ラテンアメリカにおけるポストコロニアリティの発見

The Discovery of Postcolonialism in Latin

America, Descubriendo la postcolonialidad en América Latina.

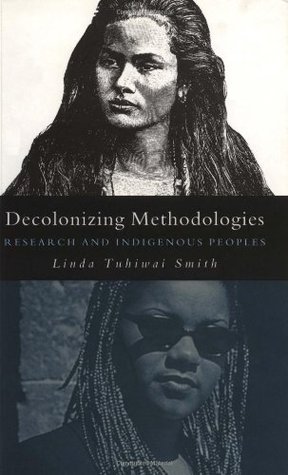

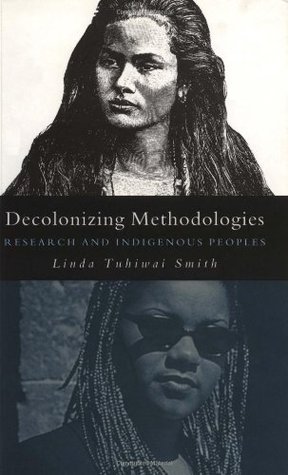

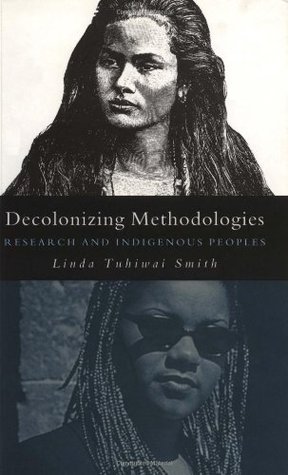

☆ 『研究』という言葉自体が、先住民の言語の中で最も汚れた言葉の一つである——リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミス『脱植民地化の方法論:研究と先住民』1999.

☆(ポスロコロニアルな条件とは)「異なる文化的・民族的背景、肌の色や生まれた場所や状況によって、この世界でどのような人生を送るのか、特権的で楽しい人生なのか、抑圧され搾取さ

れる人生なのかが決まる」ことだ——ロバート・ヤング.

★知識の脱植民地化(Decolonization of knowledge 脱 植民地化論、脱植民地化主義とも)とは、脱植民地化研究において提唱されている概念であり、西洋の知識体系の支配を批判するものである。代替となる認識 論、存在論、方法論を探求することで、他の知識体系を構築し、正当化しようとするものである。また、知識と真理の客観的な追求とはほとんど関係がないと考 えられている学術活動を「消毒」することを目的とした知的プロジェクトでもある。カリキュラム、理論、知識が植民地化されているということは、それらが政 治、経済、社会、文化的な考慮事項から部分的に影響を受けていることを意味する、という前提がある。脱植民地化知識の視点は、哲学(特に認識論)、科学、 科学史、社会科学におけるその他の基礎的なカテゴリーなど、幅広い分野をカバーしている。

☆「ラテンアメリカ」における「ポストコロニアリティ」の「発見」

| En

su nivel más simple, lo postcolonial es simplemente el producto de la

experiencia humana, pero experiencia humana del tipo que no se ha

registrado ni representado típicamente a ningún nivel institucional.

Más concretamente, es el resultado de diferentes orígenes culturales y

nacionales, de las formas en que el color de tu piel o tu lugar y

circunstancia de nacimiento definen el tipo de vida, privilegiada y

placentera, u oprimida y explotada, que tendrás en este mundo. Las

preocupaciones del postcolonialismo se centran en zonas geográficas de

intensidad que han permanecido en gran medida invisibles, pero que

suscitan o implican cuestiones de historia, etnicidad, identidades

culturales complejas y cuestiones de representación, de refugiados,

emigración e inmigración, de pobreza y riqueza, pero también, y esto es

importante, la energía, la vitalidad y la dinámica cultural creativa

que emergen de forma muy positiva de circunstancias tan exigentes. El

postcolonialismo ofrece un lenguaje de y para los que no tienen lugar,

los que parecen no pertenecer, aquellos cuyos conocimientos e historias

no se les permite contar. Es sobre todo esta preocupación por los

oprimidos, por las clases subalternas, por las minorías de cualquier

sociedad, por las preocupaciones de los que viven o proceden de otros

lugares, lo que constituye la base de la política postcolonial y sigue

siendo el núcleo que genera su continuo poder. (Robert Young) https://postcolonial.net/2019/04/what-is-postcolonial-studies/ +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ ★ポストコロニアルとは、ポスト(後の、という時間的 概念)、コロニアル (植民地的、という空間的ならびに精神的概念)という造語法によるできた形容詞で、植民地主義以降の、あるいは脱植民地状態(コロニアルな状況の後に/終 焉 後の)という意味がある。つまり、植民地主義(コロニアリズム)後の、以降の秩序や状態、その後に生じる出来事一般などをさす(→「ポストコロニアリズ ム」)。 このポストの本来的意味は、時間的経過の概念として の、「植民地後の〜」というものに他ならない。しかし、植民地後に は、さまざまな意味が含まれており、「植民地後の独立」「主権/主体の確立」「植民地状況が終 わった」「植民地状況を脱却した/しようとする」などの意味の派生が生じており、ポストコロニアルという用語を意識的に使う人たちは、そのようなポストコ ロニアルという用語が、多義的に使われることを承知で、あるいは確信犯的に、この用語を使っている。 ☆そこから転じて、政治的議論としての(1)ポストコロニアリズム(postcolonialism) とは、コロニアリズム(植民地主義,colonialism) あるいは帝国主義(imperialism) の伝統が、その後(post-)の歴史的展開なかでも、さまざまな形を通して継続しているという、時間的、空間的、そして精神的概念をめぐる議論のことを さす。そしてポストコロニアル をめぐる学術的議論としての(2)「ポストコロニアリズ ム(ポ ストコロニアル理論:Postcolonialismと も)とは、植民地主義や帝国主義の文化的、政治的、経済的遺産を批判的に学術的に研究するもので、植民地化された人々とその土地に対する人間の支配と搾取 の影響に焦点を当てている。この分野は1960年代に台頭し始め、植民地支配を受けた国の学者たちが植民地支配の残存する影響について論文を発表し、(通 常はヨーロッパの)帝国権力の歴史、文化、文学、言説に対する批判的理論分析を展開した」という。 したがって、ポストコロニアルとは、(1)コロニア ル(植民地状況)な状況や支配が終わった後の秩序や世界のことを意味すると同時に、ポストという時間性を引き受けて、現象面から(2)コロニアル(植民地 状況)な状 況や条件、あるいは支配の形態が現在もなお引き続き存続している、時代ならびに社会概念のことを意味する。 そして、例えば「私たちはポストコロニアルな存在になれるのか?」という審問は、上掲の「コロニアル(植民地状況)な状 況や条件、あるいは支配の形態が現在もなお引き続き存続している」状況のなかで、「コロニア ル(植民地状況)な状況や支配が終わった後の秩序や世界」を創造し、そのなかで生きるためには、「今何が求めれらているのか?」という、実 践上の課題を我々に突きつけるのである。 ☆「ポストコロニアリティ」とは? 「ポストコロニアル」とは、上掲のように植民地後をあらわす形容詞が、名詞化したもので、植民地後の時間的社会的位相をさすと同時に、そのような時間的社 会的位相の「性質」をあらわすと同時に、そのような時間的社会的位相が、到来しているのか?という「批判的分析」が含まれ、次第に「ポストコロニアリズ ム」における議論に接続していく過程でもある。ポストコロニアル の名詞化であり、その内実や正確性を表現する「ポストコロニアリティ」とは、ポストコロニアルとはなにか?その具体的事象やより抽象化した概念化そのもの をさす用語である。 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ アニバル・キハノは次の ように述べている。 事実上、すべての経験、歴史、資源、文化的な成果は、ヨーロッパまたは西洋の覇権を中心とする一つのグローバルな文化秩序に収束した。ヨーロッパの新しい グローバルパワーモデルに対する覇権は、主観、文化、特に知識とその生産のあらゆる形態をその支配下に集中させた。彼らは、植民地化された知識生産の形 態、意味の生産モデル、象徴的な世界観、表現と客観化、主観のモデルを可能な限り抑圧した。 [10]Ivanovic, Mladjo (2019). "Echoes of the Past: Colonial Legacy and Eurocentric Humanitarianism". The Rest Write Back: Discourse and Decolonization. BRILL. pp. 82–102 [98]. doi:10.1163/9789004398313_005. ISBN 978-90-04-39831-3. S2CID 203279612. リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミスは著書『脱植民地化の方法論: リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミスは著書『脱植民地化の方法論:研究と先住民』の中で次のように述べている。 帝国主義と植民地主義は、植民地化された人々を完全に混乱に陥れ、彼らを自分たちの歴史、風景、言語、社会関係、そして世界に対する独自の考え方、感じ方、関わり方から切り離した[11]。 [11]Rohrer, J. (2016). Staking Claim: Settler Colonialism and Racialization in Hawai'i. Critical Issues in Indigenous Studies. University of Arizona Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8165-0251-6. この見解によると、植民地主義は法的・政治的な意味では終わったが、その遺産は歴史的に植民地化された場所に住む個人やグループが疎外され搾取される多く の「植民地状況」の中で続いている。脱植民地化学者たちは、植民地主義の遺産として今も続く植民地主義を「コロニアリティ」と呼び、植民地主義が残した抑 圧と搾取を、主観や知識の領域など、相互に関連したさまざまな領域で説明している[4]。 [4]Dreyer, Jaco S. (2017). "Practical theology and the call for the decolonisation of higher education in South Africa: Reflections and proposals". HTS Theological Studies. 73 (4): 1–7 [2, 3, 5]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decolonization_of_knowledge |

最

も単純なレベルでは、ポストコロニアルとは、通常、いかなる制度レベルでも記録されたり表現されたりすることのない、人間の経験の産物である。より具体的

には、異なる文化的・民族的背景、肌の色や生まれた場所や状況によって、この世界でどのような人生を送るのか、特権的で楽しい人生なのか、抑圧され搾取さ

れる人生なのかが決まる。ポストコロニアル主義の関心は、これまでほとんど目に見えなかったが、歴史、民族、複雑な文化的アイデンティティ、表現の問題、

難民、移民、貧困や富の問題などを喚起したり、それらに関与したりする、地理的に集中した地域を中心としている。しかし、それだけでなく、そのような厳し

い状況から非常に前向きな形で生まれるエネルギー、活気、創造的な文化のダイナミズムも重要である。ポストコロニアル主義は、居場所のない人々、所属して

いないように見える人々、知識や歴史が尊重されない人々のための言語を提供する。それは何よりも、あらゆる社会における被抑圧者、下層階級、少数民族、他

地域から移住してきた人々、他地域出身者に対する関心であり、ポストコロニアル政治の基礎をなし、その継続的な力を生み出す核となっている。

(ロバート・ヤング) https://postcolonial.net/2019/04/what-is-postcolonial-studies/ +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Poscolonial es un adjetivo acuñado a partir del concepto temporal de poscolonial y del concepto espacial y mental de colonial, que significa después del colonialismo o del estado decolonial (después de la situación colonial/después de su fin). En otras palabras, se refiere al orden poscolonial o al estado de cosas después del colonialismo (poscolonialismo ), o a los acontecimientos que ocurren después en general (→ « poscolonialismo »). El significado original de post no es otro que « poscolonial » como concepto del paso del tiempo. Sin embargo, poscolonial tiene diversos significados, con derivaciones como «independencia poscolonial», «establecimiento de la soberanía/sujeto», «fin de la situación colonial», «superación/intento de superación de la situación colonial», etc. Quienes utilizan conscientemente el término poscolonial utilizan el término a sabiendas o con la convicción de que puede utilizarse en múltiples sentidos. En el debate político (1) postcolonialismo se refiere a la continuación de la tradición del colonialismo o imperialismo en diversas formas en desarrollos (post)históricos posteriores, y (2) postcolonialismo como debate político. Se refiere al debate sobre la concepción temporal, espacial y espiritual de la continuidad de la tradición colonial o imperialista a través de diversas formas en desarrollos (post)históricos posteriores. (2) « El Postcolonialismo (también Teoría Postcolonial) es el estudio académico crítico de los legados culturales, políticos y económicos del colonialismo y el imperialismo, y del impacto de la dominación y la explotación humanas sobre los pueblos colonizados y sus tierras». Se centra en los efectos de la dominación y la explotación humanas. El campo empezó a surgir en la década de 1960, cuando estudiosos de países colonizados publicaron artículos sobre los efectos residuales del dominio colonial y desarrollaron análisis teóricos críticos de la historia, la cultura, la literatura y el discurso del poder imperial (normalmente europeo)». Así pues, postcolonial significa (1) el orden y el mundo posteriores al fin de las condiciones y la domin ación coloniales, y al mismo tiempo, asumiendo la temporalidad de lo post, (2) un periodo y una concepción social en los que aún persisten las condiciones, las condiciones o las formas de dominación coloniales desde un punto de vista fenomenológico. (3) el tiempo y la concepción social en los que aún persisten las condiciones coloniales, las condiciones o formas de dominación en el presente. Y, por ejemplo, «¿Podemos ser postcoloniales? ». La pregunta «¿Podemos ser poscoloniales?» es una pregunta práctica: «¿Qué se requiere de nosotros ahora?» para crear y vivir en un « orden y mundo poscoloniales “ en el que ”aún persisten las condiciones y las condiciones o formas de dominación coloniales», como se ha mencionado anteriormente. La cuestión de la «poscolonialidad» nos plantea a todos un reto práctico. ¿Qué es la poscolonialidad? El término «poscolonialidad» es una nominalización del adjetivo «poscolonial», como ya se ha dicho, y se refiere a la fase temporal y social del periodo poscolonial, así como a la «naturaleza» de dicha fase temporal y social y al «análisis crítico» de si ha llegado dicha fase temporal y social. El proceso implica un «análisis crítico» de la «naturaleza» de tales fases temporales y sociales, y está gradualmente conectado con el debate sobre el «postcolonialismo». La «postcolonialidad», que es la nominalización del postcolonialismo y expresa su interioridad y precisión, es un proceso de preguntar: ¿qué es la postcolonialidad? El término se refiere al hecho concreto y a su propia conceptualización más abstracta. +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Afirmó Aníbal Quijano: En efecto, todas las experiencias, historias, recursos y productos culturales fueron a parar a un orden cultural global que giraba en torno a la hegemonía europea u occidental. La hegemonía de Europa sobre el nuevo modelo de poder global concentró bajo su hegemonía todas las formas de control de la subjetividad, la cultura y, especialmente, el conocimiento y la producción de conocimiento... Reprimieron al máximo las formas colonizadas de producción de conocimiento, los modelos de producción de sentido, su universo simbólico, el modelo de expresión y de objetivación y subjetividad[10]. En su libro Metodologías descolonizadoras: La Investigación y los Pueblos Indígenas, Linda Tuhiwai Smith escribe El imperialismo y el colonialismo desordenaron por completo a los pueblos colonizados, desconectándolos de sus historias, sus paisajes, sus lenguas, sus relaciones sociales y sus propias formas de pensar, sentir e interactuar con el mundo[11]. Según este punto de vista, el colonialismo ha terminado en el sentido jurídico y político, pero su legado continúa en muchas «situaciones coloniales» en las que se margina y explota a individuos y grupos de lugares históricamente colonizados. Los eruditos descoloniales se refieren a este legado continuado del colonialismo como «colonialidad», que describe la opresión y explotación dejadas por el colonialismo en una variedad de ámbitos interrelacionados, incluido el ámbito de la subjetividad y el conocimiento[4]. |

