グアテマラ先住民における『音と癒し』の感性の人類学的研究

Anthropology for Sensual Experience: an ethnography

Iglesia de San Juan

Chamelco, Departamento de Alta Varapaz, Guatelama.

グアテマラ先住民における『音と癒し』の感性の人類学的研究

Anthropology for Sensual Experience: an ethnography

Iglesia de San Juan

Chamelco, Departamento de Alta Varapaz, Guatelama.

このページは池田光穂が、科学研究費 補助金申請計画「グアテマラ先住民における『音と癒し』の感性の人類学的研究」を書いた時のメモである(滝奈々子の部分的協力はあるが、文責は池田にあ る)。不幸にも、この研究計画は採択されなかったが、計画案としては、それほど悪ものではなく、また、昨今のインターネット情報の豊富化により、さらに研 究を他の人が受け継いで深化させることができる。そのため、ここに公開する。

(概要)この「グアテマラ先住民における『音と癒 し』の感性の人類学的研究」は、グアテマラを中心とした先住民——とりわけ中北東部高地から低地さらにベリーズに居住する——ケクチ・マヤ (Q'eqchi-Maya)の「音と癒し」に関する感性の人類学的文献研究とグアテマラ先住民族研究者とのジョイント現地エスノグラフィー調査である。 この調査の特色は、(1)音楽人類学者の研究代表者、(2)医療人類学者の研究分担者、ならびに(3)グアテマラ・マヤ言語アカデミーのケクチ言語共同体 (ALMG-CLQ)先住民フィールド言語学者による、「音」的感覚が「癒し(ヒーリング)」にどのような影を落とすのかケクチ語による「詩的表現」の言 語によるエスノグラフィー構成をめざす共同研究に挑戦する。

(本文)

この研究すなわち「グアテマラ先住民における『音と 癒し』の感性の人類学的研究」は、グアテマラを中心とした先住民——とりわけ中北東部高地から低地さらにベリーズに居住する——ケクチ・マヤ (Q'eqchi-Maya)の「音と癒し」に関する感性の人類学的文献研究とグアテマラ先住民族研究者とのジョイント現地エスノグラフィー調査である。

(1)本研究の学術的背景。研究課題の核心をなす学 術的「問い」

本研究は、グアテマラを中心とした先住民——とり わけ中北東部高地から低地さらにベリーズに居住する——ケクチ・マヤ(Q'eqchi-Maya)の「音と癒し」に関する感性の人類学的文献研究とグアテ マラ先住民族研究者とのジョイント現地エスノグラフィー調査である。この調査の特色は、(1)音楽人類学者の研究代表者、(2)医療人類学者の研究分担 者、ならびに(3)グアテマラ・マヤ言語アカデミーのケクチ言語共同体(ALMG-CLQ)先住民フィールド言語学者による、「音」的感覚が「癒し(ヒー リング)」にどのような影を落とすのかケクチ語による「詩的表現」の言語によるエスノグラフィー構成をめざす共同研究だということである。

レヴィ=ストロースの「象徴効果」論文 (1958)以降、シャーマンの奏でる詩的言語である呪文が、難産で苦しむ女性の身体に対して何らかの隠喩連関効果をもつことが明らかにされてきた (Laderman & Roseman 1996)。このような言語的研究は、メキシコ・チアパス高原のマヤ系先住民(ツォツィル、ツェルタル)において、劇的パフォーマンスとユーモアーを誘発 して、伝統的祭礼に参加する人たちのカタルシスを生じせしめると考えられている(Bricker 1973)。ハーバードチアパスプロジェクト等のチアパス高原での組織的なエスノグラフィー研究の刺激をうけてグアテマラにおいても調査研究がはじまった が内戦の激化による中断のやむなきに至る。

すなわち、1961年より続いていた内戦の反政府 ゲリラ活動家たちが、1980年代当初より西部高地先住民地域において活動を開始し、またゲリラ軍たちが連携をとり組織的な反政府活動に転じたために、 1982-83年にかけて政府軍による組織的なゲリラ摘発や先住民への選択的かつ組織的な虐殺作戦を展開された。グアテマラ内戦では40万から60万人の 人が失踪あるいは命を落としたといわれる。1996年暮れに和平合意調印がおこなわれたが、その後の経済復興政策や南米コロンビアからの麻薬密売ルートが 活発になり、都市部では若者を中心とする麻薬カルテルのグループが組織化され急速に治安が激化し二千年紀の当初頃までは社会不安が続いていた。この時期以 降、和平合意後の社会復興運動のなかで、先住民文化の復権やマヤ先住民の学士号取得者が急増し、2010年代以降ようやく政治腐敗や軍事政権時代の関係者 が政界を引退ししだし、社会が安定し文化復興運動が社会の中で一定の地歩を占めるようになった。

そのような中で、グアテマラ・マヤ言語アカデミー (Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala, ALMG)は22言語に分類されるマヤ語ならびにシンカとガリフナという非マヤ語を含めた24の先住民言語の調査言語センターとして機能して、言語の中心 地の各地に言語共同体(comunidad lingüística)という地域支所を置き、現地母語話者のフィールド言語学者の育成ならびに、教育用教科書や新造語語彙集(スマートフォンやコン ピュータ等は従来語彙になく日常で使えるためには造語作業が必要)の作成に従事している。しかしながら、それまで北米やヨーロッパの人類学者たちが研究し てきたエスノグラフィーのテーマは専門に特化しすぎ、またそれらの英語文献のスペイン語への「移植」も遅々として進まず、翻訳されてもなお、日常の生活体 験とは程遠い高等な学術著作物として、先住民の一般の人々にはその本の販売部数や価格の高さも加えて「敷居の高い書物」になっている。

そのために、21世紀におけるマヤ先住民のエスノ グラフィーは「先住民の、先住民による、先住民のための」エスノグラフィーでなければならないという声が、先住民・非先住民を問わず現地の教育関係者、大 学教員、そして若い世代の外国人の社会活動家のみならず人類学研究者からも出ている。

そのため、本研究は、ケクチ言語共同体(ALMG -CLQ)先住民フィールド言語学者と、日本の研究者が共同して、彼らの日常経験に近い、伝統的祭礼やあるいはワクチンや母子保健、そして近年はコロナウ イルス感染症対策といった生物医学の公衆衛生学恩恵に預かる時に重要になる「音と癒しの感覚のエスノグラフィー」調査を、スペイン語ならびにケクチ語とし て公刊したり、あるいは頒布したりして、現地の言語芸術文化運動に寄与することが目的とされた。

(2)本研究の目的および学術的独自性と創造性

この「音と癒し」現象に焦点を当てた「感覚のエス ノグラフィー」(→関連ページ「音と感覚のエスノグラフィー」)の書記法の開発に挑戦する ものである。これまで、先住民社会における文化復興運動の台頭は指摘されてきたが、従来の伝統的なエスノグラ フィー(民族誌記述)には馴染みにくいこともあり、その取り扱いもマイナーなままに留まっている。他方「音と癒し」経験には、外部からのポピュラーカル チャーの影響を受けている若い世代を中心に、世代間の違いに着目する必要がある。とりわけ、若い世代が担い手になっているポピュラーカルチャーの記述は、 先進国の中産階級から下層の都市文化の抵抗運動的性格をもつものが中心で、先住民社会におけるポピュラーカルチャーにおける「音と癒し」情報の蓄積と分析 は手薄になっている。

感覚のエスノグラフィーとは、David Howes(2005)によるとセンススケープ(sensescape)の描写であり、それはArjun Appadurai(1996)の5つのスケープ(ethno-, media-, techno-, finance-, ideo-,)に加えたモダニティの第6のスケープと称されるものである。この研究は民族音楽のSteven Feld, 視覚表象のOliver Sacks, メディアのMarshall McLuhan らによって先鞭がつけられ、記憶における Susan Stewart, シャーマンのフェミニニティにおけるSusan Stewart、料理における Lisa Law, 匂い経験の Jim Drobnick などの野心的な研究が続いている。

さて、本研究の舞台であるグアテマラは、22のマ

ヤ系先住民の言語集団のほかに、シンカ、ガリフナといった少数民族が人口半数以上を占めており、民族文化の多様性も大きい。1996年の内戦の和平合意後

の難民の帰還や漸進的な外来文化の流入、麻薬物流と共に到来したマフィア音楽 (narcocorrido)

文化など、複雑なポピュラーカルチャーがさまざまな社会階層や民族文化単位で形成され、レイヤーのように重なっている。一方、低地のケクチ民族は、隣接し

て居住するガリフナの伝統音楽であるプンタ(喪)のリンズムパターンとダンスを発展したプンタ・ロックが勃興し、その影響を無視することができない。ま

た、プエルトリコにおいては、マイノリティー文化やその社会問題に触発されたミュージシャンと、これに共鳴する低所得者層(カセリオ)が母体となり、

2000年代からレゲトンが興盛しており、レゲトンはグアテマラ先住民やメスティソ(ラディーノ=混血)の若者に大きな影響力をもつ。以上のような音響の

芸術表出における諸感覚——とりわけ医療人類学が着目する「癒し=ヒーリング」に着目し、精査することを本研究の主要な目標であると同時に、最大の特徴で

ある。

(3)本研究で何をどのように、どこまで明らかにしようとするのか

研究方法論は、文化人類学のフィールドワークによ

るエスノグラフィー資料の収集である。感覚にまつわる社会現象の収集のために、参与観察の他に、Gopher等をつかった動態的映像記録、ナラティブ映像

などを現場で再生して被調査者自身がメタコメンタリーをするなど、《感覚経験にまつわる内省》と《感覚経験の言語化》手法を動員することが主眼になる。研

究代表者のNTは、聴覚を中心とした音的経験の記述を担当する。グアテマラ高地に居住するケクチやマムのマヤのポピュラー音楽(ロック・マヤやプエルトリ

コ発祥のレゲトン)や生活音を感覚のエスノグラフィーの手法を用いて考察する。研究分担者のMIは、祭礼を中心とした「癒し」経験を中心を担当する。また

「癒し」の身体構築経験には食生活における味覚の経験の分析も重要であり、ケクチ言語共同体先住民フィールド言語学者との協力を得て、ケクチ語の食生活の

「詩的言語」に関する語彙を集積する。先住民の主食であるトルティーヤ中心の食事に加えて、時に中華料理由来のchaominと呼ばれるあんかけ麺を家庭

で作り、Pollo Campero

などの外食チェーンへ出向き、食事をとる。食するということは、直接的に生命と繋がりながらも、その作られる過程、作法、味覚の捉え方に変容がみられる。

このような食という社会的で個人的な行動が、どのような感覚的価値や「癒し」という文化経験を形づくるのかを検証する。以上のような文化的場面や日常生活

で生じる五つの感覚を中心とした経験に「霊的な世界=マヤ儀礼の宇宙観」が示す「音と癒し」の感覚のエスノグラフィー、ひいては感覚のグローバリゼーショ

ン化という問題を、他の地域の文献資料も参照しながら明らかにする。

(この研究に至った経緯)

