音楽美学批判

Critique of the Aesthetics of Music

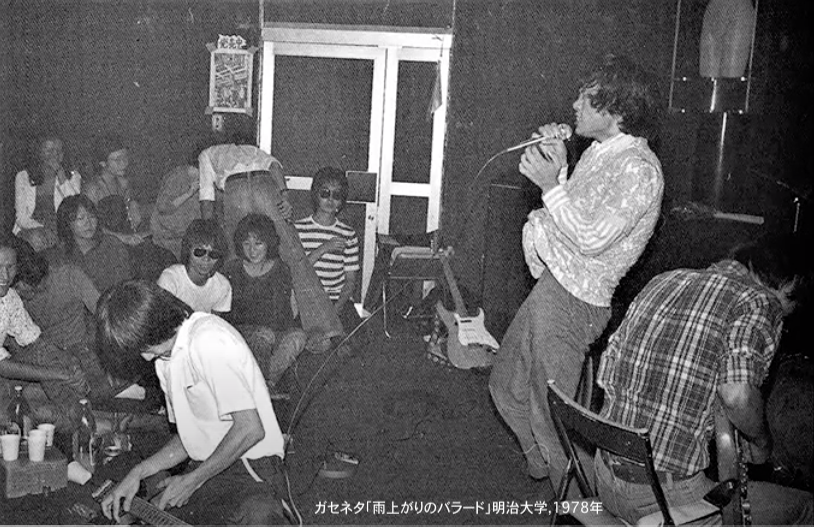

ガセネタ「雨上がりのバラード」1978年/Simon Vouet, Saint Cecilia, c. 1626

☆ 音楽美学(Aesthetics of music)は哲学の一分野であり、芸術の本質、音楽における美と趣味、そして音楽における美の創造や鑑賞を扱う[1]。近代以前の伝統で は、音楽の美学や 音楽美学は、リズム組織の数学的・宇宙論的次元を探求した。18世紀には、音楽を聴くという体験に焦点が移り、その結果、音楽の美と人間の音楽の楽しみ (プレジールとジュイサンス[快楽と享楽])に関する問題に焦点が移った。この哲学的転換(→美学)の起源は、18世紀のバウムガルテンにあるとされることがあり、その後カントが これに続いた。19世紀、20世紀とこれらの考えが継承議論されてきた。そ の議論の核心は、人間の美的判断というものが、どこからやってくるのか?それらは文化的に依存するものなのか?それとも普遍的美学というものがあるという ことに終始した。他方、これらの議論の進展と同時に、音楽そのものもさまざまな多様化をとげて、20世紀以降、ポピュラー音楽が、全世界の人の音楽消費の 大部分を占めるにつれて、西洋古典音楽とそれに支えられた音楽理論の硬直化がすすみ、西洋古典音楽美学研究者は、新しい議論の領域を広げることができな かった。その流れの中で唯一の希望が20世紀中葉から爆発的に発展する「民族音楽 学(ethnomusicology)」あるいは「音楽人類学」 という分野の誕生である(→「まとめ」に続く)。

★ティモシー・ローリーの音楽美学批判は,その言説が「鑑賞,熟考,内省の観点から完全に組み立てられたものであること」が聴き手(演奏家は究極のそれ)を完璧なマシーンにしてしまい多様な経験の内実に踏み込めないので,そのような前提論文は最初から破綻していると慧眼

Laurie, Timothy (2014). "Music Genre as Method". Cultural Studies Review. 20 (2). doi:10.5130/csr.v20i2.4149

★目次

★

| Aesthetics of

music

(/ɛsˈθɛtɪks, iːs-, æs-/) is a branch of philosophy that deals with the

nature of art, beauty and taste in music, and with the creation or

appreciation of beauty in music.[1] In the pre-modern tradition, the

aesthetics of music or musical aesthetics explored the mathematical and

cosmological dimensions of rhythmic and harmonic organization. In the

eighteenth century, focus shifted to the experience of hearing music,

and thus to questions about its beauty and human enjoyment (plaisir and

jouissance) of music. The origin of this philosophic shift is sometimes

attributed to Baumgarten in the 18th century, followed by Kant. Aesthetics is a sub-discipline of philosophy. In the 20th century, important contributions to the aesthetics of music were made by Peter Kivy, Jerrold Levinson, Roger Scruton, and Stephen Davies. However, many musicians, music critics, and other non-philosophers have contributed to the aesthetics of music. In the 19th century, a significant debate arose between Eduard Hanslick, a music critic and musicologist, and composer Richard Wagner regarding whether instrumental music could communicate emotions to the listener. Wagner and his disciples argued that instrumental music could communicate emotions and images; composers who held this belief wrote instrumental tone poems, which attempted to tell a story or depict a landscape using instrumental music. Although history portrays Hanslick as Wagner's opponent, in 1843 after the premiere of Tannhäuser in Dresden, Hanslick gave the opera rave reviews. He called Wagner, “The great new hope of a new school of German Romantic opera.”[2] Thomas Grey, a musicologist specializing in Wagnerian opera at Stanford University argues, “On the Beautiful in Music was written in riposte of Wagner's polemic grandstanding and overblown theorizing.” [3] Hanslick and his partisans asserted that instrumental music is simply patterns of sound that do not communicate any emotions or images. Since ancient times, it has been thought that music has the ability to affect our emotions, intellect, and psychology; it can assuage our loneliness or incite our passions. The Ancient Greek philosopher Plato suggests in The Republic that music has a direct effect on the soul. Therefore, he proposes that in the ideal regime, music would be closely regulated by the state (Book VII). There has been a strong tendency in the aesthetics of music to emphasize the paramount importance of compositional structure; however, other issues concerning the aesthetics of music include lyricism, harmony, hypnotism, emotiveness, temporal dynamics, resonance, playfulness, and color (see also musical development). |

音

楽美学(おんがくびがく、/ɛsˈθ%s-,

æs-/)は哲学の一分野であり、芸術の本質、音楽における美と趣味、そして音楽における美の創造や鑑賞を扱う[1→※]。近代以前の伝統では、音楽の美

学や

音楽美学は、リズム組織の数学的・宇宙論的次元を探求した。18世紀には、音楽を聴くという体験に焦点が移り、その結果、音楽の美と人間の音楽の楽しみ

(プレジールとジュイサンス)に関する問題に焦点が移った。この哲学的転換の起源は、18世紀のバウムガルテンにあるとされることがあり、その後カントが

これに続いた。 ※音楽美学入門 / 国安洋著, 春秋社 , 1981; 「藝術」の終焉 / 国安洋著, 春秋社 , 1991; 芸術の終焉・芸術の未来 / H・フリードリヒ, H-G・ガダマー [ほか] 著 ; 大森淳史 [ほか] 訳, 勁草書房 , 1989. 美学は哲学の一分野である。20世紀には、ピーター・キヴィ、ジェロルド・レビンソン、ロジャー・スクルトン、スティーブン・デイヴィスらが音楽の美学に 重要な貢献をした。しかし、多くの音楽家や音楽評論家など、哲学者以外の人々も音楽の美学に貢献している。19世紀、音楽批評家であり音楽学者でもあった エドゥアルド・ハンスリックと作曲家リヒャルト・ワーグナーの間で、器楽音楽が聴き手に感情を伝えることができるかどうかについて重要な議論が起こった。 ワーグナーとその弟子たちは、器楽音楽は感情やイメージを伝えることができると主張し、この信念を持つ作曲家たちは、器楽音楽を使って物語を語ったり、風 景を描いたりしようとする器楽トーンポエムを書いた。歴史上、ハンスリックはワーグナーの敵対者として描かれているが、1843年、ドレスデンで『タンホ イザー』が初演された後、ハンスリックはこのオペラを絶賛した。スタンフォード大学でワーグナー・オペラを専門とする音楽学者トーマス・グレイは、「音楽 の美について」は、ワーグナーの極論的な大言壮語と大げさな理論化に対する反撃として書かれたものである、と論じている[3]。[3]ハンスリックと彼の 支持者たちは、器楽は単なる音のパターンであり、感情やイメージを伝えるものではないと主張した。 古来より、音楽には人間の感情や知性、心理に影響を与える能力があると考えられてきた。古代ギリシャの哲学者プラトンは、『共和国』の中で、音楽は魂に直 接的な影響を与えると示唆している。それゆえ彼は、理想的な体制においては、音楽は国家によって綿密に規制されるべきだと提唱している(第7巻)。しか し、音楽の美学に関するその他の問題には、叙情性、和声、催眠術、感情、時間的ダイナミクス、共鳴、遊び心、色彩などが含まれる(音楽の発展も参照)。 |

Music

critics listen to symphony orchestra concerts and write a review which

assesses the conductor and orchestra's interpretation of the pieces

they played. The critic uses a range of aesthetic evaluation tools to

write their review. They may assess the tone of the orchestra, the

tempos that the conductor chose for the symphony movements, the taste

and judgement showed by the conductor in their creative choices, and

even the selection of pieces which formed the concert program. Music

critics listen to symphony orchestra concerts and write a review which

assesses the conductor and orchestra's interpretation of the pieces

they played. The critic uses a range of aesthetic evaluation tools to

write their review. They may assess the tone of the orchestra, the

tempos that the conductor chose for the symphony movements, the taste

and judgement showed by the conductor in their creative choices, and

even the selection of pieces which formed the concert program. |

音

楽評論家は交響楽団のコンサートを聴き、指揮者とオーケストラの演奏曲の解釈を評価する批評を書く。批評家は、さまざまな美的評価ツールを使って批評を書

く。オーケストラの音色、指揮者が交響曲の楽章に選んだテンポ、指揮者が創造的な選択で示したセンスと判断力、さらにはコンサートのプログラムを形成した

曲の選択などを評価することもある。 音

楽評論家は交響楽団のコンサートを聴き、指揮者とオーケストラの演奏曲の解釈を評価する批評を書く。批評家は、さまざまな美的評価ツールを使って批評を書

く。オーケストラの音色、指揮者が交響曲の楽章に選んだテンポ、指揮者が創造的な選択で示したセンスと判断力、さらにはコンサートのプログラムを形成した

曲の選択などを評価することもある。 |

| 18th century In the 18th century, music was considered so far outside the realm of aesthetic theory (then conceived of in visual terms) that music was barely mentioned in William Hogarth's treatise The Analysis of Beauty. He considered dance beautiful (closing the treatise with a discussion of the minuet), but treated music important only insofar as it could provide the proper accompaniment for the dancers. However, by the end of the century, people began to distinguish the topic of music and its own beauty from music as part of a mixed media, as in opera and dance. Immanuel Kant, whose Critique of Judgment is generally considered the most important and influential work on aesthetics in the 18th century, argued that instrumental music is beautiful but ultimately trivial. Compared to the other fine arts, it does not engage the understanding sufficiently, and it lacks moral purpose. To display the combination of genius and taste that combines ideas and beauty, Kant thought that music must be combined with words, as in song and opera. |

