セファルディム

Sephardic Jews, Sephardim; セファルディユダヤ人

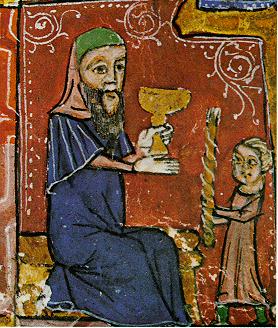

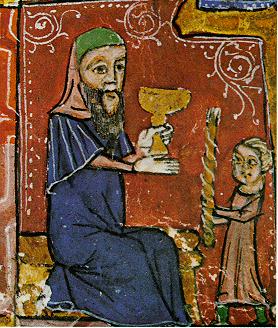

Observing the Havdalah ritual, 14th-century Spain / A representation of the 1506 Jewish Massacre in Lisbon.

☆ セファルディム(Sephardic Jews: יְהוּדֵי סְפָרַד、ローマ字表記: Yehudei Sfarad、訳:『スペインのユダヤ人』;ラディノ語:Djudíos Sefardíes)は、セファルディムまたはセファルディ人とも呼ばれ、イベリア半島ユダヤ人とも呼ばれることがあるが、イベリア半島(スペインとポル トガル)に関連するユダヤ人のディアスポラ集団である。この用語はヘブライ語のセファラド(スペインの意)に由来し、 また、中東および北アフリカのユダヤ人にも用いられることがあるが、彼らもまたセファルディの法や慣習に大きな影響を受けていた。イベリア半島の多くのユ ダヤ人亡命家族も後にそれらのユダヤ人社会に避難し、その結果、数世紀にわたってそれらの社会と民族や文化の統合が進んだ。セファルディの大多数はイスラ エルに住んでいる。イベリア半島のユダヤ人社会は、ウマイヤ朝によるヒスパニア征服の後、アル・アンダルスとしてイスラム教徒の支配下で数世紀にわたって 繁栄したが、スペインを奪還しようとするキリスト教徒のレコンキスタ運動により、その繁栄は衰退し始めた。1492年にはスペインのカトリック両王による アルハンブラ勅令がユダヤ人の追放を命じ、1496年にはポルトガルのマヌエル1世がユダヤ人とイスラム教徒の追放を命じる同様の勅令を発した。これらの 措置により、国内および国外への移住、大規模な改宗、処刑が相次いだ。15世紀後半までに、セファルディムのユダヤ人の多くはスペインから追放され、北ア フリカ、西アジア、南ヨーロッパ、南東ヨーロッパに散らばった。彼らは既存のユダヤ人コミュニティの近くに住み着いたり、シルクロード沿いなど、新天地の 開拓者として移住した。 歴史的に、セファルディムのユダヤ人と彼らの子孫の母国語は、スペイン語、ポルトガル語、カタルーニャ語の変種であったが、彼らは他の言語も採用し、適応 させてきた。セファルディムの異なるコミュニティが共通して話していたスペイン語の歴史的形態は、イベリア半島からの出発時期と、その時点での新キリスト 教徒またはユダヤ人としての地位に関連していた。 ユダヤ・スペイン語はラディノ語とも呼ばれ、1492年のスペイン追放後に東地中海に定住した東セファルディム・ユダヤ人が話していた旧スペイン語に由来 するロマンス語である。ハケティア語( アルジェリアでは「テトゥアニ・ラディーノ」とも呼ばれる)は、ユダヤ・スペイン語にアラブ語の影響を受けたもので、1492年のスペイン追放後に北アフ リカに移住したセファルディムが話していた。 追放から5世紀以上が経過した2015年、スペインとポルトガルは、両国に先祖代々住んでいたことを証明できるセファルディム系ユダヤ人に市民権を申請す ることを認める法律を制定した。セファルディム系ユダヤ人の子孫に市民権を与えるスペインの法律は2019年に失効したが、その後、スペイン政府は、新型 コロナウイルス感染症(COVID-19)のパンデミックにより、保留中の 書類を提出し、スペインの公証人の面前で遅延した申告書に署名できるようにした。 ポルトガルでは、2022年に国籍法が改正され、セファルディムの新規申請者に対する要件が非常に厳しくなった。ポルトガルへの個人旅行歴(以前の永住に 相当する)や、相続した不動産の所有、ポルトガル国内の関心事の証拠なしに申請が成功する可能性は事実上なくなった。

| Sephardic Jews

(Hebrew: יְהוּדֵי סְפָרַד, romanized: Yehudei Sfarad, transl. 'Jews of

Spain'; Ladino: Djudíos Sefardíes), also known as Sephardi Jews or

Sephardim,[a][1] and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews,[2] are a Jewish

diaspora population associated with the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and

Portugal).[2] The term, which is derived from the Hebrew Sepharad

(lit. 'Spain'), can also refer to the Jews of the Middle East and North

Africa, who were also heavily influenced by Sephardic law and

customs.[3] Many Iberian Jewish exiled families also later sought

refuge in those Jewish communities, resulting in ethnic and cultural

integration with those communities over the span of many centuries.[2]

The majority of Sephardim live in Israel.[4] The Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula prospered for centuries under the Muslim reign of Al-Andalus following the Umayyad conquest of Hispania, but their fortunes began to decline with the Christian Reconquista campaign to retake Spain. In 1492, the Alhambra Decree by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain called for the expulsion of Jews, and in 1496, King Manuel I of Portugal issued a similar edict for the expulsion of both Jews and Muslims.[5] These actions resulted in a combination of internal and external migrations, mass conversions, and executions. By the late 15th century, Sephardic Jews had been largely expelled from Spain and scattered across North Africa, Western Asia, Southern and Southeastern Europe, either settling near existing Jewish communities or as the first in new frontiers, such as along the Silk Road.[6] Historically, the vernacular languages of the Sephardic Jews and their descendants have been variants of either Spanish, Portuguese, or Catalan, though they have also adopted and adapted other languages. The historical forms of Spanish that differing Sephardic communities spoke communally were related to the date of their departure from Iberia and their status at that time as either New Christians or Jews. Judaeo-Spanish, also called Ladino, is a Romance language derived from Old Spanish that was spoken by the eastern Sephardic Jews who settled in the Eastern Mediterranean after their expulsion from Spain in 1492; Haketia (also known as "Tetuani Ladino" in Algeria), an Arabic-influenced variety of Judaeo-Spanish, was spoken by North African Sephardic Jews who settled in the region after the 1492 Spanish expulsion. In 2015, more than five centuries after the expulsion, both Spain and Portugal enacted laws allowing Sephardic Jews who could prove their ancestral origins in those countries to apply for citizenship.[7] The Spanish law that offered citizenship to descendants of Sephardic Jews expired in 2019, although subsequent extensions were granted by the Spanish government —due to the COVID-19 pandemic— in order to file pending documents and sign delayed declarations before a notary public in Spain.[8] In the case of Portugal, the nationality law was modified in 2022 with very stringent requirements for new Sephardic applicants,[9][10] effectively ending the possibility of successful applications without evidence of a personal travel history to Portugal —which is tantamount to prior permanent residence— or ownership of inherited property or concerns on Portuguese soil.[11] |

セファルディム(ヘブライ語: יְהוּדֵי

סְפָרַד、ローマ字表記: Yehudei Sfarad、訳:『スペインのユダヤ人』;ラディノ語:Djudíos

Sefardíes)は、セファルディムまたはセファルディ人とも呼ばれ、イベリア半島ユダヤ人とも呼ばれることがあるが、[2]

イベリア半島(スペインとポルトガル)に関連するユダヤ人のディアスポラ集団である。[2]

この用語はヘブライ語のセファラド(スペインの意)に由来し、

また、中東および北アフリカのユダヤ人にも用いられることがあるが、彼らもまたセファルディの法や慣習に大きな影響を受けていた。[3]

イベリア半島の多くのユダヤ人亡命家族も後にそれらのユダヤ人社会に避難し、その結果、数世紀にわたってそれらの社会と民族や文化の統合が進んだ。[2]

セファルディの大多数はイスラエルに住んでいる。[4] イベリア半島のユダヤ人社会は、ウマイヤ朝によるヒスパニア征服の後、アル・アンダルスとしてイスラム教徒の支配下で数世紀にわたって繁栄したが、スペイ ンを奪還しようとするキリスト教徒のレコンキスタ運動により、その繁栄は衰退し始めた。1492年にはスペインのカトリック両王によるアルハンブラ勅令が ユダヤ人の追放を命じ、1496年にはポルトガルのマヌエル1世がユダヤ人とイスラム教徒の追放を命じる同様の勅令を発した。[5] これらの措置により、国内および国外への移住、大規模な改宗、処刑が相次いだ。15世紀後半までに、セファルディムのユダヤ人の多くはスペインから追放さ れ、北アフリカ、西アジア、南ヨーロッパ、南東ヨーロッパに散らばった。彼らは既存のユダヤ人コミュニティの近くに住み着いたり、シルクロード沿いなど、 新天地の開拓者として移住した。 歴史的に、セファルディムのユダヤ人と彼らの子孫の母国語は、スペイン語、ポルトガル語、カタルーニャ語の変種であったが、彼らは他の言語も採用し、適応 させてきた。セファルディムの異なるコミュニティが共通して話していたスペイン語の歴史的形態は、イベリア半島からの出発時期と、その時点での新キリスト 教徒またはユダヤ人としての地位に関連していた。 ユダヤ・スペイン語はラディノ語とも呼ばれ、1492年のスペイン追放後に東地中海に定住した東セファルディム・ユダヤ人が話していた旧スペイン語に由来 するロマンス語である。ハケティア語( アルジェリアでは「テトゥアニ・ラディーノ」とも呼ばれる)は、ユダヤ・スペイン語にアラブ語の影響を受けたもので、1492年のスペイン追放後に北アフ リカに移住したセファルディムが話していた。 追放から5世紀以上が経過した2015年、スペインとポルトガルは、両国に先祖代々住んでいたことを証明できるセファルディム系ユダヤ人に市民権を申請す ることを認める法律を制定した。[7] セファルディム系ユダヤ人の子孫に市民権を与えるスペインの法律は2019年に失効したが、その後、スペイン政府は、新型コロナウイルス感染症 (COVID-19)のパンデミックにより、保留中の 書類を提出し、スペインの公証人の面前で遅延した申告書に署名できるようにした。[8] ポルトガルでは、2022年に国籍法が改正され、セファルディムの新規申請者に対する要件が非常に厳しくなった。[9][10] ポルトガルへの個人旅行歴(以前の永住に相当する)や、相続した不動産の所有、ポルトガル国内の関心事の証拠なしに申請が成功する可能性は事実上なくなっ た。[11] |

| Etymology The name Sephardi means "Spanish" or "Hispanic", derived from Sepharad (Hebrew: סְפָרַד, Modern: Sfarád, Tiberian: Səp̄āráḏ), a Biblical location.[12] The location of the Biblical Sepharad points to the Iberian peninsula, then the westernmost outpost of Phoenician maritime trade.[13] Jewish presence in Iberia is believed to have started during the reign of King Solomon,[14] whose excise imposed taxes on Iberian exiles. Although the first date of arrival of Jews in Iberia is the subject of ongoing archaeological research, there is evidence of established Jewish communities as early as the 1st century CE.[15] Modern transliteration of Hebrew romanizes the consonant פ (pe without a dagesh dot placed in its center) as the digraph ph, in order to represent fe or the single phoneme /f/ , the English sound that is voiceless labiodental fricative. In other languages and scripts, "Sephardi" may be translated as plural Hebrew: סְפָרַדִּים, Modern: Sfaraddim, Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm; Spanish: Sefardíes; Portuguese: Sefarditas; Catalan: Sefardites; Aragonese: Safardís; Basque: Sefardiak; French: Séfarades; Galician: Sefardís; Italian: Sefarditi; Greek: Σεφαρδίτες, Sephardites; Serbo-Croatian: Сефарди, Sefardi; Judaeo-Spanish: Sefaradies/Sefaradim; and Arabic: سفارديون, Safārdiyyūn. |

語源 セファルディ(Sephardi)という名称は、「スペイン」または「ヒスパニック」を意味し、聖書に登場するセファラド(Sepharad、ヘブライ 語:סְפָרַד、現代ヘブライ語:Sfarád、ティベリアンヘブライ語:Səpāráḏ)に由来する。聖書に登場するセファラドの位置はイベリア半 島を指しており、当時フェニキアの海上貿易の最西端の拠点であった。[13] イベリア半島におけるユダヤ人の存在は、ソロモン王の治世の間に始まったと考えられている。[14] ソロモン王はイベリア半島への亡命者に物品税を課した。 イベリア半島へのユダヤ人の最初の到着時期は現在も考古学的な研究が続けられているが、紀元1世紀には早くもユダヤ人コミュニティが存在していたことを示 す証拠がある。[15] 現代ヘブライ語の翻字では、無声唇歯摩擦音である英語の音/f/を表すため、子音字「פ(ペ)」の中央に点(ダゲシュ)を置かずに、二重文字「ph」とし て表記する。他の言語や文字では、「セファルディ」は複数形のヘブライ語: סְפָרַדִּים、現代ヘブライ語: Sfaraddim、ティベリアンヘブライ語: Səp̄āraddîm、スペイン語: Sefardíes、ポルトガル語: Sefarditas、カタロニア語: Sefardites、アラゴン語: Safardís、バスク語: Sefardiak、フランス語: Séfarades、ガリシア語: Sefardís、イタリア語:Sefarditi、ギリシャ語:Σεφαρδίτες、セルビア・クロアチア語:Сефарди、ヘブライ語: Sefardi、ユダヤ・スペイン語:Sefaradies/Sefaradim、アラビア語:سفارديون、Safārdiyyūn。 |

