Orientalism

Odalisque,

1840 Natale

Schiavoni (1777 - 1858) / Charles

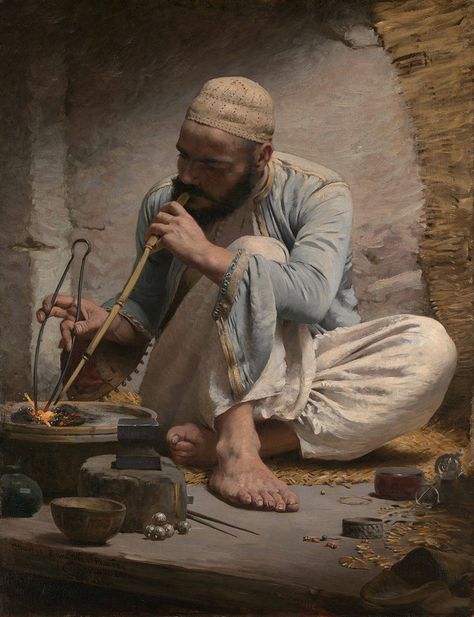

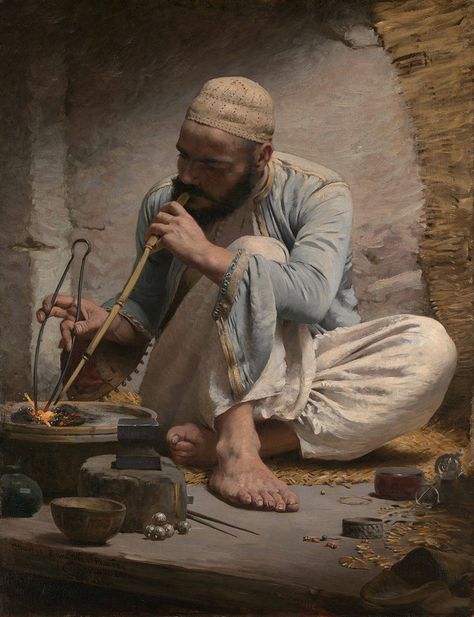

Sprague Pearce, The Arab Jeweler, 1882

オリエンタリズム

Orientalism

Odalisque,

1840 Natale

Schiavoni (1777 - 1858) / Charles

Sprague Pearce, The Arab Jeweler, 1882

解説:池田光穂

オリエンタリズムには、2つの意味があります。ひとつは、一般名詞あるいは芸術形式としての「オ リエンタリ ズム」あるいは東洋趣味と呼ばれるもの。もうひとつは、エドワード・サイード(1935- 2003)の著作『オリエンタリズム』(1978)であり、その著作では、知識と権力ア ンサンブルとしての「東洋を見る眼」あるいはイデオロギー的レンズとして、西洋が東洋を見る「知の形式」としてのそれ(=「オリエンタリズム」)がありま す。ここでは前者のことを中心に解説します。後者の解説はこちらです。

サイードの定義によるオリエンタリズム(Orientalism - book)とは「オリエンタリ ズムとは、オリエントを支配し再構成し威圧するための西洋のスタイル」のことである。つまり、西洋によって、オリエント(東洋ないしは近東)政治的に/文 化的に支配するときに生まれた知識(=情報と学知)と権力(=政治的力から象徴的権力まで)の融合の形式のことを指す。サイードは、このよ うな独特の文化 批判概念としてのオリエンタリズムを、知と権力の結びつきについて思想史的に批判したミッシェル・フーコー(Paul-Michel Foucault, 1926-1984)の諸研究からヒントを得たことを、その著作などで述べている。(→「異文化理解」)

もちろん、これまでの「オリエンタリズム」という言葉には、芸術の様式や(西洋世界にとっての) エキゾチックな文化表象を指し示す一般的な用語法があるが、人文社会学者が頻繁に言う批判的概念としてのオリエンタリズムは、次のような特徴があることに 注意しなければならない。

1.オリエンタリズムの反 対は、オクシデンタリズムではないこと(つまり過度の認識論的相対化をしないこと)

オリエント(東方)の反対は、西洋(オクシデント)なので、これはお互いに、東西の文化から みた、政治的中立な立場をとった他者表象であると思ってはならない。オリエンタリズムの独自性とは、その逆がなりたたないこと。言い換えれば、他者を表象 する側と、表象される側の権力的な不均衡関係に由来する言葉である(→2.を参照)(→「「寛容であること」と相対主義の関係」)。

2.オリエントを表象する 認識的作用は、権力と無関係ではないこと.を忘れないように

この著書におけるサイードの批判的視点の源泉に、フーコー的な意味での、権力と知識の不可分 な実態あるいは相互補完関係というものがある。何かを見る(=分析する)、表象する、それらの表象について考えるという一連の知的作業は、権力の真空状態 の中で生まれるものではなく、我々の社会関係と同様、権力的なプロセスと深い関係にある、ということがポイントである。何かを表象する〈主体〉がもつ力 は、表象される〈主体〉の構築にも関連してくることが、これで理解されるだろう。

※いい加減なメモですので、是非原典にあたることを前提に、入門として参考にしてください ね。以下は、ウィキペディア(英語)「オリエンタリズム一般」の解説です。

●芸術や文化表象における用語とし てのオリエンタリズム(→「音楽におけるオリエンタリズム」 はこちら)

| Outline In art history, literature and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects in the Eastern world. These depictions are usually done by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. In particular, Orientalist painting, depicting more specifically the Middle East,[1] was one of the many specialisms of 19th-century academic art, and the literature of Western countries took a similar interest in Oriental themes. Since the publication of Edward Said's Orientalism in 1978, much academic discourse has begun to use the term "Orientalism" to refer to a general patronizing Western attitude towards Middle Eastern, Asian, and North African societies. In Said's analysis, the West essentializes these societies as static and undeveloped—thereby fabricating a view of Oriental culture that can be studied, depicted, and reproduced in the service of imperial power. Implicit in this fabrication, writes Said, is the idea that Western society is developed, rational, flexible, and superior.[2]This allows Western imagination to see “Eastern” cultures and people as both alluring and a threat to Western civilization. [3] |

概略 美術史、文学、文化研究において、オリエンタリズムとは、東洋の世界の 様相を模倣したり描写したりすること。これらの描写は、通常、西洋世界の作家、デザイナー、芸術家によって行われる。特に、より具体的に中東を描いたオリ エンタリズム絵画[1]は、19世紀の学術芸術の数ある専門分野の1つであり、西洋諸国の文学も同様に東洋のテーマに関心を寄せていた。 1978年にエドワード・サイードが『オリエンタリズム』を出版して以来、多くの学問的言説は、中東、アジア、北アフリカの社会に対する西洋の一般的な見 下し姿勢を指す言葉として「オリエンタリズム」という言葉を使うようになった。サイードの分析によれば、西洋はこれらの社会を静的で未発達なものとして本 質化し、それによって、帝国権力のために研究し、描写し、再生産することができる東洋文化というものを作り上げているのである。この捏造には、西洋社会が 発展し、合理的で、柔軟で、優れているという考えが含まれているとサイードは書いている[2]。このため西洋の想像力は、「東洋」の文化や人々を魅力的で あると同時に西洋文明に対する脅威として見ることができる。[3] |

| Etymology Orientalism refers to the Orient, in reference and opposition to the Occident; the East and the West, respectively.[4][5] The word Orient entered the English language as the Middle French orient. The root word oriēns, from the Latin Oriēns, has synonymous denotations: The eastern part of the world; the sky whence comes the sun; the east; the rising sun, etc.; yet the denotation changed as a term of geography. In the "Monk's Tale" (1375), Geoffrey Chaucer wrote: "That they conquered many regnes grete / In the orient, with many a fair citee." The term orient refers to countries east of the Mediterranean Sea and Southern Europe. In In Place of Fear (1952), Aneurin Bevan used an expanded denotation of the Orient that comprehended East Asia: "the awakening of the Orient under the impact of Western ideas." Edward Said said that Orientalism "enables the political, economic, cultural and social domination of the West, not just during colonial times, but also in the present."[6] |

語源 オリエンタリズムとは、オリエント(東洋)を指し、オクシデント(西洋)と対比して、それぞれ東洋と西洋を指す[4][5]。ラテン語のOriēnsを語 源とするoriēnsは、同義語のような意味合いを持つ。世界の東の部分、太陽が来る空、東、昇る太陽などであるが、地理用語として変化した。 Geoffrey Chaucerは "Monk's Tale"(1375)で、"That they conquered many regnes grete / In the orient, with many a fair citee." と書いている。オリエントとは、地中海と南ヨーロッパより東の国々を指す。アニューリン・ベヴァンは『恐怖の場所』(1952年)で、東アジアを含むオリ エントを拡大して表現している。「西洋の思想の影響下での東洋の目覚め "と。エドワード・サイードはオリエンタリズムが「植民地時代だけでなく、現在も西洋の政治的、経済的、文化的、社会的支配を可能にしている」と述べてい る[6]。 |

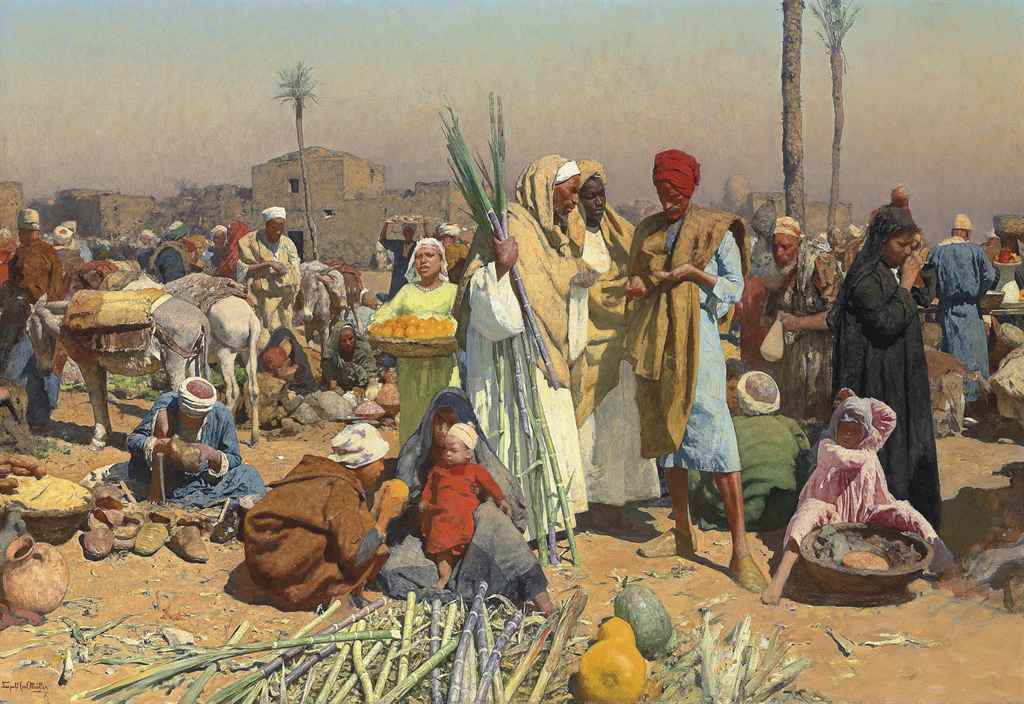

| Art In art history, the term Orientalism refers to the works of mostly 19th-century Western artists who specialized in Oriental subjects, produced from their travels in Western Asia, during the 19th century. In that time, artists and scholars were described as Orientalists, especially in France, where the dismissive use of the term "Orientalist" was made popular by the art critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary.[7] Despite such social disdain for a style of representational art, the French Society of Orientalist Painters was founded in 1893, with Jean-Léon Gérôme as the honorary president;[8] whereas in Britain, the term Orientalist identified "an artist."[9] The formation of the French Orientalist Painters Society changed the consciousness of practitioners towards the end of the 19th century, since artists could now see themselves as part of a distinct art movement.[10] As an art movement, Orientalist painting is generally treated as one of the many branches of 19th-century academic art; however, many different styles of Orientalist art were in evidence. Art historians tend to identify two broad types of Orientalist artist: the realists who carefully painted what they observed and those who imagined Orientalist scenes without ever leaving the studio.[11] French painters such as Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) are widely regarded as the leading luminaries of the Orientalist movement.[12] |

美術 美術史においてオリエンタリズムとは、主に19世紀に西アジアを旅して制作された、東洋の題材を専門とする西洋の芸術家たちの作品を指す言葉である。特に フランスでは、美術評論家のジュール=アントワーヌ・カスタニャリーによって「オリエンタリスト」という言葉の否定的な使用が広まった[7]。このように 具象美術のスタイルが社会的に軽蔑されていたにもかかわらず、1893年にジャン=レオン・ジェロームを名誉会長とするフランスの東洋画家協会が創設され た[8]が、イギリスでは「芸術家」という言葉が用いられていた[9]。 フランス東洋画家協会の設立は、19世紀末に芸術家の意識を変え、芸術家は自分たちが明確な芸術運動の一部であると認識できるようになった[10]。芸術 運動として、東洋画は一般的に19世紀の学術芸術の多くの部門の1つとして扱われるが、多くの異なるスタイルの東洋芸術が見受けられた。美術史家は、オリ エンタリズムの画家を大きく2つのタイプに分類する傾向がある:観察したものを注意深く描くリアリストと、スタジオから出ることなくオリエンタリズムの場 面を想像した人々だ[11]。ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワ(1798-1863)やジャン=レオン・ジェローム(1824-1904)などのフランスの画家 は、オリエンタリズム運動の主要な著名人として広く見なされている[12]。 |

| Oriental studies In the 18th and 19th centuries, the term Orientalist identified a scholar who specialized in the languages and literatures of the Eastern world. Among such scholars were officials of the East India Company, who said that the Arab culture, the Indian culture, and the Islamic cultures should be studied as equal to the cultures of Europe.[16] Among such scholars is the philologist William Jones, whose studies of Indo-European languages established modern philology. Company rule in India favored Orientalism as a technique for developing and maintaining positive relations with the Indians—until the 1820s, when the influence of "anglicists" such as Thomas Babington Macaulay and John Stuart Mill led to the promotion of a Western-style education.[17] Additionally, Hebraism and Jewish studies gained popularity among British and German scholars in the 19th and 20th centuries.[18] The academic field of Oriental studies, which comprehended the cultures of the Near East and the Far East, became the fields of Asian studies and Middle Eastern studies. |

