Simon Vouet, Saint Cecilia, c. 1626

音楽と感情

Music and Emotion

Simon Vouet, Saint Cecilia, c. 1626

このページは「感情経験の人類学」プロジェクトの企画ページである。「グアテマラ先住民における『音と癒し』の感性の人類学的研究」

は、このページが「音楽と感情」として独立するまえに、パラサイトしていたページである。あわせて参考にしていただきたい(→「音楽」「民族音楽学・音楽人類学」)。

| Music and

emotion This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. (June 2023) |

音楽と感情(この項目は改善の余地あり)Wiki Pedia |

| Research into music and emotion

seeks to understand the psychological relationship between human affect

and music. The field, a branch of music psychology, covers numerous

areas of study, including the nature of emotional reactions to music,

how characteristics of the listener may determine which emotions are

felt, and which components of a musical composition or performance may

elicit certain reactions. The research draws upon, and has significant implications for, such areas as philosophy, musicology, music therapy, music theory, and aesthetics, as well as the acts of musical composition and of musical performance like a concert. |

音楽と感情に関する研究は、人間の感情と音楽の心理的関係を理解しよう

とするものである。音楽心理学の一分野であるこの分野は、音楽に対する感情反応の性質、聴き手の特徴がどのような感情を引き起こすか、作曲や演奏のどの要

素が特定の反応を引き起こすかなど、多くの研究分野をカバーしている。 その研究は、哲学、音楽学、音楽療法、音楽理論、美学、そして作曲行為やコンサートのような演奏行為といった分野に多大な影響を及ぼしている。 |

| Philosophical approaches Appearance emotionalism Two of the most influential philosophers in the aesthetics of music are Stephen Davies and Jerrold Levinson.[1][2] Davies calls his view of the expressiveness of emotions in music "appearance emotionalism", which holds that music expresses emotion without feeling it. Objects can convey emotion because their structures can contain certain characteristics that resemble emotional expression. He says, "The resemblance that counts most for music's expressiveness ... is between music's temporally unfolding dynamic structure and configurations of human behaviour associated with the expression of emotion."[3] The observer can note emotions from the listener's posture, gait, gestures, attitude, and comportment.[4] Associations between musical features and emotion differ among individuals. Appearance emotionalism claims many listeners' perceiving associations constitutes the expressiveness of music. Which musical features are more commonly associated with which emotions is part of music psychology. Davies says that expressiveness is an objective property of music and not subjective in the sense of being projected into the music by the listener. Music's expressiveness is certainly response-dependent, i.e. it is realized in the listener's judgement. Skilled listeners very similarly attribute emotional expressiveness to a certain piece of music, thereby indicating according to Davies that the expressiveness of music is somewhat objective because if the music lacked expressiveness, then no expression could be projected into it as a reaction to the music.[5] Process theory The philosopher Jennifer Robinson assumes the existence of a mutual dependence between cognition and elicitation in her description of "emotions as process, music as process" theory, or process theory. Robinson argues that the process of emotional elicitation begins with an "automatic, immediate response that initiates motor and autonomic activity and prepares us for possible action" causing a process of cognition that may enable listeners to name the felt emotion. This series of events continually exchanges with new, incoming information. Robinson argues that emotions may transform into one another, causing blends, conflicts, and ambiguities that make impede describing with one word the emotional state that one experiences at any given moment; instead, inner feelings are better thought of as the products of multiple emotional streams. Robinson argues that music is a series of simultaneous processes, and that it therefore is an ideal medium for mirroring such more cognitive aspects of emotion as musical themes' desiring resolution or leitmotif's mirrors memory processes. These simultaneous musical processes can reinforce or conflict with each other and thus also express the way one emotion "morphs into another over time".[6][page needed] |

哲学的アプローチ 外見的表現主義 音楽美学において最も影響力のある哲学者の2人、スティーブン・デイヴィスとジェロルド・レヴィンソン。[1][2] デイヴィスは音楽における感情表現の考え方を「外見的表現主義」と呼び、音楽は感情を感じることなく表現するものであると主張している。物体は感情表現に 似た特定の特性を構造に含むことができるため、感情を伝えることができる。彼は「音楽の表現力において最も重要な類似性は、音楽の時間的に展開するダイナ ミックな構造と、感情表現に伴う人間の行動様式との類似性である」と述べている。[3] 観察者は、リスナーの姿勢、歩行、ジェスチャー、態度、立ち居振る舞いから感情を読み取ることができる。[4] 音楽の特徴と感情の関連性は個人によって異なる。外見的エモーショナリズムは、多くのリスナーが関連付けているものが音楽の表現力であると主張している。 どの音楽の特徴がどの感情と関連付けられることが多いかは、音楽心理学の一部である。デイヴィスは、表現力は音楽の客観的な特性であり、リスナーが音楽に 投影する主観的なものではないと述べている。音楽の表現力は、確かに反応に依存しており、すなわち、リスナーの判断によって実現される。熟練したリスナー は、特定の楽曲に感情的な表現力を非常に似た形で帰属させるため、デイヴィスによれば、音楽の表現力はいくらか客観的である。なぜなら、音楽に表現力が欠 けていれば、音楽に対する反応として音楽に表現を投影することはできないからだ。[5] プロセス理論 哲学者のジェニファー・ロビンソンは、「感情はプロセスであり、音楽もプロセスである」という理論、すなわちプロセス理論の説明において、認知と引き出し の間に相互依存関係が存在すると仮定している。ロビンソンは、感情の引き出しのプロセスは「運動と自律神経活動を起動し、起こりうる行動に備える自動的か つ即時の反応」から始まり、その結果、リスナーが感じた感情を名指しできる認知プロセスが引き起こされると主張している。この一連の出来事は、絶えず新し い入力情報とやりとりを続ける。ロビンソンは、感情は互いに変化し、融合、葛藤、曖昧さをもたらし、その瞬間に経験している感情の状態を一言で表現するこ とを妨げると主張している。むしろ、内面の感情は、複数の感情の流れの産物として考える方が適切である。ロビンソンは、音楽は一連の同時進行のプロセスで あり、したがって、音楽のテーマが解決を望むものや、ライトモチーフが記憶のプロセスを反映するものなど、感情のより認知的な側面を映し出す理想的な媒体 であると主張している。これらの同時進行の音楽プロセスは、互いに強化し合ったり、対立したりすることがあり、それによって、ある感情が「時間とともに別 の感情へと変化する」様子も表現できる。[6][要出典] |

