カント『判断力批判』ノート

Introduction to Kant's Critique of Judgment.

美とは感覚に快楽をもたらす対象である、より移

転計画

『判断力批判』(KdU)は、『純粋理性批判』『実践理性批判』に続くイマヌエル・カントの第三の大著であり、1790年にラガルドとフリードリッヒに

よってベルリンとリバウで出版された。第1部にはカントの美学(美的判断の教義)が、第2部には目的論(目的カテゴリーによる自然の解釈の教義)が収めら

れている。イマヌエル・

カント

『判断力批判』

『判断力批判』(KdU)は、『純粋理性批判』『実践理性批判』に続くイマヌエル・カントの第三の大著であり、1790年にラガルドとフリードリッヒに

よってベルリンとリバウで出版された。第1部にはカントの美学(美的判断の教義)が、第2部には目的論(目的カテゴリーによる自然の解釈の教義)が収めら

れている。イマヌエル・

カント

『判断力批判』 ——判断力批判は第一部の美的判断批判と、第二部の目的論的判断批判の2部に分かれる。第一部美的判断批判とは、煎じつめれば「美とは感覚に快楽をもたら

す対象」であり、その感覚は各人で異なっているために、他人の感覚にごちゃごちゃいちゃもんをつけることはできない。ただし、自分の趣味感覚(テ

イスト)

つまり感覚にもとづく好みを(社会的に)正当化したいのなら、それを公的な対話や発言の場に求める他はない、ということになります(=義務ではなく自発性

にもとづく個人の活動)。

——判断力批判は第一部の美的判断批判と、第二部の目的論的判断批判の2部に分かれる。第一部美的判断批判とは、煎じつめれば「美とは感覚に快楽をもたら

す対象」であり、その感覚は各人で異なっているために、他人の感覚にごちゃごちゃいちゃもんをつけることはできない。ただし、自分の趣味感覚(テ

イスト)

つまり感覚にもとづく好みを(社会的に)正当化したいのなら、それを公的な対話や発言の場に求める他はない、ということになります(=義務ではなく自発性

にもとづく個人の活動)。

判断力批判は第一部の美的判断批判と、第二部の目的論的判断批判の2部に分かれる。そして第二部は目 的論的判断批判であるが、これは、第一批判(純粋理性批判)と第二批判(実践理性批判)で生じた、理性(理念)と経験の分離・分裂が引きずっている哲学 を、自然の合目的性という統制理念でそれらを繋ぎ合わせようとする目論見がある。そのため、第三批判であるこの書は、完全に2つに分裂した書物ということ もできる。

| Die Kritik der Urteilskraft (KdU)

ist Immanuel Kants drittes Hauptwerk nach der Kritik der reinen

Vernunft und der Kritik der praktischen Vernunft, erschienen 1790 im

Verlag Lagarde und Friedrich in Berlin und Libau. Sie enthält in einem

ersten Teil Kants Ästhetik (Lehre vom ästhetischen Urteil) und im

zweiten Teil die Teleologie (Lehre von der Auslegung der Natur mittels

Zweckkategorien). |

『判断力批判』(KdU)は、『純粋理性批判』『実践理性批判』に続く

イマヌエル・カントの第三の大著であり、1790年にラガルドとフリードリッヒによってベルリンとリバウで出版された。第1部にはカントの美学(美的判断

の教義)が、第2部には目的論(目的カテゴリーによる自然の解釈の教義)が収められている。 |

| Stellung im Werk Kants Absicht – in den beiden sich in Teilen widersprechenden Einleitungen zur KdU umfangreich dargelegt – bestand darin, in dieser dritten Kritik die Vermittlung zwischen Natur (Gegenstand der theoretischen Vernunft) und Freiheit (Gegenstand der praktischen Vernunft) zu leisten und so das Gebäude der kritischen Philosophie zu vollenden. Dieser Gedanke der Vollendung der Kant’schen Systemarchitektur findet heute außerhalb der Spezialforschung nur geringen Widerhall. Die dritte Kritik ist mit den zwei vorhergehenden Werken der Vernunftkritik eng verbunden. Für Kant zerfiel die Philosophie danach zunächst in zwei Bereiche: einen theoretischen (der reinen Vernunft) und einen praktischen (Ethik, Rechts- und Religionsphilosophie). Damit die sinnliche und die moralische Welt, Natur und Freiheit nicht unvermittelt (unversöhnlich) nebeneinanderstehen, bedarf es einer Vermittlungsinstanz, die Kluft zu überwinden, einer „Brücke“ zwischen Sinnlichkeit und Moral, denn die Freiheit will praktisch werden, soll sich in der Sinnenwelt entfalten. Diese Vermittlung ist für Kant die Urteilskraft, die das Besondere im Allgemeinen erkennt.[1] Mit der dritten Kritik soll nicht nur zwischen Natur und Freiheit vermittelt werden, sondern sie versucht auch Phänomene wie das Schöne in Natur und Kunst, das Genie, das Organische und die systematische Einheit der Natur mit Hilfe eines Konzepts der Urteilskraft zu klären. Kant unterteilt die Tätigkeit der Urteilskraft grundlegend in zwei Bereiche: Zum einen die bestimmende, bei der ein Konkretes unter ein Allgemeines subsumiert und zum zweiten die reflektierende, bei der zu einem Konkreten das Allgemeine gesucht und benannt wird. Weil er sich für erstere auf eine bereits bestehende Tradition berufen kann und diese Tätigkeit seiner Meinung nach nicht die Mühe einer eigenen Kritik lohnt, liegt der Fokus der Darstellung auf der zweiteren. Für Kant ist die Zweckmäßigkeit der zentrale Begriff, der die Leistung der reflektierenden Urteilskraft und ihre Vermittlung zwischen Natur und Freiheit bezeichnet. Wird etwas als zweckmäßig angesehen, betrachtet man die Phänomene als Ganzes und geht von einem Zweck des Ganzen aus. Dabei ist die Zweckmäßigkeit der Natur für Kant die a priori angenommene Erwartung, die Natur strukturiert und nicht chaotisch vorzufinden.  |

作品における位置づけ カントの意図は、KdUの2つの部分的に矛盾する序論で幅広く述べられているが、この第3の批評において、自然(理論的理性の対象)と自由(実践的理性の 対象)を媒介し、批判哲学の建築を完成させることであった。今日、カントの体系的な建築を完成させるというこの考えは、専門的な研究以外ではほとんど反響 を呼んでいない。 第三批判は、理性批判の先行する二つの作品と密接に結びついている。カントにとって哲学は当初、理論的な領域(純粋理性)と実践的な領域(倫理学、法哲 学、宗教哲学)に分かれていた。官能的な世界と道徳的な世界、自然と自由が(不倶戴天に)隣り合わせにならないようにするためには、官能と道徳の間の「橋 渡し役」が必要である。カントにとってこの媒介とは、一般的なものの中に特殊なものを認識する判断力である[1]。 第三の批評は、自然と自由を媒介するだけでなく、自然や芸術における美、天才性、自然の有機的な統一性と体系的な統一性といった現象を、判断力という概念の助けを借りて解明しようとするものである。 カントは、判断の活動を根本的に二つの領域に分割している: 一方は、具体的なものが一般的なものの下に包摂される決定的なものであり、もう一方は、具体的なものとの関係において一般的なものを求め、名づける反省的 なものである。前者については既存の伝統を参照することができ、彼の考えでは、この活動は彼自身の批評の努力に値しないので、発表の焦点は後者に当てられ る。 カントにとって便宜性とは、反省的判断の実行と、自然と自由との間の媒介を説明する中心的概念である。何かが目的的であると見なされる場合、人は現象を全 体として考え、全体が目的を持っていると仮定する。カントにとって、自然の目的性とは、自然が構造化されており、混沌としていないという先験的な期待であ る。  |

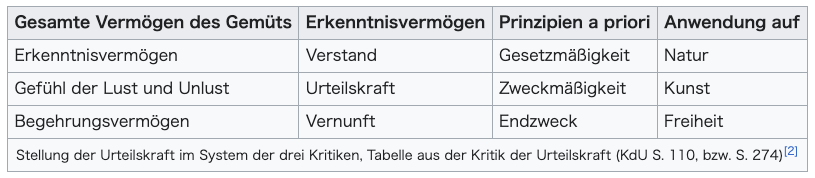

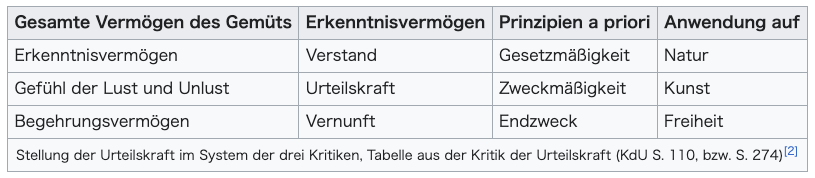

| Gesamte Vermögen des

Gemüts Erkenntnisvermögen

Prinzipien a priori Anwendung auf Erkenntnisvermögen Verstand Gesetzmäßigkeit Natur Gefühl der Lust und Unlust Urteilskraft Zweckmäßigkeit Kunst Begehrungsvermögen Vernunft Endzweck Freiheit Stellung der Urteilskraft im System der drei Kritiken, Tabelle aus der Kritik der Urteilskraft (KdU S. 110, bzw. S. 274)[2] |

心の全能力 認識能力 原理 先験的 適用対象 認知能力 理解法則性 自然 快不快の感情 判断力 目的性 芸術 欲望 理性 究極の目的 自由 三批判体系における判断力の位置、『判断力批判』(KdU 110頁、あるいは274頁)の表[2]。 |

| Inhalt Im ersten Teil analysiert Kant zunächst die Besonderheit von Geschmacksurteilen. Sie sind a) ästhetisch, nicht logisch, b) interesselos, c) arbeiten ohne Begriffe und Zweckvorstellungen und beanspruchen eine besondere Form der Allgemeingültigkeit. Geschmack In seiner kritischen Begründung der Ästhetik untersucht Kant den Geltungsanspruch ästhetischer Urteile. Wer zu ästhetischen Urteilen über das Schöne fähig sei, beweise Geschmack. Geschmacksurteile sind subjektiv und empirisch auf einen Einzelfall, eine Landschaft, ein Kunstwerk bezogen: „Das Geschmacksurteil ist also kein Erkenntnisurteil, mithin nicht logisch, sondern ästhetisch, worunter man dasjenige versteht, dessen Bestimmungsgrund nicht anders als subjektiv sein kann.“[3] |

内容 第一部でカントはまず、嗜好判断の特殊性を分析する。a)美的であり、論理的ではない、b)無関心である、c)概念や目的観念なしに働き、特殊な形の一般的妥当性を主張する。 趣味判断 美学を批判的に正当化する中で、カントは美的判断の妥当性の主張について検討している。美について審美的判断ができる者は、誰でも味覚を証明することがで きる。味覚の判断は主観的であり、経験的に個々の事例、風景、芸術作品に関係する。「したがって、味覚の判断は認識的判断ではなく、したがって論理的でも なく、美的なものである。 |

| Subjektive Allgemeinheit Obwohl Geschmacksurteile nicht beweisbar sind, beanspruchen sie, allgemein zustimmungsfähig zu sein, richten sich also auf eine Allgemeingültigkeit und sind entsprechend formuliert („Das Bild ist schön“, nicht: „Das Bild ist für mich schön“). Sie beanspruchen Allgemeingültigkeit, insofern sie „das Wohlgefallen an einem Gegenstande jedermann ansinne(n)…“[4] Im Gegensatz zu wissenschaftlichen und moralischen Aussagen haben ästhetische Urteile für Kant keine objektive, sondern eine subjektive Allgemeinheit. Wie in den vorhergehenden kritischen Werken nimmt Kant hier eine Mittelstellung zwischen rationalistischen und sensualistischen Positionen ein. Von der Ästhetik Alexander Gottlieb Baumgartens, der in Geschmacksurteilen eine niedere Form des Erkennens sah, grenzt er sich ebenso ab wie von Edmund Burke, der diese auf ein bloßes Gefühl zurückführte. |

