On

the Generation Z, or Internet-Based

Generation

ネットジェネレーションの特徴

On

the Generation Z, or Internet-Based

Generation

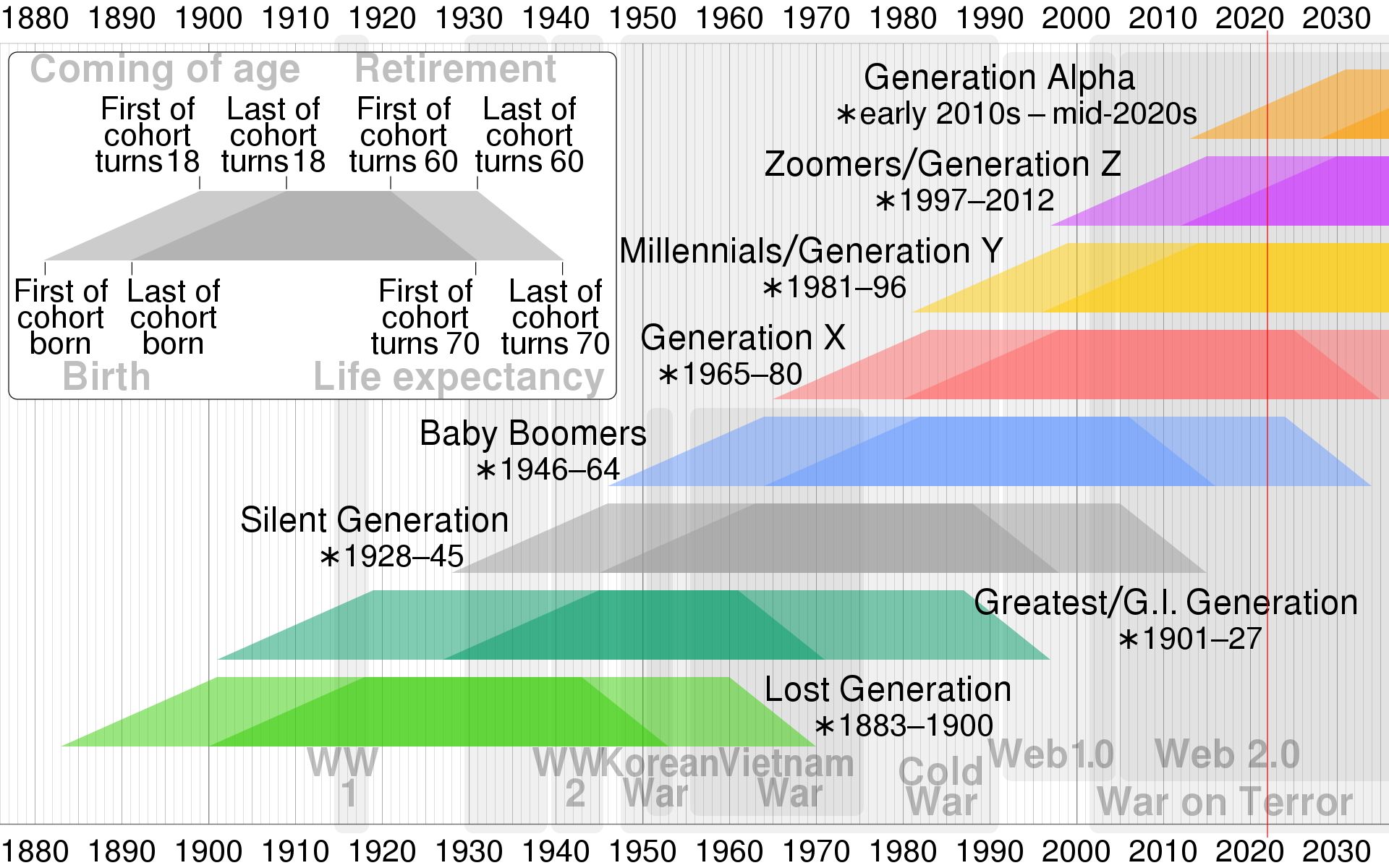

"Generation Z (also known as Post-Millennials, Plurals, or the Homeland Generation in the United States) is the demographic cohort after the Millennials. There are no precise dates for when the Gen Z cohort starts or ends; demographers and researchers typically use starting birth years that range from the mid-1990s to early 2000s, and as of yet there is little consensus about ending birth years" - Generation Z, by Wikipedia

| ベービーブーマー |

Baby boomers |

Me 世代(Me generation)は ベービーブーマー(Baby boomers) は、1946年から1964年ごろまで生まれたアメリカの世代。第二次大戦から復員してきた若い世代による子どもたちで、実際にベービーブームと呼ばれる 高い出生率に裏付けられる世代。後の世代の"Generation Me"(Jean Twenge, 2006)とは異なる。 | |

| X世代 | Generation X | X世代は、1965年から1980年ま での世代。青年期 以降にネット環境に触れることができ、それに適応している世代。 | |

| Y世代 | Generation Y | 生まれたのが1980年から1996年 ぐらいまでの世代。Jean Twenge (2006)のいう "Generation Me"はこの世代に相当する。ベビー・ブーマーである"Me 世代;Me generation" とは異なる。 | 【日本型世代区分】木村忠正『デジタルネイティブの時代』平凡社、

p.20、2012年に

よる世代区分 1)1980年前後〜1982年生まれ(第一世代) 2)1983年〜1987年生まれ(第二世代) 3)1988年〜1990年生まれ(第三世代) 4)1991年以降の世代(第四世代) |

| "Generation Me" | The Associated Press calls them

'In

this provocative new book, headline-making psychologist and social

commentator Dr. Jean Twenge documents the self-focus of what she calls

'Generation Me' -- people born in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Herself

