フランツ・オマー・ファノン

Frantz Omar Fanon, 1925-61

★フ ランツ・オマー・ファノン(/ˈfænən/,[1] 米国: /1925年7月20日 - 1961年12月6日)は、フランスの植民地マルティニーク(現在はフランスの県)出身のフランス語圏のアフロカリブ人、精神科医、政 治哲学者、マルクス主義者。知識人であると同時に、ファノンは植民地化の精神病理学と脱植民地化の人間的、社会的、文化的帰結 に関心を持つ政治的急進主義者、汎アフリカ主義者、マルクス主義的ヒューマニストでもあった。 医師、精神科医としての活動の過程で、ファノンはフランスからのアルジェリア独立戦争を支持し、アルジェリア民族解放戦線のメンバーであった。ファノンは 「同時代で最も影響力のある反植民地思想家」と評されている。50年以上もの間、ファノンの生涯と作品はパレスチナ、スリランカ、南アフリカ、ア メリカにおける民族解放運動やその他の自由運動、政治運動に影響を与えた。また、サン・アルバンでフランソワ・トスケルとジャ ン・オリーの下で働きながら、施設精神療法の分野の創設にも貢献した(→「ファノン年譜」)。

★ファノンと同時代人の医師2人

| Frantz Omar Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (/ˈfænən/,[2] US: /fæˈnɒ̃/;[3] French: [fʁɑ̃ts fanɔ̃]; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a Franchophone Afro-Caribbean[4][5][6] psychiatrist, political philosopher, and Marxist from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have become influential in the fields of post-colonial studies, critical theory, and Marxism.[7] As well as being an intellectual, Fanon was a political radical, Pan-Africanist, and Marxist humanist concerned with the psychopathology of colonization[8] and the human, social, and cultural consequences of decolonization.[9][10][11] In the course of his work as a physician and psychiatrist, Fanon supported the Algerian War of independence from France and was a member of the Algerian National Liberation Front. Fanon has been described as "the most influential anticolonial thinker of his time".[12] For more than five decades, the life and works of Fanon have inspired national liberation movements and other freedom and political movements in Palestine, Sri Lanka, South Africa, and the United States.[13][14][15] He formulated a model for community psychology, believing that many mental health patients would do better if they were integrated into their family and community instead of being treated with institutionalized care. He also helped found the field of institutional psychotherapy while working at Saint-Alban under Francois Tosquelles and Jean Oury.[16] |

フランツ・オマール・ファノン フランツ・オマール・ファノン (/ˈfænən/,[2] 米国: /fæˈnɒ̃/;[3] フランス語: [fʁɑ̃ts fanɔ̃]; 1925年7月20日 – 1961年12月6日)は、フランス語圏のアフリカ系カリブ人[4][5][6]の精神科医、政治哲学者、マルクス主義者で、フランスの植民地だったマル ティニーク島(現在はフランスの県)出身。彼の著作は、ポストコロニアル研究、批判理論、マルクス主義の分野で大きな影響を与えている。[7] 知識人であるだけでなく、ファノンは政治的急進派、汎アフリカ主義者、マルクス主義的人道主義者であり、植民地化の精神病理学[8]および脱植民地化の人 間的、社会的、文化的影響に懸念を抱いていた。[9][10][11] 医師および精神科医としての活動の中で、ファノンはフランスからのアルジェリア独立戦争を支持し、アルジェリア民族解放戦線のメンバーでした。ファノンは 「その時代で最も影響力のある反植民地思想家」と評されています[12]。50 年以上にわたり、ファノンの生涯と著作は、パレスチナ、スリランカ、南アフリカ、米国における民族解放運動やその他の自由と政治の運動に影響を与えてきま した。[13][14][15] 彼は、多くの精神保健患者は、施設での治療を受けるよりも、家族やコミュニティに溶け込むほうがより良くなるだろうと信じ、コミュニティ心理学のモデルを 策定した。また、フランソワ・トスケルとジャン・ウーリーのもとでサン・アルバンで働いていた間、施設内心理療法の分野の確立にも貢献した。[16] |

|

Francesc Tosquelles (Reus, August 22, 1912 – Granges-sur-Lot, September

25, 1994), also known as François Tosquelles due to having lived in

France for many years, was a Catalan psychiatrist.[1] During the

Spanish Civil War, he fought on the Republican side for the Workers'

Party of Marxist Unification.[2] During World War II, he was the doctor

at the psychiatric hospital of Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole, Lozère,

France. He is credited as one of the creators of institutional

psychotherapy, an influential movement in the second half of the 20th

century. His 1948 doctoral thesis for the University of Paris was

titled 'The Psychopathology of Lived Experience' - "Part gestalt

psychology, part phenomenology, part neurobiology, part psychoanalysis,

it revived the Hippocratic notion of the medic–philosopher – iatros

philosophos." After experiencing military occupations throughout his

lifetime (German in France, Spanish in Catalonia, Francoist in Spain,

and Stalinist in the Spanish communist parties), he concluded that

"occupation" was not simply a historical reality but created a psychic

structure in the individual, and that to achieve freedom, one must

proceed by "disoccupation". The Martinican doctor and later revolutionary activist Frantz Fanon was one of his students, who then used his techniques to some degree of success while living in Blida, Algeria, in the mid-1950s. |

フランセスク・トスケレス(Francesc

Tosquelles、1912年8月22日 -

1994年9月25日)は、フランスで長年暮らしたことからフランソワ・トスケレス(François

Tosquelles)としても知られる、カタルーニャ出身の精神科医だ。[1]

スペイン内戦では、マルクス主義統一労働者党(PUM)の共和派として戦った。[2]

第二次世界大戦中、彼はフランス・ロゼール県のサン=アルバン=シュル=リマニョールにある精神病院の医師を務めた。彼は、20世紀後半に大きな影響を与

えた「機関内心理療法」の創始者の一人として知られている。1948年にパリ大学で提出した博士論文のタイトルは『経験の精神病理学』で、「ゲシュタルト

心理学、現象学、神経生物学、精神分析を融合させたこの著作は、ヒポクラテスの『医者は哲学者である』という概念を復活させた」と評価されている。生涯に

わたって軍事占領を経験した(フランスでのドイツ占領、カタルーニャでのスペイン占領、スペインでのフランコ政権占領、スペイン共産党でのスターリン主義

占領)彼は、「占領」は単なる歴史的現実ではなく、個人に心理的構造を築くものだと結論付け、自由を達成するためには「占領からの解放」を進める必要があ

ると主張した。 マルティニーク出身の医師で後に革命活動家となったフランツ・ファノンは彼の弟子の一人で、1950年代半ばにアルジェリアのブリダで生活していた際、彼の技法を一定程度の成功を収めて活用した。 |

| Jean Oury (5 March 1924 – 15 May 2014) was a French psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who helped found the school of institutional psychotherapy.[1][2] He was the founder and director of the psychiatric hospital La Borde clinic at Cour-Cheverny, France where he worked until he died. He was a member of the Freudian School of Paris, founded by Jacques Lacan from inception until its dissolution. His brother, Fernand Oury, founded the school of institutional pedagogy. | ジャン・ウリー(1924年3月5日 -

2014年5月15日)は、フランスの精神科医、精神分析医であり、制度精神療法の学派を創設した人物です。[1][2]

彼は、フランス・クール・シュヴェルニーにある精神病院「ラ・ボルドクリニック」の創設者であり、同病院の院長を務め、亡くなるまでそこで働きました。彼

は、ジャック・ラカンによって設立されたパリのフロイト学派の創設メンバーであり、その解散までメンバーとして活動しました。彼の兄、フェルナン・ウー

リーは、機関教育学派を設立した。 |

★ファノンリンク集

★ファノン生涯(英語ウィキペディア)

| Biography | バイオグラフィー |

|

Early life Frantz Fanon was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique, which was then a French colony and is now a French single territorial collectivity. His father, Félix Casimir Fanon, was a descendant of African slaves, and worked as a customs agent. His mother, Eléanore Médélice, was of Afro-Martinican and white Alsatian descent, and worked as a shopkeeper.[16] Frantz was the third of four sons in a family of eight children. Two of them died young, including his sister Gabrielle, with whom Frantz was very close. His family was socio-economically middle-class. They could afford the fees for the Lycée Schoelcher, at the time the most prestigious high school in Martinique, where Fanon came to admire one of the school's teachers, poet and writer Aimé Césaire.[17] Fanon left Martinique in 1943, when he was 18 years old, in order to join the Free French forces.[18] |

生い立ち フランツ・ファノンはカリブ海に浮かぶマルティニーク島(当時はフランスの植民地、現在はフランスの単一領土)で生まれた。父はアフリカ人奴隷の子孫で、 税関職員として働いていた。母親のエレノア・メデリスはアフロ・マルティニカ人とアルザス系白人の血を引いており、商店主をしていた[16]。そのうちの 2人は若くして亡くなっており、そのうちの1人はフランツと非常に親しかった妹のガブリエルであった。彼の家庭は社会経済的には中流階級であった。当時、 マルティニークで最も権威のある高校であったリセ・ショエルシェの学費を払う余裕があり、ファノンは同校の教師の一人であった詩人で作家のエメ・セゼール を敬愛するようになる[17]。ファノンは1943年、18歳の時に自由フランス軍に参加するためにマルティニークを離れる[18]。 |

|

Martinique and World War II After France fell to the Nazis in 1940, Vichy French naval troops were blockaded on Martinique. Forced to remain on the island, French sailors took over the government from the Martiniquan people and established a collaborationist Vichy regime. In the face of economic distress and isolation under the blockade, they instituted an oppressive regime; Fanon described them as taking off their masks and behaving like "authentic racists".[19] Residents made many complaints of harassment and sexual misconduct by the sailors. The abuse of the Martiniquan people by the French Navy influenced Fanon, reinforcing his feelings of alienation and his disgust with colonial racism. At the age of seventeen, Fanon fled the island as a "dissident" (a term used for Frenchmen joining Gaullist forces), traveling to Dominica to join the Free French Forces.[20]: 24 After three attempts, he made it to Dominica, but it was too late to enlist. After the pro-Vichy Robert regime was deposed in Martinique in June 1943, Fanon returned to Fort-de-France to join the newly created, all black 5e Bataillon de marche des Antilles [fr].[21] He enlisted in the Free French army and joined an Allied convoy that reached Casablanca. He was later transferred to an army base at Béjaïa on the Kabylia coast of Algeria. Fanon left Algeria from Oran and served in France, notably in the battles of Alsace. In 1944 he was wounded at Colmar and received the Croix de guerre.[22] When the Nazis were defeated and Allied forces crossed the Rhine into Germany along with photojournalists, Fanon's regiment was "bleached" of all non-white troops as Fanon and his fellow Afro-Caribbean soldiers were sent to Toulon (Provence).[13] Later, they were transferred to Normandy to await repatriation.[23] During the war, Fanon was exposed to more white European racism. For example, European women liberated by black soldiers often preferred to dance with fascist Italian prisoners, rather than fraternize with their liberators.[16] In 1945, Fanon returned to Martinique. He lasted a short time there. He worked for the parliamentary campaign of his friend and mentor Aimé Césaire, who would be a major influence in his life. Césaire ran on the communist ticket as a parliamentary delegate from Martinique to the first National Assembly of the Fourth Republic. Fanon stayed long enough to complete his baccalaureate and then went to France, where he studied medicine and psychiatry. |