主観的一般性 味覚の判断は証明することはできないが、一般的な承認が可能であることを主張する。ある対象が誰にとっても楽しいものであることを示唆する」[4]限りにおいて、普遍的に妥当であると主張するのである。 科学的・道徳的言明とは対照的に、カントにとって美的判断は客観的なものではなく、主観的な一般性を持っている。これまでの批評的著作と同様に、カントは 合理主義的立場と官能主義的立場の中間に位置している。彼は、味覚の判断を認識の低次の形態と見なしたアレクサンダー・ゴットリープ・バウムガルテンの美 学や、味覚の判断を単なる感覚に矮小化したエドマンド・バークの美学とは距離を置く。 |

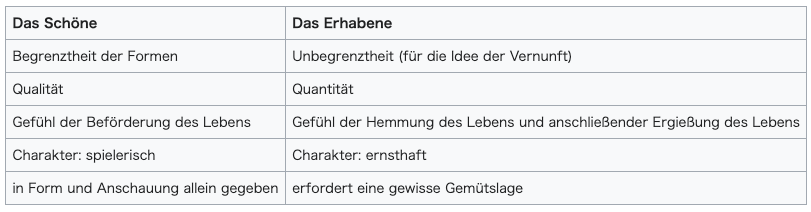

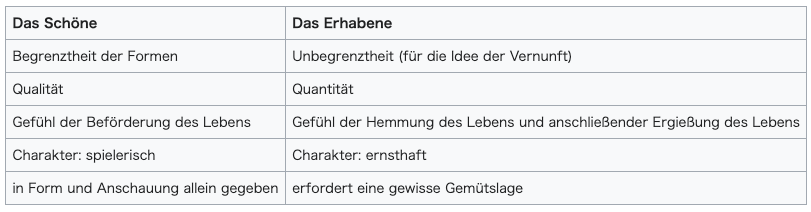

| Das Schöne und das Erhabene Kant unterscheidet im analytischen Teil der KdU, welcher sich der Ästhetik widmet, zwischen dem Schönen und dem Erhabenen. Beide gliedern sich wiederum in freie Schönheit und anhängende Schönheit beziehungsweise das mathematisch Erhabene und das dynamisch Erhabene. In grober Gegenüberstellung lassen sich die folgenden Unterscheidungen treffen:  |

美と崇高 美学に特化したKdUの分析的な部分で、カントは美しいものと崇高なものを区別している。両者は、自由な美と執着する美、あるいは数学的な崇高さと動的な崇高さに細分化される。大まかに比較すると、次のような区別ができる:  |

| Das Schöne Das Erhabene Begrenztheit der Formen Unbegrenztheit (für die Idee der Vernunft) Qualität Quantität Gefühl der Beförderung des Lebens Gefühl der Hemmung des Lebens und anschließender Ergießung des Lebens Charakter: spielerisch Charakter: ernsthaft in Form und Anschauung allein gegeben erfordert eine gewisse Gemütslage |

美しいもの 崇高なもの 形の限定 無限性(理性の観念のために) 質 量 生命の促進を感じる 生命の抑制とそれに続く生命の発露を感じる 性格:遊び好き 性格:真面目 形や見方だけで与えられるものには、ある種の精神状態が必要である。 |

| Das Genie Mit seiner Lehre des Genies ergänzt Kant seine Lehre vom ästhetischen Urteil um eine Theorie der „schönen Kunst“. Er folgt in seiner Theorie der Kunstpraxis nicht mehr dem alten Nachahmungsprinzip (Mimesis), wie es z. B. noch von Baumgarten vertreten wurde, sondern legt den schöpferischen Prozess ins Subjekt. Allerdings heißt dies noch nicht, dass von nun ab der Mensch gleichsam aus sich heraus die Gegenstände der Kunst hervorbringe. Vielmehr ist das Genie mit einer Naturbegabung versehen, welche ihm eine große Einbildungskraft und Originalität verleiht. Das Genie ist kein gesellschaftliches Wesen, sondern vielmehr ein Naturwesen, welches in der Gesellschaft lebt. So gibt Kants Ansicht nach die Natur vermittels des Genies der Kunst ihre Regeln. (Schneider, S. 51)[5] Das Moment des Genialen ist für Kant zwar eine notwendige, aber nicht hinreichende Bedingung der Möglichkeit schöner Kunst. Der Künstler ist nicht bloßes Organ der Natur, sein Tun ist „Hervorbringung durch Freiheit“ und schließt eine „künstliche“ Komponente ein. Diese kommt dadurch zu ihrem Recht, dass Kant als zweite produktionsästhetische Komponente den Geschmack einführt, der die Vermittlung von Einbildungskraft und Verstand leiste. |

天才 天才の理論によって、カントは美的判断の理論を「優れた芸術」の理論で補う。芸術実践の理論において、カントはもはや、例えばバウムガルテンが依然として 提唱しているような、古い模倣(ミメーシス)の原理には従わず、創造的過程を主体の中に位置づける。しかし、このことは、これから先、人間が芸術の対象 を、いわば自分自身の内部から生み出すことを意味するのではない。むしろ、天才には、偉大な想像力と独創性を与える天賦の才能が備わっている。天才は社会 的存在ではなく、むしろ社会の中で生きる自然的存在なのである。したがって、カントの考えでは、自然は天才によって芸術にルールを与えるのである。(シュ ナイダー、51頁)[5] カントにとって、天才の瞬間は、美しい芸術の可能性にとって必要条件ではあるが十分条件ではない。芸術家は単なる自然の器官ではなく、その活動は「自由に よる生産」であり、「人為的」要素を含んでいる。このことは、カントが想像力と理性の間を媒介する第二の生産=美的要素として味覚を導入したときに本領を 発揮する。 |

| Wirkung Hegel Betreffend Kants Analytik der Teleologie: Bezeichnend ist zum einen, dass Kant in der Kritik der Urteilskraft eine scharfe Trennung zwischen objektiven Erkenntnissen und subjektiven Urteilen einführt: so können uns nur die in der Kritik der reinen Vernunft ausgemachten Verstandesbegriffe objektive Erkenntnisse verschaffen, hingegen die Urteilskraft an die Vorstellung eines Zwecks geknüpft ist. „Zweck“ jedoch ist, so Kant, kein objektives Urteil, welches den Dingen zukomme, sondern lediglich eine von der Urteilskraft in die Dinge gelegte Eigenschaft – bezüglich der Vorstellung einer Endursache sagt Kant: „Wir legen, sagt man, Endursachen in die Dinge hinein und heben sie nicht gleichsam aus ihrer Wahrnehmung heraus.“ (KdU S. 33, bzw. S. 194)[2] Von Hegel und anderen Zeitgenossen Kants wurde dies keineswegs als unproblematisch angesehen, da sich bei der Beobachtung eines Organismus, also z. B. eines Tieres, ihrer Ansicht nach sehr wohl ein objektiver Zweck dieses Organismus feststellen ließe, also das Tier seinen Zweck tatsächlich in sich selbst habe. Hingegen erschien es ihnen unplausibel anzunehmen, dass diese doch so offensichtliche Tatsache eine bloß nützliche Funktion unserer Urteilskraft sei. Aus diesem Problemfeld heraus sollte dann auch später Hegel seine Dialektik entwickeln, welche zum Anspruch hat, dieses Problem zu vermeiden. Zwar kommen für Hegel noch andere Motive hinzu, jedoch ist ein historischer Anknüpfungspunkt in diesem Fall plausibel. Um die oben beschriebenen Ungereimtheiten zu vermeiden, identifiziert Hegel die Zweckmäßigkeit mit dem Organismus. (Statt „Organismus“ könnte man auch sagen „Begriff“, denn ein Begriff kommt nach Hegel nur Organismen zu.) Hierzu koppelt Hegel an die von Kant in der KdU eingeführte Vorstellung eines intuitiven Verstandes an: dieser kann seine Gegenstände anschaulich auffassen, ist also nicht auf begriffliche Operationen angewiesen und erkennt somit anschaulich die Struktur des Organismus. Für Hegel hat so zwar Kant «Mit dem Begriffe von der inneren Zweckmäßigkeit (…) die Idee überhaupt und insbesondere die des Lebens wiedererweckt», jedoch, da er ihr keinen objektiven Gehalt zubilligte, ihr Potential nicht ausgeschöpft. Hingegen behauptet Hegel, dass man „nur das als wirklich oder in Wahrheit seiend ansehen kann, zu dem es einen Begriff gibt, und das nur das einen Begriff hat, was nach dem Muster eines Organismus gedeutet werden kann.“ (Emundts/Horstmann S. 72)[6] |

影響 ヘーゲル カントのテオロジーの分析について: 一方では、カントが『判断力批判』において、客観的知識と主観的判断との間に鋭い区別を導入していることは重要である。したがって、『純粋理性批判』にお いて特定された理解の概念のみが客観的知識をわれわれに提供することができるのに対し、判断力は目的の観念と結びついている。しかし、カントによれば、 「目的」は物自体に帰属する客観的判断ではなく、判断力によって物自体に付与される性質にすぎない。最終原因の観念について、カントは次のように述べてい る。「われわれは、物自体に最終原因を付与するというが、いわば、物自らをその認識から引き離すのではない。(ヘーゲルをはじめとするカントと同時代の人 びとは、このことをまったく問題ないとは考えなかった。なぜなら、彼らの見解では、ある生物、たとえば動物の客観的な目的は、それを観察するときに決定さ れうる、すなわち、その動物は実際にそれ自体に目的を持っているからである。一方、この明白な事実が、単に人間の判断力の有用な機能であると考えるのは、 彼らにとってはありえないことであった。 ヘーゲルが後に弁証法を発展させたのは、この問題領域からであった。ヘーゲルには他の動機もあるが、この場合、歴史的出発点はもっともである。上述の矛盾 を避けるために、ヘーゲルは便宜を有機体と同一視する。(ヘーゲルによれば、概念を持つのは生物だけだからである)。この目的のために、ヘーゲルはKdU でカントによって導入された直観的理解という考え方と結びついている。この理解は対象を鮮明に把握することができ、したがって概念操作に依存せず、した がって生物の構造を鮮明に認識する。ヘーゲルにとって、カントはこうして「内的な目的意識(...)の概念によって、一般的な観念、とりわけ生命の観念を 再認識した」のであるが、彼はそれに客観的な内容を与えなかったので、その潜在的可能性を完全に実現したわけではなかった。他方、ヘーゲルは、「概念をも つものだけが現実的あるいは真理的とみなすことができ、生物の型にしたがって解釈できるものだけが概念をもつ」と主張している (Emundts/Horstts)。(Emundts/Horstmann p.72)[6]。 |

| Aktuelle Rezeption Kants Analyse des Ästhetischen erregt bis heute großes Interesse und ist vielfach auch für das Verstehen moderner Kunst fruchtbar gemacht worden. Zu ihr gehören die Aspekte das Schöne als „interesseloses Wohlgefallen“ ohne begriffliche Aneignung des Gegenstandes aufzufassen der paradoxe Status des Geschmacksurteils als subjektiv und verallgemeinerbar die ästhetische Erfahrung als freies Spiel der Erkenntnisvermögen Sinnlichkeit und Verstand die Analyse des Erhabenen |

