ポストコロニアリズム

Postcolonialism

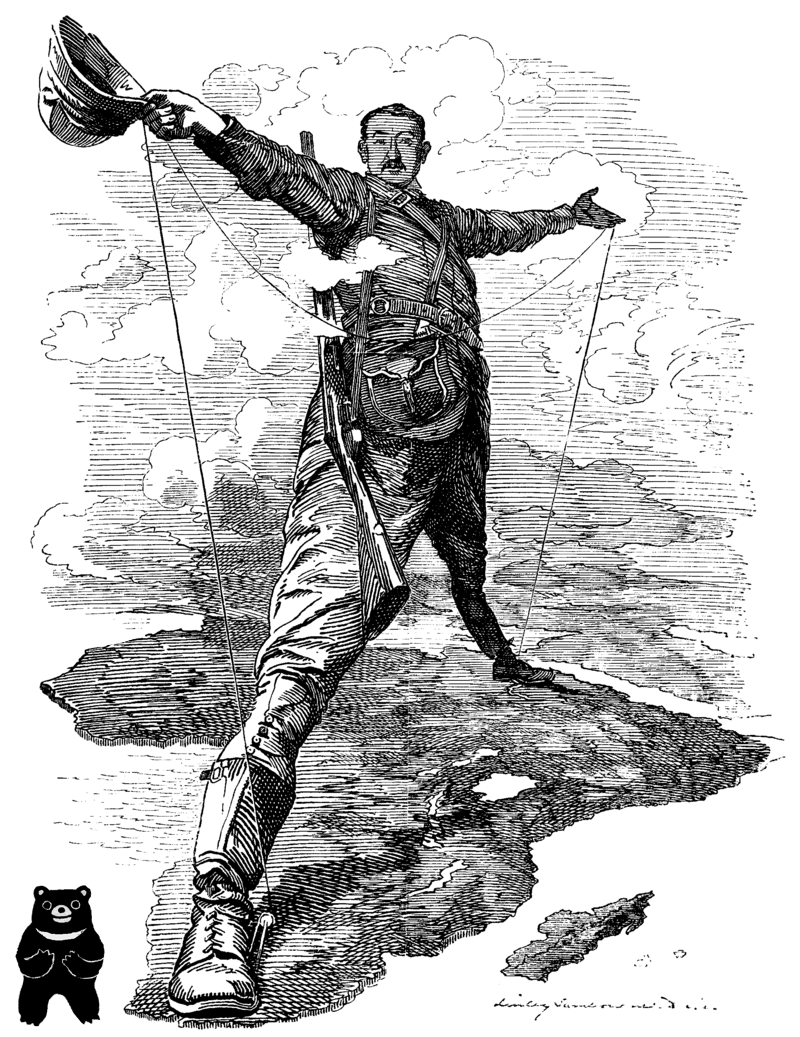

I would annex the planets if I could -

Cecil Rhodes (from PUNCH, public domain)

☆ 政治的議論としての(1)ポ ストコロニアリズム(postcolonialism) とは、コロニアリズム(植民地主義,colonialism) あるいは帝国主義(imperialism) の伝統が、その後(post-)の歴史的展開なかでも、さまざまな形を通して継続しているという、時間的、空間的、そして精神的概念をめぐる議論のことを さす。そしてポストコロニアル をめぐる学術的議論としての(2)「ポ ストコロニアリズム(ポ ストコロニアル理論:Postcolonialismと も)とは、植民地主義や帝国主義の文化的、政治的、経済的遺産を批判的に学術的に研究するもので、植民地化された人々とその土地に対する人間の支配と搾取 の影響に焦点を当てている。この分野は1960年代に台頭し始め、植民地支配を受けた国の学者たちが植民地支配の残存する影響について論文を発表し、(通 常はヨーロッパの)帝国権力の歴史、文化、文学、言説に対する批判的理論分析を展開した」という(→「ポストコロニアル 」を参照)。

★「ポストコロニアリティ」(=ポスト植民地性)とは、ポストコロニアル(=ポスト植民地的)という言葉や概念について、ポストコロニアルとはなにか?その具体的事象やより抽象化した概念化そのものをさす用語(=概念の名詞化)である(→ポストコロニアル理性批判)。

|

★ ポストコロニアリズム批判の定番メニュー(ロバート・ J・C・ヤングの同名の書籍より)

|

★

ポ

ストコロニアリズム批判の定番メニュー(本橋哲也の同

名の書籍より)

|

︎▶ポストコロニアリティ︎▶︎︎先住民の視点からグローバル・スタディーズを再構築する領域横断研究▶︎︎ポストコロニアル人類学▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶

︎︎▶︎脱植民地人類学への模索▶植民地主義︎︎▶︎植民地状況における心理学▶︎︎人類学における自己と他者▶︎入植植民地主義▶︎︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

︎▶サバルタン︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

▶︎ポストモダン人類学▶ポスト真実の政治状況︎▶︎︎ポストヒューマニズム▶︎多文化主義とその批判の理論家たち▶︎︎ポストモダン人類学用語集▶︎ポストモダン的主体のゆくえ▶︎︎︎ポストリベラリズムとはなにか?▶︎ポストモダニズムなんか、たいしたことない▶ポストモダンと文化批判︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶

| Postcolonialism Postcolonialism (also post-colonial theory) is the critical academic study of the cultural, political and economic legacy of colonialism and imperialism, focusing on the impact of human control and exploitation of colonized people and their lands. The field started to emerge in the 1960s, as scholars from previously colonized countries began publishing on the lingering effects of colonialism, developing a critical theory analysis of the history, culture, literature, and discourse of (usually European) imperial power. |

ポ

ストコロニアリズム ポ ストコロニアリズム(ポストコロニアル理論とも)とは、植民地主義や帝国主義の文化的、政治的、経済的遺産を批判的に学術的に研究するもので、植民地化さ れた人々とその土地に対する人間の支配と搾取の影響に焦点を当てている。この分野は1960年代に台頭し始め、植民地支配を受けた国の学者たちが植民地支 配の残存する影響について論文を発表し、(通常はヨーロッパの)帝国権力の歴史、文化、文学、言説に対する批判的理論分析を展開した。 |

| Purpose and basic concepts As an epistemology (i.e., a study of knowledge, its nature, and verifiability), ethics (moral philosophy), and as a political science (i.e., in its concern with affairs of the citizenry), the field of postcolonialism addresses the matters that constitute the postcolonial identity of a decolonized people, which derives from:[1] 1. the colonizer's generation of cultural knowledge about the colonized people; and 2. how that Western cultural knowledge was applied to subjugate a non-European people into a colony of the European mother country, which, after initial invasion, was effected by means of the cultural identities of 'colonizer' and 'colonized'. Postcolonialism is aimed at disempowering such theories (intellectual and linguistic, social and economic) by means of which colonialists "perceive," "understand," and "know" the world. Postcolonial theory thus establishes intellectual spaces for subaltern peoples to speak for themselves, in their own voices, and thus produce cultural discourses of philosophy, language, society, and economy, balancing the imbalanced us-and-them binary power-relationship between the colonist and the colonial subjects.[citation needed][2] Approaches Postcolonialism encompasses a wide variety of approaches, and theoreticians may not always agree on a common set of definitions. On a simple level, through anthropological study, it may seek to build a better understanding of colonial life—based on the assumption that the colonial rulers are unreliable narrators—from the point of view of the colonized people. On a deeper level, postcolonialism examines the social and political power relationships that sustain colonialism and neocolonialism, including the social, political and cultural narratives surrounding the colonizer and the colonized. This approach may overlap with studies of contemporary history, and may also draw examples from anthropology, historiography, political science, philosophy, sociology, and human geography. Sub-disciplines of postcolonial studies examine the effects of colonial rule on the practice of feminism, anarchism, literature, and Christian thought.[3] At times, the term postcolonial studies may be preferred to postcolonialism, as the ambiguous term colonialism could refer either to a system of government, or to an ideology or world view underlying that system. However, postcolonialism (i.e., postcolonial studies) generally represents an ideological response to colonialist thought, rather than simply describing a system that comes after colonialism, as the prefix post- may suggest. As such, postcolonialism may be thought of as a reaction to or departure from colonialism in the same way postmodernism is a reaction to modernism; the term postcolonialism itself is modeled on postmodernism, with which it shares certain concepts and methods.[4] Colonialist discourse  In La Réforme intellectuelle et morale (1871), the orientalist Ernest Renan, advocated imperial stewardship for civilizing the non–Western peoples of the world. Colonialism was presented as "the extension of civilization," which ideologically justified the self-ascribed racial and cultural superiority of the Western world over the non-Western world. This concept was espoused by Ernest Renan in La Réforme intellectuelle et morale (1871), whereby imperial stewardship was thought to affect the intellectual and moral reformation of the coloured peoples of the lesser cultures of the world. That such a divinely established, natural harmony among the human races of the world would be possible, because everyone has an assigned cultural identity, a social place, and an economic role within an imperial colony. Thus:[5] The regeneration of the inferior or degenerate races, by the superior races is part of the providential order of things for humanity.... Regere imperio populos is our vocation. Pour forth this all-consuming activity onto countries, which, like China, are crying aloud for foreign conquest. Turn the adventurers who disturb European society into a ver sacrum, a horde like those of the Franks, the Lombards, or the Normans, and every man will be in his right role. Nature has made a race of workers, the Chinese race, who have wonderful manual dexterity, and almost no sense of honour; govern them with justice, levying from them, in return for the blessing of such a government, an ample allowance for the conquering race, and they will be satisfied; a race of tillers of the soil, the Negro; treat him with kindness and humanity, and all will be as it should; a race of masters and soldiers, the European race.... Let each do what he is made for, and all will be well. — La Réforme intellectuelle et morale (1871), by Ernest Renan From the mid- to the late-nineteenth century, such racialist group-identity language was the cultural common-currency justifying geopolitical competition amongst the European and American empires and meant to protect their over-extended economies. Especially in the colonization of the Far East and in the late-nineteenth century Scramble for Africa, the representation of a homogeneous European identity justified colonization. Hence, Belgium and Britain, and France and Germany proffered theories of national superiority that justified colonialism as delivering the light of civilization to unenlightened peoples. Notably, la mission civilisatrice, the self-ascribed 'civilizing mission' of the French Empire, proposed that some races and cultures have a higher purpose in life, whereby the more powerful, more developed, and more civilized races have the right to colonize other peoples, in service to the noble idea of "civilization" and its economic benefits.[6][7] Postcolonial identity  Spanish colonial architecture in Antigua Guatemala. Postcolonial theory holds that decolonized people develop a postcolonial identity that is based on cultural interactions between different identities (cultural, national, and ethnic as well as gender and class based) which are assigned varying degrees of social power by the colonial society.[citation needed] In postcolonial literature, the anti-conquest narrative analyzes the identity politics that are the social and cultural perspectives of the subaltern colonial subjects—their creative resistance to the culture of the colonizer; how such cultural resistance complicated the establishment of a colonial society; how the colonizers developed their postcolonial identity; and how neocolonialism actively employs the 'us-and-them' binary social relation to view the non-Western world as inhabited by 'the other'. As an example, consider how neocolonial discourse of geopolitical homogeneity often includes the relegating of decolonized peoples, their cultures, and their countries, to an imaginary place, such as "the Third World." Oftentimes the term "the third World" is over-inclusive: it refers vaguely to large geographic areas comprising several continents and seas, i.e. Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania. Rather than providing a clear or complete description of the area it supposedly refers to, it instead erases distinctions and identities of the groups it claims to represent. A postcolonial critique of this term would analyze the self-justifying usage of such a term, the discourse it occurs within, as well as the philosophical and political functions the language may have. Postcolonial critiques of homogeneous concepts such as the "Arabs," the "First World," "Christendom," and the "Ummah", often aim to show how such language actually does not represent the groups supposedly identified. Such terminology often fails to adequately describe the heterogeneous peoples, cultures, and geography that make them up. Accurate descriptions of the world's peoples, places, and things require nuanced and accurate terms.[8] By including everyone under the Third World concept, it ignores the why those regions or countries are considered Third World and who is responsible. Difficulty of definition As a term in contemporary history, postcolonialism occasionally is applied, temporally, to denote the immediate time after the period during which imperial powers retreated from their colonial territories. Such is believed to be a problematic application of the term, as the immediate, historical, political time is not included in the categories of critical identity-discourse, which deals with over-inclusive terms of cultural representation, which are abrogated and replaced by postcolonial criticism. As such, the terms postcolonial and postcolonialism denote aspects of the subject matter that indicate that the decolonized world is an intellectual space "of contradictions, of half-finished processes, of confusions, of hybridity, and of liminalities."[9] As in most critical theory-based research, the lack of clarity in the definition of the subject matter coupled with an open claim to normativity makes criticism of postcolonial discourse problematic, reasserting its dogmatic or ideological status.[10]  Campeche Cathedral, located in Campeche City, Mexico. In Post-Colonial Drama: Theory, Practice, Politics (1996), Helen Gilbert and Joanne Tompkins clarify the denotational functions, among which:[11] The term post-colonialism—according to a too-rigid etymology—is frequently misunderstood as a temporal concept, meaning the time after colonialism has ceased, or the time following the politically determined Independence Day on which a country breaks away from its governance by another state. Not a naïve teleological sequence, which supersedes colonialism, post-colonialism is, rather, an engagement with, and contestation of, colonialism's discourses, power structures, and social hierarchies... A theory of post-colonialism must, then, respond to more than the merely chronological construction of post-independence, and to more than just the discursive experience of imperialism. The term post-colonialism is also applied to denote the Mother Country's neocolonial control of the decolonized country, affected by the legalistic continuation of the economic, cultural, and linguistic power relationships that controlled the colonial politics of knowledge (i.e., the generation, production, and distribution of knowledge) about the colonized peoples of the non-Western world. [9][12] The cultural and religious assumptions of colonialist logic remain active practices in contemporary society and are the basis of the Mother Country's neocolonial attitude towards her former colonial subjects—an economical source of labour and raw materials.[13] It acts as a non interchangeable term that links the independent country to its colonizer, depriving countries of their Independence, decades after building their own identities. |

