ロバート・ピアリー

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. 1856-1920

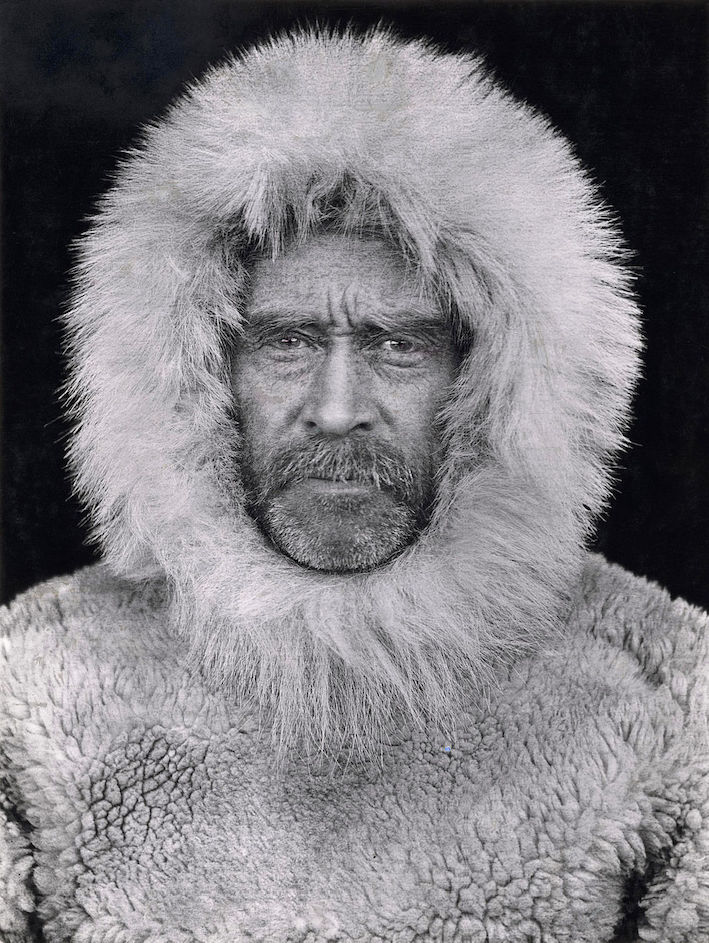

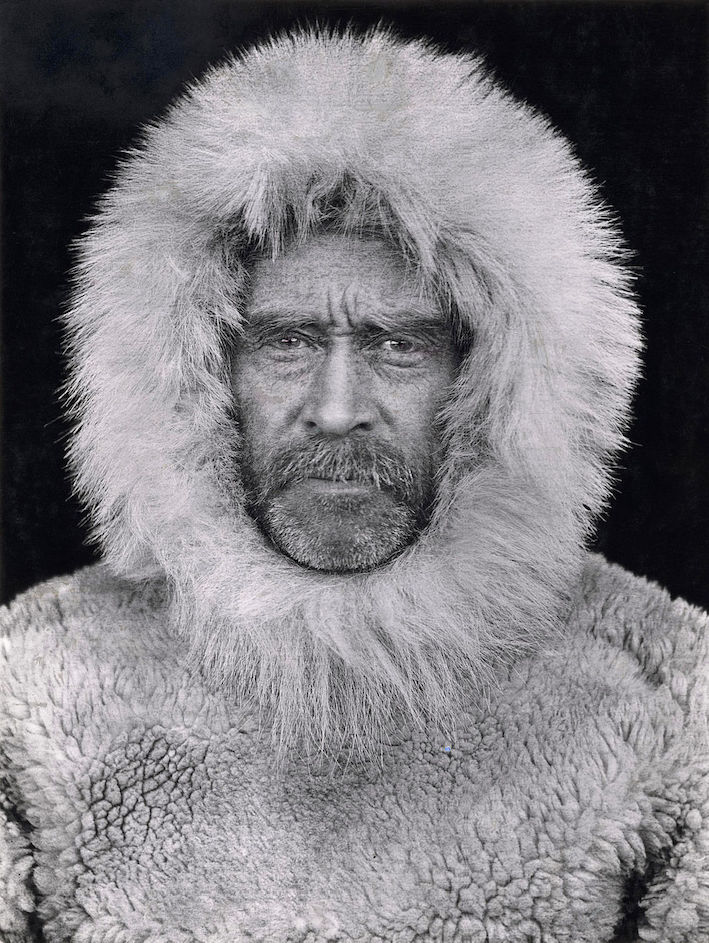

Robert Peary (1856-1920) Self-Portrait, Cape Sheridan, Canada, 1909,

gelatin silver print

ロバート・ピアリー

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. 1856-1920

Robert Peary (1856-1920) Self-Portrait, Cape Sheridan, Canada, 1909,

gelatin silver print

★ロバート・エドウィン・ピアリ・シニア(/ˈpɪ, 1856年5月6日 - 1920年2月20日)は、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて北極圏に何度か遠征したアメリカ人の探検家、アメリカ海軍の将校であった。1909年4 月、北極に初めて到達したと主張する探検隊を率いたことで最もよく知られている。探検隊の一員であったマシュー・ヘンソンは、ピアリーよりわずかに先に北 極点と思われる場所に到達したと考えられている。

| Robert Edwin Peary

Sr. (/ˈpɪəri/; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American

explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several

expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He

is best known for, in April 1909, leading an expedition that claimed to

be the first to have reached the geographic North Pole. Explorer

Matthew Henson, part of the expedition, is thought to have reached what

they believed to be the North Pole narrowly before Peary. Peary was born in Cresson, Pennsylvania, but, following his father's death at a young age, was raised in Portland, Maine. He attended Bowdoin College, then joined the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey as a draftsman. He enlisted in the navy in 1881 as a civil engineer. In 1885, he was made chief of surveying for the Nicaragua Canal, which was never built. He visited the Arctic for the first time in 1886, making an unsuccessful attempt to cross Greenland by dogsled. In the Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892, he was much better prepared, and by reaching Independence Fjord in what is now known as Peary Land, he proved conclusively that Greenland was an island. He was one of the first Arctic explorers to study Inuit survival techniques.[a] During an expedition in 1894, he was the first Western explorer to reach the Cape York meteorite and its fragments, which were then taken from the native Inuit population who had relied on it for creating tools. During that expedition, Peary deceived six indigenous individuals, including Minik Wallace, to travel to America with him by promising they would be able to return with tools, weapons and gifts within the year. This promise was unfulfilled and four of the six Inuit died of illnesses within a few months.[1] On his 1898–1902 expedition, Peary set a new "Farthest North" record by reaching Greenland's northernmost point, Cape Morris Jesup. Peary made two more expeditions to the Arctic, in 1905–1906 and in 1908–1909. During the latter, he claimed to have reached the North Pole. Peary received several learned society awards during his lifetime, and, in 1911, received the Thanks of Congress and was promoted to rear admiral. He served two terms as president of The Explorers Club before retiring in 1911. Peary's claim to have reached the North Pole was widely debated along with a competing claim made by Frederick Cook, but eventually won widespread acceptance. In 1989, British explorer Wally Herbert concluded Peary did not reach the pole, although he may have come within 60 mi (97 km).[2] |

