バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス

Bartolomé de las Casas, 1484-1566

ラ ス・カサスの肖像画。セビーリャ、コロンブス図書館蔵

☆ バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス(Bartolomé de las Casas OP, US: /lɑːˈ lahss KAH-səss; スペイン語: [1484年11月11日[1] - 1566年7月18日)スペインの聖職者、作家、活動家。信徒としてイスパニョーラに到着し、ドミニコ会修道士となった。チアパスの最初の司教に任命さ れ、公式に任命された最初の「インディオの保護者」となった。西インド諸島の植民地化の最初の数十年間を記した『インディオの破壊に関する短い記述』(A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies)と『ラス・インディアスの歴史』(Historia de Las Indias)が最も有名である。彼は植民者が先住民に対して行った残虐行為を記述した。

★バ ルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス(Bartolomé de las Casas, 1484-1566)について知ろう、8項目:

| Bartolomé

de las Casas, OP (US: /lɑːs ˈkɑːsəs/ lahss KAH-səss; Spanish:

[baɾtoloˈme ðe las ˈkasas] ⓘ; 11 November 1484[1] – 18 July 1566) was a

Spanish clergyman, writer, and activist best known for his work as a

historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman,

then became a Dominican friar. He was appointed as the first resident

Bishop of Chiapas, and the first officially appointed "Protector of the

Indians". His extensive writings, the most famous being A Short Account

of the Destruction of the Indies and Historia de Las Indias, chronicle

the first decades of colonization of the West Indies. He described the

atrocities committed by the colonizers against the indigenous

peoples.[2] Arriving as one of the first Spanish settlers in the Americas, Las Casas initially participated in, but eventually felt compelled to oppose the abuses committed by European colonists against the indigenous peoples of the Americas.[3] As a result, in 1515 he gave up his Native American slaves and encomienda, and advocated, before Charles V, on behalf of rights for the natives. In his early writings, he advocated the use of African and white slaves instead of Natives in the West Indian colonies but did so without knowing that the Portuguese were carrying out "brutal and unjust wars in the name of spreading the faith".[4] Later in life, he retracted this position, as he regarded both forms of slavery as equally wrong.[5] In 1522, he tried to launch a new kind of peaceful colonialism on the coast of Venezuela, but this venture failed. Las Casas entered the Dominican Order and became a friar, leaving public life for a decade. He traveled to Central America, acting as a missionary among the Maya of Guatemala and participating in debates among colonial churchmen about how best to bring the natives to the Christian faith. Travelling back to Spain to recruit more missionaries, he continued lobbying for the abolition of the encomienda, gaining an important victory by the passage of the New Laws in 1542. He was appointed Bishop of Chiapas, but served only for a short time before he was forced to return to Spain because of resistance to the New Laws by the encomenderos, and conflicts with Spanish settlers because of his pro-Indian policies and activist religious stance. He served in the Spanish court for the remainder of his life; there he held great influence over Indies-related issues. In 1550, he participated in the Valladolid debate, in which Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda argued that the Indians were less than human, and required Spanish masters to become civilized. Las Casas maintained that they were fully human, and that forcefully subjugating them was unjustifiable. Bartolomé de las Casas spent 50 years of his life actively fighting slavery and the colonial abuse of indigenous peoples, especially by trying to convince the Spanish court to adopt a more humane policy of colonization. Unlike some other priests who sought to destroy the indigenous peoples' native books and writings, he strictly opposed this action.[6] Although he did not completely succeed in changing Spanish views on colonization, his efforts did result in improvement of the legal status of the natives, and in an increased colonial focus on the ethics of colonialism. |

バ

ルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス(Bartolomé de las Casas, OP, US: /lɑːˈ lahss KAH-səss;

スペイン語: [1484年11月11日[1] -

1566年7月18日)スペインの聖職者、作家、活動家。信徒としてイスパニョーラに到着し、ドミニコ会修道士となった。チアパスの最初の司教に任命さ

れ、公式に任命された最初の「インディオの保護者」となった。西インド諸島の植民地化の最初の数十年間を記した『インディオの破壊に関する短い記述』(A

Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies)と『ラス・インディアスの歴史』(Historia

de Las Indias)が最も有名である。彼は植民者が先住民に対して行った残虐行為を記述した[2]。 アメリカ大陸の最初のスペイン人入植者の一人としてやってきたラス・カサスは、当初はアメリカ大陸の先住民に対するヨーロッパ人入植者の虐待に加担してい たが、やがてそれに反対せざるを得なくなった。1522年、ラス・カサスはベネズエラの海岸で新しい平和的植民地主義を始めようとしたが、これは失敗に終 わった。ラス・カサスはドミニコ会に入り、修道士となった。中米に渡り、グアテマラのマヤ族の宣教師として活動し、原住民をキリスト教に入信させる最善の 方法について、植民地の教会関係者の議論に参加した。 宣教師を増やすためにスペインに戻り、エンコミエンダ廃止のためのロビー活動を続け、1542年に新法を成立させて重要な勝利を得た。チアパス司教に任命 されるも、わずかな期間しか務めることができず、その後スペインに戻ることを余儀なくされた。その理由は、エンコメンデロスの新法に対する抵抗と、彼の親 インディアン政策と宗教活動家としての姿勢によるスペイン人入植者との対立にあった。その後、彼は生涯スペインの宮廷に仕え、そこでインディアン関連の問 題に大きな影響力を持った。1550年、ラス・カサスはバリャドリッドで行われた討論会に参加した。この討論会では、フアン・ジネス・デ・セプルベダが、 インディアンは人間以下であり、文明化するためにはスペインの主人が必要だと主張した。ラス・カサスは、インディオは完全に人間であり、彼らを強制的に服 従させることは正当化できないと主張した。 バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、特にスペイン宮廷に、より人道的な植民地化政策を採用するよう説得することで、奴隷制度と先住民の植民地的虐待と積極的 に闘う50年の生涯を送った。カサスは、先住民の土着の書物や著作を破壊しようとした他の司祭たちとは異なり、この行為に厳しく反対した[6]。植民地化 に対するスペインの見解を変えることに完全に成功したわけではなかったが、彼の努力は先住民の法的地位の向上と、植民地主義の倫理に対する植民地側の関心 の高まりという結果をもたらした。 |

| Life and time Background and arrival in the New World  Depiction of Spanish atrocities committed in the conquest of Cuba in Las Casas's "Brevisima relación de la destrucción de las Indias". The print was made by two Flemish artists who had fled the Southern Netherlands because of their Protestant faith: Joos van Winghe was the designer and Theodor de Bry the engraver. Bartolomé de las Casas was born in Seville in 1484, on 11 November.[7] For centuries, Las Casas's birthdate was believed to be 1474; however, in the 1970s, scholars conducting archival work demonstrated this to be an error, after uncovering in the Archivo General de Indias records of a contemporary lawsuit that demonstrated he was born a decade later than had been supposed.[8] Subsequent biographers and authors have generally accepted and reflected this revision.[9] His father, Pedro de las Casas, a merchant, descended from one of the families that had migrated from France to found the Christian Seville; his family also spelled the name Casaus.[10] According to one biographer, his family was of converso heritage,[11] although others refer to them as ancient Christians who migrated from France.[10] Following the testimony of Las Casas's biographer Antonio de Remesal, tradition has it that Las Casas studied a licentiate at Salamanca, but this is never mentioned in Las Casas's own writings.[12] Las Casas' first encounter with Indigenous peoples happened before he even sailed to the Americas. In his Historia general de las Indias, he wrote of Christopher Columbus' return to Seville, in 1493.[13] Las Casas recorded having seen "seven Indians" in the entourage of Christopher Columbus, being exhibited in the vicinity of the Iglesia de San Nicolás de Bari, along with "beautiful green parrots, vibrant in color" and Indigenous artifacts.[14] Pedro de Las Casas, Bartolomé's merchant father, left in Christopher Columbus' second expedition. Upon his return, in 1499, Pedro de Las Casas brought to his son "a young Amerinidian."[15] Three years later, in 1502, Las Casas immigrated with his father to the island of Hispaniola, on the expedition of Nicolás de Ovando. Las Casas became a hacendado and slave owner, receiving a piece of land in the province of Cibao.[16] He participated in slave raids and military expeditions against the native Taíno population of Hispaniola.[17] In 1506, he returned to Spain and completed his studies of canon law at Salamanca. That same year, he was ordained a deacon and then traveled to Rome, where he was ordained a secular priest in 1507.[18] In September 1510, a group of Dominican friars arrived in Santo Domingo led by Pedro de Córdoba; appalled by the injustices they saw committed by the slaveowners against the Indians, they decided to deny slave owners the right to confession. Las Casas was among those denied confession for this reason.[19] In December 1511, a Dominican preacher Fray Antonio de Montesinos preached a fiery sermon that implicated the colonists in the genocide of the native peoples. He is said to have preached: "Tell me by what right of justice do you hold these Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? On what authority have you waged such detestable wars against these people who dealt quietly and peacefully on their own lands? Wars in which you have destroyed such an infinite number of them by homicides and slaughters never heard of before. Why do you keep them so oppressed and exhausted, without giving them enough to eat or curing them of the sicknesses they incur from the excessive labor you give them, and they die, or rather you kill them, in order to extract and acquire gold every day."[20] Las Casas himself argued against the Dominicans in favor of the justice of the encomienda. The colonists, led by Diego Columbus, dispatched a complaint against the Dominicans to the King, and the Dominicans were recalled from Hispaniola.[21][22] |

生涯と時間 背景と新大陸への到着  ラス・カサスの『インディアスの破壊に関する簡潔な報告』に描かれた、キューバ征服におけるスペインの残虐行為。この版画は、プロテスタント信仰のために 南オランダを逃れてきた2人のフランドル人芸術家によって制作された: ヨース・ファン・ヴィンゲがデザイナー、テオドール・デ・ブライが版画家である。 バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは1484年11月11日にセビリアで生まれた[7]。何世紀もの間、ラス・カサスの生年月日は1474年であると信じられ ていたが、1970年代に、インディアス公文書館(Archivo General de Indias)で、彼がそれまで考えられていたよりも10年遅く生まれたことを証明する同時代の訴訟の記録を発見した学者たちによって、これが誤りである ことが証明された[8]。 [9] 彼の父であるペドロ・デ・ラス・カサスは商人であり、フランスから移住してキリスト教国セビリアを建国した一族の末裔であった。 [10]ラス・カサスの伝記作者アントニオ・デ・レメサルの証言によれば、ラス・カサスはサラマンカで修士号を取得したという伝承があるが、このことはラ ス・カサス自身の著作では言及されていない[12]。 ラス・カサスと先住民との最初の出会いは、彼がアメリカ大陸に航海する前に起こった。ラス・カサスは、『インディアスの歴史』(Historia general de las Indias)の中で、1493年にクリストファー・コロンブスがセビリアに帰還したときのことを書いている[13]。ラス・カサスは、クリストファー・ コロンブスの側近の「7人のインディオ」が、「色鮮やかな美しい緑色のオウム」や先住民の工芸品とともに、サン・ニコラス・デ・バリ教会(Iglesia de San Nicolás de Bari)の近辺に展示されているのを見たことを記録している[14]。バルトロメの商人の父ペドロ・デ・ラス・カサスは、クリストファー・コロンブスの 第2次遠征に出発した。帰国後の1499年、ペドロ・デ・ラス・カサスは息子のもとに「若いアメリニジア人」を連れてきた[15]。 その3年後の1502年、ラス・カサスはニコラス・デ・オバンドの遠征に同行し、父親とともにイスパニョーラ島に移住した。1506年、スペインに戻り、 サラマンカでカノン法を学ぶ。同年、助祭に叙階され、その後ローマに渡り、1507年に世俗司祭に叙階された[18]。 1510年9月、ペドロ・デ・コルドバ率いるドミニコ会修道士の一団がサント・ドミンゴに到着し、奴隷所有者がインディオに対して行った不正に愕然とした 彼らは、奴隷所有者が告解を受ける権利を拒否することを決定した。1511年12月、ドミニコ会の説教師フレイ・アントニオ・デ・モンテシーノスは、先住 民の大量虐殺に植民者たちを関与させる激しい説教を行った。彼はこう説いたと言われている: 「このような残酷でおぞましい隷属に、インディオたちを拘束しているのは、どのような正義に基づいているのか。自分たちの土地で静かに平和に暮らしていた インディアンに対して、あなた方はどのような権限に基づいてこのような憎むべき戦争を仕掛けたのか。その戦争では、かつて聞いたこともないような殺人や虐 殺によって、これほど多くのインディアンを滅ぼした。なぜあなたは、彼らに十分な食事も与えず、過重な労働を強いることで生じる病気を治すこともせず、毎 日黄金を採り、獲得するために、彼らを死なせ、むしろ殺すのだ」[20]。ラス・カサス自身、ドミニカ人に対して、エンコミエンダの正義を主張した。ディ エゴ・コロンブスに率いられた植民者たちは、ドミニカ人に対する苦情を国王に提出し、ドミニカ人はイスパニョーラから呼び戻された[21][22]。 |

