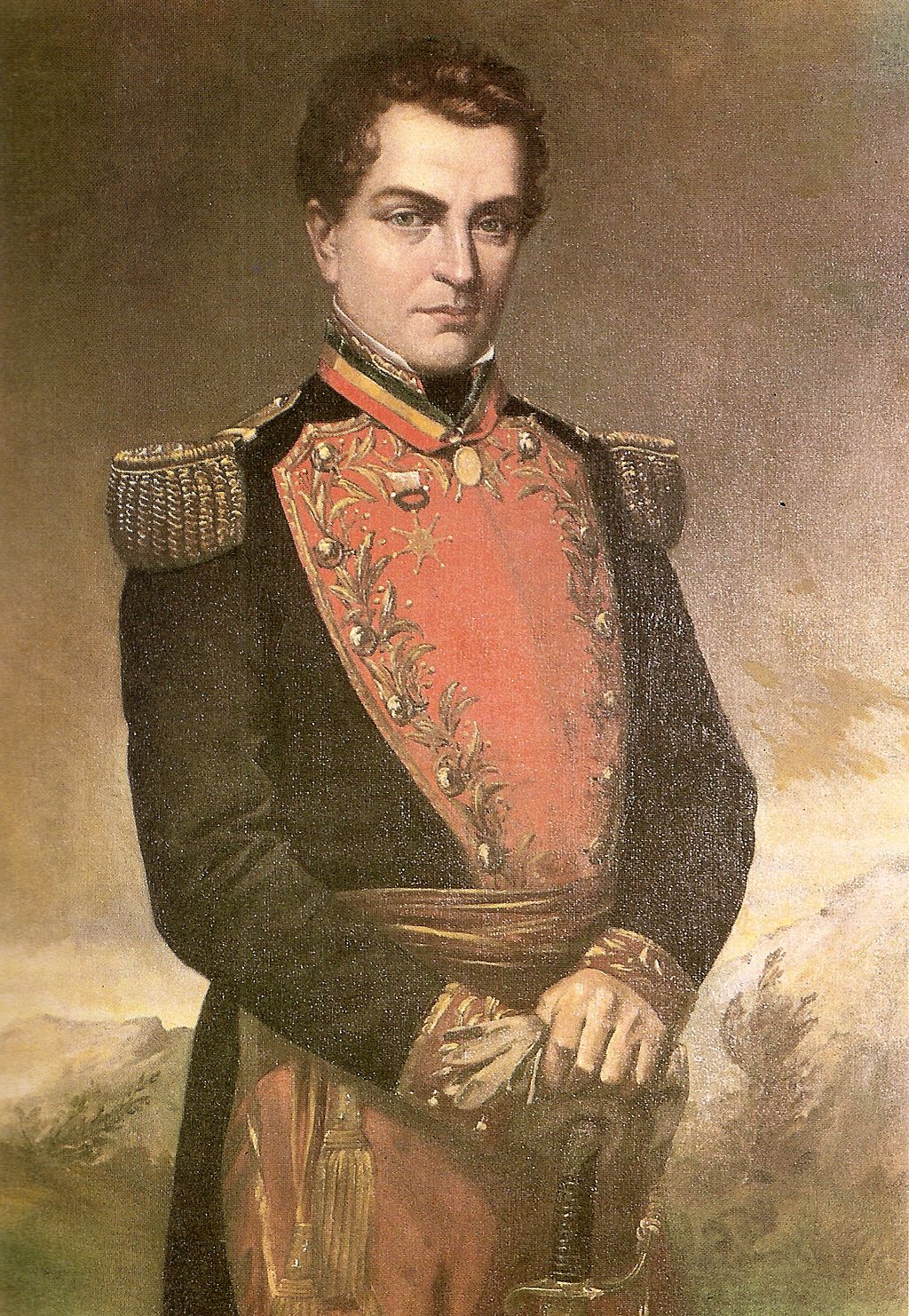

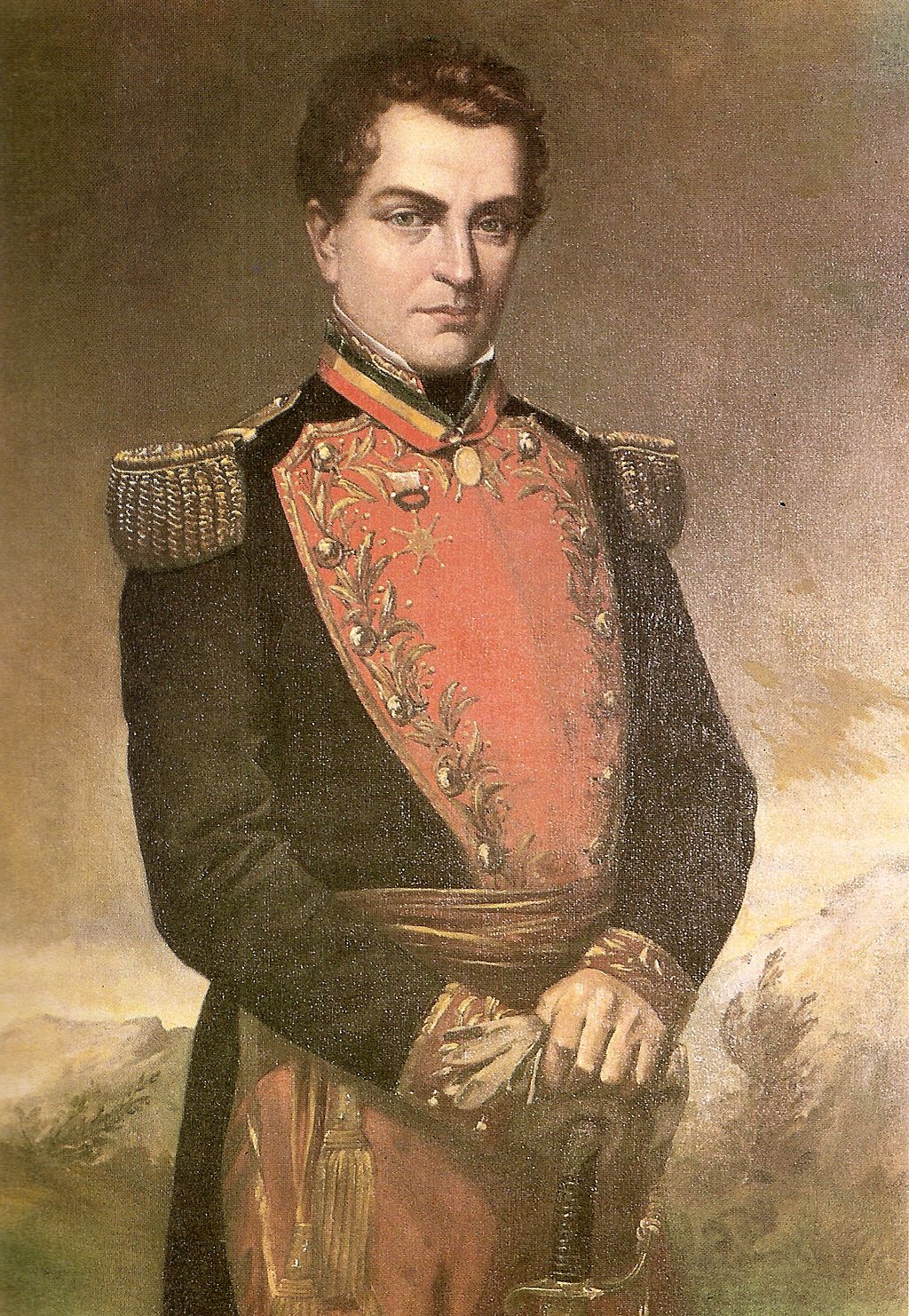

シモン・ボリーバル

Simón Bolívar, Simón José Antonio

de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar Palacios Ponte y Blanco, 1783-1830

by Toro Moreno, José. 1922

☆ シモン・ホセ・アントニオ・デ・ラ・サンティシマ・トリニダッド・ボリーバル・パラシオス・ポンテ・イ・ブランコ(Simón Bolívar)(1783年7月24日 - 1830年12月17日)は、ベネズエラの政治家であり軍人であった。スペイン帝国からの独立を目指し、現在のコロンビア、ベネズエラ、エクアドル、ペ ルー、パナマ、ボリビアを率いた。彼は一般的に「エル・リベルタドール」、すなわち「アメリカの解放者」として知られている。 シモン・ボリバルは、ベネズエラ総督領のカラカスで、アメリカ生まれのスペイン人(クリオーリョ)の裕福な家庭に生まれたが、幼少時に両親を失った。ボリ バルは海外で教育を受け、当時の上流階級の家庭の男性たちと同様にスペインで暮らした。1800年から1802年にかけてマドリードに滞在していた間、彼 は啓蒙主義哲学に触れ、マリア・テレサ・ロドリゲス・デル・トロ・イ・アライサと結婚した。彼女は1803年に黄熱病でベネズエラで死去した。1803年 から1805年にかけて、ボリバルはグランドツアーに出発し、ローマで終えた。そこで彼は、アメリカ大陸におけるスペインの支配を終わらせることを誓っ た。1807年、ボリバルはベネズエラに戻り、富裕なクリオールたちにベネズエラの独立を推進した。ナポレオンによる半島戦争により、アメリカ大陸におけ るスペインの権威が弱まると、ボリバルはスペイン系アメリカ独立戦争において熱心な戦士および政治家となった。 ボリバルは1810年、ベネズエラ独立戦争において民兵の士官として軍人としてのキャリアをスタートさせ、第一および第二ベネズエラ共和国、そしてニュー グラナダ連合州の王党派軍と戦った。1815年にスペイン軍がニューグラナダを制圧した後、ボリバルはジャマイカへの亡命を余儀なくされた。ハイチで、ボ リバルはハイチの革命指導者アレクサンドル・ペティオンと出会い、親交を結んだ。スペイン領アメリカにおける奴隷制度廃止を約束したボリバルは、ペティオ ンから軍事支援を受け、ベネズエラに戻った。1817年に第三共和制を樹立し、1819年にはアンデス山脈を越えてニューグラナダの解放に向かった。ボリ バルとその同盟軍は、1819年にニューグラナダ、1821年にベネズエラとパナマ、1822年にエクアドル、1824年にペルー、1825年にボリビア でスペイン軍を打ち破った。ベネズエラ、ニューグラナダ、エクアドル、パナマは合併してコロンビア共和国(大コロンビア)となり、ボリバルはペルーとボリ ビアの大統領も兼任した。 晩年、ボリバルは南米の共和国に幻滅を深め、中央集権主義の思想からそれらから距離を置くようになった。彼は次々と役職を解任され、ついにコロンビアの大 統領を辞任し、1830年に結核で死去した。彼の遺産はラテンアメリカおよびその外の世界に多様かつ広範囲にわたって影響を与えている。彼はラテンアメリ カ全域で英雄、そして国民的・文化的な象徴とみなされている。ボリビアとベネズエラ(ベネズエラ・ボリバル共和国)の国民は彼にちなんで名付けられ、公共 芸術や通りの名前、大衆文化の形で世界中で記念されている。

| Simón José Antonio

de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar Palacios Ponte y Blanco[c] (24 July

1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan statesman and military

officer who led what are currently the countries of Colombia,

Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia to independence from the

Spanish Empire. He is known colloquially as El Libertador, or the

Liberator of America. Simón Bolívar was born in Caracas in the Captaincy General of Venezuela into a wealthy family of American-born Spaniards (criollo) but lost both parents as a child. Bolívar was educated abroad and lived in Spain, as was common for men of upper-class families in his day. While living in Madrid from 1800 to 1802, he was introduced to Enlightenment philosophy and married María Teresa Rodríguez del Toro y Alaysa, who died in Venezuela from yellow fever in 1803. From 1803 to 1805, Bolívar embarked on a Grand Tour that ended in Rome, where he swore to end the Spanish rule in the Americas. In 1807, Bolívar returned to Venezuela and promoted Venezuelan independence to other wealthy creoles. When the Spanish authority in the Americas weakened due to Napoleon's Peninsular War, Bolívar became a zealous combatant and politician in the Spanish-American wars of independence. Bolívar began his military career in 1810 as a militia officer in the Venezuelan War of Independence, fighting Royalist forces for the first and second Venezuelan republics and the United Provinces of New Granada. After Spanish forces subdued New Granada in 1815, Bolívar was forced into exile on Jamaica. In Haiti, Bolívar met and befriended Haitian revolutionary leader Alexandre Pétion. After promising to abolish slavery in Spanish America, Bolívar received military support from Pétion and returned to Venezuela. He established a third republic in 1817 and then crossed the Andes to liberate New Granada in 1819. Bolívar and his allies defeated the Spanish in New Granada in 1819, Venezuela and Panama in 1821, Ecuador in 1822, Peru in 1824, and Bolivia in 1825. Venezuela, New Granada, Ecuador, and Panama were merged into the Republic of Colombia (Gran Colombia), with Bolívar as president there and in Peru and Bolivia. In his final years, Bolívar became increasingly disillusioned with the South American republics, and distanced from them because of his centralist ideology. He was successively removed from his offices until he resigned the presidency of Colombia and died of tuberculosis in 1830. His legacy is diverse and far-reaching within Latin America and beyond. He is regarded as a hero and national and cultural icon throughout Latin America; the nations of Bolivia and Venezuela (as the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela) are named after him, and he has been memorialized all over the world in the form of public art or street names and in popular culture. |

