アーサー・ダントー

By David Diaz Martinez(?) from the FaceBook, "Banksy" fun site

池田光穂

アーサー・ダントー

By David Diaz Martinez(?) from the FaceBook, "Banksy" fun site

池田光穂

「あるものが美しいかそうでないかを区別

するために。われわれは認識をめざして表象を悟性によって客体へと関連づけるのではなく、(おそらくは

悟性と結びついた)構想力によって主体に、しかも、主体の快・不快の感情へと関連づける」——カント『判断力批判』

アート作品とは※受肉化された意味である [※具体化された]——アーサー・ダントー(2018: 48)

「私たちの物語では、最初はミメーシス (模 倣)だけが芸術で あり、次にいくつかのものが芸術であったが、それぞれが競争相手を消滅させようとし、そして最後に、様式や哲学的な制約がないことが明らかになったのであ る。芸術作品がそうでなければならない特別な方法はない。そして、それが現在であ り、マスターシナリオの最後の瞬間であると言うだろう。つまり(芸術 とい う)物語の終わりなのである」(→「芸術の終わり」)

旧クレジット:「アーサー・ダントーと芸術の終わり」

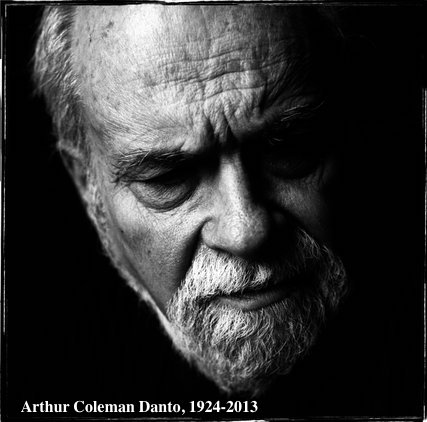

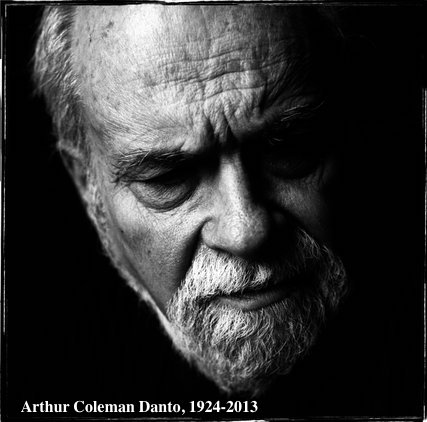

●Arthur Coleman Danto, 1924-2013

| Arthur Coleman Danto

(January 1, 1924 – October 25, 2013) was an American art critic,

philosopher, and professor at Columbia University. He was best known

for having been a long-time art critic for The Nation and for his work

in philosophical aesthetics and philosophy of history, though he

contributed significantly to a number of fields, including the

philosophy of action. His interests included thought, feeling,

philosophy of art, theories of representation, philosophical

psychology, Hegel's aesthetics, and the philosophers Friedrich

Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre. |

アーサー・コールマン・ダント(Arthur Coleman

Danto、1924年1月1日 -

2013年10月25日)は、アメリカの美術評論家、哲学者、コロンビア大学教授であった。『ネーション』誌の美術批評家として長く活躍し、哲学的美学や

歴史哲学の研究で最もよく知られているが、行為の哲学を含む多くの分野に多大な貢献をした。思想、感情、芸術哲学、表象理論、哲学的心理学、ヘーゲルの美

学、フリードリヒ・ニーチェやジャン=ポール・サルトルなどの哲学者にも関心を寄せていた。 |

| Life and career Danto was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan, January 1, 1924, and grew up in Detroit.[2] He was raised in a Reform Jewish home.[3] After spending two years in the Army, Danto studied art and history at Wayne University (now Wayne State University). While an undergraduate he intended to become an artist, and began making prints in the Expressionist style in 1947 (these are now great rarities). He then pursued graduate study in philosophy at Columbia University.[2] From 1949 to 1950, Danto studied in Paris on a Fulbright scholarship under Jean Wahl,[4] and in 1951 returned to teach at Columbia.[2] In 1992 he was named Johnsonian Professor Emeritus of Philosophy.[2] He was twice awarded fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Arthur Danto died on October 25, 2013, aged 89 in Manhattan, New York City.[2] |

生涯と経歴 1924年1月1日、ミシガン州アナーバーで生まれ、デトロイトで育った[2]。 改革派ユダヤ人の家庭に育った[3]。2年間の軍隊生活を経て、ウェイン大学(現ウェイン州立大学)で芸術と歴史を学んだ。在学中から芸術家を志し、 1947年から表現主義的な版画の制作を始める(現在では非常に稀少な作品となっている)。1949年から1950年にかけてフルブライト奨学生としてパ リでジャン・ウォールに師事し[4]、1951年にコロンビア大学に戻り教鞭をとった[2]。 1992年には哲学のジョンソン名誉教授となった[2]。 グッゲンハイム財団から2度のフェローシップを受け、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミー会員であった。 アーサー・ダントーは2013年10月25日、ニューヨークのマンハッタンで89歳で死去した[2]。 |

| Philosophical work Arthur Danto argued that "a problem is not a philosophical problem unless it is possible to imagine that its solution will consist in showing how appearance has been taken for reality."[5] While science deals with empirical problems, philosophy according to Danto examines indiscernible differences that lie outside of experience.[6] Danto "believe[d] that persons are essentially systems of representation."[7] |

