琉球諸語

Ryukyuan languages

☆ 琉球列島では日本語が話されているが、琉球語と日本語は相互に理解できるものではない。これらの言語の話者が何人残っているかは不明だが、標準日本語や沖 縄日本語のような方言の使用への言語シフトによって、これらの言語は絶滅の危機に瀕している。ユネスコは、4つの言語を「確実に絶滅の危機に瀕してい る」、他の2つの言語を「深刻な絶滅の危機に瀕している」と分類している(→Ethnologue.)。

★ それにもかかわらず、日本政府の文化庁は、琉球諸語を「方言」といってはばからない。これは、文化庁が、琉球諸語を「日本語」のカテゴリーの中に領有する 文化帝国主義[者]のあらわれであり、言語学上の諸語の言語の尊厳を毀損するものである。あるいは、それぞれユニークな言語体系である琉球諸語を、日本語 の傘のもとにある「方言」とみなすことで、それらの言語話者を日本語という権能の範囲[これをヘゲモニーという]のもとに従属させる行為であると言える(→文化庁「令和4年度消滅の危機にある方言の記録作成及び啓発事業の募集」)。

| The Ryukyuan languages

(琉球語派, Ryūkyū-goha, also 琉球諸語, Ryūkyū-shogo or 島言葉 in Ryukyuan, Shima

kutuba, literally "Island Speech"), also Lewchewan or Luchuan

(/luːˈtʃuːən/), are the indigenous languages of the Ryukyu Islands, the

southernmost part of the Japanese archipelago. Along with the Japanese

language and the Hachijō language, they make up the Japonic language

family.[1] Although Japanese is spoken in the Ryukyu Islands, the Ryukyu and Japanese languages are not mutually intelligible. It is not known how many speakers of these languages remain, but language shift toward the use of Standard Japanese and dialects like Okinawan Japanese has resulted in these languages becoming endangered; UNESCO labels four of the languages "definitely endangered" and two others "severely endangered".[2] |

琉球諸語派(りゅうきゅうしょごは)、琉球諸語(りゅうきゅうしょご)、琉球語(りゅうきゅうご)、 琉球語、琉球語諸語、琉球語ではリュウキュウショウゴ語、島語ではシマクツバ語。日本語、八丈語とともに日本語族を構成する[1]。 琉球列島では日本語が話されているが、琉球語と日本語は相互に理解できるものではない。これらの言語の話者が何人残っているかは不明だが、標準日本語や沖 縄日本語のような方言の使用への言語シフトによって、これらの言語は絶滅の危機に瀕している。ユネスコは、4つの言語を「確実に絶滅の危機に瀕してい る」、他の2つの言語を「深刻な絶滅の危機に瀕している」と分類している[2]。 |

| Overview Phonologically, the Ryukyuan languages have some cross-linguistically unusual features. Southern Ryukyuan languages have a number of syllabic consonants, including unvoiced syllabic fricatives (e.g. Ōgami Miyako /kss/ [ksː] 'breast'). Glottalized consonants are common (e.g. Yuwan Amami /ʔma/ [ˀma] "horse"). Some Ryukyuan languages have phonemic central vowels, e.g. Yuwan Amami /kɨɨ/ "tree". Ikema Miyako has a voiceless nasal phoneme /n̥/. Many Ryukyuan languages, like Standard Japanese and most Japanese dialects, have contrastive pitch accent. Ryukyuan languages are generally SOV, dependent-marking, modifier-head, nominative-accusative languages, like Japanese. Adjectives are generally bound morphemes, occurring either with noun compounding or using verbalization. Many Ryukyuan languages mark both nominatives and genitives with the same marker. This marker has the unusual feature of changing form depending on an animacy hierarchy. The Ryukyuan languages have topic and focus markers, which may take different forms depending on the sentential context. Ryukyuan also preserves a special verbal inflection for clauses with focus markers—this unusual feature was also found in Old Japanese, but lost in Modern Japanese. |

