エドワード・ウィリアム・サイード

Edward William Said, 1935-2003

Edward

Wadie Said Edward

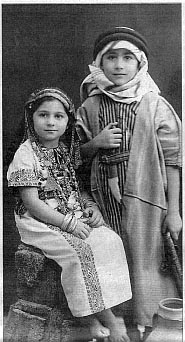

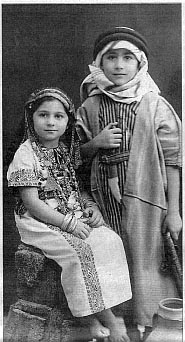

Wadie SaidEdward Wadie Said (/sɑːˈiːd/; Arabic: إدوارد وديع سعيد, romanized: Idwārd Wadīʿ Saʿīd, [wædiːʕ sæʕiːd]; 1 November 1935 – 24 September 2003) was a Palestinian-American professor of literature at Columbia University, a public intellectual, and a founder of the academic field of postcolonial studies.[3] Born in Mandatory Palestine, he was a citizen of the United States by way of his father, a U.S. Army veteran. Educated in the Western canon at British and American schools, Said applied his education and bi-cultural perspective to illuminating the gaps of cultural and political understanding between the Western world and the Eastern world, especially about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in the Middle East; his principal influences were Antonio Gramsci, Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Michel Foucault, and Theodor Adorno.[4] As a cultural critic, Said is known for the book Orientalism (1978), a critique of the cultural representations that are the bases of Orientalism—how the Western world perceives the Orient.[5][6][7][8] Said's model of textual analysis transformed the academic discourse of researchers in literary theory, literary criticism, and Middle-Eastern studies—how academics examine, describe, and define the cultures being studied.[9][10] As a foundational text, Orientalism was controversial among scholars of Oriental Studies, philosophy, and literature.[11][4] As a public intellectual, Said was a controversial member of the Palestinian National Council, due to his public criticism of Israel and the Arab countries, especially the political and cultural policies of Muslim régimes who acted against the national interests of their peoples.[12][13] Said advocated the establishment of a Palestinian state to ensure equal political and human rights for the Palestinians in Israel, including the right of return to the homeland. He defined his oppositional relation with the status quo as the remit of the public intellectual who has "to sift, to judge, to criticize, to choose, so that choice and agency return to the individual" man and woman. In 1999, with conductor Daniel Barenboim, Said co-founded the West–Eastern Divan Orchestra, based in Seville. Said was also an accomplished pianist, and, with Barenboim, co-authored the book Parallels and Paradoxes: Explorations in Music and Society (2002), a compilation of their conversations and public discussions about music held at New York's Carnegie Hall.[14] *Edward Said and his sister, Rosemarie Said (1940) |

エ

ドワード・ワディ・サイード エ

ドワード・ワディ・サイードエ ドワード・ワディ・サイード(/sɑˈː; アラビア語:إدوارد وديع سعيد, romanized: 1935年11月1日 - 2003年9月24日)は、コロンビア大学のパレスチナ系アメリカ人の文学教授であり、公の知識人であり、ポストコロニアル研究の学術分野の創始者である [3]。 イギリスとアメリカの学校で西洋の正典の教育を受け、サイードはその教育と多文化的な視点を西洋世界と東洋世界の間の文化的、政治的理解のギャップを、特 に中東のイスラエルとパレスチナ紛争について明らかにするために適用した。 文化批評家としてサイードは『オリエンタリズム』(1978年)で知られ、西洋世界が東洋をどのように認識しているかのオリエンタリズムの基盤である文化 的表象の批評である。 [5][6][7][8] サイードのテキスト分析のモデルは、文学理論、文学批評、中東研究の研究者の学術的言説を変革し、学者が研究対象の文化を検証し、記述し、定義するものと なりました[9][10] 基礎的テキストとして、Orientalismは東洋学、哲学、文学の研究者の間で論争がありました[11][4]。 公の知識人として、サイードはイスラエルとアラブ諸国、特に国民の国益に反して行動するイスラム政権の政治的・文化的政策を公に批判したため、パレスチナ 国民評議会のメンバーとして物議を醸した[12][13]。 サイードは祖国への帰還権を含め、イスラエルのパレスチナ人に平等な政治と人権の確保するパレスチナ国家の設立を提唱している。彼は現状との対立関係を、 「選別し、判断し、批判し、選択することで、選択と代理権を個々の男女に返す」公的知識人の任務と定義した。 1999年、指揮者ダニエル・バレンボイムと共同で、セビリアを拠点とする西東京ディヴァン管弦楽団を設立した。ピアニストとしても活躍し、バレンボイム との共著に『Parallels and Paradoxes: 2002年、ニューヨークのカーネギーホールで行われた音楽についての対談や公開討論をまとめた『Parallels and Paradoxes: Explorations in Music and Society』(邦訳『音楽と社会の探求』)をバレンボイムと共著で出版した[14]。 ※エドワード・サイードと妹のローズマリー・サイード(1940年)。 |

| Early life Edward Wadie Said was born on 1 November 1935,[15] to Hilda Said and Wadie Said, a businessman in Jerusalem, then part of the British mandate of Palestine (1920–1948).[16] Wadie Said was a Palestinian who joined the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I. This war-time military service earned American citizenship for Said's father and his family. Edward's mother Hilda Said was of Palestinian and Lebanese parentage, born and raised in Nazareth, Ottoman Empire.[17][18][19] In 1919, in partnership with a cousin, Wadie Said established a stationery business in Cairo. Like her husband, Hilda Said was an Arab Christian, and the Said family practiced Protestantism.[20][21] Edward and his sister Rosemarie Saïd Zahlan (1937–2006) both pursued academic careers. He became an agnostic in his later years.[22][23][24][25][26] Education Said lived his boyhood between the worlds of Cairo and Jerusalem; in 1947, he attended St. George's School, Jerusalem, a British-style school whose teaching staff consisted of stern Anglicans. About being there, Said said: With an unexceptionally Arab family name like "Saïd", connected to an improbably British first name...I was an uncomfortably anomalous student all through my early years: a Palestinian going to school in Egypt, with an English first name, an American passport, and no certain identity, at all. To make matters worse, Arabic, my native language, and English, my school language, were inextricably mixed: I have never known which was my first language, and have felt fully at home in neither, although I dream in both. Every time I speak an English sentence, I find myself echoing it in Arabic, and vice versa. — Between Worlds, Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (2002) pp. 556–57[27] By the late 1940s, Said's schooling included the Egyptian branch of Victoria College, where "classmates included Hussein of Jordan, and the Egyptian, Syrian, Jordanian, and Saudi Arabian boys whose academic careers would progress to their becoming ministers, prime ministers, and leading businessmen in their respective countries."[28] During the period of Palestinian history under the British mandate, the function of a European-style school such as the Victoria College was to educate selections of young men from the Arab and Levantine upper classes to become anglicized post-colonial politicians who would administer their countries upon decolonization. About Victoria College, Said said: The moment one became a student at Victoria College, one was given the student handbook, a series of regulations governing every aspect of school life—the kind of uniform we were to wear, what equipment was needed for sports, the dates of school holidays, bus schedules, and so on. But the school's first rule, emblazoned on the opening page of the handbook, read: "English is the language of the school; students caught speaking any other language will be punished." Yet, there were no native speakers of English among the students. Whereas the masters were all British, we were a motley crew of Arabs of various kinds, Armenians, Greeks, Italians, Jews, and Turks, each of whom had a native language that the school had explicitly outlawed. Yet all, or nearly all, of us spoke Arabic—many spoke Arabic and French—and so we were able to take refuge in a common language, in defiance of what we perceived as an unjust colonial structure. In 1951, Victoria College expelled Said, who had proved a troublesome boy, despite his academic achievements. He then attended Northfield Mount Hermon School, Massachusetts, a socially élite, college-prep boarding-school where he lived a difficult year of social alienation. Nonetheless, he excelled academically, and achieved the rank of either first (valedictorian) or second (salutatorian) in a class of one hundred sixty students.[27] In retrospect, being sent far from the Middle East he viewed as a parental decision much influenced by "the prospects of deracinated people, like us the Palestinians, being so uncertain that it would be best to send me as far away as possible."[27] The realities of peripatetic life—of interwoven cultures, of feeling out of place, and of homesickness—so affected the schoolboy Edward that themes of dissonance feature in the work and worldview of the academic Said.[27] At school's end, he had become Edward W. Said—a polyglot intellectual (fluent in English, French, and Arabic). He graduated with an A.B. in English from Princeton University in 1957 after completing a senior thesis titled "The Moral Vision: André Gide and Graham Greene."[30] He later received Master of Arts (1960) and Doctor of Philosophy (1964) degrees in English Literature from Harvard University.[31][32] |

