言語復興運動

Language

revitalization movement

言語復興(Language revitalization)は、言語再生や言語逆交替とも呼ばれ、ある 言語の衰退を食い止め、逆に消滅した言語を復活させようとする試みである。それには、言語学者、文化団体、地域団体、政府などの関係者が関与する。言語復 興(母語話者の存在しない消滅言語の復活)と言語再活性化(「死にゆく」言語の救済)を区別して考える意見もある。完全な言語復興に成功した例はヘブライ 語の例を除けば非常に少なく、その復興においては既存の母語話者を手本にすることなく、新しい世代の母語話者を生み出したという指摘がある。言語復興の対 象となる言語には、(植民地化や社会的差別を通して)使用や著名性が著しく制限されている言語が含まれる。また、絶滅した言語を復興させるために、さまざ まな言語復興化の手法が用いられることもある。言語復興化の目標はケースによって大きく異なるが、一般的には、(1)ある言語の話者と使用者の数を拡大す ること、または(2)現在の使用レベルを維持し、その言語を絶滅や言語死から保護することが挙げられる。

言語が消滅することによる物理的な危険、先住民の天 然資源開発などの経済的な危険、大量虐殺などの政治的な危険、文化的な危険や同化など、再生させる理由はさまざまである。過去1世紀だけでも、すでに 2000以上の言語が消滅したと推定されている。国連は、現在話されている言語の半数以上が1万人以下、4分の1が1000人以下であり、何らかの維持努 力がない限り、今後100年以内にそのほとんどが絶滅すると推定している。これらの数字は、言語多様性を維持するために言語復興化が必要である理由として よく挙げられる例である。文化やアイデンティティも言語復興化の理由としてよく挙げられるが、これは言語がユニークな「文化的遺産」であると認識されてい るからである。言語コミュニティはしばしば、言語を自分たちの文化のユニークな一部とみなし、祖先や土地と結びつけ、自分たちの歴史や自己イメージの重要 な部分を構成していると考えているからであろう。

言語復興は、言語学的な分野である記述言語学とも密 接に関連している。この分野では、言語学者が、ある言語の文法、語彙、言語的特徴を完全に記録することを試みている。このような実践は、研究対象である特 定の言語の復興化に対する関心を高めることにつながることが多い。さらに、言語復興という目標を念頭に置いて、言語記述化(ドキュメンテーション)という 作業に取り組むことも多い。

先住民言語復興運動においては、先住民の言語使用の当事者と記述言語学者が協働して、表記法 の確立、文法書や辞書の編纂、ネオロジズム(=コンピュータ用語のような新語用語集の編纂)、オーディオ・ビジュアル教材や幼年向けの教科書の制作、ロー カルラジオ局の先住民言語による放送、公的集会におけるバイリンガル使用、古代文字(使用)の普及、言語復興と文化復興に関するさまざまな文化事業など、 言語使用に纏わるさまざまな活動があげられる。

| Language

revitalization,

also referred to as language revival or reversing language shift, is an

attempt to halt or reverse the decline of a language or to revive an

extinct one.[1][2] Those involved can include linguists, cultural or

community groups, or governments. Some argue for a distinction between

language revival (the resurrection of an extinct language with no

existing native speakers) and language revitalization (the rescue of a

"dying" language). There has only been one successful instance of a

complete language revival: that of the Hebrew language.[3] Languages targeted for language revitalization include those whose use and prominence is severely limited. Sometimes various tactics of language revitalization can even be used to try to revive extinct languages. Though the goals of language revitalization vary greatly from case to case, they typically involve attempting to expand the number of speakers and use of a language, or trying to maintain the current level of use to protect the language from extinction or language death. Reasons for revitalization vary: they can include physical danger affecting those whose language is dying, economic danger such as the exploitation of indigenous natural resources, political danger such as genocide, or cultural danger/assimilation.[4] In recent times[when?] alone, it is estimated that more than 2000 languages have already become extinct. The UN estimates that more than half of the languages spoken today have fewer than 10,000 speakers and that a quarter have fewer than 1,000 speakers; and that, unless there are some efforts to maintain them, over the next hundred years most of these will become extinct.[5] These figures are often cited as reasons why language revitalization is necessary to preserve linguistic diversity. Culture and identity are also frequently cited reasons for language revitalization, when a language is perceived as a unique "cultural treasure."[6] A community often sees language as a unique part of their culture, connecting them with their ancestors or with the land, making up an essential part of their history and self-image.[7] Language revitalization is also closely tied to the linguistic field of language documentation. In this field, linguists try to create a complete record of a language's grammar, vocabulary, and linguistic features. This practice can often lead to more concern for the revitalization of a specific language on study. Furthermore, the task of documentation is often taken on with the goal of revitalization in mind.[8] |

言語再生(げんご

ふっこう)とは、言語復興(げんごふっこう)、言語転換(げんごふっこう)とも呼ばれ、言語の衰退を食い止めたり逆転させたり、消滅した言語を復活させた

りする試みである[1][2]。言語復興(母語話者が存在しない絶滅言語の復活)と言語再活性化(「死にかけ」の言語の救済)を区別して論じる人もいる。

完全な言語復興に成功した例は、ヘブライ語のみである[3]。 言語再生の対象となる言語には、その使用や普及が著しく制限されている言語も含まれる。言語再生のさまざまな戦術が、消滅した言語の復活を試みるために使 われることさえある。言語活性化の目標はケースによって大きく異なるが、一般的には、その言語の話者数や使用数を拡大しようとするもの、あるいは、その言 語を絶滅や言語死から守るために現在の使用レベルを維持しようとするものである。 活性化の理由はさまざまで、言語が死滅しつつある人々に影響を及ぼす物理的な危険、先住民の天然資源の搾取などの経済的な危険、大量虐殺などの政治的な危 険、文化的な危険・同化などがある[4]。国連は、現在話されている言語の半数以上が話者数1万人未満、4分の1が話者数1000人未満であり、これらの 言語を維持するための何らかの取り組みがない限り、今後100年間でこれらの言語のほとんどが絶滅すると推定している[5]。これらの数字は、言語の多様 性を維持するために言語活性化が必要な理由としてしばしば引用される。ある言語が独自の「文化的宝物」[6]として認識されている場合、文化やアイデン ティティも言語活性化の理由としてよく挙げられる。コミュニティはしばしば、言語を自分たちの文化の独自の一部とみなし、祖先や土地と結びつけ、自分たち の歴史や自己イメージの重要な部分を構成していると考える[7]。 言語活性化はまた、言語の文書化という言語学分野とも密接に結びついている。この分野では、言語学者が言語の文法、語彙、言語的特徴を完全に記録しようと する。このような実践は、研究対象の特定の言語の活性化に対する関心を高めることにつながることが多い。さらに、文書化という作業は、活性化という目標を 念頭に置いて行われることが多い[8]。 |

| Degrees of language endangerment This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Language revitalization" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) UNESCO's Language Vitality and Endangerment Framework Uses a six-point scale is as follows:[citation needed][9] Safe: All generations use language in variety of settings Stable: Multilingualism in the native language and one or more dominant language(s) has usurped certain important communication context. Definitively Endangered: spoken by older people; not fully used by younger generations. Severely Endangered: Only a few adult speakers remain; no longer used as native language by children. Critically Endangered: The language is spoken only by grandparents and older generations. Extinct: There is no one who can speak or remember the language. Another scale Another scale for identifying degrees of language endangerment is used in a 2003 paper ("Language Vitality and Endangerment") commissioned by UNESCO from an international group of linguists. The linguists, among other goals and priorities, create a scale with six degrees for language vitality and endangerment.[10] They also propose nine factors or criteria (six of which use the six-degree scale) to "characterize a language’s overall sociolinguistic situation".[10] The nine factors with their respective scales are: Intergenerational language transmission safe: all generations use the language unsafe: some children use the language in all settings, all children use the language in some settings definitively endangered: few children speak the language; predominantly spoken by the parental generation and older severely endangered: spoken by older generations; not used by the parental generation and younger critically endangered: few speakers remain and are mainly from the great grandparental generation extinct: no living speakers Absolute number of speakers Proportion of speakers within the total population safe: the language is spoken by approximately 100% of the population unsafe: the language is spoken by nearly but visibly less than 100% of the population definitively endangered: the language is spoken by a majority of the population severely endangered: the language is spoken by less than 50% of the population critically endangered: the language has very few speakers extinct: no living speakers Trends in existing language domains universal use (safe): spoken in all domains; for all functions multilingual parity (unsafe): multiple languages (2+) are spoken in most social domains; for most functions dwindling domains (definitively endangered): mainly spoken in home domains and is in competition with the dominant language; for many functions limited or formal domains (severely endangered): spoken in limited social domains; for several functions highly limited domains (critically endangered): spoken in highly restricted domains; for minimal functions extinct: no domains; no functions Response to new domains and media dynamic (safe): spoken in all new domains robust/active (unsafe): spoken in most new domains receptive (definitively endangered): spoken in many new domains coping (severely endangered): spoken in some new domains minimal (critically endangered): spoken in minimal new domains inactive (extinct): spoken in no new domains Materials for language education and literacy safe: established orthography and extensive access to educational materials unsafe: access to educational materials; children developing literacy; not used by administration definitively endangered: access to educational materials exist at school; literacy in language is not promoted severely endangered: literacy materials exist however are not present in school curriculum critically endangered: orthography is known and some written materials exist extinct: no orthography is known Governmental and institutional language attitudes and policies (including official status and use) equal support (safe): all languages are equally protected differentiated support (unsafe): primarily protected for private domains passive assimilation (definitively endangered): no explicit protective policy; language use dwindles in public domain active assimilation (severely endangered): government discourages use of language; no governmental protection of language in any domain forced assimilation (critically endangered): language is not recognized or protected; government recognized another official language prohibition (extinct): use of language is banned Community members' attitudes towards their own language safe: language is revered, valued, and promoted by whole community unsafe: language maintenance is supported by most of the community definitively endangered: language maintenance is supported by much of the community; the rest are indifferent or support language loss severely endangered: language maintenance is supported by some of the community; the rest are indifferent or support language loss critically endangered: language maintenance is supported by only a few members of the community; the rest are indifferent or support language loss extinct: complete apathy towards language maintenance; prefer dominant language Amount and quality of documentation. superlative (safe): extensive audio, video, media, and written documentation of the language good (unsafe): audio, video, media, and written documentation all exist; a handful of each fair (definitively endangered): some audio and video documentation exists; adequate written documentation fragmentary (severely endangered): limited audio and video documentation exists at low quality; minimal written documentation inadequate (critically endangered): only a handful of written documentation exists undocumented (extinct): no documentation exists |