Conquest of Cuba and change of

heart Reconstruction of a Taíno village from Las Casas's times in contemporary Cuba In 1513, as a chaplain, Las Casas participated in Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar's and Pánfilo de Narváez' conquest of Cuba. He participated in campaigns at Bayamo and Camagüey and in the massacre of Hatuey.[23] He witnessed many atrocities committed by Spaniards against the native Ciboney and Guanahatabey peoples. He later wrote: "I saw here cruelty on a scale no living being has ever seen or expects to see."[24] Las Casas and his friend Pedro de la Rentería were awarded a joint encomienda which was rich in gold and slaves, located on the Arimao River close to Cienfuegos. During the next few years, he divided his time between being a colonist and his duties as an ordained priest. In 1514, Las Casas was studying a passage in the book Ecclesiasticus (Sirach)[25] 34:18–22[a] for a Pentecost sermon and pondering its meaning. Las Casas was finally convinced that all the actions of the Spanish in the New World had been illegal and that they constituted a great injustice. He made up his mind to give up his slaves and encomienda, and started to preach that other colonists should do the same. When his preaching met with resistance, he realized that he would have to go to Spain to fight there against the enslavement and abuse of the native people.[26] Aided by Pedro de Córdoba and accompanied by Antonio de Montesinos, he left for Spain in September 1515, arriving in Seville in November.[27][28] Las Casas and King Ferdinand  A contemporary painting of King Ferdinand "The Catholic" Las Casas arrived in Spain with the plan of convincing the King to end the encomienda system. This was easier thought than done, as most of the people who were in positions of power were themselves either encomenderos or otherwise profiting from the influx of wealth from the Indies.[29] In the winter of 1515, King Ferdinand lay ill in Plasencia, but Las Casas was able to get a letter of introduction to the king from the Archbishop of Seville, Diego de Deza. On Christmas Eve of 1515, Las Casas met the monarch and discussed the situation in the Indies with him; the king agreed to hear him out in more detail at a later date. While waiting, Las Casas produced a report that he presented to the Bishop of Burgos, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, and secretary Lope Conchillos, who were functionaries in complete charge of the royal policies regarding the Indies; both were encomenderos. They were not impressed by his account, and Las Casas had to find a different avenue of change. He put his faith in his coming audience with the king, but it never came, for King Ferdinand died on 25 January 1516.[30] The regency of Castile passed on to Ximenez Cisneros and Adrian of Utrecht who were guardians for the under-age Prince Charles. Las Casas was resolved to see Prince Charles who resided in Flanders, but on his way there he passed Madrid and delivered to the regents a written account of the situation in the Indies and his proposed remedies. This was his "Memorial de Remedios para Las Indias" of 1516.[31] In this early work, Las Casas advocated importing black slaves from Africa to relieve the suffering Indians, a stance he later retracted, becoming an advocate for the Africans in the colonies as well.[32][33][34][b] This shows that Las Casas's first concern was not to end slavery as an institution, but to end the physical abuse and suffering of the Indians.[35] In keeping with the legal and moral doctrine of the time Las Casas believed that slavery could be justified if it was the result of Just War, and at the time he assumed that the enslavement of Africans was justified.[36] Worried by Las Casas' descriptions of the situation in the Indies, Cardinal Cisneros decided to send a group of Hieronymite monks to take over the government of the islands.[37] |

キューバ征服と心変わり 現代キューバにおけるラス・カサス時代のタイノ族の村の復元 1513年、ラス・カサスは聖職者としてディエゴ・ベラスケス・デ・ク エジャールとパンフィロ・デ・ナルバエスによるキューバ征服に参加した。バヤモとカ マグエイでの作戦、ハトゥエイの虐殺に参加した[23]。スペイン人が先住民のシボニー族とグアナハタベイ族に対して行った残虐行為を数多く目撃した。ラ ス・カサスは、友人のペドロ・デ・ラ・レンテリアとともに、シエンフエゴスに近いアリマオ川沿いに、金と奴隷が豊富にある共同エンコミエンダを与えられ た。その後数年間、ラス・カサスは、植民者としての仕事と聖職者としての仕事の両方をこなした。 1514年、ラス・カサスは聖霊降臨祭の説教のために『伝道者の書(シラク書)』[25] 34:18-22[a]の一節を学び、その意味を考えていた。ラス・カサスはついに、新大陸におけるスペイン人の行動はすべて違法であり、大きな不正義で あると確信した。ラス・カサスは、自分の奴隷とエンコミエンダを放棄する決心を固め、他の入植者たちも同じようにするべきだと説き始めた。ラス・カサス は、ペドロ・デ・コルドバに助けられ、アントニオ・デ・モンテシーノスを伴って1515年9月にスペインに向かい、11月にセビリアに到着した[27] [28]。 ラス・カサスとフェルディナンド王  フェルディナンド "カトリック "王の肖像画 ラス・カサスは、エンコミエンダ制度を廃止するよう国王を説得する計画 を持ってスペインに到着した。1515年の冬、フェルディナンド王はプラセンシアで 病床にあったが、ラス・カサスはセビリアの大司教ディエゴ・デザから国王への紹介状を得ることができた。1515年のクリスマス・イヴ、ラス・カサスは国 王に会い、インド諸島の状況について話し合った。国王は、後日ラス・カサスの話を詳しく聞くことに同意した。ラス・カサスは待っている間に報告書を作成 し、ブルゴス司教フアン・ロドリゲス・デ・フォンセカと、インド諸島に関する王室の政策を完全に担当していた秘書ロペ・コンチージョス(両者ともエンコメ ンデロス)に提出した。ラス・カサスは、別の道を探さなければならなかった。1516年1月25日、フェルディナンド王が死去したため、ラス・カサスは国 王との謁見を信じたが、それは実現しなかった[30]。 カスティーリャの摂政権は、未成年のチャールズ皇太子の後見人であったヒメネス・シスネロスとユトレヒトのアドリアンに引き継がれた。ラス・カサスは、フ ランドルに住むシャルル皇太子に会うことを決意したが、その途中でマドリードを通過し、摂政たちにインド諸島の情勢と改善案を文書で伝えた。この初期の著 作でラス・カサスは、苦しむインディオを救済するためにアフリカから黒人奴隷を輸入することを提唱していたが、この姿勢は後に撤回され、植民地におけるア フリカ人の擁護者にもなっている[32][33][34][b]。このことは、ラス・カサスの最初の関心が、制度としての奴隷制を廃止することではなく、 インディオの身体的虐待と苦痛をなくすことであったことを示している。 [35] ラス・カサスは、当時の法学的・道徳的教義に則り、奴隷制度は正義戦争の結果であれば正当化されると考えており、当時はアフリカ人の奴隷化が正当化される と想定していた[36]。 ラス・カサスによるインド諸島の状況に関する記述に憂慮したシスネロス枢機卿は、ヒエロニム派の修道士たちを派遣して島々の統治を引き継がせることを決定 した[37]。 |

| Protector of the Indians Three Hieronymite monks, Luis de Figueroa, Bernardino de Manzanedo, and Alonso de Santo Domingo, were selected as commissioners to take over the authority of the Indies. Las Casas had a considerable part in selecting them and writing the instructions under which their new government would be instated, largely based on Las Casas's memorial. Las Casas himself was granted the official title of Protector of the Indians, and given a yearly salary of one hundred pesos. In this new office Las Casas was expected to serve as an advisor to the new governors with regard to Indian issues, to speak the case of the Indians in court, and send reports back to Spain. Las Casas and the commissioners traveled to Santo Domingo on separate ships, and Las Casas arrived two weeks later than the Hieronimytes. During this time the Hieronimytes had time to form a more pragmatic view of the situation than the one advocated by Las Casas; their position was precarious as every encomendero on the Islands was fiercely against any attempts to curtail their use of native labor. Consequently, the commissioners were unable to take any radical steps towards improving the situation of the natives. They did revoke some encomiendas from Spaniards, especially those who were living in Spain and not on the islands themselves; they even repossessed the encomienda of Fonseca, the Bishop of Burgos. They also carried out an inquiry into the Indian question at which all the encomenderos asserted that the Indians were quite incapable of living freely without their supervision. Las Casas was disappointed and infuriated. When he accused the Hieronymites of being complicit in kidnapping Indians, the relationship between Las Casas and the commissioners broke down. Las Casas had become a hated figure by Spaniards all over the islands, and he had to seek refuge in the Dominican monastery. The Dominicans had been the first to indict the encomenderos, and they continued to chastise them and refuse the absolution of confession to slave owners, and even stated that priests who took their confession were committing a mortal sin. In May 1517, Las Casas was forced to travel back to Spain to denounce to the regent the failure of the Hieronymite reforms.[38] Only after Las Casas had left did the Hieronymites begin to congregate Indians into towns similar to what Las Casas had wanted.[39] Las Casas and Emperor Charles V: The peasant colonization scheme  Contemporary portrait of the young Emperor Charles V When he arrived in Spain, his former protector, regent, and Cardinal Ximenez Cisneros, was ill and had become tired of Las Casas's tenacity. Las Casas resolved to meet instead with the young king Charles I. Ximenez died on 8 November, and the young King arrived in Valladolid on 25 November 1517. Las Casas managed to secure the support of the king's Flemish courtiers, including the powerful Chancellor Jean de la Sauvage. Las Casas's influence turned the favor of the court against Secretary Conchillos and Bishop Fonseca. Sauvage spoke highly of Las Casas to the king, who appointed Las Casas and Sauvage to write a new plan for reforming the governmental system of the Indies.[40] Las Casas suggested a plan where the encomienda would be abolished and Indians would be congregated into self-governing townships to become tribute-paying vassals of the king. He still suggested that the loss of Indian labor for the colonists could be replaced by allowing importation of African slaves. Another important part of the plan was to introduce a new kind of sustainable colonization, and Las Casas advocated supporting the migration of Spanish peasants to the Indies where they would introduce small-scale farming and agriculture, a kind of colonization that did not rely on resource depletion and Indian labor. Las Casas worked to recruit a large number of peasants who would want to travel to the islands, where they would be given lands to farm, cash advances, and the tools and resources they needed to establish themselves there. The recruitment drive was difficult, and during the process the power relation shifted at court when Chancellor Sauvage, Las Casas's main supporter, unexpectedly died. In the end a much smaller number of peasant families were sent than originally planned, and they were supplied with insufficient provisions and no support secured for their arrival. Those who survived the journey were ill-received, and had to work hard even to survive in the hostile colonies. Las Casas was devastated by the tragic result of his peasant migration scheme, which he felt had been thwarted by his enemies. He decided instead to undertake a personal venture which would not rely on the support of others, and fought to win a land grant on the American mainland which was in its earliest stage of colonization.[41] |

インディオの保護者 ルイス・デ・フィゲロア、ベルナルディーノ・デ・マンサネード、アロンソ・デ・サント・ドミンゴの3人のヒエロニム会修道士が、インディオの権威を引き継 ぐ使節として選ばれた。ラス・カサスは、彼らの人選と、ラス・カサスの追悼文に基づく新政府樹立のための指示書の作成に大きな役割を果たした。ラス・カサ ス自身は、インディオ保護官という正式な称号を与えられ、100ペソの年俸を与えられた。この新しい役職でラス・カサスは、インディアンの問題に関して新 しい総督たちのアドバイザーとなり、法廷でインディアンの主張を述べ、スペインに報告を送ることが期待された。ラス・カサスと委員たちは別々の船でサン ト・ドミンゴに向かい、ラス・カサスはヒエロニミテより2週間遅れて到着した。この間、ヒエロニミテ族はラス・カサスの主張よりも現実的な見解を形成する 時間があった。諸島のすべてのエンコメンデロは、先住民の労働力利用を抑制しようとする試みに猛反対していたため、彼らの立場は不安定だった。その結果、 委員たちは先住民の状況を改善するための抜本的な措置を取ることができなかった。しかし、スペイン人、特に島ではなくスペインに住んでいたスペイン人から は、いくつかの寄進を取り消し、ブルゴス司教フォンセカの寄進地も差し押さえた。彼らはまた、インディオ問題についての調査も行ったが、そこではすべての エンコメンデーロが、インディオは彼らの監視なしに自由に生活することはできないと主張した。ラス・カサスは失望し、激怒した。インディオの誘拐にヒエロ ニ派が加担していると非難すると、ラス・カサスと委員たちの関係は崩壊した。ラス・カサスは島中のスペイン人から嫌われる存在となり、ドミニコ会の修道院 に避難することになった。ドミニコ会修道院はエンコメンデロスを最初に起訴し、彼らを懲らしめ続け、奴隷所有者への告解を拒否し、彼らの告解を受けた司祭 は大罪を犯しているとまで述べた。1517年5月、ラス・カサスはヒエロニム派の改革の失敗を摂政に糾弾するためにスペインに戻ることを余儀なくされた [38]。ラス・カサスが去った後になって初めて、ヒエロニム派はラス・カサスが望んだのと同じような町にインディオを集め始めた[39]。 ラス・カサスと皇帝シャルル5世:農民入植計画  若き皇帝シャルル5世の肖像 ラス・カサスがスペインに到着したとき、かつての庇護者であり摂政であったヒメネス・シスネロス枢機卿は病気で倒れており、ラス・カサスの粘り強さに嫌気 がさしていた。ラス・カサスは、代わりに若い国王シャルル1世と会うことを決意した。ヒメネスは11月8日に亡くなり、若い国王は1517年11月25日 にバリャドリッドに到着した。ラス・カサスは、有力な宰相ジャン・ド・ラ・ソバージュを含む、王のフランドルの廷臣たちの支持を得ることに成功した。ラ ス・カサスの影響力は、コンキージョス長官とフォンセカ司教に対する宮廷の好意を覆した。ソーヴァージュはラス・カサスを王に高く評価し、王はラス・カサ スとソーヴァージュを任命して、インド諸島の政府制度を改革するための新しい計画を書かせた[40]。 ラス・カサスは、エンコミエンダを廃止し、インディオを自治都市に集め て王の貢納臣とする計画を提案した。彼はなおも、植民者がインディアンの労働力を失 う代わりに、アフリカ人奴隷の輸入を認めることを提案した。ラス・カサスは、資源の枯渇やインディアンの労働力に頼らない植民地化、すなわち小規模農業と 農業を導入するために、スペイン人農民のインドへの移住を支援することを提唱した。ラス・カサスは、島への渡航を希望する農民を大勢集め、耕作地や現金の 前借り、島での生活に必要な道具や資源を提供することに努めた。ラス・カサスの主要な支持者であったソーバージュ首相が突然死去したため、宮廷内の力関係 は変化した。結局、派遣された農民の家族の数は当初の予定よりはるかに少なく、十分な食糧も供給されず、到着時の支援も確保されなかった。旅を生き延びた 人々は不評を買い、敵対的な植民地で生き延びるためにさえ懸命に働かなければならなかった。ラス・カサスは、自分の農民移住計画が敵に邪魔されたと感じ、 悲劇的な結果に打ちのめされた。彼はその代わりに、他人の支援に頼らない個人的な事業を行うことを決意し、植民地化の初期段階にあったアメリカ本土の土地 交付を勝ち取るために戦った[41]。 |