概要 音韻学的に、琉球諸語には言語学的に珍しい特徴がいくつかある。南琉球語には音節子音が多数あり、その中には無声の音節摩擦音も含まれる(例:Ōgami Miyako /kss/ [ks↪Lm_2D0]「乳房」)。声門化子音は一般的である(例:奄美大湾 /ʔ [ˀma]「馬」)。いくつかの琉球語には音素の中心母音がある(例:ユワン奄美 /kɨɨ/「木」)。池間宮古には無声鼻音音素 /n̥/ がある。多くの琉球語は、標準日本語やほとんどの日本の方言と同様に、対照的なピッチアクセントを持つ。 琉球語は一般に、日本語と同じようにSOV、従属格、修飾語頭、名詞格、使役格の言語である。形容詞は一般に結合形態素であり、名詞の複合語か動詞化に よって生じます。多くの琉球語は、名詞と主格の両方を同じマーカーで表します。このマーカーは、アニマシー階層によって形が変わるという珍しい特徴があ る。琉球語にはトピックマーカーとフォーカスマーカーがあり、文の文脈によって異なる形をとることがある。琉球語はまた、フォーカス・マーカーを持つ節の ための特殊な動詞の屈折を保持している。この珍しい特徴は、古い日本語にも見られたが、現代日本語では失われている。 |

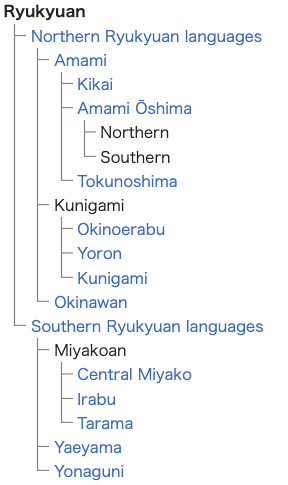

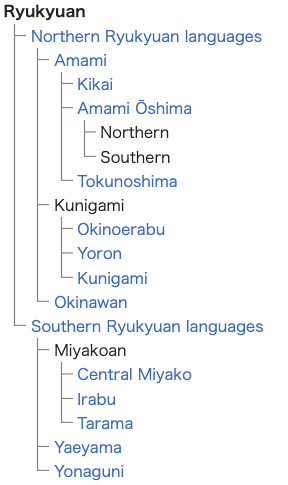

Classification and varieties Classification and varietiesThe Ryukyuan languages belong to the Japonic language family, related to the Japanese language.[3][4] The Ryukyuan languages are not mutually intelligible with Japanese—in fact, they are not even mutually intelligible with each other—and thus are usually considered separate languages.[3] However, for socio-political and ideological reasons, they have often been classified within Japan as dialects of Japanese.[3] Since the beginning of World War II, most mainland Japanese have regarded the Ryukyuan languages as a dialect or group of dialects of Japanese. The Okinawan language is only 71% lexically similar to, or cognate with, standard Japanese. Even the southernmost Japanese dialect (Kagoshima dialect) is only 72% cognate with the northernmost Ryukyuan language (Amami). The Kagoshima dialect of Japanese, however, is 80% lexically similar to Standard Japanese.[5] There is general agreement among linguistics experts that Ryukyuan varieties can be divided into six languages, conservatively,[6] with dialects unique to islands within each group also sometimes considered languages. A widely accepted hypothesis among linguists categorizes the Ryukyuan languages into two groups, Northern Ryukyuan (Amami–Okinawa) and Southern Ryukyuan (Miyako–Yaeyama).[4][7] Many speakers of the Amami, Miyako, Yaeyama and Yonaguni languages may also be familiar with Okinawan since Okinawan has the most speakers and once acted as the regional standard. Speakers of Yonaguni are also likely to know the Yaeyama language due to its proximity. Since Amami, Miyako, Yaeyama, and Yonaguni are less urbanized than the Okinawan mainland, their languages are not declining as quickly as that of Okinawa proper, and some children continue to be brought up in these languages.[citation needed] Each Ryukyuan language is generally unintelligible to others in the same family. There is wide diversity among them. For example, Yonaguni has only three vowels, whereas varieties of Amami may have up to seven, excluding length distinctions. The table below illustrates the different phrases used in each language for "thank you" and "welcome", with standard Japanese provided for comparison.  |