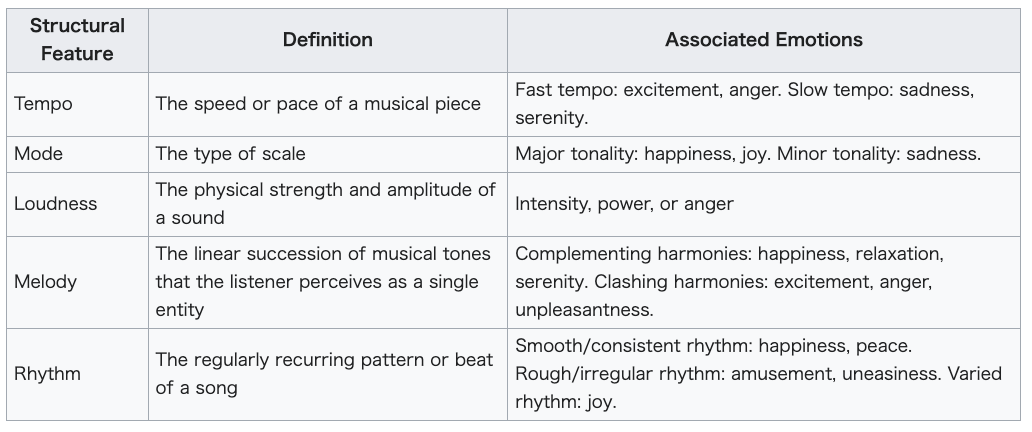

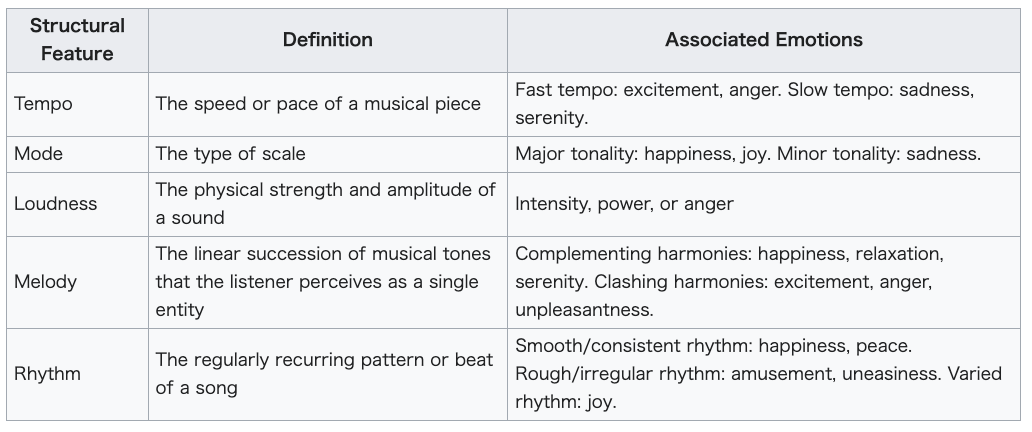

| Conveying emotion through music The ability to perceive emotion in music is said[weasel words] to develop early in childhood, and improve significantly throughout development.[7] The capacity to perceive emotion in music is also subject to cultural influences, and both similarities and differences in emotion perception have been observed in cross-cultural studies.[8][9] Empirical research has looked at which emotions can be conveyed as well as what structural factors in music help contribute to the perceived emotional expression. There are two schools of thought on how we interpret emotion in music. The cognitivists' approach argues that music simply displays an emotion, but does not allow for the personal experience of emotion in the listener. Emotivists argue that music elicits real emotional responses in the listener.[10][11] It has been argued that the emotion experienced from a piece of music is a multiplicative function of structural features, performance features, listener features, contextual features and extra-musical features of the piece, shown as: Experienced Emotion = Structural features × Performance features × Listener features × Contextual features × Extra-Musical features where: Structural features = Segmental features × Suprasegmental features Performance features = Performer skill × Performer state Listener features = Musical expertise × Stable disposition × Current motivation Contextual features = Location × Event[10] Extra-musical features = Non-auditory features × Expertise[12] Structural features Structural features are divided into two parts, segmental features and suprasegmental features. Segmental features are the individual sounds or tones that make up the music; this includes acoustic structures such as duration, amplitude, and pitch. Suprasegmental features are the foundational structures of a piece, such as melody, tempo and rhythm.[10] There are a number of specific musical features that are highly associated with particular emotions.[13] Within the factors affecting emotional expression in music, tempo is typically regarded as the most important, but a number of other factors, such as mode, loudness, and melody, also influence the emotional valence of the piece.[13]  Some studies find that perception of basic emotional features are a cultural universal, though people can more easily perceive emotion, and perceive more nuanced emotion, in music from their own culture.[14][15][16] Music without lyrics is unlikely to elicit social emotions like anger, shame, and jealousy; it typically only elicits basic emotions, like happiness and sadness.[17] Music has a direct connection to emotional states present in human beings. Different musical structures have been found to have a relationship with physiological responses. Research has shown that suprasegmental structures such as tonal space, specifically dissonance, create unpleasant negative emotions in participants. The emotional responses were measured with physiological assessments, such as skin conductance and electromyographic signals (EMG), while participants listened to musical excerpts.[18] Further research on psychophysiological measures pertaining to music were conducted and found similar results; musical structures of rhythmic articulation, accentuation, and tempo were found to correlate strongly with physiological measures, the measured used here included heart rate and respiratory monitors that correlated with self-report questionnaires.[19] These associations can be innate, learned, or both. Studies on young children and isolated cultures show innate associations for features are similar to a human voice (e.g. low and slow is sad, faster and high is happy). Cross-cultural studies show that associations between major mode vs. minor mode and consonance vs. dissonance are probably learned.[20][21] Music also affects socially-relevant memories, specifically memories produced by nostalgic musical excerpts (e.g., music from a significant time period in one’s life, like music listened to on road trips). Musical structures are more strongly interpreted in certain areas of the brain when the music evokes nostalgia. The interior frontal gyrus, substantia nigra, cerebellum, and insula were all identified to have a stronger correlation with nostalgic music than not.[22] Brain activity is a very individualized concept with many of the musical excerpts having certain effects based on individuals’ past life experiences, thus this caveat should be kept in mind when generalizing findings across individuals. Performance features Performance features refer to the manner in which a piece of music is executed by the performer(s). These are broken into two categories: performer skills, and performer state. Performer skills are the compound ability and appearance of the performer; including physical appearance, reputation, and technical skills. The performer state is the interpretation, motivation, and stage presence of the performer.[10] Listener features Listener features refer to the individual and social identity of the listener(s). This includes their personality, age, knowledge of music, and motivation to listen to the music.[10] Contextual features Contextual features are aspects of the performance such as the location and the particular occasion for the performance (i.e., funeral, wedding, dance).[10] Extra-musical features Extra-musical features refer to extra-musical information detached from auditory music signals, such as the genre or style of music. [12] These different factors influence expressed emotion at different magnitudes, and their effects are compounded by one another. Thus, experienced emotion is felt to a stronger degree if more factors are present. The order the factors are listed within the model denotes how much weight in the equation they carry. For this reason, the bulk of research has been done in structural features and listener features.