The Cumaná venture View over the landscape of Mochima National Park in Venezuela, close to the original location of Las Casas's colony at Cumaná  The Natives of Cumaná attack the mission after Gonzalo de Ocampo's slaving raid. Colored copperplate by Theodor de Bry, published in the "Relación brevissima" Following a suggestion by his friend and mentor Pedro de Córdoba, Las Casas petitioned a land grant to be allowed to establish a settlement in northern Venezuela at Cumaná. Founded in 1515, there was already a small Franciscan monastery in Cumana, and a Dominican one at Chiribichi, but the monks there were being harassed by Spaniards operating slave raids from the nearby Island of Cubagua. To make the proposal palatable to the king, Las Casas had to incorporate the prospect of profits for the royal treasury.[42] He suggested fortifying the northern coast of Venezuela, establishing ten royal forts to protect the Indians and starting up a system of trade in gold and pearls. All the Indian slaves of the New World should be brought to live in these towns and become tribute paying subjects to the king. To secure the grant, Las Casas had to go through a long court fight against Bishop Fonseca and his supporters Gonzalo de Oviedo and Bishop Quevedo of Tierra Firme. Las Casas's supporters were Diego Columbus and the new chancellor Gattinara. Las Casas's enemies slandered him to the king, accusing him of planning to escape with the money to Genoa or Rome. In 1520 Las Casas's concession was finally granted, but it was a much smaller grant than he had initially proposed; he was also denied the possibilities of extracting gold and pearls, which made it difficult for him to find investors for the venture. Las Casas committed himself to producing 15,000 ducats of annual revenue, increasing to 60,000 after ten years, and to erecting three Christian towns of at least 40 settlers each. Some privileges were also granted to the initial 50 shareholders in Las Casas's scheme. The king also promised not to give any encomienda grants in Las Casas's area. That said, finding fifty men willing to invest 200 ducats each and three years of unpaid work proved impossible for Las Casas. He ended up leaving in November 1520 with just a small group of peasants, paying for the venture with money borrowed from his brother in-law.[43] Arriving in Puerto Rico, in January 1521, he received the terrible news that the Dominican convent at Chiribichi had been sacked by Indians, and that the Spaniards of the islands had launched a punitive expedition, led by Gonzalo de Ocampo, into the very heart of the territory that Las Casas wanted to colonize peacefully. The Indians had been provoked to attack the settlement of the monks because of the repeated slave raids by Spaniards operating from Cubagua. As Ocampo's ships began returning with slaves from the land Las Casas had been granted, he went to Hispaniola to complain to the Audiencia. After several months of negotiations Las Casas set sail alone; the peasants he had brought had deserted, and he arrived in his colony already ravaged by Spaniards.[44] Las Casas worked there in adverse conditions for the following months, being constantly harassed by the Spanish pearl fishers of Cubagua island who traded slaves for alcohol with the natives. Early in 1522, Las Casas left the settlement to complain to the authorities. While he was gone the native Caribs attacked the settlement of Cumaná, burned it to the ground, and killed four of Las Casas's men.[45] He returned to Hispaniola in January 1522, and heard the news of the massacre. The rumours even included him among the dead.[46] To make matters worse, his detractors used the event as evidence of the need to pacify the Indians using military means. |

クマナの冒険 ベネズエラのモチマ国立公園の風景。ラス・カサスがクマナに植民した当初の場所に近い。  ゴンサロ・デ・オカンポの奴隷狩りの後、ミッションに襲いかかるクマナの先住民たち。テオドール・デ・ブライによる彩色銅版画、"Relación brevissima "に掲載。 ラス・カサスは、友人であり師であったペドロ・デ・コルドバの提案に従って、ベネズエラ北部のクマナに入植地を設立することを許可するよう土地の供与を請 願した。1515年に設立されたクマナには、すでにフランシスコ会の小さな修道院があり、チリビチにはドミニコ会の修道院があったが、そこの修道士たち は、近くのクバグア島から奴隷狩りをするスペイン人たちから嫌がらせを受けていた。ラス・カサスは、この提案を国王の気に入るものにするために、国庫に利 益をもたらす見込みを盛り込む必要があった。彼は、ベネズエラの北海岸を要塞化し、インディオを保護するために10の砦を設置し、金と真珠の貿易システム を立ち上げることを提案した[42]。新世界のすべてのインディオ奴隷をこれらの町に住まわせ、国王に貢納する臣民とすべきであった。ラス・カサスは、こ の交付金を確保するために、フォンセカ司教とその支持者であるゴンサロ・デ・オビエド司教、ティエラフィルメのケベド司教との長い法廷闘争を経なければな らなかった。ラス・カサスの支持者は、ディエゴ・コロンブスと新しい議長ガッティナーラであった。ラス・カサスの敵は、ラス・カサスが金を持ってジェノバ かローマに逃亡するつもりだと非難し、国王に中傷した。1520年、ラス・カサスの租借権は最終的に認められたが、それは当初彼が提案したものよりはるか に小さなものであった。ラス・カサスは、年間15,000ドゥカート(10年後には60,000ドゥカートに増加)の収入を得ること、少なくとも40人ず つの入植者からなる3つのキリスト教の町を建設することを約束した。また、ラス・カサスの計画の最初の株主50人には、いくつかの特権が与えられた。国王 はまた、ラス・カサスの地域にはエンコミエンダを与えないことも約束した。とはいえ、一人200ドゥカットを投資し、3年間無給で働いてくれる50人を見 つけることは、ラス・カサスにとって不可能であることが判明した。ラス・カサスは結局、1520年11月、義理の兄から借りた金で事業費を支払い、少数の 農民たちとともに出発した[43]。 1521年1月、プエルトリコに到着したラス・カサスは、チリビチのドミニコ会修道院がインディオに略奪されたという恐ろしい知らせを受けた。インディオ たちは、クバグアで活動するスペイン人による度重なる奴隷襲撃のために、修道士たちの入植地を攻撃するよう挑発されたのだった。オカンポの船がラス・カサ スに与えられた土地から奴隷を連れて戻り始めると、彼はイスパニョーラに行き、オーディエンシアに苦情を申し立てた。数ヶ月の交渉の後、ラス・カサスは単 独で出航した。彼が連れてきた農民たちは脱走し、彼はすでにスペイン人に荒らされた植民地に到着した[44]。 ラス・カサスはその後数ヶ月間、クバグア島のスペイン人真珠漁師たちから絶えず嫌がらせを受け、原住民と酒と奴隷を交換するという悪条件の中でそこで働い た。1522年の初め、ラス・カサスは当局に文句を言うために居留地を離れた。彼が留守の間に先住民のカリブ族がクマナの集落を襲い、焼き払い、ラス・カ サスの部下4人を殺害した[45]。さらに悪いことに、ラス・カサスの支持者たちは、この出来事を、軍事的手段を用いてインディオを平和化する必要性を示 す証拠として利用した[46]。 |

| Las

Casas as a Dominican friar Devastated, Las Casas reacted by entering the Dominican monastery of Santa Cruz in Santo Domingo as a novice in 1522 and finally taking holy vows as a Dominican friar in 1523.[47] There he continued his theological studies, being particularly attracted to Thomist philosophy. He oversaw the construction of a monastery in Puerto Plata on the north coast of Hispaniola, subsequently serving as prior of the convent. In 1527 he began working on his History of the Indies, in which he reported much of what he had witnessed first hand in the conquest and colonization of New Spain. In 1531, he wrote a letter to Garcia Manrique, Count of Osorno, protesting again the mistreatment of the Indians and advocating a return to his original reform plan of 1516. In 1531, a complaint was sent by the encomenderos of Hispaniola that Las Casas was again accusing them of mortal sins from the pulpit. In 1533 he contributed to the establishment of a peace treaty between the Spanish and the rebel Taíno band of chief Enriquillo.[48] In 1534, Las Casas made an attempt to travel to Peru to observe the first stages of conquest of that region by Francisco Pizarro. His party made it as far as Panama, but had to turn back to Nicaragua due to adverse weather. Lingering for a while in the Dominican convent of Granada, he got into conflict with Rodrigo de Contreras, Governor of Nicaragua, when Las Casas vehemently opposed slaving expeditions by the Governor.[49] In 1536, Las Casas followed a number of friars to Guatemala, where they began to prepare to undertake a mission among the Maya Indians. They stayed in the convent founded some years earlier by Fray Domingo Betanzos and studied the Kʼicheʼ language with Bishop Francisco Marroquín, before traveling into the interior region called Tuzulutlan, "The Land of War", in 1537.[50]  Toribio de Benavente "Motolinia", Las Casas's Franciscan adversary. Also in 1536, before venturing into Tuzulutlan, Las Casas went to Oaxaca, Mexico, to participate in a series of discussions and debates among the bishops of the Dominican and Franciscan orders. The two orders had very different approaches to the conversion of the Indians. The Franciscans used a method of mass conversion, sometimes baptizing many thousands of Indians in a day. This method was championed by prominent Franciscans such as Toribio de Benavente, known as "Motolinia", and Las Casas made many enemies among the Franciscans for arguing that conversions made without adequate understanding were invalid. Las Casas wrote a treatise called "De unico vocationis modo" (On the Only Way of Conversion) based on the missionary principles he had used in Guatemala. Motolinia would later be a fierce critic of Las Casas, accusing him of being all talk and no action when it came to converting the Indians.[51] As a direct result of the debates between the Dominicans and Franciscans and spurred on by Las Casas's treatise, Pope Paul III promulgated the Bull "Sublimis Deus," which stated that the Indians were rational beings and should be brought peacefully to the faith as such.[52] Las Casas returned to Guatemala in 1537 wanting to employ his new method of conversion based on two principles: 1) to preach the Gospel to all men and treat them as equals, and 2) to assert that conversion must be voluntary and based on knowledge and understanding of the faith. It was important for Las Casas that this method be tested without meddling from secular colonists, so he chose a territory in the heart of Guatemala where there were no previous colonies and where the natives were considered fierce and war-like. Because the land had not been possible to conquer by military means, the governor of Guatemala, Alonso de Maldonado, agreed to sign a contract promising that if the venture was successful he would not establish any new encomiendas in the area. Las Casas's group of friars established a Dominican presence in Rabinal, Sacapulas, and Cobán. Through the efforts of Las Casas's missionaries the so-called "Land of War" came to be called "Verapaz", "True Peace". Las Casas's strategy was to teach Christian songs to merchant Indian Christians who then ventured into the area. In this way he was successful in converting several native chiefs, among them those of Atitlán and Chichicastenango, and in building several churches in the territory named Alta Verapaz. These congregated a group of Christian Indians in the location of what is now the town of Rabinal.[53] In 1538 Las Casas was recalled from his mission by Bishop Marroquín who wanted him to go to Mexico and then on to Spain to seek more Dominicans to assist in the mission.[54] Las Casas left Guatemala for Mexico, where he stayed for more than a year before setting out for Spain in 1540. |

