アルセニオ・ロドリゲス

Arsenio Rodríguez, 1911-1970

Conjunto

de Arsenio Rodríguez. Standing, left to right: Carmelo Álvarez, Alfredo

"Chocolate" Armenteros, René Scull, Arsenio Rodríguez, Antolín "Papa

Kila" Suárez, Félix Chappottín, Carlos Ramírez. Crouching, left to

right: Félix Alfonso, Lázaro Prieto, Lilí Martínez.

☆アルセニオ・ロドリゲス(Ignacio Arsenio Travieso Scull、1911年8月31日 - 1970年12月30日)[2][3]はキューバのミュージシャン、作曲家、バンドリーダー。トレス、トゥンバドーラを演奏し、ソン、ルンバ、その他のア フロ・キューバン・ミュージックを得意とした。1940年代から1950年代にかけて、ロドリゲスはコンフント・フォーマットを確立し、現代のサルサの 基本テンプレートであるソン・モントゥーノの発展に貢献した。彼はマンボの真の生みの親であり、重要な作曲家であると同時に、200曲近くを書いた多作な 作曲家でもあった。

| Arsenio Rodríguez (born Ignacio Arsenio Travieso Scull;

August 31, 1911 – December 30, 1970)[2][3] was a Cuban musician,

composer and bandleader. He played the tres, as well as the tumbadora,

and he specialized in son, rumba and other Afro-Cuban music styles. In the 1940s and 1950s Rodríguez established the conjunto format and contributed to the development of the son montuno, the basic template of modern-day salsa.

He claimed to be the true creator of the mambo and was an important as

well as a prolific composer who wrote nearly two hundred songs. Despite being blind since the age of seven, Rodríguez quickly managed to become one of Cuba's foremost treseros. Nonetheless, his first hit, "Bruca maniguá" by Orquesta Casino de la Playa, came as a songwriter in 1937. For the following two years, Rodríguez worked as composer and guest guitarist for the Casino de la Playa, before forming his conjunto in 1940, one of the first of its kind. After recording over a hundred songs for RCA Victor over the course of twelve years, Rodríguez moved to New York in 1952, where he remained active, releasing several albums. In 1970, Rodríguez moved to Los Angeles, where he died of pneumonia shortly before the end of the year. |

アルセニオ・ロドリゲス(Ignacio Arsenio Travieso Scull、1911年8月31日 - 1970年12月30日)[2][3]はキューバのミュージシャン、作曲家、バンドリーダー。トレス、トゥンバドーラを演奏し、ソン、ルンバ、その他のアフロ・キューバン・ミュージックを得意とした。1940年代から1950年代にかけて、ロドリゲスはコンフント・フォーマットを確立し、現代のサルサの基本テンプレートであるソン・モントゥーノの発展に貢献した。彼はマンボの真の生みの親であり、重要な作曲家であると同時に、200曲近くを書いた多作な作曲家でもあった。 ロドリゲスは7歳のときから盲目であったにもかかわらず、すぐにキューバを代表するトレセーロのひとりとなった。それにもかかわらず、彼の最初のヒット は、オルケスタ・カジノ・デ・ラ・プラヤの 「Bruca maniguá 」で、1937年にソングライターとして誕生した。その後2年間、ロドリゲスはカジノ・デ・ラ・プラヤの作曲家兼ゲスト・ギタリストとして活動し、 1940年にコンフントを結成した。12年間にわたりRCAビクターで100曲以上のレコーディングを行った後、1952年にニューヨークに移り住ん だ。1970年、ロサンゼルスに移り住んだロドリゲスは、年末に肺炎で亡くなった。 |

| Life and career Early life Ignacio Arsenio Travieso Scull was born on August 31, 1911, in Güira de Macurijes in Bolondrón (Pedro Betancourt), Matanzas Province, as the third of fifteen children, fourteen boys and one girl, to Bonifacio Travieso, a veteran of the Cuban War of Independence who worked as a farmer, and Dorotea Rodríguez Scull.[4] His family had Kongo origins, and both his grandfather and great-grandfather were practitioners of Palo Monte.[5] By the time Arsenio was four, in 1915, his family moved to the town of Güines, where his three younger siblings (Estela, Israel "Kike" and Raúl) were born.[4] In 1918, at around seven years of age, Arsenio was blinded when a horse kicked him in the head after he accidentally hit the animal with a broom.[1] This tragic event prompted Arsenio to become very close with his brother Kike, and to become interested in writing and performing songs.[5] The young brothers began playing the tumbadora at rumba performances in Matanzas and Güines, and became also immersed in the traditions of Palo Monte and its secular counterpart, yuka.[6] Furthermore, their neighbour in the neighbourhood of Leguina, Güines, was a Santería practitioner who hosted celebrations for Changó, exposing Arsenio and Kike to West African drumming and chanting.[6] In rural parties such as guateques, they also learned the son, a genre of music that originated in the eastern region of the island. Arsenio learned how to play the marímbula and the botija, two rudimentary instruments used in the rhythm section, and more importantly he took up the tres, a small guitar, now considered Cuba's national instrument. He received classes from Víctor González, a renowned tresero from Güines.[6] Following the destruction of their home by a Category 4 hurricane in 1926, Arsenio and his family moved from Güines to Havana, where he started playing in local groups around Marianao (his older brother Julio had already been living and working there).[7] By 1928 he had formed the Septeto Boston which often performed in third-tier, working-class cabarets in the area.[8] His father died in 1933 and sometime in the early 1930s, Arsenio changed his stage name from Travieso (which means "mischievous" or "naughty") to his mother's maiden name, Rodríguez, a fairly common Spanish surname.[4] After dissolving the unsuccessful Septeto Boston in 1934, Rodríguez joined the Septeto Bellamar, directed by his uncle-in-law José Interián and featuring his cousin Elizardo Scull on vocals. The group often played at dance academies such as Sport Antillano.[5] Rise to fame By 1938, Rodríguez was the de facto musical director of the Septeto Bellamar and his name had become familiar to important figures such as Antonio Arcaño and Miguelito Valdés.[9] His acquaintance with the latter made it possible for one of his songs, "Bruca maniguá", to be recorded by the famous Orquesta Casino de la Playa in June 1937. The song, featuring Valdés on vocals, became an international hit and Rodríguez's breakthrough composition.[10] The band also recorded Rodríguez's "Ben acá Tomá" in the same recording session, becoming their next A-side. In 1938 they recorded "Yo son macuá", "Funfuñando" (also a hit) and "Se va el caramelero", which included Rodríguez's first recorded performance, a remarkable solo on the tres.[11] In 1940, on the wave of his success with Casino de la Playa, Rodríguez formed his own conjunto, which featured three singers (playing claves, maracas and guitar), two trumpets, tres, piano, bass, tumbadora and bongo.[12] At the time, only two other conjuntos existed: Conjunto Casino and Alberto Ruiz's Conjunto Kubavana. This type of ensemble would replace the former septetos, although some such as the Septeto Nacional would perform on and off for years. Of all the conjuntos, Arsenio Rodríguez's became the most successful and critically acclaimed one during the 1940s. His popularity earned him the nickname El Ciego Maravilloso (The Marvellous Blind Man). The first single by his conjunto was "El pirulero no vuelve más", a pregón which tried to capitalize on the success of "Se va el caramelero".[11] In 1947, Rodríguez went to New York for the first time. There, he hoped to get cured of his blindness but eye specialist Ramón Castroviejo was told that his optic nerves had been completely destroyed.[13] This experience led him to compose the bolero "La vida es un sueño" (Life is a dream). He returned to New York in 1948 and 1950 before establishing himself in the city in 1952. He played with influential artists such as Chano Pozo, Machito, Dizzy Gillespie and Mario Bauzá. On March 18, 1952, Rodríguez made his final recordings with his band for RCA Victor in Cuba.[14] He finally left Havana on March 22, 1952, having handed the direction of the conjunto to trumpeter Félix Chappottín.[14] Chappottín and the other remaining members, including pianist Lilí Martínez and singer Miguelito Cuní, formed Conjunto Chappottín.[14] He would return to Havana for the last time in 1956. Later life and death During the 1960s, the mambo craze petered out, and Rodríguez continued to play in his typical style, although he did record some boogaloo numbers, without much success. As times changed, the popularity of his group declined. He tried a new start in Los Angeles. He invited his friend Alfonso Joseph to fly out to Los Angeles with him but died there only a week later, on December 30, 1970, from pneumonia. His body was returned for burial to New York. There is much speculation about his financial status during his last years, but Mario Bauzá denied that he died in poverty, arguing that Rodríguez had a modest income from royalties.[15] |

