聴覚のチーズケーキとしての音楽

Music as Auditory Cheesecake

☆ 「それが音楽の基本的なデザインなのだ。しかし、もし音楽が生存に何のメリットも与えないとしたら、音楽はどこから来て、なぜ機能するのだろうか?私は、音 楽は聴覚的チーズケーキであり、私たちの精神的能力の少なくとも6つの敏感な部分をくすぐるように作られた絶妙なお菓子だと考えている。標準的な曲は、そ れらすべてを一度にくすぐるが、私たちは、そのうちの1つまたは複数を省いた様々な種類の音楽ではないものに、その材料を見ることができる」——スティーブン・ピンカー(Pinker 1997:407)

☆I suspect that music is auditory cheesecake, an exquisite confection crafted to tickle the sensitive spots of at least six of our mental faculties. - Steven Pinker (1997)

★「音楽も楽しむことも、音楽を作りだす能力も、ともに人間の通常の生活に直接の役には立っていないので、これは人間の能力のなかでも、最も不思議なものの一つに数えられるべきだろう」——チャールズ・ダーウィン『人間の進化と性淘汰』(1871)

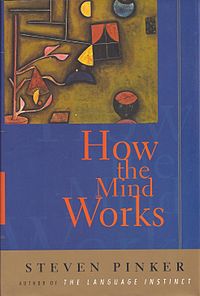

| How the Mind Works is a 1997 book by the Canadian-American cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker,

in which the author attempts to explain some of the human mind's poorly

understood functions and quirks in evolutionary terms. Drawing heavily

on the paradigm of evolutionary psychology articulated by John Tooby

and Leda Cosmides, Pinker covers subjects such as vision, emotion,

feminism, and "the meaning of life". He argues for both a computational

theory of mind and a neo-Darwinist, adaptationist approach to

evolution, all of which he sees as the central components of

evolutionary psychology. He criticizes difference feminism

because he believes scientific research has shown that women and men

differ little or not at all in their moral reasoning.[1] The book was a

Pulitzer Prize Finalist. |

『心の働き』は、カナダ系アメリカ人の認知心理学者スティーブン・ピン

カーが1997年に発表した著書である。この本の中で著者は、あまり理解されていない人間の心の機能や特徴を、進化論の観点から説明しようとしている。ピ

ンカーは、ジョン・トゥービーとレダ・コズミデスが明確化した進化心理学のパラダイムを大いに活用し、視覚、感情、フェミニズム、「人生の意味」といった

テーマを取り上げている。彼は、心の計算理論と進化論に対する新ダーウィニズム、適応主義的アプローチの双方を主張しており、これらすべてを進化心理学の

中心的な要素と見なしている。彼は、女性と男性の道徳的推論にはほとんど、あるいはまったく違いがないという科学的調査結果があると考えているため、差異

のフェミニズム(difference feminism)を批判している。[1] この本はピュリッツァー賞の最終候補作となった。 |

| Reception Jerry Fodor, considered one of the fathers of the computational theory of mind, criticized the book. Fodor wrote a book called The Mind Doesn't Work That Way, saying "There is, in short, every reason to suppose that the Computational Theory is part of the truth about cognition. But it hadn't occurred to me that anyone could suppose that it's a very large part of the truth; still less that it's within miles of being the whole story about how the mind works". He continued, "I was, and remain, perplexed by an attitude of ebullient optimism that's particularly characteristic of Pinker's book. As just remarked, I would have thought that the last forty or fifty years have demonstrated pretty clearly that there are aspects of higher mental processes into which the current armamentarium of computational models, theories and experimental techniques offers vanishingly little insight."[2] Pinker responded to Fodor's criticisms in Mind & Language. Pinker argued that Fodor had attacked straw man positions, wryly suggesting a possible title for his riposte as No One Ever Said it Did.[3] Daniel Levitin has criticized Pinker for referring to music as an "auditory cheesecake" in the book.[4] In his book This Is Your Brain on Music (2006), Levitin takes some time in the last chapter to rebut Pinker’s arguments. When asked about Levitin's book by New York Times journalist Clive Thompson, Pinker said he hadn't read it.[5] |

レセプション 心の計算理論の父の一人とされるジェリー・フォドーは、この本を批判した。フォドーは『心はそのようには働かない』 という本を書き、「計算理論が認知に関する真実の一部であると考える理由は、要するにいくらでもある。しかし、それが真実の非常に大きな一部であると考え る人がいるとは思いもよらなかった。ましてや、それが心の働きに関する全体像に限りなく近いなどとは、なおさら考えもしなかった」と述べた。彼はさらに次 のように述べている。「私は、特にピンカーの本に顕著な、高揚した楽観主義的な態度に困惑し、今も困惑している。先ほども述べたように、私は、過去 40~50年の間に、現在の計算モデル、理論、実験技術では、高度な精神過程の側面についてほとんど理解が得られていないことがはっきりと示されたと考え ている。」[2] ピンカーは『Mind & Language』でフォドーの批判に反論している。ピンカーは、フォドーはストローマンの立場を攻撃していると主張し、反論のタイトルを「No One Ever Said it Did(誰もそんなことは言っていない)」とする可能性を皮肉交じりに示唆した[3]。 ダニエル・レヴィティンはこの本の中でピンカーが音楽を「聴覚的チーズケーキ」と呼んだことを批判している[4]。レヴィティンは著書『This Is Your Brain on Music』(2006年)の最終章でピンカーの議論に反論している。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のジャーナリスト、クライヴ・トンプソンからレヴィティンの本について質問されたピンカーは、読んでいないと答えた[5]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/How_the_Mind_Works |

|

| Jerry Fodor, The Mind Doesn't Work That Way, What Darwin Got Wrong is a remarkable book, one that dares to challenge the theory of natural selection as an explanation for how evolution worksa devastating critique not in the name of religion but in the name of good science. Jerry Fodor and Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, a distinguished philosopher and a scientist working in tandem, reveal major flaws at the heart of Darwinian evolutionary theory. Combining the results of cutting-edge work in experimental biology with crystal-clear philosophical arguments, they mount a reasoned and convincing assault on the central tenets of Darwins account of the origin of species. The logic underlying natural selection is the survival of the fittest under changing environmental pressure. This logic, they argue, is mistaken, and they back up the claim with surprising evidence of what actually happens in nature. This is a rare achievementa concise argument that is likely to make a great deal of difference to a very large subject. What Darwin Got Wrong will be controversial. The authors arguments will reverberate through the scientific world. At the very least they will transform the debate about evolution and move us beyond the false dilemma of being either for natural selection or against science. |

ジェリー・フォドー『心はそのようには働かない』 宗教の名においてではなく、優れた科学の名において破壊的な批判を行う。 ジェリー・フォドーとマッシモ・ピアッテリ=パルマリーニは、卓越した哲学者と科学者のコンビであり、ダーウィン進化論の核心にある重大な欠陥を明らかに している。実験生物学における最先端の研究成果を、明快な哲学的議論と組み合わせることで、彼らはダーウィンの種の起源に関する説明の中心的な信条に対し て、理性的で説得力のある攻撃を仕掛けている。自然淘汰の根底にある論理は、変化する環境圧力の下での適者生存である。この論理は間違いであると彼らは主 張し、自然界で実際に起こっている驚くべき証拠でその主張を裏付けている。これは、非常に大きなテーマを大きく変える可能性のある簡潔な議論であり、稀有 な成果である。ダーウィンは何を間違えたか』は物議を醸すだろう。著者の主張は科学界に響き渡るだろう。少なくとも、進化論に関する論争を一変させ、自然 淘汰に賛成か科学に反対かという誤ったジレンマを乗り越えさせるだろう。 |

★ピンカー「音 楽は聴覚的チーズケーキであり、私たちの精神的能力の少なくとも6つの敏感な部分をくすぐるように作られた絶妙なお菓子だと考えている」How the mind works / Steven Pinker.London : Allen Lane, Penguin Press , 1997.

☆I suspect that music is auditory cheesecake, an exquisite confection crafted to tickle the sensitive spots of at least six of our mental faculties. - Steven Pinker (1997)

| 「音楽は、無視されなかった場合でさえ、人間

の言語能力の副産物にすぎないとして片づけられて

きた。言語学者にしてダーウィン主義者のスティーヴン・ピンカーは、さまざまな意味で非常にすぐ

れた野心的な著書『心の仕組み』(1997)の660ページ中、音楽については1ページしか

割いていない。それどころか、音楽が人間の知性の主要部分であるという考えを完全に捨て去ってい

る。ピンカーにとって音楽は、進化した他の性向から派生したものであり、人間が娯楽のために生み

だしたものでしかない。「生物学的な因果関係だけを考えると、音楽は無益だ。(中略)言語とはま

ったく異なり、(中略)テクノロジーであって適応ではない」。/

学究人生を音楽の研究に捧げる人たちにすれば、音楽がたんなる聴覚のチーズケーキで、「ポロロ

ンと音をだすこと」にすぎないというピンカーの言い草は、当然、癪に障るものだった。もっとも雄

弁に反応したのは、ケンブリッジを拠点にする音楽学者イアン・クロスだ。クロスは、人間活動とし

ての音楽の価値を擁護したいという個人的な動機からだと認めつつ、音楽は人間の生態に深く根ざし

ているだけでなく、子どもの認知発達にとっても重要だと主張した。

」ミズン『歌うネアンデルタール』

邦訳、2006:16-17. |

・ピンカーの「チーズケーキ」の箇所は、ミズンは指摘しておらず、「ポ ロロ ンと音をだすこと」についてはPinker (1997:528)- How the mind works / Steven Pinker.New York : W.W. Norton , c1997の引用箇所を指摘している(→「ミズン『歌うネアンデルタール』」)。 |

| How the mind works / Steven Pinker.London : Allen Lane, Penguin Press , 1998, c1997 |

