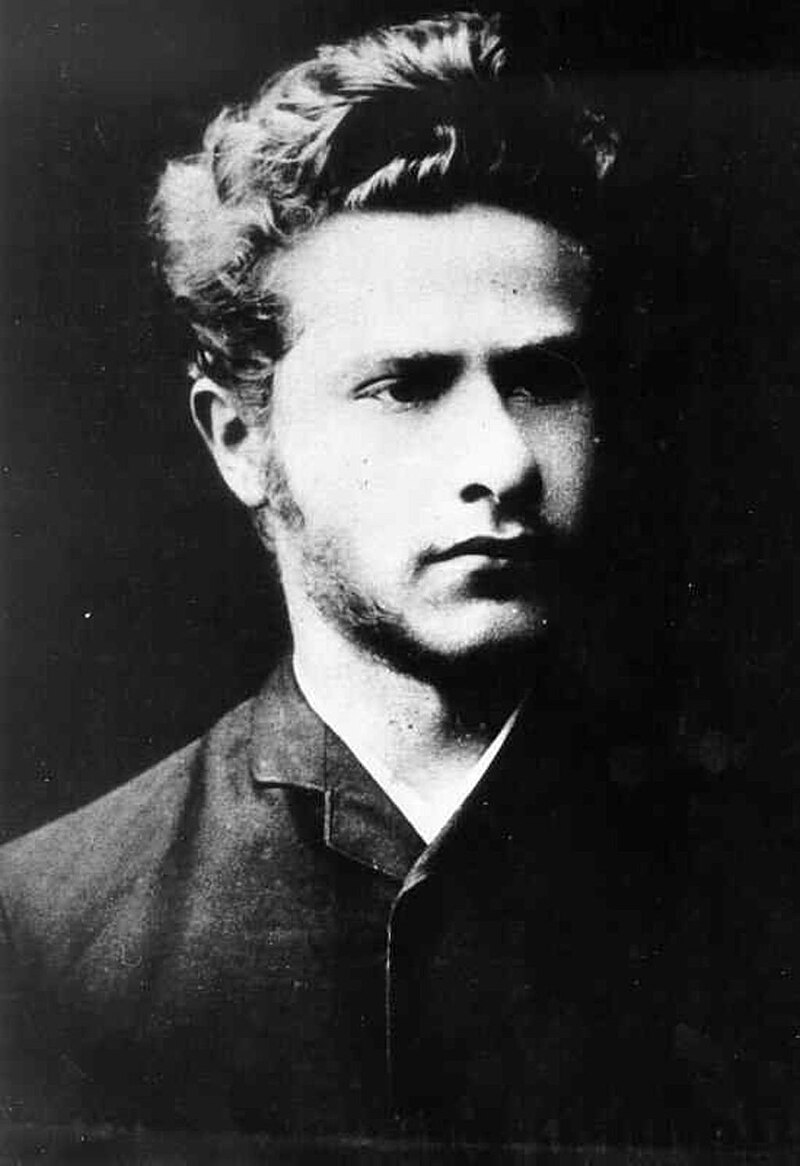

ローザ・ルクセンブルグ

Rosa Luxemburg, 1871-1919

☆ローザ・ルクセンブルク (/ˈlʌksəmbɜːrɡ/ LUK-səm-burg;[1] ポーランド語: Róża Luksemburg

[ˈruʐa ˈluksɛmburk] ⓘ; ドイツ語: [ˈʁoːza ˈlʊksm̩bʊʁk] ⓘ; 本名:ロザリア・ルクセンブルク;

1871年3月5日 –

1919年1月15日)は、ポーランド出身でドイツ国籍を取得したマルクス主義の理論家、哲学者、経済学者、革命的社会主義者だった。ポーランド・リトア

ニア王国社会民主党(SDKPiL)、ドイツ社会民主党(SPD)、ドイツ共産党(KPD)の党員であり、SPDの主要な理論家であり、第二インターナ

ショナルの主要人物の一人だった。帝国主義反対、軍国主義反対、マルクス主義伝統における民主主義の主要な思想家として知られ、主要な理論書『資本の蓄

積』(1913年)と、1918年から1919年のドイツ革命におけるスパルタクス団の革命的指導者として最もよく知られている。

ロシア支配下のポーランドでユダヤ人の家庭に生まれたルクセンブルクは、1898年に政略結婚によりドイツ国籍を取得した。パートナーのレオ・ヨギッチと

ともに、ポーランドのナショナリズムを拒否し、ポーランドの独立はドイツ、オーストリア、ロシアにおける社会主義革命によってのみ達成できると主張する政

党、SDKPiL

を共同設立した。ドイツでは、SPDの革命派の主要指導者となり、エドゥアルト・ベルンシュタインの理論に対抗する小冊子『社会改革か革命か』(1900

年)でマルクス主義の改革論を確立した。1905年のロシア革命から教訓を抽出し、プロレタリアートの最も重要な革命的手段として「大衆ストライキ」の理

論を確立したが、これによりSPDの慎重な指導部との対立が深まった。

第一次世界大戦に反対を表明した彼女は、反戦団体「スパルタクス同盟」を共同設立し、戦争中のほとんどを刑務所で過ごした。刑務所から、戦争とSPDのナ

ショナリズムへの屈服を非難する影響力のある『ユニウス・パンフレット』(1915年)を執筆した。彼女はロシア革命を歓迎したが、死後に出版された原稿

では、ボルシェビキたちの権威主義的な政策を厳しく批判し、民主的自由を擁護し、「自由とは、常に、そしてもっぱら、異なる考えを持つ者の自由である」と

いう有名な言葉を残した。

ドイツ革命中に釈放された後、ルクセンブルクは KPD を共同設立し、1919 年 1

月のベルリンでのスパルタクス蜂起の中心人物となった。この反乱は、政府支援の民兵組織である自由騎兵隊によって鎮圧され、ルクセンブルク、カール・リー

プクニヒト、その他の支持者たちは捕らえられ、即決処刑された。彼女の死後、その遺産は激しい議論の対象となった。彼女は、革命の殉教者として多くの左翼

から崇拝されている一方、その理論、特に自発性と民主主義を強調した部分は、正統的な共産主義のレーニン主義やスターリン主義の伝統から厳しく批判されて

いる。

| Rosa Luxemburg

(/ˈlʌksəmbɜːrɡ/ LUK-səm-burg;[1] Polish: Róża Luksemburg [ˈruʐa

ˈluksɛmburk] ⓘ; German: [ˈʁoːza ˈlʊksm̩bʊʁk] ⓘ; born Rozalia

Luksenburg; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and

naturalised-German Marxist theorist, philosopher, economist, and

revolutionary socialist. A member of the Social Democracy of the

Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL), the Social Democratic Party

of Germany (SPD), and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), she became

a leading theorist of the SPD and a prominent figure in the Second

International. An anti-imperialist, anti-militarist, and foremost

thinker of democracy within the Marxist tradition, she is best known

for her major theoretical work, The Accumulation of Capital (1913), and

for her revolutionary leadership of the Spartacus League during the

German Revolution of 1918–1919. Born in Russian-ruled Poland to a Jewish family, Luxemburg became a German citizen in 1898 through a marriage of convenience. Together with her partner Leo Jogiches, she co-founded the SDKPiL, a party that rejected Polish nationalism and argued that Polish independence could only be achieved through a socialist revolution in Germany, Austria, and Russia. In Germany, she became the foremost leader of the SPD's revolutionary wing, defining the Marxist position on reform in her pamphlet Social Reform or Revolution? (1900) against the theories of Eduard Bernstein. Drawing lessons from the 1905 Russian Revolution, she developed a theory of the mass strike as the proletariat's most important revolutionary tool, which brought her into increasing conflict with the SPD's cautious leadership. Her outspoken opposition to World War I led her to co-found the anti-war Spartacus League, and she was imprisoned for most of the war. From prison, she wrote the influential Junius Pamphlet (1915), condemning the war and the SPD's capitulation to nationalism. She celebrated the Russian Revolution, but in a posthumously published manuscript she sharply criticised the authoritarian policies of the Bolsheviks, championing democratic freedoms and famously stating, "Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently." After her release during the German Revolution, Luxemburg co-founded the KPD and was a central figure in the January 1919 Spartacist uprising in Berlin. When the revolt was crushed by the Freikorps, a government-sponsored paramilitary group, Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, and other supporters were captured and summarily executed. After her death, her legacy became a subject of intense debate. She has been revered by many on the left as a martyr for the revolution, while her theories, particularly her emphasis on spontaneity and democracy, were sharply criticized by the Leninist and Stalinist traditions of orthodox communism. |

ローザ・ルクセンブルク (/ˈlʌksəmbɜːrɡ/

LUK-səm-burg;[1] ポーランド語: Róża Luksemburg [ˈruʐa ˈluksɛmburk] ⓘ; ドイツ語:

[ˈʁoːza ˈlʊksm̩bʊʁk] ⓘ; 本名:ロザリア・ルクセンブルク; 1871年3月5日 –

1919年1月15日)は、ポーランド出身でドイツ国籍を取得したマルクス主義の理論家、哲学者、経済学者、革命的社会主義者だった。ポーランド・リトア

ニア王国社会民主党(SDKPiL)、ドイツ社会民主党(SPD)、ドイツ共産党(KPD)の党員であり、SPDの主要な理論家であり、第二インターナ

ショナルの主要人物の一人だった。帝国主義反対、軍国主義反対、マルクス主義伝統における民主主義の主要な思想家として知られ、主要な理論書『資本の蓄

積』(1913年)と、1918年から1919年のドイツ革命におけるスパルタクス団の革命的指導者として最もよく知られている。 ロシア支配下のポーランドでユダヤ人の家庭に生まれたルクセンブルクは、1898年に政略結婚によりドイツ国籍を取得した。パートナーのレオ・ヨギッチと ともに、ポーランドのナショナリズムを拒否し、ポーランドの独立はドイツ、オーストリア、ロシアにおける社会主義革命によってのみ達成できると主張する政 党、SDKPiL を共同設立した。ドイツでは、SPDの革命派の主要指導者となり、エドゥアルト・ベルンシュタインの理論に対抗する小冊子『社会改革か革命か』(1900 年)でマルクス主義の改革論を確立した。1905年のロシア革命から教訓を抽出し、プロレタリアートの最も重要な革命的手段として「大衆ストライキ」の理 論を確立したが、これによりSPDの慎重な指導部との対立が深まった。 第一次世界大戦に反対を表明した彼女は、反戦団体「スパルタクス同盟」を共同設立し、戦争中のほとんどを刑務所で過ごした。刑務所から、戦争とSPDのナ ショナリズムへの屈服を非難する影響力のある『ユニウス・パンフレット』(1915年)を執筆した。彼女はロシア革命を歓迎したが、死後に出版された原稿 では、ボルシェビキたちの権威主義的な政策を厳しく批判し、民主的自由を擁護し、「自由とは、常に、そしてもっぱら、異なる考えを持つ者の自由である」と いう有名な言葉を残した。 ドイツ革命中に釈放された後、ルクセンブルクは KPD を共同設立し、1919 年 1 月のベルリンでのスパルタクス蜂起の中心人物となった。この反乱は、政府支援の民兵組織である自由騎兵隊によって鎮圧され、ルクセンブルク、カール・リー プクニヒト、その他の支持者たちは捕らえられ、即決処刑された。彼女の死後、その遺産は激しい議論の対象となった。彼女は、革命の殉教者として多くの左翼 から崇拝されている一方、その理論、特に自発性と民主主義を強調した部分は、正統的な共産主義のレーニン主義やスターリン主義の伝統から厳しく批判されて いる。 |

| Early life (1871–1890) Rozalia Luksenburg was born on 5 March 1871 in Zamość, a town in the Russian-controlled Congress Poland.[2][3] She was the fifth and youngest child of a moderately well-off, assimilated Jewish family.[4][5] Her father, Elias (or Eduard) Luxemburg, was a timber merchant with a German education who was sympathetic to the Polish national movement.[6][3] Her mother, Lina Löwenstein, was descended from a long line of rabbis.[3] The family was committed to the values of the Haskalah, the Jewish enlightenment movement, and embraced progressive European culture.[5] The family had largely abandoned a conscious Jewish life; they spoke Polish and German at home, and Rosa, like her four siblings, received a secular education.[7] She had a complex relationship with her Jewish identity; while proud of her heritage, she rejected any specific Jewish political cause, stating later in life: "I have no special place in my heart for the [Jewish] ghetto. I feel at home in the entire world wherever there are clouds and birds and human tears."[8][9] Rory Castle writes: From her grandfather and father [Rosa] inherited the belief that she was a Pole first and a Jew second, with her emotional connection to the Polish language and culture and her passionate opposition to Tsarism being of central importance. Although her parents were religious, they did not consider themselves to be Jewish by nationality, rather 'Poles of the Mosaic persuasion'.[10] In 1873, the family moved to Warsaw to seek better business opportunities, a better education for their children, and to escape the ever-present anti-Jewish sentiment and Orthodox-Hasidic dominance in Zamość.[11][12] At age five, Luxemburg developed a hip disease, probably a congenital hip dislocation. It was misdiagnosed as tuberculosis and resulted in a year-long confinement in a cast, during which she taught herself to read and write.[13] The illness left her with a permanent limp, a condition that deeply affected her and which she later blamed her parents for not detecting earlier.[11][13][14]  Luxemburg at about age 12, c. 1883 In 1880, she enrolled at the Second Girls' High School in Warsaw.[15] Admission for Jewish students was subject to a quota, a humiliation which intensified her sense of being an outsider.[15] The school was an instrument of Russification, forbidding the use of Polish.[16] The 1881 Warsaw pogrom, which her family experienced, left her with a permanent fear of mob violence.[17] In response to this frightening reality, she found refuge in the poetry of the Polish Romantic Adam Mickiewicz, whose appeal to rebellion and dreams of universal freedom became a source of inspiration.[18] During this time, Luxemburg became involved in clandestine student circles associated with the revolutionary Proletariat party.[19][20] This was the first Polish socialist party, founded in 1882 by Ludwik Waryński. The party was internationalist in outlook, prioritising the economic struggle of the working class over Polish independence.[21] By her final year, Luxemburg was known to the authorities as a politically active and rebellious student, and she was denied the gold medal for academic achievement which her scholastic merits had earned.[19] After graduating in 1887, she continued her revolutionary activities.[22] She was part of a cell of the "Second Proletariat", one of the successor groups to the original party which had been broken up by arrests in the mid-1880s.[19] By 1889, threatened with arrest, she was smuggled out of Poland with the help of her mentor, Marcin Kasprzak. According to one account, she was hidden under straw in a peasant's cart and taken across the border by a Catholic priest who had been told she was a Jewish girl fleeing to be baptized.[23][24] |

