Colonialism

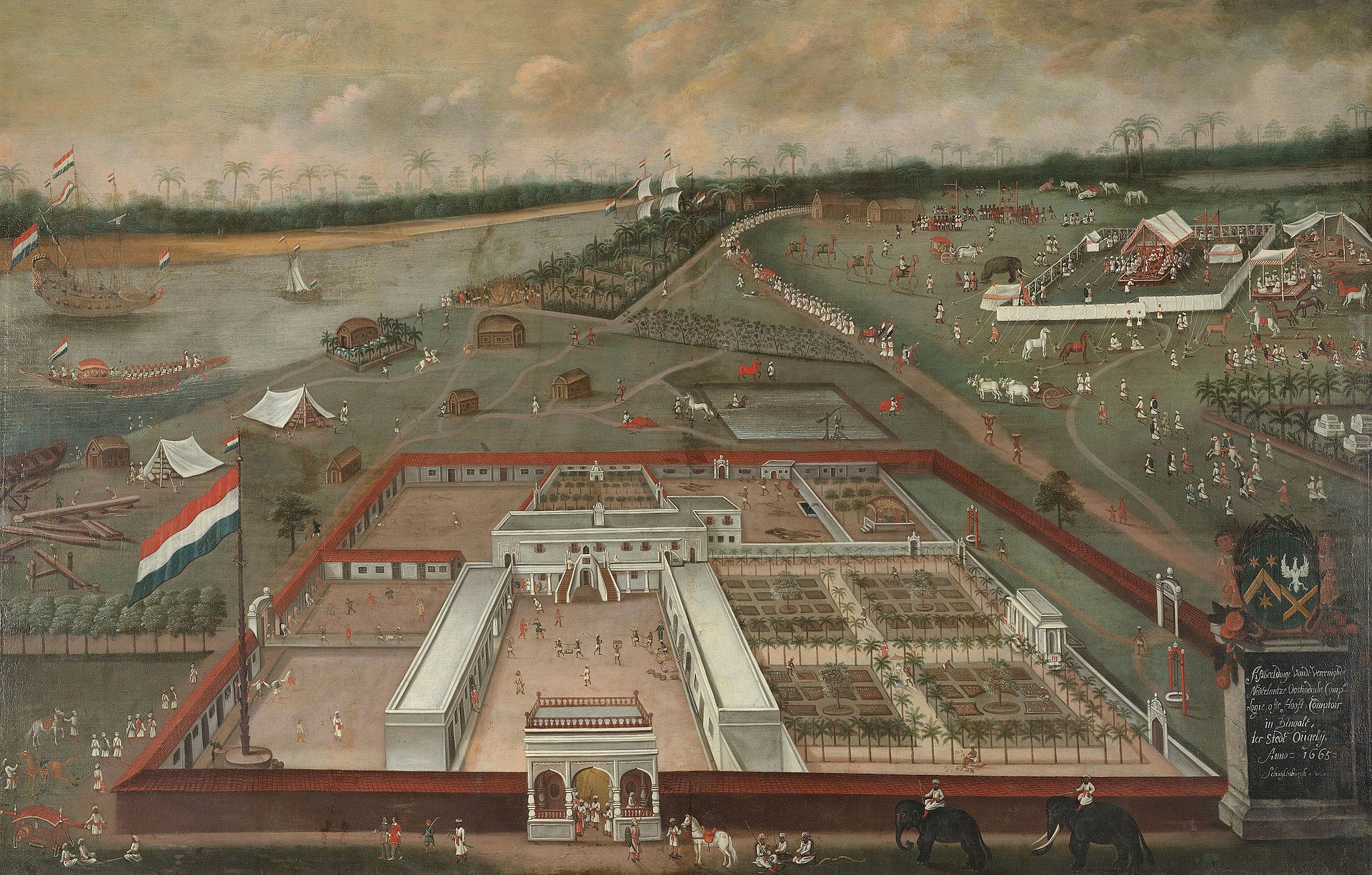

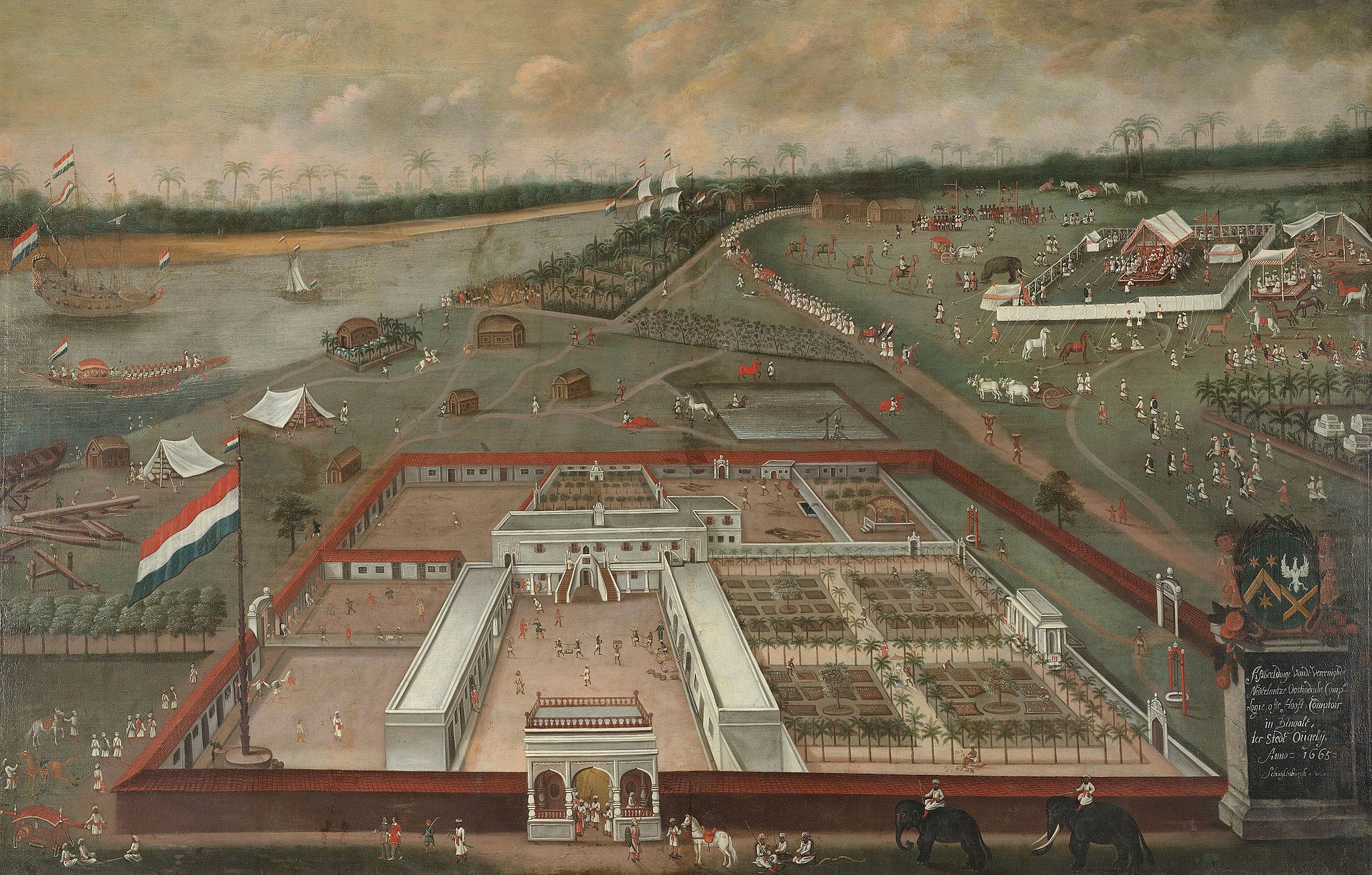

Cecil John Rhodes / A factory entrepôt, a basic example of colonialism illustrating its different elements, hierarchies and impact on the land and people (the Dutch V.O.C. factory in Hugli-Chuchura, Bengal, in 1665)

Colonialism

Cecil John Rhodes / A factory entrepôt, a basic example of colonialism illustrating its different elements, hierarchies and impact on the land and people (the Dutch V.O.C. factory in Hugli-Chuchura, Bengal, in 1665)

植民地主義 (colonialism)あるいはコロニアリズムとは、植民地を建設し、そこから資源(人的、天然、交易的など)を得 ること が至上になる政治的イ デオロギーならびに入植などの実践行為を正当化する言説のことである。 別言すれば、植民国家建設のためには、その統治領域空間(国土、植民地、帝国領内)に おいて、その支配のシステムを支える殖民技術および殖民技法というものが確立すること必要であるいう侵略思想を、植民・殖民による植民地主義 (settler colonialism)という(→入植植民地主義)。

"Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing coloniesand generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their religion, language, economics, and other cultural practices. The foreign administrators rule the territory in pursuit of their interests, seeking to benefit from the colonised region's people and resources. It is associated with but distinct from imperialism."-Colonialism.

「植民地主義とは、ある人々や権力者が他の人々や地域を支配する行為や政策実践(=イデオロギー)のことであり、多くの場合は、経済的支配を目的として植民地を設 立すること。植民地化の過程で、植民者は自分たちの宗教、言語、経済、その他の文化的慣習を押し付けることがある。外国人行政官は、植民地化された地域の 人々や資源から利益を得ようと、自分たちの利益を追求するためにその地域を支配する。帝国主義と関連しているが、帝国主義とは異なるものである」といわれ る。(上掲の"Colonialism" の翻訳)

"Imperialism is a policy or ideology of extending the rule over peoples and other countries, for extending political and economic access, power and control, often through employing hard power, especially military force, but also soft power. While related to the concepts of colonialism and empire, imperialism is a distinct concept that can apply to other forms of expansion and many forms of government."-Imperialism.

「帝国主義とは、政治的・経済的アクセス、権力、支配を拡大するために、国民や他国に対する支配を拡大する政策やイデオロギーであり、ハー ドパワー、特に軍事力を用いることが多いが、ソフトパワーを用いることもある。帝国主義は、植民地主義や帝国の概念に関連しているが、他の形態の拡張や多 くの政府形態にも適用可能な明確な概念である」。(上掲の"Imperialism"の翻訳)

植民国家あるいは殖民国家 (settler state)とは開拓移民国家ともいい、国家主権や領土を確立する際に、先にそこに存在していた人々 すなわち先住民を、 排他的にあるいは包摂する形で、成立が保証される国家のこ と。植民国家建設のためには、その統治領域空間(国土、植民地、帝国領内)における「植民・殖民による植民地主義」(settler colonialism:→殖民・植民地主義)という考え方とそれを支える殖民技術および殖民 技法というものが確立あるいは、開発途上にある必要があり、このことは歴史上の植民国家の成立にもみることができる。この定義によると、近代の国家形 態の成立経緯は、ほとんどこの植民国家としての性格をもつことになる。

★植民地言説

植民地言説「それは、人種的/文化的/歴史的諸差異の認識と否認を作動させる装置である。その支配的な戦略 機能は、諸知識の生産を通し て「被支配民族」のための空間を作り出すことであり、それに基づいて監視が行われ、快楽/不快の複合形式が刺激される。その装置は、植民者と被植民者に関 する諸知識(ステレオタイプでありながら、対照的な評価を受ける)を生産することによって、その戦略のための権威づけを求める。」[ホミ・バーバ 2004](p.65)(→「差異、差別、植民地主義の言説」ノート)

「知識と、何が真の知識であるのかを定義する力は、植民地主義の認識論の核心にある」(リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミス 2025:11)

