サイバーシン計画

Project Cybersyn, ProyectoSynco

The

2 "algedonic displays", the 4 screen Data Feed, and the black board.

The control panels visible on the armrests./

☆ プロジェクト・サイバーシン(Project Cybersyn)は、1971年から1973年にかけて、サルバドール・アジェンデ大統領の在任中に、チリで実施された、国民経済の運営を支援 するための分散型意思決定支援システムの構築プロジェクトだった。このプロジェクトは、経済シミュレーター、工場のパフォーマンスをチェックするカスタム ソフトウェア、オペレーションルーム、1台のメインフレームコンピュータに接続されたテレックス機の全国ネットワークという4つのモジュールで構成されて いた。[2] プロジェクト・サイバーシンは、組織設計に実行可能なシステムモデル理論アプローチを採用し、当時としては革新的な技術を採用していた。このプロジェクト には、サンティアゴの政府機関と情報を送受信する、国営企業間のテレックス機(サイバネット)のネットワークが含まれていた。 現場からの情報は、統計モデリングソフトウェア(サイバーストライド)に投入され、原材料の供給状況や従業員の欠勤率などの生産指標を監視した。このシス テムは、ほぼリアルタイムで従業員にアラートを発信した。パラメーターが許容範囲を大幅に下回った場合、中央政府に通知された。情報はまた、経済シミュ レーションソフトウェア(CHECO、チリ経済シミュレーター)にも入力された。政府はこれを利用して、経済政策の決定による結果を予測することができ た。最後に、高度なオペレーションルーム(Opsroom)が、経営陣が関連経済データを確認できるスペースを提供していた。経営陣は、緊急事態に対する 実行可能な対応策を策定し、テレックスネットワークを利用して、警報状況にある企業や工場に助言や指示を送信していた。 このシステムの主な設計者は、英国のオペレーションズリサーチの科学者、スタッフォード・ビアであり、このシステムは、彼の産業経営における経営サイバネ ティクスの概念を体現したものだった。その主な目的の一つは、産業企業内の意思決定権を従業員に委譲し、工場の自主規制を発展させることだった。 サイバーシンプロジェクトは、1973年のチリクーデターによるアジェンデの追放と死によって終了した。クーデター後、サイバーシンは放棄され、オペレー ションルームは破壊された。[3]

★スペイン語版

| Synco o Cybersyn fue

un proyecto chileno de planificación económica controlada en tiempo

real, desarrollado en los años del gobierno de Salvador Allende

Gossens, entre 1971 y 1973.[1] En esencia, se trataba de una red de

máquinas de teletipo que buscaba comunicar, en tiempo real, a las

fábricas del país con un único centro de cómputo en Santiago, donde el

gobierno, a través de un software de análisis bayesiano,[2]

pronosticaría el comportamiento de los medios de producción

industrial.[3] Es decir, se recibiría, procesaría y analizaría

información sobre la producción de las fábricas, empleando los

principios de la cibernética.[1] El arquitecto del sistema fue el cibernetista británico Stafford Beer, quien entendía que la cibernética, desde el período de la Posguerra mundial, podría ser la próxima ciencia del estudio del control y la comunicación, una que permitiría encontrar asuntos en común entre el funcionamiento complejo de los sistemas sociales (organizaciones), biológicos (organismos) y mecánicos (máquinas).[1] El presidente Allende también veía en el proyecto la posibilidad de construir otra forma de gobierno, una tercera vía, un "socialismo a la chilena" que se apartaba parcialmente de la Unión Soviética o de Cuba. Por ello, la relación entre ambos personajes ha sido caracterizada como el encuentro de dos utopías, una política, la de implementar un cambio socialista, pacífico y dentro de la democracia, y una tecnológica.[1][4] En medio de un contexto como el chileno para la década de 1970, con limitados recursos tecnológicos, Synco resulta un proyecto innovador para la historia de la tecnología a nivel mundial, pues para entonces ARPANET, el predecesor estadounidense de la Internet, aún estaba en proceso de desarrollo. Su contribución novedosa también puede rastrearse en América Latina, en donde los estudios sobre la relación entre Estados, gobiernos y desarrollo tecnológico muestran pocos casos similares.[1] |

シンコ(Synco)またはサイバーシン(Cybersyn)は、サル

バドール・アジェンデ・ゴセンス政権下の1971年から1973年にかけてチリで実施された、リアルタイムで管理される経済計画プロジェクトだった。

[1]

本質的には、国内の工場とサンティアゴにある単一のコンピュータセンターをリアルタイムで接続するテレタイプマシンネットワークで、政府はベイジアン分析

ソフトウェア[2]を用いて、産業生産手段の動向を予測していた。[3]

つまり、サイバネティクスの原理を用いて、工場の生産に関する情報を受け取り、処理、分析するシステムだった。[1] このシステムの設計者は、英国のサイバネティクス学者、スタッフォード・ビアだった。彼は、サイバネティクスは、第二次世界大戦後の時代において、制御と コミュニケーションの研究における次の科学となり、社会システム(組織)、生物(生物)、機械(機械)の複雑な機能に共通する問題を見つけることを可能に するだろうと考えていた。[1] アジェンデ大統領も、このプロジェクトに、ソ連やキューバから部分的に離脱した、別の形の政府、第三の道、つまり「チリ流の社会主義」を構築する可能性を 見出していた。そのため、この2人の人物の関係は、政治的なユートピア、つまり民主主義の中で平和的な社会主義変革を実現するというユートピアと、技術的 なユートピアという、2つのユートピアの出会いと特徴づけられている。[1][4] 1970年代のチリのような、技術的資源が限られていた状況の中で、Synco は世界的な技術史においても革新的なプロジェクトだった。当時、インターネットの前身である ARPANET はまだ開発段階にあったからだ。その革新的な貢献は、国家、政府、技術開発の関係に関する研究において類似の事例がほとんど見られないラテンアメリカでも 確認できる。[1] |

| Historia A manera de contexto, el gobierno de Salvador Allende, al nacionalizar y anexar diversas empresas expropiadas al área social del Estado entre los años 1970 y 1973, comenzó a replantear el sistema económico coordinando la información de las empresas existentes estatales y las recientemente nacionalizadas. La rápida nacionalización trajo consigo el incremento de los empleados estatales, en lo que fue entendido como una política para disminuir el desempleo, pero esto también implicó visibilizar la ausencia de mano de obra calificada para mantener la producción, sortear la escasez de materiales y materias primas.[1] En 1970, Fernando Flores había sido nombrado director general técnico de la Corporación de Fomento de la Producción (Corfo) bajo la dirección e instrucción de Pedro Vuskovic,[5] y con el objetivo de liderar la gestión y coordinación entre las empresas nacionalizadas y el Estado. Flores conocía las teorías y las soluciones propuestas por el británico Stafford Beer desde que era estudiante de ingeniería, y, posteriormente, por su relación profesional con la empresa de consultoría de Stafford Beer, llamada SIGMA.[1] Junto a Juan Bulnes y Raúl Espejo,[6]quien también trabajaba en CORFO y posteriormente sería gerente operacional del proyecto, Flores escribió una carta a Stafford Beer con el propósito inicial de obtener su guía en la implementación en Chile del Modelo del Sistema Viable (VSM), modelo que Beer describía en su libro The Brain of the Firm.[7]Beer no sólo aceptó guiar a Flores y su equipo en dicha tarea, sino que, entusista, solicitó ser parte integral del proyecto,[6] cuyo desarrollo comenzó en noviembre de 1971.[1] Luego de casi dos años de trabajo y avances muy importantes, la sala de operaciones del proyecto de gobierno cibernético fue presentada al presidente Salvador Allende,[8] quien más tarde habría solicitado trasladarla desde el lugar donde había sido construida hasta el Palacio de la Moneda.[1] Tomó un año el construirlo (desde noviembre de 1971 al mismo mes de 1972), aunque nunca se finalizó del todo. En 1971, el gobierno de Allende comenzó a desarrollar en Chile el innovador sistema cibernético de gestión y transferencia de información. El proyecto se llamó Cybersyn, "sinergia cibernética" (del inglés Cybernetic Synergy), o Synco, "sistema de información y control".[1] Entre sus objetivos se encontraba: Primero, la transferencia de información, casi en tiempo real, en formatos dinámicos, flexibles y estructurados, sobre la producción industrial en las empresas de propiedad del Estado de Chile hacia el gobierno. En segundo lugar, permitir su procesamiento y análisis por parte de los técnicos estatales para tomar decisiones que permitieran la planificación efectiva de la economía del país.[1] El sistema tuvo la oportunidad de demostrar su utilidad en octubre de 1972, durante el paro patronal realizado en dicho mes, cuando 50 000 camioneros en paro bloquearon las calles de Santiago. Mediante las máquinas de teletipos, el gobierno fue capaz de coordinar el transporte de alimentos a la ciudad con los cerca de 200 camiones leales a Allende y que no se encontraban en paro. Comentando este hecho, Beer señalaba modestamente: "Comunicación es control".[9] Varios miembros de su equipo también referían que Synco podría convertirse en una manera de involucrar, de manera más sistemática, a los trabajadores en las decisiones de las fábricas. Tras el golpe militar del 11 de septiembre de 1973, el centro de control fue destruido. Cybersyn o Synco nunca pudo ser aplicado y fue abortado irrevocablemente. |

歴史 背景として、サルバドール・アジェンデ政権は、1970年から1973年にかけて、国有化され、国家の社会部門に編入されたさまざまな企業を再編し、既存 の国有企業と新たに国有化された企業の情報を調整して、経済システムの再構築に着手した。急速な国有化により、国家公務員の数が増加した。これは失業率低 下政策と理解されたが、生産を維持するための熟練労働力の不足、資材や原材料の不足という課題も浮き彫りになった。[1] 1970年、フェルナンド・フローレスは、ペドロ・ヴスコヴィッチの指導と指示の下、生産振興公社(Corfo)のテクニカルディレクターに任命され、国 有企業と国家間の管理と調整を指揮することになった。フローレスは、工学部の学生時代から、英国人スタッフォード・ビアが提唱した理論と解決策を知ってお り、その後、スタッフォード・ビアのコンサルティング会社 SIGMA との仕事を通じて、彼と親交があった。[1] フアン・ブルネスとラウル・エスペホ[6](同じく CORFO に勤務し、後にプロジェクトの運営責任者となった)とともに、フローレスは、ビールが著書『The Brain of the Firm』で述べた「実行可能なシステムモデル(VSM)」をチリで導入するための指導を求める手紙をビールに送った。[7]ビールは、フローレスとそ のチームを指導することを承諾しただけでなく、このプロジェクトに熱意を持って参加することを希望し、[6] 1971年11月にプロジェクトが開始された。[1] 2年近くの作業と大きな進歩を経て、サイバー政府プロジェクトのオペレーションルームはサルバドール・アジェンデ大統領に紹介された[8]。アジェンデ大 統領はその後、このオペレーションルームを建設地からモネダ宮殿に移設するよう要請した[1]。建設には1年(1971年11月から1972年11月)を 要したが、結局、完成には至らなかった。 1971年、アジェンデ政権は、チリで革新的なサイバー情報管理・転送システムの開発を開始した。このプロジェクトは、Cybersyn(「サイバーシナ ジー」、英語ではCybernetic Synergy)またはSynco(「情報制御システム」)と名付けられた。[1] その目的としては、以下のものが挙げられていた。 まず、チリの国有企業における工業生産に関する情報を、ほぼリアルタイムで、ダイナミックかつ柔軟で構造化された形式で政府に転送すること。 次に、その情報を国家の技術者が処理・分析し、国の経済を効果的に計画するための意思決定を行うこと。[1] このシステムは、1972年10月に実施されたストライキで、5万人のトラック運転手がサンティアゴの道路を封鎖した際、その有用性を発揮した。テレタイ プ機を用いて、政府は、アジェンデに忠実でストライキに参加していない約200台のトラックを利用して、都市への食糧の輸送を調整することができた。この 事実について、ビールは「コミュニケーションはコントロールだ」と謙虚に述べている。[9] 彼のチームメンバーの何人かは、シンコが工場での意思決定に労働者をより体系的に関与させる手段になる可能性があると指摘していた。 1973年9月11日の軍事クーデター後、コントロールセンターは破壊された。サイバースインまたはシンコは、結局実施されることはなく、永久に中止された。 |

El sistema Los teletipos eran dispositivos telegráficos de transmisión de datos, que hoy en día están obsoletos. Dado que el gobierno disponía de una dotación de máquinas teletipos adquiridos durante la administración del presidente Eduardo Frei Montalva, unas pocas decenas de estas máquinas,[10]y no 500 como se ha reportado anteriormente,[11] fueron instaladas en las fábricas que participaron del proyecto. En el centro de procesamiento en Santiago, un computador del tipo mainframe IBM 360/50 procesaba a diario la información recibida desde las fábricas – información que llega antes, todos los días alrededor de las 15:00 h, a un teletipo instalado en CORFO.[12] Al procesar tal información, se obtenían predicciones de corto plazo y recomendaciones para realizar mejoras. Existían cuatro niveles de control (compañía, rama, sector y total) que contaban con retroalimentación algedónica (si el nivel de control inferior no podía solucionar un problema en un intervalo de tiempo determinado, el nivel superior era notificado al respecto). Los resultados eran discutidos en la sala de operación y se elaboraba un plan global.[4] El software del proyecto Synco se llamaba Cyberstride y empleaba filtros bayesianos y control bayesiano.[2] Fue escrito fundamentalmente por un equipo de programadores británicos de la firma Arthur Andersen[1]y luego implementenda en las oficinas de la Empresa Nacional de Computación, ECOM, junto a programadores e ingenieros chilenos.[13] El cuarto de operaciones (Opsroom) contaba con un aspecto bastante futurista, parecía (según el propio Beer) "el escenario de una película de ciencia ficción... En ella no hay ningún papel. La información se refleja en pantallas y en modelos electrónicos animados, que se despliegan alrededor de la sala".[9] Constaba de un mobiliario compuesto por 7 sillas giratorias (consideradas las mejores para la creatividad) con un panel de botones; estos botones controlaban varias pantallas gigantes en que se podía proyectar la información y otros paneles con información del estado de operaciones. El proyecto es mencionado en el libro Platform for Change, de Stafford Beer. |