目的と基本概念 認識論(すなわち、知識、その性質、検証可能性の研究)、倫理学(道徳哲学)、政治学(すなわち、市民の問題への関心)として、ポストコロニアリズムの分 野は、脱植民地化された人々のポストコロニアル・アイデンティティを構成する事柄を扱っている。 1. 植民地化された人々に関する、植民地化した側の文化的知識の生成。 2. その西洋の文化的知識が、非ヨーロッパ民族をヨーロッパ母国の植民地として服従させるためにどのように適用されたか。 ポストコロニアリズムは、植民地主義者が世界を「認識」し、「理解」し、「知る」ための理論(知的、言語的、社会的、経済的)を無力化することを目的とし ている。こうしてポストコロニアル理論は、サブ・インターンの人々が彼ら自身の声で彼ら自身のために語り、哲学、言語、社会、経済の文化的言説を生み出 し、植民地主義者と植民地主体との間の不均衡な我々と彼らとの二元的な力関係のバランスをとるための知的空間を確立するのである[要出典][2]。 アプローチ ポストコロニアリズムは多種多様なアプローチを包含しており、理論家が必ずしも共通の定義に同意するとは限らない。単純なレベルでは、人類学的研究を通じ て、植民地支配者は信頼できない語り手であるという仮定に基づき、植民地生活をよりよく理解することを目指す。より深いレベルでは、ポストコロニアリズム は、植民者と被植民者を取り巻く社会的、政治的、文化的な物語を含め、植民地主義や新植民地主義を支えている社会的、政治的な力関係を検証する。このアプ ローチは、現代史研究と重なることもあり、人類学、歴史学、政治学、哲学、社会学、人文地理学などの事例を参考にすることもある。ポストコロニアル研究の 下位分野では、植民地支配がフェミニズム、アナキズム、文学、キリスト教思想の実践に与えた影響を検証している[3]。 植民地主義という曖昧な用語は、政府のシステムを指すこともあれば、そのシステムの根底にあるイデオロギーや世界観を指すこともあるため、ポストコロニア ル研究という用語がポストコロニアリズムよりも好まれることもある。しかし、ポストコロニアリズム(すなわち、ポストコロニアル研究)は、一般的に植民地 主義思想に対するイデオロギー的な反応を示すものであり、むしろ接頭辞post-が示唆するように、植民地主義の後に来るシステムを単に記述するものでは ない。そのためポストコロニアリズムは、ポストモダニズムがモダニズムに対する反動であるのと同じように、植民地主義に対する反動、あるいは植民地主義か らの離脱であると考えることができる。ポストコロニアリズムという用語自体はポストモダニズムをモデルとしており、ポストモダニズムとは特定の概念や方法 を共有している[4]。 植民地主義的言説  オリエンタリストのアーネスト・ルナンは、『知性と道徳の改革』 (1871年)の中で、非西欧諸国民を文明化するための帝国の執政を提唱した(→エルネスト・ルナンのレイシズム)。 植民地主義は「文明の延長」として提示され、非西洋世界に対する西洋世界の自称人種的・文化的優位性をイデオロギー的に正当化した。この概念は、アーネス ト・ルナンが『知性と道徳の改革』(La Réforme intellectuelle et morale、1871年)の中で唱えたもので、帝国の統治は、世界の劣等文化圏の有色人種の知的・道徳的改革に影響を与えると考えられていた。帝国植民 地内では、誰もが文化的アイデンティティ、社会的居場所、経済的役割を与えられているため、このような神によって確立された、世界の人類種族間の自然な調 和が可能になると考えられたのである。このように[5]。 劣った民族や退化した民族が優れた民族によって再生されることは、人類にとって摂理にかなった摂理の一部である......。Regere imperio populosはわれわれの使命である。中国のように、外国からの征服を求めて声高に叫んでいる国々に、このすべてを消費する活動を注ごう。ヨーロッパ社 会を乱す冒険者たちを、フランク人、ロンゴバルド人、ノルマン人のようなヴェル・サクラム、すなわち大群に変えれば、すべての人間が正しい役割を果たすこ とになる。自然は、素晴らしい手先の器用さとほとんど名誉の感覚を持たない労働者の種族、中華民族を作った。彼らを正義をもって統治し、そのような政府の 祝福の見返りとして、彼らから征服民族のために十分な手当を徴収すれば、彼らは満足するだろう。それぞれが自分のために作られたことをすれば、すべてはう まくいく。 - 『知性と道徳の改革』(1871年)アーネスト・ルナン著 19世紀半ばから後半にかけて、このような人種主義的な集団アイデンティティの言葉は、ヨーロッパとアメリカの帝国間の地政学的競争を正当化し、拡大しす ぎた経済を守るための文化的共通通貨だった。特に極東の植民地化や19世紀末のスクランブル・フォア・アフリカでは、均質なヨーロッパ人のアイデンティ ティを示すことが植民地化を正当化した。それゆえ、ベルギーやイギリス、フランスやドイツは、未開の民族に文明の光を届けるものとして植民地主義を正当化 する民族的優越性の理論を提示した。特に、フランス帝国の自称「文明化ミッション」であるla mission civilisatriceは、ある民族や文化には人生においてより高い目的があり、それによって、より強大で、より発展し、より文明化された民族は、 「文明」という崇高な理念とその経済的利益に奉仕するために、他の民族を植民地化する権利があると提唱した[6][7]。 ポストコロニアル・アイデンティティー  アンティグア・グアテマラのスペイン植民地建築。 ポストコロニアル理論では、脱植民地化された人々は、植民地社会によってさまざまな程度の社会的権力を割り当てられたさまざまなアイデンティティ(文化 的、国民的、民族的なもの、ジェンダーや階級に基づくもの)の間の文化的相互作用に基づくポストコロニアル・アイデンティティを発達させるとしている。 [ポストコロニアル文学では、反征服の物語は、サブアルタンである植民地主体の社会的・文化的視点であるアイデンティティ・ポリティクスを分析する。植民 地の文化に対する彼らの創造的な抵抗、そのような文化的抵抗がいかに植民地社会の確立を複雑にしたか、植民地支配者がいかにポストコロニアル・アイデン ティティを発展させたか、そして新植民地主義がいかに「われわれと彼ら」という二元的な社会関係を積極的に用いて、非西洋世界を「他者」の住む世界とみな しているかを分析する。 一例として、地政学的同質性を求める新植民地主義的言説が、脱植民地化された人々やその文化、そして彼らの国を、しばしば「第三世界」のような架空の場所 に追いやることを含んでいることを考えてみよう。アフリカ、アジア、ラテンアメリカ、オセアニアなど、いくつかの大陸や海からなる広い地理的地域を漠然と 指しているのだ。第三世界とは、アフリカ、アジア、ラテンアメリカ、オセアニアなど、いくつかの大陸や海からなる広大な地理的地域を漠然と指しているので ある。この用語に対するポストコロニアル批評は、このような用語の自己正当化的な用法や、その用語が内包する言説、さらにはその言語が持つ哲学的・政治的 機能を分析するものである。アラブ人」、「第一世界」、「キリスト教」、「ウンマ」といった同質的な概念に対するポストコロニアル批評は、しばしば、その ような言葉が実際には特定された集団を代表していないことを示すことを目的としている。このような用語は、それらを構成する異質な民族、文化、地理を適切 に説明できないことが多い。世界の人々、場所、物事を正確に記述するには、ニュアンスのある正確な用語が必要である。 定義の難しさ 現代史における用語として、ポストコロニアリズムは時折、帝国列強が植民地から撤退した時期の直後を指す言葉として適用されることがある。このような用語 の適用には問題があると考えられている。というのも、直近の、歴史的、政治的な時間は、批評的アイデンティティ言説のカテゴリーには含まれないからであ る。そのため、ポストコロニアルやポストコロニアリズムという用語は、脱植民地化された世界が「矛盾の、中途半端なプロセスの、混乱の、混血性の、限界性 の」知的空間であることを示す主題の側面を示している[9]。ほとんどの批評理論に基づく研究と同様に、規範性に対する開かれた主張と相まって、主題の定 義における明確性の欠如は、ポストコロニアル言説の批評を問題とし、その独断的あるいはイデオロギー的な地位を再び主張させている[10]。  メキシコのカンペチェ市にあるカンペチェ大聖堂。 ポストコロニアル・ドラマ Theory, Practice, Politics』(1996年)において、ヘレン・ギルバートとジョアン・トンプキンスは、以下のような意味機能を明らかにしている[11]。 ポストコロニアリズムという用語は、厳密すぎる語源によれば、植民地支配が終わった後の時間、あるいは政治的に決定された独立記念日の後に、ある国が他の 国家による統治から脱却する時間を意味する時間的概念として誤解されることが多い。ポストコロニアリズムとは、植民地主義に取って代わるようなナイーブな 目的論的順序ではなく、むしろ植民地主義の言説、権力構造、社会的ヒエラルキーに関与し、それに異議を唱えることである...。ポストコロニアリズムの理 論は、単に独立後を時系列的に構築する以上のものであり、帝国主義の言説的経験以上のものでなければならない。 ポストコロニアリズムという用語は、非西洋世界の植民地化された人々に関する知の植民地政治(すなわち、知の生成、生産、流通)を支配していた経済的、文 化的、言語的な力関係の合法的な継続によって影響を受けた、脱植民地化された国に対する母国による新植民地支配を示すためにも適用される。[9][12] 植民地主義の論理の文化的、宗教的な前提は、現代社会においても積極的な慣行として残っており、かつての植民地臣民-労働力と原材料の経済的な供給源-に 対する母なる国の新植民地主義的な態度の基礎となっている[13]。 独立国を植民地化した国と結びつける非交換的な用語として機能し、独自のアイデンティティを築いた数十年後に、国から独立を奪う。 |