現在の受容 美学に関するカントの分析は、今日でも大きな関心を呼び起こし、しばしば現代美術を理解する上で有益なものとなっている。これには次のような側面がある。 美を、対象への概念的な流用なしに「無関心な快楽」として理解する。 主観的で一般化可能な味覚判断の逆説的な地位 官能と理解という認識能力の自由な遊びとしての美的体験 崇高さの分析 |

| Literatur Kritik der Urteilskraft : Schriften zur Ästhetik und Naturphilosophie; [Text und Kommentar] / Immanuel Kant. Herausgegeben von Manfred Frank und Véronique Zanetti, Deutscher Klassiker-Verlag, Frankfurt/Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-618-68037-6. Otfried Höffe (Hrsg.): Immanuel Kant. Kritik der Urteilskraft. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-05-004342-5. Jens Kulenkampff: Kants Logik des ästhetischen Urteils. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1994 (2), ISBN 978-3-465-02646-4 Birgit Recki: Ästhetik der Sitten. Die Affinität von ästhetischem Gefühl und praktischer Vernunft. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 978-3-465-03150-5. Wolfgang Wieland: Urteil und Gefühl. Kants Theorie der Urteilskraft. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001 (ISBN 3-525-30137-5 bzw. 30136-7) Achim, Geisenhanslüke: Der Geschmack der Freiheit: Kant und das politisch Unbewusste der Ästhetik (= Texturen. Band 9). Rombach Wissenschaft, Baden-Baden 2024, ISBN 978-3-9885803-6-8. |

文献 判断力批判 : 美学と自然哲学に関する著作; [テキストと解説] / イマヌエル・カント. Manfred Frank, Véronique Zanetti 編, Deutscher Klassiker-Verlag, Frankfurt/Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-618-68037-6. Otfried Höffe (ed.): Immanuel Kant. Critique of Judgement. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-05-004342-5. Jens Kulenkampff: Kant's Logic of Aesthetic Judgement. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1994 (2), ISBN 978-3-465-02646-4. Birgit Recki: Aesthetics of Morals. 美的感覚と実践的理性の親和性。Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 978-3-465-03150-5. Wolfgang Wieland: Judgement and feeling. カントの判断理論。Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001 (ISBN 3-525-30137-5 または 30136-7) Achim, Geisenhanslüke: Der Geschmack der Freiheit: Kant und das politisch Unbewusste der Ästhetik (= Texturen. Band 9). Rombach Wissenschaft, Baden-Baden 2024, ISBN 978-3-9885803-6-8. |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kritik_der_Urteilskraft |

☆

心の全能力 認識能力 原理 先験的 適用対象

認知能力 理解法則性 自然

快不快の感情 判断力 目的性 芸術

欲望 理性 究極の目的 自由

三批判体系における判断力の位置、『判断力批判』(KdU 110頁、あるいは274頁)の表[2]。

美しいもの 崇高なもの

形の限定 無限性(理性の観念のために)

質 量

生命の促進を感じる 生命の抑制とそれに続く生命の発露を感じる

性格:遊び好き 性格:真面目

形や見方だけで与えられるものには、ある種の精神状態が必要である。

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

☆共通感覚論としての「判断力批判」

| Kant: In aesthetic taste |

カント 美的趣味において |

| Immanuel Kant developed a new

variant of the idea of sensus communis, noting how having a sensitivity

for what opinions are widely shared and comprehensible gives a sort of

standard for judgment, and objective discussion, at least in the field

of aesthetics and taste: |

イマヌエル・カントは、「共通感覚(Sensus

communis)」の考えを新たに展開し、どのような意見が広く共有され理解されているかという感性を持つことが、少なくとも美学や趣

味の分野では、判断や客観的議論のための一種の基準となることを(次のように)指摘した。 |

| The

common Understanding of men [gemeine Menschenverstand], which, as the

mere sound (not yet cultivated) Understanding, we regard as the least

to be expected from any one claiming the name of man, has therefore the

doubtful honour of being given the name of common sense [Namen des

Gemeinsinnes] (sensus communis); and in such a way that by the name

common (not merely in our language, where the word actually has a

double signification, but in many others) we understand vulgar, that

which is everywhere met with, the possession of which indicates

absolutely no merit or superiority. But under the sensus communis we

must include the Idea of a communal sense [eines gemeinschaftlichen

Sinnes], i.e. of a faculty of judgement, which in its reflection takes

account (a priori) of the mode of representation of all other men in

thought; in order as it were to compare its judgement with the

collective Reason of humanity, and thus to escape the illusion arising

from the private conditions that could be so easily taken for

objective, which would injuriously affect the judgement.[73] |

人

間の共通理解[gemeine

Menschenverstand]は、単なる音としての(まだ培われていない)理解として、人間の名を名乗る者に最も期待されていないものと考えられる

ので、共通感覚(Namen des Gemeinsinnes)という疑わしい名誉を与えられている(Sensus

Communis)。そして、そのような意味で、一般的という名前によって(この言葉が実際には二重の意味を持つ我々の言語だけでなく、他の多くの言語

で)、我々は、どこでも出会うことができ、その所有が全くメリットや優越性を示さない低俗なものを理解しています。しかし、sensus

communisの下には、共同体的感覚(eines gemeinschaftlichen

Sinnes)、すなわち、その反射において、思考における他のすべての人間の表現様式を(先験的に)考慮に入れる判断能力のイデアを含まなければならな

い。これは、その判断を人類の集団的理性と比較するため、そして、そうして、判断に有害な影響を与える、非常に簡単に客観視できる私的条件から生じる幻想

から逃れるためである[73]。 |

| Kant saw this concept as

answering a particular need in his system: "the question of why

aesthetic judgments are valid: since aesthetic judgments are a

perfectly normal function of the same faculties of cognition involved

in ordinary cognition, they will have the same universal validity as

such ordinary acts of cognition".[74] |

カントはこの概念を彼の体系における特定の必要性に答えるものと考えていた。「美的判断がなぜ妥当なのかという問題:美的判断は通常の認知に関わるのと同 じ認知能力の完全に正常な機能であるので、そのような通常の認知行為と同じ普遍的妥当性を持つことになる」[74]。 |

| But Kant's overall approach was

very different from those of Hume or Vico. Like Descartes, he rejected

appeals to uncertain sense perception and common sense (except in the

very specific way he describes concerning aesthetics), or the

prejudices of one's "Weltanschauung", and tried to give a new way to

certainty through methodical logic, and an assumption of a type of a

priori knowledge. He was also not in agreement with Reid and the

Scottish school, who he criticized in his Prolegomena to Any Future

Metaphysics as using "the magic wand of common sense", and not properly

confronting the "metaphysical" problem defined by Hume, which Kant

wanted to be solved scientifically—the problem of how to use reason to

consider how one ought to act. |

しかしカントの全体的なアプローチはヒュームやヴィーコのそれとは非常

に異なっていた。彼はデカルトと同様に、不確かな感覚認識や常識(美学に関して述べ

た非常に特殊な方法を除く)、あるいは自分の「世界観」の偏見への訴えを拒否し、方法的論理と一種の先験的知識の仮定によって確実性への新しい道を与えよ

うとした。また、『未来の形而上学への提議』でリードやスコットランド学派を「常識という魔法の杖」を使っていると批判し、ヒュームの定義した「形而上学

的」問題、すなわち理性を使っていかに行動すべきかを考えるという問題に科学的に向き合おうとしていなかったことにも異を唱えている。 |

| Kant used different words to

refer to his aesthetic sensus communis, for which he used Latin or else

German Gemeinsinn, and the more general English meaning which he

associated with Reid and his followers, for which he used various terms

such as gemeinen Menscheverstand, gesunden Verstand, or gemeinen

Verstand.[75] |

カントはラテン語や他のドイツ語のGemeinsinnを使った彼の美

的感覚を指す言葉と、リードと彼の信奉者と関連したより一般的な英語の意味を指す言 葉、それに対してgemeinen

Menscheverstand, gesunden Verstand, またはgemeinen

Verstandといった様々な用語を使った[75]。 |

| According to Gadamer, in

contrast to the "wealth of meaning" brought from the Roman tradition

into humanism, Kant "developed his moral philosophy in explicit

opposition to the doctrine of 'moral feeling' that had been worked out

in English philosophy". The moral imperative "cannot be based on

feeling, not even if one does not mean an individual's feeling but

common moral sensibility".[76] For Kant, the sensus communis only

applied to taste, and the meaning of taste was also narrowed as it was

no longer understood as any kind of knowledge.[77] Taste, for Kant, is

universal only in that it results from "the free play of all our

cognitive powers", and is communal only in that it "abstracts from all

subjective, private conditions such as attractiveness and emotion".[78] |

ガダマーによれば、ローマの伝統から人文主義にもたらされた「意味の豊

かさ」とは対照的に、カントは「イギリス哲学において取り組まれてきた『道徳感情』

の教義に明確に反対して彼の道徳哲学を発展させた」のである。道徳的命令は「個人の感覚ではなく、共通の道徳的感性を意味するとしても、感覚に基づくこと

はできない」[76]。 カントにとって、sensus

communisは味覚にのみ適用され、味覚はもはやいかなる種類の知識としても理解されなかったため、その意味も狭められた[77]。

カントにとって、味は「我々のすべての認識力の自由な遊び」から生じるという点でのみ普遍であり、「魅力や感情といったすべての主観的、私的条件から抽出

する」点においてのみ共同性あるものである[78]。 |

| Kant himself did not see himself

as a relativist, and was aiming to give knowledge a more solid basis,

but as Richard J. Bernstein remarks, reviewing this same critique of

Gadamer: |

カント自身は自分を相対主義者だとは思っておらず、知識にもっと強固な根拠を与えることを目指していたが、リチャード・J・バーンスタインがガダマーに対 するこの同じ批判を見直しながら(次のように)指摘しているように。 |

| Once we begin to question

whether there is a common faculty of taste (a sensus communis), we are

easily led down the path to relativism. And this is what did happen

after Kant—so much so that today it is extraordinarily difficult to

retrieve any idea of taste or aesthetic judgment that is more than the

expression of personal preferences. Ironically (given Kant's

intentions), the same tendency has worked itself out with a vengeance

with regards to all judgments of value, including moral judgments.[79] |

ひとたび共通の味覚の能力(a sensus

communis)が存在するかどうかを疑い始めると、私たちは容易に相対主義への道を歩むことになる。そして、これはカント以後に起こったことであり、

今日、個人の好みの表現以上の味覚や美的判断の考えを取り戻すことは非常に困難である。皮肉なことに(カントの意図を考えると)、同じ傾向が道徳的判断を

含む全ての価値判断に関しても復讐のように働いている[79]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_sense |

「共通感覚」 |

★両津勘吉の判断力批判(これは第三批判というよりも、理念の限界を、経験概念の理論的分析を通して乗り越えようとする第二批判「実践理性批判」の主張だということも可能である)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

