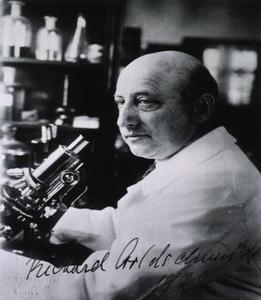

リチャード・ゴールドシュミット

Richard Goldschmidt, 1878-1958

リチャード・ゴールドシュミット

Richard Goldschmidt, 1878-1958

リチャード[リヒャルト]・ゴールドシュミット(Richard Benedict Goldschmidt、1878年4月12日 - 1958年4月24日)は、ドイツ生まれのアメリカ人遺伝学者である。彼は遺伝学、発生、進化を統合しようとした最初の人物と考えられている。

| Richard Benedict Goldschmidt (April

12, 1878 – April 24, 1958) was a German-born American geneticist. He is

considered the first to attempt to integrate genetics, development, and

evolution.[1] He pioneered understanding of reaction norms, genetic

assimilation, dynamical genetics, sex determination, and

heterochrony.[2] Controversially, Goldschmidt advanced a model of

macroevolution through macromutations popularly known as the "Hopeful

Monster" hypothesis.[3] Goldschmidt also described the nervous system of the nematode, a piece of work that influenced Sydney Brenner to study the wiring diagram of Caenorhabditis elegans,[4] winning Brenner and his colleagues the Nobel Prize in 2002. |

リ

チャード・ゴールドシュミット(Richard Benedict Goldschmidt、1878年4月12日 -

1958年4月24日)は、ドイツ生まれのアメリカ人遺伝学者である。彼は遺伝学、発生、進化を統合しようとした最初の人物と考えられている[1]。

彼は反応規範、遺伝的同化、動的遺伝学、性決定、異時性についての理解を広めた[2]。論争となったのは、「ホープフルモンスター(希望に満ちた怪物)」

仮説として一般的に知られる大変異による大進化のモデルを推進したこと[3]であった。 また、ゴールドシュミットは線虫の神経系を記述したが、この研究はシドニー・ブレナーに影響を与え、線虫の配線図を研究させ、ブレナーらは2002年にノーベル賞を受賞した[4]。 |

| Childhood and education Goldschmidt was born in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany to upper-middle class parents of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage.[5] He had a classical education and entered the University of Heidelberg in 1896, where he became interested in natural history. From 1899 Goldschmidt studied anatomy and zoology at the University of Heidelberg with Otto Bütschli and Carl Gegenbaur. He received his Ph.D. under Bütschli in 1902, studying development of the trematode Polystomum.[2] |

幼少期と教育 ゴールドシュミットはドイツのフランクフルト・アム・マインでアシュケナージ・ユダヤ人の血を引く中流階級の両親のもとに生まれた[5]。 古典的な教育を受け、1896年にハイデルベルク大学に入学し、自然史に興味を持つようになった。1899年からハイデルベルク大学でオットー・ビュッチ リ、カール・ゲーゲンバウルのもとで解剖学と動物学を学んだ。1902年、ビュッチュリのもとで震虫ポリストマムの発生を研究し、博士号を取得した [2]。 |

| Career In 1903 Goldschmidt began working as an assistant to Richard Hertwig at the University of Munich, where he continued his work on nematodes and their histology, including studies of the nervous system development of Ascaris and the anatomy of Amphioxus. He founded the histology journal Archiv für Zellforschung while working in Hertwig's laboratory. Under Hertwig's influence, he also began to take an interest in chromosome behavior and the new field of genetics.[2] In 1909 Goldschmidt became professor at the University of Munich and, inspired by Wilhelm Johannsen's genetics treatise Elemente der exakten Erblichkeitslehre, began to study sex determination and other aspects of the genetics of the gypsy moth of which he was crossbreeding different races. He observed different stages of their sexual development. Some of the animals were neither male, nor female, nor hermaphrodites, but represented a whole spectrum of gynandromorphism. He named them 'intersex', and the phenomenon accordingly 'intersexuality' (Intersexualität).[6] His studies of the gypsy moth, which culminated in his 1934 monograph Lymantria, became the basis for his theory of sex determination, which he developed from 1911 until 1931.[2] Goldschmidt left Munich in 1914 for the position as head of the genetics section of the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology.[7] During a field trip to Japan in 1914 he was not able to return to Germany due to the outbreak of the First World War and got stranded in the United States. He ended up in an internment camp in Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia for "dangerous Germans".[8] After his release in 1918 he returned to Germany in 1919 and worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Sensing that it was unsafe for him to remain in Germany he emigrated to the United States in 1936, where he became professor at the University of California, Berkeley. During World War 2, the Nazi party published a propaganda poster entitled "Jewish World Domination" displaying the Goldschmidt family tree.[9] |

