音楽

Music;

ミュージック;おんがく

Conjunto

musical religional, Dolores Copan, Honduras, ca. 1985; Caveza, Victot

Chavez

★ロラン・バルトによると音楽は2種類ある。(1)聴く音楽と、(2)自分で演奏する音楽(ムシカ・プラクティカ)である(バルト 1984:177)——もうひとつ、「聞く(entendre)は生理学的現象である。聴く(écouter)は心理学的行為である」(バルト 1984:155)

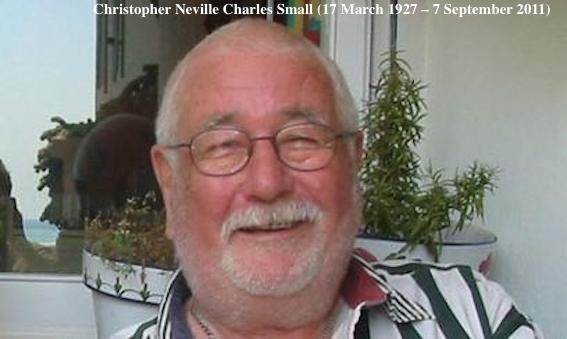

★ 最初、僕は「音楽(music)とは、形式、和声、旋律、リズム、またはその他の表現的な内容の何らかの組み合わせを作り出 すための音の配置である」と 書いた。しかし、クリストファー・スモール(Christopher Neville Charles Small, 1927-2011)さんの"Musicking : the meanings of performing and listening"という本に触れて、このような、人間性 ぬきの音楽の定義は間違っていると確信するにいたった。スモールさんは、音楽と人間が関わる以下のような画面をまず、列挙する。このことを 「音楽のあたらしい定義」と呼んでみてもいいだろう。

1) 大きなクラシックのコンサートホールがまさに始まろうとしている瞬間

2) スーパーマケットのなかで、無味乾燥な音が流れ、誰も関心をもたれないような状況

3) 爆音のような音が鳴り響く巨大なロックコンサート会場

4) イヤフォンやヘッドフォンをした若者があるいている——彼の耳からは外部からはわからないような音が流れているのだろう

5) ジャズの即興演奏がいまおわったサクソフォニストが汗をふいている。即興のパートはいま、ピアニストが引き継いでいる

6) 教会のオルガン奏者が賛美歌の一節をひきはじめると、会衆が歌い始めるが、そのユニゾンは不揃いである

7) 多数のパトリオットが起立している巨大なスタジアムで愛国歌がうたわれている

8) きらびやかな衣装を着たオペラ歌手が劇の途中で熱唱している。瀕死のヒロインを演じているが、公演がおわると、生き返ったかのように、聴衆のスタンディン グオベーションを受けている

9) 主婦が古いポピュラーソングをハミンングしながら朝のベッドメイクしている。彼女は、その歌詞をあいまいに歌っているが、まんざら嫌いではなさそうだ

★

以上のような情景描写(=引用者は、そこから想像して多少脚色をしている)をしたあと、音楽とはこういうものだと示す(=定義する);「これらのあまりに多種多様な状況と行為、それにサウンドを有意味に組織させるようなさまざまな

やり方のすべてが、音楽と名づけられている」(スモール

2023:18-19)。スモールさんは、音楽はモノではなく行為だと端的に指摘する;「音楽の本質とその根本的な意味とは、対象、すなわち音楽作品のなかにあるのではなく、人びとの

行為のなかにある」(スモール 2023:29)と。

☆ よって(再度引用する)陳腐化した過去の定義はこちらである→ 音楽(music)とは、形式、和声、旋律、リズム、またはその他の表現的な内容の何らかの組み合わせを作り出 すための音の配置である。音楽の定義は 文化によって異なるが、音楽はすべての人間社会の側面であり、文化的普遍である。 音楽の創作は一般的に作曲、即興、演奏に分けられるが、このテーマ自体は学問、批評、哲学、心理学、治療の文脈にまで及ぶ。音楽は、人間の声を含 む膨大な種類の楽器を用いて演奏されたり即興されたりすることがあり、そのためその極めて多様な創造性の機会がしばしば評価される。音楽を研究する方法や アプローチを「音楽理論」ないしは音楽理論研究とよぶ。世界の音楽の多様性を研究する 学問を「音楽人類学あるいは民族音楽学」という。

★ クリストファー・ネヴィル・チャールズ・スモール(Christopher Neville Charles Small、1927年3月17日 - 2011年9月7日)の紹介

「ク

リストファー・ネヴィル・チャールズ・スモール(Christopher Neville Charles Small、1927年3月17日 -

2011年9月7日)は、ニュージーランド生まれの音楽家、教育者、講師であり、音楽学、社会音楽学、民族音楽学の分野で多くの影響力のある著書や論文の

著者である。彼は音楽を目的語(名詞)ではなく、過程(動詞)として強調するためにミュジッキングという言葉を作った。

スモールはニュージーランドのパーマストン・ノースで歯科医と元教師の間に生まれ、3人兄弟の末っ子だった。

初期の学校教育はテラス・エンド小学校とラッセル・ストリート小学校(1932-39年)、パーマストン・ノース・ボーイズ・ハイスクール(1940-

41年)、ワンガヌイ・カレッジ・スクール(1942-44年)で行われた。1945年から1952年までオタゴ大学、その後ビクトリア・ユニバーシ

ティー・カレッジに通う。1953年から1958年までホロウェヌア・カレッジで(同時にモロー・プロダクションズ社で教育用アニメーション映画の制作に

携わる)、1959年から1960年までワイヒ・カレッジで教鞭をとる。

1960年にはニュージーランド政府から奨学金を授与され、1961年にはイギリスを旅行し、その後ロンドンでプリオール・レーニエに作曲を師事、バー

ナード・ランズ、ルイジ・ノーノ、ヴィトルド・ルトスワフスキらとも交流した。留学後はイギリスに留まり、バーミンガムのアンスティ教育大学などで教鞭を

とった。1971年から86年までロンドンのイーリング高等教育カレッジで音楽の上級講師を務め、1979年にはダーティントン・カレッジ・オブ・アーツ

でも教鞭をとった。1977年から1986年にかけては、シラキュース大学ロンドンセンターで音楽史の非常勤教授を務め、1981年から1984年にかけ

ては、サセックス大学のBEdコースのサマースクールで音楽のチューターを務めた。

スモールは1986年に教職を退き、スペインのシッチェスに移り住み、2006年に結婚したパートナーのネヴィル・ブレイスウェイト(ジャマイカ生まれの

ダンサー、歌手、ユースワーカー)と暮らした。スペイン滞在中、スモールはカタルーニャの合唱団を指揮し、彼の作品を賞賛するヨーロッパとアメリカの人々

が定期的に訪れていた。アメリカでは、チャールズ・ケイル、ロバート・ウォルザー、スーザン・マクラリー、『ヴィレッジ・ヴォイス』誌のロック評論家ロ

バート・クリストガウといった著名な音楽学者たちが彼の考えを支持している[2]。

ネヴィル・ブレイスウェイトは2006年に、スモールは2011年に死去。妹のローズマリーがいる。

生前は多くの本を出版し、『Music in Education』、『Tempo』、『The Musical Times』、『Music and

Letters』、『Musical

America』などの雑誌に記事を掲載。イギリス、ノルウェー、アメリカの多くの教育機関で講義を行い、英国作曲家協会(1984年)、即興演奏家協会

(1985年)、音楽教育者全国会議(コネチカット州ハートフォード、1985年、ワシントンDC、1989年)、民族音楽学会(マサチューセッツ州ケン

ブリッジ、1988年)などの組織に論文を寄稿した」→「世界音楽化」より)

「ク

リストファー・ネヴィル・チャールズ・スモール(Christopher Neville Charles Small、1927年3月17日 -

2011年9月7日)は、ニュージーランド生まれの音楽家、教育者、講師であり、音楽学、社会音楽学、民族音楽学の分野で多くの影響力のある著書や論文の

著者である。彼は音楽を目的語(名詞)ではなく、過程(動詞)として強調するためにミュジッキングという言葉を作った。

スモールはニュージーランドのパーマストン・ノースで歯科医と元教師の間に生まれ、3人兄弟の末っ子だった。

初期の学校教育はテラス・エンド小学校とラッセル・ストリート小学校(1932-39年)、パーマストン・ノース・ボーイズ・ハイスクール(1940-

41年)、ワンガヌイ・カレッジ・スクール(1942-44年)で行われた。1945年から1952年までオタゴ大学、その後ビクトリア・ユニバーシ

ティー・カレッジに通う。1953年から1958年までホロウェヌア・カレッジで(同時にモロー・プロダクションズ社で教育用アニメーション映画の制作に

携わる)、1959年から1960年までワイヒ・カレッジで教鞭をとる。

1960年にはニュージーランド政府から奨学金を授与され、1961年にはイギリスを旅行し、その後ロンドンでプリオール・レーニエに作曲を師事、バー

ナード・ランズ、ルイジ・ノーノ、ヴィトルド・ルトスワフスキらとも交流した。留学後はイギリスに留まり、バーミンガムのアンスティ教育大学などで教鞭を

とった。1971年から86年までロンドンのイーリング高等教育カレッジで音楽の上級講師を務め、1979年にはダーティントン・カレッジ・オブ・アーツ

でも教鞭をとった。1977年から1986年にかけては、シラキュース大学ロンドンセンターで音楽史の非常勤教授を務め、1981年から1984年にかけ

ては、サセックス大学のBEdコースのサマースクールで音楽のチューターを務めた。

スモールは1986年に教職を退き、スペインのシッチェスに移り住み、2006年に結婚したパートナーのネヴィル・ブレイスウェイト(ジャマイカ生まれの

ダンサー、歌手、ユースワーカー)と暮らした。スペイン滞在中、スモールはカタルーニャの合唱団を指揮し、彼の作品を賞賛するヨーロッパとアメリカの人々

が定期的に訪れていた。アメリカでは、チャールズ・ケイル、ロバート・ウォルザー、スーザン・マクラリー、『ヴィレッジ・ヴォイス』誌のロック評論家ロ

バート・クリストガウといった著名な音楽学者たちが彼の考えを支持している[2]。

ネヴィル・ブレイスウェイトは2006年に、スモールは2011年に死去。妹のローズマリーがいる。

生前は多くの本を出版し、『Music in Education』、『Tempo』、『The Musical Times』、『Music and

Letters』、『Musical

America』などの雑誌に記事を掲載。イギリス、ノルウェー、アメリカの多くの教育機関で講義を行い、英国作曲家協会(1984年)、即興演奏家協会

(1985年)、音楽教育者全国会議(コネチカット州ハートフォード、1985年、ワシントンDC、1989年)、民族音楽学会(マサチューセッツ州ケン

ブリッジ、1988年)などの組織に論文を寄稿した」→「世界音楽化」より)

| ★音楽人類学・民族音楽学▶︎音楽と感情▶音楽・身 体・芸術︎︎▶いわゆる「食いつき力」について︎▶︎︎音楽と時間性▶音楽の文化研究︎▶︎︎ポリフォニー▶︎聴覚のチーズケーキとしての音楽▶プエルトリコの音楽▶︎マヤ・マリンバ音楽用語集▶サルサ音楽の歴史︎︎▶︎世 界音楽化▶ピタゴラスと音楽︎︎▶︎音楽とナショナリズム▶コール&レスポンス︎︎▶︎進化音楽学▶ラップ音楽 ︎︎▶︎宗教と音楽性▶︎︎北米のフォーク・ミュージック・アンソロジー▶︎音楽美学批判▶日本におけるキリスト教布教と西洋音楽の導入︎︎▶︎プエルトリコの抵抗の音▶︎︎▶︎ラップ音楽・黒人アイデンティティ・身体経験▶︎︎クレズマー音楽▶︎ラッ プ音楽におけるミソジニー▶︎︎メレンゲ音楽▶︎ガリフナの人と音楽経験▶︎︎歌うネアンデルタールとスティヴン・ミズン▶︎ニーチェと音楽▶ポストヴァナキュラーな音楽としてのクレズマー︎︎▶︎君もラッパーになれる!!▶︎︎ギャングス タ・ラップからナルコ・コリードまで▶︎▶︎記 憶=記録の悪魔▶キリスト教のカントール︎︎▶︎ラテン・ヒップ・ポップ▶レゲトンとデムボウ︎︎▶︎ミュージコフィリア▶▶︎キングヘロイン▶音響的な世界︎︎▶︎︎︎▶︎ワールドミュージックとグローバリゼーション▶︎︎▶︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎ | ︎☆マーレー・シェイファーとサウンドスケープ▶︎ルベン・ブラデス▶︎︎ラ

ファエル・トルヒージョと『チボの祝宴』︎︎▶▶︎︎カート・コバーンとその生涯▶︎ドミートリイ・ショスタコーヴィチ▶セリア・クルス︎▶︎エクトル・ラ

ボ▶カノ・エストレメーラ︎▶︎︎皆川達夫の研究▶グレン・グールド▶︎︎ロバート・ラッハマン︎▶︎︎オリヴァー・サックス▶︎ピタゴラスと音楽▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎ |

| ︎︎☆カンティガス・デ・サンタ・マリア▶︎セギディージャ▶︎︎カンティーガ▶︎中世音楽▶イベリア世界の宗教音楽︎︎▶先史時代からアルアンダルスからレコンキスタまで︎▶スペインの音楽▶︎︎ヴィリャンシーコ資料集▶ヴィリャンシーコ︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎ |

Grooved

side of the Voyager Golden Record launched along the Voyager probes to

space, which feature music from around the world.

