ラムズフェルド主義認識論

Rumsfeldian epistemology

ラムズフェルド主義認識論

Rumsfeldian epistemology

"How are we to clarify this elusive difference between Hegel and Freud? Mladen Dolar proposed to read "Hegel is Freud" as the ultimate philosophical infinite judgment, since Hegel and Freud cannot but appear absolute opposites: Absolute Knowing (the unity of the subject and the Absolute) versus the unconscious (the subject not master in his own house); excessive knowledge versus lack of knowledge. The first complication in this simple opposition is that, for Freud and Lacan, the unconscious is not a blind instinctual field but also a kind of knowledge, an unconscious knowledge, a knowledge which does not know itself ("unknown knowns;' in terms of Rumsfeldian epistemology)-so what if Absolute Knowing is to be located into the very tension between the knowledge aware of itself and the unknown knowledge? What if the "absoluteness" of knowing refers not to our access to the divine Absolute-in-itself, or to a total selfreflection through which we would gain full access to our "unknown knowing" and thus achieve subjective self-transparency, but to a much more modest (and all the more difficult to think) overlapping between the lack of our "conscious" knowledge and the lack inscribed into the very heart of our unknown knowledge? It is at this level that one should locate the parallel between Hegel and Freud: if Hegel discovers unreason ( contradiction, the mad dance of opposites which unsettles any rational order) in the heart of reason, Freud discovers reason in the heart of unreason (in slips of tongue, dreams, madness). What they share is the logic of retroactivity: in Hegel, the One is a retroactive effect of its loss, the very return to the lost One constitutes it; and in Freud, repression and the return of the repressed coincide, the repressed is the retroactive effect of its return." Zizek, Less than nothing : Hegel and the shadow of dialectical materialism, p.484.

「ヘーゲルとフロイトの間のこのとらえどころのない 差異をどのように明らかにすればよいのだろうか。ムラデン・ドラルは、「ヘーゲルはフロイトである」を、ヘーゲルとフロイトが絶対的な相反に見えるしかな いことから、究極の哲学的な無限判断として読むことを提案した。絶対的な知(主体と絶対的なものの一体化)対無意識(自分の家の主人ではない主体)、過剰 な知識対知識の欠如。この単純な対立における最初の複雑さは、フロイトとラカンにとって、無意識は盲目の本能的な場ではなく、一種の知識、無意識の知識、 自分自身を知らない知識(ラムズフェルドの認識論から言えば、「未知の知識」) でもあるということだ。では、絶対的な知が、自分自身を認識している知識と未知の知識の間のまさに緊張に位置しているとしたらどうだろう。もし、知ること の「絶対性」が、神の絶対的存在へのアクセスや、「未知の知」への完全なアクセスを獲得し、それによって主観的な自己透明性を達成するような完全な自己反 省ではなく、我々の「意識的」知識の欠如と我々の未知の知のまさに中心に刻まれた欠如の間のもっと控えめな(そして考えることがもっと難しい)重なりに言 及するとしたらどうだろうか。ヘーゲルが理性の中心で理不尽(矛盾、あらゆる合理的秩序を揺るがす対立の狂騒)を発見するなら、フロイトは理不尽の中心で 理性を(舌禍、夢、狂気の中で)発見するのである。ヘーゲルでは、唯一者はその喪失の遡及的効果であり、失われた唯一者への回帰がまさにそれを構成する。 フロイトでは、抑圧と抑圧されたものの回帰が一致し、抑圧されたものは、その回帰の遡及的効果なのである」- Zizek, Less than nothing : Hegel and the shadow of dialectical materialism, p.484.

