帝国主義

Imperialism

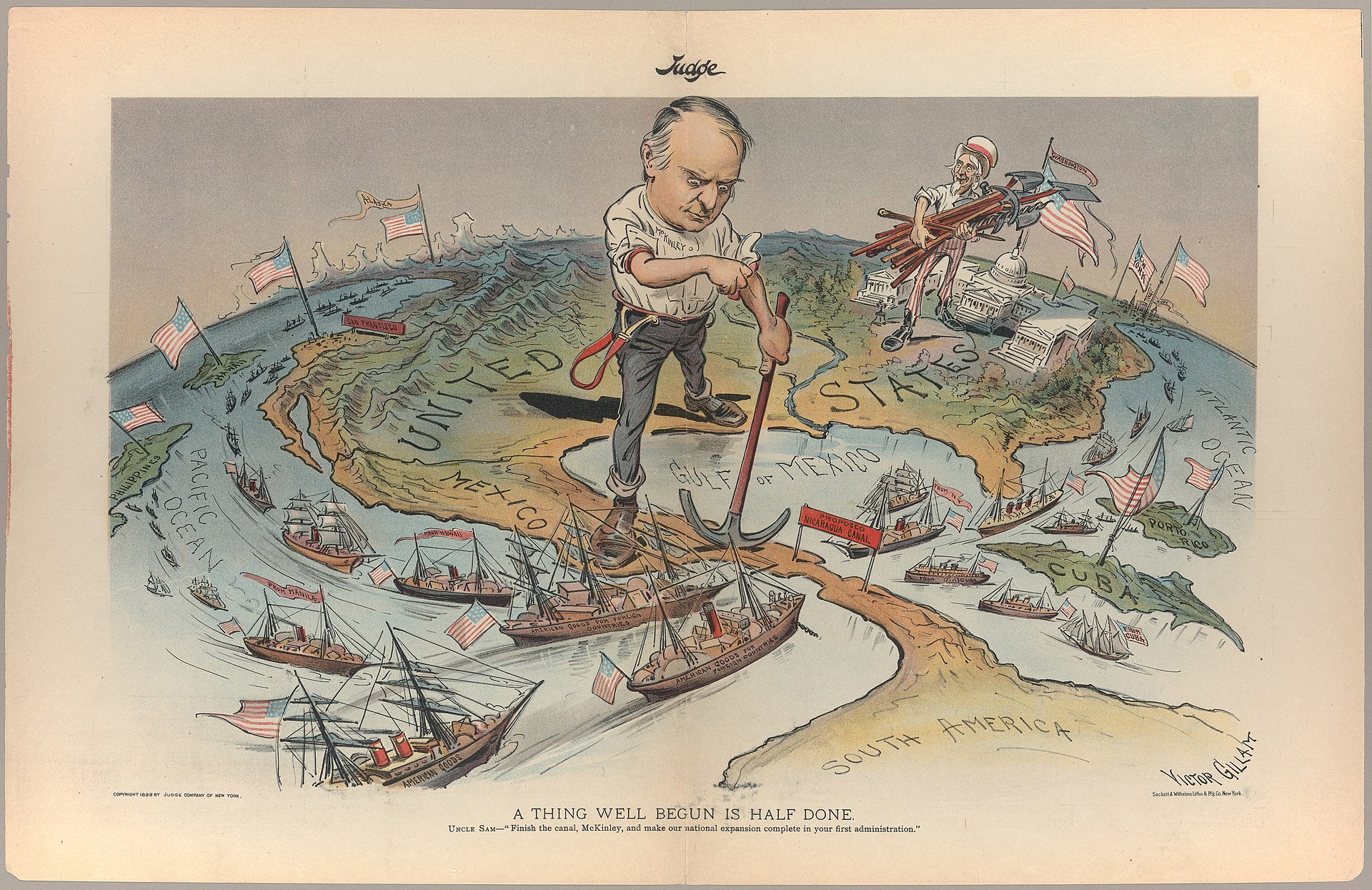

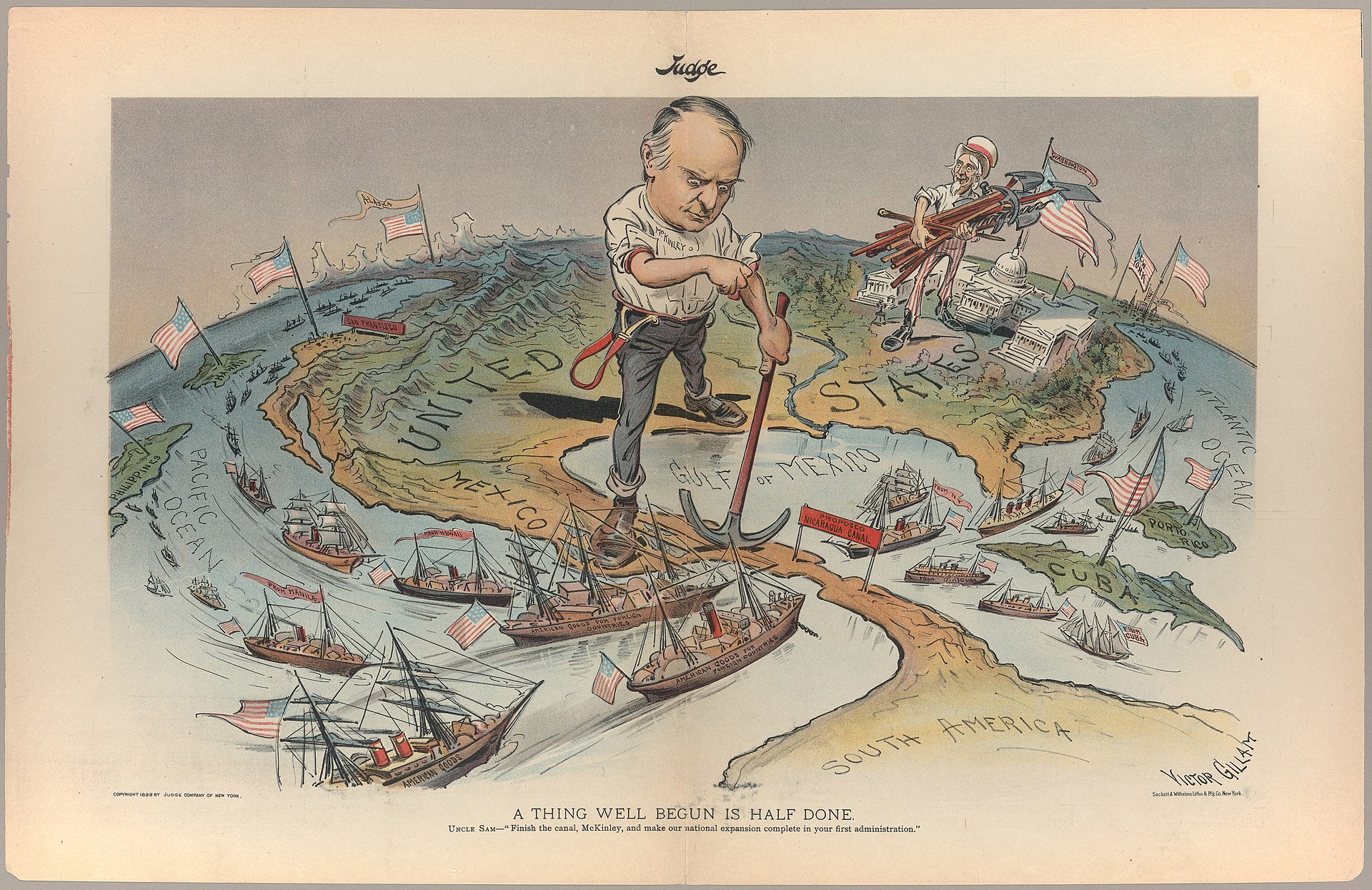

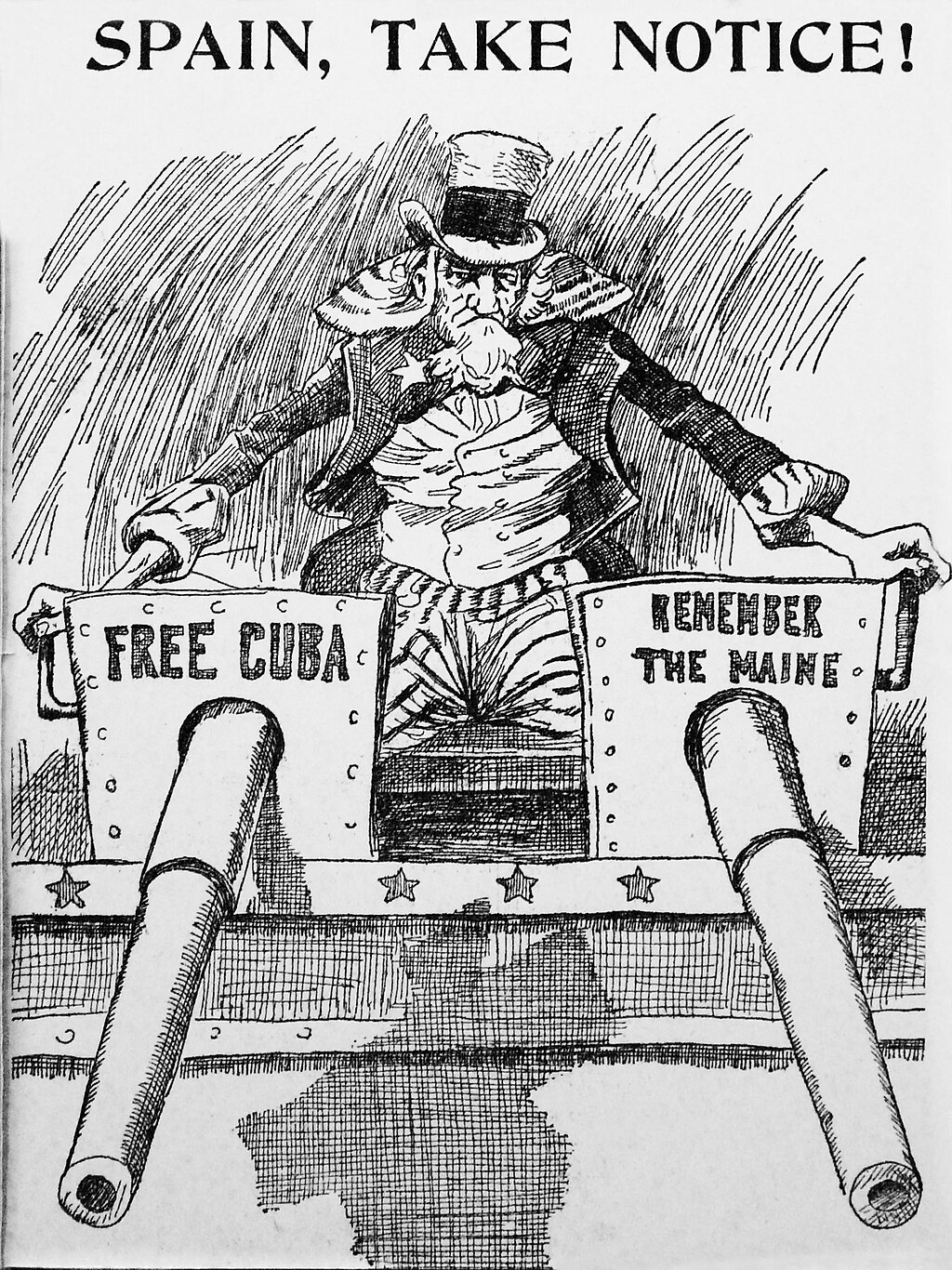

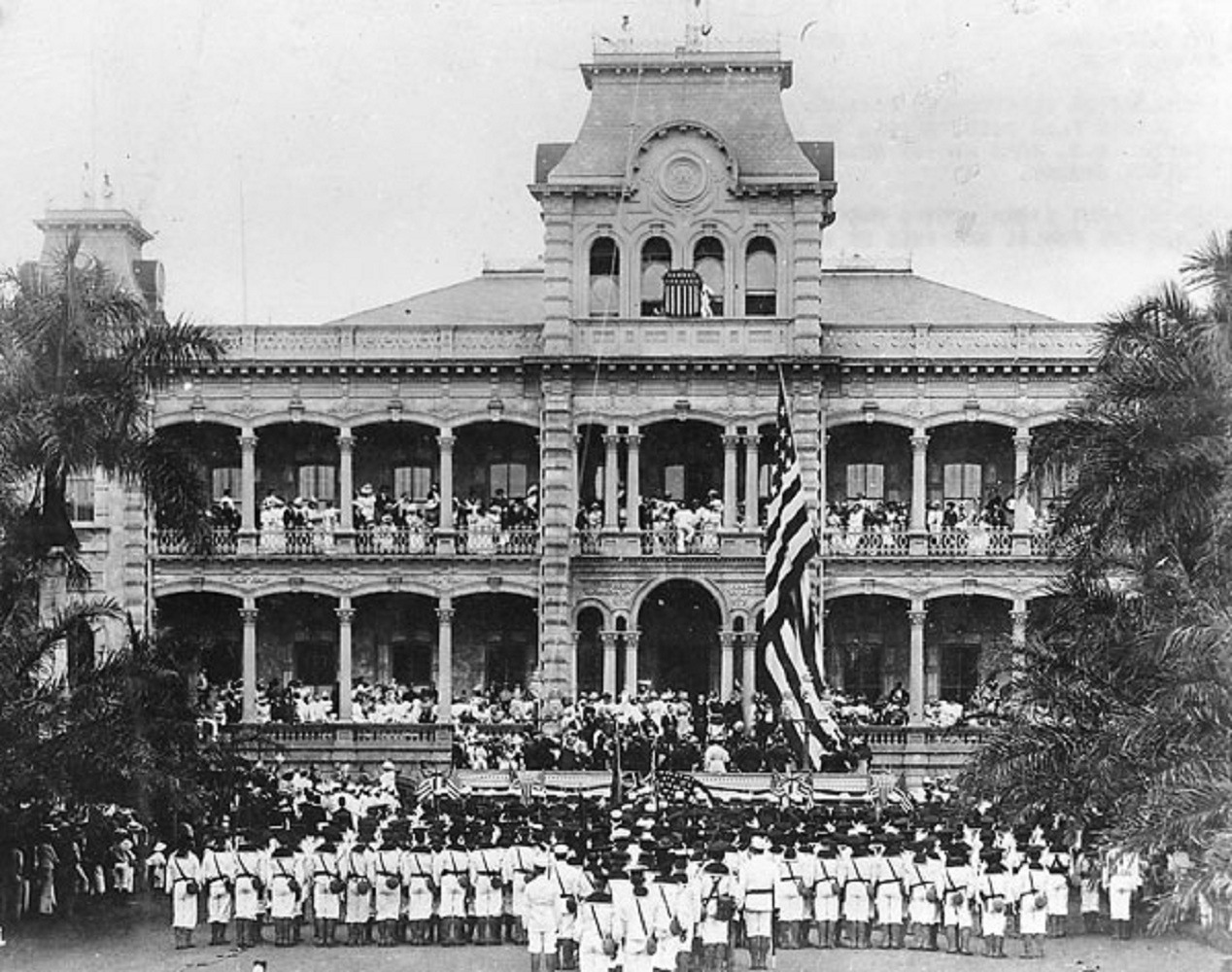

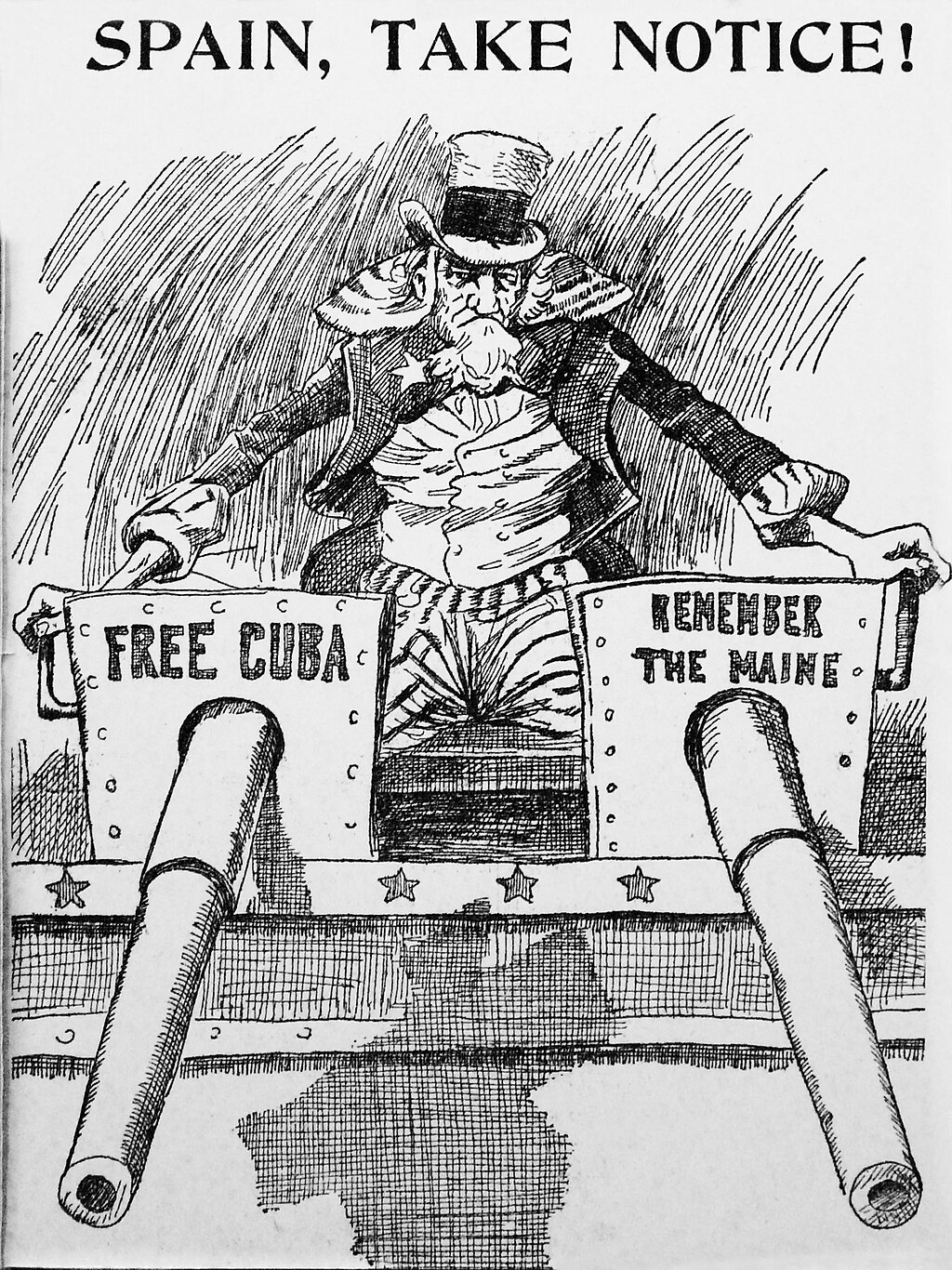

This

cartoon reflects the view of Judge magazine regarding America's

imperial ambitions following McKinley's quick victory in the

Spanish–American War of 1898.