幼少期(1871年~1890年) ロザリア・ルクセンブルクは、1871年3月5日、ロシア支配下の国会ポーランドにある町ザモシチで生まれた。[2][3] 彼女は、中流の同化ユダヤ人家庭で5人兄弟の末っ子として生まれた。[4][5] 彼女の父親、エリアス(またはエドゥアルド)ルクセンブルクは、ドイツで教育を受けた木材商人であり、ポーランドの民族運動に共感していた。[6][3] 母親のリーナ・ローウェンシュタインは、代々ラビの家に生まれ育った。[3] 家族は、ユダヤ人啓蒙運動であるハスカラー(Haskalah)の価値観を重んじ、進歩的なヨーロッパ文化を受け入れていた。[5] 家族は意識的なユダヤ教の生活をほとんど放棄しており、家庭ではポーランド語とドイツ語を話し、ローザは4人の兄弟姉妹同様、世俗的な教育を受けました。 [7] 彼女はユダヤ人としてのアイデンティティに対して複雑な感情を抱いていました。祖先の遺産には誇りを持っていましたが、特定のユダヤ教の政治的運動を拒否 し、後年次のように述べています:「私の心には、[ユダヤ人の]ゲットーに対する特別な場所はありません。雲と鳥と人間の涙があるところなら、どこも私の 故郷だ」と述べています。[8][9] ロリー・キャッスルは次のように書いています。 祖母と父親から、彼女はまずポーランド人であり、次にユダヤ人であるという信念を受け継いだ。ポーランド語とポーランド文化への感情的な結びつき、そして 帝政ロシアに対する熱烈な反対が、彼女にとって最も重要なものだった。彼女の両親は宗教的だったが、自分たちをユダヤ人という国籍ではなく、「モザイクの 信条を持つポーランド人」だと考えていた。[10] 1873年、家族は、より良いビジネスチャンスと子供たちの教育を求めて、またザモシチで絶え間なく続く反ユダヤ感情と正統派ハシディズムの支配から逃れ るために、ワルシャワに移住した。[11][12] 5歳の時、ルクセンブルクは股関節の病気(おそらく先天性の股関節脱臼)を発症した。これは結核と誤診され、1年間ギプスで固定されることになり、その 間、彼女は独学で読み書きを習得した。[13] この病気は彼女に永久的な足を引きずる後遺症を残し、この状態は彼女に深い影響を与え、後に両親が早期に発見しなかったことを非難した。[11][13] [14]  12歳頃のルクセンブルク、1883年頃 1880年、彼女はワルシャワの第二女子高校に入学した。[15] ユダヤ人学生は入学に定員制が課せられており、その屈辱は彼女の疎外感を一層強めた。[15] この学校はロシア化政策の手段であり、ポーランド語の使用は禁じられていた。[16] 1881年のワルシャワ・ポグロムを家族と共に経験した彼女は、群衆の暴力に対する永久的な恐怖を抱くようになった。[17] この恐ろしい現実に対抗するため、彼女はポーランドのロマン派詩人アダム・ミツキェヴィッチの詩に救いを求めた。彼の反乱への呼びかけと普遍的な自由の夢 は、彼女にとってのインスピレーションの源となった。[18] この時期、ルクセンブルクは革命的なプロレタリアート党と関連する秘密の学生団体に参画した。[19][20] これは1882年にルドヴィク・ワルィンスキーによって設立された最初のポーランド社会主義党だった。この党は国際主義的立場をとり、ポーランドの独立よ りも労働者の経済闘争を優先していた。[21] 卒業年までに、ルクセンブルクは当局から政治的に活発で反逆的な学生として知られ、学業成績で獲得したはずの金メダルを拒否された。[19] 1887年に卒業後、彼女は革命活動を継続した。[22] 彼女は、1880年代半ばの逮捕で解散した元の党の後継グループの一つである「第二プロレタリアート」の細胞の一員だった。[19] 1889年、逮捕の脅威にさらされた彼女は、メンターのマルチン・カシュプザクの手助けでポーランドから密かに脱出させた。ある記録によると、彼女は農民 の荷車に藁の下に隠され、カトリックの司祭によって国境を越えた。司祭は、彼女が洗礼を受けるために逃亡中のユダヤ人の少女だと聞かされていた。[23] [24] |

| Zurich and early political

career (1890–1898) Luxemburg arrived in Zurich in early 1889.[25] At the time, Switzerland was the most important centre of Russian and Polish revolutionary Marxism in exile.[26] In 1890, she enrolled at the University of Zurich, where women were admitted on an equal footing with men. She initially studied natural sciences and mathematics, but in 1892 she switched to the faculty of law, where she studied public law and political economy under Professor Julius Wolf.[27][28] Wolf later acknowledged that "she came to me from Poland already as a thorough Marxist".[28]  Leo Jogiches c. 1890 In early autumn 1890, she met Leo Jogiches, a famous revolutionary from Vilna who had also recently escaped from the Russian Empire.[29] They fell in love and by the summer of 1891 had become lovers, beginning a tumultuous fifteen-year relationship that she considered a marriage, referring to him in her letters as her husband.[30] Jogiches became the most dominant figure in her personal and political life. Their relationship was a complex fusion of personal intimacy and political collaboration, marked by both deep affection and intense intellectual conflict.[31] Jogiches provided the financial support for their activities, while Luxemburg became the partnership's public voice and theorist.[32] He insisted on absolute secrecy about their relationship, which Luxemburg alternately rebelled against and accepted.[33] Soon after their arrival, Jogiches and Luxemburg came into conflict with the established leadership of Russian Marxism, centred around Georgi Plekhanov in Geneva. Jogiches, with his characteristic self-assurance, proposed a publishing partnership with Plekhanov on equal terms and was promptly rejected.[34] The ensuing quarrel isolated them from the main Russian socialist movement and pushed their activities increasingly towards Polish affairs.[35] They began to gather a small group of Polish students and exiles around them, including Julian Marchlewski and Adolf Warszawski.[36] In 1893, this group founded a new party, the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland (SDKP), in opposition to the recently unified Polish Socialist Party (PPS).[37][38] The SDKP's programme, largely formulated by Luxemburg, rejected the PPS's central demand for Polish independence. Instead, it argued for close collaboration with Russian socialists to achieve a revolution in the Russian Empire, within which Poland would have territorial autonomy.[39][40] At the International's third congress in Zurich in 1893, Luxemburg, as a delegate for the SDKP's newspaper Sprawa Robotnicza (The Workers' Cause), had her mandate challenged by the PPS delegation.[41] Small and frail, she climbed onto a chair to make herself heard and, with "magnetism in her eyes and in such fiery words", defended her cause.[42] Although the congress ultimately voted to reject her mandate, she achieved a moral victory by framing the dispute as one of principle rather than personal rivalry.[43] This conflict over the "national question" became the central and most enduring division in Polish socialism. The polemics between the two parties forced both to sharpen their positions: the PPS became more openly nationalist, while the SDKP's opposition to Polish independence became a core doctrine.[44] At the next congress in London in 1896, the International passed a compromise resolution supporting the right of all nations to self-determination but without specific mention of Poland.[45] In 1897, Luxemburg successfully defended her doctoral dissertation, Die industrielle Entwicklung Polens (The Industrial Development of Poland), which argued that the industrial growth of Russian Poland was inextricably linked to the Russian market and that Polish independence was therefore an economic and political negation of progress.[46][47] She was one of the first women in the world, and the first Polish woman, to be awarded a doctorate in political economy.[48][49] To obtain German citizenship and the ability to work within the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), she entered into a marriage of convenience with Gustav Lübeck, son of her Zurich friend Olympia Lübeck, in April 1898.[50][51] On 12 May 1898, she moved to Berlin.[52][51] Despite living in Germany for most of her adult life, Luxemburg remained the principal theoretician of the SDKP (and later SDKPiL), leading the party in a partnership with Jogiches, its principal organiser.[48] She was sentimental towards Polish culture, Mickiewicz remained her favourite poet, and she vehemently opposed the Germanisation of Poles in the Prussian Partition; in 1893, she wrote against the Russification of Poles by the Russian Empire's absolutist government[53] and in 1900 she published a brochure against the Germanisation of Poles by the Kingdom of Prussia in Poznań.[54] |

チューリッヒと初期の政治活動(1890年~1898年) ルクセンブルクは1889年初めにチューリッヒに到着した。[25] 当時、スイスは亡命中のロシアおよびポーランドの革命的マルクス主義の最も重要な中心地だった。[26] 1890年、彼女はチューリッヒ大学に入学した。この大学では、女性は男性と同等の立場で入学が認められていた。当初は自然科学と数学を学んでいたが、 1892年に法学部へ転部し、ユリウス・ヴォルフ教授のもとで公法と政治経済学を学んだ。[27][28] ヴォルフは後に、「彼女はすでに徹底したマルクス主義者としてポーランドから私のところにやってきた」と認めている。[28]  レオ・ヨギッチ、1890年頃 1890年の初秋、彼女は、同じくロシア帝国から逃亡してきた、ヴィルナ出身の有名な革命家、レオ・ヨギッチと出会った[29]。2人は恋に落ち、 1891年の夏までに恋人となり、彼女が結婚とみなした15年にわたる激動の関係が始まった。彼女は手紙の中で彼を夫と呼んでいた[30]。ヨギッチは、 彼女の私生活と政治活動において最も支配的な人物となった。彼らの関係は、個人的な親密さと政治的協力が複雑に融合したもので、深い愛情と激しい知的対立 の両方が特徴だった[31]。ヨギチェスは彼らの活動に必要な資金援助を行い、ルクセンブルクはパートナーシップの公的なスポークスパーソンおよび理論家 となった[32]。ヨギチェスは、彼らの関係について絶対的な秘密保持を主張したが、ルクセンブルクはそれに反抗したり、受け入れたりした。[33] 到着後まもなく、ヨギチェスとルクセンブルクは、ジュネーブを拠点とするゲオルギー・プレハーノフを中心とした、ロシアのマルクス主義の既成指導部と対立 した。ヨギチェスは、彼特有の自信に満ちた態度で、プレハーノフと対等な立場での出版提携を提案したが、即座に拒否された。[34] その結果、彼らはロシアの社会主義運動の主流から孤立し、その活動はますますポーランドの問題に傾倒していくことになった。[35] 彼らはジュリアン・マルチェフスキーやアドルフ・ワルシャフスキーを含むポーランドの学生と亡命者からなる小さなグループを周囲に集め始めた。[36] 1893年、このグループはポーランド社会主義党(PPS)の統一に反対する新たな政党、ポーランド王国社会民主党(SDKP)を設立した。[37] [38] SDKPの綱領は主にルクセンブルクによって策定され、PPSのポーランド独立の主要要求を拒否した。代わりに、ロシア帝国内での革命を実現するため、ロ シアの社会主義者との緊密な協力を主張し、その中でポーランドは領土的自治を獲得すると主張した。[39][40] 1893年にチューリヒで開催された国際社会主義者連盟の第3回大会で、SDKPの機関紙『Sprawa Robotnicza(労働者の大義)』の代表として出席したルクセンブルクは、PPSの代表団からその代表権が争われた。[41] 小柄で虚弱な彼女は、自分の声を届けるために椅子に登り、「その目には魅力があり、その言葉は熱く燃え盛っていた」と、自分の主張を擁護した。[42] 結局、大会は彼女の委任を拒否する決議を採択したが、彼女は、この論争を個人的な対立ではなく、原則の問題として位置づけたことで、道義的な勝利を収め た。この「国民問題」をめぐる対立は、ポーランド社会主義の中心的かつ最も長きにわたる分裂要因となった。両党間の論争は、それぞれの立場を明確にする結 果となり、PPS はより公然とナショナリスト的になり、SDKP はポーランドの独立反対を基本方針とした。[44] 1896年にロンドンで開催された次の大会で、国際社会主義者連盟は、すべての国民が自己決定権を有することを支持する妥協決議を採択したが、ポーランド については具体的に言及しなかった。 1897年、ルクセンブルクは博士論文『ポーランドの産業発展』(Die industrielle Entwicklung Polens)を成功裡に防衛した。この論文は、ロシア領ポーランドの産業成長がロシア市場と不可分であり、したがってポーランドの独立は経済的・政治的 な進歩の否定であると主張した。[46][47] 彼女は世界で最初の女性の一人であり、ポーランド人女性として初めて政治経済学の博士号を授与された。[48][49] ドイツ国籍を取得し、ドイツ社会民主党(SPD)内で活動する能力を得るため、彼女はチューリヒの友人オリンピア・リューベックの息子グスタフ・リュー ベックと便宜結婚を結び、1898年4月に結婚した。[50][51] 1898年5月12日、彼女はベルリンに移住した。[52][51] 成人期のほとんどをドイツで過ごしたにもかかわらず、ルクセンブルクは SDKP(後の SDKPiL)の主要理論家であり続け、その主要組織者であるヨギチェスと協力して党を率いた。[48] 彼女はポーランド文化に深い愛情を抱き、ミツキェヴィチを最も愛する詩人としていた。また、プロイセン分割下でのポーランド人のドイツ化に激しく反対し、 1893年にはロシア帝国の絶対主義政府によるポーランド人のロシア化に反対する文章を執筆した[53]。1900年には、プロイセン王国によるポズナン におけるポーランド人のドイツ化に反対する小冊子を出版した[54]。 |

