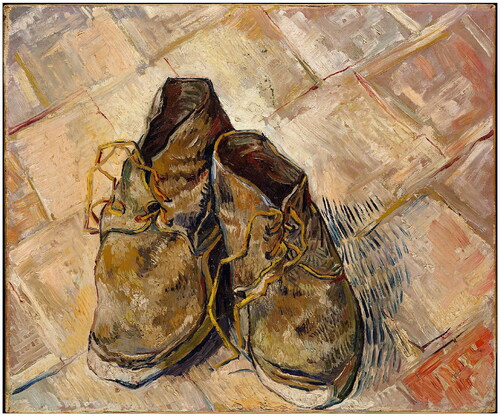

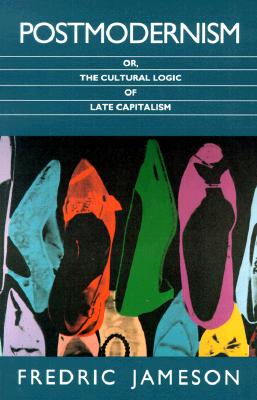

| Postmodernism,

or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. |

Source: Postmodernism, or, The

Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism Verso, 1991. Just two sections from

Chapter 1 reproduced here.

|

I

|

|

The last few years have been

marked by an inverted millenarianism in which premonitions of the

future, catastrophic or redemptive, have been replaced by senses of the

end of this or that (the end of ideology, art, or social class; the

“crisis” of Leninism, social democracy, or the welfare state, etc.,

etc.); taken together, all of these perhaps constitute what is

increasingly called postmodernism. The case for its existence depends

on the hypothesis of some radical break or coupure, generally traced

back to the end of the 1950s or the early 1960s.

As the word itself suggests, this break is most often related to

notions of the waning or extinction of the hundred-year-old modern

movement (or to its ideological or aesthetic repudiation). Thus

abstract expressionism in painting, existentialism in philosophy, the

final forms of representation in the novel, the films of the great

auteurs, or the modernist school of poetry (as institutionalised and

canonised in the works of Wallace Stevens) all are now seen as the

final, extraordinary flowering of a high-modernist impulse which is

spent and exhausted with them. The enumeration of what follows, then,

at once becomes empirical, chaotic, and heterogeneous: Andy Warhol and

pop art, but also photorealism, and beyond it, the “new expressionism”;

the moment, in music, of John Cage, but also the synthesis of classical

and “popular” styles found in composers like Phil Glass and Terry

Riley, and also punk and new wave rock (the Beatles and the Stones now

standing as the high-modernist moment of that more recent and rapidly

evolving tradition); in film, Godard, post-Godard, and experimental

cinema and video, but also a whole new type of commercial film (about

which more below); Burroughs, Pynchon, or Ishmael Reed, on the one

hand, and the French nouveau roman and its succession, on the other,

along with alarming new kinds of literary criticism based on some new

aesthetic of textuality or écriture ... The list might be extended

indefinitely; but does it imply any more fundamental change or break

than the periodic style and fashion changes determined by an older

high-modernist imperative of stylistic innovation?

It is in the realm of architecture, however, that modifications in

aesthetic production are most dramatically visible, and that their

theoretical problems have been most centrally raised and articulated;

it was indeed from architectural debates that my own conception of

postmodernism – as it will be outlined in the following pages –

initially began to emerge. More decisively than in the other arts or

media, postmodernist positions in architecture have been inseparable

from an implacable critique of architectural high modernism and of

Frank Lloyd Wright or the so-called international style (Le Corbusier,

Mies, etc), where formal criticism and analysis (of the high-modernist

transformation of the building into a virtual sculpture, or monumental

“duck,” as Robert Venturi puts it), are at one with reconsiderations on

the level of urbanism and of the aesthetic institution. High modernism

is thus credited with the destruction of the fabric of the traditional

city and its older neighbourhood culture (by way of the radical

disjunction of the new Utopian high-modernist building from its

surrounding context), while the prophetic elitism and authoritarianism

of the modern movement are remorselessly identified in the imperious

gesture of the charismatic Master.

Postmodernism in architecture will then logically enough stage itself

as a kind of aesthetic populism, as the very title of Venturi’s

influential manifesto, Learning from Las Vegas, suggests. However we

may ultimately wish to evaluate this populist rhetoric, it has at least

the merit of drawing our attention to one fundamental feature of all

the postmodernisms enumerated above: namely, the effacement in them of

the older (essentially high-modernist) frontier between high culture

and so-called mass or commercial culture, and the emergence of new

kinds of texts infused with the forms, categories, and contents of that

very culture industry so passionately denounced by all the ideologues

of the modern, from Leavis and the American New Criticism all the way

to Adorno and the Frankfurt School. The postmodernisms have, in fact,

been fascinated precisely by this whole “degraded” landscape of schlock

and kitsch, of TV series and Reader’s Digest culture, of advertising

and motels, of the late show and the grade-B Hollywood film, of

so-called paraliterature, with its airport paperback categories of the

gothic and the romance, the popular biography, the murder mystery, and

the science fiction or fantasy novel: materials they no longer simply

“quote” as a Joyce or a Mahler might have done, but incorporate into

their very substance.

|

ここ数年は逆転した千年王国思想が特徴だ。未来への予感――破滅的であ

れ救済的であれ――は、あれこれの終焉(イデオロギーの終焉、芸術の終焉、社会階級の終焉;レーニン主義の「危機」、社会民主主義の「危機」、福祉国家の

「危機」などなど)に取って代わられた。これら全てを総合すると、おそらくますますポストモダニズムと呼ばれるものを構成しているのだろう。その存在を主

張する根拠は、1950年代末あるいは1960年代初頭に遡る急激な断絶やクープレの存在を仮定することにある。

言葉が示す通り、この断絶は往々にして百年続く近代運動の衰退や消滅(あるいはそのイデオロギー的・美的拒絶)と結びつけられる。したがって絵画における

抽象表現主義、哲学における実存主義、小説における表現の最終形態、偉大なauteursの映画、あるいは(ウォレス・スティーヴンスの作品で制度化・正

典化された)モダニズム詩派は、すべてハイ・モダニズム的衝動の最終的かつ非凡な開花と見なされ、それらはその衝動を消耗させ枯渇させた。したがって、そ

の後を列挙するものは、即座に経験的、混沌的、そして異質な性質を帯びる:アンディ・ウォーホルとポップアート、しかし同時にフォトリアリズム、そしてそ

れを超えた「ニュー・エクスプレッショニズム」;

音楽においてはジョン・ケージの瞬間、しかしフィル・グラスやテリー・ライリーのような作曲家に見られる古典的スタイルと「大衆的」スタイルの融合、さら

にパンクやニューウェーブ・ロック(ビートルズやストーンズは今や、より近くて急速に進化する伝統におけるハイ・モダニズムの瞬間として位置づけられ

る);映画においてはゴダール、ポスト・ゴダール、実験映画やビデオ、しかし全く新しいタイプの商業映画も

(これについては後述する);一方ではバロウズ、ピンチョン、イシュマエル・リード、他方ではフランスのヌーヴォー・ロマンとその後継者たち、さらにテキ

スト性やエクリチュールという新たな美学に基づく驚くべき新しい文学批評...このリストは無限に延ばせるだろう。しかし、それは、より古いハイ・モダニ

ズムの様式革新の要請によって決定づけられた、周期的な様式や流行の変化よりも、より根本的な変化や断絶を意味しているのだろうか?