経歴 1903年、ゴールドシュミットはミュンヘン大学でリチャード・ヘルトヴィヒの助手として働き始め、アスカリスの神経系の発達やアンフィオクサスの解剖学 など、線虫とその組織学に関する研究を継続した。彼は、ヘルトヴィッヒの研究室に在籍しながら、組織学雑誌『Archiv für Zellforschung』を創刊した。また、ハートヴィッヒの影響により、染色体の挙動や新しい分野である遺伝学に関心を持ち始めた[2]。 1909年、ゴールドシュミットはミュンヘン大学の教授と なり、ヴィルヘルム・ヨハンセンの遺伝学の論文『Elemente der exakten Erblichkeitslehre』に触発されて、異なる種を交配したマイマイガについて性決定や遺伝学の他の側面を研究するようになった。彼は、彼ら の性発生のさまざまな段階を観察した。 その中には、雄でもなく、雌でもなく、両性具有でもない、あらゆる種類の雌雄異形を代表する動物がいた。彼はそれらを「インターセックス」と名付け、その 現象を「インターセクシュアル性」(Intersexualität)と呼んだ[6]。1934年のモノグラフ『Lymantria』に結実したマイマイ ガの研究は、1911年から1931年まで彼が展開した性決定理論の基礎となった[2]。 1914年に日本を訪問した際、第一次世界大戦の勃発によりドイツに戻ることができず、米国に足止めを食らった。1918年に解放された後、1919年にドイツに戻り、カイザー・ヴィルヘルム研究所に勤務した(副所長)[8]。ドイツに留まるのは危険と判断し、1936年にアメリカに移住し、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の教授となった。第二次世界大戦中、ナチス党はゴールドシュミットの家系図を表示した「ユダヤ人の世界征服」というプロパガンダポスターを発行した[9]。 |

| Evolution Goldschmidt was the first scientist to use the term "hopeful monster". He thought that small gradual changes could not bridge the divide between microevolution and macroevolution. In his book The Material Basis of Evolution (1940), he wrote "the change from species to species is not a change involving more and more additional atomistic changes, but a complete change of the primary pattern or reaction system into a new one, which afterwards may again produce intraspecific variation by micromutation." Goldschmidt believed the large changes in evolution were caused by macromutations (large mutations). His ideas about macromutations became known as the hopeful monster hypothesis, a type of saltational evolution, and attracted widespread ridicule.[10] According to Goldschmidt, "biologists seem inclined to think that because they have not themselves seen a 'large' mutation, such a thing cannot be possible. But such a mutation need only be an event of the most extraordinary rarity to provide the world with the important material for evolution".[11] Goldschmidt believed that the neo-Darwinian view of gradual accumulation of small mutations was important but could account for variation only within species (microevolution) and was not a powerful enough source of evolutionary novelty to explain new species. Instead he believed that large genetic differences between species required profound "macro-mutations", a source for large genetic changes (macroevolution) which once in a while could occur as a "hopeful monster".[12][13] Goldschmidt is usually referred to as a "non-Darwinian"; however, he did not object to the general microevolutionary principles of the Darwinians. He veered from the synthetic theory only in his belief that a new species develops suddenly through discontinuous variation, or macromutation. Goldschmidt presented his hypothesis when neo-Darwinism was becoming dominant in the 1940s and 1950s, and strongly protested against the strict gradualism of neo-Darwinian theorists. His ideas were accordingly seen as highly unorthodox by most scientists and were subjected to ridicule and scorn.[14] However, there has been a recent interest in the ideas of Goldschmidt in the field of evolutionary developmental biology, as some scientists, such as Günter Theißen and Scott F. Gilbert, are convinced he was not entirely wrong.[15][16] Goldschmidt presented two mechanisms by which hopeful monsters might work. One mechanism, involving "systemic mutations", rejected the classical gene concept and is no longer considered by modern science; however, his second mechanism involved "developmental macromutations" in "rate genes" or "controlling genes" that change early development and thus cause large effects in the adult phenotype. These kinds of mutations are similar to those considered in contemporary evolutionary developmental biology.[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Goldschmidt |