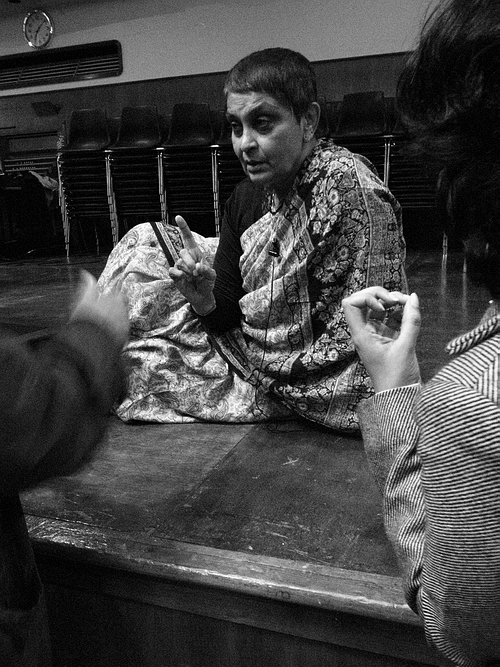

| Notable theoreticians and

theories Frantz Fanon and subjugation In The Wretched of the Earth (1961), psychiatrist and philosopher Frantz Fanon analyzes and medically describes the nature of colonialism as essentially destructive. Its societal effects—the imposition of a subjugating colonial identity—is harmful to the mental health of the native peoples who were subjugated into colonies. Fanon writes that the ideological essence of colonialism is the systematic denial of "all attributes of humanity" of the colonized people. Such dehumanization is achieved with physical and mental violence, by which the colonist means to inculcate a servile mentality upon the natives. For Fanon, the natives must violently resist colonial subjugation.[14] Hence, Fanon describes violent resistance to colonialism as a mentally cathartic practise, which purges colonial servility from the native psyche, and restores self-respect to the subjugated.[citation needed] Thus, Fanon actively supported and participated in the Algerian Revolution (1954–62) for independence from France as a member and representative of the Front de Libération Nationale.[15] As postcolonial praxis, Fanon's mental-health analyses of colonialism and imperialism, and the supporting economic theories, were partly derived from the essay "Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism" (1916), wherein Vladimir Lenin described colonial imperialism as an advanced form of capitalism, desperate for growth at all costs, and so requires more and more human exploitation to ensure continually consistent profit-for-investment.[16] Another key book that predates postcolonial theories is Fanon's Black Skins, White Masks. In this book, Fanon discusses the logic of colonial rule from the perspective of the existential experience of racialized subjectivity. Fanon treats colonialism as a total project which rules every aspect of colonized peoples and their reality. Fanon reflects on colonialism, language, and racism and asserts that to speak a language is to adopt a civilization and to participate in the world of that language. His ideas show the influence of French and German philosophy, since existentialism, phenomenology, and hermeneutics claim that language, subjectivity, and reality are interrelated. However, the colonial situation presents a paradox: when colonial beings are forced to adopt and speak an imposed language which is not their own, they adopt and participate in the world and civilization of the colonized. This language results from centuries of colonial domination which is aimed at eliminating other expressive forms in order to reflect the world of the colonizer. As a consequence, when colonial beings speak as the colonized, they participate in their own oppression and the very structures of alienation are reflected in all aspects of their adopted language.[17] Edward Said and orientalism Cultural critic Edward Said is considered by E. San Juan, Jr. as "the originator and inspiring patron-saint of postcolonial theory and discourse" due to his interpretation of the theory of orientalism explained in his 1978 book, Orientalism.[18] To describe the us-and-them "binary social relation" with which Western Europe intellectually divided the world—into the "Occident" and the "Orient"—Said developed the denotations and connotations of the term orientalism (an art-history term for Western depictions and the study of the Orient). Said's concept (which he also termed "orientalism") is that the cultural representations generated with the us-and-them binary relation are social constructs, which are mutually constitutive and cannot exist independent of each other, because each exists on account of and for the other.[19] Notably, "the West" created the cultural concept of "the East," which according to Said allowed the Europeans to suppress the peoples of the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, and of Asia in general, from expressing and representing themselves as discrete peoples and cultures. Orientalism thus conflated and reduced the non-Western world into the homogeneous cultural entity known as "the East." Therefore, in service to the colonial type of imperialism, the us-and-them orientalist paradigm allowed European scholars to represent the Oriental World as inferior and backward, irrational and wild, as opposed to a Western Europe that was superior and progressive, rational and civil—the opposite of the Oriental Other. Reviewing Said's Orientalism (1978), A. Madhavan (1993) says that "Said's passionate thesis in that book, now an 'almost canonical study', represented Orientalism as a 'style of thought' based on the antinomy of East and West in their world-views, and also as a 'corporate institution' for dealing with the Orient."[20] In concordance with philosopher Michel Foucault, Said established that power and knowledge are the inseparable components of the intellectual binary relationship with which Occidentals claim "knowledge of the Orient." That the applied power of such cultural knowledge allowed Europeans to rename, re-define, and thereby control Oriental peoples, places, and things, into imperial colonies.[12] The power-knowledge binary relation is conceptually essential to identify and understand colonialism in general, and European colonialism in particular. Hence, To the extent that Western scholars were aware of contemporary Orientals or Oriental movements of thought and culture, these were perceived either as silent shadows to be animated by the orientalist, brought into reality by them or as a kind of cultural and international proletariat useful for the orientalist's grander interpretive activity.— Orientalism (1978), p. 208.[21] Nonetheless, critics of the homogeneous "Occident–Orient" binary social relation, say that Orientalism is of limited descriptive capability and practical application, and propose instead that there are variants of Orientalism that apply to Africa and to Latin America. Said response was that the European West applied Orientalism as a homogeneous form of The Other, in order to facilitate the formation of the cohesive, collective European cultural identity denoted by the term "The West."[22] With this described binary logic, the West generally constructs the Orient subconsciously as its alter ego. Therefore, descriptions of the Orient by the Occident lack material attributes, grounded within the land. This inventive or imaginative interpretation subscribes female characteristics to the Orient and plays into fantasies that are inherent within the West's alter ego. It should be understood that this process draws creativity, amounting an entire domain and discourse. In Orientalism (p. 6), Said mentions the production of "philology [the study of the history of languages], lexicography [dictionary making], history, biology, political and economic theory, novel-writing and lyric poetry." Therefore, there is an entire industry that exploits the Orient for its own subjective purposes that lack a native and intimate understanding. Such industries become institutionalized and eventually become a resource for manifest Orientalism or a compilation of misinformation about the Orient.[23] The ideology of Empire was hardly ever a brute jingoism; rather, it made subtle use of reason and recruited science and history to serve its ends.— Rana Kabbani, Imperial Fictions: Europe's Myths of Orient (1994), p. 6 These subjective fields of academia now synthesize the political resources and think-tanks that are so common in the West today. Orientalism is self-perpetuating to the extent that it becomes normalized within common discourse, making people say things that are latent, impulsive, or not fully conscious of its own self.[24]: 49–52 Gayatri Spivak and the subaltern In establishing the Postcolonial definition of the term subaltern, the philosopher and theoretician Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak cautioned against assigning an over-broad connotation. She argues:[25] ... subaltern is not just a classy word for "oppressed", for The Other, for somebody who's not getting a piece of the pie... In postcolonial terms, everything that has limited or no access to the cultural imperialism is subaltern—a space of difference. Now, who would say that's just the oppressed? The working class is oppressed. It's not subaltern.... Many people want to claim subalternity. They are the least interesting and the most dangerous. I mean, just by being a discriminated-against minority on the university campus; they don't need the word 'subaltern'... They should see what the mechanics of the discrimination are. They're within the hegemonic discourse, wanting a piece of the pie, and not being allowed, so let them speak, use the hegemonic discourse. They should not call themselves subaltern.  Engaging the voice of the Subaltern: the philosopher and theoretician Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, at Goldsmith College. Spivak also introduced the terms essentialism and strategic essentialism to describe the social functions of postcolonialism. Essentialism denotes the perceptual dangers inherent to reviving subaltern voices in ways that might (over) simplify the cultural identity of heterogeneous social groups and, thereby, create stereotyped representations of the different identities of the people who compose a given social group. Strategic essentialism, on the other hand, denotes a temporary, essential group-identity used in the praxis of discourse among peoples. Furthermore, essentialism can occasionally be applied—by the so-described people—to facilitate the subaltern's communication in being heeded, heard, and understood, because strategic essentialism (a fixed and established subaltern identity) is more readily grasped, and accepted, by the popular majority, in the course of inter-group discourse. The important distinction, between the terms, is that strategic essentialism does not ignore the diversity of identities (cultural and ethnic) in a social group, but that, in its practical function, strategic essentialism temporarily minimizes inter-group diversity to pragmatically support the essential group-identity.[8] Spivak developed and applied Foucault's term epistemic violence to describe the destruction of non-Western ways of perceiving the world and the resultant dominance of the Western ways of perceiving the world. Conceptually, epistemic violence specifically relates to women, whereby the "Subaltern [woman] must always be caught in translation, never [allowed to be] truly expressing herself," because the colonial power's destruction of her culture pushed to the social margins her non–Western ways of perceiving, understanding, and knowing the world.[8] In June of the year 1600, the Afro–Iberian woman Francisca de Figueroa requested from the King of Spain his permission for her to emigrate from Europe to New Granada, and reunite with her daughter, Juana de Figueroa. As a subaltern woman, Francisca repressed her native African language, and spoke her request in Peninsular Spanish, the official language of Colonial Latin America. As a subaltern woman, she applied to her voice the Spanish cultural filters of sexism, Christian monotheism, and servile language, in addressing her colonial master:[26] I, Francisca de Figueroa, mulatta in colour, declare that I have, in the city of Cartagena, a daughter named Juana de Figueroa; and she has written, to call for me, in order to help me. I will take with me, in my company, a daughter of mine, her sister, named María, of the said colour; and for this, I must write to Our Lord the King to petition that he favour me with a licence, so that I, and my said daughter, can go and reside in the said city of Cartagena. For this, I will give an account of what is put down in this report; and of how I, Francisca de Figueroa, am a woman of sound body, and mulatta in colour.… And my daughter María is twenty-years-old, and of the said colour, and of medium size. Once given, I attest to this. I beg your Lordship to approve and order it done. I ask for justice in this. [On the twenty-first day of the month of June 1600, Your Majesty's Lords Presidents and Official Judges of this House of Contract Employment order that the account she offers be received, and that testimony for the purpose she requests given.]— Afro–Latino Voices: Narratives from the Early Modern Ibero–Atlantic World: 1550–1812 (2009) Moreover, Spivak further cautioned against ignoring subaltern peoples as "cultural Others", and said that the West could progress—beyond the colonial perspective—by means of introspective self-criticism of the basic ideas and investigative methods that establish a culturally superior West studying the culturally inferior non–Western peoples.[8][27] Hence, the integration of the subaltern voice to the intellectual spaces of social studies is problematic, because of the unrealistic opposition to the idea of studying "Others"; Spivak rejected such an anti-intellectual stance by social scientists, and about them said that "to refuse to represent a cultural Other is salving your conscience…allowing you not to do any homework."[27] Moreover, postcolonial studies also reject the colonial cultural depiction of subaltern peoples as hollow mimics of the European colonists and their Western ways; and rejects the depiction of subaltern peoples as the passive recipient-vessels of the imperial and colonial power of the Mother Country. Consequent to Foucault's philosophic model of the binary relationship of power and knowledge, scholars from the Subaltern Studies Collective, proposed that anti-colonial resistance always counters every exercise of colonial power. Homi K. Bhabha and hybridity In The Location of Culture (1994), theoretician Homi K. Bhabha argues that viewing the human world as composed of separate and unequal cultures, rather than as an integral human world, perpetuates the belief in the existence of imaginary peoples and places—"Christendom" and the "Islamic World", "First World," "Second World," and the "Third World." To counter such linguistic and sociological reductionism, postcolonial praxis establishes the philosophic value of hybrid intellectual spaces, wherein ambiguity abrogates truth and authenticity; thereby, hybridity is the philosophic condition that most substantively challenges the ideological validity of colonialism.[28] R. Siva Kumar and alternative modernity In 1997, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of India's Independence, "Santiniketan: The Making of a Contextual Modernism" was an important exhibition curated by R. Siva Kumar at the National Gallery of Modern Art.[29] In his catalogue essay, Kumar introduced the term Contextual Modernism, which later emerged as a postcolonial critical tool in the understanding of Indian art, specifically the works of Nandalal Bose, Rabindranath Tagore, Ramkinkar Baij, and Benode Behari Mukherjee.[30] Santiniketan artists did not believe that to be indigenous one has to be historicist either in theme or in style, and similarly to be modern one has to adopt a particular trans-national formal language or technique. Modernism was to them neither a style nor a form of internationalism. It was critical re-engagement with the foundational aspects of art necessitated by changes in one's unique historical position.[31] In the post-colonial history of art, this marked the departure from Eurocentric unilateral idea of modernism to alternative context sensitive modernisms. The brief survey of the individual works of the core Santiniketan artists and the thought perspectives they open up makes clear that though there were various contact points in the work they were not bound by a continuity of style but by a community of ideas. Which they not only shared but also interpreted and carried forward. Thus they do not represent a school but a movement.— Santiniketan: The Making of a Contextual Modernism, 1997 Several terms including Paul Gilroy's counterculture of modernity and Tani E. Barlow's Colonial modernity have been used to describe the kind of alternative modernity that emerged in non-European contexts. Professor Gall argues that 'Contextual Modernism' is a more suited term because "the colonial in colonial modernity does not accommodate the refusal of many in colonized situations to internalize inferiority. Santiniketan's artist teachers' refusal of subordination incorporated a counter vision of modernity, which sought to correct the racial and cultural essentialism that drove and characterized imperial Western modernity and modernism. Those European modernities, projected through a triumphant British colonial power, provoked nationalist responses, equally problematic when they incorporated similar essentialisms."[32] Dipesh Chakrabarty In Provincializing Europe (2000), Dipesh Chakrabarty charts the subaltern history of the Indian struggle for independence, and counters Eurocentric, Western scholarship about non-Western peoples and cultures, by proposing that Western Europe simply be considered as culturally equal to the other cultures of the world; that is, as "one region among many" in human geography.[33][34] Derek Gregory and the colonial present Derek Gregory argues the long trajectory through history of British and American colonization is an ongoing process still happening today. In The Colonial Present, Gregory traces connections between the geopolitics of events happening in modern-day Afghanistan, Palestine, and Iraq and links it back to the us-and-them binary relation between the Western and Eastern world. Building upon the ideas of the other and Said's work on orientalism, Gregory critiques the economic policy, military apparatus, and transnational corporations as vehicles driving present-day colonialism. Emphasizing ideas of discussing ideas around colonialism in the present tense, Gregory utilizes modern events such as the September 11 attacks to tell spatial stories around the colonial behavior happening due to the War on Terror.[35] Amar Acheraiou and Classical influences Acheraiou argues that colonialism was a capitalist venture moved by appropriation and plundering of foreign lands and was supported by military force and a discourse that legitimized violence in the name of progress and a universal civilizing mission. This discourse is complex and multi-faceted. It was elaborated in the 19th century by colonial ideologues such as Ernest Renan and Arthur de Gobineau, but its roots reach far back in history. In Rethinking Postcolonialism: Colonialist Discourse in Modern Literature and the Legacy of Classical Writers, Acheraiou discusses the history of colonialist discourse and traces its spirit to ancient Greece, including Europe's claim to racial supremacy and right to rule over non-Europeans harboured by Renan and other 19th-century colonial ideologues. He argues that modern colonial representations of the colonized as "inferior," "stagnant," and "degenerate" were borrowed from Greek and Latin authors like Lysias (440–380 BC), Isocrates (436–338 BC), Plato (427–327 BC), Aristotle (384–322 BC), Cicero (106–43 BC), and Sallust (86–34 BC), who all considered their racial others—the Persians, Scythians, Egyptians as "backward," "inferior," and "effeminate."[36] Among these ancient writers Aristotle is the one who articulated more thoroughly these ancient racial assumptions, which served as a source of inspiration for modern colonists. In The Politics, he established a racial classification and ranked the Greeks superior to the rest. He considered them as an ideal race to rule over Asian and other 'barbarian' peoples, for they knew how to blend the spirit of the European "war-like races" with Asiatic "intelligence" and "competence."[37] Ancient Rome was a source of admiration in Europe since the enlightenment. In France, Voltaire (1694-1778) was one of the most fervent admirers of Rome. He regarded highly the Roman republican values of rationality, democracy, order and justice. In early-18th century Britain, it was poets and politicians like Joseph Addison (1672–1719) and Richard Glover (1712 –1785) who were vocal advocates of these ancient republican values. It was in the mid-18th century that ancient Greece became a source of admiration among the French and British. This enthusiasm gained prominence in the late-eighteenth century. It was spurred by German Hellenist scholars and English romantic poets, who regarded ancient Greece as the matrix of Western civilization and a model of beauty and democracy. These included: Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768), Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835), and Goethe (1749–1832), Lord Byron (1788–1824), Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834), Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822), and John Keats (1795–1821).[36][38] In the 19th century, when Europe began to expand across the globe and establish colonies, ancient Greece and Rome were used as a source of empowerment and justification to Western civilizing mission. At this period, many French and British imperial ideologues identified strongly with the ancient empires and invoked ancient Greece and Rome to justify the colonial civilizing project. They urged European colonizers to emulate these "ideal" classical conquerors, whom they regarded as "universal instructors." For Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859), an ardent and influential advocate of la "Grande France," the classical empires were model conquerors to imitate. He advised the French colonists in Algeria to follow the ancient imperial example. In 1841, he stated:[39] [W]hat matters most when we want to set up and develop a colony is to make sure that those who arrive in it are as less estranged as possible, that these newcomers meet a perfect image of their homeland....the thousand colonies that the Greeks founded on the Mediterranean coasts were all exact copies of the Greek cities on which they had been modelled. The Romans established in almost all parts of the globe known to them municipalities which were no more than miniature Romes. Among modern colonizers, the English did the same. Who can prevent us from emulating these European peoples?. The Greeks and Romans were deemed exemplary conquerors and "heuristic teachers,"[36] whose lessons were invaluable for modern colonists ideologues. John-Robert Seeley (1834-1895), a history professor at Cambridge and proponent of imperialism stated in a rhetoric which echoed that of Renan that the role of the British Empire was 'similar to that of Rome, in which we hold the position of not merely of ruling but of an educating and civilizing race."[40] The incorporation of ancient concepts and racial and cultural assumptions into modern imperial ideology bolstered colonial claims to supremacy and right to colonize non-Europeans. Because of these numerous ramifications between ancient representations and modern colonial rhetoric, 19th century's colonialist discourse acquires a "multi-layered" or "palimpsestic" structure.[36] It forms a "historical, ideological and narcissistic continuum," in which modern theories of domination feed upon and blend with "ancient myths of supremacy and grandeur."[36] |