シモン・ホセ・アントニオ・デ・ラ・サントゥシマ・トリニダッド・ボ

リーバル・パラシオス・ポンテ・イ・ブランコ(1783年7月24日 -

1830年12月17日)は、ベネズエラの政治家であり軍人であった。スペイン帝国からの独立を目指し、現在のコロンビア、ベネズエラ、エクアドル、ペ

ルー、パナマ、ボリビアを率いた。彼は一般的に「エル・リベルタドール」、すなわち「アメリカの解放者」として知られている。 シモン・ボリバルは、ベネズエラ総督領のカラカスで、アメリカ生まれのスペイン人(クリオーリョ)の裕福な家庭に生まれたが、幼少時に両親を失った。ボリ バルは海外で教育を受け、当時の上流階級の家庭の男性たちと同様にスペインで暮らした。1800年から1802年にかけてマドリードに滞在していた間、彼 は啓蒙主義哲学に触れ、マリア・テレサ・ロドリゲス・デル・トロ・イ・アライサと結婚した。彼女は1803年に黄熱病でベネズエラで死去した。1803年 から1805年にかけて、ボリバルはグランドツアーに出発し、ローマで終えた。そこで彼は、アメリカ大陸におけるスペインの支配を終わらせることを誓っ た。1807年、ボリバルはベネズエラに戻り、富裕なクリオールたちにベネズエラの独立を推進した。ナポレオンによる半島戦争により、アメリカ大陸におけ るスペインの権威が弱まると、ボリバルはスペイン系アメリカ独立戦争において熱心な戦士および政治家となった。 ボリバルは1810年、ベネズエラ独立戦争において民兵の士官として軍人としてのキャリアをスタートさせ、第一および第二ベネズエラ共和国、そしてニュー グラナダ連合州の王党派軍と戦った。1815年にスペイン軍がニューグラナダを制圧した後、ボリバルはジャマイカへの亡命を余儀なくされた。ハイチで、ボ リバルはハイチの革命指導者アレクサンドル・ペティオンと出会い、親交を結んだ。スペイン領アメリカにおける奴隷制度廃止を約束したボリバルは、ペティオ ンから軍事支援を受け、ベネズエラに戻った。1817年に第三共和制を樹立し、1819年にはアンデス山脈を越えてニューグラナダの解放に向かった。ボリ バルとその同盟軍は、1819年にニューグラナダ、1821年にベネズエラとパナマ、1822年にエクアドル、1824年にペルー、1825年にボリビア でスペイン軍を打ち破った。ベネズエラ、ニューグラナダ、エクアドル、パナマは合併してコロンビア共和国(大コロンビア)となり、ボリバルはペルーとボリ ビアの大統領も兼任した。 晩年、ボリバルは南米の共和国に幻滅を深め、中央集権主義の思想からそれらから距離を置くようになった。彼は次々と役職を解任され、ついにコロンビアの大 統領を辞任し、1830年に結核で死去した。彼の遺産はラテンアメリカおよびその外の世界に多様かつ広範囲にわたって影響を与えている。彼はラテンアメリ カ全域で英雄、そして国民的・文化的な象徴とみなされている。ボリビアとベネズエラ(ベネズエラ・ボリバル共和国)の国民は彼にちなんで名付けられ、公共 芸術や通りの名前、大衆文化の形で世界中で記念されている。 |

| Early life and family Simón Bolívar was born on 24 July 1783 in Caracas, capital of the Captaincy General of Venezuela, the fourth and youngest child of Juan Vicente Bolívar y Ponte [es] and María de la Concepción Palacios y Blanco [es].[5] He was baptized as Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios on 30 July.[6] The first of Bolívar's family to have emigrated to the Americas was a similarly named minor Spanish governmental official named Simón de Bolívar, who had been a notary in the Spanish Basque region, and who had later arrived in Venezuela in the 1580s.[7] The earlier Simón de Bolívar's descendants had served in the colonial bureaucracy and had married into various wealthy Caracas families over the years.[8] By the time Simón Bolívar was born, the Bolívar family was one of the wealthiest and most prestigious criollo (creole) families in the Spanish Americas.[9] Simón Bolívar's childhood was described by British historian John Lynch as "at once privileged and deprived."[10] Juan Vicente died of tuberculosis on 19 January 1786,[11] leaving María de la Concepción Palacios and her father, Feliciano Palacios y Sojo [es],[12] as legal guardians over the Bolívar children's inheritances.[13] Those children – María Antonia [es] (born 1777), Juana [es] (born 1779), Juan Vicente [es] (born 1781), and Simón[14] – were raised separately from each other and their mother, and, following colonial custom, by African house slaves;[15] Simón was raised by a slave named Hipólita [es] whom he viewed as both a motherly and fatherly figure.[16] On 6 July 1792,[17] María de la Concepción also died of tuberculosis.[18] Believing that his family would inherit the Bolívars' wealth,[19] Feliciano Palacios arranged marriages for María Antonia and Juana and,[20] before dying on 5 December 1793,[21] assigned custody of Juan Vicente and Simón to his sons, Juan Félix Palacios and Carlos Palacios y Blanco [es], respectively.[22] Bolívar came to loathe Carlos Palacios,[23] who had no interest in the boy other than his inheritance.[24]  House that hosted Simón Bolívar during his stay in Bilbao between March 1801 and April 1802. |

幼少期と家族 シモン・ボリーバルは1783年7月24日、ベネズエラ総督領の首都カラカスで、フアン・ビセンテ・ボリーバル・イ・ポンテとマリア・デ・ラ・コンセプシ オン・パラシオス・イ・ブランコの4番目で末っ子として生まれた。[5] 7月30日にシモン・ホセ・アントニオ・デ・ラ・サントシマ・トリニダッド・ボリーバル・イ・パラシオスとして洗礼を受けた。[6] ボリーバルの一族で初めてアメリカ大陸に移住したのは、 同様にシモン・デ・ボリバルという名のスペインの政府高官がおり、スペインのバスク地方で公証人を務めていたが、1580年代にベネズエラに到着した。 [7] それ以前のシモン・デ・ボリバルの子孫は植民地官僚として仕え、長年にわたってカラカス市の富裕な家柄の女性と結婚していた。[8] シモン・ボリバルが生まれたときには、ボリバル家はスペイン領アメリカで最も裕福で名門の スペイン領アメリカにおけるクリオーリョ(クレオール)の富裕な一族であった。 シモン・ボリバルの幼少期は、イギリスの歴史家ジョン・リンチによって「特権的でありながら奪われたもの」と表現されている。[10] フアン・ビセンテは1786年1月19日に結核で死去し、[11] ボリバルの子供たちの遺産の法定後見人として、マリア・デ・ラ・コンセプシオン・パラシオスと父親のフェリシアーノ・パラシオス・イ・ソホ[es]、 [12]が残された。[13] 子供たち、すなわちマリア・アントニア[es](17 1777年生まれ)、フアナ(1779年生まれ)、フアン・ビセンテ(1781年生まれ)、シモン[14]は、互いに、また母親とも別々に育てられ、植民 地時代の慣習に従ってアフリカ人の家奴隷によって育てられた。[15] シモンはヒポリタという名の奴隷に育てられ、彼女を母親と父親の両方の存在として見ていた。[16] 179年7月6日、 2年7月6日、[17] マリア・デ・ラ・コンセプシオンも結核で死去した。[18] 家族がボリーバルの財産を相続できると信じていたフェリシアーノ・パラシオスは、マリア・アントニアとフアナの結婚をとりはからい、[20] 1793年12月5日に死去する前に、[21] フアン・ビセンテとシモンの後見人をそれぞれ、息子であるフアン・フェリックス・パラシオスとカルロス・パラシオス・イ・ブランコに指定した。[22] ボリーバルは カルロス・パラシオスを嫌うようになった。[23] カルロスは、相続財産以外には少年に何の関心も持っていなかった。[24]  1801年3月から1802年4月までビルバオに滞在していたシモン・ボリバルが滞在していた家。 |

| Education and first journey to Europe: 1793–1802 As a child, Bolívar was notoriously unruly[25] and neglected his studies.[19] Before his mother died, he spent two years under the tutelage of the Venezuelan lawyer Miguel José Sanz at the direction of the Real Audiencia of Caracas [es], the Spanish court of appeals in Caracas.[26] In 1793, Carlos enrolled Bolívar at a rudimentary primary school [es] run by Venezuelan educator Simón Rodríguez.[27] In June 1795, Bolívar fled his uncle's custody for the house of his sister María Antonia and her husband.[28] The couple sought formal recognition of his change of residence,[29] but the Real Audiencia decided the matter in favor of Palacios, who sent Simón to live with Rodríguez.[30] After two months there, the Real Audiencia directed that he be returned to the Palacios family home.[31] Bolívar promised the Real Audiencia that he would focus on his education and was subsequently taught full-time by Rodríguez and the Venezuelan intellectuals Andrés Bello and Francisco de Andújar [es].[32] In 1797, Rodríguez's connection to the pro-independence Gual and España conspiracy forced him to go into exile,[33] and Bolívar was enrolled in an honorary militia force. When he was commissioned as an officer after a year,[34] his uncles Carlos and Esteban Palacios y Blanco [es] decided to send Bolívar to join the latter in Madrid.[35] There, Esteban was friends with Queen Maria Luisa's favorite, Manuel Mallo.[36]  Miniature portrait of Bolívar in 1800 Miniature portrait of Bolívar in 1800  Bolívar at the age of 20 (1804) On 19 January 1799, Bolívar boarded the Spanish warship San Ildefonso at the port of La Guaira,[37] bound for Cádiz.[38] He arrived in Santoña, on the northern coast of Spain, in May 1799.[39] A little over a week later,[40] he arrived in Madrid and joined Esteban,[41] who found Bolívar to be "very ignorant."[42] Esteban asked Gerónimo Enrique de Uztáriz y Tovar, a Caracas native and government official, to educate Bolívar.[43][44] Bolívar moved into Uztáriz's residence in February 1800 and was educated in the Classics, literature, and social studies.[45][46] At the same time, Mallo fell out of the Queen's favor and Manuel Godoy, her previous favorite, returned to power.[47] As members of Mallo's faction at court, Esteban was arrested on pretense,[48] and Bolívar was banished from court following a public incident at the Puerta de Toledo over the wearing of diamonds without royal permission.[49] Bolívar also at this time met María Teresa Rodríguez del Toro y Alaysa, the daughter of another wealthy Caracas creole.[50] They were engaged in August 1800,[51] but were separated when the del Toros left Madrid for a summer home in Bilbao.[52] After Uztáriz left Madrid for a government assignment in Teruel in 1801,[51][53] Bolívar himself left for Bilbao and remained there when the del Toros returned to the capital in August 1801.[54] Early in 1802, Bolívar traveled to Paris while he awaited permission to return to Madrid, which was granted in April.[55] |

教育と最初のヨーロッパ旅行:1793年~1802年 幼少期のボリーバルは手に負えない子供として悪名高く[25]、勉強も疎かにしていた[19]。母親が亡くなる前、彼はカラカス控訴院(スペインのカラカ スにある上訴裁判所)の指示により、ベネズエラ人弁護士ミゲル・ホセ・サンズの指導の下で2年間を過ごした[26]。1793年、カルロスはボリーバルを ベネズエラ人教育者シモン・ロドリゲスが運営する初等教育学校に入学させた[27]。 。[27] 1795年6月、ボリバルは叔父の保護下を離れ、姉のマリア・アントニアとその夫の家に向かった。[28] 夫妻は彼の転居を正式に認めるよう求めたが、[29] 最高裁判所はパラシオス家の主張を認め、シモンをロドリゲスのもとに送った。[30] 2か月後、王立聴聞会は彼をパラシオス家の実家に戻すよう指示した。[31] ボリバルは王立聴聞会に教育に専念することを約束し、その後、ロドリゲスとベネズエラの知識人アンドレス・ベロとフランシスコ・デ・アンドゥハル[es] からフルタイムで教育を受けることになった。[32] 1797年、ロドリゲスが独立派のグアルとスペインの陰謀に関与していたことが原因で、彼は亡命を余儀なくされた。[33] ボリバルは名誉民兵隊に入隊した。1年後、士官として任務に就くと、叔父のカルロス・パラシオス・イ・ブランコとエステバン・パラシオス・イ・ブランコ は、ボリバルをマドリードにいる後者に合流させることを決めた。  1800年のボリバルの肖像画 1800年のボリバルの肖像画  20歳のボリバル(1804年) 1799年1月19日、ボリバルはラ・グアイラ港からスペインの軍艦サン・イルデフォンソ号に乗り込み、カディスに向かった。[38] 1799年5月、スペイン北部の海岸沿いの町サントーニャに到着した。[39] それから1週間余りが経った後、[40] マドリードに到着し、エステバンと合流した。[41] エステバンはボリバルを「非常に無知」であると感じた。[42] エステバンは、カラカス出身で政府高官のヘロニモ・エンリケ・デ・ウスタリス・イ・トバルに、ボリバルの教育を依頼した。[43][44] ボリバルは1800年2月にウスタリスの邸宅に移り住み、古典、文学、社会科学を学んだ。[45][46] 同時に、マヨは女王の寵愛を失い、以前女王のお気に入りであったマヌエル・ゴドイが権力を取り戻した。[47] 宮廷におけるマヨ派のメンバーとして、エステバンは口実をつけて逮捕され、[48] また、ボルヒバルはトレド門でのダイヤモンド着用をめぐる公の事件により宮廷から追放された。[49] また、この時期にボルヒバルは、 別の富裕なカラカス・クリオール(スペイン系カリブ人)の娘であるマリア・テレサ・ロドリゲス・デル・トロ・イ・アライサと出会った。[50] 1800年8月に婚約したが[51]、デル・トロ一家がマドリードからビルバオの別荘へ引っ越したため、2人は離れ離れになった。[52] 1801年にウスタリスがマドリードを離れ、テルエルの政府任務に就いた後、[51][53] ボリーバル自身もビルバオへ向かい、1801年8月にデル・トロ一家が首都に戻った際にもビルバオに残った。[5 1802年初頭、ボリバルはマドリードへの帰還許可を待つ間、パリを訪れた。4月に許可が下りた。[55] |

Return to Venezuela and second journey to Europe: 1802–1805 Wedding of Bolívar and del Toro as painted by Tito Salas, 1921 Bolívar and del Toro, aged 18 and 21 respectively, were married in Madrid on 26 May 1802.[56] The couple boarded the San Ildefonso in La Coruña[57] on 15 June and sailed for La Guaira, where they arrived on 12 July.[51] They settled in Caracas, where del Toro fell ill and died of yellow fever on 22 January 1803.[58] Bolívar was devastated by del Toro's death and later told Louis Peru de Lacroix, one of his generals and biographers, that he swore to never remarry.[59] By July 1803,[60] Bolívar had decided to leave Venezuela for Europe. He entrusted his estates to an agent and his brother and in October boarded a ship bound for Cádiz.[61] Bolívar arrived in Spain in December 1803, then traveled to Madrid to console his father-in-law.[62] In March 1804, the municipal authorities of Madrid ordered all non-residents in the city to leave to alleviate a bread shortage brought about by Spain's resumed hostilities with Britain.[63][64] Over April, Bolívar and Fernando Rodríguez del Toro [es], a childhood friend and relative of his wife, made their way to Paris and arrived in time for Napoleon to be proclaimed Emperor of the French on 18 May 1804.[65] They rented an apartment on the Rue Vivienne [fr] and met with other South Americans such as Carlos de Montúfar, Vicente Rocafuerte, and Simón Rodríguez, who joined Bolívar and del Toro in their apartment. While in Paris, Bolívar began a dalliance with the Countess Dervieu du Villars,[66] at whose salon he likely met the naturalists Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland, who had traveled through much of Spanish America from 1799 to 1804. Bolívar allegedly discussed Spanish American independence with them.[67] I swear before you ... that I will not rest body or soul until I have broken the chains binding us to the will of Spanish might! Simón Bolívar, 15 August 1805[68] In April 1805, Bolívar left Paris with Rodríguez and del Toro on a Grand Tour to Italy.[69] Beginning in Lyon, they traveled through the Savoy Alps and then to Milan.[70] The trio arrived on 26 May 1805 and witnessed Napoleon's coronation as King of Italy.[71] From Milan, they traveled down the Po Valley to Venice, then to Florence, and then finally Rome,[72] where Bolívar met, among others, Pope Pius VII, French writer Germaine de Staël, and Humboldt again.[73] Rome's sites and history excited Bolívar. On 18 August 1805, when he, del Toro, and Rodríguez traveled to the Mons Sacer, where the plebs had seceded from Rome in the 4th century BC, Bolívar swore to end Spanish rule in the Americas.[74] |

