ソーシャル・メディア

Social media

☆ ソーシャルメディアとは、仮想コミュニティやネットワークにおいて、コンテンツ(アイデアや関心事、その他の表現形態など)の作成、共有、集約を容易にす る新しいメディア技術である。[1][2] 一般的な特徴は以下の通りだ。[2] オンラインプラットフォームは、ユーザーがコンテンツを作成・共有し、ソーシャルネットワーキングに参加することを可能にする。[2][3][4] ユーザー生成コンテンツ(テキスト投稿やコメント、デジタル写真や動画、オンライン交流で生成されるデータなど)。[2][3] ソーシャルメディア組織が設計・管理するサービス固有のプロファイル。[2][5] ソーシャルメディアは、ユーザーのプロフィールを他の個人やグループと結びつけることで、オンラインソーシャルネットワークの発展を助ける。[2][5] メディアにおける「ソーシャル」という用語は、プラットフォームが共同活動を可能にすることを示唆している。ソーシャルメディアは人間のネットワークを強 化し拡張する。[6] ユーザーはウェブベースのアプリやモバイル端末のカスタムアプリを通じてソーシャルメディアにアクセスする。これらのインタラクティブなプラットフォーム は、個人、コミュニティ、企業、組織がユーザー生成または自己キュレーションされたコンテンツを共有、共同作成、議論、参加、修正することを可能にする。 [7][5][1] ソーシャルメディアは記憶を記録し、学び、友情を形成するために利用される。[8] 人民、企業、製品、アイデアを宣伝するためにも利用される。[8] ニュースの消費、公開、共有にも活用可能だ。

★2019年、メリアム=ウェブスター辞典はソーシャルメディアを「ユーザーが情報、 アイデア、個人的メッセージ、その他のコンテンツ(動画など)を共有するオンラインコミュニティを形成する電子通信形態(ソーシャルネットワーキングやマ イクロブログのウェブサイトなど)」と定義した[29]

| Social media are new

media technologies that facilitate the creation, sharing and

aggregation of content (such as ideas, interests, and other forms of

expression) amongst virtual communities and networks.[1][2] Common

features include:[2] Online platforms enable users to create and share content and participate in social networking.[2][3][4] User-generated content—such as text posts or comments, digital photos or videos, and data generated through online interactions.[2][3] Service-specific profiles that are designed and maintained by the social media organization.[2][5] Social media helps the development of online social networks by connecting a user's profile with those of other individuals or groups.[2][5] The term social in regard to media suggests platforms enable communal activity. Social media enhances and extends human networks.[6] Users access social media through web-based apps or custom apps on mobile devices. These interactive platforms allow individuals, communities, businesses, and organizations to share, co-create, discuss, participate in, and modify user-generated or self-curated content.[7][5][1] Social media is used to document memories, learn, and form friendships.[8] They may be used to promote people, companies, products, and ideas.[8] Social media can be used to consume, publish, or share news. Social media platforms can be categorized based on their primary function. Social networking sites like Facebook and LinkedIn focus on building personal and professional connections. Microblogging platforms, such as Twitter (now X), Threads and Mastodon, emphasize short-form content and rapid information sharing. Media sharing networks, including Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and Snapchat, allow users to share images, videos, and live streams. Discussion and community forums like Reddit, Quora, and Discord facilitate conversations, Q&A, and niche community engagement. Live streaming platforms, such as Twitch, Facebook Live, and YouTube Live, enable real-time audience interaction. Decentralized social media platforms like Mastodon and Bluesky aim to provide social networking without corporate control, offering users more autonomy over their data and interactions. |

ソーシャルメディアとは、仮想コミュニティやネットワークにおいて、コ

ンテンツ(アイデアや関心事、その他の表現形態など)の作成、共有、集約を容易にする新しいメディア技術である。[1][2]

一般的な特徴は以下の通りだ。[2] オンラインプラットフォームは、ユーザーがコンテンツを作成・共有し、ソーシャルネットワーキングに参加することを可能にする。[2][3][4] ユーザー生成コンテンツ(テキスト投稿やコメント、デジタル写真や動画、オンライン交流で生成されるデータなど)。[2][3] ソーシャルメディア組織が設計・管理するサービス固有のプロファイル。[2][5] ソーシャルメディアは、ユーザーのプロフィールを他の個人やグループと結びつけることで、オンラインソーシャルネットワークの発展を助ける。[2][5] メディアにおける「ソーシャル」という用語は、プラットフォームが共同活動を可能にすることを示唆している。ソーシャルメディアは人間のネットワークを強 化し拡張する。[6] ユーザーはウェブベースのアプリやモバイル端末のカスタムアプリを通じてソーシャルメディアにアクセスする。これらのインタラクティブなプラットフォーム は、個人、コミュニティ、企業、組織がユーザー生成または自己キュレーションされたコンテンツを共有、共同作成、議論、参加、修正することを可能にする。 [7][5][1] ソーシャルメディアは記憶を記録し、学び、友情を形成するために利用される。[8] 人民、企業、製品、アイデアを宣伝するためにも利用される。[8] ニュースの消費、公開、共有にも活用可能だ。 ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームは主要機能に基づき分類できる。 FacebookやLinkedInのようなソーシャルネットワーキングサイトは、個人・職業上の繋がり構築を主眼とする。 Twitter(現X)、Threads、Mastodonなどのマイクロブログプラットフォームは、短文コンテンツと迅速な情報共有を重視する。 Instagram、TikTok、YouTube、Snapchatなどのメディア共有ネットワークでは、画像、動画、ライブストリームの共有が可能 だ。 Reddit、Quora、Discordなどのディスカッション・コミュニティフォーラムは、会話、Q&A、ニッチなコミュニティ参加を促進す る。 Twitch、Facebook Live、YouTube Liveなどのライブストリーミングプラットフォームは、リアルタイムでの視聴者との交流を可能にする。 MastodonやBlueskyのような分散型ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームは、企業の管理下になくソーシャルネットワーキングを提供することを 目指し、ユーザーが自身のデータや交流に対してより自律性を得られるようにしている。 |

| Popular

social media platforms with over 100 million registered users include

Twitter, Facebook, WeChat, ShareChat, Instagram, Pinterest, QZone,

Weibo, VK, Tumblr, Baidu Tieba, Threads and LinkedIn. Depending on

interpretation, other popular platforms that are sometimes referred to

as social media services include YouTube, Letterboxd, QQ, Quora,

Telegram, WhatsApp, Signal, LINE, Snapchat, Viber, Reddit, Discord, and

TikTok. Wikis are examples of collaborative content creation. Social media outlets differ from old media (e.g. newspapers, TV, and radio broadcasting) in many ways, including quality,[9] reach, frequency, usability, relevancy, and permanence.[10] Social media outlets operate in a dialogic transmission system (many sources to many receivers) while traditional media operate under a monologic transmission model (one source to many receivers). For instance, a newspaper is delivered to many subscribers, and a radio station broadcasts the same programs to a city.[11] Social media has been criticized for a range of negative impacts on children and teenagers, including exposure to inappropriate content, exploitation by adults, sleep problems, attention problems, feelings of exclusion, and various mental health maladies.[12][13] Social media has also received criticism as worsening political polarization and undermining democracy, with journalist Maria Ressa deeming it "toxic sludge" for exacerbating distrust among members of society.[14] Major news outlets often have strong controls in place to avoid and fix false claims, but social media's unique qualities bring viral content with little to no oversight. "Algorithms that track user engagement to prioritize what is shown tend to favor content that spurs negative emotions like anger and outrage. Overall, most online misinformation originates from a small minority of "superspreaders," but social media amplifies their reach and influence."[15] |

登

録ユーザー数が1億人を超える主要なソーシャルメディアプラットフォームには、Twitter、Facebook、WeChat、ShareChat、

Instagram、Pinterest、QZone、Weibo、VK、Tumblr、Baidu

Tieba、Threads、LinkedInがある。解釈によっては、ソーシャルメディアサービスと呼ばれることもある他の人気プラットフォームには、

YouTube、Letterboxd、QQ、Quora、Telegram、WhatsApp、Signal、LINE、Snapchat、

Viber、Reddit、Discord、TikTokなどがある。ウィキは共同コンテンツ作成の例だ。 ソーシャルメディアは、質[9]、到達範囲、頻度、使いやすさ、関連性、永続性など、多くの点で旧来のメディア(新聞、テレビ、ラジオ放送など)とは異な る。ソーシャルメディアはダイアロジック伝達システム(複数の発信者から複数の受信者へ)で機能する一方、伝統的メディアは単方向的伝達モデル(単一の発 信者から多数の受信者へ)で機能する。例えば新聞は多数の購読者に配達され、ラジオ局は同一番組を都市全体に放送する。[11] ソーシャルメディアは、不適切なコンテンツへの接触、大人による搾取、睡眠障害、注意力の問題、疎外感、様々な精神健康上の問題など、子供や十代に及ぼす 様々な悪影響について批判されてきた。[12][13] また、政治的分極化を悪化させ民主主義を損なうとして批判も受けており、ジャーナリストのマリア・レッサは、社会成員間の不信感を助長する「有害な汚泥」 と評している。[14] 主要ニュース媒体は虚偽の主張を回避・修正するため強力な管理体制を敷いているが、ソーシャルメディアの特性上、監視がほとんどない状態で拡散するコンテ ンツが生まれる。「ユーザーの関与を追跡し表示優先順位を決めるアルゴリズムは、怒りや憤りといった負の感情を煽るコンテンツを好む傾向がある。全体とし て、オンライン上の誤情報のほとんどはごく少数の『スーパースプレッダー』に起因するが、ソーシャルメディアはその影響力と到達範囲を増幅させる。」 [15] |

| History See also: Timeline of social media Early computing The PLATO system was launched in 1960 at the University of Illinois and subsequently commercially marketed by Control Data Corporation. It offered early forms of social media features with innovations such as Notes, PLATO's message-forum application; TERM-talk, its instant-messaging feature; Talkomatic, perhaps the first online chat room; News Report, a crowdsourced online newspaper, and blog and Access Lists, enabling the owner of a note file or other application to limit access to a certain set of users, for example, only friends, classmates, or co-workers. ARPANET, which came online in 1969, had by the late 1970s enabled exchange of non-government/business ideas and communication, as evidenced by the network etiquette (or "netiquette") described in a 1982 handbook on computing at MIT's Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.[16] ARPANET evolved into the Internet in the 1990s.[17] Usenet, conceived by Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis in 1979 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University, was the first open social media app, established in 1980.  A bulletin board system menu, featuring opinion polls and a "Who's been on today?" query A precursor of the electronic bulletin board system (BBS), known as Community Memory, appeared by 1973. Mainstream BBSs arrived with the Computer Bulletin Board System in Chicago, which launched on February 16, 1978. Before long, most major US cities had more than one BBS, running on TRS-80, Apple II, Atari 8-bit computers, IBM PC, Commodore 64, Sinclair, and others. CompuServe, Prodigy, and AOL were three of the largest BBS companies and were the first to migrate to the Internet in the 1990s. Between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s, BBSes numbered in the tens of thousands in North America alone.[18] Message forums were the signature BBS phenomenon throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. In 1991, Tim Berners-Lee integrated HTML hypertext software with the Internet, creating the World Wide Web. This breakthrough led to an explosion of blogs, list servers, and email services. Message forums migrated to the web, and evolved into Internet forums, supported by cheaper access as well as the ability to handle far more people simultaneously. These early text-based systems expanded to include images and video in the 21st century, aided by digital cameras and camera phones.[19] |