ボイジャー探査機とともに宇宙へ打ち上げられたゴールデンレコードの溝付き側面には、世界中の音楽が収録されている。

| In

the most general of terms, music

is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of form,

harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise expressive content.[1][2][3]

Definitions of music vary depending on culture,[4] though it is an

aspect of all human societies and a cultural universal.[5] While

scholars agree that music is defined by a few specific elements, there

is no consensus on their precise definitions.[6] The creation of music

is commonly divided into musical composition, musical improvisation,

and musical performance,[7] though the topic itself extends into

academic disciplines, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and

therapeutic contexts. Music may be performed or improvised using a vast

range of instruments, including the human voice, and thus is often

credited for its extreme versatility and opportunity for creativity.[8] In some musical contexts, a performance or composition may be to some extent improvised. For instance, in Hindustani classical music, the performer plays spontaneously while following a partially defined structure and using characteristic motifs. In modal jazz, the performers may take turns leading and responding while sharing a changing set of notes. In a free jazz context, there may be no structure whatsoever, with each performer acting at their discretion. Music may be deliberately composed to be unperformable or agglomerated electronically from many performances. Music is played in public and private areas, highlighted at events such as festivals, rock concerts, and orchestra performances, and heard incidentally as part of a score or soundtrack to a film, TV show, opera, or video game. Musical playback is the primary function of an MP3 player or CD player, and a universal feature of radios and smartphones. Music often plays a key role in social activities, religious rituals, rite of passage ceremonies, celebrations, and cultural activities. The music industry includes songwriters, performers, sound engineers, producers, tour organizers, distributors of instruments, accessories, and sheet music. Compositions, performances, and recordings are assessed and evaluated by music critics, music journalists, and music scholars, as well as amateurs. |

最も一般的な用語では、音楽(music)

とは、形式、和声、旋律、リズム、またはその他の表現的な内容の何らかの組み合わせを作り出すための音の配置である[1][2][3][→音楽理論]。音楽の定義は文化

によって異なるが[4]、音楽はすべての人間社会の側面であり、文化的普遍である[5]。

[音楽の創作は一般的に作曲、即興、演奏に分けられるが[7]、このテーマ自体は学問、批評、哲学、心理学、治療の文脈にまで及ぶ。音楽は、人間の声を含

む膨大な種類の楽器を用いて演奏されたり即興されたりすることがあり、そのためその極めて多様な創造性の機会がしばしば評価される[8]。 音楽の文脈によっては、演奏や作曲がある程度即興で行われることもある。例えば、ヒンドゥスターニー古典音楽では、演奏者は部分的に定義された構造に従 い、特徴的なモチーフを用いながら自発的に演奏する。モーダル・ジャズでは、演奏者が交代でリードしたり反応したりしながら、変化する音符のセットを共有 することがある。フリー・ジャズでは、構成は一切なく、各演奏者が自由に演奏する。音楽は、演奏不可能なように意図的に作曲されることもあれば、多くの演 奏から電子的に集積されることもある。音楽は公共の場やプライベートな場所で演奏され、フェスティバル、ロックコンサート、オーケストラの演奏などのイベ ントで脚光を浴び、映画、テレビ番組、オペラ、ビデオゲームのスコアやサウンドトラックの一部として付随的に聴かれる。音楽再生はMP3プレーヤーやCD プレーヤーの主な機能であり、ラジオやスマートフォンの普遍的な機能でもある。 音楽は社会活動、宗教儀式、通過儀礼、祝典、文化活動において重要な役割を果たすことが多い。音楽産業には、作詞作曲家、演奏家、サウンドエンジニア、プ ロデューサー、ツアー主催者、楽器、アクセサリー、楽譜の流通業者などが含まれる。作曲、演奏、録音は、アマチュアだけでなく、音楽評論家、音楽ジャーナ リスト、音楽学者によっても評価・査定される。 |

Etymology and terminology In Greek mythology, the nine Muses were the inspiration for many creative endeavors, including the arts, and eventually became closely aligned with music specifically. The modern English word 'music' came into use in the 1630s.[9] It is derived from a long line of successive precursors: the Old English 'musike' of the mid-13th century; the Old French musique of the 12th century; and the Latin mūsica.[10][8][n 1] The Latin word itself derives from the Ancient Greek mousiké (technē)—μουσική (τέχνη)—literally meaning "(art) of the Muses".[10][n 2] The Muses were nine deities in Ancient Greek mythology who presided over the arts and sciences.[13][14] They were included in tales by the earliest Western authors, Homer and Hesiod,[15] and eventually came to be associated with music specifically.[14] Over time, Polyhymnia would reside over music more prominently than the other muses.[11] The Latin word musica was also the originator for both the Spanish música and French musique via spelling and linguistic adjustment, though other European terms were probably loanwords, including the Italian musica, German Musik, Dutch muziek, Norwegian musikk, Polish muzyka and Russian muzïka.[14] The modern Western world usually defines music as an all-encompassing term used to describe diverse genres, styles, and traditions.[16] This is not the case worldwide, and languages such as modern Indonesian (musik) and Shona (musakazo) have recently adopted words to reflect this universal conception, as they did not have words that fit exactly the Western scope.[14] Before Western contact in East Asia, neither Japan nor China had a single word that encompasses music in a broad sense, but culturally, they often regarded music in such a fashion.[17] The closest word to mean music in Chinese, yue, shares a character with le, meaning joy, and originally referred to all the arts before narrowing in meaning.[17] Africa is too diverse to make firm generalizations, but the musicologist J. H. Kwabena Nketia has emphasized African music's often inseparable connection to dance and speech in general.[18] Some African cultures, such as the Songye people of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Tiv people of Nigeria, have a strong and broad conception of 'music' but no corresponding word in their native languages.[18] Other words commonly translated as 'music' often have more specific meanings in their respective cultures: the Hindi word for music, sangita, properly refers to art music,[19] while the many Indigenous languages of the Americas have words for music that refer specifically to song but describe instrumental music regardless.[20] Though the Arabic musiqi can refer to all music, it is usually used for instrumental and metric music, while khandan identifies vocal and improvised music.[21] |

語源と用語 ギリシャ神話では、9人のミューズが芸術を含む多くの創造的な活動のインスピレーションを与え、最終的には特に音楽と密接に結びついた。 現代英語の「music」は1630年代に使用されるようになった[9]。この語は、13世紀半ばの古英語の「musike」、12世紀の古フランス語の 「musique」、ラテン語の「mūsica」という長い前身に由来する。 [10][8][n1]ラテン語自体は古代ギリシア語のmousiké(technē)-μουσική(τέχνη)に由来し、文字通り「ミューズの (芸術)」を意味する[10][n2]。 ミューズは古代ギリシア神話に登場する9人の神で、芸術と科学を司った。 [13][14]彼らは西洋最古の作家であるホメロスやヘシオドスの物語に登場し[15]、やがて特に音楽と結び付けられるようになった。 [11]ラテン語のmusicaは、綴りや言語的な調整を経て、スペイン語のmúsicaとフランス語のmusiqueの語源にもなったが、他のヨーロッ パの言葉はおそらく借用語であり、イタリア語のmusica、ドイツ語のmusik、オランダ語のmuziek、ノルウェー語のmusikk、ポーランド 語のmuzyka、ロシア語のmuzïkaなどがある[14]。 現代の西洋世界は通常、音楽を多様なジャンル、スタイル、伝統を表現するために使われる包括的な用語として定義している[16]。 これは世界的にそうではなく、現代のインドネシア語(musik)やショナ語(musakazo)のような言語は、西洋の範囲にぴったり合う単語を持って いなかったため、この普遍的な概念を反映する単語を最近採用した。 [14]。東アジアで西洋と接触する以前は、日本も中国も広義に音楽を包括する単一の単語を持っていなかったが、文化的には音楽をそのように捉えることが 多かった[17]。中国語で音楽を意味する最も近い単語であるyueは、喜びを意味するleと字を共有しており、元々はすべての芸術を指していたが、意味 が狭まった[17]。コンゴ民主共和国のソンイェ族やナイジェリアのティヴ族など、アフリカの文化の中には「音楽」という強く広い概念を持っていながら、 彼らの母国語にはそれに対応する言葉がないものもある[18]。 [18]その他、一般的に「音楽」と訳される単語は、それぞれの文化においてより具体的な意味を持つことが多い。ヒンディー語で音楽を意味するサンギータ は、正しくは芸術音楽を指す[19]。一方、アメリカ大陸の多くの先住民の言語には、特に歌を指す音楽の単語があるが、それとは関係なく器楽音楽を表す [20]。アラビア語のmusiqiはすべての音楽を指すことができるが、通常は器楽音楽と計量音楽に使用され、khandanは声楽と即興音楽を指す [21]。 |