言語の危険度 このセクションでは、検証のために追加の引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただき たい。ソースのないものは、異議申し立てされ削除されることがある。 出典を探す 「言語活性化」 - ニュース - 新聞 - 本 - 学術 - JSTOR (October 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) ユネスコの言語活性化・危機管理フレームワーク は、以下の6段階評価を用いている[要出典][9]。 安全である: すべての世代が様々な場面で言語を使用している 安定している: 母国語と1つまたは複数の支配的言語による多言語主義が、ある重要なコミュニケーション文脈を簒奪している。 決定的に絶滅危惧:高齢者によって使用され、若い世代では十分に使用されていない。 深刻な絶滅危惧: 数少ない成人の話者が残っているだけで、もはや子供たちの母語としては使われていない。 危機的に絶滅危惧: 祖父母やそれ以上の世代によってのみ話されている。 絶滅危惧種:その言語を話したり記憶したりできる人がいない。 別の尺度 ユネスコが国際的な言語学者グループに依頼した2003年の論文(「Language Vitality and Endangerment」)では、言語の絶滅の程度を特定するための別の尺度が用いられている。この言語学者たちは、他の目標や優先事項の中で、言語の 活力と絶滅危惧度を6段階で表す尺度を作成している[10]。 また、「言語の社会言語学的状況全体を特徴づける」ために、9つの要因や基準(うち6つは6段階の尺度を使用)を提案している[10]。9つの要因とそれ ぞれの尺度は以下の通りである: 世代間の言語伝達 安全:すべての世代がその言語を使用する 安全でない:すべての環境で一部の子どもがその言語を使用し、一部の環境ですべての子どもがその言語を使用する。 決定的に危うい:その言語を話す子どもはほとんどいない。 深刻な絶滅危惧:年長世代が使用し、親世代以下は使用しない。 危機的絶滅危惧種:話す人がほとんど残っておらず、主に曽祖父母世代が話す。 絶滅:現存する話者がいない 話者の絶対数 全人口に占める話者の割合 安全:人口のおよそ100%がその言語を話す。 安全でない:その言語を話す人は人口のほぼ100%だが、目に見えて100%未満である。 決定的に絶滅危惧:その言語は人口の過半数によって話されている 深刻な絶滅危惧:その言語は人口の50%以下で話されている。 危機的絶滅危惧種:その言語を話す人が非常に少ない。 絶滅:現存する話者がいない 既存の言語ドメインの傾向 普遍的使用(安全):すべての領域で話されている。 多言語パリティ(安全でない):ほとんどの社会領域で複数の言語(2つ以上)が話されている。 減少しつつある領域(決定的に危機的):主に自国語領域で話 され、支配的な言語と競合している。 限定的または形式的な領域(深刻な絶滅危惧種):限られた社会的領域で話されている。 非常に限定された領域(危機的絶滅危惧):非常に限定された領域で話されている。 絶滅:領域も機能もない 新しい領域やメディアへの対応 動的(安全):すべての新しい領域で話される 頑健/能動的(安全ではない):ほとんどの新ドメインで話されている 受容的(決定的に絶滅危惧):多くの新ドメインで話される 対処的(著しく絶滅の危機に瀕している):いくつかの新しいドメ インで話される 最小(危機的絶滅危惧):最小限の新しいドメインで話されている 不活性(絶滅):新しいドメインで話されていない 言語教育と読み書きのための教材 安全:正書法が確立され、教材へのアクセスが広範にある。 安全でない:教材にアクセスできない。 決定的に危機的:学校での教材へのアクセスはある。 著しく危機的:識字教材は存在するが、学校のカリキュラムに組み込まれていない。 決定的に絶滅危惧:正書法が判明しており、いくつかの教材が存在する。 絶滅:正書法が知られていない 政府および組織の言語意識と政策(公的地位と使用を含む) 平等な支援(安全):すべての言語が平等に保護されている。 差別化された支援(安全でない):主に私的な領域で保護される 受動的同化(決定的に危機的):明確な保護政策がない。 能動的同化(深刻な絶滅危惧):政府が言語の使用を奨励する。 強制的同化(危機的絶滅危惧種):言語が認知も保護もされていない。 禁止(絶滅):言語の使用が禁止されている。 コミュニティメンバーの自国語に対する意識 安全:コミュニティ全体で言語が尊ばれ、重んじられ、推進されている。 安全でない:言語維持が地域社会の大部分によって支持されている。 決定的に絶滅の危機に瀕している: 言語維持がコミュニティの多くに支持されている。 著しく絶滅の危機に瀕している:言語維持はコミュニティの一部によって支持されているが、残りは無関心であるか、言語喪失を支持している。 絶滅の危機に瀕している:言語維持を支持しているのはコミュニティの数人だけで、残りは無関心か言語喪失を支持している。 絶滅:言語維持に完全に無関心である。 文書の量と質 最上級(安全):言語の音声、ビデオ、メディア、文書による文書が充実している。 良い(安全ではない):音声、映像、メディア、文章による文書がすべて存在する。 可もなく不可もなく(決定的に絶滅の危機に瀕している):オーディオとビデオによる文書がいくつか存在する。 断片的(絶滅の危機に瀕している):限られた音声と映像の文書が低品質で存在する。 不十分(絶滅危惧種):わずかな文書資料しか存在しない。 文書化されていない(絶滅):文書が存在しない。 |

| Theory One of the most important preliminary steps in language revitalization/recovering involves establishing the degree to which a particular language has been “dislocated.” This helps involved parties find the best way to assist or revive the language.[11] Steps in reversing language shift There are many different theories or models that attempt to lay out a plan for language revitalization. One of these is provided by celebrated linguist Joshua Fishman. Fishman's model for reviving threatened (or sleeping) languages, or for making them sustainable,[12][13] consists of an eight-stage process. Efforts should be concentrated on the earlier stages of restoration until they have been consolidated before proceeding to the later stages. The eight stages are: Acquisition of the language by adults, who in effect act as language apprentices (recommended where most of the remaining speakers of the language are elderly and socially isolated from other speakers of the language). Create a socially integrated population of active speakers (or users) of the language (at this stage it is usually best to concentrate mainly on the spoken language rather than the written language). In localities where there are a reasonable number of people habitually using the language, encourage the informal use of the language among people of all age groups and within families and bolster its daily use through the establishment of local neighbourhood institutions in which the language is encouraged, protected and (in certain contexts at least) used exclusively. In areas where oral competence in the language has been achieved in all age groups, encourage literacy in the language, but in a way that does not depend upon assistance from (or goodwill of) the state education system. Where the state permits it, and where numbers warrant, encourage the use of the language in compulsory state education. Where the above stages have been achieved and consolidated, encourage the use of the language in the workplace. Where the above stages have been achieved and consolidated, encourage the use of the language in local government services and mass media. Where the above stages have been achieved and consolidated, encourage use of the language in higher education, government, etc. This model of language revival is intended to direct efforts to where they are most effective and to avoid wasting energy trying to achieve the later stages of recovery when the earlier stages have not been achieved. For instance, it is probably wasteful to campaign for the use of a language on television or in government services if hardly any families are in the habit of using the language. Additionally, Tasaku Tsunoda describes a range of different techniques or methods that speakers can use to try to revitalize a language, including techniques to revive extinct languages and maintain weak ones. The techniques he lists are often limited to the current vitality of the language. He claims that the immersion method cannot be used to revitalize an extinct or moribund language. In contrast, the master-apprentice method of one-on-one transmission on language proficiency can be used with moribund languages. Several other methods of revitalization, including those that rely on technology such as recordings or media, can be used for languages in any state of viability.[14] |

理論 言語の活性化/回復における最も重要な前段階のひとつは、特定の言語がどの程度「脱臼」しているのかを明らかにすることである。これによって関係者は、そ の言語を支援したり復活させたりするための最善の方法を見つけることができる[11]。 言語シフトを逆転させるためのステップ 言語再生のための計画を立てようとする理論やモデルは数多く存在する。そのひとつが、著名な言語学者であるジョシュア・フィッシュマンによるものである。 フィッシュマンのモデルは、危機に瀕した(あるいは眠っている)言語を復活させる、あるいは持続可能なものにするためのもので、8段階のプロセスから構成 されている[12][13]。後の段階に進む前に、修復の初期段階が固まるまで、その段階に努力を集中すべきである。その8つの段階とは以下の通りであ る: 実質的に言語の見習いとして機能する大人たちによる言語の習得(その言語の残存話者のほとんどが高齢者であり、他の言語の話者から社会的に孤立している場 合に推奨される)。 その言語の活動的な話者(または使用者)からなる社会的に統合された集団を作る(この段階では通常、書き言葉よりも話し言葉に集中するのが最善である)。 その言語を習慣的に使用する人がそれなりにいる地域では、あらゆる年齢層の人々や家族の間でその言語を非公式に使用することを奨励し、その言語が奨励さ れ、保護され、(少なくとも特定の文脈では)独占的に使用されるような地域の近隣機関を設立することによって、その言語の日常的な使用を強化する。 その言語の口頭能力がすべての年齢層で達成されている地域では、その言語の識字を奨励する。ただし、国の教育制度からの援助(あるいは善意)に依存しない 方法で。 国が許可し、人数が許す限り、義務教育でのその言語の使用を奨励する。 上記の段階が達成され、統合された場合には、職場での言語使用を奨励する。 上記の段階が達成され、統合された場合には、地方自治体のサービスやマスメディアでの言語使用を奨励する。 上記の段階が達成され、定着した場合、高等教育や政府などでの言語使用を奨励する。 この言語復興モデルは、最も効果的な場所に努力を向けること、また、初期の段階が達成されていないのに、後期の復興段階を達成しようとするエネルギーの浪 費を避けることを意図している。たとえば、ある言語を使う習慣のある家庭がほとんどないのに、テレビや行政サービスでその言語を使うようキャンペーンを張 るのは、おそらく無駄である。 さらに角田太作は、消滅した言語を復活させたり、弱体化した言語を維持したりするテクニックを含め、ある言語を活性化させるために話者が使えるさまざまな テクニックや方法について述べている。角田氏が挙げる技法は、多くの場合、その言語の現在の活力に限定されている。 彼は、イマージョン法は絶滅した言語や衰弱した言語の活性化には使えないと主張する。対照的に、言語の習熟度を1対1で伝達する師弟法は、死滅した言語に も使える。録音やメディアなどの技術に依存するものも含め、他のいくつかの活性化方法は、どのような状態の言語にも使用することができる[14]。 |

Degree of endangerment Degree of endangerment is an evaluation assigned by UNESCO to the languages in the Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[1] Evaluation is given according to nine criteria, the most important of which is the criterion of language transmission between generations.[2] |

