ロバート・ノックス

Robert Knox, 1791-1862

☆ ロ バート・ノックス FRSE FRCSE(1791年9月4日 - 1862年12月20日)[Robert Knox, 1791-1862] は、スコットランドの解剖学者・民族学者である。バークとヘアの殺人事件への関与で最もよく知られている。スコットランドのエ ディンバラ生まれのノックスは、やがて解剖学者で元教師のジョン・バークレイと提携し、同市で解剖学の講師となった。そこで彼は超越解剖学の理論を導入し た。しかし、1832年の解剖法成立前に解剖用の死体を不注意な方法で入手したことや、専門家の同僚との意見の相違が、スコットランドにおける彼の評判を 台無しにした。こうした経緯から、彼はロンドンに移住したが、それでも彼のキャリアは復活しなかった。 ノックスの人間観は生涯を通じて徐々に変化し、当初は(エティエンヌ・ジョフロワ・サンティレの理想に影響された)楽観的な見解から、次第に悲観的な見解 へと移行した。ノックスはまた、キャリアの後半を進化論と民族学の研究・理論化に捧げた。この時期、彼は科学的人種主義を擁護する数多くの著作も執筆し た。後者の研究は彼の遺産をさらに傷つけ、人種的差異の説明に用いた進化論への貢献を覆い隠してしまった。

| Robert

Knox FRSE FRCSE (4 September 1791 – 20 December 1862) was a

Scottish anatomist and ethnologist best known for his involvement in

the Burke and Hare murders. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Knox

eventually partnered with anatomist and former teacher John Barclay and

became a lecturer on anatomy in the city, where he introduced the

theory of transcendental anatomy. However,

Knox's incautious methods of obtaining cadavers for dissection before

the passage of the Anatomy Act 1832 and disagreements with professional

colleagues ruined his reputation in Scotland. Following these

developments, he moved to London, though this did not revive his career. Knox's views on humanity gradually shifted over the course of his lifetime, as his initially positive views (influenced by the ideals of Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire) gave way to a more pessimistic view. Knox also devoted the latter part of his career to studying and theorising on evolution and ethnology; during this period, he also wrote numerous works advocating scientific racism. His work on the latter further harmed his legacy and overshadowed his contributions to evolutionary theory, which he used to account for racial differences. |

ロバート・ノックス FRSE FRCSE(1791年9月4日 -

1862年12月20日)は、スコットランドの解剖学者・民族学者である。バークとヘアの殺人事件への関与で最もよく知られている。スコットランドのエ

ディンバラ生まれのノックスは、やがて解剖学者で元教師のジョン・バークレイと提携し、同市で解剖学の講師となった。そこで彼は超越解剖学の理論を導入し

た。しかし、1832年の解剖法成立前に解剖用の死体を不注意な方法で入手したことや、専門家の同僚との意見の相違が、スコットランドにおける彼の評判を

台無しにした。こうした経緯から、彼はロンドンに移住したが、それでも彼のキャリアは復活しなかった。 ノックスの人間観は生涯を通じて徐々に変化し、当初は(エティエンヌ・ジョフロワ・サンティレの理想に影響された)楽観的な見解から、次第に悲観的な見解 へと移行した。ノックスはまた、キャリアの後半を進化論と民族学の研究・理論化に捧げた。この時期、彼は科学的人種主義を擁護する数多くの著作も執筆し た。後者の研究は彼の遺産をさらに傷つけ、人種的差異の説明に用いた進化論への貢献を覆い隠してしまった。 |

| Life Early life Robert Knox was born in 1791[1] in Edinburgh's North Richmond Street, the eighth child of Mary (née Scherer) and Robert Knox (d. 1812), a teacher of mathematics and natural philosophy at Heriot's Hospital in Edinburgh. As an infant, he contracted smallpox, which destroyed his left eye and disfigured his face.[2] He was educated at the Royal High School of Edinburgh,[3] where he was remembered as a 'bully' who thrashed his contemporaries "mentally and corporeally". He won the Lord Provost's gold medal in his final year.[4] In 1810, he joined medical classes at the University of Edinburgh. He soon became interested in transcendentalism[5] and the work of Xavier Bichat.[6] He was twice president of the Royal Physical Society, an undergraduate club to which he presented papers on hydrophobia and nosology.[7] The final recorded event of his university years was his just failing the anatomy examination. Knox joined the "extramural" anatomy class of the famous John Barclay. Barclay was an anatomist of the highest distinction, and perhaps the greatest anatomical teacher in Britain at that time. Redoubling his efforts, Knox passed competently the second time around. |

生涯 幼少期 ロバート・ノックスは1791年[1]、エディンバラのノース・リッチモンド・ストリートで生まれた。母メアリー(旧姓シェラー)と父ロバート・ノックス (1812年没)の八人目の子である。父はエディンバラのヘリオット病院で数学と自然哲学を教えていた。幼少期に天然痘に感染し、左目を失明し顔に瘢痕が 残った[2]。エディンバラ王立高等学校で教育を受け[3]、同級生を「精神的・肉体的に」打ちのめす「いじめっ子」として記憶されている。最終学年で市 長金メダルを受賞した。[4] 1810年、エディンバラ大学の医学部に入学した。すぐに超越論[5]とザビエル・ビシャの著作[6]に興味を持った。学部生クラブである王立物理学会の 会長を二度務め、狂犬病と病名分類に関する論文を発表した。[7] 大学時代の最後の記録された出来事は、解剖学試験に惜しくも不合格となったことである。ノックスは著名なジョン・バークレーの「学外」解剖学講座に参加し た。バークレーは最高峰の解剖学者であり、おそらく当時英国で最も優れた解剖学教師であった。努力を重ねたノックスは二度目の受験で見事に合格した。 |

| Life abroad Knox graduated from the University of Edinburgh in 1814, with a Latin thesis on the effects of narcotics which was published the following year.[8] He joined the army and was commissioned Hospital Assistant on 24 June 1815, after having studied for a year under John Abernethy at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London. He was sent immediately to Belgium to attend the wounded from the Battle of Waterloo and returned two weeks later with the first batch of wounded aboard a hospital ship; during the voyage he successfully employed Abernethy's technique of leaving wounds open to the air.[9] His army work at the Brussels military hospital (near Waterloo) impressed upon him the need for a comprehensive training in anatomy if surgery were to be successful. Knox was intelligent, critical and irritable. He did not suffer fools gladly and—in an aside with terrible consequences for his future career—he was critical of the surgical work of Charles Bell with casualties at the Battle of Waterloo. After a further trip to Belgium he was placed in charge of Hilsea hospital near Portsmouth, where he experimented with non-mercurial cures for syphilis.[10] In April 1817, he joined the 72nd Highlanders and sailed with them to South Africa. There were few army surgeons in the Cape Colony but Knox found the people healthy and his duties were light. He enjoyed riding, shooting and the beauty of the landscape with which he felt in spiritual harmony—an early expression of his transcendental world view.[11] Knox developed an interest in observing racial types, and disapproved of what he saw as the Boers' contempt for the indigenous peoples. However, after an abortive Xhosa rebellion against the colonial forces, he was involved in a retaliatory raid commanded by Andries Stockenström, a magistrate and future Lieutenant Governor.[11][12] Relations with Stockenström were marred when Knox accused O. G. Stockenström, Andries' brother, of theft, a charge apparently prompted by ill feeling between British and Boer officers. A court martial acquitted O. G. of the charge and Andries called Knox's conduct shameful.[13] One of Stockenström's supporters, a former naval officer named Burdett, challenged Knox to a duel. Knox initially refused to fight, and Burdett "soundly horse whipped him on the parade before every Officer of the Garrison." Knox then grabbed a sabre and inflicted a slight wound to Burdett's arm. Knox's promotion to Assistant Surgeon was cancelled and he returned to Britain in disgrace, arriving on Christmas Day 1820.[14] He remained only until the following October, after which he went to Paris to study anatomy for just over a year (1821–22). It was then that he met both Georges Cuvier and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, who were to remain his heroes for the rest of life, to populate his later medical journalism, and to become the subject of his hagiography, Great artists and great anatomists.[15] While in Paris he befriended Thomas Hodgkin, with whom he shared a dissecting room at l'Hôpital de la Pitié.[16] |

海外での生活 ノックスは1814年にエディンバラ大学を卒業し、麻薬の影響に関するラテン語の論文を発表した。この論文は翌年に出版された。[8] 彼は軍に入隊し、ロンドンのセント・バーソロミュー病院でジョン・アバーネシーのもと1年間研修を受けた後、1815年6月24日に病院助手として任官し た。直ちにベルギーへ派遣され、ワーテルローの戦いで負傷した兵士の治療にあたった。2週間後、病院船で最初の負傷者グループを乗せて帰還する途中、ア バーネシーの「傷口を開放する」という技法を成功裏に適用した[9]。ブリュッセル軍病院(ワーテルロー近郊)での軍医業務を通じ、外科手術を成功させる には解剖学の包括的な訓練が必要だと痛感した。ノックスは聡明で批判的、かつ短気だった。愚か者を苦悩なく見下し、さらに彼の将来のキャリアに壊滅的な影 響を与える発言として、ワーテルローの戦いで負傷者を手術したチャールズ・ベルの技法を批判した。ベルギーへの再派遣後、ポーツマス近郊のヒルシー病院の 責任者に任命され、そこで水銀を用いない梅毒治療法を実験した。[10] 1817年4月、彼は第72高地連隊に配属され、同連隊と共に南アフリカへ渡った。ケープ植民地には軍医が少なかったが、ノックスは住民が健康で職務も軽 かった。乗馬や狩猟、そして精神的に調和を感じる美しい風景を楽しんだ——これは彼の超越的な世界観の初期表現であった[11]。ノックスは人種類型観察 に興味を持ち、ボーア人が先住民を軽蔑しているように見えることを非難した。しかし、コサ族による植民地軍への反乱が失敗に終わった後、彼はアンドリー ス・ストックエンストローム(治安判事であり後の副総督)指揮下の報復襲撃に関与した[11][12]。ストックエンストローム家との関係は、ノックスが アンドリースの弟O・G・ストックエンストロームを窃盗で告発したことで悪化した。この告発は、英国人将校とボーア人将校の間の確執が背景にあったよう だ。軍法会議はO・Gの容疑を無罪とし、アンドリースはノックスの行為を「恥ずべきもの」と非難した[13]。ストックエンストロームの支持者の一人、元 海軍士官バーデットがノックスに決闘を挑んだ。ノックスは当初応じなかったため、バーデットは「駐屯地の全将校の前で、パレード中に彼を馬鞭で激しく打ち 据えた」のである。するとノックスはサーベルを掴み、バーデットの腕に軽い傷を負わせた。ノックスの副外科医昇進は取り消され、不名誉な形で英国へ帰国。 1820年のクリスマス日に到着した[14]。彼は翌年10月まで滞在した後、パリへ渡り1年余り(1821-22年)解剖学を学んだ。この時、彼はジョ ルジュ・キュヴィエとエティエンヌ・ジョフロワ・サンティレールに出会った。彼らはその後も生涯の英雄であり続け、彼の後の医学ジャーナリズムに登場し、 伝記『偉大な芸術家と偉大な解剖学者』の主題となった[15]。パリ滞在中、彼はトーマス・ホジキンと親交を深め、ピティエ病院の解剖室を共に使用した [16]。 |

