ミュージコフィリア

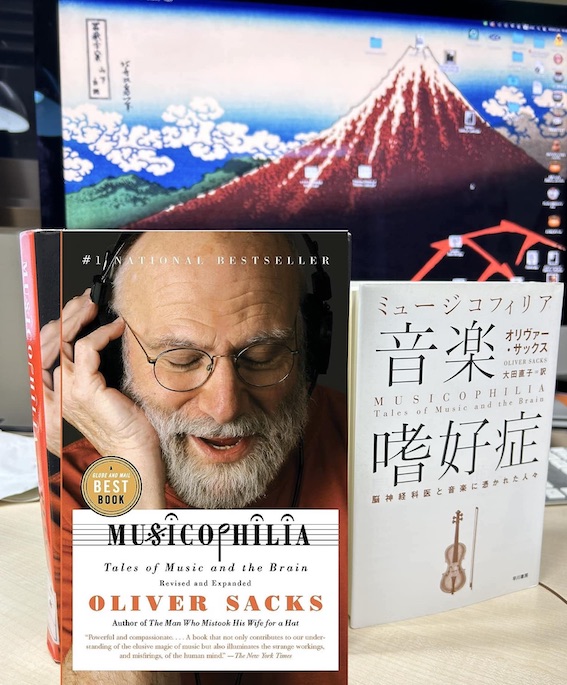

Musicophilia, 2007, by Oliver Sacks

★

ミュージコフィリア(musicophilia)とは、ミュージック(music 音楽)に「〜が大好き」(-philia

嗜好や嗜癖をあらわす接尾辞)という造語です。オリバー・サックスの著作のなかでも、とても人気のあるものです。なぜなら、多くの人たちは「音楽を聞く/

聴く」ことがとても大好きだからです。神経内科医のサックスは、そのことを、音楽への病的な嗜好や嫌悪、突然音楽の才能がつくひと/逆に喪失するひと、た

ちの症例から、音楽を聞いている人のこころの中に、なにが行われているのかを明らかにします。

☆ 「雷に打たれ蘇生したとたん音楽を渇望するようになった医師、ナポリ民謡を聴くと発作を起こす女性、フランク・シナトラの歌声が頭から離れず悩む男性、数 秒しか記憶がもたなくてもバッハを演奏できる音楽家…。音楽と精神や行動が摩訶不思議に関係する人々を、脳神経科医が豊富な臨床経験をもとに温かくユーモ ラスに描く、医学知識満載のエッセイ。 目次 第1部 音楽に憑かれて(青天の霹靂—突発性音楽嗜好症;妙に憶えがある感覚—音楽発作 ほか) 第2部 さまざまな音楽の才能(感覚と感性—さまざまな音楽の才能;ばらばらの世界—失音楽症と不調和 ほか) 第3部 記憶、行動、そして音楽(瞬間を生きる—音楽と記憶喪失;話すこと、歌うこと—失語症と音楽療法 ほか) 第4部 感情、アイデンティティ、そして音楽(目覚めと眠り—音楽の夢;誘惑と無関心 ほか)」https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB16771430

★Oliver

Sacks has been hailed by the New York Times as 'one of the great

clinical writers of the twentieth century'. In this eagerly awaited new

book, the subject of his uniquely literate scrutiny is music: our

relationship with it, our facility for it, and what this most universal

of passions says about us. In chapters examining savants and

synaesthetics, depressives and musical dreamers, Sacks succeeds not

only in articulating the musical experience but in locating it in the

human brain. He shows that music is not simply about sound, but also

movement, visualization, and silence. He follows the experiences of

patients suddenly drawn to or suddenly divorced from music. And in so

doing he shows, as only he can, both the extraordinary spectrum of

human expression and the capacity of music to heal. Wise, compassionate

and compellingly readable, Musicophilia promises, like all the best

writing, to alter our conception of who we are and how we function, to

lend a fascinating insight into the mysteries of the mind, and to show

us what it is to be human. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA85338097

「オ

リバー・サックスは、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙から「20世紀の偉大な臨床作家の一人」と賞賛されている。待望の新刊である本書では、音楽との関係、音楽