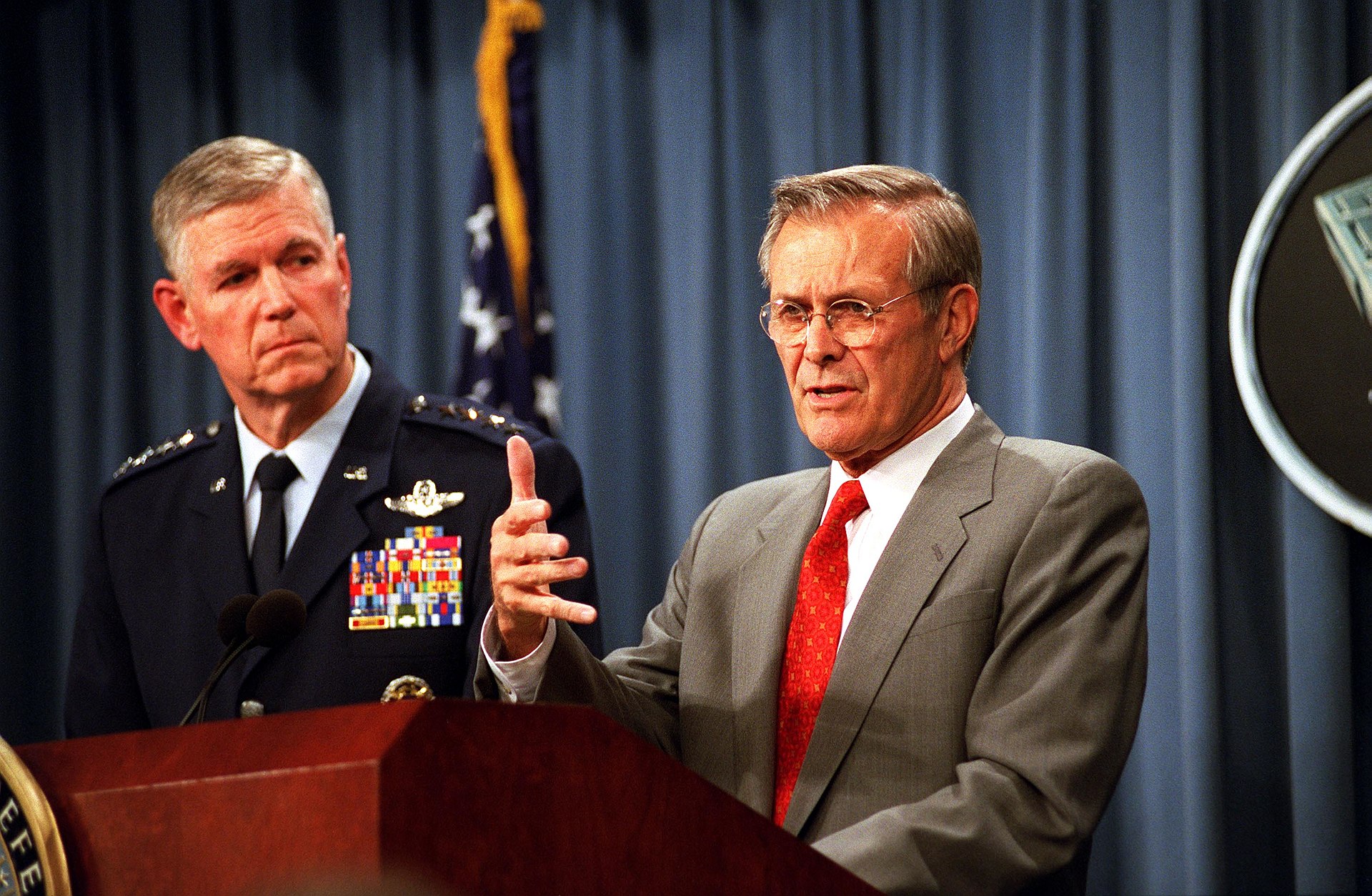

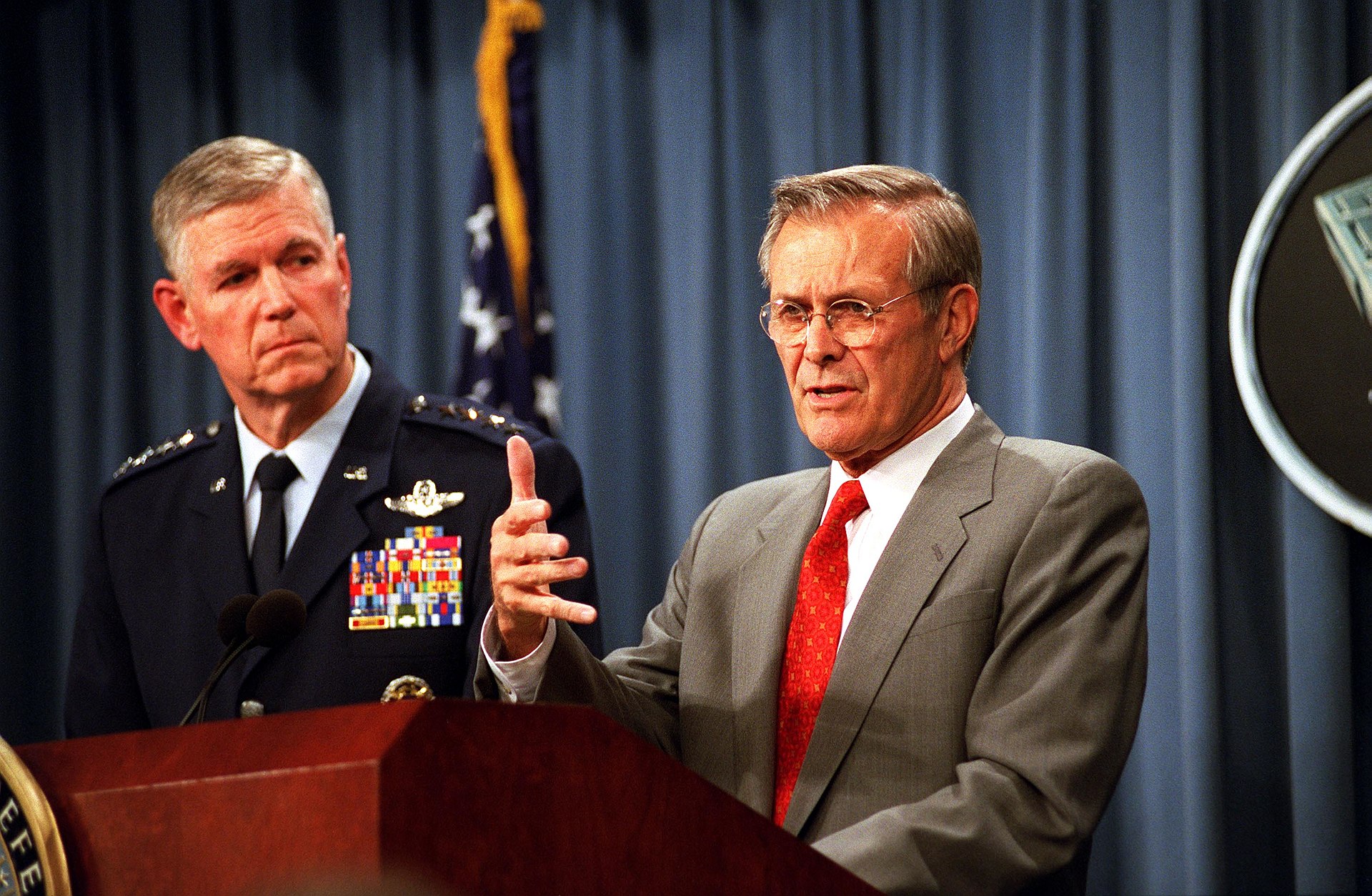

