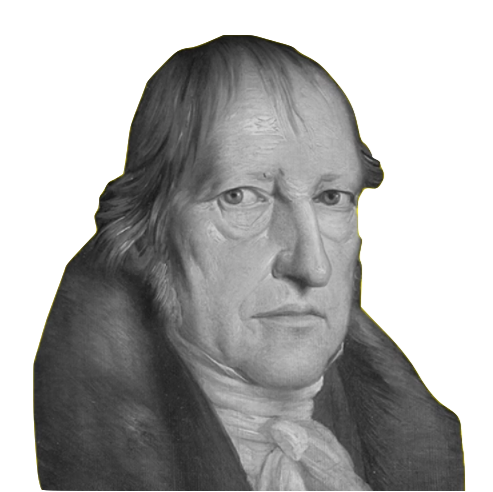

ヘーゲルにとっての「美」とは?

What

is beauty and/or aestetics

for Herr Hegel ?

加藤尚武ほか編『ヘーゲル事典』弘文堂、1992年にみられる、美学や美の概念について、考 察する。(→音楽については「こちら」)(→「ヘーゲルの美学(スタンフォード哲学百科 事典)」「ヘーゲルの美学」)

まず、ヘーゲルの美に対する考え方は、かれの思索の探求の時期により、それぞれ大きく異なっ

ていることが特徴である。すなわち、ヘーゲルにおける美の概念の取り扱いかたは、かなり多様性があり、固定化した確固たる信念をもっていなかったことがあ

げられる。しかし、ヘーゲルにとり「美がイデー

の一つ,つまり概念と実在性との統ーの直接

的な仕方である」ことは確実である。しかしながら、美のイデアは「生

のイデーと認識のイデーとの中間に

位置」するというアンビバレントな態度をとっていた。

それは、自然に美的なものを見なさなかったが、同時に、自然である生命に美を見出してもいたことであきらかである。

「美[Schönes, Schönheit] バウムガルテン(Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten 1714-62) が美を「感覚的認識 の完全性」と規定して以来,近世哲学は美を 主観的な方向に探求し,カントも美の客観的 原理を呈示することを不可能とし,それを美 的判断の可能性として問い,美的判断におい ては認識諸能力は「自由な遊戯」(freies Spiel) のうちにあると思惟した。しかしシ ラーは美を客観的に呈示しようとして,それ を「現象における自由」(Freiheit in der Erscheinung) と規定した。/ ヘーゲルは『最古の体系プログラム』でヘ ルダーリンとともにプラトン的な「美のイデ ー」に体系の最高点を求め[l. 235], フラン クフルト時代には美は真理に等しいとした [ 『キリスト教の精神』1. 288]。しかし彼はイェ ーナ時代から美の問題を芸術の問題として扱 うようになり, 1805/06 年の『精神哲学』で は芸術の要素としての直観は「真理を蔽うヴ ェール」に貶められる『イェーナ体系 III 』GW 8. 279]。しかしヘーゲルにとって美がイデー の一つ,つまり概念と実在性との統ーの直接 的な仕方であることには変わりない[『美学』 13. 157]。確かに『大論理学」は美のイデー を挙げていない。しかしニュルンベルク時代 の「中級のための論理学」(1810/11) が生の イデーの項で美のイデーに言及しており [『ニュルンベルク著作集』4 . 202], またもしも 美のイデーが採り上げられるとすれば,この ように生のイデーと認識のイデーとの中間に 位置すべきはずであることは『美学』[13 167] からも推測できる。しかし美はイデア そのものではなく,「イデーの感性的映現 (das sinnliche Scheinen der Idee) であり, この「自らの定在における概念の自己自身と の一致」の「結合の威力」は主体性にして個 体性である[同13. 151,52]。「美しい対象は その現実存在においてそれ自身の概念を実現 されたものとして現象させ,それ自身におい て主体的な統ーと生命性を示す」[同13. 155]。/ ヘーゲルはその美学の本来的な対象を芸術 美に制限し,自然美を排除する。その根拠は 彼にとって自然は精神によってその他者とし て定立されたものであり,精神とその所産の 方が自然とその現象よりも高いからである [同13. 14,128f.]。しかしイデーのさしあたっ ての定在は自然の「生命」(Leben) である [同13. 160]。「自然は既に生命として観念論 的哲学がその精神的領野で成就していること を事実的に行っておりJ, 生命過程は区別と 統一という二重の観念化の活動性を自己目的 として包括しているが[同13. 162f., 165], このように身体(惑性)のうちに魂(イデ 一)が現れてくる限りにおいて生命は美であ る[同13. 166f.]。しかし自然美は単に他者 にとってのみ美しく,対自的に美しいわけで はない[同13. 157]。自然美の根本的欠陥は ヘーゲルにとって魂と主体性が完全な仕方で 現象しない点にある[同13. 193ff ・Jo - 仮象 【参】Baumgarten (1750/58), Kant (1790), Schiller (1793), Kuhn (1931) (四日谷敬子)」(Pp.405-406)。

ヘーゲルにとり、美学というものは、どのような位置付けであったか? まず、美学は「芸術の形

而上学」だった。他方、審美主義一辺倒ではなく、醜さの概念も美学的考察に加えるように、美醜と超えるような観想にも至っている。それが芸

術は「絶対者〔イデー〕そのものの感性的描出」という表現である。し

かしながら、あるいは、それゆえに、芸術、とりわけロマン派芸術は、最終的には自己意識と反省の時代には、もはや過去のものになる。これは、ヘーゲル派の

哲学者あるいは美術評論家のアーサー・ダントーと同じ立場をとるのだ(=時間的・論理的関係では、ヘーゲルの立場をダントーは受け継いで、のほうがより正

確)。ただし、ヘーゲルは、ロマン派の芸術はおわり、次の時代には、ヒューマニズム(人間中心主義)的な、芸術の聖性を獲得するだろうという(このあたり

は「誠実とほんもの」の議論に関連する)。

「美学 芸術 [Ästhetik., .Ku.ns.t]. . ヘーゲル美学は「美しい芸術の哲学」を意 味する[『美学』13. 13]。(1)それはバウムガル テン(Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten 17 14-62) の「感覚の学」ではなく,芸術の形 而上学である。(2) またフィッシャー(Friedrich Theodor Vischer 1807.6.30〜87.9.14) が後に是正したが,伝統的な美学の主要対象 であった自然美をその考察から排除した。(3) そして芸術を「美しい」と限定することによ って美の領域を制限するとともに,弟子のロ ーゼンクランツが仕上げたように,美の概念 を醜なども含むものに拡大している。その際 芸術は自己意識を本質とする人間が一切を対 自的にしようとする「絶対的要求」から発す るとされ[同13. 50f], その内容,課題は宗 教や哲学と共通で,イデー(絶対者,真理) を意識にもたらす。しかしそのための形式, 手段として芸術は,宗教の表象,哲学の概念 に対して「感性的直観」を用いる[同13. 20 f., 139f.J。こうして芸術は「絶対者〔イデ 一〕そのものの感性的描出」である[同13. 100]。/ ヘーゲルは(1) まずイデーと形態との完成し た統一を「理想」(Ideal) として考察する [同13. 105]。(2)次に芸術史を理想達成以前の オリエントの象徴的芸術からその達成として のギリシアの古典的芸術,そしてその達成以 後のキリスト教のロマン的芸術という「世界 観の歴史」[Gadamer (1960)] として構成する [同13. 107ff.]。(3)そして最後に感性的素材の 精神化を原理として個別的諸芸術の体系を企 投する。その際ヘーゲルは,建築には象徴的 芸術を,彫刻には古典的芸術を,絵画,音楽, ボエジーにはロマン的芸術をその根本類型と して呼応させる[同13. 114ff.]。こうしてヘ ーゲル美学は芸術の形而上学と芸術の歴史性 とを体系的に綜合し,芸術を歴史的な真理経 験の一仕方として把握する。/ しかし彼の美学はその芸術の規定に基づい て同時に芸術の終末(過去性)のテーゼを掲 げ,芸術そのものを止揚する。「芸術制作と その作品の固有の仕方は我々の最高の要求を もはや満たさない」,「これらのあらゆる関係 において,芸術はその最高の使命の側面にし たがえば,我々にとって過去のものである」 [同13. 24f.]。つまりヘーゲルは,イデーの 描出という芸術の「最高の使命」が,惑性的 描出という「固有の仕方」のために,自己意 識と反省の時代にある「我々にとって」過去 のものとなったと主張する。芸術の解消は 「芸術の完成」に達した古典的芸術を超えた ロマン的芸術に既に始まっているが,特にそ の崩壊現象と看傲されるのは, 17世紀オランダの絵画や当時のドイツのフモールの芸術, また近代的エポスとしてのロマーンや近代悲 劇における実体的世界観の欠如である。しか し他方ヘーゲルは,一定の世界観から解放さ れた現代に芸術の無限の可能性を認め,「フ マーヌス」がその芸術の「新しい聖なるも の」となるであろうと予言する[同14. 127, 237]。 【参】Baumgarten (1750/58), Vischer (1846- 57), Rosenkranz (1853), Gadamer (1960) (四日谷敬子)」(Pp.406-407)

●Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten(→アレクサンダー・ゴットリーブ・バウムガルテン、に移転)

●トリリング、ライオネル『誠実とほんもの:近代自我の確立と崩壊』野島秀勝訳、法政大学出 版局、1989年/Sincerity and authenticity / Lionel Trilling, Oxford University Press / Harvard University Press , 1972

音楽は、主観的内面性を没対象的で内面的なままに表 出する。音楽の主要課題は対象の再現=表象ではない。内面の自己が主観性と心にまかせて「自己内運動するそのさまを反響させることだという——『美学』 (15:135)。その表現手段は、リズムと和声と旋律だ。

ヘーゲルによると器楽音楽(=純音楽的素材で構成さ れる自立的音楽)よりも声楽の伴奏音楽のほうが重要である。器楽音楽のあいだの「自由と必然の闘争」(『美学』18:189) は、通の人しかわからない点で、難解で一般性を欠くと考える。声楽は、楽器よりも歌詞の内容が優勢になると、音楽が従になり、より好ましいものになると考 える。その意味で、ヘーゲルはヨハン・セバスチャン・バッハの宗教曲を評価するが、研究家によると、実際に聴いて評価したのかは、疑わしいらしい。美学の 講義日程は、『マタイ受難曲』のメンデルスゾーンによる復活上演の時期が後になるからである。

ヘーゲルの器楽曲批判は、同時期のベートーベンの批 判が念頭(つまり目的)にあるらしい。この時期より先に(1750年代前半)ブフォン論争があった。この論争は、フランスの百科全書派を中心としてイタリ ア派が、フランスの宮廷オペラを批判したことと類似する。(百科全書派の)ルソーは、フランス音楽には快い旋律が欠けていて、和声や装飾音で飾っているに すぎないとした。ルソーは、イタリアのオペラ・ブッファを支持した。ヘーゲルの器楽曲批判は、このルソーの立場と似ている。声は、動物が有機的自己(主観 性)を全体として表現する。「声は純粋自己で、己を普遍的なものとして措定し、苦痛、欲望、喜び、満足を表現する」(『自然哲学』358節、補遺;『精神 哲学』401節、補遺)。また、声は、楽器の音色を総合した観念的総体性をもつ(『美学』15:175/『歴史哲学』12:298)

参照文献:石川伊織「音楽」『ヘーゲル事典』 p.52、弘文堂、1992年。

●ヘーゲルの美学(『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-aesthetics/)

| 1. ヘーゲルの芸術知識 | 1. ヘーゲルの芸術知識 ヘーゲルの『精神の現象学』(1807年)には、古代ギリシアの「芸術宗教」(Kunstreligion)に関する章と、ソフォクレスの『アンチゴー ヌ』と『オイディプス王』に示された世界観に関する章がある。しかし、彼の芸術哲学は、(現象学ではなく)精神哲学の一部を形成している。現象学』は、 ヘーゲルの哲学体系の序論とみなすことができる。この体系自体は、論理学、自然哲学、精神哲学の3つの部分からなり、ヘーゲルの『哲学科学百科事典』 (1817年、1827年、1830年)に(段落番号付きで)記載されている。精神の哲学は、主観的精神、客観的精神、絶対的精神の3つのセクションに分 かれている。ヘーゲルの芸術哲学あるいは「美学」は、彼の絶対精神哲学の最初のサブセクションを構成し、それに宗教哲学と哲学史の説明が続く。 ヘーゲルの芸術哲学は、美の概念そのものから、さまざまな美の形態と個々の芸術をアプリオリに導き出す。しかし、カントとは明らかに対照的に、ヘーゲルは 美の哲学的研究の中に、個々の芸術作品への数多くの言及と分析を織り込んでいる。その程度は、カイ・ハンマーマイスターの言葉を借りれば、彼の美学が「芸 術の真の世界史」(Hammermeister, 24)を構成するほどである。 ヘーゲルはギリシア語とラテン語の両方を読み(実際、14歳のときから日記の一部をラテン語で書いている)、英語とフランス語も読んだ。そのため、ホメロ ス、アイスキュロス、ソフォクレス、エウリピデス、ヴァージル、シェイクスピア、モリエールの作品を原語で学ぶことができた。ギリシャやイタリアを旅行す ることはなかったが、ベルリン(1818年に教授に就任)からドレスデン(1820年、1821年、1824年)、低地諸国(1822年、1827年)、 ウィーン(1824年)、パリ(1827年)へと何度か長旅をした。これらの旅で彼は、ラファエロの『システィーナの聖母』とコレッジョの絵画数点(ドレ スデン)、レンブラントの『夜警』(アムステルダム)、ファン・エイク兄弟の『仔羊の礼拝』の中央部分(ゲント)(翼のパネルは当時ベルリンにあった)、 そして「最も高貴な巨匠の有名な作品は、銅版画で100回は見たことがある: ラファエロ、コレッジョ、レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチ、ティツィアーノ」(パリにて)(Hegel: The Letters, 654)。旅先でもベルリンでも、劇場やオペラを好んで訪れ、アンナ・ミルダー=ハウプトマン(1814年、ベートーヴェンの『フィデリオ』の初演で歌っ た)や作曲家フェリックス・メンデルスゾーン=バルトルディ(1829年3月、ヘーゲルが参加したJ.S.バッハの『聖マタイ受難曲』の再演)などの一流 歌手と知り合った。ヘーゲルはゲーテとも親交があり、彼の戯曲や詩を特によく知っていた(フリードリヒ・シラーの戯曲も同様)。 アドルノは「ヘーゲルとカントは[......]芸術について何も理解することなく、主要な美学を書くことができた」(Adorno, 334)と苦言を呈している。カントについてはそうかもしれないし、そうでないかもしれないが、ヘーゲルについては明らかに真実ではない。ヘーゲルの知識 や関心は西洋美術に限定されていたわけではなく、インドやペルシャの詩の作品を(翻訳で)読んだり、ベルリンでエジプト美術の作品を直接見たりしていた (Pöggeler 1981, 206-8)。このように、ヘーゲルの芸術哲学は、美の諸形態をアプリオリに導き出すものであり、アドルノと同様に、世界中の個々の芸術作品に対する徹底 的な知識と理解によってもたらされ、媒介されるものなのである。 Hegel’s Knowledge of Art https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-aesthetics/ |

