ロバート・ラッハマン

Robert Lachmann (28 November 1892 – 8 May 1939)

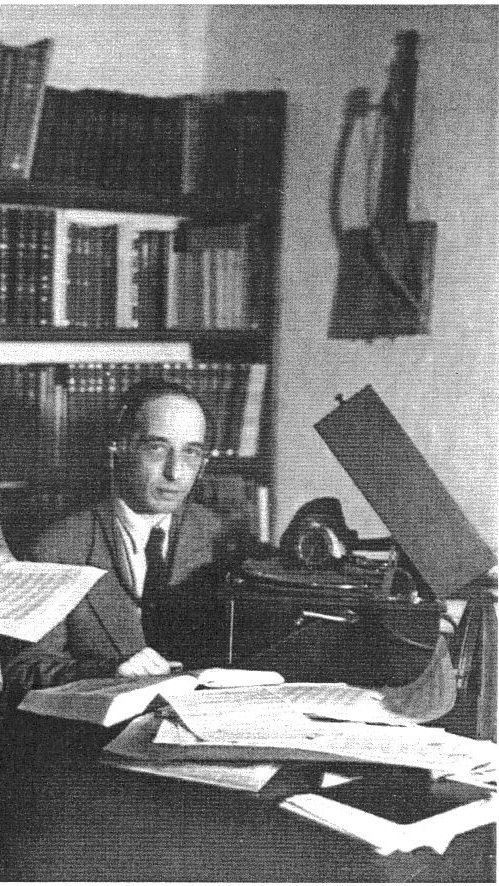

Robert Lachmann

transcribing

from a recording, Jerusalem

☆ ロベルト・ラッハマン(1892年11月28日-1939年5月8日) は、ドイツの民族音楽学者、ポリグロット(ドイツ語、英語、フランス語、アラビア語)、東洋学者、図書館員。中東の音楽伝統の専門家であり、ベルリン比較 音楽学派のメンバーで、その創立者の一人でもある。1935年、ユダヤ人であることを理由にナチス政権下のドイツを追われた後、パレスチナに移住し、エル サレム・ヘブライ大学のために民族音楽学的記録の豊富なアーカイヴを設立した

| Robert Lachmann

(28

November 1892 – 8 May 1939) was a German ethnomusicologist, polyglot

(German, English, French, Arabic), orientalist and librarian. He was an

expert in the musical traditions of the Middle East, a member of the

Berlin School of Comparative Musicology and one of its founding

fathers. After having been forced to leave Germany under the Nazis in

1935 because of his Jewish background, he emigrated to Palestine and

established a rich archive of ethnomusicological recordings for the

Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[1] |

ロベルト・ラッハマン(1892年11月28日-1939年5月8日)