18世紀 18世紀、音楽は美学理論(当時は視覚的な用語で考えられていた)の領域から大きく外れていると考えられていたため、ウィリアム・ホガースの論文『美の分 析』では音楽についてほとんど触れられていなかった。彼はダンスを美しいと考え(論考の最後をメヌエットの考察で締めくくっている)、音楽はダンサーに適 切な伴奏を提供できる限りにおいてのみ重要なものとして扱った。 しかし、世紀末になると、人々は、音楽とそれ自体の美の話題と、オペラやダンスのような混合メディアの一部としての音楽とを区別するようになった。イマヌ エル・カントは、その『判断力批判』が一般に18世紀の美学に関する最も重要で影響力のある著作とみなされているが、器楽は美しいが究極的にはつまらない ものだと主張した。他の芸術と比べると、理解力を十分に刺激しないし、道徳的な目的にも欠ける。カントは、思想と美を結びつける天才と趣味の結合を示すた めには、歌曲やオペラのように、音楽は言葉と組み合わされなければならないと考えた。 |

| 19th century In the 19th century, the era of romanticism in music, some composers and critics argued that music should and could express ideas, images, emotions, or even a whole literary plot. Challenging Kant's reservations about instrumental music, in 1813 E. T. A. Hoffmann argued that music was fundamentally the art of instrumental composition. Five years later, Arthur Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation argued that instrumental music is the greatest art, because it is uniquely capable of representing the metaphysical organization of reality. He felt that because music neither represents the phenomenal world, nor makes statements about it, it bypasses both the pictorial and the verbal. He believed that music was much closer to the true nature of all things than any other art form. This idea would explain why, when the appropriate music is set to any scene, action or event is played, it seems to reveal its innermost meaning, appearing to be the most accurate and distinct commentary of it.[4] Although the Romantic movement accepted the thesis that instrumental music has representational capacities, most did not support Schopenhauer's linking of music and metaphysics. The mainstream consensus endorsed music's capacity to represent particular emotions and situations. In 1832, composer Robert Schumann stated that his piano work Papillons was "intended as a musical representation" of the final scene of a novel by Jean Paul, Flegeljahre. The thesis that the value of music is related to its representational function was vigorously countered by the formalism of Eduard Hanslick, setting off the "War of the Romantics." This fight, according to Carl Dahlhaus, divided aestheticians into two competing groups: On the one side were formalists (e.g., Hanslick) who emphasized that the rewards of music are found in appreciation of musical form or design, while on the other side were anti-formalists, such as Richard Wagner, who regarded musical form as a means to other artistic ends. Recent research, however, has questioned the centrality of that strife: "For a long time, accounts of aesthetic concerns during that century have focused on a conflict between authors who were sympathetic to either form or content in music, favouring either ‘absolute’ or ‘programme music’ respectively. That interpretation of the period, however, is worn out."[5] Instead, Andreas Dorschel places the tension between music's sensual immediacy and its intellectual mediations centre stage for 19th century aesthetics: "Music seems to touch human beings more immediately than any other form of art; yet it is also an elaborately mediated phenomenon steeped in complex thought. The paradox of this ‘immediate medium’, discovered along with the eighteenth-century invention of ‘aesthetics’, features heavily in philosophy's encounters with music during the nineteenth century. [...] It seems more fruitful now to unfold the paradox of the immediate medium through a web of alternative notions such as sound and matter, sensation and sense, habituation and innovation, imagination and desire, meaning and interpretation, body and gesture."[6] |

19世紀 音楽におけるロマン主義の時代である19世紀、一部の作曲家や批評家は、音楽は思想やイメージ、感情、あるいは文学の筋書き全体を表現すべきであり、また 表現できると主張した。1813年、E.T.A.ホフマンは、器楽に対するカントの留保に異議を唱え、音楽は基本的に器楽の作曲芸術であると主張した。そ の5年後、アーサー・ショーペンハウアーは『意志と表象としての世界』で、器楽こそが最も偉大な芸術であると主張した。彼は、音楽は現象世界を表象するも のでも、それについて述べるものでもないため、絵画的なものも言語的なものも回避することができると考えた。彼は、音楽は他のどの芸術形式よりも万物の本 質に近いと信じていた。この考えは、どのような場面、行為、出来事であっても、それにふさわしい音楽が演奏されると、その音楽がその内奥の意味を明らかに し、最も正確で明確な解説であるかのように見える理由を説明することになる[4]。 ロマン主義運動は器楽音楽には表象能力があるというテーゼを受け入れたが、大半はショーペンハウアーによる音楽と形而上学の結びつきを支持しなかった。主 流派のコンセンサスは、音楽が特定の感情や状況を表現する能力を持つことを支持していた。1832年、作曲家ロベルト・シューマンは、ピアノ作品『パピヨ ン』は、ジャン・パウルの小説『フレーゲルヤハレ』の最終場面の「音楽的表現として意図された」と述べている。音楽の価値はその表象機能に関係するという テーゼは、エドゥアルド・ハンスリックの形式主義によって激しく反論され、"ロマン派の戦争 "が勃発した。 カール・ダールハウスによれば、 この戦いは美学者を2つのグループに分裂させた: 一方は、音楽の報酬は音楽の形式やデザインの鑑賞にあると強調する形式主義者(ハンスリックなど)であり、もう一方は、音楽の形式を他の芸術的目的のため の手段とみなすリヒャルト・ワーグナーのような反形式主義者であった。しかし、最近の研究では、この争いの重要性に疑問が投げかけられている: 長い間、この世紀の美学的関心についての説明は、音楽の形式か内容のどちらかに同調し、それぞれ "絶対音楽 "か "プログラム音楽 "を支持する作者たちの対立に焦点を当ててきた。しかし、この時代のそのような解釈は時代遅れである」[5] 代わりに、アンドレアス・ドルシェールは、音楽の感覚的な即時性と知的な媒介の間の緊張を、19世紀の美学の中心に据えている: 「音楽は、他のどの芸術形態よりも即座に人間に触れるように思われるが、同時に複雑な思考に彩られた、精巧に媒介された現象でもある。18世紀の "美学 "の発明とともに発見されたこの "即時的な媒体 "の逆説は、19世紀の哲学と音楽との出会いにおいて大きく取り上げられている。[音と物質、感覚とセンス、慣れと革新、想像力と欲望、意味と解釈、身体 とジェスチャーといった代替概念の網の目を通して、即物的媒体のパラドックスを展開することは、今となってはより実り多いように思われる」[6]。 |

| 20th century A group of modernist writers in the early 20th century (including the poet Ezra Pound) believed that music was essentially pure because it didn't represent anything, or make reference to anything beyond itself. In a sense, they wanted to bring poetry closer to Hanslick's ideas about the autonomous, self-sufficient character of music. (Bucknell 2002) Dissenters from this view notably included Albert Schweitzer, who argued against the alleged 'purity' of music in a classic work on Bach. Far from being a new debate, this disagreement between modernists and their critics was a direct continuation of the 19th-century debate about the autonomy of music. Among 20th-century composers, Igor Stravinsky is the most prominent composer to defend the modernist idea of musical autonomy. When a composer creates music, Stravinsky claims, the only relevant thing "is his apprehension of the contour of the form, for the form is everything. He can say nothing whatever about meanings" (Stravinsky 1962, p. 115). Although listeners often look for meanings in music, Stravinsky warned that these are distractions from the musical experience. The most distinctive development in the aesthetics of music in the 20th century was that attention was directed at the distinction between 'higher' and 'lower' music, now understood to align with the distinction between art music and popular music, respectively. Theodor Adorno suggested that culture industries churn out a debased mass of unsophisticated, sentimental products that have replaced more 'difficult' and critical art forms that might lead people to actually question social life. False needs are cultivated in people by the culture industries. These needs can be both created and satisfied by the capitalist system, and can replace people's 'true' needs: freedom, full expression of human potential and creativity, and genuine creative happiness. Thus, those trapped in the false notions of beauty according to a capitalist mode of thinking can only hear beauty in dishonest terms (citation necessary). Beginning with Peter Kivy's work in the 1970s, analytic philosophy has contributed extensively to the aesthetics of music. Analytic philosophy pays very little attention to the topic of musical beauty. Instead, Kivy inspired extensive debate about the nature of emotional expressiveness in music. He also contributed to the debate over the nature of authentic performances of older music arguing that much of the debate was incoherent because it failed to distinguish among four distinct standards of authentic performance of music (1995). |

20世紀 20世紀初頭のモダニズム作家のグループ(詩人のエズラ・パウンドを含む)は、音楽は本質的に純粋であり、何も表象しないし、それ自体を超えた何かを言及 することもないと信じていた。ある意味、彼らは音楽の自律的で自給自足的な性格についてのハンスリックの考えに詩を近づけたかったのである (Bucknell 2002)。(この考え方に異を唱えたのは、バッハに関する古典的な著作の中で、音楽の「純粋性」に異議を唱えたアルベルト・シュヴァイツァーである (Bucknell 2002)。このようなモダニストと批評家たちの意見の相違は、新しい議論とは言い難く、音楽の自律性に関する19世紀の議論をそのまま引き継いだもので あった。 20世紀の作曲家の中では、イーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキーが音楽の自律性というモダニズムの考えを擁護する最も著名な作曲家である。ストラヴィンスキー は、作曲家が音楽を創作するとき、関係するのは「形式の輪郭を理解することだけである。彼は意味については何も言うことができない」(ストラヴィンスキー 1962、p.115)。聴き手はしばしば音楽に意味を求めるが、ストラヴィンスキーは、それは音楽体験の邪魔になると警告している。 20世紀における音楽の美学における最も特徴的な発展は、「高次」と「低次」の音楽の区別に注意が向けられたことであり、現在ではそれぞれ芸術音楽とポ ピュラー音楽の区別と一致していると理解されている。テオドール・アドルノは、文化産業が堕落した素朴で感傷的な製品を大量に生産し、それが人々に社会生 活への疑問を抱かせるような、より「難解」で批評的な芸術形態に取って代わったと指摘した。虚偽の欲求は、文化産業によって人々に培われる。これらの欲求 は、資本主義システムによって生み出され、満たされるものであり、人々の「真の」欲求、すなわち自由、人間の可能性と創造性の完全な表現、真の創造的幸福 に取って代わることができる。こうして、資本主義的思考様式による美の誤った概念に囚われた人々は、不誠実な言葉でしか美を聞くことができないのである (要出典)。 1970年代のピーター・キヴィの研究に始まり、分析哲学は音楽の美学に幅広く貢献してきた。分析哲学は、音楽の美というテーマにはほとんど注意を払って いない。その代わり、キヴィは音楽における感情表現の本質について広範な議論を引き起こした。彼はまた、古い音楽の本格的な演奏の本質をめぐる議論にも貢 献し、音楽の本格的な演奏の4つの異なる基準を区別できなかったために、議論の多くが支離滅裂であったと論じている(1995年)。 |

| 21st century In the 21st century, philosophers such as Nick Zangwill have extended the study of aesthetics in music as studied in the 20th century by scholars such as Jerrold Levinson and Peter Kivy. In his 2014 book on the aesthetics of music titled Music and Aesthetic Reality: Formalism and the Limits of Description, Zangwill introduces his realist position by stating, "By 'realism' about musical experience, I mean a view that foregrounds the aesthetic properties of music and our experience of these properties: Musical experience is an awareness of an array of sounds and out the sound structure and its aesthetic properties. This is the content of musical experience."[7] Contemporary music in the 20th and 21st centuries has had both supporters and detractors. Theodor Adorno in the 20th century was a critic of much popular music. Others in the 21st century, such as Eugene W. Holland, have constructively proposed jazz improvisation as a socio-economic model, and Edward W. Sarath has constructively proposed jazz as a useful paradigm for understanding education and society.[8] Constructive reception Eugene W. Holland has proposed jazz improvisation as a model for social and economic relations in general.[9][10] Similarly, Edward W. Sarath has constructively proposed jazz improvisation as a model for change in music, education, and society.[11] Criticism Simon Frith (2004, p. 17-9) argues that, "'bad music' is a necessary concept for musical pleasure, for musical aesthetics." He distinguishes two common kinds of bad music: the Worst Records Ever Made type, which include "Tracks which are clearly incompetent musically; made by singers who can't sing, players who can't play, producers who can't produce," and "Tracks involving genre confusion. The most common examples are actors or TV stars recording in the latest style." Another type of "bad music" is "rock critical lists," such as "Tracks that feature sound gimmicks that have outlived their charm or novelty" and "Tracks that depend on false sentiment [...], that feature an excess of feeling molded into a radio-friendly pop song." Frith gives three common qualities attributed to bad music: inauthentic, [in] bad taste (see also: kitsch), and stupid. He argues that "The marking off of some tracks and genres and artists as 'bad' is a necessary part of popular music pleasure; it is a way we establish our place in various music worlds. And 'bad' is a key word here because it suggests that aesthetic and ethical judgements are tied together here: not to like a record is not just a matter of taste; it is also a matter of argument, and argument that matters" (p. 28). Frith's analysis of popular music is based in sociology. Theodor Adorno was a prominent philosopher who wrote on the aesthetics of popular music. A Marxist, Adorno was extremely hostile to popular music. His theory was largely formulated in response to the growing popularity of American music in Europe between World War I and World War II. As a result, Adorno often uses "jazz" as his example of what he believed was wrong with popular music; however, for Adorno this term included everyone from Louis Armstrong to Bing Crosby. He attacked popular music claiming that it is simplistic and repetitive, and encourages a fascist mindset (1973, p. 126). Besides Adorno, Theodore Gracyk provides the most extensive philosophical analysis of popular music. He argues that conceptual categories and distinctions developed in response to art music are systematically misleading when applied to popular music (1996). At the same time, the social and political dimensions of popular music do not deprive it of aesthetic value (2007). In 2007 musicologist and journalist Craig Schuftan published The Culture Club, a book drawing links between modernism art movements and popular music of today and that of past decades and even centuries. His story involves drawing lines between art, or high culture, and pop, or low culture.[12] A more scholarly study of the same topic, Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde, was published five years earlier by philosopher Bernard Gendron. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthetics_of_music |