++

|

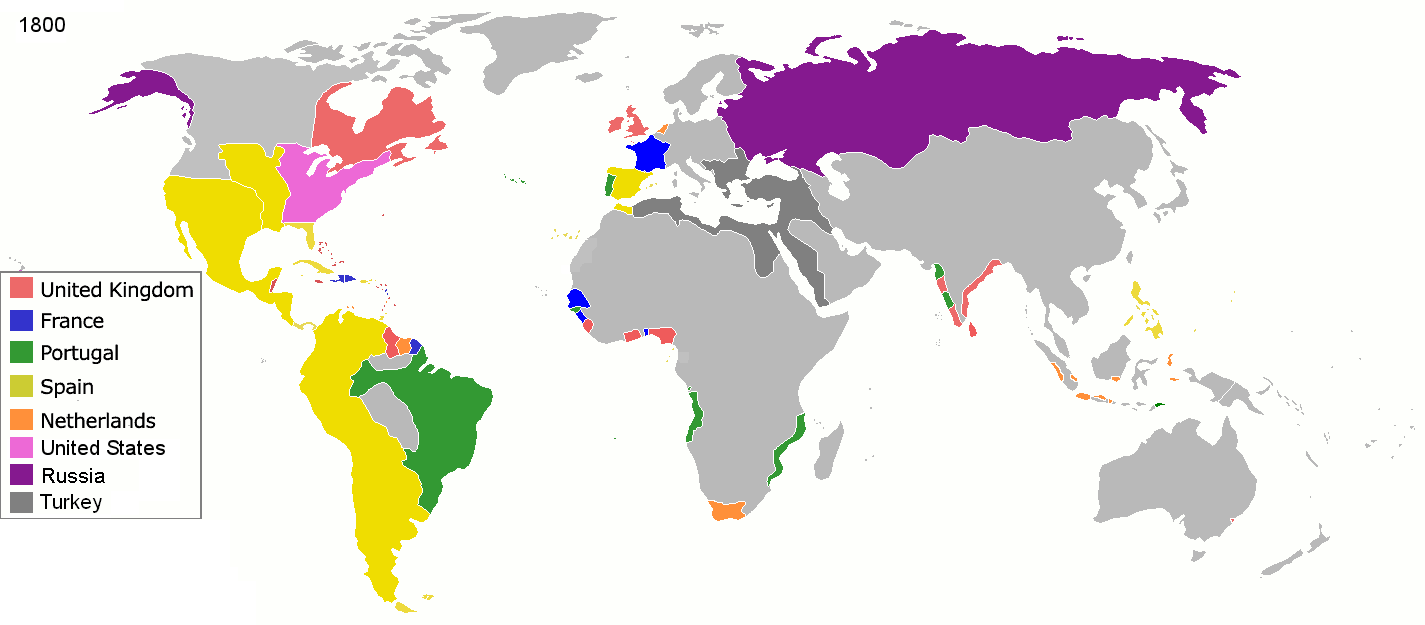

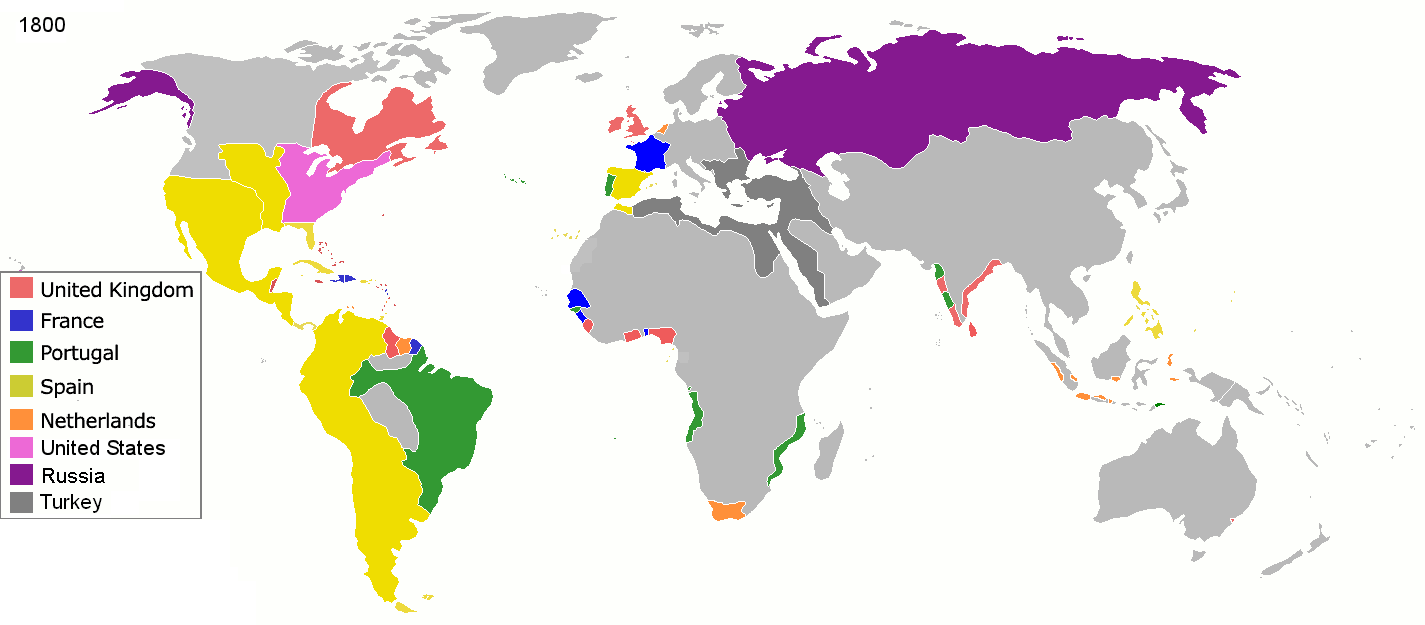

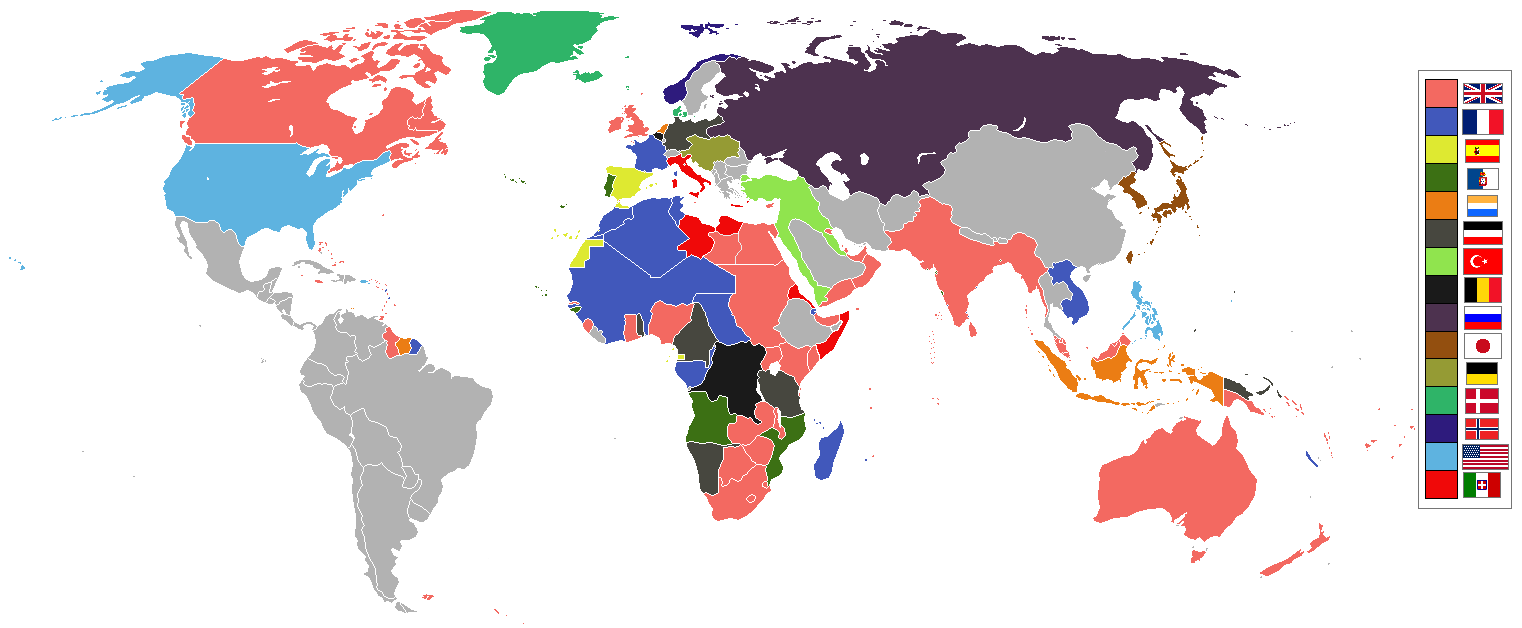

1800年の世界の植民地 |

|

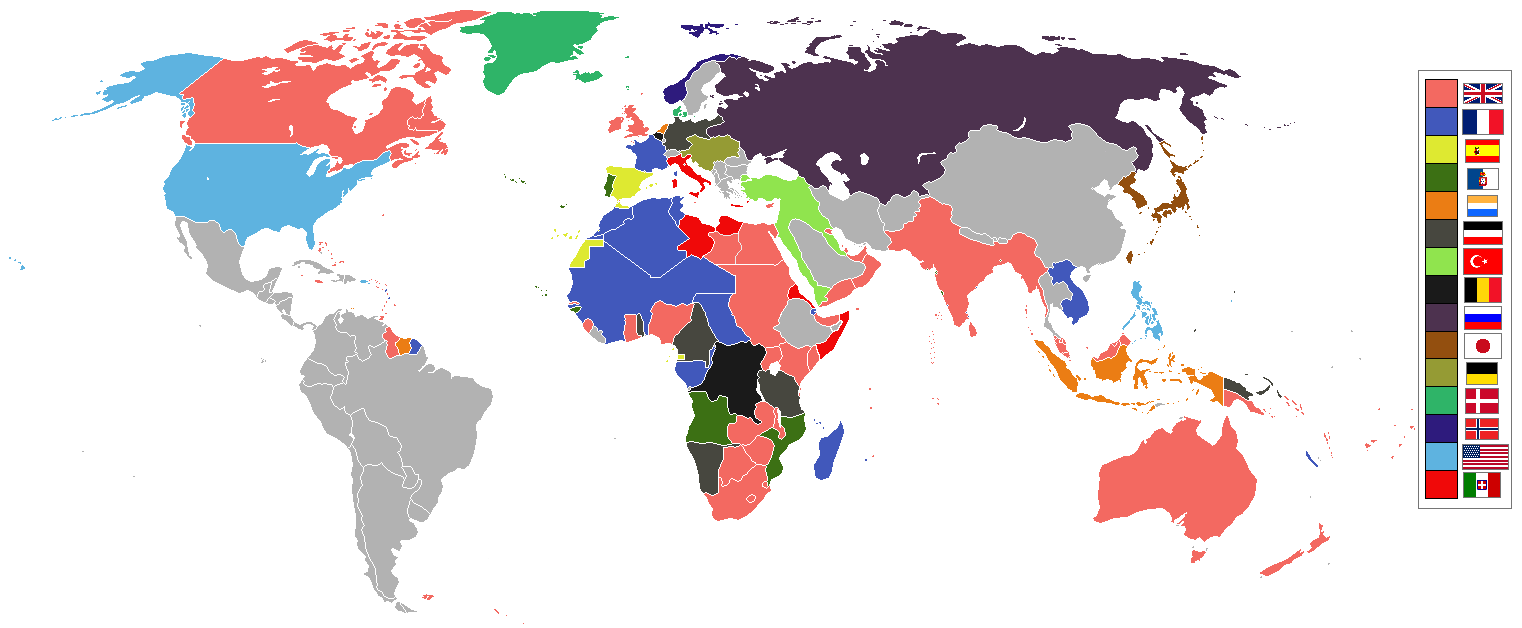

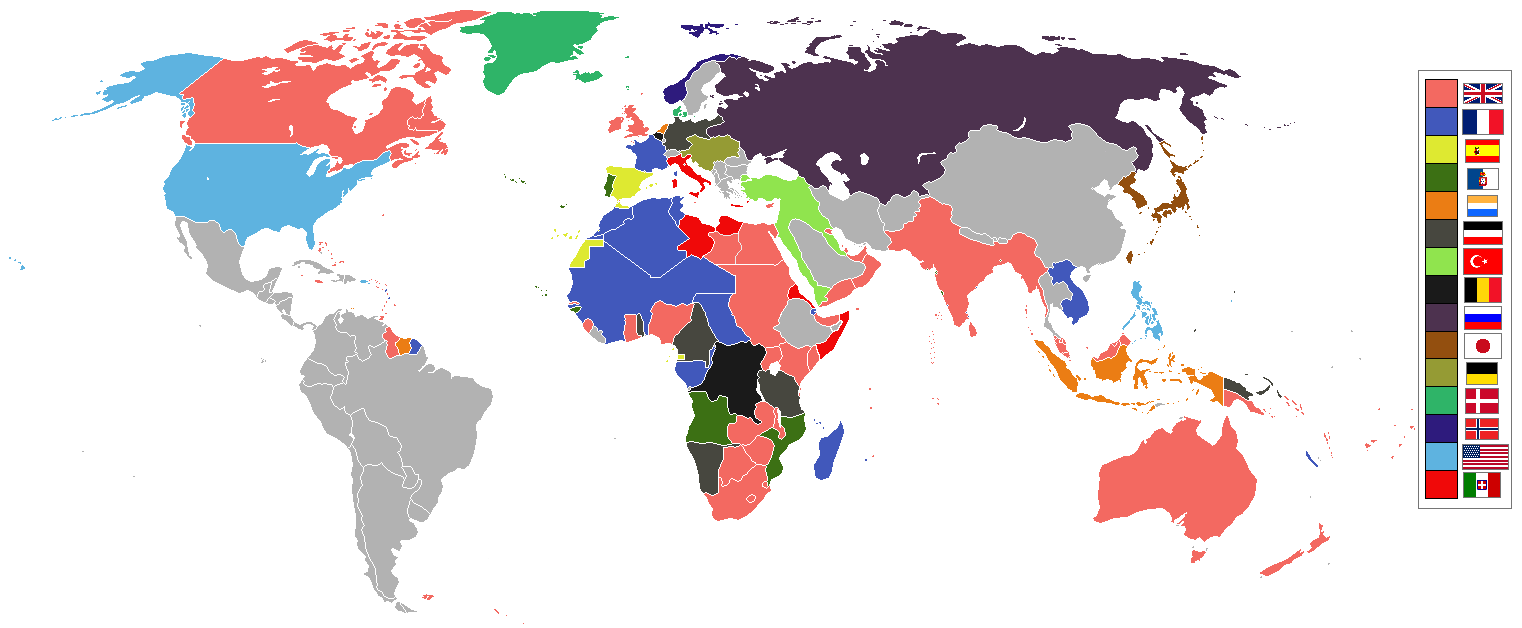

第一次世界大戦勃発時の世界の植民地 |

|

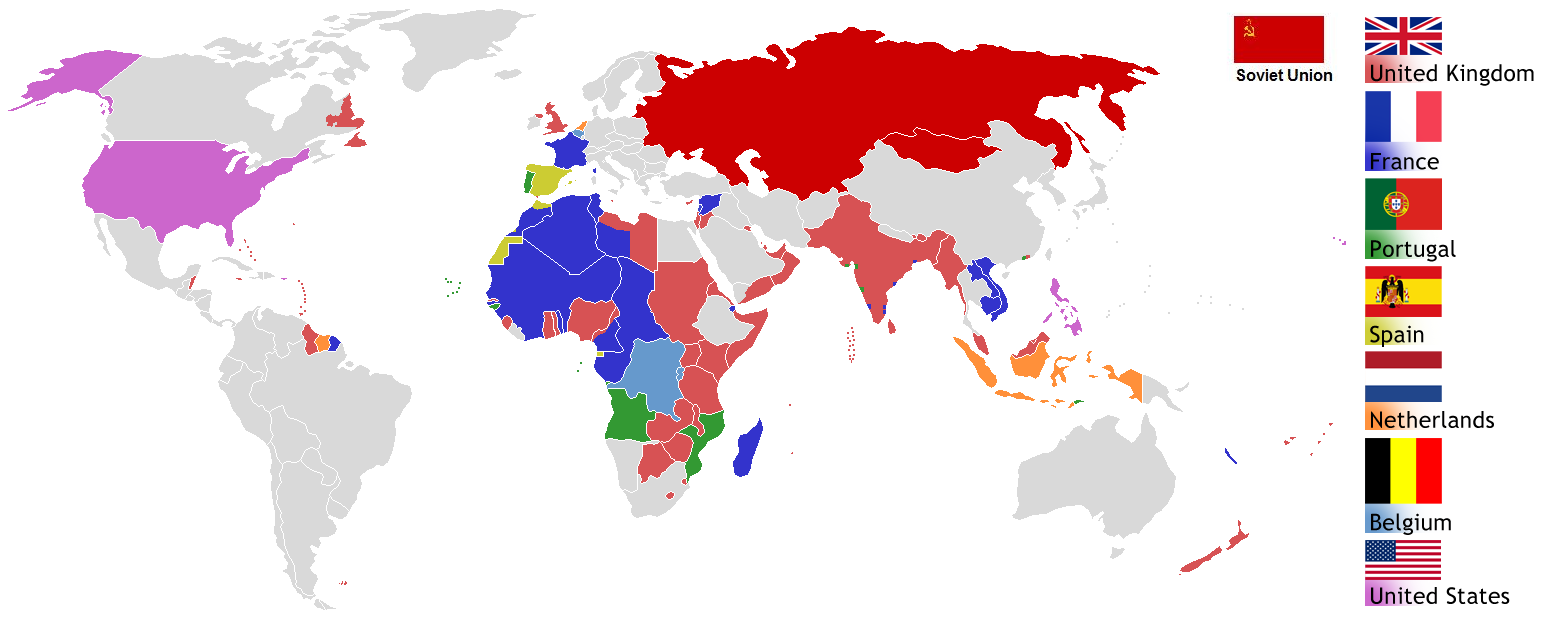

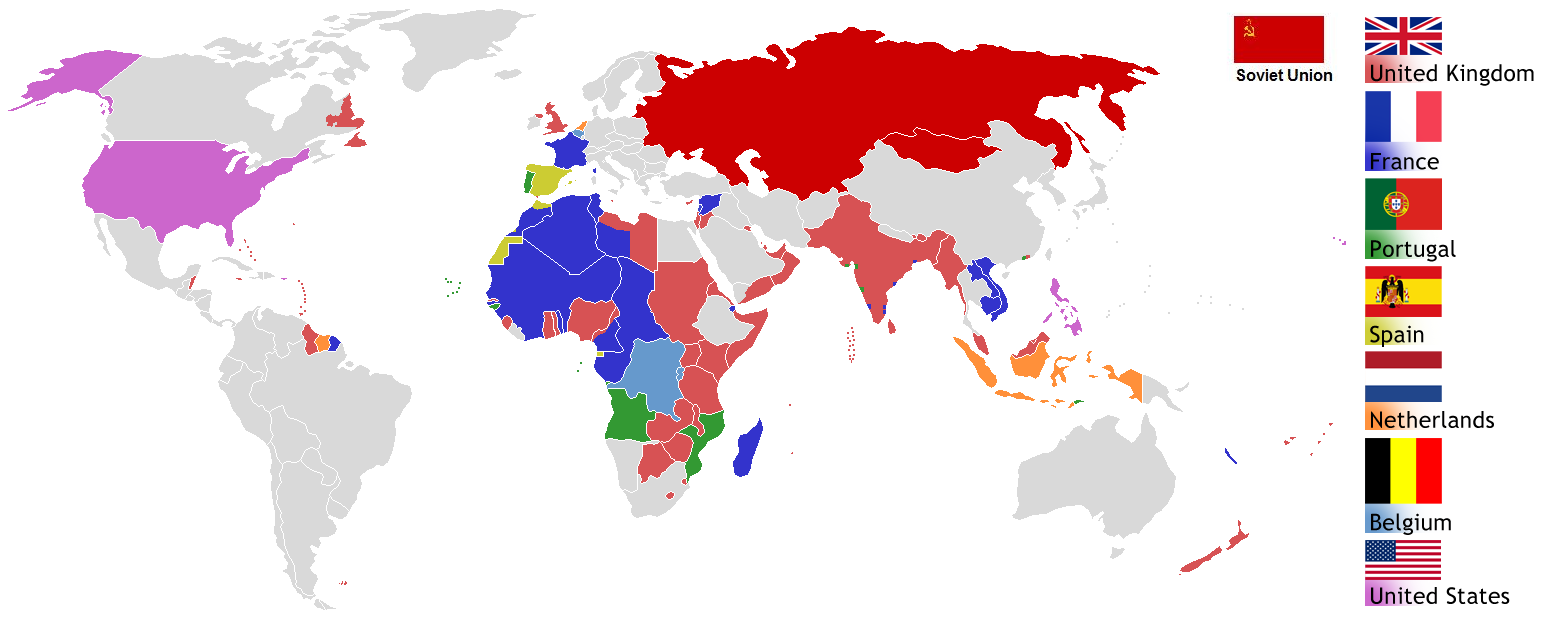

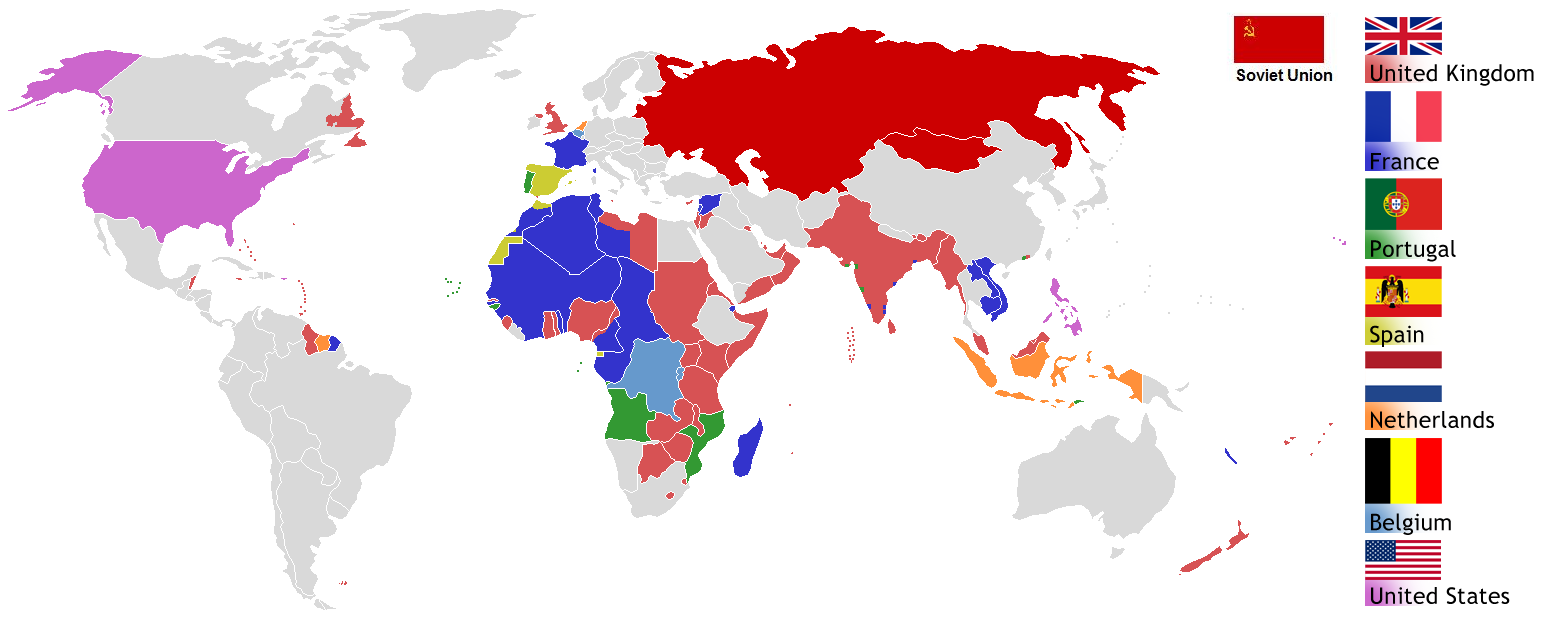

第二次世界大戦終結時の1945年の世界

の植民地 |

|

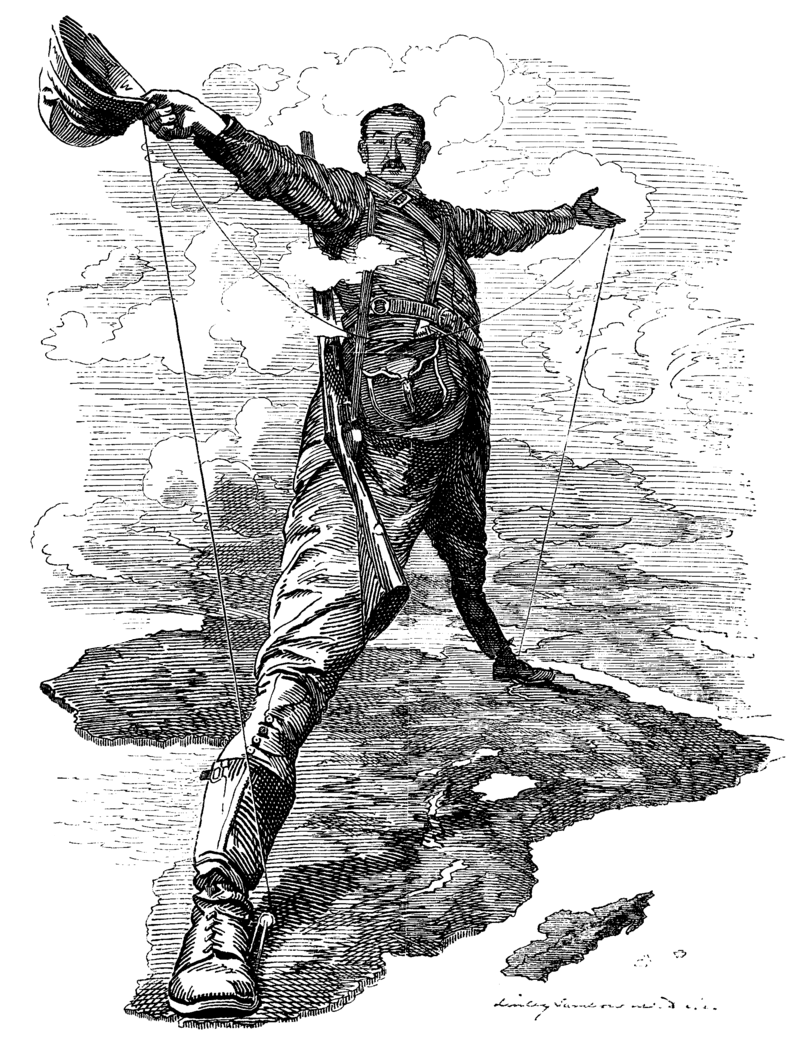

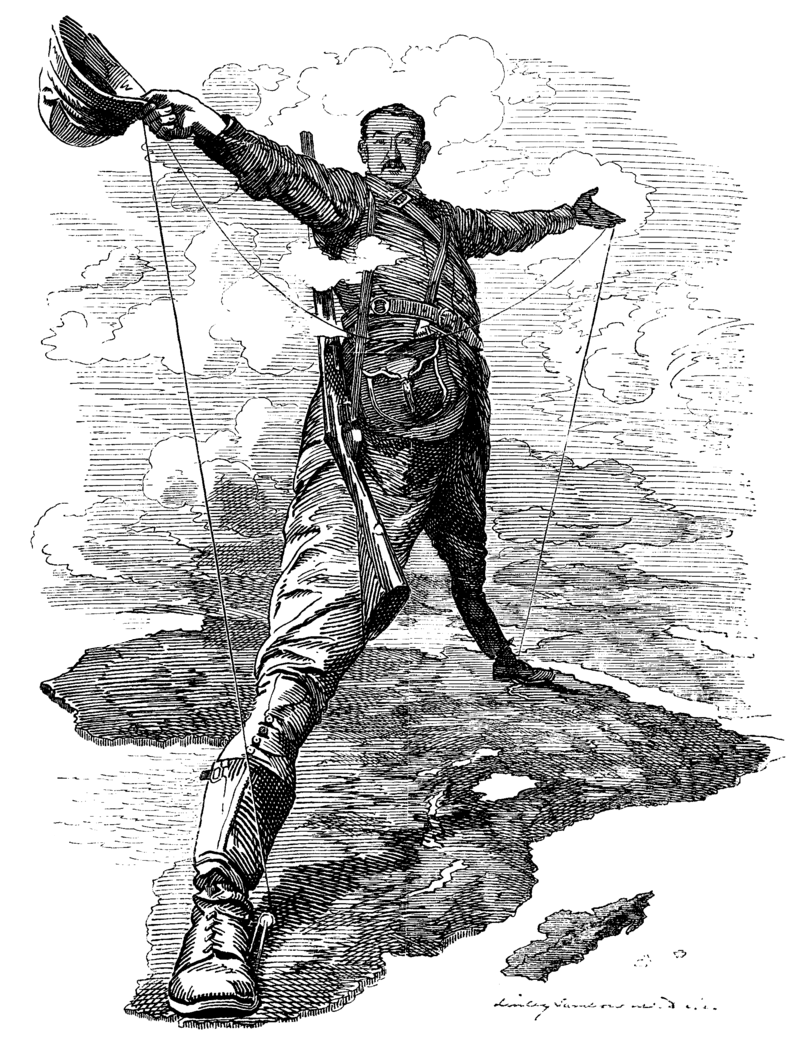

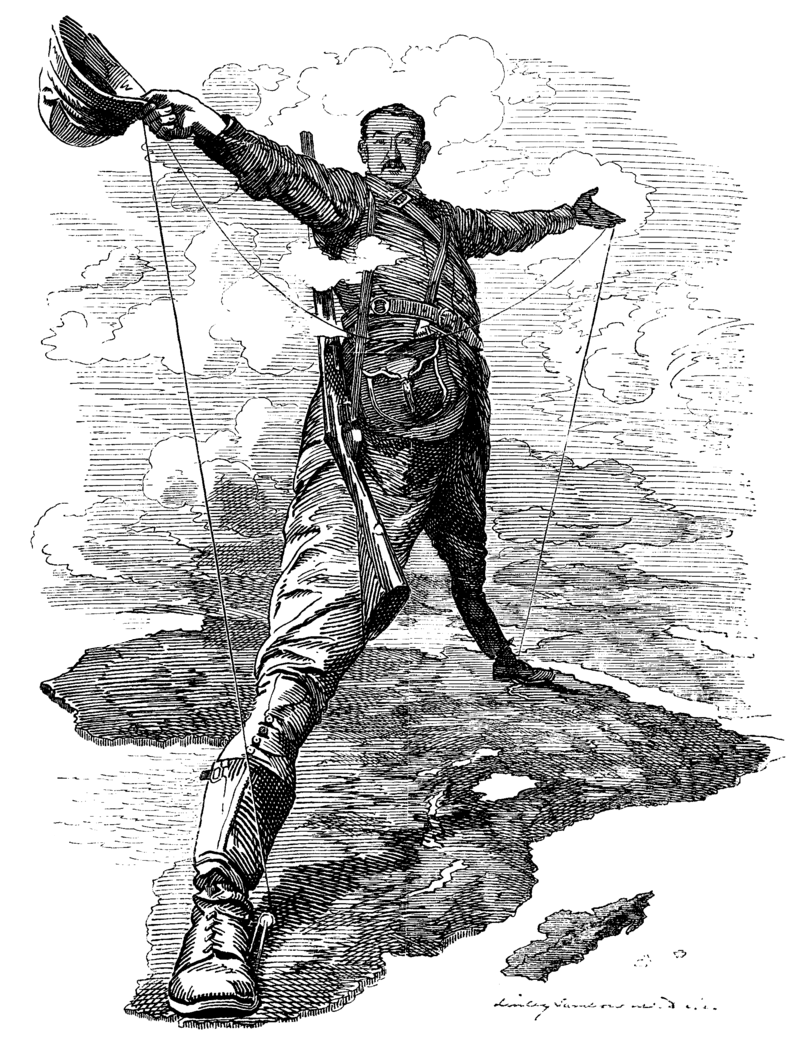

「2020年5月にアメリカのミネアポリスで起こった白人警官による過

剰拘束で黒人容疑者が死んだ事件で、アメリカだけでなく世界中で黒人差別の歴史に対する見直しを迫る動きが出ている。イギリスのブリストルでは、奴隷商人

の銅像が引き倒され、アメリカのリッチモンドでは南軍司令官リー将軍の銅像の撤去が問題となっている。イギリスのオックスフォード大学では、セシル・ロー

ズは成功した実業者として多額の寄付金を出しているので、大学の学寮のひとつオリオル・カレッジでは正面玄関上部に巨大なセシル・ロー

ズ像が立っている。

こちらはすでに2016年に学生の中から植民地主義者・差別主義者の銅像は撤去すべき、との声が起こっていたが、その時は大学当局はそのまま保存すると決

定していた。今度のミネアポリスの事件で、この問題が再燃すると思われる。」英オックスフォード大、差

別主義象徴と抗議の実業家像は撤去せず) |

+++

★植民地主義、解説

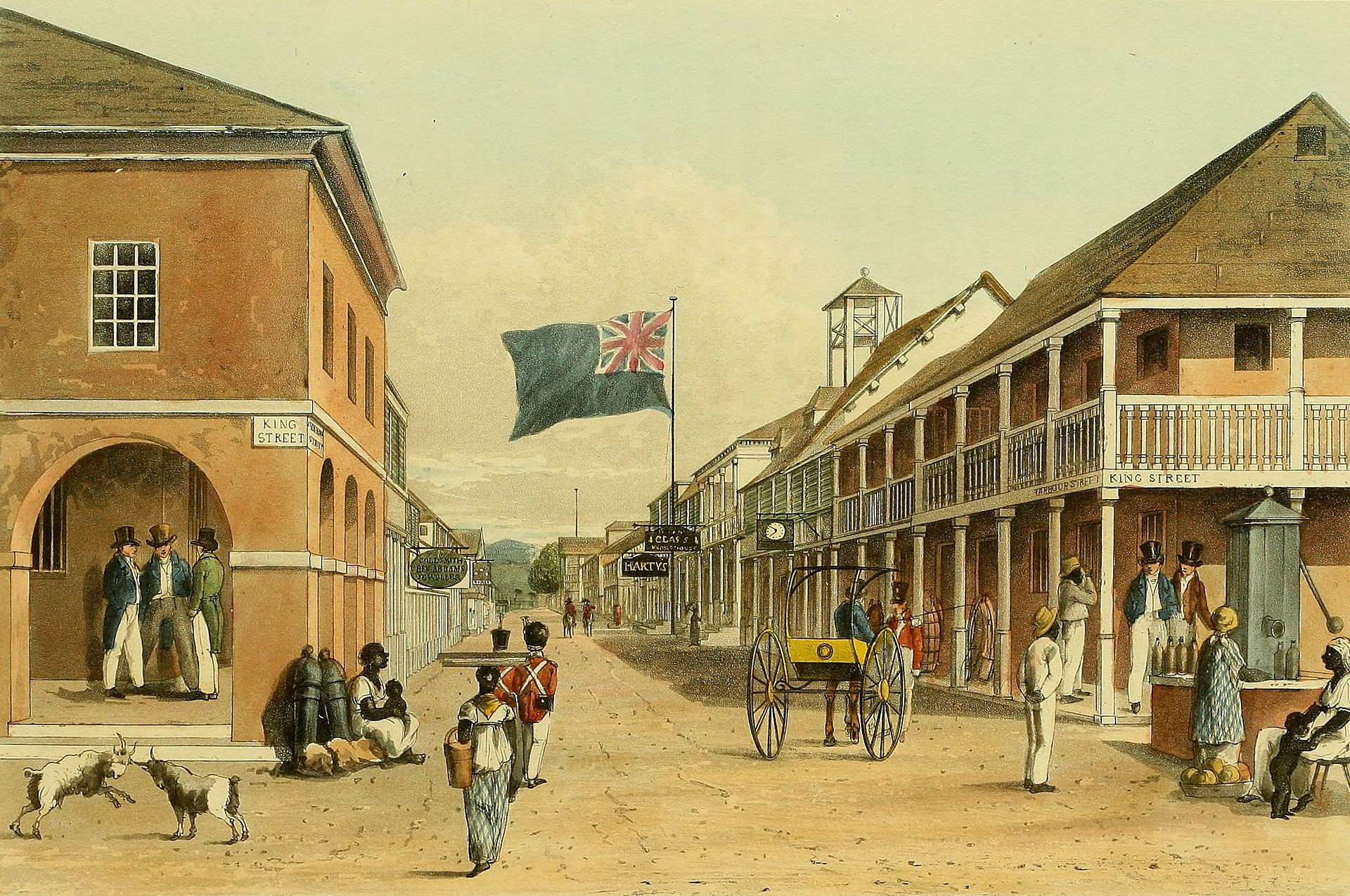

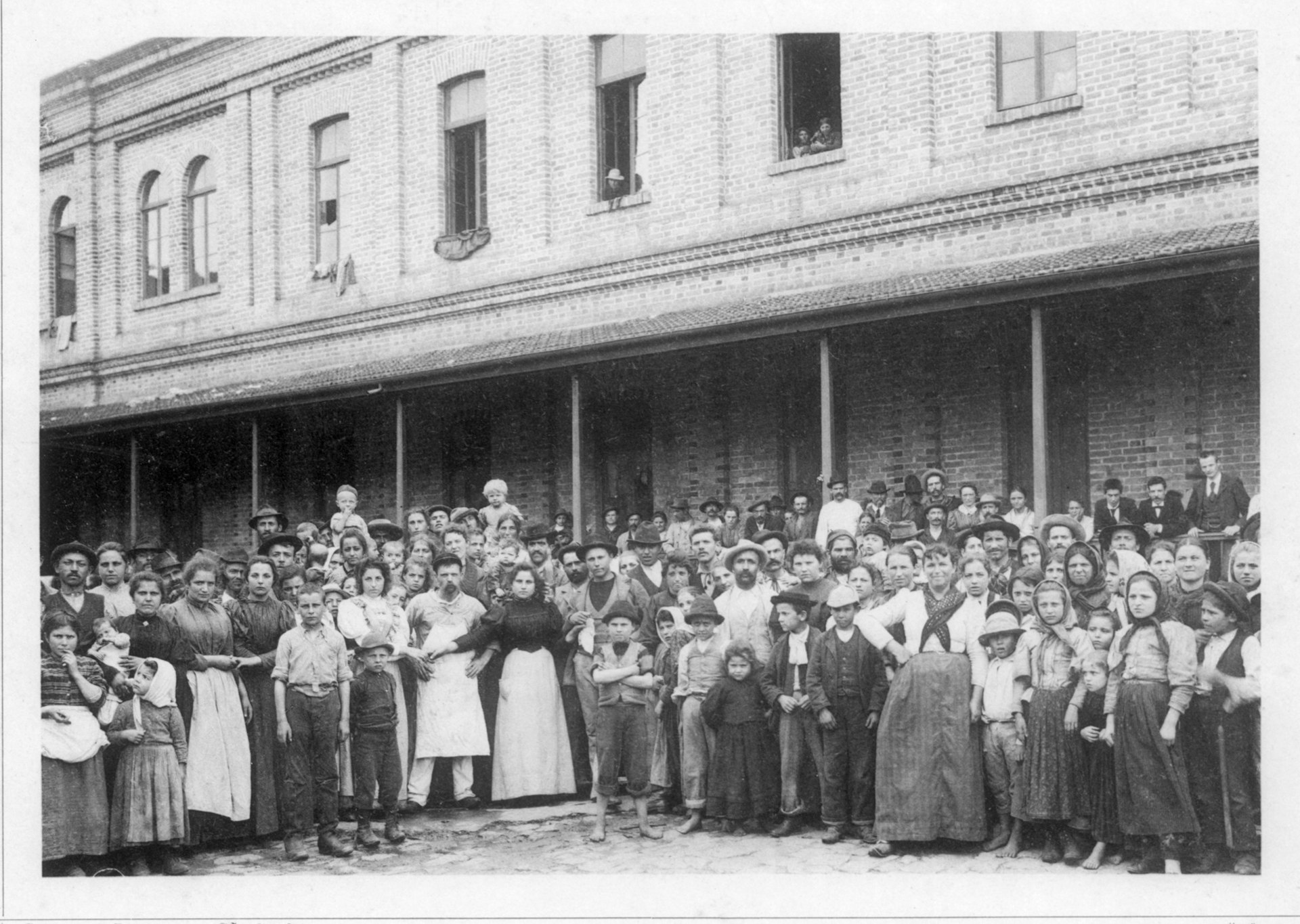

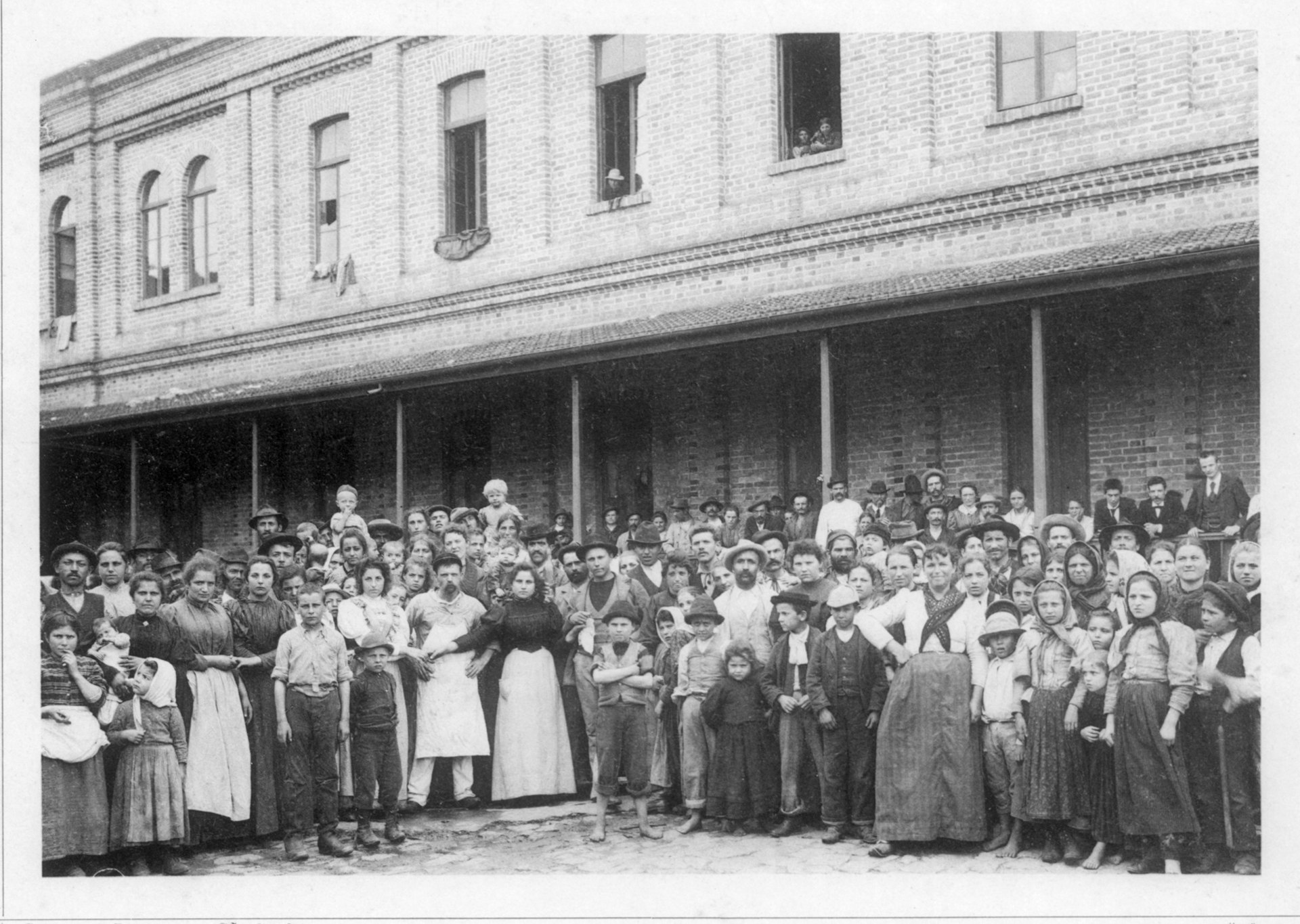

A factory

entrepôt, a basic example of colonialism illustrating its different

elements, hierarchies and impact on the land and people (the Dutch

V.O.C. factory in Hugli-Chuchura, Bengal, in 1665)/

植民地主義の典型的な例である工場倉庫は、土地や人々に対するさまざまな要素、階層、影響力を示す(1665年、ベンガル州フグリ・チョールチウラのオラ

ンダVOCの工場)。

| Colonialism is

the

pursuing, establishing and maintaining of control and exploitation of

people and of resources by a foreign group.[1][2][3][4][5] Colonizers

monopolize political power and hold conquered societies and their

people to be inferior to their conquerors in legal, administrative,

social, cultural, or biological terms.[6][7] While frequently advanced

as an imperialist regime, colonialism can also take the form of settler

colonialism, whereby colonial settlers invade and occupy territory to

permanently replace an existing society with that of the colonizers,

possibly towards a genocide of native populations.[8][9] Colonialism developed as a concept describing European colonial empires of the modern era, which spread globally from the 15th century to the mid-20th century, spanning 35% of Earth's land by 1800 and peaking at 84% by the beginning of World War I.[10] European colonialism employed mercantilism and chartered companies, and established coloniality, which keeps the colonized socio-economically othered and subaltern through modern biopolitics of sexuality, gender, race, disability and class, among others, resulting in intersectional violence and discrimination.[11][12] Colonialism has been justified with beliefs of having a civilizing mission to cultivate land and life, based on beliefs of entitlement and superiority, historically often rooted in the belief of a Christian mission. Because of this broad impact different instances of colonialism have been identified from around the world and in history, starting with when colonization was developed by developing colonies and metropoles, the base colonial separation and characteristic.[8] Decolonization, which started in the 18th century, gradually in waves led to the independence of colonies, with a particular large wave of decolonizations happening in the aftermath of World War II between 1945 and 1975.[13][14] Colonialism has a persistent impact on a wide range of modern outcomes, as scholars have shown that variations in colonial institutions can account for variations in economic development,[15][16][17] regime types,[18][19] and state capacity.[20][21] Some academics have used the term neocolonialism to describe the continuation or imposition of elements of colonial rule through indirect means in the contemporary period.[22][23] |

植民地主義とは、外国の集団が他国民および資源を支配し搾取することを

追求、確立、維持することである。[1][2][3][4][5]

植民地主義者は政治的権力を独占し、征服した社会とその住民を、法律上、行政上、社会上、文化上、あるいは生物学的に征服者よりも劣っているとみなす。ま

たは生物学的な面で劣っているとみなす。[6][7]

帝国主義体制として頻繁に主張される一方で、植民地主義は入植者植民地主義という形態を取ることもあり、植民地入植者が領土を侵略し占領することで、既存

の社会を植民地主義者の社会に恒久的に置き換える。場合によっては、先住民の大量虐殺を目的としていることもある。[8][9] 植民地主義は、15世紀から20世紀半ばにかけて世界的に広がり、1800年までに地球上の陸地の35%を占領し、第一次世界大戦の開始時には84%に達 した、近代ヨーロッパの植民地帝国を説明する概念として発展した。ヨーロッパの植民地主義は重商主義と勅許状会社を採用し、植民地を確立した 植民地化された人々は、近代の生政治的な性、ジェンダー、人種、障害、階級などの問題によって、社会経済的に他者として、サバルタンとして扱われ続け、そ の結果、交差する暴力や差別が生じている。[11][12] 植民地主義は、土地や生命を育成するという文明化の使命という信念に基づいて正当化されてきた。その信念は、権利と優越性という信念に基づいており、歴史 的にはキリスト教の使命という信念に根ざしていることが多い。 この広範な影響により、植民地主義のさまざまな事例が世界中で歴史的に確認されており、植民地化が発展途上国と先進国によって進められた時期から始まり、 植民地化の基本的な分離と特徴が現れた。 18世紀に始まった脱植民地化は、徐々に波状的に植民地の独立へとつながり、特に大きな脱植民地化の波は第二次世界大戦後の1945年から1975年の間 に起こった。[13][14] 学者たちが示しているように、植民地制度の変化は経済発展、[15][16][17] 政権形態、[18][19] 国家能力の変化を説明できるため、植民地主義は現代のさまざまな結果に根強く影響を与えている。植民地制度の多様性が経済発展の多様性、[15][16] [17] 政権形態、[18][19] 国家能力の多様性を説明できることを学者たちが示しているように、植民地主義は現代のさまざまな結果に根強く影響を与えている。[20][21] 一部の学者は、現代において間接的な手段を通じて植民地支配の要素が継続または強制されていることを説明する際に、新植民地主義という用語を使用してい る。[22][23] |

| Etymology See also: Colony § Etymology, and Colonization § Etymology Colonialism is etymologically rooted in the Latin word "Colonus", which was used to describe tenant farmers in the Roman Empire.[4] The coloni sharecroppers started as tenants of landlords, but as the system evolved they became permanently indebted to the landowner and trapped in servitude. Definitions  The East Offering its Riches to Britannia, painted by Spiridione Roma for the boardroom of the British East India Company The earliest uses of colonialism referred to plantations that men emigrated to and settled.[24] The term expanded its meaning in the early 20th century to primarily refer to European imperial expansion and the imperial subjection of Asian and African peoples.[24] Collins English Dictionary defines colonialism as "the practice by which a powerful country directly controls less powerful countries and uses their resources to increase its own power and wealth".[3] Webster's Encyclopedic Dictionary defines colonialism as "the system or policy of a nation seeking to extend or retain its authority over other people or territories".[2] The Merriam-Webster Dictionary offers four definitions, including "something characteristic of a colony" and "control by one power over a dependent area or people".[25] The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy uses the term "to describe the process of European settlement and political control over the rest of the world, including the Americas, Australia, and parts of Africa and Asia". It discusses the distinction between colonialism, imperialism and conquest and states that "[t]he difficulty of defining colonialism stems from the fact that the term is often used as a synonym for imperialism. Both colonialism and imperialism were forms of conquest that were expected to benefit Europe economically and strategically," and continues "given the difficulty of consistently distinguishing between the two terms, this entry will use colonialism broadly to refer to the project of European political domination from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries that ended with the national liberation movements of the 1960s".