分類と品種 分類と品種琉球諸語は日本語に関連するジャポニック語族に属する[3][4]。琉球諸語は日本語と相互理解不可能であり、実際には相互理解すら不可能であるため、通 常は別の言語と考えられている[3]。しかし、社会政治的およびイデオロギー的な理由から、日本国内ではしばしば日本語の方言として分類されてきた [3]。第二次世界大戦が始まって以来、本土の日本人の多くは琉球諸語を日本語の方言または方言群と見なしてきた。 沖縄の言語は、語彙的には標準語と71%しか類似していない。日本語の最南端の方言(鹿児島弁)でさえ、最北端の琉球語(奄美)とは72%しか同義ではな い。言語学の専門家の間では、琉球語は控えめに見ても6つの言語に分けられるというのが一般的な見解であり[6]、各グループ内の島に特有の方言も言語と みなされることがある。 言語学者の間で広く受け入れられている仮説では、琉球語は北部琉球語(奄美-沖縄)と南部琉球語(宮古-八重山)の2つのグループに分類される[4] [7]。奄美語、宮古語、八重山語、与那国語の話者の多くは沖縄語にも精通しているかもしれない。与那国語の話者は、八重山語も近いので知っている可能性 が高い。奄美、宮古、八重山、与那国は沖縄本島よりも都市化が進んでいないため、沖縄本島の言語ほど急速に衰退することはなく、これらの言語で育ち続ける 子供もいる[要出典]。 それぞれの琉球語は、同じ系列の他の言語とは一般的に理解できない。琉球語には多様性がある。例えば、与那国語には母音が3つしかないが、奄美語には長さ の違いを除いて7つまである。下の表は、各言語で「ありがとう」と「ようこそ」に使われるフレーズの違いを示しており、比較のために標準的な日本語が示さ れている。  |

