ソン・モントゥーノ

Son montuno

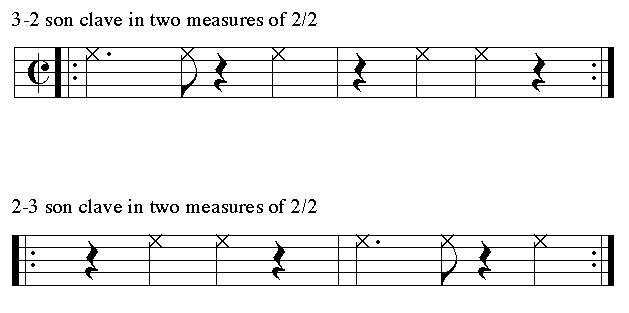

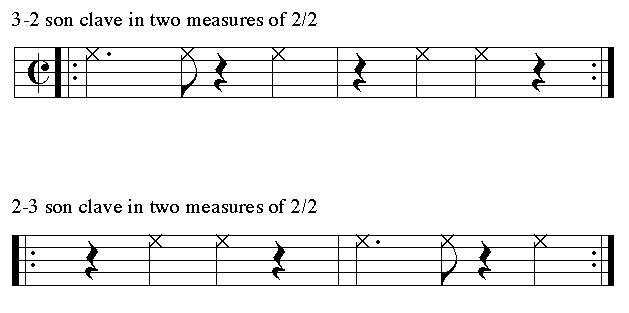

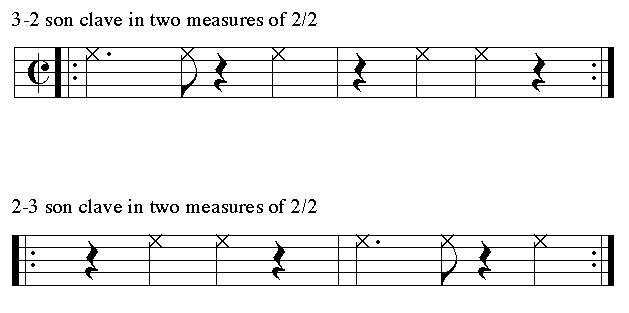

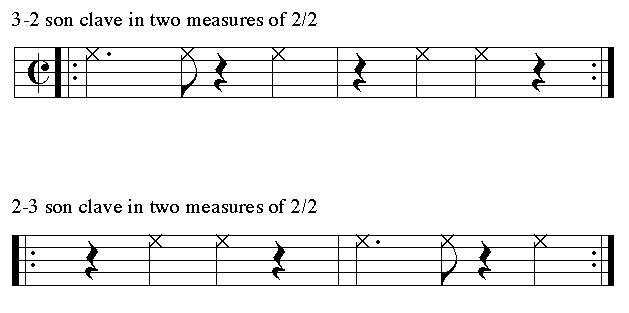

☆ 3-2 clave (Play) and 2-3 clave (Play) written in cut-time

ソ ン・モントゥーノは、1940年代にアルセニオ・ロドリゲスによって開発されたソン・クバーノのサブジャンルである。モントゥーノ(「山の音」)は、それ まではキューバ東部の山岳地帯で演奏されていたソンを指していたが、アルセニオは、モントゥーノ・セクションに複雑なホーン・アレンジを含む、このジャン ルへの高度に洗練されたアプローチを示すためにこの言葉を再利用した。 彼はまた、ピアノ・ソロを取り入れ、しばしばモントゥーノから循環的に始めることで、曲の構造を覆した。彼のアプローチのために、アルセニオは既存のセプ テート・アンサンブルを、1940年代にビッグバンドと並んで主流となったコンフント形式に拡張する必要があった。アルセニオの発展は、やがてサルサ、ソ ンゴ、ティンバといったジャンルの発展の雛形となった。