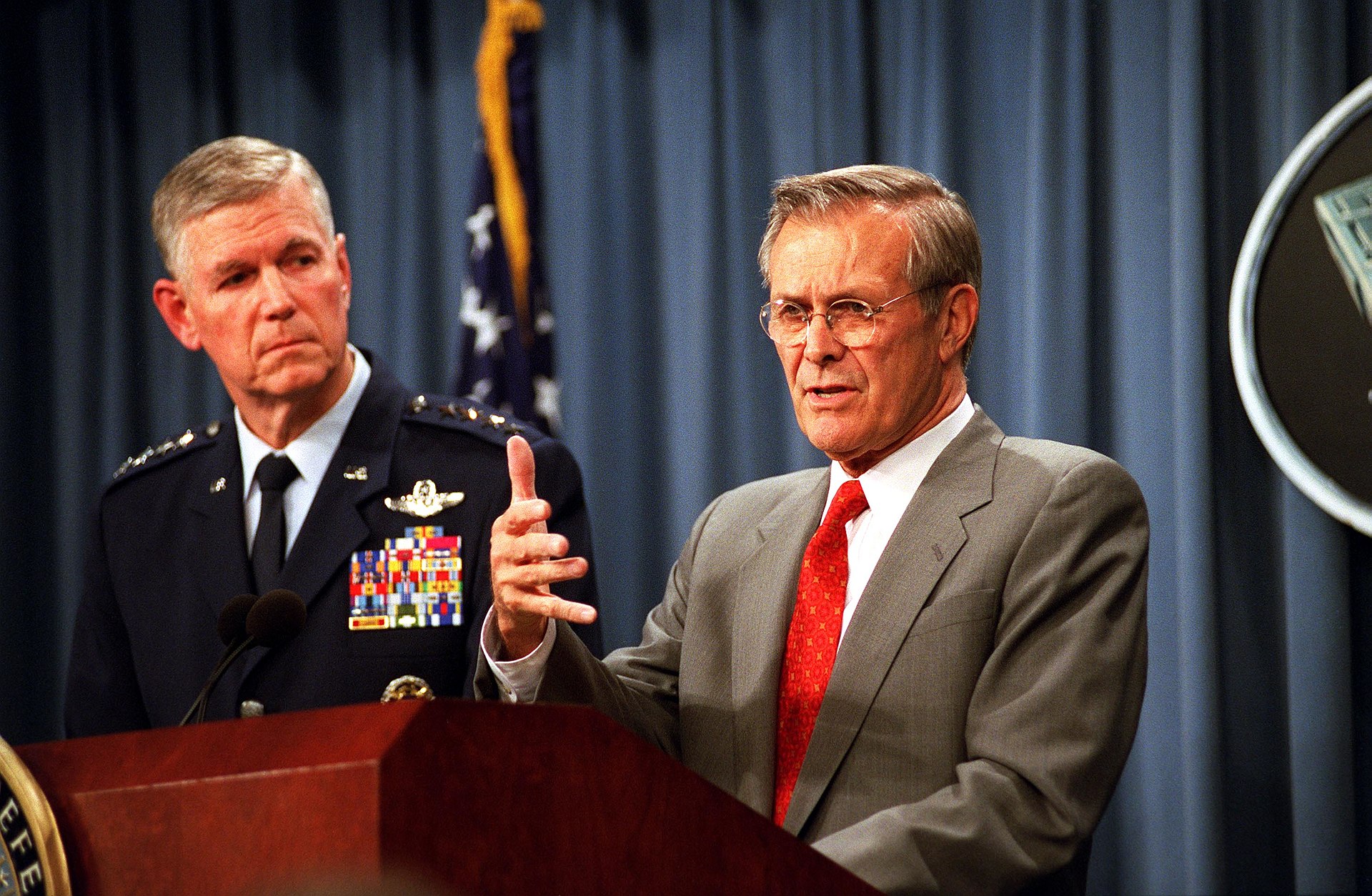

★Rumsfeld with the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Richard B. Myers at a Pentagon press conference in February 2002.

"Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because, as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we now know we don't know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we do not know we don't know." - Kellogg, Carolyn (January 24, 2011). "Donald Rumsfeld talks about his upcoming memoir". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 1, 2012. [Source; Known and Unknown: A Memoir]

「何も起こらなかったという報告は、私にとって常に興味深い。なぜなら、周知の事実として、(1)私たちが知っていることを知っているということがあるからだ。周知の事実

として、(2)私たちが知らないことを知っているということもある。

つまり、(3)今では知らないことを知っているということがある。し

かし、周知の事実として、(3')知らないことを知らないということも

ある。つまり、(3')知らないことを知らないということがある。」

+++

☆ジジェク「身体なき器官」でのオントロジーは4分類されている(187-188)

1)知られている知られていることが存在する(ある)

2)知られていないことがあるということが知られている——我々が知らないことがあるということを我々は知っている

3)知られていない知られていないことがある——我々は知らないことを知らないことがある(存在する)、ということ

4)知られていること(A)があるにもかかわらず、それが[我々に]知られていない、ということ——我々が知らないことでも、実際に知られていること(A)がある。これはAは、フロイトの無意識ようなもの。

この4番目のことが、ラムズフェルドがいうイラクの脅威であり(結局はみつからなかった)大量破壊兵器の存在のことである。これは[結果的に]存在しないものがすでにあるということを前提にして、その存在を探し出すという、論点先取(Begging the question, Petitio Principi)

