サント・ドミンゴ・デ・コバンの歴史

History of Santo Domingo de Cobán, Alta

Verapaz, Guatemala

1959年

☆ コバン(Kekchí: Kob'an)は、グアテマラ中部のアルタ・ベラパス県の県都。グアテマラ中部、アルタ・ベラパス県の県都であり、周辺のコバン自治体の行政の中心地でも ある。グアテマラ・シティから219kmに位置する。コバンの名はQ'eqchi'語の「雲のあいだ」という意味に由来する。[1544年以後の3年間の 間に]バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスとアングーロはラビナルを設立し、コバン市は新しいカトリックの教義の中心となった。数年後、原住民はスペ インのモデルに従って定住を始め、タクティックのようにいくつかの町が定住した。戦争地域 "という名称は、1547年に正式名称となった "ベラ・パス(真の平和)"に変更された。コバンは神聖ローマ皇帝カレル5世によって帝国都市の称号を与えられ、1599年にコバンは司教座となっ た。この時期、一時的にカルロス1世(カール5世)にちなんでシウダー・インペリアル(スペイン語で「帝都」の意)と呼ばれた[3]。

★Capitulaciones de Tezulutlán は、1537年5月2日、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスとアロンソ・デ・マルドナードが、グアテマラ総督府と新スペイン総督府の間で、テスルトラン(後の グアテマラ・アルタベラパス)とラカンドン密林(メキシコ・チアパス)を平和的に征服するために締結した協定である。

| Cobán (Kekchí: Kob'an), fully Santo Domingo de Cobán,[2][3]

is the capital of the department of Alta Verapaz in central Guatemala.

It also serves as the administrative center for the surrounding Cobán

municipality. It is located 219 km from Guatemala City. As of the 2018 census the population of the city of Cobán was at 212,047. The population of the municipality, which covers a total area of 1,974 km², was at 212,421, according to the 2018 census.[4] Cobán, at a height of 1,320 metres or 4,330 feet above sea level, is located at the center of a major coffee-growing area. Etymology The name "Cobán" comes from Q'eqchi' (between clouds) |

コバン(Kekchí: Kob'an)は、グアテマラ中部のアルタ・ベラパス県の県都[2][3]。グアテマラ中部、アルタ・ベラパス県の県都であり、周辺のコバン自治体の行政の中心地でもある。グアテマラ・シティから219kmに位置する。 2018年国勢調査によるコバン市の人口は212,047人。総面積1,974 km²の自治体の人口は、2018年の国勢調査によると212,421人であった[4]。 海抜1,320メートル(4,330フィート)のコバンは、主要なコーヒー栽培地域の中心に位置している。 語源 コバンの名はQ'eqchi'語の「雲のあいだ」という意味に由来する。 |