生い立ち エドワード・ワディ・サイードは1935年11月1日、当時イギリスのパレスチナ委任統治領(1920-1948)であったエルサレムの実業家ワディ・サ イードとヒルダ・サイードの間に生まれた[15]。エドワードの母ヒルダ・サイードは、パレスチナ人とレバノン人の両親を持ち、オスマン帝国のナザレで生 まれ育った[17][18][19]。 1919年、ワディ・サイードは従兄弟と共同でカイロに文房具屋を設立した。ヒルダ・サイードは夫と同じくアラブ系キリスト教徒であり、サイード家はプロ テスタントを実践していた[20][21]。 エドワードと姉のローズマリー・サイード・ザーラン(1937-2006)は共に学問の道を歩んだ。晩年は不可知論者となった[22][23][24] [25][26]。 教育 1947年、彼はエルサレムのセント・ジョージズ・スクールに入学した。この学校は英国式の学校で、教師は厳格な英国国教会の信者だった。そこでサイード はこう語った。 エジプトで学校に通うパレスティナ人で、英語のファーストネーム、アメリカのパスポートを持ち、アイデンティティが確立されていないのです。さらに悪いこ とに、私の母国語であるアラビア語と、学校で使う英語は、表裏一体で混ざり合っていた。どちらが自分の母語なのか分からないし、どちらにも馴染めなかった が、どちらの言語でも夢を見る。英語の文章を話すたびに、それをアラビア語で話している自分に気づき、またその逆もしかりである。 - Between Worlds, Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (2002) pp.556-57[27]。 1940年代後半までにサイードの学校教育にはヴィクトリア・カレッジのエジプト分校が含まれており、「クラスメートにはヨルダンのフセインや、学問的 キャリアを経てそれぞれの国で大臣や首相、主要な実業家となるエジプト、シリア、ヨルダン、サウジアラビアの少年たちがいた」[28][28]。 イギリスの委任統治下にあったパレスチナの歴史の期間において、ヴィクトリア・カレッジのようなヨーロッパ式の学校の機能は、アラブとレバンテの上流階級 から選ばれた若者を、脱植民地化の際に自国を統治する、英国式のポストコロニアルの政治家にするために教育することであった。ヴィクトリア・カレッジにつ いて、サイードはこう語っている。 制服の種類、スポーツの道具、休みの日、バスの時刻表など、学校生活のあらゆる面を規定したものである。しかし、この学校の最初の規則は、ハンドブックの 最初のページにこう書かれていた。「英語は学校の言葉であり、それ以外の言葉を話している生徒は罰せられる」。しかし、生徒の中に英語を母国語とする者は いない。校長先生たちは全員イギリス人だが、私たちはアラブ人、アルメニア人、ギリシャ人、イタリア人、ユダヤ人、トルコ人などさまざまな人種の混成で、 それぞれが学校が明確に禁止している母国語を持っていた。しかし、私たちは全員、あるいはほとんど全員がアラビア語を話し、多くはアラビア語とフランス語 を話していたため、不当な植民地支配と思われる構造に反抗し、共通の言語に避難することができた。 1951年、ビクトリア・カレッジはサイードを退学処分にした。彼は、学業優秀であったにもかかわらず、問題児であることが判明した。その後、マサチュー セッツ州のノースフィールド・マウントハーモン・スクールという社会的にエリートな大学進学準備のための寄宿舎に入り、社会から疎外された辛い1年間を過 ごす。それでも彼は学業に優れ、160人のクラスで1位(卒業生総代)または2位(卒業生総代)の地位を得た[27]。 振り返ってみると、中東から遠く離れた場所に送られたことを、彼は「私たちパレスチナ人のような脱落した人々の将来は不確かなので、できるだけ遠くへ送っ た方がいい」という親の判断に大きく影響されたと考えている。 「そのため、学究的なサイードの作品や世界観に不協和音のテーマが登場することになる[27]。1957年にプリンストン大学で英語の学士号を取得し、 「道徳的ビジョン」と題する卒業論文を完成させた。その後、ハーバード大学で英文学の修士号(1960年)、哲学博士号(1964年)を取得した[31] [32]。 |

| Career In 1963, Said joined Columbia University as a member of the English and Comparative Literature faculties, where he taught and worked until 2003. In 1974, he was Visiting Professor of Comparative Literature at Harvard; during the 1975–76 period, he was a Fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in Behavioral Science, at Stanford University. In 1977, he became the Parr Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, and subsequently was the Old Dominion Foundation Professor in the Humanities; and in 1979 was Visiting Professor of Humanities at Johns Hopkins University.[33] Said also worked as a visiting professor at Yale University, and lectured at more than 200 other universities in North America, Europe, and the Middle East.[34][35] In 1992, Said was promoted to full professor.[36] Editorially, Said served as president of the Modern Language Association, as editor of the Arab Studies Quarterly in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, on the executive board of International PEN, and was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Royal Society of Literature, the Council of Foreign Relations,[33] and the American Philosophical Society.[37] In 1993, Said presented the BBC's annual Reith Lectures, a six-lecture series titled Representation of the Intellectual, wherein he examined the role of the public intellectual in contemporary society, which the BBC published in 2011.[38] In his work, Said frequently researches the term and concept of the cultural archive, especially in his book Culture and Imperialism (1993). He states the cultural archive is a major site where investments in imperial conquest are developed, and that these archives include "narratives, histories, and travel tales."[39] Said emphasizes the role of the Western imperial project in the disruption of cultural archives, and theorizes that disciplines such as comparative literature, English, and anthropology can be directly linked to the concept of empi |

経歴 1963年、コロンビア大学の英語・比較文学科に入学し、2003年まで教鞭をとる。1974年ハーバード大学比較文学客員教授、1975-76年スタン フォード大学行動科学高等研究センター研究員。1977年にはコロンビア大学のパー教授(英語・比較文学)となり、その後オールドドミニオン財団教授(人 文科学)、1979年にはジョンズ・ホプキンス大学客員教授(人文科学)となった[33]。 またエール大学の客員教授、北米、ヨーロッパ、中東の200以上の大学で講義を行った[34][35]。 編集者としては、現代言語学会の会長、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミーにおけるアラブ研究誌の編集者、国際ペンの執行委員、アメリカ芸術文学アカデミー、英国 文学会、外交問題評議会、アメリカ哲学協会のメンバーであった[33]。 [1993年、サイードはBBCの年次リース講義を行い、現代社会における公的知識人の役割を検討した『知識人の表象』と題する6つの講義シリーズを行 い、BBCは2011年にこれを出版した[37]。 サイードはその仕事の中で、特に『文化と帝国主義』(1993年)という本の中で、文化的アーカイブという用語と概念について頻繁に研究している。彼は文 化的アーカイブが帝国征服への投資が展開される主要な場であり、これらのアーカイブには「物語、歴史、旅行物語」が含まれると述べている[39]。サイー ドは文化的アーカイブの崩壊における西洋帝国プロジェクトの役割を強調し、比較文学、英語、人類学などの分野が直接エンピの概念に結びつくことができると 理論付けている[40]。 |

| Literary production Said's first published book, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography (1966), was an expansion of the doctoral dissertation he presented to earn the PhD degree. Abdirahman Hussein said in Edward Saïd: Criticism and Society (2010), that Conrad's novella Heart of Darkness (1899) was "foundational to Said's entire career and project".[40][41] In Beginnings: Intention and Method (1974), Said analyzed the theoretical bases of literary criticism by drawing on the insights of Vico, Valéry, Nietzsche, de Saussure, Lévi-Strauss, Husserl, and Foucault.[42] Said's later works included The World, the Text, and the Critic (1983), Nationalism, Colonialism, and Literature: Yeats and Decolonization (1988), Culture and Imperialism (1993), Representations of the Intellectual: The 1993 Reith Lectures (1994), Humanism and Democratic Criticism (2004), and On Late Style (2006). |