| History Main article: History of music Origins and prehistory Further information: Origins of music and Prehistoric music  Bone flute from Geissenklösterle, Germany, dated around c. 43,150–39,370 BP.[22] B_1431 Sha-Amun-en-su, Egyptian singer.[23] It is often debated to what extent the origins of music will ever be understood,[24] and there are competing theories that aim to explain it.[25] Many scholars highlight a relationship between the origin of music and the origin of language, and there is disagreement surrounding whether music developed before, after, or simultaneously with language.[26] A similar source of contention surrounds whether music was the intentional result of natural selection or was a byproduct spandrel of evolution.[26] The earliest influential theory was proposed by Charles Darwin in 1871, who stated that music arose as a form of sexual selection, perhaps via mating calls.[27] Darwin's original perspective has been heavily criticized for its inconsistencies with other sexual selection methods,[28] though many scholars in the 21st century have developed and promoted the theory.[29] Other theories include that music arose to assist in organizing labor, improving long-distance communication, benefiting communication with the divine, assisting in community cohesion or as a defense to scare off predators.[30] Prehistoric music can only be theorized based on findings from paleolithic archaeology sites. The Divje Babe flute, carved from a cave bear femur, is thought to be at least 40,000 years old, though there is considerable debate surrounding whether it is truly a musical instrument or an object formed by animals.[31] The earliest objects whose designations as musical instruments are widely accepted are bone flutes from the Swabian Jura, Germany, namely from the Geissenklösterle, Hohle Fels and Vogelherd caves.[32] Dated to the Aurignacian (of the Upper Paleolithic) and used by Early European modern humans, from all three caves there are eight examples, four made from the wing bones of birds and four from mammoth ivory; three of these are near complete.[32] Three flutes from the Geissenklösterle are dated as the oldest, c. 43,150–39,370 BP.[22][n 3] Antiquity Main article: Ancient music The earliest material and representational evidence of Egyptian musical instruments dates to the Predynastic period, but the evidence is more securely attested in the Old Kingdom when harps, flutes and double clarinets were played.[33] Percussion instruments, lyres, and lutes were added to orchestras by the Middle Kingdom. Cymbals[34] frequently accompanied music and dance, much as they still do in Egypt today. Egyptian folk music, including the traditional Sufi dhikr rituals, are the closest contemporary music genre to ancient Egyptian music, having preserved many of its features, rhythms and instruments.[35][36] The "Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal", found on clay tablets in the ancient Syrian city of Ugarit, is the oldest surviving notated work of music, dating back to approximately 1400 BCE.[37][38] Music was an important part of social and cultural life in ancient Greece, in fact it was one of the main subjects taught to children. Musical education was considered to be important for the development of an individual's soul. Musicians and singers played a prominent role in Greek theater,[39] and those who received a musical education were seen as nobles and in perfect harmony (as can be read in the Republic, Plato). Mixed gender choruses performed for entertainment, celebration, and spiritual ceremonies.[40] Instruments included the double-reed aulos and a plucked string instrument, the lyre, principally a special kind called a kithara. Music was an important part of education, and boys were taught music starting at age six. Greek musical literacy created significant musical development. Greek music theory included the Greek musical modes, that eventually became the basis for Western religious and classical music. Later, influences from the Roman Empire, Eastern Europe, and the Byzantine Empire changed Greek music. The Seikilos epitaph is the oldest surviving example of a complete musical composition, including musical notation, from anywhere in the world.[41] The oldest surviving work written on the subject of music theory is Harmonika Stoicheia by Aristoxenus.[42] Asian cultures Main article: Music of Asia Asian music covers a swath of music cultures surveyed in the articles on Arabia, Central Asia, East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Several have traditions reaching into antiquity.  Indian women dressed in regional attire playing a variety of musical instruments popular in different parts of India Indian classical music is one of the oldest musical traditions in the world.[43] Sculptures from the Indus Valley civilization show dance[44] and old musical instruments, like the seven-holed flute. Stringed instruments and drums have been recovered from Harappa and Mohenjo Daro by excavations carried out by Mortimer Wheeler.[45] The Rigveda, an ancient Hindu text, has elements of present Indian music, with musical notation to denote the meter and mode of chanting.[46] Indian classical music (marga) is monophonic, and based on a single melody line or raga rhythmically organized through talas. The poem Cilappatikaram provides information about how new scales can be formed by modal shifting of the tonic from an existing scale.[47] Present day Hindi music was influenced by Persian traditional music and Afghan Mughals. Carnatic music, popular in the southern states, is largely devotional; the majority of the songs are addressed to the Hindu deities. There are songs emphasizing love and other social issues.  Indonesia is the home of gong chime, there are variants across Indonesia, especially in Java and Bali. Indonesian music has been formed since the Bronze Age culture migrated to the Indonesian archipelago in the 2nd-3rd centuries BCE. Indonesian traditional music uses percussion instruments, especially kendang and gongs. Some of them developed elaborate and distinctive instruments, such as the sasando stringed instrument on the island of Rote, the Sundanese angklung, and the complex and sophisticated Javanese and Balinese gamelan orchestras. Indonesia is the home of gong chime, a general term for a set of small, high pitched pot gongs. Gongs are usually placed in order of note, with the boss up on a string held in a low wooden frame. The most popular form of Indonesian music is gamelan, an ensemble of tuned percussion instruments that include metallophones, drums, gongs and spike fiddles along with bamboo suling (like a flute).[48][49] Chinese classical music, the traditional art or court music of China, has a history stretching over about 3,000 years. It has its own unique systems of musical notation, as well as musical tuning and pitch, musical instruments and styles or genres. Chinese music is pentatonic-diatonic, having a scale of twelve notes to an octave (5 + 7 = 12) as does European-influenced music.[50] Western classical Main article: Classical music Early music Breves dies hominis Duration: 3 minutes and 32 seconds.3:32 by Léonin or Pérotin Problems playing this file? See media help.  Musical notation from a Catholic Missal, c. 1310–1320 The medieval music era (500 to 1400), which took place during the Middle Ages, started with the introduction of monophonic (single melodic line) chanting into Catholic Church services. Musical notation was used since ancient times in Greek culture, but in the Middle Ages, notation was first introduced by the Catholic Church, so chant melodies could be written down, to facilitate the use of the same melodies for religious music across the Catholic empire. The only European Medieval repertory that has been found, in written form, from before 800 is the monophonic liturgical plainsong chant of the Catholic Church, the central tradition of which was called Gregorian chant. Alongside these traditions of sacred and church music there existed a vibrant tradition of secular song (non-religious songs). Examples of composers from this period are Léonin, Pérotin, Guillaume de Machaut, and Walther von der Vogelweide.[51][52][53][54] Renaissance music (c. 1400 to 1600) was more focused on secular themes, such as courtly love. Around 1450, the printing press was invented, which made printed sheet music much less expensive and easier to mass-produce (prior to the invention of the press, all notated music was hand-copied). The increased availability of sheet music spread musical styles quicker and across a larger area. Musicians and singers often worked for the church, courts and towns. Church choirs grew in size, and the church remained an important patron of music. By the middle of the 15th century, composers wrote richly polyphonic sacred music, in which different melody lines were interwoven simultaneously. Prominent composers from this era include Guillaume Du Fay, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Thomas Morley, Orlando di Lasso and Josquin des Prez. As musical activity shifted from the church to aristocratic courts, kings, queens and princes competed for the finest composers. Many leading composers came from the Netherlands, Belgium, and France; they are called the Franco-Flemish composers.[55] They held important positions throughout Europe, especially in Italy. Other countries with vibrant musical activity included Germany, England, and Spain. Common practice period Baroque Main article: Baroque music Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 5 Duration: 8 minutes and 34 seconds.8:34 Toccata and Fugue by J.S. Bach  The Baroque era of music took place from 1600 to 1750, as the Baroque artistic style flourished across Europe; and during this time, music expanded in its range and complexity. Baroque music began when the first operas (dramatic solo vocal music accompanied by orchestra) were written. During the Baroque era, polyphonic contrapuntal music, in which multiple, simultaneous independent melody lines were used, remained important (counterpoint was important in the vocal music of the Medieval era). German Baroque composers wrote for small ensembles including strings, brass, and woodwinds, as well as for choirs and keyboard instruments such as pipe organ, harpsichord, and clavichord. During this period several major music forms were defined that lasted into later periods when they were expanded and evolved further, including the fugue, the invention, the sonata, and the concerto.[56] The late Baroque style was polyphonically complex and richly ornamented. Important composers from the Baroque era include Johann Sebastian Bach (Cello suites), George Frideric Handel (Messiah), Georg Philipp Telemann and Antonio Vivaldi (The Four Seasons). Classicism Main article: Classical period (music) Symphony No. 40 G minor Duration: 8 minutes and 14 seconds.8:14 Symphony 40 G minor by W.A. Mozart Problems playing this file? See media help.  Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. The music of the Classical period (1730 to 1820) aimed to imitate what were seen as the key elements of the art and philosophy of Ancient Greece and Rome: the ideals of balance, proportion and disciplined expression. (Note: the music from the Classical period should not be confused with Classical music in general, a term which refers to Western art music from the 5th century to the 2000s, which includes the Classical period as one of a number of periods). Music from the Classical period has a lighter, clearer and considerably simpler texture than the Baroque music which preceded it. The main style was homophony,[57] where a prominent melody and a subordinate chordal accompaniment part are clearly distinct. Classical instrumental melodies tended to be almost voicelike and singable. New genres were developed, and the fortepiano, the forerunner to the modern piano, replaced the Baroque era harpsichord and pipe organ as the main keyboard instrument (though pipe organ continued to be used in sacred music, such as Masses). Importance was given to instrumental music. It was dominated by further development of musical forms initially defined in the Baroque period: the sonata, the concerto, and the symphony. Other main kinds were the trio, string quartet, serenade and divertimento. The sonata was the most important and developed form. Although Baroque composers also wrote sonatas, the Classical style of sonata is completely distinct. All of the main instrumental forms of the Classical era, from string quartets to symphonies and concertos, were based on the structure of the sonata. The instruments used chamber music and orchestra became more standardized. In place of the basso continuo group of the Baroque era, which consisted of harpsichord, organ or lute along with a number of bass instruments selected at the discretion of the group leader (e.g., viol, cello, theorbo, serpent), Classical chamber groups used specified, standardized instruments (e.g., a string quartet would be performed by two violins, a viola and a cello). The practice of improvised chord-playing by the continuo keyboardist or lute player, a hallmark of Baroque music, underwent a gradual decline between 1750-1800.[58] One of the most important changes made in the Classical period was the development of public concerts. The aristocracy still played a significant role in the sponsorship of concerts and compositions, but it was now possible for composers to survive without being permanent employees of queens or princes. The increasing popularity of classical music led to a growth in the number and types of orchestras. The expansion of orchestral concerts necessitated the building of large public performance spaces. Symphonic music including symphonies, musical accompaniment to ballet and mixed vocal/instrumental genres, such as opera and oratorio, became more popular.[59][60][61] The best known composers of Classicism are Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Christoph Willibald Gluck, Johann Christian Bach, Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert. Beethoven and Schubert are also considered to be composers in the later part of the Classical era, as it began to move towards Romanticism. Romanticism Main article: Romantic music Die Walküre Duration: 27 minutes and 57 seconds.27:57 Die Walküre by Richard Wagner Problems playing this file? See media help.  The piano was the centrepiece of social activity for middle-class urbanites in the 19th century (Moritz von Schwind, 1868). The man at the piano is composer Franz Schubert. Romantic music (c. 1820 to 1900) from the 19th century had many elements in common with the Romantic styles in literature and painting of the era. Romanticism was an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement was characterized by its emphasis on emotion and individualism as well as glorification of all the past and nature. Romantic music expanded beyond the rigid styles and forms of the Classical era into more passionate, dramatic expressive pieces and songs. Romantic composers such as Wagner and Brahms attempted to increase emotional expression and power in their music to describe deeper truths or human feelings. With symphonic tone poems, composers tried to tell stories and evoke images or landscapes using instrumental music. Some composers promoted nationalistic pride with patriotic orchestral music inspired by folk music. The emotional and expressive qualities of music came to take precedence over tradition.[62] Romantic composers grew in idiosyncrasy, and went further in the syncretism of exploring different art-forms in a musical context, (such as literature), history (historical figures and legends), or nature itself. Romantic love or longing was a prevalent theme in many works composed during this period. In some cases, the formal structures from the classical period continued to be used (e.g., the sonata form used in string quartets and symphonies), but these forms were expanded and altered. In many cases, new approaches were explored for existing genres, forms, and functions. Also, new forms were created that were deemed better suited to the new subject matter. Composers continued to develop opera and ballet music, exploring new styles and themes.[39] In the years after 1800, the music developed by Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert introduced a more dramatic, expressive style. In Beethoven's case, short motifs, developed organically, came to replace melody as the most significant compositional unit (an example is the distinctive four note figure used in his Fifth Symphony). Later Romantic composers such as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Antonín Dvořák, and Gustav Mahler used more unusual chords and more dissonance to create dramatic tension. They generated complex and often much longer musical works. During the late Romantic period, composers explored dramatic chromatic alterations of tonality, such as extended chords and altered chords, which created new sound "colors." The late 19th century saw a dramatic expansion in the size of the orchestra, and the industrial revolution helped to create better instruments, creating a more powerful sound. Public concerts became an important part of well-to-do urban society. It also saw a new diversity in theatre music, including operetta, and musical comedy and other forms of musical theatre.[39] 20th and 21st century Main article: 20th-century music  Landman's 2006 Moodswinger, a 3rd-bridged overtone zither and an example of experimental musical instruments In the 19th century, a key way new compositions became known to the public, was by the sales of sheet music, which middle class amateur music lovers would perform at home, on their piano or other common instruments, such as the violin. With 20th-century music, the invention of new electric technologies such as radio broadcasting and mass market availability of gramophone records meant sound recordings heard by listeners (on the radio or record player), became the main way to learn about new songs and pieces.[63] There was a vast increase in music listening as the radio gained popularity and phonographs were used to replay and distribute music, anyone with a radio or record player could hear operas, symphonies and big bands in their own living room. During the 19th century, the focus on sheet music had restricted access to new music to middle and upper-class people who could read music and who owned pianos and other instruments. Radios and record players allowed lower-income people, who could not afford an opera or symphony concert ticket to hear this music. It meant people could hear music from different parts of the country, or even different parts of the world, even if they could not afford to travel to these locations. This helped to spread musical styles.[64] The focus of art music in the 20th century was characterized by exploration of new rhythms, styles, and sounds. The horrors of World War I influenced many of the arts, including music, and composers began exploring darker, harsher sounds. Traditional music styles such as jazz and folk music were used by composers as a source of ideas for classical music. Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, and John Cage were influential composers in 20th-century art music. The invention of sound recording and the ability to edit music gave rise to new subgenres of classical music, including the acousmatic[65] and Musique concrète schools of electronic composition. Sound recording was a major influence on the development of popular music genres, because it enabled recordings of songs and bands to be widely distributed. The introduction of the multitrack recording system had a major influence on rock music, because it could do more than record a band's performance. Using a multitrack system, a band and their music producer could overdub many layers of instrument tracks and vocals, creating new sounds that would not be possible in a live performance.[66][67] Jazz evolved and became an important genre of music over the course of the 20th century, and during the second half, rock music did the same. Jazz is an American musical artform that originated in the beginning of the 20th century, in African American communities in the Southern United States from a confluence of African and European music traditions. The style's West African pedigree is evident in its use of blue notes, improvisation, polyrhythms, syncopation, and the swung note.[68]  A selection of guitars and amps at Apple Music Row Rock music is a genre of popular music that developed in the 1950s from rock and roll, rockabilly, blues, and country music.[69] The sound of rock often revolves around the electric or acoustic guitar, and it uses a strong back beat laid down by a rhythm section. Along with the guitar or keyboards, saxophone and blues-style harmonica are used as soloing instruments. In its "purest form", it "has three chords, a strong, insistent back beat, and a catchy melody."[70] The traditional rhythm section for popular music is rhythm guitar, electric bass guitar, drums. Some bands have keyboard instruments such as organ, piano, or, since the 1970s, analog synthesizers. In the 1980s, pop musicians began using digital synthesizers, such as the DX-7 synthesizer, electronic drum machines such as the TR-808 and synth bass devices (such as the TB-303) or synth bass keyboards. In the 1990s, an increasingly large range of computerized hardware musical devices and instruments and software (e.g. digital audio workstations) were used. In the 2020s, soft synths and computer music apps make it possible for bedroom producers to create and record types of music, such as electronic dance music, in their home, adding sampled and digital instruments and editing the recording digitally. In the 1990s, bands in genres such as nu metal began including DJs in their bands. DJs create music by manipulating recorded music, using a DJ mixer.[71][72] Innovation in music technology continued into the 21st century, including the development of isomorphic keyboards and Dynamic Tonality. |