東洋学 18世紀から19世紀にかけて、東洋学者という言葉は、東洋世界の言語や文学を専門とする学者を指すものであった。そのような学者の中には、東インド会社 の役人がおり、アラブ文化、インド文化、イスラム文化はヨーロッパの文化と同等に研究されるべきであるとした[16] そのような学者の中には、インドヨーロッパ言語の研究により近代言語学を確立した言語学者ウィリアム・ジョーンズがいる。インドにおける会社支配は、イン ド人と良好な関係を築き維持するための手法としてオリエンタリズムを支持したが、1820年代になると、トーマス・バビントン・マコーレーやジョン・ス チュアート・ミルのような「英国学者」の影響により、西洋式の教育が推進されるようになった[17]。 また、19世紀から20世紀にかけて、イギリスやドイツの学者の間でヘブライズムやユダヤ教研究が盛んになった[18]。 近東や極東の文化を包括する東洋学の学術分野は、アジア学や中東学の分野となった |

| Edward Said In his book Orientalism (1978), cultural critic Edward Said redefines the term Orientalism to describe a pervasive Western tradition—academic and artistic—of prejudiced outsider-interpretations of the Eastern world, which was shaped by the cultural attitudes of European imperialism in the 18th and 19th centuries.[19] The thesis of Orientalism develops Antonio Gramsci's theory of cultural hegemony, and Michel Foucault's theorisation of discourse (the knowledge-power relation) to criticise the scholarly tradition of Oriental studies. Said criticised contemporary scholars who perpetuated the tradition of outsider-interpretation of Arabo-Islamic cultures, especially Bernard Lewis and Fouad Ajami.[20][21] Furthermore, Said said that "The idea of representation is a theatrical one: the Orient is the stage on which the whole East is confined",[22] and that the subject of learned Orientalists "is not so much the East itself as the East made known, and therefore less fearsome, to the Western reading public".[23] In the academy, the book Orientalism (1978) became a foundational text of post-colonial cultural studies.[21] The analyses in Said's works are of Orientalism in European literature, especially French literature, and do not analyse visual art and Orientalist painting. In that vein, the art historian Linda Nochlin applied Said's methods of critical analysis to art, "with uneven results".[24] Other scholars see Orientalist paintings as depicting a myth and a fantasy that didn't often correlate with reality.[25] There is also a critical trend within the Islamic world. In 2002 it was estimated that in Saudi Arabia alone some 200 books and 2000 articles discussing Orientalism had been penned by local or foreign scholars.[26] |

エドワード・サイード 文化評論家のエドワード・サイードは、著書『オリエンタリズム』(1978年)の中で、18世紀から19世紀にかけてのヨーロッパ帝国主義の文化的態度に よって形成された、東洋世界に対する偏ったアウトサイダー的解釈という西洋の伝統(学術的、芸術的)を表すためにオリエンタリズムという用語を再定義して いる[19]。オリエンタリズム』の論文は、アントニオ・グラムシの文化ヘゲモニーの理論やミシェル・フーコーの談話の理論(知識-権力関係)により、学 問の伝統的東洋研究を批判している。サイードは、特にバーナード・ルイスやフアード・アジャミといった、アラブ・イスラム文化のアウトサイダー的解釈の伝 統を永続させる現代の学者を批判していた[20][21]。さらにサイードは、「表現という考えは演劇的なもので、オリエントは東洋全体を閉じ込める舞 台」だとし[22]、学んだオリエンタリストたちの対象が「西洋人の読者に知られ、それゆえに恐怖を感じない東洋そのものというより」であると述べていた [23]。 学会では、『オリエンタリズム』(1978年)がポストコロニアル文化研究の基礎となるテキストとなった[21]。 サイードの著作における分析は、ヨーロッパ文学、特にフランス文学におけるオリエンタリズムであり、視覚芸術やオリエンタリズム絵画を分析することはして いない。その流れで、美術史家のリンダ・ノクリンはサイードの批評的分析の方法を美術に適用したが、「結果はばらばら」だった[24]。 他の学者はオリエンタリズム絵画を、現実とあまり相関しなかった神話や幻想を描いていると見ている[25]。 また、イスラム世界の中にも批判的な傾向がある。2002年には、サウジアラビアだけで200冊の本と2000本のオリエンタリズムを論じた記事が国内外 の学者によって書かれたと推定されている[26] |

| Soviet scholarship From the Bolsháya sovétskaya entsiklopédiya (1951):[27] Reflecting the colonialist-racist worldview of the European and American bourgeoisie, from the very beginning bourgeois orientology diametrically opposed the civilizations of the so-called "West" with those of the "East" slanderously declaring that Asian peoples are racially inferior, some |

ソビエトの学問 ボルシャイヤ・ソヴェツカヤ・エンティクロペディヤ』(1951年)より:[27]。 ヨーロッパとアメリカのブルジョアジーの植民地主義的・人種主義的世界観を反映して、ブルジョア指向学は当初から、いわゆる「西洋」の文明と「東洋」の文 明を正反対に論じ、アジア人は人種的に劣ると中傷し、ある者は「東洋人」、またある者は「西洋人」であると宣言している。 |

| In European architecture and

design The Moresque style of Renaissance ornament is a European adaptation of the Islamic arabesque that began in the late 15th century and was to be used in some types of work, such as bookbinding, until almost the present day. Early architectural use of motifs lifted from the Indian subcontinent is known as Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture. One of the earliest examples is the façade of Guildhall, London (1788–1789). The style gained momentum in the west with the publication of views of India by William Hodges, and William and Thomas Daniell from about 1795. Examples of "Hindoo" architecture are Sezincote House (c. 1805) in Gloucestershire, built for a nabob returned from Bengal, and the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. Turquerie, which began as early as the late 15th century, continued until at least the 18th century, and included both the use of "Turkish" styles in the decorative arts, the adoption of Turkish costume at times, and interest in art depicting the Ottoman Empire itself. Venice, the traditional trading partner of the Ottomans, was the earliest centre, with France becoming more prominent in the 18th century. Chinoiserie is the catch-all term for the fashion for Chinese themes in decoration in Western Europe, beginning in the late 17th century and peaking in waves, especially Rococo Chinoiserie, c. 1740–1770. From the Renaissance to the 18th century, Western designers attempted to imitate the technical sophistication of Chinese ceramics with only partial success. Early hints of Chinoiserie appeared in the 17th century in nations with active East India companies: England (the East India Company), Denmark (the Danish East India Company), the Netherlands (the Dutch East India Company) and France (the French East India Company). Tin-glazed pottery made at Delft and other Dutch towns adopted genuine Ming-era blue and white porcelain from the early 17th century. Early ceramic wares made at Meissen and other centers of true porcelain imitated Chinese shapes for dishes, vases and teawares (see Chinese export porcelain). Pleasure pavilions in "Chinese taste" appeared in the formal parterres of late Baroque and Rococo German palaces, and in tile panels at Aranjuez near Madrid. Thomas Chippendale's mahogany tea tables and china cabinets, especially, were embellished with fretwork glazing and railings, c. 1753–70. Sober homages to early Xing scholars' furnishings were also naturalized, as the tang evolved into a mid-Georgian side table and squared slat-back armchairs that suited English gentlemen as well as Chinese scholars. Not every adaptation of Chinese design principles falls within mainstream "chinoiserie". Chinoiserie media included imitations of lacquer and painted tin (tôle) ware that imitated japanning, early painted wallpapers in sheets, and ceramic figurines and table ornaments. Small pagodas appeared on chimneypieces and full-sized ones in gardens. Kew has a magnificent Great Pagoda designed by William Chambers. The Wilhelma (1846) in Stuttgart is an example of Moorish Revival architecture. Leighton House, built for the artist Frederic Leighton, has a conventional facade but elaborate Arab-style interiors, including original Islamic tiles and other elements as well as Victorian Orientalizing work. After 1860, Japonism, sparked by the importing of ukiyo-e, became an important influence in the western arts. In particular, many modern French artists such as Claude Monet and Edgar Degas were influenced by the Japanese style. Mary Cassatt, an American artist who worked in France, used elements of combined patterns, flat planes and shifting perspective of Japanese prints in her own images.[28] The paintings of James Abbott McNeill Whistler's The Peacock Room demonstrated how he used aspects of Japanese tradition and are some of the finest works of the genre. California architects Greene and Greene were inspired by Japanese elements in their design of the Gamble House and other buildings. Egyptian Revival architecture became popular in the early and mid-19th century and continued as a minor style into the early 20th century. Moorish Revival architecture began in the early 19th century in the German states and was particularly popular for building synagogues. Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture was a genre that arose in the late 19th century in the British Raj. |

ヨーロッパの建築・デザインにおいて ルネサンス期のモレスク様式は、15世紀後半に始まったイスラムのアラベスクをヨーロッパでアレンジしたもので、ほぼ現代に至るまで、製本など一部の作品 に使用されることになった。インド亜大陸のモチーフを取り入れた初期の建築は、インド・サラセン復興期建築と呼ばれる。ロンドンのギルドホール(1788 -1789)のファサードがその代表例である。1795年頃、ウィリアム・ホッジス、ウィリアム・ダニエルとトーマス・ダニエルがインドの風景を出版し、 西洋でもこの様式が広まりました。ヒンドゥー建築の例としては、ベンガルから帰国した貴族のために建てられたグロスターシャーのセジンコート邸(1805 年頃)やブライトンのロイヤル・パビリオンなどがあります。 15世紀後半に始まったトルコ趣味は、少なくとも18世紀まで続き、装飾美術に「トルコ」様式を用い、時にはトルコの衣装を採用し、オスマン帝国そのもの を描いた美術品に関心を寄せました。オスマントルコとの伝統的な貿易相手国であったヴェネツィアが初期の中心地であり、18世紀にはフランスがより顕著に なった。 シノワズリーとは、西欧で中国をテーマにした装飾が流行したことの総称で、17世紀後半に始まり、1740~1770年頃のロココ・シノワズリーを中心に 波及していった。ルネサンス期から18世紀にかけて、西洋のデザイナーは中国陶磁の精巧な技術を模倣しようと試みたが、部分的な成功にとどまった。17世 紀、東インド会社が存在した国々で、シノワズリーの初期のヒントが現れた。イギリス(東インド会社)、デンマーク(デンマーク東インド会社)、オランダ (オランダ東インド会社)、フランス(フランス東インド会社)である。デルフトをはじめとするオランダの錫釉陶器は、17世紀初頭に明代の本格的な青花磁 器を取り入れたものである。マイセンをはじめとする本格的な磁器の産地では、初期の陶磁器が中国の形を真似て皿や花瓶、茶器などを作った(「中国輸出磁 器」の項を参照)。 バロック後期やロココ期のドイツの宮殿の花壇や、マドリード近郊のアランフェスのタイルパネルに、「中国趣味」の遊楽殿が登場する。トーマス・チッペン デールのマホガニー製ティー・テーブルやチャイナ・キャビネットは、特にフレットワーク・グレージングと手すりで装飾されている(1753-70年頃)。 また、タンはジョージア王朝中期にサイドテーブルや四角い背もたれのアームチェアに進化し、中国人学者だけでなく英国紳士にも似合うようになり、初期の興 学徒の調度品への地味なオマージュも自然発生した。中国のデザイン原理を応用したものが、すべて「シノワズリー」の主流になるわけではありません。シノワ ズリーには、漆の模造品やジャパニングを模した錫の絵付け陶器、初期の板状の絵付け壁紙、陶器の置物やテーブルオーナメントなどが含まれます。小さなパゴ ダは煙突の上に、大きなパゴダは庭に飾られた。キューにはウィリアム・チェンバースの設計による壮大な大パゴダがある。シュトゥットガルトのヴィルヘルマ (1846年)は、ムーア様式のリバイバル建築の一例である。画家フレデリック・レイトンのために建てられたレイトンハウスは、ファサードは普通だが、内 装はアラブ風の凝った造りで、オリジナルのイスラムタイルなどに加え、ヴィクトリア朝のオリエンタル化した細工が施されている。 1860年以降、浮世絵の輸入に端を発したジャポニズムは、西洋美術に重要な影響を与えるようになった。特に、クロード・モネやエドガー・ドガなど、近代 フランスの画家たちの多くは、日本のスタイルに影響を受けている。また、フランスで活躍したアメリカ人画家メアリー・カサットは、日本の版画の組み合わせ 模様、平面、遠近法の変化などの要素を自身の絵に取り入れた[28]。ジェームズ・アボット・マクニール・ウィスラーが描いた『孔雀の間』は、彼が日本の 伝統の側面をいかに利用しているかを示し、このジャンルにおける最も優れた作品の一つである。カリフォルニアの建築家グリーン・アンド・グリーンは、ギャ ンブルハウスなどの設計で日本の要素に触発された。 エジプト・リバイバル建築は、19世紀初頭から半ばにかけて流行し、20世紀初頭までマイナーなスタイルとして続いた。ムーア様式リバイバル建築は、19 世紀初頭にドイツ諸国で始まり、特にシナゴーグの建築に人気があった。インド・サラセニク・リバイバル建築は、19世紀後半にイギリスのラージ地方で生ま れたジャンルである。 |

