DuckDuckGo、Qwant、Startpage.com、Disconnect、Searxなどの匿名検索エンジンやパーソナライズされていない 検索エンジンを使って、企業によるウェブ検索データの収集を防いでいる人もいる。スイスの日刊紙Neue Zürcher Zeitungは、パーソナライズされたニュースエンジンアプリのベータテストを行っている。このアプリは、機械学習を使用して、ユーザーがどのようなコ ンテンツに興味があるかを推測する一方で、「常に驚きの要素を含む」。 欧州連合(EU)は、フィルター・バブルの影響を軽減するための対策を講じている。欧州議会は、フィルターバブルが人々の多様なニュースへのアクセス能力 にどのような影響を与えるかについての調査を後援している[78]。さらに、ソーシャルメディアについて市民を教育することを目的としたプログラムを導入 した[79]。ニュース・アグリゲーター・アプリは、現在のニュース記事をすべてスキャンし、あるトピックに関するさまざまな視点に誘導する。ユーザー は、多様性を意識したニュースバランサーを使うこともできる。このバランサーは、メディア消費者がニュースを読むときに左寄りか右寄りかを視覚的に表示 し、右寄りは赤いバーが大きく、左寄りは青いバーが大きく表示される。このニュースバランサーを評価した研究では、「フィードバックを見たユーザーの読書 行動が、対照群と比べて、よりバランスの取れた露出へと、小さいながらも顕著に変化した」ことがわかった[80]。 メディア企業による ソーシャルメディア上の情報フィルタリングに関する最近の懸念に鑑みて、フェイスブックはフィルターバブルの存在を認め、フィルターバブルの除去に向けて 前進した[81]。 2017年1月、フェイスブックは、一部のユーザーがそこで非常に話題になっている出来事を見ることができないという問題に対応して、トレンドトピックの リストからパーソナライゼーションを削除した[82]。 フェイスブックの戦略は、ユーザーが共有された記事を読んだ後に関連するニュース記事を投稿するという、2013年に実装した関連記事機能を逆転させるこ とである。今、刷新された戦略は、このプロセスを反転させ、同じトピックに関する異なる視点からの記事を投稿する。フェイスブックはまた、信頼できる情報 源からの記事のみを表示するような審査プロセスも試みている。フェイスブックは、Craigslistの創設者や他の数社とともに、「世界中のジャーナリ ズムの信頼を高め、公共の会話をよりよく伝える」取り組みに1,400万ドルを投資している[81]。 同様にグーグルも、2018年1月30日現在、そのプラットフォーム内にフィルターバブルの困難が存在することを認めている。現在のグーグル検索は、特定 の検索結果を表示したり非表示にしたりする「権威性」と「関連性」に基づいてアルゴリズム的にランク付けされた結果を引っ張ってくるため、グーグルはこれ に対抗しようとしている。質問の文字通りの構文ではなく、検索の意図を認識するように検索エンジンを訓練することで、グーグルはフィルターバブルの大きさ を制限しようとしている。現時点では、このトレーニングの初期段階は2018年第2四半期に導入される予定だ。偏見および/または物議を醸す意見を含む質 問は、より後の時期まで対処されず、検索エンジンが真実の裁定者として、またはそれによって意思決定を行うための知識豊富なガイドとして機能するかどうか という、依然として存在する大きな問題を促している[83]。 2017年4月、フェイクニュースを排除し、より誠実なニュースメディアを作ることを目的としたCUNYの「News Integrity Initiative」にフェイスブック、モジラ、クレイグスリストが1,400万ドルの寄付の大部分を拠出したというニュースが表面化した[84]。 その後8月、FirefoxウェブブラウザのメーカーであるMozillaは、Mozilla Information Trust Initiative(MITI)の設立を発表した。MITIは、フィルターバブルの影響とフェイクニュースの拡散に対抗するための製品、研究、コミュニ ティベースのソリューションを開発するための集団的な取り組みとして機能する。Mozillaのオープンイノベーションチームはこのイニシアチブをリード し、リテラシー、研究、創造的な介入に関して製品に特に焦点を当て、誤報と闘うよう努めている[85]。 |