[4] In his preface to Jürgen Osterhammel's Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview, Roger Tignor says "For Osterhammel, the essence of colonialism is the existence of colonies, which are by definition governed differently from other territories such as protectorates or informal spheres of influence."[1] In the book, Osterhammel asks, "How can 'colonialism' be defined independently from 'colony?'"[26] He settles on a three-sentence definition: Colonialism is a relationship between an indigenous (or forcibly imported) majority and a minority of foreign invaders. The fundamental decisions affecting the lives of the colonised people are made and implemented by the colonial rulers in pursuit of interests that are often defined in a distant metropolis. Rejecting cultural compromises with the colonised population, the colonisers are convinced of their own superiority and their ordained mandate to rule.[27] According to Julian Go, "Colonialism refers to the direct political control of a society and its people by a foreign ruling state... The ruling state monopolizes political power and keeps the subordinated society and its people in a legally inferior position."[6] He also writes, "colonialism depends first and foremost upon the declaration of sovereignty and/or territorial seizure by a core state over another territory and its inhabitants who are classified as inferior subjects rather than equal citizens."[7] According to David Strang, decolonization is achieved through the attainment of sovereign statehood with de jure recognition by the international community or through full incorporation into an existing sovereign state.[28] |

語源 参照:植民地 § 語源、植民地化 § 語源 植民地主義の語源はラテン語の「Colonus」であり、これはローマ帝国における小作農を指す言葉であった。[4] 農場労働者であるコロニーは地主の小作人として始まったが、制度が発展するにつれ、彼らは地主に対して永続的な負債を負うこととなり、奴隷状態に陥った。 定義  スピリディオーネ・ローマがイギリス東インド会社の役員室のために描いた『東がブリタニアに富を捧げる』 植民地主義という用語が最初に用いられたのは、人々が移住して定住したプランテーションを指してであった。[24] この用語は20世紀初頭に意味を拡大し、主にヨーロッパの帝国主義的拡大とアジアおよびアフリカの人々に対する帝国支配を指すようになった。[24] コリンズ英語辞典は、植民地主義を「強力な国が、より弱小な国々を直接的に支配し、それらの資源を自国の権力と富を増大させるために利用する行為」と定義 している。[3] ウェブスターの百科辞典は、植民地主義を「 他国や他地域に対する権限の拡大または維持を求める国家の体制または政策」と定義している。[2] メリアム・ウェブスター辞典では、「植民地の特徴」や「従属地域や人々に対する支配」など4つの定義が提示されている。[25] スタンフォード哲学事典では、「ヨーロッパによるアメリカ、オーストラリア、アフリカおよびアジアの一部を含む、その他の地域への入植と政治的支配のプロ セスを説明する」ためにこの用語を使用している。 植民地主義、帝国主義、征服の相違について論じ、「植民地主義の定義の難しさは、この用語が帝国主義と同義語として使用されることが多いという事実から生 じている。植民地主義と帝国主義はどちらも、ヨーロッパに経済的・戦略的利益をもたらす征服の形態であった」と述べ、さらに「この2つの用語を一貫して区 別することが難しいことを踏まえ、本稿では、16世紀から20世紀にかけてのヨーロッパによる政治的支配のプロジェクトを指す場合、植民地主義という用語 を広く使用する。 ユルゲン・オスターハメル著『植民地主義:理論的概観』の序文で、ロジャー・ティグナーは次のように述べている。理論的概観』の序文で、ロジャー・ティグ ナーは「オスターハメルにとって、植民地主義の本質は植民地の存在であり、それは定義上、保護領や非公式な勢力圏といった他の領土とは異なる統治形態であ る」と述べている。[1] 著書の中で、オスターハメルは「植民地主義」を「植民地」から独立して定義することは可能か、と問いかけている。[26] 彼は3つの文章からなる定義を提示している。 植民地主義とは、土着の(あるいは強制的に移住させられた)多数派と外国からの侵略者の少数派との関係である。植民地支配者の利益追求のために、植民地の 人々の生活に影響を与える基本的な決定が下され、実施される。植民地支配者は、植民地の人々との文化的妥協を拒絶し、自らの優越性と支配の正当性を確信し ている。 ジュリアン・ゴーによると、「植民地主義とは、外国の支配国家による社会とその住民に対する直接的な政治的支配を指す。支配国家は政治的権力を独占し、従 属する社会とその住民を法的に劣った立場に置く」[6]。また、ゴーは「植民地主義は、まず何よりも、中心となる国家が別の領土とその住民に対して主権を 宣言し、その領土と住民を劣った支配対象としてではなく、対等な市民として分類することに依存している」[7]とも述べている。 デビッド・ストレンジによると、脱植民地化は、国際社会による法的な承認を得た主権国家としての地位の獲得、または既存の主権国家への完全な編入によって 達成される。[28] |

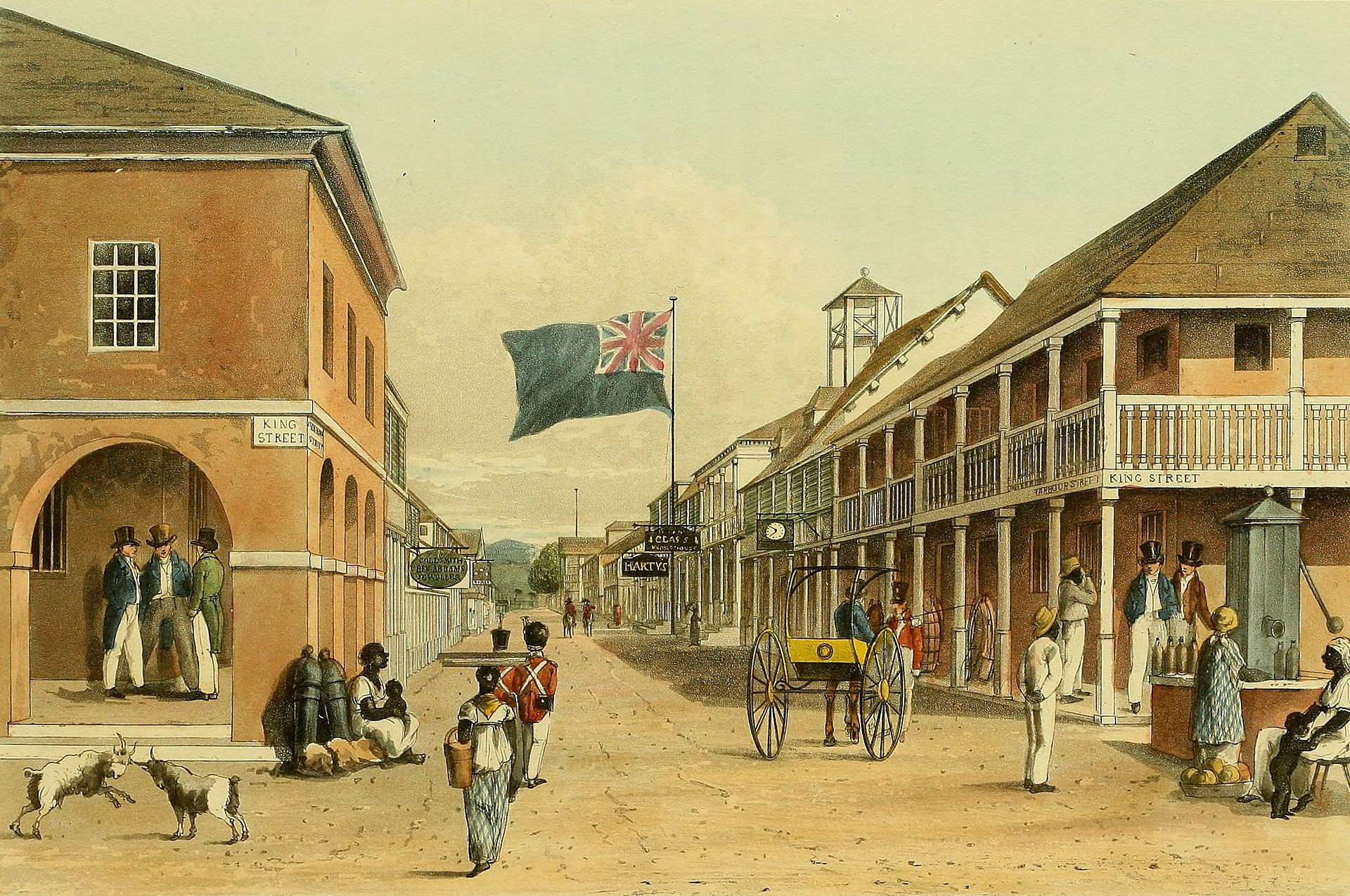

Types of colonialism Dutch family in Java, 1927 The Times once quipped that there were three types of colonial empire: "The English, which consists in making colonies with colonists; the German, which collects colonists without colonies; the French, which sets up colonies without colonists."[29] Modern studies of colonialism have often distinguished between various overlapping categories of colonialism, broadly classified into four types: settler colonialism, exploitation colonialism, surrogate colonialism, and internal colonialism. Some historians have identified other forms of colonialism, including national and trade forms.[30] Settler colonialism involves large-scale immigration by settlers to colonies, often motivated by religious, political, or economic reasons. This form of colonialism aims largely to supplant prior existing populations with a settler one, and involves large number of settlers emigrating to colonies for the purpose of establishing settlements.[30] Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China,[31] New Zealand, Russia, South Africa, United States, Uruguay, and (controversially) Israel, are examples of nations created or expanded in their contemporary form by settler colonization.[32][33][34][35][36] Exploitation colonialism involves fewer colonists and focuses on the exploitation of natural resources or labour to the benefit of the metropole. This form consists of trading posts as well as larger colonies where colonists would constitute much of the political and economic administration. The European colonization of Africa and Asia was largely conducted under the auspices of exploitation colonialism.[37] Surrogate colonialism involves a settlement project supported by a colonial power, in which most of the settlers do not come from the same ethnic group as the ruling power, as it has been (controversially) argued was the case of Mandatory Palestine and the Colony of Liberia.[38][39] Internal colonialism is a notion of uneven structural power between areas of a state. The source of exploitation comes from within the state. This is demonstrated in the way control and exploitation may pass from people from the colonizing country to an immigrant population within a newly independent country.[40][41]  Harbour Street, Kingston, Jamaica, c. 1820 National colonialism is a process involving elements of both settler and internal colonialism, in which nation-building and colonization are symbiotically connected, with the colonial regime seeking to remake the colonized peoples into their own cultural and political image. The goal is to integrate them into the state, but only as reflections of the state's preferred culture. The Republic of China in Taiwan is the archetypal example of a national-colonialist society.[42] Trade colonialism involves the undertaking of colonialist ventures in support of trade opportunities for merchants. This form of colonialism was most prominent in 19th-century Asia, where previously isolationist states were forced to open their ports to Western powers. Examples of this include the Opium Wars and the opening of Japan.[43][44] |