| Pre-19th century Depictions of Islamic "Moors" and " Turks" (imprecisely named Muslim groups of southern Europe, North Africa and West Asia) can be found in Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque art. In Biblical scenes in Early Netherlandish painting, secondary figures, especially Romans, were given exotic costumes that distantly reflected the clothes of the Near East. The Three Magi in Nativity scenes were an especial focus for this. In general art with Biblical settings would not be considered as Orientalist except where contemporary or historicist Middle Eastern detail or settings is a feature of works, as with some paintings by Gentile Bellini and others, and a number of 19th-century works. Renaissance Venice had a phase of particular interest in depictions of the Ottoman Empire in painting and prints. Gentile Bellini, who travelled to Constantinople and painted the Sultan, and Vittore Carpaccio were the leading painters. By then the depictions were more accurate, with men typically dressed all in white. The depiction of Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting sometimes draws from Orientalist interest, but more often just reflects the prestige these expensive objects had in the period.[29] Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789) visited Istanbul and painted numerous pastels of Turkish domestic scenes; he also continued to wear Turkish attire for much of the time when he was back in Europe. The ambitious Scottish 18th-century artist Gavin Hamilton found a solution to the problem of using modern dress, considered unheroic and inelegant, in history painting by using Middle Eastern settings with Europeans wearing local costume, as travelers were advised to do. His huge James Dawkins and Robert Wood Discovering the Ruins of Palmyra (1758, now Edinburgh) elevates tourism to the heroic, with the two travelers wearing what look very like togas. Many travelers had themselves painted in exotic Eastern dress on their return, including Lord Byron, as did many who had never left Europe, including Madame de Pompadour.[30] The growing French interest in exotic Oriental luxury and lack of liberty in the 18th century to some extent reflected a pointed analogy with France's own absolute monarchy.[31] Byron's poetry was highly influential in introducing Europe to the heady cocktail of Romanticism in exotic Oriental settings which was to dominate 19th century Oriental art. |

19世紀以前 中世、ルネサンス、バロックの美術には、イスラムの「ムーア人」や「トルコ人」(南ヨーロッパ、北アフリカ、西アジアのイスラム集団の正確な名称ではな い)が描かれている。ネーデルラント初期の絵画では、聖書の場面で、二次的な人物、特にローマ人に、近東の衣服を遠まわしに反映したエキゾチックな衣装が 与えられている。特にキリスト降誕のシーンに登場する三人のマギはその代表格である。聖書を舞台にした美術は、ジェンティーレ・ベリーニなどの作品や19 世紀の作品のように、現代的あるいは歴史主義的な中東のディテールや設定が作品の特徴である場合を除いて、一般にオリエンタリズムとは見なされない。ルネ サンス期のヴェネツィアは、オスマン帝国を描いた絵画や版画に特に関心を寄せていた時期があった。コンスタンティノープルに渡り、スルタンを描いたジェン ティーレ・ベリーニや、ヴィットーレ・カルパッチョが代表的な画家である。そのころには、男性の服装はすべて白で統一されるのが一般的で、描写はより正確 になっていた。ルネサンス絵画における東洋の絨毯の描写は、オリエンタリズムの関心を引くこともあるが、単にこの時代に高価な品物が持っていた威信を反映 したものであることが多い[29]。 ジャン=エティエンヌ・リオタール(1702-1789)はイスタンブールを訪れ、トルコの家庭風景をパステル画で数多く描いている; 彼はまた、ヨーロッパに戻った後も、多くの期間、トルコ服を着続けた。18世紀スコットランドの野心的な画家ギャヴィン・ハミルトンは、英雄的でなく優雅 でないとされる近代的な服装を歴史画に用いることの問題を、旅行者が勧めるようにヨーロッパ人が現地の衣装を着た中東の舞台を用いることで解決したのであ る。彼の巨大な《パルミラの遺跡を発見するジェームズ・ドーキンスとロバート・ウッド》(1758年、現エジンバラ)は、二人の旅行者がトーガらしきもの を身につけ、観光を英雄的なものに昇華させている。バイロン卿をはじめ、多くの旅行者が帰国後、東洋のエキゾチックな衣装を身にまとい、ポンパドゥール夫 人など、ヨーロッパを離れたことのない多くの旅行者が絵を描いた[30]。18世紀、東洋のエキゾチックな豪華さと自由のなさに対するフランスの関心が高 まっていたことは、フランス自身の絶対王政との鋭い類似をある程度反映していた[31]。バイロンの詩は、19世紀東洋美術を席巻した、異国の地における ロマンチズムという強烈なカクテルでヨーロッパに影響を及ぼした。 |

| French Orientalism French Orientalist painting was transformed by Napoleon's ultimately unsuccessful invasion of Egypt and Syria in 1798–1801, which stimulated great public interest in Egyptology, and was also recorded in subsequent years by Napoleon's court painters, especially Antoine-Jean Gros, although the Middle Eastern campaign was not one on which he accompanied the army. Two of his most successful paintings, Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa (1804) and Battle of Abukir (1806) focus on the Emperor, as he was by then, but include many Egyptian figures, as does the less effective Napoleon at the Battle of the Pyramids (1810). Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson's La Révolte du Caire (1810) was another large and prominent example. A well-illustrated Description de l'Égypte was published by the French Government in twenty volumes between 1809 and 1828, concentrating on antiquities.[32] Eugène Delacroix's first great success, The Massacre at Chios (1824) was painted before he visited Greece or the East, and followed his friend Théodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa in showing a recent incident in distant parts that had aroused public opinion. Greece was still fighting for independence from the Ottomans, and was effectively as exotic as the more Near Eastern parts of the empire. Delacroix followed up with Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1827), commemorating a siege of the previous year, and The Death of Sardanapalus, inspired by Lord Byron, which although set in antiquity has been credited with beginning the mixture of sex, violence, lassitude and exoticism which runs through much French Orientalist painting.[33] In 1832, Delacroix finally visited what is now Algeria, recently conquered by the French, and Morocco, as part of a diplomatic mission to the Sultan of Morocco. He was greatly struck by what he saw, comparing the North African way of life to that of the Ancient Romans, and continued to paint subjects from his trip on his return to France. Like many later Orientalist painters, he was frustrated by the difficulty of sketching women, and many of his scenes featured Jews or warriors on horses. However, he was apparently able to get into the women's quarters or harem of a house to sketch what became Women of Algiers; few later harem scenes had this claim to authenticity.[34] When Ingres, the director of the French Académie de peinture, painted a highly colored vision of a Turkish bath, he made his eroticized Orient publicly acceptable by his diffuse generalizing of the female forms (who might all have been the same model). More open sensuality was seen as acceptable in the exotic Orient.[35] This imagery persisted in art into the early 20th century, as evidenced in Henri Matisse's orientalist semi-nudes from his Nice period, and his use of Oriental costumes and patterns. Ingres' pupil Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856) had already achieved success with his nude The Toilette of Esther (1841, Louvre) and equestrian portrait of Ali-Ben-Hamet, Caliph of Constantine and Chief of the Haractas, Followed by his Escort (1846) before he first visited the East, but in later decades the steamship made travel much easier and increasing numbers of artists traveled to the Middle East and beyond, painting a wide range of Oriental scenes. In many of these works, they portrayed the Orient as exotic, colorful and sensual, not to say stereotyped. Such works typically concentrated on Arab, Jewish, and other Semitic cultures, as those were the ones visited by artists as France became more engaged in North Africa. French artists such as Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painted many works depicting Islamic culture, often including lounging odalisques. They stressed both lassitude and visual spectacle. Other scenes, especially in genre painting, have been seen as either closely comparable to their equivalents set in modern-day or historical Europe, or as also reflecting an Orientalist mind-set in the Saidian sense of the term. Gérôme was the precursor, and often the master, of a number of French painters in the later part of the century whose works were often frankly salacious, frequently featuring scenes in harems, public baths and slave auctions (the last two also available with classical decor), and responsible, with others, for "the equation of Orientalism with the nude in pornographic mode";[36] (Gallery, below) |

フランス・オリエンタリズム フランスのオリエンタリズム絵画は、1798年から1801年にかけてのナポレオンのエジプトとシリアへの侵攻作戦が最終的に失敗し、エジプト学に対する 人々の大きな関心を呼び起こし、その後、ナポレオンの宮廷画家、特にアントワーヌ=ジャン・グロが、中東での作戦に同行したわけではありませんが、記録も 残しています。彼の最も成功した2つの絵、「ヤッファのペスト患者を見舞うボナパルト」(1804)と「アブキールの戦い」(1806)は、そのころの皇 帝に焦点を当てているが、多くのエジプトの人物が含まれており、「ピラミッドの戦いのナポレオン」(1810)はあまり効果的でない。アンヌ=ルイ・ジロ デ・ド・ルーシー=トリオソンの『カイールの大乱』(1810年)も大型で目立つ例であった。1809年から1828年にかけて、フランス政府によって、 よく描かれた『Description de l'Égypte』が20巻出版され、古代史に焦点が当てられた[32]。 ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワの最初の大成功作『キオスの虐殺』(1824年)は、彼がギリシャや東洋を訪れる前に描かれ、友人のテオドール・ジェリコーの『メ デューサのいかだ』に続いて、世論を刺激した遠方の最近の事件を描いている。ギリシャはまだオスマントルコからの独立を争っており、事実上、帝国の近東地 域と同じようにエキゾチックな時代であった。ドラクロワは、前年の包囲を記念した《ミソロンギ遺跡のギリシャ》(1827年)と、バイロン卿の影響を受け た《サルダナパルスの死》を制作した。古代を舞台にしながら、フランスの多くの東洋絵画に見られる、性、暴力、倦怠、異国情緒の混合を始めたとされる作品 である。 [1832年、ドラクロワは、モロッコのスルタンへの外交使節団の一員として、フランスに征服されたばかりの現在のアルジェリアとモロッコをようやく訪問 した。北アフリカの生活様式を古代ローマ人のそれと比較しながら見たものに大きな衝撃を受け、フランスに帰国してからもこの旅の題材を描き続けました。し かし、後の東洋画家の多くがそうであるように、女性を描くのは難しく、ユダヤ人や馬に乗った戦士を描いた作品が多かった。しかし、「アルジェの女たち」の スケッチのために、ある家の女性部屋やハーレムに入ることができたようで、後のハーレムの場面でこのような真正性を主張するものはほとんどなかった [34]。 フランス絵画アカデミーの館長であったアングルは、トルコ風呂を色鮮やかに描いたが、女性の姿(すべて同じモデルかもしれない)を広く一般化することに よって、エロティックなオリエントを公的に受け入れられるようにした。このイメージは、アンリ・マティスのニース時代のオリエンタルなセミヌードや、東洋 の衣装や模様の使用に見られるように、20世紀初頭まで美術の中に残っていた[35]。アングルの弟子テオドール・シャセリオー(1819-1856) は、東洋を訪れる以前に、裸婦像《エステルのトワレ》(1841年、ルーヴル)や騎馬像《アリ=ベン=ハメット、コンスタンティンのカリフ、ハラクトの 長》(1846)で成功していたが、その後、蒸気船によって旅が容易になると、中東をはじめ、多くの芸術家が旅に出て、さまざまな東洋的風景画を描くよう になった。 これらの作品の多くは、オリエントをエキゾチックで色彩豊かな官能的なものとして描いており、ステレオタイプなものであったことは言うまでもない。こうし た作品は、アラブやユダヤなどセム系の文化が中心で、フランスが北アフリカに進出する際に画家たちが訪れた場所でもありました。ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワ、 ジャン=レオン・ジェローム、ジャン=オーギュスト・ドミニク・アングルらは、イスラム文化を描いた作品を数多く制作し、その中には寝そべるオダリスクも 多く含まれています。彼らは怠惰と視覚的なスペクタクルの両方を強調したのである。また、特に風俗画では、近現代や歴史的なヨーロッパに類似した場面、あ るいはサイード的な意味でのオリエンタリズムの考え方を反映していると考えられている。ジェロームは、ハーレム、公衆浴場、奴隷の競売(最後の2つは古典 的な装飾もある)の場面を頻繁に描いた、しばしば率直に言って卑猥な作品を制作した世紀後半の多くのフランスの画家たちの先駆者であり、しばしば師となっ た人物であり、他者とともに「オリエンタリズムとポルノ的な裸体を同一視」する原因となった[36] (Gallery, below) |