システム テレタイプは、データ伝送用の電信装置で、現在では廃止されている。 エドゥアルド・フレイ・モンタルバ大統領の政権時代に政府が購入したテレタイプ機が数十台[10](以前報告されていた 500 台ではない[11])あったため、このプロジェクトに参加した工場にこれらのテレタイプ機が設置された。サンティアゴの処理センターでは、IBM 360/50 型のメインフレームコンピュータが、工場から毎日 15 時頃に CORFO に設置されたテレタイプに送信される情報を受け取り、処理していた[12]。この情報を処理することで、短期的な予測や改善のための提言が得られた。4 つの管理レベル(会社、部門、セクター、全体)があり、アルゴリズムによるフィードバック機能があった(下位の管理レベルが一定期間内に問題を解決できな かった場合、上位の管理レベルに通知される)。結果はオペレーションルームで議論され、総合的な計画が策定された。[4] Synco プロジェクトのソフトウェアは Cyberstride と呼ばれ、ベイジアンフィルタとベイジアン制御を採用していた。[2] これは主に、アーサー・アンダーセン社の英国人プログラマーチームによって作成され[1]、その後、チリのプログラマーやエンジニアとともに、国立コン ピュータ企業 ECOM のオフィスで実装された。[13] オペレーションルーム(Opsroom)は、かなり未来的な外観で、ビール氏自身によると「SF映画のセットのような...。紙は一切なく、情報は画面や アニメーション化された電子モデルに表示され、部屋中に展開される」とのことだ。[9] 7脚の回転椅子(創造性に最適とされる)とボタンパネルで構成された家具があり、このボタンで、情報を投影できる複数の巨大スクリーンや、業務状況に関す る情報を表示する他のパネルを操作することができた。 このプロジェクトは、スタッフォード・ビアの著書『Platform for Change』でも紹介されている。 |

| Cybernet Cybernet fue la red de telecomunicaciones entre fábricas y el centro de procesamiento del proyecyo Synco. Si bien los métodos de transmisión y procesamiento de datos que esta red permitía eran innovadores, su infraestructura era heredera del, en esa época ya casi centenario, desarrollo de las comunicaciones telegráficas en la región.[14] Consistía en una red de télex en diferentes fábricas a lo largo de Chile. Este proceso se comenzó a realizar en noviembre de 1971. La coordinación de esta red estuvo a cargo del ingeniero, ex marino y traductor de Stafford Beer, Roberto Cañete, quien ya contaba con experiencia en redes comunicacionales. Los datos enviados a través de esta red eran producto de un sofisticado método de cuantificación de los procesos productivos, el cual Beer y el equipo local de Synco llamaban flujogramación cuantificada.[15]Los datos eran transmitidos una vez al día por las empresas a una estación de tráfico en CORFO y desde ahí reenviados a la central de procesamiento en ECOM.[12] Estos datos eran cargos en un computador mainframe por ingenieros dirigidos por Isaquino Benadof, quienes, una vez que la información era procesada, imprimían reportes periódicos que eran luego analizados por los ingenieros de CORFO.[16] Esta acción fundamentaría las bases para la realización de una de las primeras experiencias de transferencia de información económica en tiempo real en Chile usando un inédito sistema cibernético. |

サイバーネット サイバーネットは、工場とシンコプロジェクトの処理センターを結ぶ通信ネットワークだった。このネットワークが実現したデータ伝送および処理方法は革新的だったが、そのインフラは、当時すでに100年近く経っていたこの地域の電信通信の発展を継承したものだった。[14] これは、チリ全土のさまざまな工場に設置されたテレックスネットワークで構成されていた。このプロジェクトは1971年11月に開始された。このネット ワークの調整は、通信ネットワークの経験豊富な、元海軍兵士でスタッフォード・ビアの翻訳者でもあるエンジニア、ロベルト・カニェテが担当した。 このネットワークを通じて送信されたデータは、生産プロセスの高度な定量化手法、つまりビールとSyncoの現地チームが「定量化されたフローチャート」 と呼んだものによって得られたものだった[15]。データは1日1回、各企業からCORFOのトラフィックステーションに送信され、そこからECOMの処 理センターに転送された。[12] このデータは、イサキノ・ベナドフ率いるエンジニアたちによってメインフレームコンピュータに入力され、情報が処理されると、定期的な報告書が印刷され、 CORFO のエンジニアたちによって分析された。[16] この取り組みは、チリで初めて、前例のないサイバーシステムを用いたリアルタイムの経済情報転送の実現に向けた基礎を築いた。 |

| Cyberstride Cyberstride fue el nombre del software diseñado para el proyecto Cybersyn. Su función era procesar la información que llegaba desde las empresas para transformarla en variables predefinidas y generar informes casi en tiempo real y por excepción. La información era enviada y recibida por las empresas a través de télex y procesada por un computador IBM S/360.[4] El propósito era enviar los informes a aquellos que podían tomar decisiones con ellos, en particular a los administradores de las empresas. La información agregada de las empresas iba a los administradores de la CORFO y a la sala de operaciones en un formato de simple comprensión. Para identificar las variaciones que reflejaban cotidianamente las empresas se utilizó estadística bayesiana, y en particular se usó el modelo de Harrison-Stevens,[17] definiendo sus actividades con amplificadores, filtros y formas predeterminadas de normalidad, alerta y crisis, creando un modelo prospectivo dinámico que anticipaba posibles crisis, ayudando a aplicar soluciones antes de que estas ocurrieran. Fue realizado por el equipo de la Empresa de Computación e Informática de Chile (ECOM) junto a la filial inglesa de la empresa Arthur Andersen. Isaquino Benadof, director del área de investigación y desarrollo de ECOM, tomó a su cargo este proyecto. Durante la realización de Cybersyn, Espejo viajó a Inglaterra para negociar la contribución de Arthur Andersen y Benadof viajó a Estados Unidos y a Canadá para investigar y evolucionar el sistema. Sin embargo, Cyberstride solo fue aplicado en forma piloto, quedando frustrada una de las principales iniciativas técnicas del proyecto Cybersyn. Podría haber sido un modelo de transferencia de información creado en Chile paralelo a Internet. |

Cyberstride Cyberstride は、Cybersyn プロジェクトのために設計されたソフトウェアの名前だった。その機能は、企業から送信される情報を処理して、あらかじめ定義された変数に変換し、ほぼリアルタイムで例外報告を生成することだった。 情報は、テレックスを介して企業間で送受信され、IBM S/360 コンピュータによって処理されていた。[4] その目的は、その情報に基づいて意思決定を行う者、特に企業の管理者たちに報告書を送信することだった。企業から集約された情報は、CORFO の管理者たちとオペレーションルームに、わかりやすい形式で送信された。 企業が日々反映する変動を特定するために、ベイジアン統計、特にハリソン・スティーブンスのモデル[17] が使用され、その活動をアンプ、フィルター、および正常、警告、危機という所定の形式で定義し、潜在的な危機を予測する動的な予測モデルを構築し、危機が 発生する前に解決策を適用するのに役立てた。 これは、チリのコンピュータ・情報処理会社 ECOM のチームと、アーサー・アンダーセン社の英国支社が共同で実施した。 ECOM の研究開発部門責任者である Isaquino Benadof がこのプロジェクトを担当した。 Cybersyn の実施期間中、エスペホはアーサー・アンダーセンの協力を得るためイギリスを訪れ、ベナドフはシステムの調査と改良のためアメリカとカナダを訪れた。しか し、Cyberstride はパイロット版としてのみ適用され、Cybersyn プロジェクトの主要な技術的取り組みの一つは挫折に終わった。これは、インターネットと並行してチリで創出された情報伝達モデルとなる可能性があった。 |

