サルサ音楽

Salsa Music

☆ サルサ音楽は、キューバ、プエルトリコ、アメリカの影響を受けた要素を組み合わせたラテンアメリカ音楽のスタイルである。基本的な音楽要素のほとんどはサ ルサと呼ばれるようになる以前からあったため、その起源については多くの論争があった。サルサと考えられているほとんどの曲は、主にソン・モントゥーノと ソン・クバーノをベースにしており[10]、グアラチャ、チャ・チャ・チャ、ダンソン、デスカルガ、ボレロ、グアヒーラ、ルンバ、マンボ、ジャズ、ファン ク、R&B、ロック、ボンバ、プレナの要素が含まれている。

★ 街角(バリオ)で野外音楽をする伝統は、ラテンアメリカではムルガといわれており、これは、カーニバ ルに仮装や風刺劇と音楽を組み合わせたものが起源だと いう。ムルガ(murga)という名称は、スペインの大西洋に面したイベリア半島南端のカディス(地名)で言われてものから由来する。もし、そのような祭 礼のジャンルがうまれて、それが、街角でのサルサになり、それは、ダンスホールでの舞踊やどんちゃん騒ぎふうのコンサートになったとしたら、その芸能の伝 統は、きわめて長い伝統をもつものになるようである。音楽と踊りとリクリエーションの融合というのは素敵で、ごった煮のサルサにもそのような伝統があると いう可能性は否定できない——写真はブエノスアイレス市フニンのカーニバル・ムルガ、1916年。アルゼンチンのムルガ(最新映像)——6分 ぐらいからの歌はサルサ風に聴こえるというのは、私だけだろうか?

☆ 冷戦構造のなかでサルサは生まれた?あるいは「サルサ」の命名者としてのファニア・レーベル;「1959年、キューバ革命が起きると、程なく米国はキュー バと国交を断絶。ニューヨークへはパチャンガを最後にキューバの最新流行音楽が入らなくなった。当時プエルトリコ人を中心とするニューヨークのラティーノ 人口はかなり増えており、彼等は自分たちの手で新しいサウンドを作り出して行く事になった。/60年代、ラテン・ロックの元祖とも言えるブーガルーも流行 した。R&Bにラテンリズムを加えたようなサウンドで、英語で歌われた曲も多い。 また、デスカルガ、つまりキューバ風のジャム・セッションも多く行われた。これまで流行した様々なキューバ音楽とジャズやロックやソウルなどを掛け合わせ る様々な実験が行われたのである。そして、弁護士ジェリー・マスッチとジョニー・パチェーコにより64年に設立されたファニア・レーベルにより、このムーブメントはサルサと名付けられた」http://www.salsa.org/salsahistory.html ※ただしこの見解は、下記の説明の「サルサを自認する最初のバンドは、チェオ・マルケッティ・イ・ス・コン フント〜ロス・サルセロス(Los Salseros)である。1959年にキューバで、その後1962年にアメリカでリリースされた彼らのファースト・アルバム『Salsa y Sabor』(Sonero) は、ジャケットにサルサと記載された最初のアルバムでもある」とは矛盾するからである。

★サルサ音楽の個別の特徴(Chat-GPT 4.0等によるものに加筆)

| リズムとタイムシグネチャー |

-

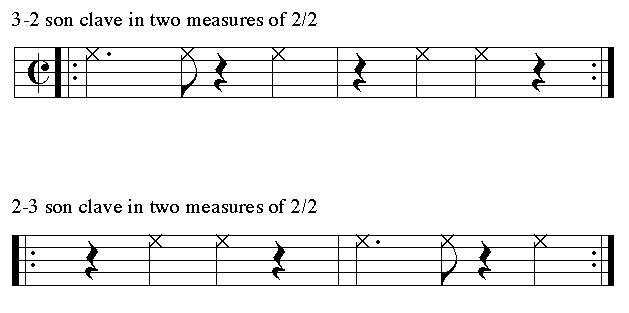

サルサ音楽は通常、4/4のタイムシグネチャーを持つ。 - クラーベという特有のリズムパターンが基礎となっている。クラーベは2-3または3-2のパターンで、楽曲のリズム的な骨組みを提供する。 |

| 打楽器の使用 |

-

サルサではコンガ、ボンゴ、ティンバレス、カウベル、マラカス、クラーベなどのラテン打楽器が重要な役割を果たす。 - 打楽器は、ダンスのリズムを刺激し、音楽の躍動感を高める。 |

| 複層的なリズム(ポリリズム) |

-

複数のリズム層が同時に演奏され、複雑で豊かなリズミックなテクスチャを生み出す。 |

| 即興(インプロビゼーション) |

-

ソロ部分(特に管楽器やピアノのソロ)で即興演奏が行われることが多く、演奏者の技術と創造性が強調される。 |

| ハーモニーとメロディ |

-

主にマイナーとメジャーのコード進行を使用し、時にはジャズの影響を受けた複雑なハーモニーが見られる。 - メロディは覚えやすく、リズムに合わせてリピーティブなことが多い。 |

| 歌詞の内容 |

-

恋愛、社会的なメッセージ、日常生活の話、祝祭など、さまざまなテーマの歌詞が含まれている。 |

| ダンスとの関連性 |

-

サルサ音楽はサルサダンスと密接に関連しており、音楽とダンスは互いに影響を与え合っている。 |

| 楽器編成 |

-

サルサバンドには、トランペット、トロンボーン、サクソフォーンなどの管楽器セクション、ピアノ、ベース、ときにギター、そして上述の打楽器が含まれる。 |

| モンターニョやマンボセクション |

-

曲の中には、特にダンサーに向けてエネルギーを高めるセクションがある。これはモンターニョやマンボと呼ばれ、楽器のソロやコールアンドレスポンスの

パターンが特徴である。 |

サ ルサ音楽は、キューバのソンやマンボ、プエルトリコのボンバやプレーナ、ジャズや他のカリブ海地域の音楽スタイルから影響を受けており、その結果、非常に エネルギッシュでダンスに適した音楽スタイルになっている。

サ ルサ音楽のリズムは、ソン・モントゥーノにより構成される。そのリズムをもとに、アルベ ジオ・オクターブ・また、四度進行などをひたすら繰り返すのが特徴である。あくまでも医療人類学上の仮説であるが、そのため演奏家のみならずダンスを伴う 聴衆者も、映像をみるかぎり一種のトランス状態になるのではなかろうか。ラップ音楽ではどうか? ジェームス・ブラウンの”Get Up, I Feel Like Being A Sex Machine”の強力な一つのセンテンスを16ビートで繰り返すことで歌詞やメッセージは、いささか隠喩的表現になる が、リズムとは独自に音符の中に溶け込んでいくのだ。モントゥーノにしろ、ラップにしろ、聴衆がトランス状態になるのは、言語的メッセージが音響的メッセージと相乗効果をもたらすからであろう。

ソン・モントゥーノは、ソン・クバー

ノから、1940年代に、アルセニオ・ロドリゲスが創案したもので

ある。

3-

2クラーベ(プ

レイⓘ)と2-3クラーベ(プレイⓘ)は

カットタイムで書かれる

★ サルサ音楽リンク集

︎▶プエルトリコの音楽︎▶︎︎エクトル・ラボ▶︎ソン・モン

トゥーノ▶ラテン・ヒップ・ポップ︎︎▶︎ルベン・ブラデス▶︎︎プエルトリコ人の言語とアイデンティティ▶︎音楽と政治▶︎︎ムルガ▶マヤ・ポピュラー音楽とラテン・西洋音楽︎▶︎︎音楽とナショナリズム▶︎カチカチ音楽▶︎︎キューバの

音楽▶︎レゲトン:Reggaeton▶セリア・クルスの"Que le den candela"[悪い男に火を放て]▶︎ヌヨリカン運動▶︎︎

アフロ-カリビアン音楽▶︎グアラチャ▶カノ・エストレメーラ︎︎▶ファン・ルイス・グェラ︎▶︎︎クアトロ(楽器)▶︎レゲトンとデムボウ▶︎︎セリア・クルスの受賞・ディスコグラフィー等▶メレンゲ音楽︎▶︎︎プエルトリコ調査関

係リンク▶民俗音楽・フォークミュージック▶ダンソン・マンボとチャンガ▶︎

キューバン・ルンバ▶中米・カリブにおける感覚のエスノグラフィーに

関する実証研究︎︎▶︎プエルトリコの文化▶音楽︎︎▶私の

センチメンタルジャーニー︎▶︎︎セリア・クルス▶宗教と音楽性▶グアテマラの音楽︎︎▶︎音楽人類学・民族音楽学▶︎︎感覚経験の人類学▶水は敵を持たず︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

★

ウィキペディア(英語)の「サルサ・ミュージック」から。

| Salsa music

is a

style of Latin American music, combining elements of Cuban, Puerto

Rican, and American influences. Because most of the basic musical

components predate the labeling of salsa, there have been many

controversies regarding its origin. Most songs considered as salsa are

primarily based on son montuno and son cubano,[10]

with elements of guaracha, cha-cha-chá, danzón, descarga, bolero,

guajira, rumba, mambo, jazz, funk, R&B, rock, bomba, and plena.[11]

All of these elements are adapted to fit the basic Son montuno template

when performed within the context of salsa.[12] Originally the name salsa was used to label commercially several styles of Latin dance music, but nowadays it is considered a musical style on its own and one of the staples of Latin American culture.[13][14] While the term salsa today is a rebranding of various Latin musical styles, the first self-identified salsa band is Cheo Marquetti y su Conjunto - Los Salseros.[15] Their first album released in Cuba in 1959 and later in the United States in 1962, “Salsa y Sabor” is also the first album to mention Salsa on its cover. Later on self-identified salsa bands were predominantly assembled by Cuban and Puerto Rican musicians in New York City in the 1970s. The music style was based on the late son montuno of Arsenio Rodríguez, Conjunto Chappottín and Roberto Faz. These musicians included Celia Cruz, Willie Colón, Rubén Blades, Johnny Pacheco, Machito and Héctor Lavoe.[16][17] During the same period a parallel modernization of Cuban son was being developed by Los Van Van, Irakere, NG La Banda, Charanga Habanera and other artists in Cuba under the name of songo and timba, styles that at present are also labelled as salsa. Though limited by an embargo, the continuous cultural exchange between salsa-related musicians inside and outside of Cuba is undeniable.[18] |

サルサ音楽は、キューバ、プエルトリコ、アメリカの影響を受けた要素を

組み合わせたラテンアメリカ音楽のスタイルである。基本的な音楽要素のほとんどはサルサと呼ばれるようになる以前からあったため、その起源については多く

の論争があった。サルサと考えられているほとんどの曲は、主にソン・モントゥーノとソン・クバーノを

ベースにしており[10]、グアラチャ、チャ・チャ・

チャ、ダンソン、デスカルガ、ボレロ、グアヒーラ、ルンバ、マンボ、ジャズ、ファンク、R&B、ロック、ボンバ、プレナの要素が含まれている

[11]。 元々サルサという名前は、商業的にラテン・ダンス・ミュージックのいくつかのスタイルにラベルを貼るために使われていたが、今日ではそれ自体が音楽スタイ ルであり、ラテン・アメリカ文化の定番の1つと考えられている[13][14]。 今 日のサルサという言葉は、様々なラテン音楽のスタイルを再ブランド化したものだが、サルサを自認する最初のバンドは、チェオ・マルケッティ・イ・ス・コン フント〜ロス・サルセロス(Los Salseros)である。1959年にキューバで、その後1962年にアメリカでリリースされた彼らのファースト・アルバム『Salsa y Sabor』(Sonero) は、ジャケットにサルサと記載された最初のアルバムでもある。その後、自称サルサ・バンドは、1970年代にニューヨークでキューバ人とプ エ ルトリコ人ミュージシャンによって主に結成された。その音楽スタイルは、アルセニ オ・ロドリゲス、コンフント・チャポティン、ロベルト・ファズの後期ソ ン・モントゥーノをベースにしていた。これらのミュージシャンには、セリア・クルス、ウィリー・コロン、ルベン・ブラデス、ジョニー・パチェコ、マチー ト、エクトル・ラボエらがいた[16][17]。同時期にキューバでは、ロス・ヴァン・ヴァン、イラケレ、NGラ・バンダ、チャランガ・ハバネラなどの アーティストによって、ソンゴやティンバという名前でキューバ・ソンの現代化が並行して進められていた。禁輸措置によって制限されてはいるが、キューバ内 外のサルサ関連ミュージシャンたちの継続的な文化交流は否定できない[18]。 |

