エルネスト・ルナンのレイシズム

Joseph Ernest Renan's Racism

エルネスト・ルナンのレイシズム

Joseph Ernest Renan's Racism

ジョゼフ・エルネス ト・ルナン(Joseph Ernest Renan、1823年2月28日コート=ダルモール県トレギエ - 1892年10月12日パリ)は、フランスの宗教史家、思想家。近代合理主義的な観点によって書かれたイエス・キリストの伝記『イエス伝』の著者。「反セ ム主義」という語を最初に用いたともされる[1]。エルネスト・ルナンのヒューマニズムのベースになっているのは、人間的キリストの像で、そこには、ユダ ヤ=キリスト教的な思想の連続性の概念はない。よき継承者である西洋人の人間性の見本をキリストとすれば、キリストを人間化すればするほど、イエス——彼 もまたユダヤ人だったが——を処刑に追いやったユダヤ人への憎悪は増すことになる。植民地人種主義者エルネスト・ルナンのレイシズムは、反ユダヤ主義(= 反 セム思想)からきているのである。

「ルナンは「ネイション」の定義についての有名な言 説で知られる。1882年にソルボンヌで行った "Qu'est-ce qu'une nation?"(国民とは何か?)という講演で示されたその内容は、かつてフィヒテが講演『ドイツ国民に告ぐ』で示した「ネイ ション」とは異なるものであった。フィヒテの「ネイション」概念が、人種・エスニック集団・言語などといった、明確にある集団と他の集団を区分できるよう な基準に基づくのに対し、ルナンにとっての「ネイション」とは精神的原理であり、人々が過去において行い、今後も行う用意のある犠牲心によって構成された 連帯心に求められるとする。とりわけ、この講演の中で示された「国民の存在は…日々の国民投票なのです」という言葉は有名である。(→ルソーの変奏?)/ こうしたルナンの主張 は、仏独ナショナリズムの比較として採り上げられることが多い。フィヒテの説く「ナショナリズム」が民族に基づくものであり、ルナンの主張は理念や集合的 意識に基づく ナショナリズムなどと理解するものである。しかし、ルナンの主張も普仏戦争で奪われたアルザス=ロレーヌ(住民使用言語はドイツ語に近い)が、フランスに 帰属するものであるという彼個人の信念とも結びついている。王党派でもあり「諸君は王権神授説を信じなくても、王党派となることができるのだ」と述べてい る。」

★共和主義的人種主義:「1791年、国民議会がユダヤ人の解放を決定したとき、国民議会は

人種にはほとんど

関心を示さなかった。人は血筋によってではなく、道徳的、知的価値によって判断されるべきであると考えたのである。このような問題を人間的な側面から取り

上げたことは、フランスの栄光である。19世紀の仕事は、あらゆるゲットーを取り壊すことであり、ゲットーを再建しようとする人々を賞賛することはできな

い。イスラエル民族は過去において、世界に最大の奉仕をしてきた。さまざまな国民と融合し、ヨーロッパの多様な国民性と調和しながら、イスラエル民族は過

去に行ったことを将来も続けるだろう。ヨーロッパのすべての自由主義勢力と協力することによって、人類の社会的進歩にきわめて大きく貢献するだろう

[44][45]。……ヨーロッパ各地、特にフランス第三共和政において人種主義論が勃興していた頃、ルナ

ンはこの問題に重要な影響を及ぼしていた。彼は人民の自決の概念の擁護者であったが[50]、その一方で、実際には「確立された」と彼が言う「人民のあい

だの人種的ヒエラルキー」を確信していた[51]。この微妙な人種主義はジル・マンセロンによって「共和主義的人種主義」[54]と呼ば

れ、第三共和制期

のフランスでは一般的なものであり、政治においてもよく知られた偏向的言説であった。植民地主義の支持者たちは文化的優越性の概念を用い、植民地行動と領

土拡張を正当化するために自らを「文明の保護者」と表現した。」

| Joseph Ernest Renan

(French pronunciation: [ʒozɛf ɛʁnɛst ʁənɑ̃]; 27 February 1823 – 2

October 1892)[2] was a French Orientalist and Semitic scholar, writing

on Semitic languages and civilizations, historian of religion,

philologist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and critic.[3] He wrote

works on the origins of early Christianity,[3] and espoused popular

political theories especially concerning nationalism, national

identity, and the alleged superiority of White people over other human

"races".[4] Renan is known as being among the first scholars to advance

the now-discredited[5] Khazar theory, which held that Ashkenazi Jews

were descendants of the Khazars,[6] Turkic peoples who had adopted

Jewish religion and migrated to Western Europe following the collapse

of their khanate.[6] |

ジョセフ・エルネスト・ルナン(フランス語発音:

[1823年2月27日 - 1892年10月2日)[2]はフランスの東洋学者、セム語学者であり、セム語やセム文明(→セム族)に関する著作、宗教史家、言語学者、哲学者、聖書学者、批評家であった。

