人種平等提案

Racial Equality Proposal, 1919;

[人種的差別撤廃提案]

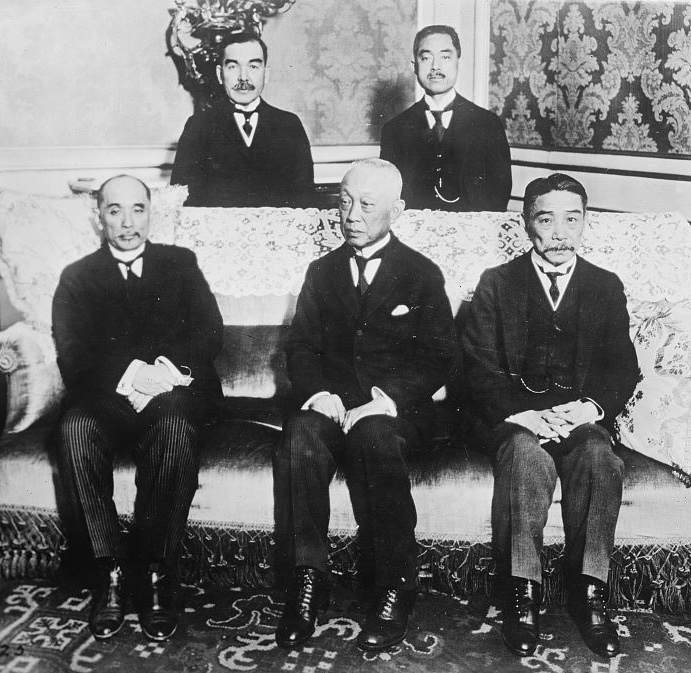

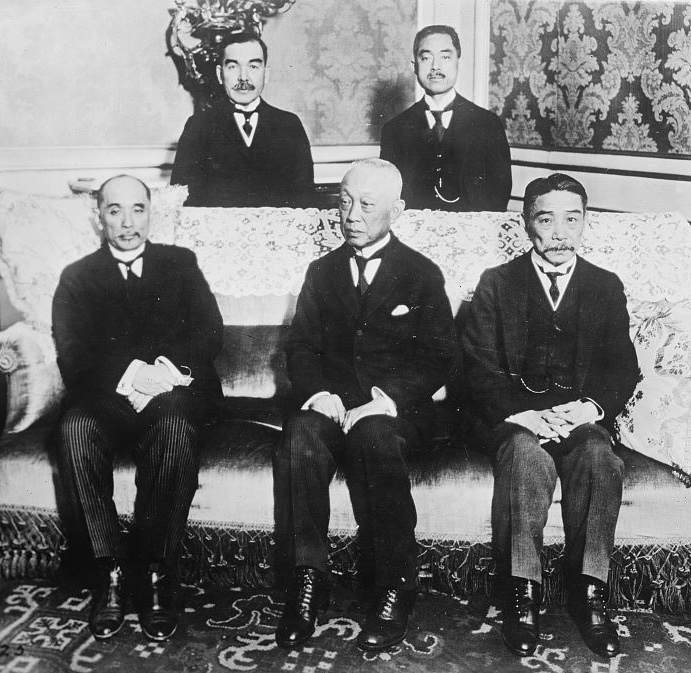

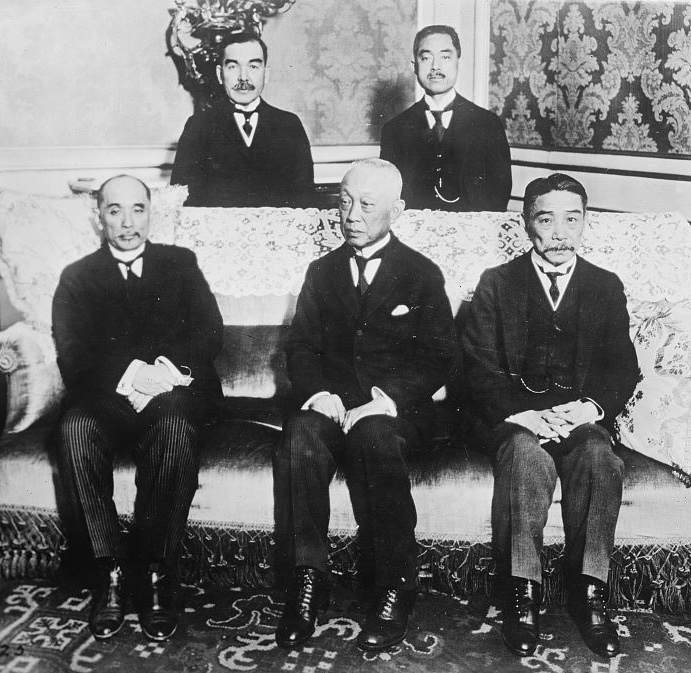

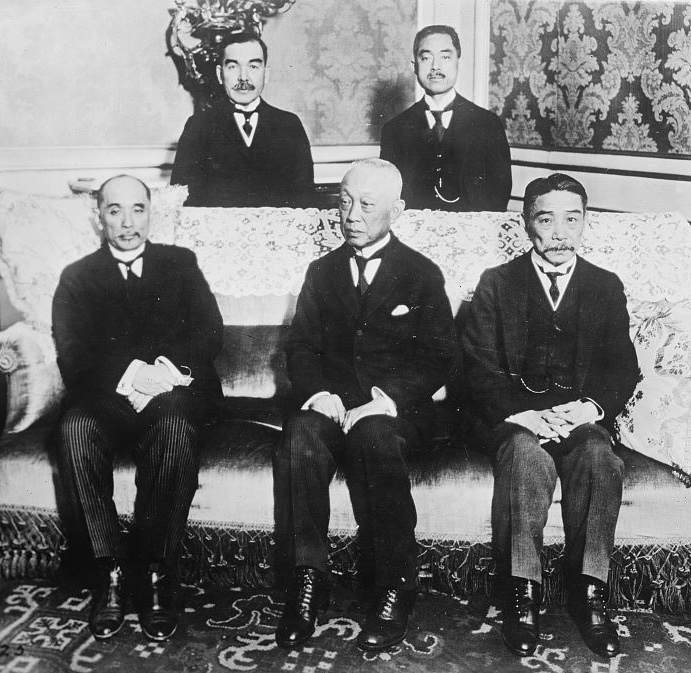

1919 年のパリ講和会議に出席した日本の代表団。左側に座っているのが牧野元外相、中央に座っているのが西園寺元首相、左側に立っているのが伊集院彦吉駐イタリ ア大使など。

☆ 人種平等提案(人種的差別撤廃提案)は、1919年のパリ講和会議で検討されたベルサイユ条約の修正案である。日本が提案したこの提案は、普遍的な意味合 いを持つことを意図したものではなかったが、結果的にそのような意味合いが付け加えられたため、論争を巻き起こした。[1] 1919年6月、日本の外務大臣内田康哉は、この提案は有色人種すべての人種平等を要求するものではなく、国際連盟の加盟国のみを対象とするものであると 述べた。[1] この提案は広く支持されたが、アメリカ合衆国と英連邦代表団(オーストラリア、カナダ、ニュージーランド)の反対により、最終的には条約の一部とはならな かった。 人種平等という原則は戦後に再検討され、1945年には国際正義の基本原則として国連憲章に盛り込まれた。しかし、国連加盟国を含むいくつかの国では、戦 後数十年にわたって人種差別的な法律が維持され続けた。

| The Racial Equality

Proposal (Japanese: 人種的差別撤廃提案, lit. "Proposal to abolish racial

discrimination") was an amendment to the Treaty of Versailles that was

considered at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Proposed by Japan, it

was never intended to have any universal implications, but one was

attached to it anyway, which caused its controversy.[1] Japanese

Foreign Minister Uchida Kōsai stated in June 1919 that the proposal was

intended not to demand the racial equality of all coloured peoples but

only that of members of the League of Nations.[1] Though it was broadly supported, the proposal did not become part of the treaty, largely because of opposition by the United States and the dominions of the British Empire Delegation, namely Australia, Canada and New Zealand.[2] The principle of racial equality was revisited after the war and incorporated into the United Nations Charter in 1945 as a fundamental principle of international justice. However, several countries, including members of the United Nations, would continue to retain racially discriminatory laws for decades after the end of the war. |

人種平等提案(人種的差別撤廃提案)は、1919年のパリ講和会議で検

討されたベルサイユ条約の修正案である。日本が提案したこの提案は、普遍的な意味合いを持つことを意図したものではなかったが、結果的にそのような意味合

いが付け加えられたため、論争を巻き起こした。[1]