21世紀 21世紀、ニック・ザングウィルのような哲学者たちは、ジェロルド・レビンソンやピーター・キヴィのような学者が20世紀に研究した音楽における美学の研 究を拡張してきた。音楽の美学に関する2014年の著書『音楽と美的現実』(原題:Music and Aesthetic Reality)には、次のように書かれている: ザングウィルは、『音楽と美的現実:形式主義と記述の限界』と題した2014年の著書で、「音楽体験に関する "実在論 "とは、音楽の美的特性と、その特性に対する私たちの体験を前景化する見解を意味する:音楽体験とは、音の配列と、それらが決定する美的特性の認識であ る。私たちの経験は、音の構造とその美的特性に向けられる。これが音楽的経験の内容である」と[7]。 20世紀と21世紀の現代音楽には、支持者と否定者の両方がいた。20世紀のテオドール・アドルノは、多くのポピュラー音楽を批判していた。21世紀に は、ユージン・W・ホランドのように、社会経済モデルとしてジャズの即興演奏を建設的に提唱する者もおり、エドワード・W・サラスは、教育と社会を理解す るための有用なパラダイムとしてジャズを建設的に提唱している[8]。 建設的な受容 ユージン・W・ホランドはジャズ・インプロヴィゼイションを社会・経済関係全般のモデルとして提唱している[9][10]。 同様にエドワード・W・サラスはジャズ・インプロヴィゼイションを音楽・教育・社会の変革のモデルとして建設的に提唱している[11]。 批判 サイモン・フリス(2004, p. 17-9)は、「"悪い音楽 "は音楽の楽しみ、音楽の美学にとって必要な概念である」と主張している。歌えない歌手、演奏できないプレイヤー、プロデュースできないプロデューサーに よって作られた、音楽的に明らかに無能な楽曲」と「ジャンルの混乱を伴う楽曲」である。最も一般的な例は、俳優やテレビスターが最新のスタイルでレコー ディングしたものである。" もうひとつの "悪い音楽 "のタイプは、"ロック批判リスト "である。"魅力や目新しさを失ったサウンド・ギミックをフィーチャーしたトラック "や "偽りの感情に依存したトラック[...]、ラジオ・フレンドリーなポップ・ソングに成形された過剰な感情をフィーチャーしたトラック "などである。 フリスは、悪い音楽に共通する3つの特質を挙げている:不真面目、悪趣味(キッチュも参照)、愚か。ある曲やジャンルやアーティストを "バッド "と決めつけることは、ポピュラー音楽の楽しみの必要な部分であり、さまざまな音楽の世界における自分の居場所を確立する方法なのだ。なぜなら、美的判断 と倫理的判断がここで結びついていることを示唆しているからだ。あるレコードを好きになれないということは、単に好みの問題ではなく、議論の問題でもあ り、議論は重要なのだ」(p.28)。フリスのポピュラー音楽分析は社会学に基づいている。 テオドール・アドルノは、ポピュラー音楽の美学について書いた著名な哲学者である。マルクス主義者であったアドルノは、ポピュラー音楽を極端に敵視してい た。彼の理論は、第一次世界大戦と第二次世界大戦の間にヨーロッパでアメリカ音楽の人気が高まったことを受けて、主に定式化された。その結果、ア ドルノはしばしば「ジャズ」をポピュラー音楽の問題点の例として挙げるが、アドルノにとってこの言葉には、ルイ・アームストロングからビング・クロスビー まですべての人が含まれていた。彼は、ポピュラー音楽は単純で反復的であり、ファシズム的な考え方を助長すると主張して、ポピュラー音楽を攻撃した (1973年、126頁)。ポピュラー音楽について最も広範な哲学的分析を行っているのは、アドルノに加え、セオドア・グラチクである。彼 は、芸術音楽に対応して開発された概念的なカテゴリーや区別は、ポピュラー音楽に適用すると体系的に誤解を招くと主張している(1996年)。同時に、ポ ピュラー音楽の社会的・政治的側面は、美的価値を奪うものではないとも述べている(2007年)。 2007年、音楽学者でありジャーナリストでもあるクレイグ・シュフタンは、モダニズム芸術運動と今日のポピュラー音楽、そして過去数十年、さらには数世 紀のポピュラー音楽との関連を描いた『カルチャー・クラブ』を出版した。彼のストーリーは、アート、つまりハイカルチャーと、ポップ、つまりローカル チャーの間に線を引くことを含んでいる[12]: ポピュラー音楽とアヴァンギャルド』は、その5年前に哲学者のベルナール・ジェンドロンによって出版されている。 |

| Aesthetics Culturology List of aesthetic principles of music Music and emotion Musicology Music history Music psychology Music theory Music therapy Sociomusicology Philosophy of music |

美学 文化学 音楽の美学原理一覧 音楽と感情 音楽学 音楽史 音楽心理学 音楽理論 音楽療法 社会音楽学 音楽哲学 |

| 音楽美学 : 新しいモデルを求めて

/ H. エッゲブレヒト他著 ; 戸澤義夫, 庄野進編訳, 勁草書房 , 1987 音楽美学の限界?(ハンス・ハインリヒ・エッゲブレヒト) 「絶対音楽と標題音楽との間に」—ドイツ・ロマン派交響曲の解釈について(ルートヴィヒ・フィンシャー) ベートーヴェンの『ディアベリ変奏曲』における歴史の受容—分析的カテゴリー、美的カテゴリー、歴史的カテゴリーの媒介に向けて(マルティン・ツェンク) オペラ歌手の動作と表情の記号学的分析(ニコレ・スコット・ディ・カルロ) 音楽学における検証と社会学的解釈(オットー・E・ラスケ) 音環境と日常音楽(クルト・ブラウコプフ) 滝のごとき流れ—カルリ音楽理論の隠喩(スティーブン・フェルド) ことばと音《—中心かつ不在》(イワンカ・ストイァノーヴァ) 音‐時間のイマージュ(ダニエル・シャルル) |

【レコード=複製芸術の美学的課題】 「レコードの悪しき聴取者とは、そこに機械論的な因果関係しか見ず……必然的な循環しか聴かない人間である。……良き聴取者にとってレコードをかけ直すこ とはまさに遊び直す(re-play)である」——細川周平(1990).-細川周平『レコードの美学』勁草書房、1990年. |

| 《まとめ》summary 音楽美学は哲学の一分野であり、芸術の本質、音楽における美と趣味、そして音楽における美の創造や鑑賞を扱う[1]。近代以前の伝統では、音楽の美学や 音楽美学は、リズム組織の数学的・宇宙論的次元を探求した。18世紀には、音楽を聴くという体験に焦点が移り、その結果、音楽の美と人間の音楽の楽しみ (プレジールとジュイサンス)に関する問題に焦点が移った。この哲学的転換の起源は、18世紀のバウムガルテンにあるとされることがあり、その後カントが これに続いた。19世紀、20世紀とこれらの考えが継承議論されてきた。そ の議論の核心は、人間の美的判断というものが、どこからやってくるのか?それらは文化的に依存するものなのか?それとも普遍的美学というものがあるという ことに終始した。他方、これらの議論の進展と同時に、音楽そのものもさまざまな多様化をとげて、20世紀以降、ポピュラー音楽が、全世界の人の音楽消費の 大部分を占めるにつれて、西洋古典音楽とそれに支えられた音楽理論の硬直化がすすみ、西洋古典音楽美学研究者は、新しい議論の領域を広げることができな かった。その流れの中で唯一の希望が20世紀中葉から爆発的に発展する「民族音楽 学(ethnomusicology)」あるいは「音楽人類学」 という分野の誕生である。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthetics_of_music |

|

| ☆アー

サー・ダントーは 「芸術作品とは

具現化された意味である」と述べている。スタンフォード哲学百科事典(https://plato.stanford.edu/)

によれば、ダントーの(芸術)定義は次のように説明されている。 |

|

| 「何

かが芸術作品であ るのは、(i)それが主題を持ち(ii)それについて何らかの態度や観

点を投影する(スタイルを持つ)(iii)修辞的省略(通常は比喩)を用いて、省略が足りないものを埋めるために観客を参加させ、

(iv)問題の作品とその解釈には美術史的文脈が必要になる場合だけ」である。その延長上に、ダントーは「芸術」という言葉の基本的な意味

は、何世紀にも

わたって何度も変化し、20世紀にも進化を続けてきた。ダントーは、ヘーゲルの弁証法的芸術史の現代版として、芸術の歴史を描いている。「誰もアートを作

らなくなったとか、良いアートが作られなくなったとか言っているわけではない」。 |

|

| しかし彼[ダントー]は、「ヘーゲルが

示唆したような方法で、西洋美術のある歴史が終

焉を迎えたと考えている」ようである。「芸術の終焉」とは、芸術がもはや模倣理論の制約に従わず、新しい目的を果たす現代の芸術の時代の始まりを指してい

る。芸術は「模倣の時代から始まり、イ

デオロギーの時代、そして資格さえあれば何でもありの我々のポスト歴史的時代へと続く...」【Cloweny, David W.

(December 21, 2009). "Arthur Danto". Rowan university.

】。私たちの物語では、最初はミメーシス(模 倣)だけが芸術で

あり、次にいくつかのものが芸術であったが、それぞれが競争相手を消滅させようとし、そして最後に、様式や哲学的な制約がないことが明らかになったのであ

る。芸術作品がそうでなければならない特別な方法はない。そして、それが現在であり、マスターシナリオの最後の瞬間であると言うだろう。つまり(芸術とい

う)物語の終わりなのである」。ダントーのレトリックはこう。芸術が終わったのでは

なく芸術を語る物語が(なにかをもって正当な芸術だとする)「物語」が終わったという。芸術がそうなければならないという時代は過ぎ去ったということ。だ

から、バロックも、ロマン派も、ケージも、グールド流バッハも、全部、残って芸術概念の多

様性の存続(つまり時間的継続性)が担保されている。だから、アーカイブとその再現と、それについての社会的文脈に関する知識が残っていれば、これまで人

類が芸術だと考えてきたものについての自由な議論が可能になる(→「美的コミュニケーションとは?」)。 |

|

| Philosophy of music, by Nich

Zangwill In the 21st century, philosophers such as Zangwill have extended the study of aesthetics in music, as studied in the 20th century by scholars such as Jerrold Levinson and Peter Kivy. In his 2015 book on the aesthetics of music titled Music and Aesthetic Reality: Formalism and the Limits of Description, Zangwill introduces his realist position by stating, "By 'realism' about musical experience, I mean a view that foregrounds the aesthetic properties of music and our experience of these properties: musical experience is an awareness of an array of sounds and of the aesthetic properties that they determine. Our experience is directed onto the sound structure and its aesthetic properties. This is the content of musical experience."[8] |