| British Orientalism Though British political interest in the territories of the unravelling Ottoman Empire was as intense as in France, it was mostly more discreetly exercised. The origins of British Orientalist 19th-century painting owe more to religion than military conquest or the search for plausible locations for nude women. The leading British genre painter, Sir David Wilkie was 55 when he travelled to Istanbul and Jerusalem in 1840, dying off Gibraltar during the return voyage. Though not noted as a religious painter, Wilkie made the trip with a Protestant agenda to reform religious painting, as he believed that: "a Martin Luther in painting is as much called for as in theology, to sweep away the abuses by which our divine pursuit is encumbered", by which he meant traditional Christian iconography. He hoped to find more authentic settings and decor for Biblical subjects at their original location, though his death prevented more than studies being made. Other artists including the Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt and David Roberts (in The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia) had similar motivations,[37] giving an emphasis on realism in British Orientalist art from the start.[38] The French artist James Tissot also used contemporary Middle Eastern landscape and decor for Biblical subjects, with little regard for historical costumes or other fittings. William Holman Hunt produced a number of major paintings of Biblical subjects drawing on his Middle Eastern travels, improvising variants of contemporary Arab costume and furnishings to avoid specifically Islamic styles, and also some landscapes and genre subjects. The biblical subjects included The Scapegoat (1856), The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860), and The Shadow of Death (1871). The Miracle of the Holy Fire (1899) was intended as a picturesque satire on the local Eastern Christians, of whom, like most European visitors, Hunt took a very dim view. His A Street Scene in Cairo; The Lantern-Maker's Courtship (1854–61) is a rare contemporary narrative scene, as the young man feels his fiancé's face, which he is not allowed to see, through her veil, as a Westerner in the background beats his way up the street with his stick.[39] This a rare intrusion of a clearly contemporary figure into an Orientalist scene; mostly they claim the picturesqueness of the historical painting so popular at the time, without the trouble of researching authentic costumes and settings. When Gérôme exhibited For Sale; Slaves at Cairo at the Royal Academy in London in 1871, it was "widely found offensive", partly because the British involvement in successfully suppressed the slave trade in Egypt, but also for cruelty and "representing fleshiness for its own sake".[40] But Rana Kabbani believes that "French Orientalist painting, as exemplified by the works of Gérôme, may appear more sensual, gaudy, gory and sexually explicit than its British counterpart, but this is a difference of style not substance ... Similar strains of fascination and repulsion convulsed their artists"[41] Nonetheless, nudity and violence are more evident in British paintings set in the ancient world, and "the iconography of the odalisque ... the Oriental sex slave whose image is offered up to the viewer as freely as she herself supposedly was to her master – is almost entirely French in origin",[35] though taken up with enthusiasm by Italian and other European painters. John Frederick Lewis, who lived for several years in a traditional mansion in Cairo, painted highly detailed works showing both realistic genre scenes of Middle Eastern life and more idealized scenes in upper class Egyptian interiors with no traces of Western cultural influence yet apparent. His careful and seemingly affectionate representation of Islamic architecture, furnishings, screens, and costumes set new standards of realism, which influenced other artists, including Gérôme in his later works. He "never painted a nude", and his wife modelled for several of his harem scenes,[42] which, with the rare examples by the classicist painter Lord Leighton, imagine "the harem as a place of almost English domesticity, ... [where]... women's fully clothed respectability suggests a moral healthiness to go with their natural good looks".[35] Other artists concentrated on landscape painting, often of desert scenes, including Richard Dadd and Edward Lear. David Roberts (1796–1864) produced architectural and landscape views, many of antiquities, and published very successful books of lithographs from them.[43] |

イギリスのオリエンタリズム オスマン帝国崩壊後の領土に対するイギリスの政治的関心は、フランスと同様に強かったが、そのほとんどはより控えめに行使されていた。19世紀の英国オリ エンタリズム絵画の起源は、軍事的征服や裸婦のもっともらしい場所を探すことよりも、宗教に負うところが大きいのです。イギリスを代表する風俗画家デイ ヴィッド・ウィルキー卿は、1840年に55歳でイスタンブールとエルサレムを訪れ、帰路のジブラルタル沖で亡くなりました。宗教画家としては知られてい なかったが、ウィルキーは宗教画の改革というプロテスタント的な意図を持ってこの旅をした。「絵画におけるマルティン・ルターは、神学と同様に、我々の神 聖な探求の妨げとなっている悪弊を一掃するために必要である」。彼は、聖書の題材を、本来の場所で、より本物の設定や装飾を見つけることを望んだが、彼の 死によって、研究以上のものはできなかった。ラファエル前派のウィリアム・ホルマン・ハントやデヴィッド・ロバーツ(『聖地、シリア、イドゥメア、アラビ ア、エジプト、ヌビア』)らも同様の動機で、イギリスのオリエンタリズム美術は当初から写実性を重視していた[37]。 また、フランスの画家ジェームズ・ティソは現代の中東の風景や装飾を用いて、聖書の主題とし、歴史の衣装やその他の装飾品にはほとんどこだわりを持たな かった[38]。 ウィリアム・ホルマン・ハントは、中東の旅を題材に、聖書の主題を描いた大作を数多く制作し、イスラム特有の様式を避け、現代のアラブの衣装や調度品を即 興で変形させ、また風景画や風俗画もいくつか描いている。聖書の題材としては、《スケープゴート》(1856年)、《神殿での救い主の発見》(1860 年)、《死の影》(1871年)などがある。聖なる火の奇跡』(1899年)は、現地の東方キリスト教徒を風刺したもので、多くのヨーロッパ人旅行者と同 様、ハントも彼らを非常に低く見ていた。カイロの街角の風景;提灯屋の求愛』(1854-61)は、ベール越しに見ることを許されない婚約者の顔を青年が 感じながら、背景の西洋人が杖をついて道を進んでいくという、現代では珍しい物語の場面である[39] これは、明らかに現代の人物が、オリエンタリズムの場面に入り込む珍しいことで、大抵、本物の衣装や設定を調べる苦労もなく、当時人気のあった歴史画の絵 画調であることが主張しているのだ。 ジェロームが1871年にロンドンのロイヤル・アカデミーで《For Sale; Slaves at Cairo》を展示したとき、「広く不快感を抱かれた」。これは、イギリスの関与によってエジプトでの奴隷貿易がうまく抑制されたこともあるが、残酷さと 「それ自体のために肉感を表現した」ことも原因であった[40]。 [しかし、ラナ・カバニは、「ジェロームの作品に代表されるフランスのオリエンタリズム絵画は、イギリスのそれよりも官能的で派手で血生臭く、性的に露骨 に見えるかもしれないが、これはスタイルの違いであって、中身の違いではない......」と考えている。しかし、裸体や暴力は古代世界を舞台にしたイギ リスの絵画でより顕著であり、「オダリスクの図像学...東洋の性奴隷は、彼女自身が彼女の主人にされたと思われるように、見る者に自由にイメージを提供 する-イタリアや他のヨーロッパの画家が熱心に取り上げたものの、ほぼ完全にフランス起源」[35]であると言えるでしょう。 カイロの伝統的な邸宅に数年間住んだジョン・フレデリック・ルイスは、中東の生活を写実的に描いた風俗画や、エジプトの上流階級の室内をより理想的に描い た作品を精密に描き、西洋文化の影響の痕跡はまだ見られない。イスラム建築、調度品、屏風、衣装などの丁寧で愛情に満ちた表現は、リアリズムの新しい基準 を打ち立て、後のジェロームを含む他の画家たちにも影響を与えた。古典主義の画家レイトン卿による珍しい例もあり、「ハーレムはほとんどイギリスの家庭的 な場所であり、......」と想像される。[そこで...女性の完全に服を着た立派さは、彼らの自然な美貌と一緒に行くために道徳的な健全さを示唆して いる」[35]。 また、リチャード・ダッドやエドワード・リアなど、砂漠の風景画に集中した画家もいる。デイヴィッド・ロバーツ(1796-1864)は、建築物や風景画 を制作し、その多くは古代のもので、それらをリトグラフにした本を出版し、大きな成功を収めた[43]。 |

| Russian Orientalism Russian Orientalist art was largely concerned with the areas of Central Asia that Russia was conquering during the century, and also in historical painting with the Mongols who had dominated Russia for much of the Middle Ages, who were rarely shown in a good light.[44] The explorer Nikolai Przhevalsky played a major role in popularising an exotic view of "the Orient" and advocating imperial expansion.[45] "The Five" Russian composers were prominent 19th-century Russian composers who worked together to create a distinct national style of classical music. One hallmark of "The Five" composers was their reliance on orientalism.[46] Many quintessentially "Russian" works were composed in orientalist style, such as Balakirev's Islamey, Borodin's Prince Igor and Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade.[46] As leader of "The Five," Balakirev encouraged the use of eastern themes and harmonies to set their "Russian" music apart from the German symphonism of Anton Rubinstein and other Western-oriented composers.[46] |

ロシア・オリエンタリズム ロシア・オリエンタリズムの芸術は、その世紀にロシアが征服していた中央アジアの地域に大きく関わっており、また歴史画においては、中世の大部分において ロシアを支配していたモンゴル人を良いイメージで描くことはほとんどなかった[44]。探検家ニコライ・プルシェバルスキーは、「東洋」に対するエキゾ チックな見方を広め、帝国拡大を支持する上で大きな役割を演じた[45]。 19世紀ロシアの著名な作曲家である「5人の」ロシア人作曲家は、クラシック音楽の明確な国家的スタイルを作るために協力し合った。バラキレフの『イスラ メイ』、ボロディンの『イーゴリ公』、リムスキー=コルサコフの『シェヘラザード』など、東洋的な様式で「ロシア」らしい作品が多く作曲された[46] 「5人」のリーダーとして、バラキレフは、アントン・ルビンシュタインのドイツ交響曲や他の西洋志向の作曲家から「ロシア」音楽を差別化すべく、東洋の主 題やハーモニーの使用を奨励した[46] 。 |

| German Orientalism Edward Said originally wrote that Germany did not have a politically motivated Orientalism because its colonial empire did not expand in the same areas as France and Britain. Said later stated that Germany "had in common with Anglo-French and later American Orientalism [...] a kind of intellectual authority over the Orient," However, Said also wrote that "there was nothing in Germany to correspond to the Anglo-French presence in India, the Levant, North Africa. Moreover, the German Orient was almost exclusively a scholarly, or at least a classical, Orient: it was made the subject of lyrics, fantasies, and even novels, but it was never actual."[47] According to Suzanne L. Marchand, German scholars were the "pace-setters" in oriental studies.[48] Robert Irwin wrote that "until the outbreak of the Second World War, German dominance of Orientalism was practically unchallenged."[49] |

ドイツのオリエンタリズム エドワード・サイードはもともと、ドイツはフランスやイギリスのように植民地帝国を拡大しなかったので、政治的な動機によるオリエンタリズムを持たなかっ たと書いている。また「英仏のインド、レヴァント、北アフリカでの存在に対応するものはドイツにはなかった」とも書いている。さらに、ドイツのオリエント はほとんど学問的な、あるいは少なくとも古典的なオリエントであり、歌詞や空想や小説の主題にさえされたが、現実には決してされなかった」[47]。スザ ンヌ・L・マルシャンによれば、ドイツの学者はオリエンタル研究における「ペースセッター」だった[48]。 ロバート・アーウィンによれば「第二次世界大戦が勃発するまでオリエンタリズムにおけるドイツの優位は実質的に挑戦を受けていなかった」と述べている [49]。 |

| Elsewhere Nationalist historical painting in Central Europe and the Balkans dwelt on oppression during the Ottoman Empire period, battles between Ottoman and Christian armies, as well as themes like the Ottoman Imperial Harem, although the latter was a less common theme than in French depictions.[50] The Saidian analysis has not prevented a strong revival of interest in, and collecting of, 19th century Orientalist works since the 1970s, the latter was in large part led by Middle Eastern buyers.[51] |

その他の地域 中央ヨーロッパとバルカン半島におけるナショナリストの歴史画は、オスマン帝国時代の抑圧、オスマン帝国軍とキリスト教軍の間の戦い、オスマン帝国ハーレ ムなどのテーマを扱っていたが、後者はフランスの描写に比べるとあまり一般的ではないテーマであった[50]。 サイード的な分析は、1970年代以降、19世紀のオリエンタリズム作品への関心と蒐集の強い復活を妨げず、後者は主に中東のバイヤーが主導していた [51]。 |

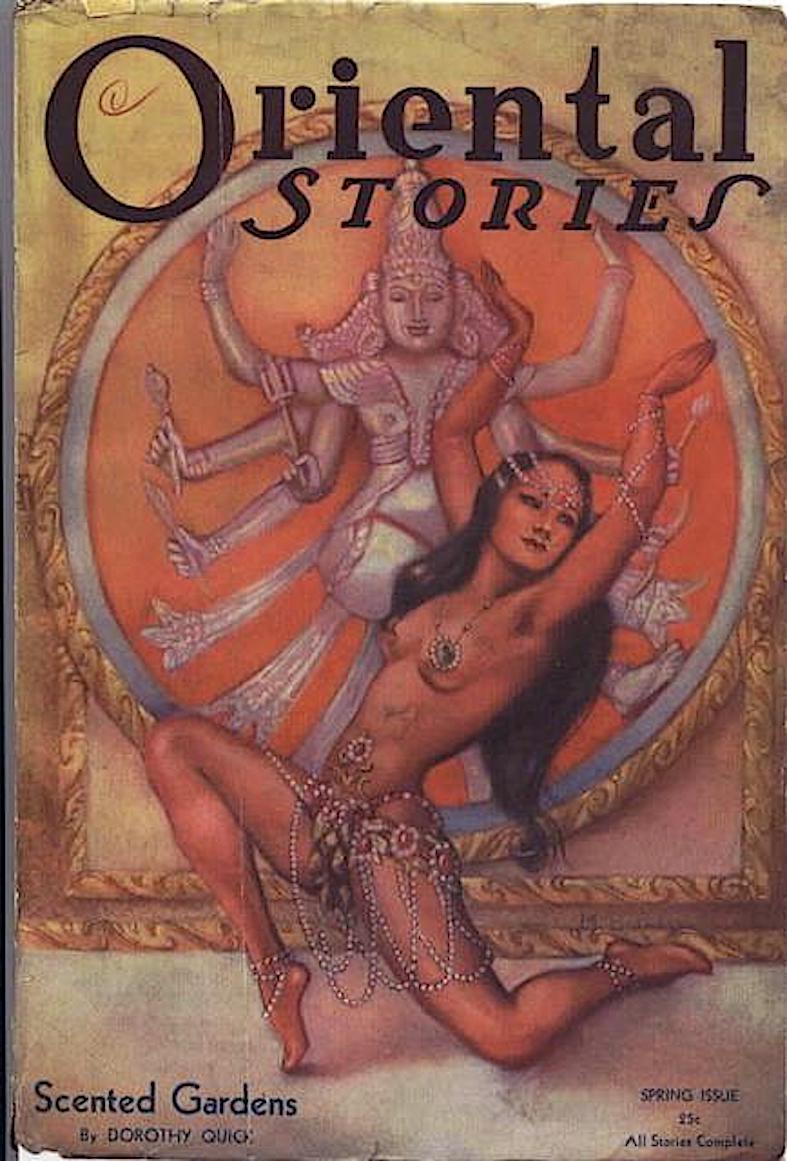

| Pop culture Authors and composers are not commonly referred to as "Orientalist" in the way that artists are, and relatively few specialized in Oriental topics or styles, or are even best known for their works including them. But many major figures, from Mozart to Flaubert, have produced significant works with Oriental subjects or treatments. Lord Byron with his four long "Turkish tales" in poetry, is one of the most important writers to make exotic fantasy Oriental settings a significant theme in the literature of Romanticism. Giuseppe Verdi's opera Aida (1871) is set in Egypt as portrayed through the content and the visual spectacle. "Aida" depicts a militaristic Egypt's tyranny over Ethiopia.[52] Irish Orientalism had a particular character, drawing on various beliefs about early historical links between Ireland and the East, few of which are now regarded as historically correct. The mythical Milesians are one example of this. The Irish were also conscious of the views of other nations seeing them as comparably backward to the East, and Europe's "backyard Orient."[53] |