Decolonizing methodologies : research and indigenous peoples (3ed. ed.) / Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Zed Books , 2021,. Decolonizing methodologies : research and indigenous peoples (3ed. ed.) / Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Zed Books , 2021,.To the colonized, the term 'research' is conflated with European colonialism; the ways in which academic research has been implicated in the throes of imperialism remains a painful memory. This essential volume explores intersections of imperialism and research - specifically, the ways in which imperialism is embedded in disciplines of knowledge and tradition as 'regimes of truth.' Concepts such as 'discovery' and 'claiming' are discussed and an argument presented that the decolonization of research methods will help to reclaim control over indigenous ways of knowing and being. Now in its eagerly awaited third edition, this bestselling book includes a co-written introduction and features contributions from indigenous scholars on the book's continued relevance to current research. It also features a chapter with twenty-five indigenous projects and a collection of poetry. Introduction to the Third Edition Foreword Introduction 1. Imperialism, History, Writing and Theory 2. Research through Imperial Eyes 3. Colonizing Knowledges 4. Research Adventures on Indigenous Land 5. Notes from Down Under 6. The Indigenous People's Project: Setting a New Agenda 7. Articulating an Indigenous Research Agenda 8. Twenty-Five Indigenous Projects 9. Responding to the Imperatives of an Indigenous Agenda: A Case Study of Maori 10. Towards Developing Indigenous Methodologies: Kaupapa Maori Research 11. Choosing the Margins: The Role of Research in Indigenous Struggles for Social Justice 12. Getting the Story Right, Telling the Story Well: Indigenous Activism, Indigenous Research Conclusion: A Personal Journey Twenty Further Indigenous Projects Poems Index |

Para

los colonizados, el término «investigación» se confunde con el

colonialismo europeo; las formas en que la investigación académica se

ha visto implicada en los estertores del imperialismo siguen siendo un

doloroso recuerdo. Este volumen esencial explora las intersecciones

entre imperialismo e investigación, en concreto, las formas en que el

imperialismo está incrustado en las disciplinas del conocimiento y la

tradición como «regímenes de verdad». Se debaten conceptos como

«descubrimiento» y «reivindicación» y se presenta el argumento de que

la descolonización de los métodos de investigación ayudará a reclamar

el control sobre las formas indígenas de conocer y ser. Ahora, en su

esperada tercera edición, este libro superventas incluye una

introducción coescrita y presenta contribuciones de estudiosos

indígenas sobre la continua relevancia del libro para la investigación

actual. También incluye un capítulo con veinticinco proyectos indígenas

y una colección de poesía. Para

los colonizados, el término «investigación» se confunde con el

colonialismo europeo; las formas en que la investigación académica se

ha visto implicada en los estertores del imperialismo siguen siendo un

doloroso recuerdo. Este volumen esencial explora las intersecciones

entre imperialismo e investigación, en concreto, las formas en que el

imperialismo está incrustado en las disciplinas del conocimiento y la

tradición como «regímenes de verdad». Se debaten conceptos como

«descubrimiento» y «reivindicación» y se presenta el argumento de que

la descolonización de los métodos de investigación ayudará a reclamar

el control sobre las formas indígenas de conocer y ser. Ahora, en su

esperada tercera edición, este libro superventas incluye una

introducción coescrita y presenta contribuciones de estudiosos

indígenas sobre la continua relevancia del libro para la investigación

actual. También incluye un capítulo con veinticinco proyectos indígenas

y una colección de poesía.植民地化された人々にとって、「研究」という言葉はヨーロッパの植民地主義と結びつけられ、学術研究が帝国主義の苦悩に関与してきたことは、今もなお痛ま しい記憶として残っている。 この重要な本は、帝国主義と研究との交差点を探求している。特に、帝国主義が「真実の体制」として知識と伝統の分野に組み込まれている方法を探求してい る。「発見」や「主張」といった概念が議論され、研究方法の脱植民地化が、先住民の知と存在に対する支配権を取り戻すのに役立つという主張が提示されてい る。待望の第三版となったこのベストセラーには、共著による序文が収録され、先住民の学者による寄稿が掲載されている。寄稿では、この本が現在の研究に引 き続き関連性を持つことが述べられている。また、25の先住民のプロジェクトを紹介する章や詩のコレクションも収録されている。 第3版への序文 まえがき はじめに 1. 帝国主義、歴史、記述、理論 2. 帝国主義の視点による研究 3. 知識の植民地化 4. 先住民居住地における研究冒険 5. オーストラリアからのメモ 6. 先住民プロジェクト:新たな課題の設定 7. 先住民の研究課題の明確化 8. 25の先住民プロジェクト 9. 先住民の課題の緊急性への対応: マオリ族の事例研究 10. 先住民の方法論の開発に向けて:カウパマオリ研究 11. 境界線を選ぶ:先住民の社会正義を求める闘いにおける研究の役割 12. 物語を正しく伝え、上手に語る:先住民の活動、先住民の研究 結論:個人的な旅 20のさらなる先住民プロジェクト 詩 索引 |

リンダ・トゥヒワイ・テ・リナ・スミス(旧

姓ミード、1950年生)は、以前はニュージーランド・ハミルトンにあるワイカト大学の先住民教育学の教授だった

が[2][3][4]、現在はテ・ワハレ・ワナング・オ・アワヌアランギの名誉教授である。スミスの学術的貢献は、知識とシステムの脱植民地化に関するも

のである。王立協会テ・アパランギは、スミスが教育に与えた影響について、「学生や研究者がアイデンティティを受け入れ、支配的な物語を乗り越えるための

知的空間」を創出したと説明している[5]。 リンダ・トゥヒワイ・テ・リナ・スミス(旧

姓ミード、1950年生)は、以前はニュージーランド・ハミルトンにあるワイカト大学の先住民教育学の教授だった

が[2][3][4]、現在はテ・ワハレ・ワナング・オ・アワヌアランギの名誉教授である。スミスの学術的貢献は、知識とシステムの脱植民地化に関するも

のである。王立協会テ・アパランギは、スミスが教育に与えた影響について、「学生や研究者がアイデンティティを受け入れ、支配的な物語を乗り越えるための

知的空間」を創出したと説明している[5]。生い立ちと教育 スミスはニュージーランドのワカタネで生まれた[6]。父親は同じく教授のNgāti Awaのシドニー・モコ・ミード、母親はNgāti Porouのジュン・テ・リナ・ミード(旧姓ウォーカー)である[7]。彼女は成人後にトゥヒワイという名を与えられた[7]。スミスは、ニュージーラン ド北島の東端にあるマオリ族の部族、Ngāti AwaとNgāti Porouの出身である[5]。 スミスが10代の頃、父親が博士号取得のためにアメリカに滞在していたため、スミスもアメリカに移住した。彼女の家族はイリノイ州南部に住んでおり、彼女 はカーボンデール・コミュニティ高校に通っていた。アメリカで教育を受けたことで、スミスは学習者としての新たな自信を手に入れた[6]。スミスはその後 マサチューセッツ州セーラムに移り、セーラム・ピーボディ博物館で地下のラベル入力の助手として働いていた[8]。ニュージーランドに戻った後、彼女は ニュージーランドの学生、特にマオリ族の学生たちに、学生としての自信という価値観を応用した。 1970年代、スミスは活動家グループ「Ngā Tamatoa」の創設メンバーであった[9]。彼女はマルコムXとフランツ・ファノンの著作に影響を受けた。Ngā Tamatoaにおける彼女の役割は、マオリ族の人々とワイタンギ条約についてコミュニケーションをとることだった。スミスは、マオリ族の自由を求める闘 いにおいて、教育が最も重要な要素であると考えていた[6]。彼女は大学生時代にNgā Tamatoaのメンバーであった[7]。 スミスはオークランド大学で学士号、修士号(優等)、博士号を取得した。1996年の論文のタイトルは「Ngā aho o te kakahu matauranga: the multiple layers of struggle by Maori in education(マオリ族の教育における闘いの重層性)」であった[10][11]。 経歴 スミスは、ワイカト大学マオリ族副学長、マオリ族・太平洋開発学部長、テ・コタヒ研究所所長である[12]。 スミスの著書『Decolonising Methodologies, Research and Indigenous Peoples』は1999年に初めて出版された[13]。 2013年の新年叙勲で、スミスはマオリ族と教育への貢献により、ニュージーランド勲章コンパニオン章を授与された マオリ族と教育への貢献が認められたためである[14]。2017年、スミスはニュージーランドにおける知識への女性の貢献を称えるロイヤル・ソサエ ティ・テ・アパランギの「150人の女性150の言葉」の1人に選ばれた[15]。 2016年11月、彼女はワイタンギ裁判所のメンバーに任命された[16]。同年、彼女はマオリ族副学長を退任し、新たに設立されたマオリ族・先住民学部 でマオリ族・先住民学教授として短期契約を結んだ[17]。 マオリ族副学長を退任し、新たに設立されたマオリ族・先住民学部でマオリ族・先住民学教授として短期契約を結んだ[17]。 2020年9月、スミスが教育における人種差別について教育省に公開書簡を書いた学者グループの一員であったこと[18]、そして彼女の契約が更新されな いというニュースが報じられた際、#BecauseOfLindaTuhiwaiSmithというハッシュタグが話題となった。手紙の主張についてワイカ ト大学が委託した報告書では、同大学が構造的にマオリ族に対して差別的であることが明らかになった[19]が、手紙の他の主張については支持しなかった [19]。 2021年、スミスはテ・ワレ・ワナンガ・オ・アワヌアランギの名誉教授に就任した[20]。彼女は2021年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーに選出された初のマオリ族学者となった[1]。2021年に、 王立協会から最高の名誉であるラザフォード・メダルがスミスに授与された。このメダルは、「Te Ao Māori(マオリ族の教育と研究の発展における彼女の卓越した役割、研究方法論の脱植民地化における彼女の画期的な研究、そして先住民族のための研究を 世界的に変革する彼女の先駆的な貢献)」に対して贈られたものである[21]。スミスは、この受賞について次のように述べている。 「マオリ族や先住民族にとって、自分たちの知識が認められ、大きな知識の機関の中に自分たちの居場所を確保し、創造していくことはとても重要なことだと思う。」(リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミス、2023年)[22] 脱植民地化の方法論 メイン記事:脱植民地化の方法論 スミスは『Decolonising Methodologies, Research and Indigenous Peoples』(Zed Books、1999年、2012年、2021年)の著者であり、この本は、先住民族文化の植民地化プロセスにおいて西洋の学術研究が果たした役割を批判 的に分析したものである。この作品は、社会正義研究における研究手法への大きな貢献とみなされている[13][23][24]。2023年のニュース記事 で、王立協会テ・アパランギは、この作品が5言語に翻訳され、これまでに28万3千回の引用があるとしている[5]。 私生活 スミスは、同じ学者のグラハム・スミスと結婚している[4]。 主な著作 スミス、リンダ・トゥヒワイ。 Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books Ltd., 2013. デンジン、ノーマン・K、イヴォンナ・S・リンカーン、リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミス編。 Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies. Sage, 2008. スミス、リンダ・トゥヒワイ。 On tricky ground: 不確かな時代における先住民の研究。N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.) The Landscape of Qualitative Research." (2008): 113–143. Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Kaupapa Māori research: Reclaiming indigenous voice and vision (2000): 225–247. Cram, Fiona, Linda Smith, and Wayne Johnstone. マオリ族の健康に関する話題のマッピング。 (2003) Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Building a research agenda for indigenous epistemologies and education. Anthropology & education quarterly 36, no. 1 (2005): 93–95. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linda_Tuhiwai_Smith |

『脱植民地化の方法論:研究と先住民』は、ニュージーランドの学者リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミスによる著書である。1999年に初版が発行された『脱植民地化の方法論』は、先住民研究の基礎となるテキストであり、植民地主義と研究方法論の交差点を探求している。 『脱植民地化の方法論:研究と先住民』は、ニュージーランドの学者リンダ・トゥヒワイ・スミスによる著書である。1999年に初版が発行された『脱植民地化の方法論』は、先住民研究の基礎となるテキストであり、植民地主義と研究方法論の交差点を探求している。概要 この本は、「『研究』という言葉自体が、先住民の言語の中で最も汚れた言葉の一つである」という一文で始まる。スミスは、西洋の研究パラダイムは「ヨーロッパ帝国主義と植民地主義と密接不可分」であると主張している。 この本には、マオリ文化の価値観と態度の発展を概説し、マオリの学者によるマオリのテーマの研究を支援する研究フレームワークを作成するためのマオリ研究の概要が記載されている[1]。 スミスは、カウパマオリの研究方法をどのように実施できると考えているかを説明し、この本を締めくくっている。 影響と評価 『脱植民地化の方法論』は、非常に大きな影響力を持つカウパマオリ研究の方法論のビジョンを示している。Ranginui Walkerは、この本を「支配、闘争、解放の力関係をダイナミックに解釈したもの」と評した[2]。Laurie Anne Whittは、この本を「支配的な研究手法に対する強力な批判」と賞賛した[2]。 Linda Tuhiwai Smithは、2023年にニュージーランド科学アカデミーRoyal Society Te Apārangiから最高栄誉であるラザフォードメダルを授与された[3]。彼らは次のように述べた。 『脱植民地化の方法論、研究、先住民』(1999年)は社会科学全般に多大な影響を与えた。(王立協会 Te Apārangi 2023) この本は5言語に翻訳されている[3]。 他の学者たちからも広く引用されており、2023年末までに28万3,000回引用されている[3]。 0回であった[3]。 ニュージーランドの歴史家ピーター・マンズは、この本の政治的意図を非難し、「著者が「植民地化」と呼ぶ研究は、文化の偏狭な自己イメージを批判的に精査 すること以上のものではない。このような研究は、古い習慣や信念を弱め、偏狭な社会が広く、おそらくはグローバルなコミュニティへと円滑に移行することを 促すという意味で、解放的である。それを「植民地化」と呼ぶのは、感情的な政治に他ならない。 ニュージーランド政府機関である社会開発省のカールラ・ウィルソンによる書評では、先住民ではない研究者やパケハの研究者が先住民コミュニティの研究を行 う際に、どのような指針となるかを考察している。ウィルソンの書評によると、この本の主な焦点は「先住民コミュニティ内の「内部者」による研究」であり、 この問題については詳しく触れていない[1]。 この本は、自身の文化、価値観、思い込み、信念について考え、批判的に捉え、それらが「普通」ではないことを認識する必要性について、貴重な気づきを与えてくれる。(カーラ・ウィルソン 2001年) 2021年、LOM社から出版された同書のスペイン語訳『脱植民地化の方法論』は、エリサ・ロンコンによってチリ憲法制定会議の「多民族図書館」に届けられた[5]。 批判理論 脱植民地化 知識の脱植民地化 マオリの伝統 |