生涯とキャリア 生い立ち 1911年8月31日、イグナシオ・アルセニオ・トラヴィエソ・スカルは、マタンサス県ボロンドロン(ペドロ・ベタンコート)のグイラ・デ・マクリヘス で、キューバ独立戦争の退役軍人で農夫をしていたボニファシオ・トラヴィエソとドロテア・ロドリゲス・スカルの間に、14男1女の15人兄弟の3番目とし て生まれた。 [4]彼の家族はコンゴに起源を持ち、祖父と曽祖父はパロ・モンテの修行者であった。 [5]1915年、アルセニオが4歳になる頃、一家はグイネスの町に移り住み、そこで3人の弟妹(エステラ、イスラエル・「キケ」、ラウル)が生まれた [4]。 1918年、アルセニオは7歳頃、誤ってほうきで馬を蹴った後、馬に頭を蹴られて失明した[1]。 幼い兄弟は、マタンサスとグイネスでのルンバ演奏会でトゥンバドーラを演奏するようになり、パロ・モンテの伝統と、それと対をなす世俗的なユカにものめり 込んでいった[6]。 [6]さらに、グイネスのレギーナの隣人は、チャンゴの祝祭を主催するサンテリア信者であり、アルセニオとキケは西アフリカの太鼓と詠唱に触れることにな る。アルセニオは、リズムセクションで使われる2つの初歩的な楽器であるマリーンブラとボティージャの弾き方を学び、さらに重要なこととして、現在キュー バの国民的楽器とされている小型ギターのトレスを始めた。グイネス出身の有名なトレセーロ、ビクトル・ゴンサレスからレッスンを受けた[6]。 1926年にカテゴリー4のハリケーンによって家が破壊された後、アルセニオは家族と共にグイネスからハバナに移り住み、マリアナオ周辺の地元のグループ で演奏を始めた(兄のフリオはすでにマリアナオに住み、そこで活動していた)[7]。1928年までに彼はセプテート・ボストンを結成し、この地域の労働 者階級の第3層のキャバレーでしばしば演奏した。 [8]1933年に父親が亡くなり、1930年代初頭にアルセニオは芸名をトラヴィエソ(「いたずら好き」「いたずらっ子」の意味)から母親の旧姓である ロドリゲス(スペインではかなり一般的な苗字)に変えた。1934年にセプテート・ボストンを解散した後、ロドリゲスは義理の叔父ホセ・インテリアンが指 揮し、従兄弟のエリザルド・スカルがヴォーカルを務めるセプテート・ベラマールに参加した。このグループは、スポルト・アンティリャーノなどのダンス・ア カデミーでしばしば演奏した[5]。 有名になる 1938年までに、ロドリゲスはセプテート・ベラマールの事実上の音楽監督となり、アントニオ・アルカーニョやミゲリート・バルデスといった重要人物にそ の名を知られるようになった[9]。後者との知己により、1937年6月、有名なカジノ・デ・ラ・プラヤ管弦楽団によってロドリゲスの曲のひとつ 「Bruca maniguá」が録音された。バルデスがヴォーカルをとったこの曲は世界的なヒットとなり、ロドリゲスのブレイクのきっかけとなった[10]。バンドは 同じレコーディング・セッションでロドリゲスの「Ben acá Tomá」も録音し、次のA面となった。1938年には、「Yo son macuá」、「Funfuñando」(これもヒット)、「Se va el caramelero 」をレコーディング。 1940年、カジノ・デ・ラ・プラヤでの成功の波に乗って、ロドリゲスは自身のコンフントを結成し、3人の歌手(クラベス、マラカス、ギターを演奏)、 2本のトランペット、トレス、ピアノ、ベース、トゥンバドーラ、ボンゴをフィーチャーした[12]: コンフント・カジノとアルベルト・ルイスのコンフント・クババーナである。このタイプのアンサンブルはかつてのセプテットに取って代わるが、セプテー ト・ナシオナルのように何年も演奏したりしなかったりするものもあった。すべてのコンフントの中で、アルセニオ・ロドリゲスのコンフントは1940年 代に最も成功し、高い評価を得た。その人気から、彼はエル・シエゴ・マラヴィローソ(驚異の盲人)というニックネームで呼ばれるようになった。彼のコン ジュントによる最初のシングルは 「El pirulero no vuelve más 」で、「Se va el caramelero 」の成功を利用しようとしたプレゴンであった[11]。 1947年、ロドリゲスは初めてニューヨークに渡る。そこで彼は失明が治ることを望んだが、眼科医のラモン・カストロビエホに視神経が完全に破壊されてい ると告げられた[13]。この経験から、彼はボレロ「La vida es un sueño(人生は夢)」を作曲。1948年と1950年にニューヨークに戻り、1952年にニューヨークでの地位を確立。チャノ・ポゾ、マチート、ディ ジー・ガレスピー、マリオ・バウサといった影響力のあるアーティストと共演した。1952年3月18日、ロドリゲスはキューバのRCAビクターで最後のレ コーディングを行った[14]。1952年3月22日、トランペッターのフェリックス・チャポッティンにコンフントの指揮を譲り、ロドリゲスはついにハ バナを去った[14]。チャポッティンと、ピアニストのリリ・マルティネス、歌手のミゲリート・クニを含む残りのメンバーでコンフント・チャポッティン を結成。 その後の人生と死 1960年代、マンボ・ブームは下火になり、ロドリゲスは典型的なスタイルで演奏を続けたが、ブーガルー・ナンバーをいくつかレコーディングしたが、あま り成功しなかった。時代の移り変わりとともに、彼のグループの人気も落ちていった。彼はロサンゼルスで新たなスタートを切ろうとした。友人のアルフォン ソ・ジョセフを誘って一緒にロサンゼルスに飛んだが、わずか1週間後の1970年12月30日、肺炎のため現地で死去。彼の遺体は埋葬のためニューヨーク に戻された。晩年の彼の経済状態については様々な憶測があるが、マリオ・バウサは、ロドリゲスは印税からささやかな収入を得ていたと主張し、彼が貧困の中 で亡くなったことを否定した[15]。 |