ロバート・エドウィン・ピアリ・シニア(/ˈpɪ,

1856年5月6日 -

1920年2月20日)は、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて北極圏に何度か遠征したアメリカ人の探検家、アメリカ海軍の将校であった。1909年4

月、北極に初めて到達したと主張する探検隊を率いたことで最もよく知られている。探検隊の一員であったマシュー・ヘンソンは、ピアリーよりわずかに先に北

極点と思われる場所に到達したと考えられている。 ピアリーはペンシルベニア州クレソンに生まれたが、幼い頃に父親を亡くし、メイン州ポートランドで育った。ボウディン大学(Bowdoin College)を経て、米国沿岸測地局(United States Coast and Geodetic Survey)に製図工として入局した。1881年に海軍に入隊し、土木技師となる。1885年、ニカラグア運河の測量主任となるが、この運河は建設され ることはなかった。1886年、初めて北極を訪れ、犬ぞりでグリーンランドを横断することに成功した。1891年から1892年にかけてのピアリー探検で は、より良い準備をし、現在のピアリーランドにあるインデペンデンス・フィヨルドに到達し、グリーンランドが島であることを決定的に証明した。1894年 の探検では、西洋の探検家として初めてヨーク岬隕石とその破片に到達し、道具を作るためにそれを利用していた先住民のイヌイットたちからその破片を取り上 げた。この探検でピアリーは、ミニク・ウォレスら6人の先住民をだまし、1年以内に道具や武器、贈り物を持って帰ってこられると約束して、一緒にアメリカ へ渡航した。この約束は果たされず、6人のイヌイットのうち4人は数ヶ月のうちに病死した[1]。 1898年から1902年にかけての遠征で、ピアリーはグリーンランドの最北端、モリス・ジェサップ岬に到達し、「最北端」の新記録を樹立した。1905 -1906年と1908-1909年の2回、北極探検を行った。後者では、北極に到達したと主張している。1911年、議会から感謝状を授与され、海軍少 将に昇進した。また、1911年に引退するまでの間、探検家クラブの会長を2期務めた。 ピアリーの北極点到達の主張は、フレデリック・クックの主張と並んで広く議論されたが、最終的には広く受け入れられることになった。1989年、イギリス の探検家ウォーリー・ハーバートは、60マイル(97km)以内に入ったかもしれないが、ピアリーは極点に到達していないと結論づけた[2]。 |

| Robert Edwin Peary was born on

May 6, 1856, in Cresson, Pennsylvania to Charles N. and Mary P. Peary.

After his father died in 1859, Peary and his mother moved to Portland,

Maine.[3] After growing up there, Peary attended Portland High School

(Maine) where he graduated in 1873. Peary made his way to Bowdoin

College, some 36 mi (58 km) to the north, where he was a member of the

Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity and the Phi Beta Kappa honor society.[4]

He was also part of the rowing team.[4] He graduated in 1877 with a

civil engineering degree.[4][5] From 1878 to 1879, Peary lived in Fryeburg, Maine. During that time, he made a profile survey from the top of Fryeburg's Jockey Cap Rock. The 360-degree survey names the larger hills and mountains visible from the summit. After Peary's death, his boyhood friend, Alfred E. Burton, suggested that the profile survey be made into a monument. It was cast in bronze and set atop a granite cylinder and erected to his memory by the Peary family in 1938.[6] After college, Peary worked as a draftsman making technical drawings at the U.S. National Geodetic Survey office in Washington, D.C. He joined the United States Navy and on October 26, 1881, was commissioned in the Civil Engineer Corps, with the relative rank of lieutenant.[3] From 1884 to 1885, he was an assistant engineer on the surveys for the Nicaragua Canal and later became the engineer in charge. As reflected in a diary entry he made in 1885, during his time in the Navy, he resolved to be the first man to reach the North Pole.[5] In April 1886, he wrote a paper for the National Academy of Sciences proposing two methods for crossing Greenland's ice cap. One was to start from the west coast and trek about 400 mi (640 km) to the east coast. The second, more difficult path, was to start from Whale Sound at the top of the known portion of Baffin Bay and travel north to determine whether Greenland was an island or if it extended all the way across the Arctic.[7] Peary was promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander on January 5, 1901, and to commander on April 6, 1902.[3] |

ロバート・エドウィン・ピアリーは1856年5月6日にペンシルベニア

州クレソンでチャールズ・N・ピアリーとメアリー・P・ピアリー夫妻の間に生まれた。1859年に父親が亡くなり、母親とともにメイン州ポートランドに移

り住んだ[3]。ポートランドで育った後、メイン州のポートランド高校に入学し、1873年に卒業した。北に36マイル(58km)離れたボウディン大学

へ進み、デルタ・カッパ・エプシロン友愛会とファイ・ベータ・カッパの会員であった[4]。 また、ボートチームの一員でもあった[4]

1877年に土木工学の学位を得て卒業した[4][5]。 1878年から1879年にかけて、ピアリーはメイン州フライバーグに住んでいた。この間、彼はフライバーグのジョッキー・キャップ・ロックの頂上からプ ロファイルの測量を行った。この360度の測量では、山頂から見える大きな丘や山の名前が記されている。ピアリーの死後、彼の少年時代の友人であるアルフ レッド・E・バートンは、この測量図を記念碑にすることを提案した。それはブロンズに鋳造され、花崗岩の円筒の上に設置され、1938年にピアリー家に よって彼を記念して建立された[6]。 大学卒業後、ワシントンD.C.の米国測地局で製図工として働き、米国海軍に入隊、1881年10月26日に土木工兵隊に入隊し、中尉の階級となる [3]。 1884年から1885年にかけて、ニカラグア運河の測量で技術補佐員を務め、その後担当技術者となる。1885年の日記にあるように、海軍時代には「人 類初の北極点到達を目指す」と決意していた[5]。 1886年4月、彼はグリーンランドの氷冠を横断する2つの方法を提案する論文を全米科学アカデミーに寄稿した。1つは、西海岸から出発し、東海岸まで約 400マイル(640km)の道のりを歩くというもの。もう1つは、より困難な方法で、バフィン湾の既知の部分の頂上にあるホエールサウンドから出発し、 グリーンランドが島であるか、北極を横切ってずっと広がっているかを判断するために北上するというものだった[7]。 ピアリーは1901年1月5日に中佐、1902年4月6日に司令官に昇格した[3]。 |