ドミニコ会修道士としてのラス・カサス 打ちのめされたラス・カサスは、1522年にサント・ドミンゴのサン タ・クルス修道院に修練生として入り、1523年にドミニコ会修道士として聖なる誓い を立てた[47]。イスパニョーラ北岸のプエルト・プラタに修道院の建設を監督し、その後、修道院の院長を務めた。1527年、『インド史』の執筆に着手 し、ニュー・スペインの征服と植民地化で直接目撃したことの多くを報告した。1531年、オソルノ伯爵ガルシア・マンリケに書簡を送り、インディオの虐待 に再び抗議し、1516年の改革案に戻ることを勧めた。1531年、ラス・カサスが再び説教壇から自分たちの大罪を告発しているとの苦情がイスパニョーラ のエンコメンデロスから送られた。1533年、ラス・カサスはスペインとエンリキージョ族長の反乱軍タイノ族との和平条約締結に貢献した[48]。 1534年、ラス・カサスはフランシスコ・ピサロによるペルー征服の第一段階を観察するためにペルーへの渡航を試みた。彼の一行はパナマまで行ったが、悪 天候のためニカラグアに引き返さなければならなかった。グラナダのドミニコ会修道院にしばらく滞在していたラス・カサスは、ニカラグア総督ロドリゴ・デ・ コントレラスと対立し、総督による奴隷探検に激しく反対した[49]。1536年、ラス・カサスは多くの修道士たちとともにグアテマラへ向かい、そこでマ ヤ・インディアンの間での宣教を行う準備を始めた。数年前にドミンゴ・ベタンソス修道士によって設立された修道院に滞在し、フランシスコ・マロキン司教の もとでKʼicheʼ語を学んだ後、1537年にトゥズルトラン(「戦争の地」)と呼ばれる内陸部へ向かった[50]。  ラス・カサスのフランシスコ会の敵、トリビオ・デ・ベナベンテ "モトリニア"。 1536年、ラス・カサスはトゥズルトランに入る前にメキシコのオアハカに行き、ドミニコ会とフランシスコ会の司教たちの間で行われた一連の議論に参加し た。この2つの修道会は、インディオの改宗に対してまったく異なるアプローチをしていた。フランシスコ会は集団改宗の方法を用い、時には一日に何千人もの インディオに洗礼を授けることもあった。この方法は、「モトリニア」として知られるトリビオ・デ・ベナベンテのような著名なフランシスコ会によって支持さ れ、ラス・カサスは、十分な理解なしに行われた改宗は無効であると主張したため、フランシスコ会の中で多くの敵を作った。ラス・カサスは、グアテマラでの 宣教原理に基づいて『改宗の唯一の道』という論文を書いた。モトリニアは後にラス・カサスを激しく批判し、ラス・カサスがインディオの改宗に関して口先だ けで行動を起こさないことを非難するようになる[51]。ドミニコ会とフランシスコ会の論争が直接のきっかけとなり、ラス・カサスの論文によって拍車がか かった結果、教皇パウロ3世は、インディオは理性的な存在であり、そのような存在として平和的に信仰に導くべきであるとする "Sublimis Deus "という勅書を公布した[52]。 ラス・カサスは1537年にグアテマラに戻り、2つの原則に基づく新しい改宗方法を採用することを望んだ: 1)すべての人に福音を宣べ伝え、平等に扱うこと、2)改宗は自発的なものでなければならず、信仰の知識と理解に基づくものでなければならないと主張する こと、であった。ラス・カサスにとって、この方法が世俗的な植民地主義者の干渉を受けずに試されることが重要であったため、彼はグアテマラの中心部に、そ れまで植民地がなく、原住民が獰猛で戦争を好むと考えられていた土地を選んだ。グアテマラ総督のアロンソ・デ・マルドナドは、軍事的な征服が不可能な土地 であったため、この事業が成功した場合、この地域に新たなアンコミエンダを設立しないことを約束する契約書に署名することに同意した。ラス・カサスの修道 士グループは、ラビナル、サカプラス、コバンにドミニコ会を設立した。ラス・カサスの宣教師たちの努力により、いわゆる「戦争の地(Tuzulutlan)」は「ベラパス」、「真 の平和」と呼ばれるようになった。ラス・カサスの戦略は、この地域に進出してきた商人のインディアン・キリスト教徒にキリスト教の歌を教えることだった。 こうしてラス・カサスは、アティトランやチチカステナンゴをはじめとする何人かの先住民の首長を改宗させ、アルタ・ベラパスと名付けられた領土にいくつか の教会を建てることに成功した。1538年、ラス・カサスはマロキン司教によって宣教から呼び戻された。マロキン司教は、ラス・カサスにメキシコに行き、 さらにスペインに行って宣教を助けるドミニコ会士を探すよう求めた[54]。ラス・カサスはグアテマラからメキシコに向かい、1年以上滞在した後、 1540年にスペインに向かった。 |

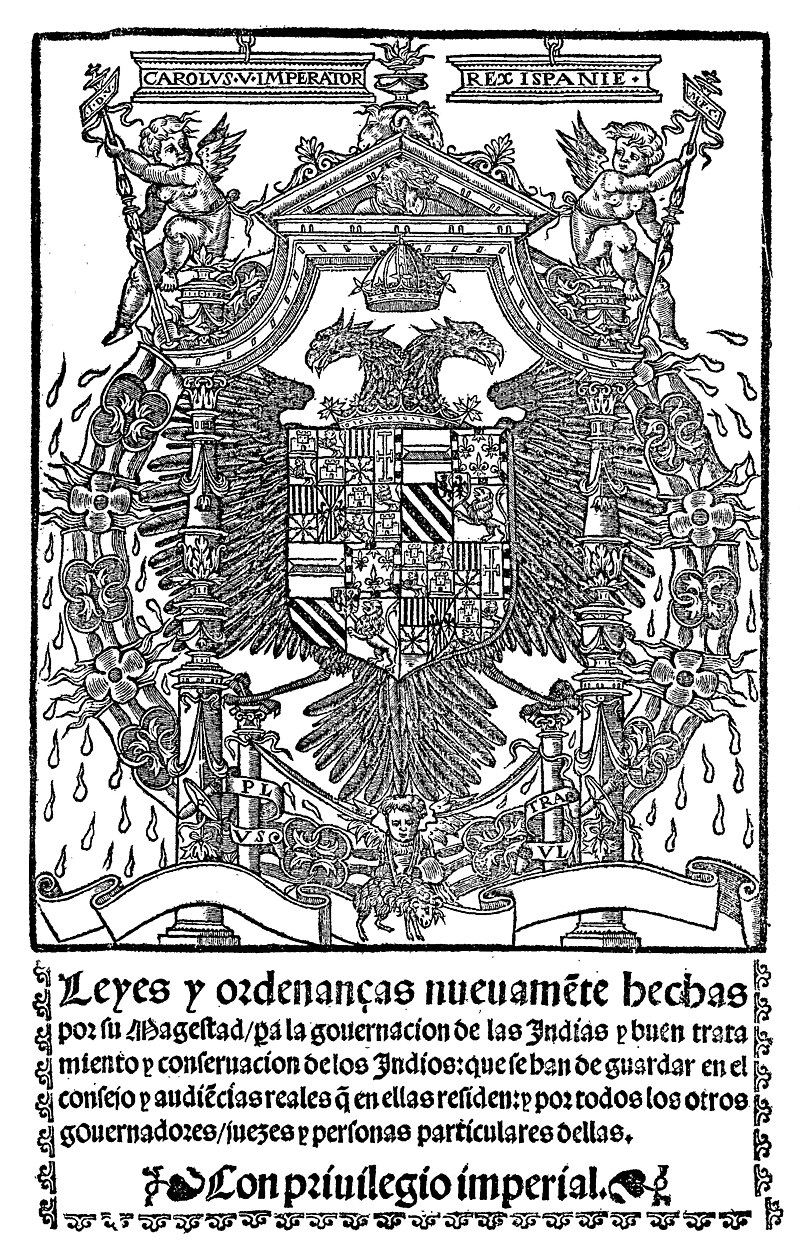

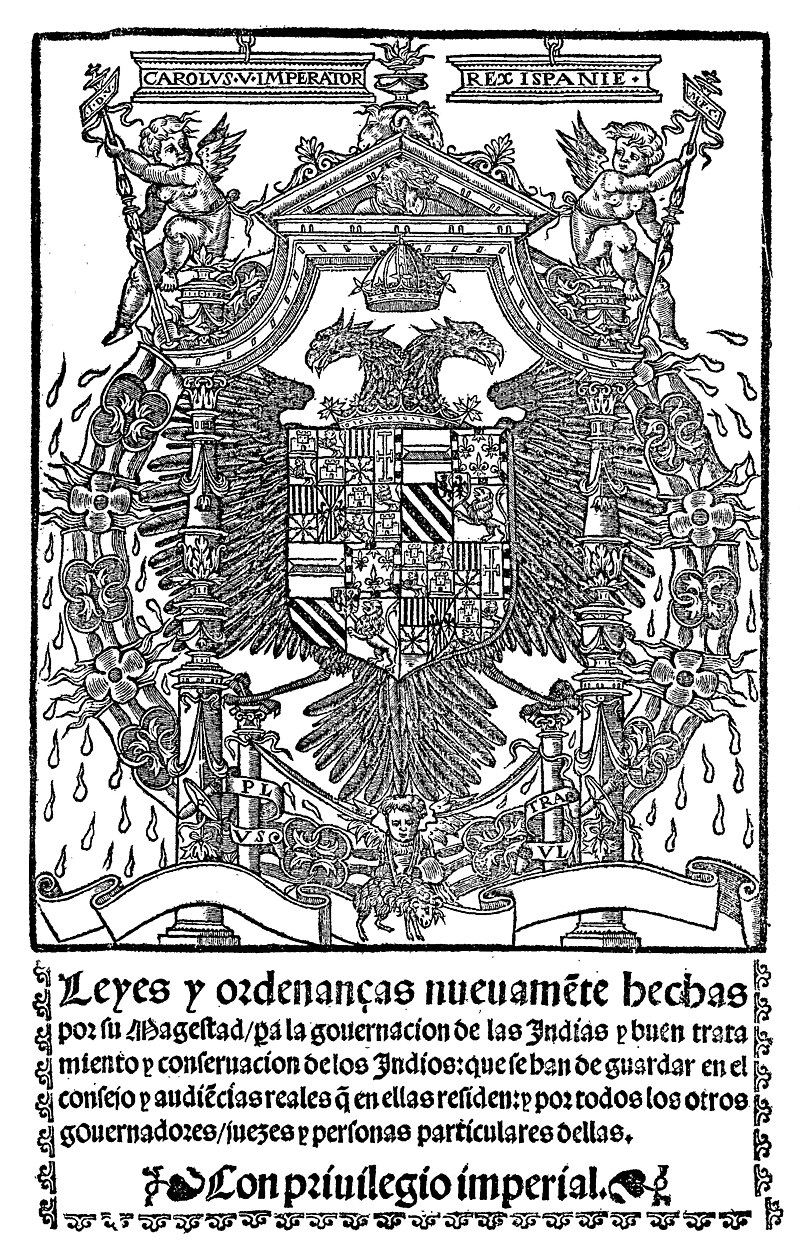

The New Laws s sCover of the New Laws of 1542 In Spain, Las Casas started securing official support for the Guatemalan mission, and he managed to get a royal decree forbidding secular intrusion into the Verapaces for the following five years. He also informed the Theologians of Salamanca, led by Francisco de Vitoria, of the mass baptism practiced by the Franciscans, resulting in a dictum condemning the practice as sacrilegious.[55] But apart from the clerical business, Las Casas had also traveled to Spain for his own purpose: to continue the struggle against the colonists' mistreatment of the Indians.[56] The encomienda had, in fact, legally been abolished in 1523, but it had been reinstituted in 1526, and in 1530 a general ordinance against slavery was reversed by the Crown. For this reason it was a pressing matter for Bartolomé de las Casas to plead once again for the Indians with Charles V who was by now Holy Roman Emperor and no longer a boy. He wrote a letter asking for permission to stay in Spain a little longer to argue for the emperor that conversion and colonization were best achieved by peaceful means.[57] When the hearings started in 1542, Las Casas presented a narrative of atrocities against the natives of the Indies that would later be published in 1552 as A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Before a council consisting of Cardinal García de Loaysa, the Count of Osorno, Bishop Fuenleal, and several members of the Council of the Indies, Las Casas argued that the only solution to the problem was to remove all Indians from the care of secular Spaniards, by abolishing the encomienda system and putting them instead directly under the Crown as royal tribute-paying subjects.[58] On 20 November 1542, the emperor signed the New Laws abolishing the encomiendas and removing certain officials from the Council of the Indies.[59] The New Laws made it illegal to use Indians as carriers, except where no other transport was available, it prohibited all taking of Indians as slaves, and it instated a gradual abolition of the encomienda system, with each encomienda reverting to the Crown at the death of its holders. It also exempted the few surviving Indians of Hispaniola, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Jamaica from tribute and all requirements of personal service. However, the reforms were so unpopular in the New World that riots broke out and threats were made against Las Casas's life. The Viceroy of New Spain, himself an encomendero, decided not to implement the laws in his domain, and instead sent a party to Spain to argue against the laws on behalf of the encomenderos.[60] Las Casas himself was also not satisfied with the laws, as they were not drastic enough and the encomienda system was going to function for many years still under the gradual abolition plan. He drafted a suggestion for an amendment arguing that the laws against slavery were formulated in such a way that it presupposed that violent conquest would still be carried out, and he encouraged once again beginning a phase of peaceful colonization by peasants instead of soldiers.[61] |

新法 1542年の新法の表紙 スペインでラス・カサスは、グアテマラ宣教に対する公的支援を得るために動き出し、その後5年間はベラパレスへの世俗的な侵入を禁じる勅令を得ることに成 功した。彼はまた、フランシスコ・デ・ビトリア率いるサラマンカの神学者たちにフランシスコ会の集団洗礼について報告し、その結果、その実践を冒涜的なも のとして非難する独断を下した[55]。 しかし、ラス・カサスは、聖職者としての仕事とは別に、彼自身の目的、すなわち植民地主義者によるインディオへの虐待に対する闘いを続けるためにスペイン を訪れていた[56]。このため、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、神聖ローマ皇帝であり、もはや少年ではなかったシャルル5世に、インディオのためにも う一度嘆願することが急務となった。バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、改宗と植民地化は平和的手段によって達成されるのが最善であると皇帝に主張するた め、もう少しスペインに滞在する許可を求める手紙を書いた[57]。 1542年に公聴会が始まると、ラス・カサスは、後に1552年に『インディオの破壊に関する短い記述』として出版されることになる、先住民(インディ オ)に対する残虐行為の物語 を発表した。ラス・カサスは、ガルシア・デ・ロアイサ枢機卿、オソルノ伯爵、フエンレアル司教、および印度評議会のメンバー数名で構成された評議会の前 で、問題の唯一の解決策は、すべてのインディオを世俗的なスペイン人の管理から排除することであると主張した。 [1542年11月20日、皇帝はエンコミエンダを廃止する新法に署名し、一部の役人をインド評議会から解任した[59]。新法は、他に輸送手段がない場 合を除き、インディオを運搬人として使用することを違法とし、インディオを奴隷として連行することを全面的に禁止し、エンコミエンダ制度を段階的に廃止 し、各エンコミエンダの所有者の死後は王室に返還することを定めた。また、イスパニョーラ、キューバ、プエルトリコ、ジャマイカのわずかな残存インディオ には、貢納と個人的な奉仕の条件をすべて免除した。しかし、この改革は新大陸では大不評で、暴動が起き、ラス・カサスの命を脅かす脅迫がなされた。ラス・ カサス自身もまた、この法律には十分な思い切りがなく、漸進的な廃止計画のもとでエンコミエンダ制度はまだ何年も機能する予定であったため、満足していな かった。彼は、奴隷制禁止法が暴力的な征服が依然として行われることを前提とした形で制定されているとして修正案を起草し、兵士の代わりに農民による平和 的な植民地化の段階を再び開始することを奨励した[61]。 |

