アフリカ争奪戦

Scramble for Africa

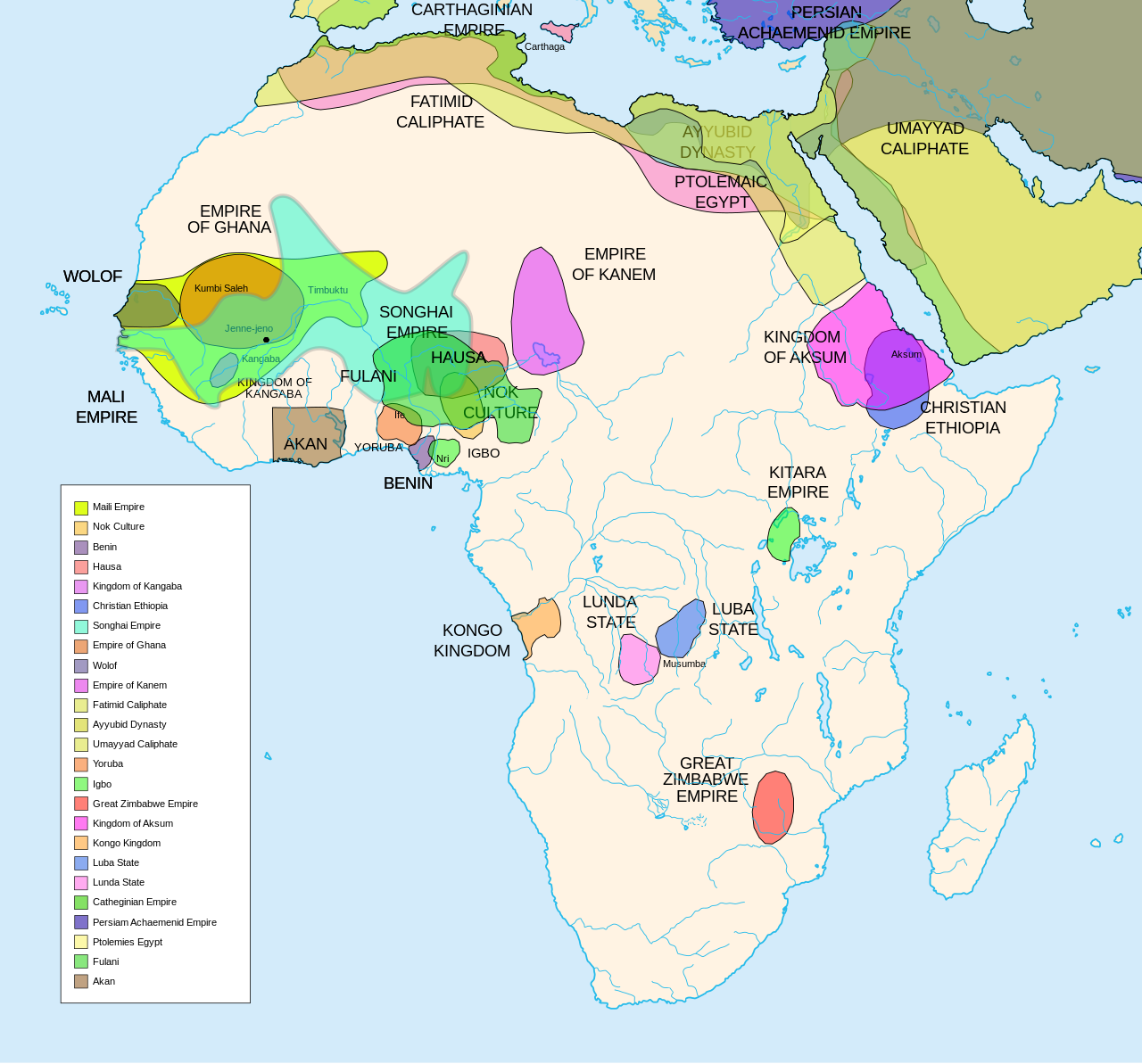

Left: Major pre-colonial states in Africa (excluding East African states such as Ajuran, Adal, Buganda, Rwanda, Kilwa, and Imerina, and southern African ones

Right: Areas of Africa controlled by Western European colonial powers in 1913: Belgian (orange), British (pink), French (purple), German (blue), Italian (lime green), Portuguese (dark green), and Spanish (yellow) empires

Areas

of Africa controlled by Western European colonial empires in 1913,

shown with current national boundaries

☆ アフリカ争奪戦、すなわちスクランブル・フォア・アフリカ(Scramble for Africa) とは、「新帝国主義」の時代(1833-1914年)に、第二次産業革命に後押しされた西欧の7つの大国がアフリカの大部分を征服し、植民地化したことで ある: ベルギー、フランス、ドイツ、イギリス、イタリア、ポルトガル、スペインである。 ベルギー、フランス、ドイツ、イギリス、イタリア、ポルトガル、スペインである。1870年には、大陸の10%が正式にヨーロッパの支配下にあった。 1914年までに、この数字はほぼ90%に上昇し、リベリアとエチオピアだけが主権を保持し、エグバ、[b]セヌシヤ、[2]ムブンダ、[3]オヴァンボ 王国[4][5]が後に征服された。 1884年のベルリン会議は、ヨーロッパのアフリカにおける植民地化と貿易を規制するものであり、「スクランブル」の象徴とみなされている[6]。19世 紀の最後の四半世紀には、ヨーロッパ帝国間の政治的な対立がかなりあり、それが植民地化の原動力となった[7]。 19世紀後半には、軍事的影響力と経済的支配力という「非公式な帝国主義」から直接的な支配への移行が見られた[8]。 二度の世界大戦を経てヨーロッパの植民地帝国が衰退する中、アフリカの植民地の多くは冷戦期に独立を果たし、1964年のアフリカ統一機構会議では、内戦 や地域の不安定化を懸念し、汎アフリカ主義を重視して植民地の国境を維持することを決定した[9]。

| The Scramble for

Africa[a] was the conquest and colonisation of most of Africa by seven

Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution

during the era of "New Imperialism" (1833–1914): Belgium, France,

Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, Portugal and Spain. In 1870, 10% of the continent was formally under European control. By 1914, this figure had risen to almost 90%, with only Liberia and Ethiopia retaining sovereignty, along with Egba,[b] Senusiyya,[2] Mbunda,[3] and the Ovambo kingdoms,[4][5] which were later conquered. The 1884 Berlin Conference regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa, and is seen as emblematic of the "scramble".[6] In the last quarter of the 19th century, there were considerable political rivalries between the European empires, which provided the impetus for the colonisation.[7] The later years of the 19th century saw a transition from "informal imperialism" – military influence and economic dominance – to direct rule.[8] With the decline of the European colonial empires in the wake of the two world wars, most African colonies gained independence during the Cold War, and decided to keep their colonial borders in the Organisation of African Unity conference of 1964 due to fears of civil wars and regional instability, placing emphasis on pan-Africanism.[9] |

アフリカ争奪戦、すなわちスクランブル・フォア・アフリカ[a]とは、

「新帝国主義」の時代(1833-1914年)に、第二次産業革命に後押しされた西欧の7つの大国がアフリカの大部分を征服し、植民地化したことである:

ベルギー、フランス、ドイツ、イギリス、イタリア、ポルトガル、スペインである。 ベルギー、フランス、ドイツ、イギリス、イタリア、ポルトガル、スペインである。1870年には、大陸の10%が正式にヨーロッパの支配下にあった。 1914年までに、この数字はほぼ90%に上昇し、リベリアとエチオピアだけが主権を保持し、エグバ、[b]セヌシヤ、[2]ムブンダ、[3]オヴァンボ 王国[4][5]が後に征服された。 1884年のベルリン会議は、ヨーロッパのアフリカにおける植民地化と貿易を規制するものであり、「スクランブル」の象徴とみなされている[6]。19世 紀の最後の四半世紀には、ヨーロッパ帝国間の政治的な対立がかなりあり、それが植民地化の原動力となった[7]。 19世紀後半には、軍事的影響力と経済的支配力という「非公式な帝国主義」から直接的な支配への移行が見られた[8]。 二度の世界大戦を経てヨーロッパの植民地帝国が衰退する中、アフリカの植民地の多くは冷戦期に独立を果たし、1964年のアフリカ統一機構会議では、内戦 や地域の不安定化を懸念し、汎アフリカ主義を重視して植民地の国境を維持することを決定した[9]。 |

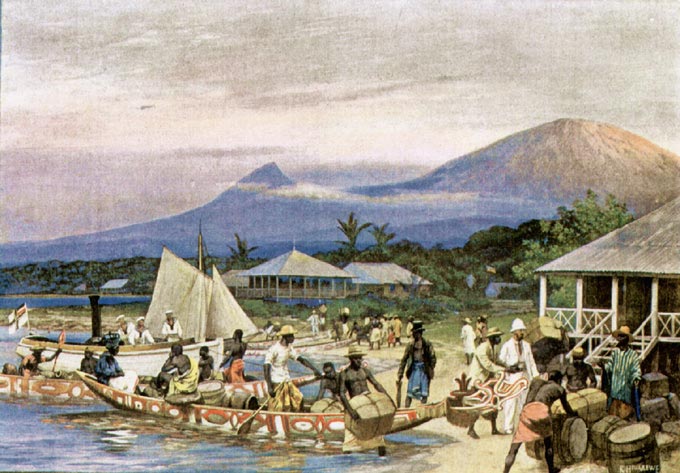

| Background By 1841, businessmen from Europe had established small trading posts along the coasts of Africa, but they seldom moved inland, preferring to stay near the sea. They primarily traded with locals. Large parts of the continent were essentially uninhabitable for Europeans because of their high mortality rates from tropical diseases such as malaria.[10] In the middle of the 19th century, European explorers mapped much of East Africa and Central Africa. As late as the 1870s, Europeans controlled approximately 10% of the African continent, with all their territories located near the coasts. The most important holdings were Angola and Mozambique, held by Portugal; the Cape Colony, held by the United Kingdom; and Algeria, held by France. By 1914, only Ethiopia and Liberia remained outside European control, with the former eventually being occupied by Italy in 1936 while the latter having strong connections with its historical colonizer, the United States.[11] Technological advances facilitated European expansion overseas. Industrialization brought about rapid advancements in transportation and communication, especially in the forms of steamships, railways and telegraphs. Medical advances also played an important role, especially medicines for tropical diseases, which helped control their adverse effects. The development of quinine, an effective treatment for malaria, made vast expanses of the tropics more accessible for Europeans.[12] |

背景 1841年までに、ヨーロッパからの実業家たちはアフリカの海岸沿いに小さな交易基地を設けたが、内陸に移動することはほとんどなく、海の近くに留まるこ とを好んだ。彼らは主に現地の人々と交易していた。アフリカ大陸の大部分は、マラリアなどの 熱帯病による死亡率が高かったため、ヨーロッパ人にとっては基本的に居住不可能な場所であった[10]。19世紀半ば、ヨーロッパの探検家たちは東アフリ カと 中央アフリカの大部分を地図に描いた。 1870年代の時点で、ヨーロッパ人はアフリカ大陸の約10%を支配しており、その領土はすべて海岸近くに位置していた。最も重要な領土は、ポルトガルの アンゴラと モザンビーク、イギリスの ケープ植民地、フランスの アルジェリアであった。1914年までには、エチオピアと リベリアだけがヨーロッパの支配の外に残っており、前者は最終的に1936年にイタリアに占領され、後者は歴史的な植民地支配者であるアメリカと強い結び つきがあった。 技術の進歩は、ヨーロッパの海外進出を促進した。工業化は、特に蒸気船、鉄道、電信といった形で、輸送と通信に急速な進歩をもたらした。医学の進歩も重要 な役割を果たし、特に熱帯病の治療薬は、その悪影響を抑えるのに役立った。マラリアの効果的な治療薬であるキニーネの開発により、広大な熱帯地域がヨー ロッパ人にとって利用しやすくなった[12]。 |