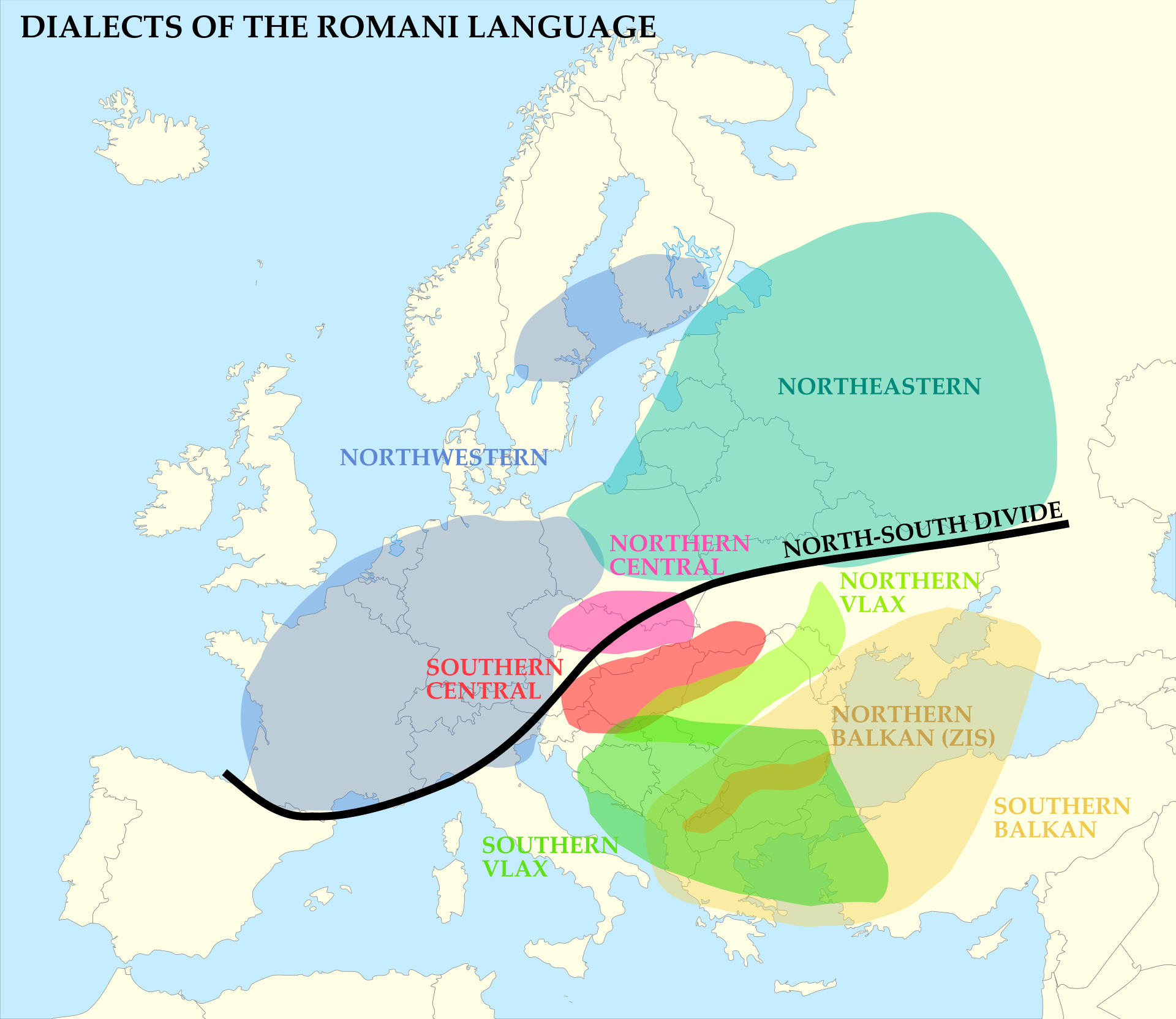

The picture shows the dialects of the Romani, which are under threat of disappearance. 写真は、消滅の危機に瀕しているロマニ族の方言である。 危険度 絶滅危惧度は、ユネスコが「危機に瀕する世界の言語アトラス」に掲載されている言語に付けた評価である[1]。評価は9つの基準に従って行われるが、その 中で最も重要なのは世代間の言語伝達の基準である[2]。 |

| Factors in successful language

revitalization David Crystal, in his book Language Death, proposes that language revitalization is more likely to be successful if its speakers: increase the language's prestige within the dominant community; increase their wealth and income; increase their legitimate power in the eyes of the dominant community; have a strong presence in the education system; can write down the language; can use electronic technology.[15] In her book, Endangered Languages: An Introduction, Sarah Thomason notes the success of revival efforts for modern Hebrew and the relative success of revitalizing Maori in New Zealand (see Specific Examples below). One notable factor these two examples share is that the children were raised in fully immersive environments.[16] In the case of Hebrew, it was on early collective-communities called kibbutzim.[17] For the Maori language In New Zealand, this was done through a language nest.[18] Revival linguistics Ghil'ad Zuckermann proposes "Revival Linguistics" as a new linguistic discipline and paradigm. Zuckermann's term 'Revival Linguistics' is modelled upon 'Contact Linguistics'. Revival linguistics inter alia explores the universal constraints and mechanisms involved in language reclamation, renewal and revitalization. It draws perspicacious comparative insights from one revival attempt to another, thus acting as an epistemological bridge between parallel discourses in various local attempts to revive sleeping tongues all over the globe.[19] According to Zuckermann, "revival linguistics combines scientific studies of native language acquisition and foreign language learning. After all, language reclamation is the most extreme case of second-language learning. Revival linguistics complements the established area of documentary linguistics, which records endangered languages before they fall asleep."[20] Zuckermann proposes that "revival linguistics changes the field of historical linguistics by, for instance, weakening the family tree model, which implies that a language has only one parent."[20] There are disagreements in the field of language revitalization as to the degree that revival should concentrate on maintaining the traditional language, versus allowing simplification or widespread borrowing from the majority language. Compromise Zuckermann acknowledges the presence of "local peculiarities and idiosyncrasies"[20] but suggests that "there are linguistic constraints applicable to all revival attempts. Mastering them would help revivalists and first nations' leaders to work more efficiently. For example, it is easier to resurrect basic vocabulary and verbal conjugations than sounds and word order. Revivalists should be realistic and abandon discouraging, counter-productive slogans such as "Give us authenticity or give us death!"[20] Nancy Dorian has pointed out that conservative attitudes toward loanwords and grammatical changes often hamper efforts to revitalize endangered languages (as with Tiwi in Australia), and that a division can exist between educated revitalizers, interested in historicity, and remaining speakers interested in locally authentic idiom (as has sometimes occurred with Irish). Some have argued that structural compromise may, in fact, enhance the prospects of survival, as may have been the case with English in the post-Norman period.[21] Traditionalist Other linguists have argued that when language revitalization borrows heavily from the majority language, the result is a new language, perhaps a creole or pidgin.[22] For example, the existence of "Neo-Hawaiian" as a separate language from "Traditional Hawaiian" has been proposed, due to the heavy influence of English on every aspect of the revived Hawaiian language.[23] This has also been proposed for Irish, with a sharp division between "Urban Irish" (spoken by second-language speakers) and traditional Irish (as spoken as a first language in Gaeltacht areas). Ó Béarra stated: "[to] follow the syntax and idiomatic conventions of English, [would be] producing what amounts to little more than English in Irish drag."[24] With regard to the then-moribund Manx language, the scholar T. F. O'Rahilly stated, "When a language surrenders itself to foreign idiom, and when all its speakers become bilingual, the penalty is death."[25] Neil McRae has stated that the uses of Scottish Gaelic are becoming increasingly tokenistic, and native Gaelic idiom is being lost in favor of artificial terms created by second-language speakers.[26] |

言語再生の成功要因 デイヴィッド・クリスタルは、その著書『Language Death』(邦訳『言語の死』)の中で、言語活性化は次のような場合に成功しやすいと提唱している: その言語の話者が、支配的なコミュニティ内でその言語の威信を高める; 話者の富と収入を増やす; 支配的コミュニティから見て、正当な権力が増す; 教育システムにおいて強い存在感を示す; その言語を書き記すことができる; 電子技術を使うことができる。 彼女の著書『Endangered Languages: サラ・トマソンは著書『Endangered Languages: An Introduction』の中で、現代ヘブライ語の復興努力の成功と、ニュージーランドのマオリ語の復興が比較的成功していることに言及している(下記 の「具体例」を参照)。ヘブライ語の場合、それはキブツジムと呼ばれる初期の集団コミュニティで行われた[16]。 ニュージーランドのマオリ語の場合、これはランゲージ・ネストを通じて行われた[18]。 復興言語学 ギルアド・ズッカーマンは、新しい言語学的学問分野とパラダイムとして「復興言語学」を提唱している。 ズッカーマンの「復興言語学」という言葉は、「接触言語学」をモデルとしている。リバイバル言語学は特に、言語の再生、更新、活性化に関わる普遍的な制約 とメカニズムを探求する。それは、ある復活の試みから別の復活の試みへの鋭い比較的洞察を引き出し、その結果、世界中で眠っている言語を復活させようとす るさまざまなローカルな試みにおける並行する言説間の認識論的橋渡しとして機能する[19]。 ズッカーマンによれば、「復興言語学は母語習得と外国語学習の科学的研究を組み合わせたもの」である。結局のところ、言語再生は第二言語学習の最も極端な ケースなのである。復興言語学は、絶滅の危機に瀕した言語が眠りにつく前に記録する、文書言語学という確立された分野を補完するものである」[20]。 ズッカーマンは、「復興言語学は、例えば、言語には親が一人しかいないとする家系モデルを弱めることによって、歴史言語学の分野を変える」と提案している [20]。 言語復興の分野では、復興が伝統的な言語の維持に集中すべきなのか、それとも多数派の言語からの簡略化や広範な借用を認めるべきなのかについて、意見が分 かれている。 妥協 Zuckermannは「地域の特殊性や特異性」[20]の存在を認めているが、次のように提案している。 「すべてのリバイバルの試みに当てはまる言語的制約がある。それらをマスターすることは、リバイバリストや先住国民の指導者がより効率的に活動するのに役 立つだろう。たとえば、音や語順よりも、基本的な語彙や動詞の活用を復活させる方が簡単である。リバイバリストは現実的であるべきであり、「真正性を与え るか、死を与えるか!」といった落胆させるような逆効果のスローガンは捨てるべきである[20]。 ナンシー・ドリアンは、借用語や文法上の変化に対する保守的な態度が、(オーストラリアのティウィ語のように)絶滅の危機に瀕した言語の再活性化の妨げに なることがしばしばあること、また、(アイルランド語のように)歴史性に関心を持つ教養ある再活性化論者と、地元に根差したイディオムに関心を持つ残存話 者の間に分裂が生じることがあることを指摘している。また、構造的な妥協がかえって存続の可能性を高めると主張する者もいる(ノルマン朝以降の英語の場 合)[21]。 伝統主義者 他の言語学者は、言語の活性化が多数派の言語から多くを借用する場合、その結果、新しい言語、おそらくクレオールやピジンが生まれると主張している [22]。例えば、復活したハワイ語のあらゆる面で英語の影響が大きいことから、「伝統的なハワイ語」とは別の言語として「ネオ・ハワイアン語」の存在が 提唱されている[23]。 [23]これはアイルランド語でも提唱されており、「アーバン・アイルランド語」(第二言語話者によって話されている)と伝統的なアイルランド語(ゲール タハト地域で第一言語として話されている)を峻別している。オ・ベアラは次のように述べている: 「英語の構文や慣用句に従うことは、アイルランドのドラッグの中で英語以上のものを生み出すことになる」[24]と述べている。O'Rahillyは「あ る言語が外国語の慣用句に身を委ね、その言語を話す者すべてがバイリンガルになった時、その罰は死である」と述べている[25]。ニール・マクレーは、ス コットランド・ゲール語の用法はますます形骸化し、第二言語話者が作り出した人工的な用語のために、ネイティブなゲール語の慣用句が失われつつあると述べ ている[26]。 |