(1)本研究にいたった経緯と準備状況

研究者代表者と分担者はラテン・アメリカで総計で 25年以上に渡り、現地調査を行っており、それぞれマヤ研究の文化人類学(民族音楽学ならびに医療人類学)とグアテマラ・マヤ言語アカデミーのケクチ言語 共同体(ALMG-CLQ)先住民フィールド言語学者からなる。先住民フィールド言語学者は、グアテマラ政府の政府役人の任用制度が大統領選挙後や組閣に よる所轄大臣の更迭や辞任に応じて変化するので、何名かのリストアップは済んでいるが、現地訪問前から照会をかけ、調査許可や調査協力をとる。現地協力者 のネットワーク化は完了している。全員が当該地域における調査経験と多数の著書・論文がある研究者であり、スペイン語・英語・そして(現地での追加の訓練 は必要なものの)ケクチ語でのインタビューや論文作成の能力をもつ。代表者NTは、音楽学を専門とし、主にグアテマラ高地のケクチの伝統音楽と宗教性を研 究してきた。近著に「思想を記譜することを考える−グアテマラにおけるロック・マヤにみられる『調和(sumk’uub/Kab’awil)』の思想と ロック・マヤの事例から」(2020年)、『Un Trabajo del Profesor Usaburo Mabuchi de 1976-グアテマラ高地チャフル・イシルのたて笛と両面太鼓』(2019年)がある。において、イシルの人びとの縦笛を記譜することとポストコロニアル な思想の関係について言及した。分担者のMIは、医療人類学(文化人類学)、中米民族誌学、臨床コミュニケーションなど、幅広く活動し、まさしく感性=身 体を言及するのにふさわしい。著作に『実践の医療人類学:中央アメリカ・ヘルスケアシステムにおける医療の地政学的展開』(2001)『暴力の民族誌:現 代マヤ先住民の経験と記憶』(2020)、『犬からみた人類史』(2019)などがある。

研究者代表者と分担者は、過去3年間にわたり、 「感覚のエスノグラフィー」に関する私的な研究を組織し、この分野の専門家との交流を深めてきた。NTはK市立芸術大学芸術資源研究センターでの研究をつ づけて、MIは犬の感覚経験を、擬人化という修辞技法をつかって「イヌとニンゲンの〈共存〉についての覚え書き」を『犬からみた人類史』(2019)の中 で執筆し、これまでに数本の専門誌による書評でとりあげられ「感情の寄生虫」論は高い評価を得た。

(2)国内外における研究動向と本研究の位置付け

感覚のエスノグラフィーとは、David Howes(2005)によるとセンススケープ(sensescape)の描写であり、それはArjun Appadurai(1996)の5つのスケープ(ethno-, media-, techno-, finance-, ideo-,)に加えたモダニティの第6のスケープと称されるものである。この研究は民族音楽のSteven Feld, 視覚表象のOliver Sacks, メディアのMarshall McLuhan らによって先鞭がつけられ、記憶における Susan Stewart, シャーマンのフェミニニティにおけるSusan Stewart、料理における Lisa Law, 匂い経験の Jim Drobnick などの野心的な研究が続いている。

しかし、ワッセンのパナマ・クナ民族誌を下敷きに

したレヴィ=ストロース(1955)の象徴効果の論文以降、世界的にみても「音と癒し」の研究はLaderman &

Roseman(1996)のぞいて少ない。

(応募者の研究遂行能力及び研究環境)

省略

(人権の保護及び法令等の遵守への対応)

1.本研究は、フィールドワーク(現地における参与

観

察と聴き取り調査)に基づいているため、参与観察、インタビュー、データの収集等において、個人のプライバシーに関わる情報を取得する可能性を有する。研

究代表者ならびに分担者は、25年以上にわたる現地調査経験を有しており、この間に築いた人的ネットワークに依拠しながら慎重に調査研究を進めてきた経

験を活かし、プラバシーの保持には特に留意する。

2.本調査地であるグアテマラ(および北米に在住する)研究対象者には、内戦期における自らの立場・役割などから、匿名を希望することがある。公開の

回避のみならず特定されない匿名化の手続きに関しては調査時におけるスペイン語ならびにケクチ語による口頭ならびに文書によるインフォームドコンセントを

確実なものにする。

3.研究情報の保護に関しては、調査対象者に文書および口頭において、事前に確認をとり、被調査者との信頼性の担保に務める。また、データを記載した

フィールドノートならびにパーソナル端末などは二重パスワードによるセキュリティならびに鍵のかかる保管庫を使い管理を厳格にして漏えいがないように努め

る。

4.現地側のとの国際共同研究調査においては、直面する具体的な研究倫理上議題を定期的に取り上げ、各種の問題に対処し、議論の機会を設け、日本側なら

びに相手国側の研究チーム全体のコンセンサスを確立する。

5.これらの調査上における個人情報の保護と、それぞれの分野としての研究上の責務に関しては「日本文化人類学会倫理綱領」

(www.jasca.org/onjasca/ethics.html);「日本社会学会倫理綱領」(

http://www.gakkai.ne.jp/jss/about/ethicalcodes.php

)に記載されている理念を本研究に関わるすべての人と共有するように努める。これらの要綱は印刷配布して、倫理上のミスコンダクトがおこらないように留意

する。したがって、この調整過程は、本研究における「感覚の人類学」研究倫理のあり方に対する提言あるいはモデル提案としても位置づけることができる。

「理論的備忘」と「五感についての覚書」は、「★感覚経験の人類学:リーディングス」 を参照してください。

| Music and

emotion This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. (June 2023) |

音楽と感情(この項目は改善の余地あり) |

| Research into music and emotion

seeks to understand the psychological relationship between human affect

and music. The field, a branch of music psychology, covers numerous

areas of study, including the nature of emotional reactions to music,

how characteristics of the listener may determine which emotions are

felt, and which components of a musical composition or performance may

elicit certain reactions. The research draws upon, and has significant implications for, such areas as philosophy, musicology, music therapy, music theory, and aesthetics, as well as the acts of musical composition and of musical performance like a concert. |

音楽と感情に関する研究は、人間の感情と音楽の心理的関係を理解しよう

とするものである。音楽心理学の一分野であるこの分野は、音楽に対する感情反応の性質、聴き手の特徴がどのような感情を引き起こすか、作曲や演奏のどの要

素が特定の反応を引き起こすかなど、多くの研究分野をカバーしている。 その研究は、哲学、音楽学、音楽療法、音楽理論、美学、そして作曲行為やコンサートのような演奏行為といった分野に多大な影響を及ぼしている。 |

| Philosophical approaches Appearance emotionalism Two of the most influential philosophers in the aesthetics of music are Stephen Davies and Jerrold Levinson.[1][2] Davies calls his view of the expressiveness of emotions in music "appearance emotionalism", which holds that music expresses emotion without feeling it. Objects can convey emotion because their structures can contain certain characteristics that resemble emotional expression. He says, "The resemblance that counts most for music's expressiveness ... is between music's temporally unfolding dynamic structure and configurations of human behaviour associated with the expression of emotion."[3] The observer can note emotions from the listener's posture, gait, gestures, attitude, and comportment.[4] Associations between musical features and emotion differ among individuals. Appearance emotionalism claims many listeners' perceiving associations constitutes the expressiveness of music. Which musical features are more commonly associated with which emotions is part of music psychology. Davies says that expressiveness is an objective property of music and not subjective in the sense of being projected into the music by the listener. Music's expressiveness is certainly response-dependent, i.e. it is realized in the listener's judgement. Skilled listeners very similarly attribute emotional expressiveness to a certain piece of music, thereby indicating according to Davies that the expressiveness of music is somewhat objective because if the music lacked expressiveness, then no expression could be projected into it as a reaction to the music.[5] Process theory The philosopher Jennifer Robinson assumes the existence of a mutual dependence between cognition and elicitation in her description of "emotions as process, music as process" theory, or process theory. Robinson argues that the process of emotional elicitation begins with an "automatic, immediate response that initiates motor and autonomic activity and prepares us for possible action" causing a process of cognition that may enable listeners to name the felt emotion. This series of events continually exchanges with new, incoming information. Robinson argues that emotions may transform into one another, causing blends, conflicts, and ambiguities that make impede describing with one word the emotional state that one experiences at any given moment; instead, inner feelings are better thought of as the products of multiple emotional streams. Robinson argues that music is a series of simultaneous processes, and that it therefore is an ideal medium for mirroring such more cognitive aspects of emotion as musical themes' desiring resolution or leitmotif's mirrors memory processes. These simultaneous musical processes can reinforce or conflict with each other and thus also express the way one emotion "morphs into another over time".[6][page needed] |