| 2. 美学に関するヘーゲルのテキストと講義 | 2. 美学に関するヘーゲルのテキストと講義 ヘーゲルが美学について発表した思想は、1830年の『百科全書』のpars. 1830年の『百科全書』の556-63節にある。ヘーゲルはまた、1818年にハイデルベルクで、1820/21年(冬学期)、1823年と1826年 (夏学期)、1828/29年(冬学期)にベルリンで美学に関する講義を行っている。1820/21年、1823年、1826年、1828/29年にヘー ゲルの学生たちが行った講義の記録は、現在出版されている(ただし、今のところ英訳されているのは1823年の講義のみである)(参考文献参照)。 1835年(そして1842年にも)、ヘーゲルの弟子の一人であるハインリヒ・グスタフ・ホトーは、ヘーゲルの手稿(現在は失われている)と一連の講義録 に基づいて、美学に関するヘーゲルの講義の版を出版した。これは英語で G.W.F. Hegel, Aesthetics. 英語版は、G.W.F. Hegel, Aesthetics. T.M. Knox, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975). ヘーゲルの美学に関する(英語とドイツ語の)二次文献のほとんどは、ホトーの版を参照している。しかし、ヘーゲルの美学に関する主要な専門家の一人である アンネマリー・ゲスマン=シーフェルトによれば、ホトーはさまざまな方法でヘーゲルの思想を歪めている。彼はヘーゲルの芸術に関する説明に、ヘーゲル自身 が与えたよりもはるかに厳格な体系的構造を与え、ヘーゲルの説明を彼自身の資料で補足している(PKÄ, xiii-xv)。それゆえ、ヘーゲルの美学を理解するためには、ホトーの版に頼るのではなく、入手可能な講義録に基づいて解釈すべきだとゲトマン=シー フェルトは主張する。 ホトがヘーゲルの美学を理解する上で拠り所としたヘーゲルの手稿はすでに失われており、ホトがヘーゲルの芸術論をどの程度歪曲したのか(もし歪曲していた としても)、それを確実に判断することはもはや不可能なのである。また、ゲスマン=シーフェルト自身のヘーゲル美学の解釈にも疑問が投げかけられている (Houlgate 1986a参照)。とはいえ、ゲトマン=シーフェルトがドイツ語の知識のある読者に、出版された講演録を参照するよう勧めるのは正しい。なぜなら、講演録 には重要な資料が豊富に含まれており、場合によってはホト版には欠けている資料もあるからである(たとえば、1820/21年の講演[VÄ, 192]におけるカスパー・ダーヴィト・フリードリヒへの短い言及など)。 ヘーゲルの芸術哲学は、1831年の彼の死後、かなりの議論を引き起こしてきた。ヘーゲルはギリシア芸術だけが美しいと考えているのだろうか。芸術は近代 で終焉を迎えると考えているのか。というのも、悲しいことに、ヘーゲル自身によって公式に支持された、ヘーゲルの芸術哲学は存在しないからである。百科事 典の段落はヘーゲルが書いたものだが、非常に簡潔で凝縮されたものであり、彼の講義によって補足されることを意図したものである。講義録はヘーゲルの学生 たちによって書かれたものであり(あるものは授業中に書き留められたものであり、あるものは授業中に取られたメモを後から編集したものである)、ヘーゲル の講義の「標準」版は、彼の弟子であるホトによってまとめられたものである(ヘーゲル自身による原稿を使用したものではあるが)。したがって、ヘーゲルが 完全に発展させた美学理論の決定版は存在しないのである。 https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-aesthetics/ |

| 3. ヘーゲルの体系における芸術、宗教、哲学 | 3. ヘーゲルの体系における芸術、宗教、哲学 ヘーゲルの芸術哲学は、彼の哲学体系全体の一部を形成している。したがって、彼の芸術哲学を理解するためには、彼の哲学の主な主張を全体として理解しなけ ればならない。ヘーゲルは思弁的論理学の中で、存在とは自己決定する理性、すなわち「イデア」(Idee)として理解されるべきものであると主張してい る。理性は抽象的なものではなく、実体のないロゴスでもなく、合理的に組織された物質の形をとる。ヘーゲルによれば、そこにあるのは単なる純粋な理性では なく、理性的原則に従う物理的、化学的、そして生命的な物質である。 生命は単なる物理的物質よりも、より明確に合理的であり、それはより明確に自己決定するからである。つまり、想像し、言語を使用し、思考し、自由を行使で きる生命である。このような自己意識的な生命を、ヘーゲルは「精神」(Geist)と呼ぶ。それゆえ、理性(イデア)は、それが自己意識的な精神の形態を とるとき、完全に自己決定的で理性的なものとなる。ヘーゲルの考えでは、これは人間存在の出現とともに起こる。ヘーゲルにとって、人間は単なる自然の事故 ではなく、理性そのもの、つまり自然に内在する理性そのものであり、それが生命を獲得し、自らを意識するようになったのである。人間(あるいは他の惑星に 存在するかもしれない他の有限の理性的存在)を超えて、ヘーゲルの宇宙には自己意識的な理性は存在しない。 客観的精神の哲学において、ヘーゲルは、精神、すなわち人間性が正しく自由で自己決定的であるために必要な制度的構造を分析している。これには、権利、家 族、市民社会、国家の制度が含まれる。次にヘーゲルは、絶対精神の哲学において、精神が自分自身についての究極的な「絶対的」理解を明確にするさまざまな 方法を分析する。精神に関する最も高度で、最も発展した、そして最も適切な理解は、哲学によって達成される(その世界理解の骨子は、今しがた描かれたとお りである)。哲学は、理性やイデアの本質について、明確に合理的で概念的な理解を提供する。哲学は、なぜ理性が空間、時間、物質、生命、自意識のある精神 という形をとらなければならないのかを正確に説明する。 宗教では、とりわけキリスト教では、精神は哲学と同じように理性とそれ自身についての理解を表現する。しかし宗教では、イデアが自己意識的な精神になる過 程は、イメージや比喩の中で、「神」が人間に宿る「聖霊」になる過程として表現される。さらにこのプロセスは、私たちが信仰と信頼を置くものであり、概念 的な理解よりもむしろ、感情や信念の対象である。 ヘーゲルの考えでは、哲学と宗教、つまりヘーゲル自身の思弁哲学とキリスト教は、どちらも同じ真理を理解している。しかし、宗教は真理の表象を信じている のに対し、哲学はその真理を完全に概念的に明確に理解している。哲学があるのに宗教が必要なのは奇妙に思えるかもしれない。しかし、ヘーゲルにとって、人 類は概念だけでは生きられず、真理をイメージし、想像し、信仰する必要がある。実際、ヘーゲルは、「民族が何を真実と考えるかを定義する」のは、何よりも 宗教においてであると主張している(『世界史哲学講義』105)。 ヘーゲルにとって芸術もまた、精神が自己を理解することを表現するものである。しかし、芸術は哲学や宗教とは異なり、精神の自己理解を純粋な概念や信仰の イメージで表現するのではなく、人間によってこの目的のために特別に作られた対象を通して表現する。石や木や色や音や言葉から作り出されたそのような物体 は、精神の自由を聴衆に見えたり聴こえたりするようにする。ヘーゲルの考えでは、この自由な精神の官能的な表現こそが美なのである。ヘーゲルにとっての芸 術の目的は、このように、自由の真の性格が感覚的に表現された美しい対象物を創造することである。 したがって、芸術の主な目的は、自然を模倣することでも、身の回りを装飾することでも、道徳的・政治的行動を促すことでも、自己満足に浸っている私たちに 衝撃を与えることでもない。それは、私たち自身の精神的自由、つまり、私たちの自由を表現しているからこそ美しいイメージについて、私たちが熟考し、創造 されたイメージを楽しむことなのである。言い換えれば、芸術の目的は、私たちが自分自身についての真実を思い浮かべることができるようにすることであり、 それによって私たちが真に何者であるかを自覚できるようにすることである。芸術は芸術のためだけにあるのではなく、美のために、つまり、人間の自己表現と 自己理解の独特な感覚的形式のためにあるのだ。 https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-aesthetics/ |

| 4. 美と自由に関するカント、シラー、ヘーゲル | 4. 美と自由に関するカント、シラー、ヘーゲル ヘーゲルが芸術を美と自由と密接に結びつけていることは、彼がカントと シラーに明らかに恩義を感じていることを示している。カントもまた、美の経験は自由の経験であると主張している。しかし彼は、美はそれ自 体、事物の客観的な性質ではないと主張した。カ ントの考えでは、私たちが自然物や芸術作品を美しいと判断するとき、確かに私たちは対象物について判断しているが、その対象物が私たちに一定の効果をもた らす(そして、それを見るすべての人に同じ効果をもたらすはずである)と主張しているのである。「美しい」対象がもたらす効果は、私たちの理解と想像力を 互いに「自由な遊び」の中に置くことであり、この自由な遊びによって生み出される快楽こそが、私たちに対象を美しいと判断させるのである(Kant, 98, 102-3)。 カントとは対照的に、シラーは美を対象そのものが持つ性質と理解してい る。 それは、生物にも芸術作品にも備わっている、自由であるように見えて実は自由でないという性質である。シラーが「カリアス」の手紙の中で述べているよう に、美とは「見かけの自由、見かけの自律」である(Schiller, 151)。シラーは、自由そのものは(カントの用語を使えば)「根源的」なものであり、感覚の領域では決して現れないと主張する。私たちは、空間と時間の 世界で自由が働いているのを見ることはできない。それゆえ、美しい対象については、それが自然の産物であれ、人間の想像力の産物であれ、「重要なのは、そ の対象が自由であるように見えること[......]だけであって、実際にそうであることではない」(Schiller, 151)。 ヘーゲルは、美が事物の客観的な性質であるという点では、(カントに対して)シラーに同意している。しかし、ヘーゲルの考えでは、美とは自由の直接的な感 覚的現われであり、単に自由の外観や模倣ではない。自由が感覚的に表現されるとき、自由が実際にどのように見え、どのように聞こえるかを(理想化の程度の 差はあるにせよ)示してくれるのである。真の美は精神の自由の直接的な感覚的表現であるため、自由な精神によって自由な精神のために生み出されなければな らない。自然には形式的な美があり、生命にはヘーゲルが「感覚的な」美と呼ぶものがある(PK, 197)が、真の美は、自由な精神とは何であるかを私たちの心にもたらすために人間が自由に創造した芸術作品にのみ見出されるのである。 ヘーゲルにとっての美とは、ある種の形式的な特質を持つものである。それは、さまざまな要素が単に規則正しく対称的に配置されているのではなく、有機的に 統一されている統一性や調和である。ヘーゲルは、ギリシア彫刻についての考察の中で、真に美しい形の例を挙げている。有名なギリシアの横顔が美しいのは、 額と鼻とが継ぎ目なく流れ込んでいるからであり、額と鼻との間に鋭角的な角度があるローマの横顔とは対照的である、と言われている(『美学』2: 727-30)。 しかし、美とは形だけの問題ではなく、内容の問題でもある。これはヘーゲルの最も論争の的となる考え方の一つであり、芸術はどのような内容でも受け入れる ことができ、実際、内容を完全に排除することができると主張する現代の芸術家や芸術理論家たちと対立するものである。これまで見てきたように、ヘーゲルが 主張する真の美(したがって真の芸術)の中心的かつ不可欠な内容とは、精神の自由と豊かさである。別の言い方をすれば、その内容とは、自己認識する精神と してのイデア、すなわち絶対的理性である。イデアは宗教において「神」として描かれるため、真に美しい芸術の内容は、ある一点において神である。しかし、 上で見たように、ヘーゲルは、イデア(あるいは「神」)は、有限な人間の中で、また有限な人間を通してのみ、それ自体を意識するようになると主張してい る。したがって、美しい芸術の内容は、人間の姿をした神、あるいは人間そのものの中にある神(純粋に人間の自由と同様)でなければならない。 ヘーゲルは、芸術が動物や植物や無機的な自然を描くことができることを認めているが、神と人間の自由を提示することが芸術の主要な仕事であると考えてい る。いずれの場合も、特に人間の姿に注目する。ヘーゲルの考えでは、理性の最も適切な感覚的化身であり、精神の最も明確な目に見える表現が人間の姿だから である。色や音はそれ自体で確かに気分を伝えることができるが、精神と理性を実際に体現しているのは人間の姿だけである。真に美しい芸術とは、ギリシャ神 話の神々やイエス・キリストの彫刻、絵画、詩的なイメージ、つまり人間の姿をした神、あるいは人間の自由な生活そのもののイメージを私たちに示すものなの だ。 https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-aesthetics/ |