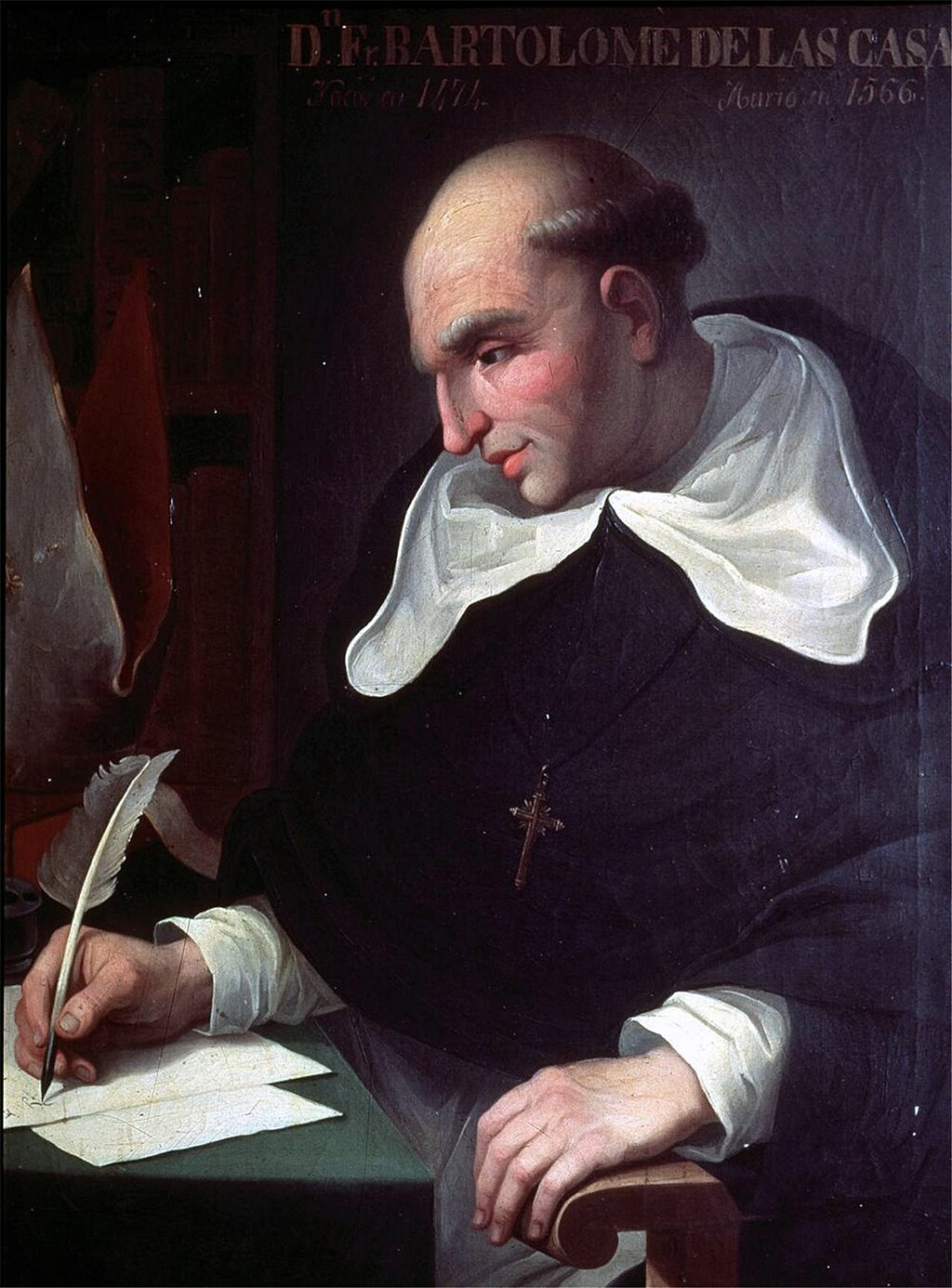

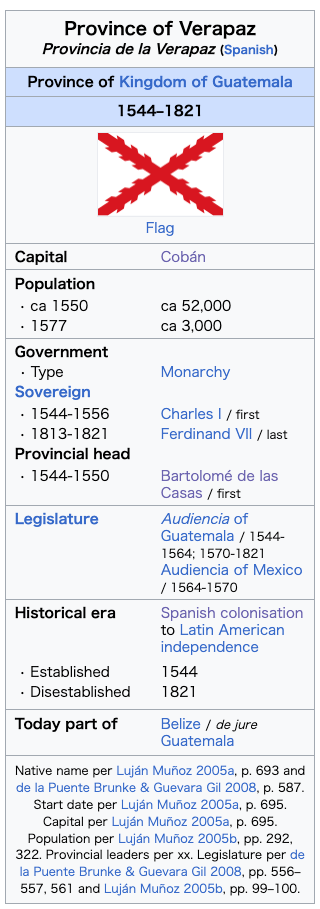

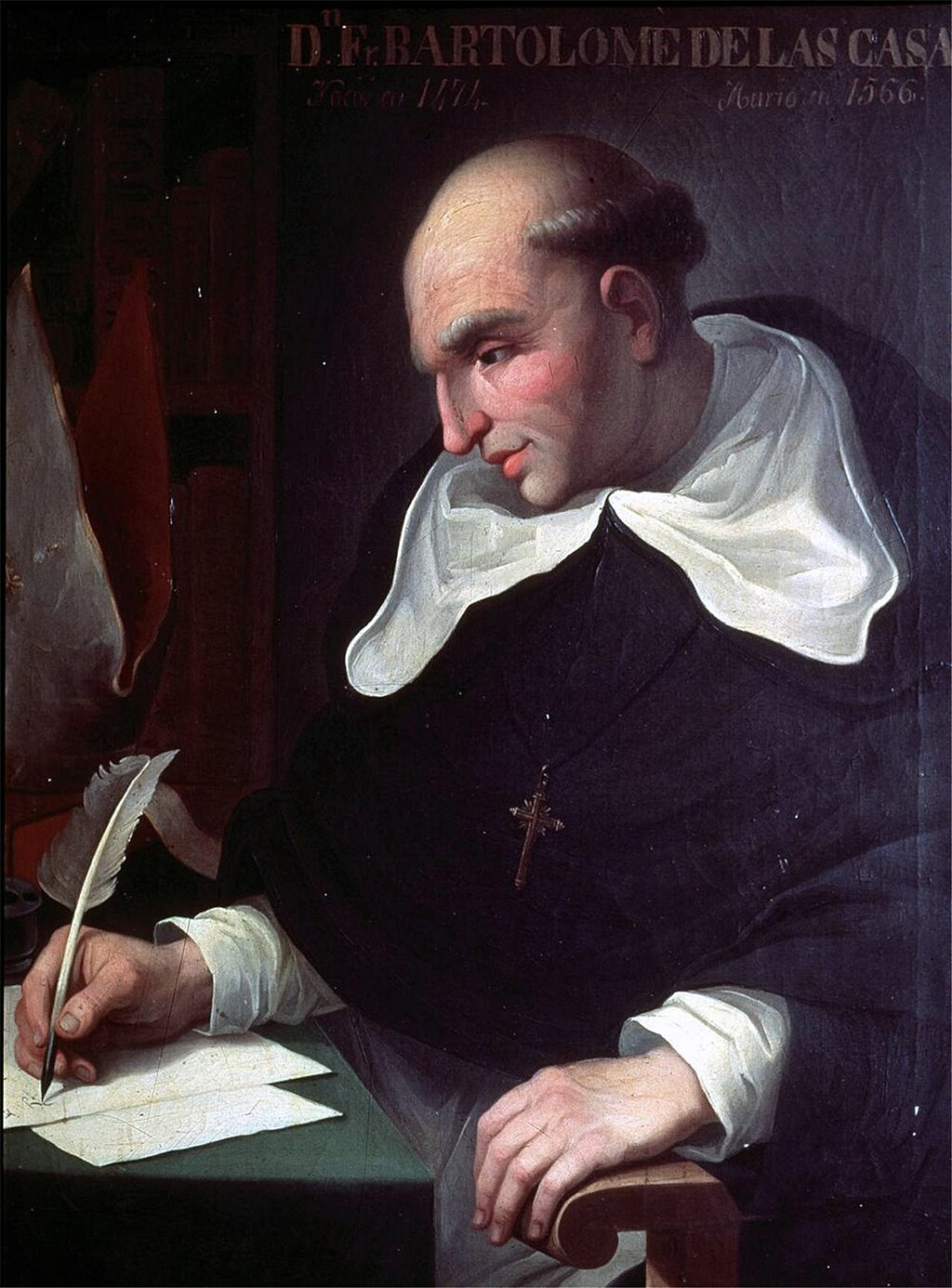

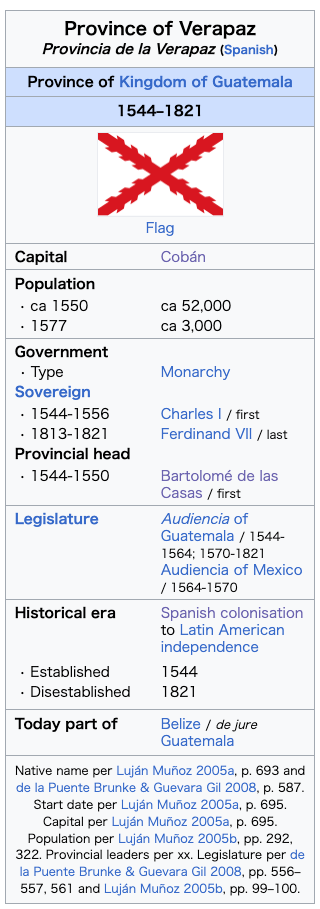

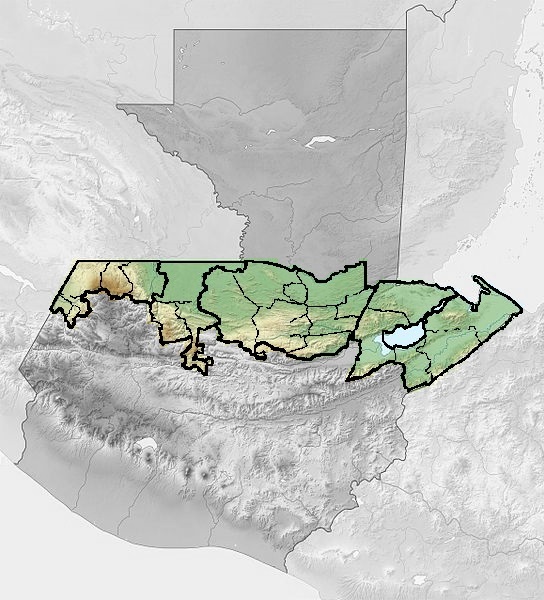

| Order of Preachers in the Vera Paz Main article: Bartolomé de Las Casas  Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, O.P. who along friars Rodrigo de Landa, Pedro Angulo and Luis de Cáncer, O.P, started Vera paz Christian indoctrination in 1542. Between 1530 and 1531, captain Alonso de Ávila [es] on his way to Ciudad Real accidentally discovered the lagoon and hill of Lacam-Tún [es]. People of that place had historically traded with all the people that the Spaniards had conquered, so, knowing what was coming, they sought refuge in the jungle. The Spaniards tried in vain to conquer the lacandones: from Nueva España Juan Enríquez de Guzman tried; from the Yucatán Peninsula, Francisco de Montejo tried; Pedro de Alvarado attempted it from Guatemala along with captain Francisco Gil Zapata and, finally, Pedro Solórzano from Chiapas.[5] That is when the Order of Preachers tried to convert the Tezulutlán "War Zone" into a peaceful region. In the meantime, after a series of setbacks in La Española, the island Audiencia allowed Bartolomé de las Casas to accept Friar Tomás de Berlanga's invitation to go to Nueva Granada in 1534, where he had just been appointed as Bishop. Both sailed toward Panamá, to then continued to Lima, but during the trip a storm tossed their ship to Nicaragua, where Las Casas chose to remain in the Granada convent. in 1535, he proposed to the King and the Council of the Indies to start a peaceful colonization of the unexplored rural zones in the Guatemala region; however, in spite of Bernal Díaz de Luco and Mercado de Peñaloza intentions to help him, his suggestion was rejected. In 1536 Nicaraguan governor Rodrigo de Contreras organized a military expedition, but Las Casas was able to postpone it by a couple of years after he notified queen Isabel de Portugal, wife of Carlos V. Given the authorities' hostility, Las Casas left Nicaragua and went to Guatemala.[6] In November 1536, Las Casas settled in Santiago de Guatemala, then the capital of Guatemala; a few months later, his friend, bishop Juan Garcés, invited him to move to Tlascala, but after a few weeks he came back to Guatemala. On May 2, 1537 governor Alonso de Maldonado granted him the Tezulutlán Capitulations - a written commitment ratified on July 6, 1539 by Antonio de Mendoza, México Viceroy- in which everybody agreed that Tezulutlán natives, once conquered, would not be given as encomienda but would be King's subjects.[7] Las Casas, along with friars Rodrigo de Landa, Pedro Angulo and Luis de Cancer, looked for four Christian natives and taught them Christian hymns where the Gospel's basic principles were explained. Luis de Cancer visited the cacique of Sacapulas and was able to perform the first baptisms among his people. Later, Las Casas lead a retinue to bring girts to the cacique, who was so impressed that he decided to convert and become his people preacher[clarification needed]. The cacique was baptized with the name of Don Juan and the natives granted permission to build a small church; however, Cobán, another cacique, burned the church. Don Juan, along sixty men, Las Casas and Pedro Angulo, went to talk to Cobán's people and convinced them of their good intentions;[8] Don Juan even took the initiative to marry one of his daughters with cacique Cobán by the Catholic Church. In 1539 pope Paul III authorized the diocese of Ciudad Real;[a] that year, Alonso de Maldonado—under pressure by Spanish settlers—began a military campaign in Tezulutlán [...] gave all the natives in encomiendas. This flagrant violation of the Capitulations enraged Las Casas, who traveled to Spain to denounce it before king Charles V. On January 9, 1540 a royal document was issues which the Tezulutlán Capitulations [es] were ratified and gave the region to the protection of the Order of Preachers. On October 17 of that year, Cardinal García de Loaysa -then president of the Indias Council- ordered the México Audiencia to comply with these laws. The Capitulations were officially published on January 21, 1541 in the church of Sevilla.[9] Las Casas was appointed bishop of Chiapas in 1544, but he tried to apply the new ways in his diocese, they were flatly rejected by the encomenderos.[5] In 1545, Guatemala bishop Francisco Marroquín visited Tezulutlán and met with the preachers. Back in the city of Gracias a Dios, where the Audiencia de los Confines had its main office- met with Las Casas and with Nicaragua bishop Antonio de Valdivieso. There was a lot of tension between Marroquín and Las Casas in this meeting[b] The conflict moved on to Ciudad de México and finally everybody agreed to favor the freedom of the natives; however, this could not be accomplished for the Lacandon Jungle would not be conquered for another two century, becoming the rebel maya people favorite hideout.[10] Las Casas and Angulo founded Rabinal, and the city of Cobán was the center of the new Catholic doctrine. A few years later, the natives started settling following the Spanish model and several towns were settled, like Tactic. The name "War zone" was change for "Vera Paz" (true peace), name that became official in 1547.[5] Cobán received the title of an imperial city by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and in 1599 Cobán became bishop's see. It was briefly known during this period as Ciudad Imperial (Spanish for "Imperial City") in Charles's honor.[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cob%C3%A1n +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++  Verapaz, formerly Tezulutlan, was a second order subdivision of the former Kingdom of Guatemala, itself a constituent part of New Spain.[n 1] Geography Extent The northern limits of Tezulutlan and later Verapaz were the subject of heated debates between competing authorities of Santiago de Guatemala and Mérida de Yucatán.[1] Particularly questioned were the lowlands now comprising northern and eastern Alta Verapaz, southern Belize, and all of Izabal and Petén.[1][n 2] Commonly accepted as unquestionably part of the province, on the other hand, were the highlands now comprising southwestern Alta Verapaz, and all of Baja Verapaz.[1] Physical Human In the early 16th century, Tezulutlan is said to have housed Q’eqchi’ and Poqomchi’ speakers, whose polities were reportedly wedged ‘between the uninhabited sierras de Chuacús and de las Minas, to the south, and the jungles of Petén, to the north.’[2][n 3] They therefore bordered the quiché–achí state (on the Carchelá River, between Tactic and Tzalamá) to the southwest, and choles, manchés, acalaes, lacandones polities to the north and east.[3] The Q’eqchi’ state lay in ‘the sierras which stretch between the Polochic River, to the south, and the Cahabón River, to the north,’ and thus bordered the Poqomchi’ polity to the west, said border falling somewhere between modern Cobán (then a Q’eqchi’ city) and Santa Cruz Munchú (then a Poqomchi’ city).[4] The Q’eqchi’ heartland is thought to have been among the colonial towns Carchá, Chamelco, and Cobán.[2] The Poqomchi’ state lay in ‘a narrow strip from west to east, from the middle Chixoy River to Panzós, in the lower Polochic valley,’ and thereby formed a western and southern buffer, from Chamá to Panzós, for the Q’eqchi’ state from the southwesterly K’iche’ one.[5] The western Poqomchi’ heartland was probably near San Cristóbal Cagcoh, and the eastern one amidst Tactic, Tamahú, and Tucurú.[6] History Spanish contact Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo and Sancho de Barahona reportedly lead a military campaign against the Q’eqchi’ city of Cobán, in Tezulutlan, in mid 1528, but details remain muddled.[7] Nonetheless, the expedition is now deemed to have probably founded no Spanish settlement in the region.[7] Similarly, Diego de Alvarado is thought to have lead a military campaign against the Poqomchi’ polity in Tezulutlan in 1530 or 1531, with details likewise remaining confused.[7] The expedition reportedly returned within the year as the captain had ‘forgotten about this corner when Peru rang,’ or returned in April 1531 as troops were ‘devastated [...] asking for shelter and ministrations.’[7] A further campaign or entrada founded Nueva Sevilla in 1543 on the Río Polochic; it grew to 60 vecinos but the Dominicans protested the settlement, such that in 1548 the Audiencia ordered its desertion, effected in 1549.[8] A similar attempt was later made by Núñez de Landecho, who founded Monguía or Munguía about 1568 on Lake Izabal, but it likewise failed.[8] Frustrated too was the attempt by Martín Alfonso Tovilla, then alcalde mayor of the province, who founded Toro de Acuña in the former Manche on 13 May 1631; the villa was abandoned within the year.[9][n 4] Dominican entry The asiento or capitulación of Tezulutlan was secretely signed on 2 May 1537 in Santiago de Guatemala by Alonso Maldonado, interim governor of the province, and Bartolomé de las Casas, episcopal vicar of the diocese.[10][n 5] Said asiento would bind the Crown to not subject to encomiendas those native Indians whom the Dominicans converted to Roman Catholicism.[11] It was ‘declared generally compliant’ by a real provisión of the viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza, and Audiencia of Mexico, dated 6 February 1539; the same was then ‘confirmed’ by a real cédula of Charles I of Spain, dated Madrid, 17 October 1540.[12][n 6] Dominican friars are thought to have entered the province in 1544 to Chamelco and Tucurú, as by mid 1545 ‘the few pueblos already reducidos (from the local population) lay near Chamelco and Tucurú, which confirms that this was not only the area of greatest population density, but also seat of the K’ekchi’ and Poqomchi’ authorities.’[1] Northern expansion Of the pre-Hispanic polities north of Verapaz, the first to be contacted was the Manche Chol Territory in the 1590s via Cahabón.[13][n 7] By 1606 the inhabitants of some six pueblos ‘had been discovered and baptised.’[13] Meanwhile, Alonso Criado de Castilla had in 1604 ‘discovered and inaugurated’ the port of Santo Tomás de Aquino in the Amatique Bay, within the former Toquegua territory.[13][n 8] Nonetheless, by 1633, ‘on the heels of a general rebellion came the loss of all those Indians, of whom had been reducidos over 6,000 souls to the Faith, spread across nine pueblos.’[14][n 9] Dominican reducciones having proved fruitless, by the mid 17th century it was thought more expedient to undertake an ‘entrada’ northwards, capture native Indians, and relocate them south, closer to Spanish dominion.[15] The earliest of these is thought to have occurred in circa 1654, when over 30 Ch’olan speakers north of Verapaz were relocated to Atiquipaque, in the Guazacapán province.[15] The new policy, however, was not assiduously pursued until the 1674–1676 entrada by Francisco Gallegos.[16] By 1680, the Dominicans reported over 3,000 reducidos from the Lacandon and Manche Chol polities.[17][n 10] The conquest of Petén, for which Verapaz served as a southern entry point, began in earnest by 1690 and was completed within five or six years.[17] The conquered lands and their pueblos de indios were placed under the political administration of Santiago de Guatemala, and the ecclesiastic oversight of Mérida de Yucatán.[18] Piratical intrusions Lutheran pirates were first sighted near Amatique Bay in 154xx. The local port of call, Bodegas del Golfo, established 154xx, came under xx. Governance In 1548–1555, Verapaz was constituted an alcaldía mayor, with jurisdiction over the province's pueblos de indios.[19] Said pueblos de indios were in turn the jurisidction of principales, that is, native Indian members of the pre-Hispanic elite, who served as members of their local cabildos and parishes.[20] In the particular case of Verapaz, additionally, the clergy held outsized authority in temporal matters.[21] Thomas Gage, for instance, noted that local principales ‘did nothing without the approval of their vicar.’[21] Legacy The earliest description in print of the ‘peaceful conquest of Verapaz’ is thought to have appeared in Antonio de Remesal's 1619 Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala.[22][n 11] Los esfuerzos de Vasco de Quiroga en Michoacán y los de los frailes dominicos en la Verapaz no dieron los frutos esperados, quizás porque sus metas eran demasiado idealistas. Es probable que la situación del claro ‘choque psicológico’ en que se encontraban los indios tras la derrota y avasallamiento, facilitó su labor. Pero entre este hecho y la utopía soñada quedó siempre un largo trecho por recorrer. The efforts of Vasco de Quiroga in Michoacán and those of the Dominican friars in Verapaz did not bear the expected results, perhaps because their goals were too idealistic. It is probable that the state of palpable 'psychological shock' in which the Indians found themselves after their defeat and subjugation facilitated the friars’ work. But between this fact and the dreamed utopia there was always a long way to go. —J. Luján Muñoz in the 1994 Historia General de Guatemala.