[10] Conflicting cues Which emotion is perceived is dependent on the context of the piece of music. Past research has argued that opposing emotions like happiness and sadness fall on a bipolar scale, where both cannot be felt at the same time.[23] More recent research has suggested that happiness and sadness are experienced separately, which implies that they can be felt concurrently.[23] One study investigated the latter possibility by having participants listen to computer-manipulated musical excerpts that have mixed cues between tempo and mode.[23] Examples of mix-cue music include a piece with major key and slow tempo, and a minor-chord piece with a fast tempo. Participants then rated the extent to which the piece conveyed happiness or sadness. The results indicated that mixed-cue music conveys both happiness and sadness; however, it remained unclear whether participants perceived happiness and sadness simultaneously or vacillated between these two emotions.[23] A follow-up study was done to examine these possibilities. While listening to mixed or consistent cue music, participants pressed one button when the music conveyed happiness, and another button when it conveyed sadness.[24] The results revealed that subjects pressed both buttons simultaneously during songs with conflicting cues.[24] These findings indicate that listeners can perceive both happiness and sadness concurrently. This has significant implications for how the structural features influence emotion, because when a mix of structural cues is used, a number of emotions may be conveyed.[24] Specific listener features Development Studies indicate that the ability to understand emotional messages in music starts early, and improves throughout child development.[7][13][25] Studies investigating music and emotion in children primarily play a musical excerpt for children and have them look at pictorial expressions of faces. These facial expressions display different emotions and children are asked to select the face that best matches the music's emotional tone.[26][27][28] Studies have shown that children are able to assign specific emotions to pieces of music; however, there is debate regarding the age at which this ability begins.[7][13][25] Infants An infant is often exposed to a mother's speech that is musical in nature. It is possible that the motherly singing allows the mother to relay emotional messages to the infant.[29] Infants also tend to prefer positive speech to neutral speech as well as happy music to negative music.[26][29] It has also been posited that listening to their mother's singing may play a role in identity formation.[29] This hypothesis is supported by a study that interviewed adults and asked them to describe musical experiences from their childhood. Findings showed that music was good for developing knowledge of emotions during childhood.[30] Pre-school children These studies have shown that children at the age of 4 are able to begin to distinguish between emotions found in musical excerpts in ways that are similar to adults.[26][27] The ability to distinguish these musical emotions seems to increase with age until adulthood.[28] However, children at the age of 3 were unable to make the distinction between emotions expressed in music through matching a facial expression with the type of emotion found in the music.[27] Some emotions, such as anger and fear, were also found to be harder to distinguish within music.[28][31] Elementary-age children In studies with four-year-olds and five-year-olds, they are asked to label musical excerpts with the affective labels "happy", "sad", "angry", and "afraid".[7] Results in one study showed that four-year-olds did not perform above chance with the labels "sad" and "angry", and the five-year-olds did not perform above chance with the label "afraid".[7] A follow-up study found conflicting results, where five-year-olds performed much like adults. However, all ages confused categorizing "angry" and "afraid".[7] Pre-school and elementary-age children listened to twelve short melodies, each in either major or minor mode, and were instructed to choose between four pictures of faces: happy, contented, sad, and angry.[13] All the children, even as young as three years old, performed above chance in assigning positive faces with major mode and negative faces with minor mode.[13] Personality effects Different people perceive events differently based upon their individual characteristics. Similarly, the emotions elicited by listening to different types of music seem to be affected by factors such as personality and previous musical training.[32][33][34] People with the personality type of agreeableness have been found to have higher emotional responses to music in general. Stronger sad feelings have also been associated with people with personality types of agreeableness and neuroticism. While some studies have shown that musical training can be correlated with music that evoked mixed feelings[32] as well as higher IQ and test of emotional comprehension scores,[33] other studies refute the claim that musical training affects perception of emotion in music.[31][35] It is also worth noting that previous exposure to music can affect later behavioral choices, schoolwork, and social interactions.[36] Therefore, previous music exposure does seem to have an effect on the personality and emotions of a child later in their life, and would subsequently affect their ability to perceive as well as express emotions during exposure to music. Gender, however, has not been shown to lead to a difference in perception of emotions found in music.[31][35] Further research into which factors affect an individual's perception of emotion in music and the ability of the individual to have music-induced emotions are needed. |