[初期キリスト教の起源に関する著作を執筆し[3]、特にナショナリズム、ナショナル・アイデンティティ、白人の他の人類に対する優越性に

関する大衆的な政治理論を支持した。

[4]ルナンは、アシュケナージ・ユダヤ人はハザール人[5]の子孫であり、そのハザール人はテュルク系民族で、ユダヤ教の宗教を取り入れ、彼らのハン国

が崩壊した後に西ヨーロッパに移住したとする、現在では否定されている[6]ハザール説を唱えた最初の学者の一人として知られている。 |

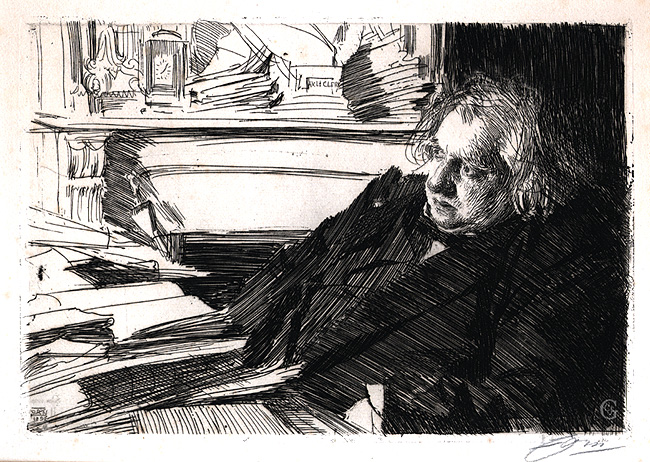

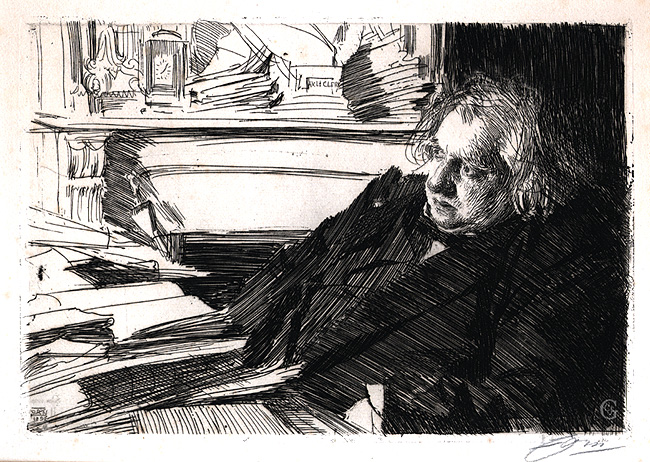

| Life Birth and family   Ernest Renan birthplace museum in Tréguier He was born at Tréguier in Brittany to a family of fishermen.[7] His grandfather, having made a small fortune with his fishing smack, bought a house at Tréguier and settled there, and his father, captain of a small cutter and an ardent republican, married the daughter of a Royalist tradesman from the neighbouring town of Lannion. All his life, Renan was aware of the conflict between his father's and his mother's political beliefs. He was five years old when his father died, and his sister, Henriette, twelve years his senior, became the moral head of the household. Having in vain attempted to keep a school for girls at Tréguier, she departed and went to Paris as a teacher in a young ladies' boarding-school.[8] Education Ernest, meanwhile, was educated in the ecclesiastical seminary of his native town.[9][8] His school reports describe him as "docile, patient, diligent, painstaking, thorough". While the priests taught him mathematics and Latin, his mother completed his education. Renan's mother was half Breton. Her paternal ancestors came from Bordeaux, and Renan used to say that in his own nature the Gascon and the Breton were constantly at odds.[10][8] During the summer of 1838, Renan won all the prizes at the college of Tréguier. His sister told the doctor of the school in Paris where she taught about her brother, and he informed F. A. P. Dupanloup, who was involved in organizing the ecclesiastical college of Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet, a school in which the young Catholic nobility and the most talented pupils of the Catholic seminaries were to be educated together, with the idea of creating friendships between the aristocracy and the priesthood. Dupanloup sent for Renan, who was then fifteen years old and had never been outside Brittany. "I learned with stupor that knowledge was not a privilege of the Church ... I awoke to the meaning of the words talent, fame, celebrity." Religion seemed to him wholly different in Tréguier and in Paris.[8] He came to view Abbé Dupanloup as a father figure.[11] Study at Issy-les-Moulineaux In 1840, Renan left St Nicholas to study philosophy at the seminary of Issy-les-Moulineaux. He entered with a passion for Catholic scholasticism. Among the philosophers, Thomas Reid and Nicolas Malebranche first attracted him, and, then he turned to G. W. F. Hegel, Immanuel Kant and J. G. Herder.[11] Renan began to see a contradiction between the metaphysics which he studied and the faith he professed, but an appetite for verifiable truths restrained his scepticism. "Philosophy excites and only half satisfies the appetite for truth; I am eager for mathematics", he wrote to Henriette. Henriette had accepted in the family of Count Zamoyski an engagement more lucrative than her former job. She exercised the strongest influence over her brother.[8] Study at college of St Sulpice It was not mathematics but philology which was to settle Renan's gathering doubts. His course completed at Issy, in 1844 he entered the college of St Sulpice in order to take his degree in philology prior to entering the church, and, here, he began the study of Hebrew. He realized that the second part of the Book of Isaiah differs from the first not only in style but in date, that the grammar and the history of the Pentateuch are later than the time of Moses, and that the Book of Daniel is clearly written centuries after the time in which it is set. At night he read the new novels of Victor Hugo; by day, he studied Hebrew and Syriac under Arthur-Marie Le Hir.[11] In October 1845, Renan left St Sulpice for Stanislas, a lay college of the Oratorians. Still feeling too much under the domination of the church, he reluctantly ended the last of his associations with religious life and entered M. Crouzet's school for boys as a teacher.[8] Scholarly career  Portrait of Joseph Ernest Renan, by F. Mulnier Renan, educated by priests, was to accept the scientific ideal with an extraordinary expansion of all his faculties. He became ravished by the splendor of the cosmos. At the end of his life, he wrote of Amiel, "The man who has time to keep a private diary has never understood the immensity of the universe." The certitudes of physical and natural science were revealed to Renan in 1846 by the chemist Marcellin Berthelot, then a boy of eighteen, his pupil at M. Crouzet's school. To the day of Renan's death, their friendship continued. Renan was occupied as usher only during evenings. During the daytime, he continued his researches in Semitic philology. In 1847, he obtained the Volney prize, one of the principal distinctions awarded by the Academy of Inscriptions, for the manuscript of his "General History of Semitic Languages." In 1847, he took his degree as Agrégé de Philosophie – that is to say, fellow of the university – and was offered a job as master in the lycée Vendôme.[8] In 1856, Renan married in Paris Cornélie Scheffer, daughter of Hendrik Scheffer and niece of Ary Scheffer, both French painters of Dutch descent. They had two children, Ary Renan, born in 1858, who became a painter, and Noémi, born in 1862, who eventually married philologist Yannis Psycharis. In 1863, the American Philosophical Society elected him an international Member.[12] Life of Jesus Within his lifetime, Renan was best known as the author of the enormously popular Life of Jesus (Vie de Jésus, 1863).[13][14] Renan attributed the idea of the book to his sister, Henriette, with whom he was traveling in Ottoman Syria and Palestine when, struck with a fever, she died suddenly. With only a New Testament and copy of Josephus as references, he began writing.[15] The book was first translated into English in the year of its publication by Charles E. Wilbour and has remained in print for the past 145 years.[16] Renan's Life of Jesus was lavished with ironic praise and criticism by Albert Schweitzer in his book The Quest of the Historical Jesus.[17] Renan argued Jesus was able to purify himself of "Jewish traits" and that he became an Aryan. His Life of Jesus promoted racial ideas and infused race into theology and the person of Jesus; he depicted Jesus as a Galilean who was transformed from a Jew into a Christian, and that Christianity emerged purified of any Jewish influences.[18] The book was based largely on the Gospel of John, and was a scholarly work.[18] It depicted Jesus as a man but not God, and rejected the miracles of the Gospel.[18] Renan believed by humanizing Jesus he was restoring to him a greater dignity.[19] The book's controversial assertions that the life of Jesus should be written like the life of any historic person, and that the Bible could and should be subject to the same critical scrutiny as other historical documents caused controversy[20] and enraged many Christians[21][22][23][24] and Jews because of its depiction of Judaism as foolish and absurdly illogical and for its insistence that Jesus and Christianity were superior.[18] American historian George Mosse, in Toward the Final Solution. A History of European Racism (pp 88, 129–130) argues that according to Renan, the intolerance would be a Jewish and not a Christian characteristic, but biblical Judaism would have lost its importance even among the Jews themselves as civilization progressed. That is why modern Jews are no longer disadvantaged by their past and are able to make important contributions to modern progress.