SON MONTUNO, SON CUBANO de antaño, TEMA CROMOS HISTORIA DE LOS TRANSPORTES Y MARAVILLAS DEL ESPACIO. |

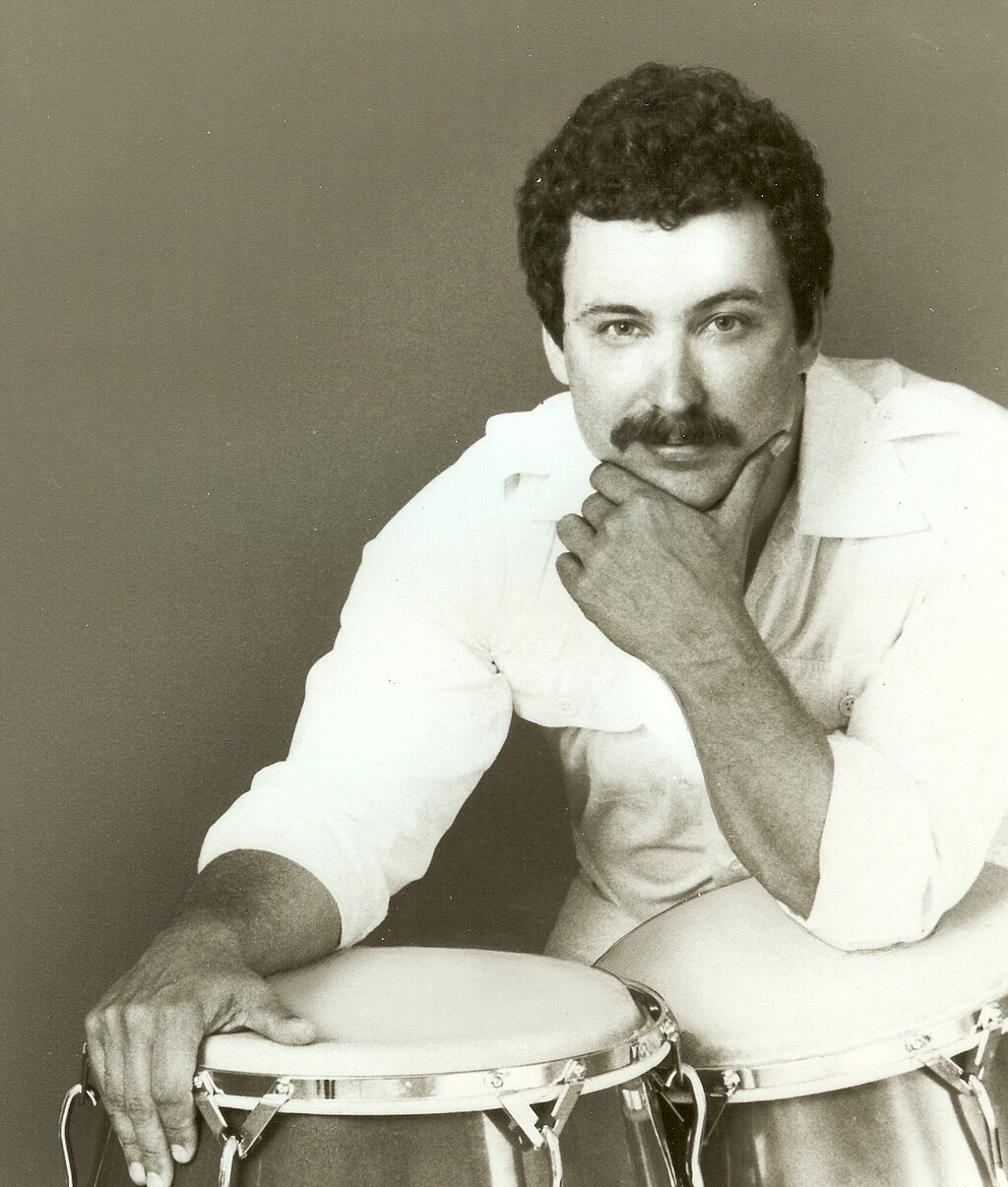

Tumbadoras (conga drums), one of the basic instruments of salsa music.Graciela on claves and her brother Machito on maracas; Machito said that salsa was much like what he had been playing from the 1940s.クラベスで演奏するグラシエラとマラカスで演奏する兄のマチート。マチートは、サルサは自分が1940年代から演奏していたものとよく似てい ると言った。 |

| Origins of the term Salsa The word Salsa means sauce in the Spanish language. The origin of the connection of this word to a style of music is disputed by various music writers and historians. The earliest evidence of the term salsa can be found in numerous newspaper articles beginning in the late 1800's from a Cuban newspaper called “Diario de la Marina”.[19][20]Some examples include: February, 28, 1885: “con su correspondiente SALSA de bailes.” August 20,1885: “SALSA de Guarachas”. October 18, 1909: “pero tendrá la alegría que es SALSA de la existencia, y la música y los bailes que son el regocijo de los pies.” October 23, 1927: “y los temas musicales son presentados sin preámbulos, sin la menor SALSA Sonora.” March 28, 1928: “El viejo palacio de Concordia, luminoso, encantado, bailando en la SALSA de su alegría.” September 28, 1929: “poetas, músicos, pintores, ministros, prelades, generales, príncipes y alguna que otra vez para variar la SALSA y divertir el gusto divos y comediantes, danzarinas y cantoras.” August 21, 1932: “y es arbitrariedad puesta en la SALSA del Tambor.” The musicologist Max Salazar believes the origin of the connection lies in 1930 when Ignacio Piñeiro composed the song Échale salsita (Put some sauce in it).[21] The phrase is seen as a cry from Piñeiro to his band, telling them to increase the tempo to "put the dancers into high gear".[22] In the mid-1940s, Cuban Cheo Marquetti emigrated to Mexico. Back in Cuba, influenced by spicy food salsas, he named his group Conjunto Los Salseros, with whom he recorded a couple of albums for the Panart and Egrem labels. Later on, while based in Mexico City, the musician Beny Moré would shout salsa during a performance to acknowledge a musical moment's heat, making a connection with the hot salsa (sauce) made in the country.[22] [23] Max Salazar, Mambo Kingdon: Latin Music in New York. 2002. First mention of Salsa in American Media – 1947. The first documented use of the term salsa can be found in the 1947 film Copacabana starring Groucho Marx and Carmen Miranda. In the final musical scene of the movie Carmen Miranda sings “Let's do the Copacabana”. One of her lyrics in the song is “They're the envy of all the other Cuban Salseros as they cry, ay ay ay”. This historical evidence documented on film establishes that by the 1940's, Cubans were already recognized as “Salseros”. Puerto Rican music promoter Izzy Sanabria claims he was the first to use the word salsa to denote a music genre. In 1973, I hosted the television show Salsa which was the first reference to this particular music as salsa. I was using [the term] salsa, but the music wasn't defined by that. The music was still defined as Latin music. And that was a very, very broad category, because it even includes mariachi music. It includes everything. So salsa defined this particular type of music ... It's a name that everyone could pronounce.[24] Sanabria's Latin New York magazine was an English language publication. Consequently, his promoted events were covered in The New York Times, as well as Time and Newsweek magazines.[25] Sanabria confessed the term salsa was not developed by musicians: "Musicians were busy creating the music but played no role in promoting the name salsa."[26] For this reason the use of the term salsa has been controversial among musicians. Some have praised its unification element. Celia Cruz said, "Salsa is Cuban music with another name. It's mambo, chachachá, rumba, son ... all the Cuban rhythms under one name."[27] Willie Colón described salsa not as a precise musical style but a power to unite in the broadest terms: "Salsa was the force that united diverse Latino and other non-Latino racial and ethnic groups ...Salsa is the harmonic sum of all Latin culture ".[28] On the other hand, even some New York based artists were originally against the commercialization of music under that name; Machito said: "There's nothing new about salsa, it is just the same old music that was played in Cuba for over fifty years."[26] Similarly, Tito Puente stated: "The only salsa I know is sold in a bottle called ketchup. I play Cuban music.[29] Cuban musicologist Mayra Martínez wrote that "the term salsa obscured the Cuban base, the music's history or part of its history in Cuba. And salsa was a way to do this so that Jerry Masucci, Fania and other record companies, like CBS, could have a hegemony on the music and keep the Cuban musicians from spreading their music abroad."[30] Izzy Sanabria responded that Martínez was likely giving an accurate Cuban viewpoint, "but salsa was not planned that way".[30] Johnny Pacheco, co-founder of Fania Records gave his definition of the term “Salsa” during various interviews. “La salsa es, y siempre ha sido la musica Cubana.” “Salsa is, and always has been, Cuban music.”. [31][32][33] The marketing potential from the name was so big, that eventually both Machito, Puente and even musicians in Cuba embraced the term as a financial necessity.[34][35][36] |

サルサの語源 サルサという言葉はスペイン語でソースを意味する。この言葉が音楽のスタイルと結びついた起源については、さまざまな音楽ライターや歴史家によって異論が ある。 サルサという言葉の最も古い証拠は、「Diario de la Marina」と呼ばれるキューバの新聞から1800年代後半に始まる数多くの新聞記事で見つけることができる[19][20]: 1885年2月28日:"con su correspondiente SALSA de bailes." 1885年8月20日:「SALSA de Guarachas」。1909年10月18日: "pero tendrá la alegría que es SALSA de la existencia, y la música y los bailes que el regocijo de los pies.". 1927年10月23日 "そして、音楽的な主題は、前置詞なしに提示され、SALSAソノラの劣等感はない。" 1928年3月28日 "コンコルディアの古い宮殿は、明るく、魅惑的で、SALSAの歓喜に包まれている" 1929年9月28日 "詩人、ミュージシャン、ピンサロ、大臣、プレラード、将軍、プリンシペス、その他、歌人、コメディアン、ダンツァリーナ、カンタオール" 1932年8月21日 "y es arbitrariedad puesta en la SALSA del Tambor". 音楽学者のマックス・サラザール(Max Salazar)は、1930年にイグナシオ・ピニェイロが「Échale salsita(ソースを入れて)」という曲を作曲したことが、このつながりの起源だと考えている[21]。 このフレーズは、ピニェイロが自分のバンドに対して、「ダンサーをハイギアに入れる」ためにテンポを上げるように指示した叫びだと見られている[22]。 1940年代半ば、キューバ人のチェオ・マルケッティはメキシコに移住した。キューバに戻った彼は、辛い食べ物のサルサに影響され、自分のグループをコン フント・ロス・サルセロス(Conjunto Los Salseros)と名付け、パナート(Panart)とエグレム(Egrem)のレーベルで数枚のアルバムを録音した。その後、メキシコ・シティを拠点 に活動していたミュージシャンのベニー・モレは、演奏中にサルサと叫んで音楽の熱さを表現し、メキシコで作られる辛いサルサ(ソース)と結びつけた [22] [23] 。 Max Salazar, Mambo Kingdon: Latin Music in New York. 2002. アメリカのメディアにおけるサルサの最初の言及 - 1947年。 サルサという言葉が初めて使われたのは、1947年のグルーチョ・マル クスとカーメン・ミランダ主演の映画『コパカバーナ』である。映画の最後のミュージ カルシーンで、カルメン・ミランダは「コパカバーナをやろう」と歌っている。この歌の中で彼女が歌う歌詞のひとつが、「彼らは他のキューバ人サルセロスの 羨望の的だ。フィルムに記録されたこの歴史的証拠は、1940年代までにキューバ人がすでに「サルセロス」として認知されていたことを立証している。 プエルトリコの音楽プロモーター、イジー・サナブリアは、音楽のジャンルを示すサルサという言葉を最初に使ったのは自分だと主張している。 1973年、私はテレビ番組『サルサ』の司会を務めた。私はサルサという言葉を使っていたが、音楽はサルサで定義されていなかった。音楽はまだラテン音楽 として定義されていた。ラテン・ミュージックは、マリアッチ・ミュージックも含む、とても広いカテゴリーだった。ラテン音楽にはマリアッチも含まれるから だ。だからサルサは、この特定のタイプの音楽を定義したんだ......。誰もが発音できる名前だったのです」[24]。 サナブリアの『ラテン・ニューヨーク』誌は英語の出版物だった。その結果、彼が宣伝したイベントはニューヨーク・タイムズ紙やタイム誌、ニューズウィーク 誌でも取り上げられた[25]。サナブリアは、サルサという言葉はミュージシャンによって開発されたものではないと告白した: 「ミュージシャンは音楽を創ることに忙しかったが、サルサという名前を広めることには何の役割も果たさなかった」[26] 。その統一的な要素を賞賛する者もいる。セリア・クルスは「サルサはキューバ音楽に別の名前をつけたもの。マンボ、チャチャチャ、ルンバ、ソ ン......すべてのキューバのリズムをひとつの名前にしたものだ」[27]。ウィリー・コロンは、サルサを正確な音楽スタイルとしてではなく、最も広 い意味で団結させる力として表現した: 「サルサは、多様なラテン系、非ラテン系の人種や民族を結びつける力であった......サルサは、すべてのラテン文化の調和的な総体である」[28]。 一方、ニューヨークを拠点とするアーティストの中にも、もともとその名のもとに音楽が商業化されることに反対だった者もいた: 「サルサに新しいものなど何もない。50年以上もキューバで演奏されてきた古い音楽に過ぎない」[26]。同様に、ティト・プエンテはこう述べている: 「私が知っているサルサは、ケチャップという瓶に入って売られているものだけだ。キューバの音楽学者マイラ・マルティネスは、「サルサという言葉は、 キューバのベース、キューバにおける音楽の歴史、あるいはその歴史の一部をあいまいにしていた。そしてサルサは、ジェリー・マスッチやファニア、そして CBSのようなレコード会社が音楽に対して覇権を握り、キューバのミュージシャンたちが自分たちの音楽を海外に広めないようにするための手段だった」 [30]。イジー・サナブリアは、マルティネスはキューバの正確な見解を述べているのだろうと答え、「しかし、サルサはそのように計画されたものではな い」[30]。ファニア・レコードの共同設立者であるジョニー・パチェコは、様々なインタビューの中で「サルサ」という言葉の定義を述べている。"ラ・サ ルサ・エス、イ・シエンプレ・ハ・シド・ラ・ミュージカ・クバーナ"。「サルサはキューバ音楽であり、常にそうであった」。[31][32][33] この名前から得られるマーケティングの可能性は非常に大きく、最終的にマチートもプエンテも、そしてキューバのミュージシャンたちでさえも、この言葉を経 済的に必要なものとして受け入れた[34][35][36]。 |

Instrumentation Bongos. The instrumentation in salsa bands is mostly based on the son montuno ensemble developed by Arsenio Rodriguez, who added a horn section, as well as tumbadoras (congas) to the traditional Son cubano ensemble; which typically contained bongos, bass, tres, one trumpet, smaller hand-held percussion instruments (like claves, güiro, or maracas) usually played by the singers, and sometimes a piano. Machito's band was the first to experiment with the timbales.[37] These three drums (bongos, congas and timbales) became the standard percussion instruments in most salsa bands and function in similar ways to a traditional drum ensemble. The timbales play the bell pattern, the congas play the supportive drum part, and the bongos improvise, simulating a lead drum. The improvised variations of the bongos are executed within the context of a repetitive marcha, known as the martillo ('hammer'), and do not constitute a solo. The bongos play primarily during the verses and the piano solos. When the song transitions into the montuno section, the bongo player picks up a large hand held cowbell called the bongo bell. Often the bongocero plays the bell more during a piece, than the actual bongos. The interlocking counterpoint of the timbale bell and bongo bell provides a propelling force during the montuno. The maracas and güiro sound a steady flow of regular pulses (subdivisions) and are ordinarily clave-neutral. Nonetheless, some bands instead follow the Charanga format, which consists of a string section (of violins, viola, and cello), tumbadoras (congas), timbales, bass, flute, claves and güiro. Bongos are not typically used in charanga bands. Típica 73, Orquesta Broadway, Orquesta Revé and Orquesta Ritmo Oriental where popular Salsa bands with charanga instrumentation. Johnny Pacheco, Charlie Palmieri, Mongo Santamaría and Ray Barretto also experimented with this format. Throughout its 50 years of life, Los Van Van have always experimented with both types of ensembles. The first 15 years the band was a pure charanga, but later a trombone section was added. Nowadays the band could be considered a hybrid. |