【ご注意!!】これ以外に、美的判断と政治的判断の 「共通性」を論 じている「ハンナ・アーレント の『カントの政治哲学講義』ノート」「カント流植民地主義」な どがあります。

| The Critique

of

Judgment (German: Kritik der Urteilskraft), also translated as the

Critique of the Power of Judgment, is a 1790 book by the German

philosopher Immanuel Kant. Sometimes referred to as the "third

critique," the Critique of Judgment follows the Critique of Pure Reason

(1781) and the Critique of Practical Reason (1788). |

『判断力批判』(はんだんりょくひはん、ドイツ語:Kritik

der

Urteilskraft)は、ドイツの哲学者イマヌエル・カントが1790年に発

表した著作である。純粋理性批判』(1781年)、『実践理性批判』

(1788年)に続く「第三の批判」と呼ばれることもある。 |

| Immanuel Kant's Critique of

Judgment is the third critique in Kant's Critical project begun in the

Critique of Pure Reason and the Critique of Practical Reason (the First

and Second Critiques, respectively). The book is divided into two main

sections: the Critique of Aesthetic Judgment and the Critique of

Teleological Judgment, and also includes a large overview of the

entirety of Kant's Critical system, arranged in its final form. The

so-called First Introduction was not published during Kant's lifetime,

for Kant wrote a replacement for publication. The Critical project, that of exploring the limits and conditions of knowledge, had already produced the Critique of Pure Reason, in which Kant argued for a Transcendental Aesthetic, an approach to the problems of perception in which space and time are argued not to be objects. The First Critique argues that space and time provide ways in which the observing subject's mind organizes and structures the sensory world. The end result of this inquiry in the First Critique is that there are certain fundamental antinomies in the dialectical use of Reason, most particularly that there is a complete inability to favor on the one hand the argument that all behavior and thought is determined by external causes, and on the other that there is an actual "spontaneous" causal principle at work in human behavior. The first position, of causal determinism, is adopted, in Kant's view, by empirical scientists of all sorts; moreover, it led to the Idea (perhaps never fully to be realized) of a final science in which all empirical knowledge could be synthesized into a full and complete causal explanation of all events possible to the world. The second position, of spontaneous causality, is implicitly adopted by all people as they engage in moral behavior; this position is explored more fully in the Critique of Practical Reason. The Critique of Judgment constitutes a discussion of the place of Judgment itself, which must overlap both the Understanding ("Verstand") (whichsoever operates from within a deterministic framework) and Reason ("Vernunft") (which operates on the grounds of freedom). |

イマヌエル・カントの『判断力批判』は、『純粋理性批判』『実践理性批

判』(それぞれ『第一批判』『第二批判』)で始まったカントの批判プロジェクトにおける第三批判である。本書は、「美的判断の批判」と「目的論的判断の批

判」の2つの主要なセクションに分けられ、さらに、カントの批判体系の全体を最終形態に整理した大総覧が含まれている。いわゆる「第一序」は、カントが出

版用に代筆したため、カントの存命中には出版されなかった。 知識の限界と条件を探るという批判的プロジェクトは、すでに『純粋理性批判』を生み出し、その中でカントは超越論的美学を主張し、空間と時間を物体ではな いと主張する知覚の問題へのアプローチを行っていた。第一次批判では、空間と時間は、観察者の心が感覚世界を組織化し、構造化する方法を提供すると主張す る。この第一次批判の最終的な成果は、理性の弁証法的使用にはある種の根本的な矛盾があること、とりわけ、すべての行動と思考が外的原因によって決定され るという議論と、人間の行動には実際に「自発的」な因果原理が働いているという議論を一方では完全に支持できないことであった。 第一の立場である因果的決定論は、カントの考えでは、あらゆる種類の経験的科学者によって採用されている。さらに、この立場は、すべての経験的知識が、世 界に起こりうるすべての出来事の完全かつ完璧な因果的説明に統合されうる最終科学のアイデア(おそらく完全に実現することはなかった)につながったのであ る。 第二の立場は、自発的な因果関係というもので、すべての人が道徳的な行動をとる際に暗黙のうちに採用している。この立場は、『実践理性批判』でより詳細に 検討されている。 判断力批判』は、判断力の位置づけそのものを論じたものであり、それは、理解("Verstand")(決定論的枠組みの中で操作するもの)と理性 ("Vernunft")(自由の根拠に基づいて操作するもの)の双方に重なるはずのものである。 |

| Introduction to the Critique of

Judgement The first part of Kant's Critique of Aesthetic Judgement presents what Kant calls the four moments of the "Judgement of Taste". These are given by Kant in sequence as the (1) First Moment. Of the Judgement of Taste: Moment of Quality"; (2) Second Moment. Of the Judgement of Taste: Moment of Quantity"; (3) Third Moment: Of Judgement of Taste: Moment of the Relation of the ends brought under Review in such Judgements"; and (4) Fourth Moment: Of the Judgement of Taste: Moment of the Modality of the Delight in the Object". After the presentation of the four moments of the Judgement of Taste, Kant then begins his discussion of Book 2 of the Third Critique titled Analytic of the Sublime. |

『判断力批判』序章 カントの『美的判断批判』の第一部は、カントが「味覚の判断」の4つの瞬間と呼ぶものを提示している。これらはカントによって、(1)第一の瞬間 として順に与えられている。趣味感覚(テイスト)の判断の 質の瞬間」、(2)第二の瞬間。趣味感覚(テイスト)の判断の瞬間: 量の瞬間」、(3) 第三の瞬間: 趣味感覚(テイスト)の判断の瞬間」: (4)第四の瞬間: 趣味感覚(テイスト)の判断について: 対象への喜びの様態の瞬間」。趣味感覚(テイスト)の判断の4つの瞬間の提示の後、カントは『崇高の分析』と題された『第三批判』第2巻の議論を始める。 ※趣味感覚(テイスト)=Geschmack |

| Aesthetic Judgement The first part of the book discusses the four possible aesthetic reflective judgments: the agreeable, the beautiful, the sublime, and the good. Kant makes it clear that these are the only four possible reflective judgments, as he relates them to the Table of Judgments from the Critique of Pure Reason. "Reflective judgments" differ from determinative judgments (those of the first two critiques). In reflective judgment we seek to find unknown universals for given particulars; whereas in determinative judgment, we just subsume given particulars under universals that are already known, as Kant puts it: It is then one thing to say, “the production of certain things of nature or that of collective nature is only possible through a cause which determines itself to action according to design”; and quite another to say, “I can according to the peculiar constitution of my cognitive faculties judge concerning the possibility of these things and their production, in no other fashion than by conceiving for this a cause working according to design, i.e. a Being which is productive in a way analogous to the causality of an intelligence.” In the former case I wish to establish something concerning the Object, and am bound to establish the objective reality of an assumed concept; in the latter, Reason only determines the use of my cognitive faculties, conformably to their peculiarities and to the essential conditions of their range and their limits. Thus the former principle is an objective proposition for the determinant Judgment, the latter merely a subjective proposition for the reflective Judgment, i.e. a maxim which Reason prescribes to it.[1] The agreeable is a purely sensory judgment — judgments in the form of "This steak is good," or "This chair is soft." These are purely subjective judgments, based on inclination alone. The good is essentially a judgment that something is ethical — the judgment that something conforms with moral law, which, in the Kantian sense, is essentially a claim of modality — a coherence with a fixed and absolute notion of reason. It is in many ways the absolute opposite of the agreeable, in that it is a purely objective judgment — things are either moral or they are not, according to Kant. The remaining two judgments — the beautiful and the sublime — differ from both the agreeable and the good. They are what Kant refers to as "subjective universal" judgments. This apparently oxymoronic term means that, in practice, the judgments are subjective, and are not tied to any absolute and determinate concept. However, the judgment that something is beautiful or sublime is made with the belief that other people ought to agree with this judgment — even though it is known that many will not. The force of this "ought" comes from a reference to a sensus communis — a community of taste. Hannah Arendt, in her Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy, suggests the possibility that this sensus communis might be the basis of a political theory that is markedly different from the one that Kant lays out in the Metaphysic of Morals. The central concept of Kant's analysis of the judgment of beauty is what he called the ″free play″ between the cognitive powers of imagination and understanding.[2] We call an object beautiful, because its form fits our cognitive powers and enables such a ″free play″ (§22) the experience of which is pleasurable to us. The judgment that something is beautiful is a claim that it possesses the "form of finality" — that is, that it appears to have been designed with a purpose, even though it does not have any apparent practical function. We also do not need to have a determinate concept for an object in order to find it beautiful (§9). In this regard, Kant further distinguishes between free and adherent beauty. Whereas judgments of free beauty are made without having one determinate concept for the object being judged (e.g. an ornament or well-formed line), a judgment of beauty is adherent if we do have such a determined concept in mind (e.g. a well-built horse that is recognized as such). The main difference between these two judgments is that purpose or use of the object plays no role in the case of free beauty. In contrast, adherent judgments of beauty are only possible if the object is not ill-suited for its purpose. The judgment that something is sublime is a judgment that it is beyond the limits of comprehension — that it is an object of fear. However, Kant makes clear that the object must not actually be threatening — it merely must be recognized as deserving of fear. Kant's view of the beautiful and the sublime is frequently read as an attempt to resolve one of the problems left following his depiction of moral law in the Critique of Practical Reason — namely that it is impossible to prove that we have free will, and thus impossible to prove that we are bound under moral law. The beautiful and the sublime both seem to refer to some external noumenal order — and thus to the possibility of a noumenal self that possesses free will. In this section of the critique Kant also establishes a faculty of mind that is in many ways the inverse of judgment — the faculty of genius. Whereas judgment allows one to determine whether something is beautiful or sublime, genius allows one to produce what is beautiful or sublime. |