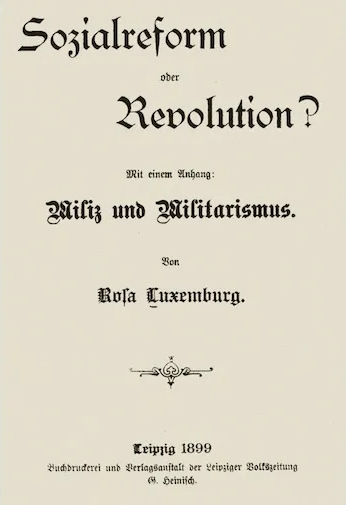

Activism in the SPD (1898–1905) Luxemburg c. 1900 Luxemburg arrived in Germany at a pivotal moment for the SPD. After years of operating under the Anti-Socialist Laws, the party had grown into a massive but politically isolated organisation. Its official doctrine, codified in the 1891 Erfurt Program, combined a Marxist prediction of capitalism's inevitable collapse with a practical focus on immediate, minimal reforms.[55] This inherent contradiction was brought to the fore by the revisionist controversy, which began in earnest in 1898.[56] Eduard Bernstein, a respected party veteran living in London, published a series of articles arguing that many of Marx's predictions were outdated. He proposed that the party should abandon its revolutionary goals and "dare to appear as what it actually was: a democratic Socialist party of reform".[57][58]  Title page of Luxemburg's Social Reform or Revolution? (1899) Luxemburg immediately plunged into the debate, seeing it as a crucial opportunity to establish her career and defend what she saw as the core of Marxism.[59] She became a leading voice of the party's revolutionary left, along with Alexander Parvus.[60] Her most significant contribution was the pamphlet Social Reform or Revolution?, first published as a series of articles in the Leipziger Volkszeitung in late 1898 and early 1899.[61][62] In it, she argued that the distinction between social reform and social revolution was a false one for a revolutionary party.[61][63] The daily struggle for reforms, she contended, was the only way for the proletariat to develop the class consciousness necessary for the revolutionary seizure of power. To abandon the final goal of revolution would be to sever practice from theory, transforming the socialist movement into a mere reformist, petit-bourgeois party.[64][65] She dismantled Bernstein's economic arguments, reasserting the Marxist theses of capitalist crisis and collapse.[66] The pamphlet established her reputation as a major theorist and the "hammer of revisionism".[67] At the party congresses of 1898, 1899, and 1901, Luxemburg was a prominent speaker, crossing swords not only with revisionists but also with the party leadership, which she often saw as too accommodating.[68] She formed a close intellectual and personal alliance with Karl Kautsky, the party's leading theorist, and his wife Luise.[69][70] Together with Kautsky, she led the "orthodox" Marxist camp against Bernstein, though her approach was always more radical and action-oriented than Kautsky's more academic defence of principles.[71] By 1903, the revisionist challenge had been officially defeated within the party, and the orthodox line was resoundingly confirmed at the 1904 Amsterdam congress of the Second International.[72][73] Throughout this period, Luxemburg led a dual political life, maintaining her central role in the SDKP while becoming a major figure in the SPD.[74] She deliberately kept her German and Polish activities separate, a division facilitated by Jogiches's insistence on conspiratorial methods.[74] From her base in Berlin, she directed much of the SDKP's strategy, particularly its unrelenting campaign against the PPS in Germany and in the International.[75] In 1899, the SDKP merged with a group of Lithuanian social democrats led by Felix Dzerzhinsky, becoming the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL).[76][77] Her influence and the support of the SPD leadership were instrumental in establishing the SDKPiL as a recognised, albeit small, force in international socialism.[78] |

SPD における活動(1898年~1905年 1900年頃のルクセンブルク ルクセンブルクは、SPD にとって重要な時期にドイツに到着した。反社会主義法の下で長年にわたり活動してきたこの党は、大規模な組織へと成長したが、政治的には孤立していた。 1891年のエルフルト綱領で体系化された公式教義は、資本主義の不可避的な崩壊を予測するマルクス主義と、即時の最小限の改革に焦点を当てた実践的なア プローチを組み合わせたものだった。[55] この内在的な矛盾は、1898年に本格化した修正主義論争によって浮き彫りになった。[56] ロンドン在住の党の重鎮エドゥアルト・ベルンシュタインは、マルクスの予測の多くが時代遅れだと主張する一連の論文を発表した。彼は、党は革命の目標を放 棄し、「その実体である、民主的な社会主義改革政党として敢えて姿を現すべきだ」と提案した[57][58]。  ルクセンブルクの『社会改革か、革命か?(1899年)のタイトルページ ルクセンブルクは、この議論を自分のキャリアを確立し、マルクス主義の核心であると考えるものを擁護する絶好の機会と捉え、すぐに議論に飛び込んだ。 [59] 彼女は、アレクサンダー・パルバスとともに、党の革命左派の指導的な人物となった。[60] 彼女の最も重要な貢献は、1898 年後半から 1899 年初めにライプツィヒ・フォルクスツァイトゥング紙に連載記事として掲載された小冊子『社会改革か革命か?[62] そこでは、社会改革と社会革命の区別は、革命政党にとっては誤ったものであると主張した。[61][63] 改革のための日々の闘争こそが、プロレタリアが革命による権力奪取に必要な階級意識を育む唯一の方法であると彼女は主張した。革命の最終目標を放棄するこ とは、実践と理論を切り離し、社会主義運動を単なる改革主義的、小市民的な党に変質させることになるとした。[64][65] 彼女はベルンシュタインの経済的論拠を解体し、資本主義の危機と崩壊に関するマルクス主義のテーゼを再主張した。[66] この小冊子は、彼女を主要な理論家として確立し、「修正主義のハンマー」としての地位を確立した。[67] 1898年、1899年、1901年の党大会では、ルクセンブルクは著名な演説者として、修正主義者たちだけでなく、しばしば過度に融和的であると彼女が 見なしていた党指導部とも激論を交わした[68]。彼女は、党の主要理論家であるカール・カウツキーとその妻ルイーズと、知的かつ個人的な緊密な同盟関係 を築いた[69][70]。カウツキーと共に、彼女はベルンシュタインに対する「正統派」マルクス主義派を率いたが、彼女の立場はカウツキーのより学問的 な原則擁護よりも、常により過激で行動指向的なものであった。[71] 1903年までに、修正主義の挑戦は党内で公式に敗北し、1904年のアムステルダムで開催された第二インターナショナル大会で正統派の路線が圧倒的に確 認された。[72][73] この期間、ルクセンブルクは、SDKP での中心的な役割を維持しながら、SPD の主要人物として、二重の政治生活を送った。[74] 彼女は、ヨギチェスの陰謀的な手法の主張も助けとなり、ドイツとポーランドでの活動を意図的に分離した。[74] ベルリンを拠点に、彼女は SDKP の戦略の多く、特にドイツおよび国際社会における PPS に対する執拗なキャンペーンを指揮した。[75] 1899年、SDKPはフェリックス・ジェルジンスキー率いるリトアニアの社会民主主義者グループと合併し、ポーランド・リトアニア王国社会民主党 (SDKPiL)となった。[76][77] 彼女の影響力とSPD指導部の支援は、SDKPiLを国際社会主義において認められた、 albeit 小さな勢力として確立する上で決定的だった。[78] |

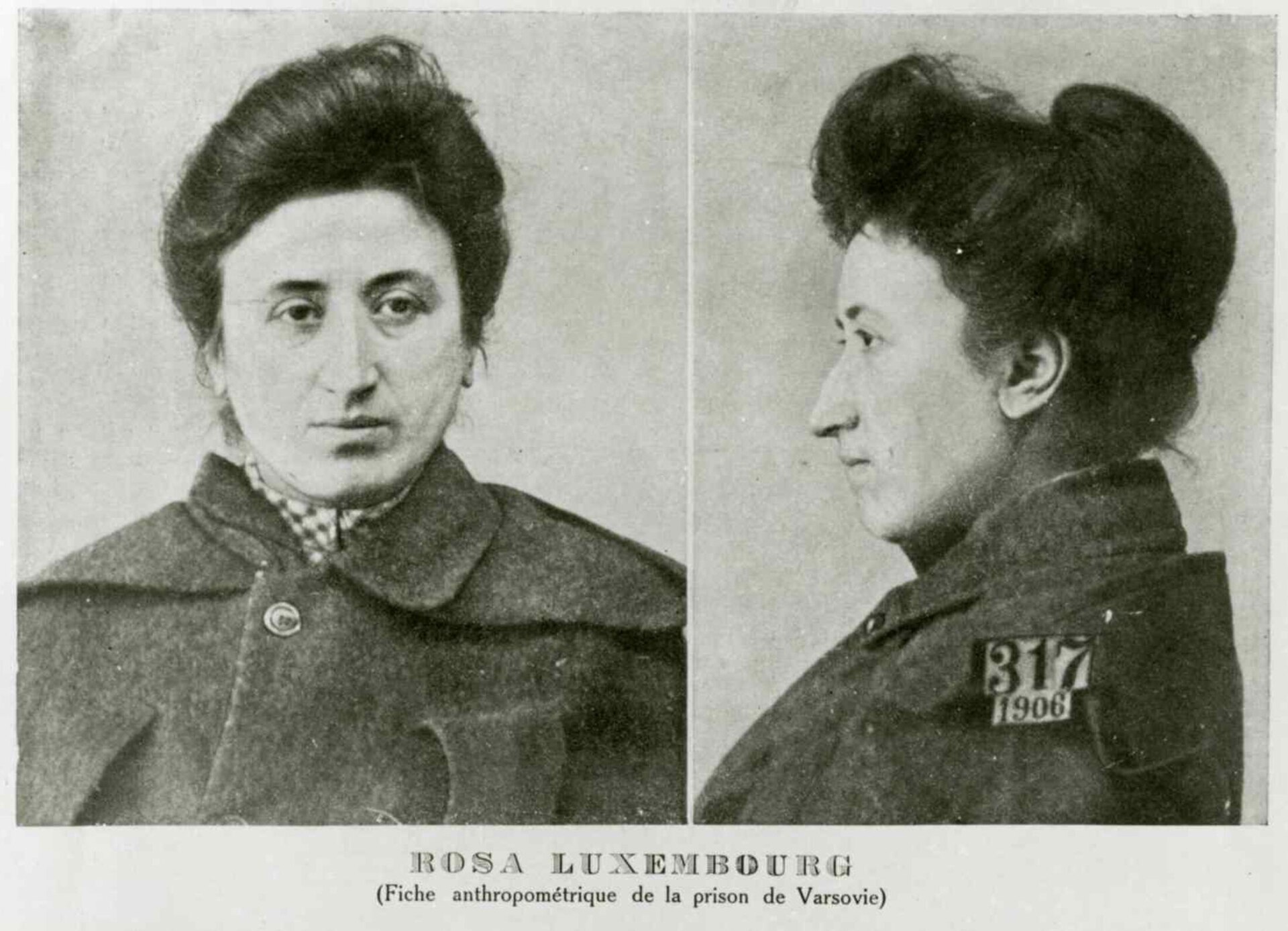

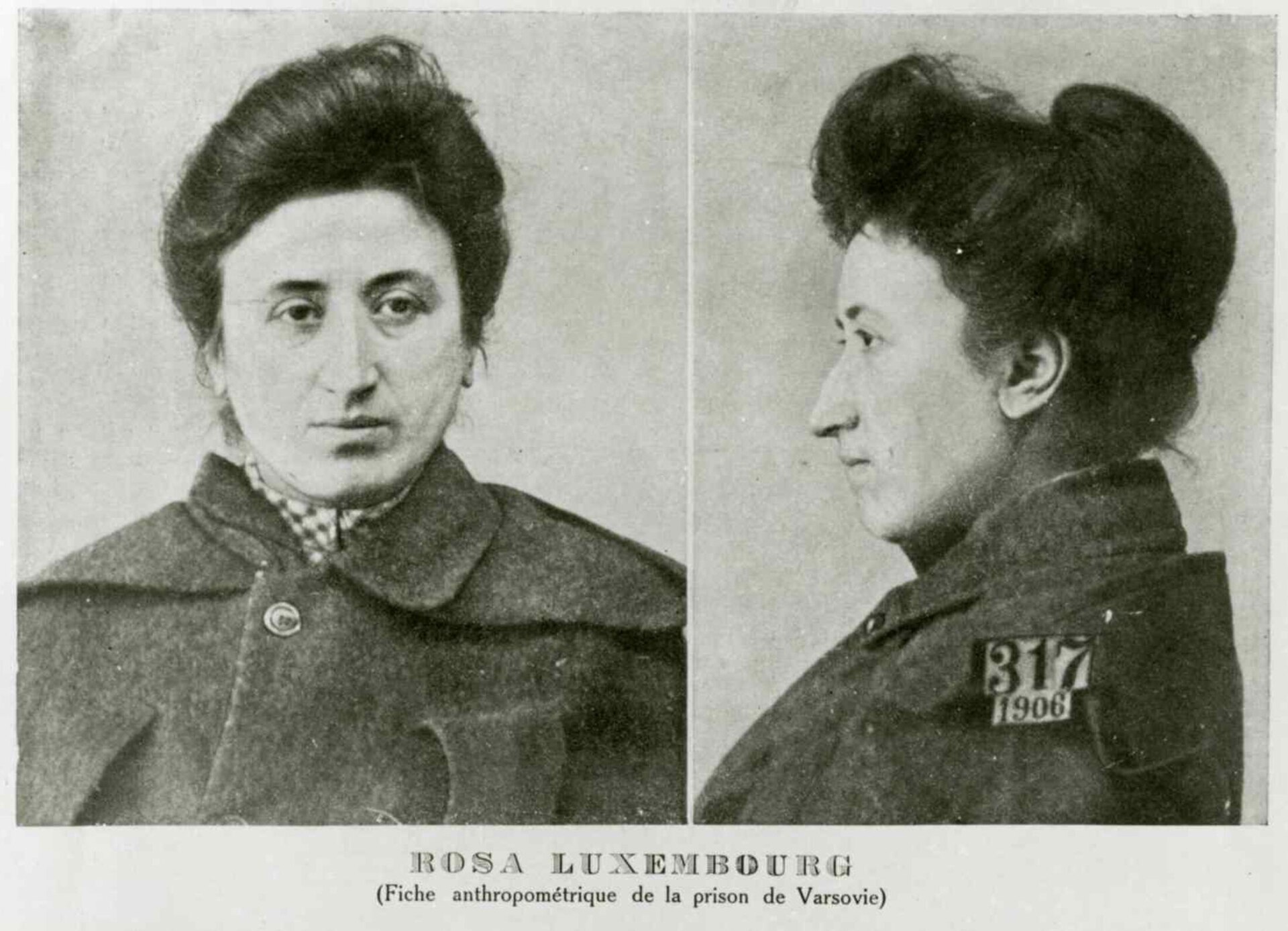

| 1905 Revolution and aftermath

(1905–1911) Role in the 1905 Revolution The 1905 Russian Revolution erupted dramatically in January and had a profound impact on Luxemburg's thought and activity.[79][80] The wave of mass strikes, peasant uprisings, and military mutinies that swept across the Russian Empire, including Poland, seemed to confirm her revolutionary predictions. She immediately began to analyse the events for the German and Polish socialist press, calling the revolution a "dress rehearsal" for a future upheaval.[81][82] In her articles, she celebrated the mass strike as the central weapon of the revolution, a form of action that fused the economic and political struggles and spontaneously raised the class consciousness of the proletariat.[83]  Mugshot taken after Luxemburg's arrest in Warsaw, 1906 As the revolution in Poland intensified, her position in Berlin became increasingly untenable. Feeling isolated from the "real revolution", she decided to go to Warsaw.[84] Her relationship with Jogiches had entered a period of crisis, triggered in part by a brief affair she had with another revolutionary, which she confessed to Jogiches in August 1905.[85] Despite warnings from her German and Polish colleagues about the dangers, she left Berlin on 28 December 1905, travelling on false papers under the name Anna Matschke.[86][87][88] In Warsaw, she joined Jogiches and other SDKPiL leaders, plunging into the heart of the revolutionary turmoil. She wrote prolifically for the party's newspapers, helped to formulate its programme, and participated in clandestine meetings.[89] However, her stay was short-lived. On 4 March 1906, she and Jogiches were arrested in a police raid.[90][91][92] Luxemburg was imprisoned for four months, first in the Town Hall jail, then in the Pawiak prison, and finally in the notorious Pavilion X of the Warsaw Citadel.[93] Her health deteriorated rapidly, but her spirits remained high. Through the combined efforts of her family and the German SPD, including a bail of 3,000 roubles paid by her brother Jozef, she was released on 28 July 1906.[94][91][95] Forbidden to leave Warsaw, she spent the next month arranging her departure. She eventually left for Kuokkala, Finland, where she joined Vladimir Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders for several weeks of discussion about the lessons of the revolution.[96][91][97] |