音楽を通して感情を伝える 音楽から感情を読み取る能力は、[言葉を選んで]幼少期に発達し、成長過程で著しく向上すると言われている。[7] 音楽から感情を読み取る能力は文化の影響も受けるため、感情の知覚における類似点と相違点が異文化研究で観察されている。[8][9] 実証的研究では、音楽のどの構造的要因が知覚される感情表現に貢献するのか、また、どのような感情が伝達されるのかが調査されている。音楽における感情の 解釈については、2つの学説がある。認知主義のアプローチでは、音楽は単に感情を表出するだけで、リスナーの感情に関する個人的な経験は考慮されないと主 張する。感情主義者は、音楽はリスナーに実際の感情反応を引き起こすと主張する。 音楽から得られる感情は、楽曲の構造的特徴、演奏的特徴、リスナーの特徴、文脈的特徴、音楽以外の特徴の積算関数であると主張されている。 経験する感情 = 構造的特徴 × 演奏的特徴 × リスナーの特徴 × 文脈的特徴 × 音楽以外の特徴 ここで 構造的特徴 = セグメンタル特徴 × スーパーセグメンタル特徴 演奏的特徴 = 演奏者のスキル × 演奏者の状態 リスナーの特徴 = 音楽的専門知識 × 安定した気質 × 現在の動機 コンテクストの特徴 = 場所 × イベント[10] 音楽以外の特徴 = 非聴覚的特徴 × 専門知識[12] 構造的特徴 構造的特徴は、セグメンタル特徴と超セグメンタル特徴の2つに分けられる。セグメンタル特徴は、音楽を構成する個々の音や音調であり、持続時間、振幅、 ピッチなどの音響構造が含まれる。超セグメント的特徴とは、楽曲の基礎となる構造であり、例えばメロディ、テンポ、リズムなどである。[10] 特定の感情と強く関連する音楽的特徴は数多くある。[13] 音楽における感情表現に影響を与える要因の中で、テンポは一般的に最も重要視されているが、モード、ラウドネス、メロディなど、他の多くの要因も楽曲の感 情的価値に影響を与える。[13]  一 部の研究では、基本的な感情の特徴の知覚は文化を問わず共通しているとされているが、自文化の音楽では感情をより容易に知覚でき、より微妙な感情も知覚で きるという。[14][15][16]歌詞のない音楽は、怒り、恥、嫉妬などの社会的感情を引き起こすことはほとんどなく、通常は幸福や悲しみといった基 本的な感情のみを引き起こす。[17] 音楽は人間に存在する感情状態と直接的なつながりがある。異なる音楽構造が生理学的反応と関係があることが分かっている。研究により、音調空間、特に不協 和音のような超セグメント構造が、参加者に不快な負の感情を生み出すことが示されている。音楽の抜粋を聴いている間の被験者の皮膚電気反応や筋電図信号 (EMG)などの生理学的評価により、感情的な反応が測定された。[18] 音楽に関する心理生理学的測定に関するさらなる研究が行われ、同様の結果が得られた。リズムのアーティキュレーション、アクセント、テンポなどの音楽構造 は、生理学的測定と強く相関することが分かった。ここで使用された測定には、自己申告式のアンケートと相関する心拍数や呼吸モニターが含まれていた。 [19] これらの関連性は先天的なものであっても、学習によるものであっても、あるいはその両方である可能性もある。幼児や孤立した文化に関する研究では、特徴に 対する先天的な関連性は、人間の声に似ている(例えば、低音でゆっくりとしたものは悲しく、速く高いものは幸せである)。異文化間の研究では、長調と短 調、協和音と不協和音の関連性は学習によるものである可能性が高いことが示されている。 音楽はまた、社会的に関連する記憶、特にノスタルジックな音楽の抜粋(例えば、人生の重要な時期の音楽、例えばドライブ旅行中に聞いた音楽)によって生み 出される記憶にも影響を与える。音楽がノスタルジアを呼び起こす場合、音楽構造は脳の特定の領域でより強く解釈される。内側前頭回、黒質、小脳、島はすべ て、ノスタルジックな音楽との相関が強いことが確認されている。[22] 脳の活動はきわめて個人差の大きい概念であり、音楽の抜粋の多くは個人の過去の人生経験に基づいて特定の効果をもたらすため、この注意事項は、個々人の調 査結果を一般化する際に念頭に置くべきである。 パフォーマンスの特徴 パフォーマンスの特徴とは、演奏者による楽曲の演奏方法である。これらは、演奏者のスキルと演奏者の状態の2つのカテゴリーに分けられる。演奏者のスキル とは、演奏者の複合的な能力と外見であり、外見、評判、技術的なスキルを含む。演奏者の状態とは、演奏者の解釈、動機、ステージでの存在感である。 リスナーの特徴 リスナーの特徴とは、リスナーの個人としての、あるいは社会的なアイデンティティを指す。これには、リスナーの人格、年齢、音楽に関する知識、音楽を聴く動機などが含まれる。[10] 文脈的な特徴 文脈的な特徴とは、演奏の場所や特定の機会(葬儀、結婚式、ダンスなど)といった演奏の側面を指す。[10] 音楽以外の特徴 音楽以外の特徴とは、音楽のジャンルやスタイルなど、音楽の聴覚信号から切り離された音楽以外の情報を指す。 [12] これらの異なる要因は、表現された感情に異なる程度の影響を与え、それらの効果はお互いに複合的に作用する。そのため、より多くの要因が存在すれば、経験 された感情はより強く感じられる。モデル内で要因がリスト化される順序は、方程式におけるそれらの重みを表している。このため、研究の大部分は構造的特徴 とリスナーの特徴について行われている。[10] 相反する手がかり どの感情が知覚されるかは、楽曲のコンテクストに依存する。過去の研究では、幸福と悲しみのような相反する感情は両極の尺度に位置し、同時に感じることは できないと主張されていた。[23] しかし、より最近の研究では、幸福と悲しみは別個に経験されることが示唆されており、これは同時に感じられる可能性があることを意味している。[23] ある研究では 後者の可能性を調査するために、参加者にコンピュータで操作された音楽の一部を聴かせた。その音楽には、テンポと調の合図が混在していた。次に、参加者は その楽曲がどの程度幸福や悲しみを伝えているかを評価した。その結果、混合キュー音楽は幸福と悲しみの両方を伝えることが示されたが、参加者が幸福と悲し みを同時に認識しているのか、あるいはこの2つの感情の間で揺れ動いているのかは不明のままであった。[23] これらの可能性を検証するために、追跡調査が行われた。混合キューまたは一貫キューの音楽を聴きながら、参加者は音楽が幸福を伝える場合には1つのボタン を押し、悲しみを伝える場合には別のボタンを押した。[24] その結果、相反するキューを持つ楽曲では、被験者は両方のボタンを同時に押すことが明らかになった。[24] この発見は、リスナーが幸福と悲しみを同時に知覚できることを示している。構造的キューが混合して使用される場合、多くの感情が伝達される可能性があるた め、この発見は、構造的特徴が感情に与える影響について重要な意味を持つ。[24] 特定のリスナーの特徴 発達 研究によると、音楽の感情的なメッセージを理解する能力は幼少期から始まり、発達とともに向上していくことが分かっている。[7][13][25] 子供を対象とした音楽と感情に関する研究では、主に子供たちに音楽の一部を聞かせ、顔の表情を描写した絵を見せる。これらの表情には異なる感情が表されて おり、子供たちに音楽の感情的なトーンに最も合う表情を選択させる。[26][27][28] 研究により、子供たちは特定の音楽に特定の感情を割り当てることができることが示されているが、この能力が発達し始める年齢については議論がある。[7] [13][25] 乳児 乳児は、音楽的な性質を持つ母親の話し声をよく聞く。母親の歌が、母親から乳児への感情的なメッセージの伝達を可能にしている可能性もある。[29] 乳児はまた、ニュートラルな話し方よりもポジティブな話し方を好む傾向があり、ネガティブな音楽よりもハッピーな音楽を好む傾向もある。[26][29] 母親の歌を聴くことが、アイデンティティの形成に何らかの役割を果たしている可能性も指摘されている。[29] この仮説は、成人を対象に幼少期の音楽体験についてインタビューした研究によって裏付けられている。その結果、幼少期に音楽に触れることは情動に関する知 識を育むのに役立つことが分かった。[30] 就学前児童 これらの研究により、4歳児は音楽の抜粋に含まれる情動を大人とほぼ同様の方法で区別し始めることができることが分かった。[26][27] 音楽の情動を区別する能力は年齢とともに成長し、成人期まで続くようだ。[28] しかし、3歳児は 3歳児は、音楽に表現された感情を、音楽に含まれる感情の種類と表情を一致させることで区別することができなかった。[27] 怒りや恐怖などの感情は、音楽の中で区別することがより難しいことも分かっている。[28][31] 小学校入学前の子供 4歳児と5歳児を対象とした研究では、音楽の抜粋に「幸せ」、「悲しい」、「怒り」、「恐怖」という感情的なラベルを付けるよう求められた。[7] ある研究の結果では、4歳児は 「悲しい」と「怒り」のラベル付けでは偶然以上の結果を出せず、「恐れ」のラベル付けでは5歳児が偶然以上の結果を出せなかった。[7] その後の研究では、5歳児が大人とほぼ同様の結果を出したという相反する結果が示された。しかし、どの年齢層でも「怒り」と「恐れ」の分類は混乱してい た。[7] 就学前および小学校低学年の子供たちは、それぞれ長調または短調の12の短いメロディを聴き、4枚の顔写真(幸せ、満足、悲しみ、怒り)から選ぶよう指示 された。[13] 3歳児でも、長調のメロディには幸せな顔、短調のメロディには悲しい顔を割り当てるという作業を偶然のレベルを超えて正しく行うことができた。[13] 人格の影響 異なる人々は、それぞれの特性に基づいて異なる方法で出来事を認識する。同様に、異なる種類の音楽を聴くことで引き起こされる感情は、人格や音楽の訓練歴 などの要因に影響を受けるようである。[32][33][34] 協調性のある性格の人は、音楽全般に対してより強い感情反応を示すことが分かっている。悲しい感情が強いことも、協調性や神経症傾向の人格タイプを持つ人 々に関連している。音楽教育が複雑な感情を呼び起こす音楽と相関関係にあることや、高いIQや感情理解力のテストスコアと相関関係にあることを示す研究も あるが[32][33]、音楽教育が音楽における感情の知覚に影響を与えるという主張を否定する研究もある[31][35]。音楽に以前から触れている と、その後の行動選択、学業、社会的な交流に影響を与える可能性がある。[36] したがって、音楽に以前から触れていることは、その後の人生における子供の性格や感情に影響を与えると思われ、その結果、音楽に触れている間の感情の認知 や表現能力にも影響を与えることになる。しかし、性別が音楽に含まれる感情の知覚に違いをもたらすという証拠は示されていない。[31][35] 音楽における個人の感情の知覚や、音楽によって感情が引き起こされる能力に影響を与える要因について、さらなる研究が必要である。 |