| Initial Arctic expeditions Peary made his first expedition to the Arctic in 1886, intending to cross Greenland by dog sled, taking the first of his own suggested paths. He was given six months' leave from the Navy, and he received $500 from his mother to book passage north and buy supplies. He sailed on a whaler to Greenland, arriving in Godhavn on June 6, 1886.[5] Peary wanted to make a solo trek, but Christian Maigaard, a young Danish official, convinced him he would die if he went out alone. Maigaard and Peary set off together and traveled nearly 100 mi (160 km) due east before turning back because they were short on food. This was the second-farthest penetration of Greenland's ice sheet at the time. Peary returned home knowing more of what was required for long-distance ice trekking.[7] Matthew Henson, Peary's assistant, in 1910 Back in Washington attending with the US Navy, in November 1887 Peary was ordered to survey likely routes for a proposed Nicaragua Canal. To complete his tropical outfit he needed a sun hat. He went to a men's clothing store where he met 21-year-old Matthew Henson, a black man working as a sales clerk. Learning that Henson had six years of seagoing experience as a cabin boy, Peary immediately hired him as a personal valet.[8] On assignment in the jungles of Nicaragua, Peary told Henson of his dream of Arctic exploration. Henson accompanied Peary on every one of his subsequent Arctic expeditions, becoming his field assistant and "first man", a critical member of his team.[7][8] |

最初の北極探検 1886年、ピアリーは犬ぞりでグリーンランドを横断することを目的に、最初の北極探検を行いました。彼は海軍から6ヶ月の休暇を与えられ、母親から 500ドルを受け取り、北への航路を予約し、物資を買いました。彼は捕鯨船でグリーンランドに向かい、1886年6月6日にゴッドハウンに到着した [5]。ピアリーは単独行程を希望したが、デンマークの若い役人、クリスチャン・マイガールドは、単独では死ぬと説得し、マイガールドと一緒にグリーンラ ンドに向かった。マイガードとピアリーは一緒に出発し、真東に100マイル(160km)近く進んだが、食料が不足したため引き返した。これは、当時グ リーンランドの氷床を2番目に遠くまで貫いたことになる。ピアリーは、長距離のアイス・トレッキングに何が必要かをより深く知って帰国した[7]。 1910年、ピアリーの助手、マシュー・ヘンソン。 1887年11月、アメリカ海軍の一員としてワシントンに戻ったピアリーは、ニカラグア運河のためのルートを調査するよう命じられた。南国の装いを完成さ せるために、彼は日除け帽子が必要だった。彼は紳士服店に行き、そこで21歳のマシュー・ヘンソンという黒人の店員に出会った。ヘンソンが6年間キャビン ボーイとして船旅の経験があることを知ったピアリーは、すぐに彼を個人的な付き人として雇った[8]。 ニカラグアのジャングルに赴任していたピアリーは、ヘンソンに北極探検の夢を語った。ヘンソンはその後の北極探検のすべてに同行し、彼のフィールドアシス タントと「最初の男」、彼のチームの重要なメンバーとなった[7][8]。 |

| Second Greenland expedition In the Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892, Peary took the second, more difficult route that he laid out in 1886: traveling farther north to find out whether Greenland was a larger landmass extending to the North Pole. He was financed by several groups, including the American Geographic Society, the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences (now the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University), and the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. Members of this expedition included Peary's aide Henson, Frederick A. Cook, who served as the group's surgeon; the expedition's ethnologist, Norwegian skier Eivind Astrup; bird expert and marksman Langdon Gibson, and John M. Verhoeff, who was a weatherman and mineralogist. Peary also took his wife along as dietitian, though she had no formal training.[7] Newspaper reports criticized Peary for bringing his wife.[9] On June 6, 1891, the party left Brooklyn, New York, in the seal hunting ship SS Kite. In July, as Kite was ramming through sheets of surface ice, the ship's iron tiller suddenly spun around and broke Peary's lower leg; both bones snapped between the knee and ankle.[7][9][10] Peary was unloaded with the rest of the supplies at a camp they called Red Cliff, at the mouth of MacCormick Fjord at the north west end of Inglefield Gulf. A dwelling was built for his recuperation during the next six months. Josephine stayed with Peary. Gibson, Cook, Verhoeff, and Astrup hunted game by boat and became familiar with the area and the Inuit.[7] Unlike most previous explorers, Peary had studied Inuit survival techniques; he built igloos during the expedition and dressed in practical furs in the native fashion. By wearing furs to preserve body heat and building igloos, he was able to dispense with the extra weight of tents and sleeping bags when on the march. Peary also relied on the Inuit as hunters and dog-drivers on his expeditions. He pioneered the system of using support teams and establishing supply caches for Arctic travel, which he called the "Peary system". The Inuit were curious about the Americans and came to visit Red Cliff. Josephine was bothered by the Inuit body odor from not bathing, their flea infestations, and their food. She studied the people and kept a journal of her experiences.[9][10] In September 1891, Peary's men and dog sled teams pushed inland onto the ice sheet to lay caches of supplies. They did not go farther than 30 mi (48 km) from Red Cliff.[7] In 1891, Peary shattered his leg in a shipyard accident but it healed by February 1892. By April 1892, he made some short trips with Josephine and an Inuit dog sled driver to native villages to purchase supplies. On May 3, 1892, Peary finally set out on the intended trek with Henson, Gibson, Cook, and Astrup. After 150 mi (240 km), Peary continued on with Astrup. They found the 3,300 ft (1,000 m) high view from Navy Cliff, saw Independence Fjord, and concluded that Greenland was an island. They trekked back to Red Cliff and arrived on August 6, having traveled a total of 1,250 mi (2,010 km).[7] In 1896, Peary, a Master Mason, received his degrees in Kane Lodge No. 454, New York City.[11][12] |