著名な理論家と理論 フランツ・ファノンと被支配 精神科医であり哲学者でもあるフランツ・ファノンは、『The Wretched of the Earth』(1961年)の中で、植民地主義が本質的に破壊的であることを分析し、医学的に説明している。その社会的影響、すなわち服従させる植民地的 アイデンティティの押し付けは、植民地に服従させられた先住民の精神的健康に有害である。ファノンは、植民地主義のイデオロギー的本質は、植民地化された 人々の「人間性のあらゆる属性」を体系的に否定することだと書いている。このような非人間化は肉体的・精神的暴力によって達成され、植民地主義者はそれに よって原住民に隷属的なメンタリティを植え付けることを意味する。 ファノンにとって、原住民は植民地支配に暴力的に抵抗しなければならない。それゆえ、ファノンは植民地主義に対する暴力的抵抗を、原住民の精神から植民地 的隷属性を浄化し、被支配者に自尊心を回復させる精神的カタルシスとして描写している。 ポストコロニアルの実践として、植民地主義と帝国主義に対するファノンの精神衛生的な分析、そしてそれを支える経済理論は、ウラジーミル・レーニンが植民 地帝国主義を資本主義の高度な形態であり、あらゆる犠牲を払ってでも成長しようと必死であり、そのため継続的に一貫した投資利益を確保するために、より多 くの人間的搾取を必要とすると述べたエッセイ『帝国主義、資本主義の最高段階』(1916年)から部分的に派生したものであった[16]。 ポストコロニアル理論に先駆けて書かれたもう一つの重要な本は、ファノンの『黒い皮、白い仮面』である。この本でファノンは、人種的主体性の実存的経験の 観点から植民地支配の論理を論じている。ファノンは植民地主義を、植民地化された人々とその現実のあらゆる側面を支配する総合的なプロジェクトとして扱っ ている。ファノンは植民地主義、言語、人種差別について考察し、ある言語を話すことはある文明を採用することであり、その言語の世界に参加することである と主張する。実存主義、現象学、解釈学は、言語、主観性、現実が相互に関連していると主張するからである。しかし、植民地的状況はパラドックスを提示す る。植民地的存在が、自分たちのものではない押しつけられた言語を採用し、話すことを強いられるとき、彼らは被植民地の世界と文明を採用し、それに参加す る。この言語は、何世紀にもわたる植民地支配の結果生じたものであり、植民地支配者の世界を反映するために、他の表現形式を排除することを目的としてい る。その結果、植民地的存在が被植民者として話すとき、彼らは自らの抑圧に参加し、疎外の構造そのものが彼らの採用する言語のあらゆる側面に反映されるの である[17]。 エドワード・サイードとオリエンタリズム 文化批評家エドワード・サイードは、1978年の著書『オリエンタリズム』で説明されたオリエンタリズム理論の解釈により、E.サンファンJr.によって 「ポストコロニアルの理論と言説の創始者であり、鼓舞する守護聖人」とみなされている。 [18] 西ヨーロッパが知的に世界を「西洋」と「東洋」に分けていた「二元的な社会関係」を説明するために、サイードはオリエンタリズム(西洋の描写と東洋の研究 を指す美術史用語)という言葉の意味合いと含蓄を発展させた。サイードの概念(彼は「オリエンタリズム」とも呼んでいた)は、われわれと彼らという二元的 な関係によって生み出される文化的表象は社会的構築物であり、相互に構成的であり、互いに独立して存在することはできないというものである。 特筆すべきは、「西洋」が「東洋」という文化的概念を作り出したことであり、サイードによれば、ヨーロッパ人は中東、インド亜大陸、そしてアジア全般の人 びとが、自分たちを個別の民族や文化として表現したり表現したりすることを抑圧することができた。こうしてオリエンタリズムは、非西洋世界を混同し、"東 洋 "として知られる均質な文化的存在に縮小した。したがって、植民地型の帝国主義に奉仕するため、我々と彼らというオリエンタリズムのパラダイムによって、 ヨーロッパの学者たちは東洋の世界を劣等で後進的、非合理的で野蛮なものとして表現することができた。 サイードの『オリエンタリズム』(1978年)を評して、A. Madhavan(1993年)は、「サイードのこの本における情熱的なテーゼは、現在では『ほとんど正典的な研究』となっているが、オリエンタリズム を、その世界観における東洋と西洋のアンチノミーに基づく『思考のスタイル』として、また東洋を扱うための『企業制度(corporate institution)』として表現していた」と述べている [20]。 哲学者ミシェル・フーコーと一致して、サイードは権力と知識が、西洋人が "東洋の知識 "を主張する知的二元関係の不可分の構成要素であることを立証した。そのような文化的知識の応用力によって、ヨーロッパ人は東洋の人々、場所、事物を帝国 植民地へと改名し、再定義し、それによって支配することができたのである[12]。権力と知識の二項関係は、植民地主義全般、とりわけヨーロッパの植民地 主義を特定し理解するために概念的に不可欠である。それゆえ 西洋の学者が現代の東洋人や東洋の思想や文化の動きを認識している限り において、それらはオリエンタリストによって動かされ、現実にもたらされる無言の影 として、あるいはオリエンタリストの壮大な解釈活動に役立つ一種の文化的・国際的プロレタリアートとして認識されていた。 - 『オリエンタリズム』(1978年)、208頁[21]。 それにもかかわらず、同質的な「西洋と東洋」の二元的な社会関係に対する批判者たちは、オリエンタリズムは限定的な記述能力と実践的な応用に過ぎないと し、代わりにアフリカやラテンアメリカに適用されるオリエンタリズムの変種が存在することを提案している。その回答は、ヨーロッパ西側は、「西側」という 用語によって示される凝集的で集団的なヨーロッパ文化的アイデンティティの形成を促進するために、「他者」の同質的な形態としてオリエンタリズムを適用し たというものであった[22]。 このように説明された二元論的な論理によって、西洋は一般的にオリエントをその分身として無意識のうちに構築している。したがって、西洋人によるオリエン トの描写は、土地に根ざした物質的な属性を欠いている。この独創的あるいは想像的な解釈は、オリエントに女性の特徴を付け加え、西洋の分身に内在する空想 の世界に入り込む。このプロセスが創造性を引き出し、一つの領域と言説を形成していることを理解すべきである。 サイードは『オリエンタリズム』(p.6)の中で、「言語学(言語史の研究)、辞書学(辞書の作成)、歴史学、生物学、政治経済理論、小説の執筆、抒情 詩」の生産について言及している。したがって、東洋を自らの主観的な目的のために搾取する産業全体が存在するのであり、それは土着的で親密な理解を欠いて いる。そのような産業は制度化され、やがて顕在化したオリエンタリズムのための資源、あるいはオリエントに関する誤った情報の集大成となる[23]。 帝国のイデオロギーは決して粗野なジンゴイズムではなく、むしろ理性を 微妙に利用し、その目的のために科学と歴史を利用した。- Rana Kabbani, Imperial Fictions: ヨーロッパの東洋神話 (1994), p. 6 このような主体的な学問分野が、今日の西洋で一般的な政治的資源やシンクタンクを総合している。オリエンタリズムは、それが一般的な言説の中で常態化し、 人々に潜在的な、衝動的な、あるいは自己を十分に意識していないことを言わせる限りにおいて、自己増殖的である[24]: 49-52 ガヤトリ・スピヴァクとサバルタン 哲学者であり理論家でもあるガヤトリ・チャクラヴォルティ・スピヴァクは、ポストコロニアルにおけるサバルタンという用語の定義を確立する際、過度に広範 な意味合いを持たせることに注意を促した。彼女は次のように論じている[25]。 ...サバルタンとは、単に「抑圧された者」、「他者」、「パイの一部を得ていない者」を意味する上品な言葉ではない...。ポストコロニアル的な言い方 をすれば、文化的帝国主義へのアクセスが制限されている、あるいは全くないものすべてが、差異の空間であるサバルタンなのだ。では、それが被抑圧者だけだ と言う人はいるだろうか?労働者階級は抑圧されている。それはサブ・インターンではない。多くの人々がサブアルタン性を主張したがる。彼らは最も興味深く なく、最も危険な存在だ。つまり、大学のキャンパスで差別され、マイノリティであるだけで、"subaltern "という言葉は必要ないのだ。彼らは差別のメカニズムを知るべきだ。彼らは覇権的な言説の中にいて、パイの一部を欲しがっているのに、それが許されない。 彼らは自らをサバルタンと呼ぶべきではない。  哲学者であり理論家のガヤトリ・チャクラヴォルティ・スピヴァク。 スピヴァクはまた、ポストコロニアリズムの社会的機能を説明するために、本質主義と戦略的本質主義という言葉を紹介した。 本質主義とは、異質な社会集団の文化的アイデンティティを(過度に)単純化し、それによって、ある社会集団を構成する人々のさまざまなアイデンティティを ステレオタイプ化するような形で、サブ・インターンの声を復活させることに内在する知覚的危険性を示す。一方、戦略的本質主義は、民族間の言説の実践に用 いられる一時的で本質的な集団アイデンティティを示す。さらに、戦略的本質主義(固定され、確立されたサバルタン・アイデンティティ)は、集団間の言説の 過程において、大衆的多数派により容易に把握され、受け入れられるからである。この2つの用語の重要な違いは、戦略的本質主義は社会集団におけるアイデン ティティ(文化的、民族的)の多様性を無視するのではなく、その実際的な機能において、戦略的本質主義は本質的な集団アイデンティティを実際的に支持する ために集団間の多様性を一時的に最小化するということである[8]。 スピヴァクはフーコーの認識論的暴力という用語を発展させ、それを応用して、非西洋的な世界認識の方法の破壊と、その結果として生じる西洋的な世界認識の 方法の支配を記述している。概念的には、認識論的暴力は特に女性に関連しており、それによって「サバルタン(女性)は常に翻訳に巻き込まれなければなら ず、真に自己を表現することは決して[許されない]。 1600年6月、アフロ・イベリアの女性フランシスカ・デ・フィゲロアは、スペイン国王にヨーロッパからニュー・グラナダに移住し、娘のフアナ・デ・フィ ゲロアと再会する許可を求めた。フランシスカはサブ・インターンの女性として、母国語であるアフリカ語を抑圧し、植民地時代のラテンアメリカの公用語で あった半島スペイン語で要望を述べた。従属的な女性として、彼女は植民地の主人に向かって、性差別、キリスト教の一神教、隷属的な言語というスペイン文化 のフィルターを自分の声に適用した[26]。 私、フランシスカ・デ・フィゲロアは、ムラタの血を引いていますが、カ ルタヘナ市にフアナ・デ・フィゲロアという娘がいます。そのため、私は国王に手紙を 書き、私に免許を与え、私と娘がカルタヘナの町に行き、住むことができるようにすることを請願します。そのために、私はこの報告書に書かれていることを説 明し、私フランシスカ・デ・フィゲロアがいかに健康な体つきの女性であり、色もムラータであるか......そして私の娘マリアは20歳で、同じ色をして おり、中くらいの大きさであることを説明します。私はこれを証明します。どうか閣下のご承認とご命令をお願いいたします。私は正義を求めます。[1600 年6月21日、本雇用契約院の議長閣下および正式な裁判官閣下は、彼女が申し出た説明を受理し、彼女が要求した目的のための証言を行うよう命ずる]。 - アフロ・ラティーノの声: Narratives from the Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic World: 1550-1812 (2009) さらにスピヴァクは、「文化的他者」としてのサブ・インターンの人々を無視することを戒め、文化的に優れた西洋が文化的に劣った非西洋の人々を研究する基 本的な考え方や調査方法を内省的に自己批判することによって、西洋は植民地的な視点を超えて進歩することができると述べている[8][27]。 [スピヴァクは社会科学者のこのような反知性的な姿勢を否定し、社会科学者について「文化的他者を代表することを拒否することは、自分の良心を癒すことで あり......宿題をしないことを可能にする」と述べている。 「さらに、ポストコロニアル研究は、サブ・インターンの人々をヨーロッパの植民者と彼らの西洋的なやり方の空虚な模倣者として植民地文化的に描写すること を拒否し、サブ・インターンの人々を母なる国の帝国的・植民地的権力の受動的な受け皿として描写することを拒否している。権力と知識の二項対立関係という フーコーの哲学的モデルを受けて、サブアタールン・スタディーズ・コレクティブの学者たちは、反植民地的抵抗は常に植民地権力のあらゆる行使に対抗するも のであると提唱した。 ホミ・K・バーバとハイブリディティ 理論家のホミ・K・バーバは、『The Location of Culture』(1994年)の中で、人間の世界を統合された人間の世界としてではなく、別個の不平等な文化によって構成されたものとみなすことは、 「キリスト教世界」と「イスラム世界」、「第一世界」、「第二世界」、「第三世界」といった架空の民族や場所の存在に対する信念を永続させるものだと論じ ている。このような言語学的・社会学的な還元主義に対抗するために、ポストコロニアルの実践は、曖昧さが真実と真正性を奪うハイブリッドな知的空間の哲学 的価値を確立する。 R. シヴァ・クマールとオルタナティブ・モダニティ 1997年、インド独立50周年を記念して「サンティニケタン」が出版された: クマールはカタログのエッセイの中で、コンテクスチュアル・モダニズムと いう言葉を紹介し、後にインド美術、特にナンダラール・ボース、ラビンドラナー ト・タゴール、ラムキンカル・バイジ、ベノデ・ベハリ・ムカルジーの作品を理解する上でポストコロニアル批評のツールとして登場した[30]。 サンティニケタンの芸術家たちは、土着的であるためにはテーマも様式も歴史主義的でなければならず、同様に近代的であるためには国を超えた特定の形式言語 や技法を採用しなければならないとは考えていなかった。彼らにとってモダニズムとは、スタイルでも国際主義でもなかった。それは、独自の歴史的立場の変化 によって必要とされた、芸術の基礎的側面への批判的な再挑戦であった[31]。 ポストコロニアル美術史において、これはヨーロッパ中心主義的な一方的なモダニズムの考え方から、文脈に敏感な代替的なモダニズムへの出発を示すもので あった。 サンティニケタンの中心的な芸術家たちの個々の作品と、それらが切り開 いた思想的展望を簡単に概観すると、作品にはさまざまな接点があったものの、彼らは 様式の連続性によってではなく、思想の共同体によって結びついていたことが明らかになる。彼らはそれを共有するだけでなく、解釈し、継承していった。この ように、彼らはひとつの流派ではなく、ひとつの運動を表しているのである。- 『サンティニケタン 文脈的モダニズムの形成』1997年 ポール・ギルロイのカウンターカルチャー・オブ・モダニティやタニ・E・バーロウのコロニアル・モダニティなど、いくつかの用語は、非ヨーロッパ的な文脈 で生まれたオルタナティブなモダニティを表現するために使われてきた。ギャル教授は、「植民地的モダニティにおける植民地的とは、植民地化された状況にお ける多くの人々が劣等感を内面化することを拒否していることに対応するものではない」ため、「文脈的モダニズム」の方がより適切な用語であると主張してい る。サンティニケタンの芸術家教師たちの従属の拒否は、帝国的な西洋近代とモダニズムを牽引し特徴づけていた人種的・文化的本質主義を正そうとする、近代 に対する対抗的なヴィジョンを組み込んでいた。勝利したイギリスの植民地権力を通して投影されたそれらのヨーロッパの近代性は、ナショナリストの反応を引 き起こしたが、それらが同様の本質主義を取り入れたとき、同様に問題となった」[32]。 ディペシュ・チャクラバーティ Dipesh Chakrabartyは『Provincializing Europe』(2000年)の中で、インドの独立闘争のサブアルターンの歴史を描き、非西洋の民族や文化についてのヨーロッパ中心主義的な西洋の学問に 対抗し、西ヨーロッパを単に世界の他の文化と文化的に等しいものとして、つまり人文地理学における「数ある地域の中の一つの地域」として考えることを提案 している[33][34]。 デレク・グレゴリーと植民地的現在 デレク・グレゴリーは、イギリスとアメリカの植民地化の歴史における長い軌跡は、現在も進行中のプロセスであると主張している。植民地的現在』の中でグレ ゴリーは、現代のアフガニスタン、パレスチナ、イラクで起きている出来事の地政学的つながりをたどり、それを西洋と東洋の二元的な関係に結びつけている。 グレゴリーは、他者やサイードのオリエンタリズムに関する著作を土台に、経済政策、軍事機構、多国籍企業が、現在の植民地主義を推進する手段であると批判 する。現在時制で植民地主義をめぐる思想を論じることに重点を置くグレゴリーは、9月11日の同時多発テロのような現代の出来事を利用し、対テロ戦争に よって起きている植民地的な振る舞いをめぐる空間的な物語を語る[35]。 アマール・アチェライウと古典の影響 アチェライオウは、植民地主義は外国の土地の収奪と略奪によって動かされた資本主義的な事業であり、軍事力と、進歩と普遍的な文明化の使命の名の下に暴力 を正当化する言説によって支えられていたと主張する。この言説は複雑で多面的である。この言説は、19世紀にエルネスト・ルナンやアルチュール・ド・ゴビ ノーといった植民地イデオローグによって練り上げられたが、そのルーツははるか昔に遡る。 『ポストコロニアリズムを再考する: 現代文学における植民地主義的言説と古典作家の遺産』において、アチェライオは植民地主義的言説の歴史を論じ、その精神を古代ギリシャにまで遡る。彼は、 被植民者を「劣等」「停滞」「退化」とみなす現代の植民地的表現は、リュシアス(紀元前440-380年)、イソクラテス(紀元前436-338年)のよ うなギリシアやラテンの作家から借用したものだと主張する、 プラトン(BC427-327)、アリストテレス(BC384-322)、キケロ(BC106-43)、サッルスト(BC86-34)のようなギリシア人 とラテン人の作家たちから借用したもので、彼らは皆、自分たちの人種であるペルシャ人、スキタイ人、エジプト人を「後進的」「劣等」「女々しい」と考えて いた。 "[36] これらの古代の作家の中で、アリストテレスは、このような古代の人種的前提をより徹底的に明確化した人物であり、それは近代の植民地主義者のインスピレー ションの源となった。政治学』において、彼は人種分類を確立し、ギリシア人を他より優れた人種と位置づけた。彼らはヨーロッパの「戦争のような民族」の精 神とアジアの「知性」と「能力」を融合させる方法を知っていたからである[37]。 古代ローマは、啓蒙時代以降のヨーロッパにおいて称賛の的であった。フランスでは、ヴォルテール(1694-1778)が最も熱心なローマ崇拝者の一人で あった。彼は合理性、民主主義、秩序、正義といったローマの共和制的価値を高く評価していた。18世紀初頭のイギリスでは、ジョセフ・アジソン(1672 -1719)やリチャード・グラバー(1712-1785)のような詩人や政治家が、こうした古代共和制の価値を声高に唱えていた。 古代ギリシアがフランス人やイギリス人の憧れの的となったのは、18世紀半ばのことだった。この熱狂は18世紀後半に顕著になった。古代ギリシアを西洋文 明の母体、美と民主主義の模範とみなしたドイツのヘレニスト学者やイギリスのロマン派詩人たちによって拍車がかかった。その中には次のような人物が含まれ る: ヨハン・ヨアヒム・ヴィンケルマン(1717年-1768年)、ヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルト(1767年-1835年)、ゲーテ(1749年- 1832年)、バイロン卿(1788年-1824年)、サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジ(1772年-1834年)、パーシー・ビシェ・シェリー (1792年-1822年)、ジョン・キーツ(1795年-1821年)などである[36][38]。 19世紀、ヨーロッパが世界中に拡大し、植民地を築き始めたとき、古代ギリシャとローマは、西洋文明化の使命に力を与え、正当化する源として利用された。 この時期、フランスとイギリスの帝国イデオローグの多くは古代帝国と強く結びつき、植民地文明化事業を正当化するために古代ギリシャとローマを持ち出し た。彼らはヨーロッパの植民者たちに、"普遍的な指導者 "とみなしたこれらの "理想的な "古典的征服者たちに倣うよう促した。 「大フランス」の熱烈かつ有力な支持者であったアレクシス・ド・トクヴィル(1805-1859)にとって、古典帝国は模倣すべき模範的な征服者であっ た。 彼はアルジェリアのフランス人入植者たちに、古代の帝国に倣うよう助言した。1841年、彼は次のように述べている[39]。 [植民地を設立し、発展させようとするときに最も重要なことは、そこに 到着する人々ができるだけ疎遠にならないようにすることである。ローマ人は地球上の ほとんどの地域に、ローマ帝国のミニチュアにすぎない自治体を建設した。近代の植民地支配者の中では、イギリス人が同じことをした。私たちがこれらのヨー ロッパの民族を模倣することを、誰が妨げることができようか? ギリシア人とローマ人は模範的な征服者であり、「発見的な教師」[36]であり、その教訓は近代の植民地主義者のイデオローグにとってかけがえのないもの であった。ケンブリッジ大学の歴史学教授であり、帝国主義の支持者であったジョン=ロバート・シーリー(1834-1895)は、ルナンと呼応するような レトリックで、大英帝国の役割は「ローマのそれに似ている。 古代の概念や人種的・文化的前提を近代帝国のイデオロギーに組み込むことで、覇権と非ヨーロッパ人を植民地化する権利に対する植民地の主張が強化された。 古代の表象と近代的な植民地主義的レトリックの間にはこのような数多くの関連性があるため、19世紀の植民地主義的言説は「多層的」あるいは「パリンプス ティック」な構造を獲得している[36]。 それは「歴史的、イデオロギー的、自己愛的な連続体」を形成しており、そこでは近代的な支配の理論が「覇権と壮大さに関する古代の神話」[36]を糧と し、それと融合している。 |