| Specific examples The total revival of a dead language (in the sense of having no native speakers) to become the shared means of communication of a self-sustaining community of several million first language speakers has happened only once, in the case of Hebrew, resulting in Modern Hebrew - now the national language of Israel. In this case, there was a unique set of historical and cultural characteristics that facilitated the revival. (See Revival of the Hebrew language.) Hebrew, once largely a liturgical language, was re-established as a means of everyday communication by Jews, some of who had lived in what is now the State of Israel, starting in the nineteenth century. It is the world's most famous and successful example of language revitalization. In a related development, literary languages without native speakers enjoyed great prestige and practical utility as lingua francas, often counting millions of fluent speakers at a time. In many such cases, a decline in the use of the literary language, sometimes precipitous, was later accompanied by a strong renewal. This happened, for example, in the revival of Classical Latin in the Renaissance, and the revival of Sanskrit in the early centuries AD. An analogous phenomenon in contemporary Arabic-speaking areas is the expanded use of the literary language (Modern Standard Arabic, a form of the Classical Arabic of the 6th century AD). This is taught to all educated speakers and is used in radio broadcasts, formal discussions, etc.[27] In addition, literary languages have sometimes risen to the level of becoming first languages of very large language communities. An example is standard Italian, which originated as a literary language based on the language of 13th-century Florence, especially as used by such important Florentine writers as Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio. This language existed for several centuries primarily as a literary vehicle, with few native speakers; even as late as 1861, on the eve of Italian unification, the language only counted about 500,000 speakers (many non-native), out of a total population of c. 22,000,000. The subsequent success of the language has been through conscious development, where speakers of any of the numerous Italian languages were taught standard Italian as a second language and subsequently imparted it to their children, who learned it as a first language.[citation needed] Of course this came at the expense of local Italian languages, most of which are now endangered. Success was enjoyed in similar circumstances by High German, standard Czech, Castilian Spanish and other languages. Africa The Coptic language began its decline when Arabic became the predominant language in Egypt. Pope Shenouda III established the Coptic Language Institute in December 1976 in Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Cairo for the purpose of reviving the Coptic language.[28][29] Americas North America In recent years, a growing number of Native American tribes have been trying to revitalize their languages.[30][31] For example, there are apps (including phrases, word lists and dictionaries) in many Native languages including Cree, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Lakota, Ojibwe, Oneida, Massachusett, Navajo, Halq'emeylem, Gwych'in, and Lushootseed. Wampanoag, a language spoken by the people of the same name in Massachusetts, underwent a language revival project led by Jessie Little Doe Baird, a trained linguist. Members of the tribe use the extensive written records that exist in their language, including a translation of the Bible and legal documents, in order to learn and teach Wampanoag. The project has seen children speaking the language fluently for the first time in over 100 years.[32][33] In addition, there are currently attempts at reviving the Chochenyo language of California, which had become extinct. Efforts are being made by the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community and others to keep Chinook Jargon, also known as Chinuk Wawa, alive. This is helped by the corpus of songs and stories collected from Victoria Howard and published by Melville Jacobs.[34][35] The open-source platform FirstVoices hosts community-managed websites for 85 language revitalization projects, covering multiple varieties of 33 Indigenous languages in British Columbia as well as over a dozen languages from "elsewhere in Canada and around the globe", along with 17 dictionary apps.[36] Tlingit Similar to other indigenous languages, Tlingit is critically endangered.[37] Fewer than 100 fluent Elders existed as of 2017.[37] From 2013 to 2014, the language activist, author, and teacher, Sʔímlaʔxw Michele K. Johnson from the Syilx Nation, attempted to teach two hopeful learners of Tlingit in the Yukon.[37] Her methods included textbook creation, sequenced immersion curriculum, and film assessment.[37] The aim was to assist in the creation of adult speakers that are of parent-age, so that they too can begin teaching the language. In 2020, X̱ʼunei Lance Twitchell led a Tlingit online class with Outer Coast College. Dozens of students participated.[38] He is an associate professor of Alaska Native Languages in the School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Alaska Southeast which offers a minor in Tlingit language and an emphasis on Alaska Native Languages and Studies within a Bachelorʼs degree in Liberal Arts.[39] South America Kichwa is the variety of the Quechua language spoken in Ecuador and is one of the most widely spoken indigenous languages in South America. Despite this fact, Kichwa is a threatened language, mainly because of the expansion of Spanish in South America. One community of original Kichwa speakers, Lagunas, was one of the first indigenous communities to switch to the Spanish language.[40] According to King, this was because of the increase of trade and business with the large Spanish-speaking town nearby. The Lagunas people assert that it was not for cultural assimilation purposes, as they value their cultural identity highly.[40] However, once this contact was made, language for the Lagunas people shifted through generations, to Kichwa and Spanish bilingualism and now is essentially Spanish monolingualism. The feelings of the Lagunas people present a dichotomy with language use, as most of the Lagunas members speak Spanish exclusively and only know a few words in Kichwa. The prospects for Kichwa language revitalization are not promising, as parents depend on schooling for this purpose, which is not nearly as effective as continual language exposure in the home.[41] Schooling in the Lagunas community, although having a conscious focus on teaching Kichwa, consists of mainly passive interaction, reading, and writing in Kichwa.[42] In addition to grassroots efforts, national language revitalization organizations, like CONAIE, focus attention on non-Spanish speaking indigenous children, who represent a large minority in the country. Another national initiative, Bilingual Intercultural Education Project (PEBI), was ineffective in language revitalization because instruction was given in Kichwa and Spanish was taught as a second language to children who were almost exclusively Spanish monolinguals. Although some techniques seem ineffective, Kendall A. King provides several suggestions: Exposure to and acquisition of the language at a young age. Extreme immersion techniques. Multiple and diverse efforts to reach adults. Flexibility and coordination in planning and implementation Directly addressing different varieties of the language. Planners stressing that language revitalization is a long process Involving as many people as possible Parents using the language with their children Planners and advocates approaching the problem from all directions. Specific suggestions include imparting an elevated perception of the language in schools, focusing on grassroots efforts both in school and the home, and maintaining national and regional attention.[41] Asia Hebrew Further information: Revival of the Hebrew language The revival of the Hebrew language is the only successful example of a revived dead language.[3] The Hebrew language survived into the medieval period as the language of Jewish liturgy and rabbinic literature. With the rise of Zionism in the 19th century, it was revived as a spoken and literary language, becoming primarily a spoken lingua franca among the early Jewish immigrants to Ottoman Palestine and received the official status in the 1922 constitution of the British Mandate for Palestine and subsequently of the State of Israel.[43] Sanskrit Further information: Sanskrit revival There have been recent attempts at reviving Sanskrit in India.[44][45][46] However, despite these attempts, there are no first language speakers of Sanskrit in India.[47][48][49] In each of India's recent decennial censuses, several thousand citizens[a] have reported Sanskrit to be their mother tongue. However, these reports are thought to signify a wish to be aligned with the prestige of the language, rather than being genuinely indicative of the presence of thousands of L1 Sanskrit speakers in India. There has also been a rise of so-called "Sanskrit villages",[46][50] but experts have cast doubt on the extent to which Sanskrit is really spoken in such villages.[47][51] Soyot Main article: Soyot language The Soyot language of the small-numbered Soyots in Buryatia, Russia, one of the Siberian Turkic languages, has been reconstructed and a Soyot-Buryat-Russian dictionary was published in 2002. The language is currently taught in some elementary schools.[52] Ainu Main article: Ainu language The Ainu language of the indigenous Ainu people of northern Japan is currently moribund, but efforts are underway to revive it. A 2006 survey of the Hokkaido Ainu indicated that only 4.6% of Ainu surveyed were able to converse in or "speak a little" Ainu.[53] As of 2001, Ainu was not taught in any elementary or secondary schools in Japan, but was offered at numerous language centres and universities in Hokkaido, as well as at Tokyo's Chiba University.[54] Manchu Main article: Manchu language In China, the Manchu language is one of the most endangered languages, with speakers only in three small areas of Manchuria remaining.[55] Some enthusiasts are trying to revive the language of their ancestors using available dictionaries and textbooks, and even occasional visits to Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County in Xinjiang, where the related Xibe language is still spoken natively.[56] Spanish Main articles: Spanish language in the Philippines and Philippine Spanish In the Philippines, a local variety of Spanish that was primarily based on Mexican Spanish was the lingua franca of the country since Spanish colonization in 1565 and was an official language alongside Filipino (standardized Tagalog) and English until 1987, following the ratification of a new constitution, where it was re-designated as a voluntary language. As a result of its loss as an official language and years of marginalization at the official level during and after American colonization, the use of Spanish amongst the overall populace decreased dramatically and became moribund, with the remaining native speakers left being mostly elderly people.[57][58][59] The language has seen a gradual revival, however, due to official promotion under the administration of former President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.[60][61] Most notably, Resolution No. 2006-028 reinstated Spanish as a mandatory subject in secondary schools and universities.[62] Results were immediate as the job demand for Spanish speakers had increased since 2008.[63] As of 2010, the Instituto Cervantes in Manila reported the number of Spanish-speakers in the country with native or non-native knowledge at approximately 3 million, the figure albeit including those who speak the Spanish-based creole Chavacano.[64] Complementing government efforts is a notable surge of exposure through the mainstream media and, more recently, music-streaming services.[65][66] Western Armenian Main article: Armenian language The Western Armenian language, has been classified as a definitely endangered language in the Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (2010),[67] as most speakers of the dialect remain in diasporic communities away from their homeland in Anatolia, following the Armenian genocide. In spite of this, there have been various efforts[68] to revitalize the language, especially within the Los Angeles community where the majority of Western Armenians reside. Within her dissertation, Shushan Karapetian discusses at length the decline of the Armenian language in the United States, and new means for keeping and reviving Western Armenian, such as the creation of the Saroyan Committee or the Armenian Language Preservation Committee, launched in 2013.[69] Other attempts at language revitalization can be seen within the University of California in Irvine.[70] Other Asian In Thailand, there exists a Chong language revitalization project, headed by Suwilai Premsrirat.[71] Europe In Europe, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the use of both local and learned languages declined as the central governments of the different states imposed their vernacular language as the standard throughout education and official use (this was the case in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Italy and Greece, and to some extent, in Germany and Austria-Hungary).[citation needed] In the last few [when?] decades, local nationalism and human rights movements have made a more multicultural policy standard in European states; sharp condemnation of the earlier practices of suppressing regional languages was expressed in the use of such terms as "linguicide". Basque In Francoist Spain, Basque language use was discouraged by the government's repressive policies. In the Basque Country, "Francoist repression was not only political, but also linguistic and cultural."[72] Franco's regime suppressed Basque from official discourse, education, and publishing,[73] making it illegal to register newborn babies under Basque names,[74] and even requiring tombstone engravings in Basque to be removed.[75] In some provinces the public use of Basque was suppressed, with people fined for speaking it.[76] Public use of Basque was frowned upon by supporters of the regime, often regarded as a sign of anti-Francoism or separatism.[77] in the late 1960s. Since 1968, Basque has been immersed in a revitalisation process, facing formidable obstacles. However, significant progress has been made in numerous areas. Six main factors have been identified to explain its relative success: implementation and acceptance of Unified, or Standard Basque (Euskara Batua), which was developed by the Euskaltzaindia integration of Basque in the education system creation of media in Basque (radio, newspapers, and television) the established new legal framework collaboration between public institutions and people's organisations, and campaigns for Basque language literacy.[78] While those six factors influenced the revitalisation process, the extensive development and use of language technologies is also considered a significant additional factor.[79] Overall, in the 1960s and later, the trend reversed and education and publishing in Basque began to flourish.[80] A sociolinguistic survey shows that there has been a steady increase in Basque speakers since the 1990s, and the percentage of young speakers exceeds that of the old.[81] Irish Main article: Status of the Irish language One of the best known European attempts at language revitalization concerns the Irish language. While English is dominant through most of Ireland, Irish, a Celtic language, is still spoken in certain areas called Gaeltachtaí,[82] but there it is in serious decline.[83] The challenges faced by the language over the last few centuries have included exclusion from important domains, social denigration, the death or emigration of many Irish speakers during the Irish famine of the 1840s, and continued emigration since. Efforts to revitalise Irish were being made, however, from the mid-1800s, and were associated with a desire for Irish political independence.[82] Contemporary Irish language revitalization has chiefly involved teaching Irish as a compulsory language in mainstream English-speaking schools. But the failure to teach it in an effective and engaging way means (as linguist Andrew Carnie notes) that students do not acquire the fluency needed for the lasting viability of the language, and this leads to boredom and resentment. Carnie also noted a lack of media in Irish (2006),[82] though this is no longer the case. The decline of the Gaeltachtaí and the failure of state-directed revitalisation have been countered by an urban revival movement. This is largely based on an independent community-based school system, known generally as Gaelscoileanna. These schools teach entirely through Irish and their number is growing, with over thirty such schools in Dublin alone.[84] They are an important element in the creation of a network of urban Irish speakers (known as Gaeilgeoirí), who tend to be young, well-educated and middle-class. It is now likely that this group has acquired critical mass, a fact reflected in the expansion of Irish-language media.[85] Irish language television has enjoyed particular success.[86] It has been argued that they tend to be better educated than monolingual English speakers and enjoy higher social status.[87] They represent the transition of Irish to a modern urban world, with an accompanying rise in prestige. Scottish Gaelic There are also current attempts to revive the related language of Scottish Gaelic, which was suppressed following the formation of the United Kingdom, and entered further decline due to the Highland clearances. Currently [when?], Gaelic is only spoken widely in the Western Isles and some relatively small areas of the Highlands and Islands. The decline in fluent Gaelic speakers has slowed; however, the population center has shifted to L2 speakers in urban areas, especially Glasgow.[88][89] Manx Main article: Manx language revival Another Celtic language, Manx, lost its last native speaker in 1974 and was declared extinct by UNESCO in 2009, but never completely fell from use.[90] The language is now taught in primary and secondary schools, including as a teaching medium at the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, used in some public events and spoken as a second language by approximately 1800 people.[91] Revitalization efforts include radio shows in Manx Gaelic and social media and online resources. The Manx government has also been involved in the effort by creating organizations such as the Manx Heritage Foundation (Culture Vannin) and the position of Manx Language Officer.[92] The government has released an official Manx Language Strategy for 2017–2021.[93] Cornish There have been a number of attempts to revive the Cornish language, both privately and some under the Cornish Language Partnership. Some of the activities have included translation of the Christian scriptures,[94] a guild of bards,[95] and the promotion of Cornish literature in modern Cornish, including novels and poetry. Breton Main article: Breton language § Revival efforts Caló The Romani arriving in the Iberian Peninsula developed an Iberian Romani dialect. As time passed, Romani ceased to be a full language and became Caló, a cant mixing Iberian Romance grammar and Romani vocabulary. With sedentarization and obligatory instruction in the official languages, Caló is used less and less. As Iberian Romani proper is extinct and as Caló is endangered, some people are trying to revitalise the language. The Spanish politician Juan de Dios Ramírez Heredia promotes Romanò-Kalò, a variant of International Romani, enriched by Caló words.[96] His goal is to reunify the Caló and Romani roots. Livonian Main article: Livonian language revival The Livonian language, a Finnic language, once spoken on about a third of modern-day Latvian territory,[97] died in the 21st century with the death of the last native speaker Grizelda Kristiņa on 2 June 2013.[98] Today there are about 210 people mainly living in Latvia who identify themselves as Livonian and speak the language on the A1-A2 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages and between 20 and 40 people who speak the language on level B1 and up.[99] Today all speakers learn Livonian as a second language. There are different programs educating Latvians on the cultural and linguistic heritage of Livonians and the fact that most Latvians have common Livonian descent.[100] Programs worth mentioning include: Livones.net[101] with extensive information about language, history and culture The Livonian Institute of the University of Latvia[102] doing research on the Livonian language, other Finnic languages in Latvia and providing an extensive Livonian-Latvian-Estonian dictionary with declinations/conjugations[103] Virtual Livonia[104] providing information on the Livonian language and especially its grammar Mierlinkizt:[105] An annual summer camp for children to teach children about the Livonian language, culture etc. Līvõd Īt (Livonian Union)[106] The Livonian linguistic and cultural heritage is included in the Latvian cultural canon[107] and the protection, revitalization and development of Livonian as an indigenous language is guaranteed by Latvian law[108] Old Prussian A few linguists and philologists are involved in reviving a reconstructed form of the extinct Old Prussian language from Luther's catechisms, the Elbing Vocabulary, place names, and Prussian loanwords in the Low Prussian dialect of Low German. Several dozen people use the language in Lithuania, Kaliningrad, and Poland, including a few children who are natively bilingual.[109] The Prusaspirā Society has published their translation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's The Little Prince. The book was translated by Piotr Szatkowski (Pīteris Šātkis) and released in 2015.[110] The other efforts of Baltic Prussian societies include the development of online dictionaries, learning apps and games. There also have been several attempts to produce music with lyrics written in the revived Baltic Prussian language, most notably in the Kaliningrad Oblast by Romowe Rikoito,[111] Kellan and Āustras Laīwan, but also in Lithuania by Kūlgrinda in their 2005 album Prūsų Giesmės (Prussian Hymns),[112] and in Latvia by Rasa Ensemble in 1988[113] and Valdis Muktupāvels in his 2005 oratorio "Pārcēlātājs Pontifex" featuring several parts sung in Prussian.[114] Important in this revival was Vytautas Mažiulis, who died on 11 April 2009, and his pupil Letas Palmaitis, leader of the experiment and author of the website Prussian Reconstructions.[115] Two late contributors were Prāncis Arellis (Pranciškus Erelis), Lithuania, and Dailūns Russinis (Dailonis Rusiņš), Latvia. After them, Twankstas Glabbis from Kaliningrad oblast and Nērtiks Pamedīns from East-Prussia, now Polish Warmia-Mazuria actively joined.[citation needed] Yola The Yola language revival movement has cultivated in Wexford in recent years, and the “Gabble Ing Yola” resource center for Yola materials claims there are around 140 speakers of the Yola language today.[116] Oceania Australia The European colonization of Australia, and the consequent damage sustained by Aboriginal communities, had a catastrophic effect on indigenous languages, especially in the southeast and south of the country, leaving some with no living traditional native speakers. A number of Aboriginal communities in Victoria and elsewhere are now trying to revive some of these languages. The work is typically directed by a group of Aboriginal elders and other knowledgeable people, with community language workers doing most of the research and teaching. They analyze the data, develop spelling systems and vocabulary and prepare resources. Decisions are made in collaboration. Some communities employ linguists, and there are also linguists who have worked independently,[117] such as Luise Hercus and Peter K. Austin. In the state of Queensland, an effort is being made to teach some Indigenous languages in schools and to develop workshops for adults. More than 150 languages were once spoken within the state, but today fewer than 20 are spoken as a first language, and less than two per cent of schools teach any Indigenous language. The Gunggari language is one language which is being revived, with only three native speakers left.[118][119] In the Northern Territory, the Pertame Project is an example in Central Australia. Pertame, from the country south of Alice Springs, along the Finke River, is a dialect in the Arrernte group of languages. With only 20 fluent speakers left by 2018,[120] the Pertame Project is seeking to retain and revive the language, headed by Pertame elder Christobel Swan.[121] In the far north of South Australia, the Diyari language has an active programme under way, with materials available for teaching in schools and the wider community.[122] Also in South Australia, there is a unit at the University of Adelaide which teaches and promotes the use of the Kaurna language, headed by Rob Amery, who has produced many books and course materials.[123] The Victorian Department of Education and Training reported 1,867 student enrollments in 14 schools offering an Aboriginal Languages Program in the state of Victoria in 2018.[124] New Zealand Further information: Māori language revival One of the best cases of relative success in language revitalization is the case of Maori, also known as te reo Māori. It is the ancestral tongue of the indigenous Maori people of New Zealand and a vehicle for prose narrative, sung poetry, and genealogical recital.[125] The history of the Maori people is taught in Maori in sacred learning houses through oral transmission. Even after Maori became a written language, the oral tradition was preserved.[125] Once European colonization began, many laws were enacted in order to promote the use of English over Maori among indigenous people.[125] The Education Ordinance Act of 1847 mandated school instruction in English and established boarding schools to speed up assimilation of Maori youths into European culture. The Native School Act of 1858 forbade Māori from being spoken in schools. During the 1970s, a group of young Maori people, the Ngā Tamatoa, successfully campaigned for Maori to be taught in schools.[125] Also, Kōhanga Reo, Māori language preschools, called language nests, were established.[126] The emphasis was on teaching children the language at a young age, a very effective strategy for language learning. The Maori Language Commission was formed in 1987, leading to a number of national reforms aimed at revitalizing Maori.[125] They include media programmes broadcast in Maori, undergraduate college programmes taught in Maori, and an annual Maori language week. Each iwi (tribe) created a language planning programme catering to its specific circumstances. These efforts have resulted in a steady increase in children being taught in Maori in schools since 1996.[125] Hawaiian Main article: Hawaiian language On six of the seven inhabited islands of Hawaii, Hawaiian was displaced by English and is no longer used as the daily language of communication. The one exception is Niʻihau, where Hawaiian has never been displaced, has never been endangered, and is still used almost exclusively. Efforts to revive the language have increased in recent decades. Hawaiian language immersion schools are now open to children whose families want to retain (or introduce) Hawaiian language into the next generation. The local National Public Radio station features a short segment titled "Hawaiian word of the day". Additionally, the Sunday editions of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin and its successor, the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, feature a brief article called Kauakūkalahale, written entirely in Hawaiian by a student.[127] |