| 5. 芸術と理想化 | 5. 芸術と理想化 ヘーゲルにとって、芸術とは本質的に具象的なものである。それは自然を模倣しようとするからではなく、その目的が自由な精神を表現し、具現化することであ り、それは人間のイメージを通して最も適切に達成されるからである。(より具体的に言えば、芸術の役割は、私たちが日常生活の中で見失いがちな、私たち自 身と私たちの自由についての真実を思い起こさせることである。その役割とは、自由の真の姿を私たちに示す(あるいは思い出させる)ことである。芸術は、日 常生活の偶発性を排除した、精神の自由を最も純粋な形で私たちに示すことで、この役割を果たす。つまり、芸術の最良の姿は、日常生活のあまりにも身近な依 存や苦役ではなく、自由の理想を私たちに示すのである(『美学』1: 155-6参照)。この人間的(そして神的)自由の理想が真の美であり、古代ギリシアの神々や英雄の彫刻の中にとりわけ見出されるとヘーゲルは主張する。 理想化の作業は、(現代のファッション写真のように)人生から空想の世界へと逃避するために行われるのではなく、私たちが自分の自由をより明確に見ること ができるようにするために行われるのである。したがって、理想化は、人間(そして神)の真の姿をより明確に明らかにするために行われるのである。パラドッ クスとは、芸術が人間の理想化されたイメージを通して(そして実際、絵画においては外的現実の幻想を通して)真実を伝えるということである。 この段階で注目すべきは、ヘーゲルの芸術に関する説明は、記述的であると同時に規範的であるということである。ヘーゲルは、フィディアスやプラクシテレス の彫刻、あるいはアイスキュロスやソフォクレスの戯曲のような、西洋の伝統の中で最も偉大な芸術作品の主要な特徴を、彼の説明が記述していると考えてい る。同時に、真の芸術とは何かを説く限りにおいて、彼の説明は規範的である。洞窟画、子供の絵、ギリシャ彫刻、シェイクスピアの戯曲、思春期の恋愛詩、 (20世紀の)カール・アンドレのレンガなど、私たちが「芸術」と呼ぶものはたくさんある。しかし、「芸術」と呼ばれるものすべてがその名に値するわけで はない。なぜなら、そう呼ばれるものすべてが、真の芸術が意図すること、すなわち、自由な精神に感覚的な表現を与え、それによって美の作品を創り出すこと を行っているわけではないからである。ヘーゲルは、美を生み出すための厳密なルールを規定しているわけではないが、真に美しい芸術が満たさなければならな い大まかな基準を示しており、「芸術」であると主張しながらもこれらの基準を満たさない作品に対しては批判的である。ヘーゲルは、宗教改革後の芸術におけ るある種の発展、例えば、自然を模倣する以上のことをしようとしない願望を批判しているが、それは偶発的な個人的嗜好に基づくものではなく、芸術の本質と 目的についての彼の哲学的理解に基づくものである。 https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-aesthetics/ |

| 6. ヘーゲルの体系的美学または芸術哲学 | 6. ヘーゲルの体系的美学または芸術哲学 ヘーゲルの芸術と美の哲学的説明には、3つの部分がある:1)そのようなものとしての理想的な美、あるいは本来の美、2)歴史において美がとるさまざまな 形態、3)美が出会うさまざまな芸術。まず、ヘーゲルの理想的な美についての説明を見てみよう。 |

| 6.1 そのようなものとしての理想の美 | 6.1 そのようなものとしての理想の美 ヘーゲルは、芸術がさまざまな機能を果たすことができることをよく知っている。しかし、彼の関心は、芸術の本来の、そして最も特徴的な機能を特定すること である。それは、精神の自由を直感的、感覚的に表現することだと彼は主張する。したがって、芸術のポイントは「写実的」であること、つまり日常生活の不測 の事態を模倣したり鏡に映したりすることではなく、神と人間の自由がどのようなものかを私たちに示すことなのである。このような精神的自由の官能的表現こ そ、ヘーゲルが「理想」あるいは「真の美」と呼ぶものである。 官能的なものの領域とは、空間と時間における個々の事物の領域である。それゆえ、自由が官能的な表現を与えられるのは、「自己の享楽、安息、至福 [Seligkeit]」(『美学』1: 179)において一人立ちしている個人において具現化されるときである。そのような個人は、(例えば初期ギリシアの幾何学様式のように)抽象的で形式的で あってはならないし、(多くの古代エジプトの彫刻のように)静的で硬質であってはならない。このような理想的な美は、ドレスデンのゼウス像(ヘーゲルは 1820年代初頭にその鋳型を目にした)やプラクシテレスのクニディアン・アフロディーテ像(PKÄ, 143およびHoulgate 2007, 58参照)のような、5~4世紀のギリシアの神々の彫刻にとりわけ見られるとヘーゲルは主張する。 古代ギリシア彫刻は、ヘーゲルがほとんどローマ時代の模写か石膏模型からしか知らなかったであろうが、彼が純粋な美、あるいは「絶対的な」美と呼ぶものを 提示している(PKÄ, 124)。というのも、美はその最も具体的で発展した形では私たちに与えてくれないからである。古代ギリシアの戯曲、とりわけ悲劇には、自由な個人が行動 を起こし、それが対立につながり、最後には解決に至る(ソフォクレスの『アンチゴーヌ』のように暴力的な場合もあれば、アイスキュロスの『オレステイア』 三部作のように平和的な場合もある)。ギリシア彫刻に表される神々が美しいのは、その肉体的な形が精神的な自由を完璧に体現し、肉体的な弱さや依存の痕跡 によって損なわれていないからである。ギリシア悲劇の主要な英雄やヒロインが美しいのは、彼らの自由な活動が、人間的な些細な欠点や情念に左右されるので はなく、倫理的な関心や「パトス」(例えば、アンチゴーヌの場合は家族への配慮、クレオンの場合は国家の福祉への関心など)に影響され、動かされているか らである。これらの英雄は、抽象的な美徳の寓意的表現ではなく、想像力、人格、自由意志を持った生きた人間である。しかし、彼らを動かしているのは、私た ちの倫理的生活の一面に対する情熱であり、神によって支持され、促進されている一面である。 ギリシア彫刻に見られる純粋な美と、ギリシア演劇に見られるより具体的な美との区別は、理想的な美が実際には微妙に異なる二つの形をとることを意味する。 美がこのように異なる形をとるのは、純粋な彫刻の美が、芸術の到達点の頂点であるにもかかわらず、ある種の抽象性を持っているからである。美は自由の感覚 的表現であるため、例えばエジプト彫刻に欠けている具体性、生気、人間性を示さなければならない。しかし、ギリシア彫刻に代表されるような純粋な美は、精 神的な自由を空間的、身体的な形象に浸み込ませたものであるため、時間における行為、すなわち想像力と言語によって動かされる行為のより具体的なダイナミ ズムを欠いている。これが純粋美にある種の「抽象性」(そして実際、冷たさ)を与えているのである(PKÄ, 57, 125)。しかし、芸術の役割が真の自由を感覚的に表現することであるならば、芸術は抽象性を超えて具体性へと向かわなければならない。つまり、純粋な美 を超えて、より具体的で真に人間的なドラマの美へと移行しなければならないのである。こうして、この二種類の理想的な美が芸術の最も適切な対象を構成し、 ヘーゲルが芸術の「中心」(Mittelpunkt)と呼ぶものを形成するのである(PKÄ, 126)。 |