マルティニークと第二次世界大戦 1940年にフランスがナチスに陥落した後、ヴィシー・フランス海軍はマルティニーク島を封鎖した。島に留まることを余儀なくされたフランスの船員たち は、マルティニーク人から政府を引き継ぎ、協力主義のヴィシー政権を樹立した。経済的困窮と封鎖下での孤立に直面し、彼らは抑圧的な体制を築いた。ファノ ンは彼らを、仮面を脱ぎ捨て「本物の人種差別主義者」のように振る舞ったと評した。フランス海軍によるマルティニカン人への虐待はファノンに影響を与え、 疎外感と植民地人種差別への嫌悪感を強めた。17歳のとき、ファノンは「反体制派」(ゴーリスム勢力に参加するフランス人を指す言葉)として島を脱出し、 自由フランス軍に参加するためにドミニカに向かった[20]: 24。3回の挑戦の末、ドミニカにたどり着いたが、入隊するには遅すぎた。1943年6月に親ヴィシー・ロベール政権がマルティニークで退陣すると、ファ ノンはフォール・ド・フランスに戻り、新たに創設された黒人だけの5e Bataillon de marche des Antilles [fr]に入隊した[21]。 彼は自由フランス軍に入隊し、カサブランカに到着した連合軍の輸送隊に加わった。その後、アルジェリアのカビリア海岸にあるベジャイアの陸軍基地に移され た。ファノンはオランからアルジェリアを離れ、フランスで特にアルザスの戦いに従軍した。1944年、コルマールで負傷し、クロワ・ド・ゲールを授与され た[22]。ナチスが敗北し、連合軍がフォトジャーナリストとともにライン川を越えてドイツに入ると、ファノンの連隊は白人以外の兵士を「漂白」され、 ファノンと仲間のアフロ・カリビアン兵はトゥーロン(プロヴァンス)に送られた[13]。 戦争中、ファノンはより多くのヨーロッパ白人の人種差別にさらされた。例えば、黒人兵士によって解放されたヨーロッパの女性たちは、解放者と友好的になる よりも、ファシストのイタリア人捕虜と踊ることを好むことが多かった[16]。 1945年、ファノンはマルティニークに戻った。ファノンがマルティニークに戻ったのは短い期間だった。彼は、彼の人生に大きな影響を与えることになる友 人であり師であるエメ・セゼールの国会議員選挙キャンペーンに参加した。セゼールはマルティニークから第四共和制の第一回国民議会に共産党員として立候補 した。ファノンはバカロレアを取得するのに十分な期間滞在し、その後フランスに渡り、医学と精神医学を学んだ。 |

|

France Fanon was educated in Lyon, where he also studied literature, drama and philosophy, sometimes attending Merleau-Ponty's lectures. During this period, he wrote three plays, of which two survive.[24] After qualifying as a psychiatrist in 1951, Fanon did a residency in psychiatry at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole under the radical Catalan psychiatrist François Tosquelles, who invigorated Fanon's thinking by emphasizing the role of culture in psychopathology. In 1948 Fanon started a relationship with Michelle, a medical student, who soon became pregnant. He left her for an 18-year-old high school student, Josie, whom he married in 1952. At urging of his friends he later recognized his daughter, Mireille, although he did not have contact with her.[25] In France while completing his residency, Fanon wrote and published his first book, Black Skin, White Masks (1952), an analysis of the negative psychological effects of colonial subjugation upon black people. Originally, the manuscript was the doctoral dissertation, submitted at Lyon, entitled "Essay on the Disalienation of the Black", which was a response to the racism that Fanon experienced while studying psychiatry and medicine at university in Lyon; the rejection of the dissertation prompted Fanon to publish it as a book. For his doctor of philosophy degree, he submitted another dissertation of narrower scope and different subject. Left-wing philosopher Francis Jeanson, leader of the pro-Algerian independence Jeanson network, read Fanon's manuscript and as a senior book editor at Éditions du Seuil in Paris, gave the book its new title and wrote its epilogue.[26] After receiving Fanon's manuscript at Seuil, Jeanson invited him to an editorial meeting. Amid Jeanson's praise of the book, Fanon exclaimed: "Not bad for a nigger, is it?" Insulted, Jeanson dismissed Fanon from his office. Later, Jeanson learned that his response had earned him the writer's lifelong respect, and Fanon acceded to Jeanson's suggestion that the book be entitled Black Skin, White Masks.[26] In the book, Fanon described the unfair treatment of black people in France and how they were disapproved of by white people. Black people also had a sense of inferiority when facing white people. Fanon believed that even though they could speak French, they could not fully integrate into the life and environment of white people. (See further discussion of Black Skin, White Masks under Work, below.) |

フランス リヨンで教育を受けたファノンは、文学、演劇、哲学も学び、時にはメルロ=ポンティの講義にも出席した。1951年に精神科医の資格を得たファノンは、サ ン・アルバン・シュル・リマニョールの精神科で、急進的なカタルーニャ人精神科医フランソワ・トスケルのもとで研修医を務めた。 1948年、ファノンは医学生のミシェルと交際を始めたが、彼女はすぐに妊娠した。1952年に結婚した18歳の女子高生ジョシーと別れた。友人の勧めも あり、後に娘のミレーユを認知するが、彼女とは連絡を取っていなかった[25]。 ファノンはフランスで研修医をしながら、最初の著書『黒い肌、白い仮面』(1952年)を執筆、出版した。もともとは、リヨンの大学で精神医学と医学を学 んでいたファノンが経験した人種差別への反論として提出した「黒人の剥奪に関する試論」というタイトルの博士論文であった。哲学博士号を取得するために、 彼はより狭い範囲と異なるテーマの別の論文を提出した。左翼哲学者のフランシス・ジャンソン(親アルジェリア独立ジャンソンネットワークのリーダー)は ファノンの原稿を読み、パリのエディシオン・デュ・スイユの上級書籍編集者として、この本に新しいタイトルをつけ、エピローグを執筆した[26]。 スィユ社でファノンの原稿を受け取ったジャンソンは、彼を編集会議に招いた。ジャンソンがこの本を賞賛する中、ファノンはこう叫んだ: "黒人にしては悪くないだろう?"と。侮辱されたジャンソンはファノンをオフィスから追い出した。後日、ジャンソンは彼の返答が作家の生涯の尊敬を得たこ とを知り、ファノンはジャンソンの提案に応じ、本のタイトルを『黒い肌、白い仮面』とした[26]。 この本の中でファノンは、フランスにおける黒人の不当な扱いと、彼らがいかに白人から嫌われているかを述べた。黒人はまた、白人と対峙する際に劣等感を抱 いていた。ファノンは、たとえフランス語を話せても、白人の生活や環境に完全に溶け込むことはできないと考えた。(黒い肌、白い仮面』については、後述の 『仕事』の項を参照)。 |

|

Algeria After his residency, Fanon practised psychiatry at Pontorson, near Mont Saint-Michel, for another year and then (from 1953) in Algeria. He was chef de service at the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria. He worked there until his deportation in January 1957.[27] Fanon's methods of treatment started evolving, particularly by beginning socio-therapy to connect with his patients' cultural backgrounds. He also trained nurses and interns. Following the outbreak of the Algerian revolution in November 1954, Fanon joined the Front de Libération Nationale, after having made contact with Pierre Chaulet at Blida in 1955. Working at a French hospital in Algeria, Fanon became responsible for treating the psychological distress of the French soldiers and officers who carried out torture in order to suppress anti-colonial resistance. Additionally, Fanon was also responsible for treating Algerian torture victims. Fanon made extensive trips across Algeria, mainly in the Kabylia region, to study the cultural and psychological life of Algerians. His lost study of "The marabout of Si Slimane" is an example. These trips were also a means for clandestine activities, notably in his visits to the ski resort of Chrea which hid an FLN base. |

アルジェリア 研修医として働いた後、ファノンはモン・サン・ミッシェル近くのポントルソンでさらに1年間、そして(1953年から)アルジェリアで精神科医として働い た。アルジェリアのブリダ・ジョインヴィル精神病院でシェフを務めた。1957年1月の国外追放までそこで働いた[27]。 ファノンの治療方法は進化し始め、特に患者の文化的背景とつながるための社会療法を始めた。彼はまた、看護師やインターンを訓練した。1954年11月の アルジェリア革命勃発後、ファノンは1955年にブリダでピエール・ショーレと接触した後、国民解放戦線に参加した。アルジェリアのフランス人病院に勤務 していたファノンは、反植民地レジスタンスを弾圧するために拷問を行ったフランス軍兵士や将校の精神的苦痛の治療を担当するようになった。さらに、ファノ ンはアルジェリアの拷問被害者の治療も担当した。 ファノンは、アルジェリア人の文化的・心理的生活を研究するため、カビリア地方を中心にアルジェリア全土を旅した。失われた『シ・スリマンの放蕩者』の研 究はその一例である。こうした旅はまた、秘密活動の手段でもあり、特にFLNの拠点が隠されていたスキーリゾート、シュレアを訪れた。 |

| Joining the FLN and exile from Algeria By summer 1956 Fanon realized that he could no longer continue to support French efforts, even indirectly via his hospital work. In November he submitted his "Letter of resignation to the Resident Minister", which later became an influential text of its own in anti-colonialist circles.[28] There comes a time when silence becomes dishonesty. The ruling intentions of personal existence are not in accord with the permanent assaults on the most commonplace values. For many months my conscience has been the seat of unpardonable debates. And the conclusion is the determination not to despair of man, in other words, of myself. The decision I have reached is that I cannot continue to bear a responsibility at no matter what cost, on the false pretext that there is nothing else to be done. Shortly afterwards, Fanon was expelled from Algeria and moved to Tunis where he joined the FLN openly. He was part of the editorial collective of Al Moudjahid, for which he wrote until the end of his life. He also served as Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government (GPRA). He attended conferences in Accra, Conakry, Addis Ababa, Leopoldville, Cairo and Tripoli. Many of his shorter writings from this period were collected posthumously in the book Toward the African Revolution. In this book Fanon reveals war tactical strategies; in one chapter he discusses how to open a southern front to the war and how to run the supply lines.[27] Upon his return to Tunis, after his exhausting trip across the Sahara to open a Third Front, Fanon was diagnosed with leukemia. He went to the Soviet Union for treatment and experienced some remission of his illness. When he came back to Tunis once again, he dictated his testament The Wretched of the Earth. When he was not confined to his bed, he delivered lectures to Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN) officers at Ghardimao on the Algerian–Tunisian border. He traveled to Rome for a three-day meeting with Jean-Paul Sartre who had greatly influenced his work. Sartre agreed to write a preface to Fanon's last book, The Wretched of the Earth.[29] |

FLNへの参加とアルジェリアからの亡命 1956年夏までにファノンは、病院勤務を通じて間接的にでもフランスの活動を支援し続けることはもはやできないと悟った。11月、彼は「駐在大臣への辞 表」を提出したが、この辞表は後に反植民地主義界で影響力のある文章となった[28]。 沈黙が不誠実となる時が来る。個人的存在の支配的意図は、最もありふれた価値観に対する恒常的な攻撃とは一致しない。何カ月もの間、私の良心は許されざる 議論の場であった。そしてその結論は、人間、言い換えれば自分自身に絶望しないという決意であった。私が下した決断は、他になすすべがないという偽りの口 実で、どんな代償を払っても責任を負い続けることはできないということである。 その直後、ファノンはアルジェリアから追放され、チュニスに移り、FLNに公然と参加した。アル・ムジャヒド』誌の編集に参加し、同誌で生涯を終えるまで 執筆を続けた。アルジェリア臨時政府(GPRA)の駐ガーナ大使も務めた。アクラ、コナクリ、アディスアベバ、レオポルドヴィル、カイロ、トリポリでの会 議に出席。この時期の短い著作の多くは、死後に『アフリカ革命に向けて』という本にまとめられた。この本の中でファノンは戦争の戦術的戦略を明らかにして おり、ある章では戦争の南方戦線をどのように切り開くか、補給線をどのように運営するかについて論じている[27]。 第三戦線を開くためにサハラ砂漠を横断する疲弊した旅を終えてチュニスに戻ると、ファノンは白血病と診断された。彼は治療のためにソ連に行き、病気の寛解 を経験した。再びチュニスに戻ると、『地の哀れ』を書き上げた。寝たきりでないときは、アルジェリアとチュニジアの国境にあるガルディマオで、国民解放軍 (ALN)の将校たちに講義を行った。ローマに行き、彼の仕事に多大な影響を与えたジャン=ポール・サルトルと3日間会談。サルトルは、ファノンの遺作 『The Wretched of the Earth』に序文を書くことに同意した[29]。 |

| Death and aftermath With his health declining, Fanon's comrades urged him to seek treatment in the U.S. as his Soviet doctors had suggested.[30] In 1961, the CIA arranged a trip under the promise of stealth for further leukemia treatment at a National Institutes of Health facility.[30][31] During his time in the United States, Fanon was handled by CIA agent Oliver Iselin.[32] As Lewis R. Gordon points out, the circumstances of Fanon's stay are somewhat disputed: "What has become orthodoxy, however, is that he was kept in a hotel without treatment for several days until he contracted pneumonia."[30] Fanon subsequently died from double pneumonia in Bethesda, Maryland, on 6 December 1961 after finally having begun his leukemia treatment.[33] He had been admitted under the name of Ibrahim Omar Fanon, a Libyan nom de guerre he had assumed in order to enter a hospital in Rome after being wounded in Morocco during a mission for the Algerian National Liberation Front.[34] He was buried in Algeria after lying in state in Tunisia. Later, his body was moved to a martyrs' (Chouhada) graveyard at Aïn Kerma in eastern Algeria. |