ベネズエラに戻り、二度目のヨーロッパ旅行:1802年~1805年 ティト・サラスが描いたボリーバルとデル・トロの結婚式(1921年) 1802年5月26日、それぞれ18歳と21歳だったボリーバルとデル・トロはマドリードで結婚した。[56] 6月15日、2人はラ・コルーニャでサン・イルデフォンソ号に乗り込み[57]、ラ・グアイラに向けて出航した。7月12日に到着した。[51] 2人はカラカスに住居を構えたが、デル・トロは黄熱病にかかり、1803年1月22日に死亡した。 。[58] ボリバルはデル・トロの死に打ちひしがれ、後に、彼の将軍であり伝記作家でもあるルイス・ペルー・デ・ラクロワに、二度と再婚しないと誓ったと語った。 [59] 1803年7月までに、[60] ボリバルはベネズエラを離れヨーロッパに向かうことを決意した。彼は自分の財産を代理人と兄弟に託し、10月にはカディス行きの船に乗船した。[61] ボリバルは1803年12月にスペインに到着し、その後義理の父を慰めるためにマドリードに向かった。[62] 1804年3月、マドリードの市当局は、スペインとイギリスの戦闘再開によるパン不足を緩和するために、市内に居住していない人々全員に退去を命じた。 [63][64] 4月、ボリバルとフェルナンド・ロドリゲス・デル・トロ(Fernando Rodríguez del Toro)は、幼馴染で妻の親戚である[es]、 パリに向かい、1804年5月18日にナポレオンがフランス皇帝に即位するのに間に合った。[65] 彼らはヴィヴィエンヌ通り(fr)にアパートを借り、カルロス・デ・モントゥファル、ビセンテ・ロカフエルテ、シモン・ロドリゲスといった他の南米人たち と会い、彼らはボリーバルとデルトロのいるアパートに合流した。パリ滞在中、ボリバルはデルヴュー・デュ・ヴィラール伯爵夫人と関係を持ち始めた。 [66] 彼女のサロンで、おそらく1799年から1804年にかけてスペイン領アメリカの大半を旅した博物学者のアレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトとエメ・ボン プランと出会った。ボリバルは彼らとスペイン領アメリカの独立について議論したと言われている。[67] 私はここに誓う...スペインの権力による我々の意志を縛る鎖を断ち切るまで、私は身も心も休まることはないだろう! シモン・ボリバル、1805年8月15日[68] 1805年4月、ボリバルはロドリゲスとデル・トロとともにパリを発ち、イタリアへのグランドツアーに出発した。[69] リヨンからサヴォワ・アルプスを通り、ミラノへと向かった。[70] 3人は1805年5月26日に到着し、ナポレオンのイタリア王即位式に立ち会った。[71] ミラノからポー平原を通ってヴェネツィアへ、さらにフィレンツェ、そして最終的にローマへと向かった。[72] ローマでは、 ボリバルは、教皇ピウス7世、フランスの作家ジェルメーヌ・ド・スタール、フンボルトなどと再会した。[73] ローマの史跡や歴史にボリバルは興奮した。1805年8月18日、彼とデル・トロ、ロドリゲスがモンテ・サクレ(4世紀に平民がローマから離反した地)を 訪れた際、ボリバルはアメリカ大陸におけるスペインの支配を終わらせると誓った。[74] |

| Political and military career Main article: Military career of Simón Bolívar  Portrait of Francisco de Miranda Portrait of Francisco de Miranda by Martín Tovar y Tovar By April 1806, Bolívar had returned to Paris and desired passage to Venezuela,[75] where Venezuelan revolutionary Francisco de Miranda had just attempted an invasion with American volunteers.[76] Britain's command of the sea after the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar obliged Bolívar to board an American ship in Hamburg in October 1806. Bolívar arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, in January 1807,[77] and from there traveled to Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, New York City, and Boston.[78] After six months in the United States,[79] Bolívar returned to Philadelphia and sailed for Venezuela, where he arrived in June 1807. He began to meet with other creole elites to discuss independence from Spain.[80] Finding himself to be far more radical than the rest of Caracas high society,[81] however, Bolívar occupied himself with a property dispute with a neighbor, Antonio Nicolás Briceño [es].[82] In 1807–08, Napoleon invaded the Iberian peninsula and replaced the rulers of Spain with his brother, Joseph.[83] This news arrived in Venezuela in July 1808.[84] Napoleonic rule was rejected and Venezuelan creoles, though still loyal to Ferdinand VII of Spain, sought to form their own local government in place of the existing Spanish government.[85] On 24 November 1808, a group of creoles presented a petition demanding an independent government to Juan de Casas, the Captain-General of Venezuela, and were arrested.[86] Bolívar, though he did not sign the petition and thus was not arrested, was warned to cease hosting or attending seditious meetings.[87] In May 1809, Casas was replaced by Vicente Emparán and his staff, which included Fernando Rodríguez del Toro. The creoles also resisted Emparán's government, despite his friendlier disposition towards them.[88] By February 1810, French victories in Spain prompted the dissolution of the anti-French Spanish government in favor of a five-man regency council for Ferdinand VII.[89] This news, and two delegates that included Carlos de Montúfar, arrived in Venezuela on 17 April 1810.[90] Two days later, the creoles succeeded in deposing and then expelling Emparán,[91] and created the Supreme Junta of Caracas, independent from the Spanish regency but not Ferdinand VII.[92][93] Absent from Caracas for the coup,[94] Bolívar and his brother returned to the city and offered their services to the Supreme Junta as diplomats.[95] In May 1810, Juan Vicente was sent to the United States to buy weapons,[96] while Simón secured a place in a diplomatic mission to Britain with the lawyer Luis López Méndez [es] and Andrés Bello by paying for the mission. The trio boarded a British ship in June 1810 and arrived at Portsmouth on 10 July 1810.[97] The three delegates first met Miranda at his London residence, despite instructions from the Supreme Junta to avoid him, and thereafter received the benefit of his connections and consultation.[98] On 16 July 1810, the Venezuelan delegation met Britain's foreign secretary, Richard Wellesley, at Apsley House. Led by Bolívar, the Venezuelans argued in favor of Venezuelan independence, which Wellesley stated that it was intolerable for Anglo-Spanish relations.[99] Subsequent meetings produced no recognition or concrete support from Britain.[100] Finding that he had many shared beliefs with Miranda, however, Bolívar convinced him to come back to Venezuela.[101] On 22 September 1810,[102] Bolívar left for Venezuela while López and Bello remained in London as diplomats,[103] and arrived in La Guaira on 5 December.[104] Although the British government wanted Miranda to remain in Britain, they could not prevent his departure,[105] and he arrived in Venezuela later in December.[106][d] |

政治と軍での経歴 詳細は「シモン・ボリバルの軍歴」を参照  フランシスコ・デ・ミランダの肖像 マルティン・トバル・イ・トバルによるフランシスコ・デ・ミランダの肖像 1806年4月までに、ボリバルはパリに戻り、ベネズエラへの渡航を希望した。[75] そこでは、ベネズエラの革命家フランシスコ・デ・ミランダがアメリカ人志願兵を率いて侵攻を試みたばかりであった。[76] 1805年のトラファルガーの海戦後、イギリスが制海権を握ったため、ボリバルは1806年10月にハンブルクでアメリカの船に乗り込むことを余儀なくさ れた。ボリバルは1807年1月にサウスカロライナ州チャールストンに到着し、[77] そこからワシントンD.C.、フィラデルフィア、ニューヨーク、ボストンを訪問した。[78] 6ヶ月間アメリカに滞在した後、[79] ボリバルはフィラデルフィアに戻り、ベネズエラに向けて出航し、1807年6月に到着した。彼は他のクリオーリョのエリートたちと会合を開き、スペインか らの独立について話し合いを始めた。[80] しかし、ボリバルは、自分がカラカス社交界の他の人々よりもはるかに急進的であることに気づき、[81] 近所の住人であるアントニオ・ニコラス・ブリセーニョ[es]との財産を巡る争いに時間を費やした。[82] 1807年から1808年にかけて、ナポレオンがイベリア半島に侵攻し、スペインの支配者を弟のジョゼフに置き換えた。[83] このニュースは1808年7月にベネズエラに届いた。[84] ナポレオンの支配は拒絶され、ベネズエラのクリオールたちは、スペインのフェルディナンド7世には依然として忠誠を誓っていたものの、既存のスペイン政府 に代わる独自の地方自治体を樹立しようとした。[85] 1808年11月24日、 クレオール人のグループが、ベネズエラ総督フアン・デ・カサスに独立政府樹立を要求する請願書を提出し、逮捕された。[86] ボリバルは請願書に署名せず、逮捕は免れたが、反乱的な集会の主催や参加を中止するよう警告された。[87] 1809年5月、カサスはビセンテ・エンパランとそのスタッフに交代させられた。スタッフにはフェルナンド・ロドリゲス・デル・トロが含まれていた。彼ら に対しては友好的な態度を示していたにもかかわらず、クレオール人もエンパランの政府に抵抗した。 1810年2月までに、スペインにおけるフランスの勝利により、反仏派スペイン政府は解散し、フェルナンド7世を支持する5人の摂政評議会が設置された。 [89] このニュースと、カルロス・デ・モンタフアルを含む2人の代表団が、1810年4月17日にベネズエラに到着した。[90] 2日後、クレオール人はエンパランの追放と追放に成功し、[91] 最高会議(スペイン摂政政府から独立しているが、フェルナンド7世からは独立していない)を設立した。スペインの摂政からは独立したが、フェルディナンド 7世からは独立していなかった。[92][93] クーデターのためにカラカスを留守にしていた[94]ボリバルと彼の兄弟は、カラカスに戻り、外交官として最高会議に奉仕することを申し出た。[95] 1810年5月、フアン・ビセンテは武器を購入するためにアメリカ合衆国に派遣され[96]、シモンは弁護士のルイス・ロペス・メンデス[es]とアンド レス・ベジョとともに、イギリスへの外交使節団の一員となることを確保した。 ミッションの費用を負担することで、英国への外交使節団への参加枠を確保した。3人は1810年6月に英国船に乗り込み、1810年7月10日にポーツマ スに到着した。 最高会議からミランダとの接触を避けるよう指示されていたにもかかわらず、3人の代表団はまずロンドンのミランダ邸で彼と会い、その後、ミランダの人的 ネットワークと助言の恩恵を受けた。[98] 1810年7月16日、ベネズエラ代表団は英国外務大臣リチャード・ウェルズリーとアプスリー・ハウスで会談した。ボリバルに率いられたベネズエラ代表団 は、ベネズエラの独立を支持する旨を主張し、ウェルズリーは、それは英西関係にとって耐え難いことだと述べた。[99] その後の会合では、英国からの承認や具体的な支援は得られなかった。[100] しかし、ミランダと多くの共通の信念を持っていることを知ったボリバルは、ミランダを説得してベネズエラに戻らせた。[101] 1810年9月22日、[102] ボリバルはベネズエラに向けて出発し、 ロペスとベロは外交官としてロンドンに残り、[103] 12月5日にラ・グアイラに到着した。[104] 英国政府はミランダに英国に留まることを望んでいたが、彼の出国を阻止することはできず、[105] 12月後半にベネズエラに到着した。[106][d] |

Venezuela: 1811–1812 Oil on canvas "Terremoto de 1812", by Venezuelan painter Tito Salas While Bolívar was in England, the Supreme Junta passed liberal economic reforms[112] and began to hold elections for representatives to a congress to be held in Caracas.[113] It had also alienated Caracas from the Venezuelan provinces of Coro, Maracaibo, and Guayana, which professed loyalty to the regency council,[114] and began hostilities with them.[115][116] Co-founding the Patriotic Society, a political organization advocating for independence from Spain, Bolívar and Miranda campaigned for and secured the latter's election to the congress.[117] The congress first met on 2 March 1811 and declared its allegiance to Ferdinand VII.[118] After it was discovered that one of the men leading the congress was a Spanish agent who had escaped with military documents, however,[119] discourse – which Bolívar was prominent in – changed decidedly in favor of independence over 3 and 4 July.[120] Finally, on 5 July, the congress declared Venezuela's independence.[121] The declaration of independence created the first Republic of Venezuela. It had a weak base of support and enemies in conservative whites, disenfranchised people of color, and the already hostile Venezuelan provinces, which received troops and supplies from the Captaincy-Generals of Puerto Rico and Cuba.[122] On 13 July 1811, the republic raised militias to fight the pro-Spanish Royalists.[123] The congress appointed Francisco Rodríguez del Toro [es], the Marquis of Toro [es], to command these forces,[124] which opened a breach between Bolívar and Miranda. Bolívar and del Toro were close friends, while del Toro and Miranda and their families were enemies.[125] After he failed to suppress a Royalist uprising in the city of Valencia later in July,[126] the congress replaced del Toro with Miranda, and he recaptured Valencia [es] on 13 August.[127] As a condition of assuming command of the Republican forces, Miranda had Bolívar stripped of his command of a militia unit.[128] Bolívar nonetheless fought in the Valencia campaign as part of del Toro's militia[129] and was selected by Miranda to bring news of its recapture to Caracas,[130] where he argued for more punitive and forceful campaigning against the Royalists.[131] I left my house for the Cathedral ... and the earth began to shake with a huge roar. ... I saw the church of San Jacinto collapse on its own foundations. ... I climbed over the ruins and entered, and I immediately saw about forty persons dead or dying under the rubble. I climbed out again and I shall never forget that moment. On the top of the ruins I found Don Simón Bolívar ... He saw me and [said], "We will fight nature itself if it opposes us, and force it to obey." Royalist historian José Domingo Díaz [es], quoted by John Lynch[132] Beginning in November 1811, Royalist forces began pushing back the Republicans from the north and east.[133] On 26 March 1812, a powerful earthquake devastated Republican Venezuela; Caracas itself was almost totally destroyed.[134] Bolívar, who was still near Caracas,[135] rushed into the city to participate in the rescue of survivors and exhumation of the dead.[136] The earthquake destroyed public support for the republic, as it was believed to have been divine retribution for declaring independence from Spain.[137] By April, a Royalist army under the Spanish naval officer Juan Domingo de Monteverde overran western Venezuela. Miranda,[138] retreating east with a disintegrating army,[139] ordered Bolívar to assume command of the coastal city of Puerto Cabello and its fortress,[140] which contained Royalist prisoners and most of the republic's remaining arms and ammunition.[141] Bolívar arrived at Puerto Cabello on 4 May 1812.[142] On 30 June, an officer of the fort's garrison loyal to the Royalists released its prisoners, armed them, and turned its cannons on Puerto Cabello.[139][143] Weakened by shelling, defections, and lack of supplies, Bolívar and his remaining troops fled for La Guaira on 6 July.[144] Believing the republic to be doomed,[139] Miranda decided to capitulate,[145] shocking Bolívar and other Republican officers.[146] After formally surrendering his command to Monteverde on 25 July,[147] Miranda made his way to La Guaira, where a group of officers including Bolívar arrested Miranda on 30 July on charges of treason against the republic.[148] La Guaira declared for the Royalists the next day and closed its port on Monteverde's orders.[149] Miranda was taken into Spanish custody and moved to a prison in Cádiz, where he died on 16 July 1816.[150] |