は、ドイツの民族音楽学者、ポリグロット(ドイツ語、英語、フランス語、アラビア語)、東洋学者、図書館員。中東の音楽伝統の専門家であり、ベルリン比較

音楽学派のメンバーで、その創立者の一人でもある。1935年、ユダヤ人であることを理由にナチス政権下のドイツを追われた後、パレスチナに移住し、エル

サレム・ヘブライ大学のために民族音楽学的記録の豊富なアーカイヴを設立した[1]。 |

| Life and contributions to

ethnomusicology of the Middle East Robert Lachmann was born in Berlin, and had learned French and English as a young man. Having been assigned as interpreter at a German camp for prisoners of war (POW)[2] during World War I, he became interested in the languages, songs and customs of POWs from North Africa and India, and started to learn Arabic, which he later followed up at Berlin university. He also studied comparative musicology with Johannes Wolf, Erich von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs and published his Ph.D. dissertation in 1922, based on urban music in Tunisia. Apart from his study Musik des Orients (Music of the Orient), 1929, that compares musical systems of various “Oriental” traditions from North Africa to the Far East, and a translation of a musical treatise by the ninth-century Arab scholar Al-Kindi in 1931, he edited the "Zeitschrift für vergleichende Musikwissenschaft" (Journal of Comparative Musicology)[3] from 1932-35. In 1935, he was dismissed from his position as music librarian at the Berlin State Library, because he was Jewish, and emigrated to Jerusalem. On the invitation of Judah L. Magnes, chancellor and later president (1935–1948) of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Lachmann established a center for Middle Eastern music and the university's archive for "Oriental music". With the assistance of only one sound technician, he recorded almost 1000 new examples of secular and liturgical music.[4] His sound archive was later incorporated into the National Sound Archives of the National Library of Israel. Lachmann died in Jerusalem at age 46. Apart from his earlier field studies in Tunisia and Morocco, he participated in the 1932 Cairo Congress of Arab Music and was responsible for recording the performances of the artists and ensembles invited to the conference.[4] His important contribution to the ethnomusicology of North Africa and the Middle East is reflected in a description of his radio programmes, transmitted by the English language programme of the Palestine Broadcasting Service (PBS) in 1936-1937, by British musicologist Ruth F. Davis:[5] Focusing on sacred and secular musical traditions of different “Oriental” communities living in and around Jerusalem, including Bedouin and Palestinian Arabs, Yemenite, Kurdish and Baghdadi Jews, Copts and Samaritans, Lachmann's lectures were illustrated by more than thirty musical examples performed live in the studio by local musicians and singers and simultaneously recorded on metal disc. In two lectures (numbers 10 and 11), based on commercial recordings, he contextualized the live performances with wide-ranging surveys of the urban musical traditions of North Africa and the Middle East, extending beyond the Arab world to Turkey, Persia, and Hindustan."[1] |

生涯と中東民族音楽学への貢献 ロベルト・ラッハマンはベルリンに生まれ、若い頃にフランス語と英語を学んだ。第一次世界大戦中、ドイツ軍の捕虜収容所[2]で通訳を務めたことをきっか けに、北アフリカやインドの捕虜の言語、歌、習慣に興味を持ち、アラビア語を学び始める。また、ヨハネス・ヴォルフ、エーリッヒ・フォン・ホルンボステ ル、クルト・ザックスのもとで比較音楽学を学び、1922年にチュニジアの都市音楽に基づく博士論文を発表した。1929年には、北アフリカから極東に至 る様々な「東洋」の伝統の音楽体系を比較した研究書『東洋の音楽』(Musik des Orients)を、1931年には9世紀のアラブ人学者アル=キンディの音楽論を翻訳したほか、1932年から35年にかけては『比較音楽学雑誌』 (Zeitschrift für vergleichende Musikwissenschaft)[3]の編集に携わった。 1935年、ユダヤ人であることを理由にベルリン国立図書館の音楽司書の職を解かれ、エルサレムに移住。エルサレム・ヘブライ大学の総長であり、後に学長 (1935~1948年)となったユダ・L・マグネスの招きで、ラッハマンは中東音楽センターと同大学の「東洋音楽」アーカイブを設立した。たった一人の 音響技師の助けを借りながら、彼は世俗音楽と典礼音楽のほぼ1000曲を新たに録音した[4]。ラフマンは46歳でエルサレムで亡くなった。 北アフリカと中東の民族音楽学に対する彼の重要な貢献は、イギリスの音楽学者ルース・F・デイヴィスによる、1936年から1937年にかけてパレスチナ 放送(PBS)の英語番組で放送された彼のラジオ番組についての記述に反映されている[5]。 ベドウィンやパレスチナ・アラブ人、イエメン人、クルド人、バグダディ系ユダヤ人、コプト教徒、サマリア人など、エルサレム周辺に住むさまざまな「東洋 人」コミュニティの聖俗音楽の伝統に焦点を当てたラッハマンの講義は、地元の音楽家や歌手によってスタジオで生演奏され、同時に金属ディスクに録音された 30以上の音楽例によって説明された。商業録音に基づく2つの講義(10番と11番)では、北アフリカと中東の都市音楽の伝統に関する広範な調査によって ライブ演奏の文脈を説明し、アラブ世界を超えてトルコ、ペルシャ、ヒンドゥスタンにまで及んだ」[1]。 |