歴史 関連項目: ソーシャルメディアの年表 初期のコンピューティング PLATOシステムは1960年にイリノイ大学で開始され、その後コントロール・データ・コーポレーションによって商業化された。このシステムは、ノート (PLATOのメッセージ・フォーラムアプリケーション)、TERM-talk(インスタントメッセージング機能)、Talkomatic(おそらく最初 のオンラインチャットルーム)、News Report(クラウドソーシングによるオンライン新聞)、ブログ、アクセスリスト(ノートファイルやその他のアプリケーションの所有者が、特定のユー ザーグループ、例えば友人、同級生、同僚のみにアクセスを制限できるようにする機能)などの革新的な機能を備え、ソーシャルメディアの初期形態を提供し た。 1969年に運用開始したARPANETは、1970年代後半までに非政府・非ビジネスのアイデアやコミュニケーションの交換を可能にした。これは 1982年にMIT人工知能研究所で発行されたコンピューティングハンドブックに記載されたネットワークエチケット(ネットエチケット)からも明らかであ る[16]。ARPANETは1990年代にインターネットへと進化した。[17] 1979年にノースカロライナ大学チャペルヒル校とデューク大学のトム・トラスコットとジム・エリスによって考案されたユーセンネットは、1980年に設 立された最初のオープンなソーシャルメディアアプリケーションであった。  世論調査や「今日アクセスしたユーザー」検索機能を備えた掲示板システムのメニュー 電子掲示板システム(BBS)の先駆けとなる「コミュニティ・メモリー」は1973年までに登場した。主流のBBSは1978年2月16日にシカゴで開始 された「コンピュータ・ブレットンボード・システム」によって普及した。間もなく、米国の主要都市のほとんどには複数のBBSが存在し、TRS-80、 Apple II、Atari 8ビットコンピュータ、IBM PC、Commodore 64、Sinclairなどの機種で稼働していた。CompuServe、Prodigy、AOLは三大BBS企業であり、1990年代に最初にインター ネットへ移行した。1980年代半ばから1990年代半ばにかけて、北米だけでBBSは数万に上った[18]。メッセージ掲示板は1980年代から 1990年代初頭にかけてBBSの象徴的な現象だった。 1991年、ティム・バーナーズ=リーはHTMLハイパーテキストソフトウェアをインターネットに統合し、ワールドワイドウェブを創出した。この画期的な 進歩により、ブログ、メーリングリスト、電子メールサービスが爆発的に増加した。メッセージ掲示板はウェブへ移行し、より安価なアクセス環境と同時接続者 数の大幅な増加を背景に、インターネット掲示板へと進化した。 これらの初期のテキストベースシステムは、デジタルカメラやカメラ付き携帯電話の普及により、21世紀には画像や動画を含むように拡大した。[19] |

Social media platforms SixDegrees, launched in 1997, is often regarded as the first social media site. The evolution of online services progressed from serving as channels for networked communication to becoming interactive platforms for networked social interaction with the advent of Web 2.0.[6] Social media started in the mid-1990s with the invention of platforms like GeoCities, Classmates.com, and SixDegrees.com.[20] While instant messaging and chat clients existed at the time, SixDegrees was unique as it was the first online service designed for people to connect using their actual names instead of anonymously. It boasted features like profiles, friends lists, and school affiliations, making it "the very first social networking site".[20][21] The platform's name was inspired by the "six degrees of separation" concept, which suggests that every person on the planet is just six connections away from everyone else.[22] In the early 2000s, social media platforms gained widespread popularity with BlackPlanet (1999) preceding Friendster and Myspace,[23][24] followed by Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter.[25] Research from 2015 reported that globally, users spent 22% of their online time on social networks,[26] likely fueled by the availability of smartphones.[27] As of 2023, as many as 4.76 billion people used social media[28] some 59% of the global population. |

ソーシャルメディアプラットフォーム 1997年に開始されたSixDegreesは、しばしば最初のソーシャルメディアサイトと見なされている。 オンラインサービスの進化は、ネットワーク通信のチャネルとしての役割から、Web 2.0の登場により、ネットワーク化された社会的交流のための双方向プラットフォームへと進展した。 ソーシャルメディアは1990年代半ば、GeoCities、Classmates.com、SixDegrees.comといったプラットフォームの発 明と共に始まった。[20] 当時インスタントメッセージングやチャットクライアントは存在したが、SixDegreesは実名で接続するよう設計された初のオンラインサービスという 点で独自性を有した。プロフィール、友達リスト、学校所属などの機能を誇り、「最初のソーシャルネットワーキングサイト」と評された。[20] [21] このプラットフォームの名称は「六次の隔たり」という概念に由来する。これは地球上のあらゆる人格が、たった六つの繋がりを介して互いに繋がっているとい う考え方だ。[22] 2000年代初頭、ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームは広く普及した。FriendsterやMyspaceに先駆けてBlackPlanet(1999年)が登場し、[23][24]その後Facebook、YouTube、Twitterが続いた。[25] 2015年の調査によれば、世界的にユーザーはオンライン時間の22%をソーシャルネットワークに費やしていた[26]。これはスマートフォンの普及が後 押しした可能性が高い[27]。2023年時点で、47億6000万人もの人々がソーシャルメディアを利用しており[28]、これは世界人口の約59%に 相当する。 |

| Definition A 2015 review identified four features unique to social media services:[2] Web 2.0 Internet-based applications.[2][3] User-generated content[2][3] User-created self profiles[2][5] Social networks formed by connections between profiles,[2][5] such as followers, groups, and lists. In 2019, Merriam-Webster defined social media as "forms of electronic communication (such as websites for social networking and microblogging) through which users create online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other content (such as videos)."[29] |

定義 2015年のレビューでは、ソーシャルメディアサービスに特有の4つの特徴が特定された[2]: Web 2.0に基づくインターネットアプリケーション[2][3] ユーザー生成コンテンツ[2][3] ユーザー作成の自己プロフィール[2][5] プロフィール間の接続によって形成されるソーシャルネットワーク[2][5]。例えばフォロワー、グループ、リストなど。 2019年、メリアム=ウェブスター辞典はソーシャルメディアを「ユー ザーが情報、アイデア、個人的メッセージ、その他のコンテンツ(動画など)を共有するオンラインコミュニティを形成する電子通信形態(ソーシャルネット ワーキングやマイクロブログのウェブサイトなど)」と定義した[29]。 |

| Services Social media encompasses an expanding suite of services:[30] Blogs (ex. HuffPost, Boing Boing) Business networks (ex. LinkedIn, XING) Collaborative projects (Mozilla, GitHub) Enterprise social networks (Yammer, Socialcast, Slack) Forums (Gaia Online, IGN) Microblogs (Twitter, Tumblr, Weibo) Photo sharing (Pinterest, Flickr, Photobucket) Products/services review (Amazon, Upwork) Social bookmarking (Delicious, Pinterest) Social gaming including MMORPGs (Fortnite, World of Warcraft) Social network (Facebook, Instagram, Baidu Tieba, VK, QZone, ShareChat, WeChat, LINE) Video sharing (YouTube, DailyMotion, Vimeo) Virtual worlds (Second Life, Twinity) Some services offer more than one type of service.[5] |

サービス ソーシャルメディアは拡大を続ける一連のサービスを含む:[30] ブログ(例:ハフポスト、ボインボイン) ビジネスネットワーク(例:リンクトイン、XING) 共同プロジェクト(モジラ、GitHub) 企業向けソーシャルネットワーク(ヤマー、ソーシャルキャスト、スラック) フォーラム(ガイアオンライン、IGN) マイクロブログ(ツイッター、タンブラー、ウェイボー) 写真共有(Pinterest、Flickr、Photobucket) 製品・サービスレビュー(Amazon、Upwork) ソーシャルブックマーク(デリシャス、ピンタレスト) ソーシャルゲーム(MMORPG含む)(フォートナイト、ワールドオブウォークラフト) ソーシャルネットワーク(フェイスブック、インスタグラム、百度貼吧、VK、QQゾーン、シェアチャット、ウィーチャット、LINE) 動画共有(ユーチューブ、デイリーモーション、ヴィメオ) 仮想世界(セカンドライフ、トゥイニティ) 複数のサービス形態を提供するケースもある。[5] |

| Mobile social media Mobile social media refers to the use of social media on mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets. It is distinguished by its ubiquity, since users no longer have to be at a desk in order to participate on a computer. Mobile services can further make use of the user's immediate location to offer information, connections, or services relevant to that location. According to Andreas Kaplan, mobile social media activities fall among four types:[31] Space-timers (location and time-sensitive): Exchange of messages with relevance for a specific location at a specific point in time (posting about a traffic jam) Space-locators (only location sensitive): Posts/messages with relevance for a specific location, read later by others (e.g. a restaurant review) Quick-timers (only time sensitive): Transfer of traditional social media mobile apps to increase immediacy (e.g. posting status updates) Slow-timers (neither location nor time sensitive): Transfer of traditional social media applications to mobile devices (e.g. watching a video) |

モバイルソーシャルメディア モバイルソーシャルメディアとは、スマートフォンやタブレットなどのモバイル端末でソーシャルメディアを利用することを指す。その特徴は遍在性にある。 ユーザーはもはやデスクに縛られず、コンピュータを通じて参加できるからだ。モバイルサービスはさらに、ユーザーの現在地を活用して、その場所に関連する 情報や接続、サービスを提供できる。 アンドレアス・カプランによれば、モバイルソーシャルメディア活動は四つのタイプに分類される[31]: 空間-時間依存型(位置と時間に敏感):特定の場所と時間に関連するメッセージの交換(例:渋滞についての投稿) 空間位置依存型(位置のみに敏感):特定の場所に関連する投稿/メッセージで、後から他者が読むもの(例:レストランのレビュー) クイックタイマー(時間のみ依存):即時性を高めるための従来型ソーシャルメディアのモバイルアプリ移行(例:ステータス更新の投稿) スロータイマー(位置・時間とも非依存):従来型ソーシャルメディアのモバイルデバイスへの移行(例:動画視聴) |

| Elements and function Virality Main article: Viral phenomenon Certain content, has the potential to spread virally, an analogy for the way viral infections spread contagiously from individual to individual. Viral videos is one example. One user spreads a post across their network, which leads those users to follow suit. A post from a relatively unknown user can reach vast numbers of people within hours. Virality is not guaranteed; few posts make the transition. Viral marketing campaigns are particularly attractive to businesses because they can achieve widespread advertising coverage at a fraction of the cost of traditional marketing campaigns. Nonprofit organizations and activists may also attempt to spread content virally. Social media sites provide specific functionality to help users re-share content, such as X's and Facebook's "like" option.[32] Bots Main article: Internet bot Bots are automated programs that operate on the internet.[33] They automate many communication tasks. This has led to the creation of an industry of bot providers.[34] Chatbots and social bots are programmed to mimic human interactions such as liking, commenting, and following.[35] Bots have also been developed to facilitate social media marketing.[36] Bots have led the marketing industry into an analytical crisis, as bots make it difficult to differentiate between human interactions and bot interactions.[37] Some bots violate platforms' terms of use, which can result in bans and campaigns to eliminate bots categorically.[38] Bots may even pose as real people to avoid prohibitions.[39] 'Cyborgs'—either bot-assisted humans or human-assisted bots[39]—are used for both legitimate and illegitimate purposes, from spreading fake news to creating marketing buzz.[40][41][42] A common use claimed to be legitimate includes posting at a specific time.[43] A human writes a post content and the bot posts it a specific time. In other cases, cyborgs spread fake news.[39] Cyborgs may work as sock puppets, where one human pretends to be someone else, or operates multiple accounts, each pretending to be a person. Patents Main article: Software patent A multitude of United States patents are related to social media, and their numbers are growing, albeit unevenly. For example, there were 897 patents in Q3 2024 and 1,674 in Q2. And even in Q3, the U.S. share of all social media patent applications was 50% of all patent applications, with second-placed China at 18%.[44] As of 2020, over 5000 social media patent applications had been published in the United States.[45] Only slightly over 100 patents had been issued.[46] Platform convergence As an instance of technological convergence, various social media platforms adapted functionality beyond their original scope, increasingly overlapping with each other. Examples are the social hub site Facebook launching an integrated video platform in May 2007,[47] and Instagram, whose original scope was low-resolution photo sharing, introducing the ability to share quarter-minute 640×640 pixel videos[48] (later extended to a minute with increased resolution). Instagram later implemented stories (short videos self-destructing after 24 hours), a concept popularized by Snapchat, as well as IGTV, for seekable videos.[49] Stories were then adopted by YouTube.[50] X, whose original scope was text-based microblogging, later adopted photo sharing,[51] then video sharing,[52][53] then a media studio for business users, after YouTube's Creator Studio.[54] The discussion platform Reddit added an integrated image hoster replacing the external image sharing platform Imgur,[55] and then an internal video hosting service,[56] followed by image galleries (multiple images in a single post), known from Imgur.[57] Imgur implemented video sharing.[58][59] YouTube rolled out a Community feature, for sharing text-only posts and polls.[60] |