a member of Generation Me, Dr. Twenge explores why her generation is

tolerant, confident, open-minded, and ambitious but also cynical,

depressed, lonely, and anxious. - Nielsen BookData. |

この刺激的な新刊で、心理学者で社会評論家のジーン・トウェンジ博士

は、彼女が「ジェネレーション・ミー」と呼ぶ、1970年代、1980年代、

1990年代生まれの人々の自己中心的な考え方を記録している。自身もジェネレーション・ミーの一員であるトゥエンジェ博士は、彼女の世代

がなぜ寛容で、自信があり、心が広く、野心的でありながら、シニカルで、落ち込みやすく、孤独で、不安なのかを探っている。 ●ベビー・ブーマー/■ジェネレーション・ミー(Twenge 2006:66) ●自己充足/ ■楽しみ ●旅・ポテンシャル・探求/■すでにそこにいる ●世界を変える/ ■君の夢に寄り添う ●プロテストやグループセッション/■TVをみる、ウェブ・サーフ、テキスト入力する ●政府の利害/ ■君自身や君の利害 ●得意なもの好きなもの/■さまざまな事物 ●生活の哲学/ ■君自身のよいと感じるもの |

|

| Z世代 | Generation Z | 1996年頃から2010年初期までの 世代。ミレニアム後、真性ネットジェネレーションなどといわれる。生まれた時からスマホやネット環境が空気のように存在している世代。SNSネイティブ。 広告がスキップできることを知り、インフルエンサーのことに精通している。プリントメディアは購入するものではなく、ネットで入手するか、プリントアウト で利用する世代。 | ・Z世代・ ジェネレーションZ.を見よ!! |

| α世代 | Generation α | 2010年ごろから2025年ぐらいまでの現代の世代。 |

●

Major generations of the Western world (site of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generation_Z

ネットジェネレーションの特徴(タプスコット 1998:92-108)〈→「Z世代」をみよ〉

■Me

generation(ベビー・ブーマー)と、Generation "Me"(1980s-1990s生まれ)

| The "Me" generation

is a term referring to Baby Boomers in the United States and the

self-involved qualities associated with this generation.[1] The 1970s

was dubbed the "Me decade" by writer Tom Wolfe;[2] Christopher Lasch

wrote about the rise of a culture of narcissism among younger Baby

Boomers.[3] The phrase became popular at a time when "self-realization"

and "self-fulfillment" were becoming cultural aspirations to which

young people supposedly ascribed higher importance than social

responsibility. |

「私」世代とは、アメリカのベビーブーマー世代とその世代に関連する自

己中心的な性質を指す言葉である[1] 。 1970年代は作家のトム・ウルフによって「私の10年」と呼ばれ[2]

、クリストファー・ラッシュは若いベビーブーマー世代のナルシズム文化の台頭について書いた。

自己実現」「自己充足」が若者の間で社会的責任よりも重要視されて文化的願望になっていた時期にこのフレーズは流行した[3] 。 |

| Origins The cultural change in the United States during the 1970s that was experienced by the Baby Boomers, upon when the majority of them became of age, is complex. The 1960s are remembered as a time of political protests, and radical experimentation with new cultural experiences (the Sexual Revolution, happenings, mainstream awareness of Eastern religions), which were practiced by older Boomers. The Civil Rights Movement, gave rebellious young people serious goals. Cultural experimentation was justified as being directed toward spiritual or intellectual enlightenment. The mid to late 1970s, in contrast, was a time of increased economic crisis and disillusionment with idealistic politics among the young, particularly after the resignation of Richard Nixon and the end of the Vietnam War. Unapologetic hedonism became acceptable among the young.[citation needed] The new introspectiveness announced the demise of an established set of traditional faiths centred on work and the postponement of gratification, and the emergence of a consumption-oriented lifestyle ethic centred on lived experience and the immediacy of daily lifestyle choices.[4] By the mid-1970s, Tom Wolfe and Christopher Lasch were speaking out critically against the culture of narcissism.[3] These criticisms were widely repeated throughout American popular media. The development of a youth culture focusing so heavily on self-fulfillment was also perhaps a reaction against the traits that characterized the older Silent Generationers, which had grown up during the Great Depression and became of age in the 1950s from when the Civil Rights Movement had begun. That generation had learned values associated with self-sacrifice. The deprivations of the Depression had taught that generation to work hard, frugally save money, and to cherish family and community ties. Loyalty to institutions, traditional religious faiths, and other common bonds were what that generation considered to be the cultural foundations of their country.[5] Generation Xers, upon maturing in the 1990s, gradually abandoned those values in large numbers, a development that was entrenched during the 1970s. The 1970s have been described as a transitional era when the self-help of the 1960s became self-gratification, and eventually devolved into the selfishness of the 1980s.[6] |

原点 ベビーブーマーたちが経験した1970年代の米国における文化的変化は、彼らの大半が成人した時点で、複雑な様相を呈している。1960年代は、政治的な 抗議行動や、新しい文化体験(性革命、ハプニング、東洋宗教の主流化など)の過激な実験が行われた時代として記憶されており、これらは年長のブーマーが実 践していたことであった。公民権運動は、反抗的な若者たちに重大な目標を与えた。文化的な実験が精神的、知的な啓発に向けられるものとして正当化された。 一方、1970年代半ばから後半にかけては、経済危機が深刻化し、特にリチャード・ニクソンの辞任とベトナム戦争の終結により、若者の間で理想主義的な政 治に対する幻滅が起こりました。特にリチャード・ニクソンの辞任とベトナム戦争が終結した後は、若者の間で無遠慮な快楽主義が受け入れられるようになった [citation needed]。 新しい内省は、労働と満足の先送りを中心とした伝統的な信仰の確立されたセットの終焉と、生きた経験と日々のライフスタイルの選択の即時性を中心とした消 費志向のライフスタイルの倫理の出現を発表した[4]。 1970年代半ばには、トム・ウルフやクリストファー・ラッシュがナルシシズムの文化に対して批判的な発言をしており、これらの批判はアメリカの大衆メ ディアを通じて広く繰り返された[3]。 自己実現に重きを置く若者文化の発展は、大恐慌の時代に発展していたサイレント世代が公民権運動が始まった1950年代から成人していったことへの反動で あったのかもしれない。この世代は、自己犠牲の精神を学んでいた。大恐慌の窮乏から、勤勉に働き、倹約し、家族や地域社会の絆を大切にすることを学んだ世 代である。制度や伝統的な宗教への忠誠心、その他の共通の絆は、その世代が自国の文化的基盤であると考えていた[5] 。ジェネレーションXは、1990年代に成熟すると、徐々にその価値観を大量に放棄し、1970年代にその傾向が強くなった。 1970年代は、1960年代の自助努力が自己満足に変わり、やがて1980年代の利己主義に発展する過渡期と言われている[6]。 |