Pinker (1997:407-409)※ただし引用はペンギン版 |

| So that

is the basic design of music. But if music confers no survival

advantage, where does it come from and why does it work? I suspect that

music is auditory cheesecake, an exquisite confection crafted to tickle

the sensitive spots of at least six of our mental faculties. A standard

piece tickles them all at once, but we can see the ingredients in

various kinds of not-quite-music that leave one or more of them out. |

そ

れが音楽の基本的なデザインなのだ。しかし、もし音楽が生存に何のメリットも与えないとしたら、音楽はどこから来て、なぜ機能するのだろうか?私は、音

楽は聴覚的チーズケーキであり、私たちの精神的能力の少なくとも6つの敏感な部分をくすぐるように作られた絶妙なお菓子だと考えている。標準的な曲は、そ

れらすべてを一度にくすぐるが、私たちは、そのうちの1つまたは複数を省いた様々な種類の音楽ではないものに、その材料を見ることができる。 |

| 1. Language. We can put words to music, and we wince when a lazy lyricist aligns an accented syllable with an unaccented note or vice versa. That suggests that music borrows some of its mental machinery from language—in particular, from prosody, the contours of sound that span many syllables. The metrical structure of strong and weak beats, the intonation contour of rising and falling pitch, and the hierarchical grouping of phrases within phrases all work in similar ways in language and in music. The parallel may account for the gut feeling that a musical piece conveys a complex message, that it makes assertions by introducing topics and commenting on them, and that it emphasizes some portions and whispers others as asides. Music has been called “heightened speech,” and it can literally grade into speech. Some singers slip into “talking on pitch” instead of carrying the melody, like Bob Dylan, Lou Reed, and Rex Harrison in My Fair Lady. They sound halfway between animated raconteurs and tone-deaf singers. Rap music, ringing oratory from preachers, and poetry are other intermediate forms. |

1.

言語 怠惰な作詞家がアクセントのある音節をアクセントのない音符に合わせたり、その逆をしたりすると、私たちはうろたえる。このことは、音楽が言語か ら、特に韻律、つまり多くの音節にまたがる音の輪郭から、その精神的機械の一部を借りていることを示唆している。強拍と弱拍の計量構造、ピッチの上昇と下 降のイントネーションの輪郭、フレーズの中のフレーズの階層的なグループ分けはすべて、言語と音楽で同じように機能する。音楽が複雑なメッセージを伝え、 トピックを導入し、それについてコメントすることで主張し、ある部分を強調し、他の部分を余談としてささやくと直感的に感じるのは、このような平行関係が あるからかもしれない。音楽は "高められたスピーチ "と呼ばれ、文字どおりスピーチのグレードを上げることができる。ボブ・ディランやルー・リード、『マイ・フェア・レディ』のレックス・ハリスンのよう に、メロディを運ぶのではなく「音程で話す」ようになる歌手もいる。そのような歌い手は、アニメのような語り手と音痴な歌手の中間のように聞こえる。ラッ プ・ミュージック、説教者の鳴り響くような弁舌、そして詩は、他の中間的な形態である。 |

| 2. Auditory scene analysis. Just

as the eye receives a jumbled mosaic of patches and must segregate

surfaces from their backdrops, the ear receives a jumbled cacophony of

frequencies and must segregate the streams of sound that come from

different sources—the soloist in an orchestra, a voice in a noisy room,

an animal call in a chirpy forest, a howling wind among rustling

leaves. Auditory perception is inverse acoustics: the input is a sound

wave, the output a specification of the soundmakers in the world that

gave rise to it. The psychologist Albert Bregman has worked out the

principles of auditory scene analysis and has shown how the brain

strings together the notes of a melody as if it were a stream of sound

coming from a single soundmaker. |

2.

聴覚による情景分析 目がごちゃごちゃしたモザイク状のパッチを受け取り、その背景から表面を分離しなければならないのと同じように、耳はごちゃごちゃし た周波数の不協和音を受け取り、異なる音源(オーケストラのソリスト、騒がしい部屋の声、さえずる森の中の動物の鳴き声、ざわめく葉の間の風の遠吠え)か ら来る音の流れを分離しなければならない。入力は音波であり、出力はその音波を発生させた世界の音の作り手の特定である。心理学者のアルバート・ブレグマ ンは、聴覚的情景分析の原理を解明し、脳がメロディーの音符を、あたかも1つのサウンドメーカーから発せられる音の流れのようにつなぎ合わせていることを 示した。 |

| One of the brain’s tricks as it

identifies the soundmakers in the world is to pay attention to harmonic

relations. The inner ear dissects a blare into its component

frequencies, and the brain glues some of the components back together

and perceives them as a complex tone. Components that stand in harmonic

relations—a component at one frequency, another component at twice that

frequency, yet another component at three times the frequency, and so

on—are grouped together and perceived as a single tone rather than as

separate tones. Presumably the brain glues them together to make our

perception of sound reflect reality. Simultaneous sounds in harmonic

relations, the brain guesses, are probably the overtones of a single

sound coming from one soundmaker in the world. That is a good guess

because many resonators, such as plucked strings, struck hollow bodies,

and calling animals, emit sounds composed of many harmonic overtones. |

脳が世界のサウンドメーカーを識別する際のトリックのひとつは、ハーモ

ニーの関係に注意を払うことである。内耳は鳴り響く音を構成する周波数に分解し、脳

はその一部をつなぎ合わせて複雑な音色として認識する。ある周波数の成分、その2倍の周波数の別の成分、さらにその3倍の周波数の別の成分といったよう

に、調和関係にある成分はグループ化され、別々の音としてではなく、一つの音として知覚される。おそらく脳は、音の知覚に現実を反映させるために、それら

をつなぎ合わせているのだろう。脳は、調和関係にある同時の音は、おそらく世界の1つの発音体から発せられた1つの音の倍音であると推測している。弦を弾

く音、空洞を叩く音、動物の鳴き声など、多くの共鳴器は多くの倍音からなる音を発するからだ。 |

| What does this have to do with

melody? Tonal melodies are sometimes said to be “serialized overtones.”

Building a melody is like slicing a complex harmonic sound into its

overtones and laying them end to end in a particular order. Perhaps

melodies are pleasing to the ear for the same reason that symmetrical,

regular, parallel, repetitive doodles are pleasing to the eye. They

exaggerate the experience of being in an environment that contains

strong, clear, analyzable signals from interesting, potent objects. A

visual environment that cannot be seen clearly or that is composed of

homogeneous sludge looks like a featureless sea of brown or gray. An

auditory environment that cannot be heard clearly or that is composed

of homogeneous noise sounds like a featureless stream of radio static.

When we hear harmonically related tones, our auditory system is

satistied that it has successfully carved the auditory world into parts

that belong to important objects in the world, namely, resonating

soundmakers like people, animals, and hollow objects. |

これが旋律とどのような関係があるのだろうか。調性旋律は

"倍音の直列化

"と言われることがある。メロディーを作るということは、複雑な和声を倍音に切り分け、特定の順序で端から端まで並べるようなものだ。おそらくメロディー

が耳に心地よいのは、左右対称で規則的、平行で反復的な落書きが目に心地よいのと同じ理由だろう。メロディーは、興味深く、強力な対象からの、強く、明確

で、分析可能な信号を含む環境にいるという経験を誇張する。はっきりと見えない、あるいは均質な汚泥で構成された視覚環境は、茶色や灰色の特徴のない海の

ように見える。はっきり聞こえない、あるいは均質なノイズで構成された聴覚環境は、特徴のないラジオのスタティック・ストリームのように聞こえる。私たち

がハーモニーに関連した音を聴くとき、聴覚システムは、聴覚の世界を、世界の重要な対象、すなわち人間や動物、空洞のある物体など、共鳴する発音体に属す

る部分にうまく切り分けられたと満足する。 |

| Continuing this line of thought,

we might observe that the more stable notes in a scale correspond to

the lower and typically louder overtones emanating from a single

soundmaker, and can confidently be grouped with the soundmakers

fundamental frequency, the reference note. The less stable notes

correspond to the higher and typically weaker overtones, and though

they may have come from the same soundmaker as the reference note, the

assignment is less secure. Similarly, notes separated by a major

interval are sure to have come from a single resonator, but notes

separated by a minor interval might be very high overtones (and hence

weak and uncertain ones), or they might come from a sound-maker with a

complicated shape and material that does not give out a nice clear

tone, or they might not come from a single soundmaker at all. Perhaps

the ambiguity of the source of a minor interval gives the auditory

system a sense of unsettledness that is translated as sadness elsewhere

in the brain. Wind chimes, church bells, train whistles, claxton horns,

and warbling sirens can evoke an emotional response with just two

harmonically related tones. Recall that a few jumps among tones are the

heart of a melody; all the rest is layer upon layer of ornamentation. |

この考え方を続けると、音階の中で安定性の高い音は、1つのサウンドメ

イカーから発せられる低音で通常より大きな倍音に対応し、サウンドメイカーの基本周

波数、つまり基準音と自信を持ってグループ分けできることがわかる。安定性の低い音は、高音で一般的に弱い倍音に対応し、基準音と同じサウンドメーカーか

ら発せられた音かもしれませんが、その割り当てはあまり確実ではありません。同様に、長音程で区切られた音は、1つの共鳴器から出た音であることは確かで

すが、短音程で区切られた音は、非常に高い倍音(つまり弱く不確かな倍音)かもしれませんし、複雑な形や材質の共鳴器から出た音で、きれいな澄んだ音色を

出さないかもしれませんし、1つの共鳴器から出た音ではないかもしれません。おそらく、マイナー・インターバルの発生源が曖昧であることが、聴覚系に落ち

着かない感覚を与え、それが脳の別の場所で悲しみとして変換されるのだろう。ウインドチャイム、教会の鐘、列車の警笛、クラクストンホーン、鳴り響くサイ

レンなどは、たった2つの和声的に関連した音で感情的な反応を呼び起こすことができる。音と音の間のわずかなジャンプがメロディの中心であり、それ以外は

何層にも重なった装飾であることを思い出してほしい。 |

| 3. Emotional calls. Darwin noticed that the calls of many birds and primates are composed of discrete notes in harmonic relations. He speculated that they evolved because they were easy to reproduce time after time. (Had he lived a century later, he would have said that digital representations are more repeatable than analog ones.) He suggested, not too plausibly, that human music grew out of our ancestors’ mating calls. But his suggestion may make sense if it is broadened to include all emotional calls. Whimpering, whining, crying, weeping, moaning, growling, cooing, laughing, yelping, baying, cheering, and other ejaculations have acoustic signatures. Perhaps melodies evoke strong emotions because their skeletons resemble digitized templates of our species’ emotional calls. When people try to describe passages of music in words, they use these emotional calls as metaphors. Soul musicians mix their singing with growls, cries, moans, and whimpers, and singers of torch songs and country-and-western music use catches, cracks, hesitations, and other emotional tics. Ersatz emotion is a common goal of art and recreation; I will discuss the reasons in a following section. |

