知識の脱植民地化

Decolonization of knowledge

★『研

究』という言葉自体が、先住民の言語の中で最も汚れた言葉の一つである——リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミス『脱植民地化の方法論:研究と先住民』1999.

☆ 知識の脱植民地化(Decolonization of knowledge ;脱 植民地化論、脱植民地化主義とも)とは、脱植民地化研究において提唱されている概 念であり、西洋の知識体系の支配を批判するものである。代替となる認識 論、存在論、方法論を探求することで、他の知識体系を構築し、正当化しようとするものである。また、知識と真理の客観的な追求とはほとんど関係がないと考 えられている学術活動を「消毒」することを目的とした知的プロジェクトでもある。カリキュラム、理論、知識が植民地化されているということは、それらが政 治、経済、社会、文化的な考慮事項から部分的に影響を受けていることを意味する、という前提がある。脱植民地化知識の視点は、哲学(特に認識 論)、科学、 科学史、社会科学におけるその他の基礎的なカテゴリーなど、幅広い分野をカバーしている。これらの批判的観点にたつためには、各人が「脱植民地化の方法論」を身につけることが不可欠な作業となる。

☆ 「第三世界は……ヨーロッパに巨大なかたまりとして向き合っているが、その目的はヨーロッパが答えをみつけだせなかった諸問題の解決を試みることにあるは ずだ」(フランツ・ファノン「地に呪われたる者」1961)。

︎▶

(西洋の)知識︎▶︎︎シルビア・ウィンター▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

2015

年4月9日、ケープタウン大学のキャンパスからセシル・ローズの銅像が撤去された。ローズ・マスト・フォール[=ローズの像は倒すべし]運動は、南アフリカの知識と教育を非植民地

化したいという願いから始まったと言われている.// Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing

Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 1999.

| Decolonization

of knowledge Decolonization of knowledge (also epistemic decolonization or epistemological decolonization) is a concept advanced in decolonial scholarship[note 1][note 2] that critiques the perceived hegemony of Western knowledge systems.[note 3] It seeks to construct and legitimize other knowledge systems by exploring alternative epistemologies, ontologies and methodologies.[4] It is also an intellectual project that aims to "disinfect" academic activities that are believed to have little connection with the objective pursuit of knowledge and truth. The presumption is that if curricula, theories, and knowledge are colonized, it means they have been partly influenced by political, economic, social and cultural considerations.[5] The decolonial knowledge perspective covers a wide variety of subjects including philosophy (epistemology in particular), science, history of science, and other fundamental categories in social science.[6] |

知識の脱植

民地化(→知と権力) 知識の脱植 民地化(脱植民地化論、脱植民地化主義とも)とは、脱植民地化研究において提唱されている概念であり、西洋の知識体系の支配を批判するものである[注釈 1][注釈 2]。代替となる認識論、存在論、方法論を探求することで、他の知識体系を構築し、正当化しようとするものである[4]。また、知識と真理の客観的な追求 とはほとんど関係がないと考えられている学術活動を「消毒」することを目的とした知的プロジェクトでもある。カリキュラム、理論、知識が植民地化されてい るということは、それらが政治、経済、社会、文化的な考慮事項から部分的に影響を受けていることを意味する、という前提がある[5]。脱植民地化知識の視 点は、哲学(特に認識論)、科学、科学史、社会科学におけるその他の基礎的なカテゴリーなど、幅広い分野をカバーしている[6]。 |

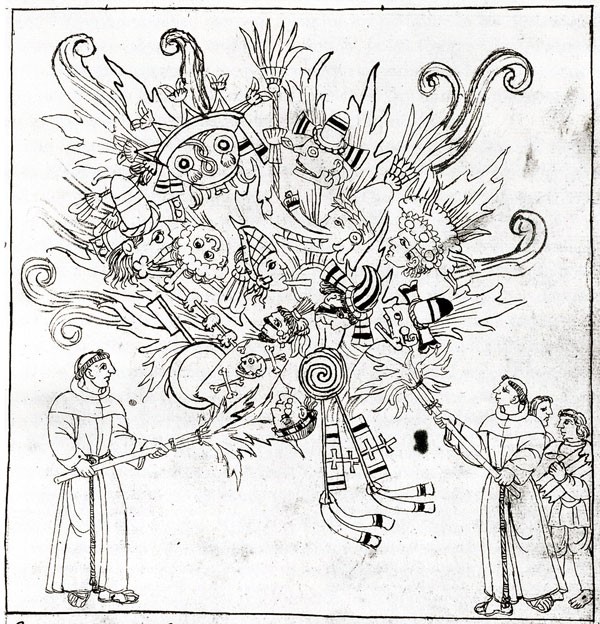

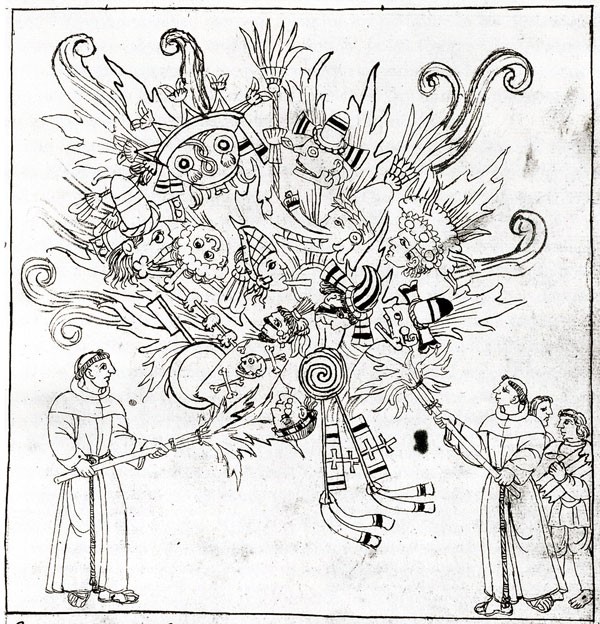

| Background Main article: Coloniality of knowledge  In his 1585 Descripción de Tlaxcala, Diego Muñoz Camargo illustrates the destruction of Mexican codices by Franciscan friars.[7] Decolonization of knowledge inquires into the historical mechanisms of knowledge production and their perceived colonial and ethnocentric foundations.[8] Budd L. Hall et al argue that knowledge and the standards that determine the validity of knowledge have been disproportionately informed by Western system of thought and ways of being in the world.[9] According to Jaco S. Dreyer, the western knowledge system that emerged in Europe during renaissance and Enlightenment was deployed to legitimise Europe’s colonial endeavour, which eventually became a part of colonial rule and forms of civilization that the colonizers carried with them.[4] This perspective maintains that the knowledge produced by the Western system was deemed superior to that produced by other systems since it had a universal quality. Decolonial scholars concur that the western system of knowledge still continues to determine as to what should be considered as scientific knowledge and continues to "exclude, marginalise and dehumanise" those with different systems of knowledge, expertise and worldviews.[4] Anibal Quijano stated: In effect, all of the experiences, histories, resources, and cultural products ended up in one global cultural order revolving around European or Western hegemony. Europe’s hegemony over the new model of global power concentrated all forms of the control of subjectivity, culture, and especially knowledge and the production of knowledge under its hegemony... They repressed as much as possible the colonized forms of knowledge production, the models of the production of meaning, their symbolic universe, the model of expression and of objectification and subjectivity.[10] [10]Ivanovic, Mladjo (2019). "Echoes of the Past: Colonial Legacy and Eurocentric Humanitarianism". The Rest Write Back: Discourse and Decolonization. BRILL. pp. 82–102 [98]. doi:10.1163/9789004398313_005. ISBN 978-90-04-39831-3. S2CID 203279612. In her book Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Linda Tuhiwai Smith writes: Imperialism and colonialism brought complete disorder to colonized peoples, disconnecting them from their histories, their landscapes, their languages, their social relations and their own ways of thinking, feeling and interacting with the world.[11] [11]Rohrer, J. (2016). Staking Claim: Settler Colonialism and Racialization in Hawai'i. Critical Issues in Indigenous Studies. University of Arizona Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8165-0251-6. According to this viewpoint, colonialism has ended in the legal and political sense, but its legacy continues in many "colonial situations" where individuals and groups in historically colonized places are marginalized and exploited. Decolonial scholars refer to this continuing legacy of colonialism as "coloniality", which describes the oppression and exploitation left behind by colonialism in a variety of interrelated domains, including the domain of subjectivity and knowledge.[4] |

背景 メイン記事: 知識の植民地主義  1585年にディエゴ・ムニョス・カマルゴが著した『トラスカラの記述』では、フランシスコ会の修道士によるメキシコ写本の破壊について述べられている [7]。 知識の脱植民地化とは、知識の生産に関する歴史的メカニズムと、その認識されている植民地主義的・民族中心主義的基盤を調査するものである[8]。バッ ド・L・ホールらは、知識とその有効性を決定づける基準は、西洋の思想体系や 世界のあり方によって決定されてきた[9]。Jaco S. Dreyer によると、ルネサンスと啓蒙主義の時代にヨーロッパで生まれた西洋の知識体系は、ヨーロッパの植民地化努力を正当化するために用いられ、最終的には植民地 支配や植民者たちが持ち込んだ文明形態の一部となった[4]。この視点では、西洋の体系によって生み出された知識は普遍的な性質を持つため、他の体系に よって生み出された知識よりも優れていると考えられていた。脱植民地化研究者は、西洋の知識体系が、何が科学的知識と見なされるべきかを決定し続け、異な る知識体系、専門知識、世界観を持つ人々を「排除し、周縁化し、人間性を奪う」ことを続けているという点では一致している[4]。アニバル・キハノは次の ように述べている。 事実上、すべての経験、歴史、資源、文化的な成果は、ヨーロッパまたは 西洋の覇権を中心とする一つのグローバルな文化秩序に収束した。ヨーロッパの新しい グローバルパワーモデルに対する覇権は、主観、文化、特に知識とその生産のあらゆる形態をその支配下に集中させた。彼らは、植民地化された知識生産の形 態、意味の生産モデル、象徴的な世界観、表現と客観化、主観のモデルを可能な限り抑圧した。 [10]Ivanovic, Mladjo (2019). "Echoes of the Past: Colonial Legacy and Eurocentric Humanitarianism". The Rest Write Back: Discourse and Decolonization. BRILL. pp. 82–102 [98]. doi:10.1163/9789004398313_005. ISBN 978-90-04-39831-3. S2CID 203279612. リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミスは著書『脱植民地化の方法論: リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミスは著書『脱植民地化の方法論:研究と先住民』の中で次のように述べている。 帝国主義と植民地主義は、植民地化された人々を完全に混乱に陥れ、彼ら を自分たちの歴史、風景、言語、社会関係、そして世界に対する独自の考え方、感じ方、関わり方から切り離した[11]。 [11]Rohrer, J. (2016). Staking Claim: Settler Colonialism and Racialization in Hawai'i. Critical Issues in Indigenous Studies. University of Arizona Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8165-0251-6. この見解によると、植民地主義は法的・政治的な意味では終わったが、その遺産は歴史的に植民地化された場所に住む個人やグループが疎外され搾取される多く の「植民地状況」の中で続いている。脱植民地化学者たちは、植民地主義の遺産として今も続く植民地主義を「コロニアルティ」と呼び、植民地主義が残した抑 圧と搾取を、主観や知識の領域など、相互に関連したさまざまな領域で説明している[4]。 |

| Origin and development In community groups and social movements in the Americas, decolonization of knowledge traces its roots back to resistance against colonialism from its very beginning in 1492.[6] Its emergence as an academic concern is rather a recent phenomenon. According to Enrique Dussel, the theme of epistemological decolonization has originated from a group of Latin American thinkers.[12] Although the notion of decolonization of knowledge has been an academic topic since the 1970s, Walter Mignolo says it was the ingenious work of Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano that "explicitly linked coloniality of power in the political and economic spheres with the coloniality of knowledge."[13] It has developed as "an elaboration of a problematic" that began as a result of several critical stances such as postcolonialism, subaltern studies and postmodernism. Enrique Dussel says epistemological decolonization is structured around the notions of coloniality of power and transmodernity, which traces its roots in the thoughts of José Carlos Mariátegui, Frantz Fanon and Immanuel Wallerstein.[12] According to Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, although the political, economic, cultural and epistemological dimensions of decolonization were and are intricately connected to each other, attainment of political sovereignty was preferred as a "practical strategic logic of struggles against colonialism." As a result, political decolonization in the twentieth century failed to attain epistemological decolonization, as it did not widely inquire into the complex domain of knowledge.[14] |

