ロマン派音楽

Romantic music

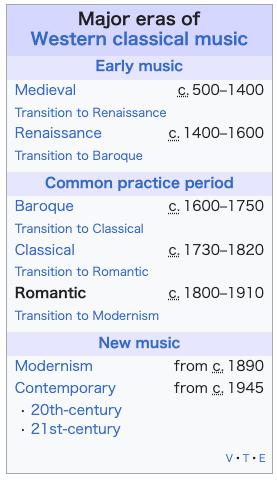

ア レクサンドル・デュマ、エクトル・ベルリオーズ、ジョルジュ・サンド、ニコロ・パガニーニ、ジョアキーノ・ロッシーニ、マリー・ダグールに囲まれ、

ピ アノを弾くリストの絵と、ピアノの上に置かれたルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンの胸像

☆ ロマン派音楽(ロマンはおんがく、英: Romantic music)は、西洋古典音楽の様式運動であり、一般にロマン派時代(またはロマン主義時代)と呼ばれる19世紀の時期に関連する。1798年頃から 1837年頃まで西洋文化において顕著となった知的、芸術的、文学的運動であるロマン主義という広義の概念と密接な関係がある[1]。 ロマン派の作曲家たちは、個性的で、感情的で、劇的で、しばしばプログラム的な音楽を創り出そうとした。ロマン派の音楽は、表向きは自然、文学、詩、超自 然的要素、美術など、音楽以外の刺激に触発された(あるいはそれを呼び起こそうとした)ものが多かった[2]。半音階の増加などの特徴を含み、伝統的な形 式から離れていった[3]。

| Romantic music is a

stylistic movement in Western Classical music associated with the

period of the 19th century commonly referred to as the Romantic era (or

Romantic period). It is closely related to the broader concept of

Romanticism—the intellectual, artistic, and literary movement that

became prominent in Western culture from about 1798 until 1837.[1] Romantic composers sought to create music that was individualistic, emotional, dramatic, and often programmatic; reflecting broader trends within the movements of Romantic literature, poetry, art, and philosophy. Romantic music was often ostensibly inspired by (or else sought to evoke) non-musical stimuli, such as nature,[2] literature,[2] poetry,[2] super-natural elements, or the fine arts. It included features such as increased chromaticism and moved away from traditional forms.[3] |

ロマン派音楽(ロマンはおんがく、英: Romantic

music)は、西洋古典音楽の様式運動であり、一般にロマン派時代(またはロマン主義時代)と呼ばれる19世紀の時期に関連する。1798年頃から

1837年頃まで西洋文化において顕著となった知的、芸術的、文学的運動であるロマン主義という広義の概念と密接な関係がある[1]。 ロマン派の作曲家たちは、個性的で、感情的で、劇的で、しばしばプログラム的な音楽を創り出そうとした。ロマン派の音楽は、表向きは自然、文学、詩、超自 然的要素、美術など、音楽以外の刺激に触発された(あるいはそれを呼び起こそうとした)ものが多かった[2]。半音階の増加などの特徴を含み、伝統的な形 式から離れていった[3]。 |

Josef Danhauser's 1840 painting of Franz Liszt at the piano surrounded by (from left to right) Alexandre Dumas, Hector Berlioz, George Sand, Niccolò Paganini, Gioachino Rossini and Marie d'Agoult, with a bust of Ludwig van Beethoven on the piano |

ヨーゼフ・ダンハウザーが1840年に描いた、アレクサンドル・デュマ、エクトル・ベルリオーズ、ジョルジュ・サンド、ニコロ・パガニーニ、ジョアキー ノ・ロッシーニ、マリー・ダグールに囲まれ、ピアノを弾くリストの絵と、ピアノの上に置かれたルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンの胸像。 |

| Background Main articles: Romanticism and Scholarship of Romanticism  Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, by Caspar David Friedrich, is an example of Romantic painting. The Romantic movement was an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe and strengthened in reaction to the Industrial Revolution.[4] In part, it was a revolt against social and political norms of the Age of Enlightenment and a reaction against the scientific rationalization of nature.[5] It was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, literature,[6] and education,[7] and was in turn influenced by developments in natural history.[8] One of the first significant applications of the term to music was in 1789, in the Mémoires by the Frenchman André Grétry, but it was E. T. A. Hoffmann who established the principles of musical romanticism, in a lengthy review of Ludwig van Beethoven's Fifth Symphony published in 1810, and an 1813 article on Beethoven's instrumental music. In the first of these essays Hoffmann traced the beginnings of musical Romanticism to the later works of Haydn and Mozart. It was Hoffmann's fusion of ideas already associated with the term "Romantic", used in opposition to the restraint and formality of Classical models, that elevated music, and especially instrumental music, to a position of pre-eminence in Romanticism as the art most suited to the expression of emotions. It was also through the writings of Hoffmann and other German authors that German music was brought to the center of musical Romanticism.[9] |

背景 主な記事 ロマン主義、ロマン主義の学問  カスパー・ダーヴィト・フリードリッヒの『霧の上の放浪者』は、ロマン主義絵画の代表作のひとつ。 ロマン主義は、18世紀後半にヨーロッパで発生し、産業革命に対する反動として強まった芸術、文学、思想の運動。[4] 一部では、啓蒙時代の社会的・政治的規範への反乱であり、自然の科学的合理化への反動でもあった。[5] これは視覚芸術、音楽、文学[6]、教育[7]において最も強く現れ、自然史の進展からも影響を受けた。[8] この用語が音楽に初めて重要に使用されたのは、1789年にフランス人アンドレ・グレトリの『回顧録』だったが、音楽ロマン主義の原則を確立したのは、 1810年に発表されたルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンの「第5交響曲」の長い評論と、1813年のベートーヴェンの器楽に関する記事で、E. T. A. ホフマンだっ た。これらのエッセイの最初のものにおいて、ホフマンは音楽的ロマン主義の起源をハイドンとモーツァルトの晩年の作品に遡らせた。ホフマンは、「ロマン ティック」という用語と既に結びついていたアイデアを融合させ、古典主義の抑制と形式性に反対する概念として位置付け、音楽、特に器楽をロマン主義におい て感情の表現に最も適した芸術として、卓越した地位に高めた。また、ホフマンや他のドイツの著者の著作を通じて、ドイツ音楽は音楽的ロマン主義の中心に据 えられるようになった。[9] |

| Traits The classical period often used short, even fragmentary, thematic material while the Romantic period tended to make greater use of longer, more fully defined and more emotionally evocative themes.[10] Characteristics often attributed to Romanticism: a new preoccupation with and surrender to nature;[11] a turn towards the mystic and supernatural, both religious and unearthly;[12] a focus on the nocturnal, the ghostly, the frightful, and terrifying;[13] a new attention given to national identity;[11] discontent with musical formulas and conventions;[11] a greater emphasis on melody to sustain musical interest;[14] increased chromaticism;[11] a harmonic structure based on movement from tonic to subdominant or alternative keys rather than the traditional dominant, and use of more elaborate harmonic progressions (Wagner and Liszt are known for their experimental progressions);[11] large, grand orchestras were common during this period;[11] increase in virtuosic players featured in orchestrations;[11] the use of new or previously not so common musical structures like the song cycle, nocturne, concert etude, arabesque, and rhapsody, alongside the traditional classical genres;[14] Program music became somewhat more common;[14] the use of a wider range of dynamics, for example from ppp to fff (from pianississimo, or very, very quiet to fortississimo, very, very loud), supported by large orchestration;[11] a greater tonal range (for example, using the lowest and highest notes of the piano);[11] In music, there is a relatively clear dividing line in musical structure and form following the death of Beethoven. Whether one counts Beethoven as a "romantic" composer or not, the breadth and power of his work gave rise to a feeling that the classical sonata form and, indeed, the structure of the symphony, sonata and string quartet had been exhausted.[15] |

特徴 古典派は、短く、断片的な主題素材を多用することが多かったのに対し、ロマン派は、より長く、より明確に定義され、より感情を刺激する主題をより多く用い ました。[10] ロマン主義にしばしば見られる特徴: 自然への新たな関心と自然への降伏[11] 宗教的および超自然的な神秘主義への転換[12] 夜、幽霊、恐ろしい、恐ろしいものへの注目[13] 国民的アイデンティティへの新たな関心[11] 音楽の定式や慣習への不満[11] 音楽的な興味を維持するためのメロディの強調[14] 半音階の使用の増加[11] 伝統的なドミナントではなく、トニックからサブドミナントまたは代替調への動きに基づく和声構造、およびより精巧な和声進行の使用(ワーグナーとリストは 実験的な進行で知られている)[11] この時代には、大規模で壮大なオーケストラが一般的だった。[11] オーケストラの編曲に、技巧に優れた演奏家が登場するようになった。[11] 伝統的な古典的なジャンルと並んで、歌曲集、夜想曲、コンサート・エチュード、アラベスク、狂詩曲など、新しい、またはこれまであまり一般的ではなかった 音楽形式が採用された。[14] プログラム音楽がやや一般的になった。[14] ダイナミクスの範囲が広くなり、例えばppp(ピアニッシモ、非常に静か)からff(フォルティッシモ、非常に大きい)まで、大規模なオーケストレーショ ンによって支えられた。[11] 音域が広くなった(例えば、ピアノの最低音と最高音を使用)。[11] 音楽において、ベートーヴェンの死後、音楽の構造と形式には比較的明確な境界線が引かれるようになった。ベートーヴェンを「ロマン派」の作曲家とみなすか どうかに関わらず、彼の作品の幅広さと力強さは、古典的なソナタ形式、そして実際、交響曲、ソナタ、弦楽四重奏曲の構造が尽きたという感覚を生んだ。 [15] |

| Trends of the 19th century Non-musical influences Events and changes in society such as ideas, attitudes, discoveries, inventions, and historical events often affect music. For example, the Industrial Revolution was in full effect by the late 18th century and early 19th century. This event profoundly affected music: there were major improvements in the mechanical valves and keys that most woodwinds and brass instruments depend on. The new and innovative instruments could be played with greater ease and they were more reliable.[16] Another development that affected music was the rise of the middle class.[2] Composers before this period lived under the patronage of the aristocracy. Many times their audience was small, composed mostly of the upper class and individuals who were knowledgeable about music.[16] The Romantic composers, on the other hand, often wrote for public concerts and festivals, with large audiences of paying customers, who had not necessarily had any music lessons.[16] Composers of the Romantic Era, like Elgar, showed the world that there should be "no segregation of musical tastes"[17] and that the "purpose was to write music that was to be heard".[18] "The music composed by Romantic [composers]" reflected "the importance of the individual" by being composed in ways that were often less restrictive and more often focused on the composer's skills as a person than prior means of writing music.[2] |

19世紀の傾向 音楽以外の影響 思想、態度、発見、発明、歴史的出来事などの社会的な出来事や変化は、しばしば音楽に影響を与える。例えば、18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけて、産業 革命が本格化した。この出来事は音楽に大きな影響を与えた。木管楽器や金管楽器の多くが依存する機械式バルブやキーに大幅な改良が加えられた。新しい革新 的な楽器は、より簡単に演奏でき、信頼性も高まった。[16] 音楽に影響を与えたもう一つの発展は、中産階級の台頭だった。[2] この時代以前の作曲家は、貴族の庇護の下で生活していた。多くの場合、彼らの聴衆は、上流階級や音楽に精通した個人で構成される少人数だった。[16] ロマン派の作曲家たちは、一方、有料の聴衆を前にした公開コンサートやフェスティバル向けに作曲することが多く、聴衆は必ずしも音楽の教育を受けていない 人々だった。[16] ロマン派の作曲家たちは、エルガーのように、「音楽の趣味の分離はない」[17] ことを示し、「聴かれるための音楽を書くことが目的」だと主張した。[18] 「ロマン派の作曲家たちによって作曲された音楽」は、それまでの作曲手法よりも制限が少なく、作曲家の人格に焦点を当てた作曲手法が多く採用され、「個人 の重要性」を反映していた[2]。 |

| Nationalism Main article: Musical nationalism During the Romantic period, music often took on a much more nationalistic purpose. Composers composed with a distinct sound that represented their home country and traditions. For example, Jean Sibelius' Finlandia has been interpreted to represent the rising nation of Finland, which would someday gain independence from Russian control.[19] Frédéric Chopin was one of the first composers to incorporate nationalistic elements into his compositions. Joseph Machlis states, "Poland's struggle for freedom from tsarist rule aroused the national poet in Poland. ... Examples of musical nationalism abound in the output of the Romantic era. The folk idiom is prominent in the Mazurkas of Chopin".[20] His mazurkas and polonaises are particularly notable for their use of nationalistic rhythms. Moreover, "During World War II the Nazis forbade the playing of ... Chopin's Polonaises in Warsaw because of the powerful symbolism residing in these works".[20] Other composers, such as Bedřich Smetana, wrote pieces that musically described their homelands. In particular, Smetana's Vltava is a symphonic poem about the Moldau River in the modern-day Czech Republic, the second in a cycle of six nationalistic symphonic poems collectively titled Má vlast (My Homeland).[21] Smetana also composed eight nationalist operas, all of which remain in the repertory. They established him as the first Czech nationalist composer as well as the most important Czech opera composer of the generation who came to prominence in the 1860s.[22] |