| Characteristics Health and exercise fads, New Age spirituality such as Scientology, hot tub parties, self-help programs such as EST (Erhard Seminars Training), and the growth of the self-help book industry became identified with the Baby Boomers during 1970s. Human potential, emotional honesty, "finding yourself", and new therapies became signatures of the culture.[7] The marketing of lifestyle products, eagerly consumed by Baby Boomers with disposable income during the 1970s, became an inescapable part of the culture. Revlon's marketing staff did research into young women's cultural values during the 1970s, revealing that young women were striving to compete with men in the workplace and to express themselves as independent individuals. Revlon launched the "lifestyle" perfume Charlie, with marketing aimed at glamorizing the values of the new 1970s woman, and it became the world's best-selling perfume.[8] The introspection of the Baby Boomers and their focus on self-fulfillment has been examined in a serious light in pop culture. Films such as An Unmarried Woman (1978), Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), Ordinary People (1980) and The Big Chill (1983) brought the inner struggles of Baby Boomers to a wide audience. The self-absorbed side of 1970s life was given a sharp and sometimes poignant satirization in Manhattan (1979). More acerbic lampooning came in Shampoo (1975) and Private Benjamin (1980). The Me generation has also been satirized in retrospect, as the generation called "Baby Boomers" reached adulthood, for example, in Parenthood (1989). Forrest Gump (1994) summed up the decade with Gump's cross-country jogging quest for meaning during the 1970s, complete with a tracksuit, which was worn as much as a fashion statement as an athletic necessity during the era. The satirization of the Me generation's "me first" attitude was the focus of the television sitcom Seinfeld, which does not include conscious moral development for its Boomer characters, but rather the opposite. Its plots do not have teaching lessons for its audience and its creators explicitly held that it was a "show about nothing".[9] |

特徴 健康や運動の流行、サイエントロジーのようなニューエイジの精神性、温泉パーティー、EST(エアハードセミナーズトレーニング)のような自己啓発プログ ラム、自己啓発本の産業の成長は、1970年代にベビーブーマーと同一視されるようになった[7]。人間の可能性、感情的な正直さ、「自分探し」、新しい 療法が文化の特徴になった[7] 。また、ライフスタイル製品のマーケティングは、1970年代に可処分所得をもつベビーブーマーが熱心に消費し、文化の不可避な一部となった。レブロンの マーケティング担当者は、1970年代の若い女性の文化的価値観を調査し、若い女性が職場で男性と競争し、独立した個人として自己表現することに努力して いることを明らかにした。レブロンは「ライフスタイル」香水チャーリーを発売し、新しい1970年代の女性の価値観を華やかにすることを目的としたマーケ ティングを行い、世界で最も売れた香水となった[8]。 ベビーブーマーの内省と自己実現への志向は、ポップカルチャーの中で真剣に検討されてきた。『未婚の女』(1978年)、『クレイマーVSクレイマー』 (1979年)、『普通の人々』(1980年)、『ビッグチル』(1983年)などの映画は、ベビーブーマーの内なる葛藤を多くの観客に知らしめた。マン ハッタン』(1979年)では、1970年代の自己中心的な生活が鋭く、時に痛烈に風刺された。シャンプー』(1975年)や『プライベート・ベンジャミ ン』(1980年)では、より辛辣な風刺がなされた。また、「ベビーブーマー」と呼ばれる世代が大人になるにつれ、『Parenthood』(1989) など、「私」の世代が回顧的に風刺されるようになった。フォレスト・ガンプ』(1994年)は、1970年代にガンプがクロスカントリー・ジョギングで意 味を追求し、トラックスーツを着用することでこの10年を総括している。トラックスーツは、この時代、運動するための必需品というより、ファッションとし て着用されていたものである。 ミー世代の「自分が一番」という態度の風刺は、テレビのシットコム『となりのサインフェルド』の焦点であった。この作品は、ブーマーの登場人物に意識的な 道徳的成長を含まず、むしろその逆をいっている。そのプロットは視聴者への教訓を持たず、制作者は「何もない番組」であることを明確に掲げた[9]。 |

| Persistence of the label The term "Me generation" has persisted over the decades and is connected to Baby Boomers.[10] Some writers, however, have also named the Millennials, upon maturing in the 2010s, as "The Me Generation" or "Generation Me",[11] and Elspeth Reeve in The Atlantic noted that narcissism is a symptom of youth in most generations. Presumably, this even includes the Greatest Generationers, upon maturing in the 1930s.[12] The 1970s was also an era of rising unemployment among the young, continuing erosion of faith in conventional social institutions, and political and ideological aimlessness. This was the environment that popularized Punk rock among America's disaffected youth. By 1980, when Ronald Reagan was elected president, Baby Boomers increasingly adopted conservative political and cultural priorities. As Eastern religions and rituals such as yoga grew during the 1970s, at least one writer observed a New Age corruption of the popular understanding of "realization" taught by Neo-Vedantic practitioners, away from spiritual realization and toward "self-realization".[13] The leading edge of the Baby Boomers, who were counter-culture "hippies" and political activists during the 1960s, have been referred to sympathetically as the "Now generation", in contrast to the Me generation.[14] |