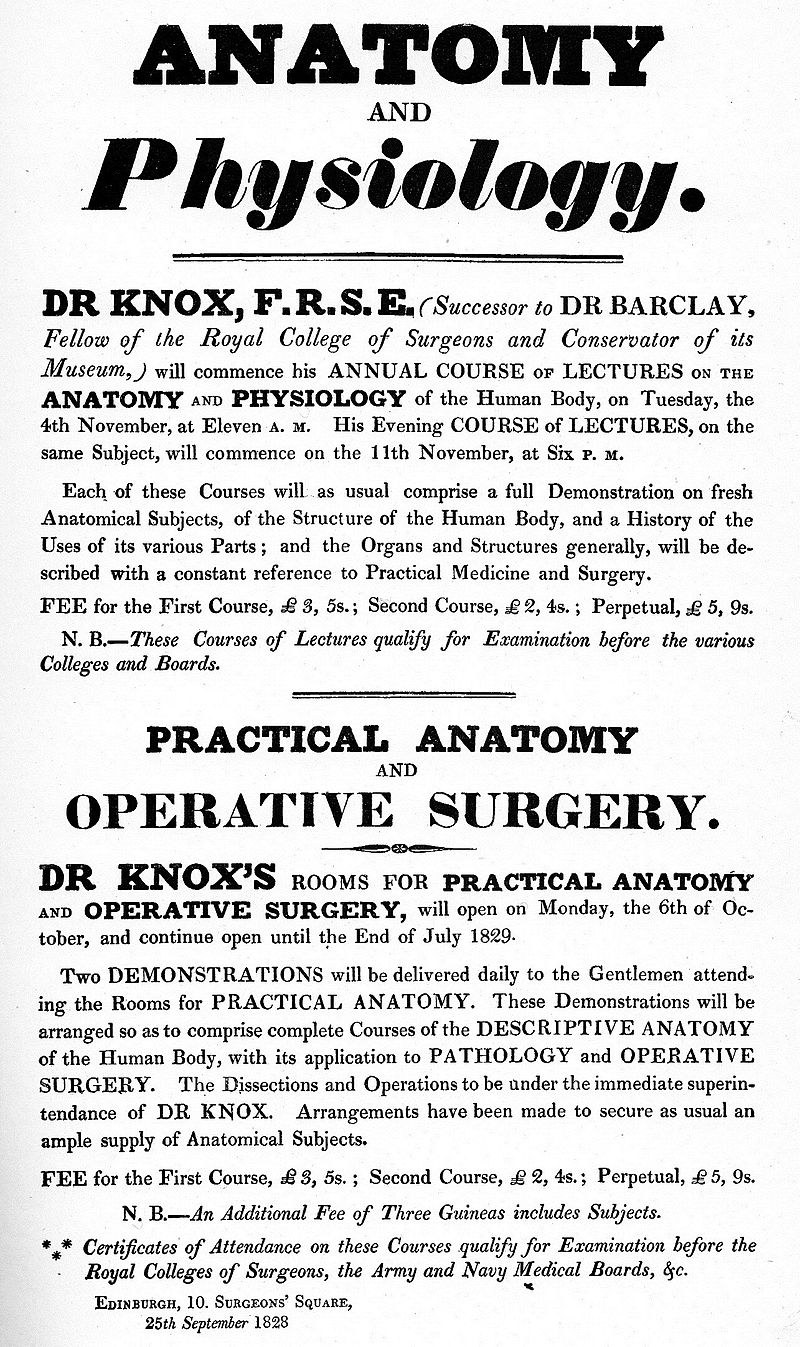

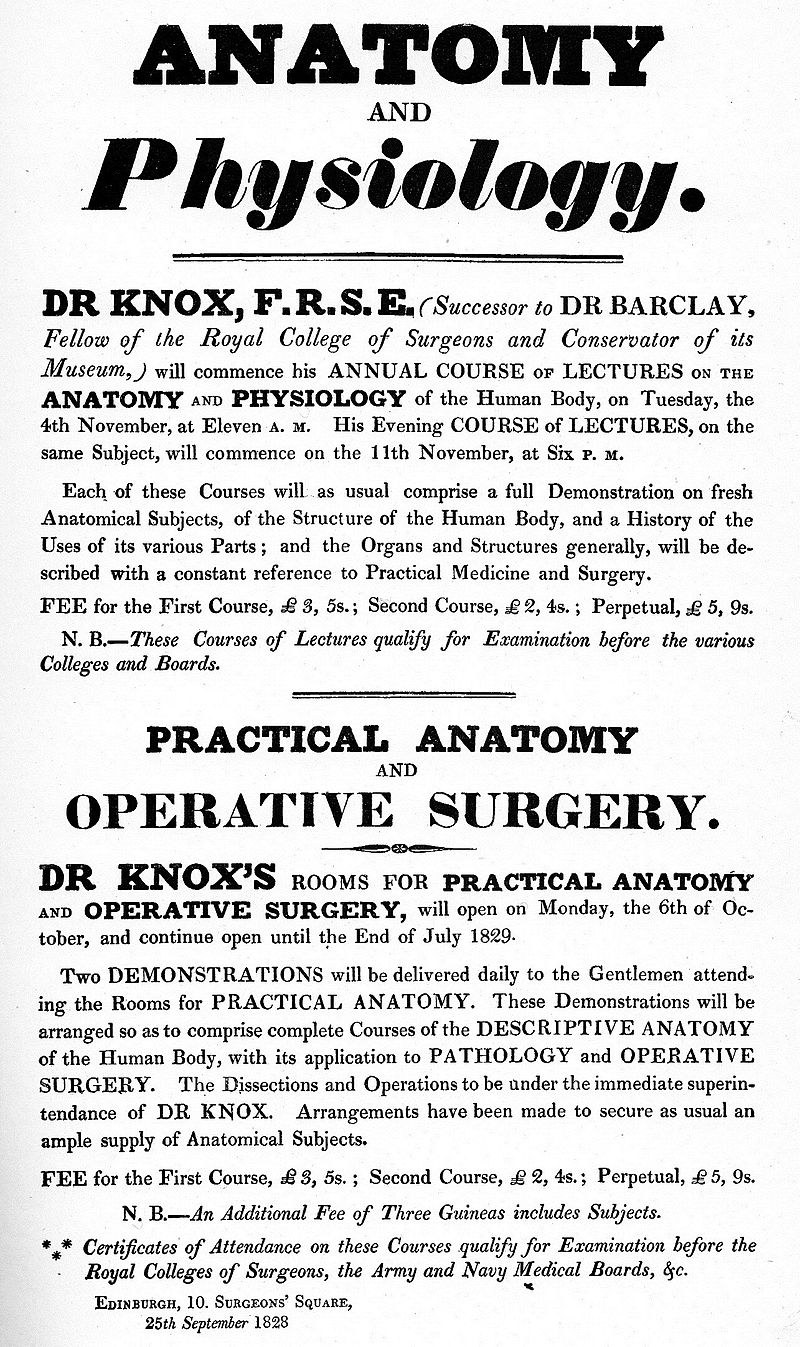

Career in Edinburgh Bill advertising Knox's anatomy lectures in 1828 Knox returned to Edinburgh by Christmas 1822. On 1 December 1823 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. During these years he communicated a number of well-received papers to the Royal and Wernerian societies of Edinburgh on zoological subjects, including a paper suggesting that the "Hottentot" or "Bosjesman" Khoe and San people descended from "Mongolic" Chinese people.[17] Soon after his election he submitted a plan to the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh for a Museum of Comparative Anatomy, which was accepted, and on 13 January 1825 he was appointed curator of the museum with a salary of £100.[18] In 1825, John Barclay offered him a partnership at his anatomy school in Surgeon's Square, Edinburgh. In order for his lectures to be recognised by the Edinburgh College of Surgeons, Knox had to be admitted to its fellowship; a formality, but, at £250, an expensive one.[19] At this time most professorships were in the gift of the town council, resulting in such uninspiring teachers as the professor of anatomy Alexander Monro, who put off many of his students (including the young Charles Darwin who took the course 1825–1827). This created a demand for private tuition, and the flamboyant Knox—in sole charge after Barclay's death in 1826—had more students than all the other private tutors put together. He turned his sharp wit on the elders and the clergy of the city, satirising religion and delighting his students. Knox routinely referred to the Bridgewater Treatises as the "bilgewater treatises" and his 'continental' lectures were not for the squeamish. John James Audubon was in Edinburgh at the time to find subscribers for his Birds of America. Shown round the dissecting theatre by Knox, "dressed in an overgown and with bloody fingers", Audubon reported that "The sights were extremely disagreeable, many of them shocking beyond all I ever thought could be. I was glad to leave this charnel house and breathe again the salubrious atmosphere of the streets".[20] Knox's school flourished and he took on three assistants, Alexander Miller, Thomas Wharton Jones and William Fergusson. |

エディンバラでの経歴 1828年のノックスの解剖学講義を宣伝するビラ ノックスは1822年のクリスマスまでにエディンバラに戻った。1823年12月1日、彼はエディンバラ王立協会のフェローに選出された。この数年間、彼 はエディンバラ王立協会とヴェルネリアン協会に、動物学に関する数々の好評を得た論文を提出した。その中には、「ホッテントット」または「ボージェスマ ン」と呼ばれるコー族とサン族が「モンゴロイド」系の中国人に由来するという主張を含む論文もあった。[17] 選任直後、彼はエディンバラ王立外科医協会に比較解剖学博物館の計画書を提出し、これが承認された。1825年1月13日、彼は年俸100ポンドで同博物 館の学芸員に任命された。[18] 1825年、ジョン・バークレーがエディンバラの外科医広場にある自身の解剖学校での共同経営を提案した。ノックスの講義をエディンバラ外科医学院が認定 するには、同学院のフェロー資格取得が必要だった。形式的な手続きだが、250ポンドという高額な費用がかかった。[19] 当時、教授職の大半は市議会が任命権を握っていた。その結果、解剖学教授アレクサンダー・モンローのような魅力に欠ける教師が生まれ、多くの学生 (1825年から1827年にかけてこの講義を受講した若きチャールズ・ダーウィンを含む)を遠ざけた。この状況が個人指導の需要を生み、1826年に バークレーが死去した後、華やかなノックスは単独で指導を担当し、他の全ての個人教師を合わせたよりも多くの生徒を抱えた。 彼は鋭い機知で町の長老や聖職者を嘲り、宗教を風刺して生徒を喜ばせた。ノックスはブリッジウォーター論文集を常習的に「汚水論文集」と呼び、彼の『大 陸』講義は神経質な者には向かない内容だった。ジョン・ジェームズ・オーデュボンは当時、自身の『アメリカの鳥類』の購読者を募るためエディンバラに滞在 していた。解剖劇場を案内したノックスは「長衣をまとい、血まみれの指」で、オーデュボンは「その光景は極めて不快で、その多くは想像を絶する衝撃的なも のだった」と記している。この死体安置所を後にし、再び街路の清々しい空気を吸えることを嬉しく思った」と記している。[20] ノックスの学校は繁栄し、彼はアレクサンダー・ミラー、トーマス・ワートン・ジョーンズ、ウィリアム・ファーガソンの3人の助手を迎えた。 |

| Marriage and personal life Little is known of Knox's wife, Susan Knox, whom he married in 1824.[21] According to Knox's friend Henry Lonsdale the marriage was kept secret as she was 'of inferior rank.'[22] During his time in Edinburgh, Knox lived at 4 Newington Place[23] with his sisters Mary and Jessie, while Susan and his four children lived at Lilliput Cottage in Trinity, west of Leith. They had seven children, but only two of them survived into adulthood.[24] |