楽器編成 ボンゴ。 サルサ・バンドの楽器編成は、伝統的なソ ン・クバーノのアンサンブルにホーン・セクションとトゥンバドーラ(コンガ)を加えたアルセニオ・ロドリゲスが 開 発したソン・モントゥーノ・ア ンサンブルがほとんどで、通常、ボンゴ、ベース、トレス、トランペット1本、クラベス、グイロ、マラカスなどの小型の手持ち 打楽器(通常は歌手が演奏)、時にはピアノが含まれていた。この3つのドラム(ボンゴ、コンガ、ティンバレス)は、ほとんどのサルサ・バンドで標準的な打 楽器となり、伝統的なドラム・アンサンブルと同様の働きをする。ティンバレスはベル・パターンを演奏し、コンガはサポート・ドラム・パートを演奏し、ボン ゴはリード・ドラムをシミュレートしながら即興で演奏する。ボンゴの即興的なバリエーションは、マルティージョ(「ハンマー」)として知られる反復的な マーチアの中で演奏され、ソロにはならない。ボンゴは主に詩とピアノ・ソロで演奏される。曲がモントゥーノ・セクションに移行すると、ボンゴ奏者はボン ゴ・ベルと呼ばれる大きなカウベルを手に取る。多くの場合、ボンゴセロは曲中、実際のボンゴよりもベルを多く演奏する。ティンバレ・ベルとボンゴ・ベルの 連動した対位法は、モントゥーノ中に推進力を与える。マラカスとグイロは、規則的なパルス(小分割)の安定した流れを鳴らし、通常はクラーベ・ニュートラ ルである。 それにもかかわらず、一部のバンドは、弦楽器セクション(ヴァイオリン、ヴィオラ、チェロ)、トゥンバドーラ(コンガ)、ティンバレス、ベース、フルー ト、クラベス、グイロで構成されるチャランガ・フォーマットに従う。ボンゴは通常、チャランガ・バンドでは使用されない。ティピカ73(Típica 73)、オルケスタ・ブロードウェイ(Orquesta Broadway)、オルケスタ・レヴェ(Orquesta Revé)、オルケスタ・リトモ・オリエンタル(Orquesta Ritmo Oriental)などは、チャランガ楽器を使用した人気サルサバンドである。ジョニー・パチェコ、チャーリー・パルミエリ、モンゴ・サンタマリア、レ イ・バレットもまた、このフォーマットを実験的に取り入れていた。 ロス・ヴァン・ヴァンは、その50年間を通して、常に両方のタイプのアンサンブルを試してきた。最初の15年間は純粋なチャランガだったが、後にトロン ボーン・セクションが加わった。現在では、このバンドはハイブリッドと言えるかもしれない。 |

| Rhythm Salsa music typically ranges from 150 bpm (beats per minute) to around 250 bpm, with most songs falling between 160 and 220 bpm, which is suitable for dancing.  The key instrument that provides the core groove of a salsa song is the clave. It is often played with two wooden sticks (called clave) that are hit together. Every instrument in a salsa band is either playing with the clave (generally: congas, timbales, piano, tres guitar, bongos, claves (instrument), strings) or playing independent of the clave rhythm (generally: bass, maracas, güiro, cowbell). Melodic components of the music and dancers can choose to be in clave or out of clave at any point. For salsa, there are four types of clave rhythms, the 3-2 and 2-3 Son claves being the most important, and the 3-2 and 2-3 Rumba claves. Most salsa music is played with one of the son claves, though a rumba clave is occasionally used, especially during rumba sections of some songs. As an example of how a clave fits within the 8 beats of a salsa dance, the beats of the 2-3 Son clave are played on the counts of 2, 3, 5, the "and" of 6, and 8. There are other common rhythms found in salsa music: the chord beat, the tumbao, and the Montuno rhythm. The chord beat (often played on cowbell) emphasizes the odd-numbered counts of salsa: 1, 3, 5 and 7 while the tumbao rhythm (often played on congas) emphasizes the "off-beats" of the music: 2, 4, 6, and 8. Some dancers like to use the strong sound of the cowbell to stay on the Salsa rhythm. Alternatively, others use the conga rhythm to create a jazzier feel to their dance since strong "off-beats" are a jazz element. Tumbao is the name of the rhythm that is typically played with the conga drums. It sounds like: "cu, cum.. pa... cu, cum... pa". Its most basic pattern is played on the beats 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8. Tumbao rhythm is helpful for learning to dance contra-tiempo ("On2"). The beats 2 and 6 are emphasized when dancing On2, and the Tumbao rhythm heavily emphasizes those beats as well. The Montuno rhythm is a rhythm that is often played with a piano. The Montuno rhythm loops over the 8 counts and is useful for finding the direction of the music. By listening to the same rhythm, that loops back to the beginning after eight counts, one can recognize which count is the first beat of the music. |

リズム サルサ・ミュージックは通常、150bpm(ビート・パー・ミニッツ)から250bpm前後で、ほとんどの曲は160bpmから220bpmの間で、ダン スに適している。  サルサ曲の核となるグルーヴを生み出す重要な楽器がクラーベだ。2本の木の棒(クラーベと呼ばれる)を打ち合わせて演奏することが多い。サルサ・バンドの すべての楽器は、クラーベと一緒に演奏するか(一般的に:コンガ、ティンバレス、ピアノ、トレス・ギター、ボンゴ、クラベス(楽器)、弦楽器)、クラーベ のリズムとは無関係に演奏するか(一般的に:ベース、マラカス、グイロ、カウベル)。音楽とダンサーのメロディーの構成要素は、どの時点でもクラーベに入 るか入らないかを選ぶことができる。 サルサには4種類のクラーベ・リズムがあり、3-2と2-3のソン・ク ラーベが最も重要で、3-2と2-3のルンバ・クラーベがある。ほとんど のサルサ音 楽はソンクラーベの1つで演奏されるが、特に曲のルンバ・セクションではルンバ・クラーベが使われることもある。サルサ・ダンスの8拍子の中でクラーベが どのようにフィットするかの例として、2-3ソンクラーベの拍は、2、3、5、6の「と」、8のカウントで演奏される。 サルサ音楽には、他にもコード・ビート、トゥンバオ、モントゥーノ・リズムという一般的 なリズムがある。 コード・ビート(カウベルで演奏されることが多い)は、サルサの奇数カウントである1、3、5、7を強調し、トゥンバオ・リズム(コンガで演奏されること が多い)は、音楽の「オフ・ビート」である2、4、6、8を強調する。カウベルの強い音でサルサのリズムを刻むのが好きなダンサーもいる。また、強い "オフ・ビート "はジャズの要素なので、コンガのリズムを使ってジャズっぽい雰囲気を出すダンサーもいる。 トゥンバオ(Tumbao)とは、一般的にコ ンガ・ドラムで演奏されるリズムの名前である。音はこうだ: 「cu、cum...pa...cu、cum...pa」。その最も基本的なパターンは、2、3、4、6、7、8拍で演奏される。トゥンバオのリズムは、 コントラ・テンポ("On2")のダンスを学ぶのに役立つ。On2を踊るときには2拍目と6拍目が強調されるが、トゥンバオ・リズムも同様にこれらの拍を 大きく強調する。 モントゥーノ(Montuno)のリズムは、ピアノと一緒に演奏されること が多いリズムだ。モントゥーノのリズムは、8カウントの上をループしており、音 楽の方向性を見つけるのに便利である。同じリズムでも、8カウントでループして最初に戻るリズムを聴けば、どのカウントが音楽の1拍目なのかがわかる。 |

| Musical structure Main article: Salsa (musical structure) Most salsa compositions follow the basic son montuno model based on the Afro-Cuban clave rhythm and composed of a verse section, followed by a coro-pregón (call-and-response) chorus section known as the montuno. The verse section can be short, or expanded to feature the lead vocalist and/or carefully crafted melodies with clever rhythmic devices. Once the montuno section begins, it usually continues until the end of the song. The tempo may gradually increase during the montuno in order to build excitement. The montuno section can be divided into various sub-sections sometimes referred to as mambo, diablo, moña, and especial.[38] |

音楽的構造 主な記事 サルサ(音楽構造) ほとんどのサルサ曲は、アフロ・キューバのクラーベ・リズムに基づく基本的なソン・モントゥーノ・モデルに従っており、ヴァース・セクションと、モン トゥーノとして知られるコロ・プレゴン(コール・アンド・レスポンス)のコーラス・セクションで構成されている。ヴァース・セクションは短くすることもで きるし、リード・ヴォーカリストや、巧みなリズムの仕掛けで入念に作られたメロディーをフィーチャーするために拡大することもできる。モントゥーノ・セク ションが始まると、通常は曲の終わりまで続く。興奮を高めるために、モントゥーノではテンポを徐々に上げることもある。モントゥーノ・セクションは、マン ボ、ディアブロ、モニャ、スペシャルと呼ばれる様々なサブセクションに分けられる[38]。 |