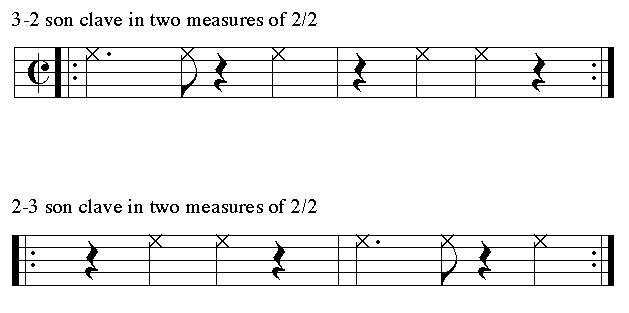

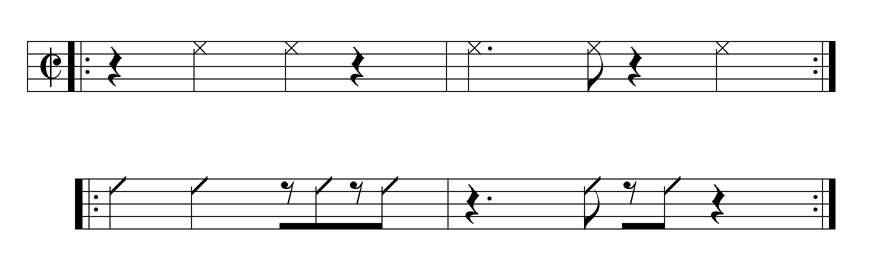

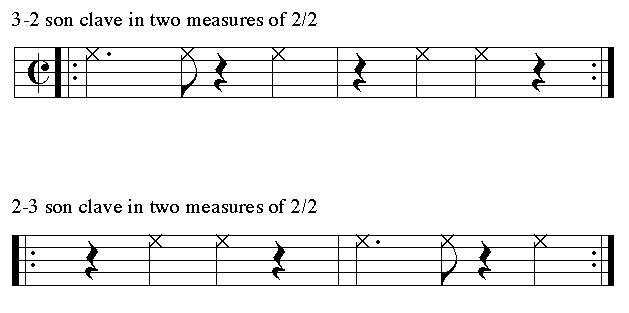

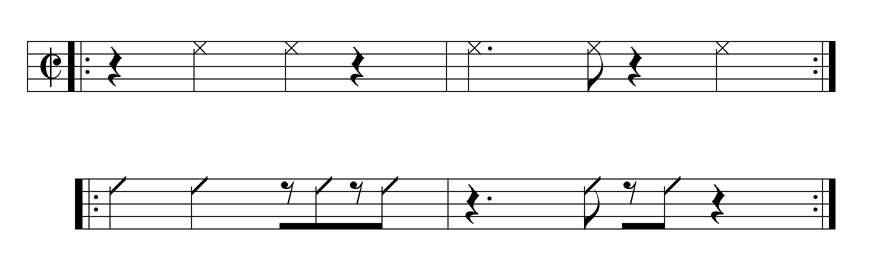

| Innovations Rodríguez's chief innovation, his interpretation of the son montuno, established the basic template for Cuban popular dance music and salsa that continues to this day. "It took fifty years for Latin music to catch up with what Arsenio was doing in the 1940s"—Kevin Moore (2007: web).[16] Clave-based structure and offbeat emphasis The decades of the 1920s and 1930s were a period which produced some of the most beautiful and memorable melodies of the son genre. At the same time, the rhythmic component had become increasingly deemphasized, or in the opinion of some, "watered-down". Rodríguez brought a strong rhythmic emphasis back into the son. His compositions are clearly based on the key pattern known in Cuba as clave, a Spanish word for 'key', or 'code'.  3-2 clave (Playⓘ) and 2-3 clave (Playⓘ) written in cut-time. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arsenio_Rodr%C3%ADguez When clave is written in two measures, as shown above, the measure with three strokes is referred to as the three-side, and the measure with two strokes—the two-side. When the chord progression begins on the three-side, the song, or phrase is said to be in 3-2 clave. When it begins on the two-side, it's in 2-3 clave.[17] The 2-3 bass line of "Dame un cachito pa' huele" (1946) coincides with the three-side of the clave's five-note pattern.[18][19] David García identifies the accents of "and-of-two" (in cut-time) on the three-side, and the "and-of-four" (in cut-time) on the two-side of the clave, as crucial contributions of Rodríguez's music.[20] The two offbeats are present in the following 2-3 bass line from Rodríguez's "Mi chinita me botó" (1944).[21] The two offbeats are especially important because they coincide with the two syncopated steps in the son's basic footwork. The conjunto's collective and consistent accentuation of these two important offbeats gave the son montuno texture its unique groove and, hence, played a significant part in the dancer's feeling the music and dancing to it, as Bebo Valdés noted "in contratiempo" ['offbeat timing'] — García (2006: 43).[20] Moore points out that Rodríguez's conjunto introduced the two-celled bass tumbaos, that moved beyond the simpler, single-cell tresillo structure.[22] This type of bass line has a specific alignment to clave, and contributes melodically to the composition. Rodríguez's brother Raúl Travieso recounted, Rodríguez insisted that his bass players make the bass "sing."[20] Moore states: "This idea of a bass tumbao with a melodic identity unique to a specific arrangement was critical not only to timba, but also to Motown, rock, funk, and other important genres."[23] In other words, Rodríguez is a creator of the bass riff. Breaks ('cierres') Rodríguez's "Juventud amaliana" (1946) contains an example of one of his rhythmically dynamic unison breaks, strongly rooted in clave.[24] Most of Arsenio's classic tracks from the golden period of 1946-1951 feature a virtuousic and highly-polyrhythmic solo by either Luis "Lilí" Martínez Griñán on piano, Arsenio himself on tres, or occasionally Félix Chappottín or one of the other trumpeters. The solo usually ends with Arsenio's signature [break] lead-in phrase: . X X X X . . . [first measure in the example above]. The figure is usually played on the two-side in 3-2 clave and on the three-side in 2-3 clave, and leads directly to what most timba musicians call a bloque but which in Arsenio's day was called a cierre. It consists of everyone in the band playing the same series of punches, creating extreme rhythmic tension with a combination of cross-rhythms and deceptive harmonies. As [David] García points out, the first four beats of the actual [break] have a rhythm [below] which was used repeatedly in the subsequent decades, most famously by Tito Puente and later Carlos Santana in "Oye Como Va — Moore (2007).[25] Moore is referring to the second and third measures of the break in the previous example. Here is that figure in relation to 2-3 clave. When the pattern is used as a type of block chord guajeo, as in "Oye Como Va", it's referred to as ponchando.[26]  2-3 clave (top) with ponchando figure (bottom). Layered guajeos Rodríguez introduced the idea of layered guajeos (typical Cuban ostinato melodies)—an interlocking structure consisting of multiple contrapuntal parts. This aspect of the son's modernization can be thought of as a matter of "re-Africanizing" the music. Helio Orovio recalls: "Arsenio once said his trumpets played figurations the 'Oriente' tres-guitarists played during the improvisational part of el son" (1992: 11).[27] Oriente is the easternmost province of Cuba, where the son was born. It is common practice for treseros to play a series of guajeo variations during their solos. Perhaps it was only natural then that it was Rodríguez, the tres master, who conceived of the idea of layering these variations on top of each other. The following example is from the "diablo" section of Rodríguez's "Kila, Quique y Chocolate" (1950).[28] The excerpt consists of four interlocking guajeos: piano (bottom line), tres (second line), 2nd and 3rd trumpets (third line), and 1st trumpet (fourth line). 2-3 Clave is shown for reference (top line). Notice that the piano plays a single celled (single measure) guajeo, while the other guajeos are two-celled. It's common practice to combine single and double-celled ostinatos in Afro-Cuban music. During the 1940s, the conjunto instrumentation was in full swing, as were the groups who incorporated the jazz band (or big band) instrumentation in the ensemble, guajeos (vamp-like lines) could be divided among each instrument section, such as saxes and brass; this became even more subdivided, featuring three or more independent riffs for smaller sections within the ensemble. By adopting polyrhythmic elements from the son, the horns took on a vamp-like role similar to the piano montuno and tres (or string) guajeo — Mauleón (1993: 155).[29] Expansion of the son conjunto The denser rhythmic weave of Rodríguez's music required the addition of more instruments. Rodríguez added a second, and then, third trumpet—the birth of the Latin horn section. He made the bold move of adding the conga drum, the quintessential Afro-Cuban instrument. Today, we are so used to seeing conga drums in Latin bands, and that practice began with Rodríguez. His bongo player used a large, hand-held cencerro ('cowbell') during montunos (call-and-response chorus sections).[30] Rodríguez also added a variety of rhythms and harmonic concepts to enrich the son, the bolero, the guaracha and some fusions, such as the bolero-son. Similar changes had been made somewhat earlier by the Lecuona Cuban Boys, who (because they were mainly a touring band) had less influence in Cuba. The overall 'feel' of the Rodríguez conjunto was more African than other Cuban conjuntos. Piano guajeos Rodríguez took the pivotal step of replacing the guitar with the piano, which greatly expanded the contrapuntal and harmonic possibilities of Cuban popular music. "Como traigo la yuca", popularly called "Dile a Catalina", recorded in 1941 and Arsenio's first big hit, may be his most famous composition. The first half uses the changüí/son method of paraphrasing the vocal melody but the second half strikes out into bold new territory – using contrapuntal material not based on the song's melody and employing a cross-rhythm based on sequences of three ascending notes — Moore (2011: 39).[31] The piano guajeo for "Dame un cachito pa' huele" (1946) completely departs from both the generic son guajeo and the song's melody. The pattern marks the clave by accenting the backbeat on the two-side. Moore observes: "Like so many aspects of Arsenio's music, this miniature composition is decades ahead of its time. It would be forty years before groups began to consistently apply this much creative variation at the guajeo level of the arranging process" (2009: 41).[32] "No me llores más" [1948] stands out for its beautiful melodies and the incredible amount of emotional intensity it packs into its ultra‐slow 58 bpm groove. The guajeo is based on the vocal melody and marks the clave relentlessly — Moore (2009: 48).[33] The piano guajeo for "Jumba" (a.k.a. "Zumba") (1951) is firmly aligned with clave, but also has a very strong nengón flavor — something which had rarely, or never, been used in Havana popular music. While Rodríguez was not from Oriente province (where nengón and changüí are played), he had a thorough knowledge of many folkloric styles and his creative partner, the pianist/composer Luis "Lilí" Martínez Griñán, in fact came from that part of the island.[34] Arsenio's use of modal harmonies pre-echoes not only songo, salsa, and timba, but rock and soul as well. "Guaragüí" [1951] has not one but two shockingly original chord progressions. [The guajeo] is in D, but the chord progression is in the Mixolydian mode: I – bVII – IV (D – C – G). This virulently addictive little sequence would remain dormant for fifteen years until becoming a pop juggernaut in songs such as "Hey Jude" and "Sympathy for the Devil". In the early 70s, when Juan Formell of Los Van Van reintroduced it to Latin pop, it sounded like a clear borrowing from rock & roll, but here it is in Arsenio's music when rock and rollers were limited to I – IV – V and I – vimi – IV – V, and even Tin Pan Alley had yet to incorporate modal harmonies. Equally interesting from a harmonic standpoint, is "Guaragüí'"s opening progression: imi – IV – bVII – imi (Ami – D – G – Ami). It's the same progression, but in minor, with the IV and bVII inverted — Moore (2009: 53).[35] Diablo, the proto-mambo? Leonardo Acosta is not convinced by Rodríguez's claim to have invented the mambo, if by mambo Rodríguez meant the big-band arrangements of Dámaso Pérez Prado. Rodríguez was not an arranger: his lyrics and musical ideas were worked over by the group's arranger. The compositions were published with just the minimal bass and treble piano lines. To achieve the big-band mambo such as by Pérez Prado, Machito, Tito Puente or Tito Rodríguez requires a full orchestration where the trumpets play counterpoint to the rhythm of the saxophones. This, a fusion of Cuban with big-band jazz ideas, is not found in Rodríguez, whose musical forms are set in the traditional categories of Cuban music.[36] While it is true that the mambo of the 1940s, and 1950s contains elements not present in Rodríguez's music, there is considerable evidence that the contrapuntal structure of the mambo began in the conjunto of Arsenio Rodríguez.[37] While working in the charanga Arcaño y Sus Maravillas, Orestes López "Macho" and his brother Israel López "Cachao" composed "Mambo" (1938), the first piece to use the term. A prevalent theory is that the López brothers were influenced by Rodríguez's use of layered guajeos (called diablo), and introduced the concept into the charanga's string section with their historical composition. As Ned Sublette observes: "Arsenio maintained till the end of his life that the mambo — the big band style that exploded in 1949 — came out of his diablo, the repeating figures that the trumpets in the band played. Arsenio claimed to have already been doing that in the late 1930s" (2004: 508).[38] As Rodríguez himself asserts: "In 1934, I was experimenting with a new sound which I fully developed in 1938."[39] Max Salazar concurs: "It was Arsenio Rodríguez's band that used for the first time the rhythms which today are typical for every mambo" (1992: 10).[37] In an early article on mambo, published in 1948, the writer Manuel Cuéllar Vizcaíno suggests that Rodríguez and Arcaño's styles emerged concurrently, which might account for the decades-long argument concerning the identity of the "true" inventor of the mambo.[40] In the late 1940s Pérez Prado codified the contrapuntal structure of the mambo within a horn-based big band format. Throughout the 1940s Arsenio's son montuno style was never referred to as mambo, even though central principles and procedures of his style, such as playing in contratiempo (against the beat), are to be found in mambo. What had made the conjunto and son montuno style so innovative was in fact Arsenio's and his musicians' deep knowledge and utilization of aesthetic principles and performance procedures rooted in Afro-Cuban traditional music in which Arsenio had been immersed as a youngster in rural areas of Matanzas and La Habana. Drawing from these principles and procedures, Arsenio and his colleagues formulated new ways of performing Cuban son and danzón music that arrangers for big bands soon after adapted and popularized internationally as mambo — García (2006: 42).[41] |