歴史 主な記事 音楽の歴史 起源と前史 さらに詳しい情報 音楽の起源と先史時代の音楽  43,150-39,370BP頃とされるドイツ、ガイセンクレステル出土の骨製フルート[22]。 B_1431 Sha-Amun-en-su、エジプトの歌手[23]。 多くの学者が音楽の起源と言語の起源との関係を強調しており、音楽が言語の前に発達したのか、言語の後に発達したのか、それとも言語と同時に発達したのか を巡って意見が分かれている[26]。 [26]最も初期の有力な説は、1871年にチャールズ・ダーウィンによって提唱されたもので、ダーウィンは、音楽はおそらく交尾の呼びかけを介して、性 淘汰の一形態として生じたと述べている[27]。 [29]その他の説としては、音楽は労働の組織化を助けるために生まれた、長距離コミュニケーションを改善するために生まれた、神とのコミュニケーション を助けるために生まれた、共同体の結束を助けるために生まれた、あるいは捕食者を追い払うための防衛手段として生まれた、などがある[30]。 先史時代の音楽は、旧石器時代の考古学的遺跡からの発見に基づいてのみ理論化することができる。ホラアナグマの大腿骨から彫られたディヴィエ・バベのフ ルートは、少なくとも4万年前のものと考えられているが、それが本当に楽器なのか、それとも動物によって形成された物体なのかについてはかなりの議論があ る[31]。楽器として広く受け入れられている最古の物体は、ドイツのシュヴァーベン・ジュラ地方、すなわちガイセンクレステル、ホーレ・フェルス、 フォーゲルヘルトの洞窟から出土した骨のフルートである[32]。 [32]オーリニア紀(後期旧石器時代)のものとされ、ヨーロッパ初期の現生人類が使用していた。3つの洞窟すべてから8つの例があり、4つは鳥の翼の骨 から、4つはマンモスの象牙から作られている。 古代 主な記事 古代音楽 エジプトの楽器に関する最古の資料や表象的な証拠は前王朝時代のものであるが、ハープ、フルート、ダブルクラリネットが演奏されていた古王国時代には、そ の証拠がより確実に証明されている[33]。シンバル[34]は、今日のエジプトでもそうであるように、音楽や舞踊の伴奏によく使われた。伝統的なスー フィーのディクルの儀式を含むエジプトの民族音楽は、その特徴、リズム、楽器の多くを保存しており、古代エジプト音楽に最も近い現代音楽のジャンルである [35][36]。 古代シリアの都市ウガリトの粘土板で発見された「ニッカルへのヒュリア賛歌」は、紀元前約1400年に遡る、現存する最古の楽譜化された音楽作品である [37][38]。 古代ギリシャにおいて、音楽は社会的・文化的生活の重要な一部であり、実際、音楽は子供たちに教えられる主要科目の一つであった。音楽教育は個人の魂の成 長にとって重要であると考えられていた。ギリシア演劇では音楽家や歌手が重要な役割を果たし[39]、音楽教育を受けた者は高貴で完璧な調和を保った者と みなされた(『共和国』プラトンにその記述がある)。楽器はダブルリードのアウロスと撥弦楽器のライアー、主にキタラと呼ばれる特殊なものであった [40]。音楽は教育の重要な一部であり、男子は6歳から音楽を教えられた。ギリシアの音楽リテラシーは、音楽の大きな発展をもたらした。ギリシアの音楽 理論には、ギリシアの音楽様式が含まれ、それはやがて西洋の宗教音楽やクラシック音楽の基礎となった。その後、ローマ帝国、東ヨーロッパ、ビザンチン帝国 からの影響がギリシャ音楽を変えた。セイキロスの墓碑銘は、楽譜を含む完全な楽曲の現存する世界最古の例である[41]。音楽理論を主題として書かれた現 存する最古の著作は、アリストクセヌスのHarmonika Stoicheiaである[42]。 アジアの文化 主な記事 アジアの音楽 アジアの音楽は、アラビア、中央アジア、東アジア、南アジア、東南アジアの各記事で調査した音楽文化を網羅している。いくつかの伝統は古代にまで及んでい る。  インド各地で親しまれているさまざまな楽器を演奏する、民族衣装をまとったインドの女性たち。 インド古典音楽は、世界で最も古い音楽の伝統のひとつである[43]。インダス渓谷文明の彫刻には、舞踊[44]や7つの穴のある笛のような古い楽器が描 かれている。古代ヒンドゥー教のテキストである『リグヴェーダ』には、現在のインド音楽の要素があり、詠唱のメーターとモードを示す楽譜が記されている [46]。現在のヒンディー音楽は、ペルシアの伝統音楽とアフガニスタンのムガール人の影響を受けている。南部の諸州で人気のあるカルナティック音楽は、 主に献身的な音楽であり、曲の大半はヒンドゥー教の神々に捧げられたものである。恋愛やその他の社会問題を強調する曲もある。  インドネシアはゴング・チャイムの故郷であり、インドネシア全土、特にジャワ島とバリ島に変種がある。 インドネシア音楽は、紀元前2~3世紀に青銅器時代の文化がインドネシア諸島に移住して以来、形成されてきた。インドネシアの伝統音楽は打楽器、特にケン ダンと銅鑼を使う。中には、ローテ島の弦楽器ササンド、スンダのアンクルン、複雑で洗練されたジャワやバリのガムラン・オーケストラなど、精巧で個性的な 楽器を開発したものもある。インドネシアはゴング・チャイムの本場であり、小型で高音のポット・ゴングのセットの総称である。ゴングは通常、低い木枠に繋 がれた弦の上にボスを立てて、音順に配置される。インドネシア音楽の最もポピュラーな形態はガムランであり、メタロフォン、ドラム、ゴング、スパイク・ フィドルに竹製のスリン(フルートのようなもの)を加えた調律打楽器のアンサンブルである[48][49]。 中国古典音楽は、中国の伝統的な芸術または宮廷音楽であり、約3,000年以上の歴史がある。楽譜、調律、音程、楽器、スタイルやジャンルなど、独自のシ ステムを持っている。中国の音楽はペンタトニック・ディアトニックであり、ヨーロッパの影響を受けた音楽と同様に1オクターブに対して12音(5+7= 12)の音階を持つ[50]。 西洋クラシック 主な記事 クラシック音楽 初期の音楽 ブレーヴス・ディエス・ホ ミニス 演奏時間 3分32秒 レオナンまたはペロタン作 このファイルの再生に問題がありますか?メディアヘルプをご覧ください。  カトリック・ミサ典礼書の楽譜、1310-1320年頃 中世に起こった音楽の時代(500年から1400年)は、カトリック教会の礼拝に単旋律(単一の旋律線)の聖歌が導入されたことから始まった。ギリシャ文 化圏では古くから楽譜が使われていたが、中世になるとカトリック教会によって初めて楽譜が導入され、聖歌の旋律を書き留めることができるようになり、カト リック帝国全体で同じ旋律を宗教音楽に使用しやすくなった。800年以前のヨーロッパ中世のレパートリーで楽譜が発見されているのは、カトリック教会の単 旋律の典礼聖歌だけで、その中心的な伝統はグレゴリオ聖歌と呼ばれていた。このような聖歌や教会音楽の伝統と並行して、世俗歌曲(非宗教歌曲)の活気ある 伝統も存在した。この時代の作曲家の例としては、レオニン、ペロタン、ギョーム・ド・マショー、ワルター・フォン・デア・フォーゲルヴァイデなどが挙げら れる[51][52][53][54]。 ルネサンス音楽(1400年頃~1600年頃)は、宮廷恋愛などの世俗的なテーマに重きを置いていた。1450年頃に印刷機が発明され、印刷された楽譜は より安価で大量生産が容易になった(印刷機が発明される以前は、楽譜はすべて手書きでコピーされていた)。楽譜の入手性が高まったことで、音楽のスタイル はより早く、より広い地域に広まった。音楽家や歌手は教会や宮廷、町のために働くことが多くなった。教会の聖歌隊は規模を拡大し、教会は音楽の重要な後援 者であり続けた。15世紀半ばには、作曲家たちは、異なる旋律線を同時に織り交ぜた、豊かな多声部の聖楽を作曲した。この時代の著名な作曲家には、ギョー ム・デュ・フェイ、ジョヴァンニ・ピエルルイジ・ダ・パレストリーナ、トマス・モーリー、オルランド・ディ・ラッソ、ジョスカン・デ・プレなどがいる。音 楽活動が教会から貴族の宮廷に移ると、王、王妃、王侯が最高の作曲家を競い合うようになった。代表的な作曲家の多くはオランダ、ベルギー、フランス出身 で、彼らはフランコ・フレミッシュと呼ばれる[55]。その他、ドイツ、イギリス、スペインなどでも活発な音楽活動が行われた。 共通練習期間 バロック 主な記事 バロック音楽 トッカータとフーガ ニ短調 BWV 5 演奏時間: 8分34秒8:34 トッカータとフーガ by J.S. Bach  バロック音楽の時代は1600年から1750年までで、ヨーロッパ全土でバロック芸術様式が花開いた。バロック音楽は、最初のオペラ(オーケストラを伴う 劇的な独唱曲)が書かれたときに始まった。バロック時代には、複数の独立した旋律線を同時に用いるポリフォニックな対位法音楽が引き続き重要視された(中 世の声楽音楽では対位法が重要だった)。ドイツ・バロックの作曲家たちは、弦楽器、金管楽器、木管楽器などの小編成のアンサンブルや、合唱団、パイプオル ガン、チェンバロ、クラヴィコードなどの鍵盤楽器のために作曲した。この時代には、フーガ、インヴェンション、ソナタ、協奏曲など、いくつかの主要な音楽 形式が定義され、それらは後の時代まで続き、さらに拡張され進化した。バロック時代の重要な作曲家としては、ヨハン・セバスティアン・バッハ(チェロ組 曲)、ジョージ・フリデリック・ヘンデル(メサイア)、ゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン、アントニオ・ヴィヴァルディ(四季)などが挙げられる。 古典主義 主な記事 古典派時代(音楽) 交響曲第40番 ト短調 演奏時間:8分14秒8:14 交響曲第40番 ト短調 by W.A. Mozart このファイルの再生に問題がありますか? メディアヘルプをご覧ください。  ヴォルフガング・アマデウス・モーツァルトは、古典派時代に多作で影響力のある作曲家である。 古典派時代(1730年~1820年)の音楽は、古代ギリシャ・ローマの芸術と哲学の重要な要素であると考えられていた、バランス、比率、規律ある表現の 理想を模倣することを目的としていました。(注:古典派音楽とは、5世紀から2000年代までの西洋の芸術音楽を指す言葉で、古典派音楽もその中に含まれ る)。古典派の音楽は、それ以前のバロック音楽よりも軽く、明瞭で、かなり単純なテクスチュアを持つ。主な様式はホモフォニーであり[57]、著名な旋律 と従属的な和音伴奏部分が明確に区別されている。古典楽器の旋律は、ほとんど声楽的で歌いやすい傾向があった。新しいジャンルが開発され、現代のピアノの 前身であるフォルテピアノが、バロック時代のチェンバロやパイプオルガンに代わって主要な鍵盤楽器となった(ただし、ミサ曲などの神聖な音楽ではパイプオ ルガンが使われ続けた)。 器楽が重視された。ソナタ、協奏曲、交響曲など、バロック時代に定義された音楽形式がさらに発展した。その他、トリオ、弦楽四重奏曲、セレナード、ディ ヴェルティメントなどがあった。ソナタは最も重要で発展した形式である。バロックの作曲家もソナタを書いたが、古典派のソナタ様式はまったく異なる。弦楽 四重奏曲から交響曲、協奏曲に至るまで、古典派時代の主要な器楽曲の形式はすべてソナタの構成に基づいている。室内楽やオーケストラで使われる楽器は、よ り標準化された。チェンバロ、オルガン、リュートと、グループリーダーの裁量で選ばれた数種類の低音楽器(ヴィオール、チェロ、テオルボ、サーペントな ど)で構成されていたバロック時代の通奏低音グループに代わって、古典派の室内楽グループは、指定された標準化された楽器を使用するようになった(例え ば、弦楽四重奏は、2本のヴァイオリン、ヴィオラ、チェロで演奏される)。バロック音楽の特徴であった通奏低音奏者やリュート奏者による即興的な和音演奏 は、1750年から1800年にかけて徐々に衰退していった[58]。 古典派時代に起こった最も重要な変化のひとつは、公開コンサートの発展であった。貴族は依然としてコンサートや作曲のスポンサーとして重要な役割を果たし ていたが、作曲家が王妃や王侯の正社員になることなく生き残ることが可能になった。クラシック音楽の人気が高まるにつれ、オーケストラの数も種類も増えて いった。オーケストラ・コンサートの拡大により、大規模な公共演奏スペースの建設が必要となった。交響曲、バレエの伴奏音楽、オペラやオラトリオのような 声楽と器楽の混成ジャンルを含む交響曲が人気を博した[59][60][61]。 古典主義の最も有名な作曲家は、カール・フィリップ・エマニュエル・バッハ、クリストフ・ウィリバルト・グルック、ヨハン・クリスチャン・バッハ、ヨーゼ フ・ハイドン、ヴォルフガング・アマデウス・モーツァルト、ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェン、フランツ・シューベルトである。ベートーヴェンと シューベルトは、古典派がロマン派に移行し始めた後期の作曲家とも言われている。 ロマン主義 主な記事 ロマン派音楽 ワルキューレ 演奏時間:27分57秒27:57 リヒャルト・ワーグナーの「ワルキューレ このファイルの再生に問題がありますか? メディアヘルプをご覧ください。  ピアノは19世紀、中流階級の都市生活者にとって社会活動の中心であった(Moritz von Schwind, 1868)。ピアノの前にいるのは作曲家フランツ・シューベルト。 19世紀のロマン派音楽(1820年頃~1900年頃)は、当時の文学や絵画におけるロマン派の様式と共通する要素を多く持っていた。ロマン主義とは、芸 術的、文学的、知的な運動であり、感情や個人主義を強調し、過去や自然を賛美することを特徴としていた。ロマン派の音楽は、古典派時代の堅苦しいスタイル や形式を超え、より情熱的でドラマチックな表現力豊かな曲や歌へと拡大した。ワーグナーやブラームスといったロマン派の作曲家たちは、より深い真理や人間 の感情を表現するために、音楽における感情表現やパワーを高めようとした。交響的トーンポエムでは、作曲家たちは器楽曲を使って物語を語り、イメージや風 景を喚起しようとした。民族音楽に触発された愛国的な管弦楽曲で民族的な誇りを高めた作曲家もいた。音楽の感情的で表現的な特質は、伝統よりも優先される ようになった[62]。 ロマン派の作曲家たちは特異性を増し、音楽の文脈の中で異なる芸術形式(文学など)、歴史(歴史上の人物や伝説)、あるいは自然そのものを探求するシンク レティズムをさらに推し進めた。ロマンティックな愛や憧れは、この時期に作曲された多くの作品に共通するテーマであった。場合によっては、古典派時代の形 式構造が引き続き使われることもあったが(弦楽四重奏曲や交響曲で使われるソナタ形式など)、これらの形式は拡張され、変更された。多くの場合、既存の ジャンル、形式、機能に対して新しいアプローチが模索された。また、新しい主題に適した新しい形式も生まれた。作曲家たちは新しいスタイルやテーマを探求 しながら、オペラやバレエ音楽を発展させ続けた[39]。 1800年以降の数年間、ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンとフランツ・シューベルトによって開発された音楽は、より劇的で表現力豊かなスタイルを導 入した。ベートーヴェンの場合、有機的に展開される短いモチーフが、旋律に代わって最も重要な作曲単位となった(例として、彼の交響曲第5番で使用された 特徴的な4音図形が挙げられる)。ピョートル・イリイチ・チャイコフスキー、アントニン・ドヴォルザーク、グスタフ・マーラーといった後のロマン派の作曲 家たちは、劇的な緊張感を生み出すために、より珍しい和音や不協和音を多用した。彼らは複雑で、しばしばはるかに長い音楽作品を生み出した。後期ロマン派 の時代には、作曲家たちは、延長和音や変和音など、調性の劇的な半音階的変化を探求し、新しい音の "色 "を生み出した。19世紀後半には、オーケストラの規模が劇的に拡大し、産業革命によってより優れた楽器が作られ、よりパワフルなサウンドが生み出され た。公共コンサートは裕福な都市社会で重要な位置を占めるようになった。また、オペレッタ、ミュージカル・コメディ、その他の音楽劇など、劇場音楽にも新 たな多様性が生まれた[39]。 20世紀と21世紀 主な記事 20世紀の音楽  ランドマンが2006年に発表した、実験的楽器の一例である3rd-bridged overtone zither「Moodswinger 19世紀には、新曲が一般に知られるようになる重要な方法は楽譜の販売であり、中産階級のアマチュア音楽愛好家たちは、自宅のピアノやヴァイオリンなどの 一般的な楽器で演奏していた。20世紀の音楽では、ラジオ放送のような新しい電気技術の発明や、蓄音機によるレコードの大量販売によって、リスナーが(ラ ジオやレコードプレーヤーで)聴く音源が、新しい曲や楽曲を知るための主な手段となった[63]。ラジオが普及し、蓄音機が音楽の再生や配信に使われるよ うになると、音楽を聴く機会が大幅に増え、ラジオやレコードプレーヤーがあれば、誰でもオペラや交響曲、ビッグバンドを自宅の居間で聴くことができるよう になった。19世紀には、楽譜が中心だったため、新しい音楽を聴くことができたのは、楽譜が読め、ピアノやその他の楽器を所有している中流階級や上流階級 の人々に限られていた。ラジオやレコードプレーヤーは、オペラやシンフォニーのコンサートのチケットを買う余裕のない低所得者層にも、こうした音楽を聴か せることができた。つまり、たとえ旅行する余裕がなくても、国内のさまざまな地域、あるいは世界のさまざまな地域の音楽を聴くことができたのである。これ は音楽スタイルの普及に役立った[64]。 20世紀の芸術音楽の焦点は、新しいリズム、スタイル、サウンドの探求によって特徴づけられた。第一次世界大戦の恐怖は、音楽を含む多くの芸術に影響を与 え、作曲家たちはより暗く、より過酷なサウンドを探求し始めた。ジャズや民族音楽といった伝統的な音楽スタイルは、作曲家たちによってクラシック音楽のア イデアの源として利用された。イーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキー、アーノルド・シェーンバーグ、ジョン・ケージは、20世紀の芸術音楽に影響を与えた作曲家で ある。録音技術が発明され、音楽を編集できるようになったことで、電子音楽のアクースマティック[65]やムジーク・コンクレートなど、クラシック音楽の 新しいサブジャンルが生まれた。録音は、歌やバンドの録音を広く流通させることができたため、ポピュラー音楽のジャンルの発展に大きな影響を与えた。マル チトラック・レコーディング・システムの導入はロック音楽に大きな影響を与えた。マルチトラックシステムを使うことで、バンドとその音楽プロデューサー は、楽器のトラックやヴォーカルを何層にも重ねてオーバーダビングすることができ、ライブパフォーマンスでは不可能な新しいサウンドを作り出すことができ た[66][67]。 ジャズは20世紀の間に進化し、音楽の重要なジャンルとなり、後半にはロックも同じようになった。ジャズは20世紀初頭にアメリカ南部のアフリカ系アメリ カ人のコミュニティでアフリカとヨーロッパの音楽の伝統の合流から生まれたアメリカの音楽芸術である。このスタイルの西アフリカの血統は、ブルーノート、 即興演奏、ポリリズム、シンコペーション、スイングノートの使用において明らかである[68]。  Apple Music Rowのギターとアンプのセレクション ロック・ミュージックは、1950年代にロックンロール、ロカビリー、ブルース、カントリー・ミュージックから発展したポピュラー音楽のジャンルである [69]。ロックのサウンドはエレキギターやアコースティック・ギターを中心に展開されることが多く、リズム・セクションによる強力なバック・ビートが使 われる。ギターやキーボードとともに、サックスやブルース・スタイルのハーモニカがソロ楽器として使われる。ポピュラー音楽の伝統的なリズム・セクション は、リズム・ギター、エレキ・ベース、ドラムスである。オルガンやピアノ、1970年代以降はアナログ・シンセサイザーなどの鍵盤楽器を持つバンドもあ る。1980年代に入ると、ポップ・ミュージシャンはDX-7シンセサイザーなどのデジタル・シンセサイザー、TR-808などの電子ドラム・マシン、シ ンセ・ベース・デバイス(TB-303など)やシンセ・ベース・キーボードを使い始めた。1990年代には、コンピュータ化されたハードウェア音楽機器や 楽器、ソフトウェア(デジタル・オーディオ・ワークステーションなど)がますます幅広く使われるようになった。2020年代には、ソフトシンセやコン ピューター音楽アプリによって、ベッドルーム・プロデューサーが自宅でエレクトロニック・ダンス・ミュージックなどのタイプの音楽を制作・録音し、サンプ リングやデジタル楽器を加え、録音をデジタル編集することが可能になった。1990年代には、ニューメタルなどのジャンルのバンドがDJをバンドに加える ようになった。DJはDJミキサーを使い、録音された音楽を操作することで音楽を創作する[71][72]。 音楽技術の革新は21世紀に入っても続き、同形キーボードやダイナミック・トーナリティの開発もそのひとつである。 |