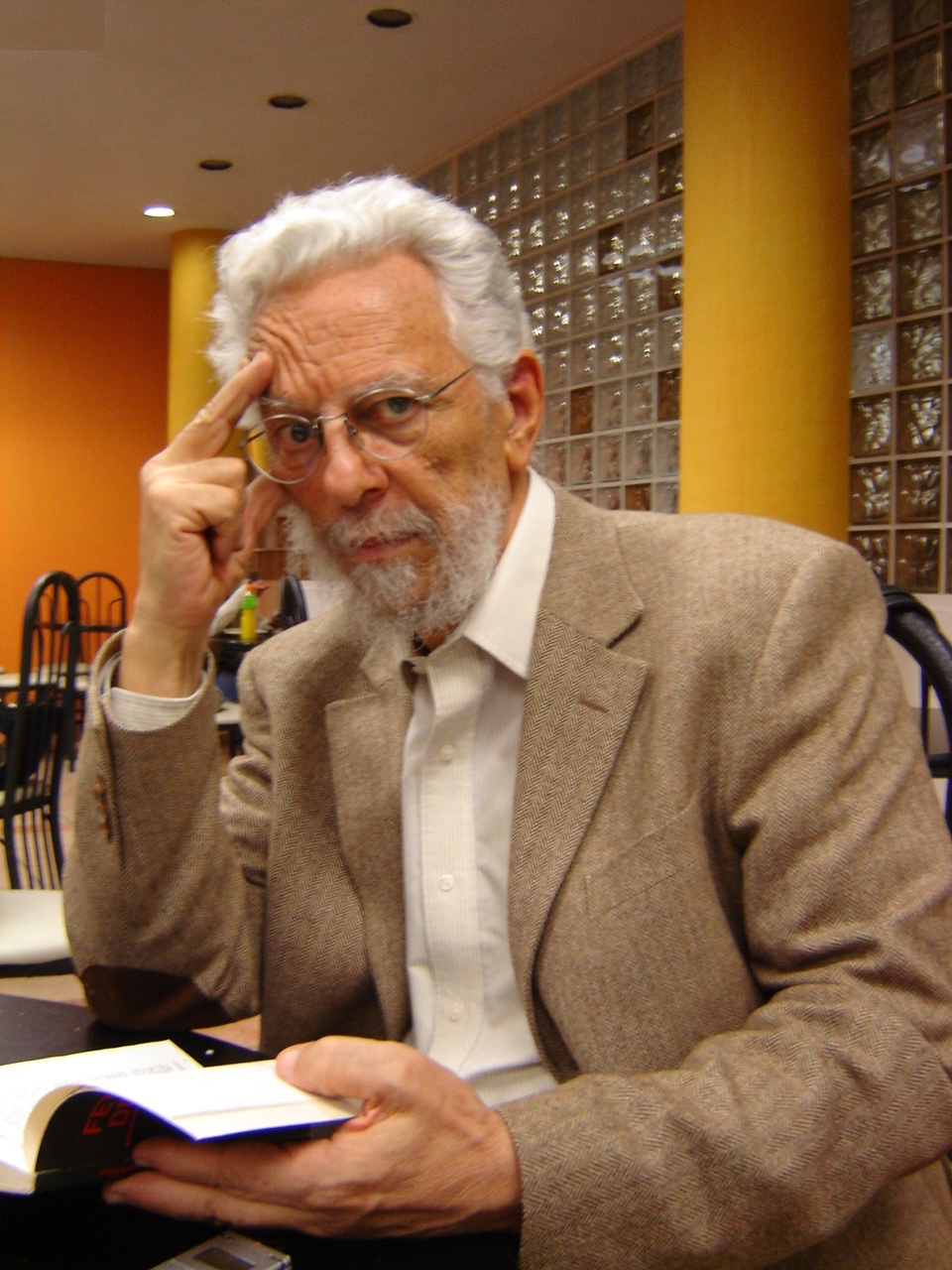

【より詳しくは】→ア

ニバル・キハノへ 【より詳しくは】→ア

ニバル・キハノへAníbal Quijano (17 November 1928 – 31 May 2018) was a Peruvian sociologist and humanist thinker, known for having developed the concepts of "coloniality of power" and "coloniality of knowledge".[1] His body of work has been influential in the fields of decolonial studies and critical theory. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/An%C3%ADbal_Quijano |

【より詳しくは】→ア

ニバル・キハノへ 【より詳しくは】→ア

ニバル・キハノへア ニバル・キハノ(Aníbal Quijano、1928年11月17日 - 2018年5月31日)は、ペルーの社会学者、人文主義思想家であり、「権力の植民地主義」と「知の植民地主義」の概念を提唱したことで知られる[1]。 彼の業績は、脱植民地化研究や批判理論の分野に影響を与えている。 |

| Coloniality of knowledge Coloniality of knowledge is a concept that Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano developed and adapted to contemporary decolonial thinking. The concept critiques what proponents call the Eurocentric system of knowledge, arguing the legacy of colonialism survives within the domains of knowledge. For decolonial scholars, the coloniality of knowledge is central to the functioning of the coloniality of power and is responsible for turning colonial subjects into victims of the coloniality of being, a term that refers to the lived experiences of colonized peoples. Origin and development Fregoso Bailón and De Lissovoy argue that Hatuey, a Taíno warrior from La Española (which contains Haiti and the Dominican Republic), was among the first to recognize "Western knowledge as a colonial discourse".[2] Inspired by Hatuey, Antonio de Montesinos began his career as an educator in 1511, teaching Bartolomé de las Casas critical thinking.[2] In the contemporary era, Frantz Fanon is considered an influential figure for his critique of the intellectual aspects of colonialism. According to Fanon, "colonialism is a psychic and epistemological process as much as a material one." Quijano built on this insight, advancing the critique of colonialism's intellectual dimensions.[2] The concept of coloniality of knowledge comes from coloniality theories,[note 1] encompassing coloniality of power, coloniality of being, and coloniality of knowledge.[note 2] Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano introduced the concept of coloniality of knowledge in 1992,[note 3] discussing global power systems, knowledge, racial hierarchy, and capitalism in Latin American history from the fourteenth century to the present.[note 4] Decolonial thinkers like Walter Mignolo, Enrique Dussel, and Santiago Castro-Gómez later expanded on the concept.[7] Background According to Quijano, colonialism has had a particular influence on colonized cultures' modes of knowing, knowledge production, perspectives, visions; and systems of images, symbols, and modes of signification; along with their resources, patterns, and instruments of formalized and objectivised expression. For Quijano, this suppression of knowledge accompanied the annihilation of indigenous populations throughout the continent, as well as indigenous societies and traditions. Quijano said the patterns of suppression, expropriation, and imposition of knowledge created during the colonial period, as refracted through conceptions of race and racial hierarchy, persisted after colonialism was overturned as "an explicit political order".[8] This persists in numerous "colonial situations" in which individuals and groups in historically colonized regions are excluded and exploited. Decolonial scholars refer to this ongoing legacy of colonialism as "coloniality", which describes colonialism's perceived legacy of oppression and exploitation across many inter-related domains, including knowledge. Ndlovu-Gatsheni cites Quijano, referring to "control of economy; control of authority, control of gender and sexuality; and, control of subjectivity and knowledge".[9] |

知識の植民地性 知識の植民地性は、ペルーの社会学者アニバル・キハノが開発し、現代の脱植民地化思想に適応させた概念である。この概念は、知識の分野に植民地主義の遺産 が残存していると主張する支持者たちが「ヨーロッパ中心主義的知識体系」と呼ぶものを批判している。脱植民地化学者にとって、知識の植民地性は権力の植民 地性の機能にとって中心的なものであり、植民地化された人々が生きた経験を表す「存在の植民地性」の犠牲者に植民地化された人々を変化させる原因となって いる。 起源と発展 Fregoso BailónとDe Lissovoyは、ラ・エスパニョーラ(ハイチとドミニカ共和国を含む)出身のタイノ族の戦士ハトゥエイが、「西洋の知識は植民地的な言説である」と最 初に認識した人物の一人であったと主張している[2]。 現代では、フランツ・ファノンが植民地主義の知的側面を批判した人物として影響力を持つ人物とされている。ファノンによれば、「植民地主義は物質的なもの だけでなく、精神的かつ認識論的なプロセスでもある」[2]。キハノは、この洞察に基づいて、植民地主義の知的側面に対する批判を進めた[2]。 知識の植民地主義の概念は、植民地主義理論から生まれた[注釈 1]もので、権力の植民地主義、存在の植民地主義、知識の植民地主義を包含している[注釈 2]。ペルーの社会学者アニバル・キハノは、 1992年に「知識の植民地主義」の概念を導入し、14世紀から現在に至るラテンアメリカ史におけるグローバルな権力システム、知識、人種的ヒエラル キー、資本主義について論じた[注4]。ウォルター・ミニョーロ、エンリケ・ドゥッセル、サンティアゴ・カストロ=ゴメスといった脱植民地主義思想家たち が、後に この概念を発展させた。 背景 キハノによると、植民地主義は被植民地の文化における認識の仕方、知識の生産、視点、ビジョン、イメージ、シンボル、意味づけのシステム、そしてそれらの 資源、パターン、形式化され客観化された表現の手段に特別な影響を与えてきた。キハノ氏によると、この知識の抑圧は、大陸全域における先住民人口の絶滅、 先住民の社会や伝統の消滅を伴っていた。キハノは、植民地時代に形成された知識の抑圧、収奪、押し付けのパターンが、人種や人種的ヒエラルキーの概念を通 して屈折し、植民地主義が「明白な政治的秩序」として覆された後も続いていると述べた[8]。これは、歴史的に植民地化された地域の個人やグループが排除 され搾取される数多くの「植民地状況」で続いている。脱植民地化論の学者たちは、この植民地主義の遺産を「コロニアルシティ」と呼び、知識を含む多くの相 互に関連する領域における植民地主義の遺産として認識されている抑圧と搾取を表現している。ンドロヴ・ガツェニはキハノの言葉を引用し、「経済、権威、 ジェンダーとセクシュアリティ、そして主観と知識のコントロール」を挙げている[9]。 |

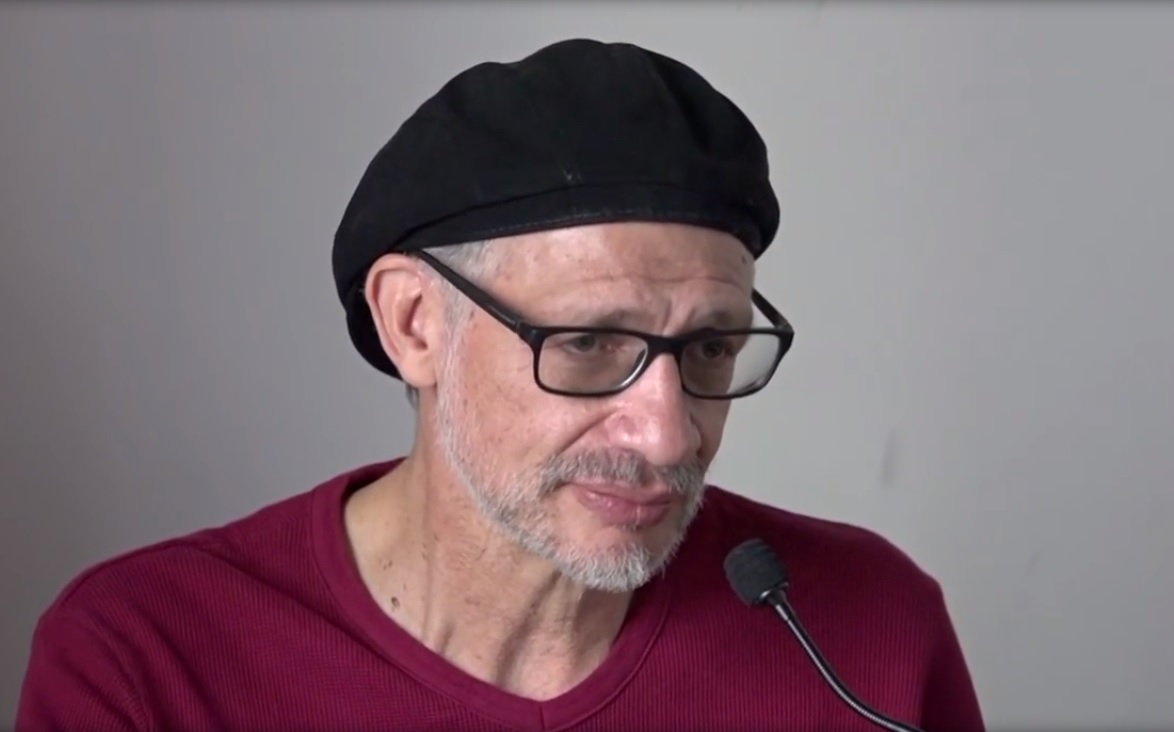

Walter D. Mignolo Walter D. MignoloWalter D. Mignolo (born May 1, 1941) is an Argentine semiotician (School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences) and professor at Duke University, US, who has published extensively on semiotics and literary theory, and worked on different aspects of the modern and colonial world, exploring concepts such as decoloniality, global coloniality, the geopolitics of knowledge, transmodernity, border thinking, and pluriversality. He is one of the founders of the modernity/coloniality critical school of thought.[1] |