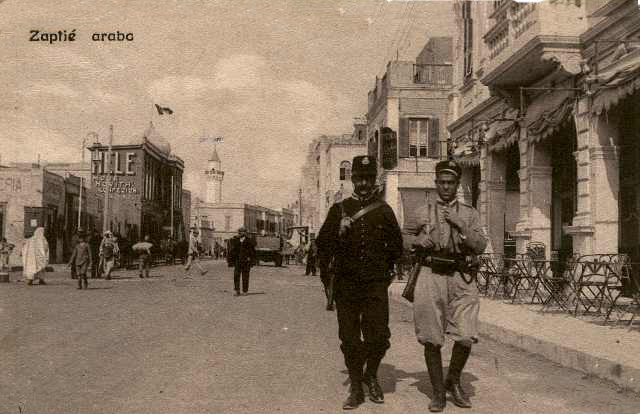

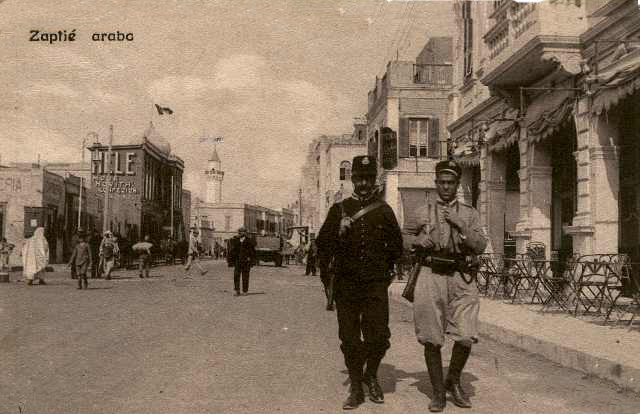

| Causes Africa and global markets Sub-Saharan Africa, one of the last regions of the world largely untouched by "informal imperialism", was attractive to business entrepreneurs. During a time when Britain's balance of trade showed a growing deficit, with shrinking and increasingly protectionist continental markets during the Long Depression (1873–1896), Africa offered Britain, Germany, France, and other countries an open market that would garner them a trade surplus: a market that bought more from the colonial power than it sold overall.[8][13] Surplus capital was often more profitably invested overseas, where cheap materials, limited competition, and abundant raw materials made a greater premium possible. Another inducement for imperialism arose from the demand for raw materials, especially ivory, rubber, palm oil, cocoa, diamonds, tea, and tin. Additionally, Britain wanted control of areas of the southern and eastern coasts of Africa for stopover ports on the route to Asia and its empire in India.[14] But, excluding the area that became the Union of South Africa in 1910, European nations invested relatively limited amounts of capital in Africa. Pro-imperialist colonial lobbyists such as the Alldeutscher Verband, Francesco Crispi and Jules Ferry, argued that sheltered overseas markets in Africa would solve the problems of low prices and overproduction caused by shrinking continental markets. John A. Hobson argued in Imperialism that this shrinking of continental markets was a key factor of the global "New Imperialism" period.[15] William Easterly, however, disagrees with the link made between capitalism and imperialism, arguing that colonialism is used mostly to promote state-led development rather than corporate development. He has said that "imperialism is not so clearly linked to capitalism and the free markets... historically there has been a closer link between colonialism/imperialism and state-led approaches to development."[16] Strategic rivalry  Contemporary French propaganda poster hailing Major Marchand's trek across Africa toward Fashoda in 1898 While tropical Africa was not a large zone of investment, other overseas regions were. The vast interior between Egypt and the gold and diamond-rich Southern Africa had strategic value in securing the flow of overseas trade. Britain was under political pressure to build up lucrative markets in India, Malaya, Australia and New Zealand. Thus, it wanted to secure the key waterway between East and West – the Suez Canal, completed in 1869. However, a theory that Britain sought to annex East Africa during 1880 onwards, out of geo-strategic concerns connected to Egypt (especially the Suez Canal),[17][7] has been challenged by historians such as John Darwin (1997) and Jonas F. Gjersø (2015).[18][19] The scramble for African territory also reflected concern for the acquisition of military and naval bases, for strategic purposes and the exercise of power. The growing navies, and new ships driven by steam power, required coaling stations and ports for maintenance. Defence bases were also needed for the protection of sea routes and communication lines, particularly of expensive and vital international waterways such as the Suez Canal.[20] Colonies were seen as assets in balance of power negotiations, useful as items of exchange at times of international bargaining. Colonies with large native populations were also a source of military power; Britain and France used large numbers of British Indian and North African soldiers, respectively, in many of their colonial wars (and would do so again in the coming World Wars). In the age of nationalism there was pressure for a nation to acquire an empire as a status symbol; the idea of "greatness" became linked with the "White Man's Burden", or sense of duty, underlying many nations' strategies.[20] In the early 1880s, Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza was exploring the region along the Congo River for France, at the same time Henry Morton Stanley explored it on behalf of the Committee for Studies of the Upper Congo, backed by Leopold II of Belgium, who would have it as his personal Congo Free State.[21] Leopold had earlier hoped to recruit Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, but turned to Henry Morton Stanley when the latter was recruited by the French government. France occupied Tunisia in May 1881, which may have convinced Italy to join the German-Austrian Dual Alliance in 1882, thus forming the Triple Alliance.[22] The same year, Britain occupied Egypt (hitherto an autonomous state owing nominal fealty to the Ottoman Empire), which ruled over Sudan and parts of Chad, Eritrea, and Somalia. In 1884, Germany declared Togoland, the Cameroons and South West Africa to be under its protection;[23] and France occupied Guinea. French West Africa was founded in 1895 and French Equatorial Africa in 1910.[24][25] In French Somaliland, a short-lived Russian colony in the Egyptian fort of Sagallo was briefly proclaimed by Terek Cossacks in 1889.[26]  David Livingstone, early explorer of the interior of Africa and fighter against the slave trade Germany's Weltpolitik  The Askari colonial troops in German East Africa, c. 1906 Germany, divided into small states, was not initially a colonial power. In 1862, Otto von Bismarck became Minister-President of the Kingdom of Prussia, and through a series of wars with both Austria in 1866 and France in 1870 was able to unify all of Germany under Prussian rule. The German Empire was formally proclaimed on 18 January 1871. At first, Bismarck disliked colonies but gave in to popular and elite pressure in the 1880s. He sponsored the 1884–85 Berlin Conference, which set the rules of effective control of African territories and reduced the risk of conflict between colonial powers.[27] Bismarck used private companies to set up small colonial operations in Africa and the Pacific. Pan-Germanism became linked to the young nation's new imperialist drives.[28] In the beginning of the 1880s, the Deutscher Kolonialverein was created, and published the Kolonialzeitung. This colonial lobby was also relayed by the nationalist Alldeutscher Verband. Weltpolitik (world policy) was the foreign policy adopted by Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1890, intending to transform Germany into a global power through aggressive diplomacy, and the development of a large navy.[29] Germany became the third-largest colonial power in Africa, the location of most of its 2.6 million square kilometres of colonial territory and 14 million colonial subjects in 1914. The African possessions were Southwest Africa, Togoland, the Cameroons, and Tanganyika. Germany tried to isolate France in 1905 with the First Moroccan Crisis. This led to the 1905 Algeciras Conference, in which France's influence on Morocco was compensated by the exchange of other territories, and then to the Agadir Crisis in 1911. Italy's expansion  An Italian Carabiniere and a Libyan colonial Zaptié patrolling in Tripoli, Italian Tripolitania, 1914 After fighting alongside France during the Crimean War (1853–1856), the Kingdom of Sardinia sought to unify the Italian peninsula, with French support. Following a war with Austria in 1859, Sardinia, under the leadership of Giuseppe Garibaldi, was able to unify most of the peninsula by 1861, establishing the Kingdom of Italy. Following unification, Italy sought to expand its territory and become a great power, taking possession of parts of Eritrea in 1870[30][31] and 1882. In 1889–90, it occupied territory on the south side of the Horn of Africa, forming what would become Italian Somaliland.[32] In the disorder that followed the 1889 death of Emperor Yohannes IV, General Oreste Baratieri occupied the Ethiopian Highlands along the Eritrean coast, and Italy proclaimed the establishment of a new colony of Eritrea, with its capital moved from Massawa to Asmara. When relations between Italy and Ethiopia deteriorated, the First Italo-Ethiopian War broke out in 1895; Italian troops were defeated as the Ethiopians had numerical superiority, better organization, and support from Russia and France.[33] In 1911, Italy engaged in a war with the Ottoman Empire, in which it acquired Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, that together formed what became known as Italian Libya. In 1919 Enrico Corradini developed the concept of Proletarian Nationalism, which was supposed to legitimise Italy's imperialism by a mixture of socialism with nationalism: We must start by recognizing the fact that there are proletarian nations as well as proletarian classes; that is to say, there are nations whose living conditions are subject...to the way of life of other nations, just as classes are. Once this is realised, nationalism must insist firmly on this truth: Italy is, materially and morally, a proletarian nation.[34] The Second Italo-Abyssinian War (1935–1936), ordered by the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, was the last colonial war (that is, intended to colonise a country, as opposed to wars of national liberation),[35] occupying Ethiopia—which had remained the last independent African territory, apart from Liberia. Italian Ethiopia was occupied by fascist Italian forces in World War II as part of Italian East Africa though much of the mountainous countryside had remained out of Italian control due to resistance from the Arbegnoch.[36] The occupation is an example of the expansionist policy that characterized the Axis powers as opposed to the Scramble for Africa. |

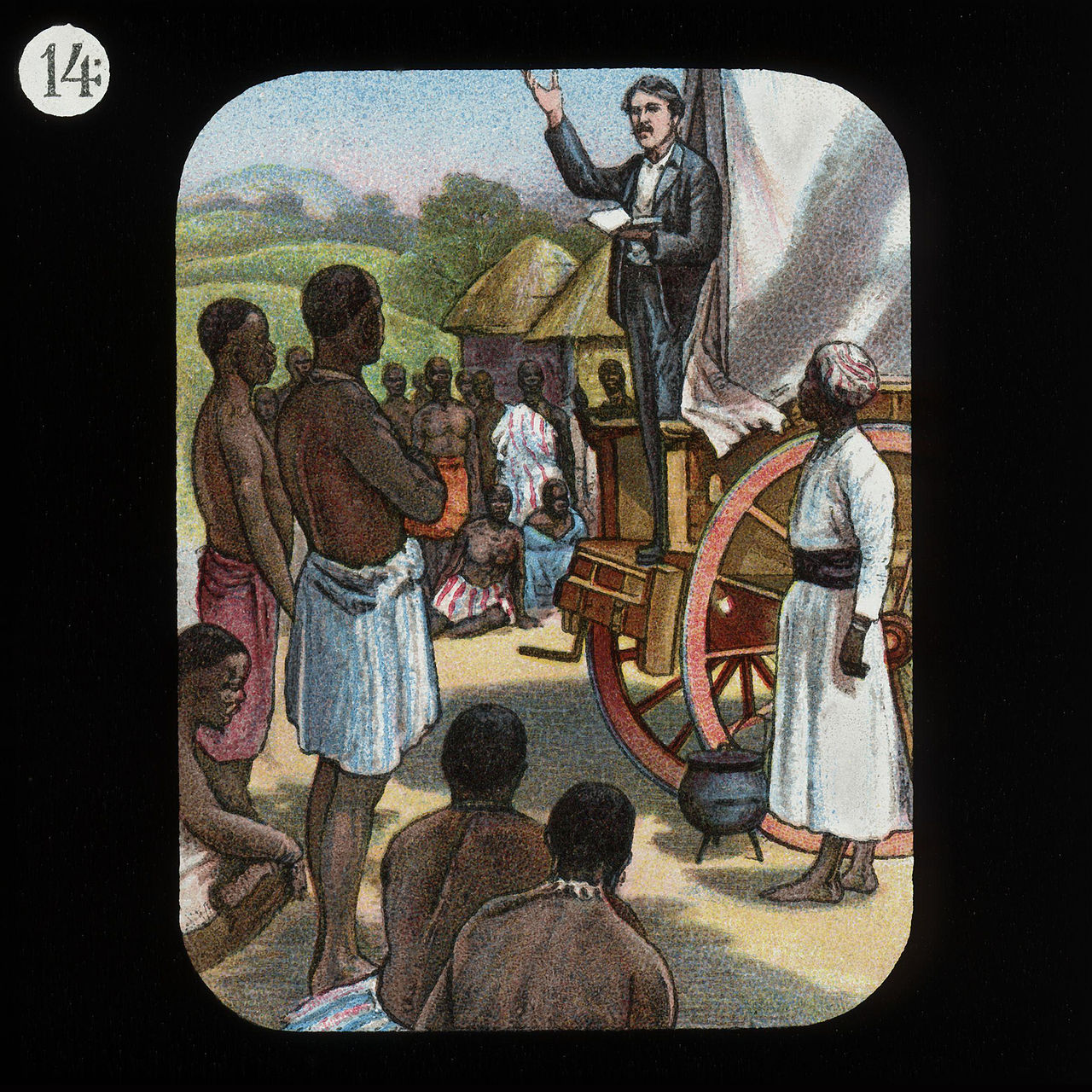

原因 アフリカとグローバル市場 サハラ以南のアフリカは、「非公式な帝国主義」がほとんど手をつけていない世界最後の地域のひとつであり、企業家にとって魅力的だった。長期恐慌 (1873年~1896年)においてイギリスの貿易収支が赤字を拡大し、大陸市場が縮小し保護主義が強まっていた時期に、アフリカはイギリス、ドイツ、フ ランス、その他の国々に貿易黒字をもたらす開放的な市場を提供した。 余剰資本は、安価な材料、限られた競争相手、豊富な原材料によってより大きなプレミアムを得ることが可能な海外に投資されることが多く、より収益性の高い ものであった。帝国主義のもう一つの誘因は、原材料、特に象牙、ゴム、パーム油、ココア、ダイヤモンド、茶、錫の需要から生じた。さらにイギリスは、アジ アやインド帝国に向かうルートの中継港として、アフリカの南岸と東岸の地域の支配権を欲していた[14]。しかし、1910年に南アフリカ連邦となった地 域を除くと、ヨーロッパ国民がアフリカに投資した資本は比較的限られていた。 アルドイチェ連盟、フランチェスコ・クリスピ、ジュール・フェリーのような帝国主義的な植民地ロビイストは、アフリカの保護された海外市場が、大陸市場の 縮小による低価格と過剰生産の問題を解決すると主張した。ジョン・A・ホブソンは『帝国主義』の中で、この大陸市場の縮小が世界的な「新帝国主義」時代の 重要な要因であると論じている[15]。しかし、ウィリアム・イースタリーは、資本主義と帝国主義の結びつきに異を唱え、植民地主義は企業の発展よりもむ しろ国家主導の開発を促進するために利用されることがほとんどであると主張している。彼は「帝国主義は資本主義や自由市場とそれほど明確に結びついている わけではない......歴史的には植民地主義/帝国主義と国家主導の開発アプローチとの間にはより緊密な結びつきがあった」と述べている[16]。 戦略的ライバル関係  1898年、マルシャン少佐がファショダを目指してアフリカを横断したことを称える現代のフランスのプロパガンダ・ポスター 熱帯アフリカは大きな投資対象ではなかったが、他の海外地域は投資対象だった。エジプトと、金とダイヤモンドが豊富な南部アフリカとの間の広大な内陸部 は、海外貿易の流れを確保する上で戦略的価値があった。イギリスは、インド、マレー、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドに有利な市場を構築する政治的圧力 を受けていた。そのため、東西を結ぶ重要な水路であるスエズ運河(1869年完成)を確保したかったのだ。しかし、イギリスが1880年以降、エジプト (特にスエズ運河)に関連する地政学的な懸念から東アフリカの併合を目指したという説[17][7]は、ジョン・ダーウィン(1997年)やヨナス・F・ ギェルソ(2015年)といった歴史家によって否定されている[18][19]。 アフリカの領土をめぐる争いは、戦略的目的と権力行使のための軍事・海軍基地の獲得に対する懸念も反映していた。増大する海軍と蒸気動力を動力源とする新 造船は、整備のための給油所と港を必要とした。防衛基地はまた、海路や通信線、特にスエズ運河のような高価で重要な国際水路の保護のためにも必要であった [20]。 植民地は勢力均衡交渉における資産とみなされ、国際的な駆け引きの際の交換品として有用であった。イギリスとフランスは、植民地戦争の多くで、それぞれ大 量のイギリス領インド人兵士と北アフリカ人兵士を使用した(そして来るべき世界大戦でもまた使用することになる)。ナショナリズムの時代には、国民がス テータスシンボルとして帝国を獲得することへの圧力があった。「偉大さ」という考え方は、多くの国の戦略の根底にある「白人の重荷」、すなわち義務感と結 びついた[20]。 1880年代初頭、ピエール・サヴォルニャン・ド・ブラッツァはフランスのためにコンゴ川沿いの地域を探検していたが、同じ頃、ヘンリー・モートン・スタ ンレーはベルギーのレオポルド2世の支援を受けたコンゴ上流研究委員会のためにコンゴ川沿いの地域を探検していた。レオポルドはピエール・サヴォルニャ ン・ド・ブラッツァの採用を希望していたが、ヘンリー・モートン・スタンレーがフランス政府に採用されたため、ヘンリー・モートン・スタンレーを採用した [21]。フランスは1881年5月にチュニジアを占領し、このことがイタリアに1882年のドイツ・オーストリア二国同盟への参加を説得し、三国同盟を 成立させたと考えられる[22]。同年、イギリスはエジプト(それまではオスマン帝国に名目上の忠誠を誓っていた自治国家)を占領し、スーダンとチャド、 エリトリア、ソマリアの一部を支配した。1884年、ドイツはトーゴランド、カメルーン、南西アフリカを自国の保護下に置くと宣言し[23]、フランスは ギニアを占領した。フランス領ソマリランドでは、1889年にテレク・コサックによってエジプトのサガロの砦に短期間のロシア植民地が宣言された [26]。  デイヴィッド・リヴィングストン、アフリカ奥地の初期の探検家であり、奴隷貿易に反対する闘士であった。 ドイツのヴェルトポリティーク  ドイツ領東アフリカのアスカリ植民地軍(1906年頃 小さな国家に分割されたドイツは、当初は植民地大国ではなかった。1862年、オットー・フォン・ビスマルクがプロイセン王国の公使兼大統領に就任し、 1866年にはオーストリア、1870年にはフランスとの一連の戦争を経て、ドイツ全土をプロイセンの支配下に統一した。ドイツ帝国は1871年1月18 日に正式に宣言された。当初、ビスマルクは植民地を嫌っていたが、1880年代には民衆とエリートの圧力に屈した。ビスマルクは1884年から85年にか けてのベルリン会議を後援し、アフリカ領土の実効支配のルールを定め、植民地支配国間の紛争のリスクを軽減した[27]。 1880年代の初めには、ドイツ植民地協会が設立され、『コロニアルツァイトゥング』を発行した。この植民地ロビー活動は、民族主義的なアルドイチェ連盟 (Alldeutscher Verband)からも発信された。世界政策(Weltpolitik)とは、1890年に皇帝ヴィルヘルム2世が採用した外交政策であり、積極的な外交 と大規模な海軍の発展を通じてドイツを世界的な大国に変えることを意図していた[29]。アフリカの領有地は、南西アフリカ、トーゴランド、カメルーン、 タンガニーカであった。ドイツは1905年、第一次モロッコ危機でフランスを孤立させようとした。これが1905年のアルヘシラス会議につながり、モロッ コに対するフランスの影響力は他の領土の交換によって補われ、さらに1911年のアガディール危機へと発展した。 イタリアの拡大  トリポリ(イタリア領トリポリタニア)でパトロールするイタリアのカラビニエーレとリビア植民地のザプティエ(1914年 クリミア戦争(1853~1856年)でフランスとともに戦ったサルデーニャ王国は、フランスの支援を得てイタリア半島の統一を目指した。1859年の オーストリアとの戦争の後、ジュゼッペ・ガリバルディの指導の下、サルデーニャは1861年までに半島の大部分を統一し、イタリア王国を樹立した。統一 後、イタリアは領土を拡大し、大国となることを目指し、1870年[30][31]と1882年にエリトリアの一部を占領した。1889年から90年にか けては、アフリカの角の南側の領土を占領し、後のイタリア領ソマリランドを形成した[32]。1889年に皇帝ヨハネス4世が死去した後の混乱期に、オレ ステ・バラティエリ将軍はエリトリア沿岸のエチオピア高地を占領し、イタリアは首都をマサワからアスマラに移した新たなエリトリア植民地の樹立を宣言し た。イタリアとエチオピアの関係が悪化すると、1895年に第一次イタリア・エチオピア戦争が勃発し、エチオピア軍が数的優位と優れた組織、ロシアとフラ ンスからの支援を受けていたため、イタリア軍は敗北した。1919年、エンリコ・コッラディーニは、社会主義と国民主義の混合によってイタリアの帝国主義 を正当化するプロレタリア国民主義の概念を打ち出した: すなわち、階級がそうであるように、生活条件が他国の生活様式に...従う国民が存在する。イタリアは、物質的にも道徳的にもプロレタリア国家である。 ファシストの独裁者ベニート・ムッソリーニによって命じられた第二次イタリア・アビシニア戦争(1935年-1936年)は、最後の植民地戦争(つまり、 民族解放戦争とは対照的に、一国を植民地化することを目的とした戦争)であり、リベリアを除けば最後の独立したアフリカ領土であり続けたエチオピアを占領 した[35]。イタリア領エチオピアは、第二次世界大戦においてイタリア東アフリカの一部としてファシスト・イタリア軍によって占領されたが、山岳地帯の 多くはアルベグノフの抵抗によってイタリアの支配下にはなかった[36]。 |