具体例 死語(母語話者がいないという意味での)であった言語が完全に復活し、数百万人の第一言語話者を擁する自立したコミュニティが共有するコミュニケーション 手段となった例は、ヘブライ語の場合、一度だけある。この場合、復活を促した歴史的・文化的特徴があった。(ヘブライ語は、かつては主に典礼用の言語で あったが、19世紀以降、現在のイスラエルに住んでいたユダヤ人たちによって、日常的なコミュニケーション手段として再確立された。これは世界で最も有名 な言語再生の成功例である。 これに関連して、母語話者のいない文語は、しばしば一度に数百万人の流暢な話者を数え、国際共通語として大きな名声と実用性を享受した。多くの場合、その ような文語の使用は、時には急激に減少したが、後に力強い再興を伴った。例えば、ルネサンス期における古典ラテン語の復興や、紀元後数世紀初頭におけるサ ンスクリット語の復興がそうである。現代のアラビア語圏における類似の現象は、文語(現代標準アラビア語、西暦6世紀の古典アラビア語の一形態)の使用拡 大である。これはすべての教養ある話者に教えられており、ラジオ放送や正式な議論などで使用されている[27]。 さらに、文学的な言語が、非常に大きな言語共同体の第一言語となるレベルまで上昇することもある。その一例が標準イタリア語であり、これは13世紀のフィ レンツェの言語、特にダンテ、ペトラルカ、ボッカッチョといったフィレンツェの重要な作家が使っていた言語に基づく文学言語として生まれた。1861年の イタリア統一前夜でさえ、総人口2,200万人のうち、この言語を話す人は約50万人(多くは非ネイティブ)にすぎなかった。その後のイタリア語の成功 は、意識的な発展によるもので、多数のイタリア語のいずれかを話す人々が、第二言語として標準イタリア語を教えられ、その後子供たちに教えられ、子供たち は第一言語として学んだ[要出典]。同様の状況下で成功を収めたのは、高級ドイツ語、標準チェコ語、カスティーリャ・スペイン語などであった。 アフリカ エジプトでアラビア語が主流になると、コプト語は衰退し始めた。教皇シェヌーダ3世は1976年12月、コプト語を復活させる目的で、カイロのサン・マル コ・コプト正教会大聖堂にコプト語研究所を設立した[28][29]。 アメリカ大陸 北米 近年、ネイティブアメリカンの部族の数が増えており、言語の活性化を試みている[30][31]。 例えば、クリー語、チェロキー語、チカソー語、ラコタ語、オジブエ語、オナイダ語、マサチューセッツ語、ナバホ語、ハルクエメレム語、グウィチン語、ル シュートシード語など、多くのネイティブ言語のアプリ(フレーズ、単語リスト、辞書を含む)がある。 ワンパノアグ語は、マサチューセッツ州の同名の人々が話す言語で、訓練を受けた言語学者ジェシー・リトル・ドゥー・ベアードが主導する言語復興プロジェク トが行われた。この部族のメンバーは、ワンパノアグ語を学び教えるために、聖書の翻訳や法律文書など、彼らの言語で書かれた膨大な記録を利用している。こ のプロジェクトによって、子どもたちは100年以上ぶりにこの言語を流暢に話すようになった[32][33]。さらに現在、絶滅していたカリフォルニアの チョチェニョ語を復活させる試みが行われている。 チヌーク・ワワとしても知られるチヌーク・ジャーゴンを存続させるために、グランド・ロンド地域連合部族などが努力している。これはビクトリア・ハワード から収集され、メルヴィル・ジェイコブズによって出版された歌と物語のコーパスによって支えられている[34][35]。 オープンソースのプラットフォームであるFirstVoicesは、85の言語活性化プロジェクトのためのコミュニティ管理ウェブサイトをホストしてお り、ブリティッシュ・コロンビア州の33の先住民言語と「カナダの他の地域や世界中の」10以上の言語の複数の品種をカバーし、17の辞書アプリも提供し ている[36]。 トリンギット語 他の先住民言語と同様に、トリンギット語は危機的に絶滅の危機に瀕している[37]。 2017年現在、流暢な長老は100人に満たない[37]。2013年から2014年にかけて、言語活動家、作家、教師であるシルックス国民出身の Sʔímlaʔxw Michele K. Johnsonは、ユーコンでトリンギット語の希望に満ちた学習者2人に教えようと試みた。 [37]彼女の方法には、教科書の作成、連続したイマージョン・カリキュラム、映画による評価などが含まれる[37]。その目的は、親となる年齢を迎えた 成人話者の作成を支援し、彼らもまた言語を教え始めることができるようにすることだった。2020年には、X̱ʼunei Lance Twitchellがアウター・コースト・カレッジでトリンギット語のオンラインクラスを指導した。彼はアラスカ大学サウスイースト校の芸術科学部でアラ スカ先住民言語の准教授を務めており、リベラルアーツの学士号でトリンギット語の副専攻とアラスカ先住民の言語と研究に重点を置いている[39]。 南アメリカ キチュワ語はエクアドルで話されているケチュア語の一種で、南米で最も広く話されている先住民言語のひとつである。この事実にもかかわらず、キチュワ語 は、主に南米におけるスペイン語の拡大により、危機に瀕している言語である。キチュワ語の原語話者のコミュニティのひとつであるラグナスは、スペイン語に 切り替えた最初の先住民コミュニティのひとつである[40]。 キングによれば、これは近くにスペイン語を話す大きな町ができたため、貿易やビジネスが増えたためだという。ラグナス族は、自分たちの文化的アイデンティ ティを非常に重視しているため、文化的同化のためではなかったと主張している[40]。しかし、一度この接触が行われると、ラグナス族の言語は世代を経 て、キチュワ語とスペイン語のバイリンガルへと移行し、現在は基本的にスペイン語単一言語主義となっている。ラグナス族はスペイン語のみを話し、キチュワ 語は数単語しか知らない。 キチュワ語再生の見込みは、親たちが学校教育に頼っているため、あまり期待できない。ラグナス・コミュニティの学校教育は、意識的にキチュワ語を教えるこ とに重点を置いてはいるが、主に受動的な交流、キチュワ語の読み書きで構成されている[42]。草の根の努力に加え、CONAIEのような言語再生の国民 組織は、国内で大きな少数派を占めるスペイン語を話さない先住民の子どもたちに注目している。もうひとつの国民的取り組みであるバイリンガル・インターカ ルチュラル教育プロジェクト(PEBI)は、キチュワ語で指導が行われ、ほとんどスペイン語しか話さない子どもたちにスペイン語を第二言語として教えてい たため、言語活性化には効果がなかった。効果がないと思われる手法もあるが、ケンダル・A・キングはいくつかの提案をしている: 幼少期にその言語に触れ、習得する。 極端なイマージョン・テクニック 成人にアプローチするための、複数かつ多様な努力。 計画と実施における柔軟性と調整。 異なる言語種に直接取り組む。 言語活性化は長いプロセスであることを強調する。 できるだけ多くの人を巻き込む 親が子供と一緒に言語を使っている プランナーや提唱者は、あらゆる方向からこの問題にアプローチする。 具体的な提案としては、学校において言語に対する認識を高めること、学校と家庭の両方における草の根的な取り組みに焦点を当てること、国民や地域の関心を 維持することなどが挙げられる[41]。 アジア ヘブライ語 さらなる情報 ヘブライ語の復興 ヘブライ語の復活は、死語が復活した唯一の成功例である[3]。ヘブライ語は、ユダヤ教の典礼やラビ文学の言語として中世まで存続した。19世紀にシオニ ズムが台頭すると、話し言葉および文学言語として復活し、主にオスマン・パレスチナへの初期のユダヤ人移民の間で話し言葉の共通語となり、1922年のイ ギリス委任統治領パレスチナ憲法、その後のイスラエル国家憲法において正式な地位を得た[43]。 サンスクリット語 さらに詳しい情報 サンスクリット語の復興 インドでは近年サンスクリット語の復活が試みられている[44][45][46]が、こうした試みにもかかわらず、インドでサンスクリット語を母語とする 者はいない[47][48][49]。しかし、これらの報告は、インドに何千人ものサンスクリット語を母語とする人々が存在することを真に示しているとい うよりは、言語の威信に並びたいという願望を意味していると考えられている。また、いわゆる「サンスクリット村」も増加している[46][50]が、専門 家はそのような村で本当にサンスクリット語が話されているのかについて疑問を投げかけている[47][51]。 ソヨット 主な記事 ソヨット語 シベリアのテュルク系言語のひとつである、ロシアのブリヤート地方に住む少数民族ソヨト族のソヨト語は再構築され、2002年にソヨト語・ブリヤート語・ ロシア語の辞書が出版された。この言語は現在、一部の小学校で教えられている[52]。 アイヌ語 主な記事 アイヌ語 北日本の先住民族であるアイヌのアイヌ語は現在消滅しているが、アイヌ語を復活させるための努力が続けられている。2006年に行われた北海道アイヌの調 査では、アイヌ語で会話ができる、または「少し話すことができる」アイヌ人は調査対象者のわずか4.6%であった[53]。2001年現在、アイヌ語は日 本の小中学校では教えられていないが、北海道の多くの言語センターや大学、東京の千葉大学で教えられている[54]。 満州語 主な記事 満州語 中国では、満州語は最も絶滅の危機に瀕している言語のひとつであり、満州の3つの小さな地域にしか話者が残っていない[55]。一部の愛好家は、入手可能 な辞書や教科書を使い、関連する西部語が今もネイティブに話されている新疆ウイグル自治区のカプカル西部自治県を時折訪れ、祖先の言語を復活させようとし ている[56]。 スペイン語 主な記事 フィリピンのスペイン語、フィリピン・スペイン語 フィリピンでは、1565年にスペインが植民地化して以来、主にメキシコのスペイン語を基にした現地スペイン語がフィリピンの共通語であり、1987年の 新憲法批准まではフィリピン語(標準タガログ語)、英語と並ぶ公用語であった。しかし、グロリア・マカパガル・アロヨ(Gloria Macapagal Arroyo)前大統領の政権下でスペイン語が公式に奨励され、徐々に復活を遂げた[60][61] 。2006-028号は、スペイン語を中等学校と大学の必修科目として復活させた[62]。 2008年以降、スペイン語話者の求人需要が増加していたため、その成果はすぐに現れた[63]。 2010年現在、マニラのセルバンテス協会は、スペイン語を母語とする、または母語ではないスペイン語話者の数は約300万人であると報告している。政府 の取り組みを補完するものとして、主要メディアや、最近では音楽ストリーミングサービスを通じた露出の急増が顕著である[65][66]。 西アルメニア語 主な記事 アルメニア語 西アルメニア語は、『危機に瀕する世界の言語アトラス』(2010年)[67]において、確実に絶滅の危機に瀕している言語に分類されている。にもかかわ らず、特に西アルメニア人の大半が住むロサンゼルスのコミュニティでは、この言語を活性化させようとする様々な取り組みが行われてきた[68]。 シュシャン・カラペチアンは学位論文の中で、アメリカにおけるアルメニア語の衰退と、2013年に発足したサローヤン委員会やアルメニア語保存委員会の設 立など、西アルメニア語を維持・復活させるための新たな手段について詳しく論じている[69]。他にも、カリフォルニア大学アーバイン校でも言語活性化の 試みが見られる[70]。 その他のアジア タイでは、Suwilai Premsriratが代表を務めるチョン語復興プロジェクトが存在する[71]。 ヨーロッパ ヨーロッパでは、19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、各州の中央政府が教育や公式の場を通じて標準語として地方語を押し付けたため、地方語と学問語の両方 の使用が減少した(イギリス、フランス、スペイン、イタリア、ギリシャ、そしてドイツとオーストリア=ハンガリーではある程度そうであった)[要出典]。 この数十年の間に、地域のナショナリズムと人権運動が、ヨーロッパ諸国においてより多文化的な政策を標準とするようになった。地域言語を抑圧する以前の慣 行に対する鋭い非難は、「言語殺し」といった用語の使用によって表現された。 バスク フランコ主義下のスペインでは、バスク語の使用は政府の抑圧政策によって抑制された。バスク地方では、「フランコ主義による抑圧は政治的なものだけでな く、言語的、文化的なものでもあった」[72]。フランコ政権は、公式の言論、教育、出版からバスク語を抑圧し[73]、新生児をバスク名で登録すること を違法とし[74]、バスク語で刻まれた墓碑銘の撤去まで要求した。 [1960年代後半には、バスク語の公の使用は反フランコ主義や分離主義の表れとみなされ、政権支持者の顰蹙を買った[77]。 1968年以降、バスク語は、手ごわい障害に直面しながら、再活性化のプロセスに没頭してきた。しかし、多くの分野で大きな進展が見られた。その相対的な 成功を説明するために、6つの主な要因が挙げられている: エウスカルツァインディアによって開発された統一バスク語(標準バスク語:Euskara Batua)の導入と受け入れ 教育制度におけるバスク語の統合 バスク語によるメディアの創設(ラジオ、新聞、テレビ) 新しい法的枠組みの確立 公的機関と住民組織との連携 バスク語の識字率向上のためのキャンペーン[78]。 これら6つの要因が活性化のプロセスに影響を与えた一方で、言語技術の広範な発展と利用もまた重要な追加要因であると考えられている[79]。 全体として、1960年代以降、トレンドは逆転し、バスク語による教育と出版が盛んになった[80]。 社会言語学的調査によれば、1990年代以降、バスク語話者は着実に増加しており、若年話者の割合は高齢者の割合を上回っている[81]。 アイルランド語 主な記事 アイルランド語の地位 ヨーロッパで最もよく知られている言語活性化の試みのひとつに、アイルランド語がある。アイルランドの大部分は英語が支配的であるが、ケルト語であるアイ ルランド語は、ゲルタチと呼ばれる特定の地域ではまだ話されている[82]が、そこでは深刻な衰退が見られる[83]。過去数世紀にわたってアイルランド 語が直面した課題には、重要な領域からの排除、社会的な否定、1840年代のアイルランド飢饉の際の多くのアイルランド語話者の死や移住、その後の継続的 な移住などがある。しかし、1800年代半ばからアイルランド語を活性化させようとする努力は行われており、それはアイルランドの政治的独立への願望と関 連していた[82]。現代のアイルランド語活性化には、主に英語圏の学校でアイルランド語を義務教育として教えることが含まれている。しかし、効果的で魅 力的な方法でアイルランド語を教えることができないため、(言語学者のアンドリュー・カーニーが指摘するように)生徒たちはアイルランド語の永続的な存続 に必要な流暢さを身につけることができず、退屈や憤りを感じるようになる。カーニーはまた、アイルランド語のメディアが不足していることも指摘している (2006年)[82]。 ゲールタハティの衰退と国家主導の再活性化の失敗は、都市再活性化運動によって対抗された。これは主に、一般にゲールスコイレアンナとして知られる、独立 したコミュニティベースの学校制度に基づいている。これらの学校は、すべてアイルランド語を使って教えており、その数は増加の一途をたどっており、ダブリ ンだけでも30校を超える[84]。これらの学校は、若く、教育水準が高く、中流階級に属する傾向のある、都市部のアイルランド語話者(ゲイルジョアリと して知られる)のネットワークを形成する上で重要な要素となっている。現在、このグループはクリティカル・マスを獲得していると考えられ、この事実はアイ ルランド語メディアの拡大にも反映されている[85]。 アイルランド語テレビは特に成功を収めている[86]。彼らは英語を母国語とする人々よりも高い教育を受け、高い社会的地位を享受している傾向があると論 じられている[87]。 スコットランド・ゲール語 関連言語であるスコットランド・ゲール語を復活させようという試みも現在行われている。スコットランド・ゲール語は、連合王国成立後に弾圧され、ハイラン ド地方の開拓によってさらに衰退した。現在[いつ?]、ゲール語が広く話されているのは西諸島とハイランド諸島の比較的小さな地域だけである。ゲール語を 流暢に話す話者の減少は緩やかになったが、人口の中心は都市部、特にグラスゴーでL2話者に移っている[88][89]。 マンクス語 主な記事 マンクス語の復興 もうひとつのケルト語であるマンクス語は、1974年に最後の母語話者を失い、2009年にユネスコによって絶滅が宣言されたが、完全に使用されなくなる ことはなかった[90]。マンクス語は現在、Bunscoill Ghaelgaghの教育媒体を含め、初等・中等学校で教えられており、一部の公的行事で使用され、約1800人が第二言語として話している[91]。再 活性化の取り組みとして、マンクス語のラジオ番組やソーシャルメディア、オンラインリソースがある。マンクス政府も、マンクス遺産財団(Culture Vannin)やマンクス語オフィサーの役職などの組織を設立し、この取り組みに関与している[92]。政府は2017年から2021年までの公式なマン クス語戦略を発表している[93]。 コーニッシュ語 コーニッシュ語を復活させようとする試みは、民間でもコーニッシュ言語パートナーシップの下でも数多く行われている。その中にはキリスト教聖典の翻訳 [94]、吟遊詩人ギルド[95]、小説や詩を含む現代コーニッシュ語によるコーニッシュ文学の振興などがある。 ブルトン語 主な記事 ブルトン語§復興への取り組み カロ イベリア半島に到着したロマニ人は、イベリア・ロマニ方言を発達させた。時が経つにつれ、ロマニ語は完全な言語ではなくなり、イベリア・ロマンス語の文法 とロマニ語の語彙が混ざったカロー語となった。定住化が進み、公用語の教育が義務化されたため、Calóが使われることは少なくなった。イベリア・ロマー ニャ語は絶滅し、カロー語も絶滅の危機に瀕しているため、この言語を復活させようとする人々がいる。スペインの政治家 Juan de Dios Ramírez Heredia は、国際ロマーニ語の変種である Romanò-Kalò を推進し、Caló の単語を強化している[96]。彼の目標は、Caló とロマーニ語のルーツを再統一することである。 リボニア語 主な記事 リボニア語の復興 かつては現代のラトビア領土の約3分の1で話されていたフィンランド系の言語であるリボニア語[97]は、2013年6月2日に最後の母語話者であるグリ ゼルダ・クリスティオクタが亡くなったことにより、21世紀に消滅した[98]。リヴォニア人の文化的・言語的遺産や、ほとんどのラトヴィア人がリヴォニ ア人の血を引いているという事実について、ラトヴィア人を教育する様々なプログラムがある[100]。 特筆すべきプログラムには以下のものがある: Livones.net[101]には言語、歴史、文化に関する幅広い情報が掲載されている。 ラトヴィア大学リボニア語研究所[102]は、リボニア語やラトヴィアの他のフィンランド語に関する研究を行っており、辞定形・活用を含む広範なリボニア 語・ラトヴィア語・エストニア語辞書を提供している[103]。 バーチャル・リヴォニア[104] リヴォニア語、特にその文法に関する情報を提供している。 Mierlinkizt:[105] リヴォニア語や文化などについて子供たちに教える、毎年恒例の子供向けサマーキャンプ。 Līvõd Īt(リボニア連合)[106]。 リヴォニア語の言語的・文化的遺産はラトヴィアの文化規範に含まれており[107]、固有言語としてのリヴォニア語の保護、活性化、発展はラトヴィアの法 律によって保証されている[108]。 旧プロイセン語 数人の言語学者や文献学者が、ルターのカテキズム、エルビング語彙、地名、低地ドイツ語の低地プロイセン方言に含まれるプロイセン語の借用語などから、消 滅した旧プロイセン語の再構築に携わっている。リトアニア、カリーニングラード、ポーランドでは数十人がこの言語を使用しており、ネイティブのバイリンガ ルの子供も数人いる[109]。 プルサスピラー協会は、アントワーヌ・ド・サン=テグジュペリの『星の王子さま』の翻訳を出版した。この本はPiotr Szatkowski(Pīteris Šātkis)によって翻訳され、2015年に発売された[110]。バルト海沿岸のプルシア協会によるその他の取り組みとしては、オンライン辞書、学習 アプリ、ゲームの開発が挙げられる。また、復活したバルト・プロイセン語で書かれた歌詞の音楽を制作する試みもいくつか行われており、特にカリーニング ラード州ではRomowe Rikoito、[111] Kellan、Āustras Laīwanが行っている、 またラトヴィアでは1988年にラサ・アンサンブル[113]が、2005年にはヴァルディス・ムクトゥパーヴェルスがオラトリオ 『Pārcēlātājs Pontifex』をプロイセン語で歌っている。 [114] この復活において重要な役割を果たしたのは、2009年4月11日に死去したヴィタウタス・マジュリスと、その弟子で実験の指導者であり、ウェブサイト 「プロイセンの再構築」の著者であるレタス・パルマイティスであった[115]。後期には、リトアニアのプラーンチス・アレリス(Pranciškus Erelis)とラトヴィアのダイルンス・ルシニス(Dailūns Russinis)が貢献した。その後、カリーニングラード州のトワンクスタス・グラビスと東プロイセン(現在のポーランド領ウォルミア=マズリア)の ネールティクス・パメディンスが積極的に参加した[要出典]。 ヨーラ語 ヨーラ語復活運動は近年ウェックスフォードで発展しており、ヨーラ語の資料センター「ガブル・イング・ヨーラ」は、現在約140人のヨーラ語話者がいると 主張している[116]。 オセアニア オーストラリア ヨーロッパ人によるオーストラリアの植民地化と、その結果アボリジニ・コミュニティが被った被害は、特に南東部と南部の先住民の言語に壊滅的な影響を及ぼ し、伝統的な母語話者が生存していないものもある。現在、ビクトリア州をはじめとする多くのアボリジニ・コミュニティが、これらの言語のいくつかを復活さ せようとしている。この活動は通常、アボリジニの長老やその他の知識を持つ人々からなるグループが指揮を執り、コミュニティの言語ワーカーが調査や指導の ほとんどを行っている。彼らはデータを分析し、綴り方や語彙を開発し、資料を準備する。意思決定は共同で行われる。言語学者を雇用しているコミュニティも あるが、ルイーズ・ヘルクスやピーター・K・オースティンのように、独立して活動している言語学者もいる[117]。 クイーンズランド州では、いくつかの先住民言語を学校で教え、大人向けのワークショップを開発する取り組みが行われている。かつて同州では150以上の言 語が話されていたが、現在、第一言語として話されているのは20以下であり、先住民の言語を教えている学校は全体の2%にも満たない。グンガリ語は復活し つつある言語のひとつであり、母語話者は3人しか残っていない[118][119]。 ノーザン・テリトリーでは、中央オーストラリアのペルタメ・プロジェクトがその一例である。ペルタメ語はアリススプリングスの南、フィンケ川沿いの地域の 言語で、アーレンテ語群の方言である。2018年までに流暢な話し手が20人しか残っていないため[120]、ペルタメ長老のクリストベル・スワンが率い るペルタメ・プロジェクトが言語の保持と復活を目指している[121]。 南オーストラリア州の北部では、ディヤリ語の活発なプログラムが進行中であり、学校やより広範なコミュニティで教えるための教材が用意されている [122]。同じく南オーストラリア州のアデレード大学には、多くの書籍や教材を制作しているロブ・アメリーが率いる、カウルナ語の教授と使用を促進する ユニットがある[123]。 ビクトリア州教育訓練省は、2018年にビクトリア州でアボリジニ言語プログラムを提供している14校に1,867人の生徒が在籍していると報告している [124]。 ニュージーランド さらなる情報 マオリ語の復興 言語復興に比較的成功した事例として、マオリ語(te reo Māori)が挙げられる。マオリ語は、ニュージーランドの先住民マオリ族の祖先の言葉であり、散文的な物語、歌詩、系図を語るための手段である [125]。マオリ族の歴史は、神聖な学問の館で口承によってマオリ語で教えられている。マオリ語が文字言語となった後も、口承の伝統は守られてきた [125]。 ヨーロッパの植民地化が始まると、先住民の間でマオリ語よりも英語の使用を促進するために多くの法律が制定された[125]。 1847年の教育条例法は英語による学校教育を義務付け、マオリの若者のヨーロッパ文化への同化を早めるために寄宿学校を設立した。1858年の先住民学 校法は、学校でマオリ語を話すことを禁じた。 1970年代、若いマオリの人々のグループであるンガ・タマトアは、マオリを学校で教えるよう運動し、成功した[125]。 また、コハンガ・レオ(Kōhanga Reo)と呼ばれる、言語の巣と呼ばれるマオリ語の幼稚園が設立された[126]。1987年にはマオリ語委員会が設立され、マオリ語の活性化を目的とし た多くの国民改革が行われた[125]。マオリ語で放送されるメディア番組、マオリ語で教えられる大学の学部課程、毎年開催されるマオリ語週間などであ る。各イウィ(部族)はそれぞれの状況に合わせた言語計画プログラムを作成した。こうした努力の結果、1996年以降、学校でマオリ語で教えられる子ども たちが着実に増えている[125]。 ハワイ語 主な記事 ハワイ語 ハワイの7つの有人島のうち6つでは、ハワイ語は英語に取って代わられ、もはや日常的なコミュニケーション言語としては使われていない。ただし、ニイハウ 島だけは例外で、ハワイ語が使われなくなったことはなく、絶滅の危機に瀕したこともない。ここ数十年、ハワイ語を復活させようとする動きが活発化してい る。ハワイ語イマージョン・スクールは、ハワイ語を次世代に残したい(あるいは導入したい)と考える子供たちのために開かれている。地元の国民ラジオ局で は、「今日のハワイ語」と題した短いコーナーを放送している。また、ホノルル・スター・ブルletin紙とその後継紙であるホノルル・スター・アドバタイ ザー紙の日曜版には、生徒がハワイ語で書いた「カウアクウカラハレ」という短い記事が掲載されている[127]。 |