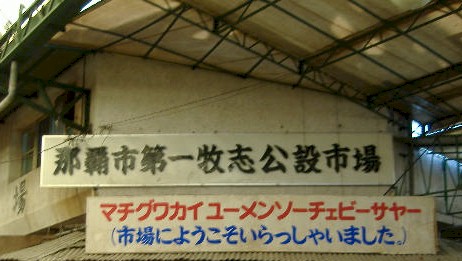

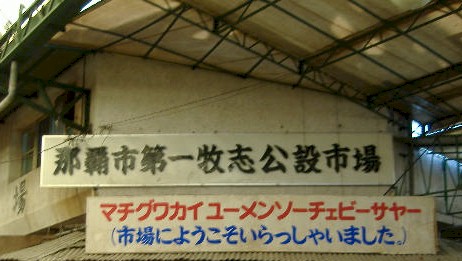

Status A market sign in Naha, written in Okinawan (red) and Japanese (blue)  Traffic safety slogan signs in Kin, Okinawa, written in Japanese (center) and Okinawan (left and right). There is no census data for the Ryukyuan languages, and the number of speakers is unknown.[7] As of 2005, the total population of the Ryukyu region was 1,452,288, but fluent speakers are restricted to the older generation, generally in their 50s or older, and thus the true number of Ryukyuan speakers should be much lower.[7] The six Ryukyuan languages are listed in the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. UNESCO said all Ryukyuan languages are on course for extinction by 2050.[10] Starting in the 1890s, the Japanese government began to suppress the Ryukyuan languages as part of their policy of forced assimilation in the islands. Children being raised in the Ryukyuan languages are becoming increasingly rare throughout the islands, and usually occurs only when the children are living with their grandparents. The Ryukyuan languages are still used in traditional cultural activities, such as folk music, folk dance, poem and folk plays. There has also been a radio news program in the Naha dialect since 1960.[11] Circa 2007, in Okinawa, people under the age of 40 have little proficiency in the native Okinawan language.[12] A new mixed language, based on Japanese and Okinawan, has developed, known as "Okinawan Japanese".[13] Although it has been largely ignored by linguists and language activists, this is the language of choice among the younger generation.[13] Similarly, the common language now used in everyday conversations in Amami Ōshima is not the traditional Amami language, but rather a regional variation of Amami-accented Japanese, known as Amami Japanese. It’s locally known as トン普通語 (Ton Futsūgo, literally meaning "potato [i.e. rustic] common language").[14][15] To try to preserve the language, the Okinawan Prefectural government proclaimed on March 31, 2006, that September 18 would be commemorated as Shimakutuba no Hi (しまくとぅばの日, "Island Languages Day"),[16] as the day's numerals in goroawase spell out ku (9), tu (10), ba (8); kutuba is one of the few words common throughout the Ryukyuan languages meaning "word" or "language" (a cognate of the Japanese word kotoba (言葉, "word")). A similar commemoration is held in the Amami region on February 18 beginning in 2007, proclaimed as Hōgen no Hi (方言の日, "Dialect Day") by Ōshima Subprefecture in Kagoshima Prefecture. Each island has its own name for the event: Amami Ōshima: Shimayumuta no Hi (シマユムタの日) or Shimakutuba no Hi (シマクトゥバの日) (also written 島口の日) On Kikaijima it is Shimayumita no Hi (シマユミタの日) On Tokunoshima it is Shimaguchi no Hi (シマグチ(島口)の日) or Shimayumiita no Hi (シマユミィタの日) On Okinoerabujima it is Shimamuni no Hi (島ムニの日) On Yoronjima it is Yunnufutuba no Hi (ユンヌフトゥバの日). Yoronjima's fu (2) tu (10) ba (8) is the goroawase source of the February 18 date, much like with Okinawa Prefecture's use of kutuba.[17] |

ステータス 那覇の市場看板。沖縄語(赤)と日本語(青)で書かれている。  沖縄県金武町の交通安全標識。日本語(中央)と沖縄語(左と右)で書かれている。 琉球語については国勢調査のデータがなく、話者数は不明である[7]。2005年時点の琉球地域の総人口は1,452,288人であるが、流暢に話すのは概ね50代以上の高齢者に限られているため、本当の話者数はもっと少ないはずである[7]。 6つの琉球語はユネスコの「危機に瀕する世界の言語アトラス」に掲載されている。ユネスコは、2050年までにすべての琉球言語が絶滅の危機に瀕していると述べている[10]。 1890年代から、日本政府は琉球諸島における強制的な同化政策の一環として、琉球語の弾圧を始めた。 琉球諸語で育てられる子どもは、島全体でますます珍しくなっており、通常は祖父母と一緒に暮らしている場合にのみ見られる。琉球語は、民族音楽、民族舞 踊、詩、民俗劇などの伝統的な文化活動では今でも使われている。1960年以来、那覇弁のラジオニュース番組もある[11]。 2007年頃、沖縄では、40歳未満の人々は沖縄の母国語をほとんど使いこなせていない[12]。日本語と沖縄語をベースにした新しい混合言語が発達し、 「沖縄日本語」として知られている[13]。言語学者や言語活動家からはほとんど無視されているが、若い世代の間ではこの言語が選択されている[13]。 同様に、現在奄美大島の日常会話で使われている共通語は、伝統的な奄美の言葉ではなく、奄美なまりの日本語を地域的に変化させたもので、「奄美日本語」と して知られている。地元では「トン普通語」(とんふつうご、文字通り「イモ(=素朴な)共通語」という意味)と呼ばれている[14][15]。 沖縄県は2006年3月31日に9月18日を「島唄の日」とすることを宣言した[16]; クトゥバは、「言葉」や「言語」を意味する琉球諸語に共通する数少ない言葉のひとつである(日本語の「言葉」の同義語)。奄美地方でも2007年から2月 18日に「方言の日」として鹿児島県大島町が制定した。方言の日」は、鹿児島県大島郡が2007年から「方言の日」として制定している: 奄美大島 奄美大島:「シマユムタの日」または「シマクトゥバの日」(島口の日とも書く 喜界島では「シマユミタの日」。 徳之島では「シマグチの日」または「シマユミタの日」。 沖永良部島では「島むにの日」。 与論島ではユンヌフトゥバの日。 与論島のフ(2)トゥ(10)バ(8)は、沖縄県がクツバを使うのと同じように、2月18日の日付のゴロ合わせの出典である[17]。 |