| 6.2 芸術の特殊な形態 | 6.2 芸術の特殊な形態 ヘーゲルはまた、芸術がそのような理想的な美に及ばず、またそれを超えなければならないことも認めている。象徴芸術の形態をとる場合には、理想的な美を下 回ることになり、ロマン主義芸術の形態をとる場合には、理想的な美を超えることになる。理想的な美そのものを特徴とする芸術が古典芸術である。これらは、 ヘーゲルが芸術の理念そのものによって必要とされると考える、芸術の三つの形式(Kunstformen)、すなわち「美の形式」(PKÄ, 68)である。一つの形式から別の形式への芸術の発展は、ヘーゲルが芸術の特徴的な歴史とみなすものを生み出す。 これら三つの芸術形式を生み出すのは、芸術の内容-精神としてのイデア-とその表現様式との間の関係の変化である。この関係の変化は、芸術の内容そのもの がどのように構想されるかによって決定される。象徴芸術では、内容は抽象的に構想され、感覚的で目に見える形では十分に現れない。対照的に、古典芸術で は、内容は感覚的で目に見える形で完全な表現を見出すことができるように構想される。ロマン派芸術では、内容は官能的で目に見える形の中に十分な表現を見 出すことができ、しかも最終的には官能的で目に見える領域を超越するように構想される。 古典芸術が理想的な美の本場であるのに対し、ロマン主義芸術は、ヘーゲルが「内なる美」(Schönheit der Innigkeit)と呼ぶもの、あるいはノックスが訳したように「深い感情の美」(Aesthetics, 1: 531)の本場である。これとは対照的に、象徴芸術は、真の美にはまったく及ばない。だからといって、単に悪い芸術というわけではない: ヘーゲルは、象徴芸術がしばしば最高水準の芸術性の産物であることを認めている。象徴芸術が美に欠けるのは、神と人間の精神の本質を十分に理解していない からである。それゆえ、象徴芸術が生み出す芸術的造形が欠落しているのは、その根底にある精神に対する概念、すなわち宗教の中にとりわけ含まれている概念 が欠落しているからなのである(PKÄ, 68)。 6.2.1 象徴芸術 ヘーゲルの象徴芸術に関する説明は、多くの異なる文明の芸術を包含しており、非西洋芸術に対する彼の相当な理解と評価を示している。しかし、ヘーゲルが論 じているすべての種類の象徴芸術が、完全かつ適切に象徴的であるとは限らない。では、それらすべてを結びつけるものは何なのか?それらはすべて、ヘーゲル が「前芸術」(Vorkunst)と呼ぶ領域に属するという事実である(PKÄ, 73)。ヘーゲルにとっての芸術とは、自由な精神の感覚的な表現であり、自由を表現するために人間によって意図的に形づくられ、加工された媒体(金属、 石、色彩など)における自由な精神の顕現である。プレ・アート」の領域は、ある意味で本来の芸術には及ばない芸術で構成されている。これは、自分自身が真 に自由であることをまだ理解していない精神の産物であるか、あるいは、自分自身の自由の感覚は持っているが、その自由が、その目的のために特別に形作られ た感覚的な媒体に自分自身を現すことをまだ理解していない精神の産物であるかのいずれかである。いずれにせよ、本物の芸術に比べれば、「芸術以前」は比較 的抽象的な精神の概念の上に成り立っている。 象徴芸術についてのヘーゲルの意図は、あらゆる種類の「前芸術」を網羅的に論評することではない。例えば、先史時代の芸術(洞窟画など)については何も 語っていないし、中国の芸術や仏教の芸術についても論じていない(宗教哲学の講義では中国の宗教と仏教の両方について論じているが)。象徴芸術についての ヘーゲルの目的は、芸術の概念そのものによって必要とされるさまざまな種類の芸術、すなわち芸術が芸術以前から芸術そのものに至るまでに通過しなければな らない段階を考察することである。 最初の段階は、精神が自然との直接的な一体性にあると考えられる段階である。この段階は、古代ペルシャの宗教ゾロアスター教に見られる。ヘーゲルによれ ば、ゾロアスター教徒は神の力(善)を信じているが、彼らはこの神性を自然そのものの一側面、すなわち光と同一視している。光は別個の神や善を象徴したり 指し示したりするのではなく、ゾロアスター教では(ヘーゲルが理解するように)光こそが善であり、神なのである(『美学』1: 325)。光は万物に宿る物質であり、すべての動植物に生命を与えるものである。この光はオルムズド(あるいはアフラ・マズダ)として擬人化されていると ヘーゲルは説く。しかし、ユダヤ人の神とは異なり、オルムズドは自由で自意識的な主体ではない。彼(またはそれ)は光そのものの姿をした善であり、太陽、 星、火といったあらゆる光源の中に存在する。 我々が問わねばならないのは、善を光として見ること(あるいは、そのような直観を口にすること)が芸術として数えられるかどうかということだ、とヘーゲル は指摘する(PKÄ, 76)。一方では、善は光とは異なる自由な精神であると理解されるのではなく、光の中に自らを現すものであると理解され、他方では、善が存在する感覚的な 要素、すなわち光そのものは、自由な精神によって自己表現のために形成されたり生み出されたりするものではなく、善がただちに同一である自然の所与の特徴 であると理解される。 ゾロアスター教における光としての善のヴィジョンにおいて、私たちは「神的なものの感覚的な提示(Darstellung)」(PKÄ, 76)に遭遇する。しかし、このヴィジョンは、よく練られた祈りや発話の中で表現されているとはいえ、芸術作品にはならない。 前芸術の発展における第二段階は、精神と自然との間に直接的な差異が存在する段階である。ヘーゲルの考えでは、これはヒンドゥー芸術の中に見られる。精神 的なものと自然的なものとの間に差異があるということは、精神的なもの、すなわち神的なものを、(ペルシアにおけるように)自然のただちに与えられた側面 と単純に同一視することはできないということである。一方、ヘーゲルは、ヒンドゥー教における神とは、抽象的で不確定なものであり、感覚的で外的で自然的 なものの中にのみ、またそれらを通してのみ、確定的な形を獲得するものだと主張する。こうして神とは、感覚的で自然なものの形そのものに存在すると理解さ れる。ヘーゲルは1826年の美学講義でこう言っている: 「自然物-人間、動物-は神聖なものとして崇められる」(PKÄ, 79)。 ヒンドゥー芸術は、神が存在すると想像される自然の形態を拡張し、誇張し、歪めることによって、精神的なもの(あるいは神的なもの)と単なる自然との違い を示す。したがって、神的なものは動物や人間の純粋に自然な姿ではなく、不自然に歪んだ姿で描かれる。(たとえば、シヴァ神は多くの腕を持ち、ブラフマー は4つの顔を持つ姿で描かれる)。 ヘーゲルは、このような描写には、表現媒体を「形作る」あるいは「形成する」作業が含まれると指摘する(PKÄ, 78)。その意味で、ヒンドゥー教の "芸術 "を語ることができる。しかし彼は、ヒンドゥー芸術は自由な精神に適切で十分な形を与えず、それによって美のイメージを創造しないので、芸術の真の目的を 果たしていないと主張する。むしろ、動物や人間の自然な姿を、「醜い」(unscön)、「怪物的な」、「グロテスクな」、「奇妙な」(PKÄ, 78, 84)姿に歪めることで、自然的・感覚的なものでなければ理解できない神性や霊性が、自然的・感覚的な領域とは異なるものであり、自然的・感覚的な領域で は適切な表現が見いだせないことを示そうとしている。ヒンドゥー教の神性は自然の形態と不可分であるが、それが採用する自然の形態の不自然さによって、そ の独特な存在を示している。 ところで、ヒンドゥー芸術に対するヘーゲルの判断は、そのような芸術にまったく長所を見出さないという意味ではない。彼はヒンドゥー芸術の素晴らしさと、 そのような芸術が示すことのできる「最も優しい感情」と「最も優れた感覚的自然性の豊かさ」について述べている。しかし彼は、ヒンドゥー芸術は、精神がそ れ自体で自由であることを示し、適切な自然で目に見える形を与えられる芸術の高みに到達できていないと主張する(PKÄ, 84)。 前芸術」の発展における第三の段階は、純粋に象徴的な芸術の段階であり、そこでは形やイメージが、「内面性」(Innerlichkeit)の確定され た、まったく別の領域を指し示すために、意図的にデザインされ、創造される(PKÄ, 86)。これは古代エジプト美術の領域である。ヘーゲルによれば、エジプト人は、精神が内面的なものであり、それ自体が分離し独立したものであるという考 えを「固定」(fixieren)した最初の人々である(PKÄ, 85)。(この文脈でヘーゲルは、エジプト人が「魂の不滅の教義を提唱した最初の人々」[Herodotus, 145 [2: 123]]であると主張したヘロドトスを参照している)。ヘーゲルが(主観的精神と客観的精神の哲学において)理解するところの精神とは、イメージ、言 葉、行為、制度において自らを外在化し、表現する活動である。それゆえ、「内面性」としての精神という考え方には、この内面的な精神に外的な形を与えよう とする、つまり、精神そのものから精神の形を生み出そうとする衝動が必然的に生じる。内的領域が自らを知らしめることができるような形やイメージ-芸術作 品-を創造しようとする衝動は、このようにエジプト人の精神理解の仕方に深く根ざした「本能」なのである。この意味で、ヘーゲルに言わせれば、エジプト文 明はヒンドゥー文明よりも深遠な芸術文明なのである(『美学』1: 354; PKÄ, 86)。 しかし、エジプトの芸術は象徴芸術でしかなく、完全な意味での芸術ではない。というのも、エジプト美術の創造された形やイメージは、精神に直接的で適切な 表現を与えるものではなく、ただ、見え隠れする内面性を指し示し、象徴しているにすぎないからである。さらに、内なる精神は、エジプト人の理解では「独立 した内面」(PKÄ, 86)として固定されているが、それ自体が完全に自由な精神として理解されているわけではない。実際、エジプト人にとって精神の領域は、自然や生命の領域 の単純な否定として理解されている。つまり、何よりも死者の領域として理解されているのである。 死が魂の独立性を維持する主要な領域であるという事実は、エジプト人にとって魂の不滅の教義が重要である理由を説明する。また、ヘーゲルがエジプトの象徴 芸術を象徴するイメージとしてピラミッドを見ている理由も説明できる。ピラミッドは創造された形であり、その中に何か別のもの、つまり死体が隠されてい る。それゆえ、ピラミッドは、エジプトの象徴の完璧なイメージとして機能する。ピラミッドは、それ自体を明らかにし、表現することはないが、独立した内面 性の領域を指し示しているのである。 ヘーゲルにとって、ギリシア美術は象徴的要素(ゼウスの力を象徴する鷲など)を含むが、ギリシア美術の核心は象徴ではない。これとは対照的に、エジプト美 術は徹頭徹尾象徴的である。実際、ヘーゲルの考えでは、エジプト人の意識は全体として本質的に象徴的である。たとえば動物は、より深いものの象徴あるいは 仮面とみなされ、動物の顔はしばしば仮面として使われる(とりわけ防腐処理師によって)。不死鳥のイメージは、消滅と再出現という自然(特に天体)のプロ セスを象徴しているとヘーゲルは主張するが、そのプロセス自体が精神的な再生の象徴とみなされている(PKÄ, 87)。 前述したように、ピラミッドはエジプト人の象徴芸術を象徴している。しかし、そのような芸術は、単に死者の領域を象徴的に指し示すだけでなく、真の内面性 は生きている人間の精神の中にあるという、初期的ではあるがまだ未発達な意識の証しでもある。ヘーゲルは、人間の精神が動物から抜け出そうと奮闘する姿を 描くことによって、そうしているのだと主張する。この出現を最もよく表しているのは、もちろんスフィンクス(ライオンの体と人間の頭を持つ)のイメージで ある。また、ホルス(人間の体とハヤブサの頭を持つ)のような神々のイメージにも、人間の姿と動物の姿が混在している。しかし、このようなイメージは、完 全な人間の姿にある自由な精神を十分に表現できていないため、完全な意味での芸術とはいえない。なぜなら、それらは完全な人間の形をした自由な精神を十分 に表現できていないからである。それらは、その真の性格が見えないまま(エジプト人自身にとっても謎のまま)の内面性を部分的に開示する象徴にすぎない。 エジプト美術の中で人間の形が不純物なしに描かれたとしても、それは純粋に自由で生きた精神に生かされているわけではないので、自由そのものの形にはなら ない。西テーベにあるアメンヘテプ3世のメムノン・コロッシのような人物は、ヘーゲルに言わせれば「動きの自由」(PKÄ, 89)を示さないし、腕を両脇に押しつけ、足をしっかりと地面につけて立っている他の小さな人物は、「動きの優美さ」(Grazie)を欠いている。ヘー ゲルはエジプト彫刻を「賞賛に値する」と賞賛している。実際、プトレマイオス朝時代(紀元前305-30年)のエジプト彫刻は素晴らしい「繊細さ」(ある いは「優雅さ」)(Zierlichkeit)を示していたと彼は主張している。それにもかかわらず、エジプト美術はその長所にもかかわらず、真の自由と 生命を形にしていないため、美術の真の目的を果たしていないのである。 芸術以前の第四段階は、精神が自由と独立の度合いを増し、精神と自然が「バラバラになる」段階である(PKÄ, 89)。この段階は3つに細分される。第一は、崇高な芸術、すなわちユダヤ人の詩的芸術である。 ユダヤ教では、精神は完全に自由で独立したものであるとヘーゲルは主張する。しかし、この自由と独立は、人間の精神というよりもむしろ神に帰せられる。こ うして神は「自由な霊的主体」(PKÄ, 75)として考えられ、世界の創造者であり、自然で有限なものすべてを支配する力を持っている。それとは対照的に、自然で有限なものは、神との関係におい て「否定的」なもの、つまり、それ自身のために存在するのではなく、神に仕えるために創造されたものと見なされる(PKÄ, 90)。 ヘーゲルに言わせれば、ユダヤ教の精神性は、真の美を生み出すことはできない。なぜなら、ユダヤ教の神は、自然と有限性の世界を超越しており、その世界に 自らを現すことも、その世界に目に見える形を与えることもできないからである。