1905年の革命とその余波(1905年~1911年 1905年の革命における役割 1905年のロシア革命は1月に激発し、ルクセンブルクの思想と活動に大きな影響を与えた。[79][80] ポーランドを含むロシア帝国全土を襲った大規模なストライキ、農民の反乱、軍隊の反乱の波は、彼女の革命的な予測を裏付けるもののように見えた。彼女は直 ちにドイツとポーランドの社会主義メディア向けに事件の分析を開始し、この革命を「将来の激変の予行演習」と称した。[81][82] 彼女の論文では、大衆ストライキを革命の中心的武器として称賛し、経済的・政治的闘争を融合させ、プロレタリアートの階級意識を自発的に高める行動形態と 位置付けた。[83]  1906年、ワルシャワで逮捕された後のルクセンブルクの逮捕写真 ポーランドでの革命が激化する中、ベルリンでの彼女の立場はますます不安定になった。「本当の革命」から孤立していると感じた彼女は、ワルシャワに行くこ とを決めた。[84] ジョギチェスとの関係は危機的状況に陥っていた。これは、彼女が別の革命家との短い関係を持ったことがきっかけの一つで、彼女は1905年8月にジョギ チェスに告白した。[85] ドイツとポーランドの同僚から危険を警告されたにもかかわらず、彼女は1905年12月28日、偽名アンナ・マッツケを名乗り、偽の書類でベルリンを離れ た。[86][87][88] ワルシャワで、彼女はジョギチェスと他のSDKPiL指導者たちと合流し、革命の渦中に飛び込んだ。彼女は党の新聞に精力的に執筆し、党の綱領の策定に協 力し、秘密の会合に参加した。[89] しかし、彼女の滞在は短命に終わった。1906年3月4日、彼女とジョギチェスは警察の襲撃で逮捕された。[90][91][92] ルクセンブルクは 4 か月間、最初は市庁舎の牢獄、次にパヴィアク刑務所、そして最後にワルシャワ城塞の悪名高いパビリオン X に投獄された。[93] 彼女の健康は急速に悪化したものの、気力は衰えることがなかった。彼女の家族とドイツの SPD の協力、そして兄のヨゼフが 3,000 ルーブルの保釈金を支払った結果、彼女は 1906 年 7 月 28 日に釈放された。[94][91][95] ワルシャワを離れることを禁じられた彼女は、次の1ヶ月間、出発の手配に費やした。最終的に彼女はフィンランドのクオッカラへ出発し、ウラジーミル・レー ニンをはじめとするボリシェヴィキ指導者たちと数週間にわたり、革命の教訓について議論を交わした。[96][91][97] |

| Mass strike doctrine and SPD

Party School The experience of the 1905 revolution became the foundation for Luxemburg's most influential work on revolutionary strategy, the pamphlet The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions, written in Finland and published in Germany in 1906.[98][99][100] In it, she generalized from the Russian experience, arguing that the mass strike was not a single, isolated act but a continuous process, a period of heightened class struggle in which the economic and political spheres were inseparable. It was, she argued, a spontaneous expression of the revolutionary energy of the masses, which the party could not artificially "make" but must lead and give political direction.[101][102] The pamphlet was a direct challenge to the German trade union leadership, which saw the mass strike as a threat to their organizations and a recipe for "revolutionary romanticism".[103] At the 1906 SPD congress in Mannheim, a major confrontation occurred between the party's revolutionary wing, represented by Luxemburg, and the trade union leaders led by Carl Legien. Luxemburg passionately defended the lessons of the Russian revolution, but the congress ultimately passed a resolution that effectively gave the trade unions a veto over any future mass strike action.[104] A similar debate took place at the 1907 International congress in Stuttgart, where an amendment drafted by Luxemburg, Lenin, and Julius Martov was attached to the main resolution on war and militarism. It committed the socialist parties not only to prevent war but also to use any war crisis to "hasten the abolition of capitalist class rule".[105][106]  Luxemburg (fourth from left against bookcase) among attendees at the SPD party school in 1907 The years from 1907 to 1910 were a period of relative political quietism for Luxemburg in Germany. Following the SPD's electoral defeat in the 1907 "Hottentot elections", the party leadership became increasingly cautious and resistant to radical tactics.[107] Disillusioned with the party's direction, Luxemburg withdrew from day-to-day agitation and focused on her theoretical work and teaching.[108] In October 1907, she became a lecturer in political economy and economic history at the SPD's new Central Party School in Berlin, a post she held until 1914.[109][110] The school was intended to train an elite of party and trade union functionaries. Luxemburg was an enthusiastic and highly successful teacher, known for her Socratic method of questioning students to help them develop "an airtight solution" for themselves. Her lectures formed the basis for two of her major economic works, Introduction to Political Economy and The Accumulation of Capital.[98][111] This period also marked the definitive end of Luxemburg's relationship with Jogiches. He crossed the border illegally and arrived in Berlin in April 1907, only to be told their relationship was over. His violent reaction, including threats to kill her, shocked and frightened her.[112] Luxemburg had already begun a new relationship with Konstantin (Kostja) Zetkin, the 22-year-old son of her close friend and comrade Clara Zetkin.[113][114] The separation from Jogiches left her emotionally devastated.[115] |

大衆ストライキ理論とSPD党学校 1905年の革命の経験は、ルクセンブルクがフィンランドで執筆し、1906年にドイツで出版した、革命戦略に関する最も影響力のある著作『大衆ストライ キ、政党、労働組合』の基礎となった。[98][99][100] 彼女はロシアの経験から一般化して、マスストライキは単発の孤立した行為ではなく、経済的・政治的領域が不可分な、階級闘争が激化する継続的な過程である と主張した。それは、党が人工的に「作り出す」ことのできない、大衆の革命的エネルギーの自発的な表現であり、党はそれを導き、政治的な方向性を与えるべ きだと主張した。[101][102] この小冊子は、大衆ストライキを組織への脅威と見なし、「革命的ロマンティシズム」の処方箋だと考えたドイツの労働組合指導部に対する直接的な挑戦だっ た。[103] 1906年のSPDマンハイム大会では、ルクセンブルクが代表する党の革命派とカール・レギエン率いる労働組合指導部との間で重大な対立が発生した。ルク センブルクはロシア革命の教訓を熱烈に擁護したが、大会は最終的に、労働組合に今後の大規模ストライキ行動に対する拒否権を事実上付与する決議を可決し た。[104] 1907年のシュトゥットガルト国際会議でも同様の議論が展開され、ルクセンブルク、レーニン、ユリウス・マルトフが起草した修正案が、戦争と軍国主義に 関する主要決議に付帯された。この修正案は、社会主義政党が戦争を防止するだけでなく、戦争危機を「資本主義的階級支配の廃止を早める」ために利用するこ とを約束するものだった。[105][106]  1907年のSPD党学校での参加者たち(左から4番目、本棚の前に立っているのがルクセンブルク) 1907年から1910年までは、ルクセンブルクにとってドイツでは比較的政治的に静かな時期だった。1907年の「ホッテントット選挙」でSPDが選挙 で敗北した後、党指導部はますます慎重になり、過激な戦術に抵抗を示すようになった。[107] 党の進路に失望したルクセンブルクは、日常的な活動から離れ、理論研究と教育に専念した。[108] 1907年10月、彼女はSPDの新中央党学校(ベルリン)で政治経済学と経済史の講師に就任し、この職を1914年まで務めた。[109][110] この学校は、党と労働組合の幹部候補を養成する目的で設立された。ルクセンブルクは熱心で非常に優秀な教師として知られ、学生に質問を投げかけ、彼ら自身 が「完璧な解決策」を導き出すよう促すソクラテス式教育法を採用していた。彼女の講義は、主要な経済著作『政治経済学入門』と『資本の蓄積』の基礎となっ た。[98][111] この時期は、ルクセンブルクとヨギチェスの関係が完全に終焉を迎えた時期でもあった。ヨギチェスは不法に国境を越え、1907年4月にベルリンに到着した が、2人の関係は終わったと告げられた。彼の暴力的な反応、特に彼女を殺すとの脅迫は、彼女を驚かせ、恐怖に陥れた。[112] ルクセンブルクは既に、親しい友人であり同志であるクララ・ツェトキンの22歳の息子、コンスタンティン(コスタ)・ツェトキンとの新しい関係を始めてい た。[113][114] ヨギチェスとの別れは、彼女を感情的に打ちのめした。[115] |

Break with Kautsky Luxemburg (near centre, wearing bow) and Karl Kautsky (back row, third from right) at the Amsterdam Congress of the Second International, 1904 The temporary truce in the SPD between the radicals and the leadership ended abruptly in 1910 over the question of Prussian suffrage. The Prussian three-class franchise was a long-standing grievance, and a new government bill that failed to introduce equal suffrage sparked a wave of mass demonstrations and strikes.[116] Luxemburg saw this as a golden opportunity to put her mass strike theory into practice and to push the party in a more revolutionary direction.[117] She embarked on an intensive speaking tour, and in a series of articles, beginning with "What Next?", she called for the party to escalate the struggle, including through republican agitation.[118] The party executive, however, was wary of such radical tactics, fearing they would alienate bourgeois allies and jeopardize the upcoming Reichstag elections. Kautsky, now the chief defender of the party's cautious "strategy of attrition" (Ermattungsstrategie), refused to publish her article in Die Neue Zeit.[119] This refusal marked the beginning of a bitter and public polemic between the two former allies, which permanently destroyed their friendship and intellectual partnership.[120][121][122] Luxemburg accused Kautsky of cowardice and of abandoning Marxist principles for parliamentary expediency. Kautsky, in turn, portrayed her as a reckless adventurer whose "rebel's impatience" threatened to lead the party to ruin.[123] The controversy effectively ended Luxemburg's influence with the SPD's centrist leadership. She was now increasingly isolated, a leader of a small but growing radical opposition within the party.[124] Although her resolution on the mass strike was defeated at the 1910 Magdeburg congress, the debate had drawn a clear line between her revolutionary strategy and the executive's policy of waiting for history to run its course.[125] The conflict intensified in 1911 during the Agadir Crisis, when she again clashed with the leadership over what she saw as their passive and inadequate response to the threat of imperialist war.[126][127] |

カウツキーとの決別 ルクセンブルク(中央付近、リボンを付けた人物)とカール・カウツキー(後列、右から3番目)が、1904年にアムステルダムで開催された第二インターナ ショナル大会に出席した。 SPD内の急進派と指導部との一時的な休戦は、1910年にプロイセンの選挙権問題をめぐって突然終了した。プロイセンの三階級選挙権は長年の不満の種で あり、平等な選挙権を導入しなかった新たな政府法案は、大規模なデモとストライキの波を引き起こした。[116] ルクセンブルクは、これを自身の大量ストライキ理論を実践し、党をより革命的な方向へ推進する絶好の機会と捉えた。[117] 彼女は集中的な講演ツアーを開始し、「次に何をするか?」と題した一連の記事で、共和制の宣伝を含む闘争の激化を求めた。[118] しかし、党執行部は、このような過激な戦術がブルジョア同盟者を離反させ、迫る帝国議会選挙を危うくする恐れがあるとして警戒した。カウツキーは、党の慎 重な「消耗戦戦略」(Ermattungsstrategie)の主な擁護者となり、彼女の論文を『ディ・ノイエ・ツァイト』に掲載することを拒否した。 [119] この拒否は、かつての盟友である二人の間で激しい公開論争の始まりを告げ、彼らの友情と知的パートナーシップを永久に破壊した。[120][121] [122] ルクセンブルクはカウツキーを臆病者と呼び、議会主義的な便宜主義のためにマルクス主義の原則を放棄したと非難した。カウツキーは逆に、彼女を「反逆者の 焦り」が党を破滅に導く危険な冒険家だと描いた。[123] この論争により、ルクセンブルクはSPDの中道派指導部における影響力を事実上失った。彼女はますます孤立し、党内で小規模ながらも成長する急進的な反対 派の指導者となった。[124] 1910年のマクデブルク大会で、彼女の大量ストライキに関する決議は否決されたが、この議論は、彼女の革命戦略と、歴史の成り行きを待つという執行部の 政策との明確な違いを浮き彫りにした。[125] 1911年のアガディール危機において、彼女は帝国主義戦争の脅威に対する指導部の消極的で不十分な対応を批判し、再び指導部と対立した。[126] [127] |