革新 ロドリゲスの主な革新であるソン・モントゥーノの解釈は、今日まで続くキューバのポピュラー・ダンス・ミュージックとサルサの基本的なテンプレートを確立 した。「アルセニオが1940年代にやっていたことにラテン音楽が追いつくのに50年かかった」-ケヴィン・ムーア(2007:web)[16]。 クラーベの構造とオフビートの強調 1920年代と1930年代の数十年間は、ソンというジャンルで最も美しく印象的なメロディーを生み出した時代であった。同時に、リズムの要素はますます 軽視されるようになり、一部の意見では「水増し」されていた。ロドリゲスは、ソンに再び強いリズムの強調をもたらした。彼の作曲は、キューバでは「クラー ベ」(スペイン語で「鍵」または「コード」を意味する)と呼ばれるキー・パターンに明確に基づいている。  3-2クラーベ(プレイⓘ)と2-3クラーベ(プレイⓘ)はカットタイムで書かれる。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arsenio_Rodr%C3%ADguez 上記のように、クラーベが2小節で書かれている場合、3つのストロークがある小節は3面、2つのストロークがある小節は2面と呼ばれます。コード進行が3 面から始まる場合、その曲、またはフレーズは3-2クラーベであると言われます。Dame un cachito pa' huele」(1946年)の2-3ベース・ラインは、クラーヴェの5音パターンの3面と一致する[18][19]。 [18][19]ダヴィッド・ガルシアは、クラーヴェの3面における「and-of-two」(カット・タイム)と2面における「and-of- four」(カット・タイム)のアクセントをロドリゲスの音楽の重要な貢献として挙げている[20]。2つのオフビートは、ロドリゲスの「Mi chinita me botó」(1944年)の以下の2-3ベース・ラインに存在する[21]。 この2つのオフビートは、息子の基本的なフットワークにおける2つのシンコペーションのステップと一致するため、特に重要である。ベボ・バルデスが「in contratiempo」[「オフビートのタイミング」]と述べているように、コンフントはこの2つの重要なオフビートを集団的かつ一貫して強調する ことで、ソン・モントゥーノのテクスチャーに独特のグルーヴを与え、それゆえダンサーが音楽を感じ、それに合わせて踊る上で重要な役割を果たした。 - ガルシア (2006: 43)[20]。 ムーアは、ロドリゲスのコンフントが、より単純な単細胞のトレシージョの構造を超えて、2つの細胞を持つ低音のトゥンバオを導入したことを指摘している [22]。ロドリゲスの弟であるラウール・トラヴィエソは、ロドリゲスはベース奏者にベースを「歌わせる」よう主張していたと語っている[20]: 「特定のアレンジに固有のメロディを持つベース・タンバオというこのアイデアは、ティンバだけでなく、モータウン、ロック、ファンク、その他の重要なジャ ンルにとっても重要だった」[23] つまり、ロドリゲスはベース・リフのクリエイターなのだ。 ブレイク ロドリゲスの 「Juventud amaliana」(1946)には、クラーベに強く根ざした、彼のリズミカルでダイナミックなユニゾン・ブレイクの一例が含まれている[24]。 1946年から1951年の黄金期におけるアルセニオの代表曲のほとんどは、ピアノのルイス・「リリ」・マルティネス・グリニャン、トレスのアルセニオ自 身、時にはフェリックス・チャポティンや他のトランペット奏者の一人による名人芸的で高度なポリリズムのソロをフィーチャーしている。ソロは通常、アルセ ニオの特徴的な[ブレイク]リード・イン・フレーズで終わる。X X X X X . . [上の例の最初の小節)。このフィギュアは通常、3-2クラーベでは2面、2-3クラーベでは3面で演奏され、ほとんどのティンバ・ミュージシャンがブロ ケと呼ぶが、アルセニオの時代にはシエレと呼ばれていたものへと直接つながる。バンド全員が同じパンチを連打することで、リズムの交差と欺瞞的なハーモ ニーを組み合わせて、極度のリズムの緊張を作り出す。ダヴィド・)ガルシアが指摘するように、実際の[ブレイク]の最初の4拍には[以下の]リズムがあ り、このリズムはその後の数十年で繰り返し使われ、最も有名なのはティト・プエンテで、後にカルロス・サンタナが「Oye Como Va - ムーア(2007年)[25]。 ムーアは、前の例のブレイクの2小節目と3小節目を指している。ここに、2-3クラーベに関連したその図がある。Oye Como Va」のように、このパターンがブロック・コード・グアジェオの一種として使われる場合は、ポンチャンドと呼ばれる[26]。  2-3クラーベ(上)とポンチャンドの図(下)。 何層にも重なるグアヘオ ロドリゲスは、レイヤード・グアヘオ(キューバの典型的なオスティナートの旋律)-複数の対位法的な部分からなる連動した構造-のアイデアを導入した。息 子の現代化のこの側面は、音楽の「再アフリカ化」の問題と考えることができる。ヘリオ・オロヴィオは回想する: アルセニオはかつて、彼のトランペットが、「オリエンテ 」のトレス・ギタリストたちがエル・ソンの即興パートで演奏したフィギュレーションを演奏したと言っていた」(1992: 11)[27] オリエンテはキューバの最東端の州で、ソンが生まれた場所である。トレセーロがソロの最中にグアヘオの変奏を連発するのは一般的なことである。このような 変奏を重ねることを思いついたのが、トレスの名手であるロドリゲスであったのは、当然のことであったのかもしれない。次の例は、ロドリゲスの「キラ、キ ケ・イ・チョコレート」(1950年)の「ディアブロ」セクションからのものである[28]。この抜粋は、4つの連動したグアヘオで構成されている:ピア ノ(最下行)、トレス(第2行)、第2、第3トランペット(第3行)、第1トランペット(第4行)。参考までに2-3クラーベを示す(上段)。ピアノは単 房(1小節)のグアヘオを演奏しているが、他のグアヘオは2房であることに注意。アフロ・キューバ音楽では、単セルと複セルのオスティナートを組み合わせ るのが一般的だ。 コンフントの楽器編成が本格化した1940年代には、ジャズバンド(またはビッグバンド)の楽器編成をアンサンブルに取り入れたグループもあり、グアヘ オ(ヴァンプのようなライン)は、サックスやブラスなど各楽器セクションに分けられるようになった。これがさらに細分化され、アンサンブル内の小さなセク ションごとに3つ以上の独立したリフがフィーチャーされるようになった。ソンからポリリズムの要素を取り入れることで、ホルンはピアノのモントゥーノやト レス(または弦楽器)のグアヘオに似たバンプ的な役割を担うようになった。 - マウレオン(1993: 155)[29]。 コンフントの拡大 ロドリゲスの音楽は、より密度の高いリズムを織り成すため、より多くの楽器を加える必要があった。ロドリゲスは2本目、そして3本目のトランペットを加 え、ラテン・ホルン・セクションを誕生させた。彼は、アフロ・キューバの真髄であるコンガ・ドラムを加えるという大胆な行動に出た。今日、私たちはラテ ン・バンドでコンガ・ドラムを見慣れたが、その習慣はロドリゲスから始まった。