☆帝国主義(Imperialism) とは、特に膨張主義を通じて、軍事力(軍事力および経済力)とソフトパワー(外交力および文化的帝国主義)の両方を用い、外国に対する支配力を維持または 拡大する行為、理論、または態度である。帝国主義は、覇権の確立または維持、およびある程度は形式的な帝国の確立に重点を置いている。 帝国主義は、植民地主義の概念と関連しているが、他の形態の拡張や多くの形態の政府にも適用できる、明確に区別される概念である。

★またエドワード・サイードによると、帝国主義とは「遠く離れた地域を支配する支配的中核都市の支配の実践、理論、態度」である(→「文化と帝国主義」)

☆またシステムとしての帝国主義は、植民地主義よりも統一された組織形態であり、世界の文明化計画を担うという自己規定をしているために、(経験主義的カテゴリーが強い)植民地主義とは一線を画す。そのため、帝国主義は、官僚組織、テクノロジー、および管理体制(→「統治性」)に特徴づけられる。

★帝国 主義とは、特に膨張主義を通じて、軍事力(軍事力および経済力)とソフトパワー(外交力および文化的帝国主義)の両方を用い、外国に対する支配力を維持ま たは拡大する行為、理論、または態度である。帝国主義は、覇権の確立または維持、およびある程度は形式的な帝国の確立に重点を置いている。帝国主義は、植民地主義の概念と関連しているが、他の形態の拡張や多くの形態の政府にも適用できる、明確に区別される概念である。

| Imperialism

is the practice, theory or attitude of maintaining or extending power

over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both

hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic

power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism focuses on establishing or

maintaining hegemony and a more or less formal empire.[2][3][4] While

related to the concepts of colonialism, imperialism is a distinct

concept that can apply to other forms of expansion and many forms of

government.[5] |

帝国

主義とは、特に膨張主義を通じて、軍事力(軍事力および経済力)とソフトパワー(外交力および文化的帝国主義)の両方を用い、外国に対する支配力を維持ま

たは拡大する行為、理論、または態度である。帝国主義は、覇権の確立または維持、およびある程度は形式的な帝国の確立に重点を置いている。[2][3]

[4] 帝国主義は、植民地主義の概念と関連しているが、他の形態の拡張や多くの形態の政府にも適用できる、明確に区別される概念である。[5] |

| Etymology and usage The word imperialism originated from the Latin word imperium,[6] which means "to command", "to be sovereign", or simply "to rule".[7] The word “imperialism” was first produced in the 19th century to decry Napoleon III's despotic militarism and his attempts at obtaining political support through foreign military interventions.[8][9] The term became common in the current sense in Great Britain during the 1870s; by the 1880's it was used with a positive connotation.[10] By the end of the 19th century it was being used to describe the behavior of empires at all times and places.[11] Hannah Arendt and Joseph Schumpeter defined imperialism as expansion for the sake of expansion.[12] The term was and is mainly applied to Western and Japanese political and economic dominance, especially in Asia and Africa, in the 19th and 20th centuries. Its precise meaning continues to be debated by scholars. Some writers, such as Edward Said, use the term more broadly to describe any system of domination and subordination organized around an imperial core and a periphery.[13] This definition encompasses both nominal empires and neocolonialism. |

語源と用法 帝国主義という語はラテン語のimperiumに由来し、[6]「命令する」、「主権を持つ」、または単に「支配する」という意味である。[7] 「帝国主義」という語は、19世紀にナポレオン3世の専制的な軍国主義と、外国への軍事介入による政治的支持の獲得を非難するために初めて使用された。 [8][9] この用語は、 1870年代には英国で一般的な意味となり、1880年代には肯定的な意味合いで使われるようになった。[10] 19世紀末には、あらゆる時代や場所における帝国の行動を表現する言葉として使われるようになった。[11] ハンナ・アレントとヨーゼフ・シュンペーターは、帝国主義を拡大のための拡大と定義した。[12] この用語は、19世紀から20世紀にかけて、主に西洋と日本の政治的・経済的支配、特にアジアとアフリカにおけるものに対して用いられてきた。その正確な 意味については、学者の間で議論が続いている。エドワード・サイードなどの作家は、帝国の中核と周辺を軸に組織された支配と従属のあらゆる体制をより広く 説明する用語として使用している。[13] この定義は名目上の帝国と新植民地主義の両方を包含している。 |