進化論 ゴールドシュミットは、「希望に満ちた怪物」という言葉を最初に使った科学者である。彼は、小さな漸進的な変化では、ミクロ進化とマクロ進化の間の溝を埋 めることはできないと考えたのである。彼は著書『進化の物質的基礎』(1940年)の中で、"種から種への変化は、より多くの付加的な原子的変化を伴う変 化ではなく、原型または反応系が新しいものに完全に変化することであり、その後、微小変異によって再び種内変異を生じうる。"と書いている。ゴールドシュ ミットは、進化における大きな変化は、マクロ変異(大きな突然変異)によって引き起こされると考えた。マクロ変異に関する彼の考えは、塩類化進化の一種で ある希望的観測に基づく怪物仮説として知られるようになり、広く嘲笑を浴びた[10]。 ゴールドシュミットによれば、「生物学者たちは、自分たちが『大きな』突然変異を見たことがないから、そんなことはあり得ないと考える傾向があるようだ。 しかし、そのような突然変異は、進化のための重要な材料を世界に提供するために、最も並外れた稀な出来事である必要があるだけだ」[11] 。ゴールドシュミットは、小さな突然変異が徐々に蓄積されていくという新ダーウィン主義の見解は重要だが、種内の変異(微小進化)しか説明できず、新種を 説明できるほど進化の新奇性の強力な源にはならないと考えたのである。その代わりに彼は、種間の大きな遺伝的差異には深遠な「マクロ変異」が必要であり、 それは「希望に満ちた怪物」としてたまに起こりうる大きな遺伝的変化(マクロ進化)の源であると考えた[12][13]。 ゴールドシュミットは通常「非ダーウィン主義者」と呼ばれる。しかし、彼はダーウィン主義者の一般的な微小進化論に異を唱えていたわけではない。ただ、不 連続な変異、すなわちマクロ変異によって新しい種が突然発生するという信念においてのみ、合成説から逸脱していたのである。ゴールドシュミットは、 1940年代から1950年代にかけて新ダーウィン主義が主流となった時期に自分の仮説を発表し、新ダーウィン主義者の厳格な漸進主義に強く抗議した。そ れゆえ、彼の考えはほとんどの科学者から非常に異端視され、嘲笑と軽蔑の対象となった[14] 。しかし、最近、進化発生生物学の分野でゴールドシュミットの考えに対する関心が高まっており、ギュンター・テイセンやスコット F. ギルバートなどの一部の科学者は彼が完全に間違っていなかったと確信している[15] [16] 。ゴールドシュミットには希望に満ちた怪物が機能するかもしれないという二つのメカニズムが提示されている。一つは、「全身的な突然変異」を伴うメカニズ ムで、古典的な遺伝子概念を否定し、現代科学ではもはや考慮されていない。しかし、彼の第二のメカニズムは、「速度遺伝子」または「制御遺伝子」における 「発生的大変異」を含み、初期の発生を変え、それによって成人の表現型に大きな影響を与えるものであった。この種の突然変異は、現代の進化的な発生生物学 で考えられているものと類似している[17]。 |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報