文学作品 サイードが最初に出版した『ジョセフ・コンラッドと自伝のフィクション』(1966年)は、博士号を取得するために提出した博士論文を発展させたもので あった。アブディラフマン・フセインは、Edward Saïd: Criticism and Society (2010)で、コンラッドの小説『闇の奥』(1899)は「サイードの全キャリアとプロジェクトの基礎となった」と述べています[40][41] Beginnings.で、コンラッドの小説『闇の奥』は「サイードの全キャリアとプロジェクトの基礎となった」と述べています。Intention and Method」(1974年)では、ヴィーコ、ヴァレリー、ニーチェ、ド・ソシュール、レヴィ=ストロース、フッサール、フーコーの洞察に基づいて文学批 評の理論基盤を分析しています[42]。 世界、テクスト、批評家(1983年)。 ナショナリズム、植民地主義、そして文学。イェイツと脱植民地化』(1988年)。 文化と帝国主義』(1993年)。 Representations of the Intellectual: The 1993 Reith Lectures (1994)など。 ヒューマニズムと民主主義批評』(2004年)、『晩年のスタイル』(2006年)。 On Late Style (2006)がある。 |

| Orientalism Said became an established cultural critic with the book Orientalism (1978), a critique of Orientalism as the source of the false cultural representations with which the Western world perceives the Middle East—the narratives of how The West sees The East. The thesis of Orientalism proposes the existence of a "subtle and persistent Eurocentric prejudice against Arabo–Islamic peoples and their culture",[43] which originates from Western culture's long tradition of false, romanticized images of Asia, in general, and the Middle East in particular. Such cultural representations have served, and continue to serve, as implicit justifications for the colonial and imperial ambitions of the European powers and of the U.S. Likewise, Said denounced the political and the cultural malpractices of the régimes of the ruling Arab élites who have internalized the false and romanticized representations of Arabic culture that were created by Anglo–American Orientalists.[43] This painting shows the back side of a naked man standing with a snake wrapped around his waist and shoulders. The man is lifting up the head of the snake with his left hand. Another man to his right is sitting on the ground playing a pipe. A group of 10 men are sitting on the floor facing the snake handler with their backs against an ornate blue mosaic wall decorated with Arabic calligraphy. So far as the United States seems to be concerned, it is only a slight overstatement to say that Moslems and Arabs are essentially seen as either oil suppliers or potential terrorists. Very little of the detail, the human density, the passion of Arab–Moslem life has entered the awareness of even those people whose profession it is to report the Arab world. What we have, instead, is a series of crude, essentialized caricatures of the Islamic world, presented in such a way as to make that world vulnerable to military aggression. [44] Orientalism proposed that much Western study of Islamic civilization was political intellectualism, meant for the self-affirmation of European identity, rather than objective academic study; thus, the academic field of Oriental studies functioned as a practical method of cultural discrimination and imperialist domination—that is to say, the Western Orientalist knows more about "the Orient" than do "the Orientals".[43][45]: 12 According to Said, the cultural representations of the Eastern world that Orientalism purveys are intellectually suspect, and cannot be accepted as faithful, true, and accurate representations of the peoples and things of the Orient. Moreover, the history of European colonial rule and political domination of Asian civilizations distorts the writing of even the most knowledgeable, well-meaning, and culturally sympathetic Orientalist. I doubt if it is controversial, for example, to say that an Englishman in India, or Egypt, in the later nineteenth century, took an interest in those countries, which was never far from their status, in his mind, as British colonies. To say this may seem quite different from saying that all academic knowledge about India and Egypt is somehow tinged and impressed with, violated by, the gross political fact—and yet that is what I am saying in this study of Orientalism. — Introduction, Orientalism, p. 11.[45]: 11 Western Art, Orientalism continues, has misrepresented the Orient with stereotypes since Antiquity, as in the tragedy The Persians (472 BCE), by Aeschylus, where the Greek protagonist falls because he misperceived the true nature of The Orient.[45]: 56–57 The European political domination of Asia has biased even the most outwardly objective Western texts about The Orient, to a degree unrecognized by the Western scholars who appropriated for themselves the production of cultural knowledge—the academic work of studying, exploring, and interpreting the languages, histories, and peoples of Asia. Therefore, Orientalist scholarship implies that the colonial subaltern (the colonised people) were incapable of thinking, acting, or speaking for themselves, thus are incapable of writing their own national histories. In such imperial circumstances, the Orientalist scholars of the West wrote the history of the Orient—and so constructed the modern, cultural identities of Asia—from the perspective that the West is the cultural standard to emulate, the norm from which the "exotic and inscrutable" Orientals deviate.[45]: 38–41 |

オリエンタリズム サイードは、西洋世界が中東を認識する際の誤った文化的表象、すなわち西洋が東洋をどのように見ているかの物語の源泉としてのオリエンタリズムを批判した 『オリエンタリズム』(1978年)で、文化評論家として確立されました。オリエンタリズムの論旨は、「アラブ・イスラムの人々とその文化に対する微妙で 根強いヨーロッパ中心主義の偏見」[43]の存在を提案し、それは西洋文化によるアジア全般、特に中東に対する誤った、ロマンチックなイメージの長い伝統 に由来しているとしています。同様にサイードは、英米のオリエンタリストによって作られたアラビア文化の誤ったロマンティックな表現を内面化したアラブの 支配的エリートの政権の政治的・文化的不正行為を非難している[43]。 この絵は、腰と肩に蛇を巻きつけて立っている裸の男の後ろ姿を描いている。男は左手で蛇の頭を持ち上げている。その右側にいる別の男は、地面に座ってパイ プを吹いている。10人ほどの男たちが、アラビア文字で装飾された青いモザイクの壁に背を向けて、蛇使いに向かって床に座っています。 米国が考える限り、モスレムやアラブ人は基本的に石油の供給者か潜在的なテロリストのどちらかと見ていると言っても、少し言い過ぎではないだろうか。アラ ブ・モスリムの生活の細部、人間的な密度、情熱は、アラブ世界の報道を職業とする人々でさえ、ほとんど意識に上ってきていない。その代わりに私たちが手に するのは、イスラム世界の粗雑で本質的な戯画の数々であり、この世界を軍事的侵略に対して脆弱にするような形で提示されている。 [44] オリエンタリズムは、西洋のイスラム文明研究の多くが、客観的な学術研究ではなく、ヨーロッパのアイデンティティの自己確認のための政治的な知識主義であ り、したがって、東洋学という学術分野は、文化差別と帝国主義的支配の実践的方法として機能する、すなわち、西洋のオリエンタリストは「東洋人」よりも 「東洋」についてよく知っているのだ、と提起したのである[43][45]。 12 サイードによれば、オリエンタリズムが提供する東洋世界の文化的表象は知的に疑わしいものであり、東洋の人々や物事を忠実に、真実に、正確に表現したもの として受け入れられることはない。さらに、ヨーロッパによるアジア文明の植民地支配と政治的支配の歴史は、最も知識豊富で善意ある、文化的に共感できるオ リエンタリストの著作を歪めてしまうのである。 例えば、19世紀後半にインドやエジプトにいたイギリス人が、それらの国に関心を持ったと言うことは、彼の心の中では、イギリスの植民地としての地位から 決して離れてはいなかったと言うことは、議論の余地があるのかどうか疑問である。このように言うことは、インドやエジプトに関するすべての学問的知識が、 重大な政治的事実によって侵され、何らかの影響を受けていると言うこととは全く異なるように思われるかもしれません。 - 序章、『オリエンタリズム』、11頁[45]。 11 西洋の芸術は、古代以来、ステレオタイプによってオリエントを誤って表現してきた。例えば、アイスキュロスの悲劇『ペルシャ人』(前472年)では、ギリ シャ人の主人公がオリエントの本質を誤って認識したために倒れる場面がある[45]。 56-57 ヨーロッパのアジアに対する政治的支配は、オリエントに関する最も外見上客観的な西洋のテキストでさえも、文化的知識の生産-アジアの言語、歴史、民族を 研究し、探求し、解釈するという学術作業-を自らのために占有した西洋の学者には認識されない程度に偏りを持たせているのである。したがって、オリエンタ リズムの学問は、植民地のサバルタン(被植民者)が自分自身で考え、行動し、話すことができず、したがって自分自身の国の歴史を書くことができないことを 暗示しているのである。このような帝国的状況において、西洋のオリエンタリズムの学者たちは、西洋が模倣すべき文化的基準であり、「エキゾチックで不可解 な」東洋人が逸脱する規範であるという観点から、東洋の歴史を書き、それによってアジアの近代文化的アイデンティティを構築した[45]: 38-41 |