ラベルの永続性 しかし、一部の作家は2010年代に成熟したミレニアル世代を「ミー世代」または「ジェネレーション・ミー」と呼んでおり[11]、Elspeth Reeve『The Atlantic』は、自己愛はほとんどの世代で若者の症状であると指摘している。おそらくこれは、1930年代に成熟したグレイテストジェネレーション も含む[12]。1970年代はまた、若者の失業率が上昇し、従来の社会制度への信頼が失われ続け、政治的・思想的無目標の時代であった。このような環境 が、アメリカの不満を抱えた若者の間でパンクロックを流行らせたのである。1980年、レーガンが大統領になると、ベビーブーマーは保守的な政治・文化志 向を強めていく。 1970年代に東洋の宗教やヨーガのような儀式が発展するにつれて、少なくともある作家は、ネオ・ヴェダンティックの実践者によって教えられた「実現」の 一般的な理解が、精神的実現から「自己実現」へと向かうニューエイジの腐敗を観察した[13]。1960年代にカウンターカルチャー「ヒッピー」や政治活 動家だったベビーブーマーの先端は、ミーの世代と対比して「今世代」として共感的に呼ばれている[14]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Me_generation |

|

| ●Generation "Me"(1980s-1990s生まれ) The Associated Press calls them 'the entitlement generation', and they are storming into schools, colleges, and businesses all over the country. They are today's young people, a new generation with sky-high expectations and a need for constant praise and fulfillment. In this provocative new book, headline-making psychologist and social commentator Dr. Jean Twenge documents the self-focus of what she calls 'Generation Me' -- people born in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Herself a member of Generation Me, Dr. Twenge explores why her generation is tolerant, confident, open-minded, and ambitious but also cynical, depressed, lonely, and anxious. Using findings from the largest intergenerational study ever conducted -- with data from 1.3 million respondents spanning six decades -- Dr. Twenge reveals how profoundly different today's young adults are -- and makes controversial predictions about what the future holds for them and society as a whole. But Dr. Twenge doesn't just talk statistics -- she highlights real-life people and stories and vividly brings to life the hopes and dreams, disappointments and challenges of Generation Me. With a good deal of irony, humor, and sympathy she demonstrates that today's young people have been raised to aim for the stars at a time when it is more difficult than ever to get into college, find a good job, and afford a house -- even with two incomes. GenMe's expectations have been raised just as the world is becoming more competitive, creating an enormous clash between expectations and reality. Dr. Twenge also presents the often-shocking truths about her generation's dramatically different sexual behavior and mores. GenMe has created a profound shift in the American character, changing what it means to be an individual in today's society. Engaging, controversial, prescriptive, and often funny, Generation Me will give Boomers new insight into their offspring, and help GenMe'ers in their teens, 20s, and 30s finally make sense of themselves and their goals and find their road to happiness. - Nielsen BookData. |

●ジェネレーション・ミー AP通信は彼らを「権利世代」と呼び、全米の学校、大学、企業に押し寄せている。彼らは、期待値が非常に高く、常に賞賛と充足感を必要とする新しい世代で あり、今日の若者たちである。この刺激的な新刊で、心理学者で社会評論家のジーン・トウェンジ博士は、彼女が「ジェネレーション・ミー」と呼ぶ、1970年代、1980年代、1990年代生まれの 人々の自己中心的な考え方を記録している。 自身もジェネレーション・ミーの一員であるトゥエンジェ博士は、彼女の世代がなぜ寛容で、自信があり、心が広く、野心的でありながら、シニカルで、落ち込 みやすく、孤独で、不安なのかを探っている。60年にわたる130万人の回答者から得たデータを用いた史上最大の世代間調査の結果を用いて、今日のヤング アダルトがいかに大きく異なっているかを明らかにし、彼らや社会全体が将来どうなるのかについて論議を呼ぶ予測を立てている。しかし、Twenge博士は 単に統計を語るだけではなく、実在の人物や物語を取り上げ、ジェネレーション・ミーの希望や夢、失望や課題を生き生きと描き出している。皮肉とユーモアと 共感を込めて、彼女は、大学に入り、良い仕事を見つけ、家を買うことがかつてないほど困難な時代に、今日の若者たちが星を目指すように育てられたことを実 証している--たとえ収入が2つあったとしても。世界がより競争的になり、期待と現実の間に大きな衝突が起きている中で、GenMeは期待を高めてきた。 また、同世代の性行動や風俗習慣が大きく異なるという衝撃的な事実も紹介されている。GenMeは、アメリカ人の性格に大きな変化をもたらし、現代社会で 個人であることの意味を変えている。また、10代、20代、30代のGenMe'erは、自分自身と自分の目標を理解し、幸せへの道を見つけることができ るようになる。 |

| ●Generation A generation refers to all of the people born and living at about the same time, regarded collectively.[1] It can also be described as, "the average period, generally considered to be about 20–30 years, during which children are born and grow up, become adults, and begin to have children."[2] In kinship terminology, it is a structural term designating the parent-child relationship. It is known as biogenesis, reproduction, or procreation in the biological sciences. Generation is also often used synonymously with birth/age cohort in demographics, marketing, and social science; under this formulation it means "people within a delineated population who experience the same significant events within a given period of time."[3] Generations in this sense of birth cohort, also known as "social generations", are widely used in popular culture, and have been the basis for sociological analysis. Serious analysis of generations began in the nineteenth century, emerging from an increasing awareness of the possibility of permanent social change and the idea of youthful rebellion against the established social order. Some analysts believe that a generation is one of the fundamental social categories in a society, while others view its importance as being overshadowed by other factors including class, gender, race, and education, among others. |