美的判断 本書の前半では、美的反省判断として可能な4つの判断、すなわち、快、美、崇高、善について論じている。カントは、『純粋理性批判』の「判断の表」と関連 させながら、この4つだけが可能な反省的判断であることを明らかにしている。 「反省的判断」は決定的判断(最初の2つの批判の判断)とは異なる。反省的判断では、与えられた特殊に対して未知の普遍を見つけようとするが、決定論的判 断では、カントの言うように、与えられた特殊を既に知られている普遍の下に置くだけである。 そして、「自然のあるものの生産や集合的な自然の生産は、設計に従って行動を決定する原因によってのみ可能である」と言うことと、「私は私の認識能力の特 殊な構成に従って、設計に従って働く原因、すなわち知性の因果性に類似した方法で生産的な存在をこのために想像する以外に、これらのものとその生産の可能 性について判断することができない」と言うことは全く別のものである。前者の場合、私は対象に関する何かを立証したいと願い、想定された概念の客観的実在 性を立証しなければならない。後者の場合、理性は私の認識能力の使用を、その特殊性、その範囲と限界の本質的条件に適合するように決定するだけである。し たがって、前者の原理は決定論的判断のための客観的命題であり、後者は反省的判断のための主観的命題、すなわち理性がそれに規定する格言に過ぎない [1]。 「このステーキはうまい」「この椅子は柔らかい」というような感覚的な判断である。これらは、純粋に主観的な判断であり、気の持ちようだけに基づいてい る。 善とは、本質的に何かが倫理的であるという判断、つまり、何かが道徳律に適合しているという判断であり、カント的には、本質的に様相の主張、つまり、理性 の固定的かつ絶対的概念との首尾一貫性である。カントによれば、これは純粋に客観的な判断であり、物事は道徳的かそうでないかのどちらかであるという点 で、多くの点で「好ましい」とは正反対である。 残りの二つの判断、すなわち美しいものと崇高なものは、同意できるものとも善いものとも異なる。これらはカントの言うところの「主観的普遍」判断である。 この一見矛盾した言葉は、実際には、これらの判断は主観的であり、いかなる絶対的で確定的な概念にも縛られないということを意味している。しかし、「美し い」「崇高だ」という判断は、多くの人が同意しないことがわかっているにもかかわらず、「他の人も同意するはずだ」という信念のもとになされる。この「べ き」という言葉は、sensus communis、つまりテイスト(趣味感覚)の共同体への言及からくるものである。ハンナ・アーレントは『カント政治哲学講義』の中で、この「共同体感 覚」が、カントが 『道徳の形而上学』で示したものとは明らかに異なる政治理論の基礎となる可能性を示唆している。 カントが美の判断について分析した中心的な概念は、想像力と理解力の間の″自由な遊び″と呼ばれるものである[2] 我々がある対象を美しいと呼ぶのは、その形が我々の認識力に適合し、その″自由な遊び″(§22)を可能にし、その経験が我々にとって快楽的であるからで ある。美しいという判断は、それが「最終的な形」を持っているという主張であり、つまり、それが実用的な機能を持たないにもかかわらず、目的を持って設計 されているように見えるということである。また、ある対象を美しいと感じるためには、その対象に対して確定的な概念を持つ必要はない(§9)。この点で、 カントはさらに自由な美と固執した美を区別している。自由な美の判断が、判断の対象に対して一つの確定的な概念を持たずに行われる(例えば、装飾や整った 線)のに対し、美の判断は、そのような確定的な概念を持つ場合(例えば、よくできた馬がそのように認識される)、固執的であるという。この二つの判断の大 きな違いは、「自由な美」の場合には、対象物の目的や用途が関係しないことです。これに対して、固執的な美の判断は、対象がその目的に不適当でない場合に のみ可能である。 何かが崇高であるという判断は、それが理解の限界を超えている、つまり恐怖の対象であるという判断である。しかし、カントは、その対象が実際に脅威であっ てはならず、ただ恐怖に値すると認識されなければならないと明言している。 カントの美と崇高に関する見解は、『実践理性批判』における道徳律の描写の後に残された問題の一つ、すなわち、人間に自由意志があることを証明することは 不可能であり、したがって、人間が道徳律に拘束されていることを証明することも不可能であることを解決しようとする試みとしてよく読まれるものである。美 しいものと崇高なものは、いずれも外的な自然界の秩序を指しているように思われ、したがって、自由意志を有する自然的な自己の可能性を指しているように思 われる。 また、カントは、この批判において、判断の逆をいく心の能力、すなわち天才の能力を確立している。判断力は、何かが美しいか崇高であるかを決定することを 可能にするのに対し、天才は、何が美しいか崇高であるかを生み出すことを可能にする。 |

| Teleology The second half of the Critique discusses teleological judgement. This way of judging things according to their ends (telos: Greek for end) is logically connected to the first discussion at least regarding beauty but suggests a kind of (self-) purposiveness (that is, meaningfulness known by one's self). Kant writes about the biological as teleological, claiming that there are things, such as living beings, whose parts exist for the sake of their whole and their whole for the sake of their parts. This allows him to open a gap in the physical world: since these "organic" things cannot be brought under the rules that apply to all other appearances, what are we to do with them? Kant says explicitly that while efficiently causal explanations are always best (x causes y, y is the effect of x), it is absurd to hope for "another Newton" who could explain a blade of grass without invoking teleology, and so the organic must be explained "as if" it were constituted as teleological.[3] This portion of the Critique is, from some modern theories, where Kant is most radical; he posits man as the ultimate end, that is, that all other forms of nature exist for the purpose of their relation to man, directly or not, and that man is left outside of this due to his faculty of reason. Kant claims that culture becomes the expression of this, that it is the highest teleological end, as it is the only expression of human freedom outside of the laws of nature. Man also garners the place as the highest teleological end due to his capacity for morality, or practical reason, which falls in line with the ethical system that Kant proposes in the Critique of Practical Reason and the Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals. Kant attempted to legitimize purposive categories in the life sciences, without a theological commitment. He recognized the concept of purpose has epistemological value for finality, while denying its implications about creative intentions at life and the universe's source. Kant described natural purposes as organized beings, meaning that the principle of knowledge presupposes living creatures as purposive entities. He called this supposition the finality concept as a regulative use, which satisfies living beings specificity of knowledge.[4] This heuristic framework claims there is a teleology principle at purpose's source and it is the mechanical devices of the individual original organism, including its heredity. Such entities appear to be self-organizing in patterns. Kant's ideas allowed Johann Friedrich Blumenbach and his followers to formulate the science of types (morphology) and to justify its autonomy.[5] Kant held that there was no purpose represented in the aesthetic judgement of an object's beauty. A pure aesthetic judgement excludes the object's purpose.[6] |

目的論(テレオロジー) 『批判』の後半=第二部では、「目的論的判断」が論じられている。この目的(テロス:ギリシャ語で終わりの意)に従って物事を判断する方法は、少なくとも美に関し て は最初の議論と論理的につながっているが、一種の(自己)目的性(つまり、自己によって知られる意味づけ)を示唆している。 カントは、生物学的なものを目的論的なものとして書き、生物のように、その部分が全体のために存在し、その全体が部分のために存在するものがあると主張す る。このような「有機的」なものは、他のすべての外見に適用されるルールの下に置くことができないので、我々はそれらをどうしたらよいのだろうか、という 物理的世界のギャップを開くことができる。 カントは、効率的な因果関係の説明が常に最善である(xがyを引き起こし、yはxの結果である)一方で、テレロジー=目的論を発動せずに草の葉を説明できる「別の ニュートン」を望むのは不合理であり、有機物はテレロジーとして構成されている「ように」説明しなければならないと明示している[3]。 [つまり、他のすべての自然の形態は、直接的であろうとなかろうと、人間との関係のために存在し、人間は理性という能力によってその外に取り残されている のである。カントは、文化がその表現となり、自然の法則の外にある人間の自由の唯一の表現であるとして、それが最高の目的であると主張する。また、人間は 道徳、すなわち実践理性の能力によって最高の目的としての地位を獲得するが、これはカントが『実践理性批判』と『道徳の形而上学の基本原理』で提唱する倫 理体系と一致する。 カントは、神学的なコミットメントなしに、生命科学における目的のカテゴリーを正統化しようとした。彼は、目的という概念が、生命や宇宙の根源における創 造的意図についての含意を否定しつつも、最終的なものとしての認識論的価値を持つことを認識したのである。カントは自然の目的を組織された存在として説明 したが、これは知識の原理が生き物を目的のある存在として仮定していることを意味する。彼はこの仮定を、生き物の知の特異性を満たす規制的使用としての最 終概念と呼んだ[4]。この発見的枠組みは、目的の源泉に目的原理があり、それは遺伝を含む個々の原生生物の機械的装置であると主張している。そのような 実体は、パターンで自己組織化されているように見える。カントの考えはヨハン・フリードリヒ・ブルーメンバッハとその追随者たちに、型の科学(形態学)を 形成させ、その自律性を正当化させた[5]。 カントは物体の美しさを判断する美的判断には目的が表されていないとした。純粋な美的判断は対象の目的を除外する[6]。 |

| Though Kant consistently

maintains that the human mind is not an "intuitive

understanding"—something that creates the phenomena which it

cognizes—several of his readers (starting with Fichte, culminating in

Schelling) believed that it must be (and often give Kant credit). Kant's discussions of schema and symbol late in the first half of the Critique of Judgement also raise questions about the way the mind represents its objects to itself, and so are foundational for an understanding of the development of much late 20th-century continental philosophy: Jacques Derrida is known to have studied the book extensively. In Truth and Method (1960), Hans-Georg Gadamer rejects Kantian aesthetics as ahistorical in his development of a historically-grounded hermeneutics.[7][8][9] |

カントは一貫して、人間の心は「直観的理解」-認識する現象を生み出す

何か-ではないと主張しているが、彼の読者の何人かは(フィヒテに始まりシェリングに至るまで)、そうでなければならないと信じていた(そしてしばしばカ

ントを信用していた)。 カントが『判断力批判』の前半で行ったシェーマと象徴に関する議論も、心が対象を自らに表象する方法についての問題を提起しており、20世紀後半の多くの 大陸哲学の発展を理解する上で基礎となるものである。ジャック・デリダは、この本を広く研究していたことが知られている。 ハンス・ゲオルク・ガダマーは『真理と方法』(1960年)において、歴史的根拠に基づく解釈学を展開する中で、カント的美学を非歴史的なものとして否定している[7][8][9]。 |

| Schopenhauer’s comments Schopenhauer noted that Kant was concerned with the analysis of abstract concepts, rather than with perceived objects. "…he does not start from the beautiful itself, from the direct, beautiful object of perception, but from the judgement [someone’s statement] concerning the beautiful…."[10] Kant was strongly interested, in all of his critiques, with the relation between mental operations and external objects. "His attention is specially aroused by the circumstance that such a judgement is obviously the expression of something occurring in the subject, but is nevertheless as universally valid as if it concerned a quality of the object. It is this that struck him, not the beautiful itself."[10] The book's form is the result of concluding that beauty can be explained by examining the concept of suitableness. Schopenhauer stated that “Thus we have the queer combination of the knowledge of the beautiful with that of the suitableness of natural bodies into one faculty of knowledge called power of judgement, and the treatment of the two heterogeneous subjects in one book.”[10] Kant is inconsistent, according to Schopenhauer, because “…after it had been incessantly repeated in the Critique of Pure Reason that the understanding is the ability to judge, and after the forms of its judgements are made the foundation–stone of all philosophy, a quite peculiar power of judgement now appears which is entirely different from that ability.”[11] With regard to teleological judgement, Schopenhauer claimed that Kant tried to say only this: "…although organized bodies necessarily seem to us as though they were constructed according to a conception of purpose which preceded them, this still does not justify us in assuming it to be objectively the case."[12] This is in accordance with Kant's usual concern with the correspondence between subjectivity (the way that we think) and objectivity (the external world). Our minds want to think that natural bodies were made by a purposeful intelligence, like ours. |

ショーペンハウアーのコメント ショーペンハウアーは、カントが知覚された対象ではなく、抽象的な概念 の分析に関心を寄せていることを指摘した。"・・・彼は美しいものそれ自体から、直 接の美しい知覚の対象からではなく、美しいものに関する判断[誰かの発言?]から出発している・・・"[10]。 カントはすべての批評において、精神作用と外的対象との関係に強い関心を抱いていた。彼の関心は、このような判断が明らかに主体に生じる何かの表現である にもかかわらず、あたかも対象の品質に関わるかのように普遍的に有効であるという事情によって特別に喚起される」[10]。彼が心を打たれたのはこの点で あって、美しいことそのものではなかった」[10]。 本書の形式は、美は適合性の概念を検討することによって説明できると結論づけた結果である。ショーペンハウアーは「こうしてわれわれは、美しいという知識 と自然体の適合性という知識を、判断力という一つの知識能力に奇妙に組み合わせ、この二つの異質な主題を一つの書物で扱うことになった」と述べている [10]。 ショーペンハウアーによれば、カントが矛盾しているのは、「...純粋理性批判において、理解とは判断する能力であると絶え間なく繰り返され、その判断の 形式がすべての哲学の基礎とされた後に、今度はその能力とは全く異なる極めて特異な判断力が現れるからである」[11]という。 目的論的判断に関して、ショーペンハウアーはカントがこうだけ言おうとしていたと主張している。「このことは、主観性(私たちの考え方)と客観性(外界) の間の対応関係に対するカントの通常の関心に沿うものである。私たちの心は、自然体は私たちのような目的を持った知性によって作られたと思いたがる。 |

| Lessons on the Analytic of the

Sublime The Differend Jean-François Lyotard Aesthetic distance Schopenhauer's criticism of Kant's schemata Schopenhauer's criticism of the Kantian philosophy |