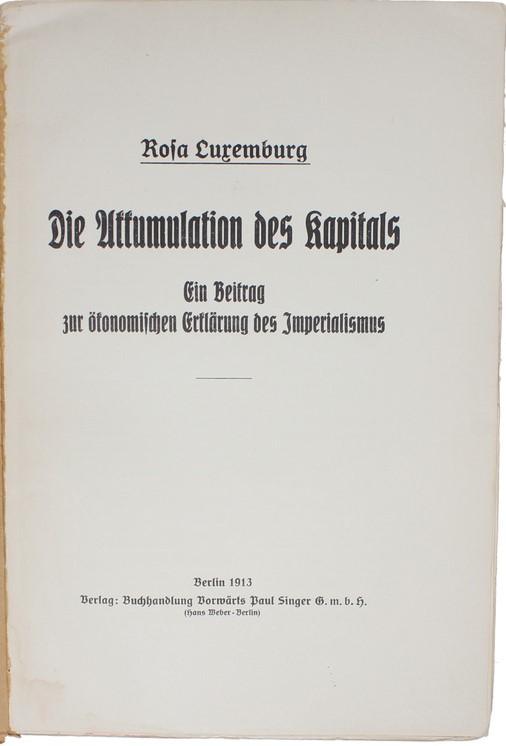

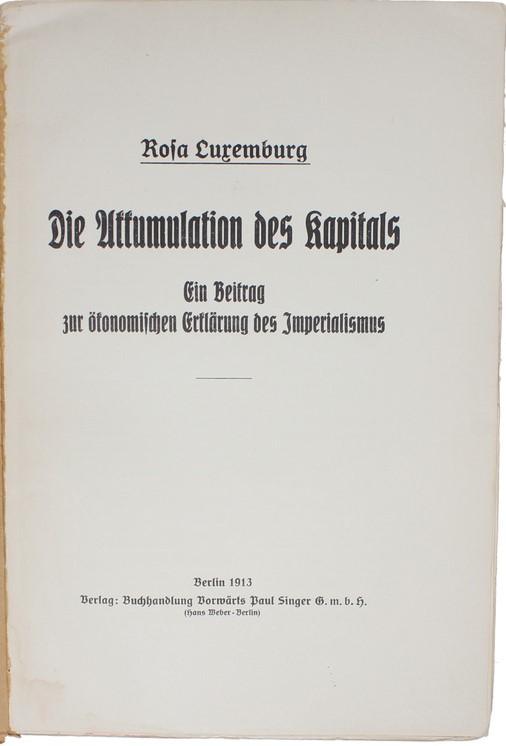

Theorist of imperialism

(1911–1914) Luxemburg in 1912 The years before the outbreak of World War I were marked by Luxemburg's growing alienation from the SPD's leadership and her development of a comprehensive theory of imperialism.[128] The party's electoral victory in 1912, which made it the largest party in the Reichstag, was followed by an electoral pact with the liberal Progressive Party in the run-off elections. When the Progressives failed to reciprocate the SPD's support, Luxemburg launched a scathing critique, arguing that "real class interests are stronger than any 'arrangements'".[129] For her, the episode demonstrated the futility of parliamentary tactics and the naive belief in alliances with bourgeois parties.[130] She became increasingly disillusioned with the parliamentary group's growing influence, which she saw as corroding the party's revolutionary spirit.[131] This period of opposition culminated in her major theoretical work, The Accumulation of Capital, published in 1913. The book originated from her teaching at the SPD party school and her attempt to resolve a technical problem in Marx's theory of capitalist reproduction.[132][133] Her central thesis was that capitalism, as a closed system, could not realise the surplus value it generated and was therefore dependent on a constant expansion into non-capitalist economies and social strata for its survival and accumulation. This "cannibalization" of pre-capitalist societies was, for Luxemburg, the economic root of imperialism.[134][133][135] The book was a monumental effort, which she later claimed to have written in an ecstatic state in just four months.[136][133] The book's reception was overwhelmingly negative, even from the left, but it established her reputation as a brilliant, if unorthodox, theorist and provided the intellectual foundation for her intensifying struggle against imperialism.[137][138] Luxemburg's anti-militarist agitation also brought her into direct conflict with the state. In September 1913, she gave a speech in Bockenheim, near Frankfurt, in which she called on German workers to refuse to take up arms against their "French and other brethren".[139] She was charged with inciting soldiers to mutiny and tried in February 1914. She used the trial as a platform to launch a political assault on militarism and the ruling class, turning her defence into an indictment of the society that was prosecuting her.[140][141] Sentenced to a year in prison, she embarked on a whistle-stop speaking tour while her appeal was pending, drawing large and sympathetic crowds.[142] A second trial for insulting the army followed, based on her allegations of routine abuse of soldiers in the German military. The authorities, hoping to make a test case, were flooded with evidence of such maltreatment, and the trial was eventually adjourned indefinitely.[143] These trials raised Luxemburg's public profile to a height not seen since 1910 and rallied a growing opposition around the banner of anti-militarism.[144] During the trials, she began a brief but intense affair with her lawyer, Paul Levi.[145] |

帝国主義の理論家(1911年~1914年) 1912年のルクセンブルク 第一次世界大戦勃発前の数年間は、ルクセンブルクがSPDの指導部からますます疎外され、包括的な帝国主義理論を展開した時期だった[128]。1912 年の選挙でSPDは帝国議会で最大党となり、決選投票では自由主義の進歩党と選挙協定を結んだ。進歩党がSPDの支援に応じなかったため、ルクセンブルク は「真の階級的利益は、いかなる『取り決め』よりも強い」と主張し、激しい批判を展開した。[129] 彼女にとって、この出来事は議会戦術の無意味さと、ブルジョア政党との同盟への naive な信仰を証明するものだった。[130] 彼女は、党の革命的精神を腐食させていると見た議会派の勢力の拡大に、ますます幻滅していった。[131] この反対運動の期間は、1913年に出版された彼女の主要な理論著作『資本の蓄積』で最高潮に達した。この本は、SPD党学校での彼女の教鞭と、マルクス の資本主義再生産論における技術的な問題を解決しようとしたことから生まれた。[132][133] 彼女の中心的な主張は、資本主義は閉鎖系システムとして、自らが生み出した剰余価値を実現できず、生存と蓄積のためには非資本主義経済と社会層への恒常的 な拡大に依存しているというものだった。この「前資本主義社会へのカニバリズム」が、ルクセンブルクにとって帝国主義の経済的根源だった。[134] [133][135] この本は、彼女が後に「4ヶ月間で恍惚状態の中で書いた」と主張する、壮大な努力の結晶だった。[136][133] 書籍の反応は左派からも圧倒的に否定的だったが、彼女は brillant ながら非正統的な理論家としての評価を確立し、帝国主義との闘いを強化するための知的基盤を築いた。[137][138] ルクセンブルクの反軍国主義運動は、彼女を国家と直接対立させることになった。1913年9月、彼女はフランクフルト近郊のボッケンハイムで演説を行い、 ドイツの労働者に「フランス人およびその他の兄弟たち」に対して武器を取ることを拒否するよう呼びかけた。[139] 彼女は兵士に反乱を扇動した罪で起訴され、1914年2月に裁判にかけられた。彼女は裁判をプラットフォームとして、軍国主義と支配階級に対する政治的攻 撃を展開し、自身の弁護を、彼女を起訴した社会への告発に変えた。[140][141] 1年の禁固刑を言い渡された彼女は、上訴審の間に各地を回る演説ツアーを開始し、多くの同情的な聴衆を惹きつけた。[142] ドイツ軍での兵士への日常的な虐待を指摘した主張に基づき、軍への侮辱罪で第2の裁判が続き、 当局はテストケースとして利用しようとしたが、虐待の証拠が殺到し、裁判は最終的に無期限延期となった。[143] これらの裁判は、ルクセンブルクの人気を1910年以来の最高潮に押し上げ、反軍国主義の旗印の下で拡大する反対派を結束させた。[144] 裁判中、彼女は弁護士のポール・レヴィと短くも激しい恋愛関係に陥った。[145] |

World War I (1914–1918) Luxemburg in 1910 The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 and the subsequent collapse of the Second International was the defining catastrophe of Luxemburg's political life. On 4 August, the SPD's Reichstag delegation voted unanimously for war credits, a decision that signified the capitulation of European social democracy to nationalism.[146] Luxemburg, who was in Berlin, was devastated.[147] Together with Karl Liebknecht, Clara Zetkin, Franz Mehring and a small circle of friends, she immediately began to organize an opposition.[147][148] On 10 September 1914, they issued their first public declaration against the party's policy, disassociating themselves from the SPD leadership and calling for a new International.[149] This group, initially known as the Gruppe Internationale, became the nucleus of the Spartacus League (Spartakusbund). Most of the war Luxemburg spent in prison. Her sentence from the 1914 Frankfurt trial was executed, and she was imprisoned from February 1915 to February 1916.[150][151][152] After only a few months of freedom, during which she was a central figure in the Spartacist opposition, she was re-arrested in July 1916 and held in "protective custody" without trial, first in Warsaw and then in Breslau, until her release during the November 1918 revolution.[153] |

第一次世界大戦(1914年~1918年 1910年のルクセンブルク 1914年8月の第一次世界大戦の勃発と、それに続く第二インターナショナル(国際社会主義運動の国際組織)の崩壊は、ルクセンブルクの政治人生における 決定的な大惨事でした。8月4日、SPDの帝国議会代表団は、戦争予算案を全会一致で可決しました。この決定は、ヨーロッパの社会民主主義がナショナリズ ムに屈服したことを意味しました。[146] ベルリンにいたルクセンブルクは絶望に陥った。[147] カール・リープクネヒト、クララ・ツェトキン、フランツ・メーリング、および少数の友人たちと、彼女は直ちに反対派の組織化を開始した。[147] [148] 1914年9月10日、彼らは党の政策に反対する最初の公開声明を発表し、SPD指導部から離脱し、新たなインターナショナルの結成を呼びかけた。 [149] このグループは当初「インターナショナル派」と呼ばれ、スパルタクス同盟(Spartakusbund)の核となった。 戦争中、ルクセンブルクはほとんどを獄中で過ごした。1914年のフランクフルト裁判での判決が執行され、1915年2月から1916年2月まで投獄され た。[150][151][152] 自由を享受したわずか数ヶ月間、スパルタクス派の反対派の中心人物として活動した彼女は、1916年7月に再逮捕され、裁判なしの「保護拘禁」下に置か れ、ワルシャワを経てブレスラウで拘禁され、1918年11月の革命時に釈放された。[153] |

| Imprisonment and writings Prison became a period of intense intellectual and personal activity for Luxemburg. Though cut off from direct political action, she maintained a prolific correspondence with her friends, particularly Clara Zetkin, Luise Kautsky, and Sophie Liebknecht.[154] In her letters to a new set of confidantes, including Mathilde Jacob, who acted as her link to the outside world, she revealed her vulnerability, her deep love of nature, and her profound empathy for the suffering of others.[155] While in her cell, she collected flowers and plants during her walks, studied botany, and cared for injured animals, once nursing a disabled pigeon back to health.[156] She famously wrote to Sophie Liebknecht about her encounter with abused Romanian buffaloes in the prison yard, an episode that crystallized for her the intertwined cruelty of war and the human capacity for empathy.[157] From prison, she also continued her political work, smuggling out articles and pamphlets that became the theoretical touchstones of the Spartacus League. The most famous of these was the Junius Pamphlet (officially The Crisis of Social Democracy), written in 1915 and illegally distributed in 1916.[158][159][160] In it, she delivered a devastating analysis of the war as an imperialist conflict for which all sides were responsible and a searing indictment of the SPD's betrayal. She argued that in the age of imperialism, national wars of defence were no longer possible and that the only alternative for the proletariat was international class struggle against the war, summed up in the slogan "socialism or barbarism".[161][162] The Russian Revolution of 1917 was a source of both hope and profound concern for Luxemburg. She celebrated the overthrow of Tsarism but became increasingly critical of the Bolsheviks after they seized power in October. In a manuscript written in her Breslau prison in 1918 (published posthumously by Paul Levi in 1922 as The Russian Revolution), she offered a comradely but sharp critique of Bolshevik policy.[163][164][165] While praising Lenin and Leon Trotsky for having the courage to make a revolution, she condemned their resort to terror, their suppression of the Constituent Assembly, and their abolition of democratic freedoms like the freedom of the press and assembly. She famously argued that "Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently."[166][167][168] She also criticised their agrarian policy and their policy of national self-determination, which she believed had weakened the revolution and opened the door to German imperialism.[169][170] For Luxemburg, the Bolsheviks' errors stemmed from the isolation of the Russian Revolution, which could only be saved by a successful proletarian revolution in Germany and the West.[171][172][168] |

投獄と著作 刑務所は、ルクセンブルクにとって、知的かつ個人的な活動が活発な時期となった。直接的な政治活動からは切り離されていたが、彼女は友人たち、特にクラ ラ・ツェトキン、ルイーズ・カウツキー、ソフィー・リープクネヒトと、多作な書簡のやり取りを続けていた。[154] 彼女と外界との連絡役を務めたマチルデ・ヤコブをはじめとする新しい友人たち宛ての手紙では、彼女は自分の脆弱さ、自然への深い愛情、他者の苦悩に対する 深い共感を明らかにしている[155]。独房では、散歩中に花や植物を収集し、植物学を学び、負傷した動物を世話し、かつては障害のある鳩を看護して健康 に戻したこともある。[156] 彼女は、刑務所の庭で虐待されているルーマニアのバッファローたちとの出会いについて、ソフィー・リープクネヒトに有名な手紙を書いた。この出来事は、戦 争の残酷さと人間の共感能力の相互関係について、彼女の中で明確になった。 刑務所からも、彼女は政治活動を続け、スパルタクス同盟の理論的指針となった記事やパンフレットを密かに持ち出した。その中でも最も有名なのは、1915 年に執筆され、1916年に違法に配布された『ユニウス小冊子』(正式タイトル『社会民主主義の危機』)だ。[158][159][160] その中で、彼女は戦争を帝国主義的な紛争として徹底的に分析し、すべての側が責任を負うものだと指摘し、SPDの背信行為を痛烈に非難した。彼女は、帝国 主義の時代には、国防のための国家戦争はもはや不可能であり、プロレタリアートの唯一の選択肢は、「社会主義か野蛮か」というスローガンに要約される、戦 争に対する国際的な階級闘争だけだと主張した。[161][162] 1917年のロシア革命は、ルクセンブルクにとって希望と深い懸念の両方の源だった。彼女はツァリズムの打倒を歓迎したが、10月に権力を掌握したボリ シェヴィキに対して次第に批判的になった。1918年にブレスラウの獄中で執筆した原稿(1922年にポール・レーヴィによって『ロシア革命』として遺作 として出版された)で、彼女はボリシェヴィキの政策に対して同志的ながらも鋭い批判を提示した。[163][164][165] 彼女は、革命を起こす勇気を持ったレーニンとレオン・トロツキーを称賛する一方で、彼らのテロへの依存、憲法制定議会の弾圧、報道や集会の自由などの民主 的自由の廃止を非難した。彼女は、「自由とは、常に、そしてもっぱら、異なる考えを持つ者の自由である」という有名な主張をした[166][167] [168]。また、彼女は、彼らの農業政策と民族自決政策も批判し、それらが革命を弱体化させ、ドイツ帝国主義の侵入の門戸を開いたと信じていました。 [169][170] ルクセンブルクにとって、ボルシェビキたちの誤りは、ロシア革命の孤立に起因しており、ドイツと西側諸国でのプロレタリア革命の成功によってのみ救われる と信じていました。[171][172][168] |

| German Revolution and death Luxemburg was released from prison on 9 November 1918, in the midst of the German Revolution of 1918–1919. Her hair had turned white, and her health had deteriorated.[173][174] She travelled immediately to Berlin and plunged into the revolutionary turmoil.[175] Together with Karl Liebknecht, she took over the leadership of the Spartacus League and began publishing its daily newspaper, Die Rote Fahne (The Red Flag).[176][177][178] She forcefully articulated the Spartacist programme: the overthrow of the provisional government of Friedrich Ebert, the disarming of the counter-revolutionary troops, and the transfer of all power to the workers' and soldiers' councils.[179] At the turn of the year, from 30 December 1918 to 1 January 1919, the Spartacus League, along with other radical groups, founded the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).[180][181][182] In her programme speech to the founding congress, Luxemburg laid out her vision of revolution. She rejected both a Blanquist-style seizure of power by a minority and a purely parliamentary path to socialism. Revolution, she argued, must be the work of the masses themselves, a protracted process of class struggle from below, in which the workers would learn to wield power through their own action and experience.[183] Although she and the other leaders advised participation in the upcoming elections for a National Assembly, the congress, dominated by young and impatient radicals, voted against their advice.[184][185] |