起源と発展 アメリカ大陸の地域社会グループや社会運動における知識の脱植民地化は、1492年の植民地化当初からの植民地主義への抵抗にそのルーツがある[6]。学 問的な関心事として浮上したのは、比較的最近の現象である。エンリケ・ドゥッセルによると、認識論的脱植民地化のテーマはラテンアメリカの思想家グループ から生まれたという[12]。知識の脱植民地化の概念は1970年代から学術的なトピックであったが、ウォルター・ミニョーロ(ミグノーロと表記すること もあるが同一)は、ペルーの社会学者アニバ ル・キハノの独創的な研究が 「政治と経済における権力の植民地主義と知識の植民地主義を明確に結びつけた」[13] のは、ペルーの社会学者アニバル・キハノの独創的な業績であった。それは、ポストコロニアリズム、サバルタン研究、ポストモダニズムといったいくつかの批 判的立場から始まった「問題提起の精緻化」として発展してきた。エンリケ・ドゥッセルは、認識論的脱植民地化は、植民地性(coloniality of power)とトランスモダニティ(transmodernity)の概念を中心に構成されていると述べており、そのルーツはホセ・カルロス・マリアテ ギ、フランツ・ファノン、イマニュエル・ウォーラーステインの思想にあるとしている[12]。 J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni によると、脱植民地化の政治的、経済的、文化的、認識論的側面は複雑に絡み合っていたが、「植民地主義との闘いにおける実践的戦略的論理」として政治的主 権の獲得が優先されていた。その結果、20世紀における政治的脱植民地化は、複雑な知識の領域について広く探究されなかったため、認識論的脱植民地化を達 成することができなかった[14]。 |

| Themes According to Alex Broadbent, decolonization is sometimes understood as a rejection of the notion of objectivity, which is seen as a legacy of colonial thought. He argues that universal conception of ideas such as "truth" and "fact" are Western constructs that are imposed on other foreign cultures. This tradition considers notions of truth and fact as "local", arguing that what is "discovered" or "expressed" in one place or time may not be applicable in another.[5] The concerns of decolonization of knowledge are that the western knowledge system has become a norm for global knowledge and that its methodologies are the only ones deemed appropriate for use in knowledge production. This perceived hegemonic approach towards other knowledge systems is said to have reduced epistemic diversity and established the center of knowledge, eventually suppressing all other knowledge forms.[15] Boaventura de Sousa Santos says "throughout the world, not only are there very diverse forms of knowledge of matter, society, life and spirit, but also many and very diverse concepts of what counts as knowledge and criteria that may be used to validate it."[16] However, it is claimed that this variety of knowledge systems has not gained much recognition.[17] According to Lewis Gordon, the formulation of knowledge in its singular form itself was unknown to times before the emergence of European modernity. Modes of knowledge production and notions of knowledge were so diversified that knowledges, in his opinion, would be more appropriate description.[18] According to Walter Mignolo, the modern foundation of knowledge is thus territorial and imperial. This foundation is based on "the socio-historical organization and classification of the world founded on a macro narrative and on a specific concept and principles of knowledge" which finds its roots in European modernity.[19] He articulates epistemic decolonization as an expansive movement that identifies "geo-political locations of theology, secular philosophy and scientific reason" while also affirming "the modes and principles of knowledge that have been denied by the rhetoric of Christianization, civilization, progress, development and market democracy."[14] According to Achille Mbembe, decolonization of knowledge means contesting the hegemonic western epistemology that suppresses anything that is foreseen, conceived and formulated from outside of western epistemology.[20] It has two aspects: a critique of Western knowledge paradigms and the development of new epistemic models.[15] Savo Heleta states that decolonization of knowledge "implies the end of reliance on imposed knowledge, theories and interpretations, and theorizing based on one’s own past and present experiences and interpretation of the world."[8] |

テーマ アレックス・ブロードベントによると、脱植民地化は、植民地時代の思考の遺産と見な される客観性の概念の拒絶として理解されることがある。彼は、「真実」 や「事実」といった普遍的な概念は、西洋の文化が他国の文化に押し付けたものであると主張している。この伝統では、真実や事実の概念は「局所的」であると 見なされ、ある場所や時代で「発見」されたり「表現」されたりしたものは、別の場所や時代では当てはまらない可能性があるとしている[5]。知識の脱植民 地化の懸念は、西洋の知識体系が世界の知識の規範となり、その方法論が知識の生産に使用されるのにふさわしい唯一の方法であるとみなされていることであ る。このような他の知識体系に対する覇権主義的アプローチは、認識論的多様性を減少させ、知識の中心を確立し、最終的に他のすべての知識形 態を抑制したと されている[15]。ボアベントゥラ・デ・ソウザ・サントス[Boaventura de Sousa Santos]は、「世 界中で、物質、社会、生命、精神に関する非常に多様な知識形態が存在するだけでなく、 また、知識として認められるもの、それを検証するための基準についても、非常に多様な概念が存在する」[16]。しかし、こうした知識シス テムの多様性 は、あまり認知されていないという指摘もある[17]。ルイス・ゴードンによると、ヨーロッパの近代化以前には、知識を一元的に定義すること自体が知られ ていなかった。知識の生産様式や知識の概念は多様化しており、知識という表現の方がより適切だと彼は考えている[18]。 ウォルター・ミ ニョーロによると、知識の近代的基盤はこのように領土的かつ帝国主義的である。この基盤は、「マクロな物語と特定の概念や知識の原則に基づ いて構築された、社会史的な世界の組織化と分類」に基づいているが、そのルーツはヨーロッパの近代性にある[19]。彼は、エピステメーの脱植民地化を、 「神学、世俗哲学、科学的理性の地政学的位置」を明らかにする拡大的な運動として定義し、同時に 「キリスト教化、文明化、進歩、開発、市場民主主義のレトリックによって否定されてきた知識の様式と原理」[14]を肯定することでもある。アシル・ムベ ンベによると、知識の脱植民地化とは、西洋の知識論の外側から予測、構想、策定されたものをすべて抑圧する西洋の知識論のヘゲモニーに異議を唱えることで ある[20] 脱植民地化には2つの側面がある。西洋の知識パラダイムの批判と、 新しい認識論モデルの開発である[15]。サヴォ・ヘレタは、脱植民地化とは「押し付け られた知識、理論、解釈への依存の終わり、そして自らの過去と現在の経験と世界への解釈に基づく理論化を意味する」[8]と述べる。 |

| Significance According to Anibal Quijano, epistemological decolonization is necessary for opening up new avenues for intercultural communication and the sharing of experiences and meanings, laying the groundwork for an alternative rationality that could rightfully stake a claim to some degree of universality.[21] Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni says epistemological decolonization is essential for addressing the "asymmetrical global intellectual division of labor" in which Europe and North America not only act as teachers of the rest of the world but also serve as the centers for the production of theories and concepts that are ultimately "consumed" by the entire human race.[22] |

意義 アニバル・キハノによると、認識論的脱植民地化は、異文化間のコミュニケーションや経験や意味の共有に新たな道を開くために必要であり、ある程度の普遍性 を正当に主張できる代替の合理性の基礎を築くものである[21]。サベロ・J・ンド ロヴ-ガツェニは、ヨーロッパと北米が世界の教師であるだけでなく、最終的に全人類が「消費」する理論や概念を生み出す中心地でもあると いう「非対称的なグローバルな知的分業」に対処するには、認識論的脱植民地化が 不可欠であると述べている[22]。 |