Bishop of Chiapas The Church of the Dominican Convent of San Pablo in Valladolid where Bartolomé de Las Casas was consecrated as Bishop on March 30, 1544. Before Las Casas returned to Spain, he was also appointed as Bishop of Chiapas, a newly established diocese of which he took possession in 1545 upon his return to the New World. He was consecrated in the Dominican Church of San Pablo on 30 March 1544. As Archbishop Loaysa strongly disliked Las Casas,[62] the ceremony was officiated by Loaysa's nephew, Diego de Loaysa, Bishop of Modruš,[63] with Pedro Torres, Titular Bishop of Arbanum, and Cristóbal de Pedraza, Bishop of Comayagua, as co-consecrators.[64] As a bishop Las Casas was involved in frequent conflicts with the encomenderos and secular laity of his diocese: among the landowners there was the conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo. In a pastoral letter issued on 20 March 1545, Las Casas refused absolution to slave owners and encomenderos even on their death bed, unless all their slaves had been set free and their property returned to them.[65] Las Casas furthermore threatened that anyone who mistreated Indians within his jurisdiction would be excommunicated. He also came into conflict with the Bishop of Guatemala Francisco Marroquín, to whose jurisdiction the diocese had previously belonged. To Las Casas's dismay Bishop Marroquín openly defied the New Laws. While bishop, Las Casas was the principal consecrator of Antonio de Valdivieso, Bishop of Nicaragua (1544).[64] The New Laws were finally repealed on 20 October 1545, and riots broke out against Las Casas, with shots being fired against him by angry colonists.[65] After a year he had made himself so unpopular among the Spaniards of the area that he had to leave. Having been summoned to a meeting among the bishops of New Spain to be held in Mexico City on 12 January 1546, he left his diocese, never to return.[65][66] At the meeting, probably after lengthy reflection, and realizing that the New Laws were lost in Mexico, Las Casas presented a moderated view on the problems of confession and restitution of property, Archbishop Juan de Zumárraga of Mexico and Bishop Julián Garcés of Puebla agreed completely with his new moderate stance, Bishop Vasco de Quiroga of Michoacán had minor reservations, and Bishops Francisco Marroquín of Guatemala and Juan Lopez de Zárate of Oaxaca did not object. This resulted in a new resolution to be presented to viceroy Mendoza.[67] His last act as Bishop of Chiapas was writing a confesionario, a manual for the administration of the sacrament of confession in his diocese, still refusing absolution to unrepentant encomenderos. Las Casas appointed a vicar for his diocese and set out for Europe in December 15 |

チアパス司教 1544年3月30日、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスが司教として奉献されたバリャドリッドのドミニコ会サン・パブロ修道院の教会。 ラス・カサスはスペインに戻る前に、1545年に新大陸に戻り、新たに設立されたチアパス教区の司教にも任命された。1544年3月30日、サン・パブロ のドミニコ教会で奉献された。ロアイサ大司教はラス・カサスを強く嫌っていたため[62]、式の司式はロアイサの甥でモドゥルシュ司教のディエゴ・デ・ロ アイサが行い[63]、アルバヌム司教座のペドロ・トーレスとコマヤグア司教のクリストバル・デ・ペドラサが共同司式者となった。 [64] ラス・カサスは司教として、教区の土地所有者や世俗的な信徒たちと頻繁に対立した。1545年3月20日に出された司牧書簡の中で、ラス・カサスは奴隷所 有者やエンコメンデロに対して、たとえ死の床にあっても、すべての奴隷が解放され、財産が返還されない限り、赦免を拒否した[65]。ラス・カサスはさら に、自分の管轄区域内でインディオを虐待する者は破門されると脅した。ラス・カサスはまた、グアテマラ司教フランシスコ・マロキンと対立した。ラ ス・カサ スを失望させたのは、マロキン司教が公然と新法に背いたことだった。司教時代、ラス・カサスはニカラグア司教アントニオ・デ・バルディビエ ソ(1544 年)の主要な奉献者であった[64]。 1545年10月20日、新法はついに廃止され、ラス・カサスに対する暴動が勃発し、怒った入植者たちがラス・カサスに対して発砲した[65]。1546 年1月12日、メキシコ・シティで開催されるニュー・スペインの司教会議に招集された彼は、教区を去り、二度と戻ることはなかった。 [65][66]この会議で、ラス・カサスは、おそらく長い内省の末に、新法がメキシコで失われていることを理解し、告解と財産返還の問題について穏健な 見解を示した、 メキシコのフアン・デ・ズマラガ大司教とプエブラのフリアン・ガルセス司教は彼の新しい穏健な姿勢に完全に同意し、ミチョアカンのバスコ・デ・キロガ司教 は若干の留保をつけ、グアテマラのフランシスコ・マロキン司教とオアハカのフアン・ロペス・デ・ザラテ司教は反対しなかった。ラス・カサスがチアパス司教 として最後に行ったことは、教区における告解の秘跡を管理するためのマニュアルであるコンフェシオナリオ(confesionario)を書くことであっ た[67]。ラス・カサスは、教区の牧師を任命し、15年12月、ヨーロッパに向けて出発した。 |

| The Valladolid debate Main article: Valladolid debate  Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, Las Casas's opponent in the Valladolid debate Las Casas returned to Spain, leaving behind many conflicts and unresolved issues. Arriving in Spain he was met by a barrage of accusations, many of them based on his Confesionario and its 12 rules, which many of his opponents found to be in essence a denial of the legitimacy of Spanish rule of its colonies, and hence a form of treason. The Crown had for example received a fifth of the large number of slaves taken in the recent Mixtón War, and so could not be held clean of guilt under Las Casas's strict rules. In 1548, the Crown decreed that all copies of Las Casas's Confesionario be burnt, and his Franciscan adversary, Motolinia, obliged and sent back a report to Spain. Las Casas defended himself by writing two treatises on the "Just Title" – arguing that the only legality with which the Spaniards could claim titles over realms in the New World was through peaceful proselytizing. All warfare was illegal and unjust and only through the papal mandate of peacefully bringing Christianity to heathen peoples could "Just Titles" be acquired.[69] As a part of Las Casas's defense by offense, he had to argue against Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda. Sepúlveda was a doctor of theology and law who, in his book Democrates Alter, sive de justis causis apud Indos (Another Democrates, or A New Democrates, or on the Just Causes of War against the Indians) had argued that some native peoples were incapable of ruling themselves and should be pacified forcefully. The book was deemed unsound for publication by the theologians of Salamanca and Alcalá for containing unsound doctrine, but the pro-encomendero faction seized on Sepúlveda as their intellectual champion.[70] To settle the issues, a formal debate was organized, the famous Valladolid debate, which took place in 1550–51 with Sepúlveda and Las Casas each presenting their arguments in front of a council of jurists and theologians. First Sepúlveda read the conclusions of his Democrates Alter, and then the council listened to Las Casas read his counterarguments in the form of an "Apología". Sepúlveda argued that the subjugation of certain Indians was warranted because of their sins against Natural Law; that their low level of civilization required civilized masters to maintain social order; that they should be made Christian and that this in turn required them to be pacified; and that only the Spanish could defend weak Indians against the abuses of the stronger ones.[71] Las Casas countered that the scriptures did not in fact support war against all heathens, only against certain Canaanite tribes; that the Indians were not at all uncivilized nor lacking social order; that peaceful mission was the only true way of converting the natives; and finally that some weak Indians suffering at the hands of stronger ones was preferable to all Indians suffering at the hands of Spaniards.[72] The judge, Fray Domingo de Soto, summarised the arguments. Sepúlveda addressed Las Casas's arguments with twelve refutations, which were again countered by Las Casas. The judges then deliberated on the arguments presented for several months before coming to a verdict.[73] The verdict was inconclusive, and both debaters claimed that they had won.[74] Sepúlveda's arguments contributed to the policy of "war by fire and blood" that the Third Mexican Provincial Council implemented in 1585 during the Chichimeca War.[75] According to Lewis Hanke, while Sepúlveda became the hero of the conquistadors, his success was short-lived, and his works were never published in Spain again during his lifetime.[76] Las Casas's ideas had a more lasting impact on the decisions of the king, Philip II, as well as on history and human rights.[77] Las Casas's criticism of the encomienda system contributed to its replacement with reducciones.[78] His testimonies on the peaceful nature of the native Americans also encouraged nonviolent policies concerning the religious conversions of the Indians in New Spain and Peru. It also helped convince more missionaries to come to the Americas to study the indigenous people, such as Bernardino de Sahagún, who learned the native languages to discover more about their cultures and civilizations.[79] The impact of Las Casas's doctrine was also limited. In 1550, the king had ordered that the conquest should cease, because the Valladolid debate was to decide whether the war was just or not. The government's orders were hardly respected; conquistadors such as Pedro de Valdivia went on to wage war in Chile during the first half of the 1550s. Expanding the Spanish territory in the New World was allowed again in May 1556, and a decade later, Spain started its conquest of the Philippines.[77] |

バリャドリッド論争 主な記事 バリャドリッド論争  バリャドリード論争におけるラス・カサスの対戦相手、フアン・ヒネス・デ・セプルベダ ラス・カサスは、多くの対立と未解決の問題を残したままスペインに戻った。スペインに到着したラス・カサスは、非難の嵐に見舞われた。その多くは、ラス・ カサスのコンフェシオナリオとその12の規則に基づくもので、ラス・カサスに反対する多くの人々は、その本質がスペインの植民地支配の正当性を否定するも のであり、それゆえ反逆罪の一種であると考えた。例えば、ラス・カサスの厳格な規則のもとでは、王室は先のミクセン戦争で連行された大量の奴隷の5分の1 を受け取っていたため、罪を免れることはできなかった。1548年、王室はラス・カサスのコンフェシオナリオをすべて焼却することを命じ、フランシスコ会 の敵対者であったモトリニアはこれに応じ、スペインに報告書を送り返した。ラス・カサスは、スペイン人が新大陸の領有権を主張できる唯一の合法性は、平和 的な布教活動であると主張する「正当な称号」に関する2冊の論文を書き、自らを弁護した。すべての戦争は違法かつ不当であり、異教徒にキリスト教を平和的 に伝えるという教皇の命令によってのみ、「正当な称号」を獲得することができた[69]。 攻撃によるラス・カサスの弁護の一環として、ラス・カサスはファン・ジネス・デ・セプルベダに反論しなければならなかった。セプルベダは神学・法学博士で あり、その著書『Democrates Alter, sive de justis causis apud Indos』(もう一人の民主主義者、あるいは新しい民主主義者、あるいはインディオとの戦争の正当な原因について)の中で、一部の先住民は自らを統治す る能力がないため、武力的に平和を与えるべきだと主張していた。この本は、サラマンカとアルカラの神学者たちによって、不健全な教義を含んでいるとして出 版には適さないと判断されたが、エンコメンデロ支持派はセプルベダを知的擁護者として取り立てた[70]。 この論争に決着をつけるため、1550年から51年にかけて、法学者と神学者からなる評議会の前でセプルベダとラス・カサスがそれぞれの主張を述べるとい う、有名なバリャドリッド論争が行われた。まずセプルベダが『デモクラテス・アルテル』の結論を読み上げ、次にラス・カサスが『弁明』の形で反論を読み上 げるのを評議会は聴いた。セプルベダは、特定のインディオの服従は、彼らが自然法に背く罪を犯しているために正当化されること、彼らの文明レベルが低いた めに、社会秩序を維持するために文明的な主人が必要であること、彼らをキリスト教徒にする必要があり、そのためには彼らを平和にする必要があること、スペ イン人だけが弱いインディオを強いインディオの虐待から守ることができることを主張した[71]。 [71]ラス・カサスは、聖典は実際にはすべての異教徒に対する戦争を支持しているわけではなく、特定のカナン人部族に対する戦争だけを支持しているこ と、インディオはまったく未開でもなく、社会秩序を欠いているわけでもないこと、平和的な宣教こそが原住民を改宗させる唯一の真の方法であること、そして 最後に、強いインディオの手にかかって苦しむ一部の弱いインディオのほうが、スペイン人の手にかかって苦しむすべてのインディオよりも望ましいこと、など と反論した[72]。 判事のドミンゴ・デ・ソト(Fray Domingo de Soto)が弁論を要約した。セプルベダはラス・カサスの主張に対して12の反論を行ったが、ラス・カサスはこれに再び反論した。その後、審査員たちは 数ヶ月に渡って議論した後、評決を下した[73]。評決は結論に至らず、両者とも自分の勝利を主張した[74]。 ルイス・ハンケによれば、セプルベダは征服者たちの英雄となったが、その成功は長くは続かず、彼の著作がスペインで出版されることは生涯なかった [76]。 ラス・カサスの思想は、歴史や人権だけでなく、国王フィリップ2世の決断により永続的な影響を与えた[77]。ラス・カサスのアンコミエンダ制度に対する 批判は、レドゥッチョネスへの置き換えに貢献した[78]。 また、アメリカ先住民の平和的な性質に関する彼の証言は、ニュー・スペインとペルーのインディオの宗教的改宗に関する非暴力的な政策を促した。また、先住 民の文化や文明についてより深く知るために先住民の言語を学んだベルナルディーノ・デ・サハグンのように、先住民を研究するためにアメリカ大陸にやってく る宣教師をより多く説得するのにも役立った[79]。 ラス・カサスの教義の影響も限定的であった。1550年、国王は征服の中止を命じたが、それはバリャドリッドの討論会が戦争の是非を決めることになってい たからである。政府の命令はほとんど尊重されず、ペドロ・デ・バルディビアなどの征服者たちは1550年代前半にチリで戦争を起こした。1556年5月に は新大陸でのスペイン領土の拡大が再び許可され、その10年後にはスペインはフィリピンの征服を開始した[77]。 |