| Eliciting emotion through music Along with the research that music conveys an emotion to its listener(s), it has also been shown that music can produce emotion in the listener(s).[37] This view often causes debate because the emotion is produced within the listener, and is consequently hard to measure. In spite of controversy, studies have shown observable responses to elicited emotions, which reinforces the Emotivists' view that music does elicit real emotional responses.[7][11] Responses to elicited emotion The structural features of music not only help convey an emotional message to the listener, but also may create emotion in the listener.[10] These emotions can be completely new feelings or may be an extension of previous emotional events. Empirical research has shown how listeners can absorb the piece's expression as their own emotion, as well as invoke a unique response based on their personal experiences.[25] Basic emotions In research on eliciting emotion, participants report personally feeling a certain emotion in response to hearing a musical piece.[37] Researchers have investigated whether the same structures that conveyed a particular emotion could elicit it as well. The researchers presented excerpts of fast tempo, major mode music and slow tempo, minor tone music to participants; these musical structures were chosen because they are known to convey happiness and sadness respectively.[23] Participants rated their own emotions with elevated levels of happiness after listening to music with structures that convey happiness and elevated sadness after music with structures that convey sadness.[23] This evidence suggests that the same structures that convey emotions in music can also elicit those same emotions in the listener. In light of this finding, there has been particular controversy about music eliciting negative emotions. Cognitivists argue that choosing to listen to music that elicits negative emotions like sadness would be paradoxical, as listeners would not willingly strive to induce sadness,[11] whereas emotivists purport that music can elicit negative emotions, and listeners knowingly choose to listen in order to feel sadness in an impersonal way, similar to a viewer's desire to watch a tragic film.[11][37] The reasons why people sometimes listen to sad music when feeling sad has been explored by means of interviewing people about their motivations for doing so. As a result of this research, it has been found that people sometimes listen to sad music when feeling sad to intensify feelings of sadness. Other reasons for listening to sad music when feeling sad were in order to retrieve memories, to feel closer to other people, for cognitive reappraisal, to feel befriended by the music, to distract oneself, and for mood enhancement.[38] Researchers have also found an effect between one's familiarity with a piece of music and the emotions it elicits.[39] One study suggested that familiarity with a piece of music increases the emotions experienced by the listener; half of participants were played twelve random musical excerpts one time, and rated their emotions after each piece. The other half of the participants listened to twelve random excerpts five times, and started their ratings on the third repetition. Findings showed that participants who listened to the excerpts five times rated their emotions with higher intensity than the participants who listened to them only once.[39] Emotional memories and actions Music may not only elicit new emotions, but connect listeners with other emotional sources.[10] Music serves as a powerful cue to recall emotional memories back into awareness.[40] Because music is such a pervasive part of social life, present in weddings, funerals and religious ceremonies, it brings back emotional memories that are often already associated with it.[10][25] Music is also processed by the lower, sensory levels of the brain, making it impervious to later memory distortions. Therefore creating a strong connection between emotion and music within memory makes it easier to recall one when prompted by the other.[10] Music can also tap into empathy, inducing emotions that are assumed to be felt by the performer or composer. Listeners can become sad because they recognize that those emotions must have been felt by the composer,[41][42] much as the viewer of a play can empathize for the actors. Listeners may also respond to emotional music through action.[10] Throughout history music was composed to inspire people into specific action - to march, dance, sing or fight. Consequently, heightening the emotions in all these events. In fact, many people report being unable to sit still when certain rhythms are played, in some cases even engaging in subliminal actions when physical manifestations should be suppressed.[25] Examples of this can be seen in young children's spontaneous outbursts into motion upon hearing music, or exuberant expressions shown at concerts.[25] Juslin and Västfjäll's BRECVEM model Juslin and Västfjäll developed a model of seven ways in which music can elicit emotion, called the BRECVEM model.[43][44] Brain stem reflex: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced by music because one or more fundamental acoustical characteristics of the music are taken by the brain stem to signal a potentially important and urgent event. All other things being equal, sounds that are sudden, loud, dissonant, or feature fast temporal patterns induce arousal or feelings of unpleasantness in listeners...Such responses reflect the impact of auditory sensations – music as sound in the most basic sense." Rhythmic entrainment: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is evoked by a piece of music because a powerful, external rhythm in the music influences some internal bodily rhythm of the listener (e.g. heart rate), such that the latter rhythm adjusts toward and eventually 'locks in' to a common periodicity. The adjusted heart rate can then spread to other components of emotion such as feeling, through proprioceptive feedback. This may produce an increased level of arousal in the listener."[45] Evaluative conditioning: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced by a piece of music simply because this stimulus has been paired repeatedly with other positive or negative stimuli. Thus, for instance, a particular piece of music may have occurred repeatedly together in time with a specific event that always made you happy (e.g., meeting your best friend). Over time, through repeated pairings, the music will eventually come to evoke happiness even in the absence of the friendly interaction." Emotional contagion: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced by a piece of music because the listener perceives the emotional expression of the music, and then 'mimics' this expression internally, which by means of either peripheral feedback from muscles, or a more direct activation of the relevant emotional representations in the brain, leads to an induction of the same emotion." Visual imagery: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced in a listener because he or she conjures up visual images (e.g., of a beautiful landscape) while listening to the music." Episodic memory: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced in a listener because the music evokes a memory of a particular event in the listener's life. This is sometimes referred to as the 'Darling, they are playing our tune' phenomenon."[46] Musical expectancy: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced in a listener because a specific feature of the music violates, delays, or confirms the listener's expectations about the continuation of the music." Musical expectancy With regards to violations of expectation in music several interesting results have been found. It has for example been found that listening to unconventional music may sometimes cause a meaning threat and result in compensatory behaviour in order to restore meaning.[47] Musical expectancy is defined as a process whereby an emotion is aroused in a listener because a specific feature of the music violates, delays, or confirms the listener's expectations about the continuation of the music. Every time the listener hears a piece of music, he or she has such expectations, based on music he or she has heard before. For example, the sequential progression of E-F# may set up the expectation that the music will continue with G#. In other words, some notes seem to imply other notes; and if these musical implications are not realized — if the listener's expectations are thwarted — an affective response might be induced.[48] Aesthetic judgement and BRECVEMA In 2013, Juslin created an additional aspect to the BRECVEM model called aesthetic judgement.[49] This is the criteria which each individual has as a metric for music's aesthetic value. This can involve a number of varying personal preferences, such as the message conveyed, skill presented or novelty of style or idea. Comparison of conveyed and elicited emotions Evidence for emotion in music There has been a bulk of evidence that listeners can identify specific emotions with certain types of music, but there has been less concrete evidence that music may elicit emotions.[10] This is due to the fact that elicited emotion is subjective; and thus, it is difficult to find a valid criterion to study it.[10] Elicited and conveyed emotion in music is usually understood from three types of evidence: self-report, physiological responses, and expressive behavior. Researchers use one or a combination of these methods to investigate emotional reactions to music.[10] Self-report The self-report method is a verbal report by the listener regarding what they are experiencing. This is the most widely used method for studying emotion and has shown that people identify emotions and personally experience emotions while listening to music.[10] Research in the area has shown that listeners' emotional responses are highly consistent. In fact, a meta-analysis of 41 studies on music performance found that happiness, sadness, tenderness, threat, and anger were identified above chance by listeners.[50] Another study compared untrained listeners to musically trained listeners.[50] Both groups were required to categorize musical excerpts that conveyed similar emotions. The findings showed that the categorizations were not different between the trained and untrained; thus demonstrating that the untrained listeners are highly accurate in perceiving emotion.[50] It is more difficult to find evidence for elicited emotion, as it depends solely on the subjective response of the listener. This leaves reporting vulnerable to self-report biases such as participants responding according to social prescriptions or responding as they think the experimenter wants them to.[10] As a result, the validity of the self-report method is often questioned, and consequently researchers are reluctant to draw definitive conclusions solely from these reports.[10] Physiological responses Emotions are known to create physiological, or bodily, changes in a person, which can be tested experimentally. Some evidence shows one of these changes is within the nervous system.[10] Arousing music is related to increased heart rate and muscle tension; calming music is connected to decreased heart rate and muscle tension, and increased skin temperature.[10] Other research identifies outward physical responses such as shivers or goose bumps to be caused by changes in harmony and tears or lump-in-the-throat provoked by changes in melody.[51] Researchers test these responses through the use of instruments for physiological measurement, such as recording pulse rate.[10] Expressive behavior People are also known to show outward manifestations of their emotional states while listening to music. Studies using facial electromyography (EMG) have found that people react with subliminal facial expressions when listening to expressive music.[25] In addition, music provides a stimulus for expressive behavior in many social contexts, such as concerts, dances, and ceremonies.[10][25] Although these expressive behaviors can be measured experimentally, there have been very few controlled studies observing this behavior.[10] Strength of effects Within the comparison between elicited and conveyed emotions, researchers have examined the relationship between these two types of responses to music. In general, research agrees that feeling and perception ratings are highly correlated, but not identical.[23] More specifically, studies are inconclusive as to whether one response has a stronger effect than the other, and in what ways these two responses relate.[23][39][52] Conveyed more than elicited In one study, participants heard a random selection of 24 excerpts, displaying six types of emotions, five times in a row.[39] Half the participants described the emotions the music conveyed, and the other half responded with how the music made them feel. The results found that emotions conveyed by music were more intense than the emotions elicited by the same piece of music.[39] Another study investigated under what specific conditions strong emotions were conveyed. Findings showed that ratings for conveyed emotions were higher in happy responses to music with consistent cues for happiness (i.e., fast tempo and major mode), for sad responses to music with consistent cues for sadness (i.e., slow tempo and minor mode,) and for sad responses in general.[23] These studies suggest that people can recognize the emotion displayed in music more readily than feeling it personally. Sometimes conveyed, sometimes elicited Another study that had 32 participants listen to twelve musical pieces and found that the strength of perceived and elicited emotions were dependent on the structures of the piece of music.[52] Perceived emotions were stronger than felt emotions when listeners rated for arousal and positive and negative activation. On the other hand, elicited emotions were stronger than perceived emotions when rating for pleasantness.[52] Elicited more than conveyed In another study analysis revealed that emotional responses were stronger than the listeners' perceptions of emotions.[52] This study used a between-subjects design, where 20 listeners judged to what extent they perceived four emotions: happy, sad, peaceful, and scared. A separate 19 listeners rated to what extent they experienced each of these emotions. The findings showed that all music stimuli elicited specific emotions for the group of participants rating elicited emotion, while music stimuli only occasionally conveyed emotion to the participants in the group identifying which emotions the music conveyed.[52] Based on these inconsistent findings, there is much research left to be done in order to determine how conveyed and elicited emotions are similar and different. There is disagreement about whether music induces 'true' emotions or if the emotions reported as felt in studies are instead just participants stating the emotions found in the music they are listening to.[53][54] |