ユダヤの詩(詩篇)はむしろ、万物の源である神を賛美し高揚させることに よって、神の崇高さを表現する。同時に、このような詩は、罪深い者が主との関係で感じる苦痛や恐れを「輝かしい」(glänzend)表現として与える (PKÄ, 91)。 この第四段階の前芸術の第二の下位区分は、ヘーゲルが「東洋的汎神論」と呼ぶものからなり、ペルシアの抒情詩人ハーフェズ(ドイツ語ではハーフィス) (1310年頃-1389年)のようなイスラムの「アラブ人、ペルシア人、トルコ人」(PKÄ, 93年)の詩に見られる。このような汎神論では、神もまた、有限で自然な領域から離れ、その上に崇高に立つと理解されるが、その領域との関係は否定的では なく肯定的であるとされる。神は事物をその壮大さへと引き上げ、精神で満たし、生命を与え、この意味で事物の中に実際に内在しているのである(『美学』 1: 368; PKÄ, 93)。 このことが、詩人と対象との関係を決定する。詩人もまた、事物から自由で独立しているが、同時に事物に対して肯定的な関係を持っている。つまり、詩人は事 物との同一性を感じ、その中に自らの何不自由ない自由が反映されているのを見るのである。薔薇のような自然物を、「陽気で祝福された内面」(PKÄ, 94-5)という自分自身の感情の詩的な「イメージ」(Bilder)として用いるからである。しかし、汎神論的精神は、自然物とは区別され、また自然物 との関係において、それ自身の内に自由を保っている。(ところで、ヘーゲルの美学講義のホト版では、汎神論的なイスラムの詩は、ユダヤ教の詩の後ではな く、その前に置かれていることに注意されたい。) 芸術以前の第四段階の第三の下位区分は、精神と自然または感覚の領域との間に最も明確な断絶がある段階である。この段階では、精神的な側面、つまり内面的 なもの、いわば目に見えないものは、まったく別個のはっきりとしたものの形をとる。それはまた、有限で限定されたもの、つまり人間が抱く観念や意味でもあ る。感覚的な要素もまた、意味とは別個のものである。それは意味とは本質的なつながりはなく、ヘーゲルが言うように、意味の「外部」にある。感覚的な要 素、つまり絵画的あるいは詩的なイメージは、このように詩人の主観的な「機知」や想像力以外の何ものでもなく、意味と結びついている(PKÄ, 95)。ヘーゲルは、寓話、たとえ話、寓意、隠喩、比喩においてこのようなことが起こると主張する。 この第三の下位区分は、特定の文明とは関係なく、さまざまな文明に見られる表現形式である。しかしヘーゲルは、寓意、隠喩、比喩は真に美しい芸術の中核を なすものではないと主張する。なぜなら、それらは精神そのものの自由を私たちに示すものではなく、別個独立の意味を指し示す(つまり象徴する)ものだから である。アキレウスはライオンである」というような比喩は、ギリシア彫刻がそうであるように、個々の英雄の精神を体現しているのではなく、その比喩自体と は別個の何かの比喩なのである(『美学』1: 402-8; PKÄ, 104参照)。 象徴芸術(あるいは「前芸術」)についてのヘーゲルの説明は、ハイデルベルクでの元同僚で、『古代民族、特にギリシア人の象徴と神話』(1810-12) の著者であるゲオルク・フリードリヒ・クロイツァーなど、他の作家の仕事を広く参考にしている。ヘーゲルの説明は、厳密に歴史的であることを意図している のではなく、むしろ、議論されている芸術以前のさまざまな形態を、互いに論理的な関係に置くことを意図している。この関係は、芸術以前の各形態において、 精神と自然(あるいは感覚的なもの)が互いにどの程度区別されるかによって決定される。 ゾロアスター教では、精神と自然は(光として)互いに即時的な同一性を持っている。ヒンドゥー美術では、霊的なもの(神)と自然との間に直接的な差異があ るが、霊的なものはそれ自体抽象的で不確定なままであるため、(不自然に歪められた)自然物のイメージを通してのみ思い浮かべることができる。エジプト美 術において、霊的なものはまた、単に自然で感覚的なものとは異なる。しかし、ヒンズー教の不確定な神性とは対照的に、エジプトの霊性(神々の形と人間の魂 の形)は、それ自体が固定され、分離され、決定されている。したがって、エジプト美術のイメージは、直接見ることのできない精神の領域を象徴的に指し示し ている。しかし、そのような象徴的なイメージが指し示す精神は、真の自由と生命を欠いており、しばしば死者の領域と同一視される。 ユダヤ人の崇高な詩において、神は超越的で "自由な霊的主体 "として表現される。しかし、有限の人間は、神に仕え賛美するために創造され、自らの罪深さに苦悩するという点で、神との否定的な関係で描かれる。東洋の 汎神論」の崇高な詩では、神は再び超越的な存在として描かれるが、ユダヤ教とは対照的に、神と有限の事物は互いに肯定的な関係に立つことが示される。それ ゆえ、詩人と事物との関係は、彼自身の自由な精神が周囲の自然の事物に反映されていることを見出すものである。 精神的要素("意味")と感覚的要素("形 "や "イメージ")は、今や互いに完全に独立し、外部にある。さらに、それぞれが有限であり、限定されている。これが寓意と比喩の領域である。 6.2.2 古典芸術 ヘーゲルは、芸術以前の壮麗さや優美さを否定はしないが、それは本来の芸術には及ばないと主張する。後者は古典芸術、すなわち古代ギリシアの芸術に見出さ れる。 古典芸術は、精神の自由の完璧な感覚的表現であるという点で、芸術の概念を満たしているとヘーゲルは主張する。それゆえ、古典芸術、とりわけ古代ギリシア の彫刻(および演劇)においてこそ、真の美が見出されるのである。実際、ヘーゲルは、古代ギリシアの神々が「絶対的な美」を示していると主張している: 「古典的なものほど美しいものはなく、理想的なものがある」(PKÄ, 124, 135; Aesthetics, 1: 427も参照)。 このような美は、精神的なものと感覚的なもの(あるいは自然的なもの)との完璧な融合によって成り立っている。真の美において、私たちの前にある目に見え る形は、その形の不自然な歪みによって、単に神の存在を示すだけでなく、それ自体を超えて、隠された霊性や神の超越を指し示すのでもない。むしろ、形はそ の輪郭そのものに自由な霊性を顕し、体現しているのである。したがって、真の美においては、目に見える形は、その形を超えたところにある意味の象徴や比喩 ではなく、精神の自由を直接目に見える形で表現したものなのである。美とは、官能的で目に見える形であり、それが自由そのものの目に見える体現として立つ ように変容したものである。 例えば、ゼウスの父であるクロノスが自分の子供を食したという話は、時間の破壊力を象徴している(『美学』1: 492; PKÄ, 120)。しかし、ヘーゲルの考えでは、ギリシア芸術の際立った核心は、精神の自由が歴史上初めて可視化された理想的な美の作品にある。そのような美しい 芸術が生み出されるためには、3つの条件が満たされなければならなかった。 第一に、神とは自由に自己決定する精神であり、(光のような抽象的な力ではなく)神の主観性であると理解されなければならなかった。第二に、神とは彫刻や 演劇に描かれるような個人の形をとるものと理解されなければならなかった。言い換えれば、神とは崇高な超越的存在としてではなく、さまざまな形で体現され る霊性であると理解されなければならなかった。ギリシア芸術の美は、このようにギリシアの多神教を前提としていた。第三に、自由な精神のあるべき姿は、動 物のそれではなく、人間の身体であると認識されなければならなかった。ヒンドゥー教やエジプトの神々は、しばしば人間と動物の融合した姿で描かれた。対照 的に、ギリシアの主要な神々は理想的な人間の姿で描かれた。ヘーゲルは、ゼウスが誘惑するときなど、動物の姿になることがあると記しているが、誘惑のため にゼウスが牛に変身するのは、ギリシア世界にエジプト神話の余韻を残すものだと考えている(PKÄ, 119-20参照。ヘーゲルは、別の物語で、嫉妬深いヘラから身を守るためにゼウスによって白い牛に変身させられたイオと、ヘーゲルが念頭に置いている物 語でゼウスの愛の対象であったエウロパを混同している)。 ギリシアの芸術と美は、ギリシアの宗教と神話を前提としているだけでなく、ギリシアの宗教そのものが、神々に決定的なアイデンティティを与えるために芸術 を必要としているのである。ヘーゲルが(ヘロドトスに倣って)述べているように、ギリシア人に神々を与えたのは詩人ホメロスやヘシオドスであり、ギリシア 人の神々に対する理解は、(神学的な著述よりもむしろ)彫刻や演劇のなかで発展し、表現されたのである(PKÄ, 123-4)。こうしてギリシアの宗教は、『現象学』の中でヘーゲルが "芸術の宗教 "と呼んだような形をとった。さらに、ヘーゲルに言わせれば、ギリシア芸術が最高の美を達成したのは、まさにそれがギリシア宗教に謳われている精神の自由 の最高の表現であったからである。 ギリシアの彫刻や演劇は比類なき美の高みに達したが、そのような芸術は精神の最も深い自由を表現するものではなかった。これは、神と人間の自由に対するギ リシア人の概念に欠陥があったからである。ギリシアの宗教が美的表現に非常に適していたのは、神々が肉体や感覚的生活と完全に一体化した自由な個人として 考えられていたからである。言い換えれば、神々は自然の中に没入している自由な精神だったのである(PKÄ, 132-3)。しかし、ヘーゲルの考えでは、精神が自然から自らに引きこもり、純粋な自己認識の内面性となるときに、より深い自由が達成される。そのよう な精神の理解は、ヘーゲルによれば、キリスト教において表現される。キリスト教の神は純粋な自己認識の精神と愛であり、人間を創造したのは、人間もそのよ うな純粋な精神と愛になるためである。キリスト教の出現によって、ロマン主義芸術という新しい芸術の形態が生まれた。ヘーゲルが「ロマン派」という言葉を 使うのは、18世紀末から19世紀初頭にかけてのドイツ・ロマン派(その多くはヘーゲルが個人的に知っていた)の芸術を指すのではなく、西洋キリスト教圏 で生まれた芸術の伝統全体を指すためである。 6.2.3 ロマン主義芸術 ロマン主義芸術は、古典芸術と同様、精神の自由を感覚的に表現したものである。そのため、本物の美を表現することができる。しかし、その自由は、芸術その ものではなく、宗教的な信仰や哲学の中に最高の表現と明確さを見出す、内面的な自由である。したがって、古典芸術とは異なり、ロマン主義芸術は、芸術を超 えたところにある精神の自由を表現するものなのである。古典芸術が精神と生命に満ち溢れた人間の身体に例えられるとすれば、ロマン派芸術は内なる精神と個 性を開示する人間の顔に例えられる。しかし、ロマン主義芸術は、単に内なる精神を指し示すのではなく、実際に内なる精神を開示しているのであるから、他の 点で似ている象徴芸術とは異なる。 ヘーゲルにとって、ロマン主義芸術は3つの基本的な形態をとる。第一は、明白に宗教的な芸術である。ヘーゲルは、キリスト教においてこそ精神の本性が明ら かになると主張する。キリストの生涯、死、復活の物語に表されているのは、自由と愛に満ちた真に神聖な人生とは、同時に、自分自身に「死」んで、自分に とって最も大切なものを手放すことを厭わない、完全に人間的な人生であるという考え方である。したがって、宗教的なロマン主義芸術の多くは、キリストの苦 しみと死に焦点を当てている。 ヘーゲルは、ギリシャ神話の神や英雄のような理想化された肉体でキリストを描くことは、ロマン主義芸術にはふさわしくないと指摘する。それゆえ、ロマン主 義芸術は古典的な美の理想と決別し、現実の人間の弱さ、痛み、苦しみをキリスト(そして宗教的な殉教者)のイメージに取り入れるのである。実際、そのよう な芸術は、苦しみの描写において「醜い」(unschön)とさえ言える(PKÄ, 136)。 しかし、ロマン主義芸術が芸術の目的を果たし、真の精神の自由を美という形で提示しようとするならば、苦悩するキリストや苦悩する殉教者たちが、深い内面 的な感情(Innigkeit)と真の和解の感覚(Versöhnung)を帯びていることを示さなければならない(PKÄ, 136-7)。この内なる和解の感覚を(色や言葉で)感覚的に表現することが、ヘーゲルが「内なる美」あるいは「霊的な美」(geistige Schönheit)と呼ぶものを構成するのである(PKÄ, 137)。厳密に言えば、このような精神的な美は、精神と肉体とが完全に融合した古典的な美ほど完全な美ではない。しかし、精神的な美は、古典的な美より もはるかに深遠な精神の内的自由の産物であり、それを明らかにするものである。 ヘーゲルの考えでは、視覚芸術の中で最も深遠な精神美は、聖母子像の絵画に見出される。ヘーゲルは、1827年にゲントとブルージュを訪れた際に見たフラ ンドル原始派のヤン・ファン・エイクとハンス・メムリングの絵画に特別な愛情を抱いていたが(Hegel: The Letters, 661-2)、ラファエロも高く評価しており、1820年にドレスデンで見たラファエロのシスティーナの聖母における「敬虔で慎み深い母の愛」の表現に特 に感動した(PKÄ, 39; Pöggeler et al 1981, 142)。ギリシアの彫刻家たちは、ニオベを子供たちを失った「苦痛に茫然自失」した姿として描いた。これとは対照的に、聖母マリアの絵画像は、ファン・ エイクやラファエロによって、ギリシアの彫像が決して及ばないような「永遠の愛」と「魂のこもったもの」を帯びている(PKÄ, 142, 184)。 ヘーゲルが特定したロマン主義芸術の第二の基本形式は、彼が自由精神の世俗的な「美徳」と呼ぶものを描くことである(『美学』1: 553; PKÄ, 135)。これは、ギリシア悲劇の英雄やヒロインが示すような倫理的な美徳ではなく、家族や国家といった自由のために必要な制度へのコミットメントを伴わ ない。つまり、自由な個人による、しばしば偶発的な選択や情熱に基づく、対象や他者へのコミットメントである。 このような美徳には、ロマンティックな愛(特定の偶発的な人物に集中する)、個人に対する忠誠心(自分に有利になるなら変わることもある)、勇気(遭難し た乙女を救うなど個人的な目的を追求する際に示されることが多いが、聖杯探しなど準宗教的な目的を追求する際にも示されることがある)などがある (PKÄ, 143-4)。 