しかし、美的生産における変容が最も劇的に顕在化し、その理論的問題が最も核心的に提起・明示された領域は建築である。実際、私が後述するポストモダニズ

ムの概念は、建築論争の中から最初に芽生え始めたのだ。他の芸術やメディアよりも決定的に、建築におけるポストモダニズムの立場は、建築におけるハイ・モ

ダニズムやフランク・ロイド・ライト、いわゆるインターナショナル・スタイル(ル・コルビュジエ、ミース・ファン・デル・ローエなど)に対する容赦ない批

判と切り離せないものであった。そこでは、建築を仮想的な彫刻、あるいはロバート・ベンチュリが言うところの記念碑的な「アヒル」へと変容させたハイ・モ

ダニズムの形式批判と分析が、都市計画や都市主義のレベルでの再考と一体となっている。など)に対する容赦ない批判と切り離せない。そこでは形式的批判と

分析(建築物を仮想的な彫刻、あるいはロバート・ベンチュリが言うところの記念碑的な「アヒル」へと変質させたハイ・モダニズムについて)が、都市計画や

美的制度のレベルでの再考と一体となっている。ハイ・モダニズムはこうして、伝統的な都市の構造と古い地域文化の破壊(新たなユートピア的ハイ・モダニズ

ム建築が周囲の文脈から断絶した結果として)の責任を負わされる。一方、モダン運動の予言的エリート主義と権威主義は、カリスマ的な巨匠の威圧的な姿勢に

容赦なく帰属させられる。

建築におけるポストモダニズムは、ベンチュリの影響力ある宣言書『ラスベガスから学ぶ』のタイトルが示唆するように、論理的に一種の美的ポピュリズムとし

て自らを位置づけることになる。このポピュリスト的レトリックを最終的にどう評価するにせよ、少なくとも上記のあらゆるポストモダニズムに共通する根本的

特徴の一つに注意を向ける功績はある。すなわち、それらにおいて、高文化と、いわゆる大衆文化あるいは商業文化との間の古い(本質的にハイ・モダニズム的

な)境界線が消え去り、まさにその文化産業の形態、カテゴリー、内容に浸透された新たな種類のテクストが出現していることだ。この文化産業は、リーヴィス

やアメリカのニュー・クリティシズムからアドルノやフランクフルト学派に至るまで、モダニズムのあらゆるイデオロギー家たちが熱烈に非難してきたものであ

る。ポストモダニズムは、むしろこの「堕落した」景観全体に魅了されてきたのだ。つまり、安っぽいものやキッチュ、テレビシリーズや『リーダーズ・ダイ

ジェスト』的な文化、広告やモーテル、深夜番組やB級ハリウッド映画、いわゆるパラリテラチャー――空港で売られるペーパーバックのカテゴリーであるゴ

シック小説やロマンス小説、大衆伝記、推理小説、SFやファンタジー小説といったもの――に魅了されてきたのである。もはやジョイスやマーラーがそうした

ように単に「引用」するのではなく、自らの本質そのものに組み込む材料として扱っているのだ。

|

Nor should the break in question

be thought of as a purely cultural affair: indeed, theories of the

postmodern – whether celebratory or couched in the language of moral

revulsion and denunciation – bear a strong family resemblance to all

those more ambitious sociological generalisations which, at much the

same time bring us the news of the arrival and inauguration of a whole

new type of society, most famously baptised “Postindustrial society”

(Daniel Bell) but often also designated consumer society, media

society, information society, electronic society or high tech, and the

like. Such theories have the obvious ideological mission of

demonstrating, to their own relief, that the new social formation in

question no longer obeys the laws of classical capitalism, namely, the

primacy of industrial production and the omnipresence of class

struggle. The Marxist tradition has therefore resisted them with

vehemence, with the signal except on of the economist Ernest Mandel,

whose book Late Capitalism sets out not merely to anatomise the

historic originality of this new society (which he sees as a third

stage or moment in the evolution of capital) but also to demonstrate

that it is, if an thing, a purer stage of capitalism than any of the

moments that preceded it. I will return to t is argument later; suffice

it for the moment to anticipate a point that will be argued in Chapter

2, namely, that every position on postmodernism in culture – whether

apologia or stigmatisation – is also at one and the same time, and

necessarily, an implicitly or explicitly political stance on the nature

of multinational capitalism today.

A last preliminary word on method: what follows is not to be read as

stylistic description, as the account of one cultural style or movement

among others. I have rather meant to offer a periodising hypothesis,

and that at a moment in which the very conception of historical

periodisation has come to seem most problematical indeed. I have argued

elsewhere that all isolated or discrete cultural analysis always

involves a buried or repressed theory of historical periodisation; in

any case, the conception of the “genealogy” largely lays to rest

traditional theoretical worries about so-called linear history,

theories of “stages,” and teleological historiography. In the present

context, however, lengthier theoretical discussion of such (very real)

issues can perhaps be replaced by a few substantive remarks.

One of the concerns frequently aroused by periodising hypotheses is

that these tend to obliterate difference and to project an idea of the

historical period as massive homogeneity (bounded on either side by

inexplicable chronological metamorphoses and punctuation marks). This

is, however, precisely why it seems to me essential to grasp

postmodernism not as a style but rather as a cultural dominant: a

conception which allows for the presence and coexistence of a range of

very different, yet subordinate, features.

Consider, for example, the powerful alternative position that

postmodernism is itself little more than one more stage of modernism

proper (if not, indeed, of the even older romanticism); it may indeed

be conceded that all the features of postmodernism I am about to

enumerate can be detected, full-blown, in this or that preceding

modernism (including such astonishing genealogical precursors as

Gertrude Stein, Raymond Roussel, or Marcel Duchamp, who may be

considered outright postmodernists, avant la lettre). What has not been

taken into account by this view, however, is the social position of the

older modernism, or better still, its passionate repudiation by an

older Victorian and post-Victorian bourgeoisie for whom its forms and

ethos are received as being variously ugly, dissonant, obscure,

scandalous, immoral, subversive, and generally “antisocial.” It will be

argued here, however, that a mutation in the sphere of culture has

rendered such attitudes archaic. Not only are Picasso and Joyce no

longer ugly, they now strike us, on the whole, as rather “realistic,”

and this is the result of a canonisation and academic

institutionalisation of the modern movement generally that can be to

the late 1950s. This is surety one of the most plausible explanations

for the emergence of postmodernism itself, since the younger generation

of the 1960s will now confront the formerly oppositional modern

movement as a set of dead classics, which “weigh like a nightmare on

the brains of the living,” as Marx once said in a different context.