[23] Notes and references Explanatory footnotes From 1524 to 1547, Verapaz was variously known as Tezulutlán, Tuzulutlán, or Tecolotlán, Spanish corruptions of the Nahuatl term for ‘land of the owls,’ or Tierra de Guerra, Spanish for ‘land of war’ (de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, pp. 566, 580, Luján Muñoz 2005a, p. 693). From 1547, it was also known as Vera Paz (de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, pp. 580, 584–587). Luján Muñoz 2005a, p. 695 comments, ‘whether or not Tezulutlán–Verapaz included the lowlands of the Golfo Dulce and those of southern Petén, and even those of northern Petén, as far as Yucatán, was a matter of discussion between the Dominicans, the Audiencia of Guatemala, and the authorities of Yucatán.’ Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 314 further notes, ‘in Petén as in Verapaz and Chiapas one had [pre 1697] the problem of open borders, with unconquered lands,’ further describing these as ‘undetermined boundaries.’ Though de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 5661 include ‘the Lacandon [...] the fierce Lacandon Indians’ within Verapaz in the first half of 1539. The Audiencia authorised the settlement of 20 vecinos casados via auto dated 11 May 1631 (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 136). Tovilla and the Dominican friar Francisco Morán lead the vecinos and over 150 native Indian militiamen and servants from Santiago, while the cacique Juan de la Mantilla Ortega lead 100 native militiamen from Cobán (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 136). The parties met at Manche, in Manche Chol Territory (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 136). Having been ousted from León for provocative homilies in defence of native Indians, the Dominican friars Bartolomé de las Casas, Rodrido de Ladrada, Pedro de Angulo, and possibly Luis Cáncer sought refuge in Santiago de Guatemala in mid-July 1536 (de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 584). The diocesan bishop, Francisco Marroquín, had appointed de las Casas vicario episcopal in January 1537 (de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 584). As de las Casas was additionally interim defensor de los indios during the bishop's absence, he accompanied Maldonado in February–March 1537 during the latter's visita de tasación throughout the pueblos de indios de la gobernación to assess taxes due by said native Indians (de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, pp. 584–585). The King issued further reales cédulas on 17 October 1540 forbidding entry into Tezulutlan to anyone not authorised by the Dominicans, and charging the governors of Guatemala, Chiapa, and Honduras with the prohibition's enforcement for five years (de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 586). The asiento's confirmation was renewed by real cédula dated Barcelona, 1 May 1543, on occasion of the founding of the Audiencia de los Confines (de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 586). De las Casas’s only visit to Verapaz was during mid June to mid July 1545 (de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 588, Luján Muñoz 2005a, p. 695). The friar Antonio de Remesal dates the start of efforts to reducir native Indians north of Verapaz to 1594–1596 (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 137). However, San Andrés Polochic and Santa Catarina Xocoló, both on Río Dulce within Manche Chol Territory, were reducidos by Dominican friar Domingo de Vico about 1560 (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 138). The previous port for that Bay had been Bodegas del Golfo, founded 1549 (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 475). On 7 March 1604, the pilot Francisco Navarro lobbied for the port's founding, and on 16 July 1604 the new port was populated by forcibly relocated Puerto Caballos residents (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 475). In 1631, Toro de Acuña had proved abortive, while San Andrés Polochic and Santa Catarina Xocoló had been ‘destroyed,’ and in 1632 the recently-established vicarate at San Miguel del Manché had been removed to Cahabón (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 138). J. Luján Muñoz suggests the sudden collapse of reducción efforts may have been due to ‘the pestilence which, according to various authors, devastated the entire Kingdom of Guatemala in approximately 1631’ (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 138). In 1677, and especially March–April 1678, Ch’olan speakers in Dominican reduccion towns had rebelled, ostensibly in protest against the alcalde mayor Sebastián de Olivera (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 139). This coincided with a deadly epidemic originating in San Lucas, one of the reduccion towns, which cost 400 native reducidos their lives, and prompted desertions en masse (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 139). The Dominicans attempted reducciones in 1681, 1684, and 1685, but to no avail; in 1688, San Lucas again rebelled, burning their pueblo and church house, this reportedly marking ‘the fifth or sixth time they apostatised’ (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 139). This latest revolt prompted a successful 1689 entrada from Cahabón (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 139). Wherein appears ‘an idealised description with serious chronological errors that, nevertheless, gained wide acceptance, until it was corrected by modern authors such as M. Bataillon, A. Saint-Lu and J. Rodríguez Cabal’ (Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 73). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verapaz,_Guatemala +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Las Capitulaciones de Tezulutlán fueron los acuerdos firmados el 2 de mayo de 1537 por fray Bartolomé de las Casas y Alonso de Maldonado para conquistar de forma pacífica los territorios de Tezulutlán (conformados por lo que después sería Alta Verapaz, Guatemala) y la Selva Lacandona (Chiapas, México), comprendidos entre la Capitanía General de Guatemala y el Virreinato de Nueva España. Antecedentes Entre 1530 y 1531 el capitán Alonso de Ávila accidentalmente en su ruta de Ciudad Real hacia Acalán descubrió la laguna y peñol de Lacam-Tún. Los habitantes de esta zona que comerciaban con los pueblos previamente conquistados por los españoles evitaron un enfrentamiento directo utilizando la selva como refugio. Fueron varios los intentos por conquistar a los lacandones, desde Nueva España lo intentó Juan Enríquez de Guzmán, desde la Península de Yucatán lo intentó Francisco de Montejo, desde Guatemala Pedro de Alvarado con el capitán Francisco Gil Zapata y desde Chiapa Pedro Solórzano.1 Mopones, tzeltales y choles fueron reubicados paulatinamente en pueblos de paz donde fueron evangelizados. Los lacandones que originalmente habían evitado la confrontación abierta, cambiaron de actitud y comenzaron el asalto de las localidades cercanas a la selva. Por otra parte, en Tezlulután los achíes resistían las acciones de conquista, de tal forma que estos territorios fueron referidos como "Tierra de Guerra", y fueron el objetivo militar de los conquistadores españoles.2 Las capitulaciones Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, O.P. realizó negociaciones con el oidor de la Segunda Real Audiencia de México, licenciado Alonso de Maldonado — quien se encontraba reemplazando al adelantado Pedro de Alvarado — para conquistar pacíficamente los territorios insumisos por medio de los métodos de reducción y evangelización, los cuales serían llevados a cabo por los misioneros de la Orden de Predicadores. El acuerdo fue firmado el 2 de mayo de 1537, la «Tierra de Guerra» solo podría ser sometida por medios pacíficos y sus habitantes tendrían que acceder voluntariamente para convertirse en vasallos de la corona española. Los indígenas no serían entregados por ningún motivo al sistema de encomiendas. Durante los primeros cinco años, tampoco sería permitida la entrada a ningún español so pena de grandes sanciones, a excepción del propio gobernador quien además sería acompañado por los frailes. Desarrollo de la reducción y pacificación Véase también: Bartolomé de las Casas El compromiso escrito fue ratificado el 6 de julio de 1539 por el Virrey de México Don Antonio de Mendoza, que los nativos de Tuzulutlán, cuando fueran conquistados, no serían dados en encomienda sino que serían vasallos de la Corona.3 Las Casas, junto con otros frailes como Pedro de Angulo y Rodrigo de Ladrada, buscó a cuatro indios cristianos y les enseñó cánticos cristianos donde se explicaban cuestiones básicas del Evangelio. Posteriormente encabezó una comitiva que trajo pequeños regalos a los indios -tijeras, cascabeles, peines, espejos, collares de cuentas de vidrio, entre otros- e impresionó al cacique, que decidió convertirse al cristianismo y ser predicador de sus vasallos. El cacique se bautizó con el nombre de Juan. Los nativos consintieron la construcción de una iglesia pero otro cacique llamado Cobán quemó la iglesia. Juan, con sesenta hombres, acompañado de Las Casas y Pedro de Angulo, fueron a hablar con los indios de Cobán y les convencieron de sus buenas intenciones.4 Las Casas, fray Luis de Cáncer, fray Rodrigo de Ladrada y fray Pedro de Angulo, O.P. tomaron parte en el proyecto de reducción y pacificación. Pero fue Luis de Cáncer quien fue recibido por el cacique de Sacapulas logrando realizar los primeros bautizos de los habitantes. El cacique «Don Juan» tomó la iniciativa de casar a una de sus hijas con un principal del pueblo de Cobán bajo la religión católica.5 Las Casas y Angulo fundaron el pueblo de Rabinal, siendo Cobán la cabecera de la doctrina. Tras dos años de esfuerzo el sistema de reducción comenzó a tener un éxito relativo, pues los indígenas se trasladaron a terrenos más accesibles y se fundaron localidades al modo español. El nombre de «Tierra de Guerra» fue sustituido por el de «Vera Paz» (verdadera paz), denominación que se hizo oficial en 1547.1 Violación de las capitulaciones El éxito relativo y el entusiasmo de los dominicos fue prematuro. En 1539 Alonso de Maldonado bajo presión de los colonos españoles o motivado por obtener un beneficio personal inició una campaña en Tezulutlán y distribuyó a los indígenas bajo el régimen de encomiendas. Esta flagrante violación a las capitulaciones fue protestada por Las Casas quién decidió viajar a la península ibérica para denunciar los hechos ante el rey Carlos I de España. El 9 de enero de 1540 se emitió una real cédula la cual ratificaba las Capitulaciones de Tezulutlán y concedía a la orden de Santo Domingo la protección del territorio de Verapaz. El 17 de octubre del mismo año, el cardenal García de Loaysa quien era presidente del Consejo de Indias ordenó a la Audiencia y Cancillería de México cumplir las mismas disposiciones. El 21 de enero de 1541 en la iglesia de Sevilla ante escribano y pregonero se publicó la real ratificación de las Capitulaciones de Tezulutlán.6 Por otra parte, desde 1539 el papa Paulo III ya había autorizado la creación de la sede episcopal de Ciudad Real, la cual incluía Chiapas, el Soconusco, la Vera Paz (incluida la Selva Lacandona), Tabasco y la todavía no conquistada Península de Yucatán. Pero no fue sino hasta 1544 que Las Casas fue consagrado obispo, pues este había realizado gestiones para la emisión de las Leyes Nuevas las cuales intentó hacer valer en su diócesis, pero éstas fueron abiertamente rechazadas por los encomenderos, por tal motivo, Las Casas tuvo que lidiar contra la oposición de sus feligreses.1 En 1545 el obispo de Guatemala Francisco Marroquín realizó una visita a Tuzulutlán y se entrevistó con los padres dominicos. De regreso en la ciudad de Gracias a Dios sede de la Audiencia de los Confines se reunió con el recién nombrado obispo Las Casas y con el obispo de Nicaragua Antonio de Valdivieso. El objetivo de Las Casas era transmitir su interés para el acatamiento de las Leyes Nuevas. Pero hubo grandes desavenencias entre Las Casas y Marroquín, el primero acusó al segundo de tener indios esclavos y de repartimiento así como predicar "dañosa doctrina". Marroquín por su parte lo acusó de traspasar los límites de su jurisdicción. El fin de ambos religiosos era el mismo, pero con diferencia de métodos. El conflicto prosiguió en la Ciudad de México y se concluyó favorecer la libertad de los indios, conclusión que fue publicada como letra muerta, pues nunca se pusieron en práctica las intenciones de los religiosos. La pacificación de la Selva Lacandona no se concluyó y fue el refugio preferido por los mayas rebeldes durante siglos.7 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitulaciones_de_Tezulutl%C3%A1n |