ベネズエラ:1811年~1812年 ベネズエラ人画家ティト・サラスによる油彩画「1812年の地震」 ボリバルがイギリスに滞在している間、最高会議は自由主義的な経済改革を可決し[112]、カラカスで開催される議会への代表者選挙を開始した。 [113] また、摂政評議会への忠誠を誓うベネズエラの地方都市コロ、マラカイボ、グアヤナとカラカスとの関係を悪化させ、彼らとの敵対関係が始まった。[115] [116] スペインからの独立を主張する政治組織である愛国協会を共同設立し、ボリバルとミランダは後者の議会選挙への出馬を支援し、当選を確実にした。[117] 議会は1811年3月2日に初めて会合を開き、フェルディナンド7世への忠誠を宣言した。[118] しかし、議会を主導する人物の一人が軍事文書を携えて脱出したスペインのスパイであることが発覚した。[119] ボリバルが主導した議論は、 7月3日と4日には、独立を支持する意見が優勢となった。[120] そして7月5日、ついに議会はベネズエラの独立を宣言した。[121] 独立宣言により、ベネズエラ第一共和国が誕生した。その基盤は弱く、保守的な白人、権利を剥奪された有色人種、そしてすでに敵対関係にあったベネズエラの 地方が敵対していた。これらの地方はプエルトリコとキューバの総督から軍隊と物資の支援を受けていた。[122] 1811年7月13日、共和国はスペイン王党派と戦うために民兵を組織した。[123] 議会はフランシスコ・ロドリゲス・デル・トロ(トロ侯爵)を指揮官に任命した。これらの部隊を指揮するよう任命した。これにより、ボリーバルとミランダの 間に亀裂が生じた。ボリーバルとデル・トロは親しい友人であったが、デル・トロとミランダとその家族は敵対関係にあった。[125] 7月後半にバレンシア市で王党派の蜂起を鎮圧できなかった後、[126] 議会はデル・トロをミランダと交代させ、ミランダは8月13日にバレンシアを奪還した。[127] ミランダは、共和軍の指揮官に就任する条件として、ボリーバルの民兵部隊の指揮権を剥奪させた。[12 それでもボリバルはデル・トロの民兵部隊の一員としてバレンシアの戦いに参加し[129]、ミランダによってバレンシア奪還の知らせをカラカスに伝えるよ う選ばれた[130]。そこで彼は王党派に対するより強力な懲罰的なキャンペーンを主張した[131]。 私は家を出て大聖堂に向かった...すると巨大な轟音とともに大地が揺れ始めた。...サン・ハシント教会がその基礎の上に崩れ落ちるのを見た。私は瓦礫 を乗り越えて中に入り、すぐに瓦礫の下で40人ほどの死者や瀕死の者を目にした。私は再び外へ出たが、その瞬間を決して忘れないだろう。瓦礫の上にドン・ シモン・ボリーバルを見つけた。彼は私を見ると、「我々を阻むものがあれば、自然そのものと戦い、従わせる」と言った。 王党派の歴史家ホセ・ドミンゴ・ディアス(スペイン語)の言葉。ジョン・リンチによる引用[132] 1811年11月より、王党派軍は北と東から共和党軍を押し戻し始めた。[133] 1812年3月26日、強力な地震がベネズエラの共和党を襲い、カラカスはほぼ完全に破壊された。[134] カラカス近郊にいたボリーバルは、[135] 生存者の救助と死者の掘り起こしに参加するために急いで市内に入った。[136] この地震により、 スペインからの独立宣言に対する神の報復であると考えられたため、共和国に対する国民の支持は失墜した。[137] 4月までに、スペイン海軍将校フアン・ドミンゴ・デ・モンテベルデ率いる王党派軍がベネズエラ西部を席巻した。ミランダは[138]、崩壊しつつある軍勢 を率いて東へと撤退し[139]、ボリバルにプエルト・カベヨの沿岸都市とその要塞の指揮を執るよう命じた[140]。そこには王党派の捕虜と、共和国に 残る武器や弾薬のほとんどが保管されていた[141]。 ボリバルは1812年5月4日にプエルト・カベヨに到着した。[142] 6月30日、王党派に忠誠を誓う要塞の守備隊の士官が捕虜を解放し、武器を与え、プエルト・カベヨに大砲を向けた。[139][143] 砲撃、脱走、物資不足により弱体化したボリバルと残存する軍勢は7月6日にラ・グアイラへと逃亡した。[14 4] 共和国の運命を悟ったミランダは降伏を決意し[145]、ボリバルや他の共和国軍将校たちを驚かせた[146]。7月25日にモンテベルデに正式に指揮権 を委譲した後[147]、ミランダはラ・グアイラに向かった。そこでボリバルを含む将校グループが、共和国に対する反逆罪の容疑でミランダを7月30日に 逮捕した[148]。ラ・グアイラは翌日王党派を宣言し、モンテベルデの命令で港を閉鎖した[149]。翌日にはモンテベルデの命令により港を閉鎖した。 [149] ミランダはスペインの保護下に置かれ、カディスにある刑務所に移送され、1816年7月16日に死亡した。[150] |

| New Granada and Venezuela: 1812–1815 Bolívar escaped La Guaira early on 31 July 1812 and rode to Caracas,[151] where he hid from arrest in the home of Esteban Fernández de León [es], the Marquis de Casa León [es]. Bolívar and Casa León convinced Francisco Iturbe, a friend of the Bolívar family and of Monteverde, to intercede on Bolívar's behalf and secure escape from Venezuela for him. Iturbe persuaded Monteverde to issue Bolívar a passport for his role in Miranda's arrest,[152] and on 27 August he sailed for the island of Curaçao. He and his uncles' Francisco and José Félix Ribas arrived on 1 September. Late in October, the exiles arranged for passage west to the city of Cartagena to offer their services as military leaders to the United Provinces of New Granada against the Royalists.[153] They arrived in November and were welcomed by Manuel Rodríguez Torices, president of the Free State of Cartagena [es],[154] who instructed his commanding general, Pierre Labatut, to give Bolívar a military command. Labatut, a former partisan of Miranda, begrudgingly obliged and on 1 December 1812 placed Bolívar in command of the 70-man garrison of a town on the lower Magdalena River.[155] While en route to his posting, Bolívar issued the Cartagena Manifesto, outlining what he believed to be the causes of the Venezuelan republic's defeat and his political program. In particular, Bolívar called for the disparate New Granadan republics to help him invade Venezuela to prevent a Royalist invasion of New Granada.[156] Bolívar arrived on the Magdalena River on 21 December and,[157] in spite of orders from Labatut to not act without his direction,[158] launched an offensive that secured control of the Magdalena River from Royalist forces by 8 January 1813.[159] In February, he joined forces with Republican colonel Manuel del Castillo y Rada, who requested Bolívar's assistance with stopping a Royalist advance into New Granada from Venezuela, and captured the city of Cúcuta from the Royalists.[160] In early March 1813, Bolívar set up his headquarters in Cúcuta and sent José Félix Ribas to request permission to invade Venezuela.[161] Though rewarded with honorary citizenship in New Granada and a promotion to the rank of brigadier general,[162] that permission did not come until 7 May because of del Castillo's opposition to the invasion. When a limited invasion was permitted, Castillo resigned his command and was succeeded by Francisco de Paula Santander.[163] On 14 May, Bolívar launched the Admirable Campaign,[164] in which he issued the Decree of War to the Death, ordering the death of all Spaniards in South America not actively aiding his forces.[165] Within six months, Bolívar pushed all the way to Caracas,[166] which he entered on 6 August,[167][168] and then drove Monteverde out of Venezuela in October.[169][170] Bolívar returned to Caracas on 14 October and was named "The Liberator" (El Libertador) by its town council,[171] a title first given to him by the citizens of the Venezuelan town of Mérida on 23 May.[172] |

新グラナダおよびベネズエラ:1812年~1815年 1812年7月31日早朝、ボリバルはラ・グアイラを脱出し、カラカスへ向かった。[151] そこで彼は、エステバン・フェルナンデス・デ・レオン[es](カサ・レオン侯爵[es])の邸宅に身を隠した。ボリバルとカサ・レオンは、ボリバル家と モンテベルデの友人であるフランシスコ・イトゥルベに、ボリバルのために仲裁し、彼をベネズエラから脱出させるよう説得した。イトゥルベはモンテベルデを 説得し、ミランダの逮捕におけるボリバルの役割を考慮して、彼にパスポートを発給させた。[152] そして8月27日、彼はキュラソー島に向けて出航した。彼と叔父のフランシスコとホセ・フェリックス・リバスは9月1日に到着した。10月後半、亡命者た ちは西のカルタヘナ市へ向かう船を手配し、王党派に対する新グラナダ連合国の軍事指導者として仕えることになった。[153] 彼らは11月に到着し、カルタヘナ自由州大統領マヌエル・ロドリゲス・トリセスに歓迎された。[154] トリセスは司令官ピエール・ラバトゥにボリバルに軍事指揮権を与えるよう指示した。ミランダの元パルチザンであったラバトゥは、渋々ながらその要請に応 じ、1812年12月1日に、マグダレナ川下流の町にある70人の守備隊の指揮官としてボリバルを任命した。 赴任の途上、ボリバルは「カルタヘナ宣言」を発表し、ベネズエラ共和国敗北の原因と自らの政治プログラムについて概説した。特に、ボリバルは、ニューグラ ナダ共和国の諸勢力に、王党派によるニューグラナダ侵攻を阻止するために、ベネズエラ侵攻に協力するよう呼びかけた。[156] ボリバルは12月21日にマグダレナ川に到着し、[157] ラバトゥの「ボリバルの指示なしに行動してはならない」という命令にもかかわらず、[158] 1813年1月8日までにマグダレナ川を王党派の軍勢から確保する攻勢を開始した。[159] 2月には、 彼は、ベネズエラからニューグラナダへの王党派軍の進軍を阻止するためにボリバルの支援を要請した、共和国派の大佐マヌエル・デル・カスティーリョ・イ・ ラダと合流し、王党派からククタ市を奪還した。 1813年3月初旬、ボリバルはククタに司令部を置き、ホセ・フェリックス・リバスをベネズエラ侵攻の許可を要請するために派遣した。[161] ニューグラナダの名誉市民権と准将への昇進という褒賞を得たものの、[162] デル・カスティーヨが侵攻に反対したため、許可は5月7日まで下りなかった。限定的な侵攻が許可されたとき、カスティージョは指揮官を辞任し、フランシス コ・デ・パウラ・サンタンデールが後任となった。[163] 5月14日、ボリバルは「アドミラブル作戦」を開始し、[164] 死を賭けた戦争布告を発令し、南米でボリバル軍に積極的に加担していないスペイン人全員の処刑を命じた。[165] 6か月以内に、ボリバルはカラカスまで進軍し、[166] 8月6日にカラカスに入城した 、そして10月にはモンテベルデをベネズエラから追い出した。[169][170] ボリバルは10月14日にカラカスに戻り、市議会から「解放者」(El Libertador)の称号を授けられた。[171] この称号は、5月23日にベネズエラのメリダ市の市民から初めて与えられたものである。[172] |

1874 portrait of Santiago Mariño by Martín Tovar y Tovar Portrait of Santiago Mariño by Martín Tovar y Tovar On 2 January 1814, Bolívar was made the dictator of a Second Republic of Venezuela,[173] which retained the weaknesses of the first republic.[174] Though all of Venezuela but Maracaibo, Coro, and Guayana was controlled by Republicans,[175][176] Bolívar only governed western Venezuela. The east was controlled by Santiago Mariño, a Venezuelan Republican who had fought Monteverde in the east throughout 1813[177][178] and was unwilling to subordinate himself to Bolívar.[179] Venezuela was economically devastated and could not support the republic's armies,[180] and people of color remained disenfranchised and thus unsupportive of the republic.[181] The republic was assailed from all sides by slave revolts and Royalist forces,[182] especially the Legion of Hell, an army of llaneros – the horsemen of the Llanos, to the south – led by the Spanish warlord José Tomás Boves.[183] Beginning in February 1814, Boves surged out of the Llanos and overwhelmed the republic, occupying Caracas on 16 July and then destroying Mariño's powerbase on 5 December at the Battle of Urica, where Boves died.[184][185] As Boves approached Caracas, Bolívar ordered the city stripped of its gold and silver,[186] which was moved through La Guaira to Barcelona, Venezuela,[187] and from there to Cumaná.[188] Bolívar then led 20,000 of its citizens east.[186] He arrived in Barcelona on 2 August,[189] but following another defeat at the Battle of Aragua de Barcelona on 17 August 1814, he moved to Cumaná.[190] On 26 August, he sailed with Mariño to Margarita Island with the treasure. The officer in control of the island, Manuel Piar, declared Bolívar and Mariño to be traitors and forced them to return to the mainland.[191] There, Ribas also accused Bolívar and Mariño of treachery, confiscated the treasure,[192] and then exiled the two on 8 September.[193] Bolívar arrived in Cartagena on 19 September and then met with the New Granadan congress in Tunja,[194] which tasked him with subduing the rival Free and Independent State of Cundinamarca.[195] On 12 December, Bolívar captured Cundinamarca's capital, Bogotá, and was given command of New Granada's armies in January 1815.[196] Bolívar next grappled with del Castillo, who had taken control of Cartagena.[197] Bolívar besieged the city [es] for six weeks. His change of focus allowed the Royalist forces to regain control of the Magdalena.[198] On 8 May, Bolívar made a truce with del Castillo, resigned his command, and sailed for self-exile on Jamaica as a result of this error.[199] In July, 8,000 Spanish soldiers commanded by Spanish general Pablo Morillo landed at Santa Marta and then besieged Cartagena [es], which capitulated on 6 December; del Castillo was executed.[200][201] |

1874年、マルティン・トバル・イ・トバルによるサンティアゴ・マリーニョの肖像画 マルティン・トバル・イ・トバルによるサンティアゴ・マリーニョの肖像画 1814年1月2日、ボリバルはベネズエラ第二共和政の独裁者に任命されたが、これは第一共和政の弱点をそのまま引き継いだものであった。[174] マラカイボ、コロ、グアヤナを除くベネズエラ全土は共和派によって支配されていたが、[175][176] ボリバルが統治したのはベネズエラ西部のみであった。東部は、1813年を通してモンテベルデと戦ったベネズエラ共和国のサンティアゴ・マリーニョが支配 しており[177][178]、ボリバルに従属する意思はなかった。[179] ベネズエラは経済的に荒廃し、共和国の軍隊を維持できず[180]、有色人種は依然として選挙権がなく、したがって共和国を支持しなかった。[181] 共和国は、 奴隷の反乱や王党派の軍勢、特にスペインの軍司令官ホセ・トマス・ボベスが率いる、南の平原の騎兵であるリャネロスの軍隊「地獄軍団」によって攻撃され た。[183] 1814年2月に始まったボベスの攻撃は、平原から飛び出し、共和国を圧倒し、7月16日にカラカスを占領し、12月5日のウリカの戦いでマリーニョの拠 点も破壊した。ボベスはここで戦死した。[184][185] ボベスがカラカスに近づくと、ボリバルは都市から金銀を奪うよう命じた。[186] それらはラ・グアイラからバルセロナ(ベネズエラ)へと運ばれ、[187] そこからクマナへと送られた。[188] その後、ボリバルは2万人の市民を東へと導いた。[186] 彼は8月2日にバルセロナに到着したが、[189] 1814年8月17日のアラグア・デ・バルセロナの戦いでの新たな敗北を受けて、 1814年8月17日、アラグア・デ・バルセロナの戦いで再び敗北を喫したため、クマナへと移動した。[190] 8月26日、マリーニョとともに財宝を携えてマルガリータ島へと出帆した。島の統治責任者マヌエル・ピアは、ボリバルとマリーニョを裏切り者と宣言し、本 土への帰還を強制した。[191] そこでは、リバスもまたボリバルとマリーニョを裏切り者と非難し、財宝を没収し、[192] 9月8日に2人を追放した。[193] ボリバルは9月19日にカルタヘナに到着し、その後トゥンハで新グラナダ議会と会合した。[194] 議会は彼にライバルである自由で独立したクンディナマルカ州の制圧を命じた。[195] 12月12日、ボリバルはクンディナマルカ州の首都ボゴタを占領し、1815年1月には新グラナダ軍の司令官に任命された。[196] ボリバルは次に、 カルタヘナを掌握していたデル・カスティーヨと対峙した。[197] ボリーバルは6週間、同市を包囲した。ボルが戦術を変更したことで、王党派軍がマグダレナ川の支配権を取り戻すことができた。[198] 5月8日、ボルはデル・カスティーリョと休戦協定を結び、指揮官を辞任し、この失策の結果、ジャマイカへの亡命を決意して出航した。[199] 7月、スペイン人将軍パブロ・モリージョ率いる8,000人のスペイン兵がサンタ・マルタに上陸し、カルタヘナを包囲した。カルタヘナは12月6日に降伏 し、デル・カスティーリョは 処刑された。[200][201] |