| History Index of history 01: 1930s and 1940s: Origins in Cuba 02: 1950s-1960s: Cuban music in New York City 03-01: Fania Records Era from end of 1960s 03-02: 1970s: Songo in Cuba, salsa in NYC 04: 1980s: Salsa expansion in Latin America and the birth of timba 05: 1990s: Pop salsa and timba explosion 06: Age of Timba in Cuba 07: 2010s: Timba-fusion hits ++++++++++++++++++++++ ★01: 1930s and 1940s: Origins in Cuba Many musicologists find many of the components of salsa music in the Son Montuno of several artists of the 30s and 40s like Arsenio Rodríguez, Conjunto Chappottín (Arsenio's former band now led by Félix Chappottín and featuring Luis "Lilí" Martínez Griñán) and Roberto Faz. Salsa musician Eddie Palmieri once said "When you talk about our music, you talk about before, or after, Arsenio.....Lilí Martínez was my mentor".[39] Several songs of Arsenio's band, like Fuego en el 23, El Divorcio, Hacheros pa' un palo, Bruca maniguá, No me llores and El reloj de Pastora were later covered by many salsa bands (like Sonora Ponceña and Johnny Pacheco). On the other hand, a different style, Mambo, was developed by Cachao, Beny Moré and Dámaso Pérez Prado. Moré and Pérez Prado moved to Mexico City where the music was played by Mexican big band wind orchestras.[40] ★02: 1950s-1960s: Cuban music in New York City  The Palladium Ballroom, home of the mambo, c. 1950s. During the 1950s, New York became a hotspot of Mambo with musicians like the aforementioned Pérez Prado, Luciano "Chano" Pozo, Mongo Santamaría, Machito and Tito Puente. The highly popular Palladium Ballroom was the epicenter of mambo in New York. Ethnomusicologist Ed Morales notes that the interaction of Afro-Cuban and jazz music in New York was crucial to the innovation of both forms of music. Musicians who would become great innovators of mambo, like Mario Bauzá and Chano Pozo, began their careers in New York working in close conjunction with some of the biggest names in jazz, like Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, and Dizzy Gillespie, among others. Morales noted that: "The interconnection between North American jazz and Afro-Cuban music was taken for granted, and the stage was set for the emergence of mambo music in New York, where music fans were becoming accustomed to innovation."[41] He later notes that Mambo helped pave the way for the widespread acceptance of salsa years later. Another popular style was chachacha, which originated in the Charanga bands in Cuba. By the early 1960s, there were several charanga bands in New York led by musicians (like Johnny Pacheco, Charlie Palmieri, Mongo Santamaría and Ray Barretto) who would later become salsa stars. In 1952, Arsenio Rodríguez moved for a short period to New York City taking with him his modern son montuno. During that period his success was limited (NYC was more interested in Mambo), but his guajeos (who influenced the musicians he shared the stage with, such as Chano Pozo, Machito, and Mario Bauzá), together with the piano tumbaos of Lilí Martínez, the trumpet of Félix Chappottín and the rhythmic lead vocals of Roberto Faz would become very relevant in the region a decade later.[1] In 1966, the Palladium closed because it lost its liquor license.[42] The mambo faded away, as new hybrid styles such as boogaloo, the jala-jala and the shing-a-ling had brief but important success.[42] Elements of boogaloo can be heard in some songs of Tito Puente, Eddie Palmieri, Machito and even Arsenio Rodríguez.[43] Nonetheless, Puente later recounted: "It stunk ... I recorded it to keep up with the times.[44] Popular Boogaloo songs include "Bang Bang" by the Joe Cuba Sextet and "I Like It Like That" by Pete Rodríguez and His Orchestra. ★03-01: Fania Records Era from end of 1960s During the late 1960s, the Dominican musician Johnny Pacheco and Italian-American businessman Jerry Masucci founded the recording company Fania Records. They introduced many of the artists that would later be identified with the salsa movement, including Willie Colón, Celia Cruz, Larry Harlow, Ray Barretto, Héctor Lavoe and Ismael Miranda. Fania's first record album was "Cañonazo", recorded and released in 1964. It was panned by music critics as 10 of the 11 songs were covers of previously recorded tunes by such Cuban artists as Sonora Matancera, Chappottín y Sus Estrellas and Conjunto Estrellas de Chocolate. Pacheco put together a team that included percussionist Louie Ramírez, bassist Bobby Valentín and arranger Larry Harlow to form the Fania All-Stars in 1968. Meanwhile, the Puerto Rican band La Sonora Ponceña recorded two albums named after songs of Arsenio Rodriguez (Hachero pa' un palo and Fuego en el 23). ★03-02: 1970s: Songo in Cuba, salsa in NYC The 1970s was witness to two parallel modernizations of the Cuban son in Havana and in New York. During this period the term salsa was introduced in New York, and songo was developed in Havana. The band Los Van Van, led by the bassist Juan Formell, started developing songo in the late 1960s. Songo incorporated rhythmic elements from folkloric rumba as well as funk and rock to the traditional son. With the arrival of the drummer Changuito, several new rhythms were introduced and the style had a more significant departure from the son montuno/mambo-based structure.[45] Songo integrated several elements of North American styles like jazz, rock and funk in many different ways than mainstream salsa. Whereas salsa would superimpose elements of another genre in the bridge of a song, the songo was considered a rhythmic and harmonic hybrid (particularly regarding funk and clave-based Cuban elements). The music analyst Kevin Moore stated: "The harmonies, never before heard in Cuban music, were clearly borrowed from North American pop [and] shattered the formulaic limitations on harmony to which Cuban popular music had faithfully adhered for so long."[46] During the same period, Cuban super group Irakere fused bebop and funk with batá drums and other Afro-Cuban folkloric elements; Orquesta Ritmo Oriental created a new highly syncopated, rumba-influenced son in the charanga ensemble; and Elio Revé developed changüí.[47]  Roger Dawson hosted a very popular Las Vegas radio show featuring salsa. On the other hand, New York saw in the 1970s the first use of the term salsa to commercialize several styles of Latin dance music. However, several musicians believe that salsa took on a life of its own, organically evolving into an authentic pan-Latin American cultural identity. Music professor and salsa trombonist Christopher Washburne wrote: This pan-Latino association of salsa stems from what Félix Padilla labels a 'Latinizing' process that occurred in the 1960s and was consciously marketed by Fania Records: 'To Fania, the Latinizing of salsa came to mean homogenizing the product, presenting an all-embracing Puerto Rican, Pan-American or Latino sound with which the people from all of Latin America and Spanish-speaking communities in the United States could identify and purchase.' Motivated primarily by economic factors, Fania's push for countries throughout Latin America to embrace salsa did result in an expanded market. But in addition, throughout the 1970s, salsa groups from Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Venezuela, among other Latin American nations, emerged, composing and performing music that related to their own specific cultural experiences and affiliations, which posited salsa as a cultural identity marker for those nations as well.[48]  In 1971, the Fania All-Stars sold out Yankee Stadium.[49] By the early 1970s, the music's center moved to Manhattan and the Cheetah, where promoter Ralph Mercado introduced many future Puerto Rican salsa stars to an ever-growing and diverse crowd of Latino audiences. The 1970s also brought new semi-known Salsa bands from New York City, bands such as Ángel Canales, Andy Harlow, Chino Rodríguez y su Consagracion (Chino Rodríguez was one of the first Chinese Puerto Rican artists that caught the eye of Fania Record's owner Jerry Masucci and later became the booking agent for many of the Fania artists.), Wayne Gorbea, Ernie Agusto y la Conspiración, Orchestra Ray Jay, Orchestra Fuego, and Orchestra Cimarron, among other bands that were performing in the Salsa market on the East Coast. Celia Cruz, who had had a successful career in Cuba with Sonora Matancera, was able to transition into the salsa movement, eventually becoming known as the Queen of Salsa.[50][51][52] Larry Harlow stretched out from the typical salsa record formula with his opera Hommy (1973), inspired by The Who's Tommy album, and also released his critically acclaimed La Raza Latina, a Salsa Suite. In 1975, Roger Dawson created the "Sunday Salsa Show" over WRVR FM, which became one of the highest-rated radio shows in the New York market with a reported audience of over a quarter of a million listeners every Sunday (per Arbitron Radio Ratings). Ironically, although New York's Hispanic population at that time was over two million, there had been no commercial Hispanic FM. Given his jazz and salsa conga playing experience and knowledge (working as a sideman with such bands as salsa's Frankie Dante's Orquesta Flamboyán and jazz saxophonist Archie Shepp), Dawson also created the long-running "Salsa Meets Jazz" weekly concert series at the Village Gate jazz club where jazz musicians would sit in with an established salsa band, for example Dexter Gordon jamming with the Machito band. Dawson helped to broaden New York's salsa audience and introduced new artists such as the bilingual Ángel Canales who were not given play on the Hispanic AM stations of that time. His show won several awards from the readers of Latin New York magazine, Izzy Sanabria's Salsa Magazine at that time and ran until late 1980 when Viacom changed the format of WRVR to country music.[53] Despite an openness to experimentation and a willingness to absorb non-Cuban influences, such as jazz, rock, bomba and plena, and already existing mambo-jazz, the percentage of salsa compositions based in non-Cuban genres during this period in New York is quite low, and, contrary to songo, salsa remained consistently wedded to older Cuban templates.[54][55] Some believe the pan-Latin Americanism of salsa was found in its cultural milieu, more than its musical structure.[56] An exception of this is probably found in the work of Eddie Palmieri and Manny Oquendo, who were considered more adventurous than the highly produced Fania records artists. The two bands incorporated less superficially jazz elements as well as the contemporary Mozambique (music). They were known for its virtuous trombone soloists like Barry Rogers (and other "Anglo" jazz musicians who had mastered the style). Andy González, a bass player who performed with Palmieri and Oquendo recounts: "We were into improvising ... doing that thing Miles Davis was doing — playing themes and just improvising on the themes of songs, and we never stopped playing through the whole set."[57] Andy and his brother Jerry González started showing up in the DownBeat Reader's Poll, and caught the attention of jazz critics.[citation needed] ★04: 1980s: Salsa expansion in Latin America and the birth of timba  Oscar D'Leon (2011). Celia Cruz & Oscar D'Leon - Full Concert [HD] | Live at North Sea Jazz Festival 2000 During the 1980s, several Latin American countries, such as Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Mexico and Panama, began producing their own salsa music.[58] Two of the biggest stars from this period are Oscar D'León from Venezuela and Joe Arroyo from Colombia.[59] Other popular acts are Fruko y sus Tesos, Grupo Niche and Rubén Blades (now as a soloist). During this period Cuba received international salsa musicians for the first time. Venezuelan salsa star Oscar D'León's 1983 tour of Cuba is mentioned prominently by every Cuban I've ever interviewed on the subject. Rubén Blades' album Siembra was heard everywhere on the island throughout the mid-80s and has been quoted extensively in the guías and coros of everyone from Van Van's Mayito Rivera (who quotes [Blades'] 'Plástico' in his guías on the 1997 classic Llévala a tu vacilón), to El Médico de la Salsa (quoting another major hook from 'Plástico'—'se ven en la cara, se ven en la cara, nunca en el corazón'—in his final masterpiece before leaving Cuba, Diós sabe).[60] Prior to D'León's performance, many Cuban musicians rejected the salsa movement, considering it a bad imitation of Cuban music. Some people say that D'León's performance gave momentum to a "salsa craze" that brought back some of the older templates and motivated the development of timba. Before the birth of timba, Cuban dance music lived a period of high experimentation among several bands like the charangas: Los Van Van, Orquesta Ritmo Oriental, and Orquesta Revé; the conjuntos: Adalberto Alvarez y Son 14, Conjunto Rumbavana and Orquesta Maravillas de Florida; and the jazz band Irakere. [61] Timba was created by musicians of Irakere who later formed NG La Banda under the direction of Jose Luis "El Tosco" Cortez. Many timba songs are more related to main-stream salsa than its Cuban predecessors earlier in the decade. For example, the song "La expresiva" (of NG La Banda) uses typical salsa timba/bongo bell combinations. The tumbadoras (congas) play elaborate variations on the son montuno-based tumbao, rather than in the songo style. For this reason some Cuban musicians of this period like Manolito y su Trabuco, Orquesta Sublime, and Irakere referred to this late-80s sound as salsa cubana, a term which for the first time, included Cuban music as a part of salsa movement.[36] In the mid-1990s California-based Bembé Records released CDs by several Cuban bands, as part of their salsa cubana series. Nonetheless, this style included several innovations. The bass tumbaos were busier and more complex than tumbaos typically heard in NY salsa. Some guajeos were inspired by the "harmonic displacement" technique of the Cuban jazz pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba. Curiously, it was in Cuba where hip hop and salsa first began to meet. For example, many breakdown sections in NG La Banda's album En la calle are a combination of guaguancó and hip hop rhythms. During this period, Cuban musicians had more of an impact on jazz than salsa in the United States. Even though the Mariel boatlift took hundreds of Cuban musicians to the US, many of them were astonished to hear what sounded to them like Cuban music from the 1950s. Cuban conguero Daniel Ponce summarized this sentiment: "When the Cubans arrived in New York, they all said 'Yuk! This is old music.' The music and the feelings and arrangements [haven't] changed."[62] Nonetheless, there was an awareness of the modern Cuban styles in the US. Tito Puente recorded the Irakere composition "Bacalao con pan" (1980), and Rubén Blades covered Los Van Van's "Muevete" (1985). While the Puerto Rican bands Batacumbele (featuring a young Giovanni Hidalgo) and Zaperoko fully embraced songo music under the mentorship of Changuito. During the '80s other variants of salsa like salsa romántica and salsa erótica evolved, with lyrics dwelling on love and romance. Salsa romántica can be traced back to Noches Calientes, a 1984 album by singer José Alberto "El Canario" with producer Louie Ramírez. Some viewed salsa romántica as a rhythmically watered-down version of the genre. Critics of salsa romántica, especially in the late '80s and early '90s, called it a commercialized, diluted form of Latin pop, in which formulaic, sentimental love ballads were simply put to Afro-Cuban rhythms — leaving no room for classic salsa's brilliant musical improvisation, or for classic salsa lyrics that tell stories of daily life or provide social and political commentary. Some artists of these styles include Ómar Alfann, Palmer Hernández and Jorge Luis Piloto. ★05: 1990s: Pop salsa and timba explosion  Marc Anthony performing at the White House (2009) The 1990s was marked by "pop salsa" in the US, and the "timba explosion" in Cuba. Marc Anthony - Valio La Pena (Salsa Version) Sergio George produced several albums that mixed salsa with contemporary pop styles with Puerto Rican artists like Tito Nieves, La India, and Marc Anthony. George also produced the Japanese salsa band Orquesta de la Luz. Brenda K. Starr, Son By Four, Víctor Manuelle, and the Cuban-American singer Gloria Estefan enjoyed crossover success within the Anglo-American pop market with their Latin-influenced hits, usually sung in English.[63] More often than not, clave was not a major consideration in the composing or arranging of these hits. Sergio George is up front and unapologetic about his attitude towards clave: "Though clave is considered, it is not always the most important thing in my music. The foremost issue in my mind is marketability. If the song hits, that's what matters. When I stopped trying to impress musicians and started getting in touch with what the people on the street were listening to, I started writing hits. Some songs, especially English ones originating in the United States, are at times impossible to place in clave."[64] As Washburne points out however, a lack of clave awareness does not always get a pass: Marc Anthony is a product of George's innovationist approach. As a novice to Latin music, he was propelled into band leader position with little knowledge of how the music was structured. One revealing moment came during a performance in 1994, just after he had launched his salsa career. During a piano solo he approached the timbales, picked up a stick, and attempted to play clave on the clave block along with the band. It became apparent that he had no idea where to place the rhythm. Shortly thereafter during a radio interview in San Juan (Puerto Rico), he exclaimed that his commercial success proved that you did not need to know about clave to make it in Latin music. This comment caused an uproar both in Puerto Rico and New York. After receiving the bad press, Anthony refrained from discussing the subject in public, and he did not attempt to play clave on stage until he had received some private lessons.[65] In Cuba, what came to be known as the "timba explosion" began with the debut album of La Charanga Habanera, Me Sube La Fiebre, in 1992. Like NG La Banda, Charanga Habanera used several new techniques like gear changes and song-specific tumbaos, but their musical style was drastically different and it kept changing and evolving with each album. Charanga Habanera underwent three distinct style periods in the 90s, represented by the three albums[66] Manolín "El Médico de la salsa", an amateur songwriter discovered and named by El Tosco (NG La Banda) at med school, was another superstar of the period. Manolín's creative team included several arrangers, including Luis Bu and Chaka Nápoles. As influential as Manolín was from a strictly musical point of view, his charisma, popularity and unprecedented earning power had an even more seismic impact, causing a level of excitement among musicians that had not been seen since the 1950s. Reggie Jackson referred to Manolin as "the straw that stirs the drink."—Moore (2010: v. 5: 18)[67] ★06: Age of Timba in Cuba The term salsa cubana which had barely taken hold, again fell out of favor, and was replaced with timba. Some of the other important timba bands include Azúcar Negra, Manolín "El Médico de la salsa", Havana d'Primera, Klimax, Paulito FG, Salsa Mayor, Tiempo Libre, Pachito Alonso y sus Kini Kini, Bamboleo, Los Dan Den, Alain Pérez, Issac Delgado, Tirso Duarte, Klimax, Manolito y su Trabuco, Paulo FG, and Pupy y Los que Son Son. Cuban timba musicians and New York salsa musicians have had positive and creative exchanges over the years, but the two genres remained somewhat separated, appealing to different audiences. Nonetheless, in 2000 Los Van Van were awarded the first ever Grammy Award for Best Salsa Album. In Colombia, salsa remained a popular style of music producing popular bands like Sonora Carruseles, Carlos Vives, Orquesta Guayacan, Grupo Niche, Kike Santander, and Julian Collazos. The city of Cali became known as Colombia's "capital of salsa".[68] In Venezuela, Cabijazz was playing a unique modern blend of timba-like salsa with a strong jazz influence. ★07: 2010s: Timba-fusion hits During the late 00s and the 10s, some timba bands created new hybrids of salsa, timba, hip hop and reggaeton (for example Charanga Habanera - Gozando en la Habana and Pupy y Los que Son, Son-Loco con una moto).[69][70] A few years later the Cuban reggaeton band Gente de Zona and Marc Anthony produced the timba-reggaeton international mega-hit La Gozadera reaching over a billion views in YouTube. The style known as Cubaton, that was also popular during this period, was mostly based on reggaeton with only some hints of salsa/timba. |