ナショナリズム 主な記事:音楽的ナショナリズム ロマン派時代、音楽はよりナショナリズム的な目的を帯びるようになった。作曲家は、自国や伝統を表す独特の音色を使って作曲した。例えば、ジャン・シベリ ウスの「フィンランディア」は、いつかロシアの支配から独立するフィンランドの台頭を表現したものだと解釈されている。[19] フレデリック・ショパンは、作曲にナショナリズム的な要素を取り入れた最初の作曲家の一人です。ジョセフ・マクリス氏は、「ポーランドの皇帝支配からの解 放闘争は、ポーランドの国民的詩人を刺激した。... 音楽的ナショナリズムの例は、ロマン主義時代の作品に数多く見られます。ショパンのマズルカでは、民謡の表現手法が顕著だ」と述べています。[20] 彼のマズルカやポロネーズは、ナショナリズム的なリズムの使用で特に有名です。さらに、「第二次世界大戦中、ナチスは、これらの作品に込められた強力な象 徴性から、ワルシャワでのショパンのポロネーズの演奏を禁止した」と述べています。[20] ベドジフ・スメタナなどの他の作曲家も、故郷を音楽で表現した作品を作曲した。特に、スメタナの「モルドヴァ」は、現在のチェコ共和国にあるモルダウ川を 題材にした交響詩で、6つのナショナリズム的な交響詩の連作「我が祖国」の2番目。[21] スメタナは、8つのナショナリスト的なオペラも作曲しており、そのすべてがレパートリーとして残っています。これらの作品は、彼をチェコ初のナショナリス ト作曲家として、また1860年代に台頭した世代の中で最も重要なチェコ人オペラ作曲家としての地位を確立しました。[22] |

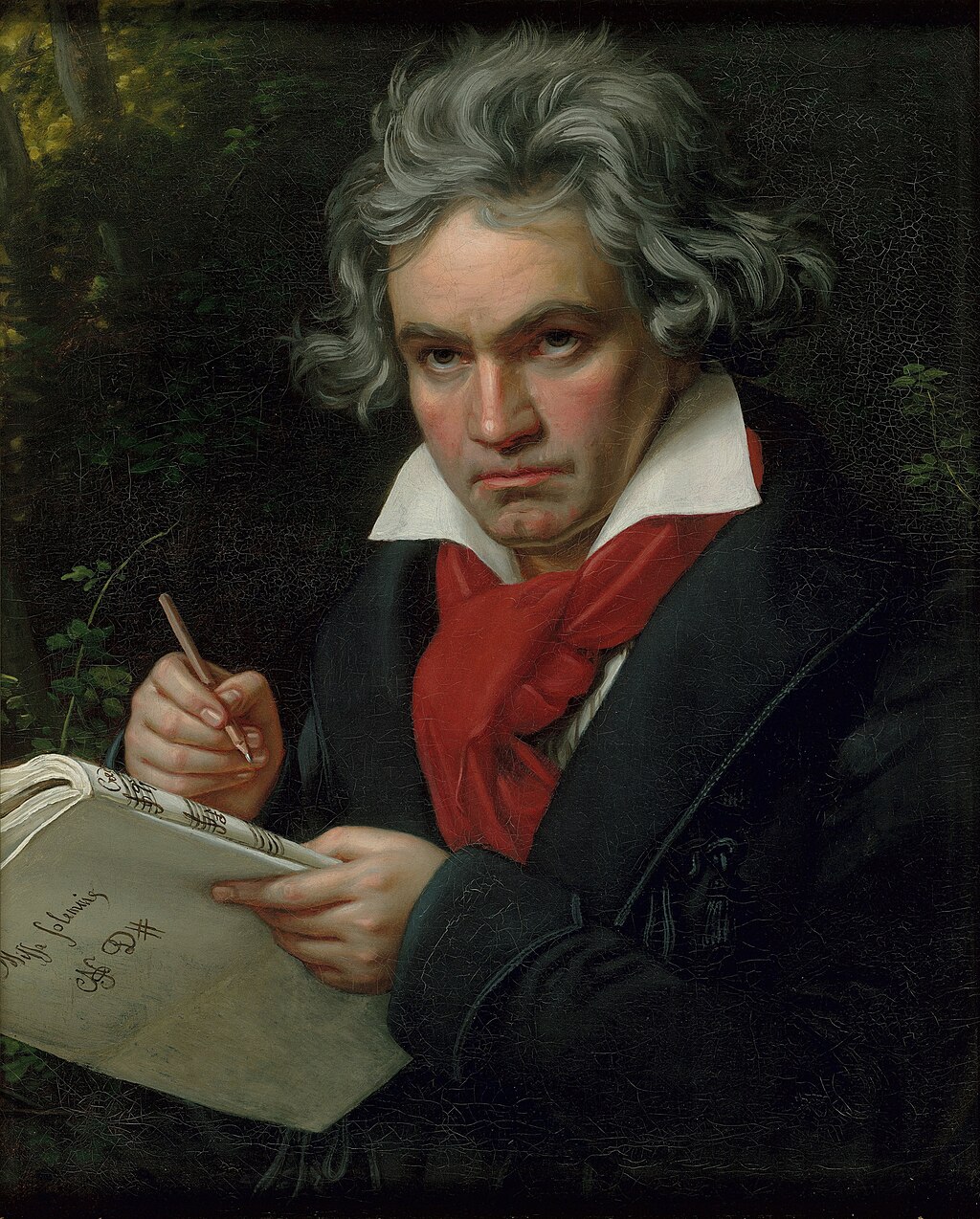

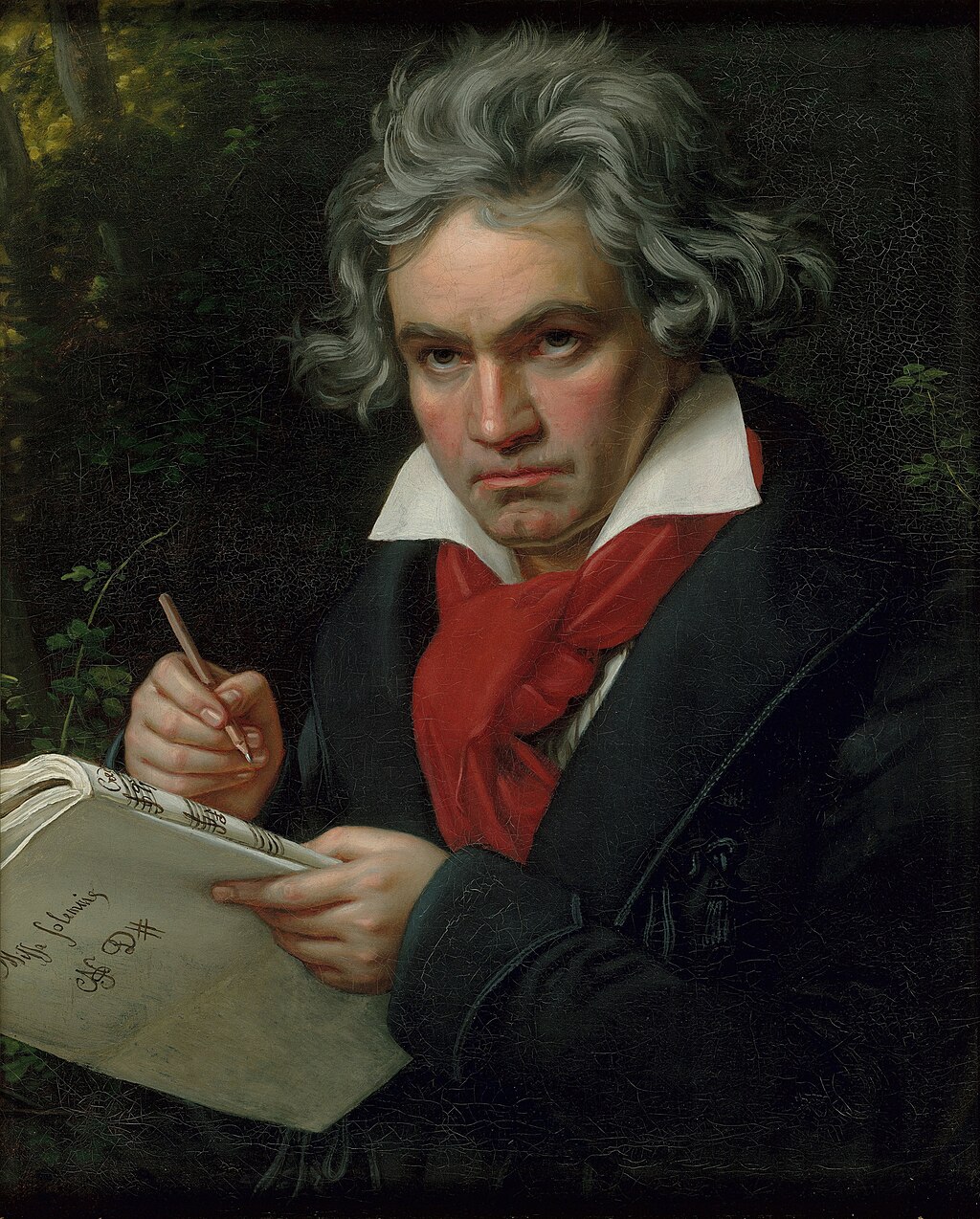

| History Early Romantic See also: Transition from Classical to Romantic music  Ludwig van Beethoven The transition of Viennese classicism to Romanticism can be found in the work of Ludwig van Beethoven. Many typically romantic elements are encountered for the first time in his works. These works stand here in contrast to vocal music and are "purely" instrumental music. According to Hoffmann, the pure instrumental music of Viennese classical music, especially that of Beethoven, since it is free of material or program, is the embodiment of the romantic art idea.[23] Another one of the most important representatives of late classicism and early romanticism is Franz Schubert. Because only with him did romantic features come into the German-language opera with his chamber music works and later also symphonies. In this field, his work is supplemented by the ballads of Carl Loewe. Carl Maria von Weber is important for the development of the German opera, especially with his popular Freischütz. In addition, there are fantastic-horrious materials by Heinrich Marschner and finally the cheerful opera by Albert Lortzing, while Louis Spohr became known mainly for his instrumental music. Still largely attached to classical music is the work of Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Ferdinand Ries, and the Frenchman George Onslow. Italy experienced the heyday of the Belcanto opera in early Romanticism, associated with the names of Gioachino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti, and Vincenzo Bellini. While Rossini's comic operas are primarily known today, often only through their rousing overtures, Donizetti and Bellini predominate tragic content. The most important Italian instrumental composer of this time was the legendary "devil's violinist" Niccolò Paganini. In France, on the one hand, the light Opéra comique developed, its representatives are François-Adrien Boieldieu, Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, and Adolphe Adam, the latter also known for his ballets. One can also quote the famous eccentric composer and harpist Robert Nicolas-Charles Bochsa (seven operas). In addition, the Grand opéra came up with pompous stage sets, ballets and large choirs. Her first representative was Gaspare Spontini, her most important Giacomo Meyerbeer. Music development has now also taken an upswing in other European countries. The Irishman John Field composed the first Nocturnes for piano, Friedrich Kuhlau worked in Denmark and the Swede Franz Berwald wrote four very idiosyncratic symphonies. |

歴史 初期ロマン派 参照:古典派からロマン派への移行  ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェン ウィーン古典派からロマン派への移行は、ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンの作品に見ることができます。彼の作品には、多くの典型的なロマン派の要素 が初めて登場しています。これらの作品は、声楽とは対照的に、「純粋な」器楽です。ホフマンによれば、ウィーン古典派の純粋な器楽、特にベートーヴェンの 作品は、素材やプログラムに縛られないため、ロマン主義の芸術観を体現したものだとしている[23]。後期古典派および初期ロマン主義のもう一人の重要な 代表者は、フランツ・シューベルトだ。彼によって初めて、ロマン主義の要素が、彼の室内楽曲、そして後に交響曲にも取り入れられ、ドイツ語オペラに登場し た。この分野では、カール・ローエのバラードが彼の作品を補完している。カール・マリア・フォン・ヴェーバーは、特に人気の高い「魔弾の射手」で、ドイツ オペラの発展に重要な役割を果たした。さらに、ハインリッヒ・マルシュナーの幻想的で恐ろしい作品、そしてアルベルト・ロルツィングの陽気なオペラがあ り、ルイ・スポールは主に器楽曲で知られるようになった。ヨハン・ネポムク・フンメル、フェルディナンド・リース、そしてフランス人のジョージ・オンス ローの作品は、依然としてクラシック音楽に大きく影響を受けている。 イタリアは、ジョアキーノ・ロッシーニ、ガエターノ・ドニゼッティ、ヴィンチェンツォ・ベッリーニといった人物たちとともに、ロマン主義初期にベルカン ト・オペラの全盛期を迎えた。今日では、ロッシーニの喜劇的なオペラが、その陽気な序曲で主に知られているが、ドニゼッティとベッリーニは悲劇的な内容の 作品が多い。この時代のイタリアで最も重要な器楽作曲家は、伝説の「悪魔のヴァイオリニスト」ニコロ・パガニーニだった。フランスでは、一方では軽快なオ ペラ・コミックが発展し、その代表者はフランソワ・アドリアン・ボワイルド、ダニエル・フランソワ・エスプリ・オーベール、そしてバレエでも有名なアドル フ・アダムだ。また、有名な風変わりな作曲家でありハープ奏者でもあるロバート・ニコラス・シャルル・ボクサ(7つのオペラ)も挙げることができる。さら に、壮大な舞台装置、バレエ、大規模な合唱を特徴とするグランド・オペラが登場した。その最初の代表者はガスパーレ・スポントーニで、最も重要な人物は ジャコモ・マイアベーアだった。 音楽の発展は、他のヨーロッパ諸国でも盛んになった。アイルランド人のジョン・フィールドは、最初のピアノのための「夜想曲」を作曲し、フリードリッヒ・ クーラウはデンマークで活躍し、スウェーデン人のフランツ・ベルヴァルドは、非常に独特な 4 つの交響曲を作曲した。 |