Jamaica, Haiti, Venezuela, and New Granada: 1815–1819 Portrait of Bolívar by Arturo Michelena Portrait of Bolívar by Arturo Michelena, 1895 Bolívar arrived in Kingston, Jamaica, on 14 May 1815 and,[202] as in his earlier exile on Curaçao, ruminated on the fall of the Venezuelan and New Granadan republics. He wrote extensively, requesting assistance from Britain and corresponding with merchants based in the Caribbean. This culminated in September 1815 with the Jamaica Letter, in which Bolívar again laid out his ideology and vision of the future of the Americas.[203] On 9 December, the Venezuelan pirate Renato Beluche brought Bolívar news from New Granada and asked him to join the Republican community in exile in Haiti.[204] Bolívar tentatively accepted and escaped assassination that night when his manservant mistakenly killed his paymaster as part of a Spanish plot.[205] He left Jamaica eight days later,[206] arrived in Les Cayes on 24 December,[207] and on 2 January 1816 was introduced to Alexandre Pétion, President of the Republic of Haiti by a mutual friend.[208] Bolívar and Pétion impressed and befriended each other and,[209] after Bolívar pledged to free every slave in the areas he occupied, Pétion gave him money and military supplies.[210][211] Returning to Les Cayes, Bolívar held a conference with the Republican leaders in Haiti and was made supreme leader with Mariño as his chief of staff.[212] The Republicans departed Les Cayes for Venezuela on 31 March 1816 and followed the Antilles eastward.[213] After a delay to allow a lover of Bolívar's to join the fleet, it arrived on 2 May at Margarita Island, controlled by Republican commander Juan Bautista Arismendi.[214] Bolívar next moved to the mainland, where he declared the emancipation of all slaves and annulled of the Decree of War to the Death.[215][e] He seized Carúpano on 31 May and sent Mariño and Piar into Guayana to build their own army,[218] then took and held Ocumare de la Costa from 6 to 14 July, when it was recaptured by the Royalists.[219][220] Bolívar fled by sea to Güiria where, on 22 August, he was deposed by Mariño and Venezuelan Republican José Francisco Bermúdez.[221]  Birthplace of Simon Bolivar in Caracas. Bolívar returned to Haiti by early September,[222] where Pétion again agreed to assist him.[223] In his absence, the Republican leaders scattered across Venezuela, concentrating in the Llanos, and became disunited warlords.[224] Unwilling to recognize Mariño's leadership, [225] Arismendi wrote to Bolívar and dispatched New Granadan Republican Francisco Antonio Zea to convince him to return. Bolívar and Zea set sail for Venezuela on 21 December with Luis Brión, a Dutch merchant,[226] and arrived ten days later at Barcelona. There, Bolívar announced his return and called for a congress for a new, third republic.[227] He wrote to the Republican leaders, especially José Antonio Páez, who controlled most of the western Llanos, to unite under his leadership.[228][229] On 8 January 1817, Bolívar marched towards Caracas but was defeated at the Battle of Clarines and pursued to Barcelona by a larger Royalist force.[230] At Bolívar's request, Mariño arrived on 8 February with Bermúdez, who then reconciled with Bolívar, and forced a Royalist withdrawal.[231] Even with their combined forces, however, Bolívar, Mariño, and Bermúdez could not hold Barcelona.[232] Instead, on 25 March 1817,[233] Bolívar began moving south to join Piar in Guayana, Piar's power base, and establish his own economic and political base there.[234][235] Bolívar met Piar on 4 April,[236] promoted him to the rank of general of the army, and then joined a force of Piar's troops besieging the city of Angostura (now Ciudad Bolívar) on 2 May.[237] Meanwhile, Mariño went east to reestablish his power base and on 8 May convened a congress of ten men, including Brión and Zea, that named Mariño as supreme commander of the Republican forces.[238] This backfired and provoked the defection of 30 officers, including Rafael Urdaneta and Antonio José de Sucre, to Bolívar.[239] On 30 June, Bolívar granted Piar leave of absence at his request,[240] and then issued an arrest warrant on 23 July after Piar began fomenting rebellion, alleging that Bolívar had dismissed him because of his mulatto heritage. Piar was captured on 27 September as he fled to join Mariño and was brought to Angostura, where he was executed by firing squad on 16 October.[241] Bolívar then sent Sucre to reconcile with Mariño,[242] who pledged loyalty to Bolívar on 26 January 1818.[243] On 17 July 1817, Angostura fell to Bolívar's forces, which gained control of the Orinoco River in early August.[244][245] Angostura became the provisional Republican capital and in September,[246] Bolívar began creating formal political and military structures for the republic.[247][248] Following a meeting at San Juan de Payara on 30 January 1818, Páez recognized Bolívar as supreme leader.[249] In February 1818, the Republicans moved north and took Calabozo, where they defeated Morillo [es],[250] who had returned to Venezuela a year earlier after conquering Republican New Granada.[251] Bolívar next advanced towards Caracas, but was defeated while en route at the Third Battle of La Puerta [es] on 16 March.[252][253] He escaped assassination by Spanish infiltrators in April. Illness and additional Republican defeats obliged Bolívar to return to Angostura in May. For the rest of the year, he focused on administering the republic, rebuilding its armed forces,[254] and organizing elections for a national congress that would meet in 1819.[255][256] |

ジャマイカ、ハイチ、ベネズエラ、および新グラナダ:1815年~1819年 アルトゥーロ・ミチェレーナによるボリバルの肖像画 アルトゥーロ・ミチェレーナによるボリバルの肖像画、1895年 ボリバルは1815年5月14日にジャマイカのキングストンに到着し、[202] 以前のキュラソー島への亡命時と同様に、ベネズエラと新グラナダ共和国の崩壊について考えを巡らせた。彼は多くの文章を書き、英国からの支援を要請し、カ リブ海に拠点を置く商人たちと文通した。1815年9月、ボリバルはジャマイカ書簡の中で再び自らの理念とアメリカ大陸の未来像を明らかにした。 [203] 12月9日、ベネズエラの海賊レナート・ベルーチェがボリバルにニューグラナダからのニュースを伝え、ハイチに亡命中の共和制派に加わるよう求めた。 [204] ボリバルはこれを暫定的に受け入れ、その夜、スペインの陰謀の一環として、使用人が会計係を誤って殺害したことで暗殺を逃れた。。8日後ジャマイカを離れ [206]、12月24日にレカイに到着した[207]。1816年1月2日、共通の友人を通じてハイチ共和国大統領のアレクサンドル・ペティオンに紹介 された[208]。ボリーバルとペティオンは互いに感銘を受け、親交を深めた[209]。ボリーバルが占領した地域にいる全ての奴隷を解放すると誓った 後、ペティオンは ペシオンは彼に金と軍事物資を提供した。 レカイに戻ったボリバルは、ハイチの共和制指導者たちと会議を開き、マリーニョを参謀として最高指導者に任命された。[212] 1816年3月31日、共和制派はレカイを出発し、ベネズエラに向かい、カリブ海諸島を東に向かって進んだ。[213] ボリバルの愛人が船団に加わるために遅延した後、船団は5月2日に、共和制派司令官フアン・バウティスタ・アリスメンディが統治するマルガリータ島に到着 した 。ボリバルは次に本土に移動し、そこで全ての奴隷の解放を宣言し、死を以ての戦争布告を無効とした。[215][e] 彼は5月31日にカラパノを占領し、マリーニョとピアルをグアヤナに派遣して軍を組織させた。[218] その後、7月6日から14日にかけてオクマレ・デ・ラ・コスタを占領し、維持した。 王党派によって奪還された。[219][220] ボリーバルは海路でグアイラに逃亡し、8月22日にマリーニョとベネズエラ共和国のホセ・フランシスコ・ベルムデスによって追放された。[221]  カラカスにあるシモン・ボリバル生誕地 ボリバルは9月初旬までにハイチに戻ったが、[222] ペシオンは再び彼を支援することに同意した。[223] ボリバル不在の間、共和国の指導者たちはベネズエラ各地に散らばり、リャノスに集中した。そして、統一されていない軍司令官となった。[224] マリニョの指導力を認めようとしなかったため、[225] アリスメンディはボリバルに手紙を書き、ニューグラナダ共和国のフランシスコ・アントニオ・ゼアを派遣して、彼を説得した。ボリバルとゼアは、オランダ人 商人ルイス・ブリオンとともに12月21日にベネズエラに向けて出帆し、10日後にバルセロナに到着した。そこでボリバルは帰還を宣言し、新たな第三共和 制のための議会開催を呼びかけた。[227] 彼は、西部の平原の大部分を支配していた共和制指導者たち、特にホセ・アントニオ・ペーニャに宛てて、彼の指揮下で団結するよう呼びかける手紙を書いた。 [228][229] 1817年1月8日、ボリバルはカラカスに向けて進軍したが、クラリネスでの戦いで敗北し、より大規模な王党派軍にバルセロナまで追われた。[230] ボリバルの要請により、 ボリバルの要請により、マリーニョは2月8日にベルムデスとともに到着し、ベルムデスはボリバルと和解し、王党派の撤退を強制した。 しかし、ボリバル、マリーニョ、ベルムデスが力を合わせても、バルセロナを維持することはできなかった。[232] 代わりに、1817年3月25日、[233] ボリバルはピアの拠点であるグアヤナでピアと合流し、そこで自身の経済的・政治的基盤を確立するために南へ移動を開始した。[234][235] ボリバルは4月4日にピアと会い、ピアを 陸軍大将に昇進させ、5月2日にはピアルの軍勢に加わってアンゴストゥーラ(現シウダー・ボリバル)を包囲した。[237] 一方、マリーニョは東に向かい、自らの権力基盤を再確立しようとし、5月8日にはブリオンやゼアを含む10人の会議を招集し、マリーニョを共和軍の最高司 令官に任命した。[238] これが裏目に出て、 ラファエル・ウルダネタやアントニオ・ホセ・デ・スクレを含む30人の士官がボリバルのもとに亡命した。[239] 6月30日、ボリバルはピアの要請により休暇を与えたが[240]、ピアが反乱を煽り始め、ボリバルが彼を解雇したのは彼が混血であることが理由だと主張 したため、7月23日には逮捕状が出された。ピアルは9月27日にマリーニョの元へ逃れようとして捕らえられ、アングストゥーラに連行された。そして10 月16日に銃殺刑に処された。[241] その後、ボリーバルはスクレをマリーニョのもとに派遣し、和解を試みた。[242] マリーニョは1818年1月26日にボリーバルへの忠誠を誓った。[243] 1817年7月17日、アンゴストゥーラはボリバル軍の手に落ち、8月初旬にはオリノコ川の支配権を握った。[244][245] アンゴストゥーラは臨時共和国首都となり、9月には、[246]ボリバルは共和国の正式な政治・軍事機構の構築を開始した。[247][248] 1818年1月30日のサン・フアン・デ・パヤラでの会議の後、 ペーニャはボリーバルを最高指導者と認めた。[249] 1818年2月、共和国軍は北上し、カラボゾを占領した。ここで、1年前に共和国領ニューグラナダを征服した後ベネズエラに戻ったモリージョを打ち負かし た。[251] ボリーバルは次にカラカスへ進軍したが、3月16日の第三次ラ・プエルタの戦いで敗北した。[252][253] 4月にはスペインの潜入工作員による暗殺を逃れた。病気と共和国のさらなる敗北により、ボリバルは5月にアンゴストゥーラに戻らざるを得なかった。その年 の残りの期間、彼は共和国の統治に専念し、軍の再建に努め[254]、1819年に開催される国民議会選挙の準備を進めた[255][256]。 |

Gran Colombia: 1819–1830 Equestrian portrait of Bolívar Equestrian portrait of Bolívar by José Hilarión Ibarra [es], c. 1826 The congress met in Angostura on 15 February 1819.[257] There, Bolívar gave a speech in which he advocated for a centralized government modeled on the British government and racial equality,[258] and relinquished civil authority to the congress.[259] On 16 February, the congress elected Bolívar as president and Zea as vice president.[256][260] On 27 February,[261] Bolívar left Angostura to rejoin Páez in the west and resumed campaigning [es] against Morillo, albeit ineffectively.[256][262] In May, as the annual wet season was beginning in the Llanos, Bolívar met with his officers and revealed his intention to invade and liberate New Granada from Royalist occupation,[263] which he had prepared for by sending Santander to build up Republican forces in Casanare Province in August 1818.[264][265] On 27 May,[266] Bolívar marched with more than 2,000 soldiers toward the Andes[267][268] and left Páez, Mariño, Urdaneta, and Bermúdez to tie down Morillo's forces in Venezuela.[269] Bolívar entered Casanare Province with his army on 4 June 1819,[270] then met up with Santander at Tame, Arauca, on 11 June.[271] The combined Republican force reached the Eastern Range of the Andes on 22 June and began a grueling crossing.[272] On 6 July, the Republicans descended from the Andes at Socha and into the plains of New Granada.[273] After a brief convalescence, the Republicans made rapid progress against the forces of Spanish colonel José María Barreiro Manjón until, on 7 August, the Royalists were routed at the Battle of Boyacá. On 10 August, Bolívar entered Bogotá, which the Spanish officials had hastily abandoned,[274][275] and captured the viceregal treasury and armories.[276] After sending forces to secure Republican control of central New Granada,[277] Bolívar paraded through Bogotá on 18 September with Santander.[278] Desiring to merge New Granada and Venezuela into a "greater republic of Colombia", Bolívar first established a provisional government in Bogotá with Santander,[279] and then left to resume campaigning against the Royalists in Venezuela on 20 September 1819.[280] En route, he learned that Zea had been replaced as vice president in September 1819 by Arismendi, who was conspiring with Mariño against Urdaneta and Bermúdez. Bolívar arrived in Angostura on 11 December and, by being conciliatory, defused the plot.[281] He then proposed the merging of New Granada and Venezuela to the congress on 14 December,[282] which was approved. On 17 December, the congress issued a decree creating the Republic of Colombia, including the regions of Venezuela, New Granada, and the still Spanish-controlled Real Audiencia of Quito, and elected Bolívar and Zea president and vice president respectively.[283] After Christmas Day, 1819,[284] Bolívar left Angostura to direct campaigns against Royalist forces along the Caribbean coasts of Venezuela and New Granada.[285] He met with Santander in Bogotá in March 1820, then rode to Cúcuta and inspected Republican forces in northern Colombia over April and May 1820.[286] Meanwhile, Morillo's military and political position was fatally undermined by the mutiny of Spanish soldiers in Cádiz on 1 January [es], which forced Ferdinand VII to accept a liberal constitution in March.[287][288] News of the mutiny and its consequences arrived in Colombia in March and was followed by orders from Spain to Morillo to publicize the constitution and negotiate a peace that would return Colombia to the Spanish Empire. Bolívar and Morillo, seeking to gain leverage over each other,[289] delayed talks until 21 November, when Colombian and Royalist delegates met in Trujillo, Venezuela.[290] The delegates completed two treaties [es] on 25 November, establishing a six-month truce, a prisoner exchange, and basic rights for combatants. Bolívar and Morillo signed the treaties on 25 and 26 November, then met the next day at Santa Ana de Trujillo [es].[291][292] After this meeting, Morillo turned his command over to Spanish general Miguel de la Torre and departed for Spain on 17 December.[293] In February 1821, as Bolívar was traveling from Bogotá to Cúcuta in anticipation of the opening of a new congress there,[294] he learned that Royalist-controlled Maracaibo had defected to Colombia and been occupied by Urdaneta.[295][296] La Torre protested to Bolívar, who refused to return Maracaibo, leading to a renewal of hostilities on 28 April.[297] Over May and June, Colombia's armies made rapid progress until, on 24 June, Bolívar and Páez decisively defeated La Torre at the Battle of Carabobo.[298][299] All Royalist forces remaining in Venezuela were eliminated by August 1823.[300] Bolívar entered Caracas in triumph on 29 June,[301] and issued a decree on 16 July dividing Venezuela into three military zones governed by Páez, Bermúdez, and Mariño.[302] Bolívar then met with the Congress of Cúcuta,[303] which had ratified the formation of Gran Colombia and elected him as president and Santander as vice president in September. Bolívar accepted and was sworn in on 3 October, although he protested the establishment of a precedent of military leaders as head of the Colombian state.[304] |