哲学的な仕事 アーサー・ダントーは「問題は、その解決が外観がいかに現実として受け取られてきた かを示すことにあると想像できるのでなければ、哲学的問題ではない」[5]と主張していた。科学が経験的問題を扱う一方で、ダントによれば 哲学は経験の外にある無分別な差異を検証している[6]。 ダントーは「人とは本質的に表象のシステムであると信じている」[7]。 |

| "Artworld" and the definition of

art Danto laid the groundwork for an institutional definition of art[8] that sought to answer the questions raised by the emerging phenomenon of twentieth-century art. The definition of the term “art” is a subject of constant contention and many books and journal articles have been published arguing over the answer to the question "What is Art?" In terms of classificatory disputes about art, Danto takes a conventional approach. Non-conventional definitions take a concept like the aesthetic as an intrinsic characteristic in order to account for the phenomena of art. Conventional definitions reject this connection to aesthetic, formal, or expressive properties as essential to defining art but rather, in either an institutional or historical sense, say that “art” is basically a sociological category. Danto's "institutional definition of art" defines art as whatever art schools, museums, and artists consider art, regardless of further formal definition. Danto wrote on this subject in several of his works and a detailed treatment is to be found in Transfiguration of the Commonplace.[9][10] Danto stated, “A work of art is a meaning given embodiment.” Danto further stated, also in Veery journal, “Criticism, other than of content, is really of the mode of embodiment.” [11] The 1964 essay "The Artworld" in which Danto coined the term “artworld” (as opposed to the existing "art world", though they mean the same), by which he meant cultural context or “an atmosphere of art theory”,[12] first appeared in The Journal of Philosophy and has since been widely reprinted. It has had considerable influence on aesthetic philosophy and, according to professor of philosophy Stephen David Ross, "especially upon George Dickie's institutional theory of art. Dickie defined an art work as an artifact 'which has had conferred upon it the status of candidate for appreciation by some person or persons acting in behalf of a certain social institution (the artworld)' (p. 43.)"[13] According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "Danto's definition has been glossed as follows: something is a work of art if and only if (i) it has a subject (ii) about which it projects some attitude or point of view (has a style) (iii) by means of rhetorical ellipsis (usually metaphorical) which ellipsis engages audience participation in filling in what is missing, and (iv) where the work in question and the interpretations thereof require an art historical context. (Danto, Carroll) Clause (iv) is what makes the definition institutionalist. The view has been criticized for entailing that art criticism written in a highly rhetorical style is art, lacking but requiring an independent account of what makes a context art historical, and for not applying to music."[12] After about 2005, Danto attempted to streamline his definition of art down to two principles: (i) art must have content or meaning and (ii) the art must embody that meaning in some appropriate manner.[14] |

"アートワールド "と芸術の定義 ダントーは、20世紀美術という新たな現象が提起した問いに答えようと、制度的な芸術の定義[8]の基礎を築いた。アート」という言葉の定義は常に論争の 対象となり、"アートとは何か?"という問いに対する答えを巡って多くの書籍や雑誌記事が出版されてきた。アートに関する分類上の論争について、ダントー は従来型のアプローチをとっています。非従来型の定義では、芸術の現象を説明するために、美学のような概念を本質的な特性として取り上げる。従来型の定義 は、芸術の定義に不可欠な美的、形式的、表現的特性との結びつきを否定し、むしろ制度的あるいは歴史的な意味において、「芸術」は基本的に社会学的なカテ ゴリーであるとするものである。ダントーの「制度的な芸術の定義」では、芸術とは、美術学校、美術館、芸術家が芸術とみなすものであれば、それ以上の形式 的な定義に関係なく定義される。ダントーはいくつかの著作でこの主題について書いており、詳細な扱いは『ありふれたものの変容』に見つけることができる [9][10]。 ダントーは「芸術作品とは具現化された意味である」と述べている[9]。ダントーはさらに、同じく『Veery journal』において、「批評とは、内容以外の、実に体現の様式のものである」と述べている[11]。[11] 1964年にダントーが「アートワールド」(既存の「芸術界」に対して、同じ意味だが)という言葉を作り、文化的文脈や「芸術論の雰囲気」を意味するエッ セイ「アートワールド」を『哲学ジャーナル』に発表し[12]、以来広く再掲載されている。この論文は美学哲学に大きな影響を与え、哲学の教授であるス ティーブン・デイヴィッド・ロスによれば、「特にジョージ・ディッキーの芸術の制度論に影響を与えた」という。ディッキーは芸術作品を「ある社会的制度 (芸術界)を代表して行動するある人物または複数の人物によって鑑賞の候補という地位を与えられた」芸術作品と定義した(43頁)[13]。 スタンフォード哲学百科事典によれば、「ダントーの定義は次のように説明されている:何かが芸術作品であるのは、(i)それが主題を持ち(ii)それにつ いて何らかの態度や観点を投影する(スタイルを持つ)(iii)修辞的省略(通常は比喩)を用いて、省略が足りないものを埋めるために観客を参加させ、 (iv)問題の作品とその解釈には美術史的文脈が必要になる場合だけだ」(ダントー、キャロル)。(Danto, Carroll) (iv)の項が、この定義を制度主義的にしている。この見解は、非常に修辞的なスタイルで書かれた美術批評が芸術であり、何が芸術史的文脈を作るのかにつ いての独立した説明を欠いているが必要とし、また音楽には当ては まらないという批判を受けている」[12]。 2005年頃以降、ダントーは芸術の定義を2つの原則に合理化しようと 試みた。(i)芸術は内容や意味を持たなければならず、(ii)芸術はその意味を何らかの適切な方法で具現化しなければならない[14]。 14, Danto, Arthur (2014). Remarks on Art and Philosophy. New York: Acadia Summer Arts Program ASAP available through D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-0-9797642-6-4. |

| The end of art The basic meaning of the term "art" has changed several times over the centuries and continued to evolve during the 20th century as well. Danto describes the history of Art in his own contemporary version of Hegel's dialectical history of art. "Danto is not claiming that no-one is making art anymore; nor is he claiming that no good art is being made any more. But he thinks that a certain history of western art has come to an end, in about the way that Hegel suggested it would."[15] The "end of art" refers to the beginning of our modern era of art in which art no longer adheres to the constraints of imitation theory but serves a new purpose. Art began with an "era of imitation, followed by an era of ideology, followed by our post-historical era in which, with qualification, anything goes... In our narrative, at first only mimesis [imitation] was art, then several things were art but each tried to extinguish its competitors, and then, finally, it became apparent that there were no stylistic or philosophical constraints. There is no special way works of art have to be. And that is the present and, I should say, the final moment in the master narrative. It is the end of the story."[16] |