に対する能力、そしてこの最も普遍的な情熱が人間について何を語っているのか、といった、彼独特の文学的精査が主題となっている。サヴァンや共感覚者、う

つ病患者や音楽的夢想家について考察する章において、サックスは音楽体験を明確にするだけでなく、それを人間の脳の中に位置づけることに成功している。

サックスは、音楽とは単に音だけでなく、動き、視覚化、そして静寂でもあることを示す。彼は、突然音楽に引き寄せられたり、突然音楽から離れたりする患者

の経験を追っている。そうすることで、彼にしかできないように、人間の表現の驚くべきスペクトルと、癒す音楽の能力の両方を示している。賢明で思いやりが

あり、説得力のある読み応えのあるこの『Musicophilia』は、他の優れた著作と同様、私たちが何者であり、どのように機能しているのかという概

念を変え、心の謎に魅惑的な洞察を与え、人間とは何かを教えてくれる。」

| ☆Music can move us

to the heights or depths of emotion. It can persuade us to buy

something, or remind us of our first date. It can lift us out of

depression when nothing else can. It can get us dancing to its beat.

But the power of music goes much, much further. Indeed, music occupies

more areas of our brain than language does–humans are a musical species. Oliver Sacks’s compassionate, compelling tales of people struggling to adapt to different neurological conditions have fundamentally changed the way we think of our own brains, and of the human experience. In Musicophilia, he examines the powers of music through the individual experiences of patients, musicians, and everyday people–from a man who is struck by lightning and suddenly inspired to become a pianist at the age of forty-two, to an entire group of children with Williams syndrome who are hypermusical from birth; from people with “amusia,” to whom a symphony sounds like the clattering of pots and pans, to a man whose memory spans only seven seconds–for everything but music. Our exquisite sensitivity to music can sometimes go wrong: Sacks explores how catchy tunes can subject us to hours of mental replay, and how a surprising number of people acquire nonstop musical hallucinations that assault them night and day. Yet far more frequently, music goes right: Sacks describes how music can animate people with Parkinson’s disease who cannot otherwise move, give words to stroke patients who cannot otherwise speak, and calm and organize people whose memories are ravaged by Alzheimer’s or amnesia. Music is irresistible, haunting, and unforgettable, and in Musicophilia, Oliver Sacks tells us why. https://www.oliversacks.com/oliver-sacks-books/musicophilia-oliver-sacks/ ★In 2007, neurologist Oliver Sacks released his book Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain in which he explores a range of psychological and physiological ailments and their intriguing connections to music. It is broken down into four parts, each with a distinctive theme; part one titled Haunted by Music examines mysterious onsets of musicality and musicophilia (and musicophobia). Part two A Range of Musicality looks at musical oddities musical synesthesia. Parts three and four are titled Memory, Movement, and Music and Emotions, Identity, and Music respectively. Each part has between six and eight chapters, each of which is in turn dedicated to a particular case study (or several related case studies) that fit the overarching theme of the section. Presenting the book in this fashion makes the reading a little disjointed if one is doing so cover to cover, however, it also means one may pick up the book and flip to any chapter for a quick read without losing any context. Four case studies from the book are featured in the NOVA program Musical Minds aired on June 30, 2009. |