Definition Jewish Festival in Tetuan, Alfred Dehodencq, 1865, Paris Museum of Jewish Art and History Narrow ethnic definition In the narrower ethnic definition, a Sephardi Jew is one descended from the Jews who lived in the Iberian Peninsula in the late 15th century, immediately prior to the issuance of the Alhambra Decree of 1492 by order of the Catholic Monarchs in Spain, and the decree of 1496 in Portugal by order of King Manuel I. In Hebrew, the term "Sephardim Tehorim" (ספרדים טהורים, literally "Pure Sephardim"), derived from a misunderstanding of the initials ס"ט "Samekh Tet" traditionally used with some proper names (which stand for sofo tov, "may his end be good" or "sin v'tin", "mire and mud"[16][17] has in recent times been used in some quarters to distinguish Sephardim proper, "who trace their lineage back to the Iberian/Spanish population", from Sephardim in the broader religious sense.[18] This distinction has also been made in reference to 21st-century genetic findings in research on 'Pure Sephardim', in contrast to other communities of Jews today who are part of the broad classification of Sephardi.[19] Ethnic Sephardic Jews have had a presence in North Africa and various parts of the Mediterranean and Western Asia due to their expulsion from Spain. There have also been Sephardic communities in South America and India.[citation needed] Katalanim Originally the Jews spoke of Sefarad referring to Al-Andalus[20] and not the entire peninsula, nor as it is understood today, in which the term Sefarad is used in modern Hebrew to refer to Spain.[21] This has caused a long misunderstanding, since traditionally the entire Iberian Diaspora has been included in a single group. But the historiographical research reveals that that word, seen as homogeneous, was actually divided into distinct groups: the Sephardim, coming from the countries of the Castilian crown, Castilian language speakers, and the Katalanim [ca] / Katalaní, originally from the Crown of Aragon, Judeo-Catalan speakers.[22][23][24][25] Broad religious definition See also: Sephardic law and customs, Sephardic Haredim, Maghrebi Jews, Mashriqi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, and Jewish ethnic divisions The modern Israeli Hebrew definition of Sephardi is a much broader, religious based, definition that generally excludes ethnic considerations. In its most basic form, this broad religious definition of a Sephardi refers to any Jew, of any ethnic background, who follows the customs and traditions of Sepharad. For religious purposes, and in modern Israel, "Sephardim" is most often used in this wider sense. It encompasses most non-Ashkenazi Jews who are not ethnically Sephardi, but are in most instances of West Asian or North African origin. They are classified as Sephardi because they commonly use a Sephardic style of liturgy; this constitutes a majority of Mizrahi Jews in the 21st century. The term Sephardi in the broad sense, describes the nusach (Hebrew language, "liturgical tradition") used by Sephardi Jews in their Siddur (prayer book). A nusach is defined by a liturgical tradition's choice of prayers, order of prayers, text of prayers and melodies used in the singing of prayers. Sephardim traditionally pray using Minhag Sefarad. The term Nusach Sefard or Nusach Sfarad does not refer to the liturgy generally recited by Sephardim proper or even Sephardi in a broader sense, but rather to an alternative Eastern European liturgy used by many Hasidim, who are Ashkenazi. Additionally, Ethiopian Jews, whose branch of practiced Judaism is known as Haymanot, have been included under the oversight of Israel's already broad Sephardic Chief Rabbinate. |

定義 テトゥアンのユダヤ人祭り、アルフレッド・ドゥオダンク、1865年、パリ・ユダヤ芸術歴史博物館 狭義の民族定義 狭義の民族定義では、セファルディム・ユダヤ人とは、1492年にスペインのカトリック両王の命によりアルハンブラ勅令が発令され、1496年にポルトガ ルのマヌエル1世の命によりポルトガル勅令が発令される直前の15世紀後半にイベリア半島に住んでいたユダヤ人の子孫である。 ヘブライ語では、「セファルディム・テオリム」(Sephardim Tehorim、文字通り「純粋なセファルディム」)という用語は、伝統的に固有名詞の一部として使用されてきた「セメク・テト」(Samekh Tet)という頭文字の誤解に由来する。「セメク・テト」は、「彼の最期が良いものでありますように」(sofo tov)または「泥と泥」(sin v'tin)を意味する。 )は、近年では「セファルディム」という用語を、広義の宗教的な意味でのセファルディムと区別して、「イベリア半島/スペインの住民にまで家系を遡ること ができるセファルディム」を指すために一部で使用されている。[18] この区別は、21世紀の遺伝学的研究における「純粋なセファルディム」に関する研究においてもなされており、広義のセファルディムに分類される今日のユダ ヤ人コミュニティとは対照的に位置づけられている。[19] スペインから追放されたことにより、セファルディム系ユダヤ人は北アフリカや地中海、西アジアの各地に居住するようになった。また、南米やインドにもセ ファルディム系ユダヤ人のコミュニティが存在している。 カタラン人 もともとユダヤ人は、アル・アンダルスを指してセファラード(Sefarad)と語っていたが[20]、半島全体を指していたわけではなく、また今日理解 されているような意味でもなかった。セファラードという用語は、現代ヘブライ語ではスペインを指して使われている。[21] 伝統的にイベリア半島のディアスポラ全体がひとつのグループに含まれていたため、このことが長い誤解の原因となってきた。しかし、歴史学的研究により、同 質的と見なされていたこの集団は、実際には明確に異なるグループに分かれていたことが明らかになっている。すなわち、カスティーリャ王国の諸国出身のセ ファルディム、カスティーリャ語話者、そしてアラゴン王国出身のカタラン人(カタルーニャ人)[ca] / カタラニ(カタルーニャ語話者)[22][23][24][25]である。 広義の宗教的定義 関連項目:セファルディの法律と習慣、セファルディ・ハレディーム、マグレブ系ユダヤ人、マシュリク系ユダヤ人、ミズラヒム、ユダヤ人の民族区分 現代のイスラエルにおけるヘブライ語でのセファルディの定義は、民族的な要素を排除した、より広義で宗教的な定義である。最も基本的な形では、この広義の 宗教的なセファルディの定義は、セファラドの習慣や伝統に従うあらゆる民族背景を持つユダヤ人を指す。宗教的な目的や現代のイスラエルでは、「セファル ディム」は通常、この広義の意味で使用される。この広義のセファルディムには、セファルディムの民族に属さない非アシュケナジム系ユダヤ人の大半が含まれ るが、そのほとんどは西アジアまたは北アフリカ出身である。彼らはセファルディムの典礼様式を一般的に用いているため、セファルディムに分類される。これ は21世紀のミズラヒムのユダヤ人の大半を占める。 広義の「セファルディ」という用語は、セファルディ・ユダヤ人がシッドゥール(祈祷書)で用いるヌサフ(ヘブライ語、「典礼の伝統」)を指す。 ヌサフは、典礼の伝統における祈祷の選択、祈祷の順序、祈祷のテキスト、祈祷の歌で用いられる旋律によって定義される。 セファルディムは伝統的にミンハグ・セファラドを用いて祈りを捧げる。 Nusach SefardまたはNusach Sfaradという用語は、セファルディム(セファルディ人)が一般的に唱える典礼を指すのではなく、より広義のセファルディ人、すなわちアシュケナジム のハシディズムの多くが用いる東ヨーロッパの代替典礼を指す。 さらに、エチオピア系ユダヤ人は、その実践するユダヤ教の宗派がハイマノットとして知られているが、イスラエルの広範なセファルディ・チーフ・ラビナート の監督下に組み込まれている。 |