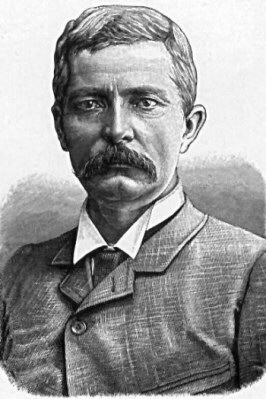

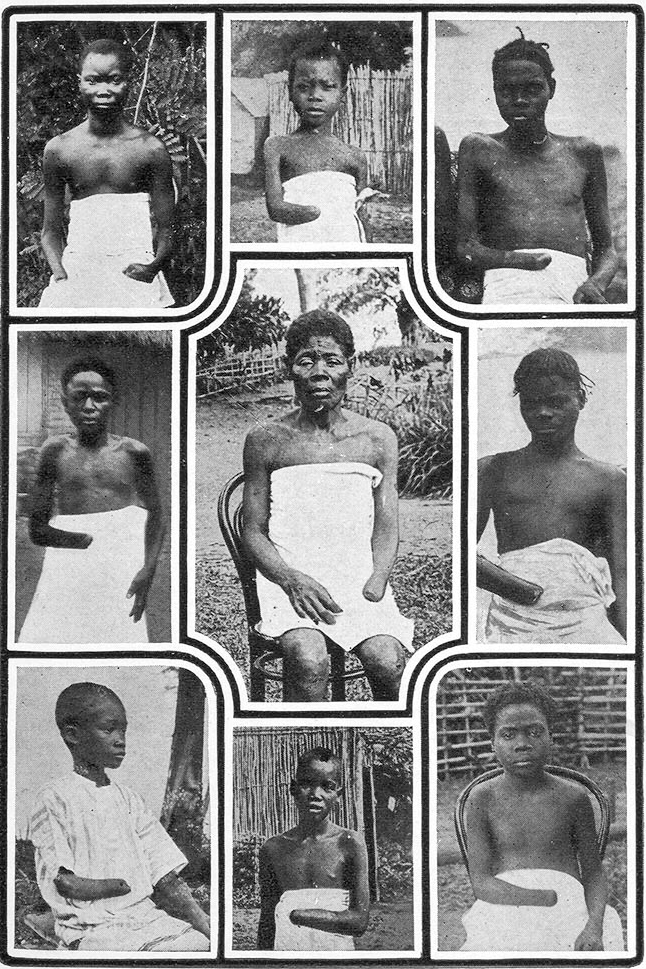

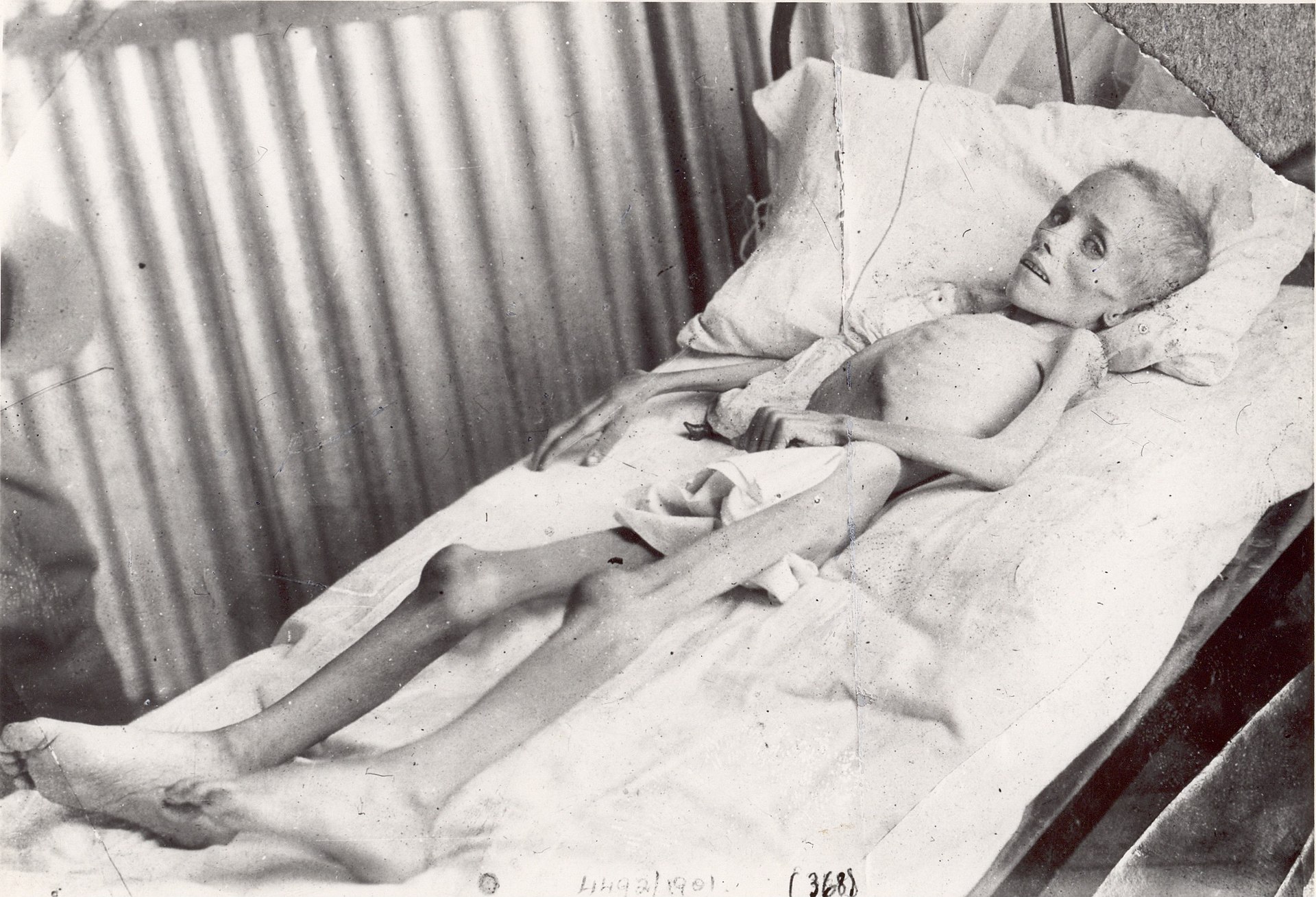

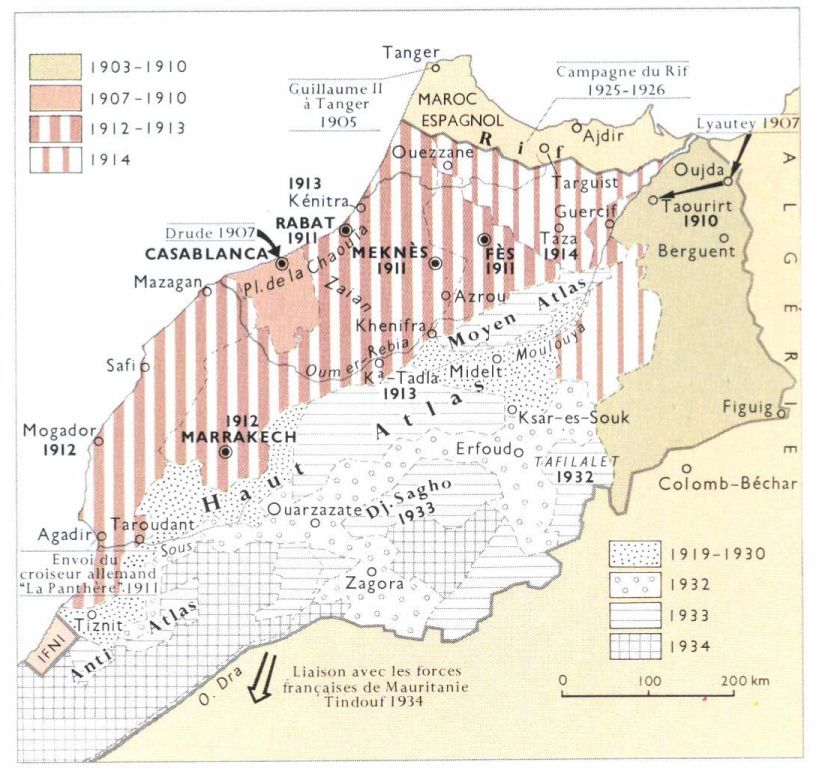

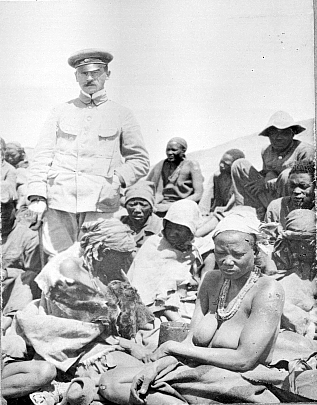

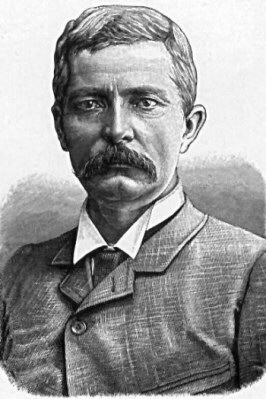

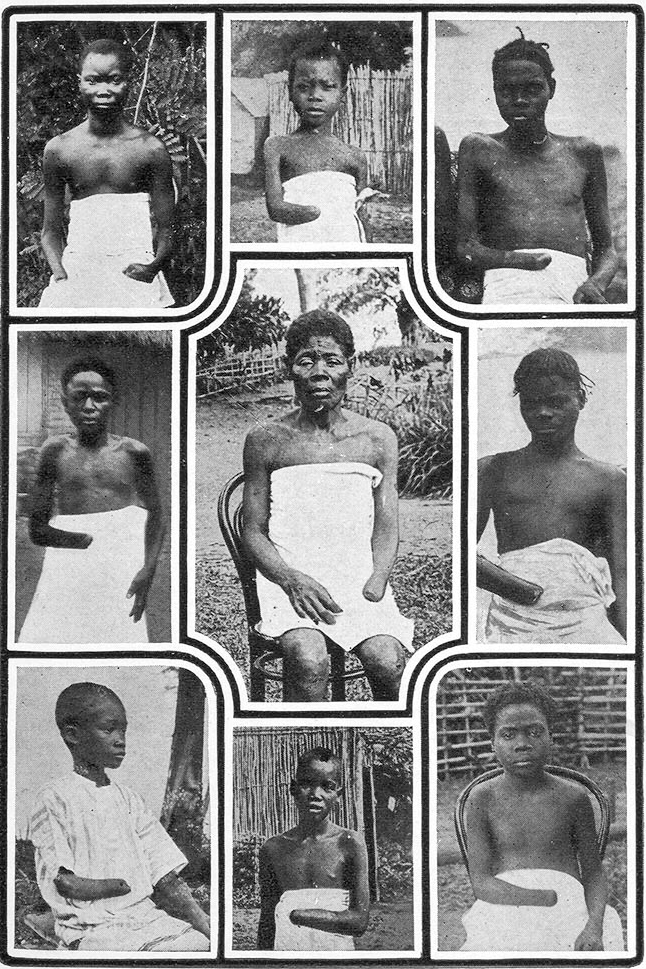

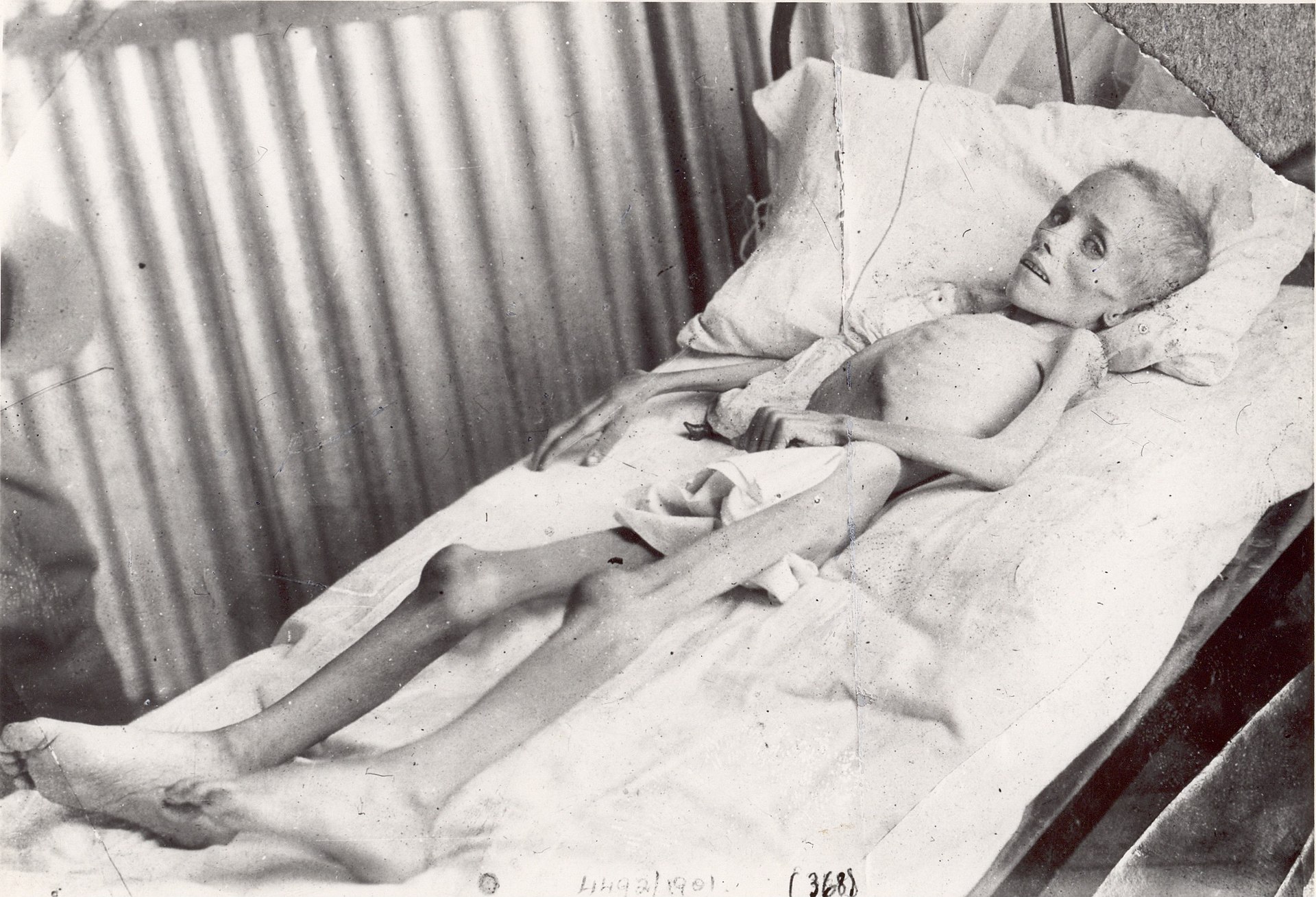

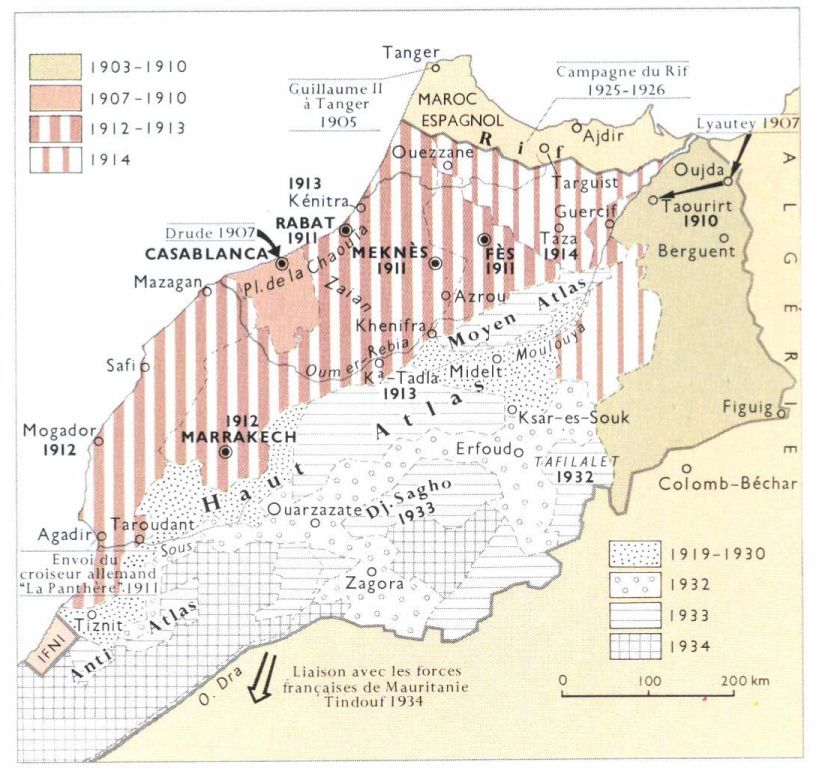

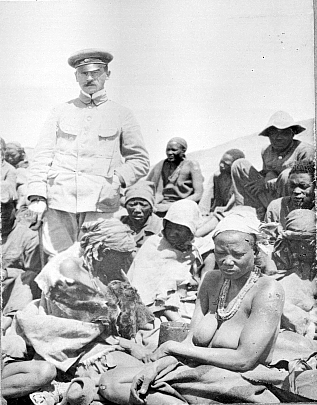

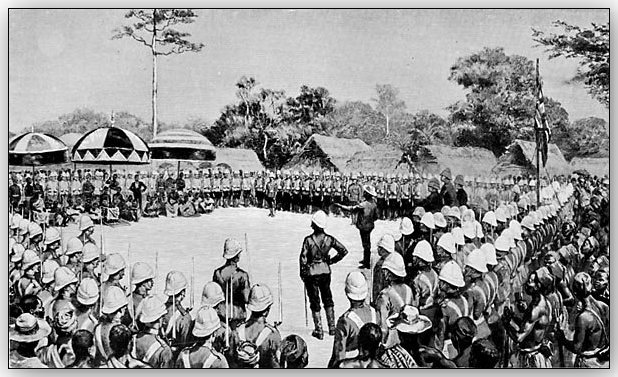

| History and characteristics Colonization before World War I Congo  Henry Morton Stanley David Livingstone's explorations, carried on by Henry Morton Stanley, excited imaginations with Stanley's grandiose ideas for colonisation; but these found little support owing to the problems and scale of action required, except from Leopold II of Belgium, who in 1876 had organised the International African Association. From 1869 to 1874, Stanley was secretly sent by Leopold II to the Congo region, where he made treaties with several African chiefs along the Congo River and by 1882 had sufficient territory to form the basis of the Congo Free State.  Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza in his version of the "native" dress, photographed by Félix Nadar While Stanley was exploring the Congo on behalf of Leopold II of Belgium, the Franco-Italian marine officer Pierre de Brazza travelled into the western Congo Basin and raised the French flag over the newly founded Brazzaville in 1881, thus occupying today's Republic of the Congo.[21] Portugal, which also claimed the area because of old treaties with the Kingdom of Kongo, made a treaty with Britain on 26 February 1884 to block off Leopold's access to the Atlantic. By 1890 the Congo Free State had consolidated control of its territory between Leopoldville and Stanleyville and was looking to push south down the Lualaba River from Stanleyville. At the same time, the British South Africa Company of Cecil Rhodes was expanding north from the Limpopo River, sending the Pioneer Column (guided by Frederick Selous) through Matabeleland, and starting a colony in Mashonaland.[37] Tippu Tip, a Zanzibari Arab based in the Sultanate of Zanzibar, also played a major role as a "protector of European explorers", ivory trader and slave trader. Having established a trading empire within Zanzibar and neighbouring areas in East Africa, Tippu Tip would shift his alignment towards the rising colonial powers in the region and at the proposal of Henry Morton Stanley, Tippu Tip became a governor of the "Stanley Falls District" (Boyoma Falls) in Leopold's Congo Free State, before being involved in the Congo–Arab War against Leopold II's colonial state.[38][39] To the west, in the land where their expansions would meet, was Katanga, the site of the Yeke Kingdom of Msiri. Msiri was the most militarily powerful ruler in the area and traded large quantities of copper, ivory and slaves—and rumours of gold reached European ears.[40] The scramble for Katanga was a prime example of the period. Rhodes sent two expeditions to Msiri in 1890 led by Alfred Sharpe, who was rebuffed, and Joseph Thomson, who failed to reach Katanga. Leopold sent four expeditions. First, the Le Marinel expedition could only extract a vaguely worded letter. The Delcommune expedition was rebuffed. The well-armed Stairs expedition was given orders to take Katanga with or without Msiri's consent. Msiri refused, was shot, and his head was cut off and stuck on a pole as a "barbaric lesson" to the people.[41] The Bia River expedition finished the job of establishing an administration of sorts and a "police presence" in Katanga. Thus, the half million square kilometres of Katanga came into Leopold's possession and brought his African realm up to 2,300,000 square kilometres (890,000 sq mi), about 75 times larger than Belgium. The Congo Free State imposed such a terror regime on the colonized people, including mass killings and forced labour, that Belgium, under pressure from the Congo Reform Association, ended Leopold II's rule and annexed it on 20 August 1908 as a colony of Belgium, known as the Belgian Congo.[42]  From 1885 to 1908, many atrocities were perpetrated in the Congo Free State; in these images, Native Congo Free State labourers who failed to meet rubber collection quotas have been punished by having their hands cut off. The brutality of King Leopold II in his former colony of the Congo Free State[43][44] was well documented; up to 8 million of the estimated 16 million native inhabitants died between 1885 and 1908.[45] According to Roger Casement, an Irish diplomat of the time, this depopulation had four main causes: "indiscriminate war", starvation, reduction of births and diseases.[46] Sleeping sickness ravaged the country and must also be taken into account for the dramatic decrease in population; it has been estimated that sleeping sickness and smallpox killed nearly half the population in the areas surrounding the lower Congo River.[47] Estimates of the death toll vary considerably. As the first census did not take place until 1924, it is difficult to quantify the population loss of the period. The Casement Report set it at three million.[48] William Rubinstein writes: "More basically, it appears almost certain that the population figures given by Hochschild are inaccurate. There is, of course, no way of ascertaining the population of the Congo before the twentieth century, and estimates like 20 million are purely guesses. Most of the interior of the Congo was literally unexplored if not inaccessible."[49] A similar situation occurred in the neighbouring French Congo, where most of the resource extraction was run by concession companies, whose brutal methods, along with the introduction of disease, resulted in the loss of up to 50% of the indigenous population according to Hochschild.[50] The French government appointed a commission headed by de Brazza in 1905 to investigate the rumoured abuses in the colony. However, de Brazza died on the return trip, and his "searingly critical" report was neither acted upon nor released to the public.[51] In the 1920s, about 20,000 forced labourers died building a railroad through the French territory.[52] Egypt, Sudan, and South Sudan Suez Canal  Port Said entrance to Suez Canal, showing De Lesseps' statue To construct the Suez Canal, French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps had obtained many concessions from Isma'il Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan in 1854–56. Some sources estimate the workforce at 30,000,[53] but others estimate that 120,000 workers died over the ten years of construction from malnutrition, fatigue, and disease, especially cholera.[54] Shortly before its completion in 1869, Khedive Isma'il borrowed enormous sums from British and French bankers at high rates of interest. By 1875, he was facing financial difficulties and was forced to sell his block of shares in the Suez Canal. The shares were snapped up by Britain, under Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, who sought to give his country practical control in the management of this strategic waterway. When Isma'il repudiated Egypt's foreign debt in 1879, Britain and France seized joint financial control over the country, forcing the Egyptian ruler to abdicate and installing his eldest son Tewfik Pasha in his place.[55] The Egyptian and Sudanese ruling classes did not relish foreign intervention. Mahdist War During the 1870s, European initiatives against the slave trade caused an economic crisis in northern Sudan, precipitating the rise of Mahdist forces.[56] In 1881, the Mahdist revolt erupted in Sudan under Muhammad Ahmad, severing Tewfik's authority in Sudan. The same year, Tewfik suffered an even more perilous rebellion by his Egyptian army in the form of the Urabi revolt. In 1882, Tewfik appealed for direct British military assistance, commencing Britain's administration of Egypt. A joint British-Egyptian military force entered the Mahdist War.[57] Additionally the Egyptian province of Equatoria (located in South Sudan) led by Emin Pasha was also subject to an ostensible relief expedition of Emin Pasha against Mahdist forces.[58] The British-Egyptian force ultimately defeated the Mahdist forces in Sudan in 1898.[57] Thereafter, Britain seized effective control of Sudan, which was nominally called Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. Berlin Conference (1884–1885) Main article: Berlin Conference  Otto von Bismarck at the Berlin Conference, 1884 The occupation of Egypt and the acquisition of the Congo were the first major moves in what came to be a precipitous scramble for African territory. In 1884, Otto von Bismarck convened the 1884–1885 Berlin Conference to discuss the African problem.[59] While diplomatic discussions were held regarding ending the remaining slave trade as well as the reach of missionary activities, the primary concern of those in attendance was preventing war between the European powers as they divided the continent among themselves.[60] More importantly, the diplomats in Berlin laid down the rules of competition by which the great powers were to be guided in seeking colonies. They also agreed that the area along the Congo River was to be administered by Leopold II as a neutral area in which trade and navigation were to be free.[61] No nation was to stake claims in Africa without notifying other powers of its intentions. No territory could be formally claimed before being effectively occupied. However, the competitors ignored the rules when convenient, and on several occasions war was only narrowly avoided (see Fashoda Incident).