|

問題の断絶を純粋に文化的な事象と考えるべきではない。実際、ポストモ

ダンの理論――それを称賛するものであれ、道徳的嫌悪や非難の言葉で表現するものであれ――は、ほぼ同時期に全く新しいタイプの社会の到来と幕開けを告げ

る、より野心的な社会学的一般化と強い類似性を帯びている。最も有名なのは「ポスト産業社会」と命名されたものだ

(ダニエル・ベル)が提唱した概念である。こうした理論には明らかなイデオロギー的使命がある。すなわち、新たな社会形成がもはや古典的資本主義の法則

――工業生産の優位性と階級闘争の遍在性――に従わないことを、自らの安堵のために証明することである。したがってマルクス主義の伝統は、経済学者エルネ

スト・マンデルを除いて、これら理論に激しく抵抗してきた。マンデルの著書『後期資本主義』は、この新社会の歴史的独自性(彼はこれを資本の進化における

第三段階と見なす)を解剖するだけでなく、それがむしろ、それ以前のどの段階よりも純粋な資本主義の段階であることを示そうとするものである。この議論に

ついては後で戻る。現時点では第2章で論じる点を予見しておくに留めよう。すなわち、文化におけるポストモダニズムへのあらゆる立場―擁護であれ非難であ

れ―は同時に、必然的に、今日の多国籍資本主義の本質に対する暗黙的あるいは明示的な政治的立場でもあるのだ。

方法論に関する最後の予備的言及:以下は単なる様式論的記述、すなわち数ある文化様式や運動の一つについての説明として読むべきではない。むしろ、歴史的

区分そのものの概念が極めて問題視されるようになったこの時点で、区分に関する仮説を提示することを意図している。私は別の場所で、あらゆる孤立した、あ

るいは分離された文化分析には、常に埋もれた、あるいは抑圧された歴史的区分理論が伴うと論じてきた。いずれにせよ、「系譜学」という概念は、いわゆる直

線的な歴史観、段階論、目的論的歴史学といった伝統的な理論的懸念をほぼ解消している。しかし現在の文脈においては、こうした(非常に現実的な)問題に関

する長大な理論的議論は、おそらくいくつかの実質的な指摘で置き換えられるだろう。

時代区分仮説が頻繁に引き起こす懸念の一つは、それらが差異を消し去り、歴史的時代を巨大な均質性(両端を説明不能な年代的変容と区切り印で囲まれた)と

して投影する傾向にあることだ。しかし、だからこそ、ポストモダニズムを単なる様式ではなく、文化の支配的な概念として捉えることが重要だと私は考える。

この概念は、非常に異なる特徴が共存するのを許容するものである。

例えば、ポストモダニズムは、モダニズム(あるいは、さらに古いロマン主義)の単なる一つの段階にすぎないという、強力な代替的見解を考えてみよう。確か

に、これから挙げるポストモダニズムの特徴はすべて、先行するモダニズム(ガートルード・スタイン、レイモン・ルーセル、マルセル・デュシャンといった、

まさにポストモダニズムの先駆者と見なせる驚くべき系譜上の先駆者たちを含む)の中で、すでに完全に開花した形で確認できると認められるかもしれない。し

かし、この見解では、古いモダニズムの社会的立場、より正確には、その形式や精神を、醜く、不調和で、難解で、スキャンダラスで、不道徳で、破壊的で、一

般的に「反社会的」であると受け止めた、古いビクトリア朝およびポストビクトリア朝のブルジョアジーによる、その熱烈な拒絶が考慮されていない。しかしこ

こで論じたいのは、文化領域における変異がこうした態度を時代遅れにしたという事実だ。ピカソやジョイスはもはや醜い存在ではなく、むしろ全体として「写

実的」に映る。これは1950年代後半までに現代運動全体が正典化され、学術的制度化された結果である。これはポストモダニズムの出現そのものに対する最

も説得力のある説明の一つである。1960年代の若い世代は、かつては対抗的な存在であったモダニズム運動を、今や「生ける者の脳裏に悪夢のように重くの

しかかる」死んだ古典群として直面するからだ。マルクスが異なる文脈で述べたように。

|

As for the postmodern revolt

against all that, however, it must equally be stressed that its own

offensive features – from obscurity and sexually explicit material to

psychological squalor and overt expressions of social and political

defiance, which transcend anything that might have been imagined at the

most extreme moments of high modernism – no longer scandalise anyone

and are not only received with the greatest complacency but have

themselves become institutionalised and are at one with the official or

public culture of Western society.

What has happened is that aesthetic production today has become

integrated into commodity production generally: the frantic economic

urgency of producing fresh waves of ever more novel-seeming goods (from

clothing to aeroplanes), at ever greater rates of turnover, now assigns

an increasingly essential structural function and position to aesthetic

innovation and experimentation. Such economic necessities then find

recognition in the varied kinds of institutional support available for

the newer art, from foundations and grants to museums and other forms

of patronage. Of all the arts, architecture is the closest

constitutively to the economic, with which, in the form of commissions

and land values, it has a virtually unmediated relationship. It will

therefore not be surprising to find the extraordinary flowering of the

new postmodern architecture grounded in the patronage of multinational

business, whose expansion and development is strictly contemporaneous

with it. Later I will suggest that these two new phenomena have an even

deeper dialectical interrelationship than the simple one-to-one

financing of this or that individual project. Yet this is the point at

which I must remind the reader of the obvious; namely, that this whole

global, yet American, postmodern culture is the internal and

superstructural expression of a whole new wave of American military and

economic domination throughout the world: in this sense, as throughout

class history, the underside of culture is blood, torture, death, and

terror.

The first point to be made about the conception of periodisation in

dominance, therefore, is that even if all the constitutive features of

postmodernism were identical with and coterminous to those of an older

modernism – a position I feel to be demonstrably erroneous but which

only an even lengthier analysis of modernism proper could dispel the

two phenomena would still remain utterly distinct in their meaning

antisocial function, owing to the very different positioning of

postmodernism in the economic system of late capital and, beyond that,

to the transformation of the very sphere of culture in contemporary

society.

This point will be further discussed at the conclusion of this book. I

must now briefly address a different kind of objection to

periodisation, a concern about its possible obliteration of

heterogeneity, one most often expressed by the Left. And it is certain

that there is a strange quasi-Sartrean irony – a “winner loses” logic

which tends to surround any effort to describe a “system,” a totalising

dynamic, as these are detected in the movement of contemporary society.

What happens is that the more powerful the vision of some increasingly

total system or logic – the Foucault of the prisons book is the obvious

example – the more powerless the reader comes to feel. Insofar as the

theorist wins, therefore, by constructing an increasingly closed and

terrifying machine, to that very degree he loses, since the critical

capacity of his work is thereby paralysed, and the impulses of negation

and revolt, not to speak of those of social transformation, are

increasingly perceived as vain and trivial in the face of the model

itself.

I have felt, however, that it was only in the light of some conception

of a dominant cultural logic or hegemonic norm that genuine difference

could be measured and assessed. I am very far from feeling that all

cultural production today is postmodern in the broad sense I will be

conferring on this term. The postmodern is, however, the force field in

which very different kinds of cultural impulses – what Raymond Williams

has usefully termed “residual” and “emergent” forms of cultural

production – must make their way. If we do not achieve some general

sense of a cultural dominant, then we fall back into a view of present

history as sheer heterogeneity, random difference, a coexistence of a

host of distinct forces whose effectivity is undecidable. At any rate,

this has been the political spirit in which the following analysis was

devised: to project some conception of a new systematic cultural norm

and its reproduction in order to reflect more adequately on the most

effective forms of any radical cultural politics today.

The exposition will take up in turn the following constitutive features

of the postmodern: a new depthlessness, which finds its prolongation

both in contemporary “theory” and in a whole new culture of the image

or the simulacrum; a consequent weakening of historicity, both in our

relationship to public History and in the new forms of our private

temporality, whose “schizophrenic” structure (following Lacan) will

determine new types of syntax or syntagmatic relationships in the more

temporal arts; a whole new type of emotional ground tone – what I will

call “intensities” – which can best be grasped by a return to older

theories of the sublime; the deep constitutive relationships of all

this to a whole new technology, which is itself a figure for a whole

new economic world system; and, after a brief account of postmodernist

mutations in the lived experience of built space itself, some

reflections on the mission of political art in the bewildering new

world space of late or multinational capital.

|

しかし、そうしたものすべてに対するポストモダンの反逆については、

同様に強調すべきは、その攻撃的特徴――難解さや露骨な性描写から心理的堕落、社会的・政治的反抗の露わな表現に至るまで、これらはハイ・モダニズムの最

も過激な瞬間でさえ想像し得なかったものを超越している――がもはや誰をも驚かせず、最大の寛容さをもって受け入れられるだけでなく、それ自体が制度化さ

れ、西洋社会の公式あるいは公的な文化と一体となっていることだ。

今日、美的生産は商品生産全体に統合された。衣服から航空機に至るまで、常に新たな商品(より斬新に見える商品)を、より速い回転率で生産するという狂乱

的な経済的要請が、美的革新と実験にますます本質的な構造的機能と位置づけを与えているのだ。こうした経済的必然性は、財団や助成金から美術館やその他の

パトロネージに至るまで、新たな芸術に向けられる多様な制度的支援において承認される。あらゆる芸術の中で、建築は本質的に経済に最も近い。建築は、発注

や土地価値という形で、経済とほぼ媒介なしの関係にあるのだ。したがって、ポストモダン建築の驚異的な開花が、その拡大と発展が厳密に同時期にある多国籍

企業の後援に根ざしていることは、驚くに値しない。後述するが、この二つの新たな現象は、個々のプロジェクトへの単純な資金提供という関係以上に、より深

い弁証法的相互関係にあると示唆したい。しかしここで読者に明白な事実を想起させる必要がある。すなわち、このグローバルでありながらアメリカ的なポスト

モダン文化全体が、世界規模で展開される新たな波のアメリカ軍事・経済支配の内的かつ上部構造的表現であるということだ。この意味で、階級史全体を通じて

そうであったように、文化の裏側には血と拷問と死と恐怖が横たわっている。

したがって、支配における時代区分という概念について最初に指摘すべき点は、たとえポストモダニズムの構成的特徴がすべて、より古いモダニズムの特徴と同

一であり、かつそれと完全に一致していたとしても

―この立場は明らかに誤りだと考えるが、それを払拭するには近代主義そのものに対するさらに長大な分析が必要だ―両現象は依然として、その意味と反社会的

機能において完全に異なるままである。なぜなら、ポストモダニズムが後期資本主義の経済システムにおいて占める位置が根本的に異なり、さらに現代社会にお

ける文化領域そのものの変容があるからだ。

この点については本書の結末でさらに論じる。ここで時期区分に対する異なる異論、すなわち異質性の抹消を懸念する声――左派が最も頻繁に表明する懸念――

に簡潔に触れておく必要がある。確かに奇妙なサルトル的皮肉が存在する――「勝者が敗者となる」という論理が、現代社会の動きに検出される「システム」や

総体化ダイナミクスを記述しようとするあらゆる試みを包み込む傾向にある。つまり、ある総体化システムや論理のビジョンが強力になればなるほど――『監獄

の書』のフーコーが顕著な例だ――読者は無力感を増すのだ。したがって理論家が、閉ざされ恐怖を喚起する機械を構築することで勝利するほど、その作品が持

つ批判的効力は麻痺し、否定や反逆の衝動――社会変革の衝動は言うまでもなく――は、モデルそのものに対して無意味で取るに足らないものと見なされるよう

になる。

しかし私は、支配的な文化的論理やヘゲモニックな規範という概念の光のもとでこそ、真の差異を測り評価できると感じてきた。今日のあらゆる文化生産が、私

がこの用語に与える広義のポストモダン的であるとは、まったく思っていない。しかしポストモダンとは、レイモンド・ウィリアムズが有用に「残存的」および

「新興的」文化生産形態と呼んだ、非常に異なる種類の文化的衝動が道を切り開かねばならない力場なのである。文化的な支配構造の一般的な感覚を何らかの形

で獲得できなければ、我々は現代史を単なる異質性、無作為な差異、その有効性が決定不能な無数の異なる力の共存として見る見解に逆戻りしてしまう。いずれ

にせよ、以下の分析はこうした政治的精神に基づいて構想された:今日における急進的な文化政治の最も効果的な形態をより適切に考察するために、新たな体系

的な文化的規範とその再生産に関する何らかの概念を提示することである。

本論述はポストモダンの構成的特徴を順次取り上げる:新たな深みの欠如——これは現代の「理論」と、イメージあるいはシミュラクルの全く新しい文化の両方

に延長される;