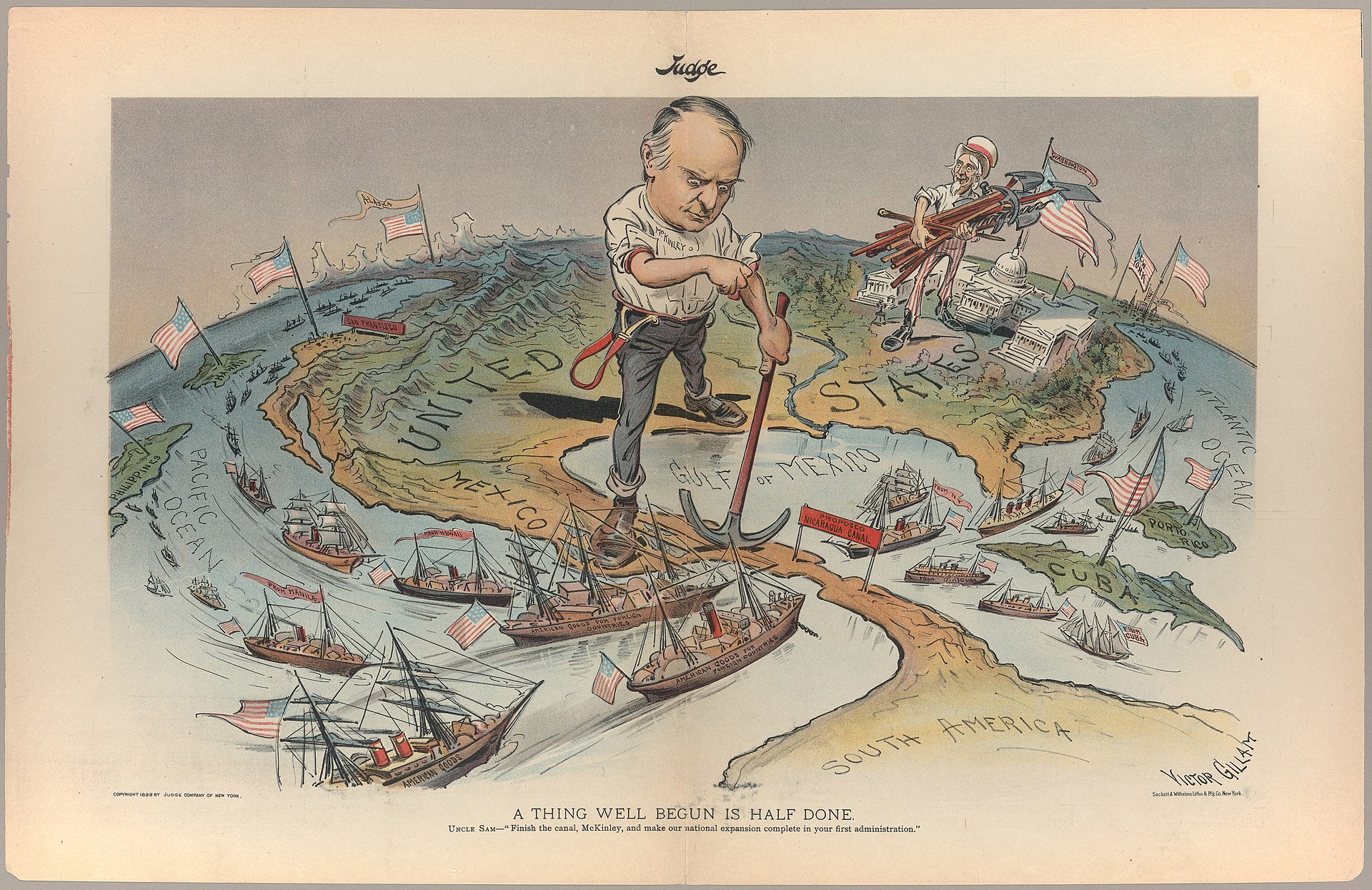

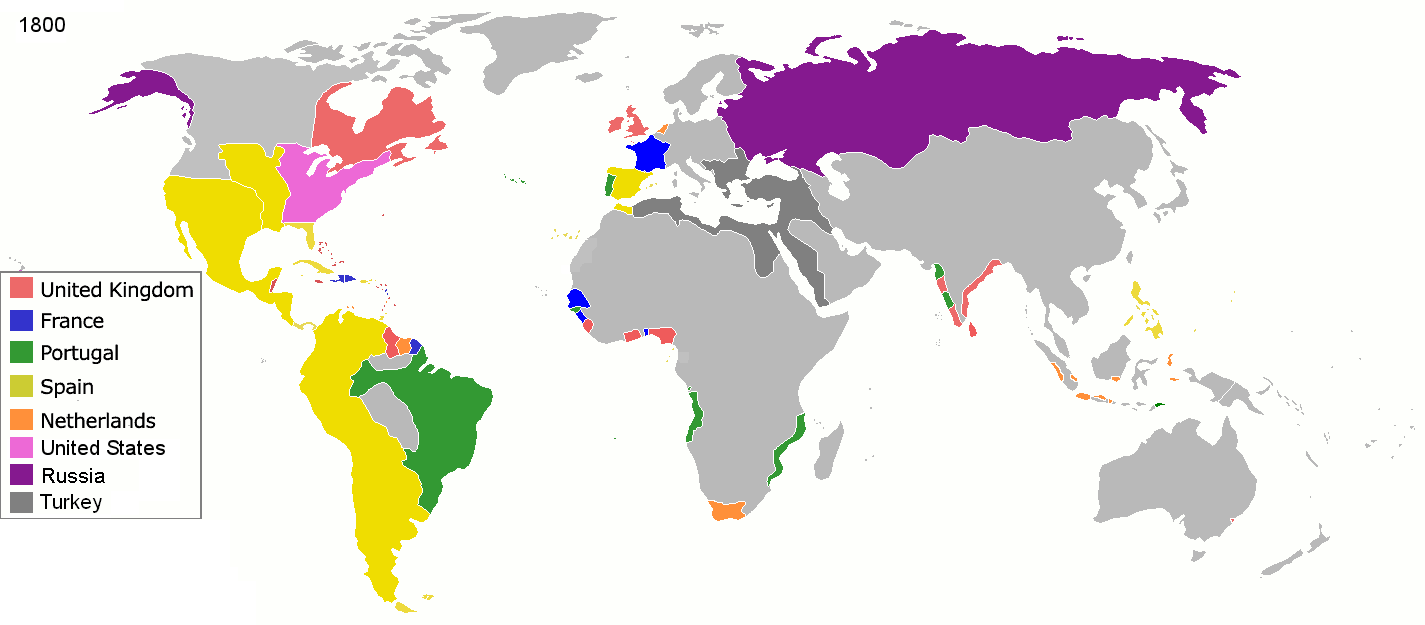

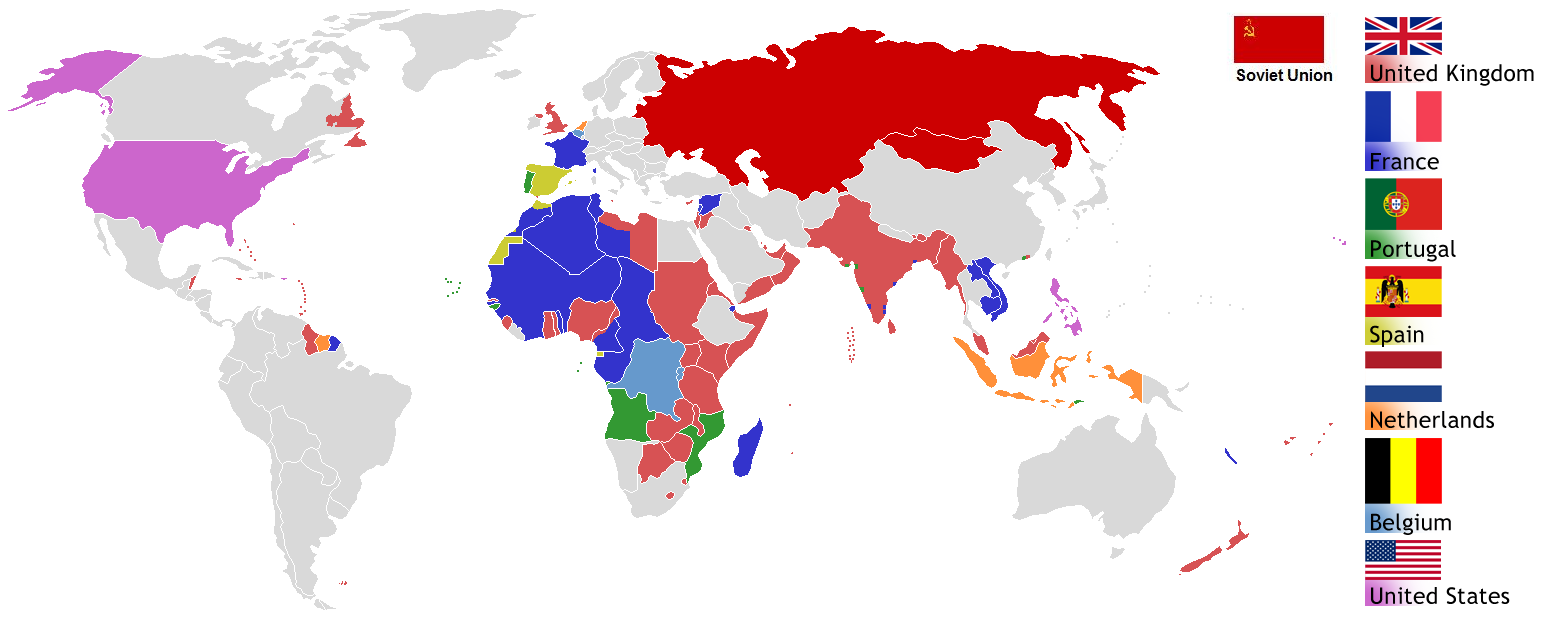

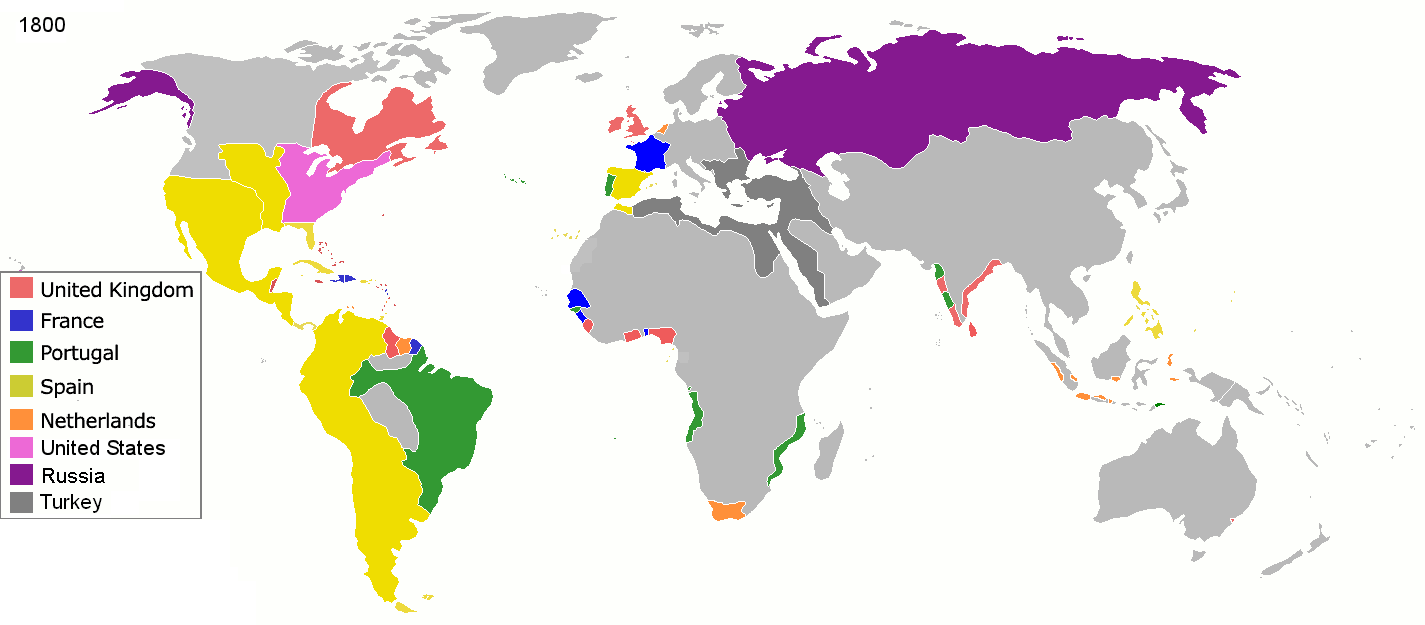

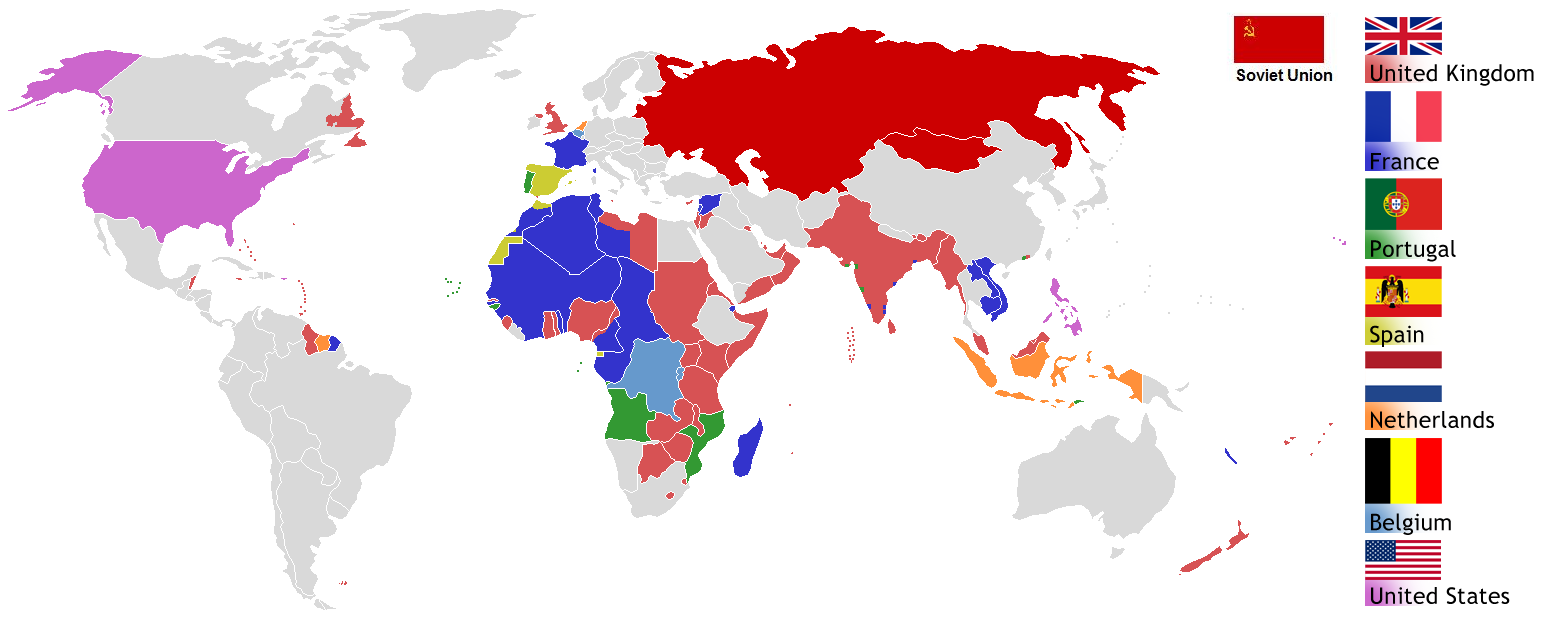

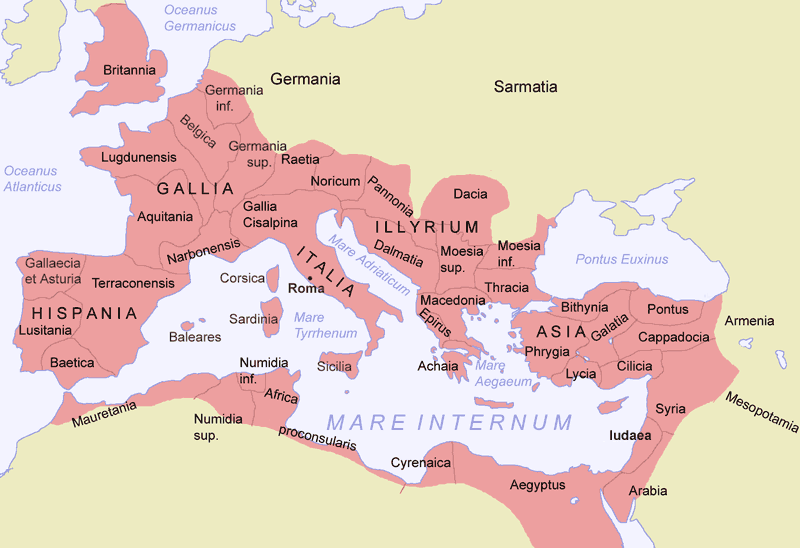

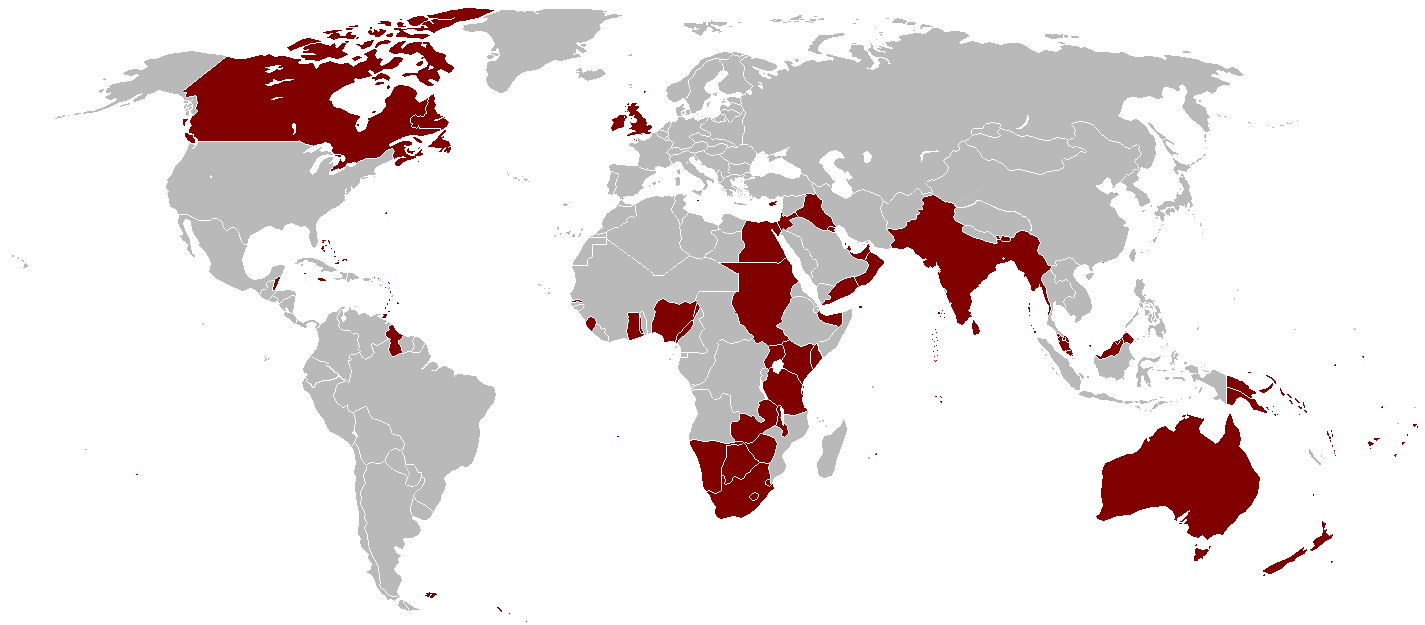

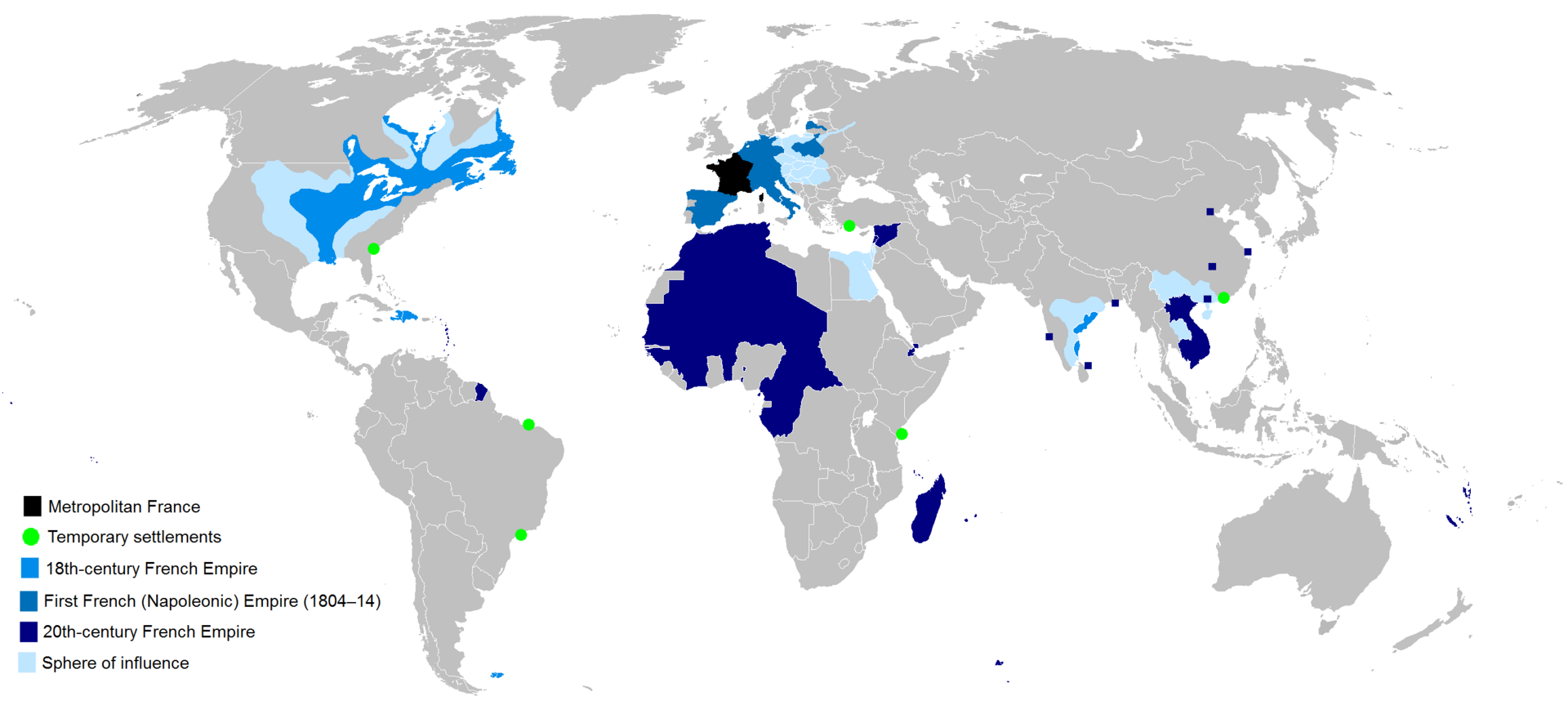

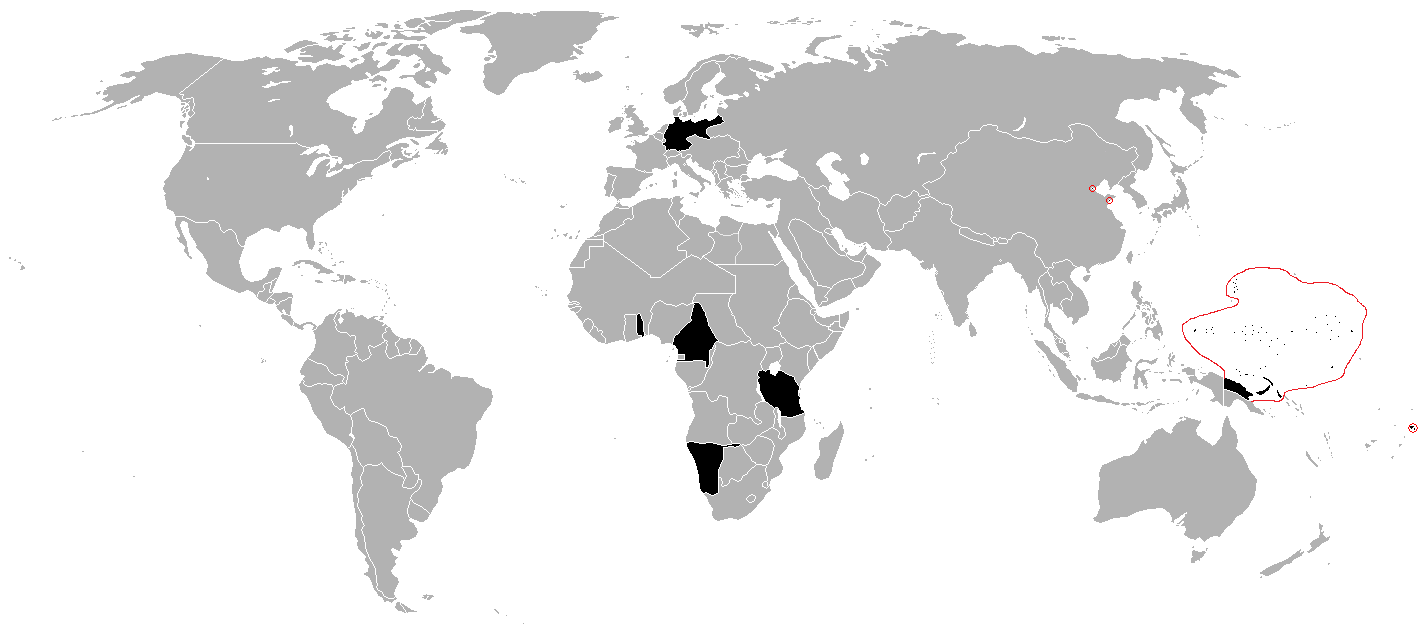

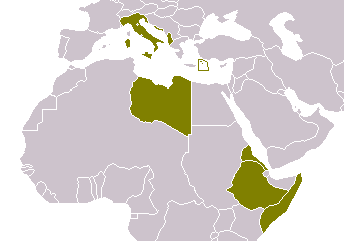

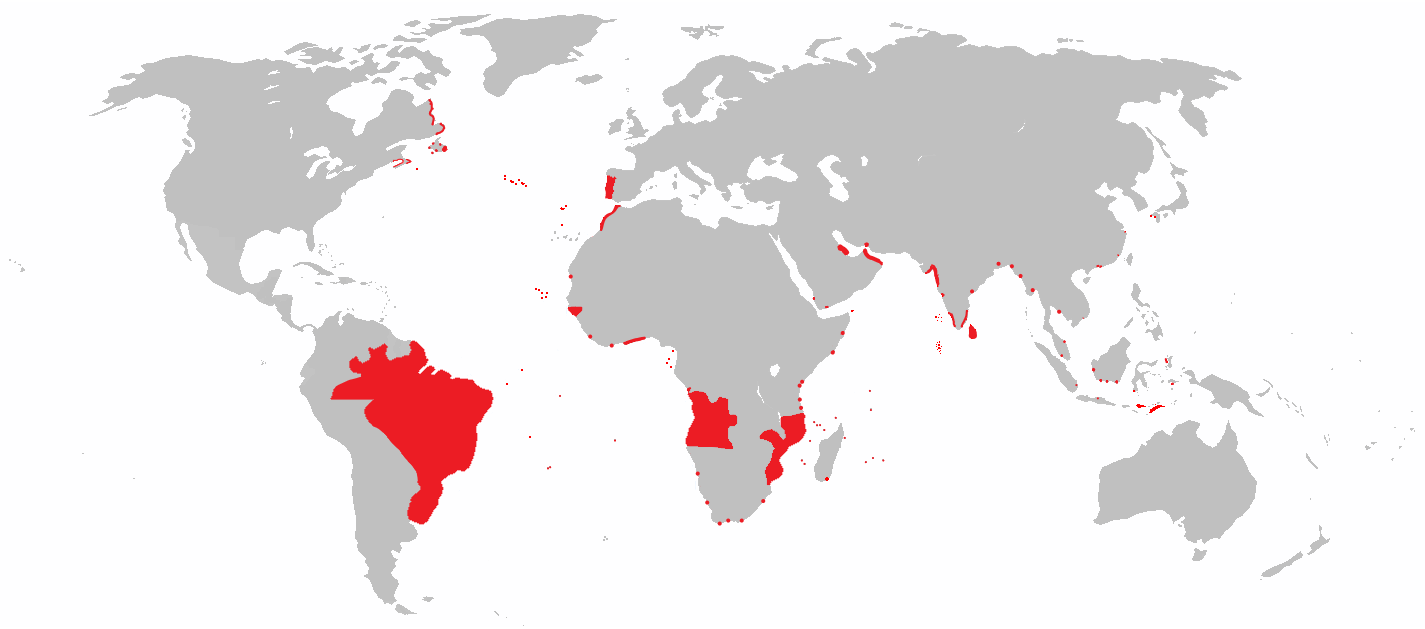

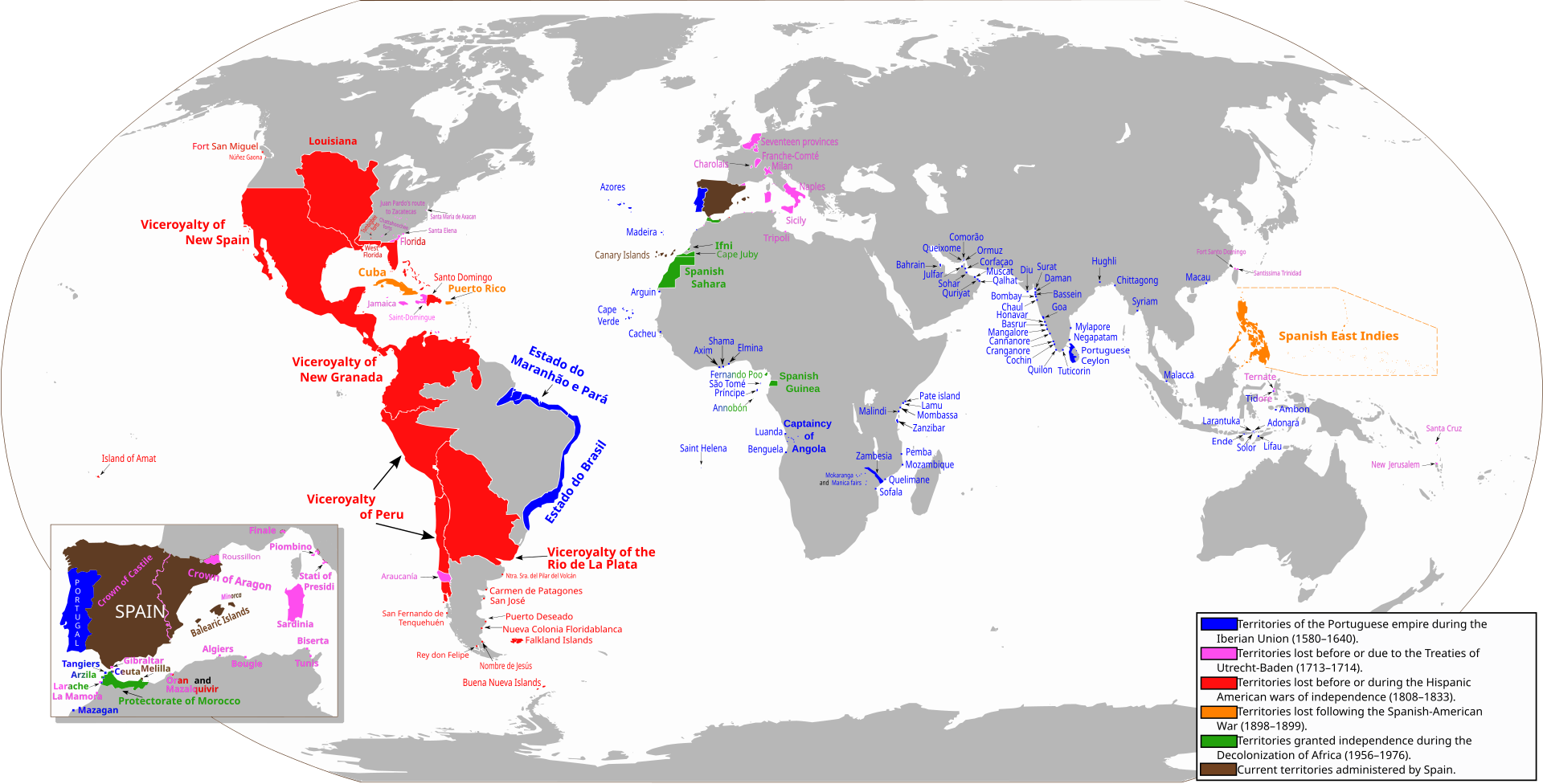

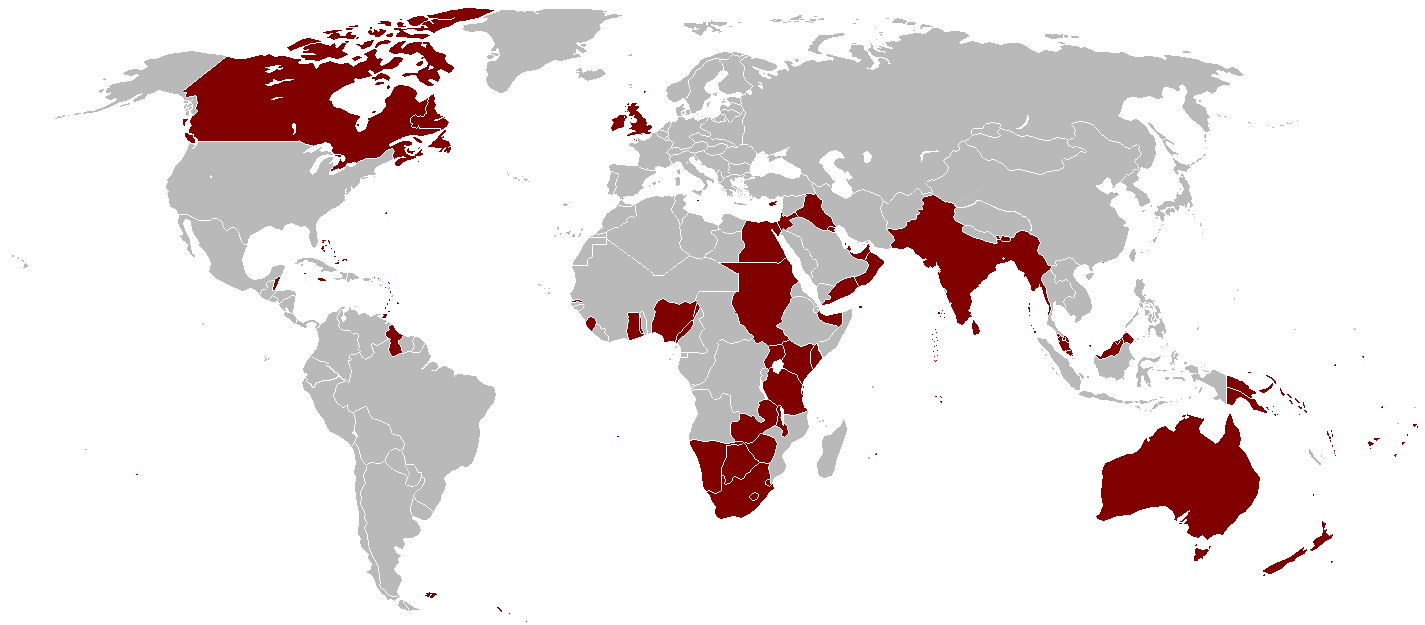

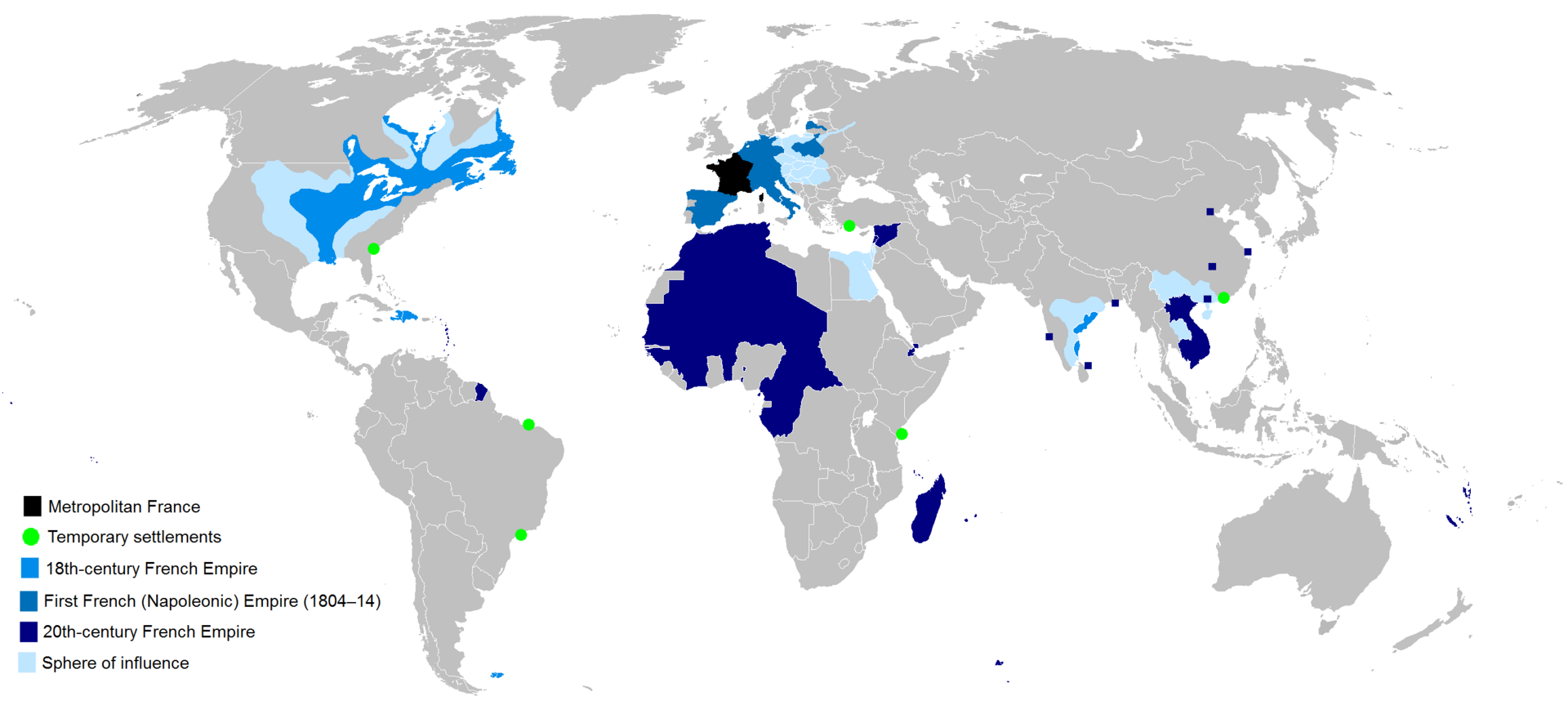

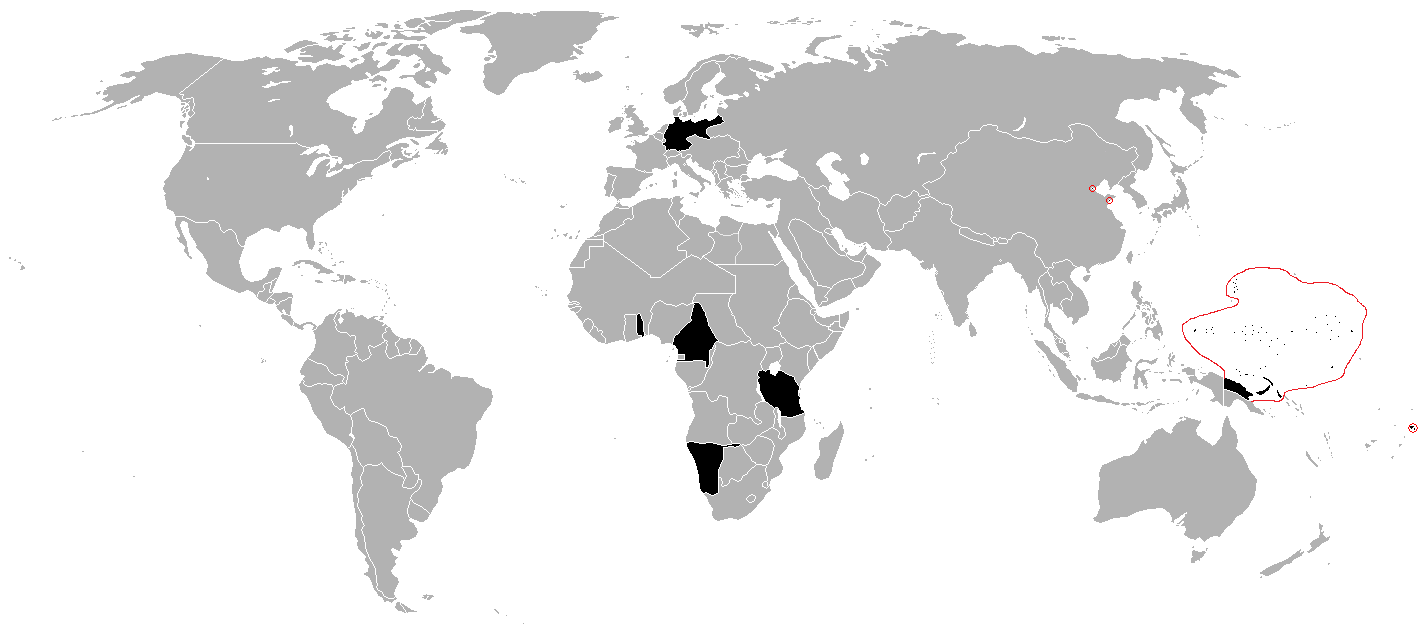

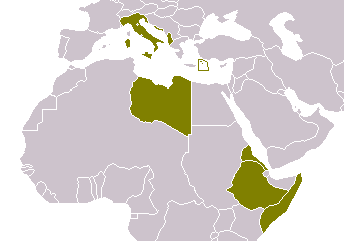

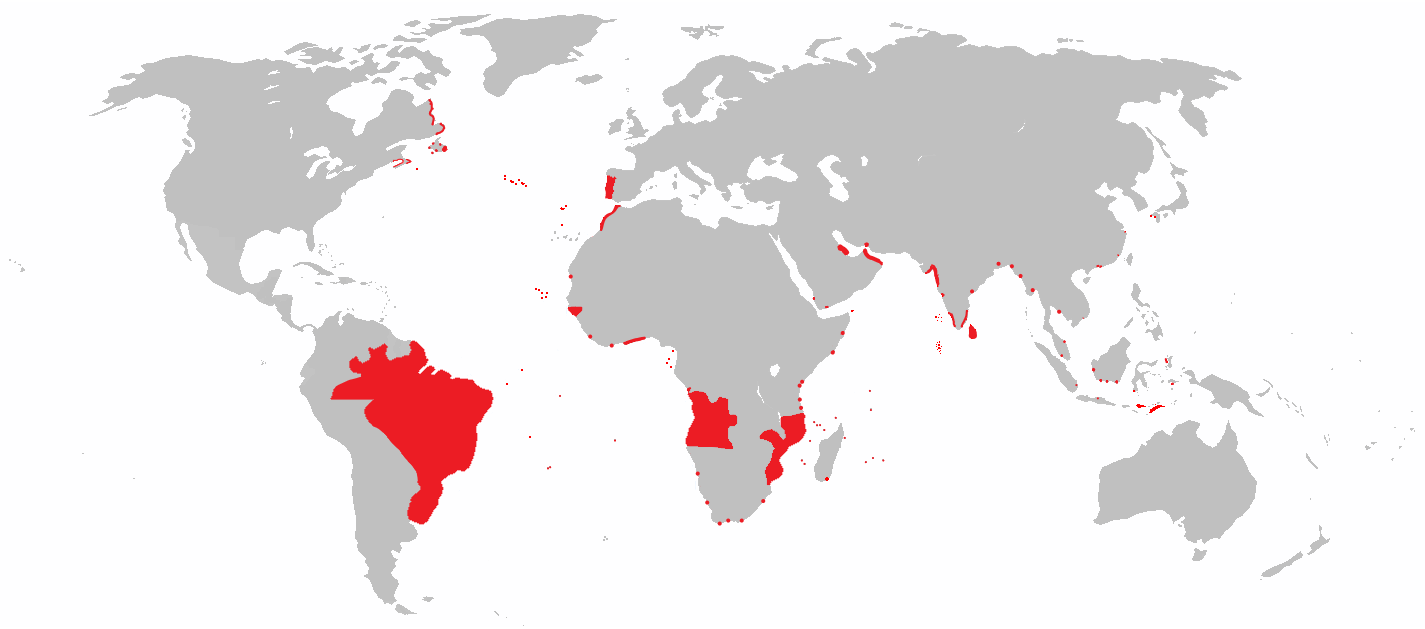

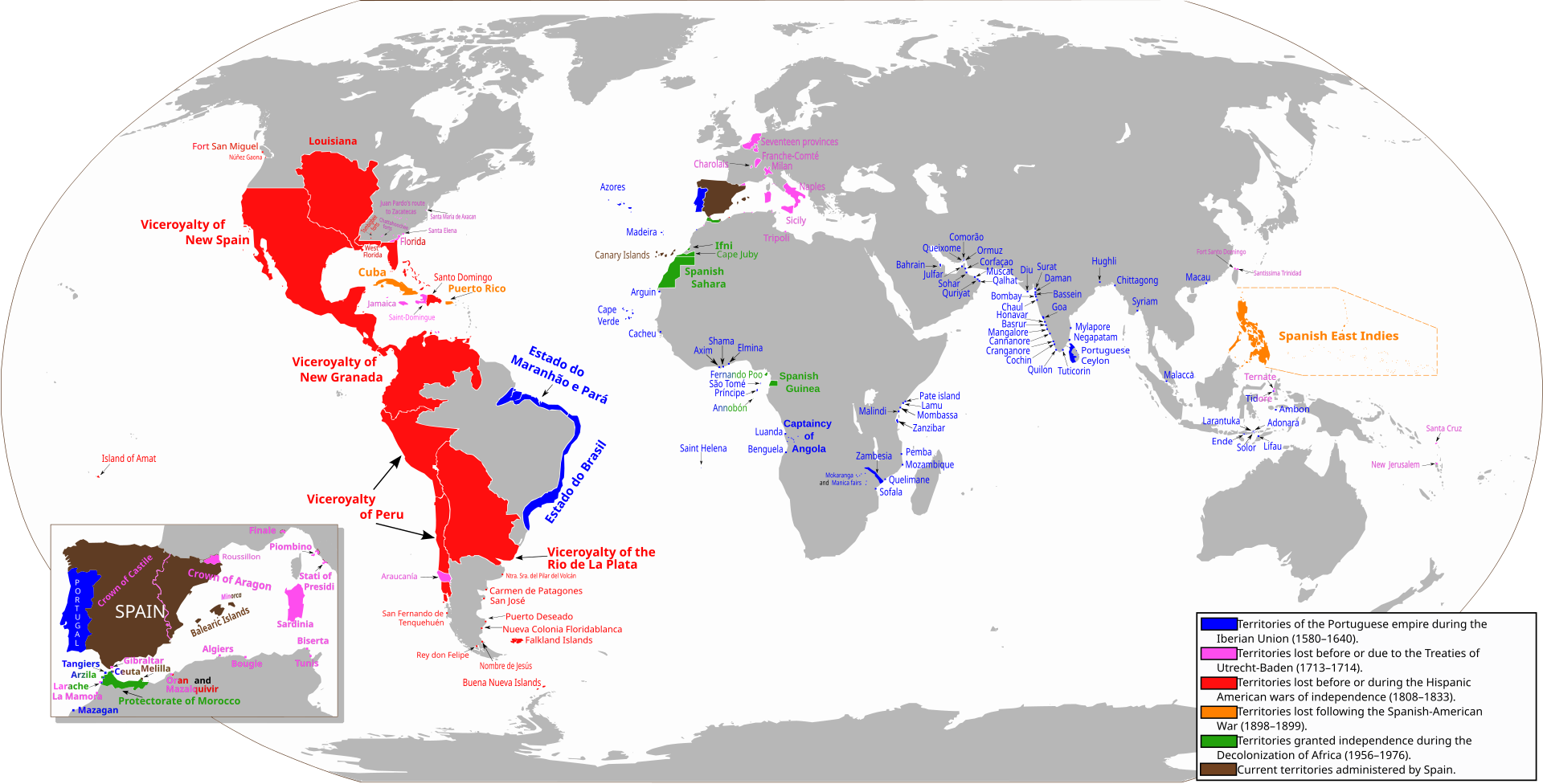

Versus colonialism Imperial powers in 1800[14]  Imperial powers in 1945 The term "imperialism" is often conflated with "colonialism"; however, many scholars have argued that each has its own distinct definition. Imperialism and colonialism have been used in order to describe one's influence upon a person or group of people. Robert Young writes that imperialism operates from the centre as a state policy and is developed for ideological as well as financial reasons, while colonialism is simply the development for settlement or commercial intentions; however, colonialism still includes invasion.[15] Colonialism in modern usage also tends to imply a degree of geographic separation between the colony and the imperial power. Particularly, Edward Said distinguishes between imperialism and colonialism by stating: "imperialism involved 'the practice, the theory and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory', while colonialism refers to the 'implanting of settlements on a distant territory.'[16] Contiguous land empires such as the Russian, Chinese or Ottoman have traditionally been excluded from discussions of colonialism, though this is beginning to change, since it is accepted that they also sent populations into the territories they ruled.[16]: 116 Imperialism and colonialism both dictate the political and economic advantage over a land and the indigenous populations they control, yet scholars sometimes find it difficult to illustrate the difference between the two.[17]: 107 Although imperialism and colonialism focus on the suppression of another, if colonialism refers to the process of a country taking physical control of another, imperialism refers to the political and monetary dominance, either formally or informally. Colonialism is seen to be the architect deciding how to start dominating areas and then imperialism can be seen as creating the idea behind conquest cooperating with colonialism. Colonialism is when the imperial nation begins a conquest over an area and then eventually is able to rule over the areas the previous nation had controlled. Colonialism's core meaning is the exploitation of the valuable assets and supplies of the nation that was conquered and the conquering nation then gaining the benefits from the spoils of the war.