| Criticism of Orientalism Orientalism provoked much professional and personal criticism for Said among academics.[46] Traditional Orientalists, such as Albert Hourani, Robert Graham Irwin, Nikki Keddie, Bernard Lewis, and Kanan Makiya, suffered negative consequences, because Orientalism affected public perception of their intellectual integrity and the quality of their Orientalist scholarship.[47][48][50] The historian Keddie said that Said's critical work about the field of Orientalism had caused, in their academic disciplines: Some unfortunate consequences ... I think that there has been a tendency in the Middle East [studies] field to adopt the word Orientalism as a generalized swear-word, essentially referring to people who take the "wrong" position on the Arab–Israeli dispute, or to people who are judged "too conservative." It has nothing to do with whether they are good or not good in their disciplines. So, Orientalism, for many people, is a word that substitutes for thought, and enables people to dismiss certain scholars and their works. I think that is too bad. It may not have been what Edward Saïd meant, at all, but the term has become a kind of slogan. — Approaches to the History of the Middle East (1994), pp. 144–45.[51] In Orientalism, Said described Bernard Lewis, the Anglo–American Orientalist, as "a perfect exemplification [of an] Establishment Orientalist [whose work] purports to be objective, liberal scholarship, but is, in reality, very close to being propaganda against his subject material."[45]: 315 Lewis responded with a harsh critique of Orientalism accusing Said of politicizing the scientific study of the Middle East (and Arabic studies in particular); neglecting to critique the scholarly findings of the Orientalists; and giving "free rein" to his biases.[52] Said retorted that in The Muslim Discovery of Europe (1982), Lewis responded to his thesis with the claim that the Western quest for knowledge about other societies was unique in its display of disinterested curiosity, which Muslims did not reciprocate towards Europe. Lewis was saying that "knowledge about Europe [was] the only acceptable criterion for true knowledge." The appearance of academic impartiality was part of Lewis's role as an academic authority for zealous "anti–Islamic, anti–Arab, Zionist, and Cold War crusades."[45]: 315 [53] Moreover, in the Afterword to the 1995 edition of the book, Said replied to Lewis's criticisms of the first edition of Orientalism (1978).[53][45]: 329–54 |

オリエンタリズムへの批判 オリエンタリズムは、学者の間でサイードに対する多くの専門的・個人的批判を引き起こした[46]。アルベルト・ホーラーニ、ロバート・グラハム・アー ウィン、ニッキー・ケディー、バーナード・ルイス、カナン・マキヤといった伝統的なオリエンタリストは、彼らの知的誠実さや東洋学研究の質に対する社会の 認識に影響を与えたため、負の影響を受けた。 47][48][50] 歴史家のケディーは、東洋学分野に対するサイードの批判の仕事は彼らの学問分野に引き起こしたと語っている。 いくつかの不幸な結果...。中東(研究)分野では、オリエンタリズムという言葉を一般的な悪口として採用する傾向があるように思う。それは本質的に、ア ラブ・イスラエル紛争について「間違った」立場をとる人々、あるいは「保守的すぎる」と判断される人々を指す。それは、彼らが自分の専門分野で優秀かそう でないかということとは関係がない。だから、オリエンタリズムというのは、多くの人にとって、思想に代わる言葉であり、特定の学者やその作品を否定するこ とを可能にするものなのです。それはあまりにひどいと思う。エドワード・サイードが言いたかったことは全然違うかもしれないのに、この言葉は一種のスロー ガンになってしまっているのです。 - 中東史へのアプローチ』(1994年)、144-45頁[51]。 サイードは『オリエンタリズム』の中で英米のオリエンタリストであるバーナード・ルイスを「客観的で自由な学問であると称しているが、現実には彼の対象物 に対するプロパガンダに極めて近いエスタブリッシュメント・オリエンタリスト(の完璧な例)」であると述べている[45]。 315 ルイスはオリエンタリズムに対して厳しい批判を行い、サイードが中東(特にアラビア語研究)の科学的研究を政治化し、オリエンタリストの学術的知見を批判 することを怠り、自分の偏見に「自由裁量」を与えていると非難している[52]。 サイードは、The Muslim Discovery of Europe (1982)において、ルイスは彼の論文に対して、他の社会についての知識を求める西洋の探求は無関心な好奇心を示す点でユニークであり、ムスリムはヨー ロッパに対してそれに応えなかったと反論している。ルイスは、"ヨーロッパに関する知識は(中略)真の知識として唯一受け入れられる基準であった "と言っていたのである。学問的な公平性の外観は、熱心な「反イスラム、反アラブ、シオニスト、冷戦十字軍」のための学問的権威としてのルイスの役割の一 部であった[45]。 315 [53] さらに、サイードは1995年版のあとがきで、ルイスの『オリエンタリズム』初版(1978年)に対する批判に答えている[53][45]。 329- 54 |

| Influence of Orientalism In the academy, Orientalism became a foundational text of the field of post-colonial studies, for what the British intellectual Terry Eagleton said is the book's "central truth ... that demeaning images of the East, and imperialist incursions into its terrain, have historically gone hand in hand."[54] Both Said's supporters and his critics acknowledge the transformative influence of Orientalism upon scholarship in the humanities; critics say that the thesis is an intellectually limiting influence upon scholars, whilst supporters say that the thesis is intellectually liberating.[55][56] The fields of post-colonial and cultural studies attempt to explain the "post-colonial world, its peoples, and their discontents",[3][57] for which the techniques of investigation and efficacy in Orientalism, proved especially applicable in Middle Eastern studies.[9] As such, the investigation and analysis Said applied in Orientalism proved especially practical in literary criticism and cultural studies,[9] such as the post-colonial histories of India by Gyan Prakash,[58] Nicholas Dirks[59] and Ronald Inden,[60] modern Cambodia by Simon Springer,[61] and the literary theories of Homi K. Bhabha,[62] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak[63] and Hamid Dabashi (Iran: A People Interrupted, 2007). In Eastern Europe, Milica Bakić–Hayden developed the concept of Nesting Orientalisms (1992), derived from the ideas of the historian Larry Wolff (Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment, 1994) and Said's ideas in Orientalism (1978).[64] The Bulgarian historian Maria Todorova (Imagining the Balkans, 1997) presented the ethnologic concept of Nesting Balkanisms (Ethnologia Balkanica, 1997), which is derived from Milica Bakić–Hayden's concept of Nesting Orientalisms.[65] In The Impact of "Biblical Orientalism" in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (2014), the historian Lorenzo Kamel, presented the concept of "Biblical Orientalism" with an historical analysis of the simplifications of the complex, local Palestinian reality, which occurred from the 1830s until the early 20th century.[66] Kamel said that the selective usage and simplification of religion, in approaching the place known as "The Holy Land", created a view that, as a place, the Holy Land has no human history other than as the place where Bible stories occurred, rather than as Palestine, a country inhabited by many peoples. The post-colonial discourse presented in Orientalism, also influenced post-colonial theology and post-colonial biblical criticism, by which method the analytical reader approaches a scripture from the perspective of a colonial reader. See: The Bible and Zionism: Invented Traditions, Archaeology and Post-colonialism in Palestine–Israel (2007).[67] Another book in this area is Postcolonial Theory (1998), by Leela Gandhi, explains Post-colonialism in terms of how it can be applied to the wider philosophical and intellectual context of history.[68] |