| Approaches According to Linda Tuhiwai Smith, decolonization "does not mean a total rejection of all theory or research or Western knowledge".[23] In Lewis Gordon's view, decolonization of knowledge mandates a detachment from the "commitments to notions of an epistemic enemy."[24] It rather emphasizes "the appropriation of any and all sources of knowledge" in order to achieve relative epistemic autonomy and epistemic justice for "previously unacknowledged and/or suppressed knowledge traditions."[25] Indigenous decolonization This section is an excerpt from Indigenous decolonization.[edit] Indigenous decolonization describes ongoing theoretical and political processes whose goal is to contest and reframe narratives about indigenous community histories and the effects of colonial expansion, cultural assimilation, exploitative Western research, and often though not inherent, genocide.[26] Indigenous people engaged in decolonization work adopt a critical stance towards western-centric research practices and discourse and seek to reposition knowledge within Indigenous cultural practices.[26] The decolonial work that relies on structures of western political thought has been characterized as paradoxically furthering cultural dispossession. In this context, there has been a call for the use of independent intellectual, spiritual, social, and physical reclamation and rejuvenation even if these practices do not translate readily into political recognition.[27] Scholars may also characterize indigenous decolonization as an intersectional struggle that "cannot liberate all people without first addressing racism and sexism."[26] Beyond the theoretical dimensions of indigenous-decolonization work, direct action campaigns, healing journeys, and embodied social struggles for decolonization are frequently associated with ongoing native resistance struggles and disputes over land rights, ecological extraction, political marginalization, and sovereignty. While native resistance struggles have gone on for centuries, an upsurge of indigenous activism took place in the 1960s - coinciding with national liberation movements in Africa, Asia, and the Americas.[28] Relational model of knowledge Decolonial scholars inquire into various forms of indigenous knowledges in their efforts to decolonize knowledge and worldviews.[29] Louis Botha et al make the case for a "relational model of knowledge," which they situate within indigenous knowledges. These indigenous knowledges are based on indigenous peoples' perceptions and modes of knowing. They consider indigenous knowledges to be essentially relational because these knowledge traditions place a high value on the relationships between the actors, objects, and settings involved in the development of knowledge.[29] Such "networked" relational approach to knowledge production fosters and encourages connections between the individuals, groups, resources, and other components of knowledge-producing communities. For Louis Botha et al, since it is built on an ontology that acknowledges the spiritual realm as real and essential to knowledge formation, this relationality is also fundamentally spiritual, and feeds axiological concepts about why and how knowledge should be created, preserved, and utilized.[29] In academia One of the most crucial aspects of decolonization of knowledge is to rethink the role of the academia, which, according to Louis Yako, an Iraqi-American anthropologist, has become the "biggest enemy of knowledge and the decolonial option."[30] He says Western universities have always served colonial and imperial powers, and the situation has only become worse in the neoliberal age. According to Yako, the first step toward decolonizing academic knowledge production is to carefully examine "how knowledge is produced, by whom, whose works get canonized and taught in foundational theories and courses, and what types of bibliographies and references are mentioned in every book and published article."[30] He criticizes Western universities for their alleged policies regarding research works that undermine foreign and independent sources while favoring citations to "elite" European or American scholars who are commonly considered "foundational" in their respective fields, and calls for an end to this practice.[30] Shose Kessi et al argue that the goal of academia is "not to reach new orders of homogeneity, but rather greater representation of pluralistic ideas and rigorous knowledge". They invite academics to carefully scrutinize the authors and voices that are presented as authorities on a subject or in the classroom, the methods and epistemologies that are taught or given preference, as well as the academic concerns that are seen as fundamental and the ones that are ignored. They must reconsider the pedagogical tools or approaches used in the learning process for students, as well as examine the indigenous or community knowledge systems that are followed, promoted, or allowed to redefine the learning agenda. The purpose and future of knowledge must also be reevaluated during this process.[31] There have been suggestions for expanding the reading list and creating an inclusive curriculum that incorporates a range of voices and viewpoints in order to represent broader global and historical perspectives. Researchers are urged to investigate outside the Western canons of knowledge to determine whether there are any alternative canons that have been overlooked or disregarded as a result of colonialism.[32] Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, who emphasizes the significance of decolonizing history, memory, and language, has stated that language, not geopolitics, should serve as the initial point of decolonization.[33] According to Mahmood Mamdani, the idea of a university based on a single language is a colonial heritage, as in the case of African universities, which began as a colonial project, with English or French being the project language, and it recognized only one intellectual tradition—the Western tradition.[33] According to Mamdani, university education needs to be more diverse and multilingual, with a focus on not only providing Westernized education in a variety of languages but also on ways to advance non-Western intellectual traditions as living traditions that can support both scholarly and public discourse. Mamdani makes the case for allocating funds to the creation of academic units that may research and instruct in non-Western intellectual traditions. He believes that learning the language in which the tradition has been historically developed is necessary if one wants to access a different intellectual tradition.[33] Louis Yako opposes the labeling of new scholars as "Marxist", "Foucauldian", "Hegelian", "Kantian", and so on, which he sees as a "colonial method of validating oneself and research" through these scholars. According to Yako, despite the fact that scholars such as Marx, Hegel, Foucault, and many others were all inspired by numerous thinkers before them, they are not identified with the names of such intellectuals. He criticizes the academic peer-review process as a system of "gatekeepers" who regulate the production of knowledge in a given field or about a certain region of the world.[30] In various disciplines In order to overcome the perceived constraints of the Western canons of knowledge, proponents of knowledge decolonization call for the decolonization of various academic disciplines, including history,[34] science and the history of science,[35][36] philosophy,[37] (in particular, epistemology),[38] psychology,[39][40] sociology,[41] religious studies,[42][43] and legal studies.[44] History According to the official web page of the University of Exeter, the "colonialist worldview," which allegedly prioritises some people's beliefs, rights, and dignity over those of others, has had an impact on the theoretical framework that underpins the modern academic field of history.[45] This modern field of study has first developed in Europe during a period of rising nationalism and colonial exploitation, which determines the historical narratives of the world.[45] This account suggests "that the very ways we are conditioned to look at and think about the past are often derived from imperialist and racialised schools of thought".[45] Decolonial approach in history requires "an examination of the non-western world on its own terms, including before the arrival of European explorers and imperialists". In an effort to understand the world before the fifteenth century, it attempts to situate Western Europe in relation to other historical "great powers" like the Eastern Roman Empire or the Abbasid Caliphate.[45] It "requires rigorous critical study of empire, power and political contestation, alongside close reflection on constructed categories of social difference".[34] According to Walter Mignolo, discovering the variety of local historical traditions are crucial for "restoring the dignity that the Western idea of universal history took away from millions of people".[46] Modern science The decolonial approach contests the notion of science as "purely objective, solely empirical, immaculately rational, and thus, singularly truth confirming”.[36] According to this account, such an outlook towards science implies "that reality is discrete and stagnant; immune to its observer’s subjectivity, including their cultural suasions; and dismountable into its component parts whose functioning can then be ascertained through verificationist means". Laila N Boisselle situates modern science within Western philosophy and Western paradigms of knowledge, saying that "different ways of knowing how the world works are fashioned from the cosmology of the observer, and provides opportunities for the development of many sciences".[36] Margaret Blackie and Hanelie Adendorff argue "that the practice of science by scientists has been profoundly influenced by Western modernity".[47] According to this perspective, modern science thus "reflects foundational elements of empiricism according to Francis Bacon, positivism as conceptualized by Comte, and neo-positivism as suggested by the School of Vienna in the early 1900s." Boisselle also suggests that the mainstream scientific perspective that downplays the function or influence of Spirit or God in any manifestation in its processes, is not only Western and modern but also secular in orientation.[36] Boisselle sought to identify two issues with Western knowledge, including "Western Modern Science". For her, it starts off by seeking to explain the nature of the universe on the basis of reason alone. The second is that it considers itself to be the custodian of all knowledge and to have the power "to authenticate and reject other knowledge."[36] The idea that modern science is the only legitimate method of knowing has been referred to as "scientific fundamentalism" or "scientism". It assumes the role of a gatekeeper by situating "science for all" initiatives on a global scale inside the framework of scientism. As a result, it acquires the power to decide what scientific knowledge is deemed to be "epistemologically rigorous".[36] According to Boaventura de Sousa Santos, in order to decolonize modern science, it is necessary to consider "the partiality of scientific knowledge", i.e. to acknowledge that, like any other system of knowledge, "science is a system of both knowledge and ignorance". For Santos, "scientific knowledge is partial because it does not know everything deemed important and it cannot possibly know everything deemed important".[48] In this regard, Boisselle argues for a "relational science" based on a "relational ontology" that respects “the interconnectedness of physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of individuals with all living things and with the star world, and the universe”.[36] Samuel Bendeck Sotillos, with reference to perennial philosophy, critiques modern science for its rejection of metaphysics and spiritual traditions from around the world. He states that "the belief that only the scientific method gives access to valid forms of knowledge is not only flawed but totalitarian, having its roots in the European Enlightenment or the so-called Age of Reason". For him, "This dogmatic outlook is not science, but an ideology known as scientism, which has nothing to do with the proper exercise of the scientific method".[49] This viewpoint challenges the idea that science is Truth, with a capital "T", saying that "contemporary science is largely relegated to dealing with approximations; in doing so, it is always modifying its understanding and thus is in no position to declare what can be finally known with certainty", and it promotes an understanding of science within the confines of its underlying philosophical assumptions concerning physical reality. In this context, Sotillos seeks to revive traditional metaphysics, also known as sacred science or scientia sacra, which is guided by metaphysical principles and is based on the sapiential teachings of world religions.[49] History of science Beginning in the middle of the 1980s, postcolonial histories of science is said to constitute a “decentered, diasporic, or ‘global’ rewriting of earlier nation-centred imperial grand narratives.” These histories seek to uncover "counter-histories of science, the legacies of precolonial knowledge, or residues and resurrections of the constitutive relations of colonial science."[50] Instead of "centering scientific institutes in colonial metropoles," this history attempts to examine what Warwick Anderson refers to "as the unstable economy of science’s shifting spatialities as knowledge is transacted, translated, and transformed across the globe". It seeks to eradicate "imperial grand narratives", which is said to provincialize science into a single "indigenous knowledge tradition".[50] Instead, it seeks to recognise "the culturally diverse and global origins of science", and build a cosmopolitan model of science history in place of the narrow view of science as the creation of "lone geniuses".[35] This perspective acknowledges the contributions of other civilizations to science, and offers a "contrageography of science that is not Eurocentric and linear". The central tenet is that the history of science should be seen as a history of transmissions. In this, Prakash Kumar et al cite Joseph Needham as saying, "modern science...[is] like an ocean into which the rivers from all the world’s civilizations have poured their waters”.[51] Philosophy Nelson Maldonado-Torres et al see the decolonial turn in philosophy "as a form of liberating and decolonising reason beyond the liberal and Enlightened emancipation of rationality, and beyond the more radical Euro-critiques that have failed to consistently challenge the legacies of Eurocentrism and white male heteronormativity (often Euro-centric critiques of Eurocentrism)".[52] According to Sajjad H. Rizvi, the shift toward global philosophy may herald a radical departure from colonial epistemology and pave the way for the decolonization of knowledge, particularly in the study of the humanities.[37] In opposition to what is said to have been the standard method in philosophy studies, he argues against focusing solely on Western philosophers. Rizvi makes the case for the inclusion of Islamic philosophy in the discussion because he thinks it will aid in the process of decolonization and may eventually replace the Eurocentric education of philosophy with an expansive "pedagogy of living and being".[37] Philip Higgs argues for the inclusion of African philosophy in the context of decolonization.[53] Similar suggestions have been made for Indian philosophy[54] and Chinese philosophy.[55] Maldonado-Torres et al discuss issues in the philosophy of race and gender as well as Asian philosophy and Latin American philosophy as instances of the decolonial turn and decolonizing philosophy, contending that "Asia and Latin America are not presented here as the continental others of Europe but as constructed categories and projects that themselves need to be decolonized".[52] Psychology According to many influential colonial and postcolonial leaders and thinkers, decolonization was "essentially a psychological project" involving a "recovery of self" and "an attempt to reframe the damaging colonial discourses of selfhood".[40] According to the decolonial perspective, Eurocentric psychology, which is based on a specific history and culture, places a strong emphasis on "experimental positivist methods, languages, symbols, and stories". A decolonizing approach in psychology thus seeks to show how colonialism, Orientalism, and Eurocentric presumptions are still deeply ingrained in modern psychological science as well as psychological theories of culture, identity, and human development.[40] Decolonizing psychology entails comprehending and capturing the history of colonization as well as its perceived effects on families, nations, nationalism, institutions, and knowledge production. It seeks to extend the bounds of cultural horizons, which should serve as a gateway "to new confrontations and new knowledge". Decolonial turn in psychology entails upending the conventional research methodology by creating spaces for indigenous knowledge, oral histories, art, community knowledge, and lived experiences as legitimate forms of knowledge.[40] Samuel Bendeck Sotillos seeks to break free from the alleged limits of modern psychology, which he claims is dominated by the precepts of modern science and which only addresses a very "restricted portion of human individuality". He instead wants to revive the traditional view of the human being as consisting of a spirit, a soul, and a body.[49] Sociology See also: Sociology of absences Decolonial scholars argue that sociological study is now dominated by the viewpoints of academics in the Global North and empirical studies that are concentrated on these countries. This leads to sociological theories that portray the Global North as "normal" or "modern," while anything outside of it is assumed to be either "deviant" or "yet to be modernized." Such theories are said to undermine the concerns of the Global South despite the fact that they make up around 84% of the world population.[56] They place a strong emphasis on taking into account the problems, perspectives, and way of life of those in the Global South who are typically left out of sociological research and theory-building; thus, decolonization in this sense refers to making non-Western social realities more relevant to academic debate.[56] Religious studies According to the decolonial perspective, the study of religion is one of many humanities disciplines that has its roots in European colonialism. Because of this, the issues it covers, the concepts it reinforces, and even the settings in which it is taught at academic institutions all exhibit colonial characteristics. According to Malory Nye, in order to decolonize the study of religion, one must be methodologically cognizant of the historical and intellectual legacies of colonialism in the field, as well as fundamental presuppositions about the subject matter, including the conception of religion and world religions.[42] For Adriaan van Klinken, a decolonial turn in the study of religions embraces reflexivity, is interactive, and challenges "the taken-for-granted Western frameworks of analysis and scholarly practice." It must accept "the pluriversality of ways of knowing and being" in the world.[57] The interpretation of the Quran in the Euro-American academic community has been cited as one such example, where "the phenomenon of revelation (Wahy)" as it is understood in Islam is very often negated, disregarded, or regarded as unimportant to comprehending the scripture.[58][59] According to Joseph Lumbard, Euro-American analytical modes have permeated Quranic studies and have a lasting impact on all facets of the discipline. He argues for more inclusive approaches that take into account different forms of analysis and make use of analytical tools from the classical Islamic tradition.[58] Legal studies Aitor Jiménez González argues that the "generalized use of the term “law” or “Law” masks the fact that the concept we are using is not a universal category but a highly provincial one premised on the westernized legal cosmovision". According to him, it was not the "peaceful spread of a superior science" that ultimately led to the universal adoption of the western notion of law. Rather, it "was the result of centuries of colonialism, violent repression against other legal cosmovisions during the colonial periods and the persistence of the process referred to as coloniality".[44] The decolonial stance on law facilitates dialogue between various understandings and epistemic perspectives on law in the first place, challenging the perceived hegemony of the westernized legal paradigm.[44] It is a strategy for transforming a legal culture that historically was based on a hegemonic or Eurocentric understanding of the law into one that is more inclusive.[60] It highlights the need for a fresh historical perspective that emphasizes diversity over homogeneity and casts doubt on the notion that the state is the "main organizer of legal and juridical life".[44] According to Asikia Karibi-Whyte, decolonization goes beyond inclusion in that it aims to dismantle the notions and viewpoints that undervalue the "other" in legal discourse. This point of view maintains that a society's values form the foundation of legal knowledge and argues for prioritizing those values when debating specific legal issues. This is because legal norms in former colonies bear the imprint of colonialism and values of colonial societies. For example, English Common Law predominates in former British colonies throughout Africa and Asia, whereas the Civil Law system is used in many former French colonies that mirrors the values of French society. In this context, decolonization of law calls "for the critical inclusion of epistemologies, ways of knowing, lived experiences, texts and scholarly works" that colonialism forced out of legal discourses.[60] Inclusive research This section is an excerpt from Neo-colonial science.[edit] Neo-colonial research or neo-colonial science,[61][62] frequently described as helicopter research,[61] parachute science[63][64] or research,[65] parasitic research,[66][67] or safari study,[68] is when researchers from wealthier countries go to a developing country, collect information, travel back to their country, analyze the data and samples, and publish the results with no or little involvement of local researchers. A 2003 study by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences found that 70% of articles in a random sample of publications about least-developed countries did not include a local research co-author.[62] Frequently, during this kind of research, the local colleagues might be used to provide logistics support as fixers but are not engaged for their expertise or given credit for their participation in the research. Scientific publications resulting from parachute science frequently only contribute to the career of the scientists from rich countries, thus limiting the development of local science capacity (such as funded research centers) and the careers of local scientists.[61] This form of "colonial" science has reverberations of 19th century scientific practices of treating non-Western participants as "others" in order to advance colonialism—and critics call for the end of these extractivist practices in order to decolonize knowledge.[69][70] This kind of research approach reduces the quality of research because international researchers may not ask the right questions or draw connections to local issues.[71] The result of this approach is that local communities are unable to leverage the research to their own advantage.[64] Ultimately, especially for fields dealing with global issues like conservation biology which rely on local communities to implement solutions, neo-colonial science prevents institutionalization of the findings in local communities in order to address issues being studied by scientists.[64][69] Shift in research methodology According to Mpoe Johannah Keikelame and Leslie Swartz, "decolonising research methodology is an approach that is used to challenge the Eurocentric research methods that undermine the local knowledge and experiences of the marginalised population groups".[72] Even though there is no set paradigm or practice for decolonizing research methodology, Thambinathan and Kinsella offer four methods that qualitative researchers might use. These four methods include engaging in transformative praxis, practicing critical reflexivity, employing reciprocity and respect for self-determination, as well as accepting "Other(ed)" ways of knowing.[73] For Sabelo Ndlovu Gatsheni, decolonizing methodology involves "unmasking its role and purpose in research". It must transform the identity of research objects into questioners, critics, theorists, knowers, and communicators. In addition, research must be redirected to concentrate on what Europe has done to humanity and the environment rather than imitating Europe as a role model for the rest of the world.[74] Data decolonization This section is an excerpt from Data decolonization.[edit] Data decolonization is the process of divesting from colonial, hegemonic models and epistemological frameworks that guide the collection, usage, and dissemination of data related to Indigenous peoples and nations, instead prioritising and centering Indigenous paradigms, frameworks, values, and data practices. Data decolonization is guided by the belief that data pertaining to Indigenous people should be owned and controlled by Indigenous people, a concept that is closely linked to data sovereignty, as well as the decolonization of knowledge.[75] Data decolonization is linked to the decolonization movement that emerged in the mid-20th century.[76] |