ウォルター・D・ミニョーロ→詳しくは、ワルター・ミグノーロ、で解説 ウォルター・D・ミニョーロ→詳しくは、ワルター・ミグノーロ、で解説ウォルター・D・ミニョーロ(Walter D. Mignolo、1941年5月1日生まれ)は、アルゼンチン出身の記号論学者(School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences)であり、デューク大学(米国)の教授である。記号論と文学理論について多くの著作を発表しており、脱植民地主義、グローバル植民地主 義、知識の地政学、トランスモダニティ、ボーダー思考、多元的宇宙論などの概念を探求しながら、近代と植民地時代のさまざまな側面について研究している。 彼は近代性/植民地主義批判学派の創設者の一人である[1]。 |

Enrique Domingo Dussel Ambrosini Enrique Domingo Dussel AmbrosiniEnrique Domingo Dussel Ambrosini (24 December 1934 – 5 November 2023) was an Argentine-Mexican academic, philosopher, historian and theologian. He served as the interim rector of the Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México from 2013 to 2014. |

エンリケ・ドミンゴ・ドゥセル・アンブロシーニ→くわしくは、 エンリケ・ドゥッセル、で解説 エンリケ・ドミンゴ・ドゥセル・アンブロシーニ→くわしくは、 エンリケ・ドゥッセル、で解説エンリケ・ドミンゴ・ドゥセル・アンブロシーニ(Enrique Domingo Dussel Ambrosini、1934年12月24日 - 2023年11月5日)は、アルゼンチン系メキシコ人の学者、哲学者、歴史学者、神学者。2013年から2014年まで、メキシコシティ自治大学の暫定学 長を務めた。 |

Santiago Castro-Gómez Santiago Castro-GómezSantiago Castro-Gómez (born 1958, Bogotá, Colombia) is a Colombian philosopher, a professor at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and the director of the Pensar Institute in Bogotá.[1][2] Career and Work Castro-Gómez began studying philosophy at Santo Tomás University in Bogotá, Colombia with members of the "Bogotá Group."[3] He received his M.A. in Philosophy at the University of Tübingen and his Ph.D at the Goethe University Frankfurt am Main in Germany.[4] In addition to his academic positions in Colombia, he has served as visiting professor at Duke University, Pittsburgh University and the Goethe University of Frankfurt. Castro-Gómez is a public intellectual in Colombia whose work has been the subject of conferences and books,[5] debates over Colombian identity,[6] research on Latin American philosophy,[7][8] as well as artistic installations.[9] He is the author or co-editor of more than ten books, many of which have been reissued in new editions.[10] As director of the Pensar Institute in Bogotá, he has led an initiative to engage the public, and specifically early public education, on the effects of racism and colonization in Colombian society.[11] Alongside Aníbal Quijano, Walter Mignolo, Enrique Dussel, Ramón Grosfoguel, Catherine Walsh, Arturo Escobar, Edgardo Lander and Nelson Maldonado-Torres, Castro-Gómez was part of the "Modernity/Coloniality" group, a circle of Latin American critical theorists formed at the beginning of the 21st century.[12][13] Castro-Gómez's work develops alternatives to dominant approaches and figures in Latin American Philosophy, an intervention he makes explicit in Critique of Latin American Reason (1996).[14][15] In addition to colleagues like Aníbal Quijano and Walter Mignolo, his major influences include the Frankfurt School, Friedrich Nietzsche, Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze.[16][17] The work of Castro-Gómez explores the "frontiers" between sociology, anthropology, literary studies and cultural studies, while also reflecting on methodological and epistemological problems within the social sciences.[18] In Zero-Point Hubris, Castro-Gómez characterizes Rene Descartes' 1637 famous statement of "I think, therefore I am" as "the moment white Europeans installed themselves above God as the sole arbiters of knowledge and truth. With this turning point, they began to think of themselves as observers whose scientific methods, morals and ethics overrode those of other cultures."[19][20] Books in Spanish El tonto y los canallas: Notas para un republicanismo transmoderno (Bogotá: Universidad Javeriana, 2019). Historia de la gubernamentalidad II. Filosofía, cristianismo y sexualidad en Michel Foucault (Bogotá: Siglo del Hombre Editores, 2016) Revoluciones sin sujeto. Slavoj Zizek y la crítica del historicismo posmoderno. D.F. (México: AKAL 2015). Historia de la gubernamentalidad. Razón de estado, liberalismo y neoliberalismo en Michel Foucault (Bogotá: Siglo del Hombre Editores, 2010). Tejidos Oníricos. Movilidad, capitalismo y biopolítica en Bogotá, 1910-1930 (Bogotá: Universidad Javeriana 2009). Genealogías de la colombianidad: formaciones discursivas y tecnologías de gobierno en los siglos XIX y XX, editores Santiago Castro-Gómez y Eduardo Restrepo (2008). Reflexiones para una diversidad epistémica más allá del capitalismo global, editores Santiago Castro-Gómez y Ramón Grosfoguel (Siglo del Hombre Editores, 2007). La poscolonialidad explicada a los niños (Editorial Universidad del Cauca, Popayán, 2005). La hybris del punto cero. Ciencia, raza e ilustración en la Nueva Granada, 1750-1816 (Bogotá: Universidad Javeriana, 2005). Teorías sin disciplina: Latinoamericanismo, poscolonialidad y globalización en debate. Santiago Castro-Gómez y Eduardo Mendieta (1998). Crítica de la razón latinoamericana (Barcelona: Puvill Libros, 1996; segunda edición: Bogotá, Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, 2011). Writings in English Critique of Latin American Reason, translated by Andrew Ascherl (Columbia University Press, 2021).[21] Zero-Point Hubris: Science, Race, and Enlightenment in 18th-Century Latin America, translated by Don T. Deere and George Ciccariello-Maher (Rowman & Littlefield International, 2021).[22][23] "The Missing Chapter of Empire: Postmodern Reorganization of Coloniality and Post-Fordist Capitalism" in Globalization and the Decolonial Option (Routledge 2009), pp. 282–302. "(Post)Coloniality for Dummies: Latin American Perspectives on Modernity, Coloniality, and the Geopolitics of Knowledge" in Coloniality at Large: Latin America and the Postcolonial Debate, edited by Mabel Moraña, Enrique Dussel, Carlos A. Jáuregui (Duke University Press, 2008). "Latin American philosophy as critical ontology of the present: Themes and motifs for a 'critique of Latin American reason,'” In Eduardo Mendieta (ed.), Latin American Philosophy: Currents, Issues, Debates (Indiana University Press, 2003), pp. 68–79. "The Social Sciences, Epistemic Violence, and the Problem of the 'Invention of the Other,'" trans. Desiree A. Martin, in Nepantla: Views from South (Duke University Press) Volume 3, Issue 2, 2002, pp. 269–285. "The Cultural and Critical Context of Postcolonialism" in Philosophia Africana (Volume 5, Issue 2, August 2002), pp. 25–34.[24] "The Convergence of World-Historical Social Science, or Can There Be a Shared Methodology for World-Systems Analysis, Postcolonial Theory and Subaltern Studies?" (with Oscar Guardiola-Rivera) in The Modern/Colonial/Capitalist World-System In The Twentieth Century (Westport Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2002), pp. 237–249. “The Challenge of Postmodernity to Latin American Philosophy" in Latin America and Postmodernity: A Contemporary Reader, edited by Pedro Lange-Churion, Eduardo Mendieta (Amherst: Humanity Books, 2001). "Traditional and Critical Theories of Culture" in Nepantla: Views From South (Duke University Press, 2000), pp. 503–518. "Traditional vs. Critical Cultural Theory," trans. Francisco González and Andre Moskowitz, in Cultural Critique No. 49, Critical Theory in Latin America (Autumn, 2001), pp. 139–154. "Latin American Postcolonial Theories" in Peace Review (Taylor and Francis, 1998), pp. 27–33. |

サンティアゴ・カストロ=ゴメス サンティアゴ・カストロ=ゴメスサンティアゴ・カストロ=ゴメス(1958年、コロンビア、ボゴタ生まれ)は、コロンビアの哲学者であり、ポンティフィシア・ウニベルシダ・ハベリアーナの教授、ボゴタのペンサル研究所の所長である[1][2]。 経歴と業績 カストロ=ゴメスは、コロンビアのボゴタにあるサント・トマス大学で、「ボゴタ・グループ」のメンバーとともに哲学の研究を始めた[3]。「ボゴタ・グ ループ」のメンバーとともに、コロンビアのボゴタにあるサント・トマス大学で哲学の勉強を始めた[3]。彼はドイツのテュービンゲン大学で哲学の修士号 を、フランクフルト・アム・マインのゲーテ大学で哲学の博士号を取得した[4]。コロンビアでの学術的立場に加え、デューク大学、ピッツバーグ大学、フラ ンクフルト・ゲーテ大学の客員教授も務めている。 カストロ=ゴメス氏は、コロンビアの公共知識人であり、彼の研究は学会や書籍で取り上げられ、[5]コロンビアのアイデンティティをめぐる議論や、[6] ラテンアメリカの哲学の研究、[7][8]芸術作品の展示でも取り上げられている。特に、コロンビア社会における人種差別と植民地化の影響について、一般 市民、特に初期の公教育に働きかけるイニシアティブを主導した[11]。 アニバル・キハノ、ウォルター・ミニョーロ、エンリケ・ドゥッセル、ラモン・グロスフォゲル、キャサリン・ウォルシュ、アルトゥロ・エスコバル、エドガル ド・ランデル、ネルソン・マルドナド=トーレスらとともに、カストロ=ゴメスも「モダニティ/コロニアリティ」グループの一員であった。21世紀初頭に結 成されたラテンアメリカの批評理論家のサークルである。[12][13] カストロ=ゴメスの研究は、ラテンアメリカ哲学における支配的なアプローチや概念に代わるものを開発しており、その介入は『ラテンアメリカ的理性批判』 (1996年)で明示されている。[14][15] アニバル・キハノやウォルター・ミニョロのような同僚に加えて、彼の主な影響源にはフランクフルト学派、フリードリヒ・ニーチェ、ミシェル・フーコー、ジ ル・ドゥルーズなどが含まれる。 カストロ=ゴメスの研究は、社会学、人類学、文学研究、文化研究間の「境界」を探求すると同時に、社会科学における方法論的・認識論的問題についても考察 している[18]。『ゼロポイント・ハブリス』の中で、カストロ=ゴメスは、ルネ・デカルトの1637年の有名な言葉「我思う、ゆえに我あり」を「白人ヨーロッパ人が知識と真理の唯一の裁定者として神の上に君臨した瞬間」と特徴づけている。この転換点をもって、彼らは科学的方法、道徳、倫理が他の文化のそれを凌駕する観察者として自らを捉えるようになった」[19][20]。 スペイン語による著書 El tonto y los canallas: Notas para un republicanismo transmoderno (ボゴタ: Universidad Javeriana, 2019). Historia de la gubernamentalidad II. ミシェル・フーコーにおける哲学、キリスト教、セクシュアリティ(ボゴタ:Siglo del Hombre Editores、2016年) 主体なき革命。 スラヴォイ・ジジェクとポストモダニズムの歴史主義批判。 D.F. (メキシコ:AKAL 2015年) 統治性の歴史。国家の論理、自由主義、新自由主義:ミシェル・フーコー論(Bogotá: Siglo del Hombre Editores, 2010)。 夢織物:移動、資本主義、生物政治学:1910-1930年のボゴタ(Bogotá: Universidad Javeriana 2009)。 『コロンビア性の系譜:19世紀と20世紀における言説の形成と統治技術』Santiago Castro-GómezとEduardo Restrepo編(2008年)。 『グローバル資本主義を超えた認識論的多様性への考察』Santiago Castro-GómezとRamón Grosfoguel編(Siglo del Hombre Editores、2007年)。 La poscolonialidad explicada a los niños (Editorial Universidad del Cauca, Popayán, 2005). La hybris del punto cero. Ciencia, raza e ilustración en la Nueva Granada, 1750-1816 (Bogotá: Universidad Javeriana, 2005). Teorías sin disciplina: Latinoamericanismo, poscolonialidad y globalización en debate. サンティアゴ・カストロ=ゴメスとエドゥアルド・メンディエタ著(1998年)。 ラテンアメリカの理性の批判』(バルセロナ:プヴィル・リブロス、1996年、第2版:ボゴタ、Pontificia Universidad Javeriana出版社、2011年)。 英語による著作 ラテンアメリカの理性の批判』(アンドリュー・アッシャーレル訳)(コロンビア大学出版、2021年)。[21] ゼロポイントの傲慢: 18世紀ラテンアメリカの科学、人種、啓蒙』(ドン・T・ディアとジョージ・チッカリエロ=マーハー訳、ローマン・アンド・リトルフィールド・インターナショナル、2021年)[22][23] 「帝国の失われた章: 『グローバリゼーションと脱植民地化への選択』(Routledge 2009年)所収「帝国主義の欠落した章:ポストモダンにおける植民地主義の再編成とポストフォード主義資本主義」282-302ページ。 『(ポスト)植民地主義入門:ラテンアメリカにおける近代、植民地主義、知識の地政学』『Coloniality at Large: ラテンアメリカとポストコロニアル論争』(Mabel Moraña、Enrique Dussel、Carlos A. Jáuregui編、デューク大学出版、2008年)所収。 「ラテンアメリカの哲学:現在における批判的実在論」『ラテンアメリカの哲学:潮流、課題、論争』(Eduardo Mendieta編、インディアナ大学出版、2003年)所収、68-79ページ。(インディアナ大学出版、2003年)、68~79ページ。 「社会科学、認識論的暴力、そして『他者の発明』の問題」、『ネパントラ:南からの視点』(デューク大学出版)第3巻第2号、2002年、269~285ページ。 「ポストコロニアリズムの文化的・批判的背景」『Philosophia Africana』(第5巻第2号、2002年8月)25-34ページ。 「世界史的社会科学の収束、あるいは世界システム分析、ポストコロニアリズム理論、サバルタン研究に共通の方法論は可能か?(オスカー・グアルディオラ= リベラとの共著)『20世紀における近代/植民地/資本主義的世界システム』(コネチカット州ウエストポート:グリーンウッドプレス、2002年) 237~249ページ。 「ポストモダニティがラテンアメリカ哲学に投げかける課題」『ラテンアメリカとポストモダニティ:現代文学選集』(ペドロ・ランゲ=チュリオン、エドゥアルド・メンディエタ編) (アマースト:ヒューマニティ・ブックス、2001年)所収。 「ネパントラ:南からの視点」(デューク大学出版、2000年)所収の「文化の伝統的・批判的理論」pp.503-518。 「伝統的対批判的文化理論」フランシスコ・ゴンザレス、アンドレ・モスコウィッツ訳、Cultural Critique No.49, Critical Theory in Latin America(2001年秋)pp.139-154。 「ラテンアメリカのポストコロニアル理論」『ピース・レビュー』(Taylor and Francis、1998年)、27-33ページ。 |