音楽の哲学 21世紀に入り、ザングウィルのような哲学者たちは、ジェロルド・レビンソンやピーター・キヴィといった研究者たちが20世紀に研究していた音楽における 美学の研究を拡張した。音楽の美学に関する2015年の著書『音楽と美的現実』(原題:Music and Aesthetic Reality)では、次のように述べている: 「音楽体験に関する "実在論 "とは、音楽の美的特性と、その特性に対する私たちの体験を前景化する見解を意味する:音楽体験とは、音の配列と、それらが決定する美的特性の認識であ る。私たちの経験は、音の構造とその美的特性に向けられる。これが音楽的経験の内容である」[8]。 |

| Jazz

improvisation

is the spontaneous invention of melodic solo lines or accompaniment

parts in a performance of jazz music. It is one of the defining

elements of jazz. Improvisation is composing on the spot, when a singer

or instrumentalist invents melodies and lines over a chord progression

played by rhythm section instruments (piano, guitar, double bass) and

accompanied by drums. Although blues, rock, and other genres use

improvisation, it is done over relatively simple chord progressions

which often remain in one key (or closely related keys using the circle

of fifths, such as a song in C Major modulating to G Major). Jazz improvisation is distinguished from this approach by chordal complexity, often with one or more chord changes per bar, altered chords, extended chords, tritone substitution, unusual chords (e.g., augmented chords), and extensive use of ii–V–I progression, all of which typically move through multiple keys within a single song. However, since the release of Kind of Blue by Miles Davis, jazz improvisation has come to include modal harmony and improvisation over static key centers, while the emergence of free jazz has led to a variety of types of improvisation, such as "free blowing", in which soloists improvise freely and ignore the chord changes. Types Jazz improvisation can be divided into soloing and accompaniment. Soloing When soloing, a performer (instrumentalist or singer) creates a new melodic line to fit a song's chord progression. During a solo, the performer who is playing the solo is the main focus of the audience's attention. The other members of the group usually accompany the solo, except for some drum solos or bass solos in which the entire band may stop while the drummer or bassist performs. When a singer improvises a new melody over chord changes, it is called scat singing. When singers are scat-singing, they typically use made-up syllables ("doo-bie-doo-ba"), rather than use the lyrics of the song. Soloing is often associated with instrumental or vocal virtuosity; while many artists do use advanced techniques in their solos, this is not always done. For example, some 1940s and 1950s-era bass solos consist of the bassist playing a walking bassline. There are a number of approaches to improvising jazz solos. During the swing era, performers improvised solos by ear by using riffs and variations on the tune's melody. During the bebop era in the 1940s, jazz composers began writing more complex chord progressions. Saxophone player Charlie Parker began soloing using the scales and arpeggios associated with the chords in the chord progression. Accompaniment In jazz, when one instrumentalist or singer is doing a solo, the other ensemble members play accompaniment parts. While fully written-out accompaniment parts are used in large jazz ensembles, such as big bands, in small groups (e.g., jazz quartet, piano trio, organ trio, etc.), the rhythm section members typically improvise their accompaniment parts, an activity called comping. In jazz, the instruments in the rhythm section depend on the type of group, but they usually include a bass instrument (double bass, electric bass), one or more instruments capable of playing chords (e.g., piano, electric guitar) and drum kit. Some ensembles may use different instruments in these roles. For example, a 1920s-style Dixieland jazz band may use tuba as a bass instrument and banjo as the chordal instrument. A 1980s-era jazz-rock fusion band may use synth bass for the bassline and a synthesizer for chords. Some bands add one or more percussionists. In small groups, the rhythm section members typically improvise their accompaniment parts. Bass instrument players improvise a bassline using the chord progression of the key as a guide. Common styles of bass comping parts include a walking bassline for 1920s-1950s jazz; rock-style ostinato riffs for jazz-rock fusion; and Latin basslines for Latin jazz. Improvised basslines typically outline the harmony of each chord by playing the root, third, seventh and fifth of each chord, and playing any other notes that the composer has requested in the chord (e.g., if the chord chart indicates a sixth chord on the tonic in C Major, the bassist might include the sixth degree of the C Major scale, an "A" note, in their bassline). The chordal instrument players improvise chords based on the chord progression. Chordal instrument players use jazz chord voicings that are different from those used in popular music and classical music from the common practice period. For example, if a pop musician or one from the Baroque music era (ca. 1600-1750) were asked to play a dominant seventh chord in the key of C Major, they would probably play a root position chord named G7 (or "G dominant seventh"), which consists of the notes G, B, D and F, which are the root, third, fifth and flat seventh of the G chord. A post-Bebop era jazz player who was asked to play a dominant seventh chord in the key of C Major might play an altered dominant chord built on G. An altered dominant contains flattened or sharpened "extensions" in addition to the basic elements of the chord. As well, in jazz, chordal musicians often omit the root, as this role is given to the bass player. The fifth of the chord is often omitted as well, if it is a perfect fifth above the root (as is the case in regular major chords and minor chords). The altered extensions played by a jazz guitarist or jazz pianist on an altered dominant chord on G might include (at the discretion of the performer) a flatted ninth A♭ (a ninth scale degree flattened by one semitone); a sharp eleventh C♯ (an eleventh scale degree raised by one semitone) and a flattened thirteenth E♭ (a thirteenth scale degree lowered by one semitone). If the chordal playing musician were to omit the root and fifth of the dominant seventh chord (the G and D) and keep the third (B) and flatted seventh (F), and add the altered tones just listed (A♭, C♯ and E♭), the resulting chord would be the pitches B, C♯, E♭, F, A♭, which is a much different-sounding chord than the standard G7 played by a pop musician (G, B, D, F). In Classical harmony and in pop music, chord voicings often double the root to emphasize the foundation of the chord progression. Soloing techniques Melodic variation and playing by ear From the dixieland era through to the swing music era, many solo performers improvised by varying and embellishing the existing melody of a song and by playing by ear over the chord changes using well-known riffs. While this approach worked well during these musical eras, given that the chord progressions were simpler and used less modulation to unusual keys, with the development of bebop in the 1940s, the embellishment and "playing by ear" approach was no longer enough. Although swing was designed for dancing, bebop was not. Bebop used complex chord progressions, unusual altered chords and extended chords, and extensive modulations, including to remote keys that are not closely related to the tonic key (the main key or home key of a song). Whereas Dixieland and swing tunes might have one chord change every two bars with some sections with one chord change per bar, bebop tunes often had two chord changes per bar with many changing key every four bars. In addition, since bebop was for listening rather than dancing, the tempo was not constrained by danceability; bebop tunes were often faster than those of the swing era. With bebop's complex tunes and chords and fast tempo, melodic embellishments and playing by ear were no longer sufficient to enable performers to improvise effectively. Saxophone player Charlie Parker began to solo by using scales associated with the chords, including altered extensions such as flattened ninths, sharpened elevenths and flattened thirteenths, and by using the chord tones and themselves as a framework for the creation of chromatic improvisation. Modes Main article: Mode (music) See also: Chord-scale system Modes are all the different musical scales and may be thought of as being derived from various chords. Musicians can use these modes as a pool of available notes. For example, if a musician comes across a C7 chord in a tune, the mode to play over this chord is a C mixolydian scale. These are various chord derivations that help musicians know which chord is associated with a certain scale or mode: C7 → C mixolydian C-7 → C dorian Cmaj7 → C Ionian (natural major) Cmaj7♯11 → C Lydian mode Csus♭9 → C phrygian C- → C Aeolian mode (natural minor) Cø/C-7♭5 → C ..Locrian See also: Jazz chord Targeting One of the key concepts of improvisation is targeting, a technique used by Parker.[1] Targeting means landing on the tones of a chord. A chord is built of a root (1st) and the notes a 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th and 13th above the root in the scale. There are a number of ways to target a chord tone. The first is by ascending or descending chromatic approach (chromatic targeting). This means playing the note a semitone above or below one of the chord tones. In the key of C, the notes in the tonic chord are C(1st or root of chord), E(3rd), G(5th), and B(7th). So by playing a D sharp at the end of a line then resolving (moving up a semitone) to an E, this would be one basic example of targeting and would be targeting the third of the chord (E♮). This may be used with any factor of any type of chord, but rhythm is played so that the chord tones fall on the downbeats.[1] In Bebop melodic improvisation, targeting often focused on the 9th, 11th and 13th of the chord - the colour tones - before resolving later in the phrase to a 7th chord tone. In bebop the 9th, 11th and 13th notes were often altered by adding sharps or flats to these notes. Ninths could be flatted or sharpened. Elevenths were typically played sharpened. Thirteenths were often played flat. Enclosure is the use of scale tone(s) above the targeted note and chromatic tone(s) below, or scale tone(s) below and chromatic tone(s) above.[1] "Flat 9" theory Main article: Flat nine chord Another technique in jazz improvisation used by Parker[1] is known "three to flat nine". These numbers refer to degrees of the scale above the root note of a given chord in a chord progression. This is a bebop approach similar to targeting. This technique can be used over any dominant chord that can be treated as a flat nine (b9) dominant chord. It entails moving from the third of a dominant chord, to the flat nine of a dominant chord, by skipping directly to the ninth, or by a diminished arpeggio (ascending: 3rd, 5th 7th, ♭9th). The chord often resolves to a major chord a perfect fourth away. For example, the third of a G7 chord is B, while the flat ninth is A♭. The chord resolves to C and the note A♭ leads to G.[1] Pentatonics Main article: Pentatonic scale § Major pentatonic scale Pentatonic scales are also commonly used in jazz improvisation, drawing perhaps from their use in the blues. Saxophone player John Coltrane used pentatonics extensively. Most scales are made up of seven notes: (in the key of C – the major scale) C D E F G A B). The major pentatonic scale comprises only five notes of the major scale (C pentatonic scale is C D E G A), whereas the minor pentatonic scale comprises the five notes (C E♭ F G B♭). Pentatonics are useful in pattern form and that is how they are usually played. One pattern using the pentatonic scale could be 3 6 5 2 3 5 (in C: E A G D E G). Pentatonic scales also became popular in rock music, jazz fusion and electric blues. Cells and lines Main article: Lick (music) Lines (also known as licks) are pre-planned ideas the artist plays over and over during an improvised solo. Lines can be obtained by listening to jazz records and transcribing what the professionals play during their solos. Transcribing is putting what you hear in a record onto music paper. Cells are short musical ideas. They are basically the same things as lines, but they are shorter. Phrasing Main article: Phrase (music) Phrasing is a very important part of jazz players' set of improvisational skills. Instead of just playing a sequence of scale and chord notes that would work based on the chords, harmony, etc., the player builds an idea based on a melodic motif or a rhythmic motif. The player in effect extemporizes a new melody for a tune's chord progression. Alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, who is considered to be an exemplar of jazz improvisation, paid special attention to the beginning and ending of his solos where he placed signature patterns that he developed over the years.[2] The middle part of his solos used more extemporaneous material that was created in the moment. This shows a developed style of musical phrasing where the shape of the melody has a logical conclusion. With his strong beginning, Parker was free to create solos that demonstrated musical phrasing, and led to a logical and memorable conclusion. Examples of this motif-based approach in a compositional context are found in classical music. In Beethoven's fifth symphony, the first rhythmic and melodic idea is played again with many variations.[2] The social dimension Jazz improvisation includes a multitude of social protocols for which the musicians have to adhere to.[3] However, "there is no Emily Post handbook for these protocols, but people who drink in the culture of jazz learn what these conventions are."[3] There are no strict rules, but rather general social protocols that guide the players through when to begin their improvisational solo and when to end.[3] These social protocols also tell the player vaguely what to solo about, for example it is a nice gesture to take parts or an end of the pervious musician's solo to then incorporate into the new improviser's solo.[3] For beginning jazz listeners, it can be difficult to understand the structure of a jazz solo and how it fits into the overall song.[4] It may take some time for a listener to even recognize that there is a distinct format for solos in jazz music.[4] Additionally, understanding the role of improvisation in jazz can be challenging to gain from just listening alone, which is why seasoned listeners may be able to recognize solos and formats after "drinking in the culture of jazz"[3] for a longer period of time, therefore, the superficial aspect of a jazz solo is inherently tied to its situational context.[4] The enjoyment and comprehension of a spectator who is unacquainted with the regulations or benchmarks of a sport is similarly lacking in comparison to the enjoyment and comprehension of a listener who is not conversant in the conventions of jazz.[4] In summary, to appreciate jazz improvisation, it is important to not only consider the sound of the music, but also the social and moral dimensions of the art form, including the underlying social structures and the ways in which musicians interact and express themselves.[5] Search for the self According to one model of repetition, defined by Gilles Deleuze, is the synthesis of time through memory that creates something new for the subject who is remembering. The past is repeated and related to other past events, creating a new understanding of the past. However, this repetition is still closed, as the subject only remembers things that confirm their existing identity. This means that any attempt at self-realization is ultimately unsuccessful.[6] Jazz improvisers must use their memory in order to interpret the form of a song and to reference how other musicians have interpreted it in their own improvisations. The challenge for the improviser is to repeat the form in a recognizable way, but to also improvise on it in a way that is original and distinguishes them from other musicians. This repetition allows the audience to recognize the form and the improviser's own style, but according to Theodor Adorno, it ultimately only reinforces the improviser's existing ideas of themselves and does not allow for true self-realization.[6] On the other hand, The concept of signifyin(g) as repetition with a difference, which means that the identity of any particular instance of signifyin(g) and the person engaging in it is constantly changing and influenced by what has come before. This idea, put forward by Henry Louis Gates and Jacques Derrida, also implies that all improvisation is connected to previous instances of the art form, making it impossible for an improviser to be truly autonomous. This complicates the identity of any particular improvisation and the improviser themselves.[7] In psychoanalysis, repetition is an important aspect of identity formation and is associated with what Sigmund Freud called the death drive. This drive goes against the pleasure principle, which states that people will avoid unpleasurable experiences, and instead compels people to repeat traumatic or unpleasant events. According to Freud, this drive is fundamental to the human psyche and is connected to the unconscious. It seeks to return the psyche to its original, quiescent state and to a sense of unity with itself. This repetition and the associated narcissism can be seen in some jazz improvisations, where the desire for self-realization can be self-absorbing and self-negating.[6] Influence Improvisational music also has a social dimension that is influenced by the time, place, history, and culture in which it is performed. This means that listening to improvisational music can be a way to engage with these specific historical and cultural contexts. Improvisation not only shows how people create and shape music, but it can also provide insight into the ways that people think and act. Particular improvisations can have significance because of the specific historical situations in which they were created.[3] Jazz performers pick up cultural attitudes and historical memory, making them their own through improvisation: “memory figures… in a memory of the form, in the first place, but also in a memory of all the ways that form has been rendered by other players and by the improviser herself”.[6] Therefore, the memory of the Jazz piece and the reiteration of the piece helps to insert fragments of the player’s self into the music, as it's hard to remember exactly what a particular Jazz piece was, primarily if it wasn't composed. In other words, the player utilizes their knowledge of past sounds and reiterates a new song based on past precedents, intuition, and culture. Ethics Many people believe that the social aspect of jazz improvisation can serve as a good foundation for ethics. Kathleen Higgins argues that the way that individuals and groups interact and improvise in jazz can be seen as a model for ethical interactions, particularly between minority and majority populations. This idea is supported by Ingrid Monson, a musicologist, and Jacques Attali, an economist and scholar.[3] Eugene W. Holland has proposed jazz improvisation as a model for social and economic relations in general.[8][9] Edward W. Sarath has proposed jazz improvisation as a model for change in music, education, and society.[10] Jazz improvisation can also be seen as a model for human interactions. Jazz improvisation presents an image or representation of the ways in which humans engage with and interact with one another and the world around them, through a variety of linguistic, gestural, and expressive means. Through this process, musicians can collectively negotiate and ultimately constitute their shared musical and cultural space.[11] Which is important to the ethics of jazz improvisation since it highlights the collaborative and interactive nature of jazz improvisation and how music reflects and engages with the world. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jazz_improvisation |