[25] Continuation of scholarly career: social views In his book on St. Paul, as in the Apostles, he shows his concern with the larger social life, his sense of fraternity, and a revival of the democratic sentiment which had inspired L'Avenir de la Science. In 1869, he presented himself as the candidate of the liberal opposition at the parliamentary election for Meaux. While his temper had become less aristocratic, his liberalism had grown more tolerant. On the eve of its dissolution, Renan was half prepared to accept the Empire, and, had he been elected to the Chamber of Deputies, he would have joined the group of l'Empire liberal, but he was not elected. A year later, war was declared with Germany; the Empire was abolished, and Napoleon III became an exile. The Franco-Prussian War was a turning-point in Renan's history. Germany had always been to him the asylum of thought and disinterested science. Now, he saw the land of his ideal destroy and ruin the land of his birth; he beheld the German no longer as a priest, but as an invader.[8]  Ernest Renan in his study by Anders Zorn In La Réforme Intellectuelle et Morale (1871), Renan tried to safeguard France's future. Yet, he was still influenced by Germany. The ideal and the discipline which he proposed to his defeated country were those of her conqueror—a feudal society, a monarchical government, an elite which the rest of the nation exists merely to support and nourish; an ideal of honor and duty imposed by a chosen few on the recalcitrant and subject multitude. The errors attributed to the Commune confirmed Renan in this reaction. At the same time, the irony always perceptible in his work grows more bitter. His Dialogues Philosophiques, written in 1871, his Ecclesiastes (1882) and his Antichrist (1876) (the fourth volume of the Origins of Christianity, dealing with the reign of Nero) are incomparable in their literary genius, but they are examples of a disenchanted and sceptical temper. He had vainly tried to make his country obey his precepts. The progress of events showed him, on the contrary, a France which, every day, left a little stronger, and he roused himself from his disbelieving, disillusioned mood and observed with interest the struggle for justice and liberty of a democratic society. The fifth and sixth volumes of the Origins of Christianity (the Christian Church and Marcus Aurelius) show him reconciled with democracy, confident in the gradual ascent of man, aware that the greatest catastrophes do not really interrupt the sure if imperceptible progress of the world and reconciled, also, if not with the truths, at least with the moral beauties of Catholicism and with the remembrance of his pious youth.[8] Definition of nationhood Renan's definition of a nation has been extremely influential. This was given in his 1882 discourse Qu'est-ce qu'une nation? ("What is a Nation?"). Whereas German writers like Fichte had defined the nation by objective criteria such as a race or an ethnic group "sharing common characteristics" (language, etc.), Renan defined it by the desire of a people to live together, which he summarized by a famous phrase, "having done great things together and wishing to do more".[a] Writing in the midst of the dispute concerning the Alsace-Lorraine region, he declared that the existence of a nation was based on a "daily plebiscite." Some authors criticize that definition, based on a "daily plebiscite", because of the ambiguity of the concept. They argue that this definition is an idealization and it should be interpreted within the German tradition and not in opposition to it. They say that the arguments used by Renan at the conference What is a Nation? are not consistent with his thinking.[26] Karl Deutsch (in "Nationalism and its alternatives") suggested that a nation is "a group of people united by a mistaken view about the past and a hatred of their neighbors." This phrase is frequently, but mistakenly, attributed to Renan himself. He did indeed write that if "the essential element of a nation is that all its individuals must have many things in common", they "must also have forgotten many things. Every French citizen must have forgotten the night of St. Bartholomew and the massacres in the 13th century in the South." Renan believed "Nations are not eternal. They had a beginning and they will have an end. And they will probably be replaced by a European confederation".[27] Renan's work has especially influenced 20th-century theorist of nationalism Benedict Anderson. Late scholarly career  Renan in his study in the College of France  Renan caricatured by GUTH in Vanity Fair, 1910 Shifting away from his pessimism regarding liberalism's prospects during the 1870s while still believing in the necessity of an intellectual elite to influence democratic society for the good, Renan rallied to support the French Third Republic, humorously describing himself as a légitimiste, that is, a person who needs "about ten years to accustom myself to regarding any government as legitimate," and adding "I, who am not a republican a priori, who am a simple Liberal quite willing to adjust myself to a constitutional monarchy, would be more loyal to the Republic than newly converted republicans."[28] The progress of the sciences under the Republic and the latitude given to the freedom of thought that Renan cherished above all had allayed many of his previous fears, and he opposed the deterministic and fatalist theories of philosophers like Hippolyte Taine.[29] As he got older, he contemplated his childhood. He was nearly sixty when, in 1883, he published the autobiographical Souvenirs d'Enfance et de Jeunesse which, after the Life of Jesus, is the work by which he is chiefly known.[8] They showed the blasé modern reader that a world no less poetic, no less primitive than that of the Origins of Christianity still existed within living memory on the northwestern coast of France. It has the Celtic magic of ancient romance and the simplicity, the naturalness, and the veracity which the 19th century prized so highly. But his Ecclesiastes, published a few months earlier, his Drames Philosophiques, collected in 1888, give a more adequate image of his fastidious critical, disenchanted, yet optimistic spirit. They show the attitude towards uncultured Socialism of a philosopher liberal by conviction, by temperament an aristocrat. We learn in them how Caliban (democracy), the mindless brute, educated to his own responsibility, makes after all an adequate ruler; how Prospero (the aristocratic principle or the mind) accepts his dethronement for the sake of greater liberty in the intellectual world, since Caliban proves an effective policeman and leaves his superiors a free hand in the laboratory; how Ariel (the religious principle) acquires a firmer hold on life and no longer gives up the ghost at the faintest hint of change. Indeed, Ariel flourishes in the service of Prospero under the external government of the many-headed brute. Religion and knowledge are as imperishable as the world they dignify. Thus, out of the depths rises unvanquished the essential idealism of Renan.[8] Renan was prolific. At sixty years of age, having finished the Origins of Christianity, he began his History of Israel, based on a lifelong study of the Old Testament and on the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum, published by the Académie des Inscriptions under Renan's direction from the year 1881 till the end of his life. The first volume of the History of Israel appeared in 1887; the third, in 1891; the last two posthumously. As a history of facts and theories, the book has many faults; as an essay on the evolution of the religious idea, it is (despite some passages of frivolity, irony, or incoherence) of extraordinary importance; as a reflection of the mind of Renan, it is the most lifelike of images. In a volume of collected essays, Feuilles Détachées, published also in 1891, we find the same mental attitude, an affirmation of the necessity of piety independent of dogma. During his last years, he received many honors, and was made an administrator of the Collège de France and grand officer of the Legion of Honor. Two volumes of the History of Israel, his correspondence with his sister Henriette, his Letters to M. Berthelot, and the History of the Religious Policy of Philippe-le-Bel, which he wrote in the years immediately before his marriage, all appeared during the last eight years of the 19th century.[8] Renan died after a few days' illness in 1892 in Paris,[8] and was buried in the Cimetière de Montmartre in the Montmartre Quarter. |