と、それに引き起こされる誤った行動原理である。しかし、これは、湾岸戦争における多国籍軍のイラク侵攻と、サダム・フセイン政権の軍事力による妥当の、

直接の理由——あるいは口実——となり。ないものをめぐって、大量破壊兵器がイラク領内に存在するという誤った論理がまかり通った。

+++

What Rumsfeld Doesn't Know

That He Knows About Abu Ghraib

by Slavoj Zizek

In These Times

May 21 2004

| Does anyone still

remember the unfortunate Muhammed Saeed al-Sahaf? As

Saddam's information minister, he heroically would deny the most

evident

facts and stick to the Iraqi line. Even as U.S. tanks were hundreds of

yards

from his office, al-Sahaf continued to claim that the· televfsion shots

of the

tanks on Baghdad streets were Hollywood special effects. Once, however,

he

did strike a strange truth. When told that the U.S. military already

controlled

parts of Baghdad, he snapped back: "They are not in control of

anythingthey

don't even control themselves!" When the scandalous news broke about

the weird-things going on in Baghdad's Abu Ghraib prison, we got a

glimpse

of this very dimension of themselves that Americans do not control. |

不

幸なムハンマド・サイード・アル・サハフを覚えている人はいるだろうか?サダム・フセインの情報大臣として、彼は最も明白な事実を英雄的に否定し、イラク

政府の主張を貫いた。米軍戦車が彼のオフィスから数百ヤードの距離まで迫っていた時でさえ、アル・サハフはバグダッドの街中を走る戦車のテレビ映像はハリ

ウッドの特殊効果だと主張し続けた。しかし、一度だけ彼は奇妙な真実をついた。米軍がすでにバグダッドの一部を制圧したと知らされると、彼は「彼らは何も

制圧していない。自分自身さえ制圧できていない!」と反論した。バグダッドの「アブグレイブ刑務所」で奇妙なことが起こっているというスキャンダラスな

ニュースが報道されると、アメリカ人が制圧できていないという彼らの本質の一端が垣間見えた。 |

| In his reaction to the photos

showing Iraqi prisoners tortured and humiliated

by U.S. soldiers, President George W. Bush, as expected, emphasized how

the deeds of the soldiers were isolated crimes that do not reflect what

America stands and fights for - the values of democracy, freedom and

personal dignity. And the fact that the case turned into a public

scandal that

put the U.S. administration on the defensive is a positive sign. In a

really

"totalitarian" regime, the case would simply be hushed up. (In the same

way,

the fact that U.S. forces did not find weapons of mass destruction is a

positive sign: A truly "totalitarian" power would have done what cops

usually do-plant drugs and then "discover" the evidence of crime.) |

米

兵によるイラク人捕虜への拷問と屈辱を示す写真に対する反応において、ジョージ・W・ブッシュ大統領は予想通り、米兵の行為は民主主義、自由、人格的尊厳

といったアメリカが何を支持し、何のために戦っているかを反映しない孤立した犯罪であると強調した。そして、この事件が公のスキャンダルとなり、米国政府

が防戦を余儀なくされたことは、好ましい兆候である。本当に「全体主義」的な政権であれば、この事件は単に隠蔽されていたであろう。(同様に、米軍が大量

破壊兵器を発見できなかったという事実も好ましい兆候である。真の「全体主義」国家であれば、警察が通常行うように、麻薬を仕掛けて犯罪の証拠を「発見」

したであろう。) |

| However, a number of disturbing

features complicate this simple picture. In

the past several months, the International Committee of the Red Cross

regularly bombarded the Pentagon with reports about the abuses in Iraqi

military prisons, and the reports were systematically ignored. So it

was not

that U.S. authorities were getting no signals about what was going on -

they

simply admitted the crimes only when ( and because) they were faced

with

their disclosure in the media. The immediate reaction of the U.S.

military

officials was surprising, to say the least.. They explained that the

soldiers

were not properly taught the Geneva Convention rules about how to treat

war prisoners - as. if one has to be taught not to humiliate and

torture

prisoners! |

し

かし、いくつかの不穏な特徴がこの単純な図式を複雑にしている。過去数ヶ月間、国際赤十字委員会はイラク軍の刑務所における虐待に関する報告書を定期的に

米国防総省に送っていたが、その報告書は組織的に無視されていた。つまり、米当局は事態について何の兆候も得ていなかったわけではなく、単にメディアでそ

の事実が暴露されたときに初めて(そして、暴露されたからこそ)その犯罪を認めたのである。米軍当局の即座の反応は、控え目に言っても驚くべきものだっ

た。彼らは、捕虜をどのように扱うかに関するジュネーブ条約の規定について、兵士たちにきちんと教えられていなかったと説明した。まるで、捕虜を侮辱した

り拷問したりしないように教えなければならないかのように! |

| But the main complication is the

contrast between the "standard" way

prisoners were tortured in Saddam's regime and how they were tortured

under U.S. occupation. Under Saddam, the accent was on direct

infliction of

pain, while the American soldiers focused on psychological humiliation.