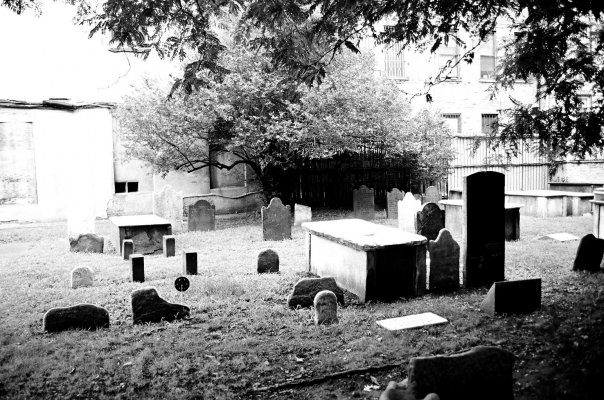

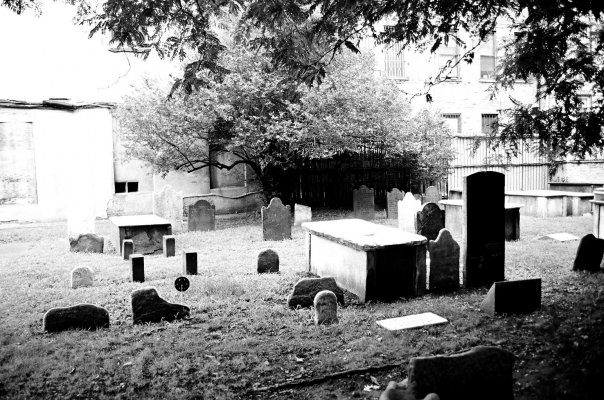

| Divisions The divisions among Sephardim and their descendants today are largely a result of the consequences of the royal edicts of expulsion. Both the Spanish and Portuguese crowns ordered their respective Jewish subjects to choose one of two options: to convert to Catholicism and be allowed to remain within the kingdom, or to remain Jewish and leave or be expelled by the stipulated deadline. In the case of the Alhambra Decree of 1492, the primary purpose was to eliminate Jewish influence on Spain's large converso population, and ensure they did not revert to Judaism. Over half of Spain's Jews had converted in the 14th century as a result of the religious persecution and pogroms which occurred in 1391. They and their Catholic descendants were not subject to the Decree or to expulsion, yet were surveilled by the Spanish Inquisition. British scholar Henry Kamen has said that "the real purpose of the 1492 edict likely was not expulsion, but compulsory conversion and assimilation of all Spanish Jews, a process which had been underway for a number of centuries. Indeed, a further number of those Jews who had not yet joined the converso community finally chose to convert and avoid expulsion as a result of the edict. As a result of the Alhambra decree and persecution during the prior century, between 200,000 and 250,000 Jews converted to Catholicism and between one third and one half of Spain's remaining 100,000 non-converted Jews chose exile, with an indeterminate number returning to Spain in the years following the expulsion."[26]  "The Banishment of the Jews", by Roque Gameiro, in Quadros da História de Portugal ("Pictures of the History of Portugal", 1917). The Portuguese king John II welcomed the Jewish refugees from Spain with the purpose of obtaining specialized artisans, which the Portuguese population lacked, imposing over them, however, a hefty fee for the right to stay in the country. His successor King Manuel I proved, at first, to also tolerate the Jewish population. However, King Manuel I issued his own expulsion decree four years later, presumably to satisfy a precondition that the Spanish monarchs had set for him in order to allow him to marry their daughter Isabella. While the stipulations were similar in the Portuguese decree, King Manuel largely prevented Portugal's Jews from leaving, by blocking Portugal's ports of exit, foreseeing a negative economic effect of a similar Jewish flight from Portugal. He decided that the Jews who stayed accepted Catholicism by default, proclaiming them New Christians by royal decree. Physical forced conversions, however, were also suffered by Jews throughout Portugal. These persecutions led to several recently converted families to flee Portugal, such as the family of Francisco Sanches who fled to Bordeaux. Sephardi Jews encompass Jews descended from those Jews who left the Iberian Peninsula as Jews by the expiration of the respective decreed deadlines. This group is further divided between those who fled south to North Africa, as opposed to those who fled eastwards to the Balkans, West Asia and beyond. Others fled east into Europe, with many settling in northern Italy and the Low Countries. Also included among Sephardi Jews are those who descend from "New Christian" conversos, but returned to Judaism after leaving Iberia, largely after reaching Southern and Western Europe.[citation needed] From these regions, many later migrated again, this time to the non-Iberian territories of the Americas. Additional to all these Sephardic Jewish groups are the descendants of those New Christian conversos who either remained in Iberia, or moved from Iberia directly to the Iberian colonial possessions in what are today the various Latin American countries. For historical reasons and circumstances, most of the descendants of this group of conversos never formally returned to the Jewish religion. All these sub-groups are defined by a combination of geography, identity, religious evolution, language evolution, and the timeframe of their reversion (for those who had in the interim undergone a temporary nominal conversion to Catholicism) or non-reversion back to Judaism. These Sephardic sub-groups are separate from any pre-existing local Jewish communities they encountered in their new areas of settlement. From the perspective of the present day, the first three sub-groups appeared to have developed as separate branches, each with its own traditions. In earlier centuries, and as late as the editing of the Jewish Encyclopedia at the beginning of the 20th century, the Sephardim were usually regarded as together forming a continuum. The Jewish community of Livorno, Italy acted as the clearing-house of personnel and traditions among the first three sub-groups; it also developed as the chief publishing centre.[improper synthesis?] Eastern Sephardim Main article: Eastern Sephardim  Sephardi Jewish couple from Sarajevo in traditional clothing (1900) Eastern Sephardim comprise the descendants of the expellees from Spain who left as Jews in 1492 or earlier. This sub-group of Sephardim settled mostly in various parts of the Ottoman Empire, which then included areas in West Asia's Near East such as Anatolia, the Levant and Egypt; in Southeastern Europe, some of the Dodecanese islands and the Balkans. They settled particularly in European cities ruled by the Ottoman Empire, including Salonica in present-day Greece; Constantinople, which today is known as Istanbul on the European portion of modern Turkey; and Sarajevo, in what is today Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sephardic Jews also lived in Bulgaria, where they absorbed into their community the Romaniote Jews they found already living there. They had a presence as well in Walachia in what is today southern Romania, where there is still a functioning Sephardic Synagogue.[27] Their traditional language is referred to as Judezmo ("Jewish [language]"). It is Judaeo-Spanish, sometimes also known as Ladino, which consisted of the medieval Spanish and Portuguese they spoke in Iberia, with admixtures of Hebrew, and the languages around them, especially Turkish. This Judeo-Spanish language was often written in Rashi script.  A 1902 Issue of La Epoca, a Ladino newspaper from Salonica (Thessaloniki) Regarding the Middle East, some Sephardim went further east into the West Asian territories of the Ottoman Empire, settling among the long-established Arabic-speaking Jewish communities in Damascus and Aleppo in Syria, as well as in the Land of Israel, and as far as Baghdad in Iraq. Although technically Egypt was a North African Ottoman region, those Jews who settled in Alexandria are included in this group, due to Egypt's cultural proximity to the other West Asian provinces under Ottoman rule. For the most part, Eastern Sephardim did not maintain their own separate Sephardic religious and cultural institutions from pre-existing Jews. Instead the local Jews came to adopt the liturgical customs of the recent Sephardic arrivals. Eastern Sephardim in European areas of the Ottoman Empire, as well as in Palestine, retained their culture and language, but those in the other parts of the West Asian portion gave up their language and adopted the local Judeo-Arabic dialect. This latter phenomenon is just one of the factors which have today led to the broader and eclectic religious definition of Sephardi Jews. Thus, the Jewish communities in Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Egypt are partly of Spanish Jewish origin and they are counted as Sephardim proper. The great majority of the Jewish communities in Iraq, and all of those in Iran, Eastern Syria, Yemen, and Eastern Turkey, are descendants of pre-existing indigenous Jewish populations. They adopted the Sephardic rites and traditions through cultural diffusion, and are properly termed Mizrahi Jews.[citation needed] Going even further into South Asia, a few of the Eastern Sephardim followed the spice trade routes as far as the Malabar coast of southern India, where they settled among the established Cochin Jewish community. Their culture and customs were absorbed by the local Jews. [citation needed]. Additionally, there was a large community of Jews and crypto-Jews of Portuguese origin in the Portuguese colony of Goa. Gaspar Jorge de Leão Pereira, the first archbishop of Goa, wanted to suppress or expel that community, calling for the initiation of the Goa Inquisition against the Sephardic Jews in India. In recent times, principally after 1948, most Eastern Sephardim have since relocated to Israel, and others to the US and Latin America. Eastern Sephardim still often carry common Spanish surnames, as well as other specifically Sephardic surnames from 15th-century Spain with Arabic or Hebrew language origins (such as Azoulay, Abulafia, Abravanel) which have since disappeared from Spain when those that stayed behind as conversos adopted surnames that were solely Spanish in origin. Other Eastern Sephardim have since also translated their Hispanic surnames into the languages of the regions they settled in, or have modified them to make them sound more local. North African Sephardim  19th-century Moroccan Sephardic wedding dress Main article: North African Sephardim North African Sephardim consists of the descendants of the expellees from Spain who also left as Jews in 1492. This branch settled in North Africa (except Egypt, see Eastern Sephardim above). Settling mostly in Morocco and Algeria, they spoke a variant of Judaeo-Spanish known as Haketia. They also spoke Judeo-Arabic in a majority of cases. They settled in the areas with already established Arabic-speaking Jewish communities in North Africa and eventually merged with them to form new communities based solely on Sephardic customs.[citation needed] Several of the Moroccan Jews emigrated back to the Iberian Peninsula to form the core of the Gibraltar Jews.[citation needed] In the 19th century, modern Spanish, French and Italian gradually replaced Haketia and Judeo-Arabic as the mother tongue among most Moroccan Sephardim and other North African Sephardim.[28] In recent times, with the Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries, principally after the creation of Israel in 1948, most North African Sephardim have relocated to Israel (total pop. est. 1,400,000 in 2015), and most others to France (361,000)[29] and the US (300,000), as well as other countries. As of 2015 there was a significant community still in Morocco (10,000).[30] In 2021, among Arab countries, the largest Jewish community now exists in Morocco with about 2,000 Jews and in Tunisia with about 1,000.[31] North African Sephardim still also often carry common Spanish surnames, as well as other specifically Sephardic surnames from 15th century Spain with Arabic or Hebrew language origins (such as Azoulay, Abulafia, Abravanel) which have since disappeared from Spain when those that stayed behind as conversos adopted surnames that were solely Spanish in origin. Other North African Sephardim have since also translated their Hispanic surnames into local languages or have modified them to sound local.[citation needed] Western Sephardim Main article: Spanish and Portuguese Jews See also: Anusim, Marrano, and Crypto-Judaism  First Cemetery of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, Shearith Israel (1656–1833) in Manhattan, New York City  Emma Lazarus, American poet, born into a large New York Sephardi family. Western Sephardim (also known more ambiguously as "Spanish and Portuguese Jews", "Spanish Jews", "Portuguese Jews" and "Jews of the Portuguese Nation") are the community of Jewish ex-conversos whose families initially remained in Spain and Portugal as ostensible New Christians,[32][33] that is, as Anusim or "forced [converts]". Western Sephardim are further sub-divided into an Old World branch and a New World branch. Henry Kamen and Joseph Perez estimate that of the total Jewish origin population of Spain at the time of the issuance of the Alhambra Decree, those who chose to remain in Spain represented the majority, up to 300,000 of a total Jewish origin population of 350,000.[34] Furthermore, a significant number returned to Spain in the years following the expulsion, on condition of converting to Catholicism, the Crown guaranteeing they could recover their property at the same price at which it was sold. Discrimination against this large community of conversos nevertheless remained, and those who secretly practiced the Jewish faith specifically suffered severe episodes of persecution by the Inquisition. The last such episode of persecution occurred in the mid-18th century. External migrations out of the Iberian peninsula coincided with these episodes of increased persecution by the Inquisition. As a result of this discrimination and persecution, a small number of marranos (conversos who secretly still practiced Judaism) later emigrated to more religiously tolerant Old World countries outside the Iberian cultural sphere, such as the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Italy, Germany and England.[citation needed] In these lands conversos reverted to Judaism, rejoining the Jewish community sometimes up to the third or even fourth generations after the initial decrees stipulating conversion, expulsion, or death. It is these returnees to Judaism that represent Old World Western Sephardim. Among this community of Sephardic Jews, the philosopher Baruch de Spinoza was born from a Portuguese Jewish family. He was also, famously, expelled from said community over his religious and philosophical views. New World Western Sephardim, on the other hand, are the descendants of those Jewish-origin New Christian conversos who accompanied the millions of Old Christian Spaniards and Portuguese that emigrated to the Americas. More specifically, New World Western Sephardim are those Western Sephardim whose converso ancestors migrated to various of the non-Iberian colonies in the Americas in whose jurisdictions they could return to Judaism. New World Western Sephardim are juxtaposed to yet another group of descendants of conversos who settled in the Iberian colonies of the Americas who could not revert to Judaism. These comprise the related but distinct group known as Sephardic Bnei Anusim (see the section below). Due to the presence of the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisition in the Iberian American territories, initially, converso immigration was barred throughout much of Ibero-America. Because of this, very few converso immigrants in Iberian American colonies ever reverted to Judaism. Of those conversos in the New World who did return to Judaism, it was principally those who had come via an initial respite of refuge in the Netherlands and/or who were settling the New World Dutch colonies such as Curaçao and the area then known as New Holland (also called Dutch Brazil). Dutch Brazil was the northern portion of the colony of Brazil ruled by the Dutch for under a quarter of a century before it also fell to the Portuguese who ruled the remainder of Brazil. Jews who had only recently reverted in Dutch Brazil then again had to flee to other Dutch-ruled colonies in the Americas, including joining brethren in Curaçao, but also migrating to New Amsterdam, in what is today Lower Manhattan in New York City. The oldest congregations in the non-Iberian colonial possessions in the Americas were founded by Western Sephardim, many who arrived in the then Dutch-ruled New Amsterdam, with their synagogues being in the tradition of "Spanish and Portuguese Jews". In the United States in particular, Congregation Shearith Israel, established in 1654, in what is now New York City, is the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States. Its present building dates from 1897. Congregation Jeshuat Israel in Newport, Rhode Island, is dated to sometime after the arrival of Western Sephardim there in 1658 and prior to the 1677 purchase of a communal cemetery, now known as Touro Cemetery. See also List of the oldest synagogues in the United States. The intermittent period of residence in Portugal (after the initial fleeing from Spain) for the ancestors of many Western Sephardim (whether Old World or New World) is a reason why the surnames of many Western Sephardim tend to be Portuguese variations of common Spanish surnames, though some are still Spanish. Among a few notable figures with roots in Western Sephardim are the current president of Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro, and former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, Benjamin N. Cardozo. Both descend from Western Sephardim who left Portugal for the Netherlands, and in the case of Maduro, from the Netherlands to Curaçao, and ultimately Venezuela. Sephardic Bnei Anusim Main article: Sephardic Bnei Anusim See also: Converso and New Christian  Sephardi family from Misiones Province, Argentina, circa 1900. The Sephardic Bnei Anusim consists of the contemporary and largely nominal Christian descendants of assimilated 15th century Sephardic anusim. These descendants of Spanish and Portuguese Jews forced or coerced to convert to Catholicism remained, as conversos, in Iberia or moved to the Iberian colonial possessions across various Latin American countries during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. Due to historical reasons and circumstances, Sephardic Bnei Anusim had not been able to return to the Jewish faith over the last five centuries,[35] although increasing numbers have begun emerging publicly in modern times, especially over the last two decades. Except for varying degrees of putatively rudimentary Jewish customs and traditions which had been retained as family traditions among individual families, Sephardic Bnei Anusim became a fully assimilated sub-group within the Iberian-descended Christian populations of Spain, Portugal, Hispanic America and Brazil. In the last 5 to 10 years,[when?] however, "organized groups of [Sephardic] Benei Anusim in Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Dominican Republic and in Sefarad [Iberia] itself"[36] have now been established, some of whose members have formally reverted to Judaism, leading to the emergence of Neo-Western Sephardim (see group below). The Jewish Agency for Israel estimates the Sephardic Bnei Anusim population to number in the millions.[37] Their population size is several times larger than the three Jewish-integrated Sephardi descendant sub-groups combined, consisting of Eastern Sephardim, North African Sephardim, and the ex-converso Western Sephardim (both New World and Old World branches). Although numerically superior, Sephardic Bnei Anusim is, however, the least prominent or known sub-group of Sephardi descendants. Sephardic Bnei Anusim are also more than twice the size of the total world Jewish population as a whole, which itself also encompasses Ashkenazi Jews, Mizrahi Jews and various other smaller groups. Unlike the Anusim ("forced [converts]") who were the conversos up to the third, fourth or fifth generation (depending on the Jewish responsa) who later reverted to Judaism, the Bnei Anusim ("[later] sons/children/descendants [of the] forced [converts]") were the subsequent generations of descendants of the Anusim who remained hidden ever since the Inquisition in the Iberian Peninsula and its New World franchises. At least some Sephardic Anusim in the Hispanosphere (in Iberia, but especially in their colonies in Ibero-America) had also initially tried to revert to Judaism, or at least maintain crypto-Jewish practices in privacy. This, however, was not feasible long-term in that environment, as Judaizing conversos in Iberia and Ibero-America remained persecuted, prosecuted, and liable to conviction and execution. The Inquisition itself was only finally formally disbanded in the 19th century. Historical documentation shedding new light on the diversity in the ethnic composition of the Iberian immigrants to the Spanish colonies of the Americas during the conquest era suggests that the number of New Christians of Sephardi origin that actively participated in the conquest and settlement was more significant than previously estimated. A number of Spanish conquerors, administrators, settlers, have now been confirmed to have been of Sephardi origin. [citation needed] Recent revelations have only come about as a result of modern DNA evidence and newly discovered records in Spain, which had been either lost or hidden, relating to conversions, marriages, baptisms, and Inquisition trials of the parents, grandparents and great-grandparents of the Sephardi-origin Iberian immigrants. Overall, it is now estimated that up to 20% of modern-day Spaniards and 10% of colonial Latin America's Iberian settlers may have been of Sephardic origin, although the regional distribution of their settlement was uneven throughout the colonies. Thus, Iberian settlers of New Christian Sephardi-origin ranged anywhere from none in most areas to as high as 1 in every 3 (approx. 30%) Iberian settlers in other areas. With Latin America's current population standing at close to 590 million people, the bulk of which consists of persons of full or partial Iberian ancestry (both New World Hispanics and Brazilians, whether they're criollos, mestizos or mulattos), it is estimated that up to 50 million of these possess Sephardic Jewish ancestry to some degree. In Iberia, settlements of known and attested populations of Bnei Anusim include those in Belmonte, in Portugal, and the Xuetes of Palma de Mallorca, in Spain. In 2011 Rabbi Nissim Karelitz, a leading rabbi and Halachic authority and chairman of the Beit Din Tzedek rabbinical court in Bnei Brak, Israel, recognized the entire Xuete community of Bnei Anusim in Palma de Mallorca, as Jews.[38] That population alone represented approximately 18,000 to 20,000 people,[39] or just over 2% of the entire population of the island. The proclamation of the Jews' default acceptance of Catholicism by the Portuguese king actually resulted in a high percentage being assimilated into the Portuguese population. Besides the Xuetas, the same is true of Spain. Many of their descendants observe a syncretist form of Christian worship known as Xueta Christianity.[40][41][42][43] Almost all Sephardic Bnei Anusim carry surnames which are known to have been used by Sephardim during the 15th century. However, almost all of these surnames are not specifically Sephardic per se, and most are in fact surnames of gentile Spanish or gentile Portuguese origin which only became common among Bnei Anusim because they deliberately adopted them during their conversions to Catholicism, in an attempt to obscure their Jewish heritage. Given that conversion made New Christians subject to Inquisitorial prosecution as Catholics, crypto-Jews formally recorded Christian names and gentile surnames to be publicly used as their aliases in notarial documents, government relations and commercial activities, while keeping their given Hebrew names and Jewish surnames secret.[44] As a result, very few Sephardic Bnei Anusim carry surnames that are specifically Sephardic in origin, or that are exclusively found among Bnei Anusim. |