1919年6月、日本の外務大臣内田康哉は、この提案は有色人種すべての人種平等を要求するものではなく、国際連盟の加盟国のみを対象とするものであると

述べた。[1] この提案は広く支持されたが、アメリカ合衆国と英連邦代表団(オーストラリア、カナダ、ニュージーランド)の反対により、最終的には条約の一部とはならな かった。 人種平等という原則は戦後に再検討され、1945年には国際正義の基本原則として国連憲章に盛り込まれた。しかし、国連加盟国を含むいくつかの国では、戦 後数十年にわたって人種差別的な法律が維持され続けた。 |

| Background Japan attended the 1919 Paris Peace Conference as one of five great powers, the only one which was non-Western.[3] The presence of Japanese delegates in the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles signing the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919 reflected the culmination of a half-century intensive effort by Japan to transform the nation into a modern state on the international stage.[3] Japanese domestic politics Prime Minister Hara Takashi had come into power in September 1918 and was determined for Japan to adopt a pro-western foreign policy (欧米協調主義, ōbei kyōchō shugi) at the peace conference.[4] That was largely in consequence of the World War I governments under Prime Ministers Ōkuma Shigenobu and Terauchi Masatake, whose expansionist policies had the effect of alienating Japan from both the United States and Britain.[4] Takashi was determined to support the creation of the League of Nations at the peace conference to steer Japan back to the West.[4] However, there was quite a bit of scepticism towards the League. Domestic opinion was divided into Japanese who supported the League and those who opposed it, the latter being more common in national opinion (国論, kokuron).[5] Hence, the proposal had the role of appeasing the opponents by allowing Japan's acceptance of the League to be conditional on having a Racial Equality Clause inserted into the covenant of the League.[5] Despite the proposal, Japan itself had racial discrimination policies, especially towards non-Yamato people.[6][7][8] |

背景 日本は1919年のパリ講和会議に五大国の一員として出席したが、そのうち西洋以外の国は日本だけだった。[3] 1919年6月28日、ベルサイユ宮殿の鏡の回廊で日本代表団がヴェルサイユ条約に署名したことは、半世紀にわたる日本国民の努力の結晶であり、国際社会 における近代国家への変革を象徴する出来事であった。[3] 日本国内の政治 1918年9月に首相に就任した原敬は、日本が講和会議において親欧米的な外交政策(欧米協調主義)を採用するよう強く決意していた。[4] これは、第一次世界大戦中の大隈重信 、その拡張主義的政策は日本をアメリカとイギリスの両国から疎遠にする結果となった。[4] 原敬は、日本を再び西洋に導くために、平和会議で国際連盟の創設を支持することを決意していた。[4] しかし、国際連盟に対する懐疑的な見方もかなりあった。国内の意見は、国際連盟を支持する日本人と反対する日本人に分かれており、後者の意見が国民の意見 (国論)では一般的であった。[5] したがって、日本の連盟加盟を条件付きで認めるという提案は、連盟規約に人種平等条項を挿入することで反対派をなだめる役割を果たしていた。[5] 提案にもかかわらず、日本自体が人種差別政策をとり、特に大和民族以外の人々に対して差別的で あった。[6][7][8] |