[citation needed] The Swahili coast territories of the Sultanate of Zanzibar were partitioned between Germany and Britain, initially leaving the archipelago of Zanzibar independent until 1890, when that remnant of the Sultanate was made into a British protectorate with the Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty.[62] Britain's administration of Egypt and South Africa  Boer child in a British concentration camp during the Second Boer War (1899–1902) Britain's administration of Egypt and the Cape Colony contributed to a preoccupation over securing the source of the Nile River.[63] Egypt was taken over by the British in 1882, leaving the Ottoman Empire in a nominal role until 1914, when London made it a protectorate. Egypt was never an actual British colony.[64] Sudan, Nigeria, Kenya, and Uganda were subjugated in the 1890s and early 20th century; and in the south, the Cape Colony (first acquired in 1795) provided a base for the subjugation of neighbouring African states and the Dutch Afrikaner settlers who had left the Cape to avoid the British and then founded their republics. Theophilus Shepstone annexed the South African Republic in 1877 for the British Empire, after it had been independent for twenty years.[65] In 1879, after the Anglo-Zulu War, Britain consolidated its control of most of the territories of South Africa. The Boers protested, and in December 1880 they revolted, leading to the First Boer War.[66] British Prime Minister William Gladstone signed a peace treaty on 23 March 1881, giving self-government to the Boers in the Transvaal. The Jameson Raid of 1895 was a failed attempt by the British South Africa Company and the Johannesburg Reform Committee to overthrow the Boer government in the Transvaal. The Second Boer War, fought between 1899 and 1902, was about control of the gold and diamond industries; the independent Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic were this time defeated and absorbed into the British Empire. The French thrust into the African interior was mainly from the coasts of West Africa (present-day Senegal) eastward, through the Sahel along the southern border of the Sahara. Their ultimate aim was to have an uninterrupted colonial empire from the Niger River to the Nile, thus controlling all trade to and from the Sahel region by their existing control over the caravan routes through the Sahara. The British, on the other hand, wanted to link their possessions in Southern Africa with their territories in East Africa and these two areas with the Nile basin.  Muhammad Ahmad, leader of the Mahdists. This fundamentalist group of Muslim dervishes overran much of Sudan and fought British forces. The Sudan (which included most of present-day Uganda) was the key to the fulfilment of these ambitions, especially since Egypt was already under British control. This "red line" through Africa is made most famous by Cecil Rhodes. Along with Lord Milner, the British colonial minister in South Africa, Rhodes advocated such a "Cape to Cairo" empire, linking the Suez Canal to the mineral-rich South Africa by rail. Though hampered by the German occupation of Tanganyika until the end of World War I, Rhodes successfully lobbied on behalf of such a sprawling African empire. Britain had sought to extend its East African empire contiguously from Cairo to the Cape of Good Hope, while France had sought to extend its holdings from Dakar to the Sudan, which would enable its empire to span the entire continent from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. If one draws a line from Cape Town to Cairo (Rhodes's dream), and one from Dakar to the Horn of Africa (the French ambition), these two lines intersect somewhere in eastern Sudan near Fashoda, explaining its strategic importance. A French force under Jean-Baptiste Marchand arrived first at the strategically located fort at Fashoda, soon followed by a British force under Lord Kitchener, commander in chief of the British Army since 1892. The French withdrew after a standoff and continued to press claims to other posts in the region. The Fashoda Incident ultimately led to the signature of the Entente Cordiale of 1904, which guaranteed peace between the two. Anglo-French Agreement In 1890, both the United Kingdom and France were able to reach a diplomatic solution over a colonial dispute that would guarantee freedom of trade for the British Empire while allowing France to expand their influence in North Africa.[67] In exchange for France recognizing Britain's protectorate over Zanzibar, the British Empire recognized France's claim to Madagascar as well as their sphere of influence in North Africa stretching down to the border region of Sokoto.[68] However, finely demarcating this border was difficult to do without a large map.[69] Moroccan Crises Main articles: First Moroccan Crisis and Agadir Crisis  Map depicting the staged pacification of Morocco through to 1934 Although the Berlin Conference had set the rules for the Scramble for Africa, it had not weakened the rival imperialists. As a result of the Entente Cordiale, the German Kaiser decided to test the solidity of such influence, using the contested territory of Morocco as a battlefield. Kaiser Wilhelm II visited Tangier on 31 March 1905 and made a speech in favour of Moroccan independence, challenging French influence in Morocco. France's presence had been reaffirmed by Britain and Spain in 1904. The Kaiser's speech bolstered French nationalism, and with British support, the French foreign minister, Théophile Delcassé, took a defiant line. The crisis peaked in mid-June 1905 when Delcassé was forced out of the ministry by the more conciliation-minded premier Maurice Rouvier. But by July 1905 Germany was becoming isolated, and the French agreed to a conference to solve the crisis.  The Moroccan Sultan Abdelhafid, who led the resistance to French expansionism during the Agadir Crisis The 1906 Algeciras Conference was called to settle the dispute. Of the thirteen nations present, the German representatives found their only supporter was Austria-Hungary, which had no interest in Africa. France had firm support from Britain, the U.S., Russia, Italy, and Spain. The Germans eventually accepted an agreement, signed on 31 May 1906, whereby France yielded certain domestic changes in Morocco but retained control of key areas. However, five years later the Second Moroccan Crisis (or Agadir Crisis) was sparked by the deployment of the German gunboat Panther to the port of Agadir in July 1911. Germany had started to attempt to match Britain's naval supremacy—the British navy had a policy of remaining larger than the next two rival fleets in the world combined. When the British heard of the Panther's arrival in Morocco, they wrongly believed that the Germans meant to turn Agadir into a naval base on the Atlantic. The German move was aimed at reinforcing claims for compensation for acceptance of effective French control of the North African kingdom, where France's pre-eminence had been upheld by the 1906 Algeciras Conference. In November 1911, a compromise was reached under which Germany accepted France's position in Morocco in return for a slice of territory in the French Equatorial African colony of Middle Congo.[70] France and Spain subsequently established a full protectorate over Morocco on 30 March 1912, ending what remained of the country's formal independence. Furthermore, British backing for France during the two Moroccan crises reinforced the Entente between the two countries and added to Anglo-German estrangement, deepening the divisions that would culminate in the First World War. Dervish resistance Following the Berlin Conference, the British, Italians, and Ethiopians sought to claim lands inhabited by the Somalis. The Dervish movement, led by Sayid Muhammed Abdullah Hassan, existed for 21 years, from 1899 until 1920. The Dervish movement successfully repulsed the British Empire four times and forced it to retreat to the coastal region. Because of these successful expeditions, the Dervish movement was recognized as an ally by the Ottoman and German empires. The Turks named Hassan Emir of the Somali nation, and the Germans promised to officially recognise any territories the Dervishes were to acquire. After a quarter of a century of holding the British at bay, the Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920 as a direct consequence of Britain's use of aircraft. Herero Wars and the Maji Maji Rebellion Main articles: Herero Wars and Maji Maji Rebellion See also: Herero and Namaqua genocide  Lieutenant von Durling with prisoners at Shark Island, one of the German concentration camps used during the Herero and Namaqua genocide Between 1904 and 1908, Germany's colonies in German South West Africa and German East Africa were rocked by separate, contemporaneous native revolts against their rule. In both territories the threat to German rule was quickly defeated once large-scale reinforcements from Germany arrived, with the Herero rebels in German South West Africa being defeated at the Battle of Waterberg and the Maji-Maji rebels in German East Africa being steadily crushed by German forces slowly advancing through the countryside, with the natives resorting to guerrilla warfare.[71][72] German efforts to clear the bush of civilians in German South West Africa resulted in a genocide of the population. In total, as many as 65,000 Herero (80% of the total Herero population), and 10,000 Namaqua (50% of the total Namaqua population) either starved, died of thirst, or were worked to death in camps such as Shark Island concentration camp between 1904 and 1908. Between 24,000 and 100,000 Hereros, 10,000 Nama, and an unknown number of San died in the genocide.[73][74][75][76][77][78][79] Characteristic of this genocide was death from starvation, thirst, and possibly the poisoning of the population's wells, whilst they were trapped in the Namib Desert.[80][81][82] |