ジャ

ズの即興演奏とは、ジャズ音楽の演奏において、メロディックなソロ・ラインや伴奏パートを自発的に創作することである。ジャズを定義する要素のひとつであ

る。即興演奏とは、リズムセクションの楽器(ピアノ、ギター、コントラバス)が演奏し、ドラムが伴奏するコード進行の上で、歌手や楽器奏者がメロディーや

ラインを創作することで、その場で作曲することである。ブルース、ロック、その他のジャンルでも即興演奏は使われるが、それは比較的単純なコード進行の上

で行われ、1つのキー(または、ハ長調の曲がト長調に転調するような、5分の5拍子を使った密接に関連したキー)に留まることが多い。 ジャズ・インプロヴィゼーションは、コードの複雑さによってこのアプローチと区別され、しばしば1小節に1つ以上のコード・チェンジ、変化コード、拡張 コード、三連音置換、珍しいコード(例えば、オーギュメンテッド・コード)、i-V-I進行の多用などがあり、これらはすべて、通常1曲の中で複数のキー を移動する。しかし、マイルス・デイヴィスによる『カインド・オブ・ブルー』の発表以降、ジャズの即興演奏には、モーダル・ハーモニーや静的なキー・セン ター上での即興演奏が含まれるようになり、フリー・ジャズの出現により、ソリストがコード・チェンジを無視して自由に即興演奏する「フリー・ブロー」な ど、さまざまなタイプの即興演奏が見られるようになった。 種類 ジャズのアドリブはソロと伴奏に分けられます。 ソロ ソロでは、演奏者(楽器奏者または歌手)が曲のコード進行に合わせて新しいメロディラインを作ります。ソロの間、聴衆の注目はソロを演奏している演奏者に 集中します。ただし、ドラムソロやベースソロの場合は、ドラマーやベーシストが演奏している間、バンド全体が止まっていることがあります。 シンガーがコード・チェンジの上で即興的に新しいメロディーを歌うことをスキャット・シンギングという。スキャット・シンキングの場合、シンガーは通常、 曲の歌詞を使うのではなく、作り物の音節(「ドゥ・ビ・ドゥ・バ」)を使う。ソロというと、楽器やボーカルの妙技を連想しがちだが、多くのアーティストが ソロに高度なテクニックを使っている一方で、それが常に行われているわけではない。例えば、1940年代や1950年代のベース・ソロの中には、ベーシス トがウォーキング・ベースラインを弾いているものもある。 ジャズ・ソロの即興演奏には、いくつかのアプローチがあります。スウィング時代には、演奏者はリフや曲のメロディーのバリエーションを使って、耳で聞いて 即興ソロを演奏しました。1940年代のビ・バップ時代には、ジャズの作曲家はより複雑なコード進行を書くようになりました。サックス奏者のチャーリー・ パーカーは、コード進行のコードに関連したスケールやアルペジオを使ってソロを始めました。 伴奏 ジャズでは、ある楽器奏者や歌手がソロを演奏しているとき、他のアンサンブルメンバーは伴奏パートを演奏します。ビッグバンドのような大規模なジャズ・ア ンサンブルでは、完全に書き込まれた伴奏パートが使われますが、小規模なグループ(ジャズ・カルテット、ピアノ・トリオ、オルガン・トリオなど)では、リ ズム・セクションのメンバーが即興で伴奏パートを演奏するのが一般的で、これはコンピングと呼ばれる活動です。ジャズでは、リズムセクションの楽器はグ ループの種類によって異なりますが、通常、ベース楽器(コントラバス、エレキベース)、コードを演奏できる楽器(ピアノ、エレキギターなど)、ドラムキッ トが含まれます。アンサンブルによっては、これらの役割に異なる楽器を使うこともある。例えば、1920年代スタイルのディキシーランド・ジャズバンド は、チューバをベース楽器として使い、バンジョーをコード楽器として使うことがある。1980年代のジャズ・ロック・フュージョン・バンドは、ベースライ ンにシンセベースを使い、コードにシンセサイザーを使うかもしれません。パーカッションを1人以上加えるバンドもある。 少人数のグループでは、リズム・セクションのメンバーが伴奏パートを即興で演奏するのが一般的です。ベース楽器奏者は、キーのコード進行を参考にベースラ インを即興で演奏します。一般的なベース・コンピング・パートのスタイルとしては、1920年代~1950年代のジャズではウォーキング・ベースライン、 ジャズ・ロック・フュージョンではロック・スタイルのオスティナート・リフ、ラテン・ジャズではラテン・ベースラインなどがあります。即興ベースラインは 通常、各コードのルート、サード、セブンス、ファイブを演奏し、作曲家がコードに要求したその他の音を演奏することで、各コードのハーモニーを概説する (例えば、コード・チャートがハ長調のトニック上に第6コードを示している場合、ベーシストはベースラインにハ長調スケールの第6度である「A」音を含め るかもしれない)。 和音楽器奏者は、コード進行に基づいてコードを即興演奏します。和音楽器奏者は、ポピュラー音楽や一般的な練習期間のクラシック音楽で使われるものとは異 なるジャズのコード・ヴォイシングを使います。例えば、ポップミュージシャンやバロック音楽時代(1600~1750年頃)のミュージシャンが、ハ長調の ドミナントセブンスコードを弾くように言われたら、おそらくG7(または「Gドミナントセブンス」)というルートポジションのコードを弾くでしょう。ビ バップ以降のジャズ・プレイヤーは、Cメジャーのキーでドミナント・セブンス・コードを弾くように言われた場合、Gをベースに作られた変名ドミナント・ コードを弾くかもしれません。変名ドミナントは、コードの基本要素に加えて、平坦化またはシャープ化された「拡張」を含んでいます。また、ジャズでは、 コード・ミュージシャンはルートを省略することが多く、この役割はベース奏者に与えられています。コードの5thも、ルートより完全5thの場合は省略さ れることが多い(通常のメジャー・コードやマイナー・コードの場合)。 ジャズ・ギタリストやジャズ・ピアニストがG上のドミナント・コードの変拍子で演奏する変拍子には、(演奏者の判断で)♭9th A♭(9番目の音階度を半音下げる)、シャープな11th C♯(11番目の音階度を半音上げる)、♭13th E♭(13番目の音階度を半音下げる)などがあります。和音奏者がドミナント・セブンス・コードのルートと5th(GとD)を省略し、3rd(B)と ♭7th(F)を残し、今挙げた変化音(A♭、 C♯、E♭)を加えると、B、C♯、E♭、F、A♭というコードになり、ポップ・ミュージシャンが演奏する標準的なG7(G、B、D、F)とはかなり違っ た響きを持つコードになる。クラシックの和声やポップスでは、コード進行の基礎を強調するために、コード・ヴォイシングはルートを2倍にすることが多い。 ソロのテクニック メロディック・バリエーションと耳コピ ディキシーランドの時代からスウィング・ミュージックの時代にかけて、多くのソロ演奏家は、曲の既存のメロディーを変化させたり装飾したり、よく知られた リフを使ってコード・チェンジを耳コピしたりすることで、即興演奏を行っていました。これらの音楽時代には、コード進行がよりシンプルで、珍しいキーへの 転調も少なかったため、このアプローチはうまく機能したが、1940年代にビ・バップが発展すると、装飾や「耳コピ」のアプローチはもはや十分ではなく なった。 スウィングは踊るために作られたが、ビバップはそうではなかった。ビバップでは、複雑なコード進行、珍しい変拍子や拡張コード、トニック・キー(曲の主調 またはホーム・キー)とは密接に関係しない離れたキーへの転調など、大規模な転調が用いられた。ディキシーランドやスウィングの曲では、2小節に1回の コード・チェンジがあり、1小節に1回のコード・チェンジのセクションもあるのに対し、ビバップの曲では1小節に2回のコード・チェンジがあり、4小節ご とにキーが変わるものも多い。加えて、ビバップは踊るためというより聴くためのものであったため、テンポは踊りやすさに縛られることはなかった。 ビバップの複雑な曲調やコード、速いテンポでは、演奏者が効果的に即興演奏を行うには、メロディックな装飾や耳コピだけではもはや不十分だった。サックス 奏者のチャーリー・パーカーは、平坦化された9分音符、シャープ化された11分音符、平坦化された13分音符のような変化した拡張音符を含む、コードに関 連した音階を使用し、コードトーンとそれ自体を半音階的な即興を生み出すための枠組みとして使用することによって、ソロを始めた。 モード 主な記事 モード(音楽) こちらも参照: コード・スケール・システム モードとは様々な音階のことで、様々な和音から派生したものと考えることができる。音楽家はこれらのモードを、使用可能な音のプールとして使用することが できる。例えば、ある曲でC7のコードに出会った場合、このコードの上で演奏するモードはCミクソリディアン・スケールです。 これらは、ミュージシャンがどのコードが特定のスケールやモードに関連しているかを知るのに役立つ、さまざまなコードの派生です: C7 → Cミクソリディアン C-7 → Cドリアン Cmaj7 → Cイオニアン(ナチュラル・メジャー) Cmaj7♯11 → Cリディアンモード Csus♭9 → Cフリジアン C- → C エオリアンモード(自然短調) Cø/C-7♭5 → C ...ロックリアン こちらも参照: ジャズ・コード ターゲット インプロヴィゼイションの重要なコンセプトのひとつにターゲティングがあるが、これはパーカーが用いたテクニックである[1]。ターゲティングとは、コー ドの音に着地すること。コードはルート(1st)と、スケールのルートより3、5、7、9、11、13番目の音で構成される。コード・トーンをターゲット にする方法はいくつかあります。1つ目は、半音階的なアプローチ(クロマティック・ターゲティング)です。これは、コード・トーンの半音上または半音下の 音を演奏することを意味します。C調の場合、トニック・コードの音はC(コードの1番またはルート)、E(3番)、G(5番)、B(7番)です。つまり、 行末でDシャープを弾いてからEにリゾルブ(半音上げる)することで、これはターゲティングの基本的な一例となり、コードの3番目(E♮)をターゲットに することになります。これはどのタイプのコードのどのファクターでも使うことができるが、リズムはコードトーンがダウンビートに落ちるように演奏される [1]。 ビバップのメロディック・インプロヴィゼーションでは、フレーズの後半で7thコード・トーンに解決する前に、コードの9th、11th、13th(カ ラー・トーン)に焦点を当てることが多い。ビバップでは、9th、11th、13thの音にシャープやフラットを加えて変化させることが多い。第9音はフ ラットにしたりシャープにしたりすることができる。11分音符は通常、シャープで演奏された。13分音符はしばしばフラットに演奏された。囲い込みとは、 対象となる音の上の音階音(複数可)と下の半音階音(複数可)、または下の音階音(複数可)と上の半音階音(複数可)を使用することである[1]。 「フラット9」理論 主な記事 フラット9コード パーカー[1]が用いたジャズ・アドリブにおけるもう1つのテクニックは、「スリー・トゥ・フラット・ナイン」と呼ばれるものである。これらの数字は、 コード進行におけるあるコードのルート音より上の音階の度数を指す。これはターゲティングに似たビバップのアプローチである。この奏法は、♭9(b9)ド ミナント・コードとして扱えるドミナント・コードであれば、どのようなコードにも使えます。ドミナント・コードの3rdから♭9へ、またはディミニッ シュ・アルペジオ(上行:3rd、5th、7th、♭9th)で移動します。コードはしばしば、完全4分の1離れたメジャー・コードに解決します。例え ば、G7コードの3rdはBで、♭9thはA♭です。コードはCに解決し、A♭の音はGにつながる[1]。 ペンタトニック 主な記事 ペンタトニック・スケール§メジャー・ペンタトニック・スケール ペンタトニック・スケールはジャズのアドリブでもよく使われるが、これはおそらくブルースでの使用からきている。サックス奏者のジョン・コルトレーンはペ ンタトニックを多用した。ほとんどのスケールは7つの音で構成されている: (メジャー・スケールであるCのキーでは)C D E F G A B)。メジャー・ペンタトニック・スケールはメジャー・スケールの5つの音(Cペンタトニック・スケールはC D E G A)で構成され、マイナー・ペンタトニック・スケールは5つの音(C E♭ F G B♭)で構成される。ペンタトニックはパターン形式が便利で、通常そのように演奏される。ペンタトニックスケールを使ったパターンのひとつは、3 6 5 2 3 5(Cの場合:E A G D E G)である。ペンタトニック・スケールは、ロック・ミュージック、ジャズ・フュージョン、エレクトリック・ブルースでも人気がある。 (ペンタトニック:「ペンタトニックスケールとは、5音でできた音階(スケール)の こと。 メジャー・ペンタトニックスケールは、メジャースケール上の4,7番目を除いた5つの音で構成されているスケール。 マイナー・ペンタトニックスケールはマイナースケールから2番目と6番目の音を除いた5音で構成される」) セルとライン 主な記事 リック(音楽) ライン(リックとも呼ばれる)とは、アーティストが即興ソロの最中に何度も演奏する、あらかじめ計画されたアイデアのことである。ラインは、ジャズのレ コードを聴き、プロがソロ中に演奏するものを書き写すことで得ることができる。写譜とは、レコードで聴いたものを楽譜用紙に書き写すことです。セルは短い 音楽のアイデアです。基本的にはラインと同じものですが、より短いものです。 フレーズ 主な記事 フレーズ(音楽) フレーズは、ジャズ・プレイヤーのインプロヴィゼーション・スキルにおいて非常に重要な部分です。コードやハーモニーなどに基づいて、ただスケールやコー ドの音を連続して演奏するのではなく、メロディーのモチーフやリズムのモチーフに基づいてアイデアを構築します。奏者は事実上、曲のコード進行に合わせて 新しいメロディーを即興で作るのだ。ジャズ・インプロヴィゼイションの模範とされるアルト・サックス奏者のチャーリー・パーカーは、ソロの最初と最後に、 長年培ってきた特徴的なパターンを配置することに特別な注意を払っていた[2]。これは、メロディの形が論理的な結論を持つ、音楽的フレージングの発展し たスタイルを示している。冒頭がしっかりしていたからこそ、パーカーは音楽的なフレージングを発揮し、論理的で印象的な結論につながるソロを自由に作るこ とができたのである。作曲の文脈におけるこのモチーフ・ベースのアプローチの例は、クラシック音楽に見られる。ベートーヴェンの交響曲第5番では、最初の リズムとメロディーのアイデアが、多くのバリエーションを伴って再び演奏される[2]。 社会的側面 ジャズの即興演奏には、ミュージシャンが遵守しなければならない多数の社会的プロトコルが含まれている[3]。しかし、「これらのプロトコルのためのエミ リー・ポストのハンドブックは存在しないが、ジャズの文化に飲み込まれた人々は、これらの慣習が何であるかを学ぶ」[3]。厳密なルールは存在せず、むし ろ、いつ即興ソロを始め、いつ終わるかを通して、プレイヤーを導く一般的な社会的プロトコルが存在する。 [例えば、前のミュージシャンのソロの一部や終わりを取り、それを新しいインプロヴァイザーのソロに取り入れるのは良いジェスチャーである。[3] ジャズを聴き始めたばかりのリスナーにとって、ジャズソロの構造と、それが曲全体の中でどのようにフィットするかを理解するのは難しいかもしれない。 [4]さらに、ジャズにおける即興演奏の役割を理解することは、ただ聴いているだけでは難しいかもしれません。そのため、聴き慣れたリスナーは、「ジャズ の文化に長く浸って」[3]ソロやフォーマットを認識することができるかもしれません。 [4]スポーツのレギュレーションや基準を知らない観客の楽しみや理解は、ジャズの慣習に精通していないリスナーの楽しみや理解とは比較にならないのと同 様である。[4]まとめると、ジャズの即興演奏を鑑賞するためには、音楽のサウンドだけでなく、その根底にある社会構造やミュージシャンの相互作用や自己 表現の方法など、芸術形式の社会的・道徳的な側面も考慮することが重要である[5]。 自己の探求 ジル・ドゥルーズによって定義された反復の一つのモデルによれば、記憶による時間の統合は、記憶している主体にとって新しい何かを生み出す。過去は繰り返 され、他の過去の出来事と関連づけられ、過去に対する新しい理解を生み出す。しかし、この反復はまだ閉鎖的であり、主体は自分の既存のアイデンティティを 確認するものしか記憶していない。ジャズの即興演奏者は、曲の形式を解釈し、他のミュージシャンが自分の即興演奏の中でどのように解釈したかを参照するた めに、記憶を使わなければならない。インプロヴァイザーにとっての挑戦は、認識可能な方法でフォームを繰り返すことであるが、同時に、他のミュージシャン とは一線を画すオリジナルな方法で、そのフォームを即興演奏することでもある。テオドール・アドルノによれば、この反復は結局のところ、即興演奏者の既存 の自己概念を強化するだけであり、真の自己実現を可能にするものではないのである。ヘンリー・ルイス・ゲイツとジャック・デリダによって提唱されたこの考 え方は、すべての即興が以前の芸術形式と結びついていることを意味し、即興者が真に自律的であることを不可能にしている。このことは、特定の即興と即興者 自身のアイデンティティを複雑にしている[7]。 精神分析では、反復はアイデンティティ形成の重要な側面であり、ジークムント・フロイトが死の衝動と呼んだものと関連している。この衝動は、人は不快な経 験を避けるという快楽原則に反し、代わりにトラウマになるような出来事や不快な出来事を繰り返させる。フロイトによれば、この衝動は人間の精神の根源的な ものであり、無意識と結びついている。この衝動は、精神を元の静穏な状態に戻し、自分自身との一体感を取り戻そうとする。この反復とそれに伴うナルシシズ ムは、ジャズの即興演奏に見られることがあり、そこでは自己実現の欲求が自己吸収的で自己否定的であることがある[6]。 影響 即興音楽には、それが演奏される時間、場所、歴史、文化の影響を受ける社会的な側面もある。つまり、即興音楽を聴くことは、こうした特定の歴史的・文化的 コンテクストに関わることができるのだ。即興演奏は、人々がどのように音楽を創り、形づくるかを示すだけでなく、人々の考え方や行動のあり方についての洞 察も与えてくれる。ジャズの演奏家たちは、即興演奏を通して文化的態度や歴史的記憶を拾い上げ、自分たちのものにしていく: 「したがって、ジャズ曲の記憶と曲の反復は、演奏者の自己の断片を音楽に挿入するのに役立つ。言い換えれば、プレーヤーは過去の音に関する知識を活用し、 過去の前例、直感、文化に基づいて新しい曲を繰り返し演奏するのである。 倫理 ジャズ・インプロヴィゼーションの社会的側面が、倫理の良い基礎になると考える人は多い。キャスリーン・ヒギンズは、ジャズにおける個人やグループの相互 作用や即興演奏のあり方は、特に少数派と多数派の間の倫理的相互作用のモデルとして見ることができると主張している。この考えは、音楽学者であるイング リッド・モンソンや、経済学者であり学者であるジャック・アタリによって支持されている[3]。ユージン・W・ホランドは、社会的・経済的関係全般のモデ ルとしてジャズの即興演奏を提唱している[8][9]。エドワード・W・サラスは、音楽、教育、社会における変化のモデルとしてジャズの即興演奏を提唱し ている[10]。 ジャズの即興演奏は、人間関係のモデルとしても見ることができる。ジャズの即興演奏は、さまざまな言語的、ジェスチャー的、表現的手段を通して、人間が互 いに、そして周囲の世界と関わり、相互作用する方法のイメージや表現を提示する。このプロセスを通じて、ミュージシャンは集団的に交渉し、最終的に共有す る音楽的・文化的空間を構成することができる。これは、ジャズ即興の共同的・相互的な性質と、音楽がどのように世界を反映し、世界と関わっているかを浮き 彫りにするので、ジャズ即興の倫理にとって重要である。 |