アプローチ リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミスによると、脱植民地化は「すべての理論や研究、西洋の知識の完全な拒絶を意味するものではない」[23]。ルイス・ゴードンの 知識の脱植民地化とは、「認識論的敵対概念へのコミットメント」からの脱却を意味する[24]。むしろ、「これまで認知されていなかった、あるいは抑圧さ れていた知識の伝統」[25]に対して、相対的な認識論的自律性と認識論的正義を実現するために、「あらゆる知識源の適切な利用」が強調される。 先住民の脱植民地化 このセクションは、『先住民の脱植民地化』からの抜粋である[編集]。 先住民の脱植民地化とは、先住民のコミュニティの歴史や、植民地拡大、文化的同化、搾取的な西洋の研究、そしてしばしば内在的ではないが大量虐殺の影響に 関する物語を争い、再構築することを目的とした、現在進行中の理論的・政治的プロセスである その目的は、先住民族の歴史や、植民地拡大、文化同化、搾取的な西洋の研究、そしてしばしば(本質的ではないが)大量虐殺の影響に関する物語に異議を申し 立て、再構築することである[26]。脱植民地化活動に従事する先住民族は、西洋中心の研究手法や言説に対して批判的な姿勢をとり、先住民族の文化慣習の 中で知識を再配置することを模索している[26]。 西洋の政治思想の構造に依存する脱植民地化活動は、逆説的に文化の剥奪を助長するものとして特徴づけられてきた。このような状況において、これらの実践が 政治的な認知を得られない場合でも、独立した知的、精神的、社会的、身体的再生と若返りの利用が求められている[27]。学者たちはまた、先住民の脱植民 地化を「人種差別と性差別に対処しない限り、すべての人々を解放することはできない」[26]交差型闘争として特徴づけることもある。 先住民による脱植民地化の理論的側面を超えて、直接行動キャンペーン、癒しを求める旅、そして脱植民地化に向けた具体的な社会闘争は、土地所有権、生態系 からの資源採取、政治的疎外、主権をめぐる先住民の抵抗闘争や紛争と密接に関連していることが多い。先住民の抵抗運動は数世紀にわたって続いてきたが、 1960年代には先住民のアクティヴィズムの高まりが見られた。これはアフリカ、アジア、アメリカ大陸における民族解放運動と時期を同じくしていた [28]。 知識の相互関係モデル 脱 植民地化からの脱却を目指し、脱植民地化学者たちは、さまざまな形態の土着の知識について研究している[29]。ルイ・ボータらは、「知識の相互関係モデ ル」を提唱しており、これを土着の知識の中に位置付けている。これらの土着の知識は、先住民の認識や知識の様式に基づいています。 これらの知識の伝統は、知識の発展に関わる行為者、対象、状況間の関係を重視しているため、土着の知識は本質的に関係的であると彼らは考えています [29]。このような「ネットワーク化された」関係論的アプローチは、知識生産コミュニティを構成する個人、グループ、リソース、その他の要素間のつなが りを促進し、奨励します。ルイ・ボタらによれば、精神的な領域を現実かつ知識形成に不可欠なものとして認める存在論に基づいて構築されているため、この関 係性は本質的に精神的なものであり、知識がなぜ、どのようにして創造、保存、利用されるべきかという価値概念を養うものである[29]。 学術界において 知識の脱植民地化において最も重要な側面の一つは、 知識の脱植民地化において最も重要なことの1つは、学術界の役割を再考することである。イラク系アメリカ人の人類学者ルイ・ヤコによると、学術界は「知識 と脱植民地化の選択肢にとって最大の敵」となっている[30]。彼は、西洋の大学は常に植民地支配者や帝国主義者のために奉仕してきたとし、新自由主義の 時代になってその状況はさらに悪化したと語る。ヤコ氏によると、学問的知識生産の脱植民地化に向けた第一歩は、「知識がどのように生産され、誰によって、 誰の著作が基礎理論や基礎科目で正典化され教えられているのか、また、あらゆる本や出版された論文でどのような書誌や参考文献が言及されているのか」を慎 重に検証することである[30]。彼は、欧米の大学が、外国の 欧米のエリート学者たちの研究を引用することを推奨し、その一方で、外国や独立系の情報源を軽視する傾向があると指摘し、この慣習を改めるよう求めている [30]。 Shose Kessi らは、学術の目的は「新たな均質性を追求することではなく、多様なアイデアや厳密な知識を幅広く紹介すること」であると主張している。彼らは、学問に携わ る人々に、ある主題や教室での権威として提示される著者や声、教授される方法や認識論、また基礎的と見なされる学問的関心事や無視される関心事について、 慎重に吟味するよう呼びかけている。学生たちの学習プロセスで使用される教授法やアプローチを再考し、また学習アジェンダを再定義するために従われ、推進 され、または許容されている土着の、あるいはコミュニティの知識体系を検証しなければならない。このプロセスにおいて、知識の目的と未来も再評価されなけ ればならない[31]。より広範なグローバルな視点と歴史的視点を反映するために、読書リストを拡大し、さまざまな声や視点を盛り込んだ包括的なカリキュ ラムを作成すべきだという提案がなされている。研究者には、植民地主義の結果として見過ごされたり無視されたりした、西洋の規範以外の知識があるかどうか を調査することが求められている[32]。 歴史、記憶、言語の脱植民地化の重要性を強調するンゴ・ワ・ティオンゴは、脱植民地化の最初のステップとなるのは 、地政学ではなく、言語こそが脱植民地化の最初のステップとなるべきだと述べている[33]。マフムード・マンダニによると、単一言語に基づく大学の考え 方は植民地時代の遺産であり、アフリカの大学の場合、英語やフランス語がプロジェクトの言語として用いられ、 西洋の伝統という一つの知的伝統しか認めなかった[33]。マムダーニによると、大学教育はより多様で多言語的である必要がある。西洋化された教育をさま ざまな言語で提供することに重点を置くだけでなく、学術的および公共の議論を支える生きた伝統として、西洋以外の知的伝統を発展させる方法にも重点を置く 必要がある。マンダニは、非西洋の知的伝統の研究と教育を行う学術ユニットの創設に資金を配分すべきだと主張している。彼は、異なる知的伝統にアクセスし たいのであれば、その伝統が歴史的に発展してきた言語を学ぶことが必要だと考えている[33]。 ルイ・ヤコは、新しい学者の研究を「マルクス主義」「フーコー主義」「ヘーゲル主義」「カント主義」などとレッテルを貼ることに反対している。ヤコによれ ば、マルクス、ヘーゲル、フーコー、その他多くの学者は、先人たちの数多くの思想家から影響を受けているにもかかわらず、そのような知識人の名前と同一視 されていない。彼は学術的なピアレビュープロセスを、特定の分野や世界の特定の地域に関する知識の生産を規制する「門番」のシステムであると批判している [30]。 さまざまな学問分野において 西洋の知識の規範による制約を克服するために、知識の脱植民地化の支持者は、歴史[34]、科学と科学史[35][36]、哲学[37]( 特に、認識論)[38]、心理学[39][40]、社会学[41]、宗教学[42][43]、法学[44] 歴史 エクセター大学の公式ウェブサイトによると、「植民地主義的世界観」は、一部の人の信念、権利、尊厳を他の人よりも優先するとされ、近代の歴史学という学 問分野を支える理論的枠組みに影響を与えている[45]。この分野の研究は、ナショナリズムの高まりと植民地搾取が盛んだったヨーロッパで発展し、世界の 歴史的物語を決定づけた[45]。この説明によると、「私たちが過去をどのように見て考えるように条件付けられているかは、しばしば帝国主義や人種差別的 な思想から派生している」[45]。歴史における脱植民地化のアプローチでは、「ヨーロッパの探検家や帝国主義者が到来する以前を含む、非西洋世界独自の 条件に基づく検証」[45]が必要とされる。15世紀以前の時代を理解する試みとして、西欧を東ローマ帝国やアッバース朝カリフ制といった他の歴史上の 「大国」と関連づけて位置づけることを試みる[45]。それは「帝国、権力、政治的対立について厳密な批判的研究を行うとともに、社会的な 」[34] ウォルター・ミニョーロによると、地域ごとの歴史的伝統の多様性を発見することは、「西洋の普遍史観によって何百万人もの人々から奪われた尊厳を取り戻 す」ために不可欠である[46]。 現代科学 脱植民地化のアプローチは、「純粋に客観的、もっぱら経験的、非の打ちどころのない 、そして唯一真実を証明するもの」[36] であるとする。この見解によると、このような科学に対する見方は、「現実が断片的で停滞しており、観察者の主観(文化的な影響を含む)の影響を受けず、検 証主義的な手段によってその機能を確かめることができる構成要素に分解できる」ことを意味する。ライラ・N・ボワセルは、西洋哲学と西洋の知識のパラダイ ムの中に現代科学を位置づけ、「世界がどのように機能しているかを理解するさまざまな方法は、観察者の宇宙論から形作られ、多くの科学の発展の機会を提供 する」と述べている[36]。マーガレット・ブラックとハネリー・アデンドルフは、「科学者による科学の実践は、西洋の近代性に深く影響されてきた」と主 張している[47]。科学者による科学の実践は、西洋の近代性に多大な影響を受けている」と主張している[47]。この見解によると、近代科学は「フラン シス・ベーコンによる経験主義、コンテが概念化した実証主義、1900年代初頭にウィーン学派が提唱した新実証主義の基礎的要素を反映している」というこ とになる。また、ボワセルは、そのプロセスにおけるあらゆる現れにおける精神や神の機能や影響を軽視する主流の科学的視点は、西洋的かつ近代的であるだけ でなく、世俗的な志向性をも備えていると指摘している[36]。 ボワセルは、「西洋近代科学」を含む西洋の知識について、2つの問題点を指摘しようとした。彼女にとって、それはまず、理性のみに基づいて宇宙の本質を説 明しようとする点にある。2つ目は、自らをあらゆる知識の保管者であり、「他の知識を認証し、拒否する」力を持っているとみなすことである[36]。近代 科学が唯一の正当な知識の手段であるという考え方は、「科学的原理主義」または「科学主義」と呼ばれてきた。これは、「すべてのための科学」イニシアティ ブを世界規模で科学主義の枠組みに位置づけることで、門番の役割を果たす。その結果、科学知識が「認識論的に厳密」であるとみなされるものを決定する力を 獲得する[36]。ボアベントゥラ・デ・ソウザ・サントスによると、近代科学の脱植民地化には、「科学知識の偏り」、すなわち、他のあらゆる知識体系と同 様に、「科学は知識と無知の両方を含む体系」であることを認識することが必要である。サントスにとって、「科学的知識は部分的である。なぜなら、重要だと 考えられていることをすべて知っているわけではなく、また、重要だと考えられていることをすべて知ることも不可能だから」[48]である。この点につい て、ボワセルは、「個人の身体的、精神的、感情的、精神的な側面と、すべての生物、星の世界、宇宙との相互関係」[36]を尊重する「関係論的実在論」に 基づく「関係論的科学」を提唱している。 サミュエル・ベンデック・ソティロスは、永続的な哲学を参照しながら、形而上学や世界中の精神的な伝統を否定する現代科学を批判している。彼は、「科学的 方法だけが有効な知識へのアクセスを可能にするという信念は、欠陥があるだけでなく、ヨーロッパの啓蒙主義やいわゆる理性時代にそのルーツを持つ全体主義 的である」と述べている。彼にとって、「この独断的な見方は科学ではなく、サイエンティズムとして知られるイデオロギーであり、科学的方法の適切な運用と は何の関係もない」[49]。この視点は、「現代科学は、近似値の処理にほぼ限定されている。 現代の科学は、近似値の処理にほぼ限定されており、その過程で常に理解が修正されるため、最終的に確実に知ることのできることを宣言できる立場にはない」 とし、物理的現実に関する根本的な哲学的前提の枠内で科学を理解することを推進している。このような背景から、ソティリョスは、形而上学の原理に導かれ、 世界の宗教の叡智の教えに基づく、神聖科学または聖なる科学としても知られる伝統的な形而上学の復興を目指している[49]。 科学史 1980年代半ばから、脱植民地化後の科学史は、「脱中心化、ディアスポラ、または『グローバル』な、以前の国家中心の帝国的大叙事詩の書き換え」を構成 すると言われている。これらの歴史は、「科学のカウンターヒストリー、植民地化以前の知識の遺産、あるいは植民地時代の科学の構成的関係の名残と復活」を 明らかにしようとするものである[50]。