| Current revitalization efforts Language revitalization efforts are ongoing around the world. Revitalization teams are utilizing modern technologies to increase contact with indigenous languages and to record traditional knowledge. Mexico In Mexico, the Mixtec people's language heavily revolves around the interaction between climate, nature, and what it means for their livelihood[citation needed]. UNESCO's LINKS (Local and Indigenous Knowledge) program recently underwent a project to create a glossary of Mixtec terms and phrases related to climate. UNESCO believes that the traditional knowledge of the Mixtec people via their deep connection with weather phenomena can provide insight on ways to address climate change. Their intention in creating the glossary is to "facilitate discussions between experts and the holders of traditional knowledge".[128] Canada In Canada, the Wapikoni Mobile project travels to indigenous communities and provides lessons in film making. Program leaders travel across Canada with mobile audiovisual production units, and aims to provide indigenous youth with a way to connect with their culture through a film topic of their choosing. The Wapikona project submits its films to events around the world as an attempt to spread knowledge of indigenous culture and language.[129] Chile Of the youth in Rapa Nui (Easter Island), ten percent learn their mother language. The rest of the community has adopted Spanish in order to communicate with the outside world and support its tourism industry. Through a collaboration between UNESCO and the Chilean Corporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indigena, the Department of Rapa Nui Language and Culture at the Lorenzo Baeza Vega School was created. Since 1990, the department has created primary education texts in the Rapa Nui language. In 2017, the Nid Rapa Nui, a non-governmental organization was also created with the goal of establishing a school that teaches courses entirely in Rapa Nui.[130] Singapore An initiative known as Kodrah Kristang has been created to revitalize the critically endangered Kristang language. It includes an audio course on Soundcloud, known as Kontah Kristang[131] and a vocabulary course on Memrise, known as Kriseh Kristang.[132] The success of the Memrise project has "inspired the start of similar projects among speakers of other Indigenous languages," like Unangam Qilinĝingin to teach the Aleut language spoken in Alaska.[133] The Kodrah Kristang revitalization initiative in Singapore seeks to revive the critically endangered Kristang creole.[134] Criticism John McWhorter has argued that programs to revive indigenous languages will almost never be very effective because of the practical difficulties involved. He also argues that the death of a language does not necessarily mean the death of a culture. Indigenous expression is still possible even when the original language has disappeared, as with Native American groups and as evidenced by the vitality of black American culture in the United States, among people who speak not Yoruba but English. He argues that language death is, ironically, a sign of hitherto isolated peoples migrating and sharing space: "To maintain distinct languages across generations happens only amidst unusually tenacious self-isolation—such as that of the Amish—or brutal segregation".[135] Kenan Malik has also argued that it is "irrational" to try to preserve all the world's languages, as language death is natural and in many cases inevitable, even with intervention. He proposes that language death improves communication by ensuring more people speak the same language. This may benefit the economy and reduce conflict.[136][137] The protection of minority languages from extinction is often not a concern for speakers of the dominant language. There is often prejudice and deliberate persecution of minority languages, in order to appropriate the cultural and economic capital of minority groups.[138] At other times governments deem that the cost of revitalization programs and creating linguistically diverse materials is too great to take on.[139] |