| Publications Die Musik in den tunisischen Städten (Music in the cities of Tunisia), 1922, (Ph.D. dissertation) Musik des Orients (Music of the Orient), Berlin, 1929 with Mahmoud el-Hefni, eds., Ja'qūb Ibn Isḥāq al-Kindi: Risāla fī Khubr tā'līf al-alhān: Über die Komposition der Melodien, Veröffentlichungen der Gesellschaft zur Erforschung der Musik des Orients, 1 (Leipzig: Fr. Kistner and C. F. W. Siegel, 1931). Editor of the Zeitschrift für vergleichende Musikwissenschaft (Journal of Comparative Musicology), 1933-35 (Gesellschaft zur Erforschung des Musik des Orients - The Society for the Study of Oriental Music,) from 1930-1935 Jewish Cantillation and Song in the Isle of Djerba. (Archives of Oriental Music) Hebrew University, Jerusalem, 1940 |

|

| Contemporary perspectives from "Ethnomusicology

and Political Ideology in Mandatory Palestine: Robert Lachmann’s

“Oriental Music” Projects" by RUTH F. DAVIS |

RUTH F. DAVISの"Ethnomusicology and Political Ideology in Mandatory Palestine: Robert Lachmann’s “Oriental Music” Projects"の結論部分 |

| As

an early experiment in applied ethnomusicology, Lachmannn’s “Oriental

music” projects resonate with more recent initiatives that use music as

a means to promote understanding between the different peoples of

Israel and Palestine. The signing of the Oslo Peace Accords in

September 1993[39] created a window of unprecedented opportunity,

inspiring and enabling collaborative initiatives between Israeli Jews

and Israeli and Palestinian Arabs. In 1999, the Israeli musician Daniel

Barenboim and the Palestinian intellectual Edward Said co-founded the

West-Eastern Divan orchestra in which young musicians from Israel,

Palestine, the wider Arab world and Spain perform together under

Barenboim’s baton.[40] Based strategically in Andalusia, near Seville,

symbolically evoking the legendary time of Al-Andalus when Jews,

Christians and Muslims co-existed in relative harmony, the orchestra

presents itself as a model and ideal for Israeli—Palestinian society in

which musical collaboration is perceived as a metaphor for constructive

social collaboration. Yet by privileging the symphony orchestra and

Western art music, icons of European cultural and political supremacy,

the goals of Barenboim and Said diverge radically from those of

Lachmann who insisted on the need for his European listeners to engage

with and at least aspire to understand the musical expressions of the

Other. More attuned to Lachmann’s vision and aims is the Israeli-based “musical scene” documented by Benjamin Brinner,[41] known locally as musika etnit Yisraelit (Israeli ethnic music). Building upon Lachmann’s premonition, on his arrival in Mandatory Palestine, that “young Jewish or Arab composers may find, one day, a new way of expressing themselves [. . . ] somewhere between the Western and the Eastern tradition”, Israeli ethnic music consists of ensembles of Israeli Jews and Israeli and Palestinian Arabs collaborating in the creation of new types of musical synthesis whose sounds, styles and forms of expression are grounded in different types of Middle Eastern music. Focusing on two leading bands that emerged in the early 1990s, Alei Hazayit (The Olive Branches) and Bustan Abraham (The Garden of Abraham),[42] Brinner describes a vibrant, highly diversified grassroots musical scene with a trans-national circulation and representation and a continuing vitality that has endured regardless of the vicissitudes of the official peace process. The very existence of such a musical scene, Brinner posits, is “indicative of a much broader phenomenon, a shift in cultural balance and orientation of a sizeable proportion of the Israeli public that has been characterized [. . .] as ‘the decolonization of Eurocentric power structures and epistemology’.”[43] Musically, this broader socio-cultural phenomenon can be traced back at least to the 1980s, with the acceptance and eventual absorption of musika mizrahit (literally, Eastern music), originally the pan-ethnic party music of socially marginalized Jewish communities of Middle Eastern and Mediterranean origins, into the Israeli popular musical mainstream.[44] For Brinner, the particular significance of Israeli ethnic music, apart from its high artistic quality, consists in the creative and egalitarian aspect of the musical collaboration, and in the nature of the musical sources, derived from different Middle Eastern traditions. Thus in contrast to the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, in which “the musicians’ sense of ownership or connection to this music, however much it meant to them on personal level, must necessarily be attenuated by historical and cultural distance,” in Israeli ethnic music the musicians participate as equals in acts of collective composition and improvisation, thus literally “jointly owning” the sounds they produce: Because such music is a collaborative production that draws heavily on the idioms of the Middle East, I content that it “Speaks” to audiences differently than a Mozart symphony. This is not a question of relative aesthetic value, but of incorporating a broader range of cultural resources, whereas the imposition by Said and Barenboim, of the classics of European art music reinscribes Western cultural hierarchy. [45] The processes of musical transformation, adaptation and the acquiring of new musical competencies required by such creative collaborations may, Brinner suggests, provide deeper, more enduring foundations for peaceful co-existence than those provided by other collaborative initiatives. In political terms they imply a “third way” in which fear of compromise and loss is replaced by mutual benefit: Because such collaborations produce a new kind of music, their effect is not just humanizing. It also presents new possibilities for the future. By expanding musical vocabulary, techniques, and understanding, they have staked out common ground . . . Like the music [these bands] have created, peaceful co-existence is a matter of improvising within compatible frameworks. These must be collectively created and negotiated, not imposed. [46] It was precisely the quest for “new possibilities for the future” combined with his passionate belief in the need to “stake out common ground” that, sixty and more years earlier, motivated Lachmann’s various “Oriental music” projects in collaboration with local musicians and scholars in Mandatory Palestine. These motives manifested themselves intrinsically in his inclusive, multidisciplinary approach as a comparative musicologist; in his defense of local music and his selective promotion of new, hybrid musical styles; and in his conviction, as a lecturer and broadcaster, that not only was it crucial for his European listeners to understand the minds of their Oriental neighbours; but that there was no surer way of doing so than through their music and song. https://x.gd/h3wqu |