☆音楽は私たちを感情の高みにも深みにも感動させることができる。何か

を買うように説得することもできるし、初めてのデートを思い出させることもできる。音楽は、他の何ものにも変えられない時に、私たちを憂鬱な気分から立ち

直らせてくれる。そのビートに合わせて踊ることもできる。しかし、音楽の力はもっともっと奥が深い。実際、音楽は言語よりも脳の多くの領域を占めている。 オリヴァー・サックスは、さまざまな神経症状に適応しようと奮闘する人々の思いやりに満ちた説得力のある物語によって、私たち自身の脳、そして人間の経験 に対する考え方を根本的に変えた。ムジコフィリア』では、雷に打たれ、突然ピアニストになることを思い立った42歳の男性から、生まれつき音楽過多のウィ リアムズ症候群の子供たち、交響曲が鍋やフライパンのカタカタという音にしか聞こえない「無音症」の人々、音楽以外のすべての記憶が7秒しかない男性ま で、患者、音楽家、そして日常生活者の個々の体験を通して、音楽の力を検証している。 サックスは、キャッチーな曲が私たちを何時間も頭の中で再生させることや、驚くほど多くの人が昼夜を問わず襲ってくる音楽の幻覚に襲われることを探求して いる。しかし、音楽がうまくいくことの方がはるかに多い: サックスは、音楽が、動くことのできないパーキンソン病患者を生き生きとさせ、話すことのできない脳卒中患者に言葉を与え、アルツハイマー病や健忘症で記 憶を失っている人々を落ち着かせ、整理することができると述べている。 オリバー・サックスは『ミュージック・フィリア』の中で、その理由を語っている。 https://www.oliversacks.com/oliver-sacks-books/musicophilia-oliver-sacks/ ★2007 年、神経科医オリバー・サックスは著書 『Musicophilia』を発表した: この本では、さまざまな心理的・生理的な病気と音楽との興味深い結びつきを探求している。Haunted by Musicと題されたパート1では、音楽性と音楽恐怖症(および音楽恐怖症)の不思議な発症について考察している。第2部A Range of Musicalityは、音楽的な奇妙さ、音楽的共感覚について考察している。第3部と第4部は、それぞれ「記憶、運動、音楽」と「感情、アイデンティ ティ、音楽」と題されている。各パートには6章から8章があり、それぞれの章は、そのセクションの包括的なテーマに合致する特定の事例研究(あるいは関連 するいくつかの事例研究)を取り上げている。このような形で構成されているため、隅から隅まで読むとなると少しバラバラになってしまうが、本を手に取り、 どの章をめくっても文脈を見失うことなくさらっと読むことができる。2009年6月30日に放映されたNOVAの番組『Musical Minds』では、本書から4つのケーススタディが紹介されている。 |

| Purpose According to Sacks[citation needed], Musicophilia was written in an attempt to widen the general populace's understanding of music and its effects on the brain. As Sacks states at the outset of the book's preface, music is omnipresent, influencing human's everyday lives in how we think and act. However, unlike other animal species (such as birds) whose musical prowess is easier to understand in relation on a biological/evolutionary level, humanity's draw towards music and song is less clear-cut. There is no "music center" of the brain, yet the vast majority of humans have an innate ability to distinguish, "music, perceive tones, timbre, pitch intervals, melodic contours, harmony, and (perhaps most elementally) rhythm." With that in mind, Sacks examines human's musical inclination through the lens of musical therapy and treatment, as a fair number of neurological injuries and diseases have been documented to be successfully treated with music. This understanding (along with a medical case Sacks witnessed in 1966 wherein a Parkinson's patient was able to be successfully treated via music therapy) is what galvanized Sacks to create an episodic compilation of patient cases that all experienced and were treated by music to some capacity. In doing so, Sacks concertizes each example by explaining the neurological factors that play into each patient's healing and treatment in ways that relate to a lay yet curious audience. |

目的 サックス[要出典]によれば、『ムジコフィリア』は、音楽とその脳への影響についての一般大衆の理解を広げようとして書かれた。サックスが本書の序文の冒 頭で述べているように、音楽は遍在しており、人間の日常生活における考え方や行動に影響を与えている。しかし、他の動物種(鳥類など)の音楽的才能は、生 物学的/進化論的なレベルとの関連で理解しやすいが、人類が音楽や歌に惹かれるのはそれほど明確ではない。脳の "音楽中枢 "は存在しないが、大多数の人間には "音楽、音色、音程、メロディーの輪郭、ハーモニー、そして(おそらく最も本質的な)リズム "を区別する能力が生得的に備わっている。このことを念頭に置いて、サックスは人間の音楽的傾向を音楽療法と治療のレンズを通して考察している。この理解 は(1966年にサックスが目撃した、パーキンソン病患者が音楽療法によって治療を成功させたという医療事例とともに)、サックスを活気づけ、すべての患 者が何らかの形で音楽を経験し、音楽によって治療された事例をエピソードとしてまとめたものを創作するきっかけとなった。そうすることで、サックスは、そ れぞれの患者の治癒と治療に関与する神経学的要因を、素人でありながら好奇心の強い聴衆に関係する方法で説明することで、それぞれの事例を協調させてい る。 |

| Reviews In a review for The Washington Post, Peter D. Kramer wrote, "In Musicophilia, Sacks turns to the intersection of music and neurology -- music as affliction and music as treatment." Kramer wrote, "Lacking the dynamic that propels Sacks's other work, Musicophilia threatens to disintegrate into a catalogue of disparate phenomena." Kramer went on to say, "What makes Musicophilia cohere is Sacks himself. He is the book's moral argument. Curious, cultured, caring, in his person Sacks justifies the medical profession and, one is tempted to say, the human race." Kramer concluded his review by writing, "Sacks is, in short, the ideal exponent of the view that responsiveness to music is intrinsic to our makeup. He is also the ideal guide to the territory he covers. Musicophilia allows readers to join Sacks where he is most alive, amid melodies and with his patients."[1] Musicophilia was listed as one of the best books of 2007 by The Washington Post.[2] |