このような美徳は、主に中世騎士道の世界に見られる(そして、セルバンテスの『ドン・キホーテ』では嘲笑の対象になっているとヘーゲルは指摘する)(『美 学』1: 591-2; PKÄ, 150)。しかし、これらの美点は、より現代的な作品にも現れることがあり、実際、ヘーゲルが何も知らなかった芸術形式、すなわちアメリカの西部劇にこそ 表れているのである。 ロマン主義芸術の第三の基本形式は、形式的な自由と人格の独立を描くことである。このような自由は、倫理的原則とも、(少なくとも主要な)形式的美徳とも 結びつかないが、単純に人格の「堅固さ」(Festigkeit)から成っている(『美学』1: 577; PKÄ, 145-6)。これが現代の世俗的な自由である。それは、シェイクスピアの戯曲に登場するリチャード三世、オセロ、マクベスといった人物によって、最も見 事に示されるとヘーゲルは考えている。そのような人物について私たちが関心を抱くのは、道徳的な目的(いずれにせよ、彼らは必ず欠如している)ではなく、 単に彼らが示すエネルギーと自己決定力(そしてしばしば冷酷さ)であることに留意してほしい。そのようなキャラクターは、(想像力と言語によって明らかに される)内面的な豊かさを持っていなければならず、ただ一面的であるだけであってはならないが、彼らの主な魅力は、自らの命を犠牲にしてでも行動方針にコ ミットする形式的な自由である。これらの登場人物は、道徳的・政治的理想を構成するものではないが、最も世俗的で非道徳的な形であっても自由を描くことを 任務とする近代ロマン主義芸術の対象としてふさわしい。 ヘーゲルはまた、シェイクスピアのジュリエットのような、より内面的に繊細な登場人物にもロマンティックな美を見出す。ヘーゲルは、ロミオと出会った後、 ジュリエットは突然、バラのつぼみのような、子供のような素朴さに満ちた愛に目覚める。彼女の美しさは、このように愛の体現であることにある。ゲーテが考 えたように)ハムレットは単に弱いのではなく、ヘーゲルに言わせれば、深く高貴な魂の内なる美しさを示しているのである(『美学』1: 583; PKÄ, 147-8)。 6.2.4 芸術の「終わり ヘーゲルが言うように、ロマン主義芸術の発展には、芸術の世俗化と人間化の進行が含まれていることに注意すべきである。中世とルネサンスでは(古代ギリシ アと同様)、芸術は宗教と密接に結びついていた。しかし宗教改革によって、宗教は内側に向かい、芸術のイコンやイメージの中ではなく、信仰のみに神が存在 することを見出した。その結果、宗教改革以降に生きる私たちは「もはや芸術作品を崇めることはない」(VPK, 6)とヘーゲルは指摘する。さらに、芸術そのものが宗教との密接な結びつきから解き放たれ、完全に世俗的なものになることを許された。ヘーゲルは、「プロ テスタンティズムにとって重要なことは、生活の散文において確かな足場を得ること、宗教的な結びつきとは無関係にそれ自体として絶対的に成立するようにす ること、そして、制限のない自由のうちに発展させることである」と述べている(『美学』1: 598)。 ヘーゲルの考えでは、このような理由から、現代における芸術はもはや私たちの最高の欲求を満たすものではなく、以前の文化や文明が与えてくれたような満足 感を私たちに与えてはいないのである。芸術が私たちの最高の欲求を満たしていたのは、それが私たちの宗教生活に不可欠な部分を形成し、神の本質(そしてギ リシアにおけるように、私たちの基本的な倫理的義務の真の性格)を私たちに明らかにしていたときであった。しかし、宗教改革後の近代世界では、芸術は宗教 への従属から解放された(あるいは解放された)。その結果、「芸術は、その最高の使命において考慮されるものであり、私たちにとって過去のものである」 (『美学』1: 11)。 だからといって、芸術には何の役割もなく、何の満足も得られないというわけではない。芸術はもはや、(ヘーゲルによれば、5世紀のアテネにおいてそうで あったように)真理を表現する最高で最も適切な方法ではない。私たち現代人は今や、芸術よりもむしろ、宗教的信仰や哲学に究極の、あるいは「絶対的な」真 理を求めている。(実際、ヘーゲルに言わせれば、私たちが哲学を重要視していることは、近代における芸術そのものの哲学的研究が際立っていることからも明 らかである[『美学』1: 11; VPK, 6]。しかし、近代における芸術は、人間的な自由を目に見えたり耳に聞こえたりする形で表現し、有限な人間性のすべてにおいて自分自身を理解するという重 要な機能を果たし続けている。 したがって、ヘーゲルは、芸術全体が近代において単に終焉を迎える、あるいは「死ぬ」と主張しているのではない。彼の見解は、むしろ、芸術は古代ギリシャ や中世の時代よりも限定された役割を果たす(あるいは少なくとも果たすべきである)というものである。しかしヘーゲルは、近代における芸術は、ある点では 終焉を迎えると考えている。なぜそう考えるのかを理解するためには、近代における芸術は、一方では日常的な偶発性の探求に、他方では機知に富んだ「ユーモ ラス」な主観性の賛美に「分解」(zerfällt)するという彼の主張を検討する必要がある(PKÄ, 151)。 ヘーゲルに言わせれば、宗教改革以降の絵画や詩の多くは、宗教的愛の親密さや悲劇的英雄の壮大な決意やエネルギーよりも、日常生活の平凡な細部に注意を向 けている。そのような芸術作品が、もはや神や人間の自由を表現することを目的とせず、(少なくとも見かけ上は)「自然を模倣する」ことだけを目的としてい る限りにおいて、ヘーゲルは、(より一般的に受け入れられている意味とは対照的に)厳密には哲学的な意味での「芸術作品」として数えられるかどうかを検討 することになる。20世紀において、「これは芸術なのか?「これは芸術なのか?しかし、ヘーゲルの考えでは、この問いを提起するのは、純粋に自然主義的で 「表象的」に見える作品である。そのような作品は、単に自然を模倣する以上のことをして初めて、本物の芸術作品として数えられるというのが彼の見解であ る。この基準を最もよく満たす自然主義的で平凡な作品は、16~17世紀のオランダの巨匠たちの絵画だと彼は主張する。 ヘーゲルは、このような作品において、画家は単にブドウや花や木がどのように見えるかを示すことが目的ではないと主張する。画家はむしろ、物事の、しばし ばはかない「生命」(Lebendigkeit)を捉えようとしている: 金属の光沢、蝋燭の光に照らされた葡萄の房のきらめき、月や太陽の消え入りそうな片鱗、微笑み、過ぎ去る感情の表情」(『美学』1: 599)。実際、画家はしばしば、金、銀、ビロード、毛皮の色彩の生き生きとした戯れによって、私たちを特別に喜ばせようとする。ヘーゲルは、そのような 作品において、われわれは単なる事物の描写ではなく、「いわば客観的な音楽、色彩の歓声[ein Tönen in Farben]」(『美学』1: 598-600)に出会うのだと指摘する。 真の芸術作品とは、神または人間の自由と生命を感覚的に表現したものである。したがって、日常的な物や人間の活動を平凡な自然主義的描写で描いただけの絵 画は、真の芸術とは言えないように思われる。しかし、オランダの芸術家たちは、対象物に "完全な生命 "を吹き込むことによって、そのような描写を真の芸術作品に変えるのである。そうすることで、彼らは彼ら自身の自由、「快適さ」、「満足感」の感覚と、彼 ら自身の高揚した主観的技巧を表現するのだとヘーゲルは主張する(『美学』1: 599; PKÄ, 152)。そのような画家たちの絵画は、ギリシア美術のような古典的な美しさには欠けるかもしれないが、日常的な現代生活の微妙な美しさや喜びを見事に表 現している。 ヘーゲルは、主観性のもっとあからさまな表現を、近代的なユーモアの作品に見出している。そのような機知に富んだ、皮肉に満ちた、ユーモラスな主観性は、 現在では「アナーキー」と表現されるかもしれないが、対象物と戯れたり「スポーツ」したり、素材を「錯乱」させたり「倒錯」させたり、「あちこちを漫然と 行き来」したり、「主観的な表現、見解、態度が十字に動き回り、それによって作者は自分自身とそのテーマを同様に犠牲にする」(『美学』1: 601)ことに現れる。ヘーゲルは、ローレンス・スターンの『トリストラム・シャンディ』(1759年)のような「真のユーモア」の作品は、「実質的なも のを偶発性から出現させる」ことに成功していると主張する。その「くだらなさ(こうして)こそが、深みという至高の観念をもたらす」(『美学』1: 602)。これとは対照的に、ヘーゲルと同時代に活躍したジャン・パウル・リヒターの作品では、私たちが遭遇するのは、「客観的に互いに最もかけ離れた物 事のバロック的な寄せ集め」であり、「彼自身の主観的想像力の中だけで関連づけられた話題の、最も混乱した無秩序なごちゃまぜ」である(『美学』1: 601)。このような作品では、人間の自由がそれ自体に客観的な表現を与えるのではなく、主観性が「自らを客観的なものとし、現実の中で確固たる形を勝ち 取ろうとするあらゆるものを破壊し、溶解させる」(『美学』1: 601)のを目撃するのである。 ユーモアの作品が、真の自己決定的な自由と生命を体現するものではなく、また「深みの至高の理念」を与えるものではなく、ただ恣意的で主観的な機知が定 まった秩序を破壊する力を示すものである限り、ヘーゲルに言わせれば、そのような作品はもはや本物の芸術作品とは言えない。その結果、「主体がこのように 自らを解放するとき、芸術はそれによって終焉を迎える[so hört damit die Kunst auf]」(PKÄ, 153)。この点で、ヘーゲルは近代において芸術が終焉を迎えることを宣言している。それは、芸術がもはや宗教的な機能を果たさなくなり、芸術の最高の使 命を果たさなくなったからではなく、近代において、もはや人間の真の自由と生の表現ではなく、真正の芸術作品ではなくなってしまったある種の「芸術作品」 が出現するからである。 しかし、前述したように、これは芸術全体が19世紀初頭に終焉を迎えることを意味するものではない。ヘーゲルの考えでは、芸術にはまだ未来がある: 「われわれは、芸術がつねにより高く、完全なものへと到達することを希望してもよい」(『美学』1: 103)。ヘーゲルにとって、現代(そして未来)における真の芸術、ひいては真に近代的な芸術の特徴は二つある。一方では、それは具体的な人間の生活と自 由を表現することに縛られたままであり、他方では、もはや3つの芸術形式のいずれにも限定されない。つまり、古典芸術の礼儀を守る必要もなければ、ロマン 主義芸術に見られるような激しい感情の内面や英雄的な自由、あるいは心地よい平凡さを追求する必要もない。ヘーゲルにとっての現代芸術は、人間生活の表現 において、あらゆる芸術形式(象徴芸術を含む)の特徴を利用することができる。実際、自然の描写を通して間接的に人間の生活と自由を表現することもでき る。 したがって、現代美術の焦点は、人間の自由に関するある特定の概念に絞られる必要はない。芸術における新たな "聖なるもの "は、人間性そのもの--"Humanus"--すなわち「人間の心の深みと高み、喜びと悲しみ、努力、行い、運命における人間」(『美学』1: 607)である。ヘーゲルに言わせれば、近代芸術は「人間の心の無限性」を多様な方法で探求する、かつてない自由を享受しているのである(VÄ, 181)。だからこそ、ヘーゲルが今後の芸術の進むべき道について語ることはほとんどできない。 ヘーゲルの判断によれば、現代の芸術家たちは、好きなスタイルを採用する自由があり、それは極めて当然なことなのだが、ヘーゲルが1831年に亡くなって からの芸術の歴史は、それを確かに裏付けている。しかし、ヘーゲルがヘーゲル以後の芸術の発展の多くを歓迎しなかったかもしれないと疑う理由はある。とい うのも、ヘーゲルは近代芸術を支配するルールを定めてはいないものの、近代芸術が真の芸術であるために満たすべき一定の条件を示しているからである。例え ばヘーゲルは、そのような芸術は「単純に美しく、芸術的処理が可能であるという形式的法則に反してはならない」(『美学』1: 605; VPK, 204)と指摘している。彼は、近代芸術家はその内容を自らの人間の精神から引き出すべきであり、"人間の胸に生きている(lebendig)ものは、そ の精神から異質なものであってはならない "と主張している。彼はまた、近代芸術は「人間という存在がくつろぐことのできるすべてのもの」(『美学』1: 607)を表現することができると述べている。これらは一見何の変哲もない条件のように見えるが、ヘーゲル以後のある種の芸術作品は、ヘーゲルの目には本 物の芸術作品としてカウントされないことを示唆している。これには、どう考えても「美しい」とは呼べないような作品(ウィレム・デ・クーニングやフランシ ス・ベーコンの絵画など)や、明らかに「くつろぎ」を感じにくい作品(フランツ・カフカの著作など)が含まれるかもしれない。ヘーゲルが彫刻や絵画といっ た異なる芸術について語ったことは、彼が具象芸術から抽象芸術への移行を適切なものとは考えていなかったことを示唆している: ネーデルラントやオランダの画家たちは、色彩の戯れを通して「客観的な音楽」を創造することに秀でていたが、それは抽象的なものではなく、具体的で識別可 能な物体の描写そのものにおいてなされたのである。(この最後の点については、ロバート・ピピンは異なる見解を示している(ピピン2007参照)。 20世紀や21世紀の視点から見れば、ヘーゲルの姿勢は保守的に見えるかもしれない。しかし、ヘーゲルの視点からすれば、芸術作品が本物の芸術作品であ り、純粋に近代的であるためには、どのような条件が満たされなければならないかを理解しようとしていたのである。ヘーゲルが特定した条件、すなわち、芸術 は人間の自由と生活の豊かさを提示すべきであり、その描写の中で私たちがくつろげるようにすべきものであるという条件は、多くの近代芸術家(たとえば、モ ネ、シスレー、ピサロなどの印象派)が満たすことに何の問題も感じなかったものである。しかし、他の画家にとっては、このような条件はあまりにも制限的で ある。こうして、ヘーゲル的観点からすれば、近代芸術はもはや真の意味での芸術ではなくなってしまったのである。 |

