Mitzub'ixi Qu'q Ch'ij

Source: Ikeda, Mitsuho, 2020, Repatriation

of human remains and burial materials of Indigenous peoples in Japan :

Who owns their cultural heritages and dignity? CO*Design, 7:1-16. info:doi/10.18910/75574

Direct downlod from our internet cite: cod_07_001X.pdf without password

After ratification

of the UNDRIP, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples by Japanese government in 2007, the Ainu minority began to

promote repatriations of human remains and burial materials that had

been collected -- "pillaged" explaining by the Ainu activists -- and

maintained in Japanese universities, chiefly national ex-imperial

universities as "academic purposes" from collected tombs and

archaeological sites in Hokkaido.

Today the debate

of translocation of US military base in southern Japan, Okinawa evokes

the rising Ryukyuan nationalism and also similar with the Ainu

repatriation thought and methodology with the among the Ryukyuan. The

concepts of repatriation of human remains can challenge us to rethink

modernist thought on collective property and ownership.

I will discuss the

ethical, legal, and social aspects of the

debates regarding the Rykyuan human remains between scholars, lawyers,

and civil activists (so called "plaintiff") and Japanese mainland

universities officials ("defendant"). These disputes come to a

deadlock. The plaintiffs want to establish the collective entitlement

of indigenous rights for the repatriation that has not been enacted on.

The defendants reject their demands legal conformity of "successors to

the rituals of the family" according to present Japanese civil laws.

From this actual

debate, we, cultural anthropologist should ask a series of questions

mentioned below;

1. What is the concept

of property or repatriation of human remains and burial materials?

2. What is the

collective human rights of Indigenous peoples?

3. Why do

indigenous people ask to have both collective human rights and

repatriation their "ancestral" heritage from universities?

4. What is the

difference of property right among indigenous people from ordinary

neighborhood citizen?

The speaker

will

relativize modern property rights and disposable rights and advocate

what the repatriation rights of indigenous people in the

anthropological point of view.

*Credit:

the paper [will be] presented at Spring meeting of the Korean Society

of Cultural Anthropology, April 26, 2019.