●世代論 世代とは、ほぼ同時期に生まれ、生活している人々を総称して言う [1]。 また、「子供が生まれ、成長し、成人し、子供を持ち始める、一般的には20-30年程度とされる平均的な期間」[2]とも表現できる。親族用語としては、 親子関係を表す構造用語である。生物科学分野では生物発生、生殖、子孫繁栄と呼ばれる。 世代はまた、人口統計学、マーケティング、社会科学において出生/年齢コホートと同義に用いられることが多く、この定式化の下では「一定の期間内に同じ重 要な出来事を経験した、区切られた集団内の人々」を意味する[3]。この出生コホートの意味での世代は「社会世代」としても知られ、大衆文化の中で広く使 われており、社会学分析の基礎にもなっている。世代に関する本格的な分析は19世紀に始まり、永続的な社会変化の可能性に対する意識の高まりや、既成の社 会秩序に対する若者の反抗という考えから生まれたものである。世代は社会の基本的なカテゴリーの一つであると考える分析者もいれば、階級、性別、人種、教 育など他の要因によってその重要性が影を潜めていると考える者もいる。 |

| Etymology The word generate comes from the Latin generāre, meaning "to beget".[4] The word generation as a group or cohort in social science signifies the entire body of individuals born and living at about the same time, most of whom are approximately the same age and have similar ideas, problems, and attitudes (e.g., Beat Generation and Lost Generation).[5] |

語源 社会科学における集団またはコホートとしての世代という言葉は、ほぼ同時期に生まれ生きている個人の全体を意味し、そのほとんどがほぼ同じ年齢で、同様の 考え、問題、態度を持つ(例:ビートジェネレーションとロストジェネレーション)[5]。 |

| Familial generation A familial generation is a group of living beings constituting a single step in the line of descent from an ancestor.[6] In developed nations the average familial generation length is in the high 20s and has even reached 30 years in some nations.[7] Factors such as greater industrialisation and demand for cheap labour, urbanisation, delayed first pregnancy and a greater uncertainty in both employment income and relationship stability have all contributed to the increase of the generation length from the late 18th century to the present. These changes can be attributed to social factors, such as GDP and state policy, globalization, automation, and related individual-level variables, particularly a woman's educational attainment.[8] Conversely, in less-developed nations, generation length has changed little and remains in the low 20s.[7][9] An intergenerational rift in the nuclear family, between the parents and two or more of their children, is one of several possible dynamics of a dysfunctional family. Coalitions in families are subsystems within families with more rigid boundaries and are thought to be a sign of family dysfunction.[10] |

家族世代 家族世代とは、祖先から続く血統の一段階を構成する生物の集団である[6]。先進国では、家族世代の平均年齢は20代後半で、一部の国では30年に達して いる[7]。工業化の進展と安価な労働力の需要、都市化、初産年齢の遅れ、雇用収入と関係の安定性における不確実性の増加などの要因が、18世紀後半から 現在までの世代期間の延長に貢献してきたと考えられる。これらの変化は、GDPや国家政策などの社会的要因、グローバル化、自動化、そして関連する個人レ ベルの変数、特に女性の学歴に起因しています[8]。 逆に、低開発国では世代長はほとんど変化せず、20代前半で推移しています[7][9]。 核家族における世代間、つまり両親と2人以上の子どもの間の亀裂は、機能不全家族のいくつかの可能な力学の1つである。家族内の連合は、より厳格な境界を 持つ家族内のサブシステムであり、家族機能不全の徴候であると考えられている[10]。 |

| Social generation Social generations are cohorts of people born in the same date range and who share similar cultural experiences.[11] The idea of a social generation has a long history and can be found in ancient literature,[12] but did not gain currency in the sense that it is used today until the 19th century. Prior to that the concept "generation" had generally referred to family relationships and not broader social groupings. In 1863, French lexicographer Emile Littré had defined a generation as "all people coexisting in society at any given time."[13]: 19 Several trends promoted a new idea of generations, as the 19th century wore on, of a society divided into different categories of people based on age. These trends were all related to the processes of modernisation, industrialisation, or westernisation, which had been changing the face of Europe since the mid-18th century. One was a change in mentality about time and social change. The increasing prevalence of enlightenment ideas encouraged the idea that society and life were changeable, and that civilization could progress. This encouraged the equation of youth with social renewal and change. Political rhetoric in the 19th century often focused on the renewing power of youth influenced by movements such as Young Italy, Young Germany, Sturm und Drang, the German Youth Movement, and other romantic movements. By the end of the 19th century, European intellectuals were disposed toward thinking of the world in generational terms—in terms of youth rebellion and emancipation.[13] Two important contributing factors to the change in mentality were the change in the economic structure of society. Because of the rapid social and economic change, young men particularly were less beholden to their fathers and family authority than they had been. Greater social and economic mobility allowed them to flout their authority to a much greater extent than had traditionally been possible. Additionally, the skills and wisdom of fathers were often less valuable than they had been due to technological and social change.[13] During this time, the period between childhood and adulthood, usually spent at university or in military service, was also increased for many people entering white-collar jobs. This category of people was very influential in spreading the ideas of youthful renewal.[13] Another important factor was the breakdown of traditional social and regional identifications. The spread of nationalism and many of the factors that created it (a national press, linguistic homogenisation, public education, suppression of local particularities) encouraged a broader sense of belonging beyond local affiliations. People thought of themselves increasingly as part of a society, and this encouraged identification with groups beyond the local.[13] Auguste Comte was the first philosopher to make a serious attempt to systematically study generations. In Cours de philosophie positive, Comte suggested that social change is determined by generational change and in particular conflict between successive generations.[14] As the members of a given generation age, their "instinct of social conservation" becomes stronger, which inevitably and necessarily brings them into conflict with the "normal attribute of youth"—innovation. Other important theorists of the 19th century were John Stuart Mill and Wilhelm Dilthey. |