歴史性の相対的弱体化。これは公的な歴史への関わり方と、私的な時間性の新たな形態の両方において生じる。後者の「分裂症的」構造(ラカンに倣う)は、よ

り時間的な芸術における新たな文法や連鎖的関係性を決定づける。全く新しいタイプの感情的基調――私が「強度」と呼ぶもの――。これは崇高に関する古い理

論に立ち返ることによって最もよく把握できる。これら全てが、全く新しい技術と深く構成的に結びついていること。この技術自体が、全く新しい経済世界シス

テムの象徴であること。そして最後に、建築空間そのものの生きた経験におけるポストモダニズム的変容を簡潔に述べた後、後期あるいは多国籍資本による混乱

した新たな世界空間における政治的芸術の使命についての考察を述べる。

|

VI

|

|

The conception of postmodernism

outlined here is a historical rather than a merely stylistic one. I

cannot stress too greatly the radical distinction between a view for

which the postmodern is one (optional) style among many others

available and one which seeks to grasp it as the cultural dominant of

the logic of late capitalism: the two approaches in fact generate two

very different ways of conceptualising the phenomenon as a whole: on

the one hand, moral judgments (about which it is indifferent whether

they are positive or negative), and, on the other, a genuinely

dialectical attempt to think our present of time in History.

Of some positive moral evaluation of postmodernism little needs to be

said: the complacent (yet delirious) camp-following celebration of this

aesthetic new world (including its social and economic dimension,

greeted with equal enthusiasm under the slogan of “postindustrial

society”) is surely unacceptable, although it may be somewhat less

obvious that current fantasies about the salvational nature of high

technology, from chips to robots – fantasies entertained not only by

both left and right governments in distress but also by many

intellectuals – are also essentially of a piece with more vulgar

apologies for postmodernism.

But in that case it is only consequent to reject moralising

condemnations of the postmodern and of its essential triviality when

juxtaposed against the Utopian “high seriousness” of the great

modernisms: judgments one finds both on the Left and on the radical

Right. And no doubt the logic of the simulacrum, with its

transformation of older realities into television images, does more

than merely replicate the logic of late capitalism; it reinforces and

intensifies it. Meanwhile, for political groups which seek actively to

intervene in history and to modify its otherwise passive momentum

(whether with a view toward channelling it into a socialist

transformation of society or diverting it into the regressive

re-establishment of some simpler fantasy past), there cannot but be

much that is deplorable and reprehensible in a cultural form of image

addiction which, by transforming the past into visual mirages,

stereotypes, or texts, effectively abolishes any practical sense of the

future and of the collective project, thereby abandoning the thinking

of future change to fantasies of sheer catastrophe and inexplicable

cataclysm, from visions of “terrorism” on the social level to those of

cancer on the personal. Yet if postmodernism is a historical

phenomenon, then the attempt to conceptualise it in terms of moral or

moralising judgments must finally be identified as a category mistake.

All of which becomes more obvious when we interrogate the position of

the cultural critic and moralist; the latter, along with all the rest

of us, is now so deeply immersed in postmodernist space, so deeply

suffused and infected by its new cultural categories, that the luxury

of the old-fashioned ideological critique, the indignant moral

denunciation of the other, becomes unavailable.

The distinction I am proposing here knows one canonical form in Hegel’s

differentiation of the thinking of individual morality or moralising

from that whole very different realm of collective social values and

practices. But it finds its definitive form in Marx’s demonstration of

the materialist dialectic, most notably in those classic pages of the

Manifesto which teach the hard lesson of some more genuinely

dialectical way to think historical development and change. The topic

of the lesson is, of course, the historical development of capitalism

itself and the deployment of a specific bourgeois culture. In a

well-known passage Marx powerfully urges us to do the impossible,

namely, to think this development positively and negatively all at

once; to achieve, in other words, a type of thinking that would be

capable of grasping the demonstrably baleful features of capitalism

along with its extraordinary and liberating dynamism simultaneously

within a single thought, and without attenuating any of the force of

either judgment. We are somehow to lift our minds to a point at which

it is possible to understand that capitalism is at one and the same

time the best thing that has ever happened to the human race, and the

worst.

|

ここで概説するポストモダニズムの概念は、単なる様式論ではなく歴史的

なものである。ポストモダニズムを数ある様式の一つ(任意の選択肢)と捉える見方と、後期資本主義の論理における文化的支配形態として把握しようとする見

方との根本的な差異は、いくら強調してもしすぎることはない。実際、この二つのアプローチは現象全体を概念化する上で全く異なる二つの方法を生み出す。一

方では(肯定的か否定的かを問わない)道徳的判断であり、他方では歴史における現代を真に弁証法的に思考しようとする試みである。

ポストモダニズムに対する肯定的な道徳的評価については、ほとんど語る必要もない。この美的新世界を(社会経済的側面も含め、「ポスト産業社会」というス

ローガンの下で同様に熱狂的に歓迎する)安逸な(だが狂気の)追随者たちの称賛は、確かに受け入れがたい。(「ポスト産業社会」というスローガンの下で同

等に熱狂的に迎えられた社会的・経済的側面を含む)は確かに容認できない。しかし、チップからロボットに至るハイテクノロジーの救済的性質に関する現在の

幻想——苦境にある左右両方の政府だけでなく多くの知識人も抱く幻想——が、ポストモダニズムに対するより下品な弁明と本質的に同類であることは、やや明

白ではないかもしれない。

だがそうだとすれば、偉大なモダニズムのユートピア的「高尚な真剣さ」と対比してポストモダンとその本質的な瑣末さを道徳的に非難する姿勢を拒絶するのは

当然だ。この種の判断は左派にも急進的右派にも見られる。そして疑いなく、古い現実をテレビ映像へと変容させるシミュラークルの論理は、単に後期資本主義

の論理を複製するだけでなく、それを強化し増幅する。一方、歴史に積極的に介入し、その受動的な勢いを変容させようとする政治集団(社会主義的変革へと導

くためであれ、あるいは単純化された幻想的な過去への回帰という退行的な再構築へと逸らすためであれ)にとって、

過去を視覚的蜃気楼や固定観念、あるいはテキストへと変容させることで、未来や集団的プロジェクトに対する実践的な感覚を事実上消滅させ、その結果として

未来の変革に関する思考を、社会レベルでの「テロリズム」のビジョンから個人的レベルでの癌のビジョンに至るまで、純然たる災厄や不可解な大変動の幻想へ

と委ねてしまうような、イメージ中毒という文化的形態には、嘆かわしく非難すべき点が多々あるに違いない。しかしポストモダニズムが歴史的現象であるなら

ば、それを道徳的あるいは道徳主義的な判断で概念化しようとする試みは、結局のところカテゴリー誤謬であると認めざるを得ない。こうしたことは、文化批評

家や道徳主義者の立場を問い直せばより明らかになる。後者は、我々その他全ての人々と同様に、今やポストモダニズムの空間に深く浸り、その新たな文化的カ

テゴリーに深く浸透し感染しているため、旧来のイデオロギー批判という贅沢、すなわち他者に対する憤慨に満ちた道徳的糾弾は、もはや不可能となっているの

だ。

ここで私が提案する区別は、ヘーゲルが個人道徳や道徳主義の思考と、それとは全く異なる集団的社会価値・実践の領域とを区別したことに一つの規範的形態を

見いだす。しかし決定的な形態は、マルクスが唯物弁証法を実証した点、とりわけ『共産党宣言』の古典的章節において、歴史的発展と変革を考えるより真に弁

証法的な方法を教える厳しい教訓の中に現れる。この教訓の主題は、言うまでもなく資本主義そのものの歴史的発展と、特定のブルジョア文化の展開である。よ

く知られた一節で、マルクスは我々に不可能を強く迫る。すなわち、この発展を肯定的かつ否定的に同時に考えること、言い換えれば、資本主義の明らかに有害

な側面と、その並外れて解放的な動力を、一つの思考の中で同時に把握し、いずれの判断の力も弱めることなく達成する思考様式を確立することを。我々は、資

本主義が人類にとって史上最高の出来事であると同時に最悪の出来事でもあるという事実を理解できる境地へ、何とかして精神を高めなければならないのだ。

|

The lapse from this austere

dialectical imperative into the more comfortable stance of the taking

of moral positions is inveterate and all too human: still, the urgency

of the subject demands that we make at least some effort to think the

cultural evolution of late capitalism dialectically, as catastrophe and

progress all together.