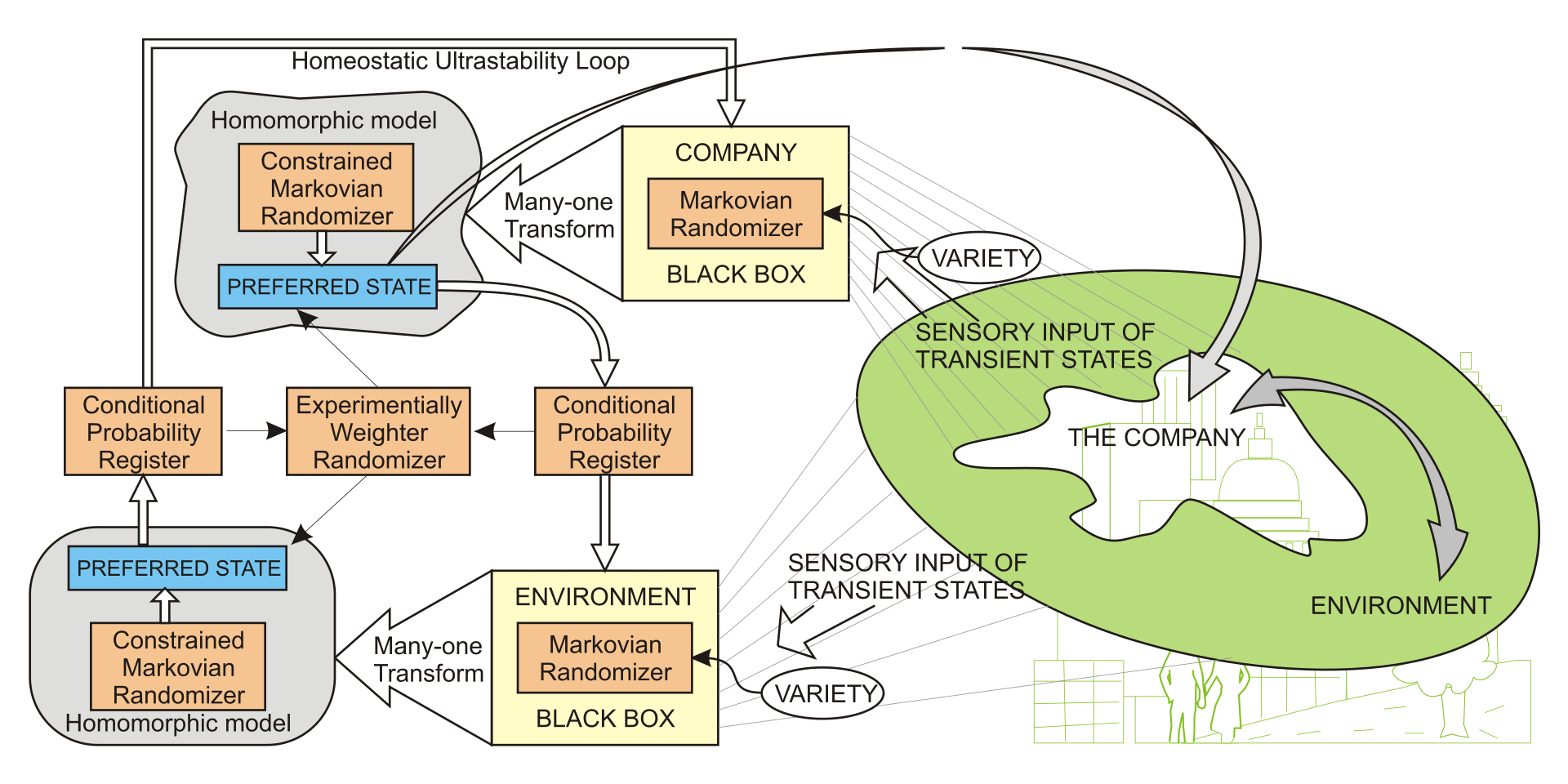

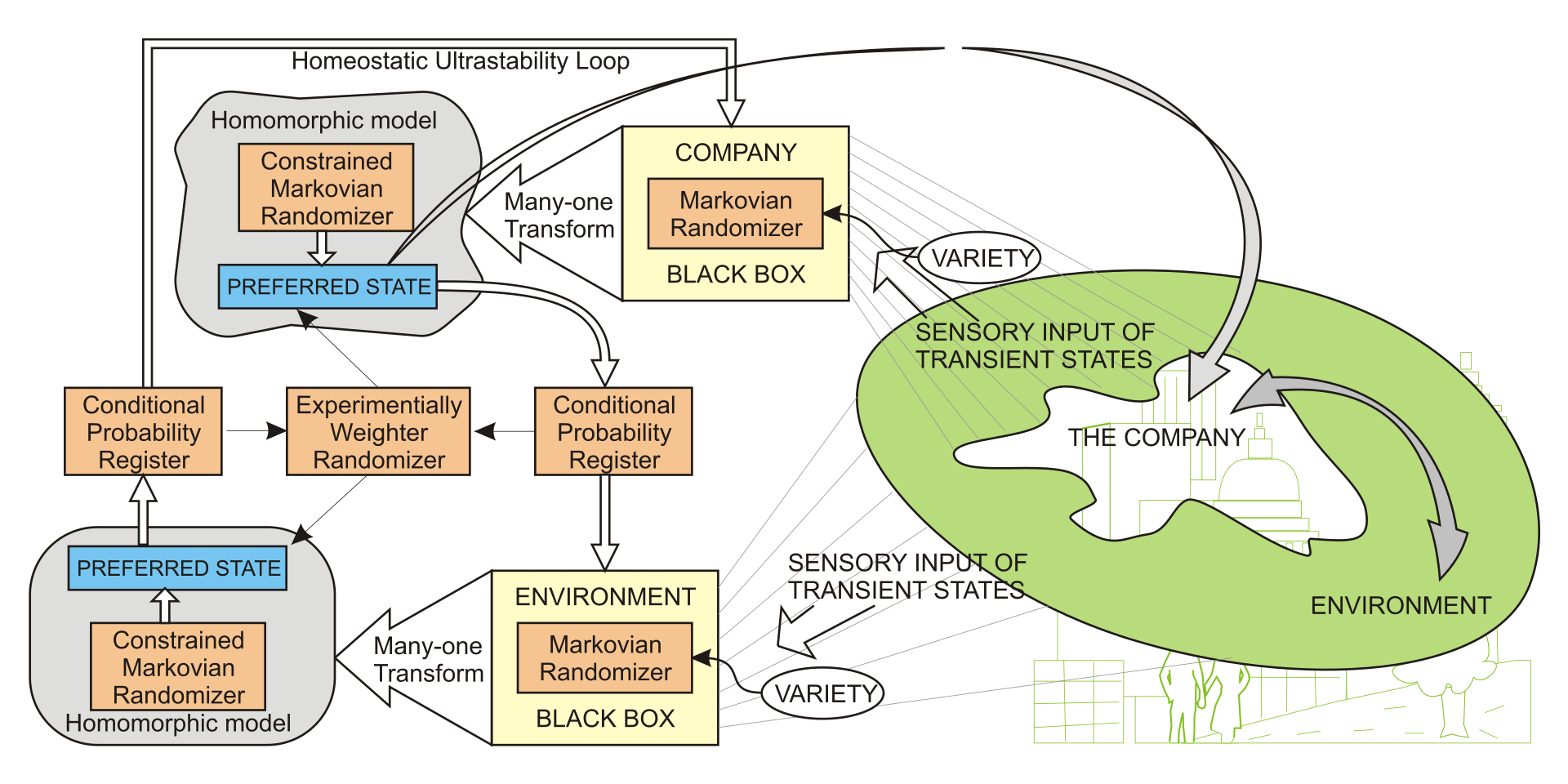

| VSM El Viable System Model (VSM), o Modelo del Sistema Viable, fue desarrollado por Stafford Beer y guio la implementación del proyecto CYBERSYN. Tiene tres componentes elementales que incuban la gestión y dinámica de los procesos: El ambiente o entorno de la organización. La operación. La administración. El VSM es un modelo de la estructura de cualquier sistema viable. Un sistema viable es cualquier sistema organizado que reúna las demandas de supervivencia en un ambiente cambiante. Una de las características primarias de los sistemas que sobreviven es que son adaptables a las condiciones ambientales. Componentes cibernéticos del VSM Los componentes de un sistema viable son cinco subsistemas que trabajan recíprocamente y que pueden ser identificados a través de los diversos aspectos de la estructura de cada organización. |

VSM 実行可能システムモデル(VSM)は、スタッフォード・ビアによって開発され、CYBERSYN プロジェクトの実施を導いた。 このモデルには、プロセスの管理とダイナミクスを育む 3 つの基本的な要素がある。 組織の環境または周囲の状況。 運営。 管理。 VSM は、実行可能なあらゆるシステムの構造をモデル化したものである。実行可能なシステムとは、変化する環境において生存の要求を満たす、組織化されたあらゆるシステムのことだ。生存するシステムの主な特徴の一つは、環境条件に適応できることだ。 VSM のサイバネティックな構成要素 実行可能なシステムの構成要素は、相互に作用する 5 つのサブシステムであり、各組織の構造のさまざまな側面から特定することができる。 |

| Opsroom El Opsroom o sala de operaciones fue el punto de unión de los diferentes proyectos realizados en el contexto de Cybersyn. La necesidad de construir una sala de operaciones había sido identificada y explicada en el libro The Brain of the Firm. Era el espacio de presentación de la información enviada por las empresas y estaba disponible para la toma de decisiones. Fue construida en un edificio en la avenida Santa María, cerca de las oficinas de Philips.[18] Fue diseñada siguiendo los principios de la Gestalt, para entregarle a los usuarios una plataforma en donde la información pudiera ser absorbida de una manera simple y profunda. Fue diseñada por INTEC (Instituto de Investigaciones Tecnológicas de Chile) bajo la coordinación general del ingeniero Jorge Barrientos. A la cabeza del equipo de diseño estaba Gui Bonsiepe, quien trabajaba en Chile desde 1968, luego de haber sido académico y uno de los principales gestores de la Universidad HFG (Hochschule für Gestaltung) de Ulm, en Alemania, una de las academias que continuó la labor de la escuela Bauhaus después de su desaparición. El equipo de diseñadores industriales estuvo conformado por Rodrigo Walker, Guillermo Capdevila, Alfonso Gómez, Guillermo Cintolesi, Fernando Shultz, Michel Weiss (Alemania), Wolfgang Eberhagen (Alemania) y Werner Zemp (Suiza). El equipo de diseño gráfico, encargado de preparar las imágenes que se mostrarían en las pantallas, estaba conformado por Pepa Foncea, Lucía Wormald, Eddy Carmona y Jessie Cintolesi. La sala era hexagonal, forma orgánica que permitía la correcta disposición de los dispositivos. Incluía 7 sillas giratorias con cojines naranjas —fabricadas en un taller en Puente Alto— encima de una alfombra café, paredes cubiertas por paneles de madera, una pantalla llamada Futuro, un esquema del VSM (Staffy), una serie de pantallas con reportes sobre la producción en tiempo real de diferentes fábricas, una pantalla con información sobre estados de excepción o urgencia, una pared con una imagen de un modelo cibernético basado en el Sistema Nervioso Humano, y un Data Feed. Cada silla tenía en su brazo derecho un dispositivo de control interactivo que, a través de la combinación de sus botones (objetos geométricos), activaba órdenes de proyección en las pantallas de información según los requerimientos de los usuarios, como gráficas de barras, tablas y fotografías de la producción industrial, optimizando la comunicación externa e interna.[1] |

Opsroom Opsroom(オペレーションルーム)は、Cybersyn の枠組みの中で実施されたさまざまなプロジェクトの拠点だった。オペレーションルームの建設の必要性は、著書『The Brain of the Firm』で指摘され、説明されていた。ここは、企業から送信された情報を表示し、意思決定を行うためのスペースだった。サンタマリア通り、フィリップス のオフィス近くのビルに建設された。[18] ゲシュタルトの原則に従って設計され、ユーザーが情報をシンプルかつ深く吸収できるプラットフォームを提供することを目的としていた。チリ技術研究所 (INTEC)が、エンジニアのホルヘ・バリエントスの総合調整のもとで設計した。設計チームのリーダーは、1968年からチリで働いていたギ・ボンシエ ペだった。彼は、ドイツ・ウルムにあるHFG(Hochschule für Gestaltung)大学の学者であり、同大学の主要管理者であった。HFGは、バウハウスが消滅した後、その活動を継承したアカデミーのひとつだ。 工業デザイナーチームは、ロドリゴ・ウォーカー、ギジェルモ・カプデビラ、アルフォンソ・ゴメス、ギジェルモ・シントレシー、フェルナンド・シュルツ、ミ シェル・ヴァイス(ドイツ)、ヴォルフガング・エバーハーゲン(ドイツ)、ヴェルナー・ツェンプ(スイス)で構成されていた。スクリーンに表示される画像 の準備を担当したグラフィックデザインチームは、ペパ・フォンセア、ルシア・ウォームアルド、エディ・カルモナ、ジェシー・シントレージで構成されていま した。 部屋は六角形の有機的な形状で、機器を適切に配置することができた。部屋には、プエンテ・アルトの工房で製造されたオレンジ色のクッション付き回転椅子 7 脚が、茶色のカーペットの上に置かれ、壁は木製のパネルで覆われ、Futuro というスクリーン、VSM(Staffy)の図、 さまざまな工場のリアルタイムの生産状況に関するレポートを表示する一連のスクリーン、非常事態や緊急事態に関する情報を表示するスクリーン、人間の神経 系をモデルにしたサイバネティックモデルの画像が貼られた壁、そしてデータフィードがあった。各椅子の右腕部分には、ボタン(幾何学的な形状のオブジェク ト)の組み合わせにより、ユーザーの要求に応じて情報画面に棒グラフ、表、工業生産の写真などの投影コマンドを起動するインタラクティブな制御装置が設置 されており、外部および内部のコミュニケーションを最適化していた。[1] |

| Proyecto Checo El proyecto CHECO (de "chilean economy") tuvo por objetivo modelar la economía chilena y crear simulaciones del comportamiento económico a futuro. Esto se realizaba a través de un programa llamado DYNAMO, desarrollado originalmente para el Club de Roma, por el profesor Jay Forrester, del Instituto de Tecnología de Massachusetts (MIT). En la sala de control, esta aplicación se desplegaba en la pantalla “FUTURO”, convirtiendo a esta herramienta en un espacio de reflexión para apoyar decisiones de mediano y largo plazo. La aplicación DYNAMO fue implementada en el proyecto Cybersyn por Ron Atherton de la Universidad de Lancaster, Reino Unido, y aplicada por el equipo de trabajo liderado por el ingeniero químico Mario Grandi. |

チェコプロジェクト CHECO(チリ経済)プロジェクトは、チリ経済をモデル化し、将来の経済動向のシミュレーションを作成することを目的としていた。これは、マサチュー セッツ工科大学(MIT)のジェイ・フォレスター教授がローマクラブのために開発した「DYNAMO」というプログラムを使用して行われていた。 コントロールルームでは、このアプリケーションが「FUTURO」という画面に表示され、このツールは中長期の意思決定を支援する検討の場となった。 DYNAMOアプリケーションは、英国ランカスター大学のロン・アサートンによってサイバースンプロジェクトに導入され、化学エンジニアのマリオ・グランディが率いるチームによって適用された。 |

| Cyberfolk Cyberfolk fue un experimento realizado por el equipo de Cybersyn. Consistía conceptualmente en entregar a la gente la posibilidad de tener una conexión a distancia y en tiempo real con políticos y administradores debatiendo decisiones de gobierno y así participar democráticamente en las decisiones. El sistema que se diseñó para estos efectos permitía a los participantes de una reunión expresar su acuerdo o desacuerdo con el progreso de las conversaciones. Para esto los participantes usaban un botón rotatorio personal que les permitía enviar una señal en tiempo real a un aparato de madera y circuitos analógicos. Este aparato agregaba las señales personales y el resultado era representado en un gráfico semicircular, que decía en un extremo “de acuerdo” y en el otro “en desacuerdo”. Este aparato permitía apreciar la satisfacción de los participantes con el progreso de la reunión (Beer llamó a este aparato algedonometer). El sistema representaba una herramienta para la democratización del proceso de toma de decisiones del gobierno, entregando las herramientas de la ciencia al pueblo para expresarse y participar activamente en la toma de decisiones de sus empresas y comunidades. Sin embargo, el sistema fue demasiado adelantado para ser aplicado en un sistema social no acostumbrado a lidiar con este tipo de herramientas. Esta especie de "People Meter" analógico pudo haber sido utilizado de manera errónea por la población y por el gobierno. Este sistema requería del más profundo compromiso y honestidad de las partes del sistema, situación imposible en esa época por la inestabilidad socioeconómica en que vivía Chile. Los grupos de oposición al gobierno de Allende acusaron a este experimento de ser una herramienta tecnológica de control social. |

サイバーフォーク サイバーフォークは、サイバースィンチームによって実施された実験だった。これは、概念的には、政治家や行政官が政府の決定について議論している様子を、人々が遠隔地からリアルタイムで視聴し、民主的に意思決定に参加できる仕組みを提供するものだった。 この目的のために設計されたシステムでは、会議の参加者は、議論の進捗について賛成か反対かを表明することができた。参加者は、回転式の個人用ボタンを使 用して、木製の装置とアナログ回路にリアルタイムで信号を送信した。この装置は、各参加者の信号を合計し、その結果を半円形のグラフに表示した。グラフの 一方の端は「賛成」、もう一方の端は「反対」を表していた。この装置により、会議の進捗に対する参加者の満足度を把握することができた(ビールは、この装 置を「アルゲドノメーター」と呼んだ)。 このシステムは、政府の意思決定プロセスの民主化のためのツールとなり、科学のツールを国民に提供して、企業やコミュニティの意思決定に積極的に参加できるようにした。 しかし、このシステムは、このようなツールを扱うことに慣れていない社会では、あまりにも先進的すぎて適用できなかった。この種のアナログ「ピープルメー ター」は、国民や政府によって誤用される可能性があった。このシステムは、システムに参加する関係者全員の深いコミットメントと誠実さを必要としたが、当 時のチリは社会経済的に不安定な状況にあり、それは不可能だった。 アジェンデ政権に反対するグループは、この実験を社会統制のための技術的ツールだと非難した。 |

| Revolucionarios cibernéticos. Tecnología y política en el Chile de Salvador Allende Internet ARPANET Debate sobre el cálculo económico en el socialismo Sistema de planificación de recursos empresariales |

サイバー革命家たち。サルバドール・アジェンデのチリにおけるテクノロジーと政治 インターネット ARPANET 社会主義における経済計算に関する議論 企業資源計画システム |

| 1. Medina, Eden (2011). MIT, ed.

Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende's Chile

(en inglés). Boston, USA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01649-0. Consultado

el 05092023. 2. Harrison, P. J.; Stevens, C. F. (1971). «A Bayesian Approach to Short-Term Forecasting». Operational Research Quarterly (1970-1977) 22 (4): 341-362. ISSN 0030-3623. doi:10.2307/3008187. Consultado el 21 de febrero de 2025. 3. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (14 de agosto de 2024). «Forecasting the Present: A Media Archaeo-genealogical Inquiry into Project Cybersyn». Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin (Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin). doi:10.18452/29151. Consultado el 21 de febrero de 2025. 4. Medina, Edén (2014). «Diseñar La Libertad, Regular Una Nación. El Socialismo Cibernético En El Chile De Salvador Allende». Redes 20 (38): 123-166. ISSN 0328-3186. Consultado el 14 de mayo de 2021. 5. «Designing freedom, regulating a nation: socialist cybernetics in Allende’s Chile». Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 38, Nº 3, pp. 571-606. Archivado desde el original el 13 de diciembre de 2021. Consultado el 13 de diciembre de 2021. 6. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (2023). «Encoding from/to the Real: On Cybersyn’s Symbolic Politics of Transmission». En Diego Gómez-Venegas, ed. Frictions: Inquiries into Cybernetic Thinking and Its Attempts towards Mate[real]ization (en inglés). Lüneburg: meson press. p. 93-95. doi:10.14619/2164. 7. Beer, Stafford (1995). Brain of the firm. The managerial cybernetics of organization / Stafford Beer (2. ed., reprinted edición). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-94839-1. 8. Medina, Eden (2014). Cybernetic revolutionaries: technology and politics in Allende's Chile (en inglés) (First MIT Press paperback edition edición). MIT Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-262-52596-1. 9. Chile bajo la Unidad Popular, Tomo 10. Revista Que Pasa 10. Gómez-Venegas (14 de agosto de 2024). «Forecasting the Present: A Media Archaeo-genealogical Inquiry into Project Cybersyn». Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin (Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin): 135-136. doi:10.18452/29151. 11. Beckett, Andy (8 de septiembre de 2003). «Santiago dreaming». The Guardian (en inglés británico). ISSN 0261-3077. Consultado el 21 de febrero de 2025. 12. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (14 de agosto de 2024). «Forecasting the Present: A Media Archaeo-genealogical Inquiry into Project Cybersyn». Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin (Berlin: Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin): 171-172. doi:10.18452/29151. Consultado el 21 de febrero de 2025. 13. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (14 de agosto de 2024). «Forecasting the Present: A Media Archeo-genealogical Inquiry into Project Cybersyn». Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin (Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin): 178-188. doi:10.18452/29151. Consultado el 21 de febrero de 2025. 14. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (14 de agosto de 2024). «Forecasting the Present: A Media Archaeo-genealogical Inquiry into Project Cybersyn». Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin (Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin): 35-51. doi:10.18452/29151. Consultado el 21 de febrero de 2025. 15. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (14 de agosto de 2024). «Forecasting the Present: A Media Archaeo-genealogical Inquiry into Project Cybersyn». Humboldt-Univesitaet zu Berlin (en inglés) (Humboldt-Univesitaet zu Berlin): 124-131. doi:10.18452/29151. 16. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (2023). «Encoding from/to the Real: On Cybersyn’s Symbolic Politics of Transmission». En Diego Gómez-Venegas, ed. Frictions: Inquiries into Cybernetic Thinking and Its Attempts towards Mate[real]ization (en inglés). Lüneburg: meson press. pp. 110-115. ISBN 978-3-95796-216-4. doi:10.14619/2164. 17. Operational Research Quarterly Vol. 22, No4, Dec. 1971 18. «El sueño cibernético de Allende». The Clinic. 28 de agosto de 2011. Consultado el 19 de enero de 2022. |

1. Medina, Eden (2011). MIT, ed.

Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende's Chile

(英語). ボストン, アメリカ合衆国: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01649-0. 2023年9月5日に閲覧。 2. Harrison, P. J.; Stevens, C. F. (1971). 「短期予測へのベイジアンアプローチ」『オペレーションズ・リサーチ・クォータリー』(1970-1977)22 (4): 341-362。ISSN 0030-3623。doi:10.2307/3008187。2025年2月21日閲覧。 3. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (2024年8月14日). 「現在を予測する:プロジェクト・サイバーシンに関するメディア考古学・系譜学的研究」. ベルリン・フンボルト大学 (ベルリン・フンボルト大学). doi:10.18452/29151. 2025年2月21日アクセス。 4. メディナ、エデン(2014)。「自由を設計し、国家を規制する。サルバドール・アジェンデのチリにおけるサイバーネティクス社会主義」。Redes 20 (38): 123-166。ISSN 0328-3186。2021年5月14日閲覧。 5. 「自由の設計、国家の規制:アジェンデのチリにおける社会主義サイバネティクス」。Journal of Latin American Studies、第 38 巻、第 3 号、571-606 ページ。2021 年 12 月 13 日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021 年 12 月 13 日閲覧。 6. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (2023). 「現実からの/現実へのエンコーディング:サイバーシンの伝達に関する象徴的な政治について」。Diego Gómez-Venegas 編『Frictions: Inquiries into Cybernetic Thinking and Its Attempts towards Mate[real]ization』(英語)。リューネブルク:メゾンプレス。93-95 ページ。doi:10.14619/2164. 7. Beer, Stafford (1995). Brain of the firm. The managerial cybernetics of organization / Stafford Beer (第2版、再版). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-94839-1. 8. メディナ、エデン(2014)。『サイバネティック革命家たち:アジェンデのチリにおける技術と政治』(英語)(MIT Press ペーパーバック初版)。MIT Press。168 ページ。ISBN 978-0-262-52596-1。 9. チリ、人民連合の支配下、第 10 巻。雑誌 Que Pasa 10. ゴメス・ベネガス (2024年8月14日)。「現在を予測する:プロジェクト・サイバーシンに関するメディア考古学・系譜学的研究」。フンボルト大学ベルリン (フンボルト大学ベルリン): 135-136。doi:10.18452/29151. 11. ベケット、アンディ(2003年9月8日)。「サンティアゴの夢」。ガーディアン(英国英語)。ISSN 0261-3077。2025年2月21日閲覧。 12. ゴメス・ベネガス、ディエゴ (2024年8月14日)。「現在の予測:プロジェクト・サイバーシンに関するメディア考古学・系譜学的研究」。フンボルト大学ベルリン (ベルリン:フンボルト大学ベルリン): 171-172. doi:10.18452/29151. 2025年2月21日アクセス。 13. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (2024年8月14日). 「現在を予測する:プロジェクト・サイバーシンに関するメディア考古学・系譜学的研究」. Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin (Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin): 178-188. doi:10.18452/29151。2025年2月21日アクセス。 14. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (2024年8月14日). 「現在を予測する:プロジェクト・サイバーシンに関するメディア考古学・系譜学的研究」. フンボルト大学ベルリン(フンボルト大学ベルリン):35-51。doi:10.18452/29151。2025年2月21日閲覧。 15. Gómez-Venegas, Diego (2024年8月14日)。「現在を予測する:プロジェクト・サイバーシンに関するメディア考古学・系譜学的研究」。フンボルト大学ベルリン(英語)(フ ンボルト大学ベルリン):124-131。doi:10.18452/29151. 16. ゴメス・ベネガス、ディエゴ(2023)。「現実からの、そして現実へのエンコーディング:サイバーシンの伝達に関する象徴的な政治について」。ディエ ゴ・ゴメス・ベネガス編『Frictions: Inquiries into Cybernetic Thinking and Its Attempts towards Mate[real]ization』(英語)。リューネブルク:メゾンプレス。110-115 ページ。ISBN 978-3-95796-216-4。doi:10.14619/2164. 17. Operational Research Quarterly Vol. 22, No4, Dec. 1971 18. 「アジェンデのサイバネティックな夢」。The Clinic. 2011年8月28日。2022年1月19日閲覧。 |

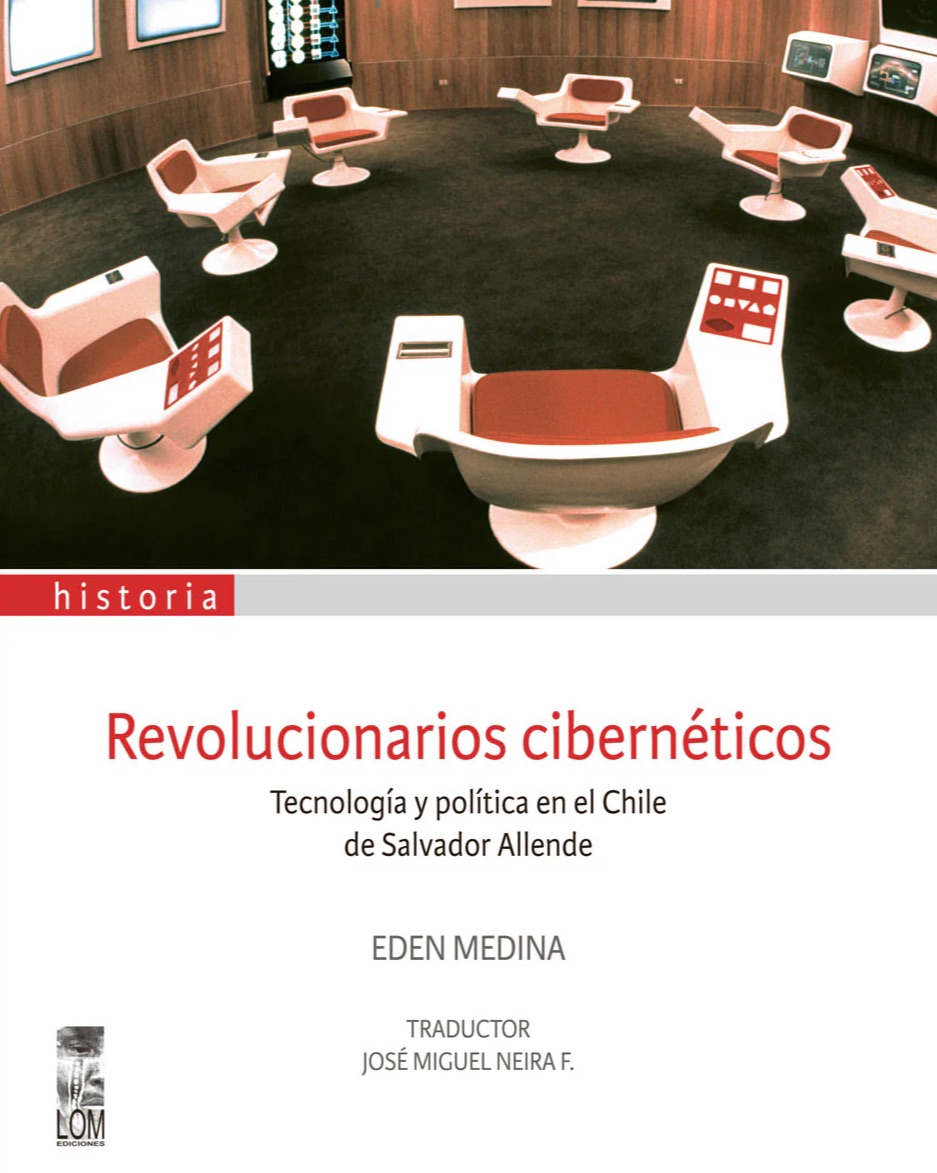

| Revolucionarios

cibernéticos. Tecnología y política en el Chile de Salvador Allende es

un libro cuyo origen es la investigación realizada por la historiadora

Eden Medina sobre el proyecto Synco. El libro fue publicado el año 2013

por la Editorial Lom. Esta obra es la traducción del libro de la autora

Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende's Chile

publicado por The MIT Press en Estados Unidos en 2011. |

『サイバー革命家たち。サルバドール・アジェンデのチリにおけるテクノ

ロジーと政治』は、歴史家エデン・メディナがシンコ・プロジェクトについて行った調査を基にした本です。この本は、2013年にロム出版社から出版されま

した。この作品は、2011年に米国で MIT Press から出版された著者の『Cybernetic Revolutionaries:

Technology and Politics in Allende's Chile』を翻訳したものです。 |

| La historia un proyecto revolucionario El libro relata la historia del proyecto Synco, realizado en Chile durante el gobierno de Salvador Allende. El proyecto Synco tuvo por objetivo la gestión de la economía del país usando los métodos de la cibernética, en un contexto de profundos cambios políticos y económicos. El proyecto surge de la convergencia intelectual entre el cibernético Stafford Beer, el ingeniero Fernando Flores ministro de la Unidad Popular, más la colaboración entre ingenieros chilenos y cibernéticos británicos. Stafford Beer fue uno de los precursores de la ciencia cibernética.[1] El proyecto Synco fue diseñado como un sistema que permitiría recabar datos de producción en tiempo real, diseñar programas estadísticos, construir simulaciones computarizadas de la economía chilena y comunicarse con las fábricas al localizar problemas que afectaran su rendimiento. El proyecto fue considerado relevante en el contexto de transformación de la economía chilena, marcado por un programa de nacionalización de la producción. La vía al socialismo democrático defendida por el gobierno de Allende confluyó en las ideas cibernéticas de Stafford Beer, quien, a través de su Modelo de Sistema Viable, se propuso configurar un sistema de gestión que favoreciera la transversalidad en la cadena de mando.[1] |

革命的なプロジェクトの歴史 この本は、サルバドール・アジェンデ政権下のチリで実施されたシンコ・プロジェクトの歴史を綴ったものだ。シンコ・プロジェクトは、深刻な政治的・経済的 変化の真っ只中に、サイバネティクスの手法を用いて国の経済運営を行うことを目標としていた。このプロジェクトは、サイバネティクスの専門家スタッフォー ド・ビア、人民統一党のエンジニア兼大臣フェルナンド・フローレス、そしてチリ人エンジニアとイギリス人サイバネティクスの専門家たちの知的交流から生ま れた。スタッフォード・ビアは、サイバネティクスの先駆者の一人だ。[1] シンコプロジェクトは、生産データをリアルタイムで収集し、統計プログラムを設計し、チリ経済のコンピュータシミュレーションを構築し、工場のパフォーマ ンスに影響を与える問題を特定して工場と連絡を取ることを可能にするシステムとして設計された。このプロジェクトは、生産の国有化プログラムによって特徴 づけられたチリ経済の変革の文脈において、重要なものとみなされた。アジェンデ政権が提唱した民主的社会主義への道筋は、スタッフォード・ビアのサイバネ ティクスの思想と合流し、ビアは「実行可能なシステムモデル」を通じて、指揮系統の横断性を促進する管理システムの構築を目指した。[1] |

| Sobre la autora Eden Medina es Doctora en Historia y Estudios Sociales de Ciencia y Tecnología del Instituto Tecnológico de Massachusetts (MIT). Es Master en Derecho de la Escuela de Leyes de Yale. Además de ser Licenciada en Ingeniería eléctrica de la Universidad de Princeton. Ha recibido el IEEE Life Members’ Prize in Electrical History y un Scholar’s Award from the National Science Foundation de Estados Unidos. Actualmente es Associate Professor of Science, Technology, and Society en el Instituto Tecnológico de Massachusetts (MIT). Fue coeditora del volume Beyond Imported Magic: Essays on Science, Technology, and Society in Latin America (MIT Press, 2014) recibiendo el Premio Amsterdamska por la Sociedad europea para el estudio de la ciencia y la tecnología.[2] |