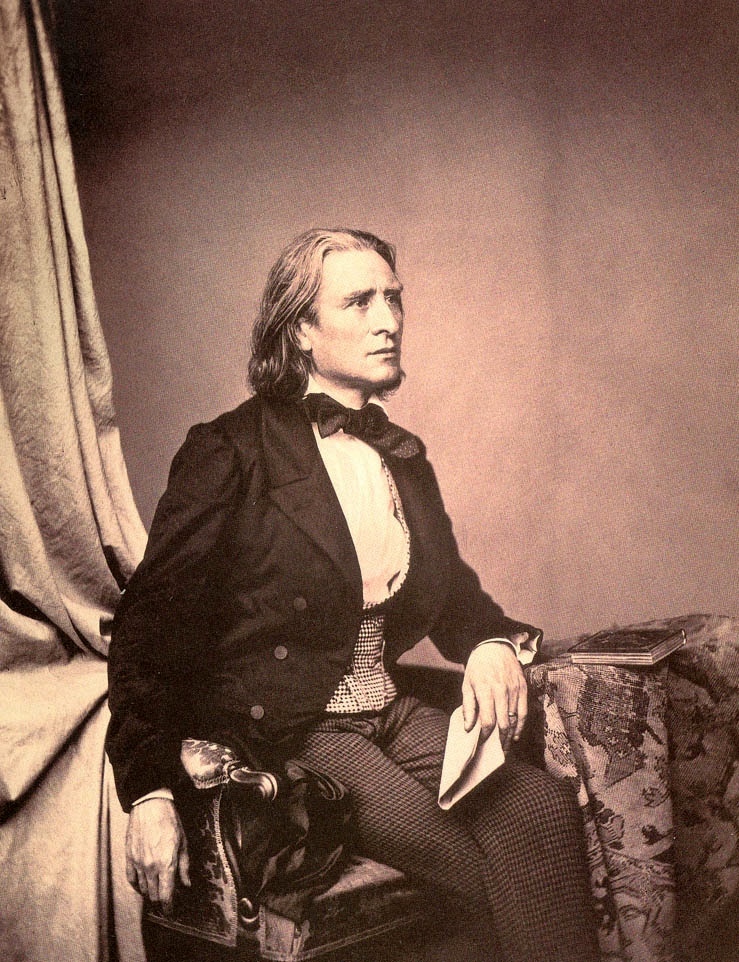

| High Romantic This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) See also: Neo-romanticism and War of the Romantics  A photograph of the upper half of a man of about fifty viewed from his front right. He wears a cravat and frock coat. He has long sideburns and his dark hair is receding at the temples. Richard Wagner in Paris, 1861 The high romanticism can be divided into two phases. In the first phase, the actual romantic music reaches its peak. The Polish composer Frédéric Chopin explored previously unknown depths of emotion in his character pieces and dances for piano. Robert Schumann, mentally immersed at the end of his life, represents in person as well as in music almost the prototype of the passionate romantic artist, shadowed by tragedy. His idiosyncratic piano pieces, chamber music works and symphonies should have a lasting influence on the following generation of musicians. Franz Liszt, who came from the German minority in Hungary, was on the one hand a swarmed piano virtuoso, but on the other hand also laid the foundation for the progressive "New German School" with his harmoniously bold symphonic poems. Also committed to program music was the technique of the Idée fixe (leitmotif) of the Frenchman Hector Berlioz, who also significantly expanded the orchestra. Felix Mendelssohn was again more oriented towards the classicist formal language and became a role model especially for Scandinavian composers such as the Dane Niels Wilhelm Gade. In opera, the operas of Otto Nicolai and Friedrich von Flotow still dominated in Germany when Richard Wagner wrote his first romantic operas. The early works of Giuseppe Verdi were also still based on the Belcanto ideal of the older generation. In France, the Opéra lyrique was developed by Ambroise Thomas and Charles Gounod. Russian music found its own language in the operas of Mikhail Glinka and Alexander Dargomyzhsky. The second phase of high romanticism runs in parallel with the style of realism in literature and the visual arts. In the second half of his creation, Wagner now developed his leitmotif technique, with which he holds together the four-part ring of the Nibelungen, composed without arias; the orchestra is treated symphonically, the chromaticism reaches its extreme in Tristan and Isolde. A whole crowd of disciples is under the influence of Wagner's progressive ideas, among them, for example, Peter Cornelius. On the other hand, an opposition arose from numerous more conservative composers, to whom Johannes Brahms, who sought a logical continuation of classical music in symphony, chamber music and song, became a model of scale due to the depth of the sensation and a masterful composition technique. Among others, Robert Volkmann, Friedrich Kiel, Carl Reinecke, Max Bruch, Josef Gabriel Rheinberger, and Hermann Goetz are included in this party. In addition, some important loners came on the scene, among whom Anton Bruckner particularly stands out. Although a Wagner supporter, his clear-form style differs significantly from that of that composer. For example, the block-based instrumentation of Bruckner's symphonies is derived from the registers of the organ. In the ideological struggle against Wagner's adversaries, he was portrayed by his followers as a counterpart of Brahms. Felix Draeseke, who originally wrote "future music in classical form" starting from Liszt, also stands between the parties in composition. Verdi also reached the way to a well-composed musical drama, albeit in a different way than Wagner. His immense charisma made all other composers fade in Italy, including Amilcare Ponchielli and Arrigo Boito, who was also the librettist of his late operas Otello and Falstaff. In France, on the other hand, the light muse triumphed first in the form of the socio-critical operettas of Jacques Offenbach. Lyrical opera found its climax in the works of Jules Massenet, while in the Carmen by Georges Bizet, realism came for the first time. Louis Théodore Gouvy built a stylistic bridge to German music. The operas, symphonies and chamber music works of the extremely versatile Camille Saint-Saëns were, as were the ballets of Léo Delibes, more tradition-oriented. New orchestra colors were found in the compositions of Édouard Lalo and Emmanuel Chabrier. The Belgian-born César Franck was accompanied by a revival of organ music, which was continued by Charles-Marie Widor, later Louis Vierne and Charles Tournemire. A specific national romanticism had by now emerged in almost all European countries. The national Russian current started by Glinka was continued in Russia by the "Group of Five": Mily Balakirev, Alexander Borodin, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and César Cui. More western oriented were Anton Rubinstein and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, whose ballets and symphonies gained great popularity. Bedřich Smetana founded Czech national music with his operas and the Symphony poems oriented towards Liszt. The symphonies, concerts and chamber music works of Antonín Dvořák, on the other hand, have Brahms as a model. In Poland, Stanisław Moniuszko was the leading opera composer, in Hungary Ferenc Erkel. Norway produced its best-known composers with Edvard Grieg, creator of lyrical piano works, songs and orchestral works such as the Peer-Gynt Suite; England's voice resonated with the Brahms-oriented Hubert Parry and symphonist, as well as the comic operas of Arthur Sullivan. |

ハイ・ロマン主義 このセクションには出典が記載されていません。信頼できる出典を追加して、このセクションを改善してください。出典が記載されていない内容は、削除される 可能性があります。(2024年11月) (このメッセージの削除方法についてはこちらをご覧ください) 参照:新ロマン主義、ロマン派戦争  50歳くらいの男性の上半身を正面から右側に見た写真。彼はネクタイとフロックコートを着ている。彼は長いもみあげがあり、黒髪はこめかみで後退してい る。 1861年、パリのリヒャルト・ワーグナー 高ロマン主義は2つの段階に分けることができる。最初の段階では、実際のロマン主義音楽が最盛期を迎える。ポーランドの作曲家フレデリック・ショパンは、 ピアノのための性格曲や舞曲で、それまで知られていなかった感情の深みを探求した。ロベルト・シューマンは、人生の終わりに精神的に没頭し、その人格と音 楽の両方で、悲劇の影を背負った情熱的なロマン派芸術家の原型をほぼ体現していた。彼の独特なピアノ曲、室内楽作品、交響曲は、次の世代の音楽家に永続的 な影響を与えた。 ハンガリーのドイツ人少数派出身のフランツ・リストは、一方では熱狂的なピアノの巨匠であり、他方では調和のとれた大胆な交響詩で進歩的な「新ドイツ楽 派」の基礎を築いた。プログラム音楽にコミットしたフランス人作曲家ヘクトル・ベルリオーズは、イデ・フィックス(レチタティーヴォ)の技法を採用し、 オーケストラの規模を大幅に拡大した。フェリックス・メンデルスゾーンは再び古典主義の形式言語に傾倒し、特にデンマークのニールス・ヴィルヘルム・ガデ のようなスカンジナビアの作曲家たちの模範となった。オペラでは、リヒャルト・ワーグナーが最初のロマンティック・オペラを執筆した当時、ドイツではオッ トー・ニコライとフリードリヒ・フォン・フロトのオペラが依然として主流だった。ジュゼッペ・ヴェルディの初期作品も、まだ旧世代のベルカントの理想に基 づいていました。フランスでは、アンブロワーズ・トマとシャルル・グノーによってオペラ・リリクが発展しました。ロシア音楽は、ミハイル・グリンカとアレ クサンダー・ダルゴミシュスキーのオペラで独自の表現方法を見出しました。 高ロマン主義の第 2 段階は、文学や視覚芸術におけるリアリズムのスタイルと並行して進行しました。創作活動の後半、ワーグナーは、アリアのない「ニーベルングの指輪」の 4 部構成を結びつける「ライトモチーフ」の技法を開発した。オーケストラは交響曲のように扱われ、「トリスタンとイゾルデ」では色彩表現が極限に達してい る。ワーグナーの進歩的な思想の影響を受けた弟子たちは、ピーター・コルネリウスなど、数多くいた。一方、より保守的な作曲家たちからは反対運動が起こ り、交響曲、室内楽、歌曲において古典音楽の論理的な継続を追求したヨハネス・ブラームスは、その深い感性と卓越した作曲技法により、この運動の模範と なった。この派には、ロベルト・フォルクマン、フリードリッヒ・キール、カール・ライネッケ、マックス・ブルッフ、ヨーゼフ・ガブリエル・ラインベル ガー、ヘルマン・ゲッツなどが属している。 さらに、いくつかの重要な孤独な人物も登場し、その中ではアントン・ブルックナーが特に際立っている。彼はワーグナーの支持者だったが、その明快な形式の スタイルは、ワーグナーのそれとは大きく異なる。例えば、ブルックナーの交響曲のブロックベースの楽器編成は、オルガンの音域から派生している。ワーグ ナーの敵対者たちとのイデオロギー闘争において、彼はその支持者たちからブラームスの対極にある人物として描かれた。もともとリストから「古典形式の未来 音楽」を志したフェリックス・ドレーゼケも、作曲の分野では両陣営の間に立ちました。 ヴェルディも、ワーグナーとは異なる方法で、よく構成された音楽劇への道を見出しました。彼の絶大なカリスマ性により、イタリアでは、アミルカーレ・ポン キエッリや、彼の晩年のオペラ「オテロ」と「ファルスタッフ」の台本を書いたアリゴ・ボイトなど、他の作曲家たちは皆、その存在感を失いました。一方、フ ランスでは、ジャック・オッフェンバッハの社会批判的なオペレッタの形で、軽やかなミューズが最初に勝利を収めた。リリック・オペラはジュール・マスネの 作品で頂点を迎え、ジョルジュ・ビゼーの『カルメン』では初めて現実主義が導入された。ルイ・テオドール・グーヴィは、ドイツ音楽へのスタイルの橋渡し役 を果たした。非常に多才なカミーユ・サン=サーンスのオペラ、交響曲、室内楽作品は、レオ・ドリーブのバレエ作品と同様、より伝統に重きを置いたものだっ た。エドゥアール・ラロとエマニュエル・シャブリエの作曲には、新しいオーケストラの色彩が見られた。ベルギー生まれのセザール・フランクは、オルガン音 楽の復活を伴い、その流れはシャルル=マリー・ヴィドール、後にルイ・ヴィエルヌ、シャルル・トゥルヌミールによって受け継がれた。 この頃には、ほぼすべてのヨーロッパ諸国において、それぞれの国特有のロマン主義が台頭していた。グリンカによって始まったロシアの国民的潮流は、ミ リー・バラキレフ、アレクサンダー・ボロディン、モデスト・ムソルグスキー、ニコライ・リムスキー=コルサコフ、セザール・クイからなる「五人組」によっ て引き継がれた。より西洋志向だったアントン・ルビンシュタインとピョートル・イリイチ・チャイコフスキーは、バレエ曲や交響曲で大きな人気を博した。ベ ドジフ・スメタナは、オペラやリストの影響を受けた交響詩で、チェコの国民音楽を創設した。一方、アントニン・ドヴォルザークの交響曲、協奏曲、室内楽作 品は、ブラームスをモデルとしている。ポーランドではスタニスワフ・モニウシュコがオペラ作曲家のリーダーであり、ハンガリーではフェレンツ・エルケルが 活躍した。ノルウェーは、抒情的なピアノ作品、歌曲、管弦楽作品『ペール・ギュント組曲』などの創作者であるエドヴァルド・グリーグを輩出した。イギリス では、ブラームスを模範としたハブート・パリーと交響曲作曲家、およびアーサー・サリヴァンの喜歌劇が響き渡った。 |