社会的世代 社会的世代は同じ日付の範囲に生まれ、同様の文化的経験を共有する人々のコホートである[11]。社会的世代の考え方は長い歴史を持ち、古代文献にも見つ けることができるが[12]、今日使われるような意味で普及したのは19世紀になってからである。それ以前は、「世代」という概念は一般的に家族関係を指 しており、より広い社会的集団を指していたわけではなかった。1863年、フランスの辞書学者エミール・リットレは世代を「ある時点で社会に共存するすべ ての人々」と定義した[13]。 19 19世紀が進むにつれて、年齢によって異なるカテゴリーに分けられた社会という、世代という新しい考えを促進するいくつかの傾向が見られた。これらの動向 はすべて、18世紀半ばからヨーロッパの様相を変えつつあった近代化、工業化、あるいは西洋化の過程と関連していた。ひとつは、時間や社会の変化に対する メンタリティーの変化である。啓蒙思想の普及が進み、社会や生活は変化しうるものであり、文明は進歩しうるという考え方が広まった。このことは、若さを社 会の再生や変化と同一視することを促した。19世紀の政治的レトリックは、ヤング・イタリア、ヤング・ドイツ、シュトゥルム・ウント・ドラング、ドイツ青 年運動、その他のロマン主義的運動の影響を受けて、若者の刷新的パワーにしばしば焦点を当てたものであった。19世紀の終わりまでに、ヨーロッパの知識人 は世界を世代的な用語で、つまり若者の反乱と解放という用語で考える傾向にあった[13]。 このような精神的な変化をもたらした二つの重要な要因は、社会の経済構造の変化であった。社会と経済の急激な変化のため、特に若い男性は、それまでよりも 父親や家族の権威に従わなくなった。社会的、経済的な流動性が高まったことで、従来よりもはるかに大きな範囲で権威に背くことができるようになったのであ る。さらに、父親の技術や知恵は、技術や社会の変化により、以前よりも価値が下がっていることが多かった[13]。この時期、ホワイトカラーの仕事に就く 多くの人々にとって、通常大学や兵役で過ごす子供と大人との間の期間も長くなった。このカテゴリーの人々は、若者の刷新の考えを広めるのに大きな影響力を もっていた[13]。 もうひとつの重要な要因は、伝統的な社会的・地域的アイデンティティの崩壊であった。ナショナリズムの広がりとそれを生み出した多くの要因(全国紙、言語 の均質化、公教育、地域の特殊性の抑圧)は、地域の所属を超えたより広い帰属意識を促していた。人々は自分たちが社会の一部であると考えるようになり、そ れが地域を超えた集団との同一化を促した[13]。オーギュスト・コントは、世代を 体系的に研究する本格的な試みを行った最初の哲学者であった。コントはCours de philosophie positiveにおいて、社会の変化は世代間の変化、特に連続する世代間の対立によって決定されることを示唆した[14]。 ある世代のメンバーが年をとるにつれて、彼らの「社会的保存の本能」は強くなり、それは必然的に「若者の通常の属性」-イノベーションと対立させることに なる。19世紀の他の重要な理論家は、ジョン・スチュアート・ミルとヴィルヘルム・ディルタイであった。 |

| Generational theory Sociologist Karl Mannheim was a seminal figure in the study of generations. He elaborated a theory of generations in his 1923 essay The Problem of Generations.[3] He suggested that there had been a division into two primary schools of study of generations until that time. Firstly, positivists such as Comte measured social change in designated life spans. Mannheim argued that this reduced history to "a chronological table". The other school, the "romantic-historical" was represented by Dilthey and Martin Heidegger. This school focused on the individual qualitative experience at the expense of social context. Mannheim emphasised that the rapidity of social change in youth was crucial to the formation of generations, and that not every generation would come to see itself as distinct. In periods of rapid social change a generation would be much more likely to develop a cohesive character. He also believed that a number of distinct sub-generations could exist.[3] According to Gilleard and Higgs, Mannheim identified three commonalities that a generation shares:[15] Shared temporal location – generational site or birth cohort Shared historical location – generation as actuality or exposure to a common era Shared sociocultural location – generational consciousness or "entelechy" Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe developed the Strauss–Howe generational theory outlining what they saw as a pattern of generations repeating throughout American history. This theory became quite influential with the public and reignited an interest in the sociology of generations. This led to the creation of an industry of consulting, publishing, and marketing in the field[16] (corporations spent approximately 70 million dollars on generational consulting in the U.S. in 2015).[17] The theory has alternatively been criticized by social scientists and journalists who argue it is non-falsifiable, deterministic, and unsupported by rigorous evidence.[18][19][20] There are psychological and sociological dimensions in the sense of belonging and identity which may define a generation. The concept of a generation can be used to locate particular birth cohorts in specific historical and cultural circumstances, such as the "Baby boomers".[12] Historian Hans Jaeger shows that, during the concept's long history, two schools of thought coalesced regarding how generations form: the "pulse-rate hypothesis" and the "imprint hypothesis."[21] According to the pulse-rate hypothesis, a society's entire population can be divided into a series of non-overlapping cohorts, each of which develops a unique "peer personality" because of the time period in which each cohort came of age.[22] The movement of these cohorts from one life-stage to the next creates a repeating cycle that shapes the history of that society. A prominent example of pulse-rate generational theory is Strauss and Howe's theory. Social scientists tend to reject the pulse-rate hypothesis because, as Jaeger explains, "the concrete results of the theory of the universal pulse rate of history are, of course, very modest. With a few exceptions, the same goes for the partial pulse-rate theories. Since they generally gather data without any knowledge of statistical principles, the authors are often least likely to notice to what extent the jungle of names and numbers which they present lacks any convincing organization according to generations."[23] Social scientists follow the "imprint hypothesis" of generations (i.e., that major historical events — such as the Vietnam War, the September 11 attacks, the COVID-19 pandemic, etc. — leave an "imprint" on the generation experiencing them at a young age), which can be traced to Karl Mannheim's theory. According to the imprint hypothesis, generations are only produced by specific historical events that cause young people to perceive the world differently than their elders. Thus, not everyone may be part of a generation; only those who share a unique social and biographical experience of an important historical moment will become part of a "generation as an actuality."[24] When following the imprint hypothesis, social scientists face a number of challenges. They cannot accept the labels and chronological boundaries of generations that come from the pulse-rate hypothesis (like Generation X or Millennial); instead, the chronological boundaries of generations must be determined inductively and who is part of the generation must be determined through historical, quantitative, and qualitative analysis.[25] While all generations have similarities, there are differences among them as well. A 2007 Pew Research Center report called "Millennials: Confident. Connected. Open to Change" noted the challenge of studying generations: "Generational analysis has a long and distinguished place in social science, and we cast our lot with those scholars who believe it is not only possible, but often highly illuminating, to search for the unique and distinctive characteristics of any given age group of Americans. But we also know this is not an exact science. We are mindful that there are as many differences in attitudes, values, behaviors, and lifestyles within a generation as there are between generations. But we believe this reality does not diminish the value of generational analysis; it merely adds to its richness and complexity."[26] Another element of generational theory is recognizing how youth experience their generation, and how that changes based on where they reside in the world. "Analyzing young people's experiences in place contributes to a deeper understanding of the processes of individualization, inequality, and of generation."[27] Being able to take a closer looks at youth cultures and subcultures in different times and places adds an extra element to understanding the everyday lives of youth. This allows a better understanding of youth and the way generation and place play in their development.[28] It is not where the birth cohort boundaries are drawn that is important, but how individuals and societies interpret the boundaries and how divisions may shape processes and outcomes. However, the practice of categorizing age cohorts is useful to researchers for the purpose of constructing boundaries in their work.[29] |