要素と機能 バイラル性 主な記事: バイラル現象 特定のコンテンツは、ウイルス感染が人から人へ伝染するように拡散する可能性を秘めている。バイラル動画はその一例だ。一人のユーザーが自身のネットワー クに投稿を拡散すると、他のユーザーもそれに追随する。比較的無名のユーザーによる投稿が、数時間のうちに膨大な人民に届くこともある。バイラル性は保証 されていない。成功する投稿はごく一部だ。 バイラルマーケティングキャンペーンは、従来のマーケティングキャンペーンのわずかなコストで広範な広告効果を得られるため、企業にとって特に魅力的だ。非営利団体や活動家もコンテンツをバイラルに拡散しようとする場合がある。 ソーシャルメディアサイトは、XやFacebookの「いいね」機能など、ユーザーがコンテンツを再共有するのを助ける特定の機能を提供している。[32] ボット 主な記事: インターネットボット ボットはインターネット上で動作する自動化されたプログラムだ。[33] 多くのコミュニケーション業務を自動化する。これにより、ボット提供業者の産業が生まれた。[34] チャットボットやソーシャルボットは、いいね、コメント、フォローといった人間の交流を模倣するようプログラムされている。[35] ボットはソーシャルメディアマーケティングを促進するためにも開発されている。[36] ボットは人間の交流とボットの交流を区別しにくくするため、マーケティング業界を分析上の危機に陥れている。[37] 一部のボットはプラットフォームの利用規約に違反し、利用停止処分やボット排除運動を招くことがある。[38] ボットは禁止を回避するため、実在の人間を装うことさえある。[39] 「サイボーグ」——ボット支援型人間または人間支援型ボット[39]——は、偽ニュースの拡散からマーケティングの話題作りまで、正当な目的と不正な目的 の両方に利用される。[40][41][42] 正当と主張される一般的な用途には、特定時刻への投稿が含まれる。[43] 人間が投稿内容を書き、ボットが指定時刻に投稿する。他のケースでは、サイボーグが偽ニュースを拡散する。[39] サイボーグは偽アカウントとして機能し、一人の人間が別人を装ったり、複数アカウントを操作してそれぞれが別の人格であるかのように振る舞う。 特許 詳細記事: ソフトウェア特許 ソーシャルメディア関連の米国特許はマルチチュード存在し、その数は不均一ながら増加している。例えば2024年第3四半期には897件、第2四半期には 1,674件の特許があった。第3四半期においても、ソーシャルメディア特許出願全体の米国シェアは全出願の50%を占め、2位の中国は18%だった。 [44] 2020年時点で、米国では5000件以上のソーシャルメディア特許出願が公開されていた。[45] 実際に発行された特許はわずか100件強であった。[46] プラットフォームの収束 技術的収束の一例として、様々なソーシャルメディアプラットフォームは本来の機能範囲を超えて適応し、互いに重なり合う傾向が強まっている。 例として、ソーシャルハブサイトであるFacebookが2007年5月に統合型動画プラットフォームを立ち上げたこと[47]、またInstagram が低解像度写真共有という本来の目的を超えて、640×640ピクセルの15秒動画共有機能を導入したこと[48](後に解像度を向上させ1分間に延長) が挙げられる。Instagramはその後、Snapchatで普及した「ストーリー」(24時間後に自動削除される短編動画)や、検索可能な動画プラッ トフォーム「IGTV」を導入した[49]。このストーリー機能は後にYouTubeにも採用された。[50] Xは、当初テキストベースのマイクロブログサービスだったが、後に写真共有[51]、動画共有[52][53]、そしてYouTubeのクリエイタースタジオに倣ったビジネスユーザー向けメディアスタジオを導入した[54]。 ディスカッションプラットフォームのRedditは、外部画像共有プラットフォームImgurに代わる統合型画像ホスティング機能を追加した[55]。そ の後、内部動画ホスティングサービス[56]を導入し、さらにImgurで知られる画像ギャラリー(単一投稿内の複数画像)機能を追加した[57]。 Imgurは動画共有機能を導入した[58][59]。 YouTubeはテキスト投稿と投票を共有する「コミュニティ」機能を展開した[60]。 |

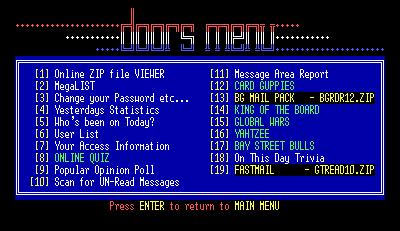

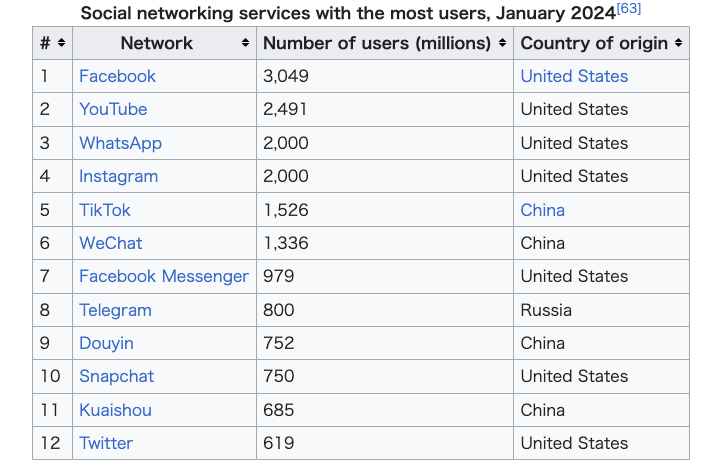

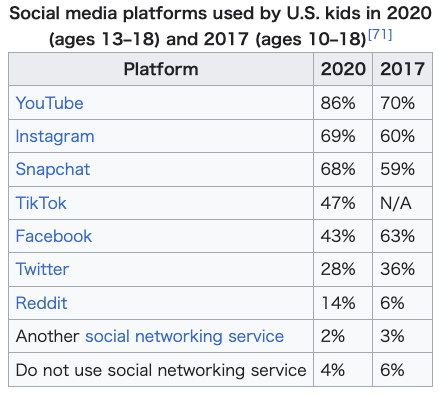

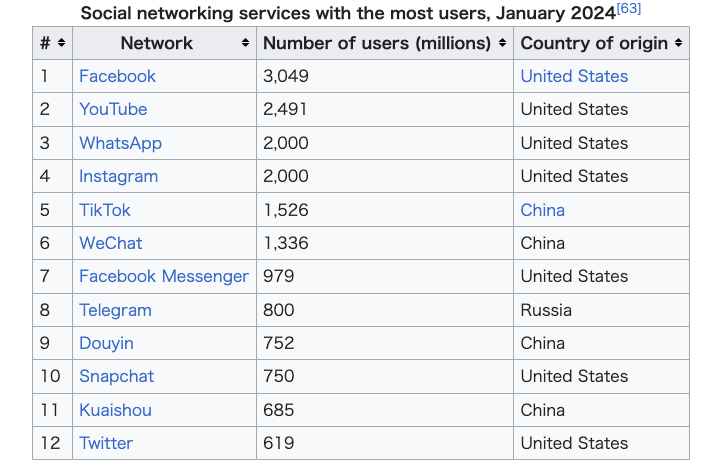

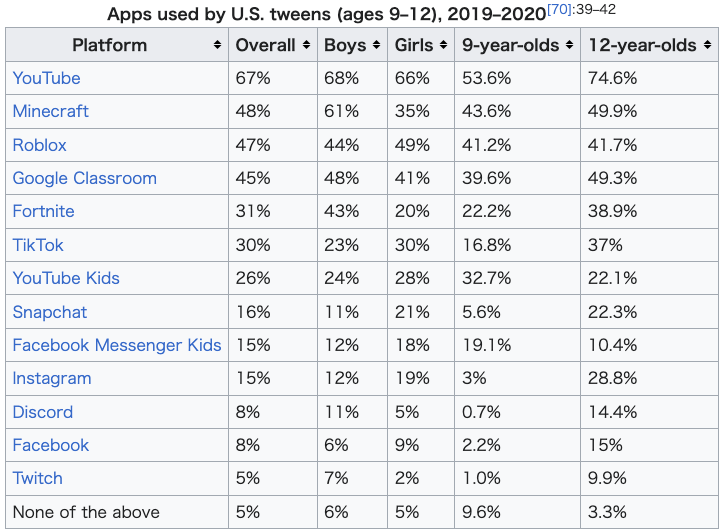

| Usage statistics Main article: List of social platforms with at least 100 million active users According to Statista, it is estimated that, in 2022, around 3.96 billion people were using social media globally. This number is up from 3.6 billion in 2020.[61] The following is a list of the most popular social networking services based on the number of active users as of January 2024 per Statista.[62] Social networking services with the most users, January 2024[63]  Usage: before the pandemic A 2009 study suggested that individual differences may help explain who uses social media: extraversion and openness have a positive relationship with social media, while emotional stability has a negative sloping relationship with social media.[64] A 2015 study reported that people with a higher social comparison orientation appear to use social media more heavily than people with low social comparison orientation.[65] Common Sense Media reported that children under age 13 in the United States use social networking services although many social media sites require users to be 13 or older.[66] In 2017, the firm conducted a survey of parents of children from birth to age 8 and reported that 4% of children at this age used social media sites such as Instagram, Snapchat, or (now-defunct) Musical.ly "often" or "sometimes".[67] Their 2019 survey surveyed Americans ages 8–16 and reported that about 31% of children ages 8–12 use social media.[68] In that survey, teens aged 16–18 were asked when they started using social media. the median age was 14, although 28% said they started to use it before reaching 13. Usage: during the pandemic Usage by minors Social media played a role in communication during the COVID-19 pandemic.[69] In June 2020, a survey by Cartoon Network and the Cyberbullying Research Center surveyed Americans tweens (ages 9–12) and reported that the most popular application was YouTube (67%).[70] (as age increased, tweens were more likely to have used social media apps and games.) Similarly, Common Sense Media's 2020 survey of Americans ages 13–18 reported that YouTube was the most popular (used by 86% of 13- to 18-year-olds).[71] As children aged, they increasingly utilized social media services and often used YouTube to consume content. Apps used by U.S. tweens (ages 9–12), 2019–2020[70]: 39–42  Social media platforms used by U.S. kids in 2020 (ages 13–18) and 2017 (ages 10–18)[71]  Reasons for use by adults While adults were using social media before the COVID-19 pandemic, more started using it to stay socially connected and to get pandemic updates. "Social media have become popularly use to seek for medical information and have fascinated the general public to collect information regarding corona virus pandemics in various perspectives. During these days, people are forced to stay at home and the social media have connected and supported awareness and pandemic updates."[72] Healthcare workers and systems became more aware of social media as a place people were getting health information: "During the COVID-19 pandemic, social media use has accelerated to the point of becoming a ubiquitous part of modern healthcare systems."[73] This also led to the spread of disinformation. On December 11, 2020, the CDC put out a "Call to Action: Managing the Infodemic".[74] Some healthcare organizations used hashtags as interventions and published articles on their Twitter data:[75] "Promotion of the joint usage of #PedsICU and #COVID19 throughout the international pediatric critical care community in tweets relevant to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and pediatric critical care."[75] However others in the medical community were concerned about social media addiction, as it became an increasingly important context and therefore "source of social validation and reinforcement" and were unsure whether increased social media use was harmful.[76] |