著者について エデン・メディナは、マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)で科学技術史・社会学の博士号を取得。イェール大学法学部で法学修士号を取得。プリンストン大学 で電気工学の学士号を取得。IEEE Life Members’ Prize in Electrical History(IEEE 電気歴史生涯功労賞)および米国国立科学財団(NSF)のScholar’s Award(学者賞)を受賞。現在は、マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)で科学、技術、社会学の准教授を務めている。著書に『Beyond Imported Magic: Essays on Science, Technology, and Society in Latin America』(MITプレス、2014年)があり、この著作で欧州科学技術研究協会からアムステルダム賞を受賞した。[2] |

| Synco |

このページの上の翻訳 |

| Eden Medina, Revolucionarios cibernéticos. Tecnología y política en el Chile de Salvador Allende. 2013. Editorial Lom. |

★「サイバーシン計画」の英語版ウィキペディアの記事

| Project Cybersyn was

a Chilean project from 1971 to 1973 during the presidency of Salvador

Allende aimed at constructing a distributed decision support system to

aid in the management of the national economy. The project consisted of

4 modules: an economic simulator, custom software to check factory

performance, an operations room, and a national network of telex

machines that were linked to one mainframe computer.[2] Project Cybersyn was based on viable system model theory approach to organizational design and featured innovative technology for its time. It included a network of telex machines (Cybernet) in state-run enterprises that would transmit and receive information to and from the government in Santiago. Information from the field would be fed into statistical modeling software (Cyberstride) that would monitor production indicators, such as raw material supplies or high rates of worker absenteeism. It alerted workers in near real time. If parameters fell significantly outside acceptable ranges, it notified the central government. The information would also be input into economic simulation software (CHECO, for CHilean ECOnomic simulator). The government could use this to forecast the possible outcome of economic decisions. Finally, a sophisticated operations room (Opsroom) would provide a space where managers could see relevant economic data. They would formulate feasible responses to emergencies and transmit advice and directives to enterprises and factories in alarm situations by using the telex network. The principal architect of the system was British operations research scientist Stafford Beer, and the system embodied his notions of management cybernetics in industrial management. One of its main objectives was to devolve decision-making power within industrial enterprises to their workforce to develop self-regulation of factories. Project Cybersyn was ended with Allende's removal and subsequent death during the 1973 Chilean coup d'état. After the coup, Cybersyn was abandoned and the operations room was destroyed.[3] |

プロジェクト・サイバーシン(Project Cybersyn)は、1971年から1973年にかけて、サ

ルバドール・アジェンデ大統領の在任中に、チリで実施された、国民経済の運営を支援するための分散型意思決定支援システムの構築プロジェクトだった。この

プロジェクトは、経済シミュレーター、工場のパフォーマンスをチェックするカスタムソフトウェア、オペレーションルーム、1台のメインフレームコンピュー

タに接続されたテレックス機の全国ネットワークという4つのモジュールで構成されていた。[2] プロジェクト・サイバーシンは、組織設計に実行可能なシステムモデル理論アプローチを採用し、当時としては革新的な技術を採用していた。このプロジェクト には、サンティアゴの政府機関と情報を送受信する、国営企業間のテレックス機(サイバネット)のネットワークが含まれていた。 現場からの情報は、統計モデリングソフトウェア(サイバーストライド)に投入され、原材料の供給状況や従業員の欠勤率などの生産指標を監視した。このシス テムは、ほぼリアルタイムで従業員にアラートを発信した。パラメーターが許容範囲を大幅に下回った場合、中央政府に通知された。情報はまた、経済シミュ レーションソフトウェア(CHECO、チリ経済シミュレーター)にも入力された。政府はこれを利用して、経済政策の決定による結果を予測することができ た。最後に、高度なオペレーションルーム(Opsroom)が、経営陣が関連経済データを確認できるスペースを提供していた。経営陣は、緊急事態に対する 実行可能な対応策を策定し、テレックスネットワークを利用して、警報状況にある企業や工場に助言や指示を送信していた。 このシステムの主な設計者は、英国のオペレーションズリサーチの科学者、スタッフォード・ビアであり、このシステムは、彼の産業経営における経営サイバネ ティクスの概念を体現したものだった。その主な目的の一つは、産業企業内の意思決定権を従業員に委譲し、工場の自主規制を発展させることだった。 サイバーシンプロジェクトは、1973年のチリクーデターによるアジェンデの追放と死によって終了した。クーデター後、サイバーシンは放棄され、オペレー ションルームは破壊された。[3] |

A 3D render of the Operations Room (or Opsroom): a physical location where economic information was to be received, stored, and made available for speedy decision-making. It was designed in accordance with Gestalt principles to give users a platform that would enable them to absorb information in a simple but comprehensive way.[1] * The 2 "algedonic displays", the 4 screen Data Feed, and the black board. The control panels visible on the armrests. |

オペレーションルーム(Opsroom)の 3D レンダリング:経済情報を受け取り、保存し、迅速な意思決定のために利用できるようにするための物理的な場所。ユーザーが情報をシンプルかつ包括的に吸収 できるプラットフォームを提供するために、ゲシュタルトの原則に従って設計された。[1] * 2つの「アルゲドンディスプレイ」、4画面のデータフィード、および黒板。アームレストに見えるコントロールパネル。 |

| Name The project's name in English ('Cybersyn') is a portmanteau of the words 'cybernetics' and 'synergy'. Since the name is not euphonic in Spanish, in that language the project was called Synco, both an initialism for the Spanish Sistema de Información y Control ('System of Information and Control'), and a pun on the Spanish cinco, the number 5, alluding to the 5 levels of Beer's viable system model.[4] |

名前 このプロジェクトの英語名(「サイバーシン」)は、「サイバネティクス」と「シナジー」という 2 つの単語を組み合わせた造語だ。この名称はスペイン語では響きが良くないため、スペイン語では「Synco」と名付けられた。これは、スペイン語の 「Sistema de Información y Control」(情報と制御のシステム)の頭文字を取った略語であり、同時にスペイン語の「cinco」(5)にかけて、ビール氏の「生存可能なシステ ムモデル」の5つのレベルを暗示している。[4] |

| System A few dozen of teleprinters acquired by the previous administration,[5] and not 500 as previously reported,[6] were then put into factories. Each factory would send quantified indices of production processes such as raw material input, production output, number of absentees, etc.[7] These indices would later feed a statistical analysis program that, running on a mainframe computer in Santiago, would make short-term predictions about the factories' performance and suggest necessary adjustments,[8] which, after discussion in an operations room, would be fed back to the factories. This process occurred at 4 levels: firm, branch, sector, and total. A fundamental phase of the project was to quantify the production processes in the factories. This began with operational research (OR) engineers visiting the factories and modeling their production flows using a technique that Beer and the local team called "quantified flowcharting".[9] It consisted of drawing a flowchart of the entire production process of a given factory, focusing on the "bottlenecks" of such a process.[10] The connections from one point in the process to another had to be quantified in order to find those bottlenecks. This was a time-consuming process, for which only one OR engineer was assigned to model a given factory. This is likely the reason why, at the end of the project, only about twenty factories were modeled and connected to the transmission and processing system.[11] Once a factory was modeled, it was necessary to collect indices of processes on a daily basis. The "quantified flowcharting" technique used by the project team explicitly required the modelers to rely on the factory operators' knowledge of their own relationships to their machines to generate these indices.[12] This is reminiscent of earlier bottom-up cybernetic processes, such as those signaled by Pasquinelli in his article "Italian Operaismo and the Information Machine".[13] The collected indexes were then recorded on a paper form and given to a typist secretary at the factory who, using an in-house teletype machine, sent these data to a traffic station,[14] where the information was first checked for format accuracy.[15] Algedonic feedback improved system adaptability and viability. If one level of control did not remedy a problem in a certain interval, the higher level was notified. The results were discussed in the operations room and a top-level plan was made. The network of telex machines, called 'Cybernet', was the first operational component of Cybersyn, and the only one regularly used by the Allende government.[4] Beer proposed what was initially called Project Cyberstride, a system that would take in information and metrics from production centers like factories, process it on a central mainframe, and output predictions of future trends based on historical data. The software used Bayesian filtering and Bayesian control. It was fundamental written by British engineers of the Arthur Andersen[16][17] consultancy company and implemented in Santiago with Chilean engineers of the National Company of Computation, ECOM.[18] Cybersyn first ran on an IBM 360/50, but later was transferred to a less heavily used Burroughs 3500 mainframe.[4] New research, however, suggests that the project's software suite always ran on ECOM's IBM 360/50 mainframe computer.[19] The futuristic operations room was designed by a team led by the interface designer Gui Bonsiepe. It was furnished with 7 swivel chairs, considered the best for creativity. The chairs had buttons to control several large screens that projected data, and status panels that showed slides of preprepared graphs.[20] The tulip chairs were similar in style to those in Star Trek, but the designers claimed no science fiction influence.[21] The project is described in some detail in the second edition of Stafford Beer's books Brain of the Firm[22] and Platform for Change.[23] The latter book includes proposals for social innovations such as having representatives of diverse 'stakeholder' groups into the control center. A related development known as Project Cyberfolk, which Beer envisioned as an extension of Cybersyn but never realized, would allow citizens to send real-time feedback to the government about their level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with policies announced on television.[24][25] Next a rapid partial implementation started realization of the system vision. |

システム 前政権が購入した数十台のテレタイプ機[5](以前報告されていた 500 台ではない[6])が工場に設置された。各工場は、原材料の投入量、生産量、欠勤者数など、生産プロセスの定量化された指標を送信した。[7] これらの指標は、サンティアゴのメインフレームコンピュータで実行される統計分析プログラムに入力され、工場のパフォーマンスに関する短期的な予測と必要 な調整案が作成された[8]。この調整案は、オペレーションルームで議論された後、工場にフィードバックされた。このプロセスは、企業、支店、部門、全体 の 4 つのレベルで行われた。 プロジェクトの根本的な段階は、工場の生産プロセスを定量化することだった。これは、オペレーションズ・リサーチ(OR)エンジニアが工場を訪問し、ビー ルと現地チームが「定量化フローチャート」と呼ぶ手法を用いて生産フローをモデル化することから始まった。[9] これは、特定の工場の生産プロセス全体をフローチャート化し、そのプロセスの「ボトルネック」に焦点を当てるものだった。[10] プロセス内の1つのポイントから別のポイントへの接続を定量化することで、これらのボトルネックを特定する必要があった。これは時間がかかるプロセスであ り、1つの工場のモデル化には1人のORエンジニアが割り当てられた。これが、プロジェクト終了時にモデル化され、伝送・処理システムに接続された工場が 約20工場に留まった主な理由と考えられる。[11] 工場がモデル化されると、プロセスに関する指標を毎日収集する必要がありました。プロジェクトチームが使用した「定量化されたフローチャート作成」技術で は、モデル作成者は、工場のオペレーターが自身の機械との関係に関する知識に依存してこれらの指標を生成することが明示的に求められていました。[12] これは、パスクイネッリが論文「イタリアのオペライズモと情報マシン」で指摘したような、以前のボトムアップ型サイバネティクスプロセスを想起させます。 [13] 収集された指標は、紙のフォームに記録され、工場のタイピスト秘書に渡され、社内のテレタイプ機を使用して、これらのデータが交通局に送信された [14]。そこで、情報の形式の正確性が最初にチェックされた。[15] アルゲドニック・フィードバックにより、システムの適応性と実行可能性が向上した。あるレベルの制御で一定期間内に問題が解決しなかった場合、その問題は 上位レベルに通知された。その結果はオペレーションルームで議論され、トップレベルの計画が立てられた。「サイバーネット」と呼ばれるテレックス機のネッ トワークは、サイバーシンの最初の運用コンポーネントであり、アジェンデ政権が定期的に使用した唯一のコンポーネントだった。[4] ビアは、当初「プロジェクト・サイバースライド」と呼ばれていた、工場などの生産センターから情報や測定値を取り込み、中央のメインフレームで処理し、 過去のデータに基づいて将来の傾向を予測するシステムを提案した。このソフトウェアは、ベイズフィルタリングとベイズ制御を使用していた。このソフトウェ アは、コンサルティング会社アーサー・アンダーセン[16][17] の英国人エンジニアによって作成され、チリの国立計算会社 ECOM のエンジニアによってサンティアゴで実装された。[18] サイバーシンは、最初は IBM 360/50 で動作していましたが、後に使用頻度の少ない Burroughs 3500 メインフレームに移行されました。[4] しかし、新しい研究によると、このプロジェクトのソフトウェアスイートは、常に ECOM の IBM 360/50 メインフレームコンピュータで動作していたことが示唆されています。[19] この未来的なオペレーションルームは、インターフェースデザイナーのGui Bonsiepeが率いるチームによって設計された。創造性に最適な7脚の回転椅子で整えられていた。椅子には、データを投影する複数の大型スクリーンを 操作するボタンと、事前に準備されたグラフのスライドを表示するステータスパネルが備わっていた。[20] チューリップ型の椅子は、スタートレックに登場する椅子とスタイルが似ていたが、デザイナーたちはSFの影響は受けていないと主張している。[21] このプロジェクトは、スタッフォード・ビアの著書『Brain of the Firm』[22] および『Platform for Change』[23] の第 2 版で詳しく紹介されている。後者の著書には、多様な「ステークホルダー」グループの代表者をコントロールセンターに参加させるなど、社会革新に関する提案 が掲載されている。 ビールがサイバーシンの延長として構想したが実現しなかった、プロジェクト・サイバーフォークという関連開発では、市民がテレビで発表された政策に対する 満足度や不満度を、政府にリアルタイムでフィードバックすることが可能になる予定だった。[24][25] 次に、システム構想の実現に向けて、迅速な部分的な導入が開始された。 |

| Implementation See also: Chile truckers' strike, Planned economy, Decentralization, Socialist economics, and Self-organization in cybernetics  Leon Trotsky's critique of the Soviet Union influenced Beer's shifting political views and the design of the Cybersyn model. Stafford Beer was a British consultant in management cybernetics. He also sympathized with the stated ideals of Chilean socialism of maintaining Chile's democratic system and the autonomy of workers instead of imposing a USSR-style system of top-down command and control. He also read Leon Trotsky's critique of Soviet bureaucracy, which influenced his design of the system in Chile.[26] In July 1971, Fernando Flores, a high-level employee of the Chilean Production Development Corporation (CORFO) under the instruction of Pedro Vuskovic,[4] contacted Beer for advice on incorporating cybernetic theories into the management of the newly nationalized sectors of Chile's economy. Beer saw this as a unique opportunity to implement his ideas on a national scale. More than just offering advice, he left most of his other consulting contracts and devoted much of his time to what became Project Cybersyn.[27] He traveled to Chile often to collaborate with local implementors and used his personal contacts to secure help from British technical experts. With an initial implementation date of March 1972,[28] the aggressive implementation schedule led to the system reaching prototype stage in 1972.[4] As Cybersyn took shape, it impacted events in Chile. |