生涯 誕生と家族   トレギエにあるアーネスト・ルナン生家博物館 祖父は漁船で小金を築き、トレギエに家を買って定住した[7]。父は小型カッターの船長で熱心な共和主義者であったが、隣町ラニオンの王党派の商人の娘と 結婚した。ルナンは生涯、父と母の政治的信条が対立していることに気づいていた。父親が亡くなったのはルナンが5歳の時で、12歳年上の姉アンリエットが 家政を取り仕切るようになった。トレギエで女学校を開こうとしても無駄であったため、彼女はパリに出て、若い女性の寄宿学校の教師となった[8]。 教育 一方、アーネストは生まれ故郷の神学校で教育を受けた[9][8]。神父たちが彼に数学とラテン語を教える一方で、彼の母親が彼の教育を完成させた。ルナ ンの母は半分ブルトン人であった。彼女の父方の先祖はボルドー出身で、ルナンはよく、自分の本性ではガスコン人とブルトン人は常に対立していると言ってい た[10][8]。 1838年の夏、ルナンはトレギエの大学ですべての賞を獲得した。ルナンの妹は、ルナンが教鞭を執っていたパリの学校の校長に弟のことを話し、校長は、貴 族と神職の間に友好関係を築こうと、カトリックの若い貴族とカトリックの神学校の最も優秀な生徒を一緒に教育する学校であるサン=ニコラ=デュ=シャルド ネ教会大学の組織に関わっていたF・A・P・デュパンルーに知らせた。デュパンルーは、当時15歳でブルターニュの外に出たことのなかったルナンを呼び寄 せた。「知識は教会の特権ではないことを茫然と学んだ。才能、名声、有名人という言葉の意味に目覚めた」。宗教は、トレギエとパリでは全く異なっているよ うに思えた[8]。彼はアベ・デュパンルーを父親のように思うようになった[11]。 イッシー・レ・ムリノーでの勉学 1840年、ルナンはイッシー・レ・ムリノー神学校で哲学を学ぶために聖ニコラウスを去った。ルナンはカトリックのスコラ学への情熱に燃えていた。哲学者 の中では、まずトマス・リードとニコラ・マルブランシュに惹かれ、その後、G.W.F.ヘーゲル、イマヌエル・カント、J.G.ヘルダーに目を向けた [11]。ルナンは、自分が学んだ形而上学と自分が公言している信仰との間に矛盾を感じ始めたが、検証可能な真理への貪欲さが彼の懐疑心を抑制した。「哲 学は真理への欲求を刺激するが、半分しか満たしてくれない。アンリエットは、ザモイスキ伯爵の家で、以前の仕事よりも有利な仕事を引き受けた。彼女は兄に 最も強い影響力を行使した[8]。 サン・シュルピス大学で学ぶ ルナンが抱いていた疑問を解決したのは、数学ではなく言語学だった。イッシーでの課程を修了したルナンは、1844年、教会に入る前に言語学の学位を取る ためにサン・シュルピス大学に入学し、ここでヘブライ語の勉強を始めた。イザヤ書の第二部が文体だけでなく年代においても第一部と異なっていること、五書 の文法と歴史がモーセの時代より後であること、ダニエル書が明らかに舞台となった時代より何世紀も後に書かれたものであることを知った。1845年10 月、ルナンはサン・シュルピスを離れ、オラトリオ会の信徒大学であるスタニスラスに向かった[11]。それでも教会の支配を強く感じていたルナンは、不本 意ながら宗教生活との最後の関わりを断ち切り、M.クルゼの少年学校に教師として入学した[8]。 学者としてのキャリア  ジョゼフ・アーネスト・ルナンのポートレート F. ミュルニエ撮影 司祭から教育を受けたルナンは、科学的理想を受け入れ、あらゆる能力を驚異的に拡張した。彼は宇宙の素晴らしさに魅了された。その生涯の終わりに、彼はア ミエルについてこう書いている。"私的な日記をつける暇のある人間は、宇宙の広大さを理解したことがない"。1846年、化学者マルセラン・ベルテロー は、当時18歳の少年であったルナンに、物理学と自然科学の真理を明らかにした。ルナンが亡くなるまで、二人の友情は続いた。ルナンは夜の間だけ案内係を していた。昼間はセム語文献学の研究を続けた。1847年、ルナンは "セム諸語の通史 "の原稿で、ヴォルネイ賞を受賞した。1847年、哲学アグレジェ、つまり大学のフェローの学位を取得し、ヴァンドーム・リセの校長として働くことになっ た[8]。 1856年、ルナンはパリで、ヘンドリック・シェフェールの娘でオランダ系フランス人画家アーリー・シェフェールの姪であるコルネリー・シェフェールと結 婚。1858年生まれのアーリー・ルナンは画家に、1862年生まれのノエミは言語学者ヤニス・サイカリスと結婚した。1863年、アメリカ哲学協会から 国際会員に選出された[12]。 イエスの生涯 ルナンは生前、非常に人気の高い『イエスの生涯』(Vie de Jésus, 1863)の著者として最もよく知られていた[13][14]。ルナンはこの本の構想を、オスマン・トルコ時代のシリアとパレスチナを一緒に旅していた姉 のアンリエットが熱病に冒され、急死したことに起因するとしていた。ルナンの『イエスの生涯』は、アルベルト・シュヴァイツァーの著書『歴史的イエスの探 求』の中で、皮肉たっぷりの賞賛と批判を浴びた[17]。 ルナンは、イエスは「ユダヤ人の特質」から自らを清めることができ、アーリア人に なったと主張した。 彼の『イエスの生涯』は人種的思想を促進し、神学とイエスの人物像に人種を吹き込んだ。彼はイエスをユダヤ人からキリスト者に変身したガリラヤ人として描 き、キリスト教はユダヤ人の影響から浄化されて現れたとした。 [19] イエスの生涯はあらゆる歴史的人物の生涯のように書かれるべきであり、聖書は他の歴史的文書と同じように批判的な精査を受けることができ、また受けるべき であるというこの本の論争的な主張は論争を引き起こし[20]、ユダヤ教を愚かで不条理な非論理なものとして描き、イエスとキリスト教が優れているという その主張のために多くのキリスト教徒[21][22][23][24]とユダヤ人を激怒させた[18]。 アメリカの歴史家ジョージ・モッセは、『最終的解決に向けて』(Toward the Final Solution. A History of European Racism (pp 88, 129-130)は、ルナンによれば、不寛容はキリスト教の特徴ではなくユダヤ教の特徴であろうが、聖書的ユダヤ教は文明が進歩するにつれてユダヤ人自身 の間でもその重要性を失っていっただろうと論じている。だからこそ、現代のユダヤ人はもはや過去によって不利な立場に立たされることはなく、現代の進歩に 重要な貢献をすることができるのである[25]。 学者としてのキャリアの継続:社会的見解 聖パウロについての著書では、使徒たちと同様に、より大きな社会生活への関心、友愛の感覚、そして『科学の旅』にインスピレーションを与えた民主主義的感 情の復活を示している。1869年、彼はモーの議会選挙でリベラルな野党の候補者として出馬した。彼の気質は貴族的ではなくなり、自由主義はより寛容に なった。帝政解散前夜、ルナンは半ば帝政を受け入れる覚悟を固め、もし下院議員に当選していれば、エンパイア・リベラルのグループに加わっていただろう が、落選した。1年後、ドイツとの宣戦が布告され、帝政は廃止され、ナポレオン3世は亡命者となった。普仏戦争はルナンの歴史の転機となった。ドイツは彼 にとって、常に思想と無関心な科学の隠れ家であった。今、彼は自分の理想の国が、自分の生まれた国を破壊し、破滅させるのを目の当たりにし、ドイツ人をも はや司祭としてではなく、侵略者として見ていた[8]。  アンダース・ゾーンによる著作でのアーネスト・ルナン ルナンは『知性と道徳の改革』(1871年)の中で、フランスの未来を守ろうとした。しかし、彼はまだドイツの影響を受けていた。彼が敗戦国に提案した理 想と規律は、征服者のものであった。封建的な社会、君主制の政府、残りの国民がただ支え養うためだけに存在するエリート、選ばれた少数の者が不従順で従順 な大衆に押し付ける名誉と義務の理想。コミューンの誤りは、ルナンのこうした反応を裏付けている。同時に、彼の作品には常に皮肉が感じられるが、その皮肉 はますます辛辣になっていく。1871年に書かれた『哲学対話』(Dialogues Philosophiques)、『伝道の書』(Ecclesiastes)(1882年)、『反キリスト』(Antichrist)(1876年)(ネ ロの治世を扱った『キリスト教の起源』第4巻)は、その文学的才能において比類ないものであるが、これらは幻滅し、懐疑的な気質の一例である。彼は自分の 戒律に国を従わせようとしたが、それはむなしいものだった。彼は不信と幻滅の気分から自らを奮い立たせ、民主主義社会の正義と自由のための闘争を興味深く 観察した。キリスト教の起源』の第5巻と第6巻(キリスト教会とマルクス・アウレリウス)には、彼が民主主義と和解し、人間の漸進的な上昇を確信し、最大 の破局は、知覚できないにしても世界の確実な進歩を妨げるものではないことを認識し、また、真理と和解しないまでも、少なくともカトリシズムの道徳的な美 と、敬虔な青春時代の思い出と和解している様子が描かれている[8]。 国民性の定義 ルナンの国民性の定義は、非常に大きな影響力を持っている。これは1882年に発表した『国家とは何か』(Qu'est-ce qu'une nation? (国民とは何か?) フィヒテのようなドイツの作家が、民族や民族集団の「共通の特徴」(言語など)といった客観的な基準によって国家を定義していたのに対し、ルナンは、「共 に偉大なことを成し遂げ、さらに成し遂げたいと願う」という有名な言葉で要約される、共に生きたいという人々の願望によって国家を定義した[a]。 アルザ ス・ロレーヌ地方をめぐる紛争のさなかに書かれたこの文章で、彼は、国家の存在は "毎日の国民投票 "に基づくものだと宣言した。ある著者は、「毎日の国民投票」に基づくこの定義を、その概念の曖昧さから批判している。彼らは、この定義は理想化であり、 ドイツの伝統の中で解釈されるべきであり、対立するものではないと主張する。彼らは、「国家とは何か」という会議でルナンが用いた議論は、彼の思考と一致 していないと言う[26]。 カール・ドイッチュは(『ナショナリズムとその代案』において)、国家とは「過去についての誤った見解と隣人への憎悪によって結ばれた人々の集団」である と示唆した。この言葉は、しばしばルナン自身の言葉とされるが、誤りである。確かにルナンは、「国家の本質的な要素は、すべての個人が多くの共通点を持っ ていること」であるとすれば、「多くのことを忘れていること」であるとも書いている。フランス国民は皆、聖バルトロメオの夜や13世紀に南部で起こった虐 殺を忘れているに違いない」。 ルナンは「国家は永遠ではない。始まりがあり、終わりがある。そして、それらはおそらくヨーロッパ連合に取って代わられるだろう」[27]。 ルナンの研究は、特に20世紀のナショナリズムの理論家ベネディクト・アン ダーソンに影響を与えた。 晩年の学者としてのキャリア  コレージュ・ド・フランスで研究するルナン  Vanity Fair』誌でGUTHによって風刺されたルナン(1910年) ルナンは、1870年代には自由主義の前途に対する悲観論から脱却しつつも、民主主義社会に良い影響を与える知的エリートの必要性を信じ、フランス第三共 和制を支持するために結集した、 先験的な共和主義者ではなく、立憲君主制に馴染むことを厭わない単純な自由主義者である私は、新しく改宗した共和主義者よりも共和主義に忠実であろう」 [28]。 「共和制のもとでの科学の進歩や、ルナンが何よりも大切にしていた思想の自由へのゆとりは、ルナンのそれまでの不安の多くを和らげ、イポリット・テーヌの ような哲学者の決定論的で運命論的な理論に反対していた[29]。 年をとるにつれて、彼は自分の子供時代について考えるようになった。1883年に自伝的な『幼年と青年の思い出』(Souvenirs d'Enfance et de Jeunesse)を出版したとき、彼は60歳近くになっていた。 それらは、キリスト教の起源に勝るとも劣らない詩的で原始的な世界が、フランス北西部の海岸にまだ生きている記憶の中に存在していることを、無頓着な現代 の読者に示した。そこには古代ロマンスのケルト的な魔力と、19世紀が高く評価した単純さ、自然さ、真実味がある。しかし、その数ヶ月前に出版された『伝 道の書』や、1888年に収集された『哲学の書』は、彼の潔癖な批評精神、幻滅的でありながら楽観的な精神をより適切に表している。これらの作品には、リ ベラルな哲学者でありながら貴族気質であった彼の、無教養な社会主義に対する態度がよく表れている。カリバン(民主主義)が、自分の責任について教育され た心なき獣でありながら、結局は適切な支配者となっていること、プロスペロー(貴族主義または精神)が、カリバンが効果的な警察官であることを証明し、研 究室では上司に自由裁量を委ねたため、知的世界におけるより大きな自由のために、いかに彼の退位を受け入れたか、アリエル(宗教主義)が、いかに人生をよ り強固なものとし、もはや変化のかすかな気配にも幽霊を見放さないようになったかを、私たちはこれらの作品から学ぶ。実際、アリエルはプロスペロに仕え、 多頭獣の外的統治のもとで繁栄する。宗教と知識は、それらが威厳を与える世界と同様に不滅である。こうして、ルナンの本質的な観念論が、深淵から打ち負か されることなく立ち上がる[8]。 ルナンは多作であった。キリスト教の起源』を書き終えた60歳の時、旧約聖書と『セム語碑文集成』(Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum)の終生にわたる研究に基づいて『イスラエル史』を書き始め、1881年から晩年までルナンの指導のもとアカデミィ・デ・ディスク リプションズから出版された。イスラエル史』の第1巻は1887年、第3巻は1891年、最後の2巻は死後に出版された。この本は、事実と理論の歴史書と しては多くの欠点があるが、宗教思想の進化に関するエッセイとしては、(軽薄、皮肉、支離滅裂な箇所もあるが)非常に重要であり、ルナンの心の反映として は、最も生き生きとしたイメージである。1891年に出版されたエッセイ集『Feuilles Détachées』にも、教義から独立した敬虔さの必要性の肯定という、同じような精神的態度が見られる。晩年、彼は多くの栄誉を受け、コレージュ・ ド・フランスの管理者、レジオン・ドヌール勲章の大勲位を授与された。イスラエル史』2巻、妹アンリエットとの書簡、ベルテローへの書簡、結婚直前の数年 間に書いた『フィリップ=ル=ベルの宗教政策史』は、すべて19世紀最後の8年間に出版された[8]。 ルナンは1892年にパリで数日の闘病の後に亡くなり[8]、モンマルトル地区のモンマルトル・シメティエールに埋葬された。 |