芸術の終焉 「芸術」という言葉の基本的な意味は、何世紀にもわたって何度も変化し、20世紀にも進化を続けてきた。ダントーは、ヘーゲルの弁証法的芸術史の現代版と して、芸術の歴史を描いている。「ダントーは、誰もアートを作らなくなったとか、良 いアートが作られなくなったとか言っているわけではない。しかし彼は、ヘーゲルが示唆したような方法で、西洋美術のある歴史が終焉を迎えたと考えている」[15] 「芸術の終焉」とは、芸術がもはや模倣理論の制約に従わず、新しい目的を果たす現代の芸術の時代の始まりを指している。芸術は「模倣の時代から始まり、イ デオロギーの時代、そして資格さえあれば何でもありの我々のポスト歴史的時代へと続く...」。私たちの物語では、最初はミメーシス(模倣)だけが芸術で あり、次にいくつかのものが芸術であったが、それぞれが競争相手を消滅させようとし、そ して最後に、様式や哲学的な制約がないことが明らかになったのである。芸術作品がそうでなければならない特別な方法はないのだ。そして、それが現在であ り、マスターシナリオの最後の瞬間であると言うべきだろう。(つまり)物語の終わりなのである」[16]。 |

| Art criticism Arthur Danto was an art critic for The Nation from 1984 to 2009, and also published numerous articles in other journals. In addition, he was an editor of The Journal of Philosophy and a contributing editor of the Naked Punch Review and Artforum. In art criticism, he published several collected essays, including Encounters and Reflections: Art in the Historical Present (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1990), which won the National Book Critics Circle Prize for Criticism in 1990; Beyond the Brillo Box: The Visual Arts in Post-Historical Perspective (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1992); Playing With the Edge: The Photographic Achievement of Robert Mapplethorpe (University of California, 1995); The Madonna of the Future: Essays in a Pluralistic Art World (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000); and Unnatural Wonders: Essays from the Gap Between Art and Life (Columbia University Press, 2007). In 1996, he received the Frank Jewett Mather Award for art criticism from the College Art Association.[17] He was one of the signers of the Humanist Manifesto.[18] |

美術評論家 アーサー・ダントーは1984年から2009年まで『ネイション』誌の美術評論家として活躍し、他の雑誌にも多数の記事を掲載した。また、「The Journal of Philosophy」の編集者、「Naked Punch Review」や「Artforum」の寄稿編集者も務めた。美術批評では、「Encounters and Reflections」を含むいくつかのエッセイ集を出版。1990年にNational Book Critics Circle Prize for Criticismを受賞した「Art in the Historical Present」(Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1990)、「Beyond the Brillo Box: The Visual Arts in Post-Historical Perspective (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1992); Playing With the Edge: The Photographic Achievement of Robert Mapplethorpe (University of California, 1995); The Madonna of the Future.Odyssey (邦題:未来のマドンナ): エッセイ:多元的な芸術世界』(ファーラー、ストラウス&ジルー、2000年)、『アンナチュラル・ワンダーズ』(同)。Essays from the Gap Between Art and Life (Columbia University Press, 2007)がある。 1996年、大学美術協会から美術批評のためのフランク・ジュエット・メイザー賞を受賞した[17]。 ヒューマニスト宣言の署名者の一人である[18]。 |

| Books Nietzsche as Philosopher (1965) Analytical Philosophy of History (1965) What Philosophy Is (1968) Analytical Philosophy of Knowledge (1968), republished, within additional material, as Narration and Knowledge (1985) Mysticism and Morality: Oriental Thought and Moral Philosophy (1969) Analytical Philosophy of Action (1973) Jean-Paul Sartre (1975), second edition Sartre (1991) The Transfiguration of the Commonplace (1981) The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art (1986) Connections to the World: The Basic Concepts of Philosophy (1989; with new preface, 1997) Encounters and Reflections: Art in the Historical Present (1990) Beyond the Brillo Box: The Visual Arts in Post-Historical Perspective (1992) After the End of Art (1997) The Abuse of Beauty (2003) Andy Warhol (2009) What Art Is (2013) Remarks on Art and Philosophy (2014) Art and Posthistory, Conversations on the End of Aesthetics written with Demetrio Paparoni (2022) |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Danto |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| In an obituary for the New York

Times, Ken Johnson described Arthur Danto (1924–2013) as “one of the

most widely read art critics of the Postmodern era.” Danto, who was

both a critic and a professor of philosophy, is celebrated for his

accessible and affable prose. Despite this, Danto’s best-known essay,

“The End of Art,” continues to be cited more than it is understood.

What was Danto’s argument? Is art really over? And if so, what are the

implications for art history and art-making? Danto’s twin passions were art and philosophy. He initially embarked on a career as an artist (much of his work is now part of the Wayne State University art collection) before pursuing an academic career in philosophy. In 1951, Danto began teaching at Columbia University, earning his doctorate the next year. He was an art critic for The Nation between 1984–2009 and was a regular contributor to publications such as Artforum. https://hyperallergic.com/191329/an-illustrated-guide-to-arthur-dantos-the-end-of-art/ |

ケン・ジョンソンはニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の追悼記事で、アーサー・

ダントー(1924-2013)を「ポストモダン時代に最も広く読まれた美術批評家の一人」と評した。批評家であると同時に哲学の教授でもあったダント

は、その親しみやすく親しみやすい文章で名高い。にもかかわらず、ダントの最も有名なエッセイ「芸術の終焉」は、理解されるよりも引用され続けている。ダ

ントの主張は何だったのか?芸術は本当に終わったのか?もしそうだとしたら、美術史や芸術制作にはどのような意味があるのだろうか? ダントーの双子の情熱は、芸術と哲学であった。彼は当初、芸術家としてのキャリアをスタートさせ(彼の作品の多くは現在、ウェイン州立大学のアートコレク ションに収蔵されている)、その後、哲学の学問的キャリアを追求した。1951年、コロンビア大学で教鞭をとり、翌年博士号を取得。1984年から 2009年まで『The Nation』の美術評論家として活躍し、『Artforum』などの出版物にも定期的に寄稿している。 |

| In 1964, Danto visited an

exhibition of Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes at the Stable Gallery, New