世代論 社会学者のカール・マンハイムは、世代研究において重要な人物である。彼は1923年のエッセイThe Problem of Generationsで世代の理論を詳しく説明した[3]。彼はそれまで世代の研究において2つの主要な学派に分かれていたことを示唆した。第一に、コ ントのような実証主義者たちは、社会的変化を指定された寿命で測定していた。マンハイムの主張は、これによって歴史が「年表」に還元されてしまうというも のであった。もう一つの派は、ディルタイやマルティン・ハイデガーに代表される「ロマン主義-歴史主義」である。この学派は、社会的文脈を犠牲にして、個 人の質的経験を重視した。マンハイムは、若者の社会変化の速さが世代の形成に重要であり、すべての世代が自らを区別して見るようになるわけではないことを 強調した。社会変化の激しい時代には、世代がまとまった性格をもつようになる可能性が高い。また彼は多くの異なる亜世代が存在しうると考えていた[3]。 ギリアードとヒッグスによれば、マンハイムは世代が共有する3つの共通性を特定していた[15]。 時間的位置の共有 - 世代的な場所または出生コホート 歴史的位置の共有 - 現実としての世代、あるいは共通の時代への曝露 社会文化的位置の共有 - 世代意識または "エンテレケイア" 著述家のウィリアム・ストラウスとニール・ハウは、アメリカの歴史を通して繰り返される世代のパターンとして見たものを概説するストラウス=ハウ世代理論 を開発した。この理論は世間に大きな影響を与え、世代の社会学への関心を再び呼び起こした。これはこの分野におけるコンサルティング、出版、マーケティン グの産業の創造につながった[16](企業は2015年に米国で世代コンサルティングにおよそ7000万ドルを費やした)[17]。この理論は逆に社会科 学者やジャーナリストによって批判され、それは検証不可能、決定論的、厳格な証拠によってサポートされていないと主張している[18][19][20]。 世代を定義する帰属意識やアイデンティティには、心理学的、社会学的な側面がある。世代という概念は、「ベビーブーマー」のような特定の歴史的・文化的状 況において特定の出生コーホートを位置づけるために使われることがある[12]。歴 史家のハンス・イエーガーは、この概念の長い歴史の中で、世代がどのように形成されるかについて「パルスレート仮説」と「インプリント仮説」という二つの 学派の合体した考えを示している[21]。 「パルスレート仮説によれば、社会の全人口は一連の重複しないコーホートに分割することができ、それぞれのコーホートは、それぞれのコーホートが成人した 時間帯のためにユニークな「仲間の個性」を形成する[22]。 これらのコーホートがあるライフステージから次へと動くことによって、その社会の歴史を形作る繰り返しのサイクルが形成される。パルスレート世代説の著名 な例としてストラウスとハウの理論がある。社会科学者がパルスレート仮説を否定する傾向があるのは、イェーガーが説明するように、「歴史の普遍的パルス レート説の具体的成果は、当然ながら非常に控えめである。一部の例外を除いて、部分的なパルスレート説も同様である。彼らは一般に統計的な原理を全く知らずにデータを 集めているので、彼らが提示する名前と数字のジャングルが、世代に応じた説得力のある整理をどの程度欠いているのか、著者たちはしばしば最も気づきにく い」[23]。 社会科学者は、世代に関する「刻印仮説」(ベトナム戦争、9.11テロ、COVID-19の大流行など、歴史的に大きな出来事は、それを若いうちに経験し た世代に「刻印」を残すというもの)に従っており、これはカール・マンハイムの理論に遡ることができる。インプリント仮説によれば、世代は、若者が年長者 と異なる世界を認識する原因となる特定の歴史的出来事によってのみ生み出される。したがって、誰もが世代の一部となるわけではなく、重要な歴史的瞬間のユ ニークな社会的・伝記的経験を共有する者だけが「現実としての世代」の一部となる[24]。インプリント仮説に従うとき、社会科学者は多くの課題に直面す る。彼らはパルスレート仮説から来る世代のラベルや年代的境界(ジェネレーションXやミレニアルのような)を受け入れることができず、その代わりに世代の 年代的境界は帰納的に決定されなければならず、誰が世代の一部であるのかは歴史的、量的、質的分析を通じて決定されなければならない[25]。 すべての世代には類似点があるが、世代間の相違点もある。2007年のピュー・リサーチ・センターの報告書「ミレニアル世代。Confident. Connected. Open to Change "と呼ばれる2007年のPew Research Centerのレポートは、世代を研究することの難しさを指摘している。 「世代分析には、社会科学における長い歴史と卓越した位置づけがある。しかし、私たちはこれが厳密な科学ではないことも知っています。私たちは、世代間と 同様に、世代内でも態度、価値観、行動、ライフスタイルに多くの違いがあることに留意しています。しかし、私たちはこの現実が世代分析の価値を下げるもの ではなく、単にその豊かさと複雑さを増すものであると信じています」[26]。 世代論のもう一つの要素は、若者がどのように自分たちの世代を経験するのか、そしてそれが世界のどこに居住しているかによってどのように変化するのかを認 識することです。「若者の経験を場所によって分析することは、個人化、不平等、そして世代のプロセスに対するより深い理解に寄与する」[27]。異なる時 代や場所における若者文化やサブカルチャーを詳しく見ることができることは、若者の日常生活を理解する上でさらなる要素を追加している。28] 重要なのは、出生コホートの境界線がどこに引かれるかではなく、個人や社会がその境界線をどのように解釈し、その区分がどのようにプロセスや結果を形成し うるかである。しかし、年齢コーホートを分類する習慣は、研究者が仕事において境界を構築する目的で使われている[29]。 |