彼のボンゴ奏者は、モントゥーノ(コール・アンド・レスポンスのコーラス・ セクション)では、大きな手持ちのチェンセロ(「カウベル」)を使っていた[30]。ロドリゲスはまた、ソン、ボレロ、グアラチャ、そしてボレロ・ソンな どのいくつかのフュージョンを豊かにするために、様々なリズムとハーモニーのコンセプトを加えた。同じような変更は、レクオーナ・キューバン・ボーイズが やや前に行っていたが、彼らは主にツアー・バンドであったため、キューバでの影響力は少なかった。ロドリゲスのコンフントの全体的な「感じ」は、他の キューバのコンフントよりもアフリカ的だった。 ピアノ・グアジェオ ロドリゲスは、ギターをピアノに置き換えるという重要なステップを踏み、キューバのポピュラー音楽の対位法と和声の可能性を大きく広げた。 「Como traigo la yuca 「は 」Dile a Catalina "と呼ばれ、1941年に録音され、アルセニオの最初の大ヒット曲となった。前半はヴォーカル・メロディをパラフレーズするチャンギュイ/ソン・メソッド を用いているが、後半は大胆な新境地を開拓している。 - ムーア(2011:39)[31]。 Dame un cachito pa' huele"(1946)のピアノ・グアジェオは、一般的なソン・グアジェオからも曲のメロディからも完全に逸脱している。このパターンは、2面の裏拍に アクセントをつけることでクラーヴェをマークしている。ムーアは言う: 「アルセニオの音楽の多くの側面がそうであるように、このミニチュアの構成は時代を何十年も先取りしている。グループが、アレンジ・プロセスのグアジェ オ・レベルで、これほど創造的なバリエーションを一貫して適用するようになるのは、40年後のことである」(2009: 41)[32]。 「No me llores más" [1948]は、その美しいメロディーと、58bpmという超スローなグルーヴの中に詰め込まれた、信じられないほどの感情の強さで際立っている。グアヘオはヴォーカル・メロディをベースに、執拗にクラーヴェを刻む。 - ムーア(2009:48)[33]。 Jumba」(別名「Zumba」)(1951年)のピアノ・グアジェオは、クラーヴェにしっかりと沿っているが、ハバナのポピュラー音楽ではほとんど、 あるいは一度も使われたことのない、非常に強いネンゴンの風味も持っている。ロドリゲスはオリエンテ州(ネンゴンとチャングイが演奏される)の出身ではな かったが、多くの民俗様式に精通しており、彼の創作パートナーであったピアニスト/作曲家のルイス・「リリ」・マルティネス・グリニャンは実際に同州の出 身であった[34]。 アルセニオのモーダルなハーモニーの使い方は、ソンゴ、サルサ、ティンバだけでなく、ロックやソウルにも影響を与えている。「Guaragüí」 [1951]には、1つだけでなく2つの衝撃的なオリジナルのコード進行がある。[グアージョは)D調だが、コード進行はミクソリディアン・モードだ: I - bVII - IV(D-C-G)である。この強烈に中毒性のある小さなシークエンスは、「ヘイ・ジュード」や「悪魔を憐れむ歌」などでポップ・ジャガーノートとなるま で、15年間眠ったままだった。70年代初頭、ロス・ヴァン・ヴァンのフアン・フォルメルがラテン・ポップに再び取り入れたときは、明らかにロックンロー ルからの借用のように聴こえたが、ロックンローラーがI - IV - VやI - vimi - IV - Vに限定され、ティン・パン・アレーでさえまだモーダル・ハーモニーを取り入れていなかった時代に、アルセニオの音楽がここにある。和声の観点からも同様 に興味深いのは、「Guaragüí'」の冒頭の進行であるimi - IV - bVII - imi(Ami-D-G-Ami)である。同じ進行だが、短調で、IVとbVIIが反転している。 - ムーア (2009: 53)[35]。 ディアボロ、マンボの原型? レオナルド・アコスタは、ロドリゲスがマンボを発明したという主張には納得していない。もしロドリゲスがマンボというのが、ダマソ・ペレス・プラドのビッ グバンド・アレンジを意味しているのであれば。ロドリゲスはアレンジャーではなかった。彼の歌詞と音楽的アイデアは、グループのアレンジャーによって調整 された。作曲は、最小限の低音と高音のピアノ・ラインだけで発表された。ペレス・プラド、マチート、ティト・プエンテ、ティト・ロドリゲスのようなビッグ バンドのマンボを実現するには、トランペットがサックスのリズムと対位法を奏でるフル編成が必要だ。このような、キューバ音楽とビッグバンド・ジャズのア イデアの融合は、キューバ音楽の伝統的な範疇に音楽形式が設定されているロドリゲスには見られない[36]。 1940年代、1950年代のマンボがロドリゲスの音楽にはない要素を含んでいるのは事実だが、マンボの対位法的な構造がアルセニオ・ロドリゲスのコン ジュントから始まったという証拠はかなりある[37]。チャランガ「アルカーニョ・イ・スス・マラビージャス」で活動していた頃、オレステス・ロペス 「マッチョ 」と彼の弟イスラエル・ロペス 「カチャオ 」は、この言葉を使った最初の作品である「マンボ」(1938年)を作曲した。有力な説は、ロペス兄弟がロドリゲスのグアヘオ(ディアブロと呼ばれる)の 重ね使いに影響を受け、彼らの歴史的な作曲によってチャランガの弦楽器セクションにそのコンセプトを導入したというものだ。 ネッド・サブレットはこう語る: 「アルセニオは、1949年に爆発的に流行したビッグバンドのスタイルであるマンボは、彼のディアブロ、つまりバンドのトランペットが演奏する繰り返しの 数字から生まれたのだと、最後まで主張していた。アルセニオは、1930年代後半にはすでにそうしていたと主張していた」(2004: 508)[38]: 「1934年、私は1938年に完全に開発した新しいサウンドを試していた」[39] マックス・サラザールも同意する: 「今日、あらゆるマンボの典型となっているリズムを初めて使ったのは、アルセニオ・ロドリゲスのバンドだった」(1992: 10)。 [37]1948年に出版されたマンボに関する初期の記事で、作家のマヌエル・クエリャール・ビスカイノは、ロドリゲスとアルカーニョのスタイルは同時に 生まれたと示唆しており、これはマンボの「真の」発明者の正体に関する数十年にわたる論争を説明するかもしれない[40]。 1940年代後半、ペレス・プラドは、ホーンを中心としたビッグバンドのフォーマットの中で、マンボのコントラプンタルの構造を体系化した。 1940年代を通して、アルセニオのソン・モントゥーノ・スタイルはマンボと呼ばれることはなかったが、彼のスタイルの中心的な原理や手順、例えばコント ラティエンポ(拍子に逆らう)での演奏などはマンボに見られるものである。コンフントとソン・モントゥーノのスタイルを革新的なものにしたのは、実はア ルセニオと彼のミュージシャンたちが、アルセニオが若い頃にマタンサスとラ・ハバナの田舎町で没頭していたアフロ・キューバの伝統音楽に根ざした美的原理 と演奏手順を深く知り、活用していたからである。アルセニオと彼の仲間たちは、これらの原理と手順に基づいて、キューバのソンやダンソンを演奏する新しい 方法を編み出した。 - ガルシア (2006: 42)[41]。 |