York. The show changed his life. It wasn’t Warhol’s subject matter that shocked the philosopher, but its form. Whereas Warhol’s paintings of coke bottles and soup cans were visual representations, the artist’s Brillo box sculptures — silkscreened plywood facsimiles of actual Brillo boxes — were virtually indistinguishable from the real thing. If one placed one of Warhol’s sculptures beside a real Brillo box, who could tell the difference? What made one of the boxes an artwork and the other an ordinary object? Danto outlined his conclusions in an essay entitled “The Artworld” (1964): What in the end makes the difference between a Brillo box and a work of art consisting of a Brillo box is a certain theory of art. It is theory that takes it up into the world of art, and keeps it from collapsing into the real object which it is. [Warhol’s Brillo boxes] could not have been art fifty years ago. The world has to be ready for certain things, the artworld no less than the real one. It is the role of artistic theories, these days as always, to make the artworld, and art, possible. |

1964年、ダントはニューヨークのステーブル・ギャラリーで開催され

たアンディ・ウォーホルのブリロ・ボックス展を訪れた。哲学者に衝撃を与えたのはウォーホルの主題ではなく、その形式だった。ウォーホルがコーラの瓶や

スープ缶を描いた絵画が視覚的な表現であったのに対し、このアーティストのブリロ・ボックスの彫刻は、実際のブリロ・ボックスをシルクスクリーンでベニヤ

板に複製したもので、本物とほとんど見分けがつかなかった。ウォーホルの彫刻を本物のブリロ・ボックスの横に置いたとして、誰がその違いを見分けられるだ

ろうか。何が片方をアート作品にし、もう片方を普通のオブジェにしたのだろうか?ダントーは『アートワールド』(1964年)というエッセイの中で、次の

ように結論を述べている。「ブリロの箱と、ブリロの箱からなる芸術作品との違いを生み出すのは、結局のところ、ある種の芸術理論である。理論こそが、ブリ

ロ・ボックスを芸術の世界に引き上げ、ブリロ・ボックスが現実のオブジェとして崩壊しないようにしているのだ。[ウォーホルのブリーロ・ボックスは)50

年前にはアートではありえなかった。芸術の世界も現実の世界と同じように、世界はある種のものに対して準備が整っていなければならない。芸術の世界、そし

て芸術を可能にするのが、最近も昔も芸術理論の役割である。 |

| Essentially, Warhol’s Brillo

boxes are art because the work has an audience which understands it via

a certain theory (to use Danto’s term) of what art can be. The artworld

(comprised of critics, curators, collectors, dealers, etc.) plays a

part in which theories are embraced or snubbed. As Danto surmises, “To

see something as art requires something the eye cannot descry — an

atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an

artworld.” This idea, later expanded upon by the philosopher George

Dickie, is also popularly known as the institutional theory of art. The

question lingering in the background is how and why these so-called

theories change and develop over time. Danto was fascinated by historical change. What made Warhol’s Brillo boxes acceptable as art in 1964? What would Neo-classical painter Jacques-Louis David have thought of Warhol’s work? How would Leonardo da Vinci, Phidias, or a caveman react? Do the Brillo boxes represent some sort of art historical progress? Was art history heading in a discernible direction? Danto’s investigations into history, progress, and art theory, coalesced into his best-known essay, “The End of Art.” Before tackling “The End of Art,” we need to briefly consider how the history of art is traditionally understood. Art history is generally thought of as a linear progression of one movement or style after another (Romanticism, Realism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, etc.), punctuated by the influence of individual geniuses (Delacroix, Courbet, Monet, Cézanne … ). This fundamental approach is the visual basis of Sara Fanelli’s 40-meter-long timeline of 20th-century art (which was formerly displayed on the Tate Modern’s second floor). The timeline pinpoints the historical inception of particular movements, while also naming key historic artists (note how Fanelli’s timeline trails off after the year 2000. We’ll come back to this later). |

本質的に、ウォーホルのブリロ・ボックスがアートであるのは、その作品

が、アートとは何かについてのある理論(ダントの言葉を借りれば)を通じてそれを理解する観客を持っているからである。アートワールド(批評家、キュレー

ター、コレクター、ディーラーなどで構成)は、どの理論が受け入れられ、あるいは否定されるかに一役買っている。ダントが推測するように、「何かを芸術と

見なすには、目には見えない何かが必要である-芸術理論の雰囲気、芸術史の知識、つまりアートワールドである」。この考え方は、後に哲学者のジョージ・

ディッキーによって拡張され、芸術の制度論としてもよく知られている。背景には、こうしたいわゆる理論が時代とともにどのように変化し、発展していくのか

という疑問が残る。 ダントは歴史的変化に魅了された。1964年、ウォーホルのブリロ・ボックスがアートとして受け入れられたのはなぜか。新古典主義の画家ジャック=ルイ・ ダヴィッドはウォーホルの作品をどう思っただろうか?レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチやフィディアス、原始人ならどう反応するだろうか?ブリロの箱は、ある種の 美術史的進歩を象徴しているのだろうか?美術史は明確な方向に向かっていたのだろうか?歴史、進歩、芸術理論に対するダントの探求は、彼の最もよく知られ たエッセイ "芸術の終わり "に集約された。 「芸術の終わり」に取り組む前に、美術史が伝統的にどのように理解されてきたかを簡単に考えておく必要がある。 美術史は一般に、ある運動や様式(ロマン主義、写実主義、印象主義、ポスト印象主義など)が、個々の天才たち(ドラクロワ、クールベ、モネ、セザン ヌ......)の影響によって区切られながら、次から次へと直線的に進行していくものと考えられている。 この基本的なアプローチが、サラ・ファネリの40メートルにも及ぶ20世紀美術年表(以前はテート・モダンの2階に展示されていた)の視覚的基礎となって いる。この年表は、特定のムーブメントの歴史的な始まりをピンポイントで示すと同時に、歴史的な主要アーティストの名前を挙げている(ファネッリの年表が 2000年以降、どのようにずれていくかに注目してほしい。これについては、また後で触れることにしよう)。 |