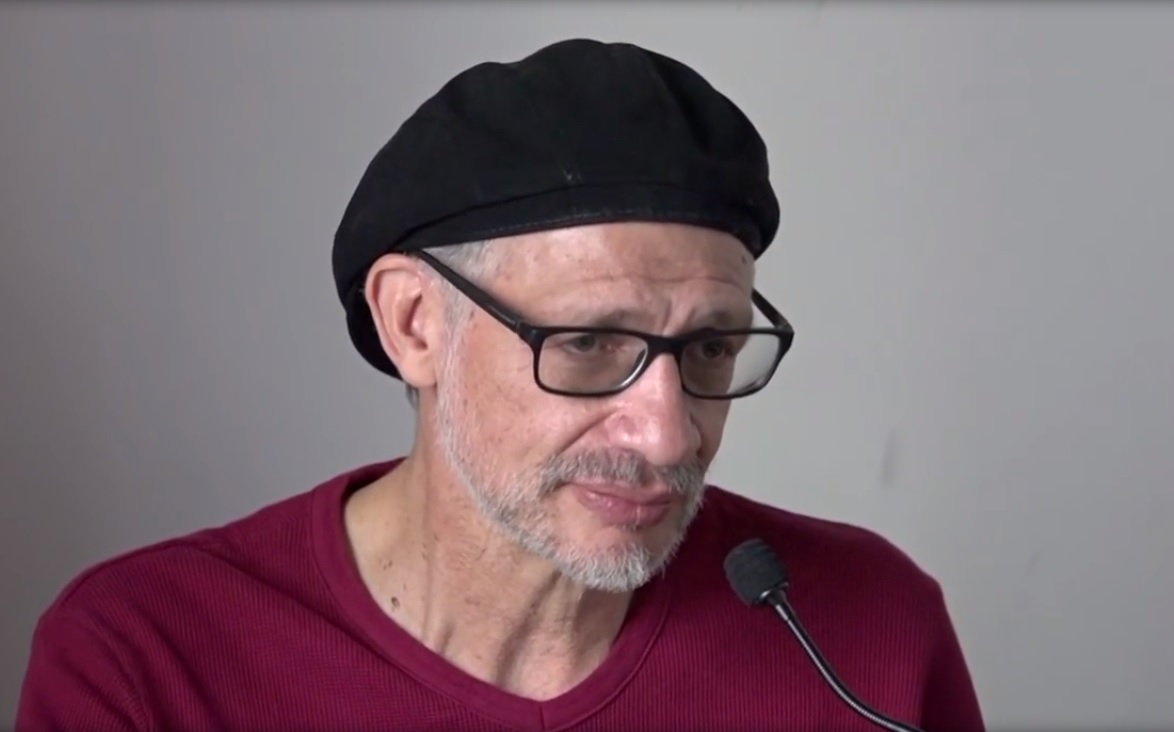

Robert J. C. Young Robert J. C. YoungRobert J. C. Young FBA (born 1950) is a British postcolonial theorist, cultural critic, and historian. Life Young was educated at Repton School and Exeter College, Oxford, where he read for a B.A. and D.Phil., taught at the University of Southampton, and then returned to Oxford University where he was Professor of English and Critical Theory and a fellow of Wadham College. In 2005, he moved to New York University where he is Julius Silver Professor of English and Comparative Literature.[1] From 2015 - 2018, he was Dean of Arts & Humanities at NYU Abu Dhabi. As a graduate student at Oxford, he was one of the founding editors of the Oxford Literary Review, the first British journal devoted to literary and philosophical theory. Young is Editor of Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies which is published eight times a year.[2] His work has been translated into over twenty languages.[3] In 2013 he was elected a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy,[4] in 2017 he was elected to an honorary life fellowship at Wadham College, Oxford.[5] Young is currently President of the AILC/ICLA Research Committee on Literary Theory.[6] Works Young's work has been described as being 'at least partially instrumental in the radicalisation of postcolonialism'.[2] His first book, White Mythologies: Writing History and the West (1990)[7] argues that Marxist philosophies of history had claimed to be world histories but had really only ever been histories of the West, seen from a Eurocentric—even if anti-capitalist—perspective. Offering a detailed critique of different versions of European Marxist historicism from Lukács to Jameson, Young suggests that a major intervention of postcolonial theory has been to enable different forms of history and historicisation that operate outside the paradigm of Western universal history. While postcolonial theory uses certain concepts from post-structuralism to achieve this, Young argues that post-structuralism itself involved an anti-colonial critique of Western philosophy, pointing to the role played by the experience of the Algerian War of Independence in the lives of many French philosophers of that generation, including Derrida, Cixous, Lyotard, Althusser, and Bourdieu. White Mythologies was the first book to characterise postcolonial theory as a field in itself, and to identify the work of Edward W. Said, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Homi K. Bhabha and the Subaltern Studies historians as its intellectual core.[citation needed] In Colonial Desire (1995)[8] Young examined the history of the concept of 'hybridity', showing its genealogy through nineteenth-century racial theory and twentieth-century linguistics, prior to its counter-appropriation and transformation into an innovative cultural-political concept by postcolonial theorists in the 1990s. Young demonstrates the extent to which racial theory was always developed in historical, scientific and cultural terms, and argues that this complex formation accounts for the ability of racialised thinking to survive into the modern era despite all the attempts made since 1945 to refute it. The most significant mistake that has been made, he suggests, involves the assumption that race was developed in the nineteenth-century purely as a 'science' which can be challenged on purely scientific grounds. Having deconstructed 'white Marxism' through the lens of postcolonial theory in White Mythologies, in Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction (2001),[9] Young charted the genealogy of postcolonial theory in the very different trajectory of Marxism as the major ideological component of twentieth-century anti-colonial struggles. The book provides the first genealogy of the anticolonial thought and practice which form the roots of postcolonialism,[10] tracing the relation of the history of the national liberation movements to the development of postcolonial theory.[11] Stressing the significance of the work of the Third International, as well as Mao Zedong's reorientation of the landless peasant as the revolutionary subject, Young points to the importance of the Havana Tricontinental of 1966 as the first independent coming together of the three continents of the South—Africa, Asia and Latin America—in political solidarity, and argues that this was the moment in which what is now called 'postcolonial theory' was first formally constituted as a specific knowledge-base of non-Western political and cultural production. In Postcolonialism: A Very Short Introduction (2003)[12] Young links this genealogy of postcolonialism to the contemporary activism of the New Social Movements in non-Western countries. Intended as an introduction to postcolonialism for the general reader, the book is written in a highly accessible style and unorthodox format, mixing history with fiction, cultural analysis with moments of poetic intensity that stage and evoke postcolonial experience rather than merely describe it. Instead of approaching postcolonialism through its often abstract and esoteric theories, the book works entirely out of particular examples. These examples emphasise issues of migration, gender, language, indigenous rights, 'development' and ecology as well as addressing the more usual postcolonial ideas of ambivalence, hybridity, orientalism and subalternity. In The Idea of English Ethnicity (2008)[13] Young returned to the question of race to address an apparent contradiction—the idea of an English ethnicity. Why does ethnicity not seem to be a category applicable to English people? To answer this question, Young reconsiders the way that English identity was classified in historical and racial terms in the nineteenth century. He argues that what most affected this was the relation of England to Ireland after the Act of Union of 1800–1. Initial attempts at excluding the Irish were followed by a more inclusive idea of Englishness which removed the specificities of race and even place. Englishness, Young suggests, was never really about England at all,[14] but was developed as a broader identity, intended to include not only the Irish (and thus deter Irish nationalism) but also the English diaspora around the world—North Americans, South Africans, Australians and New Zealanders, and even, for some writers, Indians and those from the Caribbean. By the end of the nineteenth century, this had become appropriated as an ideology of empire. The delocalisation of the country England from ideas of Englishness (Kipling's "What do they know of England who only England know?") could account for why recent commentators have found Englishness so hard to define—while at the same time providing an explanation of why some of the most English of Englishmen have been Americans. On the other hand, Young argues, its broad principle of inclusiveness also helps to explain why Britain has been able to transform itself into one of the more integrated, or hybridized, of modern multiethnic nations.[15] In 2015, together with Jean Khalfa, Young published a 680-page collection of writings by Frantz Fanon, the first new work by Fanon to be published in over 50 years, Écrits sur l’aliénation et la liberté[16] which includes two previously unpublished plays, together with psychiatric and political essays, letters, editorials from the weekly journals at the hospitals at Saint Alban (Trait d'union) and Blida (Notre Journal), as well as a complete list of Fanon's library and his annotations to his books.[17] |

ロバート・J・C・ヤング ロバート・J・C・ヤングロバート・J・C・ヤング FBA(1950年生まれ)は、イギリスのポストコロニアル理論家、文化評論家、歴史学者である。 経歴 ヤングはレプトン校とオックスフォード大学エクセター・カレッジで教育を受け、そこで文学士号と博士号を取得した。サザンプトン大学で教鞭をとった後、 オックスフォード大学に戻り、英語と批評理論の教授、ワドハム・カレッジのフェローとなった。2005年、ニューヨーク大学に移り、ジュリアス・シルバー 英語・比較文学教授に就任した[1]。2015年から2018年まで、ニューヨーク大学アブダビ校の芸術・人文科学学部長を務めた。 オックスフォード大学の大学院生だった頃、文学と哲学理論を専門とする英国初の学術誌『オックスフォード・リテラリー・レビュー』の創刊編集者の一人と なった。ヤングは、『Interventions: 年に8回発行される『Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies』の編集者でもある[2]。彼の作品は20以上の言語に翻訳されている[3]。2013年には英国学士院の通信会員に選出された[4]。 2017年にはオックスフォード大学ワドハム・カレッジの名誉終身会員に選出された[5]。オックスフォード大学ワドハム・カレッジの名誉終身研究員に選 出された[5]。ヤングは現在、AILC/ICLA文学理論研究委員会の委員長を務めている[6]。 著作 ヤングの著作は、「ポストコロニアリズムの急進化に少なくとも部分的に貢献した」と評されている[2]。彼の最初の著書『White Mythologies: (1990年)[7]では、マルクス主義の歴史哲学は世界史であると主張しているが、実際には反資本主義的視点を持つヨーロッパ中心主義の観点から見た西 洋の歴史にすぎない、と論じている。ルーカスからジェイムソンに至るヨーロッパのマルクス主義の歴史主義のさまざまなバージョンについて詳細な批判を展開 したヤングは、ポストコロニアル理論の主な介入は、西洋の普遍的な歴史というパラダイムの外で機能するさまざまな形式の歴史と歴史化を実現することだった と示唆している。ポストコロニアル理論は、ポスト構造主義の概念を援用してこれを達成しているが、ヤングは、ポスト構造主義自体が西洋哲学に対する反植民 地主義的批判を含んでいたと主張している。その根拠として、デリダ、シクスー、リオタール、アルチュセール、ブルデューなど、同世代の多くのフランス人哲 学者の人生において、アルジェリア独立戦争の経験が果たした役割を挙げている。『White Mythologies』は、ポストコロニアル理論をひとつの分野として特徴づけた最初の著作であり、エドワード・W・サイード、ガヤトリ・チャクラヴォ ルティ・スピヴァク、ホミ・K・ババ、サバルタン・スタディーズの歴史学者の業績をその知的中核として特定した[要出典]。 『Colonial Desire』(1 1995年)[8] ヤングは「ハイブリッド性」という概念の歴史を検証し、19世紀の人種理論や20世紀の言語学を通じてその系譜を示し、1990年代にポストコロニアル理 論家たちによってその概念が革新的な文化政治的概念として再解釈・再構築されるまでの経緯を明らかにした。ヤングは、人種理論が常に歴史的、科学的、文化 的な観点から発展してきたことを示し、この複雑な形成が、1945年以降、人種差別的思考を否定する試みがなされてきたにもかかわらず、それが現代まで生 き延びている理由であると主張している。彼が指摘する最も重大な過ちは、人種が19世紀に純粋に「科学」として発展し、純粋に科学的根拠に基づいて反論で きるという考えに基づいていることである。 『White Mythologies』でポストコロニアル理論の観点から「白人マルクス主義」を解体した後、ヤングは『Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction』(2001年)[9]で、20世紀の反植民地闘争における主要なイデオロギー的要素であるマルクス主義の全く異なる軌跡の中 で、ポストコロニアル理論の系譜を明らかにした。この本は、ポストコロニアリズムのルーツとなる反植民地主義思想と実践の最初の系譜を提供しており、 [10] 民族解放運動の歴史とポストコロニアリズム理論の発展との関係を追跡している[11]。第三インターナショナルの活動と、毛沢東による土地を持たない農民 を革命の主題として再方向づけることの重要性を強調し、 ヤングは、1966年のハバナ・トライコンティネンタルが、南アフリカ、アジア、ラテンアメリカの3大陸が初めて政治的連帯のもとに集まった独立イベント であったことの重要性を指摘し、これが「ポストコロニアル理論」と呼ばれるものが、非西洋の政治・文化生産の特定の知識基盤として初めて正式に構成された 瞬間であったと主張している。 『ポストコロニアリズム:超入門』(2003年)[12]で、ヤングはポストコロニアリズムの系譜を、非西洋諸国の新しい社会運動の現代的活動と結びつけ ている。一般読者向けのポストコロニアリズム入門として書かれたこの本は、非常に読みやすく、型にはまらないスタイルで書かれており、歴史とフィクショ ン、文化分析と詩的な表現を織り交ぜ、ポストコロニアリズムの経験を単に描写するのではなく、それを舞台化し、喚起するような構成となっている。この本 は、抽象的で難解な理論を通してポストコロニアリズムを論じるのではなく、具体的な事例をすべて取り上げて論じている。これらの事例は、移住、ジェン ダー、言語、先住民の権利、「開発」、エコロジーの問題を強調するとともに、両義性、ハイブリッド性、オリエンタリズム、サブオルタナリティといった、よ り一般的なポストコロニアリズムの概念にも言及している。 『The Idea of English Ethnicity』(2008年)[13]でヤングは、人種というテーマに立ち返り、一見矛盾しているように見える「イングランド民族」という概念につ いて考察している。 なぜイングランド民族という概念は、イングランド人にとって当てはまらないカテゴリーであるように見えるのだろうか? この疑問に答えるため、ヤングは19世紀にイングランド人のアイデンティティが歴史的、人種的な観点からどのように分類されていたかを再考している。彼 は、1800年から1801年の連合法以降、イングランドとアイルランドの関係がこの考え方に最も影響を与えたと主張している。当初、アイルランド人を排 除しようとする動きがあったが、その後、人種や場所といった特定の要素を排除した、より包括的なイングランド人としての考え方が生まれた。ヤングは、イン グランドらしさとは実際にはイングランドについてのことでは決してなかったと主張している[14]。イングランドらしさは、より広範なアイデンティティと して発展し、アイルランド人(そしてアイルランド民族主義の抑止)だけでなく、北米、南アフリカ、オーストラリア、ニュージーランド、さらには一部の作家 にとってはインドやカリブ海諸国の人々も含むことを意図していた。19世紀末までに、これは帝国のイデオロギーとして定着した。イングランドという国を、 イングランドらしさという概念から切り離す(キップリングの「イングランドを知る者はイングランドを知るのみ」という一節)ことで、最近の論評家たちがイ ングランドらしさを定義するのが難しいと感じている理由を説明できる。一方、ヤングは、その包括的な原則が、イギリスが現代多民族国家の中でもより統合さ れた、あるいはハイブリッド化された国家へと変貌を遂げることができた理由も説明していると主張している[15]。 2015年、ヤングはジャン・カルファとともに、50年ぶりに出版されたファン・ファノンの新作『 50年ぶりに出版された『隷属と自由についての諸論考』[16]には、2つの未発表戯曲、精神医学や政治に関するエッセイ、手紙、サン・アルバン病院 (Trait d'union)とブリダ病院(Notre Journal)の週刊誌に掲載された論説、ファノンの蔵書リスト、ファノンが書籍に付けた注釈などが含まれている[17]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_J._C._Young |