実施・実装 関連項目:チリのトラック運転手ストライキ、計画経済、地方分権、社会主義経済、サイバネティクスにおける自己組織化  レオン・トロツキーのソ連批判は、ビアの政治観の変化とサイバーシンモデルの設計に影響を与えた。 スタッフォード・ビールは、経営サイバネティクスの英国人コンサルタントだった。彼はまた、チリの民主主義体制と労働者の自治を維持し、ソ連式のトップダ ウン型の指揮統制システムを押し付けないというチリ社会主義の掲げる理想に共感していた。彼はまた、レオン・トロツキーのソ連官僚機構に対する批判を読 み、それがチリでのシステム設計に影響を与えた。[26] 1971年7月、ペドロ・ヴスコヴィッチの指示を受けたチリ生産開発公社(CORFO)の高官、フェルナンド・フローレス[4] が、チリの経済で新たに国有化されたセクターの経営にサイバネティクス理論を取り入れることについて、ビールに助言を求めました。ビールは、これを自分の 考えを全国規模で実現するまたとない機会と捉えました。彼は単なるアドバイスにとどまらず、他のコンサルティング契約のほとんどを辞め、サイバーシンプロ ジェクトに多くの時間を費やした[27]。彼は、現地の実施者たちと協力するため、チリを頻繁に訪れ、個人的な人脈を駆使して英国の技術専門家の支援を確 保した。 1972年3月を最初の実施予定日とした[28]、積極的な実施スケジュールにより、このシステムは1972年にプロトタイプ段階に到達した[4]。サイ バーシンが形になるにつれ、チリの情勢にも影響を与えた。 |

| Impact The Chilean government found success in its initial nationalization efforts, achieving a 7.7% rise in GDP and 13.7% rise in production in its first year, but needed to maintain continued growth to find long-term success.[28] According to technology historian Eden Medina, 26.7% of the nationalized industries which were responsible for 50% of the sector revenue had been incorporated to some degree into the Cybersyn system by May 1973.[29] The total costs of the economic simulator amounted to £5,000 at the time of design ($38,000 in 2009 dollars).[30] The Cybersyn system was used effectively in October 1972.[31] The telex network enabled communication across regions and the maintenance of distribution of essential goods across the country.[32] According to Gustavo Silva, then the executive secretary of energy in CORFO, the system's telex machines helped organize the transport of resources into the city with only about 200 trucks, lessening the potential damage caused by the employers' truck strike.[4] The government of Salvador Allende relied on real-time data to respond to the changing strike situation.[33] The strike actions against the Allende government were funded by the United States as part of an economic warfare. The elected Allende government survived in part due to the Cybersyn system.[34] Eventually the Allende government was brought down by a CIA-supported coup d'état in 1973.[33] Other governments, such as those in Brazil and South Africa, expressed interest in building up their own Cybersyn system. In the history of computing hardware, Project Cybersyn was a conceptual leap forward, in that computation was no longer put exclusively to work by the military or scientific institutions.[35] |

影響 チリ政府は、最初の国有化政策で成功を収め、初年度に GDP が 7.7%、生産高が 13.7% 増加したが、長期的な成功には継続的な成長を維持する必要があった[28]。技術史家のエデン・メディナによると、このセクターの収益の 50% を占めていた国有化産業の 26.7% は、1973 年 5 月までにサイバーシンシステムに何らかの形で組み込まれていた[29]。この経済シミュレーターの総費用は、設計当時で 5,000 ポンド(2009 年のドルで 38,000 ドル)だった[30]。 サイバーシンシステムは 1972 年 10 月に効果的に活用された[31]。テレックスネットワークにより、地域間の通信と、全国への生活必需品の流通の維持が可能になった[32]。CORFO のエネルギー担当事務局長だったグスタボ・シルバ氏によると、このシステムのテレックス機により、わずか 200 台ほどのトラックで都市への資源の輸送を組織することができ、雇用者によるトラックのストライキによる被害を最小限に抑えることができた。[4] サルバドール・アジェンデ政権は、変化するストライキの状況に対応するために、リアルタイムのデータに依存していた。[33] アジェンデ政権に対するストライキは、経済戦争の一環として米国によって資金援助されていた。選出されたアジェンデ政権は、サイバーシンシステムのおかげ で一部は生き残った。[34] 結局、アジェンデ政権は 1973 年に CIA が支援したクーデターによって倒された。[33] ブラジルや南アフリカなどの他の政府も、独自のサイバーシンシステムの構築に関心を示した。コンピュータハードウェアの歴史において、プロジェクト・サイ バーシンは、計算がもはや軍や科学機関によってのみ利用されるものではなくなったという点で、概念上の飛躍的な進歩だった。 |

Left to right: the magnetic "Panel of the Future", 2 slide screens, and "Staffy", the reminder of the Viable Systems Model |

左から右へ:磁気式の「未来のパネル」、2つのスライドスクリーン、そして「スタッフ」と呼ばれる、実行可能システムモデルを想起させるオブジェ。 |

Close-up of the data Feed |

データフィードのクローズアップ |

| Legacy The legacy of Project Cybersyn extended beyond supporting the Allende government, inspiring others to explore innovations in economic planning. Historical significance Computer scientist Paul Cockshott and economist Allin Cottrell referenced Project Cybersyn in their 1993 book Towards a New Socialism, citing it as an inspiration for their own proposed model of computer-managed socialist planned economy.[36] The Guardian in 2003 called the project "a sort of socialist internet, decades ahead of its time".[3] While Cockshott and Cottrell created a proposed model, another author explored fictional alternatives. Fictional portrayals Chilean author Jorge Baradit published a Spanish-language science fiction novel SYNCO in 2008. It is set in an alternate history year 1979 where the 1973 coup had failed and "the socialist government consolidated and created 'the first cybernetic state, a universal example, the true third way, a miracle'."[37] Baradit's novel imagines the realized project as an oppressive dictatorship of totalitarian control, disguised as a bright utopia.[38] Defenses and critiques In defense of the project, former operations manager of Cybersyn Raul Espejo wrote: "the safeguard against any technocratic tendency was precisely in the very implementation of CyberSyn, which required a social structure based on autonomy and coordination to make its tools viable. [...] Of course, politically it was always possible to use information technologies for coercive purposes, but that would have been a different project, certainly not Synco".[39] More recently, a journalist saw Cybersyn prefiguring algorithmic monitoring concerns. In a 2014 essay for The New Yorker, technology journalist Evgeny Morozov argued that Cybersyn helped pave the way for big data and anticipated how Big Tech would operate, citing Uber's use of data and algorithms to monitor supply and demand for their services in real time as an example.[25] Contemporary relevance Writers explored Cybersyn as a model for planned economies using contemporary processing power. Authors Leigh Phillips and Michał Rozworski also dedicated a chapter on the project in their 2019 book The People's Republic of Walmart. The authors presented a case to defend the feasibility of a planned economy aided by contemporary processing power used by large organizations such as Amazon, Walmart and the Pentagon. The authors question whether much can be built on Project Cybersyn, specifically, "whether a system used in emergency, near–civil war conditions in a single country—covering a limited number of enterprises and, admittedly, only partially ameliorating a dire situation—can be applied in times of peace and at a global scale." The project remained uncompleted due to the military coup in 1973, which led to economic reforms by the Chicago Boys.[40] Media coverage Cybersyn also caught the attention of podcasters. In October 2016, the podcast 99% Invisible produced an episode about the project.[41] The Radio Ambulante podcast covered some history of Allende and Project Cybersyn in their 2019 episode The Room That Was A Brain.[42] Finally, Morozov expanded from an essay into his own podcast series. In July 2023, Morozov produced a nine-part podcast about Cybersyn, Stafford Beer and the group around Salvador Allende, titled 'The Santiago Boys'.[43] |

遺産 プロジェクト・サイバーシンの遺産は、アジェンデ政権の支援にとどまらず、経済計画における革新を探求する人々にも影響を与えた。 歴史的意義 コンピュータ科学者のポール・コックショットと経済学者アリン・コトレルは、1993年の著書『Towards a New Socialism(新しい社会主義に向けて)』の中で、プロジェクト・サイバーシンを、彼らが提案したコンピュータによる社会主義計画経済モデルのイン スピレーションの源として挙げている。[36] 2003年のガーディアン紙は、このプロジェクトを「その時代を数十年先取りした、一種の社会主義的インターネット」と評した。[3] コックショットとコットレルが提案モデルを作成した一方、別の著者は架空の代替案を探求した。 架空の描写 チリの作家ホルヘ・バラディットは、2008年にスペイン語のSF小説『SYNCO』を出版した。この小説は、1973年のクーデターが失敗し、「社会主 義政府が確立し、『最初のサイバネティック国家、普遍的な模範、真の第三の道、奇跡』を築いた」という代替歴史の1979年を舞台にしている。[37] バラディットの小説は、実現したプロジェクトを、明るいユートピアを装った全体主義的支配の抑圧的な独裁政権として描いている。[38] 擁護と批判 このプロジェクトを擁護するサイバーシン元オペレーションマネージャーのラウル・エスペホは、次のように書いている。「テクノクラート的な傾向に対する予 防策は、まさにサイバーシンの導入そのものにありました。サイバーシンは、そのツールを機能させるために、自律性と調整に基づく社会構造を必要としていた からです。[...] もちろん、政治的には、情報技術を強制的な目的のために利用することは常に可能でしたが、それはまったく異なるプロジェクトであり、シンコではないことは 確かです」。[39] 最近では、ジャーナリストがサイバーシンをアルゴリズムによる監視の問題を予見したものだと捉えている。2014年に『The New Yorker』誌に掲載されたエッセイで、テクノロジージャーナリストのエフゲニー・モロゾフ氏は、サイバーシンはビッグデータの道を開き、ビッグテック の運営方法を予見していたと主張し、その例として、Uber がデータとアルゴリズムを使用してサービスの需要と供給をリアルタイムで監視していることを挙げた。[25] 現代的意義 作家たちは、現代の処理能力を用いた計画経済モデルとしてサイバーシンを探求した。作家であるリー・フィリップスとミハウ・ロズウォルスキーも、2019 年の著書『The People's Republic of Walmart』の中で、このプロジェクトに 1 章を割いて紹介している。著者たちは、アマゾン、ウォルマート、国防総省などの大組織が利用する現代の処理能力に支えられた計画経済の実現可能性を擁護す る論拠を提示している。著者たちは、サイバーシンプロジェクトを基盤として多くのことを構築できるかどうか、具体的には、「1 つの国で、限られた数の企業を対象に、内戦に近い緊急事態において使用され、確かに悲惨な状況を部分的にしか改善できなかったシステムが、平和な時代、そ して世界規模で適用できるかどうか」について疑問を投げかけています。このプロジェクトは、1973 年の軍事クーデターにより、シカゴ・ボーイズによる経済改革が行われ、未完成のまま終了しました。[40] メディアの報道 サイバーシンはポッドキャスターの注目も集めた。2016年10月、ポッドキャスト「99% Invisible」がこのプロジェクトに関するエピソードを放送した。[41] ポッドキャスト「Radio Ambulante」は、2019年のエピソード「The Room That Was A Brain」で、アジェンデとサイバーシンプロジェクトの歴史について取り上げた。[42] 最後に、モロゾフはエッセイから、自身のポッドキャストシリーズへと展開した。2023年7月、モロゾフは、サイバーシン、スタッフォード・ビア、サルバ ドール・アジェンデの周辺グループについて、9回シリーズのポッドキャスト「The Santiago Boys」を制作した。[43] |

| Alexander

Kharkevich, the director of the Institute for Information Transmission

Problems in Moscow (later Kharkevich Institute)[44] Comparison of system dynamics software Critique of political economy Cyberocracy Cybernetics in the Soviet Union Economic calculation debate Economic planning Enterprise resource planning Fernando Flores Victor Glushkov (1923–1982) Soviet mathematician and founding father of Soviet cybernetics History of Chile History of computer hardware in Eastern Bloc countries Material balance planning OGAS Planned economy Post-scarcity Socialist democracy Scientific socialism System dynamics The Lucas Plan Viable system model |

アレクサンダー・ハルケヴィッチ、モスクワ情報伝達問題研究所(後のハルケヴィッチ研究所)所長[44]。 システムダイナミクスソフトウェアの比較 政治経済批判 サイバークラシー ソビエト連邦のサイバネティクス 経済計算論争 経済計画 エンタープライズリソースプランニング フェルナンド・フローレス ヴィクトル・グルシュコフ (1923–1982) ソ連の数学者、ソ連サイバネティクスの創始者 チリの歴史 東側諸国のコンピュータハードウェアの歴史 物質収支計画 OGAS 計画経済 ポスト・スカーシティ 社会主義民主主義 科学的社会主義 システムダイナミクス ルカーチ計画 実行可能なシステムモデル |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Cybersyn |