哲学的アプローチ 外見的感情主義 音楽の美学において最も影響力のある哲学者は、スティーヴン・デイヴィスとジェロルド・レビンソンの2人である[1][2]。デイヴィスは、音楽における 感情の表現力に関する彼の見解を「外見感情主義」と呼び、音楽は感情を感じることなく感情を表現すると主張している。物体が感情を伝えることができるの は、その構造が感情表現に似たある特徴を含むことができるからである。彼は「音楽の表現力にとって最も重要な類似性は、...音楽の時間的に展開する動的 構造と、感情の表現に関連する人間の行動の構成との間にある」と言う[3]。 音楽の特徴と感情との関連は個人によって異なる。外見的感情主義は、多くの聴き手が関連性を知覚することが音楽の表現力を構成すると主張する。どの音楽的 特徴がどの感情とより一般的に関連づけられるかは、音楽心理学の一部である。デイヴィスは、表現力は音楽の客観的な性質であり、聴き手によって音楽に投影 されるという意味での主観的なものではないと言う。音楽の表現力は確かに反応に依存する。熟練した聴き手は、ある楽曲に感情的な表現力を与えるが、これは デイヴィスによれば、音楽の表現力がある程度客観的なものであることを示している。 プロセス理論 哲学者のジェニファー・ロビンソンは、「プロセスとしての感情、プロセスとしての音楽」理論、すなわちプロセス理論の記述において、認知と誘発の間の相互 依存の存在を仮定している。ロビンソンは、感情誘発のプロセスは「自動的で即時的な反応から始まり、運動や自律神経活動を開始し、可能な行動の準備をす る」ことで、聴き手が感じた感情に名前をつけることができる認知のプロセスを引き起こすと主張している。この一連の出来事は、新しく入ってくる情報と絶え ず交換される。ロビンソンは、感情は互いに変化し、混ざり合い、葛藤し、曖昧になるため、ある瞬間に経験する感情状態を一言で表現することが難しくなると 主張する。ロビンソンは、音楽とは一連の同時進行プロセスであり、それゆえ、音楽テーマが解決を望んだり、ライトモチーフが記憶プロセスを映し出すよう な、より認知的な感情の側面を映し出すのに理想的なメディアであると主張する。これらの同時的な音楽プロセスは、互いに補強し合ったり衝突したりするた め、ある感情が「時間の経過とともに別の感情に変容する」様子を表現することもできる[6][要ページ]。 |

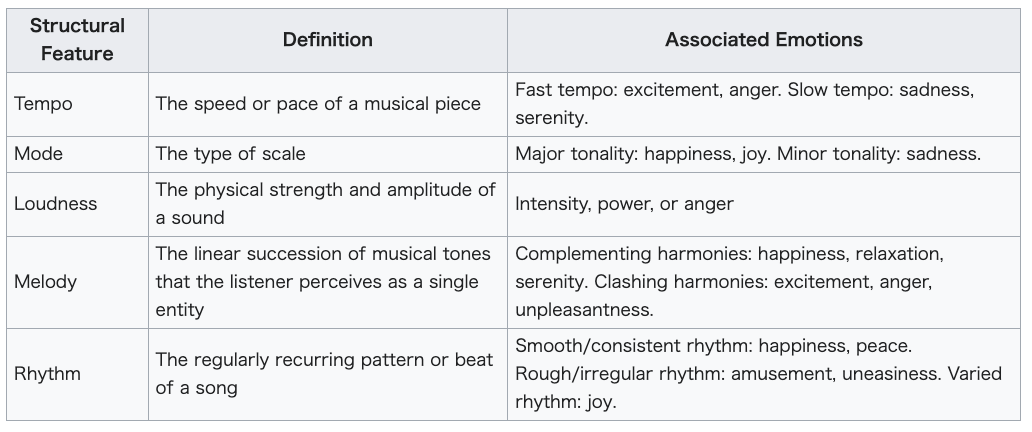

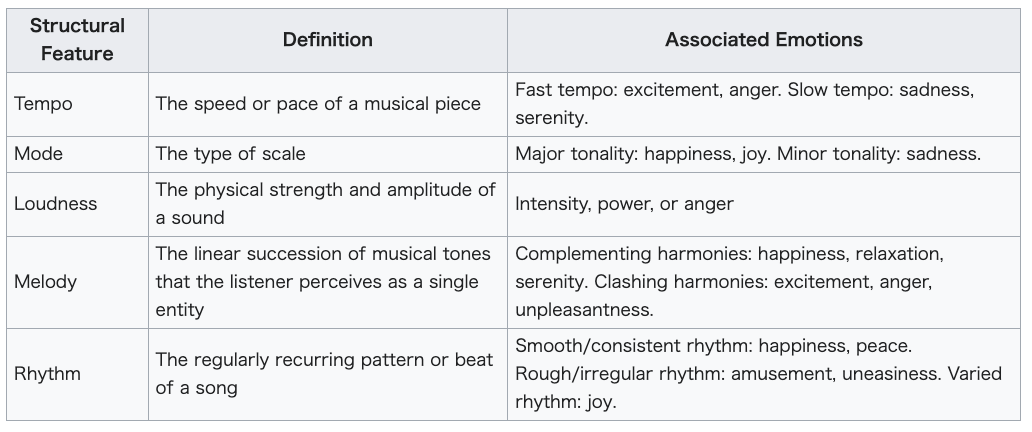

| Conveying emotion through music The ability to perceive emotion in music is said[weasel words] to develop early in childhood, and improve significantly throughout development.[7] The capacity to perceive emotion in music is also subject to cultural influences, and both similarities and differences in emotion perception have been observed in cross-cultural studies.[8][9] Empirical research has looked at which emotions can be conveyed as well as what structural factors in music help contribute to the perceived emotional expression. There are two schools of thought on how we interpret emotion in music. The cognitivists' approach argues that music simply displays an emotion, but does not allow for the personal experience of emotion in the listener. Emotivists argue that music elicits real emotional responses in the listener.[10][11] It has been argued that the emotion experienced from a piece of music is a multiplicative function of structural features, performance features, listener features, contextual features and extra-musical features of the piece, shown as: Experienced Emotion = Structural features × Performance features × Listener features × Contextual features × Extra-Musical features where: Structural features = Segmental features × Suprasegmental features Performance features = Performer skill × Performer state Listener features = Musical expertise × Stable disposition × Current motivation Contextual features = Location × Event[10] Extra-musical features = Non-auditory features × Expertise[12] Structural features Structural features are divided into two parts, segmental features and suprasegmental features. Segmental features are the individual sounds or tones that make up the music; this includes acoustic structures such as duration, amplitude, and pitch. Suprasegmental features are the foundational structures of a piece, such as melody, tempo and rhythm.[10] There are a number of specific musical features that are highly associated with particular emotions.[13] Within the factors affecting emotional expression in music, tempo is typically regarded as the most important, but a number of other factors, such as mode, loudness, and melody, also influence the emotional valence of the piece.[13]  Some studies find that perception of basic emotional features are a cultural universal, though people can more easily perceive emotion, and perceive more nuanced emotion, in music from their own culture.[14][15][16] Music without lyrics is unlikely to elicit social emotions like anger, shame, and jealousy; it typically only elicits basic emotions, like happiness and sadness.[17] Music has a direct connection to emotional states present in human beings. Different musical structures have been found to have a relationship with physiological responses. Research has shown that suprasegmental structures such as tonal space, specifically dissonance, create unpleasant negative emotions in participants. The emotional responses were measured with physiological assessments, such as skin conductance and electromyographic signals (EMG), while participants listened to musical excerpts.[18] Further research on psychophysiological measures pertaining to music were conducted and found similar results; musical structures of rhythmic articulation, accentuation, and tempo were found to correlate strongly with physiological measures, the measured used here included heart rate and respiratory monitors that correlated with self-report questionnaires.[19] These associations can be innate, learned, or both. Studies on young children and isolated cultures show innate associations for features are similar to a human voice (e.g. low and slow is sad, faster and high is happy). Cross-cultural studies show that associations between major mode vs. minor mode and consonance vs. dissonance are probably learned.[20][21] Music also affects socially-relevant memories, specifically memories produced by nostalgic musical excerpts (e.g., music from a significant time period in one’s life, like music listened to on road trips). Musical structures are more strongly interpreted in certain areas of the brain when the music evokes nostalgia. The interior frontal gyrus, substantia nigra, cerebellum, and insula were all identified to have a stronger correlation with nostalgic music than not.[22] Brain activity is a very individualized concept with many of the musical excerpts having certain effects based on individuals’ past life experiences, thus this caveat should be kept in mind when generalizing findings across individuals. Performance features Performance features refer to the manner in which a piece of music is executed by the performer(s). These are broken into two categories: performer skills, and performer state. Performer skills are the compound ability and appearance of the performer; including physical appearance, reputation, and technical skills. The performer state is the interpretation, motivation, and stage presence of the performer.[10] Listener features Listener features refer to the individual and social identity of the listener(s). This includes their personality, age, knowledge of music, and motivation to listen to the music.[10] Contextual features Contextual features are aspects of the performance such as the location and the particular occasion for the performance (i.e., funeral, wedding, dance).[10] Extra-musical features Extra-musical features refer to extra-musical information detached from auditory music signals, such as the genre or style of music. [12] These different factors influence expressed emotion at different magnitudes, and their effects are compounded by one another. Thus, experienced emotion is felt to a stronger degree if more factors are present. The order the factors are listed within the model denotes how much weight in the equation they carry. For this reason, the bulk of research has been done in structural features and listener features.[10] Conflicting cues Which emotion is perceived is dependent on the context of the piece of music. Past research has argued that opposing emotions like happiness and sadness fall on a bipolar scale, where both cannot be felt at the same time.[23] More recent research has suggested that happiness and sadness are experienced separately, which implies that they can be felt concurrently.[23] One study investigated the latter possibility by having participants listen to computer-manipulated musical excerpts that have mixed cues between tempo and mode.[23] Examples of mix-cue music include a piece with major key and slow tempo, and a minor-chord piece with a fast tempo. Participants then rated the extent to which the piece conveyed happiness or sadness. The results indicated that mixed-cue music conveys both happiness and sadness; however, it remained unclear whether participants perceived happiness and sadness simultaneously or vacillated between these two emotions.[23] A follow-up study was done to examine these possibilities. While listening to mixed or consistent cue music, participants pressed one button when the music conveyed happiness, and another button when it conveyed sadness.[24] The results revealed that subjects pressed both buttons simultaneously during songs with conflicting cues.[24] These findings indicate that listeners can perceive both happiness and sadness concurrently. This has significant implications for how the structural features influence emotion, because when a mix of structural cues is used, a number of emotions may be conveyed.[24] Specific listener features Development Studies indicate that the ability to understand emotional messages in music starts early, and improves throughout child development.[7][13][25] Studies investigating music and emotion in children primarily play a musical excerpt for children and have them look at pictorial expressions of faces. These facial expressions display different emotions and children are asked to select the face that best matches the music's emotional tone.[26][27][28] Studies have shown that children are able to assign specific emotions to pieces of music; however, there is debate regarding the age at which this ability begins.[7][13][25] Infants An infant is often exposed to a mother's speech that is musical in nature. It is possible that the motherly singing allows the mother to relay emotional messages to the infant.[29] Infants also tend to prefer positive speech to neutral speech as well as happy music to negative music.[26][29] It has also been posited that listening to their mother's singing may play a role in identity formation.[29] This hypothesis is supported by a study that interviewed adults and asked them to describe musical experiences from their childhood. Findings showed that music was good for developing knowledge of emotions during childhood.[30] Pre-school children These studies have shown that children at the age of 4 are able to begin to distinguish between emotions found in musical excerpts in ways that are similar to adults.[26][27] The ability to distinguish these musical emotions seems to increase with age until adulthood.[28] However, children at the age of 3 were unable to make the distinction between emotions expressed in music through matching a facial expression with the type of emotion found in the music.[27] Some emotions, such as anger and fear, were also found to be harder to distinguish within music.[28][31] Elementary-age children In studies with four-year-olds and five-year-olds, they are asked to label musical excerpts with the affective labels "happy", "sad", "angry", and "afraid".[7] Results in one study showed that four-year-olds did not perform above chance with the labels "sad" and "angry", and the five-year-olds did not perform above chance with the label "afraid".[7] A follow-up study found conflicting results, where five-year-olds performed much like adults. However, all ages confused categorizing "angry" and "afraid".[7] Pre-school and elementary-age children listened to twelve short melodies, each in either major or minor mode, and were instructed to choose between four pictures of faces: happy, contented, sad, and angry.[13] All the children, even as young as three years old, performed above chance in assigning positive faces with major mode and negative faces with minor mode.[13] Personality effects Different people perceive events differently based upon their individual characteristics. Similarly, the emotions elicited by listening to different types of music seem to be affected by factors such as personality and previous musical training.[32][33][34] People with the personality type of agreeableness have been found to have higher emotional responses to music in general. Stronger sad feelings have also been associated with people with personality types of agreeableness and neuroticism. While some studies have shown that musical training can be correlated with music that evoked mixed feelings[32] as well as higher IQ and test of emotional comprehension scores,[33] other studies refute the claim that musical training affects perception of emotion in music.[31][35] It is also worth noting that previous exposure to music can affect later behavioral choices, schoolwork, and social interactions.[36] Therefore, previous music exposure does seem to have an effect on the personality and emotions of a child later in their life, and would subsequently affect their ability to perceive as well as express emotions during exposure to music. Gender, however, has not been shown to lead to a difference in perception of emotions found in music.[31][35] Further research into which factors affect an individual's perception of emotion in music and the ability of the individual to have music-induced emotions are needed. |