Such an effort suggests two immediate questions, with which we will

conclude these reflections. Can we in fact identify some “moment of

truth” within the more evident “moments of falsehood” of postmodern

culture? And, even if we can do so, is there not something ultimately

paralysing in the dialectical view of historical development proposed

above; does it not tend to demobilise us and to surrender us to

passivity and helplessness by systematically obliterating possibilities

of action under the impenetrable fog of historical inevitability? It is

appropriate to discuss these two (related) issues in terms of current

possibilities for some effective contemporary cultural politics and for

the construction of a genuine political culture.

To focus the problem in this way is, of course, immediately to raise

the more genuine issue of the fate of culture generally, and of the

function of culture specifically, as one social level or instance, in

the postmodern era. Everything in the previous discussion suggests that

what we have been calling postmodernism is inseparable from, and

unthinkable without the hypothesis of, some fundamental mutation of the

sphere of culture in the world of late capitalism which includes a

momentous modification of its social function. Older discussions of the

space, function, or sphere of culture (mostly notably Herbert Marcuse’s

classic essay The Affirmative Character of Culture) have insisted on

what a different language would call the “semi-autonomy” of the

cultural realm: its ghostly, yet Utopian, existence, for good or ill,

above the practical world of the existent, whose mirror image it throws

back in forms which vary from the legitimations of flattering

resemblance to the contestatory indictments of critical satire or

Utopian pain.

What we must now ask ourselves is whether it is not precisely this

semi-autonomy of the cultural sphere which has been destroyed by the

logic of late capitalism. Yet to argue that culture is today no longer

endowed with the relative autonomy it once enjoyed as one level among

others in earlier moments of capitalism (let alone in pre-capitalist

societies) is not necessarily to imply its disappearance or extinction.

Quite the contrary; we must go on to affirm that the dissolution of an

autonomous sphere of culture is rather to be imagined in terms of an

explosion: a prodigious expansion of culture throughout the social

realm, to the point at which everything in our social life – from

economic value and state power to practices and to the very structure

of the psyche itself – can be said to have become “cultural” in some

original and yet untheorised sense. This proposition is, however,

substantively quite consistent with the previous diagnosis of a society

of the image or the simulacrum and a transformation of the “real” into

so many pseudo-events.

It also suggests that some of our most cherished and time-honoured

radical conceptions about the nature of cultural politics may thereby

find themselves outmoded. However distinct those conceptions – which

range from slogans of negativity, opposition, and subversion to

critique and reflexivity – may have been, they all shared a single,

fundamentally spatial, presupposition, which may be resumed in the

equally time-honoured formula of “critical distance.” No theory of

cultural politics current on the Left today has been able to do without

one notion or another of a certain minimal aesthetic distance, of the

possibility of the positioning of the cultural act outside the massive

Being of capital, from which to assault this last. What the burden of

our preceding demonstration suggests, however, is that distance in

general (including “critical distance” in particular) has very

precisely been abolished in the new space of postmodernism. We are

submerged in its henceforth filled and suffused volumes to the point

where our now postmodern bodies are bereft of spatial coordinates and

practically (let alone theoretically) incapable of distantiation;

meanwhile, it has already been observed how the prodigious new

expansion of multinational capital ends up penetrating and colonising

those very pre-capitalist enclaves (Nature and the Unconscious) which

offered extraterritorial and Archimedean footholds for critical

effectivity. The shorthand language of co-optation is for this reason

omnipresent on the left, but would now seem to offer a most inadequate

theoretical basis for understanding a situation in which we all, in one

way or another, dimly feel that not only punctual and local

counter-culture forms of cultural resistance and guerrilla warfare but

also even overtly political interventions like those of The Clash are

all somehow secretly disarmed and reabsorbed by a system of which they

themselves might well be considered a part, since they can achieve no

distance from it.

What we must now affirm is that it is precisely this whole

extraordinarily demoralising and depressing original new global space

which is the “moment of truth” of postmodernism. What has been called

the postmodernist “sublime” is only the moment in which this content

has become most explicit, has moved the closest to the surface of

consciousness as a coherent new type of space in its own right – even

though a certain figural concealment or disguise is still at work here,

most notably in the high-tech thematics in which the new spatial

content is still dramatised and articulated. Yet the earlier features

of the postmodern which were enumerated above can all now be seen as

themselves partial (yet constitutive) aspects of the same general

spatial object.

The argument for a certain authenticity in these otherwise patently

ideological productions depends on the prior proposition that what we

have been calling postmodern (or multinational) space is not merely a

cultural ideology or fantasy but has genuine historical (and

socioeconomic) reality as a third great original expansion of

capitalism around the globe (after the earlier expansions of the

national market and the older imperialist system, which each had their

own cultural specificity and generated new types of space appropriate

to their dynamics). The distorted and unreflexive attempts of newer

cultural production to explore and to express this new space must then

also, in their own fashion, be considered as so many approaches to the

representation of (a new) reality (to use a more antiquated language).

As paradoxical as the terms may seem, they may thus, following a

classic interpretive option, be read as peculiar new forms of realism

(or at least of the mimesis of reality), while at the same time they

can equally well be analysed as so many attempts to distract and divert

us from that reality or to disguise its contradictions and resolve them

in the guise of various formal mystifications.