書評 ワシントン・ポスト』紙の書評で、ピーター・D・クレイマーは「『ミュージコフィリア』において、サックスは音楽と神経学の交差点に目を向けた。クレイ マーは、"サックスの他の仕事を推進するダイナミックさを欠いている『ミュージコフィリア』は、バラバラな現象のカタログに崩壊する恐れがある "と書いた。さらにクレイマーは、「『ミュージコフィリア』をまとめあげているのは、サックス自身である。彼はこの本の道徳的主張者である。好奇心旺盛 で、教養があり、思いやりがあり、サックスという人物は、医学の専門家、そして人類を正当化している。サックスは、要するに、音楽への反応性が人間の本質 的な構造であるという見解の理想的な説明者である。彼はまた、彼がカバーする領域への理想的なガイドでもある。ミュージコフィリア』によって、読者はサッ クスが最も生き生きとしている場所、メロディーの中や患者とともにいる場所に加わることができる」[1]。 Musicophilia』はワシントン・ポスト紙の2007年ベストブックのひとつに選ばれた[2]。 |

| Music and the brain Sacks includes discussions of several different conditions associated with music as well as conditions that are helped by music. These include musical conditions such as musical hallucinations, absolute pitch, and synesthesia, and non-musical conditions such as blindness, amnesia, and Alzheimer’s disease. Musical conditions Sacks first discusses musical seizures, and he mainly writes about someone who had a tumor in his left temporal lobe which caused him to have seizures, during which he heard music. Sacks then writes about musical hallucinations that often accompany deafness, partial hearing loss, or conditions like tinnitus. Sacks also focuses a lot on absolute pitch, where a person is able to immediately identify the pitch of a musical note. Another condition Sacks spends a lot of time on is synesthesia. Sacks discusses several different types of synesthesia: key synesthesia, non-musical synesthesia centered on numbers, letters, and days, synesthesia centered on sounds in general, synesthesia centered on rhythm and tempo, and synesthesia in which the person sees lights and shapes instead of colors. Sacks also describes cases where synesthesia has accompanied blindness. Conditions affected Sacks discusses how blindness can affect the perception of music and musical notes, and he also writes that absolute pitch is much more common in blind musicians than it is in sighted musicians. Sacks writes about Clive Wearing, who suffers from severe amnesia. Sacks writes about how, even though Clive suffers from such severe amnesia, he still remembers how to read piano music and play the piano. However, Clive can only remember how to do so in the moment. Sacks also writes about Tourette syndrome and the effects that music can have on tics, for example, slowing tics down to match the tempo of a song. Sacks writes about Parkinson’s disease, and how, similar to with people who suffer from Tourette’s, music with a strong rhythmic beat can help with movement and coordination. Sacks briefly discusses Williams syndrome and how children with Williams syndrome were found to be very responsive to music. Sacks finishes his book with a discussion of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. He discusses how music therapy can help people with these conditions regain memory. Behavioral effects Certain portions of the brain are associated with how we use the brain to interact with music. For example, the cerebellum, a portion that coordinates movement and stores muscle memory, responds well to the introduction of music. For example, an Alzheimer's patient would not be able to recognize his wife, but would still remember how to play the piano because he dedicated this knowledge to muscle memory when he was young. Those memories never fade. Another example is the Putamen. This portion of the brain processes rhythm and regulates body movement and coordination. When introduced to music, if the amount of dopamine in the area is increased, it increases our response to rhythm. By doing this, music has the ability to temporarily stop the symptoms of such diseases as Parkinson’s Disease. The music serves as a cane to these patients, and when the music is taken away, the symptoms return. When it comes to which music people respond best to, it is a matter of individual background. In patients with dementia, it is found that most patients respond to music from their youth, rather than relying on a certain rhythm or element. Neuroscientist Kiminobu Sugaya explains “That means memories associated with music are emotional memories, which never fade out-even in Alzheimer’s patients”.[3] |