★Stafford Beer, 1926-2002

| Anthony Stafford Beer

(25 September 1926 – 23 August 2002) was a British theorist, consultant

and professor at Manchester Business School.[1] He is known for his

work in the fields of operational research and management cybernetics,

and for his heuristic in systems thinking, "the purpose of a system is

what it does."[2] |

アンソニー・スタッフォード・ビア[機械翻訳はビールとも記載]

(1926年9月25日 - 2002年8月23日)は、イギリスの理論家、コンサルタント、マンチェスター・ビジネススクールの教授だった。[1]

彼は、オペレーションズリサーチと経営サイバネティクスの分野での研究、およびシステム思考における「システムの目的は、そのシステムが何をするかであ

る」という発見で知られている。[2] |

| Biography Early life Anthony Stafford Beer was born in Putney, London, on 25 September 1926. His father was William John Beer, chief statistician at Lloyd's Register of Shipping, who shared a birthday with Stafford's mother, Doris Ethel Beer.[3] At the age of 17 Stafford was expelled from Whitgift School. He enrolled for a degree in philosophy at University College London before leaving to join the British Army as a gunner in the Royal Artillery in 1944, during the Second World War. He soon received commissions, first in the Royal Fusiliers, and then as a company commander in the 9th Gurkha Rifles. Beer served in the British Raj until 1947, when he returned to England and was assigned to the human factors branch of operations research at the War Office. In 1949 he was demobilised, having reached the rank of captain.[4] Beer did not use his given first name, "Anthony", instead preferring his middle name, "Stafford". His younger brother, Ian, also shared this middle name. When Ian was sixteen, Beer persuaded him to sign a document promising not to use "Stafford" as part of his name because Beer "wanted the ‘copyright’ of [the name] Stafford Beer."[5] |

略歴 幼少期 アンソニー・スタッフォード・ビアは、1926年9月25日にロンドンのパトニーで生まれた。父親はロイド船級協会の統計部長だったウィリアム・ジョン・ ビアで、母親のドリス・エセル・ビアと同じ誕生日だった。[3] 17歳の時、スタッフォードはウィットギフト・スクールを退学になった。ロンドン大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジで哲学の学位を取得するために入学したが、 1944年、第二次世界大戦中にイギリス陸軍に入隊し、王立砲兵隊の砲兵として従軍した。彼はすぐに昇進し、まず王立フュージリア連隊に配属され、その 後、第9グルカ連隊の会社指揮官に任命された。ビールは 1947 年まで英領インド帝国で軍務に就き、その後イギリスに戻り、戦争省でオペレーションズリサーチの人間要因部門に配属された。1949 年、大尉の階級に達して除隊した。[4] ビアは、自分のファーストネーム「アンソニー」を使わず、ミドルネーム「スタッフォード」を好んで使っていた。彼の弟、イアンも、このミドルネームを共有 していた。イアンが16歳のとき、ビールは「スタッフォード」という名前を自分の名前の一部として使用しないことを約束する文書に署名するよう彼に説得し た。ビールは「スタッフォード・ビール」という名前の「著作権」を欲しがっていたからだ。[5] |

| United Steel In 1956 he joined United Steel and persuaded the management to fund an operational research group, the Department of Operations Research and Cybernetics, which he headed. This was based in Cybor House, and they installed a Ferranti Pegasus computer, the first in the world dedicated to management cybernetics.[6] SIGMA In 1961 he left United Steel to start an operational research consultancy in partnership with Roger Eddison called SIGMA (Science in General Management). Beer left SIGMA in 1966 to work for a SIGMA client, the International Publishing Corporation (IPC). He left IPC in 1970 to work as an independent consultant, focusing on his growing interest in social systems.[7] His engagement in Latin America began in the 1960s through SIGMA, which worked on industrial optimisation projects in Chile and unsuccessfully explored expansion into other regional markets.[8] |

ユナイテッド・スチール 1956年にユナイテッド・スチールに入社し、経営陣を説得して、オペレーションズ・リサーチ部門「オペレーションズ・リサーチ・アンド・サイバネティク ス」の設立資金を調達し、その責任者を務めた。この部門はサイバーハウスに拠点を置き、経営サイバネティクス専用としては世界初のコンピュータ「フェラン ティ・ペガサス」を導入した。[6] SIGMA 1961年、ユナイテッド・スチールを退職し、ロジャー・エディソンと提携して、SIGMA(Science in General Management)というオペレーションズリサーチのコンサルティング会社を設立した。ビールは1966年にSIGMAを退職し、SIGMAの顧客で あるインターナショナル・パブリッシング・コーポレーション(IPC)に就職した。1970年にIPCを退社し、独立コンサルタントとして、社会システム への関心の高まりに焦点を当てた活動を開始した。[7] ラテンアメリカでの活動は1960年代にSIGMAを通じて始まり、チリでの産業最適化プロジェクトに従事し、他の地域市場への進出を模索したが失敗に終 わった。[8] |

Cybersyn Project Cybersyn was an early form of computational economic planning.  Leon Trotsky's critique of the Soviet Union influenced Beer’s shifting political views and the design of the Cybersyn model. In mid-1971 Beer was approached by Fernando Flores, then a high-ranking member of the Chilean Production Development Corporation (CORFO) in the newly elected socialist government of Salvador Allende, for advice on applying his cybernetic theories to the management of the state-run sector of the Chilean economy.[9][10] This led to Beer's involvement in the never-completed Cybersyn project, which aimed to use computers and a telex-based communication network to allow the government to maximise production while preserving the autonomy of workers and lower management. Beer also was reported to have read and been influenced by Leon Trotsky's critique of the Soviet bureaucracy.[11] According to another senior member of the Cybersyn team, Herman Schwember, Beer's political background and readings completely derived from works written by Trotsky and Trotskyists. Schwember himself disapproved of Trotsky's approach.[12] Although Cybersyn was abandoned after Allende's death during the Pinochet coup in 1973, Beer continued to work in the Americas, consulting for the governments of Canada, Mexico, Uruguay and Venezuela. Beer was particularly involved in the 1980s and 1990s on various governmental cybernetic projects, including Uruguay's successful URUCIB executive information system (1986–1988), Colombia's application of the Viable System Model to public sector reform (1990s–2000s) and unsuccessful ventures in Mexico and Venezuela that were undermined by corruption and political instability.[13][14] |

サイバーシン サイバーシンプロジェクトは、計算機による経済計画の初期の形だった。  レオン・トロツキーのソ連批判は、ビアの政治観の変化とサイバーシンモデルの設計に影響を与えた。 1971年半ば、ビアは、サルバドール・アジェンデの新政権下でチリ生産開発公社(CORFO)の高官だったフェルナンド・フローレスから、チリ経済の国有部門の管理に彼のサイバネティクス理論を適用するアドバイスを求められた。[9][10] これにより、ビアは、コンピュータとテレックスベースの通信ネットワークを利用して、労働者と下級管理職の自主性を維持しながら生産を最大化することを目指した、結局完成しなかったサイバーシンプロジェクトに関わることになった。 ビアは、レオン・トロツキーのソ連官僚機構に対する批判を読んだ影響も受けたと伝えられている[11]。サイバーシンチームの別の幹部、ハーマン・シュ ウェンバーによると、ビアの政治的背景や読書は、トロツキーやトロツキストたちの著作に完全に由来していた。シュウェンバー自身は、トロツキーのアプロー チを否定していた。[12] サイバーシンは、1973年のピノチェトのクーデターでアジェンデが死亡した後、廃止されたが、ビールはアメリカ大陸で働き続け、カナダ、メキシコ、ウル グアイ、ベネズエラの政府に顧問として助言を行った。ビールは 1980 年代から 1990 年代にかけて、ウルグアイの成功した URUCIB 行政情報システム(1986 年~1988 年)、コロンビアの公共部門改革への実行可能システムモデルの適用(1990 年代~2000 年代)、および汚職と政情不安によって失敗に終わったメキシコとベネズエラでの事業など、さまざまな政府のサイバネティクスプロジェクトに特に深く関わっ た。[14] |

| Later activity In the mid-1970s he moved to Mid Wales,[15] where he lived an almost austere lifestyle, developing strong interests in poetry and art. In the 1980s he established a second home on the west side of downtown Toronto.[16] He was a visiting professor at almost 30 universities and received an earned higher doctorate (DSc) from the University of Sunderland and honorary doctorates from the University of Leeds, the University of St. Gallen and the University of Valladolid. He was president of the World Organization of Systems and Cybernetics.[17] Falcondale Collection  Falcondale House In July 1994 Beer ran a residential course at Falcondale House in Lampeter. Nine sessions were recorded as a video learning resource, and are collectively known as the Falcondale collection. They are available online at the Data Repository of Liverpool John Moores University.[18] The sessions covered art, science and philosophy as well as the practical application of cybernetics in society, government, community, management and business. Transcripts were made of the discussions and are also available from the same repository.[18] Family life He was married twice, in 1947 to Cynthia Hannaway, and in 1968 to Sallie Steadman. His partner for the last twenty years of his life was Allenna Leonard, a fellow cybernetician. Beer had five sons and two daughters, one of whom is Vanilla Beer, an artist and essayist.[citation needed] |

その後の活動 1970年代半ば、彼はミッドウェールズに移住し[15]、質素な生活を送る一方で、詩や芸術に強い関心を抱くようになった。1980年代には、トロント のダウンタウン西側に第二の住居を構えた[16]。彼はほぼ30の大学で客員教授を務め、サンダーランド大学から名誉博士号(DSc)を、リーズ大学、サ ンクトガレン大学、バジャドリード大学から名誉博士号を授与された。彼は世界システムとサイバネティクス組織の会長を務めた。[17] ファルコンデール・コレクション  ファルコンデール・ハウス 1994年7月、ビアはランピーターにあるファルコンデール・ハウスで宿泊型講座を開催した。9回のセッションがビデオ学習資料として記録され、総称して ファルコンデール・コレクションと呼ばれている。これらの資料は、リバプール・ジョン・ムーアズ大学のデータリポジトリでオンラインで閲覧可能だ。 [18] セッションでは、芸術、科学、哲学に加え、社会、政府、コミュニティ、管理、ビジネスにおけるサイバネティクスの実践的な応用が取り上げられた。議論の記 録はテキスト化され、同じリポジトリから入手可能だ。[18] 家族生活 彼は 1947 年にシンシア・ハナウェイと、1968 年にサリー・ステッドマンと 2 度結婚した。彼の最後の 20 年間のパートナーは、同じサイバネティックス研究者のアレンナ・レオナルドだった。ビールには 5 人の息子と 2 人の娘がおり、そのうちの 1 人はアーティスト兼エッセイストのバニラ・ビールだ。[要出典] |

Work Sketch for a cybernetic factory, 1959[19] Management cybernetics According to Mike Jackson, a systems scientist, "Beer was the first to apply cybernetics to management, defining cybernetics as the science of effective organization". In the 1960s and early 1970s "Beer was a prolific writer and an influential practitioner" in management cybernetics. It was during that period that he developed the viable system model, to diagnose the faults in any existing organisational system. In that time Jay Wright Forrester invented systems dynamics, which "held out the promise that the behaviour of whole systems could be represented and understood through modelling the dynamical feedback process going on within them".[20] |

仕事 サイバネティック工場のスケッチ、1959年[19] 経営サイバネティクス システム科学者のマイク・ジャクソンによると、「ビールは、サイバネティクスを経営に初めて応用し、サイバネティクスを「効果的な組織化の科学」と定義し た人物だ。1960年代から1970年代初頭にかけて、ビールは経営サイバネティクスの分野において「多作な作家であり、影響力のある実践者」だった。そ の時期に、彼は既存の組織システムの欠陥を診断するための「生存可能システムモデル」を開発した。同じ時期にジェイ・ライト・フォレスターはシステムダイ ナミクスを考案し、これは「システム全体の行動を、その内部で進行する動的フィードバックプロセスをモデル化することで表現し理解できる可能性を示した」 [20]。 |

| Cybersyn Main article: Project Cybersyn  Cybersyn operations room, 1972 During the presidency of Salvador Allende in Chile in the early 1970s, Beer was closely involved with a visionary project, Cybersyn, to apply his cybernetic theories in government. The project's ultimate goal was to create a network of computers and communications equipment that would support the management of the state-run sector of Chile's economy; at its core would be an operations room where government managers could view important information about economic processes in real time, formulate plans of action, and transmit advice and directives to managers at plants and enterprises in the field.[21] However, consistent with cybernetic principles and the ideals of the Allende government, its designers aimed to preserve worker and lower-management autonomy instead of implementing a top-down system of centralised control. The system used a network of about 500 telex machines located at enterprises throughout the country and in government offices in Santiago, some of which were connected to a government-operated mainframe computer that would receive information on production operations, feed that information into economic modelling software, and report on variables (such as raw material supplies) that were outside normal parameters and might require attention. The project, implemented by a multidisciplinary group of both Chileans and foreigners, reached an advanced prototype stage, but was interrupted by the 1973 coup d'état.[21] |

サイバーシン 主な記事:プロジェクト・サイバーシン  1972年のサイバーシン操作室 1970年代初頭、チリのサルバドール・アジェンデ大統領の在任期間中、ビールは、彼のサイバネティクス理論を政府に適用する先見的なプロジェクト「サイ バーシン」に深く関わっていた。このプロジェクトの最終目標は、チリの経済の公的部門の管理を支援するコンピュータと通信機器のネットワークを構築するこ とだった。その中心には、政府の管理者が経済プロセスに関する重要な情報をリアルタイムで確認し、行動計画を策定し、現場の工場や企業に指示や助言を伝達 できるオペレーションルームが置かれる予定だった。[21] しかし、サイバネティクスの原則とアレンデ政権の理想に沿って、設計者は中央集権的なトップダウンシステムを導入するのではなく、労働者と下級管理職の自 律性を維持することを目指した。このシステムは、全国にある企業とサンティアゴの政府機関に設置された約500台のテレックス機からなるネットワークを使 用し、その一部は政府が運営するメインフレームコンピュータに接続されていた。このコンピュータは、生産運営に関する情報を受け取り、経済モデル化ソフト ウェアに情報を入力し、正常な範囲外で注意が必要な変数(原材料の供給状況など)を報告する仕組みになっていた。チリ人と外国人からなる多分野の専門家グ ループによって実施されたこのプロジェクトは、高度なプロトタイプ段階に達したが、1973年のクーデターにより中断された。[21] |