ヴェラパスへの布教命令 主な記事 バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス  バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス修道士(O.P.)は、ロドリゴ・デ・ランダ修道士、ペドロ・アングロ修道士、ルイス・デ・カンセール修道士(O.P.)とともに、1542年にヴェラパスのキリスト教布教を開始した。 1530年から1531年にかけて、船長のアロンソ・デ・アビラ[es]がシウダ・レアルに向かう途中、偶然ラカム・トゥン[es]のラグーンと丘を発見 した。その場所の人々は、スペイン人が征服したすべての人々と歴史的に交易をしていたため、何が起こるかを知っていた彼らはジャングルに避難した。ヌエ バ・エスパーニャのフアン・エンリケス・デ・グスマン、ユカタン半島のフランシスコ・デ・モンテホ、グアテマラのペドロ・デ・アルバラード、隊長のフラン シスコ・ジル・サパタ、そしてチアパスのペドロ・ソロルサノ[5]が、ラカンドン人の征服を試みたが無駄だった。 一方、ラ・エスパニョーラでの一連の挫折の後、島のアウディエンシアは、1534年、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスが司教に任命されたばかりのヌエバ・グ ラナダへ行くようにとのトマス・デ・ベルランガ修道士の招待を受けることを許可した。1535年、ラス・カサスは国王とインド評議会に、グアテマラ地域の 未開拓の農村地帯を平和的に植民地化することを提案したが、ベルナル・ディアス・デ・ルコとメルカド・デ・ペニャロサの協力の意向にもかかわらず、彼の提 案は却下された。1536年、ニカラグア総督ロドリゴ・デ・コントレラスは軍事遠征を組織したが、ラス・カサスはカルロス5世の妻イサベル・デ・ポルトガ ル王妃に通告し、遠征を数年延期することができた。 1536年11月、ラス・カサスは当時グアテマラの首都であったサンティアゴ・デ・グアテマラに定住した。数ヵ月後、友人の司教フアン・ガルセスに誘われ てトラスカラに移ったが、数週間後にグアテマラに戻ってきた。1537年5月2日、グアテマラ総督アロンソ・デ・マルドナド(Alonso de Maldonado)は、ラス・カサスにテスルトラン盟約書(1539年7月6日、メキシコ総督アントニオ・デ・メンドーサ(Antonio de Mendoza)によって批准された文書)を与えた。 [7] ラス・カサスは、ロドリゴ・デ・ランダ修道士、ペドロ・アングロ修道士、ルイス・デ・キャンサー修道士とともに、4人のキリスト教徒の原住民を探し、彼ら にキリスト教の賛美歌を教え、福音の基本原理を説明した。ルイス・デ・キャンサーはサカプラスのカシケを訪ね、彼の民の間で最初の洗礼を行うことができ た。後日、ラス・カサスは従者を率いてカシケにガートを持って行き、感銘を受けたカシケは改宗して民衆の伝道師になることを決意した[要出典]。カシケは ドン・ファンという名の洗礼を受け、原住民は小さな教会を建てることを許可したが、もう一人のカシケであるコバンは教会を燃やしてしまった。ドン・ファン は、ラス・カサスとペドロ・アングロという60人の部下とともにコバンの民衆に話を聞きに行き、彼らの善意を説得した[8]。ドン・ファンは、カトリック 教会の主導により、娘の一人をコバンのカシケと結婚させるという行動も起こした。 1539年、教皇パウロ3世はシウダ・レアル教区を認可した[a]。その年、アロンソ・デ・マルドナドはスペイン人入植者の圧力の下、テズルトランで軍事 作戦を開始し、[中略]すべての原住民にencomiendasを与えた。この盟約違反に激怒したラス・カサスはスペインに渡り、国王シャルル5世の前で 糾弾した。1540年1月9日、テスルトラン盟約[es]が批准され、この地域が説教者修道会の保護下に置かれるという勅書が発行された。その年の10月 17日、ガルシア・デ・ロアイサ枢機卿(当時インディアス公会議議長)は、メヒコ聴聞会にこの法律に従うよう命じた。1541年1月21日、ラス・カサス はセビージャの教会で正式に公布された[9]。 1544年、ラス・カサスはチアパス司教に任命されたが、彼の教区でこの新しい方法を適用しようとしたところ、エンコメンデーロスたちに拒絶された [5]。グラシアス・ア・ディオスの町に戻って、ラス・カサス、ニカラグアのアントニオ・デ・バルディビエソ司教と会談した。この会議では、マロキンとラ ス・カサスの間に多くの緊張があった[b]。紛争はシウダー・デ・メヒコに移り、最終的に誰もが原住民の自由を支持することに同意した。しかし、ラカンド ン・ジャングルはさらに2世紀も征服されず、反乱軍のマヤ族のお気に入りの隠れ家となったため、これは達成されなかった[10]。 [1544年以後の3年間の間に]ラス・カサスとアングーロはラビナルを設立し、コバン市は新しいカトリックの教義の中心となった。数年後、原住民はスペ インのモデルに従って定住を始め、タクティックのようにいくつかの町が定住した。戦争地域 "という名称は、1547年に正式名称となった "ベラ・パス(真の平和)"に変更された[5]。コバンは神聖ローマ皇帝カルロス1世(カール5世)によって帝国都市の称号を与えられ、1599年にコバンは司教座となっ た。この時期、一時的にカルロス1世にちなんでシウダー・インペリアル(スペイン語で「帝都」の意)と呼ばれた[3]。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cob%C3%A1n +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++  ベラパス(旧テズルトラン)は、かつてのグアテマラ王国の第二級小国であり、ニュースペインの一部であった[n 1]。 地理 面積 テスルトランと後のベラパスの北方限界は、サンティアゴ・デ・グアテマラとメリダ・デ・ユカタンの競合する当局の間で激しい議論の対象となった[1]。特 に疑問視されたのは、現在のアルタ・ベラパス北部と東部、ベリーズ南部、イザバルとペテンの全域を構成する低地であった[1][n 2]。一方、疑いなく州の一部であると一般的に受け入れられたのは、現在のアルタ・ベラパス南西部とバハ・ベラパス全域を構成する高地であった[1]。 物理的 人間 16世紀初頭、テスルトランにはケクチ語族とポコムチ語族が住んでいたとされ、彼らの政治は「南は無人のチュアクス山脈とデ・ラス・ミナス山脈に挟まれ、 北はペテンのジャングルに挟まれていた」と伝えられている[2][3]。 2][n3]そのため、南西にキチェ・アチ州(カルチェラ川沿い、タクティックとツァラマの間)、北と東にチョレス、マンチェス、アカラエス、ラカンドネ ス諸民族と接していた。 [3]ケチ州は「南のポロチク川と北のカハボン川の間に広がる山脈」にあり、西はポコンチ州と接していた。この国境は現在のコバン(当時はケチ州の都市) とサンタ・クルス・ムンチュー(当時はポコンチ州の都市)の間にある。 [4]ケチ州の中心地は植民地時代の町カルチャ、チャメルコ、コバンの間であったと考えられている[2]。ポコンチ州は「ポロチック渓谷下流のチキソイ川 中流域からパンソスまでの西から東への狭い帯状地域」にあり、チャマからパンソスまで、ケチ州と南西のキチェ州の西と南の緩衝地帯を形成していた。 [5]西部のポコンチの中心地はおそらくサン・クリストバル・カグコー付近であり、東部はタクティック、タマフー、トゥクルー付近であった[6]。 歴史 スペインとの接触 フアン・ロドリゲス・カブリージョとサンチョ・デ・バラホナは、1528年半ばにテスルトランのケチ族の都市コバンに対する軍事作戦を指揮したと伝えられ ているが、詳細は不明である[7]。 [7]同様に、ディエゴ・デ・アルバラードは1530年か1531年にテスルトランでポコムチ族に対する軍事作戦を指揮したと考えられているが、同様に詳 細は混同されたままである[7]。この遠征隊は、隊長が「ペルーが鳴動したときにこの一角のことを忘れていた」ため年内に帰還したとも、部隊が「荒廃した [...]」ため1531年4月に帰還したとも伝えられている。 1543年、さらなる遠征または入城により、ヌエバ・セビージャがポロチック川沿いに建設され、60人のベシノを擁するまでに成長したが、ドミニコ会は入 植に抗議したため、1548年、アウディエンシアはヌエバ・セビージャの放棄を命じ、1549年に放棄が実現した[8]。 [8]その後、ヌニェス・デ・ランデチョが同様の試みを行い、1568年頃にイサバル湖にモングイア(Monguía)またはムングイア (Munguía)を設立したが、同様に失敗した[8]。1631年5月13日に旧マンシュ県にトロ・デ・アクーニャ(Toro de Acuña)を設立した当時のアルカルデ県長マルティン・アルフォンソ・トビージャの試みも挫折した[9][n 4]。 ドミニコ教会の進出 1537年5月2日、サンティアゴ・デ・グアテマラで、暫定州知事アロンソ・マルドナドと同教区の司教総督バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスによって、テスル トランのアシエントまたはカピチュラシオンが秘密裏に調印された[10][n 5]。このアシエントは、ドミニコ会がローマ・カトリックに改宗させた原住民インディオをアンコミエンダの対象としないことを王権に拘束するものであった [11]。 [11] これは1539年2月6日付のメキシコ総督アントニオ・デ・メンドーサとメキシコの監査院による勅書によって「一般的に遵守されることが宣言」され、 1540年10月17日付のマドリードによるスペイン王チャールズ1世の勅書によって「確認」された[12][n 6]。 ドミニコ会修道士は1544年にチャメルコとトゥクルに入域したと考えられている。1545年半ばには、「(地元住民から)すでに減少していた数少ないプ エブロがチャメルコとトゥクルの近くにあり、このことは、この地域が最も人口密度の高い地域であっただけでなく、クエッキとポコンチの当局の所在地であっ たことを裏付けている」[1]。 北方への拡大 ベラパスの北にあった先ヒスパニックの諸政体のうち、最初に接触したのは1590年代にカハボンを経由したマンチェ・チョル領であった[13][13] [n 7] 1606年までに6つのプエブロの住民が「発見され、洗礼を受けた」[13]。 一方、アロンソ・クリアド・デ・カスティーリャは1604年、旧トケグア領内のアマティーク湾にサント・トマス・デ・アキノ港を「発見し、開港させた」 [13][n 8]。それにもかかわらず、1633年までには、「一般的な反乱の煽りを受けて、9つのプエブロにまたがる6,000人以上の魂を信仰に復帰させたすべて のインディオを失った」[14][n 9]。 ドミニコ教会のレドゥクショオン(教区)は実を結ばず、17世紀半ばには、北方への「エントラーダ」を実施し、先住民インディオを捕らえ、スペインの支配 下に近い南方へ移住させることがより好都合であると考えられた[15]。 [1680年までに、ドミニコ教会はラカンドン族とマンチェ族から3,000人以上の人口減少者を出したと報告している[17][n 10]。 ベラパスが南の入口として機能したペテンの征服は1690年までに本格的に始まり、5、6年で完了した[17]。征服された土地とそのインディオのプエブロはサンティアゴ・デ・グアテマラの政治的管理とメリダ・デ・ユカタンの教会的監督下に置かれた[18]。 海賊の侵入 154xx年、ルター派の海賊が初めてアマティーク湾付近で目撃された。154xx年に設立された地元の寄港地ボデガス・デル・ゴルフォはxx年の支配下に置かれた。 統治 1548年から1555年にかけて、ベラパスはアルカルディア・マヨールとなり、州のプエブロ・デ・インディオを管轄した[19]。プエブロ・デ・イン ディオは、プリンシパル、つまり先住インディオのエリートたちの管轄であり、彼らは地元のカビルドや小教区のメンバーであった。 [20]さらに、ベラパスの場合、聖職者は時間的な問題において非常に大きな権限を持っていた[21]。 例えば、トマス・ゲイジは、地元のプリンシパルは「牧師の承認なしには何もしなかった」と述べている[21]。 遺産 「ベラパスの平和的征服」に関する印刷物での最古の記述は、アントニオ・デ・レメサル(Antonio de Remesal)の1619年の『Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala』に登場すると考えられている[22][n 11]。 ミチョアカンのバスコ・デ・キロガやベラパスのドミニコ兄弟たちの努力 は、期待された成果を得ることはなかった。恐らく、餓死と拉致の後、インディオが「精神的な窮地」に立たされた状況が、彼らの労働を促進したのだろう。し かし、このような理想郷と、このような理想郷の間には、まだまだ長い道のりがあった。 ミチョアカン州でのバスコ・デ・キロガの努力も、ベラパス州でのドミニ コ修道士の努力も、その目標があまりにも理想主義的であったためか、期待された結果をもたらさなかった。敗戦と征服の後、インディオたちが置かれた明白な 「心理的ショック」の状態が、修道士たちの活動を促進したのだろう。しかし、この事実と夢見たユートピアの間には、常に長い道のりがあった。 -J. 1994年の『グアテマラ一般史』(Historia General de Guatemala)におけるJ.ルハン・ムニョス(J. Luján Muñoz)[23]。 注釈と参考文献 脚注 1524年から1547年まで、ベラパスはナワトル語で「フクロウの土地」を意味するTezulutlán、Tuzulutlán、または Tecolotlán、またはスペイン語で「戦争の土地」を意味するTierra de Guerraとして知られていた(de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, pp.566, 580, Luján Muñoza 2005, p.693)。