区分 セファルディムとその子孫の現在の区分は、追放令の結果によるものが大きい。スペインとポルトガルの両王は、それぞれの国のユダヤ教徒に対して、2つの選 択肢のどちらかを選ぶよう命じた。 カトリックに改宗し王国内に留まるか、 ユダヤ教のままで期限内に国を出るか追放されるか、 1492年のアルハンブラ勅令の場合、主な目的はスペイン国内の多数派を占めるコンベルソ(改宗ユダヤ教徒)のユダヤ教への影響力を排除し、彼らがユダヤ 教に回帰しないようにすることだった。1391年に発生した宗教迫害と暴動の結果、14世紀にはスペインのユダヤ人の半数以上が改宗していた。彼らと彼ら のカトリック教徒の子孫は、この法令の対象外であり、追放されることもなかったが、スペイン異端審問の監視下に置かれた。英国の学者ヘンリー・カーメン は、 「1492年の勅令の真の目的は、追放ではなく、スペイン在住のユダヤ人全員の強制改宗と同化であった可能性が高い。実際、コンベルソ(キリスト教に改宗 したユダヤ人)のコミュニティに加わっていなかった多くのユダヤ人が、この勅令の結果、最終的に改宗して追放を免れることを選んだ。アルハンブラ勅令と前 世紀の迫害の結果、20万から25万人のユダヤ人がカトリックに改宗し、スペインに残った10万人の改宗しなかったユダヤ人の3分の1から2分の1が追放 を選び、追放後の数年間に不確定な人数がスペインに戻った。」[26]  「ユダヤ人の追放」ロケ・ガメイロ著、ポルトガルの歴史の絵画(1917年) ポルトガル王ジョアン2世は、ポルトガルに不足していた専門職人を得る目的でスペインからのユダヤ人難民を歓迎したが、国内に滞在する権利を得るには高額 な料金を支払う必要があった。彼の後継者マヌエル1世も当初はユダヤ人に対して寛容であった。しかし、マヌエル1世は4年後に追放令を発布した。これは、 スペイン王女イザベラとの結婚を認めるためにスペイン王が課した条件を満たすためだったと思われる。ポルトガル王令の条件はスペイン王令と類似していた が、マヌエル1世はポルトガルの港を封鎖し、ポルトガルからの同様のユダヤ人の流出による経済的悪影響を予測して、ポルトガルのユダヤ人が国外に出ること をほぼ阻止した。彼は、残ったユダヤ人は自動的にカトリックに改宗したと見なし、勅令によって彼らを「新キリスト教徒」と宣言した。しかし、物理的な強制 改宗もポルトガル中のユダヤ人が経験した。こうした迫害により、最近改宗したフランシスコ・サンチェス(Francisco Sanches)の家族のように、ポルトガルを逃れた家族もいた。 セファルディム(Sephardi)のユダヤ人とは、イベリア半島を離れる際にユダヤ人であった人々の子孫である。このグループはさらに、北アフリカに逃 れた者と、バルカン半島や西アジア、その他の地域に東に逃れた者とに分かれる。また、東ヨーロッパに逃れた者もおり、その多くは北イタリアやネーデルラン トに定住した。セファルディムには、イベリア半島を離れた後にキリスト教に改宗した「新キリスト教徒」コンベルソの子孫で、イベリア半島を離れた後にユダ ヤ教に復帰した者も含まれる。 これらの地域から、後に多くの人々が再び移住した。今度はアメリカ大陸のイベリア半島以外の地域へである。 これらすべてのセファルディム系ユダヤ人グループに加えて、イベリア半島に残ったか、あるいはイベリア半島から直接、現在のラテンアメリカ諸国であるイベ リア半島の植民地に移住した新キリスト教改宗者の子孫がいる。歴史的な理由と状況により、この改宗者グループの子孫のほとんどは、正式にユダヤ教に復帰す ることはなかった。 これらのサブグループはすべて、地理、アイデンティティ、宗教的変遷、言語の変遷、および(その間に一時的にカトリックへの名目上の改宗をした人々につい ては)ユダヤ教への復帰、または非復帰の時期によって定義される。 これらのセファルディムのサブグループは、彼らが移住した先の地域に元から存在していたユダヤ人コミュニティとは別個のものである。今日から見ると、最初 の3つのサブグループはそれぞれ独自の伝統を持つ別々の分派として発展してきたように見える。 それ以前の数世紀の間、そして20世紀初頭の『ユダヤ百科事典』の編集時まで、セファルディムは通常、ひとつの連続体としてみなされていた。イタリアのリ ヴォルノのユダヤ人社会は、最初の3つのサブグループ間の人材と伝統の交流の場として機能し、また主要な出版センターとしても発展した。[不適切な合成? 東セファルディム 詳細は「東セファルディム」を参照  サラエヴォのセファルディム系ユダヤ人カップル(1900年)の伝統衣装 東セファルディムは、1492年またはそれ以前にスペインから追放されたユダヤ人の子孫である。このセファルディムのサブグループは、主にアナトリア、レ バント、エジプトなど西アジアの近東地域を含むオスマン帝国の各地方、および南東ヨーロッパのドデカネス諸島やバルカン半島に定住した。彼らは特に、オス マン帝国が支配していたヨーロッパの都市に定住した。その中には、現在のギリシャのテッサロニキ、現在のトルコのヨーロッパ部分にあるイスタンブールとし て知られるコンスタンティノープル、現在のボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナのサラエヴォなどが含まれる。セファルディムのユダヤ人はブルガリアにも居住し、すで にそこに住んでいたロマニート(ギリシャ系ユダヤ人)を自分たちのコミュニティに吸収していった。彼らは、現在のルーマニア南部にあたるワラキアにも居住 しており、現在でもセファルディムのシナゴーグが機能している。彼らの伝統的な言語はジュデズモ(「ユダヤ人の言語」)と呼ばれる。これは、イベリア半島 で話されていた中世のスペイン語とポルトガル語にヘブライ語や周囲の言語、特にトルコ語が混ざったユダヤ・スペイン語であり、ラディーノ語とも呼ばれる。 このユダヤ・スペイン語は、ラシ文字で書かれることが多かった。  1902年発行のラ・エポカ紙(ラディーノ語の新聞、テッサロニキ(現・ギリシャの都市)発 中東に関しては、セファルディムの一部はさらに東のオスマン帝国の西アジア領土に入り、シリアのダマスカスやアレッポ、イスラエル、さらにはイラクのバグ ダッドにまで存在した、古くからあるアラブ語を話すユダヤ人コミュニティの間に定住した。厳密にはエジプトは北アフリカのオスマン帝国領であったが、アレ キサンドリアに定住したユダヤ人は、オスマン帝国支配下の他の西アジアの州とエジプトの文化が近かったため、このグループに含まれる。 概して、東セファルディムは既存のユダヤ教徒とは別に、独自のセファルディムの宗教的・文化的機関を維持することはなかった。むしろ、地元のユダヤ教徒 は、最近到着したセファルディムの典礼上の慣習を取り入れるようになった。オスマン帝国のヨーロッパ地域やパレスチナに居住した東セファルディムは、自分 たちの文化と言語を保持したが、西アジアの他の地域に居住したセファルディムは、自分たちの言語を放棄し、現地のユダヤ・アラブ語の方言を採用した。この 後者の現象は、今日セファルディムの宗教的定義がより広範で折衷的なものになっている要因のひとつに過ぎない。 そのため、パレスチナ、レバノン、シリア、エジプトのユダヤ人コミュニティは、スペイン系ユダヤ人の子孫であり、正統なセファルディムとして数えられる。 イラクのユダヤ人コミュニティの大半、およびイラン、東シリア、イエメン、トルコ東部のユダヤ人コミュニティはすべて、先住のユダヤ人集団の子孫である。 彼らは文化の拡散を通じてセファルディムの儀式や伝統を取り入れ、正統なミズラヒム(Mizrahi Jews)と呼ばれるようになった。 さらに南アジアに目を向けると、東セファルディムの一部は香辛料貿易のルートに従ってインド南部のマラバル海岸まで行き、そこでコチン・ユダヤ人コミュニ ティに定住した。彼らの文化や習慣は現地のユダヤ人に吸収された。さらに、ポルトガル領ゴアにはポルトガル系ユダヤ人と隠れユダヤ人の大きなコミュニティ があった。ゴアの初代大司教ガスパール・ジョルジェ・デ・レオン・ペレイラは、このコミュニティを弾圧または追放しようとし、インドのセファルディム系ユ ダヤ人に対するゴア異端審問の開始を求めた。 近年では、主に1948年以降、ほとんどの東セファルディムはイスラエルに移住し、その他は米国やラテンアメリカに移住した。 東セファルディムの人々は、現在でもスペインの一般的な名字を名乗っていることが多いが、その他にも、15世紀のスペインでアラビア語やヘブライ語を起源 とするセファルディム特有の名字(アズーライ、アブラファエル、アブラヴァネルなど)も存在する。これらの名字は、スペインに残ったコンベルソ(隠れキリ シタン)がスペイン起源の名字のみを名乗るようになったため、スペインでは現在では消滅している。それ以降、他の東セファルディムの人々は、定住した地域 の言語にヒスパニック系の姓を翻訳したり、より現地の言葉に聞こえるように変更したりしている。 北アフリカのセファルディム  19世紀のモロッコのセファルディムの結婚式の衣装 詳細は「北アフリカのセファルディム」を参照 北アフリカのセファルディムは、1492年にスペインから追放されたユダヤ人たちの子孫である。この一派は北アフリカ(エジプトを除く、上記東セファル ディムを参照)に定住した。主にモロッコとアルジェリアに定住した彼らは、ハケティアと呼ばれるユダヤ・スペイン語の方言を話していた。また、ユダヤ・ア ラビア語も話していた場合がほとんどであった。彼らは北アフリカで既に確立されていたアラビア語を話すユダヤ人コミュニティのある地域に定住し、最終的に は彼らと合併して、セファルディムの習慣のみに基づく新たなコミュニティを形成した。 モロッコ系ユダヤ人の一部はイベリア半島に戻り、ジブラルタル系ユダヤ人の中心となった。 19世紀には、モロッコ系セファルディムやその他の北アフリカ系セファルディムの多くが、ハケティア語やユダヤ・アラビア語に代わって、スペイン語、フラ ンス語、イタリア語を母語として使用するようになった。 近年では、1948年のイスラエル建国を機にアラブ諸国やイスラム諸国から多くのユダヤ人が流出したため、北アフリカのセファルディムのほとんどがイスラ エルに移住し(2015年の推定総人口は140万人)、その他ほとんどがフランス(36万1000人)[29]や米国(30万人)をはじめとする他の国々 へ移住した。2015年の時点で、モロッコには依然として大きなコミュニティが存在している(1万人)。[30] 2021年現在、アラブ諸国の中で最大のユダヤ人コミュニティはモロッコに約2,000人、チュニジアに約1,000人存在している。[31] 北アフリカのセファルディムは、現在でもスペイン系の一般的な名字を名乗っていることが多い。また、15世紀のスペインに起源を持つセファルディム特有の 名字(アズーライ、アブラファ、アブラバネルなど)も名乗っているが、これらはスペインから姿を消した。スペインに残ったコンベルソたちがスペイン起源の 名字のみを名乗るようになったためである。また、他の北アフリカのセファルディムは、それ以来、ヒスパニック系の名字を現地の言語に翻訳したり、現地の言 葉に聞こえるように変更したりしている。 西ヨーロッパのセファルディム 詳細は「スペイン人とポルトガル人のユダヤ人」を参照 アヌシム、マラーノ、隠れユダヤ教も参照  ニューヨーク市マンハッタン区にあるスペイン人とポルトガル人のシナゴーグ、シェアリス・イスラエル(1656年-1833年)の最初の墓地  ニューヨークのセファルディムの大家族に生まれたアメリカの詩人、エマ・ラザルス 西セファルディム(「スペイン・ポルトガル系ユダヤ人」、「スペイン系ユダヤ人」、「ポルトガル系ユダヤ人」、「ポルトガル国民のユダヤ人」など、より曖 昧な名称でも知られている)は、元キリスト教徒のユダヤ人(ニュー・クリスチャン)のコミュニティであり、その家族は当初、スペインとポルトガルに残っ た。西セファルディムはさらに、旧世界系と新世界系に細分化される。 ヘンリー・カーメンとジョセフ・ペレスは、アルハンブラ勅令が発布された当時のスペインのユダヤ系住民総数のうち、スペイン残留を選んだ人々が多数派を占 め、総数35万人のうち最大30万人に達したと推定している 。さらに、追放後もかなりの数の改宗ユダヤ教徒がスペインに戻った。カトリックに改宗することを条件に、王が彼らの財産を売却された価格で買い戻すことを 保証したためである。 しかし、この大規模な改宗者コミュニティに対する差別は依然として残り、ひそかにユダヤ教を信仰する人々は特に異端審問による厳しい迫害を受けた。このよ うな迫害の最後のエピソードは18世紀半ばに起こった。イベリア半島からの国外移住は、異端審問による迫害が増加した時期と一致している。 こうした差別と迫害の結果、少数のマラーノ(秘密裏にユダヤ教を信仰し続けたコンベルソ)が、イベリア文化圏外の旧世界諸国、すなわちオランダ、ベル ギー、フランス、イタリア、ドイツ、イギリスなど、より宗教的に寛容な国々へと移住した。これらの国々では、コンベルソがユダヤ教に改宗し、改宗、追放、 死を命じた最初の法令から3世代、あるいは4世代を経てから、ユダヤ人社会に再び加わった。旧世界西セファルディムを代表するのは、こうしたユダヤ教に復 帰した人々である。このセファルディム・ユダヤ人のコミュニティの中で、哲学者のバルーク・デ・スピノザはポルトガル系ユダヤ人の家庭に生まれた。スピノ ザは、その宗教的・哲学的見解により、このコミュニティから追放されたことでも有名である。 一方、新世界セファルディムは、キリスト教に改宗したユダヤ教徒であるコンベルソの子孫であり、キリスト教徒であった何百万人ものスペイン人やポルトガル 人がアメリカ大陸に移住した際に同行した。より具体的には、新世界セファルディムとは、コンベルソであった先祖が、ユダヤ教に復帰できる管轄権下にあるア メリカ大陸のイベリア半島以外の様々な植民地に移住したセファルディムである。 新世界スペイン系セファルディムは、アメリカ大陸のイベリア系植民地に移住したコンベルソの子孫で、ユダヤ教への復帰ができなかった別のグループと対比さ れる。これらは、セファルディム・ブネイ・アヌシム(下記参照)として知られる、関連性はあるが異なるグループである。 イベリア系アメリカ領土にはスペインとポルトガルの異端審問が存在していたため、当初は、コンベルソの移住はイベロ・アメリカの大半で禁止されていた。こ のため、イベロアメリカ植民地に移住したコンベルソのほとんどがユダヤ教に改宗することはなかった。新世界でユダヤ教に改宗したコンベルソは、主にオラン ダに一時的に避難していた人々や、オランダ領のキュラソー島やニューホランド(後にオランダ領ブラジルと呼ばれる)などの新世界に移住した人々であった。 オランダ領ブラジルは、25年間にわたってオランダが統治したブラジル植民地の北部地域であったが、その後ポルトガルに占領され、ポルトガルがブラジルを 統治するようになった。 オランダ領ブラジルで改宗したばかりのユダヤ人は、その後、他のオランダ領アメリカ植民地へと再び逃れる必要に迫られた。その中には、キュラソー島に移住 した同胞に加わる者もいたが、ニューアムステルダム(現在のニューヨーク市マンハッタン区)に移住した者もいた。 イベリア半島以外のアメリカ大陸の植民地で最も古い会衆は、多くの人々が当時オランダ領であったニューアムステルダムに到着した西セファルディムによって 設立された。彼らのシナゴーグは「スペイン・ポルトガル系ユダヤ人」の伝統を受け継いでいた。 特にアメリカ合衆国では、1654年に現在のニューヨーク市に設立されたシナゴーグ、シェアリス・イスラエル会衆が、アメリカ合衆国で最も古いユダヤ教の 会衆である。現在の建物は1897年に建てられた。ロードアイランド州ニューポートのイェシュア・イスラエル・コンゲグーションは、1658年に西セファ ルディムが到着した後、1677年に現在のトゥーロ墓地として知られる共同墓地を購入する前に建てられた。 米国最古のシナゴーグの一覧も参照のこと。 多くの西欧セファルディム(旧世界出身か新世界出身かは問わない)の祖先が、スペインから逃れた後にポルトガルに居住していた断続的な期間があったこと が、多くの西欧セファルディムの姓が一般的なスペインの姓のポルトガル語風バリエーションである傾向の理由となっているが、中にはスペインの姓を名乗る者 もいる。 西セファルディムにルーツを持つ著名人としては、ベネズエラのニコラス・マドゥーロ大統領や、元米国連邦最高裁判事のベンジャミン・N・カードーゾなどが いる。 両者ともポルトガルからオランダへ移住した西セファルディムの子孫であり、マドゥーロの場合はオランダからキュラソー島、そして最終的にベネズエラへと移 住した。 セファルディ・ブネイ・アヌシム 詳細は「セファルディ・ブネイ・アヌシム」を参照 関連項目:コンベルソ、新キリスト教徒  1900年頃のアルゼンチン、ミシオネス州出身のセファルディ系家族。 セファルディ・ブネイ・アヌシムは、15世紀に同化されたセファルディ人のアヌシムの子孫で、現代のキリスト教徒(多くは名目上のキリスト教徒)で構成さ れている。スペインとポルトガルのユダヤ人であった彼らの子孫は、カトリックへの改宗を強制されたり、迫害されたりしたため、コンベルソとしてイベリア半 島に残ったり、スペインによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化の過程で、ラテンアメリカ諸国のイベリア半島植民地に移住したりした。 歴史的な理由と状況により、セファルディム・ブネイ・アヌシムは過去5世紀の間、ユダヤ教への改宗を果たすことができなかったが、[35] 近年、特に過去20年間で、公に姿を現す者が増え始めている。程度の差こそあれ、一応のユダヤ教の慣習や伝統が各家庭で家族の伝統として保持されていたこ とを除けば、セファルディム・ベネイ・アヌシムはスペイン、ポルトガル、ラテンアメリカ、ブラジルといったイベリア半島に起源を持つキリスト教徒の集団に 完全に同化したサブグループとなった。しかし、過去5年から10年の間に[いつ?]、「ブラジル、コロンビア、コスタリカ、チリ、エクアドル、メキシコ、 プエルトリコ、ベネズエラ、ドミニカ共和国 そしてイベリア半島自体」[36]に組織化されたグループが設立され、その一部のメンバーは正式にユダヤ教に改宗し、新西洋セファルディム(下記グループ 参照)の出現につながった。 イスラエル・ユダヤ人エージェンシーは、セファルディム系ブネイ・アヌシムの人口は数百万人に上ると推定している。[37] 彼らの人口規模は、東セファルディム、北アフリカ・セファルディム、元コンベルソの西セファルディム(新世界と旧世界の両方)の3つのユダヤ人系セファル ディム子孫のサブグループを合わせた数よりも数倍大きい。 数の上では優勢であるものの、セファルディム系ベネイ・アヌシムは、セファルディム系ユダヤ人の子孫の中でも最も目立たず、知られていないグループであ る。 また、セファルディム系ベネイ・アヌシムは、アシュケナジム系ユダヤ人、ミズラヒム系ユダヤ人、およびその他の小規模なグループを含む世界全体のユダヤ人 人口の2倍以上である。 アヌシム(「強制改宗者」)は、ユダヤ教への改宗から3代目、4代目、5代目(ユダヤ教の回答書による)までコンベルソ(改宗者)であったが、後にユダヤ 教に復帰した人々である。一方、ブネイ・アヌシム(「強制改宗者の息子/子供/子孫」)は、イベリア半島とその新大陸の植民地における異端審問以来、隠れ 続けてきたアヌシムの子孫のその後の世代である。少なくとも、イベロアメリカ(イベリア半島およびイベロアメリカ植民地)のセファルディ系アヌシムの一部 は、当初はユダヤ教への改宗を試みたり、少なくとも秘密裏にユダヤ教の慣習を維持しようとした。しかし、イベリア半島およびイベロアメリカで改宗したユダ ヤ教徒は迫害され、起訴され、有罪判決を受け、処刑される可能性があったため、そのような環境では長期的に維持することは不可能であった。異端審問自体 は、19世紀になってようやく正式に解散された。 征服時代におけるスペインのアメリカ植民地へのイベリア半島からの移民の民族構成の多様性について新たな光を投げかける歴史的資料によると、征服と入植に 積極的に参加したセファルディ系新キリスト教徒の数は、以前の推定よりも多いことが示唆されている。スペインの征服者、行政官、入植者のうち、セファル ディ系であることが確認された人物が多数いる。 [要出典] 最近の新たな発見は、現代のDNA鑑定や、スペインで新たに発見された記録(紛失または隠匿されていたもの)によるもので、それらの記録は、セファルディ 系イベリア移民の両親、祖父母、曾祖父母の改宗、結婚、洗礼、異端審問に関するものである。 全体として、現代のスペイン人の20%、植民地時代のラテンアメリカのイベリア系入植者の10%がセファルディ系である可能性があると推定されているが、 入植者の地域分布は植民地全体で不均一であった。したがって、新キリスト教徒のセファルディ系イベリア系入植者は、ほとんどの地域では皆無であるが、他の 地域ではイベリア系入植者の3人に1人(約30%)に達する地域もある。現在のラテンアメリカの人口は5億9000万人近くに達しており、その大半はイベ リア半島に完全または部分的にルーツを持つ人々(新大陸のヒスパニック系住民とブラジル人、クリオーリョ、メスチゾ、ムラートなど)で占められている。そ のうち、セファルディムのユダヤ人としてのルーツをある程度持つ人は5000万人に上ると推定されている。 イベリア半島では、ベニー・アヌシムとして知られ、証明された集団の居住地として、ポルトガルのベルモンテ、スペインのパルマ・デ・マヨルカのシュエタ族 などが挙げられる。2011年、イスラエルのベイト・ディン・ツェデクのラビ裁判所の議長であり、著名なラビであり、ハラハーの権威であるニッシム・カレ リッツは、パルマ・デ・マヨルカのシュエタ族全体をユダヤ人として認めた パルマ・デ・マヨルカのユダヤ人として認めた。[38] その人口だけでも約1万8000人から2万人[39]、すなわち島の全人口の2%強に相当する。ポルトガル王によるユダヤ人のカトリックへの帰依の宣言 は、実際には高い割合でポルトガル人口に同化される結果となった。シュエタ族以外でも、スペインでは同様のことが言える。彼らの子孫の多くは、シュエタ・ キリスト教として知られるキリスト教のシンクレティズム(混成宗教)の形を信仰している。 セファルディム系ベネイ・アヌシムのほとんどは、15世紀にセファルディムが使用していたことが知られている姓を名乗っている。しかし、これらの姓のほと んどは、セファルディム特有のものではなく、実際には異教徒のスペイン人や異教徒のポルトガル人の姓であり、ユダヤ人の血筋を隠すためにカトリックへの改 宗時に意図的にそれらの姓を名乗るようになったため、ベネイ・アヌシムの間で一般的になったものである。改宗した新キリスト教徒は、カトリック信者として 異端審問の対象となったため、隠れユダヤ人は公証人による文書や政府関係、商業活動において、公的に使用する別名として、キリスト教の名前と異教徒の姓を 正式に記録した。一方で、彼らは与えられたヘブライ人の名前とユダヤ人の姓は秘密にしていた ユダヤ人の姓は秘密にしていた。[44] その結果、セファルディムのブネイ・アニームが、セファルディムに特有の姓、あるいはブネイ・アニームの間でしか見られない姓を名乗ることは非常にまれで あった。 |