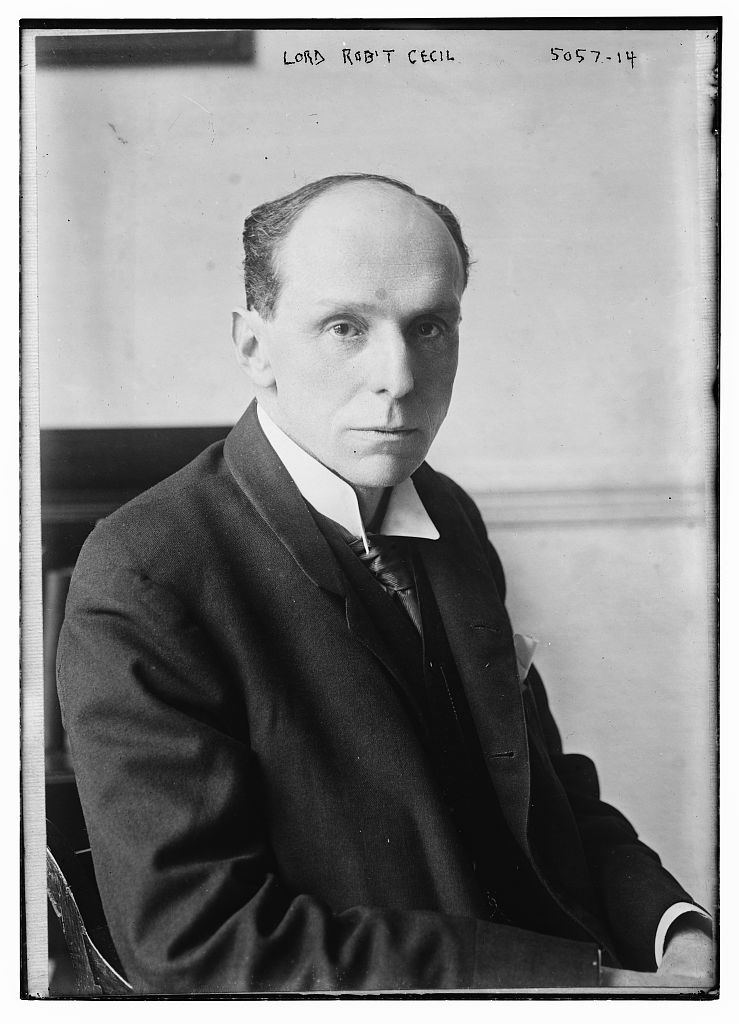

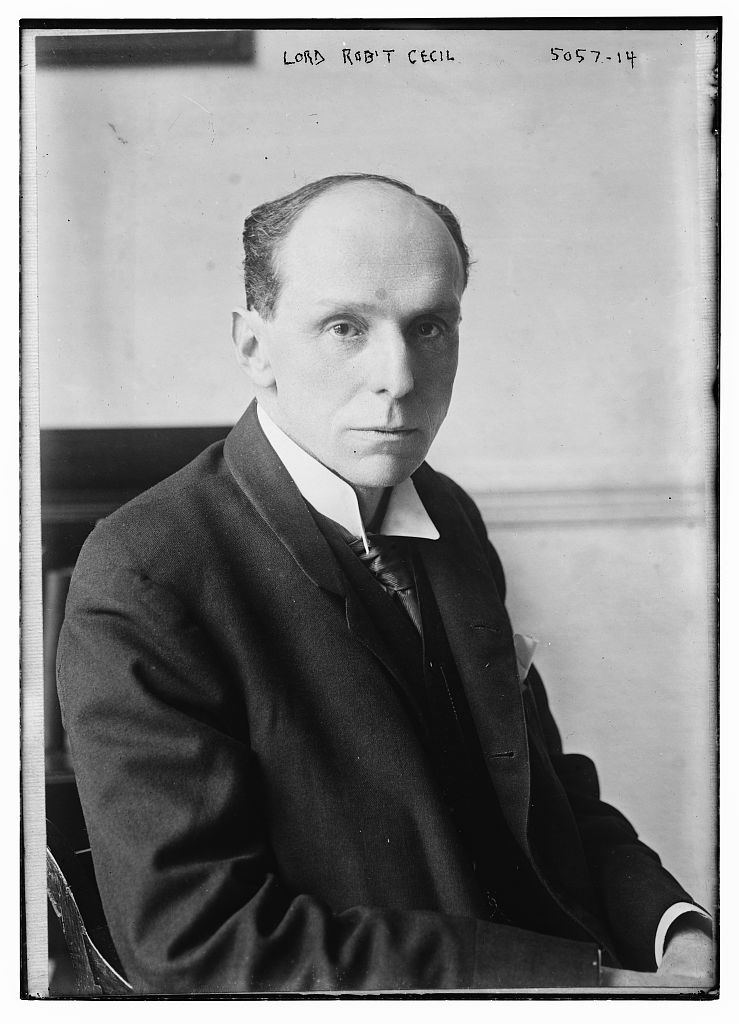

Proposal  Baron Makino Nobuaki Japan's delegation to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference consisting of former Foreign Minister Baron Makino (seated on the left), former Prime Minister Marquis Saionji (seated, center), and Japanese ambassador to Italy Ijūin Hikokichi (standing, left), among others.  Lord Cecil After the end of seclusion in the 1850s, Japan signed unequal treaties, the so-called Ansei Treaties, but soon came to demand equal status with the Western powers. Correcting that inequality became the most urgent international issue of the Meiji government. In that context, the Japanese delegation to the Paris peace conference proposed the clause in the Covenant of the League of Nations. The first draft was presented to the League of Nations Commission on 13 February as an amendment to Article 21: The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord as soon as possible to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality. In a speech, the Japanese diplomat Makino Nobuaki stated that during the war men of different races had fought together on the Allied side, leading to say: "A common bond of sympathy and gratitude has been established to an extent never before experienced."[9] The Japanese delegation had not realized the full ramifications of their proposal[citation needed] since its adoption would have challenged aspects of the established norms of the day's Western-dominated international system, which involved the colonial rule over non-white people. The intention of the Japanese was to secure equality of their nationals and the equality for members of the League of Nations,[1] but a universalist meaning and implication of the proposal became attached to it within the delegation, which drove its contentiousness at the conference.[10] After Makino's speech, Lord Cecil stated that the Japanese proposal was a very controversial one and he suggested that perhaps the matter was so controversial that it should not be discussed at all.[9] Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos also suggested that a clause banning religious discrimination should also be removed since that was also a very controversial matter.[9] Cecil removed all references to clauses that forbade racial and religious discrimination from the text of the peace treaty, but the Japanese made it clear that they would seek to have the clause restored.[9] By then, the clause was beginning to draw widespread public attention. Demonstrations in Japan demanded the end of the "badge of shame" as policies to exclude Japanese immigration in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand received much attention in the Japanese media.[9] In the United States, the clause received much negative media coverage on the West Coast.