| Creation Composition Main article: Musical composition  French Baroque music composer Michel Richard Delalande (1657–1726), pen in hand  People composing music in 2013 using electronic keyboards and computers "Composition" is the act or practice of creating a song, an instrumental music piece, a work with both singing and instruments, or another type of music. In many cultures, including Western classical music, the act of composing also includes the creation of music notation, such as a sheet music "score", which is then performed by the composer or by other singers or musicians. In popular music and traditional music, the act of composing, which is typically called songwriting, may involve the creation of a basic outline of the song, called the lead sheet, which sets out the melody, lyrics and chord progression. In classical music, the composer typically orchestrates his or her own compositions, but in musical theatre and in pop music, songwriters may hire an arranger to do the orchestration. In some cases, a songwriter may not use notation at all, and instead, compose the song in her mind and then play or record it from memory. In jazz and popular music, notable recordings by influential performers are given the weight that written scores play in classical music.[73][74] Even when music is notated relatively precisely, as in classical music, there are many decisions that a performer has to make, because notation does not specify all of the elements of music precisely. The process of deciding how to perform music that has been previously composed and notated is termed "interpretation". Different performers' interpretations of the same work of music can vary widely, in terms of the tempos that are chosen and the playing or singing style or phrasing of the melodies. Composers and songwriters who present their own music are interpreting their songs, just as much as those who perform the music of others. The standard body of choices and techniques present at a given time and a given place is referred to as performance practice, whereas interpretation is generally used to mean the individual choices of a performer.[75] Although a musical composition often uses musical notation and has a single author, this is not always the case. A work of music can have multiple composers, which often occurs in popular music when a band collaborates to write a song, or in musical theatre, when one person writes the melodies, a second person writes the lyrics, and a third person orchestrates the songs. In some styles of music, such as the blues, a composer/songwriter may create, perform and record new songs or pieces without ever writing them down in music notation. A piece of music can also be composed with words, images, or computer programs that explain or notate how the singer or musician should create musical sounds. Examples range from avant-garde music that uses graphic notation, to text compositions such as Aus den sieben Tagen, to computer programs that select sounds for musical pieces. Music that makes heavy use of randomness and chance is called aleatoric music,[76] and is associated with contemporary composers active in the 20th century, such as John Cage, Morton Feldman, and Witold Lutosławski. A commonly known example of chance-based music is the sound of wind chimes jingling in a breeze. The study of composition has traditionally been dominated by examination of methods and practice of Western classical music, but the definition of composition is broad enough to include the creation of popular music and traditional music songs and instrumental pieces as well as spontaneously improvised works like those of free jazz performers and African percussionists such as Ewe drummers. Performance Main article: Performance  Chinese Naxi musicians  Assyrians playing zurna and Davul, instruments that go back thousands of years Performance is the physical expression of music, which occurs when a song is sung or piano piece, guitar melody, symphony, drum beat or other musical part is played. In classical music, a work is written in music notation by a composer and then performed once the composer is satisfied with its structure and instrumentation. However, as it gets performed, the interpretation of a song or piece can evolve and change. In classical music, instrumental performers, singers or conductors may gradually make changes to the phrasing or tempo of a piece. In popular and traditional music, the performers have more freedom to make changes to the form of a song or piece. As such, in popular and traditional music styles, even when a band plays a cover song, they can make changes such as adding a guitar solo or inserting an introduction.[77] A performance can either be planned out and rehearsed (practiced)—which is the norm in classical music, jazz big bands, and many popular music styles–or improvised over a chord progression (a sequence of chords), which is the norm in small jazz and blues groups. Rehearsals of orchestras, concert bands and choirs are led by a conductor. Rock, blues and jazz bands are usually led by the bandleader. A rehearsal is a structured repetition of a song or piece by the performers until it can be sung or played correctly and, if it is a song or piece for more than one musician, until the parts are together from a rhythmic and tuning perspective. Many cultures have strong traditions of solo performance (in which one singer or instrumentalist performs), such as in Indian classical music, and in the Western art-music tradition. Other cultures, such as in Bali, include strong traditions of group performance. All cultures include a mixture of both, and performance may range from improvised solo playing to highly planned and organized performances such as the modern classical concert, religious processions, classical music festivals or music competitions. Chamber music, which is music for a small ensemble with only one or a few of each type of instrument, is often seen as more intimate than large symphonic works.[78] Improvisation Main article: Musical improvisation Musical improvisation is the creation of spontaneous music, often within (or based on) a pre-existing harmonic framework, chord progression, or riffs. Improvisers use the notes of the chord, various scales that are associated with each chord, and chromatic ornaments and passing tones which may be neither chord tones nor from the typical scales associated with a chord. Musical improvisation can be done with or without preparation. Improvisation is a major part of some types of music, such as blues, jazz, and jazz fusion, in which instrumental performers improvise solos, melody lines, and accompaniment parts..[79] In the Western art music tradition, improvisation was an important skill during the Baroque era and during the Classical era. In the Baroque era, performers improvised ornaments, and basso continuo keyboard players improvised chord voicings based on figured bass notation. As well, the top soloists were expected to be able to improvise pieces such as preludes. In the Classical era, solo performers and singers improvised virtuoso cadenzas during concerts. However, in the 20th and early 21st century, as "common practice" Western art music performance became institutionalized in symphony orchestras, opera houses, and ballets, improvisation has played a smaller role, as more and more music was notated in scores and parts for musicians to play. At the same time, some 20th and 21st century art music composers have increasingly included improvisation in their creative work. In Indian classical music, improvisation is a core component and an essential criterion of performances. |