| Postcolonial literary study As a literary theory, postcolonialism deals with the literatures produced by the peoples who once were colonized by the European imperial powers (e.g. Britain, France, and Spain) and the literatures of the decolonized countries engaged in contemporary, postcolonial arrangements (e.g. Organisation internationale de la Francophonie and the Commonwealth of Nations) with their former mother countries.[41][42] Postcolonial literary criticism comprehends the literatures written by the colonizer and the colonized, wherein the subject matter includes portraits of the colonized peoples and their lives as imperial subjects. In Dutch literature, the Indies Literature includes the colonial and postcolonial genres, which examine and analyze the formation of a postcolonial identity, and the postcolonial culture produced by the diaspora of the Indo-European peoples, the Eurasian folk who originated from Indonesia; the peoples who were the colony of the Dutch East Indies; in the literature, the notable author is Tjalie Robinson.[43] Waiting for the Barbarians (1980) by J. M. Coetzee depicts the unfair and inhuman situation of people dominated by settlers. To perpetuate and facilitate control of the colonial enterprise, some colonized people, especially from among the subaltern peoples of the British Empire, were sent to attend university in the Imperial Motherland; they were to become the native-born, but Europeanised, ruling class of colonial satraps. Yet, after decolonization, their bicultural educations originated postcolonial criticism of empire and colonialism, and of the representations of the colonist and the colonized. In the late 20th century, after the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, the constituent Soviet Socialist Republics became the literary subjects of postcolonial criticism, wherein the writers dealt with the legacies (cultural, social, economic) of the Russification of their peoples, countries, and cultures in service to Greater Russia.[44] Postcolonial literary study is in two categories: 1. the study of postcolonial nations; and 2. the study of the nations who continue forging a postcolonial national identity. The first category of literature presents and analyzes the internal challenges inherent to determining an ethnic identity in a decolonized nation. The second category of literature presents and analyzes the degeneration of civic and nationalist unities consequent to ethnic parochialism, usually manifested as the demagoguery of "protecting the nation," a variant of the us-and-them binary social relation. Civic and national unity degenerate when a patriarchal régime unilaterally defines what is and what is not "the national culture" of the decolonized country: the nation-state collapses, either into communal movements, espousing grand political goals for the postcolonial nation; or into ethnically mixed communal movements, espousing political separatism, as occurred in decolonized Rwanda, the Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo; thus the postcolonial extremes against which Frantz Fanon warned in 1961. |