1547年からは、ベラ・パスとも呼ばれるようになった(de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, pp.580, 584-587)。 Luján Muñoz 2005a, p. 695は、「テスルトラン・ヴェラパスがゴルフォ・ドゥルセの低地とペテン南部の低地、さらにはペテン北部のユカタンまでの低地を含むかどうかは、ドミニ コ会、グアテマラ監査院、ユカタン当局の間で議論された問題であった」とコメントしている。ルハン・ムニョス2005b, p. 314はさらに、「ベラパスやチアパスと同様、ペテンでも[1697年以前]未征服の土地と開かれた国境の問題があった」と指摘し、これらを「未確定の境 界」と表現している。 しかし、デ・ラ・プエンテ・ブルンケ&ゲバラ・ギル2008年、5661頁には、1539年前半にベラパス内に「ラカンドン[...]の獰猛なインディオ」が含まれている。 アウディエンシアは、1631年5月11日付の自動車により、20人のインディオの定住を許可した(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 136)。トビージャとドミニコ会修道士フランシスコ・モランは、サンティアゴからベシノスと150人以上のインディオの民兵と召使を率いて、コバンから はカシケのフアン・デ・ラ・マンティージャ・オルテガが100人のインディオの民兵を率いて来た(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 136)。両者はマンチェ・チョール領のマンチェで会合した(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 136)。 先住民を擁護する挑発的な説教のためにレオンから追放されたドミニコ会修道士バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス、ロドリド・デ・ラドラーダ、ペドロ・デ・アン グロ、そしておそらくルイス・カンセルは、1536年7月中旬にサンティアゴ・デ・グアテマラに避難した(de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 584)。教区司教フランシスコ・マロキンは1537年1月、デ・ラス・カサスを司教総督に任命した(de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 584)。デ・ラス・カサスは、司教不在の間の暫定的なインディオの守護者であったため、1537年2月から3月にかけて、マルドナドがインディオの税金 を査定するためにインディオの居住地を訪問する際に同行した(de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 584-585)。 1540年10月17日、国王はさらにレアル・セドゥラ(reales cédulas)を発布し、ドミニコ会の許可を得ていない者のテズルトランへの入国を禁止し、グアテマラ、チアパ、ホンジュラスの総督に5年間の禁止令の 執行を命じた(de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 586)。1543年5月1日、バルセロナで盟約者団が設立された際、盟約者団はセドゥラによって更新された(de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 586)。デ・ラス・カサスのベラパス訪問は1545年6月中旬から7月中旬にかけてのみであった(de la Puente Brunke & Guevara Gil 2008, p. 588, Luján Muñoza 2005a, p. 695)。 アントニオ・デ・レメサル修道士は、ベラパス北部の先住民インディオの削減努力の開始を1594-1596年とした(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 137)。しかし、マンチェ・チョール領内のリオ・ドゥルセにあるサン・アンドレス・ポロチッチとサンタ・カタリーナ・ソコロは、1560年頃にドミニカ 人修道士ドミンゴ・デ・ヴィコによって削減された(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p.138)。 その湾の以前の港は、1549年に設立されたボデガス・デル・ゴルフォ(Bodegas del Golfo)であった(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 475)。1604年3月7日、水先案内人フランシスコ・ナバロがこの港の設立を働きかけ、1604年7月16日、強制移住させられたプエルト・カバロス の住民によって新しい港が建設された(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 475)。 1631年、トロ・デ・アクーニャは頓挫し、サン・アンドレス・ポロチッチとサンタ・カタリーナ・ソコロは「破壊」され、1632年、サン・ミゲル・デ ル・マンシェに設立されたばかりの司教座はカハボンに移された(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 138)。ルハン・ムニョス(J. Luján Muñoz)は、「様々な著者によれば、1631年頃にグアテマラ王国全体を荒廃させた疫病」(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p.138)が、レドゥッチオン活動の突然の崩壊の原因であった可能性を示唆している。 1677年、特に1678年3月から4月にかけて、ドミニカン・レドゥクシオンの町でチョラン語を話す人々が、表向きはアルカルデのセバスティアン・デ・ オリベラ市長に抗議して反乱を起こした(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 139)。これは、レドゥクシオンの町のひとつであるサン・ルーカスで発生した致命的な伝染病と重なり、400人のレドゥクシオン出身者が命を落とし、集 団脱走を促した(Luján Muñozb 2005, p. 139)。ドミニコ会は1681年、1684年、1685年にもレドゥクシオンを試みたが、効果はなかった。1688年、サン・ルーカスは再び反乱を起こ し、プエブロと教会堂を焼き払ったが、これは「彼らが棄教した5、6回目」の出来事であったと伝えられている(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 139)。この最新の反乱により、カハボンからの1689年の侵入が成功した(Luján Muñozb 2005, p. 139)。 そこには、「深刻な年代的誤りのある理想化された記述があり、それにもかかわらず、M. Bataillon、A. Saint-Lu、J. Rodríguez Cabalのような現代作家によって修正されるまで、広く受け入れられた」(Luján Muñoz 2005b, p. 73)。 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 1537年5月2日、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスとアロンソ・デ・マルドナードが、グアテマラ総督府と新スペイン総督府の間で、テスルトラン(後のグアテマラ・アルタベラパス)とラカンドン密林(メキシコ・チアパス)を平和的に征服するために締結した協定である。 背景 1530年から1531年にかけて、アロンソ・デ・アビラ大尉がシウダ・レアルからアカランに向かう途中、ラカン・トゥン・ラグーンと岩場を偶然発見し た。スペイン人に征服された人々と交易していたこの地域の住民は、ジャングルを避難場所として直接対決することを避けた。新スペインからはフアン・エンリ ケス・デ・グスマン、ユカタン半島からはフランシスコ・デ・モンテホ、グアテマラからはフランシスコ・ジル・サパタ大尉とペドロ・デ・アルバラード、チア パからはペドロ・ソロサノがラカンドン人征服を試みた1。 モポネス、ツェルタレス、チョレスは徐々に平和村に移され、そこで伝道された。モポネス、ツェルターレス、チョレスは徐々に平和村に移され、そこで伝道さ れた。当初は公然の対立を避けていたラカンドン人は態度を変え、ジャングルに近い町への襲撃を開始した。一方、テズルルタンでは、アチ族が征服行動に抵抗 したため、これらの領土は「戦争の地(Tierra de Guerra)」と呼ばれ、スペイン人征服者の軍事目標地となった2。 降伏 フレイ・バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスO.P.は、アデランタド・ペドロ・デ・アルバラドに代わって、メキシコ第二王室聴聞会のオイドール、リセンシア ド・アロンソ・デ・マルドナドと交渉を行い、説教者修道会の宣教師が行う縮小と伝道の方法によって、未征服地を平和的に征服することを決めた。 この協定は1537年5月2日に調印され、「ティエラ・デ・ゲラ 」は平和的手段によってのみ征服することができ、その住民は自発的にスペイン王家の家臣となることに同意しなければならなかった。インディオはいかなる理 由があってもエンコミエンダ制度に引き渡されることはなかった。最初の5年間は、総督と修道士を除いてスペイン人の立ち入りを禁止した。 縮小の進展と平定 関連項目: バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス 1539年7月6日、メキシコ総督ドン・アントニオ・デ・メンドーサは、トゥズルトランの原住民を征服した場合、エンコミエンダを与えず、王家の臣下とす ることを文書で約束した3。ラス・カサスは、ペドロ・デ・アングロやロドリゴ・デ・ラドラーダなどの他の修道士とともに、4人のキリスト教徒インディオを 探し出し、福音の基本的な事柄を説明するキリスト教の歌を教えた。その後、彼は従者を率いて、ハサミ、鈴、櫛、鏡、ガラスビーズのネックレスなど、小さな 贈り物をインディオに持参し、カチケに感銘を与え、カチケはキリスト教に改宗して家臣の伝道師になることを決意した。カチケはフアンという名の洗礼を受け た。原住民は教会を建てることに同意したが、コバンという別の酋長が教会を燃やしてしまった。フアンは、ラス・カサスとペドロ・デ・アングーロを伴い、 60人の部下を引き連れてコバンのインディオたちに話を聞きに行き、自分の善意を納得させた4。 ラス・カサス、ルイス・デ・カンセル師、ロドリゴ・デ・ラドラーダ師、ペドロ・デ・アングロ師(O.P.)が、この縮小と平和化のプロジェクトに参加し た。しかし、サカプラスのカチケに迎えられ、住民に最初の洗礼を施すことに成功したのはルイス・デ・カンセルであった。カシケの「ドン・ファン」は、率先 して娘の一人をコバンの町の校長と結婚させ、カトリックの宗教に従わせた5。 ラス・カサスとアングーロは、コバンを教義上の首長としてラビナルの町を設立した。ラス・カサスとアングーロは、コバンを教主とするラビナルの町を設立し た。2年間の努力の後、インディオがよりアクセスしやすい土地に移動し、スペイン式に町が設立されたため、減封制度は比較的成功し始めた。Tierra de Guerra(戦争の地)」という名称は、1547年に正式名称となった「Vera Paz(真の平和)」に取って代わられた1。 盟約違反 ドミニコ会の相対的な成功と熱意は時期尚早であった。1539年、アロンソ・デ・マルドナドはスペインの植民者たちから圧力を受け、あるいは個人的な利益 から、テスルトランでキャンペーンを開始し、インディオたちをエンコミエンダ制度で分配した。この明白な盟約違反にラス・カサスは抗議し、イベリア半島に 渡ってスペイン国王シャルル1世に事実を糾弾することにした。 1540年1月9日、テスルトランの盟約を批准する勅令が出され、サント・ドミンゴ騎士団にベラパス領の保護が与えられた。同年10月17日、インド評議 会の議長であったガルシア・デ・ロアイサ枢機卿は、メキシコの監査院と大法院に同じ規定を遵守するよう命じた。1541年1月21日、テスルトラン盟約の 勅許批准書は、公証人と町の使者の前でセビリア教会で公表された6。 一方、1539年以来、教皇パウロ3世は、チアパス、ソコヌスコ、ベラ・パス(ラカンドン密林を含む)、タバスコ、そしてまだ征服されていないユカタン半 島を含むシウダ・レアル司教座の創設をすでに承認していた。しかし、ラス・カサスが司教に任命されたのは1544年のことであった。ラス・カサスは、教区 で施行しようとした新法令を公然と拒否したため、ラス・カサスは教区民の反対と戦わなければならなかったからである1。 1545年、グアテマラの司教フランシスコ・マロキンがトゥズルトランを訪れ、ドミニコ会の神父たちと会談した。グラシアス・ア・ディオスの町に戻り、盟 約者団の所在地で、新しく任命された司教ラス・カサスとニカラグアの司教アントニオ・デ・バルディビエソと会談した。ラス・カサスの目的は、新法遵守への 関心を伝えることだった。しかし、ラス・カサスとマロキンの間には大きな意見の相違があり、前者はラス・カサスが奴隷やレパルティミエントのインディオを 持ち、「有害な教義」を説いていると非難した。マロキンは、ラス・カサスが自分の管轄権の限度を超えていると非難した。 両宗教の目的は同じであったが、方法は異なっていた。対立はメキシコシティで続き、結論はインディオの自由を支持することであった。ラカンドン密林の平和化は結論が出ず、何世紀にもわたって反抗的なマヤの避難場所となった7。 |