死とその後 健康状態が悪化する中、ファノンの同志たちは、ソ連の医師たちが提案したように、アメリカで治療を受けるよう促した[30]。 1961年、CIAは、国立衛生研究所(National Institutes of Health)の施設で白血病の治療を受けるため、極秘裏に渡航を手配した[30][31]。 アメリカ滞在中、ファノンはCIA諜報員のオリヴァー・イゼリンに扱われた[32]。ルイス・R・ゴードンが指摘するように、ファノンの滞在の経緯にはや や異論がある: 「しかし、正統派となっているのは、彼が肺炎に罹患するまで数日間、治療も受けずにホテルに監禁されていたということである」[30]。 ファノンはその後、ようやく白血病の治療を開始した後、1961年12月6日にメリーランド州ベセスダで二重の肺炎により死亡した[33]。彼はイブラヒ ム・オマール・ファノンという名で入院していたが、これはアルジェリア民族解放戦線の任務中にモロッコで負傷した後、ローマの病院に入るために名乗ったリ ビア人の名であった[34]。その後、遺体はアルジェリア東部のアイン・ケルマにある殉教者の墓地に移された。 |

★ファノン著作関連

Fanon's final resting place in Aïn Kerma, Algeria Fanon's grave in Aïn Kerma, Algeria |

アルジェリアのアイン・ケルマにあるファノンの終焉の地 アルジェリアのアイン・ケルマにあるファノンの墓 |

| Wikispore has a related page: Bio:Josie Fanon Frantz Fanon was survived by his French wife, Josie (née Dublé), their son, Olivier Fanon, and his daughter from a previous relationship, Mireille Fanon-Mendès France. Josie Fanon later became disillusioned with the government and after years of depression and drinking died by suicide in Algiers in 1989.[27][35] Mireille became a professor of international law and conflict resolution and serves as president of the Frantz Fanon Foundation. Olivier became president of the Frantz Fanon National Association, which was created in Algiers in 2012.[36] |

ウィキスポアに関連ページあり: バイオグラフィー:ジョジー・ファノン フランツ・ファノンには、フランス人の妻ジョシー(旧姓デュブレ)、息子のオリヴィエ・ファノン、以前交際していた娘ミレイユ・ファノン=メンデス=フラ ンスがいる。ミレイユは国際法と紛争解決の教授となり、フランツ・ファノン財団の会長を務める。オリヴィエは、2012年にアルジェで創設されたフラン ツ・ファノン全国協会の会長となった[36]。 |

| Work Black Skin, White Masks Black Skin, White Masks was first published in French as Peau noire, masques blancs in 1952 and is one of Fanon's most important works. In Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon psychoanalyzes the oppressed Black person who is perceived to have to be a lesser creature in the White world that they live in, and studies how they navigate the world through a performance of Whiteness.[16] Particularly in discussing language, he talks about how the black person's use of a colonizer's language is seen by the colonizer as predatory, and not transformative, which in turn may create insecurity in the black's consciousness.[37] He recounts that he himself faced many admonitions as a child for using Creole French instead of "real French", or "French French", that is, "white" French.[16] Ultimately, he concludes that "mastery of language [of the white/colonizer] for the sake of recognition as white reflects a dependency that subordinates the black's humanity".[37] The reception of his work has been affected by English translations which are recognized to contain numerous omissions and errors, while his unpublished work, including his doctoral thesis, has received little attention. As a result, it has been argued Fanon has often been portrayed as an advocate of violence (it would be more accurate to characterize him as a dialectical opponent of nonviolence) and that his ideas have been extremely oversimplified. This reductionist vision of Fanon's work ignores the subtlety of his understanding of the colonial system. For example, the fifth chapter of Black Skin, White Masks translates, literally, as "The Lived Experience of the Black" ("L'expérience vécue du Noir"), but Markmann's translation is "The Fact of Blackness", which leaves out the massive influence of phenomenology on Fanon's early work.[38] |

著作 黒い肌、白い仮面 『黒い肌、白い仮面』は、1952年に『Peau noire, masques blancs』としてフランス語で出版されたファノンの最も重要な作品のひとつである。黒い肌、白い仮面』の中でファノンは、抑圧された黒人が、自分たち の住む白人の世界では劣った生き物でなければならないと認識されることを精神分析し、彼らが白人性のパフォーマンスを通してどのように世界をナビゲートす るかを研究している。 [最終的に彼は、「白人として認識されるための(白人/植民者の)言語の習得は、黒人の人間性を従属させる依存を反映している」と結論付けている [37]。 博士論文を含む彼の未発表の著作はほとんど注目されていない一方で、彼の著作の受容は、多くの脱落や誤りを含むと認識されている英訳によって影響を受けて いる。その結果、ファノンはしばしば暴力の擁護者として描かれ(非暴力の弁証法的反対者というのがより正確だろう)、彼の思想は極端に単純化されすぎてい ると論じられてきた。ファノンの著作に対するこのような還元主義的な見方は、植民地体制に対する彼の理解の繊細さを無視している。例えば、『黒い肌、白い 仮面』の第5章は、文字どおり「黒人の生きた経験」("L'expérience vécue du Noir")と訳されているが、マークマンの訳は「黒人の事実」であり、ファノンの初期の仕事に現象学が与えた多大な影響を省いている[38]。 |

| "The Negro and Language" Chapter 1 of Black Skin, White Masks is entitled "The Negro and Language".[39] In this chapter, Fanon discusses how colored people were perceived by the whites. He says that the black man has two dimensions: One with his fellows, the other with the white man. A Negro behaves differently with a white man than with another Negro. Fanon claimed that whether this self-division is a direct result of colonialist subjugation is beyond question. To speak a language is to take on a world, a culture. The Antilles Negro who wants to be white will be the whiter as he gains greater mastery of the cultural tool that language is. Fanon concludes his theorizing by saying: "Historically, it must be understood that the Negro wants to speak French because it is the key that can open doors which were still barred to him fifty years ago. In the Antilles Negro who comes within this study we find a quest for subtleties, for refinements of language—so many further means of proving to himself that he has measured up to the culture." |

黒人(ニグロ)と言語 『黒 い肌、白い仮面』の第1章のタイトルは「黒人と言語」である。彼は、黒人には二つの次元があると言う: ひとつは仲間との関係、もうひとつは白人との関係である。黒人は白人と接するときと、他の黒人と接するときとでは、異なる行動をとる。ファノンは、この自 己分裂が植民地支配の直接的な結果であるかどうかは疑問の余地がないと主張する。ある言語を話すことは、ある世界、ある文化を引き受けることである。白人 になりたいと願うアンティル黒人は、言語という文化的道具をより使いこなすことで、より白くなる。ファノンは理論化の最後をこう締めくくっている: 「歴史的に見れば、黒人がフランス語を話したいと思うのは、それが50年前にはまだ閉ざされていた扉を開く鍵だからである。この研究の対象であるアンティ ル黒人の中には、繊細さや洗練された言語への探求が見られる。 |

| "The Woman of Color and the

White Man" Chapter 2 of Black Skin, White Masks is entitled “The woman of color and the white man”.[39] The focus of the chapter is on the extent to which authentic love between women of color and European males is hindered by unconscious tensions. It discusses how a feeling of inferiority has manifested in women of color because of colonialism. Fanon introduces the reader to the cases of two women from novels, Mayotte Capécia's semi-autobiographical I Am a Martinican Woman (1948) and Abdoulaye Sadji's Nini, mulâtresse du Sénégal (1954). Mayotte Capécia is a black woman who Fanon claims has idealized whiteness. She wants above all to be with a white man, and strives to be as close to communities of white people as possible. Fanon also discusses how mulatto women see themselves as superior to black men. This is the case with the black man Mactar´s love letter to Nini (a mulatto woman), where he acknowledges his inferiority as a black man, but argues that his devotion to her is reason enough to choose him. The idealization of whiteness both in white people and people of color is discussed. |

「有色の女と白人の男」 『黒 い肌、白い仮面』の第2章は「有色人種の女性と白人男性」と題されている[39]。この章の焦点は、有色人種の女性とヨーロッパ人男性との間の本物の愛 が、無意識の緊張によってどの程度妨げられているかにある。植民地主義のせいで、有色人種の女性にどのような劣等感が現れているかを論じている。ファノン は、マヨット・カペシアの半自伝的作品『私はマルティニカの女』(1948年)と、アブドゥライェ・サジの『セネガルの女、ニニ』(1954年)という小 説から、二人の女性のケースを読者に紹介する。マヨット・カペシアは、ファノンが白人性を理想化したと主張する黒人女性である。彼女は何よりも白人男性と 一緒になることを望み、白人の共同体にできるだけ近づこうと努力する。ファノンはまた、混血の女性が黒人男性よりも自分たちの方が優れていると考えている ことについても論じている。黒人男性マクターがニニ(混血女性)に宛てたラブレターがそうで、彼は黒人男性としての劣等感を認めながらも、彼女への献身は 自分を選ぶ十分な理由になると主張している。白人と有色人種の両方における白人の理想化について論じている。 |

| "The Man of Color and the White

Woman" Chapter 3 of Black Skin, White Masks is entitled “The man of color and the white woman”.[39] In this chapter Fanon discusses the desire of the black man to be white. Firstly by telling the story of the Antillean man who upon arrival has one goal: to sleep with a white woman. For the black man, an unconscious need to prove that their worth is similar to the white man is fulfilled through sexual interaction with the white woman. Fanon then analyzes the story of Jean Veneuse written by René Maran, a work believed to be autobiographic. Jean Veneuse is a black man from the Antilles living in Bourdeaux. He is a part of the social and cultural elite and falls in love with a white woman. He is aware of the stereotype of the black man´s desire to sleep with a white woman and is therefore hesitant to become one of them thereby confirming the stereotype. Fanon goes on to explore the psychodynamics of Venuese´s personality type – the negative-aggressive abandonment-neurotic, and what role his personality type has in his romantic interactions. The negative-aggressive abandonment-neurotic displays a “fear of showing oneself as one actually is” resulting from a doubt that one can be loved as one is, as they had experiences of abandonment in childhood. Towards the end of the chapter, Fanon emphasizes the lack of generalizability for the findings on Jean Veneuse to the experiences of all black men in France, as the course of his development to a great extent is also part of his personality type. As Fanon writes “… we would like to think that we have discouraged any attempt to connect the failure of Jean Veneuse to the amount of melanin in his epidermis.” |