ポストコロニアル文学研究 文学理論としてのポストコロニアリズムは、かつてヨーロッパの帝国列強(イギリス、フランス、スペインなど)によって植民地化された人々によって生み出さ れた文学と、かつての母国と現代のポストコロニアル協定(国際フランコフォニー機構や英連邦など)を結んでいる脱植民地化された国々の文学を扱う[41] [42]。 ポストコロニアル文学批評は、植民地化した側と植民地化された側によって書かれた文学を包括するものであり、その主題には植民地化された人々の肖像や帝国 臣民としての彼らの生活が含まれる。オランダ文学では、植民地文学とポストコロニアル文学のジャンルがあり、ポストコロニアル・アイデンティティの形成 や、インドネシアを起源とするユーラシア系民族、つまりオランダ領東インドの植民地であったインド・ヨーロッパ系民族のディアスポラによって生み出された ポストコロニアル文化を検証・分析している。 [43]J・M・クッツェーの『野蛮人を待ちながら』(1980年)は、入植者によって支配される人々の不公平で非人間的な状況を描いている。 植民地事業を永続させ、支配を容易にするために、植民地化された人々、特に大英帝国のサブ・インターンの中から何人かが祖国の大学に送られた。しかし、脱 植民地化後、彼らのバイカルチュラルな教育は、帝国と植民地主義、そして植民者と被植民者の表象に対するポストコロニアル批判を生み出した。20世紀後 半、1991年のソ連邦解体後、ソビエト社会主義共和国の構成国はポストコロニアル批評の文学的主題となり、作家たちは大ロシアのために自国の民族、国、 文化をロシア化した遺産(文化、社会、経済)を扱った[44]。 ポストコロニアル文学研究には2つのカテゴリーがある: 1. ポストコロニアル諸国民の研究 2. ポストコロニアルな国民のアイデンティティを鍛え上げる(=捏造する)の国民の研究 第1のカテゴリーの文学は、脱植民地化された国家において民族的アイデンティティを決定するために内在する内的課題を提示し、分析する。 第二のカテゴリーは、民族偏狭主義に起因する市民的・民族主義的団結の堕落を提示・分析するもので、通常、「国家を守る」というデマゴギーとして現れる。 何が脱植民地化された国の「国民文化」であり、何がそうでないかを家父長制的な体制が一方的に定義するとき、市民的・国民的団結は堕落する: 脱植民地化されたルワンダ、スーダン、コンゴ民主共和国で起こったように、政治的分離主義を主張する民族混合の共同体運動へと、国民国家は崩壊する。 |