オリエンタリズムの影響力 アカデミーにおいて、オリエンタリズムはポストコロニアル研究の分野の基礎となるテキストとなり、イギリスの知識人であるTerry Eagletonがこの本の「東洋に対する卑屈なイメージとその領域への帝国主義の侵略が歴史的に手を取り合ってきたという...中心的真実」であるとし ている[54]。 サイードの支持者と批判者の両方が人文科学における学問に対するオリエンタリズムの変革的影響を認めており、批判者はその論文が学者に対して知的に制限す る影響であると言い、支持者はその論文が知的に解放的であると言っている[55][56]。ポスト・コロニアル研究やカルチュラル・スタディーズの分野は 「ポスト・コロニアルの世界、その人々、その不満」について説明しようとし、そのためにオリエンタリズムにおける調査と効果の技法を特に中東研究で適用で きることが証明された[3][57]。 このようにサイードがオリエンタリズムにおいて適用した調査と分析は、ギャン・プラカシュ[58]、ニコラス・ダークス[59]、ロナルド・インデンによ るインドのポストコロニアル史[60]、サイモン・スプリンガーによる近代カンボジア、そしてホミ・カバハ[62]、ガヤトリー・チャクラヴォルティ・ス ピヴァク[63]、ハミド・ダバシの文学理論(Iran: A People Interrupted, 2007)など文学批判や文化研究にとりわけ実践可能であったと言える[9]。 東欧では、ミリカ・バキッチ=ヘイデンが歴史家ラリー・ウォルフの考えから派生した「入れ子のオリエンタリズム」(1992)の概念を構築した (Inventing Eastern Europe: 64] ブルガリアの歴史家であるマリア・トドロヴァは(Imagining the Balkans, 1997)、ミリカ・バキッチ=ヘイデンの入れ子型オリエンタリズムの概念から派生した入れ子型バルカニズム(Ethnologia Balkanica, 1997)という民族学の概念を提示している[65]。 19世紀後半から20世紀初頭のパレスチナにおける「聖書的オリエンタリズム」の影響(2014年)において、歴史家のロレンゾ・カメルは、1830年代 から20世紀初頭まで起こった複雑でローカルなパレスチナの現実の単純化の歴史分析によって「聖書的オリエンタリズム」の概念を提示した。 [66] カメルは、「聖地」として知られる場所へのアプローチにおいて、宗教の選択的使用と単純化が、場所として、聖地は多くの民族が住む国であるパレスチナとし てではなく、聖書の物語が起こった場所として以外に人間の歴史を持たないという見方を作り出したと述べた。 オリエンタリズム』で提示されたポストコロニアル言説は、ポストコロニアル神学やポストコロニアル聖書批評にも影響を与え、分析的読者が植民地時代の読者 の視点から聖典にアプローチする手法が取られた。参照。この領域におけるもう一つの本はリーラ・ガンジーによる『ポストコロニアル理論』(1998年)で あり、ポストコロニアリズムを歴史のより広い哲学的・知的文脈にどのように適用することができるのかという観点から説明している[68]。 |

| Politics In 1967, consequent to the Six-Day War (5–10 June 1967), Said became a public intellectual when he acted politically to counter the stereotyped misrepresentations (factual, historical, cultural) with which the U.S. news media explained the Arab–Israeli wars; reportage divorced from the historical realities of the Middle East, in general, and Palestine and Israel, in particular. To address, explain, and correct such Orientalism, Said published "The Arab Portrayed" (1968), a descriptive essay about images of "the Arab" that are meant to evade specific discussion of the historical and cultural realities of the peoples (Jews, Christians, Muslims) who are the Middle East, featured in journalism (print, photograph, television) and some types of scholarship (specialist journals).[69] In the essay "Zionism from the Standpoint of its Victims" (1979), Said argued in favour of the political legitimacy and philosophic authenticity of the Zionist claims and right to a Jewish homeland; and for the inherent right of national self-determination of the Palestinian people.[70] Said's books about Israel and Palestine include The Question of Palestine (1979), The Politics of Dispossession (1994), and The End of the Peace Process (2000). |

政治問題 1967年、六日間戦争(1967年6月5日~10日)の結果、サイードは、米国の報道機関がアラブ・イスラエル戦争を説明する際に用いたステレオタイプ な誤報(事実、歴史、文化)、特に中東、パレスチナとイスラエルの歴史的現実から切り離された報道に対して政治的行動を起こし、公的知識人となった。この ようなオリエンタリズムに対処し、説明し、修正するために、サイードは「描かれたアラブ」(1968年)を発表し、ジャーナリズム(印刷、写真、テレビ) やある種の学問(専門誌)で取り上げられる、中東の人々(ユダヤ人、キリスト教徒、ムスリム)の歴史的・文化的現実の具体的議論を回避しようとする「アラ ブ」のイメージについての記述的エッセイであった[69]。 サイードは「犠牲者の立場からのシオニズム」(1979年)という論文で、シオニストの主張とユダヤ人の故郷への権利の政治的正当性と哲学的信憑性を支持 し、パレスチナ人の民族自決の固有の権利を主張した[70]。イスラエルとパレスチナに関するサイードの著書には『パレスチナ問題』(1979)、『占有 権の政治』(1994)、『平和プロセスの終わり』(2000)などがある。 |

| Palestinian National Council From 1977 until 1991, Said was an independent member of the Palestinian National Council (PNC).[71] In 1988, he was a proponent of the two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and voted for the establishment of the State of Palestine at a meeting of the PNC in Algiers. In 1993, Said quit his membership in the Palestinian National Council, to protest the internal politics that led to the signing of the Oslo Accords (Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, 1993), which he thought had unacceptable terms, and because the terms had been rejected by the Madrid Conference of 1991. Said disliked the Oslo Accords for not producing an independent State of Palestine, and because they were politically inferior to a plan that Yasir Arafat had rejected—a plan Said had presented to Arafat on behalf of the U.S. government in the late 1970s.[72] Especially troublesome to Said was his belief that Yasir Arafat had betrayed the right of return of the Palestinian refugees to their houses and properties in the Green Line territories of pre-1967 Israel, and that Arafat ignored the growing political threat of the Israeli settlements in the occupied territories that had been established since the conquest of Palestine in 1967. In 1995, in response to Said's political criticisms, the Palestinian Authority (PA) banned the sale of Said's books; however, the PA lifted the book ban when Said publicly praised Yasir Arafat for rejecting Prime Minister Ehud Barak's offers at the Middle East Peace Summit at Camp David (2000) in the U.S.[73][74] In the mid-1990s, Said wrote the foreword to the history book Jewish History, Jewish Religion: The Weight of Three Thousand Years (1994), by Israel Shahak, about Jewish fundamentalism, which presents the cultural proposition that Israel's mistreatment of the Palestinians is rooted in a Judaic requirement (of permission) for Jews to commit crimes, including murder, against Gentiles (non-Jews). In his foreword, Said said that Jewish History, Jewish Religion is "nothing less than a concise history of classic and modern Judaism, insofar as these are relevant to the understanding of modern Israel"; and praised the historian Shahak for describing contemporary Israel as a nation subsumed in a "Judeo–Nazi" cultural ambiance that allowed the dehumanization of the Palestinian Other:[75] In all my works, I remained fundamentally critical of a gloating and uncritical nationalism. . . . My view of Palestine . . . remains the same today: I expressed all sorts of reservations about the insouciant nativism, and militant militarism of the nationalist consensus; I suggested, instead, a critical look at the Arab environment, Palestinian history, and the Israeli realities, with the explicit conclusion that only a negotiated settlement, between the two communities of suffering, Arab and Jewish, would provide respite from the unending war.[76] In 1998, Said made In Search of Palestine (1998), a BBC documentary film about Palestine, past and present. In the company of his son, Wadie, Said revisited the places of his boyhood, and confronted injustices meted out to ordinary Palestinians in the contemporary West Bank. Despite the social and cultural prestige afforded to BBC cinema products in the U.S., the documentary was never broadcast by any American television company.[77][78] In 1999, the American Jewish public affairs monthly Commentary cited ledgers kept at the Land Registry Office in Jerusalem during the Mandatory period as background for his boyhood recollections, claiming that his "Palestinian boyhood" was, in fact, no more than occasional visits from Cairo, where his parents lived, owned a business and raised their family.[79] |