| Distribution Pre-1492 Prior to 1492, substantial Jewish populations existed in most Spanish and Portuguese provinces. Among the larger Jewish populations were the Jewish communities in cities like Lisbon, Toledo, Córdoba, Seville, Málaga and Granada. In these cities, however, Jews constituted only substantial minorities of the overall population. In several smaller towns, however, Jews composed majorities or pluralities, as the towns were founded or inhabited principally by Jews. Among these towns were Ocaña, Guadalajara, Buitrago del Lozoya, Lucena, Ribadavia, Hervás, Llerena, and Almazán. In Castile, Aranda de Duero, Ávila, Alba de Tormes, Arévalo, Burgos, Calahorra, Carrión de los Condes, Cuéllar, Herrera del Duque, León, Medina del Campo, Ourense, Salamanca, Segovia, Soria, and Villalón were home to large Jewish communities or aljamas. Aragon had substantial Jewish communities in the Calls of Girona, Barcelona, Tarragona, Valencia and Palma (Majorca), with the Girona Synagogue serving as the centre of Catalonian Jewry The first Jews to leave Spain settled in what is today Algeria after the various persecutions that took place in 1391.  The Expulsion of the Jews from Spain (in the year 1492) by Emilio Sala Francés Post-1492 The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion) was an edict issued on 31 March 1492, by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain (Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon) ordering the expulsion of practicing Jews from the Kingdoms of Castile and Aragon and its territories and possessions by 31 July, of that year.[45] The primary purpose was to eliminate their influence on Spain's large converso population and ensure they did not revert to Judaism. Over half of Spain's Jews had converted as a result of the religious persecution and pogroms which occurred in 1391, and as such were not subject to the Decree or to expulsion. A further number of those remaining chose to avoid expulsion as a result of the edict. As a result of the Alhambra decree and persecution in prior years, over 200,000 Jews converted to Catholicism,[46] and between 40,000 and 100,000 were expelled, an indeterminate number returning to Spain in the years following the expulsion.[47] The Spanish Jews who chose to leave Spain instead of converting dispersed throughout the region of North Africa known as the Maghreb. In those regions, they often intermingled with the already existing Mizrahi Arabic-speaking communities, becoming the ancestors of the Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, and Libyan Jewish communities. Many Spanish Jews fled to the Ottoman Empire where they had been given refuge. Sultan Bayezid II of the Ottoman Empire, learning about the expulsion of Jews from Spain, dispatched the Ottoman Navy to bring the Jews safely to Ottoman lands, mainly to the cities of Salonika (currently Thessaloniki, now in Greece) and Smyrna (now known in English as İzmir, currently in Turkey).[48][better source needed] Some believe that Persian Jewry (Iranian Jews), as the only community of Jews living under the Shiites, probably suffered more than any Sephardic community (Persian Jews are not[49] Sephardic in descent[50][51]).[52] Many of these Jews also settled in other parts of the Balkans ruled by the Ottomans such as the areas that are now Bulgaria, Serbia, and Bosnia. Throughout history, scholars have given widely differing numbers of Jews expelled from Spain. However, the figure is likely preferred by minimalist scholars to be below the 100,000 Jews - while others suggest larger numbers - who had not yet converted to Christianity by 1492, possibly as low as 40,000 and as high as 200,000 (while Don Isaac Abarbanel stated he led 300,000 Jews out of Spain) dubbed "Megorashim" ("Expelled Ones", in contrast to the local Jews they met whom they called "Toshavim" - "Citizens") in the Hebrew they had spoken.[53] Many went to Portugal, gaining only a few years of respite from persecution. The Jewish community in Portugal (perhaps then some 10% of that country's population)[54] were then declared Christians by Royal decree unless they left. Such figures exclude the significant number of Jews who returned to Spain due to the hostile reception they received in their countries of refuge, notably Fez. The situation of returnees was legalized with the Ordinance of 10 November 1492 which established that civil and church authorities should be witness to baptism and, in the case that they were baptized before arrival, proof and witnesses of baptism were required. Furthermore, all property could be recovered by returnees at the same price at which it was sold. Returnees are documented as late as 1499. On the other hand, the Provision of the Royal Council of 24 October 1493 set harsh sanctions for those who slandered these New Christians with insulting terms such as tornados.[55] As a result of the more recent Jewish exodus from Arab lands, many of the Sephardim Tehorim from Western Asia and North Africa relocated to either Israel or France, where they form a significant portion of the Jewish communities today. Other significant communities of Sephardim Tehorim also migrated in more recent times from the Near East to New York City, Argentina, Costa Rica, Mexico, Montreal, Gibraltar, Puerto Rico, and Dominican Republic.[56][better source needed] Because of poverty and turmoil in Latin America, another wave of Sephardic Jews joined other Latin Americans who migrated to the United States, Canada, Spain, and other countries of Europe. Permanence of Sephardim in Spain According to the genetic study "The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula" at the University Pompeu Fabra of Barcelona and the University of Leicester, led by Briton Mark Jobling, Francesc Calafell, and Elena Bosch, published by the American Journal of Human Genetics, genetic markers show that nearly 20% of Spaniards have Sephardic Jewish markers (direct male descent male for Y, equivalent weight for female mitochondria); residents of Catalonia have approximately 6%. This shows that there was historic intermarriage between ethnic Jews and other Spaniards, and essentially, that some Jews remained in Spain. Similarly, the study showed that some 11% of the population has DNA associated with the Moors.[57] Sephardim in modern Iberia Today, around 50,000 recognized Jews live in Spain, according to the Federation of Jewish Communities in Spain.[58][59] The tiny Jewish community in Portugal is estimated between 1,740 and 3,000 people.[60] Although some are of Ashkenazi origin, the majority are Sephardic Jews who returned to Spain after the end of the protectorate over northern Morocco. A community of 600 Sephardic Jews live in Gibraltar.[61][better source needed] In 2011 Rabbi Nissim Karelitz, a leading rabbi and Halachic authority and chairman of the Beit Din Tzedek rabbinical court in Bnei Brak, Israel, recognized the entire community of Sephardi descendants in Palma de Mallorca, the Chuetas, as Jewish.[38] They number approximately 18,000 people or just over 2% of the entire population of the island. Of the Bnei Anusim community in Belmonte, Portugal, some officially returned to Judaism in the 1970s. They opened a synagogue, Bet Eliahu, in 1996.[62] The Belmonte community of Bnei Anusim as a whole, however, have not yet been granted the same recognition as Jews that the Chuetas of Palma de Majorca achieved in 2011. Spanish citizenship by Iberian Sephardic descent See also: Spanish nationality law § Sephardi Jews In 1924, the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera approved a decree to enable Sephardi Jews to obtain Spanish nationality. Although the deadline was originally the end of 1930, diplomat Ángel Sanz Briz used this decree as the basis for giving Spanish citizenship papers to Hungarian Jews in the Second World War to try to save them from the Nazis. Today, Spanish nationality law generally requires a period of residency in Spain before citizenship can be applied for. This had long been relaxed from ten to two years for Sephardi Jews, Hispanic Americans, and others with historical ties to Spain. In that context, Sephardi Jews were considered to be the descendants of Spanish Jews who were expelled or fled from the country five centuries ago following the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492.[63] In 2015 the Government of Spain passed Law 12/2015 of 24 June, whereby Sephardi Jews with a connection to Spain could obtain Spanish nationality by naturalization, without the usual residency requirement. Applicants must provide evidence of their Sephardi origin and some connection with Spain, and pass examinations on the language, government, and culture of Spain.[64] The Law establishes the right to Spanish nationality of Sephardi Jews with a connection to Spain who apply within three years from 1 October 2015. The law defines Sephardic as Jews who lived in the Iberian Peninsula until their expulsion in the late fifteenth century, and their descendants.[65] The law provides for the deadline to be extended by one year, to 1 October 2019; it was extended in March 2018.[66] It was modified in 2015 to remove a provision that required persons acquiring Spanish nationality by law 12/2015 must renounce any other nationality held.[67] Most applicants must pass tests of knowledge of the Spanish language and Spanish culture, but those who are under 18, or handicapped, are exempted. A Resolution in May 2017 also exempted those aged over 70.[68] The Sephardic citizenship law was set to expire in October 2018 but was extended for an additional year by the Spanish government.[69] The Law states that Spanish citizenship will be granted to "those Sephardic foreign nationals who prove that [Sephardic] condition and their special relationship with our country, even if they do not have legal residence in Spain, whatever their [current] ideology, religion or beliefs." Eligibility criteria for proving Sephardic descent include: a certificate issued by the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain, or the production of a certificate from the competent rabbinic authority, legally recognized in the country of habitual residence of the applicant, or other documentation which might be considered appropriate for this purpose; or by justifying one's inclusion as a Sephardic descendant, or a direct descendant of persons included in the list of protected Sephardic families in Spain referred to in the Decree-Law of 29 December 1948, or descendants of those who obtained naturalization by way of the Royal Decree of 20 December 1924; or by the combination of other factors including surnames of the applicant, spoken family language (Spanish, Ladino, Haketia), and other evidence attesting descent from Sephardic Jews and a relationship to Spain. Surnames alone, language alone, or other evidence alone will not be determinative in the granting of Spanish nationality. The connection with Spain can be established, if kinship with a family on a list of Sephardic families in Spain is not available, by proving that Spanish history or culture have been studied, proof of charitable, cultural, or economic activities associated with Spanish people, or organizations, or Sephardic culture.[64] The path to Spanish citizenship for Sephardic applicants remained costly and arduous.[70] The Spanish government takes about 8–10 months to decide on each case.[71] By March 2018, some 6,432 people had been granted Spanish citizenship under the law.[69] A total of about 132,000[72] applications were received, 67,000 of them in the month before the 30 September 2019 deadline. Applications for Portuguese citizenship for Sephardis remained open.[73] The deadline for completing the requirements was extended until September 2021 due to delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but only for those who had made a preliminary application by 1 October 2019.[72] In what appeared to be a reciprocal gesture, Natan Sharansky, chairman of the quasi-governmental Jewish Agency for Israel, said "the state of Israel must ease the way for their return", referring to the millions of descendants of conversos around Latin America and Iberia. Some hundreds of thousands maybe exploring ways to return to the Jewish people.[37] Portuguese citizenship by Portuguese Sephardic descent See also: Portuguese nationality law § Jewish Law of Return In April 2013 Portugal amended its Law on Nationality to confer citizenship to descendants of Portuguese Sephardic Jews who were expelled from the country five centuries ago following the Portuguese Inquisition. The amended law gave descendants of Portuguese Sephardic Jews the right to become Portuguese citizens, wherever they lived, if they "belong to a Sephardic community of Portuguese origin with ties to Portugal."[74] Portugal thus became the first country after Israel to enact a Jewish Law of Return. On 29 January 2015, the Portuguese Parliament ratified the legislation offering dual citizenship to descendants of Portuguese Sephardic Jews. Like the law later passed in Spain, the newly established legal rights in Portugal apply to all descendants of Portugal's Sephardic Jews, regardless of the current religion of the descendant, so long as the descendant can demonstrate "a traditional connection" to Portuguese Sephardic Jews. This may be through "family names, family language, and direct or collateral ancestry."[75] Portuguese nationality law was amended to this effect by Decree-Law n.º 43/2013, and further amended by Decree-Law n.º 30-A/2015, which came into effect on 1 March 2015.[76] «Applicants for Portuguese citizenship via this route are assessed by experts at one of Portugal's Jewish communities in either Lisbon or Porto».[77] In a reciprocal response to the Portuguese legislation, Michael Freund, Chairman of Shavei Israel told news agencies in 2015 that he "call[s] on the Israeli government to embark on a new strategic approach and to reach out to the [Sephardic] Bnei Anousim, people whose Spanish and Portuguese Jewish ancestors were compelled to convert to Catholicism more than five centuries ago."[78] By July 2017 the Portuguese government had received about 5,000 applications, mostly from Brazil, Israel, and Turkey. 400 had been granted, with a period between application and resolution of about two years.[71] In 2017 a total of 1,800 applicants had been granted Portuguese citizenship.[79] By February 2018, 12,000 applications were in process.[79] |