応

用民族音楽学の初期の試みとして、ラッハマンが行った「東洋の音楽」プロジェクトは、イスラエルとパレスチナの異なる民族間の理解を促進する手段として音

楽を用いる最近の取り組みと共鳴している。1993年9月のオスロ和平合意[39]の調印は、イスラエルのユダヤ人とイスラエルおよびパレスチナのアラブ

人の間の共同イニシアチブを鼓舞し、可能にする、前例のない機会の窓を作った。1999年、イスラエルの音楽家ダニエル・バレンボイムとパレスチナの知識

人エドワード・サイードが、バレンボイムの指揮の下、イスラエル、パレスチナ、アラブ世界、スペインの若い音楽家たちが共演するオーケストラ「ウェスト=

イースタン・ディヴァン」を共同設立した。

[40]セビリア近郊のアンダルシア地方に戦略的に拠点を置き、ユダヤ教徒、キリスト教徒、イスラム教徒が比較的調和して共存していた伝説的なアル・アン

ダルスの時代を象徴的に想起させるこのオーケストラは、音楽的コラボレーションが建設的な社会的コラボレーションのメタファーとして認識されるイスラエ

ル・パレスチナ社会の模範であり理想である。しかし、ヨーロッパの文化的・政治的優位の象徴である交響楽団と西洋の芸術音楽を特権化することで、バレンボ

イムとサイードの目標は、ヨーロッパの聴衆が他者の音楽表現と関わり、少なくともそれを理解しようとする必要性を主張したラッハマンの目標とは根本的に乖

離している。 ラッハマンのヴィジョンと狙いにより近いのは、ベンジャミン・ブリナー[41]が記録した、現地では「ムジカ・エトニット・イスラレリット(イスラエル民 族音楽)」として知られる、イスラエルを拠点とする「音楽シーン」である。ユダヤ人やアラブ人の若い作曲家たちが、いつか西洋と東洋の伝統の間のどこか に、自分たちを表現する新しい方法を見出すかもしれない」という、委任統治下のパレスチナに到着したときのラッハマンの予感に基づき、イスラエルの民族音 楽は、イスラエルのユダヤ人とイスラエル人およびパレスチナ人のアラブ人によるアンサンブルで構成されている。1990年代初頭に登場した2つの代表的な バンド、Alei Hazayit(The Olive Branches)とBustan Abraham(The Garden of Abraham)に焦点を当てながら[42]、ブリナーは、国を超えた流通と表現、そして公式な和平プロセスの波乱に関係なく持続する活力を持つ、活気に 満ちた高度に多様化した草の根の音楽シーンについて述べている。このような音楽シーンの存在そのものが、「より広範な現象、すなわちイスラエル国民のかな りの割合における文化的バランスと志向性の変化を示しており、それは『ヨーロッパ中心主義的な権力構造と認識論の脱植民地化』として特徴づけられている」 [43]とブリナーは指摘する。 「音楽的には、この広範な社会文化的現象は少なくとも1980年代まで遡ることができ、もともとは中東や地中海に起源をもつ、社会的に疎外されたユダヤ人 コミュニティの汎民族的パーティー音楽であったミズラヒト音楽(文字通り、東洋の音楽)が、イスラエルのポピュラー音楽の主流に受け入れられ、最終的に吸 収された。 [ブリナーにとって、イスラエルの民族音楽の特別な意義は、その高い芸術性の他に、音楽的コラボレーションの創造的で平等主義的な側面と、異なる中東の伝 統に由来する音源の性質にある。したがって、西東部のディヴァン・オーケストラでは、「音楽家がこの音楽を所有しているという感覚や、個人的なレベルでこ の音楽とつながっているという感覚は、それがどんなに彼らにとって意味のあるものであったとしても、歴史的・文化的な距離によって必然的に減衰せざるを得 ない」のとは対照的に、イスラエルの民族音楽では、音楽家たちは対等な立場で集団的な作曲と即興の行為に参加し、その結果、自分たちが生み出す音を文字通 り「共同で所有」することになる: このような音楽は、中東のイディオムを多用した共同制作であるため、モーツァルトの交響曲とは異なって聴衆に「語りかける」のだと私(RUTH F. DAVIS) は主張する。