音楽による感情の引き出し 音楽がリスナーに感情を伝えるという研究に加え、音楽がリスナーに感情を生み出す可能性があることも示されている。[37] この見解はしばしば議論の的となる。なぜなら、感情はリスナーの中で生み出されるものであり、結果として測定が困難だからである。論争はあるものの、音楽 が引き起こす感情に対する観察可能な反応が研究によって示されており、音楽が実際に感情的な反応を引き起こすというエモティビストの見解を裏付けている。 [7][11] 引き出された感情に対する反応 音楽の構造的特徴は、感情的なメッセージをリスナーに伝える手助けをするだけでなく、リスナーに感情を生み出す可能性もある。[10] これらの感情は、まったく新しい感覚である場合もあれば、過去の感情的な出来事の延長である場合もある。 経験的研究では、リスナーが楽曲の表現を自身の感情として吸収し、また、自身の経験に基づく独特な反応を引き起こすことが示されている。[25] 基本的な感情 感情を引き出す研究では、参加者は特定の楽曲を聴いたときに、個人的に特定の感情を感じたと報告している。[37] 研究者は、特定の感情を伝えたのと同じ構造が、その感情を引き出すこともできるかどうかを調査した。研究者は、参加者に、テンポの速いメジャー調の音楽と テンポの遅いマイナー調の音楽の一部を提示した。これらの音楽構造は、それぞれ幸福と悲しみを伝えることが知られているため選ばれた。[23] 参加者は、幸福を伝える音楽を聴いた後では幸福の度合いが高まり、悲しみを伝える音楽を聴いた後では悲しみの度合いが高まったと評価した。[23] この証拠は、音楽で感情を伝えるのと同じ構造が、リスナーにも同じ感情を引き起こす可能性を示唆している。この発見を踏まえて、特に否定的な感情を引き起 こす音楽について論争が起こっている。認知主義者は、悲しみのような否定的な感情を引き起こす音楽を聴くことを選択することは逆説的であると主張する。な ぜなら、リスナーは自ら進んで悲しみを引き起こそうとはしないからだ[11]。一方、感情主義者は、音楽は否定的な感情を引き起こすことができると主張 し、リスナーは 悲劇的な映画を見たいと思う視聴者の気持ちと同様に、非個人的な方法で悲しみを感じたいと思って、意図的に選んでいるというのだ。[11][37] 人が悲しい時に悲しい音楽を聴く理由については、その動機について人々にインタビューを行うことで調査が行われている。この調査の結果、悲しい時に悲しい 音楽を聴くのは、悲しみという感情を強めるためであることが分かった。悲しい時に悲しい音楽を聴くその他の理由は、思い出を呼び起こすため、他人との親近 感を高めるため、認知的再評価のため、音楽に親近感を抱くため、気を紛らわすため、気分を高めるためなどである。 また、音楽作品に対する親しみやすさと、それが引き起こす感情との間にも影響があることが研究により明らかになっている。ある研究では、音楽作品に対する 親しみやすさが、リスナーが経験する感情を増大させることが示唆された。参加者の半数は、12のランダムな音楽抜粋を1回ずつ聴き、それぞれの音楽を聴い た後に感情を評価した。もう半分の参加者は、12のランダムな抜粋を5回聴き、3回目の繰り返しから評価を開始した。その結果、5回試聴した参加者は、1 回しか試聴しなかった参加者よりも、より強い感情を評価することが分かった。[39] 感情的な記憶と行動 音楽は新たな感情を引き起こすだけでなく、聴く人を他の感情的な源と結びつけることもある。[10] 音楽は、感情的な記憶を意識に呼び戻す強力な手がかりとなる。[40] 音楽は社会生活に広く浸透しており、結婚式や 、葬儀、宗教儀式など、社会生活のあらゆる場面で音楽が流れるため、音楽と関連付けられている感情的な記憶が呼び起こされることが多い。[10][25] 音楽は、脳の感覚をつかさどる低次レベルでも処理されるため、後から記憶が歪められることがない。そのため、記憶の中で感情と音楽が強く結びつくと、一方 が想起されたときに他方も想起されやすくなる。[10] 音楽はまた、共感を呼び起こし、演奏者や作曲者が感じていると想定される感情を引き起こすこともある。聴衆は、作曲家がその感情を経験したに違いないと認 識することで悲しくなることがある。これは、演劇の観客が俳優に感情移入するのと同じようなものである。 また、聴衆は感情的な音楽に反応して行動を起こすこともある。[10] 歴史を通じて、音楽は人々をある特定の行動へと駆り立てるために作曲されてきた。すなわち、行進、ダンス、歌、戦いなどである。その結果、これらのすべて のイベントで感情が高まる。実際、特定のリズムが流れるとじっとしていられなくなるという人も多く、場合によっては、身体的な表現を抑えるべき場面でも無 意識のうちに反応してしまうこともある。[25] その例として、音楽を聴くと自然に動き出す幼児や、コンサートで興奮して感情をあらわにする様子が挙げられる。[25] ジャスリンとヴェストフィエルによるBRECVEMモデル ユスリンとヴェストフィエルは、音楽が感情を引き出す7つの方法をまとめたBRECVEMモデルを開発した。 脳幹反射:「これは、音楽の1つまたは複数の基本的な音響特性が脳幹によって重要な緊急事態の可能性を示すシグナルとして認識されることで、音楽によって 感情が引き起こされるプロセスを指す。他の条件がすべて同じであれば、突然の、大きな、不協和音、または速いテンポのパターンを持つ音は、聴く人に覚醒や 不快な感情を引き起こす...このような反応は、最も基本的な意味での音としての音楽という聴覚感覚の影響を反映している。」 リズム同調:「これは、音楽の持つ強力な外部リズムがリスナーの身体の内部リズム(例えば心拍数)に影響を与えることで、音楽によって感情が呼び起こされ るプロセスを指す。その結果、後者のリズムは共通の周期性に向かって調整され、最終的にその周期性と「同調」する。調整された心拍数は、固有感覚フィード バックを通じて感情の他の要素、例えば感覚などに広がる可能性がある。これにより、リスナーの覚醒レベルが高まる可能性がある。」[45] 評価的条件付け:「これは、ある音楽が他のポジティブまたはネガティブな刺激と繰り返し組み合わされたため、その刺激によって感情が引き起こされるという プロセスを指す。例えば、ある特定の音楽が、いつも幸せな気分にさせてくれる特定の出来事(例えば、親友との再会)と繰り返し同時に起こる場合がある。繰 り返し組み合わされることで、その音楽は、やがてその友好的な交流がなくても幸せな気分を引き起こすようになる。」 感情伝染:「これは、音楽の感情表現をリスナーが知覚し、その感情表現を内面で『模倣』するプロセスを指す。このプロセスは、筋肉からの周辺フィードバック、または脳内の関連する感情表現のより直接的な活性化によって、同じ感情の誘発につながる。」 視覚的イメージ:「これは、音楽を聴いているときに聴者が視覚的イメージ(例えば美しい風景など)を思い浮かべることで、聴者に感情が引き起こされるプロセスを指す。」 エピソード記憶:「これは、音楽が聴者の人生における特定の出来事の記憶を呼び起こすことで、聴者に感情が引き起こされるプロセスを指す。これは時に「ダーリン、彼らは私たちの曲を演奏している」現象とも呼ばれる。[46] 音楽的予期:これは、音楽の特定の特徴が、音楽の継続に対するリスナーの期待を裏切ったり、遅らせたり、あるいは確認したりすることで、リスナーに感情が引き起こされるプロセスを指す。 