流通 1492年以前 1492年以前、スペインとポルトガルのほとんどの州には、かなりの数のユダヤ人が居住していた。 リスボン、トレド、コルドバ、セビリア、マラガ、グラナダなどの都市には、大きなユダヤ人コミュニティが存在していた。 しかし、これらの都市では、ユダヤ人は人口全体から見るとかなりの少数派に過ぎなかった。 一方、いくつかの小さな町では、ユダヤ人が人口の過半数または多数派を占めていた。 これらの町は、主にユダヤ人によって創設または居住されていたためである。これらの町には、オカーニャ、グアダラハラ、ブイトラゴ・デル・ロソヤ、ルセ ナ、リバダビア、エルバス、レレナ、アルマサンの町が含まれる。 カスティーリャでは、アランダ・デ・ドゥエロ、アビラ、アルバ・デ・トルメス、アレバロ、ブルゴス、カラオラ、カリオン・デ・ロス・コンデス、クエジャー ル、エレラ・デル・ドゥケ、レオン、メディナ・デル・カンポ、オウレンセ、サラマンカ、セゴビア、ソリア、ビジャロンに大規模なユダヤ人コミュニティ、ま たはアルハマが存在した。アラゴンには、ジローナ、バルセロナ、タラゴナ、バレンシア、パルマ(マヨルカ島)に大きなユダヤ人コミュニティがあり、ジロー ナのシナゴーグはカタルーニャのユダヤ人の中心地となっていた 1391年に起こったさまざまな迫害の後、スペインを離れた最初のユダヤ人たちは、現在のアルジェリアに定住した。  エミリオ・サラ・フランセスによる「スペインからのユダヤ人の追放(1492年)」 1492年以降 アルハンブラ勅令(追放令としても知られる)は、1492年3月31日にスペインのカトリック両王(カスティーリャ女王イザベル1世とアラゴン王フェルナ ンド2世)によって発令された勅令で、 同年7月31日までにカスティーリャ王国とアラゴン王国、およびその領土と領有地からユダヤ教徒を追放するよう命じたものである。[45] 主な目的は、スペイン国内に多数存在した改宗ユダヤ人(コンベルソ)への影響力を排除し、彼らが再びユダヤ教に改宗しないようにすることであった。 1391年に発生した宗教迫害と暴動の結果、スペインのユダヤ人の半数以上が改宗しており、彼らはこの法令の対象外であったため追放されることはなかっ た。さらに、残っていたユダヤ人のうち、勅令の結果として追放を避けることを選んだ者もいた。アルハンブラ勅令とそれ以前の迫害の結果、20万人以上のユ ダヤ人がカトリックに改宗し[46]、4万人から10万人が追放され、追放後の数年間に不確定な数の人々がスペインに戻ってきた[47]。 改宗せずにスペインを去ることを選んだスペインのユダヤ人は、マグレブとして知られる北アフリカ地域全体に散らばった。これらの地域では、彼らはしばしば すでに存在していたミズラヒ(中東や北アフリカのユダヤ人)のアラビア語話者コミュニティと混ざり合い、モロッコ、アルジェリア、チュニジア、リビアのユ ダヤ人コミュニティの祖先となった。 多くのスペイン系ユダヤ人は、オスマン帝国に逃れ、保護された。オスマン帝国のスルタン・バヤズィッド2世は、スペインからのユダヤ人の追放を知ると、オ スマン帝国海軍を派遣し、ユダヤ人を主にテッサロニキ(現ギリシャ領テッサロニキ)とイズミル(現トルコ領イズミル)の都市に無事に移送した。[48] [より良い情報源が必要] 一部では、ペルシア系ユダヤ人(イラン系ユダヤ人)は、 シーア派の支配下で暮らす唯一のユダヤ人コミュニティであるペルシア系ユダヤ人(イラン系ユダヤ人)は、おそらくセファルディムのどのコミュニティよりも 苦難を強いられたと考えられている(ペルシア系ユダヤ人はセファルディムの血筋ではない[50][51])。[52] これらのユダヤ人の多くも、現在のブルガリア、セルビア、ボスニアなど、オスマン帝国が支配していたバルカン半島の他の地域に移住した。 歴史を通じて、スペインから追放されたユダヤ人の数については、学者の間で大きく異なる数字が挙げられてきた。しかし、1492年までにキリスト教に改宗 しなかったユダヤ人の数は、控えめな学者が好む数字では10万人以下であるが、他の学者はそれより多い数字を挙げている。おそらく4万人から20万人の間 であろう(ドン・イサク・アバルバンは 彼は30万人のユダヤ人をスペインから連れ出したと述べている)は、彼らが話していたヘブライ語で「メゴラシム」(「追放された者たち」、彼らが出会った 地元のユダヤ人「トシャビム」(「市民」)と対比して)と呼ばれた。多くの人々はポルトガルに向かい、迫害からわずか数年の休息を得た。ポルトガルのユダ ヤ人社会(おそらく当時の同国の人口の10%程度)は、退去しなければ王令によりキリスト教に改宗するよう命じられた。 このような数字は、避難先で敵対的な扱いを受けたためにスペインに戻った多数のユダヤ人を除外している。特にフェズではその傾向が顕著であった。帰還者の 状況は、1492年11月10日の勅令によって合法化され、民事および教会当局が洗礼の証人となること、また、到着前に洗礼を受けていた場合は、洗礼の証 明と証人が必要とされた。さらに、帰還者は、売却された価格で、すべての財産を回復することができた。帰還者の記録は、1499年まで残っている。一方、 1493年10月24日の王立評議会規定では、これらの新キリスト教徒をトルネード(竜巻)などの侮辱的な言葉で中傷した者に対して厳しい制裁が科せられ た。[55] アラブ諸国からの最近のユダヤ人の流出の結果、西アジアと北アフリカ出身のセファルディム・テオヒムの多くはイスラエルかフランスに移住し、今日では両国 でユダヤ人社会の重要な部分を占めている。また、セファルディム・テオヒムの重要なコミュニティは、近東からニューヨーク、アルゼンチン、コスタリカ、メ キシコ、モントリオール、ジブラルタル、プエルトリコ、ドミニカ共和国にも、より最近になって移住している。[56][より良い情報源が必要]ラテンアメ リカにおける貧困と混乱のため、セファルディム・ユダヤ人の新たな波が、アメリカ合衆国、カナダ、スペイン、その他のヨーロッパ諸国に移住したラテンアメ リカ人たちに加わった。 スペインにおけるセファルディムの永続性 イギリス人のマーク・ジョブリング、フランセスク・カラフェル、エレナ・ボッシュが主導した、バルセロナのポンペウ・ファブラ大学とレスター大学の共同に よる遺伝学的研究「宗教的多様性と不寛容の遺伝的遺産:イベリア半島のキリスト教徒、ユダヤ教徒、イスラム教徒の父系家系」によると、 遺伝子マーカーの調査によると、スペイン人の約20%がセファルディムのユダヤ人(Y染色体では男性直系、女性ミトコンドリアでは同等の重み)の遺伝子 マーカーを持っていることが示されている。カタルーニャ州の住民は約6%である。これは、ユダヤ人とスペイン人の間で歴史的に婚姻関係があったことを示し ており、また、本質的には、スペインにユダヤ人が残っていたことを示している。同様に、この研究では、人口の約11%がムーア人に関連するDNAを持って いることも示されている。[57] 現代のイベリア半島のセファルディム スペインのユダヤ人共同体連盟によると、現在スペインには約5万人の認定されたユダヤ人が住んでいる。[58][59] ポルトガルの小さなユダヤ人コミュニティは、1,740人から3,000人と推定されている。[60] 一部はアシュケナジム系であるが、大半はモロッコ北部の保護領が終了した後にスペインに戻ってきたセファルディム系ユダヤ人である。ジブラルタルには 600人のセファルディム系ユダヤ人のコミュニティが存在する。 2011年、イスラエルのブネイ・ブラクにあるベイト・ディン・ツェデクのラビ裁判所の議長であり、ラビおよびハラーハーの権威者であるニッシム・カレ リッツは、パルマ・デ・マヨルカのチュエタスと呼ばれるセファルディムの子孫であるコミュニティ全体をユダヤ人であると認めた。[38] 彼らの数は約1万8000人で、島の全人口の2%強である。 ポルトガルのベルモンテのブネイ・アニシムのコミュニティでは、1970年代に公式にユダヤ教に改宗した者もいる。彼らは1996年にベイト・エリアフと いうシナゴーグを開設した。[62] しかし、ベルモンテのブネイ・アニシムのコミュニティ全体としては、2011年にパルマ・デ・マヨルカのチュエタが獲得したようなユダヤ人としての認定は まだ受けていない。 イベリア半島系セファルディムのスペイン国籍 参照:スペイン国籍法 § セファルディム 1924年、プリモ・デ・リベラ独裁政権は、セファルディムのユダヤ人がスペイン国籍を取得することを可能にする法令を承認した。当初は1930年末が期 限となっていたが、外交官のアンヘル・サンツ・ブリスは、この法令を根拠に第二次世界大戦中のハンガリー系ユダヤ人にスペイン国籍を与えることで、彼らを ナチスから救おうとした。 現在、スペイン国籍法では、通常、スペイン国籍の申請にはスペインでの居住期間が必要である。 セファルディ系ユダヤ人、ヒスパニック系アメリカ人、その他スペインとの歴史的なつながりを持つ人々については、この居住期間が10年から2年に緩和され ていた。 セファルディ系ユダヤ人は、1492年のスペインからのユダヤ人追放により、5世紀前にスペインから追放されたり、スペインを離れたりしたスペイン系ユダ ヤ人の子孫であるとみなされている。 2015年、スペイン政府は6月24日付の法律第12/2015号を可決し、スペインとのつながりを持つセファルディ系ユダヤ人は、通常の居住要件なしに 帰化によってスペイン国籍を取得できるようになった。申請者は、セファルディ系ユダヤ人としての出自とスペインとのつながりを証明し、スペイン語、スペイ ンの政治、文化に関する試験に合格しなければならない。 この法律は、2015年10月1日から3年以内に申請したスペインと何らかのつながりを持つセファルディム系ユダヤ人にスペイン国籍を取得する権利を定め ている。この法律では、セファルディとは15世紀後半に追放されるまでイベリア半島に住んでいたユダヤ人とその子孫を指す。[65] この法律では期限を1年延長し、2019年10月1日までと定めている。2018年3月に延長された。[66] 2015年に修正され、2015年12月12日の法律によってスペイン国籍を取得する者は、保有する他の国籍を放棄しなければならないという規定が削除さ れた。[67] ほとんどの申請者はスペイン語とスペイン文化に関する知識のテストに合格しなければならないが、18歳未満または障害者は免除される。2017年5月の決 議では、70歳以上の者も免除された。[68] セファルディ人の市民権法は2018年10月に期限切れとなる予定であったが、スペイン政府によってさらに1年間延長された。[69] この法律では、「セファルディ人の外国籍保持者で、スペインに合法的な居住地を持たない場合でも、そのセファルディ人の地位とスペインとの特別な関係を証 明できる者、およびその者の(現在の)思想、宗教、信条に関わらず」スペイン国籍が付与されると規定されている。 セファルディの血筋を証明するための条件には、スペインのユダヤ人コミュニティ連盟が発行する証明書、または申請者の常居所国で法的に認められている管轄 のラビ当局が発行する証明書の提出、またはこの目的に適切であるとみなされるその他の書類の提出、またはセファルディの末裔、または1948年12月29 日付の政令で言及されているスペインの保護対象セファルディ家族のリストに記載されている人物の直系の子孫であることを証明すること、 1948年12月29日付の政令で言及されているスペインの保護対象セファルディム家族のリストに記載されている人物の直系の子孫、または1924年12 月20日付の勅令により帰化を果たした人物の子孫であることを証明すること、または申請者の姓、話されている家庭内の言語(スペイン語、ラディノ語、ハケ ティア語)、その他セファルディム系ユダヤ人の子孫であることやスペインとの関係を証明する証拠を組み合わせること、などである。苗字、言語、その他の証 拠のみでは、スペイン国籍の付与を決定づけるものではない。 スペインとのつながりは、スペインのセファルディム家族のリストに載っている家族との親族関係が利用できない場合、スペインの歴史や文化を学んだこと、ス ペイン人やスペインに関連する慈善活動、文化活動、経済活動を行ったこと、またはセファルディム文化に関連する組織に所属したことを証明することで、確立 できる。 セファルディム系申請者のスペイン国籍取得への道は、依然として費用がかかり困難である。[70] スペイン政府は、各案件の決定に約8~10か月を要する。[71] 2018年3月までに、 この法律に基づきスペイン国籍が認められた。申請総数は約13万2000件[72]で、そのうち6万7000件は2019年9月30日の期限の1か月前に 提出された。セファルディムのポルトガル国籍申請は引き続き受け付けられた。[73] 2019年10月1日までに予備申請を行っていた人々については、新型コロナウイルス感染症による遅延のため、要件を満たすための期限が2021年9月ま で延長されたが、[72] 見返りとして、準政府機関であるイスラエル・ユダヤ人移住局のナタン・シャランスキー会長は、ラテンアメリカとイベリア半島周辺の改宗者の子孫数百万人に ついて言及し、「イスラエル国は彼らの帰還を容易にしなければならない」と述べた。数十万人がユダヤ人への帰還の道を探っているのかもしれない。 ポルトガル系セファルディムのポルトガル国籍 関連項目:ポルトガル国籍法 § ユダヤ人の帰還法 2013年4月、ポルトガルは、5世紀前にポルトガル異端審問により国外追放されたポルトガル系セファルディムのユダヤ人の子孫に国籍を与える国籍法を改 正した。 改正法では、「ポルトガルにルーツを持ち、ポルトガルとつながりを持つセファルディムのコミュニティに属する」場合、ポルトガル系セファルディムのユダヤ 人の子孫は、どこに住んでいてもポルトガル国籍を取得できる権利が与えられた。[74] これにより、ポルトガルはイスラエルに次いで「ユダヤ人の帰還法」を制定した最初の国となった。 2015年1月29日、ポルトガル議会は、ポルトガル系セファルディムのユダヤ人の子孫に二重国籍を与える法案を可決した。後にスペインで可決された法律 と同様に、ポルトガルで新たに制定された法的権利は、ポルトガル系セファルディムのユダヤ人との「伝統的なつながり」を証明できる限り、現在の宗教に関わ らず、ポルトガル系セファルディムのユダヤ人の子孫全員に適用される。これは「家族の姓、家族の言語、直系または傍系の家系」を通じて証明できる可能性が ある。[75] ポルトガルの国籍法は、政令第43/2013号によりこの趣旨で改正され、さらに政令第30-A/2015号により改正された。30-A/2015により 改正され、2015年3月1日に施行された。[76] 「このルートでポルトガル国籍を申請する者は、リスボンまたはポルトのポルトガル・ユダヤ人コミュニティのいずれかの専門家によって審査される」[77] ポルトガル法への相互対応として、2015年にShavei Israelの会長であるマイケル・フレイントは報道機関に対し、「イスラエル政府に新たな戦略的アプローチに着手し、5世紀以上前にスペイン語やポルト ガル語を話すユダヤ人の先祖がカトリックへの改宗を余儀なくされたセファルディムのBnei Anousim(ブネイ・アヌシム)に手を差し伸べるよう呼びかけている」と述べた。 2017年7月までに、ポルトガル政府には主にブラジル、イスラエル、トルコから約5,000件の申請が寄せられた。400件が許可され、申請から許可ま での期間は約2年であった。[71] 2017年には、合計1,800人の申請者がポルトガル国籍を付与された。[79] 2018年2月までに、12,000件の申請が処理中であった。[79] |