| Fanelli’s timeline is part of a

long tradition of attempting to visually map historic progression, a

nebulous and tricky concept. The first director of the Museum of Modern

Art, Alfred Barr, famously designed his own timeline of 20th-century

art, as did George Maciunas, the founder of Fluxus (Maciunas was really

into diagrams; he reportedly spent five years on his incomplete 6 x

12–foot art historical timeline). These timelines often implicitly

support certain ideas about what art is, what it was, and where it’s

headed. One such concept that appears regularly throughout the history

of art (albeit, in varying forms), is mimesis: the imitation and

representation of reality. Art historians have long argued that the ancient Greeks sought to imitate the human body with ever greater degrees of verisimilitude, a model that was resurrected during the Renaissance. This concept holds that artists should seek to master the imitation of reality (the story of the painting contest between Zeuxis and Parrhasius typifies this ideal). A number of early art historians sought to demonstrate how various artists had progressed (and in some cases, stunted) this ultimate goal, and in doing so, engineered one of the dominant narratives of art history. The result is a basic (and very reductive) interpretation of art history. Summed up crudely, it resembles something like this: The craftsman of the so-called Dark Ages ‘forgot’ the mimetic skills and values of the ancients. Classical ideals were then resurrected during the Renaissance and were constantly reevaluated up to the late nineteenth century. By the early 20th century, art had fractured into a multitude of concurrent movements. The story Danto tells in “The End of Art” follows on from this model. According to Danto, the commitment to mimesis began to falter during the nineteenth century due to the rise of photography and film. These new perceptual technologies led artists to abandon the imitation of nature, and as a result, 20th-century artists began to explore the question of art’s own identity. What was art? What should it do? How should art be defined? In asking such questions, art had become self-conscious. Movements such as Cubism questioned the process of visual representation, and Marcel Duchamp exhibited a urinal as an artwork. The twentieth century oversaw a rapid succession of different movements and ‘isms,’ all with their own notions of what art could be. “All there is at the end,” Danto wrote, “is theory, art having finally become vaporized in a dazzle of pure thought about itself, and remaining, as it were, solely as the object of its own theoretical consciousness.” |

ファネリの年表は、歴史的な進歩を視覚的にマッピングしようとする長い

伝統の一部である。近代美術館の初代館長であるアルフレッド・バーが20世紀美術の年表をデザインしたのは有名な話だし、フルクサスの創始者であるジョー

ジ・マチューナスもそうだった(マチューナスは図に凝っていて、6×12フィートの未完成の美術史年表に5年を費やしたと言われている)。これらの年表

は、アートとは何か、アートとは何であったか、そしてアートはどこへ向かうのか、というある種の考えを暗黙のうちに支持していることが多い。そのようなコ

ンセプトのひとつは、芸術の歴史を通じて(形はさまざまだが)定期的に登場する「ミメーシス」、つまり現実の模倣と表現である。 美術史家たちは長い間、古代ギリシア人が人体をより忠実に模倣しようと し、ルネサンス期にその模倣が復活したと主張してきた。この概念は、芸術家は現実の 模倣を極めるべきであるとするものである(ゼウキスとパルハシウスの絵画コンテストの話は、この理想を代表するものである)。初期の美術史家たちは、さま ざまな芸術家たちがこの究極の目標をどのように達成したのか(場合によっては達成を妨げたのか)を示そうとし、そうすることで美術史の支配的な物語のひと つを作り上げた。その結果が、美術史の基本的な(そして非常に還元的な)解釈である。ざっくりまとめると、次のようなものだ: いわゆる暗黒時代の職人たちは、古代人の模倣技術や価値観を「忘れてしまった」。古典の理想はルネサンス期に復活し、19世紀後半まで絶えず再評価され た。20世紀初頭には、芸術は同時多発的な運動へと分裂した。 ダントーが『芸術の終焉』で語る物語は、このモデルを踏襲している。ダ ントーによれば、19世紀には写真と映画の台頭により、ミメーシスへのコミットメン トが揺らぎ始めた。これらの新しい知覚技術によって、芸術家たちは自然の模倣を放棄するようになり、その結果、20世紀の芸術家たちは芸術自身のアイデン ティティーの問題を探求し始めた。芸術とは何か?芸術は何をなすべきか?芸術はどのように定義されるべきなのか?そのような問いかけをすることで、芸術は 自意識を持つようになった。キュビスムのような運動は、視覚的表現のプロセスに疑問を投げかけ、マルセル・デュシャンは小便器を作品として展示した。20 世紀には、さまざまな運動や「イズム」が次々と起こり、芸術のあり方について独自の概念を持つようになった。「最後にあるのは理論だけであり、芸術は最終 的にそれ自身についての純粋な思考の眩惑の中で蒸発し、いわば、それ自身の理論的意識の対象としてのみ残ったのである」とダントーは書いている。 |

| Warhol’s Brillo boxes and

Duchamp’s readymades demonstrated to Danto that art had no discernible

direction in which to progress. The grand narrative of progression — of

one movement reacting to another — had ended. Art had reached a

post-historical state. All that remains is pure theory: Of course, there will go on being art-making. But art-makers, living in what I like to call the post-historical period of art, will bring into existence works which lack the historical importance or meaning we have for a long time come to expect […] The story comes to an end, but not the characters, who live on, happily ever after doing whatever they do in their post-narrational insignificance […] The age of pluralism is upon us…when one direction is as good as another. In hindsight, it’s easy to see how Danto began to approach this conclusion during the 1960s. Movements such as Pop art and Fluxus were actively breaking down the barriers between art and the everyday. Relativist philosophies such as poststructuralism and existentialism were in full swing, critiquing the narratives and certainties which Western academia had previously held dear. Having blown open the definition of what it could be, art had undermined its own belief in linear progression. After all, what movement or ‘ism’ could logically follow the dematerialization of the art object (conceptualism) or the pervasive skepticism of grand theories and ideologies (postmodernism)? Danto believed that any subsequent movements were nonessential in that they would no longer contribute to the pursuit of art’s self-definition. “We are entering a more stable, more happy period of artistic endeavor where the basic needs to which art has always been responsive may again be met,” he wrote. Although Danto claimed the end of art wasn’t in itself a bad thing, he nonetheless appeared to later lament its demise. In his review of the 2008 Whitney Biennial, Danto lambasted the themeless state of the artworld. “It is heading in no direction to speak of,” the philosopher wrote. Whilst devising “The End of Art,” Danto was “astonished” to turn to one of the unlikeliest of sources, the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831). |