歴史と特徴 第一次世界大戦前の植民地化 コンゴ  ヘンリー・モートン・スタンレー デイヴィッド・リビングストンの探検は、ヘンリー・モートン・スタンレーによって続けられ、スタンレーの植民地化に関する壮大なアイデアによって想像力を かき立てられた。しかし、必要とされる問題や行動の規模から、1876年に国際アフリカ協会を組織したベルギーのレオポルド2世以外からは、ほとんど支持 を得られなかった。1869年から1874年にかけて、スタンリーはレオポルド2世から密かにコンゴ地方に派遣され、コンゴ川沿いのいくつかのアフリカ人 酋長と条約を結び、1882年までにコンゴ自由国の基礎を形成するのに十分な領土を手に入れた。  ピエール・サヴォルニャン・ドゥ・ブラッツァが「先住民」の服装で撮影(フェリックス・ナダル撮影 スタンリーがベルギーのレオポルド2世の代理としてコンゴを探検していた頃、イタリア系フランス人の海兵士官ピエール・ド・ブラッツァはコンゴ盆地西部に 入り、1881年に新しく建国されたブラザヴィルにフランス国旗を掲げ、現在のコンゴ共和国を占領した[21]。コンゴ王国との古い条約により、この地域 の領有権を主張していたポルトガルも、1884年2月26日にイギリスと条約を結び、レオポルドの大西洋へのアクセスを遮断した。 1890年までにコンゴ自由国はレオポルドヴィルとスタンレーヴィルの間の領土を支配下に置き、スタンレーヴィルからルアラバ川を南下しようとしていた。 同じ頃、セシル・ローズのイギリス南アフリカ会社はリンポポ川から北に拡大し、マタベレランドに開拓隊(フレデリック・セルース率いる)を送り込み、マ ショナランドで植民を始めていた[37]。 ザンジバルのスルタンに本拠を置くザンジバルのアラブ人ティップ・ティップもまた、「ヨーロッパ人探検家の保護者」、象牙商人、奴隷商人として大きな役割 を果たした。ザンジバルと東アフリカの近隣地域に交易帝国を築いたティプ・ティップは、この地域で台頭する植民地大国との同盟関係を強めることになり、ヘ ンリー・モートン・スタンリーの提案により、ティプ・ティップはレオポルドのコンゴ自由国の「スタンリー・フォールズ地区」(ボヨマ・フォールズ)の総督 となり、その後、レオポルド2世の植民地国家に対するコンゴ・アラブ戦争に関与した[38][39]。 西側には、両者の拡大が出会うことになるカタンガがあり、そこにはイェケ王国のムシリ王国があった。ムシリはこの地域で最も軍事的に強力な支配者であり、 大量の銅、象牙、奴隷を取引していた。ローデスは1890年、アルフレッド・シャープとジョセフ・トムソン率いる2つの遠征隊をミシリに送ったが、彼は拒 絶され、ジョセフ・トムソンはカタンガに到達できなかった。レオポルドは4つの探検隊を送った。まず、ル・マリネル探検隊は、曖昧な言葉の手紙を引き出す ことしかできなかった。デルコミューン探検隊は拒絶された。武装したステアーズ遠征隊は、ムシリの同意の有無にかかわらず、カタンガを占領する命令を受け た。ムシリは拒否し、銃殺され、その首は切り落とされ、人々への「野蛮な教訓」として棒に刺された[41]。ビア川遠征隊は、カタンガに一種の行政と「警 察の存在」を確立する仕事を終えた。こうして、カタンガの50万平方キロメートルはレオポルドの所有となり、彼のアフリカ領域はベルギーの約75倍にあた る230万平方キロメートルとなった。コンゴ自由国は、大量殺戮や強制労働など、植民地化された人々に恐怖政治を課したため、ベルギーはコンゴ改革協会の 圧力を受け、レオポルド2世の支配を終わらせ、1908年8月20日にベルギーの植民地として併合し、ベルギー領コンゴとして知られるようになった [42]。  1885年から1908年まで、コンゴ自由国では多くの残虐行為が行われた。これらの画像では、ゴムの徴収ノルマを達成できなかったコンゴ自由国の先住民労働者は、手を切り落とされるという罰を受けた。 旧植民地であるコンゴ自由国におけるレオポルド2世の蛮行[43][44]はよく知られており、1885年から1908年の間に推定1,600万人の先住 民のうち800万人が死亡した[45]。当時のアイルランドの外交官であったロジャー・ケースメントによると、この過疎化には4つの主な原因があった: 「無差別戦争」、飢餓、出産の減少、病気である[46]。眠り病はこの国を荒廃させ、人口の劇的な減少も考慮に入れなければならない。最初の国勢調査は 1924年まで行われなかったため、この時期の人口損失を定量化することは困難である。ケースメント報告書では300万人とされている[48]。ウィリア ム・ルビンシュタインは次のように書いている:「より基本的に、ホッホシルトによって与えられた人口の数字が不正確であることはほぼ確実のようである。も ちろん、20世紀以前のコンゴの人口を確認する方法はなく、2,000万人のような見積もりは単なる推測にすぎない。コンゴの内陸部のほとんどは、文字通 り未踏の地であった。 同じような状況は隣接するフランス領コンゴでも起こり、資源採掘のほとんどは租界企業によって運営され、その残忍な方法と伝染病の侵入によって、ホーチシ ルトによれば、先住民の人口の最大50%が失われた[50]。しかし、ド・ブラッツァは帰途に死亡し、彼の「痛烈に批判的な」報告書は法的措置もとられ ず、一般にも公表されなかった[51]。 1920年代には、フランス領内を通る鉄道の建設で約2万人の強制労働者が死亡した[52]。 エジプト、スーダン、南スーダン スエズ運河  デ・レスプスの銅像があるスエズ運河のポートサイド入口 スエズ運河を建設するため、フランスの外交官フェルディナン・ド・レセップスは1854年から56年にかけてエジプトとスーダンの首長イスマイル・パシャ から多くの利権を得ていた。労働人口は3万人と推定する資料もあるが[53]、10年間の建設期間中に栄養失調、疲労、病気、特にコレラによって12万人 の労働者が死亡したと推定する資料もある[54]。1869年の完成直前、イスマイル首長はイギリスとフランスの銀行家から高利で巨額の借金をした。 1875年までには財政難に直面し、スエズ運河の株式の売却を余儀なくされた。この株式は、ベンジャミン・ディズレーリ首相率いるイギリスによって買い取 られ、ディズレーリ首相はこの戦略的な水路の管理における実質的な支配権を自国に与えようとした。1879年にイスマイルがエジプトの対外債務を否認する と、イギリスとフランスは共同でエジプトの財政を掌握し、エジプトの支配者を退位させ、代わりに長男のテューフィク・パシャを据えた[55]。 マフディスト戦争 1870年代、奴隷貿易に対するヨーロッパの取り組みがスーダン北部の経済危機を引き起こし、マフディスト勢力の台頭を促した[56]。1881年、ムハ ンマド・アフマドの下でマフディストの反乱がスーダンで勃発し、スーダンにおけるテューフィクの権威は断絶した。同年、テューフィクはウラビの反乱という 形でエジプト軍によるさらに危険な反乱に見舞われた。1882年、テウフィックは英国に直接軍事支援を要請し、英国によるエジプト統治が開始された。イギ リス・エジプト連合軍はマフディスト戦争に参戦した[57]。 さらに、エミン・パシャ率いるエジプトのエクアトリア州(南スーダンに位置)も、マフディスト軍に対するエミン・パシャの表向きの救援遠征の対象となった [58]。 イギリス・エジプト連合軍は最終的に1898年にスーダンのマフディスト軍を撃破した[57]。その後、イギリスはスーダンの実効支配を掌握し、名目上ア ングロ・エジプト・スーダンと呼ばれた。 ベルリン会議(1884年-1885年) 主な記事 ベルリン会議  ベルリン会議でのオットー・フォン・ビスマルク(1884年) エジプトの占領とコンゴの獲得は、アフリカの領土をめぐる熾烈な争いの最初の大きな動きだった。1884年、オットー・フォン・ビスマルクはアフリカ問題 を議論するために1884年から1885年にかけてベルリン会議を招集した[59]。残された奴隷貿易の終結や布教活動の範囲に関する外交的な議論が行わ れた一方で、出席者の最大の関心事は、ヨーロッパ列強が大陸を分割する際の戦争を防ぐことであった[60]。彼らはまた、コンゴ川沿いの地域はレオポルド 2世によって中立地域として管理され、そこでは貿易と航海が自由に行われることに合意した[61]。事実上占領される前に正式に領有権を主張することはで きなかった。しかし、競合国は都合の良い時にはこの規則を無視し、何度か戦争はギリギリのところで回避された(ファショダ事件参照)[要出典] ザンジバル・スルタン国のスワヒリ海岸の領土はドイツとイギリスの間で分割され、当初ザンジバル群島は1890年まで独立したままであった。 イギリスによるエジプトと南アフリカの統治  第二次ボーア戦争(1899年~1902年)中、イギリスの強制収容所に入れられたボーア人の子供。 イギリスによるエジプトとケープ植民地の統治は、ナイル川の源流を確保することに夢中になる一因となった[63]。エジプトは1882年にイギリスに占領 され、1914年にロンドンが保護国とするまでオスマン帝国は名目的な役割に留まった。スーダン、ナイジェリア、ケニア、ウガンダは1890年代から20 世紀初頭にかけて征服され、南部ではケープ植民地(1795年に獲得)が近隣のアフリカ諸国と、イギリスを避けるためにケープを離れ、その後共和国を建国 したオランダ系アフリカーナー入植者を征服する拠点となった。テオフィラス・シェプストンは、20年間独立していた南アフリカ共和国を1877年に大英帝 国のために併合した[65]。1879年、アングロ・ズールー戦争の後、イギリスは南アフリカの領土のほとんどを支配下に置いた。イギリス首相ウィリア ム・グラッドストンは1881年3月23日に和平条約に調印し、トランスバールのボーア人に自治権を与えた[66]。1895年のジェイムソン襲撃は、イ ギリス南アフリカ会社とヨハネスブルグ改革委員会がトランスバールのボーア人政府を転覆させようとして失敗したものであった。1899年から1902年に かけて行われた第2次ボーア戦争は、金とダイヤモンド産業の支配をめぐるもので、独立したボーア共和国であるオレンジ自由国と南アフリカ共和国は、今度は 敗北し、大英帝国に吸収された。 フランスのアフリカ内陸部への進出は、主に西アフリカ(現在のセネガル)の海岸から東へ、サハラ砂漠の南境に沿ってサヘルを通過するものだった。彼らの最 終的な目的は、ニジェール川からナイル川まで途切れることのない植民地帝国を築き、サハラ砂漠を通るキャラバンルートを支配することで、サヘル地域とのす べての貿易をコントロールすることだった。一方、イギリスは南部アフリカと東部アフリカ、そしてこの2つの地域とナイル川流域を結びつけたいと考えてい た。  マフディストの指導者ムハンマド・アフマド。スーダンの大部分を制圧し、イギリス軍と戦った。 スーダン(現在のウガンダの大部分を含む)は、特にエジプトがすでにイギリスの支配下にあったため、こうした野望を実現する鍵だった。アフリカを貫くこの 「赤線」は、セシル・ローズによって最も有名になった。南アフリカの英国植民地大臣ミルナー卿とともに、ローズはスエズ運河と鉱物資源の豊富な南アフリカ を鉄道で結ぶ「ケープ・トゥ・カイロ」帝国を提唱した。第一次世界大戦が終わるまで、タンガニーカはドイツに占領されていたため、ローデスはこのようなア フリカの広大な帝国の実現に向けたロビー活動に成功した。 イギリスは東アフリカ帝国をカイロから喜望峰まで、フランスはダカールからスーダンまで、大西洋から紅海まで大陸全域にまたがる帝国として拡張しようとし ていた。ケープタウンからカイロ(ローデスの夢)、ダカールからアフリカの角(フランスの野望)へと線を引くと、この2本の線はスーダン東部のファショダ 付近で交わる。 ジャン=バティスト・マルシャン率いるフランス軍が、戦略上重要な位置にあるファショダの砦に最初に到着し、すぐに1892年以来イギリス陸軍の最高司令 官であったキッチナー卿率いるイギリス軍が続いた。フランス軍はにらみ合いの末に撤退したが、その後もこの地域の他の砦の領有権を主張し続けた。ファショ ダ事件は、最終的に1904年の英仏和親条約(Entente Cordiale)の締結につながった。 英仏協定 1890年、イギリスとフランスは植民地紛争を外交的に解決することに成功し、大英帝国は貿易の自由を保証する一方で、フランスは北アフリカにおける影響 力を拡大することができるようになった[67]。フランスがイギリスのザンジバル保護領を承認する代わりに、大英帝国はフランスのマダガスカルへの領有権 と、ソコトの国境地帯まで広がる北アフリカの勢力圏を承認した[68]。しかし、この国境を細かく画定することは、大きな地図がなければ困難であった [69]。 モロッコ危機 主な記事 第一次モロッコ危機とアガディール危機  1934年までのモロッコの段階的平和化を描いた地図 ベルリン会議はアフリカのためのスクランブルのルールを定めたが、対立する帝国主義者を弱体化させるものではなかった。エンタント・コルディアルの結果、 ドイツ皇帝はモロッコという紛争地域を戦場として、その影響力の強固さを試すことにした。カイザー・ヴィルヘルム2世は1905年3月31日にタンジール を訪れ、モロッコの独立を支持する演説を行い、モロッコにおけるフランスの影響力に異議を唱えた。フランスの存在は1904年にイギリスとスペインによっ て再確認されていた。カイザーの演説はフランスの国民主義を強め、イギリスの支援を受けてフランス外相のテオフィル・デルカッセは反抗的な態度をとった。 危機は1905年6月中旬にピークに達し、デルカッセは融和志向の強いモーリス・ルヴィエ首相によって省を追われた。しかし、1905年7月にはドイツは 孤立しつつあり、フランスは危機を解決するための会議に同意した。  アガディール危機の際、フランスの膨張主義に対する抵抗を指揮したモロッコのスルタン、アブデルハフィド 1906年、アルヘシラス会議が紛争解決のために招集された。出席した13カ国のうち、ドイツ代表の唯一の支持者はオーストリア=ハンガリーであった。フ ランスはイギリス、アメリカ、ロシア、イタリア、スペインから確固たる支持を得ていた。ドイツは最終的に1906年5月31日に調印された協定を受け入 れ、フランスはモロッコ国内の一定の変更を譲歩したが、重要地域の支配権は保持した。 しかしその5年後、1911年7月にドイツの砲艦パンサーがアガディール港に入港したことがきっかけで、第二次モロッコ危機(アガディール危機)が勃発し た。ドイツはイギリスの海軍力優位に対抗しようとし始めていた。イギリス海軍は、世界のライバル2艦隊の合計よりも大きな艦隊を維持するという方針を持っ ていた。パンサーがモロッコに到着したと聞いたイギリスは、ドイツがアガディールを大西洋の海軍基地にするつもりだと誤解した。ドイツの動きは、1906 年のアルヘシラス会議によってフランスの優位が維持されていた北アフリカ王国のフランスによる実効支配を受け入れることで、賠償請求を強化することを目的 としていた。1911年11月、フランス赤道アフリカ植民地であるコンゴ中部の領土の一部と引き換えに、ドイツがモロッコにおけるフランスの立場を受け入 れるという妥協案が成立した[70]。 その後、フランスとスペインは1912年3月30日にモロッコの完全な保護領を確立し、モロッコの正式な独立は終了した。さらに、2度のモロッコ危機の際 にイギリスがフランスを支持したことで、2国間のアンチェントが強化され、英独間の疎遠に拍車がかかり、第一次世界大戦で頂点に達することになる分裂が深 まった。 ダルビッシュの抵抗 ベルリン会議の後、イギリス、イタリア、エチオピアはソマリア人の住む土地の領有権を主張した。サイード・ムハメッド・アブドゥッラー・ハッサンに率いら れたダルビッシュ運動は、1899年から1920年までの21年間存在した。ダルビッシュ運動は大英帝国を4度撃退し、沿岸地域に撤退させることに成功し た。これらの遠征の成功により、ダルビッシュ運動はオスマン帝国とドイツ帝国から同盟国として認められた。オスマン帝国はハッサンをソマリア国民の首長に 任命し、ドイツ帝国はダルビッシュが獲得する領土を公式に承認することを約束した。四半世紀にわたってイギリスを寄せ付けなかったダルビッシュは、 1920年、イギリスが航空機を使用した結果、ついに敗北した。 ヘレロ戦争とマジマジの反乱 主な記事 ヘレロ戦争とマジマジの反乱 こちらも参照: ヘレロ人虐殺とナマクア人虐殺  ヘレロ族とナマクア族の大虐殺に使われたドイツの強制収容所のひとつ、シャーク島の囚人とフォン・ダーリング中尉。 1904年から1908年にかけて、ドイツの植民地であったドイツ領南西アフリカとドイツ領東アフリカは、同時期にドイツの支配に対する先住民の反乱に見 舞われた。ドイツ領南西アフリカのヘレロの反乱軍はウォーターベルグの戦いで敗北し、ドイツ領東アフリカのマジマジの反乱軍は、ゲリラ戦に頼る原住民を尻 目にゆっくりと地方を進むドイツ軍によって着実に鎮圧されていった[71][72]。 ドイツ領南西アフリカにおける民間人の潅木を除去するためのドイツの努力は、住民の大量虐殺をもたらした。1904年から1908年にかけて、合計で 65,000人ものヘレロ人(ヘレロ人総人口の80%)、10,000人のナマクア人(ナマクア人総人口の50%)が餓死、渇死、あるいはシャーク島強制 収容所などの収容所で死ぬまで働かされた。24,000人から100,000人のヘレロ人、10,000人のナマ人、そして未知の数のサンが大量虐殺で死 亡した[73][74][75][76][77][78][79]。この大量虐殺の特徴は、ナミブ砂漠に閉じ込められている間の餓死、渇き、そしておそら くは井戸の毒による死であった[80][81][82]。 |