植民地主義の類型 1927年、ジャワのオランダ人家族 かつて『タイムズ』紙は、植民地帝国には3つのタイプがある、と皮肉った。「植民地入植者とともに植民地を築くイギリス、植民地を持たずに植民地入植者を 集めるドイツ、植民地入植者を伴わずに植民地を築くフランス」[29] 植民地主義に関する近年の研究では、植民地主義のさまざまな重複するカテゴリーを区別することが多く、大きく4つのタイプに分類される。入植者植民地主 義、搾取植民地主義、代理植民地主義、内部植民地主義である。一部の歴史家は、国家形態や貿易形態を含む、その他の植民地主義の形態を特定している。 [30] 入植者による植民地主義は、宗教、政治、経済上の理由から、入植者による植民地への大規模な移住を伴う。この形態の植民地主義は、主に既存の住民を入植者 に入れ替えることを目的としており、入植地を確立することを目的として、多数の入植者が植民地に移住する。[30] アルゼンチン、オーストラリア、ブラジル、カナダ、チリ、中国、[31 、ニュージーランド、ロシア、南アフリカ、アメリカ、ウルグアイ、そして(論争の的となっている)イスラエルは、入植者による植民地化によって現代的な国 家が形成された、あるいは拡大した例である。 搾取植民地主義は、入植者の数が少なく、本国が利益を得るために天然資源や労働力を搾取することに重点を置いている。この形態は、交易所や、入植者が政 治・経済の大部分を管理する大規模な植民地からなる。ヨーロッパによるアフリカとアジアの植民地化は、主に搾取植民地主義の庇護の下で行われた。 代理植民地主義は、宗主国が支援する入植事業であり、入植者の大半が支配勢力と同じ民族ではない。これは、委任統治領パレスチナやリベリア植民地の場合に 当てはまると(議論の余地はあるが)主張されている。 内部植民地主義とは、国家内の地域間の構造的不均衡を指す概念である。搾取の源は国家内部にある。これは、植民地化を行った国の人々による支配や搾取が、 新たに独立した国における移民人口へと引き継がれる可能性があることを示している。  ハーバー・ストリート、ジャマイカ、キングストン、1820年頃 国家による植民地主義とは、入植者による植民地主義と国内植民地主義の両方の要素を含むプロセスであり、国家建設と植民地化が共生関係にある。植民地体制 は、被植民地の人々を自国の文化的・政治的イメージに作り変えようとする。その目的は、彼らを国家に統合することだが、あくまでも国家が望ましいとする文 化の反映としてである。台湾の中華民国は、国家植民地主義社会の典型的な例である。[42] 貿易植民地主義は、商人の貿易機会を支援する植民地主義的企業を伴う。この形態の植民地主義は、19世紀のアジアで最も顕著であった。それ以前は鎖国政策 をとっていた国家が、西洋列強に対して開国を余儀なくされた。この例としては、アヘン戦争や日本の開国などがある。[43][44] |