第二次グリーンランド遠征 1891年から1892年にかけてのピアリー探検では、1886年に計画した第二の、より困難なルート、すなわちグリーンランドが北極まで延びる大きな地 塊であるかどうかを調べるためにさらに北上するルートをとった。この探検には、アメリカ地理学会、フィラデルフィア自然科学アカデミー(現ドレクセル大学 自然科学アカデミー)、ブルックリン芸術科学研究所など複数の団体が資金を提供した。この探検隊のメンバーには、ピアリーの側近ヘンソン、一行の外科医を 務めたフレデリック・A・クック、探検隊の民族学者でノルウェー人スキーヤーのエイヴィンド・アストラップ、鳥類専門家で射撃手のラングドン・ギブソン、 気象学者で鉱物学者のジョン・M・ヴァーフが含まれていた。またピアリーは、正式な訓練を受けていないにもかかわらず、栄養士として妻を連れて行った [7]。新聞はピアリーが妻を連れてきたことを批判した[9]。 1891年6月6日、一行はアザラシ狩りの船SSカイト号でニューヨークのブルックリンを出発した。7月、カイト号が表層の氷を突き進む中、船の鉄製舵柄 が突然回転し、ピアリーの下腿を骨折した。その後6ヶ月間、彼の療養のために住居が建てられた。ジョセフィーヌはピアリーと一緒にいた。ギブソン、クッ ク、ヴァーホフ、アストラップはボートで狩猟を行い、この地域とイヌイットに親しんだ[7]。 それまでの探検家とは異なり、ピアリーはイヌイットの生存技術を研究していた。彼は探検中にイグルーを作り、先住民の流儀に従って実用的な毛皮を身にま とった。体温を保つために毛皮を着用し、イグルーを作ることで、行軍の際にテントや寝袋の余分な重さを省くことができたのだ。さらにピアリーは、イヌイッ トの猟師や犬飼を利用した遠征も行った。北極圏を移動する際に、支援部隊を使ったり、物資の貯蔵所を設置したりするシステムを「ピアリーシステム」と呼 び、先駆的な存在となった。イヌイットたちはアメリカ人に興味を持ち、レッドクリフを訪ねてきた。ジョセフィンは、イヌイットの入浴しないことによる体 臭、ノミの発生、食事に悩まされた。1891年9月、ピアリーの部下と犬ぞり隊が内陸の氷床を進み、物資の貯蔵を開始した。彼らはレッドクリフから30マ イル(48km)より遠くには行かなかった[7]。 1891年、ピアリーは造船所の事故で足を粉々にしたが、1892年2月までに治った。1892年4月までに、彼はジョセフィーヌとイヌイットの犬ぞり運 転手と共に、先住民の村に物資を買いに行く小旅行をした。1892年5月3日、ピアリーはヘンソン、ギブソン、クック、アストラップとともに、ついに目的 の旅に出発した。150マイル(240km)を走った後、ピアリーはアストラップと共にさらに前進した。彼らは、ネイビークリフから3,300フィート (1,000m)の高さの景色を見つけ、インデペンデンスフィヨルドを見て、グリーンランドが島であると結論づけたのである。彼らはレッドクリフに戻り、 8月6日に到着し、合計1,250マイル(2,010km)を旅した[7]。 1896年、マスターメイソンであるピアリーはニューヨークのケイン・ロッジNo.454で学位を取得した[11][12]。 |

| 1898–1902 expeditions Peary used abandoned Fort Conger on Ellesmere Island during his 1898–1902 expedition As a result of Peary's 1898–1902 expedition, he claimed an 1899 visual discovery of "Jesup Land" west of Ellesmere Island.[13] He claimed that this sighting of Axel Heiberg Island was prior to its discovery by Norwegian explorer Otto Sverdrup's expedition around the same time. This contention has been universally rejected by exploration societies and historians.[14] However, the American Geographical Society and the Royal Geographical Society of London honored Peary for tenacity, mapping of previously uncharted areas, and his discovery in 1900 of Cape Morris Jesup at the north tip of Greenland. Peary also achieved a "farthest north" for the western hemisphere in 1902 north of Canada's Ellesmere Island. Peary was promoted to lieutenant commander in the Navy in 1901 and to commander in 1902.[15] |

1898-1902年の遠征 ピアリーは1898年から1902年の遠征で、エルズミア島の放棄されたコンガー砦を使用した。 1898-1902年の探検の結果、彼は1899年にエルズミア島の西に「イエサップランド」を視覚的に発見したと主張した[13]。 彼はこのアクセル・ヘイベルグ島の目撃は、同時期にノルウェーの探検家オットー・スヴェルドラップが発見する以前であったと主張した。しかし、アメリカ地 理学会とロンドン王立地理学会はピアリーを、粘り強さ、未開拓地の地図作成、そして1900年にグリーンランド北端のモリス・ジェサップ岬を発見したこと で表彰している[14]。またピアリーは、1902年にカナダのエレスメア島の北で西半球の「最北端」を達成した。ピアリーは1901年に海軍の中佐に、 1902年に中佐に昇進した[15]。 |

| 1905–1906 expedition Peary's next expedition was supported by fundraising through the Peary Arctic Club, with gifts of $50,000 from George Crocker, the youngest son of banker Charles Crocker, and $25,000 from Morris K. Jesup, to buy Peary a new ship.[16] The SS Roosevelt navigated through the ice between Greenland and Ellesmere Island, establishing an American hemisphere "farthest north by ship". The 1906 "Peary System" dogsled drive for the pole across the rough sea ice of the Arctic Ocean started from the north tip of Ellesmere at 83° north latitude. The parties made well under 10 mi (16 km) a day until they became separated by a storm. As a result, Peary was without a companion sufficiently trained in navigation to verify his account from that point northward. With insufficient food, and uncertainty whether he could negotiate the ice between himself and land, he made the best possible dash and barely escaped with his life from the melting ice. On April 20, he was no farther north than 86°30' latitude. This latitude was never published by Peary. It is in a typescript of his April 1906 diary, discovered by Wally Herbert in his assessment commissioned by the National Geographic Society. The typescript suddenly stopped there, one day before Peary's April 21 purported "farthest". The original of the April 1906 record is the only missing diary of Peary's exploration career.[17] He claimed the next day to have achieved a Farthest North world record at 87°06' and returned to 86°30' without camping. This implied a trip of at least 72 nautical miles (133 km; 83 mi) between sleeping, even assuming direct travel with no detours. After returning to Roosevelt in May, Peary began weeks of difficult travel in June heading west along the shore of Ellesmere. He discovered Cape Colgate, from whose summit he claimed in his 1907 book[18] that he had seen a previously undiscovered far-north "Crocker Land" to the northwest on June 24, 1906. A later review of his diary for this time and place found that he had written, "No land visible."[19] On December 15, 1906, the National Geographic Society of the United States, certified Peary's 1905–1906 expedition and "Farthest" with its highest honor, the Hubbard Medal. No major professional geographical society followed suit. In 1914, Donald Baxter MacMillan and Fitzhugh Green's expedition found that Crocker Land did not exist. |