3. 感情的な鳴き声 ダーウィンは、多くの鳥類や霊長類の鳴き声が、調和関係にある個別の音で構成されていることに気づいた。ダーウィンは、鳴き声は何度でも再現しやすいこと から進化したのだと推測した。(もし彼が100年後に生きていたら、デジタル表現はアナログ表現よりも再現性が高いと言っていただろう)。彼は、人間の音 楽は祖先の交尾の鳴き声から生まれたと、あまり信憑性は高くないが示唆した。しかし、彼の提案は、すべての感情的な呼び声を含むように広げれば、理にか なっているかもしれない。泣き声、むせび声、泣き声、うめき声、うなり声、クーイング、笑い声、雄叫び、吠え声、歓声、その他の射精には音響的特徴があ る。おそらくメロディーが強い感情を呼び起こすのは、その骨格がデジタル化された私たちの種の感情の叫びのテンプレートに似ているからだろう。人は音楽の 一節を言葉で表現しようとするとき、このような感情の叫びをメタファーとして使う。ソウル・ミュージシャンは、うなり声、叫び声、うめき声、うめき声を混 ぜて歌うし、トーチ・ソングやカントリー&ウェスタン・ミュージックの歌手は、キャッチ、ひび割れ、ためらい、その他の感情的なチックを使う。偽りの感情 は、芸術とレクリエーションの共通の目標である。 |

| 4. Habitat selection We pay attention to features of the visual world that signal safe, unsafe, or changing habitats, such as distant views, greenery, gathering clouds, and sunsets (see Chapter 6). Perhaps we also pay attention to features of the auditory world that signal safe, unsafe, or changing habitats. Thunder, wind, rushing water, birdsong, growls, footsteps, heartbeats, and snapping twigs all have emotional effects, presumably because they are thrown off by attention-worthy events in the world. Perhaps some of the stripped-down figures and rhythms at the heart of a melody are simplified templates of evocative environmental sounds. In the device called tone painting, composers intentionally try to evoke environmental sounds like thunder or birdsong in a melody. |

4.

生息地の選択 私たちは、遠くの景色、緑、集まってくる雲、夕日など、安全、安全でない、あるいは変化する生息地を知らせる視覚世界の特徴に注意を払う (第6章参照)。おそらく私たちは、安全、危険、または生息地の変化を知らせる聴覚世界の特徴にも注意を払うだろう。雷、風、水のせせらぎ、鳥のさえず り、うなり声、足音、心臓の鼓動、小枝の折れる音はすべて感情的な効果をもたらすが、それはおそらく、世界の注目すべき出来事によって引き起こされるから だろう。おそらく、メロディーの中心にある削ぎ落とされた数字やリズムのいくつかは、喚起的な環境音を単純化したテンプレートなのだろう。トーンペイン ティングと呼ばれる手法では、作曲家が意図的に雷や鳥のさえずりのような環境音をメロディーの中に呼び起こそうとする。 |

| Perhaps a pure example of the

emotional tug of music may be found in cinematic soundtracks. Many

movies and television shows literally orchestrate the viewers’ emotions

from beginning to end with quasi-musical arrangements. They have no

real rhythm, melody, or grouping, but can yank the moviegoer from

feeling to feeling: the climactic rising scales of silent films, the

lugubrious strings in the mushy scenes of old black-and-white movies

(the source of the sarcastic violin-bowing gesture that means “You are

trying to manipulate my sympathy”), the ominous two-note motif from

Jaws, the suspenseful cymbal and drumbeats in the Mission Impossible

television series, the furious cacophony during fights and chase

scenes. It’s not clear whether this pseudo-music distills the contours

of environmental sounds, speech, emotional cries, or some combination,

but it is undeniably effective. |

音楽が感情に訴える純粋な例は、映画のサウンドトラックにあるかもしれ

ない。多くの映画やテレビ番組は、最初から最後まで、視聴者の感情を擬似的な音楽ア

レンジで文字通りオーケストレーションしている。リズムもメロディーもグループ分けもないが、映画ファンを感情から感情へと引っ張ることができる:

サイレント映画のクライマックスで盛り上がる音階、古いモノクロ映画のムズムズするシーンで使われる重苦しい弦楽器(「私の同情を操作しようとしている」

という意味の、皮肉たっぷりのバイオリンでお辞儀をするジェスチャーの元ネタ)、『ジョーズ』の不吉な2音符のモチーフ、テレビシリーズ『ミッション・イ

ンポッシブル』のサスペンスフルなシンバルとドラムのビート、戦いや追跡シーンの激しい不協和音。この擬似音楽が、環境音の輪郭を抽出したものなのか、話

し声なのか、感情の叫びなのか、あるいはその組み合わせなのかは定かではないが、紛れもなく効果的である。 |

| 5. Motor control. Rhythm is the universal component of music, and in many idioms it is the primary or only component. People dance, nod, shake, swing, stride, clap, and snap to music, and that is a strong hint that music taps into the system of motor control. Repetitive actions like walking, running, chopping, scraping, and digging have an optimal rhythm (usually an optimal pattern of rhythms within rhythms), which is determined by the impedances of the body and of the tools or surfaces it is working with. A good example is pushing a child on a swing. A constant rhythmic pattern is an optimal way to time these motions, and we get moderate pleasure from being able to stick to it, which athletes call getting in a groove or feeling the flow. Music and dance may be a concentrated dose of that stimulus to pleasure. Muscle control also embraces sequences of tension and release (for example, in leaping or striking), actions carried out with urgency, enthusiasm, or lassitude, and erect or slumping body postures that reflect confidence, submission, or depression. Several psychologically oriented music theorists, including Jackendoff, Manfred Clynes, and David Epstein, believe that music recreates the motivational and emotional components of movement. |

5.

運動制御 リズムは音楽の普遍的な要素であり、多くのイディオムでは、リズムが主要または唯一の要素である。人は音楽に合わせて踊ったり、うなずいたり、 揺れたり、歩いたり、拍手したり、スナップしたりする。歩く、走る、刻む、擦る、掘るなどの反復動作には最適なリズムがあり(通常はリズムの中に最適なリ ズムのパターンがある)、それは身体と作業する道具や表面のインピーダンスによって決まる。良い例は、ブランコで子供を押すことである。一定のリズムパ ターンは、このような動作のタイミングを合わせる最適な方法であり、私たちはそれにこだわることで適度な快感を得ることができる。音楽やダンスは、その快 楽への刺激を凝縮したものなのかもしれない。また、筋肉のコントロールには、緊張と解放の連続(例えば、跳躍や打撃など)、緊急性、熱意、倦怠感を伴う動 作、自信、服従、抑うつを反映する直立姿勢やうつむき姿勢なども含まれる。ジャッケンドフ、マンフレッド・クラインズ、デイヴィッド・エプスタインなど、 心理学志向の音楽理論家の何人かは、音楽は動きの動機づけや感情の要素を再現すると考えている。 |

| 6. Something else. Something that explains how the whole is more than the sum of the parts. Something that explains why watching a slide go in and out of focus or dragging a filing cabinet up a flight of stairs does not hale souls out of men’s bodies. Perhaps a resonance in the brain between neurons firing in synchrony with a soundwave and a natural oscillation in the emotion circuits? An unused counterpart in the right hemisphere of the speech areas in the left? Some kind of spandrel or crawl crawl space or short-circuit or coupling that came along as an accident of the way that auditory, emotional, language, and motor circuits are packed together in the brain? This analysis of music is speculative, but it nicely complements the discussions of the mental faculties in the rest of the book. I chose them as topics because they show the clearest signs of being adaptations. I chose music because it shows the clearest signs of not being one. |

6.

他の何か 全体が部分の総和以上であることを説明する何か。スライドのピントが合ったり合わなかったりするのを見たり、ファイリング・キャビネットを引き ずって階段を上ったりしても、なぜ人の体から魂が湧き上がらないのかを説明する何か。おそらく、音波に同期して発火するニューロンと、感情回路の自然な振 動との間で、脳内で共鳴が起きているのだろう。左の言語野の右半球における未使用の対応物?聴覚回路、感情回路、言語回路、運動回路が脳の中で偶然に組み 合わされた、ある種のスパンドレル、クロールスペース、ショートサーキット、カップリング?音楽に関するこの分析は推測の域を出ないが、本書の残りの部分 にある精神能力に関する議論をうまく補完している。私がこれらのトピックを選んだのは、それらが適応であることの最も明確な兆候を示しているからである。 音楽を選んだのは、音楽がそうでないことの最も明確な兆候を示しているからである。 |

| How the mind works / Steven Pinker.London : Allen Lane, Penguin Press , 1998, c1997 |

★ダニエル・レヴィティンによる論駁

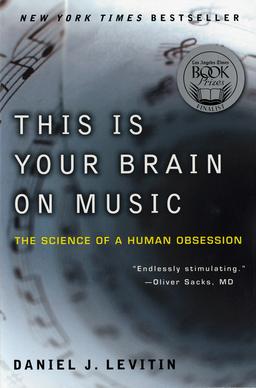

| This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession

is a popular science book written by the McGill University

neuroscientist Daniel J. Levitin, and first published by Dutton Penguin

in the U.S. and Canada in 2006, and updated and released in paperback

by Plume/Penguin in 2007. It has been translated into 18 languages and

spent more than a year on The New York Times, The Globe and Mail, and

other bestseller lists, and sold more than one million copies.[1] |

これが音楽に対するあなたの脳だ: The Science of

a Human

Obsession』は、マギル大学の神経科学者ダニエル・J・レヴィティンによって書かれたポピュラーな科学書であり、2006年にアメリカとカナダで

ダットン・ペンギン社から出版された。18カ国語に翻訳され、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙、グローブ・アンド・メール紙などのベストセラーリストに1年以上