利用統計 主な記事: アクティブユーザー1億人以上のソーシャルプラットフォーム一覧 Statistaによれば、2022年には世界で約39億6000万人がソーシャルメディアを利用していたと推定される。この数字は2020年の36億人から増加している。[61] 以下は、Statistaによる2024年1月時点のアクティブユーザー数に基づく、最も人気のあるソーシャルネットワーキングサービスのリストである。[62] Social networking services with the most users, January 2024[63]  使用例:パンデミック以前 2009年の研究によれば、個人の特性がソーシャルメディアの利用者を説明する一因となる可能性がある。外向性と開放性はソーシャルメディア利用と正の相 関関係にある一方、情緒的安定性はソーシャルメディア利用と負の相関関係にある。[64] 2015年の研究では、社会的比較志向が高い人々は、社会的比較志向が低い人々よりもソーシャルメディアを頻繁に利用する傾向があると報告されている。 [65] コモンセンスメディアは、米国の13歳未満の子供たちがソーシャルネットワーキングサービスを利用していると報告した。多くのソーシャルメディアサイトは 13歳以上をユーザー条件としているにもかかわらずである。[66] 2017年、同社は生後から8歳までの子供の親を対象に調査を実施し、この年齢層の子供の4%がInstagram、Snapchat、または(現在は廃 止された)Musical.lyなどのソーシャルメディアサイトを「頻繁に」または「時々」利用していると報告した。[67] 同社の2019年調査では、8~16歳のアメリカ人を対象に実施され、8~12歳の子供の約31%がソーシャルメディアを利用していると報告された。 [68] この調査では、16~18歳のティーンエイジャーに対し、ソーシャルメディアの利用開始時期を尋ねた。中央値は14歳だったが、28%が13歳未満で利用 を開始したと回答した。 利用状況:パンデミック期間中 未成年者の利用状況 ソーシャルメディアはCOVID-19パンデミック中のコミュニケーションに役割を果たした。[69] 2020年6月、カートゥーンネットワークとサイバーいじめ研究センターによる調査では、アメリカの9~12歳のティーンを対象に実施され、最も人気のあ るアプリケーションはYouTube(67%)と報告された。[70](年齢が上がるにつれ、ソーシャルメディアアプリやゲームを利用する傾向が強まっ た。)同様に、コモンセンスメディアが2020年に13~18歳のアメリカ人を対象に行った調査でも、YouTubeが最も人気(13~18歳の86%が 利用)と報告されている。[71] 子供たちは年齢を重ねるにつれ、ソーシャルメディアサービスをより多く利用するようになり、コンテンツを消費するためにYouTubeを頻繁に利用した。 Apps used by U.S. tweens (ages 9–12), 2019–2020[70]: 39–42  Social media platforms used by U.S. kids in 2020 (ages 13–18) and 2017 (ages 10–18)[71]  成人が利用する理由 成人はCOVID-19パンデミック以前からソーシャルメディアを利用していたが、社会的つながりを維持し、パンデミックの最新情報を得るために利用し始めた者が増えた。 「ソーシャルメディアは医療情報を求める手段として広く普及し、一般市民が様々な視点からコロナウイルスパンデミックに関する情報を収集する手段として注 目された。この期間、人民は自宅待機を余儀なくされ、ソーシャルメディアが意識啓発とパンデミック情報の共有を支えた」[72] 医療従事者や医療システムは、人々が健康情報を得る場としてソーシャルメディアの存在をより強く認識するようになった: 「COVID-19パンデミック中、ソーシャルメディアの利用は現代医療システムの普遍的な一部となるほど加速した。」[73] これは同時に偽情報の拡散も招いた。2020年12月11日、CDCは「行動要請:情報流行の管理」を発表した。[74] 一部の医療機関はハッシュタグを対策として活用し、自組織のTwitterデータに関する論文を発表した:[75] 「新型コロナウイルス感染症2019パンデミックおよび小児集中治療に関連するツイートにおいて、国際的な小児集中治療コミュニティ全体で#PedsICUと#COVID19の併用を促進する」[75] しかし医療界の他の関係者らは、ソーシャルメディア依存症を懸念していた。ソーシャルメディアがますます重要な文脈となり「社会的承認と強化の源」となったためである。彼らはソーシャルメディア利用の増加が有害かどうか確信が持てなかった。[76] |

| Use by organizations Government Governments may use social media to (for example):[77] inform their opinions to public interact with citizens foster citizen participation further open government analyze/monitor public opinion and activities educate the public about risks and public health.[78] Law enforcement Social media has been used extensively in civil and criminal investigations.[79] It has also been used to search for missing persons.[80] Police departments often make use of official social media accounts to engage with the public, publicize police activity, and burnish law enforcement's image;[81][82] conversely, video footage of citizen-documented police brutality and other misconduct has sometimes been posted to social media.[82] In the United States, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement identifies and track individuals via social media, and has apprehended some people via social media-based sting operations.[83] U.S. Customs and Border Protection (also known as CBP) and the United States Department of Homeland Security use social media data as influencing factors during the visa process, and monitor individuals after they have entered the country.[84] CBP officers have also been documented performing searches of electronics and social media behavior at the border, searching both citizens and non-citizens without first obtaining a warrant.[84] Reputation management As social media gained momentum among the younger generations, governments began using it to improve their image, especially among the youth. In January 2021, Egyptian authorities were reported to be using Instagram influencers as part of its media ambassadors program. The program was designed to revamp Egypt's image and to counter the bad press Egypt had received because of the country's human rights record. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates participated in similar programs.[85] Similarly, Dubai has extensively relied on social media and influencers to promote tourism. However, Dubai laws have kept these influencers within limits to not offend the authorities, or to criticize the city, politics or religion. The content of these foreign influencers is controlled to make sure that nothing portrays Dubai in a negative light.[86] |

組織による利用 政府 政府はソーシャルメディアを(例えば)以下の目的で利用する。[77] 公衆への意見表明 市民との対話 市民参加の促進 政府の透明性向上 世論や活動の分析・監視 リスクや健康に関する啓発。[78] 法執行機関 ソーシャルメディアは民事・刑事捜査で広く活用されている。[79] 行方不明者の捜索にも用いられる。[80] 警察当局は公式アカウントで市民との交流、警察活動の広報、イメージ向上を図る。[81][82] 一方、市民が記録した警察の暴力行為や不正行為の映像がソーシャルメディアに投稿される事例もある。[82] 米国では、米国移民関税捜査局(ICE)がソーシャルメディアを通じて個人を特定・追跡し、ソーシャルメディアを利用したおとり捜査で一部の人物を逮捕し ている。[83] 米国税関・国境警備局(CBP)及び米国国土安全保障省は、ビザ審査過程においてソーシャルメディアデータを判断材料として活用し、入国後の個人監視も 行っている。[84] CBP職員が国境で電子機器やソーシャルメディア上の行動を令状なしに市民・非市民双方に対して検索している事例も記録されている。[84] 評判管理 ソーシャルメディアが若年層の間で勢いを増すにつれ、政府は特に若年層向けのイメージ向上にこれを活用し始めた。2021年1月、エジプト当局がメディア 大使プログラムの一環としてInstagramインフルエンサーを活用していると報じられた。このプログラムはエジプトのイメージ刷新と、同国の人権記録 による悪評への対抗を目的として設計された。サウジアラビアとアラブ首長国連邦も同様のプログラムに参加した。[85] 同様に、ドバイは観光促進のためにソーシャルメディアとインフルエンサーを多用している。しかしドバイの法律は、当局を侮辱したり、都市・政治・宗教を批 判したりしないよう、これらのインフルエンサーを制限している。外国人インフルエンサーのコンテンツは、ドバイを否定的に描かないよう管理されている。 [86] |

| Business Main article: Social media use by businesses Many businesses use social media for marketing, branding,[87] advertising, communication, sales promotions, informal employee-learning/organizational development, competitive analysis, recruiting, relationship management/loyalty programs,[31] and e-Commerce. Companies use social-media monitoring tools to monitor, track, and analyze conversations to aid in their marketing, sales and other programs. Tools range from free, basic applications to subscription-based, tools. Social media offers information on industry trends. Within the finance industry, companies use social media as a tool for analyzing market sentiment. These range from marketing financial products, market trends, and as a tool to identify insider trading.[88] To exploit these opportunities, businesses need guidelines for use on each platform.[3] Business use of social media is complicated by the fact that the business does not fully control its social media presence. Instead, it makes its case by participating in the "conversation".[89] Business uses social media[90] on a customer-organizational level; and an intra-organizational level. Social media can encourage entrepreneurship and innovation, by highlighting successes, and by easing access to resources that might not otherwise be readily available/known.[91] Marketing Main article: Social media marketing Social media marketing can help promote a product or service and establish connections with customers. Social media marketing can be divided into paid media, earned media, and owned media.[92] Using paid social media firms run advertising on a social media platform. Earned social media appears when firms do something that impresses stakeholders and they spontaneously post content about it. Owned social media is the platform markets itself by creating/promoting content to its users.[93] Primary uses are to create brand awareness, engage customers by conversation (e.g., customers provide feedback on the firm) and providing access to customer service.[94] Social media's peer-to-peer communication shifts power from the organization to consumers, since consumer content is widely visible and not controlled by the company.[95] Social media personalities, often referred to as "influencers", are Internet celebrities who are sponsored by marketers to promote products and companies online. Research reports that these endorsements attract the attention of users who have not settled on which products/services to buy,[96] especially younger consumers.[97] The practice of harnessing influencers to market or promote a product or service to their following is commonly referred to as influencer marketing. In 2013, the United Kingdom Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) began advising celebrities to make it clear whether they had been paid to recommend a product or service by using the hashtag #spon or #ad when endorsing. The US Federal Trade Commission issued similar guidelines.[98] Social media platforms also enable targeting specific audiences with advertising. Users of social media can share, and comment on the advertisement, turning passive consumers into active promoters and even producers.[99] Targeting requires extra effort by advertisers to understand how to reach the right users.[3] Companies can use humor (such as shitposting) to poke fun at competitors.[100] Advertising can even inspire fanart which can engage new audiences.[101] Hashtags (such as #ejuice and #eliquid) are one way to target interested users.[102] User content can trigger peer effects, increasing consumer interest even without influencer involvement. A 2012 study focused on this communication reported that communication among peers can affect purchase intentions: direct impact through encouraging conformity, and an indirect impact by increasing product engagement. This study claimed that peer communication about a product increased product engagement.[103] |

ビジネス 主な記事: 企業のソーシャルメディア利用 多くの企業は、マーケティング、ブランディング、[87]広告、コミュニケーション、販売促進、非公式な従業員教育・組織開発、競合分析、採用活動、関係 管理・ロイヤルティプログラム、[31]電子商取引のためにソーシャルメディアを利用している。企業はソーシャルメディア監視ツールを用いて、マーケティ ング、販売その他のプログラムを支援するため、会話の監視、追跡、分析を行っている。ツールは無料の基本アプリケーションからサブスクリプション型まで様 々である。ソーシャルメディアは業界動向に関する情報を提供する。金融業界では、企業が市場センチメント分析のツールとしてソーシャルメディアを活用して いる。これには金融商品のマーケティング、市場動向の把握、インサイダー取引の特定ツールとしての利用が含まれる[88]。こうした機会を活用するには、 各プラットフォームでの利用ガイドラインが必要である[3]。 企業がソーシャルメディアを活用する際の複雑さは、自社のソーシャルメディア上の存在を完全に制御できない点にある。代わりに「会話」に参加することで主張を展開する。[89] 企業はソーシャルメディアを顧客組織レベルと組織内部レベルで活用する。[90] ソーシャルメディアは成功事例を強調し、通常は容易に入手・認知されないリソースへのアクセスを容易にすることで、起業家精神とイノベーションを促進し得る。[91] マーケティング 詳細記事: ソーシャルメディアマーケティング ソーシャルメディアマーケティングは、製品やサービスの宣伝や顧客とのつながり構築に役立つ。ソーシャルメディアマーケティングは、有料メディア、獲得メ ディア、所有メディアに分類できる。[92] 有料ソーシャルメディアでは、企業がソーシャルメディアプラットフォーム上で広告を掲載する。獲得ソーシャルメディアは、企業がステークホルダーを感銘さ せる行動を取った際、彼らが自発的にその内容について投稿する際に発生する。オウンドメディアは、企業が自らコンテンツを作成・促進し、ユーザーに発信す るプラットフォームである。[93] 主な用途は、ブランド認知度の向上、対話による顧客エンゲージメント(例:顧客が企業にフィードバックを提供)、カスタマーサービスへのアクセス提供であ る。[94] ソーシャルメディアのピアツーピアコミュニケーションは、消費者コンテンツが広く可視化され企業によって制御されないため、権力を組織から消費者へ移行さ せる。[95] ソーシャルメディア人格、いわゆる「インフルエンサー」とは、マーケターからスポンサー契約を受け、オンラインで製品や企業を宣伝するインターネット有名 人である。研究によれば、こうした推奨は、購入する製品・サービスをまだ決めていないユーザー、特に若年層の消費者の注目を集めるという。[96] [97] インフルエンサーを活用し、そのフォロワーに向けて製品やサービスをマーケティング・プロモーションする手法は、一般的にインフルエンサーマーケティング と呼ばれる。 2013年、英国広告基準局(ASA)は、有名人が製品やサービスを推奨する際、#spon または #ad のハッシュタグを使用して、報酬を受けているかどうかを明確に示すよう助言を開始した。米国連邦取引委員会も同様のガイドラインを発表した。[98] ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームは、特定のオーディエンスをターゲットにした広告配信も可能にする。ソーシャルメディアユーザーは広告を共有し、コメ ントすることで、受動的な消費者から能動的なプロモーター、さらにはプロデューサーへと変貌する。[99] ターゲティングには、適切なユーザーにリーチする方法を理解するための広告主の追加努力が必要だ。[3] 企業はユーモア(例えばシットポーティング)を用いて競合他社を揶揄することもできる。[100] 広告はファンアートを生み出し、新たな視聴者を惹きつけることさえある。[101] ハッシュタグ(例えば#ejuiceや#eliquid)は関心のあるユーザーをターゲットにする一つの方法だ。[102] ユーザーコンテンツは仲間効果を引き起こし、インフルエンサーの関与がなくても消費者の関心を高める。2012年の研究はこのコミュニケーションに注目 し、仲間同士の交流が購買意向に影響すると報告した:同調を促す直接的影響と、製品への関与を高める間接的影響である。この研究は、製品に関する仲間同士 のコミュニケーションが製品への関与を高めると主張した。[103] |