この歴史は、「植民地時代の大都市に科学研究所を集中させる」のではなく、ウォーウィック・アンダーソンが「知 識が世界中で取引、翻訳、変換される中で、科学の不安定な経済性、すなわち空間性が変化する」と表現したものを検証しようとするものである。それは、科学 を「土着の知の伝統」という単一のものに偏狭化させるという「帝国主義的大叙事詩」を根絶しようとするものである[50]。その代わりに、科学の「文化的 多様性とグローバルな起源」を認識し、 「孤独な天才」の創造物という狭い見方ではなく、科学史のコスモポリタンなモデルを構築することである[35]。この視点は、他の文明が科学にもたらした 貢献を認め、ヨーロッパ中心主義的かつ直線的ではない「科学のコントラジオグラフィー」を提供する。中心的な信条は、科学の歴史は伝達の歴史として捉える べきであるということである。これについて、プラカッシュ・クマールらは、ジョセフ・ニードハムの「近代科学は、世界中の文明から流れ出た水が注ぎ込まれ た大海のようなものである」という言葉を引用している[51]。 哲学 ネルソン・マルドナド=トーレスらは、哲学における脱植民地化の動きを「自由主義や啓蒙主義による合理性の解放や 自由主義的・啓蒙主義的な合理性の解放、そしてヨーロッパ中心主義と白人男性ヘテロ規範性の遺産(しばしばヨーロッパ中心主義に対するヨーロッパ中心主義 的批判)に一貫して挑戦できなかったより急進的なヨーロッパ批判を超えて、脱植民地化と脱植民地化としての理性の解放の一形態として」[52] 哲学における脱植民地化への転換を捉えている。H. リズヴィによれば、グローバルな哲学への移行は、植民地時代の認識論からの根本的な脱却を告げ、特に人文科学の研究において知識の脱植民地化への道を開く 可能性がある[37]。哲学研究における標準的な方法とされてきたものに対して、彼は西洋の哲学者だけに焦点を当てることに反対している。リズヴィは、イ スラム哲学を議論に含めるべきだと主張している。なぜなら、それは脱植民地化のプロセスに役立つと考えられ、最終的にはヨーロッパ中心の哲学教育を、より 広範な「生きることと存在することの教育学」に置き換える可能性があると考えているからだ[37]。フィリップ・ヒッグスは、脱植民地化の文脈においてア フリカ哲学を含めるべきだと主張している[53]。同様の提案は、インド哲学[54]や中国哲学[55]に対してもなされている。哲学[55]。マルドナ ド=トーレスらは、脱植民地化への転換と脱植民地化哲学の例として、アジア哲学とラテンアメリカ哲学だけでなく、人種とジェンダーの哲学における問題につ いて論じ、「アジアとラテンアメリカはヨーロッパの対極にある大陸としてではなく、脱植民地化されるべき構築されたカテゴリーやプロジェクトとして提示さ れている」と主張している[52]。 心理学 多くの影響力のある植民地 多くの影響力のある植民地支配者および脱植民地支配の指導者および思想家によると、脱植民地化は「本質的に心理学的プロジェクト」であり、「自己の回復」 と「自己概念に関する有害な植民地支配的言説の再構築の試み」を伴うものであった[40]。脱植民地化の観点によると、特定の歴史と文化に基づくヨーロッ パ中心主義心理学は、「実験的実証主義的方法、言語、シンボル、物語」に重点を置いている。心理学における脱植民地化のアプローチは、植民地主義、オリエ ンタリズム、ヨーロッパ中心主義の前提が、現代の心理学や文化、アイデンティティ、人間発達に関する心理学理論にいかに深く根付いているかを明らかにしよ うとするものである[40]。脱植民地化心理学は、植民地化の歴史とその影響(家族、国家、ナショナリズム、制度、知識生産など)を理解し、把握すること を必要とする。それは文化の地平線の境界線を広げ、それが「新たな対立と新たな知識」への入り口となることを目指している。心理学における脱植民地化と は、先住民の知恵、口承史、芸術、コミュニティの知識、生活体験などを正当な知識として認める空間を作り出すことで、従来の研究方法を根底から覆すことを 意味する[40]。サミュエル・ベンデック・ソティリョスは、現代心理学の限界とされるものから脱却しようとしている。彼は、現代心理学は現代科学の教義 に支配されており、人間の個性の「非常に限られた部分」にしか対応していないと主張している。彼は、人間を精神、魂、肉体から成る存在として捉える伝統的 な考え方を復活させたいと考えている[49]。 社会学 関連項目:不在の社会学 脱植民地化論者は、社会学研究は現在、グローバル・ノースの学者の視点と、これらの国々を集中的に研究する実証研究によって支配されていると主張してい る。 その結果、グローバル・ノースを「正常」または「近代的」と描写する社会学理論が生まれ、それ以外にあるものは「逸脱」または「近代化されていない」と想 定されるようになった。このような理論は、世界の人口の約84%を占めるにもかかわらず、グローバル・サウス(南半球)の懸念を損なうと言われている [56]。これらの理論は、一般的に社会学の研究や理論構築から除外されているグローバル・サウスの人々の問題、視点、生き方を考慮することに大きな重点 を置いている。したがって、この意味での脱植民地化とは、非西洋の社会現実を学術的な議論により関連付けることを指す[56]。 宗教学 脱植民地主義の観点によれば、宗教学はヨーロッパの植民地主義にルーツを持つ人文科学の1つである。そのため、宗教研究が扱うテーマ、宗教研究によって強 化される概念、そして学術機関で宗教研究が教えられている環境には、すべて植民地時代の特徴が現れている。Malory Nyeによると、宗教学の脱植民地化には、この分野における植民地主義の歴史的・知的遺産、そして宗教概念や世界宗教を含む主題に関する基本的前提条件を 方法論的に認識することが必要である。宗教観や世界宗教などである[42]。Adriaan van Klinken によると、脱植民地化への転換は宗教研究に内省性を取り入れ、双方向性を高め、「分析や学術的実践における西洋の枠組みを当然視する」という姿勢に異議を 唱えるものである。それは、世界における「知ることと存在することの多元性」を受け入れる必要がある[57]。欧米の学術界におけるコーランの解釈は、そ の一例として挙げられている。そこでは、イスラム教で理解されている「啓示(Wahy)」という現象が イスラム教で理解されている「啓示(Wahy)」という現象は、聖典を理解する上で非常に頻繁に否定されたり、無視されたり、重要ではないと見なされたり している[58][59]。ジョセフ・ランバードによると、欧米の分析手法はクルアーン研究に浸透しており、学問のあらゆる側面に対して長期的な影響を与 えている。彼は、さまざまな分析形態を考慮に入れ、古典的なイスラムの伝統から分析ツールを活用する、より包括的なアプローチを提唱している[58]。 法学研究 アイター・ヒメネス・ゴンザレスは、「法律」または「法」という用語の一般的な使用は、「私たちが使用している概念は普遍的なカテゴリーではなく、西洋化 された法的世界観を前提とした非常に地域的なものであるという事実を覆い隠している」と主張している。彼によると、西洋の法概念が最終的に普遍的に受け入 れられるようになったのは、「優れた科学の平和的な普及」によるものではない。むしろ、「それは何世紀にもわたる植民地主義、植民地時代に他の法的世界観 に対する暴力的な弾圧、そして植民地主義と呼ばれるプロセスの継続の結果である」[44]。脱植民地主義的な法律に対する姿勢は、そもそも法律に関するさ まざまな理解や認識論的視点の対話を促進し、西洋化された法的パラダイムの認識された覇権に挑戦するものである[44]。それは、歴史的に覇権主義的また は ヨーロッパ中心主義的な法律理解に基づくものから、より包括的なものへと転換するための戦略である[60]。それは、均質性よりも多様性を重視する新たな 歴史的視点の必要性を強調し、国家が「法律および司法生活の主な組織者」であるという概念に疑問を投げかけるものである[44]。 アシキア・カリビ=ホワイトによると、脱植民地化は、法律上の議論において「他者」を過小評価する概念や視点を解体することを目的としているため、包含以 上のものである。この視点は、社会の価値観が法的知識の基礎を形成しており、特定の法的問題を議論する際には、それらの価値観を優先させるべきであると主 張している。これは、旧植民地の法的規範が植民地主義と植民地社会の価値観の烙印を押されているからである。例えば、アフリカとアジアの旧イギリス植民地 では英米法が優勢であるのに対し、フランス社会の価値観を反映したフランス民法が多くの旧フランス植民地で用いられている。このような状況において、法の 脱植民地化とは、植民地主義によって法的議論から排除された「認識論、知識の在り方、生活経験、テキスト、学術研究」を批判的に取り入れることを求めてい る[60]。 包括的研究 このセクションは『ネオコロニアル・サイエンス』からの抜粋である[編集]。 ネオコロニアル研究またはネオコロニアル・サイエンスは、ヘリコプター 研究、パラシュート科学[63][64]または研究、寄生研究[66][67]、サファリ研究[68]などと呼ばれる。これは、先進国の研究者が開発途上 国に行き、情報を収集し、自国に戻ってからデータやサンプルを分析し、その結果を発表するというもので、現地の研究者がほとんど、あるいはまったく関与し ない。2003年のハンガリー科学アカデミーの研究によると、後発開発途上国に関する出版物のランダムサンプルでは、70%の記事に現地の研究者が共同執 筆者として含まれていなかったことがわかった[62]。 このような研究では、現地の同僚がフィクサーとして後方支援を行うことはよくあるが、彼らの専門知識が活用されることも、研究への参加が評価されることも ない。パラシュート・サイエンスから生まれる科学論文は、しばしば富裕国の科学者のキャリアアップにしか貢献せず、その結果、現地の科学能力(資金提供を 受けた研究センターなど)や現地の科学者のキャリアアップが制限されてしまう[61]。この「植民地」科学の形態は、19世紀の科学的な慣行、すなわち植 民地主義を推進するために非西洋圏の参加者を「他者」として扱う慣行を彷彿とさせるものであり、知識の脱植民地化を図るために、こうした搾取的な慣行を終 わらせるよう求める批判的な意見もある 知識[69][70]。 このような研究アプローチは、国際的な研究者が適切な質問を投げかけなかったり、現地の問題との関連性を導き出せなかったりするため、研究の質を低下させ る可能性がある[71]。このアプローチの結果、現地のコミュニティは研究を自分たちの利益に活用できない[64]。結局のところ、特に保全生物学のよう なグローバルな問題を取り扱う分野では、解決策の実施に現地のコミュニティに依存しているため、ネオコロニアル科学は、現地のコミュニティにおける問題の 解決に向けた知見の制度化を防ぐことになる 科学者が研究している問題に対処するために、[64][69] 研究方法論の転換 Mpoe Johannah KeikelameとLeslie Swartzによると、「研究方法論の脱植民地化は、周縁化された人口集団の地域的な知識と経験を損なうヨーロッパ中心の研究手法に異議を唱えるために用 いられるアプローチである」[72]。研究方法論の脱植民地化のための一定のパラダイムや実践は存在しないが、Thambinathanと Kinsellaは、質的研究者が用いる可能性のある4つの方法を示している。これらの4つの方法には、変革的な実践、批判的省察、相互尊重と自己決定の 尊重、そして「他者(たち)」の認識方法を受け入れることが含まれる[73]。Sabelo Ndlovu Gatsheni によれば、脱植民地化の方法論とは、「研究におけるその役割と目的を明らかにすること」である。それは、研究対象者のアイデンティティを、質問者、批評 家、理論家、知識人、コミュニケーターへと変化させるものでなければならない。さらに、研究はヨーロッパを世界の模範として模倣するのではなく、ヨーロッ パが人類と環境に与えた影響に焦点を当てるように方向転換されなければならない[74]。 データの脱植民地化 このセクションは、データの脱植民地化からの抜粋である[編集]。 データの 脱植民地化は、先住民や先住民族に関するデータの収集、使用、普及を導く植民地支配的モデルや認識論的枠組みから脱却し、代わりに先住民のパラダイム、枠 組み、価値観、データ利用を最優先し中心とするプロセスである。データ脱植民地化は、先住民に関するデータは先住民が所有し、管理すべきであるという信念 に基づいており、この概念はデータ主権や知識の脱植民地化とも密接に関連している[75]。 データ脱植民地化は、20世紀半ばに台頭した脱植民地化運動と関連している[76]。 |