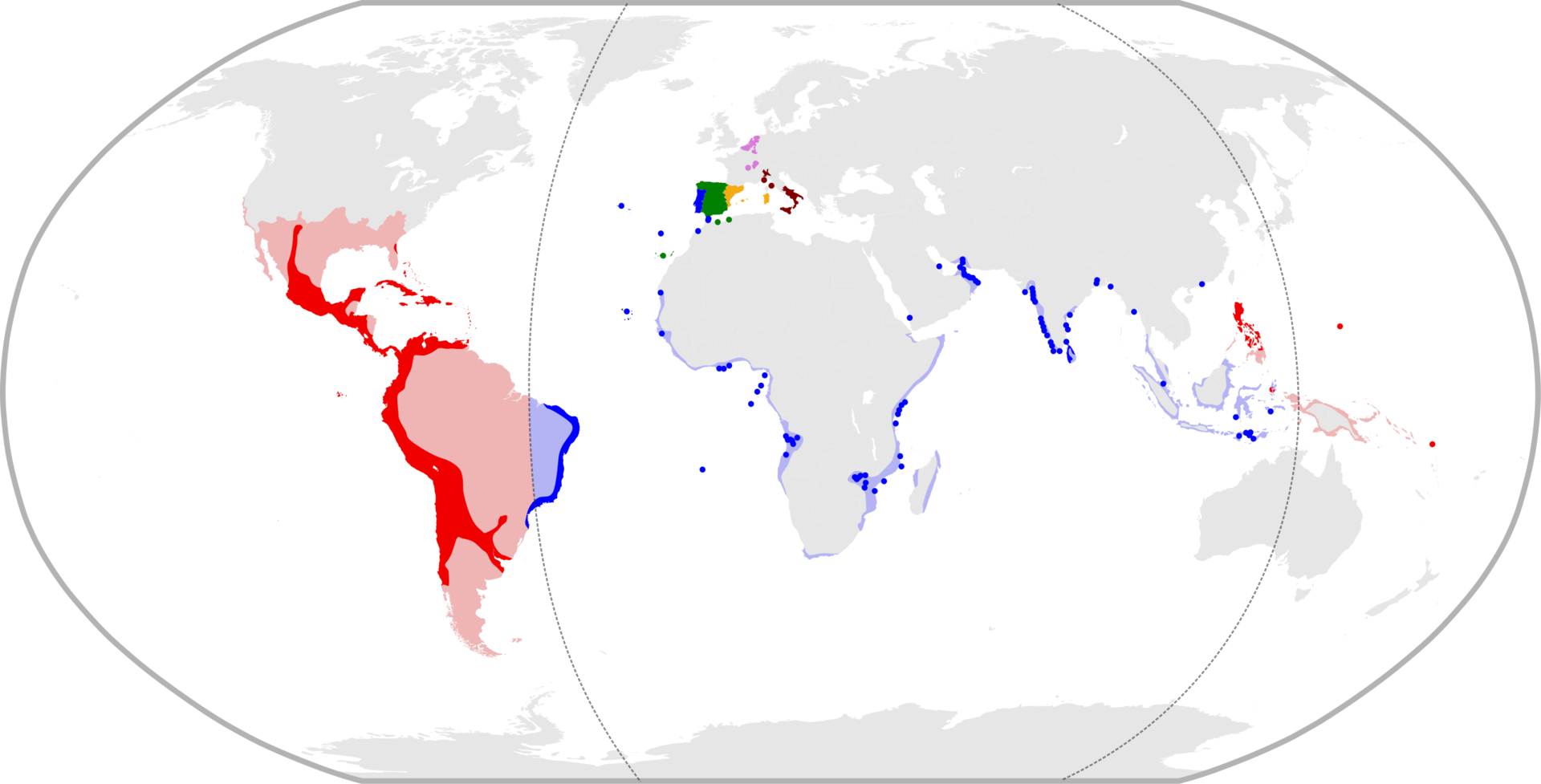

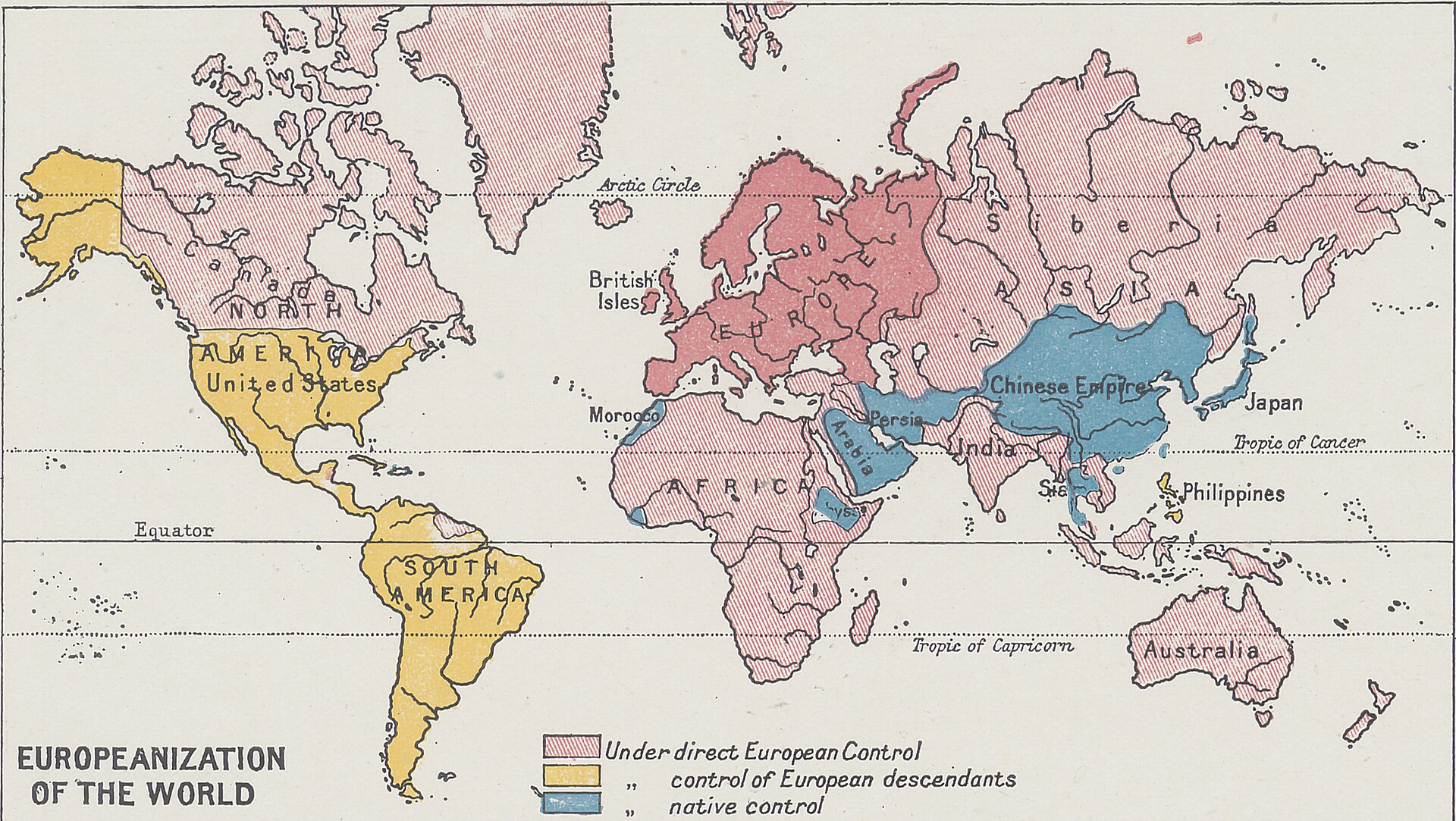

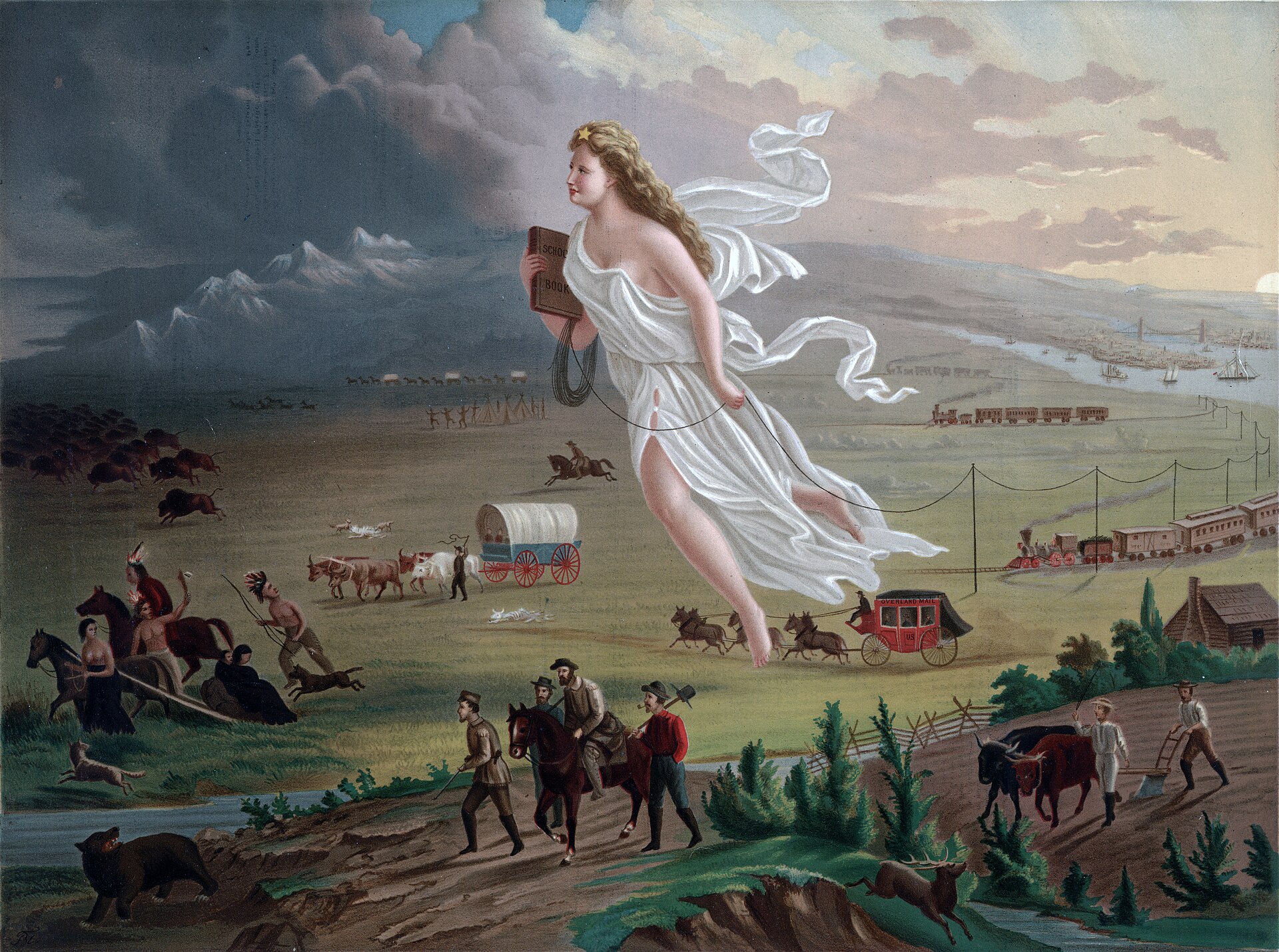

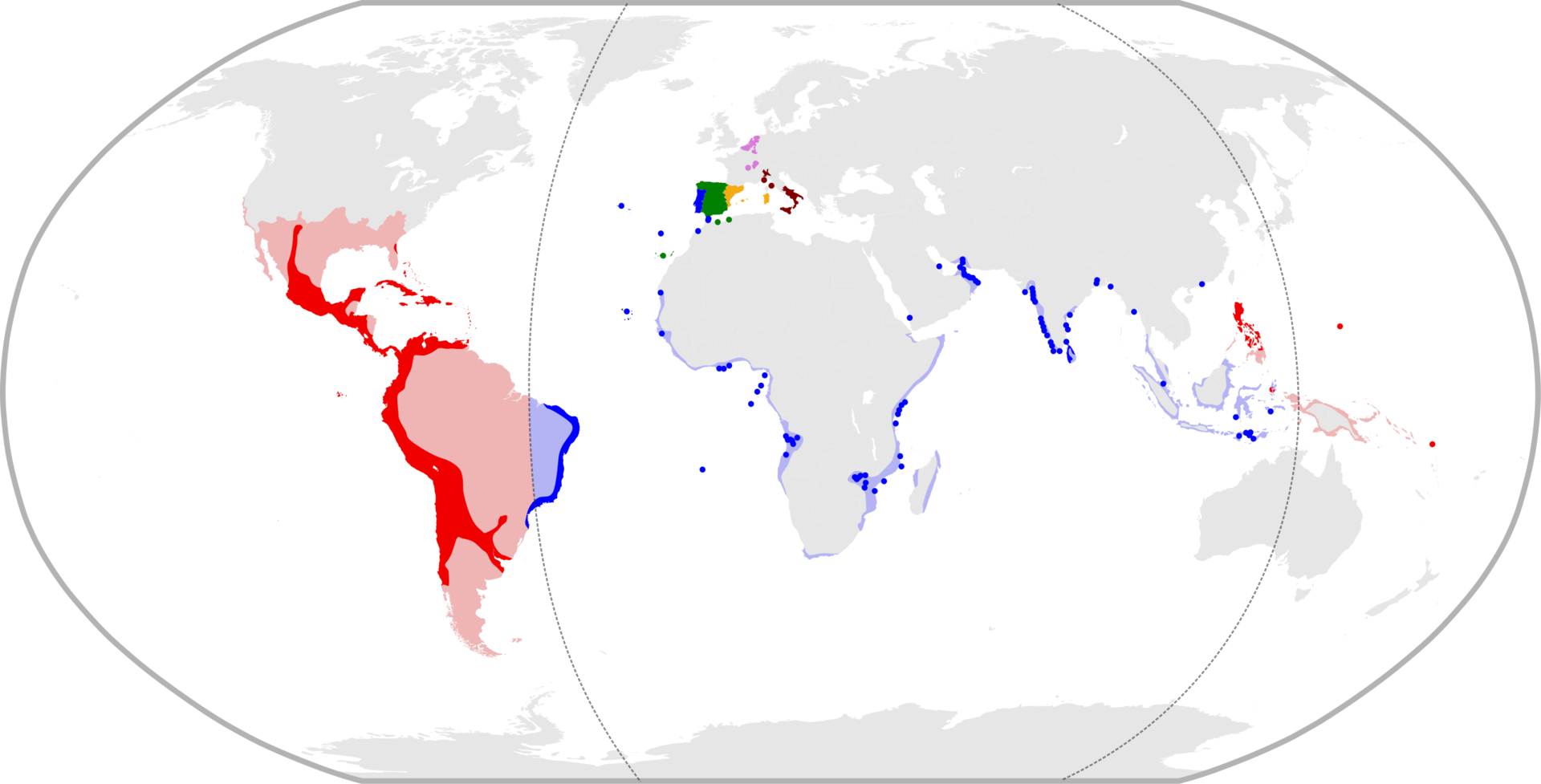

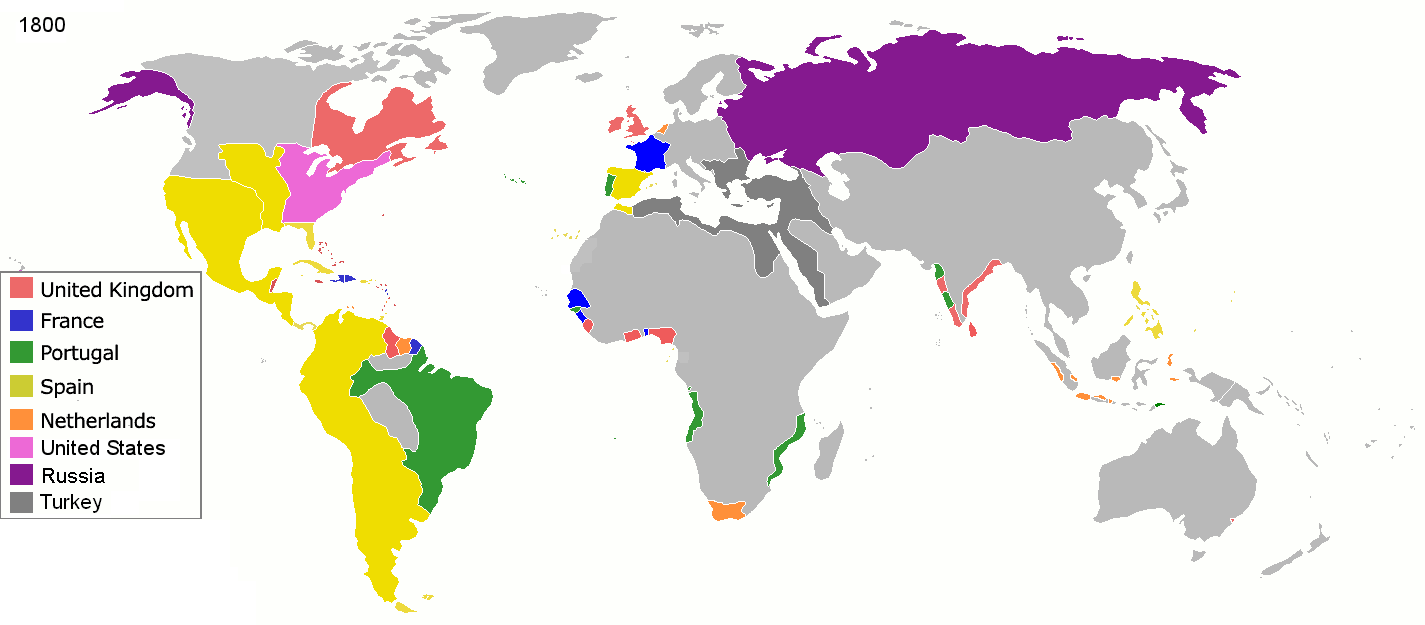

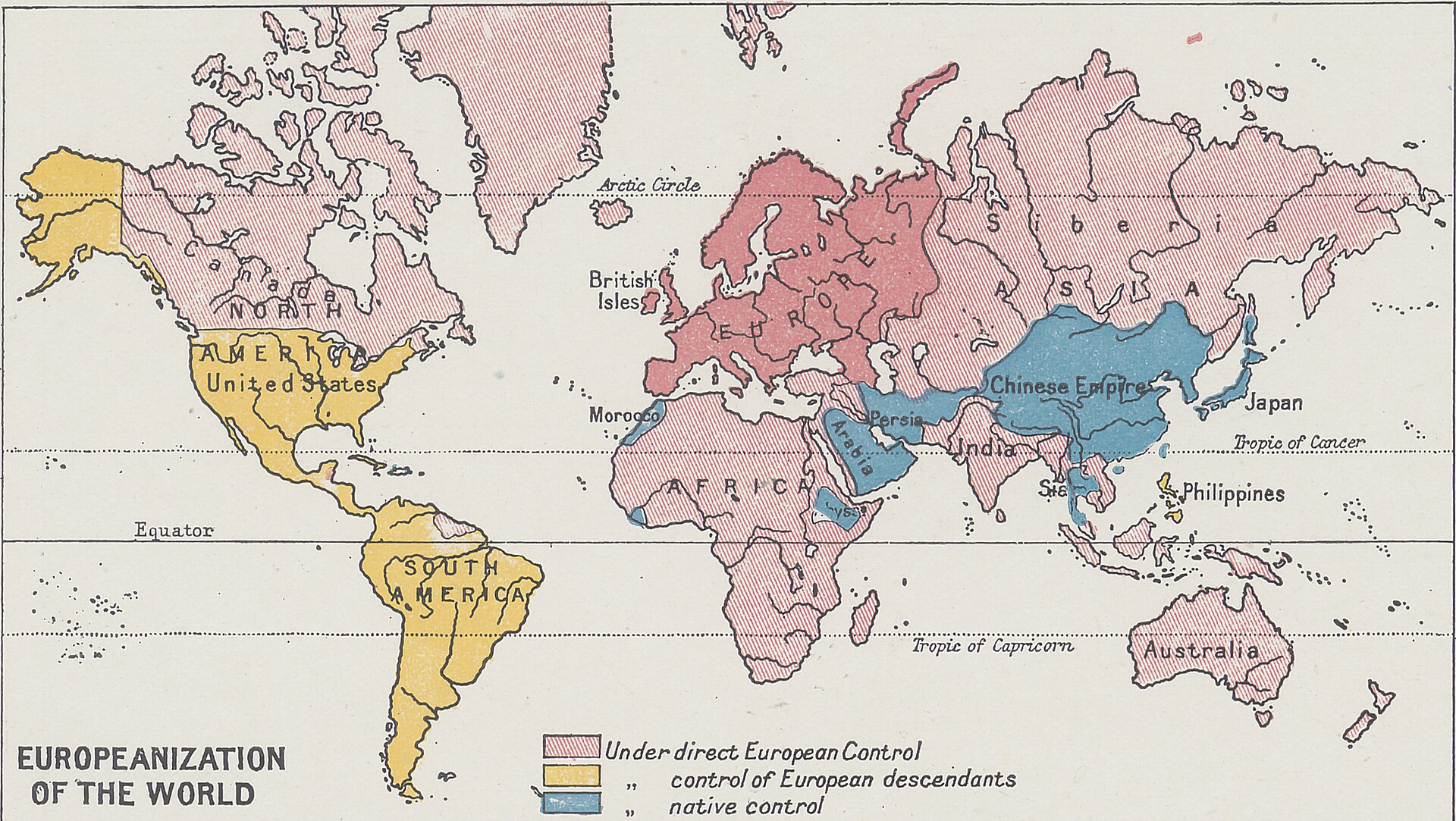

| Socio-cultural evolution Further information: Coloniality of power When colonists settled in pre-populated areas, the societies and cultures of the people in those areas permanently changed. Colonial practices directly and indirectly forced the colonized peoples to abandon their traditional cultures. For example, European colonizers in the United States implemented the residential schools program to force native children to assimilate into the hegemonic culture. Cultural colonialism gave rise to culturally and ethnically mixed populations such as the mestizos of the Americas, as well as racially divided populations such as those found in French Algeria or in Southern Rhodesia. In fact, everywhere where colonial powers established a consistent and continued presence, hybrid communities existed. Notable examples in Asia include the Anglo-Burmese, Anglo-Indian, Burgher, Eurasian Singaporean, Filipino mestizo, Kristang, and Macanese peoples. In the Dutch East Indies (later Indonesia) the vast majority of "Dutch" settlers were in fact Eurasians known as Indo-Europeans, formally belonging to the European legal class in the colony.[45][46]  American Progress (1872) by John Gast is an allegorical representation of the idea of manifest destiny. Columbia, a personification of the United States, leads settler civilization westward, bringing light, stringing telegraph wire, holding a book,[47] and highlighting different stages of economic activity and evolving forms of transportation,[48] while on the left, displacing Native Americans in the United States from their homeland History Main articles: History of colonialism, List of colonies, and Chronology of Western colonialism Antiquity Activity that could be called colonialism has a long history, starting at least as early as the ancient Egyptians. Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans founded colonies in antiquity. Phoenicia had an enterprising maritime trading-culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550 BC to 300 BC; later the Persian Empire and various Greek city-states continued on this line of setting up colonies. The Romans would soon follow, setting up coloniae throughout the Mediterranean, in North Africa, and in Western Asia. Medieval Beginning in the 7th century, Arabs colonized a substantial portion of the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia and Europe. From the 9th century Vikings (Norsemen) such as Leif Erikson established colonies in Britain, Ireland, Iceland, Greenland, North America, present-day Russia and Ukraine, France (Normandy) and Sicily.[49] In the 9th century a new wave of Mediterranean colonisation began, with competitors such as the Venetians, Genovese and Amalfians infiltrating the wealthy previously Byzantine or Eastern Roman islands and lands. European Crusaders set up colonial regimes in Outremer (in the Levant, 1097–1291) and in the Baltic littoral (12th century onwards). Venice began to dominate Dalmatia and reached its greatest nominal colonial extent at the conclusion of the Fourth Crusade in 1204, with the declaration of the acquisition of three octaves of the Byzantine Empire.[50] Modern  Iberian Union of Spain and Portugal between 1580 and 1640 The European early modern period began with the Turkish colonization of Anatolia.[51][dubious – discuss] After the Ottoman Empire colonialised Constantinople in 1453, the sea routes discovered by Portuguese Prince Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) became central to trade, and helped fuel the Age of Discovery.[52] The Crown of Castile encountered the Americas in 1492 through sea travel and built trading posts or conquered large extents of land. The Treaty of Tordesillas divided the areas of these "new" lands between the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire in 1494.[52] The 17th century saw the birth of the Dutch Empire and French colonial empire, as well as the English overseas possessions, which later became the British Empire. It also saw the establishment of Danish overseas colonies and Swedish overseas colonies.[53] A first wave of separatism started with the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), initiating the Rise of the "Second" British Empire (1783–1815).[54] The Spanish Empire largely collapsed in the Americas with the Spanish American wars of independence (1808–1833). Empire-builders established several new colonies after this time, including in the German colonial empire and Belgian colonial empire.[55] Starting with the end of the French Revolution European authors such as Johann Gottfried Herder, August von Kotzebue, and Heinrich von Kleist prolifically published so as to conjure up sympathy for the oppressed native peoples and the slaves of the new world, thereby starting the idealization of native humans.[56]  Map of colonial empires in 1800 The Habsburg monarchy, the Russian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire existed at the same time but did not expand over oceans. Rather, these empires expanded through the conquest of neighbouring territories. There was, though, some Russian colonization of North America across the Bering Strait. From the 1860s onwards the Empire of Japan modelled itself on European colonial empires and expanded its territories in the Pacific and on the Asian mainland. The Empire of Brazil fought for hegemony in South America. The United States gained overseas territories after the 1898 Spanish–American War, hence, the coining of the term "American imperialism".[57] In the late 19th century, many European powers became involved in the Scramble for Africa.[58] 20th century  The Harmsworth atlas and Gazetter 1908 European colonization map The world's colonial population at the outbreak of the First World War (1914) – a high point for colonialism – totalled about 560 million people, of whom 70% lived in British possessions, 10% in French possessions, 9% in Dutch possessions, 4% in Japanese possessions, 2% in German possessions, 2% in American possessions, 3% in Portuguese possessions, 1% in Belgian possessions and 0.5% in Italian possessions. The domestic domains of the colonial powers had a total population of about 370 million people.[59] Outside Europe, few areas had remained without coming under formal colonial tutorship – and even Siam, China, Japan, Nepal, Afghanistan, Persia, and Abyssinia had felt varying degrees of Western colonial-style influence – concessions, unequal treaties, extraterritoriality and the like. Asking whether colonies paid, economic historian Grover Clark (1891–1938) argues an emphatic "No!" He reports that in every case the support cost, especially the military system necessary to support and defend colonies, outran the total trade they produced. Apart from the British Empire, they did not provide favoured destinations for the immigration of surplus metropole populations.[60] The question of whether colonies paid is a complicated one when recognizing the multiplicity of interests involved. In some cases colonial powers paid a lot in military costs while private investors pocketed the benefits. In other cases the colonial powers managed to move the burden of administrative costs to the colonies themselves by imposing taxes.[61]  Map of colonial and land-based empires throughout the world in 1914  Imperial powers in 1945 After World War I (1914–1918), the victorious Allies divided up the German colonial empire and much of the Ottoman Empire between themselves as League of Nations mandates, grouping these territories into three classes according to how quickly it was deemed that they could prepare for independence. The empires of Russia and Austria collapsed in 1917–1918, [62] and the Soviet empire started.[63] Nazi Germany set up short-lived colonial systems (Reichskommissariate, Generalgouvernement) in Eastern Europe in the early 1940s. In the aftermath of World War II (1939–1945), decolonisation progressed rapidly. The tumultuous upheaval of the war significantly weakened the major colonial powers, and they quickly lost control of colonies such as Singapore, India, and Libya.[64] In addition, the United Nations shows support for decolonisation in its 1945 charter. In 1960, the UN issued the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, which affirmed its stance (though notably, colonial empires such as France, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States abstained). [65] The word "neocolonialism" originated from Jean-Paul Sartre in 1956,[66] to refer to a variety of contexts since the decolonisation that took place after World War II. Generally it does not refer to a type of direct colonisation – rather to colonialism or colonial-style exploitation by other means. Specifically, neocolonialism may refer to the theory that former or existing economic relationships, such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the Central American Free Trade Agreement, or the operations of companies (such as Royal Dutch Shell in Nigeria and Brunei) fostered by former colonial powers were or are used to maintain control of former colonies and dependencies after the colonial independence movements of the post–World War II period.[67] The term "neocolonialism" became popular in ex-colonies in the late 20th century.[68] Contemporary While colonies of contiguous empires[69] have been historically excluded, they can be seen as colonies.[70] Contemporary expansion of colonies is seen by some in case of Russian imperialism[71] and Chinese imperialism.[72] There is also ongoing debate in academia about Zionism as settler colonialism. |

社会文化の進化 さらに詳しい情報:権力の植民地性 入植者がすでに人が住んでいる地域に移住すると、その地域の社会や文化は恒久的に変化した。植民地支配の慣行は直接的にも間接的にも、被植民地の人々に伝 統文化を放棄することを強制した。例えば、米国におけるヨーロッパの植民地支配者は、先住民の子供たちにヘゲモニー文化に同化させるために寄宿学校制度を 実施した。 文化植民地主義は、アメリカ大陸のメスチゾのような文化・民族的に混合した集団を生み出すと同時に、フランス領アルジェリアや南ローデシアに見られるよう な人種的に分断された集団を生み出した。事実、植民地支配国が継続的に存在した場所では、どこでも混成コミュニティが存在していた。 アジアにおける著名な例としては、英領ビルマ人、英領インド人、ブルガー、シンガポール系混血、フィリピン系混血、クリスチャン、マカオ系住民などが挙げ られる。オランダ領東インド(後のインドネシア)では、入植者の大半は、実際にはインド・ヨーロッパ人として知られる混血であり、植民地では正式にヨー ロッパの法階級に属していた。  ジョン・ガストの『アメリカン・プログレス』(1872年)は、明白な使命という考えを寓話的に表現したものである。コロンビアはアメリカ合衆国を擬人化 したもので、入植者文明を西へと導き、光をもたらし、電信線を張り巡らし、書物を持ち、[47] 経済活動のさまざまな段階と進化する交通手段を強調している。[48] 一方、左側では、アメリカ合衆国における先住民を彼らの故郷から追い出している 歴史 詳細は「植民地主義の歴史」、「植民地の一覧」、および「西洋の植民地主義の年代順一覧」を参照 古代 植民地主義と呼べる活動は長い歴史があり、少なくとも古代エジプトまで遡る。フェニキア人、ギリシア人、ローマ人は古代に植民都市を建設した。フェニキア 人は、紀元前1550年から紀元前300年にかけて地中海全域に広がった進取の気性に富んだ海洋貿易文化を持っていた。その後、ペルシア帝国やさまざまな ギリシャ都市国家が、植民都市を建設するこの流れを継承した。ローマ人はすぐにこれに追随し、地中海全域、北アフリカ、西アジアに植民都市を建設した。 中世 7世紀に入ると、アラブ人は中東、北アフリカ、およびアジアとヨーロッパの一部の相当な部分を植民地化した。9世紀には、レイフ・エリクソンなどのヴァイ キング(ノース人)が、イギリス、アイルランド、アイスランド、グリーンランド、北アメリカ、現在のロシアとウクライナ、フランス(ノルマンディー)、シ チリアに植民地を建設した。[49] 9世紀には、地中海における新たな植民地化の波が始まり、ヴェネツィア人、ジェノヴァ人、アマルフィ人などの競争相手が、それまでビザンティン帝国または 東ローマ帝国の富裕な島々や土地に侵入した。ヨーロッパの十字軍は、アウトラメール(レバント、1097年から1291年)とバルト海沿岸(12世紀以 降)に植民地政権を樹立した。ヴェネツィアはダルマチアを支配し始め、1204年の第4回十字軍の結末において、ビザンティン帝国の3オクターブ分の領土 獲得を宣言し、名目上の植民地支配の最大範囲に達した。 近代  イベリア連合(1580年から1640年のスペインとポルトガル ヨーロッパの初期近代は、トルコによるアナトリアの植民地化から始まった。[51][疑わしい – 議論する] オスマン帝国が1453年にコンスタンティノープルを植民地化した後、ポルトガルのエンリケ航海王子(1394年-1460年)が発見した海路が貿易の中 心となり、大航海時代を後押しした。[52] カスティーリャ王国は1492年にアメリカ大陸を発見し、海上交易を行い、交易拠点を建設したり広大な土地を征服した。1494年のトルデシリャス条約 で、これらの「新大陸」の領有権がスペイン帝国とポルトガル帝国の間で分割された。 17世紀にはオランダ帝国とフランス植民地帝国が誕生し、またイギリスの海外領土も誕生し、後に大英帝国となった。また、デンマークの海外植民地とス ウェーデンの海外植民地が設立されたのもこの時代である。[53] 分離主義の最初の波はアメリカ独立戦争(1775年 - 1783年)に始まり、「第2次」大英帝国の勃興(1783年 - 1815年)へとつながった。[54] スペイン帝国は、スペイン系アメリカ独立戦争(1808年 - 1833年)により、アメリカ大陸でほぼ崩壊した。この時期以降、ドイツ植民地帝国やベルギー植民地帝国など、いくつかの新たな植民地が帝国建設者たちに よって建設された。[55] フランス革命の終結を皮切りに、ヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダー、アウグスト・フォン・コゼブー、ハインリヒ・フォン・クライストといったヨーロッパの 作家たちが、新世界の抑圧された先住民や奴隷たちへの同情を呼び起こすために盛んに執筆活動を行い、それによって先住民の理想化が始まった。[56]  1800年の植民地帝国の地図 ハプスブルク君主国、ロシア帝国、オスマン帝国は同時に存在していたが、海洋を越えて拡大することはなかった。むしろ、これらの帝国は近隣地域の征服を通 じて拡大した。ただし、ベーリング海峡を越えた北米へのロシアの植民地化はあった。1860年代以降、大日本帝国はヨーロッパの植民地帝国を手本とし、太 平洋およびアジア本土で領土を拡大した。ブラジル帝国は南米での覇権を巡って戦った。アメリカ合衆国は1898年の米西戦争後に海外領土を獲得し、それゆ え「アメリカ帝国主義」という用語が生まれた。 19世紀後半には、多くのヨーロッパ列強がアフリカの争奪戦に参戦した。 20世紀  ハーンスワース世界地図帳および年鑑 1908年版のヨーロッパによる植民地化地図 植民地主義の絶頂期であった第一次世界大戦(1914年)勃発時の世界の植民地人口は、およそ5億6000万人であり、そのうち70%がイギリスの植民 地、10%が フランス領に10%、オランダ領に9%、日本領に4%、ドイツ領に2%、アメリカ領に2%、ポルトガル領に3%、ベルギー領に1%、イタリア領に0.5% であった。植民地大国の国内領域の総人口は約3億7000万人であった。[59] ヨーロッパ以外の地域では、正式な植民地保護下に入らずにいた地域はほとんどなく、シャム、中国、日本、ネパール、アフガニスタン、ペルシャ、アビシニア でさえ、さまざまな程度の西洋の植民地スタイルの影響、すなわち利権、不平等条約、治外法権などを感じていた。 植民地が支払っていたかどうかという問いに対して、経済史家のグローバー・クラーク(1891~1938)は「いいえ」と断言している。彼は、どのケース においても、特に植民地を支援し防衛するために必要な軍事システムにかかる費用が、植民地が生産した貿易総額を上回っていたと報告している。大英帝国を除 いては、植民地は本国で余剰となった人口の移住先として好まれる場所ではなかった。[60] 植民地が支払ったかどうかという問題は、関与するさまざまな利害関係を認識する際に複雑なものとなる。植民地宗主国が軍事費に多額を支出した一方で、その 利益を私的投資家が手にしたケースもある。また、植民地宗主国が税を課すことで、なんとかして行政費の負担を植民地自身に転嫁したケースもある。[61]  1914年における世界中の植民地帝国と土地帝国の地図  1945年の帝国勢力 第一次世界大戦(1914年~1918年)後、連合国はドイツの植民地帝国とオスマン帝国の大部分を国際連盟の委任統治領として分割し、これらの地域を独 立への準備がどの程度整っているかによって3つのクラスに分類した。ロシアとオーストリアの帝国は1917年から1918年にかけて崩壊し、[62] ソビエト帝国が始まった。[63] ナチス・ドイツは1940年代初頭に東ヨーロッパに短命に終わった植民地制度(総督府、一般統治領)を設置した。 第二次世界大戦(1939年 - 1945年)の後、脱植民地化が急速に進んだ。戦争による激動的な動乱は主要な植民地大国を著しく弱体化させ、シンガポール、インド、リビアなどの植民地 を急速に失った。[64] さらに、国連は1945年の憲章で脱植民地化を支持している。1960年には国連が「植民地諸国および諸民族に対する独立付与宣言」を発表し、その立場を 明確にした(ただし、フランス、スペイン、イギリス、アメリカ合衆国などの植民地帝国は棄権した)。[65] 「新植民地主義」という言葉は、1956年にジャン=ポール・サルトルが使用したのが始まりであり[66]、第二次世界大戦後に起こった脱植民地化以降の さまざまな状況を指すために使われている。一般的に、これは直接的な植民地化の一形態を指すのではなく、むしろ他の手段による植民地主義や植民地的な搾取 を指す。具体的には、新植民地主義という用語は、関税貿易一般協定や中米自由貿易協定などの旧来の経済関係や、旧植民地宗主国が育成した企業(ナイジェリ アやブルネイにおけるロイヤル・ダッチ・シェルなど)が、第二次世界大戦後の植民地独立運動以降も旧植民地や従属地域を支配し続けるために利用されてき た、あるいは現在も利用されているという理論を指す場合がある。 「新植民地主義」という用語は、20世紀後半に旧植民地で広く使われるようになった。[68] 現代 歴史的に除外されてきたが、連続した帝国の植民地[69]は植民地と見なすことができる。[70] 現代における植民地の拡大は、ロシア帝国主義[71]や中国帝国主義[72]のケースに見られる。また、入植地植民地主義としてのシオニズムについても、 学術界で議論が続いている。 |