歴史 【目次】 ★01: 1930年代と1940年代 キューバでの起源 ★02: 1950年代~1960年代 ニューヨークのキューバ音楽 ★03-01: 1960年代後半からのファニア・レ コード時代 ★03-02: 1970s: キューバのソンゴ、ニューヨークのサルサ ★04: 1980s: ラテンアメリカにおけるサルサの拡大とティンバの誕生 ★05: 1990s: ポップ・サルサとティンバの爆発 ★06: ティンバの時代(キューバ) ★07: 2010s: ティンバ・フュージョンのヒット +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ ★01: 1930年代と1940年代 キューバでの起源 多くの音楽学者が、アルセニオ・ロドリゲス、コンフント・チャポティン(アルセニオの元バンドで、現在はフェリックス・チャ ポティンが率い、ルイス・" リリ"・マルティネス・グリニャンをフィーチャー)、ロベルト・ファズといった30~40年代のアーティストたちのソン・モントゥーノに、サルサ音楽の構 成要素の多くを見出す。サルサ・ミュージシャンのエディ・パルミエリはかつて、「我々の音楽について語るとき、アルセニオの前か後について語ることにな る......リリ・マルティネスは私の師だった」と語っている[39]。フエゴ・エン・エル23、エル・ディヴォルシオ、ハチェロス・パ・ウン・パロ、 ブルカ・マニグア、ノー・メ・ロウレス、エル・レロージュ・デ・パストーラなど、アルセニオのバンドのいくつかの曲は、後に多くのサルサ・バンド(ソノー ラ・ポンセーニャやジョニー・パチェコなど)によってカバーされた。 一方、異なるスタイルであるマンボは、カチャオ、ベニー・モレ、ダマソ・ペレス・プラドによって発展した。モレとペレス・プラドはメキシコシティに移り住 み、メキシコのビッグバンドの吹奏楽団によって演奏された[40]。 ★02: 1950年代~1960年代 ニューヨークのキューバ音楽  マンボの本場、パラディウム・ボールルーム(1950年代頃)。 1950年代、ニューヨークは、前述のペレス・プラド、ルチアーノ "チャノ "ポゾ、モンゴ・サンタマリア、マチート、ティト・プエンテといったミュージシャンたちによるマンボのホットスポットとなった。高い人気を誇ったパラディ ウム・ボールルームは、ニューヨークにおけるマンボの震源地だった。 民族音楽学者のエド・モラレスは、ニューヨークにおけるアフロ・キュー バン・ミュージックとジャズ・ミュージックの相互作用は、両方の音楽形態の革新に とって極めて重要だったと指摘する。マリオ・バウサやチャノ・ポゾのような、後にマンボの偉大な革新者となるミュージシャンたちは、キャ ブ・キャロウェ イ、エラ・フィッツジェラルド、ディジー・ガレスピーといったジャズ界の大物たちと密接に関わりながら、ニューヨークでキャリアをスタートさせた。モラレ スはこう指摘する: 「北米のジャズとアフロ・キューバン・ミュージックの相互関係は当然のものとされ、 音楽ファンが革新に慣れつつあったニューヨークで、マンボ音楽が出現す るための舞台が整えられた」[41]と、後に彼は記している。 もうひとつの人気スタイルはチャチャチャで、これはキューバのチャランガ・バンドに端を発する。1960年代初頭までに、ニューヨークには、後にサルサの スターとなるミュージシャン(ジョニー・パチェコ、チャーリー・パルミエリ、モンゴ・サンタマリア、レイ・バレットなど)が率いるチャランガ・バンドがい くつかあった。 1952年、アルセニオ・ロドリゲスは、現代的な息子モントゥーノを連れてニューヨークに短期間移住した。その時期の彼の成功は限定的であったが(ニュー ヨークはマンボの方に興味があった)、彼のグアジェオ(チャノ・ポゾ、マチート、マリオ・バウサといったステージを共にしたミュージシャンに影響を与え た)は、リリ・マルティネスのピアノ・トゥンバオ、フェリックス・チャポッティーンのトランペット、ロベルト・ファズのリズミカルなリード・ヴォーカルと 共に、10年後にこの地域で非常に重要な存在となる[1]。 1966年、パラディウムは酒類販売免許を失ったため閉店した[42]。ブーガルー、ジャラジャラ、シング・ア・リングのような新しいハイブリッド・スタ イルが短期間ながら重要な成功を収めたため、マンボは衰退していった[42]。 ティト・プエンテ、エディ・パルミエリ、マチート、そしてアルセニオ・ロドリゲスの曲の中にもブーガルーの要素を聴くことができる: 「臭かった.ブーガルーの人気曲には、ジョー・キューバ・セクステットの「Bang Bang」やピート・ロドリゲス&ヒズ・オーケストラの「I Like It Like That」などがある[44]。 ★03-01: 1960年代後半からのファニア・レ コード時代 1960年代後半、ドミニカ人ミュージシャンのジョニー・パチェコとイタリア系アメリカ人の実業家ジェリー・マスッチがレコーディング会社ファニア・レ コードを設立。彼らは、ウィリー・コロン、セリア・クルス、ラリー・ハーロウ、レイ・バレット、エクトル・ラヴォエ、イスマエル・ミランダなど、後にサル サ・ムーブメントを代表する多くのアーティストを紹介した。ファニアの最初のレコード・アルバムは1964年に録音・発売された "Cañonazo"。11曲中10曲が、ソノラ・マタンセラ、チャポティン・イ・サス・エストレラス、コンフント・エストレラス・デ・チョコレートと いったキューバのアーティストが過去にレコーディングした曲のカバーだったため、音楽評論家からは酷評された。パチェコは、パーカッショニストのルイ・ラ ミレス、ベーシストのボビー・ヴァレンティン、アレンジャーのラリー・ハーロウらとチームを組み、1968年にファニア・オール・スターズを結成した。一 方、プエルトリコのバンド、ラ・ソノーラ・ポンセーニャは、アルセニオ・ロドリゲスの曲にちなんだ2枚のアルバム(『Hachero pa' un palo』と『Fuego en el 23』)をレコーディングした。 ★03-02: 1970s: キューバのソンゴ、ニューヨークのサルサ 1970年代は、ハバナとニューヨークで、キューバのソングの2つの近代化が並行して進行した時代である。この時期、ニューヨークではサルサという言葉が 導入され、ハバナではソンゴが発展した。 ベーシスト、フアン・フォルメル率いるバンド、ロス・ヴァン・ヴァンは、1960年代後半にソンゴを発展させ始めた。ソンゴは伝統的なソンに、民謡ルンバ やファンク、ロックのリズム要素を取り入れた。ドラマー、チャンギートの登場により、いくつかの新しいリズムが導入され、スタイルはソン・モントゥーノ/ マンボをベースとした構成からより大きく逸脱した[45]。 ソンゴは、ジャズ、ロック、ファンクのような北米スタイルのいくつかの要素を、主流のサルサとは異なる方法で統合した。サルサが曲のブリッジで別のジャン ルの要素を重ね合わせるのに対して、ソンゴはリズムとハーモニーのハイブリッド(特にファンクとクラーベに基づくキューバの要素に関して)と考えられてい た。音楽アナリストのケヴィン・ムーアはこう述べている: 「キューバ音楽でかつて聴かれたことのないハーモニーは、明らかに北米のポップスから借用したものであり、[そして]キューバのポピュラー音楽が長い間忠 実に守ってきたハーモニーに関する定型的な制限を打ち砕いた。 「同時期、キューバのスーパーグループ、イラケレはビバップとファンクをバタ・ドラムや他のアフロ・キューバの民俗的要素と融合させ、オルケスタ・リト モ・オリエンタルはチャランガ・アンサンブルの中で高度なシンコペーションとルンバの影響を受けた新しいソンを創り出し、エリオ・レヴェはチャングイを発 展させた[47]。  ロジャー・ドーソンは、サルサを特集したラスベガスで大人気のラジオ番組を主催していた。 一方、ニューヨークでは1970年代、ラテン・ダンス・ミュージックのいくつかのスタイルを商品化するためにサルサという言葉が初めて使われた。しかし、 何人かのミュージシャンは、サルサは独自の生命を持ち、本物の汎ラテンアメリカ文化的アイデンティティへと有機的に進化したと信じている。音楽教授でサル サ・トロンボーン奏者のクリストファー・ウォッシュバーンはこう書いている: この汎ラテンアメリカ的なサルサの関連性は、フェリックス・パディージャが1960年代に起こった『ラテン化』プロセスに起因しており、ファニア・レコー ドによって意識的に売り出された: ファニアにとって、サルサのラテン化とは、製品を均質化することであり、ラテン・アメリカやアメリカ国内のスペイン語を話すコミュニティの人々が共感し、 購入できるような、プエルトリコ、パン・アメリカン、ラティーノのサウンドを提示することだった」。主に経済的な要因に突き動かされたファニアは、ラテン アメリカ中の国々にサルサを受け入れるよう働きかけ、その結果、市場は拡大した。しかしそれに加えて、1970年代を通じて、コロンビア、ドミニカ共和 国、ベネズエラなどのラテンアメリカ諸国からサルサ・グループが登場し、それぞれの文化的経験や所属に関連する音楽を作曲し演奏した。  1971年、ファニア・オール・スターズはヤンキー・スタジアムを完売させた[49]。1970年代初頭までに、音楽の中心はマンハッタンとチーターに移 り、プロモーターのラルフ・メルカードは、多くの未来のプエルトリコ人サルサ・スターを、増え続ける多様なラテン系観客に紹介した。1970年代には、ア ンヘル・カナレス(Ángel Canales)、アンディ・ハーロウ(Andy Harlow)、チノ・ロドリゲス・イ・ス・コンサグラシオン(Chino Rodríguez y su Consagracion)(チノ・ロドリゲスは、ファニア・レコードのオーナー、ジェリー・マスッチ(Jerry Masucci)の目に留まり、後に多くのファニア・アーティストのブッキング・エージェントになった最初の中国系プエルトリコ人アーティストの一人であ る。 )、ウェイン・ゴルベア、アーニー・アグスト・イ・ラ・コンスピラシオン、オーケストラ・レイ・ジェイ、オーケストラ・フエゴ、オーケストラ・シマロンな ど、東海岸のサルサ・マーケットで活躍していたバンドが名を連ねていた。 キューバでソノラ・マタンセラとともに成功を収めたセリア・クルスは、サルサ・ムーヴメントに移行することができ、最終的にはサルサの女王として知られる ようになった[50][51][52]。 ラリー・ハーロウは、ザ・フーのアルバム『Tommy』にインスパイアされたオペラ『Hommy』(1973年)で、典型的なサルサ・レコードの方式から 脱却し、絶賛された『La Raza Latina, a Salsa Suite』もリリースした。 1975年、ロジャー・ドーソンはWRVR FMで "Sunday Salsa Show "を立ち上げ、毎週日曜日のリスナーは25万人を超え、ニューヨーク市場で最も視聴率の高いラジオ番組のひとつとなった(Arbitron Radio Ratingsによる)。皮肉なことに、当時のニューヨークのヒスパニック人口は200万人を超えていたが、商業的なヒスパニックFMは存在しなかった。 ジャズとサルサのコンガ演奏の経験と知識(サルサのフランキー・ダンテのオルケスタ・フランボヤンやジャズ・サックス奏者のアーチー・シェップなどのバン ドでサイドマンとして活動)を生かしたドーソンは、ビレッジ・ゲートのジャズ・クラブで、デクスター・ゴードンがマチート・バンドとジャムをするなど、 ジャズ・ミュージシャンが定評のあるサルサ・バンドと同席する「サルサ・ミーツ・ジャズ」ウィークリー・コンサート・シリーズを長期にわたって開催した。 ドーソンは、ニューヨークのサルサの聴衆を広げるのに貢献し、バイリンガルのアンヘル・カナレスなど、当時のヒスパニック系AM局では演奏されなかった新 しいアーティストを紹介した。彼の番組は、当時のラテン・ニューヨーク誌『イジー・サナブリアのサルサ・マガジン』の読者からいくつかの賞を獲得し、 1980年後半にヴァイアコムがWRVRのフォーマットをカントリー・ミュージックに変更するまで続いた[53]。 実験に対してオープンであり、ジャズ、ロック、ボンバ、プレナ、すでに存在していたマンボ・ジャズなど、キューバ以外の影響を吸収しようとする意欲があっ たにもかかわらず、ニューヨークにおけるこの時期の非キューバ・ジャンルに基づくサルサの作曲の割合はかなり低く、ソンゴとは反対に、サルサは一貫して古 いキューバのテンプレートに縛られたままであった[54][55]。サルサの汎ラテン・アメリカ主義は、その音楽的構造よりも、その文化的環境の中に見出 されたという説もある[56]。 この例外はおそらくエディ・パルミエリとマニー・オケンドの作品に見られ、彼らは高度に生産されたファニア・レコードのアーティストよりも冒険的であると 考えられていた。この2つのバンドは、現代のモザンビーク(音楽)と同様に、あまり表面的ではないジャズの要素を取り入れていた。彼らは、バリー・ロ ジャース(そしてこのスタイルをマスターした他の "アングロ "ジャズ・ミュージシャンたち)のような高潔なトロンボーン・ソロで知られていた。パルミエリやオケンドと共演したベース奏者のアンディ・ゴンサレスはこ う語る: 「私たちは即興演奏に夢中でした......マイルス・デイヴィスがやっていたようなこと、つまり、曲のテーマを演奏したり、曲のテーマに沿って即興演奏 したりすることです。 ★04: 1980s: ラテンアメリカにおけるサルサの拡大とティンバの誕生  オスカー・ディレオン(2011年) Celia Cruz & Oscar D'Leon - Full Concert [HD] | Live at North Sea Jazz Festival 2000 1980年代には、コロンビア、ベネズエラ、ペルー、メキシコ、パナマなど、ラテンアメリカの国々が独自のサルサ音楽を作り始めた[58] 。 この時期、キューバは初めて国際的なサルサ・ミュージシャンを迎えた。 ベネズエラのサルサ・スター、オスカー・デレオンが1983年にキューバをツアーしたことは、私がこのテーマでインタビューしたキューバ人の誰もが口を揃 えて言う。ルベン・ブラデスのアルバム『Siembra』は、80年代半ばを通してキューバの至る所で聴かれ、ヴァン・ヴァンのマイト・リヴェラ(彼は 1997年の名盤『Llévala a tu vacilón』のギターで、[ブラデスの]「Plástico」を引用している)から、エル・メディコ・デ・ラ・ヴァシロン(El Médico de la vacilón)まで、あらゆるキューバ人のギターやソロで引用されている、 から、エル・メディコ・デ・ラ・サルサ(キューバを去る前の最後の傑作『Diós sabe』で、'Plástico'のもうひとつの主要なフックである'se ven en la cara, se ven en la cara, nunca en el corazón'を引用している)まで。 [60] デレオンが演奏する前、多くのキューバ人ミュージシャンはサルサ・ムーブメントをキューバ音楽の悪い模倣だと考え、拒絶していた。ディレオンの演奏が「サ ルサ・ブーム」に拍車をかけ、古いテンプレートがよみがえり、ティンバの発展の原動力となったという人もいる。 ティンバが誕生する以前、キューバのダンス・ミュージックは、チャランガのようないくつかのバンドの間で、高度に実験的な時期を過ごしていた: ロス・ヴァン・ヴァン(Los Van Van)、オルケスタ・リトモ・オリエンタル(Orquesta Ritmo Oriental)、オルケスタ・レヴェ(Orquesta Revé)、コンフント(Conjuntos): アダルベルト・アルバレス・イ・ソン14、コンフント・ルンババーナ、オルケスタ・マラビージャス・デ・フロリダなどのコンフント、ジャズバンドのイ ラケレなどである。[61] ティンバは、後にホセ・ルイス・"エル・トスコ"・コルテスの指揮のもとNGラ・バンダを結成したイラケレのミュージシャンたちによって作られた。ティン バの曲の多くは、10年代前半のキューバの先達よりもメインストリームのサルサに関連している。例えば、NGラ・バンダの "La expresiva "という曲では、典型的なサルサのティンバとボンゴのベルのコンビネーションが使われている。トゥンバドーラ(コンガ)は、ソンゴ・スタイルではなく、ソ ン・モントゥーノをベースにしたトゥンバオの凝ったバリエーションを演奏する。このため、マノリート・イ・ス・トラブーコ(Manolito y su Trabuco)、オルケスタ・サブライム(Orquesta Sublime)、イラケレ(Irakere)といったこの時期のキューバ人ミュージシャンたちは、この80年代後半のサウンドをサルサ・クバーナ (salsa cubana)と呼んだ。 それにもかかわらず、このスタイルにはいくつかの革新があった。低音のトゥンバオは、NYサルサで一般的に聴かれるトゥンバオよりも忙しく、複雑だった。 いくつかのグアジェオは、キューバのジャズ・ピアニスト、ゴンサロ・ルバルカバの "ハーモニック・ディスプレースメント "奏法にインスパイアされたものだった。不思議なことに、ヒップホップとサルサが最初に出会ったのはキューバだった。例えば、NGラ・バンダのアルバム 『En la calle』の多くのブレイクダウン・セクションは、グアガンコーとヒップホップのリズムを組み合わせたものだ。 この時期、キューバのミュージシャンたちは、アメリカではサルサよりもジャズに大きな影響を与えた。マリエル号によるボートリフトで何百人ものキューバ人 ミュージシャンがアメリカに渡ったにもかかわらず、彼らの多くは1950年代のキューバ音楽のようなサウンドを聴いて驚愕した。キューバのコンゲーロ、ダ ニエル・ポンセはこの気持ちを要約した: キューバ人たちがニューヨークに到着したとき、彼らはみな『ユック!これは古い音楽だ』と。音楽も感情もアレンジも[変わっていない]」[62] それにもかかわらず、アメリカでは現代的なキューバのスタイルが意識されていた。ティト・プエンテはイラケレ作曲の「Bacalao con pan」(1980年)をレコーディングし、ルーベン・ブラデスはロス・ヴァン・ヴァンの「Muevete」(1985年)をカヴァーした。一方、プエル トリコのバンド、バタクンベレ(若きジョバンニ・イダルゴをフィーチャー)とザペロコは、チャンギートの指導の下、ソンゴ・ミュージックを全面的に取り入 れた。 80年代には、サルサ・ロマンティカやサルサ・エロティカのような、愛やロマンスを歌詞にしたサルサの変種が発展した。サルサ・ロマンティカは、歌手ホ セ・アルベルト・"エル・カナリオ "がプロデューサー、ルイ・ラミレスと組んだ1984年のアルバム『Noches Calientes』まで遡ることができる。サルサ・ロマンチカを、このジャンルのリズミカルで水増しされたバージョンと見る向きもあった。特に80年代 後半から90年代前半にかけて、サルサ・ロマンチカを批評する人々は、ラテン・ポップの商業化された希薄な形態と呼び、定型化された感傷的なラブ・バラー ドをアフロ・キューバのリズムに乗せるだけで、クラシック・サルサの華麗な音楽的即興や、日常生活の物語や社会的・政治的な論評を綴るクラシック・サルサ の歌詞の余地を残していない、と批判した。このようなスタイルのアーティストには、オマール・アルファン、パルマー・エルナンデス、ホルヘ・ルイス・ピロ トなどがいる。 ★05: 1990s: ポップ・サルサとティンバの爆発  ホワイトハウスでパフォーマンスするマーク・アンソニー(2009年) 1990年代は、アメリカでは "ポップ・サルサ"、キューバでは "ティンバの爆発 "が起こった。 Marc Anthony - Valio La Pena (Salsa Version) セルジオ・ジョージは、ティト・ニエベス、ラ・インディア、マーク・アンソニーといったプエルトリコ出身のアーティストを起用し、サルサとコンテンポラ リーなポップ・スタイルをミックスしたアルバムを数枚プロデュースした。ジョージはまた、日本のサルサ・バンド、オルケスタ・デ・ラ・ルスもプロデュース している。ブレンダ・K・スター、サン・バイ・フォー、ビクトル・マヌエル、そしてキューバ系アメリカ人シンガーのグロリア・エステファンは、ラテン音楽 の影響を受けたヒット曲で、英米ポップス市場においてクロスオーバー的な成功を収めた。セルジオ・ジョージは、クラーベに対する自分の態度について、率直 に、そして堂々とこう語っている。私の中で一番重要なのは市場性だ。曲がヒットすればそれでいい。ミュージシャンを感動させようとするのをやめて、道行く 人が何を聴いているかに触れるようになってから、ヒット曲を書くようになった。しかし、ウォッシュバーンが指摘するように、クラーベを意識していないから といって、常にパスがもらえるわけではない: マーク・アンソニーは、ジョージの革新主義的アプローチの産物である。マーク・アンソニーは、ジョージの革新主義的なアプローチの産物である。ラテン音楽 の初心者だった彼は、音楽がどのように構成されているのかほとんど知らないまま、バンド・リーダーの地位に押し上げられた。彼がサルサのキャリアをスター トさせた直後の1994年の公演で、ある瞬間が明らかになった。ピアノ・ソロの最中、彼はティンバレスに近づき、スティックを手に取り、バンドと一緒にク ラーベ・ブロックでクラーベを弾こうとした。彼はリズムをどこに置けばいいのか見当もつかないことが明らかになった。その直後、サンフアン(プエルトリ コ)でのラジオ・インタビューで、彼は「商業的な成功は、ラテン音楽で成功するためにクラーベを知る必要はないことを証明した」と叫んだ。この発言はプエ ルトリコとニューヨークの両方で騒動を引き起こした。悪評を受けたアンソニーは、公の場でこの話題について語ることを控え、個人レッスンを受けるまではス テージでクラーベを演奏しようとしなかった[65]。 キューバでは、「ティンバの爆発」として知られるようになったのは、1992年のラ・チャランガ・ハバネラのデビュー・アルバム『Me Sube La Fiebre』からである。NGラ・バンダと同様、チャランガ・ハバネラもギアチェンジや曲固有のトゥンバオなど、いくつかの新しいテクニックを用いた が、彼らの音楽スタイルは大きく異なり、アルバムごとに変化し進化し続けた。チャランガ・ハバネラは、3枚のアルバムに代表されるように、90年代に3つ の異なるスタイルの時期を経験した[66] マノリン "エル・メディコ・デ・ラ・サルサ "は、医学部でエル・トスコ(NGラ・バンダ)に見出され、指名されたアマチュア・ソングライターで、この時期のもう一人のスーパースターだった。マノリ ンのクリエイティブ・チームには、ルイス・ブやチャカ・ナポレスなど数人のアレンジャーがいた。厳密な音楽的観点から見たマノリンの影響力もさることなが ら、彼のカリスマ性、人気、前代未聞の稼ぐ力はさらに激震的なインパクトを与え、ミュージシャンたちの間に1950年代以来の興奮を引き起こした。レ ジー・ジャクソンはマノリンを「飲み物をかき混ぜるストロー」と呼んだ。 ★06: ティンバの時代(キューバ) かろうじて定着していたサルサ・クバーナという言葉は再び人気を失い、ティンバに取って代わられた。その他の重要なティンバ・バンドには、アズーカル・ネ グラ、マノリン "エル・メディコ・デ・ラ・サルサ"、ハバナ・ドリメーラ、クリマックス、パウリートFG、サルサ・マヨール、ティエンポ・リブレ、パチート・アロンソ・ イ・サス・キニ・キニ、バンボレオ、ロス・ダン・デン、アラン・ペレス、イサック・デルガド、ティルソ・ドゥアルテ、クリマックス、マノリート・イ・ス・ トラブーコ、パウロFG、プピー・イ・ロス・ケ・ソンソンなどがいる。 キューバのティンバ・ミュージシャンとニューヨークのサルサ・ミュージシャンは、長年にわたって積極的かつ創造的な交流を続けてきたが、この2つのジャン ルは、異なる聴衆にアピールするため、やや分離したままだった。それでも2000年、ロス・ヴァン・ヴァンは史上初のグラミー賞最優秀サルサ・アルバム賞 を受賞した。 コロンビアでは、サルサはソノラ・カルセレス、カルロス・ヴィヴェス、オルケスタ・グアヤカン、グルーポ・ニッチェ、キケ・サンタンデール、ジュリアン・ コラソスといった人気バンドを輩出する人気音楽スタイルであり続けた。カリ市はコロンビアの「サルサの首都」として知られるようになった[68]。ベネズ エラでは、カビジャズがティンバのようなサルサにジャズの影響を強く加えた独自のモダン・ブレンドを演奏していた。 ★07: 2010s: ティンバ・フュージョンのヒット 00年代後半から10年代にかけて、いくつかのティンバ・バンドがサルサ、ティンバ、ヒップホップ、レゲトンの新しいハイブリッドを生み出した (Charanga Habanera - Gozando en la HabanaやPupy y Los que Son, Son-Loco con una motoなど)[69][70]。 数年後、キューバのレゲトン・バンド、Gente de Zonaとマーク・アンソニーが制作したティンバ・レゲトンの世界的メガヒットLa GozaderaはYouTubeで10億回以上の再生回数を記録した。 この時期に流行したクバトンと呼ばれるスタイルも、サルサ/ティンバをわずかに取り入れたレゲトンをベースにしたものだった。 |