1905-1906年遠征 ピアリーの次の探検は、ピアリー・アークティック・クラブを通じた資金調達によって支えられ、銀行家チャールズ・クロッカーの末息子ジョージ・クロッカー から5万ドル、モリス・K・ジェサップから2万5千ドルの寄付を得て、ピアリーに新しい船を購入した[16] SSルーズベルト号はグリーンランドとエレスミア島の間の氷を航海し、「船で最も北へ」アメリカの半球を確立することに成功した。1906年、北極海の荒 れた海氷を越えて極点を目指す犬ぞり「ピアリーシステム」は、北緯83°のエルズミアの北端から始まった。一行は1日に10マイル(16km)弱の距離を 進んだが、嵐で離ればなれになってしまった。 その結果、ピアリーにはその地点から北上する彼の記録を検証するのに十分な航海術を身につけた同行者がいなかった。食料も十分でなく、陸地との間にある氷 を乗り越えられるかどうかもわからない中、彼は可能な限りのダッシュをし、氷の融解から命からがら逃れた。4月20日、彼は北緯86度30分より北にはい なかった。この緯度はピアリーによって公表されたことはない。ウォーリー・ハーバートがナショナルジオグラフィック協会に依頼した評価で発見した1906 年4月の日記のタイプスクリプトにある。そのタイプスクリプトは、ピアリーの4月21日とされる「最果て」の1日前に、突然そこで止まっている。1906 年4月の記録の原本は、ピアリーの探検家としての経歴の中で唯一失われている日記である[17] 彼は翌日、87°06'でFarthest North世界記録を達成し、キャンプなしで86°30'まで戻ったと主張した。これは、寄り道なしの直行便を想定しても、少なくとも72海里 (133km; 83mi)の睡眠を挟んだ旅であったことを意味する。 5月にルーズベルトに戻ったピアリーは、6月から数週間、エレスメアの海岸に沿って西に向かう困難な旅を始めた。彼はコルゲート岬を発見し、その頂上から 1906年6月24日に北西にそれまで発見されていなかったはるか北の「クロッカーランド」を見たと1907年の著書[18]で主張している。後日、この 日時と場所についての日記を見直したところ、彼は「見える土地はない」と書いていた[19]。1906年12月15日、アメリカのNational Geographic Societyは、ピアリーの1905-1906年の探検と「Farthest」にその最高の名誉、ハバードメダルを認定した。その後、地理学会の主要な 専門学会が追随することはなかった。1914年、ドナルド・バクスター・マクミランとフィツュー・グリーンの探検隊は、クロッカー・ランドが存在しないこ とを発見した。 |

| Claiming to reach the North Pole On July 6, 1908, the Roosevelt departed New York City with Peary's eighth Arctic expedition of 22 men. Besides Peary as expedition commander, it included master of the Roosevelt Robert Bartlett, surgeon Dr. J.W. Goodsell, and assistants Ross Gilmore Marvin, Donald Baxter MacMillan, George Borup, and Matthew Henson. After recruiting several Inuit and their families at Cape York (Greenland), the expedition wintered near Cape Sheridan on Ellesmere Island. The expedition used the "Peary system" for the sledge journey, with Bartlett and the Inuit, Poodloonah, "Harrigan," and Ooqueah, composing the pioneer division. Borup, with three Inuit, Keshunghaw, Seegloo, and Karko, composed the advance supporting party. On February 15, Bartlett's pioneer division departed the Roosevelt for Cape Columbia, followed by 5 advance divisions. Peary, with the two Inuit, Arco and Kudlooktoo, departed on February 22, bringing to the total effort 7 expedition members, 19 Inuit, 140 dogs, and 28 sledges. On February 28, Bartlett, with three Inuit, Ooqueah, Pooadloonah, and Harrigan, accompanied by Borup, with three Inuit, Karko, Seegloo, and Keshungwah, headed North.[20]: 41 On March 14, the first supporting, composed of Dr. Goodsell and the two Inuit, Arco and Wesharkoupsi, party turned back towards the ship. Peary states this was at a latitude of 84°29'. On March 20, Borup's third supporting party, with three Inuit, started back to the ship. Peary states this was at a latitude of 85°23'. On March 26, Marvin, with Kudlooktoo and Harrigan, headed back to the ship, from a latitude estimated by Marvin as 86°38'. Marvin died on this return trip South. On 1 April, Bartlett's party started their return to the ship, after Barlett estimated a latitude of 87°46'49". Peary, with two Inuit, Egingwah and Seeglo, and Henson, with two Inuit, Ootah and Ooqueah, using 5 sledges and 40 dogs, planned 5 marches over the estimated 130 nautical miles to the pole. On 2 April, Peary led the way north.[20]: 235, 243, 252–254, 268–271, 274 [21] On the final stage of the journey toward the North Pole, Peary told Bartlett to stay behind. He continued with five assistants: Henson, Ootah, Egigingwah, Seegloo, and Ooqueah. No one except Henson, who had served as navigator and craftsman on the Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892, was capable of making navigation observations. On April 6, 1909, Peary established Camp Jesup within 3 mi (5 km) of the pole, according to his own readings.[22] Peary estimated the latitude as 89°57', after making an observation at approximate local noon using the Columbia meridian. Peary used a sextant, with a mercury trough and glass roof for an artificial horizon, to make measurements of the Sun. Peary claims, "I had now taken in all thirteen single, or six and one-half double, altitudes of the sun, at two different stations, in three different directions, at four different times." Peary states some of these observations were "beyond the Pole," and "...at some moment during these marches and counter-marches, I had passed over or very near the point where north and south and east and west blend into one."[20]: 287–298 [21]: 72–75 Henson scouted ahead to what was thought to be the North Pole site; he returned with the greeting, "I think I'm the first man to sit on top of the world," much to Peary's chagrin.[23] On April 7, 1909, Peary's group started their return journey, reaching Cape Columbia on April 23, and the Roosevelt on April 26. MacMillan and the doctor's party had reached the ship earlier, on March 21, Borup's party on April 11, Marvin's Inuit on April 17, and Bartlett's party on April 24. On July 18, the Roosevelt departed for home.[20]: 302, 316–317, 325, 332 [21]: 78–81 Upon returning to civilization, Peary learned that Dr. Frederick A. Cook, a surgeon on the Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892, claimed to have reached the North pole in 1908.[24] Despite remaining doubts, a committee of the National Geographic Society, as well as the Naval Affairs Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives, credited Peary with reaching the North Pole.[24] A reassessment of Peary's notebook in 1988 by polar explorer Wally Herbert found it "lacking in essential data", thus renewing doubts about Peary's discovery.[25][26] |