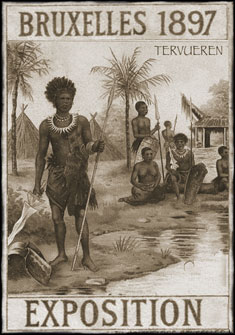

| Philosophy Colonial consciousness and exhibitions Colonial lobby  Pygmies and a European. Some pygmies would be exposed in human zoos, such as Ota Benga displayed by eugenicist Madison Grant in the Bronx Zoo. In its earlier stages, imperialism was generally the act of individual explorers as well as some adventurous merchantmen. The colonial powers were a long way from approving without any dissent the expensive adventures carried out abroad. Various important political leaders, such as William Gladstone, opposed colonization in its first years. However, during his second premiership between 1880 and 1885, he could not resist the colonial lobby in his cabinet and thus did not execute his electoral promise to disengage from Egypt. Although Gladstone was personally opposed to imperialism, the social tensions caused by the Long Depression pushed him to favour jingoism: the imperialists had become the "parasites of patriotism."[83] In France, Radical politician Georges Clemenceau was adamantly opposed to it: he thought colonization was a diversion from the "blue line of the Vosges" mountains, that is revanchism and the patriotic urge to reclaim the Alsace-Lorraine region which had been annexed by the German Empire with the 1871 Treaty of Frankfurt. Clemenceau made Jules Ferry's cabinet fall after the 1885 Tonkin disaster. According to Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), this expansion of national sovereignty on overseas territories contradicted the unity of the nation state which provided citizenship to its population. Thus, a tension between the universalist will respect human rights of the colonized people, as they may be considered as "citizens" of the nation-state, and the imperialist drive to cynically exploit populations deemed inferior began to surface. Some, in colonizing countries, opposed what they saw as unnecessary evils of the colonial administration when left to itself; as described in Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (1899)—published around the same time as Kipling's The White Man's Burden—or in Louis-Ferdinand Céline's Journey to the End of the Night (1932). Colonial lobbies emerged to legitimise the Scramble for Africa and other expensive overseas adventures. In Germany, France, and Britain, the middle class often sought strong overseas policies to ensure the market's growth. Even in lesser powers, voices like Enrico Corradini claimed a "place in the sun" for so-called "proletarian nations", bolstering nationalism and militarism in an early prototype of fascism. Colonial propaganda and jingoism A plethora of colonialist propaganda pamphlets, ideas, and imagery played on the colonial powers' psychology of popular jingoism and proud nationalism.[84] A hallmark of the French colonial project in the late 19th century and early 20th century was the civilizing mission (mission civilisatrice), the principle that it was Europe's duty to bring civilisation to benighted peoples.[85] As such, colonial officials undertook a policy of Franco-Europeanisation in French colonies, most notably French West Africa and Madagascar. During the 19th century, French citizenship along with the right to elect a deputy to the French Chamber of Deputies was granted to the four old colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guyane and Réunion as well as to the residents of the "Four Communes" in Senegal. In most cases, the elected deputies were white Frenchmen, although there were some black deputies, such as the Senegalese Blaise Diagne, who was elected in 1914.[86] Colonial exhibitions  Poster for the 1906 Colonial Exhibition in Marseilles (France)  Poster for the 1897 Brussels International Exposition. By the end of World War I the colonial empires had become very popular almost everywhere in Europe: public opinion had been convinced of the needs of a colonial empire, although most of the metropolitans would never see a piece of it. Colonial exhibitions were instrumental in this change of popular mentalities brought about by the colonial propaganda, supported by the colonial lobby and by various scientists.[87] Thus, conquests of territories were inevitably followed by public displays of the indigenous people for scientific and leisure purposes. Carl Hagenbeck, a German merchant in wild animals and a future entrepreneur of most Europeans zoos, decided in 1874 to exhibit Samoa and Sami people as "purely natural" populations. In 1876, he sent one of his collaborators to the newly conquered Egyptian Sudan to bring back some wild beasts and Nubians. Presented in Paris, London, and Berlin these Nubians were very successful. Such "human zoos" could be found in Hamburg, Antwerp, Barcelona, London, Milan, New York City, Paris, etc., with 200,000 to 300,000 visitors attending each exhibition. Tuaregs were exhibited after the French conquest of Timbuktu (visited by René Caillié, disguised as a Muslim, in 1828, thereby winning the prize offered by the French Société de Géographie); Malagasy after the occupation of Madagascar; Amazons of Abomey after Behanzin's mediatic defeat against the French in 1894. Not used to the climatic conditions, some of the indigenous died from exposure, such as some Galibis in Paris in 1892.[88] Geoffroy de Saint-Hilaire, director of the Jardin d'Acclimatation, decided in 1877 to organise two "ethnological spectacles", presenting Nubians and Inuit. Ticket sales at the Jardin d'Acclimatation doubled, with a million paying entrances that year, a huge success for these times. Between 1877 and 1912, approximately thirty "ethnological exhibitions" were presented at the zoo.[89] "Negro villages" were presented in Paris' 1878 World's Fair; the 1900 World's Fair presented the famous diorama "living" in Madagascar, while the Colonial Exhibitions in Marseilles (1906 and 1922) and in Paris (1907 and 1931)displayed human beings in cages, often nudes or quasi-nudes.[90] Nomadic "Senegalese villages" were also created, thus displaying the power of the colonial empire to all the population. In the U.S., Madison Grant, head of the New York Zoological Society, exposed Pygmy Ota Benga in the Bronx Zoo alongside the apes and others in 1906. At the behest of Grant, a scientific racist and eugenicist, zoo director William Temple Hornaday placed Ota Benga in a cage with an orangutan and labeled him "The Missing Link" in an attempt to illustrate Darwinism, and in particular that Africans like Ota Benga are closer to apes than were Europeans. Other colonial exhibitions included the 1924 British Empire Exhibition and the 1931 Paris "Exposition coloniale". Countering disease From the beginning of the 20th century, the elimination or control of disease in tropical countries became a driving force for all colonial powers.[91] The sleeping sickness epidemic in Africa was arrested through mobile teams systematically screening millions of people at risk.[92] In the 1880s cattle brought from British Asia to feed Italian soldiers invading Eritrea turned out to be infected with a disease called rinderpest. Decimation of native herds severely damaged local livelihoods, forcing people to labor for their colonizers. In the 20th century, Africa saw the biggest increase in its population because of lessening of the mortality rate in many countries through peace, famine relief, medicine, and above all, the end or decline of the slave trade.[93] Africa's population has grown from 120 million in 1900[94] to over 1 billion today.[95] Slavery abolition Main article: Slavery in Africa § Abolition The continuing anti-slavery movement in Western Europe became a reason and an excuse for the conquest and colonization of Africa. It was the central theme of the Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference 1889–90. From start of the Scramble for Africa, virtually all colonial regimes claimed to be motivated by a desire to suppress slavery and the slave trade. In French West Africa, following conquest and abolition by the French, over one million slaves fled from their masters to earlier homes between 1906 and 1911. In Madagascar, the French abolished slavery in 1896, and approximately 500,000 slaves were freed. Slavery was abolished in the French controlled Sahel by 1911. Independent nations attempting to westernize or impress Europe sometimes cultivated an image of slavery suppression. In response to European pressure, the Sokoto Caliphate abolished slavery in 1900, and Ethiopia officially abolished slavery in 1932. Colonial powers were mostly successful in abolishing slavery, though slavery remained active in Africa, even though it has gradually moved to a wage economy. Slavery was never fully eradicated in Africa.[96][97][98][99] |