パレスチナ国民評議会 1977年から1991年まで、サイードはパレスチナ国民評議会(PNC)の独立メンバーであった[71]。1988年、彼はイスラエル・パレスチナ紛争 の2国家解決策の支持者であり、アルジェでのPNCの会議でパレスチナ国家の設立に賛成票を投じている。1993年、サイードはパレスチナ国民評議会のメ ンバーを辞めた。オスロ合意(暫定自治協定に関する原則の宣言、1993年)の調印に至る内部政治に抗議し、その条件が1991年のマドリード会議で拒否 されたためである。 サイードはオスロ合意を、独立したパレスチナ国家を生み出さないこと、そしてヤシル・アラファトが拒否した計画(サイードが1970年代後半にアメリカ政 府に代わってアラファトに提示した計画)に政治的に劣ることから嫌った。 [特にサイードが問題視していたのは、アラファトがパレスチナ難民の1967年以前のグリーンラインにおける帰還の権利を裏切り、1967年のパレスチナ 征服以来、占領地におけるイスラエルの入植地が政治的脅威となっていることをアラファトが無視したということであった。 1995年、サイードの政治批判に呼応して、パレスチナ自治政府(PA)はサイードの書籍の販売を禁止したが、サイードがアメリカのキャンプ・デイビッド (2000年)での中東和平サミットでエフード・バラク首相の申し出を拒否したヤシル・アラファトを公に賞賛するとPAは書籍禁止を解いた[73] [74]。 1990年代半ば、サイードは歴史書『ユダヤの歴史、ユダヤの宗教』の序文を書いている。イスラエル・シャハクによるユダヤ原理主義についての『三千年の 重み』(1994年)は、イスラエルのパレスチナ人に対する虐待は、ユダヤ人が異邦人(非ユダヤ人)に対して殺人を含む犯罪を行うためのユダヤ教の要求 (許可)に根ざしているという文化的命題を提示している。サイードは序文で、ユダヤ人の歴史、ユダヤ人の宗教は「現代イスラエルの理解に関連する限りにお いて、古典的なユダヤ教と現代ユダヤ教の簡潔な歴史に他ならない」と述べ、歴史家のシャハクが現代イスラエルをパレスチナ人の他者の非人間化を許す「ユダ ヤ・ナチ」文化の雰囲気に包まれた国家として描写していることを賞賛している[75]。 すべての著作において、私はほくそ笑むような無批判なナショナリズムに対して根本的に批判的であり続けた。. . . 私のパレスチナに対する見方は、......今日も変わっていない。その代わりに、アラブの環境、パレスチナの歴史、そしてイスラエルの現実を批判的に見 ることを提案し、アラブとユダヤという苦しみの2つのコミュニティ間の交渉による解決のみが、終わらない戦争からの救済を提供するだろうという明確な結論 を出した[76]。 1998年、サイードはパレスチナの過去と現在についてのBBCのドキュメンタリー映画『In Search of Palestine』(1998年)を制作した。息子のワディと一緒に、サイードは少年時代を過ごした場所を再訪し、現代のヨルダン川西岸で一般のパレス チナ人が受けている不公平に立ち向かった。1999年、アメリカのユダヤ系広報誌『コメンタリー』は、彼の少年時代の回想の背景として、委任統治時代にエ ルサレムの土地登記所に保管されていた台帳を引用し、彼の「パレスチナ少年時代」は、実際には、彼の両親が住み、事業を営み、家族を育てたカイロから時々 訪れる程度であったと主張している[79]。 |

| In Palestine On 3 July 2000, whilst touring the Middle East with his son, Wadie, Said was photographed throwing a stone across the Blue Line Lebanese–Israel border, which image elicited much political criticism about his action demonstrating an inherent, personal sympathy with terrorism; and, in Commentary magazine, the journalist Edward Alexander labelled Said as "The Professor of Terror", for aggression against Israel.[80] Said explained the stone-throwing as a two-fold action, personal and political; a man-to-man contest-of-skill, between a father and his son, and an Arab man's gesture of joy at the end of the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon (1985–2000): "It was a pebble; there was nobody there. The guardhouse was at least half a mile away."[81] Despite having denied that he aimed the stone at an Israeli guardhouse, the Beirut newspaper As-Safir (The Ambassador) reported that a Lebanese local resident reported that Said was at less than ten metres (ca. 30 ft.) distance from the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) soldiers manning the two-storey guardhouse, when Said aimed and threw the stone over the border fence; the stone's projectile path was thwarted when it struck the barbed wire atop the border fence.[82] Nonetheless, in the U.S., despite a political fracas by students at Columbia University and the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith International (Sons of the Covenant), the university provost published a five-page letter defending Said's action as an academic's freedom of expression: "To my knowledge, the stone was directed at no-one; no law was broken; no indictment was made; no criminal or civil action has been taken against Professor Saïd."[83] Nevertheless, Said endured political repercussions, such as the cancellation of an invitation to give a lecture to the Freud Society, in Austria, in February 2001.[84] The President of the Freud Society justified withdrawing the invitation by explaining to Said that "the political situation in the Middle East, and its consequences" had rendered an accusation of anti-Semitism a very serious matter, and that any such accusation "has become more dangerous" in the politics of Austria; thus, the Freud Society cancelled its invitation to Said in order to "avoid an internal clash" of opinions, about him, that might ideologically divide the Freud Society.[81] In Culture and Resistance: Conversations with Edward Saïd (2003), Said likened his political situation to the situation that Noam Chomsky has endured as a public intellectual: "It's very similar to his. He's a well-known, great linguist. He's been celebrated and honored for that, but he's also vilified as an anti–Semite and as a Hitler worshiper. ... For anyone to deny the horrendous experience of anti–Semitism and the Holocaust is unacceptable. We don't want anybody's history of suffering to go unrecorded and unacknowledged. On the other hand, there's a great difference, between acknowledging Jewish oppression and using that as a cover for the oppression of another people."[85] |

パレスチナにて 2000年7月3日、息子のワディと中東を旅行中、サイードはブルーラインのレバノン-イスラエル国境を越えて石を投げる写真を撮られた。この写真は、彼 の行動がテロに対する先天的で個人的な共感を示しているという多くの政治批判を引き起こし、ジャーナリストのエドワード・アレキサンダーはサイードをイス ラエルに対する侵略のために「テロルの教授」と名づけた[80][90]。 [サイードはこの投石を、個人的な行動と政治的な行動という二つの側面から説明した。父親と息子の間の一対一の技術競争であり、イスラエルによるレバノン 南部の占領(1985-2000)の終結を喜ぶアラブ人のジェスチャーであった。) 「それは小石で、そこには誰もいなかった。守衛所は少なくとも半マイルは離れていた」[81]。 ベイルートの新聞As-Safir (The Ambassador)は、彼がイスラエルの警備隊に石を向けたことを否定したにもかかわらず、レバノンの地元住民がサイードが10メートル未満(約30 フィート)の距離にいたと報告したと報じた。 ベイルートの新聞アス・サフィール(大使)は、レバノンの地元住民が、サイードが2階建ての守衛所にいるイスラエル国防軍(IDF)の兵士から10メート ル(約30フィート)以下の距離にいたときに、サイードは石を狙って国境フェンスを越えて投擲したと報告した; その石の射程は国境フェンスの上にある鉄条網に当たったとき妨げられた[82] それにもかかわらず、アメリカでは、学生による政治的騒動にもかかわらず、そのようなことはなかった, コロンビア大学の学生やB'nai B'rith International (Sons of the Covenant)の反中傷連盟による政治的騒動にもかかわらず、大学の学長はサイードの行動を学者の表現の自由として擁護する5ページの書簡を発表して いる[82]。「私の知る限り、石は誰にも向けられておらず、法律も破られておらず、起訴もされておらず、サイード教授に対して刑事的、民事的措置が取ら れていない」[83]。 それにもかかわらず、サイードは2001年2月にオーストリアのフロイト協会での講演への招待がキャンセルされるなど、政治的な反響に耐えていた [84]。 フロイト協会の会長は、「中東の政治状況とその結果」によって反ユダヤ主義の非難が非常に深刻な問題となり、オーストリアの政治においてそのような非難は 「より危険になっている」とサイードに説明し、招待を取り消すことを正当化した[84]。したがって、フロイト協会は、フロイト協会を思想的に分裂させて しまうかもしれない彼についての意見の「内部衝突を避けるため」にサイードへの招待をキャンセルした[81]。Conversations with Edward Saïd (2003)において、サイードは自身の政治的状況を、ノーム・チョムスキーが公的知識人として耐えてきた状況になぞらえている。 「彼と非常によく似ている。彼は有名な、偉大な言語学者です。彼は有名で偉大な言語学者ですが、反ユダヤ主義者、ヒトラー崇拝者として中傷されることもあ るのです。... 反ユダヤ主義やホロコーストの悲惨な体験を否定するようなことは、誰にとっても許されないことです。私たちは、誰の苦難の歴史も記録されず、認識されない ままであって欲しくありません。一方で、ユダヤ人の抑圧を認めることと、それを他の民族の抑圧の隠れ蓑にすることとは、大きな違いがある」[85]。 |