| Style Rodríguez's style was characterized by a strong Afro-Cuban basis, his son compositions being much more africanized than those by his contemporaries. This emphasis is observed in the high number of rumba and afro numbers in his catalogue, most notably his first famous composition, "Bruca maniguá". This is also exemplified by the inclusion of musical and linguistic elements from Abakuá, Lucumí (Santería), and Palo Monte traditions into his music. Arsenio uses proverbs associated with Palo Monte and other traditional passages with Congo lexical passages... Arsenio's afrocubanos demonstrate not only the extent of his knowledge of Palo Monte spirituality but also his critique of the discourse on African inferiority and atavismas (1) manifested in racist representational tropes in Cuban popular culture and (2) implied in the ideology of mestizaje (read: racial and cultural "progress"). As he countered in his afrocubanos, these traditions of his youth, through representing a "primitive" era for most of the white Cuban elite as well as black intellectuals, continued to be a vital and powerful aspect of his music and life — García (1006: 21). On Palo Congo by Sabú Martínez (1957) Rodríguez sings and plays a traditional palo song and rhythm, a Lucumí song for Eleggua, and a rumba and a conga de comparsa accompanied by tres.[42] Rodríguez's 1963 landmark album Quindembo features an abakuá tune, a columbia, and several band adaptations of traditional palo songs, accompanied by the bona fide rhythms.[43] Rodríguez was an authentic rumbero; he both played the tumbadora and composed songs within the rumba genre, especially guaguancós. Rodríguez recorded folkloric rumbas and also fused rumba with son montuno. His "Timbilla" (1945)[44] and "Anabacoa" (1950) are examples of the guaguancó rhythm used by a son conjunto. On "Timbilla", the bongós fulfill the role of the quinto (lead drum). In "Yambú en serenata" (1964) a yambú using a quinto is augmented by a tres, bass, and horns.[45] In 1956, Rodríguez released the folkloric rumbas "Con flores del matadero" and "Adiós Roncona" in Havana.[46][47] The tracks consist of voice and percussion only. One of the last recordings Rodríguez performed on was the rumba album Patato y Totico by the conguero Carlos "Patato" Valdés and vocalist Eugenio "Totico" Arango (1967).[48] The tracks are purely folkloric, except for the unconventional addition of Rodríguez on tres and Israel López "Cachao" on bass. Additional personnel included Papaíto and Virgilio Martí. Also released in the 1960s, the album Primitivo, featuring Monguito el Único and Baby González alternating on lead vocals, is an evocation of the music played in the solares. |