한국문화인류학회

2019년 춘계학술대회,

땅과 인간 : 소유와

공유, 죽임과 살림, 재생과 건설

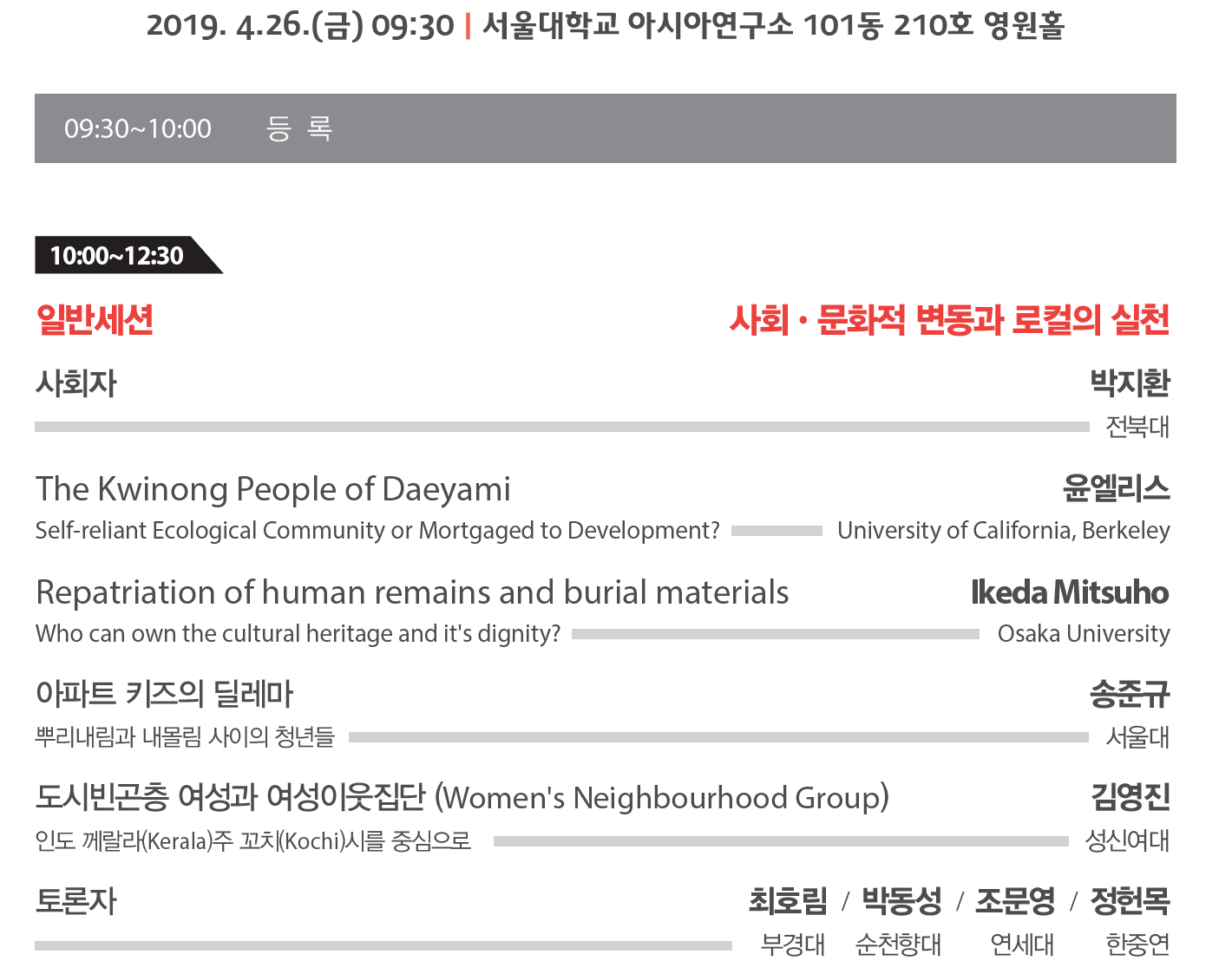

2019.

4.26.(금) 09:30 | 서울대학교 아시아연구소 101동 210호 영원홀

|

1 Repatriation of human remains

and burial materials:

Who owns cultural heritage and dignity?

|

|

2

• Following the ratification of

UNDRIP, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples by the Japanese government in 2007, the Ainu, one of Japan’s

ethnic minorities, began to promote the repatriation of human remains

and burial materials. These had been collected, or “pillaged” according

to Ainu activists, and maintained in Japanese universities, chiefly

national ex-imperial universities for “academic purposes,” following

their collection from tombs and archaeological sites in Hokkaido.

• In this meeting of the Korean

Society of Cultural Anthropology, the main subject is “Land and

Tenure,” that explores the broad sense of property, entitlement, and

ownership of an area, domain, space, and territory. During my

presentation, I will focus on socio-cultural concepts of property in

the context of the repatriation of indigenous people’s human remains.

|

|

3

• 1. what concept of property is

involved in the repatriation of human remains and burial materials?

• 2. what are the collective human rights of Indigenous people?

• 3. why do Indigenous people ask

to have both collective human rights and to repatriate their

“ancestral” heritage from universities?