現在の言語活性化の取り組み 言語活性化の取り組みは世界中で進行中である。活性化チームは、先住民の言語との接触を増やし、伝統的な知識を記録するために現代技術を活用している。 メキシコ メキシコでは、ミクステカ族の言語が、気候や自然との相互作用、そしてそれが彼らの生活にとって何を意味するのかを中心に大きく展開している[要出典]。 ユネスコのLINKS(地域と先住民の知識)プログラムは、気候に関連するミクステカ語の用語集を作成するプロジェクトを最近実施した。ユネスコは、気象 現象と深い関わりを持つミクステカ族の伝統的知識が、気候変動に対処するためのヒントを与えてくれると考えている。この用語集を作成する意図は、「専門家 と伝統的知識の保持者との間の議論を促進する」ことにある[128]。 カナダ カナダでは、ワピコニ・モバイル・プロジェクトが先住民のコミュニティを訪れ、映画制作の授業を行っている。プログラムの指導者たちは、移動式の視聴覚制 作ユニットを持ってカナダ中を回り、先住民の若者たちに、自分たちが選んだ映画のテーマを通して自分たちの文化とつながる方法を提供することを目的として いる。ワピコナ・プロジェクトは、先住民の文化や言語に関する知識を広める試みとして、世界中のイベントに映画を出品している[129]。 チリ ラパ・ヌイ(イースター島)の若者のうち、母語を学んでいるのは10パーセントである。残りのコミュニティは、外部とのコミュニケーションや観光産業を支 えるためにスペイン語を採用している。ユネスコとチリのCorporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indigenaの協力により、ロレンソ・バエサ・ベガ学校にラパ・ヌイ言語文化学科が設立された。1990年以来、同学科はラパ・ヌイ語の初等教育テキ ストを作成している。2017年には、完全にラパ・ヌイ語で授業を行う学校の設立を目的とした非政府組織「ニド・ラパ・ヌイ」も設立された[130]。 シンガポール 絶滅の危機に瀕しているクリスタン語を活性化させるために、コドラ・クリスタンとして知られるイニシアチブが創設された。Kontah Kristangとして知られるSoundcloud上の音声コース[131]と、Kriseh Kristangとして知られるMemrise上の語彙コースがある[132]。Memriseプロジェクトの成功は、アラスカで話されているアリュート 語を教えるUnangam Qilinĝinginのように、「他の先住民言語の話者の間で同様のプロジェクトが始まるきっかけとなった」[133]。 シンガポールのコドラ・クリスタン再生イニシアティブは、危機的状況にあるクリスタング・クレオールの復活を目指している[134]。 批判 ジョン・マクウォーター(John McWhorter)は、先住民の言語を復活させるプログラムは、現実的な困難が伴うため、ほとんど効果がないと主張している。彼はまた、言語の死が必ず しも文化の死を意味するとは限らないと主張している。ネイティブ・アメリカンのグループや、ヨルバ語ではなく英語を話すアメリカ黒人の文化の活力が証明し ているように、元の言語が消滅しても先住民族の表現は可能である。彼は、言語の死は皮肉にも、それまで孤立していた民族が移動し、空間を共有することの証 であると主張する: 「世代を超えて異なる言語を維持することは、アーミッシュのような異常に粘り強い自己隔離、あるいは残忍な隔離の中でしか起こらない」[135]。 ケナン・マリクはまた、世界のすべての言語を保存しようとするのは「非合理的」であると主張している。彼は、言語の死は、より多くの人々が同じ言語を話す ようにすることで、コミュニケーションを向上させると提唱している。これは経済に利益をもたらし、紛争を減少させる可能性がある[136][137]。 少数言語の消滅からの保護は、支配的な言語の話者にとっては関心事ではないことが多い。少数派グループの文化的・経済的資本を利用するために、少数派言語 に対する偏見や意図的な迫害が行われることも多い[138]。 また、活性化プログラムや言語的に多様な資料の作成にかかる費用が大きすぎて引き受けられないと政府が判断することもある[139]。 |