崇高の分析に関する教訓 差異 ジャン=フランソワ・リオタール 美的距離 ショーペンハウアーによるカントの図式批判 ショーペンハウアーによるカント哲学批判 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critique_of_Judgment |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| In The Differend,

based on Immanuel Kant's views on the separation of Understanding,

Judgment, and Reason, Lyotard identifies the moment in which language

fails as the differend, and explains it as follows: "...the unstable

state and instant of language wherein something which must be able to

be put into phrases cannot yet be… the human beings who thought they

could use language as an instrument of communication, learn through the

feeling of pain which accompanies silence (and of pleasure which

accompanies the invention of a new idiom)".[1]

Lyotard undermines the common view that the meanings of phrases can be

determined by what they refer to (the referent). The meaning of a

phrase—an event (something happens)--cannot be fixed by appealing to

reality (what actually happened). Lyotard develops this view of

language by defining "reality" in an original way, as a complex of

possible senses attached to a referent through a name. The correct

sense of a phrase cannot be determined by a reference to reality, since

the referent itself does not fix sense, and reality itself is defined

as the complex of competing senses attached to a referent. Therefore,

the phrase event remains indeterminate. Lyotard uses the example of Auschwitz and the revisionist historian Robert Faurisson’s demands for proof of the Holocaust to show how the differend operates as a double bind. Faurisson argued that "the Nazi genocide of 6 million Jewish people was a hoax and a swindle, rather than a historical fact" and that "he was one of the courageous few willing to expose this wicked conspiracy".[2] Faurisson will only accept proof of the existence of gas chambers from eyewitnesses who were themselves victims of the gas chambers. However, any such eyewitnesses are dead and are not able to testify. Either there were no gas chambers, in which case there would be no eyewitnesses to produce evidence, or there were gas chambers, in which case there would still be no eyewitnesses to produce evidence, because they would be dead. Since Faurisson will accept no evidence for the existence of gas chambers, except the testimony of actual victims, he will conclude from both possibilities (gas chambers existed and gas chambers did not exist) that gas chambers did not exist. This presents a double bind. There are two alternatives, either there were gas chambers or there were not, which lead to the same conclusion: there were no gas chambers (and no final solution).[3] The case is a differend because the harm done to the victims cannot be presented in the standard of judgment upheld by Faurisson. The Differend is considered, including by Lyotard himself, to be Lyotard's most important work. It has been seen as providing the theoretical basis for much of his later work.[4][5] Lyotard, Jean-François (1988). The differend : phrases in dispute. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Differend |

リオタールは、『差異』(The differend : phrases in dispute)

において、カントの「理解」「判断」「理性」の分離に関する見解に基づき、言語が破

綻する瞬間を「差異」とし、次のように説明している。「言語をコミュニケーションの道具として使えると思っていた人間は、沈黙に伴う苦痛

(そして新しい慣用句の発明に伴う喜び)の感覚を通して学ぶ」[1]。リオタールは、フ

レーズの意味はそれが何を参照しているか(referent)によって決定されるという一般的な見解を覆している。イベント(何かが起こる

こと)であるフレーズの意味は、現実(実際に起こったこと)に訴えることによっては確定できないのである。リオタールはこの言語観を、「現実」を、名前を通して参照者に付けられる可能な感覚の複合体と

して、独自の方法で定義することによって発展させている。あるフレーズの正しい意味は、現実への言及によって決定されることはない。なぜな

ら、言及者自身が意味を固定するのではなく、現実自体が、言及者に付随する競合する

感覚の複合体として定義されるからである。したがって、eventという語句は不確定なままである。 リオタールは、アウシュビッツと修正主義的歴史家ロベール・フォーリソンのホロコーストの証明要求の例を用いて、ディファレントがいかにダブルバインドと して機能しているかを示している。フォーリソンは、「ナチスによる600万人のユダヤ人虐殺は歴史的事実というよりも、むしろデマであり詐欺である」と主 張し、「彼はこの邪悪な陰謀を暴露しようとする勇気ある少数の一人である」とした[2]。 フォーリソンは、ガス室の存在について、ガス室の犠牲者となった目撃者からしか証拠を認めないとしている。しかし、そのような目撃者はすべて死んでおり、 証言することができない。ガス室はなかった、その場合には、証拠を提出する目撃者はいない、あるいは、ガス室はあった、その場合には、死んでしまっている ので、やはり証拠を提出する目撃者はいない、ということである。フォーリソンは、実際の犠牲者の証言以外には、ガス室の存在についての証拠を認めないの で、両方の可能性(ガス室は存在した、ガス室は存在しなかった)から、ガス室は存在しなかったと結論することになる。これは、二重拘束をもたらす。ガス室 があったか、なかったかという二つの選択肢があり、それは、ガス室はなかった(最終解決もなかった)という同じ結論に至る[3]。 この事件は、犠牲者に加えられた被害が、フォーリソンが支持する判断基準では提示できないので、異同がある。 『ディファレンド』は、リオタール自身も含めて、リオタールの最も重要な著作であると考えられている。それは、彼の後の作品の多くに理論的な基礎を提供す るものと見なされている[4][5]。 https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Aesthetic

distance

refers to the gap between a viewer's conscious reality and the

fictional reality presented in a work of art. When a reader becomes

fully engrossed in the illusory narrative world of a book, the author

has achieved a close aesthetic distance. If the author then jars the

reader from the reality of the story, essentially reminding the reader

they are reading a book, the author is said to have "violated the aesthetic distance."[1][2] |

美的距離とは、鑑賞者の意識的な現実と、芸術作品の中で提示される虚構

の現実との間のギャップのことである。読者が本の中の幻想的な物語世界に没頭してい

るとき、作者は美的距離に達している。その後、作者が読者を物語の現

実から引き離し、本質的に読者に本を読んでいることを思い出させた場合、作者は「美的距離を侵犯」したと言われる[1][2]。 |

| The concept originates from

Immanuel Kant's Critique of Judgement, where he establishes the notion

of disinterested delight which does not depend on the subject's having

a desire for the object itself, he writes, "delight in beautiful art

does not, in the pure judgement of taste, involve an immediate

interest. [...] it is not the object that is of immediate interest, but

rather the inherent character of the beauty qualifying it for such a

partnership-a character, therefore, that belongs to the very essence of

beauty."[3] The term aesthetic distance itself derives from an article by Edward Bullough published in 1912. In that article, he begins with the image of a passenger on a ship observing fog at sea. If the passenger thinks of the fog in terms of danger to the ship, the experience is not aesthetic, but to regard the beautiful scene in detached wonder is to take legitimate aesthetic attitude. One must feel, but not too much. Bullough writes, "Distance … is obtained by separating the object and its appeal from one's own self, by putting it out of gear with practical needs and ends. Thereby the 'contemplation' of the object becomes alone possible."[4] Authors of film, fiction, drama, and poetry evoke different levels of aesthetic distance. For instance, William Faulkner tends to invoke a close aesthetic distance by using first-person narrative and stream of consciousness, while Ernest Hemingway tends to invoke a greater aesthetic distance from the reader through use of third person narrative. |

この概念はイマニュエル・カントの『判断力批判』に由来し、カントは対象そのものに対する欲求に依存しない無関心な喜びという概念を確立し、「美しい芸術

に対する喜びは、純粋なテイスト(趣味)の判断においては、直接的な関心を伴わない」と書いている[3]。[中略)直接的な関心を持つのは

対象ではなく、むしろ美の固有の性質が、そのようなパートナーシップのための資格を与えるのであり、したがって、その性質はまさに美の本質に属するもので

ある」[3]。 美的距離という言葉は、1912年に出版されたエドワード・ブロウの論文に由来している。この論文で彼は、船の乗客が海上で霧を観察するイメージから始め ている。もし乗客が霧を船への危険として考えるなら、その経験は美的なものではない。しかし、美しい光景を離れた驚きとして見ることは、正当な美的態度で ある。感じなくてはならないが、感じすぎてはいけない。ブローは、「距離とは......対象物とその魅力を自分自身から切り離し、現実的な必要や目的と の歯車を外すことによって得られるものである。それによって、対象物の『観照』が単独で可能になる」[4]。 映画、フィクション、ドラマ、詩の作家は美的距離の異なるレベルを喚起する。例えば、ウィ リアム・フォークナーは一人称の語りと意識の流れを使うことによって、近い美的距離を呼び起こす傾向があり、アーネスト・ヘミングウェイは三人称の語りを 使うことによって、読者からより大きな美的距離を呼び起こす傾向がある。 |

| Violating the aesthetic distance Anything that pulls a viewer out of the reality of a work of fiction is said to be a violation of aesthetic distance. An easy example in theater or film is "breaking the fourth wall," when characters suspend the progress of the story to speak directly to the audience. When the aesthetic distance is deliberately violated in theater, it is known as the distancing effect, or Verfremdungseffekt, a concept coined by playwright Bertolt Brecht. Many examples of violating the aesthetic distance may also be found in meta-fiction. William Goldman, in The Princess Bride, repeatedly interrupts his own fairy tale to speak directly to the reader. In the musical, Stop the World I Want to Get Off, the protagonist, Littlechap, periodically stops the progress of the play to address the audience directly. In film, the aesthetic distance is often violated unintentionally. Examples might include a director's cameo, poor special effects, or perhaps blatant product placement - any can be enough to pull a viewer out of the reality of the film. David Mamet in On Directing Film asserts that any direct depiction of graphic sex or violence in film is an inherent violation of aesthetic distance, as audience members will instinctively make judgments as to whether or not what they just saw was real, and thus be pulled out of the story-telling. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthetic_distance |

美的距離の侵害 フィクション作品の現実から観客を引き離すようなことは、美的距離の侵害と言われる。演劇や映画でわかりやすい例は、登場人物が物語の進行を中断して観客 に直接語りかける「第四の壁の破壊」である。演劇において美的距離が意図的に破られることを、劇作家ベルトルト・ブレヒトの造語である「距離効果」 (Verfremdungseffekt)と呼ぶ。 美的距離の侵害の例は、メタフィクションの中にもたくさん見つけることができる。ウィリアム・ゴールドマンは、『プリンセス・ブライド』の中で、自らのお とぎ話を何度も中断して読者に直接語りかける。ミュージカル『世界を止めてくれ、降りたいんだ』では、主人公のリトルチャップが定期的に劇の進行を止め、 観客に直接語りかける。 映画では、美的な距離はしばしば無意識のうちに侵害される。例えば、監督のカメオ出演、お粗末な特殊効果、あるいは露骨なプロダクト・プレイスメントな ど、どんなものでも、観客を映画の現実から引き離すのに十分である。デヴィッド・マメットは『On Directing Film』の中で、映画における生々しいセックスや暴力の直接的な描写は、美的距離の本質的な侵害であると主張している。 https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthetic_distance |

★

イマヌエル・カント『判 断力批判』は、バウムガルデンの美学概念 批判の書物である。カントはいう「美しいものの学問は存在しない、美しいものについ てはただ批判が存在するのみである」(§44, V.304)。

インターネットで簡単にカント『判断力批判』 (1790)が手に入らないので、原点読めというのも若者に対して無粋な要求である。そこで私は、大胆にもウィキペディアの「判断力批判」(Critique of Judgment)の記述を以下に引用して、その理解を試みる。IKant_Immanuel_Critique_of_Judgment.pdf with password

"If we wish to decide whether something is beautiful or not, we do not use understanding to refer the presentation to the object so as to give rise to cognition;5 rather, we use imagination (perhaps in connection with understanding) to refer the presentation to the subject and his feeling of pleasure or displeasure. Hence a judgment of taste is not a cognitive judgment and so is not a logical judgment but an aesthetic one, by which we mean a judgment whose determining basis cannot be other than subjective. But any reference of presentations, even of sensations, can be objective (in which case it signifies what is real [rather than formal] in an empirical presentation); excepted is a reference to the feeling of pleasure and displeasure ---- this reference designates nothing whatsoever in the object, but here the subject feels himself, [namely] how he is affected by the presentation."- Kant, A Judgment of Taste Is Aesthetic, 1790.