結婚と人格生活 ノックスの妻スーザン・ノックスについてはほとんど知られていない。二人は1824年に結婚した。[21] ノックスの友人ヘンリー・ロンズデールによれば、妻が「身分が低かった」ため結婚は秘密にされたという。[22] エディンバラ滞在中、ノックスは姉妹のメアリーとジェシーと共にニューイントン・プレイス4番地に住んでいたが、[23] スーザンと4人の子供たちはリース西部のトリニティ地区にあるリリパット・コテージに住んでいた。7人の子供が生まれたが、成人まで生き延びたのは2人だ けだった。[24] |

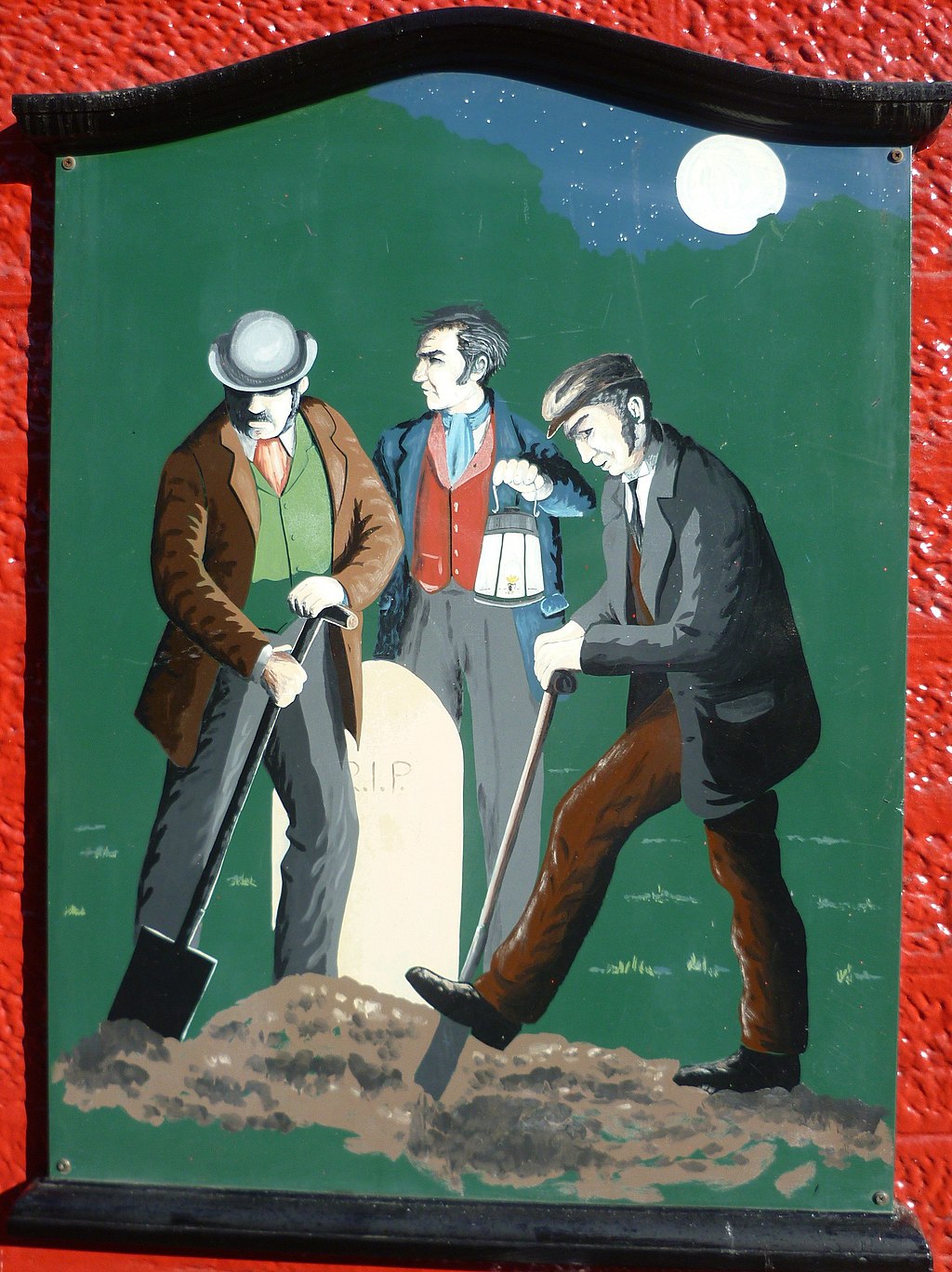

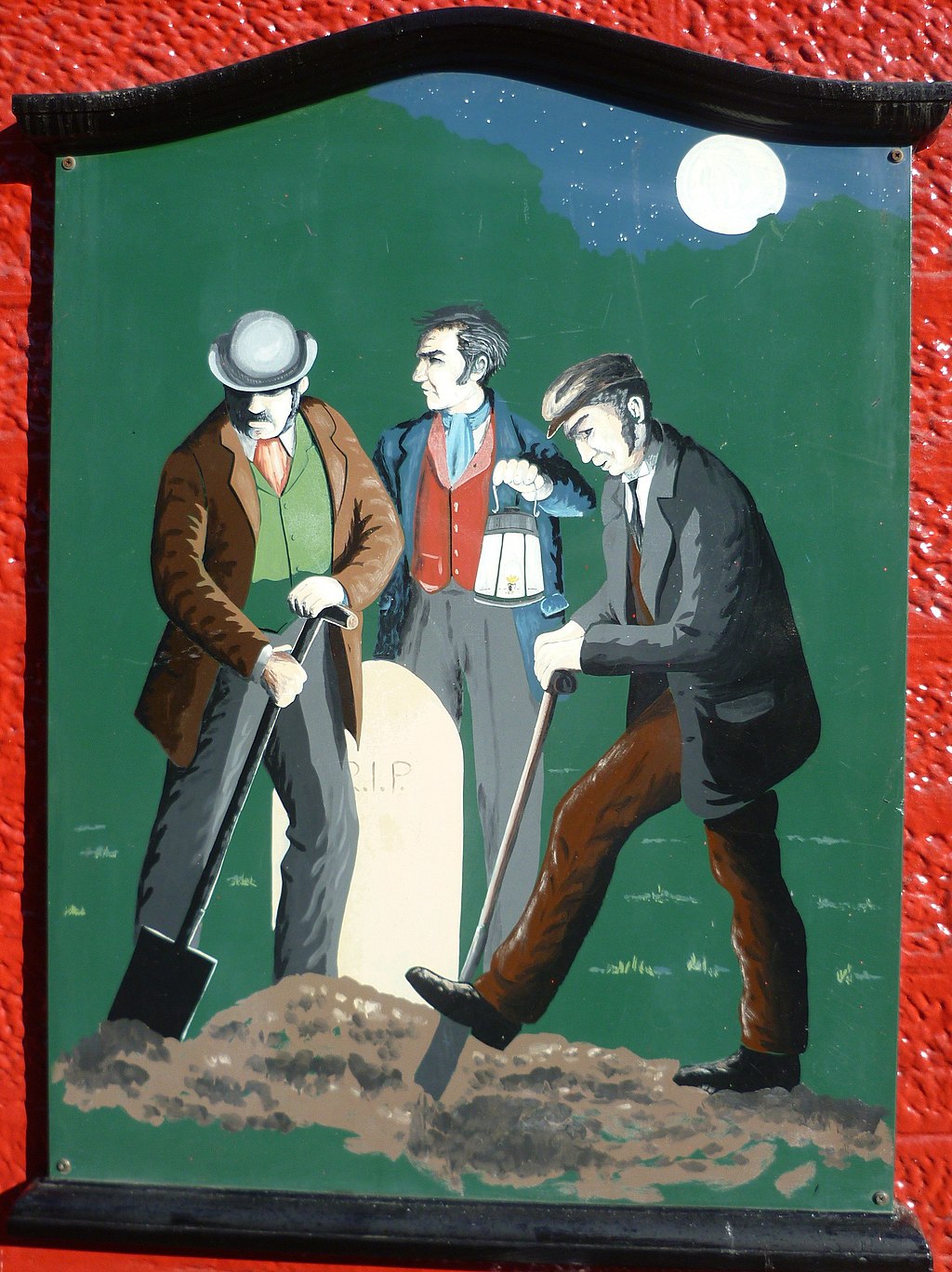

| West Port murders Main article: Burke and Hare murders See also: Anatomy murder Before the Anatomy Act 1832 widened the supply, the main legal supply of corpses for anatomical purposes in the UK were those condemned to death and dissection by the courts. This led to a chronic shortage of legitimate subjects for dissection, and this shortage became more serious as the need to train medical students grew, and the number of executions fell. In his school Knox ran up against the problem from the start, since—after 1815—the Royal Colleges had increased the anatomical work in the medical curriculum. If he taught according to what was known as 'French method' the ratio would have had to approach one corpse per pupil.  A modern depiction of body snatchers at work As a consequence, body-snatching became so prevalent that it was not unusual for relatives and friends of someone who had just died to watch over the body until burial, and then to keep watch over the grave after burial, to stop it being violated. In November 1827, William Hare began a new career when an indebted lodger died on him by chance. He was paid £7.10s (seven pounds & ten shillings) for delivering the body to Knox's dissecting rooms at Surgeons' Square. Now Hare and, his friend and accomplice, William Burke, set about murdering the city’s poor on a regular basis. After 16 more transactions, each netting £8-10, in what later became known as the West Port Murders, on 2 November 1828 Burke and Hare were caught, and the whole city convulsed with horror, fed by ballads, broadsides, and newspapers, at the reported deeds of the pair.[25] Hare turned King's evidence, and Burke was hanged, dissected and his remains were displayed.  A caricature of Dr. Knox, depicting him as a demon harvesting bodies Knox was not prosecuted, which outraged many in Edinburgh. His house was attacked by a mob of 'the lowest rabble of the Old Town,' and windows were broken.[26] A committee of the Royal Society of Edinburgh exonerated him on the grounds that he had not dealt personally with Burke and Hare, but there was no forgetting his part in the case, and many remained wary of him. Almost immediately after the Burke and Hare case, the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh began to harry him, and by June 1831 they had procured his resignation as curator of the museum he had proposed and founded.[27] In the same year he was obliged to resign his army commission to avoid further service in the Cape.[28] This removed his last source of guaranteed income, but his classes were more popular than ever, with a record 504 students.[29] His school moved to the grander premises of Old Surgeons' Hall in 1833 but his class declined after Edinburgh University made its own practical anatomy class compulsory in the mid-1830s.[30][31] Knox continued to purchase cadavers for his dissection class from such shadowy figures as the 'Black Bull Man', but after the 1832 Anatomy Act made bodies more available to all anatomists, he quarrelled with HM Inspector of Anatomy over the supply of bodies, and his competitive edge was lost.[32][33] In 1837 Knox applied for the chair in pathology at Edinburgh University but his candidature was blocked by eleven existing professors, who preferred to abolish the post rather than appoint him.[34] In 1842 he was unable to make payments to the Edinburgh funeratory system, from which bodies were supplied to private schools, and he relocated to Glasgow where, still short of subjects for dissection, he closed his school in 1844. In 1847 the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh found him guilty of falsifying a student's certificate of attendance (not an uncommon practice in private schools) and refused to accept any further certificates from him, effectively banning him from teaching in Scotland.[35] In the same year he was expelled from the Royal Society of Edinburgh and had his election retrospectively cancelled.[36] |

ウェストポート殺人事件 主な記事: バークとヘアの殺人事件 関連項目: 解剖学殺人 1832年の解剖法が供給源を拡大する以前、英国における解剖目的の死体の主な合法的な供給源は、裁判所によって死刑と解剖を宣告された者たちであった。 これにより、解剖用の合法的な対象が慢性的に不足する事態が生じた。医学部生の教育需要が高まる一方で死刑執行数が減少したため、この不足はさらに深刻化 した。ノックスの学校では、1815年以降、王立大学が医学課程の解剖実習を増やしたため、開校当初からこの問題に直面した。いわゆる「フランス式」で教 えた場合、生徒1人あたり1体の死体が必要になる計算だった。  現代的な死体泥棒の活動描写 結果として、死体泥棒が蔓延し、亡くなったばかりの人の親族や友人が、埋葬まで遺体を見守り、埋葬後も墓を見張って遺体が荒らされないようにするのは珍し いことではなかった。 1827年11月、ウィリアム・ヘアは借金まみれの下宿人が偶然死んだのを機に新たな生業を始めた。遺体を外科医広場のノックス解剖室へ届けると7ポンド 10シリングの報酬を得た。こうしてヘアと共犯者ウィリアム・バークは、市内の貧民を定期的に殺害するようになった。その後16件の取引(各8~10ポン ドの利益)を経て、後に「ウェストポート殺人事件」として知られる事件が発生。1828年11月2日、バークとヘアは逮捕された。二人の犯行が伝わるバ ラッドやビラ、新聞記事に煽られ、街全体が恐怖に震えた[25]。ヘアは王の証人となり、バークは絞首刑に処された後、解剖され遺体は公開展示された。  ノックス博士を死体を収穫する悪魔として描いた風刺画 ノックスは起訴されなかったため、エディンバラ市民の多くは激怒した。彼の家は「旧市街の最低のならず者ども」の暴徒に襲撃され、窓ガラスが割られた。 [26] エディンバラ王立協会の委員会は、彼がバークとヘアと人格的に取引した証拠がないとして無罪を認めたが、事件への関与は忘れられず、多くの人々が彼を警戒 し続けた。 バークとヘア事件の直後、エディンバラ王立外科医師会は彼を執拗に迫り、1831年6月までに彼が提案・設立した博物館の館長職を辞任させた。[27] 同年、ケープ植民地でのさらなる勤務を避けるため、軍職の辞任を余儀なくされた[28]。これにより彼の最後の安定した収入源は失われたが、講義はかつて ない人気を博し、記録的な504名の学生を集めた[29]。1833年には旧外科医会館というより立派な施設へ移転したが、1830年代半ばにエディンバ ラ大学が独自の解剖実習を必修化したことで、彼の講義は衰退した。[30][31] ノックスは解剖授業用の死体を「ブラック・ブル・マン」のような怪しげな人物から買い続けていたが、1832年の解剖法により死体が全ての解剖学者に入手 しやすくなると、王立解剖検査官と死体供給を巡って対立し、競争力を失った。[32][33] 1837年、ノックスはエディンバラ大学の病理学教授職に応募したが、既存の11人の教授陣によって阻止された。彼らはノックスを任命するより、その職を 廃止することを選んだのだ。[34] 1842年には、私立学校に遺体を供給していたエディンバラの葬儀システムへの支払いが不可能となり、グラスゴーに移転した。しかし解剖用の遺体が依然と して不足していたため、1844年に学校を閉鎖した。1847年、エディンバラ王立外科医師会は、彼が学生の出席証明書を偽造した(私立学校では珍しいこ とではない)として有罪とし、今後彼から提出される証明書を一切受け入れないと決定した。これにより、彼は事実上スコットランドでの教育活動から追放され た。[35] 同年、エディンバラ王立協会からも除名され、過去の選出も遡及的に取り消された。[36] |