北極点到達を主張 1908年7月6日、ルーズベルト号はピアリーの第8次北極探検隊22名を乗せニューヨークを出発した。ルーズベルト号の船長ロバート・バートレット、外 科医J・W・グッドセル、助手ロス・ギルモア・マーヴィン、ドナルド・バクスター・マクミラン、ジョージ・ボーラップ、マシュー・ヘンソンらであった。探 検隊は、ヨーク岬(グリーンランド)でイヌイットとその家族数名を募集した後、エルズミア島のシェリダン岬付近で冬を越した。遠征隊は「ピアリー方式」で 橇行を行い、バートレットとイヌイットのプードルナー、ハリガン、ウークイアが開拓隊を構成した。ボーラップは3人のイヌイット、ケシュンホウ、シーグ ルー、カルコとともに先発支援隊を構成した。2月15日、バートレットの開拓師団はルーズベルト号からコロンビア岬に向けて出発し、その後5つの先発師団 が続いた。ピアリーは2月22日にアルコとクドルクトゥの2人のイヌイットを連れて出発し、遠征隊員7名、イヌイット19名、犬140頭、ソリ28台で総 力戦となった。2月28日、バートレットがイヌイットのウークア、プードルナー、ハリガンの3人を連れ、ボーラップがイヌイットのカルコ、シーグルー、ケ シュングワーの3人を連れて北上する[20]。 41 3月14日、グッドセル博士と2人のイヌイット、アルコとウェシャークプシからなる第一支援隊は、船の方へ引き返した。Pearyはこれが84°29'の 緯度であったと述べている。3月20日、Borupの第3次支援隊は、3人のイヌイットを連れて、船に向かって引き返し始めた。ピアリーは、これは緯度 85°23'であったと述べている。3月26日、MarvinはKudlooktooとHarriganと共に、Marvinが推定する緯度86°38' から船へ戻った。Marvinはこの南への帰路で死亡した。4月1日、バートレット一行は、バートレットが推定した緯度87°46'49 "から船への帰還を開始した。ピアリーはエギングワとシーグロの2人のイヌイット、ヘンソンはウータとウークアの2人のイヌイットと共に、5台のソリと 40匹の犬を使って、極点までの推定130海里を5回行進する計画を立てた。4月2日、ピアリーは北へ先導した[20]: 235, 243, 252-254, 268-271, 274 [21]. 北極点への旅の最終段階において、ピアリーはバートレットに残るように言った。彼は5人の助手を連れて旅を続けた。ヘンソン、ウータ、エギギングワ、シー グルー、ウークイアの5人の助手を連れて旅を続けた。1891年から1892年にかけてのピアリーのグリーンランド遠征で航海士と職人を務めたヘンソン以 外には、航海観測を行うことができる者はいなかった。1909年4月6日、ピアリーは彼自身の測定によると、極点から3マイル(5km)以内にキャンプ・ ジェサップを設立した[22] ピアリーは、コロンビア子午線を用いておおよそ現地正午に観測を行い、緯度を89度57分と推定している。ピアリーは、水銀の谷と人工の地平線のためのガ ラスの屋根を持つ六分儀を使って、太陽の計測を行った。ピアリーは、"私は今、二つの異なる場所、三つの異なる方向、四つの異なる時刻に、全部で13の単 一、または6と1.5倍の太陽の高度を測定した "と主張している。ピアリーはこれらの観測のいくつかは「極を越えて」いたと述べ、「...これらの行進と反行進の間のある瞬間、私は北と南、東と西が一 つに混ざり合う地点の上か、その近くを通過していた」[20]: 287-298 [21]: 72-75 ヘンソンは北極点と考えられていた場所に先に偵察に行って、「世界の頂点に座った最初の人間だと思う」という挨拶で戻ってきて、ピアリーの不満を大いに満 たしたのである[23]。 1909年4月7日、ピアリー一行は帰路につき、4月23日にコロンビア岬に、4月26日にルーズベルト号に到着した。マクミランと博士の一行はそれ以前 の3月21日に、ボーラップの一行は4月11日に、マーヴィンのイヌイットは4月17日に、バートレットの一行は4月24日にそれぞれ船に到着していた。 7月18日、ルーズベルト号は帰途につく[20]。 302, 316-317, 325, 332 [21]: 78-81 文明社会に戻ったピアリーは、1891年から1892年にかけてのピアリー遠征隊の外科医であったフレデリック・A・クック博士が、1908年に北極点に 到達したと主張していることを知った[24] 疑いは残ったものの、全米地理学会の委員会と米国下院の海軍問題小委員会はピアリーの北極点到達を信認した[24]。 1988年に極地探検家ウォーリー・ハーバートがピアリーのノートを再評価したところ、「重要なデータが欠けている」ことが判明し、ピアリーの発見に対する疑念が再び生じた[25][26]。 |

| Peary

was promoted to the rank of captain in the Navy in October 1910.[27] By

his lobbying, Peary headed off a move among some U.S. Congressmen to

have his claim to the pole evaluated by other explorers. Eventually

recognized by Congress for "reaching" the pole, Peary was given the

Thanks of Congress by a special act in March 1911.[28] By the same Act

of Congress, Peary was promoted to the rank of rear admiral in the Navy

Civil Engineer Corps, retroactive to April 6, 1909. He retired from the

Navy the same day, to Eagle Island on the coast of Maine, in the town

of Harpswell. His home there has been designated a Maine State Historic

Site.[29] After retiring, Peary received many honors from scientific societies for his Arctic explorations and discoveries. He served twice as president of The Explorers Club, from 1909 to 1911, and from 1913 to 1916. In early 1916, Peary became chairman of the National Aerial Coast Patrol Commission, a private organization created by the Aero Club of America. It advocated the use of aircraft to detect warships and submarines off the U.S. coast.[30] Peary used his celebrity to promote the use of military and naval aviation, which led directly to the formation of United States Navy Reserve aerial coastal patrol units during World War I. After the war, Peary proposed a system of eight airmail routes, which became the genesis of the U.S. Postal Service's airmail system.[31] In 1914, Peary bought the house at 1831 Wyoming Avenue NW in the Adams Morgan neighborhood of Washington, D.C., where he lived until his death on February 20, 1920.[32] He began renovating the house in 1920, shortly before his death, after which the renovation was taken over by Josephine. Josephine sold the house in 1927, receiving a $12,000 promissory note.[33] He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[34] Matthew Henson was honored by being re-interred nearby on April 6, 1988.[35] |

1910

年10月に海軍大佐に昇進した[27]。彼のロビー活動によって、ピアリーは、他の探検家によって極点への彼の主張を評価させようとする一部のアメリカ下

院議員の動きを抑えた。結局、極点に「到達」したことが議会に認められ、ピアリーは1911年3月の特別法によって議会の感謝を受けた[28]。同じ議会

法によって、ピアリーは海軍土木工兵隊の少将に昇進し、1909年4月6日にさかのぼった。彼は同日、海軍を退役し、メイン州沿岸のイーグル島、ハープス

ウェルという町に移った。そこにある彼の家はメイン州の史跡に指定されている[29]。 引退後、ピアリーは北極圏の探検と発見により、科学団体から多くの栄誉を受けた。1909年から1911年、1913年から1916年の2回、探検家クラブの会長に就任している。 1916年初頭、ピアリーは、アメリカ航空クラブが設立した民間団体「国家航空沿岸警備委員会」の会長に就任した。戦後、ピアリーは8つの航空便ルートを提案し、これがアメリカ郵政公社の航空便システムの発端となった[31]。 1914年、ピアリーはワシントンD.C.のアダムズ・モーガン地区にあるワイオミング通り1831番地(NW)の家を購入し、1920年2月20日に亡 くなるまで住んでいた[32]。亡くなる少し前の1920年から家の改装を始め、その後改装はジョセフィーヌに引き継がれることになる。ジョセフィンは 1927年にこの家を売却し、12,000ドルの約束手形を受け取った[33]。 アーリントン国立墓地に埋葬された[34]。 マシュー・ヘンソンは1988年4月6日に近くに再埋葬され、その栄誉を称えられた[35]。 |

| On

August 11, 1888, Peary married Josephine Diebitsch, a business school

valedictorian who thought that women should be more than just mothers.