大コロンビア:1819年~1830年 ボリバルの騎馬像 ホセ・イラリオン・イバラ作のボリバルの騎馬像、1826年頃 1819年2月15日、議会はアンゴストゥーラで会合を開いた。[257] そこでボリバルは演説を行い、英国の政府をモデルとした中央集権政府と人種平等を提唱し、[258] 議会に民事権限を委譲した。[259] 2月16日、議会はボリバルを大統領、ゼアを副大統領に選出した。[256][260] 2月27日、[26 1] ボリバルはアンゴストゥーラを離れ、西部でペーニャと合流し、モリージョに対する選挙運動を再開した。しかし、効果はなかった。[256][262] 5月、毎年恒例の雨季が平原で始まろうとしていた頃、ボリバルは将校たちと会合し、王党派の占領から新グラナダを解放し、侵略するという意図を明らかにし た。。5月27日、ボリーバルは2,000人以上の兵士を率いてアンデス山脈方面へ進軍し[267][268]、ペス、マリーニョ、ウルダネタ、ベルムデ スをベネズエラに残してモリージョ軍と戦わせた。 ボリバルは1819年6月4日、軍を率いてカサナレ県に入り[270]、6月11日にアラウカのタメでサンタンデールと合流した[271]。 共和軍は6月22日にアンデス山脈の東山脈に到達し、過酷な山越えを開始した[272]。 7月6日、共和軍はソチャでアンデス山脈を下り、ヌエバ・グラナダの平原に降り立った[273]。一時的な回復の後、スペイン人大佐ホセ・マリア・バレイ ロ・マンホンの軍勢に対して急速に前進し、8月7日、ボヤカの戦いで王党派が敗走するまで戦い続けた。8月10日、ボリーバルはスペイン当局が急遽放棄し たボゴタに入城し[274][275]、副王領の金庫と武器庫を奪取した[276]。 ニューグラナダ中央部の共和制支配を確保するために軍を派遣した後[277]、ボリーバルは9月18日にサンタンデールとともにボゴタをパレードした [278]。 ニューグラナダとベネズエラを「大コロンビア共和国」に統合することを望んだボリバルは、まずサンタンデールとともにボゴタに臨時政府を樹立し [279]、1819年9月20日にベネズエラの王党派に対する戦いを再開するために立ち去った[280]。その途上で、ボリバルは1819年9月にゼア がアリスメンディに副大統領の座を奪われたことを知った。アリスメンディは、ウルダネタとベルムデスに対してマリーニョと共謀していた 。ボリバルは12月11日にアングストゥーラに到着し、融和的な態度で陰謀を鎮静化させた。[281] そして12月14日、彼は議会に新グラナダとベネズエラの合併を提案し、承認された。12月17日、議会はベネズエラ、新グラナダ、そしてスペインの支配 下にあったキトの王立聴聞会を含むコロンビア共和国の創設を宣言し、ボリーバルとゼアをそれぞれ大統領と副大統領に選出した。 1819年のクリスマス休暇の後、[284] ボリバルはアンゴストゥーラを離れ、ベネズエラと新グラナダのカリブ海沿岸の王党派軍に対する作戦を指揮した。[285] 1820年3月にボゴタでサンタンデールと会談し、その後ククタに向かい、1820年4月から5月にかけてコロンビア北部の共和軍を視察した。[286] 一方、モリージョの軍事的・政治的地位は、 1月1日にカディスで起きたスペイン兵の反乱により、フェルナンド7世は3月に自由主義的な憲法を受け入れざるを得なくなった。[287][288] この反乱と結果のニュースはコロンビアに3月に届き、スペインからモリージョに憲法を公表し、コロンビアをスペイン帝国に戻す和平交渉を行うよう命令が 下った。ボリーバルとモリージョは互いに優位に立とうとし、[289] 11月21日まで協議を遅らせた。その日、コロンビアと王党派の代表団がベネズエラのトゥルヒージョで会合した。[290] 代表団は11月25日に2つの条約[es]を締結し、6か月の休戦、捕虜交換、戦闘員の基本的権利を定めた。ボリーバルとモリージョは11月25日と26 日に条約に署名し、翌日にはサンタ・アナ・デ・トルヒージョで会談した。[291][292] この会談の後、モリージョはスペイン人将軍ミゲル・デ・ラ・トーレに指揮権を譲り、12月17日にスペインに向けて出発した。[293] 1821年2月、ボリバルがボゴタからククタに向かっていたとき、[294] 彼は王党派が支配するマラカイボがコロンビアに寝返り、ウルダネタが占領したことを知った。[295][296] ラ・トーレはボリバルに抗議したが、ボリバルはマラカイボの返還を拒否し、4月28日に戦闘が再開された。[297] 5月と 6月にかけて、コロンビア軍は急速に前進し、6月24日のカラボボの戦いでボリーバルとペスがラ・トーレを完膚なきまでに打ち負かした。[298] [299] 1823年8月までにベネズエラに残っていた王党派の軍勢はすべて壊滅した。[300] ボリーバルは6月29日に勝利の行進でカラカスに入場し、[301] 7月16日にベネズエラをペス、 。ボリバルはその後、ククタの議会と会合を持ち、9月にはグラン・コロンビアの結成を批准し、彼を大統領、サンタンデールを副大統領に選出した。ボリバル はこれを受け入れ、10月3日に就任宣誓を行ったが、コロンビア国家の首長に軍事指導者が選出された前例を抗議した。[304] |

| Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia: 1821–1826 After the Battle of Carabobo, Bolívar turned his attention south, to Pasto, Colombia; Quito and the Free Province of Guayaquil, Ecuador; and the Viceroyalty of Peru. Pasto and Quito were Royalist strongholds,[300][305] while Guayaquil had declared its independence on 9 October 1820[306] and had been garrisoned by Sucre on Bolívar's orders in January 1821.[307] Panama declared its independence on 28 November 1821 and joined Colombia.[308] Peru had been invaded by a Republican army led by Argentine general José de San Martín, who had liberated Chile and Peru,[309] and Bolívar feared San Martín would absorb Ecuador into Peru.[310] In October 1821, after congress empowered him to secure Ecuador for Colombia,[311] Bolívar assembled an army in Bogotá that departed on 13 December 1821.[312] His advance was halted by illness and a Pyrrhic victory at the Battle of Bomboná [es] in southern Colombia on 7 April 1822.[313][314]  1960 portrait of Manuela Sáenz by Marco Salas Yepes Portrait of Manuela Sáenz by Marco Salas Yepes, 1960 To the south, Sucre, who had been trapped in Guayaquil by Royalist advances from Quito,[315] now advanced, decisively defeated the Royalists at the Battle of Pichincha on 24 May 1822, and occupied Quito.[313][316] On 6 June, Pasto surrendered,[317] and ten days later Bolívar paraded through Quito with Sucre.[318] He also met the Ecuadorian Republican Manuela Sáenz, the wife of an English doctor, with whom he began a lasting affair.[319] From Quito, Bolívar traveled to Guayaquil in anticipation of a meeting with San Martín to discuss the city's status and to rally support for its annexation by Colombia.[320] When San Martín arrived in Guayaquil on 26 July,[321] Bolívar had already secured Guayaquil for Colombia,[322] and the two-day Guayaquil Conference produced no agreement between Bolívar and San Martín. Ill, politically isolated, and disillusioned, San Martín resigned from his offices and went into exile.[323][324] Over the rest of 1822, Bolívar traveled around Ecuador to complete its annexation while dispatching officers to suppress repeated rebellions in Pasto and resisting calls to return to Bogotá or Venezuela.[325] Meanwhile, Royalist forces under general José de Canterac overwhelmed the Peruvian republic [es].[326][327] After initially refusing Colombian assistance,[328] the Peruvian congress asked Bolívar several times in 1823 to assume command of their forces. Bolívar responded by sending an army under Sucre to assist,[329] then delayed his own departure to Peru until he obtained permission from the Colombian congress on 3 August.[330] When Bolívar arrived in Lima, Peru's capital, on 1 September,[331] Peru was split between two rival presidents, José de la Riva Agüero and José Bernardo de Tagle, and the Royalists under the Viceroy of Peru, José de la Serna.[332][333] In November 1823, Riva Agüero, who plotted with the Royalists against Bolívar, was betrayed by his officers to Bolívar and exiled from Peru.[334] While Bolívar was bedridden with fever over the first two months of 1824, Tagle defected to the Royalists with the garrison and city of Callao and briefly took Lima.[335] In response, the Peruvian congress named Bolívar dictator of Peru on 10 February 1824. Bolívar moved to northern Peru in March and began assembling an army.[333][336] His repeated demands for additional men and money strained his relationship with Santander.[337] In May 1823, conservative Royalist general Pedro Antonio Olañeta, based in the region of Upper Peru, rebelled [es] against la Serna. Bolívar seized the opportunity to advance into the Junín region, where he defeated Canterac at the Battle of Junín on 6 August, driving them out of Peru.[338][339] Choosing to ignore Olañeta, la Serna ordered his forces to concentrate at Cuzco to face Bolívar.[339][340] Heavy rainfall in September halted Bolívar's advance,[341] and on 6 October he gave command of the army to Sucre and moved to Huancayo to manage political affairs.[342] On 24 October, Bolívar received a letter from Santander informing him that because he had accepted the dictatorship of Peru the Colombian congress had stripped him of his military and civil authority in favor of Sucre and Santander, respectively.[342] Although indignant and resentful of Santander, Bolívar wrote to him on 10 November to communicate his acquiescence[343] and reoccupied Lima on 5 December 1824.[344] On 9 December, Sucre decisively defeated La Serna's Royalists at the Battle of Ayacucho and accepted the surrender [es] of all Royalist forces in Peru. The garrison of Callao and Olañeta ignored the surrender. Shortly after arriving in Lima, Bolívar began a siege of Callao that lasted until January 1826,[345][346] and sent Sucre into Upper Peru to eliminate Olañeta. However, Oleñeta was killed at the Battle of Tumusla prior to Sucre's arrival. With Irish volunteer Francisco Burdett O'Connor serving as his second in command, Sucre completed the liberation of Upper Peru in April 1825.[347]  Portrait of Bolívar by José Gil de Castro, 1825 |

エクアドル、ペルー、ボリビア:1821年~1826年 カラボボの戦いの後、ボリバルは南のコロンビアのパスト、エクアドルのキトと自由州グアヤキル、ペルー副王領に目を向けた。パストとキトは王党派の拠点で あったが[300][305]、グアヤキルは1820年10月9日に独立を宣言し[306]、1821年1月にはボリバルの命令によりスクレが駐留した [307]。パナマは1821年11月28日に独立を宣言し、コロンビアに合流した[308]。ペルーは チリとペルーを解放したアルゼンチンの将軍ホセ・デ・サン・マルティンが率いる共和軍に侵略されていた。[309] ボリーバルはサン・マルティンがエクアドルをペルーに併合することを恐れていた。[310] 1821年10月、議会がコロンビアのためにエクアドルを確保する権限を与えた後、[311] ボリーバルはボゴタで軍を集結させ、1821年12月13日に出発した。[312] 彼の進軍は病気によって阻止され、 1822年4月7日、コロンビア南部のボンボナの戦いでの勝利は、[313][314]  1960年、マルコ・サラス・イェペスによるマヌエラ・サエンスの肖像画 マルコ・サラス・イェペスによるマヌエラ・サエンスの肖像画、1960年 南では、キトからのロイヤリストの進軍によりグアヤキルに閉じ込められていたスクレが、1822年5月24日のピチンチャの戦いでロイヤリストを撃破し、 キトを占領した。6月6日にはパストが降伏し、10日後にはボリバルがスクレとともにキトをパレードした。また、イギリス人医師の妻であるエクアドル共和 国のマヌエラ・サエンスと出会い、彼女との関係は長く続いた。[319] キトから、ボリバルはサン・マルティンとの会合を予定してグアヤキルへと向かった。会合では、この都市の地位について話し合い、コロンビアへの併合への支 持を結集することが目的であった。[320] 7月26日にサン・マルティンがグアヤキルに到着したとき、[321] ボリバルはすでにグアヤキルをコロンビアのために確保していた 、2日間にわたるグアヤキル会議ではボリバルとサンマルティンとの間で合意は得られなかった。病に冒され、政治的に孤立し、幻滅したサンマルティンは、辞 任して亡命した。 1822年の残りの期間、ボリバルはエクアドル併合を完了するためにエクアドル国内を巡り、パストで繰り返された反乱を鎮圧するために将校を派遣し、ボゴ タやベネズエラに戻るよう求める声に抵抗した。[325] 一方、ホセ・デ・カンタラク将軍率いる王党派軍はペルー共和国を圧倒した。[326][327] 当初はコロンビアの支援を拒否していたが、[328] ペルー議会は1823年にボリバルに 1823年に、ペルー議会はボリバルに自国軍の指揮を執るよう再三要請した。ボリーバルはスクレ率いる軍を派遣して支援すると答え[329]、8月3日に コロンビア議会から許可を得るまでペルーへの出発を遅らせた[330]。ボリーバルが9月1日にペルーの首都リマに到着したとき[331]、ペルーは2人 の対立する大統領、ホセ・デ・ラ・リバ・アギエロとホセ・ベルナルド・デ・タグレ、そしてペルー副王ホセ・デ・ラ・セルナ率いる王党派の間で分裂していた ラ・セルナの配下にあった王党派の間で分裂した。[332][333] 1823年11月、ボリバルに対して王党派と共謀していたリヴァ・アグエロは、将校たちに裏切られてボリバルに引き渡され、ペルーから追放された。 [334] 1824年の最初の2か月間、ボリバルは熱病で寝たきりだったが、その間、タグレは王党派に寝返り、カラヨの駐屯地と都市を王党派に引き渡し、リマを一時 的に占領した。[335] これを受けて、ペルー議会は 1824年2月10日、ペルー議会はボリバルをペルーの独裁者に任命した。ボリバルは3月にペルー北部に移動し、軍の編成を開始した。[333] [336] 増員と資金調達を繰り返し要求したことで、サンタンデールとの関係は悪化した。[337] 1823年5月、ペルー上部に拠点を置く保守派王党派の将軍ペドロ・アントニオ・オラニエタは、ラ・セルナに対して反乱を起こした。ボリバルはこれを好機 と捉え、ジュニンの地に進軍し、8月6日のジュニンの戦いでカンタラクを破り、ペルーから追い出した。[338][339] オラニエタを無視することを選択したラ・セルナは、ボリバルに対抗するために軍をクスコに集結させるよう命じた。[339][340] 9月の大雨によりボリバルの進軍は停止し、[341] 10月6日、 軍の指揮をスクレに委ね、政治事務を処理するためにワンカヨへ移動した。 10月24日、ボリバルはサンタンデールから手紙を受け取り、ペルーの独裁権を彼が受け入れたため、コロンビア議会は、軍事権と民事権をそれぞれスクレと サンタンデールに譲渡したことを知らされた。[342] サンタンデールに対して憤りと憤慨を抱きながらも、ボリバルは11月10日に彼に手紙を書き、同意を伝えた[343]。そして、1824年12月5日にリ マを再占領した。[344 12月9日、スクレはアヤクチョの戦いでラ・セルナの王党派を完膚なきまでに打ち負かし、ペルーの王党派軍の降伏を受け入れた。カヤオとオラニエタの守備 隊は降伏を無視した。リマに到着後まもなく、ボリバルは1826年1月まで続いたカヤオ包囲戦を開始し、スクレを上ペルーに派遣してオラニエタを排除させ た。しかし、オラニエタはスクレが到着する前にトゥムスラの戦いで戦死した。アイルランド人志願兵フランシスコ・バードット・オコーナーを副官として従 え、スクレは1825年4月に上ペルーの解放を完了した。  ホセ・ヒル・デ・カストロによるボリバルの肖像画、1825年 |