Independence and German settlers As

of 1850, Cobán population was estimated to be at 12000.[11] Ca. 1890,

British archeologist Alfred Percival Maudslay and his wife moved to

Guatemala, and visited Cobán.[12] Around the time the Maudslays visited

Verapaz, a German colony had settled in the area thanks to generous

concessions granted by liberal presidents Manuel Lisandro Barillas

Bercián, José María Reyna Barrios and Manuel Estrada Cabrera.[13] The

Germans had a very united and solid community and had several

activities in the German Club (Deutsche Verein), in Cobán, which they

had founded in 1888. Their main commercial activity was coffee

plantations. Maudslay described the Germans like this: "There is a

larger proportion of foreigners in Coban than in any other town in the

Republic: they are almost exclusively Germans engaged in

coffee-planting, and some few of them in cattle-ranching and other

industries; although complaints of isolation and of housekeeping and

labour troubles are not unheard of amongst them, they seemed to me to

be fortunate from a business point of view in the high reputation that

the Vera Paz coffee holds in the As

of 1850, Cobán population was estimated to be at 12000.[11] Ca. 1890,

British archeologist Alfred Percival Maudslay and his wife moved to

Guatemala, and visited Cobán.[12] Around the time the Maudslays visited

Verapaz, a German colony had settled in the area thanks to generous

concessions granted by liberal presidents Manuel Lisandro Barillas

Bercián, José María Reyna Barrios and Manuel Estrada Cabrera.[13] The

Germans had a very united and solid community and had several

activities in the German Club (Deutsche Verein), in Cobán, which they

had founded in 1888. Their main commercial activity was coffee

plantations. Maudslay described the Germans like this: "There is a

larger proportion of foreigners in Coban than in any other town in the

Republic: they are almost exclusively Germans engaged in

coffee-planting, and some few of them in cattle-ranching and other

industries; although complaints of isolation and of housekeeping and

labour troubles are not unheard of amongst them, they seemed to me to

be fortunate from a business point of view in the high reputation that

the Vera Paz coffee holds in the  market,

and the very considerable commercial importance which their industry

and foresight has brought to the district; and, from a personal point

of view, in the enjoyment of a delicious climate in which their

rosy-cheeked children can be reared in health and strength, and in all

the comforts which pertain to a life half European and half tropical.

Hotels or fondas appear to be scarce; but the hospitality of the

foreign residents is proverbial."[14] market,

and the very considerable commercial importance which their industry

and foresight has brought to the district; and, from a personal point

of view, in the enjoyment of a delicious climate in which their

rosy-cheeked children can be reared in health and strength, and in all

the comforts which pertain to a life half European and half tropical.