クリエーション 構成 主な記事 作曲  フランスのバロック音楽作曲家、ミシェル・リシャール・デランド(1657-1726)。  2013年、電子キーボードやコンピューターを使って作曲する人々 「作曲」とは、歌曲、器楽曲、歌と楽器の両方を使った作品、あるいはその他の種類の音楽を創作する行為や実践のことである。西洋のクラシック音楽を含む多 くの文化では、作曲行為には楽譜の作成も含まれる。ポピュラー音楽や伝統音楽では、作曲行為は一般的にソングライティングと呼ばれ、メロディー、歌詞、 コード進行を記したリードシートと呼ばれる曲の基本的なアウトラインを作成することがある。クラシック音楽では、作曲家が自分でオーケストレーションをす るのが一般的だが、ミュージカルシアターやポップミュージックでは、ソングライターがアレンジャーを雇ってオーケストレーションをすることもある。作曲家 が楽譜をまったく使わず、頭の中で作曲し、それを記憶して演奏したり録音したりする場合もある。ジャズやポピュラー音楽では、影響力のある演奏家による著 名な録音は、クラシック音楽で楽譜が果たす重みを与えられている[73][74]。 クラシック音楽のように、音楽が比較的正確に記譜されている場合でも、楽譜は音楽のすべての要素を正確に規定しているわけではないので、演奏者が決断しな ければならないことはたくさんある。先に作曲され楽譜化された音楽をどのように演奏するかを決めるプロセスは「解釈」と呼ばれる。同じ音楽作品でも、演奏 者によって解釈は大きく異なり、テンポの選び方やメロディーの弾き方、歌い方、フレージングなどが異なります。自分の曲を演奏する作曲家や作詞家は、他人 の曲を演奏する人と同じように、自分の曲を解釈しているのだ。ある時、ある場所に存在する標準的な選択とテクニックの集合体は演奏実践と呼ばれ、解釈は一 般的に演奏者の個々の選択を意味するのに使われる[75]。 作曲はしばしば楽譜を使用し、単一の作者を持つが、これは必ずしもそうではない。ポピュラー音楽ではバンドが共同で曲を書いたり、音楽劇では一人がメロ ディーを書き、二人目が歌詞を書き、三人目がオーケストレーションをしたりする。ブルースのような音楽スタイルでは、作曲家/ソングライターが、楽譜に書 くことなく新しい曲や作品を創作し、演奏し、録音することもある。また、歌い手や音楽家がどのように楽音を作るべきかを説明したり記譜したりする言葉や画 像、コンピュータープログラムを使って作曲することもある。例えば、図形楽譜を使った前衛音楽から、『Aus den sieben Tagen』のようなテキスト作曲、楽曲の音を選択するコンピュータープログラムまで、さまざまな例がある。ランダム性や偶然性を多用する音楽はアレア トール音楽と呼ばれ[76]、ジョン・ケージ、モートン・フェルドマン、ヴィトルド・ルトスワフスキといった20世紀に活躍した現代作曲家に関連してい る。偶然性に基づく音楽の例として一般的に知られているのは、そよ風に吹かれてジャラジャラと鳴る風鈴の音である。 作曲の研究は、伝統的に西洋のクラシック音楽の手法や実践を検証することが主流であったが、作曲の定義は、ポピュラー音楽や伝統音楽の歌曲や器楽曲の創 作、フリージャズ演奏家やエウェ族の太鼓奏者のようなアフリカの打楽器奏者のような自発的な即興作品も含むほど広い。 パフォーマンス 主な記事 パフォーマンス  中国のナシ族の音楽家  数千年前の楽器、ズルナとダヴルを演奏するアッシリア人 演奏とは、音楽を身体的に表現することで、歌を歌ったり、ピアノ曲、ギターの旋律、交響曲、ドラムのビート、その他の音楽パートを演奏したりするときに行 われる。クラシック音楽では、作品は作曲家によって楽譜に書かれ、作曲家がその構成や楽器編成に満足した時点で演奏される。しかし、演奏されるにつれて、 曲や作品の解釈は進化し、変化することがある。クラシック音楽では、楽器演奏者、歌手、指揮者が曲のフレージングやテンポを少しずつ変えていくことがあ る。ポピュラー音楽や伝統音楽では、演奏者は曲や曲の形にもっと自由に変更を加えることができる。そのため、ポピュラー音楽や伝統音楽のスタイルでは、バ ンドがカバー曲を演奏する場合でも、ギターソロを追加したり、イントロを挿入したりといった変更を加えることができる[77]。 演奏は、クラシック音楽、ジャズのビッグバンド、および多くのポピュラー音楽スタイルで一般的な、計画されリハーサル(練習)されたものと、小規模なジャ ズやブルースのグループで一般的な、コード進行(コードの並び)の上に即興で演奏されたものがある。オーケストラ、コンサート・バンド、合唱団のリハーサ ルは指揮者によって指揮される。ロック、ブルース、ジャズバンドのリハーサルは、通常バンドリーダーが指揮します。リハーサルとは、歌や曲を正しく歌った り演奏したりできるようになるまで、また、複数のミュージシャンのための歌や曲であれば、リズムやチューニングの観点からパートが揃うまで、演奏者が構造 的に繰り返すことである。 多くの文化には、インド古典音楽や西洋芸術音楽の伝統のように、ソロ演奏(一人の歌手や楽器奏者が演奏する)の強い伝統がある。また、バリのようにグルー プ演奏の伝統が強い文化もある。すべての文化にはその両方が混在しており、即興的なソロ演奏から、現代のクラシックコンサート、宗教的な行列、クラシック 音楽祭、音楽コンクールのような高度に計画・組織化された演奏まで、さまざまな演奏が行われている。室内楽は、各楽器が1台または数台のみの小規模なアン サンブルのための音楽であり、大規模な交響楽作品よりも親密なものと見なされることが多い[78]。 即興演奏 主な記事 音楽即興 即興演奏とは、既存の和声的枠組みやコード進行、リフの中で(あるいはそれらに基づいて)、自発的に音楽を創作することである。即興演奏では、コードの 音、各コードに関連する様々な音階、半音階的な装飾音や通過音を使用するが、これらはコード・トーンでもなければ、コードに関連する典型的な音階のもので もない。音楽の即興演奏は、準備の有無にかかわらず行うことができる。即興演奏は、ブルース、ジャズ、ジャズ・フュージョンなど、楽器演奏者がソロ、メロ ディ・ライン、伴奏パートを即興で演奏する音楽の主要な一部である[79]。 西洋の芸術音楽の伝統では、即興演奏はバロック時代と古典派時代に重要なスキルであった。バロック時代には、演奏家は即興で装飾をつけ、通奏低音鍵盤奏者 は、フィギュアド・バスの記譜法に基づいて即興でコード・ヴォイシングをつけた。また、トップ・ソリストには前奏曲などの即興演奏が求められた。古典派の 時代には、独奏者や歌手は演奏会中にヴィルトゥオーゾ・カデンツァを即興で演奏していた。 しかし、20世紀から21世紀初頭にかけて、交響楽団、オペラハウス、バレエ団など、西洋の芸術音楽演奏の「常識」が制度化されるにつれて、即興演奏が果 たす役割は小さくなり、楽譜やパート譜に記譜されて演奏されることが多くなった。同時に、20世紀や21世紀の芸術音楽の作曲家の中には、即興演奏を創作 に取り入れるようになった者もいる。インド古典音楽では、即興演奏は演奏の中核をなす要素であり、不可欠な基準である。 |