| Criticism of U.S. foreign policy In the revised edition of Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World (1997), Said criticized the Orientalist bias of the Western news media's reportage about the Middle East and Islam, especially the tendency to editorialize "speculations about the latest conspiracy to blow up buildings, sabotage commercial airliners, and poison water supplies."[86] He criticized the American military involvement in the Kosovo War (1998–99) as an imperial action; and described the Iraq Liberation Act (1998), promulgated during the Clinton Administration, as the political license that predisposed the U.S. to invade Iraq in 2003, which was authorised with the Iraq Resolution (2 October 2002); and the continual support of Israel by successive U.S. presidential governments, as actions meant to perpetuate regional political instability in the Middle East.[14] In the event, despite being sick with leukemia, as a public intellectual, Said continued criticising the U.S. Invasion of Iraq in mid-2003;[87] and, in the Egyptian Al-Ahram Weekly newspaper, in the article "Resources of Hope" (2 April 2003), Said said that the U.S. war against Iraq was a politically ill-conceived military enterprise: My strong opinion, though I don't have any proof, in the classical sense of the word, is that they want to change the entire Middle East, and the Arab world, perhaps terminate some countries, destroy the so-called terrorist groups they dislike, and install régimes friendly to the United States. I think this is a dream that has very little basis in reality. The knowledge they have of the Middle East, to judge from the people who advise them, is, to say the least, out of date and widely speculative. . . . I don't think the planning for the post–Saddam, post-war period in Iraq is very sophisticated, and there's very little of it. U.S. Undersecretary of State Marc Grossman and U.S. Undersecretary of Defense Douglas Feith testified in Congress, about a month ago, and seemed to have no figures, and no ideas [about] what structures they were going to deploy; they had no idea about the use of [the Iraqi] institutions that exist, although they want to de–Ba'thise the higher echelons, and keep the rest. The same is true about their views of the [Iraqi] army. They certainly have no use for the Iraqi opposition that they've been spending many millions of dollars on; and, to the best of my ability to judge, they are going to improvise; of course, the model is Afghanistan. I think they hope that the U.N. will come in and do something, but, given the recent French and Russian positions, I doubt that that will happen with such simplicity.[88] Under surveillance In 2003, Haidar Abdel-Shafi, Ibrahim Dakak, Mustafa Barghouti, and Said established Al-Mubadara (The Palestinian National Initiative), headed by Dr. Mustafa Barghouti, a third-party reformist, democratic party meant to be an alternative to the usual two-party politics of Palestine. As a political party, the ideology of Al-Mubadara is specifically an alternative to the extremist politics of the social-democratic Fatah and the Islamist Hamas. Said's founding of the group, as well as his other international political activities concerning Palestine, were noticed by the U.S. government, and Said came under FBI surveillance, which became more intensive after 1972. David Price, an anthropologist at Evergreen State College, requested the FBI file on Said through the Freedom of Information Act on behalf of CounterPunch and published a report there on his findings.[89] The released pages of Said's FBI files show that the FBI read Said's books and reported on their contents to Washington.[90]: 158 [91] |

米国外交政策への批判 『カバーリング・イスラム』(1997年)の改訂版で サイードは『Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World』(1997年)において、中東とイスラムに関する西側報道機関のオリエンタリズム的偏向、特に「ビルの爆破、民間航空機の破壊工作、水道水の 汚染に関する最新の陰謀の推測」を社説にする傾向を批判している[86]。 「コソボ戦争(1998-99)へのアメリカの軍事介入を帝国的行為と批判し、クリントン政権時代に公布されたイラク解放法(1998)は、アメリカが 2003年にイラクに侵攻し、イラク決議(2002年10月2日)を承認するための政治ライセンスであり、歴代のアメリカ大統領府による継続的なイスラエ ル支援は、中東地域の政治不安を持続させるための行動と評する[14]。 その後、白血病を患いながらも、サイードは知識人として2003年半ばにアメリカのイラク侵攻を批判し続け[87]、エジプトの週刊紙アルアハラムの記事 「希望の資源」(2003年4月2日)で、アメリカのイラク戦争は政治的に誤った軍事事業であると述べている[87]。 私の強い意見は、証拠はないが、古典的な意味で、彼らは中東全体、アラブ世界を変え、おそらくいくつかの国を終わらせ、彼らが嫌ういわゆるテログループを 壊滅させ、米国に友好的な政権を設置したいのだ、ということだ。これは、現実にはほとんど根拠のない夢物語だと思う。彼らが持っている中東の知識は、彼ら に助言する人々から判断すると、控えめに言っても時代遅れで、広く憶測の域を出ない。. . . サダム後の、イラク戦争後の計画はあまり洗練されているとは思えませんし、そのようなものはほとんどないのです。マーク・グロスマン国務次官とダグラス・ ファイス国防次官は、1カ月ほど前に議会で証言しましたが、数字も、どんな構造を展開するのかについての考えもないようでした。 イラク軍に対する見方も同じです。何百万ドルも使っているイラクの反体制派に用はないのは確かです。私が判断できる限りでは、彼らは即興で動くつもりで す。彼らは国連が来て何かをしてくれることを望んでいると思いますが、最近のフランスとロシアの立場を考えると、そんな単純なことが起こるとは思えません [88]。 監視下におかれる 2003年、ハイダル・アブデル・シャフィ、イブラヒム・ダカク、ムスタファ・バルグーティ、サイードの4人は、ムスタファ・バルグーティ博士を代表とし て、パレスチナの通常の二大政党政治に代わる第三の改革派・民主派政党であるアル・ムバダラ(パレスチナ民族イニシアチブ)を設立した。政党としてのア ル・ムバダラの思想は、特に社会民主主義者ファタハとイスラム主義者ハマスの過激な政治に代わるものである。サイードがこの団体を設立したこと、またパレ スチナに関する他の国際的な政治活動を行ったことがアメリカ政府に注目され、サイードはFBIの監視下に置かれ、1972年以降、その監視はより強化され た。エバーグリーン州立大学の人類学者であるデイヴィッド・プライスは、カウンターパンチに代わって情報公開法を通じてサイードに関するFBIのファイル を要求し、そこで彼の発見に関するレポートを発表した[89]。 公開されたサイードのFBIファイルのページは、FBIがサイードの本を読み、その内容についてワシントンに報告していることを示している[90]。 158 [91] |

| Music Besides having been a public intellectual, Edward Said was an accomplished pianist, worked as the music critic for The Nation magazine, and wrote four books about music: Musical Elaborations (1991); Parallels and Paradoxes: Explorations in Music and Society (2002), with Daniel Barenboim as co-author; On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (2006); and Music at the Limits (2007) in which final book he spoke of finding musical reflections of his literary and historical ideas in bold compositions and strong performances.[92][93] Elsewhere in the musical world, the composer Mohammed Fairouz acknowledged the deep influence of Edward Said upon his works; compositionally, Fairouz's First Symphony thematically alludes to the essay "Homage to a Belly-Dancer" (1990), about Tahia Carioca, the Egyptian dancer, actress, and political militant; and a piano sonata, titled Reflections on Exile (1984), which thematically refers to the emotions inherent to being an exile.[94][95][96] In 1999, Said and Barenboim co-founded the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, composed of young Israeli, Palestinian, and Arab musicians. They also established The Barenboim–Said Foundation in Seville, to develop education-through-music projects. Besides managing the West–Eastern Divan Orchestra, the Barenboim–Said Foundation assists with the administration of the Academy of Orchestral Studies, the Musical Education in Palestine Project, and the Early Childhood Musical Education Project, in Seville.[97] |