Hotels or fondas appear to be scarce; but the hospitality of the

foreign residents is proverbial."[14]The city was developed by German coffee growers towards the end of the 19th century and was operated as a largely independent dominion until WWII.[16] In 1888 a German club was founded[17] and in 1935 a German school opened its doors in Cobán. Until 1930, about 2000 Germans populated the city.[17] In 1941, all Germans were expelled by the Guatemalan government, led at the time by Jorge Ubico because of pressure from the United States;[18] it has also been  suggested

Ubico's motivation was to seize control of the vast amounts of land

Germans owned in the area.[18] Many ended up in internment camps in

Texas and were later traded for American POW's held in Germany. A

sizable resident German population persists though most having been

completely assimilated into the Guatemalan culture through

intermarriage. Multiple German architectonic elements can still be

appreciated throughout Cobán. suggested

Ubico's motivation was to seize control of the vast amounts of land

Germans owned in the area.[18] Many ended up in internment camps in

Texas and were later traded for American POW's held in Germany. A

sizable resident German population persists though most having been

completely assimilated into the Guatemalan culture through

intermarriage. Multiple German architectonic elements can still be

appreciated throughout Cobán.The Germans also set up Ferrocarril Verapaz, a railway which connected Cobán with Lake Izabal, operated from 1895 until 1963 and was a symbol for the wealth in this coffee-growing region those days.[16] |

独立とドイツ人入植者 1850

年の時点で、コバンの人口は12000人と推定されていた[11]。1890年頃、イギリスの考古学者アルフレッド・パーシヴァル・モードスレイとその妻

がグアテマラに移住し、コバンを訪れた[12]。モードスレイ夫妻がベラパスを訪れた頃、自由主義派の大統領マヌエル・リサンドロ・バリジャス・ベルシア

ン、ホセ・マリア・レイナ・バリオス、マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラが寛大な利権を与えたおかげで、ドイツ人コロニーがこの地域に定住していた。

[13]ドイツ人は非常に団結した強固なコミュニティを持っており、1888年に設立されたコバンのドイツ・クラブ(Deutsche

Verein)でいくつかの活動を行っていた。彼らの主な商業活動はコーヒー農園であった。モードスレイはドイツ人をこう評した:

「コバンには、共和国のどの町よりも外国人の割合が多い:

彼らはほとんどコーヒー農園に従事するドイツ人ばかりで、牧畜業やその他の産業に従事するドイツ人は少数である。彼らの間では、孤立感や家事・労 1850

年の時点で、コバンの人口は12000人と推定されていた[11]。1890年頃、イギリスの考古学者アルフレッド・パーシヴァル・モードスレイとその妻

がグアテマラに移住し、コバンを訪れた[12]。モードスレイ夫妻がベラパスを訪れた頃、自由主義派の大統領マヌエル・リサンドロ・バリジャス・ベルシア

ン、ホセ・マリア・レイナ・バリオス、マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラが寛大な利権を与えたおかげで、ドイツ人コロニーがこの地域に定住していた。

[13]ドイツ人は非常に団結した強固なコミュニティを持っており、1888年に設立されたコバンのドイツ・クラブ(Deutsche

Verein)でいくつかの活動を行っていた。彼らの主な商業活動はコーヒー農園であった。モードスレイはドイツ人をこう評した:

「コバンには、共和国のどの町よりも外国人の割合が多い:

彼らはほとんどコーヒー農園に従事するドイツ人ばかりで、牧畜業やその他の産業に従事するドイツ人は少数である。彼らの間では、孤立感や家事・労 働

上のトラブルに対する不満が聞かれないわけではないが、ヴェラパス・コーヒーが市場で高い評価を得ていることや、彼らの産業と先見性がこの地域にもたらし

た非常に大きな商業的重要性という点で、ビジネスの観点からは幸運であるように私には思われた;

また、個人的な観点からは、バラ色の頬をした子供たちが健康でたくましく育ち、ヨーロッパと熱帯の半々の生活に必要なあらゆる快適さを享受できる、おいし

い気候を享受できるという点である。ホテルやフォンダは少ないようだが、外国人居住者のもてなしは格別である」[14]。 働

上のトラブルに対する不満が聞かれないわけではないが、ヴェラパス・コーヒーが市場で高い評価を得ていることや、彼らの産業と先見性がこの地域にもたらし

た非常に大きな商業的重要性という点で、ビジネスの観点からは幸運であるように私には思われた;

また、個人的な観点からは、バラ色の頬をした子供たちが健康でたくましく育ち、ヨーロッパと熱帯の半々の生活に必要なあらゆる快適さを享受できる、おいし

い気候を享受できるという点である。ホテルやフォンダは少ないようだが、外国人居住者のもてなしは格別である」[14]。1888年にはドイツ人クラブが設立され[17]、1935年にはコバンにドイツ人学校が開校した。1930年までは約2000人のドイツ人が居住していた[17]。1941年、当時ホルヘ・ユビコが率いていたグアテマラ政府によって、  ア

メリカからの圧力によりすべてのドイツ人が追放された[18]。ユビコの動機は、この地域にドイツ人が所有していた膨大な土地の支配権を奪うことであった

とも言われている[18]。多くのドイツ人はテキサスの収容所に収容され、後にドイツに収容されていたアメリカ人捕虜と交換された。現在もかなりの数のド

イツ系住民が居住しているが、そのほとんどは結婚によってグアテマラ文化に完全に同化している。コバンの至る所に、ドイツ建築の要素が残っている。 ア

メリカからの圧力によりすべてのドイツ人が追放された[18]。ユビコの動機は、この地域にドイツ人が所有していた膨大な土地の支配権を奪うことであった

とも言われている[18]。多くのドイツ人はテキサスの収容所に収容され、後にドイツに収容されていたアメリカ人捕虜と交換された。現在もかなりの数のド

イツ系住民が居住しているが、そのほとんどは結婚によってグアテマラ文化に完全に同化している。コバンの至る所に、ドイツ建築の要素が残っている。ドイツ人はまた、コバンとイザバル湖を結ぶ鉄道Ferrocarril Verapazを敷設し、1895年から1963年まで運行され、当時のこのコーヒー産地の富の象徴となった[16]。 |

| Franja Transversal del Norte Main article: Franja Transversal del Norte Cobán is located in GuatemalaCobánCobán  Location of Cobán in Franja Transversal del Norte The Northern Transverse Strip was officially created during the government of General Carlos Arana Osorio in 1970, by Legislative Decree 60-70, for agricultural development.[19] The decree literally said: "It is of public interest and national emergency, the establishment of Agrarian Development Zones in the area included within the municipalities: San Ana Huista, San Antonio Huista, Nentón, Jacaltenango, San Mateo Ixtatán, and Santa Cruz Barillas in Huehuetenango; Chajul and San Miguel Uspantán in Quiché; Cobán, Chisec, San Pedro Carchá, Lanquín, Senahú, Cahabón and Chahal, in Alta Verapaz and the entire department of Izabal."[20] 21st century: African oil palm See also: Elaeis guineensis  African oil palm plantation areas in Guatemala as of 2014.[21] There is a large demand within Guatemala and some of its neighbors for edible oils and fats, which would explain how the African oil palm became so prevalent in the country in detriment of other oils, and which has allowed new companies associated to large capitals in a new investment phase that can be found particularly in some territories that form the Northern Transversal Strip of Guatemala.[22] The investors are trying to turn Guatemala into one of the main palm oil exporters, in spite of the decline on its international price. The most active region is found in Chisec and Cobán, in Alta Verapaz Department; Ixcán in Quiché Department, and Sayaxché, Petén Department, where Palmas del Ixcán, S.A. (PALIX) is located, both with its own plantation and those of subcontractors. Another active region is that of Fray Bartolomé de las Casas and Chahal in Alta Verapaz Department; El Estor and Livingston, Izabal Department; and San Luis, Petén, where Naturaceites operates.[22] |

ノルテ横断鉄道 主な記事 フランハ・トランスバーサル・デル・ノルテ コバンはグアテマラコバンに位置する。  フランハ・トランスバーサル・デル・ノルテのコバンの位置 北部横断帯は1970年、カルロス・アラナ・オソリオ将軍の政権時代に、農業開発のために立法令60-70号によって正式に作られた[19]: 「公共利益と国家緊急事態のため、市町村に含まれる地域に農業開発地帯を設置する: フエウエテナンゴのサン・アナ・ウイスタ、サン・アントニオ・ウイスタ、ネントン、ハカルテナンゴ、サン・マテオ・イスタタン、サンタ・クルス・バリジャ ス、キチェのチャジュルとサン・ミゲル・ウスパンタン、アルタ・ベラパスのコバン、チセック、サン・ペドロ・カルチャ、ランキン、セナフー、カハボン、 チャハル、イザバル県全域。 21世紀 アフリカアブラヤシ こちらも参照: エラエス・ギネンシス  2014年現在のグアテマラのアフリカアブラヤシ農園面積[21]。 グアテマラとその近隣諸国では食用油脂の需要が大きいため、アフリカアブラヤシが他の油脂を差し置いてグアテマラで普及した理由となり、特にグアテマラ北 部横断帯を形成するいくつかの地域で見られる新たな投資段階において、大資本に関連する新たな企業の参入を許している[22]。最も活発な地域は、アル タ・ベラパス県のチセックとコバン、キチェ県のイクスカン、ペテン県のサヤクスチェで、パルマス・デル・イクスカン社(PALIX)が自社農園と下請け農 園を所有している。また、アルタ・ベラパス県のフレイ・バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスとチャハル、イザバル県のエル・エストルとリビングストン、ペテン県 のサン・ルイスも、ナチュラセイト社が操業している活動的な地域である[22]。 |