ウォーホルのブリロ・ボックスやデュシャンのレディ・メイドは、ダン

トーに芸術が進歩する明確な方向性を持たないことを示した。ある運動が別の運動に反応するという、進歩の壮大な物語は終わったのだ。芸術は歴史後の状態に

到達したのだ。残るのは純粋な理論だけである:もちろん、アートはこれからも作り続けられる。しかし、私が芸術のポスト歴史時代と呼びたい時代に生きてい

る芸術家たちは、私たちが長い間期待してきたような歴史的重要性や意味を欠いた作品を世に送り出すだろう[......]。物語は終わりを迎えるが、登場

人物たちは終わりを迎えず、物語の後の取るに足らないことの中で、何をするにも幸せそうに生き続ける[......]。 今にして思えば、1960年代にダントがどのようにこの結論に近づき始めたかを知るのは簡単だ。ポップ・アートやフルクサスといったムーブメントが、アー トと日常の垣根を積極的に取り払おうとしていた。ポスト構造主義や実存主義といった相対主義的な哲学が本格化し、西洋のアカデミズムがそれまで大切にして きた物語や確信を批判していた。芸術とは何かという定義を吹き飛ばしたことで、芸術は直線的な進行という自らの信念を根底から覆した。オブジェの非物質化 (コンセプチュアリズム)や、壮大な理論やイデオロギーへの懐疑(ポストモダニズム)に続く、論理的なムーブメントや「イズム」があるだろうか。 ダントーは、その後のいかなる動きも、もはや芸術の自己定義の追求に寄与しないという点で、本質的なものではないと考えた。「芸術が常に応えてきた基本的 なニーズが再び満たされるような、より安定した、より幸福な芸術活動の時代に入っている」と彼は書いている。ダントは芸術の終焉はそれ自体悪いことではな いと主張したが、それにもかかわらず、彼は後に芸術の終焉を嘆くようになった。2008年のホイットニー・ビエンナーレの批評で、ダントはアート界のテー マなき状態を非難した。この哲学者は、「芸術は語るべき方向へ向かっていない」と書いている。 アートの終焉」を構想していたダントーは、最も意外な情報源のひとつであるゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル(1770-1831)の哲学 に目を向け、「驚愕」した。 |

| Hegel’s philosophy was not in

vogue during the ’60s, but his teleological understanding of history

served as a useful template for Danto’s conclusions. Hegel understood progress as an overarching

dialectic — a process of self-realization and understanding that

culminates in pure knowledge. This state is ultimately achieved through

philosophy, though it is initially preceded by an interrogation into

the qualities of religion and art. As Danto summarized in a

later essay entitled “The Disenfranchisement of Art” (1984): When art internalizes its own history, when it becomes self-conscious of its history as it has come to be in our time, so that its consciousness of its history forms part of its nature, it is perhaps unavoidable that it should turn into philosophy at last. And when it does so, well, in an important sense, art comes to an end. Danto is not the only philosopher to have adopted an Hegelian dialectic. Both Francis Fukuyama and Karl Marx utilized Hegelianism to reach their own historical conclusions. Fukuyama argued that liberal democracy and free market capitalism represented the zenith of Western civilization, whilst Marx argued that communism would replace capitalism (neither of these developments have quite panned out). Sara Fanelli’s timeline appears to validate Danto’s conclusions. After the year 2000, there are no movements or -isms, only individual artists. The movements that are listed towards the end of the century aren’t really movements at all. The term “YBA” (Young British Artists) is a useful catch-all for a diverse group of artists, some of whom happened to go to the same school (Goldsmiths). Likewise, “installation” is not a movement but a means of presenting art. Recent terms such as “zombie formalism” (aka zombie abstraction) appear to confirm that we are living in an age of post-historical malaise. https://hyperallergic.com/191329/an-illustrated-guide-to-arthur-dantos-the-end-of-art/ |

ヘーゲルの哲学は60年代には流行していなかったが、彼の歴史に対する

目的論的理解は、ダントの結論にとって有益なテンプレートとなった。ヘーゲルは、進

歩とは包括的な弁証法であり、自己実現と理解の過程であり、純粋知識において頂点に達するものだと理解していた。この状態は最終的に哲学によって達成され

るが、その前に宗教と芸術の特質が問われる。ダントーは後に「芸術の権利剥奪」(1984年)と題するエッセイで次のようにまとめている:

芸術が自らの歴史を内面化し、現代に至ってその歴史を自己意識するようになり、その

歴史に対する意識が芸術の本質の一部をなすようになったとき、芸術がついに哲学に転化するのは、おそらく避けられないことであろう。そして、そうなったと

き、重要な意味で、芸術は終わりを迎える。 ヘーゲル弁証法を採用した哲学者はダントーだけではない。フランシス・フクヤマもカール・マルクスも、自らの歴史的結論に到達するためにヘーゲル主義を利 用した。フクヤマは、自由民主主義と自由市場資本主義が西洋文明の頂点に立つと主張し、マルクスは、共産主義が資本主義に取って代わると主張した(どちら も実現には至っていない)。 サラ・ファネリの年表は、ダントの結論を正当化しているように見える。2000年以降は、ムーブメントもイズムも存在せず、個々のアーティストだけが存在 する。世紀末に挙げられているムーブメントは、実際にはまったくムーブメントではない。YBA」(ヤング・ブリティッシュ・アーティスツ)という言葉は、 多様なアーティストのグループに対する便利なキャッチオールであり、そのうちの何人かは、たまたま同じ学校(ゴールドスミス)に通っていた。同様に、「イ ンスタレーション」はムーブメントではなく、アートを提示する手段のひとつだ。ゾンビフォーマリズム」(別名ゾンビ抽象主義)といった最近の用語は、私た ちがポスト歴史的な倦怠の時代に生きていることを裏付けているように見える。 |