London Knox's grave in Brookwood Cemetery Knox left for London after the death of his wife (the remaining children were left with a nephew). He found it impossible to find a university post, and from then until 1856 he worked on medical journalism, gave public lectures, and wrote several books, including his most ambitious work, The Races of Men in which he argued that each race was suited to its environment and "perfect in its own way."[37] Additionally, Knox wrote a book on fishing in Scotland, which became his best-selling work.[38] In 1854 his son Robert died of heart disease; Knox tried for a posting to the Crimea but at 63 was judged too old.[39] In 1856 he became the pathological anatomist to the Free Cancer Hospital, London. He joined the medical register at its inception in 1858 and practiced obstetrics in Hackney. On 27 November 1860 he was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Ethnological Society of London, where he spoke in public for the last time on 1 July 1862.[40] He continued working at the Cancer Hospital until shortly before his death on 20 December 1862, at 9 Lambe Terrace in Hackney.[41] He was buried at Brookwood Cemetery near Woking, Surrey.[42] |

ロンドン ブルックウッド墓地にあるノックスの墓 ノックスは妻の死後、ロンドンへ向かった(残された子供たちは甥に預けられた)。大学での職を見つけることは不可能だと悟り、その後1856年まで医学 ジャーナリズムに従事し、公開講演を行い、いくつかの著書を執筆した。中でも最も意欲的な著作『人類の種族』では、各人種がその環境に適応しており「それ ぞれの方法で完璧である」と論じた。[37] さらにノックスはスコットランドの釣りを題材にした著作を執筆し、これが彼のベストセラー作品となった。[38] 1854年には息子のロバートが心臓病で死去。ノックスはクリミア半島への赴任を志願したが、63歳という年齢が理由に不適格と判断された。[39] 1856年、彼はロンドンのフリー癌病院の病理解剖学者となった。1858年に医師登録制度が始まると登録し、ハックニーで産科医として診療した。 1860年11月27日、ロンドン民族学会の名誉会員に選出され、1862年7月1日に同学会で最後の公開講演を行った。[40] 癌病院での勤務は、1862年12月20日にハックニーのラムベ・テラス9番地で死去する直前まで続けた。[41] 埋葬はサリー州ウォーキング近郊のブルックウッド墓地で行われた。[42] |

| Ethnology

and racism Knox's interest in race began as an undergraduate. His relevant political views were radical: he was an abolitionist and anti-colonialist who criticised the Boer as "the cruel oppressor of the dark races."[11]: 99 Knox is generally considered to be a polygenist;[43][44][45] however, some have argued that he was a monogenist,[46] including biographer Alan Bates, who considers such claims to be "exaggerated."[47] Robert Knox once wrote that he believed all human races to descend from an original 'Caucasian' race.[48] In his best-selling work, The Races of Men (1850), a "Zoological history" of mankind, Knox exaggerated supposed racial differences in support of his project, asserting that, anatomically and behaviourally, "race, or hereditary descent, is everything." He offered crude characterisations of each racial group: for example the Saxon (in which race he included himself) "invents nothing", "has no musical ear", lacks "genius", and is so "low and boorish" that "he does not know what you mean by fine art."[11]: 45 No race was without its redeeming features, however; Knox described Saxons as "[t]houghtful, plodding, industrious beyond all other races, [and] a lover of labour for labour's sake."[11]: 45 Such supposed racial characteristics meant that each race was naturally fitted for a particular environment and could not endure outside it. While Knox maintained that all races were capable of some form of civilized life, he maintained that a vast gulf stood between the limited attainments available to the 'negroid' and to most 'mongoloid' races on one hand and the much greater past achievements and future potential of white men on the other. The Black, Knox remarked, "is no more a white man than an ass is a horse or a zebra."[49]: 99 Ultimately however, all races were "[d]estined ... to run, like all other animals, a certain limited course of existence", it mattering "little how their extinction is brought about".[49]: 302 In 1862 Knox took the opportunity of a second edition of The Races of Men to defend the "much maligned races" of the Cape against accusations of cannibalism, and to rebuke the Dutch for treating them like "wild beasts".[50] From the perspective of a Lowland Scot Protestant, Knox's racist works espoused extreme racial hostility to Celts in general (including the Highland Scots and Welsh people, but particularly the Irish people).[51] Due to what he observed to be a prevalence of the "peculiar Mongol face" in many Highland Scots, Knox once suggested that he considered Highland Scots to descend from an early migration of "Mongol races".[52] He considered the "Caledonian Celt" as touching "the end of his career: they are reduced to about one hundred and fifty thousand" and that the "Welsh Celts are not troublesome, but might easily become so." For Knox, "the Irish Celt is the most to be dreaded" and openly advocated their ethnic cleansing around the time that the Great Famine was happening, stating in The Races of Men: A Fragment (1850): "The source of all evil lies in the race, the Celtic race of Ireland. There is no getting over historical facts. Look at Wales, look at Caledonia; it is ever the same. [...] The race must be forced from the soil; by fair means, if possible; still they must leave. The Orange club of Ireland is a Saxon confederation for the clearing the land of all Papists and Jacobites; this means Celts. If left to themselves, they would clear them out, as Cromwell proposed, by the sword; it would not require six weeks to accomplish the work. But the Encumbered Estates Relief Bill will do it better."[53] |