African salsa Orchestra Baobab. Cuban music has been popular in sub-Saharan Africa since the mid twentieth century. To the Africans, clave-based Cuban popular music sounded both familiar and exotic.[71] The Encyclopedia of Africa v. 1. states: Beginning in the 1940s, Afro-Cuban [son] groups such as Septeto Habanero and Trio Matamoros gained widespread popularity in the Congo region as a result of airplay over Radio Congo Belge, a powerful radio station based in Léopoldville (now Kinshasa DRC). A proliferation of music clubs, recording studios, and concert appearances of Cuban bands in Léopoldville spurred on the Cuban music trend during the late 1940s and 1950s.[72] Congolese bands started doing Cuban covers and singing the lyrics phonetically. Soon, they were creating their own original Cuban-like compositions, with lyrics sung in French or Lingala, a lingua franca of the western Congo region. The Congolese called this new music rumba, although it was really based on the son. The Africans adapted guajeos to electric guitars, and gave them their own regional flavor. The guitar-based music gradually spread out from the Congo, increasingly taking on local sensibilities. This process eventually resulted in the establishment of several different distinct regional genres, such as soukous.[73] Cuban popular music played a major role in the development of many contemporary genres of African popular music. John Storm Roberts states: "It was the Cuban connection, but increasingly also New York salsa, that provided the major and enduring influences—the ones that went deeper than earlier imitation or passing fashion. The Cuban connection began very early and was to last at least twenty years, being gradually absorbed and re-Africanized."[74] The re-working of Afro-Cuban rhythmic patterns by Africans brings the rhythms full circle. The re-working of the harmonic patterns reveals a striking difference in perception. The I IV V IV harmonic progression, so common in Cuban music, is heard in pop music all across the African continent, thanks to the influence of Cuban music. Those chords move in accordance with the basic tenets of Western music theory. However, as Gerhard Kubik points out, performers of African popular music do not necessarily perceive these progressions in the same way: "The harmonic cycle of C-F-G-F [I-IV-V-IV] prominent in Congo/Zaire popular music simply cannot be defined as a progression from tonic to subdominant to dominant and back to subdominant (on which it ends) because in the performer's appreciation they are of equal status, and not in any hierarchical order as in Western music."[75] The largest wave of Cuban-based music to hit Africa was in the form of salsa. In 1974 the Fania All Stars performed in Zaire (known today as the Democratic Republic of the Congo), Africa, at the 80,000-seat Stadu du Hai in Kinshasa. This was captured on film and released as Live In Africa (Salsa Madness in the UK). The Zairean appearance occurred at a music festival held in conjunction with the Muhammad Ali/George Foreman heavyweight title fight. Local genres were already well established by this time. Even so, salsa caught on in many African countries, especially in the Senegambia and Mali. Cuban music had been the favorite of Senegal's nightspot in the 1950s to 1960s.[76] The Senegalese band Orchestra Baobab plays in a basic salsa style with congas and timbales, but with the addition of Wolof and Mandinka instruments and lyrics. According to Lise Waxer, "African salsa points not so much to a return of salsa to African soil (Steward 1999: 157) but to a complex process of cultural appropriation between two regions of the so-called Third World."[77] Since the mid-1990s African artists have also been very active through the super-group Africando, where African and New York musicians mix with leading African singers such as Bambino Diabate, Ricardo Lemvo, Ismael Lo and Salif Keita. It is still common today for an African artist to record a salsa tune, and add their own particular regional touch to it. |