Diebitsch had started working at the Smithsonian Institution when she

was 19 or 20 years old, replacing her father after he became ill and

filling his position as a linguist. In 1886, she resigned from the

Smithsonian upon becoming engaged to Peary. The newlyweds honeymooned in Atlantic City, New Jersey, then moved to Philadelphia, where Peary was assigned. Peary's mother accompanied them on their honeymoon, and she moved into their Philadelphia apartment, which caused friction between the two women. Josephine told Peary that his mother should return to live in Maine.[36] They had two children together, Marie Ahnighito (born 1893) and Robert Peary, Jr. His daughter wrote several books, including The Red Caboose (1932) a children's book about the Arctic adventures published by William Morrow and Company. As an explorer, Peary was frequently gone for years at a time. In their first 23 years of marriage, he spent only three with his wife and family. Peary and his aide, Henson, both had relationships with Inuit women outside of marriage and fathered children with them.[37] Peary appears to have started a relationship with Aleqasina (Alakahsingwah) when she was about 14 years old.[2][38] She bore him at least two children, including a son called Kaala,[38] Karree,[39] or Kali.[40] French explorer and ethnologist Jean Malaurie was the first to report on Peary's descendants after spending a year in Greenland in 1951–52.[38] S. Allen Counter, a Harvard neuroscience professor interested in Henson's role in the Arctic expeditions, went to Greenland in 1986. He found Peary's son Kali and Henson's son Anaukaq, then octogenarians, and some of their descendants.[40] Counter arranged to bring the men and their families to the United States to meet their American relatives and see their fathers' gravesites.[40] In 1991, Counter wrote about the episode in his book, North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo (1991). He also gained national recognition of Henson's role in the expeditions.[40] A documentary by the same name was also released. Wally Herbert also noted the relationship and children in his book The Noose of Laurels, published in 1989.[2] |

1888

年8月11日、ピアリーは、ビジネススクールの卒業生で、女性は母親以上の存在であるべきだと考えていたジョセフィン・ディビッチと結婚した。ディービッ

チは、19歳か20歳の時にスミソニアン博物館に就職し、病気で倒れた父親の代わりに言語学者として働いていた。1886年、ピアリーと婚約したのを機に

スミソニアン博物館を辞めた。 新婚旅行はニュージャージー州のアトランティックシティーで、その後ピアリーの赴任地であるフィラデルフィアに移った。新婚旅行にはピアリーの母親も同行 し、フィラデルフィアのアパートに引っ越してきたため、2人の間に摩擦が生じた。ジョセフィンはピアリーに、母親はメイン州に戻って生活するべきだと言っ た[36]。 二人の間にはマリー・アニギト(1893年生まれ)とロバート・ピアリー・ジュニアという二人の子供がいた。 娘はウィリアム・モロー社から出版された北極の冒険を描いた子供向けの本『The Red Caboose』(1932年)などいくつかの本を書いている。探検家であったピアリーは、何年も家を空けることが多かった。結婚してからの23年間、妻 や家族と過ごしたのはわずか3回だった。 ピアリーと側近のヘンソンは共にイヌイットの女性と結婚以外の関係を持ち、子供をもうけた[37]。ピアリーはアレカシナ(アラカシングワ)が14歳くら いの時に関係を持ったようである[2][38]。 [フランスの探検家・民族学者であるジャン・マロリーは、1951年から52年にかけてグリーンランドで1年を過ごした後、ピアリーの子孫について最初に 報告した[38]。 S. ハーバード大学の神経科学教授で、北極探検におけるヘンソンの役割に関心を持つアレン・カウンターは、1986年にグリーンランドに赴いた。カウンター は、ピアリーの息子カリとヘンソンの息子アナウカク(当時八十代)とその子孫を発見し、彼らとその家族をアメリカに招き、アメリカの親族と会い、父親の墓 を見るよう手配した[40]。 1991年にカウンターは、著書『北極点遺産:黒人、白人、エスキモー』(1991年)でこのエピソードについて書いている。また、ヘンソンが探検で果た した役割について全米に認知されるようになった[40] 同名のドキュメンタリーも公開された。ウォーリー・ハーバートも1989年に出版された著書『The Noose of Laurels』の中で、その関係や子供たちについて言及している[2]。 |

| Treatment of the Inuit Peary has received criticism for his treatment of the Inuit, for fathering children with Aleqasina and for bringing back a small group of Inughuit Greenlandic Inuit to the United States along with the Cape York meteorite, which was of significant local importance as the only source of iron for tools and Peary sold for $40,000 in 1897.[41] Working at the American Museum of Natural History, anthropologist Franz Boas had requested that Peary bring back an Inuit for study.[42][43][44] During his expedition to retrieve the Cape York meteorite, Peary convinced six individuals, including a man named Qisuk and his child Minik, to travel to America with him by promising they would be able to return with tools, weapons and gifts within the year.[1] Peary left the people at the museum when he returned with the Cape York meteorite in 1897, where they were kept in damp, humid conditions unlike their homeland. Within a few months, four died of tuberculosis; their remains were dissected and the bones of Qisuk were put on display after Minik was shown a fake burial.[44][43] Speaking as a teenager to the San Francisco Examiner about Peary, Minik said: At the start, Peary was kind enough to my people. He made them presents of ornaments, a few knives and guns for hunting and wood to build sledges. But as soon as he was ready to start home his other work began. Before our eyes he packed up the bones of our dead friends and ancestors. To the women’s crying and the men’s questioning he answered that he was taking our dead friends to a warm and pleasant land to bury them. Our sole supply of flint for lighting and iron for hunting and cooking implements was furnished by a huge meteorite. This Peary put aboard his steamer and took from my poor people, who needed it so much. After this he coaxed my father and that brave man Natooka, who were the strongest hunters and the wisest heads for our tribe, to go with him to America. Our people were afraid to let them go, but Peary promised them that they should have Natooka and my father back within a year, and that with them would come a great stock of guns and ammunition, and wood and metal and presents for the women and children … We were crowded into the hold of the vessel and treated like dogs. Peary seldom came near us.[1] Peary eventually helped Minik travel home in 1909, though it is speculated that this was to avoid any bad press surrounding his anticipated celebratory return after reaching the North Pole.[44] |