[17]: 170–75 The meaning of imperialism is to create an empire, by conquering the other state's lands and therefore increasing its own dominance. Colonialism is the builder and preserver of the colonial possessions in an area by a population coming from a foreign region.[17]: 173–76 Colonialism can completely change the existing social structure, physical structure, and economics of an area; it is not unusual that the characteristics of the conquering peoples are inherited by the conquered indigenous populations.[17]: 41 Few colonies remain remote from their mother country. Thus, most will eventually establish a separate nationality or remain under complete control of their mother colony.[18] The Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin suggested that "imperialism was the highest form of capitalism", claiming that "imperialism developed after colonialism, and was distinguished from colonialism by monopoly capitalism".[16]: 116 |

植民地主義に対する概念として 1800年の帝国主義諸国[14]  1945年の帝国主義諸国 「帝国主義」という用語は「植民地主義」と混同されることが多いが、多くの学者はそれぞれに独自の定義があることを主張している。帝国主義と植民地主義 は、個人または集団に対する影響力を説明する際に用いられてきた。ロバート・ヤングは、帝国主義は国家政策として中心から展開され、イデオロギー的および 財政的理由から発展するが、植民地主義は単に定住や商業目的のための開発であると記している。しかし、植民地主義には依然として侵略が含まれる。[15] 現代の用法における植民地主義は、植民地と帝国との間に地理的な隔たりがあることを暗示する傾向がある。特に、エドワード・サイードは次のように述べ、帝 国主義と植民地主義を区別している。「帝国主義は『遠く離れた領土を支配する大都市の中心部の支配の実践、理論、態度』を意味するが、植民地主義は『遠く 離れた領土への入植』を意味する」と述べている。[16] ロシア、中国、オスマン帝国などの陸続きの土地帝国は、伝統的に植民地主義の議論から除外されてきたが、支配下に人口を送り込んでいたことが認められるよ うになったため、この状況は変わり始めている。[16]: 116 帝国主義と植民地主義はどちらも、支配する土地と土着の住民に対して政治的・経済的な優位性を求めるものであるが、学者たちは両者の違いを説明することが 難しいと感じている。[17]: 107 帝国主義と植民地主義はどちらも他者の抑圧に重点を置いているが、植民地主義が他国が他国を物理的に支配する過程を指すのに対し、帝国主義は公式・非公式 を問わず、政治的・経済的な支配を指す。植民地主義は、ある地域を支配し始める方法を決定する建築家と見なすことができ、帝国主義は植民地主義と協力して 征服のアイデアを生み出すものと見なすことができる。植民地主義とは、帝国国家が地域に対する征服を開始し、最終的に以前の国家が支配していた地域を支配 下に置くことを指す。植民地主義の核心的な意味は、征服された国家の貴重な資産や物資を搾取することであり、征服国は戦利品から利益を得る。[17]: 170–75 帝国主義の意味は、他国の領土を征服することで帝国を築き、自国の支配力を高めることである。植民地主義とは、外国から来た人々による、ある地域における 植民地の建設と維持である。[17]: 173–76 植民地主義は、その地域の既存の社会構造、物理的構造、経済を完全に変えることができる。征服した先住民が征服者の特徴を受け継ぐことは珍しくない。 [17]: 41 植民地が本国から遠く離れたまま残ることはほとんどない。したがって、ほとんどの植民地は最終的に独自の国籍を確立するか、あるいは母国である植民地から の完全な支配下に置かれることになる。[18] ソビエト連邦の指導者ウラジーミル・レーニンは、「帝国主義は資本主義の最高形態である」と示唆し、「帝国主義は植民地主義の後に発展し、独占資本主義によって植民地主義と区別される」と主張した。[16]:116 |