ポップカルチャー 作家や作曲家は、芸術家のように「オリエンタリスト」と呼ばれることはあまりなく、東洋の話題や様式を専門にしたり、それらを含む作品で最もよく知られて いる人は比較的少ないです。しかし、モーツァルトからフローベールまで、多くの著名人が東洋を題材とした重要な作品を制作しています。バイロン卿は、4つ の長い「トルコ物語」を詩にしたことで、エキゾチックな幻想的な東洋の設定を、ロマン主義文学の重要なテーマとした最も重要な作家の一人である。ジュゼッ ペ・ヴェルディのオペラ『アイーダ』(1871年)は、エジプトを舞台とし、その内容と視覚的なスペクタクルを通して描かれている。"Aida "は軍国主義的なエジプトのエチオピアに対する専制政治を描いている[52]。 アイルランドのオリエンタリズムは、アイルランドと東洋の間の初期の歴史的なつながりに関する様々な信念をもとにした特殊な性格を持っていたが、そのうち のいくつかは現在では歴史的に正しいとみなされているものである。神話上のミレシア人はその一例である。アイルランド人はまた、自分たちを東洋に対して比 較的に後進的であり、ヨーロッパの「裏庭の東洋」であると見ている他の国々の見解も意識していた[53]。 |

| Music In music, Orientalism may be applied to styles occurring in different periods, such as the alla Turca, used by multiple composers including Mozart and Beethoven.[54] The musicologist Richard Taruskin identified in 19th-century Russian music a strain of Orientalism: "the East as a sign or metaphor, as imaginary geography, as historical fiction, as the reduced and totalized other against which we construct our (not less reduced and totalized) sense of ourselves."[55] Taruskin conceded Russian composers, unlike those in France and Germany, felt an "ambivalence" to the theme since "Russia was a contiguous empire in which Europeans, living side by side with 'orientals', identified (and intermarried) with them far more than in the case of other colonial powers".[56] Nonetheless, Taruskin characterized Orientalism in Romantic Russian music as having melodies "full of close little ornaments and melismas,"[57] chromatic accompanying lines, drone bass[58]—characteristics which were used by Glinka, Balakirev, Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, Lyapunov, and Rachmaninov. These musical characteristics evoke:[58] not just the East, but the seductive East that emasculates, enslaves, renders passive. In a word, it signifies the promise of the experience of nega, a prime attribute of the orient as imagined by the Russians.... In opera and song, nega often simply denotes S-E-X a la russe, desired or achieved. Orientalism is also traceable in music that is considered to have effects of exoticism, including the Japonisme in Claude Debussy's piano music all the way to the sitar being used in recordings by the Beatles.[54] In the United Kingdom, Gustav Holst composed Beni Mora evoking a languid, heady Arabian atmosphere. Orientalism, in a more camp fashion also found its way into exotica music in the late 1950s, especially the works of Les Baxter, for example, his composition "City of Veils." |

音楽 音楽においては、オリエンタリズムはモーツァルトやベートーヴェンを含む複数の作曲家が用いたアラ・トゥルカのような異なる時代に発生した様式に適用され ることがある[54]。音楽学者リチャード・タラスキンは19世紀のロシア音楽において、「記号または比喩としての東洋、想像上の地理としての、歴史小説 としての、縮小し全体化した他者とそれに対する我々の(少なくない縮小と全体化の)感覚を構築する」というオリエンタリズムの傾向を確認した[55] [59]。 55] タールスキンは、「ロシアは、ヨーロッパ人が『東洋人』と並んで生活し、他の植民地大国の場合よりもはるかに彼らと同一視(そして婚姻)する連続した帝国 であった」ため、フランスやドイツの作曲家とは異なり、ロシアの作曲家はこのテーマに対して「両価性」を感じていたと認めている[56]。 それにもかかわらず、タルスキンはロマン派ロシア音楽におけるオリエンタリズムを「密接な小さな装飾とメリスマに満ちた」[57]メロディ、半音階の伴奏 線、ドローンベース[58]-グリンカ、バラキレフ、ボロディン、リムスキー=コルサコフ、リアプノフ、ラフマニノフが用いた特徴を持っていると特徴づけ ている。これらの音楽的特徴は次のようなものを想起させる[58]。 東洋だけでなく、男性化し、奴隷化し、受動的にする魅惑的な東洋を。一言で言えば,ロシア人が想像する東洋の主要な属性である「ネガ」の体験が約束されて いることを意味する.......オペラや歌曲では、negaはしばしば単にS-E-X a la russe、望まれる、または達成されたを意味する。 オリエンタリズムは、クロード・ドビュッシーのピアノ曲におけるジャポニスムから、ビートルズの録音で使われたシタールまで、異国情緒の効果があるとされ る音楽にも見受けられる[54]。 イギリスでは、グスタフ・ホルストが、気だるく、頭の回転が速いアラビア風の雰囲気を醸し出す『Beni Mora』を作曲している。 オリエンタリズムは、よりキャンプ的な方法で、1950年代後半のエキゾチカ音楽、特にレス・バクスターの作品、例えば彼の作曲した "City of Veils" などに見られるようになる。 |

| Literature The Romantic movement in literature began in 1785 and ended around 1830. The term Romantic references the ideas and culture that writers of the time reflected in their work. During this time, the culture and objects of the East began to have a profound effect on Europe. Extensive traveling by artists and members of the European elite brought travelogues and sensational tales back to the West creating a great interest in all things "foreign." Romantic Orientalism incorporates African and Asian geographic locations, well-known colonial and "native" personalities, folklore, and philosophies to create a literary environment of colonial exploration from a distinctly European worldview. The current trend in analysis of this movement references a belief in this literature as a mode to justify European colonial endeavors with the expansion of territory.[59] In his novel Salammbô, Gustave Flaubert used ancient Carthage in North Africa as a foil to ancient Rome. He portrayed its culture as morally corrupting and suffused with dangerously alluring eroticism. This novel proved hugely influential on later portrayals of ancient Semitic cultures. |

文学 文学におけるロマン主義運動は、1785年に始まり、1830年頃に終焉を迎えた。ロマン派という言葉は、当時の作家が作品に反映させた思想や文化を指し ている。この時代、東洋の文化や物がヨーロッパに大きな影響を及ぼし始めた。芸術家やヨーロッパのエリートたちの大規模な旅行が、旅行記やセンセーショナ ルな物語を西洋に持ち帰り、あらゆる「外国」のものに大きな関心を抱かせたのである。ロマン主義的オリエンタリズムは、アフリカやアジアの地理的位置、植 民地や「先住民」の著名な人物、民俗学、哲学を取り入れ、ヨーロッパ独特の世界観から植民地探検の文学環境を作り上げた。この運動の分析における現在の傾 向は、領土の拡大を伴うヨーロッパの植民地的な試みを正当化するモードとしてのこの文学への信念を参照している[59]。 ギュスターヴ・フローベールは彼の小説Salammbôにおいて、北アフリカの古代カルタゴを古代ローマに対する箔付けとして使用した。彼はその文化を道 徳的に堕落し、危険なほど魅力的なエロティシズムに満ちているものとして描いている。この小説は、後の古代セム文化の描写に多大な影響を与えた。 |

| Film Said argues that the continuity of Orientalism into the present can be found in influential images, particularly through the Cinema of the United States, as the West has now grown to include the United States.[60] Many blockbuster feature films, such as the Indiana Jones series, The Mummy films, and Disney's Aladdin film series demonstrate the imagined geographies of the East.[60] The films usually portray the lead heroic characters as being from the Western world, while the villains often come from the East.[60] The representation of the Orient has continued in film, although this representation does not necessarily have any truth to it. In The Tea House of the August Moon (1956), as argued by Pedro Iacobelli, there are tropes of orientalism. He notes, that the film "tells us more about the Americans and the American's image of Okinawa rather than about the Okinawan people."[61] The film characterizes the Okinawans as "merry but backward" and "de-politicized," which ignored the real-life Okinawan political protests over forceful land acquisition by the American military at the time. Kimiko Akita, in Orientalism and the Binary of Fact and Fiction in 'Memoirs of a Geisha', argues that Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) contains orientalist tropes and deep "cultural misrepresentations." She states that Memoirs of a Geisha "reinforces the idea of Japanese culture and geisha as exotic, backward, irrational, dirty, profane, promiscuous, bizarre, and enigmatic."[62] |

映画 『インディ・ジョーンズ』シリーズ、『ミイラ』、ディズニーの『アラジン』シリーズなどの多くの大ヒット長編映画は、東洋の想像上の地理を示すものである [60]。 [60] 映画は通常、主役の英雄的キャラクターを西洋世界から来たものとして描き、悪役はしばしば東洋から来る。ペドロ・イアコベリによって論じられたように、 『八月十五夜の茶屋(The Teahouse of the August Moon)』(1956)にはオリエンタリズムのトロフィーが存在する。彼は、この映画は「沖縄の人々についてというよりも、アメリカ人とアメリカ人の 沖縄のイメージについて教えてくれる」と指摘している[61]。この映画は、沖縄の人々を「陽気だが後ろ向き」で「非政治的」であると特徴づけており、当 時のアメリカ軍による強引な土地買収に対する現実の沖縄の政治的抗議を無視しているのである。 秋田喜美子は、『芸者の思い出』におけるオリエンタリズムと事実と虚構のバイナリにおいて、『芸者の思い出』(2005)がオリエンタリズムのトロフィー と深い「文化の誤表示」を含んでいると論じている。彼女は『芸者の回想録』が「日本文化と芸者を、エキゾチックで、後進的で、不合理で、汚くて、不敬で、 乱暴で、奇妙で、謎めいたものだという考えを補強している」と述べている[62]。 |

| In dance During the Romantic period of the 19th century, ballet developed a preoccupation with the exotic. This exoticism ranged from ballets set in Scotland to those based on ethereal creatures.[63][citation needed] By the later part of the century, ballets were capturing the presumed essence of the mysterious East. These ballets often included sexual themes and tended to be based on assumptions of people rather than on concrete facts. Orientalism is apparent in numerous ballets. The Orient motivated several major ballets, which have survived since the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Le Corsaire premiered in 1856 at the Paris Opera, with choreography by Joseph Mazilier.[64] Marius Petipa re-choreographed the ballet for the Maryinsky Ballet in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1899.[64] Its complex storyline, loosely based on Lord Byron's poem,[65] takes place in Turkey and focuses on a love story between a pirate and a beautiful slave girl. Scenes include a bazaar where women are sold to men as slaves, and the Pasha's Palace, which features his harem of wives.[64] In 1877, Marius Petipa choreographed La Bayadère, the love story of an Indian temple dancer and Indian warrior. This ballet was based on Kalidasa's play Sakuntala.[65] La Bayadere used vaguely Indian costuming, and incorporated Indian inspired hand gestures into classical ballet. In addition, it included a 'Hindu Dance,' motivated by Kathak, an Indian dance form.[65] Another ballet, Sheherazade, choreographed by Michel Fokine in 1910 to music by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, is a story involving a shah's wife and her illicit relations with a Golden Slave, originally played by Vaslav Nijinsky.[65] The ballet's controversial fixation on sex includes an orgy in an oriental harem. When the shah discovers the actions of his numerous wives and their lovers, he orders the deaths of those involved.[65] Sheherazade was loosely based on folktales of questionable authenticity. Several lesser-known ballets of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century also show their Orientalism. For instance, in Petipa's The Pharaoh's Daughter (1862), an Englishman imagines himself, in an opium-induced dream, as an Egyptian boy who wins the love of the Pharaoh's daughter, Aspicia.[65] Aspicia's costume consisted of 'Egyptian' décor on a tutu.[65] Another ballet, Hippolyte Monplaisir's Brahma, which premiered in 1868 in La Scala, Italy,[66] is a story that involves romantic relations between a slave girl and Brahma, the Hindu god, when he visits earth.[65] In addition, in 1909, Serge Diagilev included Cléopâtre in the Ballets Russes' repertory. With its theme of sex, this revision of Fokine's Une Nuit d'Egypte combined the "exoticism and grandeur" that audiences of this time craved.[65] As one of the pioneers of modern dance in America, Ruth St Denis also explored Orientalism in her dancing. Her dances were not authentic; she drew inspiration from photographs, books, and later from museums in Europe.[65] Yet, the exoticism of her dances catered to the interests of society women in America.[65] She included Radha and The Cobras in her 'Indian' program in 1906. In addition, she found success in Europe with another Indian-themed ballet, The Nautch in 1908. In 1909, upon her return to America, St Denis created her first 'Egyptian' work, Egypta.[65] Her preference for Orientalism continued, culminating with Ishtar of the Seven Gates in 1923, about a Babylonian goddess.[65] While Orientalism in dance climaxed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it is still present in modern times. For instance, major ballet companies regularly perform Le Corsaire, La Bayadere, and Sheherazade. Furthermore, Orientalism is also found within newer versions of ballets. In versions of The Nutcracker, such as the 2010 American Ballet Theatre production, the Chinese dance uses an arm position with the arms bent at a ninety-degree angle and the index fingers pointed upwards, while the Arabian dance uses two dimensional bent arm movements. Inspired by ballets of the past, stereotypical 'Oriental' movements and arm positions have developed and remain. |