| Politics Main article: Social media use in politics See also: Social impact of YouTube, Use of social media in the Wisconsin protests, and Social media and political communication in the United States Social media have a range of uses in politics.[104] Politicians use social media to spread their messages and influence voters.[105] Dounoucos et al. reported that Twitter use by candidates was unprecedented during the US 2016 election.[106][107] The public increased its reliance on social-media sites for political information.[106] In the European Union, social media amplified political messages.[108] Foreign-originated social-media campaigns attempt to influence political opinion in another country.[109][110] Activism See also: Social media and the Arab Spring Social media was influential in the Arab Spring in 2011.[111][112][113][114] However, debate persists about the extent to which social media facilitated this.[115] Activists have used social media to report the abuse of human rights in Bahrain. They publicized the brutality of government authorities, who they claimed were detaining, torturing and threatening individuals. Conversely, Bahrain's government used social media to track and target activists. The government stripped citizenship from over 1,000 activists as punishment.[116] Militant groups use social media as an organizing and recruiting tool.[117] Islamic State (also known as ISIS) used social media. In 2014, #AllEyesonISIS went viral on Arabic X.[118][119] Propaganda This section is an excerpt from State-sponsored Internet propaganda.[edit] State-sponsored Internet propaganda is Internet manipulation and propaganda that is sponsored by a state. States have used the Internet, particularly social media to influence elections, sow distrust in institutions, spread rumors, spread disinformation, typically using bots to create and spread contact. Propaganda is used internally to control populations, and externally to influence other societies. |

政治 主な記事: 政治におけるソーシャルメディアの利用 関連項目: YouTubeの社会的影響、ウィスコンシン抗議活動におけるソーシャルメディアの利用、アメリカ合衆国におけるソーシャルメディアと政治コミュニケーション ソーシャルメディアは政治において様々な用途がある。[104] 政治家はソーシャルメディアを利用して自らのメッセージを広め、有権者に影響を与える。[105] Dounoucosらは、2016年米国大統領選挙において候補者によるTwitter利用が前例のない規模であったと報告している。[106] [107] 国民は政治情報源としてソーシャルメディアサイトへの依存度を高めた。[106] 欧州連合では、ソーシャルメディアが政治メッセージを増幅させた。[108] 国外発のソーシャルメディアキャンペーンは他国の政治的意見に影響を与えようとする。[109] [110] 活動主義 関連項目: ソーシャルメディアとアラブの春 ソーシャルメディアは2011年のアラブの春において影響力を持っていた。[111][112][113][114] しかし、ソーシャルメディアがこれをどの程度促進したかについては議論が続いている。[115] 活動家たちはソーシャルメディアを活用し、バーレーンにおける人権侵害を報告した。彼らは政府当局の残虐行為を公表し、当局が個人を拘束・拷問・脅迫して いると主張した。一方、バーレーン政府はソーシャルメディアを利用して活動家を監視・標的にした。政府は1,000人以上の活動家から市民権を剥奪する処 罰を行った。[116] 過激派組織はソーシャルメディアを組織化と勧誘の手段として利用している。[117] イスラム国(ISISとも呼ばれる)もソーシャルメディアを利用した。2014年には、#AllEyesonISISがアラビア語版Xで拡散した。[118] [119] プロパガンダ この節は国家主導のインターネットプロパガンダからの抜粋である。[編集] 国家主導のインターネットプロパガンダとは、国家が支援するインターネット操作およびプロパガンダを指す。国家はインターネット、特にソーシャルメディア を利用して選挙に影響を与え、制度への不信感を煽り、噂や偽情報を拡散してきた。典型的にはボットを用いて接触を創出し拡散する。プロパガンダは国内では 国民統制に、国外では他社会への影響力行使に用いられる。 |

| Recruiting This section is an excerpt from Social media use in hiring.[edit] Social media use in hiring refers to the examination by employers of job applicants' (public) social media profiles as part of the hiring assessment. For example, the vast majority of Fortune 500 companies use social media as a tool to screen prospective employees and as a tool for talent acquisition.[120] This practice raises ethical questions. Employers and recruiters note that they have access only to information that applicants choose to make public. Many Western-European countries restrict employer's use of social media in the workplace. States including Arkansas, California, Colorado, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin protect applicants and employees from surrendering usernames and passwords for social media accounts.[citation needed] Use of social media has caused significant problems for some applicants who are active on social media. A 2013 survey of 17,000 young people in six countries found that one in ten people aged 16 to 34 claimed to have been rejected for a job because of social media activity.[121][122] Social media services have been reported to affect deception in resumes. While these services do not affect deception frequency, it does increase deception about interests and hobbies.[citation needed] |

採用活動 このセクションは「採用におけるソーシャルメディアの利用」からの抜粋である。[編集] 採用におけるソーシャルメディアの利用とは、雇用主が採用審査の一環として求職者の(公開されている)ソーシャルメディアプロフィールを調査することを指 す。例えば、フォーチュン500企業の大多数は、ソーシャルメディアを候補者のスクリーニングツールおよび人材獲得の手段として利用している。[120] この慣行は倫理的な疑問を提起する。雇用主や採用担当者は、応募者が公開を選択した情報にしかアクセスできないと主張する。多くの西欧諸国では、職場にお ける雇用主のソーシャルメディア利用を制限している。アーカンソー州、カリフォルニア州、コロラド州、イリノイ州、メリーランド州、ミシガン州、ネバダ 州、ニュージャージー州、ニューメキシコ州、ユタ州、ワシントン州、ウィスコンシン州などの州では、応募者や従業員がソーシャルメディアアカウントのユー ザー名やパスワードを提出することを禁止している。[出典が必要] ソーシャルメディアの活用は、ソーシャルメディアを積極的に利用する一部の応募者に重大な問題を引き起こしている。2013年に6カ国で17,000人の 若者を対象に行った調査では、16歳から34歳の10人に1人が、ソーシャルメディア上の活動が原因で就職を拒否されたと主張している。[121] [122] ソーシャルメディアサービスは、履歴書における虚偽記載に影響を与えると報告されている。これらのサービスは虚偽記載の頻度には影響しないものの、趣味や嗜好に関する虚偽記載を増加させる。[出典が必要] |

| Science Scientists use social media to share their scientific knowledge and research on platforms such as ResearchGate, LinkedIn, Facebook, X, and Academia.edu.[123] The most common platforms are X and blogs. The use of social media reportedly has improved the interaction between scientists, reporters, and the general public.[citation needed] Over 495,000 opinions were shared on X related to science between September 1, 2010, and August 31, 2011.[124] Science related blogs respond to and motivate public interest in learning, following, and discussing science. Posts can be written quickly and allow the reader to interact in real time with authors.[125] One study in the context of climate change reported that climate scientists and scientific institutions played a minimal role in online debate, exceeded by nongovernmental organizations.[126] |

科学 科学者たちはResearchGate、LinkedIn、Facebook、X、Academia.eduといったプラットフォームで、自らの科学的知 識や研究を共有するためにソーシャルメディアを利用している。[123] 最も一般的なプラットフォームはXとブログである。ソーシャルメディアの利用は、科学者と報道関係者、一般市民の間の交流を改善したと報告されている。 [出典が必要] 2010年9月1日から2011年8月31日までの間に、X上では科学関連の意見が49万5000件以上共有された。[124] 科学関連のブログは、科学を学び、追いかけ、議論することへの一般市民の関心を喚起し、それに応える役割を果たしている。投稿は素早く書け、読者は著者と リアルタイムでやり取りできる。[125] 気候変動に関するある研究では、気候科学者や科学機関はオンライン議論で最小限の役割しか果たしておらず、非政府組織(NGO)に及ばないと報告されてい る。[126] |

| Academia Academicians use social media activity to assess academic publications,[127] to measure public sentiment,[128] identify influencer accounts,[129] or crowdsource ideas or solutions.[130] Social media such as Facebook, X are also combined to predict elections via sentiment analysis.[131] Additional social media (e.g. YouTube, Google Trends) can be combined to reach a wider segment of the voting population, minimise media-specific bias, and inexpensively estimate electoral predictions which are on average half of a percentage point off the real vote share.[132] |

学術界 学者たちはソーシャルメディアの活動を利用して学術出版物を評価し[127]、世論を測定し[128]、インフルエンサーアカウントを特定し[129]、 あるいはアイデアや解決策をクラウドソーシングする[130]。FacebookやXなどのソーシャルメディアも、感情分析を通じて選挙結果を予測するた めに組み合わされる。[131] 追加のソーシャルメディア(例:YouTube、Google Trends)を組み合わせることで、有権者層のより広いセグメントに到達し、メディア固有の偏りを最小限に抑え、実際の得票率から平均0.5パーセント ポイントの誤差で選挙予測を低コストで推定できる。[132] |

| School admissions In some places, students have been forced to surrender their social media passwords to school administrators.[133] Few laws protect student's social media privacy. Organizations such as the ACLU call for more privacy protection. They urge students who are pressured to give up their account information to resist.[134] Colleges and universities may access applicants' internet services including social media profiles as part of their admissions process. According to Kaplan, Inc, a corporation that provides higher education preparation, in 2012 27% of admissions officers used Google to learn more about an applicant, with 26% checking Facebook.[135] Students whose social media pages include questionable material may be disqualified from admission processes. "One survey in July 2017, by the American Association of College Registrars and Admissions Officers, reported that 11 percent of respondents said they had refused to admit an applicant based on social media content. This includes 8 percent of public institutions, where the First Amendment applies. The survey reported that 30 percent of institutions acknowledged reviewing the personal social media accounts of applicants at least some of the time."[136] |

学校の入学審査 一部の地域では、生徒がソーシャルメディアのパスワードを学校管理者に提出するよう強制されている。[133] 生徒のソーシャルメディア上のプライバシーを保護する法律はほとんど存在しない。ACLUなどの団体はプライバシー保護の強化を求めている。彼らはアカウ ント情報の提出を迫られた生徒に対し、抵抗するよう呼びかけている。[134] 大学は入学審査の一環として、志願者のインターネットサービス(ソーシャルメディアプロフィールを含む)にアクセスすることがある。高等教育準備を提供す る企業カプラン社によれば、2012年には入学審査官の27%がGoogleで志願者情報を調査し、26%がFacebookを確認していた[135]。 ソーシャルメディアページに問題のある内容がある学生は、入学審査から除外される可能性がある。 「2017年7月に全米大学入学審査官協会が実施した調査では、回答者の11%がソーシャルメディアの内容を理由に志願者の入学を拒否したと報告してい る。これには憲法修正第一条が適用される公立機関の8%も含まれる。調査では、30%の機関が少なくとも時折、志願者の人格ソーシャルメディアアカウント を確認していると認めた。」[136] |

| Court cases Social media comments and images have been used in court cases including employment law, child custody/child support, and disability claims. After an Apple employee criticized his employer on Facebook, he was fired. When the former employee sued Apple for unfair dismissal, the court, after examining the employee's Facebook posts, reported in favor of Apple, stating that the posts breached Apple's policies.[137] After a couple broke up, the man posted song lyrics "that talked about fantasies of killing the rapper's ex-wife" and made threats. A court reported him guilty.[137][clarification needed] In a disability claims case, a woman who fell at work claimed that she was permanently injured; the employer used her social media posts to counter her claims.[137][additional citation(s) needed] Courts do not always admit social media evidence, in part, because screenshots can be faked or tampered with.[138] Judges may consider emojis into account to assess statements made on social media; in one Michigan case where a person alleged that another person had defamed them in an online comment, the judge disagreed, noting that an emoji after the comment that indicated that it was a joke.[138] In a 2014 case in Ontario against a police officer regarding alleged assault of a protester during the G20 summit, the court rejected the Crown's application to use a digital photo of the protest that was anonymously posted online, because it included no metadata verifying its provenance.[138][additional citation(s) needed] On April 9, 2024, the Spirit Lake Tribe in North Dakota and Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin have sued social media companies (Meta Platforms-Facebook, Instagram; Snapchat, TikTok, YouTube, and Google) companies accused of ‘deliberate misconduct’. Their lawsuit describes "a sophisticated and intentional effort that has caused a continuing, substantial, and longterm burden to the Tribe and its members," leaving scarce resources for education, cultural preservation and other social programs.[139] These social media lawsuits are one of several legal actions brought against social media giants. Independently, 33 state attorneys general, including South Dakota's, sued the same defendants for targeting teens with allegedly poor content, they allege. The defendants have said they are launching new safety tools and features to protect younger users.[140][additional citation(s) needed] |