| Late Romantic See also: Post-romanticism  Middle-aged man, seated, facing towards the left but head turned towards the right. He has a high forehead, rimless glasses and is wearing a dark, crumpled suit Gustav Mahler, photographed in 1907 by Moritz Nähr at the end of his period as director of the Vienna Hofoper In late Romanticism, also called post-Romanticism, the traditional forms and elements of music are further dissolved. An increasingly colorful orchestral palette, an ever-increasing range of musical means, the spread of tonality to its limits, exaggerated emotions and an increasingly individual tonal language of the individual composer are typical features; the music is led to the threshold of modernity. Thus, the symphonies of Gustav Mahler reached previously unknown dimensions, partly give up the traditional four-sentence and often contain vocal proportions. But behind the monumental facade is the modern expressiveness of the Fin de siècle. This psychological expressiveness is also contained in the songs of Hugo Wolf, miniature dramas for voice and piano. More committed to tradition, particularly oriented towards Bruckner, are the symphonies of Franz Schmidt and Richard Wetz, while Max Reger resorted to Bach's polyphony in his numerous instrumental works, but developed it harmoniously extremely boldly. Among the numerous composers of the Reger successor, Julius Weismann and Joseph Haas stand out. Among the outstanding late romantic sound creators is also the idiosyncratic Hans Pfitzner. Although a traditionalist and decisive opponent of modern currents, quite a few of his works are quite close to the musical progress of the time. His successor include Walter Braunfels, who mainly emerged as an opera composer, and the symphonist Wilhelm Furtwängler. The opera stage was particularly suitable for increased emotions. The folk and fairy tale operas of Engelbert Humperdinck, Wilhelm Kienzl and Siegfried Wagner, the son of Richard Wagner, were still quite good. But even Eugen d'Albert and Max von Schillings irritated the nerves with a German variant of verism. Erotic symbolism can be found in the stage works of Alexander von Zemlinsky and Franz Schreker. Richard Strauss went even further to the limits of tonality with Salome and Elektra before he took more traditional paths with Der Rosenkavalier. In the style related to the works of Strauss, the compositions of Emil von Reznicek and Paul Graener are shown. In Italy, opera still dominated during this time. This is where verism developed, an exaggerated realism that could easily turn into the striking and melodramatic on the opera stage. Despite their extensive work, Ruggero Leoncavallo, Pietro Mascagni, Francesco Cilea, and Umberto Giordano have only become known through one opera at a time. Only Giacomo Puccini's work has been completely preserved in the repertoire of the opera houses, although he was also often accused of sentimentality. Despite some veristic works, Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari was mainly considered a revival of the Opera buffa. Ferruccio Busoni, a temporarily defender of modern classicity living in Germany, left behind a rather conventional, little played work. Thus, instrumental music actually only found its place in Italian music again with Ottorino Respighi, who was influenced by Impressionism. The term Impressionism comes from painting, and like there, it also developed in music in France. In the works of Claude Debussy, the structures dissolved into the finest nuances of rhythm, dynamics and timbre. This development was prepared in the work of Vincent d'Indy, Ernest Chausson and above all in the songs and chamber music of Gabriel Fauré. All subsequent French composers were more or less influenced by Impressionism. The most important among them was Maurice Ravel, a brilliant orchestral virtuoso. Albert Roussel first processed exotic topics before he anticipated Neoclassical tendencies like Ravel. Gabriel Pierné, Paul Dukas, Charles Koechlin, and Florent Schmitt also dealt with symbolic and exotic-oriental substances. The loner Erik Satie was the creator of spun piano pieces and idol of the next generation. Nevertheless, Impressionism is often attributed to the epoch of modernity, if not seen as its own epoch. Hubert Parry and the Irishman Charles Villiers Stanford initiated late Romanticism in England, which had its first important representative in Edward Elgar. While he revived the oratorio and wrote symphonies and concerts, Frederick Delius devoted himself to particularly small orchestral images with his own variant of Impressionism. Ethel Smyth wrote mainly operas and chamber music in a style that reminded Brahms. Ralph Vaughan Williams, whose works were inspired by English folk songs and Renaissance music, became the most important symphonist of his country. Gustav Holst incorporated Greek mythology and Indian philosophy into his work. Very idiosyncratic composer personalities in the transition to modernity were also Havergal Brian and Frank Bridge. In Russia, Alexander Glazunov decorated his traditional composition technique with a colorful orchestral palette. The mystic Alexander Scriabin dreamed of a synthesis of colors, sound and scents. Sergei Rachmaninov wrote melancholic-pathetic piano pieces and concertos full of intoxicating virtuosity, while the piano works of Nikolai Medtner are more lyrical. In the Czech Republic, Leoš Janáček, deeply rooted in the music of his Moravian homeland, found new areas of expression with the development of the language melody in his operas. The local sounds are also unmistakable in the music of Zdeněk Fibich, Josef Bohuslav Foerster, Vítězslav Novák, and Josef Suk. On the other hand, there is a slightly morbid exoticism and later classicist measure in the work of the Polish Karol Szymanowski. The most important Danish composer is Carl Nielsen, known for symphonies and concerts. Even more dominant in his country is the position of the Finn Jean Sibelius, also a symphonist of melancholy expressiveness and clear line design. In Sweden, the works of Wilhelm Peterson-Berger, Wilhelm Stenhammar, and Hugo Alfvén show a typical Nordic conservatism, and the Norwegian Christian Sinding also composed traditionally. The music of Spain also increased in popularity again after a long time, first in the piano works of Isaac Albéniz and Enrique Granados, then in the operas, ballets and orchestral works of Manuel de Falla, influenced by Impressionism. Finally, the first important representatives of the United States also appeared with Edward MacDowell and Amy Beach. But even the work of Charles Ives belonged only partly to late Romanticism - much of it was already radically modern and pointed far into the 20th century. |

後期ロマン主義 関連項目:ポストロマン主義  中年の男性が、左を向いて座っているが、頭は右を向いている。額が高く、縁のない眼鏡をかけ、しわの寄った暗い色のスーツを着ている。 グスタフ・マーラー、1907年にモーリッツ・ナーによって、ウィーン宮廷歌劇場の音楽監督としての任期を終えた頃に撮影された写真。 後期ロマン派(ポストロマン主義とも呼ばれる)では、音楽の伝統的な形式と要素がさらに解体される。色彩豊かな管弦楽のパレット、音楽的手段の多様化、調 性の限界への拡大、過剰な感情表現、作曲家の個性が際立つ調性の言語が特徴的で、音楽は現代の境界線に近づく。こうして、グスタフ・マーラーの交響曲は、 それまで知られていなかった次元へと到達し、伝統的な 4 楽章形式を部分的に放棄し、多くの場合、声楽的な要素も取り入れるようになった。しかし、その記念碑的な外観の背後には、フィン・ド・シークルの現代的な 表現力がある。この心理的な表現力は、声とピアノのためのミニチュア劇であるウーゴ・ヴォルフの歌曲にも含まれている。伝統に忠実で、特にブルックナーの 影響が強いのは、フランツ・シュミットとリヒャルト・ヴェッツの交響曲で、マックス・レーガーは、数多くの器楽曲でバッハのポリフォニーを採用したが、そ れを調和的に、かつ非常に大胆に発展させた。レーガーの後継者たちの中には、ユリウス・ワイズマンとヨーゼフ・ハースが際立っている。後期ロマン派の優れ た作曲家としては、独特な個性を発揮したハンス・プフィッツナーも挙げられる。彼は伝統主義者であり、現代的な潮流を断固として否定したが、彼の作品の多 くは、当時の音楽の流れにかなり近いものとなっている。彼の後継者としては、主にオペラ作曲家として頭角を現したヴァルター・ブラウンフェルス、交響曲作 曲家のヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーが挙げられる。オペラ舞台は、感情の高揚に特に適していた。エンゲルベルト・フンパーディンク、ヴィルヘルム・ キーンツル、リヒャルト・ワーグナーの息子ジークフリート・ワーグナーの民話や童話に基づくオペラは、依然としてかなり優れた作品だった。しかし、エウゲ ン・ダルベルトやマックス・フォン・シリングスも、ドイツ流のリアリズムで神経を刺激する作品を作った。アレクサンダー・フォン・ツェムリンスキーやフラ ンツ・シュレッカーの舞台作品には、エロティックな象徴主義が見られる。リヒャルト・シュトラウスは、「サロメ」や「エレクトラ」で調性の限界まで踏み込 んだ後、「ばらの騎士」でより伝統的な道に戻った。シュトラウスの作品に関連するスタイルとしては、エミール・フォン・レズニチェクやパウル・グレーナー の作曲が挙げられる。 この時代、イタリアでは依然としてオペラが主流だった。ここで、オペラ舞台では印象的でメロドラマ的なものになりやすい、誇張されたリアリズムであるヴェ リスモが発展した。ルッジェーロ・レオンカヴァッロ、ピエトロ・マスカーニ、フランチェスコ・チレア、ウンベルト・ジョルダーノは、その膨大な作品にもか かわらず、1つのオペラでしか知られていない。ジャコモ・プッチーニの作品だけが、オペラハウスのレパートリーに完全に保存されているが、彼も感傷的だと しばしば非難された。ヴェリズモの作品もいくつかあるものの、エルマーノ・ヴォルフ=フェラーリは主にオペラ・ブッファの復興派と見なされた。ドイツで一 時的に現代古典主義の擁護者だったフェルッチオ・ブゾーニは、比較的伝統的で演奏されることの少ない作品を残した。 thus, 楽器音楽は、印象派の影響を受けたオットリーノ・レスピーギによって、イタリア音楽において再びその地位を確立した。 印象派という用語は絵画から派生したもので、絵画と同様、音楽においてもフランスで発展した。クロード・ドビュッシーの作品では、構造がリズム、ダイナミ クス、音色の微妙なニュアンスに溶け込んだ。この発展は、ヴァンサン・ダンディ、エルネスト・ショーソン、そしてとりわけガブリエル・フォーレの歌曲や室 内楽作品によって準備された。その後のフランスの作曲家は、多かれ少なかれ印象派の影響を受けた。その中でも最も重要な人物は、華麗なオーケストラの巨 匠、モーリス・ラヴェルだ。アルベール・ルーセルは、ラヴェルと同様に新古典主義の傾向を先取りする前に、まずエキゾチックな題材を取り上げた。ガブリエ ル・ピエルネ、ポール・デュカス、シャルル・コックラン、フロラン・シュミットも、象徴的でエキゾチックな東洋の題材を取り上げた。孤独な作曲家、エリッ ク・サティは、紡ぎ出されるようなピアノ曲を生み出し、次世代のアイドルとなった。それにもかかわらず、印象派は、それ自体が時代を象徴するものと見なさ れない限り、しばしば現代という時代の特徴とみなされる。ヒューバート・パリーとアイルランド人のチャールズ・ヴィリアーズ・スタンフォードは、イギリス で後期ロマン主義を開始し、その最初の重要な代表者はエドワード・エルガーだった。フレデリック・デリウスは、オラトリオを復活させ、交響曲や協奏曲を作 曲する一方で、独自の印象派の手法を用いて、特に小規模のオーケストラのための作品に専心した。エセル・スミスは、ブラームスを彷彿とさせるスタイルで、 主にオペラや室内楽を作曲した。英国の民謡やルネサンス音楽から影響を受けたラルフ・ヴォーン・ウィリアムズは、英国で最も重要な交響曲作曲家となった。 グスタフ・ホルストは、ギリシャ神話やインディアン哲学を作品に取り入れた。近代への移行期に、非常に独特な作曲家として、ハーヴェルガル・ブライアンや フランク・ブリッジもいた。 ロシアでは、アレクサンダー・グラズノフが、伝統的な作曲技法に、色彩豊かなオーケストラのパレットで装飾を加えました。神秘主義者のアレクサンドル・ス クリャービンは、色、音、香りの融合を夢見ていました。セルゲイ・ラフマニノフは、憂鬱で哀愁に満ちたピアノ曲や、酔わせるような妙技に満ちた協奏曲を作 曲しましたが、ニコライ・メトネルのピアノ作品はより叙情的です。 チェコでは、モラヴィア地方の音楽に深く根ざしたレオシュ・ヤナーチェクが、オペラにおける言語の旋律の発展によって新しい表現領域を見出しました。ズデ ニェク・フィビヒ、ヨゼフ・ボフスラフ・フォエルスター、ヴィテズスラフ・ノヴァーク、ヨゼフ・スクの音楽にも、この地方特有の音色がはっきりと表れてい ます。一方、ポーランドのカロル・シマンフスキの作品には、やや陰鬱な異国情緒と後期の古典主義的な構成が見られる。デンマークで最も重要な作曲家は、交 響曲と協奏曲で知られるカール・ニールセンだ。同国では、フィンランドのジャン・シベリウスがさらに支配的な地位を占めており、彼は憂いを含んだ表現力と 明確な線描の交響曲作家としても知られている。スウェーデンでは、ヴィルヘルム・ペーターソン・ベルガー、ヴィルヘルム・ステンハンマル、ウーゴ・アルフ ヴェーンなどの作品が、典型的な北欧の保守主義を反映しており、ノルウェーのクリスチャン・シンディングも伝統的な作曲手法を採用していました。 スペインの音楽も、長い沈黙の後に再び人気を博しました。まず、イサック・アルベニスとエンリケ・グラナドスのピアノ作品、そして印象派の影響を受けたマ ヌエル・デ・ファラのオペラ、バレエ、オーケストラ作品で人気が復活しました。 最後に、エドワード・マクダウェルとエイミー・ビーチによって、アメリカ合衆国の最初の重要な代表者も登場した。しかし、チャールズ・アイヴズの作品も、 後期ロマン主義に属するのは一部に過ぎず、その多くは既に極めて現代的で、20世紀の遥か先を指し示していた。 |