Further, recording the humiliation with a camera, with the perpetrators

included in the picture, their faces stupidly smiling beside the

twisted naked

bodies of the prisoners, was an integral part of the process, in stark

contrast with the secrecy of the Saddam tortures. The very positions

and costumes of

the prisoners suggest a theatrical staging, a kind of tableau vivant,

which

brings to mind American performance art, "theatre of cruelty," the

photos of

Mapplethorpe or the unnerving scenes in David Lynch's films. |

し

かし、主な問題は、サダム政権下で囚人が拷問されていた「標準的な」方法と、米国占領下で彼らがどのように拷問されていたかという対比である。サダム政権

下では、直接的な苦痛を与えることに重点が置かれていたが、米軍兵士は心理的な屈辱を与えることに重点を置いていた。さらに、屈辱的な行為をカメラで記録

し、加害者たちを写真に含めることも、そのプロセスに不可欠な要素であった。サダム政権下の拷問が極秘裏に行われていたのと対照的に、

囚人たちの姿勢や衣装は、演劇的な演出、ある種の生きた絵画を思わせ、アメリカのパフォーマンスアート、残酷劇場、メイプルソープの写真、あるいはデ

ヴィッド・リンチの映画のぞっとするようなシーンを想起させる。 |

| This theatricality leads us to

the crux of the. matter: To anyone acquainted

with the reality of the American way of life, the photos brought to

mind the

obscene underside of U.S. popular culture - say, the initiatory rituals

of

torture and humiliation one has to undergo to be accepted into a closed

community. Similar photos appear at regular intervals in the U.S. press

after

some scandal explodes at an Army base or high school campus, when such

rituals went overboard. Far too often we are treated to images of

soldiers and

students forced to assume humiliating poses, perform debasing gestures

and

suffer sadistic punishments. |

こ

の演劇性こそが問題の本質である。アメリカのライフスタイルの現実を知る人々にとって、これらの写真は米国の大衆文化の卑猥な裏側を想起させる。例えば、

閉鎖的なコミュニティに受け入れられるために耐えなければならない、拷問や屈辱の入門儀式のようなものを。このような儀式が度を越したものとなった場合、

米軍基地や高校で何らかのスキャンダルが発覚した後、同様の写真が米国の報道機関で定期的に登場する。屈辱的なポーズを強要されたり、屈辱的なジェス

チャーをさせられたり、サディスティックな罰を受けたりする兵士や学生の画像が、あまりにも頻繁に私たちの目に触れる。 |

| The torture at Abu Ghraib was

thus not simply a case of American arrogance

toward a Third World people. In being submitted to the humiliating

tortures,

the Iraqi prisoners were effectively initiated into American culture:

They got

a taste of the culture's obscene underside that forms the necessary

supplement to the public values of personal dignity, democracy and

freedom. No wonder, then, the ritualistic humiliation of Iraqi

prisoners was

not an isolated case but part of a widespread practice. On May 6,

Donald

Rumsfeld had to admit that the photos rendered public are just the "tip

of the

iceberg," and that there were much stronger things to come, including

videos

of rape and murder. |

し

たがって、アブグレイブ刑務所での拷問は、単にアメリカが第三世界の人間に対して傲慢であったというだけの事件ではない。屈辱的な拷問を受けることで、イ

ラク人捕虜たちは事実上、アメリカ文化に「入門」させられたのである。彼らは、個人の尊厳、民主主義、自由といった公共の価値観を補完するものとして必要

な、その文化の卑猥な裏側を垣間見たのだ。それゆえ、イラク人捕虜に対する儀式的な屈辱は、孤立した事件ではなく、広範にわたって行なわれていた行為の一

部であったとしても不思議ではない。5月6日、ドナルド・ラムズフェルドは、公開された写真は「氷山の一角」に過ぎず、強姦や殺人のビデオなど、さらに強

烈なものがこれから出てくると認めざるを得なかった。 |

| This is the reality of

Rumsfeld's dismissive statement, a couple of months

ago, that the Geneva Convention rules are "out of date" in regard to

today's

warfare. |

これが、数ヶ月前にラムズフェルドが「今日の戦争においてはジュネーブ条約の規則は時代遅れだ」と軽視した発言をしたことの現実である。 |

| In the debate about the

Guantanamo prisoners, one often hears arguments

that their treatment is ethically and legally acceptable because "they

are

those who were missed by the bombs." Since they were the targets of

U.S.

bombings and accidentally survived them, and since these bombings were

part of a legitimate military operation, one cannot condemn their fate

when

they were taken prisoners after the combat-whatever their situation, it

is

better, less sevl;!re, than being dead. This reasoning tells more than

it intends

to say. It puts prisoners into a literal position of the "living dead,"

those who

are in a way already dead (their right to live forfeited by being

legitimate

targets of murderous bombings). Thus the prisoners are now what

philosopher Giorgio Agamben calls homo sacer, those who can be killed

with impunity since, in the eyes of the law, their lives no longer

count. If the

Guantanamo prisoners are located in the space "between the two deaths"

-

legally dead ( deprived of a determinate legal status) while

biologically still

alive-then the U.S. authorities that treat them this way are in an

in-between

legal status that forms the counterpart of homo sacer. They act as a

legal

power, but their acts are no longer covered and constrained by the law

- they

operate in an empty space that is nonetheless within the domain of the

law.