|

この厳格な弁証法的要請から、道徳的立場を取るというより安楽な姿勢へ

の逸脱は、根深いものであり、あまりにも人間的だ。それでもなお、この主題の緊急性は、少なくとも何らかの努力を払って、後期資本主義の文化的進化を、破

滅と進歩が同時に進行する弁証法的プロセスとして考えることを我々に要求する。

このような努力は、二つの差し迫った疑問を提示する。我々はこれらの考察を、この疑問をもって締めくくる。ポストモダン文化のより顕著な「虚偽の瞬間」の

中に、果たして何らかの「真実の瞬間」を見出すことは可能なのか?そして仮に可能だとしても、上述した歴史発展の弁証法的見解には究極的に麻痺させる要素

がないだろうか。それは歴史的必然性の不可侵な霧の下で行動の可能性を体系的に消し去ることで、我々を動員不能にし、受動性と無力感に屈服させる傾向がな

いだろうか?これらの二つの(関連する)問題を、現代において効果的な文化政策の可能性と、真の政治文化の構築の可能性という観点から議論するのが適切で

ある。

このように問題を焦点化することは、当然ながら、ポストモダン時代における文化の一般的な運命、そして特に一つの社会的レベルや事例としての文化の機能と

いう、より本質的な問題を即座に提起することになる。これまでの議論のすべてが示唆するのは、我々がポストモダニズムと呼んできたものは、後期資本主義世

界における文化領域の根本的変異——その社会的機能の重大な変容を含む——という仮説と切り離せず、またその仮説なしには考えられないということだ。文化

の空間・機能・領域に関する従来の議論(特にハーバート・マルクーゼの古典的論文『文化の肯定的性格』)は、異なる言語で言うところの「準自律性」を主張

してきた。それは幽霊的でありながらユートピア的な存在であり、善し悪しはともかく、実在する現実世界の超越した位置にあって、その鏡像を様々な形で投げ

返す。その形は、お世辞にも似た正当化の形態から、批判的風刺やユートピア的苦痛による異議申し立ての告発まで多岐にわたる。

今我々が自問すべきは、まさにこの文化領域の半自律性が、後期資本主義の論理によって破壊されたのではないかということだ。しかし、文化が今日、資本主義

の初期段階(ましてや前資本主義社会)において他の領域の一つとして享受していた相対的自律性をもはや有していないと論じることは、必ずしもその消滅や絶

滅を意味するわけではない。むしろ逆だ。自律的な文化領域の解体は爆発として想像されるべきだと断言せねばならない。つまり文化が社会領域全体に驚異的に

拡大し、経済的価値や国家権力から実践、さらには精神構造そのものに至るまで、社会生活のあらゆる側面が、ある意味で「文化的」になったと言える段階まで

達したのだ。しかしこの命題は、イメージやシミュラクルの社会という従来の診断や、「現実」が数多の擬似イベントへと変容するという見解と、実質的には全

く矛盾しない。

また、文化政治の本質に関する我々が最も尊び、古くから受け継がれてきた急進的な概念の幾つかが、それゆえに時代遅れとなる可能性を示唆している。否定

性、反対、破壊といったスローガンから批判や反省性に至るまで、それらの概念がどれほど異なっていたとしても、それらは全て単一の、根本的に空間的な前提

を共有していた。それは「批判的距離」という同様に古くからある定式に集約されうる。今日の左派で通用する文化政治理論は、資本という巨大な存在の外側に

文化的行為を位置づけ、そこから資本を攻撃する可能性を意味する、ある種の最小限の美的距離という概念なしには成り立たなかった。しかし、これまでの議論

が示唆するのは、距離一般(「批判的距離」を含む)が、ポストモダニズムという新たな空間において、まさに正確に廃止されたということだ。我々は今や、そ

の充満し浸透した空間に完全に沈み込み、ポストモダン化した身体は空間座標を失い、理論的どころか実践的にも距離化(ディスタンシエーション)をほぼ不可

能にされている。一方、多国籍資本の驚異的な新たな拡張が、批判的有効性のための域外的な足場やアルキメデスの支点を提供していたまさにそれらの前資本主

義的飛び地(自然と無意識)を、結局は浸透し植民地化してしまう様子は、すでに観察されている。このため、取り込みの略語は左派において遍在しているが、

しかし今や、この言語は理論的基盤として極めて不十分であるように思われる。なぜなら我々全員が、何らかの形で漠然と感じている状況――つまり、局所的な

カウンターカルチャーの抵抗やゲリラ戦だけでなく、クラッシュのような露骨な政治的介入さえも、それ自体がシステムの一部と見なされる可能性のあるものか

ら距離を置けず、結局は密かに無力化され吸収されてしまうという状況――を理解するには不十分だからだ。

我々が今断言すべきは、まさにこの途方もなく意気消沈させ、鬱屈させる新たなグローバル空間全体こそが、ポストモダニズムの「真実の瞬間」であるというこ

とだ。ポストモダニズムの「崇高」と呼ばれるものは、この内容が最も明示的となり、それ自体が首尾一貫した新たな空間類型として意識の表面に最も近づいた

瞬間であるに過ぎない。もっとも、ここには依然として比喩的な隠蔽や変装が働いている。特にハイテクを題材としたテーマにおいて、新たな空間的内容が依然

として劇的に表現され、明示されている点で顕著である。しかし、先に列挙したポストモダンの初期の特徴は、今やそれ自体が同じ一般的な空間的対象の部分的

(だが構成的な)側面として見ることができる。

これらの明らかにイデオロギー的な生産物に一定の真正性を見出す論拠は、我々がポストモダン(あるいは多国籍)空間と呼んできたものが単なる文化的イデオ

ロギーや幻想ではなく、資本主義が世界規模で展開した第三の偉大な拡張(国家市場の拡大と旧来の帝国主義体制という、それぞれ独自の文化的特異性を持ち、

その力学に適合した新たな空間類型を生み出した先行拡張に続く)として、真の歴史的(かつ社会経済的)現実を有するという前提に依存している。この新たな

空間を探求し表現しようとする、より新しい文化的生産の歪んだ非反省的な試みもまた、それなりの方法で、(より古めかしい言葉を使えば)新たな現実の表象

への数多くのアプローチとして考慮されねばならない。これらの用語は逆説的に思えるかもしれないが、古典的な解釈の選択肢に従えば、それらは特異な新しい

リアリズム(あるいは少なくとも現実の模倣)の形態として読み取ることが可能である。同時に、それらは同様に、その現実から我々の注意をそらし、その矛盾

を覆い隠し、様々な形式的な神秘化の装いの中で解決しようとする数々の試みとして分析することもできる。

|

As for that reality itself,

however – the as yet untheorised original space of some new “world

system” of multinational or late capitalism, a space whose negative or

baleful aspects are only too obvious – the dialectic requires us to

hold equally to a positive or “progressive” evaluation of its

emergence, as Marx did for the world market as the horizon of national

economies, or as Lenin did for the older imperialist global network.

For neither Marx nor Lenin was socialism a matter of returning to

smaller (and thereby less repressive and comprehensive) systems of

social organisation; rather, the dimensions attained by capital in

their own times were grasped as the promise, the framework, and the

precondition for the achievement of some new and more comprehensive

socialism. Is this not the case with the yet more global and totalising

space of the new world system, which demands the intervention and

elaboration of an internationalism of a radically new type? The

disastrous realignment of socialist revolution with the older

nationalisms (not only in Southeast Asia), whose results have

necessarily aroused much serious recent left reflection, can be adduced

in support of this position.

But if all this is so, then at least one possible form of a new radical

cultural politics becomes evident, with a final aesthetic proviso that

must quickly be noted. Left cultural producers and theorists –

particularly those formed by bourgeois cultural traditions issuing from

romanticism and valorising spontaneous, instinctive, or unconscious

forms of “genius,” but also for very obvious historical reasons such as

Zhdanovism and the sorry consequences of political and party

interventions in the arts have often by reaction allowed themselves to

be unduly intimidated by the repudiation, in bourgeois aesthetics and

most notably in high modernism, of one of the age-old functions of art

– the pedagogical and the didactic. The teaching function of art was,

however, always stressed in classical times (even though it there

mainly took the form of moral lessons), while the prodigious and still

imperfectly understood work of Brecht reaffirms, in a new and formally

innovative and original way, for the moment of modernism proper, a

complex new conception of the relationship between culture and pedagogy.

The cultural model I will propose similarly foregrounds the cognitive

and pedagogical dimensions of political art and culture, dimensions

stressed in very different ways by both Lukacs and Brecht (for the

distinct moments of realism and modernism, respectively).

We cannot, however, return to aesthetic practices elaborated on the

basis of historical situations and dilemmas which are no longer ours.

Meanwhile, the conception of space that has been developed here

suggests that a model of political culture appropriate to our own

situation will necessarily have to raise spatial issues as its

fundamental organising concern. I will therefore provisionally define

the aesthetic of this new (and hypothetical) cultural form as an

aesthetic of cognitive mapping.

In a classic work, The Image of the City, Kevin Lynch taught us that

the alienated city is above all a space in which people are unable to

map (in their minds) either their own positions or the urban totality

in which they find themselves: grids such as those of Jersey City, in

which none of the traditional markers (monuments, nodes, natural

boundaries, built perspectives) obtain, are the most obvious examples.

Disalienation in the traditional city, then, involves the practical

reconquest of a sense of place and the construction or reconstruction

of an articulated ensemble which can be retained in memory and which

the individual subject can map and remap along the moments of mobile,

alternative trajectories. Lynch’s own work is limited by the deliberate

restriction of his topic to the problems of city form as such; yet it

becomes extraordinarily suggestive when projected outward onto some of

the larger national and global spaces we have touched on here. Nor

should it be too hastily assumed that his model – while it clearly

raises very central issues of representation as such – is in any way

easily vitiated by the conventional poststructural critiques of the

“ideology of representation” or mimesis. The cognitive map is not

exactly mimetic in that older sense; indeed, the theoretical issues it

poses allow us to renew the analysis of representation on a higher and

much more complex level.