舞踊において 19世紀のロマン主義時代には、バレエはエキゾチックなものへの偏愛を発展させた。この異国情緒は、スコットランドを舞台にしたバレエから、幽玄な生き物 を題材にしたものまであった[63][citation needed]。世紀後半には、バレエは神秘的な東洋の推定される本質を捉えていた。これらのバレエはしばしば性的なテーマを含み、具体的な事実よりもむ しろ人々の仮定に基づく傾向があった。オリエンタリズムは、数多くのバレエに見受けられる。 19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて生き残ったいくつかの主要なバレエは、オリエントが動機となっている。1856年にパリ・オペラ座で初演された『コル セール』は、ジョセフ・マジリエの振付である[64]。1899年にロシアのサンクトペテルブルクのメリンスキー・バレエ団でマリウス・プティパが再振付 した[64]。 バイロン卿の詩を大まかに基にしたその複雑なストーリーは、トルコで起こり、海賊と美しい奴隷少女の恋物語に焦点を当てている[65]。1877年にマリ ウス・プティパが振付けた『ラ・バヤデール』は、インドの寺院の踊り子とインドの戦士の恋物語である。このバレエはカリダサの戯曲『サクンタラ』に基づく ものである[65]。『ラ・バヤデール』では、漠然としたインドの衣装が用いられ、古典バレエにインドの影響を受けた手のしぐさが取り入れられた。また、 インドの舞踊形式であるカタックに影響を受けた「ヒンドゥーダンス」も含まれていた[65]。1910年にニコライ・リムスキー=コルサコフの音楽でミ シェル・フォーキンが振り付けた別のバレエ『シェヘラザード』は、王の妻と彼女の黄金の奴隷(元々はヴァスラフ・ニジンスキーが演じていた)との不義な関 係に関わる物語だ[65]。このバレエでは性に対して議論を呼ぶ固定化した内容で、オリエンタルハーレムの乱交が行われた。このバレエでは、東洋のハーレ ムでの乱交が描かれ、多数の妻とその愛人たちの行為を知った王は、関係者の死を命じた[65]。 19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけてのあまり知られていないバレエの中にも、オリエンタリズムを感じさせるものがいくつかある。例えば、プティパの『ファ ラオの娘』(1862年)では、イギリス人がアヘンによる夢の中で、ファラオの娘アスピシアの愛を勝ち取るエジプトの少年を想像する[65]。アスピシア の衣装はチュチュに「エジプトの」装飾を施したものであった。 [また、1868年にイタリアのスカラ座で初演されたイポリット・モンプライシルの『ブラフマー』は、地上に訪れたヒンドゥー教の神ブラフマーと奴隷の少 女が恋愛関係になる物語である[65]。 また、1909年にセルジュ・ディアギレフは『クロパット』をバレエ・リュスのレパートリーとして取り上げた。フォーキンの『Une Nuit d'Egypte』を改訂したこの作品は、セックスをテーマとし、当時の観客が求めていた「異国情緒と壮大さ」を兼ね備えていた[65]。 アメリカにおけるモダンダンスのパイオニアの一人として、ルース・サン・ドニもまた彼女のダンスにおいてオリエンタリズムを探求していた。彼女のダンスは 本物ではなく、写真や本、後にはヨーロッパの博物館からインスピレーションを得た[65]。しかし、彼女のダンスのエキゾチシズムは、アメリカの社交界の 女性の興味を引き付けた[65]。さらに、彼女は1908年にインドをテーマにした別のバレエ、『ノーチ』でヨーロッパで成功を収めた。1909年、アメ リカに戻ると、セントドニは最初の「エジプト」作品『Egypta』を創作した[65]。彼女のオリエンタリズムへの好みは続き、1923年にバビロニア の女神を題材とした『Ishtar of the Seven Gates』で頂点に達する[65]。 ダンスにおけるオリエンタリズムは、19世紀後半から20世紀前半にかけて最高潮に達したが、現代でも存在する。例えば、主要なバレエ団は、『ル・コル セール』、『ラ・バヤデール』、『シェヘラザード』を定期的に上演している。さらに、オリエンタリズムは、新しいバージョンのバレエにも見られる。 2010年のアメリカン・バレエ・シアターの『くるみ割り人形』では、中国舞踊は腕を90度に曲げ、人差し指を上に向けたポジションで、アラビア舞踊は腕 を2次元に曲げた動きで踊る。過去のバレエに触発され、ステレオタイプな「東洋的」な動きや腕の位置が発展し、残っているのである。 |

| Religion An exchange of Western and Eastern ideas about spirituality developed as the West traded with and established colonies in Asia.[67] The first Western translation of a Sanskrit text appeared in 1785,[68] marking the growing interest in Indian culture and languages.[69] Translations of the Upanishads, which Arthur Schopenhauer called "the consolation of my life", first appeared in 1801 and 1802.[70][note 1] Early translations also appeared in other European languages.[72] 19th-century transcendentalism was influenced by Asian spirituality, prompting Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) to pioneer the idea of spirituality as a distinct field.[73] A major force in the mutual influence of Eastern and Western spirituality and religiosity was the Theosophical Society,[74][75] a group searching for ancient wisdom from the East and spreading Eastern religious ideas in the West.[76][67] One of its salient features was the belief in "Masters of Wisdom",[77][note 2] "beings, human or once human, who have transcended the normal frontiers of knowledge, and who make their wisdom available to others".[77] The Theosophical Society also spread Western ideas in the East, contributing to its modernisation and a growing nationalism in the Asian colonies.[67] The Theosophical Society had a major influence on Buddhist modernism[67] and Hindu reform movements.[75][67] Between 1878 and 1882, the Society and the Arya Samaj were united as the Theosophical Society of the Arya Samaj.[78] Helena Blavatsky, along with H. S. Olcott and Anagarika Dharmapala, was instrumental in the Western transmission and revival of Theravada Buddhism.[79][80][81] Another major influence was Vivekananda,[82][83] who popularised his modernised interpretation[84] of Advaita Vedanta during the later 19th and early 20th century in both India and the West,[83] emphasising anubhava ("personal experience") over scriptural authority.[85] |

宗教 西洋がアジアと交易し、植民地を設立したことにより、精神性に関する西洋と東洋の考え方の交流が発展した[67]。サンスクリット語のテキストの最初の西 洋の翻訳は1785年に現れ、インドの文化や言語に対する関心が高まっていることを示すものであった[68]。 [19世紀の超越論はアジアの精神性から影響を受け、ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソン(1803-1882)が別個の分野としての精神性の考えを開拓する きっかけとなった[73]。 東洋と西洋の精神性と宗教性の相互影響における主要な勢力は、東洋から古代の知恵を探し、西洋で東洋の宗教的な考えを広めるグループである神智学協会だっ た[74][75]。 [76][67] その顕著な特徴の1つは、「知恵の達人」[77][注2] 「通常の知識の境界を超越した、人間またはかつて人間だった存在で、その知恵を他者に提供する者」に対する信仰だった[77] 神智学協会は、東洋において西洋の思想を広め、その近代化とアジア植民地でのナショナリズムの高まりに貢献した[67]。 神智学協会は仏教の近代主義[67]とヒンドゥー教の改革運動に大きな影響を与えた[75][67]。1878年から1882年の間に、協会とアーヤ・サ マジはアーヤ・サマジの神智学協会として統合された[78] ヘレナ ブラヴァツキーはH・S・オルコットとアナガリカ・ダルマパラと共に上座仏教の西洋での伝達と復興に貢献した。[79][80][81]。 もう1つの大きな影響はヴィヴェーカナンダであり[82][83]、彼は19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてインドと西洋の両方でアドヴァイタ・ヴェー ダンタの彼の現代化した解釈[84]を普及させて、経典の権威よりもアヌバヴァ(「個人の経験」)を強調した[83]。 |

| Islam With the spread of Eastern religious and cultural ideals towards the West, came in with studies and certain illustrations that depicts certain regions and religions under the Western perspective. Many the aspects or views are often turned into the ideas that the West have adopted onto those cultural and religious ideals. One of the more adopted views can be depicted through Western context on Islam and the Middle East. Under the adopted view of Islam under the Western context, Orientalism falls under the category of the Western perspective of thinking that shifts through social constructs that refers towards representations of the religion or culture in a subjective view point.[86] The concept of Orientalism dates back to precolonial eras, as the main European powers acquired and perceived of territory, resources, knowledge, and control of the regions in the East.[86] The term Orientalism, depicts further into the historical context of antagonism and misrepresentation into the tendencies of a growing layer of Western inclusion and influence on foreign culture and ideals.[87] In the religious perspective under Islam, the term Orientalism applies in similar meaning as the outlook from the Western perspective, mainly in the eyes of the Christian majority.[87] The main contributor of the depiction of Oriental perspectives or illustrations on Islam and other Middle Eastern cultures derives from the imperial and colonial influences and powers that attribute to formation of multiple fields of geographical, political, educational, and scientific elements.[87] The combination of these different genres reveal significant division among people of those cultures and reinforces the ideals set from the Western perspective.[87] With Islam, historically scientific discoveries, research, inventions, or ideas that were presented before and contributed to many other European breakthroughs are not affiliated with the previous Islamic scientists.[87] From the exclusion of past contributions and initial works further lead to narrative of the concept of Orientalism with the passing of time generated a history and directive of presence within region and religion that historically influences the image of the East.[86] Through the recent years, Orientalism has been influenced and shirted to altering representations of various forms that all derive from the same meaning.[86] From the nineteenth century, among the Western perspectives on Orientalism, differed as the split of American and European Orientalism viewed different illustrations.[86] With mainstream media and popular production reveal many depictions of Oriental cultures and Islamic references to the current event of radicalization for Non-western cultures.[86] With references and mainstream media often utilized to contribute to an extended agenda under the construct judgement of alternate motives.[86] The approach with the generalization of the term Orientalism was embedded with under beginning of colonialism as the root of the main complexity of within modern societies perspectives of foreign cultures.[87] As mainstream media depicts illustrations to utilize many instances of discourse and on certain regions mainly among the conflict within regions in the Middle East and Africa.[87] With agenda of influencing views on non-western societies to be deemed non-compatible with differing ideologies and cultures, the elements that present diversion among Eastern societies and aspects.[87] |

イスラム教 東洋の宗教的・文化的理念が西洋に広まるにつれ、ある地域や宗教を西洋の視点で描いた研究や図版が登場するようになった。その多くは、西洋が文化的、宗教 的な理想を取り入れたものである。イスラム教と中東に関する西洋の文脈を通じて、より多くの採用された見解の1つを描くことができる。西洋の文脈で採用さ れたイスラム教の見解の下で、オリエンタリズムは主観的な視点での宗教や文化の表現に言及する社会的構成を通して移行する思考の西洋の視点のカテゴリに分 類される。 [86]オリエンタリズムの概念は、主要なヨーロッパ列強が領土、資源、知識、東洋の地域の支配を獲得し認識した先植民地時代まで遡る[86]。オリエン タリズムという言葉は、外国の文化や理想に対する西洋の包含と影響の層の増加傾向への反感と誤った表象の歴史的文脈にさらに描写されている[87]。 イスラム教の下での宗教的な視点において、オリエンタリズムという用語は、主にキリスト教徒の大多数の目における西洋の視点からの展望と同様の意味で適用 される[87]。イスラム教や他の中東文化に対する東洋の視点や図解の描写の主因は、帝国や植民地の影響や権力から派生し、地理、政治、教育、科学の要素 の複数の分野の形成に帰する[87] 。 これらの異なるジャンルの組み合わせによってこれらの文化の人々の間に大きな分裂が見られ、西洋の視点から定められた理想が強化されてしまうのである。 [87]イスラム教では、歴史的に科学的発見、研究、発明、または以前に提示され、他の多くのヨーロッパのブレークスルーに貢献したアイデアは、以前のイ スラムの科学者とは関係ない。過去の貢献や初期の作品の除外から、さらに時間の経過とともにオリエンタリズムの概念の物語につながり、歴史的に東のイメー ジに影響を与える地域や宗教内の存在の歴史と指示を生成している[86]。 19世紀から、オリエンタリズムに関する西洋の視点の中で、アメリカとヨーロッパのオリエンタリズムの分裂が異なるイラストを見たように異なっていた [86]。 [86]主流メディアと大衆的な生産は、非西洋文化のための過激化の現在のイベントへの東洋文化やイスラムの参照の多くの描写を明らかにする[86]。 [86]用語オリエンタリズムの一般化とのアプローチは、外国文化の近代社会の視点内の主な複雑さの根源として、植民地主義の始まりの下で埋め込まれた。 主流メディアは、主に中東やアフリカの地域内の紛争の間で談話の多くのインスタンスと特定の地域に活用するためのイラストを描くように[87]。非西部社 会に対する見方に影響を与えるの議題が異なるイデオロギーや文化、東部社会との側面の間の転換を提示要素と非互換性と見なされる[87]とすること。 |

| Eastern views of the West and

Western views of the East The concept of Orientalism has been adopted by scholars in East-Central and Eastern Europe, among them Maria Todorova, Attila Melegh, Tomasz Zarycki, and Dariusz Skórczewski[88] as an analytical tool for exploring the images of East-Central and Eastern European societies in cultural discourses of the West in the 19th century and during the Soviet domination. The term "re-orientalism" was used by Lisa Lau and Ana Cristina Mendes[89][90] to refer to how Eastern self-representation is based on western referential points:[91] Re-Orientalism differs from Orientalism in its manner of and reasons for referencing the West: while challenging the metanarratives of Orientalism, re-Orientalism sets up alternative metanarratives of its own in order to articulate eastern identities, simultaneously deconstructing and reinforcing Orientalism. |