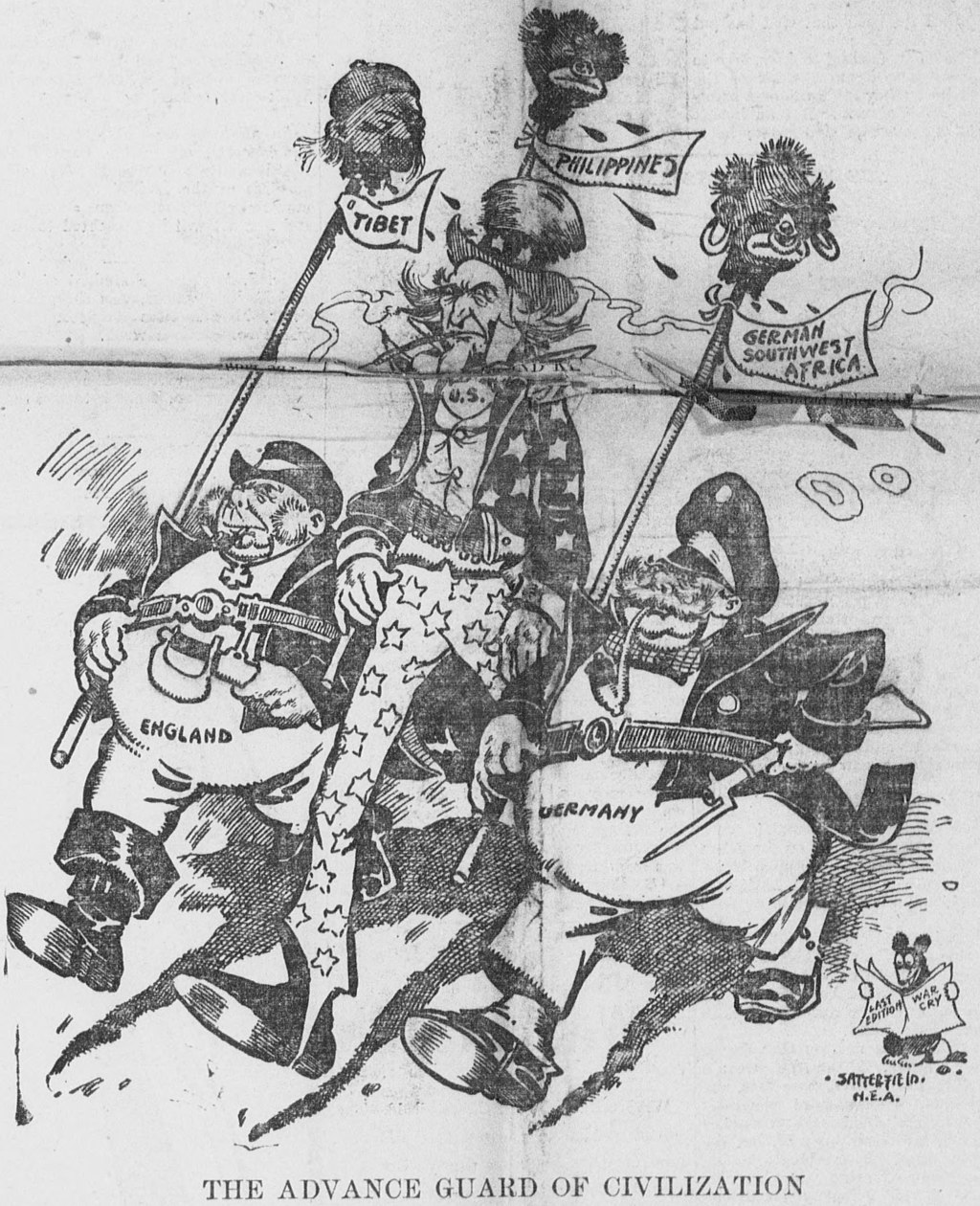

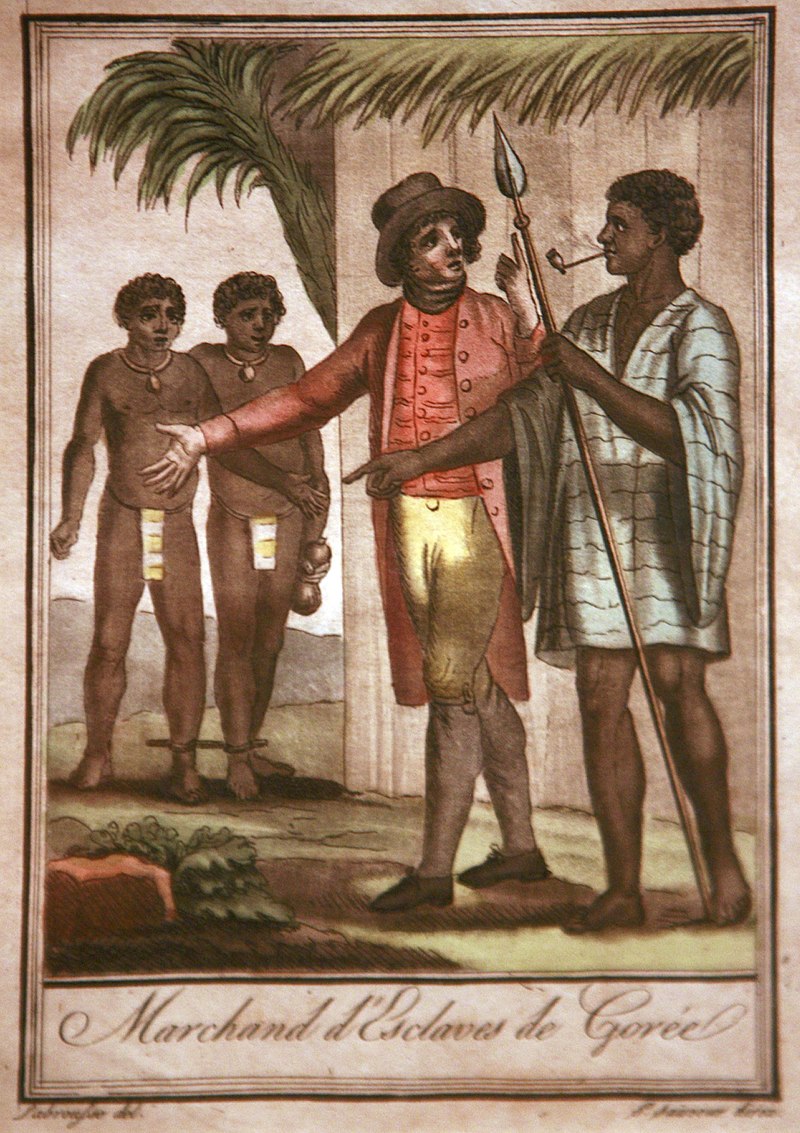

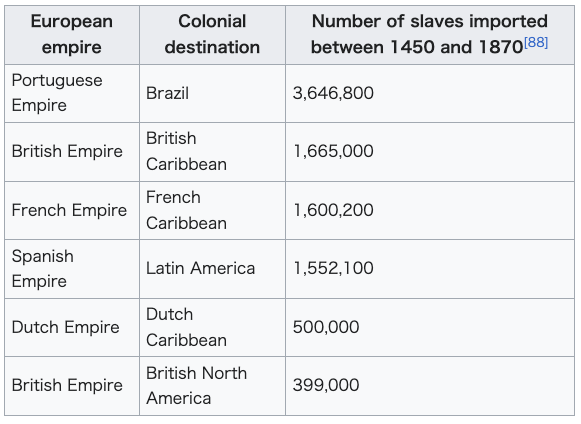

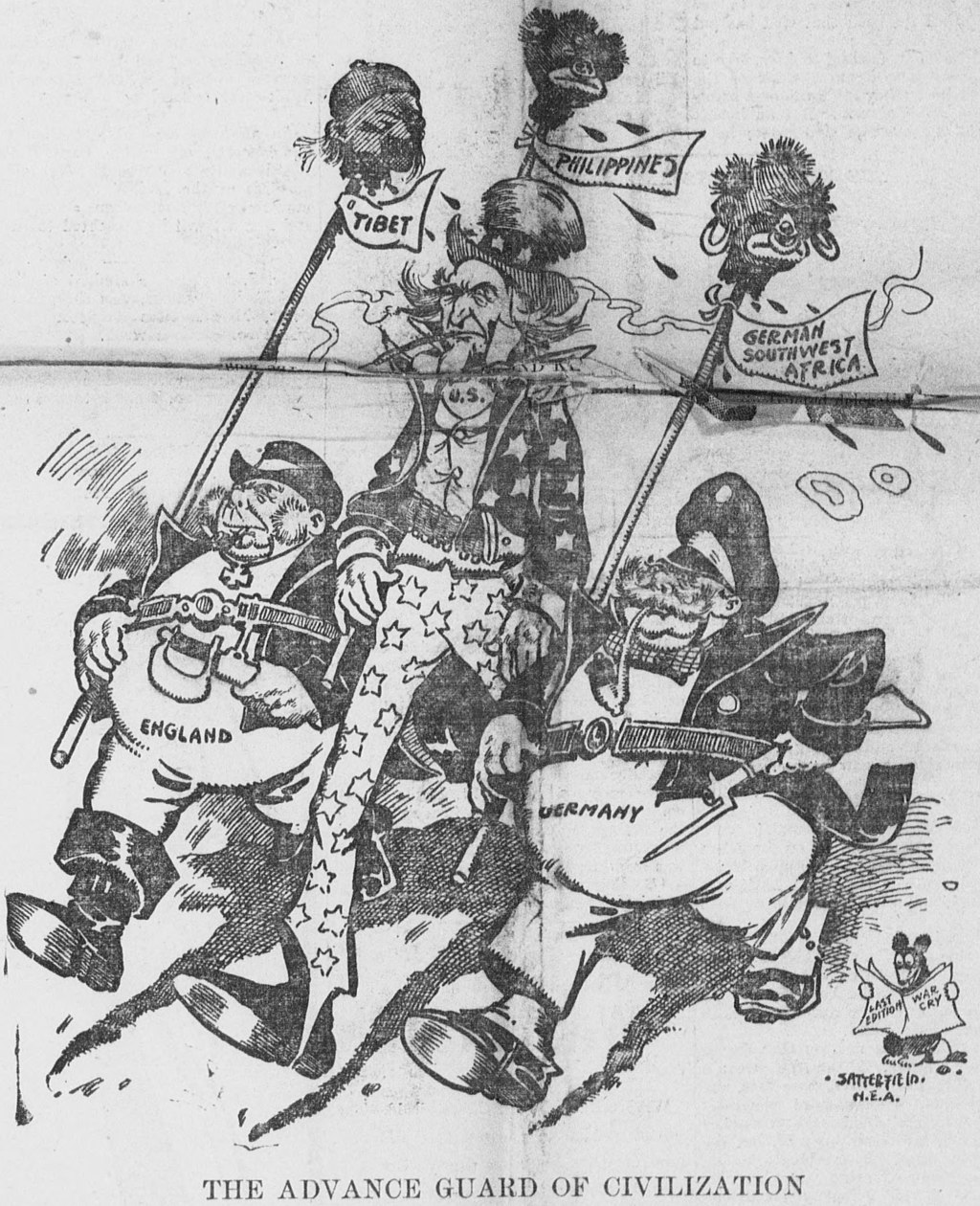

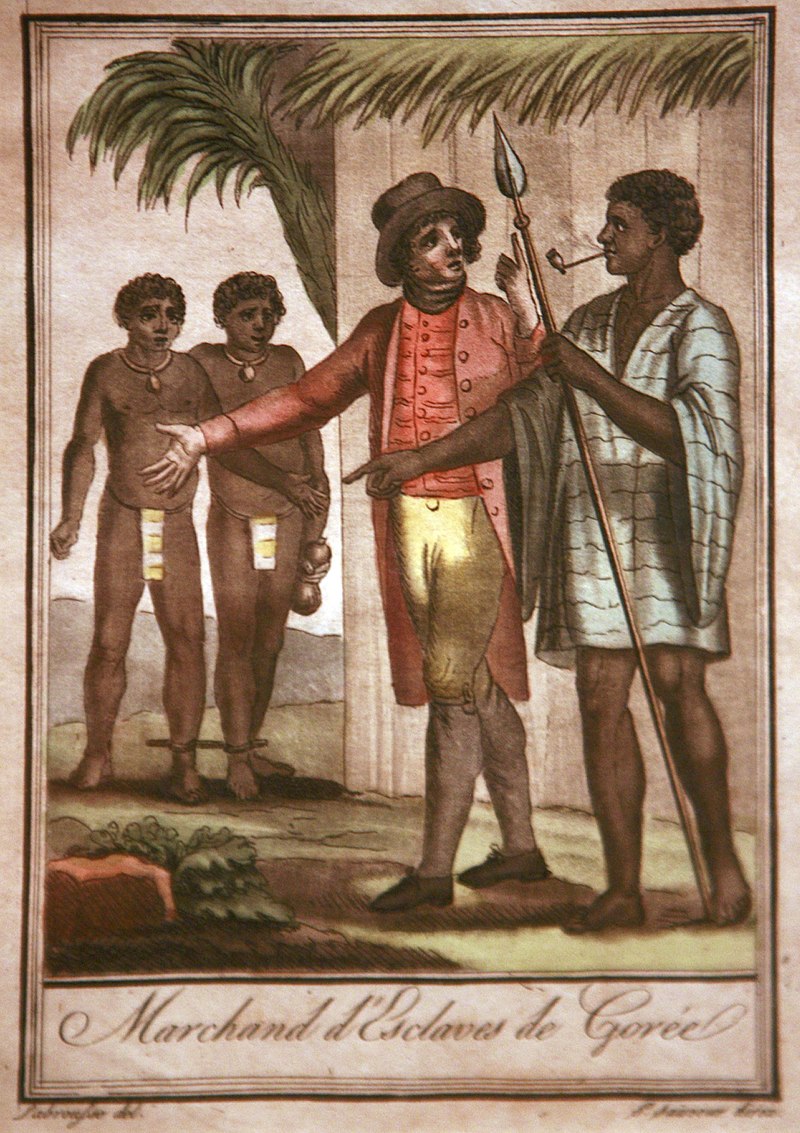

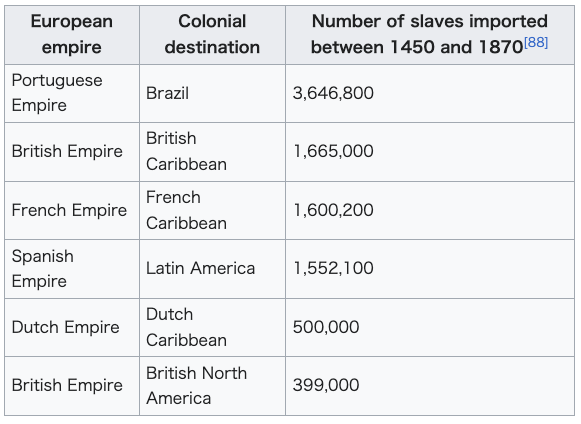

| Impact Main article: Analysis of Western European colonialism and colonization § Colonial actions and their impacts  A 1904 cartoon by Bob Satterfield about the brutality committed by Western nations: the personifications of England, the United States, and Germany carrying spears topped by the severed heads of Tibet, the Philippines, and Southwest Africa respectively. The caption describes this as "The advance guard of civilization". Duration: 1 minute and 49 seconds.1:49 The Dutch Public Health Service provides medical care for the natives of the Dutch East Indies, May 1946. The impacts of colonisation are immense and pervasive.[73] Various effects, both immediate and protracted, include the spread of virulent diseases, unequal social relations, detribalization, exploitation, enslavement, medical advances[broken anchor], the creation of new institutions, abolitionism,[74] improved infrastructure,[75] and technological progress.[76] Colonial practices also spur the spread of conquerors' languages, literature and cultural institutions, while endangering or obliterating those of Indigenous peoples. The cultures of the colonised peoples can also have a powerful influence on the imperial country.[77] With respect to international borders, Britain and France traced close to 40% of the entire length of the world's international boundaries.[78] Economy, trade and commerce Economic expansion, sometimes described as the colonial surplus, has accompanied imperial expansion since ancient times.[citation needed] Greek trade networks spread throughout the Mediterranean region while Roman trade expanded with the primary goal of directing tribute from the colonised areas towards the Roman metropole. According to Strabo, by the time of emperor Augustus, up to 120 Roman ships would set sail every year from Myos Hormos in Roman Egypt to India.[79] With the development of trade routes under the Ottoman Empire, Gujari Hindus, Syrian Muslims, Jews, Armenians, Christians from south and central Europe operated trading routes that supplied Persian and Arab horses to the armies of all three empires, Mocha coffee to Delhi and Belgrade, Persian silk to India and Istanbul.[80]  Portuguese trade routes (blue) and the rival Manila-Acapulco galleons trade routes (white) established in 1568 Aztec civilisation developed into an extensive empire that, much like the Roman Empire, had the goal of exacting tribute from the conquered colonial areas. For the Aztecs, a significant tribute was the acquisition of sacrificial victims for their religious rituals.[81] On the other hand, European colonial empires sometimes attempted to channel, restrict and impede trade involving their colonies, funneling activity through the metropole and taxing accordingly. Despite the general trend of economic expansion, the economic performance of former European colonies varies significantly. In "Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-run Growth", economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson compare the economic influences of the European colonists on different colonies and study what could explain the huge discrepancies in previous European colonies, for example, between West African colonies like Sierra Leone and Hong Kong and Singapore.[82] According to the paper, economic institutions are the determinant of the colonial success because they determine their financial performance and order for the distribution of resources. At the same time, these institutions are also consequences of political institutions – especially how de facto and de jure political power is allocated. To explain the different colonial cases, we thus need to look first into the political institutions that shaped the economic institutions.[82]  Dutch East India Company was the first-ever multinational corporation, financed by shares that established the first modern stock exchange. For example, one interesting observation is "the Reversal of Fortune" – the less developed civilisations in 1500, like North America, Australia, and New Zealand, are now much richer than those countries who used to be in the prosperous civilisations in 1500 before the colonists came, like the Mughals in India and the Incas in the Americas. One explanation offered by the paper focuses on the political institutions of the various colonies: it was less likely for European colonists to introduce economic institutions where they could benefit quickly from the extraction of resources in the area. Therefore, given a more developed civilisation and denser population, European colonists would rather keep the existing economic systems than introduce an entirely new system; while in places with little to extract, European colonists would rather establish new economic institutions to protect their interests. Political institutions thus gave rise to different types of economic systems, which determined the colonial economic performance.[82] European colonisation and development also changed gendered systems of power already in place around the world. In many pre-colonialist areas, women maintained power, prestige, or authority through reproductive or agricultural control. For example, in certain parts of sub-Saharan Africa[where?] women maintained farmland in which they had usage rights. While men would make political and communal decisions for a community, the women would control the village's food supply or their individual family's land. This allowed women to achieve power and autonomy, even in patrilineal and patriarchal societies.[83] Through the rise of European colonialism came a large push for development and industrialisation of most economic systems. When working to improve productivity, Europeans focused mostly on male workers. Foreign aid arrived in the form of loans, land, credit, and tools to speed up development, but were only allocated to men. In a more European fashion, women were expected to serve on a more domestic level. The result was a technologic, economic, and class-based gender gap that widened over time.[84] Within a colony, the presence of extractive colonial institutions in a given area has been found have effects on the modern day economic development, institutions and infrastructure of these areas.[85][86] Slavery and indentured servitude Further information: Atlantic slave trade, Indentured servant, Coolie, and Blackbirding European nations entered their imperial projects with the goal of enriching the European metropoles. Exploitation of non-Europeans and of other Europeans to support imperial goals was acceptable to the colonisers. Two outgrowths of this imperial agenda were the extension of slavery and indentured servitude. In the 17th century, nearly two-thirds of English settlers came to North America as indentured servants.[87] European slave traders brought large numbers of African slaves to the Americas by sail. Spain and Portugal had brought African slaves to work in African colonies such as Cape Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe, and then in Latin America, by the 16th century. The British, French and Dutch joined in the slave trade in subsequent centuries. The European colonial system took approximately 11 million Africans to the Caribbean and to North and South America as slaves.[88]  Slave traders in Gorée, Senegal, 18th century  |

インパクト 主な記事 西欧の植民地主義と植民地化の分析§植民地支配とその影響  ボブ・サターフィールドが1904年に描いた、西洋諸国による残虐行為についての漫画。イギリス、アメリカ、ドイツの人物像が、それぞれチベット、フィリ ピン、南西アフリカの切断された首のついた槍を持っている。キャプションはこれを「文明の先兵」と表現している。 時間は1分49秒: 1分49秒1:49 オランダ公衆衛生局がオランダ領東インドの原住民に医療を提供する(1946年5月)。 植民地化の影響は甚大かつ広範である[73]。直接的なものから長期的なものまで、様々な影響には、病原性疾患の蔓延、不平等な社会関係、非部族化、搾 取、奴隷化、医学の進歩[broken anchor]、新たな制度の創設、廃絶主義、[74]インフラストラクチャーの改善、[75]技術進歩などが含まれる[76]。植民地化された民族の文 化はまた、帝国国家に強い影響を与えることもある[77]。 国際国境に関しては、イギリスとフランスは世界の国際国境の全長の40%近くをたどった[78]。 経済、貿易、商業 植民地余剰と表現されることもある経済的拡大は、古代から帝国の膨張に伴っていた[要出典]。ギリシアの貿易網が地中海地域全体に広がる一方で、ローマの 貿易は植民地化された地域からの貢ぎ物をローマの首都に向けることを第一の目的として拡大した。ストラボによれば、アウグストゥス帝の時代には、ローマ帝 国エジプトのミョス・ホルモスからインドまで、毎年120隻ものローマ船が出航していた[79]、 グジャリ・ヒンドゥー教徒、シリアのイスラム教徒、ユダヤ教徒、アルメニア教徒、南ヨーロッパと中央ヨーロッパのキリスト教徒が交易路を運営し、ペルシャ とアラブの馬を3つの帝国の軍隊に、モカコーヒーをデリーとベオグラードに、ペルシャ絹をインドとイスタンブールに供給していた[80]。  ポルトガルの貿易ルート(青)と1568年に設立されたマニラ-アカプルコ間のガレオン船貿易ルート(白)。 アステカ文明は、ローマ帝国と同様に、征服した植民地地域から貢ぎ物を徴収することを目的とした広大な帝国へと発展した。アステカにとって重要な貢物は、 宗教儀式のための犠牲者の獲得であった[81]。 他方、ヨーロッパの植民地帝国は、植民地が関与する貿易の経路を確保し、制限し、妨げようとすることがあった。 一般的な経済拡大の傾向にもかかわらず、旧ヨーロッパ植民地の経済的パフォーマンスは大きく異なっている。経済学者のダロン・アセモグル、サイモン・ジョ ンソン、ジェームズ・A・ロビンソンは、「長期的成長の基本的原因としての制度」の中で、ヨーロッパの植民地主義者がさまざまな植民地に与えた経済的影響 を比較し、例えばシエラレオネのような西アフリカの植民地と香港やシンガポールのような過去のヨーロッパの植民地における大きな相違を説明できるものは何 かを研究している[82]。 同論文によれば、経済制度は植民地の財政的パフォーマンスと資源分配の秩序を決定するため、植民地の成功の決定要因である。同時に、こうした制度は政治制 度の結果でもあり、特に事実上の政治権力と事実上の政治権力がどのように配分されるかが重要である。したがって、さまざまな植民地事例を説明するために は、まず経済制度を形成した政治制度に注目する必要がある[82]。  オランダ東インド会社は史上初の多国籍企業であり、最初の近代的証券取引所を設立した株式によって資金を調達した。 例えば、「運命の逆転」という興味深い観察がある。1500年当時、北アメリカ、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドのようにあまり発展していなかった文明 は、インドのムガール帝国やアメリカ大陸のインカ帝国のように、植民者がやってくる前の1500年当時繁栄していた文明に属していた国々よりも、今ではは るかに豊かである。この論文で提示されている説明のひとつは、さまざまな植民地の政治制度に焦点を当てている。ヨーロッパの植民者は、その地域の資源採掘 からすぐに利益を得られるような経済制度を導入しにくかった。したがって、文明が発達し人口が密集していれば、ヨーロッパの植民者たちはまったく新しい経 済制度を導入するよりも、むしろ既存の経済制度を維持しようとした。一方、採掘できる資源がほとんどない場所では、ヨーロッパの植民者たちは自分たちの利 益を守るために、むしろ新しい経済制度を確立しようとした。政治制度はこうしてさまざまなタイプの経済制度を生み出し、それが植民地経済のパフォーマンス を決定づけた[82]。 ヨーロッパの植民地化と開発はまた、世界中ですでに存在していたジェンダー化された権力システムをも変化させた。植民地化以前の多くの地域では、女性は生 殖や農業の管理を通じて権力、威信、権威を維持していた。例えば、サハラ以南のアフリカのある地域では[どこで?]、女性は使用権を持つ農地を維持してい た。男性が共同体の政治的・共同体的な決定を下す一方で、女性は村の食糧供給や個々の家族の土地を管理していた。これによって女性は、父系社会や家父長制 社会であっても、権力と自律性を獲得することができた[83]。 ヨーロッパの植民地主義の台頭を通じて、ほとんどの経済システムの開発と工業化が大きく推進された。生産性の向上に取り組む際、ヨーロッパ人は主に男性労 働者に焦点を当てた。外国からの援助は、借款、土地、信用、開発を加速させる道具などの形でもたらされたが、それは男性にのみ割り当てられた。よりヨー ロッパ的なやり方で、女性はより家庭的なレベルで奉仕することが期待された。その結果、技術的、経済的、階級的な男女格差は時間の経過とともに拡大して いった[84]。 植民地内において、ある地域に抽出的な植民地制度が存在すると、その地域の現代の経済発展、制度、インフラに影響を及ぼすことが判明している[85] [86]。 奴隷制と年季奉公( Slavery and indentured servitude) さらなる情報 大西洋奴隷貿易、年季奉公、クーリー、ブラックバーディング ヨーロッパ諸国は、ヨーロッパの大都市を豊かにする目的で帝国事業に参入した。帝国の目標を支えるために、非ヨーロッパ人や他のヨーロッパ人を搾取するこ とは、植民地支配者にとって容認された。このような帝国的アジェンダから生まれた2つの成果は、奴隷制と年季奉公の拡大であった。17世紀には、イギリス 人入植者の3分の2近くが年季奉公人として北米に渡った[87]。 ヨーロッパの奴隷商人たちは、大量のアフリカ人奴隷を船でアメリカ大陸に運んだ。スペインとポルトガルは、16世紀までにアフリカの植民地であるカーボベ ルデやサントメ・プリンシペ、そしてラテンアメリカで働くためにアフリカ人奴隷を連れてきた。その後の数世紀には、イギリス、フランス、オランダも奴隷貿 易に加わった。ヨーロッパの植民地システムは、およそ1,100万人のアフリカ人を奴隷としてカリブ海や南北アメリカに連れて行った[88]。  18世紀、セネガル、ゴレの奴隷商人たち  |