アフリカン・サルサ オーケストラ・バオバブ キューバ音楽は、20世紀半ばからサハラ以南のアフリカで人気を博してきた。アフリカの人々にとって、クラーベをベースとしたキューバのポピュラー音楽は 親しみやすく、エキゾチックな響きをもっていた[71]: 1940年代から、セプテート・ハバネロやトリオ・マタモロスといったアフロ・キューバン・グループが、レオポルドヴィル(現コンゴ民主共和国キンシャ サ)に拠点を置く強力なラジオ局ラジオ・コンゴ・ベルジュで放送された結果、コンゴ地域で広く人気を博した。レオポルドヴィルでは、音楽クラブ、レコー ディングスタジオ、キューバ人バンドのコンサート出演が盛んになり、1940年代後半から1950年代にかけてキューバ音楽の流行に拍車がかかった [72]。 コンゴのバンドはキューバのカヴァーを始め、歌詞を音声化して歌った。やがて彼らは、フランス語やコンゴ西部の共通語であるリンガラ語で歌詞を歌い、 キューバ音楽のようなオリジナル曲を作るようになった。コンゴ人はこの新しい音楽をルンバと呼んだが、実際にはソンをベースにしていた。アフリカ人はグア ヒージョをエレクトリック・ギターに適合させ、独自の地方色を出した。ギターをベースとした音楽はコンゴから徐々に広がり、次第にその土地の感覚を取り込 んでいった。このプロセスは最終的に、スークスのようないくつかの異なる地域ジャンルの確立につながった[73]。 キューバのポピュラー音楽は、現代のアフリカのポピュラー音楽の多くのジャンルの発展に大きな役割を果たした。ジョン・ストーム・ロバーツは次のように述 べている: 「キューバとのつながり、そしてますますニューヨーク・サルサが、主要かつ永続的な影響、つまり以前の模倣や一過性の流行よりも深い影響を与えた。キュー バとのつながりは非常に早くから始まり、少なくとも20年は続き、徐々に吸収され、再アフリカ化された」[74]。アフリカ人によるアフロ・キューバのリ ズム・パターンの再加工は、リズムを一周させる。 和声パターンの再加工は、知覚の顕著な違いを明らかにする。キューバ音楽で一般的なI IV V IVの和声進行は、キューバ音楽の影響のおかげで、アフリカ大陸全土のポップミュージックで聴くことができる。これらの和音は、西洋音楽理論の基本的な考 え方に従って動いている。しかし、ゲルハルト・クービックが指摘するように、アフリカのポピュラー音楽の演奏者たちは、必ずしもこれらの進行を同じように 認識しているわけではない: 「コンゴ/ザイールのポピュラー音楽で顕著なC-F-G-F[I-IV-V-IV]の和声サイクルは、単純にトニックからサブドミナント、ドミナント、そ してサブドミナント(で終わる)に戻る進行として定義することはできない。 アフリカを襲ったキューバベースの音楽の最大の波は、サルサの形であった。1974年、ファニア・オール・スターズはアフリカのザイール(現在のコンゴ民 主共和国)で、キンシャサの8万人収容のスタドゥ・デュ・ハイで公演を行った。この模様はフィルムに収められ、『Live In Africa』(イギリスでは『Salsa Madness』)としてリリースされた。ザイールの出演は、モハメド・アリとジョージ・フォアマンのヘビー級タイトルマッチに合わせて開催された音楽祭 で行われた。この時すでに、地元のジャンルは確立されていた。それでも、サルサは多くのアフリカ諸国、特にセネガンビアとマリで流行した。キューバ音楽は 1950年代から1960年代にかけてセネガルのナイトスポットで好まれていた[76]。セネガルのバンド、オーケストラ・バオバブは、コンガとティンバ レスを使った基本的なサルサ・スタイルで演奏するが、ウォロフ語とマンディンカ語の楽器と歌詞を加えている。 リセ・ワクサーによれば、「アフリカン・サルサは、サルサがアフリカの地に戻ってきたというよりも(Steward 1999: 157)、いわゆる第三世界の2つの地域間の文化的流用の複雑なプロセスを指し示している」[77]。1990年代半ば以降、アフリカとニューヨークの ミュージシャンがバンビーノ・ディアバテ、リカルド・レンボ、イスマエル・ロー、サリフ・ケイタといったアフリカを代表するシンガーとミックスするスー パーグループ「アフリカンド」を通して、アフリカ人アーティストも活発に活動している。アフリカ人アーティストがサルサの曲をレコーディングし、そこに彼 らの地域特有のタッチを加えることは、今日でもよくあることだ。 |

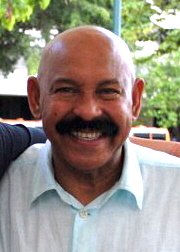

| Lyrics Salsa lyrics range from simple dance numbers, and sentimental romantic songs, to risque and politically radical subject matter. Music author Isabelle Leymarie notes that salsa performers often incorporate machoistic bravado (guapería) in their lyrics, in a manner reminiscent of calypso and samba, a theme she ascribes to the performers' "humble backgrounds" and subsequent need to compensate for their origins. Leymarie claims that salsa is "essentially virile, an affirmation of the man's pride and identity". As an extension of salsa's macho stance, manly taunts and challenges (desafio) are also a traditional part of salsa.[78] Salsa lyrics often quote from traditional Cuban sones and rumbas. Sometimes there are references to Afro-Cuban religions, such as Santeria, even by artists who are not themselves practitioners of the faith.[79] Salsa lyrics also exhibit Puerto Rican influences. Hector LaVoe, who sang with Willie Colón for nearly a decade used typical Puerto Rican phrasing in his singing.[80] It is not uncommon now to hear the Puerto Rican declamatory exclamation "le-lo-lai" in salsa.[81] Politically and socially activist composers have long been an important part of salsa, and some of their works, like Eddie Palmieri's "La libertad - lógico", became Latin, and especially Puerto Rican anthems. The Panamanian-born singer Ruben Blades in particular is well known for his socially-conscious and incisive salsa lyrics about everything from imperialism to disarmament and environmentalism, which have resonated with audiences throughout Latin America.[82] Many salsa songs contain a nationalist theme, centered around a sense of pride in black Latino identity, and may be in Spanish, English or a mixture of the two called Spanglish.[78] |

歌詞 サルサの歌詞は、シンプルなダンスナンバーや感傷的なロマンチックソングから、きわどいものや政治的に過激なものまでさまざまだ。音楽作家のイザベル・レ イマリーは、サルサのパフォーマーたちは、カリプソやサンバを彷彿とさせるようなマッチョ主義的な虚勢(グアペリア)を歌詞に取り入れることが多いと指摘 する。レイマリーは、サルサは「本質的に男らしく、男のプライドとアイデンティティを肯定するもの」だと主張する。サルサのマッチョなスタンスの延長とし て、男らしい嘲笑や挑戦(desafio)もサルサの伝統的な部分である[78]。 サルサの歌詞は伝統的なキューバのソーンやルンバから引用されることが多い。サルサの歌詞にはプエルトリコの影響も見られる。ウィリー・コロンと10年近 く一緒に歌っていたエクトル・ラヴォエは、典型的なプエルトリコ人のフレーズを使って歌っていた[80]。 サルサでプエルトリコ人の宣言的な感嘆詞「レ・ロ・ライ」を耳にすることは、今では珍しくない[81]。政治的、社会的に活動的な作曲家たちは、長い間サ ルサの重要な一部であり、エディ・パルミエリの「ラ・リベルタ~ロジコ」のような彼らの作品のいくつかは、ラテン、特にプエルトリコのアンセムとなった。 特にパナマ出身の歌手ルーベン・ブラデスは、 帝国主義から軍縮、環境保護主義に至るまで、あらゆることを社会的に意識した鋭いサルサの歌詞でよく知られており、ラテンアメリカ全土の聴衆の共感を呼ん でいる[82]。多くのサルサの歌は、黒人ラテンアメリカ人のアイデンティティに対する自負心を中心としたナショナリズムをテーマとしており、スペイン 語、英語、またはスパングリッシュと呼ばれるその2つの混合語で歌われることがある[78]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salsa_music |

|

La murga

es un género músico-teatral desarrollado en distintos países de América

Latina y en España, donde convive con la llamada "chirigota".123

Adoptado por varios países, generalmente se realiza durante alguna

festividad como el carnaval, fiestas patronales, efemérides de ciudades

o eventos deportivos. El vocablo se utiliza, por un lado, para

referirse al estilo musical y, por otro, a los conjuntos que lo

practican. Es muy popular en Argentina, Badajoz, Canarias, Chile,

Colombia, Huelva, Panamá y Uruguay, donde suele ser interpretada por un

agrupación con el acompañamiento musical de instrumentos de percusión. Murga en Argentina Murga en ArgentinaEn Argentina también se denomina murga a los conjuntos compuestos por músicos percusionistas, bailarines y fantasías (se llama así a quienes portan banderas, muñecos, sombrillas, etc.), que decoran todo el desfile murguero. Algunos conjuntos agregan lanzallamas, malabaristas, bailarines con espaldares o zancos, vedettes, estandartes y otros artistas. A estos grupos más numerosos se los denomina murga porteña. Estos conjuntos participan en los desfiles de carnaval conocidos como corsos todos los fines de semana de carnaval, es decir, un mes con anterioridad al miércoles de ceniza. Sin embargo, y a fines turísticos y organizativos, por lo general el gobierno de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires intenta organizar los corsos durante el mes de febrero, más allá del desfasaje que puede haber con la fecha de carnaval propiamente dicha. Las diferencias más destacadas entre las murgas de Buenos Aires y las originarias de otras regiones de Argentina, están dadas, no solo por los ritmos y las orquestaciones o arreglos que se utilizan, sino también por la ubicación de estos grupos en el corso. Las murgas de las provincias siempre presentan su espectáculo caminando y bailando a lo largo del corso y sin cantar, dejando su mejor parte para el escenario, donde muchas veces están ubicadas las autoridades organizadoras y estatales del lugar. Los ritmos de murga y comparsa de las provincias están diferenciados entre sí, por su origen, tempo y arreglos. En cambio, en Buenos Aires cuenta también con un lugar fijo, generalmente sobre un escenario o palco donde suben los directores o glosistas que presentan a su murga en una introducción, entonan algunas de sus canciones de murga (canción de entrada, crítica y retirada, y opcionalmente canción homenaje o murga canción). También es características su vestimenta, de coloridas galeras y levitas, herencia de la parodia que los sectores populares les hacían a las clases altas de fines del siglo xix. Otro rasgo de la murga porteña es el baile acrobático. A pesar de esto, cabe destacar que es cada vez mayor la cantidad de agrupaciones que toman la estructura de la murga porteña, y por lo tanto, la presentación en escenario, en el interior del país, fomentado esto por encuentros anuales nacionales, siendo el más importante el que se realiza en Suardi, Santa Fe, alrededor del 12 de octubre. Las murgas de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires son de dos estilos principales: el Centro Murga y la Agrupación Murguera.67 Centro Murga: Se considera el formato "ortodoxo" de la murga porteña, donde la música y el baile se destacan a ritmo de bombos con platillo, al cual en las últimas décadas se le ha agregado el redoblante y, en los últimos 15 años, instrumentos como surdos y repiques. No se suele cantar, y en el caso de hacerse se hace a forma de "coro" mientras se desfila. En cuanto al desfile, el Centro Murga tiene una primera sección de "mascotas" (o sea niños), luego las mujeres y al final, cerca de la percusión, los hombres. Centros Murga famosos por su tradición o estilo pueden ser: Los Amos de Devoto, Los Cometas de Boedo, Los Chiflados de Boedo, La Locura de Boedo, Los Chiflados de Almagro, Los Viciosos de Almagro, entre tantos.8 Agrupaciones Murgueras: Es el formato de la murga porteña donde más espacio se deja a las innovaciones. El canto es tan importante como la música, dejando el baile (en caso de haberlo) como un complemento. Siempre se hace desde arriba de un escenario (nunca desfilando, como los "centro murga"). Por su parte, la base musical está compuesta de bombos con platillo (que nunca puede faltar por considerarse típica del género porteño) y esporádicamente se le añade algún otro instrumento, como la guitarra criolla. No están obligados a tener mascotas ni a desfilar hombres y mujeres separados. Algunas Agrupaciones Murgueras reconocidas pueden ser: Atrevidos por Costumbre de Palermo, Los Calaveras de Constitución, Viva La Pepa de Barracas, Zarabanda Arrabalera de Parque de los Patricios, Los Inconscientes de Almagro y El Rechifle de Palermo, entre otras.9 Sobre el origen de la murga, es realmente poco lo que se sabe a ciencia cierta sobre la base de fuentes escritas fidedignas, más allá de que proviene de la época colonial, de la mezcla de esclavos aborígenes y negros. Una suerte de leyenda urbana cuenta que los ritmos característicos de murga porteña tienen una simbolización en lo que es la esclavitud (con el ritmo de rumba, que se baila mayormente agazapado), liberación con los tres saltos (representando tres patadas) y libertad (ritmo de matanza (de baile más "saltado" y con mayor movimiento de brazos). Independientemente de la veracidad o no de este origen de los ritmos característicos, lo cierto es que esa es gran parte de la significación actual que se le da a esta manifestación artística, donde se articulan lo artístico propiamente dicho y lo social. Montevideo - Agarrate Catalina Los carnavales más imponentes y famosos de Argentina se desarrollan en la ciudad de Gualeguaychú, a 210 km de la ciudad de Buenos Aires. Las murgas de la década del 50 y 60 se cambiaron por comparsas, similares a las de Río de Janeiro, se celebran en un corsódromo que fue construido en el predio de lo que era la Estación de Trenes. No obstante, las agrupaciones que allí desfilan reciben el nombre de comparsas dado que su origen difiere ampliamente del de las murgas en cuanto a música, vestuario y tipo de baile. Existen también murgas que a pesar de ser argentinas cultivan el estilo de la murga uruguaya. Hay numerosas agrupaciones de este estilo surgidas, en parte, a causa de la gran difusión que ha tenido este género en la Argentina a partir de la llegada de conjuntos uruguayos tales como Falta y Resto y Agarrate Catalina, entre otros. Algunas de estas agrupaciones son La Miseria es Ilegal, de Mar del Plata, La Rara Ira, Entre tanta pavada, La cuerda floja o La Cura de la Locura de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires; La Tandilera, de Tandil, La Buena Moza, de Mendoza, Puntuales pa la tardanza, de Concepción del Uruguay, La Cotorra, de Rosario, Rezonga La Ronca, de Santa Fe y La Tunga Tunga de Barrio Güemes, en Córdoba. Diego Morán - La Murga (Live)- carnaval Bs As 2020 murga fantasticos del Oeste |