「有色の男と白人の女」 『黒 い肌、白い仮面』の第3章は「有色人種の男と白い女」と題されている。まず、アンティル諸島に到着したときに、白人女性と寝るという一つの目標を持ったア ンティル諸島の男性の話をする。黒人にとって、自分の価値が白人と同じであることを証明したいという無意識の欲求は、白人女性との性的交流によって満たさ れる。続いてファノンは、ルネ・マランが書いた自伝的作品とされる『ジャン・ヴェヌーズ』の物語を分析する。ジャン・ヴェヌーズはブルドーに住むアンティ ル諸島出身の黒人男性である。彼は社会的、文化的エリートの一員であり、白人女性と恋に落ちる。彼は、黒人は白人女性と寝たがるというステレオタイプに気 づいており、そのため黒人の仲間になることをためらい、ステレオタイプを確認する。ファノンはさらに、ヴェヌースの性格タイプ(否定的-攻撃的放棄-神経 症)の心理力学を探求し、彼の性格タイプが恋愛関係においてどのような役割を果たすかを考察する。否定的攻撃的放棄神経症の人は、幼少期に見捨てられた経 験があるため、ありのままの自分を愛せるのかという疑念から、「ありのままの自分を見せることへの恐れ」を示す。この章の終わりでファノンは、ジャン・ ヴェヌーズに関する発見が、フランスにおけるすべての黒人男性の経験に一般化できるわけではないことを強調している。ファノンが書いているように、 「......我々は、ジャン・ヴェヌーズの失敗を表皮のメラニンの量と結びつけるいかなる試みも思いとどまらせたと思いたい」。 |

| "The So-Called Dependency

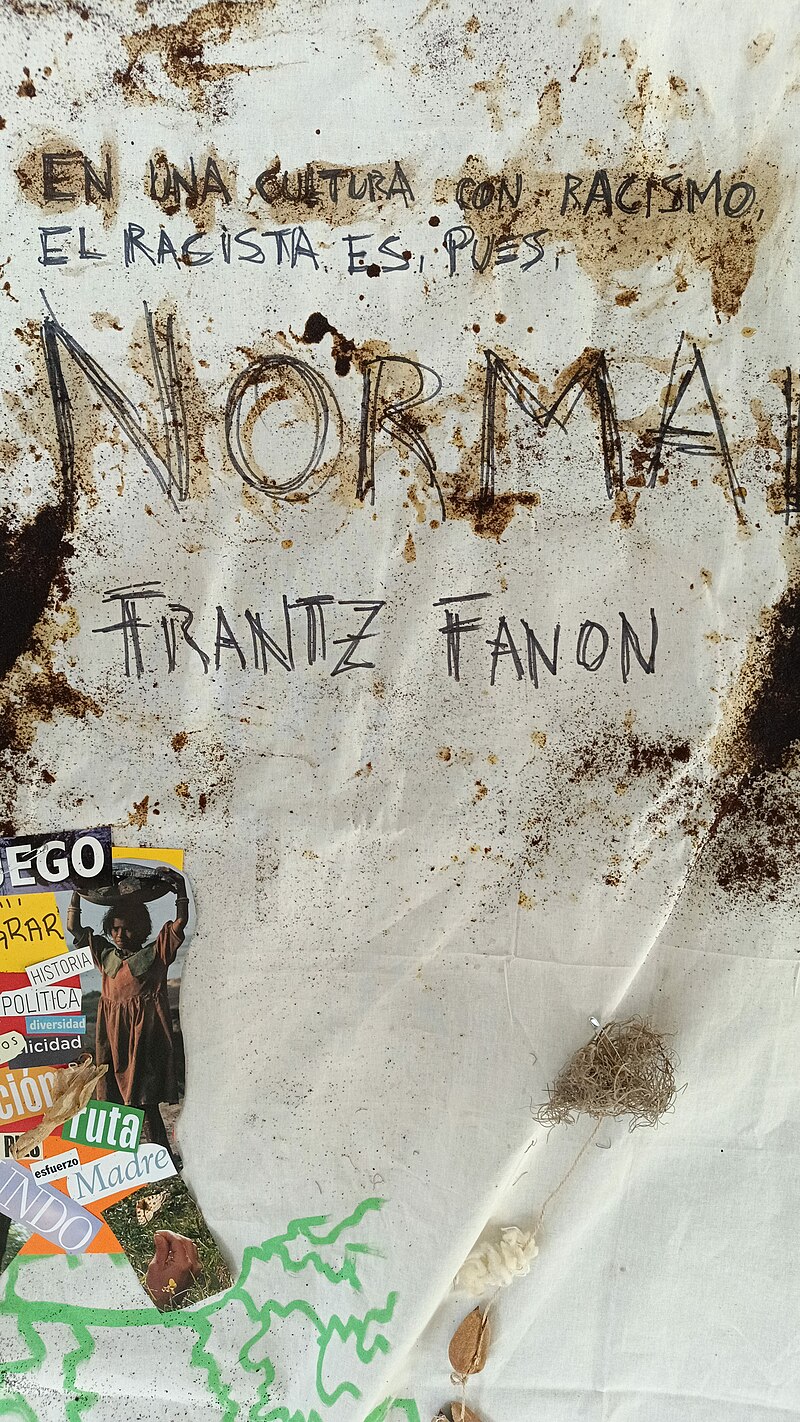

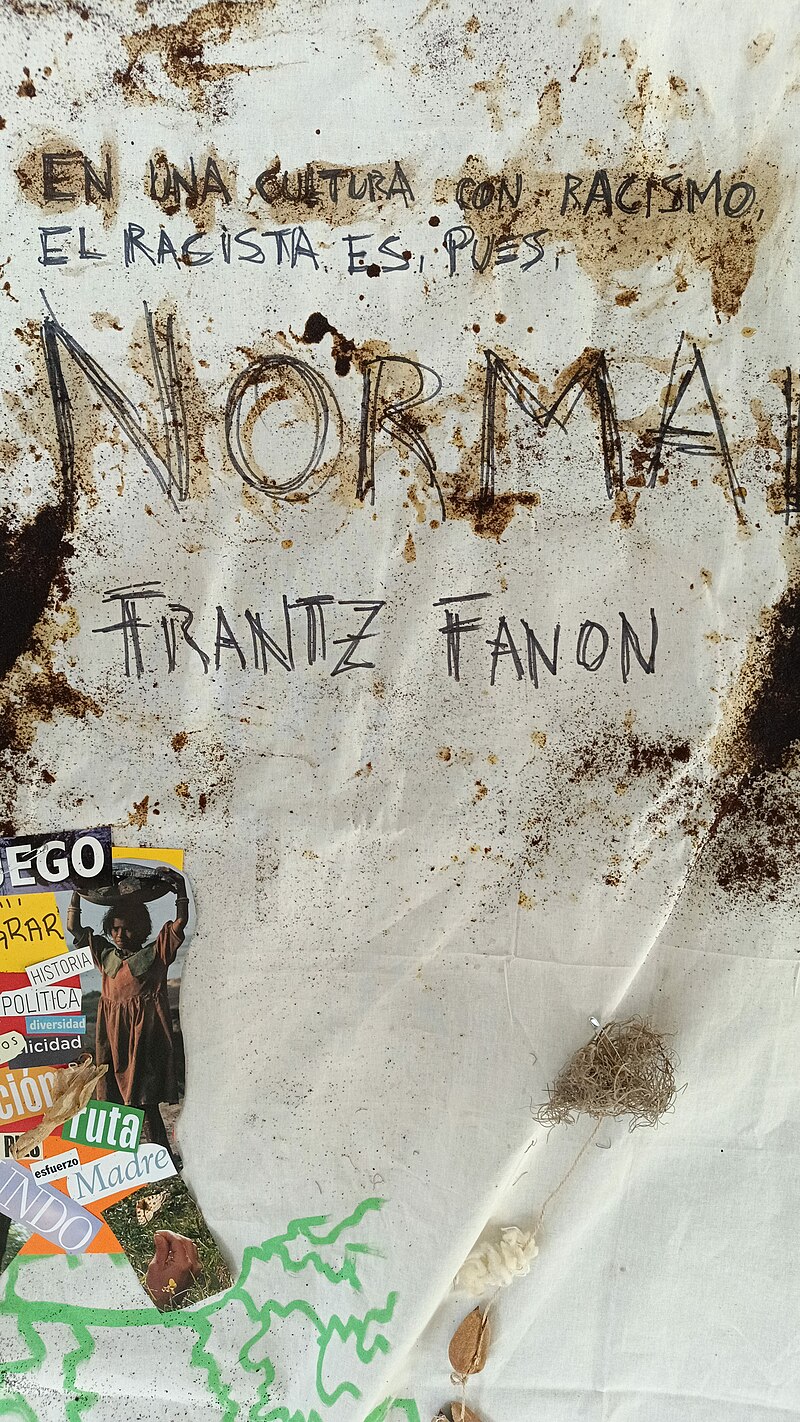

Complex of the Colonized" Chapter 4 of Black Skin, White Masks is entitled “The So-Called Dependency Complex of the Colonized”.[39] The chapter envelopes Fanon´s critique of Octave Mannoni's book “Prospero and Caliban: The Psychology of Colonization”. Mannoni launches a theory that the colonized Malagasies suffer from an inferiority complex which further leads to a dependency complex. Fanon criticizes the implication that this inferiority complex is innate in the colonized, and argues for the effect of human attitudes. He sees this complex as an effect of interactions in the colony: “The feelings of inferiority in the colonized are correlative to the feelings of superiority in the European… Let´s have the courage to say it upright. It is the racist who creates his inferior”, he writes. Mannoni is further criticized for not considering the Malagasies´ agency and ability to choose action for their own independence. |

「被

植民者のいわゆる依存コンプレックス」 『黒い肌、白い仮面』の第4 章は「被植民者のいわゆる依存コンプレックス」と題されている: 植民地化の心理学』である。マンノニ(マノーニ)は、植民地化されたマラガ人は劣等コンプレックスに苦しみ、それがさらに依存コンプレックスにつながると いう説を展開している。ファノンは、この劣等コンプレックスが植民地化された人々に生まれつき備わっているという含意を批判し、人間の態度の影響を主張す る。彼はこのコンプレックスを植民地での相互作用の影響と見ている: 「被植民者の劣等感は、ヨーロッパ人の優越感と相関している。劣等感を作り出しているのは人種差別主義者なのだ」と書いている。マンノーニはさらに、マラ ガ人の主体性や自立のための行動を選択する能力を考慮していないと批判している。 |

| "The Fact of Blackness" Chapter 5 of Black Skin, White Masks is entitled "The Fact of Blackness".[39] In this chapter, Fanon tackles many theories. One theory he addresses is the different schemas that are said to exist within a person, and how they exist differently for Black people. He talks about one's "bodily schema" (83), and theorizes that because of both the "historical-racial schema" (84),-- one that exists because of the history of racism and makes it so there is no one bodily-schema because of the context that comes with Blackness—and one's "epidermal-racial schema" (84), -- where Black people cannot be seen for their single bodily-schema because they are seen to represent their race and the history and therefore cannot be seen past their flesh—there is no universal Black schema. He describes this experience as "no longer a question of being aware of my body in the third person but in a triple person." Fanon concludes this theorizing by saying: "As long as the black man is among his own, he will have no occasion, except in minor internal conflicts, to experience his being through others." Fanon also addresses Ontology, stating that it "—does not permit us to understand the being of the black man" (82). He says that because Blackness was created in, and continues to exist in, negation to whiteness, that ontology is not a philosophy that can be used to understand the Black experience. Fanon states that this ontology can't be used to understand the Black experience because it ignores the "lived experience". He argues that a black man has to be black, while also being black in relation to the white man. (90) |

「ブラックネスの事実」 『黒 い肌、白い仮面』の第5章のタイトルは「黒さの事実」である。彼が取り上げた理論の一つは、人の中に存在すると言われるさまざまなスキーマであり、それが 黒人にとってどのように異なる存在であるかということである。彼は人の「身体的スキーマ」(83)について語り、「歴史的-人種的スキーマ」(84)-- 人種差別の歴史のために存在し、黒人に付随する文脈のために一つの身体的スキーマが存在しないようにするもの--と人の「表皮的-人種的スキーマ」 (84)--の両方があるためだと理論化している、 -- 黒人はその人種と歴史を象徴していると見なされるため、その単一の身体的スキーマを見ることができず、その肉体を超えて見ることはできない。彼はこの経験 を、「もはや自分の身体を三人称で意識するのではなく、三人称で意識することが問題なのだ」と表現している。ファノンはこの理論化をこう結んでいる: 「黒人が自分自身の中にいる限り、些細な内的葛藤を除いて、他者を通して自分の存在を経験する機会はない。 ファノンはまた、存在論を取り上げ、「黒人の存在を理解することはでき ない」(82)と述べている。黒人は白人性に対して否定される中で生まれ、否定される中で存在し続けているのだから、存在論は黒人の経験を理解するために 使える哲学ではないと言うのである。ファノンは、この存在論は「生きた経験」を無視しているため、黒人の経験を理解するためには使えないと述べる。彼は、 黒人は黒人であると同時に、白人との関係においても黒人でなければならないと主張する。 |