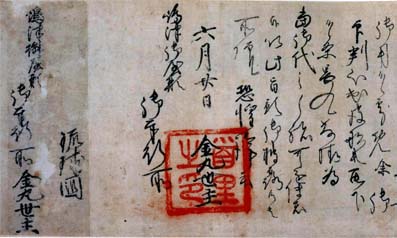

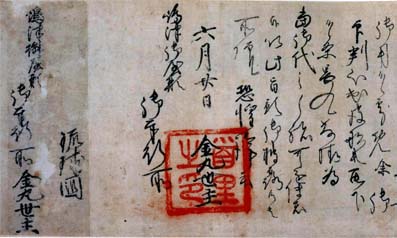

| History See also: History of the Ryukyu Islands It is generally accepted that the Ryukyu Islands were populated by Proto-Japonic speakers in the first millennium, and since then relative isolation allowed the Ryukyuan languages to diverge significantly from the varieties of Proto-Japonic spoken in Mainland Japan, which would later be known as Old Japanese. However, the discoveries of the Pinza-Abu Cave Man, the Minatogawa Man, and the Yamashita Cave Man[18] as well as the Shiraho Saonetabaru Cave Ruins[19] suggest an earlier arrival to the island by modern humans. Some researchers suggest that the Ryukyuan languages are most likely to have evolved from a "pre-Proto-Japonic language" from the Korean peninsula.[20] However, Ryukyuan may have already begun to diverge from Proto-Japonic before this migration, while its speakers still dwelt in the main islands of Japan.[7] After this initial settlement, there was little contact between the main islands and the Ryukyu Islands for centuries, allowing Ryukyuan and Japanese to diverge as separate linguistic entities from each other.[21] This situation lasted until the Kyushu-based Satsuma Domain conquered the Ryukyu Islands in the 17th century.[21] In 1846-1849 first Protestant missionary in Ryukyu Bernard Jean Bettelheim studied local languages, partially translated the Bible into them and published first grammar of Shuri Ryukyuan.[22] The Ryukyu Kingdom retained its autonomy until 1879, when it was annexed by Japan.[23] The Japanese government adopted a policy of forced assimilation, appointing mainland Japanese to political posts and suppressing native culture and language.[23] Students caught speaking the Ryukyuan languages were made to wear a dialect card (方言札 hōgen fuda), a method of public humiliation.[24][nb 1] Students who regularly wore the card would receive corporal punishment.[24] In 1940, there was a political debate amongst Japanese leaders about whether or not to continue the oppression of the Ryukyuan languages, although the argument for assimilation prevailed.[25] In the World War II era, speaking the Ryukyuan languages was officially illegal, although in practice the older generation was still monolingual.[24] During the Battle of Okinawa, many Okinawans were labeled as spies and executed for speaking the Okinawan language.[26] This policy of linguicide lasted into the post-war occupation of the Ryukyu Islands by the United States.[24] As the American occupation forces generally promoted the reforming of a separate Ryukyuan culture, many Okinawan officials continued to strive for Japanification as a form of defiance. Nowadays, in favor of multiculturalism, preserving Ryukyuan languages has become the policy of Okinawa Prefectural government, as well as the government of Kagoshima Prefecture's Ōshima Subprefecture. However, the situation is not very optimistic, since the vast majority of Okinawan children are now monolingual in Japanese. Geographic distribution The Ryukyuan languages are spoken on the Ryukyu Islands, which comprise the southernmost part of the Japanese archipelago.[3] There are four major island groups which make up the Ryukyu Islands: the Amami Islands, the Okinawa Islands, the Miyako Islands, and the Yaeyama Islands.[3] The former is in the Kagoshima Prefecture, while the latter three are in the Okinawa Prefecture.[3] Orthography  A letter from King Shō En to Shimazu oyakata (1471); an example of written Ryukyuan. See also: Okinawan scripts Older Ryukyuan texts are often found on stone inscriptions. Tamaudun-no-Hinomon (玉陵の碑文 "Inscription of Tamaudun tomb") (1501), for example. Within the Ryukyu Kingdom, official texts were written in kanji and hiragana, derived from Japan. However, this was a sharp contrast from Japan at the time, where classical Chinese writing was mostly used for official texts, only using hiragana for informal ones. Classical Chinese writing was sometimes used in Ryukyu as well, read in kundoku (Ryukyuan) or in Chinese. In Ryukyu, katakana was hardly used. Historically, official documents in Ryukyuan were primarily written in a form of classical Chinese writing known as Kanbun, while poetry and songs were often written in the Shuri dialect of Okinawan. Commoners did not learn kanji. Omoro Sōshi (1531–1623), a noted Ryukyuan song collection, was mainly written in hiragana. Other than hiragana, they also used Suzhou numerals (sūchūma すうちゅうま in Okinawan), derived from China. In Yonaguni in particular, there was a different writing system, the Kaidā glyphs (カイダー字 or カイダーディー).[27][28] Under Japanese influence, all of those numerals became obsolete. Nowadays, perceived as "dialects", Ryukyuan languages are not often written. When they are, Japanese characters are used in an ad hoc manner. There are no standard orthographies for the modern languages. Sounds not distinguished in the Japanese writing system, such as glottal stops, are not properly written. Sometimes local kun'yomi are given to kanji, such as agari (あがり "east") for 東, iri (いり "west") for 西, thus 西表 is Iriomote. Okinawa Prefectural government set up the investigative commission for orthography of shimakutuba (しまくとぅば正書法検討委員会) in 2018, and the commission proposed an unified spelling rule based on katakana for languages of Kunigami, Okinawa, Miyako, Yaeyama and Yonaguni on May 30 in 2022.[29] |