民族学と人種主義 ノックスの人種への関心は大学生時代に始まった。彼の関連する政治的見解は急進的だった。奴隷制度廃止論者であり反植民地主義者であり、ボーア人を「暗色 人種を残酷に抑圧する者」と批判した。[11]: 99 ノックスは一般的に多起源説の支持者と見なされている[43][44][45]。しかし、伝記作家アラン・ベイツを含む一部は、彼を一起源説の支持者だと 主張している[46]。ベイツはそうした主張を「誇張されている」と見なしている。[47]ロバート・ノックスはかつて、全人類が元来の「コーカサス人 種」に由来すると記している[48]。彼のベストセラー『人類の諸人種』(1850年)では、人類の「動物学的歴史」を扱い、自らの主張を裏付けるため人 種的差異を誇張した。解剖学的・行動学的に「人種、すなわち遺伝的血統が全てである」と断言したのである。彼は各人種集団を粗雑に特徴づけた。例えばサク ソン人(自身もこの人種に含めた)は「何も発明しない」「音楽的耳を持たない」「天才的資質に欠ける」上に「低俗で無作法」であり、「貴方が言う『美術』 の意味すら理解できない」と述べた。[11]: 45 とはいえ、どの人種にも救いとなる特徴はあった。ノックスはサクソン人を「思慮深く、地道で、他のどの人種よりも勤勉であり、労働そのものを愛する者」と 描写した。[11]: 45 このような人種的特性は、各人種が特定の環境に自然に適応し、その外では生きられないことを意味した。ノックスは全人種が何らかの文明的生活を営む能力を 持つと主張しつつも、『ネグロイド』や大半の『モンゴロイド』人種が到達し得る限られた水準と、白人の過去の偉大な業績及び将来の可能性との間には巨大な 隔たりがあると主張した。ノックスはこう述べた。「黒人は、ロバが馬やシマウマであるのと同じくらい、白人ではない」[49]:99。しかし結局のとこ ろ、あらゆる人種は「他の全ての動物と同様に、限られた存在の道を歩む運命にある」のであり、その絶滅が「どのようにもたらされるかはさほど重要ではな い」と。[49]: 302 1862年、ノックスは『人類の諸人種』第二版の刊行に際し、食人行為の非難を受けたケープの「不当に誹謗された人種」を擁護し、彼らを「野獣」のように 扱うオランダ人を糾弾する機会を得た。[50] 低地スコットランドのプロテスタントの視点から、ノックスの人種差別的な著作はケルト人全般(高地スコットランド人やウェールズ人を含むが、特にアイルラ ンドの人民を対象とした)に対する極端な人種的敵意を唱えていた。[51] 高地スコットランド人の多くに「独特のモンゴロイド顔」が蔓延していると観察したことから、ノックスはかつて高地スコットランド人が「モンゴロイド人種」 の初期移住に由来すると考えていたことを示唆したことがある。[52] 彼は「カレドニア・ケルト人」が「その存在の終焉を迎えつつある:その数は約15万人にまで減少した」と見ており、「ウェールズ・ケルト人は厄介ではない が、容易にそうなり得る」とも述べた。ノックスにとって「最も恐るべきはアイルランドのケルト人」であり、大飢饉が起きている頃には彼らの民族浄化を公然 と主張した。『人類の諸民族:断片』(1850年)でこう述べている:「あらゆる悪の根源は人種、すなわちアイルランドのケルト人種にある。歴史的事実を 覆すことはできない。ウェールズを見よ、カレドニアを見よ。常に同じ結果だ。」 [...] この人種は土地から追い出さねばならない。可能なら平和的に。それでも去らせるのだ。アイルランドのオレンジクラブは、全カトリック教徒とジャコバイト (ケルト人)を土地から一掃するためのサクソン人連合だ。彼らに任せておけば、クロムウェルが提案したように剣で一掃するだろう。その作業は六週間もかか らぬ。だが『抵当権付不動産救済法案』の方がより効果的だ」[53] |

| Transcendentalism This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Robert Knox" surgeon – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) In his writings Knox synthesised a perspective on nature from three of the most influential natural historians of his time. From Cuvier, he took a consciousness of the great epochs of time, of the fact of extinction, and of the inadequacy of the biblical account. From Étienne Geoffroy St-Hilaire and Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville, he gained a spatial and thematic perspective on living things. If one had the skill, all living beings could be arranged in their correct placing in a notional table, and one would see both internally and externally the elegant variation of their organs and anatomy according to the principles of connection, unity of composition and compensation. Goethe is another crucial addition to the Knoxian way of looking at nature. Goethe thought that there were transcendental archetypes in the living world which could be perceived by genus. If the natural historian were perspicacious enough to examine the creatures in this correct order he could perceive—aesthetically—the archetype that was immanent in the totality of a series, although present in none of them. Knox wrote that he was concerned to prove the existence of a generic animal, "or in other terms, proving hereditary descent to have a relation primarily to genus or natural family". This way, he could lay claim to a stability in the natural order at the level of the genus, but let species be extinguished. Man was a genus; not a species. |

超越主義 この節は出典を一切示していない。信頼できる出典を引用してこの節を改善してほしい。出典のない記述は異議を唱えられ、削除される可能性がある。 出典を探す: 「ロバート・ノックス」外科医 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学術文献 · JSTOR (2017年12月) (このメッセージを削除する方法と時期について) ノックスは著作において、当時の最も影響力のある自然史家3人から自然観を統合した。キュヴィエからは、時間の偉大な時代、絶滅の事実、聖書記述の不十分 さに対する認識を得た。エティエンヌ・ジョフロワ・サンティレールとアンリ・マリー・デュクロテ・ド・ブレヌヴィルからは、生物に対する空間的・主題的な 視点を得た。技術さえあれば、あらゆる生物を概念的な表の中で正しい位置に配置でき、接続の原理、構成の統一性、補償の原理に従って、器官や解剖学的構造 が内部的にも外部的にも優雅に変化している様子が見えるのだ。 ゲーテもまた、ノックス流の自然観に重要な要素を加えた。ゲーテは生物界に超越的な原型が存在し、属によって知覚可能だと考えた。自然史研究者がこの正し い順序で生物を観察する洞察力を持てば、個々の生物には現れないが、一連の総体には内在する原型を——美的感覚によって——知覚できるのだ。 ノックスは、ある属的な動物の存在を証明すること、すなわち「遺伝的起源が主に属または自然の家族関係に帰属することを証明すること」に関心があると記し た。こうして彼は、属のレベルにおいて自然秩序の安定性を主張しつつ、種が消滅することを許容したのである。人間は属であって、種ではない。 |

| Evolution According to Richards, The Races of Men advocated "a common material origin of life and its evolution by a process of saltatory descent"; that is to say, new species arose not by gradual change but by sudden leaps due to shifts in embryonic development.[54] Knox tentatively concluded that "simple animals ... may have produced by continuous generation the more complex animals of after ages . . . the fish of the early world may have produced reptiles, then again birds and quadrupeds; lastly, man himself?" Newly formed species survived or perished according to external conditions, which acted as "potent checks to an infinite variety of forms". For one contemporary reviewer, his claim that "Species is the product of external circumstances, acting through millions of years" was "bold, disgusting, and gratuitous atheism." In modern terms, he proposed a theory of saltatory evolution, in which "deformations" in embryonic development produced "hopeful monsters" that, if fortuitously suited to the prevailing environmental conditions, gave rise to new species in a single, macroevolutionary leap. In 1857 he wrote: "The conversion of one of these species into another cannot be so difficult a matter with Nature, especially when all or most of the specific characters are already present in the young. Thus a given species may perish, but another of the same consanguinité takes its place in space: it is a question of time... Thus parenté extends from species to genus and from genus to class and order, in characters not to be misunderstood." |

進化 リチャーズによれば、『人類の諸人種』は「生命の共通物質的起源と、飛躍的継承による進化」を提唱した。つまり、新種は漸進的変化ではなく、胚発生の変異 による突然の飛躍によって生じたというのだ。[54] ノックスは暫定的にこう結論づけた。「単純な動物は…連続的な世代交代によって、後の時代のより複雑な動物を生み出した可能性がある…初期世界の魚類は爬 虫類を生み、次に鳥類と四足動物を生み、最後に人間そのものを生み出したのではないか?」新しく形成された種は、外部環境に応じて生存または絶滅した。こ の環境は「無限の形態の多様性に対する強力な抑制要因」として作用したのである。ある同時代の批評家によれば、「種は数百万年にわたる外的環境の影響に よって生じる」という彼の主張は「大胆で、不快で、根拠のない無神論」であった。現代的に言えば、彼は飛躍的進化論を提唱した。この理論では、胚発生にお ける「変形」が「有望な怪物」を生み出し、それが偶然にも当時の環境条件に適応した場合、単一の巨視的進化の飛躍によって新種が誕生するという。1857 年、彼はこう記した。「ある種が別の種へ変化することは、特にその若齢個体に種を特徴づける形質の大半が既に備わっている場合、自然にとってさほど困難な ことではない。こうして特定の種は消滅するかもしれないが、同じ血縁関係にある別の種が空間的にその地位を引き継ぐ。それは時間の問題である... このように近縁関係は種から属へ、属から綱・目へと広がり、その特徴は誤解されることはない。」 |

| Legacy Knox is commemorated in the scientific name of a species of African lizard, Meroles knoxii.[55] |

レガシー ノックスはアフリカのトカゲの一種、Meroles knoxiiの学名にその名を刻まれている。[55] |

Knox in fiction Knox, as portrayed in Edinburgh's Surgeons' Hall Museum An Amazon original anthology television series Lore features Burke and Hare murders case in its Season 2 episode 1 named " Burke and Hare: In the Name of Science" released on 19 October 2018. Peter Cushing plays Knox in The Flesh and the Fiends (1960). Written and directed by John Gilling, the film is a reasonably accurate depiction, allowing for some dramatic licence and time constraints, of the Burke and Hare story. The Anatomist (1961) Alastair Sim as Knox. This was based on a 1930 play of the same name by James Bridie, which the BBC broadcast in 1939 with Knox played by Andrew Cruickshank[56] and in 1980 with Patrick Stewart as Knox.[57] John Hoyt played Knox in an episode of the Alfred Hitchcock Hour based on the Burke and Hare murders. The character Thomas Rock in the Dylan Thomas play The Doctor and the Devils is based on Knox. The play was filmed in 1985 with Timothy Dalton as Dr Rock. Knox was the model for the character of Thomas Potter in Matthew Kneale's epic novel English Passengers, which deals with the perceptions and perspectives of different races, nationalities and stations in society. The Knox scandal forms the background of Robert Louis Stevenson's short story "The Body Snatcher" (1884) The character Mr K- in the short story "The Body Snatcher" by Robert Louis Stevenson, is clearly a reference for Robert Knox. Later filmed The Body Snatcher in 1945, starring Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi; and TV (1966), both mentioning the West Port murders. In Burke & Hare, the last film of veteran director Vernon Sewell, Knox is portrayed by Harry Andrews. The character Doctor Knox from manga series Fullmetal Alchemist from 2001 (which got an animation adaptation in 2009) is probably a reference to the real Robert Knox since both have the same name, physical similarities and were military surgeons specialising in autopsies and Pathologists. Knox is a major character in Nicola Morgan's 2003 novel "Fleshmarket" Leslie Phillips played a version of Knox in the 2004 Doctor Who audio drama Medicinal Purposes, which pitted the Sixth Doctor (Colin Baker) against another time-traveller (Phillips) who had taken the place of the historical Knox, and was manipulating the events of the Burke and Hare murders.[58] The Horrible Histories TV series (Series 1, Episode 13) includes a sketch about Robert Knox, in which the story of the body-snatching cases is told in a song. Knox is played by Mathew Baynton and Burke and Hare by Simon Farnaby and Jim Howick respectively. Knox was played by Tom Wilkinson in the 2010 black comedy Burke and Hare. Knox was played by Marc Wootton in Episode 2 of Drunk History Comedy Central (2015) In 1942 the Dutch author Johan van der Woude published his Anatomie: Een Episode uit de Geschiedenis der Chirurgie, later published as Schandaal om Dr Knox, which is a historical novel about Knox and the Burke and Hare affair. In 1972 the television show Night Gallery (episode #70 "Deliveries in the Rear"), a callous surgeon (loosely based on Knox) turns a blind eye to "resurrectionists" who murder to supply corpses for anatomy classes – until he goes insane upon finding the latest victim is his fiancée. |