ドイツ革命と死 ルクセンブルクは、1918年から1919年にかけてのドイツ革命の最中、1918年11月9日に刑務所から釈放された。彼女の髪は白髪になり、健康も悪 化していた[173][174]。彼女はすぐにベルリンへ旅立ち、革命の混乱に飛び込んだ[175]。カール・リープクニヒトとともに、彼女はスパルタク ス同盟の指導権を握り、その日刊紙『Die Rote Fahne(赤い旗)』の発行を開始した。[176][177][178] 彼女はスパルタクス派のプログラムを力強く主張した:フリードリヒ・エベルトの暫定政府の打倒、反革命軍の武装解除、そしてすべての権力を労働者・兵士評 議会に移譲すること。[179] 年明けの1918年12月30日から1919年1月1日にかけて、スパルタクス同盟は他の急進派グループと共にドイツ共産党(KPD)を設立した。 [180][181][182] 設立大会でのプログラム演説で、ルクセンブルクは革命のビジョンを提示した。彼女は、少数派によるブランキスト式の権力奪取と、純粋に議会主義的な社会主 義への道の両方を拒否した。革命は、大衆自身による、下層からの長きにわたる階級闘争の過程であり、その過程において、労働者は自らの行動と経験を通じて 権力の行使方法を学ぶべきだと主張した。[183] 彼女や他の指導者たちは、間もなく行われる国民議会選挙への参加を勧めたが、若くてせっかちな急進派が支配的な大会は、彼らの助言に反対した。[184] [185] |

Spartacist uprising and murder 1919 photo of the graves of Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht In early January 1919, a second revolutionary wave swept Berlin. The dismissal of the popular but radical police chief of Berlin, Emil Eichhorn, by the Ebert government sparked a mass demonstration on 5 January, organized by the Revolutionary Shop Stewards, the left-wing of the Independent Social Democrats (USPD), and the KPD.[186][187][188] The demonstration was far larger than expected, and a Revolutionary Committee, including Liebknecht, was hastily formed to lead the movement.[189] This so-called Spartacist uprising was not a planned putsch by the KPD. Luxemburg initially thought it a mistake, believing the moment was not yet ripe for an overthrow of the government, but once the masses were on the streets, she felt it was the duty of revolutionaries to support them.[190][188] In Die Rote Fahne, she passionately urged the workers on. The government, led by Ebert and his defence minister Gustav Noske, moved decisively to crush the revolt. They employed the Freikorps, newly formed right-wing paramilitary units composed of demobilised soldiers and officers, to suppress the uprising.[180][191][192] By 13 January, the fighting was largely over and the revolt crushed. The Spartacist leaders went into hiding. On the evening of 15 January, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were discovered in an apartment in the Wilmersdorf district of Berlin and arrested by Freikorps soldiers.[193][194][195] They were taken to the Eden Hotel, the headquarters of the Garde-Kavallerie-Schützen-Division. There, they were interrogated and tortured. Liebknecht was taken out first, shot, and delivered to a mortuary as an "unidentified man". Luxemburg was then led out. A soldier named Otto Runge struck her on the head with his rifle butt as she left the hotel; she fell, was struck again, and then bundled into a car.[196] She was shot in the head, and her body, weighted with stones, was thrown into the Landwehr Canal.[197][196] Her body was not found until 31 May 1919.[198][199] The murders provoked widespread outrage in Germany and abroad. The subsequent military trials of the perpetrators were widely seen as a sham; the main instigator, Captain Waldemar Pabst, was never charged, and Runge received a two-year sentence.[200][201] |

スパルタクス蜂起と暗殺 1919年のルクセンブルクとカール・リープクニヒトの墓の写真 1919年1月初旬、ベルリンを第2の革命の波が襲った。エベルト政権による、人気があったが過激なベルリン警察長官エミール・アイヒホルンの解任は、1 月5日に革命的労働組合代表者会議(革命的ショップ・スチュワード)、独立社会民主党(USPD)の左派、および共産党(KPD)によって組織された大規 模なデモを引き起こした。[186][187][188] デモは予想を遥かに上回る規模となり、リープクネヒトを含む革命委員会が急遽結成され、運動を指導した。[189] このいわゆるスパルタクス蜂起は、KPDによる計画的なクーデターではなかった。ルクセンブルクは当初、政府打倒の時期はまだ熟していないと考え、この蜂 起を誤りだと考えていたが、群衆が街頭に溢れ返ると、革命家として彼らを支援する義務があると悟った。[190][188] 『ディ・ローテ・ファーネ』誌で、彼女は労働者に熱烈に呼びかけた。 エバートと国防相グスタフ・ノスケ率いる政府は、反乱を鎮圧するために断固たる措置を講じた。彼らは、復員した兵士や将校で構成される、新たに結成された 右翼の民兵組織「フライコープ」を動員して、反乱を鎮圧した。[180][191][192] 1月13日までに戦闘はほぼ終結し、反乱は鎮圧された。スパルタクス派の指導者たちは隠遁した。1月15日の夜、ルクセンブルクとリープクネヒトはベルリ ンのヴィルメルスドルフ地区の 아파트で発見され、フリーコープスの兵士たちに逮捕された。[193][194][195] 彼らは、ガルデ・カヴァレリー・シューツェン師団の本部であるエデンホテルに連行された。そこで尋問と拷問を受けた。リープクネヒトが最初に連れ出され、 射殺され、「身元不明の男」として遺体安置所に運ばれた。その後、ルクセンブルクが連れ出された。ホテルを出たところ、オットー・ルンゲという兵士がライ フル銃の銃床で彼女の頭を殴り、彼女は倒れ、再び殴られ、車に押し込まれた。[196] 彼女は頭部を撃たれ、石で重しを付けられた遺体はランドヴェール運河に投げ込まれた。[197][196] 彼女の遺体は1919年5月31日まで発見されなかった。[198][199] この殺人事件は、ドイツ国内外で大きな怒りを呼び起こした。その後の加害者の軍事裁判は、偽装裁判だと広く見なされ、主犯であるヴァルデマー・パブスト大 尉は起訴されず、ルンゲは2年の刑を言い渡された。[200][201] |

| Thoght As a significant Marxist theorist, Luxemburg's work focused on the strategy of revolution, the nature of capitalism, and the meaning of socialist democracy. She was a firm believer in the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, viewing history as a dynamic process and insisting on the inseparability of theory and practice.[202] Revolutionary socialism and critique of reformism Luxemburg's most famous contribution to political theory was her intervention in the revisionist debate in the SPD at the turn of the 20th century. In her 1900 pamphlet Social Reform or Revolution?, she mounted a defence of orthodox Marxism against the reformist theories of Eduard Bernstein.[61] Bernstein had argued that capitalism had adapted and was not heading for an inevitable collapse, and that socialists should therefore abandon the goal of revolution and work for gradual, piecemeal reforms within the existing system.[57] Luxemburg argued that this presented a false choice between reform and revolution. For her, the two were dialectically linked: the daily struggle for reforms (such as the eight-hour day or improved trade union rights) was the only means by which the proletariat could become conscious of its class power and prepare itself for the revolutionary seizure of power.[64][203] To abandon the final goal of revolution, she argued, was to transform the socialist movement into a petit-bourgeois reformist party, severing its practical activity from its ultimate purpose and effectively accepting the permanence of capitalism. The fight for reforms was the means of the class struggle; the social revolution was its aim.[204] |

思想 マ ルクス主義の重要な理論家として、ルクセンブルクは革命の戦略、資本主義の本質、社会主義民主主義の意味に焦点を当てた研究を行った。彼女はカール・マル クスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルスの弁証法的唯物論を堅く信じ、歴史を動的なプロセスと捉え、理論と実践の不可分性を主張した。[202] 革命的社会主義と改革主義の批判 ルクセンブルクが政治理論に与えた最も有名な貢献は、20 世紀初頭に SPD 内で起こった修正主義の議論への介入だった。1900年の小冊子『社会改革か革命か?』において、彼女はエドゥアルト・ベルンシュタインの改革主義理論に 対し、正統派マルクス主義を擁護した。[61] ベルンシュタインは、資本主義は適応しており、不可避的な崩壊に向かっているわけではないと主張し、社会主義者は革命の目標を放棄し、既存のシステム内で の段階的・部分的な改革を追求すべきだと主張した。[57] ルクセンブルクは、これは改革と革命の間の誤った選択であると主張した。彼女にとって、この2つは弁証法的に結びついていた。8時間労働制や労働組合の権 利の改善などの日々の改革のための闘争は、プロレタリアートが自らの階級意識を認識し、革命による権力の奪取に備えるための唯一の手段だった[64]。 [203] 革命の最終目標を放棄することは、社会主義運動を小市民的改革主義政党に変質させ、その実践的活動と最終目的を切り離し、資本主義の永続性を事実上受け入 れることになると彼女は主張した。改革のための闘争は階級闘争の手段であり、社会革命はその目的だった。[204] |

Mass strike, spontaneity, and the role of the party Luxemburg addressing a crowd in Stuttgart in 1907 Drawing on the experience of the 1905 Russian Revolution, Luxemburg developed her theory of the mass strike as the most important weapon in the proletarian struggle. In her 1906 pamphlet The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions, she argued against the SPD and trade union leadership's view of the mass strike as a single, organised, and controllable action.[103] Instead, she saw it as the characteristic form of a revolutionary period, a process in which economic and political struggles merged, and in which strikes, demonstrations, and uprisings would flow into one another.[205][102] This theory is often associated with the concept of "spontaneity". For Luxemburg, spontaneity was not a synonym for disorganisation, but rather the creative, elemental, and often unpredictable energy of the masses in action.[206][100] The role of the revolutionary party was not to "make" or "call" a mass strike in a top-down, commandist fashion, but to give political leadership, clarity, and direction to the spontaneous movement that arose from the objective conditions of the class struggle.[207] This dialectical relationship between the spontaneous action of the masses and the conscious leadership of the party stood in stark contrast to both the bureaucratic caution of the SPD leadership and Vladimir Lenin's more strictly vanguardist conception of the party.[208][209] |

大衆ストライキ、自発性、そして党の役割 1907年、シュトゥットガルトで群衆に演説するルクセンブルク 1905年のロシア革命の経験を踏まえ、ルクセンブルクは、プロレタリア闘争における最も重要な武器として、大衆ストライキの理論を確立した。1906年 の小冊子『大衆ストライキ、政治党派、労働組合』において、彼女は、SPDと労働組合指導部が主張する「大衆ストライキは単一で組織化された制御可能な行 動である」という見解に反対した。[103] 代わりに、彼女はそれを革命期の特徴的な形態、経済闘争と政治闘争が融合し、ストライキ、デモ、蜂起が相互に流れ込む過程と見なした。[205] [102] この理論は、しばしば「自発性」という概念と関連付けられる。ルクセンブルクにとって、自発性は無組織の同義語ではなく、大衆の行動における創造的、根本 的、そしてしばしば予測不可能なエネルギーを指した。[206][100] 革命的党の役割は、上から下への命令的な方法で「作る」または「呼びかける」ことではなく、階級闘争の客観的条件から生じる自発的な運動に政治的指導、明 確さ、方向性を与えることだった。[207] 大衆の自発的行動と党の意識的な指導との間のこの弁証法的関係は、SPD指導部の官僚的な慎重さと、ウラジーミル・レーニンのより厳格な先鋒隊的党観の両 方と対照的だった。[208][209] |

Imperialism, nationalism, and war Title page of Luxemburg's The Accumulation of Capital (1913) Luxemburg's major theoretical work was The Accumulation of Capital (1913), which she presented as a contribution to the economic clarification of imperialism.[210] In it, she argued that capitalism was driven by an inherent contradiction: it could not realise the surplus value generated within its own closed system. To survive and continue to accumulate, it was therefore compelled to expand into and exploit pre-capitalist spheres, both within its home countries (e.g., the peasantry and artisan classes) and, more importantly, in colonies abroad.[211][133][135] This ceaseless, competitive drive for control of non-capitalist markets and resources was, for Luxemburg, the economic foundation of imperialism and militarism.[212] This economic analysis underpinned her political stance against imperialism and war. She saw imperialism not as a mere policy choice but as the final, global stage of capitalism, which would inevitably lead to ever more destructive wars and ultimately to "barbarism" unless it was overthrown by international socialist revolution.[213][162] This conviction was the basis for her consistent internationalism and her critique of nationalism, which she saw as a bourgeois ideology used to divide the working class and tie it to the interests of its own ruling class.[37][18] Her opposition to the "right of nations to self-determination" as a universal slogan, which put her in direct conflict with Lenin, stemmed from this belief. She argued that in the age of imperialism, such a right was a hollow phrase that often served as a cover for the interests of competing imperialist powers.[169][214] |