[9] The Chinese delegation, which was otherwise in bitter enmity with the Japanese over the question of the former German colony of Qingdao and the rest of the German concessions in Shandong Province, also said that it would support the clause.[9] However, one Chinese diplomat said at the time that the Shandong question was far more important to his government than the clause.[9] Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes clarified his opposition and announced at a meeting that "ninety-five out of one hundred Australians rejected the very idea of equality."[11] Hughes had entered politics as a trade unionist and, like most others in the working class, was very strongly opposed to Asian immigration to Australia. (The exclusion of Asian immigration was a popular cause with unions in Canada, the US, Australia, and New Zealand in the early 20th century.) Hughes believed that accepting the clause would mean the end of the White Australia immigration policy that had been adopted in 1901 and wrote: "No Gov't could live for a day in Australia if it tampered with a White Australia."[12] Hughes stated, "The position is this-either the Japanese proposal means something or it means nothing: if the former, out with it; if the latter, why have it?"[12] New Zealand Prime Minister William Massey also came out in opposition to the clause though not as vociferously as Hughes.[12] Makino Nobuaki, the career diplomat who headed the Japanese delegation, then announced at a press conference: "We are not too proud to fight but we are too proud to accept a place of admitted inferiority in dealing with one or more of the associated nations. We want nothing but simple justice."[13] France declared its support for the proposal since the French position had always been that the French language and culture was a "civilizing" force open to all regardless of skin color.[12] British Prime Minister David Lloyd George found himself in an awkward situation since Britain had signed an alliance with Japan in 1902, but he also wanted to hold the British Empire's delegation together.[12] South African Prime Minister General Jan Smuts and Canadian Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden tried to work out a compromise by visiting Makino and Chinda Sutemi and Hughes, serving as mediators.[12] Borden and Smuts were able to arrange a meeting between Makino, Chinda, and Hughes, which ended badly. The Japanese diplomats wrote that Hughes was a vulgar "peasant" who was loud and obnoxious, and Hughes complained that the Japanese had been "beslobbering me with genuflexions and obsequious deference."[12] However, Borden and Smuts were able to persuade Hughes to accept the clause if it was declared that it did not affect immigration.[12] Makino and Chinda then rejected the compromise.[12] |