| "The Negro and Psychopathology" Chapter 6 of Black Skin, White Masks is entitled "The Negro and Psychopathology".[39] In this chapter, Fanon discussed how being Black can and does affect one's psyche. He makes it clear that the treatment of Black people causes emotional trauma. Fanon argues that as a result of one's skin color being Black, Black people are unable to truly process this trauma or "make it unconscious" (466). Black people are unable to not think about the fact that they are Black and all of the historical and current stigma that come with that. Fanon's work in this chapter specifically shows the short-comings of major names in psychology such as Sigmund Freud. However, Fanon repeatedly mentions the importance of Jacques Lacan's theory of language.[40] Fanon discusses the mental health of Black people to show that "traditional" psychology was created and founded without thinking about Black people and their experiences. Although Fanon wrote Black Skin, White Masks while still in France, most of his work was written in North Africa. It was during this time that he produced works such as L'An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne in 1959 (Year Five of the Algerian Revolution), later republished as Sociology of a Revolution and later still as A Dying Colonialism. Fanon's original title was "Reality of a Nation"; however the publisher, François Maspero, refused to accept this title. Fanon is best known for the classic analysis of colonialism and decolonization, The Wretched of the Earth.[41] The Wretched of the Earth was first published in 1961 by Éditions Maspero, with a preface by Jean-Paul Sartre.[42] In it Fanon analyzes the role of class, race, national culture and violence in the struggle for national liberation. The book includes an article which focuses on the ideas of violence and decolonization. He claims that decolonization is inherently a violent process, because the relationship between the settler and the native is a binary of opposites. In fact, he uses the Biblical metaphor, "The last shall be first, and the first, last", to describe the moment of decolonization. The situation of settler colonialism creates within the native a tension which grows over time and in many ways is fostered by the settler. This tension is initially released among the natives, but eventually it becomes a catalyst for violence against the settler. His work would become an academic and theoretical foundation for many revolutions.[43] Fanon uses the Jewish people to explain how the prejudice expressed towards blacks can not be generalized to other races or ethnicities. He discusses this in Black Skin, White Masks, and pulls from Jean-Paul Sartre's Reflections on the Jewish Question to inform his understanding of French colonialism's relationship with the Jewish people and how it can be compared and contrasted with the oppressions of Blacks across the world. In his seminal book, Fanon issues many rebuttals to Octave Mannoni's Prospero and Caliban: The Psychology of Colonization. Mannoni asserts that "colonial exploitation is not the same as other forms of exploitation, and colonial racialism is different from other kinds of racialism." Fanon responds by arguing that racism or anti-Semitism, colonial or otherwise, are not different because they rip away a person's ability to feel human. He says: "I am deprived of the possibility of being a man. I cannot disassociate myself from the future that is proposed for my brother. Every one of my acts commits me as a man. Every one of my silences, every one of my cowardices reveals me as a man." In this same vein, Fanon echoes the philosophies of Maryse Choisy, who believed that remaining neutral in times of great injustice implied unforgivable complicity. Specifically, Fanon mentions the ravages of racism and anti-Semitism because he believes that those who are one are necessarily the other as well. Yet he is careful to distinguish between the causes of the two. Fanon argues that the reasons for hating "The Jew" are born from a different fear than those for hating Blacks. Bigots are scared of Jews because they are threatened by what the Jew represents. The many tropes and stereotypes of Jewish cruelty, laziness, and cunning are the antithesis of the Western work ethic. The Black man is feared for perhaps similar traits, but the impetus is different. Essentially, "The Jew" is simply an idea, but Blacks are feared for their physical attributes. Jewishness is not easily detectable to the naked eye, but race is.[44] Both books established Fanon in the eyes of much of the Third World as the leading anti-colonial thinker of the 20th century. Fanon's three books were supplemented by numerous psychiatry articles as well as radical critiques of French colonialism in journals such as Esprit and El Moudjahid. The reception of his work has been affected by English translations which are recognized to contain numerous omissions and errors, while his unpublished work, including his doctoral thesis, has received little attention. As a result, it has been argued Fanon has often been portrayed as an advocate of violence (it would be more accurate to characterize him as a dialectical opponent of nonviolence) and that his ideas have been extremely oversimplified. This reductionist vision of Fanon's work ignores the subtlety of his understanding of the colonial system. For example, the fifth chapter of Black Skin, White Masks translates, literally, as "The Lived Experience of the Black" ("L'expérience vécue du Noir"), but Markmann's translation is "The Fact of Blackness", which leaves out the massive influence of phenomenology on Fanon's early work.[45] |

「ニグロと精神病理学」 『黒 い肌、白い仮面』の第6章は「黒人と精神病理学」と題されている[39] 。彼は黒人の扱いが感情的なトラウマを引き起こすことを明らかにしている。ファノンは、肌の色が黒人であることの結果として、黒人はこのトラウマを真に処 理することができない、あるいは「無意識にする」ことができないと論じている(466)。黒人は、自分が黒人であるという事実と、それに伴う歴史的・現在 のスティグマについて考えないことができないのだ。この章におけるファノンの仕事は、ジークムント・フロイトのような心理学の主要人物の欠点を具体的に示 している。しかし、ファノンはジャック・ラカンの言語理論の重要性に繰り返し言及している。ファノンは黒人の精神衛生について論じ、「伝統的な」心理学が 黒人とその経験について考えることなく創造され、創設されたことを示す。 ファノンはフランス滞在中に『黒い肌、白い仮面』を執筆したが、作品の大半は北アフリカで書かれた。1959年の『アルジェリア革命の5年目』(L'An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne)、後に『革命の社会学』(Sociology of a Revolution)、さらに後に『滅びゆく植民地主義』(A Dying Colonialism)として再出版された『アルジェリア革命の5年目』(L'An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne)などはこの時期の作品である。ファノンの原題は "Reality of a Nation "であったが、出版社のフランソワ・マスペロはこのタイトルを拒否した。 ファノンは植民地主義と脱植民地化に関する古典的な分析書『大地に呪われたること/人』(The Wretched of the Earth)で最もよく知られている[41]。『大地に呪われた人』はジャン=ポール・サルトルの序文付きで1961年にマスペロ出版社から刊行された。 この本には、暴力と脱植民地化の考え方に焦点を当てた論文が含まれている。彼は、入 植者と先住民の関係は対立の二項対立であるため、脱植民地化は本質的に 暴力的なプロセスであると主張する。実際、彼は聖書の比喩「最後の者が最初になり、最初の者が最後になる」を使って、脱植民地化の瞬間を表 現している。入 植者の植民地主義という状況は、先住民の中に緊張を生み、それは時とともに高まり、多くの点で入植者によって助長される。この緊張は、最初は先住民の間で 解放されるが、やがて入植者に対する暴力のきっかけとなる。彼の研究は、多くの革命の学問的・理論的基礎となった[43]。 ファノンはユダヤ人を使って、黒人に対する偏見が他の人種や民族に一般化できないことを説明している。彼は『黒い肌、白い仮面』の中でこのことを論じ、 ジャン=ポール・サルトルの『ユダヤ人問題についての考察』から、フランスの植民地主義とユダヤ人との関係、そしてそれが世界中の黒人に対する抑圧とどの ように比較対照されうるかについて理解を深めている。その代表的な著書の中で、ファノンはオクターヴ・マンノーニの『プロスペロとカリバン』に対して多く の反論を展開している: 植民地化の心理学』である。マンノニは、"植民地搾取は他の形態の搾取と同じではなく、植民地人種主義は他の種類の人種主義とは異なる "と主張する。ファノンは、人種差別や反ユダヤ主義は、植民地であろうとなかろうと、人間が人間であると感じる能力を奪うものであり、異なるものではない と反論する。私は人間である可能性を奪われている。私は、兄のために提案された未来から自分を切り離すことはできない。私の行為のひとつひとつが、私を人 間として裁いている。私の沈黙のひとつひとつが、私の臆病さのひとつひとつが、私を人間として明らかにしているのだ」。この同じ流れの中で、ファノンは、 大きな不正義の時代に中立を保つことは許されざる加担を意味すると考えていたマリーズ・ショワジーの哲学に共鳴している。具体的には、ファノンは人種差別 と反ユダヤ主義の弊害について言及している。しかし、彼はこの2つの原因を区別することに注意を払っている。ファノンは、「ユダヤ人」を憎む理由は、黒人 を憎む理由とは異なる恐怖から生まれると主張する。偏屈者がユダヤ人を恐れるのは、ユダヤ人が象徴するものに脅かされているからである。ユダヤ人の残酷 さ、怠惰さ、狡猾さといった多くの典型やステレオタイプは、西洋の労働倫理に対するアンチテーゼである。黒人が恐れられているのは、おそらく似たような特 徴によるものだろうが、きっかけは異なる。基本的に、"ユダヤ人 "は単なる観念であるが、黒人はその身体的特徴によって恐れられている。ユダヤ人であることは肉眼では容易に見分けられないが、人種は見分けられる。 この2冊の著書によって、ファノンは20世紀を代表する反植民地思想家として、第三世界の多くの人々の目にその地位を確立した。 ファノンの3冊の著書は、『エスプリ』や『エル・ムジャヒド』といった雑誌に掲載された数多くの精神医学論文やフランスの植民地主義に対する急進的な批評 によって補完された。 その一方で、博士論文を含む未発表の著作はほとんど注目されていない。その結果、ファノンはしばしば暴力の擁護者として描かれ(非暴力の弁証法的反対者と いうのがより正確だろう)、彼の思想は極端に単純化されすぎていると論じられてきた。ファノンの著作に対するこのような還元主義的な見方は、植民地体制に 対する彼の理解の繊細さを無視している。例えば、『黒い肌、白い仮面』の第5章は、文字どおり「黒人の生きた経験」("L'expérience vécue du Noir")と訳されているが、マークマンの訳は「黒人の事実」であり、ファノンの初期の仕事に現象学が与えた多大な影響を省いている。 |

| Fanon and the Lived Experiences

of the Black Subject. In Frantz Fanon’s first book, Black Skin, White Masks, he tasks himself with exploring the experiences of the black subject. Fanon does not look at the lived experiences in the ordinary sense of the term, but rather considers a domain of experience that is rooted in the context of the world the experience takes place in.[46] The Lived experiences of the black person is the profound sense of feeling and living through the social conditions that define a particular time and place.[47] Fanon navigates the lived experiences of the black subject by drawing inspiration from psychoanalysis, literary texts, medical terminology, philosophy, negritude, and political consciousness.[46] Fanon placed emphasis on the concepts of Political Consciousness and Negritude in the navigation of the experiences of black subjects. Political Consciousness is the way in which one is crucially a part of the world and its conditions, and how one should attempt to change the world through carefully considered political projects.[46] Political consciousness thus includes a careful consideration of facticity. These include the concrete factors that define your situation in the world, such as the actual physical environment in which you live, the place and time of birth, class membership, nationality, gender, and race, which cannot be transcended.[47] Fanon used the concept of political consciousness to show that the field of psychological phenomena, and the experiences of the black individual, always deserve a political level of analysis.[46] Negritude is both the celebration of black culture and forms of expression, as well as a resistance to the politics of assimilation.[48][46] Fanon is aware that the colonised individual accepts art of their white -scripted history and in some ways actively participate in it.[48] However, he rejects the idea that human freedom and the capacity for resistance are extinguished in structurally oppressive social circumstances, such as those in which the colonized and enslaved people lived. Fanon recognises Negritudes positive reinvention of “blackness” as social reality, constructed by the oppressed for specific socio-political, emancipatory, and therapeutic aims.[48] In Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon echoes the concepts of Political Consciousness and Negritude by recounting the experiences of the colonised individual. The entirety of the book is a recounting of the lived experiences of a black subject. In the book Fanon places importance on the freedom and agency that the black subject maintains.[48] |

ファノンと黒人主体の生きた経験。 フランツ・ファノンの最初の著書『黒い肌、白い仮面』において、彼は黒人主体の経験を探求することを自らに課している。ファノンは普通の意味での生きた経 験を見るのではなく、その経験が起こる世界の文脈に根ざした経験の領域を考察している[46]。黒人の生きた経験とは、特定の時代と場所を規定する社会的 条件を通して感じ、生きることの深い感覚である。 [ファノンは精神分析、文学テクスト、医学用語、哲学、ネグリチュード、政治的意識からインスピレーションを得ることによって、黒人主体の生きた経験をナ ビゲートしている。 政治的意識とは、自分が世界とその状況の決定的に一部であり、注意深く考慮された政治的プロジェクトを通じて世界をどのように変えようとすべきかという方 法である。政治的意識はこのように、事実性を注意深く考慮することを含む。これらには、自分が住んでいる実際の物理的環境、生まれた場所と時間、階級への 所属、国籍、ジェンダー、人種といった、超越することのできない、世界における自分の状況を規定する具体的な要因が含まれる[47]。ファノンは政治的意 識という概念を用いて、心理現象の分野、黒人個人の経験が常に政治的なレベルの分析に値することを示した[46]。 ファノンは、植民地化された個人は、白人に規定された歴史の芸術を受け入れ、ある意味では積極的にそれに参加していることを認識している[48] [46]。しかし彼は、植民地化され奴隷化された人々が生きていたような構造的に抑圧的な社会状況において、人間の自由と抵抗の能力が消滅するという考え を否定している。ファノンは、特定の社会政治的、解放的、治療的な目的のために被抑圧者によって構築された社会的現実としての「黒人性」のネグリトゥード による肯定的な再発明を認めている[48]。 『黒い肌、白い仮面』の中でファノンは、植民地化された個人の経験を語ることで、政治的意識とネグリチュードの概念と呼応している。この本の全体が、黒人 主体の生きた経験の再現である。ファノンはこの本の中で、黒人主体が維持する自由と主体性を重要視している[48]。 |

| A Dying Colonialism A Dying Colonialism is a 1959 book by Fanon that provides an account of how, during the Algerian Revolution, the people of Algeria changed centuries-old cultural patterns and embraced certain ancient cultural practices long derided by their colonialist oppressors as “primitive,” in order to destroy those oppressors. Fanon uses the fifth year of the Algerian Revolution as a point of departure for an explication of the inevitable dynamics of colonial oppression. The militant book describes Fanon's understanding that for the colonized, “having a gun is the only chance you still have of giving a meaning to your death.”[49] It also contains one of his most influential articles, "Unveiled Algeria", that signifies the fall of imperialism and describes how oppressed people struggle to decolonize their "mind" to avoid assimilation. |