これは相対的な美的価値の問題ではなく、より幅広い文化的資源を取り入れるということである。一方、サイードやバレンボイムによるヨーロッパ の芸術音楽の古典の押し付けは、西洋文化のヒエラルキーを再定義するものである。[45] このような創造的なコラボレーションが必要とする音楽的変容、適応、新たな音楽的能力の習得のプロセスは、他のコラボレーション・イニシアチブが提供する ものよりも、平和的共存のためのより深く、より永続的な基盤を提供するかもしれないとブリナーは示唆している。政治的な用語で言えば、妥協や損失への恐れ が相互利益に取って代わられる "第三の道 "を意味する: このようなコラボレーションは新しい種類の音楽を生み出すため、その効果は人間性を高めるだけではない。このようなコラボレーションは新しい種類の音楽を 生み出すので、その効果は人間性を高めるだけではない。音楽のヴォキャブラリー、テクニック、理解を広げることによって、彼らは共通の基盤を築いたのだ。 これらのバンドが)生み出した音楽がそうであるように、平和的共存とは、互換性のある枠組みの中で即興演奏することである。これらは押しつけではなく、集 団で創り出し、交渉しなければならない。[46] まさに「未来への新たな可能性」の探求と、「共通の土台を築く」必要性についての彼の情熱的な信念とが組み合わさって、60年以上も前に、ラッハマンが委 任統治領パレスチナで地元の音楽家や学者と共同で行った様々な「東洋音楽」プロジェクトの動機となったのである。これらの動機は、比較音楽学者としての彼 の包括的で学際的なアプローチ、地元音楽の擁護と新しいハイブリッドな音楽スタイルの選択的な推進、そして講師や放送作家としての、ヨーロッパのリスナー にとって、東洋の隣人の心を理解することが極めて重要であるだけでなく、そのためには彼らの音楽や歌を通して理解する以外に確実な方法はないという確信 に、本質的に現れている。 |

| https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HnCzHsCkiv0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=udTwojthNMg Description: Song chanted by the groom’s companions as he arrives at his home to greet his bride on the night of his wedding, followed by the continuation of Lachmann’s lecture. Extract from “Oriental Music”, Program 12, describing the musical rituals performed by men at an Arab village wedding in Central Palestine. Source: Israel National Sound Archive, Lachmann collection L-D698. Digital sound restoration by Simon Godsill, Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge. |

|

Alf Leila We Leila لزمن الجميل .. الف ليلة وليلة

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099