Viable System Model Principal functions of the Viable System Model, 1975. Main article: Viable system model The Viable System Model (VSM) is a model of the organisational structure of any viable or autonomous system. A viable system is any system organised in such a way as to meet the demands of surviving in the changing environment. One of the prime features of systems that survive is that they are adaptable. The VSM expresses a model for a viable system, which is an abstracted cybernetic description that is applicable to any organisation that is a viable system and capable of autonomy. |

実行可能システムモデル 実行可能システムモデルの主な機能、1975年。 主な記事:生存可能システムモデル 生存システムモデル(VSM)は、生存可能または自律的なシステムの組織構造をモデル化したものです。生存システムとは、変化する環境下で生存するための 要求を満たすように組織化されたシステムのことです。生存するシステムの主要な特徴の一つは、適応性があることです。VSMは、生存システムをモデル化し たもので、生存システムであり自律性を持つあらゆる組織に適用可能な抽象化されたサイバネティックな記述です。 |

| Syntegration and Team Syntegrity Syntegrity is a formal model presented by Beer in the 1990s and now is a registered trademark. It is a form of non-hierarchical problem solving that can be used in a small team of 10 to 42 people. It is a business consultation product that is licensed out to consulting firms. The term comes from the words "synergistic" and "tensegrity".[22] POSIWID Main article: The purpose of a system is what it does Stafford Beer coined and frequently used the term POSIWID (the purpose of a system is what it does) to refer to the commonly observed phenomenon that the de facto purpose of a system is often at odds with its official purpose. In an address to the University of Valladolid in October 2001, he said "According to the cybernetician the purpose of a system is what it does. This is a basic dictum. It stands for bald fact, which makes a better starting point in seeking understanding than the familiar attributions of good intention, prejudices about expectations, moral judgment or sheer ignorance of circumstances."[23] This principle has been used to describe Social Machines as intelligent, for example in the case of "games with a purpose",[24] and it provides a link between AI and cybernetics. |

統合とチーム統合 統合は、1990年代にビールによって提唱された正式なモデルで、現在は登録商標となっている。10人から42人の小規模チームで使用できる、非階層的な 問題解決手法だ。コンサルティング会社にライセンス供与されているビジネスコンサルティング製品だ。この用語は、「synergistic(相乗的)」と 「tensegrity(テンセグリティ)」から来ている。[22] POSIWID 主な記事:システムの目的は、その機能である スタッフォード・ビールは、システムの事実上の目的は、その公式の目的と相反することが多いという、よく見られる現象を指す用語として、POSIWID (システムの目的は、その機能である)という用語を考案し、頻繁に使用した。2001年10月、バリャドリッド大学での講演で、彼は次のように述べてい る。「サイバネティクス学者によると、システムの目的は、そのシステムが行うことにある。これは基本的な格言だ。これは、善意、期待に関する偏見、道徳的 判断、あるいは状況に対する純粋な無知といった、よく知られた帰属よりも、理解を求める上でより良い出発点となる、明白な事実を表している。[23] この原則は、例えば「目的を持つゲーム」[24] の場合のように、ソーシャル・マシンを「知的な」ものと説明するために用いられ、AIとサイバネティクスの間のリンクを提供している。 |

| Awards Beer received awards from the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences in 1958, from the United Kingdom Systems Society, the Cybernetics Society, the American Society for Cybernetics and the Operations Research Society of America.[citation needed] Legacy The Stafford Beer Medal is awarded in recognition of the most outstanding contribution to the philosophy, theory or practice of Information Systems published in the European Journal of Information Systems (EJIS) within the relevant year.[25] |

受賞 ビアは、1958年にスウェーデン王立工学アカデミー、英国システム学会、サイバネティクス学会、米国サイバネティクス学会、および米国オペレーションズ・リサーチ学会から賞を受賞した。[要出典] 遺産 スタッフォード・ビアメダルは、該当年度に『European Journal of Information Systems』(EJIS)に掲載された情報システムの哲学、理論、または実践における最も優れた貢献を称えるために授与される。[25] |

| Literature Beer wrote several books and articles:[26] 1959, Cybernetics and Management, English Universities Press. 1966, Decision and Control, Wiley, London. 1968, Management Science: The business use of operations research, Aldus Books, London, Doubleday, New York. 1972, Brain Of The Firm, Allen Lane, The Penguin Press, London, Herder and Herder, USA.Translated into German, Italian, Swedish, French and Russian. 1974, Designing Freedom, CBC Learning Systems, Toronto, 1974; and John Wiley, London and New York, 1975. Translated into Spanish and Japanese. 1975, Platform for Change, John Wiley, London and New York. Reprinted with corrections 1978. 1977, Transit; Poems, CWRW Press, Wales. Limited Edition, Private Circulation. 1979, The Heart of Enterprise, John Wiley, London and New York. Reprinted with corrections 1988. 1981, Brain of the Firm; Second Edition (much extended), John Wiley, London and New York. Reprinted 1986, 1988. Translated into Russian. 1983, Transit; Poems, Second edition (much extended). With audio cassettes: Transit – Selected Readings, and one Person Metagame; Mitchell Communications, Publisher, 2693 Route 845, Carters Point, NB, Canada, E5S 1S2. 1985, Diagnosing the System for Organizations; John Wiley, London and New York. Translated into Italian and Japanese. Reprinted 1988, 1990, 1991. 1986, Pebbles to Computer: The Thread; (with Hans Blohm), Oxford University Press, Toronto. 1994, Beyond Dispute: The Invention of Team Syntegrity; John Wiley, Chichester. Audio 1973, Stafford Beer. "Designing Freedom" The 1973 Massey Lectures RADIO CANADA INTERNATIONAL TRANSCRIPTION: E1121 "The Real Threat to all We Most Dear", E1122 "The Disregarded Tools of Modern Man", E1123, "A Liberty Machine in Prototype" E1124, "Science in The Service of Man" 1h 53:30. 1990, Stafford Beer, "Forty Years of Cybernetics", Gordon Hyde Memorial Lecture at the Cybernetics Society in London, January 1990 (audio file: 1hr 27mins). Video 1990, Stafford Beer, The Intelligent Organization on YouTube Stafford Beer at Monterrey Tec, March 1990 illustrated by Javier Livas About Stafford Beer 1994, Harnden, R and Leonard, A. (Eds.), How Many Grapes Went into the Wine: Stafford Beer on the Art and Science of Holisitic Management; John Wiley, Chichester. 2002, Rosemary Bechler and Rob Passmore, "Stafford Beer: the man who could have run the world",[27] openDemocracy, 7 November 2002 2003, Whittaker, David, Stafford Beer: A Personal Memoir; (Includes an interview with Brian Eno) Wavestone Press, Charlbury 2004, "Ten pints of Beer: The rationale of Stafford Beer's cybernetic books (1959‐94)", Kybernetes, Vol. 33 No. 3/4, pp. 828–842. https://doi.org/10.1108/03684920410523724 2006, Jonathan Rosenhead, "IFORS' Operational Research Hall of Fame Stafford Beer", in International Transactions in Operational Research Vol 13, nr.6, pp. 577–581. 2009, Whittaker, David, (Ed.) Think Before you Think: Social Complexity and Knowledge of Knowing; (Selected writings of Stafford Beer with life chronology), Foreword by Brian Eno, Wavestone Press, Charlbury Morozov, Evgeny (July 2023). "The Santiago Boys". The Santiago Boys (Podcast). Retrieved 10 April 2024. |

文献 ビアは、いくつかの著書や論文を残している[26]。 1959年、『サイバネティクスと経営』、English Universities Press。 1966年、『意思決定と制御』、Wiley、ロンドン。 1968年、『経営科学:オペレーションズ・リサーチのビジネスへの応用』、Aldus Books、ロンドン、Doubleday、ニューヨーク。 1972年、『企業の脳』、アレン・レーン、ペンギン・プレス、ロンドン、ハーダー・アンド・ハーダー、アメリカ。ドイツ語、イタリア語、スウェーデン語、フランス語、ロシア語に翻訳。 1974年、『自由の設計』、CBCラーニング・システムズ、トロント、1974年;ジョン・ワイリー、ロンドンとニューヨーク、1975年。スペイン語と日本語に翻訳。 1975年、『変化のプラットフォーム』、ジョン・ワイリー、ロンドンおよびニューヨーク。1978年に訂正を加えて再版。 1977年、『トランジット;詩集』、CWRWプレス、ウェールズ。限定版、私的流通。 1979年、『企業の心臓部』、ジョン・ワイリー、ロンドンおよびニューヨーク。1988年に訂正を加えて再版。 1981年、『Brain of the Firm; Second Edition(大幅に増補)』、ジョン・ワイリー、ロンドンおよびニューヨーク。1986年、1988年に再版。ロシア語に翻訳。 1983年、『Transit; Poems、Second edition(大幅に増補)』。オーディオカセット付き:『Transit – Selected Readings』および『One Person Metagame』。ミッチェル・コミュニケーションズ、出版社、2693 Route 845、カーターズポイント、NB、カナダ、E5S 1S2。 1985年、『組織のためのシステム診断』; ジョン・ワイリー、ロンドンおよびニューヨーク。イタリア語および日本語に翻訳。1988年、1990年、1991年に再版。 1986年、『Pebbles to Computer: The Thread』(ハンス・ブロームとの共著)、オックスフォード大学出版局、トロント。 1994年、『Beyond Dispute: The Invention of Team Syntegrity』、ジョン・ワイリー、チチェスター。 オーディオ 1973年、スタッフォード・ビア。「Designing Freedom」 1973年マッセイ・レクチャー RADIO CANADA INTERNATIONAL TRANSCRIPTION: E1121 「私たちにとって最も大切なものに対する真の脅威」、E1122 「現代人の無視されているツール」、E1123 「プロトタイプの自由マシン」、E1124 「人間のサービスにおける科学」 1時間53分30秒。 1990年、スタッフォード・ビア、「サイバネティクスの40年」、1990年1月、ロンドンで開催されたサイバネティクス協会でのゴードン・ハイド記念講演(音声ファイル:1時間27分)。 ビデオ 1990年、スタッフォード・ビア、YouTube「インテリジェント・オーガニゼーション」 1990年3月、モンテレー工科大学でのスタッフォード・ビア、イラスト:ハビエル・リバス スタッフォード・ビアについて 1994年、ハーデン、R.、レナード、A.(編)、『ワインには何粒のブドウが使われたか:スタッフォード・ビアのホリスティック・マネジメントの芸術と科学』、ジョン・ワイリー、チチェスター。 2002年、ローズマリー・ベックラー、ロブ・パスモア、「Stafford Beer: the man who could have run the world(スタッフォード・ビア:世界を運営できた男)」、openDemocracy、2002年11月7日 2003年、ウィテカー、デビッド、『Stafford Beer: A Personal Memoir(スタッフォード・ビア:個人的な回想録)』(ブライアン・イーノのインタビューを含む)、Wavestone Press、チャールベリー 2004, 「10パイントのビール:スタッフォード・ビアのサイバネティック書籍(1959-94)の根拠」, Kybernetes, Vol. 33 No. 3/4, pp. 828–842. https://doi.org/10.1108/03684920410523724 2006, Jonathan Rosenhead, 「IFORSのオペレーションズ・リサーチ殿堂 スタッフォード・ビア」, 『International Transactions in Operational Research』第13巻第6号, pp. 577–581. 2009, Whittaker, David, (編) 『Think Before you Think: Social Complexity and Knowledge of Knowing; (スタッフォード・ビアの選集と生涯年表)、序文:ブライアン・イーノ、Wavestone Press、チャールバリー モロゾフ、エフゲニー(2023年7月)。「サンティアゴの少年たち」。サンティアゴの少年たち(ポッドキャスト)。2024年4月10日取得。 |

| W. Ross Ashby Variety (cybernetics) |

|

| Pickering, Andrew (2004), "The

Science of the Unknowable: Stafford Beer's Cybernetic Informatics", in

Rayward, W. Boyd; Bowden, Mary Ellen (eds.), The History and Heritage

of Scientific and Technological Information Systems, Medford, New

Jersey: Information Today, Inc, retrieved 19 March 2013 |

Pickering, Andrew (2004), "The

Science of the Unknowable: Stafford Beer's Cybernetic Informatics", in

Rayward, W. Boyd; Bowden, Mary Ellen (eds.), The History and Heritage

of Scientific and Technological Information Systems, Medford, New

Jersey: Information Today, Inc, retrieved 19 March 2013 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stafford_Beer |

★著者(Eden Medina)のこと

| Eden Medina is

professor of science, technology, and society at MIT where she uses the

history of science, technology, and design as a way to understand

processes of political change, especially in Latin America. She

combines history, science and technology studies, and Latin American

studies in her writings. |

エデン・メディナは、MIT の科学、技術、社会学の教授であり、科学、技術、デザインの歴史を、特にラテンアメリカにおける政治変化のプロセスを理解するための手段として活用している。彼女の著作では、歴史、科学技術研究、ラテンアメリカ研究を融合させている。 |

| She is the author of Cybernetic

Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile (MIT Press,

2011), which won the Edelstein Prize for outstanding book in the

history of technology, the Computer History Museum Prize for

outstanding book in the history of computing, and the Book Prize of the

Recent History and Memory Section (honorable mention) of the Latin

American Studies Association. Her co-edited volume Beyond Imported