音楽と脳 サックスは、音楽と関連するいくつかの異なる状態や、音楽によって改善される状態について論じている。その中には、幻聴、絶対音感、共感覚といった音楽的 な症状や、失明、健忘症、アルツハイマー病といった非音楽的な症状も含まれる。 音楽的状態 サックスはまず音楽発作について論じ、主に左側頭葉に腫瘍ができて発作を起こし、その際に音楽が聴こえた人について書いている。サックスは次に、難聴や部 分難聴、耳鳴りのような症状にしばしば伴う音楽の幻覚について書いている。サックスはまた、絶対音感(音符の音程を即座に識別できること)にも焦点を当て ている。サックスが多くの時間を費やしているもう一つの症状は、共感覚である。サックスはいくつかの異なるタイプの共感覚について論じている:鍵盤の共感 覚、数字、文字、曜日を中心とした非音楽的な共感覚、音全般を中心とした共感覚、リズムやテンポを中心とした共感覚、色の代わりに光や形が見える共感覚な どである。サックスは、共感覚が失明を伴うケースについても述べている。 影響を受ける症状 サックスは、失明が音楽や音符の知覚にどのような影響を及ぼすかについて論じており、また、絶対音感は目の見える音楽家よりも目の見えない音楽家の方がは るかに一般的であるとも書いている。サックスは、重度の健忘症に苦しむクライヴ・ウェアリングについて書いている。サックスは、クライヴが重度の健忘症を 患っているにもかかわらず、ピアノの楽譜の読み方やピアノの弾き方を覚えていることについて書いている。しかし、クライブが覚えているのはその瞬間だけで ある。サックスはトゥレット症候群についても書いており、例えば、曲のテンポに合わせてチックを遅くするなど、音楽がチックに与える影響についても書いて いる。サックスはパーキンソン病についても書いており、トゥレット症候群に苦しむ人々と同様に、強いリズムのビートを持つ音楽が動きや協調性を助けること を書いている。サックスはウィリアムズ症候群についても簡単に触れており、ウィリアムズ症候群の子供たちが音楽に非常に反応することがわかったと述べてい る。サックスは、アルツハイマー病と認知症についての考察でこの本を締めくくっている。彼は、音楽療法がこれらの症状を持つ人々が記憶を取り戻すのをどの ように助けることができるかを論じている。 行動への影響 脳のある部分は、私たちがどのように脳を使って音楽と相互作用するかに関連している。例えば、運動を調整し、筋肉の記憶を保存する部分である小脳は、音楽 の導入によく反応する。例えば、アルツハイマー病患者は妻を認識できないが、ピアノの弾き方は覚えている。その記憶は決して色あせない。もうひとつの例は プタメンである。脳のこの部分はリズムを処理し、体の動きと協調性を調整する。音楽に触れると、この部分のドーパミンの量が増えれば、リズムへの反応が高 まる。これによって、音楽にはパーキンソン病などの病気の症状を一時的に止める効果がある。音楽はこれらの患者にとって杖の役割を果たし、音楽を取り上げ ると症状が戻ってしまうのだ。人々がどの音楽に最も反応するかということになると、それは個々の背景の問題である。認知症患者の場合、特定のリズムや要素 に依存するのではなく、若い頃の音楽に反応する患者が多いことが分かっている。神経科学者の菅谷公信氏は、「つまり、音楽と結びついた記憶は感情的な記憶 であり、アルツハイマー病患者であっても決して薄れることはない」と説明している[3]。 |