音楽で感情を伝える 音楽の中で感情を知覚する能力は、幼少期の早い時期に発達し、発達の過程で著しく向上すると言われている[7]。音楽の中で感情を知覚する能力は文化的な 影響も受け、異文化間の研究において、感情の知覚における類似点と相違点の両方が観察されている[8][9]。音楽における感情をどのように解釈するかに ついては、2つの考え方がある。認知主義者のアプローチは、音楽は単に感情を表示するだけで、聴き手の個人的な感情体験を許さないと主張する。情動主義者 は、音楽は聴き手の本当の情動反応を引き出すと主張する[10][11]。 楽曲から経験される感情は、楽曲の構造的特徴、演奏の特徴、聴き手の特徴、文脈的特徴、音楽外の特徴の乗法関数であると主張されており、以下のように示さ れる: 経験される感情 = 構造的特徴 × 演奏の特徴 × 聴き手の特徴 × 文脈的特徴 × 音楽外の特徴 ここで 構造的特徴=分節的特徴×超分節的特徴 演奏特徴=演奏者の技量×演奏者の状態 リスナー特徴=音楽的専門性×安定した気質×現在のモチベーション 文脈的特徴=場所×出来事[10] 音楽外特徴=非聴覚的特徴×専門性[12] 構造的特徴 構造的特徴は、分節的特徴と超分節的特徴の2つに分けられる。分節的特徴とは、音楽を構成する個々の音や音色のことで、これには継続時間、振幅、ピッチな どの音響構造が含まれる。超分節的特徴とは、メロディ、テンポ、リズムなど、楽曲の基礎となる構造のことである[10]。音楽の感情表現に影響を与える要 因の中で、テンポは一般的に最も重要であると考えられているが、モード、ラウドネス、メロディなど、他の多くの要因も楽曲の感情価に影響を与える [13]。  歌詞のない音楽は、怒り、恥、嫉妬のような社会的感情を引き出す可能性は低く、一般的には幸福や悲しみのような基本的感情のみを引き出す[17]。 音楽は人間に存在する感情状態と直接的な関係がある。異なる音楽構造は、生理的反応と関係があることがわかっている。調性空間、特に不協和音のような超分 節的構造は、参加者に不快な否定的感情を引き起こすことが研究で示されている。この情動反応は、参加者が音楽の抜粋を聴いている間、皮膚コンダクタンスや 筋電図信号(EMG)などの生理学的評価で測定された[18]。音楽に関連する心理生理学的測定に関する更なる研究が実施され、同様の結果が得られた。リ ズムのアーティキュレーション、アクセント、テンポなどの音楽構造は、生理学的測定と強い相関があることが判明しており、ここで使用された測定には、自己 報告式の質問票と相関する心拍数や呼吸モニターが含まれる[19]。 このような関連性は、生得的なもの、学習されたもの、あるいはその両方である可能性がある。幼児や孤立した文化を対象とした研究では、特徴に対す る生得的な関連性は人間の声に類似していることが示されてい る(例えば、低くて遅い音は悲しく、速くて高い音は楽しい)。異文化間の研究によると、長調対短調、協和対不協和の間の連想はおそらく学習されたものであ ることが示されている[20][21]。 音楽は社会的関連記憶にも影響を及ぼし、特にノスタルジッ クな音楽の抜粋(例えば、ドライブ旅行で聴く音楽のような、 人生において重要な時期の音楽)によって生み出される記憶に 影響を及ぼす。音楽がノスタルジアを呼び起こすと、脳の特定の領域で音楽構造がより強く解釈される。脳活動は非常に個人化された概念であり、音楽的抜粋の 多 くは個人の過去の人生経験に基づいて特定の効果を持つた め、個人間で所見を一般化する際にはこの注意点を念頭に置く 必要がある。 演奏の特徴 演奏の特徴とは、楽曲が演奏者によってどのように演奏されるかを指す。これらは演奏者の技能と演奏者の状態の2つに分類される。演奏者スキルとは、演奏者 の身体的外観、評判、技術的スキルなど、複合的な能力と外観のことである。演奏者の状態とは、演奏者の解釈、モチベーション、ステージでの存在感のことで ある[10]。 リスナーの特徴 聞き手の特徴とは、聞き手の個人的・社会的アイデンティティを指す。これには、性格、年齢、音楽に関する知識、音楽を聴く動機などが含まれる[10]。 文脈的特徴 文脈上の特徴とは、場所や演奏の特定の機会(葬式、結婚式、ダンスなど)といった演奏の側面を指す[10]。 音楽外の特徴 音楽外特徴とは、音楽のジャンルやスタイルなど、聴覚的な音楽信号から切り離された音楽外の情報のこと。[12] これらの異なる要因は、表現された感情に異なる大きさで影響を与え、その影響は互いに複合的である。したがって、より多くの要因が存在する場合、経験した 感情はより強く感じられる。モデル内の要因の並び順は、それらが方程式においてどれだけの重みを持つかを示す。このため、研究の大部分は構造的特徴と聞き 手的特徴にお いて行われている[10]。 相反する手がかり どの感情が知覚されるかは、音楽の文脈に左右される。過去の研究では、幸福と悲しみのような相反する感情は両極の尺度に当てはまり、両者を同時に感じるこ とはできないと論じている[23]。最近の研究では、幸福と悲しみは別々に経験されることが示唆されており、これは両者が同時に感じられることを示唆して いる[23]。その後、参加者はその曲がどの程度幸福や悲しみを伝えているかを評価した。その結果、ミックス・キュー音楽は幸福と悲しみの両方を伝えるこ とが示されたが、参加者が幸福と悲しみを同時に知覚するのか、それともこれら2つの感情の間で揺れ動くのかは不明であった。その結果、被験者は相反する手 がかりを持つ曲の間、両方のボタンを同時に押していることが明らかになった[24]。これらの結果は、リスナーは幸福と悲しみの両方を同時に知覚できるこ とを示している。このことは、構造的な特徴が感情にどのように影響するかについて重要な意味を持つ。なぜなら、構造的な手がかりが混在して使用される場 合、多くの感情が伝達される可能性があるからである[24]。 特定の聞き手の特徴 発達 研究では、音楽における感情的メッセージを理解する能力は早期から始まり、子どもの発達を通じて向上することが示されている[7][13][25]。子ど もの音楽と感情について調査している研究では、主に子ども向けに音楽の抜粋を演奏し、子どもたちに顔の絵の表情を見させる。これらの顔の表情は様々な感情 を表しており、子どもは音楽の感情的なトーンに最もマッチする顔を選択するよう求められる[26][27][28]。研究によると、子どもは楽曲に特定の 感情を割り当てることができるが、この能力が始まる年齢については議論がある[7][13][25]。 乳児 乳幼児は、母親の音楽的な発話にしばしばさらされる。乳児はまた、中立的な発話よりも肯定的な発話を、否定的な音楽よりも幸せな音楽を好む傾向がある [26][29]。この仮説は、母親の歌声を聴くことがアイデンティティの形成に関与している可能性があると仮定されている[29]。その結果、音楽は幼 少期に感情に関する知識を発達させるのに適していることが示された[30]。 就学前の子供 これらの研究から、4歳の子どもは、大人と同様の方法で、音楽の抜粋に見られる感情を区別し始めることができることが示されている[26][27]。これ らの音楽的感情を区別する能力は、大人になるまで年齢とともに増加するようである[28]。 小学生 4歳児と5歳児を対象とした研究では、音楽の抜粋に「happy」、 「sad」、「angry」、「fraid」という感情ラベルを付けるよう求めら れている[7]。ある研究の結果では、4歳児は「sad」と「angry」とい うラベルでは偶然の結果を上回らず、5歳児は「fraid」というラベルでは 偶然の結果を上回らなかった[7]。しかし、すべての年齢が「怒り」と「恐れ」の分類を混同していた[7]。就学前児童と小学生年齢の児童は、それぞれ長 調または短調の12曲の短いメロディーを聴き、幸せ、満足、悲しい、怒りの4つの顔の写真から選ぶように指示された[13]。3歳の幼い子どもであって も、すべての子どもは、肯定的な顔を長調に、否定的な顔を短調に割り当てることで、偶然よりも高い結果を示した[13]。 性格の影響 異なる人々は、その個人の特徴に基づいて、異なる出来事を知覚する。同様に、様々なタイプの音楽を聴くことによって引き 起こされる感情は、性格やこれまでの音楽的訓練などの要 因によって影響を受けるようである[32][33][34]。また、より強い悲しい感情は、性格タイプが「快」と「神経症」の人と関連している。音楽的訓 練が、複雑な感情を呼び起こす音楽[32]や、IQや感情理解度テストの高いスコアと相関することを示した研究もあるが[33]、音楽的訓練が音楽におけ る感情の知覚に影響するという主張に反論する研究もある。 [31][35]また、以前音楽に触れたことが、その後の行動選択、学業、社会的相互作用に影響を与える可能性があることも注目に値する[36]。した がって、以前音楽に触れたことは、その後の人生で子どもの性格や感情に影響を与えるようであり、その後、音楽に触れている間に感情を知覚するだけでなく表 現する能力にも影響を与えるだろう。しかし性別は、音楽における感情の知覚の違いにつながらないことが示されている。 |