| 6.3 個々の芸術の体系 | 6.3 個々の芸術の体系 ヘーゲルの説明では、芸術は歴史的な発展を遂げるだけでなく(象徴芸術から古典芸術を経てロマン主義芸術、そして近代芸術へ)、それ自体もさまざまな芸術 に分化する。それぞれの芸術は際立った性格を持ち、1つ以上の芸術形式と一定の親和性を示す。ヘーゲルは、認識されているすべての芸術について網羅的な説 明をしているわけではないが(例えば、舞踊についてはほとんど述べておらず、[言うまでもなく当時にはなかlちたので]映画については明らかに何も[参考 になるようなことは]述べていない)、芸術という概念そのものによって必要とされると彼が考える5つの芸術について考察している。 6.3.1 建築 芸術とは、神と人間の自由を感覚的に表現するものである。もし芸術が、精神が本当に自由であることを示すものであるならば、精神は、それ自体が自由でな く、精神を持たず、生命を持たないもの、つまり重力によって重くのしかかる三次元の無機物との関係において自由であることを示さなければならない。した がって、芸術とは、そのような野蛮で重い物質を、精神的自由の表現に変えること、あるいはヘーゲルが言うところの「無機的なものの形成」(VPK, 209)でなければならない。重い物質に精神的自由の明確な形を与え、石や金属を人間や神の形に作り上げる芸術は彫刻である。対照的に、建築は、人間の理 解によって創造された抽象的で無機的な形を物質に与える。彫刻のように物質に生気を与えるのではなく、物質に厳密な規則性、対称性、調和を与えるのである (PKÄ, 155, 166)。そうすることで、建築は物質を精神的自由の直接的な官能的表現ではなく、彫刻における精神的自由の直接的表現のための人工的かつ芸術的に形作ら れた周囲に変えるのである。したがって、建築の芸術は、神々の彫像を納めるための古典的な神殿を作るときに、その目的を果たすのである(VPK, 221)。 しかしヘーゲルは、古代ギリシアで古典建築が出現する以前には、建築は「独立」(selbständig)あるいは「象徴」建築という、より原始的な形態 をとっていたと指摘する(『美学』2: 635; PKÄ, 159)。この範疇に入る建築は、古典ギリシアの神殿のように個々の彫刻を納めたり取り囲んだりするのではなく、それ自体が部分的に彫刻的であり、部分的 に建築的である。建築彫刻あるいは彫刻建築の作品である。このような建築物は、それ自体のために建てられる限りにおいて彫刻的であり、他の何かを庇護した り囲ったりするためのものではない。しかし、あからさまに重く重厚で、彫刻のような躍動感に欠けるという点では、建築作品である。また、円柱のように一列 に並んでいることもあり、際立った個性はない。 これらの独立した建築の作品には、規則正しい無機的で幾何学的な形をしたもの(ヘロドトスが記したベル神殿など)(『ヘロドトス』79-80[1: 181]参照)、有機的な「自然界の生命の力」を明らかに具現化したもの(ファルスやリンガムなど)(『美学』2: 641)、抽象的で巨大なものではあるが人間の形をしているもの(エジプトのアメンヘテプ3世のメムノン神殿など)さえある。しかし、ヘーゲルの考えで は、このような建造物はすべて、それを建てた人々にとって象徴的な意味を持っている。それらは単に(家や城のように)人々に避難所や安全を提供するために 建てられたのではなく、象徴的な芸術作品なのである。 これらの "独立した "建造物は、それ自体に意味がある。例えば、その形や部品の数に意味があるのだ。対照的に、エジプトのピラミッドには、建造物そのものとは別の「意味」が 含まれている。その「意味」とはもちろん、死んだファラオの遺体である。ピラミッドはそれ自体以外の何かを内包しているため、ヘーゲルの考えでは、ピラ ミッドはいわば、適切な建築物であるための途上にある。ヘーゲルが言うように、ピラミッドは「亡霊を宿す結晶」なのである(VPK, 218)。さらに、ピラミッドが内包する「意味」は、ピラミッドの中に完全に隠されており、誰の目にも見えない。こうしてピラミッドは、その中に埋もれた 隠された意味を指し示す象徴芸術品であり続ける。実際、前述したように、ヘーゲルは、ピラミッドは象徴芸術のイメージあるいは象徴そのものであると主張し ている(『美学』1: 356)。 象徴芸術の典型は象徴建築(具体的にはピラミッド)である。というのも、古典期においてのみ、建築は、それ自体が自由な精神の体現である彫刻のためにその 周囲を提供し、そのために彫刻に奉仕するようになるからである。 ヘーゲルは、そのような周囲の適切な形態について多くのことを語っている。その要点はこうである。精神の自由は神の彫刻の中に具現化されるものであり、 神の家、すなわち神殿は、それが取り囲む彫刻とはまったく別個のものであ り、彫刻に従属するものである。したがって、神殿は人体の流れるような輪郭を模倣すべきではなく、規則性、対称性、調和という抽象的な原則に支配されるべ きなのである。 ヘーゲルはまた、神殿の形態は、それが奉仕する目的によって決定されるべきであ る、すなわち、神のための囲いと保護を提供するためである、と主張している(VPK, 221)。つまり、神殿の基本的な形は、その目的を果たすために必要な特徴のみを含むべきであるということである。さらに(ヘーゲルの考えでは)、神殿の 各部分は建物全体の経済の中で特定の機能を果たすべきであり、異なる機能が互いに混同されるべきではないということである。柱を必要とするのは、この後者 の要件である。ヘーゲルにとって、屋根を支えるという仕事と、与えられた空間の中に彫像を 囲むという仕事の間には違いがある。第二の課題である囲い込みは、壁によって行われる。従って、第一の仕事を第二の仕事と明確に区別するためには、壁では なく、神殿の別の 特徴によって行われなければならない。ヘーゲルによれば、古典的な神殿において柱が必要なのは、壁を形成することなく屋根を支えるという明確な役割を果た すからである。このように、古典主義的な神殿は、異なる機能が異なる建築的特徴によって遂行され、しかも互いに調和しているため、建築物の中で最も分かり やすいのである。ここにこそ、このような神殿の美しさがある(VPK, 221, 224)。 古典主義建築とは対照的に、ロマン主義建築あるいは「ゴシック」建築は、キリスト教的内面が外界から避難できる閉ざされた家という考えに基づいている。ゴ シック様式の大聖堂では、柱は閉ざされた空間の外側ではなく内側に位置し、そのあからさまな機能は、もはや単に重みに耐えることではなく、魂を天へと引き 上げることである。その結果、柱は(古典的な神殿のアーキトレーヴのような)明確な終わりを迎えるのではなく、尖ったアーチや丸天井の屋根を形成するため に合流するまで続く。このようにして、ゴシック聖堂は宗教的共同体の精神を庇護するだけでなく、その構造そのものが精神の上昇運動を象徴しているのである (PKÄ, 170-1)。 ヘーゲルが考察する建築物の範囲は比較的狭く、たとえば世俗的な建築物についてはほとんど何も語っていない。しかし、ヘーゲルが建築に関心を持つのは、そ れが芸術である限りにおいてであって、日常生活においてわれわれに保護と安全を与えるものである限りにおいてではないことを念頭に置くべきである。という のも、建築は(彫刻のように)精神的自由そのものを直接的に感覚的に表現するものでは決してないからである(『美学』2: 888参照)。これは建築の根本的な限界である。「独立した建築」の構造は、多かれ少なかれ不確定な意味を象徴している。ピラミッドは、死という隠された 意味の存在を示している。そして、古典的でロマン主義的な形態においてさえ、建築は、それが創造する構造が、それらが収容する精神から分離されたままであ る限り、「象徴的」芸術のままである(『美学』2: 888)。いかなる場合も、建築は自由な精神性そのものの明示的な顕現や体現ではない。しかし、だからといって、建築が私たちの美的・宗教的生活の一部と して必要でなくなるわけではない。また、ヘーゲルが、古典派時代とロマン派時代の両方において、建築の「芸術」(より日常的な建築の実践や事業とは対照的 なもの)を区別するものを理解しようとすることを妨げるものでもない。 6.3.2 彫刻 建築とは対照的に、彫刻は、重い物質に人間の形を与えることによって、精神的 自由を具体的に表現する。ヘーゲルにとって、彫刻の頂点は古典ギリシアで達成された。エジプト彫刻では、彫像はしばしば、片足をもう一方の足より前に置 き、両腕を体の横でしっかりと握ってしっかりと立っているため、彫像はかなり硬直した、生気のない姿をしている。これとは対照的に、フィディアスやプラク シテレスといったギリシアの彫刻家によって作られた理想化された神々の彫像は、神々が静止した状態で描かれているときでさえ、明らかに生き生きとしてい る。この躍動感は、彫像の姿勢、身体の微妙な輪郭、そして彫像の衣服の自由な落下にも現れている。ヘーゲルは、ベルリンで見たミケランジェロのピエタ像の 鋳型(『美学』2: 790)を高く評価しているが、「理想的な」彫刻美の基準を定めたのはギリシア人であると彼は考えている。実際、ヘーゲルによれば、ギリシア彫刻は、芸術 そのものが持つ最も純粋な美を体現している。(ヘーゲルの彫刻に関する記述のより詳細な研究については、Houlgate 2007, 56-89を参照のこと)。 6.3.3 絵画 ヘーゲルは、ギリシアの彫像がしばしばかなり派手に描かれていることをよく知っていた。しかし彼は、彫刻は精神的な自由と活力を、彩色された色ではなく、 像の三次元的な形 に表現すると主張する。これとは対照的に、絵画では、表現の媒体であるのは何よりも色である。ヘーゲルにとっての絵画の意味は、自由な精神が完全に具現化 されるとはどういうことかを示すことではない。自由な精神がどのように見えるか、どのように目に映るかを示すだけである。したがって、絵画のイメージは彫 刻のような立体性を欠くが、色彩によってもたらされる細部と特異性が加わる。 ヘーゲルは、絵画が古典的世界において完成の域に達したことは認めるが、ロマン主義的、キリスト教的精神性(および宗教改革後の近代の世俗的自由)の表現 には絵画が最も適していると主張する(PKÄ, 181)。身体的な堅固さがなく、色彩が存在することで、キリスト教世界のより内面的な精神性がそのようなものとして顕現するからである。彫刻が精神の物 質的な具現化であるとすれば、絵画はいわば、内なる魂が内なる魂として顕現する精神の顔を与えてくれるのである(PKÄ, 183)。 しかし絵画はまた、彫刻とは異なり、神と人間の精神を外的環境との関係において設定することができる。すなわち、キリスト、聖母マリア、聖人、あるいは世 俗的な人物が取り囲む自然の風景や建築物を、描かれたイメージの中に取り込むことができるのである(『美学』2: 854)。実際、ヘーゲルは、独立し、自立した個人を表現することに長けた彫刻とは対照的に、絵画は、環境と人間との関係において人間を表現するのに適し ていると主張する。 ヘーゲルの絵画に関する記述は、非常に豊かで幅広い。彼は、ラファエロ、ティツィアーノ、オランダの巨匠たちを特に賞賛しており、先に述べたように、画家 たちが色彩を組み合わせて、彼が「客観的音楽」(『美学』1: 599-600)と呼ぶものを作り出す方法に特に関心を寄せている。ただし、ヘーゲルは色彩の抽象的な戯れを自由な人間の描写に不可欠な部分と見なしてお り、絵画が(20世紀にそうなったように)純粋に抽象的で「音楽的」なものになることを示唆しているわけではないことに留意すべきである。 6.3.4 音楽 ヘーゲルの「諸芸術の体系」における次の芸術は、音楽そのものである。音楽もまた、ロマン派芸術の時代に本領を発揮する。彫刻や絵画と同様、しかし建築と は異なり、音楽は自由な主観性を直接的に表現する。しかし音楽は、空間の次元を完全に取り去ることで、主観性の内面性を表現する方向にさらに進む。そのた め、音楽はそのような主観性に永続的な視覚的表現を与えず、消えゆく音の組織的連続の中で後者を表現する。ヘーゲルにとって音楽とは、感情の即時的な発 露、あるいは彼が「間投詞」と呼ぶもの、すなわち「心のアー、オー」(『美学』2: 903)に由来する。しかし、音楽は単なる苦痛の叫びやため息ではなく、組織化され、発展し、「カデンツ」された間投詞なのである。音楽とは、単にそれ自 体のための音の連なりではなく、内なる主観性の構造化された音による表現なのである。リズム、ハーモニー、メロディーを通して、音楽は魂に自らの内なる動 きを聴かせ、聴いたものによって感動を与える。それは「精神であり、魂であり、即座にそれ自身のために響き、それ自身を聴くことで満足を感じる[in ihrem Sichvernehmen]」(『美学』2: 939、訳注)なのである。 音楽は、差異と不協和音を経て、それ自身との統一へと戻る魂の時間的な動きを表現し、私たちに聴かせ、楽しませる。音楽はまた、愛、憧れ、喜びといったさ まざまな感情を表現し、私たちを感動させる(『美学』2: 940)。しかし、ヘーゲルの考えでは、音楽の目的は、私たちの感情を喚起することだけでなく、すべての真の芸術と同様に、私たちが出会ったものに対して 和解と満足の感覚を享受できるようにすることである。これこそが、真に「理想的な」音楽、パレストリーナ、グルック、ハイドン、モーツァルトの音楽の秘密 なのだとヘーゲルは主張する: 悲嘆はそこでも表現されるが、それは一挙に和らげられる。歓喜が反発するような騒動に堕落しないように、すべてが抑制された形でしっかりと保たれ、嘆きで さえも最も至福に満ちた静けさを与えてくれる」(『美学』2: 939)。 ヘーゲルは、音楽が詩的なテキストを伴っているとき、特に明瞭に感情を表現することができると指摘し、教会音楽とオペラの両方を特に愛していた。というの も、魂の深遠な動きを表現するのは何よりも音楽だからである(『美学』2: 934)。しかし、音楽はテキストを伴う必要はなく、「独立した」器楽音楽であってもよい。そのような音楽もまた、魂の動きを表現し、魂を「それと共鳴す る感情」(『美学』2: 894)に向かわせることによって、芸術の目的を果たす。しかし、このような表現以上に、独立した音楽は、それ自身のために主題と和声の純粋な形式的発展 を追求する。ヘーゲルに言わせれば、これは音楽にとって完全に適切なことであり、実に必要なことである。しかし、ヘーゲルが危険視するのは、そのような形 式的な発展が、内面的な感情や主観性の音楽的表現から完全に切り離されてしまうことであり、その結果、音楽が真の芸術でなくなり、単なる芸術になってしま うことである。いわば、音楽は魂を失い、「コンパイルにおける技術と名人芸」(『美学』2: 906)に過ぎなくなる。この時点で、音楽はもはや私たちに何かを感じさせるものではなく、単に私たちの抽象的な理解に関わるものになる。こうして音楽は 「愛好家」の領域となり、「音楽の中で最も好きなのは[......]感情や考えを分かりやすく表現すること」(『美学』2: 953)である素人は置き去りにされる。 ヘーゲルは、彼が論じる他の芸術ほど音楽に精通していないことを認めている。しかし、J.S.バッハ、ヘンデル、モーツァルトの音楽には造詣が深く、リズ ム、ハーモニー、メロディーの分析は非常に示唆に富んでいる。また、同時代のカール・マリア・フォン・ウェーバーの音楽にも批判的ではあるが親しんでお り、ロッシーニには特別な愛情を持っていた(『美学』1: 159, 2: 949)。意外なことに、彼はベートーヴェンについては一切言及していない。 6.3.5 詩 ヘーゲルが考える最後の芸術もまた音の芸術であるが、音はイデアと内的表象の記号として、つまり音声としての音として理解される。これが広義の詩の芸術で ある。ヘーゲルは詩を「最も完全な芸術」(PKÄ, 197)とみなしているが、それは詩が精神的自由の最も豊かで具体的な表現を提供するからである(古典的な形式において最も純粋な理想美を与える彫刻とは 対照的である)。詩は、精神的な自由を、内面への集中として、また空間と時間における行為として示すことができる。詩は象徴芸術、古典芸術、ロマン主義芸 術のいずれにも等しく存在し、その意味で「芸術の中で最も自由なもの」(『美学』2: 626)である。 ヘーゲルにとっての詩とは、単に観念を構造化して提示することではなく、言語における観念の明瞭化であり、実際に(文字だけでなく)話し言葉における観念 の明瞭化である。詩の芸術の重要な側面、そして詩を散文から明らかに区別するものは、このように言葉そのものを音楽的に秩序づけること、すなわち "詩化 "である。この点で、古典芸術とロマン主義芸術の間には重要な違いがあるとヘーゲルは主張する。古代人は詩においてリズム構造をより重視していたのに対 し、キリスト教では(特にフランスとイタリアでは)韻律がより多く用いられていたのである(PKÄ, 201-4)。 ヘーゲルによって特定された詩の三つの基本形式は、叙事詩、抒情詩、劇詩である。 6.3.5.1 叙事詩と抒情詩 叙事詩は精神的な自由、すなわち自由な人間を、状況や出来事の世界という文脈の中で提示する。「ヘーゲルは、「叙事詩では、個人は行動し、感じるが、その 行動は独立しているわけではなく、出来事にもその権利がある」と述べている。それゆえ、このような詩で描かれるのは、「行為と出来事の間の戯れ」である (PKÄ, 208)。叙事詩の個人は、より大きな事業(ホメロスの『イーリアス』におけるトロイ戦争など)に巻き込まれた、位置づけられた個人である。そのため、彼 らの行動は、彼ら自身の意志と同じくらい、彼らが置かれた状況によって決定される。叙事詩はこのように、人間の自由の世俗的な性格とそれに伴う限界を私た ちに示している。(この点で、ヘーゲルは、アレクサンダー大王は叙事詩の題材としてふさわしくなかっただろう、と指摘する[PKÄ, 213]。 ヘーゲルが論じている偉大な叙事詩には、ホメロスの『オデュッセイア』、ダンテの『神曲』、そして中世スペインの詩『エル・シド』がある。しかし、叙事詩 について彼が語ることの多くは、ホメロスの『イーリアス』の読解に基づいている。近代においては、叙事詩は小説に道を譲るとヘーゲルは主張する(PKÄ, 207, 217)。 叙事詩の英雄とは対照的に、抒情詩の主題は、世界における仕事や旅や冒険をするのではなく、賛美歌やオードや歌の中で、自己の考えや内なる感情を表現する だけである。これは、直接的に行われることもあれば、バラやワイン、他人など、何か別のものを詩的に描写することによって行われることもある。抒情詩に関 するヘーゲルの発言は、いつものように、彼の並外れた博識と批評的洞察力を物語っている。彼は特にゲーテの『西東神話』(1819年)を賞賛しているが、 18世紀の詩人フリードリヒ・ゴットリープ・クロプシュトックについては、新しい「詩的神話」を作りたがっていると批判している(『美学』2: 1154-7; PKÄ, 218)。 6.3.5.2 劇詩 劇詩は叙事詩と抒情詩の原理を組み合わせたものである。劇詩は、登場人物がある状況において、世界の中で行動する姿を見せるが、その行動は、(本人の力で はどうにもならない出来事によって決定されるのではなく)本人の内なる意志から直接生じるものである。こうしてドラマは、人間の自由な行動そのものがもた らす、あまりにもしばしば自己破壊的な結果を提示する。 ヘーゲルにとってドラマとは、「最高の」、最も具体的な芸術であり(PKÄ, 205)、人間そのものが美的表現の媒体となる芸術である。(つまり、人間そのものが美的表現の媒体となる芸術なのである(俳優によって上演される戯曲を 見ることは、朗読を聞いたり自分で読んだりすることとは対照的に、ヘーゲルに言わせれば、戯曲の体験の中心をなすものなのである[Aesthetics, 2: 1182-5; PKÄ, 223-4])。戯曲は実に、他のすべての芸術を(事実上あるいは実際に)内包する芸術なのである: 「人間は生きた彫像であり、建築は絵画によって表象され、あるいは現実の建築があり」、特にギリシア劇においては「音楽、舞踊、パントマイム」(PKÄ, 223)がある。この時点で、ヘーゲルにとって演劇とは、リヒャルト・ワーグナーの表現を借りれば「総合芸術作品」(Gesamtkunstwerk)で あると言いたくなる。しかし、ヘーゲルがワーグナーのプロジェクトに共感したかどうかは疑わしい。ヘーゲルは、ドラマはオペラにおいて「全体性」という明 確な形式をとるが、それはドラマ本来のものというよりは音楽の領域に属するものであると述べている(PKÄ, 223)。(これとは対照的に、戯曲では言語が優位を占め、音楽は従属的な役割を果たす。ワーグナー的な「音楽劇」という考え方は、オペラでもドラマでも なく、ヘーゲルから見れば、二つの異なる芸術を混同しているように見えるだろう。 ヘーゲルにとってドラマとは、叙事詩の世界の豊かさを描いたり、抒情的な感情の内的世界を探求したりするものではない。ドラマは、登場人物が自分の意志と 利益を追求して行動し、それによって他の個人と対立する様を描くのである(たとえハムレットのように、最初はためらいがあったとしても)。ヘーゲルは悲劇 劇と喜劇を区別し、それぞれの古典版とロマン派版を区別している。(ヘーゲルはまた、ゲーテの『タウリスのイフィゲニ』のように、悲劇が脅かされつつも、 信頼や許しの行為によって回避される戯曲もあることを指摘している[Aesthetics, 2: 1204]。 古典ギリシア悲劇では、家族や国家に対する関心など、倫理的な関心や「パトス」によって個人が行動を起こす。ソフォクレスの『アンティゴネー』におけるア ンティゴネーとクレオンの対立はこの種のものであり、アイスキュロスの『オレステイア』で演じられる対立もこの種のものである。ソフォクレスの『オイディ プス王』における対立は、単純に倫理的なものではないが、2つの "権利 "の対立である。オイディプスの悲劇は、ライオス殺害の真相を暴くという自分の権利を追求するあまり、自分自身にも責任があるかもしれない、あるいは自分 自身について何か気づいていないことがあるかもしれない、ということを全く考えないところにある(『美学』2: 1213-14)。 ギリシア悲劇のヒーローやヒロインは、自分が共感する倫理的(あるいは正当化された)利益によって行動を起こさせられるが、その利益を追求するために自由 に行動する。悲劇は、そのような自由な行動がどのように対立を引き起こし、そしてその対立を暴力的に(あるいは時には平和的に)解決するのかを示してい る。ヘーゲルは、ドラマが終わったとき、私たちは登場人物の運命に打ちのめされると主張する(少なくとも暴力的な解決の場合)。また、その結果にも満足す る。なぜなら、正義が果たされたことがわかるからである。しかし、そうすることによって、彼らは自らを破滅させ、その結果、自らが仕掛けた対立そのものを 台無しにしてしまうのである。ヘーゲルは、このような「一方的に」倫理的な登場人物の自滅の中に、私たち観客は「永遠の正義」の働きを見るのだと考える (『美学』2: 1198, 1215)。これによって私たちは登場人物の運命と和解し、「芸術が決して欠けてはならない和解」(『美学』2: 1173)の感覚を得ることができる。 ヘーゲルが意味する近代悲劇とは、とりわけシェイクスピアの悲劇であるが、登場人物は倫理的関心によってではなく、野心や嫉妬といった主観的情熱によって 動かされる。しかし、これらの登場人物は、依然として自由に行動し、その情熱の自由な追求によって自滅する。それゆえ、悲劇的な個人は、古今東西を問わ ず、運命によって倒されるのではなく、最終的に自らの破滅に責任を負うのである。実際、ヘーゲルは「罪のない苦しみは高尚な芸術の対象ではない」と主張し ている(PKÄ, 231-2)。ゲオルク・ビューヒナーの『ヴォイツェック』[1836]のような、人々を主として状況や抑圧の犠牲者として見るドラマは、ヘーゲルから見 れば、真の悲劇を伴わないドラマなのである。 喜劇においても、個人は何らかの形で自らの努力を貶めるが、彼らを活気づ ける目的は、本質的に些細なものか、笑いを誘うほど不適切な方法で追求する壮大なも ののいずれかである。悲劇的な登場人物とは対照的に、真に喜劇的な人物は、笑いを誘うような目的や 手段を真剣に自認することはない。それゆえ、彼らは目的の挫折を生き延びることができ、悲劇的な人 物にはできないような方法で、しばしば自分自身を笑うようになる。この点で、ヘーゲルは、モリエール作のような多くの近代喜劇の登場人物は、しばしば滑稽 ではあるが、真に喜劇的な人物ではないと主張する。私たちはモリエールの守銭奴やシェイクスピアのマルヴォーリオを笑うが、彼らは自らの愚かさを一緒に笑 うことはない。ヘーゲルが真に滑稽な人物を見出したのは、古代ギリシアの劇作家アリストファネスの戯曲である。ヘーゲルは、そのような戯曲の中でわれわれ が出会うのは、「自分自身の内なる矛盾の上に完全に立ち、その中で苦しくも惨めでもない者が感じる無限の軽快さと自信である。ヴェルディの『ファルスタッ フ』(1893 年)やホーマー・シンプソンの比類なき喜劇の天才に、このようなアリストフォニックな軽妙さの現代的な等価性が見出されるかもしれない。 ヘーゲルに言わせれば、喜劇は「芸術の溶解」を意味する(『美学』2: 1236)。しかし、喜劇が芸術を「溶解」させる方法は、現代の皮肉なユーモアがそうさせる方法とは異なる。皮肉なユーモアとは、少なくともジャン・ポー ル・リヒターの作品に見られるような、「主観的な観念、思考の閃光の力」が「自らを客観的なものにしようとするあらゆるものを破壊し、溶解する」(『美 学』1: 601)ことを表現したものである。それは、機智の揺るぎない支配力の表現である。ヘーゲルはこのような恣意的な達観を真の自由とは見なさないため、この 達観が発揮される皮肉なユーモアの作品は、もはや真の芸術作品としてカウントされないと主張する。これとは対照的に、真の喜劇とは、主観的な自由と生命の 全体性、自信、幸福感を表現するものであり、それは自分の人生に対する支配と統制を失っても生き残るものである。そのような自由を表現する演劇は、本物の 芸術作品として数えられる。しかし、そのような作品は、自由が、私たちが引き受ける作品の中にではなく、まさに主観性の中に、笑止千万の目的の挫折に喜ん で耐える主観性の中に存在することを示すものである。 ヘーゲルによれば、真の自由とは、自らの利己的な目的を手放す、あるいは「死ぬ」覚悟のある内的精神性の中に見出されるという考え方が、宗教、特にキリス ト教の中心にある。したがって、真の喜劇は、暗黙のうちに芸術を超えて宗教を指し示している。喜劇が芸術を "溶解 "させるのは、芸術でなくなることではなく、このような方法によるのである。 喜劇はこうして芸術をその限界に導く。喜劇を超えた先には、自由を美的に表現するものはなく、あるのは宗教(と哲学)のみである。ヘーゲルに言わせれば、 宗教は自由の美的表現を冗長なものにするものではなく、実際、宗教はしばしば偉大な芸術の源泉となる。しかし、哲学が宗教よりも明確で深遠な自由の理解を 提供するように、宗教は芸術よりも深遠な自由の理解を提供する。 |