歴史 こちらも参照: 琉球列島の歴史 一般に、琉球列島には最初の千年紀に原ジャポニック語を話す人々が住んでいたと考えられており、その後、相対的な隔離によって琉球の言語は日本本土で話さ れていた原ジャポニック語から大きく分岐した。しかし、ピンザアブ洞窟人、湊川人、山下洞窟人[18]や白保早苗田原洞窟遺跡[19]の発見は、現生人類 がより早くこの島に到達していたことを示唆している。研究者の中には、琉球語は朝鮮半島から伝わった「原日本語以前の言語」から進化した可能性が高いと指 摘する者もいるが[20]、琉球語の話者がまだ日本の主要な島々に住んでいた頃、琉球語はこの移住以前にすでに原日本語から分岐し始めていた可能性があ る。 [この最初の移住の後、何世紀もの間、本島と琉球諸島の間にはほとんど接触がなかったため、琉球語と日本語は互いに別の言語的存在として乖離していった。 1846年から1849年にかけて、琉球で最初のプロテスタント宣教師ベルナール・ジャン・ベッテルハイムが現地の言語を研究し、聖書を部分的に翻訳し、首里琉球語の最初の文法を出版した[22]。 琉球王国は1879年に日本に併合されるまで自治権を保持していた[23]。 日本政府は強制的な同化政策を採用し、本土の日本人を政治的ポストに任命し、土着の文化や言語を抑圧した[23]。 琉球語を話しているところを発見された学生は、方言札(ほうげんふだ)という公衆の面前で恥をかかせる方法をとらされた[24]。 [1940年、日本の指導者たちの間では、琉球語への抑圧を続けるかどうかについて政治的な議論があったが、同化を求める主張が優勢であった[25]。 [25]第二次世界大戦の時代には、琉球語を話すことは公式には違法であったが、実際には年配の世代はまだモノリンガルであった[24]。沖縄戦の間、多 くの沖縄県民がスパイのレッテルを貼られ、沖縄の言葉を話したために処刑された。 [26]この言語差別政策は、戦後のアメリカによる琉球諸島の占領期まで続いた[24]。アメリカ占領軍が一般的に独立した琉球文化の改革を推進したた め、多くの沖縄の関係者は、反抗の形として日本化を目指し続けた。 現在では、多文化主義を支持し、琉球語の保存が沖縄県庁や鹿児島県大島振興局の方針となっている。しかし、沖縄の子どもたちの大半が日本語を母国語としないため、状況は楽観視できない。 地理的分布 琉球列島は、日本列島の最南端を占める琉球諸島で話されている[3]。 琉球列島を構成する主要な島嶼群は、奄美群島、沖縄諸島、宮古諸島、八重山諸島の4つである[3]。前者は鹿児島県に、後者3つは沖縄県にある[3]。 正書法  尚円王が島津親方に宛てた書簡(1471年)。 こちらも参照: 沖縄の文字 古い琉球文字は石碑に刻まれていることが多い。玉陵の碑文」(1501年)など。琉球王国内では、公的な文章は日本由来の漢字と平仮名で書かれていた。し かし、これは当時の日本とは対照的で、公用文にはほとんど漢文が使われ、非公式なものには平仮名しか使われなかった。琉球でも漢文が使われることがあり、 訓読みや漢文で読まれた。琉球ではカタカナはほとんど使われなかった。 歴史的に、琉球の公文書は主に漢文(かんぶん)と呼ばれる古典的な漢文で書かれ、詩や歌は沖縄の首里方言で書かれることが多かった。 庶民は漢字を学ばなかった。有名な琉歌集『おもろ草紙』(1531-1623)は主に平仮名で書かれている。ひらがな以外に、中国から伝わった蘇州数字 (沖縄語ではすーちゅーま すーうちゅうま)も使われていた。特に与那国では、カイダー文字という異なる文字体系があった[27][28]。 現在では「方言」として認識され、琉球語はあまり書かれない。その場合、日本語の文字がその場しのぎで使われている。現代語には標準的な正書法がない。声 門閉鎖音など、日本語の文字体系で区別されない音は正しく表記されない。東は「あがり」、西は「いり」のように、その土地の訓読みが漢字に当てられること もある。 沖縄県は2018年に「しまくとぅば正書法検討委員会」を設置し、2022年5月30日に国頭、沖縄、宮古、八重山、与那国の言語についてカタカナによる統一表記ルールを提案した。 [29] |