| Eliciting emotion through music Along with the research that music conveys an emotion to its listener(s), it has also been shown that music can produce emotion in the listener(s).[37] This view often causes debate because the emotion is produced within the listener, and is consequently hard to measure. In spite of controversy, studies have shown observable responses to elicited emotions, which reinforces the Emotivists' view that music does elicit real emotional responses.[7][11] Responses to elicited emotion The structural features of music not only help convey an emotional message to the listener, but also may create emotion in the listener.[10] These emotions can be completely new feelings or may be an extension of previous emotional events. Empirical research has shown how listeners can absorb the piece's expression as their own emotion, as well as invoke a unique response based on their personal experiences.[25] Basic emotions In research on eliciting emotion, participants report personally feeling a certain emotion in response to hearing a musical piece.[37] Researchers have investigated whether the same structures that conveyed a particular emotion could elicit it as well. The researchers presented excerpts of fast tempo, major mode music and slow tempo, minor tone music to participants; these musical structures were chosen because they are known to convey happiness and sadness respectively.[23] Participants rated their own emotions with elevated levels of happiness after listening to music with structures that convey happiness and elevated sadness after music with structures that convey sadness.[23] This evidence suggests that the same structures that convey emotions in music can also elicit those same emotions in the listener. In light of this finding, there has been particular controversy about music eliciting negative emotions. Cognitivists argue that choosing to listen to music that elicits negative emotions like sadness would be paradoxical, as listeners would not willingly strive to induce sadness,[11] whereas emotivists purport that music can elicit negative emotions, and listeners knowingly choose to listen in order to feel sadness in an impersonal way, similar to a viewer's desire to watch a tragic film.[11][37] The reasons why people sometimes listen to sad music when feeling sad has been explored by means of interviewing people about their motivations for doing so. As a result of this research, it has been found that people sometimes listen to sad music when feeling sad to intensify feelings of sadness. Other reasons for listening to sad music when feeling sad were in order to retrieve memories, to feel closer to other people, for cognitive reappraisal, to feel befriended by the music, to distract oneself, and for mood enhancement.[38] Researchers have also found an effect between one's familiarity with a piece of music and the emotions it elicits.[39] One study suggested that familiarity with a piece of music increases the emotions experienced by the listener; half of participants were played twelve random musical excerpts one time, and rated their emotions after each piece. The other half of the participants listened to twelve random excerpts five times, and started their ratings on the third repetition. Findings showed that participants who listened to the excerpts five times rated their emotions with higher intensity than the participants who listened to them only once.[39] Emotional memories and actions Music may not only elicit new emotions, but connect listeners with other emotional sources.[10] Music serves as a powerful cue to recall emotional memories back into awareness.[40] Because music is such a pervasive part of social life, present in weddings, funerals and religious ceremonies, it brings back emotional memories that are often already associated with it.[10][25] Music is also processed by the lower, sensory levels of the brain, making it impervious to later memory distortions. Therefore creating a strong connection between emotion and music within memory makes it easier to recall one when prompted by the other.[10] Music can also tap into empathy, inducing emotions that are assumed to be felt by the performer or composer. Listeners can become sad because they recognize that those emotions must have been felt by the composer,[41][42] much as the viewer of a play can empathize for the actors. Listeners may also respond to emotional music through action.[10] Throughout history music was composed to inspire people into specific action - to march, dance, sing or fight. Consequently, heightening the emotions in all these events. In fact, many people report being unable to sit still when certain rhythms are played, in some cases even engaging in subliminal actions when physical manifestations should be suppressed.[25] Examples of this can be seen in young children's spontaneous outbursts into motion upon hearing music, or exuberant expressions shown at concerts.[25] Juslin and Västfjäll's BRECVEM model Juslin and Västfjäll developed a model of seven ways in which music can elicit emotion, called the BRECVEM model.[43][44] Brain stem reflex: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced by music because one or more fundamental acoustical characteristics of the music are taken by the brain stem to signal a potentially important and urgent event. All other things being equal, sounds that are sudden, loud, dissonant, or feature fast temporal patterns induce arousal or feelings of unpleasantness in listeners...Such responses reflect the impact of auditory sensations – music as sound in the most basic sense." Rhythmic entrainment: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is evoked by a piece of music because a powerful, external rhythm in the music influences some internal bodily rhythm of the listener (e.g. heart rate), such that the latter rhythm adjusts toward and eventually 'locks in' to a common periodicity. The adjusted heart rate can then spread to other components of emotion such as feeling, through proprioceptive feedback. This may produce an increased level of arousal in the listener."[45] Evaluative conditioning: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced by a piece of music simply because this stimulus has been paired repeatedly with other positive or negative stimuli. Thus, for instance, a particular piece of music may have occurred repeatedly together in time with a specific event that always made you happy (e.g., meeting your best friend). Over time, through repeated pairings, the music will eventually come to evoke happiness even in the absence of the friendly interaction." Emotional contagion: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced by a piece of music because the listener perceives the emotional expression of the music, and then 'mimics' this expression internally, which by means of either peripheral feedback from muscles, or a more direct activation of the relevant emotional representations in the brain, leads to an induction of the same emotion." Visual imagery: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced in a listener because he or she conjures up visual images (e.g., of a beautiful landscape) while listening to the music." Episodic memory: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced in a listener because the music evokes a memory of a particular event in the listener's life. This is sometimes referred to as the 'Darling, they are playing our tune' phenomenon."[46] Musical expectancy: "This refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced in a listener because a specific feature of the music violates, delays, or confirms the listener's expectations about the continuation of the music." Musical expectancy With regards to violations of expectation in music several interesting results have been found. It has for example been found that listening to unconventional music may sometimes cause a meaning threat and result in compensatory behaviour in order to restore meaning.[47] Musical expectancy is defined as a process whereby an emotion is aroused in a listener because a specific feature of the music violates, delays, or confirms the listener's expectations about the continuation of the music. Every time the listener hears a piece of music, he or she has such expectations, based on music he or she has heard before. For example, the sequential progression of E-F# may set up the expectation that the music will continue with G#. In other words, some notes seem to imply other notes; and if these musical implications are not realized — if the listener's expectations are thwarted — an affective response might be induced.[48] Aesthetic judgement and BRECVEMA In 2013, Juslin created an additional aspect to the BRECVEM model called aesthetic judgement.[49] This is the criteria which each individual has as a metric for music's aesthetic value. This can involve a number of varying personal preferences, such as the message conveyed, skill presented or novelty of style or idea. Comparison of conveyed and elicited emotions Evidence for emotion in music There has been a bulk of evidence that listeners can identify specific emotions with certain types of music, but there has been less concrete evidence that music may elicit emotions.[10] This is due to the fact that elicited emotion is subjective; and thus, it is difficult to find a valid criterion to study it.[10] Elicited and conveyed emotion in music is usually understood from three types of evidence: self-report, physiological responses, and expressive behavior. Researchers use one or a combination of these methods to investigate emotional reactions to music.[10] Self-report The self-report method is a verbal report by the listener regarding what they are experiencing. This is the most widely used method for studying emotion and has shown that people identify emotions and personally experience emotions while listening to music.[10] Research in the area has shown that listeners' emotional responses are highly consistent. In fact, a meta-analysis of 41 studies on music performance found that happiness, sadness, tenderness, threat, and anger were identified above chance by listeners.[50] Another study compared untrained listeners to musically trained listeners.[50] Both groups were required to categorize musical excerpts that conveyed similar emotions. The findings showed that the categorizations were not different between the trained and untrained; thus demonstrating that the untrained listeners are highly accurate in perceiving emotion.[50] It is more difficult to find evidence for elicited emotion, as it depends solely on the subjective response of the listener. This leaves reporting vulnerable to self-report biases such as participants responding according to social prescriptions or responding as they think the experimenter wants them to.[10] As a result, the validity of the self-report method is often questioned, and consequently researchers are reluctant to draw definitive conclusions solely from these reports.[10] Physiological responses Emotions are known to create physiological, or bodily, changes in a person, which can be tested experimentally. Some evidence shows one of these changes is within the nervous system.[10] Arousing music is related to increased heart rate and muscle tension; calming music is connected to decreased heart rate and muscle tension, and increased skin temperature.[10] Other research identifies outward physical responses such as shivers or goose bumps to be caused by changes in harmony and tears or lump-in-the-throat provoked by changes in melody.[51] Researchers test these responses through the use of instruments for physiological measurement, such as recording pulse rate.[10] Expressive behavior People are also known to show outward manifestations of their emotional states while listening to music. Studies using facial electromyography (EMG) have found that people react with subliminal facial expressions when listening to expressive music.[25] In addition, music provides a stimulus for expressive behavior in many social contexts, such as concerts, dances, and ceremonies.[10][25] Although these expressive behaviors can be measured experimentally, there have been very few controlled studies observing this behavior.[10] Strength of effects Within the comparison between elicited and conveyed emotions, researchers have examined the relationship between these two types of responses to music. In general, research agrees that feeling and perception ratings are highly correlated, but not identical.[23] More specifically, studies are inconclusive as to whether one response has a stronger effect than the other, and in what ways these two responses relate.[23][39][52] Conveyed more than elicited In one study, participants heard a random selection of 24 excerpts, displaying six types of emotions, five times in a row.[39] Half the participants described the emotions the music conveyed, and the other half responded with how the music made them feel. The results found that emotions conveyed by music were more intense than the emotions elicited by the same piece of music.[39] Another study investigated under what specific conditions strong emotions were conveyed. Findings showed that ratings for conveyed emotions were higher in happy responses to music with consistent cues for happiness (i.e., fast tempo and major mode), for sad responses to music with consistent cues for sadness (i.e., slow tempo and minor mode,) and for sad responses in general.[23] These studies suggest that people can recognize the emotion displayed in music more readily than feeling it personally. Sometimes conveyed, sometimes elicited Another study that had 32 participants listen to twelve musical pieces and found that the strength of perceived and elicited emotions were dependent on the structures of the piece of music.[52] Perceived emotions were stronger than felt emotions when listeners rated for arousal and positive and negative activation. On the other hand, elicited emotions were stronger than perceived emotions when rating for pleasantness.[52] Elicited more than conveyed In another study analysis revealed that emotional responses were stronger than the listeners' perceptions of emotions.[52] This study used a between-subjects design, where 20 listeners judged to what extent they perceived four emotions: happy, sad, peaceful, and scared. A separate 19 listeners rated to what extent they experienced each of these emotions. The findings showed that all music stimuli elicited specific emotions for the group of participants rating elicited emotion, while music stimuli only occasionally conveyed emotion to the participants in the group identifying which emotions the music conveyed.[52] Based on these inconsistent findings, there is much research left to be done in order to determine how conveyed and elicited emotions are similar and different. There is disagreement about whether music induces 'true' emotions or if the emotions reported as felt in studies are instead just participants stating the emotions found in the music they are listening to.[53][54] |