東洋の西洋観と西洋の東洋観 オリエンタリズムの概念は、東中東欧の学者、中でもマリア・トドロヴァ、アッティラ・メレグ、トマシュ・ザリッキ、ダリウス・スコルチェフスキ[88]に よって、19世紀とソ連の支配下における西洋の文化言説における東中東欧社会のイメージを探る分析的ツールとして採用されてきた。 リサ・ラウとアナ・クリスティーナ・メンデス[89][90]によって「再東洋主義=リオリエント主義」という用語が用いられ、東洋の自己表象がいかに西 洋の参照点に基づいているのかを指していた[91]。 リオリエント主義(再東洋主義)は西洋を参照するその方法と理由においてオリエンタリズムとは異なる。オリエンタリズムのメタナラティブに挑戦しながら、 リオリエント主義は東洋のアイデンティティを明確にするためにそれ自身の代替メタナラティブを設定して、同時にオリエンタリズムを脱構築し、強化するので ある。 |

| Occidentalism The term occidentalism is often used to refer to negative views of the Western world found in Eastern societies, and is founded on the sense of nationalism that spread in reaction to colonialism[92] (see Pan-Asianism). Edward Said has been accused of Occidentalizing the west in his critique of Orientalism; of being guilty of falsely characterizing the West in the same way that he accuses Western scholars of falsely characterizing the East.[93] Said essentialized the West by creating a homogenous image of the area. Currently, the West consists not only of Europe, but also the United States and Canada, which have become more influential over the years.[93] |

オクシデンタリズム オクシデンタリズムという言葉は、東洋の社会で見られる西洋の世界に対する否定的な見方を指すのによく使われ、植民地主義への反動で広がったナショナリズ ム[92](汎アジア主義を参照)の感覚に基礎を置くものである。エドワード・サイードはオリエンタリズムの批判において西洋を西洋化したと非難されてい る。西洋の学者たちが東洋を誤って特徴づけていると非難するのと同じように、西洋を誤って特徴づけることに有罪であると[93] サイードは西洋をその地域の均質なイメージを作ることによって本質化していた。現在、西洋はヨーロッパだけでなく、年々影響力を増しているアメリカやカナ ダからも構成されている[93]。 |

| Othering The action of othering cultures occurs when groups are labeled as different due to characteristics that distinguish them from the perceived norm.[94] Edward Said, author of the book Orientalism, argued that western powers and influential individuals such as social scientists and artists othered "the Orient."[87] The evolution of ideologies is often initially embedded in the language, and continues to ripple through the fabric of society by taking over the culture, economy and political sphere.[95] Much of Said's criticism of Western Orientalism is based on what he describes as articularizing trends. These ideologies are present in Asian works by Indian, Chinese, and Japanese writers and artists, in their views of Western culture and tradition. A particularly significant development is the manner in which Orientalism has taken shape in non-Western cinema, as for instance in Hindi-language cinema. |

他者化 オリエンタリズム』の著者であるエドワード・サイードは、西洋の権力者や社会科学者や芸術家のような影響力のある人々が「東洋」を他者化したと主張してい る[87] イデオロギーの進化はしばしば最初に言語に埋め込まれ、文化、経済、政治領域を支配することによって社会の構造を通して波及し続ける[95] サイードの西洋オリエンタリズムに対する批判の多くは、彼が芸術化傾向として説明するものに基づくものである。これらのイデオロギーは、インド、中国、日 本の作家やアーティストによるアジアの作品において、西洋の文化や伝統に対する見解に存在している。特に重要なのは、例えばヒンディー語映画のように、非 西洋映画においてオリエンタリズムがどのように形成されてきたかという点である。 |

| Beard, David and Kenneth Gloag.

2005. Musicology: The Key Concepts. New York: Routledge. Cristofi, Renato Brancaglione. Architectural Orientalism in São Paulo - 1895 - 1937. 2016. São Paulo: University of São Paulo online, accessed July 11, 2018 Fields, Rick (1992), How The Swans Came To The Lake. A Narrative History of Buddhism in America, Shambhala Harding, James, Artistes Pompiers: French Academic Art in the 19th Century, 1979, Academy Editions, ISBN 0-85670-451-2 C F Ives, "The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints", 1974, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0-87099-098-5 Gabriel, Karen & P.K. Vijayan (2012): Orientalism, terrorism and Bombay cinema, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 48:3, 299–310 Gilchrist, Cherry (1996), Theosophy. The Wisdom of the Ages, HarperSanFrancisco Gombrich, Richard (1996), Theravada Buddhism. A Social History From Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo, Routledge Holloway, Steven W., ed. (2006). Orientalism, Assyriology and the Bible. Hebrew Bible Monographs, 10. Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-905048-37-3 Johnson, K. Paul (1994), The masters revealed: Madam Blavatsky and the myth of the Great White Lodge, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2063-8 King, Donald and Sylvester, David eds. The Eastern Carpet in the Western World, From the 15th to the 17th century, Arts Council of Great Britain, London, 1983, ISBN 0-7287-0362-9 Lavoie, Jeffrey D. (2012), The Theosophical Society: The History of a Spiritualist Movement, Universal-Publishers Mack, Rosamond E. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600, University of California Press, 2001 ISBN 0-520-22131-1 McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195183276 Meagher, Jennifer. Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. online, accessed April 11, 2011 Michaelson, Jay (2009), Everything Is God: The Radical Path of Nondual Judaism, Shambhala Nochlin, Linda, The Imaginary Orient, 1983, page numbers from reprint in The nineteenth-century visual culture reader,google books, a reaction to Rosenthal's exhibition and book. Rambachan, Anatanand (1994), The Limits of Scripture: Vivekananda's Reinterpretation of the Vedas, University of Hawaii Press Renard, Philip (2010), Non-Dualisme. De directe bevrijdingsweg, Cothen: Uitgeverij Juwelenschip Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978 ISBN 0-394-74067-X). Sinari, Ramakant (2000), Advaita and Contemporary Indian Philosophy. In: Chattopadhyana (gen.ed.), "History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization. Volume II Part 2: Advaita Vedanta", Delhi: Centre for Studies in Civilizations Taruskin, Richard. Defining Russia Musically. Princeton University Press, 1997 ISBN 0-691-01156-7. Tromans, Nicholas, and others, The Lure of the East, British Orientalist Painting, 2008, Tate Publishing, ISBN 978-1-85437-733-3 |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orientalism |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

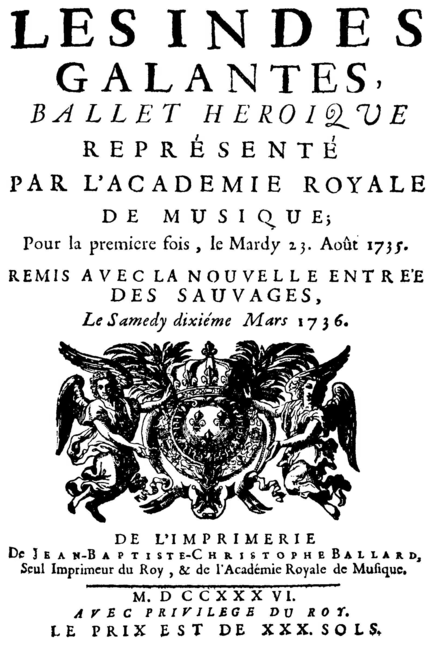

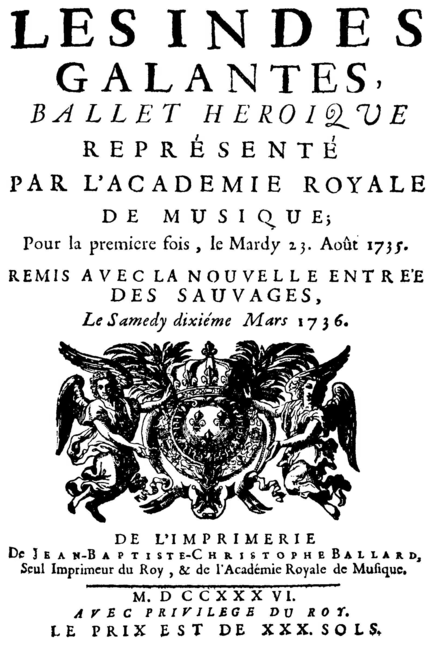

| orientalism

in Music Derek B. Scott, Orientalism and Musical Style, The Musical Quarterly Vol. 82, No. 2 (Summer, 1998), pp. 309-335 (27 pages) https://www.jstor.org/stable/742411 In Western music, Orientalist styles have related to previous Orientalist styles rather than to Eastern ethnic practices, just as myths have been described by Levi-Strauss as relating to other myths. I One might ask if it is necessary to know anything about Eastern musical pract ices; for the most part, it seems that only a knowledge of Orientalist signiliers is required. In the case of Orientalist operas, I had at ftrst thought it might be important to understand where they were set geographically. Then I began to realize that, for the most part, aliI needed to know was the simple fact that they were set in exotic, foreign places. Perhaps I should have remembered Edward Said's advice tbat "we need not look for correspondence between the language used to depict the Orient and the Orient itself, not so much because the language is inaccurate but because it is not even trying to be accurate. What it is trying to do .. . is at one and the same time to characterize the Orient as alien and to incorporate it schematically on a theatrical stage whose audience, manager, and actors are far Europe, and only for Europe. Nevertheless, the state of affairs found in a work like Rameau's Les Indis galantes (1735), where, for example, Persians are musically indistinguishable from Peruvians, was to change. Distinctions and differences developed in the representation of the exotic or cultural Other, and that, as well as the confusion that sometimes results, is my present concern. This confusion is most evident in the nineteenth century, when Western composers, especially those working in countries engaged in imperialist expansion, were tom between, on the one hand, making a simple distinction between Western Self and Oriental Other, and on the other, recognizing that there was no single homogeneous Oriental culture. Thus, even when different Orientalist styles had become established, they could sometimes be applied in a careless manner. In this article, because of its broad span, I am looking primarily for changes in representation. As a caveat, I should stress that in a genealogical critique such as this, a smooth linear narrative is impossible, and owing to the contingent nature of developments in Orientalist styles, a certain amount of lurching around on my part is unavoidable. 309 https://www.jstor.org/stable/742411  Chinois, dans Les Indes galantes et autres ballets |

音楽におけるオリエンタリズム デレク・スコット「オリエンタリズムと音楽のスタイル」 「レヴィ=ストロースが、神話が他の神話と関連していると説明したように、西洋音楽では、オリエンタリズムのスタイルは、東洋の民族的慣習というよりも、 むしろ以前のオリエンタリズムのスタイルと関連している。東洋の音楽的慣習について何か知っておく必要があるのかと問われるかもしれないが、たいていの場 合、必要なのはオリエンタリズムの記号についての知識だけだと思われる。オリエンタリズムのオペラの場合、私は最初、それが地理的にどこを舞台にしている かを理解することが重要かもしれないと考えていた。しかし、ほとんどの場合、私が知る必要があるのは、エキゾチックな異国の地を舞台にしているという単純 な事実だけだということに気づき始めた。東洋を描写するために使われる言語と東洋そのものとの対応関係を探す必要はない。オリエントがやろうとしているの は......オリエントを異質なものとして特徴づけることと、観客も支配人も役者もはるかヨーロッパの、しかもヨーロッパだけの演劇の舞台に、オリエン トを図式的に組み込むことである。 とはいえ、ラモーの『Les Indis galantes』 (1735年)のような作品に見られるような、たとえばペルシャ人とペルー人の音楽的区別がつかないような状態は、変化していくことになる。エキゾチック な、あるいは文化的な他者の表現において、区別と差異が生まれた。この混乱は19世紀に最も顕著で、西洋の作曲家たち、特に帝国主義的な拡大に従事してい た国々で活動していた作曲家たちは、一方では西洋の自己と東洋の他者を単純に区別し、他方では東洋の文化には単一の均質なものは存在しないと認識してい た。そのため、さまざまなオリエンタリズムのスタイルが確立されたとしても、時には無頓着に適用されることもあった。」 「本稿では、その広範なスパンゆえに、私は主に表象の変化を探っている。注意点として、このような系譜的な批評では、滑らかな直線的な物語は不可能であ り、オリエンタリズムのスタイルの発展には偶発的な性質があるため、私の側でもある程度の紆余曲折は避けられないことを強調しておきたい。」  ラモーのオペラ『愛すべきインド』における中国人 |