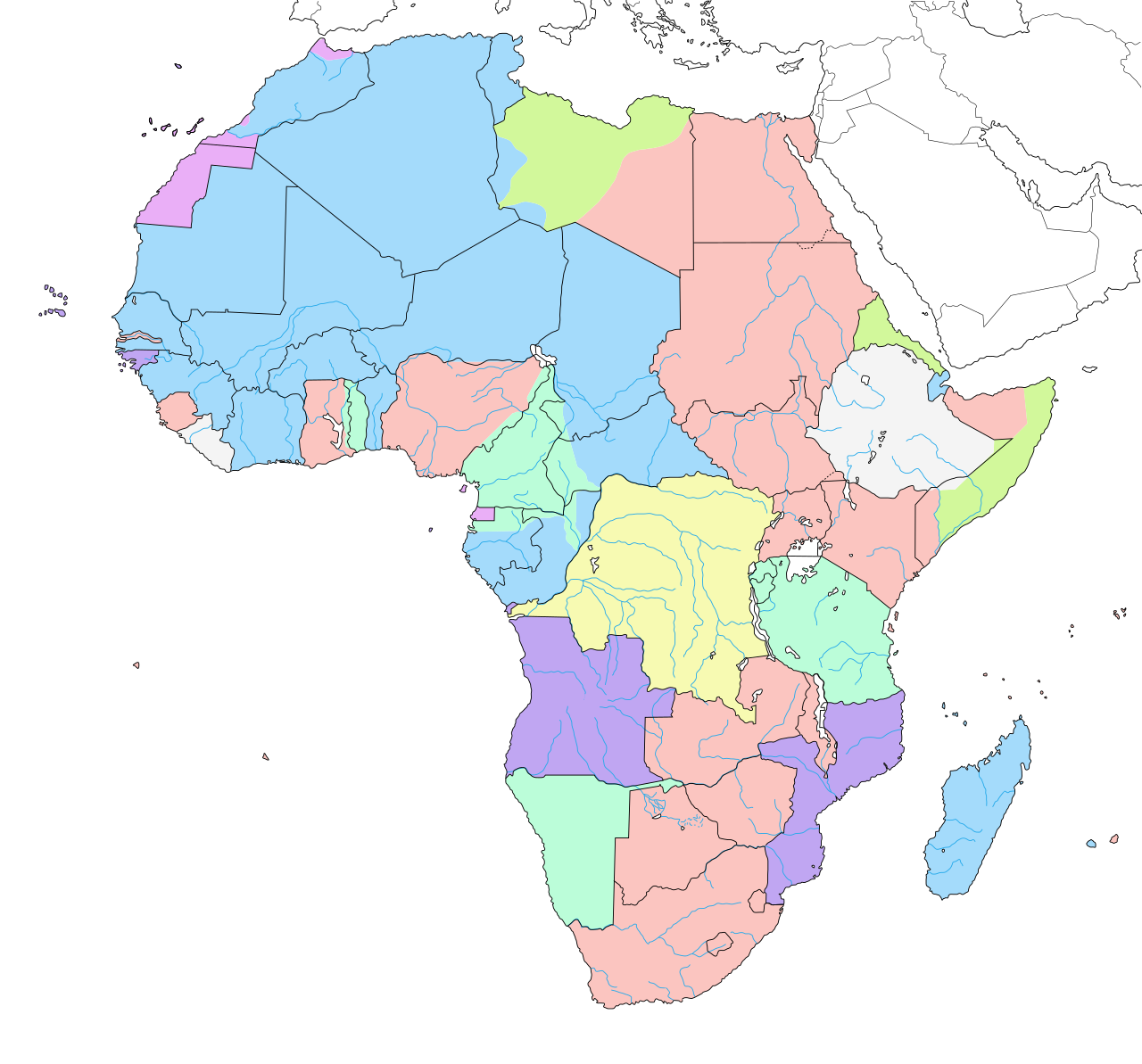

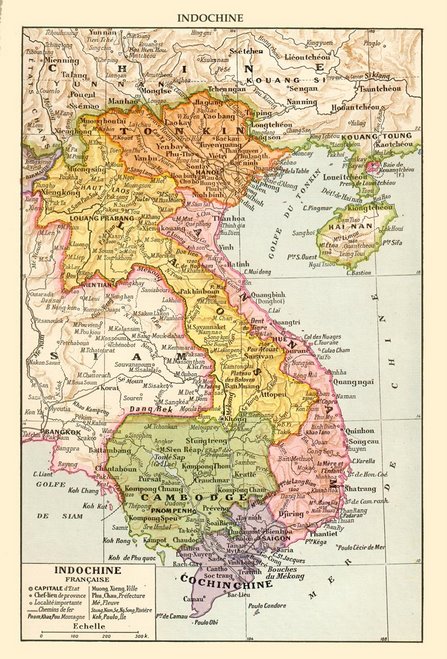

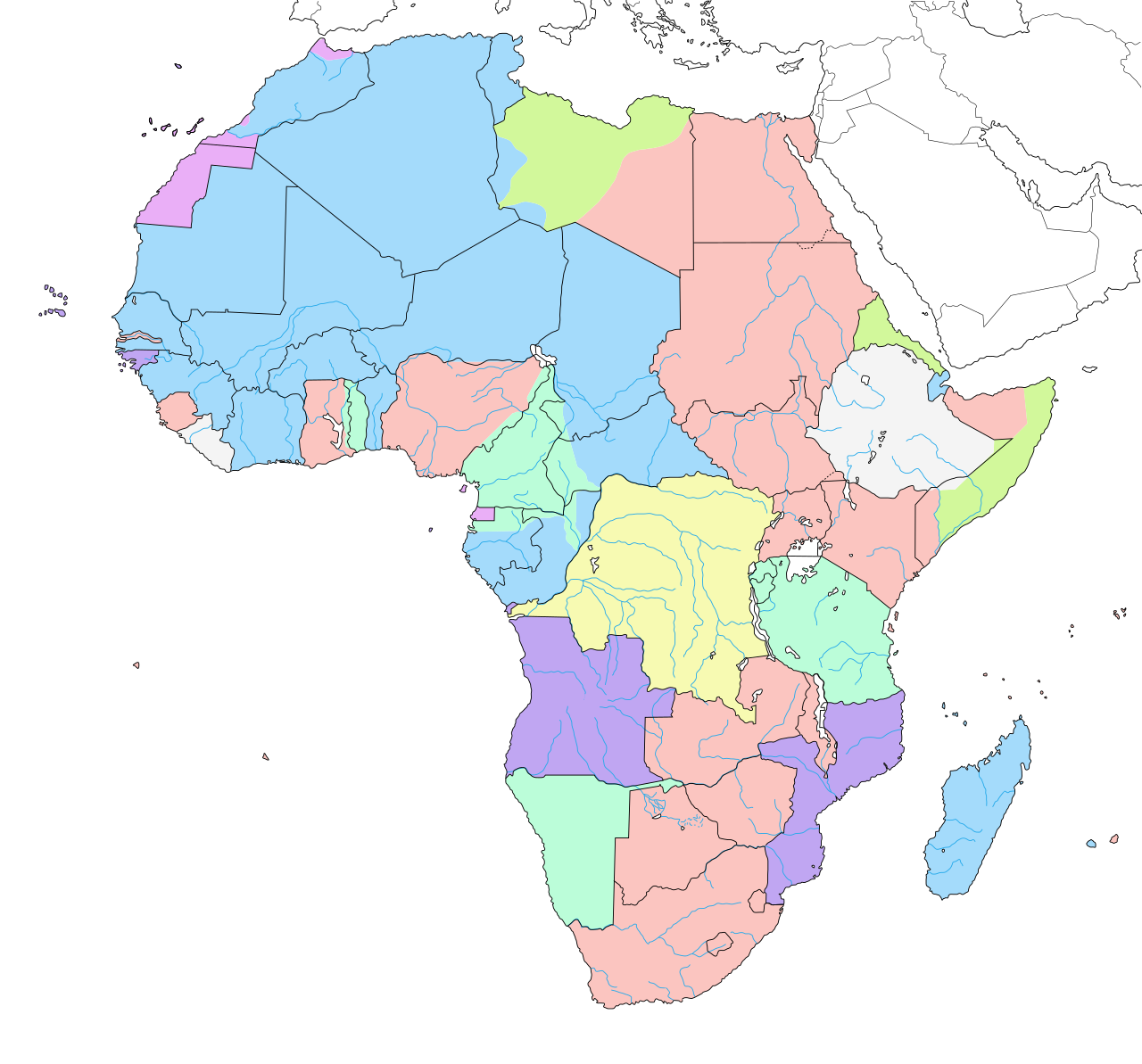

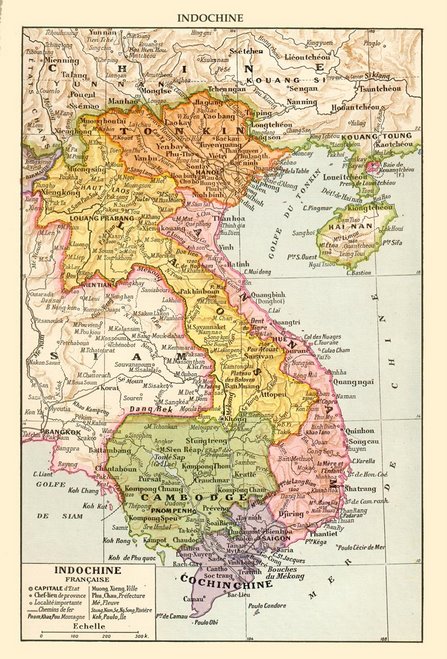

| Application Middle East In the essay "Overstating the Arab State" (2001) by Nazih Ayubi, the author deals with the psychologically-fragmented postcolonial identity, as determined by the effects (political and social, cultural and economic) of Western colonialism in the Middle East. As such, the fragmented national identity remains a characteristic of such societies, consequence of the imperially convenient, but arbitrary, colonial boundaries (geographic and cultural) demarcated by the Europeans, with which they ignored the tribal and clan relations that determined the geographic borders of the Middle East countries, before the arrival of European imperialists.[45] Hence, the postcolonial literature about the Middle East examines and analyzes the Western discourses about identity formation, the existence and inconsistent nature of a postcolonial national-identity among the peoples of the contemporary Middle East.[46]  "The Middle East" is the Western name for the countries of South-western Asia. In his essay "Who Am I?: The Identity Crisis in the Middle East" (2006), P.R. Kumaraswamy says: Most countries of the Middle East, suffered from the fundamental problems over their national identities. More than three-quarters of a century after the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, from which most of them emerged, these states have been unable to define, project, and maintain a national identity that is both inclusive and representative.[47] Independence and the end of colonialism did not end social fragmentation and war (civil and international) in the Middle East.[46] In The Search for Arab Democracy: Discourses and Counter-Discourses (2004), Larbi Sadiki says that the problems of national identity in the Middle East are a consequence of the orientalist indifference of the European empires when they demarcated the political borders of their colonies, which ignored the local history and the geographic and tribal boundaries observed by the natives, in the course of establishing the Western version of the Middle East. In the event:[47] [I]n places like Iraq and Jordan, leaders of the new sovereign states were brought in from the outside, [and] tailored to suit colonial interests and commitments. Likewise, most states in the Persian Gulf were handed over to those [Europeanised colonial subjects] who could protect and safeguard imperial interests in the post-withdrawal phase. Moreover, "with notable exceptions like Egypt, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, most [countries]...[have] had to [re]invent, their historical roots" after decolonization, and, "like its colonial predecessor, postcolonial identity owes its existence to force."[48] Africa  Colonialism in 1913: the African colonies of the European empires; and the postcolonial, 21st-century political boundaries of the decolonized countries. In the late 19th century, the Scramble for Africa (1874–1914) proved to be the tail end of mercantilist colonialism of the European imperial powers, yet, for the Africans, the consequences were greater than elsewhere in the colonized non–Western world. To facilitate the colonization the European empires laid railroads where the rivers and the land proved impassable. The Imperial British railroad effort proved overambitious in the effort of traversing continental Africa, yet succeeded only in connecting colonial North Africa (Cairo) with the colonial south of Africa (Cape Town). Upon arriving to Africa, Europeans encountered various African civilizations namely the Ashanti Empire, the Benin Empire, the Kingdom of Dahomey, the Buganda Kingdom (Uganda), and the Kingdom of Kongo, all of which were annexed by imperial powers under the belief that they required European stewardship. About East Africa, Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o wrote Weep Not, Child (1964), the first postcolonial novel about the East African experience of colonial imperialism; as well as Decolonizing the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986). In The River Between (1965), with the Mau Mau Uprising (1952–60) as political background, he addresses the postcolonial matters of African religious cultures, and the consequences of the imposition of Christianity, a religion culturally foreign to Kenya and to most of Africa. In postcolonial countries of Africa, Africans and non–Africans live in a world of genders, ethnicities, classes and languages, of ages, families, professions, religions and nations. There is a suggestion that individualism and postcolonialism are essentially discontinuous and divergent cultural phenomena.[49] Asia  Map of French Indochina from the colonial period showing its five subdivisions: Tonkin, Annam, Cochinchina, Cambodia and Laos. French Indochina was divided into five subdivisions: Tonkin, Annam, Cochinchina, Cambodia, and Laos. Cochinchina (southern Vietnam) was the first territory under French control; Saigon was conquered in 1859; and in 1887, the Indochinese Union (Union indochinoise) was established. In 1924, Nguyen Ai Quoc (aka Ho Chi Minh) wrote the first critical text against the French colonization: Le Procès de la Colonisation française ('French Colonization on Trial') Trinh T. Minh-ha has been developing her innovative theories about postcolonialism in various means of expression, literature, films, and teaching. She is best known for her documentary film Reassemblage (1982), in which she attempts to deconstruct anthropology as a "western male hegemonic ideology." In 1989, she wrote Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism, in which she focuses on the acknowledgement of oral tradition. Eastern Europe The partitions of Poland (1772–1918) and occupation of Eastern European countries by the Soviet Union after the Second World War were forms of "white" colonialism, for long overlooked by postcolonial theorists. The domination of European empires (Prussian, Austrian, Russian, and later Soviet) over neighboring territories (Belarus, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Lithuania, Moldova, Poland, Romania, and Ukraine), consisting in military invasion, exploitation of human and natural resources, devastation of culture, and efforts to re-educate local people in the empires' language, in many ways resembled the violent conquest of overseas territories by Western European powers, despite such factors as geographical proximity and the missing racial difference.[50] Postcolonial studies in East-Central and Eastern Europe were inaugurated by Ewa M. Thompson's seminal book Imperial Knowledge: Russian Literature and Colonialism (2000),[51] followed by works of Aleksander Fiut, Hanna Gosk, Violeta Kelertas,[52] Dorota Kołodziejczyk,[53] Janusz Korek,[54] Dariusz Skórczewski,[55] Bogdan Ştefănescu,[56] and Tomasz Zarycki.[57] Ireland "If by colonization we mean the conquest of one society by another more powerful society on its way to acquiring a vast empire, the settlement of the conquered territory by way of population transfers from the conquering one, the systematic denigration of the culture of the earlier inhabitants, the dismantling of their social institutions and the imposition of new institutions designed to consolidate the recently arrived settler community’s power over the ‘natives’ while keeping that settler community in its turn dependent on the ‘motherland’, then Ireland may be considered one of the earliest and most thoroughly colonized regions of the British Empire." - Joe Cleary, Postcolonial writing in Ireland (2012) Ireland experienced centuries of English/British colonialism between the 12th and 18th centuries - notably the Statute of Drogheda, 1494, which subordinated the Irish Parliament to the English (later, British) government - before the Kingdom of Ireland merged with the Kingdom of Great Britain on 1 January 1801 as the United Kingdom. Most of Ireland became independent of the U.K. in 1922 as the Irish Free State, a self-governing dominion of the British Empire. Pursuant to the Statute of Westminster, 1931 and enactment of a new Irish Constitution, Éire became fully independent of the United Kingdom in 1937; and then became a republic in 1949. Northern Ireland, in northeastern Ireland (northwestern Ireland is part of the Republic of Ireland), remains a province of the United Kingdom.[58][59] Many scholars have drawn parallels between: the economic, cultural and social subjugation of Ireland, and the experiences of the colonized regions of the world[60] the depiction of the native Gaelic Irish as wild, tribal savages and the depiction of other indigenous peoples as primitive and violent[61] the partition of Ireland by the U.K. government, analogous to the partitioning and boundary-drawing of the other future nation states by colonial powers[62] the post-independence struggle of the Irish Free State (which became the Republic of Ireland in 1949) to establish economic independence and its own identity in the world, and the similar struggles of other post-colonial nations; though, uniquely, Ireland had been independent, then become part of the U.K., then mostly independent again[63] Ireland's membership of and support for the European Union has often been framed as an attempt to break away from the United Kingdom's economic orbit.[64] In 2003, Clare Carroll wrote in Ireland and Postcolonial Theory that "the "colonizing activities" of Raleigh, Gilbert, and Drake in Ireland can be read as a "rehearsal" for their later exploits in the Americas, and argues that the English Elizabethans represent the Irish as being more alien than the contemporary European representations of Native Americans."[65] Rachel Seoighe wrote in 2017, "Ashis Nandy describes how colonisation impacts on the native’s interior life: the meaning of the Irish language was bound up with loss of self in socio-cultural and political life. The purportedly wild and uncivilised Irish language itself was held responsible for the ‘backwardness’ of the people. Holding tight to your own language was thought to bring death, exile and poverty. These ideas and sentiments are recognised by Seamus Deane in his analysis of recorded memories and testimony of the Great Famine in the 1840s. The recorded narratives of people who starved, emigrated and died during this period reflect an understanding of the Irish language as complicit in the devastation of the economy and society. It was perceived as a weakness of a people expelled from modernity: their native language prevented them from casting off ‘tradition’ and ‘backwardness’ and entering the ‘civilised’ world, where English was the language of modernity, progress and survival."[62] The Troubles (1969–1998), a period of conflict in Northern Ireland between mostly Cathlolic and Gaelic Irish nationalists (who wish to join the Irish Republic) and mostly Protestant Scots-Irish and Anglo-Irish unionists (who are a majority of the population and wish to remain part of the United Kingdom) has been described as a post-colonial conflict.[66][67][better source needed][68] In Jacobin, Daniel Finn criticised journalism which portrayed the conflict as one of "ancient hatred", ignoring the imperial context.[69] Structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) Structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) implemented by the World Bank and IMF are viewed by some postcolonialists as the modern procedure of colonization. Structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) calls for trade liberalization, privatization of banks, health care, and educational institutions.[70] These implementations minimized government's role, paved pathways for companies to enter Africa for its resources. Limited to production and exportation of cash crops, many African nations acquired more debt, and were left stranded in a position where acquiring more loan and continuing to pay high interest became an endless cycle.[70] The Dictionary of Human Geography uses the definition of colonialism as "enduring relationship of domination and mode of dispossession, usually (or at least initially) between an indigenous (or enslaved) majority and a minority of interlopers (colonizers), who are convinced of their own superiority, pursue their own interests, and exercise power through a mixture of coercion, persuasion, conflict and collaboration."[71] This definition suggests that the SAPs implemented by the Washington Consensus is indeed an act of colonization.[citation needed] |