| Reputation and controversies Hugely influential in his lifetime, Renan was eulogised after his death as the embodiment of the progressive spirit in western culture. Anatole France wrote that Renan was the incarnation of modernity. Renan's works were read and appreciated by many of the leading literary figures of the time, including James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Matthew Arnold, Edith Wharton, and Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve.[30][31] One of his greatest admirers was Manuel González Prada in Peru who took the Life of Jesus as a basis for his anticlericalism. In his 1932 document "The Doctrine of Fascism", Italian dictator Benito Mussolini also applauded perceived "prefascist intuitions" in a section of Renan's "Meditations" that argued against democracy and individual rights as "chimerical" and intrinsically opposed to "nature's plans".[32] Statue  Statue of Ernest Renan in Tréguier town square In 1903 a major controversy accompanied the installation of a monument in Tréguier designed by Jean Boucher. Placed in the local cathedral square, it was interpreted as a challenge to Catholicism, and led to widespread protests, especially because the site was normally used for the temporary pulpit erected at the traditional Catholic festival of the Pardon of St Yves. It also included the Greek goddess Athena raising her arm to crown Renan gesturing in apparent challenge towards the cathedral.[33][34] The local clergy organised a protest calvary sculpture designed by Yves Hernot as "a symbol of the triumphant ultramontaine church." Views on race Renan believed that racial characteristics were instinctual and deterministic.[35][36] He has been criticised for his claims that the Semitic race is inferior to the Aryan race.[37] Renan claimed that the Semitic mind was limited by dogmatism and lacked a cosmopolitan conception of civilisation.[38] For Renan, Semites were "an incomplete race."[39] Some authors argue that Renan developed his antisemitism from Voltaire's anti-Judaism.[40] He did not regard the Ashkenazi Jews of Europe as being a Semitic people. Renan is acknowledged for launching the so-called Khazar theory. This theory states that Ashkenazim had their origin in Turkic refugees that had converted to Judaism and later migrated from the collapsed Khazar Khanate westward into the Rhineland, and exchanged their native Khazar language for the Yiddish language while continuing to practice the Jewish religion. In his 1883 lecture "Le Judaïsme comme race et comme religion" he disputed the concept that Jewish people constitute a unified racial entity in a biological sense,[41] which made his views unpalatable within racial antisemitism. Renan was also known for being a strong critic of German ethnic nationalism, with its antisemitic undertones.[42] His notions of race and ethnicity were completely at odds with the European antisemitism of the 19th and 20th centuries. Renan wrote the following about the long history of persecution of Jews: When all nations and all ages have persecuted you, there must be some motive behind it all. The Jew, up to our own time, insinuated himself everywhere, claiming the protection of the common law; but, in reality, remaining outside the common law. He retained his own status; he wished to have the same guarantees as everyone else, and, over and above that, his own exceptions and special laws. He desired the advantages of the nations without being a nation, without helping to bear the burdens of the nations. No people has ever been able to tolerate this. The nations are military creations founded and maintained by the sword; they are the work of peasants and soldiers; towards establishing them the Jews have contributed nothing. Herein is the great fallacy inspired in Israelite pretensions. The tolerated alien can be useful to a country, but only on condition that the country does not allow itself to be invaded by him. It is not fair to claim family rights in a house which one has not built, like those birds which come and take up their quarters in a nest which does not belong to them, or like the crustaceans which steal the shell of another species.[43] However, during the 1880s, Renan shifted away from these views. In a lecture on "Judaism as a Race and as a Religion", he stated: When, in 1791, the National Assembly decreed the emancipation of the Jews, it concerned itself very little with race. It considered that men ought to be judged, not by the blood that runs in their veins, but by their moral and intellectual value. It is the glory of France to take these questions by their human side. The work of the nineteenth century is to tear down every ghetto, and I have no praise for those who seek to rebuild them. The Israelite race has in the past rendered the greatest services to the world. Blended with the different nations, in harmony with the diverse national unities of Europe, it will continue to do in the future what it has done in the past. By its collaboration with all the liberal forces of Europe, it will contribute eminently to the social progress of humanity.[44][45] In the aforementioned 1882 conference on What Is a Nation?, Renan had spoken out against the theories that were based on race: Both the principle of nations is right and legitimate, as that of the primordial right of races is wrong and full of dangers for true progress … The truth is that pure race does not exist and that to base politics on ethnographic analysis means to base it on a chimera.[46] And in 1883, in a lecture called "The Original Identity and Gradual Separation of Judaism and Christianity": Judaism, which has served so well in the past, will still serve in the future. It will serve the true cause of liberalism, of the modern spirit. Every Jew is a liberal ... The enemies of Judaism, however, if you only look at them more closely, you will see that they are the enemies of the modern spirit in general.[47][48] Other comments on race, have also proven controversial, especially his belief that political policy should take into account supposed racial differences: Nature has made a race of workers, the Chinese race, who have wonderful manual dexterity and almost no sense of honor... A race of tillers of the soil, the Negro; treat him with kindness and humanity, and all will be as it should; a race of masters and soldiers, the European race. Reduce this noble race to working in the ergastulum like Negroes and Chinese, and they rebel... But the life at which our workers rebel would make a Chinese or a fellah happy, as they are not military creatures in the least. Let each one do what he is made for, and all will be well.[49] This passage, among others, was cited by Aimé Césaire in his Discourse on Colonialism, as evidence of the alleged hypocrisy of Western humanism and its "sordidly racist" conception of the rights of man.[4] Republican racism During the arising of racism theories around Europe and specifically in French Third Republic, Renan had an important influence on the matter. He was a defender of people's self-determination concept,[50] but on the other hand was in fact convinced of a "racial hierarchy of peoples" that he said was "established".[51] Discursively, he subordinated the principle of self-determination of peoples to a racial hierarchy,[52] i.e. he supported the colonialist expansion and the racist view of the Third Republic because he believed the French to be hierarchically superior (in a racial matter) to the African nations.[53] This subtle racism, called by Gilles Manceron "Republican racism",[54] was common in France during the Third Republic and was also a well-known defensing discourse in politics. Supporters of colonialism used the concept of cultural superiority, and described themselves as "protectors of civilization" to justify their colonial actions and territorial expansion. |