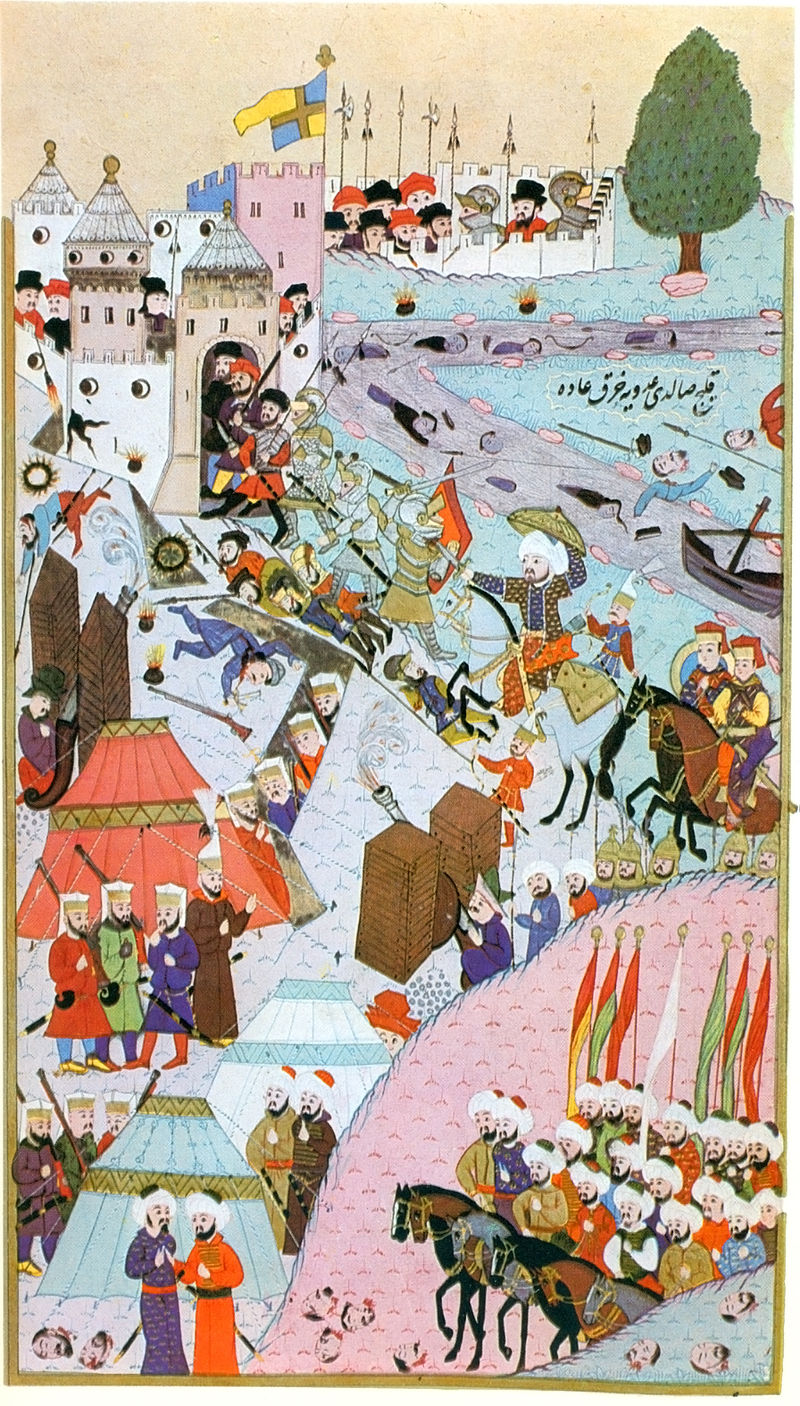

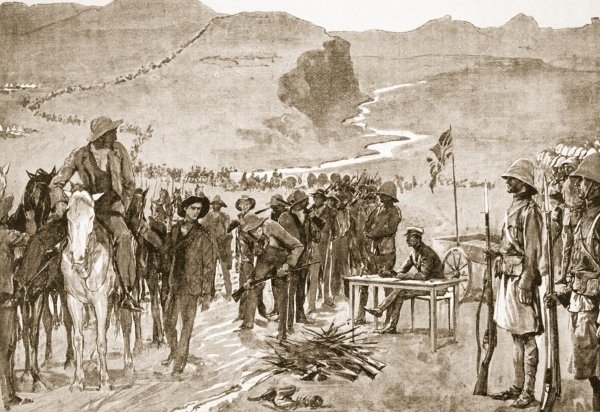

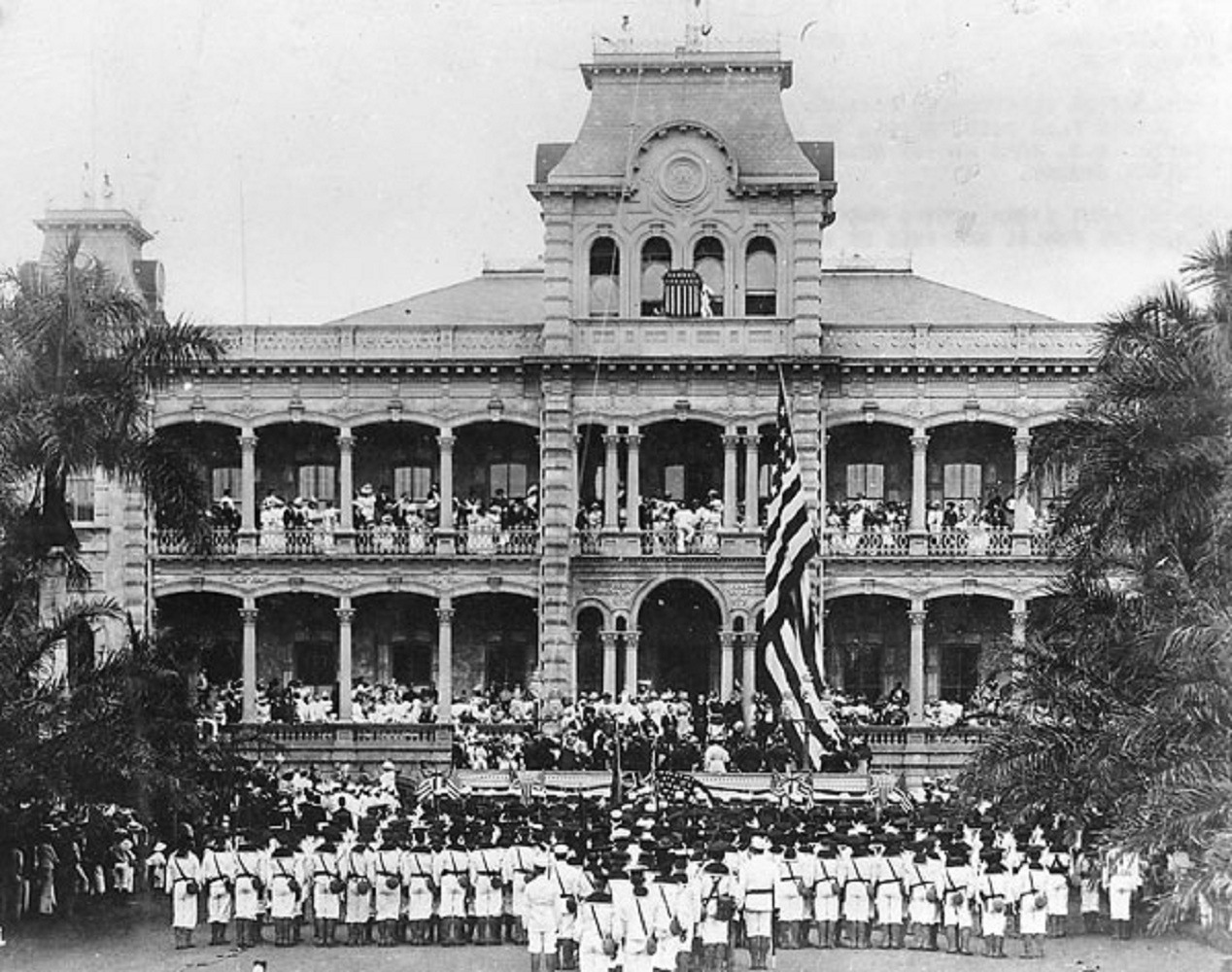

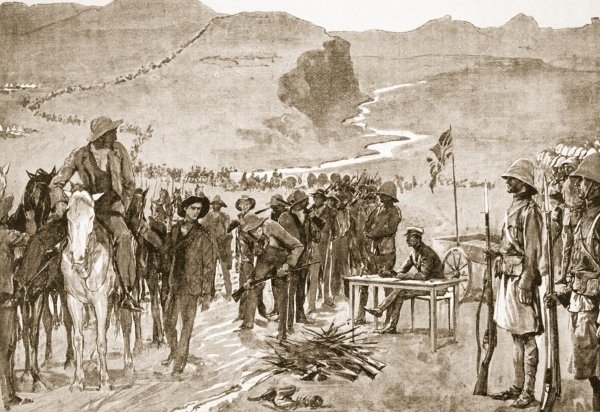

| Age of Imperialism "Imperial Age" redirects here. For the symphonic metal band, see Imperial Age (band). Main articles: International relations (1648–1814), International relations (1814–1919), and New Imperialism The Age of Imperialism, a time period beginning around 1760, saw European industrializing nations, engaging in the process of colonizing, influencing, and annexing other parts of the world.[19] 19th century episodes included the "Scramble for Africa."[20]  Africa, divided into colonies under multiple European empires, c. 1914 In the 1970s British historians John Gallagher (1919–1980) and Ronald Robinson (1920–1999) argued that European leaders rejected the notion that "imperialism" required formal, legal control by one government over a colonial region. Much more important was informal control of independent areas.[21] According to Wm. Roger Louis, "In their view, historians have been mesmerized by formal empire and maps of the world with regions colored red. The bulk of British emigration, trade, and capital went to areas outside the formal British Empire. Key to their thinking is the idea of empire 'informally if possible and formally if necessary.'"[22] Oron Hale says that Gallagher and Robinson looked at the British involvement in Africa where they "found few capitalists, less capital, and not much pressure from the alleged traditional promoters of colonial expansion. Cabinet decisions to annex or not to annex were made, usually on the basis of political or geopolitical considerations."[23]: 6 Looking at the main empires from 1875 to 1914, there was a mixed record in terms of profitability. At first, planners expected that colonies would provide an excellent captive market for manufactured items. Apart from the Indian subcontinent, this was seldom true. By the 1890s, imperialists saw the economic benefit primarily in the production of inexpensive raw materials to feed the domestic manufacturing sector. Overall, Great Britain did very well in terms of profits from India, especially Mughal Bengal, but not from most of the rest of its empire. According to Indian Economist Utsa Patnaik, the scale of the wealth transfer out of India, between 1765 and 1938, was an estimated $45 Trillion.[24] The Netherlands did very well in the East Indies. Germany and Italy got very little trade or raw materials from their empires. France did slightly better. The Belgian Congo was notoriously profitable when it was a capitalistic rubber plantation owned and operated by King Leopold II as a private enterprise. However, scandal after scandal regarding atrocities in the Congo Free State led the international community to force the government of Belgium to take it over in 1908, and it became much less profitable. The Philippines cost the United States much more than expected because of military action against rebels.[23]: 7–10 Because of the resources made available by imperialism, the world's economy grew significantly and became much more interconnected in the decades before World War I, making the many imperial powers rich and prosperous.[25] Europe's expansion into territorial imperialism was largely focused on economic growth by collecting resources from colonies, in combination with assuming political control by military and political means. The colonization of India in the mid-18th century offers an example of this focus: there, the "British exploited the political weakness of the Mughal state, and, while military activity was important at various times, the economic and administrative incorporation of local elites was also of crucial significance" for the establishment of control over the subcontinent's resources, markets, and manpower.[26] Although a substantial number of colonies had been designed to provide economic profit and to ship resources to home ports in the 17th and 18th centuries, D. K. Fieldhouse suggests that in the 19th and 20th centuries in places such as Africa and Asia, this idea is not necessarily valid:[27] Modern empires were not artificially constructed economic machines. The second expansion of Europe was a complex historical process in which political, social and emotional forces in Europe and on the periphery were more influential than calculated imperialism. Individual colonies might serve an economic purpose; collectively no empire had any definable function, economic or otherwise. Empires represented only a particular phase in the ever-changing relationship of Europe with the rest of the world: analogies with industrial systems or investment in real estate were simply misleading.[17]: 184 During this time, European merchants had the ability to "roam the high seas and appropriate surpluses from around the world (sometimes peaceably, sometimes violently) and to concentrate them in Europe".[28]  British assault on Canton during the First Opium War, May 1841 European expansion greatly accelerated in the 19th century. To obtain raw materials, Europe expanded imports from other countries and from the colonies. European industrialists sought raw materials such as dyes, cotton, vegetable oils, and metal ores from overseas. Concurrently, industrialization was quickly making Europe the centre of manufacturing and economic growth, driving resource needs.[29] Communication became much more advanced during European expansion. With the invention of railroads and telegraphs, it became easier to communicate with other countries and to extend the administrative control of a home nation over its colonies. Steam railroads and steam-driven ocean shipping made possible the fast, cheap transport of massive amounts of goods to and from colonies.[29] Along with advancements in communication, Europe also continued to advance in military technology. European chemists made new explosives that made artillery much more deadly. By the 1880s, the machine gun had become a reliable battlefield weapon. This technology gave European armies an advantage over their opponents, as armies in less-developed countries were still fighting with arrows, swords, and leather shields (e.g. the Zulus in Southern Africa during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879).[29] Some exceptions of armies that managed to get nearly on par with the European expeditions and standards include the Ethiopian armies at the Battle of Adwa, and the Japanese Imperial Army of Japan, but these still relied heavily on weapons imported from Europe and often on European military advisors.  This cartoon reflects the view of Judge magazine regarding America's imperial ambitions following McKinley's quick victory in the Spanish–American War of 1898. |

帝国主義時代 「帝国時代」は、こちらを参照。シンフォニック・メタルバンドについては、Imperial Age (バンド)を参照。 主な記事:国際関係(1648年~1814年)、国際関係(1814年~1919年)、新帝国主義 帝国主義時代(The Age of Imperialism)は、1760年頃に始まった時代区分であり、ヨーロッパの工業化国家が、世界の他の地域を植民地化、影響下に置き、併合する過程 にあった時代である。[19] 19世紀の出来事としては、「アフリカの争奪戦」がある。[20]  複数のヨーロッパ帝国の植民地に分割されたアフリカ、1914年頃 1970年代に、イギリスの歴史家ジョン・ギャラガー(1919年 - 1980年)とロナルド・ロビンソン(1920年 - 1999年)は、ヨーロッパの指導者たちは「帝国主義」が植民地地域に対する単一政府による正式な法的支配を必要とするという考えを拒絶したと主張した。 それよりも重要なのは、独立地域の非公式な支配であった。[21] ウィリアム・ロジャー・ルイスによると、「彼らの見解では、歴史家たちは形式的な帝国と、地域が赤で塗り分けられた世界地図に魅了されてきた。英国の移 民、貿易、資本の大部分は、形式的な大英帝国の外の地域へと流れていった。彼らの考え方の鍵となるのは、帝国という概念であり、それは「可能であれば非公 式に、必要であれば公式に」という考え方である。[22] オロン・ヘイルは、ギャラガーとロビンソンがアフリカにおける英国の関与を調査したところ、「資本家はほとんどおらず、資本も少なく、植民地拡大の伝統的 推進者とされる人々からの圧力もあまりなかった」と述べている。 併合するか併合しないかの閣議決定は、通常、政治的または地政学的な考慮に基づいて行われた。[23]:6 1875年から1914年までの主な帝国を概観すると、収益性に関しては、さまざまな結果が見られた。当初、植民地は製造品目のための優れた国内市場を提 供すると計画者は期待していた。インド亜大陸を除いては、これはほとんど当てはまらなかった。1890年代には帝国主義者たちは、国内の製造業部門に供給 する安価な原材料の生産に主に経済的利益を見出していた。全体として、インド、特にムガル帝国時代のベンガル地方から英国が得た利益は非常に大きかった が、その他の帝国の大半からはそうではなかった。インドの経済学者ウタ・パトナイク氏によると、1765年から1938年の間にインドから国外へ移転した 富の規模は、推定45兆ドルに上るという。[24] オランダは東インド諸島で大きな利益を得た。ドイツとイタリアは、自国の帝国からほとんど貿易や原材料を得ることができなかった。フランスは、それよりは 少し良かった。ベルギー領コンゴは、レオポルド2世が私有企業として所有・運営していた資本主義的なゴム農園として、非常に利益を上げていたことで悪名高 かった。しかし、コンゴ自由国における残虐行為に関するスキャンダルが次々と明るみに出たため、国際社会は1908年にベルギー政府に同国を接収させるよ う迫り、その結果、利益は大幅に減少した。フィリピンは、反乱軍に対する軍事行動により、米国が予想していた以上の負担となった。[23]:7-10 帝国主義によって利用可能となった資源により、第一次世界大戦前の数十年間、世界の経済は著しく成長し、相互の結びつきも強まった。その結果、多くの帝国主義国は豊かになり繁栄した。[25] ヨーロッパの領土帝国主義への拡大は、植民地から資源を集めることによる経済成長に主眼が置かれており、軍事的・政治的手段による政治的支配を伴うもので あった。18世紀半ばのインド植民地化は、この傾向の好例である。「英国はムガール帝国の政治的弱みを巧みに利用し、軍事活動が重要な役割を果たした時期 もあったが、経済的・行政的に現地のエリート層を取り込むことも、亜大陸の資源、市場、労働力に対する支配を確立する上で決定的に重要な意味を持ってい た」のである。。17世紀と18世紀には、かなりの数の植民地が経済的利益の確保と本国への資源の輸送を目的として設計されていたが、D. K. Fieldhouseは、19世紀と20世紀のアフリカやアジアなどの地域では、この考え方は必ずしも妥当ではないと指摘している。 近代の帝国は、人為的に構築された経済的な機械ではなかった。ヨーロッパの第二次拡大は、ヨーロッパとその周辺地域における政治的、社会的、感情的な力 が、計算された帝国主義よりも大きな影響力を持っていた複雑な歴史的過程であった。個々の植民地は経済的目的を果たしていたかもしれないが、全体として帝 国には経済的にもその他の面でも明確な機能はなかった。帝国は、ヨーロッパとそれ以外の地域との絶え間なく変化する関係における特定の段階に過ぎなかっ た。産業システムや不動産投資との類似は、単に誤解を招くだけである。 この時代、ヨーロッパの商人たちは「公海を航海し、世界中の余剰物資を(時には平和的に、時には暴力的に)入手し、それをヨーロッパに集中させる」能力を有していた。[28]  1841年5月、第一次アヘン戦争中の英国による広州への攻撃 19世紀にはヨーロッパの拡大が大幅に加速した。原材料を確保するために、ヨーロッパは他国および植民地からの輸入を拡大した。ヨーロッパの産業家たち は、染料、綿、植物油、金属鉱石などの原材料を海外から求めた。同時に、工業化が急速にヨーロッパを製造および経済成長の中心地とし、資源需要を押し上げ た。 ヨーロッパの拡大に伴い、通信手段は格段に進歩した。鉄道や電信の発明により、他国との通信が容易になり、本国が植民地に対して行政上の支配を拡大することが可能になった。蒸気鉄道や蒸気船により、植民地との間で大量の商品を迅速かつ安価に輸送することが可能になった。 通信手段の進歩と並行して、ヨーロッパでは軍事技術も進歩を続けた。ヨーロッパの化学者たちは、大砲の威力を飛躍的に高める新たな爆薬を開発した。 1880年代には、機関銃が信頼性の高い戦場兵器となっていた。この技術により、ヨーロッパの軍隊は他国に対して優位に立つこととなった。なぜなら、発展 途上国の軍隊は、いまだに矢や剣、革の盾で戦っていたからである(例えば、1879年のイギリス・ズールー戦争における南アフリカのズールー族など)。 [2 9] 例外的にヨーロッパの遠征軍とほぼ同等の水準に達していた軍隊としては、アドワの戦いのエチオピア軍や日本の帝国陸軍などが挙げられるが、これらの軍隊も 依然としてヨーロッパから輸入した武器に大きく依存しており、ヨーロッパの軍事顧問の支援を受けていた。  この漫画は、1898年の米西戦争におけるマッキンリーの大勝利を受けて、アメリカの帝国主義的野望について『Judge』誌の見解を反映したものである。 |