哲学 植民地時代の意識と展示 植民地ロビー  ピグミーとヨーロッパ人。ピグミーの中には、優生主義者のマディソン・グラントがブロンクス動物園で展示したオタ・ベンガのように、人間の動物園で公開されるものもいた。 初期の帝国主義は、探検家や冒険的な商人たちによるものだった。植民地列強は、海外で行われる高価な冒険を反対意見なしに承認することはできなかった。 ウィリアム・グラッドストンをはじめとするさまざまな重要な政治指導者は、植民地化の最初の時期には反対していた。しかし、1880年から1885年にか けて2度目の首相を務めたグラッドストンは、内閣内の植民地ロビーに抵抗することができず、エジプトからの離脱という選挙公約を実行することはなかった。 グラッドストンは個人的には帝国主義に反対していたが、長期恐慌によって引き起こされた社会的緊張が彼をジンゴイズムに向かわせた。 「フランスでは、急進派の政治家ジョルジュ・クレマンソーは断固として帝国主義に反対していた。植民地化は「ヴォージュ山脈の青い線」、すなわち1871 年のフランクフルト条約によってドイツ帝国に併合されたアルザス・ロレーヌ地方を取り戻そうとするレヴァンキズムと愛国心からの逸脱であると考えていた。 クレマンソーは1885年のトンキン海難事故の後、ジュール・フェリー内閣を倒閣させた。ハンナ・アーレントは『全体主義の起源』(1951年)の中で、 海外領土における国家主権の拡大は、国民に市民権を与える国民国家の統一と矛盾すると述べている。こうして、植民地化された人々は国民国家の「国民」とみ なされるかもしれないとして、その人権を尊重する普遍主義的な意志と、劣等とみなされた人々を冷笑的に搾取しようとする帝国主義的な衝動との間の緊張が表 面化し始めた。キップリングの『白人の重荷』と同時期に出版されたジョセフ・コンラッドの『闇の奥』(1899年)やルイ=フェルディナン・セリーヌの 『夜の果てへの旅』(1932年)に描かれているように、植民地化された国々では、植民地行政が放っておけば不必要な弊害をもたらすと見て反対する者もい た。 植民地ロビーは、スクランブル・フォア・アフリカやその他の高価な海外冒険を正当化するために出現した。ドイツ、フランス、イギリスでは、中産階級は市場 の成長を保証するために、しばしば強力な海外政策を求めた。小国であっても、エンリコ・コッラディーニのような声は、いわゆる「プロレタリア国民」のため の「日の当たる場所」を主張し、ファシズムの初期の原型としてナショナリズムと軍国主義を強化した。 植民地プロパガンダとジンゴイズム 19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてのフランスの植民地事業の特徴は、文明化ミッション(mission civilisatrice)、すなわち、荒廃した民族に文明をもたらすことはヨーロッパの義務であるという原則であった[85]。そのため、植民地当局 者は、フランスの植民地、特にフランス領西アフリカとマダガスカルにおいて、フランコ=ヨーロッパ化政策を行った。19世紀には、グアドループ、マルティ ニーク、ギアヌ、レユニオンの4つの旧植民地とセネガルの「4つのコミューン」の住民に、フランス市民権とフランス代議員会の代議員を選出する権利が与え られた。ほとんどの場合、選出された代議員はフランス人の白人であったが、1914年に選出されたセネガル人のブレーズ・ディアニュのような黒人代議員も いた[86]。 植民地展示会  1906年にマルセイユで開催された植民地博覧会のポスター(フランス)  1897年のブリュッセル万国博覧会のポスター。 第一次世界大戦が終わるころには、植民地帝国はヨーロッパのほぼ全域で大人気となっていた。世論は植民地帝国の必要性を確信していたが、大都会ではその一 部を目にすることはなかった。植民地展示は、植民地ロビーやさまざまな科学者によって支持された植民地宣伝によってもたらされた民衆のメンタリティのこの ような変化にとって重要な役割を果たした[87]。このように、領土の征服は必然的に、科学やレジャーを目的とした先住民の公開展示へと続いていった。 野生動物を扱うドイツの商人で、後にヨーロッパのほとんどの動物園の起業家となったカール・ハーゲンベックは、1874年にサモアとサーミの人々を「純粋 に自然な」集団として展示することを決めた。1876年、彼は協力者の一人を征服したばかりのエジプト・スーダンに派遣し、野生の獣とヌビア人を持ち帰ら せた。パリ、ロンドン、ベルリンで展示されたこれらのヌビアンは大成功を収めた。このような 「人間動物園 」は、ハンブルク、アントワープ、バルセロナ、ロンドン、ミラノ、ニューヨーク、パリなどで見られ、毎回20万人から30万人が訪れた。トゥアレグ族はフ ランスによるティンブクトゥ征服後に展示され(1828年、ルネ・カイリエがイスラム教徒に変装して訪れ、フランス地理学会の賞を受賞した)、マダガスカ ル占領後はマダガスカル人、1894年にベハンジンがフランス軍に大敗した後はアボメイのアマゾンが展示された。気候条件に慣れていないため、1892年 にパリでガリビスの何人かが被爆死したように、先住民の何人かが死亡した[88]。 1877年、順化園の園長であったジェフロワ・ド・サン=ハイレールは、ヌビア人とイヌイットを紹介する2つの「民族学的見世物」を開催することを決定し た。この年のジャルダン・ダクリマシオンのチケット売上は倍増し、有料入場者数は100万人に達し、当時としては大成功を収めた。1878年のパリの万国 博覧会では「黒人の村」が展示され、1900年の万国博覧会では有名なマダガスカルに「住む」ジオラマが展示され、マルセイユ(1906年と1922年) とパリ(1907年と1931年)の植民地展示会では檻の中の人間が展示された。 [遊牧民の「セネガルの村」も作られ、植民地帝国の権力を全住民に見せつけた。 アメリカでは、ニューヨーク動物学協会のマディソン・グラントが、1906年にピグミー・オタ・ベンガを類人猿などとともにブロンクス動物園で公開した。 科学的人種差別主義者であり優生主義者であったグラントの命令で、動物園の園長ウィリアム・テンプル・ホーナデーはオタ・ベンガをオランウータンと一緒に 檻に入れ、ダーウィニズム、特にオタ・ベンガのようなアフリカ人がヨーロッパ人よりも類人猿に近いことを説明するために「ミッシング・リンク」と名付け た。その他の植民地展示会としては、1924年の大英帝国博覧会や1931年のパリ「植民地博覧会」がある。 病気への対策 20世紀初頭から、熱帯諸国における疾病の撲滅または制御は、すべての植民地支配国の原動力となった[91]。アフリカにおける眠り病の流行は、危険にさ らされている何百万人もの人々を組織的にスクリーニングする移動チームによって阻止された[92]。 1880年代には、エリトリアに侵攻したイタリア兵の飼料としてイギリス領アジアから持ち込まれた牛が、リンダーペストと呼ばれる疾病に感染していること が判明した。在来の牛の群れは壊滅的な打撃を受け、地元の人々は植民地支配者のために労働を強いられた。 20世紀には、平和、飢饉の救済、医療、そして何よりも奴隷貿易の終焉や衰退によって多くの国で死亡率が低下したため、アフリカの人口は最も増加した[93]。 奴隷制廃止 主な記事 アフリカの奴隷制 § 廃止 西ヨーロッパで続いていた反奴隷制運動は、アフリカの征服と植民地化の理由と口実となった。1889年から90年にかけて開催されたブリュッセル反奴隷制 会議では、これが中心テーマとなった。スクランブル・フォア・アフリカが始まって以来、事実上すべての植民地政権は、奴隷制と奴隷貿易を抑制したいという 願望が動機であると主張した。フランス西アフリカでは、フランスによる征服と奴隷廃止の後、1906年から1911年の間に、100万人以上の奴隷が主人 のもとを逃れて以前の家に戻った。マダガスカルでは、1896年にフランスが奴隷制度を廃止し、約50万人の奴隷が解放された。フランスが支配するサヘル では、1911年までに奴隷制度が廃止された。ヨーロッパを西洋化しようとしたり、印象づけようとしたりする独立国民は、奴隷制抑制のイメージを植え付け ることがあった。ヨーロッパの圧力に応えて、ソコト・カリフは1900年に奴隷制を廃止し、エチオピアは1932年に正式に奴隷制を廃止した。植民地勢力 は奴隷制の廃止にほぼ成功したが、奴隷制は徐々に賃金経済に移行したとはいえ、アフリカでは依然として活発だった。アフリカにおいて奴隷制度が完全に根絶 されることはなかった[96][97][98][99]。 |

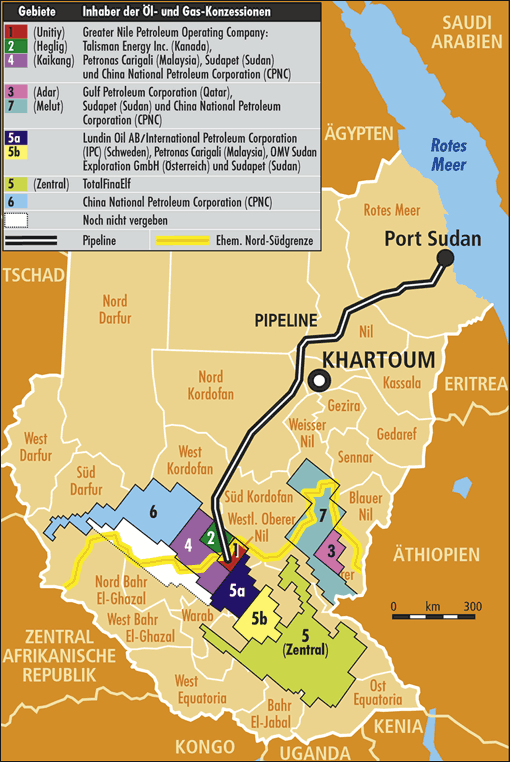

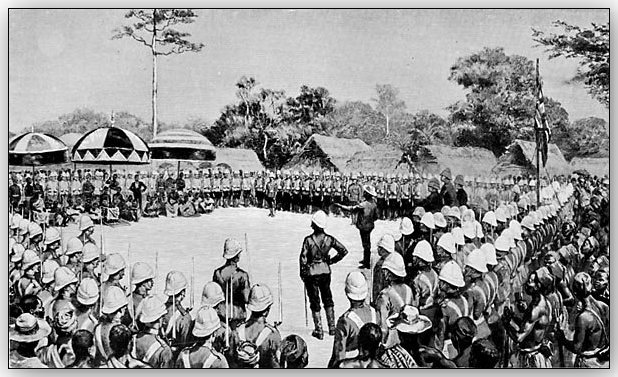

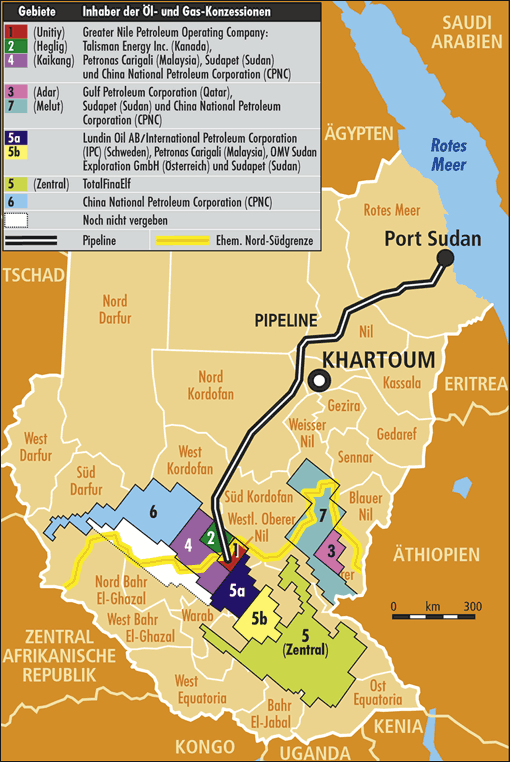

Aftermath German Cameroon, painting by R. Hellgrewe, 1908 During the New Imperialism period, by the end of the 19th century, Europe added almost 9,000,000 square miles (23,000,000 km2) – one-fifth of the land area of the globe – to its overseas colonial possessions. Europe's formal holdings included the entire African continent except Ethiopia, Liberia, and Saguia el-Hamra, the latter of which was eventually integrated into Spanish Sahara. Between 1885 and 1914, Britain took nearly 30% of Africa's population under its control; 15% for France, 11% for Portugal, 9% for Germany, 7% for Belgium and 1% for Italy.[citation needed] Nigeria alone contributed 15 million subjects, more than in the whole of French West Africa or the entire German colonial empire. In terms of surface area occupied, the French were the marginal leaders, but much of their territory consisted of the sparsely populated Sahara.[100][101] Political imperialism followed the economic expansion, with the "colonial lobbies" bolstering chauvinism and jingoism at each crisis in order to legitimise the colonial enterprise. The tensions between the imperial powers led to a succession of crises, which exploded in August 1914, when previous rivalries and alliances created a domino situation that drew the major European nations into World War I.[102] African colonies listed by colonising power Belgium  Equestrian statue of Leopold II of Belgium, the Sovereign of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908, Regent Place in Brussels, Belgium Belgian Congo (1908–1960, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) Ruanda-Urundi (1922–1962, now Rwanda and Burundi) France Further information: French Africa  The Foureau-Lamy military expedition sent out from Algiers in 1898 to conquer the Chad Basin and unify all French territories in West Africa.  The Senegalese Tirailleurs, led by Colonel Alfred-Amédée Dodds, conquered Dahomey (present-day Benin) in 1892 French West Africa: Mauritania Senegal Albreda (1681–1857, now part of Gambia) French Sudan (now Mali, 1880 – 1958) Liberia Territorial losses of Liberia French Guinea (now Guinea) Ivory Coast Niger French Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) French Dahomey (now Benin) French Togoland (1916–60, now Togo) Enclaves of Forcados and Badjibo (in modern Nigeria) French Equatorial Africa: Gabon French Cameroun (1922–60) French Congo (now Republic of the Congo) Oubangui-Chari (now Central African Republic) Chad French North Africa: French Algeria (1830–1962; was administered as an integral part of France itself from 1848) French Protectorate of Tunisia French Protectorate of Morocco Fezzan-Ghadames (1943–1951) (administration given by the UNO after its conquest by Charles de Gaulle) Egypt (ownership (1798–1801)) (Condominium of France and the United Kingdom (1876–1882))[103] French East Africa: French Madagascar Comoros Scattered islands in the Indian Ocean French Somaliland (now Djibouti) Isle de France (1715–1810) (now Mauritius) Germany German Kamerun (now Cameroon and part of Nigeria, 1884–1916) German East Africa (now Rwanda, Burundi and most of Tanzania, 1885–1919) German South-West Africa (now Namibia, 1884–1915) German Togoland (now Togo and eastern part of Ghana, 1884–1914) After the First World War, Germany's possessions were partitioned among Britain (which took a sliver of western Cameroon, Tanzania, western Togo, and Namibia), France (which took most of Cameroon and eastern Togo) and Belgium (which took Rwanda and Burundi). Italy   Italian settlers in Massawa Italian Eritrea (1882-1936) Italian Somalia (1889-1936) Italian Ethiopia (1936-1941) Oltre Giuba (annexed into Italian Somalia in 1925) Libya Italian Tripolitania (1911-1934) Italian Cyrenaica (1911-1934) Italian Libya (from the unification of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in 1934) (1934-1943; coastal regions administered as an integral part of Italy itself from 1939-1943) During the interwar period, Italian Ethiopia formed together with Italian Eritrea and Italian Somaliland the Italian East Africa (A.O.I., "Africa Orientale Italiana", also defined by the fascist government as L'Impero). Portugal  Marracuene in Portuguese Mozambique was the site of a decisive battle between Portuguese and Gaza king Gungunhana in 1895 Portuguese Angola (now Angola) (1575-1975) Mainland Angola Portuguese Congo (now Cabinda Province of Angola) Portuguese Mozambique (now Mozambique) (1505-1975) Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau) (1588-1974) Portuguese Gold Coast (now part of Ghana) (1482-1642) Portuguese Cape Verde (1462-1975) Portuguese São Tomé and Príncipe (1485-1975) São Tomé Island Príncipe Island Fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá (now Ouidah, in Benin) On 11 June 1951, Portugal would begin to administer its colonies, including its ones in Africa, as Overseas provinces. Spain Northern Spanish Morocco Chefchaouen (Chauen) Jebala (Yebala) Kert Loukkos (Lucus) Rif Spanish West Africa (1946-1958) Ifni (1934-1969) Southern Spanish Morocco (Cape Juby) Spanish Sahara (now Western Sahara) (1884-1958 as a colony of Spain; 1958-1976 as a Province of Spain) Saguia el-Hamra Río de Oro Spanish Guinea (now Equatorial Guinea) (1858-1968) Fernando Pó Río Muni Annobón United Kingdom Further information: Historiography of the British Empire  Opening of the railway in Rhodesia, 1899  Following the Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War in 1896, the British proclaimed a protectorate over the Ashanti Kingdom. The British were primarily interested in maintaining secure communication lines to India, which led to initial interest in Egypt and South Africa. Once these two areas were secure, it was the intent of British colonialists such as Cecil Rhodes to establish a Cape-Cairo railway and to exploit mineral and agricultural resources. Control of the Nile was viewed as a strategic and commercial advantage. Overall, by 1921, the British had control approximately 33.23% of Africa, or 3,897,920 mi2 (10,09,55,66 km2).[104][105] Egypt British Cyrenaica (1943–1951, now part of Libya) British Tripolitania (1943–1951, now part of Libya) Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899–1956) British Somaliland (now part of Somalia) British East Africa: Kenya Colony Uganda Protectorate Tanzania : Tanganyika Territory (1919–61) Zanzibar British Mauritius Bechuanaland (now Botswana) Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) British Seychelles British South Africa South Africa: Transvaal Colony Cape Colony Colony of Natal Orange River Colony South-West Africa (from 1915, now Namibia) British West Africa Gambia Colony and Protectorate British Sierra Leone Colonial Nigeria British Togoland (1916–56, today part of Ghana) Cameroons (1922–61, now part of Cameroon and Nigeria) Gold Coast (British colony) (now Ghana) Nyasaland (now Malawi) Basutoland (now Lesotho) Swaziland (now Eswatini) Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha Independent states Liberia was founded, colonized, established, and controlled by the American Colonization Society, a private organisation established in order to relocate freed African American and Caribbean slaves from the United States and the Caribbean islands in 1822.[106][107] Liberia declared its independence from the American Colonization Society on July 26, 1847.[108] Liberia is Africa's oldest republic and the second-oldest black republic in the world (after Haiti). Liberia maintained its independence during the period as it was viewed by European powers as either a territory, colony[109] or protectorate of the United States. The same powers assumed Ethiopia to be a protectorate of Italy although the country had never accepted this, and its independence from Italy was recognized after the Battle of Adwa which resulted in the Treaty of Addis Ababa in 1896.[110] With the exception of Italian occupation between 1936 and 1941 by Benito Mussolini's military forces, Ethiopia is Africa's oldest independent nation. Connections to modern-day events Further information: Decolonisation of Africa and Neocolonialism  Oil and gas concessions in the Sudan – 2004 Anti-neoliberal scholars connect the old scramble to a new scramble for Africa, coinciding with the emergence of an "Afro-neoliberal" capitalist movement in postcolonial Africa.[111] When African nations began to gain independence after World War II, their postcolonial economic structures remained undiversified and linear. In most cases, the bulk of a nation's economy relied on cash crops or natural resources. These scholars claim that the decolonisation process kept independent African nations at the mercy of colonial powers by structurally dependent economic relations. They also claim that structural adjustment programs led to the privatization and liberalization of many African political and economic systems, forcefully pushing Africa into the global capitalist market, and that these factors led to development under Western ideological systems of economics and politics.[112] Petrostates In the era of globalization, several African countries have emerged as petrostates (for example Angola, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Sudan). These are nations with an economic and political partnership between transnational oil companies and the ruling elite class in oil-rich African nations.[113] Numerous countries have entered into a neo-imperial relationship with Africa during this time period. Mary Gilmartin notes that "material and symbolic appropriation of space [is] central to imperial expansion and control"; nations in the globalization era who invest in controlling land internationally are engaging in neocolonialism.[114] Chinese (and other Asian countries) state oil companies have entered Africa's highly competitive oil sector. China National Petroleum Corporation purchased 40% of Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company. Furthermore, the Sudan exports 50–60% of its domestically produced oil to China, making up 7% of China's imports. China has also been purchasing equity shares in African oil fields, invested in industry related infrastructure development and acquired continental oil concessions throughout Africa.[115] |