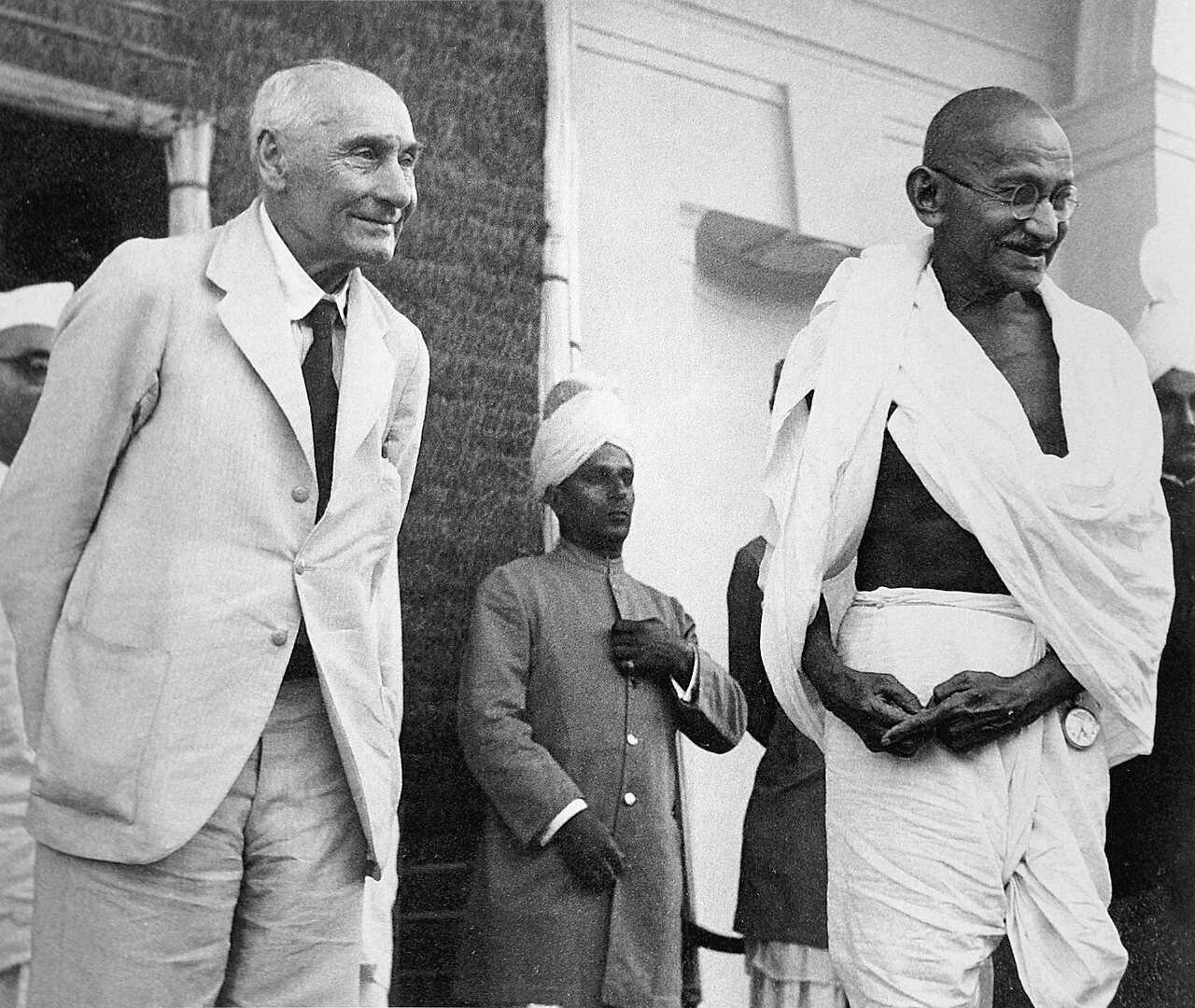

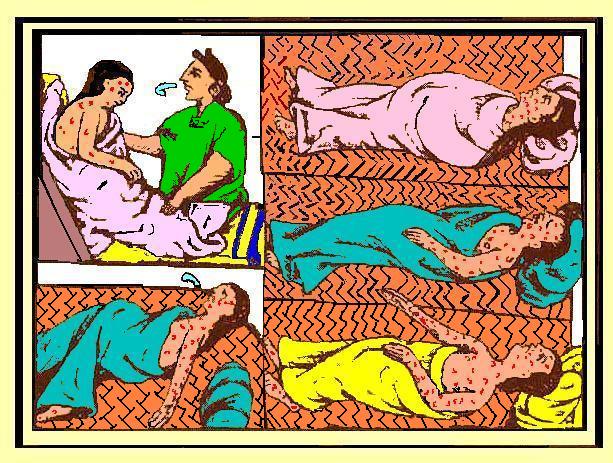

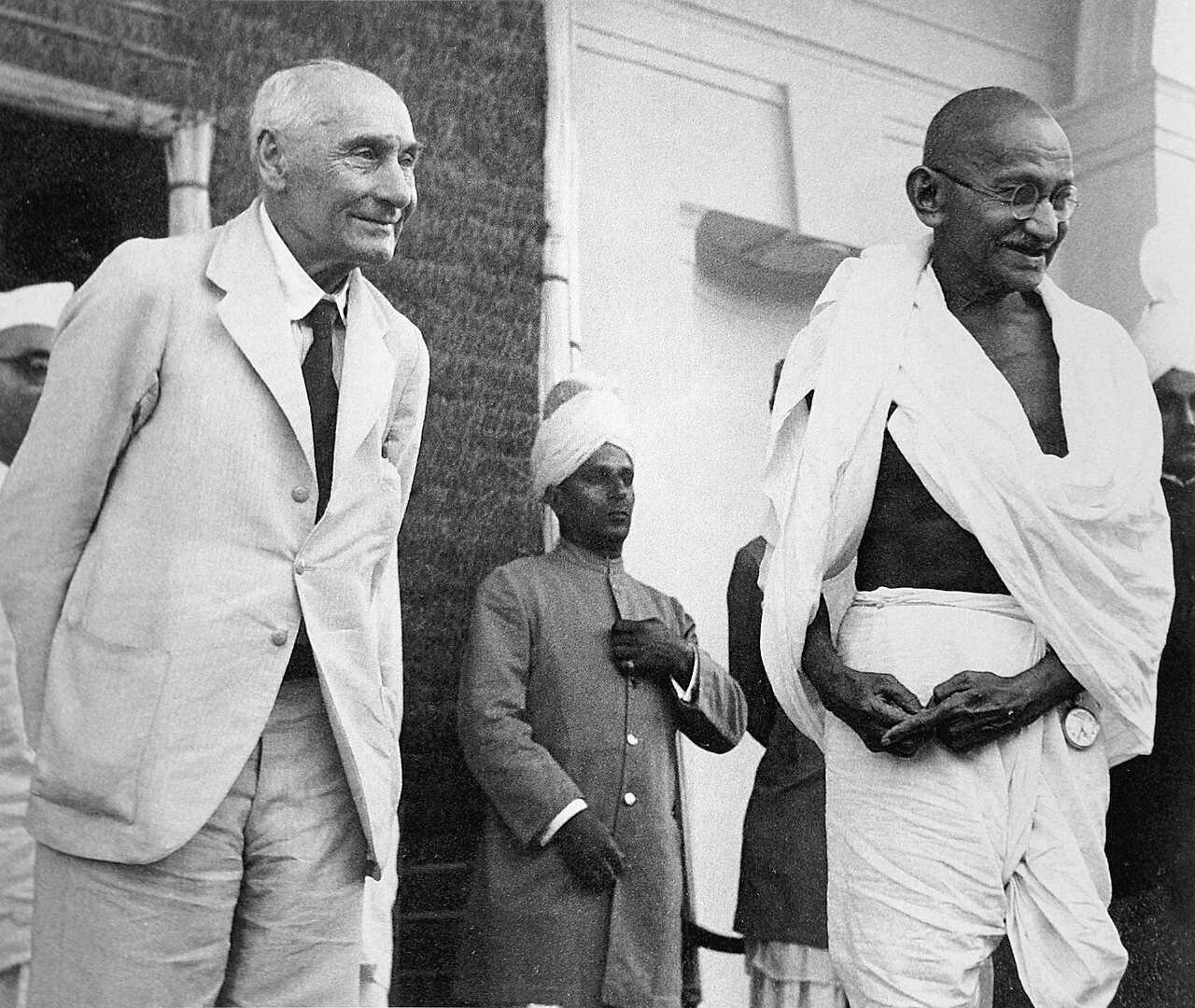

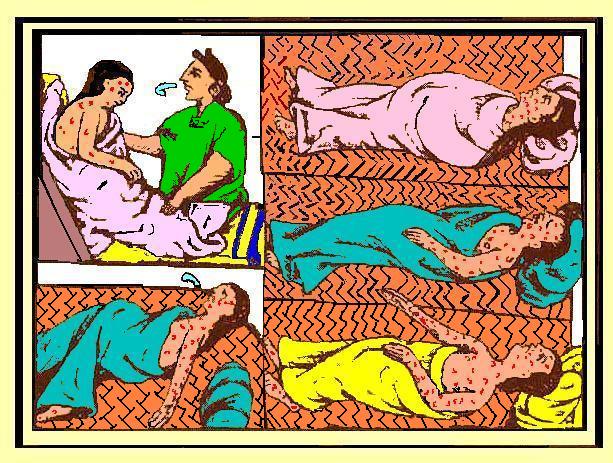

| Abolitionists

in Europe and Americas protested the inhumane treatment of African

slaves, which led to the elimination of the slave trade (and later, of

most forms of slavery) by the late 19th century. One (disputed) school

of thought points to the role of abolitionism in the American

Revolution: while the British colonial metropole started to move

towards outlawing slavery, slave-owning elites in the Thirteen Colonies

saw this as one of the reasons to fight for their post-colonial

independence and for the right to develop and continue a largely

slave-based economy.[89] British colonising activity in New Zealand from the early 19th century played a part in ending slave-taking and slave-keeping among the indigenous Māori.[90][91] On the other hand, British colonial administration in Southern Africa, when it officially abolished slavery in the 1830s, caused rifts in society which arguably perpetuated slavery in the Boer Republics and fed into the philosophy of apartheid.[92]  Planting the sugar cane, Antigua, 1823 The labour shortages that resulted from abolition inspired European colonisers in Queensland, British Guaiana and Fiji (for example) to develop new sources of labour, re-adopting a system of indentured servitude. Indentured servants consented to a contract with the European colonisers. Under their contract, the servant would work for an employer for a term of at least a year, while the employer agreed to pay for the servant's voyage to the colony, possibly pay for the return to the country of origin, and pay the employee a wage as well. The employees became "indentured" to the employer because they owed a debt back to the employer for their travel expense to the colony, which they were expected to pay through their wages. In practice, indentured servants were exploited through terrible working conditions and burdensome debts imposed by the employers, with whom the servants had no means of negotiating the debt once they arrived in the colony. India and China were the largest source of indentured servants during the colonial era. Indentured servants from India travelled to British colonies in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, and also to French and Portuguese colonies, while Chinese servants travelled to British and Dutch colonies. Between 1830 and 1930, around 30 million indentured servants migrated from India, and 24 million returned to India. China sent more indentured servants to European colonies, and around the same proportion returned to China.[93] Following the Scramble for Africa, an early but secondary focus for most colonial regimes was the suppression of slavery and the slave trade. By the end of the colonial period they were mostly successful in this aim, though slavery persists in Africa and in the world at large with much the same practices of de facto servility despite legislative prohibition.[74] Military innovation  The First Anglo-Ashanti War, 1823–1831 Conquering forces have throughout history applied innovation in order to gain an advantage over the armies of the people they aim to conquer. Greeks developed the phalanx system, which enabled their military units to present themselves to their enemies as a wall, with foot soldiers using shields to cover one another during their advance on the battlefield. Under Philip II of Macedon, they were able to organise thousands of soldiers into a formidable battle force, bringing together carefully trained infantry and cavalry regiments.[94] Alexander the Great exploited this military foundation further during his conquests. The Spanish Empire held a major advantage over Mesoamerican warriors through the use of weapons made of stronger metal, predominantly iron, which was able to shatter the blades of axes used by the Aztec civilisation and others. The use of gunpowder weapons cemented the European military advantage over the peoples they sought to subjugate in the Americas and elsewhere. End of empire This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Gandhi with Lord Pethwick-Lawrence, British Secretary of State for India, after a meeting on 18 April 1946 The populations of some colonial territories, such as Canada, enjoyed relative peace and prosperity as part of a European power, at least among the majority. Minority populations such as First Nations peoples and French-Canadians experienced marginalisation and resented colonial practices. Francophone residents of Quebec, for example, were vocal in opposing conscription into the armed services to fight on behalf of Britain during World War I, resulting in the Conscription crisis of 1917. Other European colonies had much more pronounced conflict between European settlers and the local population. Rebellions broke out in the later decades of the imperial era, such as India's Sepoy Rebellion of 1857. The territorial boundaries imposed by European colonisers, notably in central Africa and South Asia, defied the existing boundaries of native populations that had previously interacted little with one another. European colonisers disregarded native political and cultural animosities, imposing peace upon people under their military control. Native populations were often relocated at the will of the colonial administrators. The Partition of British India in August 1947 led to the Independence of India and the creation of Pakistan. These events also caused much bloodshed at the time of the migration of immigrants from the two countries. Muslims from India and Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan migrated to the respective countries they sought independence for. Post-independence population movement  The annual Notting Hill Carnival in London is a celebration led by the Trinidadian and Tobagonian British community. In a reversal of the migration patterns experienced during the modern colonial era, post-independence era migration followed a route back towards the imperial country. In some cases, this was a movement of settlers of European origin returning to the land of their birth, or to an ancestral birthplace. 900,000 French colonists (known as the Pied-Noirs) resettled in France following Algeria's independence in 1962. A significant number of these migrants were also of Algerian descent. 800,000 people of Portuguese origin migrated to Portugal after the independence of former colonies in Africa between 1974 and 1979; 300,000 settlers of Dutch origin migrated to the Netherlands from the Dutch West Indies after Dutch military control of the colony ended.[95] After WWII 300,000 Dutchmen from the Dutch East Indies, of which the majority were people of Eurasian descent called Indo Europeans, repatriated to the Netherlands. A significant number later migrated to the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.[96][97] Global travel and migration in general developed at an increasingly brisk pace throughout the era of European colonial expansion. Citizens of the former colonies of European countries may have a privileged status in some respects with regard to immigration rights when settling in the former European imperial nation. For example, rights to dual citizenship may be generous,[98] or larger immigrant quotas may be extended to former colonies.[citation needed] In some cases, the former European imperial nations continue to foster close political and economic ties with former colonies. The Commonwealth of Nations is an organisation that promotes cooperation between and among Britain and its former colonies, the Commonwealth members. A similar organisation exists for former colonies of France, the Francophonie; the Community of Portuguese Language Countries plays a similar role for former Portuguese colonies, and the Dutch Language Union is the equivalent for former colonies of the Netherlands.[99][100][101] Migration from former colonies has proven to be problematic for European countries, where the majority population may express hostility to ethnic minorities who have immigrated from former colonies. Cultural and religious conflict have often erupted in France in recent decades, between immigrants from the Maghreb countries of north Africa and the majority population of France. Nonetheless, immigration has changed the ethnic composition of France; by the 1980s, 25% of the total population of "inner Paris" and 14% of the metropolitan region were of foreign origin, mainly Algerian.[102] Introduced diseases See also: Globalisation and disease, Columbian Exchange, and Impact and evaluation of colonialism and colonization  Aztecs dying of smallpox, (Florentine Codex, 1540–1585) Encounters between explorers and populations in the rest of the world often introduced new diseases, which sometimes caused local epidemics of extraordinary virulence.[103] For example, smallpox, measles, malaria, yellow fever, and others were unknown in pre-Columbian America.[104] Half the native population of Hispaniola in 1518 was killed by smallpox. Smallpox also ravaged Mexico in the 1520s, killing 150,000 in Tenochtitlan alone, including the emperor, and Peru in the 1530s, aiding the European conquerors. Measles killed a further two million Mexican natives in the 17th century. In 1618–1619, smallpox wiped out 90% of the Massachusetts Bay Native Americans.[105] Smallpox epidemics in 1780–1782 and 1837–1838 brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the Plains Indians.[106] Some believe[who?] that the death of up to 95% of the Native American population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases.[107] Over the centuries, the Europeans had developed high degrees of immunity to these diseases, while the indigenous peoples had no time to build such immunity.[108] Smallpox decimated the native population of Australia, killing around 50% of indigenous Australians in the early years of British colonisation.[109] It also killed many New Zealand Māori.[110] As late as 1848–49, as many as 40,000 out of 150,000 Hawaiians are estimated to have died of measles, whooping cough and influenza. Introduced diseases, notably smallpox, nearly wiped out the native population of Easter Island.[111] In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population.[112] The Ainu population decreased drastically in the 19th century, due in large part to infectious diseases brought by Japanese settlers pouring into Hokkaido.[113] Conversely, researchers have hypothesised that a precursor to syphilis may have been carried from the New World to Europe after Columbus's voyages. The findings suggested Europeans could have carried the nonvenereal tropical bacteria home, where the organisms may have mutated into a more deadly form in the different conditions of Europe.[114] The disease was more frequently fatal than it is today; syphilis was a major killer in Europe during the Renaissance.[115] The first cholera pandemic began in Bengal, then spread across India by 1820. Ten thousand British troops and countless Indians died during this pandemic.[116] Between 1736 and 1834 only some 10% of East India Company's officers survived to take the final voyage home.[117] Waldemar Haffkine, who mainly worked in India, who developed and used vaccines against cholera and bubonic plague in the 1890s, is considered the first microbiologist. According to a 2021 study by Jörg Baten and Laura Maravall on the anthropometric influence of colonialism on Africans, the average height of Africans decreased by 1.1 centimetres upon colonization and later recovered and increased overall during colonial rule. The authors attributed the decrease to diseases, such as malaria and sleeping sickness, forced labor during the early decades of colonial rule, conflicts, land grabbing, and widespread cattle deaths from the rinderpest viral disease.[118] Countering disease As early as 1803, the Spanish Crown organised a mission (the Balmis expedition) to transport the smallpox vaccine to the Spanish colonies, and establish mass vaccination programs there.[119] By 1832, the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans.[120] Under the direction of Mountstuart Elphinstone a program was launched to propagate smallpox vaccination in India.[121] From the beginning of the 20th century onwards, the elimination or control of disease in tropical countries became a driving force for all colonial powers.[122] The sleeping sickness epidemic in Africa was arrested due to mobile teams systematically screening millions of people at risk.[123] In the 20th century, the world saw the biggest increase in its population in human history due to lessening of the mortality rate in many countries due to medical advances[broken anchor].[124] The world population has grown from 1.6 billion in 1900 to over seven billion today.[citation needed] |

ヨーロッパとアメリカ大陸の奴隷廃

止論者たちは、アフリカ人奴隷の非人道的な扱いに抗議し、19世紀後半には奴隷貿易(のちにほとんどの形態の奴隷制)が廃止されるに至った。ある(議論の

ある)学派は、アメリカ独立革命における奴隷廃止主義の役割を指摘している。イギリスの植民地首都が奴隷制を非合法化する方向に動き始めた一方で、13植

民地の奴隷所有エリートは、これを植民地後の独立と、主に奴隷に基づく経済を発展させ継続する権利を求めて戦う理由の1つと考えた[89]。 19世紀初頭からのニュージーランドにおけるイギリスの植民地化活動は、先住民であるマオリの奴隷制度と奴隷飼育を終わらせることに一役買った[90] [91]。他方、1830年代に奴隷制度を公式に廃止した南部アフリカにおけるイギリスの植民地行政は、間違いなくボーア共和国における奴隷制度を永続さ せ、アパルトヘイトの哲学を助長するような社会の亀裂を引き起こした[92]。  サトウキビを植える、アンティグア、1823年 奴隷制度廃止の結果生じた労働力不足は、クイーンズランド、イギリス領ギアナ、フィジーなどのヨーロッパの植民者に新たな労働力の供給源を開発するよう促 し、年季奉公制度を再採用した。年季奉公人は、ヨーロッパ人植民者との契約に同意した。契約では、使用人は少なくとも1年間は雇用主のもとで働き、雇用主 は使用人の植民地までの航海費用と、場合によっては出身国への帰国費用を支払い、使用人にも賃金を支払うことに同意した。使用人は、植民地までの旅費を使 用人に返済する義務があり、それを賃金で支払うことになっていたため、使用人の「年季奉公」となったのである。実際には、年季奉公人はひどい労働条件と、 使用者から課された重荷となる負債によって搾取され、使用者は植民地に到着した後、負債について交渉する手段を持たなかった。 植民地時代、年季奉公人の最大の供給源はインドと中国であった。インドからの年季奉公者は、アジア、アフリカ、カリブ海のイギリス植民地やフランス、ポル トガルの植民地に渡り、中国の年季奉公者はイギリスやオランダの植民地に渡った。1830年から1930年の間に、約3,000万人の年季奉公者がインド から移住し、2,400万人がインドに戻った。中国はより多くの年季奉公人をヨーロッパの植民地に送り出し、ほぼ同じ割合が中国に戻ってきた[93]。 スクランブル・フォア・アフリカの後、ほとんどの植民地政権にとって初期には二次的な課題であったが、奴隷制度と奴隷貿易の抑制に焦点が当てられた。植民 地時代の終わりまでには、この目的はほぼ成功したが、奴隷制度は、立法による禁止にもかかわらず、事実上の隷属の慣行とほぼ同じ形でアフリカや世界全体に 存続している[74]。 軍事的革新  第一次アングロ・アシャンティ戦争、1823年-1831年 征服軍は歴史を通じて、征服を目的とする人々の軍隊に対して優位に立つために技術革新を適用してきた。ギリシャ軍はファランクス方式を開発し、部隊を壁と して敵に見せることを可能にした。マケドンのフィリップ2世の時代には、入念に訓練された歩兵と騎兵の連隊をまとめることで、何千人もの兵士を強大な戦闘 力へと組織化することができた[94]。 スペイン帝国は、アステカ文明などが使用した斧の刃を砕くことができる、より強力な金属、主に鉄で作られた武器を使用することで、メソアメリカの戦士たち に対して大きな優位に立っていた。火薬兵器の使用は、アメリカ大陸やその他の地域で征服しようとした民族に対するヨーロッパ人の軍事的優位を確固たるもの にした。 帝国の終焉 このセクションは出典を引用していない。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは、異 議を唱えられ、削除される可能性がある。(2021年4月) (このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)  1946年4月18日、英国インド担当国務長官ペスウィック=ローレンス卿との会談を終えたガンジー。 カナダなどいくつかの植民地領土の住民は、少なくとも大多数の人々の間では、ヨーロッパ列強の一部として比較的平和と繁栄を享受していた。しかし、先住民 やフランス系カナダ人などの少数民族は疎外され、植民地支配に憤慨した。例えば、ケベック州のフランス語圏住民は、第一次世界大戦中、イギリスのために戦 うために徴兵されることに声を大にして反対し、1917年の徴兵危機を招いた。他のヨーロッパ植民地では、ヨーロッパ人入植者と地元住民との対立がより顕 著であった。1857年のインドのセポイの反乱など、帝国時代の後期には反乱が勃発した。 特にアフリカ中央部や南アジアでは、ヨーロッパ人入植者が押し付けた領土境界線は、それまでほとんど交流のなかった先住民の既存の境界線を無視するもので あった。ヨーロッパの植民者たちは、先住民の政治的・文化的反感を無視し、軍事支配下にある人々に平和を押し付けた。先住民はしばしば植民地行政官の意の ままに移動させられた。 1947年8月の英領インド分割は、インドの独立とパキスタンの誕生につながった。これらの出来事はまた、2つの国からの移民の移動の際に多くの流血を引 き起こした。インドからはイスラム教徒が、パキスタンからはヒンドゥー教徒とシーク教徒が、それぞれ独立を求めた国に移住した。 独立後の人口移動  毎年ロンドンで開催されるノッティングヒル・カーニバルは、トリニダード・トバゴニア系イギリス人コミュニティが主導する祭典である。 近代植民地時代に経験した移動パターンとは逆に、独立後の移動は帝国国家に戻るルートをたどった。場合によっては、ヨーロッパ出身の入植者が生まれた土地 や先祖代々の生まれ故郷に戻る動きもあった。1962年のアルジェリア独立後、90万人のフランス人入植者(ピエ・ノワールとして知られる)がフランスに 定住した。これらの移民の相当数はアルジェリア系でもあった。1974年から1979年にかけてアフリカの旧植民地が独立した後、ポルトガル系80万人が ポルトガルに移住した。オランダの軍事支配が終了した後、オランダ系30万人がオランダ領西インド諸島からオランダに移住した[95]。 第二次世界大戦後、オランダ領東インドから30万人のオランダ人がオランダに送還されたが、その大半はインド・ヨーロッパ人と呼ばれるユーラシア系の人々 であった。その後、かなりの数がアメリカ、カナダ、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドに移住した[96][97]。 世界的な旅行と移住は、ヨーロッパの植民地拡張の時代を通じて、ますます活発なペースで発展した。ヨーロッパ諸国の旧植民地の市民は、旧ヨーロッパ帝国国 家に定住する際、移民の権利に関していくつかの点で特権的な地位を有することがある。例えば、二重国籍の権利が寛大であったり[98]、旧植民地により多 くの移民枠が拡大されたりすることがある[要出典]。 場合によっては、旧ヨーロッパ帝国諸国が旧植民地との政治的・経済的な緊密な結びつきを育み続けていることもある。英連邦は、イギリスとその旧植民地であ る英連邦加盟国との間の協力を促進する組織である。フランスの旧植民地には同様の組織であるフランコフォニーが存在し、ポルトガルの旧植民地にはポルトガ ル語諸国共同体が同様の役割を果たしており、オランダの旧植民地にはオランダ語連合がこれに相当する[99][100][101]。 旧植民地からの移民はヨーロッパ諸国にとって問題であることが証明されており、旧植民地から移民してきた少数民族に対して多数派住民が敵意を示すことがあ る。フランスではここ数十年、北アフリカのマグレブ諸国からの移民とフランスの多数派住民との間で、文化的・宗教的対立がしばしば勃発している。それにも かかわらず、移民はフランスの民族構成を変えてきた。1980年代までに、「パリ市内」の総人口の25%、首都圏の14%が外国出身者であり、主にアル ジェリア人であった[102]。 伝染病 以下も参照のこと: グローバリゼーションと病気、コロンブス交換、植民地主義と植民地化の影響と評価も参照のこと。  天然痘で死亡するアステカ人(フィレンツェ写本、1540-1585年) 探検家とその他の地域の住民との遭遇は、しばしば新たな疾病を持ち込むものであり、それらは時に異常な病原性を持つ伝染病を地域的に引き起こすものであっ た[103]。例えば、天然痘、麻疹、マラリア、黄熱病などは、コロンブス以前のアメリカでは知られていなかった[104]。 1518年にはヒスパニョーラの先住民の半数が天然痘によって死亡した。天然痘は1520年代のメキシコでも猛威を振るい、テノチティトランだけで皇帝を 含む15万人が死亡し、1530年代のペルーでもヨーロッパの征服者を助けた。17世紀には、さらに200万人のメキシコ原住民が麻疹で死亡した。 1618年から1619年にかけて天然痘がマサチューセッツ湾のアメリカ先住民の90%を一掃した[105]。1780年から1782年と1837年から 1838年にかけて天然痘が流行し、平原インディアンに壊滅的な打撃と急激な過疎化をもたらした[106]。 107]。何世紀にもわたって、ヨーロッパ人はこれらの病気に対する高度な免疫力を身につけていたが、先住民にはそのような免疫力をつける時間がなかった [108]。 天然痘はオーストラリアの先住民の人口を壊滅させ、イギリス植民地化の初期にはオーストラリア先住民の約50%が死亡した[109]。 ニュージーランドのマオリ族の多くも死亡した[110]。 1848年から49年の時点で、15万人のハワイ人のうち4万人もの人々が麻疹、百日咳、インフルエンザで死亡したと推定されている。1875年には、人 口のおよそ3分の1に当たる4万人以上のフィジー人が麻疹によって死亡した[111]。 アイヌの人口は19世紀に激減したが、これは北海道に流入した日本人入植者によってもたらされた感染症によるところが大きい[113]。 逆に研究者たちは、梅毒の前駆物質がコロンブスの航海後に新大陸からヨーロッパに持ち込まれたのではないかという仮説を立てた。この発見は、ヨーロッパ人 が非七病性の熱帯細菌を故郷に持ち帰り、そこで細菌がヨーロッパの異なる条件下でより致死性の高い形に変異した可能性を示唆した[114]。 梅毒はルネサンス期のヨーロッパでは主要な殺人者であった[115]。最初のコレラの大流行はベンガルで始まり、1820年までにインド全土に広がった。 1736年から1834年にかけて、東インド会社の将校のうち、最後の航海で帰国するまでに生き残ったのはわずか10%程度であった[117]。 1890年代にコレラとペストに対するワクチンを開発し使用した、主にインドで活動したワルデマー・ハフキンは、最初の微生物学者と考えられている。 植民地主義がアフリカ人に与えた人体計測上の影響に関するイェルク・バテンとラウラ・マラヴァルの2021年の研究によると、アフリカ人の平均身長は植民 地化時に1.1cm減少し、その後、植民地支配の間に回復し、全体的に増加した。著者らは、マラリアや眠り病などの病気、植民地支配の初期の数十年間にお ける強制労働、紛争、土地の収奪、リンダーペストウイルス病による家畜の広範な死亡が減少の原因であるとした[118]。 病気への対策 早くも1803年には、スペイン王室は天然痘ワクチンをスペインの植民地に輸送し、そこで集団予防接種プログラムを確立するためのミッション(バルミス遠 征隊)を組織した[119]。 1832年までに、アメリカ連邦政府はアメリカ先住民に対する天然痘予防接種プログラムを確立した。 [120年] マウントスチュアート・エルフィンストンの指揮のもと、インドで天然痘ワクチン接種を普及させるプログラムが開始された[121] 。 20世紀初頭以降、熱帯諸国における疾病の撲滅や制圧は、すべての植民地大国の原動力となった。 [アフリカにおける眠り病の流行は、移動チームが危険にさらされている何百万人もの人々を組織的に検診したことによって阻止された[122]。 20世紀には、医学の進歩[broken anchor]によって多くの国で死亡率が低下したため、世界は人類史上最大の人口増加を見た[124]。 |