| Ethical implications As the popularity of cloud services increases, personalized algorithms used to construct filter bubbles are expected to become more widespread.[86] Scholars have begun considering the effect of filter bubbles on the users of social media from an ethical standpoint, particularly concerning the areas of personal freedom, security, and information bias.[87] Filter bubbles in popular social media and personalized search sites can determine the particular content seen by users, often without their direct consent or cognizance,[86] due to the algorithms used to curate that content. Self-created content manifested from behavior patterns can lead to partial information blindness.[88] Critics of the use of filter bubbles speculate that individuals may lose autonomy over their own social media experience and have their identities socially constructed as a result of the pervasiveness of filter bubbles.[86] Technologists, social media engineers, and computer specialists have also examined the prevalence of filter bubbles.[89] Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, and Eli Pariser, author of The Filter Bubble, have expressed concerns regarding the risks of privacy and information polarization.[90][91] The information of the users of personalized search engines and social media platforms is not private, though some people believe it should be.[90] The concern over privacy has resulted in a debate as to whether or not it is moral for information technologists to take users' online activity and manipulate future exposure to related information.[91] Some scholars have expressed concerns regarding the effects of filter bubbles on individual and social well-being, i.e. the dissemination of health information to the general public and the potential effects of internet search engines to alter health-related behavior.[16][17][18][92] A 2019 multi-disciplinary book reported research and perspectives on the roles filter bubbles play in regards to health misinformation.[18] Drawing from various fields such as journalism, law, medicine, and health psychology, the book addresses different controversial health beliefs (e.g. alternative medicine and pseudoscience) as well as potential remedies to the negative effects of filter bubbles and echo chambers on different topics in health discourse. A 2016 study on the potential effects of filter bubbles on search engine results related to suicide found that algorithms play an important role in whether or not helplines and similar search results are displayed to users and discussed the implications their research may have for health policies.[17] Another 2016 study from the Croatian Medical journal proposed some strategies for mitigating the potentially harmful effects of filter bubbles on health information, such as: informing the public more about filter bubbles and their associated effects, users choosing to try alternative [to Google] search engines, and more explanation of the processes search engines use to determine their displayed results.[16] Since the content seen by individual social media users is influenced by algorithms that produce filter bubbles, users of social media platforms are more susceptible to confirmation bias,[93] and may be exposed to biased, misleading information.[94] Social sorting and other unintentional discriminatory practices are also anticipated as a result of personalized filtering.[95] In light of the 2016 U.S. presidential election scholars have likewise expressed concerns about the effect of filter bubbles on democracy and democratic processes, as well as the rise of "ideological media".[11] These scholars fear that users will be unable to "[think] beyond [their] narrow self-interest" as filter bubbles create personalized social feeds, isolating them from diverse points of view and their surrounding communities.[96] For this reason, an increasingly discussed possibility is to design social media with more serendipity, that is, to proactively recommend content that lies outside one's filter bubble, including challenging political information and, eventually, to provide empowering filters and tools to users.[97][98][99] A related concern is in fact how filter bubbles contribute to the proliferation of "fake news" and how this may influence political leaning, including how users vote.[11][100][101] Revelations in March 2018 of Cambridge Analytica's harvesting and use of user data for at least 87 million Facebook profiles during the 2016 presidential election highlight the ethical implications of filter bubbles.[102] Co-founder and whistleblower of Cambridge Analytica Christopher Wylie, detailed how the firm had the ability to develop "psychographic" profiles of those users and use the information to shape their voting behavior.[103] Access to user data by third parties such as Cambridge Analytica can exasperate and amplify existing filter bubbles users have created, artificially increasing existing biases and further divide societies. |