提案  牧野伸顕男爵 1919年のパリ講和会議に出席した日本の代表団。左側に座っているのが牧野元外相、中央に座っているのが西園寺元首相、左側に立っているのが伊集院彦吉 駐イタリア大使など。  セシル卿 1850年代に鎖国を終えた後、日本は不平等条約、いわゆる安政条約を締結したが、すぐに欧米列強と対等の立場を要求するようになった。この不平等を是正 することが、明治政府にとって最も差し迫った国際問題となった。そのような状況下で、パリ講和会議の日本代表団は、国際連盟規約の条項を提案した。最初の 草案は、2月13日に国際連盟委員会に第21条の修正案として提出された。 「国民の平等」は国際連盟の基本原則である。締約国は、国際連盟加盟国のすべての外国人に対して、人種や国籍による差別を法律上も事実上も一切行わず、あ らゆる面で平等かつ正当な待遇をできる限り早期に与えることに同意する。 日本の外交官、牧野伸顕は演説の中で、戦争中には人種が異なる人々が連合国側で共に戦ったと述べ、次のように述べた。「共感と感謝の絆が、かつてないほど に強固に築かれた」と述べた[9]。日本代表団は、この提案が採択されれば、白人による支配が続いていた当時の国際システムにおける確立された規範に疑問 を投げかけることになるため、その提案が持つ影響力の大きさを十分に理解していなかった[要出典]。日本側の意図は自国民の平等と国際連盟加盟国の平等を 確保することにあったが[1]、提案には普遍的な意味合いと含みが含まれており、それが会議での論争を招くこととなった[10]。 牧野の演説の後、セシル卿は、日本の提案は非常に物議を醸すものであると述べ、おそらくこの問題はあまりにも物議を醸すものであるため、一切議論すべきで はないと提案した。[9] ギリシャの首相エレフテリオス・ヴェニゼロスも、宗教差別を禁止する条項もまた非常に物議を醸す問題であるため、削除すべきだと提案した。[9] セシルは、人種差別と宗教差別を禁じる条項のすべてを平和条約の条文から削除したが、日本側は条項の復活を求める意向を明らかにした。[9] それまでに、この条項は広く一般の人々の関心を集め始めていた。日本では、米国、カナダ、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドにおける日本人移民排斥政策が 日本のメディアで大きく取り上げられ、「恥の印」の廃止を求めるデモが起こった。[9] 米国では、この条項は西海岸で否定的なメディア報道を多く受けた。 また、それ以外では山東省の旧ドイツ植民地青島やその他のドイツ利権を巡って日本と激しく敵対していた中国代表団も、この条項を支持すると表明した。しか し、ある中国外交官は当時、山東問題は条項よりもはるかに自国政府にとって重要であると述べた。 オーストラリアのビリー・ヒューズ首相は反対の立場を明確にし、ある会議で「オーストラリア人の100人中95人は、平等という考えそのものを拒絶してい る」と発表した。[11] ヒューズは労働組合活動家として政界入りした人物であり、他の労働者階級の人々と同様に、アジアからのオーストラリアへの移民に強く反対していた。(アジ ア系移民の排斥は、20世紀初頭のカナダ、米国、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドの労働組合の共通の主張であった。)ヒューズは、この条項を受け入れる ことは1901年に採択された白人優遇政策の廃止を意味すると考え、「白人優遇政策に手を加えれば、オーストラリアで一日たりとも政府が存続することはで きない」と書いた。[12] ヒューズは、「立場はこうだ。つまり、日本側の提案には意味があるのか、それとも意味がないのか、どちらかだ。もし前者の意味があるというのであれば、そ の提案は受け入れられない。後者の意味がないというのであれば、なぜそのような提案をしてくるのか」[12] ニュージーランドのウィリアム・マッセイ首相も、ヒューズほどではないにしても、条項に反対の立場を表明した。 日本代表団の団長を務めたキャリア外交官の牧野伸顕は、記者会見で次のように述べた。「我々は戦うことに誇りを持っているが、1つまたは複数の連合国民と 対等ではないことを認め、その立場を受け入れることに誇りを持っているわけではない。我々はただ単純な正義を求めているだけだ」[13] フランスは、フランス語やフランス文化は肌の色に関係なく万人に開かれた「文明化」の力であるという立場を常に主張していたため、この提案を支持すると宣 言した。[12] 英国首相のデイヴィッド・ロイド・ジョージは、英国は1902年に日本と同盟を結んでいたため、厄介な立場に置かれたが、 大英帝国の代表団をまとめたいとも考えていた。南アフリカの首相ヤン・スマッツ将軍とカナダの首相ロバート・ボーデン卿は、仲介者として牧野、新渡戸、 ヒューズを訪ね、妥協案を模索しようとした。ボーデンとスマッツは、牧野、新渡戸、ヒューズの会談をセッティングしたが、それは最悪な結果に終わった。日 本の外交官たちは、ヒューズは下品な「百姓」で、大声で不快な人物だったと書き記している。また、ヒューズは日本人が「ひれ伏し、卑屈な態度で私にべった りくっついてくる」と不満を漏らしたという。[12] しかし、ボーデンとスマッツは、この条項が移民には影響しないと宣言すれば受け入れるようヒューズを説得した。[12] その後、牧野と近藤は妥協案を拒否した。[12] |