音楽的予期 音楽における期待の裏切りに関しては、いくつかの興味深い結果が発見されている。例えば、型破りな音楽を聴くことは時に意味の脅威を引き起こし、意味を回 復するための補償行動につながる可能性があることが分かっている。[47] 音楽的期待とは、音楽の特定の特徴が音楽の継続に対するリスナーの期待を裏切ったり、遅らせたり、あるいは確認したりすることで、リスナーに感情が呼び起 こされるプロセスと定義される。リスナーは音楽を聞くたびに、以前に聞いた音楽に基づいてこのような期待を抱く。例えば、E-F#の順次進行は、音楽が G#で続くという期待を抱かせる。言い換えれば、いくつかの音は他の音を暗示しているように思える。そして、これらの音楽的な暗示が実現されない場合、つ まりリスナーの期待が裏切られた場合、感情的な反応が引き起こされる可能性がある。 美的判断とBRECVEMA 2013年、ジャスリンはBRECVEMモデルに美的判断という新たな側面を加えた。[49] これは、音楽の美的価値を測る基準として各個人が持つ基準である。これには、伝えられるメッセージ、表現される技術、スタイルやアイデアの斬新性など、さ まざまな個人的な好みが含まれる。 伝えられる感情と引き出される感情の比較 音楽における感情の証拠 音楽の種類によって特定の感情を特定できるという証拠は数多くあるが、音楽が感情を引き起こすという証拠はあまり具体的ではない。[10] これは引き起こされた感情が主観的なものであるためであり、そのため、それを研究するための有効な基準を見つけるのは難しい。[10] 音楽における引き起こされた感情と伝達された感情は、通常、3つのタイプの証拠から理解される。すなわち、自己申告、生理学的反応、表現行動である。研究 者はこれらの方法の1つまたは組み合わせを用いて、音楽に対する感情的な反応を調査している。 自己申告 自己申告法とは、リスナーが経験していることを言葉で報告する方法である。これは感情を研究する上で最も広く用いられている方法であり、音楽を聴いている 間、人は感情を識別し、個人的に経験していることが示されている。実際、音楽パフォーマンスに関する41の研究のメタ分析では、幸福、悲しみ、優しさ、脅 威、怒りがリスナーによって偶然よりも高い確率で識別されたことが分かっている。[50] 別の研究では、音楽の訓練を受けていないリスナーと音楽の訓練を受けたリスナーを比較した。[50] 両グループに、同様の感情を伝える音楽の抜粋を分類するよう求めた。その結果、訓練を受けたリスナーと受けていないリスナーの間で分類に違いは見られな かった。したがって、訓練を受けていないリスナーは感情を非常に正確に感知していることが示された。[50] 引き出された感情の証拠を見つけるのはより難しい。なぜなら、それはリスナーの主観的な反応のみに依存しているからだ。そのため、参加者が社会的規範に 従って回答したり、実験者が望むような回答をしたりするなど、自己報告バイアスを受けやすい。[10] その結果、自己報告法の妥当性はしばしば疑問視され、その結果、研究者はこれらの報告のみから確定的な結論を導くことをためらう。[10] 生理学的反応 感情は、人格に生理学的、あるいは身体的な変化をもたらすことが知られており、実験的に検証することができる。 こうした変化のひとつが神経系にあることを示す証拠もある。[10] 興奮を誘う音楽は心拍数と筋肉の緊張を高め、心を落ち着かせる音楽は心拍数と筋肉の緊張を低下させ、皮膚温度を上昇させる。[10] その他の研究では、 ハーモニーの変化によって引き起こされる戦慄や鳥肌、メロディの変化によって引き起こされる涙や喉のつまりなどである。[51] 研究者は、脈拍の記録など生理学的測定用の機器を使用して、これらの反応をテストしている。[10] 表現行動 また、音楽を聴いている間、人々は感情の状態を外に表すことも知られている。顔面筋電図法(EMG)を用いた研究では、表現力豊かな音楽を聴いている時 に、人々は無意識のうちに表情で反応することが分かっている。[25] さらに、音楽はコンサート、ダンス、式典など、多くの社会的文脈において表現力豊かな行動を促す刺激となる。[10][25] これらの表現力豊かな行動は実験的に測定できるが、この行動を観察する厳密な研究はほとんど行われていない。[10] 効果の強さ 引き起こされた感情と伝達された感情の比較において、研究者たちは音楽に対するこれら2種類の反応の関係を調査している。一般的に、感情と知覚の評価は高 い相関関係にあるが、同一ではないという点で研究結果は一致している。[23] より具体的には、一方の反応が他方よりも強い影響力を持つかどうか、また、これら2つの反応がどのような形で関連しているかについては、研究結果は結論に 至っていない。[23][39][52] 引き起こされた感情よりも伝達された感情の方が強い ある研究では、参加者は6種類の感情を表す24の抜粋をランダムに選んだものを5回連続で聴いた。[39] 参加者の半数は音楽が伝えた感情を説明し、残りの半数は音楽が自分自身にどのような感情を抱かせたかを回答した。その結果、音楽が伝えた感情の方が、同じ 音楽が引き起こした感情よりも強かったことが分かった。[39] 別の研究では、どのような特定の条件下で強い感情が伝わるのかを調査した。その結果、幸せな感情を伝える音楽に対しては、一貫した幸せの兆候(すなわち、 速いテンポと長調)を持つ音楽に対する反応の方が、悲しい感情を伝える音楽に対しては、一貫した悲しみの兆候(すなわち、遅いテンポと短調)を持つ音楽に 対する反応の方が、悲しい感情を伝える音楽に対する反応全般よりも、伝達された感情に対する評価が高かったことが分かった。[23] これらの研究は、音楽に表現された感情を人々が認識するのは、その感情を個人的に感じるよりも容易であることを示唆している。 伝達される場合もあれば、引き出される場合もある 32人の参加者に12曲の楽曲を聴かせた別の研究では、知覚された感情と引き出された感情の強さは楽曲の構造に依存することが分かった。[52] 聴取者が覚醒度やポジティブおよびネガティブな活性化を評価した際には、知覚された感情の方が感じられた感情よりも強かった。一方、快楽性を評価する際に は、引き出された感情の方が知覚された感情よりも強かった。[52] 引き起こされた感情は伝達された感情よりも強い 別の研究分析では、感情反応はリスナーの感情認識よりも強いことが明らかになった。[52] この研究では、被験者間デザインが用いられ、20人のリスナーが、幸せ、悲しみ、平和、恐怖の4つの感情をどの程度認識しているかを判断した。別の19人 のリスナーは、これらの感情をどの程度経験しているかを評価した。その結果、すべての音楽刺激が、感情を評価した被験者グループに特定の感情を引き起こす 一方で、音楽刺激が音楽が伝える感情を特定するグループの被験者に感情を伝えることはまれであったことが示された。[52] これらの一貫性のない結果に基づき、伝達された感情と引き起こされた感情がどのように類似し、異なるかを判断するには、まだ多くの研究が必要である。音楽 が「真の」感情を引き起こすのか、あるいは研究で感じたと報告された感情は、むしろ参加者が聞いている音楽に含まれる感情を述べているだけなのかについて は、意見が分かれている。[53][54] |