| In early 1825, Bolívar resigned

from his offices in Colombia and Peru, but neither nation's congress

accepted his resignation; on 10 February 1825, the Peruvian congress

extended his dictatorship for another year. Accepting the

extension,[348] Bolívar settled into governing Peru and passing reforms

that were largely not carried out, such as a school system based on the

principles of English educator Joseph Lancaster that was managed by

Simón Rodríguez.[349] In April 1825, Bolívar began a tour of southern

Peru that took him to the cities of Arequipa and Cuzco by August. As

Bolívar approached Upper Peru, a congress gathered in the city of

Chuquisaca (now Sucre); on 6 August, it declared the region to be the

nation of Bolivia, named Bolívar president, and asked him to write a

constitution for Bolivia.[350] Bolívar arrived in Potosí on 5 October

and met with two Argentine agents, Carlos María de Alvear and José

Miguel Díaz Vélez, who tried without success to convince him to

intervene in the Cisplatine War against the Empire of Brazil.[351] From Potosí, Bolívar traveled to Chuquisaca and appointed Sucre to govern Bolivia on 29 December 1825;[352] he departed for Peru on 1 January 1826.[353] Bolívar arrived in Lima on 10 February and dispatched his draft of the Bolivian constitution to Sucre on 12 May.[354] That constitution [es] was ratified with modification by the Bolivian congress in July 1826.[355] Peru, whose elites chafed at Bolívar's rule and the presence of his soldiers, was also induced to accept a modified version of Bolívar's constitution on 16 August.[356] In Venezuela, Páez revolted against Santander, and in Panama, a congress of American nations organized by Bolívar convened without his attendance and produced no change in the hemispheric status quo. On 3 September, responding to pleas for his return to Colombia, Bolívar departed Peru and left it under a governing council led by Bolivian general Andrés de Santa Cruz.[357] |

1825年初頭、ボリバルはコロンビアとペルーの役職を辞任したが、両

国民議会は彼の辞任を受理しなかった。1825年2月10日、ペルー議会は彼の独裁政権をさらに1年間延長した。任期延長を受け入れた[348]ボリバル

はペルーの統治に落ち着き、シモン・ロドリゲスが管理するイギリスの教育者ジョゼフ・ランカスターの原則に基づく学校制度など、ほとんど実施されなかった

改革を行った[349]。1825年4月、ボリバルはペルー南部を視察し、8月までにアレキパとクスコの都市を訪れた。ボリバルがペルー上部に近づくと、

チュキサカ(現スクレ)に議会が召集され、8月6日にはこの地域をボリビア国民と宣言し、ボリバルを大統領に指名し、ボリビアの憲法制定を要請した。

[350]

10月5日にポトシに到着したボリバルは、アルゼンチンの2人の代理人、カルロス・マリア・デ・アルベアルとホセ・ミゲル・ディアス・ベレスと会談した。

彼らはブラジル帝国とのシスプラティーナ戦争に介入するよう説得しようとしたが、成功しなかった。

ブラジル帝国とのプラチナ戦争への介入を説得しようとしたが、成功しなかった。 ポトシからスクレをボリビアの統治者に任命し、1825年12月29日にスクレをボリビアの統治者に任命した。[352] 1826年1月1日にペルーに向けて出発した。[353] ボリバルは2月10日にリマに到着し、5月12日にボリビア憲法草案をスクレに送った。[354] その憲法は、 1826年7月にボリビア議会によって修正の上で批准された。[355] ボリバルの統治と彼の兵士の存在に不快感を抱いていたペルーのエリート層も、8月16日にボリバル憲法の修正版を受け入れるよう説得された。[356] ベネズエラでは、ペレスがサンタンデールに対して反乱を起こし、パナマでは、ボリバルが出席しないままボリバルが招集した米国民会議が開催され、南北アメ リカの現状に変化はなかった。9月3日、コロンビアへの帰還を求める嘆願に応えて、ボリバルはペルーを出発し、ボリビアの将軍アンドレス・デ・サンタ・ク ルスが率いる統治評議会にペルーを委ねた。[357] |

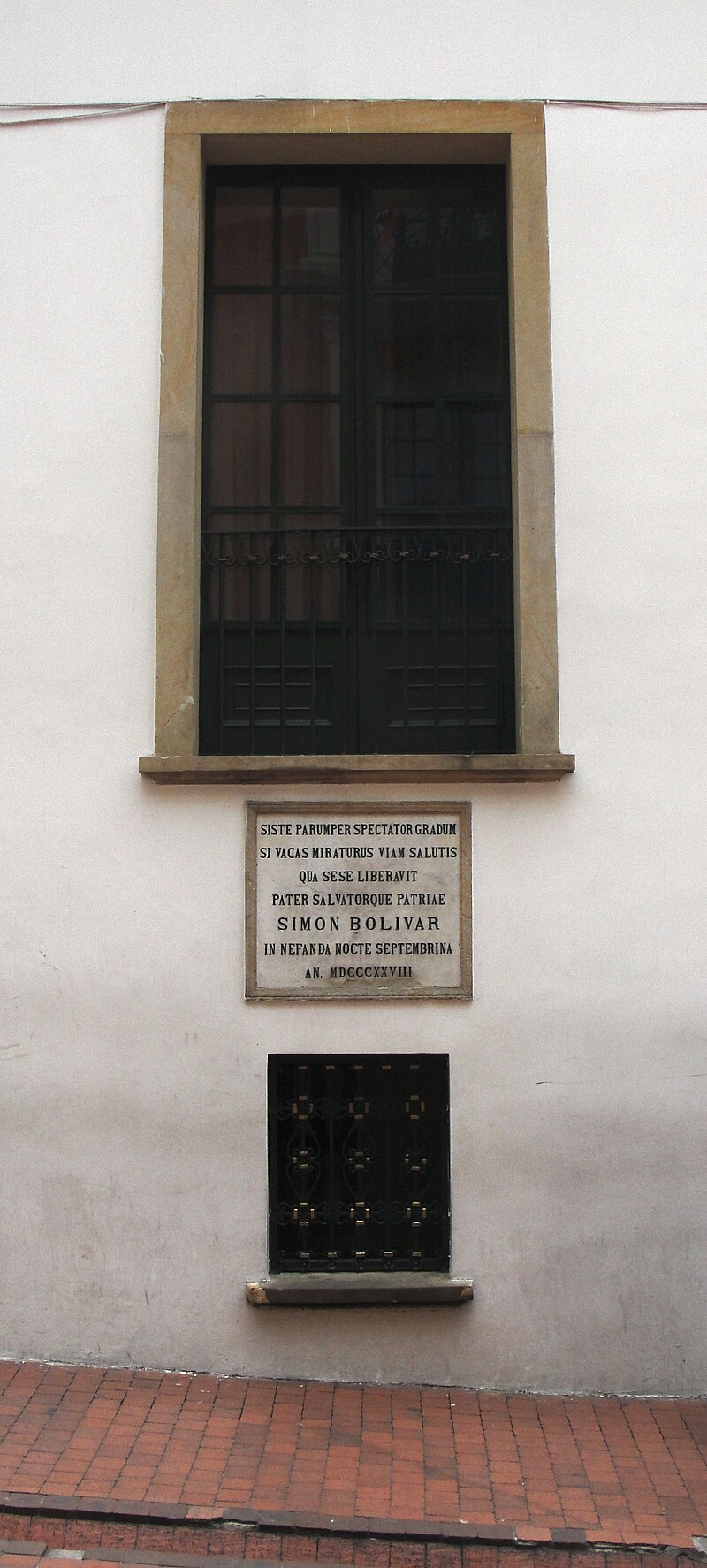

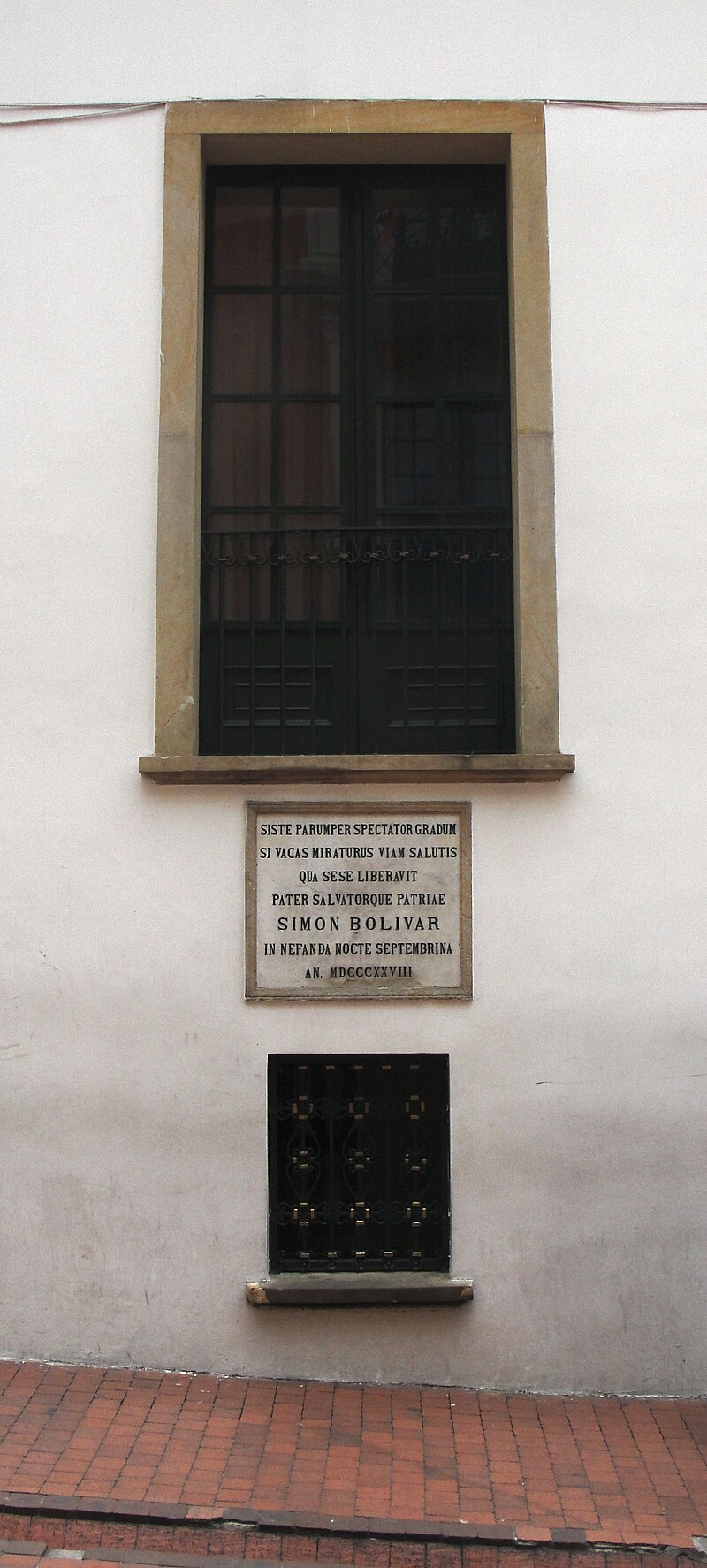

| Final years: 1826–1830 See also: Septembrine Conspiracy Bolívar arrived in Guayaquil on 13 September 1826 and heard complaints against Santander's governance from the people of Guayaquil and Quito, who declared him their dictator.[358] From Ecuador, he continued north and heard more complaints, promoted civil and military officers, and commuted prison sentences.[359] As he approached Bogotá, Bolívar was met by Santander, who hoped to persuade Bolívar to his cause in the conflict with Páez. Although Santander was annoyed at Bolívar for his desire to return to power and ratify a version of the Bolivian constitution in Colombia, they reconciled and agreed that Bolívar would resume the presidency of Colombia; congress had reelected them to a second four-year term beginning on 2 January 1827. Bolívar arrived in Bogotá on 14 November 1826.[360] On 25 November, Bolívar left Bogotá with an army supplied by Santander and arrived at Puerto Cabello on 31 December,[361] where he issued a general amnesty to Páez and his allies if they submitted to his authority. Páez accepted and in January 1827, Bolívar confirmed Páez's military authority in Venezuela and entered Caracas with him to much jubilation; for two months, Bolívar attended balls celebrating his return and the amnesty.[362] That amnesty, and clashes over Santander's handling of Colombia's finances, caused a break between Bolívar and Santander that became an open enmity in 1827.[363] In February 1827, Bolívar submitted his resignation from the Presidency of Colombia, which its congress rejected.[364] Meanwhile, the Colombian soldiers garrisoned in Lima mutinied, arrested their Venezuelan officers, and occupied Guayaquil until September 1827, allowing Bolívar's opponents in Peru to depose him as president and repeal his constitution.[365] Bolívar departed Venezuela to return to Bogotá in July 1827. He arrived on 10 September with an army he had gathered at Cartagena and secured the calling of a new congress to meet at the city of Ocaña in early 1828 to modify the Colombian constitution. The elections for this congress were held in November 1827 and, as Bolívar declined to campaign because he did not wish to be perceived as personally influencing the elections, were very favorable to his political opponents.[366] In January 1828, Bolívar was joined in Bogotá by Sáenz,[367] but on 16 March 1828 he left the capital after being informed of a Spanish-backed rebellion in Venezuela. As that revolt was crushed before he arrived, Bolívar turned his attention to the occupation of Cartagena by José Prudencio Padilla, a New Granadan admiral and Santander loyalist. Padilla's rebellion was also crushed before Bolívar arrived, however, and he was arrested and imprisoned in Bogotá. As the Convention of Ocaña opened on 9 April, Bolívar based himself at Bucaramanga to monitor its proceedings through his aides.[368]  Window of the Palacio de San Carlos through which Bolívar escaped assassination on 25 September 1828 The window of the Palacio de San Carlos through which Bolívar escaped assassination on 25 September 1828 The convention appeared likely to adopt a federalist system. To prevent this, on 11 June 1828 Bolívar's allies staged a walkout, leaving the convention without a quorum.[369] Two days later, Pedro Alcántara Herrán, a Bolívar loyalist and the governor of New Granada, called a meeting of the city's elite that denounced the Convention of Ocaña and called on Bolívar to assume absolute power in Colombia. Bolívar returned to Bogotá on 24 June and on 27 August assumed supreme power as the "president-liberator" of Colombia, abolished the office of the vice president, and assigned Santander to a diplomatic posting in Washington, D.C. On 25 September 1828, a group of young liberals that included Santander's secretary made an attempt to assassinate Bolívar and overthrow his government. The attempt was thwarted by Sáenz, who bought time for Bolívar to escape as the assassins entered the Palacio de San Carlos, and the Colombian Army. Bolívar spent the night hiding under a bridge until soldiers loyal to his regime rescued him.[370] In the aftermath of the attempted coup, Santander and the conspirators were arrested. Bolívar, depressed and ill, considered resigning from politics and pardoning the conspirators, but was dissuaded from this by his officers. Padilla, though uninvolved with the attempted coup, was executed for treason for his earlier rebellion; Santander, whom Bolívar thought responsible for the plot, was pardoned but exiled from Colombia.[371] In December 1828, Bolívar left Bogotá to respond to Peru's intervention in Bolivia and invasion of Ecuador and a revolt in Popayán and Pasto led by José María Obando. He left behind a council of ministers led by Urdaneta to govern Colombia and announced that a congress would convene in January 1830 to devise a new constitution. Over 1829, Obando was defeated by Colombian general José María Córdova at Bolívar's direction in January and then pardoned, while Sucre and Venezuelan general Juan José Flores defeated the Peruvians at the Battle of Tarqui in February, leading to an armistice in July and then the Treaty of Guayaquil in September.[372] While Bolívar was away, Urdaneta and the council of ministers planned with French envoys to have a member of the House of Bourbon succeed Bolívar on his death as King of Colombia. This plan was widely unpopular, and inspired Córdova to launch a revolt that was crushed in October 1829 by Daniel Florence O'Leary, Bolívar's aide-de-camp. In November, Bolívar ordered the council to cease its planning; instead they resigned.[373] Venezuelans, encouraged by a circular letter Bolívar had published in October, voted to secede from Colombia.[374] On 15 January 1830, Bolívar arrived in Bogotá and on 20 January the Admirable Congress [es] convened in the city. Bolívar submitted his resignation from the presidency, which the congress did not accept until 27 April, following the appointment of New Granadan politician Domingo Caycedo as interim President.[375] |