| Son

montuno is a subgenre of son cubano developed by Arsenio Rodríguez in

the 1940s. Although son montuno ("mountain sound") had previously

referred to the sones played in the mountains of eastern Cuba, Arsenio

repurposed the term to denote a highly sophisticated approach to the

genre in which the montuno section contained complex horn

arrangements.[1] He also incorporated piano solos and often subverted

the structure of songs by starting with the montuno in a cyclic

fashion. For his approach, Arsenio had to expand the existing septeto

ensemble into the conjunto format which became the norm in the 1940s

alongside big bands. Arsenio's developments eventually served as the

template for the development of genres such as salsa, songo and timba. |

ソ

ン・モントゥーノは、1940年代にアルセニオ・ロドリゲスによって開発された︎ソン・クバーノのサブジャンルである。モントゥーノ(「山の音」)は、それ

まではキューバ東部の山岳地帯で演奏されていたソンを指していたが、アルセニオは、モントゥーノ・セクションに複雑なホーン・アレンジを含む、このジャン

ルへの高度に洗練されたアプローチを示すためにこの言葉を再利用した[1]。

彼はまた、ピアノ・ソロを取り入れ、しばしばモントゥーノから循環的に始めることで、曲の構造を覆した。彼のアプローチのために、アルセニオは既存のセプ

テート・アンサンブルを、1940年代にビッグバンドと並んで主流となったコンフント形式に拡張する必要があった。アルセニオの発展は、やがてサルサ、ソ

ンゴ、ティンバといったジャンルの発展の雛形となった。 |

| Background Son cubano developed in the late 19th century and soon became the most important genre of Cuban popular music.[2] In addition, it is perhaps the most flexible of all forms of Latin American music, and is the foundation of many Cuban-based dance forms, and salsa. Its great strength is its fusion between European and African musical traditions. The son arose in Oriente, merging the Spanish guitar and lyrical traditions with Afro-Cuban percussion and rhythms. We now know that its history as a distinct form is relatively recent. There is no evidence that it goes back further than the end of the nineteenth century. It moved from Oriente to Havana in about 1909, carried by members of the Permanent (the Army), who were sent out of their areas of origin as a matter of policy. The first recordings were in 1918.[3] There are many types of son,[4] of which the son montuno is one. The term has been used in several ways. Probably the 'montuno' originally referred to its origin in the mountainous regions of eastern Cuba; eventually, it was used more to describe the final up-tempo section of a son, with its semi-improvisation, repetitive vocal refrain and brash instrumental climax.[5] The term was being used in the 1920s, when son sextetos set up in Havana and competed strongly with the older danzones. |

背景 ソン・クバーノは19世紀後半に発展し、やがてキューバのポピュラー音楽の中で最も重要なジャンルとなった[2]。 また、ラテンアメリカ音楽の中で最も柔軟性があり、キューバをベースにした多くのダンスフォームやサルサの基礎となっている。その大きな強みは、ヨーロッ パとアフリカの音楽的伝統の融合にある。 オリエンテで生まれたソンは、スペインのギターと叙情的な伝統に、アフロ・キューバのパーカッションとリズムを融合させた。現在では、独特の形式としての 歴史は比較的新しいことがわかっている。19世紀末まで遡る証拠はない。1909年頃、オリエンテからハバナへ移動し、パーマネント(陸軍)のメンバーに よって運ばれた。最初の録音は1918年である[3]。 ソンには多くの種類があり[4]、ソン・モントゥーノはそのひとつである。この言葉はいくつかの意味で使われてきた。おそらく「モントゥーノ」は、もとも とはキューバ東部の山岳地帯で生まれたことを指していたのだろうが、最終的には、半インプロヴィゼーション、繰り返されるヴォーカルのリフレイン、大胆な 楽器のクライマックスなど、ソンの最後のアップテンポの部分を表現するために使われるようになった[5]。この用語は、ソン六重奏団がハバナで結成され、 旧来のダンツォーネと強力に競合していた1920年代に使われるようになった。 |