【SCARA Robot 】Feat.Lucia(Official Music Video) |

|

| Aesthetic universals The philosopher Denis Dutton identified six universal signatures in human aesthetics:[32] 1. Expertise or virtuosity. Humans cultivate, recognize, and admire technical artistic skills. 2. Nonutilitarian pleasure. People enjoy art for art's sake, and do not demand that it keep them warm or put food on the table. 3. Style. Artistic objects and performances satisfy rules of composition that place them in a recognizable style. 4. Criticism. People make a point of judging, appreciating, and interpreting works of art. I5. mitation. With a few important exceptions like abstract painting, works of art simulate experiences of the world. 6. Special focus. Art is set aside from ordinary life and made a dramatic focus of experience. Artists such as Thomas Hirschhorn have indicated that there are too many exceptions to Dutton's categories. For example, Hirschhorn's installations deliberately eschew technical virtuosity. People can appreciate a Renaissance Madonna for aesthetic reasons, but such objects often had (and sometimes still have) specific devotional functions. "Rules of composition" that might be read into Duchamp's Fountain or John Cage's 4′33″ do not locate the works in a recognizable style (or certainly not a style recognizable at the time of the works' realization). Moreover, some of Dutton's categories seem too broad: a physicist might entertain hypothetical worlds in his/her imagination in the course of formulating a theory. Another problem is that Dutton's categories seek to universalize traditional European notions of aesthetics and art forgetting that, as André Malraux and others have pointed out, there have been large numbers of cultures in which such ideas (including the idea "art" itself) were non-existent.[33] Aesthetic ethics Aesthetic ethics refers to the idea that human conduct and behaviour ought to be governed by that which is beautiful and attractive. John Dewey[34] has pointed out that the unity of aesthetics and ethics is in fact reflected in our understanding of behaviour being "fair"—the word having a double meaning of attractive and morally acceptable. More recently, James Page[35][36] has suggested that aesthetic ethics might be taken to form a philosophical rationale for peace education. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthetics |

美的普遍性 哲学者のデニス・ダットンは、人間の美学における6つの普遍的な特徴を挙げている[32]。 1. 専門技術または名人芸。人間は技術的な芸術的技能を培い、認識し、賞賛する。 2. 非実用的な喜び。人々は芸術のために芸術を楽しみ、芸術によって暖をとったり、食卓に食べ物を並べたりすることを求めない。 3. 様式。芸術的な対象やパフォーマンスは、それらを認識可能なスタイルに位置づける構成の規則を満たす。 4. 批評。人々は芸術作品を判断し、評価し、解釈する。 I5. ミテーション。抽象絵画のようないくつかの重要な例外を除いて、芸術作品は世界の経験をシミュレートする。 6. 特別な焦点。芸術は通常の生活から切り離され、経験の劇的な焦点となる。 トーマス・ヒルシュホーンのような芸術家は、ダットンのカテゴリーには例外が多すぎると指摘している。例えば、ヒルシュホーンのインスタレーションは、技 術的な妙技を意図的に排除している。ルネサンスのマドンナを美的な理由で評価することは可能だが、そのようなオブジェにはしばしば特定の信仰的な機能が あった(そして時には今もある)。デュシャンの「泉」やジョン・ケージの「4′33″」に読み取れるかもしれない「作曲の規則」は、作品を認識可能な様式 (あるいは、作品が実現された時点で認識可能な様式ではない)に位置づけるものではない。さらに、ダットンのカテゴリーは広すぎるように思われるものもあ る。物理学者が理論を構築する過程で、想像の中で仮定の世界を楽しむかもしれない。もう一つの問題は、ダットンのカテゴリーが美学や芸術に関する伝統的な ヨーロッパの概念を普遍化しようとしていることである。アンドレ・マルローや他の人々が指摘しているように、そのような考え(「芸術」という考え自体を含 む)が存在しない文化が数多くあったことを忘れている[33]。 美的倫理 美的倫理とは、人間の行動や振る舞いは美しく魅力的なものに支配されるべきだという考え方を指す。ジョン・デューイ[34]は、美学と倫理の一体性は、行 動が「公正」であるという我々の理解に実際に反映されていると指摘している。より最近では、ジェームズ・ペイジ[35][36]が、美学的倫理が平和教育 の哲学的根拠を形成する可能性を示唆している。 |

| Derivative forms of aesthetics A large number of derivative forms of aesthetics have developed as contemporary and transitory forms of inquiry associated with the field of aesthetics which include the post-modern, psychoanalytic, scientific, and mathematical among others. Post-modern aesthetics and psychoanalysis Early-twentieth-century artists, poets and composers challenged existing notions of beauty, broadening the scope of art and aesthetics. In 1941, Eli Siegel, American philosopher and poet, founded Aesthetic Realism, the philosophy that reality itself is aesthetic, and that "The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites."[49][50] Various attempts have been made to define Post-Modern Aesthetics. The challenge to the assumption that beauty was central to art and aesthetics, thought to be original, is actually continuous with older aesthetic theory; Aristotle was the first in the Western tradition to classify "beauty" into types as in his theory of drama, and Kant made a distinction between beauty and the sublime. What was new was a refusal to credit the higher status of certain types, where the taxonomy implied a preference for tragedy and the sublime to comedy and the Rococo. Croce suggested that "expression" is central in the way that beauty was once thought to be central. George Dickie suggested that the sociological institutions of the art world were the glue binding art and sensibility into unities.[51] Marshall McLuhan suggested that art always functions as a "counter-environment" designed to make visible what is usually invisible about a society.[52] Theodor Adorno felt that aesthetics could not proceed without confronting the role of the culture industry in the commodification of art and aesthetic experience. Hal Foster attempted to portray the reaction against beauty and Modernist art in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Arthur Danto has described this reaction as "kalliphobia" (after the Greek word for beauty, κάλλος kallos).[53] André Malraux explains that the notion of beauty was connected to a particular conception of art that arose with the Renaissance and was still dominant in the eighteenth century (but was supplanted later). The discipline of aesthetics, which originated in the eighteenth century, mistook this transient state of affairs for a revelation of the permanent nature of art.[54] Brian Massumi suggests to reconsider beauty following the aesthetical thought in the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari.[55] Walter Benjamin echoed Malraux in believing aesthetics was a comparatively recent invention, a view proven wrong in the late 1970s, when Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake analyzed links between beauty, information processing, and information theory. Denis Dutton in "The Art Instinct" also proposed that an aesthetic sense was a vital evolutionary factor. Jean-François Lyotard re-invokes the Kantian distinction between taste and the sublime. Sublime painting, unlike kitsch realism, "... will enable us to see only by making it impossible to see; it will please only by causing pain."[56][57] Sigmund Freud inaugurated aesthetical thinking in Psychoanalysis mainly via the "Uncanny" as aesthetical affect.[58] Following Freud and Merleau-Ponty,[59] Jacques Lacan theorized aesthetics in terms of sublimation and the Thing.[60] The relation of Marxist aesthetics to post-modern aesthetics is still a contentious area of debate. Aesthetics and science The Mandelbrot set with continuously colored environment The field of experimental aesthetics was founded by Gustav Theodor Fechner in the 19th century. Experimental aesthetics in these times had been characterized by a subject-based, inductive approach. The analysis of individual experience and behaviour based on experimental methods is a central part of experimental aesthetics. In particular, the perception of works of art,[61] music, or modern items such as websites[62] or other IT products[63] is studied. Experimental aesthetics is strongly oriented towards the natural sciences. Modern approaches mostly come from the fields of cognitive psychology (aesthetic cognitivism) or neuroscience (neuroaesthetics[64]). In the 1970s, Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake were among the first to analyze links between aesthetics, information processing, and information theory.[65][66] In the 1990s, Jürgen Schmidhuber described an algorithmic theory of beauty which takes the subjectivity of the observer into account and postulates that among several observations classified as comparable by a given subjective observer, the most aesthetically pleasing is the one that is encoded by the shortest description. He uses the differences between these lengths to account for subjective differences between the aesthetic tastes of different observers, as one's ability to efficiently describe an observation is based on their particular mental method of encoding data and the proximity of the observation to the subject's prior knowledge.[67][68] The theory is inspired by principles of algorithmic information theory, especially minimum description length, which prefers mathematical models that use the least information to describe data. As an example, Schmidhuber notes that mathematicians tend to aesthetically prefer simple proofs with a short description in their formal language. Another concrete example describes an aesthetically pleasing human face whose proportions can be described by very few bits of information,[69][70] drawing inspiration from less detailed 15th century proportion studies by Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer. Schmidhuber's theory explicitly distinguishes between that which is beautiful and that which is interesting, stating that interestingness corresponds to the first derivative of subjectively perceived beauty. He supposes that every observer continually tries to improve the predictability and compressibility of their observations by identifying regularities like repetition, symmetry, and fractal self-similarity. Whenever the observer's learning process (which may be a predictive artificial neural network) leads to improved data compression such that the observation sequence can be described by fewer bits than before, the temporary interestingness of the data corresponds to the number of saved bits. This compression progress is proportional to the observer's internal reward, also called curiosity reward. A reinforcement learning algorithm is used to maximize future expected reward by learning to execute action sequences that cause additional interesting input data with yet unknown but learnable predictability or regularity. The principles can be implemented on artificial agents which then exhibit a form of artificial curiosity.[71][72][73][74] Truth in beauty and mathematics Mathematical considerations, such as symmetry and complexity, are used for analysis in theoretical aesthetics. This is different from the aesthetic considerations of applied aesthetics used in the study of mathematical beauty. Aesthetic considerations such as symmetry and simplicity are used in areas of philosophy, such as ethics and theoretical physics and cosmology to define truth, outside of empirical considerations. Beauty and Truth have been argued to be nearly synonymous,[75] as reflected in the statement "Beauty is truth, truth beauty" in the poem "Ode on a Grecian Urn" by John Keats, or by the Hindu motto "Satyam Shivam Sundaram" (Satya (Truth) is Shiva (God), and Shiva is Sundaram (Beautiful)). The fact that judgments of beauty and judgments of truth both are influenced by processing fluency, which is the ease with which information can be processed, has been presented as an explanation for why beauty is sometimes equated with truth.[76] Recent research found that people use beauty as an indication for truth in mathematical pattern tasks.[77] However, scientists including the mathematician David Orrell[78] and physicist Marcelo Gleiser[79] have argued that the emphasis on aesthetic criteria such as symmetry is equally capable of leading scientists astray. Computational approaches Computational approaches to aesthetics emerged amid efforts to use computer science methods "to predict, convey, and evoke emotional response to a piece of art.[80] It this field, aesthetics is not considered to be dependent on taste but is a matter of cognition, and, consequently, learning.[81] In 1928, the mathematician George David Birkhoff created an aesthetic measure M = O/C as the ratio of order to complexity.[82] Since about 2005, computer scientists have attempted to develop automated methods to infer aesthetic quality of images.[83][84][85][86] Typically, these approaches follow a machine learning approach, where large numbers of manually rated photographs are used to "teach" a computer about what visual properties are of relevance to aesthetic quality. A study by Y. Li and C.J. Hu employed Birkhoff's measurement in their statistical learning approach where order and complexity of an image determined aesthetic value.[87] The image complexity was computed using information theory while the order was determined using fractal compression.[87] There is also the case of the Acquine engine, developed at Penn State University, that rates natural photographs uploaded by users.[88] There have also been relatively successful attempts with regard to chess[further explanation needed] and music.[89] Computational approaches have also been attempted in film making as demonstrated by a software model developed by Chitra Dorai and a group of researchers at the IBM T.J. Watson Research Center.[90] The tool predicted aesthetics based on the values of narrative elements.[90] A relation between Max Bense's mathematical formulation of aesthetics in terms of "redundancy" and "complexity" and theories of musical anticipation was offered using the notion of Information Rate.[91] Evolutionary aesthetics Main article: Evolutionary aesthetics Evolutionary aesthetics refers to evolutionary psychology theories in which the basic aesthetic preferences of Homo sapiens are argued to have evolved in order to enhance survival and reproductive success.[92] One example being that humans are argued to find beautiful and prefer landscapes which were good habitats in the ancestral environment. Another example is that body symmetry and proportion are important aspects of physical attractiveness which may be due to this indicating good health during body growth. Evolutionary explanations for aesthetical preferences are important parts of evolutionary musicology, Darwinian literary studies, and the study of the evolution of emotion. Applied aesthetics Main article: Applied aesthetics As well as being applied to art, aesthetics can also be applied to cultural objects, such as crosses or tools. For example, aesthetic coupling between art-objects and medical topics was made by speakers working for the US Information Agency.[93] Art slides were linked to slides of pharmacological data, which improved attention and retention by 'simultaneous activation of intuitive right brain with rational left'[citation needed]. It can also be used in topics as diverse as cartography, mathematics, gastronomy, fashion and website design.[94][95][96][97][98] Other approaches Guy Sircello has pioneered efforts in analytic philosophy to develop a rigorous theory of aesthetics, focusing on the concepts of beauty,[99] love[100] and sublimity.[101] In contrast to romantic theorists, Sircello argued for the objectivity of beauty and formulated a theory of love on that basis. British philosopher and theorist of conceptual art aesthetics, Peter Osborne, makes the point that "'post-conceptual art' aesthetic does not concern a particular type of contemporary art so much as the historical-ontological condition for the production of contemporary art in general ...".[102] Osborne noted that contemporary art is 'post-conceptual' in a public lecture delivered in 2010. Gary Tedman has put forward a theory of a subjectless aesthetics derived from Karl Marx's concept of alienation, and Louis Althusser's antihumanism, using elements of Freud's group psychology, defining a concept of the 'aesthetic level of practice'.[103] Gregory Loewen has suggested that the subject is key in the interaction with the aesthetic object. The work of art serves as a vehicle for the projection of the individual's identity into the world of objects, as well as being the irruptive source of much of what is uncanny in modern life. As well, art is used to memorialize individuated biographies in a manner that allows persons to imagine that they are part of something greater than themselves.[104] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthetics |

美学の派生形態 美学の派生形態は、ポストモダン、精神分析、科学的、数学的など、美学の分野に関連する現代的かつ一過性の探究形態として数多く発展してきた。 ポストモダンの美学と精神分析 20世紀初頭の芸術家、詩人、作曲家たちは、既存の美の概念に挑戦し、芸術と美学の範囲を広げた。1941年、アメリカの哲学者であり詩人であったイーラ イ・シーゲルは、現実そのものが美的であり、「世界、芸術、自己は互いに説明しあう:それぞれが相反するものの美的一体性である」という哲学である美的リ アリズムを創始した[49][50]。 ポスト・モダンの美学を定義するために様々な試みがなされてきた。美が芸術や美学の中心であるという仮定に対する挑戦は、独創的であると考えられている が、実際にはより古い美学理論と連続している。アリストテレスは西洋の伝統の中で初めて、彼の演劇論のように「美」をタイプに分類したし、カントは美と崇 高さを区別した。新しいのは、特定のタイプの地位の高さを認めないことであり、その分類法は喜劇やロココよりも悲劇や崇高さを好むことを意味していた。 クローチェは、かつて美が中心であると考えられていたように、「表現」が中心であることを示唆した。ジョージ・ディッキーは、芸術界の社会学的制度が芸術 と感性を一体化させる接着剤であることを示唆した[51]。マーシャル・マクルーハンは、芸術は常に「対抗環境」として機能し、社会について通常目に見え ないものを可視化するように設計されていることを示唆した[52]。テオドール・アドルノは、芸術と美的経験の商品化における文化産業の役割に直面するこ となしに美学を進めることはできないと考えた。ハル・フォスターは『反美学』の中で、美とモダニズム芸術に対する反動を描こうとした: Essays on Postmodern Culture)の中で、美とモダニズム芸術に対する反動を描き出そうとしている。アーサー・ダントーはこの反応を「カリフォビア」(ギリシャ語で美を意 味するκάλλος kallosにちなんで)と表現している[53]。アンドレ・マルローは、美の概念はルネサンスとともに生まれ、18世紀にも支配的であった(しかし後に 取って代わられた)芸術の特定の概念と結びついていたと説明している。ブライアン・マスミは、ドゥルーズとガタリの哲学における美学的思考に従って、美を 再考することを提案している[55]。ヴァルター・ベンヤミンもマルローと同様に、美学は比較的最近の発明であると考えていたが、1970年代後半にアブ ラハム・モールズとフリーダー・ネイクが美と情報処理、情報理論との関連性を分析した際に、この見解が間違っていることが証明された。また、デニス・ダッ トンは『芸術の本能』の中で、美的感覚は進化に不可欠な要素であると提唱している。 ジャン=フランソワ・リオタールは、カントにおける嗜好と崇高の区別を再提起している。崇高な絵画は、キッチュな写実主義とは異なり、「......見る ことを不可能にすることによってのみ見ることを可能にし、苦痛を与えることによってのみ喜ばせる」[56][57]。 ジークムント・フロイトは主に美的情動としての「不気味さ」を介して精神分析における美学的思考を創始した[58]。フロイトとメルロ=ポンティに続き [59]、ジャック・ラカンは昇華と事物の観点から美学を理論化した[60]。 マルクス主義の美学とポスト・モダンの美学との関係は未だに論争の的となっている。 美学と科学 連続的に着色された環境を持つマンデルブロ集合 実験美学の分野は、19世紀にグスタフ・テオドール・フェヒナーによって創設された。この時代の実験美学は、被験者に基づく帰納的なアプローチを特徴とし ていた。実験的手法に基づく個人の経験や行動の分析は、実験美学の中心的な部分である。特に、芸術作品[61]や音楽、あるいはウェブサイト[62]やそ の他のIT製品[63]のような現代的なアイテムの知覚が研究されている。実験美学は自然科学を強く志向している。現代的なアプローチは、認知心理学(美 的認知主義)や神経科学(神経美学[64])の分野からのものが多い。 1970年代には、アブラハム・モールズとフリーダー・ネイクが美学と情報処理、情報理論との関連を分析した最初の人物の一人であった[65][66]。 1990年代、ユルゲン・シュミッドフーバーは、観察者の主観を考慮に入れた美のアルゴリズム理論を説明し、与えられた主観的観察者によって同等のものと して分類されたいくつかの観察の中で、最も美的に好ましいものは、最も短い記述によって符号化されたものであると仮定した。彼は、異なる観察者の美的嗜好 の間の主観的な差異を説明するために、これらの長さの違いを使用している。これは、ある観察を効率的に記述する能力は、データをエンコードする特定の精神 的方法と、観察が被験者の事前知識に近いことに基づいているからである[67][68]。例として、シュミッドフーバーは、数学者は、その形式言語での短 い記述による単純な証明を美的に好む傾向があることを指摘している。別の具体的な例として、レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチとアルブレヒト・デューラーによる 15世紀のあまり詳細でないプロポーション研究からヒントを得て、非常に少ない情報量でプロポーションを記述できる美的に美しい人間の顔について説明して いる[69][70]。シュミッドフーバーの理論は、美しいものと面白いものを明確に区別し、面白さは主観的に知覚される美しさの一次導関数に対応すると 述べている。彼は、すべての観察者は、繰り返し、対称性、フラクタル自己相似性のような規則性を識別することによって、観察結果の予測可能性と圧縮性を向 上させようと絶えず努力していると仮定している。観察者の学習プロセス(これは予測的な人工ニューラルネットワークかもしれない)が、観察シーケンスが以 前よりも少ないビット数で記述できるようなデータ圧縮の改善につながるときはいつでも、データの一時的な面白さは、保存されたビット数に対応する。この圧 縮の進歩は、好奇心報酬とも呼ばれる観察者の内部報酬に比例する。強化学習アルゴリズムは、まだ未知であるが学習可能な予測可能性や規則性を持つ、さらに 興味深い入力データを引き起こす行動シーケンスを実行するよう学習することで、将来期待される報酬を最大化するために使用される。この原理は、人工的な好 奇心を示す人工的なエージェントに実装することができる[71][72][73][74]。 美と数学における真実 対称性や複雑性といった数学的考察は、理論的美学における分析に用いられる。これは数学的な美の研究に用いられる応用美学の美学的考察とは異なる。対称性 や単純性といった美学的考察は、倫理学や理論物理学・宇宙論といった哲学の分野では、経験的考察とは別に、真理を定義するために用いられる。美と真理はほ ぼ同義であると主張されており[75]、ジョン・キーツの詩「グレシアの壷の歌」にある「美は真理であり、真理は美である」という言葉や、ヒンドゥー教の モットーである「サティヤム・シヴァム・スンダラム」(サティヤ(真理)はシヴァ(神)であり、シヴァはスンダラム(美しい)である)に反映されている。 美しさの判断と真実の判断がともに、情報を処理することの容易さである処理の流暢さに影響されるという事実は、美しさが時として真実と同一視される理由の 説明として提示されている[76]。最近の研究では、人は数学的パターン課題において真実の指標として美しさを用いることが発見されている[77]。 しかしながら、数学者のデビッド・オレル[78]や物理学者のマルセロ・グライザー[79]を含む科学者たちは、対称性のような美的基準の強調は科学者た ちを迷わせる可能性が同様にあると主張している。 計算論的アプローチ 美学に対する計算論的アプローチは、「芸術作品に対する感情的反応を予測し、伝え、喚起する」コンピュータ科学の手法を用いようとする取り組みの中で出現 した[80]。この分野では、美学は嗜好に依存するものではなく、認知の問題であり、結果として学習の問題であると考えられている[81]。 1928年、数学者ジョージ・デイヴィッド・バーコフは、複雑さに対する秩序の比率として美的尺度M=O/Cを作成した[82]。 2005年頃から、コンピュータ科学者は画像の美的品質を推論する自動化された方法を開発しようと試みている[83][84][85][86]。一般的 に、これらのアプローチは機械学習アプローチに従っており、手作業で評価された大量の写真が、どのような視覚的特性が美的品質に関連するかについてコン ピュータに「教える」ために使用される。Y.LiとC.J.Huによる研究では、画像の順序と複雑さが美的価値を決定するという統計的学習アプローチにお いて、バーコフの測定法を採用している[87]。 チェス[さらに説明が必要]や音楽に関しても比較的成功した試みがある[89]。このツールは物語要素の価値に基づいて美学を予測した[90]。マック ス・ベンゼの「冗長性」と「複雑性」という観点からの美学の数学的定式化と音楽的先読みの理論との関係は、情報率という概念を用いて提示された[91]。 進化論的美学 主な記事 進化美学 進化美学とは、ホモ・サピエンスの基本的な美的嗜好が、生存と繁殖の成功を高めるために進化してきたと主張する進化心理学理論のことである。別の例として は、身体の対称性とプロポーションは身体的魅力の重要な側面であり、これは身体の成長過程において健康であることを示すためであると考えられる。美的嗜好 の進化論的説明は、進化音楽学、ダーウィン文学研究、感情の進化研究の重要な部分である。 応用美学 主な記事 応用美学 美学は芸術に応用されるだけでなく、十字架や道具などの文化的対象にも応用できる。例えば、アメリカの情報局で働く講演者たちによって、美術品と医学的ト ピックの美学的結合が行われた[93]。美術品のスライドを薬理学的データのスライドにリンクさせたところ、「直感的な右脳と理性的な左脳の同時活性化」 [要出典]によって注意力と記憶力が向上した。また、地図製作、数学、美食、ファッション、ウェブサイト・デザインなど、多様なトピックで用いることがで きる[94][95][96][97][98]。 その他のアプローチ ガイ・シルセロは分析哲学において、美、[99]愛[100]、崇高さといった概念に焦点を当て、美学の厳密な理論を発展させる取り組みの先駆者である [101]。ロマン主義の理論家とは対照的に、シルセロは美の客観性を主張し、それに基づいて愛の理論を定式化した。 イギリスの哲学者でありコンセプチュアル・アートの美学の理論家であるピーター・オズボーンは、「『ポスト・コンセプチュアル・アート』の美学は、現代 アートの特定のタイプに関わるものではなく、現代アート全般の制作における歴史的=存在論的な条件に関わるものである」と指摘している[102]。 ゲイリー・テッドマンは、カール・マルクスの疎外の概念とルイ・アルチュセールの反人間主義に由来する主体なき美学の理論を提唱し、フロイトの集団心理学 の要素を用いて、「実践の美的レベル」の概念を定義している[103]。 グレゴリー・ローウェンは、美的対象との相互作用において主体が鍵となることを示唆している。芸術作品は、個人のアイデンティティをオブジェの世界に投影 するための手段としての役割を果たすだけでなく、現代生活における不気味なものの多くを生み出している。また、芸術は、自分が自分自身よりも大きなものの 一部であると想像させるような方法で、個人の伝記を記念するために用いられる[104]。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthetics |

| Criticism The philosophy of aesthetics as a practice has been criticized by some sociologists and writers of art and society. Raymond Williams, for example, argues that there is no unique and or individual aesthetic object which can be extrapolated from the art world, but rather that there is a continuum of cultural forms and experience of which ordinary speech and experiences may signal as art. By "art" we may frame several artistic "works" or "creations" as so though this reference remains within the institution or special event which creates it and this leaves some works or other possible "art" outside of the frame work, or other interpretations such as other phenomenon which may not be considered as "art".[105] Pierre Bourdieu disagrees with Kant's idea of the "aesthetic". He argues that Kant's "aesthetic" merely represents an experience that is the product of an elevated class habitus and scholarly leisure as opposed to other possible and equally valid "aesthetic" experiences which lay outside Kant's narrow definition.[106] Timothy Laurie argues that theories of musical aesthetics "framed entirely in terms of appreciation, contemplation or reflection risk idealizing an implausibly unmotivated listener defined solely through musical objects, rather than seeing them as a person for whom complex intentions and motivations produce variable attractions to cultural objects and practices".[107] 105; Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford Univ. Press, 1977), 155. 106; Pierre Bourdieu, "Postscript", in Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste (London: Routledge, 1984), 485–500. ISBN 978-0674212770; and David Harris, "Leisure and Higher Education", in Tony Blackshaw, ed., Routledge Handbook of Leisure Studies (London: Routledge, 2013), 403 107; Laurie, Timothy (2014). "Music Genre as Method". Cultural Studies Review. 20 (2). doi:10.5130/csr.v20i2.4149 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthetics |

批判 実践としての美学の哲学は、社会学者や芸術と社会に関する作家の一部によって批判されてきた。例えば、レイモンド・ウィリアムズは、芸術の世界から外挿できる唯一無二の、あるいは個別の美的対象は 存在せず、むしろ、通常の言論や経験が芸術としてシグナルを発するような、文化的形態や経験の連続体が存在すると主張している。「芸術」によって、私たち はいくつかの芸術的な「作品」や「創造物」をそのように枠にはめるかもしれないが、この参照はそれを生み出す制度や特別な出来事の中にとどまり、いくつか の作品や他の可能性のある「芸術」は枠外に残され、あるいは「芸術」とはみなされないかもしれない他の現象のような他の解釈が残される[105]。 ピエール・ブルデューはカントの「美学」の考えに同意していない。彼 は、カントの「美的」とは、カントの狭い定義の外側にある他の可能性のある等しく有効な「美的」経験とは対照的に、単に高められた階級的ハビトゥスと学問 的余暇の産物である経験を表しているに過ぎないと論じている[106]。 ティモシー・ローリーは、音楽美学の理論が「鑑賞、観想、内省の観点か ら完全に組み立てられたものであることは、彼らを複雑な意図や動機が文化的対象や実践に対する様々な魅力を生み出す人間として見るのではなく、音楽的対象 を通してのみ定義される、ありえないほど動機づけのない聴き手を理想化する危険をはらんでいる」と論じている[107]。 105; Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford Univ. Press, 1977), 155. 106; Pierre Bourdieu, "Postscript", in Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste (London: Routledge, 1984), 485–500. ISBN 978-0674212770; and David Harris, "Leisure and Higher Education", in Tony Blackshaw, ed., Routledge Handbook of Leisure Studies (London: Routledge, 2013), 403 107; Laurie, Timothy (2014). "Music Genre as Method". Cultural Studies Review. 20 (2). doi:10.5130/csr.v20i2.4149 |