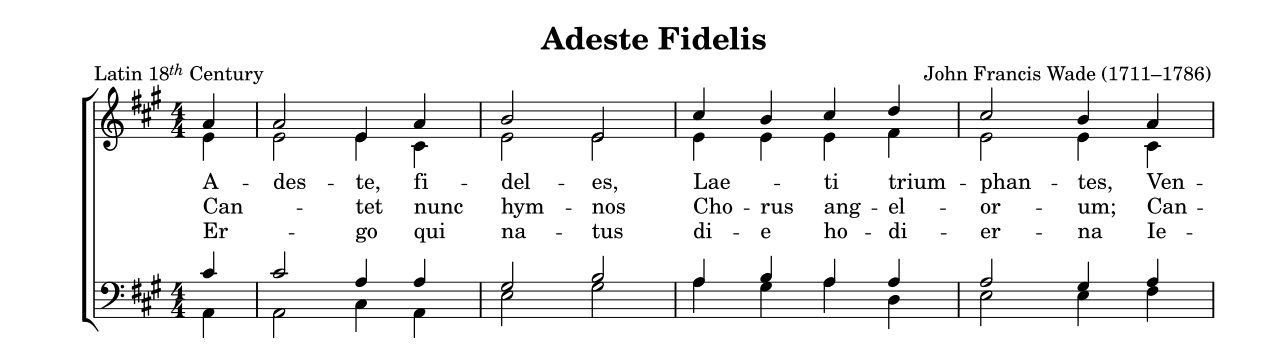

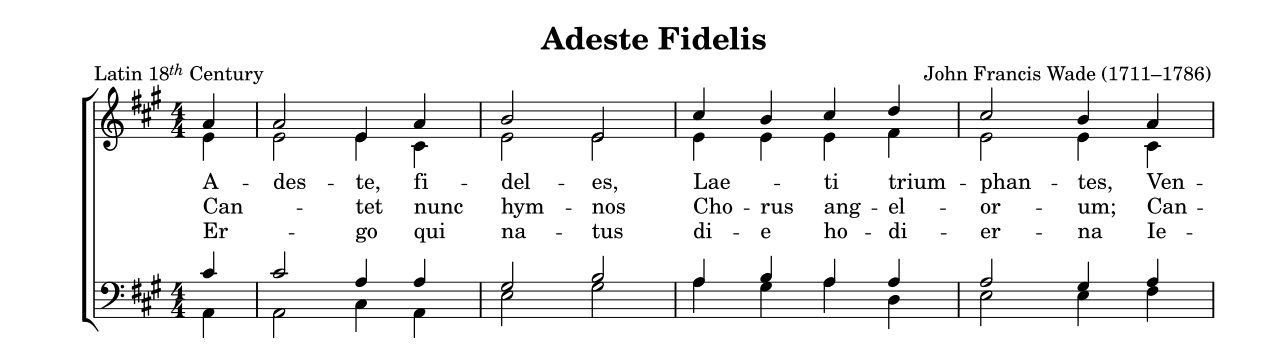

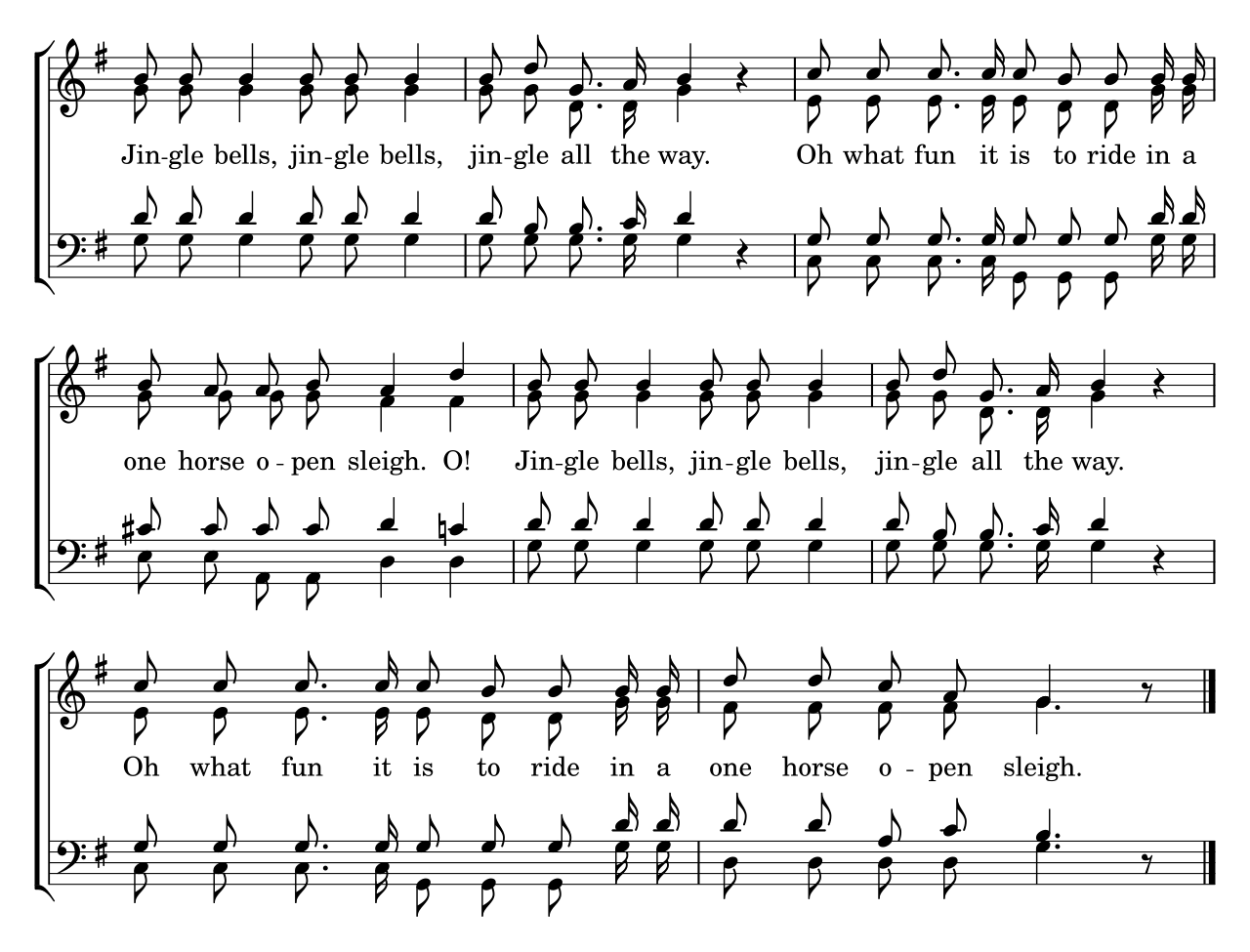

Art and entertainment Khatia Buniatishvili playing a grand piano Music is composed and performed for many purposes, ranging from aesthetic pleasure, religious or ceremonial purposes, or as an entertainment product for the marketplace. When music was only available through sheet music scores, such as during the Classical and Romantic eras, music lovers would buy the sheet music of their favourite pieces and songs so that they could perform them at home on the piano. With the advent of the phonograph, records of popular songs, rather than sheet music became the dominant way that music lovers would enjoy their favourite songs. With the advent of home tape recorders in the 1980s and digital music in the 1990s, music lovers could make tapes or playlists of favourite songs and take them with them on a portable cassette player or MP3 player. Some music lovers create mix tapes of favourite songs, which serve as a "self-portrait, a gesture of friendship, prescription for an ideal party... [and] an environment consisting solely of what is most ardently loved".[80] Amateur musicians can compose or perform music for their own pleasure and derive income elsewhere. Professional musicians are employed by institutions and organisations, including armed forces (in marching bands, concert bands and popular music groups), religious institutions, symphony orchestras, broadcasting or film production companies, and music schools. Professional musicians sometimes work as freelancers or session musicians, seeking contracts and engagements in a variety of settings. There are often many links between amateur and professional musicians. Beginning amateur musicians take lessons with professional musicians. In community settings, advanced amateur musicians perform with professional musicians in a variety of ensembles such as community concert bands and community orchestras. A distinction is often made between music performed for a live audience and music that is performed in a studio so that it can be recorded and distributed through the music retail system or the broadcasting system. However, there are also many cases where a live performance in front of an audience is also recorded and distributed. Live concert recordings are popular in both classical music and in popular music forms such as rock, where illegally taped live concerts are prized by music lovers. In the jam band scene, live, improvised jam sessions are preferred to studio recordings.[81] Notation Main article: Musical notation  Sheet music is a written representation of music. Homorhythmic (i.e., hymn-style) arrangement of the traditional "Adeste Fideles" in standard two-staff format for mixed voices. playⓘ Music notation typically means the written expression of music notes and rhythms on paper using symbols. When music is written down, the pitches and rhythm of the music, such as the notes of a melody, are notated. Music notation often provides instructions on how to perform the music. For example, the sheet music for a song may state the song is a "slow blues" or a "fast swing", which indicates the tempo and the genre. To read notation, a person must have an understanding of music theory, harmony and the performance practice associated with a particular song or piece's genre. Written notation varies with the style and period of music. Nowadays, notated music is produced as sheet music or, for individuals with computer scorewriter programs, as an image on a computer screen. In ancient times, music notation was put onto stone or clay tablets.[38] To perform music from notation, a singer or instrumentalist requires an understanding of the rhythmic and pitch elements embodied in the symbols and the performance practice that is associated with a piece of music or genre. In genres requiring musical improvisation, the performer often plays from music where only the chord changes and form of the song are written, requiring the performer to have a great understanding of the music's structure, harmony and the styles of a particular genre e.g., jazz or country music. In Western art music, the most common types of written notation are scores, which include all the music parts of an ensemble piece, and parts, which are the music notation for the individual performers or singers. In popular music, jazz, and blues, the standard musical notation is the lead sheet, which notates the melody, chords, lyrics (if it is a vocal piece), and structure of the music. Fake books are also used in jazz; they may consist of lead sheets or simply chord charts, which permit rhythm section members to improvise an accompaniment part to jazz songs. Scores and parts are also used in popular music and jazz, particularly in large ensembles such as jazz "big bands." In popular music, guitarists and electric bass players often read music notated in tablature (often abbreviated as "tab"), which indicates the location of the notes to be played on the instrument using a diagram of the guitar or bass fingerboard. Tablature was used in the Baroque era to notate music for the lute, a stringed, fretted instrument.[82] Oral and aural tradition Many types of music, such as traditional blues and folk music were not written down in sheet music; instead, they were originally preserved in the memory of performers, and the songs were handed down orally, from one musician or singer to another, or aurally, in which a performer learns a song "by ear". When the composer of a song or piece is no longer known, this music is often classified as "traditional" or as a "folk song". Different musical traditions have different attitudes towards how and where to make changes to the original source material, from quite strict, to those that demand improvisation or modification to the music. A culture's history and stories may also be passed on by ear through song.[83] |

アートとエンターテインメント グランドピアノを演奏するハティア・ブニアティシヴィリ 音楽は、美的な楽しみ、宗教的・儀式的な目的、あるいは市場向けの娯楽商品など、さまざまな目的のために作曲され、演奏される。古典派やロマン派の時代の ように、音楽が楽譜でしか手に入らなかった時代には、音楽愛好家たちはお気に入りの曲や歌の楽譜を買い求め、自宅のピアノで演奏できるようにしていた。蓄 音機の出現により、楽譜ではなくポピュラーソングのレコードが、音楽愛好家がお気に入りの曲を楽しむための主流となった。1980年代には家庭用テープレ コーダーが、1990年代にはデジタルミュージックが登場し、音楽愛好家たちはお気に入りの曲のテープやプレイリストを作り、ポータブルカセットプレー ヤーやMP3プレーヤーに入れて持ち運ぶことができるようになった。音楽愛好家の中には、お気に入りの曲のミックス・テープを作成し、「自画像、友情の ジェスチャー、理想的なパーティーの処方箋...」として活用する人もいる。[そして]最も熱烈に愛されているものだけで構成された環境」[80]とな る。 アマチュア音楽家は自分の楽しみのために作曲や演奏をし、別の場所で収入を得ることができる。プロの音楽家は、軍隊(マーチングバンド、コンサートバン ド、ポピュラー音楽グループ)、宗教団体、交響楽団、放送・映画制作会社、音楽学校などの機関や組織に雇用されている。プロの音楽家は、フリーランスや セッションミュージシャンとして、さまざまな場面で契約や仕事を求めて活動することもある。アマチュア音楽家とプロ音楽家の間には、多くのつながりがある ことが多い。初心者のアマチュア音楽家は、プロの音楽家のレッスンを受けます。コミュニティーの場では、上級アマチュア音楽家は、コミュニティー・コン サート・バンドやコミュニティー・オーケストラなどの様々なアンサンブルで、プロの音楽家と共演します。 ライブで聴衆のために演奏される音楽と、スタジオで録音され、音楽小売システムや放送システムを通じて配信されるために演奏される音楽は、しばしば区別さ れる。しかし、聴衆の前で演奏された生演奏を録音して配信する場合も多い。クラシック音楽でも、ロックなどのポピュラー音楽でも、違法に録音されたライ ブ・コンサートが音楽愛好家の間で珍重されている。ジャムバンドシーンでは、スタジオ録音よりもライブの即興ジャムセッションが好まれる[81]。 楽譜 主な記事 楽譜  楽譜とは、音楽を文字で表したもの。伝統的な「アデステ・フィデレス」のホモリズム(すなわち賛美歌スタイル)編曲で、混声のための標準的な2五線譜形 式。 楽譜とは一般的に、音符やリズムを記号で紙に書き表したものを指します。楽譜に記譜する際には、メロディーの音符など、音楽の音程やリズムが表記されま す。楽譜には、その音楽をどのように演奏するかの指示が書かれていることが多い。例えば、ある曲の楽譜には「スローブルース」や「高速スウィング」と書か れていることがあり、これはテンポとジャンルを示している。楽譜を読むには、音楽理論、和声、特定の曲や曲のジャンルに関連した演奏方法を理解していなけ ればなりません。 楽譜は音楽のスタイルや時代によって異なります。現在では、楽譜は楽譜として、あるいはコンピュータの楽譜作成プログラムを使っている人のために、コン ピュータ画面上の画像として作成されます。古くは、楽譜は石や粘土の板に書かれていた[38]。楽譜から音楽を演奏するためには、歌手や楽器奏者は、記号 に込められたリズムや音程の要素、そして楽曲やジャンルに関連した演奏方法を理解する必要がある。即興演奏を必要とするジャンルでは、演奏者はコードチェ ンジと曲の形だけが書かれた楽譜から演奏することが多く、演奏者は音楽の構造、ハーモニー、特定のジャンル(例えばジャズやカントリーミュージック)のス タイルについて十分理解している必要がある。 西洋の芸術音楽では、最も一般的な楽譜の種類は、アンサンブル曲のすべてのパート譜を含むスコアと、個々の演奏者や歌手のためのパート譜であるパート譜で ある。ポピュラー音楽、ジャズ、ブルースでは、メロディー、コード、歌詞(ヴォーカル曲の場合)、曲の構成を記したリード・シートが標準的な楽譜です。 ジャズではフェイクブックも使われます。フェイクブックはリード譜で構成されている場合もあれば、単にコード譜で構成されている場合もあり、リズムセク ションのメンバーがジャズの曲の伴奏パートを即興で演奏できるようになっています。楽譜やパート譜は、ポピュラー音楽やジャズ、特にジャズの「ビッグバン ド」のような大編成のアンサンブルでも使われます。ポピュラー音楽では、ギタリストやエレキ・ベース奏者がタブ譜(しばしば "TAB "と略される)で書かれた楽譜を読むことが多い。タブ譜はバロック時代には弦楽器であるリュートの楽譜を記譜するために使用されていた[82]。 口頭伝承と聴覚伝承 伝統的なブルースやフォーク・ミュージックのような多くの種類の音楽は、楽譜に書き記されることはなかった。その代わりに、曲はもともと演奏者の記憶の中 に保存され、音楽家や歌手から別の音楽家へと口頭で、あるいは演奏者が「耳で」曲を覚えるという聴覚で伝承されてきた。歌や曲の作曲者が分からなくなった 場合、その音楽はしばしば「伝統的な」あるいは「民謡」として分類される。音楽の伝統が異なれば、原典にどこでどのように変更を加えるかに対する考え方も 異なり、かなり厳格なものから、即興演奏や楽曲の改変を要求するものまで様々である。また、ある文化の歴史や物語は、歌を通して耳から伝えられることもあ る[83]。 |