| Criticism According to Piet Naudé, decolonization's efforts to create new epistemic models with distinct laws of validation than those developed in Western knowledge system have not yet produced the desired outcome.[77] The present "scholarly decolonial turn" has been criticised on the ground that it is divorced from the daily struggles of people living in historically colonized places. Robtel Neajai Pailey says that 21st-century epistemic decolonization will fail unless it is connected to and welcoming of the ongoing liberation movements against inequality, racism, austerity, imperialism, autocracy, sexism, xenophobia, environmental damage, militarization, impunity, corruption, media surveillance, and land theft because epistemic decolonization "cannot happen in a political vacuum".[78] "Decolonization", both as a theoretical and practical tendency, has recently faced increasing critique.[citation needed] For example, Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò[79] argued that it is analytically unsound, conflating "coloniality" with "modernity", leading it to become an impossible political project. He further argued that it risks denying the formerly colonized countries agency, in not recognizing that people often consciously accept and adapt elements of different origins, including colonial ones. Jonatan Kurzwelly and Malin Wilckens used the example of decolonisation of academic collections of human remains - originally used to further racist science and legitimize colonial oppression - to show how both contemporary scholarly methods and political practice perpetuate reified and essentialist notions of identities.[80][81] |

批判 ピエ・ノードゥーによると、脱植民地化の取り組みは、西洋の知識体系で発展したものと異なる検証の法則を持つ新たな認識論的モデルを構築しようとしている が、いまだに望ましい成果を生み出せていない[77]。現在の「学問的脱植民地化」は、歴史的に植民地化された場所で暮らす人々の日々の闘いから切り離さ れているという理由で批判されている。ロベルト・ネイジャイ・パイリーは、21世紀の脱植民地化論は、不平等、人種差別、緊縮財政、帝国主義、専制政治、 性差別、外国人嫌悪、環境破壊、軍事化、免罪、汚職、メディア監視、土地収奪に対する現在進行中の解放運動と結びつき、それを受け入れるものでなければ失 敗に終わるだろう、と述べる。なぜなら、脱植民地化論は「政治的な真空の中では起こり得ない」からだ。政治的空白」の中で起こることはできない」 [78]。 「脱植民地化」は、理論的傾向としても実践的傾向としても、近年ますます批判に直面している[要出典]。例えば、Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò[79]は、「植民地主義」と「近代性」を混同することは分析的に不適切であり、それが政治的に実現不可能なプロジェクトにつながると主張し た。さらに、植民地化された国々の人々が、植民地時代を含む異なる起源の要素をしばしば意識的に受け入れ、適応していることを認識しないことで、かつて植 民地化された国々の主体性を否定する危険性があると彼は主張した。ジョナサン・クルツウェリーとマリン・ウィルケンズは、人類の学術的な遺体コレクション の脱植民地化という例を挙げた。これは、もともと人種差別的な科学を促進し、植民地支配を正当化するために使用されていたものである。この例を用いて、現 代の学術的方法と政治的な実践の両方が、アイデンティティを具体化し本質主義的に捉える概念を永続させていることを示した。 |

| Decolonization of higher

education in South Africa Decolonization of museums Decolonising the Mind Decolonizing outer space Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