| Phonology https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyuan_languages#Phonology |

音声学、以下は省略、下記URLを参照 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyuan_languages#Phonology |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyuan_languages |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyuan_languages |

| Izuyama,

Atsuko (2012). "Yonaguni". In Tranter, Nicolas (ed.). The Languages of

Japan and Korea. Routledge. pp. 412–457. ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7. Lawrence, Wayne P. (2012). "Southern Ryukyuan". In Tranter, Nicolas (ed.). The Languages of Japan and Korea. Routledge. pp. 381–411. ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7. Pellard, Thomas (2015). "The Linguistic archeology of the Ryukyu Islands". In Heinrich, Patrick; Miyara, Shinsho; Shimoji, Michinori (eds.). Handbook of the Ryukyuan languages: History, structure, and use (PDF). Berlin: De Mouton Gruyter. pp. 13–37. doi:10.1515/9781614511151.13. ISBN 978-1-61451-115-1. S2CID 54004881. Shimoji, Michinori (2012). "Northern Ryukyuan". In Tranter, Nicolas (ed.). The Languages of Japan and Korea. Routledge. pp. 351–380. ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7. Shimoji, Michinori; Pellard, Thomas, eds. (2010). An Introduction to Ryukyuan languages (PDF). Tokyo: ILCAA. ISBN 978-4-86337-072-2. Retrieved June 10, 2018. Sugita, Yuko (2007). Language revitalization or language fossilization? Some suggestions for language documentation from the viewpoint of interactional linguistics (PDF). Proceedings of Conference on Language Documentation and Linguistic Theory. London: SOAS. ISBN 978-0-7286-0382-0. Retrieved December 19, 2009. Takara, Ben (February 2007). "On Reclaiming a Ryukyuan Culture" (PDF). Connect. 10 (4). Irifune: IMADR: 14–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 20, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2012. |