イヌイットの扱い ピアリーはイヌイットの扱いについて批判を受けている。アレカシーナと の間に子供をもうけたこと、また、道具のための唯一の鉄源として地元で重要な意味を持ち、ピアリーが1897年に4万ドルで売却したヨーク岬隕石とともに グリーンランドのイヌイットの小グループをアメリカに連れ帰ったことなどがその理由であった[41]。 アメリカ自然史博物館で働く人類学者フランツ・ボアズは、ピアリーに研 究のためにイヌイットを持ち帰るよう要請していた[42][43][44]。 ケープ・ヨーク隕石を回収するための遠征中、ピアリーはキスクという男とその子供ミニクを含む6人を、道具、武器、贈り物を年内に持って帰れると約束して 一緒にアメリカに旅するように説得している[1][44]。 [1] ピアリーは1897年にヨーク岬の隕石を持ち帰る際、人々を博物館に預けたが、彼らは祖国と違って湿気の多い環境で飼育された。数ヶ月のうちに4人が結核 で死亡した。彼らの遺骨は解剖され、ミニクが偽の埋葬を見せられた後、キスクの骨が展示されるようになった[44][43]。 ※[42]Thomas, David H. (March 14, 2000). Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archaeology, and the Battle for Native American Identity. Basic Books. p. 78. [43]Harper, Kenn (2001). Give Me My Father's Body: The Life of Minik, the New York Eskimo'. Washington Square Press. [44]Meier, Allison (March 19, 2013). "Minik and the Meteor". https://narratively.com/minik-and-the-meteor/ Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. [1]Petrone, Penny (January 1992). Northern Voices: Inuit Writing in English. University of Toronto Press. 10代の頃、サンフランシスコ・エグザミナー紙にピアリーについて語った際、ミニクは次のように語っている。 当初、ピアリーは私の仲間に十分親切だった。装飾品や狩猟用のナイフや 銃、ソリを作るための木材をプレゼントしてくれた。しかし、家に帰る準備が整うと、すぐに別の仕事が始まった。私たちの目の前で、彼は死んだ友人や先祖の 骨を梱包していったのです。女たちの泣き叫ぶ声や男たちの問いかけに、彼は「死んだ仲間を暖かくて気持ちのいい土地に連れて行って、埋めてあげるんだ」と 答えました。火をつけるための火打石と、狩猟や料理の道具となる鉄は、巨大な隕石が唯一の供給源であった。ピアリーはこれを汽船に載せて、それを必要とし ていた貧しい人々から奪ったのだ。その後、ピアリーは私の父と勇敢なナトゥーカ(Natooka)をなだめすかして、一緒にアメリカへ行くよう迫りまし た。私たちの仲間は彼らを行かせるのを恐れたが、ピアリーはナトゥーカと私の父を1年以内に連れ戻すこと、そして彼らと共に大量の銃と弾薬、木材、金属、 女性や子供へのプレゼントを用意すると約束した・・・私たちは船倉に詰め込まれ犬のように扱われた。ピアリーはめったに私たちに近づかなかった[1]。 ※[1]Petrone, Penny (January 1992). Northern Voices: Inuit Writing in English. University of Toronto Press. ピアリーは最終的に1909年にミニクの帰国を手助けしたが、これは北極点到達後の祝賀帰国を期待される中で悪い報道を避けるためだったと推測される[44]。 |

| Controversy surrounding North Pole claim(省略) |

|

| Legacy Several United States Navy ships have been named USS Robert E. Peary. The Peary–MacMillan Arctic Museum at Bowdoin College is named for Peary and fellow Arctic explorer Donald Baxter MacMillan. In 1986, the United States Postal Service issued a 22-cent postage stamp in honor of Peary and Henson;[54] Peary Land, Peary Glacier, Peary Nunatak and Cape Peary in Greenland, Peary Bay and Peary Channel in Canada, as well as Mount Peary in Antarctica, are named in his honor. The lunar crater Peary, appropriately located at the moon's north pole, is also named after him.[55] Camp Peary in York County, Virginia is named for Admiral Peary. Originally established as a Navy Seabee training center during World War II, it was repurposed in the 1950s as a Central Intelligence Agency training facility. It is commonly called "The Farm". Admiral Peary Vocational Technical School, located in a neighboring community very close to his birthplace of Cresson, PA, was named for him and was opened in 1972. Today the school educates over 600 students each year in numerous technical education disciplines. Major General Adolphus Greely, leader of the ill-fated Lady Franklin Bay Expedition from 1881 to 1884, noted that no Arctic expert questioned that Peary courageously risked his life traveling hundreds of miles from land, and that he reached regions adjacent to the pole. After initial acceptance of Peary's claim, he later came to doubt Peary's having reached 90°. In his book Ninety Degrees North, polar historian Fergus Fleming describes Peary as "undoubtedly the most driven, possibly the most successful and probably the most unpleasant man in the annals of polar exploration".[56] In 1932, an expedition was made by Robert Bartlett and Marie Ahnighito Peary Stafford, Peary's daughter, on the Effie M. Morrissey to erect a monument to Peary at Cape York, Greenland.[57] |

レガシー アメリカ海軍の艦船には、USSロバート・E・ピアリーと命名されているものがあります。ボウディン大学のピアリー・マクミラン北極圏博物館はピアリーと 仲間の北極圏探検家ドナルド・バクスター・マクミランにちなんで命名されたものである。1986年、アメリカ合衆国郵政公社はピアリーとヘンソンを記念し て22セントの郵便切手を発行した[54]。 グリーンランドのピアリーランド、ピアリー氷河、ピアリー・ヌナタク、ピアリー岬、カナダのピアリー湾、ピアリー海峡、南極のピアリー山は、彼にちなんで命名されたものである。また、月の北極にある月のクレーター「ピアリー」も彼にちなんで名付けられた[55]。 バージニア州ヨーク郡のキャンプ・ピアリーはピアリー提督にちなんで命名された。元々は第二次世界大戦中に海軍の海兵隊訓練センターとして設立されたが、1950年代に中央情報局の訓練施設として再利用されるようになった。通称「ザ・ファーム」。 アドミラル・ピアリー職業技術学校は、彼の生誕地であるペンシルベニア州クレソンに非常に近い近隣の地域にあり、彼の名を冠し、1972年に開校しました。現在、この学校では毎年600人以上の生徒が、さまざまな技術教育を受けています。 1881年から1884年にかけての不運なフランクリン湾探検隊のリーダー、アドルファス・グリーリー少将は、ピアリーが勇気を持って陸から何百マイルも 離れた場所を旅し、極点に隣接する地域に到達したことに疑問を持つ北極圏の専門家はいなかったと述べている。しかし、当初はピアリーの主張を受け入れてい たが、後にピアリーの90度到達を疑うようになる。 極地史家のファーガス・フレミングはその著書『Ninety Degrees North』の中で、ピアリーを「極地探検の歴史上、間違いなく最も駆り立てられ、おそらく最も成功し、おそらく最も不快な男」であると評している[56]。 1932年、グリーンランドのヨーク岬にピアリーの記念碑を建てるために、ロバート・バートレットとピアリーの娘であるマリー・アニギト・ピアリー・スタフォードがエフィーM・モリッシー号で探検を行った[57]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Peary |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Robert Peary (Photo courtesy Library of Congress)

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報