• 4. how are Indigenous people’s

property rights different from those of Non-Indigenous ordinary people?

|

|

4

• 1. Introduction

• 2. Brief History of the Repatriation Claims

• 3. Stories of Bones

• 4. Quest for harmony between plaintiffs and defendants

• 5. Concluding remarks

• My conclusion will explain that

Indigenous people’s desire for the repatriation of human remains refers

to their need to reclaim objects to recover from violent colonial

trauma, and to the need for a homecoming to their time and place of

origin. This ideology is represented in their ritual of returning, a

ceremony that they originally invented.

|

|

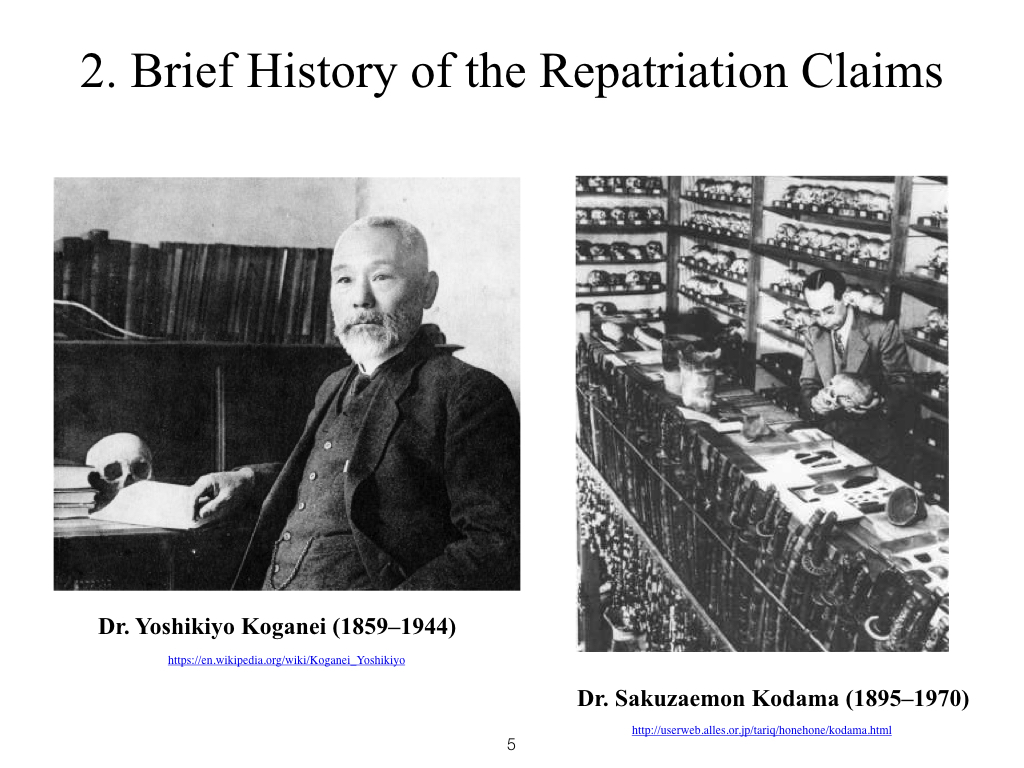

5

Dr. Yoshikiyo Koganei (1859–1944)

Dr. Sakuzaemon Kodama (1895–1970)