Later years and death The façade of the Colegio de San Gregorio in Valladolid, where Las Casas spent his final decades Having resigned the Bishopric of Chiapas, Las Casas spent the rest of his life working closely with the imperial court in matters relating to the Indies. In 1551 he rented a cell at the College of San Gregorio, where he lived with his assistant and friend Fray Rodrigo de Ladrada.[80] He continued working as a kind of procurator for the natives of the Indies, many of whom directed petitions to him to speak to the emperor on their behalf. Sometimes indigenous nobility even related their cases to him in Spain, for example, the Nahua noble Francisco Tenamaztle from Nochistlán. His influence at court was so great that some even considered that he had the final word in choosing the members of the Council of the Indies.[81] In 1552, Las Casas published A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. This book, written a decade earlier and sent to the attention of then-prince Philip II of Spain, contained accounts of the abuses committed by some Spaniards against Native Americans during the early stages of colonization. In 1555 his old Franciscan adversary Toribio de Benavente Motolinia wrote a letter in which he described Las Casas as an ignorant, arrogant troublemaker. Benavente described indignantly how Las Casas had once denied baptism to an aging Indian who had walked many leagues to receive it, only on the grounds that he did not believe that the man had received sufficient doctrinal instruction. This letter, which reinvoked the old conflict over the requirements for the sacrament of baptism between the two orders, was intended to bring Las Casas in disfavour. However, it did not succeed.[82] One matter in which he invested much effort was the political situation of the Viceroyalty of Peru. In Peru, power struggles between conquistadors and the viceroy became an open civil war in which the conquistadors led by Gonzalo Pizarro rebelled against the New Laws and defeated and executed the viceroy Blasco Núñez Vela in 1546. The emperor sent Pedro de la Gasca, a friend of Las Casas, to reinstate the rule of law, and he in turn defeated Pizarro. To restabilize the political situation the encomenderos started pushing not only for the repeal of the New Laws, but for turning the encomiendas into perpetual patrimony of the encomenderos – the worst possible outcome from Las Casas's point of view. The encomenderos offered to buy the rights to the encomiendas from the Crown, and Charles V was inclined to accept since his wars had left him in deep economic troubles. Las Casas worked hard to convince the emperor that it would be a bad economic decision, that it would return the viceroyalty to the brink of open rebellion, and could result in the Crown losing the colony entirely. The emperor, probably because of the doubts caused by Las Casas's arguments, never took a final decision on the issue of the encomiendas.[83] In 1561, he finished his Historia de las Indias and signed it over to the College of San Gregorio, stipulating that it could not be published until after forty years. In fact it was not published for 314 years, until 1875. He also had to repeatedly defend himself against accusations of treason: someone, possibly Sepúlveda, denounced him to the Spanish Inquisition, but nothing came from the case.[84] Las Casas also appeared as a witness in the case of the Inquisition for his friend Archbishop Bartolomé Carranza de Miranda, who had been falsely accused of heresy.[85][86][87] In 1565, he wrote his last will, signing over his immense library to the college. Bartolomé de Las Casas died on 18 July 1566, in Madrid.[88] |

晩年と死去 ラス・カサスが晩年を過ごしたバリャドリッドのサン・グレゴリオ大学のファサード。 チアパス司教座を辞したラス・カサスは、残りの生涯を、インド諸島に関する問題で帝国宮廷と密接に協力しながら過ごした。1551年、ラス・カサスはサ ン・グレゴリオ大学に独房を借り、そこで助手であり友人でもあったロドリゴ・デ・ラドラーダと一緒に暮らした[80]。ラス・カサスは、インディオの原住 民のための調達係のような仕事を続け、原住民の多くは、自分たちに代わって皇帝に話してくれるよう、ラス・カサスに嘆願書を託した。例えば、ノチストラン のナワ族貴族フランシスコ・テナマズトルのように。宮廷におけるラス・カサスの影響力は非常に大きく、インド評議会のメンバーを選ぶ最終的な決定権はラ ス・カサスにあると考える者さえいた[81]。 1552年、ラス・カサスは『印度滅亡小記』を出版した。この本は、その10年前に書かれ、当時のスペイン皇太子フィリップ2世の注意を引くために送られ たもので、植民地化の初期に一部のスペイン人がアメリカ先住民に対して行った虐待についての記述が含まれていた。1555年、フランシスコ会の宿敵であっ たトリビオ・デ・ベナベンテ・モトリニアは手紙を書き、その中でラス・カサスのことを無知で傲慢なトラブルメーカーであると評した。ベナベンテは、ラス・ カサスがかつて、何キロも歩いて洗礼を受けに来た年老いたインディアンに、その人が十分な教義的指導を受けたとは思えないという理由だけで洗礼を拒否した ことを憤慨して述べた。この書簡は、2つの修道会の間で洗礼の秘跡の要件をめぐる古い対立を再燃させ、ラス・カサスの不興を買うことを意図したものであっ た。しかし、それは成功しなかった[82]。 ラス・カサスが力を注いだ問題のひとつは、ペルー総督領の政治状況であった。ペルーでは、コンキスタドールと総督の権力闘争が公然の内戦となり、ゴンサ ロ・ピサロ率いるコンキスタドールは新法に反旗を翻し、1546年に総督ブラスコ・ヌニェス・ベラを破り処刑した。皇帝は、ラス・カサスの友人であったペ ドロ・デ・ラ・ガスカを法の支配を復活させるために派遣し、彼はピサロを破った。政治状況を安定させるため、エンコメンデロたちは新法の廃止だけでなく、 ラス・カサスから見れば最悪の結果である、エンコメンデロの永久財産化を推し進め始めた。ラス・カサスから見れば最悪の結果であった。エンコメンデラス は、王室からエンコミエンダの権利を買い取りたいと申し出たが、シャルル5世は戦争で経済的に困窮していたため、これを受け入れざるを得なかった。ラス・ カサスは、それは経済的に好ましくない決断であり、総督領を再び反乱の危機に陥れるものであり、王室が植民地を完全に失うことになりかねない、と皇帝を懸 命に説得した。皇帝は、ラス・カサスの主張によって生じた疑念のためか、エンコミエンダの問題について最終的な決定を下すことはなかった[83]。 1561年、ラス・カサスは『インディアスの歴史(Historia de las Indias)』を完成させ、サン・グレゴリオ大学に寄託した。実際には、1875年まで314年間出版されなかった。ラス・カサスはまた、謀反の嫌疑か ら何度も身を守る必要があった。セパルベダと思われる人物がスペイン異端審問所にラス・カサスを告発したが、結局何も解決しなかった[84]。ラス・カサ スはまた、異端の嫌疑をかけられた友人バルトロメ・カランサ・デ・ミランダ大司教のために、異端審問所の証人として出廷した[85][86][87]。 1565年、ラス・カサスは遺書を書き、膨大な蔵書をサン・グレゴリオ大学に譲渡した。バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは1566年7月18日にマドリード で死去した[88]。 |

★→

「インディアスの破壊についての簡潔な報告」

| Works Memorial de Remedios para las Indias The text, written 1516, starts by describing its purpose: to present "The remedies that seem necessary in order that the evil and harm that exists in the Indies cease, and that God and our Lord the Prince may draw greater benefits than hitherto, and that the republic may be better preserved and consoled."[89] Las Casas's first proposed remedy was a complete moratorium on the use of Indian labor in the Indies until such time as better regulations of it were set in place. This was meant simply to halt the decimation of the Indian population and to give the surviving Indians time to reconstitute themselves. Las Casas feared that at the rate the exploitation was proceeding it would be too late to hinder their annihilation unless action were taken rapidly. The second was a change in the labor policy so that instead of a colonist owning the labor of specific Indians, he would have a right to man-hours, to be carried out by no specific persons. This required the establishment of self-governing Indian communities on the land of colonists – who would themselves organize to provide the labor for their patron. The colonist would only have rights to a certain portion of the total labor, so that a part of the Indians were always resting and taking care of the sick. He proposed 12 other remedies, all having the specific aim of improving the situation for the Indians and limiting the powers that colonists were able to exercise over them.[90] The second part of the Memorial described suggestions for the social and political organization of Indian communities relative to colonial ones. Las Casas advocated the dismantlement of the city of Asunción and the subsequent gathering of Indians into communities of about 1,000 Indians to be situated as satellites of Spanish towns or mining areas. Here, Las Casas argued, Indians could be better governed, better taught and indoctrinated in the Christian faith, and would be easier to protect from abuse than if they were in scattered settlements. Each town would have a royal hospital built with four wings in the shape of a cross, where up to 200 sick Indians could be cared for at a time. He described in detail social arrangements, distribution of work, how provisions would be divided and even how table manners were to be introduced. Regarding expenses, he argued that "this should not seem expensive or difficult, because after all, everything comes from them [the Indians] and they work for it and it is theirs."[91] He even drew up a budget of each pueblo's expenses to cover wages for administrators, clerics, Bachelors of Latin, doctors, surgeons, pharmacists, advocates, ranchers, miners, muleteers, hospitalers, pig herders, fishermen, etc. |

作品紹介 インディアス救済メモリアル 1516年に書かれたこの著作は、その目的を、「インディアスに存在する悪と害をなくし、神と我々の主である王子がこれまでよりも大きな利益を引き出し、 共和国がよりよく維持され、慰められるために、必要と思われる救済策を提示すること」と述べている[89]。 ラス・カサスが最初に提案した救済策は、より良い規制が設けられるまで、インド諸島におけるインド人労働力の使用を完全に一時停止することであった。これ は、単にインディアンの人口減少を食い止め、生き残ったインディアンに自らを復興させる時間を与えることを意図したものであった。ラス・カサスは、搾取が 進む速度では、迅速に行動を起こさない限り、彼らの絶滅を妨げるには遅すぎると危惧したのである。もうひとつは、労働政策の変更である。植民者が特定のイ ンディオの労働力を所有する代わりに、労働時間に対する権利を持ち、特定の人物に労働させないようにすることである。これには、植民者の土地に自治権を持 つインディアン・コミュニティを設立することが必要であり、彼ら自身がパトロンに労働力を提供するために組織することになる。インディアンの一部は常に休 息し、病人の世話をする。彼は他にも12の救済策を提案したが、それらはすべてインディアンの状況を改善し、植民地主義者がインディアンに対して行使でき る権限を制限するという具体的な目的をもっていた[90]。 メモリアルの第二部では、植民地的なものに対するインディアン共同体の社会的・政治的組織についての提案が述べられていた。ラス・カサスは、アスンシオン 市を解体し、その後にインディオを1,000人程度の共同体に集め、スペインの町や鉱山地帯の衛星として位置づけることを提唱した。ラス・カサスは、ここ でならインディオはよりよく統治され、よりよく教えられ、キリスト教信仰を教え込まれ、散在した集落にいるよりも虐待から保護されやすいと主張した。各町 には、十字架の形をした4つの翼を持つ王立病院が建てられ、一度に200人までの病気のインディオを治療することができる。彼は、社会的な取り決め、仕事 の配分、食料の分け方、テーブルマナーの導入方法まで詳細に説明した。費用については、「これは高価で困難なものではないと思われるべきである。なぜな ら、結局のところ、すべては彼ら(インディアン)からもたらされたものであり、彼らはそのために働き、それは彼らのものだからである」[91]と主張し た。 |

| A Short Account of the

Destruction of the Indies Main article: A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies  Cover of the Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (1552), Bartolomé de las Casas A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies[c] (Spanish: Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias) is an account written in 1542 (published in Seville in 1552) about the mistreatment of the indigenous peoples of the Americas in colonial times and sent to then-Prince Philip II of Spain. One of the stated purposes for writing the account was Las Casas's fear of Spain coming under divine punishment and his concern for the souls of the native peoples. The account was one of the first attempts by a Spanish writer of the colonial era to depict the unfair treatment that the indigenous people endured during the early stages of the Spanish conquest of the Greater Antilles, particularly the island of Hispaniola. Las Casas's point of view can be described as being heavily against some of the Spanish methods of colonization, which, as he described them, inflicted great losses on the indigenous occupants of the islands. In addition, his critique towards the colonizers served to bring awareness to his audience on the true meaning of Christianity, to dismantle any misconceptions on evangelization.[92] His account was largely responsible for the adoption of the New Laws of 1542, which abolished native slavery for the first time in European colonial history and led to the Valladolid debate.[citation needed] The book became an important element in the creation and propagation of the so-called Black Legend – the tradition of describing the Spanish empire as exceptionally morally corrupt and violent. It was republished several times by groups that were critical of the Spanish realm for political or religious reasons. The first edition in translation was published in Dutch in 1578, during the religious persecution of Dutch Protestants by the Spanish crown, followed by editions in French (1578), English (1583), and German (1599) – all countries where religious wars were raging. The first edition published in Spain after Las Casas's death appeared in Barcelona during the Catalan Revolt of 1646. The book was banned by the Aragonese inquisition in 1659.[93] The images described by Las Casas were later depicted by Theodore de Bry in copper plate engravings that served as a medium of the Black Legend against Spain.[94] |