| Vote On April 11, 1919, the commission held a final session.[14] Makino stated the Japanese plea for human rights and racial equality.[15] The British representative Robert Cecil spoke for the British Empire and addressed opposition to the proposal.[16] Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando spoke in favor of the statement on human rights.[17] French Senator Léon Bourgeois urged its adoption and stated that it would be impossible to reject the proposal, which embodied "an indisputable principle of justice."[18] The proposal received a majority vote on the day,[14] with 11 of the 17 delegates present voted in favor of its amendment to the charter, and no negative vote was taken: Japan (2) Yes France (2) Yes Italy (2) Yes Brazil (1) Yes China (1) Yes Greece (1) Yes Serbia (1) Yes Czechoslovakia (1) Yes Total: 11 Yes British Empire (2) – Not Registered United States (2) – Not Registered Portugal (1) – Not Registered Romania (1) – Not Registered Belgium (2) – Absent[19] The chairman, Woodrow Wilson, overturned it by saying that although the proposal had been approved by a clear majority, the particular matter had strong opposition manifest itself (despite the lack of any actual votes against the proposal[19]) and that on this issue, a unanimous vote would be required.[20] French delegate Ferdinand Larnaude immediately stated that "a majority had voted for the amendment."[21] Meanwhile, the Japanese delegation wanted the transcript to show that a clear majority had been voted for the amendment.[21] Though the proposal itself was compatible with the British stance of equality for all subjects as a principle for maintaining imperial unity, there were significant deviations in the stated interests of its dominions, notably Australia. As it risked undermining the White Australia Policy, Billy Hughes and Joseph Cook vigorously opposed the proposal behind the scenes and advocated against it through the British delegation. Without the support of its dominions, the British delegation could not take such a stand on principle. According to the diary of Cecil, the delegate representing the British Empire at the conference: ...it is curious how all the foreigners perpetually harp on principle and right and other abstractions, whereas the Americans and still more the British are only considering what will give the best chance to the League of working properly.[22] To placate Japan, Wilson promised to support the Japanese claims on the former German possessions in China and said that it would be Japan's reward for accepting the rejection of the proposal.[23] Furthermore, over the advice of the United States Navy, Wilson also agreed to support Japanese claims to the Marianas, Marshall, and Caroline islands in the Pacific Ocean, which Japan had occupied in 1914, as mandates that Japan would administer on behalf of the League of Nations, instead of allowing the Japanese to annex the islands outright, as they had wanted.[24] In May 1919, the peace conference formally decided that Japan would receive the Carolines, Marshall, and Marianas Islands as Class C League of Nations mandates.[25] In the 1920s, Japan violated the terms of the mandates by preventing representatives of the League from visiting the islands, by bringing in settlers on the islands, and by building military bases, most notably at Truk, which became the main Japanese naval base in the Pacific.[25] The Canadian historian Margaret Macmillan noted that some of the islands (most notably Truk, Tinian, and Saipan) that had been awarded to Japan in 1919 to be developed peacefully would become the scenes for famous battles in World War II.[25] |

投票 1919年4月11日、委員会は最終会合を開いた。[14] マキノは、人権と人種平等を求める日本の主張を述べた。[15] イギリス代表のロバート・セシルは、大英帝国を代表して演説し、この提案に反対する立場を表明した。[16] イタリア首相ヴィットーリオ・オルランドは人権に関する声明に賛成の意を表明した。[17] フランスのレオン・ブルジョワ上院議員は採択を強く促し、「議論の余地のない正義の原則」を体現するこの提案を拒否することは不可能であると述べた。 [18] この提案は当日、出席した17人の代表のうち11人が賛成票を投じ、憲章改正に賛成多数で可決され、反対票はなかった。 日本(2)賛成 フランス(2)賛成 イタリア(2)賛成 ブラジル(1)賛成 中国(1)賛成 ギリシャ(1)賛成 セルビア(1)賛成 チェコスロバキア(1)賛成 合計:11票賛成 大英帝国(2) - 未登録 アメリカ(2) - 未登録 ポルトガル(1) - 未登録 ルーマニア(1) - 未登録 ベルギー(2) - 欠席[19] 議長のウッドロウ・ウィルソンは、この提案は明確な多数決で承認されたものの、この特定の案件には強い反対意見が表明されている(提案に対する反対票は実 際にはなかったが[19])とし、この問題については全会一致の 票が必要であると述べた。[20] フランスの代表フェルディナン・ラルノーはただちに「修正案には賛成多数だった」と述べた。[21] 一方、日本代表団は議事録に「修正案には明確な賛成多数だった」と記載するよう求めた。[21] この提案自体は、帝国の結束を維持するための原則として、臣民すべてに平等を求める英国の立場と一致するものであったが、特にオーストラリアなどの属領の 主張には大きな隔たりがあった。この提案は「白豪主義」を弱体化させる恐れがあったため、ビリー・ヒューズとジョセフ・クックは水面下でこの提案に強く反 対し、英国代表団を通じて反対を唱えた。植民地の支持がなければ、英国代表団はこのような原則的な立場を取ることはできなかった。英国帝国を代表する会議 出席者の日記によると、 「外国人が常に原則や権利、その他の抽象的な概念について延々と語ることは興味深い。一方、アメリカ人、そしてさらにイギリス人は、国際連盟がうまく機能 するための最善の策についてのみ考えている」[22] 日本をなだめるため、ウィルソン大統領は、中国における旧ドイツ領に対する日本の主張を支持することを約束し、その提案を拒否することを受け入れたことに 対する日本の報酬であると述べた。[23] さらに、アメリカ海軍の助言に従い、ウィルソン大統領は、1914年に日本が占領した太平洋上のマリアナ諸島、マーシャル諸島、カロリン諸島に対する日本 の主張を支持することにも同意した。これらの諸島は、日本が 。1919年5月、平和会議は正式に、日本がC級委任統治領としてカロリン諸島、マーシャル諸島、マリアナ諸島を受け取ることが決定された。[25] 1920年代、日本は委任統治領の条件に違反し、国際連盟の代表団の諸島訪問を妨害 、入植者を島に連れて行き、軍事基地を建設した。特に、トラック島には太平洋における日本の主要な海軍基地が建設された。[25] カナダの歴史家マーガレット・マクミランは、1919年に日本に割譲され平和的に開発されることになっていた島々(特にトラック島、テニアン島、サイパン 島)が、第二次世界大戦における有名な戦場の舞台となったと指摘している。[25] |