★類似項目:「知識のコロニアリティ=知識の植民地性」

知識のコロニアリティ=知識の植民地性は、ペルーの社会学者アニバル・キハノが開発し、現代の脱植民地化思想に適応させた概念である。この概念は、知識の 分野に植民地主義の遺産が残存していると主張する支持者たちが「ヨーロッパ中心主義的知識体系」と呼ぶものを批判している。脱植民地化学者にとって、知識 の植民地性は権力の植民地性を機能させる上で中心的なものであり、植民地化された人々を植民地化された存在の犠牲者に変える原因となっている。植民地化さ れた人々の生活経験を指す言葉である。

| Coloniality of knowledge Coloniality of knowledge is a concept that Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano developed and adapted to contemporary decolonial thinking. The concept critiques what proponents call the Eurocentric system of knowledge, arguing the legacy of colonialism survives within the domains of knowledge. For decolonial scholars, the coloniality of knowledge is central to the functioning of the coloniality of power and is responsible for turning colonial subjects into victims of the coloniality of being, a term that refers to the lived experiences of colonized peoples. |

知識のコロニアリティ(Coloniality of knowledge) 知識のコロニアリティ=知識の植民地性は、ペルーの社会学者アニバル・キハノが開発し、現代の脱植民地化思想に適応させた概念である。この概念は、知識の 分野に植民地主義の遺産が残存していると主張する支持者たちが「ヨーロッパ中心主義的知識体系」と呼ぶものを批判している。脱植民地化学者にとって、知識 の植民地性は権力の植民地性を機能させる上で中心的なものであり、植民地化された人々を植民地化された存在の犠牲者に変える原因となっている。植民地化さ れた人々の生活経験を指す言葉である。 |

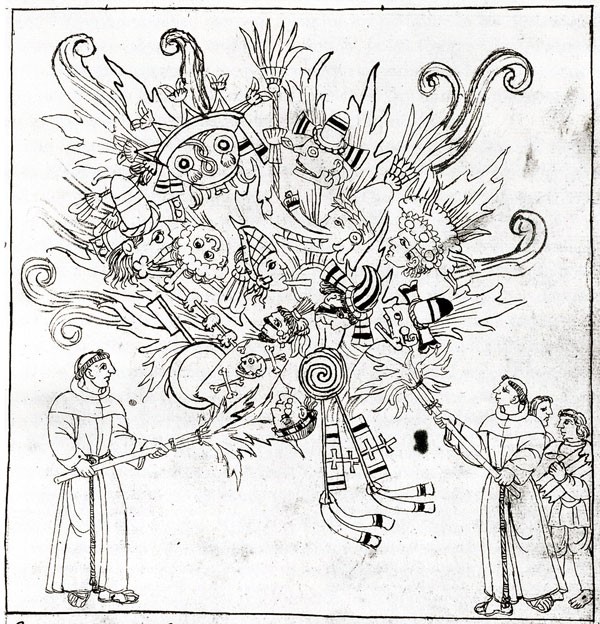

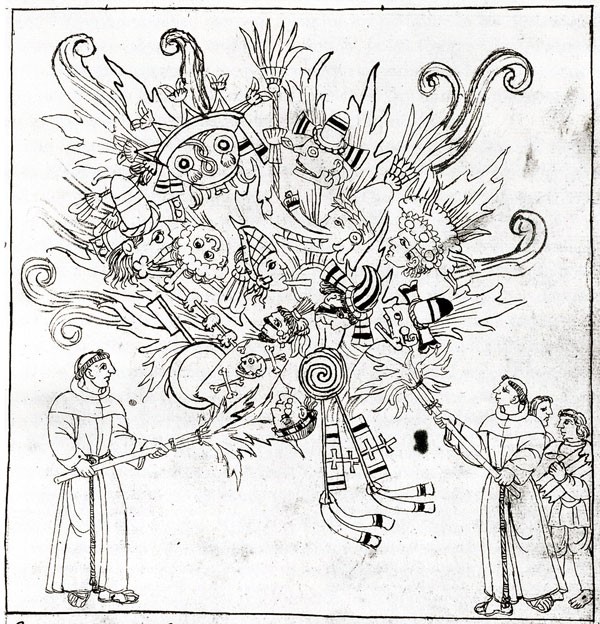

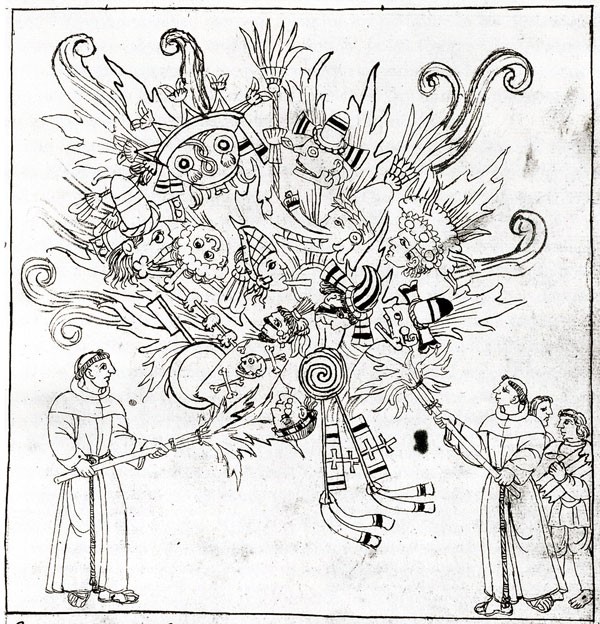

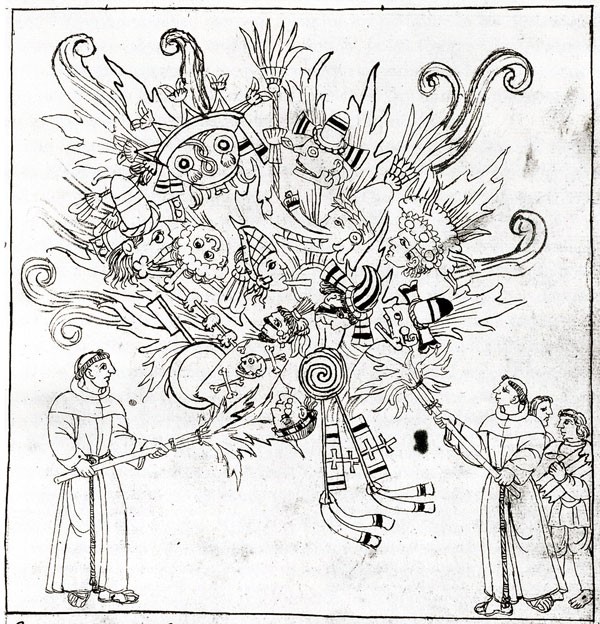

In his 1585 Descripción de Tlaxcala, Diego Muñoz Camargo illustrated the book burning of pre-Columbian codices by Franciscan friars.[1] Fig. 1: Destruction of Mexican Codices. Diego Muñoz Camargo, “Descripción de la ciudad y provincia de Tlaxcala” (c. 1585). Sp Coll MS Hunter 242 (U.3.15) folio 242r (Glasgow University). Source: Andreas Beer/Gesa Mackenthun, eds. Fugitive Knowledge 14.(coloniality of knowledge) |

1585年に出版された『トラスカラ州誌』の中で、ディエゴ・ムニョス・カマルゴは、フランシスコ会の修道士によるコロンブス以前の写本の焼却について述べている[1]。 図1:メキシコの写本の破壊。ディエゴ・ムニョス・カマルゴ 「Descripción de la ciudad y provincia de Tlaxcala」(1585年頃)。Sp Coll MS Hunter 242 (U.3.15) folio 242r(グラスゴー大学)。出典:Andreas Beer/Gesa Mackenthun, eds. Fugitive Knowledge 14.(coloniality of knowledge) |

| Origin and development Fregoso Bailón and De Lissovoy argue that Hatuey, a Taíno warrior from La Española (which contains Haiti and the Dominican Republic), was among the first to recognize "Western knowledge as a colonial discourse".[2] Inspired by Hatuey, Antonio de Montesinos began his career as an educator in 1511, teaching Bartolomé de las Casas critical thinking.[2] In the contemporary era, Frantz Fanon is considered an influential figure for his critique of the intellectual aspects of colonialism. According to Fanon, "colonialism is a psychic and epistemological process as much as a material one." Quijano built on this insight, advancing the critique of colonialism's intellectual dimensions.[2] The concept of coloniality of knowledge comes from coloniality theories,[note 1] encompassing coloniality of power, coloniality of being, and coloniality of knowledge.[note 2] Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano introduced the concept of coloniality of knowledge in 1992,[note 3] discussing global power systems, knowledge, racial hierarchy, and capitalism in Latin American history from the fourteenth century to the present.[note 4] Decolonial thinkers like Walter Mignolo, Enrique Dussel, and Santiago Castro-Gómez later expanded on the concept.[7] |

起源と発展 フレゴソ・バイロンとデ・リソヴォイは、ハイチとドミニカ共和国を含むラ・エスパニョーラ出身のタイノ族戦士ハトゥエイが、「植民地としての西洋の知識」 を最初に認識した人物の一人であったと主張している[2]。ハトゥエイに感化された 現代では、フランツ・ファノンが植民地主義の知的側面を批判した人物として影響力を持つ人物とされている。ファノンによれば、「植民地主義は物質的なもの だけでなく、精神的かつ認識論的なプロセスでもある」[2]。キハノは、この洞察に基づいて、植民地主義の知的側面に対する批判を進めた[2]。 知識の植民地主義の概念は、植民地主義理論から生まれた[注釈 1]もので、権力の植民地主義、存在の植民地主義、知識の植民地主義を包含している[注釈 2]。ペルーの社会学者アニバル・キハノは、1992年に知識の植民地主義の概念を導入し 1992年に知識の植民地主義の概念を導入し、14世紀から現在までのラテンアメリカ史におけるグローバルな権力システム、知識、人種的ヒエラルキー、資 本主義について論じた[注3][注4]。その後、ウォルター・ミニョロ、エンリケ・ドゥッセル、サンティアゴ・カストロ=ゴメスといった脱植民地主義思想 家たちがこの概念を発展させた[7]。 |

| Background According to Quijano, colonialism has had a particular influence on colonized cultures' modes of knowing, knowledge production, perspectives, visions; and systems of images, symbols, and modes of signification; along with their resources, patterns, and instruments of formalized and objectivised expression. For Quijano, this suppression of knowledge accompanied the annihilation of indigenous populations throughout the continent, as well as indigenous societies and traditions. Quijano said the patterns of suppression, expropriation, and imposition of knowledge created during the colonial period, as refracted through conceptions of race and racial hierarchy, persisted after colonialism was overturned as "an explicit political order".[8] This persists in numerous "colonial situations" in which individuals and groups in historically colonized regions are excluded and exploited. Decolonial scholars refer to this ongoing legacy of colonialism as "coloniality", which describes colonialism's perceived legacy of oppression and exploitation across many inter-related domains, including knowledge. Ndlovu-Gatsheni cites Quijano, referring to "control of economy; control of authority, control of gender and sexuality; and, control of subjectivity and knowledge".[9] |