掲載され、100万部以上を売り上げた[1]。 |

| Overview The aim of This Is Your Brain on Music was to make recent findings in neuroscience of music accessible to the educated layperson.[2] Characteristics and theoretical parameters of music are explained alongside scientific findings about how the brain interprets and processes these characteristics.[3] The neuroanatomy of musical expectation, emotion, listening and performance is discussed. This Is Your Brain on Music describes the components of music, such as timbre, rhythm, pitch, and harmony[4] and ties them to neuroanatomy, neurochemistry, cognitive psychology, and evolution,[4][5][6] while also making these topics accessible to nonexpert readers by avoiding the use of scientific jargon.[3] One particular focus of the book is on cognitive models of categorization and expectation, and how music exploits these cognitive processes.[4][5] The book challenges Steven Pinker's "auditory cheesecake" assertion that music was an incidental by-product of evolution, arguing instead that music served as an indicator of cognitive, emotional and physical health, and was evolutionarily advantageous as a force that led to social bonding and increased fitness, citing the arguments of Charles Darwin, Geoffrey Miller and others.[7] This Is Your Brain on Music was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Award in 2006–2007 for best in the Science and Engineering category, and a Quill Award for best debut author of 2006–2007. It was named one of the best books of the year by The Globe and Mail, The Independent and The Guardian.[8] A long list of prominent scientists and musicians have praised it, including Oliver Sacks, Francis Crick, Brian Greene, David Byrne, George Martin, Yoko Ono, Neil Peart, Victor Wooten, Pete Townshend and Keith Lockhart, and it has been adopted for course use in both science and literature classes at dozens of universities including MIT, Dartmouth College, UC Berkeley, Stanford, Kenyon College, the University of Wisconsin. Two documentary films were based on the book: The Musical Brain (2009) featuring Levitin as host, along with appearances by Sting, Michael Bublé, Feist, and former Fugees leader Wyclef Jean; and The Music Instinct (2009) with Levitin and Bobby McFerrin as co-hosts, with appearances by Yo Yo Ma, Jarvis Cocker, Daniel Barenboim, Oliver Sacks and others. In 2009, Harvard University announced This Is Your Brain on Music would be required reading in its Freshman Core Program in General Education.[9] In 2011–2012, the Physics Department at the California Institute of Technology adopted it as a textbook. |

概要 This Is Your Brain on Music』の目的は、音楽に関する神経科学の最新の知見を、教養のある一般人にもわかりやすく伝えることである。音楽の特徴や理論的パラメータが、脳が これらの特徴をどのように解釈し、処理するかについての科学的知見とともに説明されている[3]。 This Is Your Brain on Music』では、音楽の構成要素である音色、リズム、ピッチ、ハーモニー[4]について説明し、それらを神経解剖学、神経化学、認知心理学、進化と結び つけている[4][5][6]。 [4][5]本書は、音楽は進化の偶発的な副産物であるというスティーブン・ピンカーの「聴覚的チーズケーキ」の主張に異議を唱え、その代わりに、音楽は 認知的、感情的、身体的健康の指標として機能し、チャールズ・ダーウィンやジェフリー・ミラーなどの議論を引用しながら、社会的結合や体力向上につながる 力として進化的に有利であったと主張している[7]。 This Is Your Brain on Music』は、2006-2007年のロサンゼルス・タイムズ・ブック・アワードの科学・工学部門最優秀賞の最終選考に残り、2006-2007年のク イール賞最優秀デビュー作家に選ばれた。グローブ・アンド・メール』紙、『インディペンデント』紙、『ガーディアン』紙の年間ベストブックにも選ばれた。 [オリバー・サックス、フランシス・クリック、ブライアン・グリーン、デヴィッド・バーン、ジョージ・マーティン、オノ・ヨーコ、ニール・パート、ヴィク ター・ウーテン、ピート・タウンシェント、キース・ロックハートなど、著名な科学者や音楽家がこぞって賞賛し、MIT、ダートマス大学、カリフォルニア大 学バークレー校、スタンフォード大学、ケニオン大学、ウィスコンシン大学など、数十の大学で科学と文学の授業に採用されている。この本を基に2本のドキュ メンタリー映画が制作された: The Musical Brain』(2009年)にはレヴィティンが司会を務め、スティング、マイケル・ブーブレ、ファイスト、元フージーズのリーダー、ワイクリフ・ジーンら が出演。『The Music Instinct』(2009年)にはレヴィティンとボビー・マクフェリンが共同司会を務め、ヨーヨー・マ、ジャーヴィス・コッカー、ダニエル・バレンボ イム、オリバー・サックスらが出演している。2009年、ハーバード大学は『This Is Your Brain on Music』を一般教養の新入生コアプログラムの必読書にすると発表した[9]。2011年から2012年にかけて、カリフォルニア工科大学の物理学科が 教科書として採用した。 |

| Current editions English This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession. New York: Plume (Penguin), 2007, paperback, ISBN 978-0-452-28852-2. This Is Your Brain on Music: Understanding a Human Obsession. London: Grove/Atlantic, 2007, hardcover, ISBN 978-1-84354-715-0 This Is Your Brain on Music: Understanding a Human Obsession. London: Grove/Atlantic, 2008, paperback, ISBN 978-1-84354-716-7 Other languages Ons muzikale brein. Altas Contact, Amsterdam, 2013, ISBN 9789045024561, vertaling Robert Vernooy, paperback 320 p. De la note au cerveau. Les Éditions de l'Homme/Sogides, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 2010, ISBN 978-2-7619-2679-9 De la note au cerveau. France: Editions Heloise d'Ormesson, 2010. ISBN 2-35087-129-0 Der Musik-Instinkt: Die Wissenschaft einer menschlichen Leidenschaft. Heidelberg, Germany: Spektrum, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8274-2078-7 Fatti di musica: La scienza di un'ossessione umana. 2008, Torino, Italy: Codice, 2008, paperback, ISBN 978-88-7578-098-2 Musiikki ja aivot: Ihmisen erään pakkomielteen tiedettä. (Translated into Finnish by Timo Paukku.) Helsinki: Terra Cognita 2010. ISBN 978-952-5697-22-3 This Is Your Brain on Music. (Portuguese). Brazil: Distribuidora Record, 2009. This Is Your Brain on Music. Croatia: Vukovic & Runjic. This Is Your Brain on Music. Greece: Psihopolis, due 2010. This Is Your Brain on Music. Japan: Hakuyosha Publishing, due 2010. This Is Your Brain on Music. Romania: SC Humanitas, due 2010. This Is Your Brain on Music. Turkey: Pegasus Yayincilik, 2010. Tu cerebro y la musica. Spain: RBA Libros. ISBN 978-84-9867-336-4, 2008. Uma Paixão Humana: O seu Cérebro e a Música. Lisbon, Portugal: EditorialBizâncio, 2007, paperback, ISBN 978-972-53-0363-4 뇌의 왈츠 - 세상에서 가장 아름다운 강박 (This Is Your Brain on Music.) Korea: Mati. ISBN 978-89-92053-16-7, 2008. Ова е вашиотмозок за музика (This Is Your Brain on Music.) Macedonia: Kosta Abras Ad Ohrid, 2009. ISBN 978-9989-843-48-8 音楽好きな脳 : 人はなぜ音楽に夢中になるのか / ダニエル・J・レヴィティン著 ; 西田美緒子訳, 新版. - 東京 : ヤマハミュージックエンタテインメントホールディングス , 2021.2/ 東京 : 白揚社 , 2010.3 |

現在のエディション 英語版 これがあなたの音楽脳だ: 人間のこだわりを科学する。ニューヨーク: Plume (Penguin), 2007, ペーパーバック, ISBN 978-0-452-28852-2. これがあなたの音楽脳だ: 人間の強迫観念を理解する。ロンドン: Grove/Atlantic, 2007, ハードカバー, ISBN 978-1-84354-715-0. これがあなたの音楽脳だ: 人間のこだわりを理解する。ロンドン: グローブ/アトランティック社、2008年、ペーパーバック、ISBN 978-1-84354-716-7 その他の言語 Ons muzikale brein. Altas Contact, Amsterdam, 2013, ISBN 9789045024561, vertaling Robert Vernooy, paperback 320 p. De la note au cerveau. LesÉditions de l'Homme/Sogides, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 2010, ISBN 978-2-7619-2679-9. De la note au cerveau. フランス: Editions Heloise d'Ormesson, 2010. ISBN 2-35087-129-0 音楽インスティンクト: Die Wissenschaft einer menschlichen Leidenschaft. ドイツ、ハイデルベルク: Spektrum, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8274-2078-7 Fatti di musica: La scienza di un'ossessione umana. 2008, Torino, Italy: Codice, 2008, ペーパーバック, ISBN 978-88-7578-098-2 Musiikki ja aivot: 音楽とアイヴォット: 音楽とアイヴォット: 音楽とアイヴォット: 音楽とアイヴォット: 音楽とアイヴォット: 音楽とアイヴォット. (ティモ・パウク著、フィンランド語訳)ヘルシンキ: Terra Cognita 2010. ISBN 978-952-5697-22-3 これがあなたの音楽脳だ。(ポルトガル語)。ブラジル: Distribuidora Record, 2009. これは音楽についてのあなたの脳である。クロアチア: Vukovic & Runjic. ディス・イズ・ユア・ブレイン・オン・ミュージック. ギリシャ: プシホポリス、2010年予定。 ディス・イズ・ユア・ブレイン・オン・ミュージック. 日本: 白揚社、2010年予定。 これがあなたの音楽脳だ。ルーマニア: SC Humanitas, 2010年予定。 これがあなたの音楽脳だ。トルコ: Pegasus Yayincilik, 2010. あなたの脳と音楽。スペイン: RBA Libros. ISBN 978-84-9867-336-4, 2008. Uma Paixão Humana: O seu Cérebro e a Música. ポルトガル、リスボン: EditorialBizâncio, 2007, ペーパーバック, ISBN 978-972-53-0363-4 뇌의 왈츠 - 세상에서 가장 아름다운 강박(これがあなたの音楽脳だ) Korea: Mati. ISBN 978-89-92053-16-7, 2008. Ова е вашиотмозок за музика (This Is Your Brain on Music.) Macedonia: Kosta Abras Ad Ohrid, 2009. ISBN 978-9989-843-48-8 音楽好きな脳 : 人はなぜ音楽に夢中になるのか / ダニエル・J・レヴィティン著 ; 西田美緒子訳, 新版. - 東京 : ヤマハミュージックエンタテインメントホールディングス , 2021.2/ 東京 : 白揚社 , 2010.3 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/This_Is_Your_Brain_on_Music |