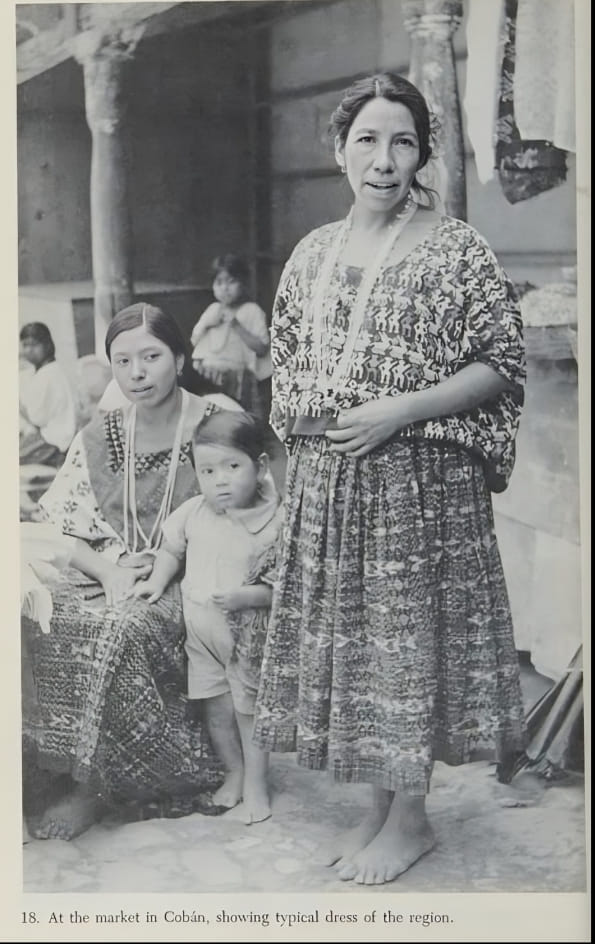

| Each

year at the end of July, a festival of Guatemala's native peoples is

held here, La Fiesta Nacional Indígena de Guatemala (Festival

Folklórico). The festivities include a beauty contest for Guatemala's

Native American women, the winner of which is crowned with the title

"Rabin Ahau", which means "the Daughter of the King" in Q'eqchi'. The

dominant ethnicity here is Q'eqchi' Mayan and the language of Q'eqchi'

is widely spoken in town, especially in and around the markets where

farmers from the surrounding hills sell their products. The

departmental fair is held in Cobán and begins on the last Sunday in

July and continues for a week. Every year, the international

half-marathon of Cobán is held during the month of May; 4,000 runners

gather in Cobán to take part of the event that has become the landmark

event for the region. The annual religious festival (fiesta titular) is

on August 4 and dedicated to Santo Domingo de Guzman. Sports Cobán Imperial Football Club is one of the traditional clubs of Guatemala and became Guatemala League champions for the first time in 2004. The club plays in the Guatemalan national league. They play their home games in the Estadio Verapaz. Cobán is also known for their basketball history. The youth leagues are the best in the country. Tourism See also: Cobán Airport Central Park in Cobán. Cobán is surrounded by mountains laden with orchids. The rare Monja blanca orchid is the departmental symbol. Nature reserves in or near Cobán include Las Victorias National Park, San José la Colonia National Park, Laguna Lachuá National Park, and Biotopo Mario Dary Rivera. There can be found multiple caves, waterfalls and forests which are home to the rare Quetzal. Thus, Cobán has become a popular spot for eco-tourism. Additional popular tourist spots in the city of Cobán include the El Calvario Church, the Dieseldorff coffee plantation, Plaza Magdalena Shopping Center and Coban's central plaza. |

毎

年7月末には、グアテマラ先住民の祭典「グアテマラ先住民祭り(La Fiesta Nacional Indígena de

Guatemala)」が開催される。このお祭りでは、グアテマラ先住民の女性たちの美人コンテストが行われ、優勝者には、ケクチ語で「王の娘」を意味す

る「ラビン・アハウ」という称号が与えられる。ここの支配的な民族はケクチ・マヤ人であり、ケクチ語は町中、特に周辺の丘陵地帯の農家が生産物を販売する

市場やその周辺で広く話されている。コバンでは、7月の最終日曜日から1週間にわたり、デパートメント・フェアが開催される。毎年5月には、コバンの国際

ハーフマラソン大会が開催され、4,000人のランナーがコバンに集まり、この地域のランドマーク的なイベントとなっている。毎年8月4日には、サント・

ドミンゴ・デ・グスマンに捧げる宗教祭(フィエスタ・ティトゥラル)が行われる。 スポーツ コバン・インペリアル・フットボール・クラブは、グアテマラの伝統的なクラブのひとつで、2004年に初めてグアテマラ・リーグのチャンピオンになった。 グアテマラ国内リーグでプレーしている。ホームゲームはエスタディオ・ベラパスで行われる。コバンはバスケットボールの歴史でも知られている。ユースリー グは国内最高峰である。 観光 こちらも参照: コバン空港 コバンの中央公園。 コバンは、ランが咲き乱れる山々に囲まれている。珍しいモンハ・ブランカ(Monja blanca)というランは、県のシンボルとなっている。コバン近郊の自然保護区には、ラス・ビクトリアス国立公園、サン・ホセ・ラ・コロニア国立公園、 ラグーナ・ラチュア国立公園、ビオトポ・マリオ・ダリ・リベラなどがある。珍しいケツァールが生息する洞窟、滝、森もある。このように、コバンはエコツー リズムの人気スポットとなっている。 コバン市のその他の人気観光スポットには、エル・カルバリオ教会、ディーセルドルフ・コーヒー農園、プラザ・マグダレーナ・ショッピングセンター、コバンの中央広場などがある。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cob%C3%A1n |

|

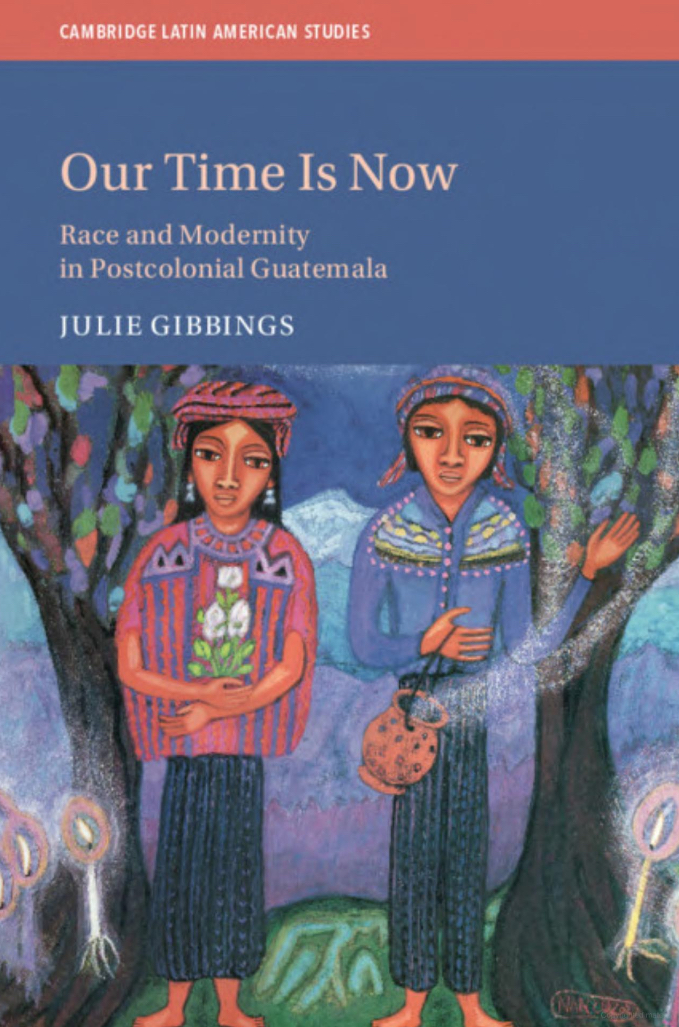

| Our time is now : race and modernity in postcolonial Guatemala / Julie Gibbings, Cambridge University Press , 2020 . - (Cambridge Latin American studies, 120) Postcolonial histories have long emphasized the darker side of narratives of historical progress, especially their role in underwriting global and racial hierarchies. Concepts like primitiveness, backwardness, and underdevelopment not only racialized and gendered peoples and regions, but also ranked them on a seemingly naturalized timeline - their 'present' is our 'past' - and reframed the politics of capitalist expansion and colonization as an orderly, natural process of evolution towards modernity. Our Time is Now reveals that modernity particularly appealed to those excluded from power, precisely because of its aspirational and future orientation. In the process, marginalized peoples creatively imagined diverse political futures that redefined the racialized and temporal terms of modernity. Employing a critical reading of a wide variety of previously untapped sources, Julie Gibbings demonstrates how the struggle between indigenous people and settlers to manage contested ideas of time and history as well as practices of modern politics, economics, and social norms were central to the rise of coffee capitalism in Guatemala and to twentieth century populist dictatorship and revolution. Introduction: History Will Write Our Names I. Translating Modernities: 1. To Live without King or Castle: Maya Patriarchal Liberalism on the Eve of a New Era, 1860-1871 2. Possessing Sentiments and Ideas of Progress: Coffee Planting, Land Privatization, and Liberal Reform, 1871-1885 3. Indolence is the Death of Character: The Making of Race and Labor, 1885-1898 4. El Q'eq Roams at Night: Plantation Sovereignty and Racial Capitalism, 1898-1914 II. Aspirations and Anxieties of Unfulfilled Modernities: 5. On the Throne of Minerva: The Making of Urban Modernities, 1908-1920 6. Freedom of the Indian: Maya Rights and Citizenship in a Democratic Experiment, 1920-1932 7. Possessing Tezulutlan: Splitting Time in Dictatorship, 1931-1939 8. Now Owners of Our Land: Nationalism, History, and Memory in Revolution, 1939-1954.  |

Our time is now : race and modernity in postcolonial Guatemala / Julie Gibbings, Cambridge University Press , 2020 . - (Cambridge Latin American studies, 120) ポストコロニアル史は長い間、歴史的進歩の物語が持つ暗黒面、とりわけグローバルな、そして人種的なヒエラルキーを支える役割を強調してきた。原始性、後 進性、低開発といった概念は、民族や地域を人種的、ジェンダー的に位置づけるだけでなく、彼らの「現在」は我々の「過去」であるといった、一見自然化され た時間軸の上に彼らを位置づけ、資本主義の拡大と植民地化の政治を、近代化に向けた秩序ある自然な進化の過程として再構築した。『われらの時は今』は、近 代が権力から排除された人々にとって特に魅力的であったことを明らかにしている。その過程で周縁化された人々は、モダニティの人種的・時間的条件を再定義 する多様な政治的未来を創造的に想像した。ジュリー・ギビングスは、これまで未開拓であったさまざまな資料を批判的に読み解きながら、先住民族と入植者と の間で争われた時間や歴史に関する観念や、近代的な政治、経済、社会規範の実践を管理するための闘争が、グアテマラにおけるコーヒー資本主義の台頭や、 20世紀のポピュリストによる独裁と革命にとっていかに中心的であったかを明らかにする。 はじめに 歴史が私たちの名前を記す I. 近代を翻訳する 1. 王も城もなく生きる: 新時代前夜のマヤの家父長制的自由主義、1860-1871年 2. 進歩の感情と思想を持つ: コーヒー栽培、土地民営化、自由主義改革、1871-1885年 3. 怠惰は人格の死である: 人種と労働の形成、1885-1898年 4. El Q'eq Roams at Night: プランテーションの主権と人種資本主義、1898-1914年 II. 満たされない近代の願望と不安 5. ミネルヴァの玉座の上で: 都市モダニティの形成、1908-1920年 6. インディアンの自由 民主的実験におけるマヤの権利と市民権、1920-1932年 7. テズルトランの所有 独裁政治における時間の分裂、1931-1939年 8. 今やわれわれの土地の所有者である: 革命における国民主義、歴史、記憶、1939-1954年。  |

Finca seb' saakuit, 1920 Municipio de Senahú Alta Verapaz Finca Sepacuité. |

|

Links

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