| Music as a therapeutic tool Main article: Music therapy Music therapy as a therapeutic tool has been shown to be an effective treatment for various ailments. Therapeutic techniques involve eliciting emotions by listening to music, composing music or lyrics and performing music.[55] Music therapy sessions may have the ability to help drug users who are attempting to break a drug habit, with users reporting feeling better able to feel emotions without the aid of drug use.[56] Music therapy may also be a viable option for people experiencing extended stays in a hospital due to illness. In one study, music therapy provided child oncology patients with enhanced environmental support elements and elicited more engaging behaviors from the child.[57] When treating troubled teenagers, a study by Keen revealed that music therapy has allowed therapists to interact with teenagers with less resistance, thus facilitating self-expression in the teenager.[citation needed] Music therapy has also shown great promise in individuals with autism, serving as an emotional outlet for these patients. While other avenues of emotional expression and understanding may be difficult for people with autism, music may provide those with limited understanding of socio-emotional cues a way of accessing emotion.[58] |

治療手段としての音楽 主な記事 音楽療法 治療手段としての音楽療法は、様々な疾患に対して効果的な治療法であることが示されている。治療技法には、音楽を聴くことで感情を引き出したり、作曲や作 詞をしたり、音楽を演奏したりすることが含まれる[55]。 音楽療法のセッションは、薬物使用を断ち切ろうとしている薬物使用者を支援する能力があるかもしれず、使用者は薬物使用の助けを借りずに感情を感じること ができるようになったと報告している[56]。ある研究では、音楽療法は小児腫瘍患者に環境的支援要素を強化し、小児からより魅力的な行動を引き出した [57]。キーンによる研究では、問題を抱えたティーンエイジャーを治療する場合、音楽療法によってセラピストがティーンエイジャーと抵抗なく接すること ができ、ティーンエイジャーの自己表現が促進されることが明らかになった[要出典]。 音楽療法は自閉症の患者にも大きな可能性を示しており、これらの患者の感情のはけ口となっている。自閉症の患者にとって、他の感情表現や理解の手段は難し いかもしれないが、音楽は、社会的感情の手がかりを理解することが難しい患者にとって、感情にアクセスする方法を提供するかもしれない[58]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_and_emotion |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j,

1996-2099

本研究は「中米・カリブにお ける感覚のエスノグラフィーに関する実証研究」研究代表者:滝奈々子の研究成果に負っている

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099