Language Dedication at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem written in Hebrew, English, Yiddish, and Judeo-Spanish The most typical traditional language of Sephardim is Judeo-Spanish, also called Judezmo or Ladino. It is a Romance language derived mainly from Old Castilian (Spanish), with many borrowings from Turkish, and to a lesser extent from Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, and French. Until recently, two different dialects of Judeo-Spanish were spoken in the Mediterranean region: Eastern Judeo-Spanish (in various distinctive regional variations) and Western or North African Judeo-Spanish (also known as Ḥakitía). The latter was once spoken, with little regional distinction, in six towns in Northern Morocco. Because of later emigration, it was also spoken by Sephardim in Ceuta and Melilla (Spanish cities in North Africa), Gibraltar, Casablanca (Morocco), and Oran (Algeria). The Eastern Sephardic dialect is typified by its greater conservatism, its retention of numerous Old Spanish features in phonology, morphology, and lexicon, and its numerous borrowings from Turkish and, to a lesser extent, also from Greek and South Slavic. Both dialects have (or had) numerous borrowings from Hebrew, especially in reference to religious matters. But the number of Hebraisms in everyday speech or writing is in no way comparable to that found in Yiddish, the first language for some time among Ashkenazi Jews in Europe. On the other hand, the North African Sephardic dialect was, until the early 20th century, also highly conservative; its abundant Colloquial Arabic loan words retained most of the Arabic phonemes as functional components of a new, enriched Hispano-Semitic phonological system. During the Spanish colonial occupation of Northern Morocco (1912–1956), Ḥakitía was subjected to pervasive, massive influence from Modern Standard Spanish. Most Moroccan Jews now speak a colloquial, Andalusian form of Spanish, with only occasional use of the old language as a sign of in-group solidarity. Similarly, American Jews may now use an occasional Yiddishism in colloquial speech. Except for certain younger individuals, who continue to practice Ḥakitía as a matter of cultural pride, this dialect, probably the most Arabized of the Romance languages apart from Mozarabic, has essentially ceased to exist. By contrast, Eastern Judeo-Spanish has fared somewhat better, especially in Israel, where newspapers, radio broadcasts, and elementary school and university programs strive to keep the language alive. But the old regional variations (i.e. Bosnia, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Romania, Greece, and Turkey for instance) are already either extinct or doomed to extinction. Only time will tell whether Judeo-Spanish koiné, now evolving in Israel—similar to that which developed among Sephardic immigrants to the United States early in the 20th century- will prevail and survive into the next generation.[80] Judæo-Portuguese was used by Sephardim — especially among the Spanish and Portuguese Jews. The pidgin forms of Portuguese spoken among slaves and their Sephardic owners were an influence in the development of Papiamento and the Creole languages of Suriname. Other Romance languages with Jewish forms, spoken historically by Sephardim, include Judeo-Catalan. Often underestimated, this language was the main language used by the Jewish communities in Catalonia, Balearic Isles and the Valencian region. The Gibraltar community has had a strong influence on the Gibraltar dialect Llanito, contributing several words to this English/Spanish patois. Other languages associated with Sephardic Jews are mostly extinct, e. g. Corfiot Italkian, formerly spoken by some Sephardic communities in Italy.[81] Judeo-Arabic and its dialects have been a large vernacular language for Sephardim who settled in North African kingdoms and Arabic-speaking parts of the Ottoman Empire. Low German (Low Saxon), formerly used as the vernacular by Sephardim around Hamburg and Altona in Northern Germany, is no longer in use as a specifically Jewish vernacular. Through their diaspora, Sephardim have been a polyglot population, often learning or exchanging words with the language of their host population, most commonly Italian, Arabic, Greek, Turkish, and Dutch. They were easily integrated with the societies that hosted them. Within the last centuries and, more particularly the 19th and 20th centuries, two languages have become dominant in the Sephardic diaspora: French, introduced first by the Alliance Israélite Universelle, and then by absorption of new immigrants to France after Tunisia, Morocco and Algeria became independent, and Hebrew in the state of Israel. [citation needed] |