| Category:Language activists Contemporary Latin Directorate of Language Planning and Implementation Endangered languages Language documentation Language nest Language planning Language policy Linguistic purism Minority language Regional language Rosetta Project Sacred language Second-language acquisition Treasure language Languages in censuses Digital projects and repositories Lingua Libre − a libre online tool used to record words and phrases of any language (thousands of recordings have already been done in endangered languages like Atikamekw, Occitan, Basque, Catalan, and are all available on Wikimedia Commons) Tatoeba contains example sentences with translations in dozens of endangered languages, including Belarusian, Breton, Basque and Cornish.[140] The Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages − contains works in endangered languages of the Northern Territory, Australia FirstVoices - contains community-managed dictionaries, songs, stories, and multimedia for Indigenous languages in British Columbia Organizations Foundation for Endangered Languages The Language Conservancy Pūnana Leo, Hawaiian language schools Resource Network for Linguistic Diversity Culture Vannin, Manx Gaelic language organization SIL International First Peoples' Cultural Council, Indigenous language, arts, and heritage revitalization in British Columbia Lists Lists of endangered languages List of endangered languages with mobile apps Lists of extinct languages List of language regulators List of revived languages |

Category:Language activists Contemporary Latin Directorate of Language Planning and Implementation Endangered languages Language documentation Language nest Language planning Language policy Linguistic purism Minority language Regional language Rosetta Project Sacred language Second-language acquisition Treasure language Languages in censuses Digital projects and repositories Lingua Libre − a libre online tool used to record words and phrases of any language (thousands of recordings have already been done in endangered languages like Atikamekw, Occitan, Basque, Catalan, and are all available on Wikimedia Commons) Tatoeba contains example sentences with translations in dozens of endangered languages, including Belarusian, Breton, Basque and Cornish.[140] The Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages − contains works in endangered languages of the Northern Territory, Australia FirstVoices - contains community-managed dictionaries, songs, stories, and multimedia for Indigenous languages in British Columbia Organizations Foundation for Endangered Languages The Language Conservancy Pūnana Leo, Hawaiian language schools Resource Network for Linguistic Diversity Culture Vannin, Manx Gaelic language organization SIL International First Peoples' Cultural Council, Indigenous language, arts, and heritage revitalization in British Columbia Lists Lists of endangered languages List of endangered languages with mobile apps Lists of extinct languages List of language regulators List of revived languages |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Language_revitalization |

★琉球諸語と文化の未来 / 波照間永吉, 小嶋洋輔, 照屋理編, 岩波書店 , 2021

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099