裁判事例 ソーシャルメディア上のコメントや画像は、雇用法、親権・養育費、障害補償請求などの裁判事例で使用されてきた。アップル社員がフェイスブックで雇用主を 批判した後、解雇された。元社員が不当解雇でアップルを訴えた際、裁判所は社員のフェイスブック投稿を検証した上で、投稿がアップルの方針に違反している と判断し、アップルに有利な判決を下した。[137] 別れたカップルにおいて、男性が「ラッパーの元妻を殺害する妄想を歌った歌詞」を投稿し脅迫した件では、裁判所が有罪判決を下した。[137][説明が必 要] 障害補償請求訴訟では、職場で転倒した女性が「永久的な障害を負った」と主張したが、雇用主は彼女のソーシャルメディア投稿を反論材料として利用した。 [137][追加引用が必要] 裁判所はソーシャルメディアの証拠を常に採用するわけではない。スクリーンショットが偽造・改ざんされる可能性があるためだ。[138] 裁判官はソーシャルメディア上の発言を評価する際、絵文字を考慮に入れることがある。ミシガン州の事例では、ある人格がオンラインコメントで誹謗されたと 主張したが、裁判官は「コメント後の絵文字が冗談であることを示していた」としてこれを退けた。[138] 2014年にオンタリオ州で起きたG20サミット中の抗議者暴行疑惑に関する警察官訴訟では、検察側がオンラインに匿名投稿された抗議活動のデジタル写真 の使用を申請したが、裁判所はこれを却下した。その理由は、写真の出所を証明するメタデータが含まれていなかったためである。[138][追加引用が必 要] 2024年4月9日、ノースダコタ州のスピリットレイク部族とウィスコンシン州のメノミニー部族は、ソーシャルメディア企業(Meta Platforms-Facebook、Instagram、Snapchat、TikTok、YouTube、Google)を「意図的な不正行為」で 提訴した。訴状では「部族とその構成員に対し継続的・重大・長期的な負担をもたらした、高度で意図主義的な行為」と説明され、教育・文化保存・社会事業へ の資源が枯渇していると指摘されている。[139] こうしたソーシャルメディア訴訟は、大手企業に対する複数の法的措置の一つである。これとは別に、サウスダコタ州を含む33州の司法長官が、未成年者を対 象に不適切なコンテンツを流したとして、同じ被告企業を提訴した。被告企業側は、若年層ユーザーを保護する新たな安全対策ツールや機能を導入すると表明し ている。[140][追加引用が必要] |

| Use by individuals News source This section is an excerpt from Social media as a news source.[edit] Social media as a news source is defined as the use of online social media platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook rather than the use of traditional media platforms like the newspaper or live TV to obtain news. Television had just begun to turn a nation of people who once listened to media content into watchers of media content between the 1950s and the 1980s when the popularity of social media had also began creating a nation of media content creators. Almost half of Americans use social media as a news source, according to the Pew Research Center.[141] As social media’s role in news consumption grows, questions have emerged about its impact on knowledge, the formation of echo chambers, and the effectiveness of fact-checking efforts in combating misinformation. Social media platforms allow user-generated content[142][143] and sharing content within one's own virtual network.[144][142] Using social media as a news source allows users to engage with news in a variety of ways including: Consuming and discovering news Sharing or reposting news Posting one's own photos, videos, or reports of news (i.e., engage in citizen or participatory journalism) Commenting on news posts Using social media as a news source has become an increasingly more popular way for people of all age groups to obtain current and important information. Just like many other new forms of technology there are going to be pros and cons. There are ways that social media positively affects the world of news and journalism but it is important to acknowledge that there are also ways in which social media has a negative effect on the news. With this accessibility, people now have more ways to consume false news, biased news, and even disturbing content. In 2019, the Pew Research Center created a poll that reported Americans are wary about the ways that social media sites share news and certain content.[145] This wariness of accuracy grew as awareness that social media sites could be exploited by bad actors who concoct false narratives and fake news.[146] |

個人の利用 ニュースソース このセクションは「ソーシャルメディアをニュースソースとして」からの抜粋である。 ソーシャルメディアをニュースソースとして利用するとは、新聞や生放送テレビといった従来のメディアプラットフォームではなく、Instagram、 TikTok、Facebookなどのオンラインソーシャルメディアプラットフォームを利用してニュースを入手することを指す。1950年代から1980 年代にかけて、テレビがメディアコンテンツを「聴く」国民を「見る」国民へと変え始めた頃、ソーシャルメディアの人気もまた、メディアコンテンツを「作 る」国民を生み出し始めていた。ピュー・リサーチ・センターによれば、アメリカ人のほぼ半数がソーシャルメディアをニュースソースとして利用している [141]。ソーシャルメディアのニュース消費における役割が拡大するにつれ、知識形成への影響、エコーチェンバーの形成、誤情報対策としてのファクト チェックの有効性について疑問が提起されている。 ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームは、ユーザー生成コンテンツ[142][143]の投稿と、自身の仮想ネットワーク内でのコンテンツ共有を可能にす る。[144][142] ニュースソースとしてのソーシャルメディア利用は、以下のような多様な方法でニュースに関与することを可能にする: ニュースの消費と発見 ニュースの共有や再投稿 自身の写真・動画・ニュース報告の投稿(市民ジャーナリズムや参加型ジャーナリズムへの関与) ニュース投稿へのコメント ソーシャルメディアをニュースソースとして利用することは、あらゆる年齢層の人民が最新かつ重要な情報を得る手段としてますます普及している。他の多くの 新技術と同様に、これには長所と短所が存在する。ソーシャルメディアがニュースやジャーナリズムの世界に良い影響を与える側面もあるが、同時にニュースに 悪影響を及ぼす側面もあることを認識することが重要だ。このアクセスの容易さゆえに、人民は今や偽ニュースや偏ったニュース、さらには不快なコンテンツに 触れる機会が増えている。 2019年、ピュー・リサーチ・センターが実施した世論調査では、アメリカ人がソーシャルメディアサイトがニュースや特定コンテンツを共有する方法を警戒 していることが報告された[145]。この正確性への警戒感は、ソーシャルメディアサイトが悪意のある者によって悪用され、虚偽の物語や偽ニュースが捏造 される可能性があるという認識が高まるにつれて強まった[146]。 |

| Social tool Social media are used to socialize with friends and family[147] pursue romance and flirt,[147] but not all social needs can be fulfilled by social media.[148] For example, a 2003 article reported that lonely individuals are more likely to use the Internet for emotional support than others.[149] A 2018 survey from Common Sense Media reported that 40% of American teens ages 13–17 thought that social media was "extremely" or "very" important for them to connect with their friends.[150] The same survey reported that 33% of teens said social media was extremely or very important to conduct meaningful conversations with close friends, and 23% of teens said social media was extremely or very important to document and share their lives.[150] A 2020 Gallup poll reported that 53% of adult social media users in the United States thought that social media was a very or moderately important way to keep in touch with people during the COVID-19 pandemic.[151] In Alone Together Sherry Turkle considered how people confuse social media usage with authentic communication.[152] She claimed that people act differently online and are less concerned about hurting others' feelings. Some online encounters can cause stress and anxiety, due to the difficulty purging online posts, fear of getting hacked, or of universities and employers exploring social media pages. Turkle speculated that many people prefer texting to face-to-face communication, which can contribute to loneliness.[152] Surveys from 2019 reported evidence among teens in the United States[150] and Mexico.[153] Some researchers reported that exchanges that involved direct communication and reciprocal messages correlated with less loneliness.[154] In social media "stalking" or "creeping" refers to looking at someone's "timeline, status updates, tweets, and online bios" to find information about them and their activities.[155] A sub-category of creeping is creeping ex-partners after a breakup.[156] Catfishing (creating a false identity) allows bad actors to exploit the lonely.[157] |

ソーシャルツール ソーシャルメディアは友人や家族との交流[147]、恋愛やいちゃつく行為[147]に利用されるが、全ての社会的ニーズがソーシャルメディアで満たされ るわけではない。例えば、2003年の記事によれば、孤独な個人は他者よりも感情的な支えを得るためにインターネットを利用する傾向が強いと報告されてい る。また、コモンセンスメディアの2018年調査では、13~17歳のアメリカ人ティーンの40%が、友人との繋がりを保つ上でソーシャルメディアが「極 めて」または「非常に」重要だと考えていると報告された。[150] 同調査では、33%のティーンが「親しい友人との有意義な会話にソーシャルメディアが極めて重要または非常に重要」と回答し、23%が「自身の生活を記 録・共有する上で極めて重要または非常に重要」と答えた。[150] 2020年のギャラップ調査によれば、米国の成人ソーシャルメディア利用者の53%が、COVID-19パンデミック下で人々との連絡手段としてソーシャ ルメディアが「非常に重要」または「やや重要」だと考えていた。[151] 『孤独な共生』においてシェリー・タークルは、人民がソーシャルメディアの利用を本物のコミュニケーションと混同する傾向を考察した[152]。彼女は、 人民はオンライン上では異なる行動を取り、他人の感情を傷つけることへの配慮が薄れると主張した。オンライン上の投稿を削除しにくいこと、ハッキングされ る恐れ、大学や雇用主によるソーシャルメディアページの閲覧などにより、一部のオンライン交流はストレスや不安を引き起こす可能性がある。タークルは、多 くの人が対面コミュニケーションよりテキストメッセージを好む傾向があり、これが孤独感の一因となり得ると推測した[152]。2019年の調査では、米 国[150]とメキシコ[153]の十代にその証拠が報告されている。一部の研究者は、直接的なコミュニケーションと相互のメッセージ交換が孤独感の軽減 と相関すると報告した[154]。 ソーシャルメディアにおける「ストーキング」や「クリーピング」とは、相手の「タイムライン、ステータス更新、ツイート、オンラインプロフィール」を閲覧 し、本人やその活動に関する情報を探す行為を指す[155]。クリーピングのサブカテゴリーとして、別れた元パートナーをストーキングする行為がある [156]。 キャットフィッシング(偽の身分を創作する行為)は、悪意のある人物が孤独な人々を搾取することを可能にする[157]。 |

| Invidious comparison Self-presentation theory proposes that people consciously manage their self-image or identity related information in social contexts.[158] One aspect of social media is the time invested in customizing a personal profile.[159] Some users segment their audiences based on the image they want to present, pseudonymity and use of multiple accounts on the same platform offer that opportunity.[160] A 2016 study reported that teenage girls manipulate their self-presentation on social media to appear beautiful as viewed by their peers.[161] Teenage girls attempt to earn regard and acceptance (likes, comments, and shares). When this does not go well, self-confidence and self-satisfaction can decline.[161] A 2018 survey of American teens ages 13–17 by Common Sense Media reported that 45% said likes are at least somewhat important, and 26% at least somewhat agreed that they feel bad about themselves if nobody responds to their photos.[150] Some evidence suggests that perceived rejection may lead to emotional pain,[162] and some may resort to online bullying.[163] according to a 2016 study, users' reward circuits in their brains are more active when their photos are liked by more peers.[164] A 2016 review concluded that social media can trigger a negative feedback loop of viewing and uploading photos, self-comparison, disappointment, and disordered body perception when social success is not achieved.[165] One 2016 study reported that Pinterest is directly associated with disordered dieting behavior.[166] People portray themselves on social media in the most appealing way.[161] However, upon seeing one person's curated persona, other people may question why their own lives are not as exciting or fulfilling. One 2017 study reported that problematic social media use (i.e., feeling addicted to social media) was related to lower life satisfaction and self-esteem.[167] Studies have reported that social media comparisons can have dire effects on physical and mental health.[168][169] In one study, women reported that social media was the most influential source of their body image satisfaction; while men reported them as the second biggest factor. While monitoring the lives of celebrities long predates social media, the ease and immediacy of direct comparisons of pictures and stories with one's own may increase their impact.[citation needed] A 2021 study reported that 87% of women and 65% of men compared themselves to others on social media.[170] Efforts to combat such negative effects focused promoting body positivity. In a related study, women aged 18–30 were reported posts that contained side-by-side images of women in the same clothes and setting, but one image was enhanced for Instagram, while the other was an unedited, "realistic" version. Women who participated in this experiment reported a decrease in body dissatisfaction.[171] |