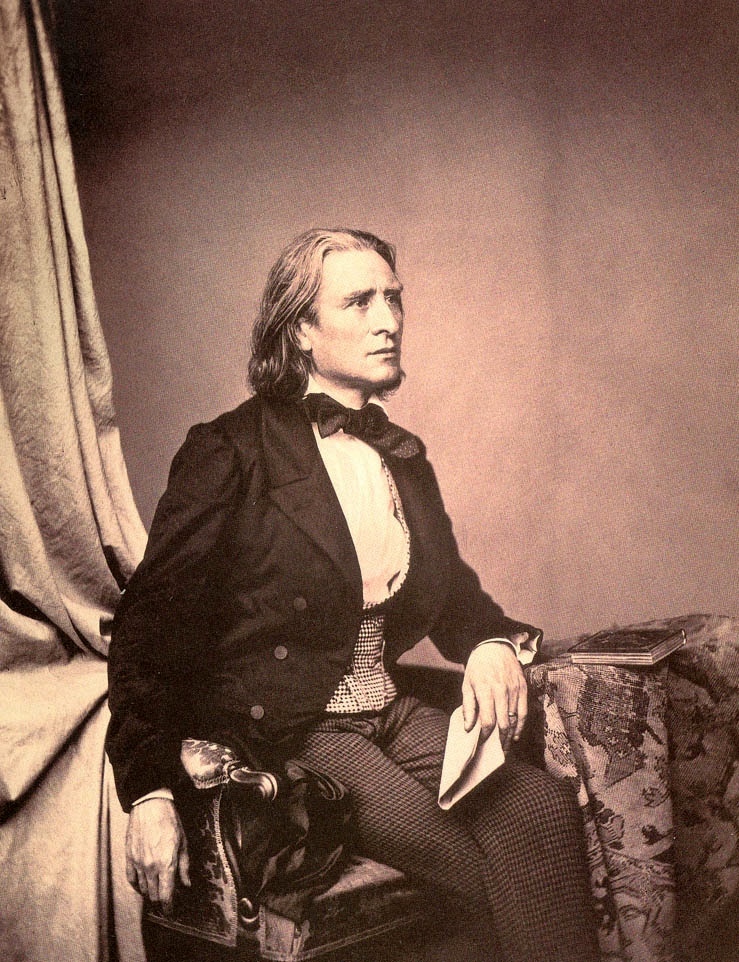

| Schools New German School Main article: New German School  Franz Liszt in 1858 by Franz Hanfstaengl The New German School was a loose collection of composers and critics informally led by Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner who strove for pushing the limits of chromatic harmony and program music as opposed to absolute music which they believed had reached its limit under Ludwig van Beethoven.[24] This group also pushed for the development and innovation of the symphonic poem, thematic transformation in musical form, and radical changes in tonality and harmony.[25] Other important members of this movement includes the critic Richard Pohl and composers Felix Draeseke, Julius Reubke, Karl Klindworth, William Mason, and Peter Cornelius. |

学校 新ドイツ楽派 主な記事:新ドイツ楽派  1858年のフランツ・リスト、フランツ・ハンフスタングル撮影 新ドイツ楽派は、フランツ・リストとリヒャルト・ワーグナーが非公式に率いた作曲家や批評家のゆるやかな集団で、ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンに よって限界に達したと彼らが考えていた絶対音楽とは対照的に、半音階的和声とプログラム音楽の可能性を追求した。[24] このグループは、交響詩、音楽形式における主題の変容、調性および和声の抜本的な変化の発展と革新も推進した。[25] この運動のその他の重要なメンバーには、批評家のリヒャルト・ポール、作曲家のフェリックス・ドレーゼケ、ユリウス・ロイプケ、カール・クリンドワルト、 ウィリアム・メイソン、ピーター・コルネリウスなどがいる。 |

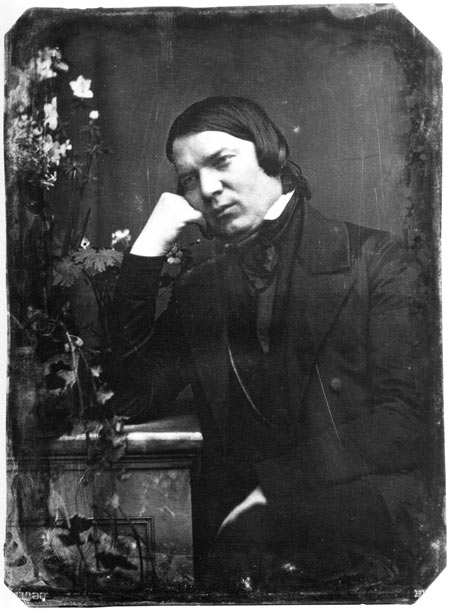

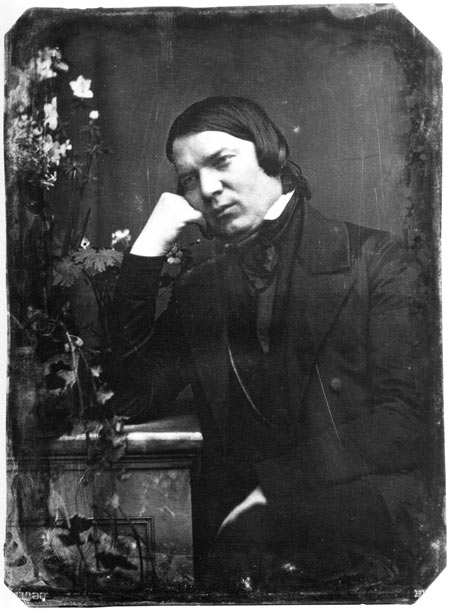

The German Conservatives Robert Schumann in an 1850 daguerreotype The conservatives were a broad group of musicians and critics who maintained the artistic legacy of Robert Schumann who adhered to composing and promoting absolute music.[26] They believed in continuing along the footsteps of Ludwig van Beethoven of composing the symphony genre in the classical mold, though they would implement their own musical language.[27] The most prominent members of this circle were Johannes Brahms, Joseph Joachim, Clara Schumann, and the Leipzig Conservatoire, which had been founded by Felix Mendelssohn. |

ドイツの保守派 1850年のダゲレオタイプに写るロベルト・シューマン 保守派は、絶対音楽作曲と普及に専心したロベルト・シューマンの芸術的遺産を継承する、幅広い音楽家や評論家たちからなるグループだった[26]。 彼らは、独自の音楽言語を取り入れながらも、ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンの足跡をたどり、古典的な形式の交響曲作曲を継続すべきだと考えてい た。[27] このサークルで最も著名なメンバーは、ヨハネス・ブラームス、ヨーゼフ・ヨアヒム、クララ・シューマン、そしてフェリックス・メンデルスゾーンによって設 立されたライプツィヒ音楽院だった。 |

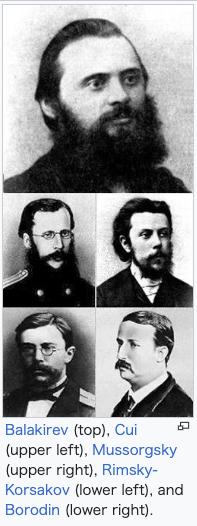

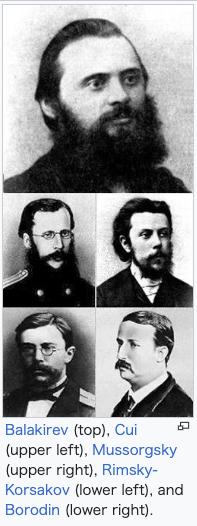

| The Mighty Five Main article: The Five (composers)  Balakirev (top), Cui (upper left), Mussorgsky (upper right), Rimsky-Korsakov (lower left), and Borodin (lower right). The Mighty Five were a group of Russian composers centered in Saint Petersburg who collaborated with each other from 1856 to 1870 to create a distinctly Russian national style of classical music. They were often at odds with Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky who favored a more Western approach to classical composition. Led by Mily Balakirev the group's main members also consisted of César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Borodin. The Belyayev Circle Main article: Belyayev circle The Belyayev circle was a society of Russian musicians who met in Saint Petersburg from 1885 and 1908 who sought to continue the development of the national Russian style of classical music following in the footsteps of the Mighty Five although they were far more tolerant of the Western compositional style of Tchaikovsky. This group was founded by Russian music publisher philanthropist Mitrofan Belyayev. The two most important composers of this group were Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov. Members also included Vladimir Stasov, Anatoly Lyadov, Alexander Ossovsky, Witold Maliszewski, Nikolai Tcherepnin, Nikolay Sokolov, and Alexander Winkler. |

マイティ・ファイブ 主な記事:5人組(作曲家)  バラキレフ(上)、クイ(左上)、ムソルグスキー(右上)、リムスキー=コルサコフ(左下)、ボロディン(右下)。 マイティ・ファイブは、1856年から1870年にかけて、サンクトペテルブルクを拠点に、ロシア独自の国民的クラシック音楽スタイルを確立するために協 力し合った作曲家グループ。より西洋的なクラシック作曲手法を好んだピョートル・イリイチ・チャイコフスキーとはしばしば対立した。 ミリー・バラキレフがリーダーを務め、主なメンバーは、チェザール・クイ、モデスト・ムソルグスキー、ニコライ・リムスキー=コルサコフ、アレクサン ダー・ボロディンで構成されていた。 ベリャエフサークル 主な記事:ベリャエフサークル ベリャエフサークルは、1885年から1908年までサンクトペテルブルクで集まったロシアの音楽家たちによる団体で、強大な5人組に続き、ロシアの国民 的なクラシック音楽の発展を目指した。 このグループは、ロシアの音楽出版者であり慈善家でもあるミトロファン・ベリャエフによって設立された。このグループで最も重要な作曲家は、ニコライ・リ ムスキー=コルサコフとアレクサンドル・グラズノフの二人だ。メンバーには、ウラジーミル・スタソフ、アナトリー・リアドフ、アレクサンドル・オソフス キー、ヴィトルト・マリシェフスキ、ニコライ・チェレプニン、ニコライ・ソコロフ、アレクサンドル・ウィンクラーなどもいた。 |

| Transition to Modernism During the later half of the 19th Century, some prominent composers began exploring the limits of the traditional tonal system. Important examples include Tristan und Isolde[28] by Richard Wagner and Bagatelle sans tonalité[29] by Franz Liszt. This limit was finally reached during the Late Romantic period where progressive tonality is demonstrated in the works of composers such as Gustav Mahler.[30] With these developments, Romanticism finally began to break apart into several new parallel movements forming in response, bringing way to Modernism. Some notable movements to form in response to Romanticism's collapse include Expressionism with Arnold Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School being its main promoters and Primitivism with Igor Stravinsky being its most influential composer. |