評判と論争 生前から大きな影響力を持っていたルナンは、死後、西洋文化における進歩的精神の体現者として讃えられた。アナトール・フランスは、ルナンは近代性の化身 であると書いた。ルナンの著作は、ジェイムズ・ジョイス、マルセル・プルースト、マシュー・アーノルド、エディット・ウォートン、シャルル・オーギュスタ ン・サント=ブーヴなど、当時を代表する多くの文学者たちに読まれ、高く評価されていた[30][31]。ルナンの最大の崇拝者のひとりは、ペルーのマヌ エル・ゴンサレス・プラダで、彼は『イエスの生涯』を反神権主義の基礎としていた。また、イタリアの独裁者ベニート・ムッソリーニは、1932年に発表し た『ファシズムの教義』の中で、ルナンの『瞑想録』の一節にある、民主主義と個人の権利を「キメラ的」であり、「自然の計画」に本質的に反していると主張 する「ファシズム以前の直観」を称賛している[32]。 銅像  トレギエ広場のルナン像 1903年、トレギエにジャン・ブーシェの設計による記念碑が設置され、大きな論争となった。地元の大聖堂の広場に設置されたこのモニュメントは、カトリ シズムへの挑戦と解釈され、広範な抗議を引き起こした。特に、この場所は、伝統的なカトリシズムの祭典である聖イヴの赦免祭で臨時に建てられる説教壇のた めに通常使用されていたためである。地元の聖職者たちは、イヴ・エルノがデザインした "ウルトラモンテーヌ教会の勝利のシンボル "である磔刑像の制作に抗議した。 人種観 ルナンは、人種的特徴は本能的で決定論的であると信じていた[35][36]。 ルナンは、セム人の精神は教条主義によって制限され、文明に対するコスモポリタンな概念を欠いていると主張した[38]。 ルナンはヨーロッパのアシュケナージ・ユダヤ人をセム人とはみなしていなかった。ルナンはいわゆるハザール説を唱えたことで知られている。この説によれ ば、アシュケナジムの起源は、ユダヤ教に改宗したテュルク系難民であり、その後、崩壊したハザール・ハン国から西のラインラント地方に移住し、ユダヤ教の 信仰を続けながら、彼らの母語であるハザール語をイディッシュ語と交換したという。1883年の講演「人種としてのユダヤ教と宗教としてのユダヤ教」にお いて、彼はユダヤ人が生物学的な意味で統一された人種を構成しているという概念に異議を唱えた[41]。ルナンはまた、反ユダヤ主義的な色彩を帯びたドイ ツの民族ナショナリズムを強く批判していたことでも知られている[42]。彼の人種と民族に関する概念は、19世紀から20世紀にかけてのヨーロッパの反 ユダヤ主義と完全に対立するものであった。 ルナンはユダヤ人迫害の長い歴史について次のように書いている: あらゆる国、あらゆる時代があなた方を迫害してきたということは、その背後に何らかの動機があるに違いない。現代に至るまで、ユダヤ人はあらゆるところに 入り込み、コモンローの保護を主張したが、実際にはコモンローの外にいた。彼は自分自身の地位を保持し、他のすべての人と同じ保証を受け、その上に自分自 身の例外と特別な法律を持つことを望んだ。国家でありながら、国家の重荷を背負うことなく、国家の利点を享受することを望んだのである。これに耐えられる 民族はいない。諸国家は剣によって築かれ、維持されてきた軍事的創造物であり、農民と兵士の仕事である。ここに、イスラエル人の気取りに触発された大いな る誤謬がある。寛容な外国人はその国にとって有用であるが、それはその国がその外国人に侵略されないという条件においてのみである。自分が建てたのでもな い家で家族の権利を主張するのは、自分のものでもない巣にやってきて居を構える鳥や、他の種の殻を盗む甲殻類のように、公平ではない。 しかし、1880年代、ルナンはこのような見解から脱却する。人種としての、そして宗教としてのユダヤ教」という講義の中で、彼はこう述べている: 1791 年、国民議会がユダヤ人の解放を決定したとき、国民議会は人種にはほとんど関心を示さなかった。人は血筋によってではなく、道徳的、知的価値によって判断 されるべきであると考えたのである。このような問題を人間的な側面から取り上げたことは、フランスの栄光である。19世紀の仕事は、あらゆるゲットーを取 り壊すことであり、ゲットーを再建しようとする人々を賞賛することはできない。イスラエル民族は過去において、世界に最大の奉仕をしてきた。さまざまな国 民と融合し、ヨーロッパの多様な国民性と調和しながら、イスラエル民族は過去に行ったことを将来も続けるだろう。ヨーロッパのすべての自由主義勢力と協力 することによって、人類の社会的進歩にきわめて大きく貢献するだろう[44][45]。 前述の1882年の「国家とは何か」に関する会議で、ルナンは人種に基づく理論に反対していた: 国家の原理はどちらも正しく正当であるが、民族の根源的な権利の原理は間違っており、真の進歩にとって危険がいっぱいである......純粋な民族は存在 しないというのが真実であり、民族誌的分析に基づいて政治を行うことは、キメラの上に政治を行うことを意味する」[46]。 そして1883年、「ユダヤ教とキリスト教の原初的同一性と漸進的分離」という講義の中で、次のように述べている: ユダヤ教は、過去において非常によく奉仕してきた。ユダヤ教は、過去において非常によく奉仕してきた。すべてのユダヤ人はリベラルである。しかし、ユダヤ 教の敵は、彼らをよく見れば、現代精神全般の敵であることがわかるだろう」[47][48]。 人種に関する他のコメントも物議を醸しており、特に、政治政策は想定される人種の違いを考慮に入れるべきだという彼の信念は有名である: 自然は、素晴らしい手先の器用さとほとんど名誉の感覚を持たない中国民族という労働者の種族を作った...。土を耕す人種、黒人。彼を親切に人道的に扱え ば、すべてが思い通りになる。この高貴な人種を、黒人や中国人のようにエルガストゥルムで働くようにすれば、彼らは反抗する...。しかし、われわれの労 働者が反抗するような生活は、中国人やフェラ人を幸福にするだろう。各自が自分のために作られたことをすれば、すべてがうまくいく」[49]。 この一節は、とりわけエメ・セゼールが『植民地主義に関する言説』の中で、西洋のヒューマニズムの偽善と人間の権利に関するその「陰険な人種差別的」概念 の疑惑の証拠として引用したものである[4]。 共和主義的人種差別 ヨーロッパ各地、 特にフランス第三共和政において人種主義論が勃興していた頃、ルナンはこの問題に重要な影響を及ぼしていた。彼は人民の自決の概念の擁護者であったが [50]、その一方で、実際には「確立された」と彼が言う「人民のあいだの人種的ヒエラルキー」を確信していた[51]。この微妙な人種主義はジル・マン セロンによって「共和主義的人種主義」[54]と呼ばれ、第三共和制期のフランスでは一般的なものであり、政治においてもよく知られた偏向的言説であっ た。植民地主義の支持者たちは文化的優越性の概念を用い、植民地行動と領土拡張を正当化するために自らを「文明の保護者」と表現した。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernest_Renan |