言語 エルサレムのヤド・ヴァシェムに捧げられた献身は、ヘブライ語、英語、イディッシュ語、ユダヤ・スペイン語で書かれている セファルディムの最も典型的な伝統的言語は、ユダヤ・スペイン語、またはジュデズモ、ラディノとも呼ばれる。これは主に旧カスティーリャ語(スペイン語) に由来するロマンス語で、トルコ語からの借用語が多く、ギリシャ語、アラビア語、ヘブライ語、フランス語からの借用語は少ない。最近まで、地中海地域では 2つの異なるユダヤ・スペイン語の方言が話されていた。東部ユダヤ・スペイン語(さまざまな特徴的な地域的バリエーション)と西部または北アフリカのユダ ヤ・スペイン語(別名:Ḥakitía)である。後者はかつてモロッコ北部の6つの町で、地域による違いはほとんどなく話されていた。その後、移民によ り、セウタとメリリャ(北アフリカのスペイン領)、ジブラルタル、カサブランカ(モロッコ)、オラン(アルジェリア)でもセファルディムによって話される ようになった。 東セファルディ語の方言は、より保守的であり、音韻論、形態論、語彙において多数の旧スペイン語の特徴を保持していること、またトルコ語からの借用語を多 数含み、また程度は低いがギリシャ語や南スラヴ語からの借用語も含んでいることが特徴である。両方言には、特に宗教に関する用語において、ヘブライ語から の借用語が多数存在する(または存在していた)。しかし、日常会話や文章におけるヘブライ語由来の単語の数は、ヨーロッパのユダヤ人(アシュケナジム)の 第一言語であるイディッシュ語のそれに比べると、比較にならないほど少ない。 一方、北アフリカのセファルディム方言も20世紀初頭までは非常に保守的であり、豊富な口語アラビア語の借用語は、アラビア語の音素のほとんどを、新し い、より豊かなイスパノ・セム語音韻体系の機能的構成要素として保持していた。スペインによる北モロッコ占領(1912年~1956年)の間、ハキティア は現代標準スペイン語の広範かつ多大な影響を受けた。現在、モロッコのユダヤ人の大半は、アンダルシア方言のスペイン語を話し、旧言語は仲間意識の象徴と して時折使用される程度である。同様に、アメリカのユダヤ人も、口語では時折イディッシュ語の表現を使うことがある。文化的な誇りとしてハキティア語を今 も使用している一部の若い人々を除いて、この方言は、モサラベ語を除いてロマンス諸語の中で最もアラブ化された方言であるが、今では実質的に消滅してい る。 これに対し、東ヨーロッパ系ユダヤ・スペイン語は、特にイスラエルにおいて、新聞、ラジオ放送、小学校や大学のプログラムでその言語の存続が図られている ため、いくらかは持ちこたえている。しかし、旧来の地域的バリエーション(例えばボスニア、マケドニア、ブルガリア、ルーマニア、ギリシャ、トルコなど) はすでに消滅しているか、あるいは消滅の運命にある。ユダヤ・スペイン語の共通語が、現在イスラエルで進化しているように、20世紀初頭に米国に移住した セファルディムの間で発展したものと同様に、次世代にまで普及し生き残るかどうかは、時が経てばわかるだろう。 ユダヤ・ポルトガル語は、特にスペインとポルトガルのユダヤ人であるセファルディムによって使用されていた。奴隷と彼らのセファルディムの所有者の間で話 されていたポルトガル語のピジン語は、パピアメント語とスリナムのクレオール言語の発展に影響を与えた。 セファルディムが歴史的に話してきたユダヤ人風のロマンス語には、ユダヤ・カタルーニャ語などがある。 しばしば過小評価されるが、この言語はカタルーニャ、バレアレス諸島、バレンシア地方のユダヤ人社会で主に使用されていた。 ジブラルタルのコミュニティはジブラルタル方言であるリャニートに強い影響を与え、英語とスペイン語の混成語にいくつかの単語を寄与した。 セファルディム・ユダヤ人と関連のあるその他の言語は、ほとんどが消滅している。例えば、かつてイタリアのセファルディム・コミュニティの一部で話されて いたコルフ島イタリア語などである。[81] ユダヤ・アラビア語とその方言は、北アフリカの王国やオスマン帝国のアラビア語圏に定住したセファルディムの間で、主要な日常語として話されてきた。かつ て北ドイツのハンブルクやアルトナ周辺に住むセファルディムが日常語として使用していた低地ドイツ語(低地ザクセン語)は、現在ではユダヤ人の日常語とし ては使用されていない。 ディアスポラを通じて、セファルディムは多言語話者集団となり、多くの場合、ホスト国の言語(最も一般的なのはイタリア語、アラビア語、ギリシャ語、トル コ語、オランダ語)を学んだり、その言語と交流したりしてきた。彼らはホスト社会に容易に溶け込んでいった。過去数世紀の間、特に19世紀と20世紀に は、セファルディムのディアスポラでは2つの言語が支配的となった。まず、アライアンス・イスラエライト・ウニヴェルセル(Alliance Israélite Universelle)によってフランス語が導入され、その後、チュニジア、モロッコ、アルジェリアが独立した後、フランスへの新たな移民が吸収され た。そして、イスラエルではヘブライ語が使われるようになった。[要出典] |

| Literature The doctrine of galut is considered by scholars to be one of the most important concepts in Jewish history, if not the most important. In Jewish literature glut, the Hebrew word for diaspora, invoked common motifs of oppression, martyrdom, and suffering in discussing the collective experience of exile in diaspora that has been uniquely formative in Jewish culture. This literature was shaped for centuries by the expulsions from Spain and Portugal and thus featured prominently in a wide range of medieval Jewish literature from rabbinic writings to profane poetry. Even so, the treatment of glut diverges in Sephardic sources, which scholar David A. Wacks says "occasionally belie the relatively comfortable circumstances of the Jewish community of Sefarad."[82] |

文学 ガルートの教義は、学者たちによって、ユダヤ人の歴史において最も重要な概念のひとつ、あるいは最も重要な概念であると考えられている。ユダヤ文学におい て、ディアスポラを意味するヘブライ語の「グルート」は、ユダヤ文化において独特な形成要因となってきたディアスポラにおける追放の集団的経験を論じる際 に、抑圧、殉教、苦悩といった共通のモチーフを想起させる。この文学は、何世紀にもわたってスペインやポルトガルからの追放によって形作られ、ラビの著作 から世俗詩まで、中世の幅広いユダヤ文学に顕著に現れている。 それでも、セファルディの資料では、ガルートの扱いが異なっている。 学者のデビッド・A・ワックスは、「セファラドのユダヤ人社会の比較的快適な状況を時折裏切っている」と述べている。[82] |