|

| Daniel Joseph Levitin,

FRSC (born December 27, 1957) is an American-Canadian polymath,[1]

cognitive psychologist, neuroscientist, writer, musician, and record

producer.[2] He is the author of four New York Times best-selling

books, including This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human

Obsession, (Dutton/Penguin 2006; Plume/Penguin 2007) which has sold

more than 1½ million copies.[3] Levitin is the James McGill Professor Emeritus of psychology, behavioral neuroscience and music at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Founding Dean of Arts & Humanities at Minerva University; and a Distinguished Faculty Fellow at the Haas School of Business, University of California at Berkeley. He is the Director of the Laboratory for Music Perception, Cognition, and Expertise at McGill.[4] He is a former member of the Board of Governors of the Grammys, a consultant to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, an elected fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a fellow of the Association for Psychological Science, a fellow of the Psychonomic Society, and a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada (FRSC). He has appeared frequently as a guest commentator on NPR and CBC. He has published scientific articles on absolute pitch, music cognition, neuroanatomy, and directional statistics.[5][6] His six books have all been international bestsellers, and collectively have sold more 3 million copies worldwide: This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession (2006),[7][8][9] The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature (2008), The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload (2014), A Field Guide to Lies: Critical Thinking in the Information Age (2016) and Successful Aging (2020). I Heard There Was A Secret Chord: Music As Medicine was released in August 2024 by W. W. Norton, receiving advance praise from Paul McCartney, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, Bob Weir, Michael Connelly and others. Levitin also worked as a music consultant, producer and sound designer on albums by Blue Öyster Cult, Chris Isaak, and Joe Satriani among others;[10] produced punk bands including MDC and The Afflicted; and served as a consultant on albums by artists including Steely Dan, Stevie Wonder, and Michael Brook;[11][12] and as a recording engineer for Santana, Jonathan Richman, O.J. Ekemode and the Nigerian Allstars, and The Grateful Dead.[13] Records and CDs to which he has contributed have sold more than 30 million copies.[12][14] |

ダニエル・ジョセフ・レヴィティン(FRSC、1957年12月27日

生まれ)は、アメリカ合衆国とカナダの博識家[1]、認知心理学者、神経科学者、作家、音楽家、レコードプロデューサーである。[2]

ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のベストセラーとなった4冊の著書があり、その中には『This Is Your Brain on Music: The

Science of a Human Obsession(邦題『音楽の脳科学』)など、4冊のニューヨーク・タイムズ・ベストセラーの著者でもある。 レヴィティンは、カナダのケベック州モントリオールにあるマギル大学のジェームズ・マッギル名誉教授(心理学、行動神経科学、音楽)であり、ミネルバ大学の 人文科学部の初代学部長、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校ハース・スクール・オブ・ビジネスの特別研究員でもある。マギル大学音楽知覚認知・専門性研究所 の所長も務めている。[4] グラミー賞理事会の元メンバーであり、ロックの殿堂のコンサルタント、アメリカ科学振興協会の選出フェロー、心理科学協会のフェロー、心理経済学会のフェ ロー、カナダ王立協会のフェロー(FRSC)でもある。彼は、NPRやCBCの番組にゲストコメンテーターとして頻繁に出演している。絶対音感、音楽認 知、神経解剖学、方向統計学に関する科学論文を発表している。 彼の6冊の著書はすべて国際的なベストセラーとなり、全世界で300万部以上を売り上げている。『音楽の脳科学:人間を虜にする科学』(2006年) [7][8][9]、『世界は6つの歌でできている:音楽を愛する脳が人間性を生み出した』(2008年)、『整理された心:情報過多時代のまっすぐな思 考』(2014年)、『嘘のフィールドガイド: Critical Thinking in the Information Age (2016年) および Successful Aging (2020年)。I Heard There Was A Secret Chord: Music As Medicineは2024年8月にW. W. Norton社から出版され、ポール・マッカートニー、ニール・ドグラース・タイソン、ボブ・ウィアー、マイケル・コナリーなどから事前評価を受けた。 また、ブルー・オイスター・カルト、クリス・イサアク、ジョー・サトリアーニなどのアルバムで音楽コンサルタント、プロデューサー、サウンドデザイナーと しても活動し[10]、MDCやザ・アフィクテッドなどのパンクバンドのプロデュースも手がけ、スティーリー・ダン、スティーヴィー・ワンダー、マイケ ル・ブルックなどのアルバムではコンサルタントを務めた[11][12]。また、サンタナ、ジョナサン・リッチマン、O.J.エケモード・アンド・ザ・ナ イジェリアン・オールスターズ、グレイトフル・デッドのレコーディングエンジニアも務めた[13]。オールスターズ、グレイトフル・デッドなどのレコー ディング・エンジニアも務めた。[13] 彼が携わったレコードやCDは、3000万枚以上を売り上げている。[12][14] |

| Biography and education Born in San Francisco,[15] the son of Lloyd Levitin, a businessman and professor, and Sonia Levitin, a novelist. Both parents are Jewish. Daniel Levitin was raised in Daly City, Moraga, and Palos Verdes, all in California.[16] He graduated after his junior year at Palos Verdes High School to attend the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where he studied applied mathematics; he later enrolled at the Berklee College of Music before dropping out of college to join a succession of bands, work as a record producer, and help found a record label, 415 Records. He returned to school in his thirties, studying cognitive psychology/cognitive science first at Stanford University where he received a BA degree in 1992 (with honors and highest university distinction) and then at the University of Oregon where he received an MSc degree in 1993 and a PhD degree in 1996. He completed post-doctoral fellowships at Paul Allen's Silicon Valley think-tank Interval Research, at Stanford University Medical School, and at the University of California, Berkeley.[16] His early influences include Susan Carey, Merrill Garrett, and Molly Potter and his scientific mentors include Roger Shepard, Karl H. Pribram, Michael Posner, Douglas Hintzman,[17] John R. Pierce,[18] and Stephen Palmer.[19] He has been a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, Stanford University, Dartmouth College, and Oregon Health Sciences University. As a cognitive neuroscientist specializing in music perception and cognition, he is credited for fundamentally changing the way that scientists think about auditory memory, showing through the Levitin Effect, that long-term memory preserves many of the details of musical experience that previous theorists regarded as lost during the encoding process.[20][21][22][23] He is also known for drawing attention to the role of cerebellum in music listening, including tracking the beat and distinguishing familiar from unfamiliar music.[21] Outside of his academic pursuits Levitin has worked on and off as a stand-up comedian and joke writer, performing at the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco with Robin Williams in 1984, and at comedy clubs in California;[24] he placed second in the National Lampoon stand-up comedy competition regionals in San Francisco in 1989, and has contributed jokes for Jay Leno and Arsenio Hall, as well as the nationally syndicated comic strip Bizarro.[25] Some comics were included in the 2006 compilation Bizarro and Other Strange Manifestations of the Art of Dan Piraro (Andrews McMeel).[26][27] |

経歴と学歴 サンフランシスコで、実業家で大学教授のロイド・レヴィティンと小説家のソニア・レヴィティンの息子として生まれた。両親ともユダヤ人である。ダニエル・ レヴィティンはカリフォルニア州のダリーシティ、モラガ、パロスバーデスで育った。[16] パロスバーデス高校を3年で中退し、マサチューセッツ工科大学に進学して応用数学を学んだ。その後、バークリー音楽大学に入学したが、大学を中退して次々 とバンドに参加し、レコードプロデューサーとして働き、レコードレーベルの415レコードの設立を手伝った。30代で再び学校に戻り、認知心理学/認知科 学を学び、まずスタンフォード大学で1992年に学士号(優等および大学最高の栄誉を得て)を取得し、その後オレゴン大学で1993年に修士号、1996 年に博士号を取得した。ポール・アレンが所有するシリコンバレーのシンクタンク、Interval Research、スタンフォード大学医学部、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校でポストドクター研究員として研究を続けた。[16] 彼の初期の研究に影響を与えた人物には、スーザン・キャリー、メリル・ギャレット、モリー・ポッターなどがおり、科学的な指導者としては、ロジャー・シェ パード、カール・H・プリブラム、マイケル・ポズナー、ダグラス・ヒンツマン、ジョン・R・ピアース、スティーブン・パーマーなどがいる。[17] [18][19] 彼は カリフォルニア大学バークレー校、スタンフォード大学、ダートマス大学、オレゴン健康科学大学の客員教授を務めたことがある。 音楽の知覚と認知を専門とする認知神経科学者として、彼は聴覚記憶に対する科学者の考え方を根本的に変えたことで知られている。レヴィティン効果によっ て、長期記憶は、エンコーディングプロセス中に失われると以前の理論家が考えていた音楽体験の多くの詳細を保存していることを示した。[20][21] [22][23] また、音楽鑑賞における小脳の役割に注目したことでも知られている。小脳は、ビートの追跡や、聞き慣れた音楽と聞き慣れない音楽の区別などを行う。。 学術研究以外では、レヴィティンはスタンドアップ・コメディアンやジョーク作家として、1984年にはサンフランシスコで開催された民主党全国大会でロビ ン・ウィリアムズと共演し、またカリフォルニアのコメディ・クラブでも公演を行っている。[24] 1989年にはサンフランシスコで開催されたナショナル・ランプーンのスタンドアップ・コメディ・コンペティション地区予選で2位に入賞し、ジェイ・レノ やアーセンio・ホール、また全国ネットの 。2006年の編集本『Bizarro and Other Strange Manifestations of the Art of Dan Piraro』(アンドリューズ・マクミール)には、いくつかの漫画が収録されている。[26][27] |