Hence, the recent disclosures about Abu Ghraib display the consequences

of

locating prisoners in this place "between the two deaths." |

グ

アンタナモ収容所の囚人に関する議論では、しばしば「彼らは爆弾の犠牲から逃れた人々である」という理由で、彼らの扱いは倫理的にも法的にも容認できると

いう主張が聞かれる。彼らは米国の爆撃の標的となり、偶然にも生き残った。そして、これらの爆撃は合法的な軍事作戦の一部であった。戦闘後に捕虜となった

彼らの境遇を非難することはできない。彼らの状況がどうであれ、死ぬよりはましである。この論理は、その意図する以上に多くのことを語っている。捕虜たち

は文字通り「生ける屍」の立場に置かれる。つまり、ある意味ではすでに死んでいる(殺人爆撃の正当な標的となったことで生きる権利を失った)人々である。

したがって、捕虜たちは今や哲学者ジョルジョ・アガンベンがホモ・サケルと呼ぶ存在、すなわち、法の目から見ればもはや命が数えられない存在であるため、

罪に問われることなく殺される可能性のある存在なのである。もしグアンタナモ収容所の囚人が「2つの死の間」に位置しているとすれば、つまり、法的には死

んでいる(明確な法的地位を剥奪されている)が、生物学的にまだ生きているとすれば、彼らをこのように扱う米国当局は、ホモ・サケル(神聖な人)の対極に

ある中間的な法的地位にあると言える。彼らは法的な権力として行動するが、その行為はもはや法によってカバーされ、制約されることはない。彼らは、法の領

域内にあるにもかかわらず、空虚な空間で活動している。したがって、アブグレイブ刑務所に関する最近の暴露は、この「2つの死の間」に囚人を置くことの帰

結を示している。 |

| In March 2003, Rumsfeld engaged

in a little bit of amateur philosophizing

about the relationship between the known and the unknown: "There are

known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known

unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don't know.

But

there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don't know we

don't

know." What he forgot to add was the crucial fourth term: the "unknown

knowns," the things we don't know that we know-which is precisely, the

Freudian unconscious, the "knowledge which doesn't know itself," as

Lacan

used to say. |

2003

年3月、ラムズフェルドは既知と未知の関係について、素人らしい哲学的な考察を少しばかり披露した。「既知の既知がある。これは、我々が知っていることを

知っていることである。既知の未知がある。つまり、我々が知らないことを知っていることがある。しかし、未知の未知もある。我々が知らないことを知らない

ことがある。」

彼が付け加え忘れたのは、重要な第4の用語である。「未知の既知」すなわち、知らないのに知っていること、つまり、フロイトの無意識、ラカンがよく言って

いたように、「自らを認識していない知識」である。 |

| If Rumsfeld thinks that the main

dangers in the confrontation with Iraq were

the "unknown unknowns," that is, the threats from Saddam whose nature

we

cannot even suspect, then the Abu Ghraib scandal shows that the main

dangers lie in the "unknown knowns" - the disavowed beliefs,

suppositions

and obscene practices we pretend not to know about, even though they

form

the background of our public values. |

ラ

ムズフェルドが、イラクとの対決における主な危険は「未知の未知」、つまり、その性質すら推測できないサダムからの脅威であると考えているのであれば、ア

ブグレイブ刑務所のスキャンダルは、主な危険は「既知の未知」、すなわち、公の価値観の背景を形成しているにもかかわらず、私たちが知らないふりをしてい

る否定された信念、仮定、卑猥な慣習にあることを示している。 |

| Thus, Bush was wrong. What we get when we see the photos of humiliated

Iraqi prisoners is precisely a direct insight into "American values," into the

core of an obscene enjoyment that sustains the American way of life. |

したがって、ブッシュは間違っていた。屈辱的な扱いを受けたイラク人捕虜の写真を見ると、まさに「アメリカの価値観」、つまりアメリカ式の生活様式を支える下品な快楽の核心に直接的に迫ることができる。 |

| https://www.lacan.com/zizekrumsfeld.htm |

「絶対的かつ無限である神は、原則として理性には理解できないものである。 ニコラスの考えによれば、理性(intellectus)は、理性の限界を認識することができるため、理性よりも高い位置にある[=これも一種の解釈学的循環]。

しかし、理性も有限であり、したがって『学識ある無知』によれば、真の神の認識には到達できない。神における相反するものの逆説的な一致[=矛盾を超越す

る無限運動に気づく]、つまり coincidentia oppositorum を、理性は実際には理解できない」(→「知恵ある無知/学ばれた無知」)

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