南アフリカにおける高等教育の脱植民地化 博物館の脱植民地化 マインドの脱植民地化 宇宙空間の脱植民地化 世界人権宣言 |

| Notes Citing Nelson Maldonado Torres, Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni states that "Decoloniality announces the broad 'decolonial turn' that involves the 'task of the very decolonization of knowledge, power and being, including institutions such as the university'"[2] Zavala, for example, comments that the decolonial project is also “a project for epistemological diversity” that “re-envisions and develops knowledges and knowledge systems (epistemologies) that have been silenced and colonized.” He says it is an attempt “to recover repressed and latent knowledges while at the same time generating new ways of seeing and being in the world.”[3] On the usage of the term "Western knowledge system", Jaco S. Dreyer writes: "I use the notion of ‘Western knowledge system’ to refer to the institutionalisation and development of scientific knowledge in Europe, and later in other ‘First World’ contexts, as part of Western modernity, and its continuation in present-day scholarship. I am aware that this is a gross simplification of hundreds of years of development of science in the Western world. This formulation also glosses over the great variety of epistemological, ontological, methodological and axiological constellations within this knowledge system."[4] |

注 ネルソン・マルドナド・トレスを引き合いに出し、サベロ・J・ンドロヴー・ガツェニは、「脱植民地性は、知識、権力、存在の真の脱植民地化という課題、例 えば大学などの制度を含む、広範な『脱植民地化への転換』を宣言する」と述べている[2]。大学」などの制度を含む、「知識、権力、存在の真の脱植民地化 という課題」[2] 例えば、ザバラは、脱植民地化プロジェクトは「沈黙させられ、植民地化された知識と知識体系(認識論)を再構想し、発展させる」という「認識 論的多様性」のためのプロジェクトでもあるとコメントしている。彼は、この試みは「抑圧され、潜在化している知識を回復すると同時に、世界の見方や在り方 を新たに生み出す」試みである、と語っている[3]。 「西洋の知識体系」という用語の使用について、Jaco S. Dreyerは 「西洋の知識体系」という概念は、西洋近代の一部として、ヨーロッパ、そして後に他の「先進国」において、科学知識の制度化と発展、そして現在の学問にお けるその継続を指すために使用している。これは、西洋世界における何百年にもわたる科学の発展を極端に単純化していることは承知している。また、この定式 化では、この知識体系における認識論、存在論、方法論、価値論の多様な組み合わせについても看過している。」[4] |