| Studies on the effects of music

therapy Since the 1970s, there have been multiple studies on the benefits of music therapy for clients with medical conditions, trauma, learning disabilities, and handicaps. Most of the documented studies for children have shown a positive effect in promoting self-actualization and developing receptive, cognitive, and expressive capabilities.[4][5] While the studies conducted with adults 18+ had overall positive effects, the conclusions were limited because of overt bias and small sample sizes. Since music is a fundamental aspect of every culture, it embodies every human emotion and even can transport us to an earlier time, an earlier memory. Oliver Sacks, author of Musicophilia, acknowledges the unconscious effects of music as our body tends to join in the rhythmic motions involuntarily.[6] Working with clients with a variety of neurological conditions, Sacks observed the therapeutic potential and susceptibility to music. Even with the loss of language, music becomes the vehicle for expression, feeling, and interaction. Well-known music therapists Paul Nordoff and Clive Robbins documented their work with audio recordings and videos of the transformative results of music with children who had emotional or behavioral problems, traumatic experiences, or handicaps. Robbins classifies the “Music Child” as the inner self in every child that evokes a healthy musical response.[4] It is music that becomes the catalyst for discovering the child’s potential. In essence, musical play creates an atmosphere that emboldens a child to free expression and reproductive skills. Sometimes family members observe immediate effects because selfhood is encouraged and nurtured and thus a child’s personality develops in response to music. First, the music therapist assesses each client to determine impairments, preferences, and skill level. Notably, every person appreciates different musical genres. Next, treatment is determined based on individualized goals and selection as well as frequency and length of sessions. Finally, the progress of the client is evaluated and updated based on effectiveness. Although sessions are typically structured, therapist also remain flexible and try to meet clients where they are at emotionally and physically. When music therapy was first introduced in tandem with other medical fields, it was mostly receptive and patients listened to live solo performances or pre-recorded songs. Today, music therapist allow for more creative interactions by having clients improvise, reproduce music or imitate melodies vocally or with an instrument, compose their own songs, and/or listen during artistic expression or with movement. Recently, studies have been conducted on the effects of music with chemo patients, stroke patients,[7][8] patients with Alzheimer,[9] spinal or brain injury,[10][11] and hospice patients.[12] According to a 2017 report from Magee, Clark, Tamplin, and Bradt,[13] a common theme of all their studies was the positive effect music had on mood, mental and physical state, increase in motivation and social engagement, and a connection with the client’s musical identity. From 2008-2012, the Department of Oncology/ Hematology of the University Medical Center in Hamburg-Eppendorf orchestrated a randomized pilot study to determine if music therapy helped patients cope with pain and reduce chemotherapy side effects.[14] The sessions were given twice a week for twenty minutes and patients could choose either receptive or active methods. Each week, the quality of life, functioning ability and level of depression/anxiety were assessed. Although emotional functioning scores increased and perception of pain improved significantly, they determined the outcome was inconclusive because patients have differing levels of manageable side effects and a hope to survive may influence expectations of treatment. However, patients rated the program helpful and potentially beneficial. Moreover, the feasibility of these studies allows for music therapists to practice in educational, psychiatric, medical, and private settings. Although there haven’t been any statistical significance based on few empirical adult studies, the trend shows improvements on most measures. |