| 7. 結論 | 7. 結論 ヘーゲルの美学は、彼の死後、ハイデガー、アドルノ、ガダマーといった哲学者たちから、しばしば非常に批判的な注目を浴びてきた。この注目の多くは、芸術の「終わり」に関する彼の理論に費やされてきた。しかし、おそらくヘーゲル の最も重要な遺産は、芸術の仕事は美の提示であり、美は形式だけでなく内容の問題で あるという主張にある。ヘーゲルにとっての美とは、単に形式的な調和や優美さの問題ではなく、精神的な自由や生命を石や色や音や言葉によっ て感覚的に表現したものである。このような美は、古典派とロマン派の時代において、 また個々の芸術においても、微妙に異なる形をとっている。しかし、近代においても、美が芸術の目的であることに変わりはない。 ヘーゲルによるこれらの主張は、単なる記述的なものではなく、規範的なものであり、近代において本物の芸術とみなされるものに一定の制限を課している。と はいえ、単なる保守主義からの主張ではない。ヘーゲルは、芸術が装飾的であることも、道徳的・政治的目標を促進することも、人間の疎外の深淵を探求するこ とも、日常生活の平凡な細部を記録することも可能であり、かなりの芸術性をもってそうすることができることをよく知っている。しかし、彼の懸念は、美を与 えることなくこれらのことを行う芸術は、私たちに自由の美的経験を与えることができないということである。そうすることで、真に人間的な生活の中心的な側 面を奪ってしまうのである。 |

| https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-aesthetics/ |

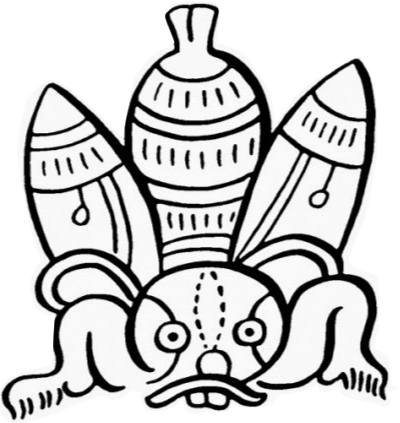

独自なるものと

してのショロイツクイントゥリ, Xoloitzcuintli as existence sui generis

++++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099