Les Indes

galantes

(French: "The Amorous Indies") is an opera by Jean-Philippe Rameau with

a libretto by Louis Fuzelier. It takes the form of an opéra-ballet with

a prologue and (in its final form) four entrées (acts). Following an

allegorical prologue, the four entrées have distinct and separate

plots, but are unified by the theme of love in exotic places (The

Ottoman Empire, Peru, Persia, and North America). The most famous

pieces from the work, Danse des Sauvages and the final Chaconne, come

from the final entrée (Les sauvages).[1] Les Indes

galantes

(French: "The Amorous Indies") is an opera by Jean-Philippe Rameau with

a libretto by Louis Fuzelier. It takes the form of an opéra-ballet with

a prologue and (in its final form) four entrées (acts). Following an

allegorical prologue, the four entrées have distinct and separate

plots, but are unified by the theme of love in exotic places (The

Ottoman Empire, Peru, Persia, and North America). The most famous

pieces from the work, Danse des Sauvages and the final Chaconne, come

from the final entrée (Les sauvages).[1]The premiere, including only the prologue and the first two of its four entrées (acts), was staged by the Académie Royale de Musique at its theatre in the Palais-Royal in Paris on 23 August 1735,[2] starring the leading singers of the Opéra: Marie Antier, Marie Pélissier, Mlle Errémans, Mlle Petitpas, Denis-François Tribou, Pierre Jélyotte, and Claude-Louis-Dominique Chassé de Chinais, and the dancers Marie Sallé and Louis Dupré. Michel Blondy provided the choreography.[3] The ballet's Premier Menuet was used in the soundtrack of the 2006 film Marie Antoinette.[4] |

Les

Indes galantes』(仏: The Amorous

Indies)は、ルイ・フゼリエの台本によるジャン=フィリップ・ラモーのオペラ。プロローグと(最終的には)4つのアントレ(幕)を持つオペラ・バレ

エの形式をとる。寓話的なプロローグに続き、4つのアントレはそれぞれ独立したプロットを持っているが、異国の地(オスマン帝国、ペルー、ペルシャ、北ア

メリカ)での愛というテーマで統一されている。作品の中で最も有名な曲であるDanse des

Sauvagesと最後のChaconneは、最後のエントレ(Les sauvages)から生まれている[1]。 Les

Indes galantes』(仏: The Amorous

Indies)は、ルイ・フゼリエの台本によるジャン=フィリップ・ラモーのオペラ。プロローグと(最終的には)4つのアントレ(幕)を持つオペラ・バレ

エの形式をとる。寓話的なプロローグに続き、4つのアントレはそれぞれ独立したプロットを持っているが、異国の地(オスマン帝国、ペルー、ペルシャ、北ア

メリカ)での愛というテーマで統一されている。作品の中で最も有名な曲であるDanse des

Sauvagesと最後のChaconneは、最後のエントレ(Les sauvages)から生まれている[1]。1735年8月23日、パリのパレ・ロワイヤルにあるアカデミー・ロワイヤル音楽院の劇場で、プロローグと4つのエントレ(幕)のうち最初の2つのみを含 む初演が行われ、オペラ座を代表する歌手たちが出演した[2]: マリー・アンティエ、マリー・ペリシエ、エレマン嬢、プティパ嬢、ドニ=フランソワ・トリブー、ピエール・ジェリョット、クロード=ルイ=ドミニク・シャ セ・ド・チネ、そしてマリー・サレとルイ・デュプレのダンサーが出演した。ミシェル・ブロンディが振付を担当した[3]。このバレエのプルミエ・メヌエッ トは、2006年の映画『マリー・アントワネット』のサウンドトラックに使用された[4]。 |

| Background In 1725, French settlers in Illinois sent Chief Agapit Chicagou of the Mitchigamea and five other chiefs to Paris. On 25 November 1725, they met with King Louis XV. Chicagou had a letter read pledging allegiance to the crown. They later danced three kinds of dances in the Théâtre-Italien, inspiring Rameau to compose his rondeau Les Sauvages.[5] In a preface to the printed libretto, Louis Fuzelier explains that the first entrée, "Le Turc généreux," "is based on an illustrious character—Grand Vizier Topal Osman Pasha, who was so well known for his extreme generosity. His story can be read in the Mercure de France from January 1734."[6] The story of Osman's generosity "was apparently based on a story published in the Mercure de Suisse in September 1734 concerning a Marseillais merchant, Vincent Arniaud, who saved a young Ottoman notable from slavery in Malta, and the unstinting gratitude and generosity returned by this young man, who later became Grand Vizier Topal Osman Pasha."[7] Performance history The premiere met with a lukewarm reception from the audience[8] and, at the third performance, a new entrée was added under the title Les Fleurs.[9] However, this caused further discontent because it showed the hero disguised as a woman, which was viewed either as an absurdity[2] or as an indecency. As a result, it was revised for the first time and this version was staged on 11 September.[3] Notwithstanding these initial problems, the first run went on for twenty-eight performances between 23 August and 25 October,[10] when, however, only 281 livres were grossed, the lowest amount ever collected at the box office by Les Indes galantes.[3] Nevertheless, when it was mounted again on 10 (or 11) March 1736, a 'prodigious' audience flocked to the theatre.[11] The entrée des Fleurs was "replaced with a version in which the plot and all the music except the divertissement was new",[2] and a fourth entrée, Les Sauvages, was added, in which Rameau reused the famous air des Sauvages he had composed in 1725 on the occasion of the American Indian chiefs' visit and later included in the Nouvelles Suites de pièces de clavecin (1728). Now in something approaching a definitive form,[12] the opera enjoyed six performances in March and was then mounted again as of 27 December.[3] Further revivals were held in 1743–1744, 1751 and 1761 for a combined total of 185 billings.[10] The work was also performed in Lyon on 23 November 1741, at the theatre of the Jeu de Paume de la Raquette Royale, and again in 1749/1750, at the initiative of Rameau's brother-in-law, Jean-Philippe Mangot.[3] Furthermore, the prologue and individual entrées were often revived separately and given within the composite operatic programs called 'fragments' or 'spectacles coupés' (cut up representations) that: "were almost constant fare at the Palais-Royal in the second half of the eighteenth century".[13] The prologue, Les Incas and Les Sauvages were last given respectively in 1771 (starring Rosalie Levasseur, Gluck's future favourite soprano, in the role of Hebé), 1772 and 1773 (also starring Levasseur as Zima).[2] Thenceforth Les Indes galantes was dropped from the Opéra's repertoire, after having seen almost every artiste of the company in the previous forty years take part in its complete or partial performances.[10] In the twentieth century the Opéra-Comique presented the first version of the Entrée des Fleurs, with a new orchestration by Paul Dukas, on 30 May 1925, in a production conducted by Maurice Frigara,[10] with Yvonne Brothier as Zaïre, Antoinette Reville as Fatima, Miguel Villabella as Tacmas and Emile Rousseau as Ali.[citation needed] Finally, Les Indes galantes was revived by the Opéra itself, at the Palais Garnier, with the Dukas orchestration supplemented for the other entrées by Henri Busser, on 18 June 1952:[10] the production, managed by the Opéra's own director, Maurice Lehmann and conducted by Louis Fourestier,[3] was notable for the lavishness of its staging[2] and enjoyed as many as 236 performances by 29 September 1961.[10] The sets were by André Arbus and Jacques Dupont (1909–1978) (prologue and finale), Georges Wakhevitch (first entrée), Jean Carzou (second entrée), Henri Raymond Fost (1905–1970) and Maurice Moulène (third entrée) and Roger Chapelain-Midy [fr] (fourth entrée); the choreography was provided by Albert Aveline (1883–1968) (first entrée), Serge Lifar (second and fourth entrées) and Harald Lander (third entrée).[3] In the 1st Entrée ("The Gracious Turk"), Jacqueline Brumaire sang Emilie, Jean Giraudeau was Valère and Hugo Santana was Osman; the dancers were Mlle Bourgeois and M Legrand. In the 2nd Entrée, ("The Incas of Peru"), Marisa Ferrer was Phani, Georges Noré was don Carlos, and René Bianco was Huascar, while Serge Lifar danced alongside Vyroubova and Bozzoni. The 3rd Entrée, ("The Flowers") had Janine Micheau as Fatima, side by side with Denise Duval as Zaïre. Giraudeau was Tacmas and Jacques Jansen, the famous Pelléas, was Ali, with Mlle Bardin dancing as the Rose, Mlle Dayde as the Butterfly, Ritz as Zéphir and Renault as a Persian. The 4th Entrée, ("The Savages of America"), had Mme Géori Boué, as Zima, with José Luccioni as Adario, Raoul Jobin as Damon and Roger Bourdin as don Alvar. The dancing for this act was executed by Mlles Darsonval, Lafon and Guillot and Messieurs Kalioujny and Efimoff.[citation needed] |

背景 1725年、イリノイ州のフランス人入植者たちは、ミッチガメア族の酋長アガピット・チカゴウと他の5人の首長(チーフ)をパリに派遣した。1725年 11月25日、彼らは国王ルイ15世と面会した。チカグーは王室への忠誠を誓う手紙を読み上げさせた。その後、彼らはイタリヤ劇場で3種類の舞曲を踊り、 ラモーはロンドー「Les Sauvages」を作曲した[5]。 印刷されたリブレットの序文で、ルイ・フゼリエは、第1曲目の「トルコ人」(Le Turc généreux)について、「非常に寛大なことで有名な大宰相トパル・オスマン・パシャを題材にしている」と説明している。彼の物語は1734年1月の 『メルキュール・ド・フランス』誌で読むことができる」[6]。オスマンの寛大さの物語は、「1734年9月の『メルキュール・ド・スイス』誌に掲載され た、マルセイユの商人ヴァンサン・アルノーが、オスマン・トルコの若い注目すべき人物をマルタの奴隷から救い、この青年が返した惜しみない感謝と寛大さに 関する物語が元になっているようで、この青年は後に大宰相トパル・オスマン・パシャとなった」[7]。 上演履歴 初演では観客の反応は鈍く[8]、3回目の上演では『Les Fleurs』という題名で新たな導入部が加えられたが[9]、主人公が女性に変装している姿が不条理[2]、あるいは猥褻であるとされ、さらなる不満を 招いた。このような当初の問題にもかかわらず、初演は8月23日から10月25日にかけて28回上演されたが[10]、興行収入は281リーヴルにとどま り、Les Indes galantesの興行収入としては最低額となった[3]。 それにもかかわらず、1736年3月10日(または11日)に再び上演されると、「驚異的な」観客が劇場に押し寄せた[11]。 [この曲では、ラモーが1725年にアメリカ・インディアンの酋長の訪問の際に作曲し、後に『クラヴサン小曲集』(1728年)に収録された有名な「ソー ヴァージュの歌」が再利用された。 1743年から1744年、1751年、1761年にも再演が行われ、合計185回上演された[3]。 [また、1741年11月23日にはリヨンのラケット・ロワイヤルのジュ・ド・ポーム劇場で、1749年と1750年にはラモーの義弟ジャン=フィリッ プ・マンゴーの主導で再演された[3]。さらに、プロローグと個々のエントレはしばしば別々に再演され、「断片」または「スペクタクル・クーペ」(切り刻 まれた表現)と呼ばれる複合的なオペラ・プログラムの中で上演された: 「プロローグ、レ・インカ、レ・ソヴァージュは、それぞれ1771年(後にグルックのお気に入りのソプラノとなるロザリー・ルヴァスールがヘベ役で出 演)、1772年、1773年(同じくルヴァスールがジーマ役で出演)に上演されたのが最後である[13]。 [2]その後、『インド・ギャラント』はオペラ座のレパートリーから外され、それ以前の40年間、オペラ座のほとんどのアーティストが全幕または部分上演 に参加していた[10]。 20世紀に入ると、オペラ・コミックは1925年5月30日、モーリス・フリガラ指揮[10]のもと、ポール・デュカスによる新しいオーケストレーション で、ザイール役のイヴォンヌ・ブロティエ、ファティマ役のアントワネット・ルヴィル、タクマス役のミゲル・ヴィラベラ、アリ役のエミール・ルソーが出演す る『花のアントレ』の初演を行った[要出典]。 オペラ座の演出家モーリス・レーマンによって管理され、ルイ・フーレスティエによって指揮されたこのプロダクションは[3]、その豪華な演出で注目され [2]、1961年9月29日までに236回もの公演が行われた[10]。 [10] セットは、アンドレ・アルブスとジャック・デュポン(1909-1978)(プロローグとフィナーレ)、ジョルジュ・ワケヴィッチ(第1幕)、ジャン・カ ルズー(第2幕)、アンリ・レイモン・フォスト(1905-1970)とモーリス・ムレーヌ(第3幕)、ロジェ・シャペラン=ミディ(第4幕); 振付は、アルベール・アヴリーヌ(1883-1968)(第1回)、セルジュ・リファール(第2回、第4回)、ハラルド・ランダー(第3回)。 [3] 第1幕(『優雅なトルコ人』)では、ジャクリーヌ・ブリュメールがエミリーを、ジャン・ジロドーがヴァレールを、ユゴ・サンタナがオスマンを歌い、ダン サーはブルジョワ嬢とルグラン嬢が務めた。第2部(『ペルーのインカ』)では、マリサ・フェレールがファニ、ジョルジュ・ノレがドン・カルロス、ルネ・ビ アンコがフアスカルを演じ、セルジュ・リファールがヴィロボワとボッツォーニとともに踊った。第3幕(『花』)では、ファティマ役のジャニーヌ・ミショー がザイール役のドゥニーズ・デュヴァルと並んで踊った。ジロドーはタクマス、有名なペレアスのジャック・ジャンセンはアリを演じ、バルダン嬢がバラ、ダイ ドー嬢が蝶、リッツがゼフィール、ルノーがペルシャ人を演じた。第4幕(「アメリカの野蛮人」)では、ジーマ役のジェオリ・ブエ女史、アダリオ役のホセ・ ルッチョーニ、デイモン役のラウール・ジョバン、ドン・アルヴァール役のロジェ・ブルダンが踊った。この演目のダンスは、ダルソンヴァル、ラフォン、ギ ヨ、カリウジュニー、エフィモフが担当した[要出典]。 |

| Roles are omitted |

|