音楽療法の効果に関する研究 1970年代以降、病状、トラウマ、学習障害、ハンディキャップを持つクライエントに対する音楽療法の効果について、複数の研究が行われてきた。18歳以 上の成人を対象に行われた研究では、全体的に肯定的な効果が認められたものの、明らかなバイアスがかかっていたり、サンプル数が少なかったりしたため、結 論は限定的であった[4][5]。 音楽はあらゆる文化の基本的な側面であるため、人間のあらゆる感情を具現化し、私たちを以前の時代、以前の記憶へといざなうことさえある。 Musicophilia』の著者であるオリヴァー・サックスは、私たちの身体は無意識のうちにリズミカルな動作に参加する傾向があるため、音楽の無意識 的な効果を認めている[6]。たとえ言語を失ったとしても、音楽は表現、感情、相互作用の手段となる。 著名な音楽療法士であるポール・ノードフとクライヴ・ロビンズは、感情や行動の問題、トラウマ体験、ハンディキャップを抱えた子どもたちとの音楽による変 容の結果を、録音やビデオに記録している。ロビンズは「ミュージック・チャイルド」を、健全な音楽的反応を呼び起こすすべての子どもの内なる自己として分 類している[4]。要するに、音楽遊びは、子供の自由な表現と再生能力を奮い立たせる雰囲気を作り出すのである。自我が促され、育まれることで、子どもの 人格が音楽に反応して発達するため、家族がすぐに効果を実感することもある。 まず、音楽療法士は、障害、好み、技術レベルを決定するために、各クライアントを評価します。特筆すべきは、人によって鑑賞する音楽のジャンルが異なるこ とである。次に、治療法は、個別の目標と選択だけでなく、セッションの頻度と長さに基づいて決定されます。最後に、クライアントの進歩が評価され、効果に 基づいて更新される。セッションは一般的に構造化されていますが、セラピストは柔軟性を保ち、クライアントの感情的、身体的な状態に合わせます。 音楽療法が他の医療分野と並行して最初に導入されたとき、それは主に受容的であり、患者はライブソロ演奏や事前に録音された曲を聴いていた。今日、音楽療 法士は、クライアントに即興演奏をさせたり、音楽を再現させたり、メロディーを声や楽器で真似させたり、自分で曲を作ったり、芸術的な表現中や動きと一緒 に聴かせたりすることで、より創造的な相互作用を可能にしている。 最近では、化学療法患者、脳卒中患者[7][8]、アルツハイマー病患者[9]、脊髄損傷患者、脳損傷患者[10][11]、ホスピス患者に対する音楽の 効果に関する研究が行われている[12]。Magee、Clark、Tamplin、Bradtによる2017年の報告書[13]によると、すべての研究 に共通するテーマは、音楽が気分、心身の状態、意欲や社会的関与の増加、クライアントの音楽的アイデンティティとのつながりにプラスの効果をもたらすこと であった。2008年から2012年にかけて、ハンブルク・エッペンドルフ大学医療センターの腫瘍学/血液学部門は、音楽療法が患者の痛みへの対処や化学 療法の副作用の軽減に役立つかどうかを調べるために、無作為化パイロット研究を実施した[14]。毎週、生活の質、機能能力、抑うつ/不安のレベルが評価 された。感情的機能のスコアは増加し、痛みの知覚は有意に改善したが、患者の管理可能な副作用のレベルは様々であり、生存への希望が治療への期待に影響す る可能性があるため、結果は決定的ではないと判断された。しかしながら、患者はこのプログラムを有用であり、潜在的に有益であると評価している。さらに、 これらの研究が実現可能であることから、音楽療法士は教育、精神科、医療、民間の環境で実践することができる。少数の実証的な成人研究に基づく統計的有意 性はないが、その傾向はほとんどの尺度で改善を示している。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musicophilia |

|

| Inspired by Musicophilia Musical Minds is a one-hour NOVA documentary on music therapy, produced by Ryan Murdock. Originally broadcast June, 23 2009 on PBS stations. Based on the 2008 BBC documentary by Alan Yentob and Louise Lockwood. This version has additional footage, including fMRI images of Dr. Sacks’s brain as he listens to music. Why the Brain Loves Music, Dr. Oliver Sacks, Columbia University |

Musicophiliaにインスパイアされた Musical Mindsは、ライアン・マードックが制作した音楽療法に関する1時間のNOVAドキュメンタリーである。2009年6月23日にPBS局で初放送され た。2008年のBBCドキュメンタリー(アラン・イェントブとルイーズ・ロックウッド制作)に基づく。このバージョンには、音楽を聴いているサックス博 士の脳のfMRI画像など、追加の映像が含まれている。 Oliver Sacks on Music and Mind |

Icelandic singer Bjork’s album Biophilia, a multimedia project combining music, nature, and technology was inspired in part by Oliver Sacks’s book Musicophilia. björk: moon. |

|

| 第26

章、頭部に損傷をうけてから、ほとんど他人に対して無感情な人になったハリーさんは、歌うとさまざまな感情がでてきて、日常の情緒能力が壊れていることを

完全に忘れさせるほどだという。損傷しているはずの脳の能力が、音楽をやっている時にだけ、感情の能力を取り戻すという話。"He would

read the daily papers conscientiously, taking in everything, but with

an uncaring, indifferent eye. Surrounded by all the emotions, the

drama, of others in the hospital—people agitated, distressed, in pain,

or (more rarely) laughing and joy-ful—surrounded by their wishes,

fears, hopes, aspirations, accidents, tragedies, and occasional

jubilations, he himself remained entirely unmoved, seemingly incapable

of feeling. He retained the forms of his previous civility, his

courtesy, but we had the sense that these were no longer animated by

any real feeling. But all this would change, suddenly, when Harry sang. He had a fine tenor voice and loved Irish songs. When he sang, he showed every emotion appropriate to the music—the jovial, the wistful, the tragic, the sublime. And this was astounding, because one saw no hint of this at any other time and might have thought his emotional capacity was entirely destroyed. It was as if music, its intentionality and feeling, could “unlock” him or serve as a sort of substitute or prosthesis for his frontal lobes and provide the emotional mechanisms he seemingly lacked. He seemed to be transformed while he sang, but when the song was over he would relapse within seconds, becoming vacant, indifferent, and inert once again." pdf(クノップ版)の、303ページからの引用 |