フィクションにおけるノックス エディンバラ外科医会館博物館に描かれたノックス Amazonオリジナルアンソロジーテレビシリーズ『Lore』では、2018年10月19日公開のシーズン2第1話「バークとヘア:科学の名のもとに」 でバークとヘア殺人事件を取り上げている。 ピーター・カッシングは『肉と悪魔』(1960年)でノックスを演じた。ジョン・ギリングが脚本・監督を務めた本作は、多少の脚色と時間的制約はあるもの の、バークとヘアの事件を比較的正確に描いている。 『解剖学者』(1961年)ではアラステア・シムがノックスを演じた。これはジェームズ・ブリディによる1930年の同名戯曲を基にしたもので、BBCは 1939年にアンドリュー・クルックシャンク[56]がノックスを演じた版を、1980年にはパトリック・スチュワートがノックスを演じた版を放送した。 [57] ジョン・ホイトは『アルフレッド・ヒッチコック・アワー』のバークとヘアの殺人事件を題材にしたエピソードでノックスを演じた。 ディラン・トーマスの戯曲『医師と悪魔たち』のトーマス・ロックという人物はノックスがモデルだ。この戯曲は1985年に映画化され、ティモシー・ダルト ンがロック博士を演じた。 ノックスはマシュー・ニーレの長編小説『イングランドの旅人』に登場するトーマス・ポッターのモデルとなった。同作は社会における異なる人種、ナショナリ ズム、階層の認識と視点を扱っている。 ノックス事件はロバート・ルイス・スティーブンソンの短編小説『死体泥棒』の背景となっている ロバート・ルイス・スティーブンソンの短編『死体泥棒』(1884年)に登場するK氏という人物は、明らかにロバート・ノックスをモデルとしている。後に 1945年にボリス・カーロフとベラ・ルゴシ主演で映画化され、1966年にはテレビドラマ化もされたが、いずれもウェストポート殺人事件に言及してい る。 ベテラン監督ヴァーノン・シューエルの遺作『バーク&ヘア』では、ハリー・アンドリュースがノックスを演じている。 2001年刊行の漫画『鋼の錬金術師』(2009年にアニメ化)に登場するキャラクター「ドクター・ノックス」は、実在のロバート・ノックスへの言及と考 えられる。両者に同名・外見的類似点があり、検死と病理学を専門とする軍医であった点で一致するからだ。 ノックスはニコラ・モーガンの2003年小説『フレッシュマーケット』の主要人物である。 レスリー・フィリップスは2004年の『ドクター・フー』オーディオドラマ『メディシナル・パーパス』でノックスの変種を演じた。この作品では第六ドク ター(コリン・ベイカー)が、歴史上のノックスに成り代わりバーク&ヘア殺人事件を操る別の時間旅行者(フィリップス)と対峙する。[58] テレビシリーズ『ホラーブル・ヒストリーズ』(シーズン1第13話)にはロバート・ノックスを題材にしたスケッチが含まれており、死体盗掘事件の経緯が歌 で語られる。ノックス役はマシュー・ベイントン、バークとヘア役はそれぞれサイモン・ファーナビーとジム・ハウイックが演じた。 2010年のブラックコメディ映画『バーク&ヘア』ではトム・ウィルキンソンがノックスを演じた。 2015年放送のコメディ・セントラル『酔っ払い歴史』第2話では、ノックス役をマーク・ウートンが演じた。 1942年、オランダ人作家ヨハン・ファン・デル・ヴォウデは『解剖学:外科史の一エピソード』を出版した。後に『ノックス博士をめぐるスキャンダル』と して刊行されたこの作品は、ノックスとバーク&ヘア事件を題材とした歴史小説である。 1972年、テレビ番組『ナイト・ギャラリー』(第70話「背後の配達」)では、冷酷な外科医(ノックスをモデルとしている)が、解剖学の授業用に死体を 供給するために殺人を行う「死体盗掘者」たちを見逃していた。しかし、最新の犠牲者が自分の婚約者だと知った時、彼は狂気に陥った。 |

| Works Engravings of the nerves: copied from the works of Scarpa, Soemmering and other distinguished anatomists. Edinburgh 1829. [Edward Mitchell, engraver] The races of men: a fragment. Renshaw, London. 1850, revised 1862. Great artists and great anatomists: a biographical and philosophical study. Van Voorst, London 1852. A manual of artistic anatomy 1852. Fish and fishing in the lone glens of Scotland, with a history of the propagation, growth and metamorphoses of the Salmon. Routledge, London 1854. Man – his structure and physiology 1857. |

作品 神経の版画:スカルパ、ゾーメリング及び他の著名な解剖学者らの著作から複製。エディンバラ、1829年。[エドワード・ミッチェル、版画家] 人類の諸人種:断片。レンショー、ロンドン。1850年、1862年改訂。 偉大な芸術家と偉大な解剖学者:伝記的・哲学的研究。ヴァン・フォールスト、ロンドン、1852年。 芸術解剖学手引書 1852年。 スコットランドの孤独な渓谷における魚と漁業、サケの繁殖・成長・変態の歴史を付す。ラウトレッジ、ロンドン 1854年。 人間―その構造と生理学 1857年。 |

| References Douglas, p. 16. Bates, A. W. (2010). The Anatomy of Robert Knox: Murder, Mad Science and Medical Regulation in Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2. Waterston, Charles D; Macmillan Shearer, A (July 2006). Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002: Biographical Index (PDF). Vol. II. Edinburgh: The Royal Society of Edinburgh. ISBN 978-0-902198-84-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2011. Lonsdale, Henry (1870). A Sketch of the Life and Writings of Robert Knox, the Anatomist. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 5. Knox, Robert (1855). "Contributions to the philosophy of zoology, with special reference to the natural history of man". Lancet. 2 (1663): 24–6, 45–6, 68–71, 162–4, 186–8, 216–18. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)53494-2. Knox, Robert (1854). "Xavier Bichat: his life and labours; a biographical and philosophical study". Lancet. 2 (1628): 393–6. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)54763-2. Bates, A. W. (2010). The Anatomy of Robert Knox: Murder, Mad Science and Medical Regulation in Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2. Knox, Robert (1815). "On the relations subsisting between the time of the day, and various functions of the human body; and on the manner in which the pulsations of the heart and arteries are affected by muscular exertion". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 11: 52–65. Knox, Robert (1856). "Contributions to surgical anatomy and operative surgery". Lancet. 1 (1689): 35–6, 535–7. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)55284-3. Bacot, John (1828). "Essays on syphilis". London Medical Gazette. 2: 289–94. Knox, Robert (1850). The Races of Men: a Fragment. London: Henry Renshaw. Hutton, C.W. (1887). The Autobiography of the Late Sir Andries Stockenström, Bart... Cape Town: J.C. Juta and Co. p. 119. Hutton, C.W. (1887). The Autobiography of the Late Sir Andries Stockenström, Bart... Cape Town: J. C. Juta and Co. pp. 161–2. Bates, A.W. (2010). The Anatomy of Robert Knox: Murder, Mad Science and Medical Regulation in Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2. Knox, Robert (1852). Great Artists and Great Anatomists. London: John van Voorst. Letter from Thomas Hodgkin to John Hodgkin, Oct 1821, Wellcome Library AMS/MF/3/1 Knox, Robert (1824). "Inquiry into the Origin and Characteristic Differences of the Native Races inhabiting the Extra-tropical Part of Southern Africa". Memoirs of the Wernerian Natural History Society. 5: 206–219 – via Internet Archive. RCSEd Minute Book 1824, p. 149. RCSEd Minute Book 19 Apr. 1825, p. 248. Audubon, Maria R. (1899). Audubon and His Journals. New York: C. Scribner. pp. 146, 152. Wilsone, W. Syme (1863). "The late Dr Robert Knox". Lancet. 1 (2054): 49. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)62739-4. Lonsdale, Henry (1870). A Sketch of the Life and Writings of Robert Knox, the Anatomist. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 36. "Edinburgh Post Office annual directory, 1832-1833". National Library of Scotland. p. 103. Retrieved 25 February 2018. Bates, A.W. (2010). The Anatomy of Robert Knox: Murder, Mad Science and Medical Regulation in Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 110–11. ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2. "The Resurrectionists". New York Academy of Medicine. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008. "Belfast News-Letter". Belfast News-Letter: 2. 17 February 1829. RCSEd Minute Book 1831, 502. Lonsdale 1870, p. 21. Bates 2010, p. 88. Richardson R. 1987. Death, dissection and the destitute. Routledge, London. [includes a reassessment of Knox's culpability in the Burke and Hare case] Richards E. 1988. The 'moral anatomy' of Robert Knox: a case study of the interplay between biological and social thought in the context of Victorian scientific naturalism. J. Hist. Biol. "The Anatomy Murders Corpse of the Day—Dr. Robert Knox". Penn Press Log, October 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2009. Rosner, Lisa (2009). "All That Remains". The Anatomy Murders: Being the True and Spectacular History of Edinburgh's Notorious Burke and Hare and of the Man of Science Who Abetted Them in the Commission of Their Most Heinous Crimes. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4191-4. Bates 2010, pp. 99-100. RCSEd Minute Book 1847, 85-6. Campbell, Neil (1983). The Royal Society of Edinburgh (1783-1983). Edinburgh: Royal Society of Edinburgh. p. 72. Richards, Evelleen (1994). "The "moral anatomy" of Robert Knox: the interplay between biological and social thought in Victorian scientific naturalism". Isis. 85 (3): 377–411. JSTOR 235460. Donaldson, Ken; Henry, Christopher (17 June 2022). "Dr Robert Knox and his book on fishing in Scotland: A window into his mind". Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 52 (2): 159–165. doi:10.1177/14782715221103720. PMID 36146986. S2CID 249830554 – via SAGEJournals. Bates 2010, p. 143. Blake, C. Carter (1870). "The life of Dr Knox". J. Anthropol. 1 (3): 332–8. doi:10.2307/3024816. JSTOR 3024816. Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. "Dr Robert Knox". Necropolis Notables. The Brookwood Cemetery Society. Archived from the original on 20 March 2007. Retrieved 23 February 2007. Jackson, John P.; Weidman, Nadine M. (2004). Race, Racism, and Science: Social Impact and Interaction (Illustrated ed.). 1 January 2004: ABC-CLIO. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-851-09448-6. Retrieved 25 April 2015. Waters, Hazel (15 February 2007). Racism on the Victorian Stage: Representation of Slavery and the Black Character. Cambridge University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-139-46265-5. Retrieved 25 April 2015. Psomiades, Kathy Alexis (Fall 2010). "Polygenist Ecosystems: Robert Knox's The Races of Man (1850)". Victorian Review. 36 (2). Victorian Studies Association of Western Canada: 32–36. doi:10.1353/vcr.2010.0034. JSTOR 41413848. S2CID 162747396. Lansdown, Richard (2006). Strangers in the South Seas: The Idea of the Pacific in Western Thought: an Anthology (Illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-824-82902-5. Bates, Alan (2010). The Anatomy of Robert Knox: Murder, Mad Science and Medical Regulation in Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh (Illustrated ed.). Sussex Academic Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-845-19381-2. Retrieved 25 April 2015. Knox, Robert (1824). "Inquiry into the Origin and Characteristic Differences of the Native Races inhabiting the Extra-tropical Part of Southern Africa". Memoirs of the Wernerian Natural History Society. 5: 206–218, 210 – via Internet Archive. "We may view the human race as derived originally from one stock, to which the arbitrary name of Caucasian has been given. This species, influenced by climate and civilization, assumed, at a very early period, five distinct forms, which has also been arbitrarily designated by the names of Caucasian, Mongolic, Ethiopian, American, and Malay." (Note: Robert Knox was skeptical whether 'Malay' could be considered its own race and he considered them to be related to the "American variety" instead.) Biddiss, M. D. (1976). "The Politics of Anatomy: Dr Robert Knox and Victorian Racism". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 69 (4). Royal Society of Medicine (published 13 March 1976): 245–250. doi:10.1177/003591577606900402. PMC 1864530. PMID 772684. Knox, Robert. The Races of Men: A Philosophical Enquiry into the Influence of Race over the Destinies of Nations. 2nd ed. London: Henry Renshaw, pp. 542, 546, 548-9, 563. Knox 1850, p. 253 Knox, Robert (1824). "Inquiry into the Origin and Characteristic Differences of the Native Races inhabiting the Extra-tropical Part of Southern Africa". Memoirs of the Wernerian Natural History Society. 5: 206–219, 217 – via Internet Archive. Knox 1850, p. 254 Richards, 1994 Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Knox, pp. 143–144). "The Anatomist (1939)(TV)". imdb. Retrieved 12 October 2009. "Play of the Month: The Anatomist (1980)". EOFF. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2009. "Medicinal Purposes". Big Finish Productions. Retrieved 14 June 2010. |