アプリケーション=応用 中東 ナジフ・アユビのエッセイ「アラブ国家の誇張」(2001年)の中で、著者は中東における西欧植民地主義の影響(政治的、社会的、文化的、経済的)によっ て決定された、心理的に断片化されたポストコロニアル・アイデンティティを扱っている。このように、断片化された国民的アイデンティティは、ヨーロッパ帝 国主義者の到来以前に中東諸国の地理的国境を決定していた部族や氏族の関係を無視して、ヨーロッパ人によって画定された、命令上便利ではあるが恣意的な植 民地的境界線(地理的および文化的)の結果として、このような社会の特徴として残っている。 [したがって、中東に関するポストコロニアル文学は、アイデンティティの形成に関する西洋の言説、現代の中東の人々の間のポストコロニアルな国民アイデン ティティの存在と矛盾した性質を検証し、分析している。  「中東」とは、南西アジアの国々に対する西洋の呼称である。 彼のエッセイ『Who Am I? The Identity Crisis in the Middle East"(2006年)の中で、P.R.クマラスワミは次のように述べている: 中東のほとんどの国々は、国家のアイデンティティをめぐる根本的な問題に苦しんでいる。中東のほとんどの国々は、その国民的アイデンティティをめぐる根本 的な問題に悩まされてきた。オスマン帝国の崩壊から4分の3世紀以上が経過したが、これらの国々は、包括的かつ代表的な国民的アイデンティティを定義し、 投影し、維持することができないでいる[47]。 独立と植民地主義の終焉は、中東における社会的分断と戦争(内戦と国際戦争)を終わらせるものではなかった: Larbi Sadikiは、『The Search for Arab Democracy: Discourses and Counter-Discourses』(2004年)の中で、中東におけるナショナル・アイデンティティの問題は、ヨーロッパ帝国が植民地の政治的境界 線を画定する際に、西洋版の中東を確立する過程で、現地の歴史や原住民が守ってきた地理的・部族的境界線を無視した東洋主義的無関心の結果であると述べて いる。その結果:[47]。 [イラクやヨルダンのような場所では、新しい主権国家の指導者たちは外部から連れてこられ、植民地的な利益とコミットメントに合うように調整された。同様 に、ペルシャ湾のほとんどの国家は、撤退後の段階で帝国の利益を守り抜くことのできる[ヨーロッパ化された植民地臣民]に引き渡された。 さらに、「エジプト、イラン、イラク、シリアのような顕著な例外を除けば、ほとんどの[国]は脱植民地化後、その歴史的ルーツを[再び]発明しなければな らなかった」のであり、「植民地時代の前任者と同様に、ポストコロニアルのアイデンティティはその存在を力に負っている」のである[48]。 アフリカ  1913年の植民地主義:ヨーロッパ帝国のアフリカ植民地、脱植民地化された国々のポストコロニアル、21世紀の政治的境界線。 19世紀後半、スクランブル・フォア・アフリカ(1874-1914)は、ヨーロッパ帝国列強の重商主義的植民地主義の末期であることを証明したが、アフ リカ人にとっては、植民地化された非西洋世界の他の地域よりも大きな結果をもたらした。植民地化を促進するために、ヨーロッパ帝国は川や土地が通れない場 所に鉄道を敷設した。イギリス帝国の鉄道敷設は、アフリカ大陸を横断するという大それたものであったが、植民地であった北アフリカ(カイロ)と植民地で あったアフリカ南部(ケープタウン)を結ぶことに成功しただけであった。 アフリカに到着したヨーロッパ人は、アシャンティ帝国、ベニン帝国、ダホメー王国、ブガンダ王国(ウガンダ)、コンゴ王国といったさまざまなアフリカの文 明に遭遇したが、これらはすべて、ヨーロッパ人の管理が必要だという信念のもと、帝国権力によって併合された。 東アフリカについては、ケニアの作家ング・ワ・ティオンゴが、植民地帝国主義による東アフリカの経験を描いた最初のポストコロニアル小説『泣かないで、子 供よ』(1964年)や、『脱植民地化する心』(1964年)を書いている: The Politics of Language in African Literature』(1986年)がある。マウマウ蜂起(1952-60年)を政治的背景とした『The River Between』(1965年)では、アフリカの宗教文化のポストコロニアル的な問題を取り上げ、ケニアやアフリカの大部分にとって文化的に異質な宗教で あるキリスト教の押し付けがもたらした結果を論じている。 アフリカのポストコロニアル諸国では、アフリカ人も非アフリカ人も、性別、民族、階級、言語、年齢、家族、職業、宗教、国家が混在する世界に住んでいる。 個人主義とポストコロニアリズムは本質的に不連続で乖離した文化現象であるという指摘がある[49]。 アジア  植民地時代のフランス領インドシナの地図: トンキン、アンナム、コーチシナ、カンボジア、ラオス。 フランス領インドシナは5つに分割された: トンキン、安南、コーチシナ、カンボジア、ラオスである。1859年にサイゴンが征服され、1887年にはインドシナ連合(Union indochinoise)が設立された。 1924年、グエン・アイ・クオック(別名ホーチミン)がフランスの植民地化に対する最初の批判的文章を書いた: Le Procès de la Colonisation française(「フランスの植民地化裁判」)。 トリン・T・ミンハは、ポストコロニアリズムに関する革新的な理論を、文学、映画、教育などさまざまな表現方法で展開してきた。ドキュメンタリー映画 『Reassemblage』(1982年)で知られる彼女は、人類学を "西洋男性の覇権的イデオロギー "として脱構築しようと試みている。1989年、『Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism)を著し、口承伝統の承認に焦点を当てている。 東ヨーロッパ ポーランドの分割統治(1772-1918年)と第二次世界大戦後のソ連による東欧諸国の占領は、ポストコロニアルの理論家が長い間見過ごしてきた「白 人」植民地主義の一形態であった。近隣の領土(ベラルーシ、ブルガリア、チェコスロバキア、ハンガリー、リトアニア、モルドバ、ポーランド、ルーマニア、 ウクライナ)に対するヨーロッパ帝国(プロイセン、オーストリア、ロシア、そして後のソビエト)の支配は、軍事的侵略、人的・天然資源の搾取、文化の荒 廃、現地の人々を帝国の言語で再教育する努力で構成されており、地理的な近接性や人種的な差異がないといった要因にもかかわらず、多くの点で西欧列強によ る海外領土の暴力的な征服と類似していた[50]。 東中東欧におけるポストコロニアル研究は、エワ・M・トンプソン(Ewa M. Thompson)の画期的な著書『帝国の知識(Imperial Knowledge)』によって始まった: ロシア文学と植民地主義』(2000年)[51]に始まり、アレクサンデル・フィウト、ハンナ・ゴスク、ヴィオレタ・ケレルタス、ドロタ・コウォジェイチ ク、ヤヌシュ・コレク、[54]ダリウシュ・スコチェフスキ、[55]ボグダン・シェファネスク、[56]トマシュ・ザリツキらの著作が続く。 アイルランド 「植民地化とは、ある社会がより強力な他の社会によって征服され、広大な帝国を獲得 することを意味するのであれば、征服した社会からの人口移転によって征服された領土に定住し、先住者の文化を組織的に否定することである、 その結果、アイルランドは大英帝国で最も早く、最も徹底的に植民地化された地域のひとつと見なされるようになった」。 ジョー・クリアリー『アイルランドのポストコロニアル・ライティング』(2012年) アイルランド王国が1801年1月1日にグレートブリテン王国と合併して連合王国となるまでの間、アイルランドは12世紀から18世紀にかけて何世紀にも わたってイギリス/英国の植民地支配を経験した。アイルランドの大部分は1922年に大英帝国の自治領であるアイルランド自由国として英国から独立した。 1931年のウェストミンスター憲章と新アイルランド憲法の制定により、アイルランドは1937年にイギリスから完全に独立し、1949年に共和制となっ た。アイルランド北東部に位置する北アイルランド(アイルランド北西部はアイルランド共和国の一部)は、依然としてイギリスの州である[58][59]: アイルランドの経済的、文化的、社会的従属と世界の植民地化された地域の経験[60]。 先住民であるゲール系アイルランド人を野生の部族的野蛮人として描くことと、他の先住民を原始的で暴力的な存在として描くこと[61]。 イギリス政府によるアイルランドの分割は、植民地勢力による他の将来の国民国家の分割と境界画定に類似していた[62]。 アイルランド自由国(1949年にアイルランド共和国となった)が経済的な独立と世界における独自のアイデンティティを確立するために行った独立後の闘 争、そして他の植民地支配後の国家が行った同様の闘争。 2003年、クレア・キャロルは『アイルランドとポストコロニアル理論』において、「アイルランドにおけるローリー、ギルバート、ドレークの "植民地化活動 "は、後のアメリカ大陸における彼らの活躍の "リハーサル "として読むことができ、イギリス人エリザベス朝がアイルランド人を、現代のヨーロッパ人のアメリカ先住民の表象よりも異質な存在として表象していると論 じている」と書いている[65]。 レイチェル・ソイゲは2017年に「アシス・ナンディは植民地化が先住民の内的生活にどのような影響を与えるかを描写している:アイルランド語の意味は社 会文化的、政治的生活における自己の喪失と結びついていた。アイルランド語の意味は、社会文化的・政治的生活における自己の喪失と結びついていたのであ る。自国語に固執することは、死、追放、貧困をもたらすと考えられていた。このような考え方や感情は、1840年代の大飢饉に関する記録や証言を分析した シェイマス・ディーンによって認識されている。この時代に飢え、移住し、亡くなった人々の記録された語りは、経済と社会の荒廃にアイルランド語が加担して いるという理解を反映している。それは、近代性から追放された人々の弱点として認識されていた。彼らの母国語は、『伝統』と『後進性』を捨て去り、英語が 近代性、進歩、生存の言語である『文明化された』世界に入ることを妨げていた」[62]。 紛争(1969年~1998年)は、北アイルランドにおいて、ほとんどがカトリック系でゲール語のアイルランド民族主義者(アイルランド共和国への加盟を 希望)と、ほとんどがプロテスタント系のスコットランド系アイルランド人およびアングロ・アイリッシュ連合主義者(人口の大多数を占め、イギリスの一部で あることを希望)との間で起こった紛争であり、ポストコロニアル紛争と評されている[66][67][要出典][68]。ダニエル・フィンは『ジャコバ ン』誌において、帝国時代の背景を無視して紛争を「古代の憎しみ」のひとつとして描いたジャーナリズムを批判している[69]。 構造調整プログラム(SAPs) 世界銀行とIMFによって実施された構造調整プログラム(SAPs) は、一部のポストコロニアリストによって植民地化の現代的な手続きとみなされている。 構造調整プログラム(SAP)は、貿易の自由化、銀行、医療、教育機関の民営化を求めている[70]。これらの実施により、政府の役割は最小化され、企業 がアフリカの資源を求めて参入する道が開かれた。換金作物の生産と輸出に制限された多くのアフリカ諸国は、より多くの負債を負い、より多くの融資を受け、 高い利子を払い続けるという終わりのないサイクルに取り残された[70]。 人文地理学辞典は、植民地主義の定義を「通常(あるいは少なくとも当初は)、先住民(あるいは奴隷化された)多数派と、自らの優位性を確信し、自らの利益 を追求し、強制、説得、対立、協力の混合を通じて権力を行使する少数派の間における、支配の永続的な関係と収奪の様式」と用いている[71]。この定義 は、ワシントン・コンセンサスによって実施されたSAPが、まさに植民地化の行為であることを示唆している[要出典]。 |

| Criticism Undermining of universal values Indian-American Marxist scholar Vivek Chibber has critiqued some foundational logics of postcolonial theory in his book Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital. Drawing on Aijaz Ahmad's earlier critique of Said's Orientalism[72] and Sumit Sarkar's critique of the Subaltern Studies scholars,[73] Chibber focuses on and refutes the principal historical claims made by the Subaltern Studies scholars; claims that are representative of the whole of postcolonial theory. Postcolonial theory, he argues, essentializes cultures, painting them as fixed and static categories. Moreover, it presents the difference between East and West as unbridgeable, hence denying people's "universal aspirations" and "universal interests." He also criticized the postcolonial tendency to characterize all of Enlightenment values as Eurocentric. According to him, the theory will be remembered "for its revival of cultural essentialism and its acting as an endorsement of orientalism, rather than being an antidote to it."[74] Fixation on national identity The concentration of postcolonial studies upon the subject of national identity has determined it is essential to the creation and establishment of a stable nation and country in the aftermath of decolonization; yet indicates that either an indeterminate or an ambiguous national identity has tended to limit the social, cultural, and economic progress of a decolonized people. In Overstating the Arab State (2001) by Nazih Ayubi, Moroccan scholar Bin 'Abd al-'Ali proposed that the existence of "a pathological obsession with...identity" is a cultural theme common to the contemporary academic field Middle Eastern Studies.[75]: 148 Nevertheless, Kumaraswamy and Sadiki say that such a common sociological problem—that of an indeterminate national identity—among the countries of the Middle East is an important aspect that must be accounted in order to have an understanding of the politics of the contemporary Middle East.[47] In the event, Ayubi asks if what 'Bin Abd al–'Ali sociologically described as an obsession with national identity might be explained by "the absence of a championing social class?"[75]: 148 In his essay The Death of Postcolonialism: The Founder's Foreword, Mohamed Salah Eddine Madiou argues that postcolonialism as an academic study and critique of colonialism is a "dismal failure." While explaining that Edward Said never affiliated himself with the postcolonial discipline and is, therefore, not "the father" of it as most would have us believe, Madiou, borrowing from Barthes' and Spivak's death-titles (The Death of the Author and Death of a Discipline, respectively), argues that postcolonialism is today not fit to study colonialism and is, therefore, dead "but continue[s] to be used which is the problem." Madiou gives one clear reason for considering postcolonialism a dead discipline: the avoidance of serious colonial cases, such as Palestine.[76] Blind spots Russian imperialism and colonialism concerning Ukraine are among the blind spots of postcolonialism.[77] |

批判 普遍的価値の毀損 インド系アメリカ人のマルクス主義学者ヴィヴェク・チバーは、その著書『ポストコロニアル理論と資本の亡霊』の中で、ポストコロニアル理論の基礎となる論 理のいくつかを批判している。アイジャズ・アフマドによるサイードのオリエンタリズム批判[72]やスミト・サルカールによるスバルタン・スタディーズ研 究者への批判[73]を踏まえながら、チバーはスバルタン・スタディーズ研究者による主要な歴史的主張に焦点を当て、それに反論している。ポストコロニア ル理論は文化を本質化し、固定的で静的なカテゴリーとして描いていると彼は主張する。さらに、東洋と西洋の違いを埋めがたいものとして提示し、人々の "普遍的な願望 "や "普遍的な利益 "を否定している。彼はまた、啓蒙主義的価値観のすべてをヨーロッパ中心主義と決めつけるポストコロニアル的傾向を批判した。彼によれば、この理論は「文 化的本質主義を復活させ、オリエンタリズムに対する解毒剤となるのではなく、オリエンタリズムを是認するものとして作用した」ことで記憶されることになる [74]。 ナショナル・アイデンティティへの固執 ポストコロニアル研究が国民的アイデンティティという主題に集中していることは、それが脱植民地化の後における安定した国家と国の創造と確立に不可欠であ ると断定しているが、不確定な、あるいは曖昧な国民的アイデンティティは、脱植民地化された人々の社会的、文化的、経済的進歩を制限する傾向があることを 示している。モロッコの学者ビン・アブド・アル・アリは、ナジ・アユビ著『アラブ国家の誇張』(2001年)の中で、「アイデンティティに対する病的な執 着」の存在が、現代の学術分野である中東研究に共通する文化的テーマであると提唱している[75]: 148 とはいえ、クマラスワミとサディキは、このような中東諸国に共通する社会学的な問題、すなわち不確定な国民的アイデンティティは、現代の中東の政治を理解 するために説明されなければならない重要な側面であると述べている[47]。 その際、アユビは、ビン・アブド・アル・アリが社会学的に国民的アイデンティティへの強迫観念と表現したものは、「支持する社会階級の不在」によって説明 されるのではないかと問うている[75]: 148 彼のエッセイ『ポストコロニアリズムの死』の中で: モハメド・サラー・エディーヌ・マディウは、「創始者の序文」の中で、植民地主義に対する学問的研究と批判としてのポストコロニアリズムは「悲惨な失敗」 であると論じている。マディウは、エドワード・サイードがポストコロニアリズムという学問分野と一度も結びついたことがなく、したがって、多くの人が信じ ているようなポストコロニアリズムの「父」ではないことを説明しながら、バルトとスピヴァクの死のタイトル(それぞれ『著者の死』と『学問の死』)を借り て、ポストコロニアリズムは今日、植民地主義を研究するのに適しておらず、したがって死んでいると主張する。マディウは、ポストコロニアリズムが死んだ学 問であると考える明確な理由のひとつを挙げている:パレスチナのような深刻な植民地事例を避けていることである[76]。 盲点 ロシア帝国主義とウクライナに関する植民地主義はポストコロニアリズムの盲点のひとつである[77]。 |