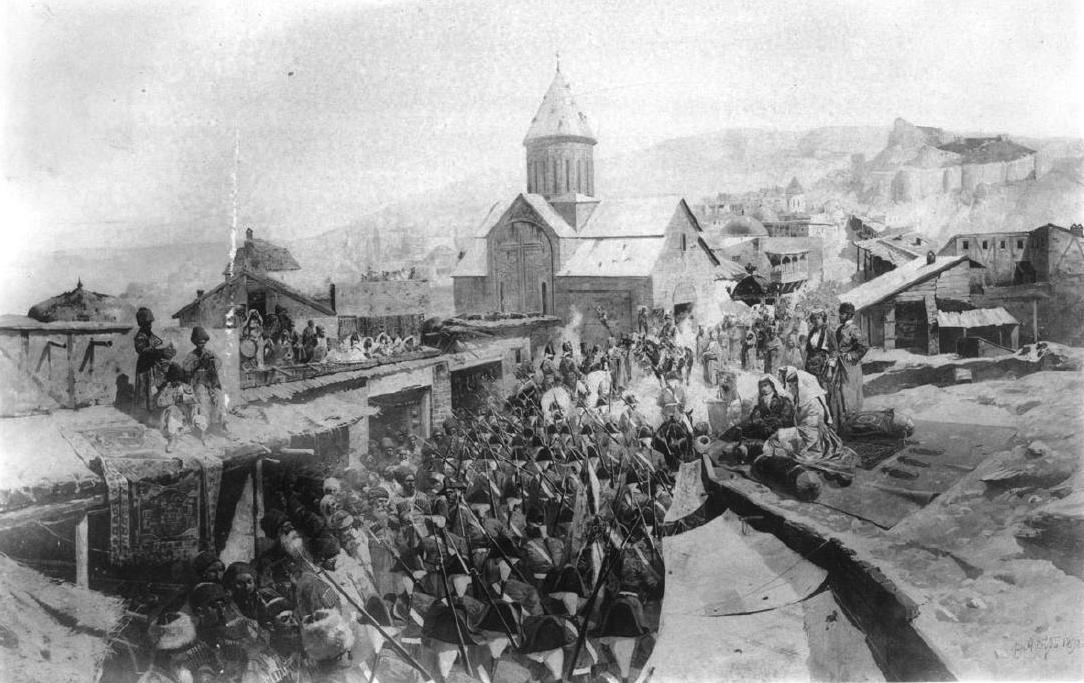

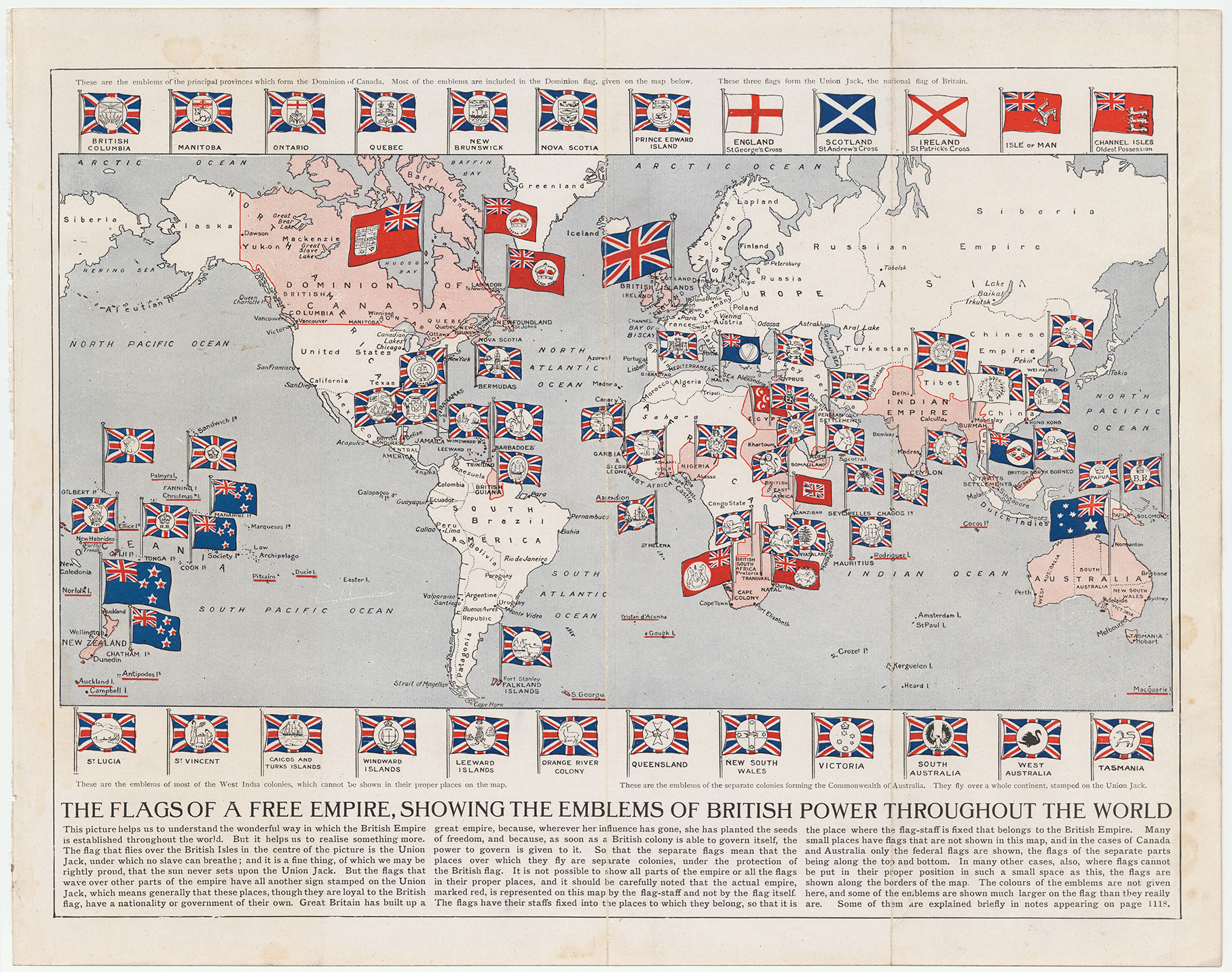

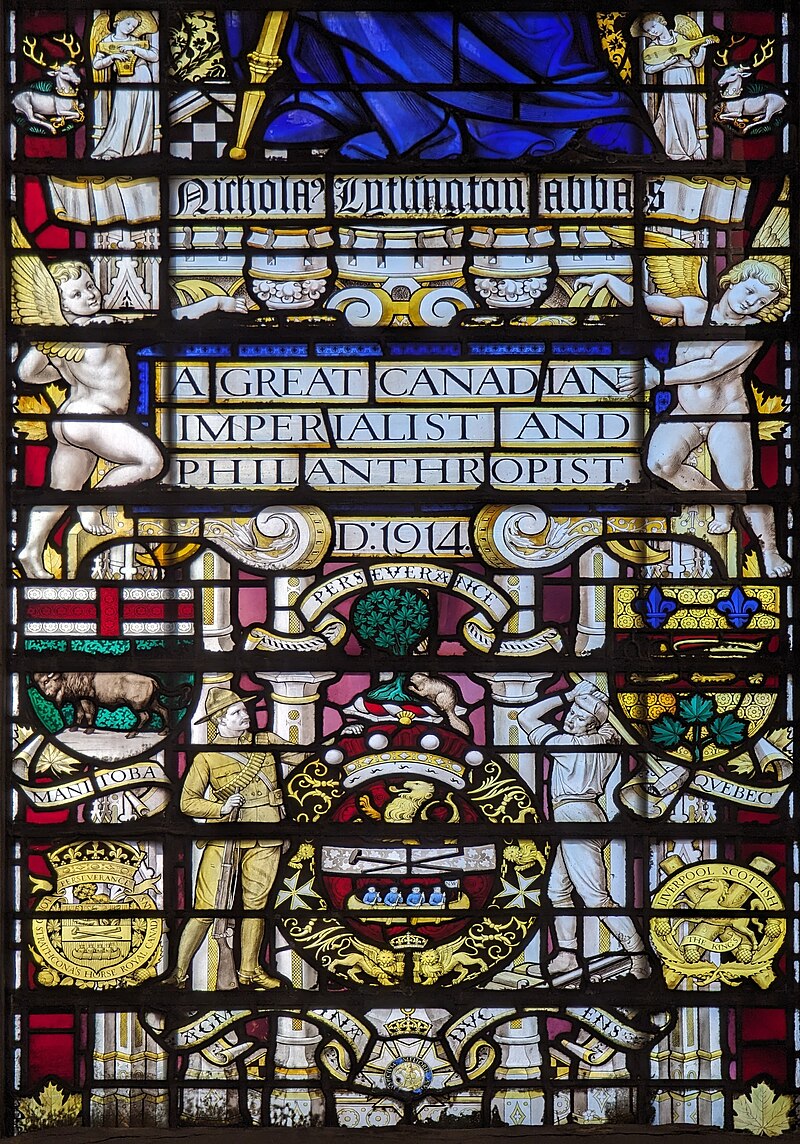

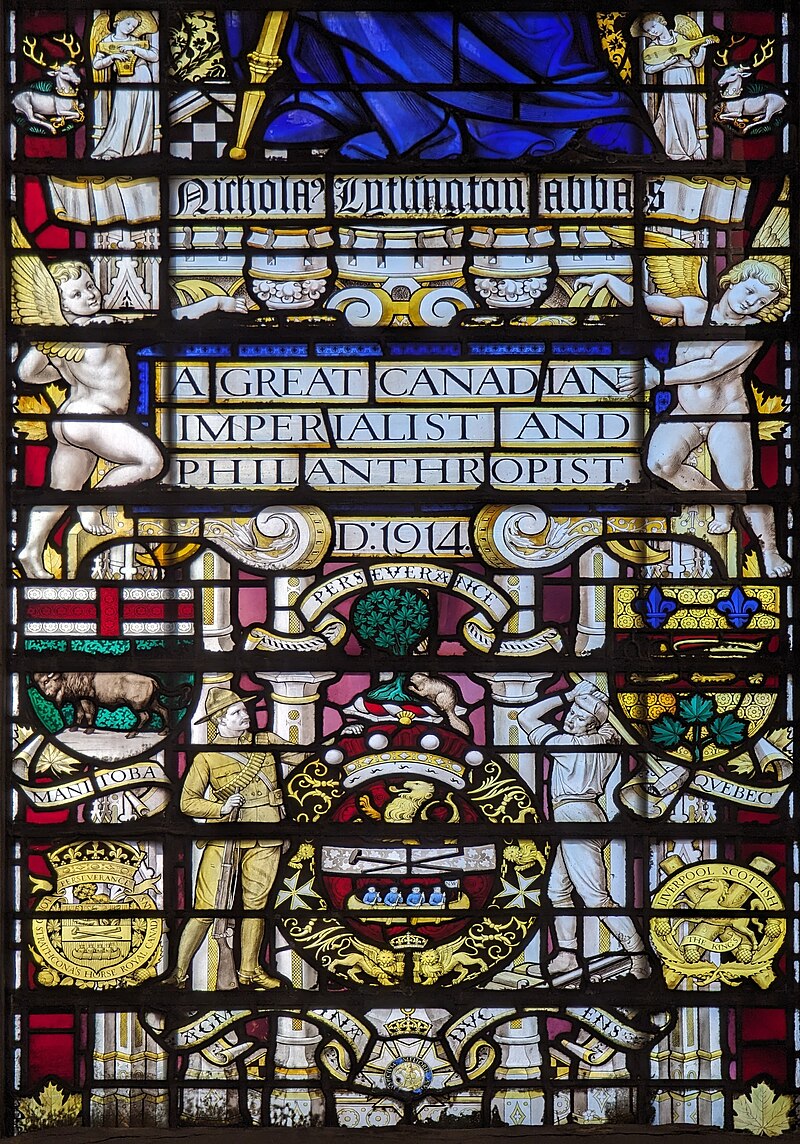

| Theories of imperialism Main article: Theories of imperialism Anglophone academic studies often base their theories regarding imperialism on the British experience of Empire. The term imperialism was originally introduced into English in its present sense in the late 1870s by opponents of the allegedly aggressive and ostentatious imperial policies of British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. Supporters of "imperialism" such as Joseph Chamberlain quickly appropriated the concept. For some, imperialism designated a policy of idealism and philanthropy; others alleged that it was characterized by political self-interest, and a growing number associated it with capitalist greed. Historians and political theorists have long debated the correlation between capitalism, class and imperialism. Much of the debate was pioneered by such theorists as John A. Hobson (1858–1940), Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950), Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929), and Norman Angell (1872–1967). While these non-Marxist writers were at their most prolific before World War I, they remained active in the interwar years. Their combined work informed the study of imperialism and its impact on Europe, as well as contributing to reflections on the rise of the military-political complex in the United States from the 1950s. In Imperialism: A Study (1902), Hobson developed a highly influential interpretation of imperialism that expanded on his belief that free enterprise capitalism had a negative impact on the majority of the population. In Imperialism he argued that the financing of overseas empires drained money that was needed at home. It was invested abroad because of lower wages paid to the workers overseas made for higher profits and higher rates of return, compared to domestic wages. So although domestic wages remained higher, they did not grow nearly as fast as they might have otherwise. Exporting capital, he concluded, put a lid on the growth of domestic wages in the domestic standard of living. Hobson theorized that domestic social reforms could cure the international disease of imperialism by removing its economic foundation, while state intervention through taxation could boost broader consumption, create wealth, and encourage a peaceful, tolerant, multipolar world order.[31][32] By the 1970s, historians such as David K. Fieldhouse[33] and Oron Hale could argue that "the Hobsonian foundation has been almost completely demolished."[23]: 5–6 It was not businessmen and bankers but politicians who went with the stream of the masses. The modern imperialism was primarily a political product caused by the national mass hysteria rather than by the much-abused capitalists.[34] The British experience failed to support it. Similarly, American Historian David Landes claims that businessmen were less enthusiastic about colonialism than statesmen and adventurers.[35] However, European Marxists picked up Hobson's ideas wholeheartedly and made it into their own theory of imperialism, most notably in Vladimir Lenin's Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916). Lenin portrayed imperialism as the closure of the world market and the end of capitalist free-competition that arose from the need for capitalist economies to constantly expand investment, material resources and manpower in such a way that necessitated colonial expansion. Later Marxist theoreticians echo this conception of imperialism as a structural feature of capitalism, which explained the World War as the battle between imperialists for control of external markets. Lenin's treatise became a standard textbook that flourished until the collapse of communism in 1989–91.[36]  Entrance of the Russian troops in Tiflis, 26 November 1799, by Franz Roubaud, 1886  The capture of Lạng Sơn during the French conquest of Vietnam in 1885 Some theoreticians on the non-Communist left have emphasized the structural or systemic character of "imperialism". Such writers have expanded the period associated with the term so that it now designates neither a policy, nor a short space of decades in the late 19th century, but a world system extending over a period of centuries, often going back to Colonization and, in some accounts, to the Crusades. As the application of the term has expanded, its meaning has shifted along five distinct but often parallel axes: the moral, the economic, the systemic, the cultural, and the temporal. Those changes reflect—among other shifts in sensibility—a growing unease, even great distaste, with the pervasiveness of such power, specifically, Western power.[37][33] Walter Rodney, in his 1972 How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, proposes the idea that imperialism is a phase of capitalism "in which Western European capitalist countries, the US, and Japan established political, economic, military and cultural hegemony over other parts of the world which were initially at a lower level and therefore could not resist domination."[38] As a result, Imperialism "for many years embraced the whole world – one part being the exploiters and the other the exploited, one part being dominated and the other acting as overlords, one part making policy and the other being dependent."[38] Imperialism has also been identified in newer phenomena like space development and its governing context.[39] |

帝国主義論 詳細は「帝国主義論」を参照 英語圏の学術研究では、帝国主義に関する理論はしばしば大英帝国の経験に基づいて論じられる。帝国主義という用語は、1870年代後半に、当時の英国首相 ベンジャミン・ディズレーリの攻撃的で派手な帝国政策の反対派によって、現在の意味で英語に導入された。ジョゼフ・チェンバレンのような「帝国主義」の支 持者たちは、この概念をすぐに利用した。ある人々にとっては、帝国主義とは理想主義と博愛主義の政策を意味し、またある人々は、それは政治的な自己利益に よって特徴づけられると主張し、さらに、資本主義の強欲と関連付ける人々も増えていった。 歴史家や政治理論家たちは、資本主義、階級、帝国主義の相関関係について長い間議論を交わしてきた。その議論の多くは、ジョン・A・ホブソン (1858~1940)、ジョセフ・シュンペーター(1883~1950)、トールステイン・ヴェブレン(1857~1929)、ノーマン・アンジェル (1872~1967)といった理論家たちによって先導された。これらの非マルクス主義の著述家たちは、第一次世界大戦前に最も多くの著作を残したが、戦 間期にも活動を続けた。彼らの著作は、帝国主義の研究やヨーロッパへの影響についての情報源となったほか、1950年代以降の米国における軍事政治複合体 の台頭に関する考察にも貢献した。 ホブソンは著書『帝国主義論』(1902年)において、自由企業資本主義が国民の大多数に悪影響を及ぼすという自身の信念をさらに発展させた、非常に影響 力のある帝国主義の解釈を展開した。『帝国主義論』の中で、ホブソンは海外帝国の資金調達が国内で必要とされる資金を流出させていると論じた。海外で労働 者に支払われる賃金が国内よりも低いため、海外に投資されるのだ。そのため、国内の賃金は依然として高かったものの、それ以外の状況であれば考えられるほ どには急速に上昇することはなかった。ホブソンは、資本の輸出は国内の賃金と国内の生活水準の成長を抑制すると結論付けた。ホブソンは、国内の社会改革は 帝国主義の経済的基盤を除去することで、国際的な病である帝国主義を治癒できると理論化した。また、課税による国家の介入は、より幅広い消費を促進し、富 を生み出し、平和的で寛容な多極的世界秩序を奨励できると主張した。 1970年代までに、デイヴィッド・K・フィールドハウス(David K. Fieldhouse)[33]やオロン・ヘイル(Oron Hale)などの歴史家は、「ホブソン的な基盤はほぼ完全に崩壊した」と主張できるようになった。[23]:5–6 民衆の流れに従ったのは実業家や銀行家ではなく、政治家であった。近代帝国主義は、悪用され続けた資本家たちよりも、むしろ国家の集団ヒステリーによって 引き起こされた政治的な産物であった。[34] イギリスの経験はそれを裏付けるものではなかった。同様に、アメリカの歴史家デビッド・ランディスは、実業家たちは政治家や冒険家たちほど植民地主義に熱 狂的ではなかったと主張している。[35] しかし、ヨーロッパのマルクス主義者たちはホブソンの考えを全面的に取り入れ、それを自分たちの帝国主義理論に取り入れた。その最も顕著な例は、ウラジー ミル・レーニンの『帝国主義、資本主義の最高段階』(1916年)である。レーニンは帝国主義を、世界市場の閉鎖と資本主義の自由競争の終焉として描い た。資本主義経済が絶えず投資、物的資源、労働力を拡大する必要性から、植民地拡大が必要となったのである。後世のマルクス主義理論家たちは、帝国主義を 資本主義の構造的特徴と捉えるこの考え方を繰り返し、帝国主義間の対外市場の支配権をめぐる戦いとして世界大戦を説明した。レーニンの論文は、1989年 から1991年の共産主義崩壊まで隆盛を誇った標準的な教科書となった。[36]  1799年11月26日、フランツ・ルーボーによるトビリシへのロシア軍の進軍  1885年のフランスによるベトナム征服におけるラングソンの陥落 非共産主義左派の理論家の中には、「帝国主義」の構造的あるいは体系的な性格を強調する者もいる。このような作家は、この用語に関連する時代を拡大し、現 在では、政策でもなければ、19世紀後半の数十年間の短い期間でもなく、数世紀にわたる世界システムを指すようになっている。しばしば植民地化にまで遡 り、一部の説明では十字軍にまで遡る。この用語の適用範囲が広がるにつれ、その意味も5つの異なる軸に沿って変化してきた。すなわち、道徳、経済、システ ム、文化、時間である。こうした変化は、感性の変化のほかの側面として、特に西洋の力が浸透することへの不安や嫌悪感の高まりを反映している。 ウォルター・ロドニーは、1972年の著書『ヨーロッパによるアフリカの未開発の仕方』で、帝国主義とは資本主義の一局面であり、「西欧資本主義諸国、米 国、日本が、当初は低水準にあり、 したがって支配に抵抗することができなかった」[38]。その結果、帝国主義は「長年にわたり全世界を巻き込んだ。一部は搾取者となり、一部は被搾取者と なり、一部は支配者となり、一部は被支配者となった」[38]。 帝国主義は、宇宙開発とその管理状況のような新しい現象にも見られる。[39] |