死にゆく植民地主義 『死 にゆく植民地主義』はファノンによる1959年の著作で、アルジェリア革命の間、アルジェリアの人々が、植民地主義による抑圧者を滅ぼすために、何世紀に もわたって続いてきた文化的パターンをどのように変化させ、植民地主義による抑圧者から長い間「原始的」と蔑まれてきたある古代の文化的慣習をどのように 受け入れたかを説明している。ファノンはアルジェリア革命の5年目を出発点として、植民地抑圧の必然的な力学を説明する。この戦闘的な本には、植民地化さ れた人々にとって「銃を持つことが、自分の死に意味を与える唯一の機会である」というファノンの理解が記されている。 |

| The Wretched of the Earth In The Wretched of the Earth (1961, Les damnés de la terre), published shortly before Fanon's death, Fanon defends the right of a colonized people to use violence to gain independence. In addition, he delineated the processes and forces leading to national independence or neocolonialism during the decolonization movement that engulfed much of the world after World War II. In defence of the use of violence by colonized peoples, Fanon argued that human beings who are not considered as such (by the colonizer) shall not be bound by principles that apply to humanity in their attitude towards the colonizer. His book was censored by the French government. For Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth, the colonizer's presence in Algeria is based on sheer military strength. Any resistance to this strength must also be of a violent nature because it is the only "language" the colonizer speaks. Thus, violent resistance is a necessity imposed by the colonists upon the colonized. The relevance of language and the reformation of discourse pervades much of his work, which is why it is so interdisciplinary, spanning psychiatric concerns to encompass politics, sociology, anthropology, linguistics and literature.[50] His participation in the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale from 1955 determined his audience as the Algerian colonized. It was to them that his final work, Les damnés de la terre (translated into English by Constance Farrington as The Wretched of the Earth) was directed. It constitutes a warning to the oppressed of the dangers they face in the whirlwind of decolonization and the transition to a neo-colonialist, globalized world.[51] An often overlooked aspect of Fanon's work is that he did not like to physically write his pieces. Instead, he would dictate to his wife, Josie, who did all of the writing and, in some cases, contributed and edited.[38] |

地に呪われたる者 ファノンが亡くなる直前に出版された『地に呪われたる者』(1961年、Les damnés de la terre)の中で、ファノンは植民地化された人々が独立を勝ち取るために暴力を行使する権利を擁護している。さらに、第二次世界大戦後、世界の大半を巻 き込んだ脱植民地化運動において、国家の独立や新植民地主義に至る過程と力を明らかにした。植民地化された人々による暴力の行使を擁護するために、ファノ ンは、(植民地化した側から)そのようにみなされていない人間は、植民地化した側に対する態度において、人類に適用される原則に拘束されることはないと主 張した。彼の著書はフランス政府によって検閲された。 地に呪われたる者』におけるファノンにとって、アルジェリアにおける植民者の存在は、圧倒的な軍事力に基づいている。この力に対する抵抗もまた暴力的なも のでなければならない。なぜなら、それが植民者が話す唯一の「言語」だからである。したがって、暴力的な抵抗は、植民地主義者が被植民者に課す必然なので ある。言語と言説の改革との関連性は、彼の作品の多くを貫いており、それゆえ彼の作品は、政治学、社会学、人類学、言語学、文学など、精神医学的な関心に またがる学際的なものとなっている[43]。 1955年からアルジェリアの国民解放戦線に参加したことで、彼の読者はアルジェリアの被植民者となった。彼の最後の作品である『Les damnés de la terre』(コンスタンス・ファリントンが英訳した『The Wretched of the Earth』)は、彼らに向けて書かれた。この作品は、被抑圧者が脱植民地化の渦中で直面する危険と、新植民地主義的でグローバル化された世界への移行に 対する警告である[44]。 ファノンの作品で見落とされがちな点は、彼が物理的に作品を書くことを好まなかったことである。その代わりに、彼は妻のジョジーに口述筆記をさせ、ジョ ジーはすべての執筆を行い、場合によっては寄稿や編集も行った[37]。 |

| Fanon, Violence and Apartheid In the first chapter of Fanon's book, The Wretched of the Earth he writes about violence and how this is a tool to fight against colonisation. Fanon expresses in this chapter that freedom can not be achieved if violence is not a part of the process. Fanon made this claim by arguing that the nature of colonisation was violent, in the way that black individuals were stripped of their land and treated as lesser people, so the retaliation for achieving freedom needed to be violent.[52] Fanon argued that for colonisers to expect the colonised to achieve freedom through peaceful means was a double standard. Fanon continued to argue that there were two types of violence in a colonial setting. One, he claimed, was the violence that the colonisers had used and the counter-violence which was used by the colonised.[52] Drawing reference to the Apartheid era in South Africa, this bookmark in history will be used as an example to express the thinking of Fanon. Apartheid was legislation put in place by the white minority in South Africa to oppress the black majority of South Africa. The legislation was used to implement racial segregation between whites and non-whites. This practice was done through the group areas act of 1950, which eventually, along with two other acts, was known as the land acts. The land acts led to people of colour being removed from specific areas that were now considered white occupations. The acts were used to set aside 80% of the land in South Africa for the white minority.[53] The fight against apartheid is often resembled by one major party, the ANC. During this period, many protests were organised in order to fight against the apartheid laws; however, many of these protests were met with violent retaliation from the South African police.[53] One of the most remembered protests was the Sharpeville massacre. The Sharpeville massacre was an organised protest in retaliation to the pass law, which stated that individuals of colour were required to carry a pass in South Africa. The protest led to a total of 249 victims who were attacked by the police. Sixty-nine people of colour were killed, while 180 were injured during this protest.[54] With protests making no progress in combating apartheid, the ANC had concluded that another method would be violence and terrorist acts, which led to the ANC forming their militant group. In 1961 the Umkhonto we Sizwe military group was formed. The head of the group was Nelson Mandela. The first acts of violence were intended to be non-lethal, as bombings occurred in buildings related to the apartheid legislation but were empty at the time of the bombings. Later the MK group continued to commit more acts of violence to combat apartheid.[55] The estimate states that the incident rate of violent attacks ranged from 23 incidents in 1977 to an estimated 136 incidents in 1985. During the latter half of the 1980s, the group continued to commit acts of violence in which South African citizens were killed. Fatal attacks include the church street boming of 1983, the Amanzimtoti bombing of 1985, the Magoo's Bar bombing of 1986 and the Johannesburg Magistrate Court boming of 1987.[56] These acts of violence contrast significantly with the earlier point, which states that the ANC were reluctant to use violence in the fight against apartheid. The acts of violence also led to the ANC being branded a terrorist group by the Government.[57] Apartheid is mentioned in this piece on Fanon because it incorporates Fanon's philosophy on violence, showing that to break colonisation, it must be met with violence due to the nature of the oppression. Apartheid is a clear example of this as the ANC, whose initial methods were to steer away from violence; however, this had not shown any results. Instead, their non-violent protests were met with mass shootings by the South African police force. The mass shootings and killing of people of colour led to the ANC and their turn to violence to fight against apartheid and break the cycle of oppression and colonisation. |

ファノン、暴力と人種隔離 ファノンの著書『The Wretched of the Earth(地に呪われたる者)』の第1章で、彼は暴力について、そして暴力がいかに植民地化に対抗する手段であるかについて書いている。ファノンはこの 章で、 暴力がプロセスの一部でなければ自由は達成できないと表現している。ファノンは、植民地化の本質が暴力的であり、黒人が土地を剥奪され、劣った人間として 扱われたことから、自由を達成するための報復は暴力的である必要があると主張した。ファノンは続けて、植民地には2種類の暴力が存在すると主張した。ひと つは、植民地支配者が行使した暴力であり、もうひとつは、被植民者が行使した反暴力であると主張した[52]。南アフリカにおけるアパルトヘイトの時代を 引き合いに出しながら、この歴史のしおりを例として、ファノンの考え方を表現する。 アパルトヘイトとは、南アフリカの少数派である白人が、南アフリカの多数派である黒人を抑圧するために導入した法律である。この法律は、白人と非白人の間 の人種隔離を実施するために使われた。この慣行は1950年の集団地域法によって行われ、最終的には他の2つの法律とともに土地法として知られるように なった。土地法によって、有色人種は白人の職業とされた特定の地域から排除されることになった。この法律は、南アフリカの土地の80%を少数派の白人のた めに確保するために使用された。この時期、アパルトヘイト法に反対するために多くの抗議活動が組織されたが、これらの抗議活動の多くは南アフリカ警察から の暴力的な報復を受けた。シャープヴィルの虐殺は、有色人種は南アフリカで通行証を携帯する必要があるという通行証法に対する報復として組織された抗議活 動であった。この抗議行動により、警察に襲撃された犠牲者は合計249人に上った。抗議活動がアパルトヘイトとの闘いに何の進展ももたらさない中、ANC は別の方法として暴力とテロ行為が必要であると結論づけ、ANCは武装集団を結成するに至った。 1961年、軍事グループ「ウムホント・ウィ・シズウェ」が結成された。グループのリーダーはネルソン・マンデラだった。最初の暴力行為は、アパルトヘイ ト法制に関連する建物で爆弾テロが起きたが、爆弾テロの時点では誰もいなかったため、非殺傷的なものであることを意図したものであった。その後、MKグ ループはアパルトヘイトと闘うためにより多くの暴力行為を続けた[55]。推定によれば、暴力攻撃の発生率は1977年の23件から1985年の推定 136件に及んだ。1980年代後半、グループは南アフリカ市民が殺害される暴力行為を続けた。これらの暴力行為は、アパルトヘイトとの闘いにおいて ANCが暴力の行使に消極的であったとする先の指摘とは大きく対照的である。暴力行為は、ANCが政府によってテロリスト集団の烙印を押されることにもつ ながった[57]。 アパルトヘイトがファノンを扱ったこの作品で言及されるのは、ファノンの暴力哲学が盛り込まれているからであり、植民地化を断ち切るには、抑圧の性質上、 暴力で対抗しなければならないことを示している。アパルトヘイトがその明確な例であり、ANCは当初、暴力から遠ざかる方法をとっていた。それどころか、 彼らの非暴力的な抗議活動は、南アフリカ警察による大量射殺に見舞われた。有色人種が大量に射殺されたことで、ANCはアパルトヘイトと闘い、抑圧と植民 地化の連鎖を断ち切るために暴力に転じた。 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frantz_Fanon |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frantz_Fanon

|

| Frantz Fanon,

né le 20 juillet 1925 à Fort-de-France (Martinique) et mort le 6

décembre 1961 à Bethesda dans un hôpital militaire de la banlieue de

Washington aux États-Unis1, est un psychiatre et essayiste de

nationalité française se considérant comme citoyen algérien2, fortement

impliqué dans la lutte pour l'indépendance de l'Algérie et dans un

combat international dressant une solidarité entre « frères » opprimés. Il est l'un des fondateurs du courant de pensée tiers-mondiste, et une figure majeure de l'anticolonialisme. Il a inspiré les études postcoloniales. Il cherche à analyser les conséquences psychologiques de la colonisation à la fois sur le colon et sur le colonisé. Dans ses livres les plus connus comme Les Damnés de la Terre, il analyse le processus de décolonisation sous les angles sociologique, philosophique et psychiatrique. |