There is, for one thing, a most interesting convergence between the

empirical problems studied by Lynch in terms of city space and the

great Althusserian (and Lacanian) redefinition of ideology as “the

representation of the subject’s Imaginary relationship to his or her

Real conditions of existence.” Surely this is exactly what the

cognitive map is called upon to do in the narrower framework of daily

life in the physical city: to enable a situational representation on

the part of the individual subject to that vaster and properly

unrepresentable totality which is the ensemble of society’s structures

as a whole.

|

しかし、その現実そのもの――多国籍資本主義あるいは後期資本主義とい

う新たな「世界システム」の、未だ理論化されていない原初的空間、その否定的あるいは有害な側面があまりにも明白な空間――については、弁証法は我々に、

マルクスが国民経済の地平としての世界市場に対して行ったように、あるいはレーニンがより古い帝国主義的グローバルネットワークに対して行ったように、そ

の出現に対する肯定的あるいは「進歩的」評価を等しく保持することを要求する。マルクスもレーニンも、社会主義を小規模な(それゆえ抑圧的で包括性の低

い)社会組織体系への回帰とは見なさなかった。むしろ、彼らが生きる時代に資本が到達した規模こそが、新たなより包括的な社会主義達成の約束であり、枠組

みであり、前提条件であると捉えたのである。これは、よりグローバルで総体的な空間である新たな世界システムにも当てはまるのではないか。このシステム

は、根本的に新しいタイプの国際主義の介入と構築を要求している。社会主義革命が古いナショナリズム(東南アジアだけでなく)と結びついた悲惨な再編は、

この立場を支持する例として挙げられる。その結果は、必然的に近年の左翼による深刻な反省を喚起してきた。

しかし、もしこれら全てが事実であるならば、少なくとも一つの新たな急進的文化政治の可能性が明らかになる。ただし、最終的な美的条件として、早急に留意

すべき点がある。左派の文化生産者や理論家たち――特にロマン主義に端を発し、自発的・本能的・無意識的な「天才」の形態を称揚するブルジョワ的文化伝統

によって形成された者たちは、

しかし、ズダーノヴィズムや芸術への政治的・党的な介入の悲惨な結果といった極めて明白な歴史的理由から、彼らはしばしば反動的に、ブルジョワ美学、特に

ハイ・モダニズムにおいて芸術の古来の機能の一つ——教育的・教訓的機能——が否定されたことに過度に脅威を感じてきた。しかし芸術の教育機能は古典時代

には常に強調されていた(主に道徳的教訓の形態をとってはいたが)。一方、ブレヒトの驚異的でありながら未だ完全には理解されていない業績は、モダニズム

の本質的な瞬間において、文化と教育の関係性に関する複雑な新たな概念を、新しく形式的に革新的かつ独創的な方法で再確認させている。

私が提案する文化的モデルも同様に、政治的芸術と文化の認知的・教育的側面を前面に押し出す。この側面は、ルカーチとブレヒト(それぞれリアリズムとモダ

ニズムの異なる局面において)によって、非常に異なる形で強調されてきた。

しかし我々は、もはや我々のものとはならない歴史的状況やジレンマに基づいて構築された美的実践に戻ることはできない。一方で、ここで展開された空間の概

念は、我々の状況に適した政治文化のモデルが、必然的に空間的問題を根本的な組織的関心として提起しなければならないことを示唆している。したがって、こ

の新たな(仮説的な)文化的形態の美学を、認知的マッピングの美学として暫定的に定義する。

古典的著作『都市のイメージ』において、ケヴィン・リンチは、疎外された都市とは何よりも、人々が自らの位置も、自身が置かれた都市全体の様相も(心の中

で)マッピングできない空間であることを教えた。ジャージーシティのようなグリッド構造は、伝統的な標識(記念碑、結節点、自然境界、構築された遠近法)

が一切存在しない最も明白な例である。したがって伝統的な都市における疎外感の解消は、場所感覚の実践的な再獲得と、記憶に留められ、個人が移動する代替

的軌跡の瞬間ごとに再構築可能な、明示的な集合体の構築または再構築を伴う。リンチ自身の研究は、都市形態そのものの問題に意図的に主題を限定している点

で制約がある。しかし、ここで触れたより広範な国家的・地球的空間へと投影される時、それは非常に示唆に富むものとなる。また、彼のモデルが―確かに表象

そのものの核心的問題を提起しているとはいえ―「表象のイデオロギー」やミメーシスに対する従来のポスト構造主義的批判によって容易に無効化されるとは、

安易に想定すべきではない。認知地図は、従来の意味でのミメーシス的ではない。むしろ、それが提起する理論的問題は、表象の分析をより高次で複雑なレベル

で刷新することを可能にする。

まず第一に、リンチが都市空間に関して研究した経験的問題と、アルチュセール(およびラカン)によるイデオロギーの再定義——すなわち「主体が自らの実在

的条件に対して抱く想像的関係性の表象」——との間には、極めて興味深い収束点がある。確かに、これはまさに認知地図が、物理的な都市における日常生活と

いうより狭い枠組みの中で果たすべき役割である。すなわち、個々の主体が、社会構造全体の集合体という、より広大で本来表現不可能な全体性に対して、状況

的な表象を可能にすることである。

|

Yet Lynch’s work also suggests a

further line of development insofar as cartography itself constitutes

its key mediatory instance. A return to the history of this science

(which is also an art) shows us that Lynch’s model does not yet, in

fact, really correspond to what will become map-making. Lynch’s

subjects are rather clearly involved in pre-cartographic operations

whose results traditionally are described as itineraries rather than as

maps: diagrams organised around the still subject-centred or

existential journey of the traveller, along which various significant

key features are marked oases, mountain ranges, rivers, monuments, and

the like. The most highly developed form of such diagrams is the

nautical itinerary, the sea chart, or portulans, where coastal features

are noted for the use of Mediterranean navigators who rarely venture

out into the open sea.

Yet the compass at once introduces a new dimension into sea charts, a

dimension that will utterly transform the problematic of the itinerary

and allow us to pose the problem of a genuine cognitive mapping in a

far more complex way. For the new instruments - compass, sextant, and

theodolite – correspond not merely to new geographic and navigational

problems (the difficult matter of determining longitude, particularly

on the curving surface of the planet, as opposed to the simpler matter

of latitude, which European navigators can still empirically determine

by ocular inspection of the African coast); they also introduce a whole

new coordinate: the relationship to the totality, particularly as it is

mediated by the stars and by new operations like that of triangulation.

At this point, cognitive mapping in the broader sense comes to require

the coordination of existential data (the empirical position of the

subject) with unlived, abstract conceptions of the geographic totality.

Finally, with the first globe (1490) and the invention of the Mercator

projection at about the same time, yet a third dimension of cartography

emerges, which at once involves what we would today call the nature of

representational codes, the intrinsic structures of the various media,

the intervention, into more naive mimetic conceptions of mapping, of

the whole new fundamental question of the languages of representation

itself, in particular the unresolvable (well-nigh Heisenbergian)

dilemma of the transfer of curved space to flat charts. At this point

it becomes clear that there can be no true maps (at the same time it

also becomes clear that there can be scientific progress, or better

still, a dialectical advance, in the various historical moments of

map-making).

Transcoding all this now into the very different problematic of the

Althusserian definition of ideology, one would want to make two points.

The first is that the Althusserian concept now allows us to rethink

these specialised geographical and cartographic issues in terms of

social space – in terms, for example, of social class and national or

international context, in terms of the ways in which we all necessarily

also cognitively map our individual social relationship to local,

national, and international class realities. Yet to reformulate the

problem in this way is also to come starkly up against those very

difficulties in mapping which are posed in heightened and original ways

by that very global space of the postmodernist or multinational moment

which has been under discussion here. These are not merely theoretical

issues; they have urgent practical political consequences, as is

evident from the conventional feelings of First World subjects that

existentially (or “empirically”) they really do inhabit a

“postindustrial society” from which traditional production has

disappeared and in which social classes of the classical type no longer

exist – a conviction which has immediate effects on political praxis.

The second point is that a return to the Lacanian underpinnings of

Althusser’s theory can afford some useful and suggestive methodological

enrichments. Althusser’s formulation remobilises an older and

henceforth classical Marxian distinction between science and ideology

that is not without value for us even today. The existential – the

positioning of the individual subject, the experience of daily life,

the monadic “point of view” on the world to which we are necessarily,

as biological subjects, restricted – is in Althusser’s formula

implicitly opposed to the realm of abstract knowledge, a realm which,

as Lacan reminds us, is never positioned in or actualised by any

concrete subject but rather by that structural void called le sujet

supposé savoir (the subject supposed to know), a subject-place of

knowledge. What is affirmed is not that we cannot know the world and

its totality in some abstract or “scientific” way. Marxian “science”

provides just such a way of knowing and conceptualising the world

abstractly, in the sense in which, for example, Mandel’s great book

offers a rich and elaborated knowledge of that global world system, of

which it has never been said here that it was unknowable but merely

that it was unrepresentable, which is a very different matter. The

Althusserian formula, in other words, designates a gap, a rift, between

existential experience and scientific knowledge. Ideology has then the

function of somehow inventing a way of articulating those two distinct

dimensions with each other. What a historicist view of this definition

would want to add is that such coordination, the production of

functioning and living ideologies, is distinct in different historical

situations, and, above all, that there may be historical situations in

which it is not possible at all – and this would seem to be our

situation in the current crisis.

But the Lacanian system is threefold, and not dualistic. To the

Marxian-Althusserian opposition of ideology and science correspond only

two of Lacan’s tripartite functions: the Imaginary and the Real,

respectively.