| Music Levitin began playing piano at age 4. He took up clarinet at age 8, and bass clarinet and saxophone at age 12.[28] He played saxophone (tenor and baritone) in high school; at age 17 he performed on baritone with the big band backing up Mel Tormé at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium.[29] He began playing guitar at age 20 and has been a member of bands including The Alsea River Band (lead guitar), The Mortals (bass), Judy Garland [band] (bass), The Shingles (lead guitar), Slings & Arrows (bass), JD Buhl (bass and guitar). He also played on recording sessions for Blue Öyster Cult, True West, and the soundtrack to Repo Man. He continues to perform regularly and has played saxophone with Sting, Ben Sidran, and Bobby McFerrin, played guitar with Rosanne Cash, Blue Öyster Cult, Rodney Crowell, Michael Brook, Gary Lucas, Victor Wooten, Steve Bailey, Peter Case, Peter Himmelman, Lenny Kaye, Jessie Farrell, and David Byrne; and appeared on vocals with Renée Fleming, Neil Young and Rosanne Cash.[30][31] In the fall of 2017 he toured the West Coast with singer-songwriter Tom Brosseau. He began writing songs at age 17. His songwriting has been praised by a number of top songwriters including Diane Warren, and Joni Mitchell, who said, "Dan is really good at what he does, and creates rich images with his words and music."[32] He released his first album of original songs, Turnaround, in January 2020 with a performance with his own band at the Rockwood Music Hall in New York City, followed by seven shows with Victor Wooten's Bass Extremes band in Los Angeles, Oakland, and Phoenix, and a performance of one of the album's songs "Just A Memory" with Renée Fleming, Victor Wooten and Hardy Hemphill sponsored by John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.[33] |

音楽 レヴィティンは4歳でピアノを始めた。8歳でクラリネットを始め、12歳でバスクラリネットとサックスを手にした。[28] 高校ではサックス(テナーとバリトン)を演奏し、17歳でサンタモニカ市民会館でメル・トーメのバックバンドとしてバリトンサックスを演奏した。[29] 20歳でギターを始め、The Alsea River Band(リードギター)、The Mortals (ベース)、ジュディ・ガーランド・バンド(ベース)、ザ・シングルズ(リード・ギター)、スリングス・アンド・アローズ(ベース)、JDビューエル (ベースおよびギター)などのバンドで活動した。また、ブルー・オイスター・カルト、トゥルー・ウェスト、映画『レポ・マン』のサウンドトラックのレコー ディング・セッションにも参加した。 現在も定期的に演奏活動を続け、スティング、ベン・シドラン、ボビー・マクファーリンとサックスを演奏し、ロザンヌ・キャッシュ、ブルー・オイスター・カ ルト、ロドニー・クロウェル、マイケル・ブルック、ゲイリー・ルーカス、ヴィクター・ウーテン、スティーブ・ベイリー、ピーター・ケース、ピーター・ヒン メルマン、レニー・ケイ、ジェシー・ファレル、デヴィッド・バーンとギターを演奏し、レネー・フレミング、ニール・ヤング、ロザンヌ・キャッシュとボーカ ルを披露している。2017年秋にはシンガーソングライターのトム・ブロソーと西海岸をツアーした。 彼は17歳で作曲を始めた。彼の作曲はダイアン・ウォーレンやジョニ・ミッチェルを含む多くの一流の作曲家から賞賛されており、ジョニ・ミッチェルは「ダンは本当に自分のやっていることが上手で、言葉と音楽で豊かなイメージを作り出す」と述べている。 彼は2020年1月に、ニューヨークのロックウッド・ミュージック・ホールで自身のバンドとのパフォーマンスを収録した初のオリジナル曲アルバム 『Turnaround』をリリースし、その後ロサンゼルス、オークランド、フェニックスでヴィクター・ウーテンのバンド「Bass Extremes」との7回のショーを行い、さらにジョン・F・ケネディ・センター・フォー・ザ・パフォーミング・アーツのスポンサーにより、ルネ・フレ ミング、ヴィクター・ウーテン、ハーディ・ヘンフィルとともにアルバム収録曲の1つ「Just A Memory」のパフォーマンスを行った 。 |

| Music producing and engineering In the late 1970s, Levitin consulted for M&K Sound as an expert listener assisting in the design of the first commercial satellite and subwoofer loudspeaker systems, an early version of which was used by Steely Dan for mixing their album Pretzel Logic (1974). After that he worked at A Broun Sound in San Rafael, California, re-coning speakers for The Grateful Dead for whom he later worked as a consulting record producer. Levitin was one of the golden ears used in the first Dolby AC audio compression tests, a precursor to MP3 audio compression.[16] From 1984 to 1988, he worked as the director, then vice president of A&R for 415 Records in San Francisco, becoming the president of the label in 1989 before the label was sold to Sony Music.[34][35] Notable achievements during that time included producing the punk classic Here Come the Cops by The Afflicted (named among the Top 10 records of 1985 by GQ magazine); engineering records by Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers, Santana, and the Grateful Dead; and producing tracks for Blue Öyster Cult, the soundtrack to Repo Man (1984), and others.[36] Two highlights of his tenure in A&R were discovering the band The Big Race (which later became the well-known soundtrack band Pray for Rain), and he had the opportunity to sign M.C. Hammer but passed.[37] After 415 was sold, he formed his own production and business consulting company, with a list of clients including AT&T, several venture capital firms, and every major record label.[38] As a consultant for Warner Bros. Records he planned the marketing campaigns for such albums as Eric Clapton's Unplugged (1992) and k.d. lang's Ingénue (1992). He was a music consultant on feature films such as Good Will Hunting (1997) and The Crow: City of Angels (1996), and served as a compilation consultant to Stevie Wonder's Song Review: A Greatest Hits Collection (1996), and to As Time Goes By (2003) and Interpretations: A 25th Anniversary Celebration (1995; updated and released as a DVD in 2003) by The Carpenters. Levitin returned to the studio in 2002, producing three albums for Quebec blues musician Dale Boyle: String Slinger Blues (2002), A Dog Day for the Purists (2004), and In My Rearview Mirror: A Story From A Small Gaspé Town (2005), the latter two of which won the annual Lys Blues Award for best Blues album.[39] He helped Joni Mitchell with the production of her three most recent albums, Shine, Love Has Many Faces: A Quartet, A Ballet, Waiting to Be Danced, and Starbucks' Artist's Choice: Joni Mitchell. In 1998, Levitin helped to found MoodLogic.com (and its sister companies, Emotioneering.com and jaboom.com), the first Internet music recommendation company, sold in 2006 to Allmusic group. He has also consulted for the United States Navy on underwater sound source separation, for Philips Electronics, and AT&T.[40] He was an occasional script consultant to The Mentalist from 2007 to 2009. |

音楽制作およびエンジニアリング 1970年代後半、レビティン氏はM&Kサウンドのコンサルタントとして、初期の商用衛星およびサブウーファー・ラウドスピーカー・システムの設 計を支援するエキスパート・リスナーとして活躍した。その初期バージョンは、アルバム『Pretzel Logic』(1974年)のミヘにスティーリー・ダンによって使用された。その後、カリフォルニア州サンラファエルのA Broun Sound社で、後にコンサルティング・レコード・プロデューサーとして働くことになるグレイトフル・デッドのスピーカーの再調整を行った。レビティン は、MP3オーディオ圧縮の先駆けとなるドルビーACオーディオ圧縮の最初のテストで使用された「ゴールデン・イヤー」の1人であった。[16] 1984年から1988年にかけて、彼はサンフランシスコの415レコードでディレクター、そしてA&R担当副社長として働き、1989年にレー ベルがソニー・ミュージックに売却される前に社長に就任した。[34][35] この時期の主な功績には、 パンクの名曲「Here Come the Cops」をThe Afflictedが制作したこと(GQ誌が1985年のトップ10レコードに選出した)、ジョナサン・リッチマンとモダン・ラバーズ、サンタナ、グレイ トフル・デッドのレコードのエンジニアリング、ブルー・オイスター・カルト、映画『レポマン』(1984年)のサウンドトラックなどの制作が含まれる。 [36] A&R在籍中のハイライトは、バンド「The Big Race」を発掘したこと(後に 後に有名なサウンドトラック・バンド、プレイ・フォー・レインとなる)を発掘したこと、また、M.C.ハマーと契約する機会があったが、それを逃したこと である。 415が売却された後、彼は自身のプロダクションおよびビジネスコンサルティング会社を設立し、AT&T、複数のベンチャーキャピタル、およびす べての主要レコードレーベルを顧客として抱えた。[38] ワーナー・ブラザース・レコードのコンサルタントとして、彼はエリック・クラプトンの『アンプラグド』(1992年)やk.d.ラングの『インジューン』 (1992年)などのアルバムのマーケティングキャンペーンを企画した。また、映画『グッド・ウィル・ハンティング』(1997年)や『クロウ/シティ・ オブ・エンジェルス』(1996年)では音楽コンサルタントを務め、スティーヴィー・ワンダーの『ソング・レビュー:グレイテスト・ヒッツ・コレクショ ン』(1996年)や、カーペンターズの『アズ・タイム・ゴーズ・バイ』(2003年)および『インタープリテーションズ: カーペンターズの『As Time Goes By』(2003年)と『Interpretations: A 25th Anniversary Celebration』(1995年、2003年にDVDとして更新・リリース)のコンピレーション・コンサルタントを務めた。レビティンは2002年 にスタジオに戻り、ケベックのブルースミュージシャン、デール・ボイルの3枚のアルバム『String Slinger Blues』(2002年)、『A Dog Day for the Purists』(2004年)、『In My Rearview Mirror: 後者の2枚は、年間最優秀ブルースアルバムに贈られるLys Blues Awardを受賞した。[39] 彼は、ジョニ・ミッチェルの最新アルバム3作、Shine、Love Has Many Faces: A Quartet, A Ballet, Waiting to Be Danced、Starbucks' Artist's Choice: Joni Mitchellの制作を手伝った。 1998年、レビティンは最初のインターネット音楽推薦会社であるMoodLogic.com(および姉妹会社であるEmotioneering.com とjaboom.com)の設立に携わり、2006年にAllmusicグループに売却された。また、米国海軍の水中音源分離、フィリップス・エレクトロ ニクス、AT&Tのコンサルタントも務めた。[40] 2007年から2009年にかけて、テレビドラマ『メンタリスト』の脚本コンサルタントを時折務めた。 |