モダニズムへの移行 19世紀後半、一部の著名な作曲家は、伝統的な調性システムの限界を探求し始めた。その代表的な例としては、リヒャルト・ワーグナーの『トリスタンとイゾ ルデ』[28] やフランツ・リストの『無調のバガテル』[29] が挙げられる。この限界は、グスタフ・マーラーなどの作曲家の作品に進行的な調性が表れる後期ロマン主義時代にようやく到達した。[30] こうした展開により、ロマン主義はついに崩壊し、それに応じていくつかの新しい並行した運動が形成され、モダニズムへと道を開いた。 ロマン主義の崩壊を受けて形成された注目すべき運動としては、アーノルド・シェーンベルクを主な推進者とする表現主義と、イゴール・ストラヴィンスキーを 最も影響力のある作曲家とするプリミティヴィズムがある。 |

| Genres Symphony Main article: Symphony Carried to the highest degree by Ludwig van Beethoven, the symphony becomes the most prestigious form to which many composers devote themselves. The most conservative respect to the Beethovenian model includes composers such as Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Camille Saint-Saëns, and Johannes Brahms. Others show an imagination that makes them go beyond this framework, in form or in the spirit: the most daring of them being Hector Berlioz. Finally, some will also tell a story throughout their symphonies; like Franz Liszt, they will create the symphonic poem, a new musical genre, usually composed of a single movement and inspired by a theme, character or literary text. Since the symphonic poem is articulated around a leitmotiv (musical motif to identify a character, the hero for example), it is to be compared to music with a symphonic program. |

ジャンル 交響曲 主な記事:交響曲 ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンによって最高潮に達した交響曲は、多くの作曲家が専心する最も権威のある形式となった。ベートーヴェンのモデルに最 も忠実な作曲家としては、フランツ・シューベルト、フェリックス・メンデルスゾーン、ロベルト・シューマン、カミーユ・サン=サーンス、ヨハネス・ブラー ムスなどが挙げられる。一方、形式や精神においてこの枠組みを超えた想像力を発揮した作曲家もおり、その最も大胆な例としては、ヘクトル・ベルリオーズが 挙げられる。 最後に、交響曲を通して物語を語る作曲家も現れる。フランツ・リストのように、彼らは、通常 1 つの楽章で構成され、テーマ、登場人物、文学作品から着想を得た、新しい音楽ジャンルである交響詩を創作する。交響詩は、ライトモチーフ(登場人物、例え ば主人公などを識別するための音楽的モチーフ)を中心に構成されているため、交響的プログラム音楽と比較することができる。 |

| Lied Main article: Lied This musical genre appeared with the evolution from pianoforte to piano during the romantic period. The lied is vocal music most often accompanied by this instrument. The singing is taken from romantic poems and this style makes it possible to bring the voice as close to feelings as possible. One of the first and most famous lieder composers is Franz Schubert, with Erlkönig, however, many other romantic composers have devoted themselves to the lied genre such as Saint-Saëns, Duparc, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Hugo Wolf, Gustav Mahler, and Richard Strauss. |

リート 主な記事:リート この音楽ジャンルは、ロマン派時代にピアノフォルテからピアノへと進化する過程で登場した。リートは、この楽器の伴奏を伴うことが多い声楽である。歌はロ マンチックな詩から引用されており、このスタイルにより、声を感情にできるだけ近づけることができる。リートの作曲家として最初で最も有名なのは、エルク 王の歌で知られるフランツ・シューベルトだけど、サン=サーンス、デュパルク、ロベルト・シューマン、ヨハネス・ブラームス、ウーゴ・ヴォルフ、グスタ フ・マーラー、リヒャルト・シュトラウスなど、多くのロマン派作曲家がリートのジャンルに専心した。 |

| Concerto Main article: Concerto It is Beethoven who inaugurates the romantic concerto, with his five piano concertos (especially the fifth) and his violin concerto where many characteristics of classicism can still be recognized. His example is followed by many composers: the concerto rivals the symphony in the repertoire of major orchestral formations. Finally, the concerto will allow instrumentalist composers to reveal their virtuosity, such as Niccolò Paganini on the violin, and Frédéric Chopin, Robert Schumann, and Franz Liszt on the piano. |

協奏曲 主な記事:協奏曲 ロマン派の協奏曲を開拓したのはベートーヴェンで、5つのピアノ協奏曲(特に第5番)や、古典主義の特徴がまだ多く残るヴァイオリン協奏曲があります。彼 の例に倣って、多くの作曲家が協奏曲を作曲し、協奏曲は、主要なオーケストラのレパートリーにおいて、交響曲と肩を並べる存在となりました。 そして、このコンチェルトによって、ヴァイオリンのニコロ・パガニーニ、ピアノのフレデリック・ショパン、ロベルト・シューマン、フランツ・リストなど、 楽器の作曲家たちがその妙技を披露する場となった。 |

| Rhapsody Main article: Rhapsody (music) A rhapsody in music is a one-movement work that is episodic yet integrated, free-flowing in structure, featuring a range of highly contrasted moods, colour, and tonality. An air of spontaneous inspiration and a sense of improvisation make it freer in form than a set of variations. |

ラプソディ 主な記事:ラプソディ(音楽) 音楽におけるラプソディとは、1楽章からなる、エピソード的でありながら統合された、自由で流れるような構造を持つ作品で、対照的な雰囲気、色彩、調性な どが特徴的だ。即興的なインスピレーションと即興演奏のような感覚が、一連の変奏曲よりも形式的に自由である。 |

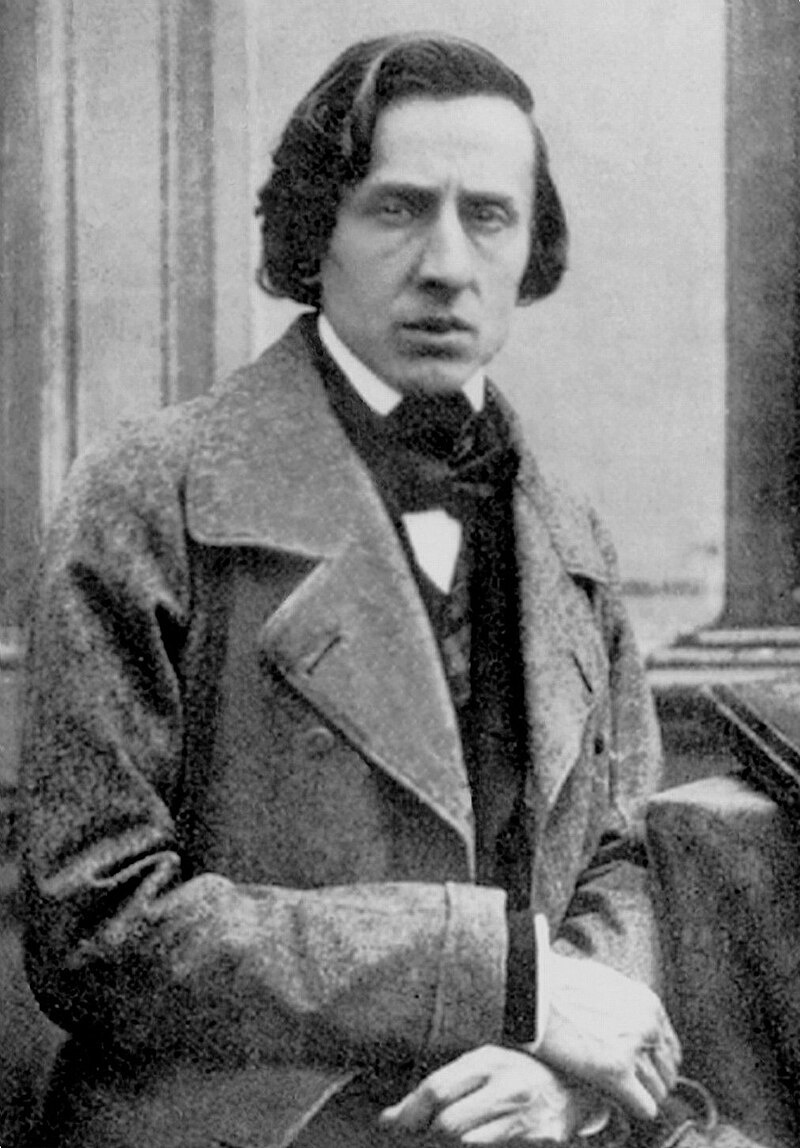

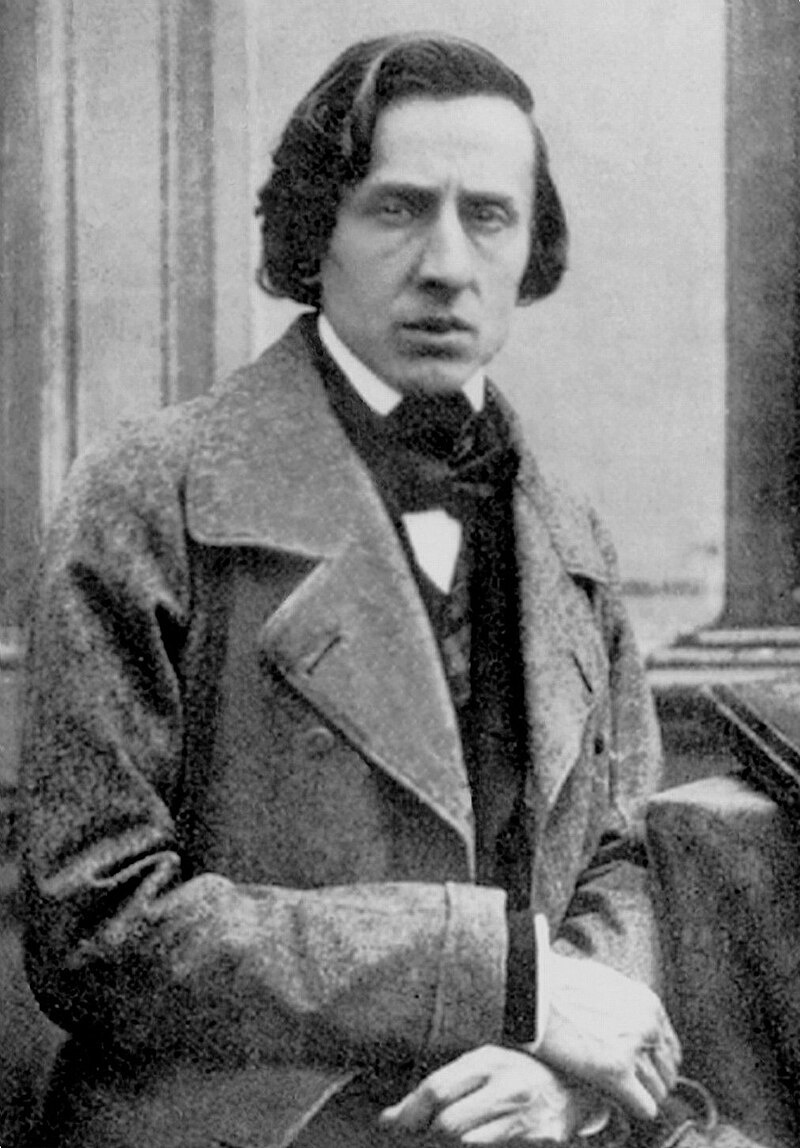

| Nocturne Main article: Nocturne  Daguerreotype of Chopin, c. 1849 The nocturne is presented as a short-lived confidential piece, which the Irish composer John Field was one of the first to cultivate. Immersed in the climate of the night, an atmosphere privileged by romantics, it is often of ABA structure, with a very flexible and ornate melody, accompanied by a left hand with undulating arpeggios. The tempo is usually slow, and the central part is often more agitated. Frédéric Chopin has set the most famous form of the nocturnes. He wrote 21, from 1827 to 1846. First published in series of three (opus 9 and 15), they are then grouped in pairs (opus 27, 32, 37, 48, 55, 62). |

ノクターン 主な記事:ノクターン  ショパンのダゲレオタイプ、1849年頃 ノクターンは、アイルランドの作曲家ジョン・フィールドが最初に育てた、短命で秘密の曲として紹介されている。ロマン派が好んだ夜の雰囲気に浸ったこの曲 は、ABA形式が多く、非常に柔軟で装飾的なメロディと、うねるようなアルペジオの左手で伴奏される。テンポは通常ゆっくりで、中央部はより激しさが増す ことが多い。 フレデリック・ショパンは、ノクターンの最も有名な形式を確立した。彼は1827年から1846年にかけて21曲を作曲した。最初に3曲ずつシリーズで出 版された(作品9と15)後、2曲ずつグループ化されて出版された(作品27、32、37、48、55、62)。 |

| Ballet Main article: Romantic ballet The Romantic ballet was developed throughout the 19th century, especially by composers such as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in Russia and Léo Delibes in France. |

バレエ 主な記事:ロマンティック・バレエ ロマンティック・バレエは、19世紀を通じて、特にロシアのピョートル・イリイチ・チャイコフスキーやフランスのレオ・ドリーブなどの作曲家によって発展 した。 |