ムルガは、ラテンアメリカ諸国やスペインで発展した音楽演劇のジャンル

で、いわゆる「チリゴタ」と共存している123。いくつかの国で採用され、一般にカーニバル、守護聖人祭、都市記念日、スポーツイベントなどの祝祭で上演

される。この用語は、一方では音楽のスタイル、他方ではそれを演奏するグループを指すのに使われる。アルゼンチン、バダホス、カナリア諸島、チリ、コロン

ビア、ウエルバ、パナマ、ウルグアイで非常に人気があり、打楽器の伴奏でグループによって演奏されるのが一般的である。 アルゼンチンのムルガ アルゼンチンのムルガアルゼンチンでは、ムルガはパレード全体を飾る打楽器奏者、踊り手、ファンタジア(旗、人形、傘などを持つ人)からなるアンサンブルの名前でもある。火炎 放射器、曲芸師、背中や竹馬を持った踊り子、ヴェデット、横断幕などのパフォーマーを加えるグループもある。このような大きなグループはムルガ・ポルテー ニャと呼ばれる。これらのグループは、毎年カーニバルの週末、つまり灰の水曜日の1ヶ月前に、コルソと呼ばれるカーニバルのパレードに参加する。しかし、 ブエノスアイレス自治州政府は、観光と組織上の理由から、カーニバルの日程とのずれを考慮して、一般的に2月中にコルソを開催するようにしている。 ブエノスアイレスのムルガとアルゼンチンの他地域のムルガとの最も重要な違いは、使用されるリズムや編成、編曲だけでなく、コルソにおけるこれらのグルー プの位置にもある。地方のムルガは、いつもコルソを歩きながら踊り、歌は歌わず、舞台のために最高の部分を残してショーを見せる。地方のムルガとコンパル サのリズムは、その起源、テンポ、アレンジによって区別される。一方、ブエノスアイレスでは、決まった場所、一般的には舞台やボックス席があり、そこに ディレクターやグロシスタが上がり、イントロダクションでムルガを紹介し、ムルガの歌(入場曲、批評と退場、オプションでトリビュート・ソングやムルガ・ ソング)を歌う。また、色とりどりのガレーやフロックコートといった衣装も特徴的で、これは19世紀末に大衆が上流階級をパロディ化したものを受け継いで いる。ムルガ・ポルテーニャのもうひとつの特徴は、アクロバティックな踊りである。毎年10月12日前後にサンタフェのスアルディで開催される全国大会が 最も重要である。 ブエノスアイレス市のムルガには、主にセントロ・ムルガとアグリュパシオン・ムルゲラの2つのスタイルがある67。 セントロ・ムルガ:ムルガ・ポルテーニャの "正統派 "とされるスタイルで、音楽と踊りは太鼓とシンバルのリズムが中心。通常、歌はなく、歌うとすればパレード中の「合唱」という形になる。パレードは、まず "マスコット"(子供たち)、次に女性たち、そして最後に打楽器の近くで男性たちがパレードを行う。伝統やスタイルで有名なムルガ・センターは以下の通り です: ロス・アモス・デ・デボト、ロス・コメタス・デ・ボエド、ロス・シフラドス・デ・ボエド、ラ・ロクラ・デ・ボエド、ロス・シフラドス・デ・アルマグロ、ロ ス・ビシオソス・デ・アルマグロなどである8。 Agrupaciones Murgueras:ムルガ・ポルテーニャの中で、最も革新の余地が残されている形式。歌は音楽と同じくらい重要で、踊りは(あれば)補足的なものであ る。常にステージの上から行われる(「セントロ・ムルガ」のようにパレードすることはない)。音楽のベースはシンバル付きのドラム(これはポルテーニョの 典型的なジャンルとされているため、決して欠かすことはできない)で構成され、クレオールギターのような他の楽器が加わることもある。マスコットをつけた り、男女別々にパレードする義務はない。有名なアグルーパシオネス・ムルゲラス(Agrupaciones Murgueras)には次のようなものがある: パレルモのAtrevidos por Costumbre、コンスティトゥシオンのLos Calaveras、バラカスのViva La Pepa、パルケ・デ・ロス・パトリシオスのZarabanda Arrabalera、アルマグロのLos Inconscientes、パレルモのEl Rechifleなどである9。 ムルガの起源については、原住民と黒人奴隷の混血による植民地時代のものであるという事実を除けば、信頼できる文献に基づく確かなことはほとんど知られて いない。都市伝説のようなもので、ムルガ・ポルテーニャの特徴的なリズムは、奴隷(主にしゃがんで踊るルンバのリズム)、解放(3回のジャンプ(3回の キックを表す))、自由(マタンザのリズム(腕の動きが多く、より "飛び跳ねる "ダンス))を象徴していると言われている。この特徴的なリズムの起源が真実かどうかはともかく、確かなことは、芸術的なものと社会的なものが融合したこ の芸術的な表現に現在与えられている意義の大部分がここにあるということだ。 carnaval Bs As 2020 murga fantasticos del Oeste アルゼンチンで最も印象的で有名なカーニバルは、ブエノスアイレス市から210キロ離れたグアレグアイチュ市で開催される。50年代から60年代のムルガ に代わって、リオデジャネイロと同じようなコンパーサが開催され、かつて駅だった場所に建てられたコルソドロモで行われる。ただし、音楽、衣装、踊りの種 類など、ムルジャとは起源が大きく異なるため、そこでパレードするグループはコンパルサと呼ばれる。 Montevideo - Agarrate Catalina また、アルゼンチン人でありながら、ウルグアイのムルガ・スタイルを受け継ぐムルガもある。ファルタ・イ・レスト(Falta y Resto)やアガラーテ・カタリナ(Agarrate Catalina)などのウルグアイのグループがアルゼンチンに上陸して以来、このジャンルがアルゼンチンに大きく広まったこともあり、このスタイルのグ ループが数多く生まれている。これらのグループの中には、マル・デル・プラタ出身のラ・ミセリア・エス・イレガル、ブエノスアイレス市出身のラ・ララ・イ ラ、エントレ・タンタ・パバダ、ラ・クエルダ・フローハ、ラ・クーラ・デ・ラ・ロクラ、タンディル出身のラ・タンディレラ、メンドーサ出身のラ・ブエナ・ モーザ、コンセプシオン・デル・ウルグアイ出身のプントゥアルレス・パ・ラ・タルダンザ、ロサリオ出身のラ・コトラ、サンタフェ出身のレゾンガ・ラ・ロン カ、コルドバのバリオ・グエメス出身のラ・トゥンガ・トゥンガなどがいる。 Diego Morán - La Murga (Live)- |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murga |

|

| The Fania

All-Stars

is a musical group formed in 1968 as a showcase for the musicians on

Fania Records, the leading salsa music record label of the time.[1] History Beginnings In 1964, Fania Records was founded in New York City by Jerry Masucci, an Italian-American lawyer with a love for Cuban music, and Johnny Pacheco, a flutist, percussionist and bandleader born in the Dominican Republic but raised in the South Bronx who had like minded musical tastes.[2] Masucci later bought out his partner Pacheco from Fania Entertainment Group, Ltd. and was the sole owner until his death in December 1997.[3] Throughout the early years, Fania used to distribute its records around New York. Eventually success from Pacheco's Cañonazo recording would lead the label to develop its roster. Masucci and Pacheco, now executive negotiator and musical director respectively, began acquiring musicians such as Bobby Valentín, Larry Harlow, and Ray Barretto. Success In 1968, Fania Records created a continuously revolving line-up of entertainers known as the Fania All-Stars. They were considered some of the best Latin Music performers in the world at that time. The original lineup consisted of: Band Leaders: Ray Barretto, Joe Bataan, Willie Colon, Larry Harlow, Monguito, Johnny Pacheco, Louie Ramirez, Ralph Robles, Mongo Santamaria, and Bobby Valentin. Singers; Héctor Lavoe, Adalberto Santiago, Pete "El Conde" Rodríguez, and Ismael Miranda. Other Musicians; La La, Ray Maldonado, Ralph Marzan, Orestes Vilató, Roberto Rodriguez, Jose Rodriguez, and Barry Rogers. Special Guests; Tito Puente, Eddie Palmieri, Ricardo Ray and Jimmy Sabater. They recorded Live At The Red Garter, Volumes 1 and 2 with this original lineup. On August 26, 1971 they recorded Fania All-Stars: Live At The Cheetah, Volumes 1 and 2.[4] It exhibited the entire All-Star family performing before a capacity audience in New York City's Cheetah Lounge. Following sell-out concerts in Puerto Rico, Chicago, and Panama, the All-Stars embarked on their first appearance at New York's Yankee Stadium on August 24, 1973.[5] The Stars performed before more than 40,000 spectators in a concert that featured Ray Barretto, Willie Colón, Edwin Tito Asencio, Rubén Blades, Larry Harlow, Johnny Pacheco, Roberto Roena, Pellín Rodríguez, Bobby Valentín, and Jorge Santana (younger brother of Carlos Santana), Celia Cruz, Héctor Lavoe, Cheo Feliciano, Ismael Miranda, Justo Betancourt, Ismael Quintana, Pete "El Conde" Rodríguez, Bobby Cruz and Santos Colón. Live at Yankee Stadium was included in the second set of 50 recordings in the U.S. National Recording Registry, solidifying the All-Stars as "culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant."[6] In 1974, the All Stars performed in Zaire, Africa, at the 80,000-seat Stade du 20 mai in Kinshasa. This was captured on film and released as Live in Africa (Salsa Madness in the UK). This Zairean appearance occurred along with James Brown and others at a music festival held in conjunction with the Muhammad Ali/George Foreman heavyweight title fight.[2] Footage of the performance was included in the 2008 documentary Soul Power.[7] To attain a wider market for salsa music, Fania made a deal with Columbia Records in the US for a series of crossover albums by the All-Stars, beginning with Delicate & Jumpy (1976), in which Steve Winwood united with the All-Stars' Pacheco, Valentin, Barreto, and Roena. During the same year, the Fania All-Stars made their sole UK appearance, at London's Lyceum Ballroom, with Winwood appearing as guest.[8] In 1978 the All-Stars released Live, recorded in concert on July 11, 1975 at San Juan's Roberto Clemente Coliseum. In 1979, they travelled to Havana, Cuba, to participate in the Havana Jam festival that took place between 2–4 March, alongside Rita Coolidge, Kris Kristofferson, Stephen Stills, the CBS Jazz All-Stars, Trio of Doom, Billy Swan, Bonnie Bramlett, Weather Report, and Billy Joel, plus Cuban artists such as Irakere, Pacho Alonso, Tata Güines, and Orquesta Aragón. Their performance is captured on Ernesto Juan Castellanos's documentary Havana Jam '79. During the same year the All-Stars released Crossover and Havana Jam on Fania, which came from a concert recorded in Havana on March 2.[9] Legacy In 2009, a historical documentary, Latin Music USA, shown on PBS TV, featured an episode on the Fania All-Stars, their evolution, career, and later demise.[10] In 2009 as well, the All-Stars returned to the stage, opening Carlos Santana's world tour in Bogotá, Colombia. The presentation caused mixed feelings inside the salsa circle though, mainly because they were treated as seconds by the concert's organizers. In March 2011, and subsequently in November 2012, a limited roster of the All-Stars performed in Lima, Peru.[11][12] One thing to note about the 2012 performance is the return of Ruben Blades. Ismael Quintana was not present in the November 2012 performance though, as well as Yomo Toro (Yomo died on June 30, 2012). In October 2013, a new, complete roster of the All-Stars performed in San Juan Puerto Rico, celebrating the 40th anniversary of their first performance in San Juan. This roster included the return of Orestes Vilato and Luigi Texidor, as well as the participation of Andy Montañez, Cita Rodriguez (Pete's daughter) and Willie Colón. This was Cheo Feliciano's last performance with the All-Stars before dying in a car accident in April 2014 in San Juan, Puerto Rico.[13] In 2015 the Fania All-Stars were chosen to receive ASCAP's honorary Latin Heritage Award.[14] The All-Stars were set to perform in Central Park, New York City on August 24 as part of the closing of the 50th anniversary celebration of the legendary Fania Records label. In 2019, many of the classic Fania records were re-issued in vinyl as part of the renewed interest in the vinyl record format.[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fania_All-Stars |

ファニア・オール・スターズは、1968年に当時のサルサ音楽の代表的