余波 ドイツ領カメルーン、R.ヘルグレーヴェ画、1908年 新帝国主義の時代、19世紀末までにヨーロッパは、地球の陸地面積の5分の1にあたる約9,000,000平方マイル(23,000,000 km2)を海外植民地として追加した。ヨーロッパの正式な所有地は、エチオピア、リベリア、サギア・エル・ハムラを除くアフリカ大陸全体であったが、後者 は最終的にスペイン領サハラに統合された。1885年から1914年の間に、イギリスはアフリカの人口の30%近くを支配下に置き、フランスは15%、ポ ルトガルは11%、ドイツは9%、ベルギーは7%、イタリアは1%を支配下に置いた。占有面積ではフランスが僅差のトップであったが、その領土の多くは人 口の少ないサハラ砂漠であった[100][101]。 政治的帝国主義は経済的拡大に追随し、「植民地ロビー」は植民地事業を正当化するために、それぞれの危機において排外主義とジンゴイズムを強化した。帝国 列強間の緊張は相次ぐ危機を招き、1914年8月には、それまでの対立や同盟関係がドミノ状況を引き起こし、ヨーロッパの主要国が第一次世界大戦に巻き込 まれる事態となった[102]。 植民地化した国別のアフリカ植民地 ベルギー  1885年から1908年までコンゴ自由国の君主であったベルギーのレオポルド2世の騎馬像(ベルギー、ブリュッセルのリージェント広場 ベルギー領コンゴ(1908年~1960年、現コンゴ民主共和国) ルアンダ・ウルンディ(1922-1962、現ルワンダ・ブルンジ) フランス さらに詳しい情報 フランス領アフリカ  1898年、チャド盆地を征服し、西アフリカの全フランス領を統一するためにアルジェから派遣されたフーロー=ラミー軍事遠征隊。  アルフレッド=アメデ・ドッズ大佐率いるセネガルのティライユールは、1892年にダホメー(現在のベナン)を征服した。 フランス領西アフリカ モーリタニア セネガル アルブレダ(1681~1857年、現ガンビアの一部) 仏領スーダン(現マリ、1880年~1958年) リベリア リベリア領土喪失 フランス領ギニア(現ギニア) コートジボワール ニジェール 仏領アッパーヴォルタ(現ブルキナファソ) 仏領ダホメー(現ベナン) 仏領トーゴランド(1916-60、現トーゴ) フォルカドスとバジボの飛び地(現ナイジェリア) フランス領赤道アフリカ ガボン 仏領カメルーン(1922-60) 仏領コンゴ(現コンゴ共和国) ウバンギ=チャリ(現中央アフリカ共和国) チャド フランス領北アフリカ フランス領アルジェリア(1830~1962年、1848年以降はフランスの一部として統治された) フランス領チュニジア保護領 モロッコ保護領 フェザン・ガダメス(1943-1951)(シャルル・ド・ゴールによる征服後、UNOにより統治された) エジプト(所有権(1798年-1801年))(フランスとイギリスのコンドミニアム(1876年-1882年))[103]。 フランス領東アフリカ フランス領マダガスカル コモロ インド洋に散在する島々 フランス領ソマリランド(現ジブチ) アイル・ド・フランス(1715-1810)(現モーリシャス) ドイツ ドイツ領カメルーン(現カメルーン、ナイジェリアの一部、1884~1916年) ドイツ領東アフリカ(現ルワンダ、ブルンジ、タンザニアの大部分、1885年~1919年) ドイツ領南西アフリカ(現ナミビア、1884~1915年) ドイツ領トーゴランド(現在のトーゴとガーナ東部、1884~1914年) 第一次世界大戦後、ドイツ領はイギリス(カメルーン西部、タンザニア、トーゴ西部、ナミビアの一部を領有)、フランス(カメルーンの大部分とトーゴ東部を領有)、ベルギー(ルワンダとブルンジを領有)に分割された。 イタリア  マサワのイタリア人入植者 イタリア領エリトリア(1882年-1936年) イタリア領ソマリア(1889年-1936年) イタリア領エチオピア(1936年-1941年) オルトレ・ジュバ(1925年にイタリア領ソマリアに併合される) リビア イタリア領トリポリタニア(1911年-1934年) イタリア領キレナイカ(1911年-1934年) イタリア領リビア(1934年のトリポリタニアとキレナイカの統合から)(1934年-1943年。) 戦間期には、イタリア領エチオピアがイタリア領エリトリア、イタリア領ソマリランドとともにイタリア領東アフリカ(A.O.I.、「Africa Orientale Italiana」、ファシスト政府はL'Imperoとも定義)を形成した。 ポルトガル  ポルトガル領モザンビークのマラクエネは、1895年にポルトガルとガザの王グングンハナが決戦を行った場所である。 ポルトガル領アンゴラ(現アンゴラ)(1575年~1975年) アンゴラ本土 ポルトガル領コンゴ (現アンゴラ・カビンダ州) ポルトガル領モザンビーク (現モザンビーク)(1505-1975) ポルトガル領ギニア (現ギニアビサウ)(1588年~1974年) ポルトガル領ゴールドコースト(現在のガーナの一部)(1482年~1642年) ポルトガル領カーボベルデ(1462年-1975年) ポルトガル領サントメ・プリンシペ(1485-1975) サントメ島 プリンシペ島 サン・ジョアン・バプティスタ・デ・アジュダの要塞 (現在のベナンのウイダ) 1951年6月11日、ポルトガルはアフリカを含む植民地を海外県として管理し始める。 スペイン スペイン領モロッコ北部 シェフシャウエン(シャウエン) ジェバラ ケルト ルーコス リフ スペイン領西アフリカ(1946-1958) イフニ(1934年~1969年) スペイン領モロッコ南部(ジュビ岬) スペイン領サハラ(現西サハラ)(1884~1958年スペインの植民地、1958~1976年スペインの州) サギア・エル・ハムラ リオ・デ・オロ スペイン領ギニア (現赤道ギニア)(1858-1968) フェルナンド・ポ リオ・ムニ アンノボン イギリス さらなる情報 大英帝国の歴史  ローデシア鉄道開通(1899年  1896年の第4次アングロ・アシャンティ戦争後、イギリスはアシャンティ王国の保護領を宣言した。 イギリスはインドとの通信路を確保することに主眼を置いており、そのため当初はエジプトと南アフリカに関心を寄せていた。この2つの地域が確保されると、 セシル・ローズをはじめとするイギリスの植民地主義者たちは、ケープ・カイロ鉄道を敷設し、鉱物資源や農業資源を開発することを意図した。ナイル川の支配 は戦略的、商業的に有利であると考えられていた。全体として、1921年までにイギリスはアフリカの約33.23%、3,897,920 mi2 (10,09,55,66 km2)を支配していた[104][105]。 エジプト 英領キレナイカ(1943年~1951年、現在はリビアの一部) 英領トリポリタニア(1943年~1951年、現リビアの一部) 英領スーダン(1899年-1956年) 英領ソマリランド(現ソマリアの一部) イギリス領東アフリカ ケニア植民地 ウガンダ保護領 タンザニア タンガニーカ領(1919~61年) ザンジバル 英領モーリシャス ベチュアナランド(現ボツワナ) 南ローデシア(現ジンバブエ) 北ローデシア(現ザンビア) 英領セーシェル イギリス領南アフリカ 南アフリカ トランスバール植民地 ケープ植民地 ナタール植民地 オレンジ川植民地 南西アフリカ(1915年~、現ナミビア) イギリス領西アフリカ ガンビア植民地・保護領 英領シエラレオネ ナイジェリア植民地 英領トーゴランド(1916~56年、現在のガーナの一部) カメルーン(1922~61年、現カメルーンとナイジェリアの一部) ゴールドコースト(イギリス植民地)(現ガーナ) ニャサランド(現マラウイ) バストランド(現レソト) スワジランド(現エスワティニ) セントヘレナ、アセンション、トリスタン・ダ・クーニャ 独立国家 リベリアは、1822年にアメリカやカリブ海の島々から解放されたアフリカ系アメリカ人やカリブ海諸国の奴隷を移住させるために設立された民間組織である アメリカ植民地化協会によって設立、植民地化、設立、支配された[106][107]。1847年7月26日にアメリカ植民地化協会からの独立を宣言した [108]。リベリアは、ヨーロッパ列強からアメリカの領土、植民地[109]、保護国として見られていた時期もあり、独立を維持した。 同じ列強は、エチオピアをイタリアの保護領とみなしていたが、エチオピアはそれを認めておらず、1896年にアディスアベバ条約が結ばれたアドワの戦いの 後、イタリアからの独立が認められた[110]。1936年から1941年にかけてのベニート・ムッソリーニ軍によるイタリア占領を除けば、エチオピアは アフリカ最古の独立国民である。 現代の出来事との関連 さらなる情報 アフリカの脱植民地化と新植民地主義  スーダンの石油・ガス利権 - 2004年 反新自由主義の学者たちは、ポストコロニアル・アフリカにおける「アフロ・新自由主義」資本主義運動の出現と時を同じくして、古いスクランブルを新しいア フリカのスクランブルと結びつけている[111]。第二次世界大戦後にアフリカ国民が独立し始めたとき、そのポストコロニアル経済構造は未分化で直線的な ままだった。ほとんどの場合、国民経済の大部分は換金作物か天然資源に依存していた。これらの学者たちは、脱植民地化プロセスによって、独立したアフリカ 国民は、構造的に依存的な経済関係によって植民地大国の言いなりになっていたと主張している。彼らはまた、構造調整プログラムは多くのアフリカの政治・経 済システムの民営化と自由化をもたらし、アフリカをグローバル資本主義市場に強制的に押し込んだと主張し、これらの要因は経済と政治における西洋のイデオ ロギー体系の下での発展をもたらしたと主張している[112]。 石油国家 グローバリゼーションの時代において、アフリカのいくつかの国は石油国家として台頭してきた(アンゴラ、カメルーン、ナイジェリア、スーダンなど)。これ らは、多国籍石油会社と石油に恵まれたアフリカ諸国の支配的エリート層が経済的・政治的パートナーシップを結んでいる国民である[113]。この時期、数 多くの国々がアフリカと新帝国関係を結んでいる。メアリー・ギルマーティンは、「空間の物質的・象徴的な充当は(中略)帝国の拡張と支配の中心である」と 指摘しており、グローバル化時代において土地の国際的な支配に投資する国民は、新植民地主義に関与している[114]。 中国(および他のアジア諸国)の国営石油会社は、競争の激しいアフリカの石油部門に参入した。中国石油天然気集団公司(China National Petroleum Corporation)は、グレーター・ナイル石油運営会社(Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company)の40%を購入した。さらに、スーダンは国内で生産された石油の50~60%を中国に輸出しており、中国の輸入量の7%を占めている。中 国はまた、アフリカの油田の株式を購入し、産業関連のインフラ開発に投資し、アフリカ全土で大陸部の石油利権を獲得している[115]。 |

| Lists Chronology of Western colonialism List of European colonies in Africa List of kingdoms in Africa throughout history List of former sovereign states List of French possessions and colonies Other topics Analysis of Western European colonialism and colonization Durand Line Economic history of Africa French colonial empire Historiography of the British Empire International relations (1814–1919) Scramble for China Sykes–Picot Agreement White Africans of European ancestry |

リスト 欧米の植民地年表 アフリカのヨーロッパ植民地リスト 歴史上のアフリカの王国のリスト 旧宗主国のリスト フランスの領土と植民地のリスト その他のトピック 西欧の植民地主義と植民地化の分析 デュランライン アフリカ経済史 フランス植民地帝国 大英帝国史 国際関係(1814-1919年) 中国のためのスクランブル サイクス・ピコ協定 ヨーロッパ系白人アフリカ人 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scramble_for_Africa |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