|

略歴

1823 2月28日コート=ダルモール県トレギエに生まれる

1828 父が死ぬ。姉アンリエット(1811-1860)が家計を助けるためにパリで教師 の職に就く

n.d. ブルターニュの神学校を卒業

n.d. パリの大学にすすむ

1853-1855 アルチュール・デ・ゴビノーEssai sur

l'inégalité des races humaines(『諸人種の不平等に関する試論』)が公刊される(→A.D.G.の人種主義)。

1855 『セム系言語の一般史および比較体系』(1855)で、セム人とアーリア人の区別

を主張し、反セム主義(Antisemitism)

という言葉を使う。

1860 政府の命によってパレスチナの学術調査の指揮を執る。同伴した姉アンリエットとも にマラリアに罹り、姉は死亡する。『近代社会の宗教の未来』(1860)で、セム人の衰退を説く。

1861 コレージュ・ド・フランスのヘブライ語主任教授

1862 開講初日にイエスのことを「比類なき人間」と呼んで即座に大きな物議をかもす(休 職の憂き目に、1870年復職)。

1863 化学者マル

スラン・ベルトゥロ(Marcellin Pierre Eugene Berthelot,

1827-1907)はルナンへの手紙で「われわれの祖先のアーリア人」と述べ、イ

ポリット・テーヌ(Hippolyte Adolphe Taine,

1828-1893)は「血と精神の共同体」であるアーリアの民を賛美する。

1863 『イエス伝』公刊。

1870 コレージュ・ド・フランスに復職。

1871 『知的道徳的改革』で、劣った人種への支配を説く。

1873 アンリエットについての回想記を書く。

1882 "Qu'est-ce qu'une

nation?"(国民とは何か?)をソルボンヌで講演。

1892 10月12日パリにて死す

++++

◎イエス伝における英雄崇拝的取り扱い 方(ヒューマニズム)

「1860年から翌年にかけて、ルナンは政府の命に よってパレスチナの学術調査の指揮を執る。ここでルナンは一帯を旅し『イエス伝』の下敷きとなるパレスチナの風物に親しく交わったが、同伴した姉アンリ エットと同時にマラリアにかかり、意識を回復した時にはアンリエットは既に死去していた。このアンリエットの人格的感化力がなければ、ルナンの『イエス 伝』はより破壊的な性格のものとなったと言われる。/帰国した1861年にコレージュ・ド・フランスのヘブライ語主任教授に就任したルナンは、翌1862 年の開講初日にイエスのことを「比類なき人間」と呼んで即座に大きな物議をかもし、1870年の復職に至るまで講義は中止を余儀なくされてしまう。講義が 中止に追い込まれた翌1863年、『イエス伝』は刊行された。イエスの天才的ヒューマニズムを賛辞して止まぬも、「奇跡や超自然」を全て非科学的伝説とし て排除したルナンの近代合理主義的な世界観による「史的イエス」の書は、すぐさま各言語に翻訳され、ヨーロッパで広く議論の的となった。/ルナンの『イエ ス伝』は、自然科学によって理論体系化不可能な要素は全てこれを迷信として排除するという聖書研究の世俗的伝統の端緒となった。/1884年、コレー ジュ・ド・フランスの学長に任命された。」

◎ネーション論における構築=維持論(この部分は、このページの冒頭の再掲部分です)