| Aftermath Cecil felt that British support for the League of Nations was far more important than the clause. The Japanese media fully covered the progress of the conference, which led to the alienation of public opinion towards the US and would foreshadow later, broader conflicts. In the US, racial riots resulted from deliberate inaction.[26] The international mood had changed so dramatically by 1945, that the contentious point of racial equality would be incorporated into that year's United Nations Charter as a fundamental principle of international justice. Some historians[who?] consider that the rejection of the clause could be listed among the many causes of conflict that led to World War II. They[who?] maintain that the rejection of the clause proved to be an important factor in turning Japan away from co-operation with the West and toward militarism.[23] In 1923, the Anglo-Japanese Alliance expired. Militarists came to power resulting in Japan's rapprochement with Hitler. Prussian militarism had already become entrenched in the Imperial Japanese Army, many of whose members had expected Germany to win World War I.[citation needed] However, relations with Germany became even stronger in the mid-1930s while Germany had greater ties with Nationalist China. After the Nazis gained power in Germany, Japan decided to not expel Jewish refugees from China, Manchuria, and Japan[27][28] and advocated the political slogan Hakkō ichiu (literally "eight crown cords, one roof", or "all the world under one roof") |

余波 セシルは、イギリスの国際連盟支持は、条項よりもはるかに重要であると感じていた。日本のメディアは会議の進展を完全に報道し、それはアメリカに対する世 論の疎外につながり、後に広範な紛争の予兆となった。 米国では、意図的な不作為により人種暴動が発生した。[26] 1945年までに国際情勢は劇的に変化し、人種平等の論点は、国際正義の根本原則として、その年の国連憲章に盛り込まれることになった。 一部の歴史家[誰?]は、この条項の拒絶が第二次世界大戦につながる多くの紛争の原因のひとつであったと見なしている。彼ら[誰?]は、この条項の拒絶 が、日本が西洋との協力を拒み、軍国主義へと向かう重要な要因となったと主張している。[23] 1923年、日英同盟は失効した。軍国主義者が政権を握り、日本はヒトラーと接近した。プロイセン的軍国主義はすでに日本帝国陸軍に根付いており、その多 くのメンバーは第一次世界大戦でドイツの勝利を期待していた。しかし、1930年代半ばにはドイツと中国の国民党との関係が深まる一方で、ドイツとの関係 はさらに強固なものとなった。 ナチスがドイツで政権を握った後、日本は中国、満州、日本からユダヤ人難民を追放しないことを決定し[27][28]、「八紘一宇(文字通りには「八つの 王冠の紐、一つの屋根」、すなわち「全世界が一つの屋根の下にある」)」という政治スローガンを提唱した。 |

| Woodrow Wilson and race#Blocking

the racial equality proposal The Race Question, UNESCO 1950 Yellow Peril |

ウッドロウ・ウィルソンと人種問題#人種平等案の阻止 人種に関するユネスコ宣言(1950) 黄禍 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