音楽 エドワード・サイードは、優れたピアニストであると同時に、『ネイション』誌の音楽評論家として活躍し、音楽に関する4冊の著書を残しています。音楽的精 緻化』(1991年)、『パラレルズ・アンド・パラドックス』(2002年、ダニエル・サイードとの共著)。ダニエル・バレンボイムとの共著『音楽と社会 の探究』(2002年)、『On Late Style: というタイトルの本が出版されており、その最後の本で彼は大胆な作曲と強力な演奏の中に彼の文学的・歴史的アイデアの音楽的反映を見出したと語っている [92][93]。 音楽の世界では他に、作曲家のモハメド・フェアウズがエドワード・サイードの作品に深い影響を与えたことを認めている。作曲的には、フェアウズの交響曲第 1番はエジプトのダンサー、女優、政治的過激派のタヒア・カリオカについてのエッセイ「ベリーダンサーへのオマージュ」(1990)を主題的に言及してお り、ピアノソナタは「亡命についての省察」(1984)と題されて、亡命者として固有の感情に主題的に言及している[94][95][96]。 1999年、サイードとバレンボイムは、イスラエル、パレスチナ、アラブの若手音楽家からなる西東京ディヴァンオーケストラを共同設立した。また、セビリ アにバレンボイム・サイード財団を設立し、音楽を通しての教育プロジェクトを展開する。バレンボイム・サイード財団は、ウエスト・イースタン・ディヴァン 管弦楽団の運営のほか、セビリアのオーケストラ研究アカデミー、パレスチナの音楽教育プロジェクト、幼児音楽教育プロジェクトの運営を支援している [97]。 |

| Death and legacy On 24 September 2003, after enduring a 12-year sickness with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Said died, at 67 years of age, in New York City.[12] He was survived by his wife, Mariam C. Said, his son, Wadie Said, and his daughter, Najla Said.[102][103][104] The eulogists included Alexander Cockburn ("A Mighty and Passionate Heart");[105] Seamus Deane ("A Late Style of Humanism");[106] Christopher Hitchens ("A Valediction for Edward Said");[107] Tony Judt ("The Rootless Cosmopolitan");[108] Michael Wood ("On Edward Said");[109] and Tariq Ali ("Remembering Edward Said, 1935–2003").[110] Said is buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Broumana, Jabal Lubnan, Lebanon. His headstone indicates he died on 25 September 2003.[111] In November 2004, in Palestine, Birzeit University renamed their music school the Edward Said National Conservatory of Music.[112] The tributes to Said include books and schools; such as Waiting for the Barbarians: A Tribute to Edward W. Said (2008) features essays by Akeel Bilgrami, Rashid Khalidi, and Elias Khoury;[113][114] Edward Said: The Charisma of Criticism (2010), by Harold Aram Veeser, a critical biography; and Edward Said: A Legacy of Emancipation and Representations (2010), essays by Joseph Massad, Ilan Pappé, Ella Shohat, Ghada Karmi, Noam Chomsky, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, and Daniel Barenboim. The Barenboim–Said Academy (Berlin) was established in 2012. In 2002, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nayhan, the founder and president of the United Arab Emirates, and others endowed the Edward Said Chair at Columbia University; it is currently filled by Rashid Khalidi.[115][116] In 2016, California State University at Fresno started examining applicants for a newly created Professorship in Middle East Studies named after Edward Said, but after months of examining applicants, Fresno State canceled the search. Some observers claim that the cancellation was due to pressure from some individuals and groups.[117] |

死と遺産 2003年9月24日、慢性リンパ性白血病で12年間の闘病生活に耐えた後、ニューヨークで67歳で死去した[12]。妻のマリアム C. サイード、息子のワディ サイード、娘のナジュラ サイードが遺族としている。 [102][103][104] 弔辞はアレクサンダー・コックバーン(「力強く情熱的な心」)、[105] シェイマス・ディーン(「ヒューマニズムの晩年のスタイル」)、[106] クリストファー・ヒッチンス(「エドワード・サイードへの賛辞」)、[107] トニー・ジャド(「根なし草」)、[108] マイケル・ウッド(「エドワード・サイードについて」)[109] そしてタリック・アリー(「アドワード・サイード追悼、1935-2003」)であった。 レバノン、ジャバル・ルブナンのブルーマナのプロテスタント墓地に埋葬されている[110]。墓碑には2003年9月25日に死去したことが記されている [111]。 2004年11月、パレスチナではビルジート大学がその音楽学校をエドワード・サイード国立音楽院と改名した[112]。 サイードへの賛辞として、『野蛮人を待ちながら』(Waiting for the Barbarians)のような書籍や学校がある。サイードへのオマージュとして、書籍や学校がある。サイードへのトリビュート』(2008年)はアキー ル・ビルグラミ、ラシッド・ハリディ、エリアス・クーリーによるエッセイを収録している[113][114]。エドワード・サイード:批判のカリスマ』 (2010年)は、ハロルド・アラム・ヴェーザーによる批判伝、エドワード・サイード:解放の遺産』(2010年)は、ハロルド・アラム・ヴェーザーによ る批判伝、そして、『サイード:批評のカリスマ』は、批評の遺産である。A Legacy of Emancipation and Representations』(2010年)、Joseph Massad、Ilan Pappé、Ella Shohat、Ghada Karmi、Noam Chomsky、Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak、Daniel Barenboimによるエッセイを収録。2012年には、バレンボイム・サイード・アカデミー(ベルリン)が設立された。 2002年、アラブ首長国連邦の創設者兼大統領であるシェイク・ザイード・ビン・スルタン・アル・ナイハンらがコロンビア大学にエドワード・サイード講座 を寄贈、現在ラシード・ハリディが務めている[115][116]。 2016年、カリフォルニア州立大学フレズノ校は、エドワード・サイードにちなんで新たに創設された中東研究の教授職の応募者の審査を開始したが、数ヶ月 後にフレズノ校はその審査を取り消した。一部のオブザーバーは、この中止は一部の個人とグループからの圧力によるものだと主張している[117]。 |

| Edward Said bibliography List of Columbia University people List of peace activists Projects working for peace among Arabs and Israelis Z Communications Orientalism |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Said |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| ・文学にはパフォーマーというものが存在しない(37) ・沈黙にはじまり、沈黙におわる(38) ・音楽には沈黙による破壊が含まれている(39) ・音楽の表記におけるアバウトな性格——バレンボイム(46) ・社会のために書かれた音楽(アドルノ)(54) ・シェーンベルグの理解——バレンボイム(58) ・ホメロスの「オデッセイア」と「イーリアス」の2つの記述タイプ(63-64) ・演奏家はイメージをもたない——バレンポイム(66) ・音楽のテキスト、文学のテキスト(67) ・芸術のタイムレス概念についてサイードが異議する(69) ・教師から独立することが重要だ(89) ・ピアノとフォルテの楽譜記述について——バレンボイム(151) ・テクストをみる2つの方法(156-157) ・テキストと現実化(159) ・サウンドの具現化(162) ・ナショナルなサウンドはある——バレンポイム(208) ・それに対するサイードの反論(209) ・ユダヤ主義——バレンボイム(231) |

***

★知識人とは何か?(→有機的知識人)

| 知識人とは何か / エドワード W. サイード著 ; 大橋洋一訳, 平凡社 , 1998 . - (平凡社ライブラリー, 236) |

|

| 「知識人とは亡命者にして周辺的存在であり、またアマチュアであり、さらには権力に対して真実を語ろうとする言葉の使い手である。」著者独自の知識人論を縦横に語った講演。 |

|

| 第1章 知識人の表象 第2章 国家と伝統から離れて 第3章 知的亡命—故国喪失者と周辺的存在 第4章 専門家とアマチュア 第5章 権力に対して真実を語る 第6章 いつも失敗する神々 |

■ リンク

■ 文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

《文化と帝国主義》目次(みすず書房のサイトより)

はじめに

第一章 重なりあう領土、からまりあう歴史 第三章 抵抗と対立 |

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