| Writing career Levitin began writing articles in 1988 for music industry magazines Billboard, Grammy, EQ, Mix, Music Connection, and Electronic Musician, and was named contributing writer to Billboard′s Reviews section from 1992 to 1997. He has contributed to The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The New Yorker,[41] and The Atlantic.[42] Levitin is the author of This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession, (Dutton/Penguin 2006; Plume/Penguin 2007) which spent more than 12 months on the New York Times[43] and the Globe and Mail bestseller lists. In that book, he shares observations related to all sorts of music listeners, telling for instance that, today, teenagers listen to more music in one month than their peers living during the 1700s during their entire existence. The book was nominated for two awards (The Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Outstanding Science & Technology Writing and the Quill Award for the Best Debut Author of 2006), named one of the top books of the year by Canada's The Globe and Mail and by The Independent and The Guardian,[44] and has been translated into 20 languages. The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature (Dutton/Penguin 2008) debuted on the Canadian and the New York Times bestseller lists,[45] and was named by the Boston Herald and by Seed Magazine as one of the best books of 2008. It was also nominated for the World Technology Awards. The Organized Mind was published by Dutton/Penguin Random House in 2014,[46] debuting at #2 on the New York Times Bestseller List[47] and reaching #1 on the Canadian best-seller lists.[48] A Field Guide to Lies was published by Dutton/Penguin Random House in 2016, and released in paperback in March 2017 under the revised title Weaponized Lies. It appeared on numerous best-seller lists in the U.S., Canada and the U.K.,[49][50] and is the most acclaimed of Levitin's four books, receiving the National Business Book Award,[51] the Mavis Gallant Prize for Non-Fiction, the Axiom Business Book Award, and was a finalist for the Donner Prize. Successful Aging: A Neuroscientist Explores the Power and Potential of Our Lives was published by Dutton/Penguin Random House in January 2020 and debuted at #10 on the New York Times bestseller list[52] in its first week of release, and at #2 on the Canadian bestseller list, and stayed on the Canadian bestseller lists for more than six months. It was named an Apple Books book-of-the-month and Next Big Idea Club selection. It was published by Penguin Life in the U.K. as The Changing Mind: A Neuroscientist's Guide to Ageing Well; it debuted at #5 on the Sunday Times Bestseller List.[53] It was named by the Sunday Times as one of the best books of 2020[54] |

執筆活動 レビティンは1988年より音楽業界誌『ビルボード』、『グラミー』、『EQ』、『ミックス』、『ミュージック・コネクション』、『エレクトロニック・ ミュージシャン』に記事を寄稿し、1992年から1997年までは『ビルボード』のレビュー欄の寄稿ライターを務めた。また、『ニューヨーク・タイム ズ』、『ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル』、『ワシントン・ポスト』、『ニューヨーカー』、『アトランティック』にも寄稿している。 レビティンは著書『音楽と脳:人間をとりこにする音楽の科学』(Dutton/Penguin 2006年、Plume/Penguin 2007年)の著者であり、この本はニューヨーク・タイムズ紙とグローブ・アンド・メール紙のベストセラーリストに12ヶ月以上ランクインした。この本の 中で、彼はあらゆる種類の音楽リスナーに関する観察を共有し、例えば、現代のティーンエイジャーは、1700年代に生きていた人々の生涯分よりも多くの音 楽を1か月で聴いていると述べている。この本は2つの賞にノミネートされ(ロサンゼルス・タイムズ・ブック・プライズの科学・テクノロジー部門と2006 年のクイル賞の最優秀新人賞)、カナダのグローブ・アンド・メール紙とインディペンデント紙、ガーディアン紙でその年のトップ本に選ばれ[44]、20言 語に翻訳された。『The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature』(Dutton/Penguin 2008年)は、カナダとニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のベストセラーリストに初登場し[45]、ボストン・ヘラルド紙とシード・マガジン誌では2008年の ベストブックの1冊に選ばれた。また、ワールド・テクノロジー・アワードにもノミネートされた。 『The Organized Mind』は2014年にダットン/ペンギン・ランダムハウスから出版され、ニューヨーク・タイムズ・ベストセラーリストで初登場第2位を記録し [47]、カナダのベストセラーリストでは第1位を獲得した[48]。『A Field Guide to Lies』は2016年にダットン/ペンギン・ランダムハウスから出版され、2017年3月には改題された『Weaponized Lies』としてペーパーバック版が発売された 。この本は、米国、カナダ、英国の多数のベストセラーリストに掲載され[49][50]、レビティンの4冊の本の中で最も高い評価を受け、ナショナル・ビ ジネス・ブック・アワード[51]、メイビス・ギャラント賞ノンフィクション部門、アクシオム・ビジネス・ブック・アワードを受賞し、ドナー賞の最終候補 にもなった。 『Successful Aging: A Neuroscientist Explores the Power and Potential of Our Lives』は2020年1月にダットン/ペンギン・ランダムハウスから出版され、発売初週のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のベストセラーリストで10位に初 登場し[52]、カナダのベストセラーリストでは2位となり、6か月以上カナダのベストセラーリストにランクインした。Apple Booksの今月の本およびNext Big Idea Clubの選書に選ばれた。英国ではPenguin Lifeから『The Changing Mind: A Neuroscientist's Guide to Ageing Well』として出版され、サンデー・タイムズ紙のベストセラーリストで5位に初登場した。[53] サンデー・タイムズ紙は2020年のベスト本の一つに選んだ。[54] |

| In popular culture In The Listener TV series, actor Colm Feore says his performance of the character Ray is based on Daniel Levitin.[55] Levitin consulted on the legal strategy used by Jimmy Page and Led Zeppelin to defend copyright infringement claim against his song Stairway To Heaven.[56][57] Media appearances From September 2006 to April 2007 Levitin served as a weekly commentator on the CBC Radio One show Freestyle. Two documentary films were based on This Is Your Brain on Music: The Music Instinct (2009, PBS), which he co-hosted with Bobby McFerrin, and The Musical Brain (2009, CTV/National Geographic Television) which he co-hosted with Sting. Levitin appeared in Artifact, a 2012 documentary directed by Jared Leto. His television and film appearances have reached more than 50 million viewers worldwide.[58] Levitin had a cameo appearance in The Big Bang Theory at the invitation of the producers, in Season 8, Episode 5, "The Focus Attenuation". He appeared in the opening scene, sitting at a table in the Caltech cafeteria over Sheldon's right shoulder. In January 2015 he was a guest on BBC Radio 4's Start the Week program alongside cognitive scientist Margaret Boden.[59] In 2019–2020 he was a script consultant and on-air guest for Season 8 of National Geographic's Brain Games. In 2020, he appeared in Stewart Copeland's Adventures in Music series on BBC 4,[60] discussing the evolutionary basis of music and the neuroscience of music. |

大衆文化において テレビドラマ『ザ・リスナー』の中で、俳優のコルム・フィオーレは、レイ役の演技はダニエル・レヴィティンを基にしていると語っている。[55] レヴィティンはジミー・ペイジとレッド・ツェッペリンが、彼らの楽曲「天国への階段」に対する著作権侵害の主張を弁護するために用いた法的戦略について助言した。[56][57] メディア出演 2006年9月から2007年4月まで、レビティンはCBCラジオ1の番組『Freestyle』で毎週コメンテーターを務めた。2本のドキュメンタリー 映画が『音楽を知覚する脳:音楽的直感』(2009年、PBS)を基にしており、彼はボビー・マクファーリンと共同司会を務めた。また、『音楽を知覚する 脳』(2009年、CTV/ナショナルジオグラフィックテレビ)は、彼がスティングと共同司会を務めた。レヴィティンは、ジャレッド・レトが監督した 2012年のドキュメンタリー映画『Artifact』に出演している。彼のテレビや映画への出演は、世界中で5000万人以上の視聴者に達している。 レヴィティンは、プロデューサーの招待により、シーズン8第5話「The Focus Attenuation」で『ビッグバン・セオリー』にカメオ出演した。彼はオープニングシーンに登場し、シェルドンの右肩越しにカリフォルニア工科大学 のカフェテリアのテーブルに座っている。2015年1月、彼は認知科学者のマーガレット・ボーデンとともにBBCラジオ4の番組『Start the Week』にゲスト出演した。 2019年から2020年にかけて、ナショナルジオグラフィックの『Brain Games』シーズン8では、脚本コンサルタントおよびオンエアゲストを務めた。2020年には、BBC 4の「スチュワート・コープランドの音楽の冒険」シリーズに出演し、音楽の進化論的根拠と音楽の神経科学について議論した。 |