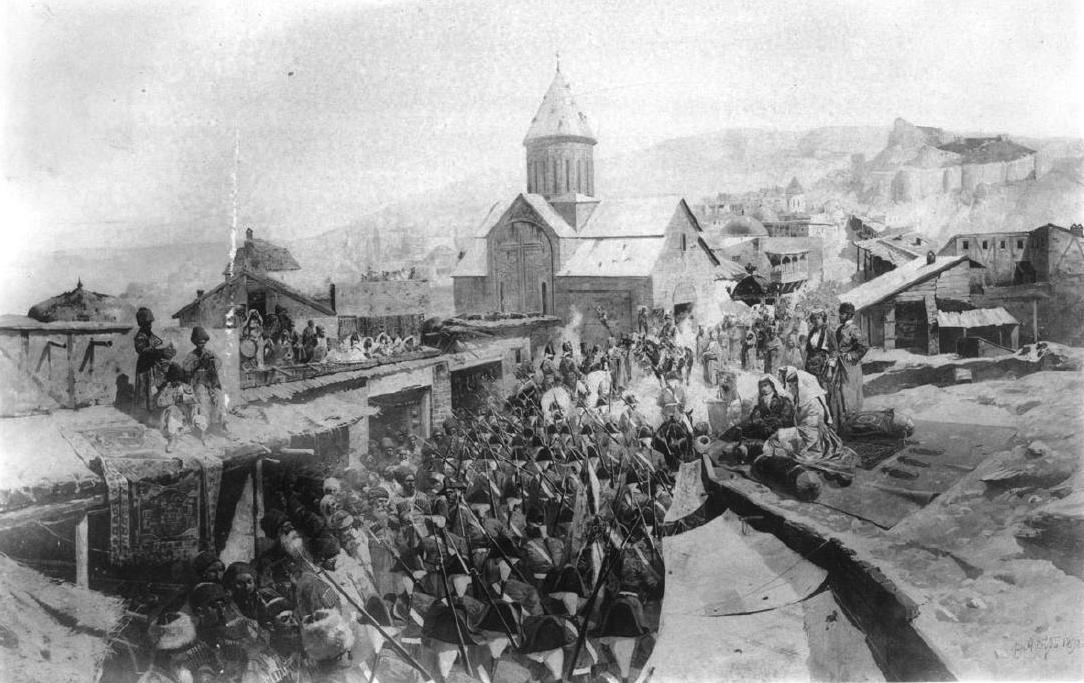

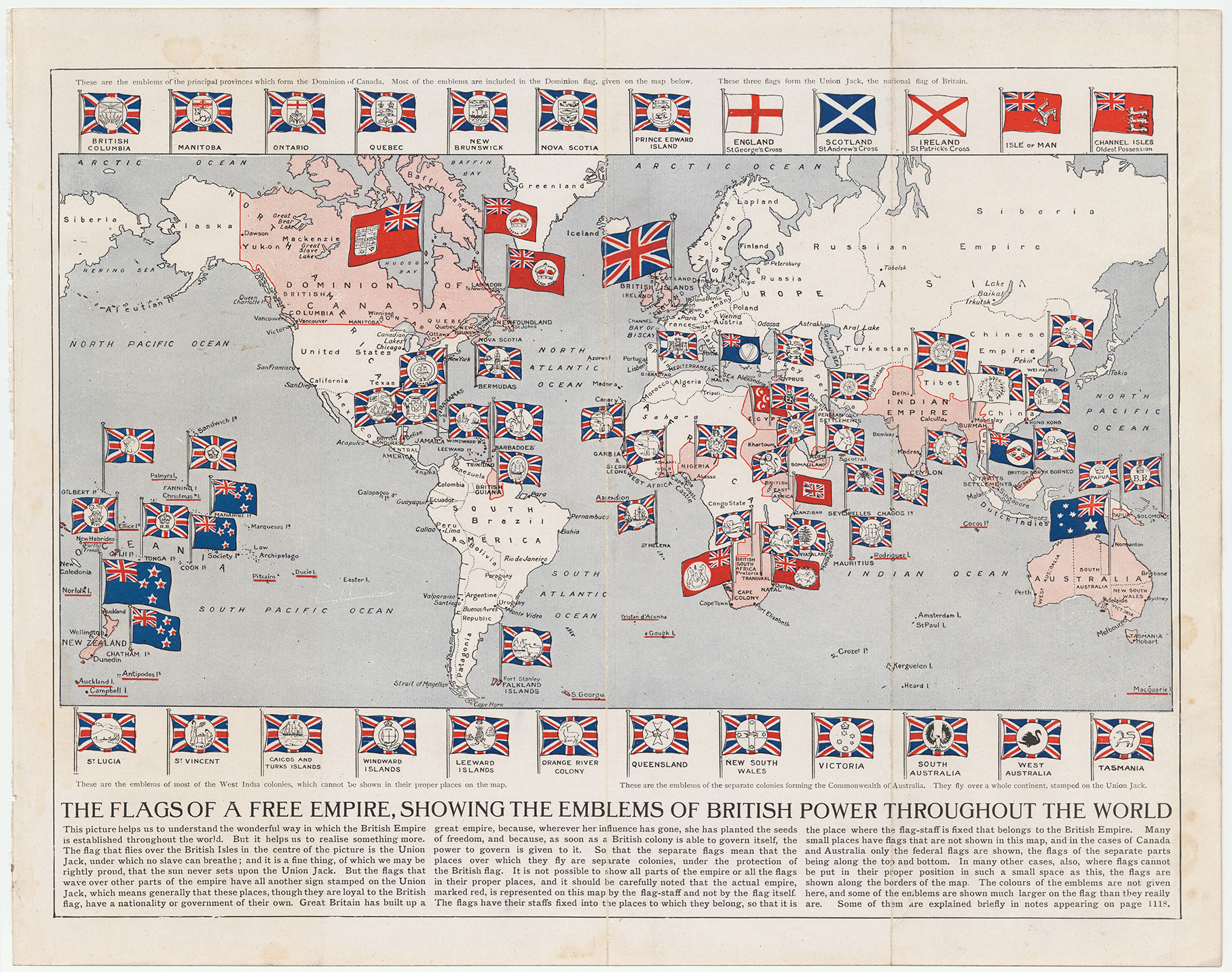

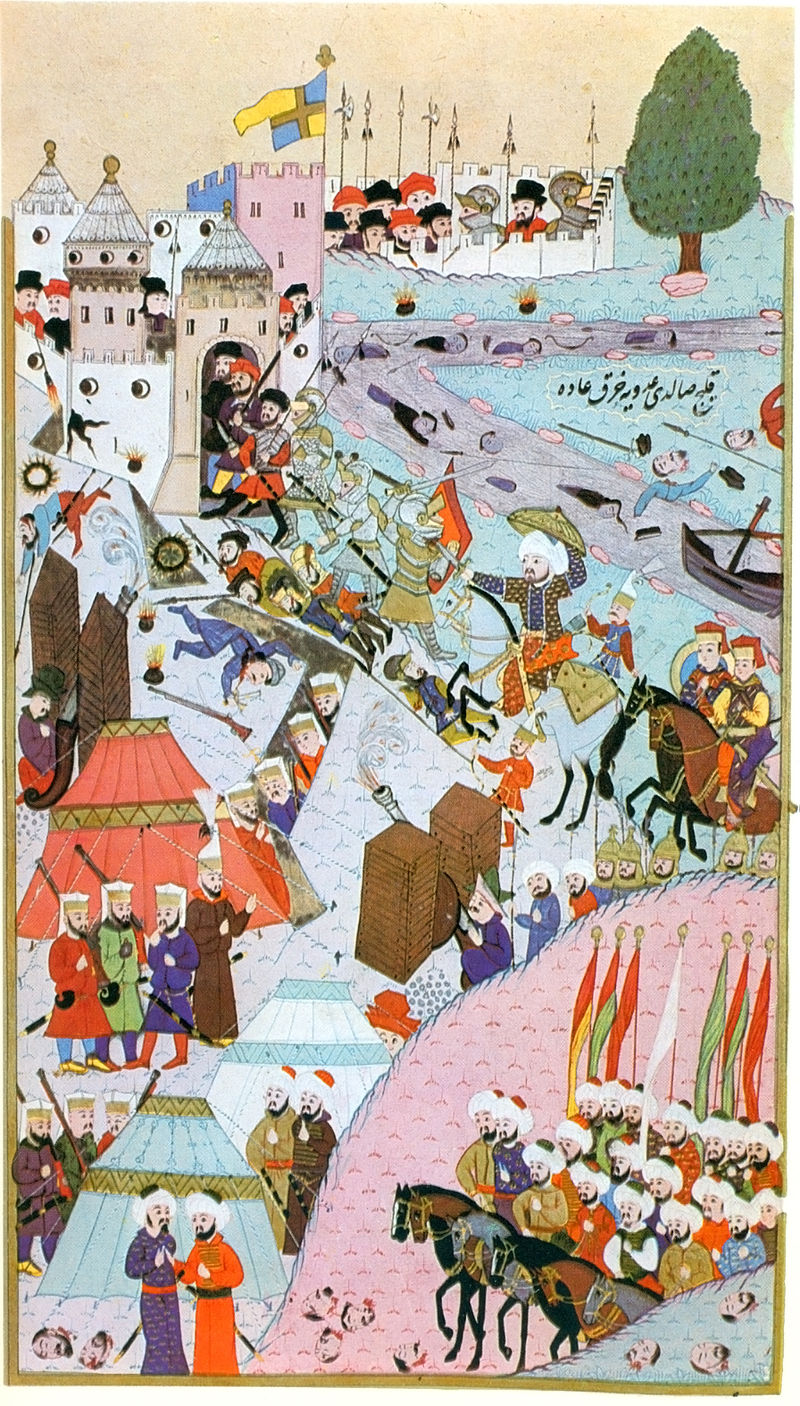

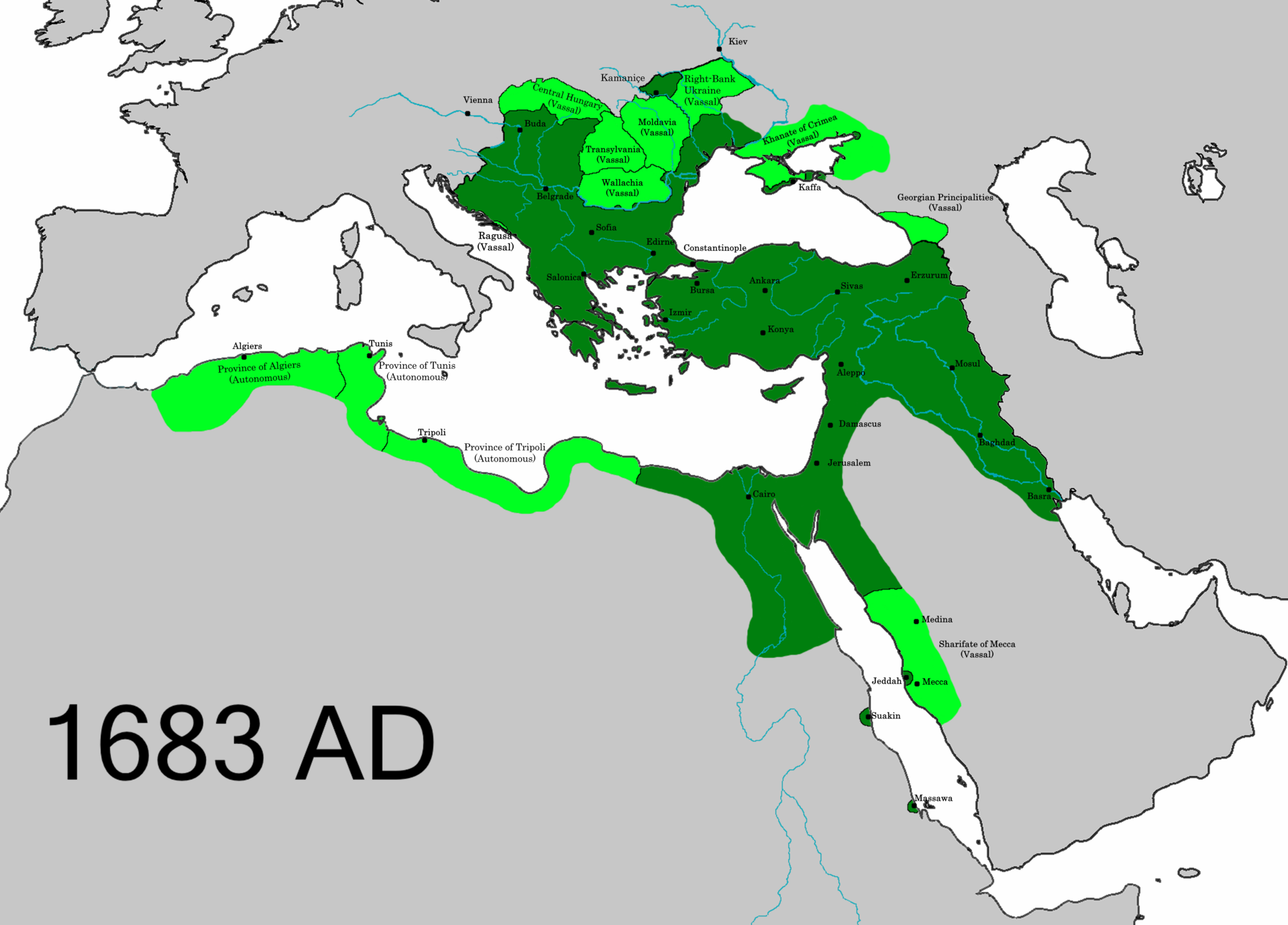

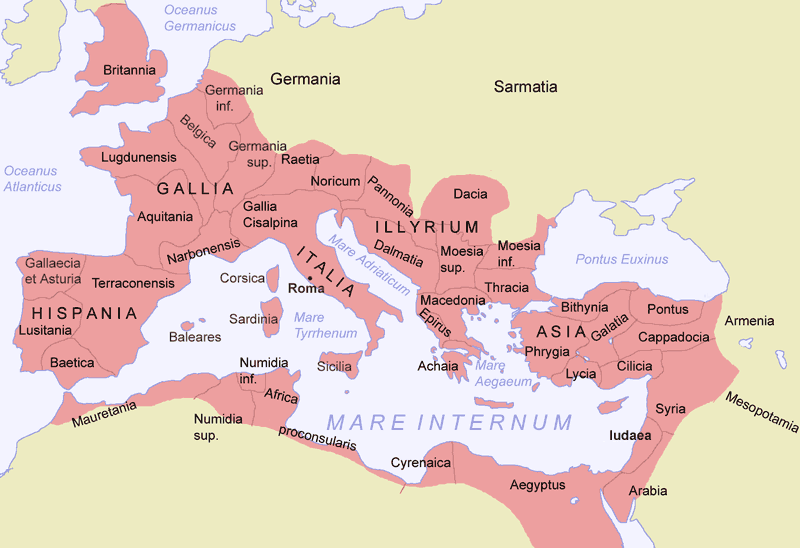

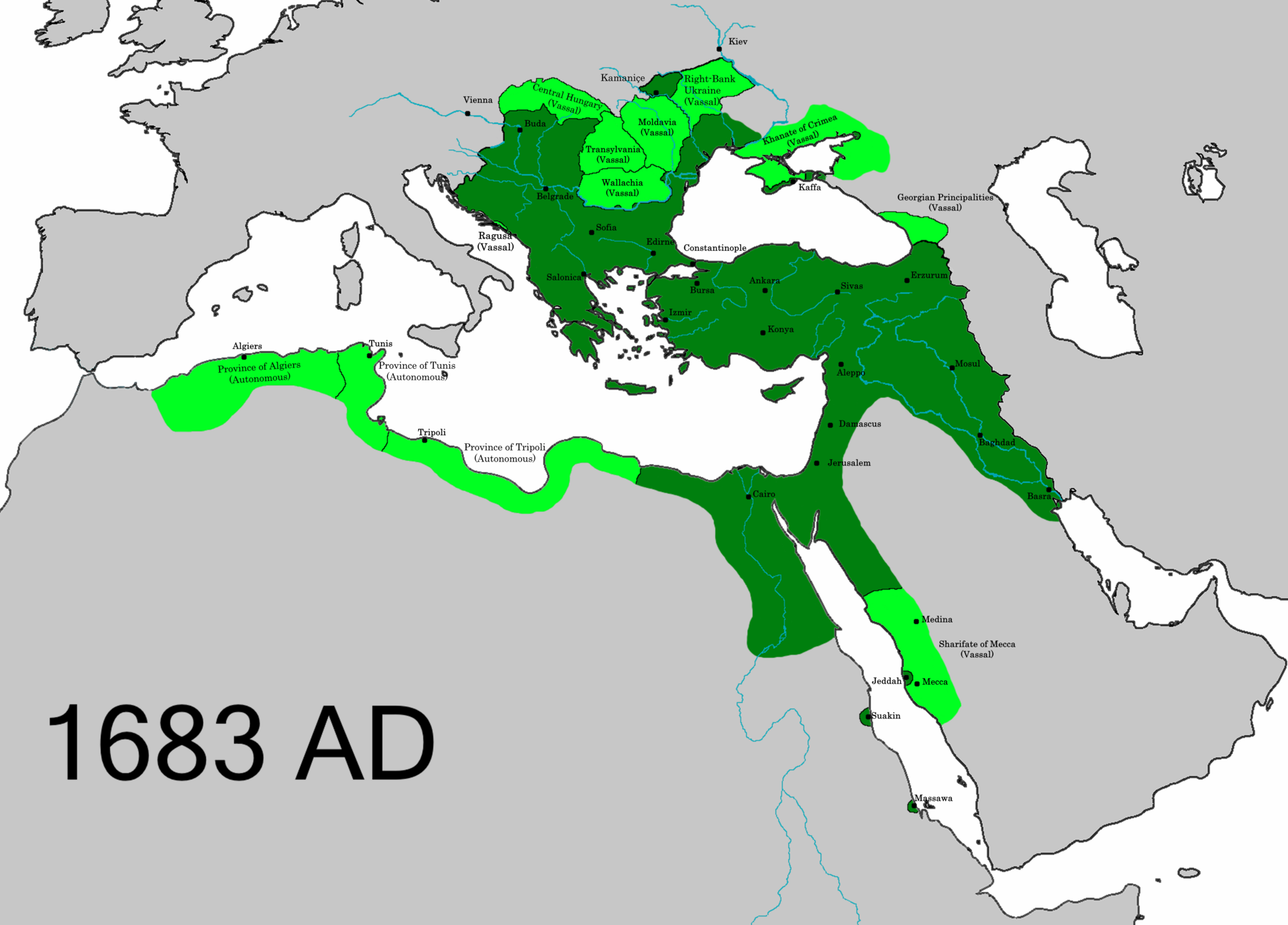

| Issues Orientalism and imaginative geography  Napoleon visiting the plague victims of Jaffa, by Antoine-Jean Gros Imperial control, territorial and cultural, is justified through discourses about the imperialists' understanding of different spaces.[40] Conceptually, imagined geographies explain the limitations of the imperialist understanding of the societies of the different spaces inhabited by the non–European Other.[40] In Orientalism (1978), Edward Said said that the West developed the concept of The Orient—an imagined geography of the Eastern world—which functions as an essentializing discourse that represents neither the ethnic diversity nor the social reality of the Eastern world.[41] That by reducing the East into cultural essences, the imperial discourse uses place-based identities to create cultural difference and psychologic distance between "We, the West" and "They, the East" and between "Here, in the West" and "There, in the East".[42] That cultural differentiation was especially noticeable in the books and paintings of early Oriental studies, the European examinations of the Orient, which misrepresented the East as irrational and backward, the opposite of the rational and progressive West.[40][43] Defining the East as a negative vision of the Western world, as its inferior, not only increased the sense-of-self of the West, but also was a way of ordering the East, and making it known to the West, so that it could be dominated and controlled.[44][45] Therefore, Orientalism was the ideological justification of early Western imperialism—a body of knowledge and ideas that rationalized social, cultural, political, and economic control of other, non-white peoples.[42][16]: 116 Cartography See also: Cartographic propaganda  By displaying oversized flags of British possessions, this map artificially increases the apparent influence and presence of the British Empire. One of the main tools used by imperialists was cartography. Cartography is "the art, science and technology of making maps"[46] but this definition is problematic. It implies that maps are objective representations of the world when in reality they serve very political means.[46] For Harley, maps serve as an example of Foucault's power and knowledge concept. To better illustrate this idea, Bassett focuses his analysis of the role of 19th-century maps during the "Scramble for Africa".[47] He states that maps "contributed to empire by promoting, assisting, and legitimizing the extension of French and British power into West Africa".[47] During his analysis of 19th-century cartographic techniques, he highlights the use of blank space to denote unknown or unexplored territory.[47] This provided incentives for imperial and colonial powers to obtain "information to fill in blank spaces on contemporary maps".[47] Although cartographic processes advanced through imperialism, further analysis of their progress reveals many biases linked to eurocentrism. According to Bassett, "[n]ineteenth-century explorers commonly requested Africans to sketch maps of unknown areas on the ground. Many of those maps were highly regarded for their accuracy"[47] but were not printed in Europe unless Europeans verified them. Expansionism  Ottoman wars in Europe Imperialism in pre-modern times was common in the form of expansionism through vassalage and conquest.[citation needed] Cultural imperialism The concept of cultural imperialism refers to the cultural influence of one dominant culture over others, i.e. a form of soft power, which changes the moral, cultural, and societal worldview of the subordinate culture. This means more than just "foreign" music, television or film becoming popular with young people; rather that a populace changes its own expectations of life, desiring for their own country to become more like the foreign country depicted. For example, depictions of opulent American lifestyles in the soap opera Dallas during the Cold War changed the expectations of Romanians; a more recent example is the influence of smuggled South Korean drama-series in North Korea. The importance of soft power is not lost on authoritarian regimes, which may oppose such influence with bans on foreign popular culture, control of the internet and of unauthorized satellite dishes, etc. Nor is such a usage of culture recent – as part of Roman imperialism, local elites would be exposed to the benefits and luxuries of Roman culture and lifestyle, with the aim that they would then become willing participants. Imperialism has been subject to moral or immoral censure by its critics[which?], and thus the term "imperialism" is frequently used in international propaganda as a pejorative for expansionist and aggressive foreign policy.[48] Psychological imperialism An empire mentality may build on and bolster views contrasting "primitive" and "advanced" peoples and cultures, thus justifying and encouraging imperialist practices among participants.[49] Associated psychological tropes include the White Man's Burden and the idea of civilizing mission (French: mission civilatrice). Social imperialism The political concept social imperialism is a Marxist expression first used in the early 20th century by Lenin as "socialist in words, imperialist in deeds" describing the Fabian Society and other socialist organizations.[50] Later, in a split with the Soviet Union, Mao Zedong criticized its leaders as social imperialists.[51] |

問題 オリエンタリズムと想像上の地理  ナポレオンがヤッファのペスト患者を訪問する様子、アントワーヌ=ジャン・グロ画 帝国による支配、領土的、文化的支配は、帝国主義者による異なる空間についての理解に関する言説によって正当化される。[40] 概念的には、想像上の地理は、非ヨーロッパの他者が居住する異なる空間における社会に対する帝国主義者の理解の限界を説明する。[40] エドワード・サイードは著書『オリエンタリズム』(1978年)の中で、西洋が東洋という概念を構築したと述べている。東洋という概念は、東洋世界の想像 上の地理であり、東洋世界の民族的多様性も社会現実も反映しない本質主義的な言説として機能している。東洋を文化の本質に還元することで、帝国主義的な言 説は、場所に基づくアイデンティティを利用して、「我々、西洋」と「彼ら、東洋」の間、そして「ここ、西洋」と「あそこ、東洋」の間に文化的相違と心理的 距離を生み出している。 この文化的な差異化は、初期の東洋学の書籍や絵画、すなわちヨーロッパによる東洋の検証において特に顕著であり、東洋を非合理的で後進的、すなわち合理的 で進歩的な西洋の対極にあるものと誤って表現していた。[40][43] 西洋世界にとって東洋を否定的なイメージとして、劣ったものとして定義することは、西洋の自己認識を高めるだけでなく、 東洋を秩序立て、西洋に知らしめることで、支配と管理を可能にする方法でもあった。[44][45] したがって、オリエンタリズムは初期の西洋帝国主義のイデオロギー的な正当化であり、非白人である他民族に対する社会的、文化的、政治的、経済的支配を正 当化する知識と思想の体系であった。[42][16]:116 地図製作 関連項目:地図製作におけるプロパガンダ  この地図では、イギリスの植民地の特大の旗を表示することで、大英帝国の存在感と影響力を人為的に増大させている。 帝国主義者が用いた主な手段のひとつが地図作成であった。地図作成とは「地図を作成する技術、科学、および芸術」[46] であるが、この定義には問題がある。地図は客観的に世界を表現していると示唆しているが、実際には地図はきわめて政治的な手段として用いられているからで ある。[46] ハーレイにとって地図は、フーコーの権力と知識の概念の例証である。 この考えをより明確に説明するために、バセットは「アフリカの争奪戦」における19世紀の地図の役割に焦点を当てて分析している。[47] 彼は、地図は「フランスとイギリスの西アフリカへの勢力拡大を促進し、支援し、正当化することで帝国に貢献した」と述べている。 [47] 19世紀の地図作成技術の分析において、彼は空白のスペースを未知の領域や未開拓の領域を示すために使用したことを強調している。[47] これにより、帝国主義国や植民地国は「現代の地図の空白スペースを埋める情報」を得るためのインセンティブが与えられた。[47] 帝国主義によって地図作成のプロセスは進歩したが、その進歩をさらに分析すると、ヨーロッパ中心主義に結びついた多くの偏見が明らかになる。バセットによ ると、「19世紀の探検家たちは、未知の地域の地図を現地でスケッチするようアフリカ人に依頼するのが一般的だった。それらの地図の多くは、その正確性か ら高く評価されていた」[47]が、ヨーロッパ人が確認しない限り、ヨーロッパでは印刷されることはなかった。 拡張主義  ヨーロッパにおけるオスマン帝国戦争 前近代の帝国主義は、従属や征服による拡張主義の形態で一般的であった。 文化帝国主義 文化帝国主義の概念は、ある支配的な文化が他の文化に及ぼす文化的影響を指し、すなわち、従属文化の道徳観、文化観、社会観を変えるソフトパワーの一形態 である。これは単に「外国の」音楽、テレビ番組、映画が若者の間で人気となるという以上のことを意味する。むしろ、人々は自らの生活に対する期待を変え、 自国が描写されている外国のようになることを望むのである。例えば、冷戦時代にソープオペラ『ダラス』で描かれたアメリカの上流階級の生活様式は、ルーマ ニア人の期待を変えた。より最近の例としては、北朝鮮における韓国のドラマシリーズの密輸の影響がある。ソフトパワーの重要性は、独裁政権も認識してお り、外国のポピュラーカルチャーの禁止、インターネットや無許可の衛星放送受信アンテナの規制などによって、そうした影響に対抗することがある。また、こ のような文化の利用は最近始まったことでもない。ローマ帝国主義の一部として、ローマのエリート層はローマ文化やライフスタイルの恩恵や贅沢に触れ、彼ら が自発的な参加者となることを目的としていた。 帝国主義は、その批判者たちによって道徳的または非道徳的な批判の対象となっており[誰によって?]、そのため「帝国主義」という用語は、拡張主義的で攻撃的な外交政策に対する軽蔑的な表現として、国際的なプロパガンダで頻繁に使用されている。 心理的帝国主義 帝国のメンタリティは、「原始的」な民族や文化と「進歩的」な民族や文化を対比する見解を強化し、帝国主義的な行為を正当化し、参加者にそれを推奨する可 能性がある。[49] 関連する心理的表現には、「ホワイト・マンズ・バーデン(White Man's Burden)」や「文明化の使命(civilizing mission)」という考え方がある。 社会的帝国主義 政治的概念である社会的帝国主義は、20世紀初頭にレーニンが「口では社会主義を唱えながら、実際には帝国主義的行動をとる」という表現で、フェビアン協 会やその他の社会主義組織を評した際に初めて使用されたマルクス主義の表現である。[50] その後、ソビエト連邦と袂を分かつ形で、毛沢東は同国の指導者たちを社会的帝国主義者と批判した。[51] |