Izuyama,

Atsuko (2012). 「与那国」。Tranter, Nicolas (ed.). The Languages of Japan and

Korea. Routledge. 412-457. ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7. Lawrence, Wayne P. (2012). 「南琉球」。Tranter, Nicolas (ed.). The Languages of Japan and Korea. Routledge. 381-411. ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7. Pellard, Thomas (2015). 「琉球列島の言語考古学」. Heinrich, Patrick; Miyara, Shinsho; Shimoji, Michinori (eds.). 琉球言語ハンドブック: 歴史、構造、使用 (PDF). ベルリン: ド・ムートン・グリュター. pp. ISBN 978-1-61451-115-1. s2cid 54004881. Shimoji, Michinori (2012). 「北方琉球」. Tranter, Nicolas (ed.). The Languages of Japan and Korea. Routledge. 351-380. ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7. Shimoji, Michinori; Pellard, Thomas, eds. (2010). 琉球語入門 (PDF). 東京: ILCAA. ISBN 978-4-86337-072-2. 2018年6月10日取得。 杉田裕子 (2007). 言語の活性化か,言語の化石化か?交流言語学から見た言語ドキュメンテーションへの提言 (PDF). Proceedings of Conference on Language Documentation and Linguistic Theory. ロンドン: SOAS. ISBN 978-0-7286-0382-0. 2009年12月19日取得。 Takara, Ben (February 2007). 「琉球文化の回復について" (PDF). Connect. 10 (4). 入船: IMADR: 14-16. 2011年5月20日に原文(PDF)からアーカイブされた。2012年8月21日閲覧。 |

| Sanseido

(1997). 言語学大辞典セレクション:日本列島の言語 (Selection from the Encyclopædia of

Linguistics: The Languages of the Japanese Archipelago). "琉球列島の言語" (The

Languages of the Ryukyu Islands). Ashworth, D. E. (1973). A generative study of the inflectional morphophonemics of the Shuri dialect of Ryukyuan (PhD dissertation). Cornell University. Heinrich, Patrick (2004). "Language Planning and Language Ideology in the Ryūkyū Islands". Language Policy. 3 (2): 153–179. doi:10.1023/B:LPOL.0000036192.53709.fc. S2CID 144605968. Heinrich, Patrick; Miyara, Shinsho; Shimoji, Michinori, eds. (2015). Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9781614511151. ISBN 978-1-61451-161-8. Serafim, Leon Angelo (1984). Shodon: the prehistory of a Northern Ryukyuan dialect of Japanese (PDF) (PhD dissertation). Yale University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-24. Shimabukuro, Moriyo (2007). The accentual history of the Japanese and Ryukyuan languages: a reconstruction. Languages of Asia series. Vol. 2. Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental. ISBN 978-1-901903-63-8. Thorpe, Maner Lawton (1983). Ryūkyūan language history (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Southern California. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-03-14. Uemura, Yukio; Lawrence, Wayne P. (2003). The Ryukyuan language. Endangered Languages of the Pacific Rim. Vol. A4-018. Osaka: ELPR. |

三省堂 (1997). 言語学大辞典セレクション:日本列島の言語: 日本列島の言語). 「琉球列島の言語」。 Ashworth, D. E. (1973). 琉球語首里方言の屈折形態素に関する生成論的研究(博士論文). コーネル大学。 Heinrich, Patrick (2004). 「琉球列島における言語計画と言語イデオロギー」. 言語政策. 3 (2): 153–179. doi:10.1023/B:LPOL.0000036192.53709.fc. s2cid 144605968. Heinrich, Patrick; Miyara, Shinsho; Shimoji, Michinori, eds. (2015). 琉球諸語ハンドブック. ベルリン: De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9781614511151. ISBN 978-1-61451-161-8. Serafim, Leon Angelo (1984). Shodon: the prehistory of a Northern Ryukyuan dialect of Japanese (PDF) (PhD dissertation). エール大学。Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-24. 島袋盛世 (2007). 日本語と琉球語のアクセント史:再構築. アジアの言語シリーズ. 第2巻: グローバル・オリエンタル. ISBN 978-1-901903-63-8. Thorpe, Maner Lawton (1983). Ryūkyan language history (PDF) (PhD thesis). 南カリフォルニア大学。Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-03-14. Uemura, Yukio; Lawrence, Wayne P. (2003). 琉球語。Endangered Languages of the Pacific Rim. A4-018. 大阪: 大阪: ELPR. |

画像をクリックすると拡大します

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