|

|

6

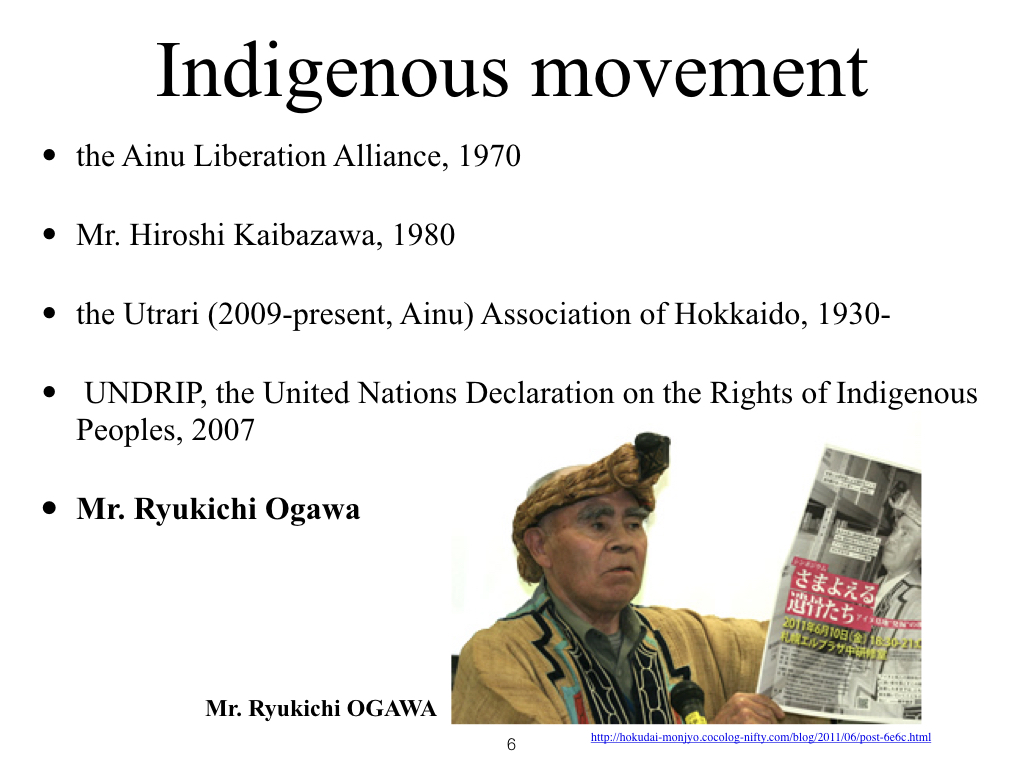

• the Ainu Liberation Alliance, 1970

• Mr. Hiroshi Kaibazawa, 1980

• the Utrari (2009-present, Ainu) Association of Hokkaido, 1930-

• UNDRIP, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007

• Mr. Ryukichi Ogawa

|

|

7

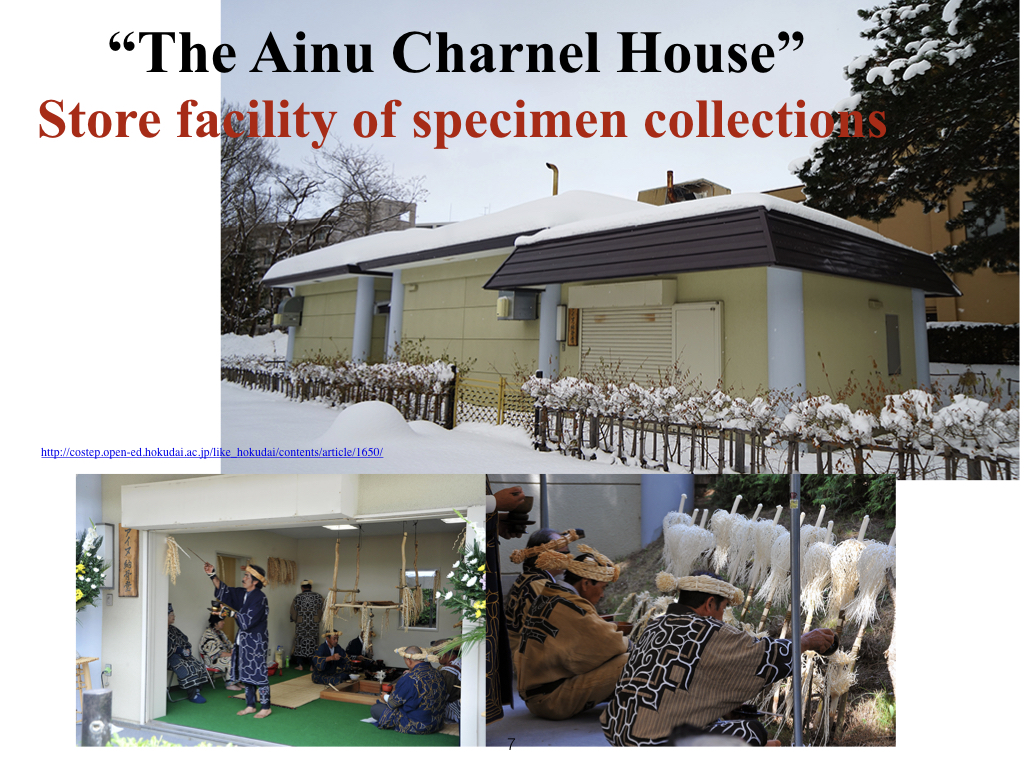

“The Ainu Charnel House”