| Development of the son montuno form Cuban tresero, songwriter and bandleader Arsenio Rodríguez is considered the main figure in the development of son montuno as a form of dance music. He made several key innovations in the way rhythm is used in son cubano, leading to more complex arrangements which revolutionized the genre. The denser rhythmic weave of Rodríguez's music required the addition of more instruments. Rodríguez added a second, and then, third trumpet, as well as the piano and the conga drum, the quintessential Afro-Cuban instrument. His bongo player used a large, hand-held cencerro ('cowbell') during montunos (call-and-response chorus section).[6] Layered guajeos Arsenio Rodríguez introduced the idea of layered guajeos (typical Cuban ostinato melodies)—an interlocking structure consisting of multiple contrapuntal parts. This aspect of the son's modernization can be thought of as a matter of "re-Africanizing" the music. Helio Orovio recalls: "Arsenio once said his trumpets played figurations the 'Oriente' tres-guitarists played during the improvisational part of el son" (1992: 11).[7] The "Oriente" is the name given to the eastern end of Cuba, where the son was born. It is common practice for treseros to play a series of guajeo variations during their solos. Perhaps it was only natural then that it was Rodríguez the tres master, who conceived of the idea of layering these variations on top of each other. The following example is from the "diablo" section of Rodríguez's "Kile, Kike y Chocolate" (1950).[8] The excerpt consists of four interlocking guajeos: piano (bottom line), tres (second line), 2nd and 3rd trumpets (third line), and 1st trumpet (fourth line). 2-3 Clave is shown for reference (top line). Notice that the piano plays a single celled (single measure) guajeo, while the other guajeos are two-celled. It is common practice to combine single and double-celled ostinatos in Afro-Cuban music. During the 1940s, the conjunto instrumentation was in full swing, as were the groups who incorporated the jazz band (or big band) instrumentation in the ensemble, guajeos (vamp-like lines) could be divided among each instrument section, such as saxes and brass; this became even more subdivided, featuring three or more independent riffs for smaller sections within the ensemble. By adopting polyrhythmic elements from the son, the horns took on a vamp-like role similar to the piano montuno and tres (or string) guajeo"—Mauleón (1993: 155).[9] Piano guajeos Arsenio Rodríguez took the pivotal step of replacing the guitar with the piano, which greatly expanded the contrapuntal and harmonic possibilities of Cuban popular music. "Dile a Catalina," sometimes called "Traigo la yuca," may be Arsenio's most famous composition. The first half uses the changüí/son method of paraphrasing the vocal melody, but the second half strikes out into bold new territory – using contrapuntal material not based on the song's melody and employing a cross‐rhythm based on sequences of three ascending notes—Moore (2011: 39).[10] With Lilí Martínez as pianist, Arsenio's conjunto recorded numerous songs with complex piano arrangements. For example, the piano guajeo for "Dame un cachito pa' huele" (1946) completely departs from both the generic son guajeo and the song's melody. The pattern marks the clave by accenting the backbeat on the two-side. Moore observes: "Like so many aspects of Arsenio's music, this miniature composition is decades ahead of its time. It would be forty years before groups began to consistently apply this much creative variation at the guajeo level of the arranging process".[11] "No me llores más" [1948] stands out for its beautiful melodies and the incredible amount emotional intensity it packs into its ultra‐slow 58 bpm groove. The guajeo is based on the vocal melody and marks the clave relentlessly—Moore (2009: 48).[12] +++++++++++++++++++++ Polyrhythm Polyrhythm is the simultaneous use of two or more rhythms that are not readily perceived as deriving from one another, or as simple manifestations of the same meter.[2] The rhythmic layers may be the basis of an entire piece of music (cross-rhythm), or a momentary section. Polyrhythms can be distinguished from irrational rhythms, which can occur within the context of a single part; polyrhythms require at least two rhythms to be played concurrently, one of which is typically an irrational rhythm. Concurrently in this context means within the same rhythmic cycle. The underlying pulse, whether explicit or implicit can be considered one of the concurrent rhythms. For example, the son clave is poly-rhythmic because its 3 section suggests a different meter from the pulse of the entire pattern.[3]  https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyrhythm |

ソン・モントゥーノ形式の発展 キューバのトレセロ、ソングライター、バンドリーダーであるアルセニオ・ロドリゲスは、ダンス・ミュージックとしてのソン・モントゥーノを発展させた中心 人物と考えられている。彼は、ソン・クバーノにおけるリズムの使い方にいくつかの重要な革新をもたらし、このジャンルに革命をもたらしたより複雑なアレン ジをもたらした。ロドリゲスの音楽はリズムの密度が濃くなったため、より多くの楽器を加える必要があった。ロドリゲスは、2本目、そして3本目のトラン ペット、ピアノ、アフロ・キューバの代表的な楽器であるコンガ・ドラムを加えた。彼のボンゴ奏者は、モントゥーノス(コール・アンド・レスポンスのコーラ ス・セクション)では、大きな手持ちのチェンセロ(「カウベル」)を使っていた[6]。 レイヤード・グアヘオ アルセニオ・ロドリゲスは、レイヤード・グアヘオ(キューバの典型的なオスティナートの旋律)-複数の対位法的な部分からなる連動した構造-のアイデアを 導入した。息子の現代化のこの側面は、音楽の「再アフリカ化」の問題と考えることができる。ヘリオ・オロヴィオは回想する: アルセニオはかつて、彼のトランペットが、エル・ソンの即興パートで "オリエンテ "のトレス・ギタリストが演奏するフィギュレーションを演奏していると言っていた」(1992: 11)[7]。"オリエンテ "とは、ソンが生まれたキューバの東端の呼び名である。トレセーロがソロの間にグアヘオの変奏を連続して演奏するのは一般的な習慣である。このような変奏 を重ねることを思いついたのが、トレスの名手ロドリゲスであったのは、当然のことであったのかもしれない。次の例は、ロドリゲスの "Kile, Kike y Chocolate"(1950年)の "diablo "セクションからのものである[8]。この抜粋は、4つの連動したグアヘオで構成されている:ピアノ(最下行)、トレス(第2行)、第2、第3トランペッ ト(第3行)、第1トランペット(第4行)。参考までに2-3クラーベを示す(上段)。ピアノは単セル(1小節)のグアヘオを演奏しているが、他のグアヘ オは2セルであることに注意。アフロ・キューバ音楽では、単セルと複セルのオスティナートを組み合わせるのが一般的である。 コンフントの楽器編成が本格化した1940年代には、ジャズバンド(またはビッグバンド)の楽器編成をアンサンブルに取り入れたグループもあり、グアジェ オ(ヴァンプのようなライン)は、サックスやブラスなど各楽器セクションに分けられるようになり、さらに細分化され、アンサンブル内の小さなセクションご とに3つ以上の独立したリフを特徴とするようになった。ソンからポリリズム(polyrhythmi)の要素を取り入れることで、ホルンはピアノのモントゥーノやトレス(または弦楽 器)のグアジェオに似たヴァンプ的な役割を担うようになった」-マウレオン(1993: 155)[9]。 ピアノ・グアジェオ アルセニオ・ロドリゲスは、ギターをピアノに置き換えるという重要な一歩を踏み出し、キューバのポピュラー音楽の対位法と和声の可能性を大きく広げた。 「ディレ・ア・カタリナ」は、「トレイゴ・ラ・ユカ」と呼ばれることもあり、アルセニオの最も有名な曲である。前半はヴォーカル・メロディをパラフレーズ するchangüí/sonの手法を使っているが、後半は大胆な新領域に踏み込んでいる--歌のメロディに基づかないコントラプンタルの素材を使い、3つ の上行音符のシーケンスに基づくクロス・リズムを採用している-Moore (2011: 39)[10]。 リリ・マルティネスをピアニストに迎えたアルセニオのコンフントは、複雑なピアノ・アレンジの曲を数多く録音した。例えば、"Dame un cachito pa' huele"(1946)のピアノ・グアジェオは、一般的な息子のグアジェオからも曲のメロディからも完全に逸脱している。このパターンは、2面の裏拍に アクセントをつけることでクラーベをマークしている。ムーアは言う: 「アルセニオの音楽の多くの側面がそうであるように、このミニチュアの構成は時代を何十年も先取りしている。グループが、アレンジ・プロセスのグアジェ オ・レベルで、これほど創造的なバリエーションを一貫して適用するようになるのは、40年後のことである」[11]。 「No me llores más" [1948]は、その美しいメロディーと、58bpmという超スローなグルーヴの中に詰め込まれた、信じられないほどの感情の強さで際立っている。グアヘ オはヴォーカル・メロディをベースに、執拗にクラーヴェを刻む-Moore (2009: 48)[12]。 +++++++++++++++++++++ 【ポリリズム】 ポリリズムとは、2つ以上のリズムを同時に使用することであり、それらは互いに由来するものとして、あるいは同じメーターの単純な現れとして、容易に認識 されることはない[2]。リズムの層は、楽曲全体(クロスリズム)の基礎となる場合もあれば、一瞬のセクションとなる場合もある。ポリリズムは、1つの パートの中で生じる不合理なリズムと区別することができる。ポリリズムは、少なくとも2つのリズムが同時に演奏されることを必要とし、そのうちの1つは通 常不合理なリズムである。ポリリズムは、少なくとも2つのリズムを同時に演奏しなければならない。基本となるパルスは、明示的であれ暗黙的であれ、同時に 演奏されるリズムのひとつとみなすことができる。例えば、ソンクラーベは、その3つのセクションがパターン全体のパルスとは異なるメーターを示唆している ため、ポリリズムである[3]。 |