| Further reading Apffel-Marglin, F.; Marglin, S.A. (1996). Decolonizing Knowledge: From Development to Dialogue. WIDER Studies in Development Economics. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-158396-4. Bendix, D.; Müller, F.; Ziai, A. (2020). Beyond the Master's Tools?: Decolonizing Knowledge Orders, Research Methods and Teaching. Kilombo: International Relations and Colonial Questions. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78661-360-8. Dhanda, A.; Parashar, A. (2012). Decolonisation of Legal Knowledge. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-51772-3. Diversi, M.; Moreira, C. (2016). Betweener Talk: Decolonizing Knowledge Production, Pedagogy, and Praxis. Qualitative Inquiry and Social Justice. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-315-43304-2. Jansen, J. (2019). Decolonisation in Universities: The politics of knowledge. Wits University Press. ISBN 978-1-77614-470-9. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S.J.; Zondi, S. (2016). Decolonizing the University, Knowledge Systems and Disciplines in Africa. African World Series. Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-61163-833-2. Rodríguez, E.G.; Boatcă, M.M.; Costa, P.D.S.; Holton, P.R. (2012). Decolonizing European Sociology: Transdisciplinary Approaches. Global Connections. Ashgate Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4094-9237-5. Wood, D.A. (2020). Epistemic Decolonization: A Critical Investigation into the Anticolonial Politics of Knowledge. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-030-49962-4. ++++++++++++++++++++++ References Chowdhury, Rashedur (2019). "From Black Pain to Rhodes Must Fall: A Rejectionist Perspective". Journal of Business Ethics. 170 (2): 287–311. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04350-1. ISSN 0167-4544. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. (2013). "Perhaps Decoloniality is the Answer? Critical Reflections on Development from a Decolonial Epistemic Perspective". Africanus. 43 (2): 1–12 [7]. doi:10.25159/0304-615X/2298. hdl:10520/EJC142701. Zavala, Miguel (2017). "Decolonizing Knowledge Production". In Peters, M.A (ed.). Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory. Springer, Singapore. pp. 361–366 [362]. doi:10.1007/978-981-287-588-4_508. ISBN 978-981-287-587-7. Dreyer, Jaco S. (2017). "Practical theology and the call for the decolonisation of higher education in South Africa: Reflections and proposals". HTS Theological Studies. 73 (4): 1–7 [2, 3, 5]. doi:10.4102/hts.v73i4.4805. ISSN 0259-9422. Broadbent, Alex (2017-06-01). "It will take critical, thorough scrutiny to truly decolonise knowledge". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2022-07-12. Retrieved 2022-07-12. Hira, Sandew (2017). "Decolonizing Knowledge Production". In Peters, M.A (ed.). Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory. Springer, Singapore. pp. 375–382 [375, 376]. doi:10.1007/978-981-287-588-4_508. ISBN 978-981-287-587-7. Beer, Andreas; Mackenthun, Gesa, eds. (2015). "Introduction". Fugitive Knowledge. The Loss and Preservation of Knowledge in Cultural Contact Zones (PDF). Waxmann Verlag GmbH. p. 13. doi:10.31244/9783830982814. ISBN 978-3-8309-3281-9. Heleta, Savo (2018). "Decolonizing Knowledge in South Africa: Dismantling the 'pedagogy of big lies'". Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies. 40 (2): 47–65 [48–50]. doi:10.5070/F7402040942. Hall, Budd L.; Tandon, Rajesh (2017-01-01). "Decolonization of knowledge, epistemicide, participatory research and higher education". Research for All. 1 (1). UCL Press: 6–19 [11–13]. doi:10.18546/rfa.01.1.02. ISSN 2399-8121. Ivanovic, Mladjo (2019). "Echoes of the Past: Colonial Legacy and Eurocentric Humanitarianism". The Rest Write Back: Discourse and Decolonization. BRILL. pp. 82–102 [98]. doi:10.1163/9789004398313_005. ISBN 978-90-04-39831-3. S2CID 203279612. Rohrer, J. (2016). Staking Claim: Settler Colonialism and Racialization in Hawai'i. Critical Issues in Indigenous Studies. University of Arizona Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8165-0251-6. Dussel, Enrique (2019). "Epistemological Decolonization of Theology". In Barreto, Raimundo; Sirvent, Roberto (eds.). Decolonial Christianities: Latinx and Latin American Perspective. Springer Nature. pp. 25, 26. ISBN 9783030241667. Andraos, Michel Elias (2012). "Engaging Diversity in Teaching Religion and Theology: An Intercultural, De-colonial Epistemic Perspective". Teaching Theology and Religion. 15 (1): 3–15 [8]. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9647.2011.00755.x. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J (2020). "The Dynamics of Epistemological Decolonisation in the 21st Century: Towards Epistemic Freedom". Strategic Review for Southern Africa. 40 (1): 16–45 [18, 21, 30]. doi:10.35293/SRSA.V40I1.268. S2CID 197907452. Naude, Piet (2017-12-13). "Decolonising Knowledge: Can Ubuntu Ethics Save Us from Coloniality?". Journal of Business Ethics. 159 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 23–37 [23–24]. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3763-4. ISSN 0167-4544. S2CID 254383348. de Sousa Santos, B. (2015). Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. Taylor & Francis. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-317-26034-9. de Sousa Santos, Boaventura; Nunes, Joao Arriscado; Meneses, Maria Paula (2007). "Introduction: Opening Up the Canon of Knowledge and Recognition of Difference". In de Sousa Santos, Boaventura (ed.). Another Knowledge is Possible: Beyond Northern Epistemologies. Verso. pp. xix. ISBN 9781844671175. Gordon, Lewis R. (2014). "Disciplinary Decadence and the Decolonisation of Knowledge". Africa Development. XXXIX (1): 81–92 [81]. Mignolo, Walter D.; Tlostanova, Madina V. (2006). "Theorizing from the Borders: Shifting to Geo- and Body-Politics of Knowledge". European Journal of Social Theory. 9 (2): 205–221 [205]. doi:10.1177/1368431006063333. S2CID 145222448. O’Halloran, Paddy (2016). "The 'African University' as a Site of Protest: Decolonisation, Praxis and the Black Student Movement at the University Currently Known as Rhodes". Interface. 8 (2): 184–210 [185]. Quijano, Anibal (2013). "Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality". In Mignolo, Walter D.; Escober, Arturo (eds.). Globalization and the Decolonial Option. Taylor & Francis. p. 31. ISBN 9781317966708. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo (2017). "The emergence and trajectories of struggles for an 'African university': The case of unfinished business of African epistemic decolonisation". Kronos. 43 (1): 51–77 [71]. doi:10.17159/2309-9585/2017/v43a4. S2CID 149517490. Kemp, Susan P.; Samuels, Gina Miranda (2019). "Theory in Social Work Science". Shaping a Science of Social Work. Oxford University Press. pp. 102–128 [120]. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190880668.003.0007. ISBN 978-0-19-088066-8. Gordon, Lewis R. (2010). "Fanon on Decolonizing Knowledge". In Hoppe, Elizabeth A.; Nicholls, Tracey Nicholls (eds.). Fanon and Decolonization of Philosophy. Lexington Books. p. 13. ISBN 9780739141274. Olivier, Bert (2019). "Decolonization, Identity, Neo-Colonialism and Power". Phornimon. 20: 1–18 [1–2]. Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books. Elliott, Michael. "Participatory parity and indigenous decolonization struggles." Constellations (2016): 1-12. Hill, Gord. 500 years of Indigenous resistance. PM Press, 2010. Botha, Louis; Griffiths, Dominic; Prozesky, Maria (2021-06-07). "Epistemological Decolonization through a Relational Knowledge- Making Model". Africa Today. 67 (4): 50-72 [52-53]. doi:10.2979/africatoday.67.4.04. S2CID 235375981. Retrieved 2022-06-28. Yako, Louis (2021-04-09). "Decolonizing Knowledge Production: a Practical Guide". CounterPunch.org. Archived from the original on 2022-07-12. Retrieved 2022-07-12. Kessi, Shose; Marks, Zoe; Ramugondo, Elelwani (2021-01-02). "Decolonizing knowledge within and beyond the classroom". Critical African Studies. 13 (1). Informa UK Limited: 1–9 [6]. doi:10.1080/21681392.2021.1920749. ISSN 2168-1392. S2CID 235336961. "Decolonising the curriculum – how do I get started?". THE Campus Learn, Share, Connect. 2021-09-14. Archived from the original on 2022-07-12. Retrieved 2022-07-12. Mamdani, Mahmood (2019-08-01). "Decolonising Universities". Decolonisation in Universities. Wits University Press. pp. 15–28 [25–26]. doi:10.18772/22019083351.6. ISBN 9781776143368. S2CID 241017315. Behm, Amanda; Fryar, Christienna; Hunter, Emma; Leake, Elisabeth; Lewis, Su Lin; Miller-Davenport, Sarah (2020). "Decolonizing History: Enquiry and Practice". History Workshop Journal. 89. Oxford University Press (OUP): 169–191 [169]. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbz052. ISSN 1363-3554. Roy, Rohan Deb (2018-04-05). "Decolonise science – time to end another imperial era". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2022-07-26. Retrieved 2022-07-26. Boisselle, Laila N. (2016-01-01). "Decolonizing Science and Science Education in a Postcolonial Space (Trinidad, a Developing Caribbean Nation, Illustrates)". SAGE Open. 6 (1). SAGE Publications: 1-11 [4-5]. doi:10.1177/2158244016635257. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 147061803. "Global and Islamic approach to philosophy highlighted". The Express Tribune. 2022-04-12. Archived from the original on 2022-07-12. Retrieved 2022-07-12. Mignolo, Walter (2011-11-01). "Decolonizing Western Epistemology / Building Decolonial Epistemologies". Decolonizing Epistemologies. Fordham University Press. pp. 19–43. doi:10.5422/fordham/9780823241354.003.0002. ISBN 9780823241354. Kessi, Shose (2016-09-27). "Decolonising psychology creates possibilities for social change". The Conversation. Retrieved 2022-07-07. Bhatia, Sunil (2020-07-02). "Decolonizing psychology: Power, citizenship and identity". Psychoanalysis, Self and Context. 15 (3). Informa UK Limited: 257–266 [258]. doi:10.1080/24720038.2020.1772266. ISSN 2472-0038. S2CID 221063253. Connell, Raewyn (2018-06-27). "Decolonizing Sociology". Contemporary Sociology: A Journal of Reviews. 47 (4). SAGE Publications: 399–407. doi:10.1177/0094306118779811. ISSN 0094-3061. S2CID 220186966. Nye, Malory (2019). "Decolonizing the Study of Religion". Open Library of Humanities. 5 (1). Open Library of the Humanities: 1–45 [10, 27]. doi:10.16995/olh.421. ISSN 2056-6700. S2CID 197716531. Tayob, Abdulkader (2018). "Decolonizing the Study of Religions: Muslim Intellectuals and the Enlightenment Project of Religious Studies". Journal for the Study of Religion. 31 (2). Academy of Science of South Africa: 7–35. doi:10.17159/2413-3027/2018/v31n2a1. ISSN 1011-7601. González, Aitor Jiménez (2018). "Decolonizing Legal Studies: A Latin Americanist perspective". In Cupples, Julie; Grosfoguel, Ramón (eds.). Unsettling Eurocentrism in the Westernized University (PDF). Routledge. pp. 131–144 [133, 138]. doi:10.4324/9781315162126. ISBN 978-1-315-16212-6. S2CID 150494638. "Decolonising History - University of Exeter". History. 2022-08-03. Archived from the original on 2022-08-03. Retrieved 2022-08-03. McClure, Julia (2020). "Connected global intellectual history and the decolonisation of the curriculum" (PDF). History Compass. 19 (1). Wiley: 1-9 [6]. doi:10.1111/hic3.12645. ISSN 1478-0542. S2CID 229434460. "It is possible to decolonise science". The Mail & Guardian. 2020-08-31. Archived from the original on 2022-07-17. Retrieved 2022-07-17. Jandrić, P.; Ford, D.R. (2022). Postdigital Ecopedagogies: Genealogies, Contradictions, and Possible Futures. Postdigital Science and Education. Springer International Publishing. p. 107. ISBN 978-3-030-97262-2. Retrieved 2022-07-18. Sotillos, Samuel Bendeck (2021). "The Decolonization of Psychology or the Science of the Soul". Spirituality Studies. 7 (1): 18–37 [20-21, 25–26, 28–29, 30-31]. NEALE, TIMOTHY; KOWAL, EMMA (2020). "5. "Related" Histories: On Epistemic and Reparative Decolonization". History and Theory. 59 (3). Wiley: 403–412 [405–406]. doi:10.1111/hith.12168. ISSN 0018-2656. S2CID 225307665. Prakash Kumar; Projit Bihari Mukharji; Amit Prasad (2018). "Decolonizing Science in Asia". Verge: Studies in Global Asias. 4 (1). Project Muse: 24-43 [32-33]. doi:10.5749/vergstudglobasia.4.1.0024. ISSN 2373-5058. S2CID 186457149. Maldonado-Torres, Nelson ; Vizcaíno, Rafael ; Wallace, Jasmine & We, Jeong Eun Annabel (2018). Decolonising Philosophy. In Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial & Kerem Nişancıoğlu (eds.), Decolonising the University. London: Pluto Press. pp. 64-90 [65-66]. HIGGS, PHILIP (2012). "African Philosophy and the Decolonisation of Education in Africa: Some critical reflections". Educational Philosophy and Theory. 44 (sup2). Informa UK Limited: 37–55. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2011.00794.x. ISSN 0013-1857. S2CID 146304371. Raina, Dhruv (2012). "Decolonisation and the Entangled Histories of Science and Philosophy in India". Polish Sociological Review (178). Polskie Towarzystwo Socjologiczne (Polish Sociological Association): 187–201. ISSN 1231-1413. JSTOR 41969440. Retrieved 2022-06-29. Song, Yang (2022-03-26). ""Does Chinese philosophy count as philosophy?": decolonial awareness and practices in international English medium instruction programs". Higher Education. 85 (2). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 437–453. doi:10.1007/s10734-022-00842-8. ISSN 0018-1560. PMC 8961491. PMID 35370300. Baur, Nina (2021), "Decolonizing Social Science Methodology. Positionality in the German-Language Debate", Historical Social Research, 46 (2), GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften: 205-243 [206], doi:10.12759/HSR.46.2021.2.205-243, retrieved 2022-06-29 van Klinken, Adriaan (2019-10-23). "Studying religion in the pluriversity: decolonial perspectives" (PDF). Religion. 50 (1). Informa UK Limited: 148–155 [153]. doi:10.1080/0048721x.2019.1681108. ISSN 0048-721X. S2CID 210456233. Lumbard, Joseph (2022-02-17). "Decolonizing Quranic Studies". Religions. 13 (2). MDPI AG: 1-14 [1]. doi:10.3390/rel13020176. ISSN 2077-1444. Rizvi, Sajjad (2020-12-17). "Reversing the Gaze? Or Decolonizing the Study of the Qurʾan". Method & Theory in the Study of Religion. 33 (2): 122–138. doi:10.1163/15700682-12341511. ISSN 0943-3058. S2CID 233295198. Retrieved 2022-07-08. Karibi-Whyte, Asikia (2021). "An Agenda for Decolonising Law in Africa: Conceptualising the Curriculum". Journal of Decolonising Disciplines. 2 (2). University of Pretoria - ESI Press: 1-20 [4-5]. doi:10.35293/jdd.v2i1.30. ISSN 2664-3405. S2CID 236380247. Minasny, Budiman; Fiantis, Dian; Mulyanto, Budi; Sulaeman, Yiyi; Widyatmanti, Wirastuti (2020-08-15). "Global soil science research collaboration in the 21st century: Time to end helicopter research". Geoderma. 373: 114299. Bibcode:2020Geode.373k4299M. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114299. ISSN 0016-7061. Dahdouh-Guebas, Farid; Ahimbisibwe, J.; Van Moll, Rita; Koedam, Nico (2003-03-01). "Neo-colonial science by the most industrialised upon the least developed countries in peer-reviewed publishing". Scientometrics. 56 (3): 329–343. doi:10.1023/A:1022374703178. ISSN 1588-2861. S2CID 18463459. "Q&A: Parachute Science in Coral Reef Research". The Scientist Magazine®. Retrieved 2021-03-24. "The Problem With 'Parachute Science'". Science Friday. Retrieved 2021-03-24. "Scientists Say It's Time To End 'Parachute Research'". NPR.org. Retrieved 2021-03-24. Health, The Lancet Global (2018-06-01). "Closing the door on parachutes and parasites". The Lancet Global Health. 6 (6): e593. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30239-0. ISSN 2214-109X. PMID 29773111. S2CID 21725769. Smith, James (2018-08-01). "Parasitic and parachute research in global health". The Lancet Global Health. 6 (8): e838. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30315-2. ISSN 2214-109X. PMID 30012263. S2CID 51630341. "Helicopter Research". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2021-03-24. Vos, Asha de. "The Problem of 'Colonial Science'". Scientific American. Retrieved 2021-03-24. "The Traces of Colonialism in Science". Observatory of Educational Innovation. Retrieved 2021-03-24. Stefanoudis, Paris V.; Licuanan, Wilfredo Y.; Morrison, Tiffany H.; Talma, Sheena; Veitayaki, Joeli; Woodall, Lucy C. (2021-02-22). "Turning the tide of parachute science". Current Biology. 31 (4): R184–R185. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.029. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 33621503. Keikelame, Mpoe Johannah; Swartz, Leslie (2019-01-01). "Decolonising research methodologies: lessons from a qualitative research project, Cape Town, South Africa". Global Health Action. 12 (1). Informa UK Limited: 1561175. doi:10.1080/16549716.2018.1561175. ISSN 1654-9716. PMC 6346712. PMID 30661464. Thambinathan, Vivetha; Kinsella, Elizabeth Anne (2021-01-01). "Decolonizing Methodologies in Qualitative Research: Creating Spaces for Transformative Praxis". International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 20. SAGE Publications: 1–9. doi:10.1177/16094069211014766. ISSN 1609-4069. S2CID 235538554. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo (2017-09-26). "Decolonising research methodology must include undoing its dirty history". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2022-07-12. Retrieved 2022-07-12. Qato, Danya M. (2022-07-21). "Reflections on 'Decolonizing' Big Data in Global Health". Annals of Global Health. 88 (1): 56. doi:10.5334/aogh.3709. ISSN 2214-9996. PMC 9306674. PMID 35936229. Leone, Donald Zachary (2021). Data Colonialism in Canada: Decolonizing Data Through Indigenous data governance (Text thesis). Carleton University. doi:10.22215/etd/2021-14697. Naudé, P. (2021). Contemporary Management Education: Eight Questions That Will Shape its Future in the 21st Century. Future of Business and Finance. Springer International Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-3-030-87775-0. Pailey, Robtel Neajai (2019-06-10). "How to truly decolonise the study of Africa - Conflict". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 2022-07-12. Retrieved 2022-07-12. Táíwò, Olúfẹ́mi (2022). Against decolonisation: taking African agency seriously. African arguments. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 978-1-78738-692-1. Kurzwelly, Jonatan; Wilckens, Malin S (2023). "Calcified identities: Persisting essentialism in academic collections of human remains". Anthropological Theory. 23 (1): 100–122. doi:10.1177/14634996221133872. ISSN 1463-4996. S2CID 254352277. Kurzwelly, Jonatan (2023). "Bones and injustices: provenance research, restitutions and identity politics". Dialectical Anthropology. 47 (1): 45–56. doi:10.1007/s10624-022-09670-9. ISSN 1573-0786. S2CID 253144587. |