インディアス滅亡小記 主な記事 先住民滅亡小記(A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies)  バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス著『インディアス滅亡略記』(1552年)の表紙。 インディアスの破壊に関する短い記述[c](スペイン語: Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias)は、植民地時代のアメリカ大陸の先住民に対する虐待について1542年に書かれ(1552年にセビリアで出版)、当時のスペインのフィリッ プ2世に送られた記述である。 ラス・カサスは、スペインが天罰を受けることを恐れ、先住民の魂を憂いた。この記録は、植民地時代のスペイン人作家が、スペインによる大アンティル諸島、 特にイスパニョーラ島征服の初期段階で先住民が耐えていた不当な扱いを描いた最初の試みのひとつである。ラス・カサスの視点は、スペインの植民地化手法の いくつかに激しく反対するものであり、彼が描写したように、島々の先住民に大きな損失を与えた。さらに、彼の植民者に対する批評は、キリスト教の真の意味 を聴衆に認識させ、伝道に対する誤解を解く役割を果たした[92]。彼の記述は、ヨーロッパの植民地史上初めて先住民の奴隷制度を廃止し、バリャドリッド 論争を引き起こした1542年の新法の採択に大きく貢献した[要出典]。 この本は、スペイン帝国が例外的に道徳的に堕落し、暴力的であったとする伝統、いわゆる「黒い伝説」を生み出し、広める重要な要素となった。政治的、宗教 的な理由からスペイン帝国に批判的なグループによって何度も再版された。最初の翻訳版は、スペイン王室によるオランダのプロテスタントへの宗教的迫害が行 われていた1578年にオランダ語で出版され、その後、フランス語版(1578年)、英語版(1583年)、ドイツ語版(1599年)と、宗教戦争が激化 していた国々で出版された。ラス・カサスの死後、スペインで出版された最初の版は、1646年のカタルーニャ反乱の最中にバルセロナで出版された。この本 は1659年にアラゴンの異端審問によって禁止された[93]。 ラス・カサスによって描かれたイメージは後にテオドール・デ・ブライによって銅版画に描かれ、スペインに対する黒い伝説の媒体として機能した[94]。 |

Apologetic History of the Indies Cover of the Disputa o controversia con Ginés de Sepúlveda (1552), Bartolomé de las Casas The Apologetic Summary History of the People of These Indies (Spanish: Apologética historia summaria de las gentes destas Indias) was first written as the 68th chapter of the General History of the Indies, but Las Casas changed it into a volume of its own, recognizing that the material was not historical. The material contained in the Apologetic History is primarily ethnographic accounts of the indigenous cultures of the Indies – the Taíno, the Ciboney, and the Guanahatabey, but it also contains descriptions of many of the other indigenous cultures that Las Casas learned about through his travels and readings. The history is apologetic because it is written as a defense of the cultural level of the Indians, arguing throughout that indigenous peoples of the Americas were just as civilized as the Roman, Greek and Egyptian civilizations – and more civilized than some European civilizations. It was in essence a comparative ethnography comparing practices and customs of European and American cultures and evaluating them according to whether they were good or bad, seen from a Christian viewpoint.[citation needed] He wrote: "I have declared and demonstrated openly and concluded, from chapter 22 to the end of this whole book, that all people of these our Indies are human, so far as is possible by the natural and human way and without the light of faith – had their republics, places, towns, and cities most abundant and well provided for, and did not lack anything to live politically and socially, and attain and enjoy civil happiness.... And they equaled many nations of this world that are renowned and considered civilized, and they surpassed many others, and to none were they inferior. Among those they equaled were the Greeks and the Romans, and they surpassed them by many good and better customs. They surpassed also the English and the French and some of the people of our own Spain; and they were incomparably superior to countless others, in having good customs and lacking many evil ones."[95] This work in which Las Casas combined his own ethnographic observations with those of other writers, and compared customs and cultures between different peoples, has been characterized as an early beginning of the discipline of anthropology.[96] |

インディアス弁明史 Disputa o controversia con Ginés de Sepúlveda(1552年)の表紙、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス。 スペイン語: Apologética historia summaria de las gentes destas Indias)は、最初『インド通史』の第68章として書かれたが、ラス・カサスは、その内容が歴史的なものでないことを認識し、一巻の本とした。弁証 史』に収められているのは、主にインド先住民の文化-タイノ族、シボニー族、グアナハタベイ族-についての民族誌的記述であるが、ラス・カサスが旅行や読 書を通じて学んだ他の多くの先住民文化についての記述も含まれている。アメリカ大陸の先住民はローマ文明、ギリシャ文明、エジプト文明と同様に文明的であ り、ヨーロッパ文明よりも文明的であったと終始主張している。それは要するに、ヨーロッパとアメリカの文化の習慣や風習を比較し、キリスト教の視点から見 て良いか悪いかで評価する比較民俗学であった[要出典]。 第22章から本書全体の終わりまで、私は公然と宣言し、実証し、結論として、これらわがインド諸島のすべての人々は、自然的かつ人間的な方法によって可能 な限り、信仰の光なしに、人間であり、その共和国、場所、町、都市は最も豊かで十分に提供され、政治的・社会的に生活し、市民的幸福を獲得し享受するため に何一つ欠けるところがなかった......。そして彼らは、この世界の有名で文明的と見なされている多くの国々に匹敵し、他の多くの国々を凌駕し、誰一 人として劣っていなかった。ギリシア人とローマ人に匹敵し、多くの優れた習慣によって彼らを凌駕した。彼らはまた、イギリス人、フランス人、そして私たち の住むスペインの人々の一部をも凌駕しており、良い風習を持ち、多くの悪い風習を欠いているという点で、数え切れないほど多くの他の人々よりも優れてい た」[95]。ラス・カサスが自身の民族誌的観察と他の作家の観察を組み合わせ、異なる民族間の風習や文化を比較したこの著作は、人類学という学問の初期 の始まりとして特徴づけられている[96]。 |

| History of the Indies The History of the Indies is a three-volume work begun in 1527 while Las Casas was in the Convent of Puerto de Plata. It found its final form in 1561, when he was working in the Colegio de San Gregorio. Originally planned as a six-volume work, each volume describes a decade of the history of the Indies from the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 to 1520, and most of it is an eye-witness account.[97][98] It was in the History of the Indies that Las Casas finally regretted his advocacy for African slavery, and included a sincere apology, writing, "I soon repented and judged myself guilty of ignorance. I came to realize that black slavery was as unjust as Indian slavery... and I was not sure that my ignorance and good faith would secure me in the eyes of God." (Vol II, p. 257)[99] "History of the Indies" has never been fully translated into English. The only translations into English are the 1971 partial translation by Andrée M. Collard, and partial translations by Cynthia L. Chamberlin, Nigel Griffin, Michael Hammer and Blair Sullivan in UCLA's Repertorium Columbianum (Volumes VI, VII and XI). Archiving Christopher Columbus' Journal De Las Casas copied Columbus' diary from his 1492 voyage to modern-day Bahamas. His copy is notable because Columbus' diary itself was lost.[100] De thesauris in Peru Main article: De thesauris in Peru |

インディアス史 『インディアス史』は、ラス・カサスがプエルト・デ・プラタの修道院にいた1527年に書き始められた全3巻の著作である。1561年、ラス・カサスがサ ン・グレ ゴリオ大学(Colegio de San Gregorio)に在籍していたころに完成した。当初は6巻からなる予定で、各巻は1492年のクリストファー・コロンブスの到着から1520年までの インド史の10年間を記述しており、そのほとんどが目撃証言である[97][98]。ラス・カサスが最終的にアフリカ人奴隷制を擁護したことを後悔したの は『インド史』においてであり、「私はすぐに悔い改め、自分の無知を罪とした。黒人の奴隷制度も、インド人の奴隷制度と同様に不当なものであることを理解 するようになった......そして、私の無知と善意が、神の目から見て私を安全なものにするかどうか確信が持てなかった"(第2巻、p.257)。(第 二巻、257頁)[99]。 『インディアス史』"は一度も完全に英訳されたことがない。唯一の英訳は、1971年のアンドレ・M・コラールによる部分訳と、UCLAの Repertorium Columbianum(第VI巻、第VII巻、第XI巻)に収録されているシンシア・L・チェンバリン、ナイジェル・グリフィン、マイケル・ハマー、ブ レア・サリバンによる部分訳である。 クリストファー・コロンブスの日記のアーカイブ化 デ・ラス・カサスは、コロンブスが1492年に現在のバハマへ航海した際の日記をコピーした。コロンブスの日記自体が失われていたため、彼の写しは注目に 値する[100]。 ペルーにおけるデ・ラス・カサス 主な記事 ペルーのデ・テサウリス |