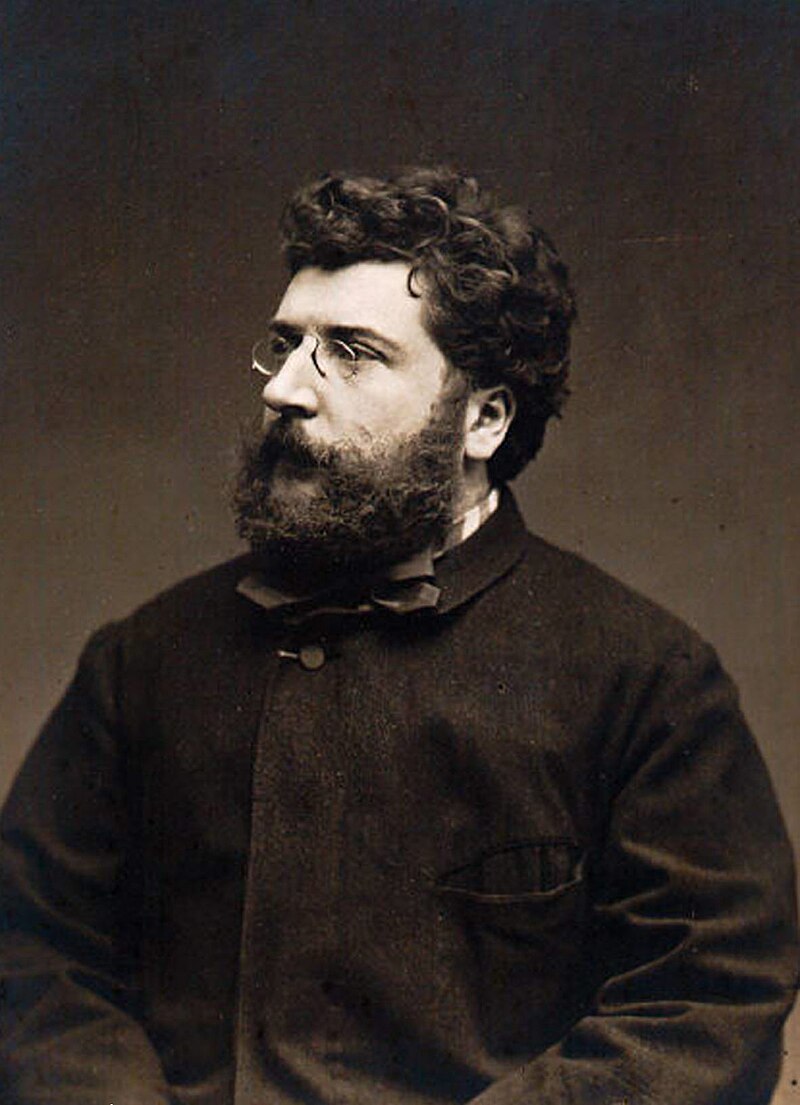

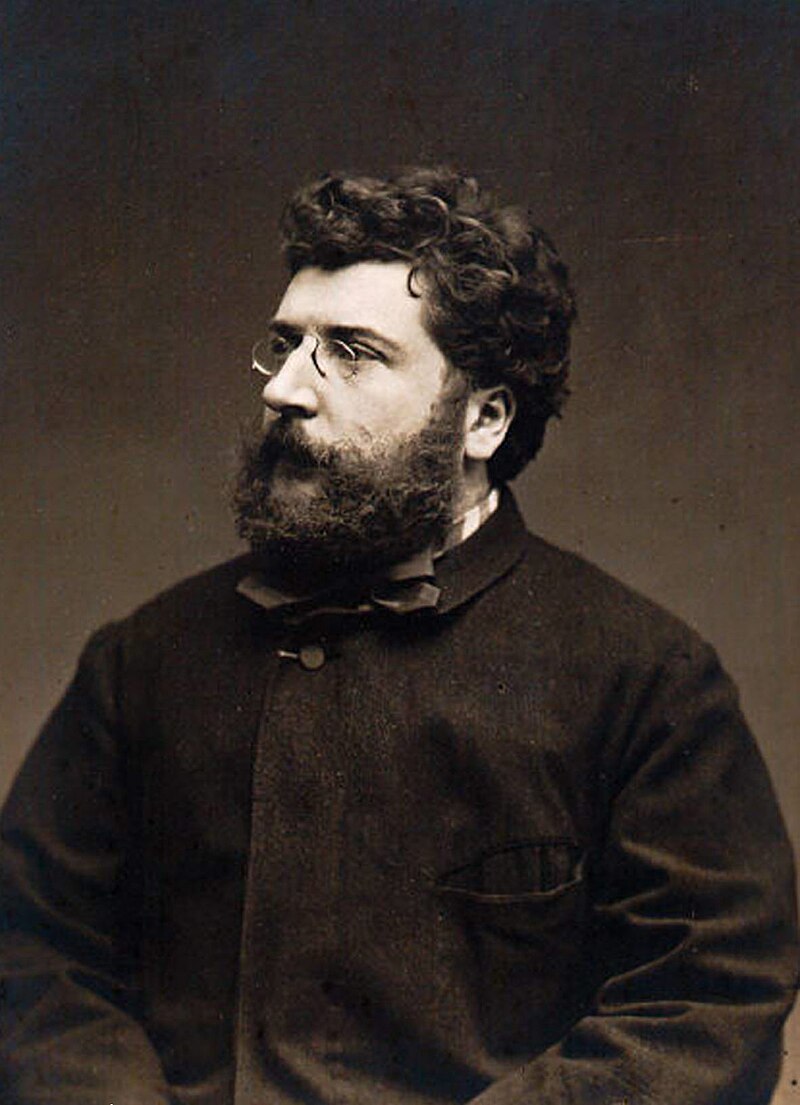

| Opera Main article: Opera France Main article: French opera  Bizet photographed by Étienne Carjat (1875) During the 19th century, romanticism took a hold of opera and it was Paris that became one of its main centers. Most romantic operas were composed by composers living in France, such as Luigi Cherubini, Gaspare Spontini, François-Adrien Boieldieu, and Daniel-François-Esprit Auber. The apogee of the style of great operas is marked by the works of Giacomo Meyerbeer. Hector Berlioz's Les Troyens was first ignored, Benvenuto Cellini is consputed during the premiere, while Charles Gounod's Faust is one of the most popular French operas of the mid-19th century. During the second part of the 19th century, Georges Bizet will revolutionize opera with Carmen: "local color based on the use of Spanish songs and dances" according to Nietzsche, it is "a ray of Mediterranean light dissipating the fog of the Wagnerian ideal". Interest in "local color" works is confirmed with Lakmé by Léo Delibes, and Samson and Dalila by Camille Saint-Saëns. The most productive French composer of operas of the last part of the century was Jules Massenet composing works such as Manon, Werther, and Thaïs. Jacques Offenbach, who composed Les Contes d'Hoffmann, established himself as the master of French opera-comique of the 19th century, inventing a new genre, the French opéra bouffe, which later was confused with the operetta. At the beginning of the 20th century, romanticism in France was gradually abandoned in favor of other currents such as Impressionism or symbolism, carried in particular by Claude Debussy's Pelléas and Mélisande (1902). Germany Main article: Opera in German Carl Maria von Weber, with Der Freischütz (1821) creates the first German romantic opera; the first important opera being Beethoven's Fidelio (1805), the only operatic work of this composer. Richard Wagner, from the Der fliegende Holländer, introduces the leitmotiv and the "cyclical melody" process. He revolutionizes opera by duration and instrumental power. His major work, Tetralogy is one of the summits of German opera. He creates the "musical drama" in which the orchestra now becomes the protagonist in the same way as the characters. In 1876, the Bayreuth Festival was created dedicated to the exclusive representation of Wagner's works. Wagner's influence continues in virtually all operas, even in Hänsel und Gretel by Engelbert Humperdinck. The dominant figure is then Richard Strauss, who uses orchestration and vocal techniques similar to those of Wagner in Salome and Elektra while developing his own path. Der Rosenkavalier is the work of Strauss that had the most flamboyant success at the time. Italy Main article: Italian opera  The iconic[31] Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi (1886) by Giovanni Boldini Italian romanticism begins with Gioachino Rossini who composed works such as The Barber of Seville and La Cenerentola. He created the "bel canto" style, a style adopted by his contemporaries Vincenzo Bellini and Gaetano Donizetti. However, the face of Italian opera is Giuseppe Verdi whose Nabucco's slave choir is a very important hymn to all of Italy. The trilogy formed by Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La traviata are among his major works but he reaches the peak of his art with Otello and Falstaff at the end of his career. He has infuled his works with unparalleled dramatic vigour and rhythmic vitality. In the second part of the 19th century, Giacomo Puccini, Verdi's undisputed successor, transcends realism into verism. La Bohème, Tosca, Madame Butterfly, and Turandot are melodic operas loaded with emotion. Other countries Other works of national inspiration: In Russia, a national school is developing with Mikhail Glinka who composed A Life for the Tsar, Ruslan and Ludmila. Other great Russian works: Sadko by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Prince Igor by Alexander Borodin, Boris Godunov by Modest Mussorgsky, Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades by Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky. In the Czech Republic, the national spirit is embodied by The Bartered Bride of Bedřich Smetana, Rusalka of Antonín Dvořák, Šárka of Zdeněk Fibich, and Jenůfa of Leoš Janáček. In Great Britain, Michael William Balfe, who composed The Bohemian Girl, the British romantic opera par excellence. He also composes for the French scene. |

オペラ 主な記事:オペラ フランス 主な記事:フランスオペラ  ビゼー、エティエンヌ・カルジャ撮影(1875年 19世紀、ロマン主義がオペラを席巻し、パリがその主要な中心地の一つとなった。ロマン派オペラのほとんどは、ルイージ・チェルビーニ、ガスパレ・スポン ティーニ、フランソワ=アドリアン・ボワールデュー、ダニエル=フランソワ=エスピリット・オーベルなど、フランス在住の作曲家によって作曲された。大オ ペラのスタイルの頂点は、ジャコモ・マイアベーアの作品によって画された。ヘクトル・ベルリオーズの『トロイア人』は当初無視され、ベンヴェヌート・チェ リーニは初演時に論争を巻き起こしたが、シャルル・グノーの『ファウスト』は19世紀中頃のフランスで最も人気のあるオペラの一つだ。 19世紀後半、ジョルジュ・ビゼーは『カルメン』でオペラを革命した。ニーチェによると、これは「スペインの歌と踊りの使用に基づく地方色」であり、 「ワーグナーの理想の霧を晴らす地中海の日差し」だ。地方色を重視した作品への関心は、レオ・ドリーブの『ラクメ』とカミーユ・サン=サーンスの『サムソ ンとダリラ』で確認された。19世紀後半のフランスで最も多作なオペラ作曲家は、マノン、ヴェルテル、タイスなどの作品を作曲したジュール・マスネだっ た。 『ホフマン物語』を作曲したジャック・オッフェンバックは、19世紀のフランス・オペラ・コミックの巨匠として確立し、後にオペレッタと混同されるように なった新しいジャンル、フランス・オペラ・ブッフを発明した。 20 世紀初頭、フランスではロマン主義が徐々に廃れ、印象派や象徴主義などの他の潮流が台頭し、その代表作として、クロード・ドビュッシーの「ペレアスとメリ ザンド」(1902 年)が挙げられる。 ドイツ 主な記事:ドイツオペラ カール・マリア・フォン・ヴェーバーは、『魔弾の射手』(1821年)で、ドイツ初のロマン派オペラを創作した。最初の重要なオペラは、ベートーヴェンの 『フィデリオ』(1805年)で、この作曲家の唯一のオペラ作品でもある。 リヒャルト・ワーグナーは、『さまよえるオランダ人』で、ライトモチーフと「循環的旋律」の手法を導入した。彼は、上演時間と楽器のパワーによってオペラ に革命をもたらした。彼の代表作「4部作」は、ドイツオペラの頂点のひとつだ。彼は、オーケストラが登場人物と同じように主役となる「音楽劇」を創り出し た。1876年、ワーグナーの作品を専属で上演するバイロイト音楽祭が創設された。 ワーグナーの影響は、エンゲルベルト・フンパーディンクの『ヘンゼルとグレーテル』を含むほぼすべてのオペラに及んでいる。その後、リヒャルト・シュトラ ウスが主導的な役割を果たし、『サロメ』や『エレクトラ』でワーグナーと類似した管弦楽法と声楽技法を用いながら、独自の道を拓いた。『ローエングリン』 は、当時最も華やかな成功を収めたシュトラウスの作品だ。 イタリア 主な記事:イタリアオペラ  象徴的な[31] ジョヴァンニ・ボルディーニによるジュゼッペ・ヴェルディの肖像画(1886年 イタリアのロマン主義は、ジョアキーノ・ロッシーニが『セビリアの理髪師』や『ラ・チェネレントラ』などの作品を作曲したことから始まります。彼は「ベル カント」というスタイルを創り出し、同時代のヴィンチェンツォ・ベッリーニやガエターノ・ドニゼッティもこのスタイルを採用しました。 しかし、イタリアオペラの顔はジュゼッペ・ヴェルディで、『ナブッコ』の奴隷の合唱はイタリア全体への重要な賛歌だ。リゴレット、イル・トロヴァトーレ、 ラ・トラヴィアータからなる三部作は彼の主要作品だが、キャリアの晩年に『オテロ』と『ファルスタッフ』で芸術の頂点を極めた。彼は作品に比類ないドラマ ティックな活力とリズムの活力を注入した。 19世紀後半、ヴェルディの確固たる後継者であるジャコモ・プッチーニは、現実主義を超越したヴェリズモへと進化した。『ラ・ボエーム』『トスカ』『蝶々 夫人』『トゥーランドット』は、感情豊かなメロディに満ちたオペラだ。 その他の国 その他の国民的インスピレーションを受けた作品 ロシアでは、ミハイル・グリンカが「皇帝の命」や「ルスランとリュドミラ」を作曲し、国民的音楽学校が発展した。その他のロシアの偉大な作品としては、ニ コライ・リムスキー=コルサコフの「サドコ」、アレクサンダー・ボロディンの「イゴール公」、モデスト・ムソルグスキーの「ボリス・ゴドゥノフ」、ピョー トル・イリイチ・チャイコフスキーの「エフゲニー・オネーギン」や「スペードの女王」がある。 チェコでは、ベドジフ・スメタナの「売られた花嫁」、アントニン・ドヴォルザークの「ルサルカ」、ズデニェク・フィビヒの「シャルカ」、レオシュ・ヤナー チェクの「イェヌーファ」が国民精神を体現している。 イギリスでは、英国ロマン派オペラの代表作「ボヘミアの娘」を作曲したマイケル・ウィリアム・バルフが活躍した。彼はフランスでも作曲活動を行った。 |