作風 ロドリゲスの作風は、アフロ・キューバンを強く意識したもので、同時代の作曲家たちよりもアフリカナイズされている。この強調は、彼のカタログにルンバや アフロ・ナンバーが多いこと、特に彼の最初の有名な作曲である 「Bruca maniguá 」に見られる。これはまた、アバクア、ルクミ(サンテリア)、パロ・モンテの伝統の音楽的・言語的要素を彼の音楽に取り入れたことでもわかる。 アルセニオは、パロ・モンテにまつわることわざや、コンゴ語の語彙を使った伝統的な文章を使用している。アルセニオのアフロクバーノは、パロ・モンテのス ピリチュアリティに関する彼の知識の広さだけでなく、(1)キューバの大衆文化における人種差別的な表現手法に現れている、(2)メスティサヘ(人種的・ 文化的 「進歩」)のイデオロギーに暗示されている、アフリカ人の劣等性と原始性についての言説に対する彼の批判を示している。彼がアフロキューバノスで反論した ように、キューバの白人エリートや黒人知識人の多くにとって「原始的」な時代を象徴するこれらの伝統は、彼の音楽と生活の重要で力強い側面であり続けた。 - ガルシア (1006: 21)。 Sabú MartínezのPalo Congo (1957)では、ロドリゲスは伝統的なパロの歌とリズム、エレグアのためのルクミの歌、ルンバとトレス伴奏のコンガ・デ・コンパルサを歌い演奏している[42] 。 ロドリゲスは正真正銘のルンベロであり、トゥンバドーラを演奏し、ルンバ、特にグアグアンコスのジャンルの曲を作曲した。ロドリゲスは民謡ルンバを録音 し、ルンバとソン・モントゥーノを融合させた。彼の 「Timbilla」(1945)[44]と 「Anabacoa」(1950)は、ソン・コントゥントで使われるグアガンコのリズムの例である。ティンビージャ」では、ボンゴがキント(リード・ドラ ム)の役割を果たしている。Yambú en serenata」(1964年)では、キントを使ったヤンブーが、トレス、バス、ホルンによって増強されている[45]。 1956年、ロドリゲスはハバナで民謡ルンバ 「Con flores del matadero 」と 「Adiós Roncona 」をリリースした[46][47]。ロドリゲスが最後に参加したレコーディングのひとつは、コンゲーロのカルロス・「パタート」・バルデスとヴォーカリス トのエウヘニオ・「トティコ」・アランゴによるルンバ・アルバム『パタート・イ・トティコ』(1967年)である[48]。追加メンバーにはパパイトーと ヴィルジリオ・マルティがいる。また、1960年代にリリースされたアルバム『Primitivo』では、モンギート・エル・ユニコとベイビー・ゴンサレ スが交互にリード・ヴォーカルを務め、ソラーレで演奏されていた音楽を彷彿とさせる。 |