背景 キハノによると、植民地主義は、植民地化された文化の認識方法、知識の生産、視点、ビジョン、イメージ、シンボル、意味づけのシステム、そして形式化され 客観化された表現の資源、パターン、手段に特別な影響を与えてきた。キハノにとって、この知識の抑圧は、大陸全体にわたる先住民人口の絶滅、先住民の社会 や伝統の消滅を伴っていた。キハノは、植民地時代に形成された知識の抑圧、収奪、押し付けのパターンが、人種や人種的ヒエラルキーの概念を通して屈折し、 植民地主義が「明白な政治的秩序」として覆された後も続いていると述べた[8]。これは、歴史的に植民地化された地域の個人やグループが排除され搾取され る数多くの「植民地状況」で続いている。脱植民地化論の学者たちは、この植民地主義の遺産を「コロニアルシティ」と呼び、知識を含む多くの相互に関連する 領域における植民地主義の遺産として認識されている抑圧と搾取を表現している。ンドロヴ・ガツェニはキハノの言葉を引用し、「経済、権威、ジェンダーとセ クシュアリティ、そして主観と知識のコントロール」を挙げている[9]。 |

| Theoretical perspective For Nelson Maldonado-Torres, coloniality denotes the long-standing power structures that developed as a result of colonialism but continue to have an impact on culture, labor, interpersonal relations, and knowledge production that extends far beyond the formal boundaries of colonial administrations. It lives on in literature, academic achievement standards, cultural trends, common sense, people's self-images, personal goals, and other aspects of modern life.[10] Anibal Quijano described this power structure as "coloniality of power" that is predicated on the idea of "coloniality of knowledge",[11] which is "central to the operation of the coloniality of power".[12] While the term coloniality of power refers to the inter-relationship between "modern forms of exploitation and domination", the term coloniality of knowledge concerns the influence of colonialism on domains of knowledge production.[13] Karen Tucker identifies the "coloniality of knowledge" as "one of multiple, intersecting forms of oppression" within a system of "global coloniality".[14] The coloniality of knowledge "appropriates meaning" in the same manner as coloniality of power "takes authority, appropriates land, and exploits labor".[15] The coloniality of knowledge raises epistemological concerns such as who creates what knowledge and for what purpose, the relevance and irrelevance of knowledge, and how specific knowledges disempower or empower certain peoples and communities.[16] The thesis directly or implicitly questions fundamental epistemological categories and attitudes such as belief and the pursuit of objective truth, the concept of the rational subject, the epistemological distinction between the knowing subject and the known object, the assumption of "the universal validity of scientific knowledge, and the universality of human nature". According to this theory, these categories and attitudes are "Eurocentric constructions" that are intrinsically infused with what may be called the "colonial will to dominate".[17] Decolonial theorists refer to "Eurocentric knowledge system", which they believe had assigned the creation of knowledge to Europeans and prioritized the use of European methods of knowledge production. According to Quijano, the hegemony of Europe over the new paradigm of global power consolidated all forms of control over subjectivity, culture and, in particular, knowledge and the creation of knowledge under its hegemony. This resulted in the denial of knowledge creation to conquered peoples on the one hand, and the repression of traditional forms of knowledge production on the other, based on the hierarchical structure's superiority/inferiority relationship.[18] Quijano characterizes Eurocentric knowledge as a "specific rationality or perspective of knowledge that was made globally hegemonic" through the intertwined operation of colonialism and capitalism. It works by constructing binary hierarchical relationships between "the categories of object" and symbolizes a specific secular, instrumental, and "technocratic rationality" that Quijano contextualizes in reference to the mid-seventeen century West European thought and the demands of nineteenth-century global capitalist expansion.[8] For Quijano, it codifies relations between Western Europe and the rest of the world using categories such as "primitive-civilized", "irrational-rational", and "traditional-modern"; and creates distinctions and hierarchies between them so "non-Europe" is aligned with the past and is thus "inferior, if not always primitive".[8] Similarly, it codifies the relationship between Western Europe and "non-Europe" as one between subject and object, perpetuating the myth that Western Europe is the only source of reliable knowledge.[19] For Quijano, the "Western epistemological paradigm" suggests: only European culture is rational, it can contain "subjects" – the rest are not rational, they cannot be or harbor "subjects". As a consequence, the other cultures are different in the sense that they are unequal, in fact inferior, by nature. They only can be "objects" of knowledge or/and of domination practices. From that perspective, the relation between European culture and the other cultures was established and has been maintained, as a relation between "subject" and "object". It blocked, therefore, every relation of communication, of interchange of knowledge and of modes of producing knowledge between the cultures, since the paradigm implies that between "subject" and "object" there can be but a relation of externality.[20] — Anibal Quijano quoted in Paul Anthony Chambers, Epistemology and Domination, 2020 The subject-object dualism proposed by Quijano and other decolonial thinkers such as Enrique Dussel is based on a particular reading of René Descartes' idea of cogito. The "I" in the iconic expression "I think, therefore I am" is an imperial "I" that, according to Quijano, "made it possible to omit every reference to any other 'subject' outside the European context".[20][21] Before Lyotard, Vattimo and Derrida in Europe, the Argentine Enrique Dussel signalled the consequences of Heidegger's critique of Western metaphysics and drew attention to the intrinsic relation between the modern subject of the Enlightenment and European colonial power. Behind the Cartesian ego cogito, which inaugurates modernity, there is a hidden logocentrism through which the enlightened subject divinizes itself and becomes a kind of demiurge capable of constituting and dominating the world of objects. The modern ego cogito thus becomes the will to power: "I think" is equivalent to "I conquer", the epistemic foundation upon which European domination has been based since the 16th century.[21] — Santiago Castro-Gómez quoted in Paul Anthony Chambers, Epistemology and Domination, 2020 According to the decolonial perspective, coloniality of knowledge thus refers to historically entrenched and racially driven intellectual practices that continuously elevate the forms of knowledge and "knowledge-generating principles" of colonizing civilizations while downgrading those of colonized societies. It stresses the role of knowledge in the "violences" that defined colonial rule, as well as the function of knowledge in sustaining the perceived racial hierarchization and oppression that were created over this time period.[14] |

理論的観点 ネルソン・マルドナド=トーレスにとって、コロニシティとは、植民地主義の結果として形成されたが、植民地行政の公式な境界をはるかに超えて文化、労働、 対人関係、知識生産に影響を与え続けている、長年にわたる権力構造を意味する。それは文学、学術的業績の基準、文化的な傾向、常識、人々の自己イメージ、 個人的な目標、そして現代生活の他の側面にも生き続けている[10]。アニバル・キハノは、この権力構造を「権力の植民地性」と表現し、それは「知識の植 民地性」という概念に基づいている[11]。権力の植民地主義」の運用に不可欠である[12]。権力の植民地主義という用語は、「近代的な搾取と支配の形 態」間の相互関係を指すのに対し、知識の植民地主義という用語は、知識生産の領域における植民地主義の影響に関するものである[13]。カレン・タッカー は、「知識の植民地主義」を、「グローバルな植民地主義」のシステムにおける「複数の重なり合う抑圧形態のひとつ」として特定している 「グローバルな植民地主義」のシステム内における「知識の植民地主義」は、「権力を奪い、土地を占有し、労働力を搾取する」という植民地主義の「意味を盗 用」するものである[15]。 知識の植民地主義は、誰がどのような目的でどのような知識を作り出すのか、知識の関連性と非関連性、特定の知識が特定の民族やコミュニティにどのような力 を与え、どのような力を奪うのかといった認識論上の懸念を引き起こす[16]。特定の民族やコミュニティを無力化したり、力づけたりする方法などである [16]。この論文は、信念や客観的真理の追求、理性的主体の概念、知覚主体と知覚対象との認識論的区別、「科学的知識の普遍的妥当性、および人間性の普 遍性」の前提など、認識論の基本的なカテゴリーや態度を直接または間接的に問うている。この理論によると、これらのカテゴリーや態度は本質的に「植民地支 配の意志」とも呼べるものが組み込まれた「ヨーロッパ中心主義的な構築物」である[17]。脱植民地化理論家は「ヨーロッパ中心主義的な知識体系」につい て言及しており、この体系は知識の創造をヨーロッパ人に割り当て、ヨーロッパの知識生産方法を優先的に使用していたと彼らは考えている。キハノによると、 ヨーロッパがグローバルな権力の新しいパラダイムを支配することで、その支配下にある主観性、文化、特に知識と知識の創造に対するあらゆる形態の統制が強 化された。その結果、被征服民族の知識創造が否定される一方で、ヒエラルキー構造に基づく優越/劣位の関係に基づいて、伝統的な知識生産形態が抑圧される こととなった[18]。 キハノは、植民地主義と資本主義の絡み合った作用を通じて「グローバルな覇権となった知識の特定の合理性または視点」として、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な知識 を特徴付けている。それは「対象カテゴリー」の間に二項対立的な上下関係を構築することで機能し、特定の世俗的、道具的、そして「テクノクラート的合理 性」を象徴している。キハノはこれを、17世紀半ばの西欧思想と19世紀の世界的な資本主義の拡大の要求を参照しながら説明している[8]。キハノにとっ て、それは西欧と 「未開文明-文明」、「非合理-合理」、「伝統-近代」などのカテゴリーを用いて、西欧とそれ以外の地域との関係を体系化し、両者の間に区別と階層を作り 出す。これにより、「非ヨーロッパ」は過去と結びつけられ、「常に未開というわけではないが、劣っている」とされる。[8] 同様に、西欧と「非ヨーロッパ」との関係も、主客の関係として体系化され、西欧だけが信頼できる知識の源であるという神話が永続する。「非ヨーロッパ」を 主体と客体の関係として規定し、西洋だけが信頼できる知識の源であるという神話を永続させている[19]。キハノにとって、「西洋の認識論的パラダイム」 は次のことを示唆している。 ヨーロッパ文化だけが合理的であり、「主体」を含むことができる。それ以外には合理性がなく、「主体」を持つことも抱えることもできない。その結果、他の 文化は本質的に不平等であり、実際劣っているという意味で異なっている。それらは知識または/および支配慣行の「客体」にすぎない。その観点から、ヨー ロッパ文化と他の文化の関係は、「主体」と「客体」の関係として確立され、維持されてきた。このパラダイムは、「主体」と「客体」の間には外部性としての 関係しか成り立たないことを意味するため、文化間のコミュニケーション、知識の交換、知識の生産様式など、あらゆる関係を妨げてきた。 — アニバル・キハノ、ポール・アンソニー・チェンバース『Epistemology and Domination』(2020年)より引用 ポール・アンソニー・チェンバース著『認識論と支配』2020年 キハノやエンリケ・ドゥセルなどの脱植民地主義思想家が提唱する主客二元論は、ルネ・デカルトの「我思う、ゆえに我あり」の解釈に基づいている。「我思 う、ゆえに我あり」という象徴的な表現における「我」は、ヨーロッパの文脈の外にある他の「主体」への言及をすべて省略することを可能にした、帝国主義的 な「我」であるとキハノは述べている[20][21]。 ヨーロッパのリオタール、ヴァティモ、デリダに先立ち、アルゼンチンのエンリケ・ドゥッセルは、ハイデガーによる西洋形而上学批判の帰結を示唆し、啓蒙主 義の近代的主体とヨーロッパの植民地支配者との本質的な関係に注目した。近代の幕開けとなったデカルトの自我「我思う」の背後には、隠されたロゴス中心主 義があり、それによって啓蒙された主体は自らを神格化し、物体の世界を創造し支配する一種のデミウルゴスとなる。こうして近代の自我「我思う」は、権力へ の意志となる。「我思う」は「我征服す」と同義であり、16世紀以来、ヨーロッパの支配の基盤となってきた認識論的基盤である[21]。 — サンティアゴ・カストロ=ゴメス、ポール・アンソニー・チェンバース『認識論と支配』(2020年)より引用 と支配、2020 脱植民地化の視点によれば、知識の植民地主義とは、植民地化文明の知識の形態と「知識生成の原理」を絶えず高め、植民地化社会の知識の形態と「知識生成の 原理」を低下させる、歴史的に定着し人種差別的な知的実践を指す。それは、植民地支配を特徴づけた「暴力」における知識の役割、また、この時代に生まれた 人種的ヒエラルキーと抑圧の認識を維持する知識の機能に重点を置いている[14]。 |

| Aspects Sarah Lucia Hoagland identified four aspects of the coloniality of "Anglo-European knowledge practice":[22] 1 The coloniality of knowledge entails Anglo-Eurocentric practices, in which "the only discourse for articulating Third World women's lives is a norming and normative Anglo-European one".[23] For Hoagland, Western researchers evaluate their non-Western subjects through the lens of the Western conception of "woman". In so doing, Western feminists interpret their subjects through Western categories and ideals by interpolating them into Western semiotics and practices. Many Western feminist researchers, she said, perceive their subjects through cultural constructs that only see them as deficient to Western notions of womanhood and hence in desperate "need of enlightened rescue".[23] 2. The research subject is analyzed solely through the perspective of rationality as defined by modern epistemology. Hoagland cites Anibal Quijano, who argues the coloniality of knowledge practices began with the Spanish colonization of the Americas in the fifteenth century, making it "unthinkable to accept the idea that a knowing subject was possible beyond the subject of knowledge postulated by the very concept of rationality" enshrined in modern epistemology.[24] 3. Research methodologies assume "knowing (authorized) subjects" are the sole agents in research activities, and it is their "prerogative" to interpret and package information inside authorizing institutions.[25] Consequently, "Western scientific practice"[25] establishes the researcher "as a judge of credibility and a gatekeeper for its authority", which she identifies as "a discursive enactment of colonial relations".[25] Such an approach is based on the assumption Western academics are disciplined to perceive "interpretation and packaging of information" as the domain of "the knowing subject", the researcher, rather than the "subject of knowing, the one being researched".[26] Because only the researcher is thought to have the rightful agency to do so.[26] According to Hoagland, the knowing subject must be examined with the same degree of care as the subjects of knowledge that the knowing subjects scrutinize.[27] A conversation of "us" with "us" about "them" is a conversation in which "them" is silenced. "Them" always stands on the other side of the hill, naked and speechless, barely presence in its absence.[25] — Trinh T. Minh-ha, Woman, Native, Other quoted in Sarah Lucia Hoagland, Aspects of the Coloniality of Knowledge, 2020 4. The coloniality of knowledge "presumes commensurability with Western discourse", and is the practice of "translating and rewriting other cultures, other knowledges, and other ways of being" into Western system of thought.[28] Hoagland said reframing indigenous claims to make them understandable inside Western institutions amounts to rewriting to the point of eliminating indigenous culture. Because such a subject of knowing of research is not "approached as a knowing subject on her own terms" as "she falls short as a knowing subject on Western terms", she is not "rational" and does not function with and embrace individuality.[29] |