| Generational tension Norman Ryder, writing in American Sociological Review in 1965, shed light on the sociology of the discord between generations by suggesting that society "persists despite the mortality of its individual members, through processes of demographic metabolism and particularly the annual infusion of birth cohorts". He argued that generations may sometimes be a "threat to stability" but at the same time they represent "the opportunity for social transformation".[30] Ryder attempted to understand the dynamics at play between generations. Amanda Grenier, in a 2007 essay published in Journal of Social Issues, offered another source of explanation for why generational tensions exist. Grenier asserted that generations develop their own linguistic models that contribute to misunderstanding between age cohorts, "Different ways of speaking exercised by older and younger people exist, and may be partially explained by social historical reference points, culturally determined experiences, and individual interpretations".[31] Karl Mannheim, in his 1952 book Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge asserted the belief that people are shaped through lived experiences as a result of social change. Howe and Strauss also have written on the similarities of people within a generation being attributed to social change. Based on the way these lived experiences shape a generation in regard to values, the result is that the new generation will challenge the older generation's values, resulting in tension. This challenge between generations and the tension that arises is a defining point for understanding generations and what separates them.[32] |

世代間の緊張 Norman Ryderは、1965年にAmerican Sociological Reviewに寄稿し、社会が「人口動態の代謝過程、特に毎年の出生コホートの注入を通じて、個々のメンバーの死亡率にもかかわらず持続する」ことを示唆 して、世代間の不和の社会学に光を当てました[30]。彼は、世代は時に「安定への脅威」であるかもしれないが、同時に「社会変革の機会」を表していると 主張した[30]。ライダーは、世代間で作用するダイナミクスを理解しようとした。 アマンダ・グレニエは『Journal of Social Issues』に掲載された2007年のエッセイで、世代間の緊張がなぜ存在するのかについて別の説明の材料を提供している。グレニアーは、世代が独自の 言語モデルを開発し、それが年齢層間の誤解に寄与していると主張し、「年長者と若年者が行使する異なる話し方が存在し、社会史的参照点、文化的に決定され た経験、個人の解釈によって部分的に説明できるかもしれない」[31]と述べている。 カール・マンハイムは1952年の著書『知識社会学論考』の中で、人々 は社会的変化の結果として生きた経験を通じて形成されるという信念を主張している。ハウとストラウスもまた、世代内の人々の類似性が社会変化に起因してい ることについて書いている。このような生活体験が価値観に関して世代を形成することに基づいて、結果として、新しい世代が古い世代の価値観に挑戦すること になり、緊張が生じることになる。この世代間の挑戦と生じる緊張は、世代とそれらを隔てるものを理解するための決定的なポイントである[32]。 |

| Criticism Philip N. Cohen, a sociology professor at the University of Maryland, criticized the use of "generation labels", stating that the labels are "imposed by survey researchers, journalists or marketing firms" and "drive people toward stereotyping and rash character judgment." Cohen's open letter, which outlines his criticism of generational labels, received at least 150 signatures from other demographers and social scientists.[33] Louis Menand, writer at The New Yorker, stated that "there is no empirical basis" for the contention "that differences within a generation are smaller than differences between generations." He argued that generational theories "seem to require" that people born at the tail end of one generation and people born at the beginning of another (e.g. a person born in 1965, the first year of Generation X, and a person born in 1964, the last of the Boomer era) "must have different values, tastes, and life experiences" or that people born in the first and last birth years of a generation (e.g. a person born in 1980, the last year of Generation X, and a person born in 1965, the first year of Generation X) "have more in common" than with people born a couple years before or after them.[17] |

批判 メリーランド大学の社会学教授であるフィリップ・N・コーエンは、「世代ラベル」の使用を批判し、ラベルは「調査研究者、ジャーナリスト、マーケティング 会社によって押し付けられる」もので、「人々をステレオタイプ化と軽率な性格判断に向かわせる」ものであると述べている[33]。世代ラベルに対する批判 をまとめたコーエンの公開書簡は、他の人口統計学者や社会科学者から少なくとも150の署名を得た[33]。 ニューヨーカー誌のライターであるルイ・メナンドは、「世代内の違いは世代間の違いより小さい」という主張には「経験的な根拠がない」と述べている。彼は 世代論が、ある世代の最後尾に生まれた人と別の世代の最初に生まれた人(例えばジェネレーションXの最初の年である1965年に生まれた人とブーマー時代 の最後である1964年に生まれた人)が「異なる価値観、好み、人生経験を持っていなければならない」あるいはある世代の最初と最後の出生年に生まれた人 (例えば、ジェネレーションXとブーマー時代の最初の年である1965年に生まれた人)が「異なる価値を持つことを要求するように見える」のだと論じてい る。 例えば、ジェネレーションXの最後の年である1980年に生まれた人とジェネレーションXの最初の年である1965年に生まれた人)は、その数年前や後に 生まれた人よりも「共通点が多い」[17]とされている。 |

| List of social generations Western world |

|

| Other areas |

|

| Other terminology |

|

| Age set Generational accounting Generationism Intergenerational equity Intergenerationality Transgenerational design Cusper |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generation |

リンク(サイト外)

リンク(サイト内)

文献

文献

その他の情報

For all undergraduate

students! - Do not paste our message to your homework reports, You

SHOULD [re]think the message in this page!!

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099