音楽による感情の誘発 音楽がリスナーに感情を伝えるという研究とともに、音楽がリスナー に感情を生み出すことも示されている[37]。論争にもかかわらず、誘発された情動に対する観察可能な反応が研究によって示されており、音楽が実際の情動 反応を引き起こすというエモティヴィストの見解が補強されている[7][11]。 誘発された情動に対する反応 音楽の構造的特徴は、リスナーに感情的なメッセージを伝えるのを助けるだけでなく、リスナーの中に感情を作り出すこともある[10]。これらの感情は、全 く新しい感情であることもあれば、以前の感情的な出来事の延長であることもある。実証的な研究により、聴き手が曲の表現を自分の感情として吸収したり、個 人的な経験に基づいた独自の反応を呼び起こしたりすることが示されている[25]。 基本的な感情 感情を引き出す研究において、参加者は楽曲を聴いたときに個人的に特定の感情を感じたと報告する[37]。研究者らは、速いテンポの長調の音楽と遅いテン ポの短調の 音楽の抜粋を参加者に提示した。これらの音楽構造は、それぞれ 幸福と悲しみを伝えることが知られているため選ばれた[23]。 この証拠は、音楽で感情を伝える同じ構造が、聴き手にも同じ感情を引き出すことができることを示唆している。この発見を踏まえて、音楽が否定的な感情を誘 発することについて、特に論争が起きている。認知論者は、悲しみのような否定的な感情を引き起こ す音楽を選ぶことは逆説的であり、聴き手は悲しみを引き起こ すために進んで努力することはないと主張する[11]。 [11][37]悲しい気分のときに悲しい音楽を聴くことがある理由は、そうする動機について人々にインタビューすることによって探求されてきた。この研 究の結果、人は悲しいときに悲しい音楽を聴くことで、悲しみの感情を強めることがあることがわかった。悲しい気分のときに悲しい音楽を聴く他の理由として は、記憶を呼び覚ますため、他人を身近に感じるため、認知的再評価のため、音楽に親しみを感じるため、気を紛らわすため、気分を高めるためなどがあった [38]。 ある研究では、ある楽曲に慣れ親しんでいることで、聴き手が経験す る感情が増大することが示唆されている[39]。残りの半分の参加者は、ランダムに12曲の抜粋を5回聴き、3回目の繰り返しで評価を開始した。その結 果、抜粋を5回聴いた参加者は、1回しか聴かなかった参加者よりも高い強度で感情を評価したことが示された[39]。 感情の記憶と行動 音楽は、新たな情動を引き出すだけでなく、聴き手を他の情動的な源と結びつけるかもしれない[10]。音楽は、情動的な記憶を意識に呼び戻す強力な手がか りとなる[40]。冠婚葬祭や宗教的な儀式など、音楽は社会生活に広く浸透しているため、音楽によって情動的な記憶が呼び戻され、それがすでに関連付けら れていることも多い[10][25]。音楽はまた、脳の低次の感覚レベルで処理されるため、後の記憶の歪みを受けにくい。そのため、記憶内で感情と音楽の 間に強い結びつきを作ることで、もう一方に促されたときにもう一方を思い出しやすくなる[10]。聴き手は、その感情が作曲者によって感じられたに違いな いと認識するため、悲しくなることがある[41][42]。 歴史を通じて、音楽は、行進、ダンス、歌、戦いなど、人々を特定の行動に駆り立てるために作曲された。その結果、これらの出来事すべてにおいて感情が高ま る。実際、多くの人が、特定のリズムが演奏されるとじっとしていられなくなり、場合によっては、身体的な表出が抑制されているはずなのに、サブリミナル的 な行動を起こすことさえあると報告している[25]。この例は、音楽を聴いた幼児が自発的に動き出したり、コンサートで見せる高揚した表情に見られる [25]。 JuslinとVästfjällのBRECVEMモデル JuslinとVästfjällは、BRECVEMモデルと呼ばれる、音楽が感情を引き出す7つの方法のモデルを開発した[43][44]。 脳幹反射:「これは、音楽の1つまたは複数の基本的な音響的特性が、潜在的に重要で緊急な出来事のシグナルとして脳幹に受け取られるために、音楽によって 感情が誘発されるプロセスを指す。他のすべての条件が同じであれば、突然の音、大きな音、不協和音、速い時間的パターンを特徴とする音は、聴き手に興奮や 不快感を引き起こす......このような反応は、聴覚感覚の影響を反映したものであり、最も基本的な意味での音としての音楽である。" リズム同調: "これは、音楽の中の強力な外的リズムが、聴き手の身体内部のリズム(例えば心拍数)に影響を与え、後者のリズムが共通の周期性に向かって調整され、最終 的に「ロックイン」されることによって、音楽によって感情が呼び起こされるプロセスを指す。調整された心拍数は、固有受容フィードバックを通じて、感情な ど他の感情の構成要素にも波及する。これにより、聞き手の覚醒レベルが高まる可能性がある」[45]。 評価的条件づけ: 「これは、この刺激が他の肯定的または否定的な刺激と繰り返し対になることで、音楽によって感情が誘発されるプロセスを指す。例えば、ある特定の音楽が、 いつもあなたを幸せにしてくれる特定の出来事(例えば、親友との出会い)と同時に繰り返し流れてきたとする。時間が経つにつれて、ペアリングが繰り返され ることで、その音楽はやがて、友好的な交流がなくても幸福感を呼び起こすようになる」。 感情の伝染: "リスナーが音楽の感情表現を知覚し、その表現を内部で「模倣」することで、筋肉からの末梢フィードバック、または脳内の関連する感情表象のより直接的な 活性化のいずれかによって、同じ感情が誘発される。" 視覚的イメージ: "音楽を聴きながら視覚的イメージ(例えば美しい風景)を思い浮かべることによって、聴き手に感情が誘発されるプロセスを指す。" エピソード記憶: "これは、音楽が聴き手の人生における特定の出来事の記憶を呼び起こすために、聴き手に感情が誘発されるプロセスを指す。これは「ダーリン、彼らは私たち の曲を演奏している」現象と呼ばれることもある[46]。 音楽的期待: "これは、音楽の特定の特徴が、音楽の継続に関する聴き手の期待に反したり、遅らせたり、確認したりするために、聴き手に感情が誘発されるプロセスを指す "[46]。 音楽的期待 音楽における期待違反に関しては、いくつかの興味深い結果が見つかっている。例えば、型にはまった音楽を聴くことは、時に意味の脅 威を引き起こし、意味を回復するために代償的な行動を引き起こすこ とが分かっている[47]。音楽的期待とは、音楽の特定の特徴が、 音楽の継続に関する聴き手の期待に違反したり、遅らせたり、確 認したりするために、聴き手の感情が喚起されるプロセスと 定義される。聴き手は、ある音楽を聴くたびに、以前に聴いた音楽に基づいて、そのような期待を抱く。例えば、E-F#の順次進行は、音楽がG#で続くとい う期待を抱かせるかもしれない。言い換えれば、いくつかの音は他の音を暗示しているように見え、これらの音楽的含意が実現されない場合、つまり聴き手の期 待が裏切られた場合、感情的反応が引き起こされる可能性がある[48]。 美的判断とBRECVEMA 2013年、ジュスリンはBRECVEMモデルに美的判断と呼ばれる付加的な側面を作り出した[49]。これには、伝えられるメッセージ、提示されるスキ ル、スタイルやアイデアの斬新さなど、さまざまな個人的嗜好が含まれる。 伝わる感情と引き出される感情の比較 音楽における感情の証拠 これは、誘発された感情は主観的なものであるため、それを研 究するための有効な基準を見つけることが難しいためである。研究者は、音楽に対する感情的反応を調査するために、これらの方法の1つまたは組み合わせを使 用する[10]。 自己報告 自己報告法は、リスナーが経験していることに関して口頭で報告する方法である。この分野の研究では、リスナーの感情反応は非常に一貫していることが示され ている[10]。実際、音楽演奏に関する41の研究のメタ分析によると、幸福、悲しみ、優しさ、脅威、怒りは、リスナーによって偶然以上に識別されたこと がわかった[50]。別の研究では、訓練を受けていないリスナーと音楽的訓練を受けたリスナーを比較した[50]。その結果、訓練を受けているリスナーと 訓練を受けていないリスナーとの間で分類に差はなかったことが示され、訓練を受けていないリスナーは感情を正確に知覚できることが実証された[50]。そ の結果、自己報告法の妥当性が疑問視されること が多く、その結果、研究者はこれらの報告のみから決定的な 結論を導き出すことに消極的である[10]。 生理的反応 情動は人に生理的、つまり身体的な変化をもたらすことが知られており、実験的に検証することができる。興奮させる音楽は心拍数や筋緊張の上昇と関係があ り、落ち着かせる音楽は心拍数や筋緊張の低下、皮膚温の上昇と関係がある[10]。他の研究では、震えや鳥肌といった外見的な身体反応は和声の変化によっ て引き起こされ、涙や喉のしこりはメロディの変化によって引き起こされることが確認されている[51]。 表現行動 人は音楽を聴いている間、感情状態を外見に表すことも知られている。顔面筋電図(EMG)を用いた研究では、表現力豊かな音楽を聴いているとき、人はサブ リミナル的な表情で反応することが分かっている[25]。さらに、音楽は、コンサート、ダンス、儀式など、多くの社会的文脈で表現行動の刺激となる [10][25]。これらの表現行動は実験的に測定することができるが、この行動を観察した対照研究はほとんどない[10]。 効果の強さ 感情の誘発と伝達の比較の中で、研究者は音楽に対するこれら2種類の反応の関係を調べてきた。より具体的には、一方の反応が他方の反応よりも強い効果を持 つかどうか、また、これら2つの反応がどのような形で関連してい るかについては、結論が出ていない[23][39][52]。 誘発よりも伝達 ある研究では、参加者は6種類の感情を示す24の抜粋からランダムに選 んだものを5回続けて聴いた[39]。その結果、音楽によって伝えられた感情は、同じ曲によって引き出された感情よりも強いことがわかった[39]。別の 研究では、どのような特定の条件下で強い感情が伝わるかを調査した。その結果、伝達された感情に対する評価は、幸福を表す一貫した手がかり(すなわち、速 いテンポと長調)がある音楽に対する幸福な反応、悲しみを表す一貫した手がかり(すなわち、遅いテンポと短調)がある音楽に対する悲しい反応、および悲し い反応全般に対してより高いことが示された[23]。これらの研究は、人は音楽に表示された感情を個人的に感じるよりも容易に認識できることを示唆してい る。 時に伝えられ、時に引き出される 32人の参加者に12の楽曲を聴かせた別の研究では、知覚された感情と誘発された感情の強さは、楽曲の構造に依存していることがわかった[52]。一方、 快感を評価する場合、誘発された感情は知覚された感情よりも強かった[52]。 伝達よりも誘発 この研究では被験者間デザインが用いられ、20人のリスナーが4つの感情(嬉しい、悲しい、平和、怖い)をどの程度知覚するかを判断した。別の19人のリ スナーは、これらの感情をそれぞれどの程度経験したかを評価した。これらの一貫性のない所見に基づき、伝達された感情と誘発された感情がどのように似てい て異なるかを決定するために、多くの研究が残されている。音楽が「真の」感情を誘発するのか、それとも研究で感じられたと報告された感情が、単に聴いてい る音楽に見出された感情を参加者が述べているだけなのかについては、意見が分かれている[53][54]。 |