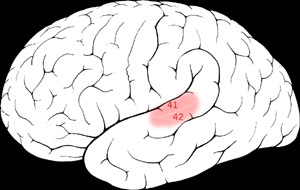

| Elements Main article: Elements of music Music has many different fundamentals or elements. Depending on the definition of "element" being used, these can include pitch, beat or pulse, tempo, rhythm, melody, harmony, texture, style, allocation of voices, timbre or color, dynamics, expression, articulation, form, and structure. The elements of music feature prominently in the music curriculums of Australia, the UK, and the US. All three curriculums identify pitch, dynamics, timbre, and texture as elements, but the other identified elements of music are far from universally agreed upon. Below is a list of the three official versions of the "elements of music": Australia: pitch, timbre, texture, dynamics and expression, rhythm, form and structure.[84] UK: pitch, timbre, texture, dynamics, duration, tempo, structure.[85] USA: pitch, timbre, texture, dynamics, rhythm, form, harmony, style/articulation.[86] In relation to the UK curriculum, in 2013 the term: "appropriate musical notations" was added to their list of elements and the title of the list was changed from the "elements of music" to the "inter-related dimensions of music". The inter-related dimensions of music are listed as: pitch, duration, dynamics, tempo, timbre, texture, structure, and appropriate musical notations.[87] The phrase "the elements of music" is used in a number of different contexts. The two most common contexts can be differentiated by describing them as the "rudimentary elements of music" and the "perceptual elements of music".[n 4] Pitch Main article: Pitch (music) Pitch is an aspect of a sound that we can hear, reflecting whether one musical sound, note, or tone is "higher" or "lower" than another musical sound, note, or tone. We can talk about the highness or lowness of pitch in the more general sense, such as the way a listener hears a piercingly high piccolo note or whistling tone as higher in pitch than a deep thump of a bass drum. We also talk about pitch in the precise sense associated with musical melodies, basslines and chords. Precise pitch can only be determined in sounds that have a frequency that is clear and stable enough to distinguish from noise. For example, it is much easier for listeners to discern the pitch of a single note played on a piano than to try to discern the pitch of a crash cymbal that is struck.[92] Melody Main article: Melody  The melody to the traditional song "Pop Goes the Weasel" playⓘ A melody, also called a "tune", is a series of pitches (notes) sounding in succession (one after the other), often in a rising and falling pattern. The notes of a melody are typically created using pitch systems such as scales or modes. Melodies also often contain notes from the chords used in the song. The melodies in simple folk songs and traditional songs may use only the notes of a single scale, the scale associated with the tonic note or key of a given song. For example, a folk song in the key of C (also referred to as C major) may have a melody that uses only the notes of the C major scale (the individual notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and C; these are the "white notes" on a piano keyboard. On the other hand, Bebop-era jazz from the 1940s and contemporary music from the 20th and 21st centuries may use melodies with many chromatic notes (i.e., notes in addition to the notes of the major scale; on a piano, a chromatic scale would include all the notes on the keyboard, including the "white notes" and "black notes" and unusual scales, such as the whole tone scale (a whole tone scale in the key of C would contain the notes C, D, E, F♯, G♯ and A♯). A low musical line played by bass instruments, such as double bass, electric bass, or tuba, is called a bassline.[93] Harmony Main article: Harmony  A player performing a chord (combination of many different notes) on a guitar Harmony refers to the "vertical" sounds of pitches in music, which means pitches that are played or sung together at the same time to create a chord. Usually, this means the notes are played at the same time, although harmony may also be implied by a melody that outlines a harmonic structure (i.e., by using melody notes that are played one after the other, outlining the notes of a chord). In music written using the system of major-minor tonality ("keys"), which includes most classical music written from 1600 to 1900 and most Western pop, rock, and traditional music, the key of a piece determines the "home note" or tonic to which the piece generally resolves, and the character (e.g. major or minor) of the scale in use. Simple classical pieces and many pop and traditional music songs are written so that all the music is in a single key. More complex Classical, pop, and traditional music songs and pieces may have two keys (and in some cases three or more keys). Classical music from the Romantic era (written from about 1820–1900) often contains multiple keys,[94] as does jazz, especially Bebop jazz from the 1940s, in which the key or "home note" of a song may change every four bars or even every two bars.[95] Rhythm Main article: Rhythm Rhythm is the arrangement of sounds and silences in time. Meter animates time in regular pulse groupings, called measures or bars, which in Western classical, popular, and traditional music often group notes in sets of two (e.g., 2/4 time), three (e.g., 3/4 time, also known as Waltz time, or 3/8 time), or four (e.g., 4/4 time). Meters are made easier to hear because songs and pieces often (but not always) place an emphasis on the first beat of each grouping. Notable exceptions exist, such as the backbeat used in much Western pop and rock, in which a song that uses a measure that consists of four beats (called 4/4 time or common time) will have accents on beats two and four, which are typically performed by the drummer on the snare drum, a loud and distinctive-sounding percussion instrument. In pop and rock, the rhythm parts of a song are played by the rhythm section, which includes chord-playing instruments (e.g., electric guitar, acoustic guitar, piano, or other keyboard instruments), a bass instrument (typically electric bass or for some styles such as jazz and bluegrass, double bass) and a drum kit player.[96] Texture Main article: Texture (music) Musical texture is the overall sound of a piece of music or song. The texture of a piece or song is determined by how the melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic materials are combined in a composition, thus determining the overall nature of the sound in a piece. Texture is often described in regard to the density, or thickness, and range, or width, between lowest and highest pitches, in relative terms as well as more specifically distinguished according to the number of voices, or parts, and the relationship between these voices (see common types below). For example, a thick texture contains many 'layers' of instruments. One layer can be a string section or another brass. The thickness is affected by the amount and the richness of the instruments.[97] Texture is commonly described according to the number of and relationship between parts or lines of music: monophony: a single melody (or "tune") with neither instrumental accompaniment nor a harmony part. A mother singing a lullaby to her baby would be an example. heterophony: two or more instruments or singers playing/singing the same melody, but with each performer slightly varying the rhythm or speed of the melody or adding different ornaments to the melody. Two bluegrass fiddlers playing the same traditional fiddle tune together will typically each vary the melody by some degree and each add different ornaments. polyphony: multiple independent melody lines that interweave together, which are sung or played at the same time. Choral music written in the Renaissance music era was typically written in this style. A round, which is a song such as "Row, Row, Row Your Boat", which different groups of singers all start to sing at a different time, is an example of polyphony. homophony: a clear melody supported by chordal accompaniment. Most Western popular music songs from the 19th century onward are written in this texture. Music that contains a large number of independent parts (e.g., a double concerto accompanied by 100 orchestral instruments with many interweaving melodic lines) is generally said to have a "thicker" or "denser" texture than a work with few parts (e.g., a solo flute melody accompanied by a single cello). Timbre Main article: Timbre  Spectrogram of the first second of an E9 suspended chord played on a Fender Stratocaster guitar. Below is the E9 suspended chord audio: Duration: 13 seconds.0:13 Timbre, sometimes called "color" or "tone color" is the quality or sound of a voice or instrument.[98] Timbre is what makes a particular musical sound different from another, even when they have the same pitch and loudness. For example, a 440 Hz A note sounds different when it is played on oboe, piano, violin, or electric guitar. Even if different players of the same instrument play the same note, their notes might sound different due to differences in instrumental technique (e.g., different embouchures), different types of accessories (e.g., mouthpieces for brass players, reeds for oboe and bassoon players) or strings made out of different materials for string players (e.g., gut strings versus steel strings). Even two instrumentalists playing the same note on the same instrument (one after the other) may sound different due to different ways of playing the instrument (e.g., two string players might hold the bow differently). The physical characteristics of sound that determine the perception of timbre include the spectrum, envelope, and overtones of a note or musical sound. For electric instruments developed in the 20th century, such as electric guitar, electric bass and electric piano, the performer can also change the tone by adjusting equalizer controls, tone controls on the instrument, and by using electronic effects units such as distortion pedals. The tone of the electric Hammond organ is controlled by adjusting drawbars. Expression Expressive qualities are those elements in music that create change in music without changing the main pitches or substantially changing the rhythms of the melody and its accompaniment. Performers, including singers and instrumentalists, can add musical expression to a song or piece by adding phrasing, by adding effects such as vibrato (with voice and some instruments, such as guitar, violin, brass instruments, and woodwinds), dynamics (the loudness or softness of piece or a section of it), tempo fluctuations (e.g., ritardando or accelerando, which are, respectively slowing down and speeding up the tempo), by adding pauses or fermatas on a cadence, and by changing the articulation of the notes (e.g., making notes more pronounced or accented, by making notes more legato, which means smoothly connected, or by making notes shorter). Expression is achieved through the manipulation of pitch (such as inflection, vibrato, slides etc.), volume (dynamics, accent, tremolo etc.), duration (tempo fluctuations, rhythmic changes, changing note duration such as with legato and staccato, etc.), timbre (e.g. changing vocal timbre from a light to a resonant voice) and sometimes even texture (e.g. doubling the bass note for a richer effect in a piano piece). Expression therefore can be seen as a manipulation of all elements to convey "an indication of mood, spirit, character etc."[99] and as such cannot be included as a unique perceptual element of music,[100] although it can be considered an important rudimentary element of music. Form See also: Binary form, Ternary form, and Development (music)  Sheet music notation for the chorus (refrain) of the Christmas song "Jingle Bells" Jingle Bells refrain vector.midⓘ In music, form describes the overall structure or plan of a song or piece of music,[101] and it describes the layout of a composition as divided into sections.[102] In the early 20th century, Tin Pan Alley songs and Broadway musical songs were often in AABA thirty-two-bar form, in which the A sections repeated the same eight bar melody (with variation) and the B section provided a contrasting melody or harmony for eight bars. From the 1960s onward, Western pop and rock songs are often in verse-chorus form, which comprises a sequence of verse and chorus ("refrain") sections, with new lyrics for most verses and repeating lyrics for the choruses. Popular music often makes use of strophic form, sometimes in conjunction with the twelve bar blues.[103] In the tenth edition of The Oxford Companion to Music, Percy Scholes defines musical form as "a series of strategies designed to find a successful mean between the opposite extremes of unrelieved repetition and unrelieved alteration."[104] Examples of common forms of Western music include the fugue, the invention, sonata-allegro, canon, strophic, theme and variations, and rondo. Scholes states that European classical music had only six stand-alone forms: simple binary, simple ternary, compound binary, rondo, air with variations, and fugue (although musicologist Alfred Mann emphasized that the fugue is primarily a method of composition that has sometimes taken on certain structural conventions.[105]) Where a piece cannot readily be broken into sectional units (though it might borrow some form from a poem, story or programme), it is said to be through-composed. Such is often the case with a fantasia, prelude, rhapsody, etude (or study), symphonic poem, Bagatelle, impromptu or similar compostion.[106] Professor Charles Keil classified forms and formal detail as "sectional, developmental, or variational."[107] |