不公平な比較 自己提示理論によれば、人は社会的文脈において自らの自己像やアイデンティティ関連情報を意識的に管理する。[158] ソーシャルメディアの特徴の一つは、個人プロフィールをカスタマイズするために費やす時間である。[159] 一部のユーザーは提示したいイメージに基づいて視聴者を区分けし、偽名や同一プラットフォームでの複数アカウント利用がその機会を提供する。[160] 2016年の研究によれば、10代の少女はソーシャルメディア上で自己表現を操作し、同世代から見た「美しい」姿を見せようとする。[161] 彼女たちは評価と受容(いいね、コメント、シェア)を得ようとする。これがうまくいかない場合、自信や自己満足感が低下する可能性がある。[161] コモンセンスメディアによる2018年の13~17歳米国人ティーン調査では、45%が「いいね」は少なくともある程度重要だと回答し、26%が「写真に 反応がなければ自己嫌悪を感じる」と少なくともある程度同意した。[150] 拒絶感は精神的苦痛につながる可能性を示す証拠もあり、[162] オンラインいじめに走る者もいる。[163] 2016年の研究によれば、同世代からより多くの「いいね」を得た場合、ユーザーの脳内の報酬回路がより活発になる。[164] 2016年の総説は、ソーシャルメディアが「写真の閲覧・投稿→自己比較→失望→身体認識の乱れ」という負のフィードバックループを引き起こし、社会的成 功が達成されない場合に悪循環を生じさせると結論づけた。[165] 2016年の研究では、Pinterestが摂食障害的行動と直接関連していると報告されている。[166] 人民はソーシャルメディア上で最も魅力的に自分を演出する。[161] しかし、他人の選りすぐられた人格を見ると、自分の人生がなぜそれほど刺激的でないのか、充実していないのかと疑問を抱くことがある。2017年の研究で は、問題のあるソーシャルメディア利用(つまり依存感)が、生活の満足度や自尊心の低下と関連していると報告されている。[167] ソーシャルメディア上での比較が、心身の健康に深刻な影響を及ぼす可能性があると複数の研究が指摘している。[168][169] ある研究では、女性はソーシャルメディアが自身の身体イメージ満足度に最も影響を与える要因だと報告したのに対し、男性は第二位の要因と回答した。有名人 の生活を監視する行為はソーシャルメディア以前から存在したが、写真やストーリーを直接比較できる手軽さと即時性が、その影響を強めている可能性がある。 [出典が必要] 2021年の研究によれば、女性の87%、男性の65%がソーシャルメディア上で他人と自分を比較していた。[170] こうした悪影響に対抗する取り組みとして、ボディポジティブの促進が注目された。関連研究では、18~30歳の女性に、同じ服装・同じ背景の女性を並べて 掲載した投稿を見せている。一方の画像はインスタグラム向けに加工され、もう一方は未編集の「現実的な」バージョンだった。この実験に参加した女性は、身 体への不満が減少したと報告している。[171] |

| Health Further information: Cyberpsychology § Social media and cyberpsychological behavior, and Social media and identity Adolescents Social media can offer a support system for adolescent health, because it allows them to mobilize around health issues that they deem relevant.[172] For example, in a clinical study among adolescent patients undergoing obesity treatment, participants' claimed that social media allowed them to access personalized weight-loss content as well as social support among other adolescents with obesity.[173][174] While social media can provide health information, it typically has no mechanism for ensuring the quality of that information.[174] The National Eating Disorders Association reported a high correlation between weight loss content and disorderly eating among women who have been influenced by inaccurate content.[174][175] Health literacy offers skills to allow users to spot/avoid such content. Efforts by governments and public health organizations to advance health literacy reportedly achieved limited success.[176] The role of parents and caregivers who proactively approach their children with ongoing guidance and open discussions on the benefits and difficulties they may encounter online, demonstrate some reductions in overall anxiety and depression among adolescents.[177] Social media such as pro-anorexia sites reportedly increase risk of harm by reinforcing damaging health-related behaviors through social media, especially among adolescents.[178][179][180] Pandemic During the coronavirus pandemic, inaccurate information from all sides spread widely via social media.[181] Topics subject to distortion included treatments, avoiding infection, vaccination, and public policy. Simultaneously, governments and others influenced social media platforms to suppress both accurate and inaccurate information in support of public policy.[182] Heavier social media use was reportedly associated with more acceptance of conspiracy theories, leading to worse mental health[183] and less compliance with public health recommendations.[184] Addiction Social media platforms can serve as a breeding ground for addiction-related behaviors, with studies report that excessive use can lead to addiction-like symptoms. These symptoms include compulsive checking, mood modification, and withdrawal when not using social media, which can result in decreased face-to-face social interactions and contribute to the deterioration of interpersonal relationships and a sense of loneliness.[185] |

健康 詳細情報:サイバー心理学 § ソーシャルメディアとサイバー心理学的行動、およびソーシャルメディアとアイデンティティ 思春期 ソーシャルメディアは、思春期の健康に対する支援システムを提供し得る。なぜなら、彼らが重要と考える健康問題について結束する手段となるからだ。 [172] 例えば、肥満治療を受ける思春期患者を対象とした臨床研究では、参加者はソーシャルメディアが肥満に悩む他の思春期層との社会的支援に加え、個人に合わせ た減量コンテンツへのアクセスを可能にしたと主張した。[173][174] ソーシャルメディアは健康情報を提供できるが、通常はその情報の質を保証する仕組みを持たない。[174] 全米摂食障害協会は、不正確な情報に影響を受けた女性において、減量コンテンツと摂食障害の間に高い相関関係があると報告している。[174][175] 健康リテラシーは、ユーザーがそのようなコンテンツを見分け回避するスキルを提供する。政府や公衆衛生機関による健康リテラシー向上の取り組みは、限定的 な成果しか得られていないと報告されている。[176] 親や保護者が積極的に子供に働きかけ、継続的な指導やオンライン上で遭遇する可能性のある利点・困難についての率直な議論を行う役割は、青少年の全体的な 不安や抑うつをある程度軽減することを示している。[177] プロ・アノレキシア(拒食症推奨)サイトなどのソーシャルメディアは、特に青少年の間で、健康を損なう行動を助長することで危害リスクを高めると報告されている。[178][179][180] パンデミック コロナウイルスパンデミック中、あらゆる方面からの不正確な情報がソーシャルメディアを通じて広く拡散した。[181] 歪曲の対象となったトピックには、治療法、感染回避策、ワクチン接種、公共政策が含まれた。同時に、政府などは公共政策を支援するため、ソーシャルメディ アプラットフォームに影響を与え、正確な情報と不正確な情報の両方を抑制した。[182] ソーシャルメディアの使用頻度が高いほど、陰謀論への受容性が高まり、精神健康の悪化[183] や公衆衛生上の推奨事項への順守低下につながると報告されている。[184] 依存症 ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームは依存症関連行動の温床となり得る。研究によれば、過度な利用は依存症に似た症状を引き起こす。これらの症状には、強 迫的なチェック行為、気分変動、ソーシャルメディア非使用時の離脱症状が含まれる。これにより対面での社会的交流が減少し、対人関係の悪化や孤独感の増大 に寄与する可能性がある。[185] |

| Cyberbullying This section is an excerpt from Cyberbullying.[edit] Cyberbullying (cyberharassment or online bullying) is a form of bullying or harassment using electronic means. Since the 2000s, it has become increasingly common, especially among teenagers and adolescents, due to young people's increased use of social media.[186] Related issues include online harassment and trolling. In 2015, according to cyberbullying statistics from the i-Safe Foundation, over half of adolescents and teens had been bullied online, and about the same number had engaged in cyberbullying.[187] Both the bully and the victim are negatively affected, and the intensity, duration, and frequency of bullying are three aspects that increase the negative effects on both of them.[188] |

ネットいじめ この節は『ネットいじめ』からの抜粋である。[編集] ネットいじめ(サイバーハラスメントまたはオンラインいじめ)とは、電子的な手段を用いたいじめや嫌がらせの一形態である。2000年代以降、若年層の ソーシャルメディア利用増加に伴い、特に十代や青少年層で急増している。[186] 関連する問題にはオンライン嫌がらせや荒らし行為が含まれる。2015年、i-Safe財団のサイバーいじめ統計によれば、10代の半数以上がオンライン でいじめを受けた経験があり、ほぼ同数の人々がサイバーいじめに加担していた。[187] いじめる側といじめられる側の双方に悪影響が及ぶ。いじめの強度、継続期間、頻度は、双方への悪影響を増大させる三つの要素である。[188] |

| Sleep disturbance A 2017 study reported on a link between sleep disturbance and the use of social media. It concluded that blue light from computer/phone displays—and the frequency rather than the duration of time spent, predicted disturbed sleep, termed "obsessive 'checking'".[189] The association between social media use and sleep disturbance has clinical ramifications for young adults.[190] A recent study reported that people in the highest quartile for weekly social media use experienced the most sleep disturbance. The median number of minutes of social media use per day was 61. Females were more likely to experience high levels of sleep disturbance.[191] Many teenagers suffer from sleep deprivation from long hours at night on their phones, and this left them tired and unfocused in school.[192] A 2011 study reported that time spent on Facebook was negatively associated with GPA, but the association with sleep disturbance was not established.[193] |

睡眠障害 2017年の研究は、睡眠障害とソーシャルメディア利用の関連性を報告した。コンピューターやスマートフォンの画面から発せられるブルーライトが、利用時 間ではなく利用頻度によって睡眠障害を予測するとの結論に至った。この現象は「強迫的な『チェック』」と呼ばれている。[189] ソーシャルメディア利用と睡眠障害の関連性は、若年成人にとって臨床的な影響を持つ。[190] 最近の研究では、週間ソーシャルメディア利用時間が最上位四分位群に属する人民が最も深刻な睡眠障害を経験した。1日あたりのソーシャルメディア利用時間 の中央値は61分であった。女性は高いレベルの睡眠障害を経験する可能性が高かった。[191] 多くの十代の若者は、夜遅くまでスマートフォンを使用することで睡眠不足に陥り、その結果、学校で疲れや集中力の低下を苦悩している。[192] 2011年の研究では、Facebookの使用時間はGPA(成績平均点)と負の相関関係にあると報告されたが、睡眠障害との関連性は確立されなかった。 [193] |

| Emotional effects One studied effect of social media is 'Facebook depression', which affects adolescents who spend too much time on social media.[8] This may lead to reclusiveness, which can increase loneliness and low self-esteem.[8] Social media curates content to encourage users to keep scrolling.[190] Studies report children's self-esteem is positively affected by positive comments and negatively affected by negative or lack of comments. This affected self-perception.[194] A 2017 study of almost 6,000 adolescent students reported that those who self-reported addiction-like symptoms of social media use were more likely to report low self-esteem and high levels of depressive symptoms.[195] A second emotional effect is social media burnout, defined as ambivalence, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization. Ambivalence is confusion about the benefits from using social media. Emotional exhaustion is stress from using social media. Depersonalization is emotional detachment from social media. The three burnout factors negatively influence the likelihood of continuing on social media.[196] A third emotional effect is "fear of missing out" (FOMO), which is the "pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent."[197] It is associated with increased scrutiny of friends on social media.[197] Social media can also offer support as Twitter has done for the medical community.[198] X facilitated academic discussion among health professionals and students, while providing a supportive community for these individuals by and allowing members to support each other through likes, comments, and posts.[199] Access to social media offered a way to keep older adults connected, after the deaths of partners and geographical distance between friends and loved ones.[200] In March 2025, a Pakistani man killed a WhatsApp group admin in anger after being removed from the chat.[201] This section is an excerpt from Social media and suicide.[edit] Since the rise of social media, there have been numerous cases of individuals being influenced towards committing suicide or self-harm through their use of social media, and even of individuals arranging to broadcast suicide attempts, some successful, on social media. Researchers have studied social media and suicide to determine what, if any, risks social media poses in terms of suicide, and to identify methods of mitigating such risks, if they exist. The search for a correlation has not yet uncovered a clear answer. |