| Tributes There have been numerous tributes to Arsenio Rodríguez, especially in the form of LPs. In 1972, Larry Harlow recorded Tribute to Arsenio Rodríguez (Fania 404) with his band Orchestra Harlow. On this LP, five of the numbers had been recorded earlier by Rodríguez' conjunto. In 1994, the Cuban revivalist band Sierra Maestra recorded Dundunbanza! (World Circuit WCD 041), an album containing four Rodríguez numbers, including the title track. Arsenio Rodríguez is mentioned in a national television production called La época,[49] about the Palladium era in New York, and Afro-Cuban music.[50] The film discusses Arsenio's contributions, and features some of the musicians he recorded with.[51] Others interviewed in the movie[52] include the daughter of legendary Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaría – Ileana Santamaría, bongocero Luis Mangual and others. Rodríguez's close friend and bassist for eight years Alfonso "El Panameño" Joseph, as well as other members of Rodríguez's band, such as Julián Lianos, who performed with Rodríguez at the Palladium Ballroom in New York during the 1960s, have had their legacies documented in a national television production called La Época,[49] released in theaters in the US in September 2008, and in Latin America in 2009. He had much success in the US and migrated there in 1952, one of the reasons being the better pay of musicians.[14] Starting in the late 1990s, jazz guitarist Marc Ribot recorded two albums mostly of Rodríguez' compositions or songs in his repertoire:Marc Ribot y los Cubanos Postizos (or Marc Ribot and the Prosthetic/Fake Cubans) and Muy Divertido!. In 1999, Rodríguez was posthumously inducted into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame.[53] Belatedly, the borough of the Bronx officially had the intersection of Intervale Ave. and Dawson St. in the area known as Longwood renamed "Arsenio Rodríguez Way" in a dedication and unveiling ceremony on Thursday, June 6, 2013. "That intersection was the center of his universe," said José Rafael Méndez, a community historian. "He lived in that area. And all the clubs he played, like the Hunts Point Palace, were practically a stone's throw away."[54] The street designation serves as the crowning jewel after an arduous series of collaborative efforts and events produced last year that rendered tribute to the band leader and resident performer of the Longwood community. |

トリビュート アルセニオ・ロドリゲスへのトリビュートは、LPを中心に数多くある。1972年、ラリー・ハーロウは自身のバンド、オーケストラ・ハーロウと共に 『Tribute to Arsenio Rodríguez』(Fania 404)を録音した。このLPには、ロドリゲスのコンフントが以前に録音したナンバーが5曲収録されている。1994年には、キューバのリバイバル・バ ンド、シエラ・マエストラがドゥンドゥンバンサを録音している!(World Circuit WCD 041)を録音した。このアルバムには、タイトル曲を含む4曲のロドリゲス・ナンバーが収録されている。 アルセニオ・ロドリゲスは、ニューヨークのパラディウム時代とアフロ・キューバン・ミュージックを題材にした『La época(ラ・エポカ)』という全国ネットのテレビ番組で言及されている[49]。 ロドリゲスの8年来の親友でベーシストのアルフォンソ・「エル・パナメーニョ」・ホセフや、1960年代にニューヨークのパラディウム・ボールルームでロ ドリゲスと共演したフリアン・リアノスなど、ロドリゲスのバンドの他のメンバーは、『La Época』という国営テレビ番組でその遺産を記録され[49]、2008年9月にアメリカで、2009年にラテンアメリカで劇場公開された。彼はアメリ カで多くの成功を収め、1952年に移住したが、その理由のひとつはミュージシャンの給料が良かったことだった[14]。 1990年代後半から、ジャズ・ギタリストのマーク・リボットが、ロドリゲスの作曲またはレパートリーの曲を中心に2枚のアルバム『Marc Ribot y los Cubanos Postizos(マーク・リボットと偽キューバ人)』と『Muy Divertido!!!』を録音した。1999年、ロドリゲスは死後、国際ラテン音楽の殿堂入りを果たした[53]。 遅ればせながら、ブロンクス区は2013年6月6日(木)、ロングウッドとして知られる地域のインターヴェイル・アヴェニューとドーソン・ストリートの交差点を「アルセニオ・ロドリゲス・ウェイ」と正式に改名し、献辞と除幕式を行った。 「あの交差点は彼の世界の中心でした」と地域史家のホセ・ラファエル・メンデスは言う。「彼はあの辺りに住んでいました。ハンツ・ポイント・パレスなど、彼がプレイしたクラブはすべて、実質的に目と鼻の先だった」[54]。 この通りの指定は、ロングウッドコミュニティのバンドリーダーであり、専属パフォーマーであった彼に敬意を表し、昨年行われた一連の共同作業とイベントの後、その頂点に立つものである。 |

| Notable compositions The following songs composed by Arsenio Rodríguez are considered Cuban standards:[55] "Bruca maniguá" "El reloj de Pastora" "Monte adentro" "Dundunbanza" "Como traigo la yuca" (also known as "La yuca de Catalina" or "Dile a Catalina") "Fuego en el 23" "Meta y guaguancó" "Kila, Kike y Chocolate" "Los sitios acere" "La fonda de el bienvenido" "Mami me gustó" "Papa Upa" "El divorcio" "Anabacoa" "Adiós Roncona" "Dame un cachito pa' huelé" "Yo no como corazón de chivo" "Juégame limpio" |

|

| Discography Main article: Arsenio Rodríguez discography |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arsenio_Rodr%C3%ADguez |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