帝国主義、ナショナリズム、戦争 ルクセンブルグの『資本蓄積』(1913年)のタイトルページ ルクセンブルクの主要な理論的著作は『資本の蓄積』(1913年)で、彼女はこれを帝国主義の経済的解明への貢献として発表した。[210] その中で彼女は、資本主義は内在的な矛盾によって駆動されていると主張した:それは、自らの閉鎖されたシステム内で生成された剰余価値を実現することがで きない。生存と蓄積を継続するため、資本主義は、自国内(例えば農民や職人階級)だけでなく、より重要なのは海外の植民地において、前資本主義的な領域へ の拡大と搾取を余儀なくされた。[211][133][135] この非資本主義的な市場と資源の支配をめぐる絶え間ない競争的な駆動力こそが、ルクセンブルクにとって帝国主義と軍国主義の経済的基盤だった。[212] この経済分析は、帝国主義と戦争に対する彼女の政治的立場を支えていた。彼女は、帝国主義を単なる政策の選択ではなく、資本主義の最終的かつ世界的な段階 であり、国際的な社会主義革命によって打倒されない限り、ますます破壊的な戦争、そして最終的には「野蛮主義」へと必然的に至るものと考えていた。 [213][162] この確信は、彼女の一貫した国際主義と、ナショナリズムに対する批判の基盤となった。彼女は、ナショナリズムを、労働者階級を分断し、その階級を支配する 階級の利益に縛り付けるためのブルジョア的イデオロギーだと考えていた。[37][18] 彼女は、「国民自決の権利」を普遍的なスローガンとして反対し、レーニンと直接対立したが、その根底にはこの信念があった。彼女は、帝国主義の時代におい て、そのような権利は、対立する帝国主義諸国の利益の覆い隠しのための空虚な言葉である、と主張した。[169][214] |

| Critique of the Russian Revolution Luxemburg enthusiastically welcomed the Russian Revolution but was deeply critical of the Bolsheviks' policies after they seized power. In a manuscript written in prison in 1918 and published after her death, she articulated a fundamental critique of the Bolshevik model of revolution.[215][216] While praising Lenin and Leon Trotsky for their revolutionary courage, she condemned their suppression of the Russian Constituent Assembly, their restriction of suffrage, and their abolition of democratic freedoms.[217][170] She argued that "without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of press and assembly, without a free struggle of opinion, life dies out in every public institution, becomes a mere semblance of life, in which only the bureaucracy remains as the active element."[166] Her most famous dictum came from this critique: "Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently."[166][167][168] For Luxemburg, socialist democracy was not something to be granted as a gift after the revolution had been secured, but was the very medium of the revolution itself—the only way for the masses to learn, correct their mistakes, and exercise power. The substitution of a dictatorship of a party or a committee for the dictatorship of the proletariat would, she feared, lead not to socialism but to a "brutalization of public life".[218] She believed the Bolsheviks' errors were a product of the fatal isolation of their revolution, and that its only salvation lay in a successful proletarian revolution in the West, especially in Germany.[219] |

ロシア革命の批判 ルクセンブルクはロシア革命を熱狂的に歓迎したが、ボルシェビキが権力を掌握した後の政策には深く批判的だった。1918年に獄中で執筆し、死後出版され た原稿で、彼女はボルシェビキの革命モデルに対する根本的な批判を明確にした。[215][216] レニンとレオン・トロツキーの革命的勇気を称賛しつつも、彼女はロシア憲法制定議会の弾圧、選挙権制限、民主的自由の廃止を非難した。[217] [170] 彼女は「一般選挙なし、報道と集会の自由なし、意見の自由な闘争なしでは、あらゆる公共機関での生活は衰え、単なる生活の仮装となり、官僚だけが活動的な 要素として残る」と主張した。[166] 彼女の最も有名な格言は、この批判から生まれた。「自由とは、常に、そしてもっぱら、異なる考えを持つ者の自由である」[166][167][168]。 ルクセンブルクにとって、社会主義民主主義は、革命が成功した後に与えられる贈り物ではなく、革命そのものの媒体、つまり大衆が学び、過ちを正し、権力を 行使するための唯一の手段だった。プロレタリアートの独裁を、党や委員会の独裁に置き換えることは、社会主義ではなく「公共生活の野蛮化」に導くと彼女は 恐れた。[218] 彼女は、ボルシェビキの誤りは彼らの革命の致命的な孤立の産物であり、その唯一の救いは西欧、特にドイツでのプロレタリア革命の成功にあると信じていた。 [219] |

Legacy Memorial to Luxemburg and Liebknecht at the Friedrichsfelde cemetery in Berlin, 1926. It was commissioned by the KPD and later destroyed by the Nazis in 1935. The murder of Rosa Luxemburg transformed her into a martyr for the revolutionary socialist cause. Her legacy, however, has been a subject of intense debate and political contestation ever since.[220][221] In the immediate aftermath, the KPD, under the leadership of Paul Levi, revered her as a founder and theorist, and began the process of collecting and publishing her works.[222] The debate over "Luxemburgism" as a distinct political tendency began in earnest after Levi published her critical manuscript on the Russian Revolution in 1922.[223][224] This move, part of an internal party struggle, prompted a sharp response from Lenin. In his famous "chicken and eagle" parable, Lenin praised Luxemburg as a revolutionary "eagle" but enumerated her theoretical "errors"—on the national question, the accumulation of capital, party organisation, and the nature of the state—which he argued must be corrected by the party.[225][226] This set the template for the official Communist interpretation for decades. During the "Bolshevisation" of the KPD in the mid-1920s, Luxemburgism was systematically constructed as a coherent but fallacious system of thought, a "syphilis bacillus" that needed to be eradicated.[227] The ultra-left faction led by Ruth Fischer and Arkadi Maslow paired Luxemburgism with Trotskyism as a heresy characterised by a theory of "spontaneity" that underestimated the role of the revolutionary party.[228] During the Stalin era, this critique hardened into dogma, and Luxemburg's ideas were either ignored or denounced as a "deadly enemy" of Leninism.[229][230] West German student movement demonstration in West Berlin in 1968, featuring an image of Luxemburg After the death of Stalin, there was a renewed interest in Luxemburg's work. In Poland and East Germany, she was partially rehabilitated and celebrated as a national revolutionary figure, though her more critical ideas were often downplayed.[231] For many socialists and communists outside the orthodox Leninist tradition, including Left Communists, Trotskyists, and democratic socialists, she remains a major theoretical and moral touchstone. Her emphasis on democracy and mass action, her critique of bureaucracy and authoritarianism, and her profound humanism continue to inspire revolutionary movements and thinkers around the world.[232] She has been reclaimed by modern scholars and activists for her relevance to feminist, anti-racist, and postcolonial critiques of capitalism.[233] |

遺産 1926年、ベルリンのフリードリヒスフェルデ墓地に建てられたルクセンブルクとリープクネヒトの記念碑。KPD の依頼により建設されたが、1935年にナチスによって破壊された。 ローザ・ルクセンブルクの殺害は、彼女を革命的社会主義運動の殉教者に変えた。しかし、彼女の遺産は、それ以来、激しい議論と政治的争いの対象となってい る[220]。[221] その後、ポール・レヴィの指導の下、KPD は彼女を創設者および理論家として崇め、彼女の著作の収集と出版を開始した。[222] 「ルクセンブルク主義」を独自の政治傾向として捉える議論は、1922年にレヴィがロシア革命に関する批判的な原稿を発表してから本格的に始まった。 [223][224] この動きは、党内の権力闘争の一部であり、レーニンから厳しい反論を引き起こした。レーニンは、有名な「鶏と鷲」の寓話で、ルクセンブルクを革命の「鷲」 として称賛する一方で、国民問題、資本の蓄積、党組織、国家の性質など、彼女の理論上の「誤謬」を列挙し、党として是正すべきだと主張した。[225] [226] これにより、数十年にわたる共産党の公式解釈のテンプレートが確立された。 1920年代半ばのKPDの「ボルシェビキ化」の過程で、ルクセンブルク主義は、一貫性はあるが誤った思想体系、根絶すべき「梅毒菌」として体系的に構築 された。[227] ルース・フィッシャーとアルカディ・マスロフが率いる極左派は、ルクセンブルク主義をトロツキズムと結びつけ、革命的党の役割を過小評価する「自発性」の 理論を特徴とする異端として位置付けた。[228] スターリン時代には、この批判は教条化され、ルクセンブルクの思想は無視されるか、レーニン主義の「致命的な敵」として非難された。[229][230]  1968年に西ベルリンで行われた西ドイツの学生運動のデモ。ルクセンブルクの肖像が掲げられている スターリンの死後、ルクセンブルクの著作に対する関心が再び高まった。ポーランドと東ドイツでは、彼女の批判的な考えはしばしば軽視されたものの、彼女は 部分的に名誉回復され、国民的革命家として称賛された[231]。左翼共産主義者、トロツキスト、民主社会主義者など、正統的なレーニン主義の伝統に属さ ない多くの社会主義者や共産主義者にとって、彼女は依然として重要な理論的・道徳的基準となっている。彼女の民主主義とマスアクションへの強調、官僚主義 と権威主義への批判、そして深いヒューマニズムは、世界中の革命運動と思想家に影響を与え続けている。[232] 彼女は、資本主義に対するフェミニスト、反人種差別、ポストコロニアルの批判との関連性から、現代の学者や活動家によって再評価されている。[233] |

Commemoration 2016 Liebknecht-Luxemburg Demonstration in Berlin, held each January in their honor In her native Poland, Luxemburg's legacy is controversial, primarily due to her opposition to Polish independence.[234] During the Polish People's Republic, several places and enterprises were named after her, including a manufacturing facility of electric lamps in the Wola district of Warsaw, the Zakłady Wytwórcze Lamp Elektrycznych im. Róży Luksemburg [pl].[235] A street in Szprotawa used to be named after Luxemburg (ulica Róży Luksemburg) until it was changed to ulica Różana (Rose street) in September 2018.[236] Many other streets and locations in Poland either used to be or still are named after her, such as those in Warsaw, Gliwice, Będzin, Szprotawa, Lublin, Polkowice, Łódź, etc.[237][238][239][240][241] Efforts to put up commemorative plaques in her memory have taken place in a number of Polish cities, such as Poznań and her birthplace Zamość. A 45-minute-long sightseeing tour around areas associated with the life of the Polish revolutionary was organised in Warsaw in 2019, where a statue of her by Alfred Jesion was also put on display at the Warsaw Citadel as part of the Gallery of Polish Sculpture of the 1950s.[238] The commemorative plaque in Poznań, on the building where she lived in during May 1903, was vandalised with paint in 2013.[242] An official petition was started in 2021 to name a square in Wrocław after her, but the local government rejected the proposal.[243] In Germany, Luxemburg and Liebknecht are honoured annually on the second weekend of January with the Liebknecht-Luxemburg-Demonstration in Berlin, which ends at the Gedenkstätte der Sozialisten (Socialists' Memorial) in the Friedrichsfelde Central Cemetery. During the German Democratic Republic, the demonstration was a state-sponsored event for the ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany. The 1988 demonstration was famously used by dissidents to protest the regime by unfurling a banner with Luxemburg's slogan, "Freiheit ist immer Freiheit der Andersdenkenden" ("Freedom is always the freedom of dissenters").[244] The German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution notes that the idolisation of Luxemburg and Liebknecht remains an important tradition for the German far-left.[245]  Memorial at the site where Luxemburg's corpse was thrown into the Landwehr Canal Numerous places in Germany bear her name, notably Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz and its U-Bahn station in Berlin. After German reunification, there were proposals to rename streets and squares in the former East Berlin honouring communist figures, but a commission recommended that Luxemburg's name, among others, should be retained.[246] A memorial to Luxemburg and Liebknecht designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was built in 1926 but destroyed by the Nazis in 1935. At the edge of the Tiergarten, a memorial marks the spot on the Landwehr Canal where her body was thrown into the water. |

記念 2016年、ベルリンで開催されたリープクネヒト・ルクセンブルクデモ。 ルクセンブルクは、ポーランド出身であるため、ポーランドの独立に反対していたことから、母国ではその遺産について論争がある[234]。ポーランド人民 共和国時代、ワルシャワのヴォラ地区にある電灯製造工場「Zakłady Wytwórcze Lamp Elektrycznych im. ルージ・ルクセンブルク[pl]。235] シュプロタワの街には、ルクセンブルクにちなんで名付けられた通り(ulica Róży Luksemburg)があったが、2018年9月にulica Różana(ローズ通り)に変更された。[236] ポーランドには、ワルシャワ、グリヴィツェ、ベンジン、シュプロタヴァ、ルブリン、ポルコヴィツェ、ウッチなど、彼女にちなんで名付けられた、またはかつ て名付けられていた多くの通りや場所がある。[237][238][239][240][241] 彼女の記憶を偲ぶ記念碑の設置が、ポズナンや彼女の故郷ザモシチを含むポーランドの複数の都市で進められている。2019年には、ワルシャワでポーランド の革命家と関連のある地域を巡る45分間の観光ツアーが開催され、アルフレッド・イエシオン作の彼女の像が、ワルシャワ要塞内の「1950年代ポーランド 彫刻ギャラリー」に展示された。[238] ポズナンにある、彼女が1903年5月に住んでいた建物の記念碑は、2013年に塗料で破壊された。[242] 2021年に、ヴロツワフに彼女の名前を冠した広場を命名する公式請願が開始されたが、地方自治体は提案を拒否した。[243] ドイツでは、毎年 1 月の第 2 週末に、ベルリンでリープクネヒト・ルクセンブルク・デモが行われ、フリードリヒスフェルデ中央墓地のゲデンクシュテッテ・デア・ソシアリスト(社会主義 者記念碑)で締めくくられる。ドイツ民主共和国時代、このデモは、与党であるドイツ社会主義統一党が主催する国家行事だった。1988年のデモでは、ルク センブルクのスローガン「Freiheit ist immer Freiheit der Andersdenkenden」(「自由は常に異議を唱える者の自由である」)と書かれた横断幕を掲げて、体制に抗議する反体制派が利用したことで有名 だ。[244] ドイツ連邦憲法擁護庁は、ルクセンブルクとリープクネヒトの偶像化がドイツの極左派にとって重要な伝統として残っていることを指摘している。[245]  ルクセンブルクの遺体がランドヴェーア運河に投棄された場所にある記念碑 ドイツには、彼女の名前を冠した場所がたくさんある。特に、ベルリンのローザ・ルクセンブルク広場とその地下鉄駅が有名だ。ドイツ再統一後、旧東ベルリン の共産主義者を称える通りや広場の名称を変更する提案があったが、委員会は、ルクセンブルクなどの名称は維持すべきだと勧告した。[246] ルードヴィヒ・ミース・ファン・デル・ローエが設計したルクセンブルクとリープクネヒトの記念碑は1926年に建設されたが、1935年にナチスによって 破壊された。ティアーガルテン公園の端には、彼女の遺体が水に投げ込まれたランドヴェール運河の地点に記念碑が立っている。 |