| Though widely read, Danto’s

theories are not wholly beloved by the art industry. Artists don’t

necessarily want to hear that their work has no developmental

potential. Danto’s work also presents a challenge for the art market

which relies on perceived historic importance as a unique selling

point. He predicted that the demand on the market would require the

“illusion of unending novelty,” later citing 1980s Neo-Expressionism as

an example of the industry’s need to continually recycle and repackage

prior aesthetic forms and ideas, a charge that parallels the

contemporary debate regarding zombie formalism. Danto’s critics typically challenge the philosopher’s reliance on traditional art historical models. In Danto and His Critics (first published in 1993) Robert C. Solomon and Kathleen M. Higgins discuss the “fallacy of linear history,” namely that our pre-dominant art historical narratives are largely a product of their retelling: As a person (or a culture) gets older, the story gets solidified and embellished in the retelling; and of course, it gets longer. Early incidents and events are recast with forward-looking meaning they could not have possibly have had at the time. If one rejects the developmental, Western art narrative that Danto describes in “The End of Art,” then the structure required for Danto’s Hegelian understanding of art collapses. It’s important to recognize that art history is largely built upon the biases and subjective opinions of others. Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), the so-called father of art history and author of The Lives of the Most Excellent painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), famously favored Florentine artists over those working in Northern Europe. Over the course of the twentieth-century, the art historical perspectives of academics such as Ernst Gombrich, Heinrich Wölfflin, and Erwin Panofsky were rigorously reassessed. Classical scholars have since problematized the mimetic interpretation of ancient Greek art. Most contemporary medieval scholars reject the term “Dark Ages” for example, since it is implicitly judgmental and ignores the fact that early Christian art had a completely different set of aesthetic priorities. The history of art becomes far more nuanced and complex when studied in microcosm. When one considers the wealth of methodologies available to art historians (iconography, semiotics, psychoanalysis, and so forth), Danto’s conclusions look all the more narrow and reductive. https://hyperallergic.com/191329/an-illustrated-guide-to-arthur-dantos-the-end-of-art/ |

広く読まれているとはいえ、ダントの理論がアート業界に全面的に支持さ

れているわけではない。アーティストたちは、自分たちの作品に発展性がないとは必ずしも言いたがらない。ダントの研究はまた、歴史的重要性を独自のセール

スポイントとするアート市場にも難題を突きつけている。彼は後に、1980年代の新表現主義を引き合いに出し、市場の需要は「終わりのない目新しさの錯

覚」を要求するようになると予測したが、これは1980年代の新表現主義が、以前の美的形式やアイデアを継続的に再利用し、再包装する必要があることを示

す例であり、ゾンビ形式主義に関する現代の議論と類似している。ダントの批評家たちは通常、哲学者が伝統的な美術史モデルに依存していることに異議を唱え

ている。ロバート・C・ソロモンとキャスリーン・M・ヒギンズは、『Danto and His

Critics』(1993年初版)の中で、「直線的な歴史の誤り」、すなわち、私たちが先行している美術史的な物語は、その大部分が語り継がれてきた産

物であるということについて論じている: ある人物(あるいはある文化)が年を取るにつれて、その物語は再話の中でより強固になり、装飾される。初期の事件や出来事は、当時はあり得なかったような 未来志向の意味を持つように再構成される。 もしダントーが「芸術の終わり」で述べているような西洋芸術の発展的な 物語を否定するなら、ダントーのヘーゲル的な芸術理解に必要な構造は崩壊する。 美術史は、その大部分が他者の偏見と主観的な意見の上に成り立っていることを認識することが重要だ。美術史の父と呼ばれ、『最も優れた画家、彫刻家、建築 家の生涯』(1550年)の著者であるジョルジョ・ヴァザーリ(1511-1574年)は、北欧の芸術家よりもフィレンツェの芸術家を好んだことで有名で ある。20世紀に入ると、エルンスト・ゴンブリッヒ、ハインリヒ・ヴェルフリン、エルヴィン・パノフスキーといった学者たちの美術史的視点が厳しく見直さ れた。古典学者たちはそれ以来、古代ギリシア美術の模倣的解釈を問題視してきた。例えば、現代の中世研究者のほとんどは、「暗黒時代」という言葉を否定し ている。なぜなら、暗黙のうちに決めつけ、初期キリスト教美術がまったく異なる美的優先順位を持っていたという事実を無視しているからである。美術史は、 ミクロコスモスで研究すると、はるかにニュアンスが複雑になる。美術史家が利用できる豊富な方法論(図像学、記号論、精神分析など)を考慮すると、ダント の結論はより狭く還元的に見える。 |

佐藤一進(たかみち)訳『アートとは何か : 芸術の存在論と目的論』人文書院, 2018年/眞田収一郎訳『哲学者としてのニーチェ』風濤社, 2014年

What art is, Yale

University Press, 2013. の全訳に、同著者による論文 'The end

of art', in Berel Lang ed., The death of art, Haven Publications, 1984.

の翻訳を併録したもの

文献一覧: p234-236

人名索引:

p237-241「何が作品をアートにするのか?ミケランジェロ、フランチェスカ、ダヴィッド、ピカソ、マティス、マネ、デュシャン、ケージ、ウォーホル

など多くの古今の傑作を取り上げ、プラトンからデカルト、カント、パースにいたる美学と哲学を検証しながら、時空を超えて通用する「アート」の定義を提示

する。ポップアート以降の芸術論を牽引し、現代美学に多大な影響を与えた著者の遺作。1984年の重要論文「アートの終焉」を特別収録。」

| 第1章 うつつの夢 |

第1章 哲学的ニヒリズム |

| 第2章 修復と意味 |

第2章 芸術と不合理 |

| 第3章 哲学とアートにおける身体 |

第3章 遠近法 |

| 第4章 抗争の終焉—絵画と写真の間のパ

ラゴーネ |

第4章 哲学的心理学 |

| 第5章 カントとアート作品 |

第5章 道徳 |

| 第6章 美学の未来 |

第6章 宗教的心理学 |

| 附論 アートの終焉(1984年) |

第7章 超人と永劫回帰 |

| 第8章 力への意志 |

|

|

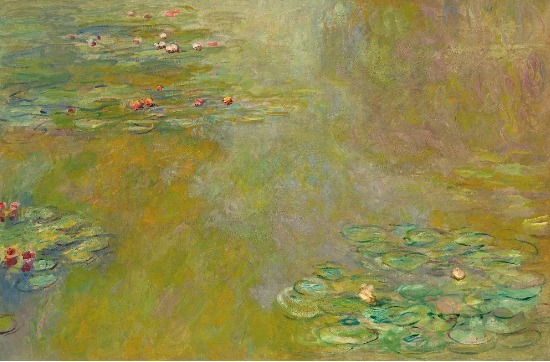

晩年目がみえにくくなったモネ(Claude Monet,

1840-1926)からみえた睡蓮を描いたキャンバスをモネがどうみえたか、そして、俺たちがどのようにモネの視覚経験をみようとしているのか、いろい

ろ考えると、なかなか、経験の絵画表象とその解釈には複雑な関係がみえてきます。もちろんこの左隣ようなギャグがモネにわかりっこないことは明らかです

が……。 クロード・モネ(Claude Monet, 1840年11月14日 - 1926年12月5日).1890年代、自宅に「花の庭」と、睡蓮の池のある「水の庭」を整えていったが、1898年ごろから睡蓮の池を集中的に描くよう になった。1900年までの『睡蓮』第1連作は、日本風の太鼓橋を中心とした構図であったが、その後1900年代後半までの第2連作は、睡蓮の花や葉、さ らに水面への反映が中心になっていき、1909年の『睡蓮』第2連作の個展に結実した。最晩年は、視力低下や家族・友人の死去といった危機に直面したが、 友人クレマンソーの励ましを受けながら、白内障の手術を乗り越えて、オランジュリー美術館に収められる『睡蓮』大装飾画の制作に没頭し、86歳で最期を迎 えた(→「睡蓮」の部屋(最晩年)) モネは、1909年の個展のとき、『睡蓮』で一室を装飾するという計画を考えついた。しかし、老化にともない視力の低下という問題に直面した[注釈 24]。さらに1911年5月には妻アリスが亡くなり、1914年2月には長男ジャンが亡くなるという不幸に見舞われた[278]。印象派の同志たちも次 々世を去っていった[279]。絵具の色も判別できないという絶望の中、多数の絵を引き裂いたため、1909年から1914年までの絵はほとんど残ってい ない[280]。モネは、気分転換のため、ジヴェルニーの自宅に、彫刻家のロダン、サージェント、詩人のポール・ヴァレリー、画商のデュラン=リュエル、 ベルネーム、劇作家サシャ・ギトリ夫妻、日本の黒木三次夫妻、政治家ジョルジュ・クレマンソーといった友人を招き、特に園芸と料理の話題を楽しんだ [281]。アリス死後は、その娘ブランシュ(ジャンの妻でもあった)がモネを精神的に支えた[282]。 |

|

1914年、大画面作品を描くための新しいアトリエを建て、制作を再開

した[284]。この年、モネ作品14点を含む収集家イザック・ド・カモンド伯爵の遺品コレクションがルーヴル美術館に収蔵されることになったが、これ

は、死後10年たたないとルーヴルに展示されないという原則からすると異例のことであった。モネは、ルーヴルに招かれ、特別室に展示される自作を目にした

[285]。第一次世界大戦中の1915年初め、友人への手紙で、大装飾画を目指していることを初めて明かしている[286]。1917年、通産大臣エ

ティエンヌ・クレメンテル(フランス語版)がジヴェルニーを訪れ、ドイツ軍の爆撃を受けて破壊されたランスのノートルダム大聖堂を描き、その蛮行を明らか

にしてほしいとの依頼をし、モネはこれを了承したが、実際には現地は爆撃が続き、制作に着手することは難しかった。ただ、政府との関係ができたことで、物

資欠乏の戦時下で、ガソリンや石炭を回してもらう便宜を受けることができた[287]。その間、アトリエで、高さ2メートル、幅4.3メートルの巨大な

キャンバスを横に4枚つなげて『睡蓮』大装飾画の制作を続けた[288]。戦争が終わった1918年、友人で当時の首相ジョルジュ・クレマンソーに、勝利

を祝って、国に一連の大装飾画を寄贈することを約束した[248]。当初は、現在のロダン美術館(ビロン邸)の庭に円形パビリオンを設置し、幅4メートル

のキャンバスが12枚取りつけられる計画であった。しかし、建物建設にかかる費用の問題などで当初の計画は修正を迫られ、モネは制作自体を断念しかけた。

クレマンソーがモネを強く説得し、1921年4月、オランジュリー美術館の2つのホールに収容する計画で了承させた[289]。 |

|

こうして、1922年4月、モネの弁護士と建築家、政府当局との間で寄

贈契約が署名された。その内容は、19枚のパネル(作品8点)を2年以内にオランジュリーのモネ・ギャラリーに納入するというものであった[290]。し

かしその後、白内障のため失明の危機に直面し、クレマンソーは仕事を放棄しようとするモネを励まし続けた。1923年、ようやく右目の白内障の手術を受

け、視力はある程度回復した[291]。当初約束していた引渡し期限を延期し、残りの生涯をかけて『睡蓮』大装飾画の制作に没頭した[284]。1924

年、ジョルジュ・プティ画廊で、生存中最大の回顧展が開催された[292]。 1926年の夏の終わり、肺硬化症[注釈 25]で病床につき、12月5日正午に86歳で永眠した[292]。息子のミシェルや、ブランシュ、クレマンソーが彼を看取った[293]。『睡蓮』大装 飾画は、テュイルリー公園内のオランジュリー美術館に収められ、1927年5月17日、除幕式が行われた[294]。『睡蓮』の部屋は、モネの考えに従っ て、楕円形の2つの部屋からなり、それぞれ4点の大画面作品で構成されている[284]。 モネの晩年には、フォーヴィスム、キュビスムなど、次々に新しい芸術潮流が生まれており、当時『睡蓮』を顧みる人は少なかった。クレマンソーは、1927 年6月、「昨日、オランジュリー美術館を訪れたが、誰一人としていなかった」と書いている。しかし、1950年代になると、ジャクソン・ポロックなど抽象 表現主義の画家・批評家がモネを引き合いに出すようになり、改めて注目を浴びるようになった[295]。アンドレ・マッソンは、『睡蓮』大装飾画を「印象 主義のシスティーナ礼拝堂」と呼び、すべての現代人に見ることを勧めた[296]。 |

サイト内リンク

サイト外リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

Do not paste, but [Re]Think our message for all undergraduate students!!!