Store facility of specimen collections

|

|

8

• the Native American Graves

Protection and Repatriation Act, NAGPRA, enacted in 1990 in the United

States

• The real problem is also the

lack of imagination in Japan’s social scientists. Despite our academic

tradition of cultural anthropology, we have never taken the plaintiff's

side because almost all Japanese anthropologists receive grants from

government and quasi-governmental agencies.

• Until today, the majority have

taken the defendant's side in repatriation cases with the rare

exception of those anthropologists who have been trained by indigenous

leaders. We do not have any authentic and politically correct

Indigenous studies. We need to tackle the ethical, legal, and social

dimensions of repatriation movements, not just academically, but

practically.

|

|

9

• A legislative repatriation

process does not objectively protect the Indigenous people’s human

remains. For government officials, human remains should be treated as

objects that must be returned to the appropriate stakeholder.

Indigenous people insist that human remains are not property but a part

of a whole body, a painful body, and a mindful body that will never be

recuperated.

|

|

10

• Even now, the government does

not approve of the collective rights of Indigenous people as recognized

by UNDRIP, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples. Indigenous people always possessed a shared sense of

collective rights before the UN began to discuss them.

|

|

11

• Because there is a significant

interrelationship between collective human rights and repatriation of

their “ancestral” bodies, Indigenous people have naturally accepted the

newly emerging concept of indigenous collective rights.

|

|

12

• The problem is that

Non-Indigenous people cannot imagine how this has affected those people

whom the government and scientists harm unintentionally.

|

|

13

• Indigenous people (plaintiffs)

insist that human remains are not property but a part of a whole body,

a painful body, and a mindful body that will never be recuperated.

• For government

officials(defendants), human remains should be treated as objects that

must be returned to the appropriate stakeholder.

• My conclusion is that the

repatriation requests of Indigenous people involve not only returning

objects but also their recovery from violent colonial trauma, which

requires a sense of homecoming to the time and place of origin.