Clave-specific bass tumbaos 3-2 clave (Playⓘ) and 2-3 clave (Playⓘ) written in cut-time Arsenio Rodríguez brought a strong rhythmic emphasis back into the son. His compositions are clearly based on the key pattern known in Cuba as clave, a Spanish word for 'key' or 'code'. When clave is written in two measures, as shown above, the measure with three strokes is referred to as the three-side, and the measure with two strokes—the two-side. When the chord progression begins on the three-side, the song, or phrase is said to be in 3-2 clave. When it begins on the two-side, it is in 2-3 clave.[13] The 2-3 bass line of "Dame un cachito pa' huele" (1946) coincides with three of the clave's five strokes.[14] Listen to a midi version of the bass line for "Dame un cachito pa' huele." David García Identifies the accents of "and-of-two" (in cut-time) on the three-side, and the "and-of-four" (in cut-time) on the two-side of the clave, as crucial contributions of Rodríguez's music.[15] The two offbeats are present in the following 2-3 bass line from Rodríguez's "Mi chinita me botó" (1944).[16] The two offbeats are especially important because they coincide with the two syncopated steps in the son's basic footwork. The conjunto's collective and consistent accentuation of these two important offbeats gave the son montuno texture its unique groove and, hence, played a significant part in the dancer's feeling the music and dancing to it, as Bebo Valdés noted "in contratiempo" ['offbeat timing']—García (2006: 43).[17] Moore points out that Arsenio Rodríguez's conjunto introduced the two-celled bass tumbaos, that moved beyond the simpler, single-cell tresillo structure.[18] This type of bass line has a specific alignment to clave, and contributes melodically to the composition. Rodríguez's brother Raúl Travieso recounted, Rodríguez insisted that his bass players make the bass "sing."[19] Moore states: "This idea of a bass tumbao with a melodic identity unique to a specific arrangement was critical not only to timba, but also to Motown, rock, funk, and other important genres."[20] Benny Moré (popularly known as El Bárbaro del Ritmo), which further evolved the genre, adding guaracha, bolero and mambo influences, helping make him extraordinarily popular and is now cited as perhaps the greatest Cuban sonero. |

クラーヴェ特有のバス・トゥンバオ 3-2クラーベ(プレイⓘ)と2-3クラーベ(プレイⓘ)はカットタイムで書かれる。 アルセニオ・ロドリゲスは、息子に再び強いリズムの強調をもたらした。彼の作曲は、キューバで「クラーベ」として知られる調のパターンに明確に基づいている。 上の図のように、クラーベが2小節で書かれる場合、3画の小節は3面と呼ばれ、2画の小節は2面と呼ばれる。コード進行が3面から始まる場合、その曲、ま たはフレーズは3-2クラーベであると言われます。Dame un cachito pa' huele"(1946)の2-3ベース・ラインは、クラーヴェの5つのストロークのうち3つと一致する[14]。ダヴィッド・ガルシアは、クラーベの3 面における「and-of-two」(カット・タイム)と2面における「and-of-four」(カット・タイム)のアクセントを、ロドリゲスの音楽の 重要な貢献として挙げている[15]。この2つのオフビートは、ロドリゲスの "Mi chinita me botó"(1944)の以下の2-3のベースラインに存在する[16]。 この2つのオフビートは、息子の基本的なフットワークにおける2つのシンコペーションのステップと一致するため、特に重要である。ベボ・バルデスが「in contratiempo」[「オフビートのタイミング」]と述べているように、コンフントはこの2つの重要なオフビートを集団的かつ一貫して強調するこ とで、ソン・モントゥーノのテクスチャーに独特のグルーヴを与え、それゆえダンサーが音楽を感じ、それに合わせて踊る上で重要な役割を果たした-ガルシア (2006: 43)[17]。 ムーアは、アルセニオ・ロドリゲスのコンフントが、より単純な単細胞のトレシージョの構造を超えて、2細胞の低音トゥンバオを導入したことを指摘している [18]。ロドリゲスの弟ラウル・トラヴィエソは、ロドリゲスはベース奏者にベースを「歌わせる」よう主張していたと語っている[19]: 「特定のアレンジに固有のメロディを持つベース・トゥンバオというこのアイデアは、ティンバだけでなく、モータウン、ロック、ファンク、その他の重要な ジャンルにとっても重要だった」[20] ベニー・モレ(エル・バルバロ・デル・リトモとして親しまれている)は、このジャンルをさらに進化させ、グアラチャ、ボレロ、マンボの影響を加え、彼を超 絶的な人気者にするのに貢献し、現在ではおそらく最も偉大なキューバ人ソネーロとして挙げられている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Son_montuno |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