側面 サラ・ルシア・ホーグランドは、「アングロ・ヨーロッパの知識実践」の植民地主義的側面を4つ挙げている[22]。 1.知識の植民地主義は、アングロ・ヨーロッパ中心主義的実践を伴い、「第三世界の女性の生活を表現する唯一の言説は、規範化され規範的なアングロ・ヨー ロッパのものである」[23]。ホーグランドによれば、西洋の研究者は西洋の「女性」概念というレンズを通して、西洋以外の対象を評価する。そうすること で、西洋のフェミニストたちは西洋の記号論や慣習に当てはめることで、西洋のカテゴリーや理想を通して対象を解釈する。多くの西洋のフェミニスト研究者 は、西洋のフェミニスト研究者は対象を西洋の女性の概念に欠けているものとしてのみとらえ、そのため「啓発された救済」を必死に求めているという文化的構 築物を通して対象を認識していると、彼女は述べた[23]。 2.研究対象は、近代認識論によって定義された合理性の観点のみを通して分析される。ホグランドは、知識の実践における植民地主義は15世紀のスペインに よるアメリカ大陸の植民地化に端を発し、近代認識論に根ざす「合理性の概念によって規定された知識の対象の外側に、知識を持つ主体が存在しうるという考え を受け入れることは考えられない」[24]と主張するアニバル・キハノを引き合いに出している。 3. 研究方法論では、「(公認の)知の主体」のみが研究活動の主体であり、公認された機関の内部で情報を解釈し、まとめるのは彼らの「特権」であると想定され ている[25]。その結果、「西洋の科学的実践」[25]は、研究者を「信頼性の判断者、権威の門番」として確立し、彼女はそれを 「植民地関係についての議論的な実践」であると彼女は指摘している[25]。このようなアプローチは、西洋の学者は「解釈と情報のパッケージ化」を「知る 主体」、すなわち研究者ではなく「知ることの主体」、すなわち研究対象者の領域として認識するように訓練されているという前提に基づいている[26]。そ うする正当な権限を持つのは研究者だけだと考えられているためである[26]。ホーグランドによると、知的な主体は、知的な主体が精査する知識の主体と同 じ程度の注意を払って検証されなければならない[27]。 「私たち」が「彼ら」について「私たち」と交わす会話は、「彼ら」が沈黙させられる会話である。「彼ら」は常に丘の向こう側に立ち、裸で無言のまま、その不在の中でかろうじて存在している[25]。 — Trinh T. Minh-ha, Woman, Native, Other, Sarah Lucia Hoagland, Aspects of the Coloniality of Knowledge, 2020 4. 知識の植民地主義は「西洋の言説との等価性を前提」しており、西洋の思考体系に「他文化、他知識、他在り方を翻訳し書き換える」実践である[28]。ホグ ランドは、先住民の主張を西洋の制度内で理解できるように言い換えることは、先住民の文化を排除するほどの書き換えに等しいと述べた。このような研究対象 は、「西洋の観点では知的な主体として不十分」であるため、「西洋の観点で知的な主体として」ではなく、「彼女自身の観点で知的な主体として」アプローチ されていない。そのため、彼女は「合理的」ではなく、個性を発揮したり受け入れたりすることができない[29]。 |

| According to Nick Shepherd, the

coloniality of knowledge has three dimensions; structural and

logistical, epistemological, and ethical and moral.[30] For Shepherd,

data or information flowed in one direction and were essentially

extractive in nature. Information, observations, and artifacts were

transported from the global south and east to Europe and North America,

where they were processed and published. Scholars in metropolitan

institutions were eventually given precedence in the discipline's rank

and hierarchy, while those in the global south were considered as

"local enablers or collaborators on the ground".[30] They were

frequently referred to as "informants", "diggers", or simply

"boys".[30] Although this has been defined as a historical situation,

Shepherd said this practice continues, and forms the structural and

logistical aspects of the coloniality of knowledge.[30] In its epistemological dimension, Shepherd said coloniality of knowledge calls into question the commonly held categories and notions that characterize the intellectual process, as well as an understanding of what knowledge is and how it works. It entails comprehending how the conjoined settings of colonialism and modernity manifest themselves in the ways knowledge is conceptualized and formed in various disciplines.[30] In its ethical and moral dimensions, coloniality of knowledge refers to the rights and entitlements that disciplinary practitioners acquire as part of their training, allowing them to interfere in locations and circumstances as a scientific right and as a moral act. Shepherd cites examples from archaeology, in which extractions were carried out in sacred places revered by the locals.[30] Similarly, Aram Ziai et al identified the "problem of coloniality" in three distinct but interconnected levels of knowledge production. |

ニック・シェパードによると、知識の植民地主義には構造的・物流的、認

識論的、倫理的・道徳的という3つの側面がある[30]。シェパードにとって、データや情報は一方向に流れ、本質的に搾取的な性質を持っていた。情報、観

察、成果物は、グローバルな南半球や東アジアからヨーロッパや北米に運ばれ、そこで処理・出版された。大都市圏の学者は、最終的に学問の序列と階層におい

て優先権を与えられ、一方、グローバルサウス(地球の南半球)の学者は「現地での協力者または協力者」と見なされた[30]。彼らは「情報提供者」、「掘

り出し屋」、あるいは単に「ボーイ」と呼ばれることが多かった[30]。これは歴史的な状況として定義されているが、

歴史的な状況として定義されているが、シェパードは、この慣習は現在も続いており、知識の植民地主義の構造的・物流的側面を形成していると述べた

[30]。 認識論的次元において、シェパードは、知識の植民地主義は、知的プロセスを特徴づける一般的に受け入れられているカテゴリーや概念、そして知識とは何か、 どのように機能するのかについての理解に疑問を投げかけると述べた。それは、植民地主義と近代性が結びついた状況がいかにして、さまざまな学問分野におけ る知識の概念化や形成に表れているかを理解することを伴う[30]。倫理的・道徳的側面において、知識の植民地主義とは、学問分野の実践者が訓練の一環と して獲得する権利や資格を指し、科学的な権利や道徳的行為として場所や状況に関与することを可能にする。シェパードは、考古学の事例を挙げている。その事 例では、地元住民が崇拝する神聖な場所で採掘が行われた。 同様に、アラム・ジアイらは、知識生産の3つの異なるが相互に関連したレベルにおいて「植民地主義の問題」を特定した。 |

| On the level of knowledge

orders, we see it in epistemology (Whose experience and knowledge

counts as valid, scientific knowledge? How is a theory of universally

valid knowledge linked to the depreciation and destruction of other

knowledge?) as well as in ontology (Which elements constitute our world

and form the basis of our research and which are seen as irrelevant?

Has this been influenced by the legitimation of domination? Do we

perceive our units of analysis as individual and discrete or as always

historically interwoven and entangled?). On the level of research

methodology, we see it in the relations of power existing between

subjects and objects of research (Who is seen as capable of producing

knowledge? Who determines the purpose of research? Who provides the

data for the research and who engages in theory building and career

making on this basis?). On the level of the academia, we see it in the

curricula (Which type of knowledge and which authors are being taught

in the universities?) as well as in the recruitment of scholars (Which

mechanisms of exclusion persist in the education system determining who

will become a producer of knowledge in institutions of higher

education?).[31] — Bendix, D.; Müller, F.; Ziai, A., Beyond the Master's Tools?: Decolonizing Knowledge Orders, Research Methods and Teaching, 2020 |

知識の秩序のレベルでは、認識論(誰の経験と知識が有効な科学的知識と

して認められるのか?普遍的に有効な知識の理論は、他の知識の価値低下や破壊とどのように結びついているのか?)だけでなく、存在論(私たちの世界を構成

し、私たちの研究の基礎となる要素と、無関係と見なされる要素は何か?支配の正当化が影響を与えているのか?分析単位を個別かつ独立したものと捉えるか、

常に歴史的に絡み合い、複雑に絡み合っているものと捉えるか)。研究方法論のレベルでは、研究の主題と対象の間に存在する権力関係にそれが表れている(知

識を生み出す能力があるとみなされるのは誰か? 研究の目的を決定するのは誰か?

研究のためのデータを提供する者は誰か?また、そのデータに基づいて理論構築やキャリア形成を行う者は誰か?)。学問のレベルでは、カリキュラム(大学で

はどのような知識と著者が教えられているのか)や学者の採用(高等教育機関で知識の生産者となる人材を決定する教育システムにどのような排除メカニズムが

根強く残っているのか)に見られる。高等教育機関における知識の生産者となるのは誰か?)[31] — Bendix, D.; Müller, F.; Ziai, A., Beyond the Master's Tools?: Decolonizing Knowledge Orders, Research Methods and Teaching, 2020 |

| Effects According to William Mpofu, the coloniality of knowledge transforms colonial subjects into "victims of the coloniality of being", "a condition of inferiorisation, peripheralization, and dehumanization", which makes "primary reference to the lived experience of colonization and its impact on language".[32][13] The coloniality of knowledge thesis asserts educational institutions reflect "the entanglement of coloniality, power, and the epistemic ego-politics of knowledge",[3] which explains the "bias" that promotes Westernized knowledge production as impartial, objective, and universal while rejecting knowledge production influenced by "sociopolitical location, lived experience, and social relations" as "inferior and pseudo-scientific".[3] Poloma et al said the worldwide domination of the Euro-American university model epitomizes coloniality of knowledge, which is reinforced through the canonization of Western curricula, the primacy of English language in instruction and research, and the fetishism of global rankings and Euro-American certification in third world countries.[3] Silova et al said the coloniality of knowledge production has unwittingly formed academic identities, both socializing "non-Western or not-so-Western" researchers into Western ways of thought and marginalizing them in knowledge creation processes,[33] resulting in "academic mimetism" or "intellectual mimicry".[34] The coloniality of knowledge has led to the formation of a knowledge barrier that prevents students and academics from generating new knowledge by adopting non-Western concepts. It also has a significant impact on the mainstream curriculum, which is founded on the same Western notions and paradigms, making it difficult for students to advance beyond the Western epistemological framework.[35] |

影響 ウィリアム・ムポフによると、知識の植民地主義は植民地化された人々を「植民地主義的であることの犠牲者」に変え、「劣等化、周辺化、非人間化の状態」を 作り出し、それは「植民地化の実体験とその言語への影響」を第一義的に意味するという。[32][13] 知識の植民地主義の理論は、教育機関が「植民地主義、権力、知識の認識論的エゴポリティックスの絡み合い」を反映していると主張している。 「知識の植民地性、権力、そして知識の認識論的エゴポリティクスが絡み合っている」[3]と主張し、西洋化された知識の生産を公平で客観的、普遍的なもの として推進する「偏り」を説明している。一方、「社会政治的な位置、生活体験、社会関係」に影響を受けた知識の生産を「劣った、疑似科学的な」ものとして 否定している[3]。Polomaらは、世界中で 欧米の大学モデルの世界的な支配は、知識の植民地主義を象徴しており、欧米のカリキュラムの標準化、教育と研究における英語優先主義、第三世界諸国におけ る世界ランキングや欧米の資格の偶像化を通じて強化されている[3]。 Silova らは、知識生産の植民地主義は、知らず知らずのうちに学術的アイデンティティを形成しており、 「非西洋的」または「あまり西洋的ではない」研究者を西洋的な思考様式に同化し、知識創造のプロセスから排除することで、結果的に「学術的模倣」や「知的 模倣」を引き起こしている[34]。知識の植民地主義は、学生や学者が西洋以外の概念を採用して新しい知識を生み出すことを妨げる知識の壁の形成につな がっている。また、同じ西洋の概念やパラダイムに基づいて構築された主流のカリキュラムにも大きな影響を与え、学生たちが西洋の認識論的枠組みを越えて前 進することを困難にしている[35]。 |

| Criticism In a 2020 article, Paul Anthony Chambers said the theory of the coloniality of knowledge, which proposes a link between the legacy of colonialism and the production, validation, and transfer of knowledge, is "problematic" in some respects, particularly in its critique of Cartesian epistemology.[36] An example of the latter is a 2012 chapter by Sarah Lucia Hoagland that cites Quijano and says that Cartesian methodology practices "the cognitive dismissal of all that lies outside of its bounds of sense ... resulting in a highly sophisticated Eurocentrism".[37] For Hoagland, this tradition maintains "power relations by denying epistemic credibility to objects/subjects of knowledge who are marginalized, written subaltern, erased, criminalized ... and thereby denying relationality".[37] (Chambers and Hoagland both cite Quijano but do not cite each other.) While Chambers agreed with much of what the theory of the coloniality of knowledge asserts, he critiqued it for "fail[ing] to adequately demonstrate" how Cartesian/Western epistemology is tied to inequitable patterns of global knowledge production as well as larger forms of dominance and exploitation.[38] Chambers recognized "the problematic political and sociological dimensions of knowledge production", which he said the decolonial thinkers also emphasized, but he objected to some of the underlying arguments of the thesis, which blamed Cartesian epistemology for "unjust structures of global knowledge production"; he argued that this thesis fails to explain how Cartesian epistemology has had the impact claimed by the decolonial thinkers.[39] Chambers said: Quijano's claims are based on a questionable connection between the Cartesian epistemological categories of subject and object and the ideological and racist belief that Europeans were naturally superior to Indians and other colonized peoples who were deemed – although not by all Europeans, e.g. Las Casas – to be inferior because incapable of rational thought and hence more akin to children and therefore effectively non-autonomous "objects".[40] He also said: "While such a view is infamously to be found in Kant, there is no evidence of it in Descartes".[40] |

批判 2020年の記事で、ポール・アンソニー・チェンバースは、植民地主義の遺産と知識の生産、検証、伝達との関連性を提唱する「知識の植民地主義」理論は、 特にデカルトの認識論に対する批判において、いくつかの点で「問題がある」と述べた[36]。後者の例として、サラ・ルシア・ホーグランドによる2012 年の章がある この章では、キハノの言葉を引用し、デカルトの方法論は「感覚の境界の外にあるものすべてを認知的に排除し、高度に洗練されたヨーロッパ中心主義をもたら す」と主張している[37]。ホグランドにとって、この伝統は「疎外され、書き残された従属者、抹消され、犯罪視された知識の対象/主体に対する認識論的 信頼性を否定することで、力関係を維持し、それにより関係性を否定する」[ 37](チェンバースとホーグランドはともにキハノを引用しているが、互いに引用はしていない)。 チェンバースは、知識の植民地主義理論の主張の多くに同意しているが、デカルト的/西洋的認識論が、不平等なグローバルな知識生産のパターンや、より大き な支配と搾取の形態と結びついていることを「適切に証明できていない」として批判している[38]。チェンバースは 知識生産の政治学的・社会学的側面における問題」を認識しており、脱植民地主義思想家たちも強調していると述べたが、この論文の根底にある議論のいくつか に異議を唱えた。この議論では、デカルトの認識論が「グローバルな知識生産における不公正な構造」の原因であると非難されていたが、彼は、この論文ではデ カルトの認識論が脱植民地主義思想家たちが主張するような影響を与えた理由を説明できていないと主張した[39]。 チャンバースは次のように述べている。 キハノの主張は、デカルトの認識論における主体と客体のカテゴリーと、ヨーロッパ人がインド人やその他の植民地化された人々よりも当然に優れているとい う、ヨーロッパ人全員の意見ではないにせよ、ラス・カサスなどが考えるような、合理的な思考ができないため劣っており、したがって子供に近い存在であり、 したがって事実上自律的ではない「客体」であるという、イデオロギー的かつ人種差別的な信念との疑わしい関連に基づいている。 また、彼は次のようにも述べている。「カントにはそのような見解が散見されるが、デカルトにはそのような証拠はない」[40]。 |