| Music as a therapeutic tool Main article: Music therapy Music therapy as a therapeutic tool has been shown to be an effective treatment for various ailments. Therapeutic techniques involve eliciting emotions by listening to music, composing music or lyrics and performing music.[55] Music therapy sessions may have the ability to help drug users who are attempting to break a drug habit, with users reporting feeling better able to feel emotions without the aid of drug use.[56] Music therapy may also be a viable option for people experiencing extended stays in a hospital due to illness. In one study, music therapy provided child oncology patients with enhanced environmental support elements and elicited more engaging behaviors from the child.[57] When treating troubled teenagers, a study by Keen revealed that music therapy has allowed therapists to interact with teenagers with less resistance, thus facilitating self-expression in the teenager.[citation needed] Music therapy has also shown great promise in individuals with autism, serving as an emotional outlet for these patients. While other avenues of emotional expression and understanding may be difficult for people with autism, music may provide those with limited understanding of socio-emotional cues a way of accessing emotion.[58] |

治療手段としての音楽 主な記事 音楽療法 治療手段としての音楽療法は、様々な疾患に対して効果的な治療法であることが示されている。治療技法には、音楽を聴くことで感情を引き出したり、作曲や作 詞をしたり、音楽を演奏したりすることが含まれる[55]。 音楽療法のセッションは、薬物使用を断ち切ろうとしている薬物使用者を支援する能力があるかもしれず、使用者は薬物使用の助けを借りずに感情を感じること ができるようになったと報告している[56]。ある研究では、音楽療法は小児腫瘍患者に環境的支援要素を強化し、小児からより魅力的な行動を引き出した [57]。キーンによる研究では、問題を抱えたティーンエイジャーを治療する場合、音楽療法によってセラピストがティーンエイジャーと抵抗なく接すること ができ、ティーンエイジャーの自己表現が促進されることが明らかになった[要出典]。 音楽療法は自閉症の患者にも大きな可能性を示しており、これらの患者の感情のはけ口となっている。自閉症の患者にとって、他の感情表現や理解の手段は難し いかもしれないが、音楽は、社会的感情の手がかりを理解することが難しい患者にとって、感情にアクセスする方法を提供するかもしれない[58]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_and_emotion |

◎“Las marimbas indígenas de Guatemala: una expresión de lo nacional en resistencia” por el etnomusicólogo Alfonso Arrivillaga, por David Marroquín

◎Rabinal Achi, patrimonio y tradición milenaria, por David Marroquín

En la semana del 21 al

27 de enero, el pueblo de Rabinal se viste de gala. Festejan a su

patrono San Pablo Apóstol, motivo por el cual un complejo de

tradiciones ancestrales aflora para dar vida a la celebración. Sin

duda, destaca entre ellas la puesta en escena -una vez más- del baile

drama del Rabinal Achi, representación que viene desde el periodo

precolombino hasta nuestros días, en la transmisión de este mito de los

rabinaleb.

◎Los garífuna y la veneración del Cristo de Esquipulas, por Alfonso Arrivillaga

Como muchos otros pueblos mesoamericanos, los garínagu también veneran al Cristo de Esquipulas y al igual que otros grupos culturales, como ha sido descrito por cronistas y viajeros, han practicado las romerías desde épocas muy tempranas de su vida en Centroamérica.