Justification A French political cartoon depicting a shocked mandarin in Manchu robe in the back, with Queen Victoria (British Empire), Wilhelm II (German Empire), Nicholas II (Russian Empire), Marianne (French Third Republic), and a samurai (Empire of Japan) stabbing into a king cake with Chine ("China" in French) written on it. A portrayal of New Imperialism and its effects on China. Stephen Howe has summarized his view on the beneficial effects of the colonial empires: At least some of the great modern empires – the British, French, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and even the Ottoman – have virtues that have been too readily forgotten. They provided stability, security, and legal order for their subjects. They constrained, and at their best, tried to transcend, the potentially savage ethnic or religious antagonisms among the peoples. And the aristocracies which ruled most of them were often far more liberal, humane, and cosmopolitan than their supposedly ever more democratic successors.[52][53] A controversial aspect of imperialism is the defense and justification of empire-building based on seemingly rational grounds. In ancient China, Tianxia denoted the lands, space, and area divinely appointed to the Emperor by universal and well-defined principles of order. The center of this land was directly apportioned to the Imperial court, forming the center of a world view that centered on the Imperial court and went concentrically outward to major and minor officials and then the common citizens, tributary states, and finally ending with the fringe "barbarians". Tianxia's idea of hierarchy gave Chinese a privileged position and was justified through the promise of order and peace. The purportedly scientific nature of "Social Darwinism" and a theory of races formed a supposedly rational justification for imperialism. Under this doctrine, the French politician Jules Ferry could declare in 1883 that "Superior races have a right, because they have a duty. They have the duty to civilize the inferior races."[54] J. A. Hobson identifies this justification on general grounds as: "It is desirable that the earth should be peopled, governed, and developed, as far as possible, by the races which can do this work best, i.e. by the races of highest 'social efficiency'".[55] The Royal Geographical Society of London and other geographical societies in Europe had great influence and were able to fund travelers who would come back with tales of their discoveries. These societies also served as a space for travellers to share these stories.[16]: 117 Political geographers such as Friedrich Ratzel of Germany and Halford Mackinder of Britain also supported imperialism.[16]: 117 Ratzel believed expansion was necessary for a state's survival and this argument dominated the discipline of geopolitics for decades.[16]: 117 British imperialism in some sparsely-inhabited regions applied a principle now termed Terra nullius (Latin expression which stems from Roman law meaning 'no man's land'). The British settlement in Australia in the 18th century was arguably premised on terra nullius, as its settlers considered it unused by its original inhabitants. The rhetoric of colonizers being racially superior appears still to have its impact. For example, throughout Latin America "whiteness" is still prized today and various forms of blanqueamiento (whitening) are common. Imperial peripheries benefited from economic efficiency improved through the building of roads, other infrastructure and introduction of new technologies. Herbert Lüthy notes that ex-colonial peoples themselves show no desire to undo the basic effects of this process. Hence moral self-criticism in respect of the colonial past is out of place.[56] Environmental determinism The concept of environmental determinism served as a moral justification for the domination of certain territories and peoples. The environmental determinist school of thought held that the environment in which certain people lived determined those persons' behaviours; and thus validated their domination. Some geographic scholars under colonizing empires divided the world into climatic zones. These scholars believed that Northern Europe and the Mid-Atlantic temperate climate produced a hard-working, moral, and upstanding human being. In contrast, tropical climates allegedly yielded lazy attitudes, sexual promiscuity, exotic culture, and moral degeneracy. The tropical peoples were believed to be "less civilized" and in need of European guidance,[16]: 117 therefore justifying colonial control as a civilizing mission. For instance, American geographer Ellen Churchill Semple argued that even though human beings originated in the tropics they were only able to become fully human in the temperate zone.[57]: 11 Across the three major waves of European colonialism (the first in the Americas, the second in Asia and the last in Africa), environmental determinism served to place categorically indigenous people in a racial hierarchy. Tropicality can be paralleled with Edward Said's Orientalism as the west's construction of the east as the "other".[57]: 7 According to Said, orientalism allowed Europe to establish itself as the superior and the norm, which justified its dominance over the essentialized Orient.[58]: 329 Orientalism is a view of a people based on their geographical location.[59] |

正当化 後ろに描かれた、満州族の衣装を身にまとったショックを受けた役人を描いたフランスの政治風刺漫画。ヴィクトリア女王(大英帝国)、ヴィルヘルム2世(ド イツ帝国)、ニコライ2世(ロシア帝国)、マリアンヌ(フランス第三共和制)、そして侍(大日本帝国)が、「Chine(フランス語で「中国」の意)」と 書かれたキングケーキにナイフを刺している。新帝国主義と中国への影響を描いたもの。 スティーブン・ハウは、植民地帝国の有益な効果に関する自身の考えを次のようにまとめている。 少なくとも、偉大な近代帝国であるイギリス、フランス、オーストリア=ハンガリー、ロシア、さらにはオスマン帝国には、あまりにも簡単に忘れ去られてきた 美徳があった。それらの帝国は、自国民に対して安定性、安全性、法秩序を提供した。また、人々の間に潜在的に存在する野蛮な民族間・宗教間の対立を抑制 し、最善を尽くしてそれを乗り越えようとした。そして、それらの帝国のほとんどを支配していた貴族階級は、その後に続くはずの民主主義的な後継者よりもは るかにリベラルで、人道主義的で、国際的であったことが多かった。 帝国主義の論争の的となる側面は、一見合理的な根拠に基づく帝国建設の正当化と擁護である。古代中国では、天下一(てんか)は、普遍的で明確な秩序の原則 によって皇帝に神聖に与えられた土地、空間、領域を意味した。この土地の中心は皇帝の宮廷に直接割り当てられ、宮廷を中心とする世界観の中心を形成し、同 心円状に主要な役人や下級役人、そして一般市民、朝貢国へと広がり、最後に辺境の「野蛮人」で終わる。天下一の階層観は中国人に特権的な地位を与え、秩序 と平和の約束によって正当化された。 社会ダーウィニズム」の科学的性質と人種理論は、帝国主義を合理的に正当化する根拠となった。この理論に基づき、フランスの政治家ジュール・フェリーは 1883年に「優れた人種には権利がある。なぜなら、彼らには義務があるからだ。彼らは劣った人種を文明化する義務があるのだ」と宣言した。[54] J. A. ホブソンは、この一般的な根拠を次のように要約している。「地球は、できる限り、この仕事を最もよくこなせる人種、すなわち最高の『社会的効率』を持つ人 種によって、開拓され、統治され、開発されることが望ましい」[55] ロンドン王立地理学会やヨーロッパの他の地理学会は大きな影響力を持ち、発見の物語を携えて戻ってくる探検家たちに資金を提供することができた。これらの 学会は、旅行者たちが発見の物語を共有する場としても機能していた。[16]: 117 ドイツのフリードリヒ・ラッツェルやイギリスのハルフォード・マキンダーといった政治地理学者も帝国主義を支持していた。[16]: 117 ラッツェルは、国家の存続には拡大が必要だと信じており、 国家の生存には拡大が必要であると主張し、この論は数十年にわたって地政学の分野を支配した。[16]: 117 イギリスの帝国主義は、一部の人口密度の低い地域において、現在では「Terra nullius(ラテン語で「無主地」を意味するローマ法に由来する表現)」と呼ばれる原則を適用した。18世紀にオーストラリアにイギリス人が入植した 際には、入植者たちはその土地が元来の住民によって利用されていないと考えていたため、おそらくテラ・ヌリアスを前提としていた。植民地化者が人種的に優 れているという主張は、今も影響を残している。例えば、ラテンアメリカでは現在でも「白人であること」が尊ばれており、さまざまな形のブランケミエント (白人化)が一般的である。 帝国の周辺地域は、道路やその他のインフラの建設、新技術の導入による経済効率の向上の恩恵を受けた。ハーバート・リュティは、元植民地の人々自身も、こ のプロセスの基本的な影響を元に戻そうとする気はないと指摘している。したがって、植民地支配の過去に関する道徳的な自己批判は的外れである。 環境決定論 環境決定論の概念は、特定の地域や人々を支配する道徳的な正当化の根拠として用いられた。環境決定論派は、特定の人々が暮らす環境がその人々の行動を決定 すると考え、それゆえに彼らの支配を正当化した。植民地帝国の傘下にある地理学者の中には、世界を気候帯に分ける者もいた。これらの学者は、北ヨーロッパ と北大西洋の温帯気候は勤勉で道徳心があり、高潔な人間を生み出すと考えた。一方、熱帯気候は怠惰な態度、性的な奔放さ、エキゾチックな文化、そして道徳 的な退廃を生み出すとされた。熱帯地域の住民は「文明化が遅れている」と考えられ、ヨーロッパの指導が必要であるとされたため、[16] 文明化を目的とした植民地支配が正当化された。例えば、アメリカの地理学者エレン・チャーチル・センプルは、人間は熱帯で誕生したにもかかわらず、温帯で こそ完全に人間になることができると主張した。[57]: 11 ヨーロッパによる3つの主要な植民地主義の波(最初の波はアメリカ大陸、2番目の波はアジア、最後の波はアフリカ)を通じて、環境決定論は先住民を人種的 ヒエラルキーに明確に位置づけるのに役立った。熱帯性は、西洋が東洋を「他者」として構築したものとして、エドワード・サイードのオリエンタリズムと並列 的に考えることができる。[57]: 7 サイードによれば、オリエンタリズムはヨーロッパが自らを優位で規範的な存在として位置づけることを可能にし、それが本質化された東洋に対する支配を正当 化した。[58]: 329 オリエンタリズムは、人々をその地理的位置に基づいて捉える見方である。[59] |