1925年7月20日にフォール・ド・フランス(マルティニーク)で生

まれ、1961年12月6日に米国ワシントン郊外の軍病院のベセスダで死去したフランツ・ファノンは、フランスの精神科医、エッセイストであり、自らをア

ルジェリア市民2であると考え、アルジェリア独立の闘いと、抑圧された「兄弟」の連帯を求める国際的な闘いに深く関わった。 彼は第三世界主義思想の創始者の一人であり、反植民地主義における重要人物である。ポストコロニアル研究に影響を与えた。植民地化が被植民者と植民地主義 者の双方に及ぼす心理的影響を分析しようとした。Les Damnés de la Terre』などの代表的な著作では、脱植民地化のプロセスを社会学的、哲学的、精神医学的な角度から分析している。 |

| Biographie Période française Frantz Fanon, né à Fort-de-France en Martinique, est le cinquième enfant d’une famille métissée (afro-caribéenne) de huit enfants. Il reçoit son instruction au lycée Victor-Schœlcher de Fort-de-France, où Aimé Césaire enseigne à l’époque3. En 1943, il s'engage dans l'Armée française de la Libération après le ralliement des Antilles françaises au général de Gaulle. Il explique ce choix par le fait que « chaque fois que la liberté et la dignité de l’homme sont en question, nous sommes tous concernés, Blancs, Noirs ou Jaunes ». Combattant sous les ordres du général de Lattre de Tassigny, il est blessé dans les Vosges. Parti se battre pour un idéal, il est confronté à « la discrimination ethnique, à des nationalismes au petit pied »4. Toujours membre de l'armée française, il est ensuite envoyé quelques semaines en Algérie, qui sont pour lui l'occasion d'observer la structure de la société coloniale qu'il conçoit comme « pyramidale » (colons riches, petits-blancs, juifs, indigènes évolués, masse du peuple) et intrinsèquement raciste5. De retour en Martinique, il passe le baccalauréat et s'engage avec son frère Joby dans le soutien à la candidature d'Aimé Césaire qui se présente aux élections législatives d'octobre 1945 pour le Parti communiste français. Ayant reçu une citation par le général Salan, il obtient une bourse d'enseignement supérieur au titre d'ancien combattant, ce qui lui permet de faire des études de médecine en France métropolitaine, tout en suivant des leçons de philosophie et de psychologie à l'université de Lyon, notamment celles de Maurice Merleau-Ponty6. Sur le plan politique, il dirige le journal étudiant Tam-Tam et participe à différentes mobilisations anticolonialistes avec les Jeunesses communistes, dont il n'est cependant pas membre5. Fanon soutient sa thèse en psychiatrie à Lyon en 19517. Il part faire son apprentissage à l'hôpital de Saint-Alban, à Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole en Lozère, pendant quinze mois. C'est là qu'il rencontre le psychiatre François Tosquelles au printemps 19528. « Cette formation est déterminante tant sur le plan de la psychiatrie que sur celui de ses futurs engagements politiques. Aux côtés de Tosquelles, il interroge l’aliénation dans tous ses registres, haut-lieu de rencontre entre physiologique et historique »9. Ses études en psychiatrie lui sont très utiles car elles lui permettent de soutenir ses idées et les causes de celles-ci. Grâce à ses études et ses rencontres, il va commencer à construire la défense de ses futures idées et thèses. En effet, Fanon explique certains problèmes psychologiques des minorités et des colonisés par l'étude de cas des victimes du colonialisme. Fanon et son équipe insistent sur la nécessité d’analyser les traumatismes coloniaux passés, pour expliquer l’état psychologique, émotionnel et physique des générations à ce jour10. Ils examinent l’histoire des opprimés et étudient les aspects psychologiques pour pouvoir démontrer les liens qui y sont associés aux générations d’aujourd’hui. Fanon affirme que plusieurs troubles à ce jour sont les résultats des traumatismes coloniaux d’autrefois. Dans ces études, se trouve la « justification » des troubles mentaux, physiques et sexuels qui seraient causés par la violence coloniale. Ce sont des études très détaillées qui tiennent à défendre le fait qu’étudier l’état psychologique, émotionnel et sexuel des opprimés d’autrefois, prouverait les traces qui ont été gardées sur les libres d’aujourd’hui[réf. nécessaire]. À partir de son expérience de noir minoritaire au sein de la société française et de ses observations en Algérie, il rédige Peau noire, masques blancs, dénonciation du racisme et de la « colonisation linguistique » dont il s'estime lui-même une des victimes en Martinique. Ce livre est mal perçu à sa publication en 1952[réf. nécessaire]. Frantz Fanon évoquera à de multiples reprises le racisme dont il se sent victime dans les milieux intellectuels parisiens, affirmant ainsi que « le Sud américain est pour le nègre un doux pays à côté des cafés de Saint-Germain »11. |

バイオグラフィー フランス時代 フランツ・ファノンはマルティニークのフォール・ド・フランスで、8人家族の混血(アフロ・カリビアン)家族の5番目の子供として生まれた。当時エメ・セ ゼールが教鞭をとっていたフォール・ド・フランスのリセ・ヴィクトル・シュルシュで教育を受ける3。 1943年、フランス領西インド諸島がド・ゴール将軍に結集した後、彼はフランス解放軍に入隊した。彼はこの選択について、「人間の自由と尊厳が危機に瀕 しているときはいつでも、白人であろうと黒人であろうと黄色人種であろうと、われわれはみな関係者なのだ」と説明している。ド・ラトル・ド・タッシニー将 軍の下で戦った彼は、ヴォージュで負傷した。理想のために戦いに出かけた彼は、「民族差別と卑小なナショナリズム」に直面した4。植民地社会の構造は「ピ ラミッド型」(富裕な入植者、小白人、ユダヤ人、上級原住民、大衆)であり、本質的に人種差別的であると彼は考えた5。 マルティニークに戻った彼は、バカロレアに合格し、兄のジョビーとともに、1945年10月の議会選挙でエメ・セゼールのフランス共産党への立候補を支援 するようになる。サラン将軍から表彰を受けた彼は、退役軍人として高等教育補助金を授与され、フランス本土で医学を学ぶ一方、リヨン大学で哲学と心理学、 特にモーリス・メルロ=ポンティの教えを受けた6。政治的には、学生新聞『Tam-Tam』を編集し、メンバーではなかったが、ジュネス・コミュニストと ともにさまざまな反植民地主義的動員に参加した5。 ファノンは1951年にリヨンで精神医学の論文を発表した17。彼はロゼール地方のサン・アルバン・シュル・リマニョールにあるサン・アルバン病院で 15ヵ月間修業することになった。1928年春、そこで精神科医フランソワ・トスケルに出会った。「この研修は、精神医学の面でも、彼の将来の政治的コ ミットメントの面でも決定的なものとなった。トスケレスとともに働きながら、彼は生理学と歴史学が出会う疎外のあらゆる側面を探求した」9。 精神医学の勉強は、彼の思想とその背景にある大義を支えることができ、彼にとって非常に有益であった。研究と出会いのおかげで、ファノンは自分の将来の思 想や論文を守るための土台を築き始めたのである。ファノンは、植民地主義の犠牲者の事例を研究することで、少数民族や被植民者のある種の心理的問題を説明 した。ファノンと彼のチームは、今日までの世代の心理的、感情的、身体的状態を説明するために、過去の植民地時代のトラウマを分析する必要性を主張した 10。 彼らは、抑圧された人々の歴史を検証し、心理的側面を研究することで、今日の世代におけるその関連性を示すことができる。ファノンは、今日の障害の多くは 過去の植民地時代のトラウマの結果であると主張している。これらの研究は、植民地時代の暴力によって引き起こされたとされる精神的、身体的、性的障害を 「正当化」するものである。これらは非常に詳細な研究であり、かつての抑圧された人々の心理的、感情的、性的状態を研究することが、今日の自由な人々に残 された痕跡を証明することになるという事実を擁護しようと躍起になっている[要参照]。 フランス社会における黒人マイノリティとしての経験とアルジェリアでの観察に基づき、マルティニークで自身が被害者であると考えた人種差別と「言語的植民 地化」を糾弾する『黒い肌、白い仮面』を執筆した。この本は1952年に出版されたが、酷評された[要参照]。フランツ・ファノンは、パリの知識人サーク ルにおいて、自身が被害者であると感じていた人種差別についてしばしば言及し、「黒人にとって、アメリカ南部はサンジェルマンのカフェの隣にある優しい国 である」と述べている11。 |