In arts and literature Portrait on Rosa-Luxemburg-Straße in Frankfurt Luxemburg's life and death have inspired numerous works of art and literature. Bertolt Brecht's 1919 poem "Epitaph" honours her, and was set to music by Kurt Weill in The Berlin Requiem. In cinema, her story was most famously depicted in Margarethe von Trotta's 1986 biographical film, Rosa Luxemburg, starring Barbara Sukowa, which won the Best Actress award at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival. The Quebec painter Jean-Paul Riopelle created a monumental thirty-painting fresco in 1992, Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg, which is on permanent display at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.[247] She has appeared as a character in several novels, including Alfred Döblin's Karl and Rosa, Jonathan Rabb's Rosa (2005), and William T. Vollmann's historical fiction Europe Central (2005). The graphic novel Red Rosa (2015) by Kate Evans provides a biographical account of her life. The feminist magazine Lux, launched in 2020, is named in her honour, describing her as "one of the most creative minds to remake the socialist tradition".[248] From 1913 until her death, Luxemburg pursued a lifelong interest in botany by collecting and studying plant specimens.[249] Her personal herbarium, comprising 18 notebooks with 377 specimens, is held at the Archive of Modern Records in Warsaw.[249] She collected many of the plants during her imprisonments, finding in the work a therapeutic escape and a connection to the outside world.[250] The collection, which features plants from Berlin, Wronki, Wrocław, and the Alps, contains handwritten notes on the species, location, and date of collection.[249] |

芸術と文学 フランクフルトのローザ・ルクセンブルク通りにある肖像画(グラフィティ?) ルクセンブルクの生涯と死は、数多くの芸術作品や文学作品に影響を与えた。ベルトルト・ブレヒトの1919年の詩「墓碑銘」は彼女を称えるもので、クル ト・ヴァイルによって『ベルリン・レクイエム』の楽曲化もされた。映画では、1986年にマーガレーテ・フォン・トロッタが監督、バーバラ・スコヴァ主演 で製作した伝記映画『ローザ・ルクセンブルグ』が最も有名で、1986年のカンヌ国際映画祭で最優秀女優賞を受賞した。ケベック出身の画家ジャン=ポー ル・リオペルは、1992年に30枚の絵画からなる巨大なフレスコ画「ローザ・ルクセンブルグへのオマージュ」を制作し、ケベック美術館に常設展示されて いる。[247] 彼女は、アルフレッド・ドブリンの『カールとローザ』、ジョナサン・ラブの『ローザ』(2005年)、ウィリアム・T・ヴォルマンの歴史小説『ヨーロッ パ・セントラル』(2005年)など、いくつかの小説にキャラクターとして登場している。ケイト・エヴァンスのグラフィックノベル『レッド・ローザ』 (2015年)は、彼女の生涯を伝記的に描いた作品だ。2020年に創刊されたフェミニスト雑誌『Lux』は、彼女を「社会主義の伝統を再構築した最も創 造的な人物の一人」と評し、彼女にちなんで名付けられた。[248] 1913年から亡くなるまで、ルクセンブルクは植物標本の収集と研究に生涯の関心を寄せた。[249] 377点の標本を含む18冊のノートで構成される彼女の個人的な植物標本集は、ワルシャワの現代記録アーカイブに保管されている。[249] 彼女は投獄中に多くの植物を収集し、その作業に癒しの逃避と外界とのつながりを見出していた。[250] ベルリン、ヴロンキ、ヴロツワフ、アルプスなどから収集された植物を含むこのコレクションには、種、採集場所、採集日に関する手書きのメモが記載されてい る。[249] |

Body identification controversy Grave of Luxemburg in Berlin On 29 May 2009, German news media reported the discovery of a preserved, unidentified female corpse in the cellar of the Berlin Charité hospital's medical history museum.[251] The forensic pathologist Michael Tsokos hypothesised that it might be the body of Rosa Luxemburg. An autopsy on the remains revealed features consistent with Luxemburg: signs of having been submerged in water, an age of 40–50, and legs of differing lengths. A radiocarbon dating test confirmed the body dated from the same period as her murder. Discrepancies in the original 1919 autopsy report on the body buried in Friedrichsfelde—which noted no hip damage and failed to find evidence of the blows to her head or a bullet—supported Tsokos's theory. In an attempt to identify the Charité corpse, authorities located a great-niece of Luxemburg, Irene Borde, who donated hair for a DNA comparison.[252] In late December 2009, the authorities announced that the DNA test was inconclusive. The identity of the body remains unconfirmed, and it is unknown whether the remains buried in 1919 are truly those of Rosa Luxemburg.[253] |

遺体の身元確認をめぐる論争 ベルリンのルクセンブルク墓 2009年5月29日、ドイツのニュースメディアは、ベルリンのシャリテ病院の医学歴史博物館の地下室で、保存状態の良い身元不明の女性の遺体が発見され たと報じた[251]。法医学者のミヒャエル・ツォコスは、この遺体はローザ・ルクセンブルクのものかもしれないとの仮説を立てた。遺体の解剖結果、水没 の痕跡、40~50 歳の年齢、両脚の長さの相違など、ルクセンブルクと一致する特徴が明らかになった。放射性炭素年代測定の結果、遺体は彼女の殺害と同じ時期のものだと確認 された。 1919年にフリードリヒスフェルデに埋葬された遺体に関する元の解剖報告書には、骨盤の損傷がなく、頭部の打撃や弾丸の痕跡が見つからなかったと記載さ れていた。この矛盾はツコスの仮説を支持するものでした。シャルテ病院の遺体を特定するため、当局はルクセンブルクの曾姪であるイレーネ・ボルデを特定 し、DNA比較のための毛髪を提供してもらった。[252] 2009年12月下旬、当局はDNA検査の結果が不確定であると発表した。遺体の身元は未確認のままであり、1919年に埋葬された遺体が本当にローザ・ ルクセンブルクのものかどうかは不明だ。[253] |

|

|

| Proletarian internationalism Rosa Luxemburg Foundation List of peace activists Nadezhda Krupskaya Alexandra Kollontai |

プロレタリア国際主義 ローザ・ルクセンブルク財団 平和活動家一覧 ナジェージダ・クルプスカヤ アレクサンドラ・コロンタイ |

| Works cited Ettinger, Elżbieta (1995) [1986]. Rosa Luxemburg: A Life. London: Pandora. ISBN 0-86358-261-3. Mills, Dana (2020). Rosa Luxemburg. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-327-0. Nettl, J. P. (1966a). Rosa Luxemburg. Vol. I. London: Oxford University Press. Nettl, J. P. (1966b). Rosa Luxemburg. Vol. II. London: Oxford University Press. |

引用文献 Ettinger, Elżbieta (1995) [1986]. Rosa Luxemburg: A Life. London: Pandora. ISBN 0-86358-261-3. Mills, Dana (2020). Rosa Luxemburg. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-327-0. ネットル、J. P. (1966a)。ローザ・ルクセンブルク。第 I 巻。ロンドン:オックスフォード大学出版局。 ネットル、J. P. (1966b)。ローザ・ルクセンブルク。第 II 巻。ロンドン:オックスフォード大学出版局。 |

| Abraham, Richard (1989). Rosa Luxemburg: A Life for the International. Basso, Lelio (1975). Rosa Luxemburg: A Reappraisal. London. Bronner, Stephen Eric (1984). Rosa Luxemburg: A Revolutionary for Our Times. Cliff, Tony (1980) [1959]. "Rosa Luxemburg". International Socialism (2/3). London. Dunayevskaya, Raya (1982). Rosa Luxemburg, Women's Liberation, and Marx's Philosophy of Revolution. New Jersey. Ettinger, Elzbieta (1988). Rosa Luxemburg: A Life. Frölich, Paul (1939). Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work. Geras, Norman (1976). The Legacy of Rosa Luxemburg. Gietinger, Klaus (1993). Eine Leiche im Landwehrkanal – Die Ermordung der Rosa L. (A Corpse in the Landwehrkanal – The Murder of Rosa L.) (in German). Berlin: Verlag. ISBN 978-3-930278-02-2. Gietinger, Klaus (2019). The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg. Translated by Halborn, L. New York: Verso. ISBN 978-1-78873-448-6. Hetmann, Frederik (1980). Rosa Luxemburg: Ein Leben für die Freiheit. Frankfurt. ISBN 978-3-596-23711-1. Jones, Mark (2016). Founding Weimar: Violence and the German Revolution of 1918–1919. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-11512-5. Joffre-Eichhorn, Hjalmar Jorge (2021, ed.), Post Rosa: Letters against Barbarism. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung: New York. Kemmerer, Alexandra (2016), "Editing Rosa: Luxemburg, the Revolution, and the Politics of Infantilization". European Journal of International Law, Vol. 27 (3), 853–864. doi:10.1093/ejil/chw046 Hudis, Peter; Anderson, Kevin B., eds. (2004). The Rosa Luxemburg Reader. Monthly Review Press. Kulla, Ralf (1999). Revolutionärer Geist und Republikanische Freiheit. Über die verdrängte Nähe von Hannah Arendt und Rosa Luxemburg. Mit einem Vorwort von Gert Schäfer. Diskussionsbeiträge des Instituts für Politische Wissenschaft der Universität Hannover. Vol. Band 25. Hannover: Offizin Verlag. ISBN 978-3-930345-16-8. Roland Holst, Henriette (1937). Rosa Luxemburg: ihr Leben und Wirken. Zürich: Jean-Christophe-Verlag. Shepardson, Donald E. (1996). Rosa Luxemburg and the Noble Dream. New York. Waters, Mary-Alice (1970). Rosa Luxemburg Speaks. London: Pathfinder. ISBN 978-0873481465. Weitz, Eric D. (1997). Creating German Communism, 1890–1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Priestand, David (2009). Red Flag: A History of Communism. New York: Grove Press. Weitz, Eric D. (1994). "'Rosa Luxemburg Belongs to Us!'" German Communism and the Luxemburg Legacy. Central European History (27: 1). pp. 27–64. Evans, Kate (2015). Red Rosa: A Graphic Biography of Rosa Luxemburg. New York: Verso. Luban, Ottokar (2017). The Role of the Spartacist Group after 9 November 1918 and the Formation of the KPD. In Hoffrogge, Ralf; LaPorte, Norman (eds.). Weimar Communism as Mass Movement 1918–1933. London: Lawrence & Wishart. pp. 45–65. |

アブラハム、リチャード(1989)。『ローザ・ルクセンブルグ:国際主義のために生きた人生』。 バッソ、レリオ(1975)。『ローザ・ルクセンブルグ:再評価』。ロンドン。 ブロナー、スティーブン・エリック(1984)。『ローザ・ルクセンブルグ:私たちの時代の革命家』。 クリフ、トニー(1980) [1959]。「ローザ・ルクセンブルク」。『国際社会主義』 (2/3)。ロンドン。 ドゥナエフスカヤ、ラヤ (1982)。『ローザ・ルクセンブルク、女性の解放、そしてマルクスの革命哲学』。ニュージャージー。 エティンガー、エルズビエタ (1988)。『ローザ・ルクセンブルク:その生涯』。 フレーリッヒ、ポール (1939)。『ローザ・ルクセンブルク:その生涯と仕事』。 ゲラス、ノーマン (1976)。ローザ・ルクセンブルグの遺産。 Gietinger, Klaus (1993). Eine Leiche im Landwehrkanal – Die Ermordung der Rosa L. (A Corpse in the Landwehrkanal – The Murder of Rosa L.) (ドイツ語). Berlin: Verlag. ISBN 978-3-930278-02-2. Gietinger, Klaus (2019). The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg. Halborn, L. 訳。ニューヨーク:Verso。ISBN 978-1-78873-448-6。 Hetmann, Frederik (1980). Rosa Luxemburg: Ein Leben für die Freiheit. フランクフルト。ISBN 978-3-596-23711-1。 ジョーンズ、マーク(2016)。ワイマール共和国の創設:暴力と 1918 年から 1919 年のドイツ革命。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-107-11512-5。 ジョフレ・アイクホルン、ヒャルマル・ホルヘ(2021、編)、『ポスト・ローザ:野蛮に対する手紙』。ローザ・ルクセンブルク財団:ニューヨーク。 ケンマー、アレクサンドラ(2016)、『ローザの編集:ルクセンブルク、革命、そして幼児化政策』。European Journal of International Law、Vol. 27 (3)、853–864。doi:10.1093/ejil/chw046 Hudis, Peter; Anderson, Kevin B., eds. (2004). ローザ・ルクセンブルク・リーダー。マンスリー・レビュー・プレス。 Kulla, Ralf (1999). Revolutionärer Geist und Republikanische Freiheit.Über die verdrängte Nähe von Hannah Arendt und Rosa Luxemburg. Mit einem Vorwort von Gert Schäfer.Diskussionsbeiträge des Instituts für Politische Wissenschaft der Universität Hannover. Vol. Band 25. ハノーファー:オフツィン・ヴェルラグ。ISBN 978-3-930345-16-8。 ローランド・ホルスト、ヘンリエッテ(1937)。ローザ・ルクセンブルク:その生涯と活動。チューリッヒ:ジャン・クリストフ・ヴェルラグ。 シェパードソン、ドナルド E.(1996)。ローザ・ルクセンブルクと高貴な夢。ニューヨーク。 ウォーターズ、メアリー・アリス(1970)。ローザ・ルクセンブルグの演説。ロンドン:パスファインダー。ISBN 978-0873481465。 ワイツ、エリック・D. (1997)。ドイツ共産主義の創造、1890-1990:民衆の抗議から社会主義国家へ。ニュージャージー州プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局。 プライスタンド、デビッド (2009)。赤旗:共産主義の歴史。ニューヨーク:グローブプレス。 ワイツ、エリック D. (1994). 「『ローザ・ルクセンブルグは私たちのものである!』」 ドイツ共産主義とルクセンブルグの遺産。中央ヨーロッパの歴史 (27: 1). pp. 27–64. エヴァンス、ケイト (2015). レッド・ローザ:ローザ・ルクセンブルグのグラフィック伝記。ニューヨーク:ヴェルソ。 ルバン、オットカー (2017)。1918年11月9日以降のスパルタキストグループの役割とKPDの結成。ホフロッゲ、ラルフ、ラポルト、ノーマン (編)。大衆運動としてのワイマール共産主義 1918-1933。ロンドン:ローレンス&ウィシャート。45-65 ページ。 |

| Brie, Michael; Schütrumpf, Jörn

(2021). Rosa Luxemburg: A Revolutionary Marxist at the Limits of

Marxism. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-67486-1. Kończal, Kornelia (2013), "Ich war, ich bin, ich werde sein'? Rosa Luxemburg in den deutschen und den polnischen Erinnerungen, (with Maciej Górny), in Germanica Wratislaviensia, No. 137, pp. 161–181. |

ブリー、ミヒャエル;シュトゥルンプフ、イェルン(2021)。『ローザ・ルクセンブルク:マルクス主義の限界における革命的なマルクス主義者』。スプリンガー・ネイチャー。ISBN 978-3-030-67486-1。 コニチャル、コルネリア(2013)、『私はあった、私はある、私はあるだろう?ドイツとポーランドの記憶におけるローザ・ルクセンブルク』(マチェイ・ゴルニーとの共著)、Germanica Wratislaviensia、No. 137、161-181 ページ。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosa_Luxemburg |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099