|

|

14

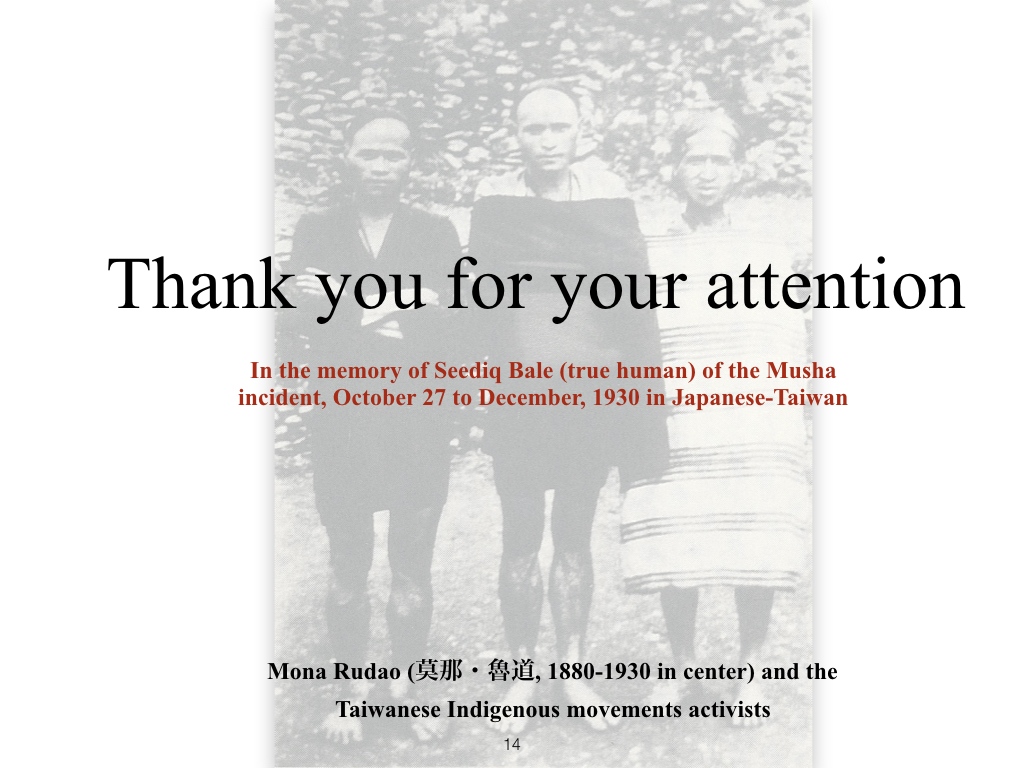

In the memory of Seediq Bale (true human) of the Musha incident, October 27 to December, 1930 in Japanese-Taiwan

Mona Rudao (莫那・魯道, 1880-1930 in center) and the Taiwanese Indigenous movements activists

|

“Stealing remains is criminal”:

Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues of “scientific research” on the

repatriation of human remains to Ryukyu islands, southern Japan

In December 4, 2018, an activist group which claims indigenous rights

has filed a lawsuit against Kyoto University for return of the remains

of royal Ryukyuan Mumujana tomb in Nakijin village. In this

presentation, I will analyze the debates regarding the Rykyuan human

remains among scholars, lawyers, and civil activists and Japanese

university authority in terms of ethical, legal, and social aspects.

The leader of activist group and his followers share the political

ideology of independence of Ryukyu island as ethnic entity from

mainland Japan. Their style of claiming for repatriation is influenced

by the Ainu indigenous activism in northern Japan. Based on the codes

of the definition of UNDRIP indigenous people the Ryukyuan activists

have been formulating collective rights of indigenousness. The

university authority delays the response to their claims because the

authority always inquires the official response by central government

office. At the moment, these disputes come to a deadlock. The

indigenous activists want to establish the collective entitlement of

indigenous rights for the repatriation of remains that has not been

enacted on. The university officials reject their demands in terms of

legal conformity of “successors to the rituals of the family” congruent

to present Japanese civil laws. The royal descendants of Ryukyu family

as well as activists are claiming that royal remains should be

repatriated with compensations and finally be re-buried in traditional

aerial sepulture. From these debates and disputes, we should ask

a series of questions such as; 1. What is their concept of property or

repatriation of human remains and burial materials? 2. What is the

collective human rights of indigenous peoples? 3. Why do indigenous

people ask to have both collective human rights and repatriation of

their “ancestral” heritage from universities? and 4. What is the

difference of property right among indigenous people from ordinary

neighborhood citizen?

|

Links

- “Stealing remains is criminal”:

Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues of the repatriation of human remains

- KAYOKO KIMURA, Japan's indigenous Ainu sue to bring their ancestors' bones back home, The Japan Times, JUL 25, 2018

- Repatriation of Historic Human Remains - Library of Congress, AUSTRALIA (pdf)

- Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, Wiki

- Museums are returning indigenous human remains but progress on repatriating objects is slow, The Conversation, December 1, 2016 6.29pm AEDT

- David Shariatmadari, ‘They’re not property’: the people who want their ancestors back from British museums. The Gardian, Apr.23, 2019.

- Reclaiming Identity: The Repatriation of Native Remains and Culture, Friends Comittee, March 17, 2008

- Human remains, Departemnt of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Partnerships, Queensland Government.

- United Nations Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 8th session, 20 – 24 July, 2015.(pdf)

- Repatriation and the disposition of the dead, Encyclopedia Britanica.

Bibliography

other informations