| History of music List of Romantic-era composers Neoromanticism (music) |

音楽の歴史 ロマン派作曲家一覧 新ロマン主義(音楽) |

| Further reading Adler, Guido. 1911. Der Stil in der Musik. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. Adler, Guido. 1919. Methode der Musikgeschichte. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. Adler, Guido. 1930. Handbuch der Musikgeschichte, second, thoroughly revised and greatly expanded edition. 2 vols. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: H. Keller. Reprinted, Tutzing: Schneider, 1961. Blume, Friedrich. 1970. Classic and Romantic Music, translated by M. D. Herter Norton from two essays first published in Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. New York: W. W. Norton. Boyer, Jean-Paul. 1961. "Romantisme". Encyclopédie de la musique, edited by François Michel, with François Lesure and Vladimir Fédorov, 3:585–87. Paris: Fasquelle. Brendel, Franz (1858). "F. Liszt's symphonische Dichtungen". Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. 49: 73–76, 85–88, 97–100, 109–112, 121–123, 133–136 & 141–143. Cavalletti, Carlo. 2000. Chopin and Romantic Music, translated by Anna Maria Salmeri Pherson. Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series. (Hardcover) ISBN 0-7641-5136-3; ISBN 978-0-7641-5136-1. Dahlhaus, Carl. 1979. "Neo-Romanticism". 19th-Century Music 3, no. 2 (November): 97–105. Dahlhaus, Carl. 1980. Between Romanticism and Modernism: Four Studies in the Music of the Later Nineteenth Century, translated by Mary Whittall in collaboration with Arnold Whittall; also with Friedrich Nietzsche, "On Music and Words", translated by Walter Arnold Kaufmann. California Studies in 19th Century Music 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03679-4 (cloth); 0520067487 (pbk). Original German edition, as Zwischen Romantik und Moderne: vier Studien zur Musikgeschichte des späteren 19. Jahrhunderts. Munich: Musikverlag Katzbichler, 1974. Dahlhaus, Carl. 1985. Realism in Nineteenth-Century Music, translated by Mary Whittall. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26115-5 (cloth); ISBN 0-521-27841-4 (pbk). Original German edition, as Musikalischer Realismus: zur Musikgeschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts. Munich: R. Piper, 1982. ISBN 3-492-00539-X. Dahlhaus, Carl. 1987. Untitled review of Leon Plantinga, Romantic Music: A History of Musical Styles in Nineteenth-Century Europe and Anthology of Romantic Music, translated by Ernest Sanders. 19th Century Music 11, no. 2:194–96. Einstein, Alfred. 1947. Music in the Romantic Era. New York: W. W. Norton. Geck, Martin. 1998. "Realismus". Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: Allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik begründe von Friedrich Blume, second, revised edition, edited by Ludwig Finscher. Sachteil 8: Quer–Swi, cols. 91–99. Kassel, Basel, London, New York, Prague: Bärenreiter; Suttgart and Weimar: Metzler. ISBN 3-7618-1109-8 (Bärenreiter); ISBN 3-476-41008-0 (Metzler). Grout, Donald Jay. 1960. A History of Western Music. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Lang, Paul Henry. 1941. Music in Western Civilization. New York: W. W. Norton. Mason, Daniel Gregory. 1936. The Romantic Composers. New York: Macmillan. Plantinga, Leon. 1984. Romantic Music: A History of Musical Style in Nineteenth-Century Europe. A Norton Introduction to Music History. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-95196-0; ISBN 978-0-393-95196-7. Rosen, Charles. 1995. The Romantic Generation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-77933-9. Rummenhöller, Peter. 1989. Romantik in der Musik: Analysen, Portraits, Reflexionen. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag; Kassel and New York: Bärenreiter. ISBN 978-3-7618-1236-5 (Bärenreiter); ISBN 978-3-7618-4493-9 (Taschenbuch Verlag); ISBN 978-3-423-04493-6 (Taschenbuch Verlag). Spencer, Stewart. 2008. "The 'Romantic Operas' and the Turn to Myth". In The Cambridge Companion to Wagner, edited by Thomas S. Grey, 67–73. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64299-X (cloth); ISBN 0-521-64439-9 (pbk). Wagner, Richard. 1995. Opera and Drama, translated by William Ashton Ellis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Originally published as volume 2 of Richard Wagner's Prose Works (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1900), a translation from Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen (Leipzig, 1871–73, 1883). Warrack, John. 2002. "Romanticism". The Oxford Companion to Music, edited by Alison Latham. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866212-2. Wedler, Sebastian. 2021. "The End(s) of Musical Romanticism". In The Cambridge Companion to Music and Romanticism, edited by Benedict Taylor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108647342. Wehnert, Martin. 1998. "Romantik und romantisch". Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik, begründet von Friedrich Blume, second revised edition. Sachteil 8: Quer–Swi, cols. 464–507. Basel, Kassel, London, Munich, and Prague: Bärenreiter; Stuttgart and Weimar: Metzler. |

さらに読む アドラー、グイド。1911年。『音楽におけるスタイル』。ライプツィヒ:ブレイトコフ&ヘルテル。 アドラー、グイド。1919年。『音楽史の方法』。ライプツィヒ:ブレイトコフ&ヘルテル。 アドラー、グイド。1930年。『音楽史ハンドブック』、第2版、全面改訂・大幅増補版。2巻。ベルリン・ヴィルマースドルフ:H. ケラー。1961年、トゥツィング:シュナイダーにより再版。 ブルーム、フリードリッヒ。1970年。クラシック音楽とロマン派音楽、M. D. ヘルター・ノートンによる翻訳、Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart に最初に掲載された 2 つのエッセイから抜粋。ニューヨーク:W. W. Norton。 ボワイエ、ジャン=ポール。1961 年。「ロマン主義」。Encyclopédie de la musique、フランソワ・ミシェル編、フランソワ・レジュール、ウラジミール・フェドロフ協力、3:585–87。パリ:Fasquelle。 ブレンデル、フランツ(1858)。「F. Liszt's symphonische Dichtungen」。Neue Zeitschrift für Musik。49: 73–76、85–88、97–100、109–112、121–123、133–136 & 141–143。 カヴァレッティ、カルロ。2000年。『ショパンとロマン派音楽』、アンナ・マリア・サルメリ・ファーソン訳。ニューヨーク州ホープポージ:バロンズ・エ デュケーショナル・シリーズ。(ハードカバー) ISBN 0-7641-5136-3; ISBN 978-0-7641-5136-1。 ダールハウス、カール。1979年。「新ロマン主義」。19世紀の音楽 3、第 2 号(11月):97-105。 ダールハウス、カール。1980年。ロマン主義とモダニズムの間:19 世紀後半の音楽に関する 4 つの研究、メアリー・ウィットールとアーノルド・ウィットールによる翻訳、フリードリヒ・ニーチェの「音楽と言葉について」の翻訳はウォルター・アーノル ド・カウフマンによる。19 世紀の音楽に関するカリフォルニア研究 1。バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版。ISBN 0-520-03679-4 (ハードカバー); 0520067487 (pbk)。ドイツ語原版は『Zwischen Romantik und Moderne: vier Studien zur Musikgeschichte des späteren 19. Jahrhunderts』として、ミュンヘン:Musikverlag Katzbichler、1974年に出版。 ダールハウス、カール。1985年。『19世紀の音楽におけるリアリズム』、メアリー・ウィットール訳。ケンブリッジおよびニューヨーク:ケンブリッジ大 学出版局。ISBN 0-521-26115-5 (cloth); ISBN 0-521-27841-4 (pbk)。ドイツ語原版は『Musikalischer Realismus: zur Musikgeschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts』として、ミュンヘン、R. Piper から 1982 年に刊行。ISBN 3-492-00539-X。 ダールハウス、カール。1987年。レオン・プランティンガ『ロマン派音楽:19 世紀ヨーロッパの音楽様式史とロマン派音楽アンソロジー』の無題の書評、アーネスト・サンダース訳。19th Century Music 11、no. 2:194–96。 アインシュタイン、アルフレッド。1947年。『ロマン派時代の音楽』。ニューヨーク:W. W. ノートン。 ゲック、マーティン。1998年。「リアリズム」。『音楽の歴史と現在:フリードリッヒ・ブルームによる音楽総合事典』、第2版改訂版、ルートヴィヒ・ フィンシャー編。Sachteil 8: Quer–Swi, cols. 91–99. カッセル、バーゼル、ロンドン、ニューヨーク、プラハ:ベーレンライター;シュトゥットガルトおよびワイマール:メッツラー。ISBN 3-7618-1109-8 (ベーレンライター); ISBN 3-476-41008-0 (メッツラー)。 Grout, Donald Jay. 1960. A History of Western Music. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Lang, Paul Henry. 1941. Music in Western Civilization. New York: W. W. Norton. Mason, Daniel Gregory. 1936. The Romantic Composers. New York: Macmillan. プランティンガ、レオン。1984年。『ロマン派音楽:19世紀ヨーロッパの音楽様式史』。ノートン音楽史入門。ニューヨーク:W. W. ノートン。ISBN 0-393-95196-0; ISBN 978-0-393-95196-7。 ローゼン、チャールズ。1995年。『ロマン派世代』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 0-674-77933-9。 ルメンヘラー、ピーター。1989年。『音楽におけるロマン主義:分析、肖像、考察』。ミュンヘン:ドイツ・ポケットブック出版社;カッセルおよびニュー ヨーク:ベーレンライター。ISBN 978-3-7618-1236-5 (Bärenreiter); ISBN 978-3-7618-4493-9 (Taschenbuch Verlag); ISBN 978-3-423-04493-6 (Taschenbuch Verlag)。 スペンサー、スチュワート。2008年。「ロマンチックなオペラと神話への回帰」 『ケンブリッジ・ワーグナー・コンパニオン』 トーマス・S・グレイ編、67-73 ページ。ケンブリッジおよびニューヨーク:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-64299-X (ハードカバー);ISBN 0-521-64439-9 (ペーパーバック)。 ワーグナー、リヒャルト。1995年。『オペラとドラマ』、ウィリアム・アシュトン・エリス訳。リンカーン:ネブラスカ大学出版。元々は、リヒャルト・ ワーグナーの『散文作品集』(ロンドン:ケガン・ポール、トレンチ、トルブナー&カンパニー、1900年)の第2巻として出版された、ゲザムルテ・シュリ フト・ウント・ディヒトゥンゲン(ライプツィヒ、1871-73、1883年)の翻訳版。 ウォーラック、ジョン。2002年。「ロマン主義」。『オックスフォード音楽事典』、アリソン・レイサム編。オックスフォードおよびニューヨーク:オック スフォード大学出版局。ISBN 0-19-866212-2。 ウェドラー、セバスチャン。2021年。「音楽ロマン主義の終焉」 『ケンブリッジ音楽とロマン主義のコンパニオン』 ベネディクト・テイラー編。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 9781108647342。 ヴェーナート、マーティン。1998年。「ロマン主義とロマンチック」。『音楽の歴史と現在:音楽に関する総合百科事典』、フリードリッヒ・ブルーム編、 第2改訂版。専門分野 8:Quer–Swi、464–507 ページ。バーゼル、カッセル、ロンドン、ミュンヘン、プラハ:ベーレンライター、シュトゥットガルト、ワイマール:メッツラー。 |

| Music of the Romantic Era The Romantic Era Era on line |

ロマン派時代の音楽 ロマン派時代 時代オンライン |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romantic_music |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