| Période algérienne Analyse des effets de la colonisation  Fanon et son équipe médicale à l'hôpital psychiatrique de Blida-Joinville. En 1953, il devient médecin-chef d'une division de l'hôpital psychiatrique de Blida-Joinville en Algérie et y introduit des méthodes modernes de « sociothérapie » ou « psychothérapie institutionnelle », qu'il adapte à la culture des patients musulmans algériens ; ce travail sera explicité dans la thèse de son élève, le futur psychiatre et psychanalyste Jacques Azoulay. Il entreprend ensuite, avec ses internes, une exploration des mythes et rites traditionnels de la culture algérienne. Sa volonté de désaliénation et de décolonisation du milieu psychiatrique algérien s'oppose de front aux thèses racistes de l'École algérienne de psychiatrie d'Antoine Porot : « Hâbleur, menteur, voleur et fainéant, le Nord-Africain musulman se définit comme un débile hystérique, sujet, de surcroît, à des impulsions homicides imprévisibles »12. « L’indigène nord-africain, dont le cortex cérébral est peu évolué, est un être primitif dont la vie essentiellement végétative et instinctive est surtout réglée par le diencéphale »13. « L’Algérien n’a pas de cortex, ou, pour être plus précis, il est dominé, comme chez les vertébrés inférieurs, par l’activité du diencéphale »14,15. Pour Fanon, c'est bien plutôt la colonisation qui entraîne une dépersonnalisation, qui fait de l'homme colonisé un être « infantilisé, opprimé, rejeté, déshumanisé, acculturé, aliéné », propre à être pris en charge par l'autorité colonisatrice15. « La première chose que l’indigène apprend, c’est à rester à sa place, à ne pas dépasser les limites ; c’est pourquoi les rêves de l’indigène sont des rêves musculaires, des rêves d’action, des rêves agressifs. Je rêve que je saute, que je nage, que je cours, que je grimpe. Je rêve que j'éclate de rire, que je franchis le fleuve d’une enjambée, que je suis poursuivi par une meute de voitures qui ne me rattrapent jamais. Pendant la colonisation, le colonisé n'arrête pas de se libérer entre neuf heures du soir et six heures du matin. Cette agressivité sédimentée dans ses muscles, le colonisé va d'abord la manifester contre les siens. C'est la période où les nègres se bouffent entre eux et où les policiers, les juges d’instruction ne savent plus où donner de la tête devant l’étonnante criminalité nord-africaine16. » Aux côtés du Front de libération nationale Dès le début de la guerre d'Algérie, en 1954, il s'engage auprès de la résistance nationaliste et noue des contacts avec certains officiers de l'Armée de libération nationale ainsi qu'avec la direction politique du Front de libération nationale (FLN), Abane Ramdane et Benyoucef Benkhedda en particulier. Il remet au gouverneur Robert Lacoste sa démission de médecin-chef de l'hôpital de Blida-Joinville en novembre 1956 puis est expulsé d'Algérie en janvier 1957. Il décide de rompre avec sa nationalité française17 et se définit comme Algérien18. Il rejoint le FLN à Tunis, où il collabore à l'organe central de presse du FLN, El Moudjahid, comme spécialiste des problèmes de torture parce qu'il avait soigné plusieurs tortionnaires en tant que psychiatre à l'hôpital de Blida. En 1958, il se fait établir un vrai-faux passeport tunisien au nom d'Ibrahim Omar Fanon19. En 1959, il fait partie de la délégation algérienne au congrès panafricain d'Accra ; il publie la même année L'An V de la révolution algérienne publié par François Maspero. En mars 1960, il est nommé ambassadeur du Gouvernement provisoire de la République algérienne (GPRA) au Ghana. Il échappe durant cette période à plusieurs attentats au Maroc et en Italie. Il entame à la même époque l'étude du Coran, sans pour autant se convertir20. Très critique sur les dirigeants africains ralliés à la Communauté française (association entre la France et ses colonies), il s'interroge sur les causes de l'attitude des bourgeoisies nationales devant le système colonial. Selon lui, le colonialisme façonne au sein de la société indigène une classe de nature bourgeoise en raison de ses privilèges matériels mais qui n'aurait aucun rôle économique (pas de "capitaines d'industrie") et serait confinée à des activités de types intermédiaires. Elle se trouve dès lors uniquement dédiée à la défense des intérêts du colonialisme. Ainsi, au moment de concéder l’indépendance, les puissances coloniales transmettent le pouvoir à des bourgeoisies asservies qui prennent le rôle de « gérantes des entreprises de l'Occident ». Pour lui, la décolonisation ne serait effective dans ces pays que sur le plan culturel (retour aux anciennes traditions) alors que le colonialisme se maintiendrait sur le plan économique5. Il considère par ailleurs que l'indépendance nationale n'a de sens qu'en intégrant les questions sociales, qui déterminent ce qu'il nomme le « degré de réalité » de cette indépendance (accès au pain, à la terre, au pouvoir pour les classes populaires). Cette approche le conduit à associer l'indépendance au socialisme, qu'il définit comme un « régime tout entier tourné vers l'ensemble du peuple, basé sur le principe que l'homme est le bien le plus précieux ». Il milite également en faveur du panafricanisme. La rencontre avec Sartre Dès ses premiers écrits, Fanon ne cesse de se référer au philosophe Jean-Paul Sartre (notamment à Réflexions sur la question juive, Orphée noir, et L'Être et le Néant). À la publication de la Critique de la raison dialectique (1960), il se fait envoyer une copie de l'ouvrage et il parvient à le lire malgré son état de faiblesse provoqué par sa leucémie. Il fait même une conférence sur la Critique de la raison dialectique aux combattants algériens de l'Armée de libération nationale. C'est en 1960 qu'il demande à Claude Lanzmann et Marcel Péju, venus à Tunis pour parler au dirigeant du GPRA, de rencontrer le philosophe. Il veut également que Sartre préface son dernier ouvrage, Les Damnés de la Terre. Ainsi écrit-il à l'éditeur François Maspéro : « Demandez à Sartre de me préfacer. Dites-lui que chaque fois que je me mets à ma table, je pense à lui »21. La rencontre a lieu à Rome, pendant l'été 1961n 1. Sartre interrompt son strict régime de travail pour passer trois jours entiers à parler avec Fanon. Comme le raconte Claude Lanzmann, « pendant trois jours, Sartre n’a pas travaillé. Nous avons écouté Fanon pendant trois jours. […] Ce furent trois journées éreintantes, physiquement et émotionnellement. Je n’ai jamais vu Sartre aussi séduit et bouleversé par un homme »22. L'admiration est réciproque, comme le rapporte Simone de Beauvoir : « Fanon avait énormément de choses à dire à Sartre et de questions à lui poser. « Je paierais vingt mille francs par jour pour parler avec Sartre du matin au soir pendant quinze jours », dit-il en riant à Lanzmann »23. La mort de Fanon  Tombe de Frantz-Fanon à Aïn Kerma. Atteint d'une leucémie, il se fait soigner à Moscou, puis, en octobre 1961, à Bethesda près de Washington, où il meurt le 6 décembre 1961 à l'âge de 36 ans, quelques mois avant l'indépendance algérienne, sous le nom d'Ibrahim Omar Fanon24. Dans une lettre laissée à ses amis, il demandera à être inhumé en Algérie. Son corps est transféré à Tunis, et sera transporté par une délégation du GPRA à la frontière. Son corps sera inhumé par Chadli Bendjedid, qui devient plus tard président algérien, dans le cimetière de Sifana près de Sidi Trad, en Algérie. Avec lui, sont inhumés trois de ses ouvrages : Peau noire, masques blancs, L'an V de la révolution algérienne et Les Damnés de la Terre. Sa dépouille sera transférée en 1965, et inhumée au cimetière des « Chouhadas » (cimetière des martyrs de la guerre) près de la frontière algéro-tunisienne, dans la commune d'Aïn El Kerma (wilaya d'El Tarf). Il laisse derrière lui son épouse, Marie-Josèphe Dublé, dite Josie (morte le 13 juillet 1989 et inhumée au cimetière d'El Kettar au centre d'Alger), et deux enfants : Olivier, né en 1955, et Mireille, qui épousera Bernard Mendès France (fils de Pierre Mendès France).  Hôpital Frantz Fanon de Béjaïa En hommage à son travail en psychiatrie et à son soutien à la cause algérienne, trois hôpitaux en Algérie, l'hôpital psychiatrique de Blida, où il a travaillé, un des hôpitaux de Béjaïa et un hôpital à Annaba, portent son nom. |

アルジェリア時代 植民地化の影響を分析する  ファノンとブリダ・ジョインヴィル精神病院の医療チーム 1953年、ファノンはアルジェリアのブリダ=ジョワンヴィル精神病院の医師長に就任し、「社会療法」あるいは「施設精神療法」と呼ばれる近代的な方法を 導入し、アルジェリアのイスラム教徒の患者の文化に適応させた。 この研究は、彼の弟子で後に精神科医・精神分析医となるジャック・アズレイの論文で説明されることになる。その後、彼は住民たちとともに、アルジェリア文 化の神話や伝統的な儀式の探求に乗り出した。アルジェリアの精神医学界を脱領域化し、脱植民地化しようとする彼の願望は、アントワーヌ・ポロのアルジェリ ア精神医学学派の人種差別的理論とはまったく対照的であった。「大脳皮質が高度に発達していない土着の北アフリカ人は、原始的な存在であり、その本質的に 植物的で本能的な生活は、主に間脳によって制御されている」13。「アルジェリア人には大脳皮質がない。もっと正確に言えば、下等脊椎動物と同じように、 間脳の活動によって支配されている」14,15。 ファノンにとって、植民地化とはむしろ非人格化をもたらすものであり、植民地化された人間を「幼稚化され、抑圧され、拒絶され、非人間化され、文化化さ れ、疎外された」存在にし、植民地化する権威に乗っ取られる準備をさせるものである15。 「先住民の夢が筋肉質の夢、行動の夢、攻撃的な夢であるのはそのためだ。跳んだり、泳いだり、走ったり、登ったりする夢だ。笑い出す夢、川を闊歩する夢、 追いつけない車の群れに追いかけられる夢。植民地化の間、被植民者は夜の9時から朝の6時までの間、決して息が切れることはなかった。彼らの筋肉に蓄積さ れたこの攻撃性は、植民地化された人々が同胞に対して最初に示すものである。この時期は、ニガーたちが互いに食べ合っていた時期であり、警察や審査判事が 北アフリカの驚くべき犯罪性にどう対処すべきか途方に暮れていた時期であった16。 民族解放戦線とともに活動する 1954年にアルジェリア戦争が始まると、彼は民族主義レジスタンスと関わりを持ち、民族解放軍の将校や民族解放戦線(FLN)の政治指導者たち、特にア バネ・ラムダンとベンユセフ・ベンクヘッダと接点を持つようになった。1956年11月、ブリダ・ジョインヴィル病院の医師長の辞表をロベール・ラコスト 知事に提出し、1957年1月にアルジェリアから追放された。 彼はフランス国籍を放棄し17、自らをアルジェリア人と定義した18。チュニスでFLNに参加し、ブリダ病院で精神科医として何人もの拷問者を治療したこ とから、拷問問題の専門家としてFLNの中央報道機関紙『エル・ムジャヒド』に寄稿した。1958年、イブラヒム・オマール・ファノン19の名前でチュニ ジアの偽パスポートを発行させた。1959年、アクラで開催された汎アフリカ会議にアルジェリア代表団の一員として参加し、同年、フランソワ・マスペロ社 から『アルジェリア革命の5年』(L'An V de la révolution algérienne)を出版した。1960年3月、ガーナのアルジェリア共和国臨時政府(GPRA)大使に任命される。この間、モロッコとイタリアで爆 弾テロを逃れた。同時に、改宗することなくコーランの勉強を始めた。 彼は、フランス共同体(フランスとその植民地との連合体)に結集したアフリカの指導者たちを強く批判し、植民地体制に対する各国のブルジョワジーの態度の 原因に疑問を呈した。彼の見解では、植民地主義は、その物質的特権のために土着社会にブルジョア階級を生み出したが、それは経済的役割を持たず(「産業界 の大将」もいない)、中間的な活動に限られていた。その唯一の目的は、植民地主義の利益を守ることだった。こうして独立が認められると、植民地権力は権力 を奴隷化されたブルジョワジーに譲り渡し、彼らは「西洋企業の経営者」の役割を担うようになった。彼の考えでは、これらの国々において脱植民地化が有効な のは文化的な面(古代の伝統への回帰)だけであり、植民地主義は経済的な面では継続する5。 彼はまた、国家の独立は社会問題を含んで初めて意味をなすと考え、その独立の「現実の程度」(労働者階級にとってのパン、土地、権力へのアクセス)を決定 づけた。このようなアプローチから、彼は独立を社会主義と結びつけた。社会主義とは、「人間が最も貴重な資産であるという原則に基づき、完全に人民全体に 向けられた体制」と定義した。彼はまた、汎アフリカ主義のキャンペーンも行った。 サルトルとの出会い 初期の著作から、ファノンは常に哲学者ジャン=ポール・サルトルに言及していた(特に『Réflexions sur la question juive』、『Orphée noir』、『L'Être et le Néant』)。弁証法的理性批判』が出版されたとき(1960年)、彼はそのコピーを送ってもらい、白血病で弱っていたにもかかわらず、何とか読むこと ができた。アルジェリアの民族解放軍の戦士たちに『弁証法的理性批判』の講義をしたこともある。 1960年には、GPRAの指導者と話すためにチュニスに来たクロード・ランズマンとマルセル・ペジュに、哲学者と会うように頼んだ。また、最新作 『Les Damnés de la Terre』の序文をサルトルに依頼した。彼は出版社のフランソワ・マスペロにこう書いた。私が食卓につくたびに、彼のことを思い出すと伝えてくれ」 21。 サルトルは厳しい仕事のスケジュールを中断して、丸3日間ファノンと語り合った。クロード・ランズマンが回想するように、「サルトルは3日間仕事をしな かった。私たちは3日間ファノンの話を聞いた。[肉体的にも精神的にも過酷な3日間だった。サルトルがこれほどまでに男に誘惑され、圧倒されるのを見たこ とがない」22。シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールが「ファノンはサルトルに言いたいこと、聞きたいことがたくさんあった。「サルトルと朝から晩まで2週間話 すためなら、1日2万フラン払ってもいい」と彼は笑いながらランツマンに語った23。 ファノンの死  アイン・ケルマにあるフランツ=ファノンの墓。 白血病に冒された彼はモスクワで治療を受け、1961年10月にはワシントン近郊のベセスダで治療を受け、1961年12月6日、アルジェリア独立の数カ 月前にイブラヒム・オマール・ファノン24の名で36歳の生涯を閉じた。友人たちに宛てた手紙の中で、彼はアルジェリアでの埋葬を希望していた。彼の遺体 はチュニスに移され、GPRAの代表団によって国境まで運ばれた。彼の遺体は、後にアルジェリア大統領となるチャドリ・ベンジディッドによって、アルジェ リアのシディ・トラッド近郊のシファナ墓地に埋葬された。黒い肌、白い仮面』(Peau noire, masques blancs)、『アルジェリア革命5年目』(L'an V de la révolution algérienne)、『地の哀れ』(Les Damnés de la Terre)の3作品が埋葬された。彼の遺骨は1965年に移送され、アルジェリアとチュニジアの国境近く、アイン・エル・ケルマ(エル・タルフのウィラ ヤ)のコミューンにある「シュハダス」墓地(戦争殉教者のための墓地)に埋葬された。 妻のマリー=ジョゼフ・デュブレ、通称ジョジー(1989年7月13日に死去、アルジェ中心部のエル・ケタール墓地に埋葬)と2人の子供が残された: オリヴィエは1955年生まれ、ミレイユはベルナール・メンデス・フランス(ピエール・メンデス・フランスの息子)と結婚した。  ベジャイアのフランツ・ファノン病院 彼の精神医学の仕事とアルジェリアの大義への支援に敬意を表し、アルジェリアの3つの病院--彼が働いていたブリダの精神病院、ベジャイアの病院、アンナ バの病院--に彼の名前がつけられている。 |