倫理的意味合い クラウドサービスの人気が高まるにつれて、フィルターバブルを構築する ために使用されるパーソナライズされたアルゴリズムは、より広まることが予想される[86]。学者たちは、特に個人の自由、セキュリティ、情報の偏りの領 域に関する倫理的な観点から、フィルターバブルがソーシャルメディアのユーザーに与える影響を検討し始めている[87]。フィルターバブルの利用を批判す る人々は、フィルターバブルの普及の結果、個人が自身のソーシャルメディア体験に対する自律性を失い、アイデンティティが社会的に構築される可能性がある と推測している[86]。 フェイスブックの創設者であるマーク・ザッカーバーグと『フィルター・ バブル』の著者であるイーライ・パリサーは、プライバシーと情報の二極化のリスクに関する懸念を表明している[90][91]。 [90][91]パーソナライズされた検索エンジンやソーシャル・メディア・プラットフォームの利用者の情報は、プライベートなものではないが、そうある べきだと考える人もいる[90]。プライバシーに対する懸念は、情報技術者が利用者のオンライン上の活動を取り上げ、関連する情報に将来触れることを操作 することが道徳的かどうかという議論につながっている[91]。 一部の学者は、フィルター・バブルが個人や社会の幸福に及ぼす影響、す なわち一般大衆への健康情報の普及や、インターネット検索エンジンが健康に関連する行動を変化させる潜在的な影響に関して懸念を表明している[16] [17][18][92]。2019年に出版された学際的な書籍は、健康誤報に関してフィルター・バブルが果たす役割に関する研究と展望を報告している。 [18] ジャーナリズム、法律、医学、健康心理学など様々な分野から引用された本書は、健康談話における様々なトピックにおけるフィルターバブルやエコーチェン バーの悪影響に対する潜在的な改善策と同様に、様々な議論を呼ぶ健康信念(代替医療や疑似科学など)を取り上げている。自殺に関連する検索エンジンの検索 結果におけるフィルターバブルの潜在的な影響に関する2016年の研究では、ヘルプラインや類似の検索結果がユーザーに表示されるか否かにアルゴリズムが 重要な役割を果たしていることを発見し、その研究が健康政策に与えるかもしれない影響について議論した。 [17] Croatian Medical journalによる2016年の別の研究では、健康情報に対するフィルターバブルの潜在的な有害影響を緩和するためのいくつかの戦略が提案されている。 例えば、フィルターバブルとその関連する影響について一般にもっと知らせること、ユーザーが(Googleに代わる)検索エンジンを試すこと、検索エンジ ンが表示結果を決定するために使用するプロセスについてもっと説明すること、などである[16]。 個々のソーシャルメディアユーザーが目にするコンテンツは、フィルター バブルを生み出すアルゴリズムによって影響を受けるため、ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームのユーザーは確証バイアスの影響を受けやすく[93]、偏っ た誤解を招く情報にさらされる可能性がある[94]。パーソナライズされたフィルタリングの結果として、ソーシャルソーティングやその他の意図しない差別 的慣行も予想される[95]。 2016年の米国大統領選挙を踏まえて、学者たちも同様に、フィルター バブルが民主主義と民主主義のプロセスに与える影響、さらには「イデオロギーメディア」の台頭について懸念を表明している[11]。 これらの学者たちは、フィルターバブルがパーソナライズされたソーシャルフィードを作り出し、多様な視点や周囲のコミュニティからユーザーを孤立させるこ とで、ユーザーが「(自分の)狭い自己利益を超えて考える」ことができなくなることを恐れている。 [96]この理由から、ますます議論されている可能性は、よりセレンディピティでソーシャルメディアをデザインすること、つまり、挑戦的な政治的情報を含 む、自分のフィルターバブルの外側にあるコンテンツを積極的に推奨すること、そして最終的には、ユーザーに力を与えるフィルターやツールを提供することで ある[97][98][99]。 関連する懸念は、フィルターバブルが「フェイクニュース」の拡散にどのように寄与しているか、そしてこれがユーザーの投票方法を含む政治的傾向にどのよう に影響を与える可能性があるかである[11][100][101]。 2018年3月に明らかになったケンブリッジ・アナリティカによる 2016年の大統領選挙中の少なくとも8700万人のフェイスブックのプロフィールのユーザーデータの採取と利用は、フィルターバブルの倫理的な意味を浮 き彫りにしている。 [102]ケンブリッジ・アナリティカの共同設立者であり内部告発者であるクリストファー・ワイリー氏は、同社がどのようにしてこれらのユーザーの「サイ コグラフィック」プロファイルを作成し、投票行動を形成するために情報を使用する能力を持っていたかを詳述している[103]。 ケンブリッジ・アナリティカのような第三者によるユーザーデータへのアクセスは、ユーザーが作り出した既存のフィルターバブルを悪化させ増幅させ、既存の バイアスを人為的に増加させ、社会をさらに分断する可能性がある。 |

| Dangers Filter bubbles have stemmed from a surge in media personalization, which can trap users. The use of AI to personalize offerings can lead to users viewing only content that reinforces their own viewpoints without challenging them. Social media websites like Facebook may also present content in a way that makes it difficult for users to determine the source of the content, leading them to decide for themselves whether the source is reliable or fake.[104] That can lead to people becoming used to hearing what they want to hear, which can cause them to react more radically when they see an opposing viewpoint. The filter bubble may cause the person to see any opposing viewpoints as incorrect and so could allow the media to force views onto consumers.[105][104][106] Researches explain that the filter bubble reinforces what one is already thinking.[107] This is why it is extremely important to utilize resources that offer various points of view.[107] |

危険性 フィルターバブルは、メディアのパーソナライゼーションの急増に起因しており、ユーザーを罠にはめる可能性がある。AIを使ってパーソナライズされたコン テンツを提供することで、ユーザーは自分の視点を強化するようなコンテンツしか見なくなり、自分の視点に挑戦しなくなる可能性がある。フェイスブックのよ うなソーシャル・メディア・ウェブサイトはまた、ユーザーがコンテンツの出典を判断することを困難にするような方法でコンテンツを提示し、その出典が信頼 できるものなのか偽物なのかをユーザー自身が判断するよう導くこともある[104]。フィルター・バブルは、反対意見を正しくないものと見なし、メディア が消費者に意見を押し付けることを可能にするかもしれない[105][104][106]。 研究者たちは、フィルター・バブルは人がすでに考えていることを強化すると説明している[107]。 |

| Algorithmic attention rents Algorithmic curation Algorithmic radicalization Allegory of the Cave Attention inequality Communal reinforcement Content farm Dead Internet theory Deradicalization Echo chamber (media) False consensus effect Group polarization Groupthink Infodemic Information silo Media consumption Narrowcasting Search engine manipulation effect Selective exposure theory Serendipitous discovery, an antithesis of filter bubble The Social Dilemma Stereotype |

アルゴリズムによるアテンション・レンタル アルゴリズム的キュレーション アルゴリズムの先鋭化 洞窟の寓話 注意の不平等 共同強化 コンテンツファーム 死んだインターネット理論 脱過激化 エコーチェンバー(メディア) 偽のコンセンサス効果 集団の分極化 集団思考 情報風土 情報のサイロ化 メディア消費 ナローキャスティング 検索エンジン操作効果 選択的露出理論 セレンディピティ発見、フィルターバブルのアンチテーゼ 社会的ジレンマ ステレオタイプ(→文化的ステレオタイプ) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filter_bubble |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