感情への影響 ソーシャルメディアの影響として研究されているものの一つが「フェイスブック鬱」だ。これはソーシャルメディアに過度に時間を費やす青少年に影響を与え る。[8] これは引きこもりにつながり、孤独感や低い自尊心を増幅させる可能性がある。[8] ソーシャルメディアはユーザーがスクロールを続けたいと思うようコンテンツを編集している。[190] 研究によれば、子供の自尊心は肯定的なコメントに好影響を受け、否定的なコメントやコメントの欠如には悪影響を受ける。これは自己認識に影響を与えた。 [194] 2017年に約6,000人の青少年学生を対象とした研究では、ソーシャルメディア利用に依存症のような症状があると自己申告した者は、自尊心が低く抑う つ症状が高いと報告する傾向が強かった。[195] 第二の感情的影響はソーシャルメディア・バーンアウトであり、これは両価性、感情的消耗、脱人格化と定義される。両価性とはソーシャルメディア利用の利点 に対する混乱である。感情的消耗とはソーシャルメディア利用によるストレスである。脱人格化とはソーシャルメディアからの感情的距離感である。これら三つ のバーンアウト要因は、ソーシャルメディア継続の可能性に悪影響を及ぼす。[196] 第三の感情的影響は「取り残される恐怖(FOMO)」である。これは「他者が自分だけが欠けている充実した体験をしているかもしれないという広範な不安」を指す。[197] これはソーシャルメディア上で友人への監視強化と関連している。[197] ソーシャルメディアは支援の場にもなり得る。Twitterが医療コミュニティに対して果たした役割がその例だ。[198] Xは健康専門家や学生間の学術的議論を促進すると同時に、メンバー同士が「いいね」やコメント、投稿を通じて支え合える支援コミュニティを提供した。 [199] パートナーの死や地理的距離によって孤立した高齢者にとって、ソーシャルメディアへのアクセスは繋がりを維持する手段となった. [200] 2025年3月、パキスタン人男性がチャットから削除された怒りから、WhatsAppグループの管理者を殺害した。[201] この節は「ソーシャルメディアと自殺」からの抜粋である。[編集] ソーシャルメディアの台頭以来、ソーシャルメディアの利用を通じて自殺や自傷行為に駆り立てられた事例が数多く報告されている。中には自殺未遂をソーシャ ルメディアで生中継する計画を立てた者もおり、成功したケースさえ存在する。研究者らはソーシャルメディアと自殺の関係を調査し、自殺リスクの有無や、も し存在するならばその軽減方法を特定しようとしている。相関関係の探求は、現時点で明確な答えを導き出せていない。 |

| Social impacts Media critic Siva Vaidhyanathan refers to social media as 'anti-social media' in reference to its negative impacts including on loneliness and political polarization.[202] Audrey Tang also uses the term antisocial in reference to its impact on democracy.[203] Disparity This section is an excerpt from Digital divide.[edit] The digital divide refers to unequal access to and effective use of digital technology, encompassing four interrelated dimensions: motivational, material, skills, and usage access.[204] The digital divide worsens inequality around access to information and resources. In the Information Age, people without access to the Internet and other technology are at a disadvantage, for they are unable or less able to connect with others, find and apply for jobs, shop, and learn.[205][206][207][208] People living in poverty, in insecure housing or homeless, elderly people, and those living in rural communities may have limited access to the Internet; in contrast, urban middle class people have easy access to the Internet. Another divide is between producers and consumers of Internet content,[209][210] which could be a result of educational disparities.[211] While social media use varies across age groups, a US 2010 study reported no racial divide.[212] |

社会的影響 メディア評論家のシヴァ・ヴァイディヤナサンは、孤独感や政治的分極化などへの悪影響を指摘し、ソーシャルメディアを「反社会的メディア」と呼んでいる[202]。オードリー・タンも民主主義への影響を理由に「反社会的」という表現を用いている[203]。 格差 この節はデジタルデバイドからの抜粋である。[編集] デジタルデバイドとは、デジタル技術へのアクセスと効果的な利用における不平等を指し、動機付け、物質的要因、スキル、利用機会という四つの相互に関連す る次元を含む。[204] デジタルデバイドは、情報や資源へのアクセスにおける不平等を悪化させる。情報化時代において、インターネットやその他の技術を利用できない人々は不利な 立場にある。なぜなら、他者とつながること、仕事を見つけて応募すること、買い物や学習を行うことが不可能、あるいは困難だからだ。[205][206] [207][208] 貧困層、不安定な住環境やホームレス状態にある人々、高齢者、農村地域住民はインターネットへのアクセスが制限される可能性がある。対照的に、都市部の中 産階級は容易にインターネットを利用できる。もう一つの格差は、インターネットコンテンツの生産者と消費者の間にある[209][210]。これは教育格 差の結果かもしれない[211]。ソーシャルメディアの利用は年齢層によって異なるが、2010年の米国調査では人種による格差は報告されていない [212]。 |

| Political polarization See also: Social media § Threat to democracy, Media bias § social media, and Rage-baiting Many critics point to studies showing social media algorithms elevate more partisan and inflammatory content.[213][214] Because of recommendation algorithms that filter and display news content that matches users' political preferences, one potential impact is an increase in political polarization due to selective exposure. Political polarization is the divergence of political attitudes towards ideological extremes. Selective exposure occurs when an individual favors information that supports their beliefs and avoids information that conflicts with them.[215] Jonathan Haidt compared the impact of social media to the Tower of Babel and the chaos it unleashed as a result.[216][217][13] Aviv Ovadya argues that these algorithms incentivize the creation of divisive content in addition to promoting existing divisive content,[218] but could be designed to reduce polarization instead.[219] In 2017, Facebook gave its new emoji reactions five times the weight in its algorithms as its like button, which data scientists at the company in 2019 confirmed had disproportionately boosted toxicity, misinformation and low-quality news.[220] Some popular ideas for how to combat selective exposure have had no or opposite impacts.[221][222][218] Some advocate for media literacy as a solution.[223] Others argue that less social media,[215] or more local journalism[224][225][226] could help address political polarization. Stereotyping See also: Stereotype A 2018 study reported that social media increases the power of stereotypes.[227] Stereotypes can have both negative and positive connotations. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, youth were accused of responsibility for spreading the disease.[228] Elderly people get stereotyped as lacking knowledge of proper behavior on social media.[229] Social media platforms usually amplify these stereotypes by reinforcing age-based biases through certain algorithms as well as user-generated content. Unfortunately, these stereotypes contribute to social divide and negatively impact the way users interact online.[230] |

政治的分極化 関連項目:ソーシャルメディア § 民主主義への脅威、メディアバイアス § ソーシャルメディア、レイジベイト 多くの批判者は、ソーシャルメディアのアルゴリズムが党派的で扇動的なコンテンツを優先的に表示するとの研究結果を指摘している[213][214]。 ユーザーの政治的好みに合致するニュースコンテンツをフィルタリングして表示する推薦アルゴリズムのため、選択的露出による政治的分極化の増大が懸念され る。政治的分極化とは、政治的態度がイデオロギー的極端へと分岐する現象である。選択的露出は、個人が自身の信念を支持する情報を好み、それに反する情報 を避ける際に生じる。[215] ジョナサン・ハイトは、ソーシャルメディアの影響をバベルの塔と、それが引き起こした混乱に例えた。[216][217][13] アヴィヴ・オヴァディアは、これらのアルゴリズムが既存の分断コンテンツを促進するだけでなく、新たな分断コンテンツの生成を助長すると主張している [218]。しかし、分極化を軽減するように設計することも可能だ[219]。2017年、フェイスブックは新機能の絵文字リアクションを「いいね」ボタ ンの5倍の重みでアルゴリズムに反映させた。2019年に同社のデータ科学者が確認したところ、この変更が有害性、誤情報、低品質ニュースを不釣り合いに 増幅させていた。[220] 選択的露出対策として提唱される人気のある手法の多くは、効果がなかったか、逆効果であった。[221][222][218] 解決策としてメディアリテラシーを提唱する者もいる。[223] 他方、ソーシャルメディアの利用削減[215] や地域密着型ジャーナリズムの強化[224][225][226] が政治的分極化対策に有効だと主張する者もいる。 ステレオタイプ 関連項目: ステレオタイプ 2018年の研究によれば、ソーシャルメディアはステレオタイプの力を増幅させる。[227] ステレオタイプには否定的な意味合いも肯定的な意味合いもある。例えば、COVID-19パンデミック時には、若者が感染拡大の責任を問われた。 [228] 高齢者はソーシャルメディア上での適切な行動知識が不足しているというステレオタイプに陥る。[229] ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームは通常、特定のアルゴリズムやユーザー生成コンテンツを通じて年齢に基づく偏見を強化し、こうしたステレオタイプを増 幅させる。残念ながら、これらのステレオタイプは社会的分断を助長し、ユーザーのオンライン上での交流方法に悪影響を及ぼす。[230] |

| Communication Social media allows for mass cultural exchange and intercultural communication, despite different ways of communicating in various cultures.[231] Social media has affected the way youth communicate, by introducing new forms of language.[232] Novel acronyms save time, as illustrated by "LOL", which is the ubiquitous shortcut for "laugh out loud". The hashtag was created to simplify searching for information and to allow users to highlight topics of interest in the hope of attracting the attention of others. Hashtags can be used to advocate for a movement, mark content for future use, and allow other users to contribute to a discussion.[233] For some young people, social media and texting have largely replaced in person communications, made worse by pandemic isolation, delaying the development of conversation and other social skills.[234] What is socially acceptable is now heavily based on social media.[235] The American Academy of Pediatrics reported that bullying, the making of non-inclusive friend groups, and sexual experimentation have increased cyberbullying, privacy issues, and sending sexual images or messages. Sexting and revenge porn became rampant, particularly among minors, with legal implications and resulting trauma risk.[236][237][238][239] However, adolescents can learn basic social and technical skills online.[240] Social media, can strengthen relationships just by keeping in touch, making more friends, and engaging in community activities.[8] |

コミュニケーション ソーシャルメディアは、様々な文化における異なるコミュニケーション方法にもかかわらず、大規模な文化交流と異文化間コミュニケーションを可能にする。[231] ソーシャルメディアは、新たな言語形態を導入することで、若者のコミュニケーション方法に影響を与えている。[232] 新しい略語は時間を節約する。例えば「LOL」は「大声で笑う」の普遍的な略語である。 ハッシュタグは情報検索を簡素化し、ユーザーが関心のあるトピックを強調して他者の注意を引くために考案された。ハッシュタグは運動の提唱、将来の使用に向けたコンテンツのマーク付け、他のユーザーによる議論への参加を可能にする。[233] 一部の若者にとって、ソーシャルメディアとテキストメッセージは対面コミュニケーションをほぼ置き換えており、パンデミックによる隔離がこれを悪化させ、会話能力やその他の社会的スキルの発達を遅らせている。[234] 社会的許容範囲は今やソーシャルメディアに大きく依存している。[235] 米国小児科学会は、いじめ、排他的な友人グループの形成、性的実験行為が増加し、サイバーいじめ、プライバシー問題、性的画像やメッセージの送信が蔓延し ていると報告した。特に未成年者間で、セクスティングやリベンジポルノが蔓延し、法的影響やトラウマリスクをもたらしている。[236][237] [238][239] しかし、青少年はオンラインで基本的な社会的・技術的スキルを習得できる。[240] ソーシャルメディアは、連絡を取り合うこと、友人を作る、コミュニティ活動に参加するだけで、人間関係を強化しうる。[8] |