参考文献 ダグラス、16ページ。 ベイツ、A. W. (2010). 『ロバート・ノックスの解剖学:19世紀エディンバラにおける殺人、狂気の科学、医療規制』. イーストボーン:サセックス・アカデミック・プレス. 16ページ. ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2. ウォーターストン、チャールズ・D; マクミラン・シアラー、A (2006年7月). 『エディンバラ王立協会元フェロー 1783–2002: 人物事典索引』(PDF). 第II巻. エディンバラ: エディンバラ王立協会. ISBN 978-0-902198-84-5. 2006年10月4日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ. 2011年2月8日取得。 ロンズデール、ヘンリー (1870). 『解剖学者ロバート・ノックスの生涯と著作の概説』. ロンドン: マクミラン社. p. 5. ノックス、ロバート (1855). 「動物学の哲学への貢献、特に人間の自然史に関する考察」. ランセット. 2 (1663): 24–6, 45–6, 68–71, 162–4, 186–8, 216–18. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)53494-2. ノックス、ロバート(1854)。「ザビエル・ビシャ:その生涯と業績;伝記的・哲学的研究」。ランセット。2 (1628): 393–6. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)54763-2. ベイツ、A. W. (2010). 『ロバート・ノックスの解剖学:19世紀エディンバラにおける殺人、狂気の科学、医療規制』. イーストボーン:サセックス・アカデミック・プレス. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2. ノックス、ロバート (1815). 「一日の時間帯と人体の様々な機能との関連性について;及び筋肉の運動が心臓と動脈の脈動に及ぼす影響について」. 『エディンバラ医学外科ジャーナル』. 11: 52–65. ノックス、ロバート (1856). 「外科解剖学と手術療法への寄稿」. ランセット. 1 (1689): 35–6, 535–7. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)55284-3. バコット、ジョン (1828). 「梅毒に関する論考」. ロンドン医学新聞. 2: 289–94. ノックス、ロバート (1850). 『人間の種族:断片』. ロンドン: ヘンリー・レンショー. ハットン、C.W. (1887). 『故アンドリース・ストッケンストローム卿の自伝』. ケープタウン: J.C. ジュタ社. p. 119. ハットン、C.W. (1887). 故アンドリース・ストックエンストローム卿の自伝...ケープタウン:J. C. ジュタ社。161–2頁。 ベイツ、A.W.(2010)。『ロバート・ノックスの解剖学:19世紀エディンバラにおける殺人、狂気の科学、医療規制』。イーストボーン:サセックス 学術出版社。39–40頁。ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2。 ノックス、ロバート(1852)。『偉大な芸術家と偉大な解剖学者たち』。ロンドン:ジョン・ヴァン・フォールスト。 トーマス・ホジキンからジョン・ホジキンへの手紙、1821年10月、ウェルカム図書館 AMS/MF/3/1 ノックス、ロバート(1824)。「南アフリカ亜熱帯地域に居住する先住民の起源と特徴的な異なる点に関する考察」. ヴェルネリアン自然史学会紀要. 5: 206–219 – インターネットアーカイブ経由. RCSEd議事録 1824年, p. 149. RCSEd議事録 1825年4月19日, p. 248. オーデュボン、マリア・R.(1899)。『オーデュボンとその日記』。ニューヨーク:C. スクリブナー。146, 152頁。 ウィルソン、W. サイム(1863)。「故ロバート・ノックス博士」。『ランセット』。1巻2054号:49頁。doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02) 62739-4. ロンズデール、ヘンリー(1870)。『解剖学者ロバート・ノックスの生涯と著作概説』。ロンドン:マクミラン社。p. 36。 「エディンバラ郵便局年次名簿、1832-1833年」。スコットランド国民図書館。103頁。2018年2月25日閲覧。 ベイツ、A.W.(2010)。『ロバート・ノックスの解剖学:19世紀エディンバラにおける殺人、狂気の科学、医療規制』。イーストボーン:サセック ス・アカデミック・プレス。pp. 110–11. ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2. 「死体盗掘者たち」. ニューヨーク医学会. 2008年5月9日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2008年4月27日閲覧. 「ベルファスト・ニュースレター」. ベルファスト・ニュースレター: 2. 1829年2月17日. RCSEd議事録 1831年、502頁。 ロンズデール 1870年、21頁。 ベイツ 2010年、88頁。 リチャードソン R. 1987. 『死、解剖、そして貧困者』. ラウトレッジ、ロンドン。[バークとヘア事件におけるノックスの責任の再評価を含む] リチャーズ E. 1988. ロバート・ノックスの『道徳解剖学』:ヴィクトリア朝科学的自然主義の文脈における生物学的思考と社会的思考の相互作用に関する事例研究. J. Hist. Biol. 「解剖殺人事件 今日の死体―ロバート・ノックス博士」. ペン・プレス・ログ, 2009年10月. 2009年11月5日取得. ロスナー、リサ (2009). 「残されたものすべて」. 『解剖殺人事件:エディンバラの悪名高きバークとヘア、そして彼らの最も凶悪な犯罪を助長した科学者の真実で衝撃的な歴史』. ペンシルベニア大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-8122-4191-4. ベイツ 2010, pp. 99-100. RCSEd議事録 1847, 85-6. キャンベル, ニール (1983). 『エディンバラ王立協会 (1783-1983)』. エディンバラ: エディンバラ王立協会. p. 72. リチャーズ, エヴェリーン (1994). 「ロバート・ノックスの『道徳解剖学』:ヴィクトリア朝科学的自然主義における生物学的思考と社会的思考の相互作用」。『アイシス』85巻3号: 377–411頁。JSTOR 235460。 ドナルドソン、ケン;ヘンリー、クリストファー(2022年6月17日)。「ロバート・ノックス博士と彼のスコットランド漁業に関する著作:その思考の 窓」エディンバラ王立医師会誌。52 (2): 159–165. doi:10.1177/14782715221103720. PMID 36146986. S2CID 249830554 – SAGEJournals経由。 ベイツ 2010, p. 143. ブレイク, C. カーター (1870). 「ノックス博士の生涯」. J. Anthropol. 1 (3): 332–8. doi:10.2307/3024816. JSTOR 3024816. 『エディンバラ王立協会元フェロー伝記索引 1783–2002』(PDF)。エディンバラ王立協会。2006年7月。ISBN 0-902-198-84-X。 「ロバート・ノックス博士」。ネクロポリス著名人。ブルックウッド墓地協会。2007年3月20日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2007年2月23日 取得。 ジャクソン、ジョン・P.; ワイドマン、ナディーン・M. (2004). 『人種、人種主義、そして科学:社会的影響と相互作用』(図版版). 2004年1月1日: ABC-CLIO. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-851-09448-6. 2015年4月25日閲覧。 ウォーターズ、ヘイゼル(2007年2月15日)。『ヴィクトリア朝舞台における人種主義:奴隷制と黒人キャラクターの表現』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 134頁。ISBN 978-1-139-46265-5。2015年4月25日閲覧。 プソミアデス、キャシー・アレクシス (2010年秋)。「多起源論的生態系:ロバート・ノックス『人類の諸人種』(1850年)」。『ヴィクトリア朝評論』36巻2号。カナダ西部ヴィクトリ ア朝研究協会:32–36頁。doi:10.1353/vcr.2010.0034。JSTOR 41413848。S2CID 162747396. ランズダウン、リチャード(2006)。『南洋の異邦人たち:西洋思想における太平洋の概念:アンソロジー』(図版付版)。ハワイ大学出版局。197頁。 ISBN 978-0-824-82902-5。 ベイツ、アラン(2010)。『ロバート・ノックスの解剖学:19世紀エディンバラにおける殺人、狂気の科学、医療規制』(図版入り版)。サセックス学術 出版。131頁。ISBN 978-1-845-19381-2。2015年4月25日取得。 ノックス、ロバート(1824)。「南アフリカ亜熱帯地域に居住する先住民人種の起源と特徴的な差異に関する考察」『ウェナー自然史学会紀要』5巻: 206–218, 210頁(インターネットアーカイブ経由)。「人類は本来、一つの系統から派生したと見なすことができる。この系統には恣意的にコーカサス人種という名称 が与えられている。」 この種は、気候と文明の影響を受け、非常に早い時期に五つの異なる形態をとり、これもまた恣意的にコーカサス人種、モンゴロイド人種、エチオピア人種、ア メリカ人種、マレー人種という名称で呼ばれるようになった。」(注:ロバート・ノックスは「マレー人種」が独立した人種と見なせるか懐疑的であり、むしろ 「アメリカ人種」と関連があると考えた。) ビディス、M. D. (1976). 「解剖学の政治学:ロバート・ノックス博士とヴィクトリア朝時代の人種主義」. 王立医学会紀要. 69 (4). 王立医学会 (1976年3月13日発行): 245–250. doi:10.1177/003591577606900402. PMC 1864530. PMID 772684. ノックス, ロバート. 『人類の諸民族:人種が国民の運命に及ぼす影響に関する哲学的考察』第2版. ロンドン: ヘンリー・レンショー, pp. 542, 546, 548-9, 563. ノックス 1850, p. 253 ノックス、ロバート (1824). 「南アフリカ温帯域外に居住する先住民人種の起源と特徴的な異なる点に関する考察」. ヴェルネリアン自然史学会紀要. 5: 206–219, 217 – インターネットアーカイブ経由. ノックス 1850, p. 254 リチャーズ、1994年 ボーレンズ、ボー;ワトキンス、マイケル;グレイソン、マイケル(2011年)。『爬虫類の命名辞典』。ボルチモア:ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学出版局。 xiii + 296頁。ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5。(ノックス、143–144頁)。 「解剖学者 (1939)(TV)」. imdb. 2009年10月12日閲覧. 「今月の演劇:『解剖学者』(1980年)」。EOFF。2008年11月21日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2009年10月12日閲覧。 「医療目的」。ビッグ・フィニッシュ・プロダクションズ。2010年6月14日閲覧。 |