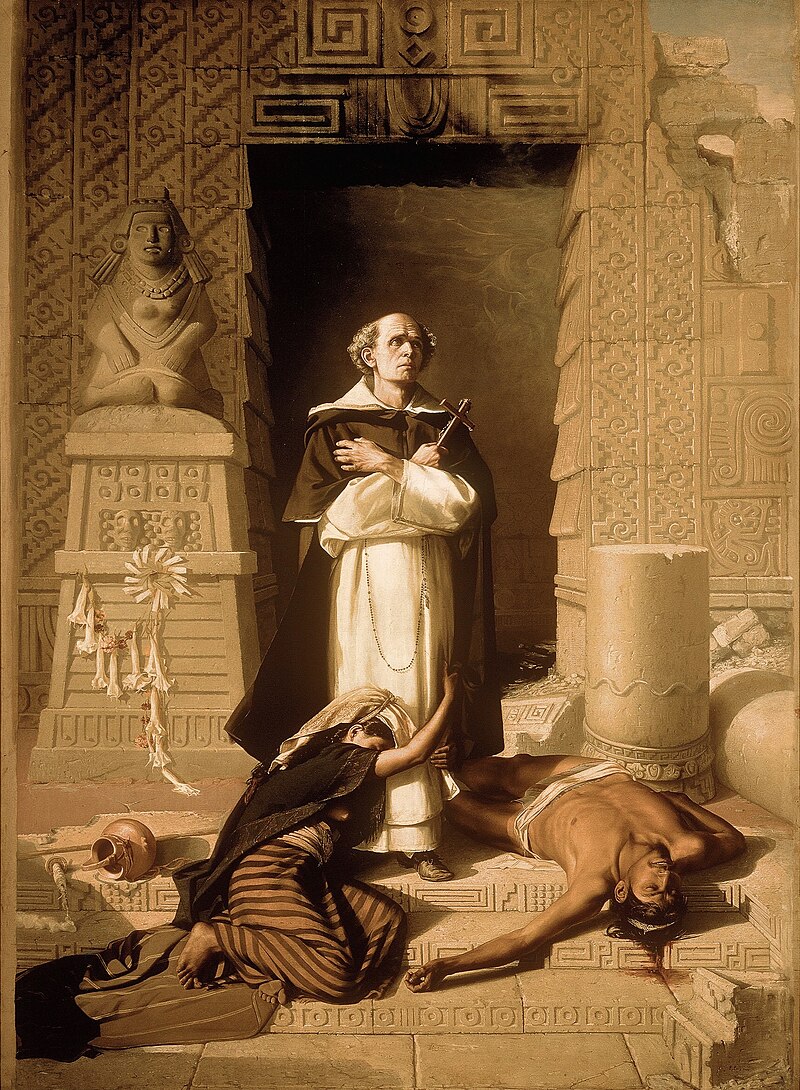

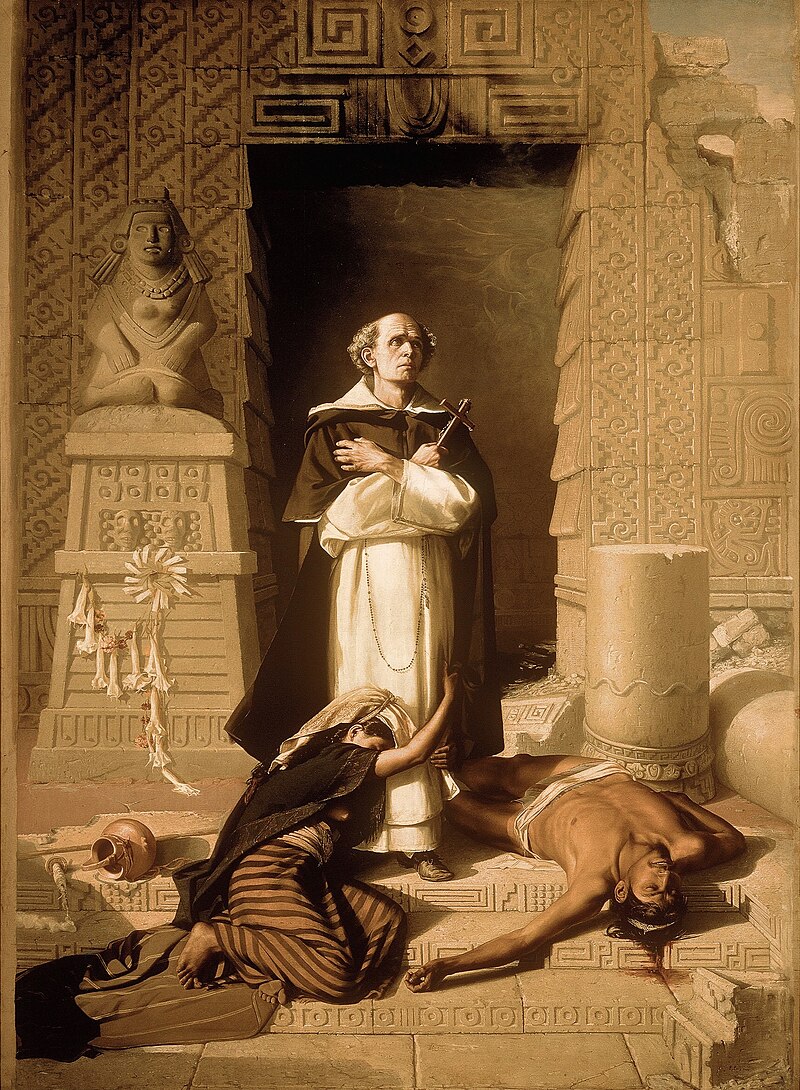

Legacy Fray Bartolomé de las Casas depicted as Savior of the Indians in a later painting by Felix Parra  "Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, convertiendo a una familia azteca", by Miguel Noreña Las Casas's legacy has been highly controversial. In the years following his death, his ideas became taboo in the Spanish realm, and he was seen as a nearly heretical extremist. The accounts written by his enemies Lopez de Gómara and Oviedo were widely read and published in Europe. As the influence of the Spanish Empire was displaced by that of other European powers, Las Casas's accounts were utilized as political tools to justify incursions into Spanish colonies. This historiographic phenomenon has been referred to by some historians as the "Black Legend", a tendency by mostly Protestant authors to portray Spanish Catholicism and colonialism in the worst possible light.[101] Opposition to Las Casas reached its climax in historiography with Spanish right-wing, nationalist historians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries constructing a pro-Spanish White Legend, arguing that the Spanish Empire was benevolent and just and denying any adverse consequences of Spanish colonialism.[102][103] Spanish pro-imperial historians such as Menéndez y Pelayo, Menéndez Pidal, and J. Pérez de Barrada depicted Las Casas as a madman, describing him as a "paranoic" and a monomaniac given to exaggeration,[104] and as a traitor towards his own nation.[105] Menéndez Pelayo also accused Las Casas of having been instrumental in suppressing the publication of Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda's "Democrates Alter" (also called Democrates Secundus) out of spite, but other historians find that to be unlikely since it was rejected by the theologians of both Alcalá and Salamanca, who were unlikely to be influenced by Las Casas.[106] Criticisms See also: Black legend (Spain) Las Casas has also often been accused of exaggerating the atrocities he described in the Indies, some scholars holding that the initial population figures given by him were too high, which would make the population decline look worse than it actually was, and that epidemics of European disease were the prime cause of the population decline, not violence and exploitation. Demographic studies such as those of colonial Mexico by Sherburne F. Cook in the mid-20th century suggested that the decline in the first years of the conquest was indeed drastic, ranging between 80 and 90%, due to many different causes but all ultimately traceable to the arrival of the Europeans.[107] The overwhelming cause was disease introduced by the Europeans. Historians have also noted that exaggeration and inflation of numbers was the norm in writing in 16th-century accounts, and both contemporary detractors and supporters of Las Casas were guilty of similar exaggerations.[108][109] The Dominican friars Antonio de Montesinos and Pedro de Córdoba had reported extensive violence already in the first decade of the colonization of the Americas, and throughout the conquest of the Americas, there were reports of abuse of the natives from friars and priests and ordinary citizens, and many massacres of indigenous people were reported in full by those who perpetrated them. Even some of Las Casas's enemies, such as Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, reported many gruesome atrocities committed against the Indians by the colonizers. All in all, modern historians tend to disregard the numerical figures given by Las Casas, but they maintain that his general picture of a violent and abusive conquest represented reality.[103] One persistent point of criticism has been Las Casas's repeated suggestions of replacing Indian with African slave labor. Even though he regretted that position later in his life and included an apology in his History of the Indies,[110] some later criticism held him responsible for the institution of the transatlantic slave trade. One detractor, the abolitionist David Walker, called Las Casas a "wretch... stimulated by sordid avarice only," holding him responsible for the enslavement of thousands of Africans.[111] Other historians, such as John Fiske writing in 1900, denied that Las Casas's suggestions affected the development of the slave trade. Benjamin Keen likewise did not consider Las Casas to have had any substantial impact on the slave trade, which was well in place before he began writing.[112] That view is contradicted by Sylvia Wynter, who argued that Las Casas's 1516 Memorial was the direct cause of Charles V granting permission in 1518 to transport the first 4,000 African slaves to Jamaica.[113] A growing corpus of scholarship has sought to deconstruct and reassess the role of Las Casas in Spanish colonialism. Daniel Castro, in his Another Face of Empire (2007), takes on such a task. He argues that he was more of a politician than a humanitarian and that his liberation policies were always combined with schemes to make colonial extraction of resources from the natives more efficient. He also argues that Las Casas failed to realize that by seeking to replace indigenous spirituality with Christianity, he was undertaking a religious colonialism that was more intrusive than the physical one.[114] The responses to his work are varied. Some claim that Castro's portrayal of Las Casas had an air of anachronism.[115][116] Others have agreed with Castro's deconstruction of Las Casas as a nuanced and contradictory historical figure.[117][118][119] Cultural legacy  Monument to Bartolomé de las Casas in Seville, Spain. In 1848, Ciudad de San Cristóbal, then the capital of the Mexican state of Chiapas, was renamed San Cristóbal de Las Casas in honor of its first bishop. His work is a particular inspiration behind the work of the Las Casas Institute at Blackfriars Hall, Oxford.[120] He is also often cited as a predecessor of the liberation theology movement. Bartolomé is remembered in the Church of England with a commemoration on 20 July,[121] on 18 July, and at the Evangelical Lutheran Church on 17 July. In the Catholic Church, the Dominicans introduced his cause for canonization in 1976.[122] In 2002 the church began the process for his beatification.[123] He was among the first to develop a view of unity among humankind in the New World, stating that "All people of the world are humans," and that they had a natural right to liberty – a combination of Thomist rights philosophy with Augustinian political theology.[124] In this capacity, an ecumenical human rights institute located in San Cristóbal de las Casas, the Centro Fray Bartolomé de las Casas de Derechos Humanos, was established by Bishop Samuel Ruiz in 1989.[125][126] Residencial Las Casas in Santurce, San Juan  Residencial Las Casas in Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico is named after Las Casas. He is also featured in the Guatemalan quetzal one cent (Q0.01) coins.[127] The small town of Lascassas, Tennessee, in the United States has also been named after him.[128] |

遺産 後のフェリックス・パラの絵画でインディオの救世主として描かれたバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス師  「フレイ・バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス、アステカの家族を改宗させる」、ミゲル・ノレーニャ作 ラス・カサスの遺産は大きな論争を呼んでいる。彼の死後数年間、彼の思想はスペイン国内ではタブーとなり、彼はほとんど異端の過激派とみなされた。彼の敵 であったロペス・デ・ゴマラやオビエドが書いた記録はヨーロッパで広く読まれ、出版された。スペイン帝国の影響力が他のヨーロッパ列強の影響力に取って代 わられるにつれ、ラス・カサスの記述はスペインの植民地への侵攻を正当化するための政治的道具として利用された。この歴史学的現象は一部の歴史家によって 「黒い伝説」と呼ばれ、主にプロテスタントの著者がスペインのカトリシズムと植民地主義を可能な限り悪いイメージで描く傾向にあった[101]。 ラス・カサスに対する反対は、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてスペインの右派の民族主義的な歴史家たちによって、親スペイン的な白色伝説を構築し、 スペイン帝国は慈悲深く正義であり、スペインの植民地主義がもたらすいかなる悪影響も否定するものであると主張する歴史学において最高潮に達した [102][103]。Pérez de Barradaはラス・カサスを狂人として描写し、「パラノイア」であり誇張が好きなモノマニアであり[104]、自国に対する裏切り者であると述べてい る[105]。 [105]またメネンデス・ペラヨは、ラス・カサスがフアン・ジネス・デ・セプルベダの『デモクラテス・アルテル』(『デモクラテス・セクンドゥス』とも 呼ばれる)の出版を恨みから弾圧するのに尽力したと非難しているが、ラス・カサスの影響を受けているとは考えにくいアルカラとサラマンカの神学者たちに よって却下されていることから、他の歴史家たちはその可能性は低いと考えている[106]。 批判 以下も参照: 黒い伝説(スペイン) ラス・カサスはまた、彼がインド諸島で描写した残虐行為を誇張しているとしばしば非難されてきた。一部の学者は、ラス・カサスが最初に示した人口数値は高 すぎたため、人口減少が実際よりも悪化したように見え、暴力や搾取ではなく、ヨーロッパ伝染病の流行が人口減少の主な原因であったと考えている。20世紀 半ばのシャーバーン・F・クックによる植民地メキシコの人口統計学的研究のようなものは、征服の最初の数年間における人口減少は実に劇的なものであり、 80%から90%の間であったことを示唆した。歴史家たちはまた、16世紀の記述では数字の誇張や誇張が常態化していたことを指摘しており、ラス・カサス の同時代の論者も支持者も同様の誇張の罪を犯していた[108][109]。 ドミニコ会の修道士アントニオ・デ・モンテシーノスとペドロ・デ・コルドバは、アメリカ大陸の植民地化の最初の10年間にすでに大規模な暴力を報告してお り、アメリカ大陸の征服の間中、修道士や司祭や一般市民から原住民に対する虐待の報告があり、先住民の虐殺の多くは、それを行った人々によって完全に報告 されていた。ラス・カサスの敵であったトリビオ・デ・ベナベンテ・モトリニアでさえも、植民者たちによるインディオに対する残虐行為の数々を報告してい る。全体として、現代の歴史家たちはラス・カサスが示した数値的な数字は無視する傾向にあるが、暴力的で虐待的な征服という彼の一般的な図式は現実を表し ていると主張している[103]。 批判の根強い点の一つは、ラス・カサスがインド人をアフリカ人の奴隷労働に置き換えることを繰り返し提案していたことである。ラス・カサスは後年になって その立場を後悔し、『インド史』の中で謝罪の言葉を述べているにもかかわらず[110]、大西洋横断奴隷貿易の制度についてラス・カサスの責任を問う批判 もあった。その一人である奴隷廃止論者のデイヴィッド・ウォーカーは、ラス・カサスを「哀れな...卑劣な欲望だけに刺激された」人物と呼び、何千人もの アフリカ人を奴隷にした責任を追及した[111]。ベンジャミン・キーンも同様に、ラス・カサスが執筆を開始する以前から行われていた奴隷貿易に実質的な 影響を与えたとは考えていなかった[112]。この見解は、ラス・カサスの1516年のメモリアルが、1518年にチャールズ5世が最初の4,000人の アフリカ人奴隷をジャマイカに輸送する許可を与えた直接的な原因であると主張したシルヴィア・ウィンターによって否定されている[113]。 スペイン植民地主義におけるラス・カサスの役割を解体し、再評価しようとする学問が増加している。ダニエル・カストロは『帝国のもう一つの顔』(2007 年)の中で、そのような課題に取り組んでいる。彼は、人道主義者というよりは政治家であり、彼の解放政策は、植民地による原住民からの資源採取をより効率 的にするための計画と常に結びついていたと主張する。彼はまた、ラス・カサスは先住民の精神性をキリスト教に置き換えようとすることで、物理的な植民地主 義よりも侵入的な宗教的植民地主義を行っていたことに気づかなかったと主張する[114]。カストロの描くラス・カサスには時代錯誤の雰囲気があると主張 する者もいれば[115][116]、ラス・カサスをニュアンスのある矛盾した歴史上の人物とするカストロの脱構築に同意する者もいる[117] [118][119]。 文化的遺産  スペインのセビリアにあるバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスの記念碑。 1848年、当時メキシコのチアパス州の州都であったサン・クリストバル市は、初代司教に敬意を表してサン・クリストバル・デ・ラス・カサスと改名され た。バルトロメは、解放の神学運動の先駆者としてもよく挙げられる。バルトロメは英国国教会では7月20日に、福音ルーテル教会では7月18日に記念式典 が行われる[121]。カトリック教会では、ドミニコ会が1976年に彼の列福のための大義を紹介した[122]。2002年、教会は彼の列福のための手 続きを開始した[123]。 彼は、新世界における人類間の統一についての見解を発展させた最初の人物の一人であり、「世界のすべての人々は人間である」と述べ、彼らには自由に対する 自然権があるとした。これは、トミスト派の権利哲学とアウグスティヌス派の政治神学の組み合わせであった[124]。このような立場から、サン・クリスト バル・デ・ラス・カサスにあるエキュメニカルな人権研究所、フレイ・バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス・デ・レチョス・ヒューマノスが、1989年にサミュエ ル・ルイス司教によって設立された[125][126]。 サンフアン州サントゥルセのレジデンシアル・ラス・カサス  プエルトリコ、サンフアンのサントゥルセにあるレジデンシアル・ラス・カサスはラス・カサスにちなんで命名された。 また、グアテマラのケツァール1セント硬貨(Q0.01)にも描かれている[127]。 アメリカ合衆国のテネシー州ラスカサスという小さな町にも彼の名前が付けられている[128]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartolom%C3%A9_de_las_Casas |

|

| 『イン

ディアスの破壊についての簡潔な報告』

(インディアスのはかいについてのかんけつなほうこく、西: Brevísima relación de la destrucción de

las

Indias)は、1552年にスペイン出身のドミニコ会士であるバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス(1484年-1566年)が著した書籍。インディアス破