| Selected publications Books The Billboard Encyclopedia of Record Producers (1999). New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, E. Olsen, C. Wolff, P. Verna, Editors; D. J. Levitin, associate editor. Foundations of Cognitive Psychology: Core Readings (2002), Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press Foundations of Cognitive Psychology: Core Readings, Second Edition (2010), Boston: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Publishing This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession, (2006), New York: Dutton/Penguin. (released in the U.K. and Commonwealth territories by Atlantic, 2007). (appeared on the New York Times Bestseller List both in hardcover and paperback) The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature (2008), New York: Dutton/Penguin and Toronto: Viking/Penguin. (New York Times bestseller) The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload (2014), New York: Dutton/Penguin Random House and Toronto: Allen Lane/Penguin Random House and London: Viking/Penguin Random House. A Field Guide to Lies: Critical Thinking in the Information Age (2016), New York: Dutton/Penguin Random House; Toronto: Allen Lane/Penguin Random House; London: Viking/Penguin Random House Successful Aging: A Neuroscientist Explores the Power and Potential of Our Lives (2020), New York: Dutton/Penguin Random House; Toronto: Allen Lane/Penguin Random House; London: Penguin Life. I Heard There Was A Secret Chord: Music as Medicine (2024), New York: W.W. Norton & Company. Scientific articles (selected) Levitin, D. J.; Grafton, S. T. (2016). "Measuring the representational space of music with fMRI: a case study with Sting". Neurocase. 22 (6): 548–567. doi:10.1080/13554794.2016.1216572. PMID 27687156. S2CID 3985554. Chanda, M. L.; Levitin, D. J. (2013). "The neurochemistry of music". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 17 (4): 179–193. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2013.02.007. PMID 23541122. S2CID 14608078. Sridharan, D.; Levitin, D. J.; Menon, V. (2008). "A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (34): 12569–12574. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10512569S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800005105. PMC 2527952. PMID 18723676. Langford, D. J.; Crager, S. E.; Shehzad, Z.; Smith, S. B.; Sotocinal, S. G.; Levenstadt, J. S.; Chanda, M. L.; Levitin, D. J.; Mogil, J. S. (2006). "Social Modulation of Pain as Evidence for Empathy in Mice". Science. 312 (5782): 1967–1970. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1967L. doi:10.1126/science.1128322. PMID 16809545. S2CID 26027821. Levitin, D. J.; Cook, P. R. (1996). "Absolute memory for musical tempo: Additional evidence that auditory memory is absolute". Perception & Psychophysics. 58 (6): 927–935. doi:10.3758/bf03205494. PMID 8768187. Discography J.D. Buhl, Remind Me. Driving Records/CD Baby, 2015. (Producer and Engineer). Diane Nalini, Songs of Sweet Fire. 2006. (Mixing Engineer, Production Consultant). Dale Boyle, In My Rearview Mirror: A Story From A Small Gaspé Town. 2005. (Production Consultant) Dale Boyle and the Barburners, A Dog Day for the Purists. 2004. (Producer). Dale Boyle and the Barburners, String Slinger Blues. 2002. (Producer). The Carpenters. As Time Goes By. A&M Records/Universal, 2000. (Consultant on song selection, liner notes writer.) Various Artists. Original motion picture soundtrack, Good Will Hunting. Hollywood/Miramax Records, 1998. (A&R Consultant. ) Stevie Wonder discographyStevie Wonder. Stevie Wonder Song Review: A Greatest Hits Collection. Motown, 1996. (Consultant on song selection. Liner notes writer.) Steely Dan, Gold, Decade, Gaucho, Aja, The Royal Scam, Katy Lied, Pretzel Logic, Countdown to Ecstasy, Can't Buy A Thrill, MCA, 1992. (Consultant on CD Remastering.) [source?] kd lang, Ingénue, Reprise, 1992. (Consultant.) Eric Clapton, Unplugged, Reprise, 1992. (Consultant.) Chris Isaak, Heart Shaped World, Warner Brothers, 1989. (Engineering (Asst), Sound Design (Soundscape)). Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers, Rockin' and Romance, Twin/Tone (U.S), Sire (U.K.), 1986. (Engineer). The Furies, Fun Around The World, Infrasonic, 1986 Rhythm Riot, Rhythm Riot, EP, Infrasonic, 1987*True West, Drifters, Passport/JEM Records, 1985. (co-producer). The Big Race, "Happy Animals," from the Soundtrack of the Paramount Film Repo Man, 1985. (Producer, Engineer) The Afflicted, Good News About Mental Health, Infrasonic, 1984. (Producer) International P.E.A.C.E. Benefit Compilation, R Radical Records, 1984 (Producer of tracks by The Afflicted and MDC), reissued 1997 New Red Archives/Lumberjack Mordam Music Group |

主な出版物 書籍 ビルボード・レコード・プロデューサー百科事典(1999年)。ニューヨーク:ワトソン・グプタ・パブリケーションズ、E.オルセン、C.ウォルフ、P.バーナ編集、D.J.レビン副編集。 認知心理学の基礎:コアリーディング(2002年)、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:M.I.T.プレス 『認知心理学の基礎:コア・リーディング』第2版(2010年)、ボストン:アリン・アンド・ベーコン/ピアソン・パブリッシング 『音楽があなたの脳に与える影響:人間の執着の科学』(2006年)、ニューヨーク:ダットン/ペンギン。(英国および英連邦地域ではアトランティックよ り2007年に発売。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のベストセラーリストにハードカバーとペーパーバックの両方でランクイン) 『世界を6つの歌で語る:音楽的脳が人間性を生み出した仕組み』(2008年)、ニューヨーク:ダットン/ペンギン、トロント:ヴァイキング/ペンギン。(ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙ベストセラー) 『整理された心:情報過多時代にまっすぐ考える』(2014年)、ニューヨーク:ダットン/ペンギン・ランダムハウス、トロント:アレン・レーン/ペンギン・ランダムハウス、ロンドン:ヴァイキング/ペンギン・ランダムハウス。 『ウソの見分け方:情報化時代の批判的思考』(2016年)、ニューヨーク:Dutton/Penguin Random House、トロント:Allen Lane/Penguin Random House、ロンドン:Viking/Penguin Random House 『Successful Aging: A Neuroscientist Explores the Power and Potential of Our Lives』(2020年)、ニューヨーク:Dutton/Penguin Random House、トロント:Allen Lane/Penguin Random House、ロンドン:Penguin Life 『I Heard There Was A Secret Chord: Music as Medicine (2024)』ニューヨーク:W.W. Norton & Company 学術論文(抜粋 レビティン、D. J.; グラフトン、S. T. (2016). 「fMRIによる音楽の表現空間の測定:スティングのケーススタディ」。Neurocase. 22 (6): 548–567. doi:10.1080/13554794.2016.1216572. PMID 27687156. S2CID 3985554. Chanda, M. L.; Levitin, D. J. (2013). 「The neurochemistry of music」. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 17 (4): 179–193. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2013.02.007. PMID 23541122. S2CID 14608078. Sridharan, D.; Levitin, D. J.; Menon, V. (2008). 「A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks」. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (34): 12569–12574. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10512569S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800005105. PMC 2527952. PMID 18723676. Langford, D. J.; Crager, S. E.; Shehzad, Z.; Smith, S. B.; Sotocinal, S. G.; Levenstadt, J. S.; Chanda, M. L.; Levitin, D. J.; Mogil, J. S. (2006). 「Social Modulation of Pain as Evidence for Empathy in Mice」. Science. 312 (5782): 1967–1970. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1967L. doi:10.1126/science.1128322. PMID 16809545. S2CID 26027821. レビティン、D. J.; クック、P. R. (1996年). 「音楽のテンポに関する絶対音感:聴覚記憶が絶対的であることを示す追加的証拠」。知覚と心理物理学。58 (6): 927–935. doi:10.3758/bf03205494. PMID 8768187. ディスコグラフィー J.D. Buhl, Remind Me. Driving Records/CD Baby, 2015. (プロデューサー兼エンジニア)。 Diane Nalini, Songs of Sweet Fire. 2006. (ミキシングエンジニア、制作コンサルタント)。 Dale Boyle, In My Rearview Mirror: A Story From A Small Gaspé Town. 2005. (制作コンサルタント) デール・ボイルとバーバーナーズ、純粋主義者のドッグ・デイ。2004年。(プロデューサー)。 デール・ボイルとバーバーナーズ、ストリング・スリンガー・ブルース。2002年。(プロデューサー)。 カーペンターズ。アズ・タイム・ゴーズ・バイ。A&Mレコード/ユニバーサル、2000年。(選曲コンサルタント、ライナーノーツ執筆者) Various Artists. 映画『グッド・ウィル・ハンティング』オリジナル・サウンドトラック。Hollywood/Miramax Records、1998年。(A&Rコンサルタント。) Stevie Wonder ディスコグラフィー Stevie Wonder. Stevie Wonder Song Review: A Greatest Hits Collection. Motown、1996年。(選曲コンサルタント。ライナーノーツ執筆者。) スティーリー・ダン、ゴールド、ディケイド、ガウチョ、アジャ、ザ・ロイヤル・スキャム、ケイティ・リート、プレッツェル・ロジック、カウントダウン・ トゥ・エクスタシー、キャント・バイ・ア・スリル、MCA、1992年。(CDリマスタリングのコンサルタント) [出典? ] kdラング、インジュヌ、リプライズ、1992年。(コンサルタント) Eric Clapton, Unplugged, Reprise, 1992. (コンサルタント) Chris Isaak, Heart Shaped World, Warner Brothers, 1989. (エンジニアリング(アシスタント)、サウンドデザイン(サウンドスケープ)) Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers, Rockin' and Romance, Twin/Tone (U.S), Sire (U.K.), 1986. (エンジニア) The Furies, Fun Around The World, Infrasonic, 1986 Rhythm Riot, Rhythm Riot, EP, Infrasonic, 1987*True West, Drifters, Passport/JEM Records, 1985. (共同プロデューサー). 『レポ・マン』サウンドトラックより「ハッピー・アニマルズ」、『ザ・ビッグ・レース』、1985年。(プロデューサー、エンジニア) 『ザ・アフィクテッド』『グッド・ニュース・アバウト・メンタル・ヘルス』、インフラソニック、1984年。(プロデューサー) インターナショナル・ピース・コンサーツ・ベネフィット・コンピレーション、Rラジカル・レコーズ、1984年(ザ・アフィリクテッドとMDCの楽曲のプロデューサー)、1997年再発行、ニュー・レッド・アーカイブス/ランバージャック・モダム・ミュージック・グループ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Levitin | |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