| Botany Colonial botany refers to the body of works concerning the study, cultivation, marketing and naming of the new plants that were acquired or traded during the age of European colonialism. Notable examples of these plants included sugar, nutmeg, tobacco, cloves, cinnamon, Peruvian bark, peppers, Sassafras albidum, and tea. This work was a large part of securing financing for colonial ambitions, supporting European expansion and ensuring the profitability of such endeavors. Vasco de Gama and Christopher Columbus were seeking to establish routes to trade spices, dyes and silk from the Moluccas, India and China by sea that would be independent of the established routes controlled by Venetian and Middle Eastern merchants. Naturalists like Hendrik van Rheede, Georg Eberhard Rumphius, and Jacobus Bontius compiled data about eastern plants on behalf of the Europeans. Though Sweden did not possess an extensive colonial network, botanical research based on Carl Linnaeus identified and developed techniques to grow cinnamon, tea and rice locally as an alternative to costly imports.[125] Geography Further information: List of colonies  British Togoland in 1953 Settlers acted as the link between indigenous populations and the imperial hegemony, thus bridging the geographical, ideological and commercial gap between the colonisers and colonised. While the extent in which geography as an academic study is implicated in colonialism is contentious, geographical tools such as cartography, shipbuilding, navigation, mining and agricultural productivity were instrumental in European colonial expansion. Colonisers' awareness of the Earth's surface and abundance of practical skills provided colonisers with a knowledge that, in turn, created power.[126] Anne Godlewska and Neil Smith argue that "empire was 'quintessentially a geographical project'".[clarification needed][127] Historical geographical theories such as environmental determinism legitimised colonialism by positing the view that some parts of the world were underdeveloped, which created notions of skewed evolution.[126] Geographers such as Ellen Churchill Semple and Ellsworth Huntington put forward the notion that northern climates bred vigour and intelligence as opposed to those indigenous to tropical climates (See The Tropics) viz a viz a combination of environmental determinism and Social Darwinism in their approach.[128] Political geographers also maintain that colonial behaviour was reinforced by the physical mapping of the world, therefore creating a visual separation between "them" and "us". Geographers are primarily focused on the spaces of colonialism and imperialism; more specifically, the material and symbolic appropriation of space enabling colonialism.[129]: 5  Comparison of Africa in the years 1880 and 1913 Maps played an extensive role in colonialism, as Bassett would put it "by providing geographical information in a convenient and standardised format, cartographers helped open West Africa to European conquest, commerce, and colonisation".[130] Because the relationship between colonialism and geography was not scientifically objective, cartography was often manipulated during the colonial era. Social norms and values had an effect on the constructing of maps. During colonialism map-makers used rhetoric in their formation of boundaries and in their art. The rhetoric favoured the view of the conquering Europeans; this is evident in the fact that any map created by a non-European was instantly regarded as inaccurate. Furthermore, European cartographers were required to follow a set of rules which led to ethnocentrism; portraying one's own ethnicity in the centre of the map. As J.B. Harley put it, "The steps in making a map – selection, omission, simplification, classification, the creation of hierarchies, and 'symbolisation' – are all inherently rhetorical."[131] A common practice by the European cartographers of the time was to map unexplored areas as "blank spaces". This influenced the colonial powers as it sparked competition amongst them to explore and colonise these regions. Imperialists aggressively and passionately looked forward to filling these spaces for the glory of their respective countries.[132] The Dictionary of Human Geography notes that cartography was used to empty 'undiscovered' lands of their Indigenous meaning and bring them into spatial existence via the imposition of "Western place-names and borders, [therefore] priming 'virgin' (putatively empty land, 'wilderness') for colonisation (thus sexualising colonial landscapes as domains of male penetration), reconfiguring alien space as absolute, quantifiable and separable (as property)."[133]  Map of the British Empire (as of 1910). At its height, it was the largest empire in history. David Livingstone stresses "that geography has meant different things at different times and in different places" and that we should keep an open mind in regards to the relationship between geography and colonialism instead of identifying boundaries.[127] Geography as a discipline was not and is not an objective science, Painter and Jeffrey argue, rather it is based on assumptions about the physical world.[126] Comparison of exogeographical representations of ostensibly tropical environments in science fiction art support this conjecture, finding the notion of the tropics to be an artificial collection of ideas and beliefs that are independent of geography.[134] Ocean and space Further information: Ocean colonization and Space colonization With contemporary advances in deep sea and outer space technologies, colonization of the seabed and the Moon have become an object of non-terrestrial colonialism.[135][136][137][138] |

植物学 植民地植物学とは、ヨーロッパの植民地時代に獲得または取引された新しい植物の研究、栽培、販売、命名に関する著作の総体を指す。砂糖、ナツメグ、タバ コ、クローブ、シナモン、ペルーの樹皮、トウガラシ、サッサフラス・アルビダム、紅茶などがその代表例である。この仕事は、植民地への野望のための資金を 確保し、ヨーロッパの拡張を支え、そのような努力の採算性を確保する上で大きな役割を果たした。ヴァスコ・デ・ガマとクリストファー・コロンブスは、モ ルッカ諸島、インド、中国から香辛料、染料、絹を海路で交易するルートを確立しようとしていた。ヘンドリック・ファン・レーデ、ゲオルク・エーベルハル ト・ルンフィウス、ヤコブス・ボンティウスといった博物学者たちは、ヨーロッパ人に代わって東洋の植物に関するデータをまとめた。スウェーデンは広範な植 民地ネットワークを持っていなかったが、カール・リンネに基づく植物学的研究は、高価な輸入品に代わるものとして、シナモン、茶、米を地元で栽培する技術 を特定し、発展させた[125]。 地理 さらなる情報 植民地一覧  1953年の英領トーゴランド 入植者は先住民族と帝国の覇権を結ぶ役割を果たし、植民者と被植民者の間の地理的、イデオロギー的、商業的ギャップを埋めた。学問としての地理学が植民地 主義にどの程度関与しているかは議論の余地があるが、地図製作、造船、航海術、鉱業、農業生産性といった地理学的手段は、ヨーロッパの植民地拡大に役立っ た。植民者たちの地表に対する認識と豊富な実践的技術は、植民者たちに知識を提供し、それがひいては権力を生み出したのである[126]。 Anne GodlewskaとNeil Smithは「帝国は『本質的に地理的なプロジェクト』であった」と論じている[clarification needed][127] 環境決定論のような歴史的地理学理論は、世界の一部の地域が未発達であるという見解を措定することによって植民地主義を正当化し、それが歪んだ進化という 概念を生み出した。 [エレン・チャーチル・センプルやエルズワース・ハンティントンなどの地理学者は、北部の気候は熱帯気候の土着的なもの(『熱帯』参照)とは対照的に活力 と知性を育むという概念を提唱し、環境決定論と社会ダーウィニズムを組み合わせたアプローチを行った[128]。 政治地理学者はまた、植民地的行動は世界の物理的なマッピングによって強化され、それゆえ「彼ら」と「我々」の間に視覚的な隔たりが生まれたと主張してい る。地理学者は主に植民地主義と帝国主義の空間、より具体的には、植民地主義を可能にする空間の物質的・象徴的な充当[129]に焦点を当てている: 5  1880年と1913年のアフリカの比較 バセットが言うように、地図は植民地主義において広範な役割を果たした。「便利で標準化されたフォーマットで地理情報を提供することで、地図製作者は西ア フリカをヨーロッパの征服、商業、植民地化に開放する手助けをした」[130]。植民地主義と地理との関係は科学的に客観的なものではなかったため、植民 地時代には地図製作がしばしば操作された。社会規範や価値観は地図の作成に影響を与えた。植民地主義の時代、地図製作者たちは境界線の形成や芸術において レトリックを用いた。レトリックは征服者であるヨーロッパ人の見解を支持した。これは、非ヨーロッパ人が作成した地図は即座に不正確なものとみなされたこ とからも明らかである。さらに、ヨーロッパの地図製作者は、地図の中心に自分の民族を描くという、民族中心主義につながる一連のルールに従うことが求めら れた。J.B.ハーレーが言うように、「地図を作成する際の段階-選択、省略、単純化、分類、階層の作成、『記号化』-はすべて本質的に修辞的なものであ る」[131]。 当時のヨーロッパの地図製作者がよく行っていたのは、未踏の地域を「空白」として地図化することであった。このことは、植民地勢力に影響を与え、これらの 地域を探検し植民地化しようとする競争を引き起こした。帝国主義者たちは、自国の栄光のために、積極的かつ情熱的にこれらの空間を埋めようとした。 [132] 『人文地理学辞典』は、地図製作が「未発見」の土地の先住民的な意味を空っぽにし、「西洋的な地名と境界線」を押し付けることによって、それらを空間的に 存在させるために用いられたと指摘している[133]。  大英帝国の地図(1910年時点)。最盛期には史上最大の帝国であった。 デイヴィッド・リヴィングストンは「地理学は時代や場所によって異なる意味を持ってきた」と強調し、地理学と植民地主義の関係に関しては、境界を特定する のではなく、オープンマインドを保つべきだと述べている[127]。ペインターとジェフリーは、学問としての地理学は、昔も今も客観的な科学ではなく、む しろ物理的世界についての仮定に基づいていると主張している。 [126]SF芸術における表向きの熱帯環境の地理外表現の比較はこの推測を支持し、熱帯という概念は地理から独立したアイデアや信念の人工的な集合体で あることを発見している[134]。 海洋と宇宙 さらなる情報 海洋植民地化と宇宙植民地化 現代の深海や宇宙技術の進歩に伴い、海底や月の植民地化は地球以外の植民地主義の対象となっている[135][136][137][138]。 |

| Versus imperialism These paragraphs are an excerpt from Imperialism § Versus colonialism.[edit] The term "imperialism" is often conflated with "colonialism"; however, many scholars have argued that each has its own distinct definition. Imperialism and colonialism have been used in order to describe one's influence upon a person or group of people. Robert Young writes that imperialism operates from the centre as a state policy and is developed for ideological as well as financial reasons, while colonialism is simply the development for settlement or commercial intentions; however, colonialism still includes invasion.[139] Colonialism in modern usage also tends to imply a degree of geographic separation between the colony and the imperial power. Particularly, Edward Said distinguishes between imperialism and colonialism by stating: "imperialism involved 'the practice, the theory and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory', while colonialism refers to the 'implanting of settlements on a distant territory.'[140] Contiguous land empires such as the Russian, Chinese or Ottoman have traditionally been excluded from discussions of colonialism, though this is beginning to change, since it is accepted that they also sent populations into the territories they ruled.[140]: 116 Imperialism and colonialism both dictate the political and economic advantage over a land and the indigenous populations they control, yet scholars sometimes find it difficult to illustrate the difference between the two.[141]: 107 Although imperialism and colonialism focus on the suppression of another, if colonialism refers to the process of a country taking physical control of another, imperialism refers to the political and monetary dominance, either formally or informally. Colonialism is seen to be the architect deciding how to start dominating areas and then imperialism can be seen as creating the idea behind conquest cooperating with colonialism. Colonialism is when the imperial nation begins a conquest over an area and then eventually is able to rule over the areas the previous nation had controlled. Colonialism's core meaning is the exploitation of the valuable assets and supplies of the nation that was conquered and the conquering nation then gaining the benefits from the spoils of the war.[141]: 170–75 The meaning of imperialism is to create an empire, by conquering the other state's lands and therefore increasing its own dominance. Colonialism is the builder and preserver of the colonial possessions in an area by a population coming from a foreign region.[141]: 173–76 Colonialism can completely change the existing social structure, physical structure, and economics of an area; it is not unusual that the characteristics of the conquering peoples are inherited by the conquered indigenous populations.[141]: 41 Few colonies remain remote from their mother country. Thus, most will eventually establish a separate nationality or remain under complete control of their mother colony.[142] The Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin suggested that "imperialism was the highest form of capitalism", claiming that "imperialism developed after colonialism, and was distinguished from colonialism by monopoly capitalism".[140]: 116 Marxism Marxism views colonialism as a form of capitalism, enforcing exploitation and social change. Marx thought that working within the global capitalist system, colonialism is closely associated with uneven development. It is an "instrument of wholesale destruction, dependency and systematic exploitation producing distorted economies, socio-psychological disorientation, massive poverty and neocolonial dependency".[143] Colonies are constructed into modes of production. The search for raw materials and the current search for new investment opportunities is a result[according to whom?] of inter-capitalist rivalry for capital accumulation.[citation needed] Lenin regarded colonialism as the root cause of imperialism, as imperialism was distinguished by monopoly capitalism via colonialism and as Lyal S. Sunga explains: "Vladimir Lenin advocated forcefully the principle of self-determination of peoples in his "Theses on the Socialist Revolution and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination" as an integral plank in the programme of socialist internationalism" and he quotes Lenin who contended that "The right of nations to self-determination implies exclusively the right to independence in the political sense, the right to free political separation from the oppressor nation. Specifically, this demand for political democracy implies complete freedom to agitate for secession and for a referendum on secession by the seceding nation."[144] Non-Russian Marxists within the RSFSR and later the USSR, like Sultan Galiev and Vasyl Shakhrai, meanwhile, between 1918 and 1923 and then after 1929, considered the Soviet regime a renewed version of Russian imperialism and colonialism. In his critique of colonialism in Africa, the Guyanese historian and political activist Walter Rodney states:[145][146] The decisiveness of the short period of colonialism and its negative consequences for Africa spring mainly from the fact that Africa lost power. Power is the ultimate determinant in human society, being basic to the relations within any group and between groups. It implies the ability to defend one's interests and if necessary to impose one's will by any means available ... When one society finds itself forced to relinquish power entirely to another society that in itself is a form of underdevelopment ... During the centuries of pre-colonial trade, some control over social political and economic life was retained in Africa, in spite of the disadvantageous commerce with Europeans. That little control over internal matters disappeared under colonialism. Colonialism went much further than trade. It meant a tendency towards direct appropriation by Europeans of the social institutions within Africa. Africans ceased to set indigenous cultural goals and standards, and lost full command of training young members of the society. Those were undoubtedly major steps backwards ... Colonialism was not merely a system of exploitation, but one whose essential purpose was to repatriate the profits to the so-called 'mother country'. From an African view-point, that amounted to consistent expatriation of surplus produced by African labour out of African resources. It meant the development of Europe as part of the same dialectical process in which Africa was underdeveloped. Colonial Africa fell within that part of the international capitalist economy from which surplus was drawn to feed the metropolitan sector. As seen earlier, exploitation of land and labour is essential for human social advance, but only on the assumption that the product is made available within the area where the exploitation takes place. According to Lenin, the new imperialism emphasised the transition of capitalism from free trade to a stage of monopoly capitalism to finance capital. He states it is, "connected with the intensification of the struggle for the partition of the world". As free trade thrives on exports of commodities[according to whom?], monopoly capitalism thrived on the export of capital amassed by profits from banks and industry. This, to Lenin, was the highest stage of capitalism. He goes on to state that this form of capitalism was doomed for war between the capitalists and the exploited nations with the former inevitably losing. War is stated to be the consequence of imperialism. As a continuation of this thought, G.N. Uzoigwe states, "But it is now clear from more serious investigations of African history in this period that imperialism was essentially economic in its fundamental impulses."[147] Liberalism and capitalism Classical liberals were generally in abstract opposition to colonialism and imperialism, including Adam Smith, Frédéric Bastiat, Richard Cobden, John Bright, Henry Richard, Herbert Spencer, H.R. Fox Bourne, Edward Morel, Josephine Butler, W.J. Fox and William Ewart Gladstone.[148] Their philosophies found the colonial enterprise, particularly mercantilism, in opposition to the principles of free trade and liberal policies.[149] Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations that Britain should grant independence to all of its colonies and also argued that it would be economically beneficial for British people in the average, although the merchants having mercantilist privileges would lose out.[148][150] |

帝国主義に対抗する この段落は帝国主義§対植民地主義からの抜粋である[編集]。 帝国主義」という用語はしばしば「植民地主義」と混同されるが、多くの学者はそれぞれ独自の定義があると主張してきた。帝国主義と植民地主義は、ある人物 や集団に対する影響力を表現するために使われてきた。ロバート・ヤングは、帝国主義は国家政策として中央から運営され、イデオロギー的な理由だけでなく財 政的な理由からも展開されるのに対して、植民地主義は単に入植や商業的な意図から展開されるものであると書いている。特にエドワード・サイードは、帝国主 義と植民地主義を区別してこう述べている: 帝国主義は「支配的な大都会の中心が遠方の領土を支配する実践、理論、態度」に関与しており、植民地主義は「遠方の領土に定住地を植え付けること」を指し ている[140]。ロシア帝国、中国帝国、オスマン帝国などの陸続きの帝国は伝統的に植民地主義の議論から除外されてきたが、彼らが支配した領土にも人口 を送り込んでいたことが認められているため、これは変わり始めている[140]: 116 帝国主義と植民地主義はどちらも、支配する土地と先住民に対する政治的・経済的優位性を規定するものであるが、学者たちは時としてこの2つの違いを説明す ることが難しいと感じることがある[141]: 107 帝国主義と植民地主義は他国を抑圧することに焦点を当てているが、植民地主義がある国が他国を物理的に支配するプロセスを指すとすれば、帝国主義は政治 的・金銭的な支配を、公式または非公式に指す。植民地主義は、どのように地域を支配し始めるかを決定する立役者と見なされ、帝国主義は、植民地主義と協力 して征服の背後にある考えを生み出すと見なされる。植民地主義とは、帝国主義国家がある地域の征服を開始し、やがて前の国家が支配していた地域を支配でき るようになることである。植民地主義の中核的な意味は、征服された国の貴重な資産や物資を搾取し、征服した国が戦利品から利益を得ることである [141]: 170-75 帝国主義の意味は、他国の国土を征服することによって帝国を創造し、それによって自国の支配力を高めることである。植民地主義とは、外国の地域から来た人 々によって、ある地域に植民地的所有地を建設し、維持することである[141]: 173-76 植民地主義は、その地域の既存の社会構造、物理的構造、経済を完全に変えてしまうことがある。征服した民族の特徴が征服された先住民に継承されることは珍 しくない[141]: 41 母国から離れている植民地はほとんどない。したがって、ほとんどの植民地は最終的に独立した国籍を確立するか、母国植民地の完全な支配下にとどまることに なる[142]。 ソ連の指導者ウラジーミル・レーニンは、「帝国主義は資本主義の最高の形態である」と示唆し、「帝国主義は植民地主義の後に発展し、独占資本主義によって 植民地主義と区別された」と主張した[140]: 116 マルクス主義 マルクス主義は、植民地主義を資本主義の一形態としてとらえ、搾取と社会変革を強要している。マルクスは、グローバルな資本主義システムの中で働く植民地 主義は、不均等な発展と密接に関連していると考えた。それは「歪んだ経済、社会心理学的混乱、大規模な貧困、新植民地依存を生み出す、大規模な破壊、依 存、組織的搾取の道具」である[143]。原材料の探索と現在の新たな投資機会の探索は、資本蓄積をめぐる資本主義間の競合の結果である(誰によれば?ウ ラジーミル・レーニンは、『社会主義革命と民族の自決権に関するテーゼ』において、社会主義国際主義の綱領に不可欠な綱領として、民族の自決の原則を力強 く提唱した」とし、「民族の自決権は、専ら政治的な意味での独立の権利、抑圧国家からの自由な政治的分離の権利を意味する」と主張したレーニンの言葉を引 用している。具体的には、この政治的民主主義の要求は、分離独立を煽動する完全な自由と、分離独立する国家による分離独立に関する国民投票の自由を意味す る」[144]。スルタン・ガリエフやヴァシル・シャクライのような、ロシア連邦、後のソ連邦内の非ロシア系マルクス主義者は、1918年から1923 年、そして1929年以降、ソビエト政権をロシア帝国主義と植民地主義の新バージョンとみなしていた。 アフリカにおける植民地主義に対する批判の中で、ガイアナの歴史家であり政治活動家であるウォルター・ロドニーは次のように述べている[145] [146]。 植民地主義の短い期間の決定的な強さとアフリカに対するその否定的な結果は、主にアフリカが力を失ったという事実から生じている。権力は人間社会における 究極の決定要因であり、あらゆる集団内および集団間の関係の基本である。それは、自分の利益を守り、必要であれば利用可能なあらゆる手段で自分の意志を押 し通す能力を意味する......。ある社会が他の社会に完全に権力を放棄せざるを得なくなったとき、それ自体が低開発の一形態となる。植民地支配以前の 何世紀もの間、アフリカでは、ヨーロッパ人との不利な交易にもかかわらず、社会的政治的経済的生活に対するある程度の統制が保たれていた。しかし、植民地 主義のもとで、そのわずかな統制も失われた。植民地主義は貿易よりもはるかに進んでいた。それは、アフリカ内の社会制度をヨーロッパ人が直接的に流用する 傾向を意味した。アフリカ人は固有の文化的目標や基準を設定することをやめ、社会の若い構成員を訓練する完全な指揮権を失った。それは間違いなく大きな後 退であった。植民地主義は単なる搾取システムではなく、その本質的な目的は、いわゆる「母国」に利益を還流させることにあった。アフリカから見れば、それ はアフリカの資源からアフリカの労働力によって生み出された余剰を一貫して国外に送還することに等しかった。それは、アフリカが未発達であったのと同じ弁 証法的プロセスの一部として、ヨーロッパが発展することを意味していた。植民地アフリカは、国際資本主義経済の一部であり、そこから余剰が引き出され、大 都市部門を養っていた。先に見たように、土地と労働力の搾取は、人類の社会的進歩に不可欠であるが、搾取が行われる地域内で生産物が利用可能であるという 前提のもとでのみ行われる。 レーニンによれば、新帝国主義は、資本主義が自由貿易から金融資本への独占資本主義の段階に移行することを強調した。彼は、それは「世界の分割をめぐる闘 争の激化と結びついている」と述べている。自由貿易が商品の輸出で繁栄するように[誰によれば]、独占資本主義は銀行と工業からの利益によって蓄積された 資本の輸出で繁栄した。レーニンにとっては、これが資本主義の最高段階であった。彼はさらに、このような資本主義の形態は、資本家と被搾取国との間で戦争 が起こる運命にあり、前者が必然的に敗北すると述べている。戦争は帝国主義の結果であると述べている。この思想の続きとして、G.N.ウゾイグエは、「し かし、帝国主義がその基本的な衝動において本質的に経済的なものであったことは、この時代のアフリカ史のより真剣な調査から今や明らかである」と述べてい る[147]。 自由主義と資本主義 アダム・スミス、フレデリックa・バスティア、リチャード・コブデン、ジョン・ブライト、ヘンリー・リチャード、ハーバート・スペンサー、H.R.フォッ クス・ボーン、エドワード・モレル、ジョセフィン・バトラー、W.J.フォックス、ウィリアム・ユワート・グラッドストン[148]などの古典的自由主義 者は、植民地主義や帝国主義に抽象的に反対していた。 [149]アダム・スミスは『国富論』の中で、イギリスはすべての植民地に独立を認めるべきだと書いており、重商主義の特権を持つ商人たちは損をするだろ うが、平均的にはイギリス国民にとって経済的に有益であるとも主張していた[148][150]。 |