「彼

は毎日、新聞を注意深く読み、すべてを吸収していたが、無関心で無感動な目で見ていた。

病院内の他人の感情、ドラマ、興奮、苦悩、痛み、あるいは(よりまれに)笑い声や喜びの声に囲まれ、彼らの願い、不安、希望、野望、事故、悲劇、そして時

折の歓喜に囲まれていたが、彼自身はまったく動じず、感情を表に出すことはなかった。彼は以前の礼儀正しさや礼儀正しさを保っていたが、それらはもはや本

物の感情によって動かされていないように感じられた。しかし、ハリーが歌うと、すべてが突然変化した。彼は素晴らしいテノールボイスを持っており、アイル

ランドの歌を愛していた。歌うとき、彼は音楽にふさわしいあらゆる感情を示した。陽気さ、切なさ、悲壮感、崇高さなどである。これは驚くべきことで、それ

以外の場面ではまったくその兆候が見られず、彼の感情表現能力は完全に破壊されてしまったのではないかと思われたほどだった。まるで音楽、その意図性や感

情が、彼を「解き放つ」か、あるいは前頭葉の代用品や補綴物となり、彼が欠いているように見える感情のメカニズムを提供しているかのようだった。彼は歌っ

ている間は変貌したように見えたが、歌が終わると数秒で元に戻り、虚ろで無関心で、再び無気力になってしまった。」 |

| パブロ・カザルスは、85年間毎朝、平均律クラヴィーアの1曲を弾いていたそう

だ----90歳の時のインタビュー。Musicophilia の第15章、HRD版(この本)のp.212 脚注9にある |

|

| Listening to music is not just

auditory and emotional, it is motoric as well: “We listen to music with

our muscles,” as Nietzsche wrote. We keep time to music, involuntarily,

even if we are not consciously attending to it, and our faces and

postures mirror the “narrative” of the melody, and the thoughts and

feelings it provokes. -O.Sacks, Musicophilia. 2007, p.xii, |

音楽を聴くことは聴覚的、感情的であるだけでなく、運動的でもある: 「私たちは筋肉で音楽を聴いている」とニーチェは書いている。ニーチェが書いたように、「私たちは筋肉で音楽を聴いている」のだ。私たちは意識していなく ても、無意識のうちに音楽に合わせて時を刻み、私たちの表情や姿勢は、メロディーの「語り」や、それが引き起こす思考や感情を映し出している。 |

| Why

We Love Music—and Freud Despised It, by Stephen A. Diamond Ph.D. |

音楽が嫌いなフロイトの弁 |

| ...I am no connoisseur in art,

but simply a layman….Nevertheless, works of art do exercise a powerful

effect on me, especially those of literature and sculpture, less often

of painting….I spend a long time before them trying to apprehend them

in my own way, i.e. to explain to myself what their effect is due to.

Wherever I cannot do this, as for instance with music, I am almost

incapable of obtaining any pleasure. Some rationalistic, or perhaps

analytic, turn of mind in me rebels against being moved by a thing

without knowing why I am thus affected and what it is that affects me. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evil-deeds/201211/why-we-love-music-and-freud-despised-it |

...私は美術の鑑定家ではなく、単なる素人に過ぎない。しかし、芸術

作品は私に強力な影響を与える。特に文学や彫刻は、絵画よりも影響を受けることが多い。私は作品を前にして、自分なりに理解しようと長い時間を費やす。つ

まり、その作品が自分にどのような影響を与えるのかを自分自身に説明しようとするのだ。音楽のように、それができない場合は、ほとんど何の喜びも得ること

ができない。私の中にある合理主義的な、あるいは分析的な考え方は、なぜ自分がそう影響を受け、何が自分を影響するのかわからないまま、何かによって感動

することに抵抗する。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099