Our digression on cartography, however, with its final revelation of a

properly representational dialectic of the codes and capacities of

individual languages or media, reminds us that what has until now been

omitted was the dimension of the Lacanian Symbolic itself.

An aesthetic of cognitive mapping – a pedagogical political culture

which seeks to endow the individual subject with some new heightened

sense of its place in the global system – will necessarily have to

respect this now enormously complex representational dialectic and

invent radically new forms in order to do it justice. This is not then,

clearly, a call for a return to some older kind of machinery, some

older and more transparent national space, or some more traditional and

reassuring perspectival or mimetic enclave: the new political art (if

it is possible at all) will have to hold to the truth of postmodernism,

that is to say, to its fundamental object – the world space of

multinational capital – at the same time at which it achieves a

breakthrough to some as yet unimaginable new mode of representing this

last, in which we may again begin to grasp our positioning as

individual and collective subjects and regain a capacity to act and

struggle which is at present neutralised by our spatial as well as our

social confusion. The political form of postmodernism, if there ever is

any, will have as its vocation the invention and projection of a global

cognitive mapping, on a social as well as a spatial scale.

|

しかしリンチの作品は、地図学そのものがその核心的な媒介的実例を構成

する点において、さらなる発展の道筋を示唆している。この科学(同時に芸術でもある)の歴史に立ち返れば、リンチのモデルは実際には、後に地図作製となる

ものとはまだ真に対応していないことがわかる。リンチの主題はむしろ、伝統的に地図ではなく旅程表として記述される前地図的操作に明確に関わっている。そ

れは旅行者という主体中心の、あるいは実存的な旅路を軸に構成された図式であり、その沿線にはオアシス、山脈、河川、記念碑など様々な重要な地物が記され

ている。こうした図表の最も高度な形態が航海行程図、すなわち海図やポルチュランである。これらは地中海航海者向けに沿岸地形を記したもので、彼らは外洋

へほとんど出なかった。

しかし羅針盤の登場は即座に海図へ新たな次元をもたらす。この次元は行程図の問題性を根本から変容させ、我々が真の認知的地図作成の問題をはるかに複雑な

形で提起することを可能にする。新たな道具――羅針盤、六分儀、セオドライト――は単に新たな地理的・航海上の問題(特に曲面である地球上で経度を測定す

る困難な課題。緯度測定は欧州の航海士がアフリカ沿岸を目視で経験的に把握できた比較的単純な問題だった)に対応するだけでなく、

それらは全く新たな座標系も導入した。すなわち全体性との関係性、特に星々や三角測量のような新たな操作によって媒介される関係性である。この時点で、広

義の認知的マッピングは、実存的データ(主体の経験的位置)と、未体験の抽象的概念としての地理的全体性との調整を必要とするようになる。

最後に、最初の地球儀(1490年)とほぼ同時期のメルカトル図法の発明により、地図学の第三の次元が浮上する。これは今日我々が表現コードの本質と呼ぶ

もの、

様々な媒体の内在的構造、より素朴な模倣的マッピング概念への介入、そして表現言語そのものの根本的な新たな問題、特に曲面空間を平面図へ移す際の解決不

能な(ハイゼンベルク的な)ジレンマが、ここに絡み合う。この時点で、真の地図は存在し得ないことが明らかになる(同時に、地図製作の様々な歴史的瞬間に

おいて科学的進歩、あるいはより正確に言えば弁証法的進展が可能であることも明らかになる)。

これら全てをアルチュセール的イデオロギー定義という全く異なる問題領域へ変換するにあたり、二点を指摘したい。第一に、アルチュセール的概念は、これら

の専門的な地理学・地図学の問題を社会空間の観点から再考することを可能にする。例えば社会階級や国家的・国際的文脈の観点から、あるいは我々が必然的に

認知的に、地域的・国家的・国際的な階級的現実に対する個人の社会的関係を地図化する方法の観点からである。しかし、このように問題を再構成することは、

まさにここで議論されてきたポストモダニズム的あるいは多国籍的な瞬間がもたらす、高度化され独自の形で提示されるマッピングの困難さに、はっきりと直面

することでもある。これらは単なる理論的問題ではない。第一世界の人々が、伝統的な生産活動が消滅し古典的な社会階級がもはや存在しない「ポスト産業社

会」を実存的(あるいは「経験的」)に確かに生きているという通念が示すように、差し迫った実践的政治的帰結を伴う。この確信は政治的実践に直接的な影響

を及ぼす。

第二の点は、アルチュセールの理論におけるラカン的基盤への回帰が、有益かつ示唆に富む方法論的深化をもたらし得るということだ。アルチュセールの理論構

築は、科学とイデオロギーの区別という古くからある、そして今なお古典的と言えるマルクス主義的区別を再動員する。この区別は今日においても我々にとって

無価値ではない。実存的要素——個々の主体の位置づけ、日常生活の経験、

生物学的主体として必然的に制限される世界に対する単子的な「視点」——は、アルチュセールの定式において、抽象的知識の領域と暗黙のうちに対立してい

る。ラカンが想起させるように、この領域は決して具体的な主体によって位置づけられたり実現されたりすることはない。むしろ、それは「知るべき主体」と呼

ばれる構造的虚無、すなわち知識の主体的場所によって位置づけられるのだ。ここで断言されているのは、我々が抽象的あるいは「科学的」な方法で世界とその

全体性を知ることができないというわけではない。マルクス主義的「科学」は、まさにそのような抽象的な世界の認識と概念化の方法を提供する。例えばマンデ

ルの偉大な著作が示すように、それはグローバルな世界システムに関する豊かで精緻な知識を提供している。ここでその世界システムが「知ることが不可能」だ

とは決して言われなかった。単に「表現不可能」だと言われたに過ぎない。これは全く異なる問題である。つまりアルチュセールの定式は、実存的経験と科学的

知識の間に存在する隔たり、断絶を指し示す。そこでイデオロギーは、この二つの異なる次元を何らかの形で結びつける方法を発明する機能を持つ。この定義に

対する歴史主義的見解が付け加えたいのは、そのような調整、すなわち機能し生きているイデオロギーの生成は、異なる歴史的状況において異なるものであり、

とりわけ、それがまったく不可能な歴史的状況が存在しうるということだ——そして現在の危機における我々の状況はまさにそれにあたるように思われる。

しかしラカン的体系は三つに分かれており、二元的ではない。マルクス主義・アルチュセール主義におけるイデオロギーと科学の対立は、ラカンの三つの機能の

うち、それぞれイマジナリーとリアルにのみ対応する。

しかし地図学に関する我々の脱線――個々の言語やメディアのコードと能力の、まさに表象的な弁証法を最終的に明らかにしたもの――は、これまで省かれてき

たのはラカンの象徴界そのものの次元であったことを我々に想起させる。

認知的マッピングの美学――グローバルシステムにおける自らの位置について、個々の主体性に新たな高揚した感覚を与えようとする教育的政治文化――は、こ

の今や極めて複雑化した表象的弁証法を尊重し、それにふさわしい形で表現するために、根本的に新しい形態を創造せざるを得ない。これは明らかに、古い機械

装置や透明性の高い国家空間、あるいは伝統的で安心感のある透視図法や模倣の領域への回帰を求めるものではない。新たな政治的芸術(もしそれが可能なら

ば)は、ポストモダニズムの真実、すなわちその根本的な対象――多国籍資本の世界空間――に固執すると同時に、この対象を表現する未だ想像すらできない新

たな様式への突破口を開かなければならない。そこにおいて我々は、個人および集団的主体としての自らの位置づけを再び把握し、取り戻すことができるのだ。

――多国籍資本の世界空間――を堅持しつつ、同時にこの世界を表現する未だ想像すらできない新たな様式への突破を成し遂げねばならない。そこにおいて我々

は、空間的・社会的混乱によって現在中立化されている、個人および集団的主体としての自らの位置づけを再び把握し始め、行動し闘争する能力を取り戻すこと

ができるのだ。ポストモダニズムの政治的形態が仮に存在するならば、その使命は社会的かつ空間的規模におけるグローバルな認知的マッピングの発明と投影と

なるだろう。

|

https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/us/jameson.htm

|

|

ドーミエ、マンドリンを弾く道化、ca.1873

からのデジタル習作(市智河團十郎「ポストモダニスト道化学者の冴えない肖像」)

ドーミエ、マンドリンを弾く道化、ca.1873

からのデジタル習作(市智河團十郎「ポストモダニスト道化学者の冴えない肖像」)

☆

☆