晩年:1826年~1830年 関連項目:セプテンブリーナ陰謀 1826年9月13日、ボリバルはグアヤキルに到着し、グアヤキルとキトの人々からサンタンデールの統治に対する不満を聞いた。彼らはボリバルを独裁者と 宣言した。[358] エクアドルからさらに北上し、ボリバルはさらに多くの不満を聞き、文民および軍の将校を昇進させ、刑期を短縮した。[359] ボリバルがボゴタに近づくと、サンタンデールが彼を出迎えた。サンタンデールはボリバルを説得し、パエスとの紛争で自分の主張を認めさせようとしていた。 。サンタンデールは、ボリバルが権力の座に復帰し、コロンビアでボリビア憲法のバージョンを批准したいという意向に苛立ちを覚えていたが、和解し、ボリバ ルがコロンビアの大統領職に復帰することで合意した。議会は1827年1月2日に始まる2期目の4年間の任期で彼らを再選した。ボリバルは1826年11 月14日にボゴタに到着した。 11月25日、ボリバルはサンタンデールから提供された軍隊を率いてボゴタを発ち、12月31日にプエルト・カベヨに到着した。[361] そこで彼は、ペーニャとその同盟者たちが自らの権威に従うならば、彼らに恩赦を与えると宣言した。ペーニャはこれを受け入れ、1827年1月、ボリバルは ベネズエラにおけるペーニャの軍事的権限を承認し、ペーニャとともにカラカスに入城し、大いに歓迎された。ボリバルは2か月間、帰還と恩赦を祝う舞踏会に 出席した。[362] この恩赦と、コロンビアの財政運営をめぐるサンタンデールとの対立により、ボリバルとサンタンデールとの関係は決裂し、1827年には公然の敵対関係と なった。[363] 1827年2月、 1827年2月、ボリバルはコロンビア大統領の辞表を提出したが、議会はこれを拒否した。[364] 一方、リマに駐留していたコロンビア兵士たちは反乱を起こし、ベネズエラ人将校を逮捕し、1827年9月までグアヤキルを占領した。これにより、ペルーの ボリバル反対派は彼を大統領の地位から追放し、憲法を廃止することが可能となった。[365] ボリバルは1827年7月にベネズエラを出発し、ボゴタに戻った。彼はカルタヘナで集めた軍隊とともに9月10日に到着し、1828年初頭にオカニャ市で 開かれるコロンビア憲法改正のための新議会招集を確保した。この議会選挙は1827年11月に実施されたが、選挙に人格的な影響力があると見られることを 望まなかったボリバルは選挙運動を行わなかったため、彼の政治的反対派に非常に有利な結果となった。[366] 1828年1月、ボリバルはボゴタでサエンスと合流した。[367] しかし、1828年3月16日、スペインが支援するベネズエラでの反乱の知らせを受け、首都を後にした。ボリーバルが到着する前にその反乱は鎮圧されたた め、ボリーバルは、新グラナダ提督でサンタンデール派のホセ・プルデンシオ・パディージャによるカルタヘナ占領に目を向けた。しかし、パディージャの反乱 もボリーバルが到着する前に鎮圧され、彼は逮捕されてボゴタで投獄された。4月9日にオカーニャ会議が開幕すると、ボリーバルはブカラマンガに拠点を置 き、側近を通じて会議の進行を見守った。  1828年9月25日、ボリバルが暗殺を逃れたサン・カルロス宮殿の窓 1828年9月25日、ボリバルが暗殺を逃れたサン・カルロス宮殿の窓 会議では連邦制が採択される可能性が高かった。これを阻止するため、1828年6月11日、ボリバルの同盟者たちは退席し、会議は定足数を満たさなくなっ た。[369] 2日後、ボリバルの忠実な支持者であり、新グラナダの知事であったペドロ・アルカンタラ・エラナンは、オカーニャ会議を非難し、コロンビアにおける絶対的 な権力をボリバルに委ねるよう呼びかける、市のエリート層による会議を招集した。ボリーバルは6月24日にボゴタに戻り、8月27日にはコロンビアの「解 放者大統領」として最高権力を握り、副大統領職を廃止し、サンタンデールをワシントンD.C.の外交ポストに任命した。1828年9月25日、サンタン デールの秘書を含む自由主義者の若者グループがボリーバルを暗殺し、政府を転覆させようとした。サンチェスが、暗殺者たちがサン・カルロス宮殿に侵入した 際にボリバルに時間を稼ぎ、コロンビア軍とともにボリバルの脱出を手助けしたことで、この企ては阻止された。ボリバルは、政権に忠実な兵士たちに救出され るまで、一晩中橋の下に身を隠していた。 クーデター未遂事件の後、サンタンデールと共謀者たちは逮捕された。 落ち込み、体調を崩したボリーバルは政治から身を引いて共謀者たちを赦免することを考えたが、側近たちに思いとどまらされた。パディージャはクーデター未 遂には関与していなかったが、以前の反乱の罪で反逆罪として処刑された。サンタンデールは、ボリバルがクーデターの首謀者と考えていたが、恩赦は受けたも ののコロンビアからの追放処分となった。[371] 1828年12月、ボリバルはコロンビアのボゴタを離れ、ペルーのボリビア介入とエクアドル侵略、ホセ・マリア・オバンド率いるポパヤンとパストの反乱に 対応した。彼はウルダネタを筆頭とする閣僚評議会をコロンビアの統治に残し、1830年1月に議会を召集して新憲法を策定すると発表した。1829年、1 月にボリバルの指示によりコロンビアの将軍ホセ・マリア・コルドバに敗れたオバンドは、その後恩赦を受けた。一方、スクレとベネズエラの将軍フアン・ホ セ・フローレスは2月のタルキの戦いでペルー軍を破り、7月に休戦、9月にはグアヤキル条約が締結された。 ボリバルが不在の間、ウルダネタと閣僚評議会はフランス大使と協議し、ボリバルの死後、ブルボン家の者がボリバルの後を継いでコロンビア王となることを計 画した。この計画は広く不評を買い、コルドバが反乱を起こすきっかけとなった。反乱は1829年10月にダニエル・フローレンス・オリアリー (Daniel Florence O'Leary)によって鎮圧された。11月、ボリバルは評議会に計画の中止を命じ、代わりに彼らは辞職した。[373] 10月にボリバルが発表した回状に勇気づけられたベネズエラ人は、コロンビアからの分離独立を投票で決定した。[374] 1830年1月15日、ボリバルはボゴタに到着し、1月20日には同市で「立派な議会」が召集された。ボリーバルは大統領職の辞任を申し出たが、議会はこ れを4月27日まで受理しなかった。その後、ニューグラナダの政治家ドミンゴ・カイセドが暫定大統領に任命された。[375] |

Death and burial Bolívar on his deathbed as painted by Antonio Herrera Toro Bolívar's death, by Venezuelan painter Antonio Herrera Toro, 1889 Determined to go into exile, Bolívar, who had given away or lost his fortune over his career, sold most of his remaining possessions and departed from Bogotá on 8 May 1830.[376] He traveled down the Magdalena to Cartagena, where he arrived by the end of June to wait for a ship to take him to England.[377] On 1 July, Bolívar was informed that Sucre had been assassinated near Pasto while en route to Quito, and wrote to Flores to ask him to avenge Sucre.[378] In September, Urdaneta installed a conservative government in Bogotá and asked Bolívar to return, but he refused.[379] With his health deteriorating and no ship forthcoming, Bolívar was moved by his staff to Barranquilla in October and then, at the invitation of a Spanish landowner in the area, to the Quinta de San Pedro Alejandrino near Santa Marta. There, on 17 December 1830, at the age of 47, Bolívar died of tuberculosis.[380] Bolívar's body, dressed in a borrowed shirt, was interred in the Cathedral Basilica of Santa Marta [es] on 20 December 1830.[381] In 1842, Páez secured the repatriation of Bolívar's remains, which were paraded through Caracas and then laid to rest in its cathedral in December together with his wife and parents; Bolívar's heart remained in Santa Marta. His remains were moved again in October 1876 into the National Pantheon of Venezuela in Caracas, created that year by President Antonio Guzmán Blanco.[382] Bolívar's death has been the subject of conspiracy theories advanced by the United Socialist Party of Venezuela. In January 2008, President Hugo Chávez set up a commission to investigate his claim that Bolívar had been poisoned by "New Granada traitors."[383][384] The commission exhumed Bolívar's remains on 16 July 2010.[385] The results, made public on 26 July 2011, were inconclusive; Vice President of Venezuela Elías Jaua announced that the commission could not prove Chávez's claim.[386][387][388] Chávez continued to claim that Bolívar had been assassinated via arsenic poisoning, citing a paper by infectious disease specialist Paul Auwaerter. Following Chávez's remarks, Auwaerter stated that the arsenic likely came from medicines Bolívar had ingested to treat his illnesses.[386][389][390] |

死と埋葬 アントニオ・エレラ・トロが描いた病床のボリバル ベネズエラ人画家アントニオ・エレラ・トロによるボリバルの死、1889年 亡命を決意したボリバルは、その経歴の中で財産を手放したり失ったりしていたため、残っていた財産のほとんどを売却し、1830年5月8日にボゴタを出発 した。[376] マグダレナ川を下ってカルタヘナに向かい、6月末に到着して、イギリス行きの船を待った。[377] 7月1日、ボリバルはスクレがキトに向かう途中のパストの近くで暗殺されたという知らせを受け取り、 スクレの仇を討つようフロレスに依頼する手紙を書いた。[378] 9月、ウルダネタはボゴタに保守派政府を樹立し、ボリバルに帰還を求めたが、ボリバルは拒否した。[379] 保健状態が悪化し、船も見込めない中、ボリバルは10月に部下たちに連れられてバランキージャに移り、その後、この地域のスペイン人地主の招待で、サンタ マルタ近郊のキンタ・デ・サン・ペドロ・アレハンドリーノに移った。1830年12月17日、47歳でボリーバルは結核により死去した。 ボリーバルの遺体は、借りたシャツを着せられ、1830年12月20日にサンタマルタ大聖堂に埋葬された。[381] 1842年、ペーニャスはボリーバルの遺骨の帰還を確保し、遺骨はカラカスでパレードされ、12月に妻と両親とともに大聖堂に埋葬された。ボリーバルの心 臓はサンタマルタに残された。1876年10月、遺体は再び移され、アントニオ・グスマン・ブランコ大統領によってその年に建設されたカラカスのベネズエ ラ国立霊廟に安置された。 ボリバルの死は、ベネズエラ統一社会党が唱える陰謀論の対象となっている。2008年1月、ウゴ・チャベス大統領は、ボリバルが「新グラナダの裏切り者」 によって毒殺されたという主張を調査するための委員会を設置した。[383][384] 委員会は2010年7月16日にボリバルの遺体を掘り起こした。[385] 2011年7月26日に結果が公表されたが、結論は出なかった。ベネズエラの副大統領エリアス・ハウアは、委員会は チャベスの主張を証明することはできなかったと発表した。[386][387][388] チャベスは、感染症専門家のポール・アウワターの論文を引用し、引き続き、ボリバルはヒ素中毒によって暗殺されたと主張した。チャベスの発言を受けて、ア ウワターは、ヒ素はボリバルが自身の病気の治療のために摂取した薬から出た可能性が高いと述べた。[386][389][390] |

| Personal beliefs Bolívar's personal beliefs were liberal and republican, and formed by Classical and Enlightenment philosophy;[391] among his favorite authors were Hobbes, Spinoza, the Baron d'Holbach, Hume, Montesquieu, and Rousseau.[21] The tutelage of Simón Rodríguez, a student of Rousseau, has been traditionally seen as foundational for Bolívar's beliefs.[32][392] Also important to Bolívar's intellectual development were his stays in Paris from 1804 to 1806 and in London in 1810.[393][394] Bolívar was an Anglophile, and sought British aid in securing Latin American independence.[395][396] The extent of Bolívar's religiosity is debated; while Bolívar resented the social capital of the Catholic Church and its Royalist leanings during the wars of independence, he sought to co-opt its social capital for the benefit of the republics he established rather than dismember the Church.[397][398] Throughout his political career, Bolívar concerned himself with the construction of liberal democracy in Latin America and the region's place in the Atlantic world.[399] By the 1820s, his goal was to create a federation of Latin American republics in Spanish America, each governed by a strong executive and a constitution modeled on the British constitution.[400] Inspired by Montesquieu, Bolívar believed that a government should conform to the needs and character of its region and inhabitants;[401] in the Cartagena Manifesto, Bolívar stated that federalism as practiced in the United States was the "perfect" government but was unworkable in Spanish America because, he believed, Spanish imperialism had left Spanish Americans unprepared for federalism.[402][403] Bolívar sought to prepare Colombia for a more liberal democracy via free, public education.[404] Over the 1820s, Bolívar became increasingly disillusioned and authoritarian until, in 1830, he declared to Flores, "all who have served the Revolution have plowed the sea."[405] |