「ルナンは「ネイション」の定義についての有名な言 説で知られる。1882年にソルボンヌで行った "Qu'est-ce qu'une nation?"(国民とは何か?)という講演で示されたその内容は、かつてフィヒテが講演『ドイツ国民に告ぐ』で示した「ネイ ション」とは異なるものであった。フィヒテの「ネイション」概念が、人種・エスニッ ク集団・言語などといった、明確にある集団と他の集団を区分できるよう な基準に基づくのに対し、ルナンにとっての「ネイション」とは精神的原理であり、人々が過去において行い、今後も行う用意のある犠牲心によって構成された 連帯心に求められるとする。とりわけ、この講演の中で示された「国民の存在は…日々の国民投票なのです」という言葉は有名である。(→ルソーの変奏?)/ こうしたルナンの主張 は、仏独ナショナリズムの比較として採り上げられることが多い。フィヒテの説く「ナショナリズム」が民族に基づくものであり、ルナンの主張は理念や集合的 意識に基づく ナショナリズムなどと理解するものである。しかし、ルナンの主張も普仏戦争で奪われ たアルザス=ロレーヌ(住民使用言語はドイツ語に近い)が、フランスに 帰属するものであるという彼個人の信念とも結びついている。王党派でもあり「諸君は王権神授説を信じなくても、王党派となることができるのだ」と述べてい る。」

| Die Reden an die

deutsche Nation (EA Berlin 1808) ist die wirkmächtigste und wohl

bekannteste Schrift des Philosophen Johann Gottlieb Fichte. Sie basiert

auf Vorlesungen, die Fichte ab dem 13. Dezember 1807 in Berlin zur Zeit

der französischen Besetzung gehalten hatte, und sind als eine

Fortsetzung der Grundzüge des gegenwärtigen Zeitalters zu betrachten. Die Reden versuchen, ein Nationalgefühl zu wecken, und zielen auf die Gründung eines deutschen Nationalstaates, der die Nachfolge des erloschenen Heiligen Römischen Reiches antreten und sich von der französischen Herrschaft emanzipieren sollte. Allein die Deutschen hätten demnach eine „reine Sprache“, die sie zu tiefen und gründlichen Überlegungen befähige. Er fordert eine außenpolitisch autarke Handelspolitik, die allgemeine Wehrpflicht und eine „Nationalerziehung“, welche „die Freiheit des Willens gänzlich vernichtet“, um den Einzelnen in ihrem Sinne zu formen. Sie wurden in der Folge beinahe von jeder Ideologie eines Nationalismus imitiert, weswegen sie auch in Verruf geraten sind, wobei indes der philosophische Gehalt oft weniger berücksichtigt wurde. Im Wesentlichen besteht er in einem Essentialismus, und zwar hinsichtlich des angeblich „deutschen Wesens“. Trotz ihrer ehedem weiten Verbreitung wurden sie selten gelesen und noch weniger verstanden, nicht zuletzt wegen der barocken Sprache und der metaphysischen Begriffsbildung Fichtes. |

『ドイツ国民(ネーション)への演説』(EAベルリン、1808年)

は、哲学者ヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテの最も効果的で、おそらく最もよく知られた著作である。これらは、ナポレオン軍占領下の1807年12月13日

からベルリンで行われたフィヒテの講義に基づくもので、現代における基本的なアウトラインを継承していると見ることができる。 この演説は、ナショナリズムを呼び起こし、消滅した神聖ローマ帝国の後継として、フ ランスの支配から解放されたドイツ民族国家の樹立を目指すものであった。したがって、ドイツ人だけが、深く徹底的に考えることができる「純粋言語」を持っ ていることになる。彼は、外交問題では自給自足の貿易政策、国民皆兵制、個人を自分たちの利益のために形成するために「意志の自由を完全に 消滅させる」「国民教育」を要求した。 その後、ほとんどすべてのナショナリズムのイデオロギーに模倣され、そのため、哲学的な内容はあまり考慮されないことが多いために、不評を買うことになっ たのである。本質的には、「ドイツの本質」とされるものについての本質論からなる。かつては広く流通していたにもかかわらず、フィヒテのバロック的な言語 と形而上学的な概念から、ほとんど読まれず、また十分に理解されることもなかった。 |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reden_an_die_deutsche_Nation |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

◎文明の使命における劣等人種の先導

「ルナンはフランスの植民地主義による侵略を、劣っ た人種を文明の域に引き上げる『文明の使命』として正当化し、普仏戦争の翌年である1871年に書いた 『知的道徳的改革』において、優秀な西洋人種が黒人 や中国人やアラブ人の「劣った人種」や「退化した人種」を征服し搾取するのは当然であると述べている[2]。ルナンは『知的道徳的改革』の中でこう述べて いる。/『優秀な人種が、劣等なあるいは退化した人種の向上をはかることは、人類にとって、神の摂理に叶った事業である。我が大陸の住民は身分の低い庶民 も、ほとんどつねに没落貴族といえる。彼は労働よりは戦いを選ぶ。すなわち、世界を征服することが我々の使命なのである[2]。』/マルティニーク出身の 黒人詩人エメ・セゼールは『植民地主義論』(1955年)のなかでルナンを厳しく批判してい る。エドワード・サイードは、ルナンの学説を初期のオリエンタ リズムとしている[3]。」

◎アーリア人種説

「アルテュール・ド・ゴビノーよりも影響力の強かっ

たルナンは第三共和制の公式のイデオローグとなり、アーリア主義の宣伝者として大きな影響力を誇った[4]。

ルナンは『セム系言語の一般史および比較体系』(1855)でセム族とアーリア族を人類の決定的区分

とし、P.M.Massingは「反セム主義」という

語を最初に用いたのはルナンとする[1](→「セム族」)。この書物でルナンはアーリア人種が数

千年の努力の末に自分の住む惑星の主人となるとき、偉大な人種を創始した聖

なるイマユス山を探検するだろうと書いた[4]。

また『近代社会の宗教の未来』(1860)で「セム人には、もはやおこなうべき基本的なものは何もない。ゲルマン人でありケルト人でありつづけよう」「セ

ム人種は使命(一神教)を達成すると急速におとろえ、アーリア人種のみが人類の運命の先頭を歩む」と書いた[4]。ルナンによれば、セム人とアーリア人の

間には深い溝があり、「世界で最も陰気な土地」であるユダヤの地は極端な一神教を生み、他方のキリスト教を作った北のガリラヤは快活で寛容でさほど厳格で

ない[5]。キリスト教の人類愛(アガペー)は、自分の兵の妻バテシバと姦淫しその夫を戦場で討死させたダビデの利己主義や、前王ヨラムを殺し、異教神バ

アルを廃した虐殺者イスラエル王エヒウ(Jehu)からではなく、異教徒であったアーリア人の祖先が産んだとした[5]。イエスの思想はユダヤ教から得た

ものでなく、完全にイエスの偉大な魂が単独で創造したのであり、イエスにはユダヤ的なものは何もなく、キリスト教とはアーリア人の宗教であり、「文明化さ

れた民族の宗教」であるキリスト教だけがヨーロッパ共通の倫理と美学を提供できるとした[5]。

またルナンは、有害なイスラム教がユダヤ教を継承したと論じた[5]。

1863年、化学者マルスラン・ベルトゥロはルナンへの手紙で「われわれの祖先のアーリア人」と述べ、イポリット・テーヌは「血と精神の共同体」である

アーリアの民を賛美した[6]。

他方、R・F・グラウ[7]

はルナンを批判して、学芸・政治の男性的な能力を持つインド・ゲルマン人に対して、セム人は宗教を独占する女性的存在であり、神はセム的精神とインドゲル

マン的性質の結婚を決定しており、この夫婦は世界を支配すると論じた[8]。イグナツ・イサーク・イェフダ・ゴルトツィーハーは「セム人は神話を持たな

い」とするルナンを批判し、ヘブライ神話もあるし、ヘブライ人もアーリア人と同様に人類史の建設者であったとし、ユダヤ人をヨーロッパ文化に同化させるこ

とを要求した[9]。」

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