| Sources Bettany, George Thomas (1892). "Knox, Robert (1791-1862)" . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 31. London: Smith, Elder & Co. Taylor, Clare L. "Knox, Robert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15787. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.) |

出典 ベタニー、ジョージ・トーマス(1892年)。「ノックス、ロバート(1791-1862)」.リー、シドニー(編)『英国人名事典』第31巻.ロンド ン:スミス・エルダー社. テイラー、クレア・L.「ノックス、ロバート」.『オックスフォード英国人名事典』(オンライン版).オックスフォード大学出版局.doi: 10.1093/ref:odnb/15787. (購読、Wikipedia Libraryアクセス、または英国公共図書館の会員資格が必要である。) |

| Further reading Bates, A.W. (2010), The Anatomy of Robert Knox: Murder, Mad Science and Medical Regulation in Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh, Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2, retrieved 14 November 2014 Lonsdale, Henry (1870), A Sketch of the Life and Writings of Robert Knox, the Anatomist, London: Macmillan and Co., retrieved 10 November 2014 Richardson, Ruth (1987), Death, Dissection and the Destitute, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7102-0919-3, retrieved 16 July 2010 Sera-Shriar, Efram (2013), The Making of British Anthropology, 1813-1871, London: Pickering & Chatto, pp.81-107 |

参考文献 ベイツ、A.W.(2010)『ロバート・ノックスの解剖学:19世紀エディンバラにおける殺人、狂気の科学、医療規制』イーストボーン:サセックス・ア カデミック・プレス、ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2、2014年11月14日取得 ロンズデール、ヘンリー(1870年)『解剖学者ロバート・ノックスの生涯と著作概説』ロンドン:マクミラン社、2014年11月10日閲覧 リチャードソン、ルース(1987年)『死、解剖、そして貧困者』ロンドン:ラウトレッジ&キーガン・ポール社、 ISBN 0-7102-0919-3, 2010年7月16日閲覧 セラ=シュリアール、エフラム(2013年)『英国人類学の形成、1813-1871年』ロンドン:ピッカリング&チャット社、pp.81-107 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Knox_%28surgeon%29 |

☆ 超越論的解剖学(transcendental anatomy)

The

osteology of the human skull was an important theory for transcendental

anatomists.

| Transcendental

anatomy, also known as philosophical anatomy, was a form of

comparative anatomy that sought to find ideal patterns and structures

common to all organisms in nature.[1] The term originated from

naturalist philosophy in the German provinces, and culminated in

Britain especially by scholars Robert Knox and Richard Owen, who drew

from Goethe and Lorenz Oken.[1] From the 1820s to 1859, it persisted as

the medical expression of natural philosophy before the Darwinian

revolution.[2] Amongst its various definitions, transcendental anatomy has four main tenets: the presupposition of an Ideal Plan among the multiplicity of visible structures in the animal and plant kingdom, and that the Plan determines function the Ideal Plan acted as a force for the maintenance of anatomical uniformity (as opposed to diversity-inducing forces of Nature) the belief that this a priori Plan was discoverable the desire to discover universal Laws underlying anatomical differences.[3] |

超越解剖学、別名哲学的解剖学は、自然界のあらゆる生物に共通する理想

的なパターンや構造を見出そうとした比較解剖学の一形態であった。[1]

この用語はドイツ地方の自然哲学者から生まれ、特にロバート・ノックスとリチャード・オーウェンによって英国で頂点を迎えた。彼らはゲーテとローレンツ・

オーケンから影響を受けた。[1] 1820年代から1859年まで、ダーウィン革命以前の自然哲学の医学的表現として存続した。[2] 超越解剖学には様々な定義があるが、主に四つの基本原理がある: 動物界と植物界に見られる多様な構造の中に理想的な設計図が存在するという前提、そしてその設計図が機能を決定するという考え 理想的な設計図が解剖学的均一性を維持する力として作用する(多様性を生む自然の力とは対照的に) このア・プリオリに設計された設計図は発見可能であるという信念 解剖学的差異の根底にある普遍的な法則を発見したいという願望である。[3] |

| History Johann Wolfgang Goethe was one of many naturalists and anatomists in the nineteenth century who was in search of an Ideal Plan in nature. In Germany, this was known as Urpflanze for the plant kingdom and Urtier for animals. He popularized the term "morphology" for this search. Transcendental anatomy first derived from the naturalist philosophy known as Naturphilosophie.[4] In the 1820s, French anatomist Etienne Reynaud Augustin Serres (1786–1868) popularized the term transcendental anatomy to refer to the collective morphology of animal development.[3] Synonymous expressions such as philosophical anatomy, higher anatomy, and transcendental morphology also arose at this time. Some advocates regarded transcendental anatomy as the ultimate explanation for biological structures, while others saw it as one of several necessary explanatory devices.[3] |

超越解剖学、別名哲学的解剖学は、自然界のあらゆる生物に共通する理想

的なパターンや構造を見出そうとした比較解剖学の一形態であった。[1]

この用語はドイツ地方の自然哲学者から生まれ、特にロバート・ノックスとリチャード・オーウェンによって英国で頂点を迎えた。彼らはゲーテとローレンツ・

オーケンから影響を受けた。[1] 1820年代から1859年まで、ダーウィン革命以前の自然哲学の医学的表現として存続した。[2] 超越解剖学には様々な定義があるが、主に四つの基本原理がある: 動物界と植物界に見られる多様な構造の中に理想的な設計図が存在するという前提、そしてその設計図が機能を決定するという考え 理想的な設計図が解剖学的均一性を維持する力として作用する(多様性を生む自然の力とは対照的に) このア・プリオリに設計された設計図は発見可能であるという信念 解剖学的差異の根底にある普遍的な法則を発見したいという願望である。[3] |

Vertebral theory The osteology of the human skull was an important theory for transcendental anatomists. Transcendental anatomists theorized that the bones of the skull were "cranial vertebra", or modified bones from the vertebrae.[1] Owen ardently supported the theory as major evidence for his theory of homology.[5] The theory has since been discredited. |

脊椎理論 人間の頭蓋骨の骨学は、超越解剖学者にとって重要な理論であった。 超越解剖学者は、頭蓋骨の骨は「頭蓋椎骨」、すなわち脊椎から変化した骨であると理論化した[1]。オーウェンはこの理論を、自身の相同性理論の主要な証 拠として熱心に支持した[5]。 この理論はその後、否定された。 |

| 1. Alan Bates (1 January 2010).

The Anatomy of Robert Knox: Murder, Mad Science and Medical Regulation

in Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 23–. ISBN

978-1-84519-381-2. Retrieved 25 June 2013. 2. Janis McLarren Caldwell (18 November 2004). Literature and Medicine in Nineteenth-Century Britain: From Mary Shelley to George Eliot. Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-1-139-45664-7. Retrieved 25 June 2013. 3. Andrew Cunningham; Nicholas Jardine (28 June 1990). Romanticism and the Sciences. CUP Archive. pp. 144–. ISBN 978-0-521-35685-5. Retrieved 25 June 2013. 4. Robert J. Richards (2 February 2009). The Meaning of Evolution: The Morphological Construction and Ideological Reconstruction of Darwin's Theory. University of Chicago Press. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-226-71205-5. Retrieved 25 June 2013. 5. Mario a Di Gregorio (2005). From Here to Eternity: Ernst Haeckel and Scientific Faith. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 268–. ISBN 978-3-525-56972-6. Retrieved 25 June 2013. |

1.

アラン・ベイツ(2010年1月1日)。『ロバート・ノックスの解剖学:19世紀エディンバラにおける殺人、狂気の科学、医療規制』。サセックス・アカデ

ミック・プレス。23頁以降。ISBN 978-1-84519-381-2。2013年6月25日取得。 2. ジャニス・マクラレン・コールドウェル(2004年11月18日)。『19世紀英国における文学と医学:メアリー・シェリーからジョージ・エリオットま で』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。14頁以降。ISBN 978-1-139-45664-7。2013年6月25日閲覧。 3. アンドリュー・カニンガム; ニコラス・ジャーディン (1990年6月28日). 『ロマン主義と科学』. CUP Archive. pp. 144–. ISBN 978-0-521-35685-5. 2013年6月25日閲覧. 4. ロバート・J・リチャーズ (2009年2月2日). 『進化の意味:ダーウィン理論の形態学的構築とイデオロギー的再構築』. シカゴ大学出版局. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-226-71205-5. 2013年6月25日閲覧. 5. マリオ・ディ・グレゴリオ(2005年)。『ここから永遠へ:エルンスト・ヘッケルと科学的信仰』。ヴァンデンホック・アンド・ルプレヒト。268ページ 以降。ISBN 978-3-525-56972-6。2013年6月25日取得。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcendental_anatomy |

☆

★

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099