もし、あるものが美しいか否かを判断したいのであれ ば、我々は、理解を用いて、その提示を対象物に言及し、認知を生じさせるのではなく、むしろ、想像力を用いて(おそらく理解と関連して)その提示を対象者 とその喜びや不快の感覚に言及するのである。したがって、テイストの判断は認知的判断ではなく、論理的判断ではなく、美的判断であり、このことは、その判 断根拠が主観的であること以外にはありえないことを意味する。しかし、提示の参照は、感覚の参照であっても、客観的でありうる(その場合、経験的提示にお いて[形式的ではなく]実在するものを意味する)。ただし、快・不快の感情への参照は例外である ---- この参照は対象において何も指定せず、ここで主体が自分自身を感じ、[すなわち]提示によってどのように影響されるかを指定する。

"Interest is what we

call the Liking we connect with the presentation of

an object's existence. Hence such a liking always refers at once to our

power of desire, either as the basis that determines it, or at any rate

as

necessarily connected with that determining basis. But if the question

is whether something is beautiful, what we want to know is not

whether we or anyone cares, or so much as might care, in any way,

about the thing's existence, but rather how we judge it in our mere

contemplation of it (intuition or reflection). Suppose someone asks

me whether I consider the palace I see before me beautiful. I might

reply that I am not fond of things of that sort, made merely to be

gaped at. Or I might reply like that Iroquois Sachem who said that he

liked nothing better in Paris than the eating-houses. I might even

go on, as Rousseau would, to rebuke the vanity of the great who

spend the people's sweat on such superfluous things. I might, finally,

quite easily convince myself that, if I were on some uninhabited

island with no hope of ever again coming among people, and

could conjure up such a splendid edifice by a mere wish, I would not

even take that much trouble for it if I already had a sufficiently

comfortable hut. The questioner may grant all this and approve of it;

but it is not to the point. All he wants to know is whether my mere

presentation of the object is accompanied by a liking, no matter

how indifferent I may be about the existence of the object of this

presentation. We can easily see that, in order for me to say that an

object is beautiful, and to prove that I have taste, what matters is

what

I do with this presentation within myself, and not the [respect]

in which I depend on the object's existence. Everyone has to admit

that if a judgment about beauty is mingled with the least interest

then it is very partial and not a pure judgment of taste. In order to

play the judge in matters of taste, we must not be in the least biased

in favor of the thing's existence but must be wholly indifferent

about it." Kant, The Liking That Determines a Judgment of Taste Is

Devoid of All Interest

関心とは、我々が物体の存在の提示と結びつける好意

と呼ぶものである。したがって、このような好意は、それを決定する基礎として、あるいは、いずれにせよ、その決定基礎と必然的に結びついているものとし

て、常に我々の欲望の力を一度に参照する。しかし、何かが美しいかどうかという問題であれば、我々が知りたいのは、我々や誰かがその物の存在を気にかける

かどうか、あるいは気にかける可能性があるかどうかではなく、我々がその物を単に観照(直観や反射)する際に、それをどのように判断するかということであ

ろう。例えば、目の前にある宮殿を美しいと思うか、と誰かに聞かれたとしよう。私は、あのような、ただ眺めるために作られたようなものは好きではない、と

答えるかもしれない。あるいは、パリの食

堂より好きなものはないと言ったイロコイ族の首長のように答えるかもしれない。ルソーのように、民衆の汗をこんな余計なものに費やす偉い人の虚栄心を叱責

することもできるかもしれない。そして最後に、もし私が無人島にいて、二度と人の中に入る見込みがなく、単なる願望でこのような立派な建物を思いついたと

しても、すでに十分に快適な小屋があれば、そのためにそれほど苦労はしないだろうと、簡単に自分に言い聞かせるかもしれない。質問者はこのようなことをす

べて認め、承認するかもしれないが、それは重要ではない。質問者が知りたいのは、私が対象を提示しただけで好感を持つかどうかということであり、提示の対

象の存在にいかに無関心であったとしても、好感を持つということなのである。私がある対象を美しいと言い、私にテイスト(趣味感覚)があることを証明する

ために重要なの

は、この提示を私自身の中でどうするかであり、対象の存在に依存する[敬意]ではないことは容易に理解できるだろう。美についての判断が、わずかな興味と

混じり合っている場合、それは非常に部分的なものであり、純粋な趣味の判断ではないことを誰もが認めざるを得ないのです。テイスト(趣味感覚)の問題で審

判を下すには、そ

の物の存在に少しも有利な偏見を持たず、完全に無関心でなければならない。

PART I: CRITIQUE OF AESTHETIC JUDGMENT

Division I: Analytic of Aesthetic Judgment

Division II: Dialectic of Aesthetic Judgment

PART II: CRITIQUE OF TELEOLOGICAL JUDGMENT

Division I: Analytic of Teleological Judgment

Divison II: Dialectic of Teleological Judgment

Appendix: Methodology of Teleological Judgment

判断力批判、

第一部を政治的判断力として読むハンナ・アーレントについて

判断力批判、

第一部を政治的判断力として読むハンナ・アーレントについて

「まず反省的判断力の働きに基づく趣味判断は、「関心」ないし「利害関心」と結びついていてはな らないということが重要です。カントの言い方では、あらゆる関心は趣 味判断を損ない、趣味判断か らその不偏不党性、つまり判断の公平性を奪う、ということになります。この見解は、この判断が存 在の認識に関わる理論的関心も、実践的行為に関わる道徳的な関心ももってはならない、という帰結 をもたらします。つまり、趣味判断は、知的欲求、感覚的・感性的欲求や道徳的意志などと関わる実 践的判断でもないのてす。したがって、趣味判断があらゆる目的とは分離された観想的な性格をもち、 こうした意味で趣味は自由であることになります。ここから、美感的判断力が自由な判 断でなければならないことが明らかでありましょう」牧野英二『カントを読む』Pp.258-259、岩波書店、2003年、より詳しくは「『判断力批判』第一部を政治的判断力として読むハンナ・アーレント」「アーレント の『カントの政治哲学講義』

| ウィキペディアの記述:「判断力批判」は、美的判断力の批判(第一部)と目的論的判断力(第 二部)に分かれる。また第三批判といわれるが、それが契機になり、純粋理性批判の序文を書き直すなどの影響を与えた→「当初は「趣味判断の批判」として構 想されたが、のちにカントは、美的判断である趣味判断と目的論的判断が、根底において同一の原理を持ち、統制的判断力というひとつの能力の展開として説明 されうるという構想をうるに至った。これは第一批判『純粋理性批判』から『プロレゴーメナ』を経て第二批判『実践理性批判』へといたるカントの思索の展 開、とりわけ理性についての把握と構想力概念の展開を反映している。このため最初は構想になかった目的論的判断力の批判が書かれ、第1版は1790年、出 版者ド・ラ・ガルドによってベルリンで刊行された。のちにカントは、自らの批判哲学体系の解説でもある第1版の序論を全面的に書き直した。以後の版には第 2版以降の序論がつねにつけられ、第1版序文は特に『判断力批判第1序論』(たんに『第1序論』とも)と呼ぶ」 | 1. Aesthetic

Judgement 2. teleological judgement. |

It is then one

thing to say, “the production of certain things of nature or that of

collective nature is only possible through a cause which determines

itself to action according to design”; and quite another to say, “I can

according to the peculiar constitution of my cognitive faculties judge

concerning the possibility of these things and their production, in no

other fashion than by conceiving for this a cause working according to

design, i.e. a Being which is productive in a way analogous to the

causality of an intelligence.” In the former case I wish to establish

something concerning the Object, and am bound to establish the

objective reality of an assumed concept; in the latter, Reason only

determines the use of my cognitive faculties, conformably to their

peculiarities and to the essential conditions of their range and their

limits. Thus the former principle is an objective proposition for the

determinant Judgment, the latter merely a subjective proposition for

the reflective Judgment, i.e. a maxim which Reason prescribes to

it.[Kant, Critique of Judgment, section 75.] |

||

| 本書の主要概念である「趣味判断」

(または「美的判断」)とは、人間が物事の美醜を判断する際、その判断の基準は個人の趣味(ドイツ語: Geschmack ; 英語:

taste)であるということを意味する。例えば「このバラは美しい」と判断する場合には、個人の感性、表象から行われたと解釈される。ここで行われる判

断とは、対象の性質を認識する事によって行われる判断ではないという考え方である。そしてこの趣味判断で美醜を判断する際には、快苦を基準として判断され

るという事であり、ある物を美しいものと知覚したならばそれは自身にとって快楽をもたらす事となるものであり趣味であるという立場となる。逆に醜いと知覚

したものならば、それは自身に苦痛をもたらす事となるものになるというわけである。ここでの知覚は人間にとって最も単純な事柄でもあるというわけであり、

趣味判断というのはこのような単純な形で行われていると位置付けられる。 |

||||

| 純粋な趣味判断は、感覚様式における純粋

な形式を把握する。善とは異なり、美は概念および関心をもたない愉悦の対象である。美の判断においては想像力と悟性とは一致する。これに対し崇高において

は想像力と理性との間には矛盾がある。崇高美は、それとの比較において一切が小さいところのものであり、感性の一切の基準を超える純粋理性そのものにおけ

る愉悦である |

||||

| 天賦の才能である天才は、芸術に対して規

則を与える。天才の作品は範型的であり流派をもつ。美的芸術は、言語的・造形的・感覚遊戯的に区分される。最高のものは詩芸術であり、悟性を実現するもの

としての想像力の自由な遊戯である。 |

||||

| 美的技術である趣味判断は、芸術にとって

欠くことができない条件として最も重要であり、ゆえに、いかなる天才といえども趣味判断を服属させることはできない。もしも趣味判断と天才の2つの特性が

対立する場合に、どちらかが犠牲にならざるを得ないのならば、その犠牲はむしろ天才の側において生じざるを得ない。恣意的な概念作用よりも、芸術の内実的

な美的技術すなわち趣味が決定的に優先されるのである。 |

||||

| 自然目的の概念は、構成に適した物質を適

所に組み入れる。有機物においては何ものも無駄でない。また例えば一本の木は種族あるいは個体として自己を生産する。自然の所産においての目的の原理は、

自然の特殊な法則を探究するための発見的原理である。全自然の理念は、原因はつねに目的論的に判断されねばならないという課題を課すものである。 |

||||

| 美はいわば道徳的なるものの象徴である。

道徳的本質としての人間の現存は、みずからに最高の目的そのものをもつ。神の概念を見出したのは理性の道徳的原理であり、神の現存の内的な道徳的目的規定

は、最高原因性を思惟すべきことを指示して自然認識を補足するものである。 |

||||

|

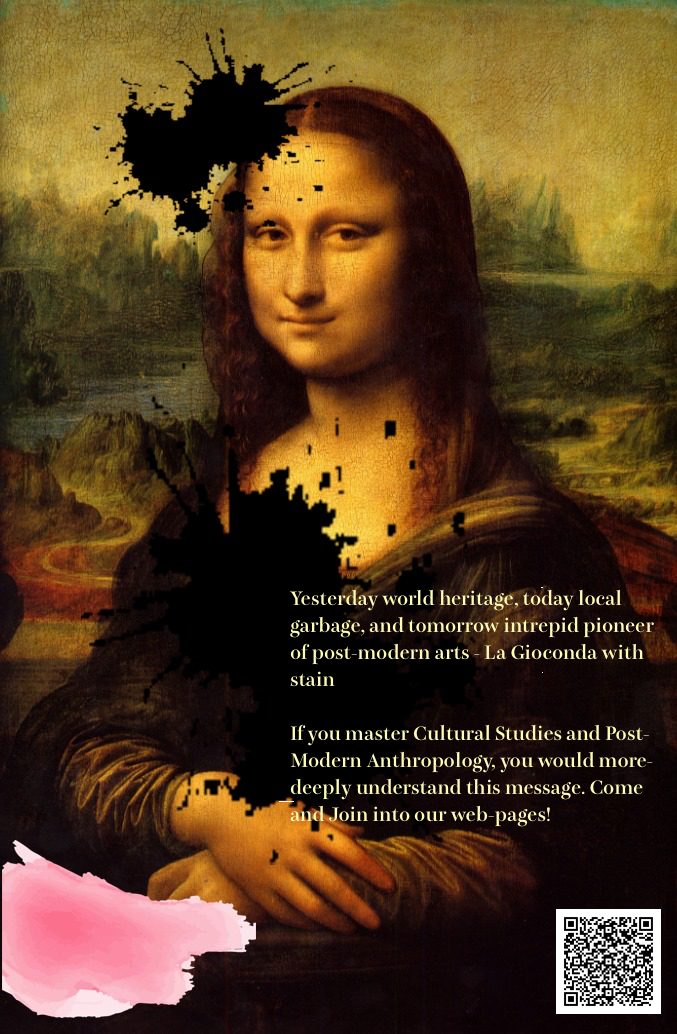

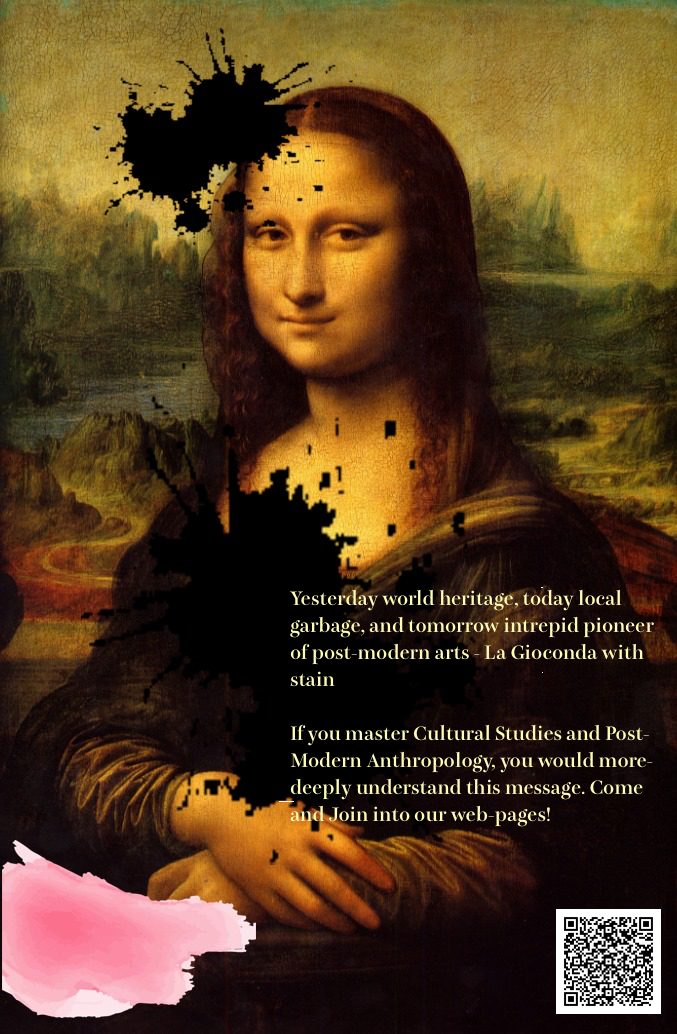

この写真の作品が「きもちわるい」とか「わかんない」というコメントを 寄せていた市井の人がいた。それでいいのです。その蓼食う虫も好き好きを「容認」す るポイントが、カント『判断力批判』第1部のテーマなんですね。「きもちわるい」人でも、そんな趣味の人がいることを、人は承認している。ここが美的判断 の多様性に道を開いているので、アーレントが、それこそが政治的判断だと喝破(ないしは異様解釈)するところなんです(→「ハンナ・アーレント の『カントの政治哲学講義』ノート」)。 |

小田部胤久(おたべ・たねひさ)巻末「用語解説」

『美学』2020年より

| 感官 |

Sinn |

sense |

感覚能力(→構想力) |

| 感性化 |

Darstellung |

presentation |

|

| 形式 |

|||

| 質量 | |||

| 構想力 |

imagination |

世界は、けっしてバラバラの感覚与件と

して与えられるのではなく、一定のゲシュタルトのもとに分節化して現れる。このような感覚ゲシュタルトを形成する能力のこと。 |

|

| 悟性 |

understanding |

||

| 理性 |

reason |

||

| 総括 |

comprehension |

||

| 内官 |

inner sense |

||

| 判断力 |

power of judgement |

特殊なものを普遍的なものに置き換える

能力。 |

|

| 美的 |

aesthetic |

||

| 美的判断 |

aesthetic judgenment |

「判断の規定根拠が概念ではなく、快不

快の感情であるとき、その判断は美的判断と呼ばれる」(解説27) |

|

| 表象 |

|||

| 遊動 |

free palay |

「趣味判断は認識判断ではない。それゆえに、論理的 ではなく美的(=感情的)である」——美的判断の一般的性質、第1節

「可知的なもの(νοητα、noēta)、すなわ ち上位能力によって認識されるものは論理学の対象であり、可感的なもの(αισθητα、aisthēta)は感性の学(aesthetica)としての 美学の対象である」——バウムガルデン「詩に関する若干の事柄についての哲学 的省察」

++

| 美学的判断力の批判 |

|

|||

| 美学的判断力の分析論 |

|

|||

| 美の分析論 |

・

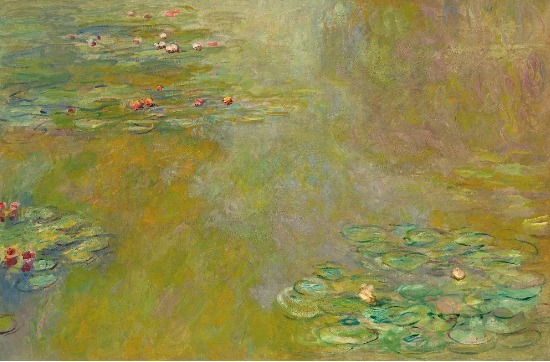

「印象主義は、再現前化的=模倣的合理性、芸術創作の個人性、模倣対象としてのパリのモデルニテの三層において、近代芸術、モダニズム芸術を完成させた。

完成はしかし崩壊の始まりである。 崩壊 は先ず何よりも印象主義

芸術、近代芸術の再現前化的=模倣的合理性から始まった。」落合仁司『美学の数理』第2章より。 ・「この映画を含む写真技術の発展が、芸術の定義からプラトン以来の模倣の概念を放逐したと考える」(ダントー説もそのとおりです)『美学の数理』第2章 より。 ・模倣の概念を凌駕、放逐というというほうがしっくりきます。現代写真の芸術としての評価は、模倣ではなく芸術創作の作家性と対象が放つオーラの技術によ る混成状況をつくりだしたからですね。複製芸術としてのアウラの喪失(ベンヤミン)は、写真作家という著者性の創造を通して、別のアウラをもつにいたると ソンタグ『写真論』で展開しています。 |

|||

| 趣味判断の第一様式 - 「性質」 |

||||

| 趣味判断の第二様式 - 「分量」 |

||||

| 趣味判断の第三様式 - 目的の「関係」 |

||||

| 趣味判断の第四様式 - 対象の「様態」 |

||||

| 崇高の分析論 |

||||

| 数学的崇高について |

||||

| 力学的崇高について |

||||

| 美的判断論の弁証論 |

||||

| 目的論的判断力の批判 |

||||

| 目的論的判断力の分析論 |

||||

| 目的論的判断力の弁証論 |

●熊野純彦先生に助けを求めて!!!

++

| まえがき | |

| 第1章 美とは目的なき合目的性である――自然は惜 しみなく美を与える | |

| 第2章 美しいものは倫理の象徴である――美への賛 嘆は宗教性をふくんでいる | |

| 第3章 哲学の領域とその区分について――自然と自 由あるいは道徳法則 | |

| 第4章 反省的判断力と第三批判の課題――美と自然 と目的とをつなぐもの | |

| 第5章 崇高とは無限のあらわれである――隠れた神 は自然のなかで顕現する | |

| 第6章 演繹の問題と経験を超えるもの――趣味判断 の演繹と趣味のアンチノミー | |

| 第7章 芸術とは「天才」の技術である――芸術と自 然をつなぐものはなにか | |

| 第8章 音楽とは一箇の「災厄」である――芸術の区 分と、第三批判の人間学的側面 | |

| 第9章 「自然の目的」と「自然目的」――自然の外 的合目的性と内的合目的性 | |

| 第10章 目的論的判断力のアンチノミー――反省的 判断力の機能と限界について | |

| 第11章 「究極的目的」と倫理的世界像――世界は なぜこのように存在するのか | |

| 第12章 美と目的と、倫理とのはざまで――自然神 学の断念と反復をめぐって | |

| あとがきにかえて――文献案内をかねつつ |

●付録:「純粋理性のアンチノミー

(antinomy of pure reason)」

人間の有限理性は、時空間のはじまりや限界があるの か、それとも無限なのかという、具体的な感性を越えようとすると、かならず自己矛盾に陥る。

「1 世界は有限(時間的、空間的に)である/世界は無限である。

2 世界におけるどんな実体も単純な部分(それ以上分割できないもの)から出来ている/世界に単純なものなど存在しない(物質は無限分割可能である)

3 世界には自由な原因が存在する/世界には自由は存在せず、世界における一切は自然法則に従って生起する。

4 世界の内か外に必然的な存在者(世界の起動者=神)がその原因として存在する/世界の内にも外にも必然的な存在者など存在しない」https://omg05.exblog.jp/17423213/

本文……

リンク

文献

その他の情報

閑話休題のジョーク ホワイトボード設置にゃう〜♪——俄相対論者の苦悩 (squareさが足りない僕)

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099