Alfonso Arrivillaga-Cortés. Antropólogo, etnomusicólogo. Investigador titular de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Autor de diversos artículos de su especialidad. Editor de la Revista de Etnomusicología Senderos.

| El martes 31 de

agosto a las 16:00 horas de Guatemala, 17:00 horas de México, el

etnomusicólogo Alfonso Arrivillaga disertará sobre “Las marimbas

indígenas de Guatemala: una expresión de lo nacional en resistencia“,

en el marco del “Seminario Antropología, historia, conservación y

documentación de la música en México y el mundo”, organizado Instituto

Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México a través de la

Coordinadora General de Difusión y la Fonoteca INAH, la cual estará

disponible en Facebook FonotecaINAH y YouTube FonotecaINAH. El

blog Investigación para todos de la DIGI le invita a leer esta breve

entrevista a Alfonso Arrivillaga-Cortés. David Marroquín (DM) ¿Cuál es la importancia de la etnomusicología en un país como Guatemala y cómo esta ciencia especializada se relaciona con la marimba? Alfonso Arrivillaga (AA) Guatemala es un país donde la oralidad sigue siendo central. Los acuerdos, los negocios, la trasmisión de conocimientos y otros campos de la vida cotidiana se basan en acuerdos verbales, mismo que suelen tener más valor y respecto que la letra escrita. La etnomusicología es la ciencia que estudia las expresiones sonoras y musicales que se transmiten por la vía de la audición y el ejemplo, podrán imaginar el amplio caudal que cubre. Siendo la marimba, además de su decreto como instrumento nacional, un icono con el que se identifican muchos y lo traen a su ámbito para formar parte de sus expresiones sonoras, la etnomusicología presta las herramientas para un mayor análisis y compresión del papel de este instrumento musical y sus expresiones. DM. ¿Háblanos sobre las marimbas indígenas de Guatemala, sus características principales y cómo se diferencian con la marimba cromática, muy difundida a nivel social y festivo, particularmente en los ámbitos urbanos? AA. Es claro que no hay una Guatemala, sino muchas Guatemala. La música es una buena expresión de esto y más las marimbas, así en plural, que por sus variantes morfológicas se diferencian unas de otras. Es en el ámbito indígena donde la marimba tiene, no solo su mayor vigencia y significado, sino donde goza de popularidad y mantienen vigencia, misma que por cierto se incorpora como un marcador de adhesión y nacionalidad. La marimba usada por los mestizos (ladinos) fue hasta el siglo XX que ingreso a la sociedad y lo hizo no solo pausado sino con mucha dificultad, reticencia que hasta el día de hoy se mantiene. DM. ¿A qué te refieres cuando manifiestas que estas marimbas son “una expresión de lo nacional en resistencia”? AA. Diversas son las teorías que atienen lo nacional, un complejo de expresiones que resultan muy difíciles hacer coincidir con los diversos ejemplos empíricos, que nos muestran diversos matices en la noción de lo nacional. Es evidente que hasta ahora los mestizos han colocado sus expresiones culturales como el estándar, y todo aquello que no responde a la cosmovisión occidental es muestra de permanencia subalterna. Resumen de la conferencia Esta conferencia realiza un recorrido por la historia de la marimba en Guatemala subrayado los espacios donde se ha manifestado contra los otros donde ha llegado por imaginarios y discursos, hasta constituirse en un instrumento nacional –en un inicio diatónico y luego mudado al cromatismo- que nos muestra una nación dividida. Esta conferencia parte de la desmitificación del papel que se alude a la marimba en la gesta del 15 de septiembre de 1821, tiempo en los cuales la marimba era aún cosa de indios y por lo tanto ajena a los espacios que representa lo oficial. |

8月31日(火)グアテマラ時間16:00、メキシコ時間17:00、

民族音楽学者アルフォンソ・アリビラガが「グアテマラのマリンバ・インディオ」について講演する:

このセミナーは、メキシコ国立人類学歴史研究所(Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de

México y el mundo)主催の「Seminario Antropología, historia, conservación y

documentación de la música en México y el

mundo(メキシコと世界における音楽の人類学、歴史、保存と記録セミナー)」の枠組みで開催され、Facebook

FonotecaINAHとYouTube FonotecaINAHで視聴することができる。DIGIのブログ "Investigación

para todos "では、アルフォンソ・アリビリャガ=コルテスへのインタビューを掲載しています。 David Marroquín (DM) グアテマラのような国での民族音楽学の重要性、そしてこの専門的な学問とマリンバとの関係は? アルフォンソ・アリビラガ(AA) グアテマラは、いまだに口承が中心となっている国です。契約、ビジネス、知識の伝達など、日常生活のあらゆる分野で、口頭による合意が基本となっていま す。民族音楽学は、聴覚や手話によって伝達される音や音楽表現を研究する学問であり、そのテーマは多岐にわたることは想像に難くない。マリンバは、国民的 な楽器であると同時に、多くの人が共感し、自分たちの音表現の一部として取り入れている象徴的な存在であり、民族音楽学は、この楽器の役割とその表現をよ り深く分析し、理解するための手段を与えてくれる。 DM.グアテマラの土着のマリンバについて、その主な特徴と、特に都市部で社会的・祝祭的なレベルで広く普及しているクロマチック・マリンバとの違いにつ いて教えてください。 AA. グアテマラはひとつではなく、多くのグアテマラがあることは明らかです。音楽はそれをよく表しており、特にマリンバは複数形であり、形態的な違いによって 互いに区別されている。マリンバが最大の関連性と意味を持つだけでなく、人気を享受し、その関連性を維持しているのは先住民の領域であり、ところで、それ は粘着性と国籍の目印として取り入れられている。メスティーソ(ラディーノ)が使うマリンバは、20世紀まで社会に入ることはなく、それはゆっくりであっ ただけでなく、非常に困難なものであった。 DM:マリンバが「抵抗する民族の表現」だというのはどういう意味ですか? AA. ナショナルという概念にはさまざまな理論があり、さまざまな経験的事例と一致させることが非常に難しい複雑な表現があります。これまでメスティーソが自分 たちの文化表現を基準としてきたことは明らかであり、西洋の世界観に対応しないものはすべて、サブ・インターンの永続性のしるしなのです。 会議の概要 この会議では、グアテマラにおけるマリンバの歴史を旅し、マリンバが他者と対立し、想像や言説を通して辿り着いた空間を明らかにする。この会議は、マリン バが1821年9月15日の英雄的行為に暗示されている役割を解明することに基づいている。 |

| Son

y Tradición. Alfonso Arrivillaga, cultura garífuna |

|

| Son y Tradición. Alfonso

Arrivillaga, cultura garífuna Alfonso Arrivillaga nació en Guatemala en 1959. Estudió Antropología en la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, (Usac). Más tarde se especializó en etnomusicología en Venezuela y realizó estudios de posgrado en Madrid. Desde 1981 es investigador del Centro de Estudios Folclóricos, actividad que ha compartido con la docencia en la Usac. Ha participado en la edición de la serie de discos Encuentros de Músicos de la Tradición Popular y Tradicional de Guatemala y es autor de numerosas publicaciones. Como consultor y asesor académico ha trabajado con el Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo, el Banco Mundial y el Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, entre otros. Algunas de sus publicaciones son: “La Música Tradicional Garífuna en Guatemala”. “Los Garífuna de Guatemala y su contexto regional en La etnografía de Mesoamérica Meridional y el área Circuncaribe” . “Los Garinagú y otros Pueblos del Caribe Guatemalteco Perspectivas y Estrategias contra el Racismo en Discriminación y Racismo”. “Etnomusicología en Guatemala”. Entre otros. Programa transmitido el 23 de noviembre de 2018. Coproducción IMER- Ciudadana 660 y Secretaría de Cultura-DGCPIU. Producción y conducción: Aideé Balderas Medina. Operación técnica: Manuel Compatitla. Web master DGCP: Roberto Nava |

音と伝統 アルフォンソ・アリビラガ、ガリフナ文化 1959年グアテマラ生まれ。サン・カルロス・デ・グアテマラ大学(Usac)で人類学を学ぶ。その後、ベネズエラで民族音楽学を専攻し、マドリードの大 学院で学ぶ。1981年より、ウサック大学で教鞭をとる傍ら、民俗音楽研究センター(Centro de Estudios Folclóricos)の研究員を務める。グアテマラのポピュラー&トラディショナル・ミュージックの記録シリーズ「Encuentros de Músicos de la Tradición and Tradicional de Guatemala」の編集に参加し、数多くの出版物を執筆。 コンサルタント、学術アドバイザーとして、国連開発計画、世界銀行、米州開発銀行などと協力。 主な著書に『グアテマラのガリフナ伝統音楽』、『グアテマラのガリフナ音楽』、『グアテマラのガリフナ音楽』、『グアテマラのガリフナ音楽』などがある。 「グアテマラのガリフナとその地域的背景、中南米と環カリブ地域の地理学」。"Los Garinagú y otros Pueblos del Caribe Guatemalteco Perspectivas y Estrategias contra el Racismo en Discriminación y Racismo(グアテマラ・カリブ海のガリナグとその他の人々:差別と人種主義における人種主義に対する展望と戦略)". 「グアテマラにおける民族音楽学」。とりわけ。 2018年11月23日放送番組。IMER- Ciudadana 660とSecretaría de Cultura-DGCPIUの共同制作。制作・司会:アイデ・バルデラス・メディナ。テクニカルオペレーション:マヌエル・コンパティトラ。ウェブマス ター:ロベルト・ナバ |

◎伝統音楽から民俗音楽、そして民衆音楽へ:グアテマラ国民文化の文化表象について(原案) 2024.02.01

昨年度第21回平安大会では、演者(滝奈々子)は

「先住民社会におけるポピュラー音楽の感性についての考察

—グアテマラの事例をあげて—」において、楽器や楽曲表現を通して、先住民社会における音楽や音的環境の受容についてさまざまな文脈における音楽表現の諸

相を紹介した。そこには教会典礼の伴奏から教会外部での伝統音楽の演奏の「あいだ」の、そして伝統音楽と現代民衆音楽の「あいだ」の、連続性と断続性が考

察の対象になった。発表者は長くグアテマラ共和国のアルタベラパス県において民族音楽調査に従事してきたが、近年は先住民の音楽受容の変化やひろくラテン

アメリカ音楽とりわけ環カリブの音楽環境の影響関係について興味をもつようなった。また国立マリンバ学校での音楽学の教鞭を通して、同国の伝統音楽が国民

文化として洗練発展してきたことを実感してきた。伝統音楽は宗教や祭礼の変化により一部では衰退の危機にあり、他方では民族アイデンティティの表象として

ロックやフォークソングとの融合により新しい展開をとげている。すなわち音楽表現を通して国家が提供するナショナリズムとは異なる様式をとおして「グアテ

マラ民衆」の音楽の中に伝統音楽の精神が息づいているのである。

◎

リンク

文献

その他の情報

CC Nanako TAKI & Mitsuho IKEDA

本研究は「中米・カリブにお ける感覚のエスノグラフィーに関する実証研究」研究代表者:滝奈々子の研究成果に負っている

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